Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes Julio A Panza

- Slides: 70

Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes Julio A. Panza, MD, FACC, FAHA Division of Cardiology, Washington Hospital Center Professor of Medicine, Georgetown University Washington Metropolitan Society of Health-System Pharmacists 2013 Annual Meeting There are no conflicts of interest related to this presentation

Learning Objectives • Explain the variability in the clinical presentation of ACS • Recognize the currently available tools for diagnosis and risk stratification • Discuss the clinical management of ACS based on the presentation type, severity of disease, comorbid disease, and other preexisting conditions • Reinforce key educational concepts and what the guidelines and recommendations are for the spectrum of ACS

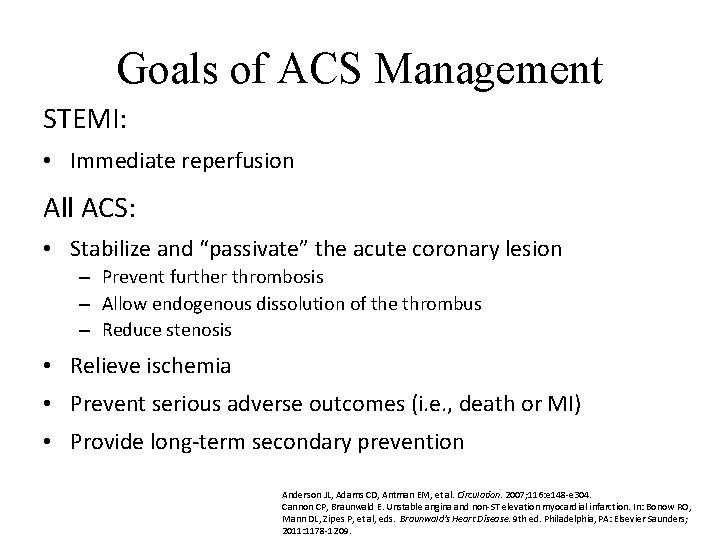

Goals of ACS Management STEMI: • Immediate reperfusion All ACS: • Stabilize and “passivate” the acute coronary lesion – Prevent further thrombosis – Allow endogenous dissolution of the thrombus – Reduce stenosis • Relieve ischemia • Prevent serious adverse outcomes (i. e. , death or MI) • Provide long-term secondary prevention Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2007; 116: e 148 -e 304. Cannon CP, Braunwald E. Unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 1178 -1209.

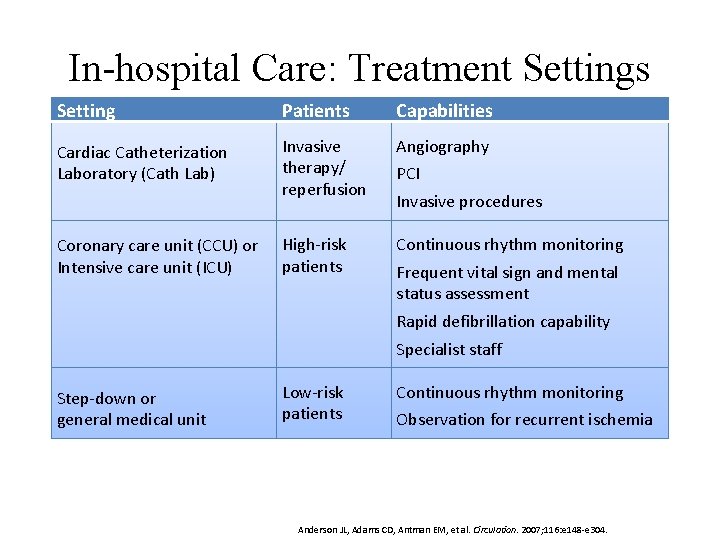

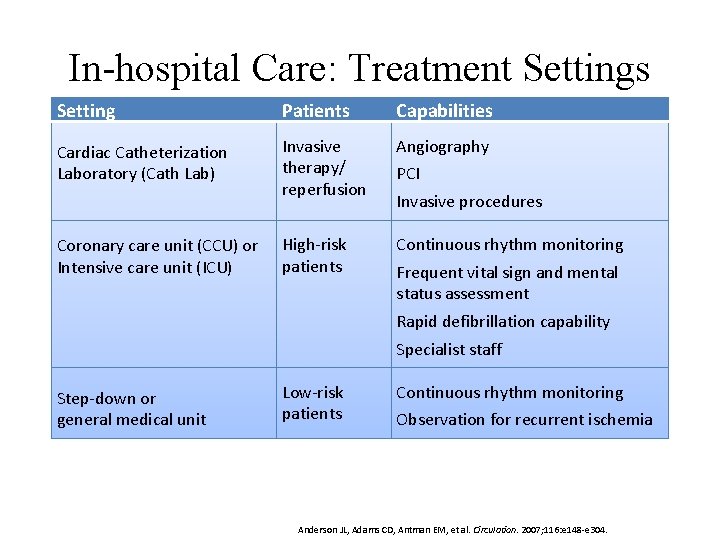

In-hospital Care: Treatment Settings Setting Patients Capabilities Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory (Cath Lab) Invasive therapy/ reperfusion Angiography High-risk patients Continuous rhythm monitoring Coronary care unit (CCU) or Intensive care unit (ICU) PCI Invasive procedures Frequent vital sign and mental status assessment Rapid defibrillation capability Specialist staff Step-down or general medical unit Low-risk patients Continuous rhythm monitoring Observation for recurrent ischemia Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2007; 116: e 148 -e 304.

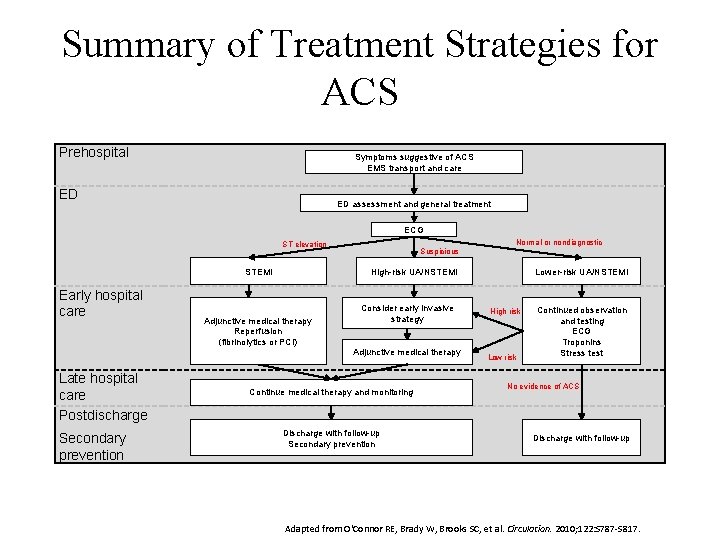

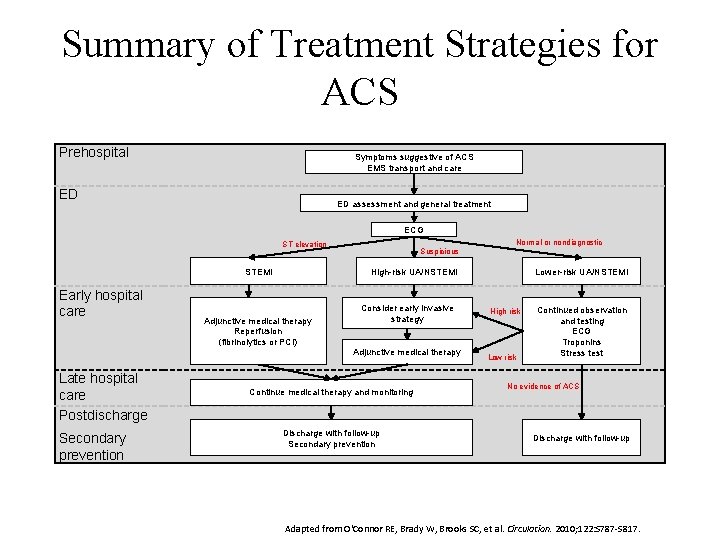

Summary of Treatment Strategies for ACS Prehospital Symptoms suggestive of ACS EMS transport and care ED ED assessment and general treatment ECG ST elevation STEMI Early hospital care Suspicious High risk UA/NSTEMI Adjunctive medical therapy Reperfusion (fibrinolytics or PCI) Consider early invasive strategy Adjunctive medical therapy Late hospital care Postdischarge Secondary prevention Normal or nondiagnostic Continue medical therapy and monitoring Discharge with follow up Secondary prevention Lower risk UA/NSTEMI High risk Low risk Continued observation and testing ECG Troponins Stress test No evidence of ACS Discharge with follow up Adapted from O'Connor RE, Brady W, Brooks SC, et al. Circulation. 2010; 122: S 787 -S 817.

Summary of Treatment Strategies for ACS: Prehospital Management Symptoms suggestive of ACS EMS transport and care Adapted from O'Connor RE, Brady W, Brooks SC, et al. Circulation. 2010; 122: S 787 -S 817.

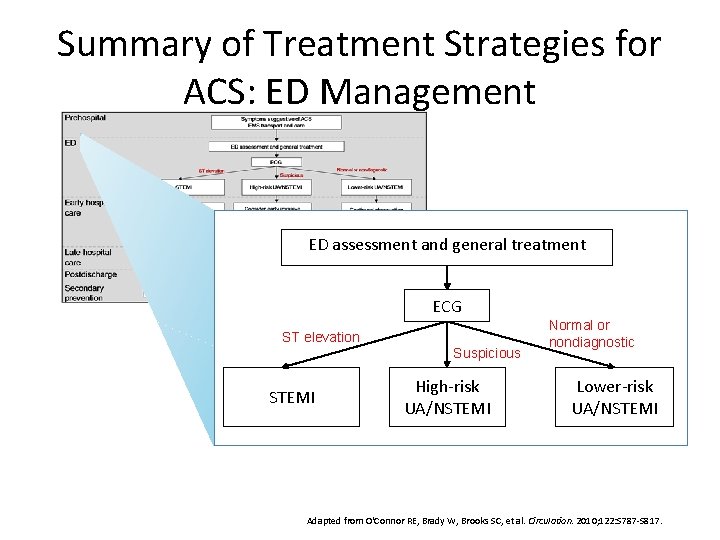

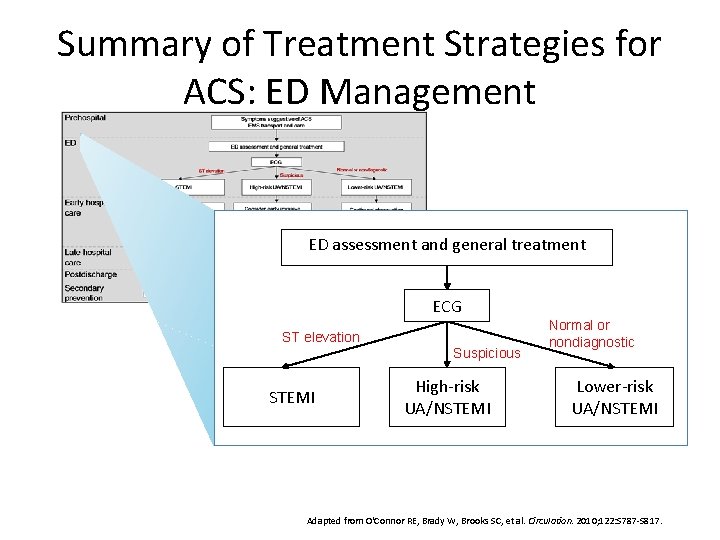

Summary of Treatment Strategies for ACS: ED Management ED assessment and general treatment ECG ST elevation Suspicious STEMI High-risk UA/NSTEMI Normal or nondiagnostic Lower-risk UA/NSTEMI Adapted from O'Connor RE, Brady W, Brooks SC, et al. Circulation. 2010; 122: S 787 -S 817.

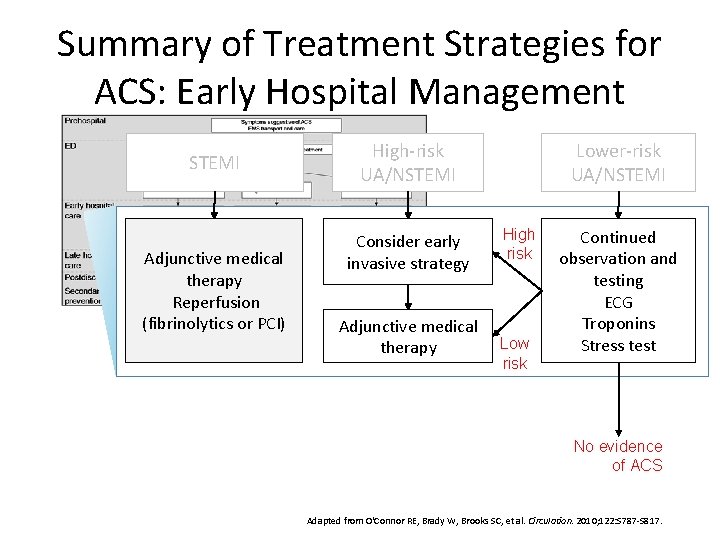

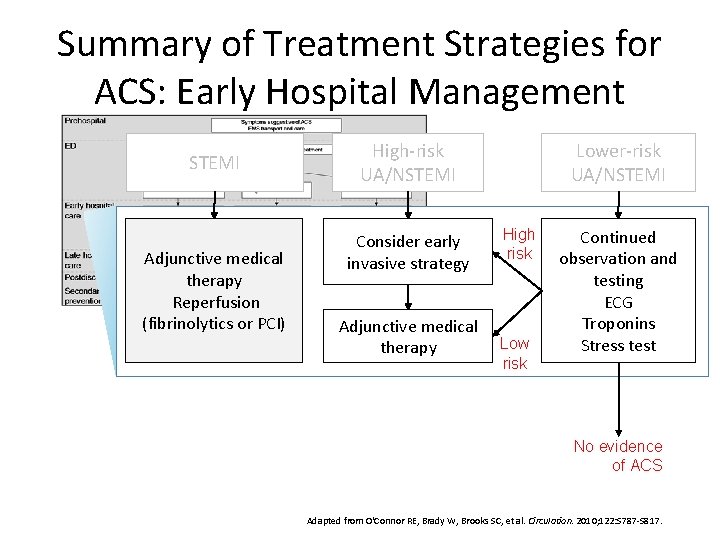

Summary of Treatment Strategies for ACS: Early Hospital Management STEMI Adjunctive medical therapy Reperfusion (fibrinolytics or PCI) High-risk UA/NSTEMI Consider early invasive strategy Adjunctive medical therapy Lower-risk UA/NSTEMI High risk Low risk Continued observation and testing ECG Troponins Stress test No evidence of ACS Adapted from O'Connor RE, Brady W, Brooks SC, et al. Circulation. 2010; 122: S 787 -S 817.

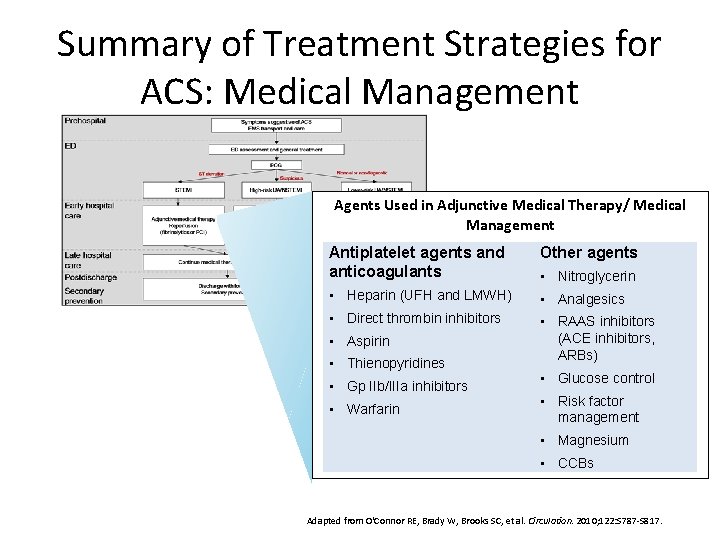

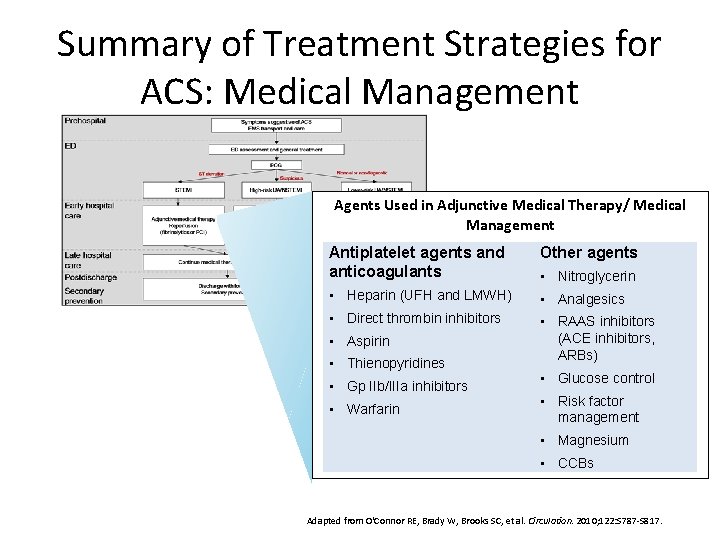

Summary of Treatment Strategies for ACS: Medical Management Agents Used in Adjunctive Medical Therapy/ Medical Management Antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants Other agents • Heparin (UFH and LMWH) • Analgesics • Direct thrombin inhibitors • RAAS inhibitors (ACE inhibitors, ARBs) • Aspirin • Thienopyridines • Gp IIb/IIIa inhibitors • Warfarin • Nitroglycerin • Glucose control • Risk factor management • Magnesium • CCBs Adapted from O'Connor RE, Brady W, Brooks SC, et al. Circulation. 2010; 122: S 787 -S 817.

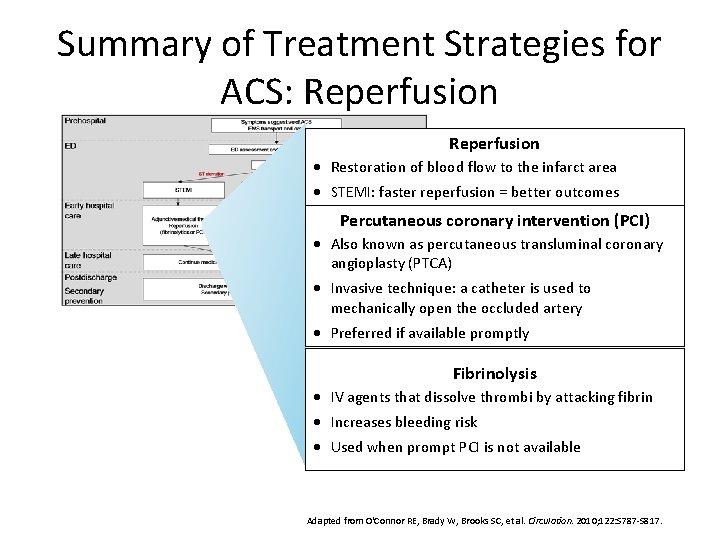

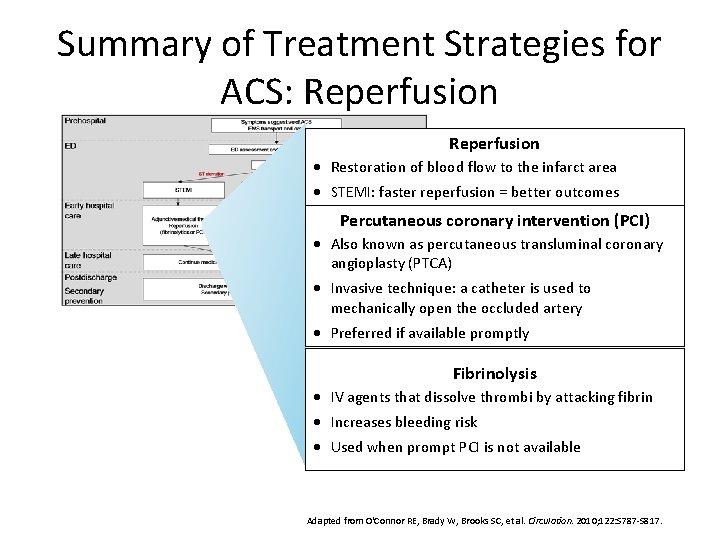

Summary of Treatment Strategies for ACS: Reperfusion · Restoration of blood flow to the infarct area · STEMI: faster reperfusion = better outcomes Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) · Also known as percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) · Invasive technique: a catheter is used to mechanically open the occluded artery · Preferred if available promptly Fibrinolysis · IV agents that dissolve thrombi by attacking fibrin · Increases bleeding risk · Used when prompt PCI is not available Adapted from O'Connor RE, Brady W, Brooks SC, et al. Circulation. 2010; 122: S 787 -S 817.

Summary of Treatment Strategies for ACS: Late Hospital Care Continue medical therapy and monitoring Adapted from O'Connor RE, Brady W, Brooks SC, et al. Circulation. 2010; 122: S 787 -S 817.

Summary of Treatment Strategies for ACS: Postdischarge Care Discharge with follow-up Secondary prevention Adapted from O'Connor RE, Brady W, Brooks SC, et al. Circulation. 2010; 122: S 787 -S 817.

Reperfusion and Revascularization Reperfusion: restoration of blood supply to a tissue or organ to relieve ischemia • Fibrinolysis • PCI (also known as angioplasty or PTCA) Revascularization: restoration of flow through part of the vascular system • PCI • CABG (coronary artery bypass grafting)

Importance of Rapid Reperfusion in STEMI “…Expeditious restoration of flow in the obstructed infarct artery after the onset of symptoms in patients with STEMI is a key determinant of short- and long-term outcomes…” 30 minutes of delay = 8% increase in relative risk of 1 -year mortality Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292. Antman E, Morrow DA. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: management. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 1111 -1177.

Coronary Angiography and PCI Angiography • Thread a balloon-tipped catheter to the occluded coronary artery using x-ray guidance • Inject a contrast medium to make the artery visible by x-ray PCI • Inflate the balloon to open the lumen (balloon angioplasty) • Usually, deploy a stent to prevent vessel closure American Heart Association. Cardiac procedures and surgeries. http: //www. heart. org/HEARTORG/Conditions/Heart. Attack/Prevention. Treatmentof. Heart. Attack/Cardiac. Procedures-and-Surgeries_UCM_303939_Article. jsp. Updated May 2, 2011. Accessed May 5, 2011. Popma JU. Coronary arteriography. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 406 -440.

PCI: Stents • Metal mesh tubes used to hold the artery open (prevent acute vessel closure) • Stent types: – Bare-metal stent (BMS) – Drug-eluting stent (DES)

Complications of Stents In-stent Restenosis: • Recurrent narrowing within the stent • Results from excessive smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation within the stent Stent thrombosis: • Thrombus develops in the stent • Causes include exposure of blood and plaque to the stent material and inflammation caused by the stent • Risk is reduced as the neointima (new intimal layer) heals and covers the stent material

Bare-metal Stents (BMS) • Uncoated metal mesh • Prevents acute vessel closure • Effects on restenosis – Short term: reduces restenosis by increasing lumen opening at the procedure – Long term: induces SMC proliferation, leading to increased restenosis • Used in 10%– 30% of patients undergoing PCI • Restenosis rates – Angiographic restenosis: 20%– 30% of patients – Clinical restenosis: 10%– 15% of patients Popma JU. Coronary arteriography. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 406 -440.

Drug-eluting Stents (DES) • Metal mesh coated with a material that reduces the risk of restenosis by releasing (eluting) a medication that slows SMC proliferation • Several types coated with different agents are available • Comparison to BMS: – Advantage: reduced restenosis rates – Disadvantage: requires a longer duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin + thienopyridine) to prevent stent thrombosis; increases bleeding risk – BMS favored for low bleeding risk Popma JU. Coronary arteriography. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 406 -440. Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, et al. Circulation. 2009; 120: 2271 -2306.

Technical Issues in PCI • Access route – Femoral (groin) vs Radial (wrist) – Brachial (armpit) and antecubital (elbow) are rarely used • Restenosis – POBA (plain old balloon angioplasty) vs PCI (stent placement) • Vascular access and closure devices

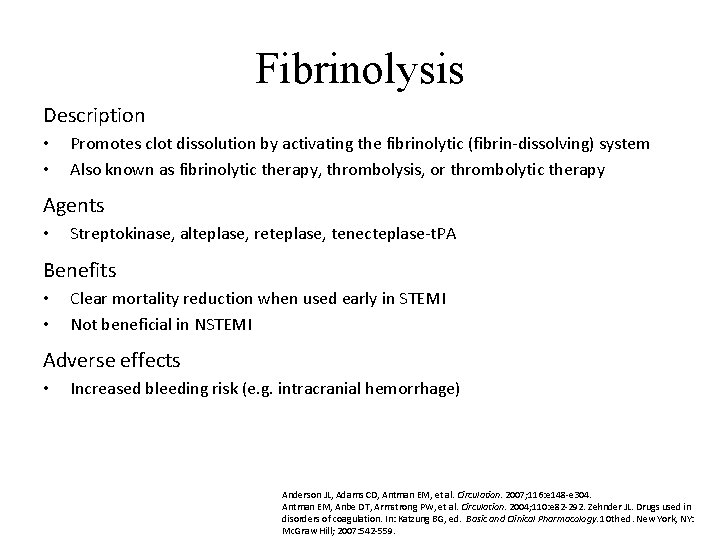

Fibrinolysis Description • • Promotes clot dissolution by activating the fibrinolytic (fibrin-dissolving) system Also known as fibrinolytic therapy, thrombolysis, or thrombolytic therapy Agents • Streptokinase, alteplase, reteplase, tenecteplase-t. PA Benefits • • Clear mortality reduction when used early in STEMI Not beneficial in NSTEMI Adverse effects • Increased bleeding risk (e. g. intracranial hemorrhage) Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2007; 116: e 148 -e 304. Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292. Zehnder JL. Drugs used in disorders of coagulation. In: Katzung BG, ed. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. 10 th ed. New York, NY: Mc. Graw Hill; 2007: 542 -559.

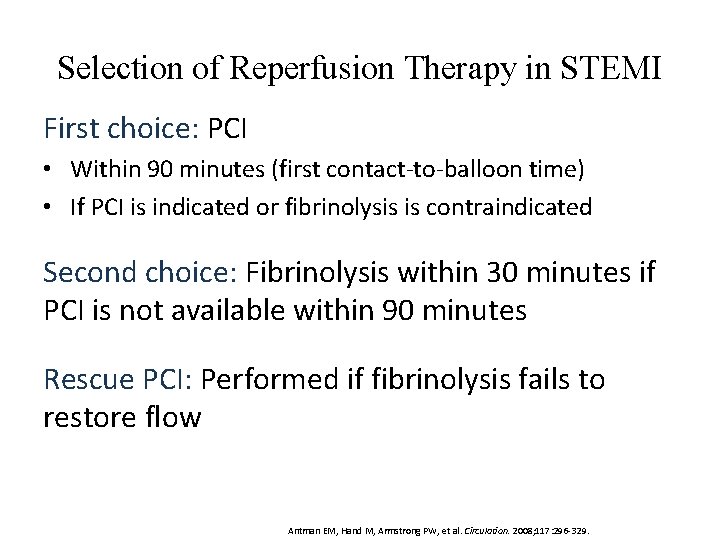

Selection of Reperfusion Therapy in STEMI First choice: PCI • Within 90 minutes (first contact-to-balloon time) • If PCI is indicated or fibrinolysis is contraindicated Second choice: Fibrinolysis within 30 minutes if PCI is not available within 90 minutes Rescue PCI: Performed if fibrinolysis fails to restore flow Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2008; 117: 296 -329.

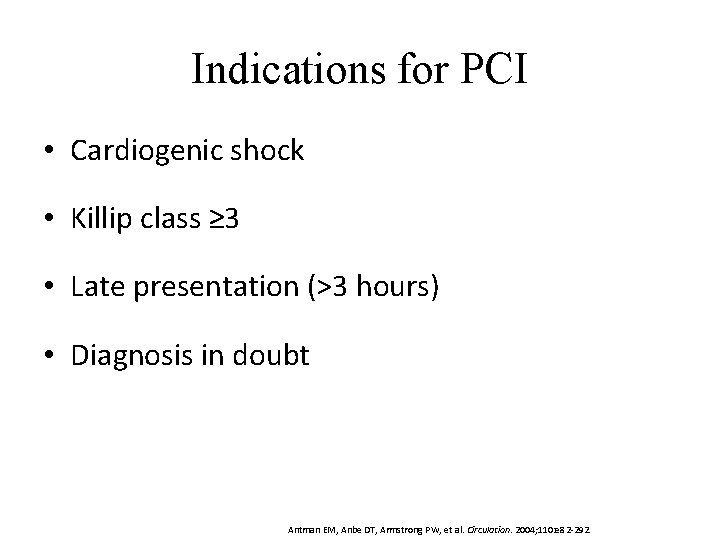

Indications for PCI • Cardiogenic shock • Killip class ≥ 3 • Late presentation (>3 hours) • Diagnosis in doubt Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292.

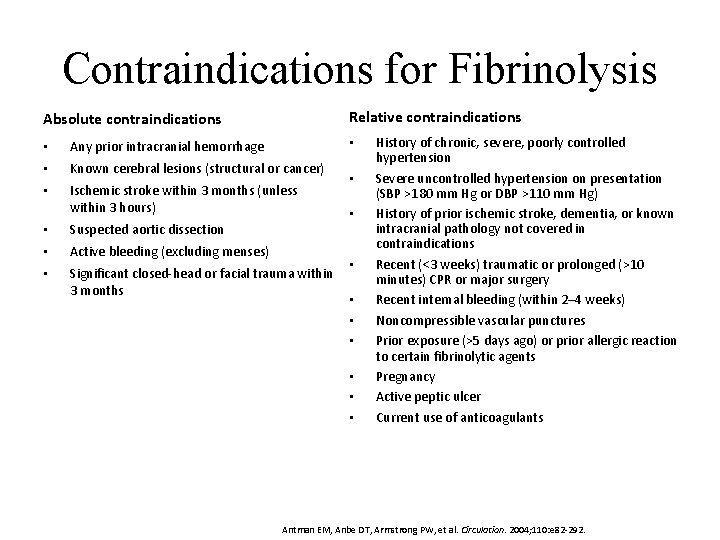

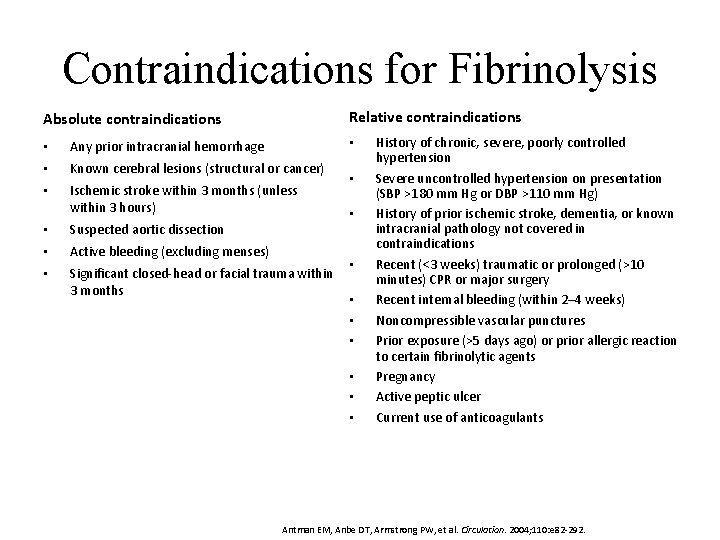

Contraindications for Fibrinolysis Relative contraindications Absolute contraindications • • Any prior intracranial hemorrhage • Known cerebral lesions (structural or cancer) • Ischemic stroke within 3 months (unless within 3 hours) • Suspected aortic dissection • Active bleeding (excluding menses) • Significant closed-head or facial trauma within 3 months • • • History of chronic, severe, poorly controlled hypertension Severe uncontrolled hypertension on presentation (SBP >180 mm Hg or DBP >110 mm Hg) History of prior ischemic stroke, dementia, or known intracranial pathology not covered in contraindications Recent (<3 weeks) traumatic or prolonged (>10 minutes) CPR or major surgery Recent internal bleeding (within 2– 4 weeks) Noncompressible vascular punctures Prior exposure (>5 days ago) or prior allergic reaction to certain fibrinolytic agents Pregnancy Active peptic ulcer Current use of anticoagulants Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292.

Other Techniques: Facilitated PCI • Planned use of fibrinolysis with PCI • Not used in UA/NSTEMI • Proven harmful with full-dose fibrinolytics; not recommended • May be considered with less than full-dose fibrinolytics • PCI is generally preferred if it can be performed in a timely manner Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2008; 117: 296 -329.

Other Techniques: Thrombectomy • Intravascular thrombus fragments may cause distal embolism – Possible obstruction of microvascular beds – Possible impairment of tissue level reperfusion (no-reflow condition) • Thrombectomy: variety of techniques used to remove the intravascular thrombus • Thrombus aspiration: thrombus is suctioned into a catheter • Embolic protection: devices to trap thrombus fragments • Manual thrombus aspiration improves mortality in primary PCI Bavry AA, Kumbhani DJ, Bhatt DL. Eur Heart J. 2008; 29: 2989 -3001. Popma JU. Coronary arteriography. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 406 -440. Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, et al. Circulation. 2009; 120: 2271 -2306.

Other Techniques: CABG (Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting) • Surgery to improve perfusion by repairing or circumventing the atherosclerotic artery or arteries with blood vessels taken from elsewhere in the body • STEMI: largely superseded for acute reperfusion by fibrinolysis and PCI; still used for some patients • UA/NSTEMI: recommended for severe CAD (e. g. , >50% stenosis of the left main artery or 3 -vessel disease) and when PCI is not feasible Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2007; 116: e 148 -e 304. Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292. Morrow DA, Boden WE. Stable ischemic heart disease. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 1210 -1269.

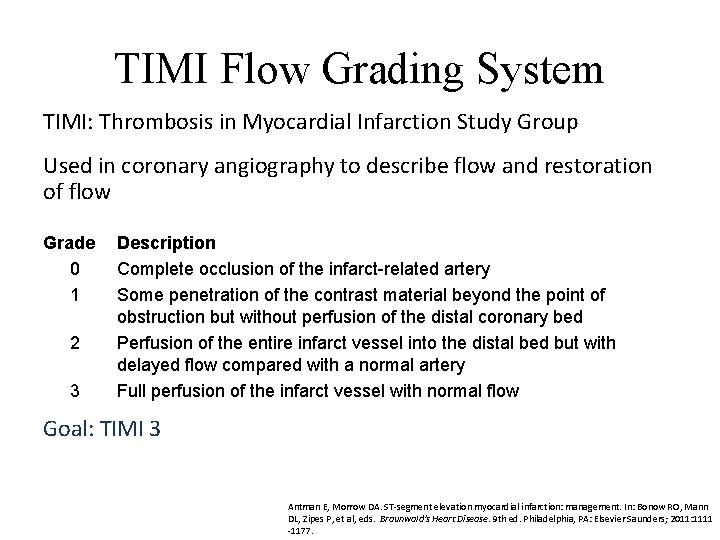

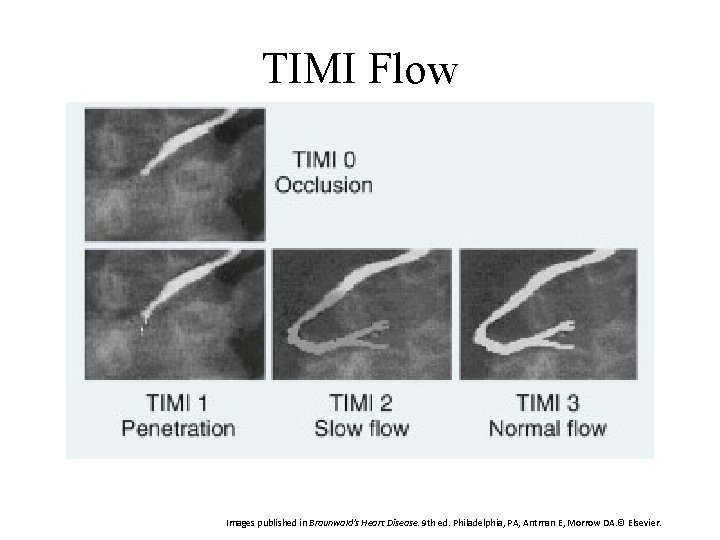

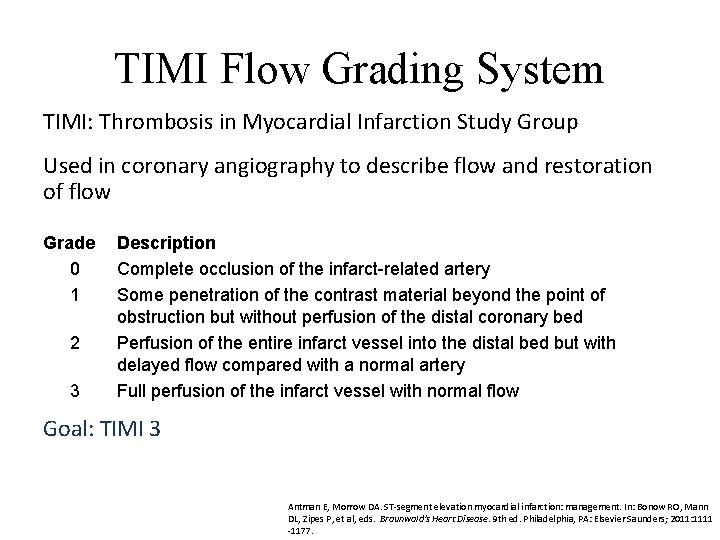

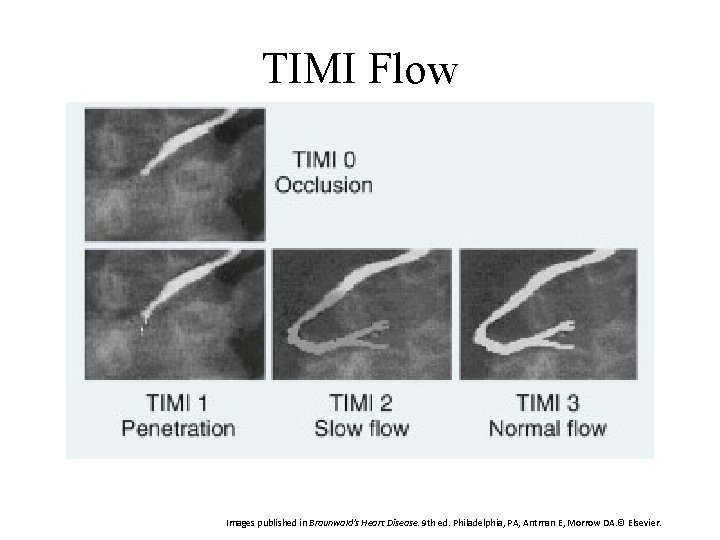

TIMI Flow Grading System TIMI: Thrombosis in Myocardial Infarction Study Group Used in coronary angiography to describe flow and restoration of flow Grade 0 1 2 3 Description Complete occlusion of the infarct related artery Some penetration of the contrast material beyond the point of obstruction but without perfusion of the distal coronary bed Perfusion of the entire infarct vessel into the distal bed but with delayed flow compared with a normal artery Full perfusion of the infarct vessel with normal flow Goal: TIMI 3 Antman E, Morrow DA. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: management. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 1111 -1177.

TIMI Flow Images published in Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA, Antman E, Morrow DA. © Elsevier.

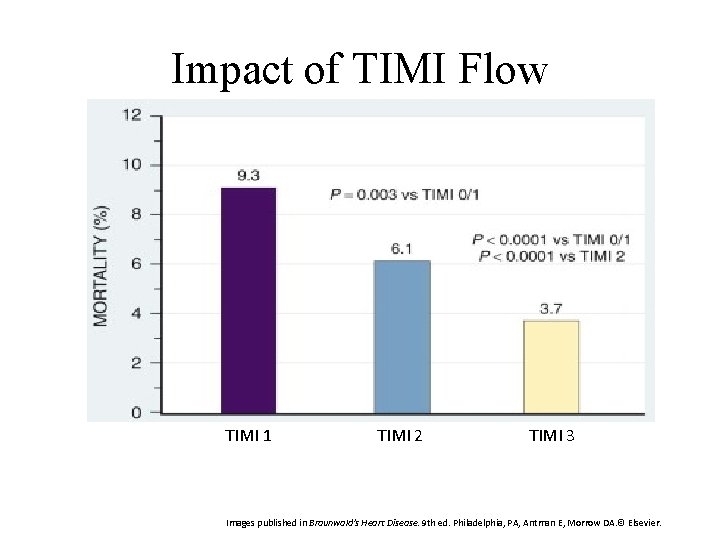

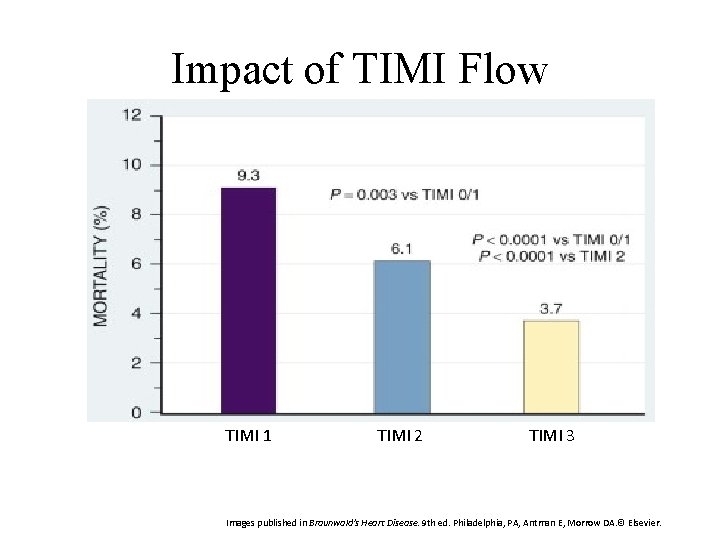

Impact of TIMI Flow TIMI 1 TIMI 2 TIMI 3 Images published in Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA, Antman E, Morrow DA. © Elsevier.

Myocardial Blush • Angiographic measure of blood flow through the microvasculature in the territory at risk • TIMI myocardial perfusion grading system extends TIMI flow grades – Usually when TIMI 3 flow is achieved – Measures dye in blood

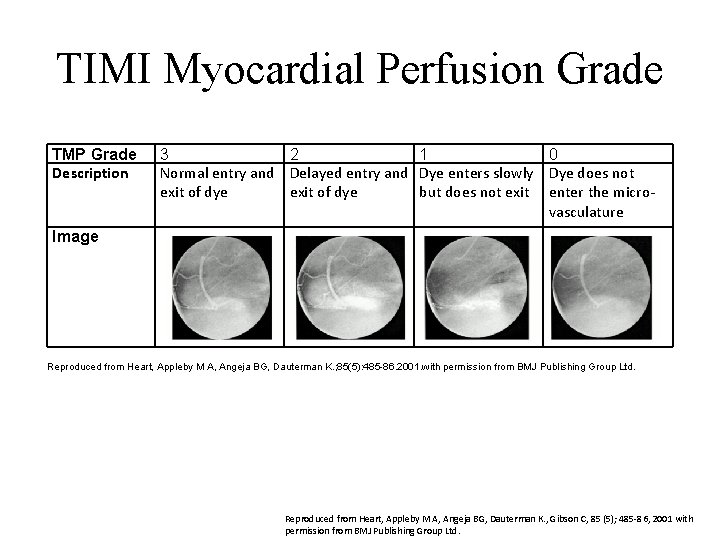

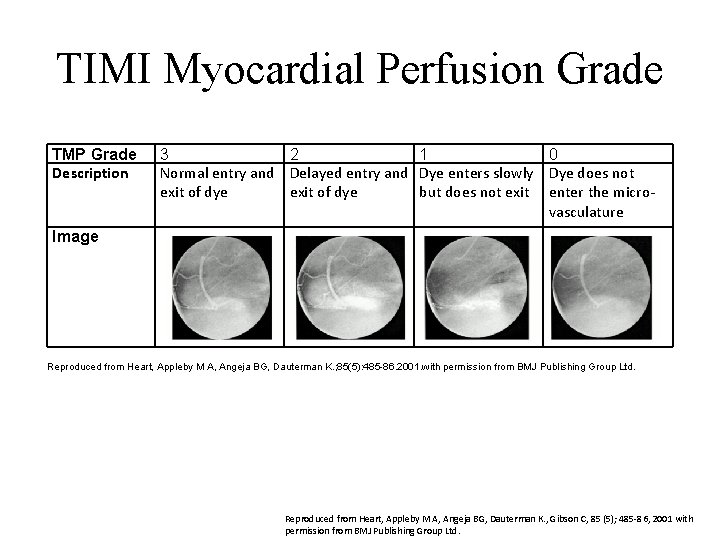

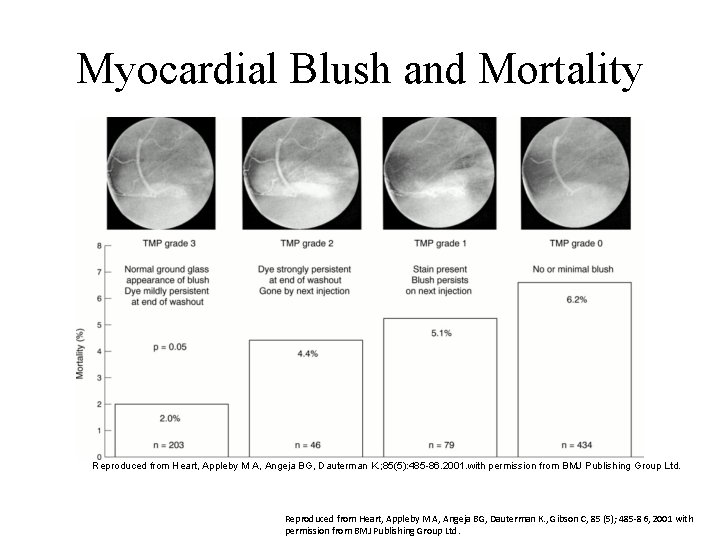

TIMI Myocardial Perfusion Grade TMP Grade Description 3 2 1 0 Normal entry and Delayed entry and Dye enters slowly Dye does not exit of dye but does not exit enter the microvasculature Image Reproduced from Heart, Appleby M A, Angeja BG, Dauterman K. ; 85(5): 485 86. 2001. with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. Reproduced from Heart, Appleby M A, Angeja BG, Dauterman K. , Gibson C, 85 (5); 485 -86, 2001 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

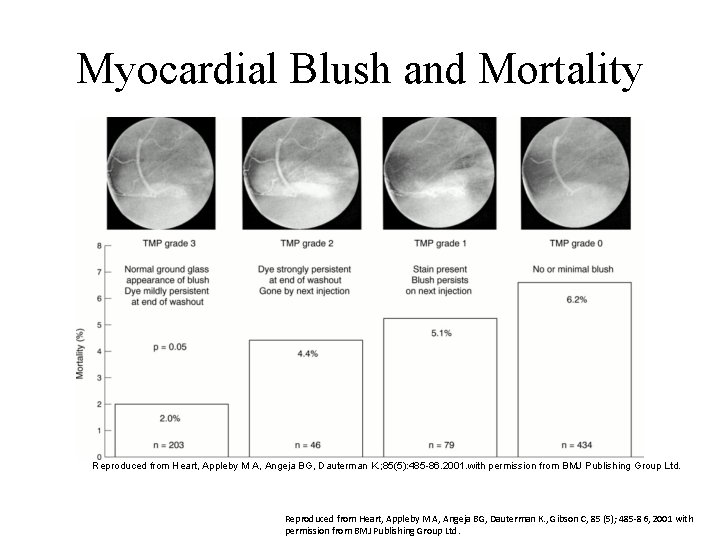

Myocardial Blush and Mortality Reproduced from Heart, Appleby M A, Angeja BG, Dauterman K. ; 85(5): 485 86. 2001. with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. Reproduced from Heart, Appleby M A, Angeja BG, Dauterman K. , Gibson C, 85 (5); 485 -86, 2001 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

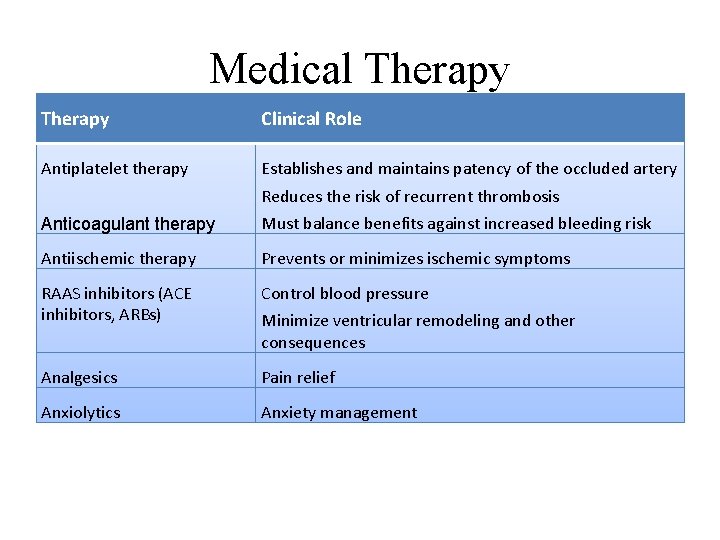

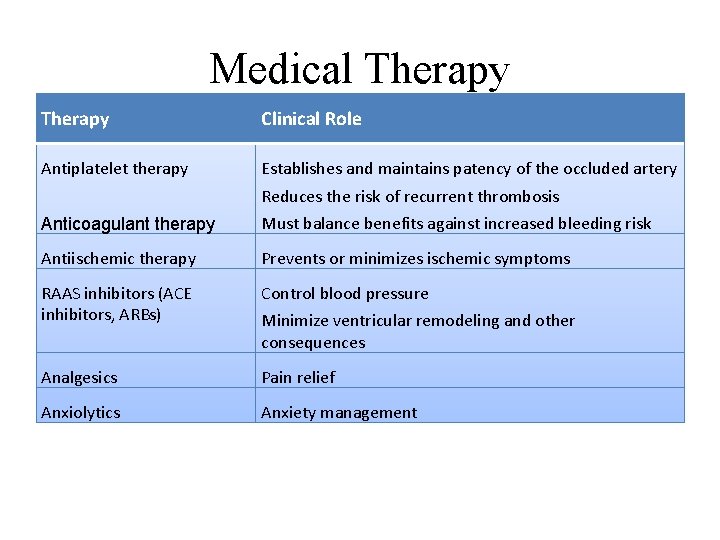

Medical Therapy Clinical Role Antiplatelet therapy Establishes and maintains patency of the occluded artery Reduces the risk of recurrent thrombosis Anticoagulant therapy Must balance benefits against increased bleeding risk Antiischemic therapy Prevents or minimizes ischemic symptoms RAAS inhibitors (ACE inhibitors, ARBs) Control blood pressure Analgesics Pain relief Anxiolytics Anxiety management Minimize ventricular remodeling and other consequences

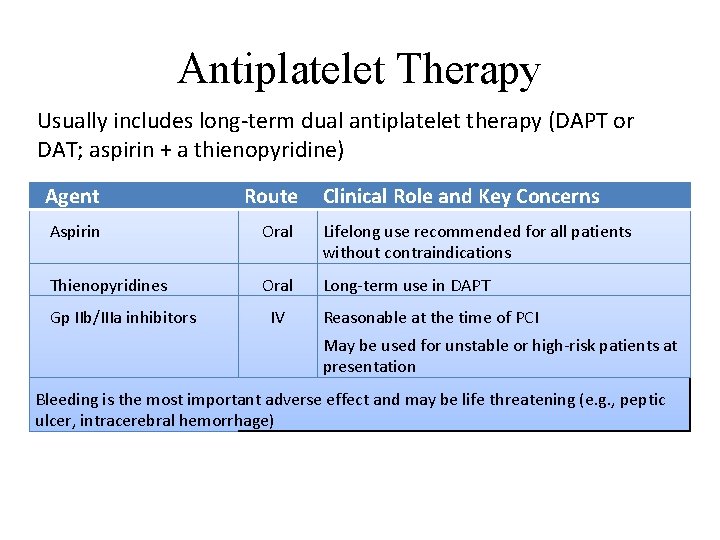

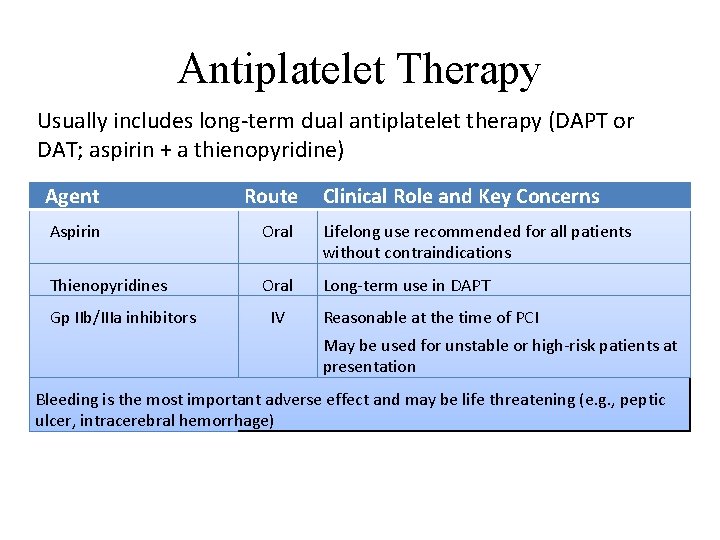

Antiplatelet Therapy Usually includes long-term dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT or DAT; aspirin + a thienopyridine) Agent Route Aspirin Oral Lifelong use recommended for all patients without contraindications Thienopyridines Oral Long-term use in DAPT Gp IIb/IIIa inhibitors IV Clinical Role and Key Concerns Reasonable at the time of PCI May be used for unstable or high-risk patients at presentation Bleeding is the most important adverse effect and may be life threatening (e. g. , peptic ulcer, intracerebral hemorrhage)

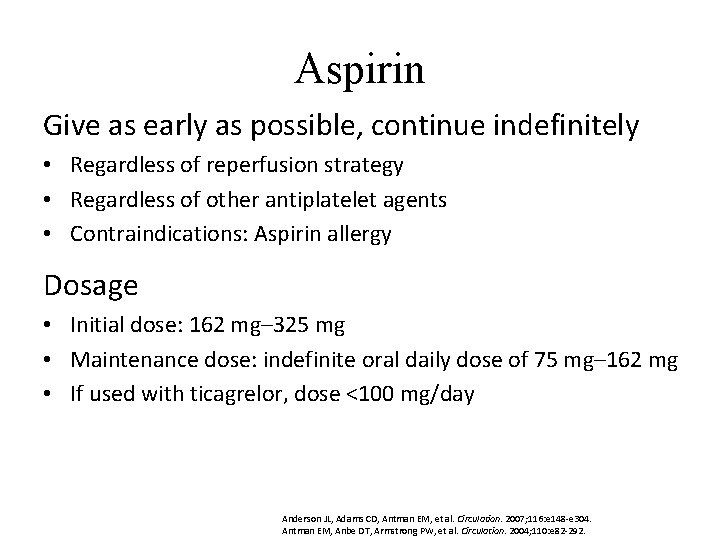

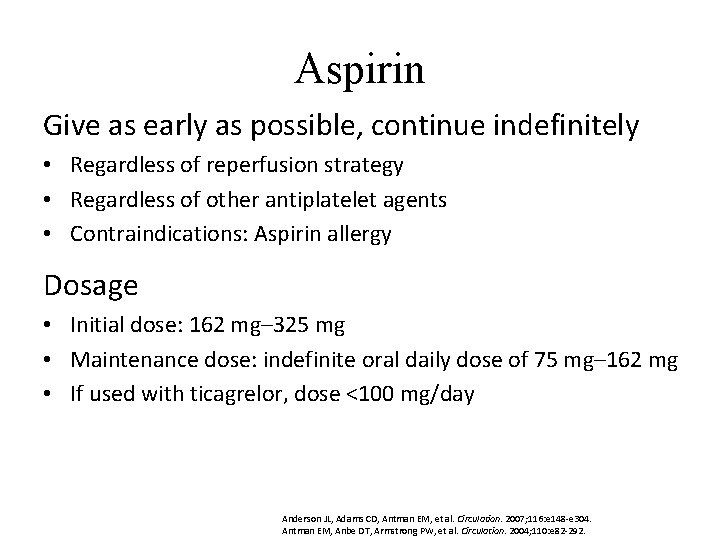

Aspirin Give as early as possible, continue indefinitely • Regardless of reperfusion strategy • Regardless of other antiplatelet agents • Contraindications: Aspirin allergy Dosage • Initial dose: 162 mg– 325 mg • Maintenance dose: indefinite oral daily dose of 75 mg– 162 mg • If used with ticagrelor, dose <100 mg/day Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2007; 116: e 148 -e 304. Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292.

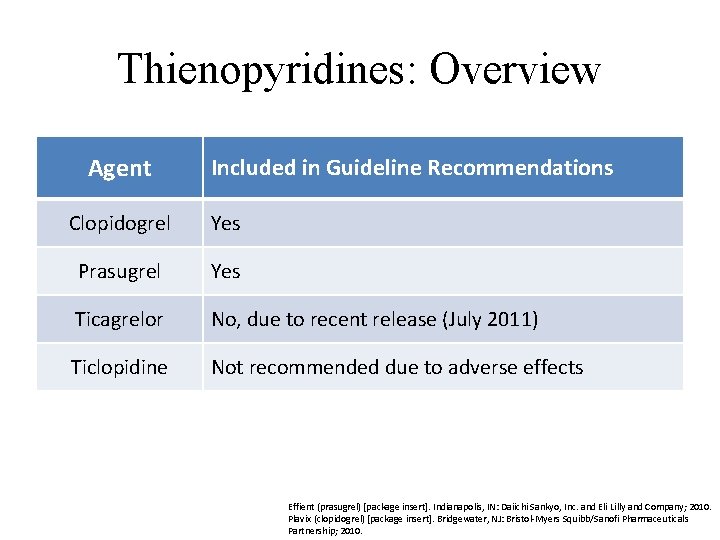

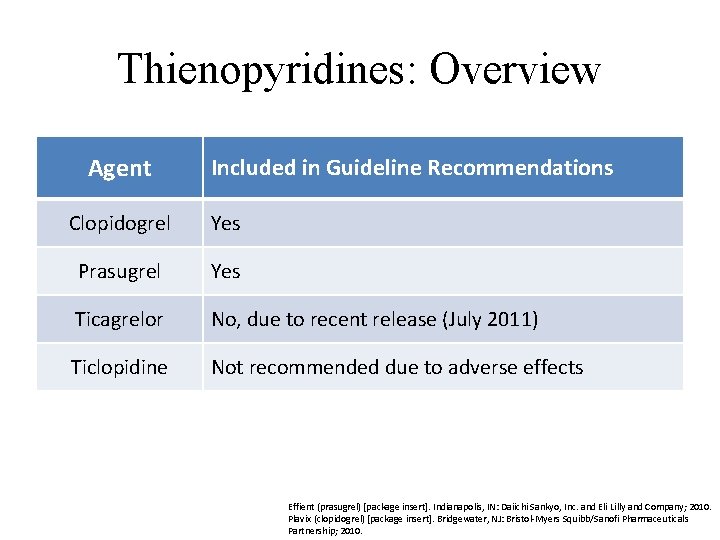

Thienopyridines: Overview Agent Included in Guideline Recommendations Clopidogrel Yes Prasugrel Yes Ticagrelor No, due to recent release (July 2011) Ticlopidine Not recommended due to adverse effects Effient (prasugrel) [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Daiichi Sankyo, Inc. and Eli Lilly and Company; 2010. Plavix (clopidogrel) [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi Pharmaceuticals Partnership; 2010.

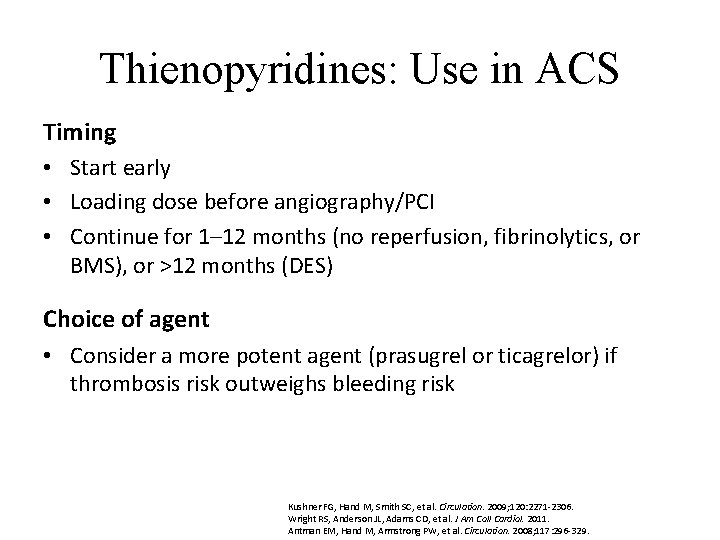

Thienopyridines: Use in ACS Timing • Start early • Loading dose before angiography/PCI • Continue for 1– 12 months (no reperfusion, fibrinolytics, or BMS), or >12 months (DES) Choice of agent • Consider a more potent agent (prasugrel or ticagrelor) if thrombosis risk outweighs bleeding risk Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, et al. Circulation. 2009; 120: 2271 -2306. Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011. Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2008; 117: 296 -329.

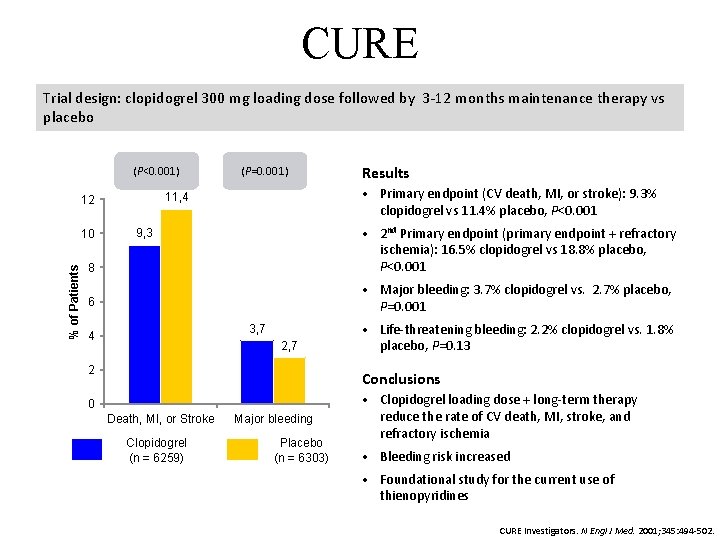

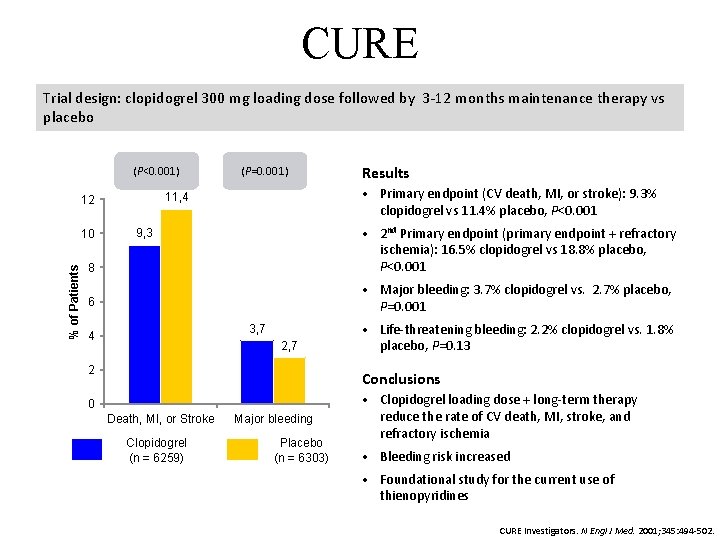

CURE Trial design: clopidogrel 300 mg loading dose followed by 3 -12 months maintenance therapy vs placebo (P<0. 001) Results • Primary endpoint (CV death, MI, or stroke): 9. 3% clopidogrel vs 11. 4% placebo, P<0. 001 11, 4 12 8 • 2 nd Primary endpoint (primary endpoint + refractory ischemia): 16. 5% clopidogrel vs 18. 8% placebo, P<0. 001 6 • Major bleeding: 3. 7% clopidogrel vs. 2. 7% placebo, P=0. 001 10 % of Patients (P=0. 001) 9, 3 3, 7 4 2, 7 2 • Life-threatening bleeding: 2. 2% clopidogrel vs. 1. 8% placebo, P=0. 13 Conclusions 0 Death, MI, or Stroke Clopidogrel (n = 6259) Major bleeding Placebo (n = 6303) • Clopidogrel loading dose + long-term therapy reduce the rate of CV death, MI, stroke, and refractory ischemia • Bleeding risk increased • Foundational study for the current use of thienopyridines CURE Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345: 494 -502.

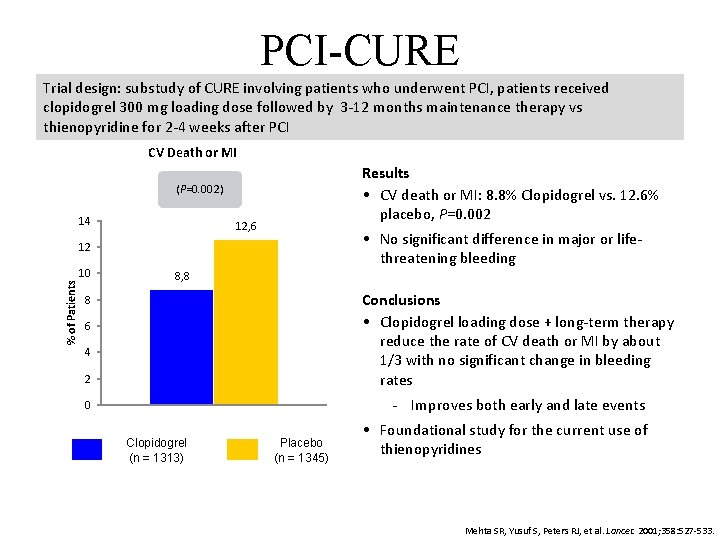

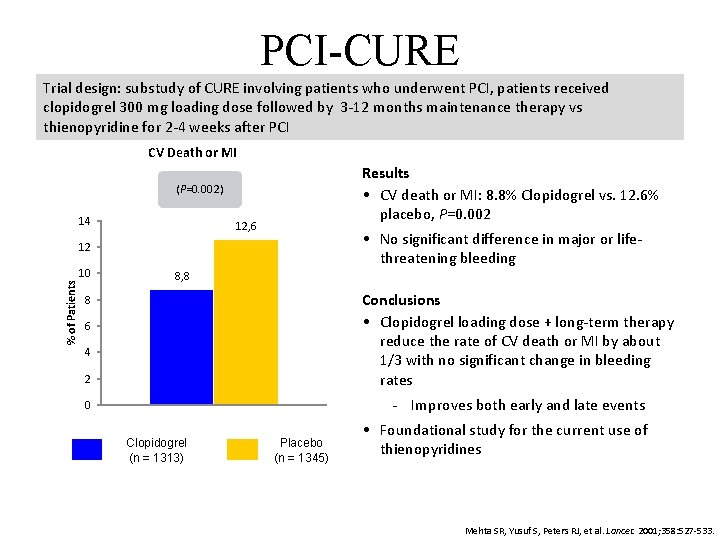

PCI-CURE Trial design: substudy of CURE involving patients who underwent PCI, patients received clopidogrel 300 mg loading dose followed by 3 -12 months maintenance therapy vs thienopyridine for 2 -4 weeks after PCI CV Death or MI Results • CV death or MI: 8. 8% Clopidogrel vs. 12. 6% placebo, P=0. 002 (P=0. 002) 14 12, 6 • No significant difference in major or lifethreatening bleeding % of Patients 12 10 8, 8 2 Conclusions • Clopidogrel loading dose + long-term therapy reduce the rate of CV death or MI by about 1/3 with no significant change in bleeding rates 0 Improves both early and late events 8 6 4 Clopidogrel (n = 1313) Placebo (n = 1345) • Foundational study for the current use of thienopyridines Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, et al. Lancet. 2001; 358: 527 -533.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitors: Overview Available agents • Eptifibatide, tirofiban, abciximab Use in ACS • To reduce thrombosis risk in selected patients, e. g. , those with – High risk – Insufficient thienopyridine preloading – Large thrombus • In combination with reduced-dose fibrinolytics for reperfusion Timing • Short-term: during the hospital stay Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292. Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, et al. Circulation. 2009; 120: 2271 -2306. Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011. Hanna EB, Rao SV, Manoukian SV, Saucedo JF. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010; 3: 1209 -1219.

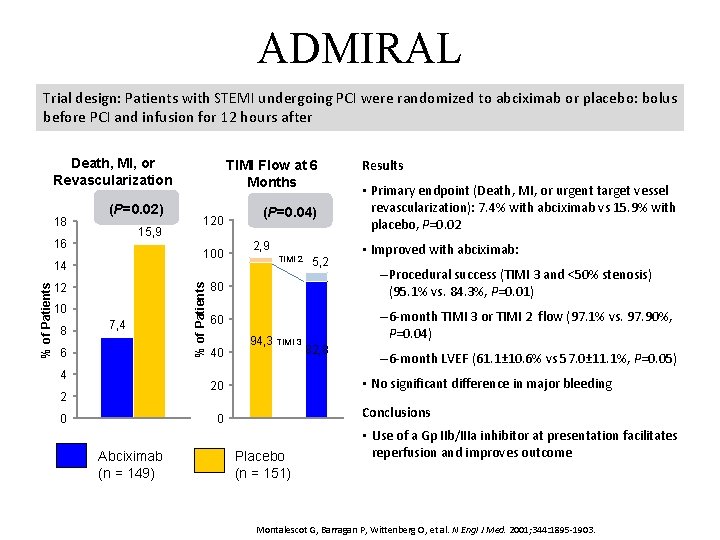

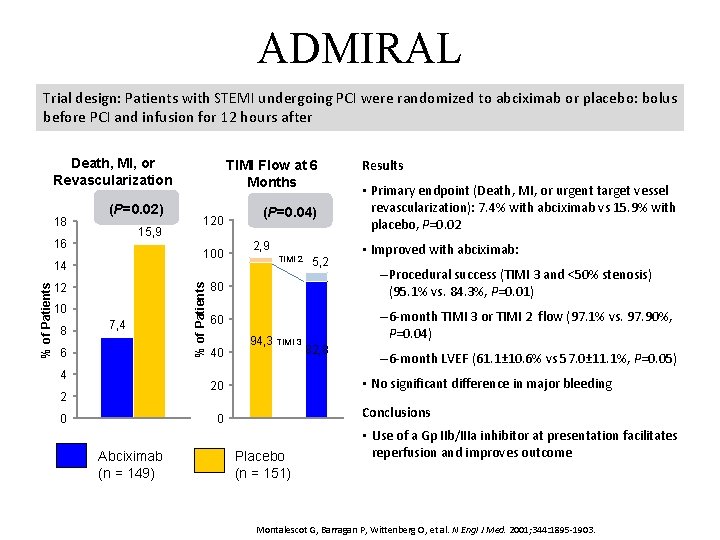

ADMIRAL Trial design: Patients with STEMI undergoing PCI were randomized to abciximab or placebo: bolus before PCI and infusion for 12 hours after Death, MI, or Revascularization (P=0. 02) 15, 9 16 100 % of Patients 14 12 10 8 120 7, 4 6 4 % of Patients 18 TIMI Flow at 6 Months (P=0. 04) 2, 9 TIMI 2 0 • Improved with abciximab: – Procedural success (TIMI 3 and <50% stenosis) (95. 1% vs. 84. 3%, P=0. 01) 60 – 6 -month TIMI 3 or TIMI 2 flow (97. 1% vs. 97. 90%, P=0. 04) 40 94, 3 TIMI 3 82, 8 – 6 -month LVEF (61. 1± 10. 6% vs 57. 0± 11. 1%, P=0. 05) • No significant difference in major bleeding Conclusions 0 Abciximab (n = 149) • Primary endpoint (Death, MI, or urgent target vessel revascularization): 7. 4% with abciximab vs 15. 9% with placebo, P=0. 02 80 20 2 5, 2 Results Placebo (n = 151) • Use of a Gp IIb/IIIa inhibitor at presentation facilitates reperfusion and improves outcome Montalescot G, Barragan P, Wittenberg O, et al. N Engl J Med. 2001; 344: 1895 -1903.

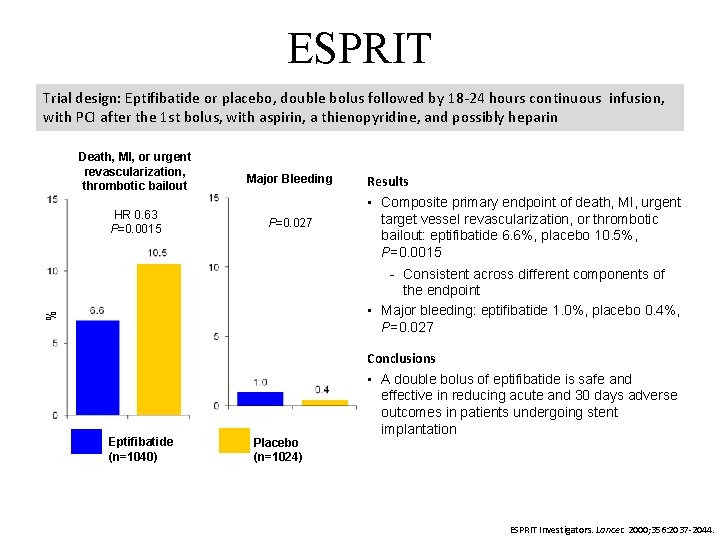

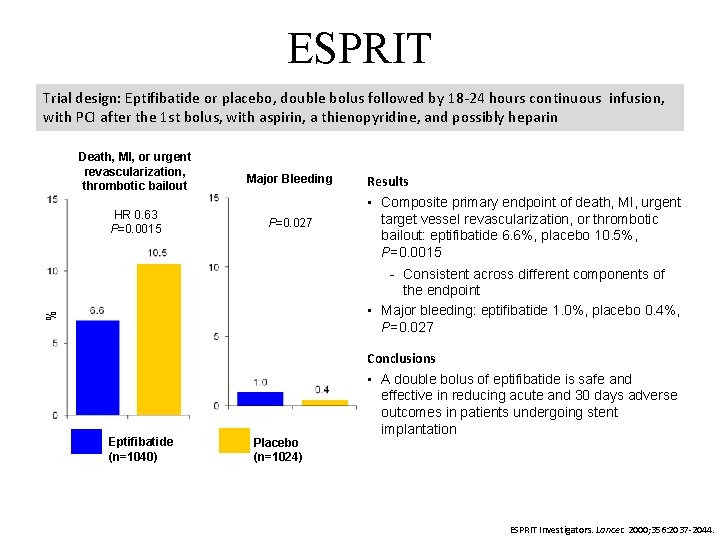

ESPRIT Trial design: Eptifibatide or placebo, double bolus followed by 18 -24 hours continuous infusion, with PCI after the 1 st bolus, with aspirin, a thienopyridine, and possibly heparin Death, MI, or urgent revascularization, thrombotic bailout HR 0. 63 P=0. 0015 Major Bleeding P=0. 027 Results • Composite primary endpoint of death, MI, urgent target vessel revascularization, or thrombotic bailout: eptifibatide 6. 6%, placebo 10. 5%, P=0. 0015 % Consistent across different components of the endpoint • Major bleeding: eptifibatide 1. 0%, placebo 0. 4%, P=0. 027 Eptifibatide (n=1040) Placebo (n=1024) Conclusions • A double bolus of eptifibatide is safe and effective in reducing acute and 30 days adverse outcomes in patients undergoing stent implantation ESPRIT Investigators. Lancet. 2000; 356: 2037 -2044.

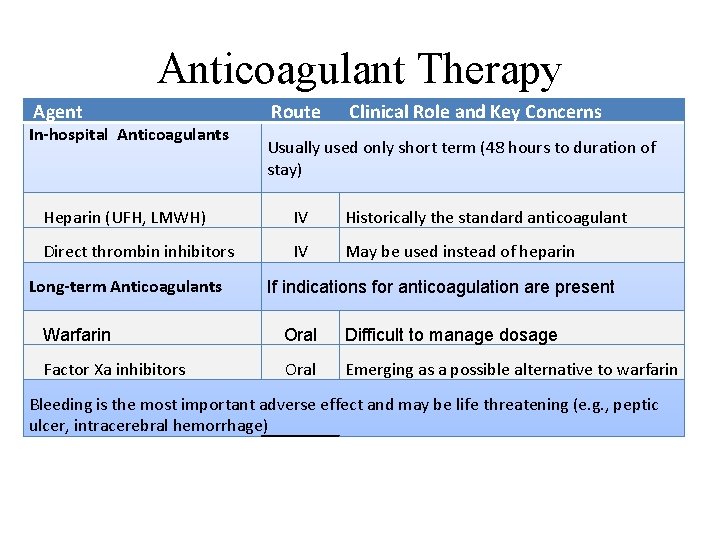

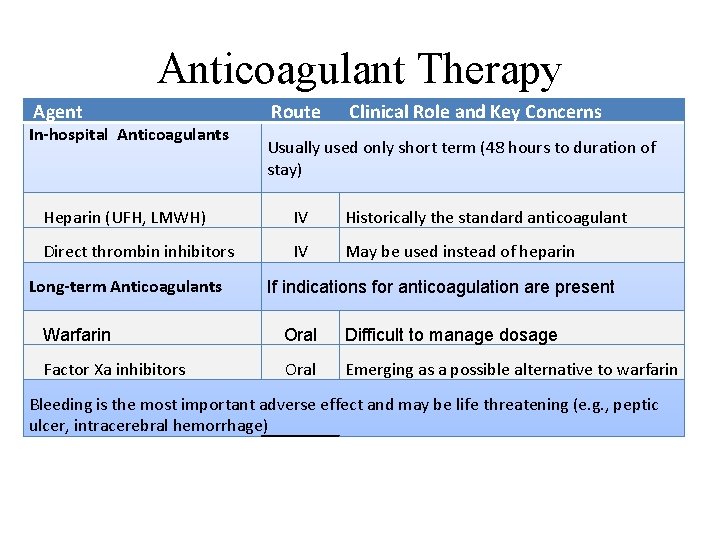

Anticoagulant Therapy Agent In-hospital Anticoagulants Route Clinical Role and Key Concerns Usually used only short term (48 hours to duration of stay) Heparin (UFH, LMWH) IV Historically the standard anticoagulant Direct thrombin inhibitors IV May be used instead of heparin Long-term Anticoagulants If indications for anticoagulation are present Warfarin Oral Difficult to manage dosage Factor Xa inhibitors Oral Emerging as a possible alternative to warfarin Bleeding is the most important adverse effect and may be life threatening (e. g. , peptic ulcer, intracerebral hemorrhage)

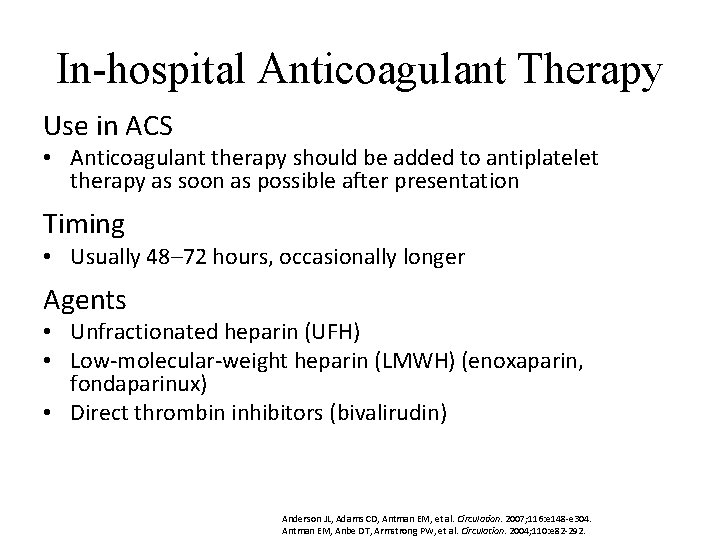

In-hospital Anticoagulant Therapy Use in ACS • Anticoagulant therapy should be added to antiplatelet therapy as soon as possible after presentation Timing • Usually 48– 72 hours, occasionally longer Agents • Unfractionated heparin (UFH) • Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) (enoxaparin, fondaparinux) • Direct thrombin inhibitors (bivalirudin) Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2007; 116: e 148 -e 304. Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292.

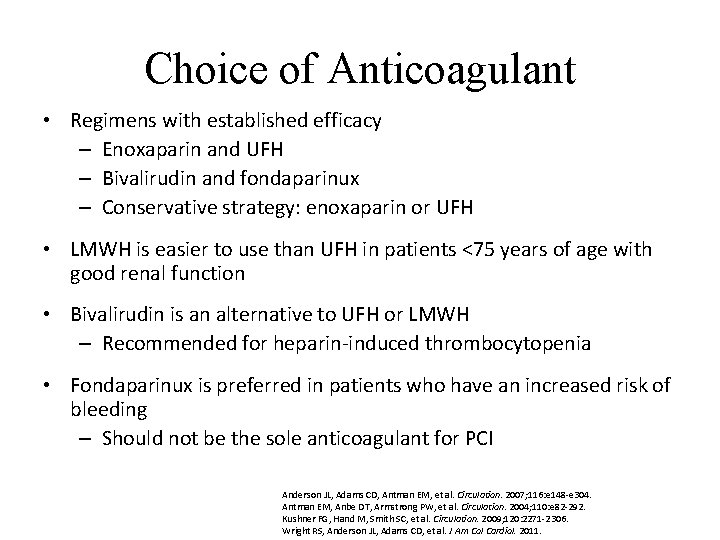

Choice of Anticoagulant • Regimens with established efficacy – Enoxaparin and UFH – Bivalirudin and fondaparinux – Conservative strategy: enoxaparin or UFH • LMWH is easier to use than UFH in patients <75 years of age with good renal function • Bivalirudin is an alternative to UFH or LMWH – Recommended for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia • Fondaparinux is preferred in patients who have an increased risk of bleeding – Should not be the sole anticoagulant for PCI Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2007; 116: e 148 -e 304. Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292. Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, et al. Circulation. 2009; 120: 2271 -2306. Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al. J Am Col Cardiol. 2011.

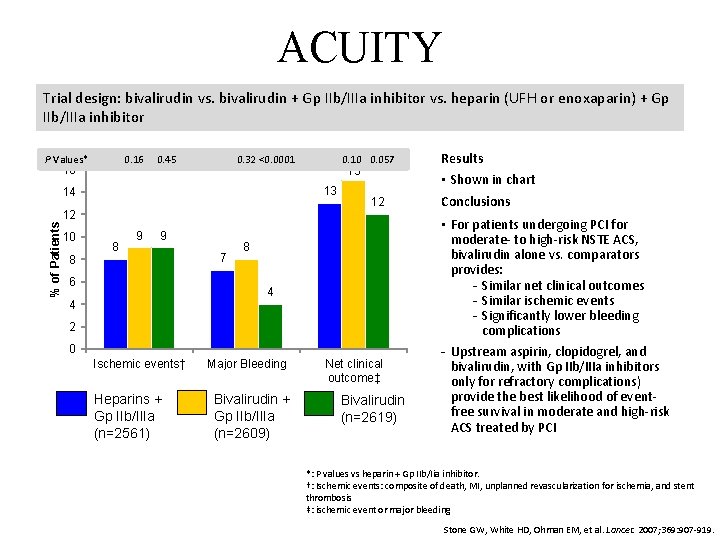

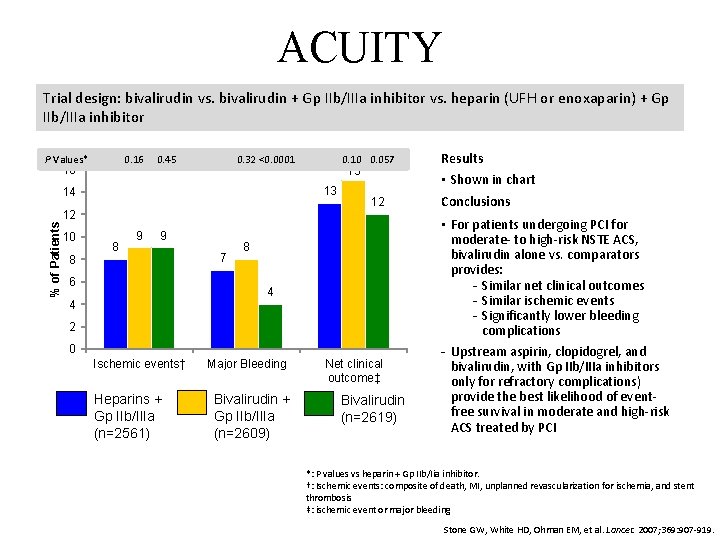

ACUITY Trial design: bivalirudin vs. bivalirudin + Gp IIb/IIIa inhibitor vs. heparin (UFH or enoxaparin) + Gp IIb/IIIa inhibitor P Values* 0. 16 16 0. 45 0. 32 <0. 0001 % of Patients 12 8 15 13 14 10 0. 057 8 9 9 6 7 12 8 4 4 2 0 Ischemic events† Heparins + Gp IIb/IIIa (n=2561) Major Bleeding Bivalirudin + Gp IIb/IIIa (n=2609) Net clinical outcome‡ Bivalirudin (n=2619) Results • Shown in chart Conclusions • For patients undergoing PCI for moderate- to high-risk NSTE ACS, bivalirudin alone vs. comparators provides: Similar net clinical outcomes Similar ischemic events Significantly lower bleeding complications Upstream aspirin, clopidogrel, and bivalirudin, with Gp IIb/IIIa inhibitors only for refractory complications) provide the best likelihood of eventfree survival in moderate and high-risk ACS treated by PCI *: P values vs heparin + Gp IIb/Iia inhibitor. †: Ischemic events: composite of death, MI, unplanned revascularization for ischemia, and stent thrombosis ‡: ischemic event or major bleeding Stone GW, White HD, Ohman EM, et al. Lancet. 2007; 369: 907 -919.

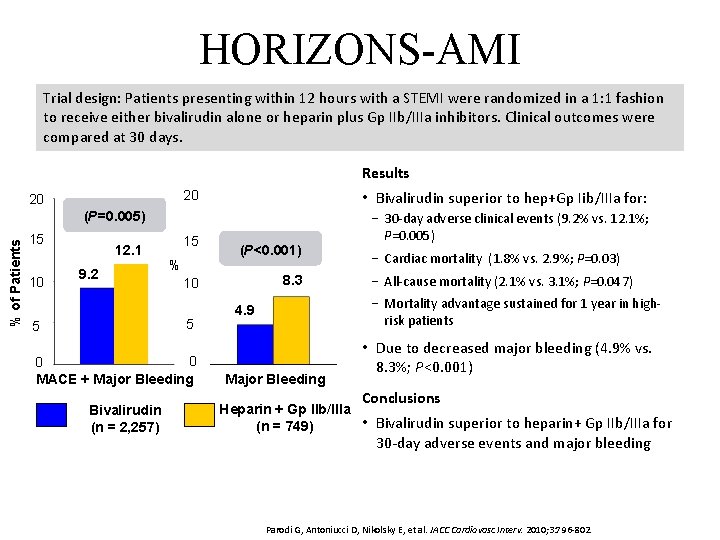

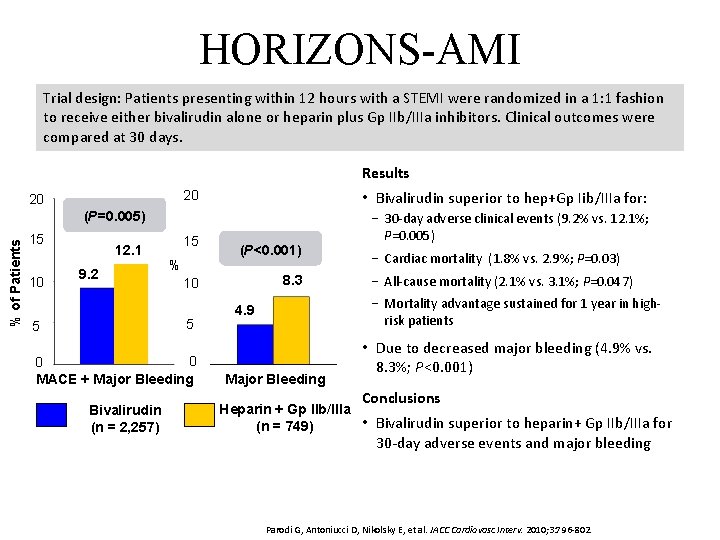

HORIZONS-AMI Trial design: Patients presenting within 12 hours with a STEMI were randomized in a 1: 1 fashion to receive either bivalirudin alone or heparin plus Gp IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Clinical outcomes were compared at 30 days. Results 20 20 • Bivalirudin superior to hep+Gp Iib/IIIa for: 15 − 30 -day adverse clinical events (9. 2% vs. 12. 1%; P=0. 005) % of Patients (P=0. 005) 15 10 12. 1 9. 2 % 0 0 MACE + Major Bleeding Bivalirudin (n = 2, 257) 8. 3 10 5 5 (P<0. 001) − Cardiac mortality (1. 8% vs. 2. 9%; P=0. 03) − All-cause mortality (2. 1% vs. 3. 1%; P=0. 047) − Mortality advantage sustained for 1 year in highrisk patients 4. 9 Major Bleeding • Due to decreased major bleeding (4. 9% vs. 8. 3%; P<0. 001) Conclusions Heparin + Gp IIb/IIIa • Bivalirudin superior to heparin+ Gp IIb/IIIa for (n = 749) 30 -day adverse events and major bleeding Parodi G, Antoniucci D, Nikolsky E, et al. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010; 3: 796 -802.

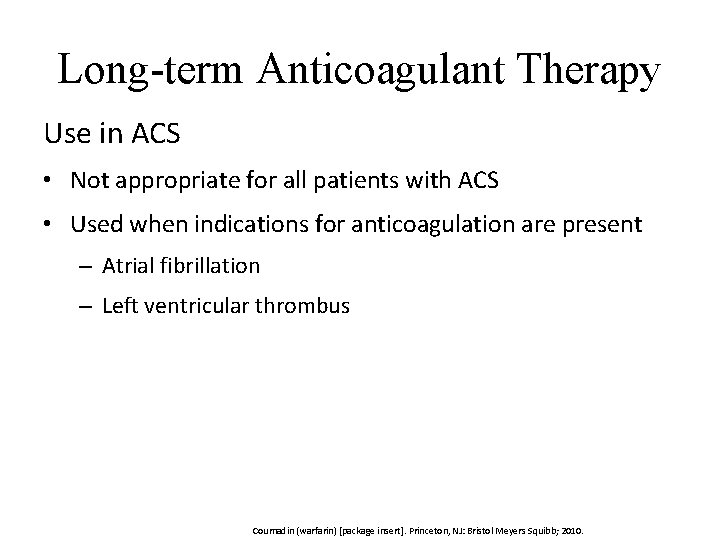

Long-term Anticoagulant Therapy Use in ACS • Not appropriate for all patients with ACS • Used when indications for anticoagulation are present – Atrial fibrillation – Left ventricular thrombus Coumadin (warfarin) [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol Meyers Squibb; 2010.

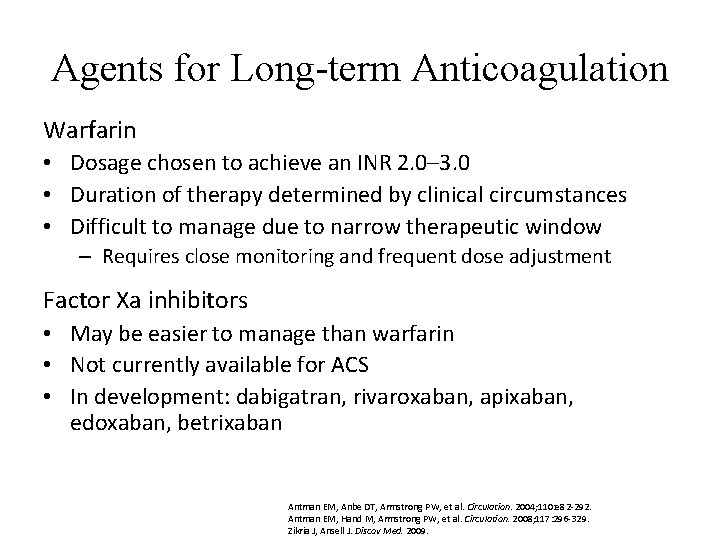

Agents for Long-term Anticoagulation Warfarin • Dosage chosen to achieve an INR 2. 0– 3. 0 • Duration of therapy determined by clinical circumstances • Difficult to manage due to narrow therapeutic window – Requires close monitoring and frequent dose adjustment Factor Xa inhibitors • May be easier to manage than warfarin • Not currently available for ACS • In development: dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, betrixaban Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292. Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2008; 117: 296 -329. Zikria J, Ansell J. Discov Med. 2009.

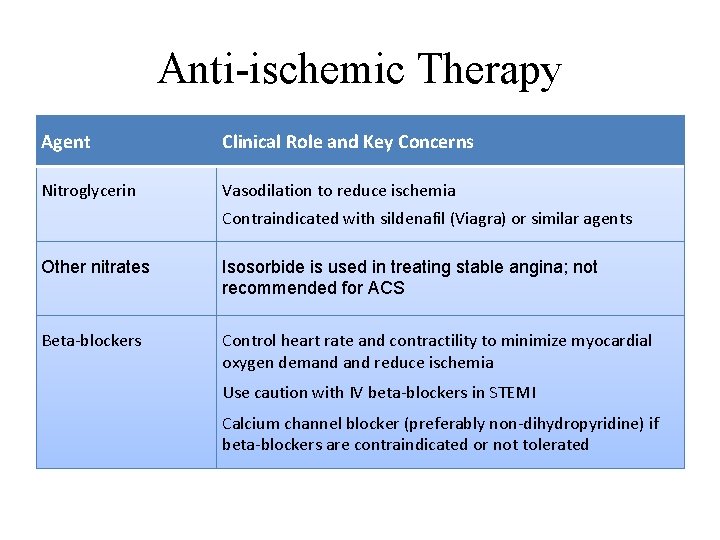

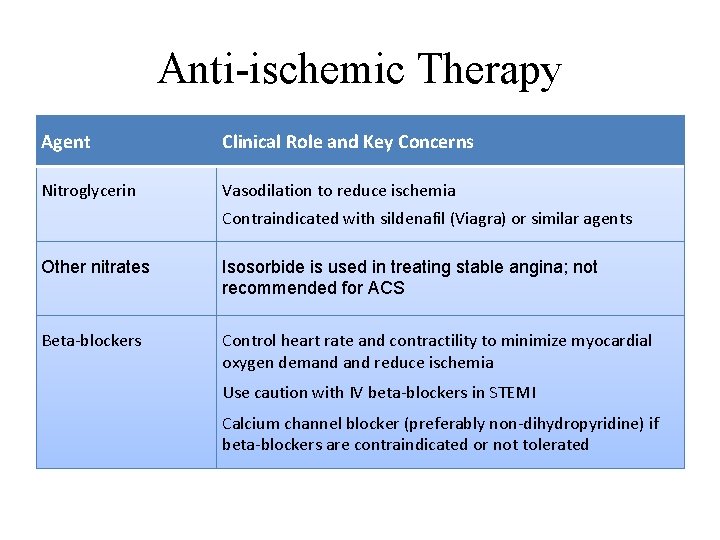

Anti-ischemic Therapy Agent Clinical Role and Key Concerns Nitroglycerin Vasodilation to reduce ischemia Contraindicated with sildenafil (Viagra) or similar agents Other nitrates Isosorbide is used in treating stable angina; not recommended for ACS Beta-blockers Control heart rate and contractility to minimize myocardial oxygen demand reduce ischemia Use caution with IV beta-blockers in STEMI Calcium channel blocker (preferably non-dihydropyridine) if beta-blockers are contraindicated or not tolerated

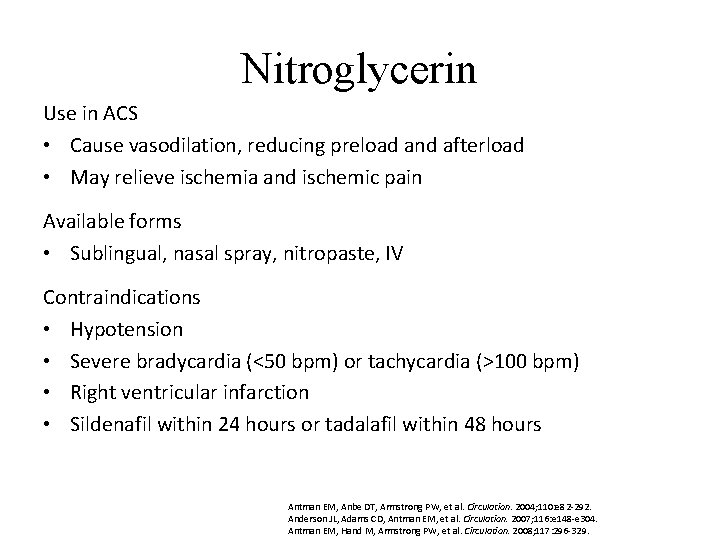

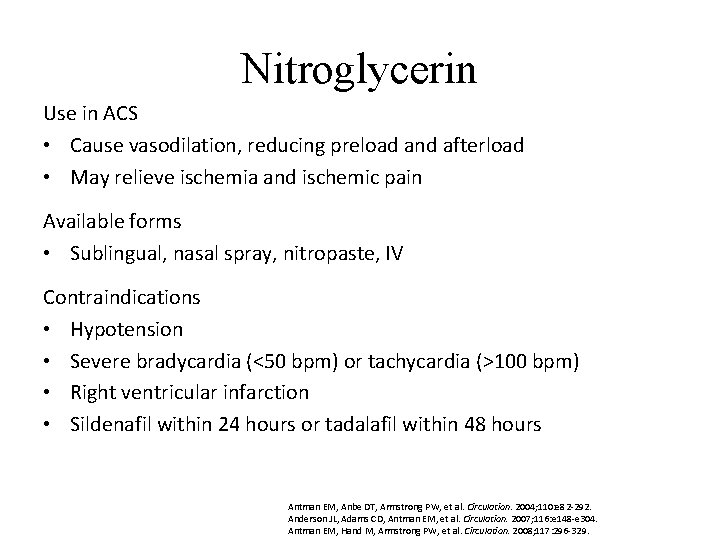

Nitroglycerin Use in ACS • Cause vasodilation, reducing preload and afterload • May relieve ischemia and ischemic pain Available forms • Sublingual, nasal spray, nitropaste, IV Contraindications • Hypotension • Severe bradycardia (<50 bpm) or tachycardia (>100 bpm) • Right ventricular infarction • Sildenafil within 24 hours or tadalafil within 48 hours Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2007; 116: e 148 -e 304. Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2008; 117: 296 -329.

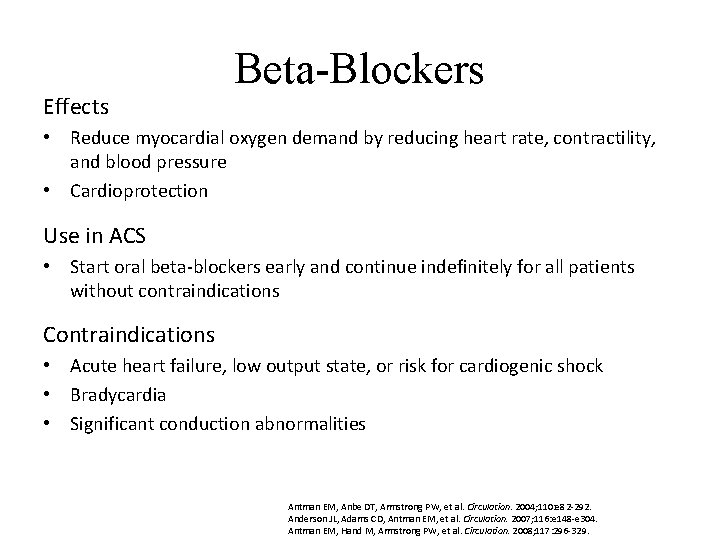

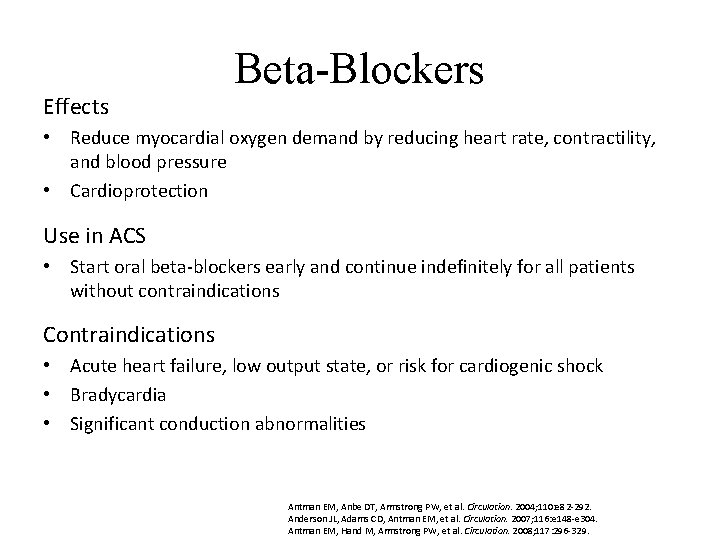

Effects Beta-Blockers • Reduce myocardial oxygen demand by reducing heart rate, contractility, and blood pressure • Cardioprotection Use in ACS • Start oral beta-blockers early and continue indefinitely for all patients without contraindications Contraindications • Acute heart failure, low output state, or risk for cardiogenic shock • Bradycardia • Significant conduction abnormalities Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2007; 116: e 148 -e 304. Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2008; 117: 296 -329.

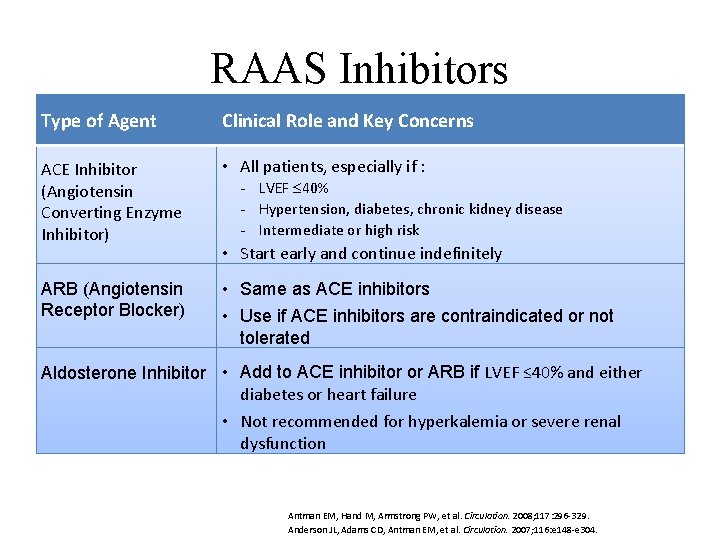

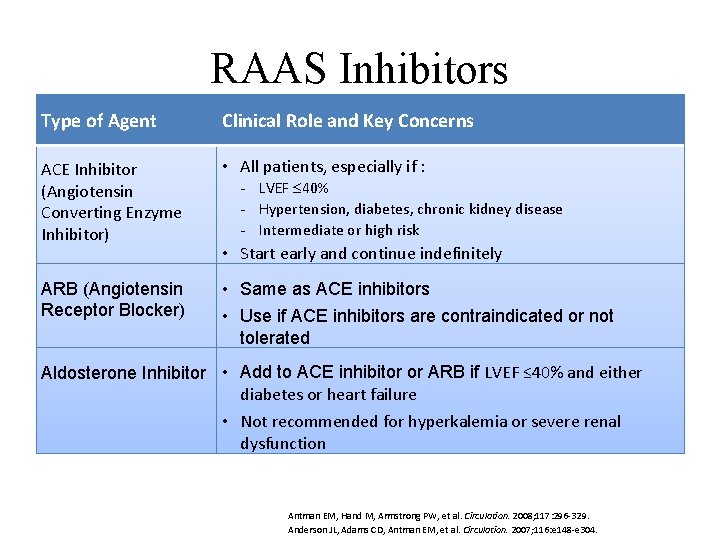

RAAS Inhibitors Type of Agent Clinical Role and Key Concerns • ACEAngiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) • All patients, especially if : Inhibitor (Angiotensin inhibitors LVEF 40% Hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease Converting Enzyme Intermediate or high risk Inhibitor) • Angiotensin • receptor blockers (ARBs) Start early and continue indefinitely • Aldosterone ARB (Angiotensin • inhibitors Same as ACE inhibitors Receptor Blocker) • Use if ACE inhibitors are contraindicated or not • Direct renin inhibitors (not generally used in tolerated the setting ACS) • Add to ACE inhibitor or ARB if LVEF ≤ 40% and either Aldosterone Inhibitor of diabetes or heart failure • Not recommended for hyperkalemia or severe renal dysfunction Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2008; 117: 296 -329. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2007; 116: e 148 -e 304.

Complications of ACS • Arrhythmias • Hemodynamic disturbances • Mechanical damage • Recurrent chest pain • Ischemic stroke • Deep venous thrombosis • Pulmonary embolism

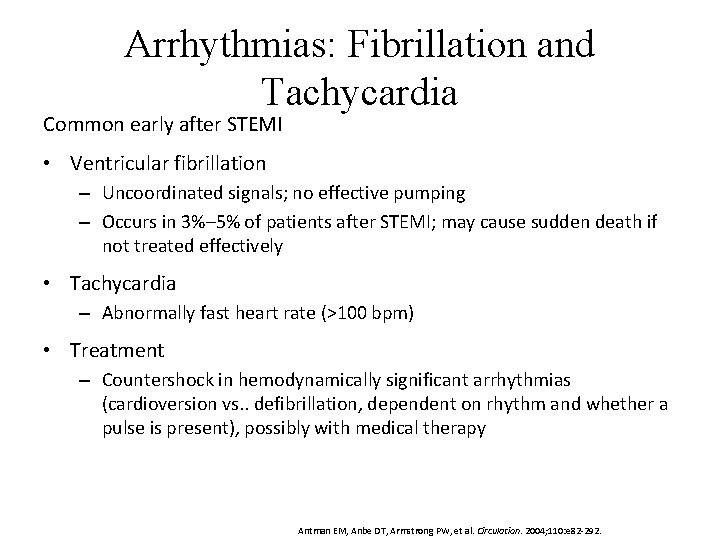

Arrhythmias: Fibrillation and Tachycardia Common early after STEMI • Ventricular fibrillation – Uncoordinated signals; no effective pumping – Occurs in 3%– 5% of patients after STEMI; may cause sudden death if not treated effectively • Tachycardia – Abnormally fast heart rate (>100 bpm) • Treatment – Countershock in hemodynamically significant arrhythmias (cardioversion vs. . defibrillation, dependent on rhythm and whether a pulse is present), possibly with medical therapy Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292.

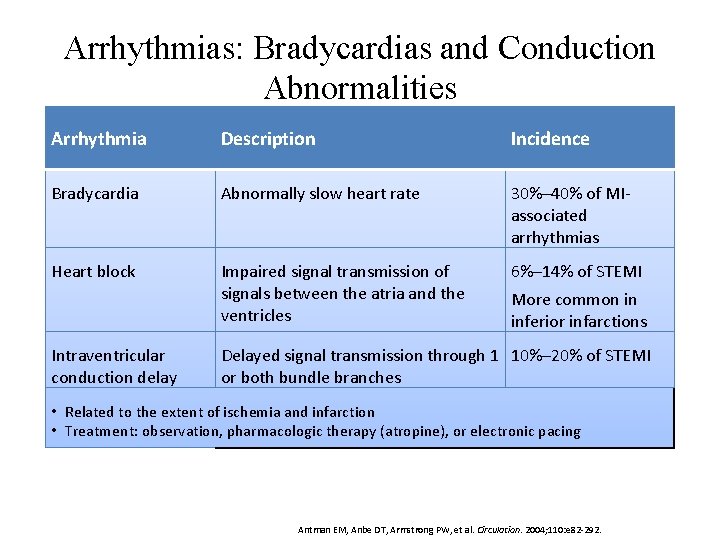

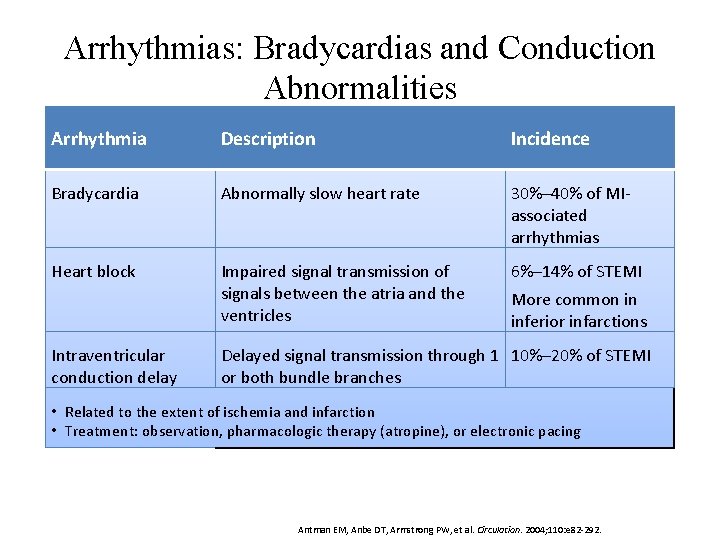

Arrhythmias: Bradycardias and Conduction Abnormalities Arrhythmia Description Incidence Bradycardia Abnormally slow heart rate 30%– 40% of MIassociated arrhythmias Heart block Impaired signal transmission of signals between the atria and the ventricles 6%– 14% of STEMI Intraventricular conduction delay More common in inferior infarctions Delayed signal transmission through 1 10%– 20% of STEMI or both bundle branches • Related to the extent of ischemia and infarction • Treatment: observation, pharmacologic therapy (atropine), or electronic pacing Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292.

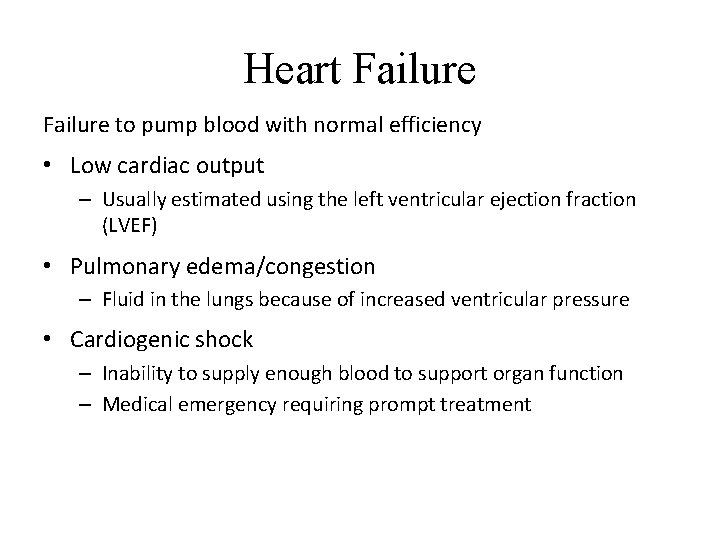

Heart Failure to pump blood with normal efficiency • Low cardiac output – Usually estimated using the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) • Pulmonary edema/congestion – Fluid in the lungs because of increased ventricular pressure • Cardiogenic shock – Inability to supply enough blood to support organ function – Medical emergency requiring prompt treatment

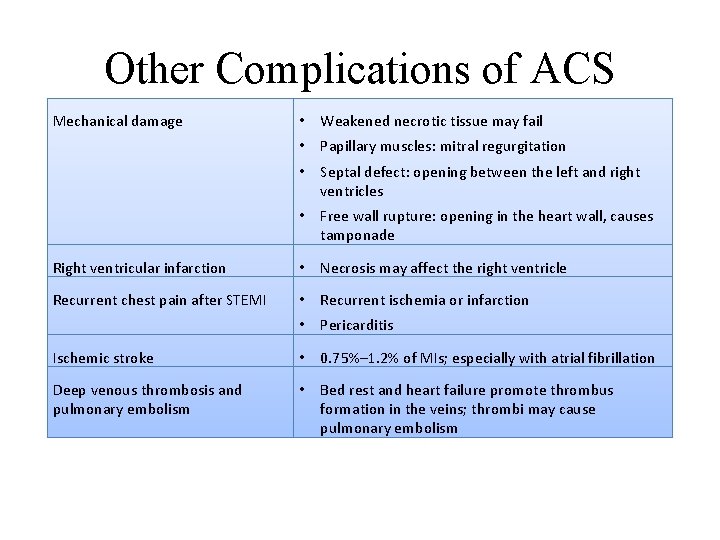

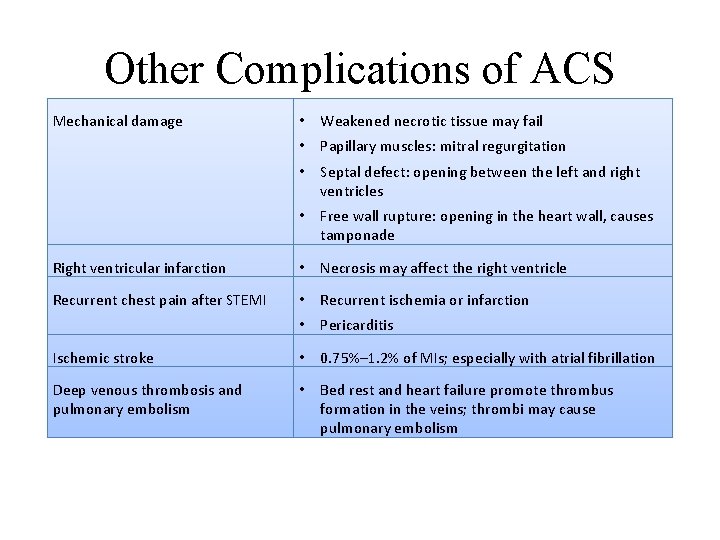

Other Complications of ACS Mechanical damage • Weakened necrotic tissue may fail • Papillary muscles: mitral regurgitation • Septal defect: opening between the left and right ventricles • Free wall rupture: opening in the heart wall, causes tamponade Right ventricular infarction • Necrosis may affect the right ventricle Recurrent chest pain after STEMI • Recurrent ischemia or infarction • Pericarditis Ischemic stroke • 0. 75%– 1. 2% of MIs; especially with atrial fibrillation Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism • Bed rest and heart failure promote thrombus formation in the veins; thrombi may cause pulmonary embolism

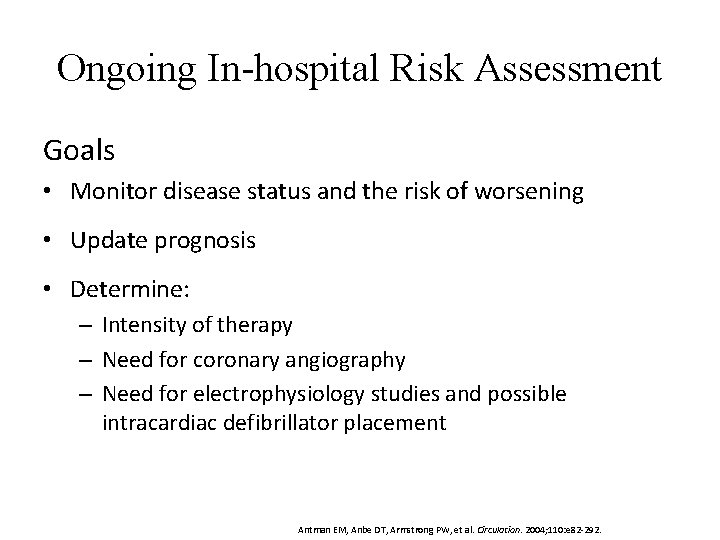

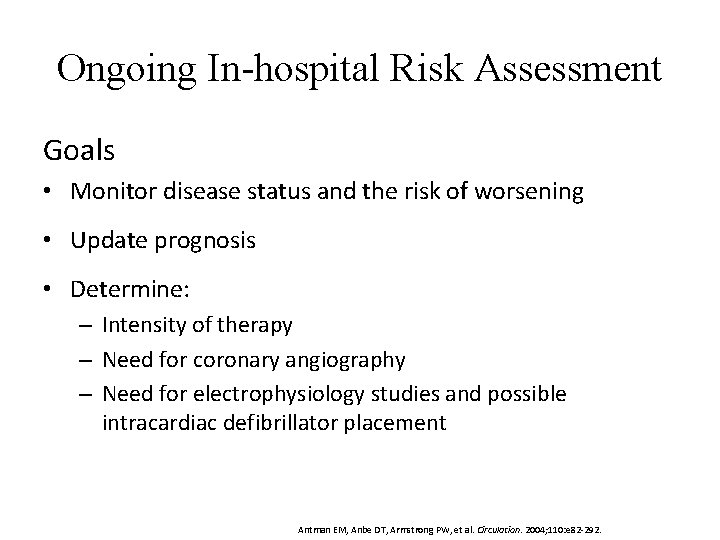

Ongoing In-hospital Risk Assessment Goals • Monitor disease status and the risk of worsening • Update prognosis • Determine: – Intensity of therapy – Need for coronary angiography – Need for electrophysiology studies and possible intracardiac defibrillator placement Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292.

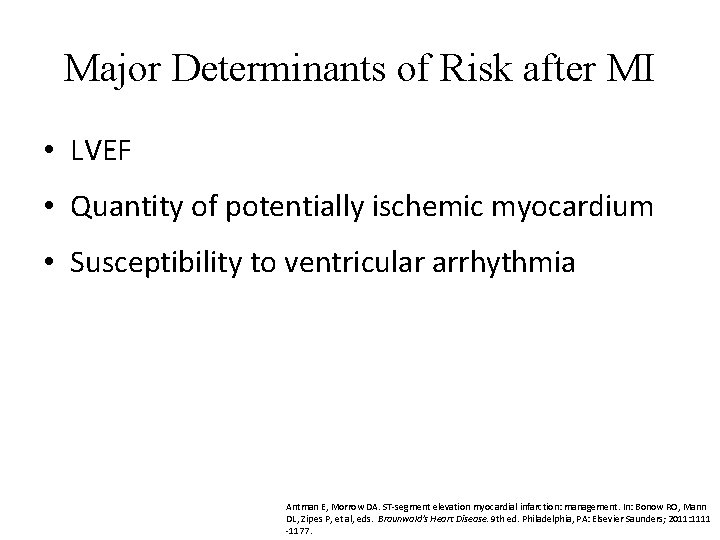

Major Determinants of Risk after MI • LVEF • Quantity of potentially ischemic myocardium • Susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmia Antman E, Morrow DA. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: management. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 1111 -1177.

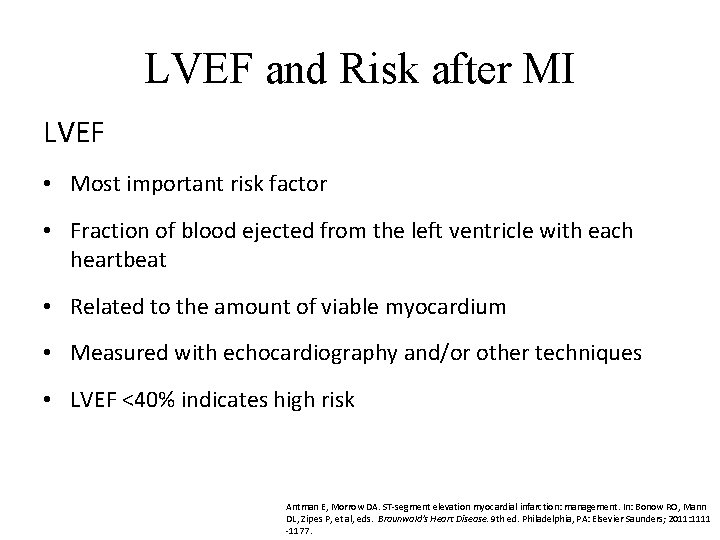

LVEF and Risk after MI LVEF • Most important risk factor • Fraction of blood ejected from the left ventricle with each heartbeat • Related to the amount of viable myocardium • Measured with echocardiography and/or other techniques • LVEF <40% indicates high risk Antman E, Morrow DA. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: management. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 1111 -1177.

Potential Extent of Ischemia and Risk after MI Quantity of potentially ischemic myocardium • Assessed with noninvasive risk stratification testing – Exercise or pharmacologic stress testing – Echocardiography or myocardial perfusion imaging • Identify provocable ischemia • Determine exercise recommendations Antman E, Morrow DA. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: management. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 1111 -1177.

Arrhythmias and Risk after MI Susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmia • Potentially fatal complication • No clearly beneficial screening tests • Prophylactic therapy with antiarrhythmic agents other than beta-blockers has been harmful in clinical trials and is not recommended Antman E, Morrow DA. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: management. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 1111 -1177.

Hospital Discharge Goals • • Prepare the patient for normal activities to the extent possible Re-evaluate the plan of care, particularly lifestyle and risk-factor modification Length of stay • If no major complications – Typically 24– 72 hours for UA/NSTEMI – Typically 5– 6 days for STEMI • With complications – Stable for several days, appropriate workup, appropriate response to therapy A “teachable moment” • Education and counseling on physical activity, risk-factor reduction, medication adherence Antman E, Morrow DA. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: management. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 1111 -1177. Cannon CP, Braunwald E. Unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes P, et al, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 1178 -1209.

Key Cardiologist Concerns • Effective transition to primary care • Adherence – Medication regimen – Lifestyle changes – Follow-up • Patient education • Physician communication Villanueva T. J Hosp Med. 2010 Sep; 5 Suppl 4: S 8 -14.

Postdischarge Care and Secondary Prevention • Goal: reduce the risk of recurrent ACS • Essential for all patients • Aggressively manage risk – Lifestyle changes – Pharmaceutical therapy • Address other health concerns Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2007; 116: e 148 -e 304. Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292.

Pharmaceutical Therapy for Secondary Prevention • Antiplatelet agents • Anticoagulants (warfarin and novel agents) • Beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers • RAAS inhibitors • Other antihypertensive agents • Statins and other lipid management agents

Follow-up and Rehabilitation Cardiac rehabilitation is recommended for most patients Follow-up • Assess cardiovascular symptoms and risk • Review and reinforce adherence to medication and lifestyle changes • Assess psychosocial status • Educate patient and caregivers on management of recurrent ACS Return to work and other activities • 63%– 94% of patients who have had an MI return to work Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110: e 82 -292.

Thank You

Global registry of acute coronary events

Global registry of acute coronary events Acute coronary syndrome

Acute coronary syndrome Julio panza md

Julio panza md Neuroendocrine syndromes in gynecology

Neuroendocrine syndromes in gynecology What is geriatric syndromes

What is geriatric syndromes Neuroendocrine syndrome in gynecology

Neuroendocrine syndrome in gynecology Brainstem stroke syndromes

Brainstem stroke syndromes Cerebellaris

Cerebellaris Cerebellar syndromes

Cerebellar syndromes Coronary sulcus

Coronary sulcus Heart sounds location

Heart sounds location Coronary personality

Coronary personality Tricuspid valve

Tricuspid valve Coronary sinusoids

Coronary sinusoids Cardiac plexus

Cardiac plexus Coronary artery disease

Coronary artery disease Coronary perfusion pressure

Coronary perfusion pressure Right and left aortic sinus

Right and left aortic sinus Coronary steal syndrome

Coronary steal syndrome Course of right coronary artery

Course of right coronary artery Anterior cardiac veins of the right ventricle

Anterior cardiac veins of the right ventricle Antianginal drugs classification

Antianginal drugs classification Pk papyrus covered coronary stent system

Pk papyrus covered coronary stent system Flow

Flow Unlocking of knee joint

Unlocking of knee joint Coronary blood flow

Coronary blood flow Anemia or hypoproteinemia will ______ blood viscosity.

Anemia or hypoproteinemia will ______ blood viscosity. Coronary artery disease pathophysiology

Coronary artery disease pathophysiology Mesa coronary calcium score

Mesa coronary calcium score Ischemic heart disease

Ischemic heart disease Cardiovascular system crash course

Cardiovascular system crash course Coronary circulation animation

Coronary circulation animation Coronary circulation of heart

Coronary circulation of heart Right atrioventricular valve

Right atrioventricular valve Mesa coronary calcium score

Mesa coronary calcium score Coronary heart disease

Coronary heart disease Shepherd crook rca

Shepherd crook rca Coronary calcium score guidelines

Coronary calcium score guidelines Qfr coronary

Qfr coronary Ligamentum arteriosum

Ligamentum arteriosum Papyrus stent graft

Papyrus stent graft Ligamentum venosum

Ligamentum venosum Coronary circulation

Coronary circulation Descripción de sancho panza

Descripción de sancho panza Adivinanza que se pela por la panza

Adivinanza que se pela por la panza Caracter de sancho panza

Caracter de sancho panza Zeul cunoasterii

Zeul cunoasterii Los caballos son rumiantes?

Los caballos son rumiantes? Ricardo panza

Ricardo panza El ingenioso hidalgo don quijote de la mancha argumento

El ingenioso hidalgo don quijote de la mancha argumento Sancho panza charakteristika

Sancho panza charakteristika Sancho panza charakteristika

Sancho panza charakteristika Ricardo panza

Ricardo panza Sancho panza era un labrador

Sancho panza era un labrador Acute pancreatitis nursing management

Acute pancreatitis nursing management Biografia de julio verne

Biografia de julio verne Julio lopes xxx

Julio lopes xxx Copper sun sharon draper summary

Copper sun sharon draper summary José júlio alves alferes

José júlio alves alferes La vie en rose julio iglesias

La vie en rose julio iglesias Un profesional joven desea reunir

Un profesional joven desea reunir Los amigos poema

Los amigos poema Safeether

Safeether Esquema de la noche boca arriba

Esquema de la noche boca arriba Donde nacio julio verne

Donde nacio julio verne Julio romero de torres pinto a la mujer morena

Julio romero de torres pinto a la mujer morena Escuela judicial rodrigo lara bonilla

Escuela judicial rodrigo lara bonilla Plataforma integra escuela industrial 20 de julio

Plataforma integra escuela industrial 20 de julio Qué es el boom latinoamericano?

Qué es el boom latinoamericano? Julio caceres arce

Julio caceres arce Julio gonzalez and lydia feliciano summary

Julio gonzalez and lydia feliciano summary