The mainstream linguistic approach Language consists of hierarchically

- Slides: 116

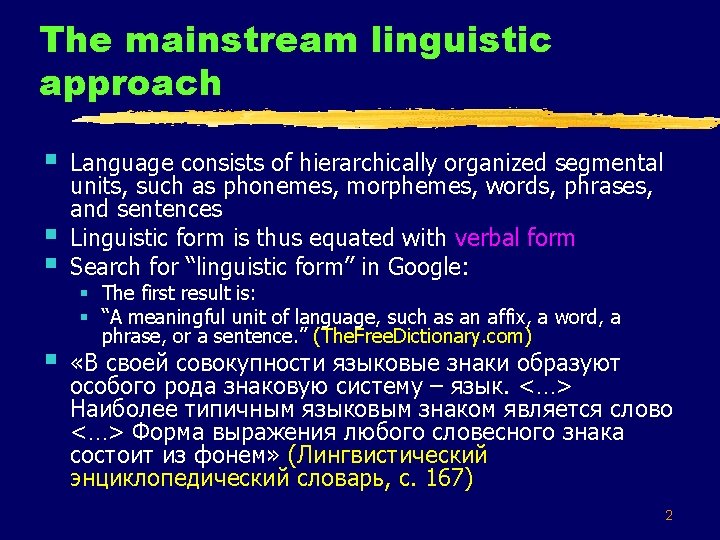

The mainstream linguistic approach § § Language consists of hierarchically organized segmental units, such as phonemes, morphemes, words, phrases, and sentences Linguistic form is thus equated with verbal form Search for “linguistic form” in Google: § The first result is: § “A meaningful unit of language, such as an affix, a word, a phrase, or a sentence. ” (The. Free. Dictionary. com) «В своей совокупности языковые знаки образуют особого рода знаковую систему – язык. <…> Наиболее типичным языковым знаком является слово <…> Форма выражения любого словесного знака состоит из фонем» (Лингвистический энциклопедический словарь, с. 167) 2

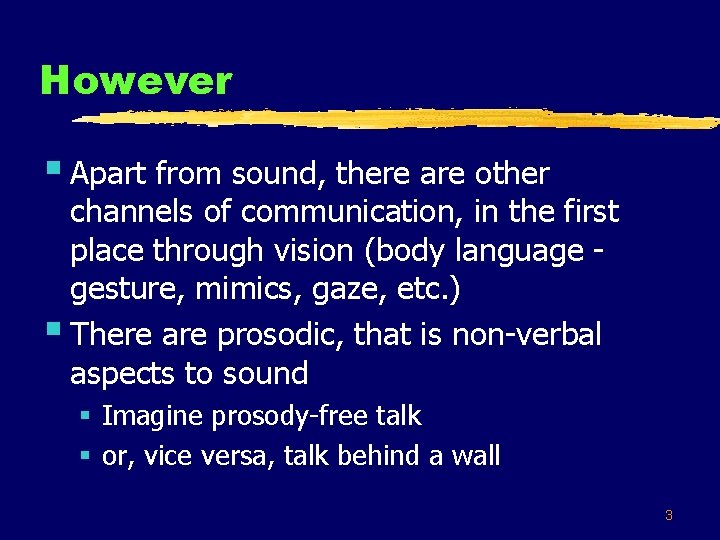

However § Apart from sound, there are other channels of communication, in the first place through vision (body language gesture, mimics, gaze, etc. ) § There are prosodic, that is non-verbal aspects to sound § Imagine prosody-free talk § or, vice versa, talk behind a wall 3

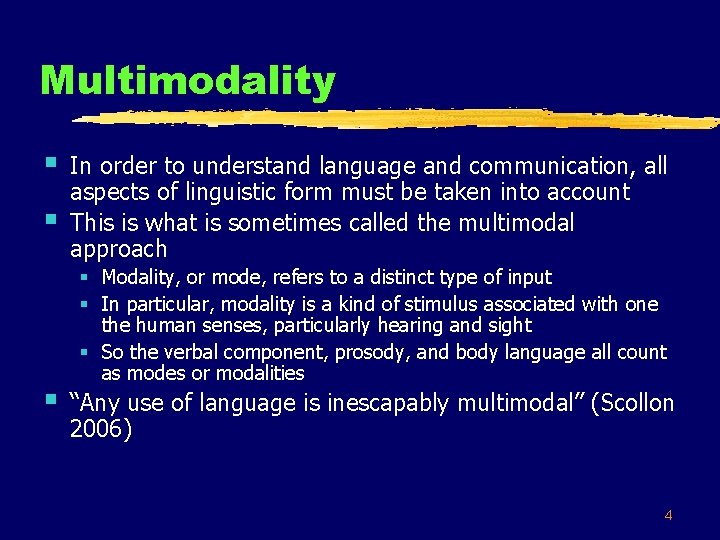

Multimodality § § § In order to understand language and communication, all aspects of linguistic form must be taken into account This is what is sometimes called the multimodal approach § Modality, or mode, refers to a distinct type of input § In particular, modality is a kind of stimulus associated with one the human senses, particularly hearing and sight § So the verbal component, prosody, and body language all count as modes or modalities “Any use of language is inescapably multimodal” (Scollon 2006) 4

Goals of this talk § Emphasize the importance of prosody and visual § § aspects of communication in linguistic research Show prosody and visual communication interact with the verbal component, thus suggesting not only the multimodal, but also the cross-modal approach Propose that linguistics cannot progress without taking multimodality seriously into account 5

Are these goals relevant and important? § After all, linguists and other scholars have § already been pursuing these issues for many decades, and the respective research traditions are quite rich But: § First, prosody and visual communication are marginalized in linguistics, they are located in certain “pockets” of the overall linguistic panorama and are tolerated by the mainstream as “paralinguistics” § Those focusing on these information channels often treat them as a “thing in itself”, without integration with the verbal component 6

Plan of talk § I. Prosody § II. Gestures § III. Relative contribution of three information channels § IV. Signed languages § V. Wider context 7

I. PROSODY § Prosodic components § «Рост интереса к просодии связан <…> с новыми семантическим задачами (описание непропозициональной семантики <. . . >)» (Кодзасов 1996: 85) Prosody is responsible for discourse segmentation into Elementary Discourse Units (EDUs), identified on the basis of several prosodic components and strongly correlated with clauses § § § § § pausing accents pitch tempo (of various scope) registers degrees of reduction glottal features loudness. . . . 8

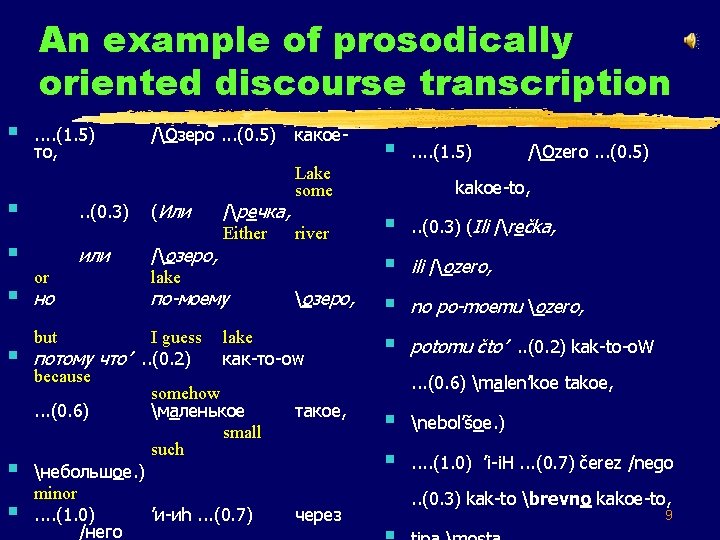

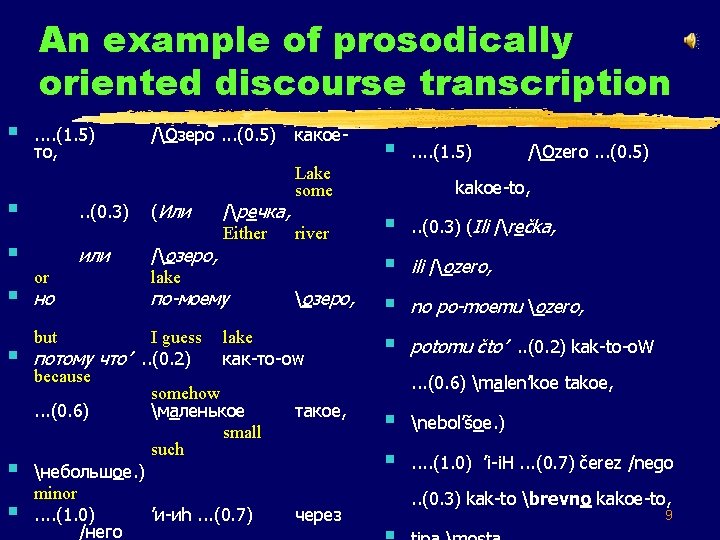

An example of prosodically oriented discourse transcription § . . (1. 5) то, /Озеро. . . (0. 5) § . . (0. 3) (Или § или /озеро, lake § § or но but какое. Lake some /речка, Either river по-моему озеро, I guess lake потому что’. . (0. 2) как-то-оw because somehow. . . (0. 6) маленькое такое, small such небольшое. ) minor. . (1. 0) ’и-иh. . . (0. 7) через /него § . . (1. 5) /Ozero. . . (0. 5) kakoe-to, § . . (0. 3) (Ili /rečka, § ili /ozero, § no po-moemu ozero, § potomu čto’. . (0. 2) kak-to-o. W. . . (0. 6) malen’koe takoe, § nebol’šoe. ) § . . (1. 0) ’i-i. H. . . (0. 7) čerez /nego. . (0. 3) kak-to brevno kakoe-to, 9

Night Dream Stories § Corpus of spoken Russian stories § Speakers: children and adolescents § Subject matter: retelling of night dreams § Discourse type: monologic narrative (personal stories) § Joint study with Vera Podlesskaya and a group of our graduate students § Kibrik and Podlesskaya eds. 2009 10

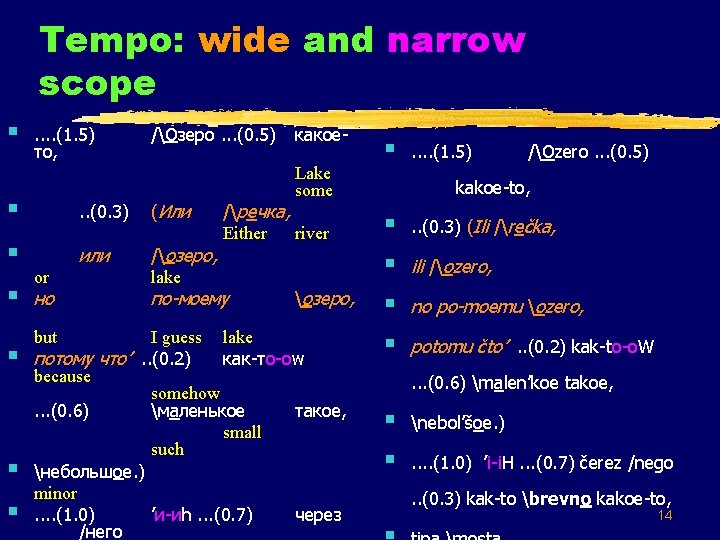

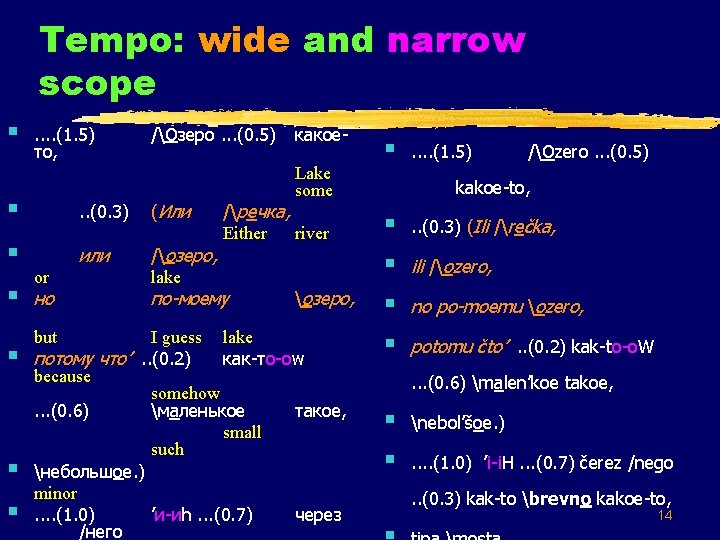

Tempo: wide and narrow scope § . . (1. 5) то, /Озеро. . . (0. 5) § . . (0. 3) (Или § или /озеро, lake § § or но but какое. Lake some /речка, Either river по-моему озеро, I guess lake потому что’. . (0. 2) как-то-оw because somehow. . . (0. 6) маленькое такое, small such небольшое. ) minor. . (1. 0) ’и-иh. . . (0. 7) через /него § . . (1. 5) /Ozero. . . (0. 5) kakoe-to, § . . (0. 3) (Ili /rečka, § ili /ozero, § no po-moemu ozero, § potomu čto’. . (0. 2) kak-to-o. W. . . (0. 6) malen’koe takoe, § nebol’šoe. ) § . . (1. 0) ’i-i. H. . . (0. 7) čerez /nego. . (0. 3) kak-to brevno kakoe-to, 14

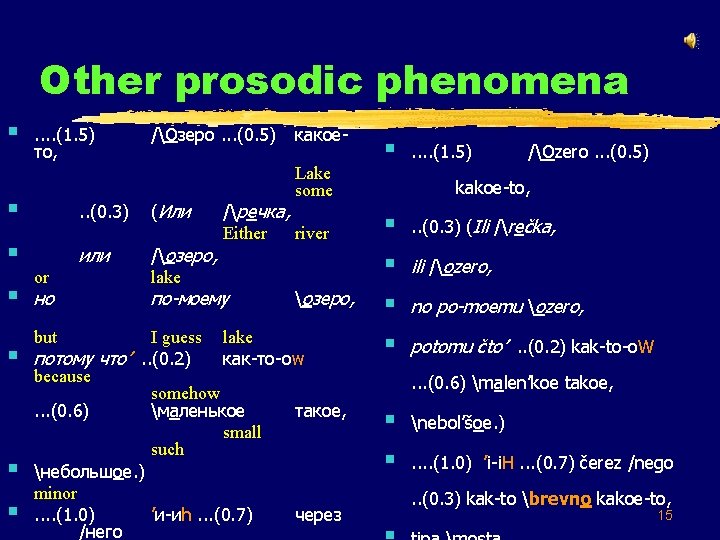

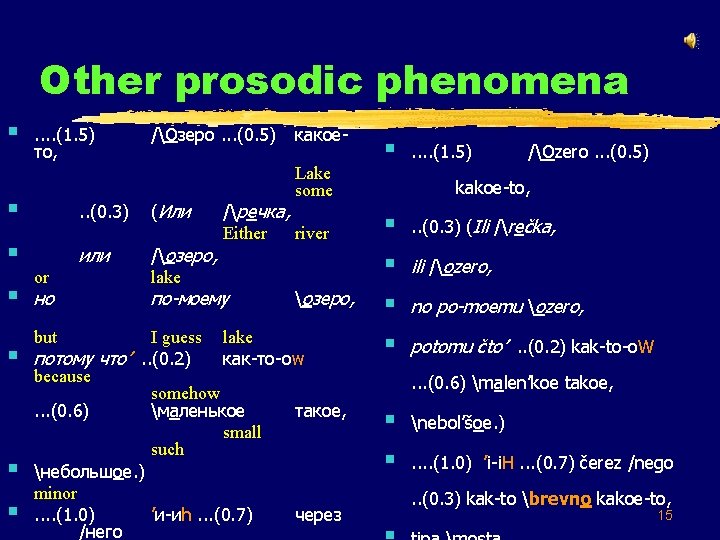

Other prosodic phenomena § . . (1. 5) то, /Озеро. . . (0. 5) § . . (0. 3) (Или § или /озеро, lake § § or но but какое. Lake some /речка, Either river по-моему озеро, I guess lake потому что’. . (0. 2) как-то-оw because somehow. . . (0. 6) маленькое такое, small such небольшое. ) minor. . (1. 0) ’и-иh. . . (0. 7) через /него § . . (1. 5) /Ozero. . . (0. 5) kakoe-to, § . . (0. 3) (Ili /rečka, § ili /ozero, § no po-moemu ozero, § potomu čto’. . (0. 2) kak-to-o. W. . . (0. 6) malen’koe takoe, § nebol’šoe. ) § . . (1. 0) ’i-i. H. . . (0. 7) čerez /nego. . (0. 3) kak-to brevno kakoe-to, 15

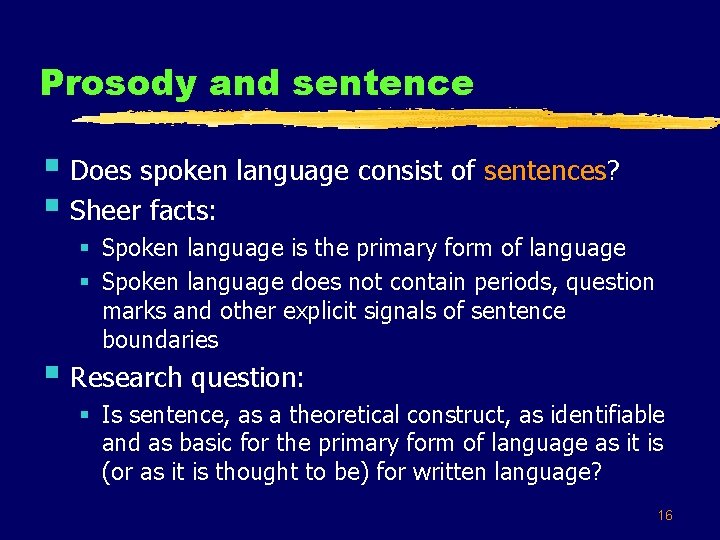

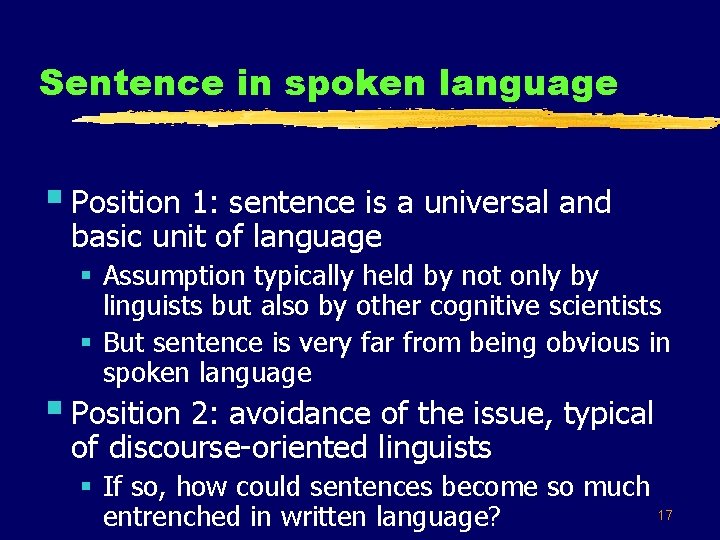

Prosody and sentence § Does spoken language consist of sentences? § Sheer facts: § Spoken language is the primary form of language § Spoken language does not contain periods, question marks and other explicit signals of sentence boundaries § Research question: § Is sentence, as a theoretical construct, as identifiable and as basic for the primary form of language as it is (or as it is thought to be) for written language? 16

Sentence in spoken language § Position 1: sentence is a universal and basic unit of language § Assumption typically held by not only by linguists but also by other cognitive scientists § But sentence is very far from being obvious in spoken language § Position 2: avoidance of the issue, typical of discourse-oriented linguists § If so, how could sentences become so much 17 entrenched in written language?

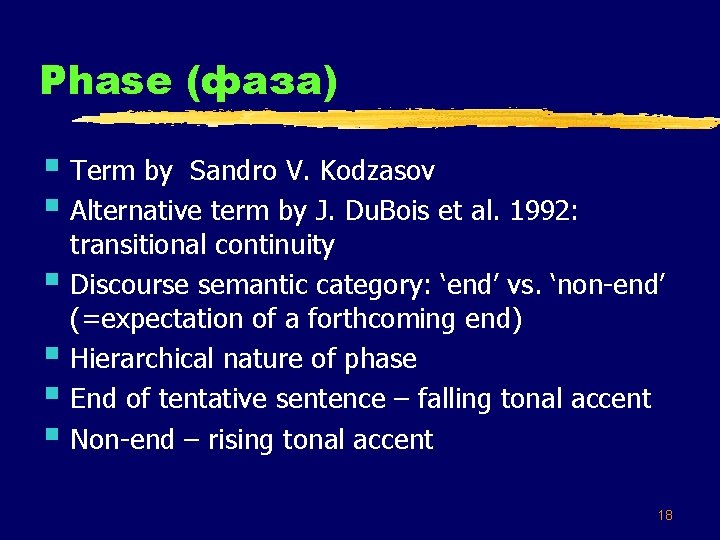

Phase (фаза) § Term by Sandro V. Kodzasov § Alternative term by J. Du. Bois et al. 1992: § § transitional continuity Discourse semantic category: ‘end’ vs. ‘non-end’ (=expectation of a forthcoming end) Hierarchical nature of phase End of tentative sentence – falling tonal accent Non-end – rising tonal accent 18

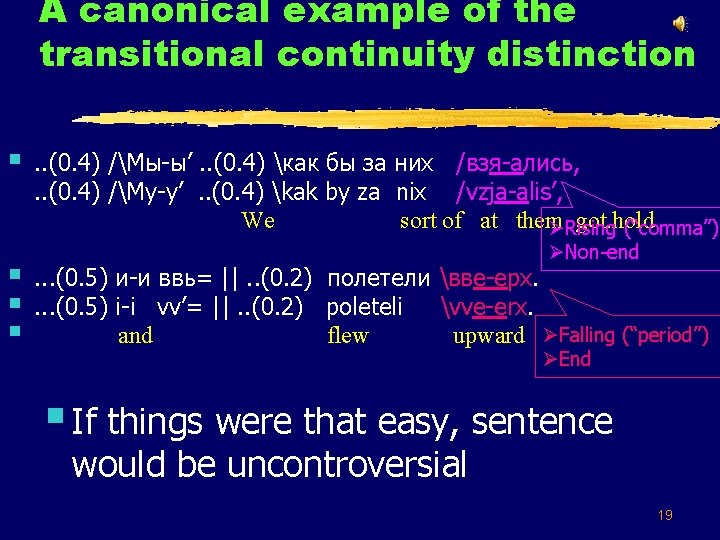

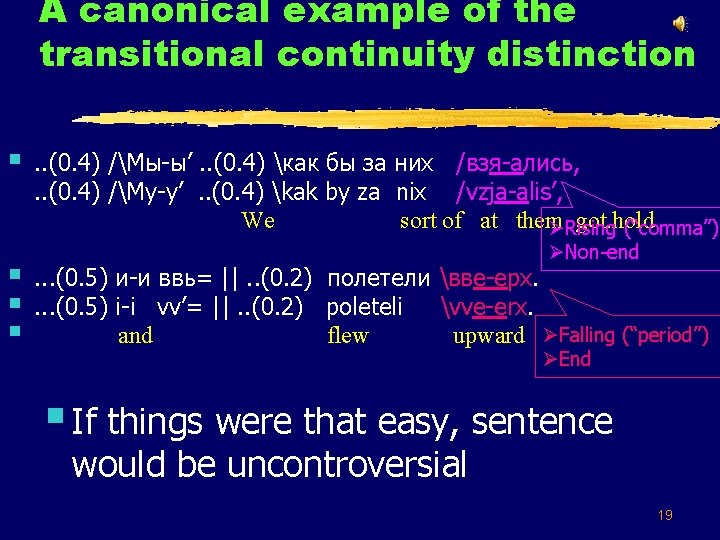

A canonical example of the transitional continuity distinction z 57: 15 -16 § § . . (0. 4) /Мы-ы’. . (0. 4) как бы за них /взя-ались, . . (0. 4) /My-y’. . (0. 4) kak by za nix /vzja-alis’, We sort of at them got. hold ØRising (“comma”) ØNon-end . . . (0. 5) и-и ввь= ||. . (0. 2) полетели вве-ерх. . (0. 5) i-i vv’= ||. . (0. 2) poleteli vve-erx. and flew upward ØFalling (“period”) ØEnd § If things were that easy, sentence would be uncontroversial 19

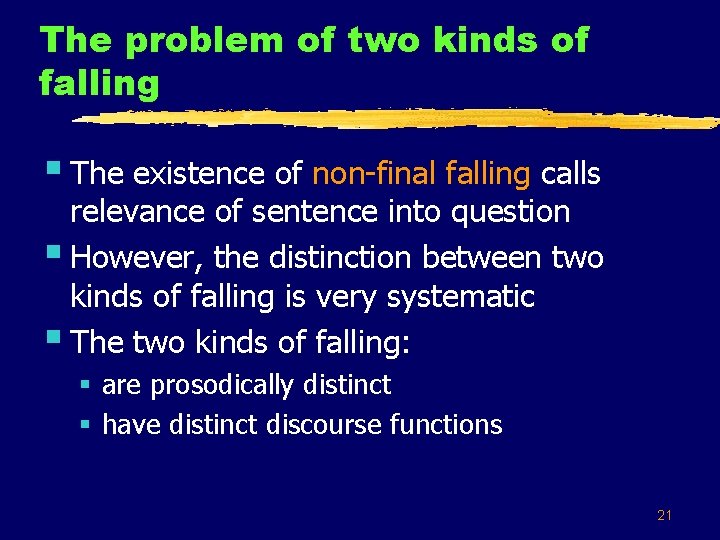

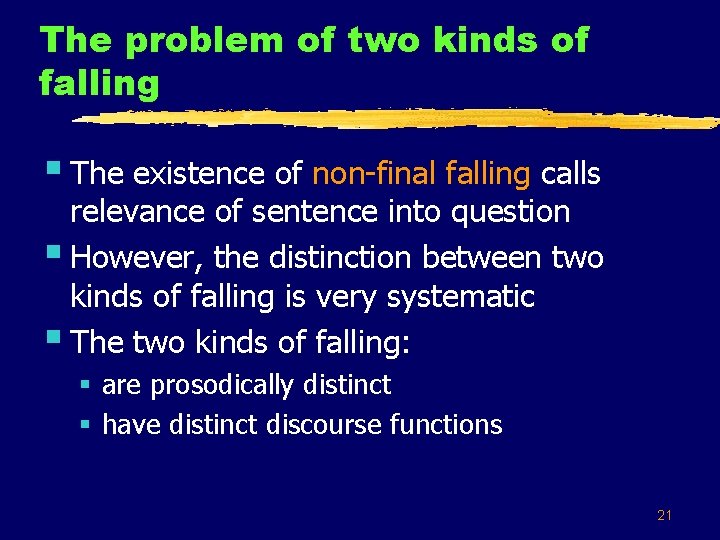

The problem of two kinds of falling § The existence of non-final falling calls relevance of sentence into question § However, the distinction between two kinds of falling is very systematic § The two kinds of falling: § are prosodically distinct § have distinct discourse functions 21

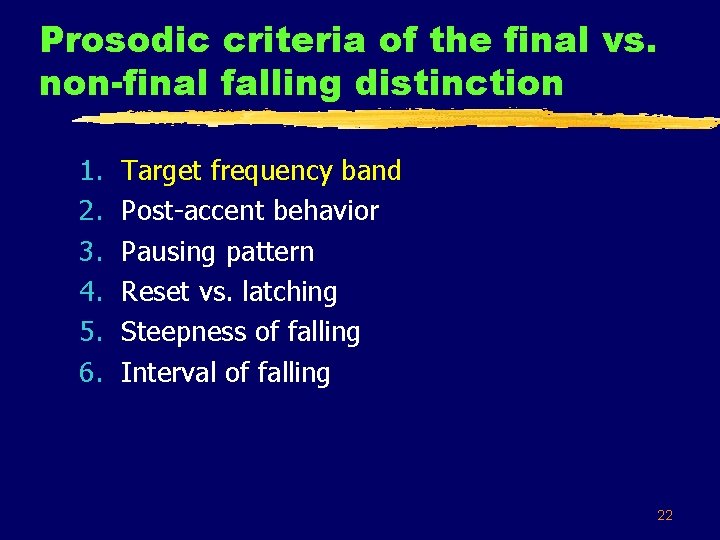

Prosodic criteria of the final vs. non-final falling distinction 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Target frequency band Post-accent behavior Pausing pattern Reset vs. latching Steepness of falling Interval of falling 22

Target frequency band § Final falling (“period”): targets at the bottom of the speaker’s F 0 range § Non-final falling (“falling comma”): targets at level several dozen Hz (several semitones) higher 23

F 0 graph for the “lake” example 12 10 12 8 5 ozero, malen’koe nebol’ takoe, šoe. brevno kakoe mosta. -to, 24

Non-final falling (210 Гц), final falling (170 Гц), rising, post-rising falling Z 54: 4 -5 170 Hz 210 Hz. . (0. 4) А A And /тогда /togda then уже uže already д= ||. . (0. 2) d= . . (0. 1) и i and /’Аня /Anja не ne not –успела –uspela managed закрывались zakryvalis’ were. closing двери, dveri, doors сесть. sest’. get. in . . . (0. 7) Иw мм(0. 4) /когда-а. . (0. 2) ’’(0. 3). . (0. 4) {ЧМОКАНЬЕ 0. 2}. . (0. 4) когда я приехала на нашу /остановку’, . . . (0. 7) IW mm(0. 4) /kogda-a. . (0. 2) ’’(0. 3). . (0. 4) {SMACKING 0. 2}. . (0. 4) kogda ja priexala na našu /ostanovku’, 25 And when I arrived to our station

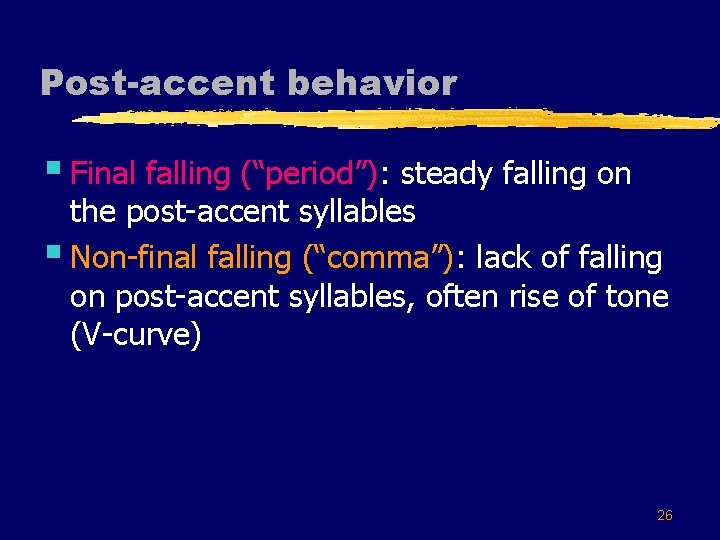

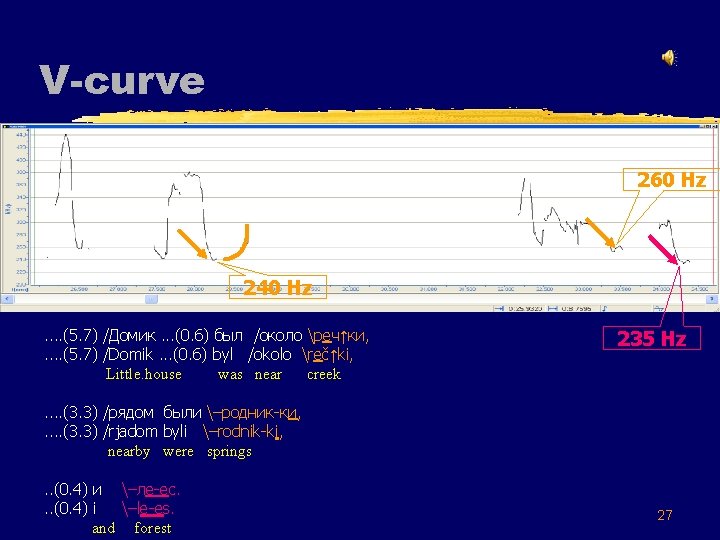

Post-accent behavior § Final falling (“period”): steady falling on the post-accent syllables § Non-final falling (“comma”): lack of falling on post-accent syllables, often rise of tone (V-curve) 26

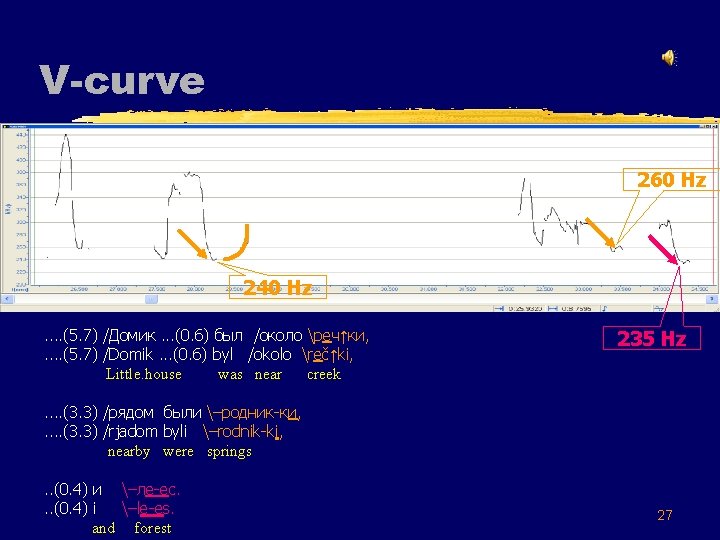

V-curve z 26 260 Hz 240 Hz. . (5. 7) /Домик. . . (0. 6) был /около реч↑ки, . . (5. 7) /Domik. . . (0. 6) byl /okolo reč↑ki, Little. house was near creek 235 Hz . . (3. 3) /рядом были –родник-ки, . . (3. 3) /rjadom byli –rodnik-ki, nearby were springs. . (0. 4) и –ле-ес. . . (0. 4) i –le-es. and forest 27

The final vs. non-final falling distinction § A speaker’s prosodic pattern must be identified § On its basis the difference between final and non-final falling distinction can be identified with a high degree of robustness 28

Contexts of non-final falling § Anticipatory mirror-image adaptation § Inset § Stepwise falling 29

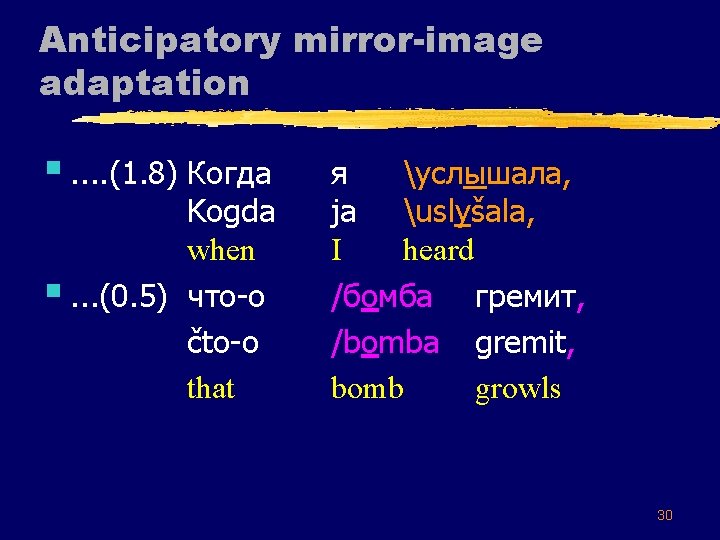

Anticipatory mirror-image adaptation §. . (1. 8) Когда Kogda when §. . . (0. 5) что-о čto-o that я услышала, ja uslyšala, I heard /бомба гремит, /bomba gremit, bomb growls 30

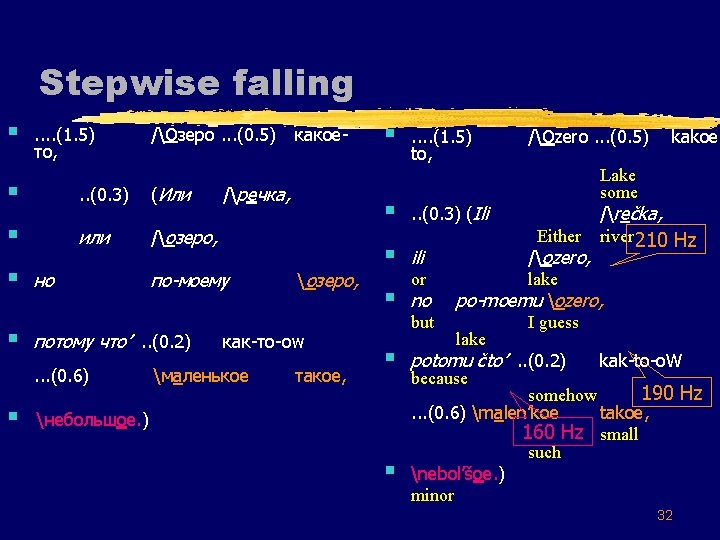

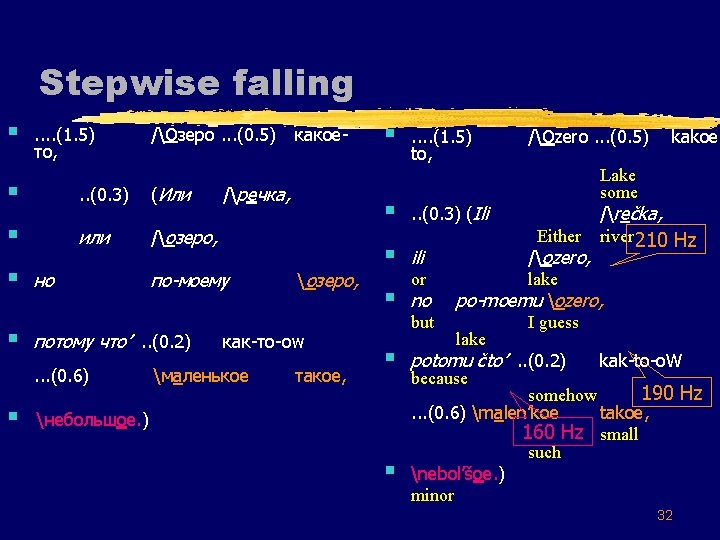

Stepwise falling § . . (1. 5) то, /Озеро. . . (0. 5) § . . (0. 3) (Или § или /озеро, § но § потому что’. . (0. 2). . . (0. 6) § какое- /речка, по-моему § озеро, как-то-оw маленькое § такое, § § § небольшое. ) § . . (1. 5) to, . . (0. 3) (Ili /Ozero. . . (0. 5) kakoe- Lake some /rečka, river 210 Hz Either ili /ozero, or lake no po-moemu ozero, but I guess lake potomu čto’. . (0. 2) kak-to-o. W because 190 Hz somehow. . . (0. 6) malen’koe takoe, 160 Hz small such nebol’šoe. ) minor 32

Representation of EDU continuity types in corpus 33

The status of sentence § In the speech of most speakers final falling is § § § clearly distinct from non-final patterns Final intonation, expressly distinct from non-final intonation (both rising and falling), makes the notion of sentence valid for spoken discourse Speakers “know” when they complete a sentence and when they do not Apparently, spoken sentences are the prototype of written sentences 34

However § § § Identification of sentences is possible only on the basis of a complex analytic procedure It is dependent on prior understanding of a speaker’s prosodic “portrait” There are prototypes of final and non-final fallings, but there are intermediate instances, therefore sentencehood may be a matter of degree Unlike EDUs, sentences are highly variable § Speakers with short sentences § Speakers with long sentences equaling stories • Clause chaining A significant tune-up is necessary to apply the procedure to a different discourse type or a different language 35

Conclusions on prosody and sentence § Sentence is an intermediate hierarchical § § § grouping between an EDU (roughly, clause) and whole discourse Sentence is an elusive, complex, non-elementary unit of spoken language These conclusions, possible only due to prosodic analysis, are of prime importance for linguistic theory The notion of sentence, so salient in theories restricted to the verbal component alone, can only be evaluated relying on prosodic evidence 36

Other languages? § Upper Kuskokwim Athabaskan § Bobby Esai, Sr. 37

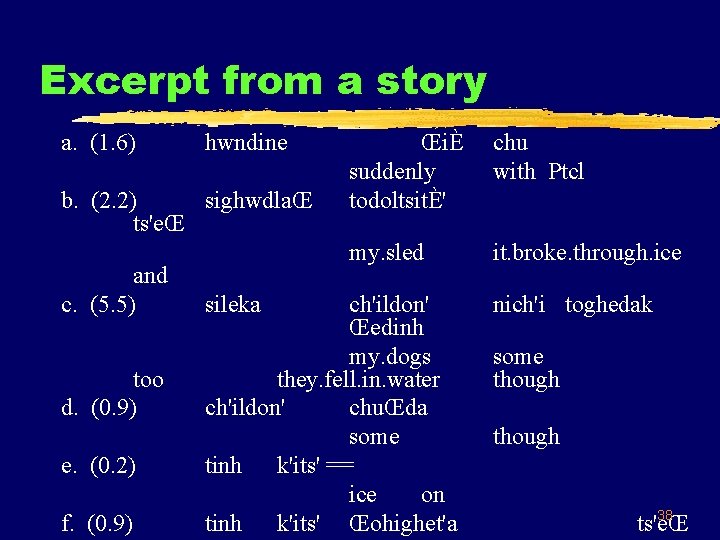

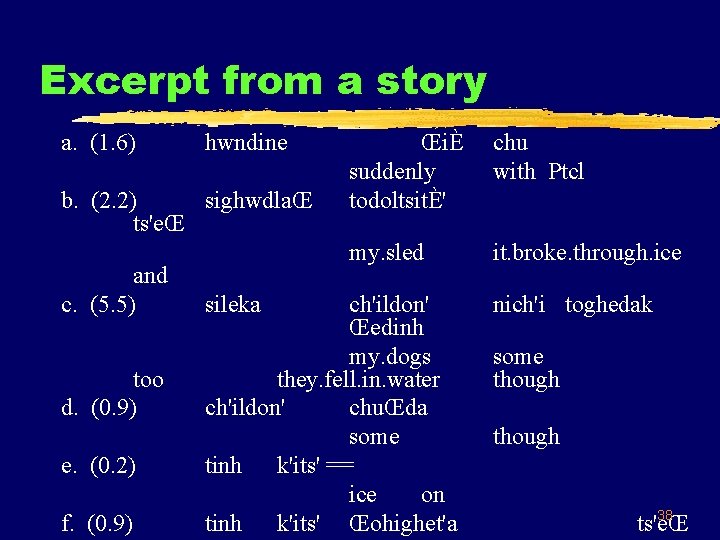

Excerpt from a story a. (1. 6) hwndine b. (2. 2) sighwdlaŒ ts'eŒ and c. (5. 5) too d. (0. 9) e. (0. 2) f. (0. 9) sileka ŒiÈ suddenly todoltsitÈ' chu with Ptcl my. sled it. broke. through. ice ch'ildon' Œedinh my. dogs they. fell. in. water ch'ildon' chuŒda some tinh k'its' == ice on tinh k'its' Œohighet'a nich'i toghedak some though 38 ts'eŒ

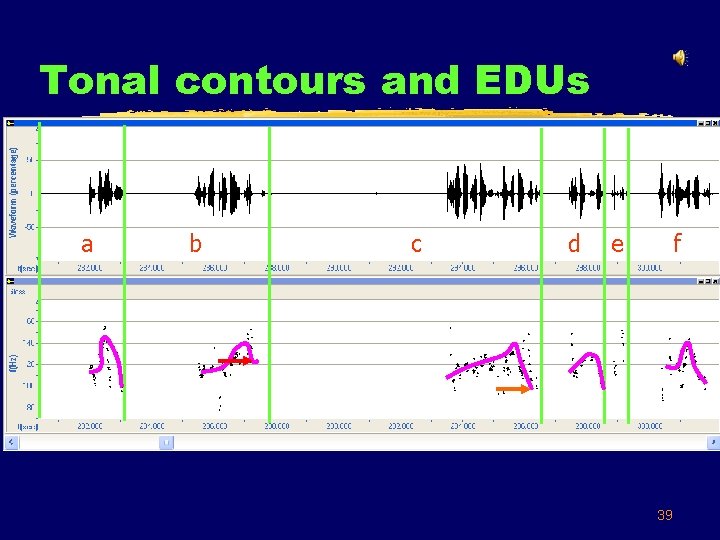

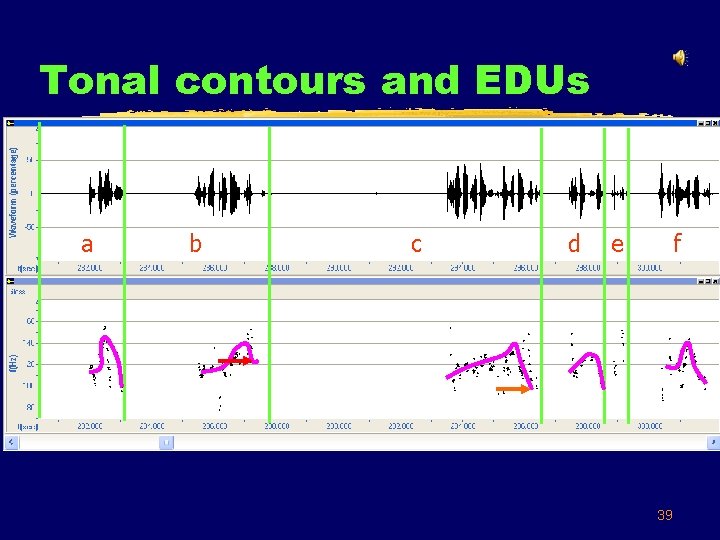

Tonal contours and EDUs a b c d e f 39

II. GESTURE § In the course of communication, it is not just that § the speaker speaks and the addressee listens In addition, the speaker displays, and the addressee observes § Gesture § Gaze § Mimics § Posture § Proxemics § Cultural symbolism §. . . . . (see, for example, Крейдлин 2002, Бутовская 2004) 40

Gestures § Gestures are kinetic § behaviors of arms and other limbs, capable of conveying meaning from speaker to addressee. Among the various types of gestures (see e. g. Mc. Neill 1992) pointing gestures are one of the most salient types. 41

Elements of a canonical pointing act 43

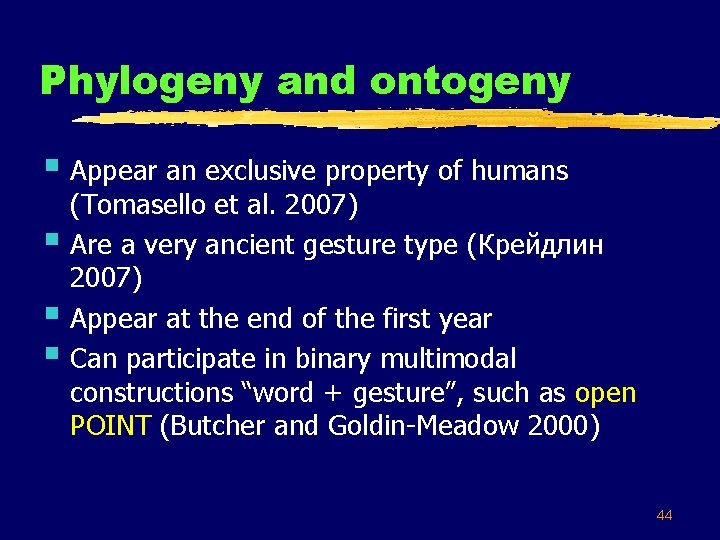

Phylogeny and ontogeny § Appear an exclusive property of humans § § § (Tomasello et al. 2007) Are a very ancient gesture type (Крейдлин 2007) Appear at the end of the first year Can participate in binary multimodal constructions “word + gesture”, such as open POINT (Butcher and Goldin-Meadow 2000) 44

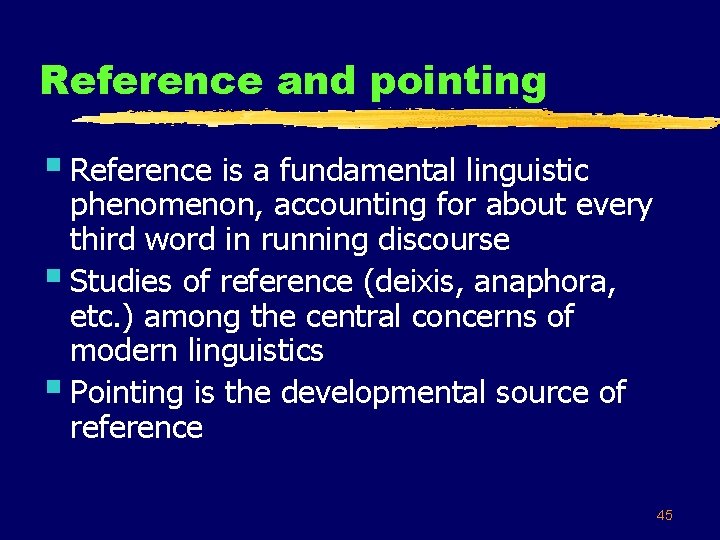

Reference and pointing § Reference is a fundamental linguistic phenomenon, accounting for about every third word in running discourse § Studies of reference (deixis, anaphora, etc. ) among the central concerns of modern linguistics § Pointing is the developmental source of reference 45

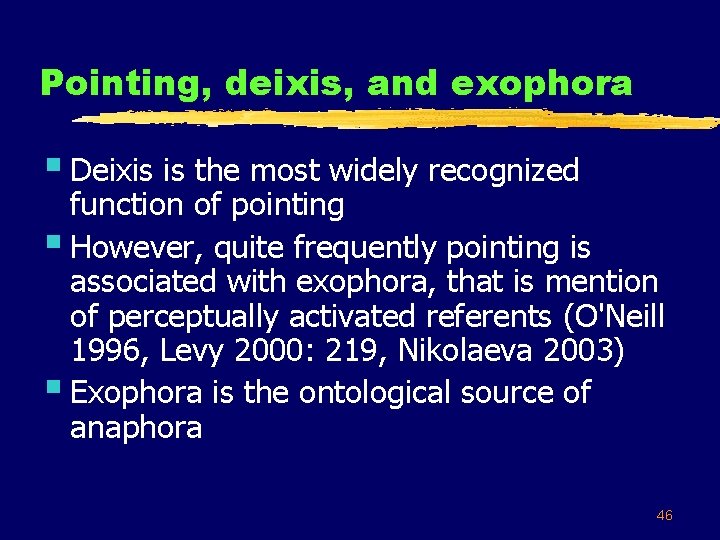

Pointing, deixis, and exophora § Deixis is the most widely recognized function of pointing § However, quite frequently pointing is associated with exophora, that is mention of perceptually activated referents (O'Neill 1996, Levy 2000: 219, Nikolaeva 2003) § Exophora is the ontological source of anaphora 46

Exophoric and anaphoric reference (from Nikolaeva 2003) § a. My s Anatoliem očen’ rabo taem, uže mnogo let <three intervening clauses> § e. on mnogo raz zavja zyval, ‘Anatolij and I have been working together for many years, <…> he was winding it up (drinking) many times’ 47

Pointing and prosody § Pointing and accentuation are analogous phenomena, both associated with making an item salient § Nikolaeva (p. c. ): pointing typically cooccurs with accent § Levy (2000): energy expenditure 48

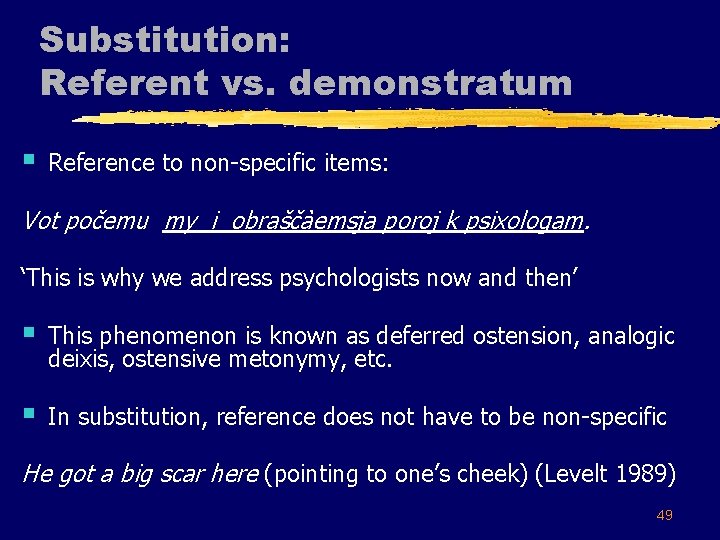

Substitution: Referent vs. demonstratum § Reference to non-specific items: Vot počemu my i obrašča emsja poroj k psixologam. ‘This is why we address psychologists now and then’ § This phenomenon is known as deferred ostension, analogic deixis, ostensive metonymy, etc. § In substitution, reference does not have to be non-specific He got a big scar here (pointing to one’s cheek) (Levelt 1989) 49

Virtual pointing § Pointing to imaginary targets § cf. Buehler’s Deixis am Phantasma, Mc. Neill’s abstract pointing 50

Frequency in two discourse types § Nikolaeva 2003 (TV shows): § 5. 4 pointing gestures per 100 EDUs § 2. 7 are virtual pointing § Nikolaeva p. c. (retelling of a film): § 4. 2 pointing gestures per 100 EDUs § All are virtual pointing § Virtual pointing in exophora/anaphora is as frequent as in deixis 51

§ a. … əə Kogda on exal po= po § b. on əə mm … doro ge, poravnjalsja s de vočkoj, ‘As he rode along the road, he passed a girl <. . . >’ Изобразительный жест 52

§ d. on zasmotre lsja na neë, ‘he gaped at her’ Указательные жесты 53

Spatial representation of referents § § By illustrative gestures in the previous example By verbal devices a. i naprotiv menja sideli dve devočki-mula tki, <21 intervening clauses> y. vot êti dve devočki i ja , ‘And across from me sat two brown-skinned girls, <…> these two girls and I <. . . >’ § There is no difference for the referential system what is used to convey spatial relations § Verbal and gestural material is jointly used to convey the inner cognitive representation from the speaker to the addressee 54

Conclusions on gestures and reference § The pointing gesture is the developmental § § § source of reference The use of pointing is intimately connected to reference Reference is performed with the help of both verbal devices and illustrative gestures Reference, a central linguistic phenomenon, cannot be understood if we fail to take gesture into account 55

III. Relative contribution of three information channels Discourse Vocal channels Verbal channel Visual channel Prosodic channel 56

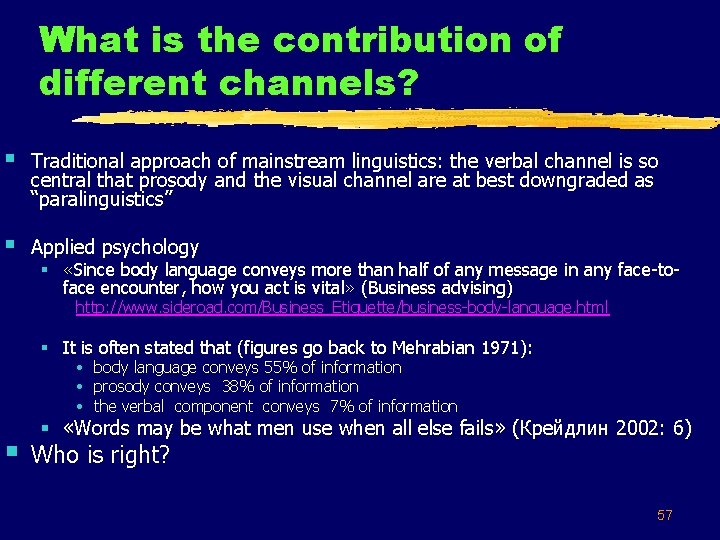

What is the contribution of different channels? § Traditional approach of mainstream linguistics: the verbal channel is so central that prosody and the visual channel are at best downgraded as “paralinguistics” § Applied psychology § «Since body language conveys more than half of any message in any face-toface encounter, how you act is vital» (Business advising) http: //www. sideroad. com/Business_Etiquette/business-body-language. html § It is often stated that (figures go back to Mehrabian 1971): • body language conveys 55% of information • prosody conveys 38% of information • the verbal component conveys 7% of information § § «Words may be what men use when all else fails» (Крейдлин 2002: 6) Who is right? 57

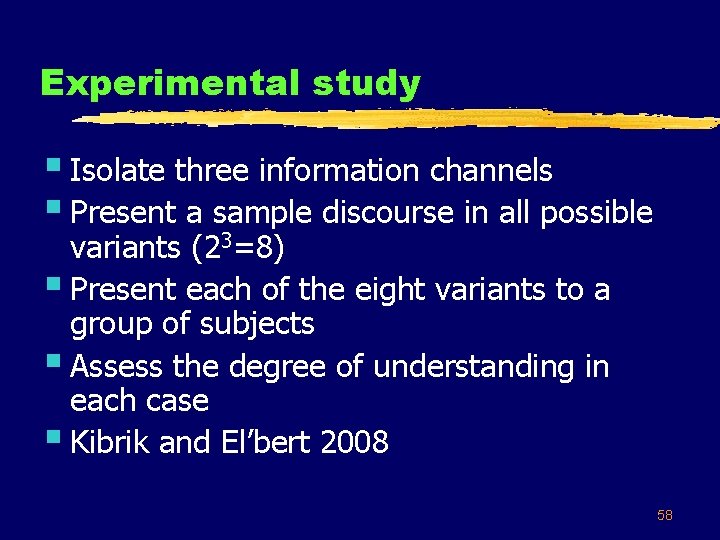

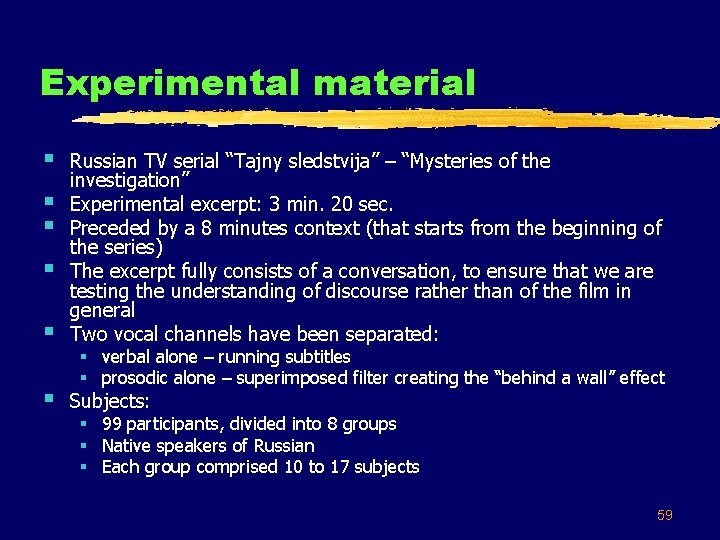

Experimental study § Isolate three information channels § Present a sample discourse in all possible variants (23=8) § Present each of the eight variants to a group of subjects § Assess the degree of understanding in each case § Kibrik and El’bert 2008 58

Experimental material § § Russian TV serial “Tajny sledstvija” – “Mysteries of the investigation” Experimental excerpt: 3 min. 20 sec. Preceded by a 8 minutes context (that starts from the beginning of the series) The excerpt fully consists of a conversation, to ensure that we are testing the understanding of discourse rather than of the film in general Two vocal channels have been separated: § Subjects: § § verbal alone – running subtitles § prosodic alone – superimposed filter creating the “behind a wall” effect § 99 participants, divided into 8 groups § Native speakers of Russian § Each group comprised 10 to 17 subjects 59

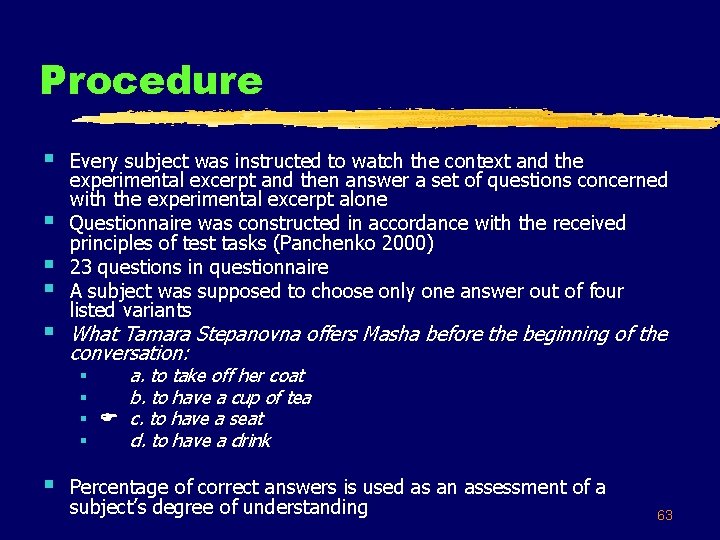

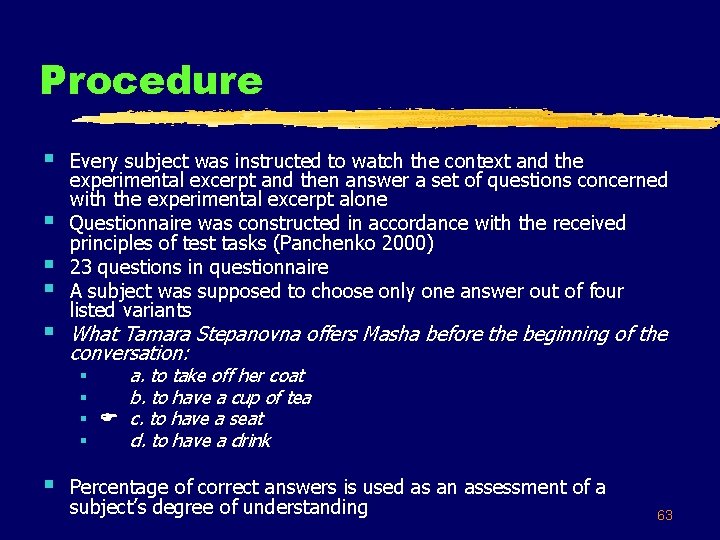

Procedure § § § Every subject was instructed to watch the context and the experimental excerpt and then answer a set of questions concerned with the experimental excerpt alone Questionnaire was constructed in accordance with the received principles of test tasks (Panchenko 2000) 23 questions in questionnaire A subject was supposed to choose only one answer out of four listed variants What Tamara Stepanovna offers Masha before the beginning of the conversation: § a. to take off her coat § b. to have a cup of tea § c. to have a seat § d. to have a drink § Percentage of correct answers is used as an assessment of a subject’s degree of understanding 63

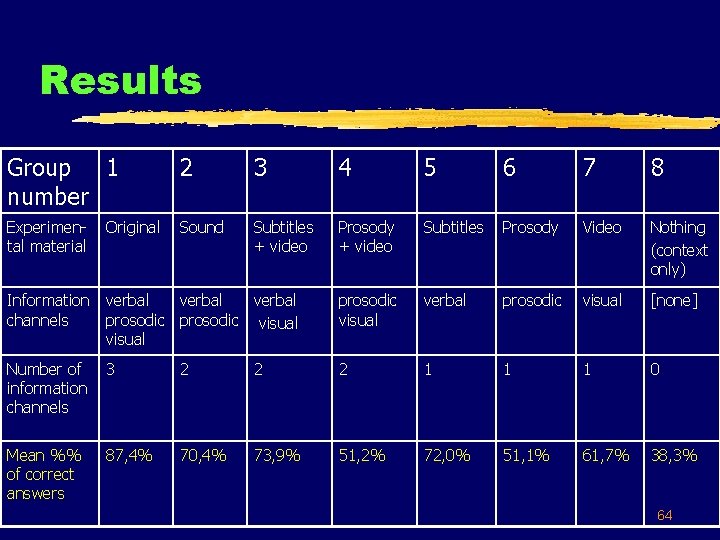

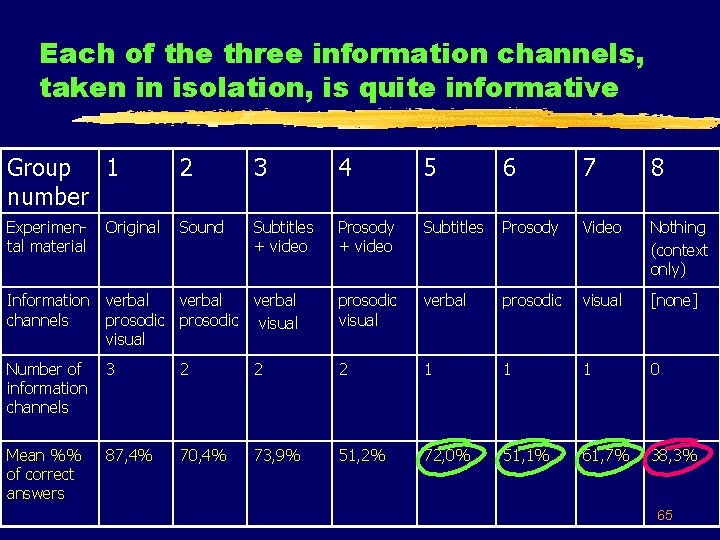

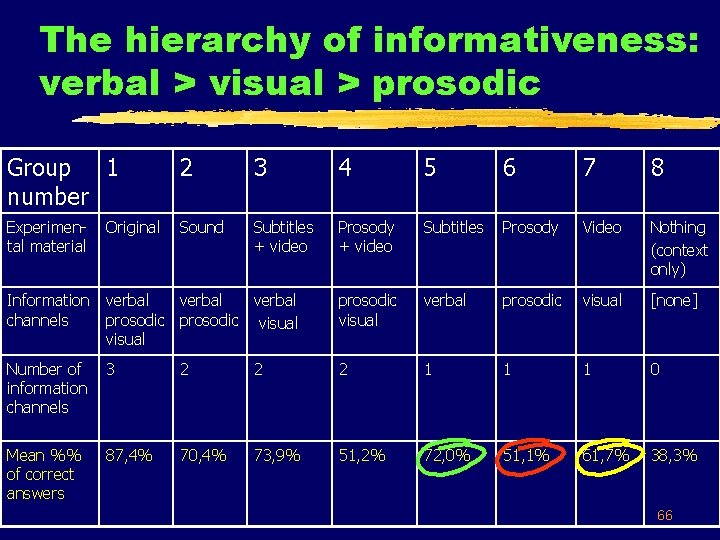

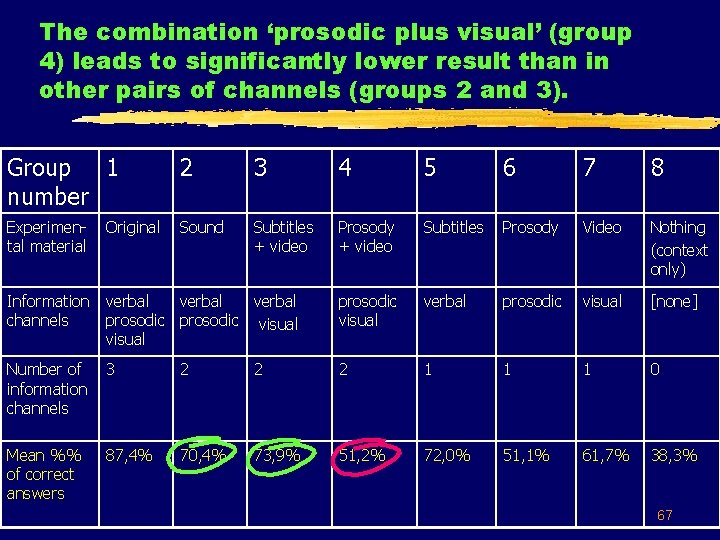

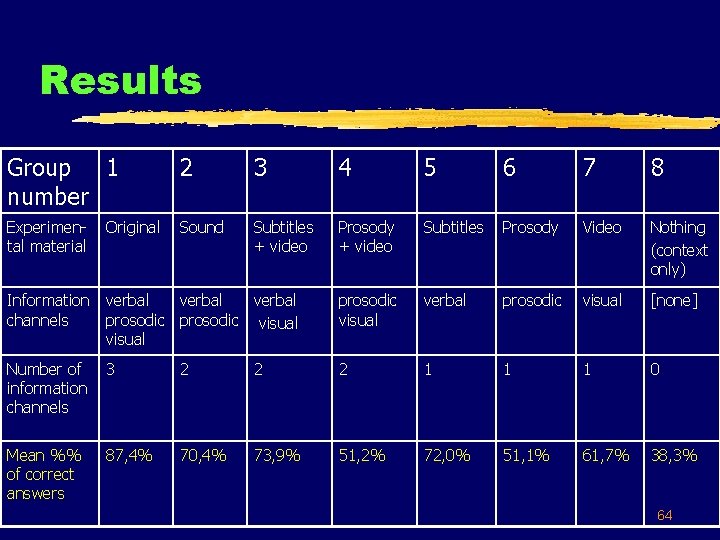

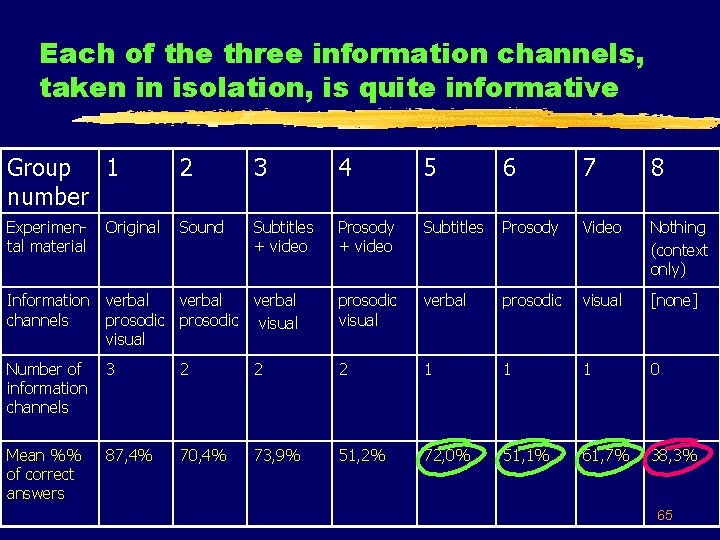

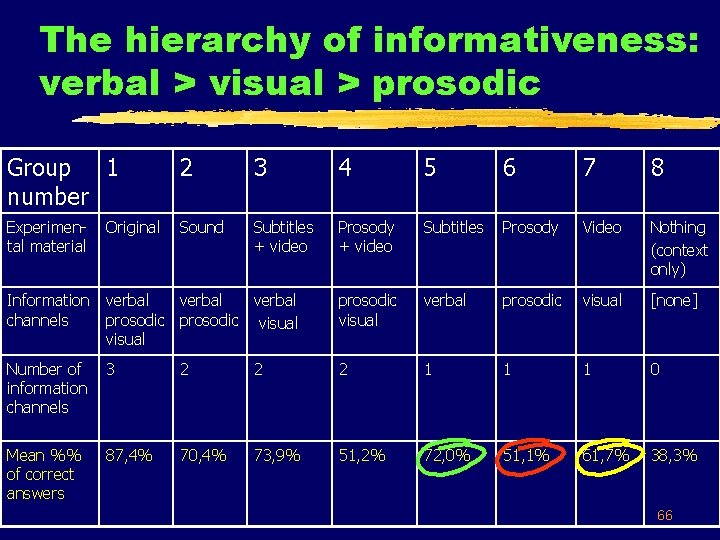

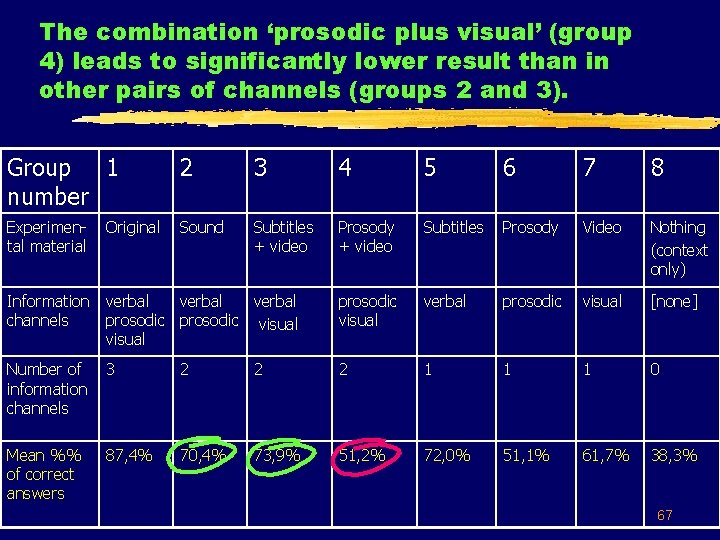

Results Group 1 number 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Experimental material Original Sound Subtitles + video Prosody + video Subtitles Prosody Video Nothing (context only) Information channels verbal prosodic visual verbal prosodic visual [none] Number of information channels 3 2 2 2 1 1 1 0 Mean %% of correct answers 87, 4% 70, 4% 73, 9% 51, 2% 72, 0% 51, 1% 61, 7% 38, 3% 64

Each of the three information channels, taken in isolation, is quite informative Group 1 number 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Experimental material Original Sound Subtitles + video Prosody + video Subtitles Prosody Video Nothing (context only) Information channels verbal prosodic visual verbal prosodic visual [none] Number of information channels 3 2 2 2 1 1 1 0 Mean %% of correct answers 87, 4% 70, 4% 73, 9% 51, 2% 72, 0% 51, 1% 61, 7% 38, 3% 65

The hierarchy of informativeness: verbal > visual > prosodic Group 1 number 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Experimental material Original Sound Subtitles + video Prosody + video Subtitles Prosody Video Nothing (context only) Information channels verbal prosodic visual verbal prosodic visual [none] Number of information channels 3 2 2 2 1 1 1 0 Mean %% of correct answers 87, 4% 70, 4% 73, 9% 51, 2% 72, 0% 51, 1% 61, 7% 38, 3% 66

The combination ‘prosodic plus visual’ (group 4) leads to significantly lower result than in other pairs of channels (groups 2 and 3). Group 1 number 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Experimental material Original Sound Subtitles + video Prosody + video Subtitles Prosody Video Nothing (context only) Information channels verbal prosodic visual verbal prosodic visual [none] Number of information channels 3 2 2 2 1 1 1 0 Mean %% of correct answers 87, 4% 70, 4% 73, 9% 51, 2% 72, 0% 51, 1% 61, 7% 38, 3% 67

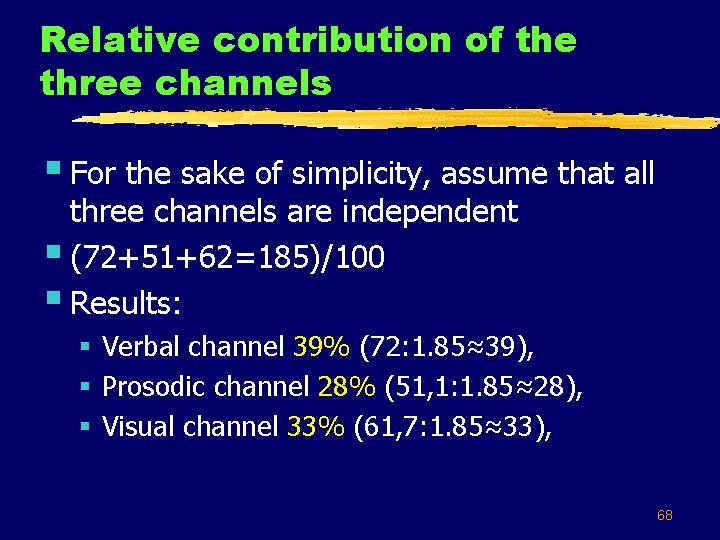

Relative contribution of the three channels § For the sake of simplicity, assume that all three channels are independent § (72+51+62=185)/100 § Results: § Verbal channel 39% (72: 1. 85≈39), § Prosodic channel 28% (51, 1: 1. 85≈28), § Visual channel 33% (61, 7: 1. 85≈33), 68

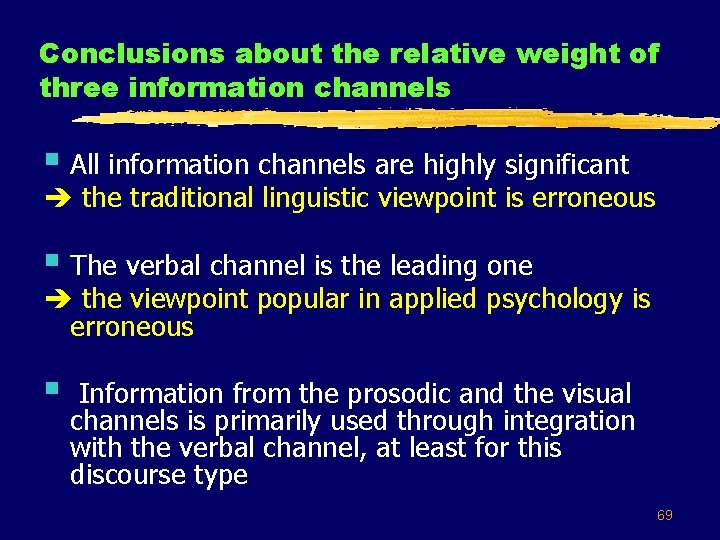

Conclusions about the relative weight of three information channels § All information channels are highly significant the traditional linguistic viewpoint is erroneous § The verbal channel is the leading one the viewpoint popular in applied psychology is erroneous § Information from the prosodic and the visual channels is primarily used through integration with the verbal channel, at least for this discourse type 69

IV. Signed languages NATURAL LANGUAGES SPOKEN SIGNED DEAF SIGN LANGUAGES § § natural, fully-fledged human languages visual-spatial languages § 121 sign languages § use hands and arms, facial expressions, eye gaze, head and body posture to encode linguistic information § manual signs are produced in a three-dimensional space immediately in front of the signer – the signing arena (http//: www. ethnologue. com) American Sign Language, Russian Sign Language … 70

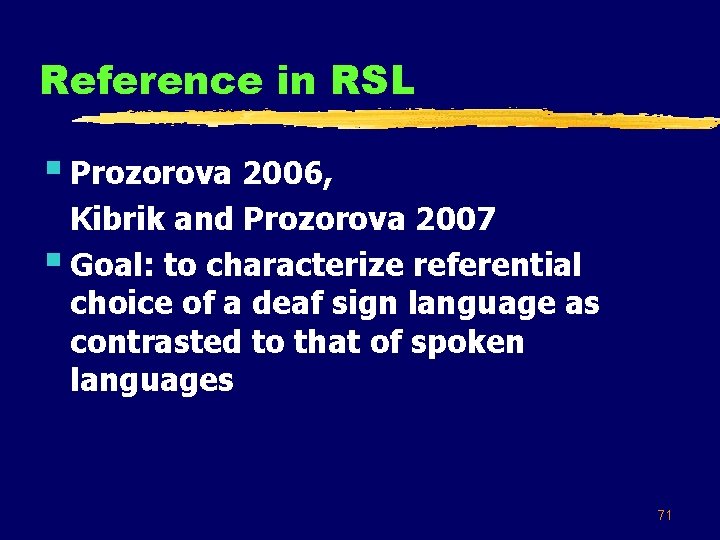

Reference in RSL § Prozorova 2006, Kibrik and Prozorova 2007 § Goal: to characterize referential choice of a deaf sign language as contrasted to that of spoken languages 71

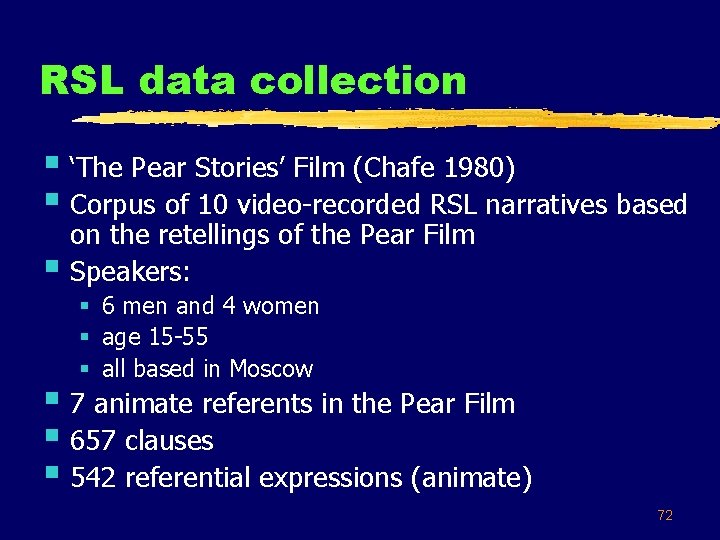

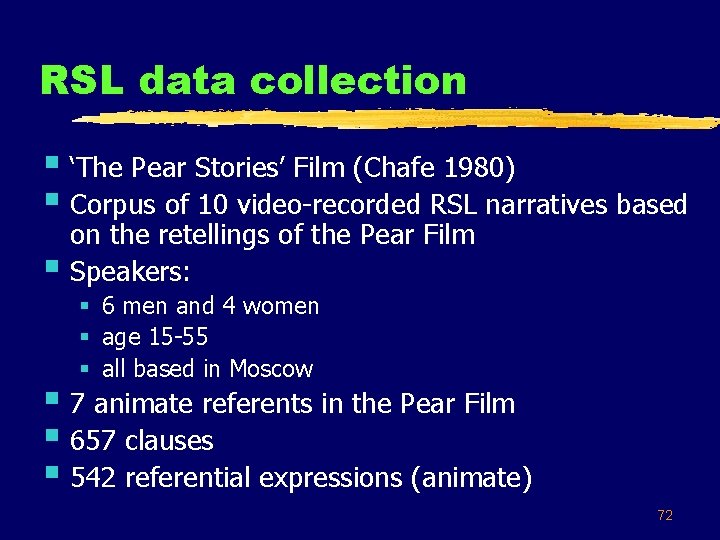

RSL data collection § ‘The Pear Stories’ Film (Chafe 1980) § Corpus of 10 video-recorded RSL narratives based § on the retellings of the Pear Film Speakers: § 6 men and 4 women § age 15 -55 § all based in Moscow § 7 animate referents in the Pear Film § 657 clauses § 542 referential expressions (animate) 72

Deictic demonstrative reference in RSL § operates in the perceived space P § deictic expressions: pointing signs § pointing with an index finger towards the intended referent (2) DEMcat ILL ‘He is ill’ 73

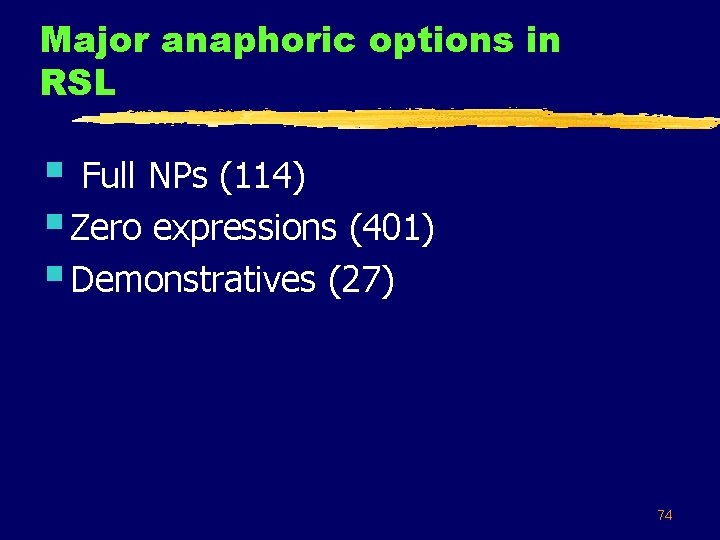

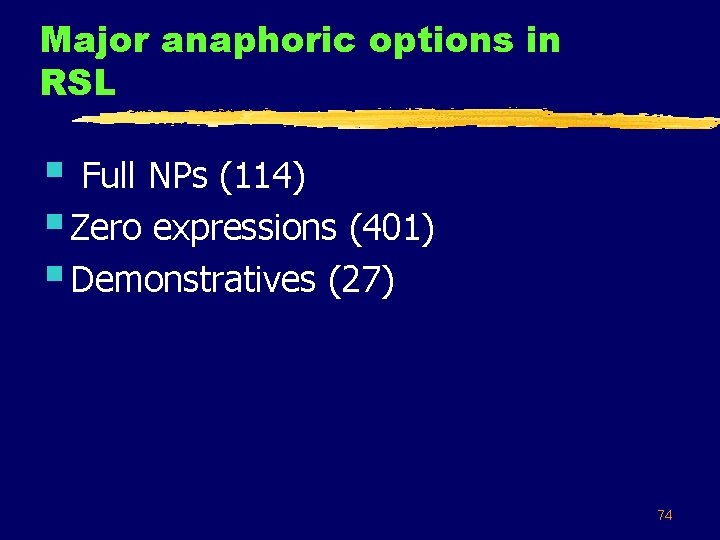

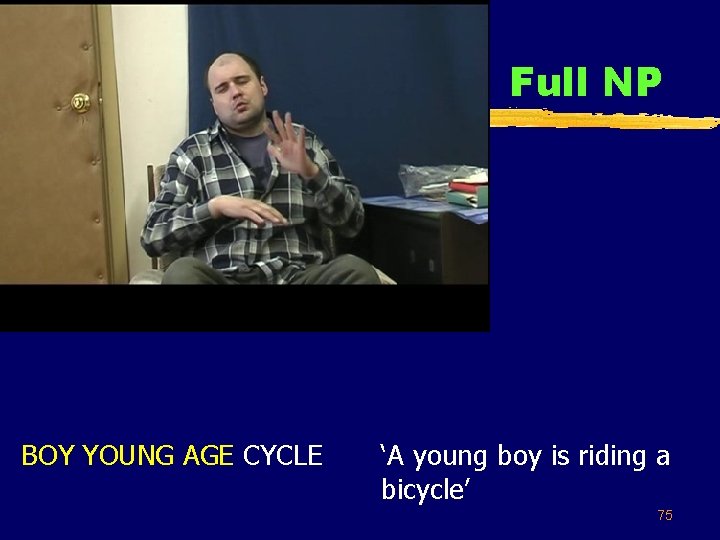

Major anaphoric options in RSL § Full NPs (114) § Zero expressions (401) § Demonstratives (27) 74

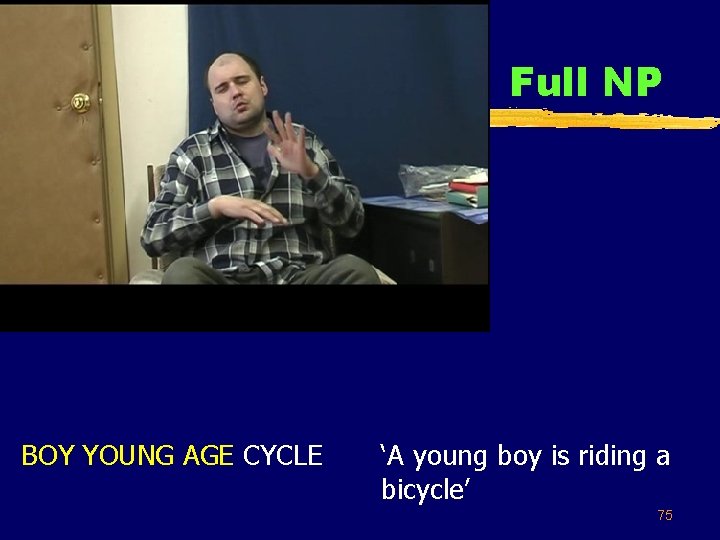

Full NP BOY YOUNG AGE CYCLE ‘A young boy is riding a bicycle’ 75

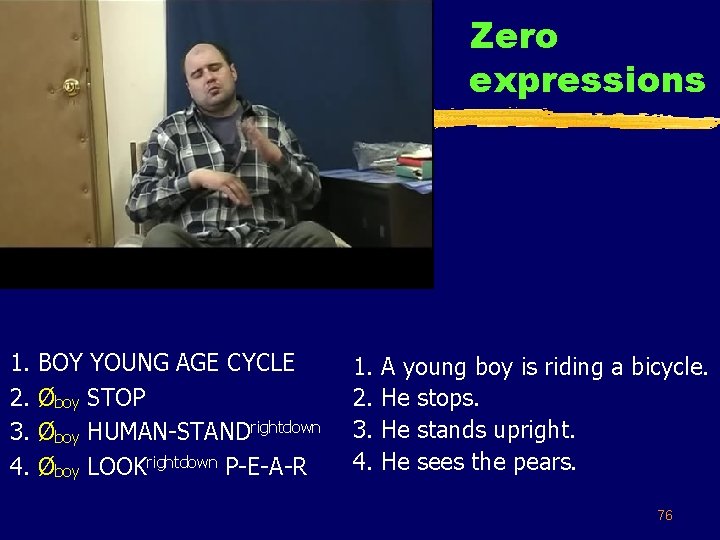

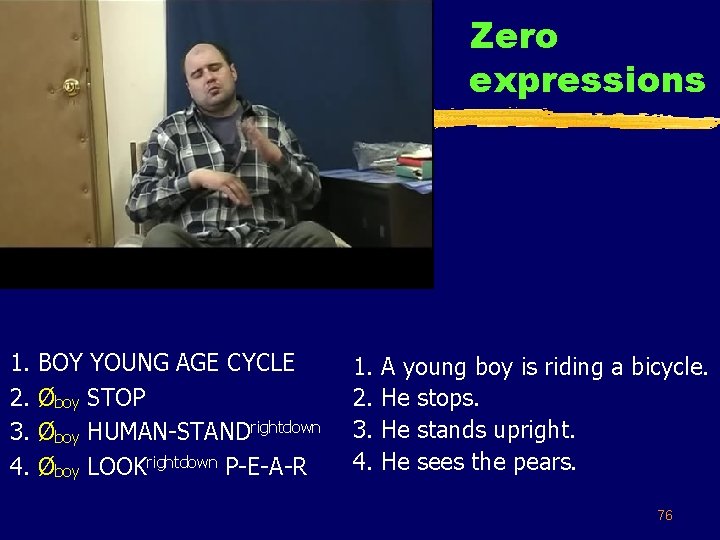

Zero expressions 1. 2. 3. 4. BOY YOUNG AGE CYCLE Øboy STOP Øboy HUMAN-STANDrightdown Øboy LOOKrightdown P-E-A-R 1. 2. 3. 4. A young boy is riding a bicycle. He stops. He stands upright. He sees the pears. 76

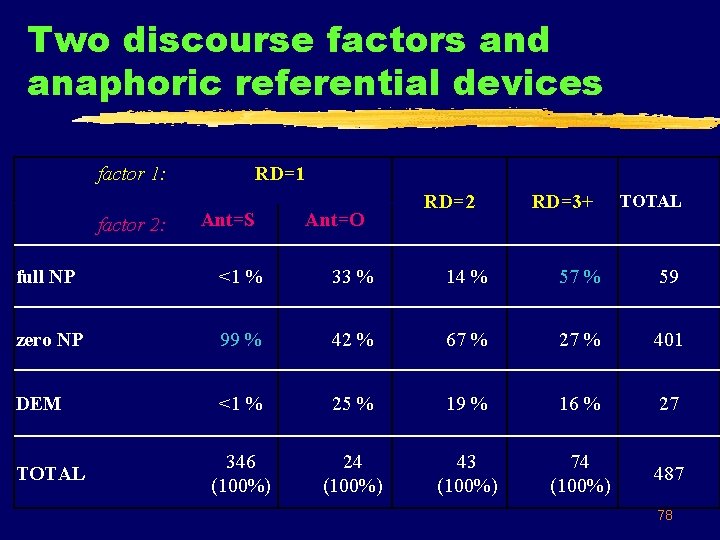

Anaphoric zero reference § § Interlocutors’ shared cognitive representation contains not only perceived referents, but also referents conceived of (remembered or imagined) We call this representation the conceived space C Mentioning referents that are present, or activated, in the conceived space is what is known as anaphora Anaphoric referential choice depends on a referent’s activation in the conceived space: § High zero § Low full NP 77

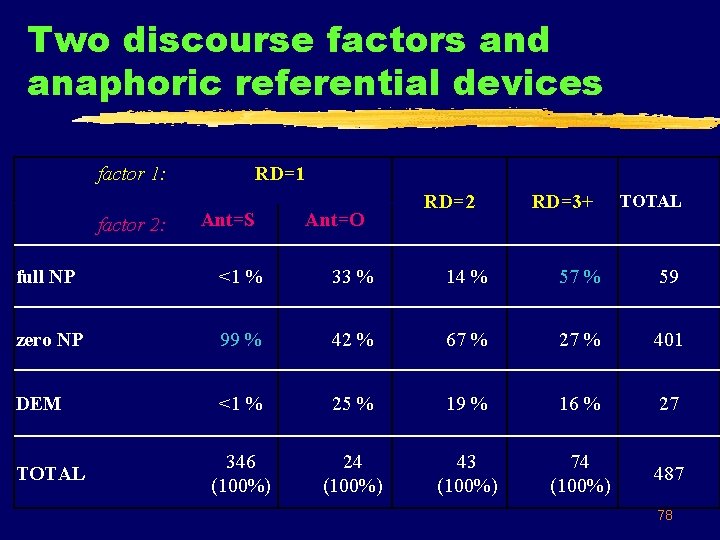

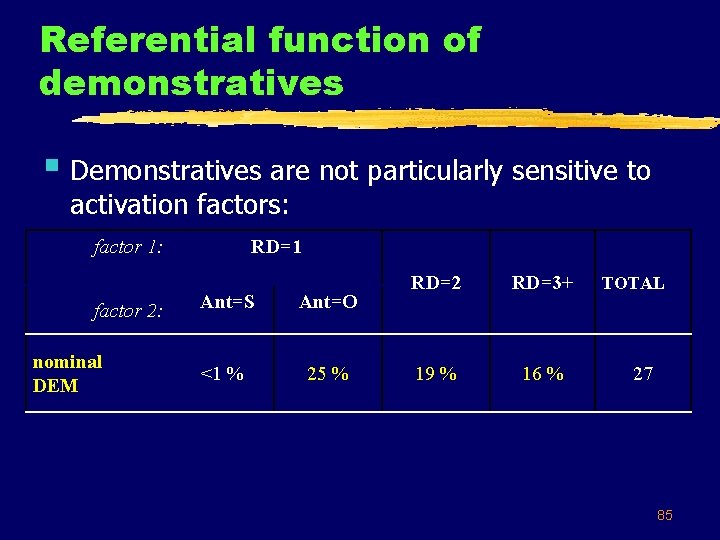

Two discourse factors and anaphoric referential devices factor 1: factor 2: RD=1 Ant=S Ant=O RD=2 RD=3+ TOTAL full NP <1 % 33 % 14 % 57 % 59 zero NP 99 % 42 % 67 % 27 % 401 DEM <1 % 25 % 19 % 16 % 27 346 (100%) 24 (100%) 43 (100%) 74 (100%) 487 TOTAL 78

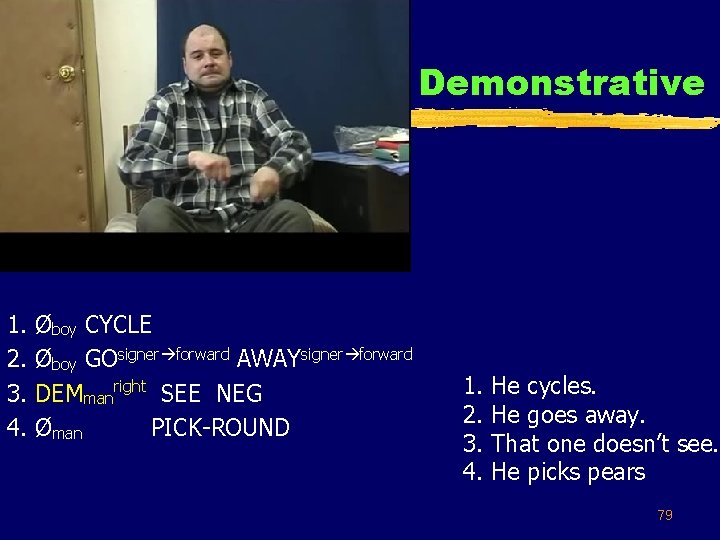

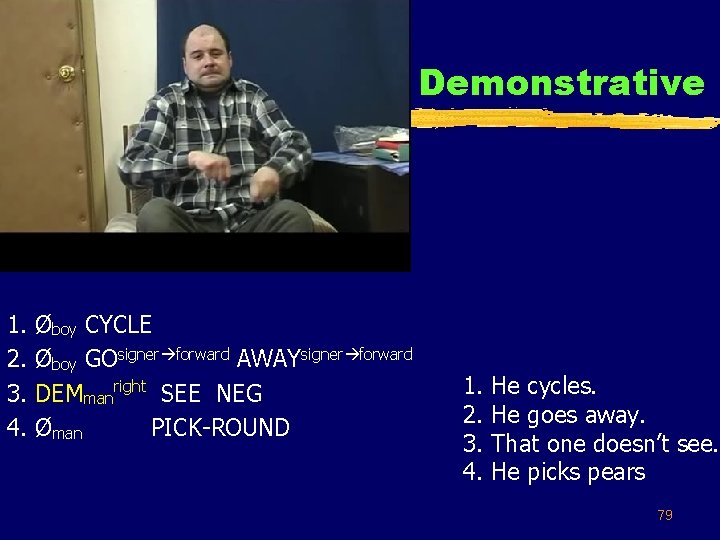

Demonstrative 1. 2. 3. 4. Øboy CYCLE Øboy GOsigner forward AWAYsigner forward DEMmanright SEE NEG Øman PICK-ROUND 1. 2. 3. 4. He cycles. He goes away. That one doesn’t see. He picks pears 79

Anaphoric demonstrative reference § § In signed discourse the signer maps referents from the inner conceived space C onto the external signing arena Mapping includes various parameters of referents: § § § locations orientations physical interactions even abstract relations between them Thus a constructed space C’ is created, inhabited by referents conceived of 80

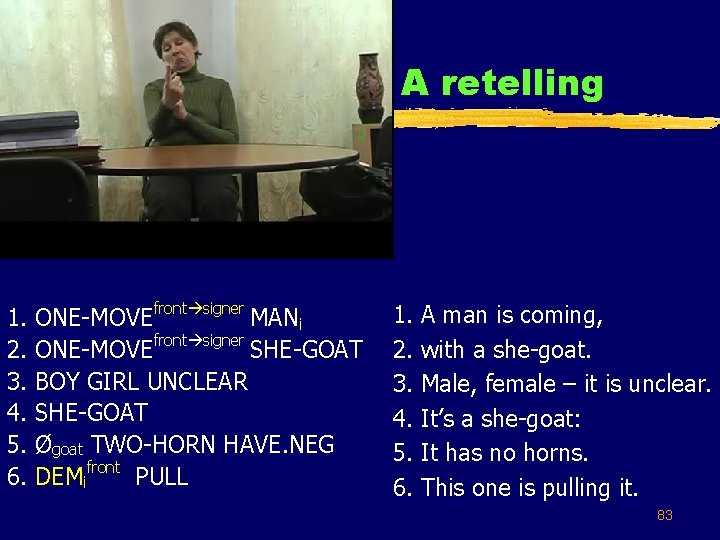

How are locations of referents established in the constructed space? § Signed discourse takes place in the three§ § § dimensional signing arena The topology of the signing arena isomorphically represents the topology of the scenes, remembered by signers from the film The signer establishes the locations of referents in his signing arena These locations are isomorphic to the locations of the referents in the film, as remembered by the signer 81

An episode from the Pear Film 82

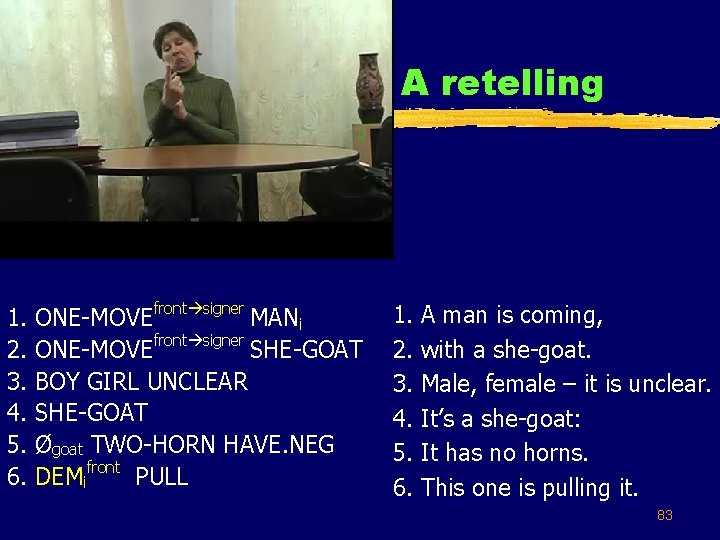

A retelling 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. ONE-MOVEfront signer MANi ONE-MOVEfront signer SHE-GOAT BOY GIRL UNCLEAR SHE-GOAT Øgoat TWO-HORN HAVE. NEG DEMifront PULL 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. A man is coming, with a she-goat. Male, female – it is unclear. It’s a she-goat: It has no horns. This one is pulling it. 83

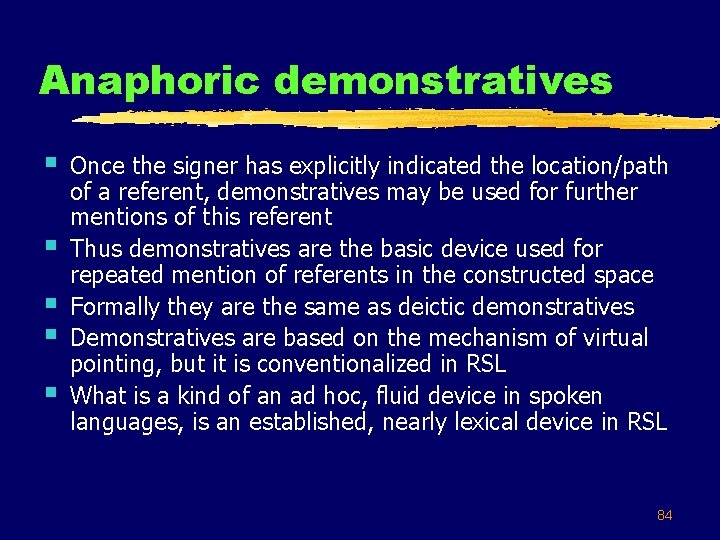

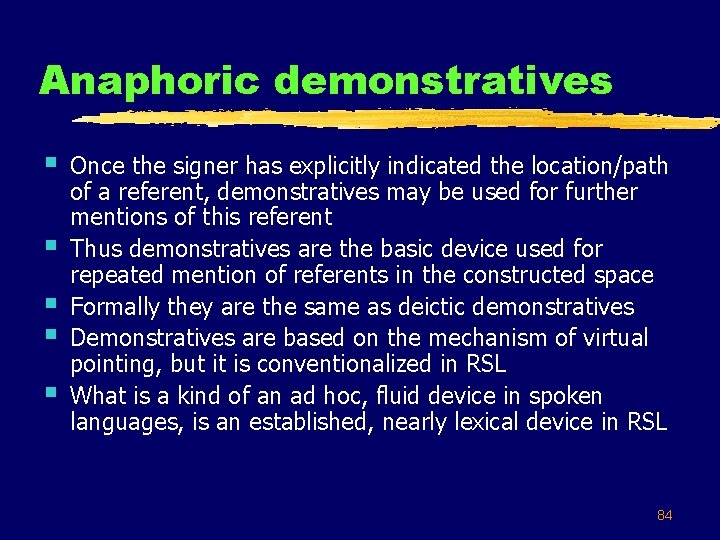

Anaphoric demonstratives § § § Once the signer has explicitly indicated the location/path of a referent, demonstratives may be used for further mentions of this referent Thus demonstratives are the basic device used for repeated mention of referents in the constructed space Formally they are the same as deictic demonstratives Demonstratives are based on the mechanism of virtual pointing, but it is conventionalized in RSL What is a kind of an ad hoc, fluid device in spoken languages, is an established, nearly lexical device in RSL 84

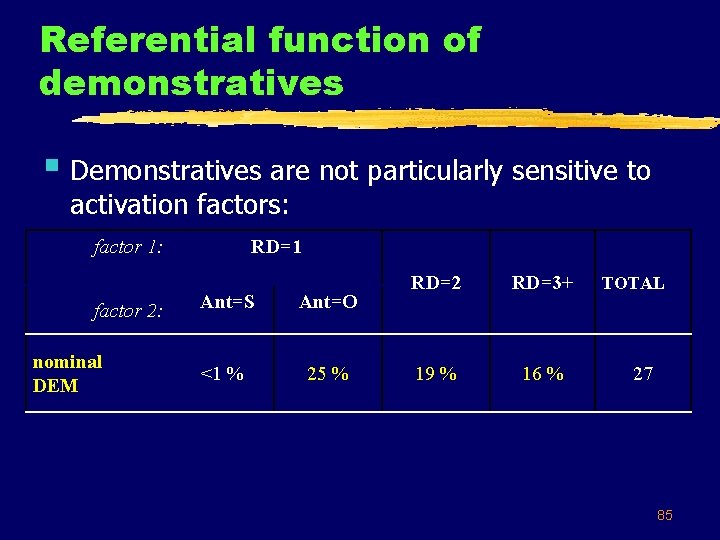

Referential function of demonstratives § Demonstratives are not particularly sensitive to activation factors: factor 1: factor 2: nominal DEM RD=1 Ant=S Ant=O <1 % 25 % RD=2 RD=3+ 19 % 16 % TOTAL 27 85

Conclusions on reference in RSL § § § Types of referential devices and factors of reference are analogous to those of spoken languages Some devices, only embryonically present in spoken languages, are strongly entrenched in RSL: § virtual pointing This is apparently due to the fundamentally spatio-visual character of RSL Studying signed languages gives us a new perspective on spoken languages Recognition of two fundamental types of languages, spoken and signed, appears indispensable for a general theory of language 86

V. A wider picture § The world surrounding us is multimodal § We are multimodal animals § Obviously language and communication are mutimodal § As it often happens, those specializing in applied fields have understood the importance of multimodality before pure scholars and theorists 87

Multimodality in technology § TV is superior to radio § Multimodal communication devices § Internet, especially Web 2. 0, is all multimodal 88

Stages of multimodal integration, from Cohen and Oviatt 2006 89

Multimodality in biological sciences § “Within biology, experimental psychology, and cognitive neuroscience, a separate rapidly growing literature has clarified that multisensory perception and integration cannot be predicted by studying the senses in isolation. ” (Cohen and Oviatt 2006) 90

Multimodality in communication studies and semiotics § Kress G & van Leeuwen T (2001). Multimodal discourse: the modes and media of contemporary communication. London: Arnold. § ‘‘A multimodal approach assumes that the message is ‘spread across’ all the modes of communication. If this is so, then each mode is a partial bearer of the overall meaning of the message. All modes, speech and writing included, are then seen as always partial bearers of meaning only. This is a fundamental challenge to hitherto current notions of ‘language’ as a full means of making meaning’’ (Kress, 2002: 6). 91

Multimodal corpora § LREC-2008 (Language Resources and Evaluation Conference) § Blache P. , Bertrand R. , Ferré G. 2008. Creating and exploiting multimodal annotated corpora. § Gallo C. G. , Jaeger T. F. , Allen J. , Swift M. 2008. Production in a multimodal corpus: How speakers communicate complex actions § Kitazawa Sh. , Kiriyama Sh. , Kasami T. , Ishikawa Sh. , Otani N. , Horiuchi H. , Takebayashii Y. 2008. A Multimodal infant behavior annotation for developmental analysis of demonstrative expressions 92

Synthesis § Le. Vine P & Scollon R (eds. ) Discourse and technology: multimodal discourse analysis. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. 2004 93

Conclusions § § § “Normal” linguists, researching conventional verbal material, need to understand that further progress in linguistics is impossible if one ignores the multimodality of language Language in the understanding of the 20 th century mainstream linguistics is an abstraction, very remote from reality. We live in the multimodal world, this is where language evolved and where it functions, and this is what we need to realize if we want to understand it Taking the multimodal perspective into account can help to adequately approach classical questions of narrow linguistics 94

Acknowledgements § Julia Nikolaeva § Vera Podlesskaya § Evgenia Prozorova § Ekaterina El’bert 95

Alm 2006, “Augmentative and Alternative Communication” § “Unimpaired § communication is, of course, inherently § § multimodal, with the speech content being modified by prosody and delivered in parallel with facial expression, gesture, posture, and a range of other nonverbal communication methods. ” 96

Schrøder 2006 § § § Kress G & van Leeuwen T (2001). Multimodal discourse: the modes and media of contemporary communication. London: Arnold/Hodder Headline Group. § NB: this is multimodal social semiotic theory § § § “The overall theoretical framework of Kress and van Leeuwen’s visual discourse semiotics is strongly akin to Fairclough’s three-dimensional model, whereas the analytical practice is inspired eclectically by theoretical and analytical work in linguistics, visual semiotics, film theory, art criticism, as well as numerous predecessors in the various fields of media research, especially the analysis of advertising (Cook, 1992; Myers, 1994; Williamson, 1978). ” § § § 97

§ Norris S (2004). Analyzing multimodal interaction: A methodological framework. London: Routledge. 98

§ Multimodal microplanning § ELL, P. 168 99

§ ELL, 514 – multimodal technology 100

Cohen and Oviatt 2006 § On technology § § § “before building high-performance multimodal systems, it is crucial that the architecture be based on an understanding of how humans communicate multimodally in different contexts. ” § § § “future multimodal systems that can detect and adapt to a user’s dominant integration pattern potentially could yield substantial improvements in system robustness and overall performance” § § “systems that allow users to distribute their content across modalities will face simpler recognition and understanding problems and thus are likely to be more robust” § § “Within biology, experimental psychology, and cognitive neuroscience, a separate rapidly growing literature has clarified that multisensory perception and integration cannot be predicted by studying the senses 101

Mc. Kay 2006 § § § § “Studying texts with images and sounds has presented challenges to conventional discourse analysis, which has valued modes of language through speech and/or writing over visual images or music. The mass media produce multimodal texts, that is, texts that draw from language, pictures, or other graphic elements and sounds in various combinations. Considerations of the multimodal nature of media texts are difficult to incorporate in language-based media analysis. <. . . > In spite of the difficulties in trying capture such multimodality, concentrating on language and ignoring the other modes is to miss much of the potential for meaning of contemporary media texts. ” 102

Busch 2006 § § § § § Media communication is inherently multimodal communication: this means that language in written and spoken form is one of several modes available for expressing a potential of meanings. For instance, in print media lay-out and image are available in addition to the written word; in radio, language is present in its spoken form, alongside music and different sounds; in television all the aforementioned modes can be drawn upon in a context in which the moving image holds a central position. Similarly, in computer-mediated communication, a wide range of modes is available. ‘‘A multimodal approach assumes that the message is ‘spread across’ all the modes of communication. If this is so, then each mode is a partial bearer of the overall meaning of the message. All modes, speech and writing included, are then seen as always partial bearers of meaning only. This is a fundamental challenge to hitherto current notions of ‘language’ as a full means of making meaning’’ (Kress, 103

Scollon 2006 § “any use of language is inescapably multimodal. § That is, spoken or written language inherently § cooccurs in grammatical interactions among § § other semiotic modes such as gesture, image, color, texture, shape, or spatial layout and configuration” 104

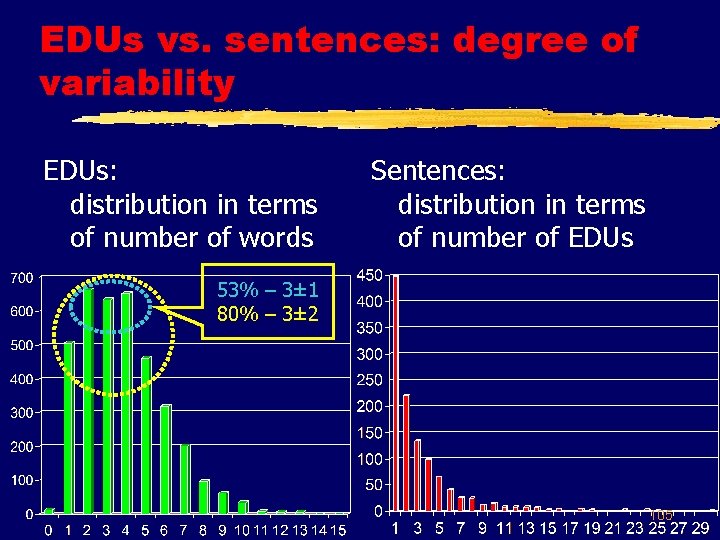

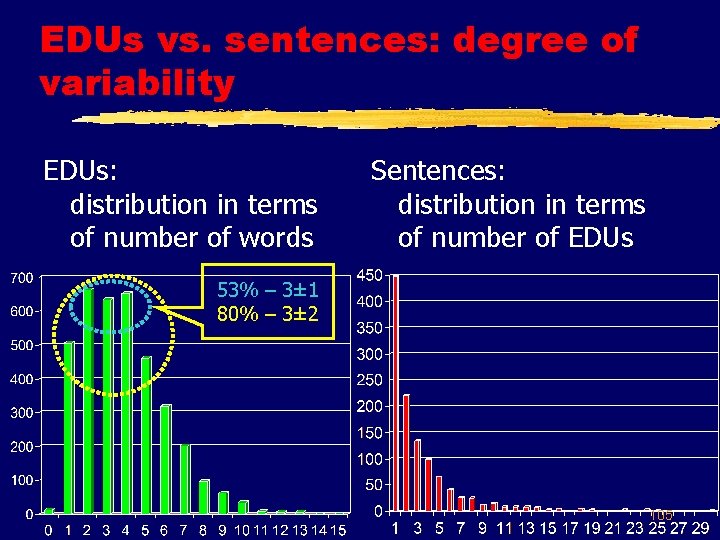

EDUs vs. sentences: degree of variability EDUs: distribution in terms of number of words Sentences: distribution in terms of number of EDUs 53% – 3± 1 80% – 3± 2 105

Gestures enhance understanding § Сutica and Bucciarelli 2006 § Cassell et al. 1998 106

Alternative theories of gestures’ functions § Alibali, Kita and Young 2000: § Lexical retrieval hypothesis § Information packaging hypothesis 107

Combining the verbal channel with one additional channel does not increase the percentage of correct answers Group 1 number 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Experimental material Original Sound Subtitles + video Prosody + video Subtitles Prosody Video Nothing (context only) Information channels verbal prosodic visual verbal prosodic visual [none] Number of information channels 3 2 2 2 1 1 1 0 Mean %% of correct answers 87, 4% 70, 4% 73, 9% 51, 2% 72, 0% 51, 1% 61, 7% 38, 3% 108

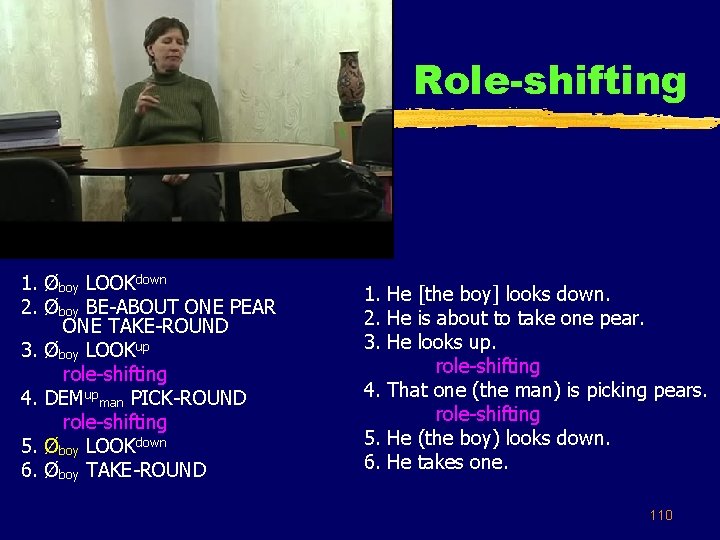

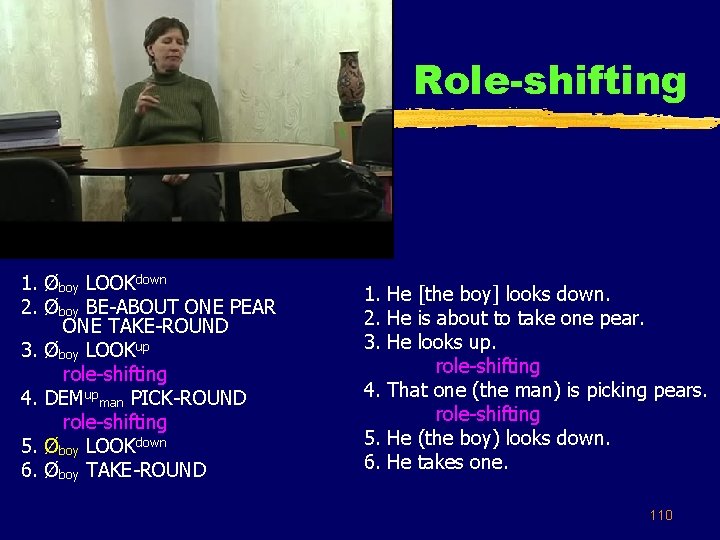

Use of zero expressions under RD > 1 § 49 usages (12% of all zeroes) § Pragmatic and semantic clues that help to identify the referent of a zero expression: § certain predicates associated with a particular referent (RIDE-BICYCLE; HOLD-BICYCLE) § The process of role-shifting (Padden 1986): § by shifting (rotating) the body and changing his/her facial expression the signer shows that s/he is currently “acting” for one of the referents 109

Role-shifting 1. Øboy LOOKdown 2. Øboy BE-ABOUT ONE PEAR ONE TAKE-ROUND 3. Øboy LOOKup role-shifting 4. DEMupman PICK-ROUND role-shifting 5. Øboy LOOKdown 6. Øboy TAKE-ROUND 1. He [the boy] looks down. 2. He is about to take one pear. 3. He looks up. role-shifting 4. That one (the man) is picking pears. role-shifting 5. He (the boy) looks down. 6. He takes one. 110

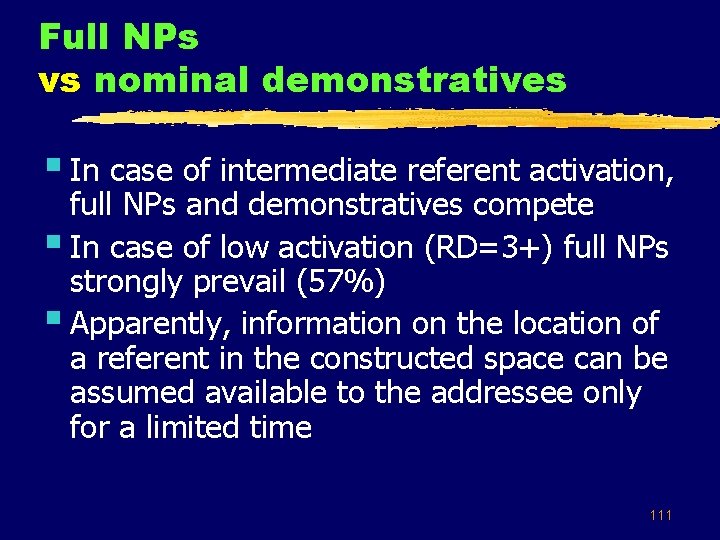

Full NPs vs nominal demonstratives § In case of intermediate referent activation, full NPs and demonstratives compete § In case of low activation (RD=3+) full NPs strongly prevail (57%) § Apparently, information on the location of a referent in the constructed space can be assumed available to the addressee only for a limited time 111

Full NPs vs demonstratives 11 2 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Øboy CYCLE Øboy OBJECT-MOVEsigner forward Øboy GO-AWAYsigner left-forward DEMup MAN STILL PICK-PEAR CYCLE DEMboyfront Øboy OBJECT-MOVEsigner forward 1. 2. 3. 4. He (the boy) is cycling. He is riding forward. He goes away. That man is still picking pears. 5. This one is cycling. 6. He is riding forward. 112

§ The multimodal flight finder enables rapid task completion by enabling the user to interact via a multiplicity of user interaction modalities 113

Multimodal Analysis Lab (Singapore): collaboration of social scientists and computer scientists 114

Multimodality in computational linguistics § Gibbon D, Mertins I & Moore R (eds. ) Handbook of multimodal and spoken dialogue systems: resources, terminology and product evaluation. Dordrecht: Kluwer. 2000 115

In related disciplines § Assumption typically held by other cognitive scientists, for example psychologists: language consists of words, sentences, and other verbal units § “With no more than 50 to 100 K words humans can create and understand an infinite number of sentences” (Bernstein et al. 1994: 349 -350) § When cognitive scientists work with “language”, they almost invariably think that language is a set of individual words or, at most, sentences 116

Hierarchically

Hierarchically Reverse mainstream

Reverse mainstream Mainstream programming languages

Mainstream programming languages Mainstream flights

Mainstream flights Mainstream vs counterculture

Mainstream vs counterculture Mainstream smoke

Mainstream smoke Sidestream smoke

Sidestream smoke Difference between assembly language and machine language

Difference between assembly language and machine language Virtual and datagram networks

Virtual and datagram networks Theoretical models of counseling

Theoretical models of counseling Country attractiveness matrix

Country attractiveness matrix Multi approach avoidance conflict

Multi approach avoidance conflict Cognitive approach vs behavioral approach

Cognitive approach vs behavioral approach Approach meaning in research

Approach meaning in research Traditional approach of development

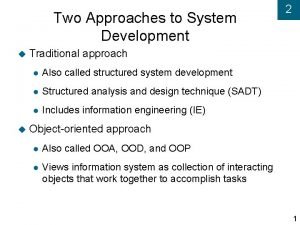

Traditional approach of development Deep learning approach and surface learning approach

Deep learning approach and surface learning approach Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay

Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay Frameset trong html5

Frameset trong html5 Bổ thể

Bổ thể Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào

Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào Tư thế worms-breton

Tư thế worms-breton Chúa yêu trần thế alleluia

Chúa yêu trần thế alleluia Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ đua

Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ đua Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

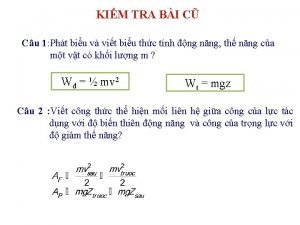

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Công của trọng lực

Công của trọng lực Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ

Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ Mật thư tọa độ 5x5

Mật thư tọa độ 5x5 101012 bằng

101012 bằng độ dài liên kết

độ dài liên kết Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Thể thơ truyền thống

Thể thơ truyền thống Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra

Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra Một số thể thơ truyền thống

Một số thể thơ truyền thống Cái miệng nó xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi

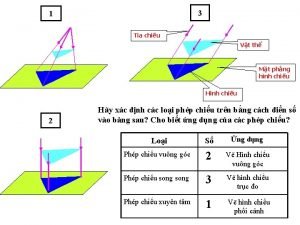

Cái miệng nó xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ

Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ

đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ V cc

V cc Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể

Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể Phối cảnh

Phối cảnh Thẻ vin

Thẻ vin đại từ thay thế

đại từ thay thế điện thế nghỉ

điện thế nghỉ Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Diễn thế sinh thái là

Diễn thế sinh thái là Các loại đột biến cấu trúc nhiễm sắc thể

Các loại đột biến cấu trúc nhiễm sắc thể Số.nguyên tố

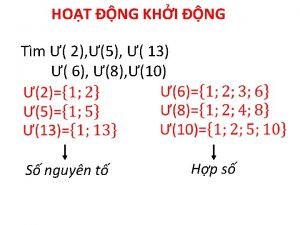

Số.nguyên tố Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Lời thề hippocrates

Lời thề hippocrates Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan

Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan ưu thế lai là gì

ưu thế lai là gì Hổ sinh sản vào mùa nào

Hổ sinh sản vào mùa nào Sự nuôi và dạy con của hổ

Sự nuôi và dạy con của hổ Sơ đồ cơ thể người

Sơ đồ cơ thể người Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu

Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu Thế nào là mạng điện lắp đặt kiểu nổi

Thế nào là mạng điện lắp đặt kiểu nổi Definition of linguistic determinism

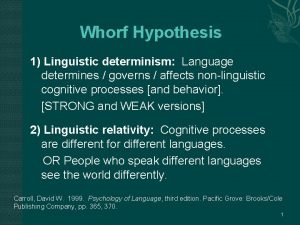

Definition of linguistic determinism Whorfs linguistic determinism

Whorfs linguistic determinism Interapersonal intelligence

Interapersonal intelligence Whorf hypothesis

Whorf hypothesis Linguistic turn meaning

Linguistic turn meaning Sapir-whorf hypothesis linguistic relativity

Sapir-whorf hypothesis linguistic relativity Universals in language

Universals in language Celebrities with bodily-kinesthetic intelligence

Celebrities with bodily-kinesthetic intelligence Confucius institute at moscow state linguistic university

Confucius institute at moscow state linguistic university Linguistic inquiry and word count

Linguistic inquiry and word count Linguistic transference

Linguistic transference Lqa language quality assurance

Lqa language quality assurance Linguistic intergroup bias

Linguistic intergroup bias Linguistic category model

Linguistic category model Linguistic analysis

Linguistic analysis Gest creda

Gest creda Klm model in hci

Klm model in hci Fuzzy logic thermostat

Fuzzy logic thermostat What is linguistic variables in fuzzy logic

What is linguistic variables in fuzzy logic It is a system of conventional spoken manual

It is a system of conventional spoken manual Principle of linguistic relativity

Principle of linguistic relativity Cross linguistic transfer

Cross linguistic transfer Thinking and language ap psychology

Thinking and language ap psychology Metalinguistic awareness

Metalinguistic awareness Blogspot

Blogspot Applied linguistics

Applied linguistics Linguistic branch

Linguistic branch Boas linguistic relativity

Boas linguistic relativity Gest creda

Gest creda The washington fuzzy cs

The washington fuzzy cs What is linguistic variables in fuzzy logic

What is linguistic variables in fuzzy logic Example of linguistic fragmentation

Example of linguistic fragmentation Language

Language Clim matrix

Clim matrix Bloomfield linguistics

Bloomfield linguistics Non verbal communication example

Non verbal communication example What is verbal linguistic intelligence

What is verbal linguistic intelligence Verbal linguistic intelligence examples

Verbal linguistic intelligence examples Prague school of linguistics

Prague school of linguistics Linguistic capital

Linguistic capital Code mixing examples

Code mixing examples Language families

Language families I language

I language Deictic expressions

Deictic expressions Definition of linguistic determinism

Definition of linguistic determinism Creativity of linguistic knowledge

Creativity of linguistic knowledge Structural linguistics and behavioral psychology

Structural linguistics and behavioral psychology Linguistic diversity definition ap human geography

Linguistic diversity definition ap human geography Basic linguistic concepts

Basic linguistic concepts The audiolingual method

The audiolingual method Linguistic anthropology example

Linguistic anthropology example Linguistic act

Linguistic act Linguistic accommodations

Linguistic accommodations Linguistic refuge area

Linguistic refuge area Linguistic competence definition

Linguistic competence definition Linguistic transparency

Linguistic transparency Neuro linguistic programming long island

Neuro linguistic programming long island Linguistic varieties and multilingual nations

Linguistic varieties and multilingual nations Example of time pattern organizer

Example of time pattern organizer