Week 1 Theoretical Inspirations Main Thesis of the

- Slides: 61

Week 1. Theoretical Inspirations

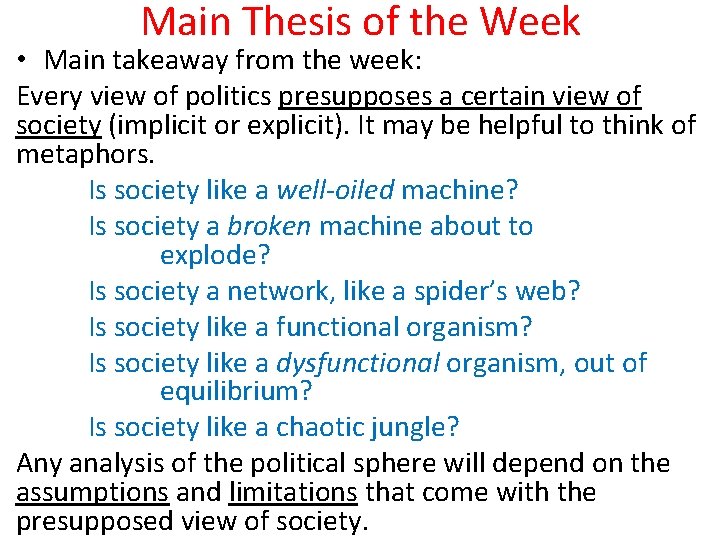

Main Thesis of the Week • Main takeaway from the week: Every view of politics presupposes a certain view of society (implicit or explicit). It may be helpful to think of metaphors. Is society like a well-oiled machine? Is society a broken machine about to explode? Is society a network, like a spider’s web? Is society like a functional organism? Is society like a dysfunctional organism, out of equilibrium? Is society like a chaotic jungle? Any analysis of the political sphere will depend on the assumptions and limitations that come with the presupposed view of society.

Change vs. Continuity One such assumption – perhaps the single most important one – about society is about its dynamism. Are we primarily interested in things changing? Or, are we primarily interested in things staying the same?

Conflict vs. Harmony Another such assumption is about social order. • Are we considering society as a harmonious, stable equilibrium? • Are we considering society as disorderly and crisis-ridden?

Society as Near-Exploding Machine • Division is inherent, making politics the center of any objective analysis. Any sociology, you might say, has to be political sociology. Typical passage: “In no period do we therefore find a more confused mixture of high-flown phrases and actual uncertainty and clumsiness, of more enthusiastic striving for innovation and more deeply rooted domination of the old routine, of more apparent harmony of the whole society and more profound estrangement of its elements” (p. 600).

Four General Views of Society Marxian: sees division, inequality, haves and have-nots, conflict, instability and perpetual change (often sudden, dramatic, violent). Weberian: sees tremendous complexity, contingency, subjectivity, variation (including between the predominance of politics vis-à-vis economics, culture, etc. ). Durkheimian: sees harmony, equilibrium, cohesion, consent, functionality, continuity, conservation, gradual evolutionary change. Simmelian: sees reciprocity, interaction, “sociation, ” networks, relational dyads and triads, interconnectedness.

Proper “Unit of Analysis” for Political Sociology • For Marx class (collectivist) Society is inherently divided, with individuals in different collectivities restricted by their position in the division. • For Weber individual (individualist) Society is nothing except the aggregate of individual subjectivities and their meaningful actions. • For Durkheim society as a whole (holist) The social whole is more than the sum of its parts. • For Simmel the interaction (interactionist) We must study neither individuals or collectivities in isolation; it is their relational interactions that are of interest.

No “true” political sociology The differences between approaches do not make some more “valid” or “true” than others in some abstract sense. They merely make some approaches more useful for some purposes than other approaches, which may be more useful for other purposes.

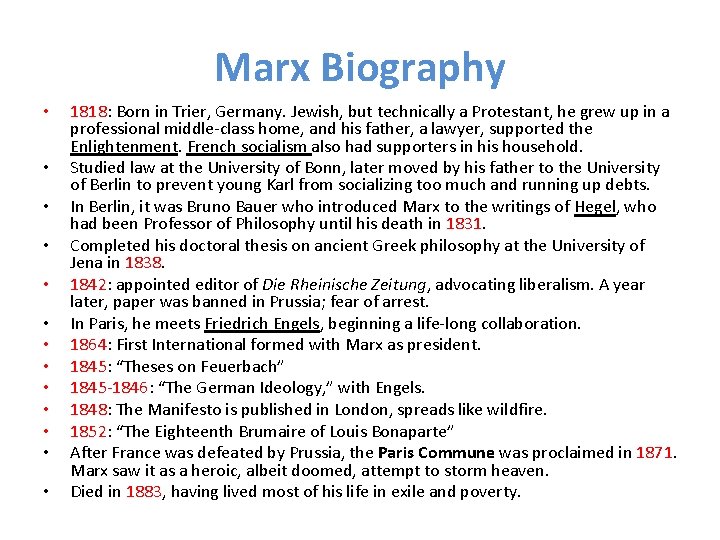

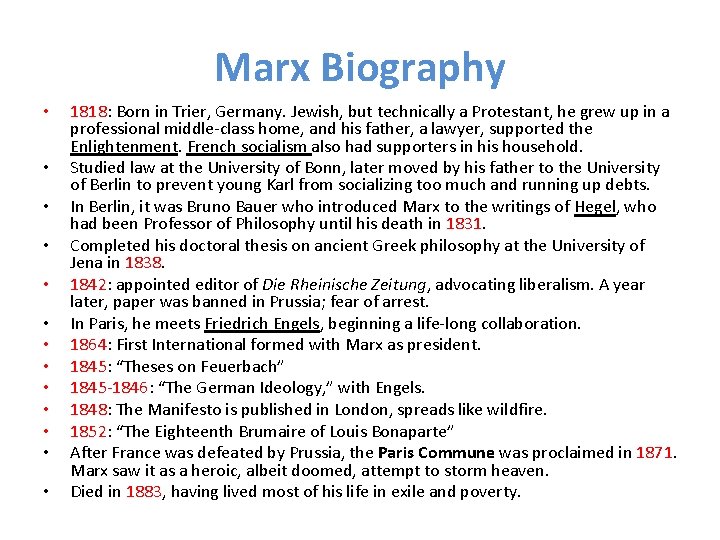

Marx Biography • • • • 1818: Born in Trier, Germany. Jewish, but technically a Protestant, he grew up in a professional middle-class home, and his father, a lawyer, supported the Enlightenment. French socialism also had supporters in his household. Studied law at the University of Bonn, later moved by his father to the University of Berlin to prevent young Karl from socializing too much and running up debts. In Berlin, it was Bruno Bauer who introduced Marx to the writings of Hegel, who had been Professor of Philosophy until his death in 1831. Completed his doctoral thesis on ancient Greek philosophy at the University of Jena in 1838. 1842: appointed editor of Die Rheinische Zeitung, advocating liberalism. A year later, paper was banned in Prussia; fear of arrest. In Paris, he meets Friedrich Engels, beginning a life-long collaboration. 1864: First International formed with Marx as president. 1845: “Theses on Feuerbach” 1845 -1846: “The German Ideology, ” with Engels. 1848: The Manifesto is published in London, spreads like wildfire. 1852: “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte” After France was defeated by Prussia, the Paris Commune was proclaimed in 1871. Marx saw it as a heroic, albeit doomed, attempt to storm heaven. Died in 1883, having lived most of his life in exile and poverty.

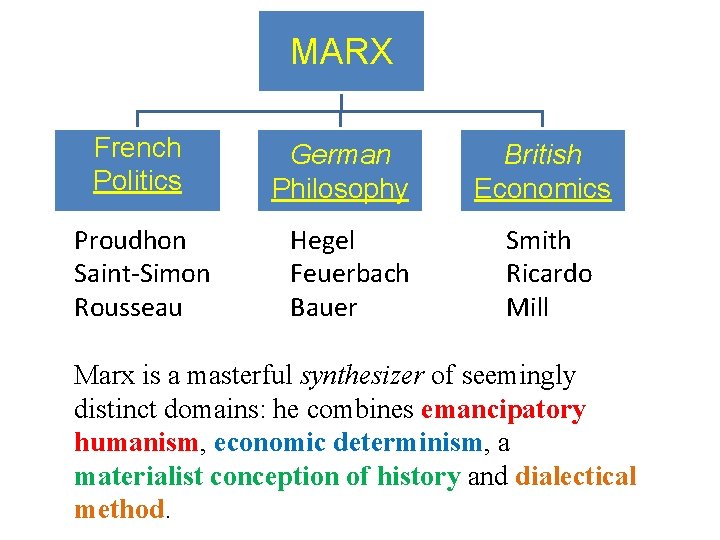

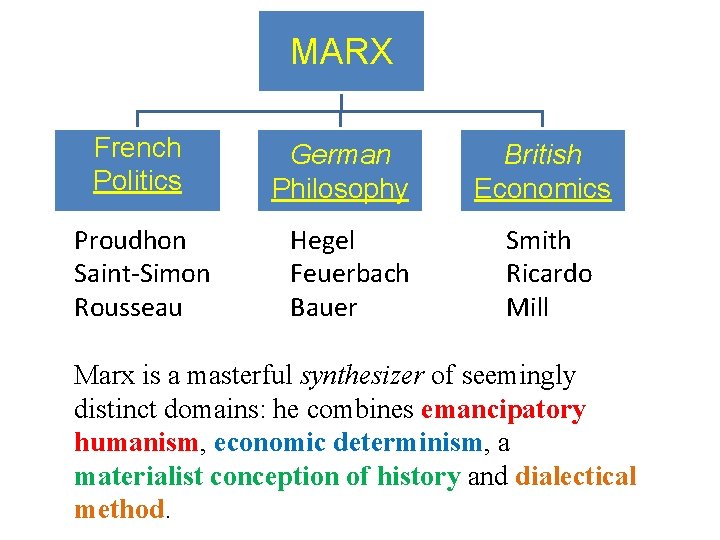

MARX French Politics Proudhon Saint-Simon Rousseau German Philosophy Hegel Feuerbach Bauer British Economics Smith Ricardo Mill Marx is a masterful synthesizer of seemingly distinct domains: he combines emancipatory humanism, economic determinism, a materialist conception of history and dialectical method.

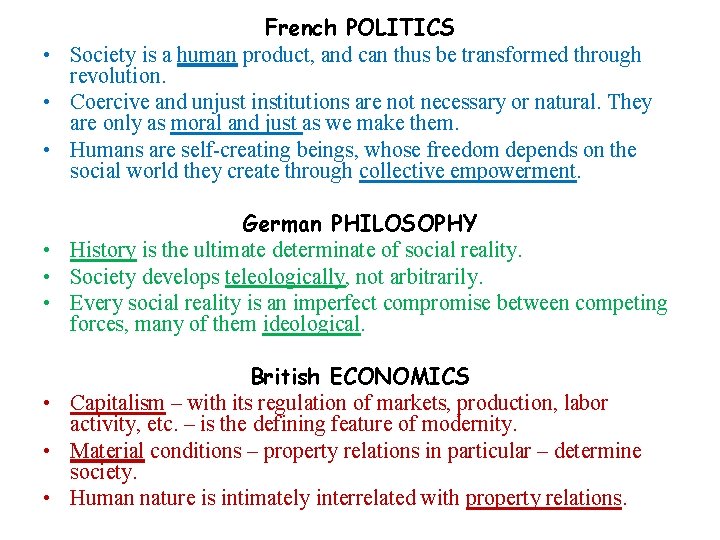

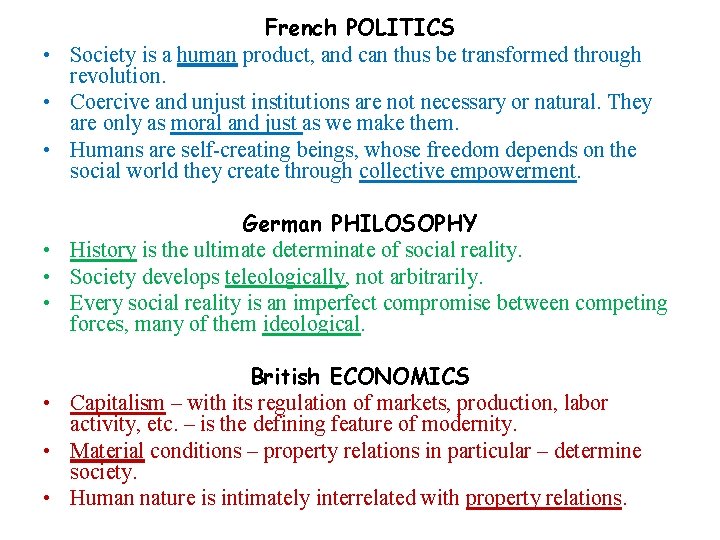

French POLITICS • Society is a human product, and can thus be transformed through revolution. • Coercive and unjust institutions are not necessary or natural. They are only as moral and just as we make them. • Humans are self-creating beings, whose freedom depends on the social world they create through collective empowerment. German PHILOSOPHY • History is the ultimate determinate of social reality. • Society develops teleologically, not arbitrarily. • Every social reality is an imperfect compromise between competing forces, many of them ideological. British ECONOMICS • Capitalism – with its regulation of markets, production, labor activity, etc. – is the defining feature of modernity. • Material conditions – property relations in particular – determine society. • Human nature is intimately interrelated with property relations.

Man, created and creator. Human beings are unique, in that they are created by the social world that they create. Hence, a major theme in Marx’s work was Alienation Entfremdung in German. Literally: estrangement

Class: A sector of society that shares a common relation to the means of production. In modern industrial societies, the bourgeoisie shares its ownership of the means of production, while the proletariat shares its lack of ownership over the means of production. The latter - the "lower" or "working" classes – are those that must sell their labor under capitalism in order to earn a living. Capitalism: A system in which the means of production are privately owned and used for profit. Relations of Production: The social structures that regulate the relation between humans in the production of goods. Means of Production: The tools and raw materials used to create a product.

Bottom Line: It’s all about economics • Economic determinism holds that politics is epiphenomenal. • Power comes from your economic position, i. e. your class.

Eighteenth Brumaire: The End of the French Revolution Main purpose: to rethink the French Revolution in terms of class. • Marx puts forth the idea of historical recapitulation whose main effect is to underscore the specificity of class formation at different moments in history. The comparison between the ascent to power of the first Napoleon and that of his nephew, says Marx, is tantamount to a transition from tragedy to farce. Marx recapitulates the phases of the French Revolution: • February Period: Overthrow of Louis Philippe. Prologue to the Revolution. Provisional government. Moment of transition. Classes in flux. The opposition to monarchical power organizes through the alliance of Orleanists (finance capital) and the proletariat. • May 4, 1848 – May 28, 1849: Constitution of the Republic or Constituent National Assembly. This period leads rapidly to the triumph and constitution of what Marx calls the “Bourgeois Republic” through the ousting of the legitimate representatives of the proletariat (Bianchi, most importantly). In Marx’s words, “Whereas [under Louis Philippe] a limited section of the bourgeoisie ruled in the name of the king, the whole of the bourgeoisie will now rule in the name of the people. • May 28, 1849 – December 2, 1851: Constitutional Republic or Legislative National Assembly. Triumph of the Party of order. Eventual ascent to power of Louis Napoleon with the support of the lumpenproletariat. Restoration of the Bourbon monarchical power in the guise of empire.

Tensions, Contradictions, Instability In this work Marx traces how class struggles are reflected in the complex web of political conflicts, and in particular the contradictory relationships between the outer form of a conflict and its real social content. The proletariat of Paris was at this time too inexperienced to win power, but the experiences of 1848 -51 would prove invaluable for the successful workers' revolution of 1871.

Determinism & Reductionism • Marx and Engels, at least in their most systematic writings, argued that they have uncovered “the natural laws of capitalist production” and that “it is a question of these laws themselves, of these tendencies working with iron necessity toward inevitable results. ” • Like most of his contemporaries, Marx saw economics as “a process of natural history, ” while the capitalist production process was said to operate “with the inexorability of a law of Nature. ”

Weber “No sociologist should think himself too good, even in his old age, to make tens of thousands of quite trivial computations in his head and perhaps for months at a time. ” - MW

Biography • 1864: Born to a family of notable heritage – merchants, politicians, public servants. • Educated at Heidelberg and Berlin, he abandoned training in law and jurisprudence to become a public intellectual. • Weber and his wife Marianne (an intellectual in her own right and early women's rights activist) soon found themselves at the center of the vibrant intellectual and cultural life of Heidelberg; the so-called “Weber Circle” attracted such intellectual luminaries as Georg Jellinek, Ernst Troeltsch, and Werner Sombart and later a number of younger scholars including Marc Bloch, Robert Michels, and György Lukács. • 1896: Nervous breakdown. • 1904 -1905: Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism • 1903 -1914: Economy and Society • 1914: WWI breaks out, Weber is staunchly nationalistic and supportive of the war (like all German intellectuals at the time). • 1917: Weber campaigns vigorously for a wholesale constitutional reform for post-war Germany, including the introduction of universal suffrage and the empowerment of parliament. • 1919: Lectures in Munich on Science as a Vocation & Politics as a Vocation. • 1920: Dies of pneumonia at fifty-six years of age.

What is Weber Rejecting? What sociology cannot do: 1) Discover universal laws of human behavior comparable with the natural sciences. 2) Confirm any evolutionary progress in human societies. 3) Develop any collective concepts (like “the state” or the “family”) unless they could be stated in terms of individual action. 4) Reduce society to the economy (or, for that matter to politics or culture). Bottom Line: power comes from many places, your class position being just one of them.

Key Question for Political Sociology: “Why and when do men obey? ” (p. 78) Consider the paradox of power. “…the generally observable need of any power, or even of any advantage of life, to justify itself. […] [People’s] never ceasing need to look upon his position as in some way ‘legitimate, ’ upon his advantage as ‘deserved, ’ and the other’s disadvantage as being brought about by the latter’s ‘fault. ’ That the purely accidental causes of the difference may be ever so obvious makes no difference” (p. 953).

Sources of Power • Class (economic order): property, capital and other material stuff. Comes with a common market destiny. • Status (social order): honor, prestige, respect, dignity in the eyes of others. “Street cred. ” Comes with a specific “style of life” and “principles of consumption of goods” (p. 193) Think occupational groups. • Party (political order): all about “social power” (p. 194), influence. Think “leverege. ” Comes with rationalized organizational order and staff (ibid).

Weber in Politics as Vocation Defined very broadly, power is all about the chance that an individual in a social relationship can achieve his or her own will even against the resistance of others (see p. 180; p. 942). This is analytically unsatisfying to Weber, so he wanted to further specify the stakes by discussing “domination” and “authority. ”

Domination vs. Authority Distinction hinges on the all-important question of legitimation (p. 78 -9). Weber defines domination as the probability that certain specific commands (or all commands) will be obeyed by a given group of persons (formal def. on p. 946). The consent of the subjegated may or may not be there. Weber defines authority as legitimate forms of domination, that is, forms of domination which followers or subordinates consider to be legitimate. Here, the “power to command” comes with “the duty to obey” (p. 943).

Bank vs. Village Patriarch • Bank has “domination” in virtue of its monopoly position. The people over whom they exercise power (i. e. debtors) “simply pursue their own interests [while] acting with formal freedom”; their acting in accordance with the will of the bank is “forced upon them by objective circumstances” (p. 943). • Village patriarch has “authority” in virtue of the obedience and loyalty of the villagers, who give tribute in the belief that the patriarch has the right to make such collections. The submission of the villagers is neither coerced nor in their own interest.

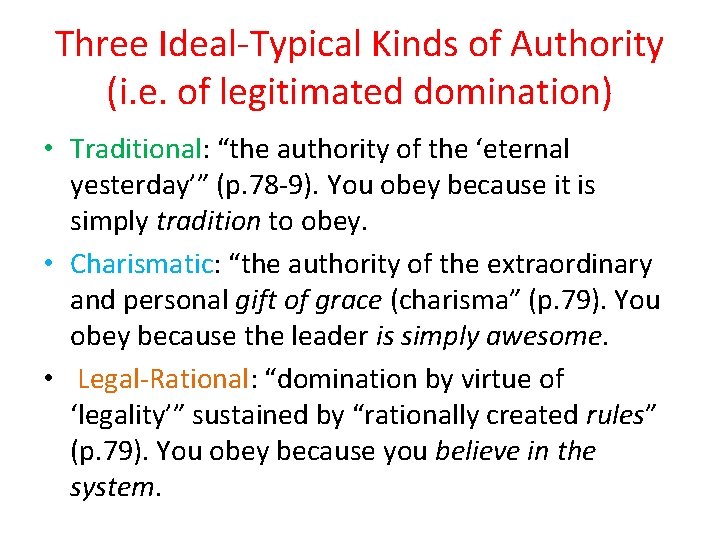

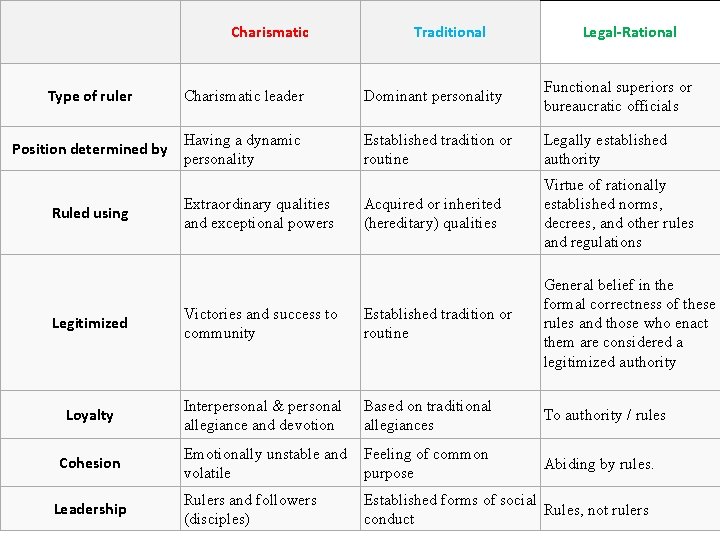

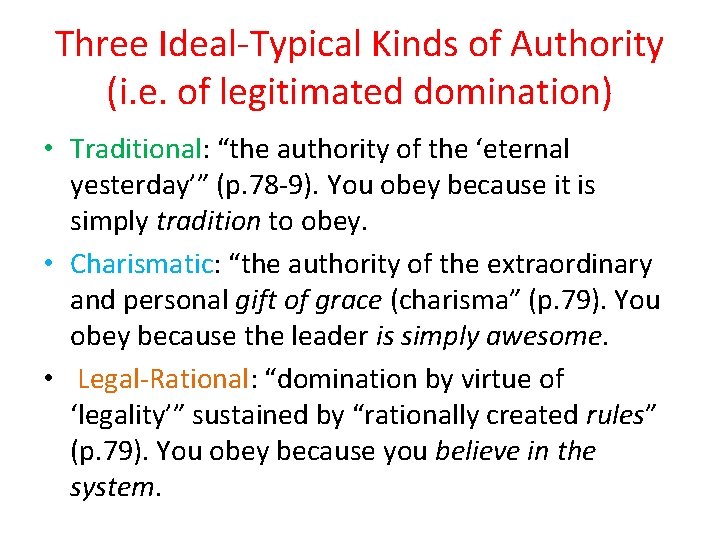

Three Ideal-Typical Kinds of Authority (i. e. of legitimated domination) • Traditional: “the authority of the ‘eternal yesterday’” (p. 78 -9). You obey because it is simply tradition to obey. • Charismatic: “the authority of the extraordinary and personal gift of grace (charisma” (p. 79). You obey because the leader is simply awesome. • Legal-Rational: “domination by virtue of ‘legality’” sustained by “rationally created rules” (p. 79). You obey because you believe in the system.

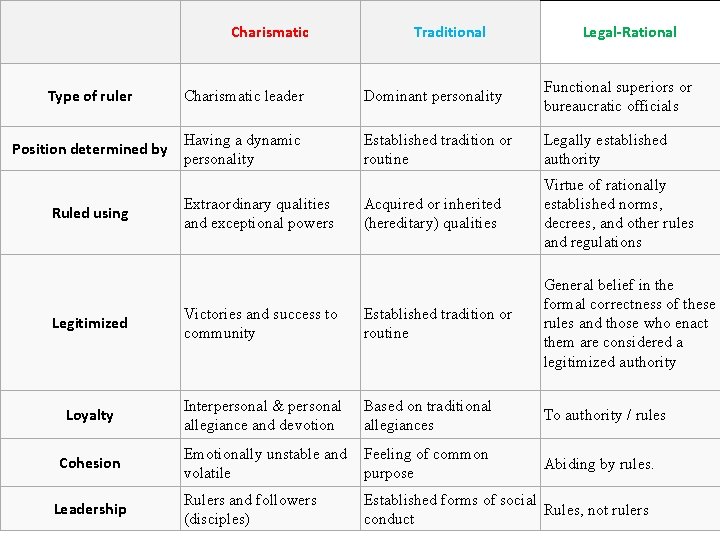

Charismatic Traditional Legal-Rational Type of ruler Charismatic leader Dominant personality Functional superiors or bureaucratic officials Position determined by Having a dynamic personality Established tradition or routine Legally established authority Acquired or inherited (hereditary) qualities Virtue of rationally established norms, decrees, and other rules and regulations Ruled using Extraordinary qualities and exceptional powers Legitimized Victories and success to community Established tradition or routine General belief in the formal correctness of these rules and those who enact them are considered a legitimized authority Loyalty Interpersonal & personal allegiance and devotion Based on traditional allegiances To authority / rules Cohesion Leadership Emotionally unstable and Feeling of common volatile purpose Rulers and followers (disciples) Abiding by rules. Established forms of social Rules, not rulers conduct

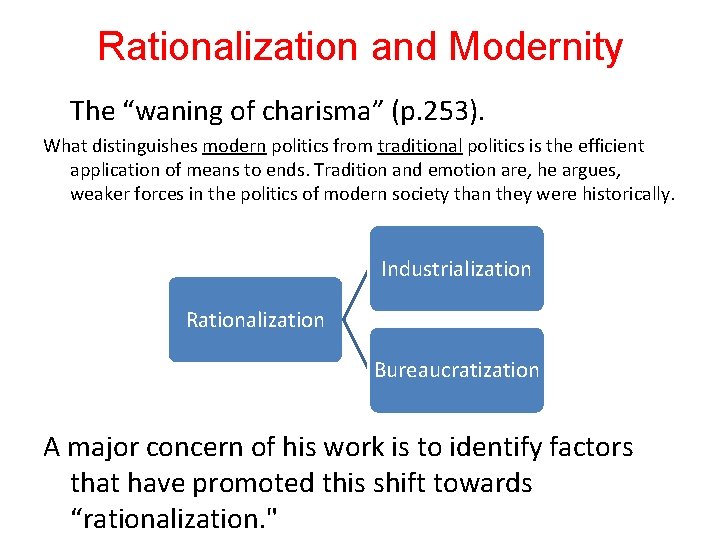

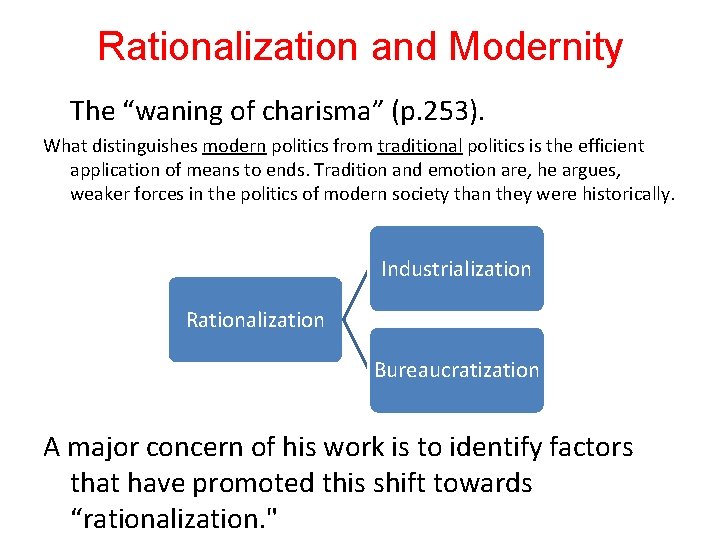

Rationalization and Modernity The “waning of charisma” (p. 253). What distinguishes modern politics from traditional politics is the efficient application of means to ends. Tradition and emotion are, he argues, weaker forces in the politics of modern society than they were historically. Industrialization Rationalization Bureaucratization A major concern of his work is to identify factors that have promoted this shift towards “rationalization. "

Discipline, mother of rationalized politics “Discipline in general, like its most rational offspring, bureaucracy, is impersonal. Unfailingly neutral, it places itself at the disposal of every power that claims its service and knows how to promote it” (p. 254). The “sense of duty” and “conscientiousness” that comes with discipline is often implicit, taken-for-granted by subservient, obedient people. But consider how much social engineering had to go into this remarkable achievement!

Defining the State A state is an entity that has a monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force (violence) within a given territory.

Durkheim: “The Secular Pope” "Sociology can then be defined as the science of institutions, of their genesis and of their functioning. “ - ED

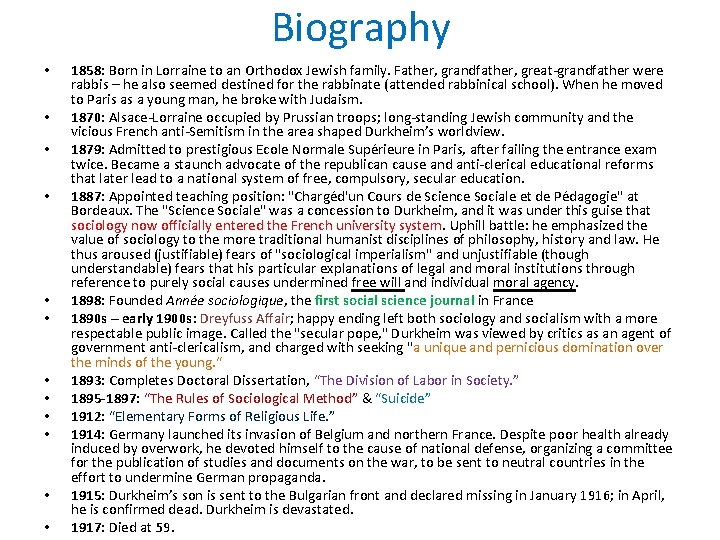

Biography • • • 1858: Born in Lorraine to an Orthodox Jewish family. Father, grandfather, great-grandfather were rabbis – he also seemed destined for the rabbinate (attended rabbinical school). When he moved to Paris as a young man, he broke with Judaism. 1870: Alsace-Lorraine occupied by Prussian troops; long-standing Jewish community and the vicious French anti-Semitism in the area shaped Durkheim’s worldview. 1879: Admitted to prestigious Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris, after failing the entrance exam twice. Became a staunch advocate of the republican cause and anti-clerical educational reforms that later lead to a national system of free, compulsory, secular education. 1887: Appointed teaching position: "Chargéd'un Cours de Science Sociale et de Pédagogie" at Bordeaux. The "Science Sociale" was a concession to Durkheim, and it was under this guise that sociology now officially entered the French university system. Uphill battle: he emphasized the value of sociology to the more traditional humanist disciplines of philosophy, history and law. He thus aroused (justifiable) fears of "sociological imperialism" and unjustifiable (though understandable) fears that his particular explanations of legal and moral institutions through reference to purely social causes undermined free will and individual moral agency. 1898: Founded Année sociologique, the first social science journal in France 1890 s – early 1900 s: Dreyfuss Affair; happy ending left both sociology and socialism with a more respectable public image. Called the "secular pope, " Durkheim was viewed by critics as an agent of government anti-clericalism, and charged with seeking "a unique and pernicious domination over the minds of the young. “ 1893: Completes Doctoral Dissertation, “The Division of Labor in Society. ” 1895 -1897: “The Rules of Sociological Method” & “Suicide” 1912: “Elementary Forms of Religious Life. ” 1914: Germany launched its invasion of Belgium and northern France. Despite poor health already induced by overwork, he devoted himself to the cause of national defense, organizing a committee for the publication of studies and documents on the war, to be sent to neutral countries in the effort to undermine German propaganda. 1915: Durkheim’s son is sent to the Bulgarian front and declared missing in January 1916; in April, he is confirmed dead. Durkheim is devastated. 1917: Died at 59.

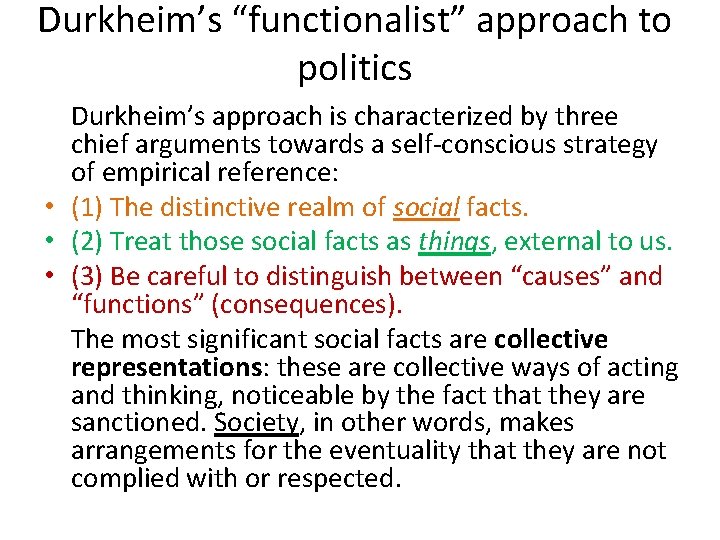

Durkheim’s “functionalist” approach to politics Durkheim’s approach is characterized by three chief arguments towards a self-conscious strategy of empirical reference: • (1) The distinctive realm of social facts. • (2) Treat those social facts as things, external to us. • (3) Be careful to distinguish between “causes” and “functions” (consequences). The most significant social facts are collective representations: these are collective ways of acting and thinking, noticeable by the fact that they are sanctioned. Society, in other words, makes arrangements for the eventuality that they are not complied with or respected.

The most important collective representation: The “Conscience collective”

Social Facts • Social facts are considered things - they are sui generis, peculiar in their characteristics: they are the effect or creation of human activities, but they are not consciously intended. They are the unanticipated consequence of human behavior/agency. • Social facts are things because they are outside us - they are a given, preexisting condition for human agency and they cannot be known by introspection, by reflection. • The human agency that produced the social facts we confront is not ours; it was exercised in the past, by collective agents pursuing collective, not individual goals. • Social facts are external to all individuals now living; they are given, the context or condition for thinking and action; they are constraining upon individuals because they pressure individuals to act in established, predictable ways. Sociology as science of society; Psychology as science of the individual. • Sociologists should look for the causes of social facts in their social conditions or social context, not in individual intentions when individuals are considered in isolation. POLITICS, ultimately, is about those social facts that regulate the functioning of authority in society.

How do we identify social facts? The nonmaterial nature of most social facts raises the problem of identification. Durkheim indicates that we can identify social facts by establishing whether or not they are sanctioned. If the context within which individuals act takes notice of whether or not individuals behave in established ways, following institutional injunctions, and rewards or punishes according to whether or not individuals are compliant, then we can be sure that we have identified a social fact. • Sanctions can be formal (e. g. , law) or informal (e. g. , social control, shaming, exclusion, etc. ).

Our Dual Nature • • • Individuals have a dual nature; their mental process contain individual characteristics mingled with the effects of collective representations; most of the representations within individual minds have been collectively produced. Collective representations are not the creation of individuals' intentions or of the sum of individuals' thought. These collective representations arise from the interaction of innumerable minds considered as a totality, as a whole from whose activities these representations emerge. Collective representations have collective origins, collective functions and they are sanctioned. There is the expectation that the collectivity will approve or disapprove of individuals actions. The existence and expectation of sanctions operates to generate similar patterns of individual reasoning and thinking; it introduces social elements into individual mental processes and transform us into social beings. Collective representations are not, therefore, products of a single mind or of the simply addition of single minds; as a totality, they are greater than the sum of its parts.

Political Sociology a la Durkheim Political society : “formed by the coming together of a fairly large number of secondary social groups, which is subject to the same one authority, where this is not itself subject to any other permanently constituted superior authority” (p. 191). Then he immediately asks about the “what the morals are that relate to it” – the “rules which specify the relation of individuals to this sovereign authority” (ibid).

The Durkheimian State as Brain • Merely the “particular group of officials entrusted with representing th[e] authority” to which everyone is subjected (p. 191). “The state is a specialised agency whose responsibility it is to work out certain ideas which apply to the collectivity. ” These ideas are said to be “more conscious and deliberate” than others, differentiating them from other collectivities’ ideas (p. 192). • Notice the repeated description of the state as “organ” (p. 196) and “inner organ” (p. 192), along with the constant use of “function. ” Remember metaphor of society as social organism.

Note Evolutionary Language “a single society can no more change its type during the course of its evolution than an animal can change its species during its individual existence” (p. 193 -4). “…as a tree having many branches which differ in greater of lesser degree. But societies are situated at varying heights on this tree, and at variable distances from the common trunk. On condition of treating them in this way, it is possible to speak of the general evolution of societies” (p. 129).

Division of Labor Division and specialization of labor was, for Durkheim and contemporaries, the most significant feature of modernity. Durkheim subscribed to the Social Darwinist view that division of labor is the human variant of a universal biological process: the progression from simple forms of life to differentiated, complex ones. However, he rejected utilitarian explanations which emphasized individual self-interest as the motor behind efficient, self-interested ways of organizing labor.

In the Old Days… Durkheim believed that early societies were constituted by the ways they respond to violations of norms. Such responses took the form of punitive sanctions, of inflictions of pain on the violators by, or in the name of, the whole society, in order to reassert universally shared and inflexible understandings. More generally, Durkheim’s emphasis on norms (as opposed to, say, “contracts”) invites us to move beyond the legalistic, psychological, and “formal rational” explanations of society.

“Mechanical Solidarity” These early societies followed a “morphological pattern”: Small population + low demographic density + large territory + use of primitive technology to extract resources = “Mechanical Solidarity” Such societies get segmented into even smaller, very similar subunits which subsist by embodying the same culture and interacting with the others on ritual occasions, which renew everyone’s feeling of “togetherness. ” These societies are homogenous and have no major fissures to be mended.

“Organic Solidarity” The equilibrium of such a society, according to Durkheim, eventually gets disturbed: Increase in population + increase in demographic density increased competitive pressure over resources. At this juncture, the society in question either falls prey to strife and disorder or it spontaneously embarks on sustained change by dividing labor. Many generations later, we are left with a profoundly different picture: Large population operating over large territory making intensive use of resources + a differentiation process forces development of different skills and technologies + diverse beliefs, norms, customs guide people within their differentiated branches = “Organic Solidarity” In this situation, violation of the norms does not evoke the wrath of the whole society. Rather, sanctions are typically not punitive but “restitutive” – they seek to remedy the damage the violation has done to the interests of given individuals, and only if those request such remedy. Normative bonds of society as a whole become fewer, and “looser, ” so mechanical solidarity is no longer possible. The “glue” that keeps society together is now due to the fact that the different parts interact with, and deliver goods and services to, one another. Think of advanced biological species, which present organs which are diverse in structure and operation but all subserve the needs of each other and of the whole.

Freedom through (Political) Society “Man is far more free in a crowd than in a small group” (p. 200). Furthermore, (s)he is freer in a small group than alone. Simmel reached a similar conclusion (albeit from different premises): “For within a mass of people in sensory contact, innumerable suggestions and nervous influences play back and forth; they deprive the individual of the calmness and autonomy of reflection and action. In a crowd, therefore, the most ephemeral incitations often grow like avalanches into the most disproprtionate impulses, and thus appear to eliminate the higher differentiated and critical functions of the individual” (p. 112).

Society as a Moral Reality • Society’s continuing existence and welfare depend on the willingness of individuals to consider each other not as instruments, but as fellow beings equally entitled to respect and solidarity. Society is the source of morality. • Society demands not just obedience but devotion. • According to Durkheim, all institutions, mundane as their themes may be, have arisen as articulations and differentiations of a single great institutional matrix: religion. It is religion that tells us the sacred from the profane, and continuously validates constraints on us as legitimate. • For instance, a tribe worshiping a totem actually worships itself. It is the manifestation of the superiority, powerfulness, generosity of the group that generates in its members the experience of the sacred – an experience which myth and ritual continuously revisit and reproduce.

God is Society Durkheim has drawn criticism from theists for insinuating that religion is, at its core, an arbitrary exercise in self-delusion, a delirium. But Durkheim’s point was precisely that it is a well-grounded delirium.

Simmel the Interactionist s fsvv Offers us a new set of concepts for understanding sociological phenomenon from the perspective of interacting individuals: social forms | social type | social distance | sociation | interaction | conflict | exchange | domination | individuality. Political sociology is the study of human interaction, or sociation. In order to be considered sociation, an interaction has to be truly reciprocal —the actions of the individuals must influence one another.

Three Kinds of Subordination • 1) to an individual • 2) to a plurality/collectivity • 3) to an impersonal, objective principle

Reciprocity is Key The lens of reciprocity for studying social relations adds a new dimension of nuance to the study of power and domination that we did not find in Marx or Durkheim, though in some form we found it in Weber. Simmel describes how the dominator and dominated are inter-subjectively tied together.

Agency of the Subordinated “Even in the most oppressive and cruel cases of subordination, there is still a considerable measure of personal freedom. We merely do not become aware of it because its manifestation would entail sacrifices which we usually never think of taking upon ourselves. Actually, the absolute coercion which even the most cruel tyrant imposes upon us is always distinctly relative. Its condition is our desire to escape from the threatened punishment or from other consequences of our disobedience” (p. 97).

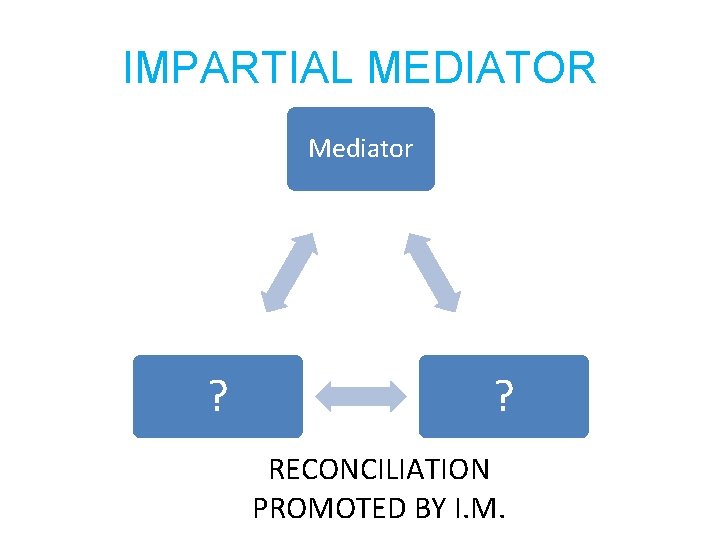

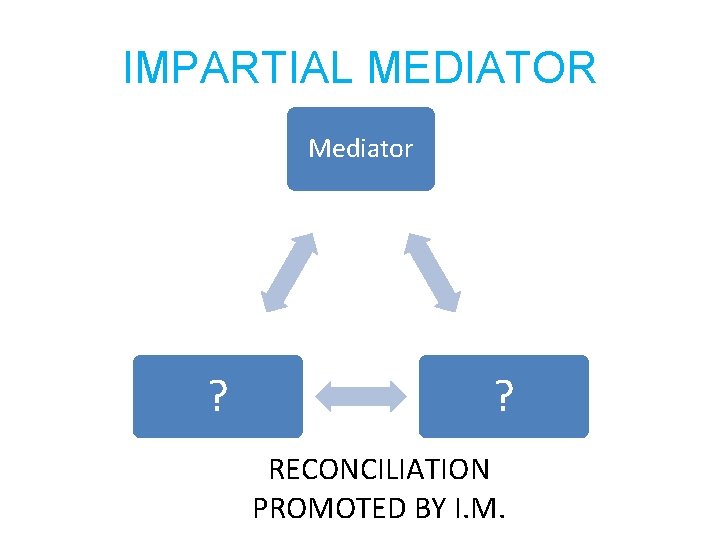

Formalism Notice how many times the words “formal, ” “forms, ” “social formation” and related derivatives appear (for instance on p. 103). Consider some triadic forms: TERTIUS GAUDENS (“the third who benefits”) DIVISOR ET IMPERATOR (“divider and conquerer”) IMPARTIAL MEDIATOR

TERTIUS GAUDENS Tertius ? ? INDEPENDENT CONFLICT

DIVISOR ET IMPERATOR Divisor/Imperator ? ? CONFLICT PROMOTED BY D. I.

IMPARTIAL MEDIATOR Mediator ? ? RECONCILIATION PROMOTED BY I. M.

External Threat: The Best Unifier “In general common enmity is one of the most powerful means for motivating a number of individuals or groups to cling together” (p. 103).

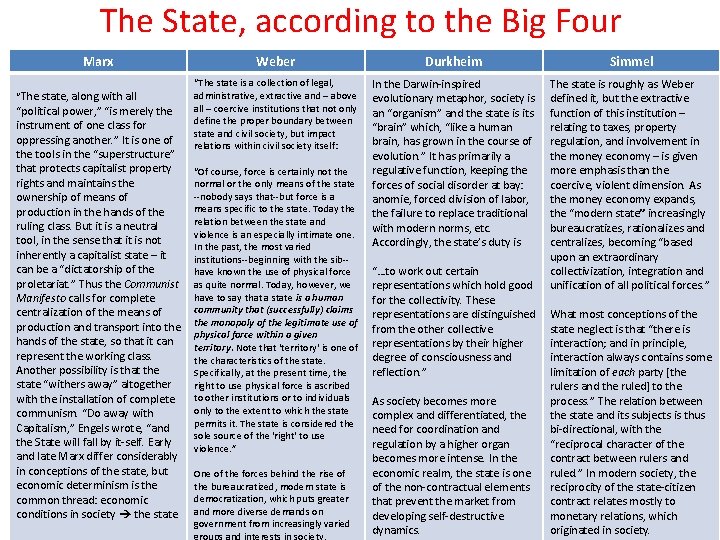

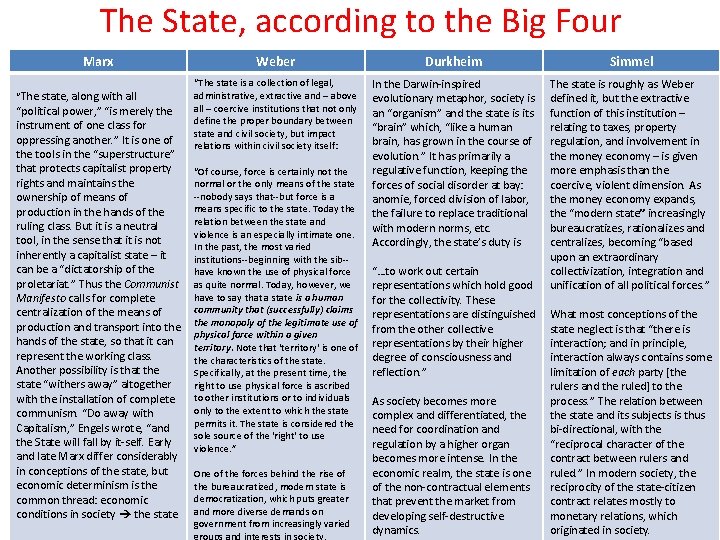

The State, according to the Big Four Marx “The state, along with all “political power, ” “is merely the instrument of one class for oppressing another. ” It is one of the tools in the “superstructure” that protects capitalist property rights and maintains the ownership of means of production in the hands of the ruling class. But it is a neutral tool, in the sense that it is not inherently a capitalist state – it can be a “dictatorship of the proletariat. ” Thus the Communist Manifesto calls for complete centralization of the means of production and transport into the hands of the state, so that it can represent the working class. Another possibility is that the state “withers away” altogether with the installation of complete communism. “Do away with Capitalism, ” Engels wrote, “and the State will fall by it-self. Early and late Marx differ considerably in conceptions of the state, but economic determinism is the common thread: economic conditions in society the state. Weber Durkheim Simmel “The state is a collection of legal, administrative, extractive and – above all – coercive institutions that not only define the proper boundary between state and civil society, but impact relations within civil society itself: “Of course, force is certainly not the normal or the only means of the state --nobody says that--but force is a means specific to the state. Today the relation between the state and violence is an especially intimate one. In the past, the most varied institutions--beginning with the sib-have known the use of physical force as quite normal. Today, however, we have to say that a state is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory. Note that 'territory' is one of the characteristics of the state. Specifically, at the present time, the right to use physical force is ascribed to other institutions or to individuals only to the extent to which the state permits it. The state is considered the sole source of the 'right' to use violence. ” One of the forces behind the rise of the bureaucratized, modern state is democratization, which puts greater and more diverse demands on government from increasingly varied groups and interests in society. In the Darwin-inspired evolutionary metaphor, society is an “organism” and the state is its “brain” which, “like a human brain, has grown in the course of evolution. ” It has primarily a regulative function, keeping the forces of social disorder at bay: anomie, forced division of labor, the failure to replace traditional with modern norms, etc. Accordingly, the state’s duty is “…to work out certain representations which hold good for the collectivity. These representations are distinguished from the other collective representations by their higher degree of consciousness and reflection. ” As society becomes more complex and differentiated, the need for coordination and regulation by a higher organ becomes more intense. In the economic realm, the state is one of the non-contractual elements that prevent the market from developing self-destructive dynamics. The state is roughly as Weber defined it, but the extractive function of this institution – relating to taxes, property regulation, and involvement in the money economy – is given more emphasis than the coercive, violent dimension. As the money economy expands, the “modern state” increasingly bureaucratizes, rationalizes and centralizes, becoming “based upon an extraordinary collectivization, integration and unification of all political forces. ” What most conceptions of the state neglect is that “there is interaction; and in principle, interaction always contains some limitation of each party [the rulers and the ruled] to the process. ” The relation between the state and its subjects is thus bi-directional, with the “reciprocal character of the contract between rulers and ruled. ” In modern society, the reciprocity of the state-citizen contract relates mostly to monetary relations, which originated in society.

Week by week plans for documenting children's development

Week by week plans for documenting children's development Closed thesis vs open thesis

Closed thesis vs open thesis The three main parts of an essay

The three main parts of an essay Thesis statement title

Thesis statement title Which statement presents the main idea of the text

Which statement presents the main idea of the text Future going to

Future going to What is the central idea of this passage?

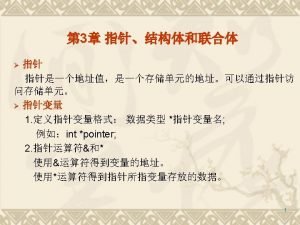

What is the central idea of this passage? Void main int main

Void main int main Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ

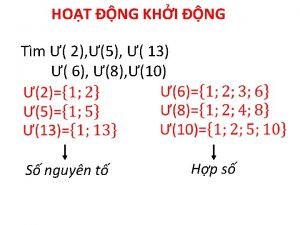

Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ So nguyen to

So nguyen to Fecboak

Fecboak Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất ưu thế lai là gì

ưu thế lai là gì Sơ đồ cơ thể người

Sơ đồ cơ thể người Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Cái miệng bé xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi

Cái miệng bé xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể

Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ

đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ Cách giải mật thư tọa độ

Cách giải mật thư tọa độ Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào

Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào Thẻ vin

Thẻ vin Thể thơ truyền thống

Thể thơ truyền thống Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu

Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu Diễn thế sinh thái là

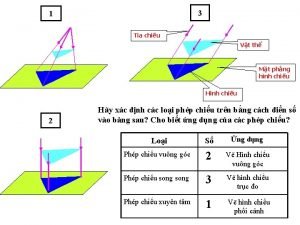

Diễn thế sinh thái là Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau Ng-html

Ng-html V. c c

V. c c Làm thế nào để 102-1=99

Làm thế nào để 102-1=99 Lời thề hippocrates

Lời thề hippocrates Hổ đẻ mỗi lứa mấy con

Hổ đẻ mỗi lứa mấy con Tư thế worm breton là gì

Tư thế worm breton là gì đại từ thay thế

đại từ thay thế Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra

Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra Công thức tính thế năng

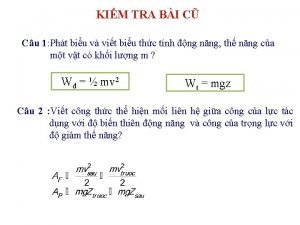

Công thức tính thế năng Thế nào là mạng điện lắp đặt kiểu nổi

Thế nào là mạng điện lắp đặt kiểu nổi Dạng đột biến một nhiễm là

Dạng đột biến một nhiễm là Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ

Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ Bổ thể

Bổ thể Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể

Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể độ dài liên kết

độ dài liên kết Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng từ đua

Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng từ đua Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan

Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan Khi nào hổ con có thể sống độc lập

Khi nào hổ con có thể sống độc lập Hát lên người ơi

Hát lên người ơi điện thế nghỉ

điện thế nghỉ Một số thể thơ truyền thống

Một số thể thơ truyền thống Limiting reactant

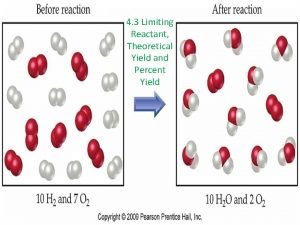

Limiting reactant Theoretical shear stress

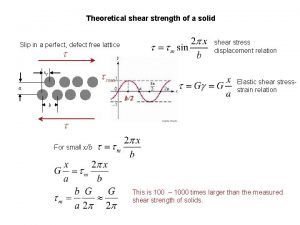

Theoretical shear stress Theoretical foundation of international business

Theoretical foundation of international business Four theoretical perspectives

Four theoretical perspectives Great theoretical ideas in computer science

Great theoretical ideas in computer science Rate theory and plate theory

Rate theory and plate theory Theoretical probability distribution table

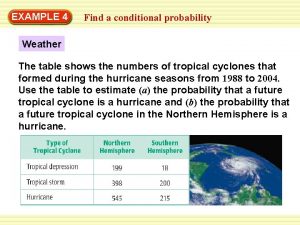

Theoretical probability distribution table How to determine theoretical yield

How to determine theoretical yield Franmework

Franmework Theoretical yield def

Theoretical yield def What is experimental probability

What is experimental probability Acid base strength and hardness and softness

Acid base strength and hardness and softness