Chapter 1 What is Politics Def of Politics

- Slides: 47

Chapter 1: What is Politics? Def. of Politics; One person votes in an election, another assassinates the ruler of a state, a third complains that taxes are too high, a fourth administers developmental aid in a poverty-stricken area, a fifth wants to ban automobiles from the inner city, a sixth wishes his government would “teach a lesson” to a small but upstart neighboring state, a seventh lobbies for legalized abortions, an eighth strives for a stronger United Nations, a ninth demands that pornographic materials be confiscated from smut stores, a tenth petitions for unemployment compensation, an eleventh merely wants to be left alone, and a twelfth believes the military services have a role to play in domestic affairs. 1

Each of these individuals is a competitor for concrete or abstract political goods, yet each would find it difficult to give a concise reply to the question: “What is politics? ” two schools of thought stand in clear juxtaposition under the key words “competition” and “cooperation. ” * May, M. A. /Doob, L. W. - Competition and Cooperation. Ann Arbor: UMI, 1995. * James Madison - politics as s constant struggle waged by individuals or groups for economic power and advantage. (경제력과 경제적 이익 을 위하여 개인 또는 집단에 의해 전개되는 끊임없는 투쟁) * opposed to this point ===> the conviction that the cause of justice is best served by political institutions which unite society, either national or global, in a common effect to achieve an equitable distribution of resources. 2

In our analysis of international relations we will endeavor to assess the strengths and weaknesses of both interpretations of political life. David Easton : politics = ‘the authoritative allocation of values’ [David Easton, The Political System: An Inquiry Into the State of Political Science, 2 nd ed. (New York: Knopf, 1971), p. 129. ] values (stands for) desired conditions or commodities authoritative (denotes) some form of legitimate (i. e. generally acceptable, official, governmental) process through which people regulate their interrelationships with respect to the question of ‘who gets what, when, and how. ’ Therefore political activities are those activities involving people’s relationships with their government - whether we are talking about the executive, legislative, or judiciary aspects of government. 3

But some might argue that this is too restrictive a definition of politics, that political relationships exist at all levels of human interaction, provided they involve a clashing of human wills and the attempt by individuals or groups to impose their will upon others. (정부의 입법, 사법, 행정 분야 불문) On the basis of this latter, and considerably broader, definition of politics, a parent’s attempt to discipline his or her children, the informal hierarchy among inmates in prisons, the “politics” played by faculty, students, and administrators in universities, the disciplinary procedures characteristic of neighborhood gangs, the interactions in large, illicit groups such as the Mafia. 4

All these could be considered forms of politics. Politics is, therefore, a concept 1) that could be restrictive or comprehensive in its focus, depending on the definition employed by a given analyst. (관련분석가 가 설정한 정의에 좌우되면서 초점 면에서 제한적일 수도 포괄적 일 수도 있는 개념). 1) A ‘concept’ is an abstraction or generalization that helps us organize knowledge for purposes of theoretical inquiry. Some of the basic concepts in the field of politics are justice, power, freedom, interest, equality, conflict, peace, and participation. 5

Politics could probably be best understood as a person’s concern with public affairs(공공문제에 대한 어떤 사람의 관심사). Public affairs affect collective interests rather than narrow personal interests. This is approximately the way that ancient Greek philosophers visualized the phenomenon of politics. Aristotle, in fact, identified man as “a political animal. ” Politics derived its name from the Greek word polis, which mean city. Concern with the affairs of the city was viewed by ancient Athenians as both an honor and a duty. Athens, as a democratic society, was predicated on the existence of free, informed, and concerned citizens participating in the affairs of that city. (politics란 개념은 city를 의미하는 그리스어인 polis에서 유래되었다. 아 테네 사람들: 도시의 문제에 참여하는 것이 의무이자 영광으로 간주) 6

# Alternative Styles of Politics Political activities can be categorized in a number of ways. (1) A very common dichotomy is that between “high” and “low” politics. High politics in international relations refers to the making of vital, large-impact decisions. (i. e. , committing a country to wars or alliance) In the case of domestic politics, high politics involves large-scale decisions and policies such as instituting path-breaking laws in order to initiate a comprehensive social security system, to call for racial or ethnic integration, to nationalized private industry, or to make radical changes in the system and form of government. 7

Low politics, on the other hand, is the type of politics usually played by bureaucrats and administrators. - It involves small-magnitude decisions that do not alter appreciably the social, political and economic structure of a country or of the international system. - It is also the politics that maintains large social systems in some form of equilibrium. Low politics has been defined additionally as bureaucratic behavior designed to implement high political decisions without disturbing the foundations of the social, political, and economic status quo. 8

Examples of low politics at the international level the routine replacement and rotation of diplomatic personnel, the administration of technical, economic, and military aid programs, and the facilitation of trade, tourist, and investment exchanges. Examples of low politics at the domestic level includes activities, such as passing regulatory laws on environmental pollution, deciding on increments in the minimum wage and in social security benefits, and introducing school-lunch programs. 9

At the international level, high politics has been equated with decisions that involve the risk of war. We could, with some justification, criticize this arbitrary association of conflict and war politics with the word high, and cooperation and regulation politics with the word low. Indeed, it might be high time in international politics to reverse our thinking and equate “high politics” with international cooperation and “low politics” with conflict and war. 10

(2) “Politics of violence” vs. “Politics of persuasion” War or the threat of it, revolution, and civil disturbances of various magnitudes are forms of violent politics. The purpose of war - to follow von Clausewitz’s reasoning - is to continue politics by violent means. A person, a group, or a country fights or threatens to fight in order to change or control the behavior of an enemy. As long as violence or the threat of it is used with political objectives in mind (namely, to change or to preserve a situation in accordance with one’s interests), then one cannot deny these violent acts the status of politics. 11

The politics of persuasion, in turn, could be referred to as the politics of logic, of morally, of cooperation and interdependency, and, on occasion, of bribery (unless one considers bribes and other forms of corruptive incentive as psychological forms of violence). The processes involved here include diplomacy, treaties, negotiations, deliberations, law making, collective bargaining, economic, social, cultural, and scientific cooperation, and even the politics of vigorous competition - provided this competition is carried out under widely accepted and predetermined (i. e. , legitimate) rule. 12

There is, however, a relatively large zone of activities that bridges the politics of persuasion and the politics of violence. In this hybrid zone finds many instances of persuasive relationships that are the result of either explicit or implicit threat of force and violence. Under this heading could be classified numerous activities that are difficult to pinpoint as purely violent or purely persuasive politics. Good examples of hybrid politics are, - in the case of domestic affairs, the public's submission to the dictates of a well/entrenched, oppressive, authoritarian regime and, - internationally, the obedience of small satellite nations to the dictates of their great-power protectors. 13

(3) “hierarchical politics” vs. “pluralistic politics” Hierarchical politics presupposes pyramidal arrangements of increasing power and authority, both domestically and internationally. Political relationships in this category involve dependencies of subordinate units on superior unites. At the apex of each hierarchical society is an ultimate, if not always legitimate, authority from which powers flow to dependent tiers of authority, which in turn control more subordinate tiers, all the way down to the common citizens. Rules are dictated downward from the top parts of this pyramid, interpreted and applied by the middle parts, and absorbed (usually without overt controversy) by the populous majority at the bases. 14

On the other hand, pluralistic politics involves relationships among equal or nearly equal actors. Here, societies consist of well/informed, active, and autonomous political units (individuals, groups, or nations) that are quite jealous of maintaining their own independence and well-being, but also recognize the virtues of cooperative and regulated coexistence for their self-interest as well as for the good of the whole society. Pluralistic politics - is practiced in societies that have enough goods and services to satisfy the demands and needs of their members. - assumes a free and competitive system of education and information that does not rely on monopolitics control of the mass media in order to develop a feeling of artificial societal consensus through highly slanted propaganda campaigns. 15

All politics is to a great extent a mixture of both the hierarchical and the pluralistic types. But one can classify political systems over time as being more or less consensual or more or less hierarchical. For instance, Western-type democracies could be said to exhibit more pluralistic than hierarchical types of political behavior. Political authority in these democracies is supposed to be considerably fragmented and diffused, and policies are the outcomes for publicly waged competition among conflicting interest groups that is referred by publicly accountable governmental institutions. In contrast, authoritarian systems or polities, whether communist or capitalist, exhibit a greater tendency toward hierarchical forms of politics. 16

One can also differentiate between hierarchical and pluralistic politics on the international scale. For example, alliances among unequals exhibit more frequent instances of hierarchical politics, whereas alliances among relatively equal partners must rely more heavily on pluralistic arrangements. To illustrate this with a concrete example, we encounter more pluralistic politics in the relations between the United States and Britain than in the relations between the United States and its smaller NATO allies, such as Portugal, Greece, and Turkey. 17

# Four Approaches to Politics There is obviously no one generally accepted set of definitions and classifications of politics. We shall therefore discuss here at least four different approaches to the study of politics (whether domestic or international), each of which is based on radically different philosophical foundations. (1) The first is the realist approach. - “politics should be played in a realistic fashion” <정치는 현실적 유형으 로 작동되어야만 한다> Power for the realist is the essence of politics. The realist approach is normative (i. e. , prescriptive) in that it recommends the use of amoral and power-oriented politics and places the highest priority on the pursuit of one’s practical interests. 18

(2) The second approach, the idealist, is also normative. - “People should act in the future as they have acted in the past. ” - argues that people should abandon ineffective modes of behavior and, instead, act with knowledge, reason, compassion, and selfrestraint. (3) The third approach, the Marxist approach, at times a subtype of the idealist approach. It posits that at the basis of politics are issues of economics and that human relationships can best be explained by focusing on the struggle between the capitalists and the working class over the control of the means of production. 19

(4) The fourth approach is the empirical/scientific. - “politics should merely be observed. ” - it should be reported for what it is or has been rather than for what it should be. These students of politics are especially concerned that one’s biases and values not be allowed to color the detached and dispassionate observations of reality - however the chips might fall. In this respect, the fourth approach does not wish to be normative. 20

1. Realist Politics Edward H. Carr, Hans Morgenthau, Arnold Wolfers, George Kennan, and others. 1) Politics as “a struggle for power. ” Power is loosely defined as a psychological relationship in which one actor is able to control the behavior of another actor. 2) A second central concept for the realists is “interest. ” A rational political actor is one who acts to promote his or her interests. The realists conveniently close the definitional gap between interest and power by practically equating these two concepts. Thus, to act rationally (that is, to act in one’s interest) is to seek power (that is, to have the ability and the willingness to control others). 21

For the realists, acting in pursuit of personal, group, and national interests is being eminently political. It is also obeying forces that are inherent in human nature. To seek power in order to promote one’s interests is to follow the basic dictates of the “laws” of nature. - quite impatient with the proponents of the idealist school of thought, who argue that politics should follow the highest moral and legal principles. The realists argue that the adoption of legalistic, moralistic, and even ideological behavior in politics tends to run contrary to the forces of nature and to result either in pacifism and defeatism on the one hand or a fierce, exclusivist, and crusading spirit on the other. 22

- to sum up, a “good political person” is a “rational political person” : a person, that is, who understands and seeks power but who also moderates the quest for power because he or she realizes that others also understand seek power. 3) The rational political person’s most important characteristic is prudence. - Their main concern : the survival and the growth of his or her social collectivity. - never risks the collectivity’s survival in the pursuit of limitless growth, or in defense of ideological, moralistic, or legalistic righteousness. - The rational political person : a pragmatist: understandings, bargains, and compromises are more likely to prevail than rules, adjudication, and moral righteousness. -Niccolo Machiavelli remains the source and the inspiration of survivaloriented behavior. -Morality, legalism, ideologies - these are luxuries that can be pursued only if they do not endanger the viability and the vital interests of the political 23 collectivity or the government that speaks for the collectivity.

2. Idealist Politics Henri de Saint-Simon, Mahatma Gandhi, Woodrow Wilson, and Bertrand Russell. - the realist maxims appear morbid, reactionary, cynical, and quite of ten self-serving. - The great variety of proponents for idealist politics: pacifists, world federalists, humanitarians, legalists, and moralists. -The reader should note that practicing politicians, unlike politicalscience scholars, frequently employ idealist rhetoric. This rhetoric generally remains, however, outside the gates of practical application. 24

Politics is “the art of good government” rather than “the art of the possible. ” A good political leader does not do what is possible; rather, he or she does what is good. Leadership provides for the good life - which involves justice, obedience to legitimate rules (that is, rules derived from universal moral principles), and respect for fellow humans, both domestically and internationally. Idealist disagree with the fatalistic orientation of the realists, who assume that “power politics” is a natural phenomenon, indeed an unchanging law of nature. For the idealist, no pattern of behavior is unchangeable. Man has the capacity to learn and to change and control his behavior. Purely interest-motivated behavior reduces a person to the instincts of the beast. Over time, humans learn, improve, and grow. Civilization means learning to coexist in societies, operating under fair laws, and banning the laws of the jungle, which permit the survival only of the most wily, the most powerful, and the most ferocious. 25

For the idealist the art of the possible, as a guideline for political action, becomes a sinfully permissive type of philosophical justification. It licenses the practitioners of politics to lie, cheat, burgle, kill, and torture, if necessary, in defense of personal, party, or national interests. Political action is thus reduced to a game of deadly violence rather than a game of political wits. in contrast, moral principles - which are universal among all of the world’s major religions - can serve as the foundation from which fair and just laws can be derived, which in turn can be applied effectively (that is, with adequate sanctions) against those who break them. Thus, for the idealist, politics should involve the abandonment of force, the encouragement of learning, and the coexistence of societies under the leadership of adequately enlightened rulers. 26

The dual problem facing the idealist, as on might suspect, is to be found in the nature and in the implementation of their ideas. For example, we must ponder whether an adequate method exists for arriving at the substance of “universal ideals. ” Will it be possible in a multi-culture world occupied by states in drastically different stages of economic development to agree on what is “good politics”? Further, how does one bring about “enlightened societies, ” both at the domestic and at the international levels? What does one do with the lawbrakers, especially if they become more numerous than those who scrupulously observe the laws? What happens if violence and oppression are employed by ruthless governments in the name of law, order, and justice? “ 27

The various proponents of the idealist school are divided with respect to how best to meet internal violence and external aggression by states. (1) The pacifists feel that fighting violence with violence is merely falling into a Machiavellian/realist trap. If one tries, that is, to have one’s way even if this way defends the principles of justice and peace by using force or violence, then one fulfills the major axiom of the realists - that conflict, regardless of its purpose, is inherent in collective human affairs. The only viable alternative, according to the pacifists, is to resist nonviolently and to hope that in the long run the cultural patterns of good political behavior will displace primitive patterns characterized by “power politics. ” 28

(2) In contrast, legalists and world federalists argue that the use of centralized and legitimate force is necessary to deter individual actors in a given society from breaking the rules that guarantee collective coexistence without sacrificing fundamental individual rights. These thinkers often point to Western democratic/competitive systems as models of societies that operate in accordance with idealistic principles. These principles include the rule of law rather than rule by men, peaceful and arbitrated change, progressive taxation that allows for gradual redistribution of incomes and properties, fragmented and accountable governmental structures, and above all, civil rights that guarantee the freedoms of speech, worship, organization, and peaceful petitioning of the government. 29

So, the legalists and world federalists argue, if Western nations (the United States primary among them, given its ethnic diversity) can coexist within bounds of controlled violence, and under enlightened and liberal principles of behavior, then a world federation with central authority that monopolizes but does not abuse force can be instituted. Thus, the world will be freed from the scourge of international war and many of its derivative civil wars. 30

3. Marxist Politics The Marxist approach: an unavoidable historical route toward the attainment of world communism. The end objective and the inevitable end-state for humanity is a classless and stateless society where justice will be understood by the simple principle “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs. ” According to the philosophical fathers of Marxism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the economic system is at the foundation of every society. Economic relations, therefore, help us explain and understand all social and political relations. 31

Class and the struggle of the classes for control of the means of production - the root of social interaction. - the most important aspect of the history of human society. The theory goes on to state that in precommunist societies one privileged class (the bourgeoisie) owns and controls the means of production (tools, machines, assembly lines) as well as the banks and related financial institutions. The bourgeoisie, in turn, dominates the state (i. e. the government and all institutions connected with it) and society at large. In such a situation, the working class (the proletariat) is at the mercy of the all-powerful bourgeoisie for whom it produces a surplus of goods at very low wages. The net result is much wealth for the capitalist and subsistence wages for the debt-ridden working masses. 32

The capitalist class (bourgeoisie) views labor just as another commodity subject to the laws of economic supply and demand. Hence, the capitalists make a systematic effort to maintain a surplus of labor or, in other words, a certain level of “tolerable” unemployment. A large supply of labor faced with a limited demand for it permits the bourgeoisie to keep wages artificially low thus enlarging its own profits. The bourgeoisie seeks to perpetuated this favorable state of affairs by using the state (as an ally and an instrument) in maintaining control over the working class. The state, in other words, becomes the sword and the shield with which the rich and the powerful maintain their domination over the workers, the weak, the poor, and the illiterate. 33

Marxist theory posits that the states has not always existed. Early societies did not require intricate governmental mechanisms until a certain state of economic development was reached. This state, which was deeply affected by rapid industrialization patterns in Central and Western Europe, led societies to fragment into distinct and unequal classes (unequal in both size and power). The powerful bourgeoisie soon developed and nurtured the state, an instrument meant to guarantee that the workers would remain permanently in their subordinate place. Simultaneously, the working class was subjected to another effective weapon of the bourgeoisie for social and cultural training. This training, according to Marxist theory, was administered by the capitalists with the aid of state-controlled educational institutions and allied religious establishments. For the marxists, there was only one credible way left to free 34 the masses from their bondage - violent revolution.

Revolution would free the proletariat from the bourgeoisie and would allow workers to take control of the means of production. Violence was viewed as a necessary midwife of revolutionary change, and the new and just society would be forged after a transitional period where the workers (through the Communist Party) would exercise all political control a period referred to as the “dictatorship of the proletariat. ” Marxist theory predicted that communism would replace capitalism everywhere just as capitalism had replaced its inferior predecessor - feudalism. The fall of capitalism, it was argued, would be the inevitable outcome of irreconcilable contradictions separating the bourgeoisie from the working classes. Marx, writing at the close of the nineteenth century, predicted that the first proletarian revolutions would take place in advanced capitalist states such as England, France, and Germany. 35

History, however, did not confirm to marxist predictions. Instead, beginning in 1917 communist revolutions have taken place in less developed states such as Russia, China, Cuba, and Vietnam. It became the task of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (Lenin), the founder of the Soviet Union’s Bolshevik revolution and theoretician of applied communism to explain this major miscalculation in the predictive capacity of Marxist theory. Lenin claimed that the ability of advanced Western states to avoid revolution rested with their effectiveness in manipulating the capitalist-inspired international system. The advanced capitalist states, according to Lenin, were given a new lease on line by pampering their own workers at home while exploiting the working masses in the colonial territories of the earth. In Lenin’s view, imperialism (the domination of new markets and the creation of political dependencies) in what is today the Third World became the highest state and the last phase of capitalism. 36

Looking at the record of nation-states where Marxist-Leninist revolutions and takeovers have occurred, we note a considerable gap separating theoretical promise and practical performance. Marxist theory predicted the development of classless and stateless societies after each revolution. But instead of the “state withering away” we have witnessed among communist/socialist states a geometric rise in the size and functional responsibility of governmental authorities. As for the transition to classless societies, we have witnessed the growth of new clusters of powerful and privileged elites (usually associated with Communist Party structure) that have secured for themselves and are perpetuating positions of prominence and power. In fact, in an attempt to provide realistic incentives for production through hard work, the idealistic maxim of marxism “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need” has been changed to read, “from each according to his ability, to each according to his work. ” 37

Finally, Marxist-Leninist theory had clearly advanced the proposition that international wars had been the product of capitalist-imperialist states searching and competing aggressively for new markets and political dependencies. The logical expectation was, therefore, that wars among socialist (i. e. , nonimperialist) states would be unthinkable. In fact, it was argued, once communism as a system of government had spread itself throughout the world, war as a social phenomenon would disappear altogether. Instead, the past two decades have been replete with inexplicable (according to marxist doctrine) inter-communist-state quarrels such as the Soviet military interventions in Hungary (1956), Czechoslovakia (1968), Afghanistan (1979), the cold war between the USSR and the People’s Republic of China, and the protracted conflicts between communist states such as China and Vietnam 38 and Kampuchea (Cambodia).

4. “Scientist” Politics They argue that it is a waste of time to analyze politics from a position of “faith” that humans are either inherently good or evil, exploitive or exploited. Likewise, it is purposeless to make arbitrary statements about violence being either a natural/hereditary phenomenon or a pattern of behavior caused by manipulable environmental conditions such as political cultures, social norms, and class confrontations. The scientists suggest, instead, - human behavior should be observed systematically and comprehensively, - only generalizations rooted in empirical evidence should be formulated, - these generalizations should then be tested and retested in accordance with the scientific method. 39

The scientists challenge the unquestioned acceptance of unscientific definitions of politics, such as the class struggle, the struggle for power, or the search for a good life. Instead, they prefer inductive definitions (based on observation), such as “Politics is what the behavior of humans illustrates it to be. ” So, for the strict scientists the root of politics is the behavior of humans. For a purist proponent of the scientific approach to politics, people are engaged in political behavior when they rule, obey, persuade, compromise, co-operate, bargain, coerce, represent, fight, and fear. Politics is thus defined in terms of observable ranges of action and behavior rather than in terms of abstract concepts and impressions. 40

The pure scientist views political man as neither good nor bad by nature, neither conflict nor cooperative, neither prudent nor adventurist. Scientist have found that individual and collective behavior fluctuate over time and that the same person, given the proper stimuli, is capable of reacting in diametrically opposed fashions. So the guidelines for the scientifically oriented political scientist are : “Observe, observe! Then proceed and generalize, but only to the extent that you can support your generalizations with observed behavior. And finally accept your generalizations only to the degree to which your data samples are adequate in terms of time, space, and numbers. ” We find, then, that scientists will rarely advance generalizations that apply to mankind in general and over all time. On the contrary, they prefer to look at a few factors and their interrelationship, assuming all other factors to be out of the scope of their study. 41

Some problems inherent in the scientific orientation to politics If an analyst argues that politics is anything that humans demonstrate it to be, then he or she equates politics with all possible cooperative and conflictive behavior - in other words, all human interaction. There is precious little interactive behavior that can be left out of this catchall definition. The problem, then, lies in the excessive permissiveness of the definition. If, for example, the label “politics” were to be attached with disinterested ease to phenomena such as assassination, bribery, hijacking, sabotage, and saturation bombing, then these violent and treacherous acts would be placed on an equal plane with benign processes such as persuasion, cooperation, compromise, arbitration, and adjudication. 42

To say that politics is all-inclusive, from the pole of love to the pole of war, is perhaps to ignore the essence of politics, which should be peaceful and dignified coexistence, peaceful and equitable regulation of competition, peaceful and equitable redistribution of wealth and status - in short, peaceful and just change. 43

a second and subtler problem Some scientists have implicitly assumed that there are two ways of making important decisions; one way is “political” and the other way is “scientific. ” The argument is then made that scientific decisions are allegedly made on the basis of adequate information and according to rational criteria concerning the common interest. In contrast, it is argued, political decisions from the collective point of view are irrational, since they are designed to maximize the power and interests of the occasional decision maker and those groups surrounding him or her. The obvious implication of all of this argumentation is that informed scientists make better decisions than selfish politicians. 44

But this entire argument proceeds from overambitious assumptions that political decisions regarding “who gets what, when, and how” can indeed be arrived at scientifically. Furthermore, the scientist (now turned politician) may pursue policies designed to maximize personal or group interests. In the last analysis, for scientists to assume the incorruptibility of fellow scientists is for them to enter securely into the idealist school of thought. The 1970 s have introduced a useful attitude of eclecticism among the four approaches discussed above. A number of scientifically oriented scholars have abandoned their self-neutralizing role of purely unobtrusive and valuefree observation. They have realized that by serving only as human cameras and tape recorders they have been fulfilling useful functions, but in no way positively affecting or changing their environment. 45

Many scientists have, therefore, returned to the values prescribed by realist, idealist, Marxist, or other orientations. In fact, they have sought to combine their rediscovered values with the very best in rigor and accuracy that a systematic application of the scientific method can provide. Other scientists wishing to become “policy-relevant, ” have become “engineers. ” Now viewed as a social engineer, the political scientist is urged to go beyond observation and explanation. Instead, he or she is urged to focus on societal variables such as population growth, gross national product (GNP) per capita, type of governmental organization, war-proneness, and other factors that are subject to manipulation and control. 46

So if the transportation engineer can build bridges and roads to avoid traffic congestion, the social engineer can recommend or impalement social legislation designed to reduce social tension that would otherwise contribute to internal or international conflict. Our “engineer” in the social sciences wishes to move beyond description and explanation and into the realm of action. But at this point, we should caution social scientist to differentiate carefully between engineering projects that are socially desirable and permissible and those that may prove harmful, especially in the long run. The choice here too - ultimately remains political. 47

Def of politics

Def of politics The politics of reconstruction chapter 12 section 1

The politics of reconstruction chapter 12 section 1 Pendleton civil service act

Pendleton civil service act Chapter 20 politics of the roaring twenties answer key

Chapter 20 politics of the roaring twenties answer key Lesson 5 african american culture and politics

Lesson 5 african american culture and politics Chapter 31 the politics of boom and bust

Chapter 31 the politics of boom and bust Reconstruction and its effects

Reconstruction and its effects Chapter 4 section 1 the divisive politics of slavery

Chapter 4 section 1 the divisive politics of slavery Chapter 7 section 3 politics in the gilded age

Chapter 7 section 3 politics in the gilded age Politics of the roaring twenties chapter 12

Politics of the roaring twenties chapter 12 Chapter 20 politics of the roaring twenties answer key

Chapter 20 politics of the roaring twenties answer key Chapter 20 politics of the roaring twenties

Chapter 20 politics of the roaring twenties World politics in a new era

World politics in a new era Power and politics in organizations

Power and politics in organizations Gayatri spivak the politics of translation

Gayatri spivak the politics of translation Parliamentary tradition

Parliamentary tradition Explain emerging patterns of state politics in india

Explain emerging patterns of state politics in india Factors contributing to organizational politics

Factors contributing to organizational politics Factors contributing to organizational politics

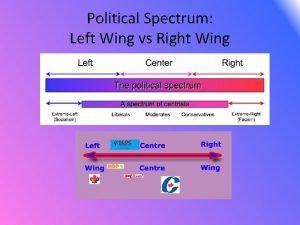

Factors contributing to organizational politics Left vs right politics

Left vs right politics Power in politics definition

Power in politics definition Opportunities and challenges in informational

Opportunities and challenges in informational Ib global politics costa rica

Ib global politics costa rica Bureaucracy and politics in india

Bureaucracy and politics in india Fallacy of equivocation

Fallacy of equivocation Andrew heywood global politics latest edition

Andrew heywood global politics latest edition Filth is my politics

Filth is my politics Nationalism edexcel politics

Nationalism edexcel politics Comparative theories politics a level

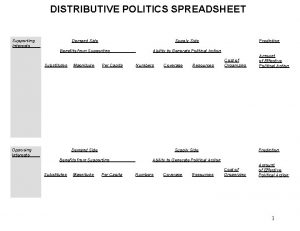

Comparative theories politics a level Distributive politics spreadsheet

Distributive politics spreadsheet Uwc global politics

Uwc global politics Power politics and conflict in organizations

Power politics and conflict in organizations Ethics and politics in social research bryman

Ethics and politics in social research bryman Uwc costa rica global politics

Uwc costa rica global politics Italian renaissance politics

Italian renaissance politics Stem cell politics

Stem cell politics Politics as an arena

Politics as an arena Bolton romanticism amp; politics 1789 1832 download

Bolton romanticism amp; politics 1789 1832 download Conflict power and politics

Conflict power and politics Definition politics

Definition politics What is regionalization

What is regionalization Philosophy, politics and economics michael munger

Philosophy, politics and economics michael munger Lesson 1 - politics and the gilded age

Lesson 1 - politics and the gilded age Engagement activity global politics

Engagement activity global politics Lesson 2 partisan politics

Lesson 2 partisan politics Whose government politics populists and progressives

Whose government politics populists and progressives What are politics

What are politics Ib global politics theories

Ib global politics theories