After deinstitutionalisation The Whole LifeWhole System Experience in

- Slides: 58

After de-institutionalisation The Whole Life-Whole System Experience in Trieste State Capitol Hearing, CA Roberto Mezzina Director, Department of Mental Health, ASUITs WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training, Trieste

Trieste demonstration n A town without a psychiatric hospital for 40 years. n From total institution to a fully community based service, without barriers, immersed in the community, and a low threshold of access. n Practice with the highest degree of freedom, following the principle of respecting user’s power of negotiation. n There are places, like the CMHC, group homes, day centres, social clubs, where anybody can live health and ill mental health in their interface in people’s lives. n Mental health issues are recognized in their intersections with mental ill health and social inclusion (with welfare systems), with justice, with general health and health needs. n The paradigm of illness is broken in favor of that of the person. n It is possible to empower diverse stakeholders and collective subjects (users, families, networks, community, society), while the vertical power of psychiatric institution has been dismantled.

Objectives / goals • Replacing psychiatric institutions with a network of community services totally alternative to them. • At the same time, enhancing rights of citizenship of people with mental health problems and providing a whole life - whole system response to their needs of care. • The subjectivitiy of clients, their life stories and their aspirations are considered as the main tools for providing treatments and developing services.

Outlook & Transferability • The practice was recognised as an experimental pilot area of mental health de-institutionalisation by the World Health Organization in 1974, became a WHO Collaborating Centre in 1987 and is reconfirmed as such until 2018. • This means assisting WHO in guiding other countries in deinstitutionalization and development of integrated and comprehensive Community Mental Health services, contributing to WHO work on person centered care and supporting WHO in strengthening Human Resources for Mental Health. • Because de-institutionalisation was so successful in Trieste, the community-based approach has been implemented in the whole Friuli Venezia Giulia region and is acting as inspiring model for services, organisations and countries in more than 40 countries - so far particularly in Europe, Asia, South America, Australia and New Zealand.

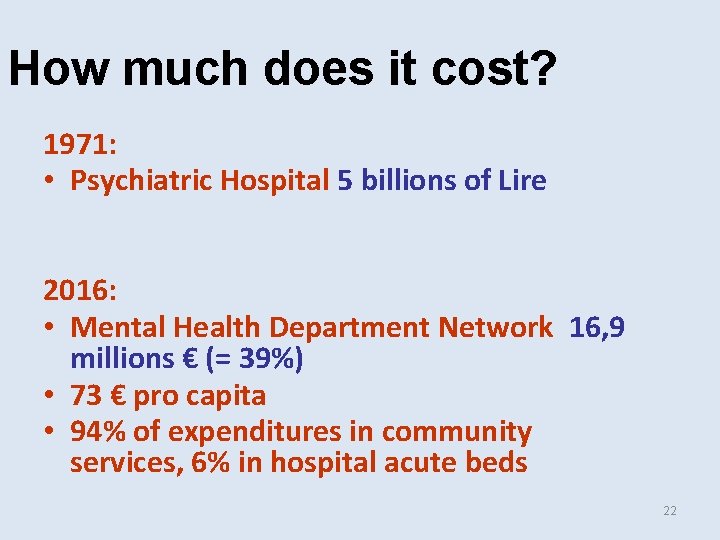

Transferability, scalability and cost-efficiency • This organization has become the regional model for all mh Services in Region Friuli-Venezia Giulia (1. 200. 000) but not for the whole country, despite the request of family and user organizations. • Many organisations from all over the world visit Trieste every year (up to 900 persons as professionals, managers, politicians and stakeholders in general). • Trieste is Lead WHO Collaborating Centre for service development from 2005. • The sustainability is demonstrated because the overall cost of services provided by the MH Dept is no more than 40% of the cost of the former asylum. • The number of people treated in a more humane system of care is about 5000 as compared to 1200 in 1971.

The Mission of MHD: integration of services and value base • The MHD shall ensure that the community mental health services of the LHC have a coherent and unique organisation as a whole, through a strict co-ordination of actions and links with the other services of LHC, particularly with general health districts and emphasizing the relationships with the Community and its institutions. • Clear values: “The MHD shall operate for the elimination of any form of stigmatisation, discrimination and exclusion concerning the mentally ill persons. ” • “The MHD is engaged to actively improve full rights of citizenship for the mentally ill persons. ”

Today’s features of the Mental Health Department in Trieste (236, 393) are: Facilities: • 4 24 hrs Community Mental Health Centres (equipped with 6 beds each and open around the clock) plus the University Clinic) • A small Unit in the General Hospital with 6 emergency beds • A Service for Rehabilitation and Residential Support (5 group-homes with a total of 35 beds, provided by staff at different levels and a Day Centre including training programs and workshops); Partners: • 15 accredited Social Co-operatives. • Families and users associations, clubs and recovery homes. Staff: 214 people 23 psychiatrists, 7 psychologists, 111 nurses, 10 psychosocial rehabilitation workers, 8 social workers, 27 support operators, 12 administrative staff. 8

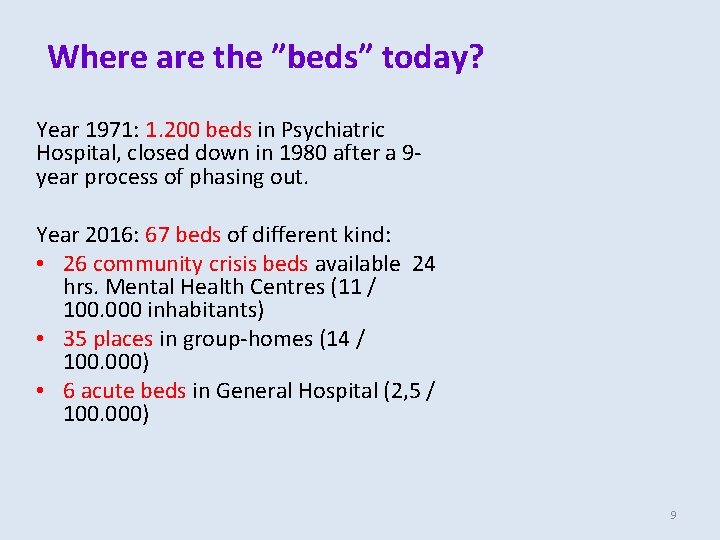

Where are the ”beds” today? Year 1971: 1. 200 beds in Psychiatric Hospital, closed down in 1980 after a 9 year process of phasing out. Year 2016: 67 beds of different kind: • 26 community crisis beds available 24 hrs. Mental Health Centres (11 / 100. 000 inhabitants) • 35 places in group-homes (14 / 100. 000) • 6 acute beds in General Hospital (2, 5 / 100. 000) 9

CSM DOMIO CSM BARCOLA

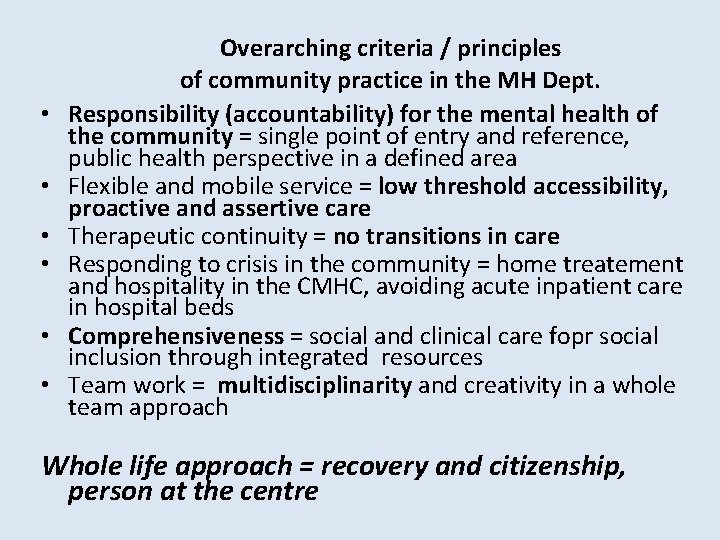

• • • Overarching criteria / principles of community practice in the MH Dept. Responsibility (accountability) for the mental health of the community = single point of entry and reference, public health perspective in a defined area Flexible and mobile service = low threshold accessibility, proactive and assertive care Therapeutic continuity = no transitions in care Responding to crisis in the community = home treatement and hospitality in the CMHC, avoiding acute inpatient care in hospital beds Comprehensiveness = social and clinical care fopr social inclusion through integrated resources Team work = multidisciplinarity and creativity in a whole team approach Whole life approach = recovery and citizenship, person at the centre

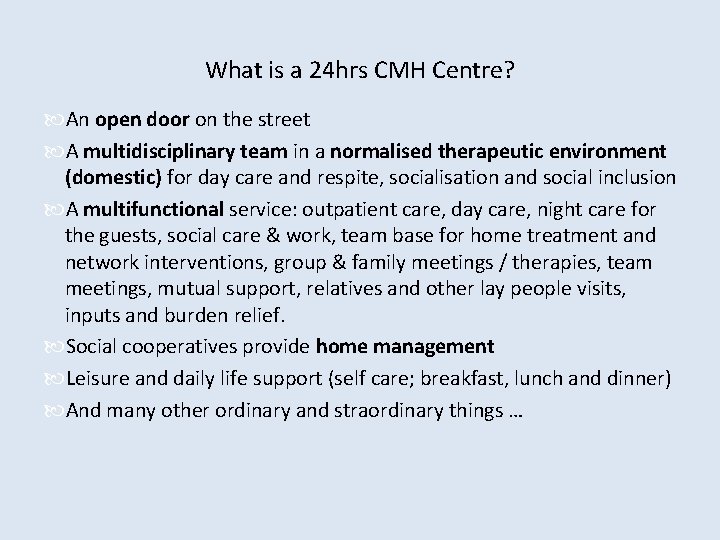

What is a 24 hrs CMH Centre? An open door on the street A multidisciplinary team in a normalised therapeutic environment (domestic) for day care and respite, socialisation and social inclusion A multifunctional service: outpatient care, day care, night care for the guests, social care & work, team base for home treatment and network interventions, group & family meetings / therapies, team meetings, mutual support, relatives and other lay people visits, inputs and burden relief. Social cooperatives provide home management Leisure and daily life support (self care; breakfast, lunch and dinner) And many other ordinary and straordinary things …

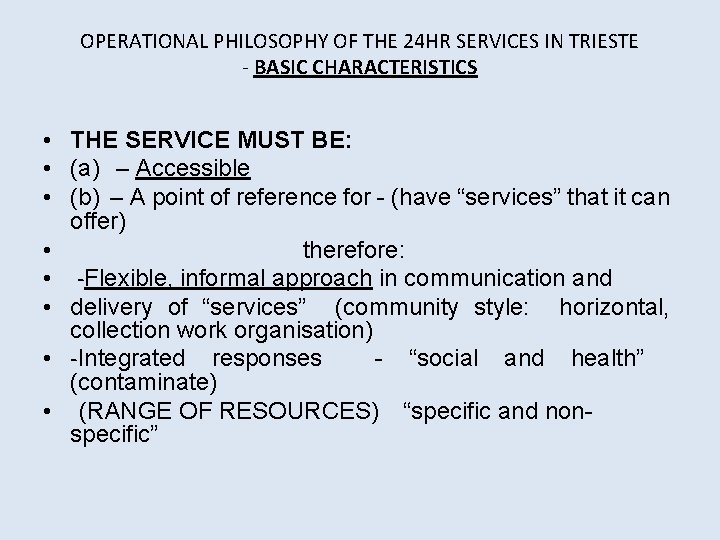

OPERATIONAL PHILOSOPHY OF THE 24 HR SERVICES IN TRIESTE - BASIC CHARACTERISTICS • THE SERVICE MUST BE: • (a) – Accessible • (b) – A point of reference for - (have “services” that it can offer) • therefore: • -Flexible, informal approach in communication and • delivery of “services” (community style: horizontal, collection work organisation) • -Integrated responses - “social and health” (contaminate) • (RANGE OF RESOURCES) “specific and nonspecific”

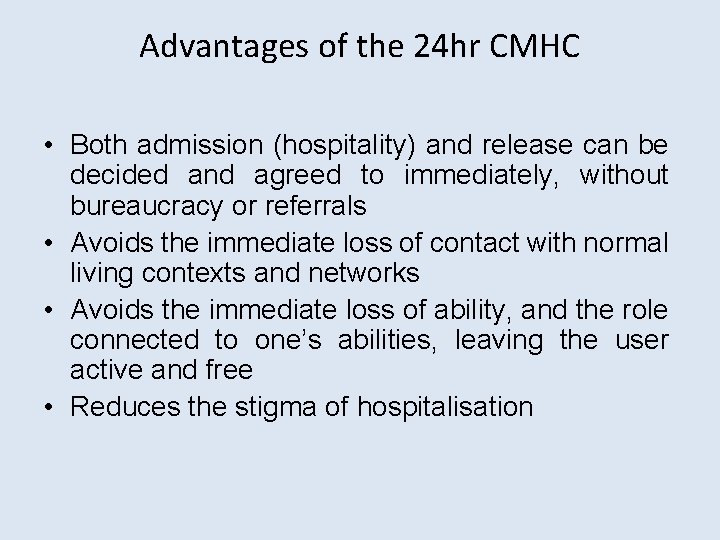

Advantages of the 24 hr CMHC · Point of reference open 24 hrs · The personnel can be utilised flexibly · Users can receive a wide range of responses · The crisis comes into immediate contact with a system of resources/options, including for rehabilitation • · The user is always assisted by a single team that has a contractual relationship with him/her • •

Advantages of the 24 hr CMHC • Both admission (hospitality) and release can be decided and agreed to immediately, without bureaucracy or referrals • Avoids the immediate loss of contact with normal living contexts and networks • Avoids the immediate loss of ability, and the role connected to one’s abilities, leaving the user active and free • Reduces the stigma of hospitalisation

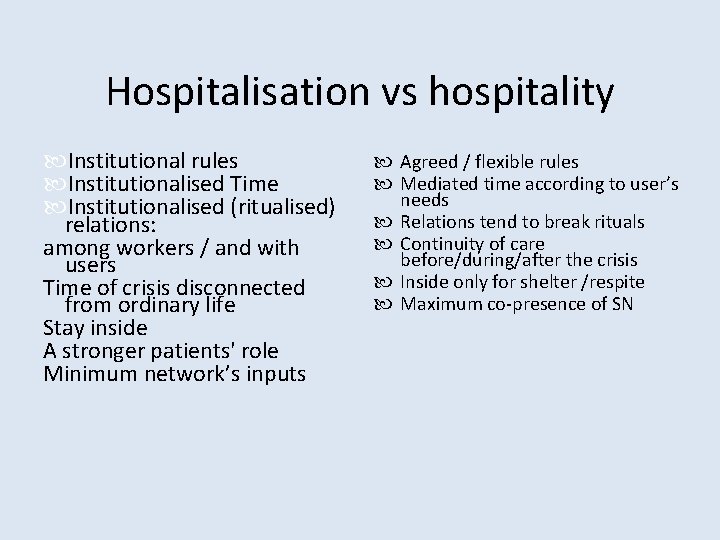

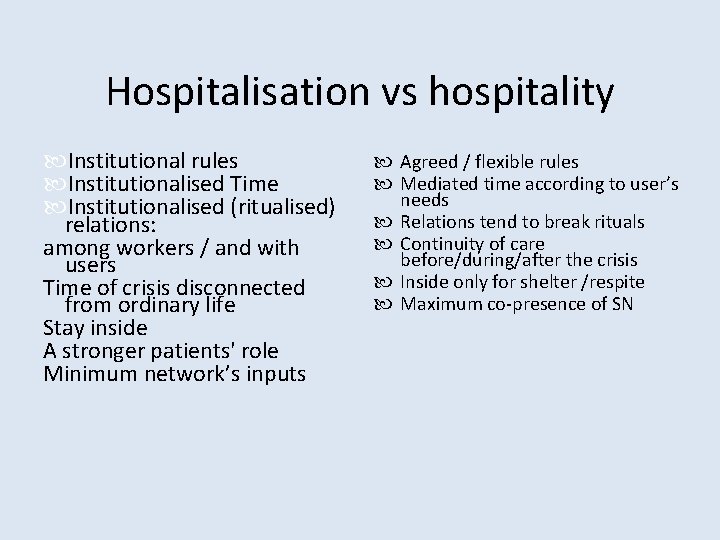

Hospitalisation vs hospitality Institutional rules Institutionalised Time Institutionalised (ritualised) relations: among workers / and with users Time of crisis disconnected from ordinary life Stay inside A stronger patients' role Minimum network’s inputs Agreed / flexible rules Mediated time according to user’s needs Relations tend to break rituals Continuity of care before/during/after the crisis Inside only for shelter /respite Maximum co-presence of SN

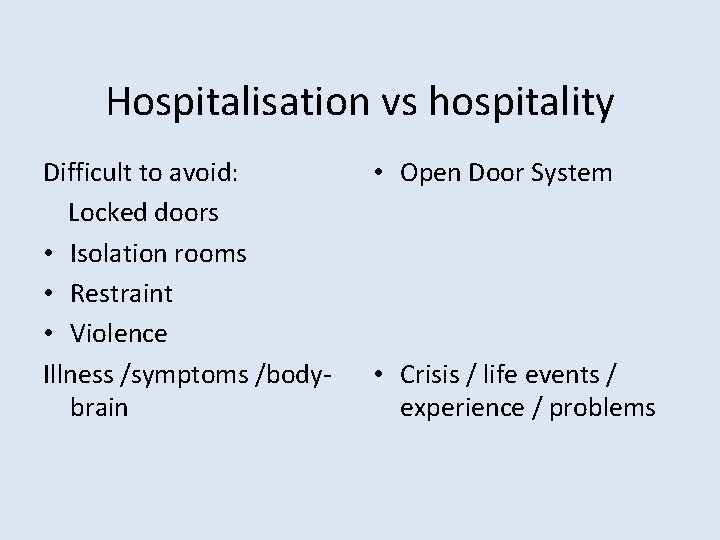

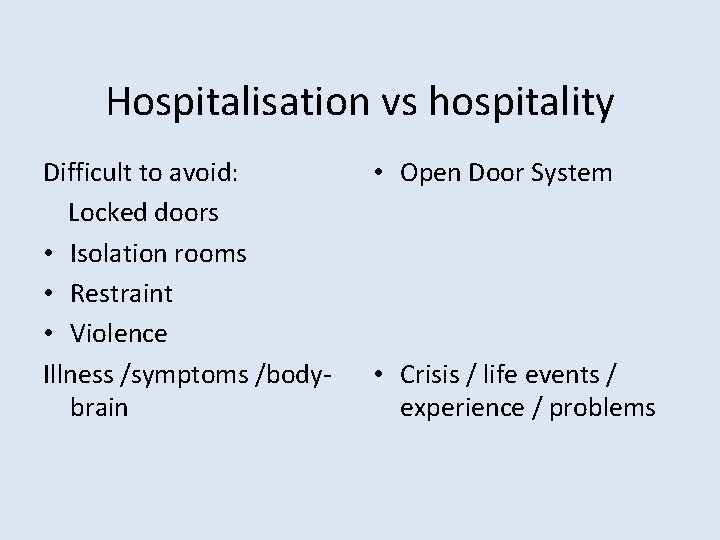

Hospitalisation vs hospitality Difficult to avoid: Locked doors • Isolation rooms • Restraint • Violence Illness /symptoms /bodybrain • Open Door System • Crisis / life events / experience / problems

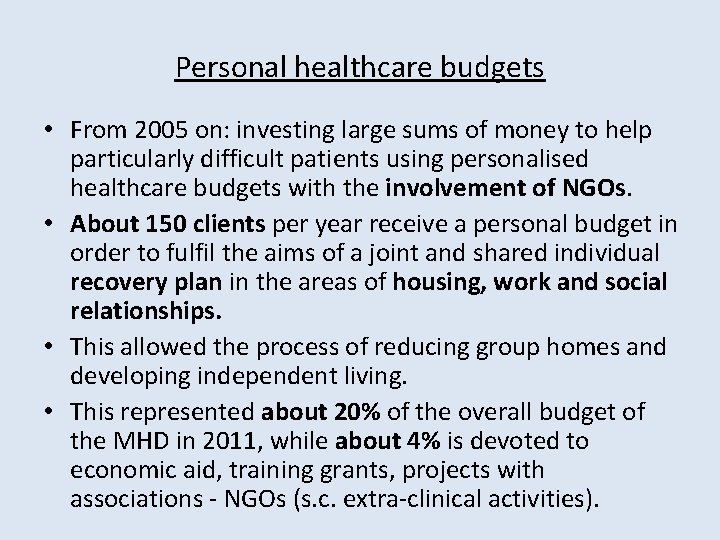

Personal healthcare budgets • From 2005 on: investing large sums of money to help particularly difficult patients using personalised healthcare budgets with the involvement of NGOs. • About 150 clients per year receive a personal budget in order to fulfil the aims of a joint and shared individual recovery plan in the areas of housing, work and social relationships. • This allowed the process of reducing group homes and developing independent living. • This represented about 20% of the overall budget of the MHD in 2011, while about 4% is devoted to economic aid, training grants, projects with associations - NGOs (s. c. extra-clinical activities).

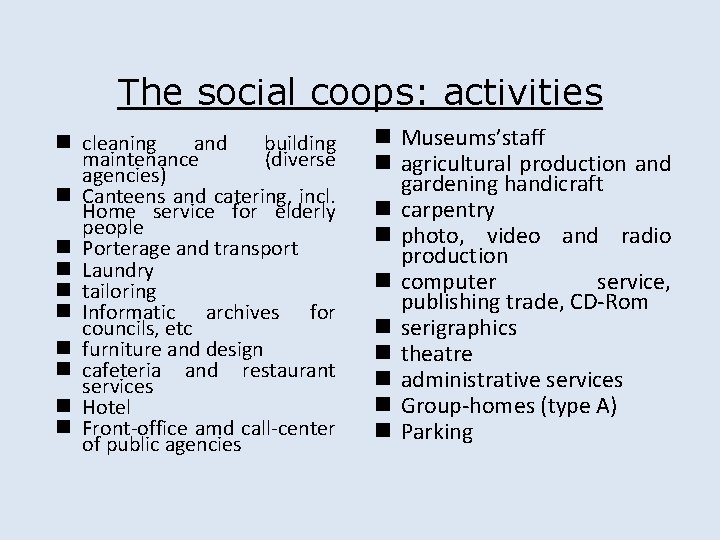

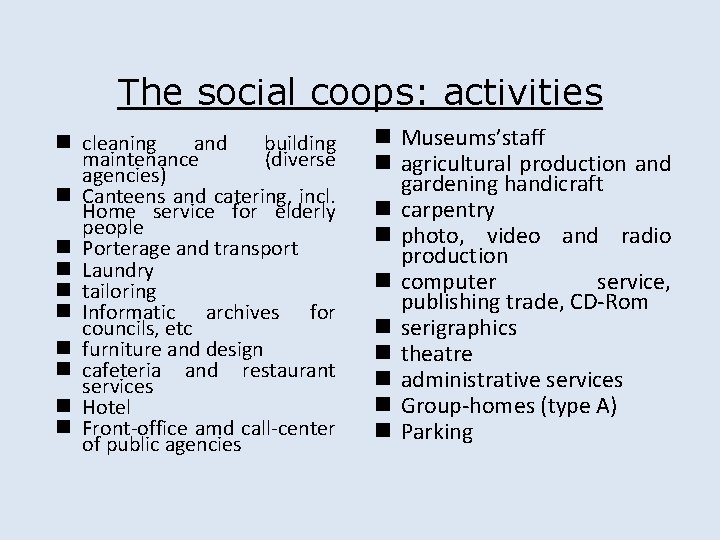

The social coops: activities n cleaning and building maintenance (diverse agencies) n Canteens and catering, incl. Home service for elderly people n Porterage and transport n Laundry n tailoring n Informatic archives for councils, etc n furniture and design n cafeteria and restaurant services n Hotel n Front-office amd call-center of public agencies n Museums’staff n agricultural production and gardening handicraft n carpentry n photo, video and radio production n computer service, publishing trade, CD-Rom n serigraphics n theatre n administrative services n Group-homes (type A) n Parking

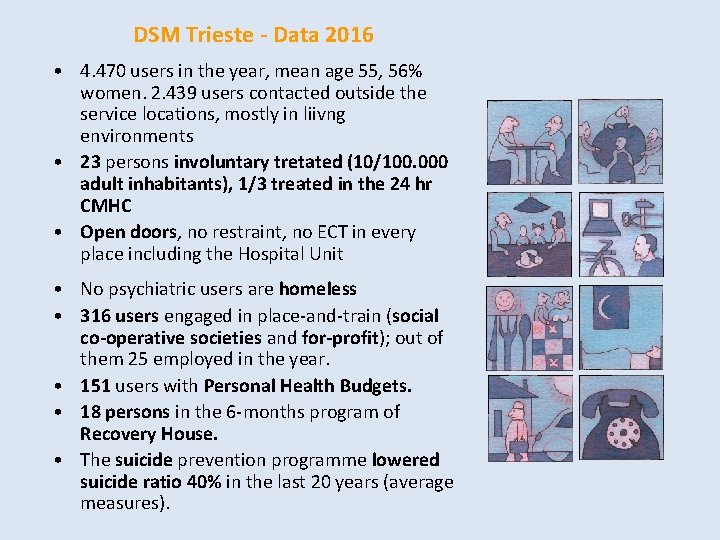

DSM Trieste - Data 2016 • 4. 470 users in the year, mean age 55, 56% women. 2. 439 users contacted outside the service locations, mostly in liivng environments • 23 persons involuntary tretated (10/100. 000 adult inhabitants), 1/3 treated in the 24 hr CMHC • Open doors, no restraint, no ECT in every place including the Hospital Unit • No psychiatric users are homeless • 316 users engaged in place-and-train (social co-operative societies and for-profit); out of them 25 employed in the year. • 151 users with Personal Health Budgets. • 18 persons in the 6 -months program of Recovery House. • The suicide prevention programme lowered suicide ratio 40% in the last 20 years (average measures).

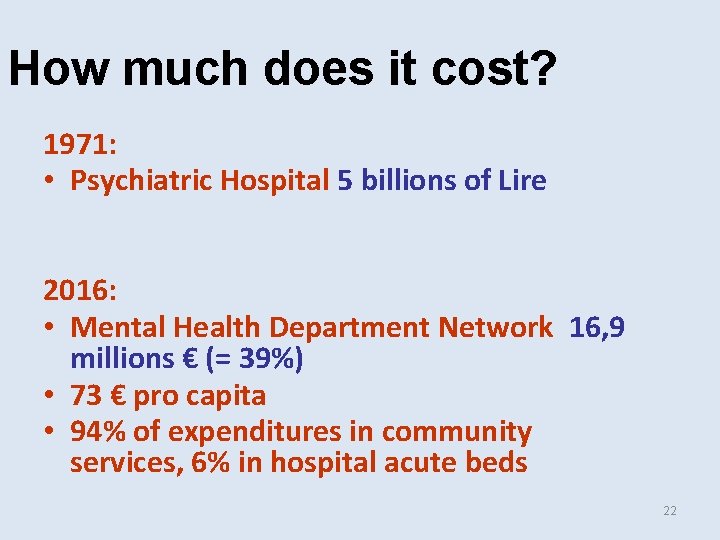

How much does it cost? 1971: • Psychiatric Hospital 5 billions of Lire 2016: • Mental Health Department Network 16, 9 millions € (= 39%) • 73 € pro capita • 94% of expenditures in community services, 6% in hospital acute beds 22

Social determinants of mental health WHO and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation • A person’s mental health and many common mental disorders are shaped by various social, economic, and physical environments operating at different stages of life. • Risk factors for many common mental disorders are heavily associated with social inequalities, whereby the greater the inequality the higher the inequality in risk. • It is of major importance that action is taken to improve the conditions of everyday life, beginning before birth and progressing into early childhood, older childhood and adolescence, during family building and working ages, and through to older age. • Action throughout these life stages would provide opportunities for both improving population mental health, and for reducing risk of those mental disorders that are associated with social inequalities.

two-way relationship • A two-way relationship exists between mental disorders and socioeconomic status: mental disorders lead to reduced income and employment, which entrenches poverty and in turn increases the risk of mental disorder. • Patterns of inequity in social distribution emerge before adulthood. • A systematic review of the literature found that the prevalence of depressed mood or anxiety was 2. 5 times higher among young people aged 10 to 15 years with low socioeconomic status than among youths with high socioeconomic status.

Inequalities • Nowadays new inequalities and human rights violations exasperate the individual and social suffering that are tied to material living conditions, alongside the persistence of forms of second-class citizenship – to arrive ultimately at the homeless, the migrant or a total absence of a relationship with the state. • Therefore the mentally ill people, everywhere in the world suffering from some level of exclusion and lackness in citizenship rights (from the most severe – even the legal and civil ones – to the social rights) is now put beside other excluded social groups.

Community health and development • Addressing social determinants of health and enhancing social capital through the involvement of MHD in the • Microarea Habitat Project (global, local, plural) activated in Trieste in collaboration with the Municipality and the Public Housing Agency. • 20 areas of the city, with an average population of approx. 1000 persons each. • A pivotal service around general health, basically: • checking health conditions, social habitat, integrated clinical and social care, reducing inappropriate hospitalisations or stays in nursing homes, appropriate medication • promoting self-help, developing collaboration among services and among other actors, such as volunteer groups and/or stakeholders. • Results: reducing hospitalization rate, improving service delivery, community cohesion and MH promotion, inclusion of migrants and asylum seekers.

‘Freedom First’ • “Freedom is therapeutic” was in the 70 s the motto in the Trieste experience, which is still preserving that legacy, and now “Freedom first” (as a pre-condition for care) can express some of the most significant movement stances, which overturns power mechanism toward people empowerment. • This is also the title of “a study of the experiences with community-based mental healthcare in Trieste, Italy, and its significance for the Netherlands” by Trimbos Institute, Utrecht, 2015

Freedom is therapeutic UGO GUARINO

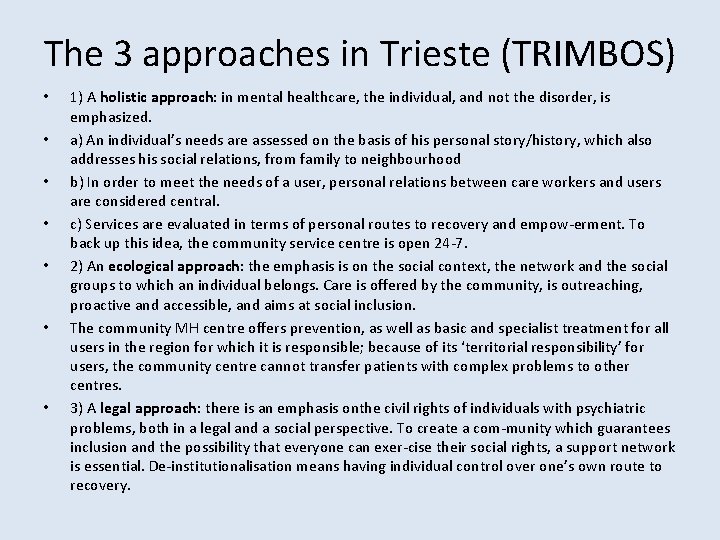

The 3 approaches in Trieste (TRIMBOS) • • 1) A holistic approach: in mental healthcare, the individual, and not the disorder, is emphasized. a) An individual’s needs are assessed on the basis of his personal story/history, which also addresses his social relations, from family to neighbourhood b) In order to meet the needs of a user, personal relations between care workers and users are considered central. c) Services are evaluated in terms of personal routes to recovery and empow-erment. To back up this idea, the community service centre is open 24 -7. 2) An ecological approach: the emphasis is on the social context, the network and the social groups to which an individual belongs. Care is offered by the community, is outreaching, proactive and accessible, and aims at social inclusion. The community MH centre offers prevention, as well as basic and specialist treatment for all users in the region for which it is responsible; because of its ‘territorial responsibility’ for users, the community centre cannot transfer patients with complex problems to other centres. 3) A legal approach: there is an emphasis onthe civil rights of individuals with psychiatric problems, both in a legal and a social perspective. To create a com-munity which guarantees inclusion and the possibility that everyone can exer-cise their social rights, a support network is essential. De-institutionalisation means having individual control over one’s own route to recovery.

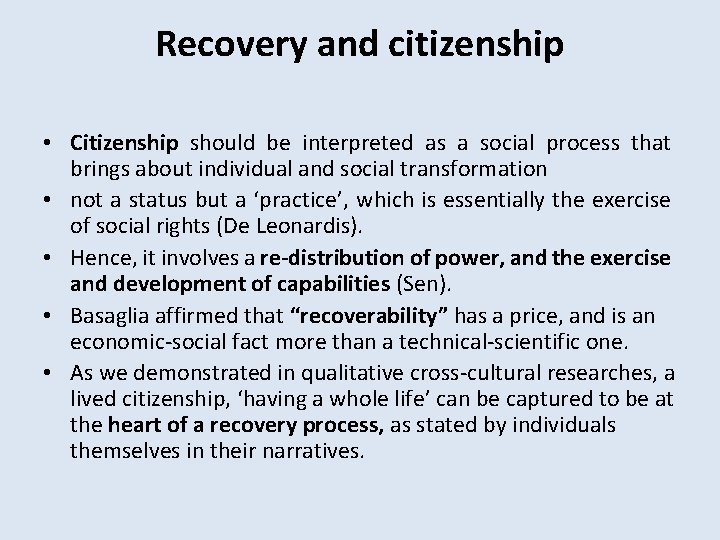

Recovery and citizenship • Citizenship should be interpreted as a social process that brings about individual and social transformation • not a status but a ‘practice’, which is essentially the exercise of social rights (De Leonardis). • Hence, it involves a re-distribution of power, and the exercise and development of capabilities (Sen). • Basaglia affirmed that “recoverability” has a price, and is an economic-social fact more than a technical-scientific one. • As we demonstrated in qualitative cross-cultural researches, a lived citizenship, ‘having a whole life’ can be captured to be at the heart of a recovery process, as stated by individuals themselves in their narratives.

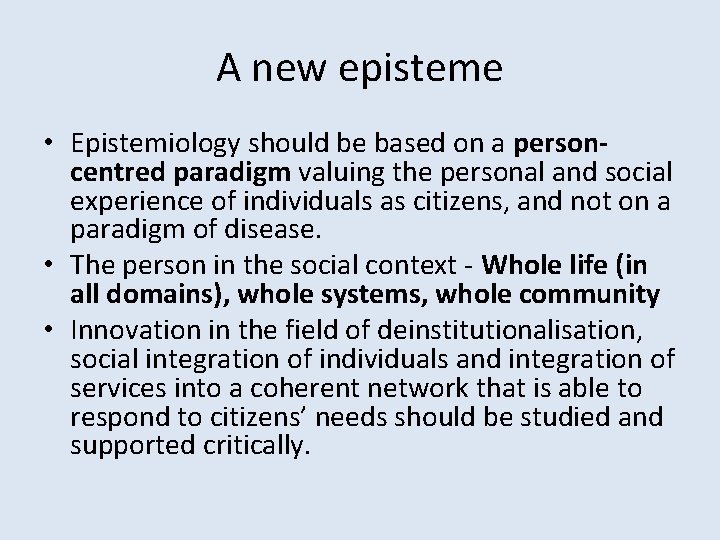

A new episteme • Epistemiology should be based on a personcentred paradigm valuing the personal and social experience of individuals as citizens, and not on a paradigm of disease. • The person in the social context - Whole life (in all domains), whole systems, whole community • Innovation in the field of deinstitutionalisation, social integration of individuals and integration of services into a coherent network that is able to respond to citizens’ needs should be studied and supported critically.

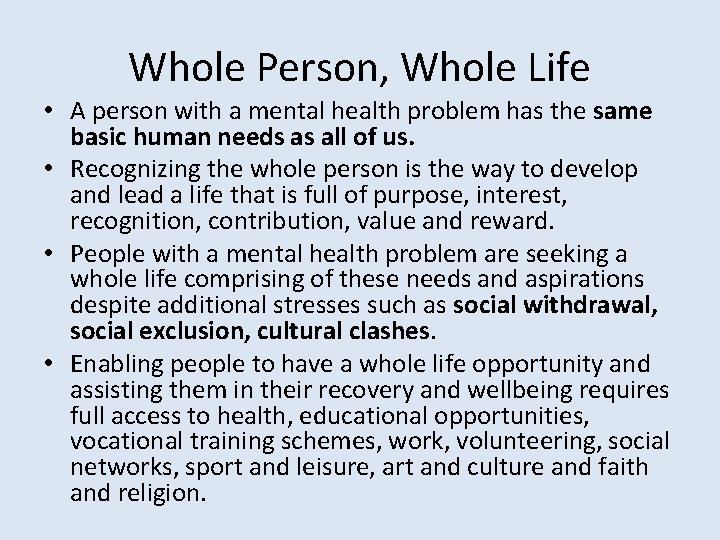

Whole Person, Whole Life • A person with a mental health problem has the same basic human needs as all of us. • Recognizing the whole person is the way to develop and lead a life that is full of purpose, interest, recognition, contribution, value and reward. • People with a mental health problem are seeking a whole life comprising of these needs and aspirations despite additional stresses such as social withdrawal, social exclusion, cultural clashes. • Enabling people to have a whole life opportunity and assisting them in their recovery and wellbeing requires full access to health, educational opportunities, vocational training schemes, work, volunteering, social networks, sport and leisure, art and culture and faith and religion.

Whole system • The Whole Life approach, as experimented in various countries and continents by IMHCN (www. IMHCN. org), promotes this by applying a Whole Systems methodology in the design, planning and implementation of a comprehensive integrated mental health system. • The Whole system has to have an agreed common purpose and objectives negotiated and owned by all community stakeholders.

Whole community • This approach actively benefits from a local communities human, economic, social and cultural resources. • All communities have the potential to provide significant opportunities for individuals and families to continue or regain a whole life in all its domains. • Ensuring the active participation of organizations and individuals from communities in designing and implementing a whole life whole system strategy lies at the core of the success of this approach. • The healthcare and welfare system with governmental and non-governmental agencies (NGO) is a vital part of this overall framework and can even enhance the social capital of individuals and groups with not only specific healthcare actions and programs, but also as catalyzer of those opportunities.

Social capital and mental health • a person’s social capital is often destroyed by illness in its dynamics with the social context, in terms of discrimination and marginalization • The concept of social capital refers to the relationship resources possessed by individuals, which support them in their actions and decisions (De Leonardis). It is composed of social networks and interactions, civil participation and commitment and institutions which enable cooperation among individuals. • It is the network of personal and social relationships which an actor (individual or group) possesses and is able to mobilise in order to reach personal/group goals and improve one’s social position (P. Bourdieu, 1980).

• It is thus a sum of relationships that an individual or group can use to advance their own interests and in this sense it can be considered ‘productive’. It is thus situated within the structure of relationships (J. Coleman, 1988). • Social capital is measured by values such as trust, reciprocity and civil participation, and many studies have correlated it positively with conditions of mental and physical health. • Bonding, bridging and linking s. c.

Enhancing community networks • Power and class structure • building or strengthening of networks: creating community, networking, new networks • culture-sensitive and culture-bound programmes and the struggle for universal access to mainstream services, without any form of discrimination, but instead making them more flexible. • Tension between specificity (ethnic origin, gender, language) and universality, between diversity and equality.

Service networking with • Beyond the acknowledgment of the value of the single individuals and the families, the need for the valorization of families and consumers as collective subjects gradually becomes imperative as far as they present themselves to the attention of the service. • Thus at a some stage in this process, a need for working out new strategies to open to more collective levels of participation startes emerging.

Development of coproduction of services • PH Budgets for co-planning and also delivery (social coops B). Coops in the co-production. • 12 point Recovery charter developed by users and in the real services • Recovery houses and crisis homes • Sponsor families • Open Dialogue • Peer support in services

IMHCN - A network of leading experiences, 35 countries - common criteria and principles: • spreading out anti-asylum practices, in order to shut down psychiatric hospitals which still persist in Europe • principle of 24 hours service as an alternative to hospitalisation • continuity of care • service’s integration, mobility and flexibility • non-selection / non exclusion of users in community practice • participation and active user involvement • partnerships with community agencies in order to tackle people’s needs • an adequate investment of economic resources which ca not be less than 5% of health expenses.

US: the continuous care strategy (Stein & Santos, 1998) • The utilization of a broad approach • Acting as a fixed point of responsibility for all aspects of the persons’life that affect his or her stability in the community • Careful monitoring • There are no arbitrary time limits on how long a person will be served by the team or on how long any specific service will be provided. • Continuous care via team with a care coordinator or primary contact person • Crisis stabilization and the proper use of hospital services

Managing system contradictions • the strategic centrality of political-healthcare governance vs. the centrality of the general population; • professionalism vs. the inclusion of all main stakeholders; • clinicalised, specialised, centralised, hospital-based and institutionalised services, based on separate healthcare services and aimed at specific pathologies • vs. • integrated, comprehensive, decentralised, small-scale, lowthreshold services, which are closely linked to social-living contexts and the local community

Trieste: general indications • Community health as passage which derives from deinstitutionalisation: systems built around both individuals and communities • Comprehensive, holistic approach which combines medicine with welfare systems for powerful synergies - concept of whole systems, whole life approach (Jenkins, Rix, 2002) • The focus on individuals and the rights of citizenship raises the issue of values which underpin practices and services (valuebased services, Fulford, 2001) • Creating personalised itineraries as organisational-strategic key, in which the person has an active role and contractual power.

Indications • Foster the service’s responsibility and accountability towards the community. The responsibility for care processes should be rooted in the community. • Recognising the importance of social contexts as producers of the meaning of health actions and as bearers of resources • Passage from reparative medicine to participatory health. • Developing the protagonism of individuals as stakeor shareholders in the healthcare system (concept of leadership linked to the activation of processes of strategic nad organisational change).

Toward a value-driven service • • • A citizen with rights Helping a person and not treating a illness Understand events of life, overcome crisis Explain and discuss experience Not losing value as a person (invalidation, neglect, violence) Keep social roles and maintaining social networks / systems Develop growth potential (recovery) Have opportunities – real empowerment Change (living conditions, style) Material resources (work, money, practical help)

Conclusion • Comprehensiveness and community integration came first as regards to treatment specialisation and avoid the risk of service fragmentation. • Theoretically, the action on social determinants is related to value of subjectivity that provides a meaningful context to care processes involving them. • A person-centered and a rights based vision and approach is required.

Paradigm Shift • from services provided, measured by outcomes (effectiveness or efficacy) • To options/opportunities • A personal(ized) “route” toward recovery and emancipation

Paradigm Shift • from legal responsibility • to for professionals (social responsibility and control) accountability on mental health of /for a • assessed in term of risks given community

Paradigm Shift • from formal (civil) rights, guaranteed by legislations • to social rights – house, work, etc (citizenship) • therefore to all politics contrasting social exclusion and providing resources and access to • social inclusion

Paradigm Shift • from “specialized” services (taylorism) fragmentation • to comprehensive services: ü person as a unity ü vision of human beings ü continuity of care (“projects for life” more than mere therapeutic or rehabilitative programs)

Paradigm Shift • Power is not only now avoiding institutional seclusion but having a voice, a say through participation and involvement • in own individual care plan (negotiation) • in the services’ life • in any moment of direct democracy

Paradigm Shift Levels of freedom • choice • opportunities • alternatives at each phase of the process • access and way out of the service network / patient’s role (informal, self refer, walk-in, no waiting lists, no selection). • (the 3 E’s: Ethics, Evidence, Thornicroft and Tansella 2009) Experience,

Contact • Roberto Mezzina, Direttore Dipartimento di Salute Mentale – ASUITS / WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training • via Weiss, 5, 34125 Trieste, Italy • +393488710355 • roberto. mezzina@asuits. sanita. fvg. it • who. cc@asuits. sanita. fvg. it