Common small and large intestinal surgical diseases Part

- Slides: 140

Common small and large intestinal surgical diseases Part I Khayal Al. Khayal, MD, FRCSC Assistant Professor of Surgery Consultant Colorectal Surgeon 2010 11/27/2020 Shwartz

Topics • • • Bowel obstruction. Small bowel neoplasms. Meckele’s diverticulum. IBD. Colorectal cancer. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

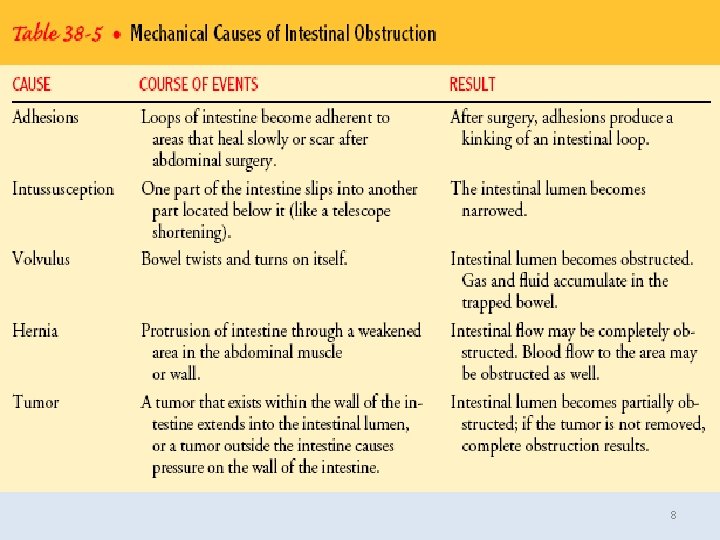

Intestinal Obstruction • Intestinal obstruction exists when blockage prevents the normal flow of intestinal contents through the intestinal tract. • Two types of processes can impede this flow. – Mechanical. – Functional. 3

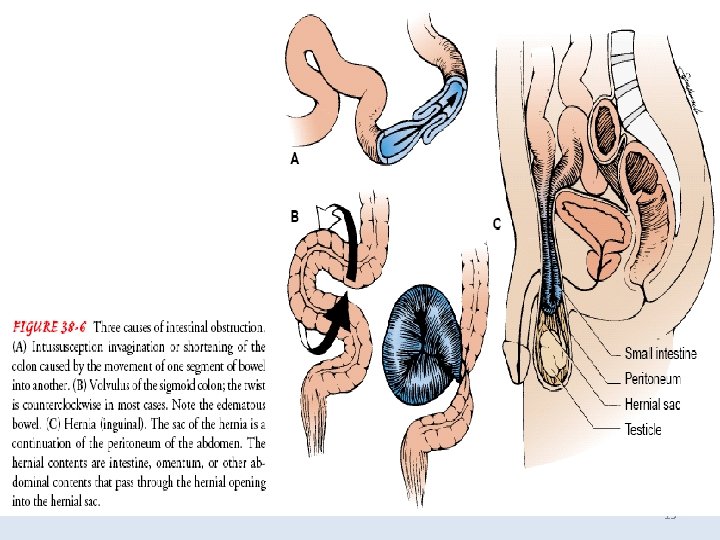

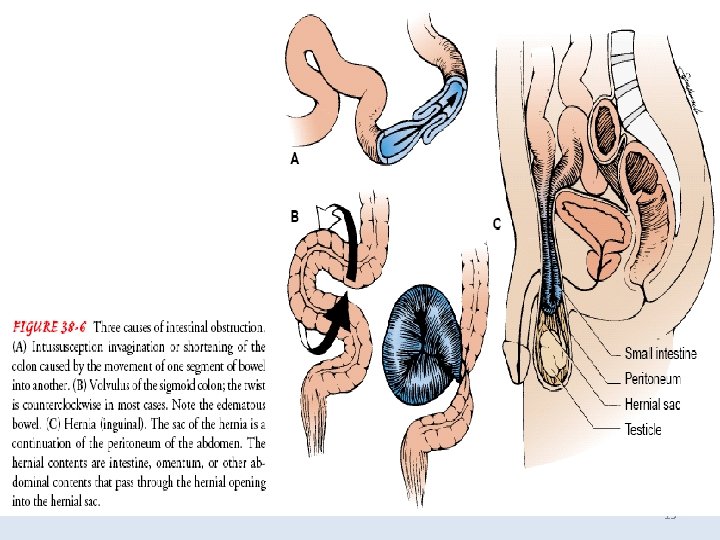

Intestinal Obstruction • Mechanical obstruction: – An intraluminal obstruction or a mural obstruction from pressure on the intestinal walls occurs. – Examples are: • intussusception • polypoid tumors and neoplasms • Stenosis • Strictures • Adhesions • Hernias • abscesses. 4

Intestinal Obstruction • Functional obstruction: – The intestinal musculature cannot propel the contents along the bowel. – Examples are: • • Amyloidosis Muscular dystrophy Endocrine disorders such as diabetes mellitus Neurologic disorders 5

Intestinal Obstruction • The obstruction can be partial or complete. • Its severity depends on: – The region of bowel affected – The degree to which the lumen is occluded – The degree to which the vascular supply to the bowel wall is disturbed. 6

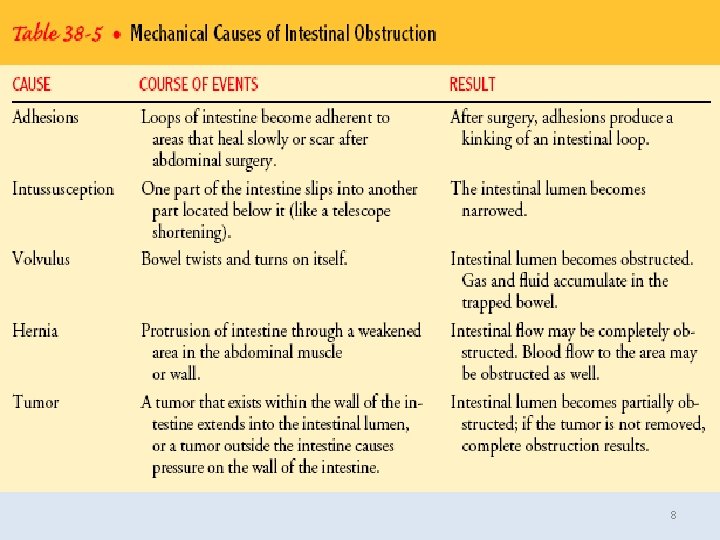

Intestinal Obstruction • Most bowel obstructions occur in the small intestine • Adhesions are the most common cause of small bowel obstruction, followed by hernias and neoplasms. • Other causes include intussusception, volvulus (ie, twisting of the bowel), and paralytic ileus. • About 15% of intestinal obstructions occur in the large bowel; most of these are found in the sigmoid colon 7

8

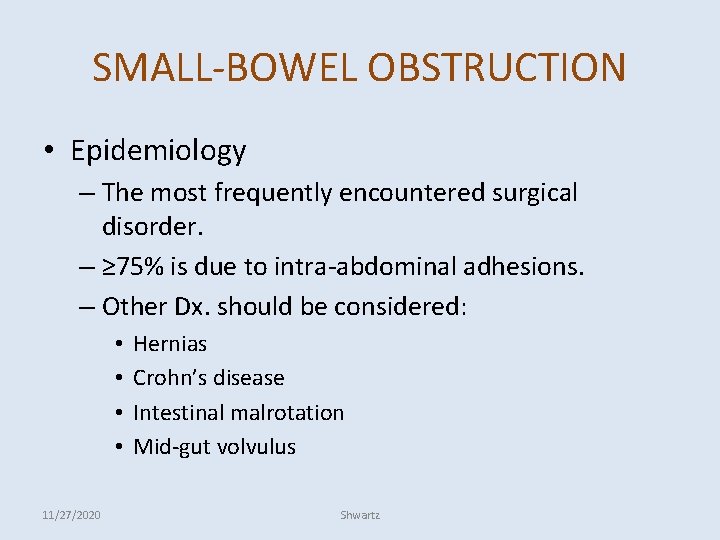

SMALL-BOWEL OBSTRUCTION • Epidemiology – The most frequently encountered surgical disorder. – ≥ 75% is due to intra-abdominal adhesions. – Other Dx. should be considered: • • 11/27/2020 Hernias Crohn’s disease Intestinal malrotation Mid-gut volvulus Shwartz

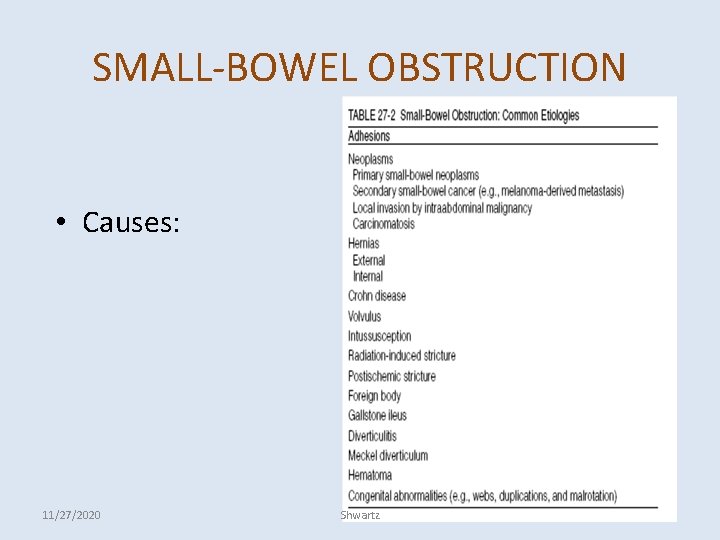

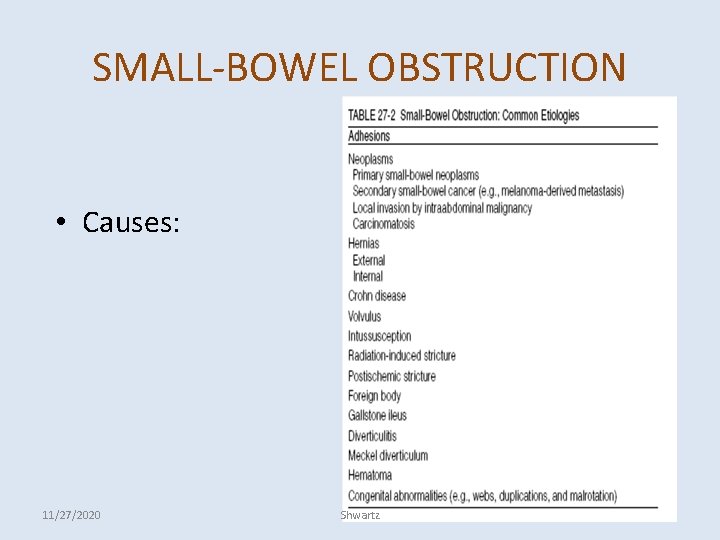

SMALL-BOWEL OBSTRUCTION • Causes: 11/27/2020 Shwartz

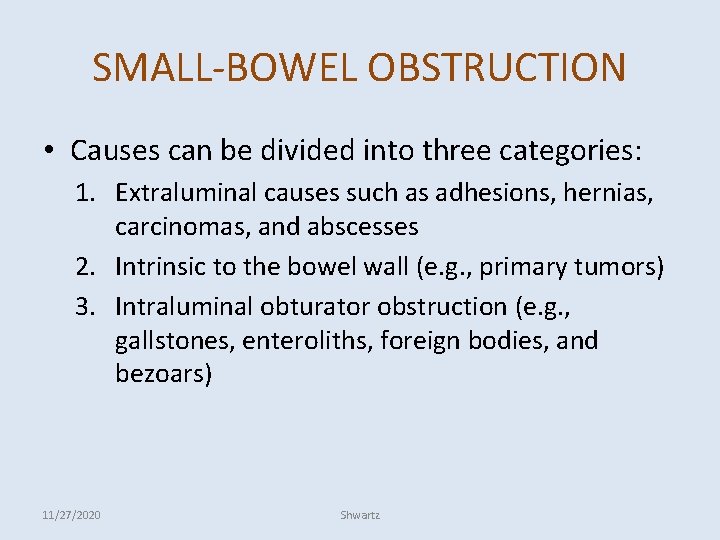

SMALL-BOWEL OBSTRUCTION • Causes can be divided into three categories: 1. Extraluminal causes such as adhesions, hernias, carcinomas, and abscesses 2. Intrinsic to the bowel wall (e. g. , primary tumors) 3. Intraluminal obturator obstruction (e. g. , gallstones, enteroliths, foreign bodies, and bezoars) 11/27/2020 Shwartz

SMALL-BOWEL OBSTRUCTION • PATHOPHYSIOLOGY: – Obstruction onset • Gas and fluid accumulate within the intestinal lumen proximal to the site of obstruction. • The bowel distends and intramural pressures rise. • Microvascular perfusion to the intestine is impaired, leading to intestinal ischemia, and, ultimately, necrosis. – ( strangulating bowel obstruction) • Progression to strangulation occurs quicker with complete bowel obstruction and more rapidly with closed loop obstruction which a segment of intestine is obstructed both proximally and distally (e. g. , with volvulus). 11/27/2020 Shwartz

13

BOWEL OBSTRUCTION • Clinical Presentation – Symptoms: • colicky abdominal pain • Nausea • Vomiting • obstipation • Continued passage of flatus and/or stool beyond 6– 12 h after onset of symptoms is characteristic of partial rather than complete obstruction. – Signs • abdominal distention • hyperactive bowel sounds. “borborygmi” • Features of strangulated obstruction include – Tachycardia – Localized abdominal tenderness – Fever – Marked leukocytosis – Acidosis 11/27/2020 Shwartz

SMALL-BOWEL OBSTRUCTION • Diagnosis – The diagnostic evaluation should focus on the following goals: 1. Distinguishing mechanical obstruction from ileus 2. Determining the etiology of the obstruction 3. Discriminating partial from complete obstruction 4. Discriminating simple from strangulating obstruction. 5. Determining the site of obstruction. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

SMALL-BOWEL OBSTRUCTION • Diagnosis – Careful history taking: • prior Hx of abdominal operations ? presence of adhesions. • Hx of abdominal disorders (e. g. , intraabdominal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease). – Careful examination: • a meticulous search for hernias (particularly in the inguinal and femoral regions) should be conducted. • The stool should be checked for gross or occult blood, the presence of which is suggestive of intestinal strangulation. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

LARGE BOWEL OBSTRUCTION : Pathophysiology • As in small bowel obstruction – large bowel obstruction results in an accumulation of intestinal contents, fluid, and gas proximal to the obstruction. – Obstruction in the large bowel can lead to severe distention and perforation unless some gas and fluid can flow back through the ileal valve. – Large bowel obstruction, even if complete, may be undramatic if the blood supply to the colon is not disturbed. 17

LARGE BOWEL OBSTRUCTION : Pathophysiology • If the blood supply is cut off intestinal strangulation and necrosis (ie, tissue death) occur; this condition is life threatening. • dehydration occurs more slowly than in the small intestine because the colon can absorb its fluid contents and can distend to a size considerably beyond its normal full capacity. 18

LARGE BOWEL OBSTRUCTION : Clinical Manifestations • Large bowel obstruction differs clinically from small bowel obstruction in that the symptoms develop and progress relatively slowly. • In patients with obstruction in the sigmoid colon or the rectum, constipation may be the only symptom for days. loops of large bowel become visibly outlined through the abdominal wall, and the patient has crampy lower abdominal pain. • Finally, fecal vomiting develops. Symptoms of shock may occur. 19

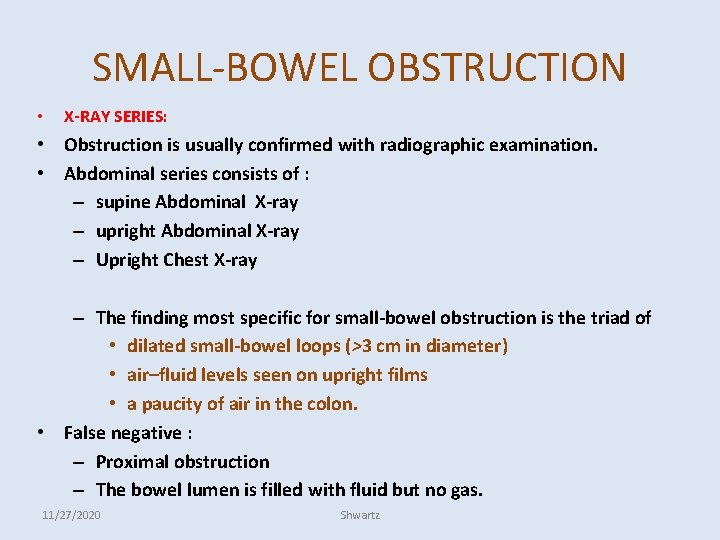

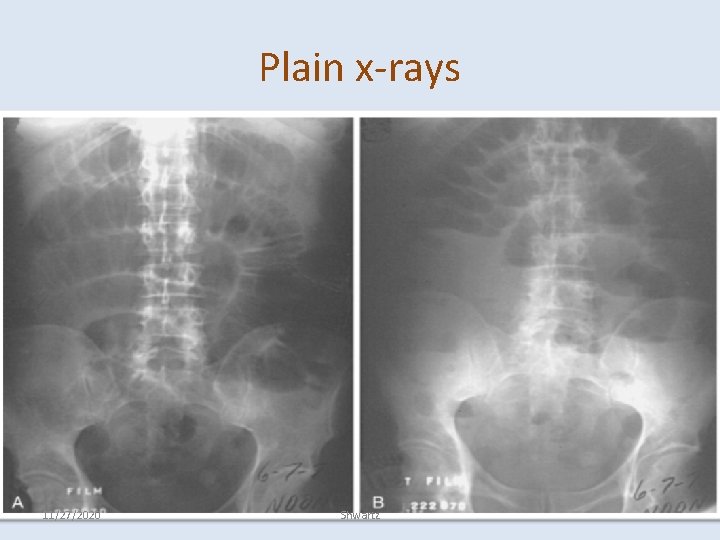

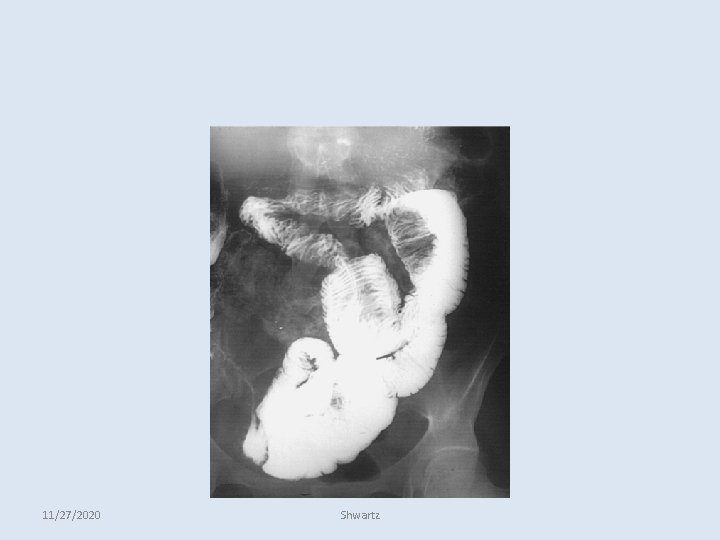

SMALL-BOWEL OBSTRUCTION • X-RAY SERIES: • Obstruction is usually confirmed with radiographic examination. • Abdominal series consists of : – supine Abdominal X-ray – upright Abdominal X-ray – Upright Chest X-ray – The finding most specific for small-bowel obstruction is the triad of • dilated small-bowel loops (>3 cm in diameter) • air–fluid levels seen on upright films • a paucity of air in the colon. • False negative : – Proximal obstruction – The bowel lumen is filled with fluid but no gas. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

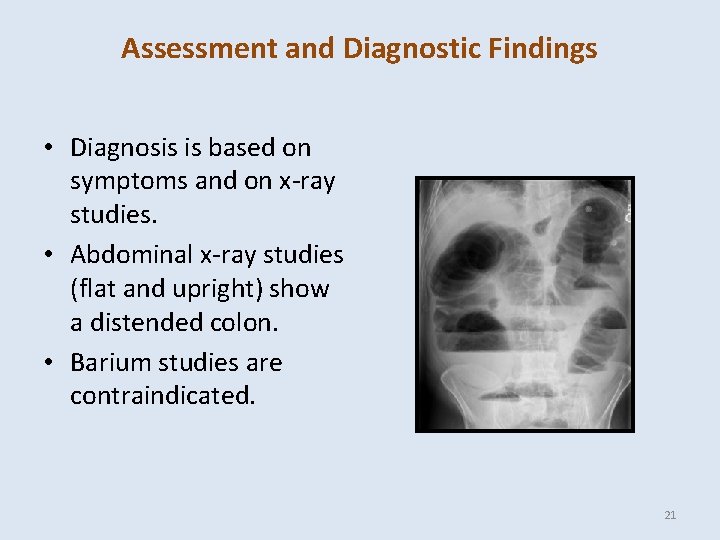

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings • Diagnosis is based on symptoms and on x-ray studies. • Abdominal x-ray studies (flat and upright) show a distended colon. • Barium studies are contraindicated. 21

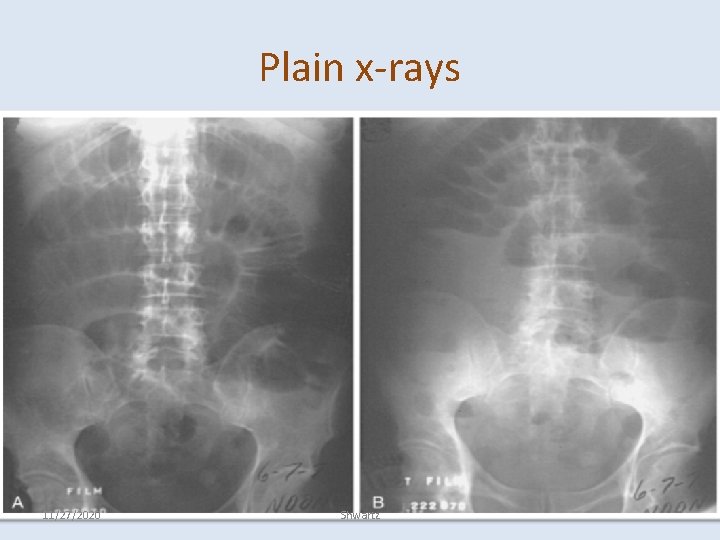

Plain x-rays 11/27/2020 Shwartz

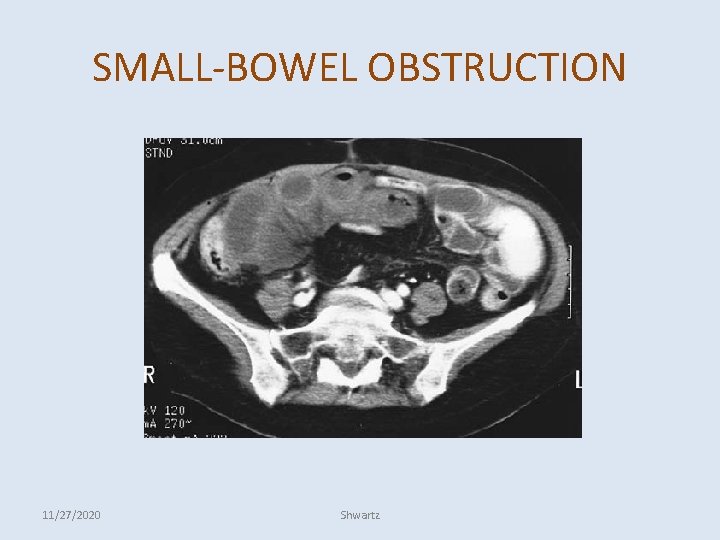

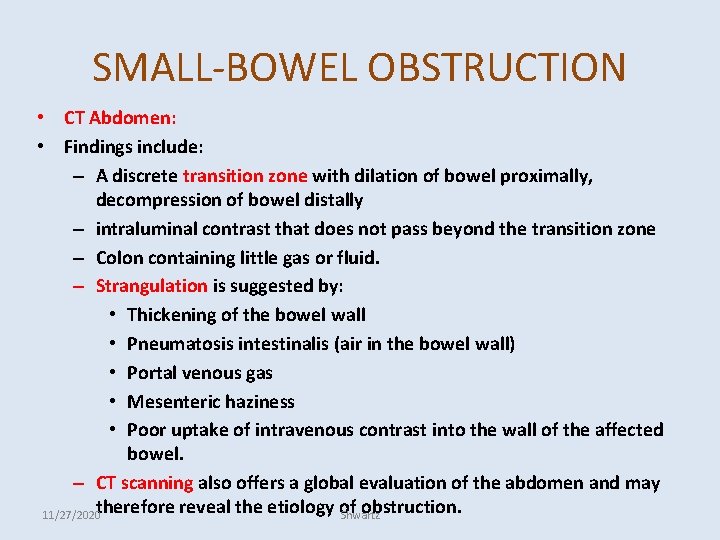

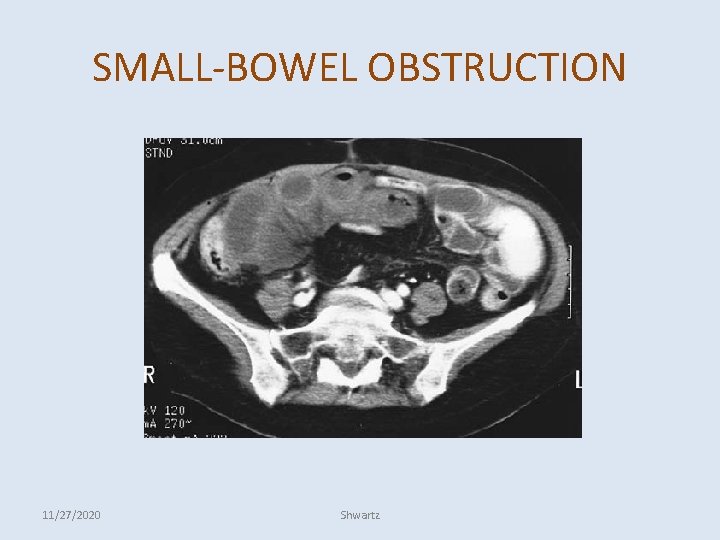

SMALL-BOWEL OBSTRUCTION • CT Abdomen: • Findings include: – A discrete transition zone with dilation of bowel proximally, decompression of bowel distally – intraluminal contrast that does not pass beyond the transition zone – Colon containing little gas or fluid. – Strangulation is suggested by: • Thickening of the bowel wall • Pneumatosis intestinalis (air in the bowel wall) • Portal venous gas • Mesenteric haziness • Poor uptake of intravenous contrast into the wall of the affected bowel. – CT scanning also offers a global evaluation of the abdomen and may 11/27/2020 therefore reveal the etiology of obstruction. Shwartz

SMALL-BOWEL OBSTRUCTION 11/27/2020 Shwartz

11/27/2020 Shwartz

11/27/2020 Shwartz

11/27/2020 Shwartz

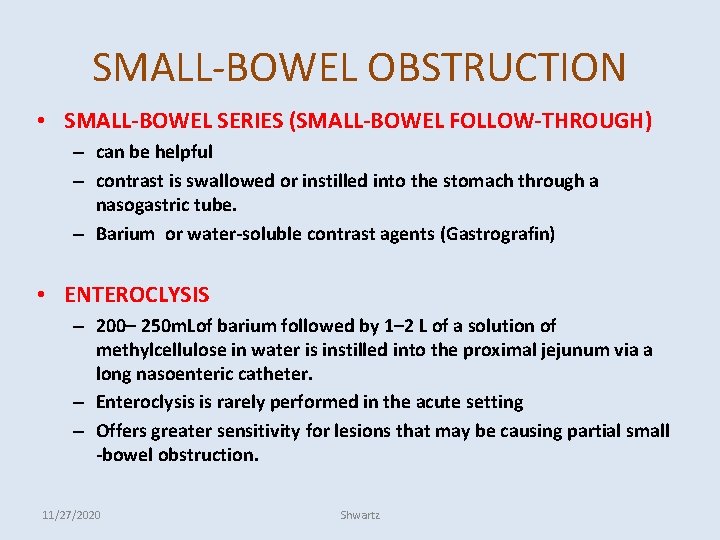

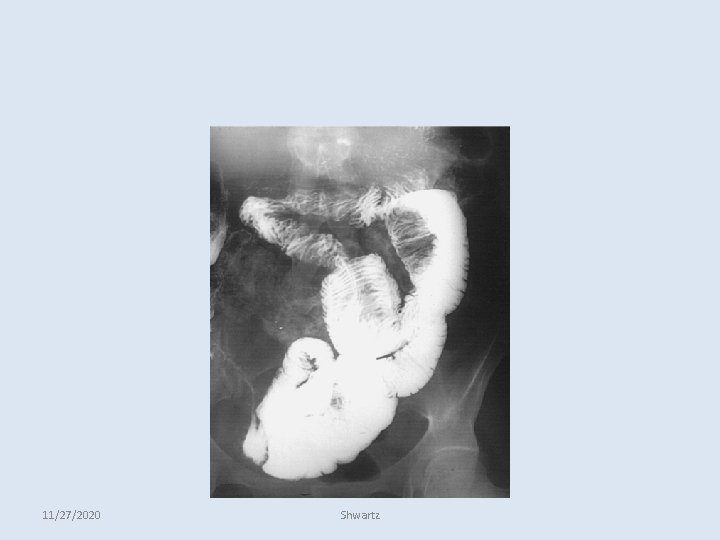

SMALL-BOWEL OBSTRUCTION • SMALL-BOWEL SERIES (SMALL-BOWEL FOLLOW-THROUGH) – can be helpful – contrast is swallowed or instilled into the stomach through a nasogastric tube. – Barium or water-soluble contrast agents (Gastrografin) • ENTEROCLYSIS – 200– 250 m. Lof barium followed by 1– 2 L of a solution of methylcellulose in water is instilled into the proximal jejunum via a long nasoenteric catheter. – Enteroclysis is rarely performed in the acute setting – Offers greater sensitivity for lesions that may be causing partial small -bowel obstruction. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

11/27/2020 Shwartz

11/27/2020 Shwartz

11/27/2020 Shwartz

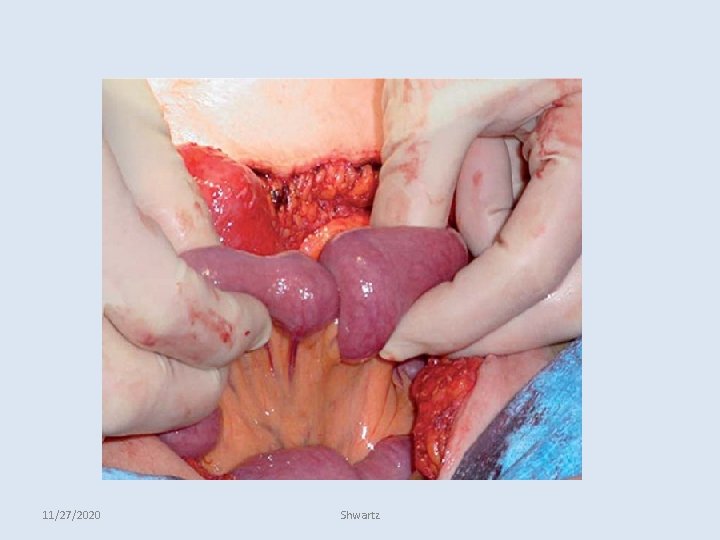

BOWEL OBSTRUCTION • Therapy Fluid resuscitation. A nasogastric (NG) tube to evacuate air and fluid from stomach. An indwelling bladder catheter to monitor urine output. Central venous or pulmonary artery catheter monitoring may be necessary – Broad-spectrum antibiotics – The standard therapy for bowel obstruction is expeditious surgery with the exception of specific situations – – 11/27/2020 Shwartz

ILEUS • Caused by impaired intestinal motility • It is characterized by S/S of intestinal obstruction in the absence of a lesion-causing mechanical obstruction. • Ileus is temporary and generally reversible if the inciting factor can be corrected. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

ILEUS • Pathophysiology • The most frequently encountered factors are – abdominal operations • How? : surgical stress-induced sympathetic reflexes, inflammatory response-mediator release, and anesthetic/analgesic effects, each of which can inhibit intestinal motility. – infection and inflammation • viral infections, such as those associated with CMV & EBV – electrolyte abnormalities – drugs. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

ILEUS • Diagnosis 1. Routine postoperative ileus should be EXPECTED and requires no diagnostic evaluation 2. If ileus persists beyond postoperatively or occurs in the absence of abdominal surgery diagnostic evaluation is needed i. rule out the presence of mechanical obstruction is warranted. 3– 5 days ii. Patient medication lists should be reviewed for the presence of drugs known to be associated with impaired intestinal motility. iii. Measurement of serum electrolytes may demonstrate hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, hypermagnesemia, or other electrolyte abnormalities iv. Abdominal radiographs v. In the postoperative setting, CT scanning is the test of choice because it can demonstrate the presence of an intraabdominal abscess or other evidence of peritoneal sepsis that may be causing ileus and can exclude the presence of complete mechanical obstruction. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

ILEUS • Therapy – limiting oral intake and correcting the underlying inciting factor. – Nasogastric decompression, If vomiting or abdominal distention are prominent, – Fluid and electrolytes should be administered intravenously until ileus resolves. – If the duration of ileus is prolonged, TPN may be required. – Surgery should be avoided if at all possible. – Prokinetic agents, such as metoclopramide and erythromycin, are associated with poor efficacy. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

SMALL-BOWEL NEOPLASMS • Epidemiology • Benign: – Adenomas are the most common benign neoplasm of the small intestine. – Other benign tumors include fibromas, lipomas, hemangiomas, lymphangiomas, and neurofibromas. • Cancer – Primary small-bowel cancers are rare – estimated incidence of 5300 cases per year in the United States. • Adenocarcinomas: comprise 35– 50 percent of all cases • carcinoid tumors comprise 20– 40 percent • lymphomas comprise approximately 10– 15 percent. • Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumors arising in the small intestine and comprise up to 15 percent of smallbowel malignancies. 11/27/2020

SMALL-BOWEL NEOPLASMS • Epidemiology – The small intestine is frequently affected by metastases from or local invasion by cancers originating at other sites. – Melanoma, in particular, is associated with a propensity for metastasis to the small intestine. – Risk factors for developing small-intestinal adenocarcinoma include: • • 11/27/2020 Consumption of red meat Ingestion of smoked or cured foods Crohn disease Celiac sprue Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) – nearly 100 % cumulative lifetime risk of developing duodenal adenomas that have the potential to undergo malignant transformation. – The risk of duodenal cancer in these patients is more than 100 -fold than in the general population. Shwartz

SMALL-BOWEL NEOPLASMS • Clinical Presentation – Most small-intestinal neoplasms are asymptomatic until they become large. – S/S of Partial small-bowel obstruction, is the most common mode of presentation. – Hemorrhage, usually indolent, is the second most common mode of presentation. – Physical examination may reveal an abdominal mass or signs of intestinal obstruction. – Fecal occult blood test may be positive. Cachexia or ascites may be present with advanced disease. • Lesions in the periampullary location cause obstructive jaundice or pancreatitis. • Adenocarcinomas located in the duodenum tend to be diagnosed earlier in their progression than those located in the jejunum or ileum, which are rarely diagnosed prior to the onset of locally advanced or metastatic disease. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

SMALL-BOWEL NEOPLASMS Carcinoid tumors of the small intestine are also usually diagnosed after the development of metastatic disease. • These tumors are associated with a more aggressive behavior than the more common appendiceal carcinoid tumors. • Approximately 25– 50% with carcinoid tumor-derived liver metastases will develop manifestations of the carcinoid syndrome. – include diarrhea, flushing, hypotension, tachycardia, and fibrosis of the endocardium and valves of the right heart. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

• Lymphoma • may involve the small intestine primarily or as a manifestation of disseminated systemic disease. • Primary small-intestinal lymphomas are most commonly located in the ileum, which contains the highest concentration of lymphoid tissue in the intestine. – partial small-bowel obstruction is the most common mode of presentation – 10 percent of patients with small intestinal lymphoma present with bowel perforation. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

• GISTs • • • 60 -70%are located in the stomach. The small intestine is the second most common site, containing 25– 35%. GISTs have a greater propensity to be associated with overt hemorrhage than the other small-intestinal malignancies. • Metastatic tumors • involving the small intestine can induce intestinal obstruction and bleeding. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

SMALL-BOWEL NEOPLASMS • Diagnosis • rarely diagnosed preoperatively. • Laboratory tests are nonspecific, with the exception of elevated serum 5 hydroxyindole acetic acid (5 -HIAA) levels in patients with the carcinoid syndrome. • Contrast radiography of the small intestine may demonstrate benign and malignant lesions. • Enteroclysis has a sensitivity of greater than 90% • Tumors associated with significant bleeding can be localized with angiography or radioisotope-tagged red blood cell (RBC) scans. • Tumors located in the duodenum can be visualized and biopsied on EGD. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

SMALL-BOWEL NEOPLASMS • Therapy – Benign neoplasms of the small intestine that are symptomatic should be surgically resected or removed endoscopically, if feasible. – The surgical therapy of small-intestinal malignancies usually consists of wide– local resection of the intestine harboring the lesion. – For most adenocarcinomas of the duodenum, except those in the distal duodenum, pancreaticoduodenectomy is required. – In the presence of locally advanced or metastatic disease, palliative intestinal resection or bypass is performed. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

SMALL-BOWEL NEOPLASMS • Chemotherapy has no proven efficacy in the adjuvant or palliative treatment of small-intestinal adenocarcinomas. • Octreotide is the most effective pharmacologic agent for management of symptoms of carcinoid syndrome. • GISTs are resistant to conventional chemotherapy agents. – Imatinib (Gleevec, formerly known as ST 1571) is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor with potent activity against tyrosine kinase KIT. • Lymphoma – Localized small-intestinal lymphoma should be treated with segmental resection – Diffused small intestine lymphoma should be treated by chemotherapy 11/27/2020 Shwartz

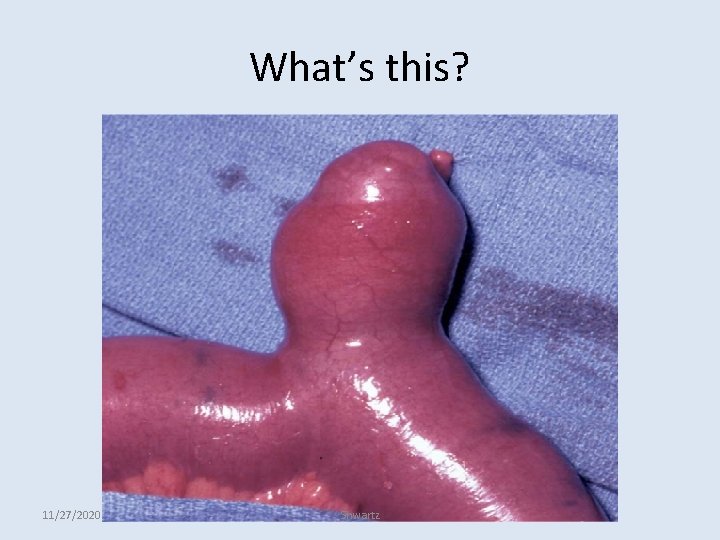

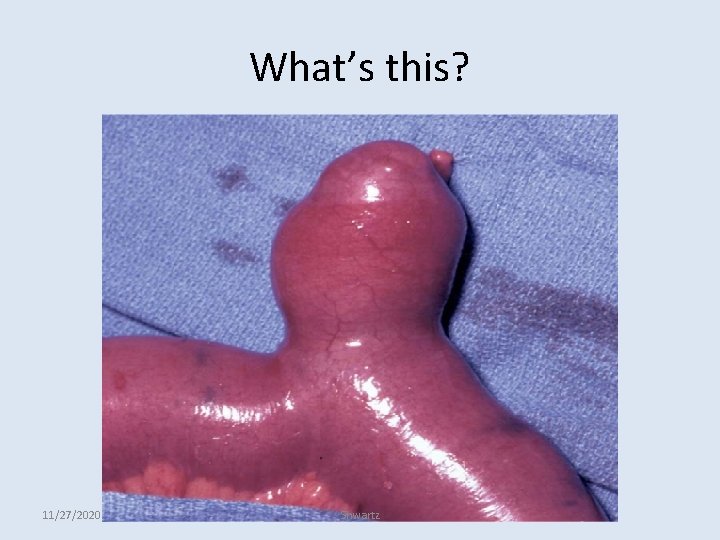

What’s this? 11/27/2020 Shwartz

11/27/2020 Shwartz

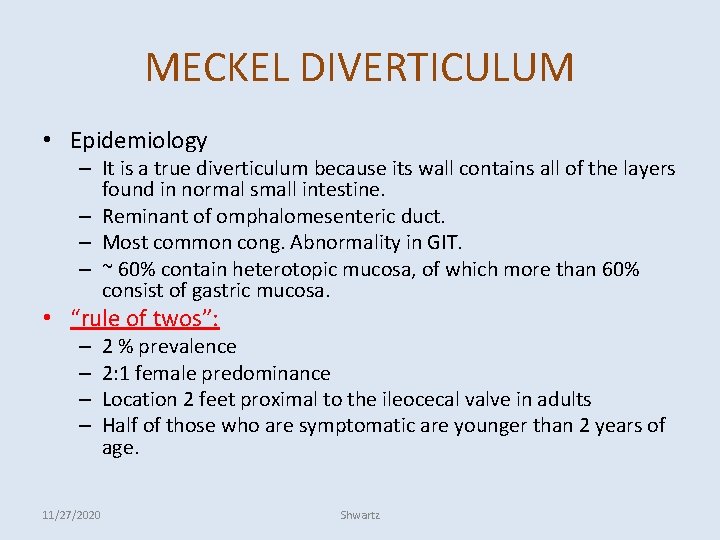

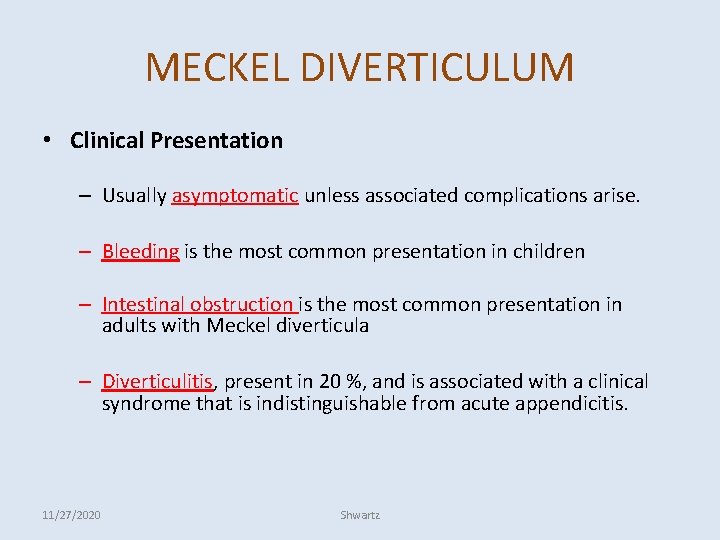

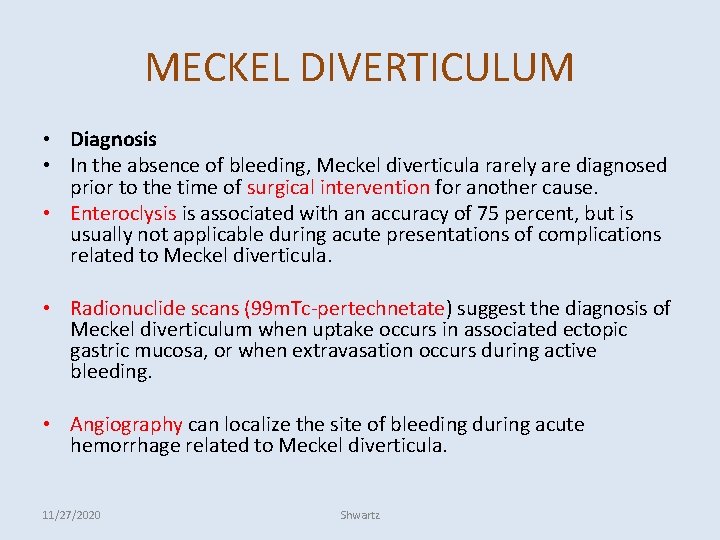

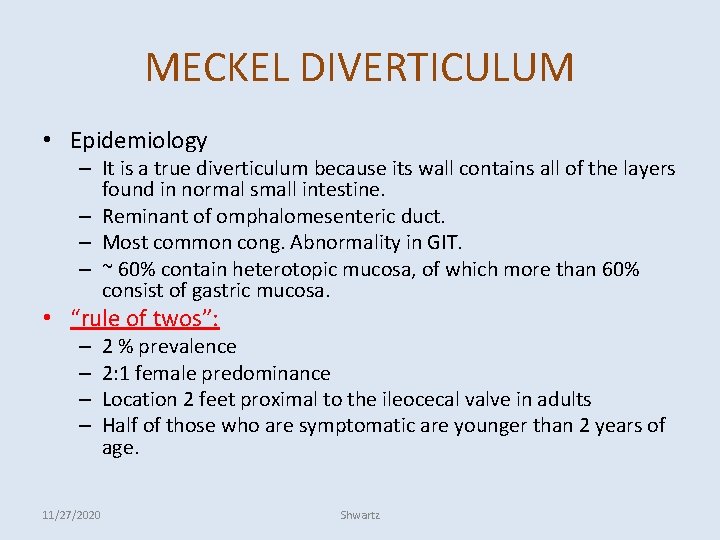

MECKEL DIVERTICULUM • Epidemiology – It is a true diverticulum because its wall contains all of the layers found in normal small intestine. – Reminant of omphalomesenteric duct. – Most common cong. Abnormality in GIT. – ~ 60% contain heterotopic mucosa, of which more than 60% consist of gastric mucosa. • “rule of twos”: – – 11/27/2020 2 % prevalence 2: 1 female predominance Location 2 feet proximal to the ileocecal valve in adults Half of those who are symptomatic are younger than 2 years of age. Shwartz

MECKEL DIVERTICULUM • Clinical Presentation – Usually asymptomatic unless associated complications arise. – Bleeding is the most common presentation in children – Intestinal obstruction is the most common presentation in adults with Meckel diverticula – Diverticulitis, present in 20 %, and is associated with a clinical syndrome that is indistinguishable from acute appendicitis. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

MECKEL DIVERTICULUM • Diagnosis • In the absence of bleeding, Meckel diverticula rarely are diagnosed prior to the time of surgical intervention for another cause. • Enteroclysis is associated with an accuracy of 75 percent, but is usually not applicable during acute presentations of complications related to Meckel diverticula. • Radionuclide scans (99 m. Tc-pertechnetate) suggest the diagnosis of Meckel diverticulum when uptake occurs in associated ectopic gastric mucosa, or when extravasation occurs during active bleeding. • Angiography can localize the site of bleeding during acute hemorrhage related to Meckel diverticula. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

MECKEL DIVERTICULUM • Therapy – The surgical treatment of symptomatic Meckel diverticula should consist of diverticulectomy with removal of associated bands connecting the diverticulum to the abdominal wall or intestinal mesentery. – incidentally found (asymptomatic) Meckel diverticula remains controversial 11/27/2020 Shwartz

MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA • 2 presentations: acute or chronic mesenteric ischemia. • Pathophysiology – Four distinct pathophysiologic mechanisms: : 1. 2. 3. 4. Arterial embolus Arterial thrombosis Vasospasm (also known as nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia, or NOMI) Venous thrombosis. – Acutely. this will lead to intestinal mucosal sloughing within 3 h of onset and full-thickness intestinal infarction by 6 h. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA • Pathophysiology – In chronic ischemia, this develops insidiously allowing for development of collateral circulation rarely leads to intestinal infarction. – Chronic mesenteric arterial ischemia results from atherosclerotic lesions in the main splanchnic arteries (celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric arteries). – In most patients with symptoms attributable to chronic mesenteric ischemia, at least two of these arteries are either occluded or severely stenosed. – A chronic form of mesenteric venous thrombosis can involve the portal or splenic veins and may lead to portal hypertension, with resulting esophagogastric varices, splenomegaly, and hypersplenism. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA: Clinical Presentation • Abdominal pain for which the severity is out of proportion to the degree of tenderness • on examination is the hallmark of acute mesenteric ischemia. Associated symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. • Physical findings are characteristically absent early in the course of ischemia. • With the onset of bowel infarction, abdominal distention, peritonitis, and passage of bloody stools occur. • With chronic mesenteric ischemia, postprandial abdominal pain is the most prevalent symptom, producing a characteristic aversion to food (“food-fear”) and weight loss. • Most patients with chronic mesenteric venous thrombosis are asymptomatic because of the presence of extensive collateral venous drainage routes. • Some patients with chronic mesenteric venous thrombosis present with bleeding from esophagogastric varices. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA: Diagnosis – High index of suspecion – It is important to consider and pursue the diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia when pain out of proportion to physical findings. – Laboratory test abnormalities, such as leukocytosis and acidosis are late findings – No laboratory tests have clinically useful sensitivity for the detection of acute mesenteric ischemia prior to the onset of intestinal infarction. • + P/E suggestive of peritonitis should undergo emergent laparotomy. • -ve P/E diagnostic imaging should be performed. – Angiography is the most reliable diagnostic method for mesenteric arterial occlusion. – BUT it is invasive, time-consuming, and costly. – Angiography is the gold standard for the diagnosis of chronic arterial mesenteric ischemia 11/27/2020 Shwartz

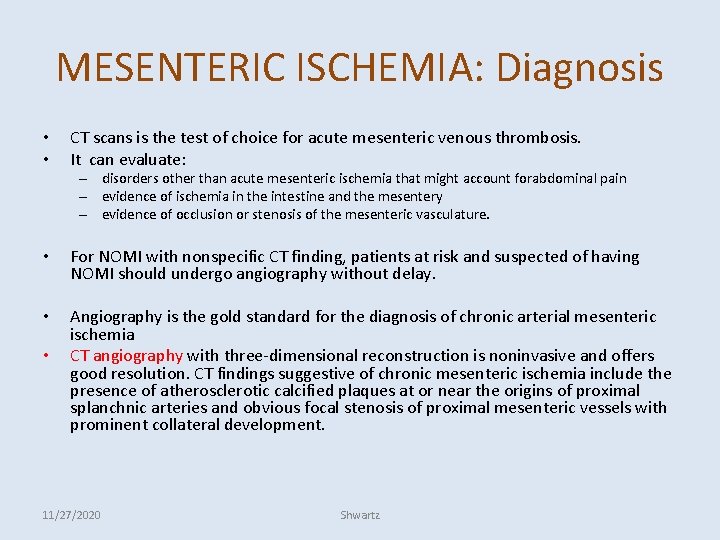

MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA: Diagnosis • • CT scans is the test of choice for acute mesenteric venous thrombosis. It can evaluate: – disorders other than acute mesenteric ischemia that might account forabdominal pain – evidence of ischemia in the intestine and the mesentery – evidence of occlusion or stenosis of the mesenteric vasculature. • For NOMI with nonspecific CT finding, patients at risk and suspected of having NOMI should undergo angiography without delay. • Angiography is the gold standard for the diagnosis of chronic arterial mesenteric ischemia CT angiography with three-dimensional reconstruction is noninvasive and offers good resolution. CT findings suggestive of chronic mesenteric ischemia include the presence of atherosclerotic calcified plaques at or near the origins of proximal splanchnic arteries and obvious focal stenosis of proximal mesenteric vessels with prominent collateral development. • 11/27/2020 Shwartz

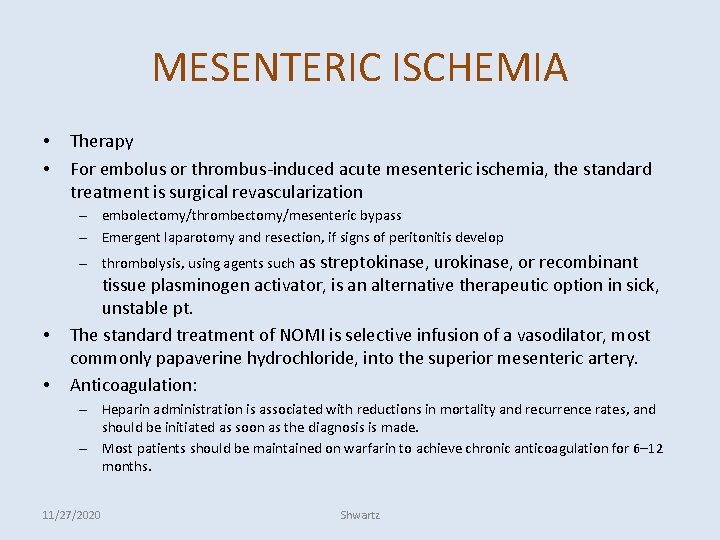

MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA • • Therapy For embolus or thrombus-induced acute mesenteric ischemia, the standard treatment is surgical revascularization – embolectomy/thrombectomy/mesenteric bypass – Emergent laparotomy and resection, if signs of peritonitis develop – thrombolysis, using agents such as streptokinase, urokinase, or recombinant • • tissue plasminogen activator, is an alternative therapeutic option in sick, unstable pt. The standard treatment of NOMI is selective infusion of a vasodilator, most commonly papaverine hydrochloride, into the superior mesenteric artery. Anticoagulation: – Heparin administration is associated with reductions in mortality and recurrence rates, and should be initiated as soon as the diagnosis is made. – Most patients should be maintained on warfarin to achieve chronic anticoagulation for 6– 12 months. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

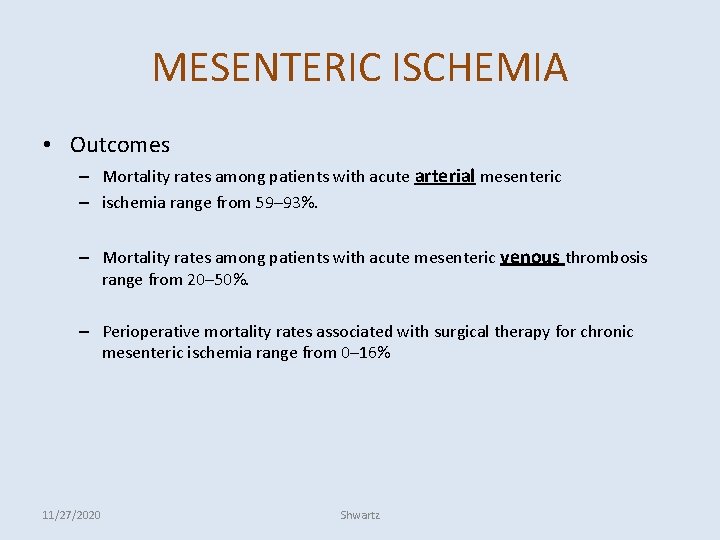

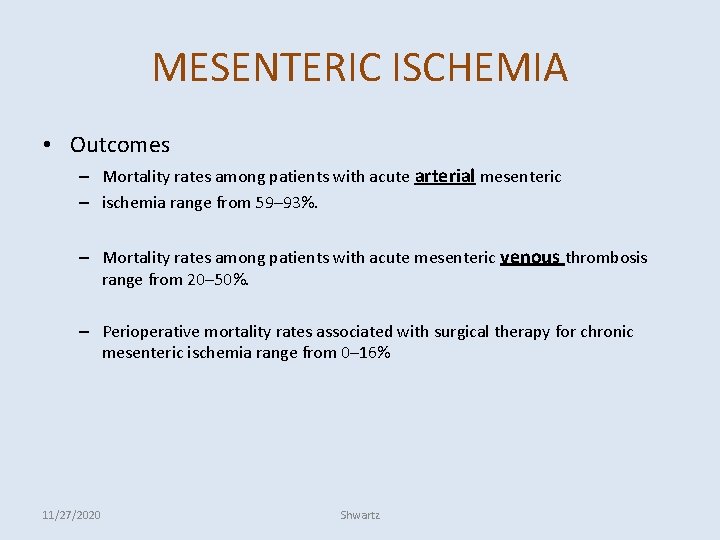

MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA • Outcomes – Mortality rates among patients with acute arterial mesenteric – ischemia range from 59– 93%. – Mortality rates among patients with acute mesenteric venous thrombosis range from 20– 50%. – Perioperative mortality rates associated with surgical therapy for chronic mesenteric ischemia range from 0– 16% 11/27/2020 Shwartz

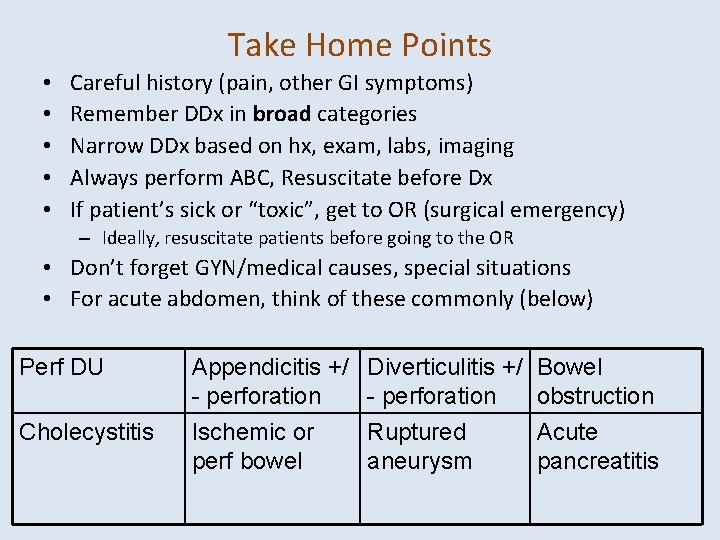

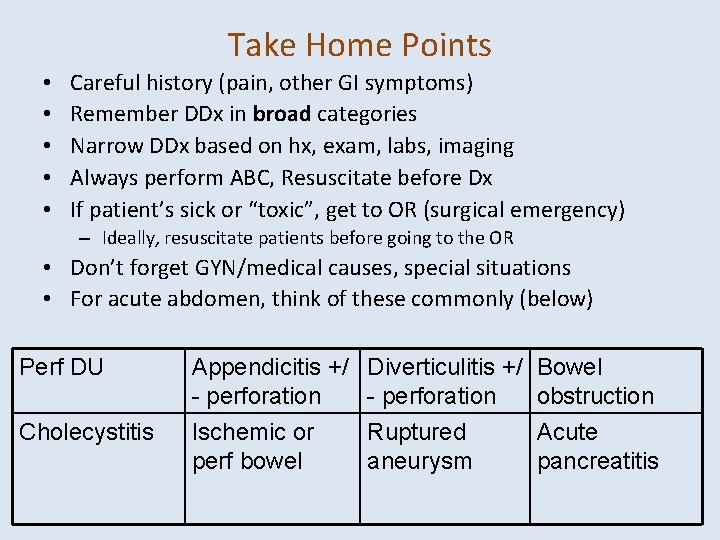

Take Home Points • • • Careful history (pain, other GI symptoms) Remember DDx in broad categories Narrow DDx based on hx, exam, labs, imaging Always perform ABC, Resuscitate before Dx If patient’s sick or “toxic”, get to OR (surgical emergency) – Ideally, resuscitate patients before going to the OR • Don’t forget GYN/medical causes, special situations • For acute abdomen, think of these commonly (below) Perf DU Appendicitis +/ Diverticulitis +/ Bowel - perforation obstruction Cholecystitis Ischemic or perf bowel Ruptured aneurysm Acute pancreatitis

ILEUS AND OTHER DISORDERS OF INTESTINAL MOTILITY • Therapy 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. limiting oral intake correcting the underlying inciting factor. Nasogastric tube decompression. Fluid and electrolytes should be administered intravenously until ileus resolves. TPN, if the duration of ileus is prolonged Prokinetic agents, such as metoclopramide and erythromycin, are associated with poor efficacy. Cisapride ? Discontinued from market, cardiac S/E Surgery should be avoided if at all possible. 11/27/2020 Shwartz

Crohn’s Disease

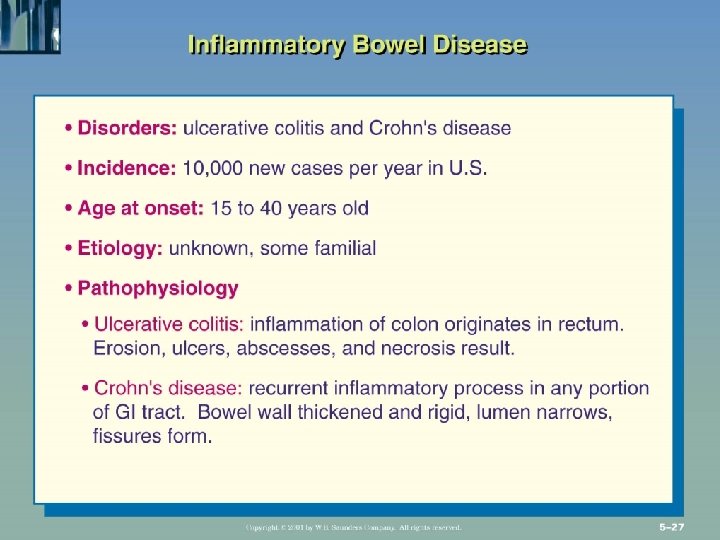

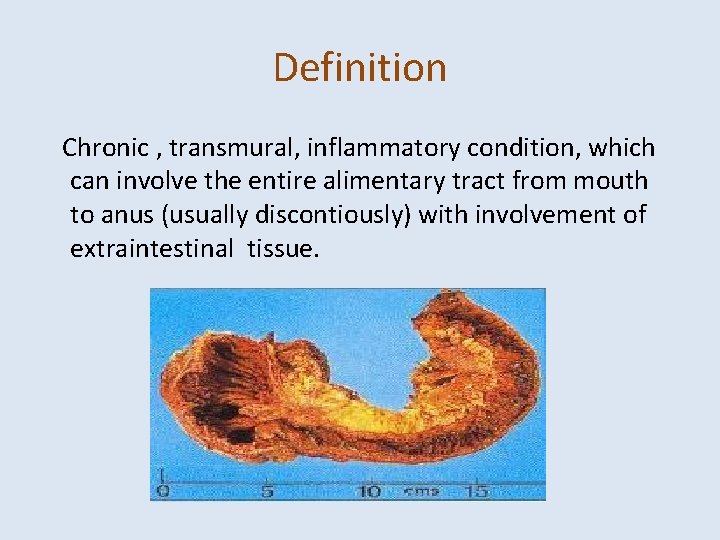

Definition Chronic , transmural, inflammatory condition, which can involve the entire alimentary tract from mouth to anus (usually discontiously) with involvement of extraintestinal tissue.

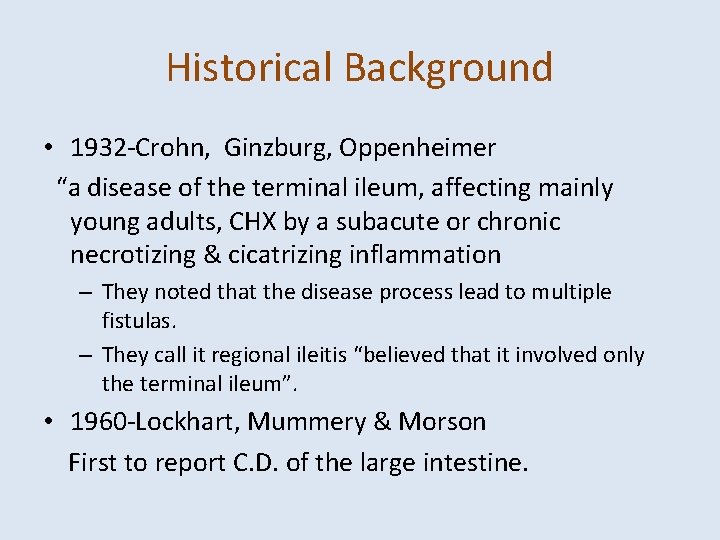

Historical Background • 1932 -Crohn, Ginzburg, Oppenheimer “a disease of the terminal ileum, affecting mainly young adults, CHX by a subacute or chronic necrotizing & cicatrizing inflammation – They noted that the disease process lead to multiple fistulas. – They call it regional ileitis “believed that it involved only the terminal ileum”. • 1960 -Lockhart, Mummery & Morson First to report C. D. of the large intestine.

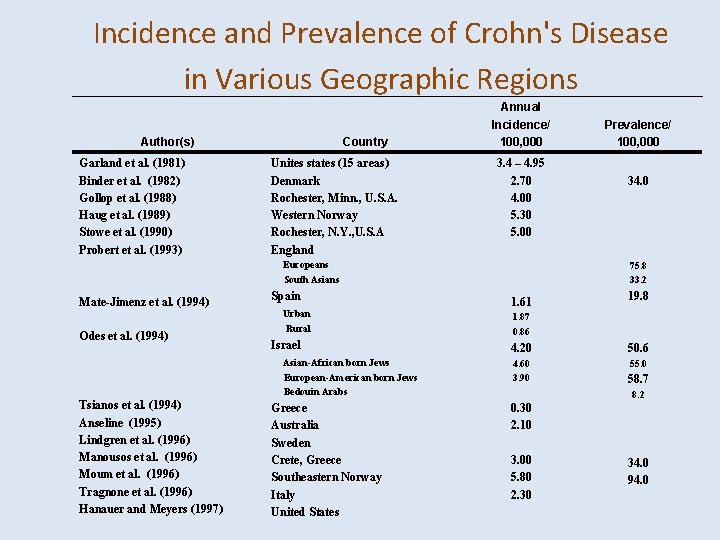

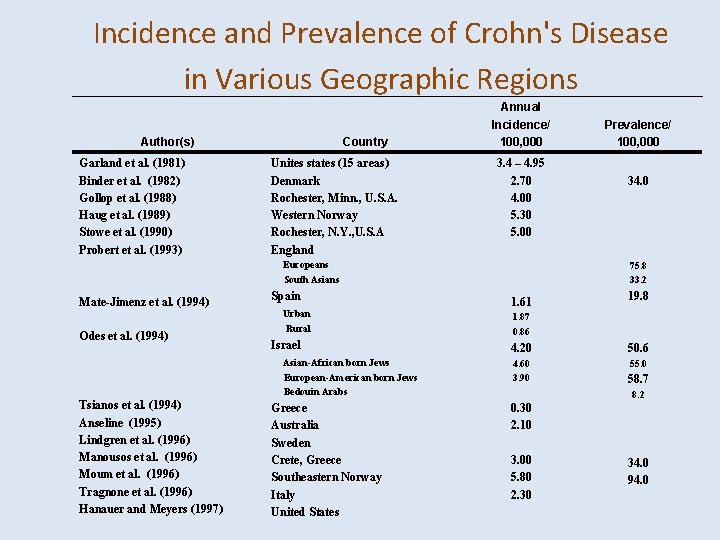

Incidence and Prevalence of Crohn's Disease in Various Geographic Regions Author(s) Garland et al. (1981) Binder et al. (1982) Gollop et al. (1988) Haug et al. (1989) Stowe et al. (1990) Probert et al. (1993) Country Unites states (15 areas) Denmark Rochester, Minn. , U. S. A. Western Norway Rochester, N. Y. , U. S. A England Annual Incidence/ 100, 000 3. 4 – 4. 95 2. 70 4. 00 5. 30 5. 00 Europeans South Asians Mate-Jimenz et al. (1994) Odes et al. (1994) Spain Urban Rural Israel Asian-African born Jews European-American born Jews Bedouin Arabs Tsianos et al. (1994) Anseline (1995) Lindgren et al. (1996) Manousos et al. (1996) Moum et al. (1996) Tragnone et al. (1996) Hanauer and Meyers (1997) Greece Australia Sweden Crete, Greece Southeastern Norway Italy United States Prevalence/ 100, 000 34. 0 75. 8 33. 2 1. 61 19. 8 1. 87 0. 86 4. 20 50. 6 4. 60 3. 90 55. 0 58. 7 8. 2 0. 30 2. 10 3. 00 5. 80 2. 30 34. 0 94. 0

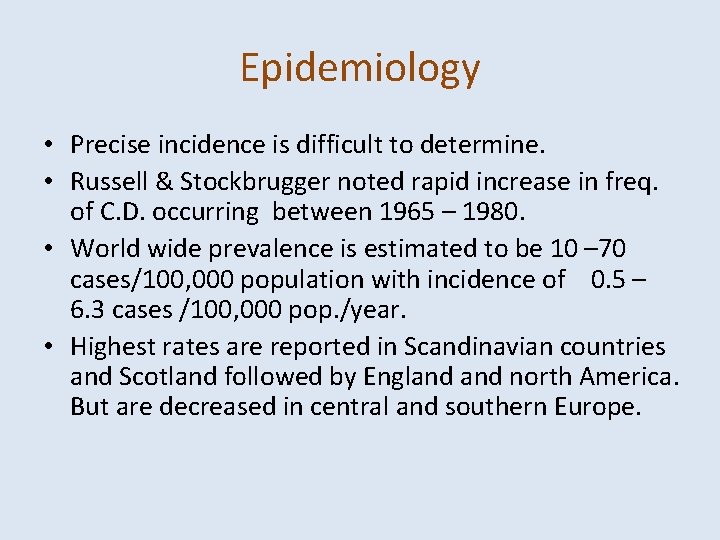

Epidemiology • Precise incidence is difficult to determine. • Russell & Stockbrugger noted rapid increase in freq. of C. D. occurring between 1965 – 1980. • World wide prevalence is estimated to be 10 – 70 cases/100, 000 population with incidence of 0. 5 – 6. 3 cases /100, 000 pop. /year. • Highest rates are reported in Scandinavian countries and Scotland followed by England north America. But are decreased in central and southern Europe.

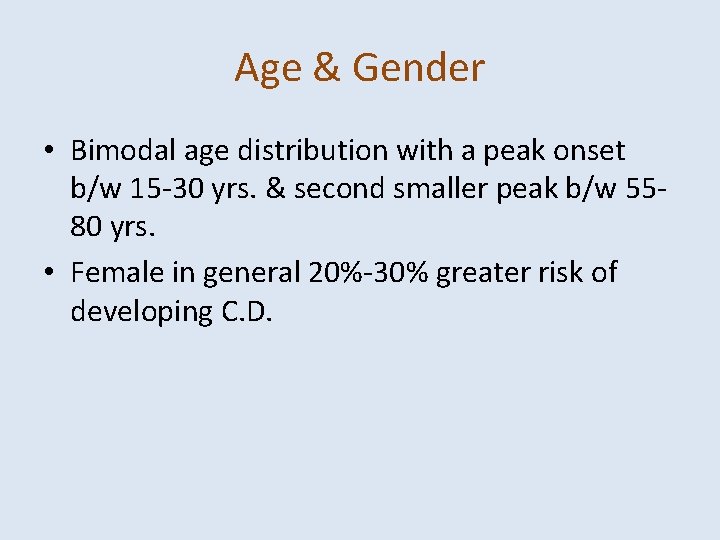

Age & Gender • Bimodal age distribution with a peak onset b/w 15 -30 yrs. & second smaller peak b/w 5580 yrs. • Female in general 20%-30% greater risk of developing C. D.

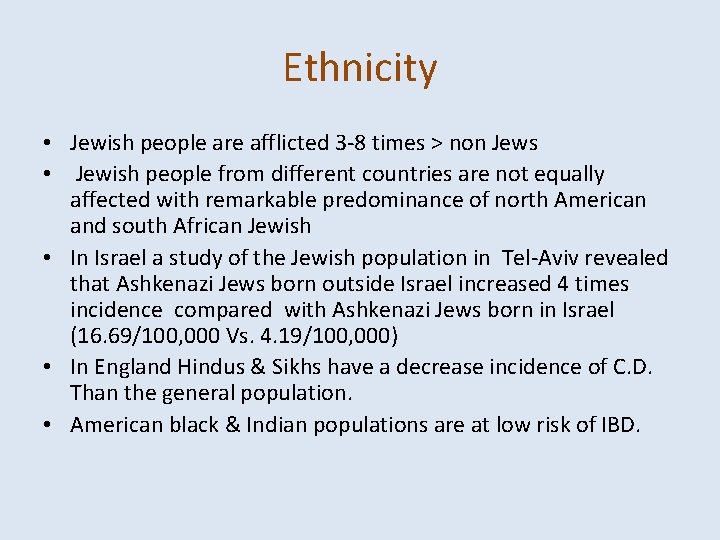

Ethnicity • Jewish people are afflicted 3 -8 times > non Jews • Jewish people from different countries are not equally affected with remarkable predominance of north American and south African Jewish • In Israel a study of the Jewish population in Tel-Aviv revealed that Ashkenazi Jews born outside Israel increased 4 times incidence compared with Ashkenazi Jews born in Israel (16. 69/100, 000 Vs. 4. 19/100, 000) • In England Hindus & Sikhs have a decrease incidence of C. D. Than the general population. • American black & Indian populations are at low risk of IBD.

Etiology & Pathogenesis UNKNOWN We know neither its cause nor its cure

Etiology & Pathogenesis Cont’d Sartor et al. reviewed 3 most recent theories of etiology of C. D. 1. Specific infectious agent 1. mycobact. Para T. B. 2. Paramoxyvirus & measles 3. Listeria monocytogens 2. Defective mucosal barrier resulting in increase exposure to Ags. 3. Abnormal host response to a ubiquitous Ags luminal constituents Dietary Ags.

Other Factors • Family history – 10%-20% increase incidence in close degree relatives – Study in Denmark showed 1 st and 2 nd generation relatives of Pts. With C. D. have 1 -3 folds increase prevalence. – Probert et al. -1 st degree relative of Pt. with C. D. increase risk up to 35 times. – Monozygotic twins > dizygotic twins • Dietary factors – Increase intake of refined sugar and starch – Decrease intake of fresh fruits • Smoking – Oxford study found R. . Of 3. 4 – Increase recurrence rate among smokers • OCP – Use of OCP for 1 -3 years has a R. . Of 2. 5 & 4. 3 > 3 years. – Risk decrease after D/C OCP

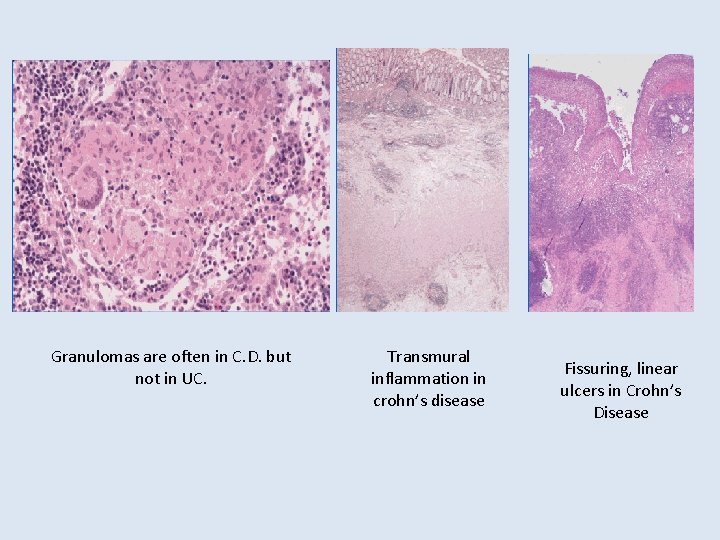

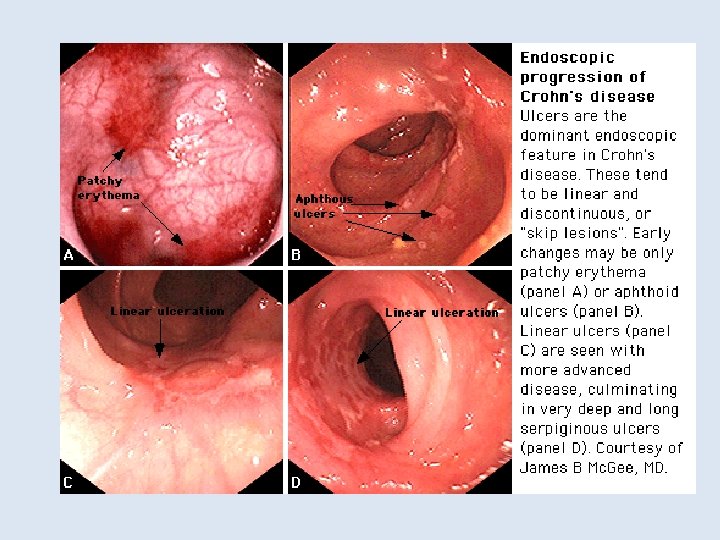

Pathology • C. D. can affect any part of GIT – Ileocecal region(41%-55%) , SI (30%-40%) , colonic (14%26%) – 2/3 of crohn’s colitis pts. have total involvement • Acute or active phase is marked by – – Aphthous mucosal ulcers Lymphoid aggregates Granulomas (2/3 of pts. ) Transmural chronic inflammation with fissures &fistulas • Heeling phase – CHX. By fibrosis with stricture formation &chronic ulcers

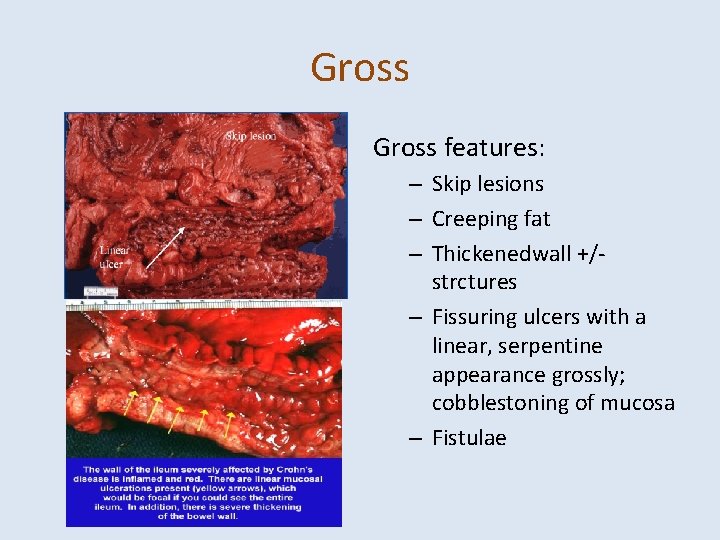

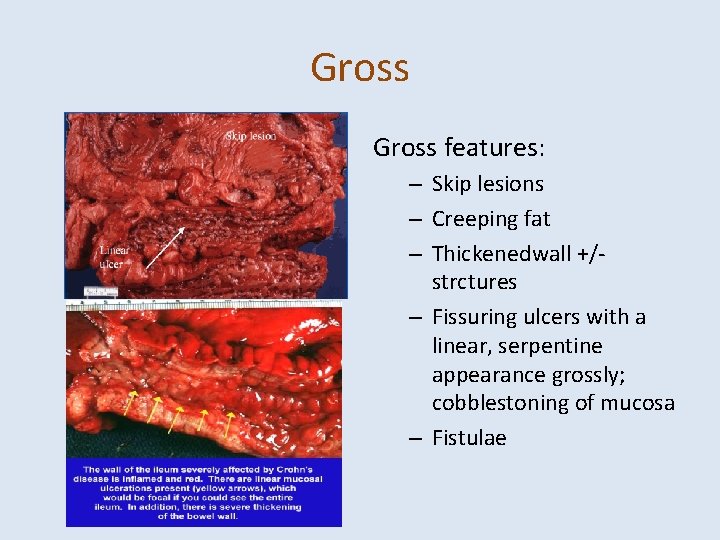

Gross features: – Skip lesions – Creeping fat – Thickenedwall +/strctures – Fissuring ulcers with a linear, serpentine appearance grossly; cobblestoning of mucosa – Fistulae

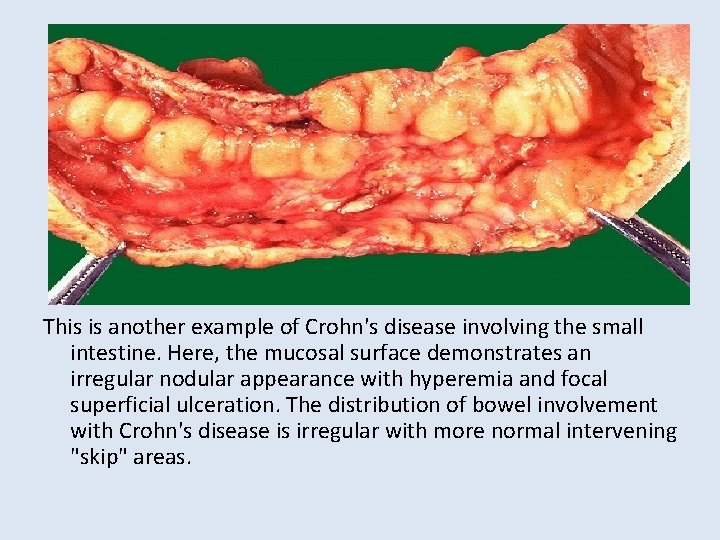

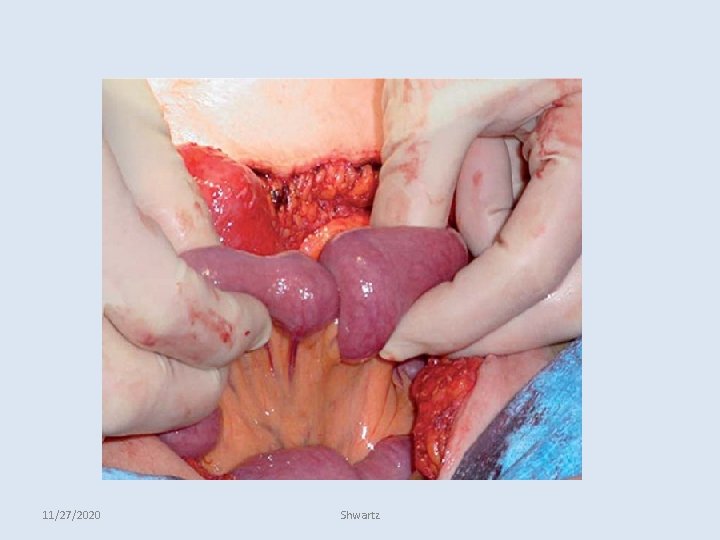

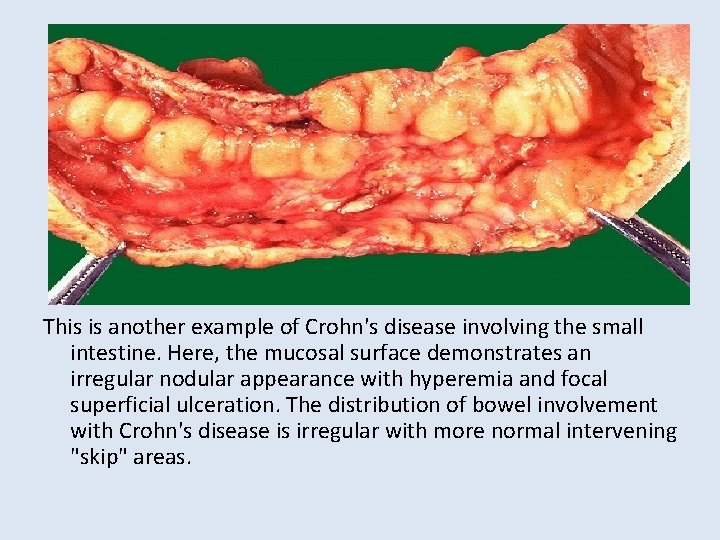

This is another example of Crohn's disease involving the small intestine. Here, the mucosal surface demonstrates an irregular nodular appearance with hyperemia and focal superficial ulceration. The distribution of bowel involvement with Crohn's disease is irregular with more normal intervening "skip" areas.

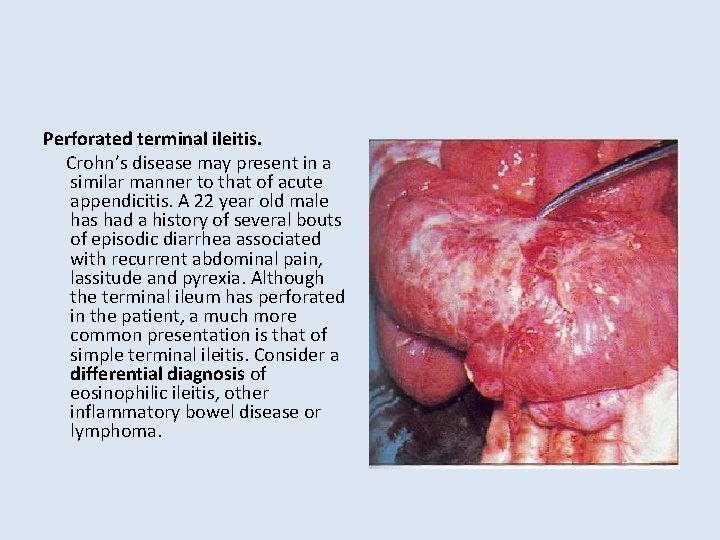

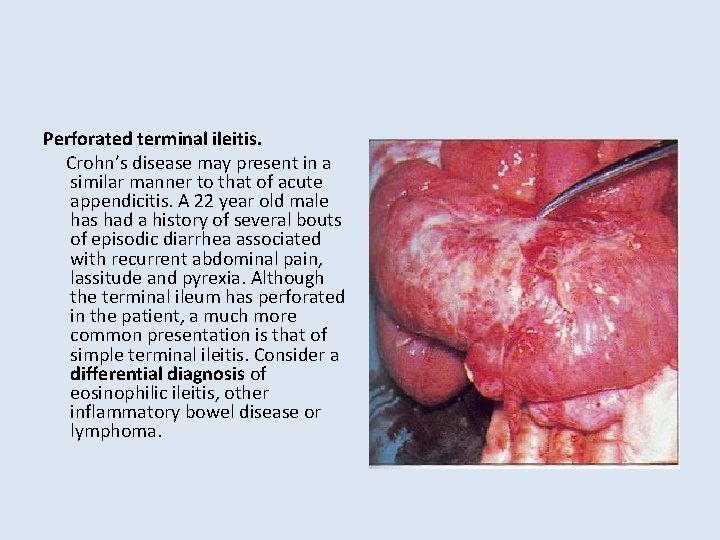

Perforated terminal ileitis. Crohn’s disease may present in a similar manner to that of acute appendicitis. A 22 year old male has had a history of several bouts of episodic diarrhea associated with recurrent abdominal pain, lassitude and pyrexia. Although the terminal ileum has perforated in the patient, a much more common presentation is that of simple terminal ileitis. Consider a differential diagnosis of eosinophilic ileitis, other inflammatory bowel disease or lymphoma.

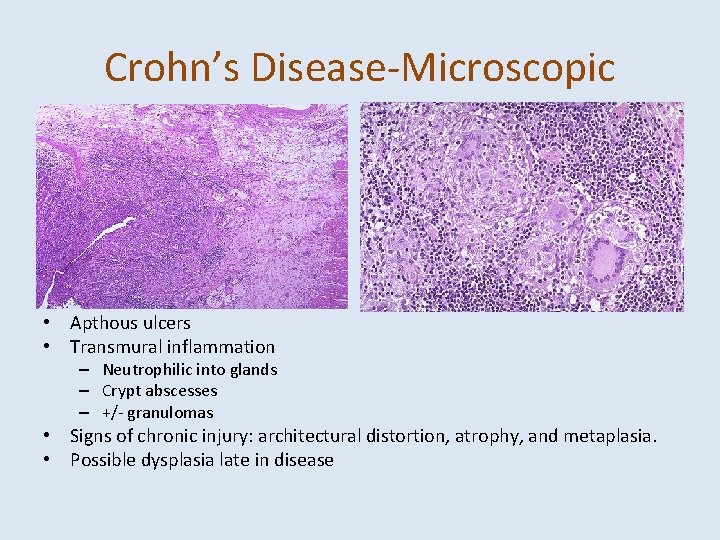

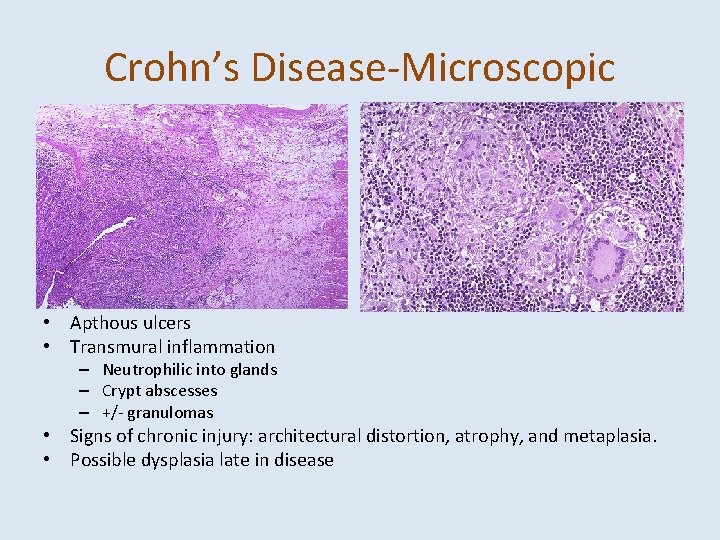

Crohn’s Disease-Microscopic • Apthous ulcers • Transmural inflammation – Neutrophilic into glands – Crypt abscesses – +/- granulomas • Signs of chronic injury: architectural distortion, atrophy, and metaplasia. • Possible dysplasia late in disease

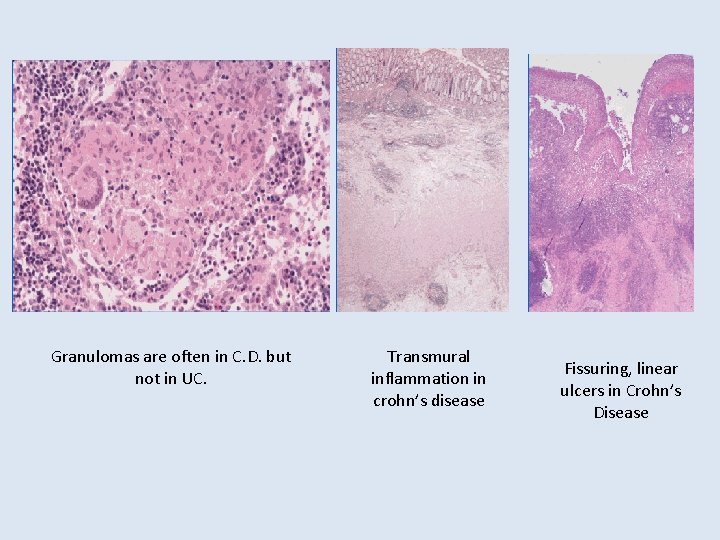

Granulomas are often in C. D. but not in UC. Transmural inflammation in crohn’s disease Fissuring, linear ulcers in Crohn’s Disease

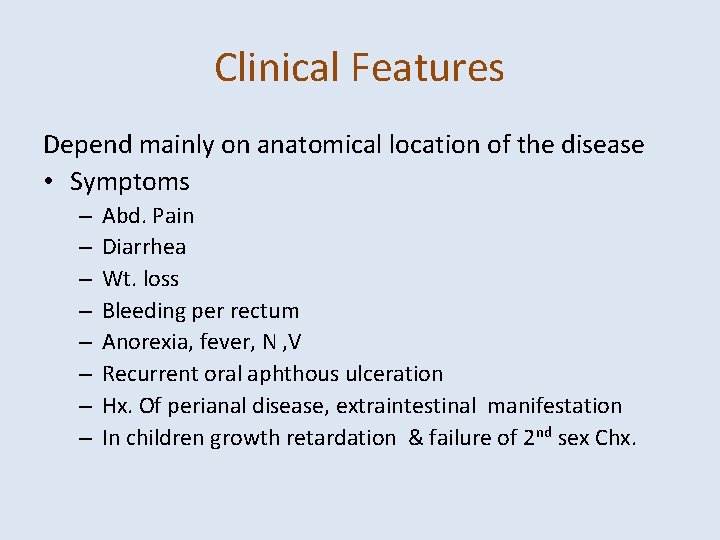

Clinical Features Depend mainly on anatomical location of the disease • Symptoms – – – – Abd. Pain Diarrhea Wt. loss Bleeding per rectum Anorexia, fever, N , V Recurrent oral aphthous ulceration Hx. Of perianal disease, extraintestinal manifestation In children growth retardation & failure of 2 nd sex Chx.

Clinical Features-cont’d • Signs – – – – Pallor Cachexia Clubbing Abdominal mass or tenderness ? Evidence of obstruction Anemia Hypoproteinemia • Exacerbating factors – – Intercurrent infection (URTI or enteric) Cigg. Smoking NSAIDs. ? Stress & psychological predisposition

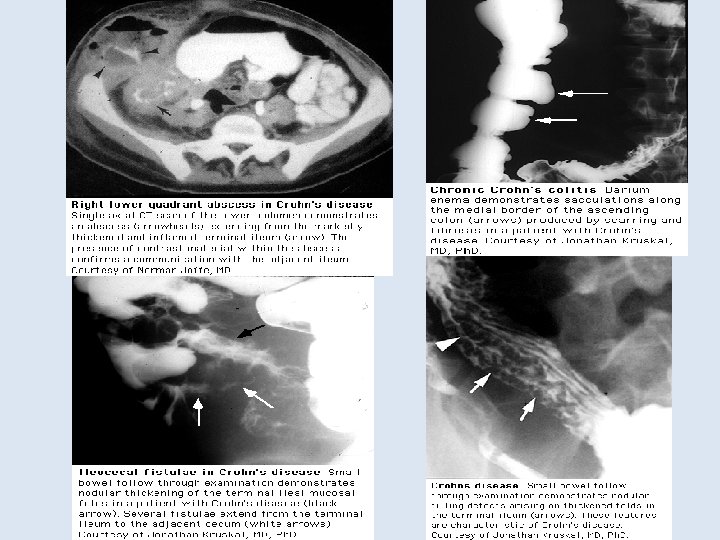

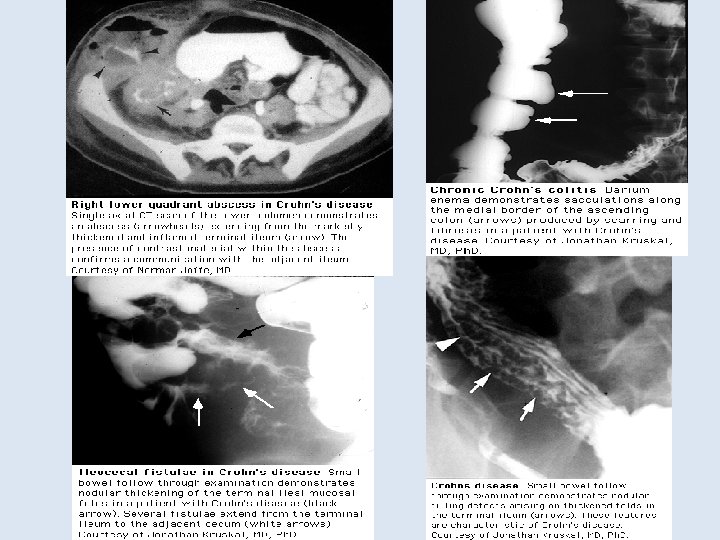

Dx. • The onset of C. D. is nearly always obscure & poorly defined thus, delayed diagnosis • In only 30% of pts. Dx. is made within one year of onset of Sx. • Dx. Is usually made during an acute exacerbation • Hx. & ph. • Radiology – Contrast radiography is essential for DDx. & to determine the severity of the disease – Indications include recurrence of Sx. After surgery & pts. With progressive disease requiring surgical Rx. or change in his medical plan. – Barium studies. – CT scan------ masses & abcesses. – ERCP ----- hepatobiliary involv. (sclerosing cholangitis).

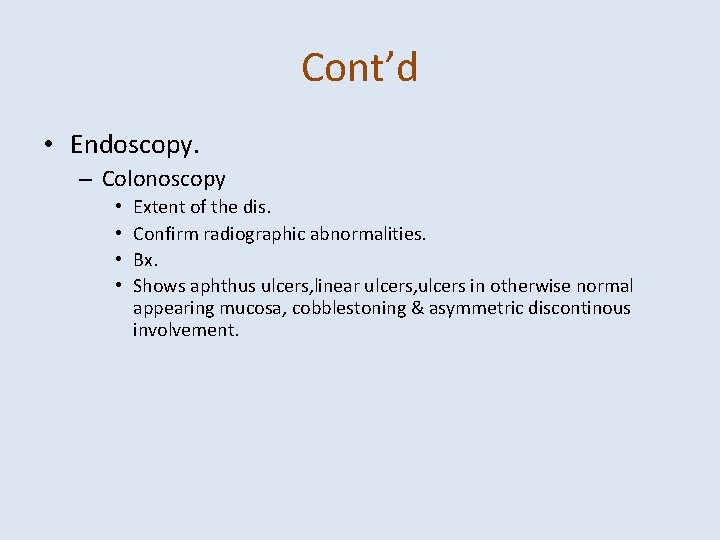

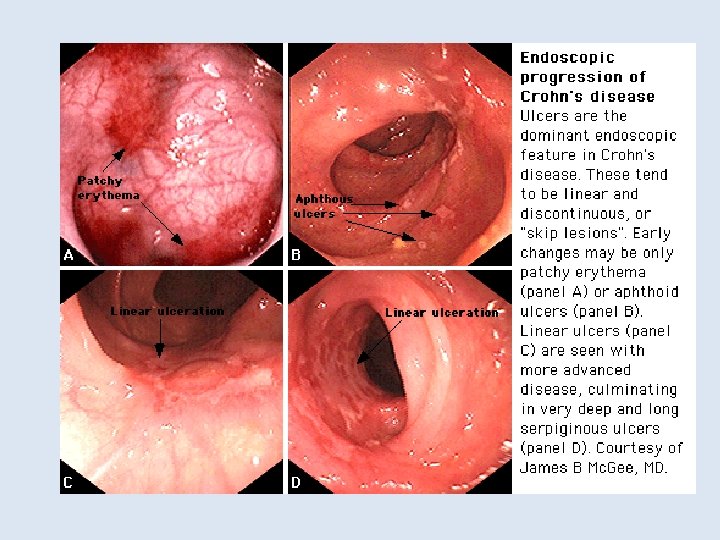

Cont’d • Endoscopy. – Colonoscopy • • Extent of the dis. Confirm radiographic abnormalities. Bx. Shows aphthus ulcers, linear ulcers, ulcers in otherwise normal appearing mucosa, cobblestoning & asymmetric discontinous involvement.

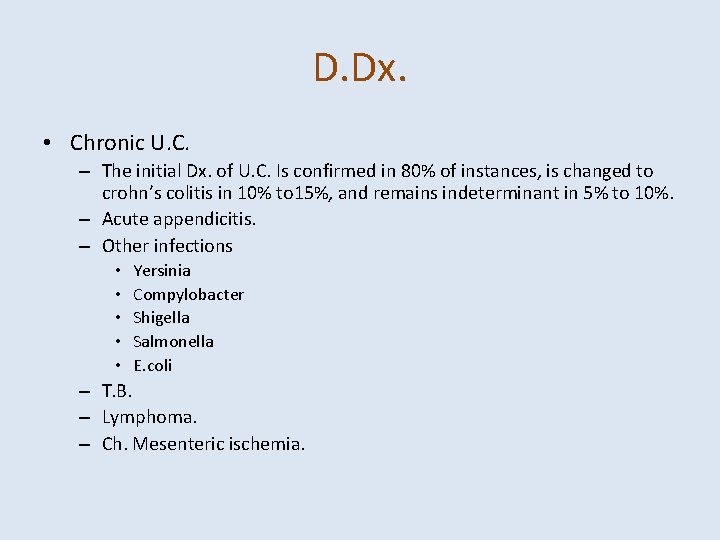

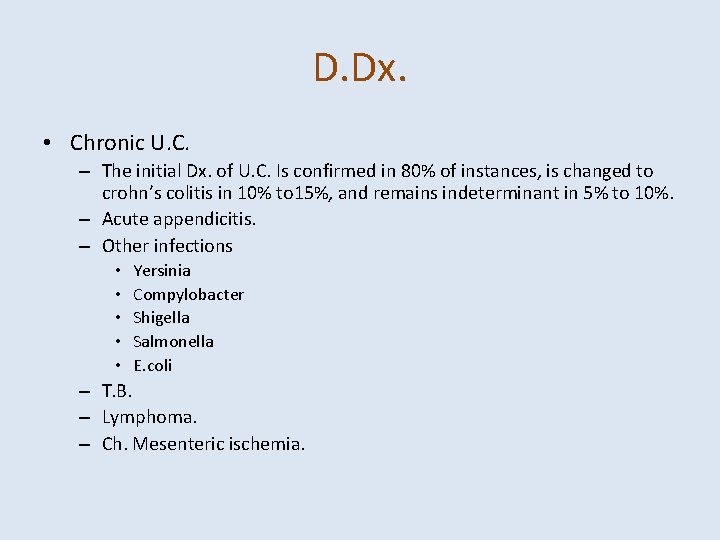

D. Dx. • Chronic U. C. – The initial Dx. of U. C. Is confirmed in 80% of instances, is changed to crohn’s colitis in 10% to 15%, and remains indeterminant in 5% to 10%. – Acute appendicitis. – Other infections • • • Yersinia Compylobacter Shigella Salmonella E. coli – T. B. – Lymphoma. – Ch. Mesenteric ischemia.

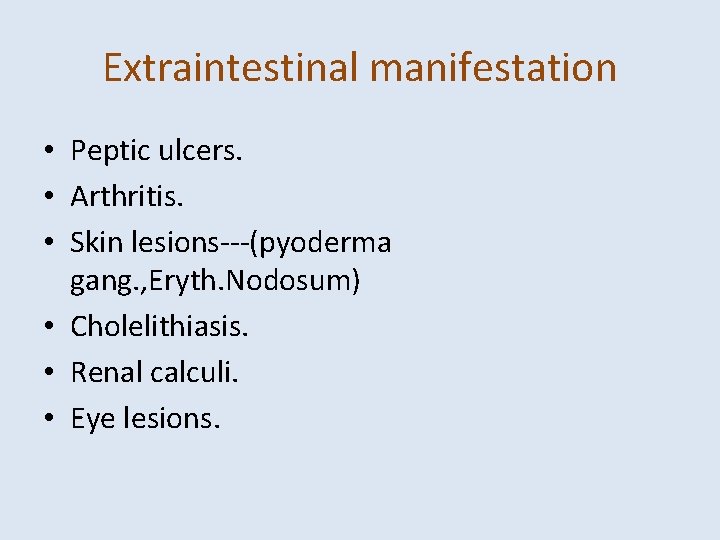

Extraintestinal manifestation • Peptic ulcers. • Arthritis. • Skin lesions---(pyoderma gang. , Eryth. Nodosum) • Cholelithiasis. • Renal calculi. • Eye lesions.

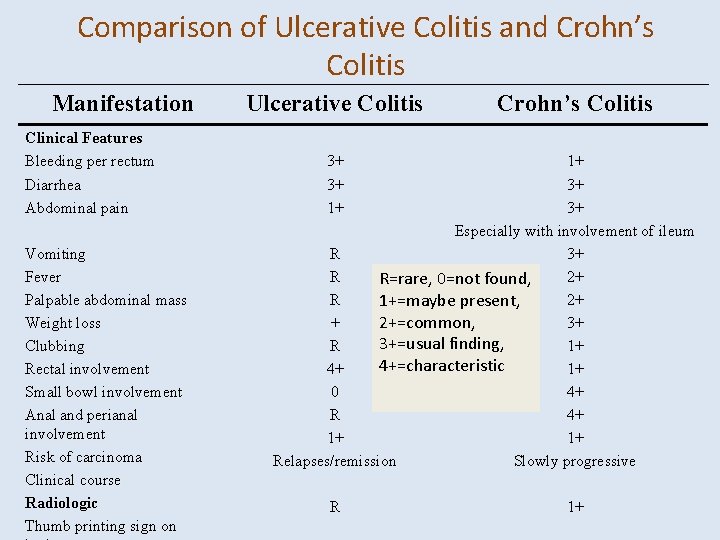

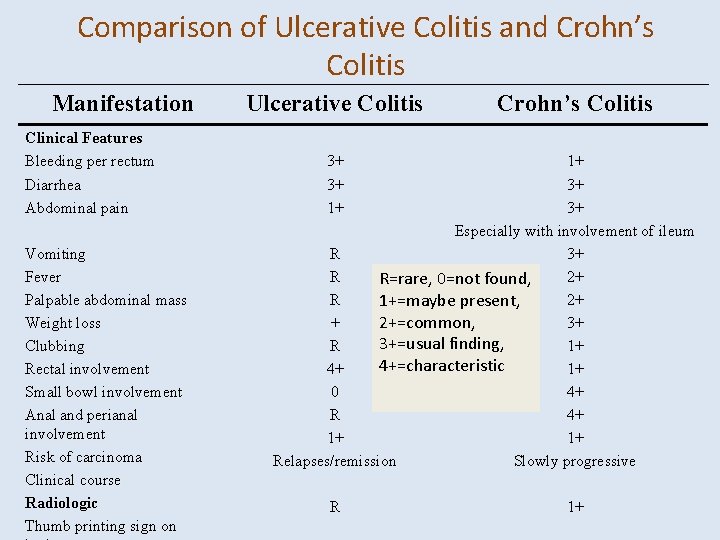

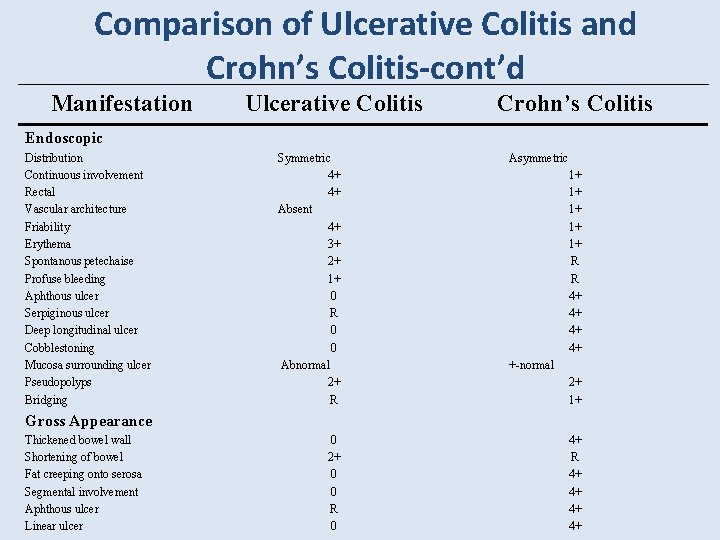

Comparison of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Colitis Manifestation Clinical Features Bleeding per rectum Diarrhea Abdominal pain Vomiting Fever Palpable abdominal mass Weight loss Clubbing Rectal involvement Small bowl involvement Anal and perianal involvement Risk of carcinoma Clinical course Radiologic Thumb printing sign on Ulcerative Colitis Crohn’s Colitis 3+ 3+ 1+ 1+ 3+ 3+ Especially with involvement of ileum R 3+ R 2+ R=rare, 0=not found, R 2+ 1+=maybe present, 2+=common, + 3+ 3+=usual finding, R 1+ 4+=characteristic 4+ 1+ 0 4+ R 4+ 1+ 1+ Relapses/remission Slowly progressive R 1+

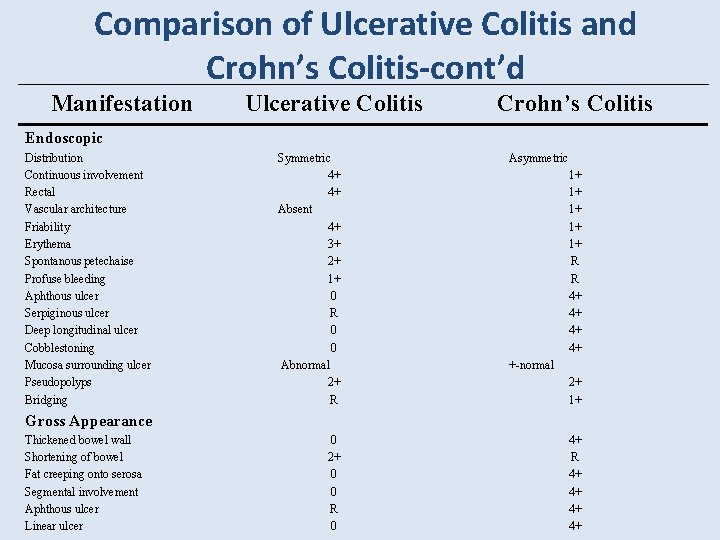

Comparison of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Colitis-cont’d Manifestation Ulcerative Colitis Crohn’s Colitis Endoscopic Distribution Continuous involvement Rectal Vascular architecture Friability Erythema Spontanous petechaise Profuse bleeding Aphthous ulcer Serpiginous ulcer Deep longitudinal ulcer Cobblestoning Mucosa surrounding ulcer Pseudopolyps Bridging Symmetric 4+ 4+ Absent 4+ 3+ 2+ 1+ 0 R 0 0 Abnormal 2+ R Asymmetric 1+ 1+ 1+ R R 4+ 4+ +-normal 2+ 1+ 0 2+ 0 0 R 0 4+ R 4+ 4+ Gross Appearance Thickened bowel wall Shortening of bowel Fat creeping onto serosa Segmental involvement Aphthous ulcer Linear ulcer

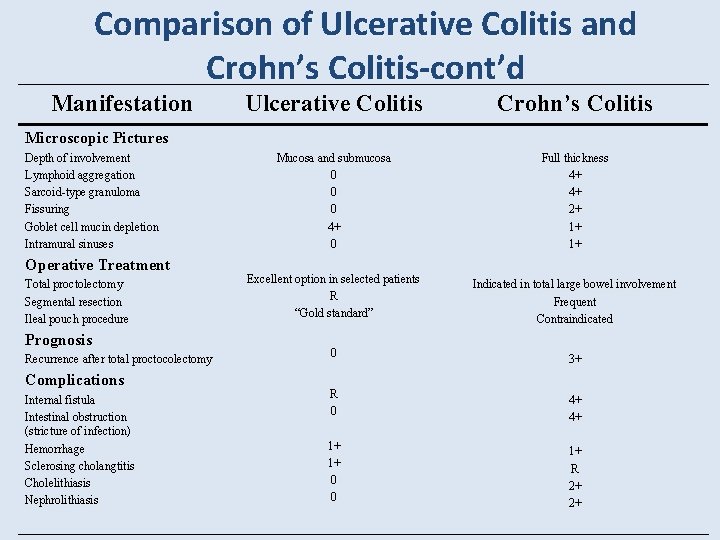

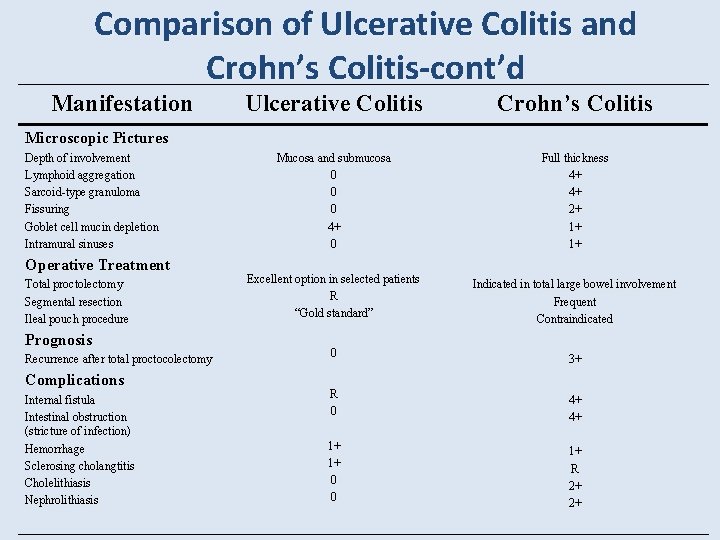

Comparison of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Colitis-cont’d Manifestation Ulcerative Colitis Crohn’s Colitis Mucosa and submucosa 0 0 0 4+ 0 Full thickness 4+ 4+ 2+ 1+ 1+ Excellent option in selected patients R “Gold standard” Indicated in total large bowel involvement Frequent Contraindicated 0 3+ R 0 4+ 4+ 1+ 1+ 0 0 1+ R 2+ 2+ Microscopic Pictures Depth of involvement Lymphoid aggregation Sarcoid-type granuloma Fissuring Goblet cell mucin depletion Intramural sinuses Operative Treatment Total proctolectomy Segmental resection Ileal pouch procedure Prognosis Recurrence after total proctocolectomy Complications Internal fistula Intestinal obstruction (stricture of infection) Hemorrhage Sclerosing cholangtitis Cholelithiasis Nephrolithiasis

Common small and large intestinal surgical diseases Part II Khayal Al. Khayal, MD, FRCSC Assistant Professor of Surgery Consultant Colorectal Surgeon 2010 11/27/2020 Shwartz

Colorectal cancer 11/27/2020 Shwartz

Outline • • • Definitions Polyps Basics of colorectal cancer Surgery Staging

Perspective

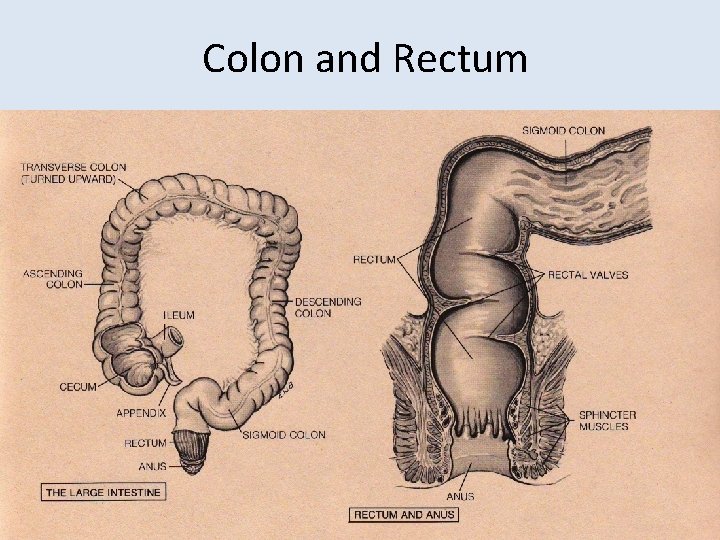

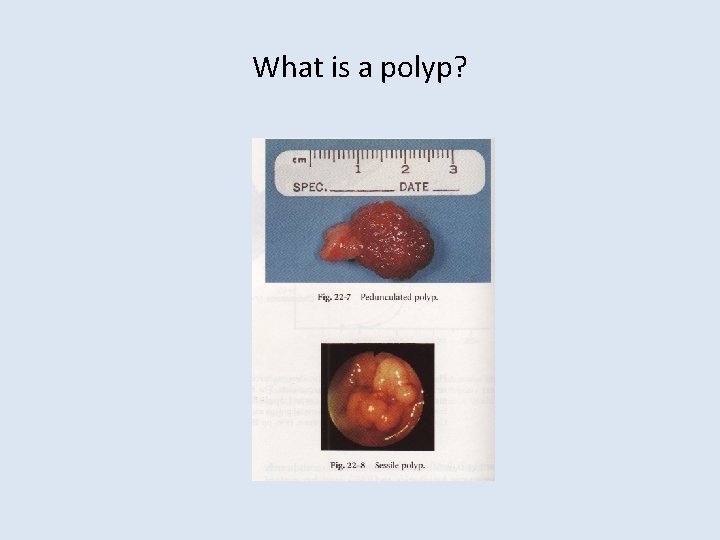

Definitions • • Colon = large bowel = large intestine Rectum - terminal portion of the colon Polyp - benign growth; not invasive Adenoma - type of polyp Cancer - malignant growth; invasive Stage - where the cancer is growing Primary - the original tumour, where it started Metastases - where the tumour has spread to

Cancer A cancer cell : • is immortal ( lives forever) • multiplies uncontrollably • can live on its own without neighbors • can live in other parts of the body

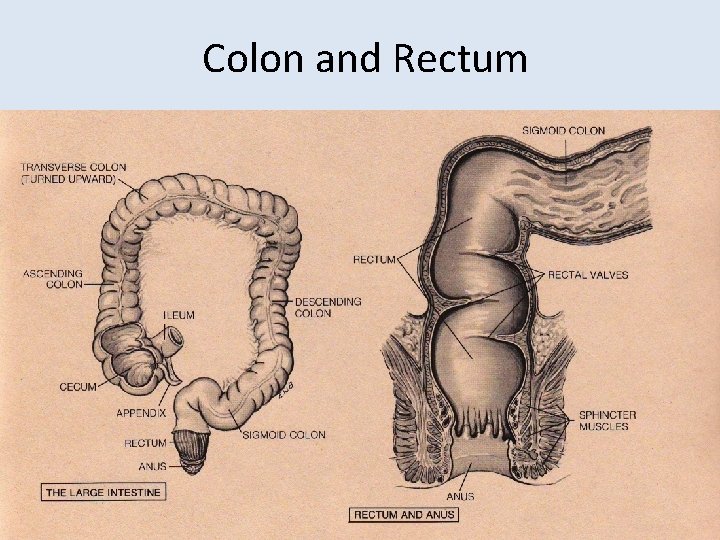

Colon and Rectum

Colorectal Cancer • Most cancers are acquired some are inherited • Almost all cancers begin as a benign polyp or adenoma • Only a tiny percentage of adenomas become cancers

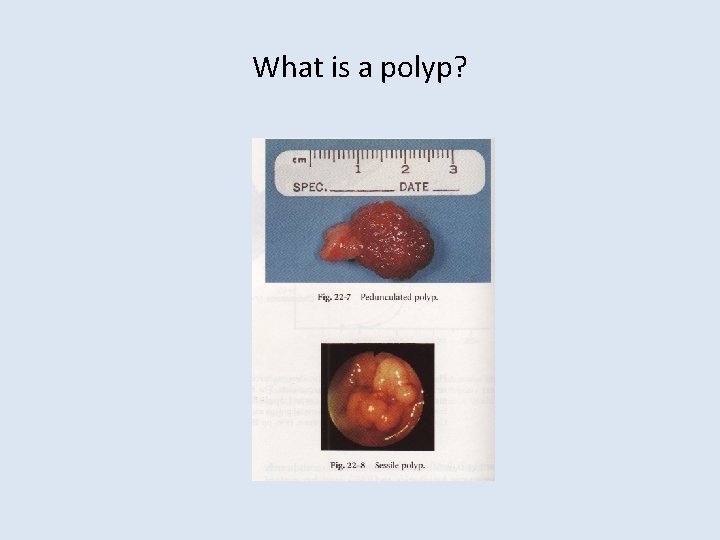

What is a polyp?

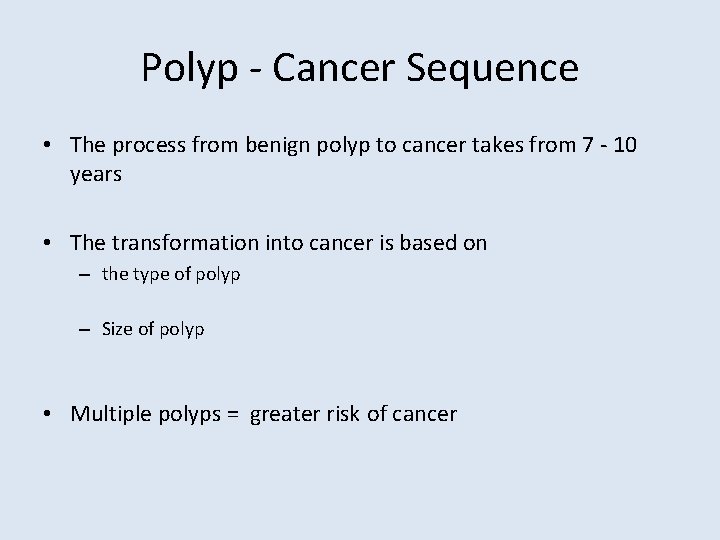

Polyp - Cancer Sequence • The process from benign polyp to cancer takes from 7 - 10 years • The transformation into cancer is based on – the type of polyp – Size of polyp • Multiple polyps = greater risk of cancer

11/27/2020 Shwartz

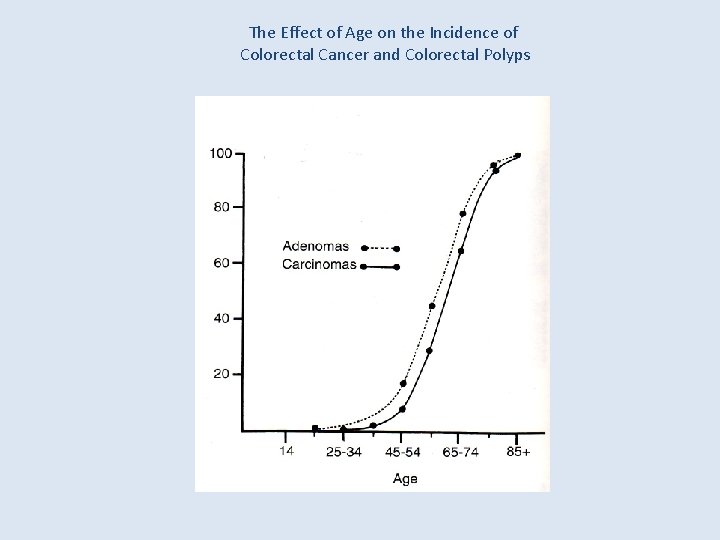

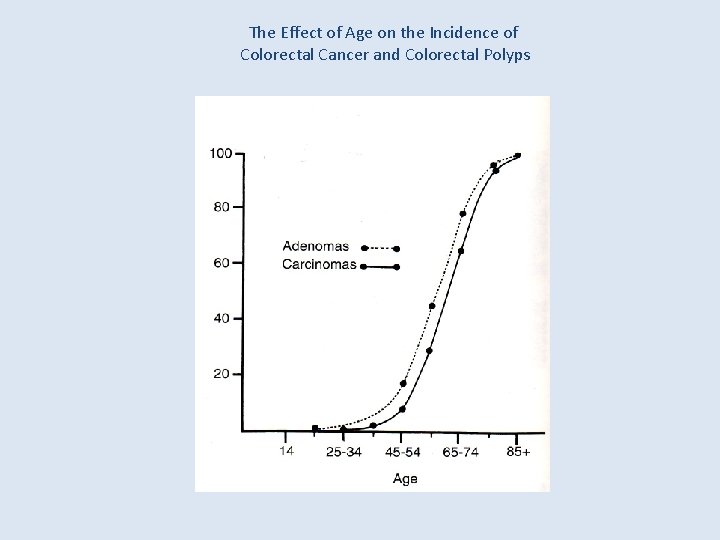

The Effect of Age on the Incidence of Colorectal Cancer and Colorectal Polyps

Removing polyps prevents cancer Colonoscopy

Colorectal Carcinoma Classification Adenocarcinoma 95% Carcinoid Lymphoma Sarcoma Squamous cell carcinoma

Epidemiology • 3 th most common malignancy worldwide. • 1 st most common in Saudi males. • second to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death • 21, 500 new cases, 8900 will die (2008) • risk of CRC – women 1/16 , men 1/14 • peek incidence in 7 th decade but it can occur at any age

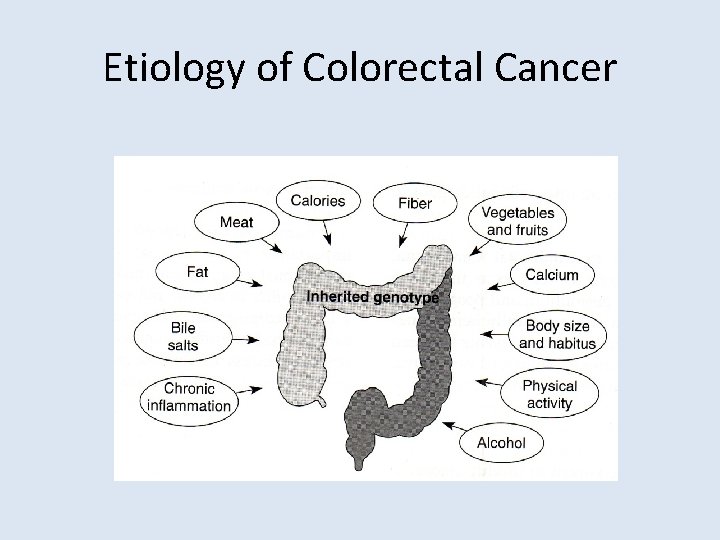

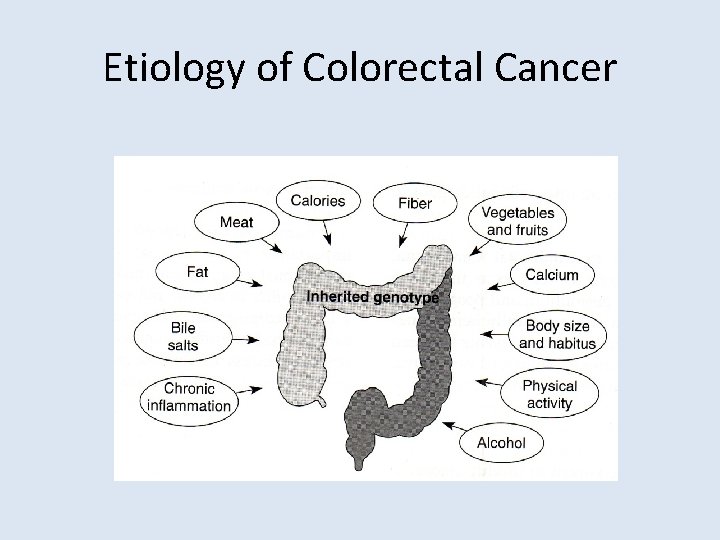

Etiology of Colorectal Cancer

Risk Factors 1. Genetics, Family history • • • Personal history One first degree family member doubles risk Hereditary colorectal cancer syndomes 2. Polyps 3. Inflammatory bowel disease 4. Other • Diet, nutrients, smoking, ETOH

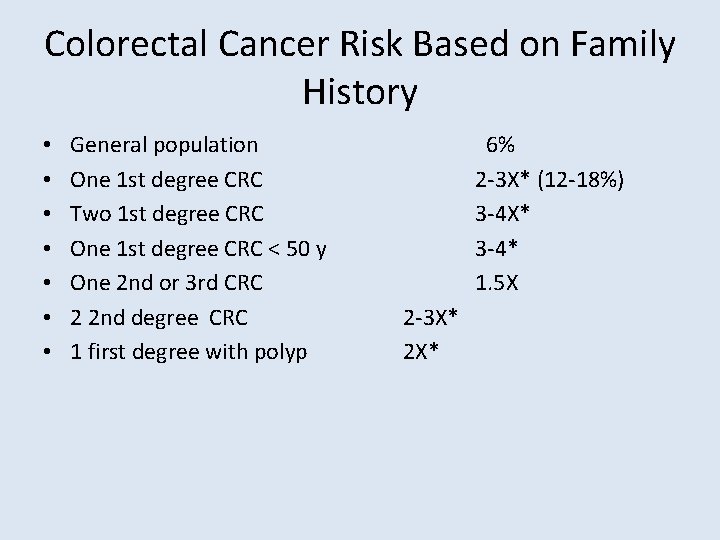

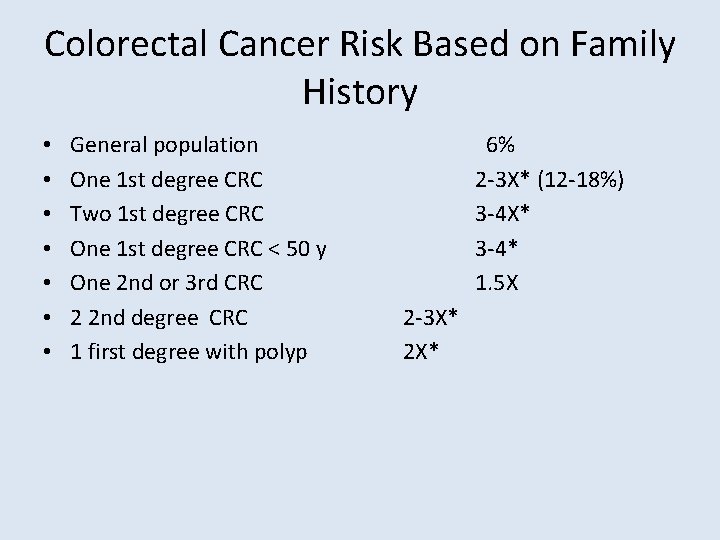

Colorectal Cancer Risk Based on Family History • • General population One 1 st degree CRC Two 1 st degree CRC One 1 st degree CRC < 50 y One 2 nd or 3 rd CRC 2 2 nd degree CRC 1 first degree with polyp 6% 2 -3 X* (12 -18%) 3 -4 X* 3 -4* 1. 5 X 2 -3 X* 2 X*

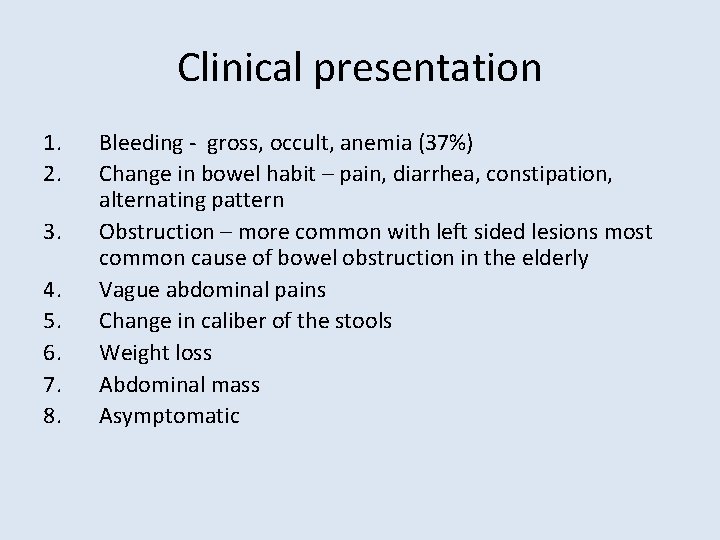

Clinical presentation 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Bleeding - gross, occult, anemia (37%) Change in bowel habit – pain, diarrhea, constipation, alternating pattern Obstruction – more common with left sided lesions most common cause of bowel obstruction in the elderly Vague abdominal pains Change in caliber of the stools Weight loss Abdominal mass Asymptomatic

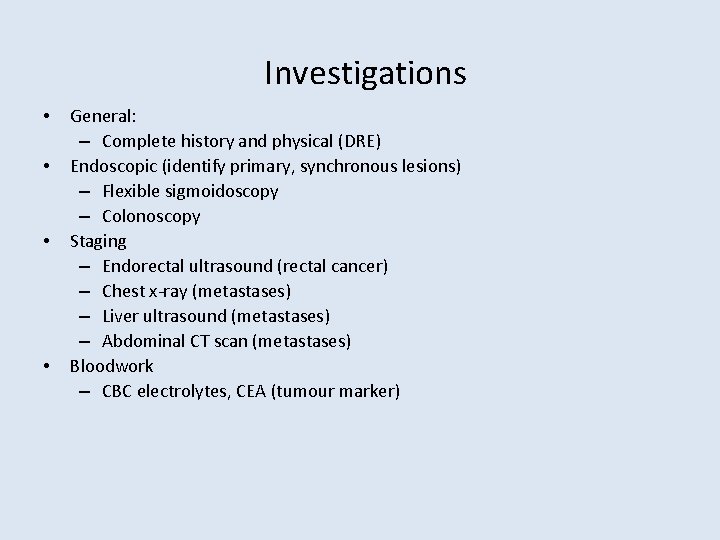

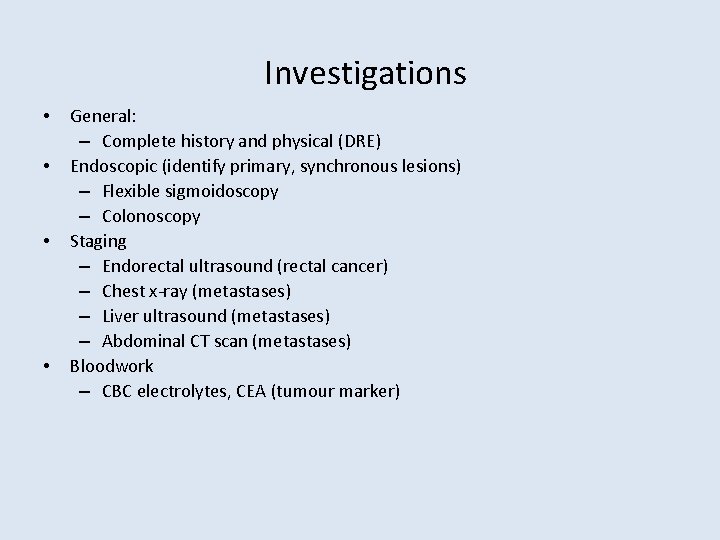

Investigations • • General: – Complete history and physical (DRE) Endoscopic (identify primary, synchronous lesions) – Flexible sigmoidoscopy – Colonoscopy Staging – Endorectal ultrasound (rectal cancer) – Chest x-ray (metastases) – Liver ultrasound (metastases) – Abdominal CT scan (metastases) Bloodwork – CBC electrolytes, CEA (tumour marker)

11/27/2020 Shwartz

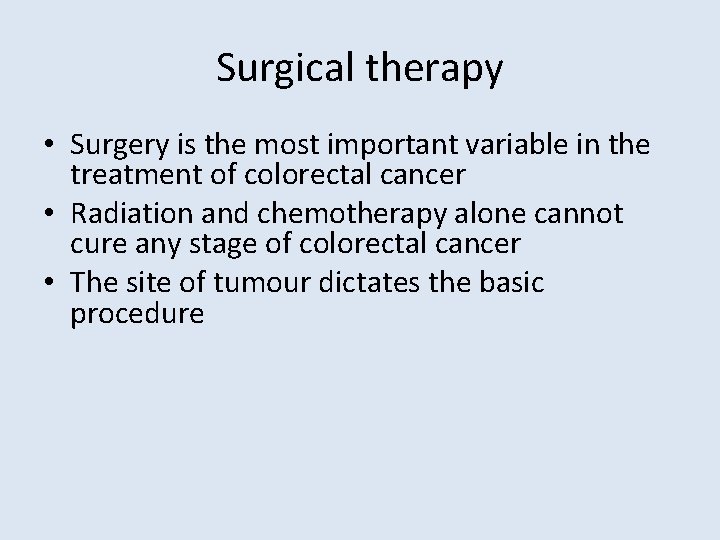

Surgical therapy • Surgery is the most important variable in the treatment of colorectal cancer • Radiation and chemotherapy alone cannot cure any stage of colorectal cancer • The site of tumour dictates the basic procedure

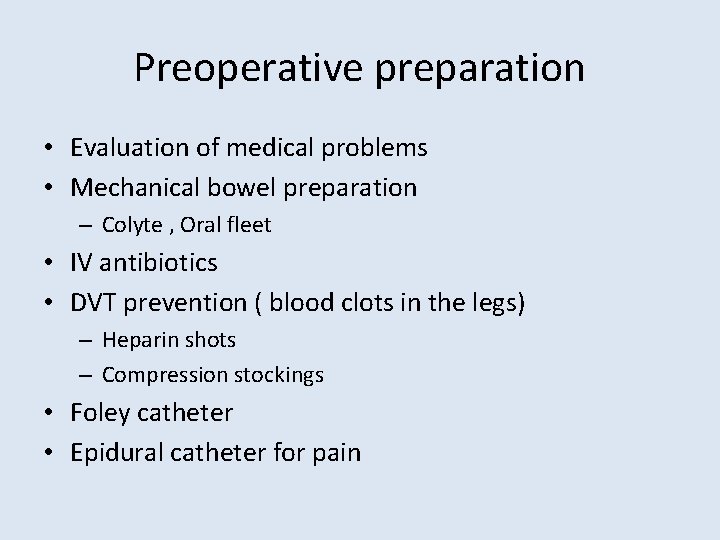

Preoperative preparation • Evaluation of medical problems • Mechanical bowel preparation – Colyte , Oral fleet • IV antibiotics • DVT prevention ( blood clots in the legs) – Heparin shots – Compression stockings • Foley catheter • Epidural catheter for pain

Principles of Surgery • Examine the entire abdomen • Remove the appropriate segment of the colon with adequate margins • Remove the corresponding lymph nodes • Open vs laparoscopic approach

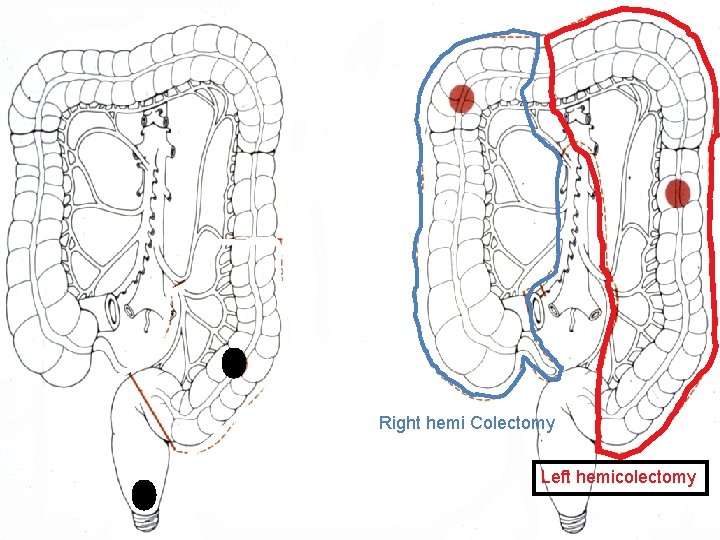

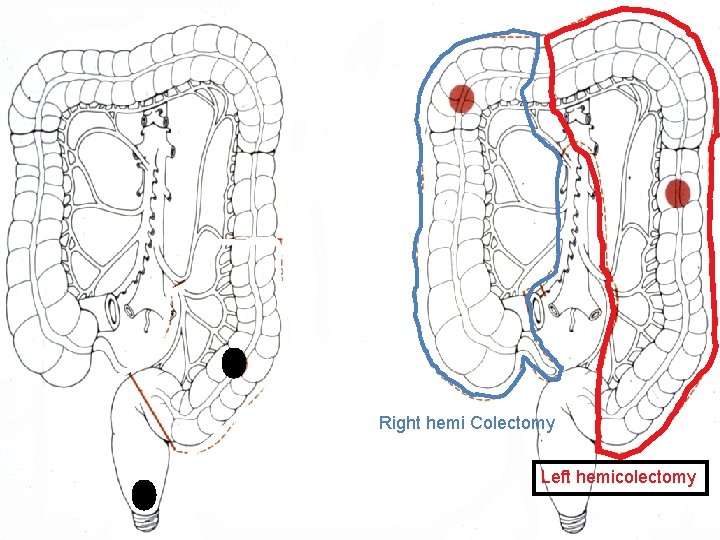

Right hemi Colectomy Abdominoperineal resection Left hemicolectomy

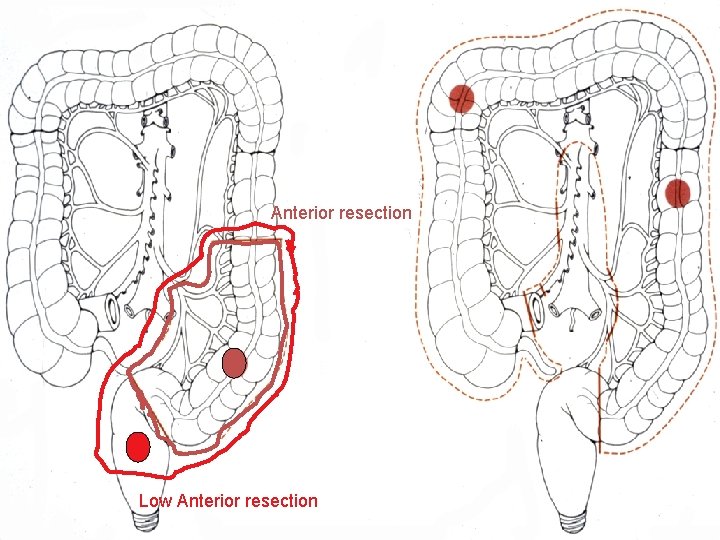

Anterior resection Subtotal Colectomy Low Anterior resection

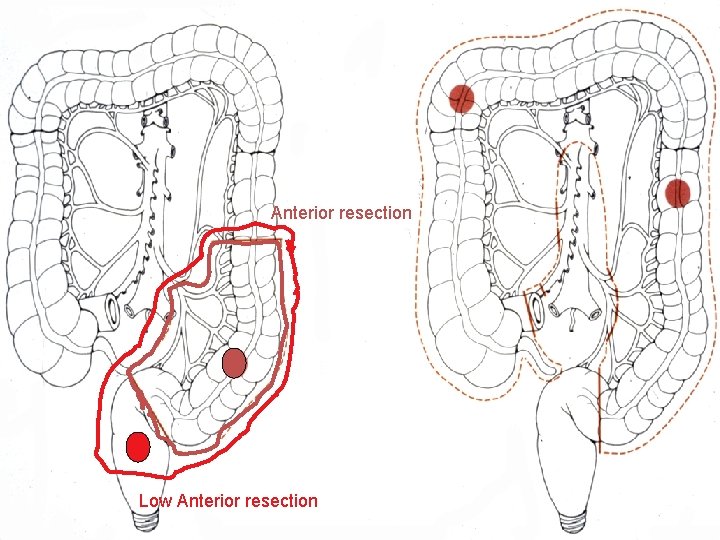

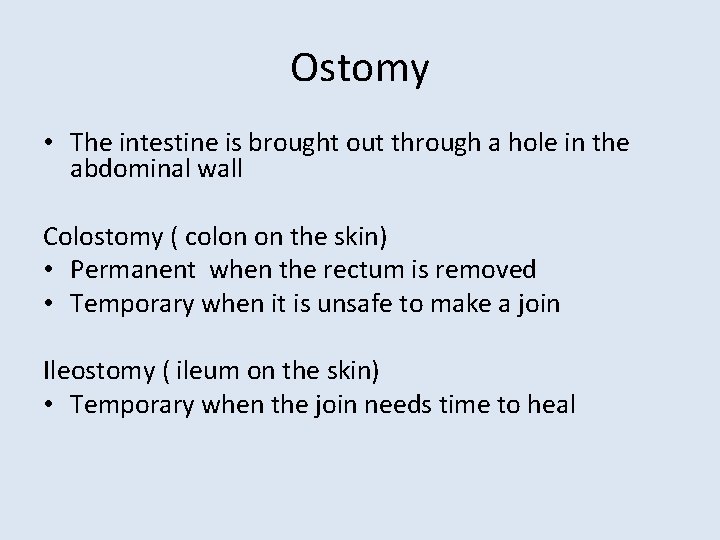

Ostomy • The intestine is brought out through a hole in the abdominal wall Colostomy ( colon on the skin) • Permanent when the rectum is removed • Temporary when it is unsafe to make a join Ileostomy ( ileum on the skin) • Temporary when the join needs time to heal

11/27/2020 Shwartz

Recovery • Surgery 2 to 4 hours • Hospital stay 4 to 10 days – IV, urine catheter, compression stockings, intravenous pain killers, blood thinner – Discharge when ambulating, eating, bowel function, good pain control • Recovery 4 weeks

Follow up • Office visit every 3 months for two years then every 6 months for 3 years • Regular blood work (CEA) • Colonoscopy at year 1 and 4 and every 5 years • CT scan yearly

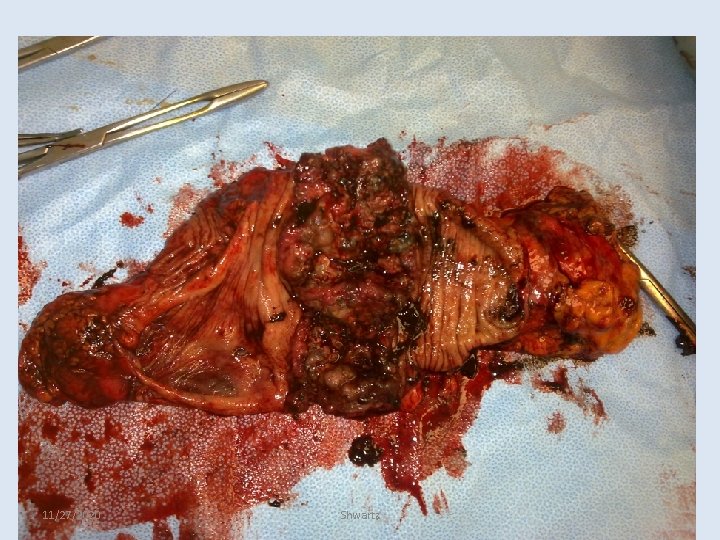

Pathology of Colorectal Cancer • Macroscopic: • Microscopic (differentiation): – Well – Moderately – Poorly • Lymph node involvement

Staging ( Where is it Growing? ) 1. How far into the wall has it grown? T stage • Tis – invasion of mucosa only • T 1 – Invasion of submucosa • T 2 – Invasion of muscularis propria • T 3 – Full thickness/perirectal fat • T 4 – Invasion into adjacent organs

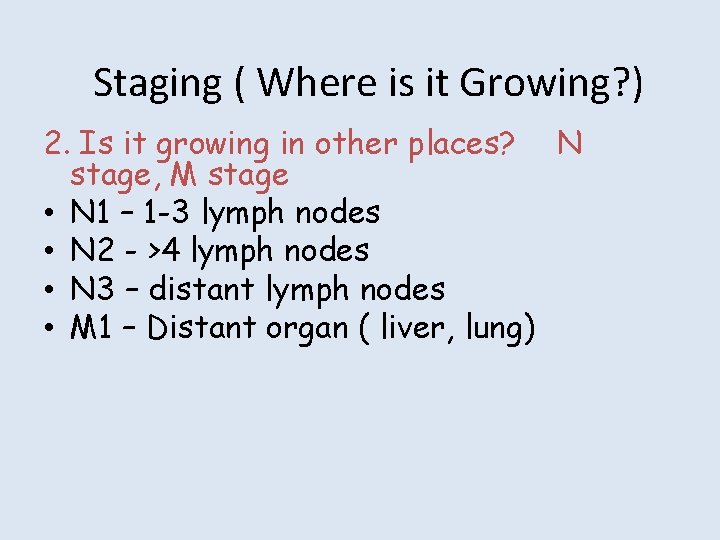

Staging ( Where is it Growing? ) 2. Is it growing in other places? N stage, M stage • N 1 – 1 -3 lymph nodes • N 2 - >4 lymph nodes • N 3 – distant lymph nodes • M 1 – Distant organ ( liver, lung)

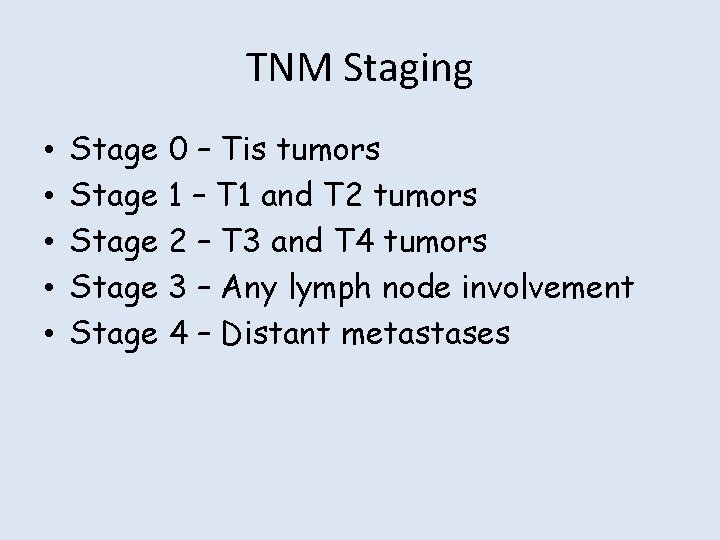

TNM Staging • • • Stage 0 – Tis tumors Stage 1 – T 1 and T 2 tumors Stage 2 – T 3 and T 4 tumors Stage 3 – Any lymph node involvement Stage 4 – Distant metastases

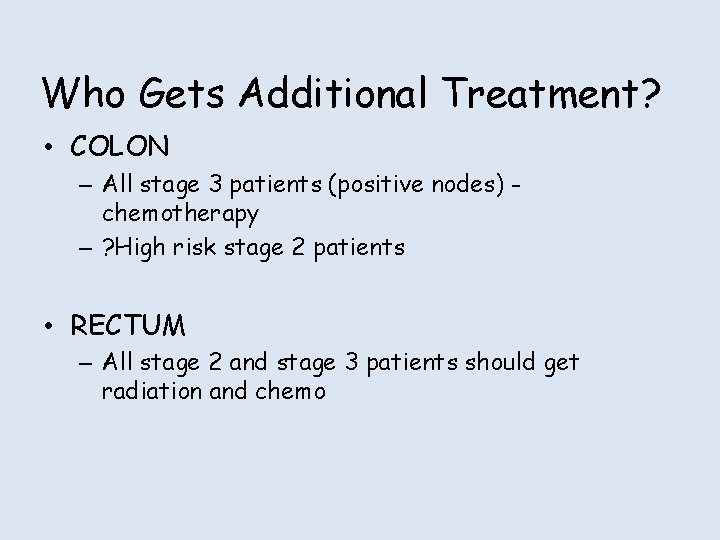

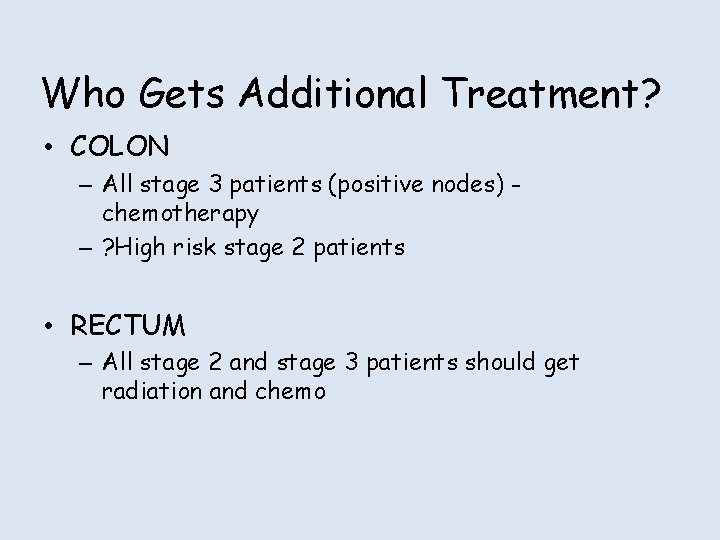

Who Gets Additional Treatment? • COLON – All stage 3 patients (positive nodes) chemotherapy – ? High risk stage 2 patients • RECTUM – All stage 2 and stage 3 patients should get radiation and chemo

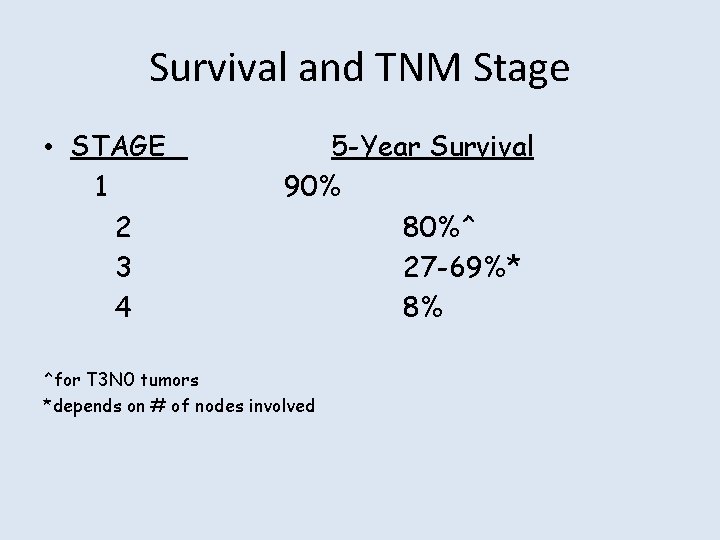

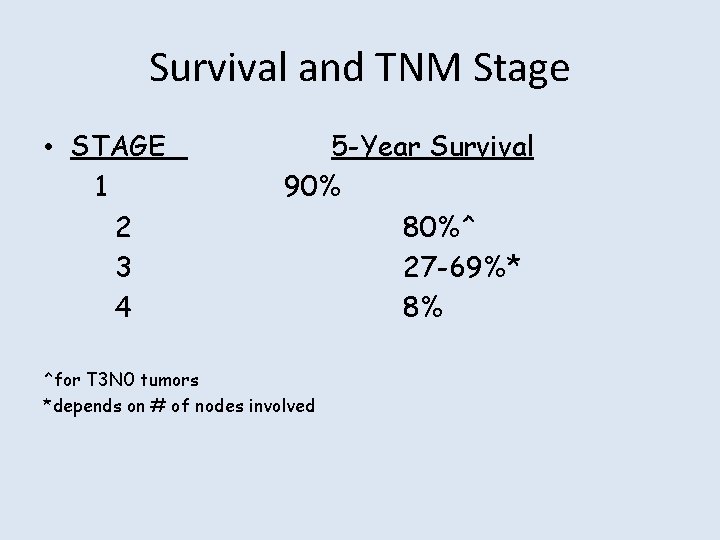

Survival and TNM Stage • STAGE 1 2 3 4 5 -Year Survival 90% 80%^ 27 -69%* 8% ^for T 3 N 0 tumors *depends on # of nodes involved

Summary 1. Common Cancer 2. Can be prevented through screening and resection of polyps 3. Surgery is the primary treatment 4. Slow but steady improvement in survival