Chapter 14 Forging the National Economy 1790 1860

- Slides: 87

Chapter 14 Forging the National Economy, 1790– 1860

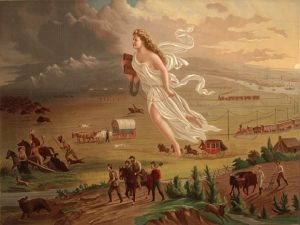

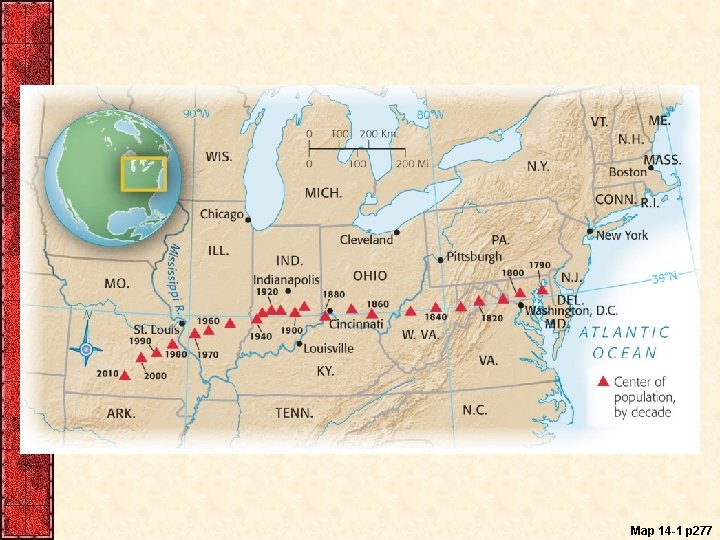

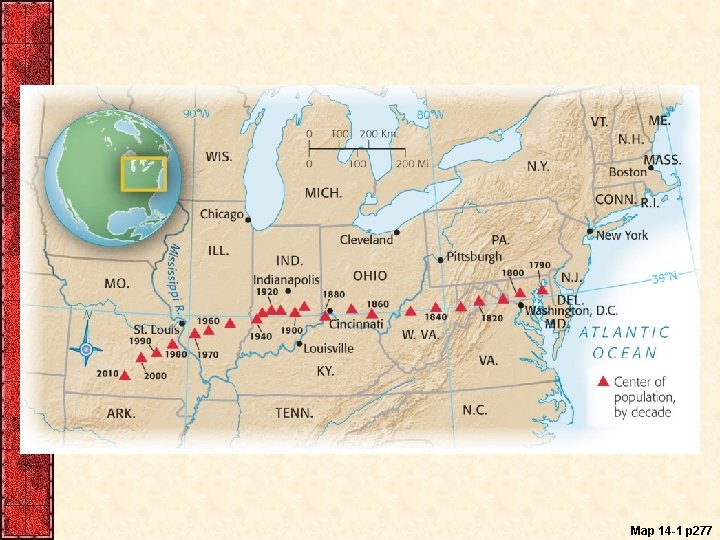

I. The Westward Movement – The rise of Andrew Jackson, the first president from beyond the Appalachian Mountains, exemplified the inexorable westward march. • The Republic late 1850 s: – Half of Americans were under the age of 30 – By 1840 the “demographic center” of the American population map had crossed the Alleghenies (see Map 14. 1). • By the eve of the Civil War, it had marched across the Ohio River.

I. The Westward Movement (cont. ) • Life across the Ohio River: – Life was downright grim for most pioneer families • Perpetual victims of diseases, depression, and premature death • Unbearable loneliness, especially for the women • Breakdowns and madness were all too frequent • Frontier life could be tough and crude for men as well

I. The Westward Movement (cont. ) – Pioneering Americans, marooned by geography, were often ill-informed, superstitious, provincial, and fiercely individualistic. – Popular literature abounded with portraits of unique, isolated figures. – Even in the days of “rugged individualism” there were exceptions. – Pioneers called upon their neighbors for help and upon the government for internal improvements.

Map 14 -1 p 277

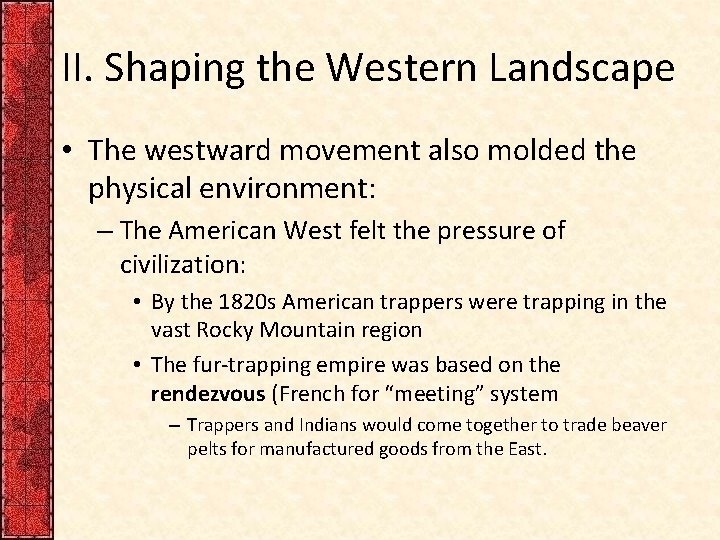

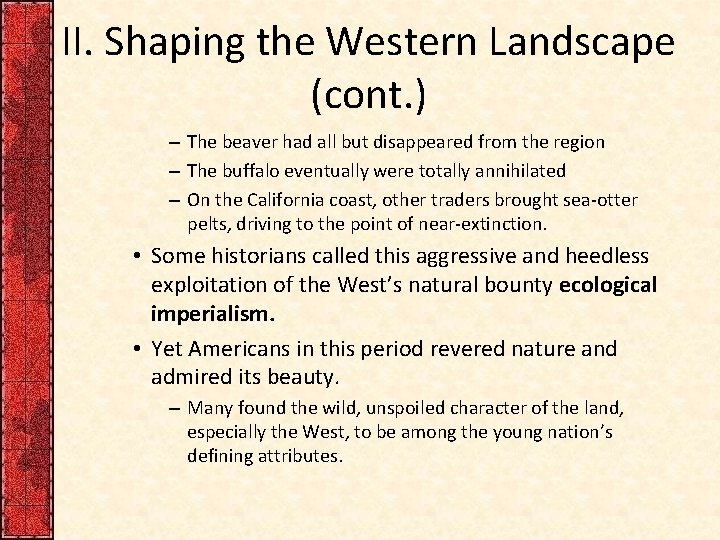

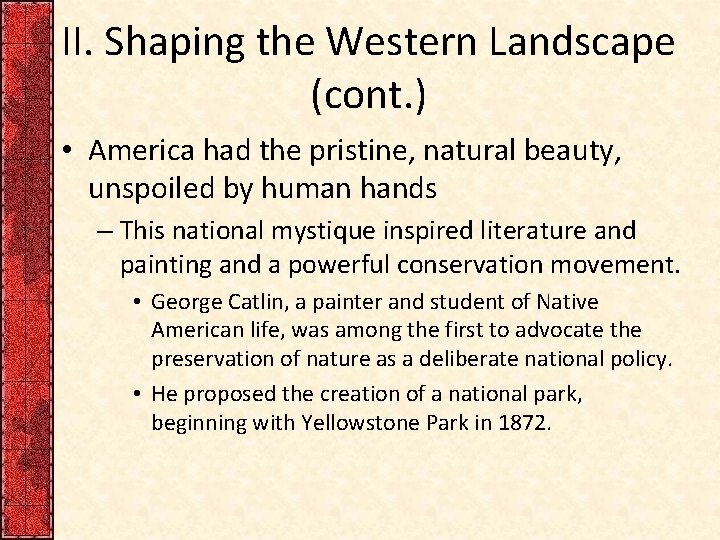

II. Shaping the Western Landscape • The westward movement also molded the physical environment: – The American West felt the pressure of civilization: • By the 1820 s American trappers were trapping in the vast Rocky Mountain region • The fur-trapping empire was based on the rendezvous (French for “meeting” system – Trappers and Indians would come together to trade beaver pelts for manufactured goods from the East.

II. Shaping the Western Landscape (cont. ) – The beaver had all but disappeared from the region – The buffalo eventually were totally annihilated – On the California coast, other traders brought sea-otter pelts, driving to the point of near-extinction. • Some historians called this aggressive and heedless exploitation of the West’s natural bounty ecological imperialism. • Yet Americans in this period revered nature and admired its beauty. – Many found the wild, unspoiled character of the land, especially the West, to be among the young nation’s defining attributes.

II. Shaping the Western Landscape (cont. ) • America had the pristine, natural beauty, unspoiled by human hands – This national mystique inspired literature and painting and a powerful conservation movement. • George Catlin, a painter and student of Native American life, was among the first to advocate the preservation of nature as a deliberate national policy. • He proposed the creation of a national park, beginning with Yellowstone Park in 1872.

III. The March of the Millions • As the American people moved West, they also multiplied at an amazing rate: – By midcentury the population was doubling every twenty-five years (see Figure 14: 1) – By 1860 the thirteen colonies had more than doubled in numbers; 33 stars graced the flag – The United States was the fourth most populous nation in the western world: • Exceeded only by Russia, France, and Austria.

III. The March of the Millions (cont. ) • Urban growth continued explosively: – 1790 only two American cities that could boast populations of 20, 000—Philadelphia, New York – 1860 there were 43 and 300 claimed over 5, 000 – New York was the metropolis; New Orleans, the “Queen of the South; ” and Chicago, the swaggering lord of the Midwest—destined to be “hog butcher for the world. ”

III. The March of the Millions (cont. ) • Over-rapid urbanization brought undesirable by-products: – It intensified the problems of smelly slums, feeble street lighting, inadequate policing, impure water, foul sewage, ravenous rats, and improper garbage disposal • Boston (1823) pioneered a sewer system • New York (1842) abandoned wells and cisterns for a piped-in water supply, thus eliminating the breeding place for many disease-carrying mosquitoes

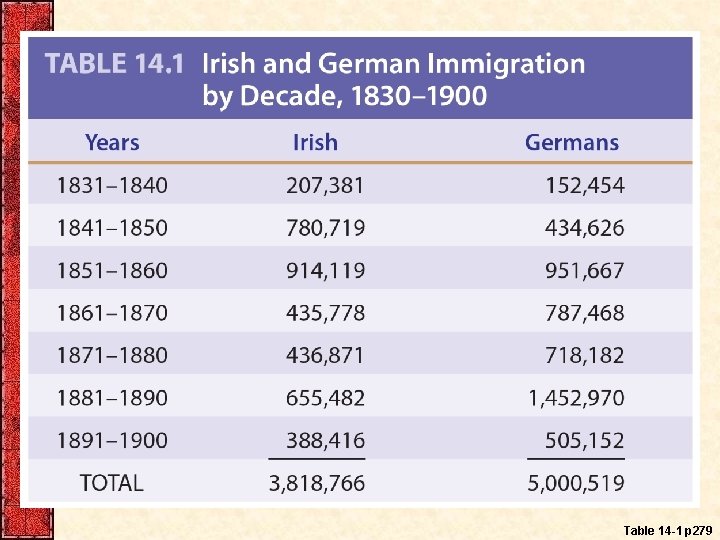

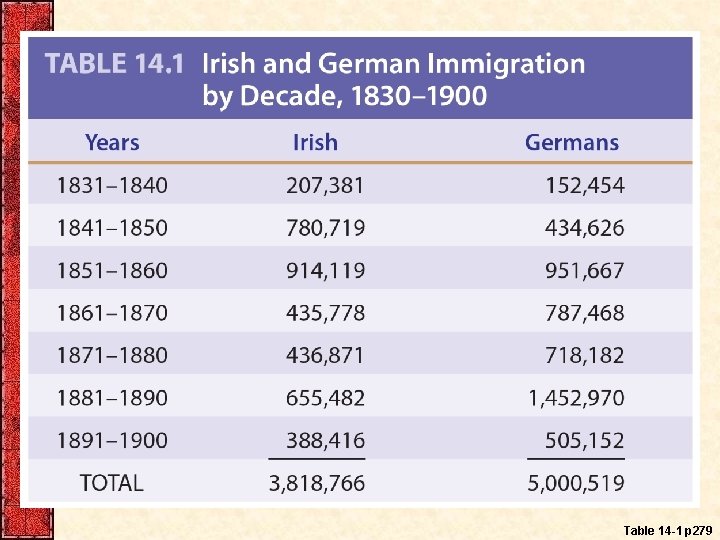

III. The March of the Millions (cont. ) • A continuing high birthrate accounted for the increase in population: – By the 1830 s the rate of increase was 60, 000 a year – The influx tripled in the 1840 s and then quadrupled in the 1850 s – During the 1840 s and 1850 s a million and half Irish, and nearly as many Germans came (see Table 14. 1)

III. The March of the Millions (cont. ) • Why did they come? • Partly because Europe seemed to be running out of room; had “surplus people” • Majority headed for the “land of freedom and opportunity” • The introduction of transoceanic steamships meant that immigrants could come speedily and cheaply • The United States received a far more diverse array of immigrants than other countries • The United States beckoned them from dozens of different nations

Figure 14 -1 p 279

Table 14 -1 p 279

IV. The Emerald Isle Moves West • Ireland was prostrated in the mid-1840 s: – 2 million perished as a result of the potato famine – 10, 000 s fled the Land of Famine for the Land of Plenty in the “Black Forties” – Ireland’s great export has been population, they took their place beside the Jews and the Africans as a dispersed people: (see “Makers of America: The Irish, ” pp. 282 -283) – Many swarmed into the larger seaboard cities.

IV. The Emerald Isle Moves West (cont. ) • Boston and particularly New York became the largest Irish city in the world • The Irish did not receive red-carpet treatment • The friendless “famine Irish” were forced to fend for themselves – The Ancient Order of Hibernians, a semisecret society founded in Ireland to fight rapacious landlords, served in America as a benevolent society, ailing the downtrodden – It also helped to spawn the Molly Maguires, a shadowy Irish miner’s union that rocked the Pennsylvania coal districts in the 1860 s and 1870 s

IV. The Emerald Isle Moves West (cont. ) • Irish conditions in America: • They tended to remain in low-skill occupations • Gradually improved their lot, usually by acquiring modest amounts of property • The education of children was cut short • Property ownership counted as a grand “success” • Politics attracted these Gaelic newcomers • They gained control of powerful city machines, notably New York’s Tammany Hall, and reaped the patronage rewards

Iv. The Emerald Isle Moves West (cont. ) • American politicians made haste to cultivate the Irish vote: • Especially in the politically potent state of New York • Irish hatred of the British lost nothing in the transatlantic transplanting • Nearly 2 million arrived between 1830 and 1860— and Washington glimpsed political gold in those emerald green hills

V. The German Forty-Eighters • The influx of refugees from Germany between 1830 and 1860 was hardly less spectacular than that from Ireland – Over a million and a half Germans stepped onto American soil (see “Makers of America: The Germans, ” pp. 286 -287) • The bulk were uprooted farmers • Some were liberal political refugees • Germany’s loss was America’s gain

V. The German Forty-Eighters (cont. ) • Germans: • Carl Schurz was a relentless foe of slavery and public corruption • They possessed a modest amount of materials goods • Most pushed to the lush lands of the Middle West, notably Wisconsin for farming • They formed an influential body of voters whom American politicians wooed • They were less potent politically since they were more widely scattered

V. The German Forty-Eighters (cont. ) – The hand of the Germans in shaping American life was widely felt: • The Conestoga wagon, the Kentucky rifle, and the Christmas tree were all German contributions • They warmly supported public schools, including their Kindergarten (children's garden) • They did much to stimulate music and the arts • They were relentless enemies of slavery

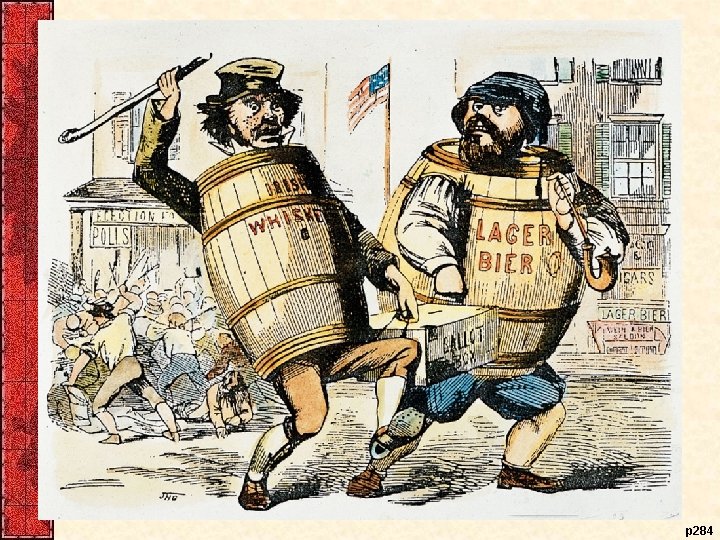

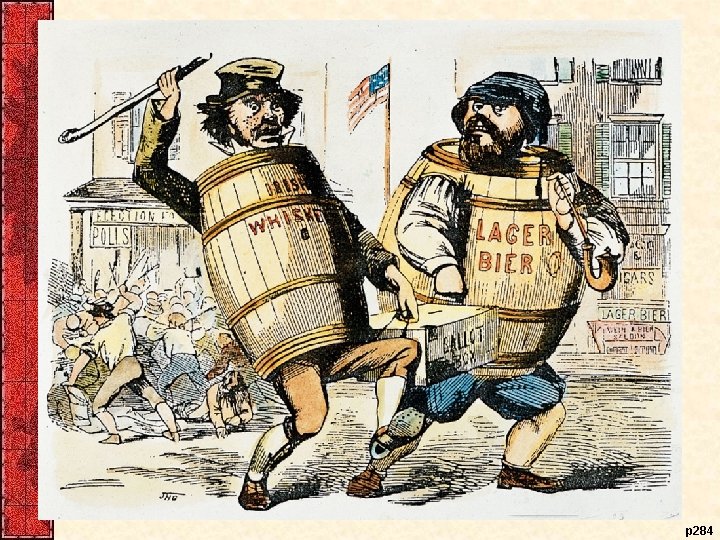

V. The German Forty-Eighters (cont. ) • They were sometimes dubbed “damned Dutchmen”: • Were regarded with suspicion • Seeking to preserve their language and customs, they sometimes settled in compact “colonies” • Keeping aloof from the surrounding communities • Accustomed to “Continental Sunday” and uncurbed by Puritan tradition, they made merry on Sunday • Their Old World drinking habits spurred advocates of temperance to redouble their efforts

VI. Flare-ups of Antiforeignism • The invasion of the immigrants in the 1840 s and 1850 s inflamed the prejudices of American “nativists” • They feared they would outbreed, outvote, and overwhelm the old “native” stock • They took jobs from “native” Americans • They were Roman Catholics – The Church of Rome was regarded as out of line by many old-line Americans as a “foreign” church.

VI. Flare-ups of Antiforeignism (cont. ) • Roman Catholics were on the move: • To avoid Protestant indoctrination in public schools, they began in the 1840 s to construct an entirely separate Catholic educational system: • Very expensive undertaking, but revealed the strength of their commitment • With the Irish and German influx, the Catholics became a powerful religious group • In 1840 they ranked fifth behind the Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians and Congregationalists

VI. Flare-ups of Antiforeignism (cont. ) • Know-Nothing Party—organized by American “nativists” for political action: – Agitated for rigid restriction on immigration and naturalization – Agitated for laws authorizing the deportation of alien paupers – Promoted a lurid literature of exposure, much of pure fiction – Example: Maria Monk’s Awful Disclosures

VI. Flare-ups of Antiforeignism (cont. ) • There was even occasional mass violence against Catholics: – Burning their churches and schools – Some killed and wounded in days of fighting • Immigrants were undeniably making America a more pluralistic society: – One of the most ethnically and racially diverse – Thus the wonder that cultural clashes occurred

VI. Flare-ups of Antiforeignism (cont. ) • The American economy: – Attracted immigrants and ensured them of the share of American wealth without jeopardizing the wealth of others – They helped fuel economic expansion – Immigrants and the American economy needed each other – Together they help bring the Industrial Revolution

p 284

VII. Creeping Mechanization • Gifted British inventors in 1750 s perfected a series of machines for mass production of textiles: • They harnessed steam to usher in the modern factory system—the Industrial Revolution • Resulting in a spectacular transformation in agriculture • As well as in methods of transportation and communication

VII. Creeping Mechanization (cont. ) • The factory system spread from Britain— “the world’s workshop”. – Why was America to become an industrial giant? • Land was cheap in America • Labor was scarce • Money for capital investment was not plentiful – The future of industrialization had to wait until the middle of the nineteenth century in America

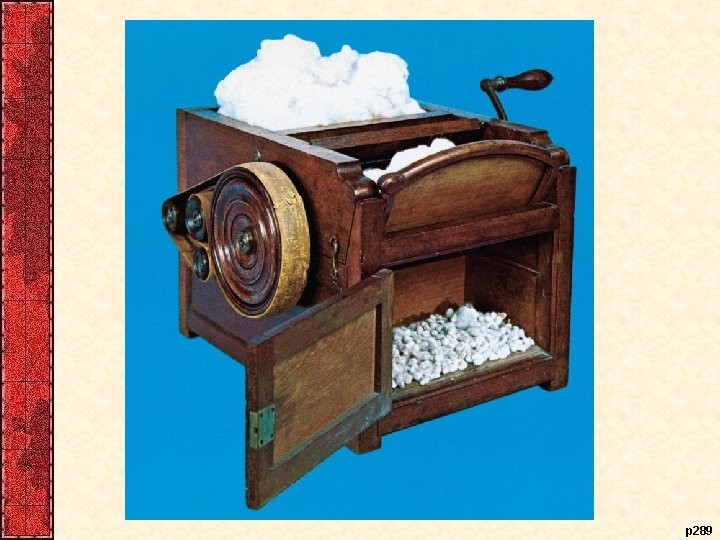

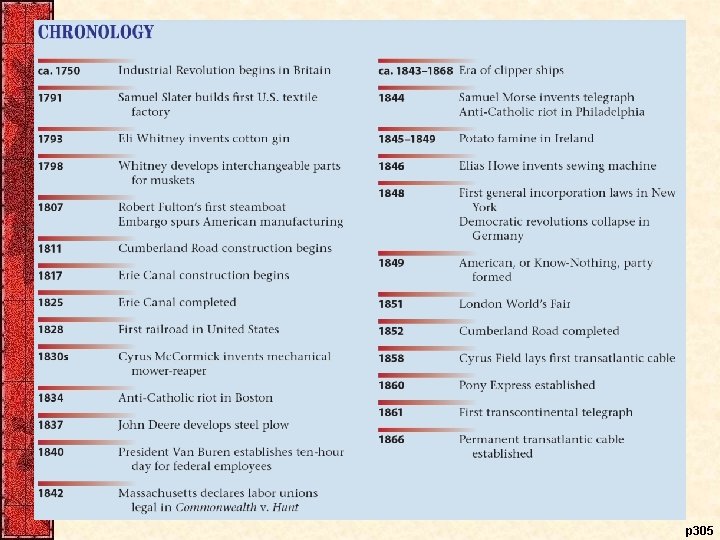

VIII. Whitney Ends the Fiber Famine • Samuel Slater— “Father of the Factory System” – After memorizing the plans for the machinery, he escaped to America – He won the backing of Moses Brown, a Quaker capitalist in Rhode Island: • Laboriously reconstructing the essential apparatus in 1791 he put together the first efficient American machinery for spinning cotton thread

VIII. Whitney Ends the Fiber Famine (cont. ) • Where was the cotton fiber: – Insatiable demand for cotton riveted the chains of the downtrodden southern blacks – Slave-driving planters cleared more land for cotton – Cotton Kingdom pushed westward – Yankee machines put out avalanches of cotton – The American phase of the Industrial Revolution, first blossomed in cotton textiles, was well on its way.

VIII. Whitney Ends the Fiber Famine (cont. ) • Factories first flourished in New England: – Then branched out to New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania – The South: • • Increasingly was wedded to the production of cotton Had little manufacturing Its capital was bound up in slaves Its local consumers for the most part were desperately poor

VIII. Whitney Ends the Fiber Famine (cont. ) • New England was singularly favored as an industrial center because: – Its narrow belt of stony soil made farming difficult and manufacturing attractive • a relatively dense population provided labor and accessible markets • shipping brought in capital • seaports made easy the import of raw materials and the export of the finish product

VIII. Whitney Ends the Fiber Famine (cont. ) – The rivers, notably the Merrimack in Mass. , provided abundant water power. – By 1860 more than 400 million pounds of southern cotton poured into the mills, mostly in New England.

IX. Marvels in Manufacturing • As the factory system flourished it embraced numerous other industries: – The manufacturing of firearms and the contribution of Eli Whitney: • Interchangeable parts adopted in 1850 • Became the basis of modern mass-production, assembly-line methods • It gave the North the vast industrial plant that ensured military preponderance over the South

IX. Marvels in Manufacturing (cont. ) – Ironically Whitney, by perfecting the cotton gin, gave slavery a renewed lease on life – By popularizing the principle of interchangeable parts, Whitney helped factories to flourish in the North, giving the Union a decided advantage. – The sewing machine: • • Invented by Elias Howe in 1846 Perfected by Isaac Singer Gave strong boost to northern industrialization Became the foundation of the ready-made clothing

IX. Marvels in Manufacturing (cont. ) • Drove many seamstresses from the shelter of the private home to the factory—human robot—tended the clattering mechanisms – Each new invention stimulated still more imaginative inventions: • Decade ending in 1800: only 306 patents were registered in Washington • Decade ending in 1860: there were 28, 000 • In 1838 the clerk of the Patent Office resigned in despair, complaining that all worthwhile inventions had been discovered

IX. Marvels in Manufacturing (cont. ) • Technical advances: – Changes in the form and legal status of business organizations: • The principle of limited liability aided the concentration of capital • The Boston Associates was created by 15 Boston families • Laws of “free incorporation” meant that businessmen could create corporation without applying for individual charters from the legislature

IX. Marvels in Manufacturing (cont. ) • Samuel F. B. Morse: – Inventor of the telegraph – Secured from Congress an appropriation of $30, 000 to support his experiment with “talking wires” – In 1844 he strung a wire 40 miles from Washington to Baltimore and tapped out the historic message, “What hath God wrought? ”

IX. Marvels in Manufacturing (cont. ) • By the time of the London World’s Fair in 1851, known as the Great Exhibition: – American products were prominent among the world’s commercial wonders – Fairgoers crowded into the Crystal Palace to see: • Mc. Cormick’s reaper, Morse’s telegraph, Colt’s firearms, and Charles Goodyear’s vulcanized rubber goods.

p 289

X. Workers and “Wage Slaves” • The factory system created an increasingly acute labor problem: – Manufacturing had been done in the home: • Master craftsman and his apprentice worked together • The Industrial Revolution submerged this personal association into impersonal ownership of stuffy factories in “spindle cities” • Around these the slumlike hovels of the “wage slaves” tended to cluster

X. Workers and “Wage Slaves” (cont. ) • Workers’ conditions: – Working people wasted away at their benches – Hours were long, wages were low, meals skimpy and hastily gulped – Workers forced to toil in unsanitary buildings, poorly ventilated, lighted, and heated – They were forbidden to form unions to raise wages Thus there were only 24 recorded strikes before 1835

X. Workers and “Wage Slaves” (cont. ) • Exploitation of child labor: – In 1820 a significant number of the nation’s industrial toilers were children under ten – Victims of factory labor, many children were mentally blighted, emotionally starved, physically stunted, and brutally whipped in special “whipping rooms” – Samuel Slater’s mill of 1791: the first machine tenders were 7 boys and 2 girls, all under 12.

X. Workers and “Wage Slaves” (cont. ) • Lot of adult wage workers in 1820 s-1830 s: – Many states granted the laboring man the vote – He first strove to lightened his burden through workingmen’s parties – Many workers gave their loyalty to the Democratic Party of Andrew Jackson: – In addition to goals of ten-hour day, higher wages, and tolerable working conditions, they demanded public education for their children and an end to inhuman practice of imprisonment for debt

X. Workers and “Wage Slaves” (cont. ) • Employers: – Fought the ten-hour day • Argued reduced hours would lessen production • Increase costs, and demoralize the workers • Laborers would have so much leisure time that the Devil would lead them to mischief – In 1840 President Van Buren established the tenhour day for federal employees on public works. • In ensuing years many states began reducing the hours of working people.

X. Workers and “Wage Slaves” (cont. ) • Day laborers tried to improve their lot: – Their strongest weapon was to lay down their tools – Dozens of strikes erupted in the 1830 s and 1840 s: • For higher wages, ten-hour days and goals such as the right to smoke on the job • Workers usually lost most strikes than they won • Employers imported strike-breakers • Labor raised its voice against these immigrants

X. Workers and “Wage Slaves” (cont. ) • Labor’s effort to organize: – Netted some 300, 000 trade unionists by 1830 – Suffered as a result of the severe depression, 1837 – Toilers won a promising legal victory in 1842 • Commonwealth v. Hunt—Mass. Supreme Court— labor unions were not illegal conspiracies, provided that their methods were “honorable and peaceful. ” – This case did not legalize the strike overnight – Trade unions had a long road to go

p 293

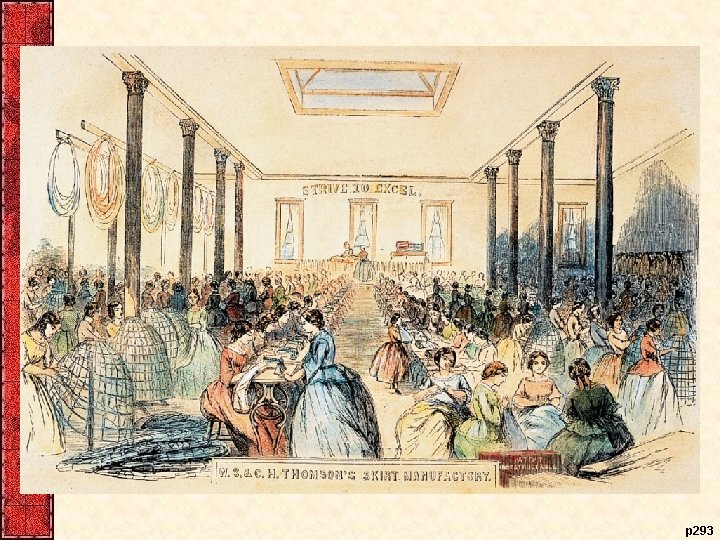

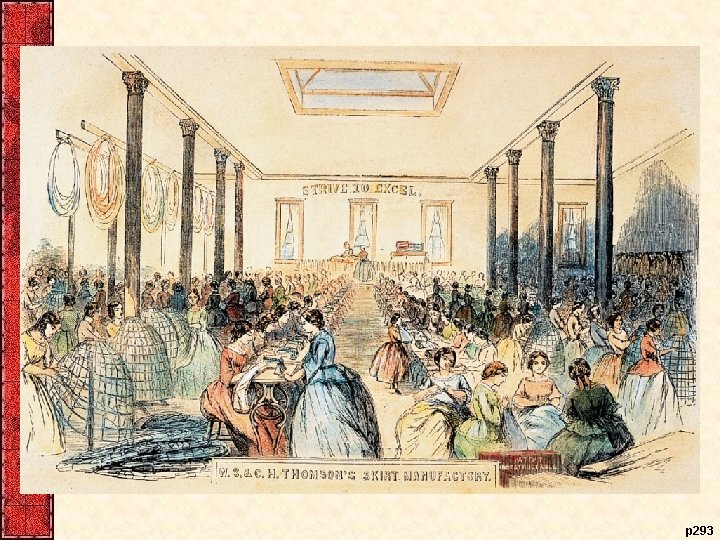

XI. Women and the Economy • Women became part of the clanging mechanism of factory production: – New factories undermined the work of women in their homes – Some factories offered work to those displayed – Factory jobs promised greater economic independence for women – And the means to buy the manufactured products of the new market economy

XI. Women and the Economy (cont. ) • “Factory girls” – Toiled six days a week, twelve to thirteen hours “from dark to dark” – Textile mill at Lowell, Mass. as a showplace: – Workers were virtually all New England farm girls – Carefully supervised on and off the job by watchful matrons – Escorted regularly to church from their company boardinghouses – Forbidden to form unions – Few opportunities to share their grueling working condition

XI. Women and the Economy (cont. ) • Factory jobs wee unusual for women: – Opportunities to be economically self-supporting were scarce – Consisted mainly of nursing, domestic services, and teaching – Catherine Beecher urged women to enter the teaching profession—became “feminized” – Other “opportunities” beckoned in household services

XI. Women and the Economy (cont. ) • Statistics: – One white family in ten employed poor white, immigrant, or black women – 10 % white women worked outside their homes – 20% of all women had been employed at some time before marriage – The vast majority of working women were single – Upon marriage they left their job to become wives and mothers, without wages.

XI. Women and the Economy (cont. ) • Cult of domesticity: – A widespread cultural creed that glorified the customary functions of the homemaker – From their pedestal: • Married women commanded immense moral power – They increasingly made decisions that altered the character of the family itself – Women’s changing roles: • The Industrial Revolution changed life in the home of nineteenth-century: traditional “women’s sphere. ”

XI. Women and the Economy (cont. ) • Love, not parental “arrangement” determined the choice of a spouse—yet parents retained the power of veto • Families became more closely knit and affectionate, providing the emotional refuge against the threatening impersonality of big-city industrialism • Families grew smaller • The “fertility rate” dropped for women between 14 and 45 • Birth control was still a taboo topic

IX. Women and the Economy (cont. ) • Women played a large part in having fewer children • This newly assertive role has been called “domestic feminism” • Smaller families meant child-centered families • What Europeans saw in the American families as permissiveness was in reality the consequence of an emerging new idea of child-rearing: – The child’s will was not simply broken, but rather shaped • Good citizens were raised not to be meekly obedient to authority, but to be independent individuals, making their own decisions on internalized morals

IX. Women and the Economy (cont. ) • The outlines of the “modern” family: – It was small, affectionate and child-centered – It provided a special area for the talents of women – It was a big step upward from the conditions of grinding toil—often alongside men in the fields.

XII. Western Farmers Reap a Revolution in the Fields • Flourishing farms were changing the face of the West: – The trans-Allegheny region—especially the Ohio. Indiana-Illinois tier—was fast becoming the nation’s breadbasket • Before long it would become a granary to the world. – Pioneer families hacked a clearing out of the forest and then planted corn fields: • The yellow grain was amazingly versatile.

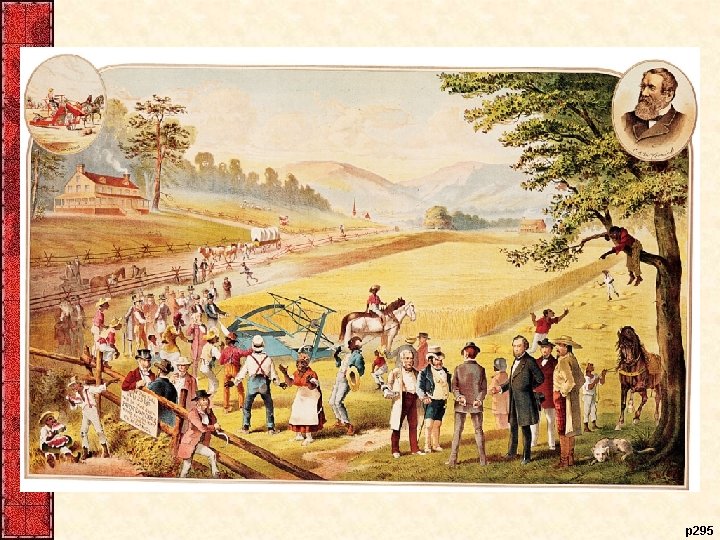

XII. Western Farmers Reap a Revolution in the Fields (cont. ) – Most western products were first floated down the Ohio-Mississippi River system – Inventions came to the aid of the farmers: • John Deere of Illinois in 1837 produced a steel plow that broke the stubborn soil: – Sharp and effective, it was light enough to be pulled by horses, rather than oxen. • 1830 Cyrus Mc. Cormick invented the mechanical mower-reaper – It was to the western farmers what the cotton gin was to the South.

XII. Western Farmers Reap a Revolution in the Fields (cont. ) – It could do the work of five men with sickles and scythes. • The Mc. Cormick reaper: – It made ambitious capitalists out of humble plowmen, who now scramble for more acres – Subsistence farming gave way to food production on a large -scale (“extensive”); specialized, cash-crop agriculture came to dominate the trans-Allegheny West – With it followed mounting indebtedness – Wanted more land more machinery to work it – They dreamed of market elsewhere—in the mushrooming factory towns of the East or across the faraway Atlantic – However, they were still landlocked—a need for a transportation revolution

p 295

XIII. Highways and Steamboats – In 1789, when the Constitution was launched, primitive methods of travel were still in use: • Waterborne commerce was slow, uncertain, and often dangerous • Stagecoaches and wagons lurched over bone-shaking roads • Cheap and efficient carriers were imperative • In 1790 s a private company completed the Lancaster Turnpike in Pennsylvania, running 60 miles from Philadelphia to Lancaster

XIII. Highways and Steamboats (cont. ) • As driver approached the tollgate, they were confronted with a barrier of sharp pikes, which were turned aside when they paid their toll—turnpike. • Western road building, always expensive, encountered many obstacles: – Noisy states’ righters, who opposed federal aid to local projects – Eastern states protested against being bled of their populations by the westward-reaching arteries – Westerners scored a notable triumph in 1811 when the federal government started the construction of the National Road—known as the Cumberland Road.

XIII. Highways and Steamboats (cont. ) • Robert Fulton started the steamboat craze: – Installed a powerful steam engine, the Clermont: • It ran in 1807 from New York City up the Hudson River toward Albany— 150 miles in 32 hours • The success of the steamboat was sensational • Fulton had changed all of America’s navigable streams into two-way arteries, doubling carrying capacity • By 1820 there were 60 steamboats on the Mississippi and its tributaries • By 1860 there were one thousand.

XIII. Highways and Steamboats (cont. ) – In April 1865 the steamer Sultana blew up, killing seventeen hundred passengers, including many Union prisoners of war. – The chugging steamboats played a vital role in the opening of the West and South.

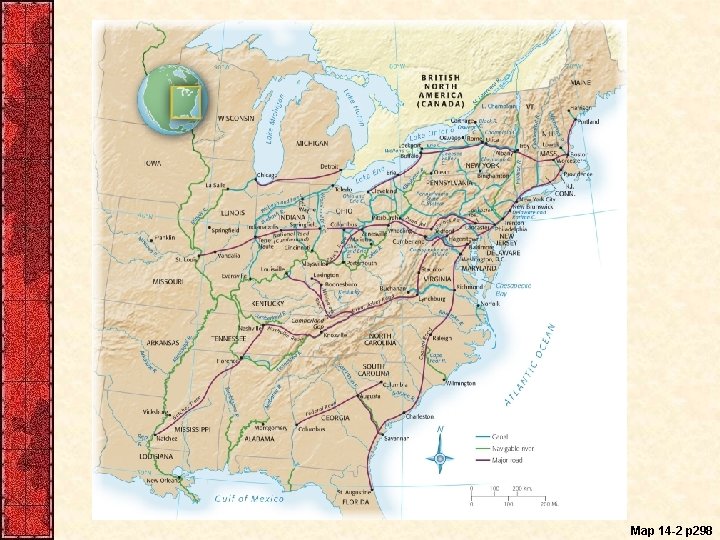

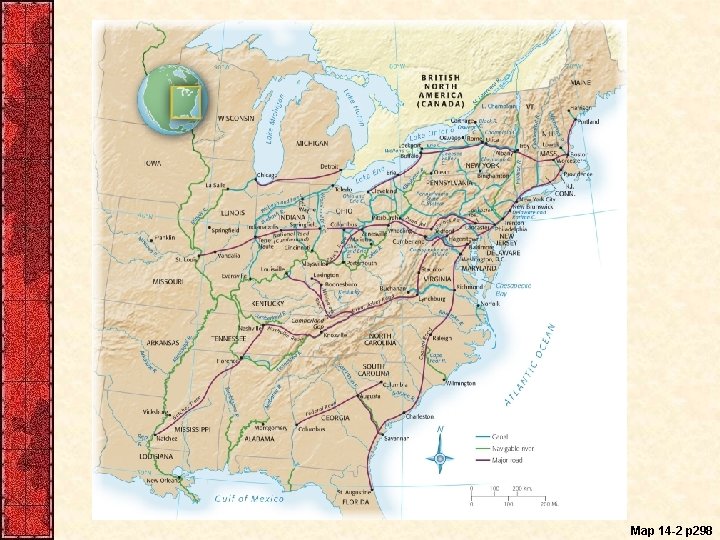

XIV. “Clinton’s Big Ditch” in New York • A canal-cutting craze paralleled the boom in turnpikes and steamboats (see Map 14. 2): – New Yorkers, cut off from federal aid by states’ righters, themselves dug the Erie Canal, linking the Great Lakes with the Hudson River • Blessed by the driving leadership of Governor De. Witt Clinton, the project was called “Clinton’s Big Ditch” or “the Governor’s Gutter. ”

XIV. “Clinton’s Big Ditch” in New York (cont. ) • Begun in 1817, the canal was 363 mi long • Went from Buffalo, on Lake Erie, to the Hudson River, on to New York harbor • The water from Clinton’s keg baptized the Empire State • Shipping was sped up as the cost/time dropped – Other economic ripples • The value of land along the route skyrocketed and new cities, Rochester and Syracuse, blossomed • The new profitability of farming in the Old Northwest. Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, and Illinois—attracted European immigrants.

XIV. “Clinton’s Big Ditch” in New York (cont. ) – Many dispirited New England farmers abandoned their rocky holdings and went elsewhere: – Finding it easier to go west over the Erie Canal, some took new farmland south of the Great Lakes – The transformation in the Northeast—canal consequences —showed how long-established local market structures: » Could be swamped by the emerging behemoth of a continental economy – American goods on the international market; far-off Europeans began to feel the effects of America’s economic vitality

Map 14 -2 p 298

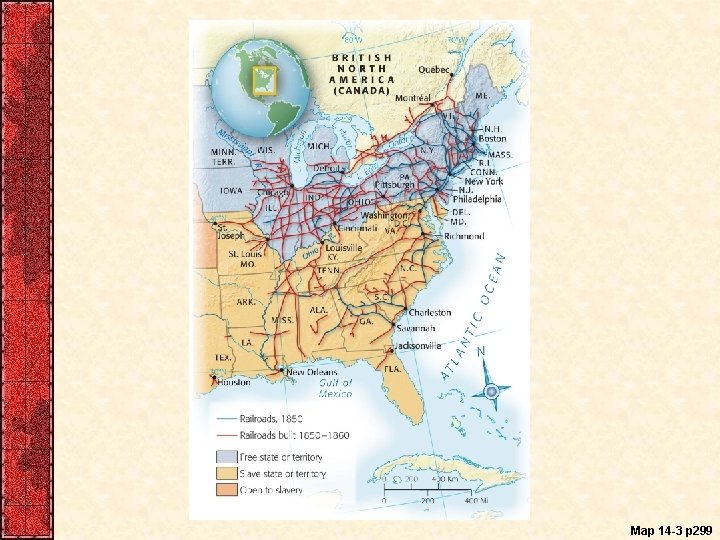

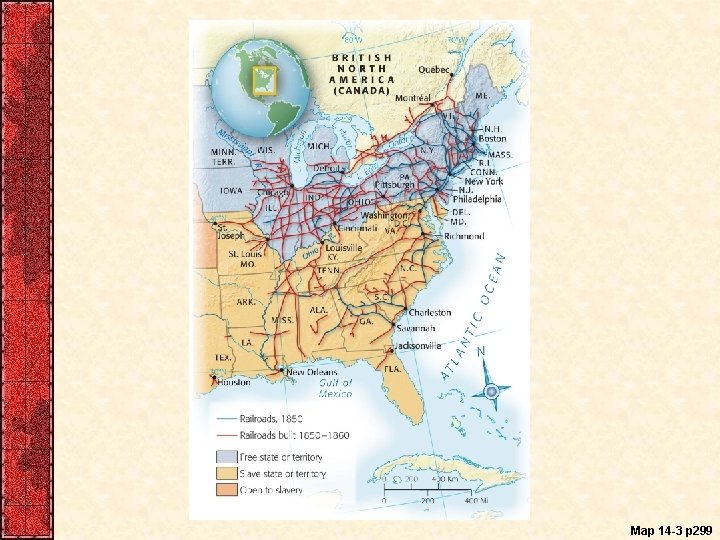

XV. The Iron Horse – The development of the railroad • It was fast, reliable, cheaper than canals to construct, and not frozen over in winter • Able to go anywhere—it defied terrain and weather • First railroad appeared in 1828 and new lines spread with amazing swiftness – Faced strong opposition from canal builders – They were prohibited, at first, to carry freight – Considered a dangerous public menace • Other obstacles: – Brakes were so feeble that engineers might miss the station – Arrivals and departures were conjectural

XV. The Iron Horse (cont. ) – Numerous differences in gauge—required passengers to make frequent changes of trains • Improvements came: – Gauges gradually became standard – Safety devices wee adopted – The Pullman “sleeping palace” was introduced in 1859. • America at long last was being bound together with braces of iron, later to be made of steel.

Map 14 -3 p 299

XVI. Cables, Clippers, and Pony Riders – Other forms of transportation and communication were binding the United States and the world: • Cyrus Field in 1858: – What he called “the greatest wire-puller in history” – The stretching of a cable from Newfoundland to Ireland – Later a heavier cable (1866) permanently linked the American and European continents • Donald Mc. Kay: – The development of the new craft called clipper ships – They sacrificed cargo space for speed – Their hour of glory was relatively brief.

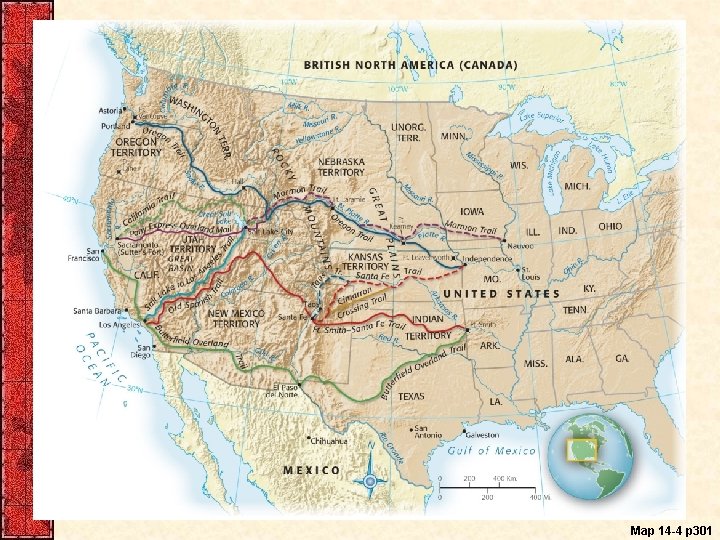

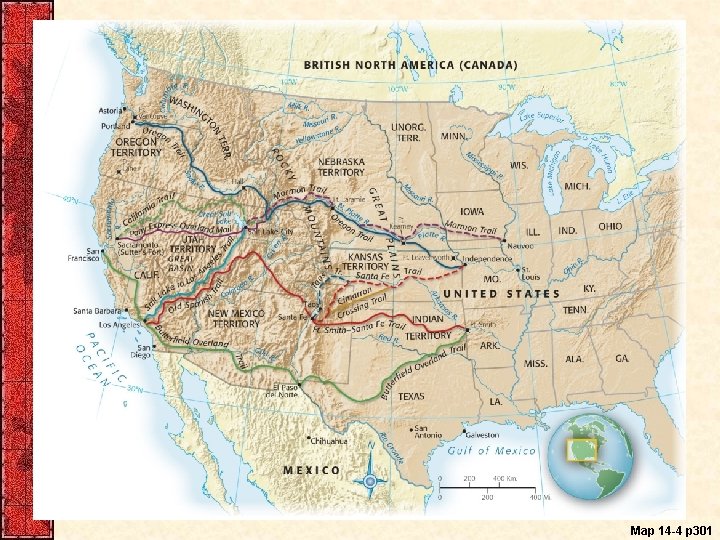

XVI. Cables, Clippers, and Pony Riders (cont. ) • Eve of the Civil War the British won the world race for maritime ascendancy with their iron tramp steamers – They were steadier, roomier, more reliable and more profitable. • Stagecoaches: – Immortalized by Mark Twain’s Roughing It – Their dusty tracks stretched from the banks of the muddy Missouri River clear to California (see Map 14. 4). • Pony Express (1860): – to carry mail speedily the 2, 000 lonely miles from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California; ten day trip – Lasted only 18 months

XVI. Cables, Clippers, and Pony Riders (cont. ) • The express riders were unhorsed by Samuel Morse’s clacking keys – Which began to tap messages to California in 1861 • The swift ships and the fleet ponies ushered out a dying technology of wind and muscle • In the future, machines would be in the saddle

Map 14 -4 p 301

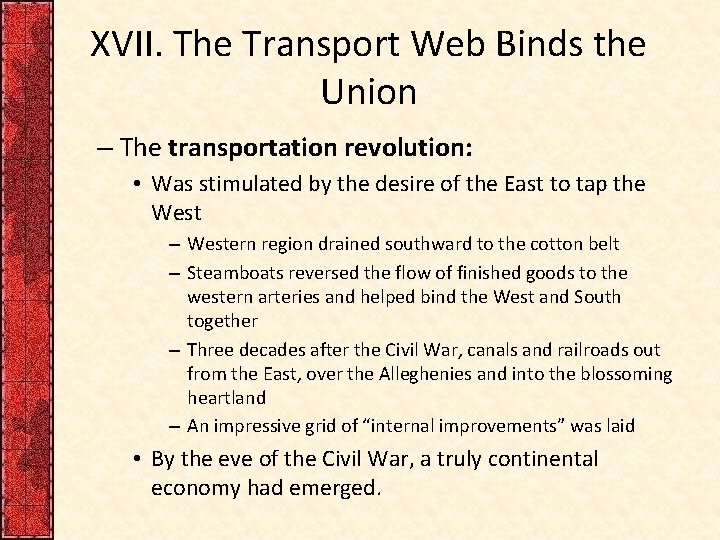

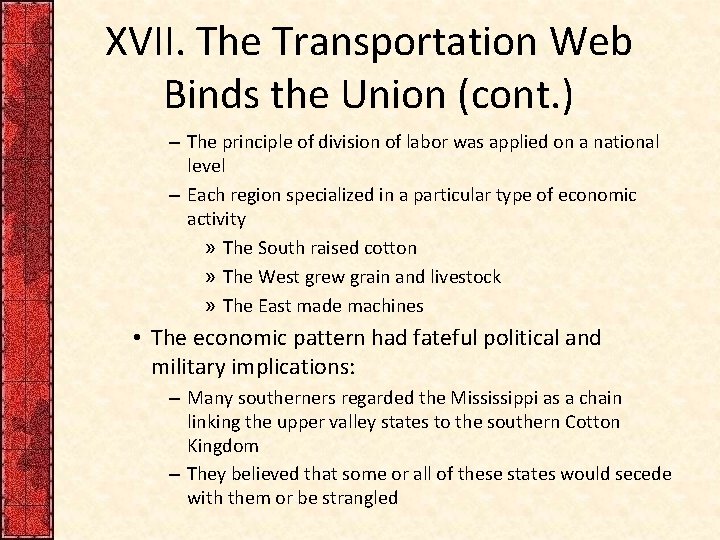

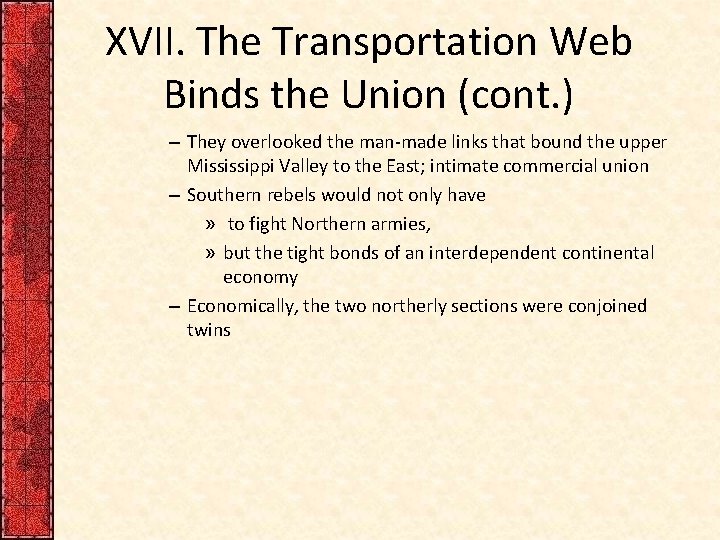

XVII. The Transport Web Binds the Union – The transportation revolution: • Was stimulated by the desire of the East to tap the West – Western region drained southward to the cotton belt – Steamboats reversed the flow of finished goods to the western arteries and helped bind the West and South together – Three decades after the Civil War, canals and railroads out from the East, over the Alleghenies and into the blossoming heartland – An impressive grid of “internal improvements” was laid • By the eve of the Civil War, a truly continental economy had emerged.

XVII. The Transportation Web Binds the Union (cont. ) – The principle of division of labor was applied on a national level – Each region specialized in a particular type of economic activity » The South raised cotton » The West grew grain and livestock » The East made machines • The economic pattern had fateful political and military implications: – Many southerners regarded the Mississippi as a chain linking the upper valley states to the southern Cotton Kingdom – They believed that some or all of these states would secede with them or be strangled

XVII. The Transportation Web Binds the Union (cont. ) – They overlooked the man-made links that bound the upper Mississippi Valley to the East; intimate commercial union – Southern rebels would not only have » to fight Northern armies, » but the tight bonds of an interdependent continental economy – Economically, the two northerly sections were conjoined twins

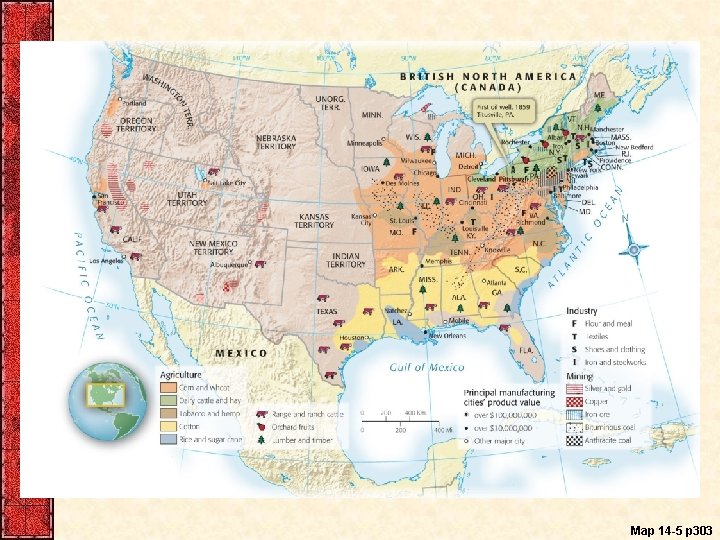

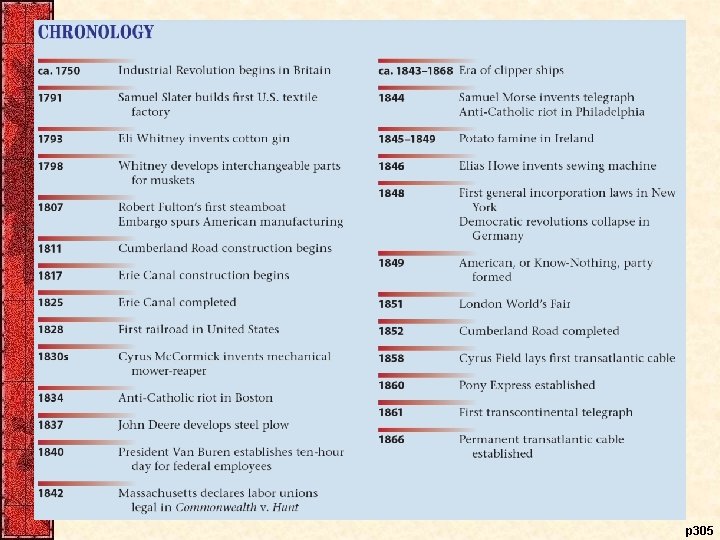

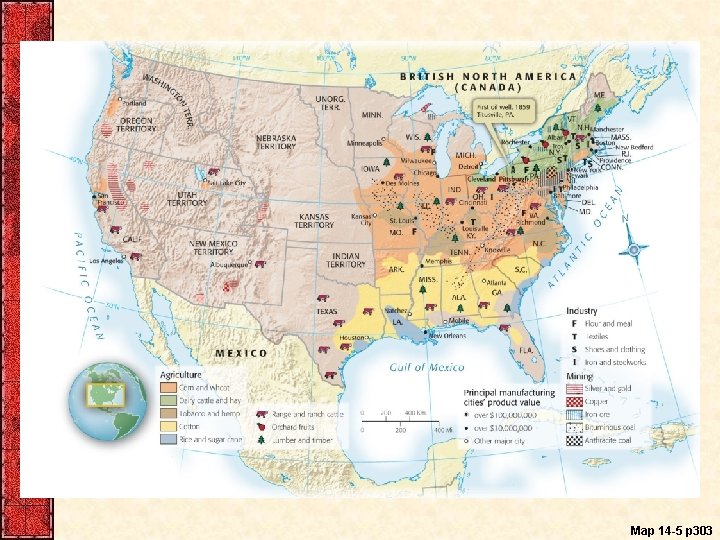

XVIII. The Market Revolution – The Market Revolution: • Transformed a subsistence economy of scattered farms and tiny workshops: – Into a national network of industry and commerce (see Map 14. 5) • Greater mechanization and robust market-oriented economy raised new legal questions: – How tightly should patents protect inventions? – Should the government regulate monopolies? – Who should own the technologies and networks? • Chief Justice John Marshall: – The U. S. Supreme Court protected contract rights by requiring state governments to grant irrevocable charters.

XVIII. The Market Revolution (cont. ) • Monopolies easily developed, as new companies found it difficult to break into markets • Chief justice Roger B. Taney argued that “the rights of the community” outweighed any exclusive corporate rights – His decision opened new entrepreneurial channels – And encouraged greater competition – So did the passage of more liberal state incorporation laws. • The self-sufficient households of colonial days were transformed: – Now families scattered to work for wages in the mills – Or they planted just a few crops for sale at market – Used the money to buy goods made by strangers in far-off factories.

XVIII. The Market Revolution (cont. ) – Store-bought products replaced homemade products – Caused a division of labor and status in the households – Traditional women’s work was rendered superfluous and devalued – The home grew into a place of refuge from the world of work that increasingly became the special and separate sphere of woman. • Revolutionary advance in manufacturing and transportation brought increased prosperity: – They widened the gulf between the rich and the poor – Several specimens of colossal financial success were strutting across the national stage. – John Jacob Astor left an estate of $30 million in 1848.

XVIII. The Market Revolution (cont. ) • Cities bred the greatest extremes of economic inequality: – Unskilled workers fared worst – Became floating mass of “drifters. ” – These wandering workers accounted for up to ½ the population of the brawling industrial centers – They are the forgotten men and women of American history • Many myths about “social mobility: ” Mobility did exist in industrializing America Rags-to riches success stories were relatively few American did provide more “opportunity” then elsewhere Millions of immigrants packed their bags and headed for New World shores. – General prosperity defused potential class conflict. – –

Map 14 -5 p 303

p 305

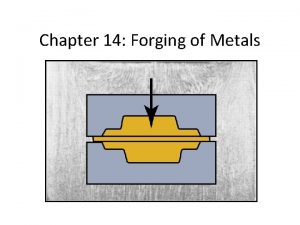

Barrelling in forging

Barrelling in forging 1790 foreign policy

1790 foreign policy Imperialism

Imperialism Rocaille meaning

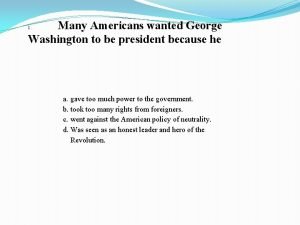

Rocaille meaning Which statement best characterizes american farmers in 1790

Which statement best characterizes american farmers in 1790 Chapter 12 religion romanticism and reform

Chapter 12 religion romanticism and reform Athenian economy vs sparta economy

Athenian economy vs sparta economy Chapter 7 lesson 2 forging a new constitution

Chapter 7 lesson 2 forging a new constitution Border states in 1860

Border states in 1860 Evolution de l'aspirateur au cours du temps

Evolution de l'aspirateur au cours du temps American romantic period

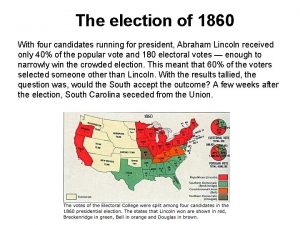

American romantic period The election of 1860 definition

The election of 1860 definition Arthur and lewis tappan apush

Arthur and lewis tappan apush What era was the 1800

What era was the 1800 Decreto 1860 de 1994

Decreto 1860 de 1994 American romanticism 1800 to 1860 worksheet answers

American romanticism 1800 to 1860 worksheet answers South carolina 1860

South carolina 1860 1860

1860 American romanticism 1800 to 1860 worksheet answers

American romanticism 1800 to 1860 worksheet answers American romanticism 1800 to 1860 worksheet answers

American romanticism 1800 to 1860 worksheet answers Map of 1860

Map of 1860 Election of 1860 pie chart

Election of 1860 pie chart American reform movements between 1820 and 1860

American reform movements between 1820 and 1860 South africa 1860

South africa 1860 National differences in political economy

National differences in political economy Ministry of national economy oman

Ministry of national economy oman National differences in political economy

National differences in political economy Penempaan adalah

Penempaan adalah Types of forging

Types of forging Hubbing forging

Hubbing forging Bulk deformation and sheet metal forming

Bulk deformation and sheet metal forming Flashless forging process

Flashless forging process What is forging

What is forging Flashless forging process

Flashless forging process Flashless forging process

Flashless forging process Forged vs cast vs billet

Forged vs cast vs billet Flashless forging process

Flashless forging process Power generation forging

Power generation forging Forging a new deal section 1 answers

Forging a new deal section 1 answers Chapter 6 the new republic

Chapter 6 the new republic Upset forging die design factory

Upset forging die design factory Squeeze casting

Squeeze casting Sticking friction in forging

Sticking friction in forging Slideshare

Slideshare Mcq on sheet metal forming

Mcq on sheet metal forming Hubbing forging

Hubbing forging Open die forging

Open die forging Forging adalah

Forging adalah Forging

Forging Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể

Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể Slidetodoc

Slidetodoc Bổ thể

Bổ thể Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào

Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào Tư thế worm breton là gì

Tư thế worm breton là gì Hát lên người ơi

Hát lên người ơi Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ f

Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ f Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

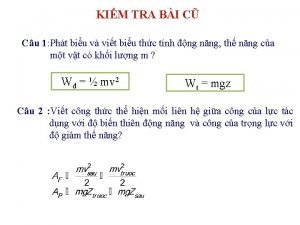

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Cong thức tính động năng

Cong thức tính động năng Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ

Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ Mật thư tọa độ 5x5

Mật thư tọa độ 5x5 Phép trừ bù

Phép trừ bù độ dài liên kết

độ dài liên kết Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Thơ thất ngôn tứ tuyệt đường luật

Thơ thất ngôn tứ tuyệt đường luật Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra

Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra Một số thể thơ truyền thống

Một số thể thơ truyền thống Bàn tay mà dây bẩn

Bàn tay mà dây bẩn Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

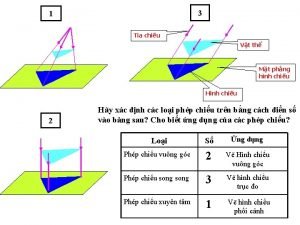

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ

Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ

đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ Ví dụ giọng cùng tên

Ví dụ giọng cùng tên Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể

Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể Tia chieu sa te

Tia chieu sa te Thẻ vin

Thẻ vin đại từ thay thế

đại từ thay thế điện thế nghỉ

điện thế nghỉ Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Diễn thế sinh thái là

Diễn thế sinh thái là Dạng đột biến một nhiễm là

Dạng đột biến một nhiễm là Các số nguyên tố

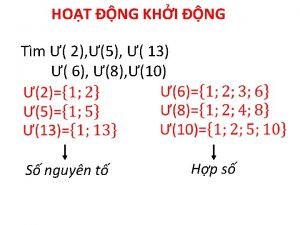

Các số nguyên tố Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Lời thề hippocrates

Lời thề hippocrates Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan

Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan ưu thế lai là gì

ưu thế lai là gì Sự nuôi và dạy con của hươu

Sự nuôi và dạy con của hươu Khi nào hổ mẹ dạy hổ con săn mồi

Khi nào hổ mẹ dạy hổ con săn mồi