Money LECTURE TOPICS What Is Money The Monetary

- Slides: 94

Money

LECTURE TOPICS <What Is Money? <The Monetary System <The Federal Reserve System

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? <Definition of Money Any commodity or token that is generally accepted as a means of payment. Any Commodity or Token • Something that can be recognized • Divided up into small parts. [Also desirable: hard to counterfeit, low resource cost, safe and easy to transport/transfer, durable, easy to assemble in large or small amounts]

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? Generally Accepted • It can be used to buy anything and everything. Means of Payment A means of payment is a method of settling a debt Modern, multi-purpose money performs three vital functions: • Medium of exchange • Unit of account • Store of value [Historically, these were often separate!]

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? <Medium of Exchange Medium of exchange Something that is generally accepted in return for goods and services. Without money, you would have to exchange goods and services directly for other goods and services— an exchange called barter. Money is the common denominator – you exchange things for money, then money for things.

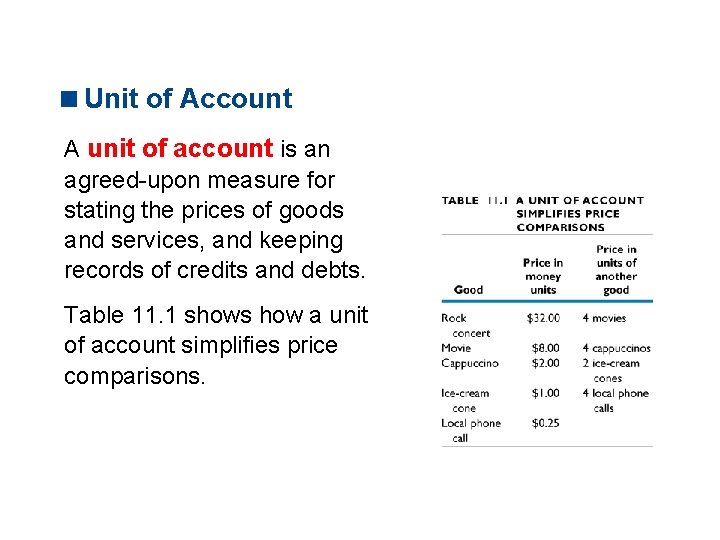

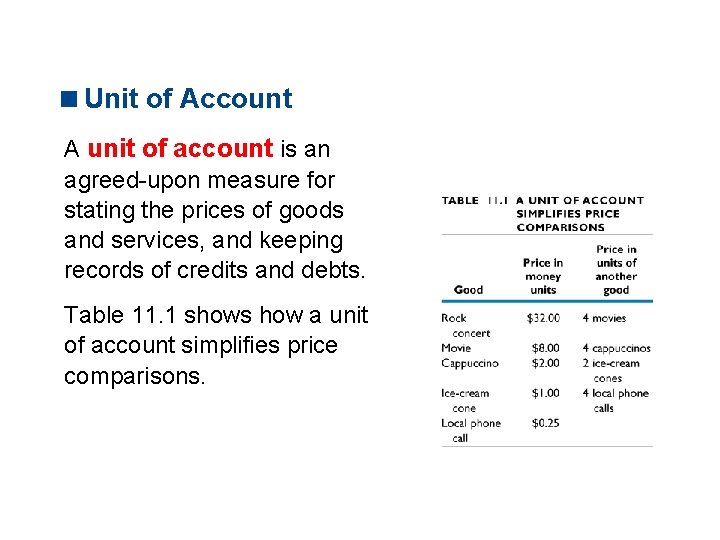

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? <Unit of Account A unit of account is an agreed-upon measure for stating the prices of goods and services, and keeping records of credits and debts. Table 11. 1 shows how a unit of account simplifies price comparisons.

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? <Store of Value A store of value is any commodity or token that can be held and exchanged later for goods and services The store of value characteristic allows us to move purchasing power, wealth, through time without having to hold real resources [which may be both costly and wasteful]. If people don’t have confidence in money or financial assets, they will hold real assets [e. g. gold, land] instead, and this may reduce the amount of productive physical capital.

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? <Money Today Money in the world today is called fiat money. Fiat money Objects that are money because the law orders them to be money. The objects that we use as money today are: • Currency • Checkable deposits at banks and other financial institutions [fiat is Latin for ‘let it be’ or ‘make it’]

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? Currency The notes (dollar bills) and coins that we use in the United States today are known as currency. Notes are money because the government declares them to be with the words printed on every dollar bill: “This note is legal tender for all debts, public and private. ”

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? Checkable Deposits on which you can write a check at banks, credit unions, savings banks, and savings and loan associations are also money. Checkable deposits are money because they can be converted into currency on demand are used directly to make payments by writing checks or using debit cards.

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? Currency in a Bank Is Not Money Checkable bank deposits are one form of money, and currency outside the banks is another form. Currency inside the banks is not money. When you get some cash from the ATM, you convert your bank deposit into currency. Checkable Deposits Are Money but Checks Are Not Checks are not money; they are an instruction to the bank or other financial institution to pay money to the payee named on the check.

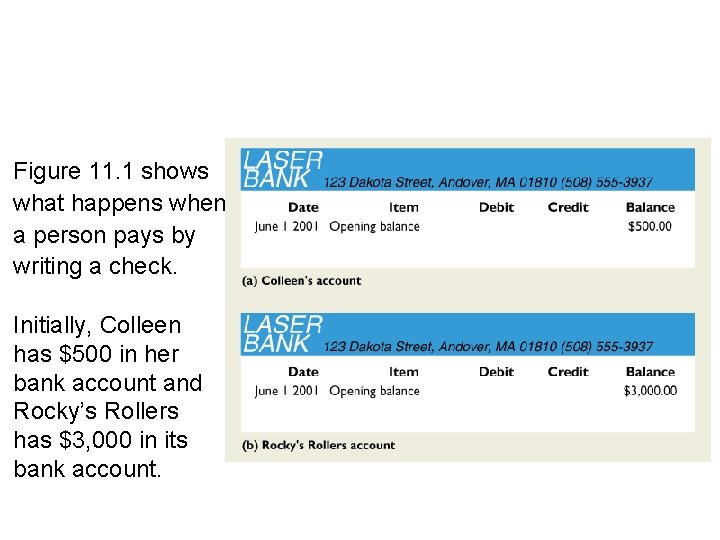

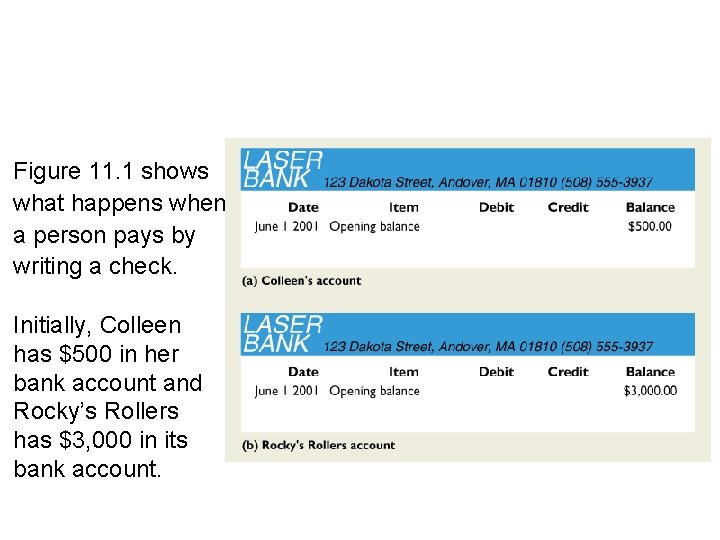

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? Figure 11. 1 shows what happens when a person pays by writing a check. Initially, Colleen has $500 in her bank account and Rocky’s Rollers has $3, 000 in its bank account.

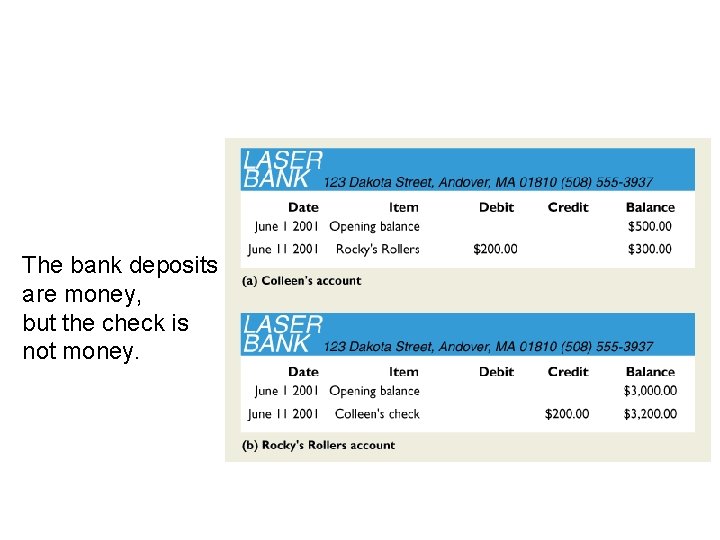

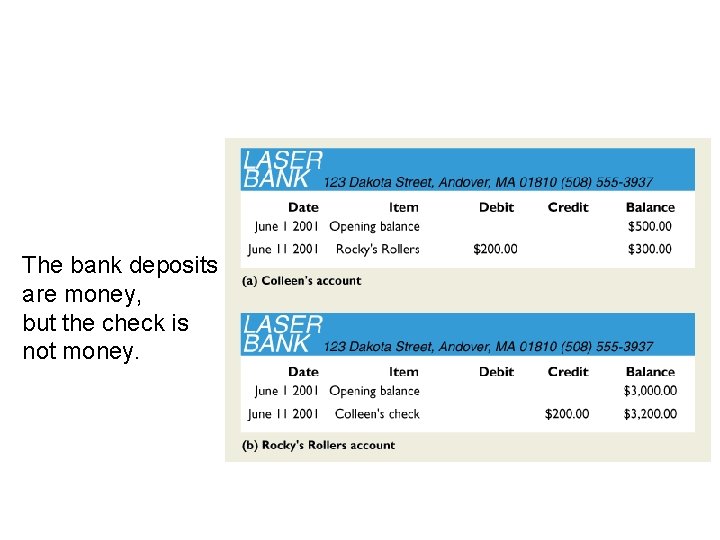

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? Colleen buys some inline skates for $200 and writes a check to pay for them. The balance on Colleen’s bank account decreases by $200 and the balance on Rocky’s bank account increases by $200.

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? The bank deposits are money, but the check is not money.

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? <Credit Cards, Debit Cards, E-Checks, and ECash Credit Cards A credit card is not money because it does not make a payment. When you use your credit card, you create a debt (the outstanding balance on your card account), which you eventually pay off with money.

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? Debit Cards A debit card is not money. It is like an electronic check. E-Checks An e-check is not money. It is an electronic equivalent of a paper check. E-Cash Works like money and when it becomes widely acceptable, it will be money.

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? <Official Measures of Money: M 1 and M 2 M 1 Currency and traveler’s checks plus checkable deposits owned by individuals and businesses. M 2 M 1 plus savings deposits and small time deposits, money market funds, and other deposits.

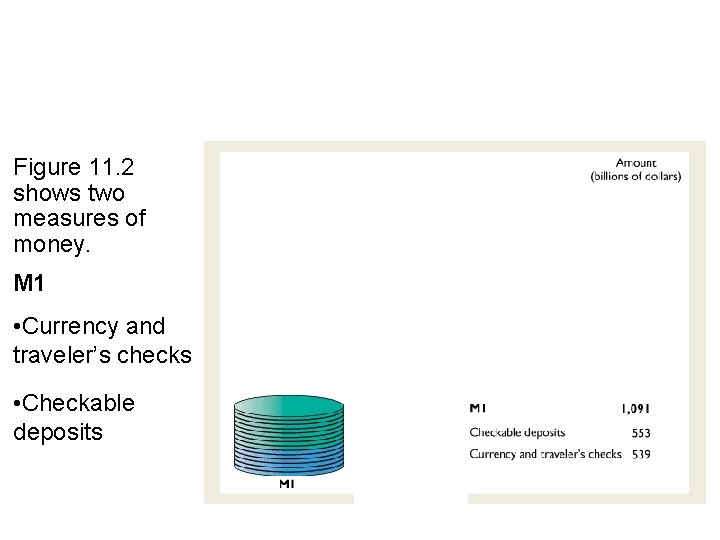

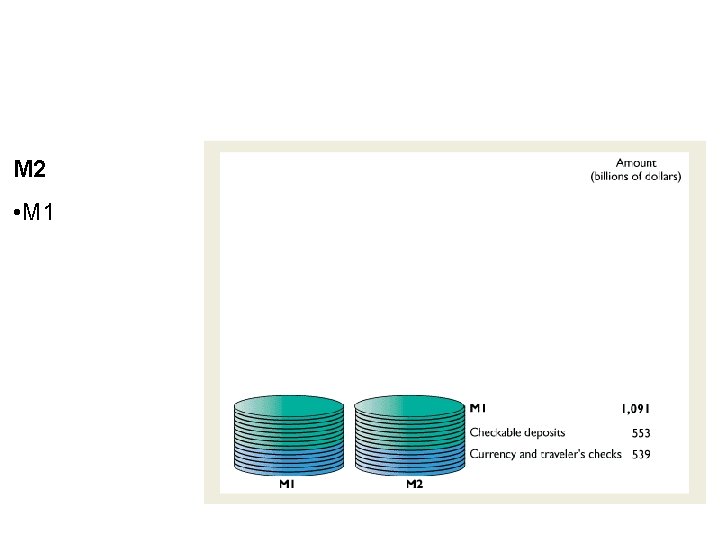

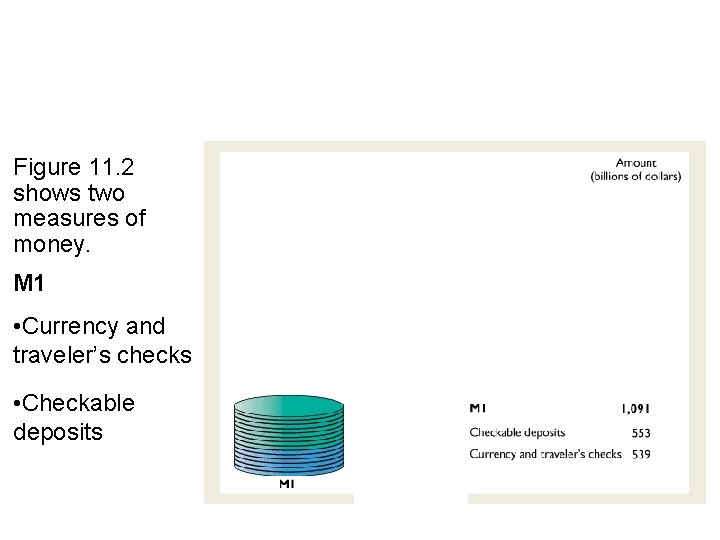

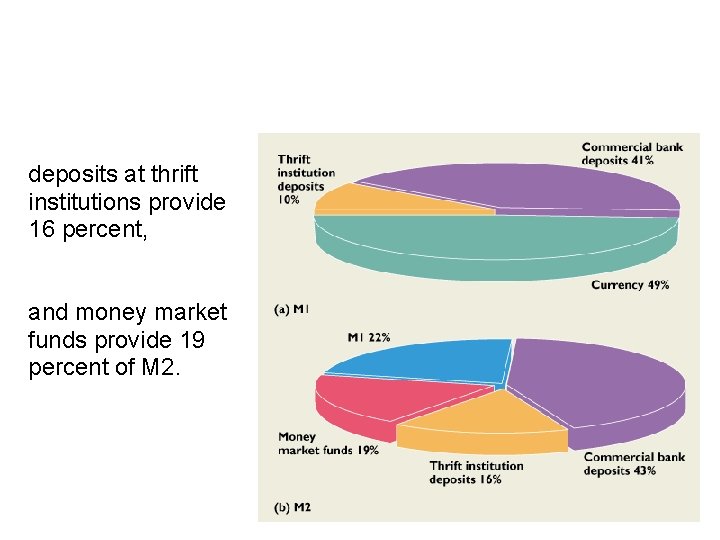

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? Figure 11. 2 shows two measures of money. M 1 • Currency and traveler’s checks • Checkable deposits

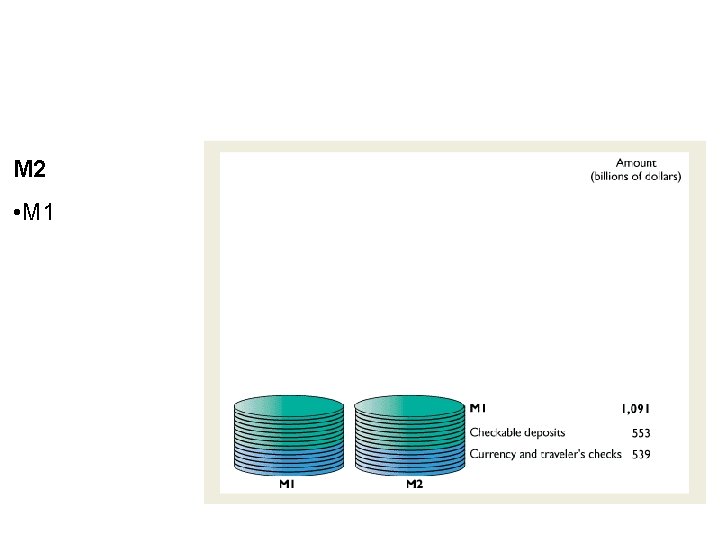

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? M 2 • M 1

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? M 2 • M 1 • Savings deposits • Small time deposits • Money market funds and other deposits

Reality check … < Currency and travelers’ checks $539 billion < Population of the USA [approx] 280 million < Currency and travelers’ checks person is $(539/280)thousand = $1, 925 per man, woman, and child in the US. Do you have your $1, 925 in cash? Do your little sister and your grandmother? What gives – even given drug and other illegal businesses, and cash intensive activities like bars, this does not make sense. Where is all the currency and why? What does this mean for the use of M 1 as an indicator of things happening in the US economy?

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? Are M 1 and M 2 Really Money? The test of whether something is money is whether it serves as a means of payment. M 1 passes this test and is money. Some savings deposits, time deposits, and money market funds do not serve as a means of payment and technically are not money. Economists often refer to M 1 as ‘narrow money’ and M 2 as ‘broad money. ’ There are many different measures of financial assets, ranging from M 0 [monetary base] up to M 7 or above; don’t worry about anything above M 2!

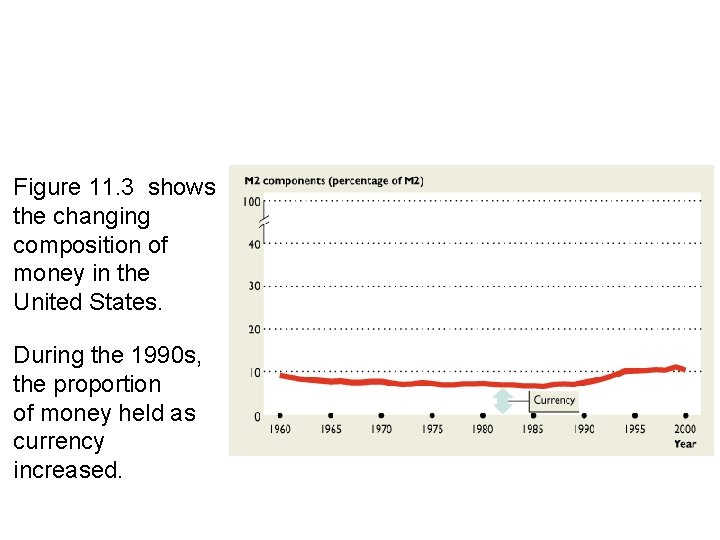

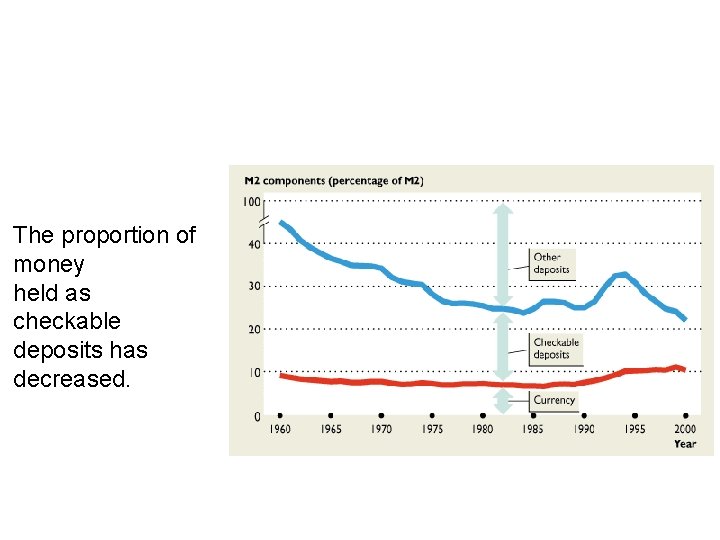

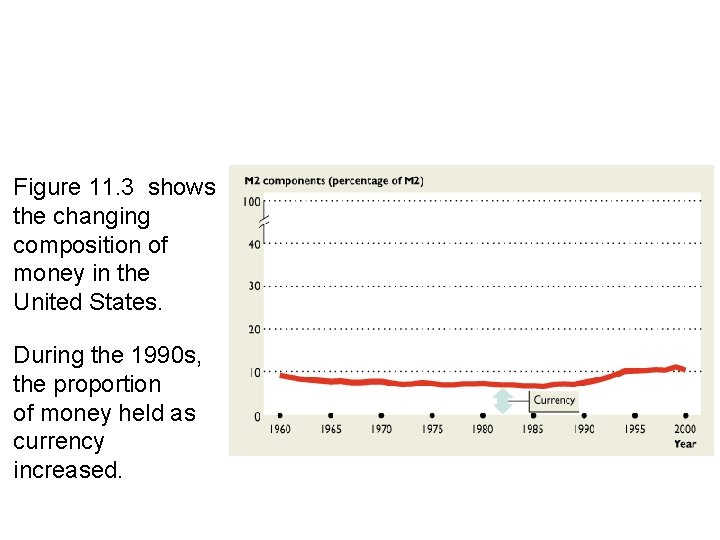

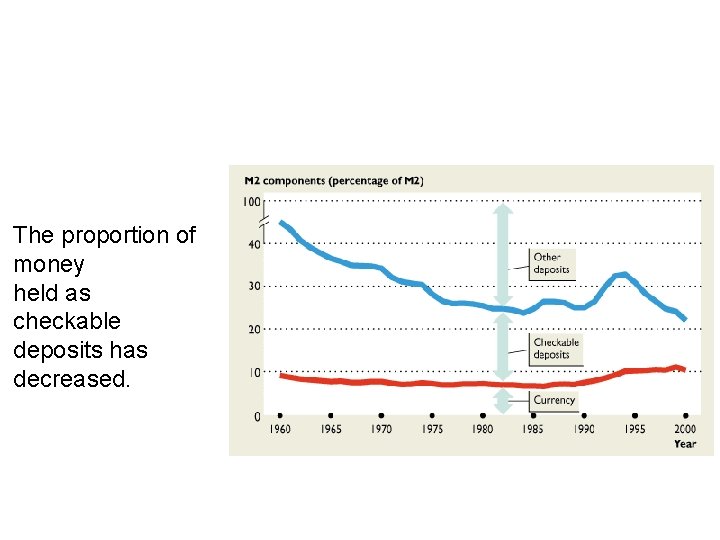

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? Figure 11. 3 shows the changing composition of money in the United States. During the 1990 s, the proportion of money held as currency increased.

11. 1 WHAT IS MONEY? The proportion of money held as checkable deposits has decreased.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM The monetary system consists of: • The Federal Reserve • The banks and other institutions that accept deposits and that provide the services that enable people and businesses to make and receive payments.

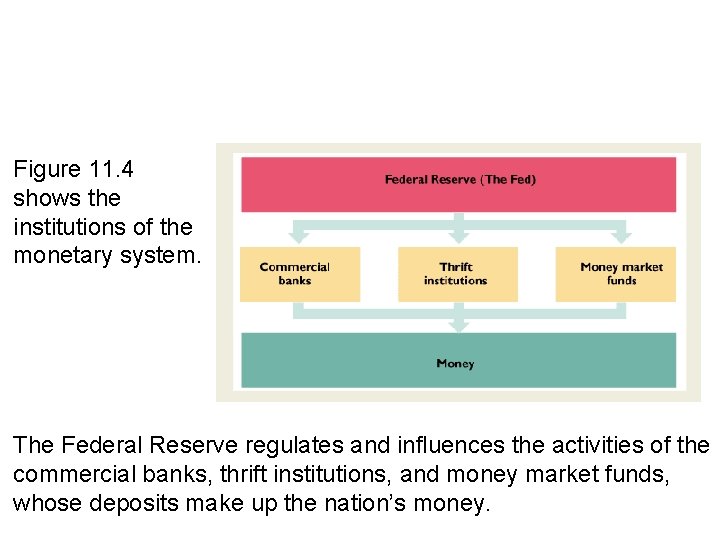

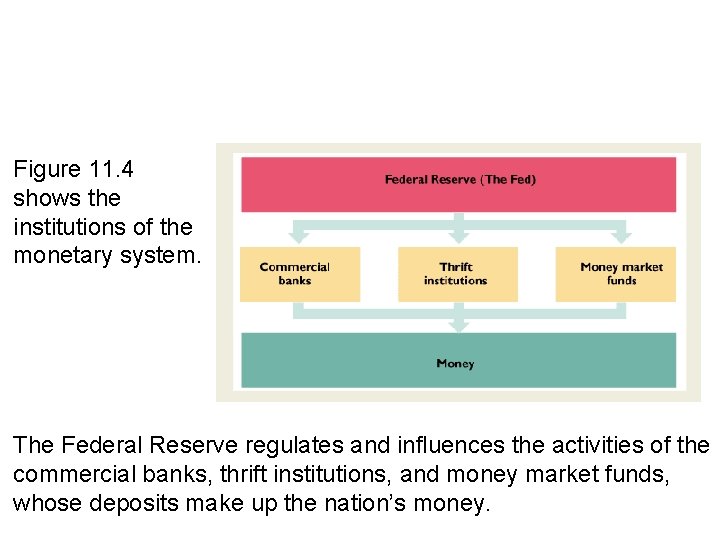

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM Figure 11. 4 shows the institutions of the monetary system. The Federal Reserve regulates and influences the activities of the commercial banks, thrift institutions, and money market funds, whose deposits make up the nation’s money.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM <Commercial Banks A commercial bank is a firm that is licensed by the Comptroller of the Currency in the U. S. Treasury (or by a state agency) to accept deposits and make loans. About 8, 600 commercial banks operate in the United States today. Because of mergers, this number is down from 13, 000 a few years ago.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM Types of Deposits • Checkable deposits • Savings deposits • Time deposits

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM Profit and Prudence: A Balancing Act The goal of a commercial bank is to maximize the long -term wealth of its stockholders. To achieve this goal, a bank must be prudent in the way it uses its depositors’ funds and balance security for the depositors against profit for its stockholders.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM Cash Assets A bank’s cash assets consist of its reserves and funds that are due from other banks as payments for checks that are being cleared. A bank’s reserves consist of the currency in the bank’s vaults plus the balance in its reserve account at a Federal Reserve Bank.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM The Fed requires the banks to hold a minimum percentage of deposits as reserves, called the required reserve ratio. Reserves that exceed those needed to meet the required reserve ratio are called excess reserves.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM Interbank Loans When banks have excess reserves, they can lend them to other banks that are short of reserves in an interbank loans market. The interbank loans market is called the federal funds market and the interest rate in that market is the federal funds rate. The Fed’s policy actions target the federal funds rate, i. e. when the Fed changes its monetary policy, it is trying to change the federal funds rate, the interest rate at which banks lend and borrow reserves. Most short-term interest rates are tied to that rate.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM Securities and Loans Securities held by banks are bonds issued by the U. S. government and by other large, safe, organizations. A bank earns a moderate interest rate on securities, but it can sell them quickly if it needs cash. Loans are the funds that banks lend to businesses and individuals and include outstanding credit card balances. Loans earn the highest interest rate but usually cannot be called in before the agreed date – meaning the bank cannot get its money back earlier than the date the loan matures.

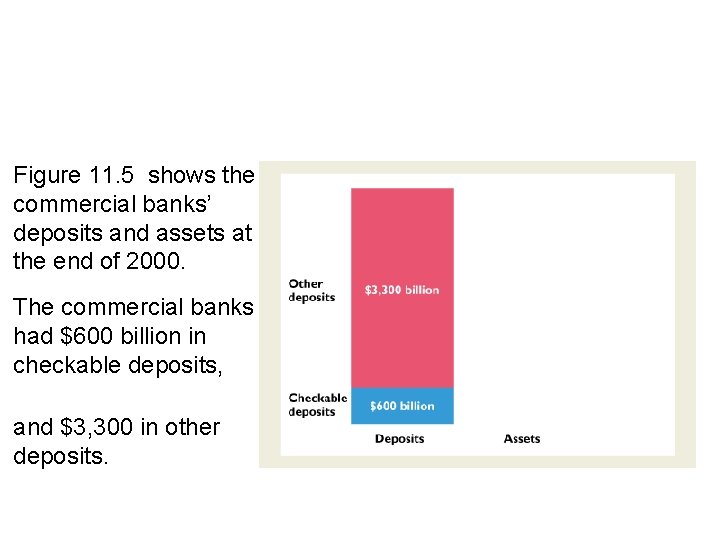

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM Bank Deposits and Assets: The Relative Magnitudes Checking deposits at commercial banks in the United States, included in M 1, are about 15 percent of total deposits. The other 85 percent of deposits are savings deposits and time deposits, which are part of M 2.

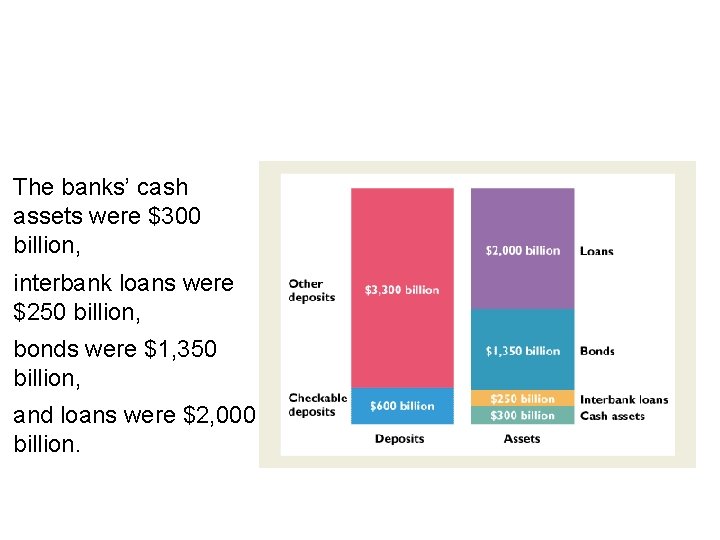

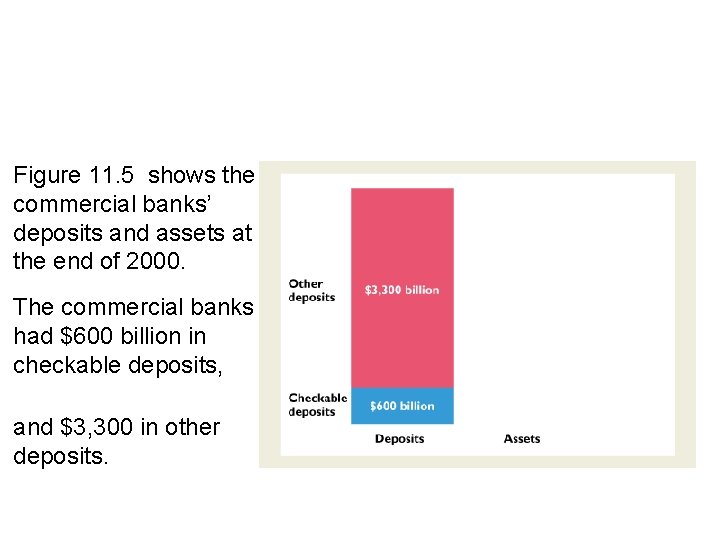

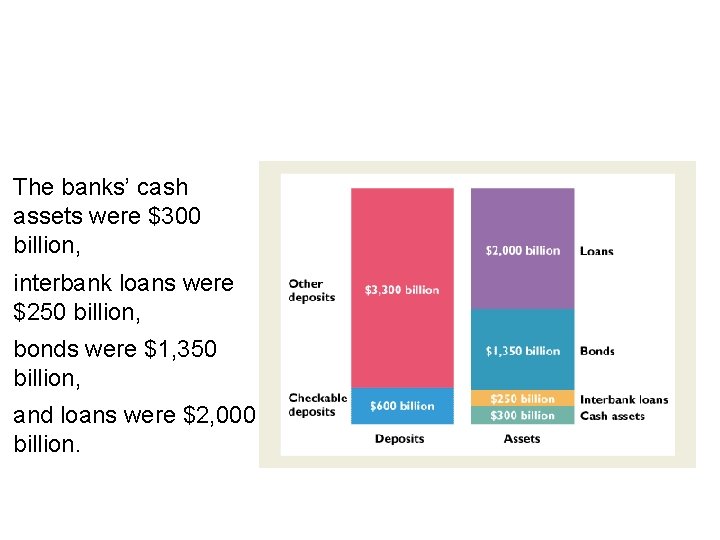

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM Figure 11. 5 shows the commercial banks’ deposits and assets at the end of 2000. The commercial banks had $600 billion in checkable deposits, and $3, 300 in other deposits.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM The banks’ cash assets were $300 billion, interbank loans were $250 billion, bonds were $1, 350 billion, and loans were $2, 000 billion.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM <Thrift Institutions A savings and loan association (S&L) is a financial institution that accepts checkable deposits and savings deposits and that makes personal, commercial, and home-purchase loans. A savings bank is a financial institution that accepts savings deposits and makes mostly consumer and home-purchase loans.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM A credit union is a financial institution owned by a social or economic group, such as a firm’s employees, that accepts savings deposits and makes mostly consumer loans. The total deposits of thrift institutions in January 2001 were $900 billion. Of these deposits, $100 billion were checkable deposits in M 1 and the rest were savings deposits and time deposits in M 2.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM <Money Market Funds A money market fund is a financial institution [mutual fund] that obtains funds by selling shares and uses these funds to buy assets such as U. S. Treasury bills. Money market fund shares act like bank deposits. Shareholders can write checks on their money market fund accounts to at least some extent. There are restrictions on most of these accounts [e. g. minimum size of check, number of checks allowed per month].

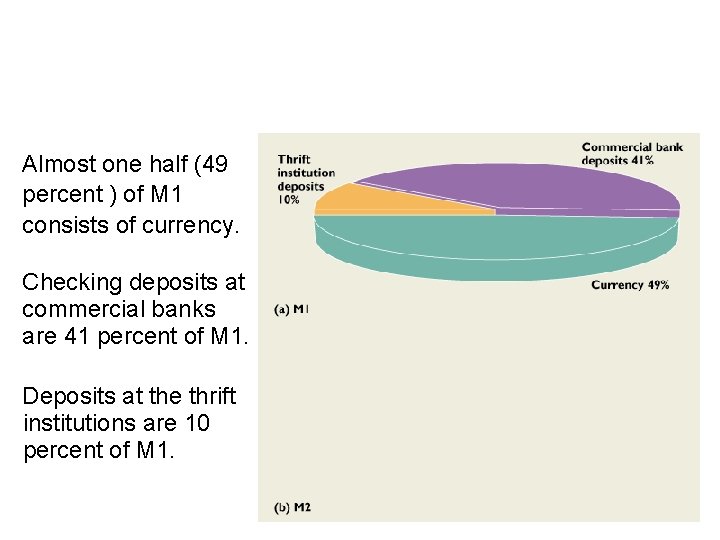

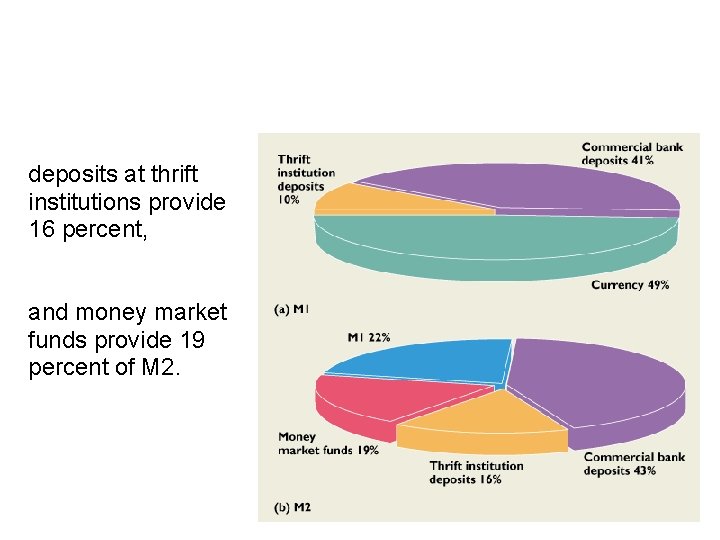

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM <Relative Size of Monetary Institutions Commercial banks provide most of the nation’s bank deposits. Figure 11. 6 shows the deposits behind M 1 and M 2

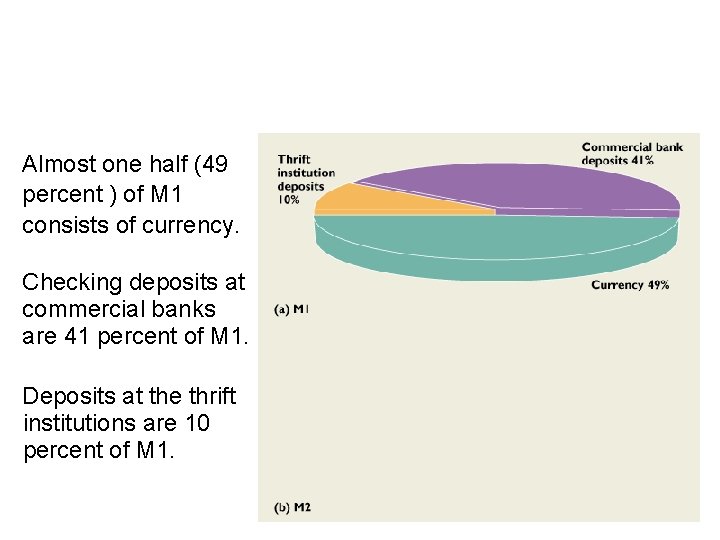

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM Almost one half (49 percent ) of M 1 consists of currency. Checking deposits at commercial banks are 41 percent of M 1. Deposits at the thrift institutions are 10 percent of M 1.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM M 1 is 22 percent of M 2. Savings deposits and time deposits at commercial banks are another 43 percent of M 2.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM deposits at thrift institutions provide 16 percent, and money market funds provide 19 percent of M 2.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM <The Economic Functions of Monetary Institutions The institutions of the monetary system earn their incomes by performing functions that people value and are willing to pay for. The four most important from our point of view are: • Create Liquidity • Lower the cost of lending and borrowing • Pool risks • Make payments

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM Create Liquidity A liquid asset is an asset that can be easily, and with certainty, converted into money. A bank creates liquid assets by borrowing short and lending long. • Borrowing short means accepting deposits and standing ready to repay them whenever the depositor requests the funds. • Lending long means making loan commitments for a longer term than the borrowing that is financing them.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM Lower Costs Banks lower the cost of lending and borrowing. • People with funds to lend can easily find the type of bank deposit that matches their plans. • People who want to borrow can do so by using the facilities offered by banks. Banks profit because people are willing to make deposits at lower interest rates than the interest rates that the banks can earn on their loans – the difference is known as the ‘interest spread’.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM Pool Risk • By lending to a large number of businesses and individuals, a bank lowers the average risk it faces. • The interest rate on a bank loan is set to ensure that the amount earned on the loans that do get repaid is sufficiently high to pay for ones that don’t get repaid. • This means that for depositors, who are providing the funds loaned, their deposits are close to riskless [and in any case are insured by FDIC, so are riskless], even though the individual loans the bank makes are each risky.

11. 2 THE MONETARY SYSTEM Make Payments • The check-clearing system – The main mechanism provided by the banks. – The banks collect a fee for each check that they clear. • The credit card payments system – The banks collect a fee for every credit card transaction.

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM <The Federal Reserve System is the central bank of the United States. A central bank is a ‘bank for bankers, ’ that provides banking services to banks and regulates financial institutions and markets. Usually a central bank has some formal relationship with its country’s government, although in day-to-day policy terms it may be independent of the government of the day. The Fed conducts the nation’s monetary policy, which means that it adjusts its policy, and thereby the quantity of money in the economy, as it thinks appropriate.

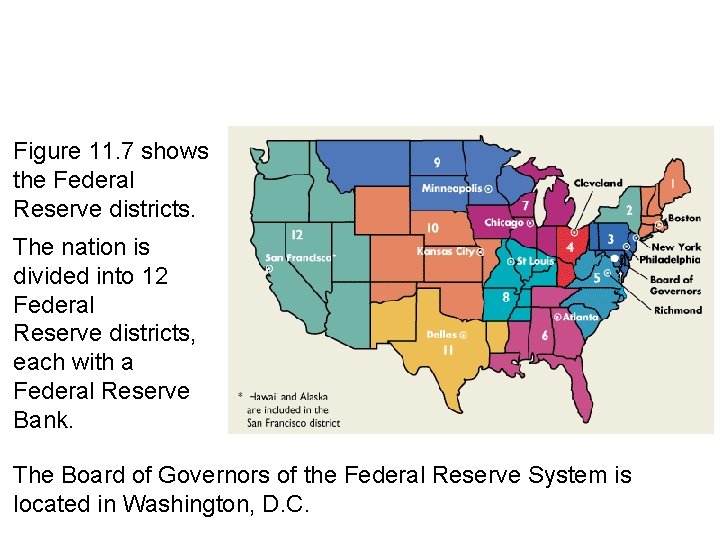

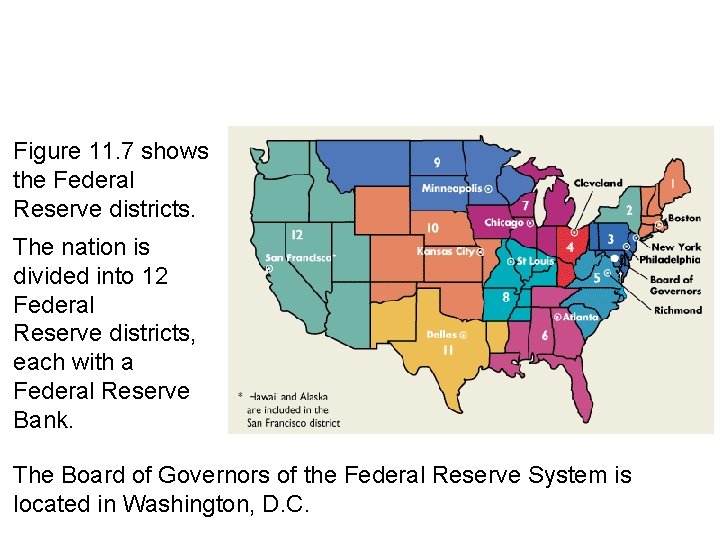

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Figure 11. 7 shows the Federal Reserve districts. The nation is divided into 12 Federal Reserve districts, each with a Federal Reserve Bank. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is located in Washington, D. C.

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM <The Structure of the Federal Reserve System The key elements in the structure of the Federal Reserve are: • The Board of Governors • The Regional Federal Reserve Banks • The Federal Open Market Committee

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM The Board of Governors • Seven members. • Appointed by the President of the United States and confirmed by the Senate. • Each for a 14 -year term. • The President appoints one of the board members as Chairman for a term of four years, which is renewable.

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM The Regional Federal Reserve Banks • There are 12 Federal Reserve banks. • One for each of 12 Federal Reserve districts. • Each Federal Reserve Bank has nine directors, three of whom are appointed by the Board of Governors and six of whom are elected by the commercial banks in the Federal Reserve district. • The Federal Reserve Bank of New York implements the Fed’s most important policy decisions.

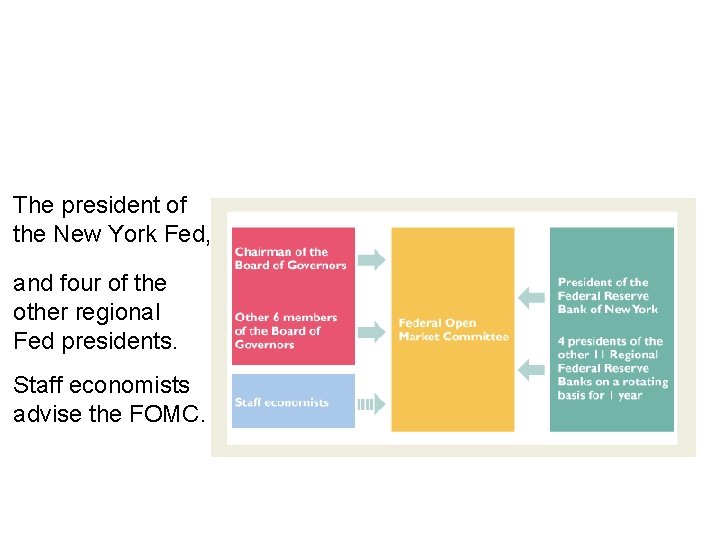

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is the Fed’s main policy-making committee. The FOMC consists of • The chairman and other six members of the Board of Governors. • The president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. • Four presidents of the other regional Federal Reserve banks (on a yearly rotating basis). The FOMC meets approximately every six weeks.

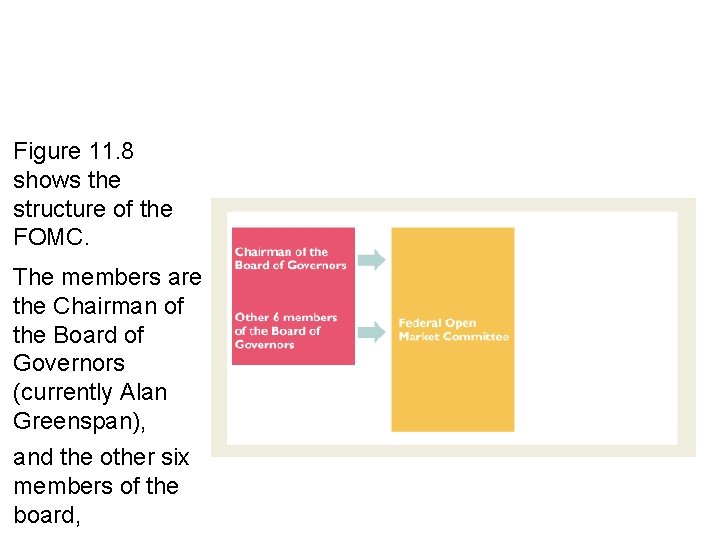

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Figure 11. 8 shows the structure of the FOMC. The members are the Chairman of the Board of Governors (currently Alan Greenspan), and the other six members of the board,

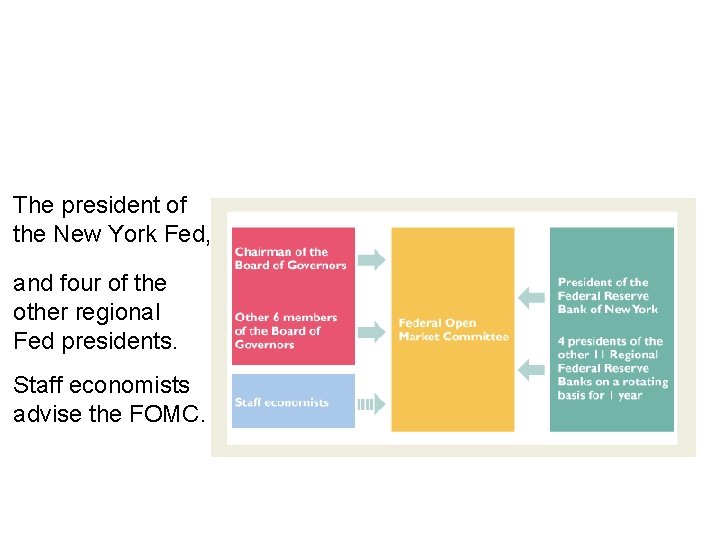

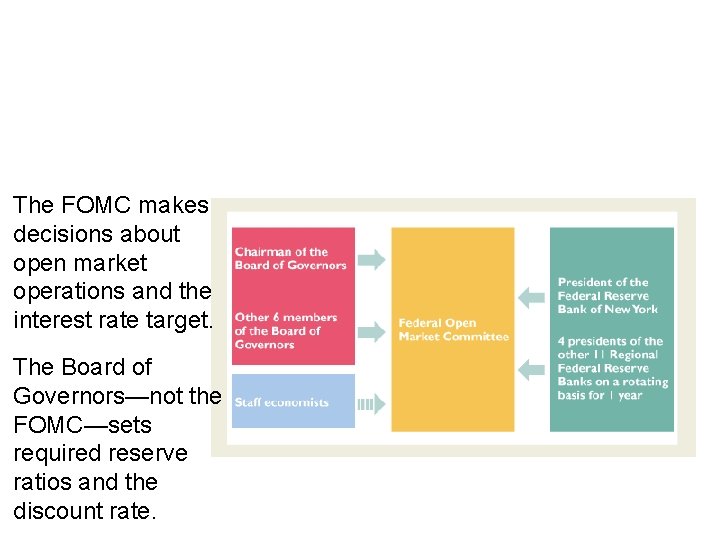

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM The president of the New York Fed, and four of the other regional Fed presidents. Staff economists advise the FOMC.

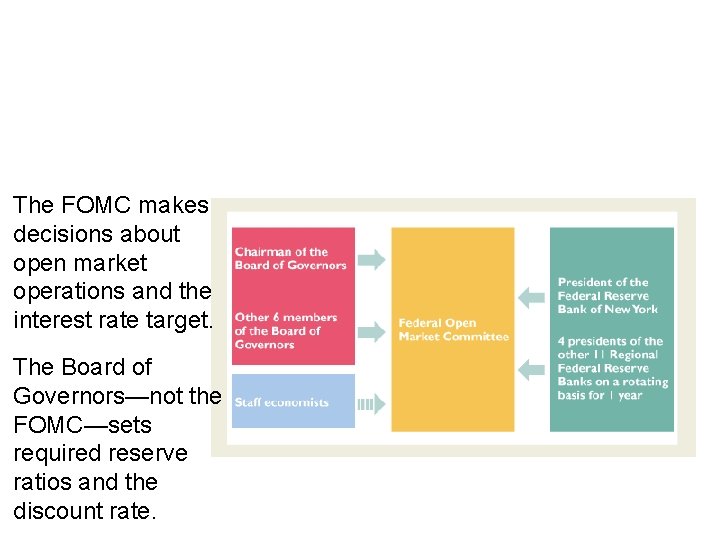

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM The FOMC makes decisions about open market operations and the interest rate target. The Board of Governors—not the FOMC—sets required reserve ratios and the discount rate.

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM <The Fed’s Power Center The chairman of the Board of Governors has the largest influence on the Fed’s monetary policy. The current chairman is Alan Greenspan: • Appointed by President Reagan in 1987. • Reappointed for a second term by President Bush in 1992. • Reappointed for a third term by President Clinton in 1996. • Reappointed for a fourth term by President Clinton in 2000.

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM The chairman’s power and influence stem from three sources: • Controls the agenda and dominates the FOMC meeting • Has day-to-day contact with staff of economists • Is the spokesperson for the Fed

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM <The Fed’s Policy Tools The Fed has three main policy tools, in theory, although as we will see only one really matters: • Required reserve ratios • Discount rate • Open market operations

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Required Reserve Ratios Banks hold reserves. These reserves are: • Currency in the institutions vaults and ATMs • Deposits held with other banks or with the Fed itself. Banks and thrifts are required to hold a minimum percentage of deposits as reserves, a required reserve ratio. If the required reserve ratio is 10%, for every $10 of deposits the banks must have $1 of reserves. This also means that for each $1 of reserves they have, they could have up to $10 of deposits.

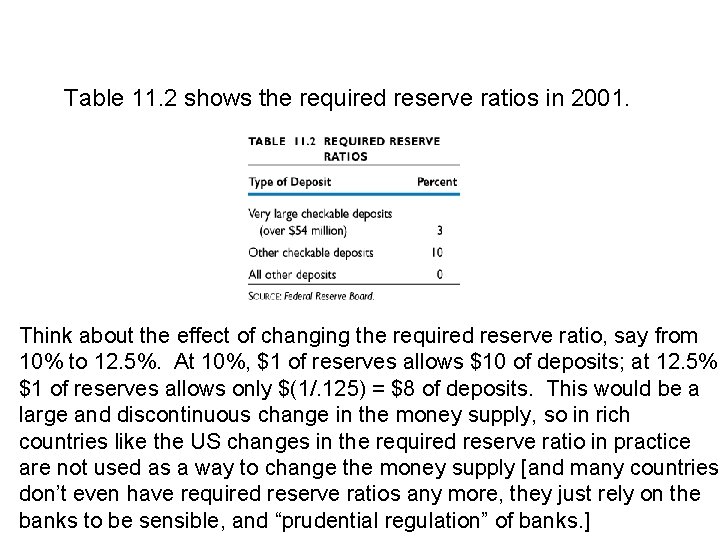

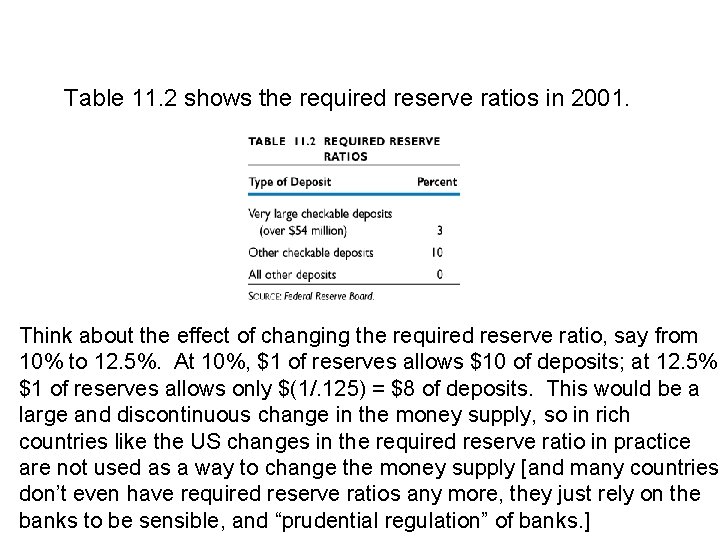

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Table 11. 2 shows the required reserve ratios in 2001. Think about the effect of changing the required reserve ratio, say from 10% to 12. 5%. At 10%, $1 of reserves allows $10 of deposits; at 12. 5%, $1 of reserves allows only $(1/. 125) = $8 of deposits. This would be a large and discontinuous change in the money supply, so in rich countries like the US changes in the required reserve ratio in practice are not used as a way to change the money supply [and many countries don’t even have required reserve ratios any more, they just rely on the banks to be sensible, and “prudential regulation” of banks. ]

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Discount Rate The interest rate at which the Fed stands ready to lend reserves to commercial banks. A change in the discount rate begins with a proposal to the FOMC by at least one of the 12 Federal Reserve banks. If the FOMC agrees that a change is required, it proposes the change to the Board of Governors for its approval. However, in practice, banks don’t usually borrow from the Fed, so the discount rate acts as a signal but has no practical effect on the money supply. The interest rate on some loans is contractually linked to the discount rate, and the target federal funds rate is usually 0. 5% higher than the discount rate.

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Open Market Operations • The purchase or sale of government securities by the Federal Reserve in the open market. • [The Fed is forbidden from buying securities directly from the federal government. ] When the Fed buys securities, it pays with a check drawn on itself. This increases the deposits with the Fed of the commercial bank through which the check reaches the Fed, and thereby increases the reserves available to the banking system. With more reserves, more deposits are supportable, and excess reserves will be lent out, creating more deposits. When the Fed sells securities, it destroys reserves.

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM <The Monetary Base The monetary base is the sum of coins, Federal Reserve bills, and banks’ reserves at the Fed. The monetary base is so called because it acts like a base that supports the nation’s money. The larger the monetary base, the greater is the quantity of money that it can support. Except for the coins [issued by the Treasury], our monetary base consists entirely of I. O. U. ’s from the Fed, so the Fed can enlarge or reduce it as it wants.

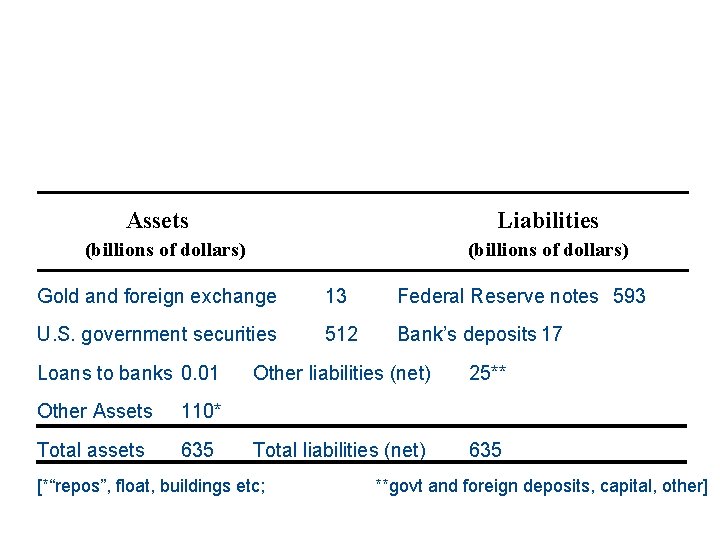

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Federal reserve bills and banks’ deposits at the Fed are liabilities of the Fed, and the Fed’s assets back these liabilities. The Fed’s assets are what it owns, and the Fed’s liabilities are what it owes. The Fed’s three main assets are: • Gold and foreign exchange • U. S. government securities • Loans to banks Securities are most of the assets, and loans to banks are negligible in amount.

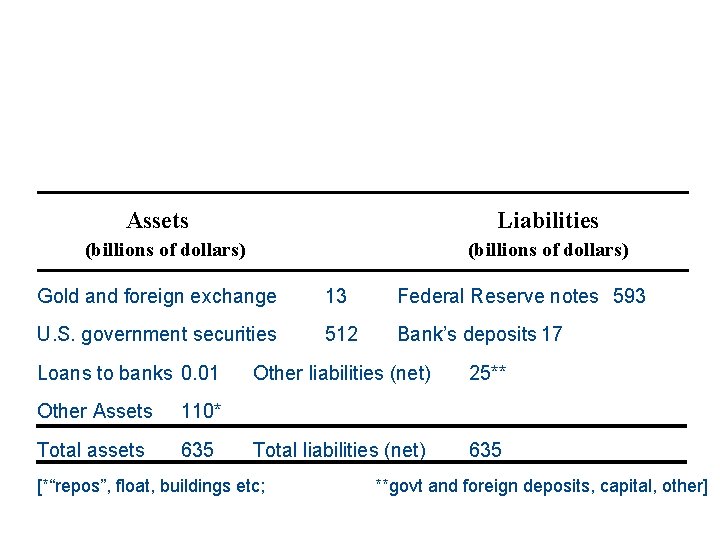

The Fed’s Balance Sheet, 3 January 2001 Assets Liabilities (billions of dollars) Gold and foreign exchange 13 Federal Reserve notes 593 U. S. government securities 512 Bank’s deposits 17 Loans to banks 0. 01 Other Assets 110* Total assets 635 Other liabilities (net) 25** Total liabilities (net) 635 [*“repos”, float, buildings etc; **govt and foreign deposits, capital, other]

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Figure 11. 9 shows the monetary base and its composition. The monetary base is the sum of banks’ deposits at the Fed, coins, and Federal Reserve notes (bills). Most of the monetary base consists of Federal Reserve notes.

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Why Are Dollar Bills a Liability of the Fed? When bank notes were invented, they gave their owner a claim on the gold reserves of the issuing bank. When a bank issued a note, it was holding itself liable to convert the note into gold or silver. Modern bank notes are nonconvertible. A nonconvertible note is not convertible into any commodity and obtains its value by government fiat—hence the term fiat money. Federal Reserve bills are backed by the Fed’s holdings of U. S. government securities.

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM <How The Fed’s Policy Tools Work: A Quick First Look By increasing the required reserve ratio, the Fed could force the banks to hold a larger quantity of monetary base. By raising the discount rate, the Fed can make it more costly for the banks to borrow reserves—borrow monetary base. By selling securities in the open market, the Fed can decrease the monetary base. This is how the Fed actually implements monetary policy, and gets close to its announced target Federal Funds Rate.

11. 3 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM By decreasing the required reserve ratio, the Fed could permit the banks to hold a smaller quantity of monetary base. By lowering the discount rate, the Fed can make it less costly for the banks to borrow monetary base. By buying securities in the open market, the Fed can increase the monetary base. Again, this is how the Fed actually implements its monetary policy, and gets close to its announced target Federal Funds Rate.

Private Electronic Money

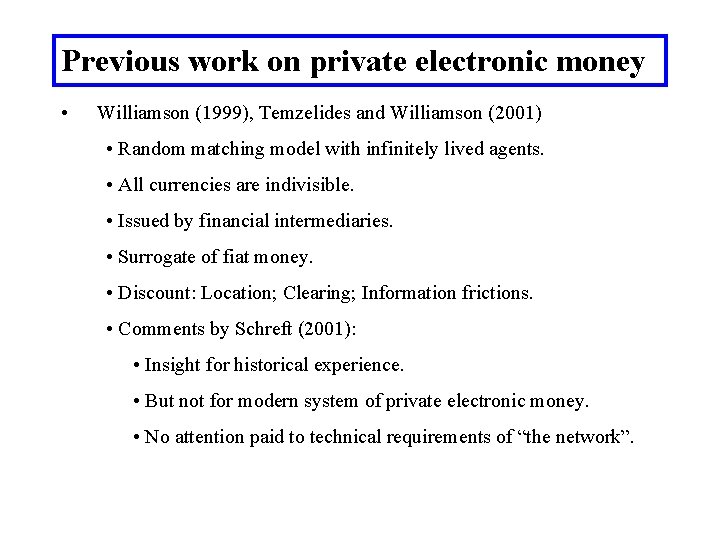

Previous work on private electronic money • Williamson (1999), Temzelides and Williamson (2001) • Random matching model with infinitely lived agents. • All currencies are indivisible. • Issued by financial intermediaries. • Surrogate of fiat money. • Discount: Location; Clearing; Information frictions. • Comments by Schreft (2001): • Insight for historical experience. • But not for modern system of private electronic money. • No attention paid to technical requirements of “the network”.

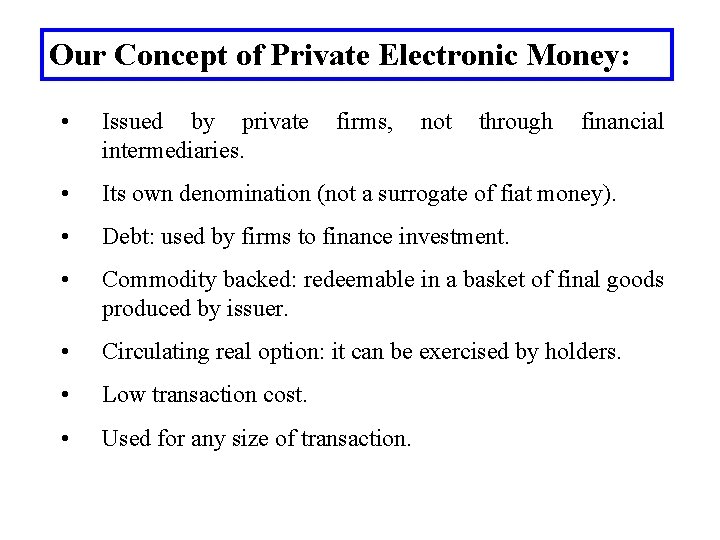

Our Concept of Private Electronic Money: • Issued by private intermediaries. • Its own denomination (not a surrogate of fiat money). • Debt: used by firms to finance investment. • Commodity backed: redeemable in a basket of final goods produced by issuer. • Circulating real option: it can be exercised by holders. • Low transaction cost. • Used for any size of transaction. firms, not through financial

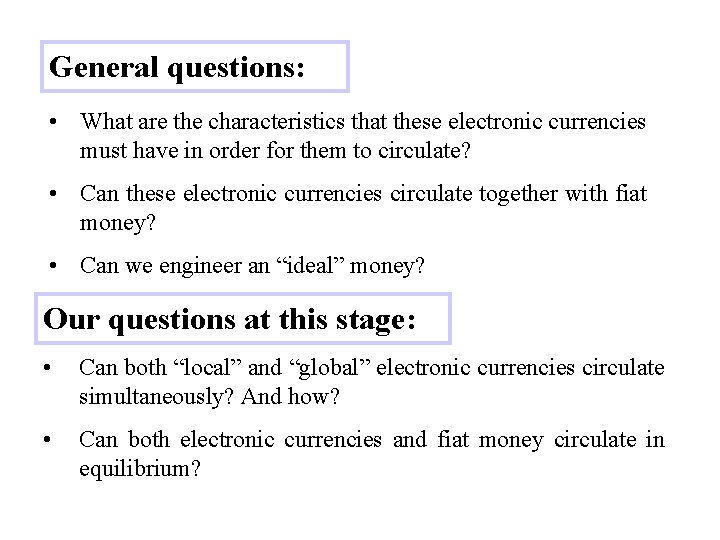

General questions: • What are the characteristics that these electronic currencies must have in order for them to circulate? • Can these electronic currencies circulate together with fiat money? • Can we engineer an “ideal” money? Our questions at this stage: • Can both “local” and “global” electronic currencies circulate simultaneously? And how? • Can both electronic currencies and fiat money circulate in equilibrium?

The Environment • Freeman (1996) payment system with Smith type of Diamond-Dybvig relocation. • Heterogeneous agents that are separated in two outer “networks. ” • Centralized network: clearing, contracts can be enforced. • Some agents face the possibility of future relocation. • Two private electronic currencies are issued: one being “local” and the other being “global”. • Taxes must be paid using fiat money.

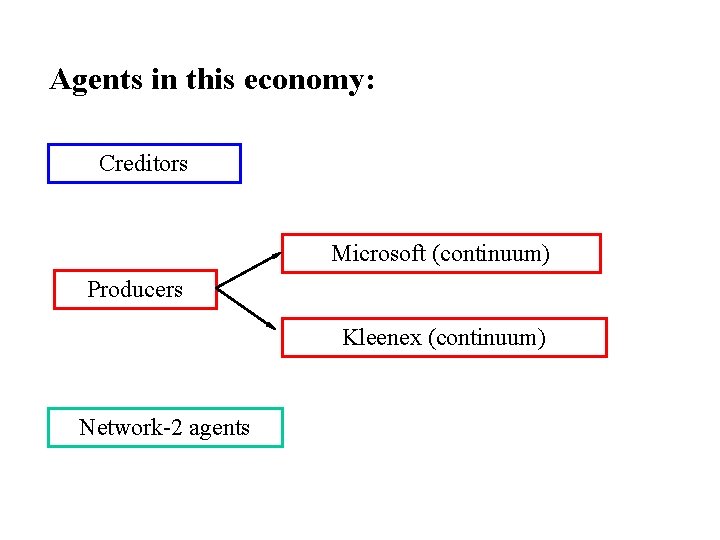

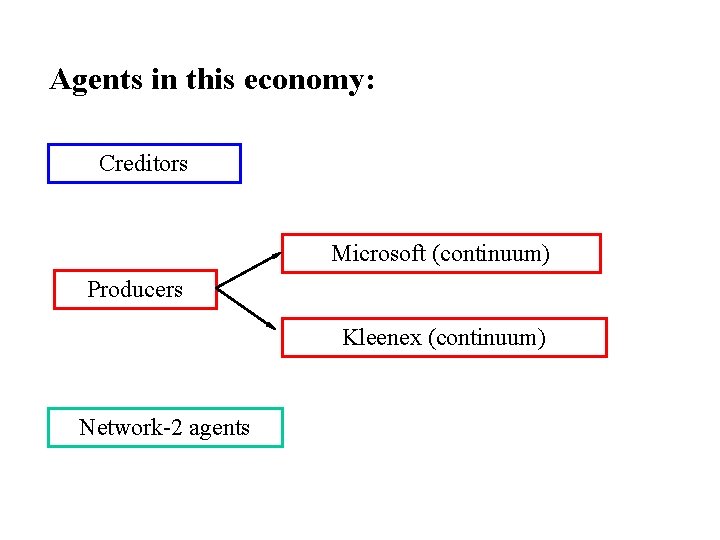

Agents in this economy: Creditors Microsoft (continuum) Producers Kleenex (continuum) Network-2 agents

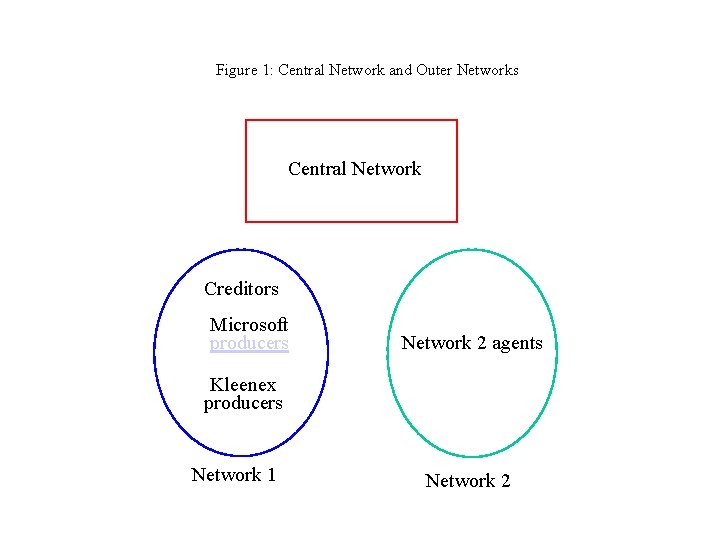

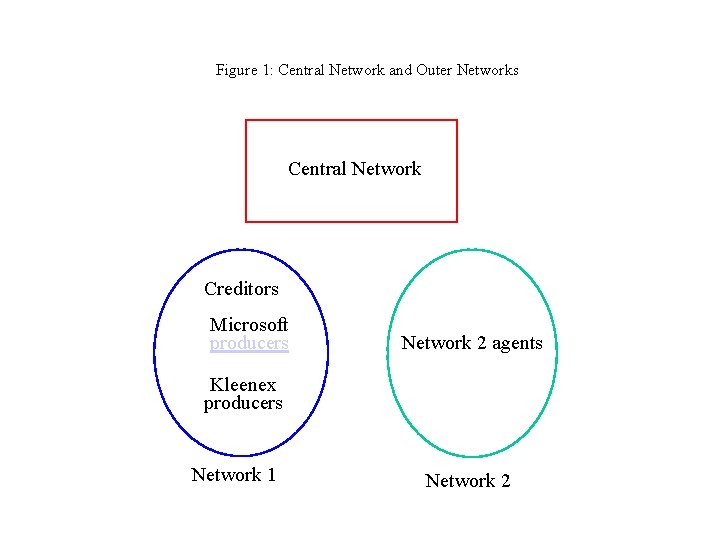

Figure 1: Central Network and Outer Networks Central Network Creditors Microsoft producers Network 2 agents Kleenex producers Network 1 Network 2

Trade and Travel Patterns < Each period has two parts. < First part of the period: In Network 1: Young creditors Young Microsoft producers Young creditors Young Kleenex producers Old creditors travel to the Central Network. In Central Network: Arrived old creditors pay tax using fiat money. They learn whether they must relocate to Network 2 or not. • If relocate, they sell Kleenex money for Microsoft money in the secondary market; travel to Network 2. • If not, they buy Kleenex money using Microsoft money; receive a transfer in fiat money from the monetary authority; travel back to Network 1. • i. e. Relocated old creditors Un-relocated old creditors

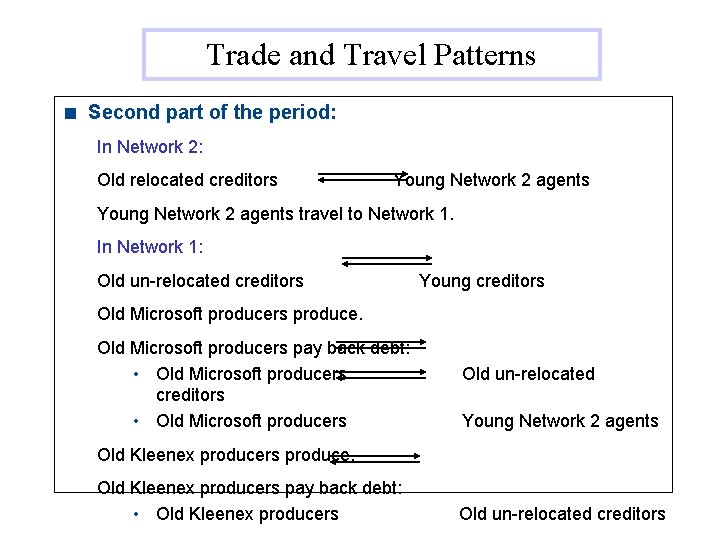

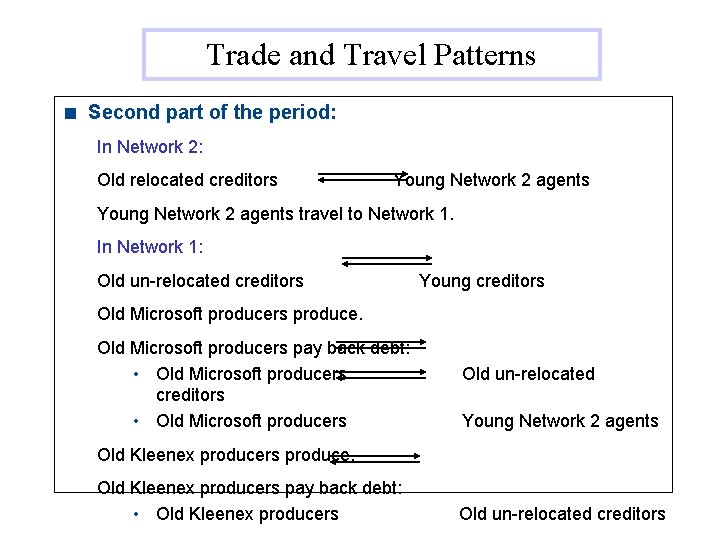

Trade and Travel Patterns < Second part of the period: In Network 2: Old relocated creditors Young Network 2 agents travel to Network 1. In Network 1: Old un-relocated creditors Young creditors Old Microsoft producers produce. Old Microsoft producers pay back debt: • Old Microsoft producers creditors • Old Microsoft producers Old un-relocated Young Network 2 agents Old Kleenex producers produce. Old Kleenex producers pay back debt: • Old Kleenex producers Old un-relocated creditors

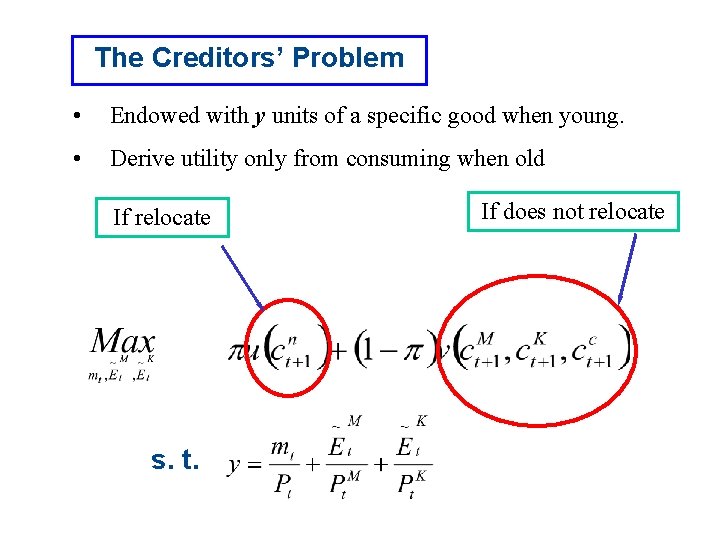

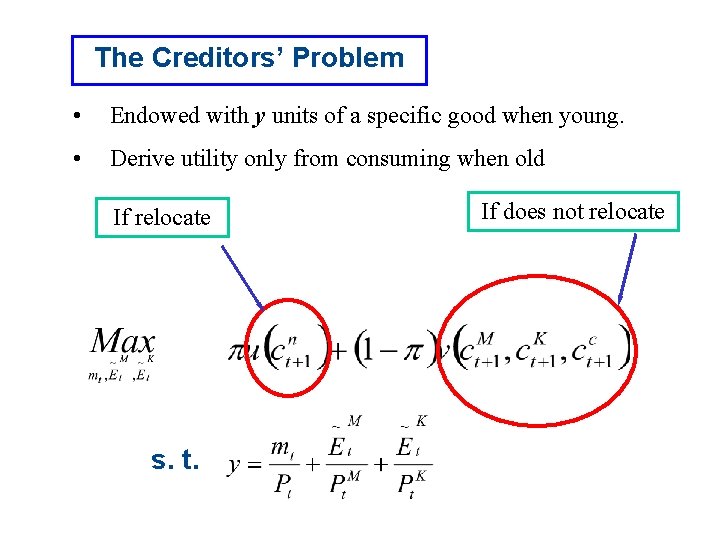

The Creditors’ Problem • Endowed with y units of a specific good when young. • Derive utility only from consuming when old If relocate s. t. If does not relocate

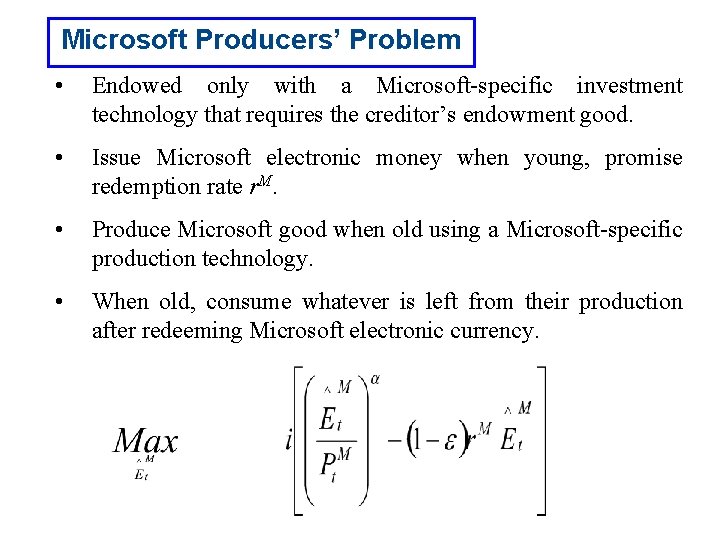

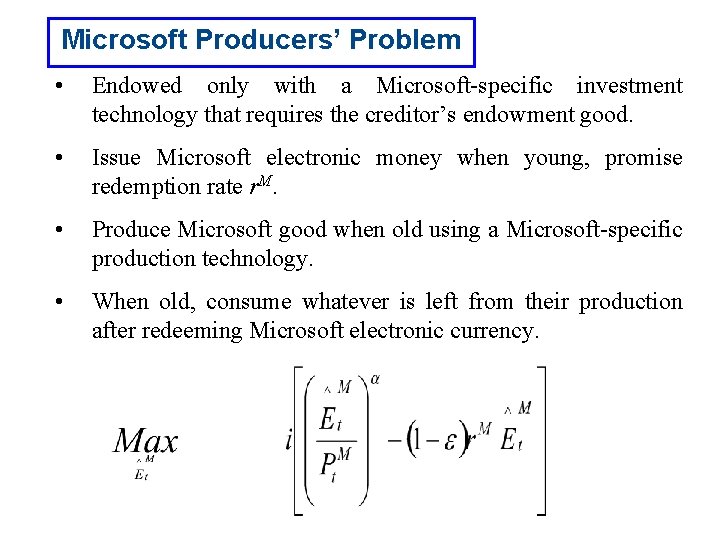

Microsoft Producers’ Problem • Endowed only with a Microsoft-specific investment technology that requires the creditor’s endowment good. • Issue Microsoft electronic money when young, promise redemption rate r. M. • Produce Microsoft good when old using a Microsoft-specific production technology. • When old, consume whatever is left from their production after redeeming Microsoft electronic currency.

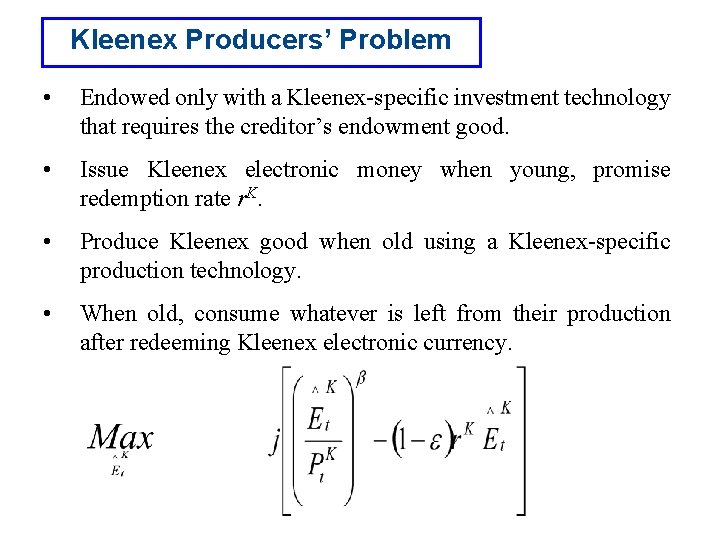

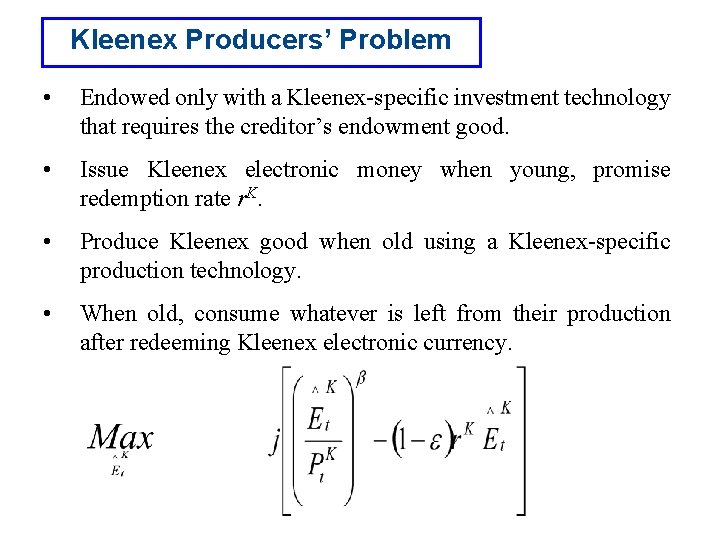

Kleenex Producers’ Problem • Endowed only with a Kleenex-specific investment technology that requires the creditor’s endowment good. • Issue Kleenex electronic money when young, promise redemption rate r. K. • Produce Kleenex good when old using a Kleenex-specific production technology. • When old, consume whatever is left from their production after redeeming Kleenex electronic currency.

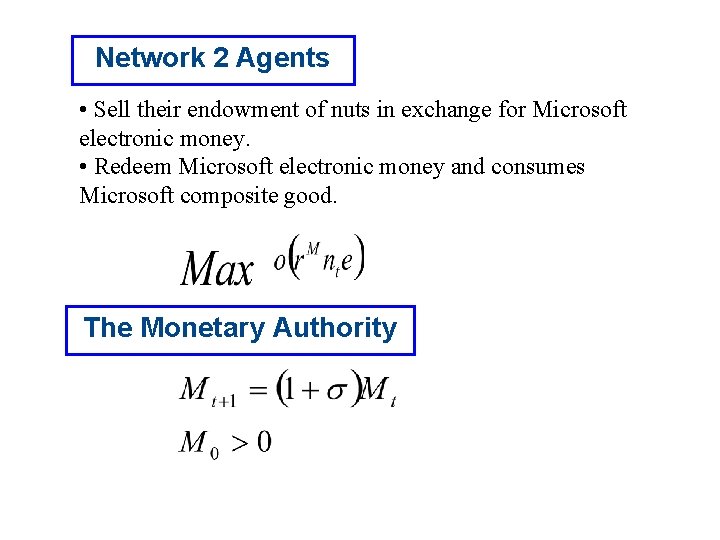

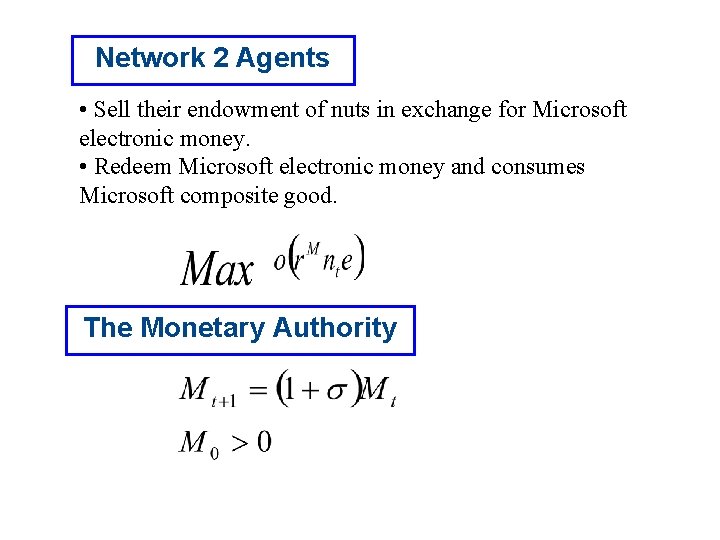

Network 2 Agents • Sell their endowment of nuts in exchange for Microsoft electronic money. • Redeem Microsoft electronic money and consumes Microsoft composite good. The Monetary Authority

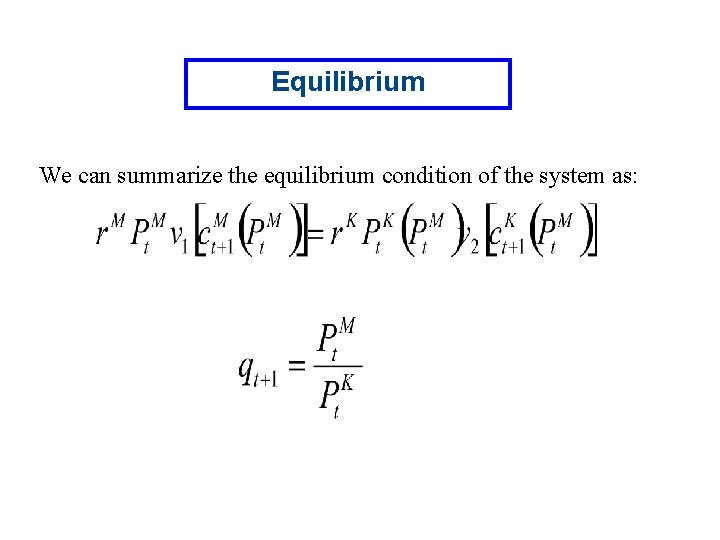

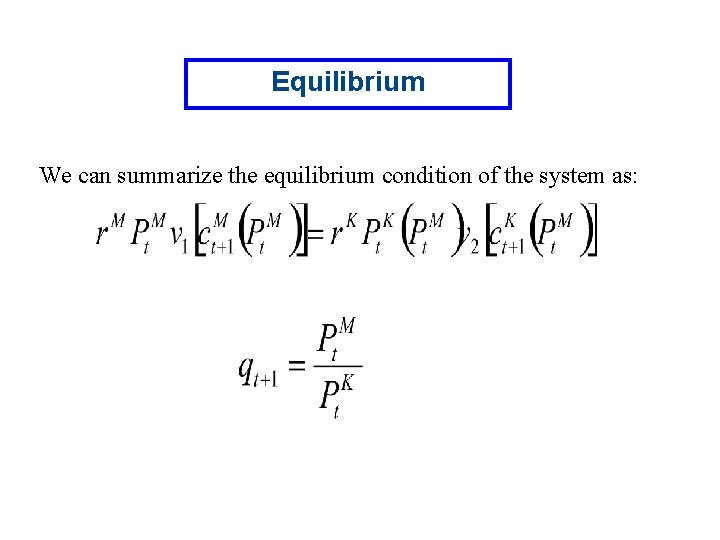

Equilibrium We can summarize the equilibrium condition of the system as:

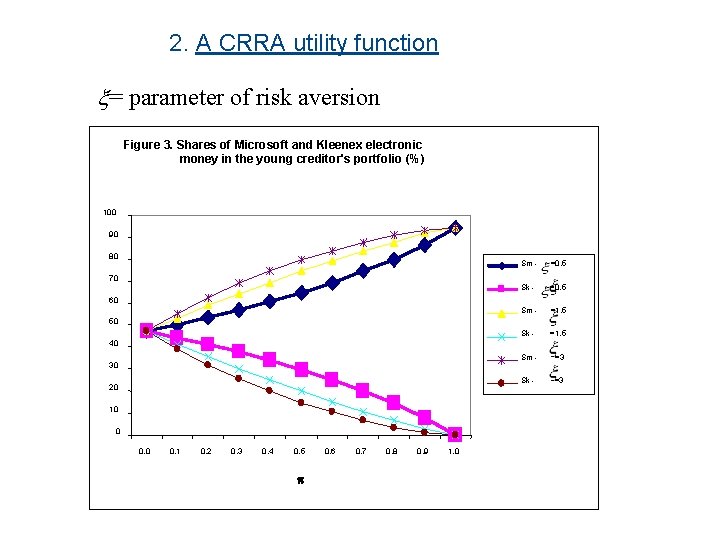

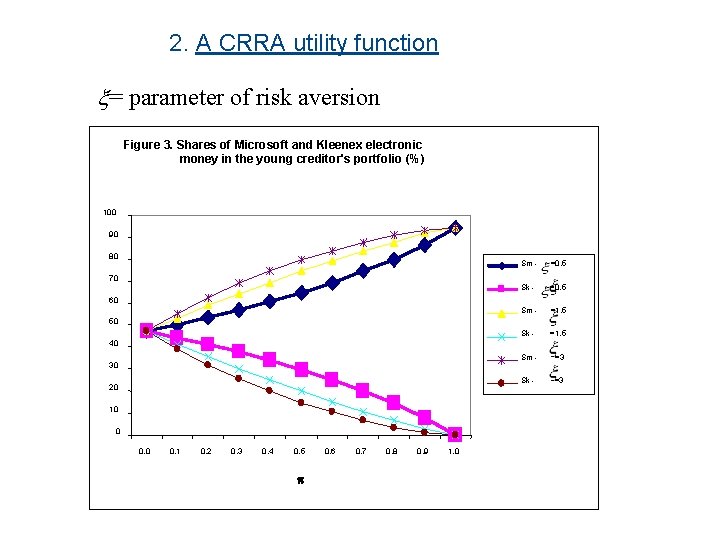

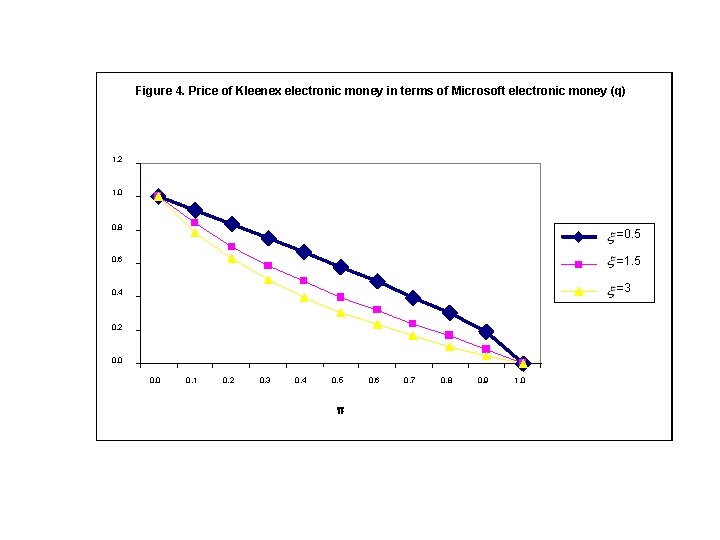

Numerical Examples In order to show existence and some equilibrium properties, we provide the results of 2 numerical examples 1. Loglinear utility 2. CRRA utility In both cases: • q is decreasing in the probability of relocation • Sm is increasing in the probability of relocation • Sk is decreasing in the probability of relocation

1. A Loglinear Utility Function

2. A CRRA utility function = parameter of risk aversion Figure 3. Shares of Microsoft and Kleenex electronic money in the young creditor's portfolio (%) 100 90 80 70 Sm - =0. 5 Sk - =0. 5 Sm - =1. 5 Sk - =1. 5 Sm - =3 Sk - =3 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0. 1 0. 2 0. 3 0. 4 0. 5 p 0. 6 0. 7 0. 8 0. 9 1. 0

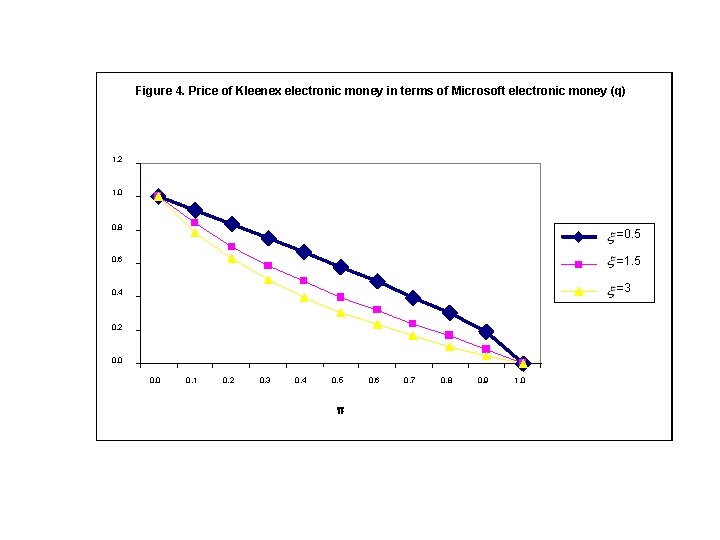

Figure 4. Price of Kleenex electronic money in terms of Microsoft electronic money (q) 1. 2 1. 0 0. 8 =0. 5 0. 6 =1. 5 0. 4 =3 0. 2 0. 0 0. 1 0. 2 0. 3 0. 4 0. 5 p 0. 6 0. 7 0. 8 0. 9 1. 0

Conclusions < Both “local” and “global” electronic currencies circulate in equilibrium along with fiat money. < Depending on several factors, local electronic currency can be sold with a premium or discount. < Monetary authority’s role in clearing and supervising Secondary market for electronic currencies proves to be welfare improving.

Extensions < Introduce default risk in the redemption of electronic money. < Add X-men: introduce privacy and anonymity as new transactional advantage of electronic currencies.

Money money money team

Money money money team Unit 4 money banking and monetary policy

Unit 4 money banking and monetary policy Unit 4 money and monetary policy

Unit 4 money and monetary policy Loanable funds graph recession

Loanable funds graph recession Unit 4 money and monetary policy

Unit 4 money and monetary policy Expansionary monetary policy aggregate demand

Expansionary monetary policy aggregate demand Unit 4 money and monetary policy

Unit 4 money and monetary policy Unit 4 money banking and monetary policy

Unit 4 money banking and monetary policy Monetary base ap macro

Monetary base ap macro 01:640:244 lecture notes - lecture 15: plat, idah, farad

01:640:244 lecture notes - lecture 15: plat, idah, farad Lecture about money

Lecture about money Money on money multiple

Money on money multiple The great gatsby historical context

The great gatsby historical context Great gatsby meaning

Great gatsby meaning Old money

Old money Money smart money match

Money smart money match đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ

đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Mật thư tọa độ 5x5

Mật thư tọa độ 5x5 ưu thế lai là gì

ưu thế lai là gì Thẻ vin

Thẻ vin Thang điểm glasgow

Thang điểm glasgow Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Cái miệng nó xinh thế

Cái miệng nó xinh thế Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu

Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Bổ thể

Bổ thể Thứ tự các dấu thăng giáng ở hóa biểu

Thứ tự các dấu thăng giáng ở hóa biểu Thể thơ truyền thống

Thể thơ truyền thống Làm thế nào để 102-1=99

Làm thế nào để 102-1=99 Sự nuôi và dạy con của hổ

Sự nuôi và dạy con của hổ đại từ thay thế

đại từ thay thế Hát lên người ơi alleluia

Hát lên người ơi alleluia Diễn thế sinh thái là

Diễn thế sinh thái là Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau Thế nào là mạng điện lắp đặt kiểu nổi

Thế nào là mạng điện lắp đặt kiểu nổi Công thức tính thế năng

Công thức tính thế năng Lời thề hippocrates

Lời thề hippocrates Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể

Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra

Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra Sự nuôi và dạy con của hổ

Sự nuôi và dạy con của hổ điện thế nghỉ

điện thế nghỉ Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng từ đua

Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng từ đua Các loại đột biến cấu trúc nhiễm sắc thể

Các loại đột biến cấu trúc nhiễm sắc thể Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ

Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay

Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay Phản ứng thế ankan

Phản ứng thế ankan Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ

Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan

Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào

Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào Một số thể thơ truyền thống

Một số thể thơ truyền thống Hệ hô hấp

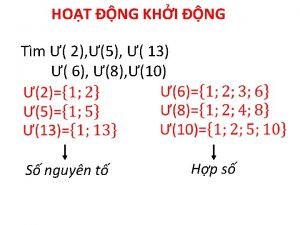

Hệ hô hấp Các số nguyên tố

Các số nguyên tố Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất West african monetary institute

West african monetary institute International monetary fund

International monetary fund What are the objectives of monetary policy

What are the objectives of monetary policy Sama exchange rate

Sama exchange rate International monetary system

International monetary system Non-monetary rewards

Non-monetary rewards Monetary transmission mechanism

Monetary transmission mechanism Monetary award program illinois

Monetary award program illinois Monetary policy baseline

Monetary policy baseline Chapter 29 the monetary system answers

Chapter 29 the monetary system answers Monetary assest

Monetary assest Contractionary money policy

Contractionary money policy Meaning of monetary

Meaning of monetary International monetary fund

International monetary fund Moral suasion bsp

Moral suasion bsp Objectives of international monetary system

Objectives of international monetary system Monetary policy simulation game

Monetary policy simulation game Monetary

Monetary What are the objectives of monetary policy

What are the objectives of monetary policy Monetary model

Monetary model What is a monetary asset

What is a monetary asset Monetary model

Monetary model Monetary policy types

Monetary policy types Azure value proposition

Azure value proposition Money neutrality

Money neutrality How to calculate expected value with perfect information

How to calculate expected value with perfect information International monetary system

International monetary system To type

To type Lesson quiz 16-1 monetary policy

Lesson quiz 16-1 monetary policy International monetary system

International monetary system International monetary and financial environment

International monetary and financial environment Monetary system definition

Monetary system definition Policy tools

Policy tools Consolidation accounting

Consolidation accounting Ecb unconventional monetary policy

Ecb unconventional monetary policy Non monetary assets

Non monetary assets Instruments of monetary policy

Instruments of monetary policy