The Making of Economic Policy A TransactionCost Politics

- Slides: 93

The Making of Economic Policy: A Transaction-Cost Politics Perspective Avinash K. Dixit MIT Press, 1996

Motivation • The reality of most countries’ trade policies is so blatantly contrary to all the normative prescriptions of the economist that there is no way to understand it except by delving into the politics.

Transaction-Costs • In economics, it has come to mean a very general class of information, negotiation, and enforcement problems that affect the internal organization of firms and the outcome of market and nonmarket relations among firms, workers and so on. • A similar and even more severe class of transaction costs (which deals with principal-agent problems, commitment and credibility) pervades political relations and affect political outcomes. • The policy process can be better understood and related to each other by thinking of them as the result of various transaction costs and of the strategies of the participants to cope with these costs.

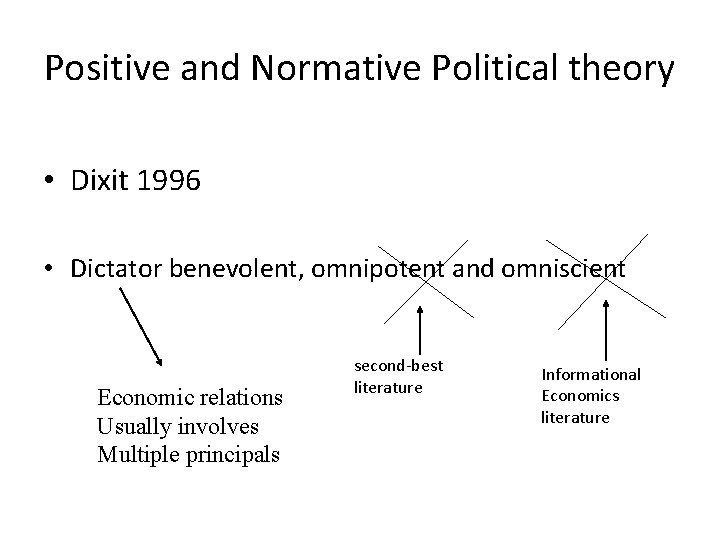

Common Agency • Within this general framework, a particularly important feature of the political process of making economic policy is the “common agency, ” where several players in the political game try to influence the actions of one decision-maker. • It leads to a severe diminution of the power of the incentives that can be offered to this decision-maker.

Market versus Government • The tradition dichotomy of market versus government, and the question of which system perform better, largely lose its relevance. – Both of them are facts of the imperfect economic life, and they unavoidable interact in complex ways. • The most we can do is to understand how the combined economic-political system evolves mechanisms to cope with the variety of transaction costs it must face that precludes a fully ideal outcome.

Principal-Agent Model

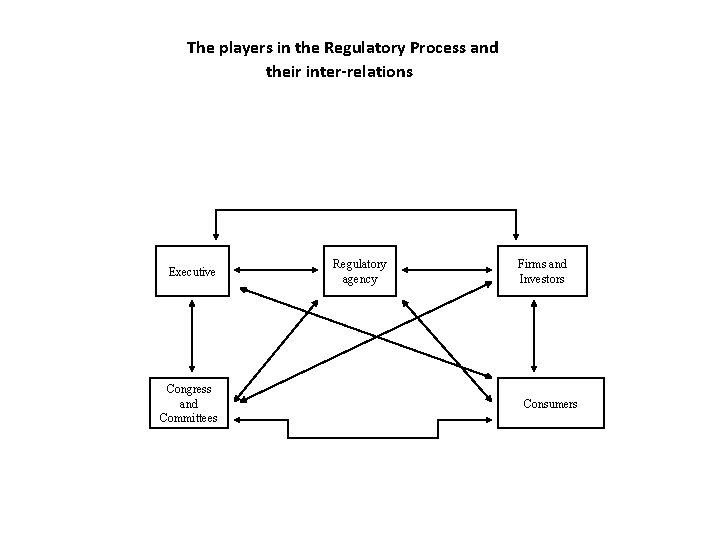

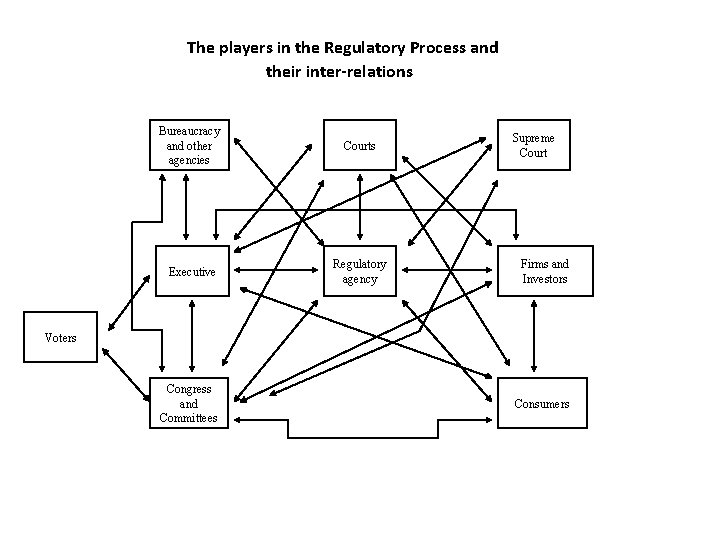

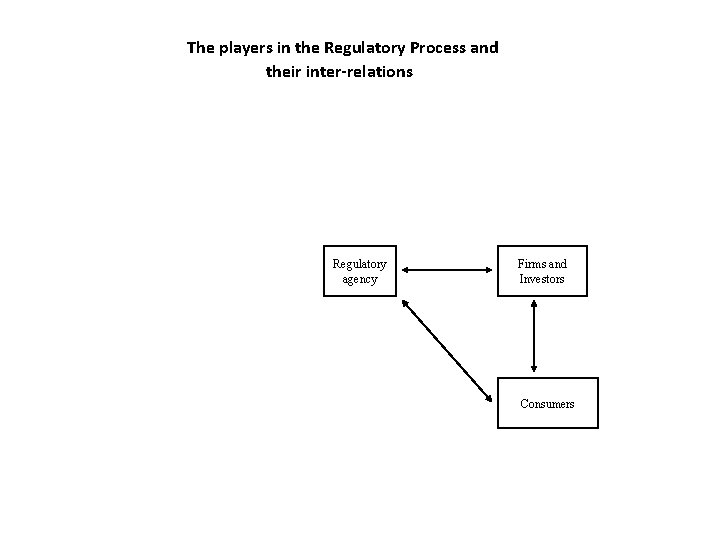

The players in the Regulatory Process and their inter-relations Regulatory agency

The players in the Regulatory Process and their inter-relations Regulatory agencies Firms and Investors

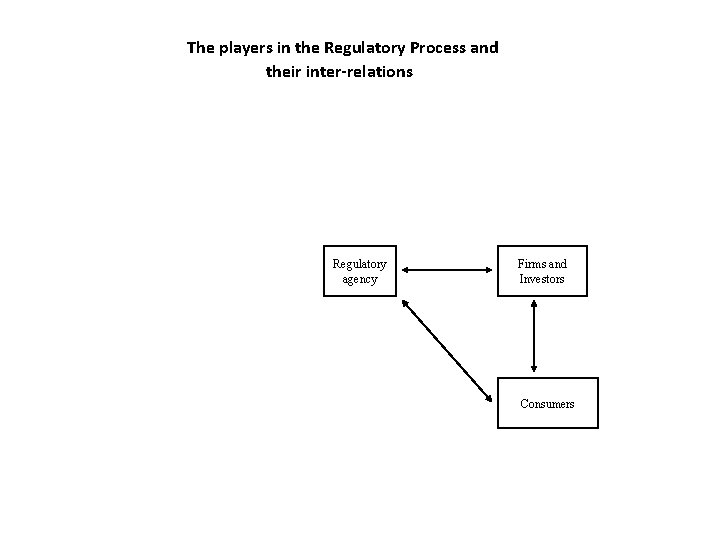

The players in the Regulatory Process and their inter-relations Regulatory agency Firms and Investors Consumers

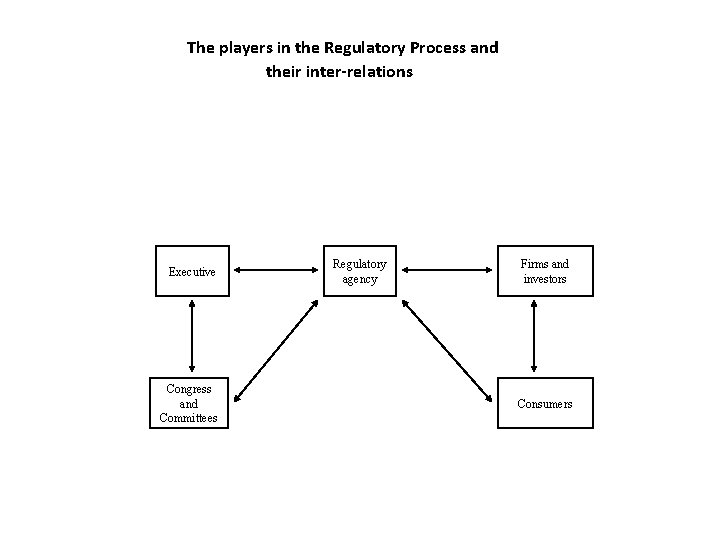

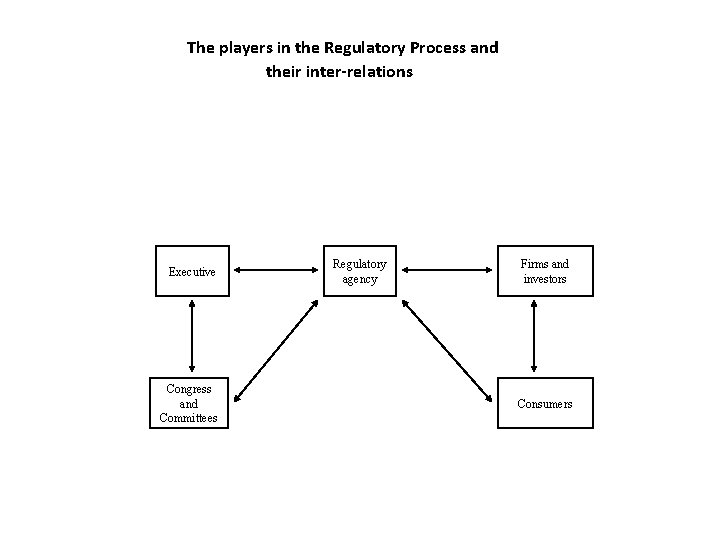

The players in the Regulatory Process and their inter-relations Executive Congress and Committees Regulatory agency Firms and investors Consumers

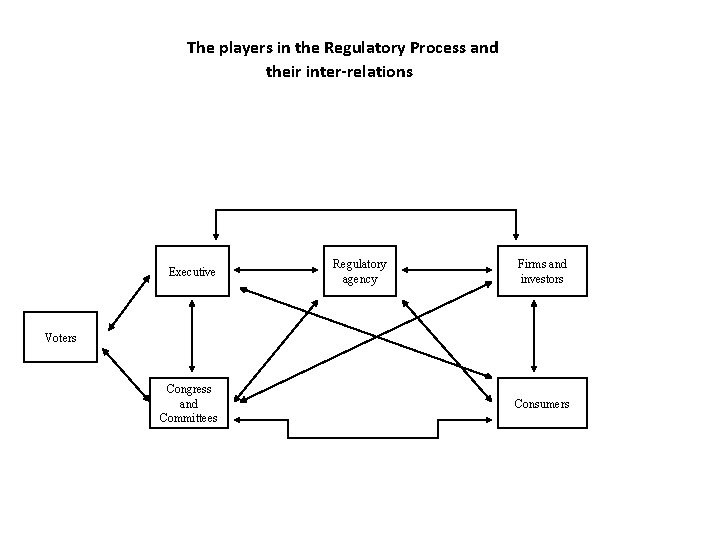

The players in the Regulatory Process and their inter-relations Executive Congress and Committees Regulatory agency Firms and Investors Consumers

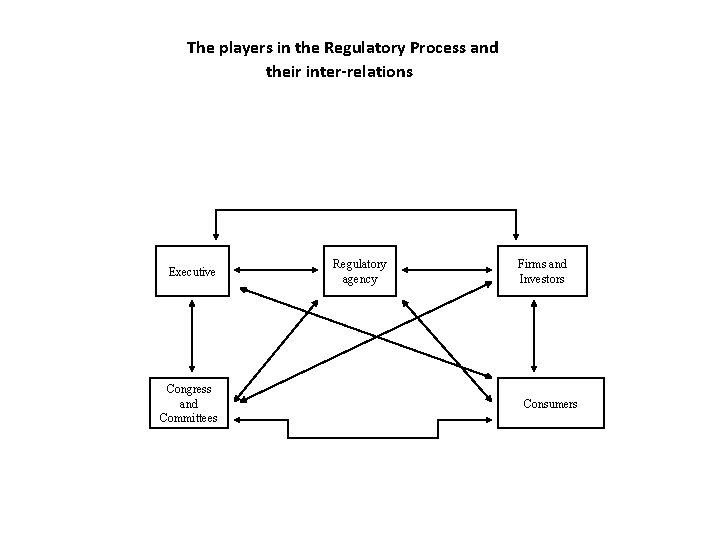

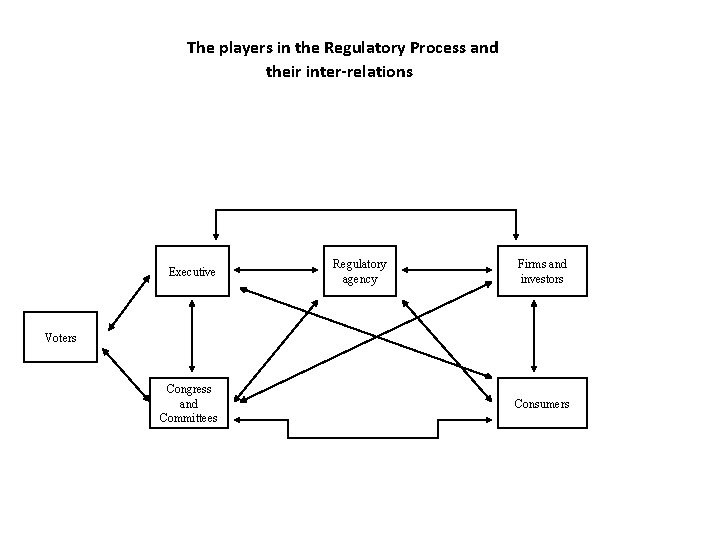

The players in the Regulatory Process and their inter-relations Executive Regulatory agency Firms and investors Voters Congress and Committees Consumers

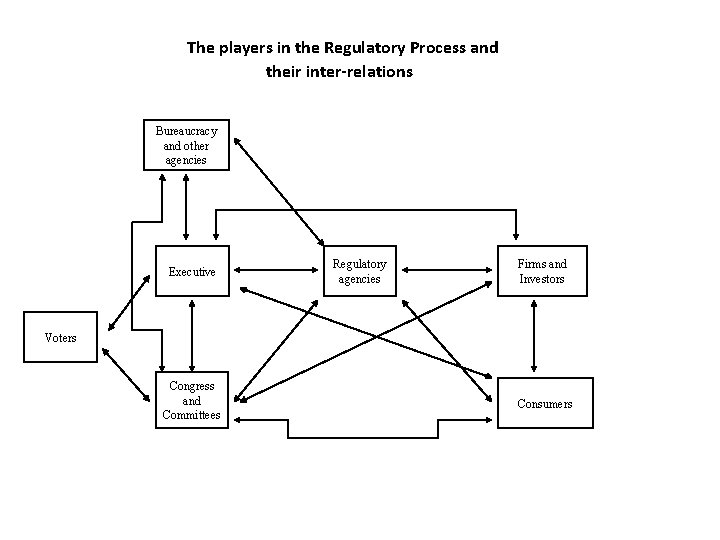

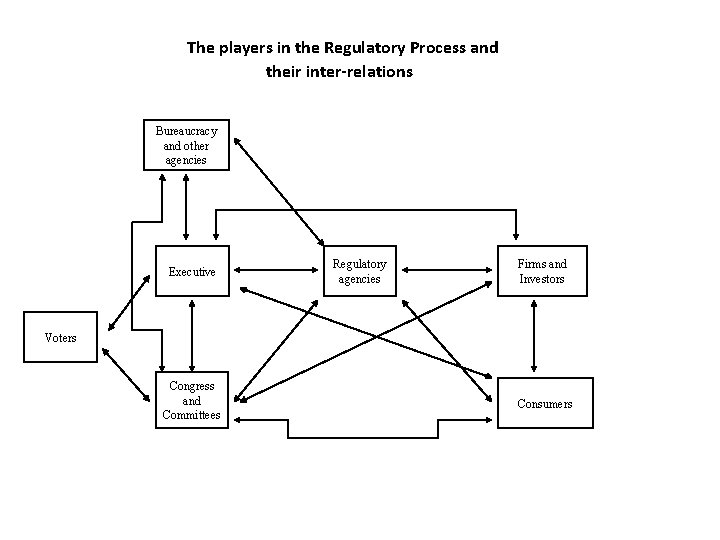

The players in the Regulatory Process and their inter-relations Bureaucracy and other agencies Executive Regulatory agencies Firms and Investors Voters Congress and Committees Consumers

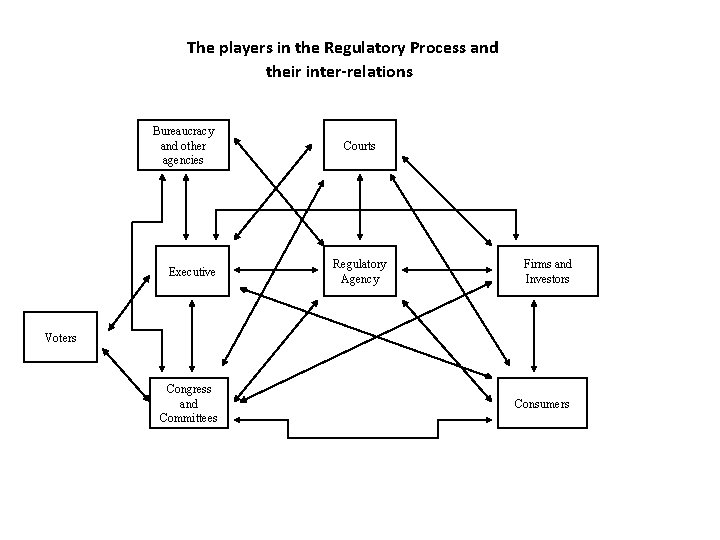

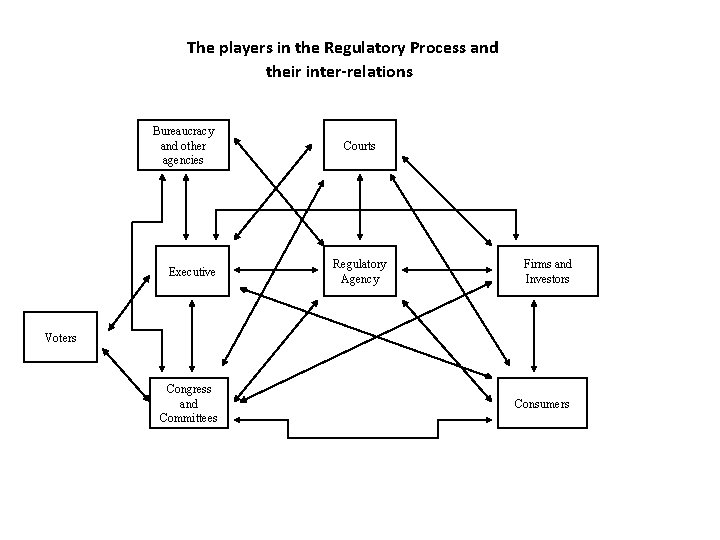

The players in the Regulatory Process and their inter-relations Bureaucracy and other agencies Executive Courts Regulatory Agency Firms and Investors Voters Congress and Committees Consumers

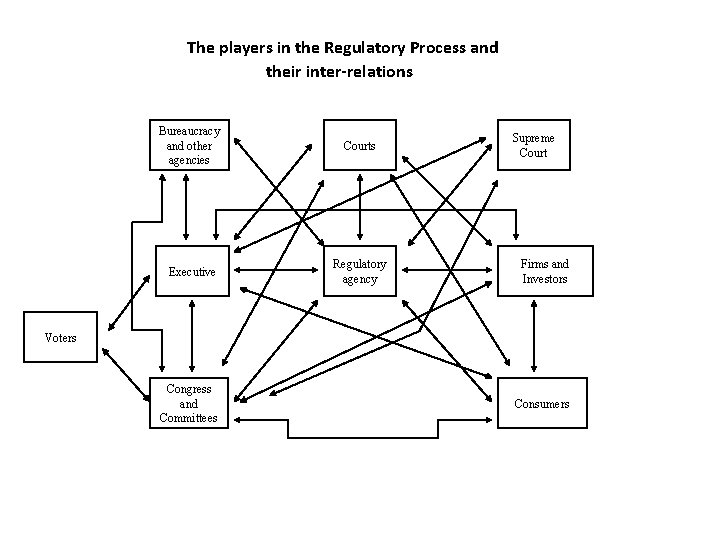

The players in the Regulatory Process and their inter-relations Bureaucracy and other agencies Courts Executive Regulatory agency Supreme Court Firms and Investors Voters Congress and Committees Consumers

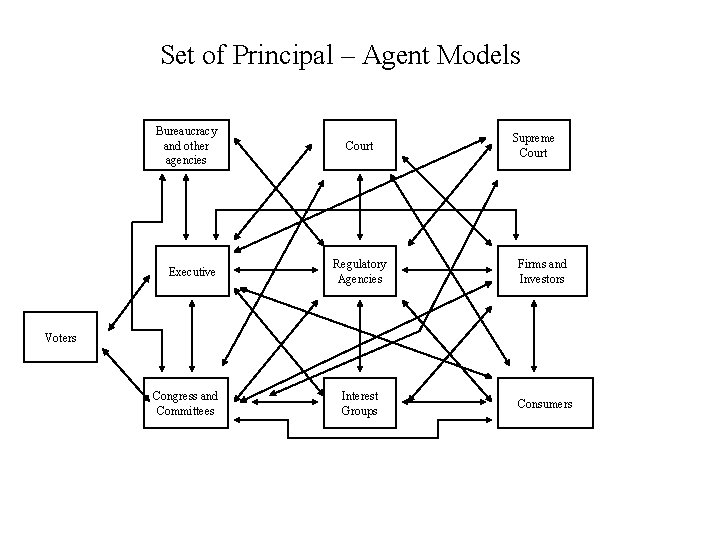

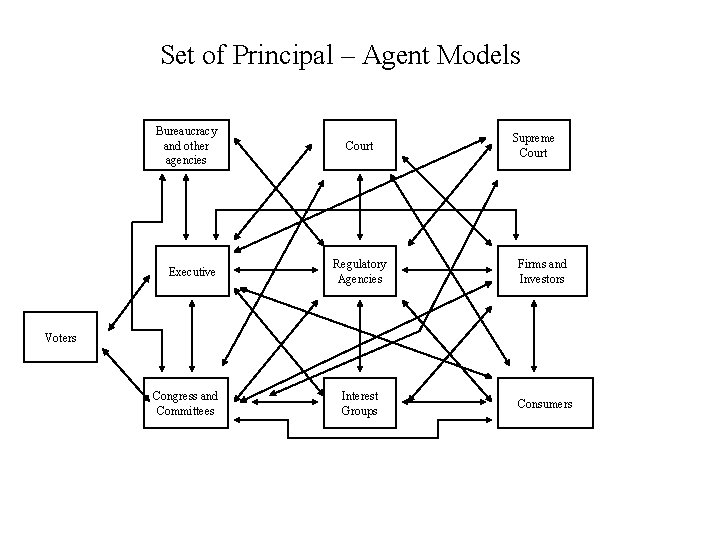

Set of Principal – Agent Models Bureaucracy and other agencies Executive Court Supreme Court Regulatory Agencies Firms and Investors Interest Groups Consumers Voters Congress and Committees

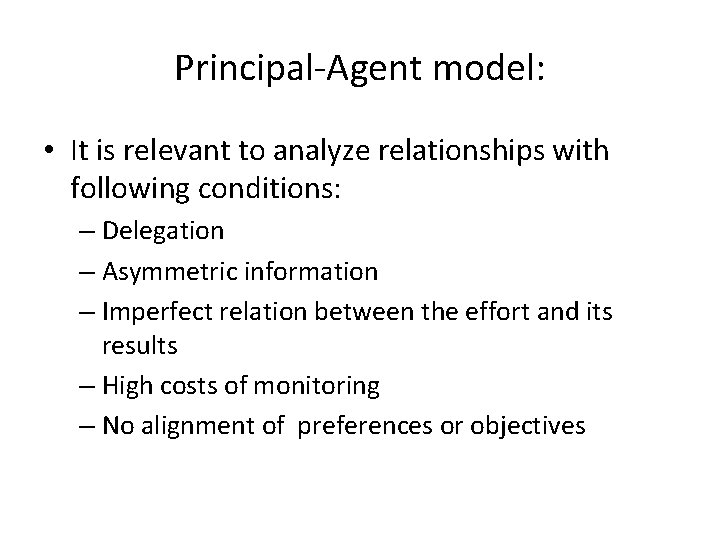

Principal-Agent model: • It is relevant to analyze relationships with following conditions: – Delegation – Asymmetric information – Imperfect relation between the effort and its results – High costs of monitoring – No alignment of preferences or objectives

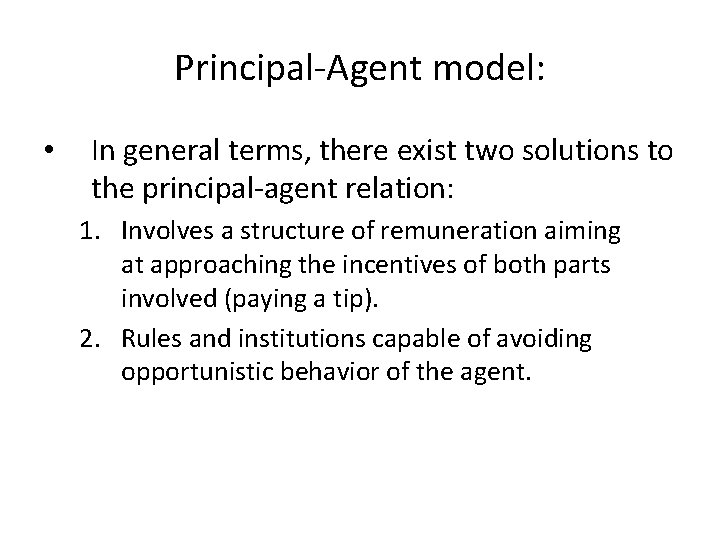

Principal-Agent model: • In general terms, there exist two solutions to the principal-agent relation: 1. Involves a structure of remuneration aiming at approaching the incentives of both parts involved (paying a tip). 2. Rules and institutions capable of avoiding opportunistic behavior of the agent.

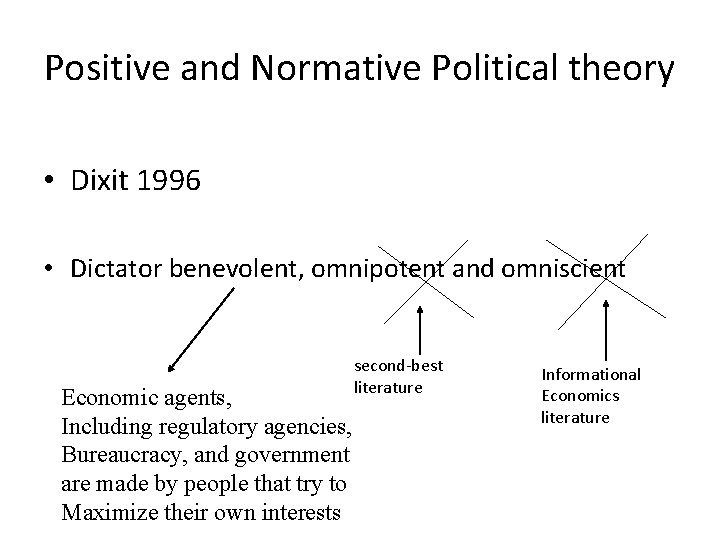

Positive versus Normative Political Theory: • To what extent those theories are excluding, complementary, or competitors? • Both are based on the premise that agents are rational and look for the own interests. • Dixit suggests a synthesis, labeled ‘transactioncost politics’ that views policymaking as a process in real time.

Normative Political Theory: • Market failure (i. e. natural monopoly) • Requires a criterion to fix with the “best” way this failure aiming at maximizing the social welfare. • Pareto-optimality (efficiency criterion) • First-best and second-best solutions (overcome the market imperfections) – Moral hazard (level of effort of the firm) – Adverse selection (the regulator has no complete information about the costs of the firm) – The regulator is obliged to pay informational rents.

Normative Political Theory: • As a consequence of asymmetric information Laffont and Tirole offer as a solution a menu of contract: – Price-caps – Repartition of profits • Thus, the firm would have incentives to revel its true effort

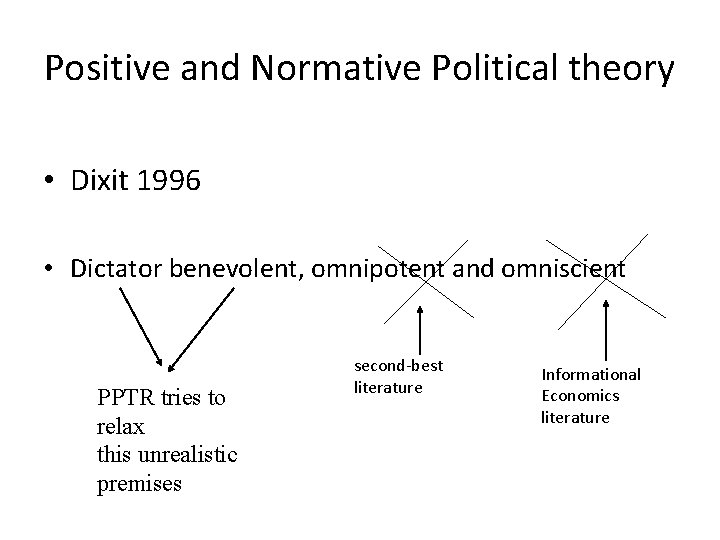

Normative Political Theory • The normative solution is rarely observed in the real life • The normative solution requires a high level of discretion of the regulator. This generates incentives for opportunistic behavior • Dixit (1996) observes that the normative theory understand the formulation and implementation of policies as a technical or organizational problems. As if political failures could be avoided through good management, namely, giving power to make and implement economic policy to an economist… • In other words, it does not take into account political and economic institutions. • The benevolent, omnipotent, and omniscient dictator would maximize the social welfare.

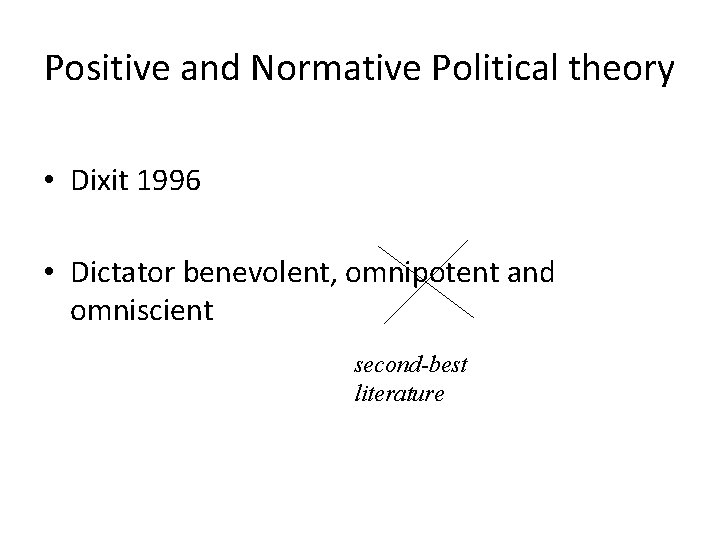

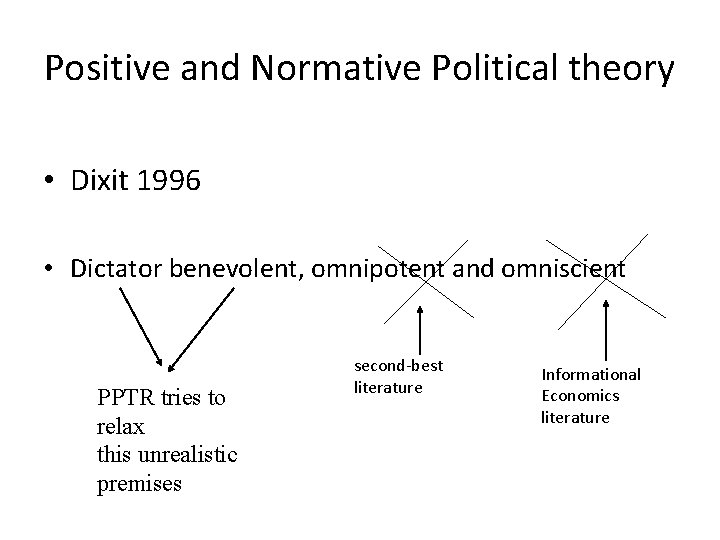

Positive and Normative Political theory • Dixit 1996 • Dictator benevolent, omnipotent and omniscient second-best literature

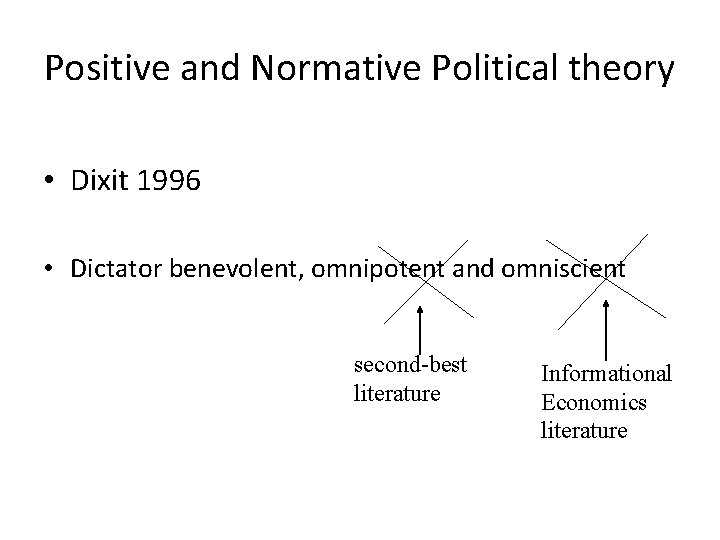

Positive and Normative Political theory • Dixit 1996 • Dictator benevolent, omnipotent and omniscient second-best literature Informational Economics literature

Positive and Normative Political theory • Dixit 1996 • Dictator benevolent, omnipotent and omniscient PPTR tries to relax this unrealistic premises second-best literature Informational Economics literature

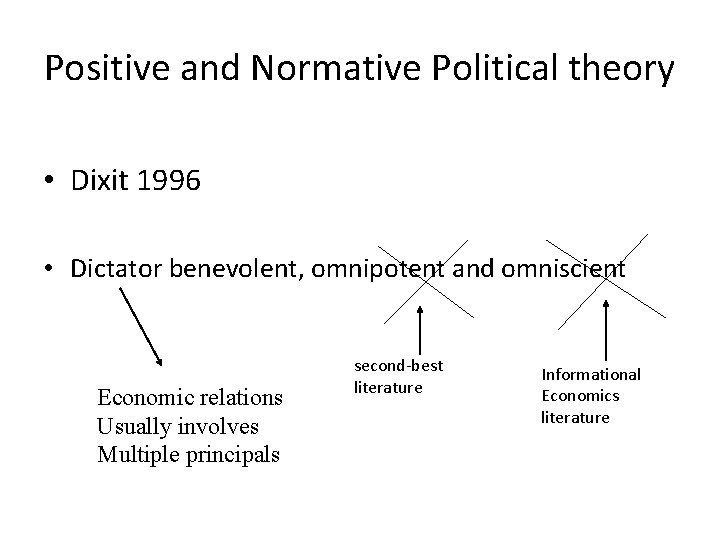

Positive and Normative Political theory • Dixit 1996 • Dictator benevolent, omnipotent and omniscient Economic relations Usually involves Multiple principals second-best literature Informational Economics literature

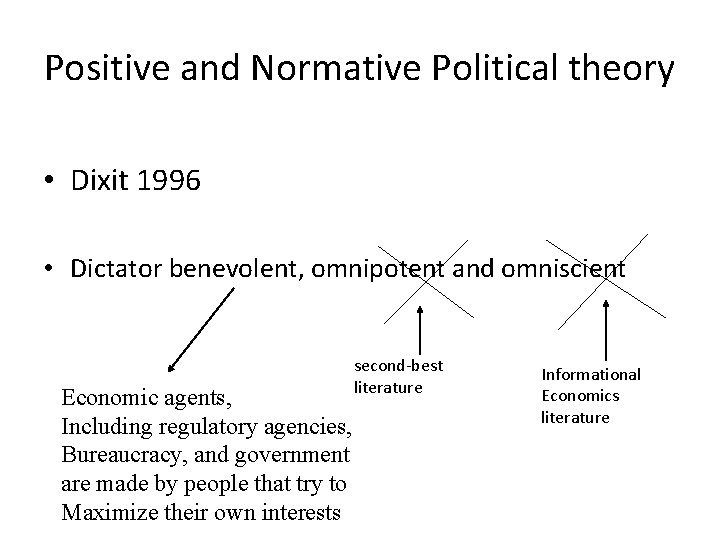

Positive and Normative Political theory • Dixit 1996 • Dictator benevolent, omnipotent and omniscient Economic agents, Including regulatory agencies, Bureaucracy, and government are made by people that try to Maximize their own interests second-best literature Informational Economics literature

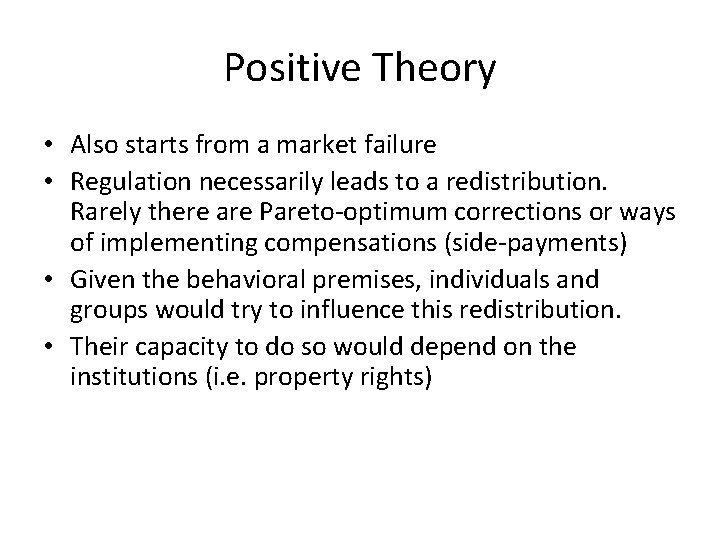

Positive Theory • Also starts from a market failure • Regulation necessarily leads to a redistribution. Rarely there are Pareto-optimum corrections or ways of implementing compensations (side-payments) • Given the behavioral premises, individuals and groups would try to influence this redistribution. • Their capacity to do so would depend on the institutions (i. e. property rights)

Positive Theory • Many situations apparently inefficient could be understood as a consequence of restrictions imposed by transaction costs among agents. The great majority of the PPTR tries to explain why such inefficient situations are observed even when there are obvious and better ways to deal with that. This involves to identify the source of restriction which are generating transaction costs and to show it affects the agent choices. Almost always it requires to take into account the political institutions.

Why does the regulation (government intervention) tend to be inefficient? • Economic reasons: – Asymmetric information – Uncertainty about effects, costs, and benefits – It does not mean that the regulation is not necessary; however, those problems should be taken into account

Why does the regulation (government intervention) tend to be inefficient? • Political reasons: – Regulation necessarily means income redistribution – Quotas, licenses, subsides, establish a price, etc. transfer rents and incomes – Interest-groups will demand this redistributions and politicians offer – Generally, the regulation tends to be inefficient – Rent-seeking – Few beneficiaries and lots of opponents

A Synthesis: A Policy Process in ‘Real Time’ • Constitutions are incomplete contracts: – The constitution never lays down the clear, firm, and comprehensive set of rules that the contractarian approach depicts; so there is room for maneuver in individual acts. – Inability to foresee all the possible contingencies and to adjust to them – Last longer than most business relationships • Constitutions are not made behind a veil of ignorance

Coase’s Theorem • Once the property rights over a disputed resource (ex. Rents of a monopoly) have been established, and given that the transaction costs are equal to zero, the private negotiations between agents approaches to the efficient level of allocation. (Coase, Ronald, (1960) The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 3, 1 -44).

Example: • A firm pollutes a river which provides a cost of $500 to a farmer along the river.

Example: • A firm pollutes a river which provides a cost of $500 to a farmer along the river. • It costs $300 to the farmer to build a station to purify the water.

Example: • A firm pollutes a river which provides a cost of $500 to a farmer along the river. • If costs $300 to the farmer to build a station to purify the water. • The firm can eliminate the harmful effect of pollution changing its production process at the cost of $100.

Questions: • Should be allowed the firm to pollute the river? • Should the firm be obliged to change its production process? • Who should pay for that? • What are the economic implications if the firm would have the property rights of polluting and the farmer would have to compensate him in order to not pollute?

Example: • And, if the property rights belong to the farmer?

The Coase’s Theorem: • Coase argues that, for the economic efficiency point of view, the result would be the same regardless the of the property rights given that the transaction costs are null.

Numeric Example I: • Cost of pollution over the farmer = $500 • Cost of cleaning from the farmer = $300 • Cost of cleaning from the firm = $100 – Case I: • The farmer has the property rights. • The firm will pay for the right to pollute, It pays $100 at maximum • The farmer would accept more than $300 only since he/she would have to clean the water in order to avoid the cost of $500 • Thus, the is no agreement and the firm purifies the water itself.

Numeric Example I: • Cost of pollution over the farmer = $500 • Cost of cleaning from the farmer = $300 • Cost of cleaning from the firm = $100 – Case II: • The firm has the property rights. • The farmer will pay for the firm to not pollute. It pays $300 at maximum • The farmer would accept to pay no more than $100 since he/she could clean the water at this price. • Thus, the farmer pays between $100 and $300 and the firm purifies the water itself.

The solution is the same in both cases • The solution is economically efficient

Efficiency vs. Equity • Although the reached solution are not affected by the property rights the distribution between the parts involved would be.

Efficiency vs. Equity • When the property rights belong to the farmer, the firm has a cost of $100.

Efficiency vs. Equity • However, when the property rights belong to the firm, the farmer pays at least $100 and part of the exceeding of $200. This “rent” of $200 will be allocated by negotiations between the parts.

What is the fairest solution? • Coase recommends that we should not conclude too fast. • He calls our attention to the reciprocal nature of the problem.

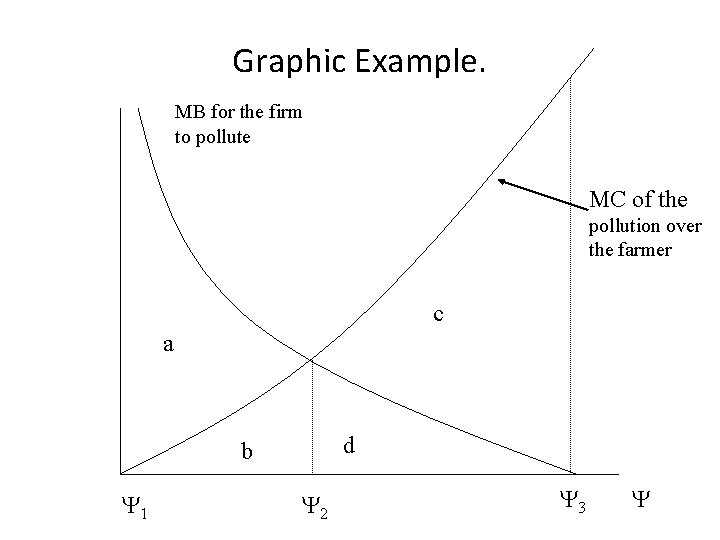

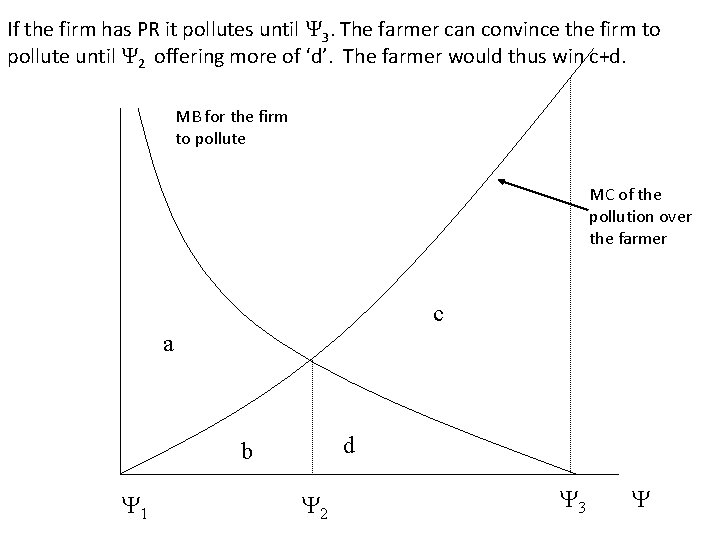

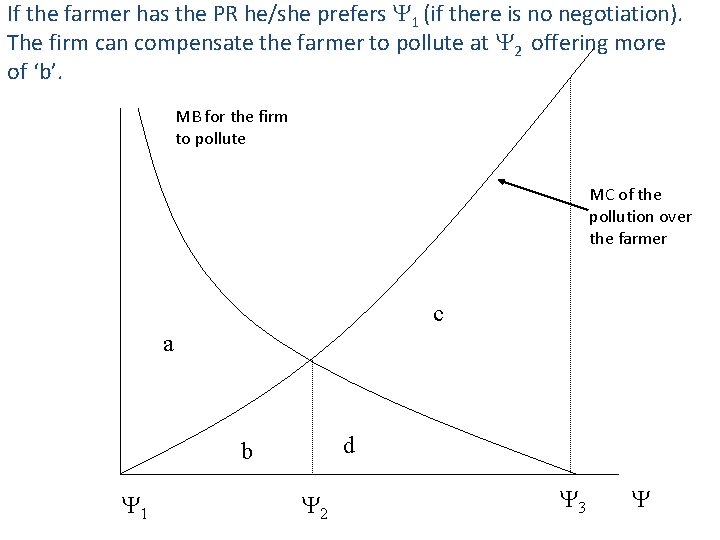

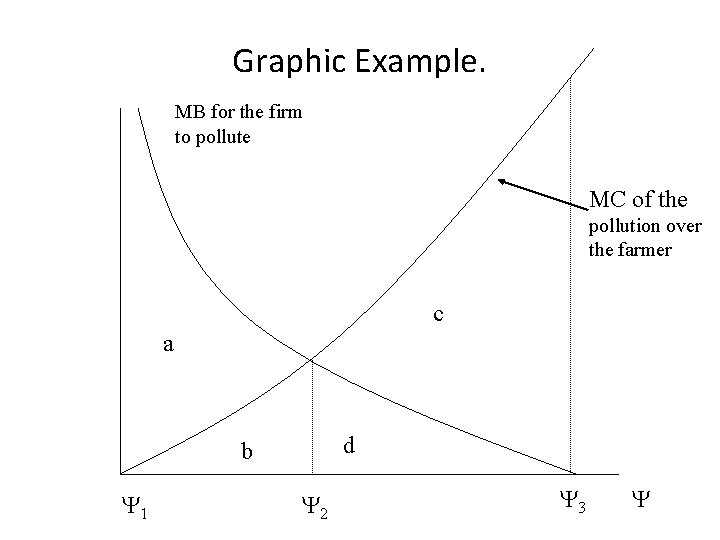

Graphic Example. MB for the firm to pollute MC of the pollution over the farmer c a d b 1 2 3

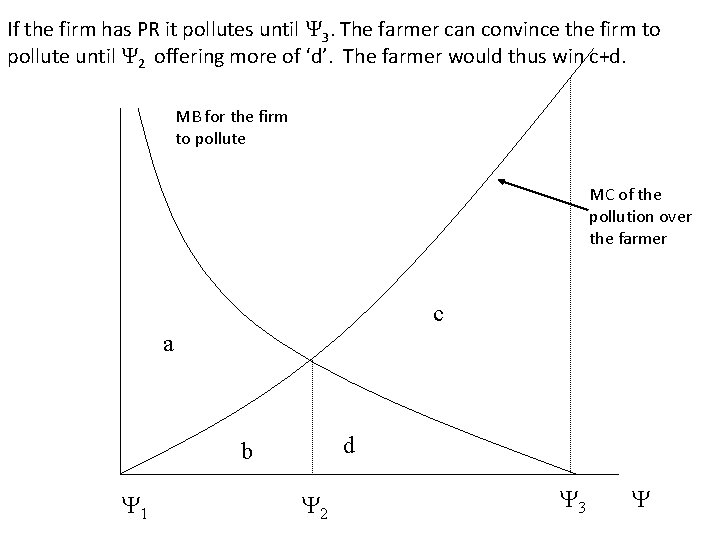

If the firm has PR it pollutes until 3. The farmer can convince the firm to pollute until 2 offering more of ‘d’. The farmer would thus win c+d. MB for the firm to pollute MC of the pollution over the farmer c a d b 1 2 3

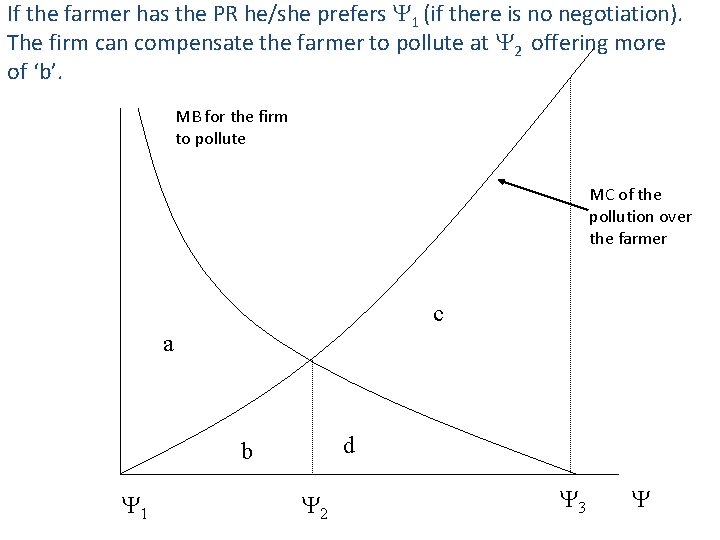

If the farmer has the PR he/she prefers 1 (if there is no negotiation). The firm can compensate the farmer to pollute at 2 offering more of ‘b’. MB for the firm to pollute MC of the pollution over the farmer c a d b 1 2 3

Necessary conditions to reach the negotiated result: • Well defined property rights. It implies political and judicial institutions that work well. • Low transaction costs • Information about all costs of each possible result for each part involved.

Polemic Implications of the Coase’s Theorem • In many cases there are no necessity of governmental interventions in order to solve problems of externalities since the private negotiations reach the economically efficient solution.

Limitations of the Coase’s Theorem: • The transactional costs usually are not small, especially when several players are involved. • There exist public and private externalities. In the public ones there are the free-ridding problem. • There exist the problem of inter-temporal transactions with future generations. • The initial distribution of the property rights can affect the capacity of negotiation of each part. • Even when theorem fits there are room for government role.

Role of the government is to help greasing the private negotiation • Property rights have to be well defined and allocated clearly. • The government has to monitor the environment aiming at identifying who are the polluters and who are victims of the pollution. This information has to be publicized for all parts that have been affected. • The government must establish, quantify, and publicize the legal rules that regulates the environment in order to make it easier the private negotiations. • Access to the judicial system has to be facilitated and cheap

Regulation and the Coase’s Theorem • As in practical terms those conditions are rarely found, the coase’s solution is not viable (this is exactly what Coase claims!) • Therefore, the regulation becomes necessary. • The transactions costs are the key. Whose are the political property rights? What are the political transaction costs? • The results usually are not efficient

Regulation and the Coase’e Theorem • Reasons why it is difficult to make side payments: – Informational problems, uncertainty, difficulties of measuring costs and benefits – Collective action problems – Inexistence of a market of political property rights (political risks)

Delegating Powers A Transaction Cost Politics Approach to Policy making under Separate Powers David Epstein & Sharyn O’Halloran

Puzzle • Why does Congress delegate broad authority to the executive in some policy areas but not in others? • Can Congress perfectly control delegated authority through administrative procedures, oversight, and administrative law?

Question • When does Congress specify the details of policy in legislation, and when does it leave these details to regulatory agencies? • What are the implications of this institutional choice for policy outcomes? å Basic question of policy making in a separation of powers system.

Transaction Cost Politics • Policy can be made (i) in Congress, (ii) through delegation authority to the executive agencies, or a (iii) mixture of these two. • When deciding where policy will be made, Congress trades off the internal policy production costs of the committee system against the external costs of delegation • (make-or-buy decision).

Theory: • A policy will be made in the politically most efficient manner; that is, maximizing legislators’ political goal: reelection. • Legislators will prefer to make policy themselves as long as the political benefits they derive from doing so outweighs the political costs; otherwise, they will delegate to the executive

Abdication versus delegation? • Implications: – To what extent can Congress control unelected regulatory agencies when delegating authority? • Lowi (1969) – Congress has surrendered their legislative authority to bureaucrats • MCNOLGAST (1987, 1989) – Legislators can control bureaucrats through oversight, administrative procedures and enfranchising third parties into the decision-making process.

Authors’ Claim: • A theory of oversight divorced from a theory of delegation will overlook the fact that those issue areas in which the executive makes policy differ from those in which Congress makes policy itself.

Legislative organization and delegation • Distributive versus informational theories – This is a false dichotomy (whether committee serves pork barrel projects or legislators’ desire to avoid the consequences of ill-informed policies): • Some policy areas are more characterized by informational concerns and other by distributive. The first ones tend to be delegated and the second tend to be made in Congress

Divided Government and Delegation • To what extend will an opposing Congress delegate more powers to the executive? • Mayhew (1991): the same number of legislation get passed under unified and divided government. It doesn't lead to gridlock. – However, the authors call our attention to the quality of bills passed: • Congress delegate less and constrains more under divided government: procedural gridlock, that is, producing executive branch agencies with less authority to make policy and increase oversight from congressional committees.

What does Transaction Cost mean? • Anything that makes reality deviate from this Coasian world: – “anything that impedes the specification, monitoring, or enforcement of an economic transaction is a transaction cost” (Dixit 1966).

Common elements of the Transaction Costs analysis: 1. The contract is the unit of analysis 2. The contracts are enforceable by some neutral thirdparty 3. Assumes the existence of multiple governance structures 4. Economic actors are assumed to be boundedly rational (agents cannot eliminate transaction costs by simply contracting) 5. Holdup problems Contracts are incomplete and ambiguous

Theory of Transaction Cost politics • Delegation to a bureaucracy is subjected to the political equivalent of a holdup problem; so Congress will delegate to the executive when the external transaction costs of doing so are less than the internal transaction costs of making policy through the normal legislative process of the committees.

Reasons not to delegate • With transaction costs equal to zero Congress might like to delegate broad discretionary authorities and agencies might like to receive such authority (please everyone). However, – – Difficult to control and monitoring Incomplete contracts Uncertainty of future opportunistic behavior Impossibility of binding the actions of agency successors

Reasons to delegate • • Save time/Reduce congress workload Take advantage of agency expertise Protect special interests Blame-shifting (avoiding the inefficiencies of committee system) – Delays, logrolling, informational inefficiencies, etc. åThese do not explain why delegate in some policy areas rather than others.

Neither alternative is perfect… • However, in some specific cases delegate or not (how mach delegate) would be relatively more attractive than from the median legislator’s preference.

Basic Assumptions • Two alternative modes of policy making – Congress: • Committee System – Regulatory Agencies: • Delegation to Executive • Legislators decide where policy is made. • Legislators’ primary goal is reelection – Authority will be allocated across the branches in a politically efficient manner

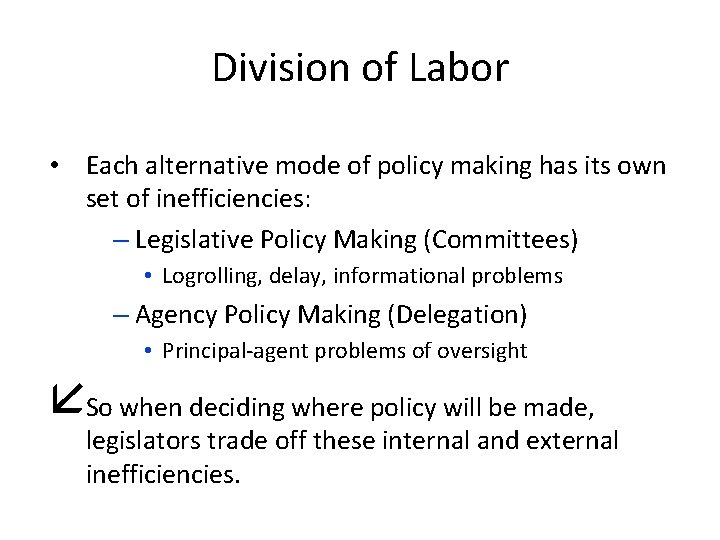

Division of Labor • Each alternative mode of policy making has its own set of inefficiencies: – Legislative Policy Making (Committees) • Logrolling, delay, informational problems – Agency Policy Making (Delegation) • Principal-agent problems of oversight åSo when deciding where policy will be made, legislators trade off these internal and external inefficiencies.

Make-or-Buy • Congress’s decision to delegate is like a firm’s make-or-buy decision. – Legislators can either produce policy internally, OR – Legislators can subcontract out (delegate) to the executive.

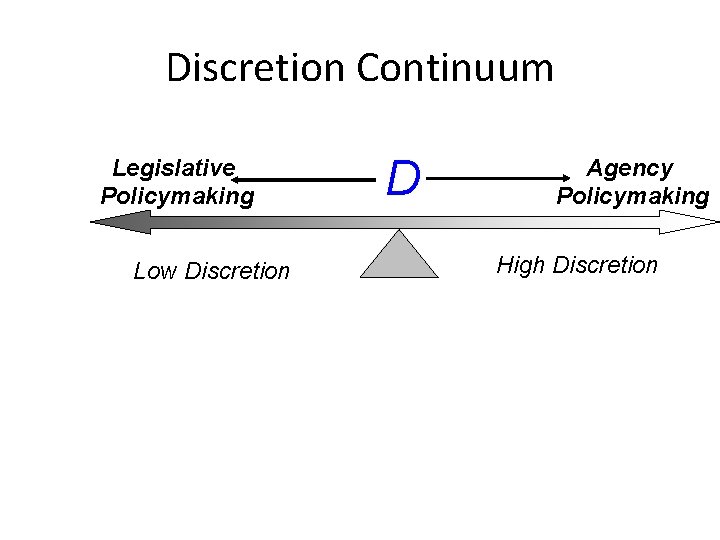

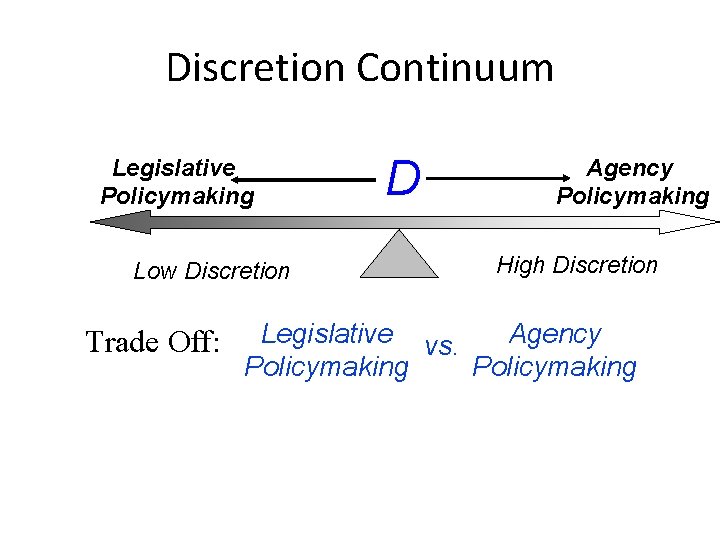

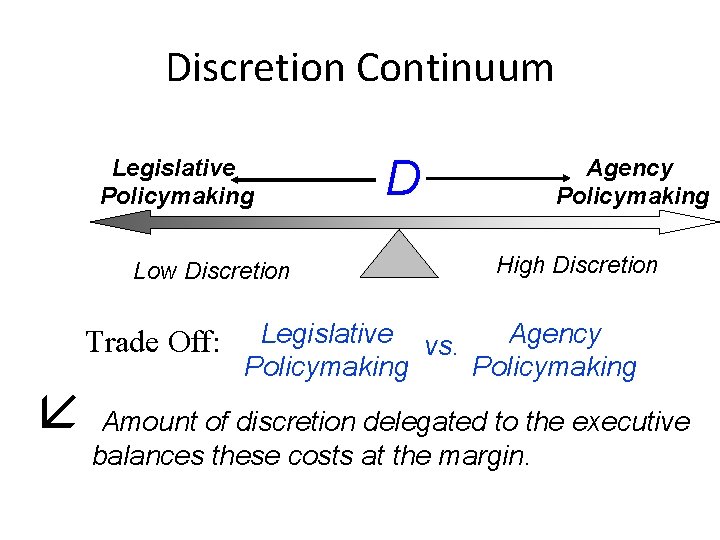

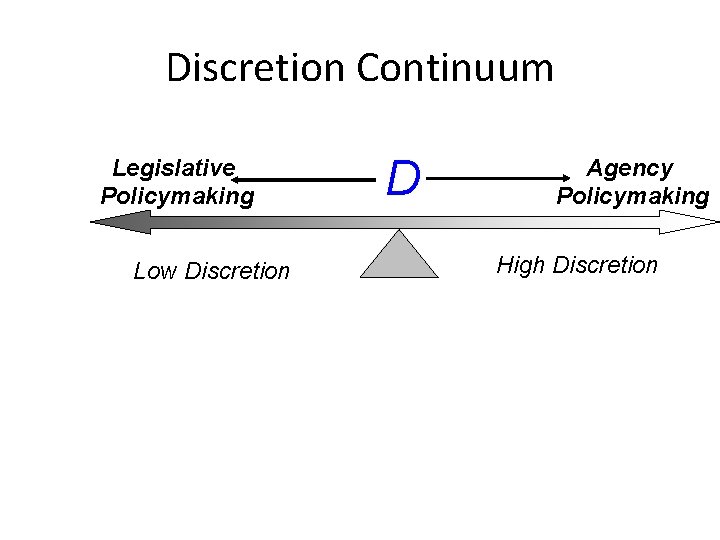

Discretion Continuum Legislative Policymaking Low Discretion D Agency Policymaking High Discretion

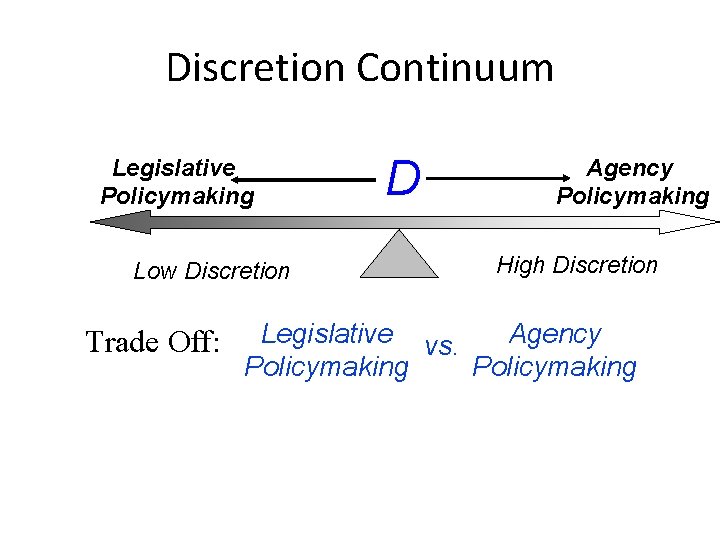

Discretion Continuum Legislative Policymaking Low Discretion Trade Off: D Agency Policymaking High Discretion Legislative vs. Agency Policymaking

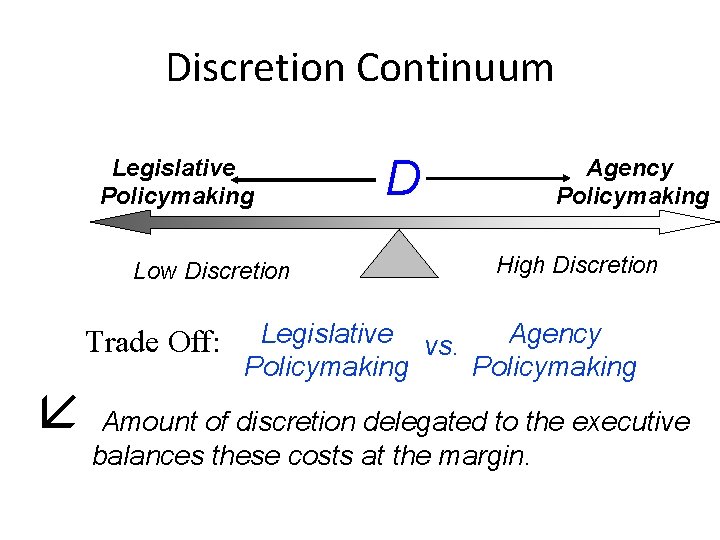

Discretion Continuum Legislative Policymaking Low Discretion Trade Off: å D Agency Policymaking High Discretion Legislative vs. Agency Policymaking Amount of discretion delegated to the executive balances these costs at the margin.

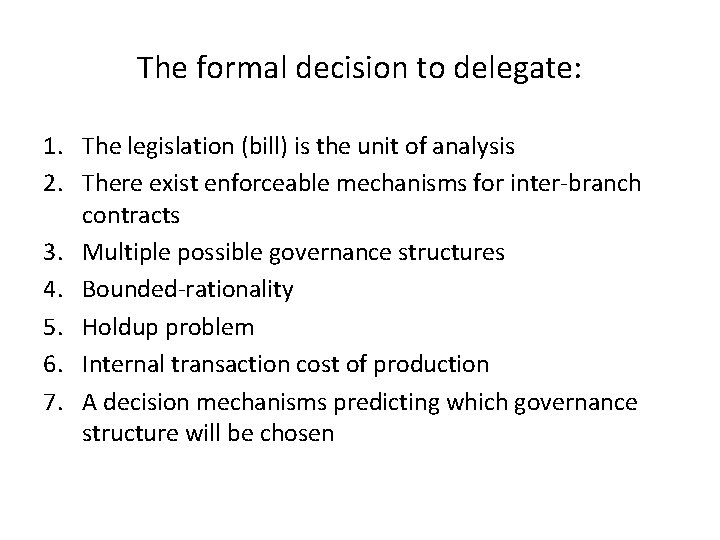

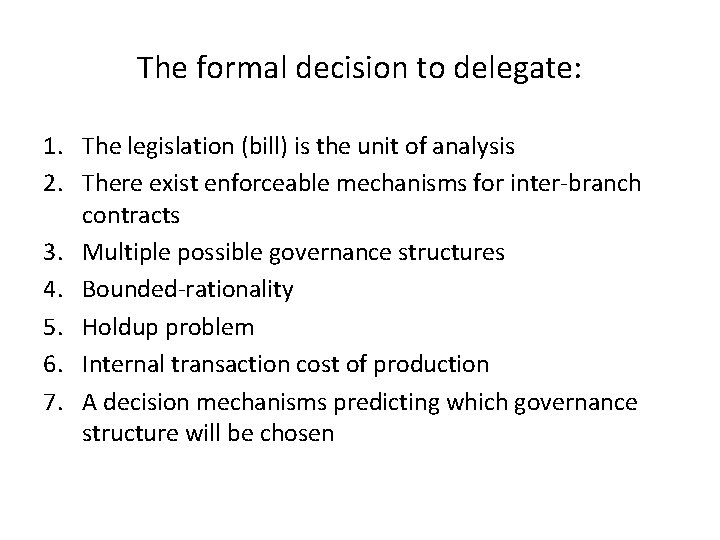

The formal decision to delegate: 1. The legislation (bill) is the unit of analysis 2. There exist enforceable mechanisms for inter-branch contracts 3. Multiple possible governance structures 4. Bounded-rationality 5. Holdup problem 6. Internal transaction cost of production 7. A decision mechanisms predicting which governance structure will be chosen

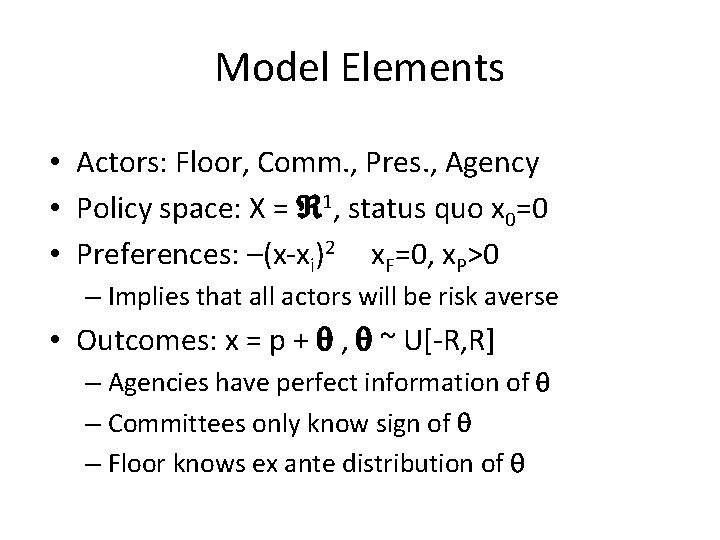

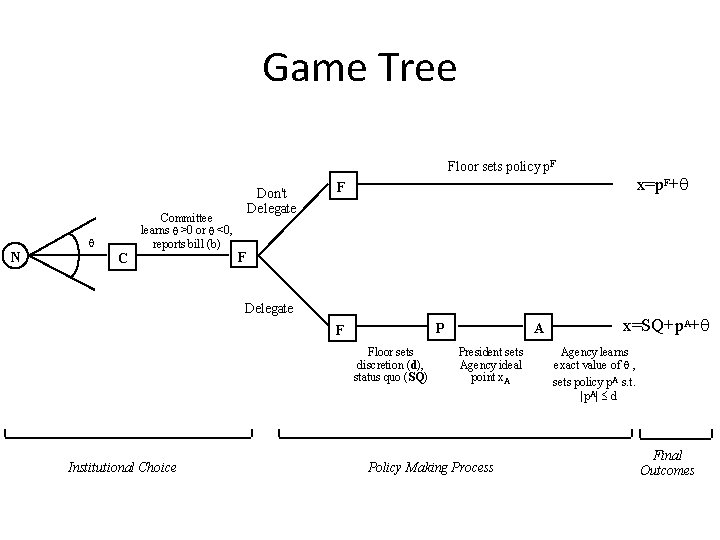

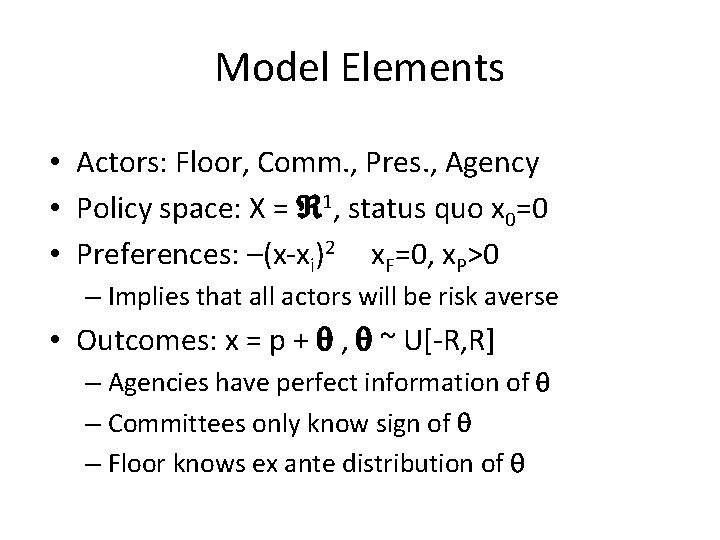

Model Elements • Actors: Floor, Comm. , Pres. , Agency • Policy space: X = 1, status quo x 0=0 • Preferences: –(x-xi)2 x. F=0, x. P>0 – Implies that all actors will be risk averse • Outcomes: x = p + , ~ U[-R, R] – Agencies have perfect information of – Committees only know sign of – Floor knows ex ante distribution of

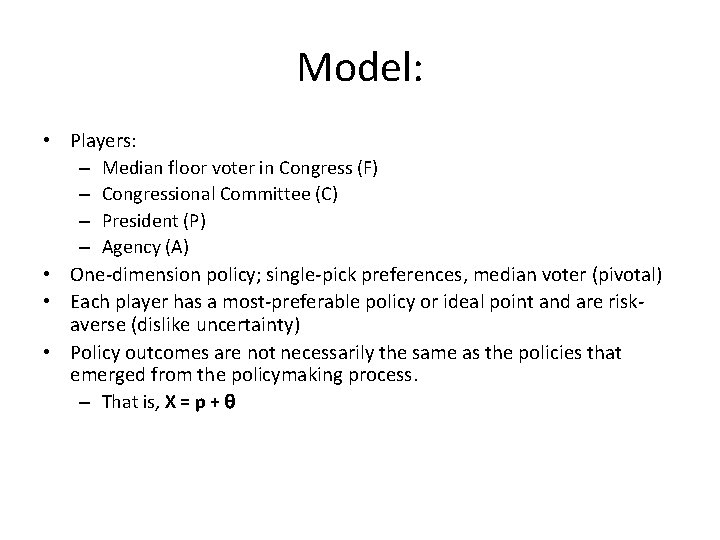

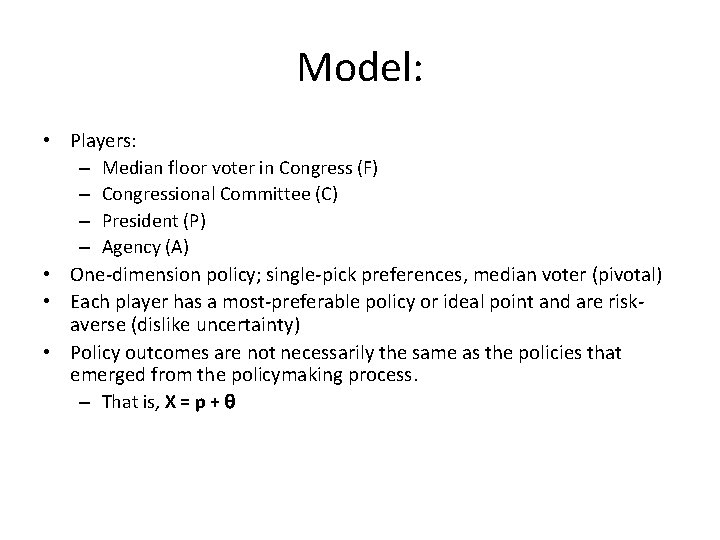

Model: • Players: – Median floor voter in Congress (F) – Congressional Committee (C) – President (P) – Agency (A) • One-dimension policy; single-pick preferences, median voter (pivotal) • Each player has a most-preferable policy or ideal point and are riskaverse (dislike uncertainty) • Policy outcomes are not necessarily the same as the policies that emerged from the policymaking process. – That is, X = p +

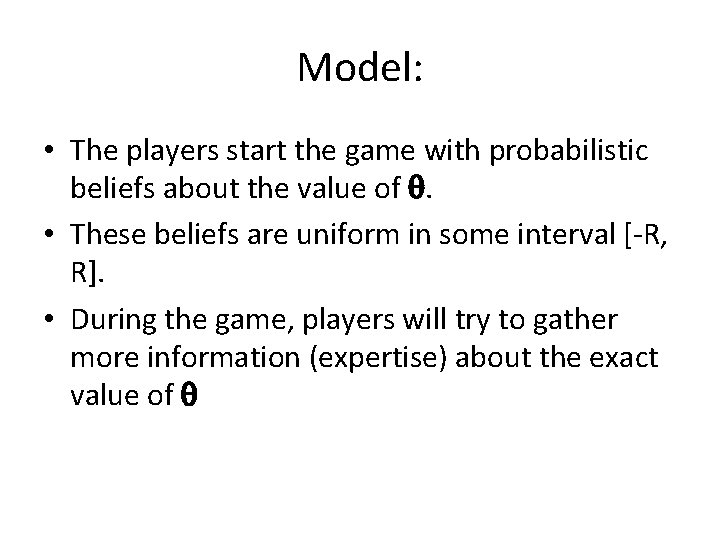

Model: • The players start the game with probabilistic beliefs about the value of . • These beliefs are uniform in some interval [-R, R]. • During the game, players will try to gather more information (expertise) about the exact value of

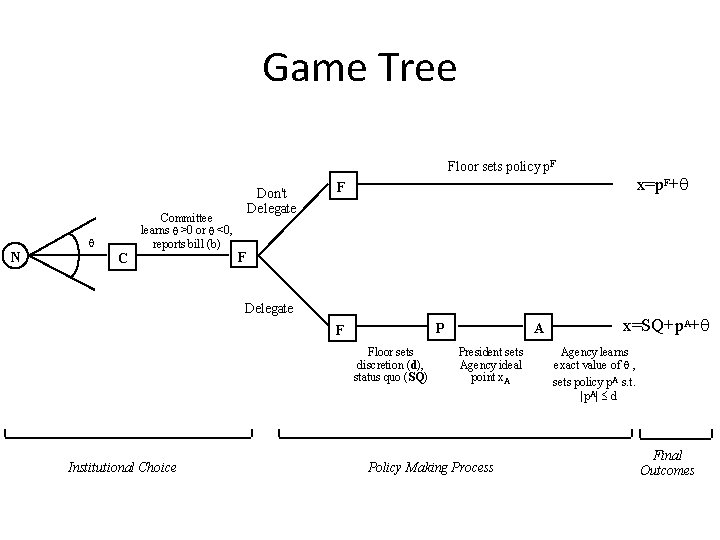

Game Tree Floor sets policy p. F N C Committee learns >0 or <0, reports bill (b) Don't Delegate F Delegate P F Floor sets discretion (d), status quo (SQ) Institutional Choice x=p. F+ F A President sets Agency ideal point x. A Policy Making Process x=SQ+p. A+ Agency learns exact value of sets policy p. A s. t. |p. A| d Final Outcomes

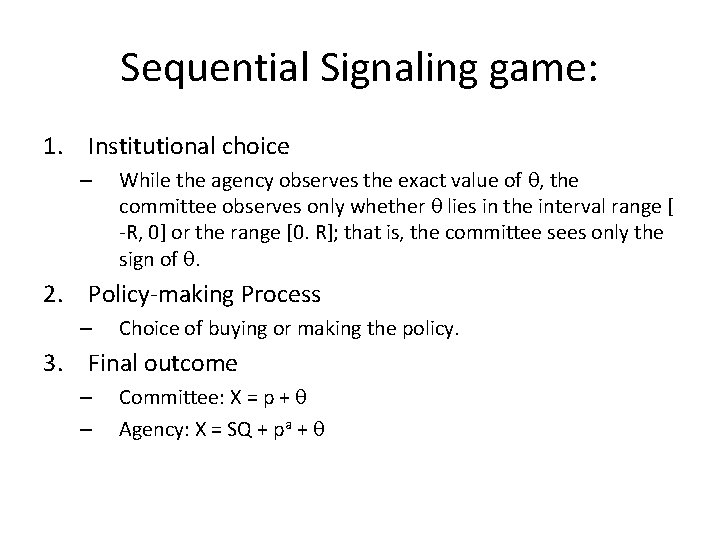

Sequential Signaling game: 1. Institutional choice – While the agency observes the exact value of , the committee observes only whether lies in the interval range [ -R, 0] or the range [0. R]; that is, the committee sees only the sign of . 2. Policy-making Process – Choice of buying or making the policy. 3. Final outcome – – Committee: X = p + Agency: X = SQ + pa +

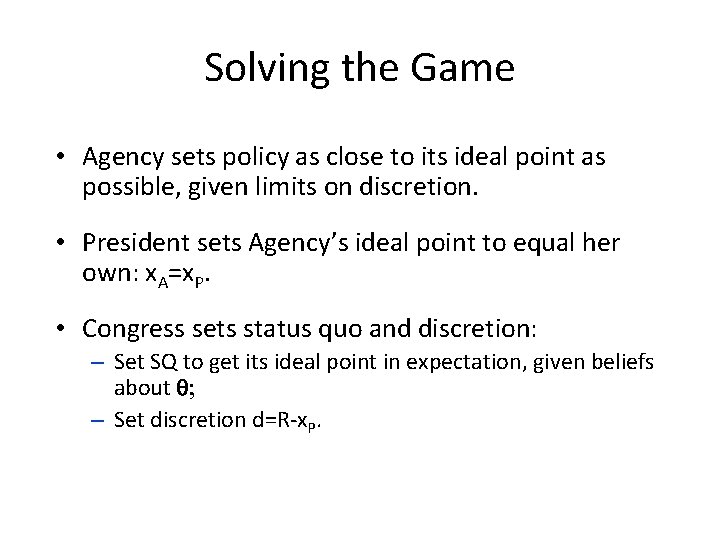

Solving the Game • Agency sets policy as close to its ideal point as possible, given limits on discretion. • President sets Agency’s ideal point to equal her own: x. A=x. P. • Congress sets status quo and discretion: – Set SQ to get its ideal point in expectation, given beliefs about ; – Set discretion d=R-x. P.

Theoretical Propositions • In equilibrium, Congress will delegate more discretionary authority to the executive: 1. The lower the level of congressionalexecutive conflict; 2. The higher the level of committee-floor conflict; 3. The higher the level of uncertainty in the policy environment.

Deliberate Discretion? The Institutional Foundation of Bureaucratic Autonomy John Huber & Charles Shipan

What this book is about? • How elected officials use the statutes to establish policy details in effort to achieve desired outcomes. • Develop and test a theory of delegation that explains the choice of how to delegate aiming at understanding how institutional context affects delegation strategies.

Two types of designing statutes: 1. To write long statutes with extremely detailed languages in a effort to micromanage the policymaking process. 2. To write vague statutes that have many details unspecified, thereby delegating policymaking authority to other actors, usually bureaucrats.

Vague (Germany) versus specific (Ireland) statutes about sexual harassment: • Why has the same policy issue been treated differently by politicians in distinct political systems? • Why these choice matter? • Is the transferred discretion a deliberate choice?

Delegation as double-edge sword • “the central reason for granting policymaking autonomy to bureaucrats – their technical expertise – also creates a big problem, as bureaucrats can use their knowledge against politicians. Bureaucratic expertise is thus a double-edge sword, creating both the incentive for legislatures to give policymaking power to bureaucrats and the opportunity for these bureaucrats to act counter to legislative preferences” (Peters 1981)

Two prevalent views: • Bureaucratic discretion (bureaucratic dominance) versus • Deliberate discretion (politicians dominance. That is, politicians would have capacity to control bureaucrats and achieve their goals by delegating)

Alternative view: • Rather than asking to what extent politicians control bureaucrats, the authors assume that in any political context there typically exists a politician who has greater opportunities than other political actors to influence bureaucratic behavior. – In parliamentary democracy = Cabinet – In presidential system = president or governors

4 factors that affect politician’s incentives to micromanage policymaking 1. Level of political conflict between politicians who adopt the statute and bureaucrats who implement them 2. The capacity of politicians to write detailed statutes 3. The bargaining environment (e. g. the existence of vetoes or bicameral conflicts) in which the statutes are adopted 4. The politicians’ expectation about non-statutory factors such as the role of courts or legislative oversight.

New economic policy

New economic policy Laissez faire theory

Laissez faire theory Hitlers economic policy

Hitlers economic policy Economic policy

Economic policy Economic growth vs economic development

Economic growth vs economic development Growth and development conclusion

Growth and development conclusion Economic systems lesson 2 our economic choices

Economic systems lesson 2 our economic choices Evidence based policy adalah

Evidence based policy adalah Policymaking process steps

Policymaking process steps The policy making process

The policy making process Policy implementation approaches

Policy implementation approaches Chapter 1 section 3 economic choices and decision making

Chapter 1 section 3 economic choices and decision making Chapter 2 economic systems and decision making

Chapter 2 economic systems and decision making Chapter 2 economic systems and decision making

Chapter 2 economic systems and decision making Chapter 2 economic systems and decision making

Chapter 2 economic systems and decision making Making inferences

Making inferences War making and state making as organized crime

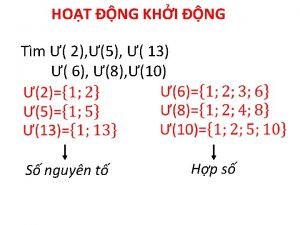

War making and state making as organized crime Số nguyên tố là gì

Số nguyên tố là gì đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ

đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ Cách giải mật thư tọa độ

Cách giải mật thư tọa độ Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Tư thế worm breton là gì

Tư thế worm breton là gì ưu thế lai là gì

ưu thế lai là gì Thẻ vin

Thẻ vin Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Bàn tay mà dây bẩn

Bàn tay mà dây bẩn Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Bổ thể

Bổ thể Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu

Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết V cc

V cc Thể thơ truyền thống

Thể thơ truyền thống Chúa yêu trần thế alleluia

Chúa yêu trần thế alleluia Sự nuôi và dạy con của hươu

Sự nuôi và dạy con của hươu đại từ thay thế

đại từ thay thế Diễn thế sinh thái là

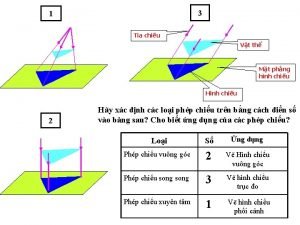

Diễn thế sinh thái là Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau Cong thức tính động năng

Cong thức tính động năng 101012 bằng

101012 bằng Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Thế nào là mạng điện lắp đặt kiểu nổi

Thế nào là mạng điện lắp đặt kiểu nổi Lời thề hippocrates

Lời thề hippocrates Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể

Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra

Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra Các môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng tiếng đua

Các môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng tiếng đua Khi nào hổ con có thể sống độc lập

Khi nào hổ con có thể sống độc lập Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay

Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay Dot

Dot Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ

Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ

Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ độ dài liên kết

độ dài liên kết Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào

Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan

Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan Phối cảnh

Phối cảnh điện thế nghỉ

điện thế nghỉ Một số thể thơ truyền thống

Một số thể thơ truyền thống Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Sơ đồ cơ thể người

Sơ đồ cơ thể người Lp html

Lp html Stem cell politics

Stem cell politics What is regionalization

What is regionalization Politics communion 000yearold holy mystery

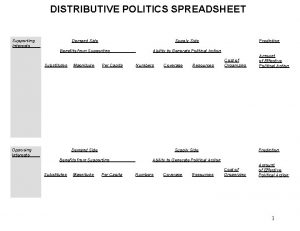

Politics communion 000yearold holy mystery Distributive politics spreadsheet

Distributive politics spreadsheet Politics

Politics Power definition

Power definition Guerrilla girls comic politics of subversion

Guerrilla girls comic politics of subversion Us government unit 1 study guide

Us government unit 1 study guide Parliamentary tradition meaning

Parliamentary tradition meaning Red herring examples in politics

Red herring examples in politics Def of politics

Def of politics Lesson 2 partisan politics

Lesson 2 partisan politics Power and politics

Power and politics Political comparative and superlative

Political comparative and superlative Ethics and politics in social research bryman

Ethics and politics in social research bryman Zhou dynasty politics

Zhou dynasty politics Filth is my politics

Filth is my politics Power and politics organization theory

Power and politics organization theory Bureaucracy and politics in india

Bureaucracy and politics in india Illegitimate political behavior

Illegitimate political behavior Politics and law atar

Politics and law atar Factors contributing to organizational politics

Factors contributing to organizational politics Pallid politics in the gilded age

Pallid politics in the gilded age What are politics

What are politics Power and politics in organizations

Power and politics in organizations Politics as an arena

Politics as an arena Philosophy, politics and economics michael munger

Philosophy, politics and economics michael munger What is politics

What is politics Uwc costa rica global politics

Uwc costa rica global politics Work experience politics

Work experience politics What is the challenges of media and information

What is the challenges of media and information Us politics

Us politics Chapter 4 section 1 the divisive politics of slavery

Chapter 4 section 1 the divisive politics of slavery Explain emerging patterns of state politics in india

Explain emerging patterns of state politics in india Chapter 15 section 3 politics in the gilded age

Chapter 15 section 3 politics in the gilded age