Purchase Commitments for Vaccines Their Uses and Their

- Slides: 146

Purchase Commitments for Vaccines: Their Uses and Their Limitations Andrew Farlow University of Oxford Department of Economics, and Oriel College Bio. Design Institute Arizona State University 5 April 2005 This version: 16 May 2005 This has been rewritten so as to be a stand-alone presentation without need of a presenter. A downloadable copy of this Power. Point and supporting papers can be found at: www. economics. ox. ac. uk/members/andrew. farlow The author very much welcomes feedback: andrew. farlow@economics. ox. ac. uk

Based on: “The Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise, Malaria Vaccines, and Purchase Commitments: What is the Fit? ” Andrew Farlow, Submission to Commission on Intellectual Property Rights, Innovation and Public Health, WHO, March 2005. Forthcoming in Innovation Strategy Today. “An Analysis of the Problems of R&D Finance for Vaccines: And an Appraisal of Advance Purchase Commitments” Andrew Farlow, April 2004.

The problem • Over 40, 000 people – many of them children – die every day in developing countries of infectious or parasitic diseases. • Many could be saved by access to already developed vaccines and drugs: “A large proportion of the disease burden in such countries is unnecessary, since it could be reduced by the effective distribution of medicines that are currently available and inexpensive. ” International Policy Network “Incentivising research and development for the diseases of poverty” 2005 p 17. • Barely more than 1% of total global pharmaceutical expenditure goes into the research and development of new products for diseases affecting 90% of the world’s population*. *10%-15% of global pharmaceutical spending goes into R&D, and barely 10% of this goes into diseases impacting 90% of the world’s population.

Recent strides • Large fresh funds to purchase currently existing vaccines and to roll out immunisation programs: – The UK – $1. 8 bn over 15 years; – Bill and Melinda Gates foundation – $750 m; – Norway – $290 m. • Proposed $4 bn budget over ten years for Immunizations, via an ‘International Financing Facility for Immunizations’: – Though this budget – and immunization initiative – could, and should, have been provided with or without the IFF possibility*. • Launch of ‘Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise’ in 2004. • UK presidency of the G 8 and EU this year: – Big opportunity…or lost opportunity? * Given the potentially controversial nature of the IFF proposal, policy makers also need to take great care that, in all their public pronouncements, the IFF is seen to there to support the immunizations and never the other way around.

A spectrum of vaccines • Low or non-use of many already existing, already cheap or even practically costless vaccines. • ‘Late-stage’ vaccines – where most of the science is already known and a viable product is close to, or already at, hand. • ‘Early-stage’ highly complex and difficult vaccines – such as those for HIV, malaria, and TB – where there are either no viable vaccines on the horizon or current candidates fall well short of 100% effectiveness, and many scientific difficulties remain. • Spectrum of vaccines often lumped together. • But, instruments needed for each case are different. • Nature of ‘purchase commitments’ for each kind of vaccine also differs.

The role of purchase commitments • Long-term purchase contracts/commitments very advantageous for underused and late-stage vaccines. • Advance Purchase Commitments (APCs) for early-stage vaccines here argued much weaker and a great deal more problematic than is often suggested: – The phrase ‘Advance Purchase Commitment’, APC, is used here, and not ‘Advance Market’, since the latter needs to be proven and not prejudged to be the case by the choice of language used. An inability of APCs to perform ‘as if’ a market is central to many of the concerns here. • For early-stage vaccine R&D, manufacture and access may even be harmed by the presence of prior precommitments (certainly as currently proposed) compared to alternative mechanisms. • Where does the boundary between the cases fall?

Lessons from vaccine introductions 1 • Past vaccine introductions: – Hepatitis B; – Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib); – Smallpox. • Recent purchase arrangements: – African trivalent meningitis vaccine; – Meningitis conjugate C. • Future late-stage vaccines: – Pneumococcus; – Rotavirus; – Issues: • Cost of manufacture; • Safety issues; • Epidemiology. All these case-studies are treated in detail in Farlow, March 2005, Section 3.

Lessons from vaccine introductions 2 • None of these case-studies remotely matches anything being proposed for HIV, malaria, and TB. • Many of the problems caused/resolved by contracts are very different for these case-studies compared to earlystage vaccines. • Case-studies illustrate current faults in need of rectification. • Current short-run contracts are inefficient – a stable long -term market matters. • Get rid of market risk: – The need for ‘distribution commitments’, ‘vaccine/health infrastructure commitments’ and commitments to tackle market risk at many levels; – APCs (as currently designed) for early-stage vaccines put market risk back on to developers!

Lessons from vaccine introductions 3 • Good information on how to efficiently set terms: – Information extracted through competitive tenders, etc. • Relatively easy to make the incentive ‘additional’ via procurement contracts, etc. • Commitments as coordination devices. • In practical cases, the breakthrough was through lowering production costs: – Incentives/competition for this? – Technological ‘shifts’ dependent on access to technology, IP, know-how, especially at manufacture and distribution stage; – Volume and regulatory issues important in lowering costs.

Lessons from vaccine introductions 4 • Incentives to install capacity quickly and for use quickly. • Product differentiation and correcting vaccine market distortions. • Ability to use IP in ways to encourage competition, to keep the market open to many potential developers and producers, and to help create cheaper-to-produce vaccines. • Wider finance in place for a wider set of players: – More open to those who cannot draw off ‘deep pocket’ finance for long periods.

Lessons from vaccine introductions 5 • Importance of role of developing/emerging country developers and manufacturers. • More ability to share information and collaborate (key for HIV? Malaria? TB? ). • ‘Relatively’ low levels of capital costs (compared to, e. g. case of HIV vaccines). • Lower risk to biotechs. • Many of these reasons are ‘fungible’ – they apply whatever the source of finance. • Not ‘committee-driven’ over long horizons. • Current purchases do matter – a lot.

Hepatitis B case-study • Hepatitis B case-study in draft versions of the recent CGD report – dropped from final report. • Hepatitis B case does not support the report’s underlying hypotheses for HIV/malaria/TB: – The original Hepatitis B vaccine developers were not the ones who developed and maintained the lower price market; – The competitive situation for hepatitis B today – a key component in achieving long-term sustainable low prices – reflects poorly on the lack of competition at a similar stage in product life cycle in the CGD report; – Emphasis in the success of the Hepatitis B case on market and competitive devices to push production prices lower – compared to insufficient emphasis in CGD report.

Why the sudden interest in HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis? 1 • Focus of attention increasingly on speculative, experimental applications to HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis, even though APCs never been used before for even the most basic of applications. • Less than a year ago these ‘difficult’ vaccines were not deemed likely doable by this approach: – Including by many now heavily advocating the approach. • By definition APCs cannot be tested except through trying: – Should ‘crash test’ the thinking, subjecting it to the harshest of possible self-critiques before trying; – Given the risks of abandoning the approach due to lack of industry response and the constant need to change the program, should learn by trying less complicated vaccines first and building up to more complicated vaccines.

Why the sudden interest in HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis? 2 • Supporters and critics all concerned with incentives and rewards for private firm involvement. • Disagreement is about: – The shape and timing of incentives and rewards; – The ability to set APC terms remotely efficiently; – Whether APCs will actually work as proposed; – The role of, and interaction with, other parts of the overall mechanism for developing these early-stage vaccines; – Order of priority, given the burden APCs place on the ‘system capacity' of GAVI/VF/WHO, and use of political capital; – The dangers of perverse results. • BIG CONCERN: Approach feeds off (and also feeds) growing budgetary pressures to cut Vaccine R&D funding – especially for HIV – given global fiscal deterioration.

Literature on this as an R&D incentive for early-stage vaccines • “Making Markets for Vaccines” (henceforth ‘MM’ in all references), Center for Global Development (henceforth CGD), Washington, D. C. , April, 2005. • “Strong Medicine: Creating Incentives for Pharmaceutical Research on Neglected Diseases”, Kremer, M, and Glennerster, R, Princeton University Press, November, 2004. • UK’s No. 10 Policy Unit 1998 -2001. • Mostly the work of a small handful of authors.

Benchmark as an R&D incentive for early-stage vaccines 1 (These details taken from MM) • ‘Legally binding’ contract before vaccine R&D: – Sponsor(s) and all actual and potential vaccine developers signon to the contract within 36 months of the initiation of the program; – All actual and potential developers agree to be monitored by the committee controlling the program; – Later entry of developers policed by the committee; – Those conducting current vaccine trials and failing to sign-on, and those initiating future vaccine trials without prior permission from the committee, are barred access to the ‘eligible’ markets controlled by the committee; – Sponsors have an opt-out if contract fails to stimulate ‘enough’ research (though current status of opt-out is a little unclear).

Benchmark as an R&D incentive 2 • ISSUE: Inability to identify all developers in advance. • ISSUE: Highly complex and evolving vaccine development process that is also moving increasingly toward emerging/developing country developers. • How to avoid biasing early-stage APCs too early in favor of large developed-country companies, stymieing this evolution, and forcing later entrants to work through current large multinationals? • Opt-outs and ‘sunset clauses’ hard to incorporate without feeding back to harm R&D incentives.

Benchmark as an R&D incentive 3 • Sponsor(s) commit $3 bn-$10 bn per disease: – Figure keeps falling. Now $3 bn each for HIV, malaria, and TB (This presentation sticks to original figures for now). • For the purchase of a vaccine or vaccines in a pre-agreed quantity (200 -300 million treatments): – Figure keeps falling. Now 200 million each for HIV, malaria, and TB. • Benchmark has changed over last year. Prior to May 2004 a simple flat subsidy on each of the first X million of ‘a vaccine’. • Now a complicated subsidy spread over first X million of several possible vaccines: – Rules for this unclear? …and un-write-able? • But this is largely a change in language: – Recent malaria announcements seem to target one vaccine.

Benchmark as an R&D incentive 4 • To ‘aid credibility’, sponsors relinquish control of their funding to a committee with discretionary powers. • Supposedly (since extremely difficult, if not impossible, to do in any practical sense for vaccines such as HIV, malaria, and TB) the size of (and distribution of) funding for the ‘first’ 200 m high-cost treatments over developers is set precisely high enough to re-create the precise size of ‘additional’ market needed to encourage the entry of the precise amount of venture capital and stock market finance needed for the remaining research and development including capital cost (though ‘remaining’ is unclear) needed to produce a ‘high quality’ vaccine or series of vaccines. • A complex ‘expected’ subsidy pattern across developers and over time (investors’ ‘expectations’ of this are key).

Benchmark as an R&D incentive 5 • All R&D costs repaid through the purchase of a successful vaccine or (since May 2004) several vaccines in a particular period in time (if there are several meeting ‘eligibility conditions’ in any period of time), or series of vaccines over time (to combat resistance perhaps and to give incentives for follow-on innovation), and only the successful vaccine(s) or series of vaccines. • This program (supposedly) funds ‘additional’ ‘eligible’ market purchases only: – Eligible and non-eligible markets are separated…somehow. • Repayment of R&D costs is from taxpayers of richer countries, foundations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and through co-payments made by developing countries themselves (that may come from third parties); • The program is foundation- and publicly-funded.

Benchmark as an R&D incentive 6 • NOTE: Overall cost of vaccine development should include all funding needed outside of the program, including subsidies, tax-breaks, and other benefits granted for research, and the spending of national governments and foundations, and any costs of ‘vaccine enterprises’. • An APC for HIV is likely to cover only a very small portion of the overall costs of HIV vaccine development. • This is ignored (so far) in CGD cost effectiveness calculations for early-stage vaccines: – All DALYs saved are apportioned to the purchase commitment even if it will represent only a small portion of the overall cost of development of an HIV vaccine.

What the winner gets • (Supposedly) winner(s) repaid all of the privately-funded (and only the privately-funded) R&D costs (including all capital costs) of all firms (both the successful and the unsuccessful) and only the private firms, who used such private funding on R&D towards the vaccine since the time the purchase commitment had been announced (and only since the announcement) and only for eligible markets covered by the mechanism. • ‘Capital costs’ refers to the costs of the finance used, and includes the required return to cover all risk being borne, including any risk created by the mechanism itself (i. e it does not refer to physical real capital investment). • Very different pricing strategies in ‘eligible’ and ‘noneligible’ markets. • Firm gets all IP to the vaccine (under current proposal).

Problems with underlying model 1 Underlying (Kremer Appendix 3) model driving the logic for early-stage vaccines is highly simplistic. The ‘critique’ here is that highly idealized perfectly-functioning APC models are contrasted with highly imperfect alternatives thus generating unfair comparisons, and not that alternatives are not themselves highly imperfect too. • The science is fixed, simple, constant, static, ‘linear’: – Extremely simple probability structure. • No patents on anything other than end vaccine products: – No financial constraints, investment hold-ups, strategic behaviors, constraints on flows of information, or concentrations of market power based on IP ownership; – CASE: When the Malaria Venture Initiative (MVI) ‘mapped’ the patent status of the MSP-1 antigen, it found 39 different families of patents with monopoly scope impinging on it; – No notion of ‘near market’ or ‘near scratch’ developers.

Problems with underlying model 2 • No benefits in sharing information across vaccine developers. No ‘know-how’ monopoly: – Not good for describing projects involving science with lots of feedback loops, ‘collaboration’ and the sharing of information (HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis vaccine research); – Lots of incentive to hoard information; – CASE: Existing developed economy patent holders, facing a potentially emerging-economy competitor, can exploit ‘secret’ know-how (as well as more general technical know-how, and undisclosed test or other data), including refusing to contract to transfer necessary know-how, thus creating a barrier to entry. Given the mechanism for distributing payments, there is a strong incentive to ‘hold out’ under APCs; – Lack of know-how (extremely important for biological products) makes many disciplining threats non-credible (e. g. compulsory licenses if vaccine developers refuse to supply).

Problems with underlying model 3 • No variation in the probabilities of discovery over the vaccine development process: – No ‘easy’ or ‘difficult’ stretches of science. • No ways for technology to improve or deteriorate over time: – No ‘technology shocks’, ‘scientific breakthroughs or deteriorations’; – No need to incentivize such breakthroughs. • No sunk costs. • No large incumbent firms – instead perfect competition everywhere and always. • No strategic behaviour of any sort, and of any firm, based on sunk costs, patent ownership, finance, or any other realworld factor.

Problems with underlying model 4 • Extremely good understanding of the state of current and future (extremely simple) science. • No coordination problems across public and private sectors in their research decisions at a single point in time and over time. • No coordination problems across public and private sectors and all countries in their vaccine purchase decisions and in their provision of vaccine delivery systems. • An idealised, non-cyclical, set of financial markets. • No pipelines of products, no problems with vaccine resistance. • No composite vaccines, and no therapeutic vaccines. • Wide range of delivery issues ignored. • APCs need to be designed to handle/avoid these issues.

Some very rough HIV figures 1 • 10 firms put in equal effort on an early-stage HIV vaccine (we maintain the fiction of competition for now; that the program encourages competition needs to be proved). • Presume this is the optimal number of firms (we can’t). • Expected 70% of capital costs (a guess - no figures released…but presumed high for an HIV APC). • Presume one firm wins (supposedly, several could). • $6. 25 bn (pre-April 2005 figures) goes to a firm having spent, in present discounted (2005) terms, less than $200 m, on private out-of-pocket research costs (this is a figure for purely illustrative purposes). • This is the efficient and ‘fair’ outcome and not being critiqued here…But it does create problems for firms and the committee running the program, as we will see later.

Some very rough HIV figures 2 • With no ‘crowding out’, the $6. 25 bn ‘pays for’: – $1. 875 bn of out-of-pocket HIV R&D costs across all firms; – $4. 375 bn of capital (i. e. finance) costs. • With 50% ‘crowding out’ (explained below) and other inefficiencies, the $6. 25 bn would pay for: – about $900 m of new out-of-pocket research costs; – about 9 months’ worth of what those working on the Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise say is actually needed. • The most likely response of firms – no response at all? • Again, these figures are very rough, and for illustrative purposes only.

Some very rough HIV figures 3 • We can look at HIV from another angle. • HIV vaccines likely to take a minimum of 15 years to develop. • $1. 2 bn per year of out-of-pocket research and trial costs needed (IAVA 2004), i. e. double the current level. • Replacing this flow for 15 years with an APC at the end, would cost: – $85 bn (if required nominal rate of return 20%); – $130 bn (if required nominal rate of return 25%); – Uncertainty about ever getting a vaccine is embedded in capital costs; – ‘Crowding out’ would make the figures worse; – ‘Reputational risk’ would make the figures worse. • These are low rates of return by venture capital standards, and exclude the (still likely very high) costs after 15 years.

Some very rough HIV figures 4 • • So, where does the MM figure of $3 bn come from? Where does the notion of multiple developers come from? Need for a mega-blockbuster if using APC route for HIV? Maybe this is why private firms currently spend so very little on HIV vaccine research in spite of there being a sizeable extant market for some clades of HIV? How large are politicians prepared to make APC funds for HIV vaccines? Are they prepared to massively ‘top up’ later? Is it realistic to believe that funding levels for such programs for HIV will be set high enough with no pressure to readjust firm payoffs down later? All MM cost effectiveness figures are worked out on basis of the $3 bn and not on the basis of these much larger figures for HIV.

Some very rough figures for firms • For a vaccine costing $25 per course of treatment, the ‘bestcase’ scenario (no crowding out, but high capital costs) is: – $1 -$2 for production and distribution; – $6 -$7 for private out-of-pocket R&D costs; – $16 -$18 for the cost of finance. • With 50% ‘crowding’ out: – About $3 for new private out-of-pocket R&D costs. • But it is not clear that an HIV vaccine could be manufactured for a dollar or so (especially in early days): – Previous experiences with vaccine introductions suggest problems; – Too little manufacturing competition to drive prices that low; – IP held in too few hands; – Ex ante worries that this will be the case, will undermine incentives to do R&D in the first place (More on this below).

Figures for currently existing and late-stage vaccines • The above are very, very rough figures, since paucity of information is such that we really do not have much of a handle on these issues. • We can say, however, that the above proportions are completely the converse for currently existing vaccines, and, indeed, for many late-stage vaccines: – Much lower capital costs because of much lower risk, especially risks of the mechanism itself; – No crowding out (because of the ability to use competitive tenders and other ‘separation’ devices); – Much more easy to set efficient terms (because of competitive tenders and other devices to reveal information, and good information on technology, etc. ).

Impossible to set size efficiently • Each APC should be set commensurate with the difficulty of the underlying science and the cost of the R&D of developing the vaccine at hand. • MM suggests $3 bn per disease for HIV, malaria, and TB. Setting this right is a “crucial detail” (MM April 2005): – For no obvious reason, the figure is much lower than in draft versions of the report (of even just a few months ago); – Though this was recently described, though not in MM itself, as for ‘illustrative’ purposes only. • Needs a methodology based on expected: – – – Complexity of underlying science; R&D costs (also depending on types of firms encouraged); Epidemiology; Production costs, etc. NOTE: Not just information on the medical condition itself.

Not a good idea to base on ‘typical market size’ • An ‘auction’ and heavy monitoring suggested to set ‘size’: – Couldn’t work – so abandoned. • Now ‘size’ based on ‘typical market size’ of new drugs and heavy monitoring to check firms are investing ‘enough’: – Implicitly this means that the size is based on the typical costs of developing such drugs, since, in equilibrium, investment in drug development should be driven to the point where this is the case; – This methodology is therefore essentially random for these early-stage vaccines; – Overestimates (per unit) innovation costs of developing and emerging country innovators, even as they struggle to take advantage of APCs, even as it underestimates eventual costs if dependent on APC and developed country developers.

Setting size too high is wasteful • • Racing, duplication. Even less incentive not to ‘share’ information. Rent-seeking/lobbying/corruption. Reduced resources made available for other vaccines and treatments, sanitation, nutrition, housing, etc. • If using an International Financing Facility, IFF, overlyhigh (and overly-low) APCs add to the risk the IFF bears. • Extra deadweight losses of taxation and the opportunity cost of the other projects that foundations, governments, and the IFF are prevented from doing. • If firms are not perfectly competitive, shareholders gain something (ceteris paribus) – but at the expense of neglected diseases and other poverty alleviation projects.

Other reasons for overpayment • ‘Me-too’ drugs/vaccines partly discipline patented drug/vaccine prices. • For purchases of underused vaccines, price disciplined by competitive tender, competition, access to IP, etc. • These disciplining devices are lost under APCs for earlystage vaccines. • Discipline in APC via committee and pre-agreed rules: – But pre-agreed rules are hard to set and to credibly follow through. • RESULT: Higher payment for given (lower) quality. • Self-fulfilling incentive ex ante also to work on ‘lower quality’. • There is also an additional ratchet effect: No adjustment downwards if R&D costs are reduced by technological advances or by improved publicly funded initiatives, etc.

Setting size too low is wasteful 1 • Get no, or too little, extra private funding into R&D. • Can raise size at the rate of interest rate. But no faster: – Raising the size of the APC acts like an extra discount factor; – Early investment becomes even more expensive; – Firms delay investment. • But the rule about raising ‘size’ is difficult to set: – How is the start level chosen? – How is the speed of rise set? – How is judgment made that not enough investment has taken place, without good monitoring and given that the ‘result’ on which to base judgment is only provided at the end? – Are politicians willing to sign on to such open-ended programs? • Current CGD thinking is that this is too difficult (or politically unacceptable), and this is not planned (or CGD are not yet saying how later re-adjustment will happen).

Setting size too low is wasteful 2 • Development costs highly uncertain. • CGD “after a long deliberation process did not narrow down beyond the range of $15 -$25 per treatment”* – The upper bound being 167% of the lower bound. • If size starts, optimistically, at the bottom of the range when actual costs are at the top of the range, and 10% interest rate – it takes 8 years till APC has any effect (or it collapses first). • If real R&D costs also grow at 5% per year (starting at the optimistic end of range) – it takes 15 years to have any effect. • Consequence is delay, and strong pressures towards ‘poorer quality’ (broadly defined) at any given APC size in order ‘to get a result’. * Maurer S. “The Right Tool(s): Designing Cost-Effective Strategies for Neglected Disease Research”, Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California at Berkeley, March 2005. Figures on this page from Maurer paper.

Some too high, others too low • Some vaccines set way too low. Get no or little response: – $3 bn for HIV? No connection to reality? – Overconfidence in ability to revise upwards later? • Other vaccines set too high and wasteful. • Other cases, strong incentive to head for more ‘limited quality’: – Current malaria vaccine policy? • We never get to see the ‘good outcomes’ that we never get because of poorly-set initial terms. • Overall a poor deal compared to alternatives? – It depends on how well alternatives cope with incentivizing ‘effort’, and dealing with failures in vaccine R&D portfolios. • Yet, funder of program reserves right to abandon the mechanism if it is not working ‘enough’?

Getting it wrong for HIV? “If scientific complexity means that R&D costs are much higher for an HIV vaccine than for other medicines, then $3 bn may be too low to stimulate sufficient investment… Note that, if the commitment is too small to stimulate industry investment, and therefore does not succeed, there is no cost to sponsors. ” CGD ‘FAQ’ sheet, April 2005.

Would a $3 bn HIV purchase commitment simply ‘collapse’? • Political limits to a program without any effect (especially if high transactions costs to GAVI, Vaccine Fund, WHO, and others of setting up and running the program). • Collapse is self-fulfilling (investors will not trust that any early investment will yield a payback, so don’t bother). • ‘Collapse’ incorporates cases where – to avoid litigation – the mechanism ‘does nothing’ but sits ready to activate – even if very destructive meanwhile – after an alternative approach has been successful. • Worse if other approaches have stalled to make room for this approach. • The sole criteria of “the (political) willingness of sponsors and recipient governments to pay” (MM p 52, word inserted) for dictating the size chosen, is a non-criterion.

More ‘pay-as-you-go’ better? • This suggests more ‘pay-as-you-go’ may be more capable of adapting to changing environment and less likely to fail to get a result (if set too low) or to overpay (if set too high). • It depends on how good PPPs and others can be made at dropping failing projects. • Note, alternative approaches still potentially include commercial involvement. • Current low levels of ‘commercial’ involvement in PPPs is more a fault of the shoestring funding of PPPs than of any specific failings of PPPs.

Technical requirements in advance? 1 • “it would be possible – though complicated – to agree to product requirements in advance…a small number of public health experts were concerned that it would be difficult to establish in advance technical requirements that a vaccine would need to meet. ” MM March 2005 p 58, and final report. • Some set of technical requirements always possible. • But ‘efficiency’ of those technical requirements requires some notion of the underlying feasibility of HIV, malaria and tuberculosis science, the potential costs of manufacture and distribution, epidemiology, etc. (i. e. many factors, and not just medical issues). • So “fixed enough to avoid the danger that the sponsor would renege, but flexible enough to accommodate contingencies that were not foreseen at the time the rules were established. ” MM March 2005 p 43, and final report.

Technical requirements in advance? 2 • Shifts problem to a different level – of having a good notion of potential unforeseen contingences when setting the original rules. • An inability to set efficient technical specifications for each vaccine far in advance: – Potential for great deal of discretion and interference later; – Risk that term-setters are unwilling to admit they ‘got it wrong’ and to reset the terms ‘more efficiently’ later (though they can only correct themselves in the downwards direction); – Risky for all developers, but more so for some than for others; – Most risky for those unable to ‘influence’ the committee; – It is expectations of all of this that matter to investors.

Minimum vaccine requirements 1 • Minimum vaccine requirements set at the start: – But, an efficient technical specification, closely resembling the eventual possible vaccine, would be impossible to set so far out for HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis. • Discretion of as few as four members of a committee to “grant waivers and make modifications” (MM April 2005) but only to lower those requirements – never to raise them. • This asymmetry is bad policy in light of future possible improvements in science and possible future epidemiology. • But symmetric ability to raise requirements as well as to lower requirements creates risks for firms, and is irreconcilable with the current MM mechanism. • A dilemma.

Minimum vaccine requirements 2 • Constant pressures to lower the minimum acceptable requirements towards the very lowest level of any epidemiological value. • In successive drafts of MM, malaria vaccine requirements gravitated ever-lower: – Final report: 50% efficacy for 24 months from up to four doses; – This requirement (and the $3 bn size) was recently described as for ‘illustrative’ purposes only. • A program that militates against the development of useful vaccines that far exceed minimum requirements?

Problems setting the long-term price • Contracts call for determination, at the time of signing, of the ‘guaranteed’ long-term price, or of an ex ante methodology for determining the long-term price. • ‘Legal’ obligation to supply at this price in the long-term in return for having had the short-term advantage of initial sales at very high, heavily subsidized, guaranteed prices. • The $3 bn is payment, in part, for this. • A “critical component of the advance market commitment” (MM report April 2005) and key to its claim as the way to end ten to fifteen year delays in access to new vaccines. • No such methodology for setting long-term price exists (see NIH evidence). • CGD advised price could range from $0. 50 to $15. 00, and that no such guarantee could be inserted into contracts. • Left blank in MM contract term sheets.

What if firms won’t/can’t supply? 1 • Firm can always refuse to supply at short-term price (e. g. in order to supply a more lucrative market for HIV first). • If cost not low enough, or firm “prefers” not to sell to ‘eligible’ countries at the long-term price, contract allows sponsor to ‘acquire’ right to produce: – Supplier(s) turn over IP to the sponsor – but supplier may not have the right to sublicense all the IP; – Conflicts because supplier retains IP rights to ’non-eligible’ markets; – Sponsor has difficulties acquiring ‘know how’ and production; – Threat undermines incentives to invest in vaccine R&D; – Threat undermines incentives to invest in vaccine delivery systems; – Severe supply shortages and damaging access delays; – Reputational damage issues for supplier and sponsor(s); – Not credible way to discipline firms.

What if firms won’t/can’t supply? 2 • Contract term sheets say “other penalties” such as “liquidated damages provisions” imposed on supplier: – Contract leaves details blank; – Threat feeds back to weaken ex ante incentives to invest in R&D in the first place (especially if provisions are so vague); – Threat can create perverse incentive not to supply eligible market in the first place or delay supplying eligible market: • HIV vaccine in particular, given richer non-eligible markets and the option value of the APC given the different HIV clades. – Threat weakens incentive to invest in vaccine delivery systems; – Not credible way to discipline firms. • Contract term sheets leave blank those sections specifying remedies in the event of a breach.

What if firms won’t/can’t supply? 3 • IP and know-how barriers have been principal causes of delays in achieving flexible, cost-effective manufacturing and quick access to vaccines for the poor in the past. • Now control of IP and know-how part of a threat mechanism to drive the contracts! • If the threats do not work, how do production costs get low enough to supply the ex post market? – – – Lack of competition; Weakened price signals due to the presence of the APC; Lack of access to technology; Insufficient pressures to lower production costs; This is all contrary to, e. g. , the Hepatitis B case, and to application of APC-type arrangements to current late-stage vaccines.

What if firms won’t/can’t supply? 4 • Legal advisors inform this author that threats in contracts at 20+ year horizons are not used in practice. • Long-term price and sustainable production capacity for ‘eligible’ countries thereby unresolved in MM report. • Excessive emphasis on getting the $3 bn to the supplier(s) of the first 200 m or so ‘eligible’ treatments, and insufficient attention to follow-on suppliers and the post 200 m treatments. • A mechanism that relies on this presumption in order for it to work should be treated with a great deal of caution, indeed skepticism – especially when, after 8+ years since the idea first surfaced, the contract writers haven’t a clue how to do it. • Vaccine developers facing many risks that a viable mechanism should seek to remove from them.

Follow-on innovation 1 “Advance purchase commitments may also stifle incremental innovation. Because they create a ‘winner takes all’ solution, it would be difficult for incremental, follow-on competitors to emerge, thus dulling the benefits of competition on cost and improvements. The innovation that wins will crowd out competing inventions because it is being given away free by the public sector. This ‘crowding out’ effect means that no improvements will be made to the winning formulation, and this may have negative consequences for resistance and effectiveness in subpopulations. ” International Policy Network “Incentivising research and development for the diseases of poverty, ” 2005 p 15.

Follow-on innovation 2 "It is difficult to get the right quality, in particular to reward follow-on products that offer higher quality. Our view is that it should be possible to set an effective quality threshold, and that the terms of the APC must allow for superior quality follow-on products to be used…(However) there may not be enough money left in the initial APC to reward the R&D involved in developing some of the superior follow-on products. This is quite possible, as the commitment is only designed to generate at least one product that meets the quality threshold. Clearly a view would have to be taken by the donors as to whether they wished to finance follow-on products with additional money. This would be a separate investment decision from the original APC. " Towse, A. and Kettler, H, “A Review of IP and Non-IP Incentives for R&D for Diseases of Poverty. What Type of Innovation is Required and How Can We Incentivise the Private Sector to Deliver It? ” April 2005, p 87.

Follow-on innovation 3 • However, so as not to harm investor incentives, this ‘additional money’ for follow-on products should be credibly promised in advance if not part of the original APC… but that makes this ‘additional money’, by default, part of an original APC-type arrangement! • Efficient incentives require each generation of products to cover its expected R&D costs. How achieved? • MM removes ‘Quantity guarantee’ to (supposedly) remove the risk that the sponsor will end up funding a non -used product, and to give incentives for follow-on products. • Multidimensional ‘quality’ problem – a quality ‘surface’ over vaccines, over time. Set terms wrong and disincentivize (dynamic) investment. Expectations are everything to investors.

Follow-on innovation 4 • MM suggests potentially very complicated rules about qualities of acceptable vaccines, and variation in allocations and prices of vaccine purchases across multiple developers and purchasers, and over time: – But no practical details of how this is done; – Hard to visualize that policy makers could derive the optimal way to ‘hold back’ on early products so as to leave funds for later products. • Hugely aggravated by the fact that the likely quality improvements, science, and costs are all highly uncertain. – Also no ex ante grasp of the potential timing of anything, or characteristics of firms such as access to finance, risk tolerance, etc. • On average, achieving ‘quality’ is more expensive. • Will investors expect the distribution of the ‘subsidy’ to be efficient?

Follow-on innovation 5 • Constant danger of ‘poor’ vaccines driving out ‘better’ vaccines (aggravated if the overall fund is set too low to start with). • Need for follow-on instruments (Towse and Kettler, ibid. ) but these need to be fully articulated and credibly promised in advance if investors are not to be harmed. • Dangers that fund becomes unbounded at top, yet still highly uncertain – killing dynamic incentives. • Original (Kremer) model is static and ignores these issues. – In particular it presumes one vaccine target. • Recently, these dynamics are simply presumed perfectly performed by the ‘committee’: – In truth the committee would fall massively short and investor and researcher expectations would respond accordingly.

Follow-on innovation 6 • Recent malaria case – so far no attention at all to dynamic incentives in CGD and UK policy announcements. • End up with a committee with discretion, risk to investors, higher risk premia, more pressure to go for lower quality, and rent seeking behaviour of big players? • ‘Follow-on products’ also covers cases of complete vaccine replacement. • Incentives to actually carry out this replacement? • Incentives to expediently create capacity when vaccines are replaced? • Replacement is only statistical. How is this handled in size and distribution rules of APC? • All the time there is the need for developing country trust of vaccine products and of ethical trials.

Follow-on problems especially severe for HIV, malaria and TB • An ‘Arms war’ between virus and drugs/vaccines. • First vaccines not necessarily the best: – More so if only therapeutic and not preventative. • Expectations about payments to the first must not stifle incentives for later needed vaccines. • Expectations about payments to non-composite vaccines must not stifle incentives for composite vaccines: – HIV vaccines: coordination, information sharing, and timing worries. • Expectations about payments for therapeutic vaccines: – Needing monitoring and even more long-term follow-on vaccines. • Worries that ‘better’ vaccines arrive after subsidies are gone. • Second-generation vaccine costs even harder to work out in advance than first-generation costs. • It is all about INVESTOR EXPECTATIONS.

The paradox of market risk 1 • For most ‘late-stage’ and underused vaccines the objective of purchase commitments is to remove market risk. • Early-stage vaccine APCs (as currently designed) put market risk back on to vaccine developers (supposedly) to, ex post, drive the ‘quality’ rules and ex ante ‘effort’ incentives. BUT: – These are resource-poor markets; – Most buyers are relatively uninformed (about current vaccines never mind about expected future vaccines); – There are no marketing budgets; – Vaccine usage needs a good distribution system, with such systems generally not under the control of vaccine companies; – There are heavy knock-on costs to purchase decisions; – There are multiple organizational problems;

The paradox of market risk 2 – – There is a severe lack of qualified personnel on the ground; There are multiple political interests; There are cultural barriers; There are plenty of ways to ‘encourage’ decision-makers to take one firm’s product over another firm’s product (even more so if the ‘other firm’s’ product does not exist yet); – There are strong ‘self-fulfilling’ pressures in the co-payment mechanism driving towards lower-quality outcomes; – This, ex ante, feeds investor expectations and R&D incentives towards the ‘low-quality’ outcomes. • Why put all these risks back on to vaccine developers in order to try get this mechanism to work for early-stage vaccines and to try to create follow-on incentives? • ‘Less’ of an issue if system collapses down to just the one vaccine – but that, supposedly, was not the point.

The paradox of market risk 3 • Maybe intention is that mechanism collapses down to a limited number of developers? • In case-studies, production scale and competition were key to low-cost vaccine production. • No sense using (expected) ‘restrictions’ and ‘holding back’ of sales of a single supplier to discipline ‘quality’. • Why inflict uncertainty on investors seeking to scale up manufacturing capacity? • It is ‘dynamically inconsistent’ anyway – hard to hold back on a ‘bird-in-the-hand’ vaccine to supposedly discipline ‘quality’ and to leave funds for later vaccines. • Leads to further pressure to lower ‘quality’ with risk to ‘quality’ investors. • More likely = just lots of uncertainty, higher capital costs, and fewer developers in the end game.

This paradox undermines R&D incentives • Hard to see how any ‘quality’ control over the whole development process could be done in the end-game in this way without conflicting with the need to get the manufacturing costs low. • RESULT: A mechanism that disciplines ‘quality’ en route is better able to achieve larger capacity, multiple suppliers, and low prices, than is the mechanism that disciplines ‘quality’ via holding back in the end market. A FUNDAMENTAL CONFLICT. • Paradoxically, undermines investors who will not believe that manufacturing costs will be pushed low enough ex post to make the whole investment exercise worthwhile ex ante (see forthcoming slide for more on this).

Incentives to block second generation products • Unlike patents, the first to market is likely to get all the subsidy if it can hold off ‘follow-on’ vaccines just long enough. Even better if it can create the reputation for this; it becomes self-fulfilling and the firm gets the subsidy quicker (if there is discretion over how to split the subsidy). • With standard patent-based systems and marketing, firms can more easily agree to split the market, so there is incentive to share/license/split the higher price for the better product. • This has all gone. • This gives strong incentives for the first-generation developers to block (advertently or inadvertently) second generation vaccines (via not ‘sharing’ IP, know-how, etc. ).

The sums don’t add up either • “Pricing structure can be designed to provide substantial insurance against demand risk for prospective vaccine developers so as to yield a net present value of revenue comparable to commercial products even under pessimistic uptake scenarios, ” MM March 2005 p 50 and p 114, emphasis added: – Indicates the complicated tradeoff that needs to take place, not that it would take place or ever could take place (it could not, because of the intractable information problems needed to make it work); – Commercial return means ‘ex ante commercial return’. What happens when that is gone? – No way to know how to set any of this many years in advance. • In reality, according to recent announcements, seems little intention to use any of these ‘dynamic’ rules anyway.

Two-stage game problems • Always better to compete for contract before sinking costs. • Award after costs are sunk runs the risk of forcing firms to compete twice: – R&D stage; – Market stage. • ‘Bygones are bygones’…After costs are sunk, always worth spending up to the value of the contract in rentseeking behavior to ‘win’ the contract. • In such situations, firms expect to face a negative rate of return from the overall project. • CONSEQUENCE: The incumbent firm signals/behaves in ways to increase the expected risk of later firms. No second firm bothers to enter whatever the size of the commitment. Competition is stifled.

Avoiding two-stage game problems • Must fix terms at the start to make it clear that no amount of lobbying/spending at the second stage will change the payouts. • BUT: – Contradicts the need for discretion to change terms; – Becomes mechanistic based on expectations at the very start: • E. g. HIV science that is 10 -20 years out of date! – Real problems if a ‘market test’ is used since firms can try to influence purchase decisions (illegal kickbacks, bundling to hide discounts. There are sanctions against the former – if detected. Hard to detect the latter and fewer sanctions); – Biased against small biotechs (can’t bundle and can’t hide other subsidies), not-for-profits (who may not be allowed to behave in these ways), and emerging developers. Again, expectations of this will disadvantage the latter groups when trying to acquire finance for R&D.

Ex ante versus ex post information problems: an unhelpful caricature • Sponsors of APCs said to need little knowledge about the ‘likely success of particular approaches’. • But, they do need a huge amount of qualitative and quantitative information about overall set of potential scientific, epidemiological, expected research and manufacturing costs, ‘existing’ market possibilities, etc. – well in advance of product development – in order to get the terms vaguely efficient. • To be credible and to minimise the risks to firms, firms need to trust that policy-makers have this ex ante information. Otherwise, lots of discretion later and risk. • Mechanism cannot claim it solves information difficulties it has ruled out at the start.

‘Crowding out’ weakens ‘pull’ 1 • “The proposal is that private investment would underpin R&D by private firms” Barder, O. , CIPIH Forum, 19 November 2004. • Has to be ‘additional’ incentive: – Additional to current R&D; – Additional to current market. • Has to be believed that it will be additional. • This is a big challenge. • Easy to achieve ‘additionality’ for underused vaccines: – It is a total non-issue. • More difficult to achieve for late-stage vaccines though still possible: – Run a competitive tender (with more access to IP) and use known scientific information, etc.

‘Crowding out’ weakens ‘pull’ 2 • Extremely difficult to achieve for early-stage vaccines. • Referring to HIV/AIDS, perinatal conditions, maternal conditions, childhood diseases, malaria, and tuberculosis: “All of these are health problems in the first world too, and, ignoring the special case of mutant strains, there are substantial incentives for the development of effective therapies. Malaria is perhaps the principal exception, but there is a lot of work on it currently. To be sure, some diseases occur primarily in the third world, but the magnitude of the problem that is uniquely without solution ought to be brought into sharper perspective. ” F. M. Scherer, CIPIH May 2005. Emphasis added. • Pull payment to any firm would need to be reduced by many times the ‘push’ payments it had ever received to achieve a level playing field between firms (unless unequal access to push efforts can be made to be part of the efficient solution).

‘Crowding out’ weakens ‘pull’ 3 • For scientific areas with a complicated interplay of push and pull and a large push element, there is great risk that the pull-motivated will lose out to the push-motivated and to those not relying on an APC for their funding: – Allowing heavily push-motivated and PPP/philanthropicfinanced players to have access to the fund, effectively weakens the expected value of the fund to the APC players. • SIMPLE EXAMPLE: – 10 firms working equally hard on HIV vaccines, 70% capital costs, no splitting of $6. 25 bn APC fund; – ‘Winning’ firm has 50% subsidies, grant support, nonprivate funding, etc. ; – Winning firm should be denied just over $3 bn of the fund; – $3 bn left ‘in the pot’ for competing and follow-on vaccines; – But every $1 m of ‘hiding’, worth nearly $17 m to the firm.

‘Crowding out’ weakens ‘pull’ 4 • Needs a great deal of monitoring. Paradoxical – given that those advocating the program often highlight the opposite. • Need for high-quality historical evidence (20 -30 years). • Need for committees, discretion, treaties? • Impossible to correctly ‘price’ streams of ‘other payments’ (e. g. appropriate capital costs? ). • ‘Repayment’ side-contracts that may not unfold for ten or twenty or more years. • The mechanism claims that to work out an optimal strategy, every firm needs to know how much privatelyfunded activity is taking place. How is this achieved…if what is going on is so opaque? • Private firms need to trust that push is being efficiently handled.

‘Crowding out’ weakens ‘pull’ 5 • Favors ‘large pharma’ players for early-stage vaccines: – Smaller firms, biotechs, not-for-profit firms, etc. have many fewer ways to hide research supports (if they can get them); – Many biotechs work on one area only – their funding flows are less opaque than ‘large pharma’ players; – Easier for ‘large pharma’ to avoid monitoring generally. • Standard procurement contracts capable of paying only for additional private funds to ‘finish a project’: – Competitive tender separates out the push from the pull funding. • Here, ‘Framework Agreement’ is the tender. • Here, highly complicated side device has to be appended to ‘the tender’ to achieve a standard property.

‘Crowding out’ weakens ‘pull’ 6 • Near-scratch versus near-market: – APC (if not ‘appropriately’ adjusted) disproportionately benefits those nearer to market, even if not the ultimately ‘best’ vaccine; – Disincentivizes ‘near-scratch’ developers; – This reduces the average expected quality of vaccines. • PPP funding: – How exactly do PPP activities “complement” and not conflict with APC-based private activities? – Should an MVI- or IAVI-funded vaccine be denied APC funds? – What if the MVI/IAVI vaccine is best? It should get all the APC fund? Or not, so as not to harm other private efforts? – If coordination of ‘repayment’ is not achieved, there will be temptations for individual countries and foundations to ‘cheat’; – It is not up to the individual funders to decide on repayment of funding. It has to be coordinated (and policed) and investors need to trust that this is so.

‘Eligible’ countries 1 • No ‘eligible’ country ‘signatories’. • They ‘commit’, via purchases, after committee has cleared a vaccine. Their purchase decisions (supposedly) drive first-, second-, third- and later-generation innovation. • They pay about 10% of the initial procurement price. • They therefore have a veto over success of the program: – Small, marginal, contributions essential to success of the whole program - involving billions of dollars; – They (or those politically connected) could use this to achieve additional benefits unless policed not to do so. • Vaccine supplier(s) (or country of vaccine supplier(s)) have inventive to exploit this via ‘subsidies’– in whatever forms these might take – targeted at winning the $13. 50 pertreatment subsidy on the first small tranche of treatments. • The tranche of vaccines using up the subsidy is, after all, only a very small part of the overall number of treatments.

‘Eligible’ countries 2 • Long-term multi-institution and multi-country monitoring and policing of such behavior. • All vaccine developers need to trust that such monitoring and policing takes place to protect their investments and to ensure that those with longer, more expensive, higher ‘quality’ R&D projects get repaid on average. • Given the risks of this, there are dangers of self-fulfilling collapse of R&D projects for ‘higher quality’ vaccines, because of risk that ‘too much’ of the subsidy has inefficiently gone to early developers because of the inefficient decisions of purchasers. • Better not to have such a high proportion of subsidy making up ‘early’ vaccine purchase prices? • Better to use other modes of payment for R&D instead, including mechanism to spread repayment over time? • Or will later innovators demand (and get) more funding on top of that already allocated once the APC has gone?

‘Non-eligible’ countries 1 • Risk that non-eligible countries harm the program. – Asia, Latin America, Africa a mix of eligible and non-eligible countries. • Non-eligible countries must be stopped from using vaccines that fail the program: – Russia purchasing HIV vaccines for its non-covered program? China? India? Who polices them? What rules to prevent them using vaccines falling short of APC requirements? – Such purchases undermine incentives of the program; – Such purchases contribute to self-fulfilling collapse of longer, more expensive, ‘higher quality’, R&D projects (by making such projects much more expensive because of higher risks and capital costs); – But such ‘non-eligible’ purchases are difficult to police. • Non-eligible countries must also be stopped from using ‘metoo’ vaccines based on the APC program vaccine: – Difficult – more so if the APC program is allowing ‘me toos’.

‘Non-eligible’ countries 2 • This refers as much to stopping the use of the technology or science of APC-based vaccines for ‘non-APC’ based research or manufacturing processes. • Need to clamp down on IP. • Extremely important issue for HIV, and TB. • Increasingly important issue for malaria (given recent evidence of the more widespread nature of malaria). • Does segmentation of the market into eligible and noneligible segments enable higher prices to be charged to non-eligible countries? – Shows up also if there are different clades etc. even if not the same vaccines (it works through an investment ‘option’ component); – Prices to those not covered might even be higher than without the mechanism.

‘Non-eligible’ countries 3 • Non-eligible countries, even if relatively poor themselves, pay higher prices (both before and after the first 200 million treatments are gone). • Tiered prices may be part of an efficient solution however. • What if these countries heavily contributed to the Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise? • In these cases they might wonder why they should ‘lose out’ under the APC and refuse to go along with it. • What if PPPs want to supply these other non-eligible countries at lower prices (thus breaking the mechanism)? – A conflict? But how is it prevented? • Chance of firms ‘abandoning’ the poor eligible segment after the 200 million treatments have gone in order to supply the (much) more profitable non-eligible segment… but with no back-up mechanism for the eligible segment.

Unlike a standard procurement contract • Firms don’t bid for the contract before sinking their investments; they sink their investments in order to bid. • ‘Competition’ driven by: – Expected behaviour of the committee after most costs are sunk (i. e. costs lost for ever); – Expectations (and worries) about the behaviour of other firms (especially larger and more influential firms) with respect to the committee; – The pre-set rules and eligibility conditions. • The firms able to take part are different: – Those who win the standard contract can use that fact to attract finance; – Those seeking the APC must already have good access to finance and ability to sink what will (in most cases) likely be irretrievable costs.

Time inconsistency is intractable 1 • ‘Time inconsistency’ - when firms have sunk R&D costs, and buyers have the power ex post to bid prices down to levels that do not cover – through the product prices of the winning firms – the collective R&D costs of all firms. Knowing this ex ante, no firm invests. • Previously, ‘dynamic inconsistency’ showed up in pricing controversies in the end market. Now, the controversy shifts to committee decisions, allocations across developers, and quality issues. • Under an APC, potentially huge levels of already (and sometimes long ago) sunk investment rest on the (discretionary) decisions of a committee or committees.

Time inconsistency is intractable 2 • Two-stage pricing to ensure that the “producer received a fair return on their investment” but that “once this return had been achieved” prices could fall. • But getting back development costs in the ex post sense is insufficient in the ex ante sense. • The relevant required return is before firms invest based on: – – Expected trial attrition rates; Expected capital costs; Expected portion of the market allowed to firm by committee; Expected pricing structure allowed by committee. • This never ‘looks fair’ ex post. • Must be fully understood by all firms, buyers, political commentators, and general public that ‘fair return’ is ex ante return. Very hard to make this credible though.

Time inconsistency is intractable 3 • Especially problematic for: – Mechanisms concentrating repayment in the end period; – Long investment horizons (even tiny amounts of uncertainty about whether the program will be fair or work as promised will compound very heavily); – The more complex the science: • The less easy it is to fix rules ex ante; • The greater the required ex post discretion; • The harder it is to judge ‘results’. – Situations where ‘quality matters’: • ‘Time inconsistency’ shows up in ‘quality’ as much as in price. • Again, it is EXPECTATIONS/RISKS that matter. • Can alternative funding mechanisms protect firms from these problems while still giving them good incentives?

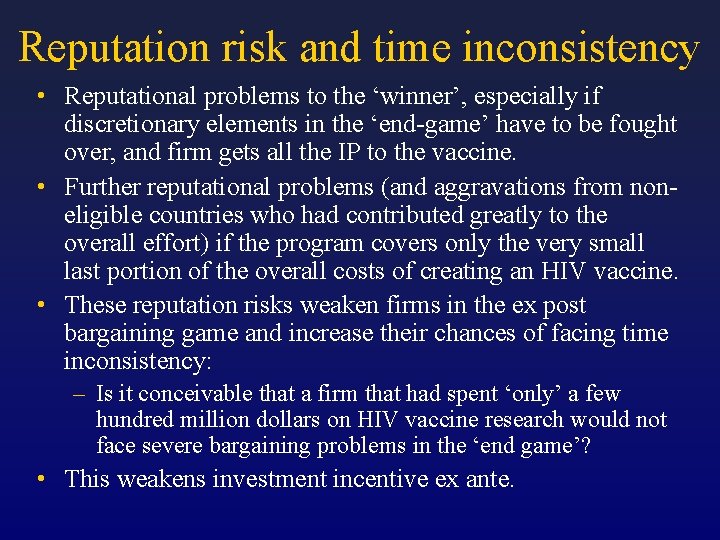

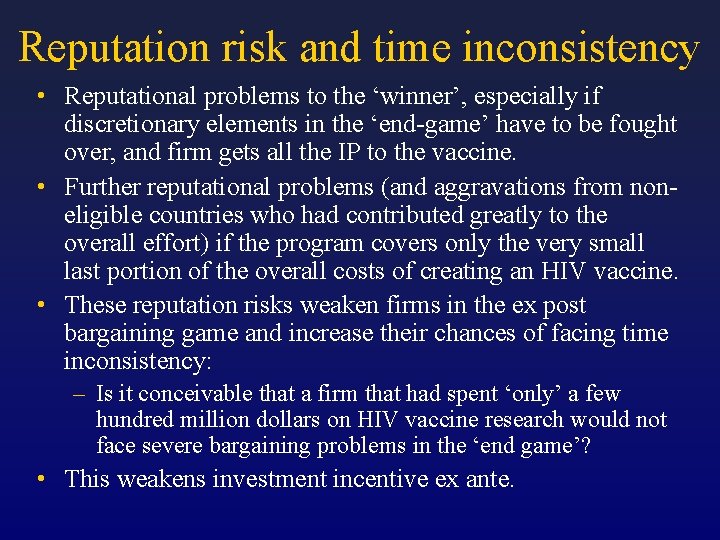

Reputation risk and time inconsistency • Reputational problems to the ‘winner’, especially if discretionary elements in the ‘end-game’ have to be fought over, and firm gets all the IP to the vaccine. • Further reputational problems (and aggravations from noneligible countries who had contributed greatly to the overall effort) if the program covers only the very small last portion of the overall costs of creating an HIV vaccine. • These reputation risks weaken firms in the ex post bargaining game and increase their chances of facing time inconsistency: – Is it conceivable that a firm that had spent ‘only’ a few hundred million dollars on HIV vaccine research would not face severe bargaining problems in the ‘end game’? • This weakens investment incentive ex ante.

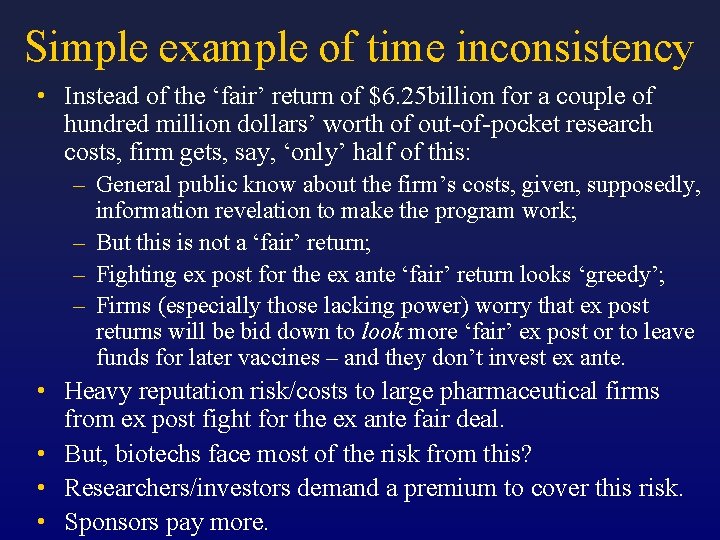

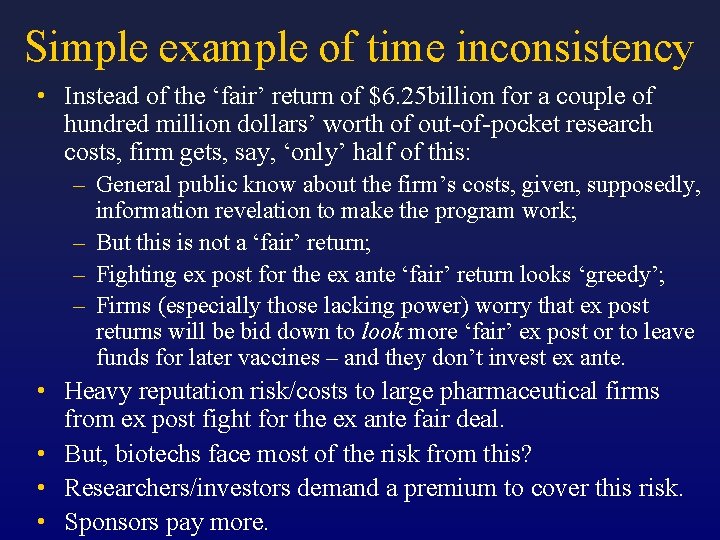

Simple example of time inconsistency • Instead of the ‘fair’ return of $6. 25 billion for a couple of hundred million dollars’ worth of out-of-pocket research costs, firm gets, say, ‘only’ half of this: – General public know about the firm’s costs, given, supposedly, information revelation to make the program work; – But this is not a ‘fair’ return; – Fighting ex post for the ex ante ‘fair’ return looks ‘greedy’; – Firms (especially those lacking power) worry that ex post returns will be bid down to look more ‘fair’ ex post or to leave funds for later vaccines – and they don’t invest ex ante. • Heavy reputation risk/costs to large pharmaceutical firms from ex post fight for the ex ante fair deal. • But, biotechs face most of the risk from this? • Researchers/investors demand a premium to cover this risk. • Sponsors pay more.

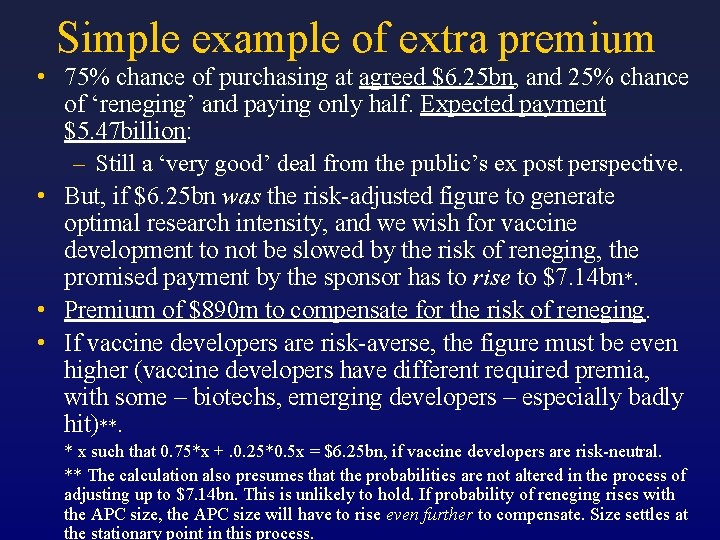

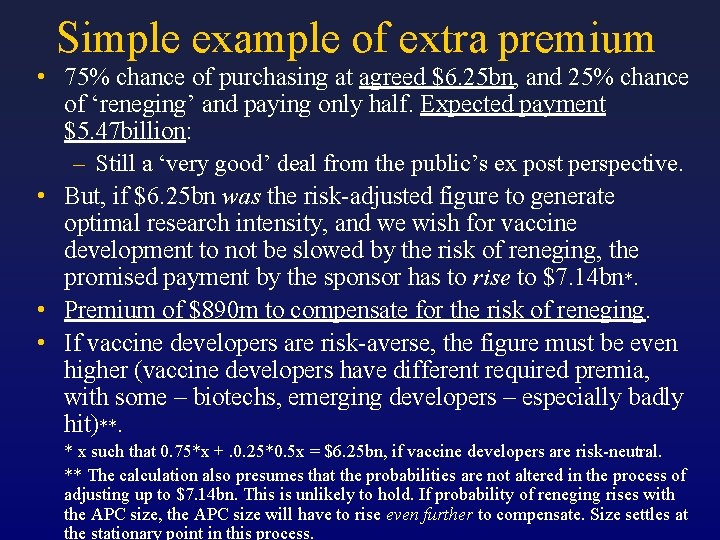

Simple example of extra premium • 75% chance of purchasing at agreed $6. 25 bn, and 25% chance of ‘reneging’ and paying only half. Expected payment $5. 47 billion: – Still a ‘very good’ deal from the public’s ex post perspective. • But, if $6. 25 bn was the risk-adjusted figure to generate optimal research intensity, and we wish for vaccine development to not be slowed by the risk of reneging, the promised payment by the sponsor has to rise to $7. 14 bn*. • Premium of $890 m to compensate for the risk of reneging. • If vaccine developers are risk-averse, the figure must be even higher (vaccine developers have different required premia, with some – biotechs, emerging developers – especially badly hit)**. * x such that 0. 75*x +. 0. 25*0. 5 x = $6. 25 bn, if vaccine developers are risk-neutral. ** The calculation also presumes that the probabilities are not altered in the process of adjusting up to $7. 14 bn. This is unlikely to hold. If probability of reneging rises with the APC size, the APC size will have to rise even further to compensate. Size settles at the stationary point in this process.

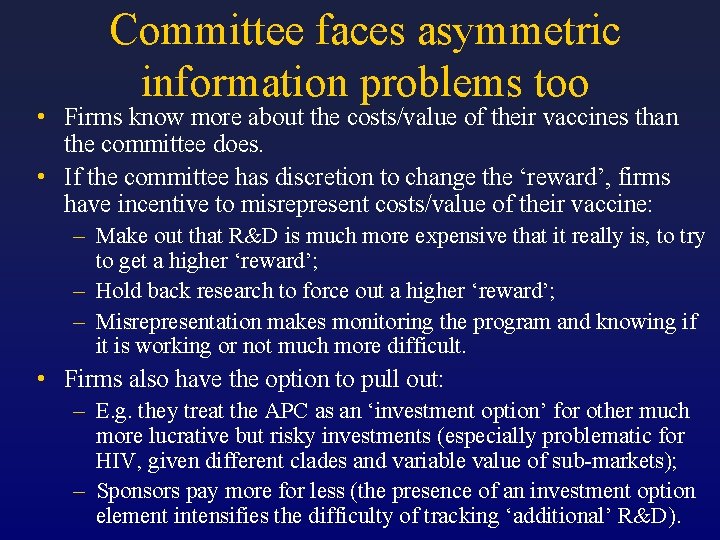

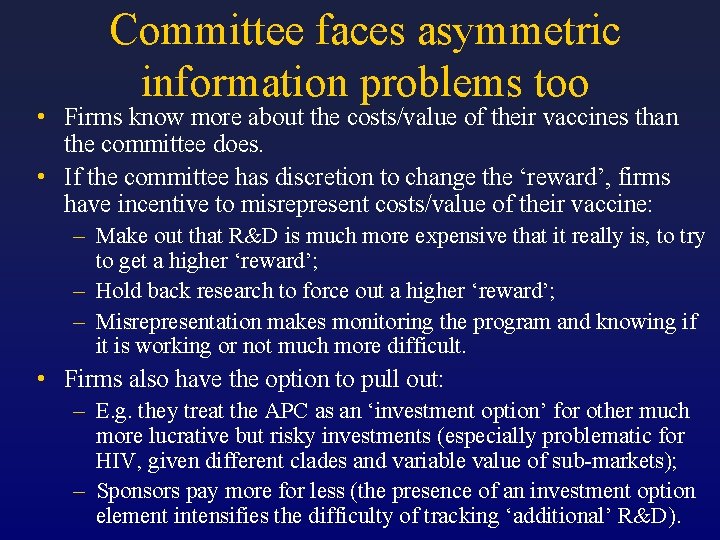

Committee faces asymmetric information problems too • Firms know more about the costs/value of their vaccines than the committee does. • If the committee has discretion to change the ‘reward’, firms have incentive to misrepresent costs/value of their vaccine: – Make out that R&D is much more expensive that it really is, to try to get a higher ‘reward’; – Hold back research to force out a higher ‘reward’; – Misrepresentation makes monitoring the program and knowing if it is working or not much more difficult. • Firms also have the option to pull out: – E. g. they treat the APC as an ‘investment option’ for other much more lucrative but risky investments (especially problematic for HIV, given different clades and variable value of sub-markets); – Sponsors pay more for less (the presence of an investment option element intensifies the difficulty of tracking ‘additional’ R&D).

Doubts about the committee? • Committee (like a central bank) has to build a reputation: – Like a central bank, setting terms wrongly unnecessarily early with need to reset later, will only harm reputation and make the committee’s job much more difficult, even as it raises private players’ risks and capital costs; – Another reason not to ‘rush in’ and risk getting it all wrong? • Worries about capture? – Would the committee do something financially ‘damaging’ to a dominant company in favour of a developing country manufacturer, like entirely replacing the former with the latter? • Small doubts at 15 -30 year horizons feed back in a big way on to investment decisions. • Hence, a high proportion of APCs for HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis are absorbed in the costs of finance – so much so that many investors would not respond.

All avoided at first… • Original CGD model avoided this: – One firm wins all, with scientific possibilities fixed and known from the start: • A fixed single-value solution; • Much easier to solve. – Easy if all hints of scientific complexity removed; – Easy if only one ever vaccine; – Easy if …. . • But we now know it is much more complicated than that… • All problems in current system get transformed into a set of problems facing the APC program organizers and firms in the APC program – the dynamic inconsistency problem changes its form. Can the committee/program/firms cope?

Rules versus discretion: costly tradeoff • Point was to get away from decision-makers with discretion! • So…use commitment devices and pre-set rules? • But policymakers then lose flexibility to change the approach if circumstances change (technology, health needs, epidemiology, other funding, other research, etc. ). And permanently ‘fixing’ terms is expensive (an option component on technology to cover worse-case scenarios, long horizons, etc. ). • Ever-growing tension between: – Non-flexible rules for credibility – but there are inefficient and raise costs; – Discretion, and other remedial features – but these cause risks for developers, higher capital costs, more complicated contract terms, stronger informational demands, and dangers of institutional failure or capture (or costly mechanisms to prevent it). • So, cannot set up product requirements…yet discretion is very, very bad. This core dilemma is downplayed in the MM report.

Features raising cost of tradeoff • No experience of operating such commitments: – No evidence of how severe these problems with ‘mechanism risk’ might be, of how to cope with them, and whether the mechanism may even have to be radically overhauled later. • Tendency to ratchet effect: – Costs can rise but they can’t fall; – Quality can fall but it can’t rise; – Excessive risk on any firm believing that the criteria would not be lowered. • The cost of this trade-off rises sharply: – The more complicated and risky is the technology; – The longer the process being held together. • Expensive APC to pay for all this.

Legal aegis of the controlling committee? 1 • Sponsors could ignore the committee. • So committee must be able to judicially enforce its own decisions. • Would firms take the World Bank, UN, WHO, Gates Foundation to court? • So committee has to be a stand-alone, independent, institution? • But vaccine regulation and IP are sovereign nation issues: – ‘Sovereign’ includes international organizations which must operate in accord with various treaties that have legal force; – Foundations operate according to the laws of the countries in which they are based.

Legal aegis of the controlling committee? 2 • Founding organizations reputations are at stake, with vital policy and financial interests that they must be able to exercise. • So it would not be independent after all? • What about jurisdiction too over non-eligible countries and non-program developers? • Political rent-seeking? Temptations to favour political or commercial allies? Project choice reflecting the preferences of bureaucrats? Priority setting resulting in R&D being directed only at one type of country, one region of the world, one disease, one company…? • Funding driven by political decision-makers and not by a ‘competitive’ process (we see this already in case of malaria).

What is the committee really doing? • Committee expected to do what patent system failing to do. • Instead of ‘winners’ and complicated patterns of IP ownership dictated by a patent system, these are now all dictated by a committee. • Current worries about the patent system not avoided, just transferred into worries about a committee (as well as the IP system, since results are still strongly dependent on that). • Problem with ex post incentive to bid down price, shifted to ex post incentive to bid down firm payoff and quality at a given price and to exclude less powerful players. • Too risky for ‘big pharma’? • Too risky for small bio, not-for-profit and emerging developers? • Best way to reduce risk…capture the Committee?

Payment and competition through one point in time and a committee? 1 • Competition through one point in time and a committee? • Always a bad idea, worse for emerging-economy and biotech developers. • Under static (perfectly known) state of science – these problems never arise. • Trivializing the science was a major failing of the original APC modeling. • Numbs the criticism that other mechanisms ‘require information’. • What is the point in criticizing vaccine scientists and ‘institutional failure’, given the heavy use of administrators, executives, layers of institutions, and vaccine scientists, in setting and updating terms of an HIV APC?

Payment and competition through one point in time and a committee? 2 • Are multiple small rewards better? – Mistakes average out. • APCs – even a few mistakes late in the process after firms have sunk costs will come to dominate the result. • Better to ‘discover’ complex development costs as go along rather than relying on ex ante guess? • To avoid ‘two-stage’ game, rent-seeking, and ‘capture’. . . give some rewards before reaching the market? • Multiple vaccine leads can be encouraged via other means? • Use other ways to build reputation: – Current purchases increase credibility (firms believe that sponsors will switch to better drugs as they come along); – History of previous commitments honored.

Extreme capital cost of earlystage vaccines 1 • Long lengths of time (20+ years? ) lead to very heavy compounding of capital costs. • Little current value in market risk reduction: – Way too far off and uncertain to have impact now; – Market risk remains very high given: i) Many forms of marketbased crowding-out; ii) Use of demand restrictions to control ‘quality’; iii) Use of ‘market demand’ in incentive mechanism even though the market in question is highly dysfunctional. • Scientific risks are very high: – Risks of ever getting a vaccine; – Risks of not internalizing the results of privately-funded research for oneself (especially if data has to be shared and the vaccine turns out not to be a pure preventative vaccine but instead composite and therapeutic).

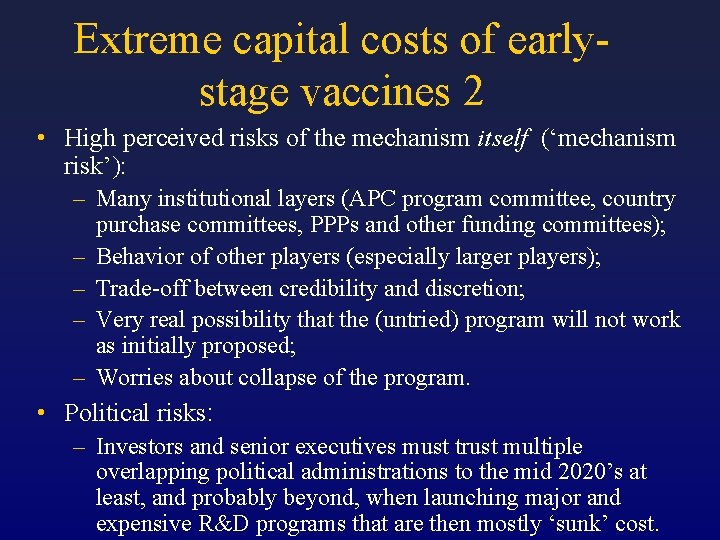

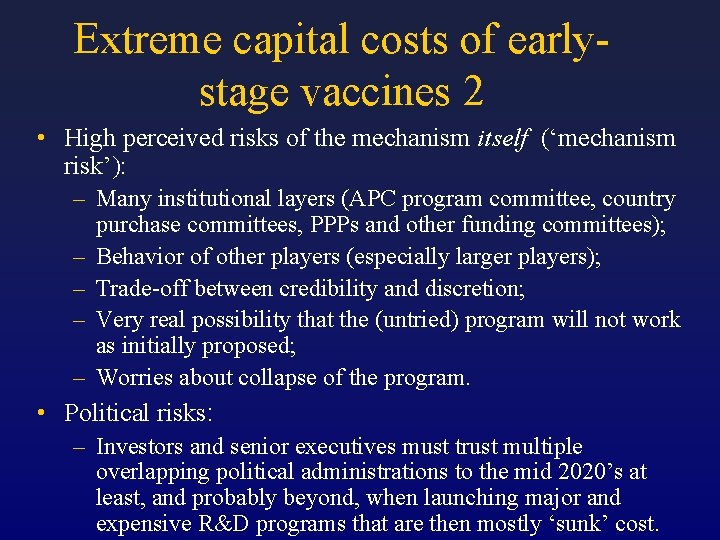

Extreme capital costs of earlystage vaccines 2 • High perceived risks of the mechanism itself (‘mechanism risk’): – Many institutional layers (APC program committee, country purchase committees, PPPs and other funding committees); – Behavior of other players (especially larger players); – Trade-off between credibility and discretion; – Very real possibility that the (untried) program will not work as initially proposed; – Worries about collapse of the program. • Political risks: – Investors and senior executives must trust multiple overlapping political administrations to the mid 2020’s at least, and probably beyond, when launching major and expensive R&D programs that are then mostly ‘sunk’ cost.

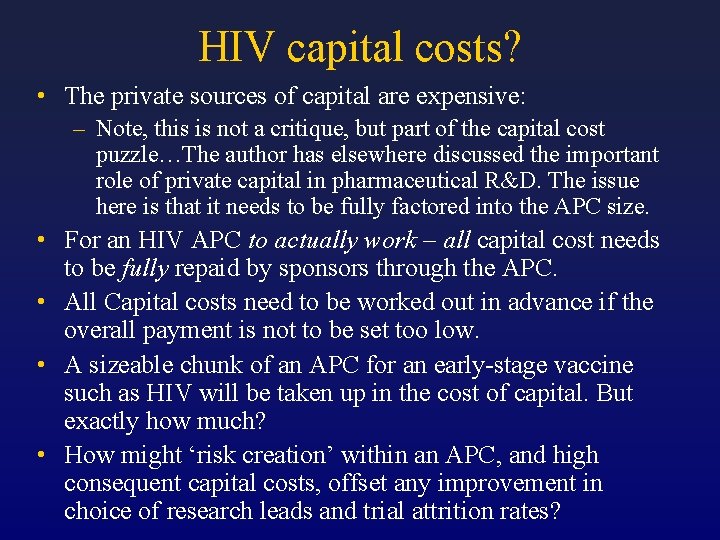

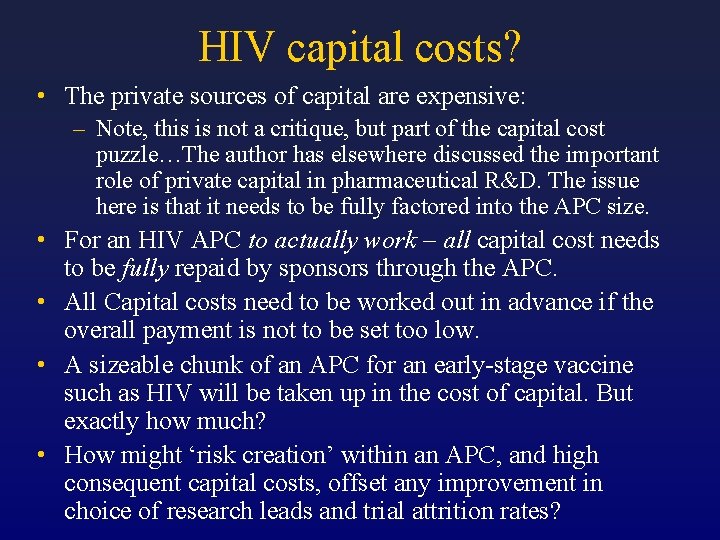

HIV capital costs? • The private sources of capital are expensive: – Note, this is not a critique, but part of the capital cost puzzle…The author has elsewhere discussed the important role of private capital in pharmaceutical R&D. The issue here is that it needs to be fully factored into the APC size. • For an HIV APC to actually work – all capital cost needs to be fully repaid by sponsors through the APC. • All Capital costs need to be worked out in advance if the overall payment is not to be set too low. • A sizeable chunk of an APC for an early-stage vaccine such as HIV will be taken up in the cost of capital. But exactly how much? • How might ‘risk creation’ within an APC, and high consequent capital costs, offset any improvement in choice of research leads and trial attrition rates?

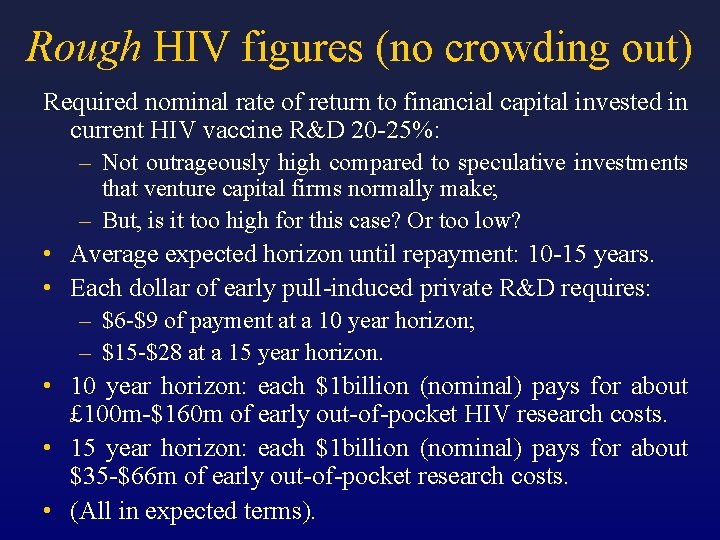

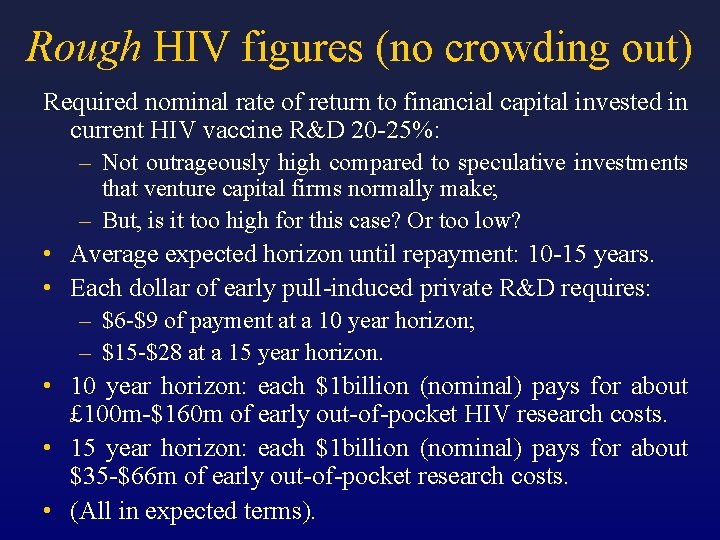

Rough HIV figures (no crowding out) Required nominal rate of return to financial capital invested in current HIV vaccine R&D 20 -25%: – Not outrageously high compared to speculative investments that venture capital firms normally make; – But, is it too high for this case? Or too low? • Average expected horizon until repayment: 10 -15 years. • Each dollar of early pull-induced private R&D requires: – $6 -$9 of payment at a 10 year horizon; – $15 -$28 at a 15 year horizon. • 10 year horizon: each $1 billion (nominal) pays for about £ 100 m-$160 m of early out-of-pocket HIV research costs. • 15 year horizon: each $1 billion (nominal) pays for about $35 -$66 m of early out-of-pocket research costs. • (All in expected terms).

It gets worse… • Add ‘crowding out’: – Say, half: • Maybe push payments prove hard to remove from ‘winners’, • And Russia, India, and China – if deemed ‘non-eligible’ countries – cannot be barred from later ‘spoiling’ markets for HIV vaccine products. • $1 billion of promised HIV payment paying for about: – $50 -$80 m of genuinely additional new early out-of-pocket private R&D at 10 year horizon; – $15 m-£ 30 m at 15 year horizon. • Maybe this is why current levels of private HIV vaccine R&D funding are so low? – “There is no market”? This is not the whole picture. • All very rough figures purely for illustration. • Where are the figures being used by policy makers?

… even worse… • This mechanism presumes a huge and rapid response that we have never seen in the past. • As global spending on HIV research has risen, very little privately financed research has been motivated – contrary to expectations. Is this not a warning sign? • Why the rush to set in place a program like this for HIV? – Private firms will not respond; – Yet it is fixed ‘for ever’ (given the discount rates, 20 -30 years is effectively ‘for ever’); – Yet terms will be set badly with unnecessary amounts of discretion (hence risk) needed later, sunset clauses a risk to investors, credibility of the approach damaged. • It invites collapse. • Where should a fresh injection of funds go? – Are the alternatives so bad?

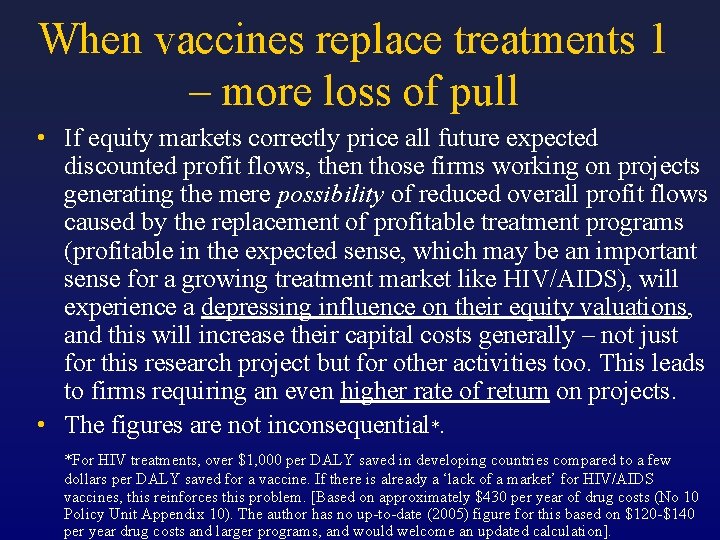

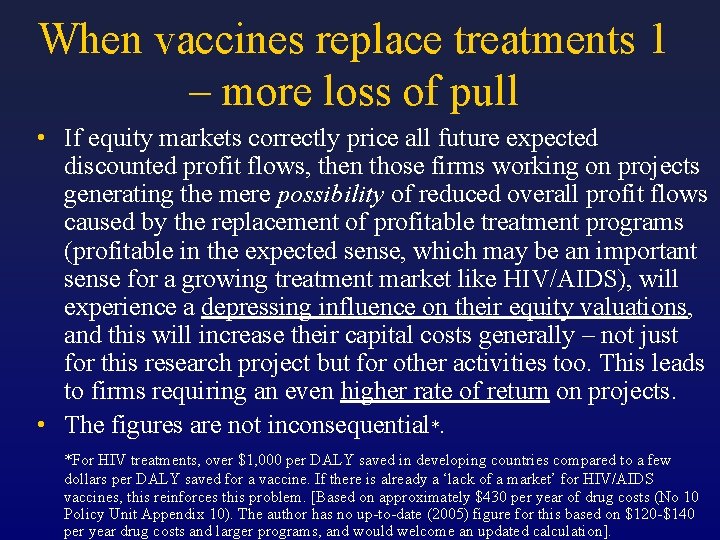

When vaccines replace treatments 1 – more loss of pull • If equity markets correctly price all future expected discounted profit flows, then those firms working on projects generating the mere possibility of reduced overall profit flows caused by the replacement of profitable treatment programs (profitable in the expected sense, which may be an important sense for a growing treatment market like HIV/AIDS), will experience a depressing influence on their equity valuations, and this will increase their capital costs generally – not just for this research project but for other activities too. This leads to firms requiring an even higher rate of return on projects. • The figures are not inconsequential*. *For HIV treatments, over $1, 000 per DALY saved in developing countries compared to a few dollars per DALY saved for a vaccine. If there is already a ‘lack of a market’ for HIV/AIDS vaccines, this reinforces this problem. [Based on approximately $430 per year of drug costs (No 10 Policy Unit Appendix 10). The author has no up-to-date (2005) figure for this based on $120 -$140 per year drug costs and larger programs, and would welcome an updated calculation].

When vaccines replace treatments 2 • Controversial, but should not stop us from tackling it. If ‘replacement effects’ are part of the problem in raising private finance for the R&D of HIV vaccines, then better policy will result from considering rather than from ignoring them. • Tradeoff between the positive incentive effect of equity finance and the ‘replacement effect’. • The fewer the number of firms being relied upon for both treatments and vaccines, the larger the ‘replacement effect’ and the lower the incentive to invest in vaccine R&D. • Part of the reason for the lack of private HIV vaccine R&D is related to the structure of the industry. • A sizeable portion of an APC would be devoted to fighting against these structural issues and ‘replacement effects’. • More sense to tackle the structural issues head-on?

When vaccines replace treatments 3 • Even if biotechs and not-for-profit firms are marginal, competitive, players and do not suffer from the ‘replacement effect’ themselves, if they cannot raise finance to take a vaccine ‘all the way’, the need to turn to firms suffering from the ‘replacement effect’ feeds the ‘replacement effect’ onto them. • Bites even for markets not competing against vaccines: – If vaccines weaken pricing power in markets where there are both treatments and vaccines (this weakening only has to be tiny for vaccines given the size and duration of treatment programs elsewhere); – If vaccine research for a clade for a low value treatment market might produce results impacting high value treatment markets for other clades; – Implications for finance when we encourage both malaria vaccine and malaria drug R&D?

When vaccines replace treatments 4 • The ‘replacement effect’ stronger the more able are incumbents (through IP, etc. ) to restrict access to information that might undermine their positions. • 50% of current vaccine research takes place in biotechs. • Currently, ‘not-profitable’ biotech firms can only take advantage of tax-breaks to the extent that they can be bought-out by much larger pharmaceutical companies to ‘cash in’ on the value of the tax-break (the smaller firms amass the unused tax-breaks as an asset reflected in their equity valuations until taken over). • Biotech research needs to boost biotech share valuations in ways that appeal to large pharmaceutical firms. • Another route for the ‘replacement effect’ to enter.

Need for more players, better finance • Different configuration of sources of R&D funding and a different industrial structure (both interdependent) create a different set of constraints. • The more players in the market, the stronger the incentive for firms to work on vaccine R&D, since success replaces products of other companies. • IP system that better works to allow firms to acquire technology that might undermine those firms experiencing (and causing) a ‘replacement effect’. • Finance mechanisms, alternative to APC, that give differentially greater impact to biotechs, not-for-profits, and all those working on ‘replacement’ projects, enabling them to take projects further without needing to rely on firms causing/suffering from ‘replacement effects’?

Need for more current purchases • ‘Demonstration effect’ of the purchases of current vaccines – in part unlocks the credit constraints (i. e. makes finance cheaper) of biotechs, not-for-profits, and emerging developers, by ‘demonstrating’ that the ‘replacement effect’ is now weaker. • Positive ‘demonstration effect’ caused by investments into healthcare infrastructure too. • Not bigger sums pitched at the same few big players…