VENTILACIN PULMONAR El arte de medicina consiste en

- Slides: 45

VENTILACIÓN PULMONAR El arte de medicina consiste en entretener al paciente mientras la naturaleza cura la enfermedad. Voltaire (1694 -1778)

Los doctores son hombres que prescriben medicinas que conocen poco, curan enfermedades que conocen menos, en seres humanos de los que no saben nada. Voltaire (1694 -1778)

La función primordial de los pulmones consiste en garantizar un intercambio de gases adecuado para las necesidades del organismo, de forma que el aporte de O 2 necesario para las demandas metabólicas de los tejidos y la eliminación de CO 2 de los mismos se lleven a cabo correctamente de forma simultánea. Estos dos gases son, junto con el nitrógeno (N 2), los tres elementos esenciales con los que el pulmón trabaja constantemente. La presión parcial (P) que ejerce cualquiera de estos tres gases fisiológicos en los 300 millones de unidades alveolares funcionales que constituyen el parénquima pulmonar viene regulada por tres factores principales:

1. 1. - La composición del gas inspirado, dependiente de la fracción inspiratoria de O 2 (FIO 2) y de la ventilación alveolar (VA); 2. 2. - Los cocientes o relaciones ventilación perfusión (VA/Q) pulmonares; y 3. 3. - La composición de la sangre venosa mixta (mezclada) (v), dependiente a su vez del flujo sanguíneo o gasto cardiaco (QT) del organismo y del consumo de O 2 (VO 2) tisular.

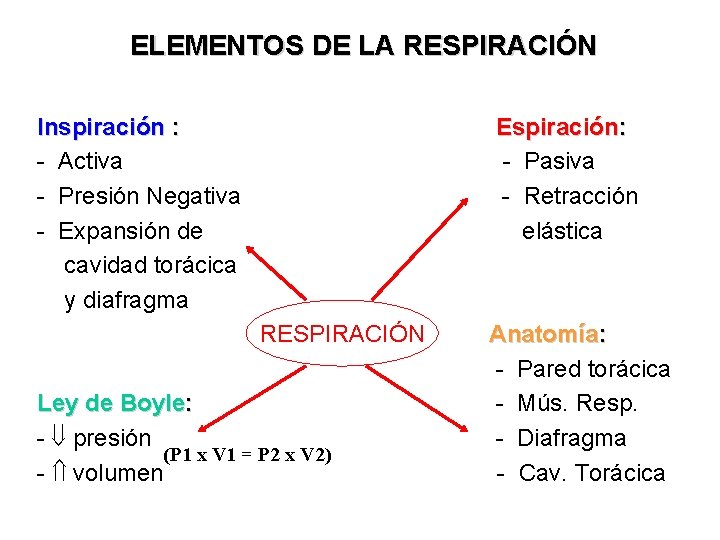

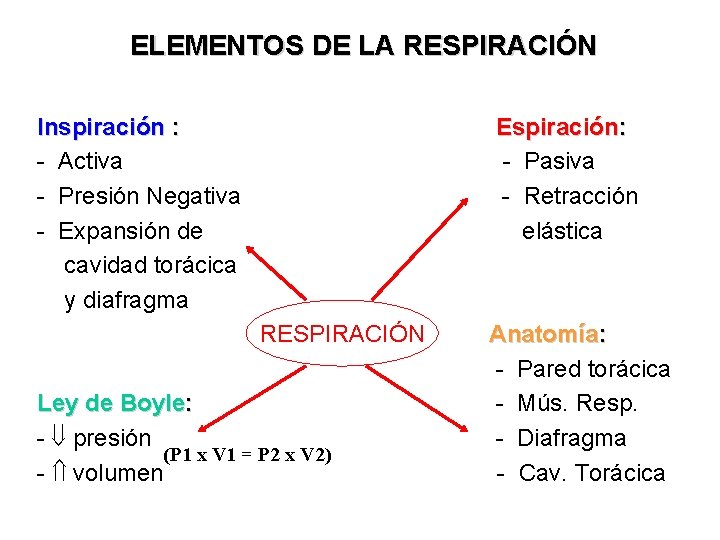

ELEMENTOS DE LA RESPIRACIÓN Inspiración : - Activa - Presión Negativa - Expansión de cavidad torácica y diafragma Espiración: - Pasiva - Retracción elástica RESPIRACIÓN Ley de Boyle: - presión (P 1 x V 1 = P 2 x V 2) - volumen Anatomía: - Pared torácica - Mús. Resp. - Diafragma - Cav. Torácica

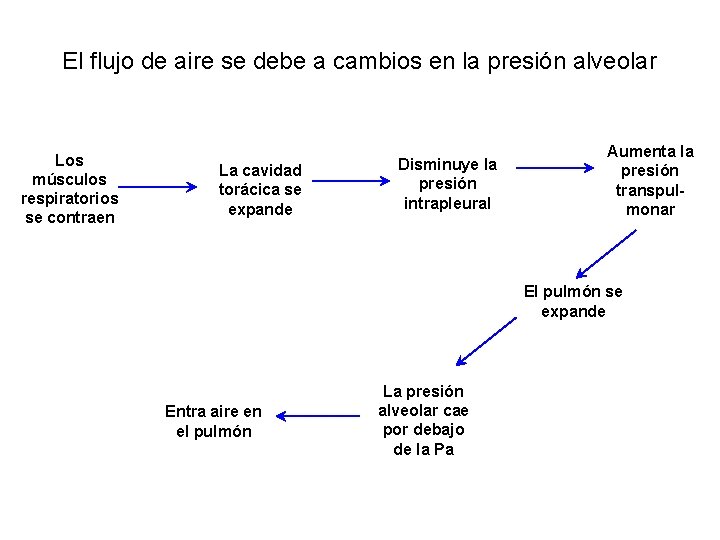

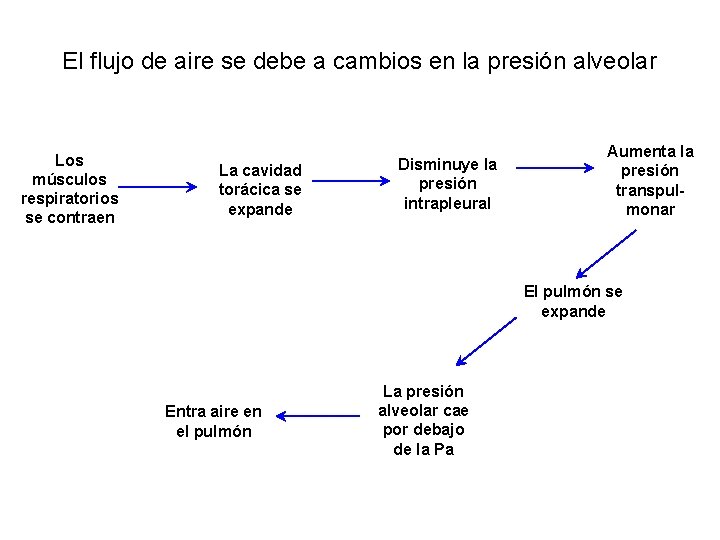

El flujo de aire se debe a cambios en la presión alveolar Los músculos respiratorios se contraen La cavidad torácica se expande Disminuye la presión intrapleural Aumenta la presión transpulmonar El pulmón se expande Entra aire en el pulmón La presión alveolar cae por debajo de la Pa

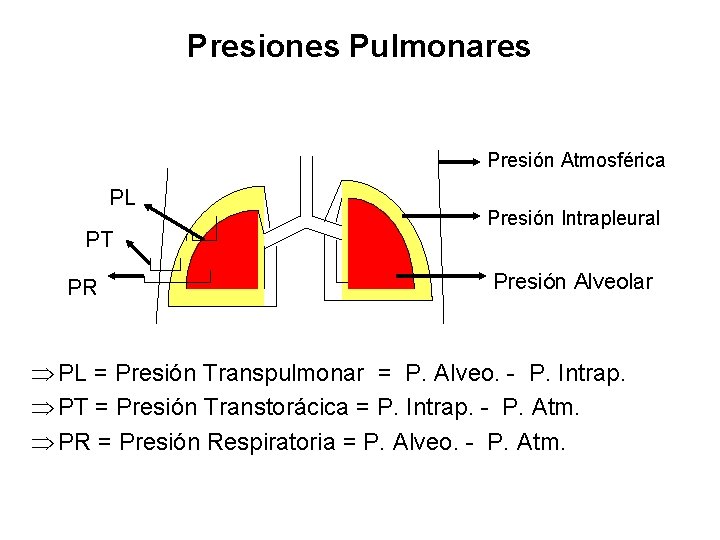

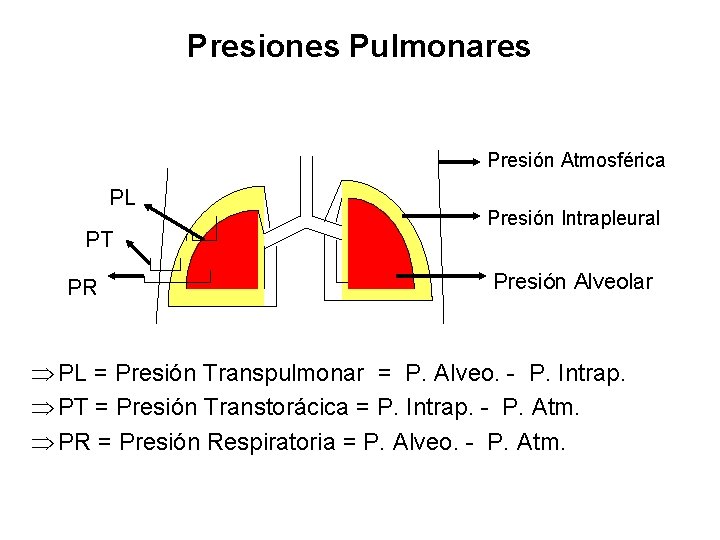

Presiones Pulmonares Presión Atmosférica PL PT PR Presión Intrapleural Presión Alveolar Þ PL = Presión Transpulmonar = P. Alveo. - P. Intrap. Þ PT = Presión Transtorácica = P. Intrap. - P. Atm. Þ PR = Presión Respiratoria = P. Alveo. - P. Atm.

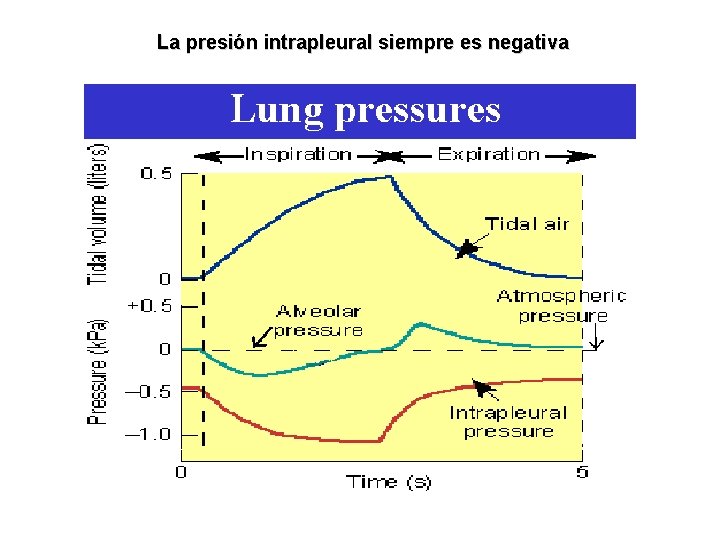

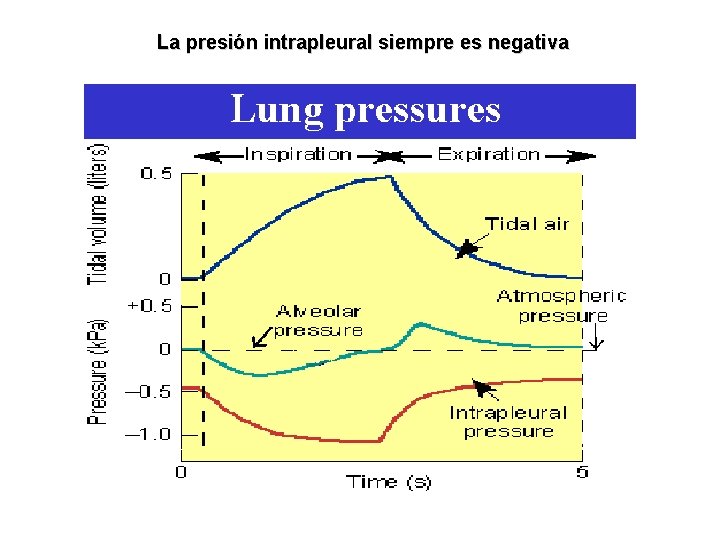

La presión intrapleural siempre es negativa

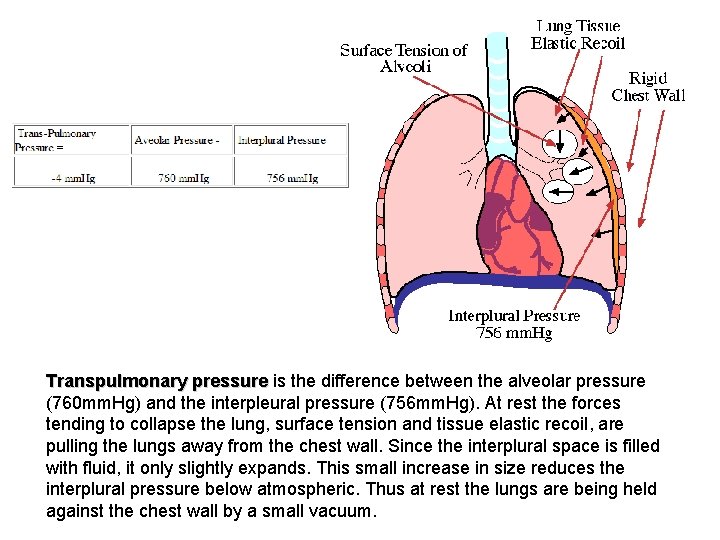

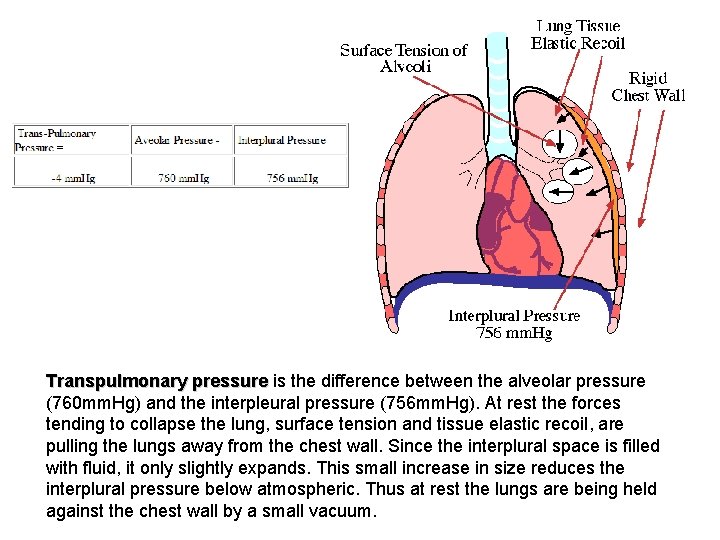

Transpulmonary pressure is the difference between the alveolar pressure (760 mm. Hg) and the interpleural pressure (756 mm. Hg). At rest the forces tending to collapse the lung, surface tension and tissue elastic recoil, are pulling the lungs away from the chest wall. Since the interplural space is filled with fluid, it only slightly expands. This small increase in size reduces the interplural pressure below atmospheric. Thus at rest the lungs are being held against the chest wall by a small vacuum.

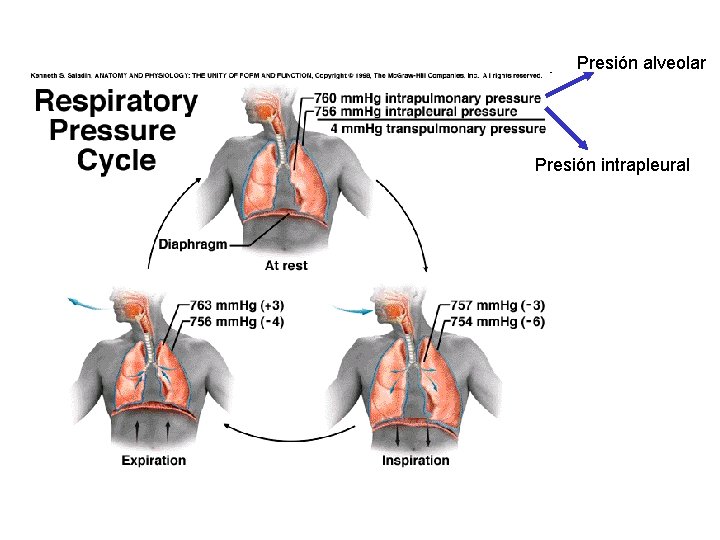

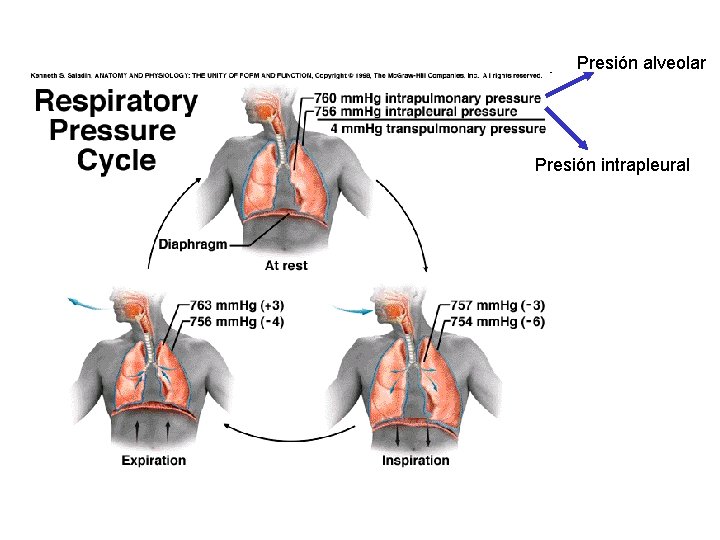

Presión alveolar Presión intrapleural

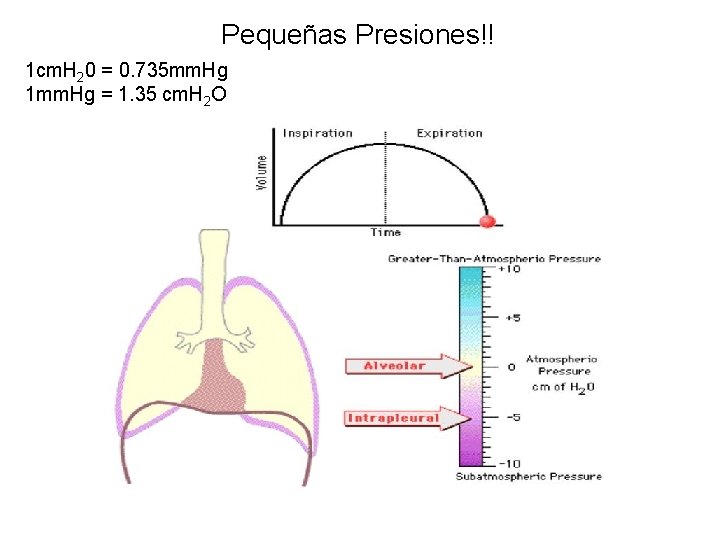

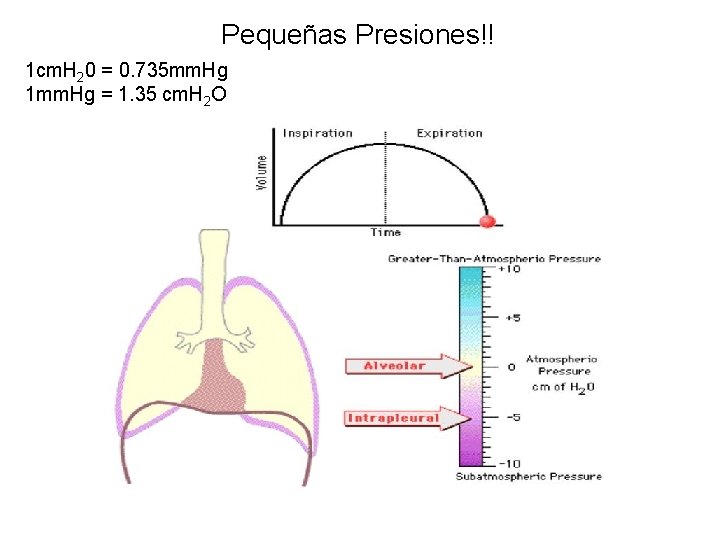

Pequeñas Presiones!! 1 cm. H 20 = 0. 735 mm. Hg 1 mm. Hg = 1. 35 cm. H 2 O

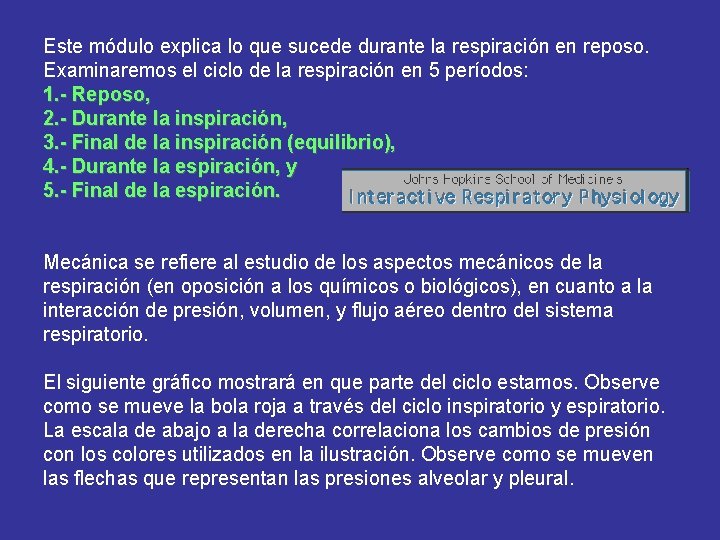

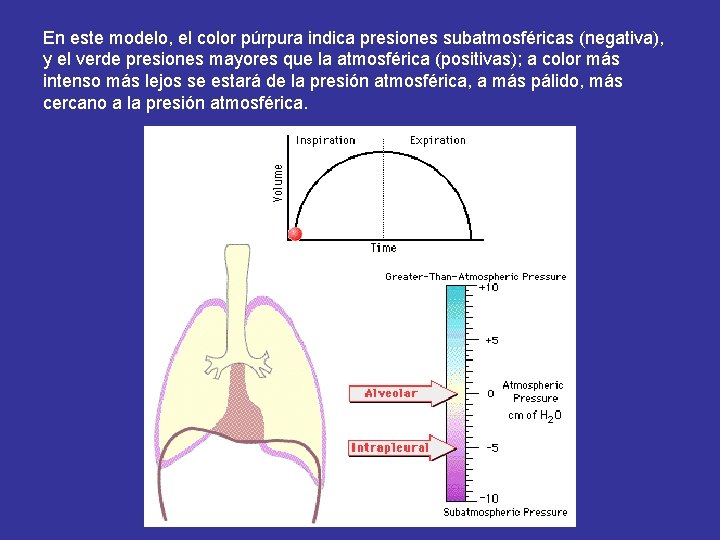

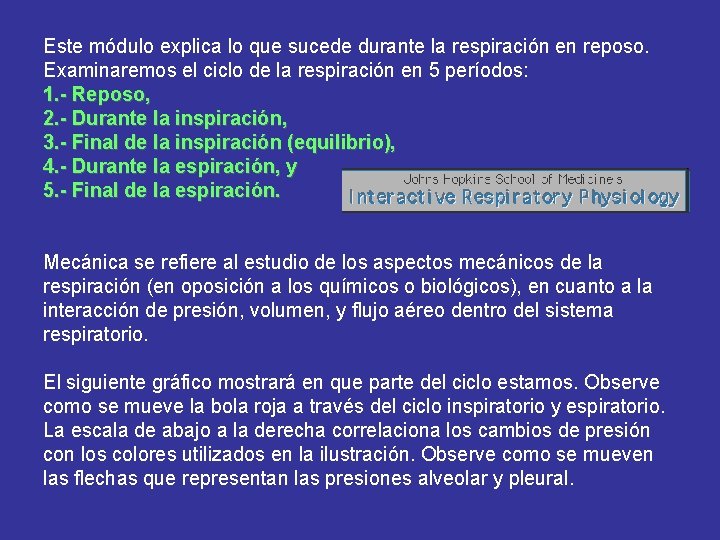

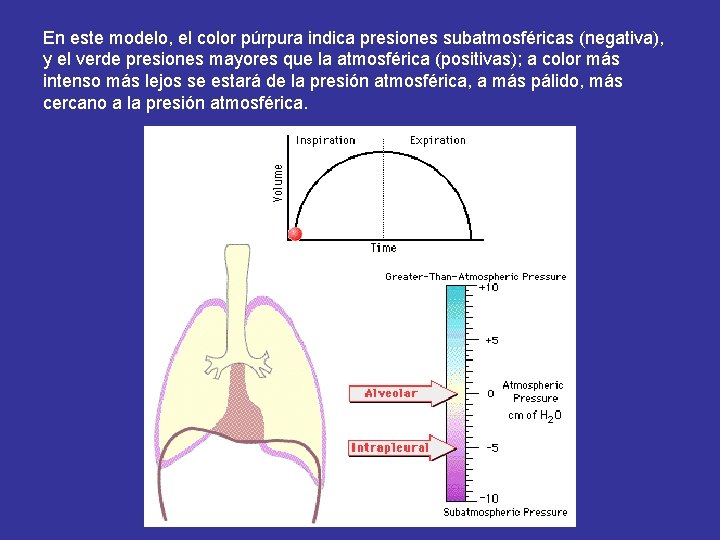

Este módulo explica lo que sucede durante la respiración en reposo. Examinaremos el ciclo de la respiración en 5 períodos: 1. - Reposo, 2. - Durante la inspiración, 3. - Final de la inspiración (equilibrio), 4. - Durante la espiración, y 5. - Final de la espiración. Mecánica se refiere al estudio de los aspectos mecánicos de la respiración (en oposición a los químicos o biológicos), en cuanto a la interacción de presión, volumen, y flujo aéreo dentro del sistema respiratorio. El siguiente gráfico mostrará en que parte del ciclo estamos. Observe como se mueve la bola roja a través del ciclo inspiratorio y espiratorio. La escala de abajo a la derecha correlaciona los cambios de presión con los colores utilizados en la ilustración. Observe como se mueven las flechas que representan las presiones alveolar y pleural.

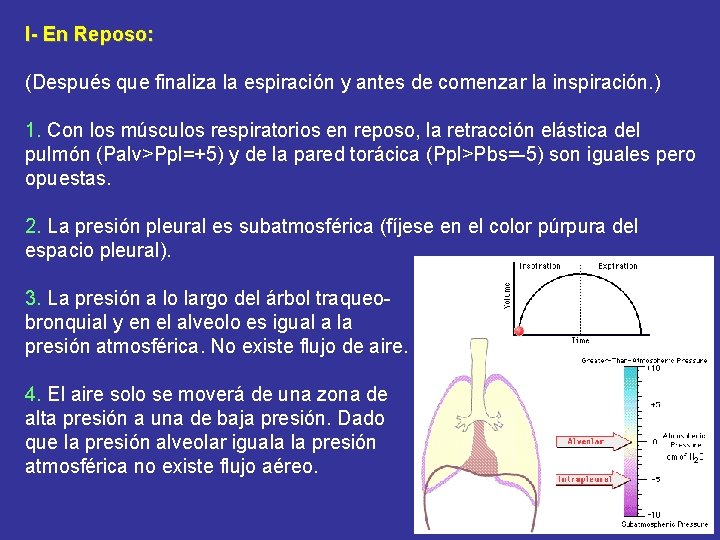

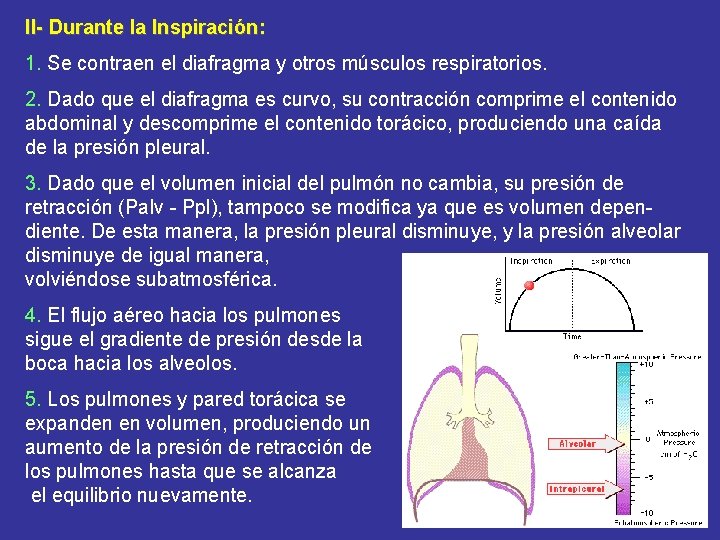

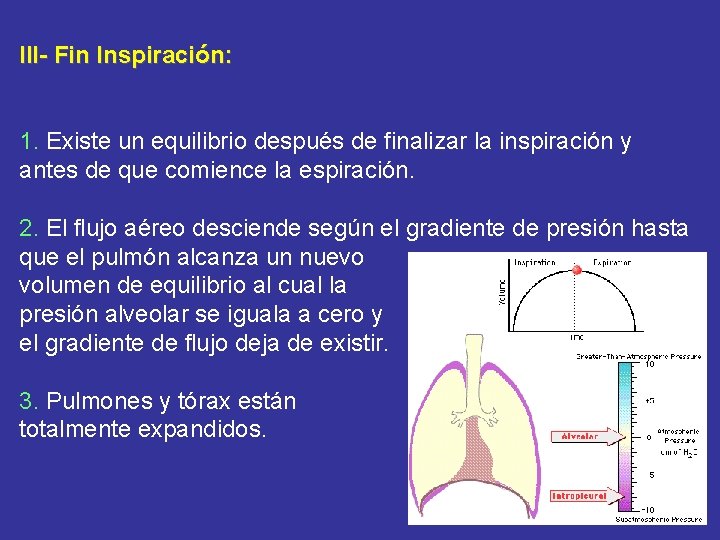

En este modelo, el color púrpura indica presiones subatmosféricas (negativa), y el verde presiones mayores que la atmosférica (positivas); a color más intenso más lejos se estará de la presión atmosférica, a más pálido, más cercano a la presión atmosférica.

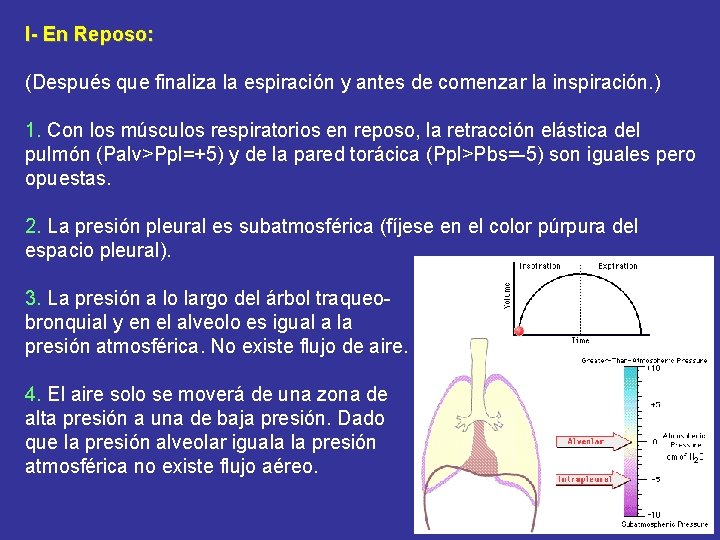

I- En Reposo: (Después que finaliza la espiración y antes de comenzar la inspiración. ) 1. Con los músculos respiratorios en reposo, la retracción elástica del pulmón (Palv>Ppl=+5) y de la pared torácica (Ppl>Pbs=-5) son iguales pero opuestas. 2. La presión pleural es subatmosférica (fíjese en el color púrpura del espacio pleural). 3. La presión a lo largo del árbol traqueobronquial y en el alveolo es igual a la presión atmosférica. No existe flujo de aire. 4. El aire solo se moverá de una zona de alta presión a una de baja presión. Dado que la presión alveolar iguala la presión atmosférica no existe flujo aéreo.

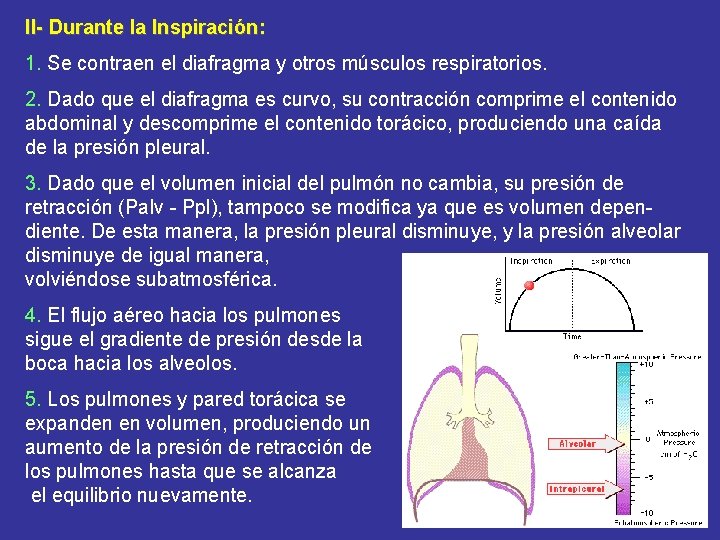

II- Durante la Inspiración: 1. Se contraen el diafragma y otros músculos respiratorios. 2. Dado que el diafragma es curvo, su contracción comprime el contenido abdominal y descomprime el contenido torácico, produciendo una caída de la presión pleural. 3. Dado que el volumen inicial del pulmón no cambia, su presión de retracción (Palv - Ppl), tampoco se modifica ya que es volumen dependiente. De esta manera, la presión pleural disminuye, y la presión alveolar disminuye de igual manera, volviéndose subatmosférica. 4. El flujo aéreo hacia los pulmones sigue el gradiente de presión desde la boca hacia los alveolos. 5. Los pulmones y pared torácica se expanden en volumen, produciendo un aumento de la presión de retracción de los pulmones hasta que se alcanza el equilibrio nuevamente.

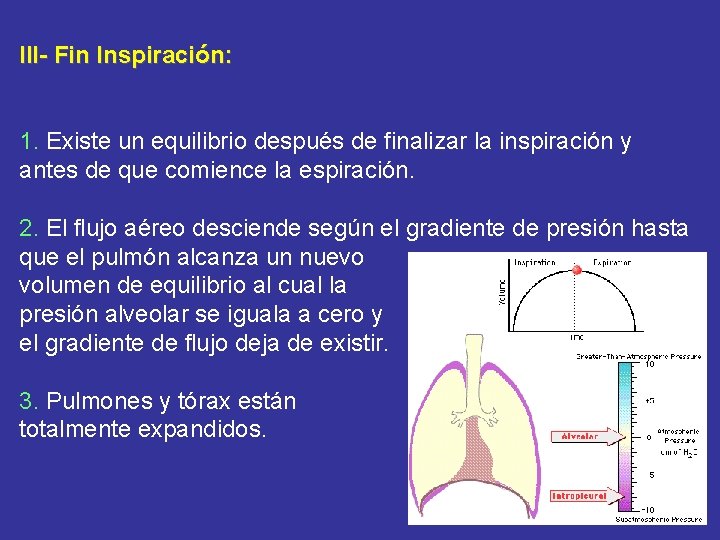

III- Fin Inspiración: 1. Existe un equilibrio después de finalizar la inspiración y antes de que comience la espiración. 2. El flujo aéreo desciende según el gradiente de presión hasta que el pulmón alcanza un nuevo volumen de equilibrio al cual la presión alveolar se iguala a cero y el gradiente de flujo deja de existir. 3. Pulmones y tórax están totalmente expandidos.

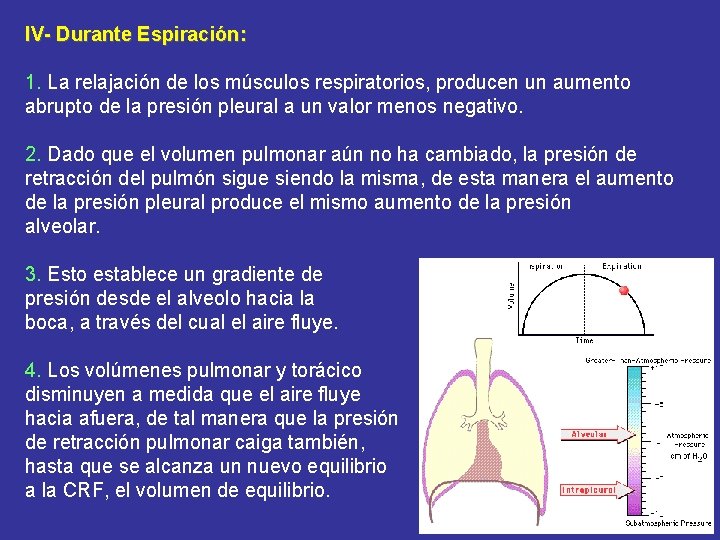

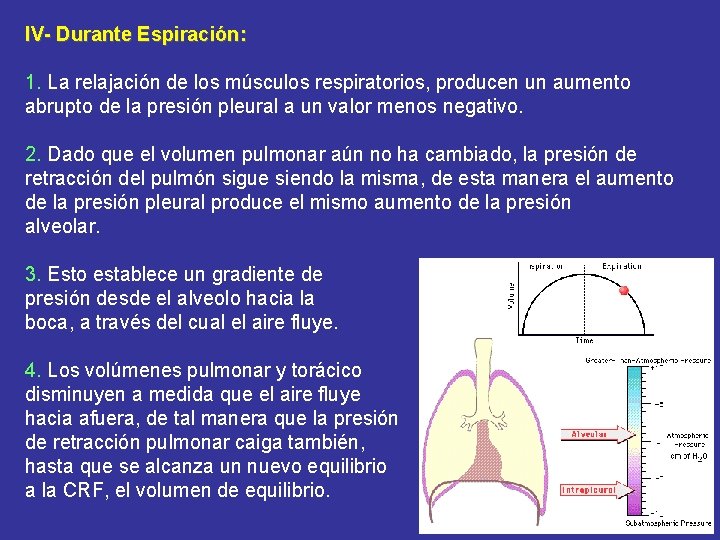

IV- Durante Espiración: 1. La relajación de los músculos respiratorios, producen un aumento abrupto de la presión pleural a un valor menos negativo. 2. Dado que el volumen pulmonar aún no ha cambiado, la presión de retracción del pulmón sigue siendo la misma, de esta manera el aumento de la presión pleural produce el mismo aumento de la presión alveolar. 3. Esto establece un gradiente de presión desde el alveolo hacia la boca, a través del cual el aire fluye. 4. Los volúmenes pulmonar y torácico disminuyen a medida que el aire fluye hacia afuera, de tal manera que la presión de retracción pulmonar caiga también, hasta que se alcanza un nuevo equilibrio a la CRF, el volumen de equilibrio.

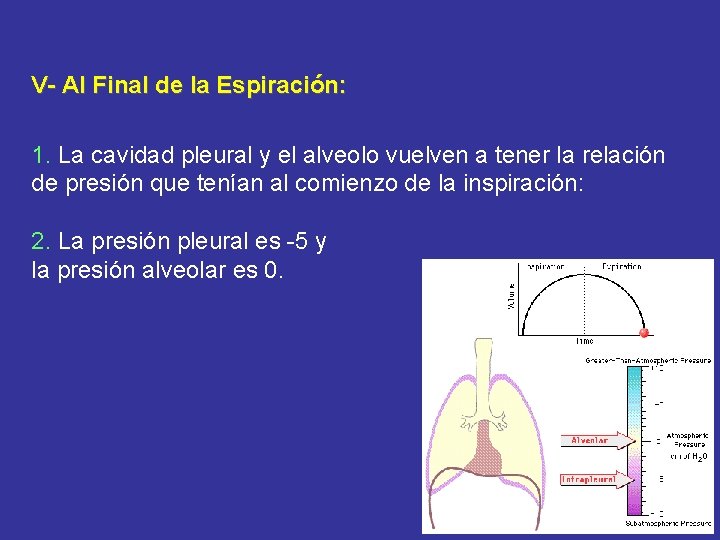

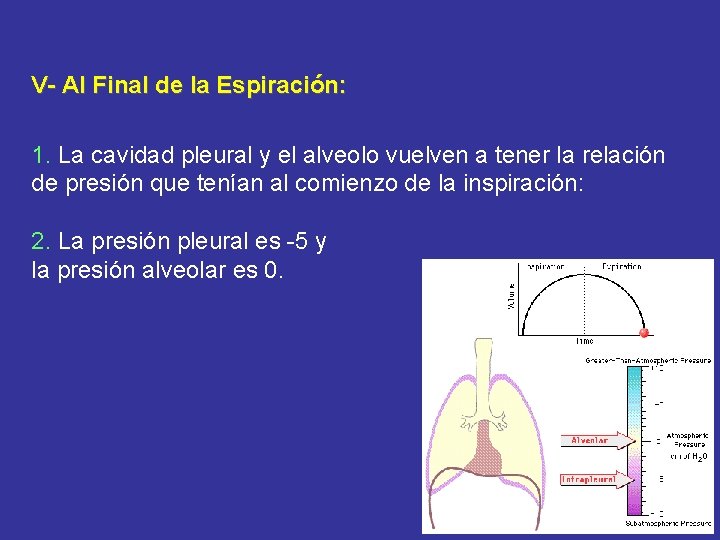

V- Al Final de la Espiración: 1. La cavidad pleural y el alveolo vuelven a tener la relación de presión que tenían al comienzo de la inspiración: 2. La presión pleural es -5 y la presión alveolar es 0.

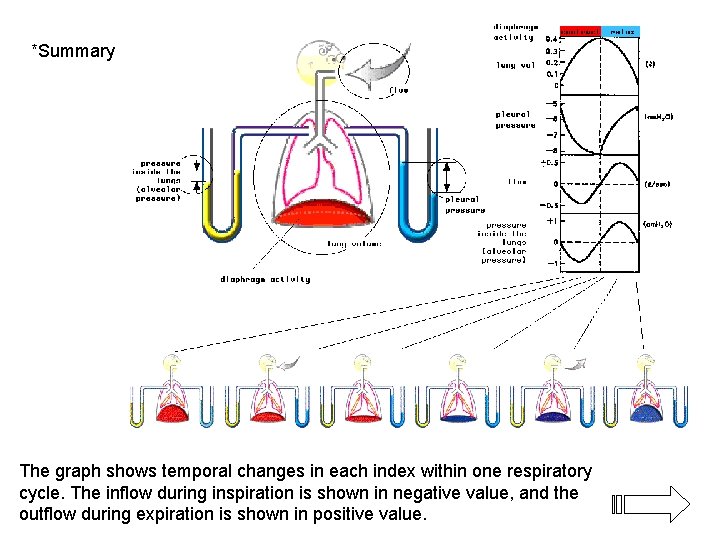

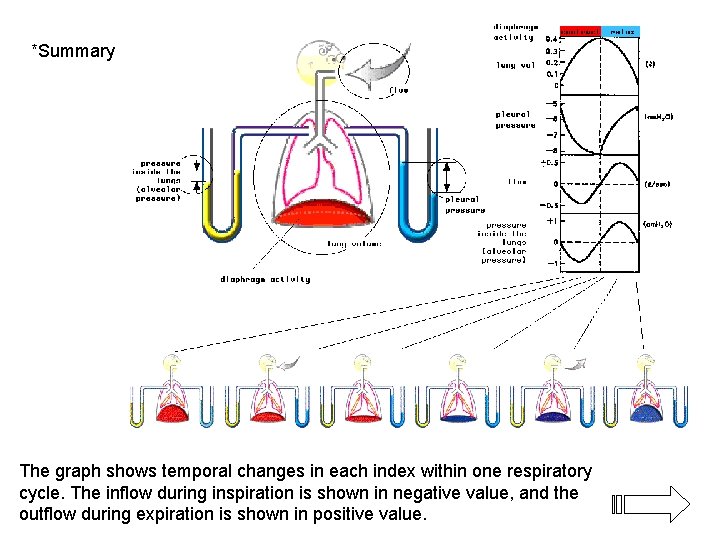

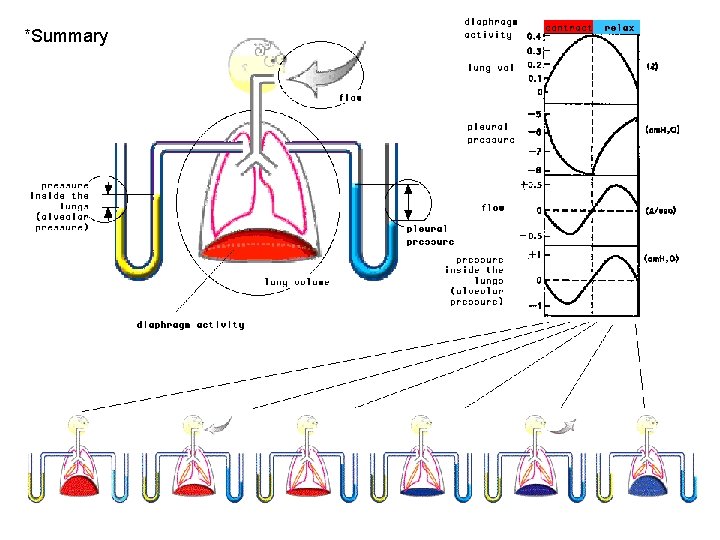

*Summary The graph shows temporal changes in each index within one respiratory cycle. The inflow during inspiration is shown in negative value, and the outflow during expiration is shown in positive value.

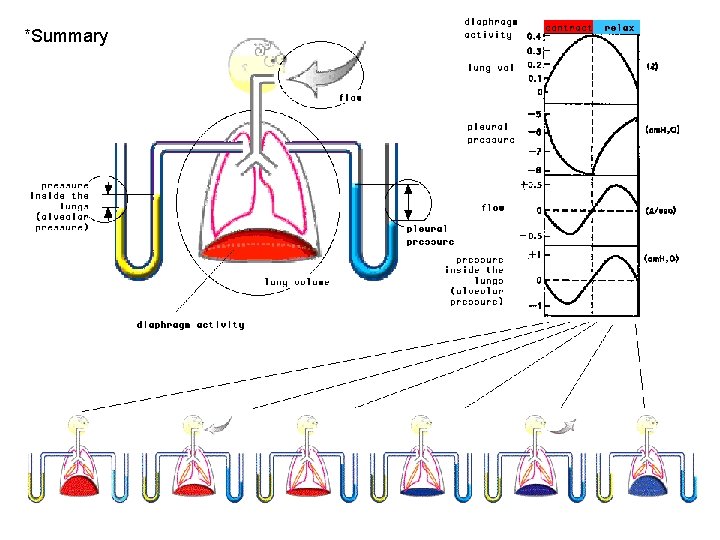

*Summary

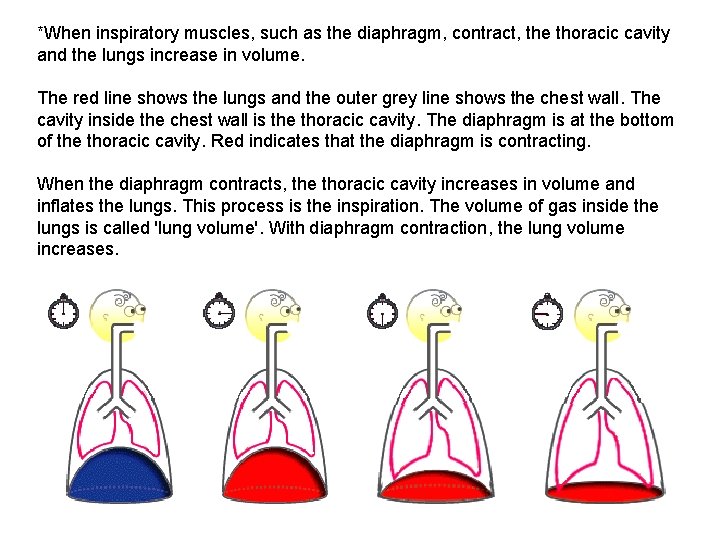

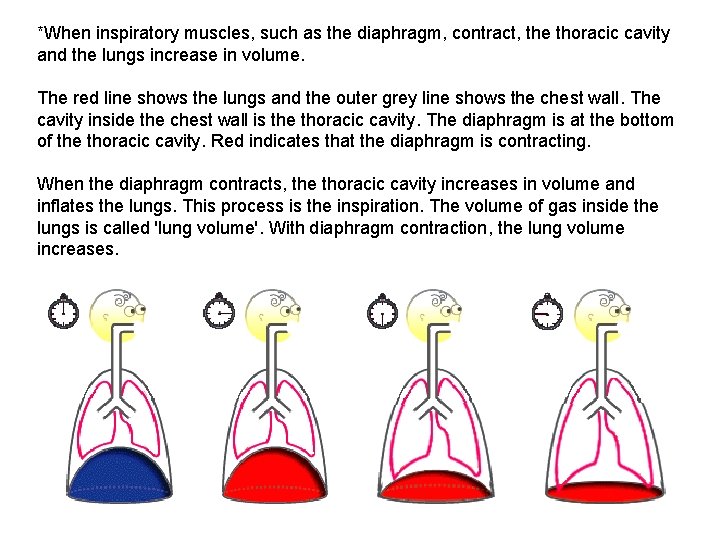

*When inspiratory muscles, such as the diaphragm, contract, the thoracic cavity and the lungs increase in volume. The red line shows the lungs and the outer grey line shows the chest wall. The cavity inside the chest wall is the thoracic cavity. The diaphragm is at the bottom of the thoracic cavity. Red indicates that the diaphragm is contracting. When the diaphragm contracts, the thoracic cavity increases in volume and inflates the lungs. This process is the inspiration. The volume of gas inside the lungs is called 'lung volume'. With diaphragm contraction, the lung volume increases.

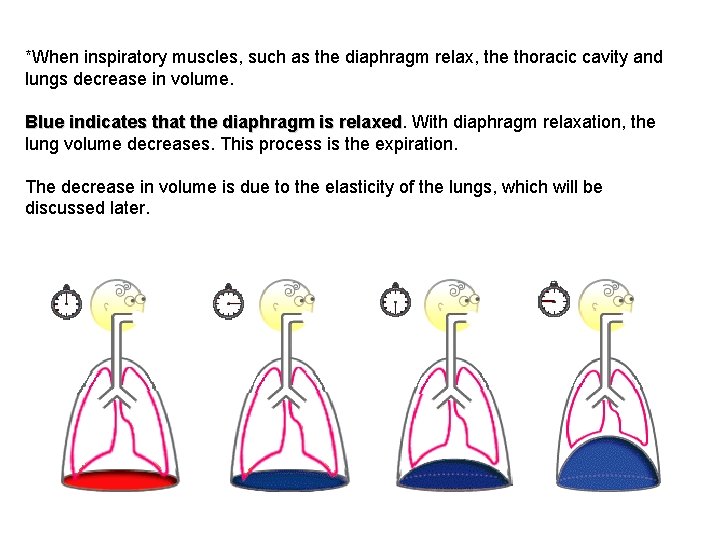

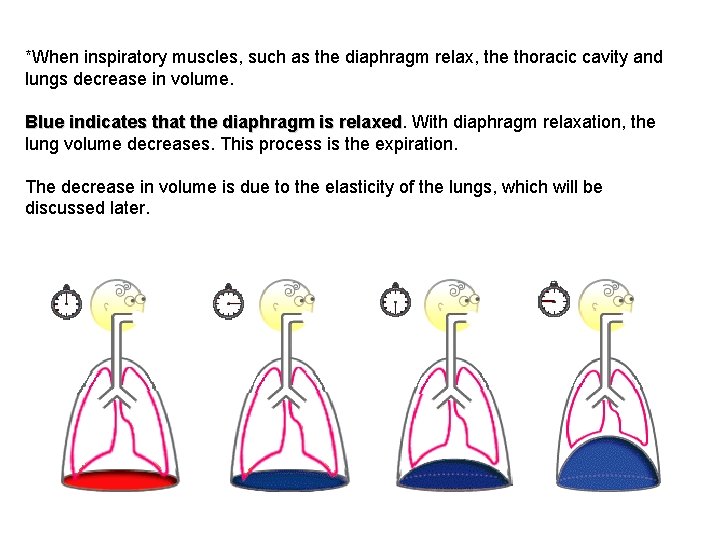

*When inspiratory muscles, such as the diaphragm relax, the thoracic cavity and lungs decrease in volume. Blue indicates that the diaphragm is relaxed With diaphragm relaxation, the lung volume decreases. This process is the expiration. The decrease in volume is due to the elasticity of the lungs, which will be discussed later.

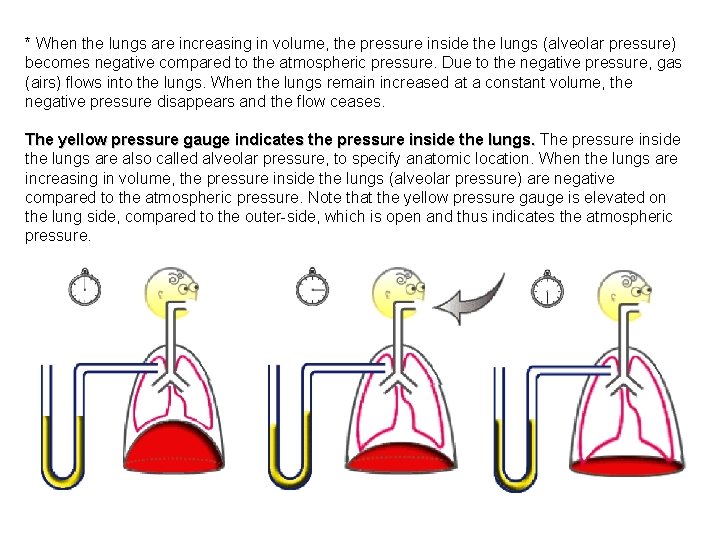

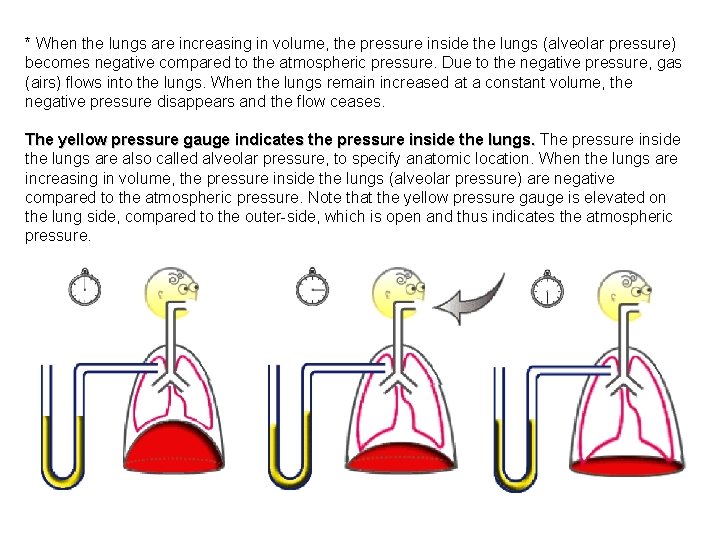

* When the lungs are increasing in volume, the pressure inside the lungs (alveolar pressure) becomes negative compared to the atmospheric pressure. Due to the negative pressure, gas (airs) flows into the lungs. When the lungs remain increased at a constant volume, the negative pressure disappears and the flow ceases. The yellow pressure gauge indicates the pressure inside the lungs. The pressure inside the lungs are also called alveolar pressure, to specify anatomic location. When the lungs are increasing in volume, the pressure inside the lungs (alveolar pressure) are negative compared to the atmospheric pressure. Note that the yellow pressure gauge is elevated on the lung side, compared to the outer-side, which is open and thus indicates the atmospheric pressure.

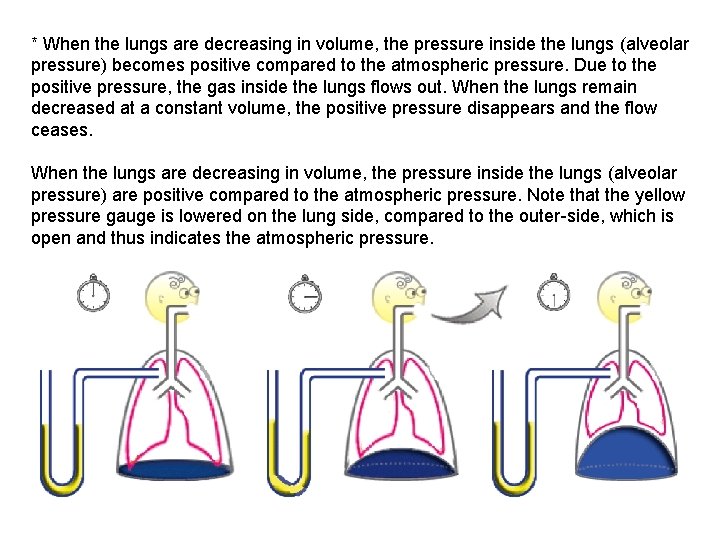

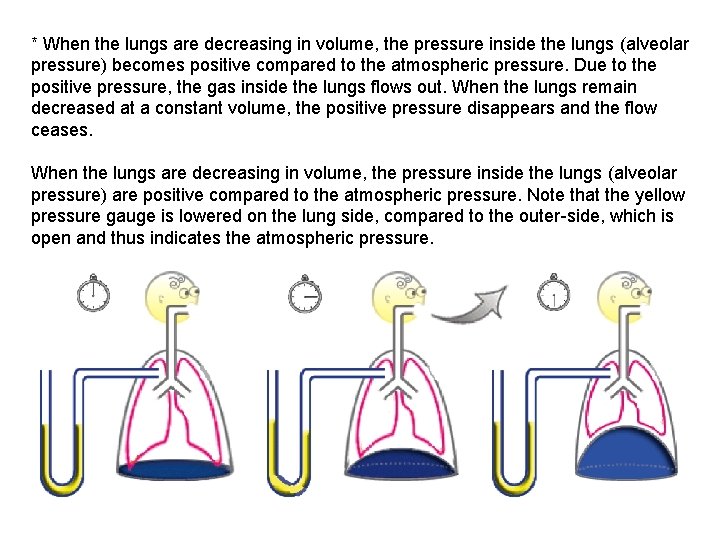

* When the lungs are decreasing in volume, the pressure inside the lungs (alveolar pressure) becomes positive compared to the atmospheric pressure. Due to the positive pressure, the gas inside the lungs flows out. When the lungs remain decreased at a constant volume, the positive pressure disappears and the flow ceases. When the lungs are decreasing in volume, the pressure inside the lungs (alveolar pressure) are positive compared to the atmospheric pressure. Note that the yellow pressure gauge is lowered on the lung side, compared to the outer-side, which is open and thus indicates the atmospheric pressure.

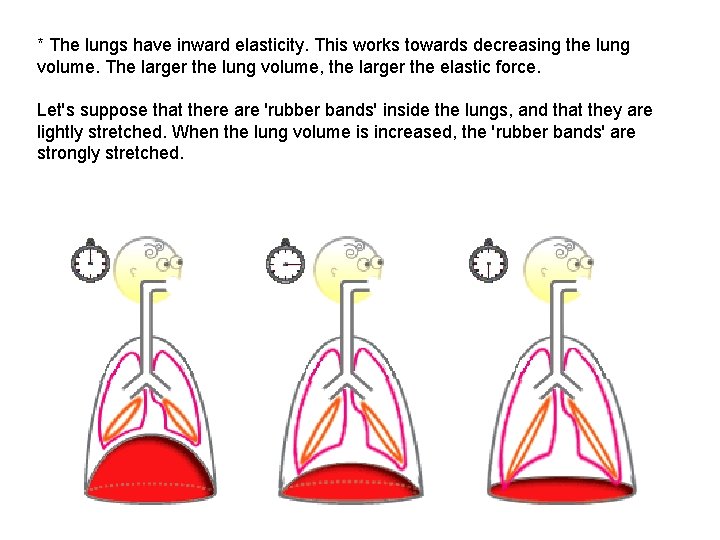

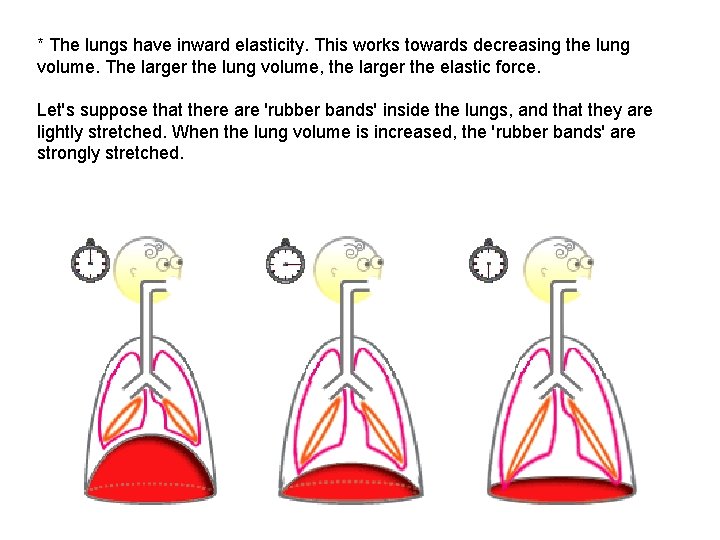

* The lungs have inward elasticity. This works towards decreasing the lung volume. The larger the lung volume, the larger the elastic force. Let's suppose that there are 'rubber bands' inside the lungs, and that they are lightly stretched. When the lung volume is increased, the 'rubber bands' are strongly stretched.

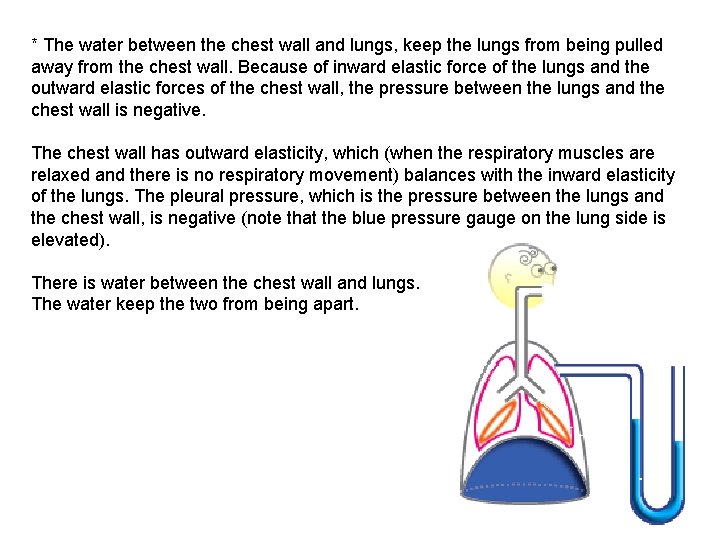

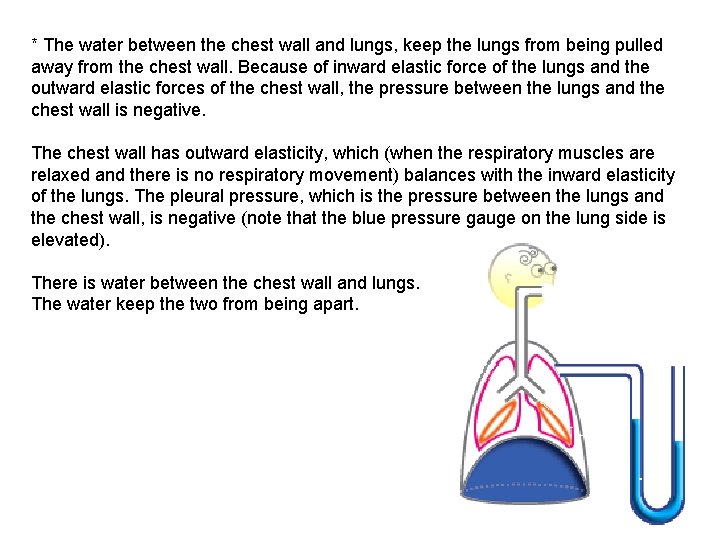

* The water between the chest wall and lungs, keep the lungs from being pulled away from the chest wall. Because of inward elastic force of the lungs and the outward elastic forces of the chest wall, the pressure between the lungs and the chest wall is negative. The chest wall has outward elasticity, which (when the respiratory muscles are relaxed and there is no respiratory movement) balances with the inward elasticity of the lungs. The pleural pressure, which is the pressure between the lungs and the chest wall, is negative (note that the blue pressure gauge on the lung side is elevated). There is water between the chest wall and lungs. The water keep the two from being apart.

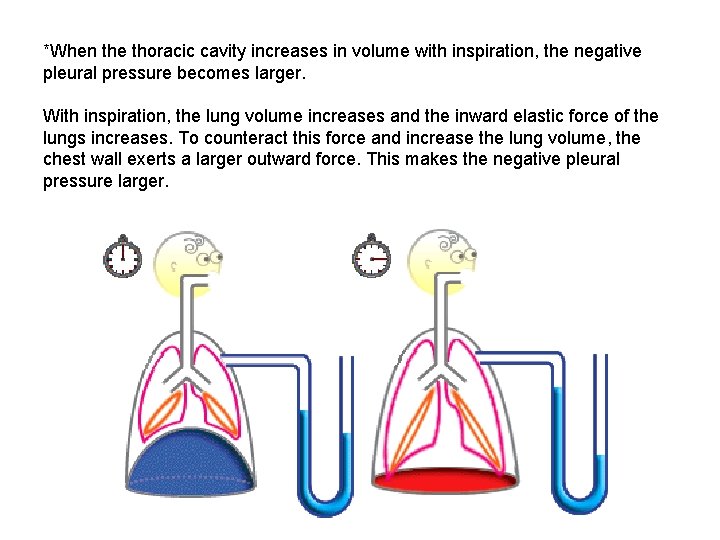

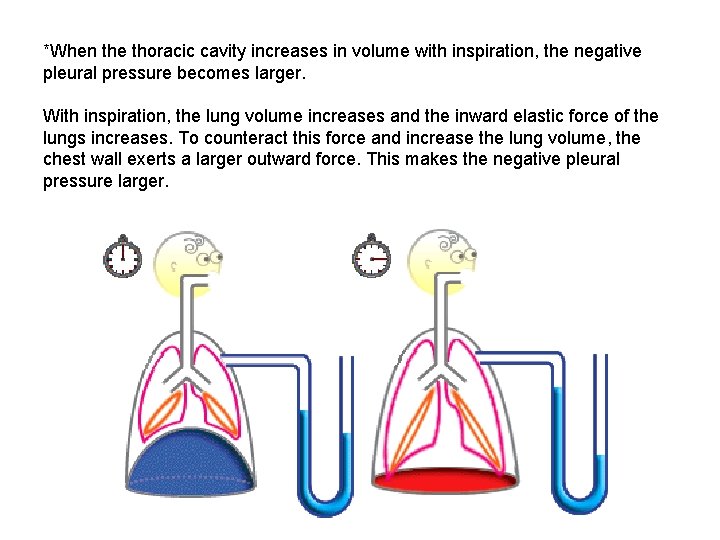

*When the thoracic cavity increases in volume with inspiration, the negative pleural pressure becomes larger. With inspiration, the lung volume increases and the inward elastic force of the lungs increases. To counteract this force and increase the lung volume, the chest wall exerts a larger outward force. This makes the negative pleural pressure larger.

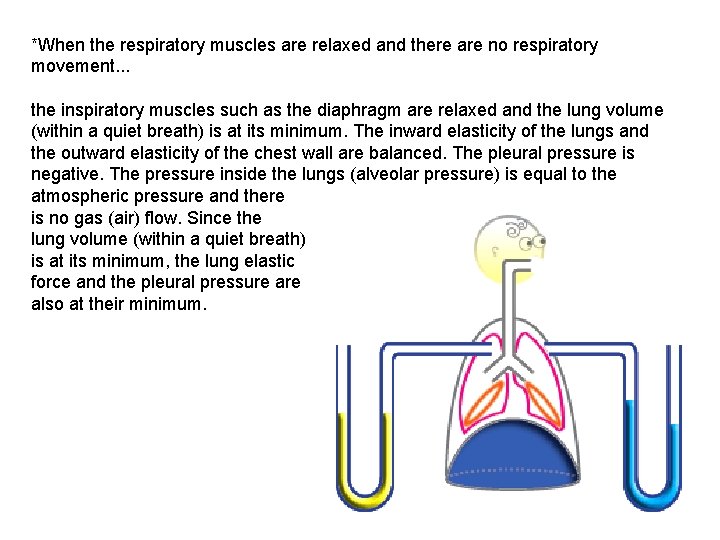

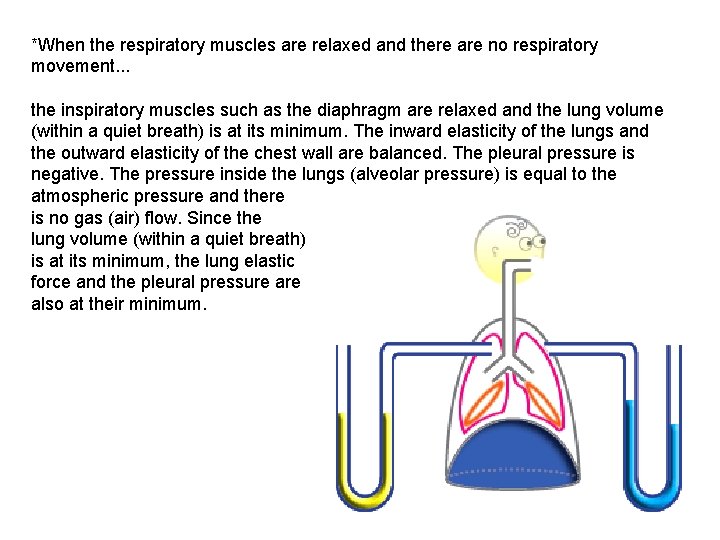

*When the respiratory muscles are relaxed and there are no respiratory movement. . . the inspiratory muscles such as the diaphragm are relaxed and the lung volume (within a quiet breath) is at its minimum. The inward elasticity of the lungs and the outward elasticity of the chest wall are balanced. The pleural pressure is negative. The pressure inside the lungs (alveolar pressure) is equal to the atmospheric pressure and there is no gas (air) flow. Since the lung volume (within a quiet breath) is at its minimum, the lung elastic force and the pleural pressure also at their minimum.

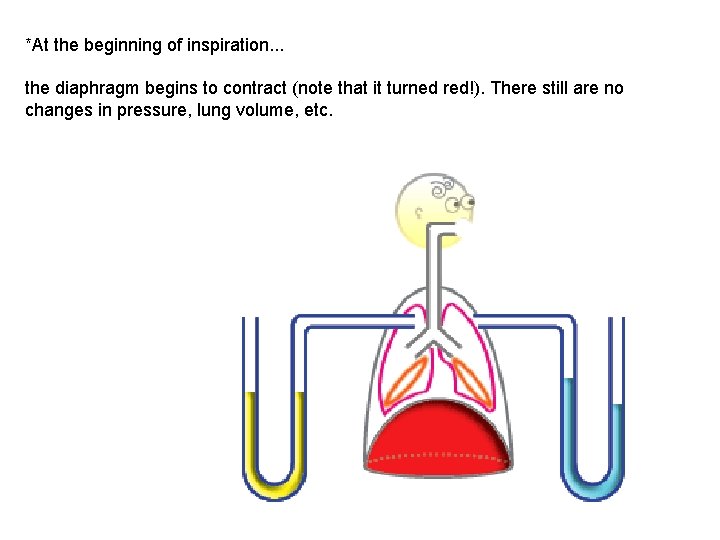

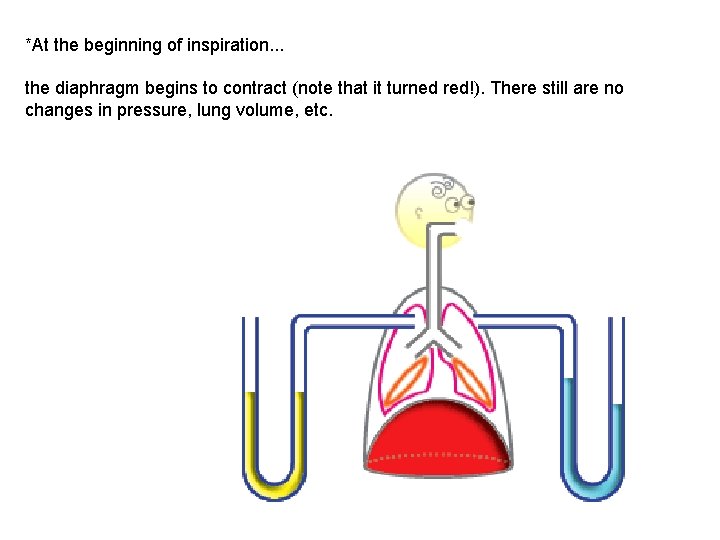

*At the beginning of inspiration. . . the diaphragm begins to contract (note that it turned red!). There still are no changes in pressure, lung volume, etc.

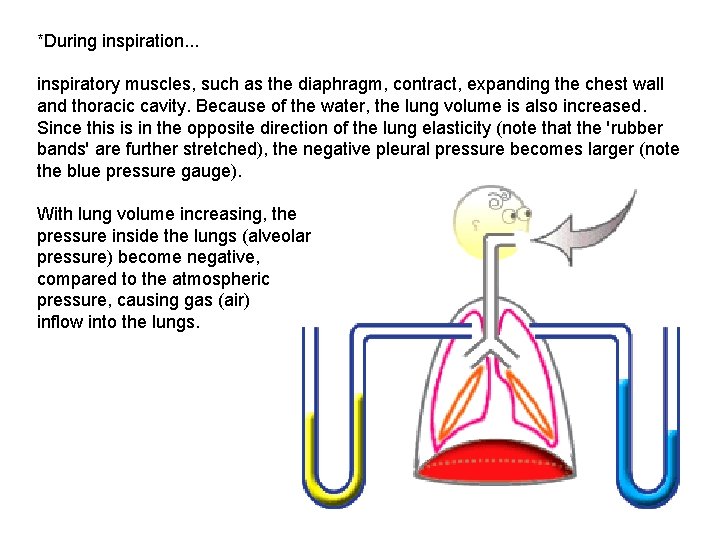

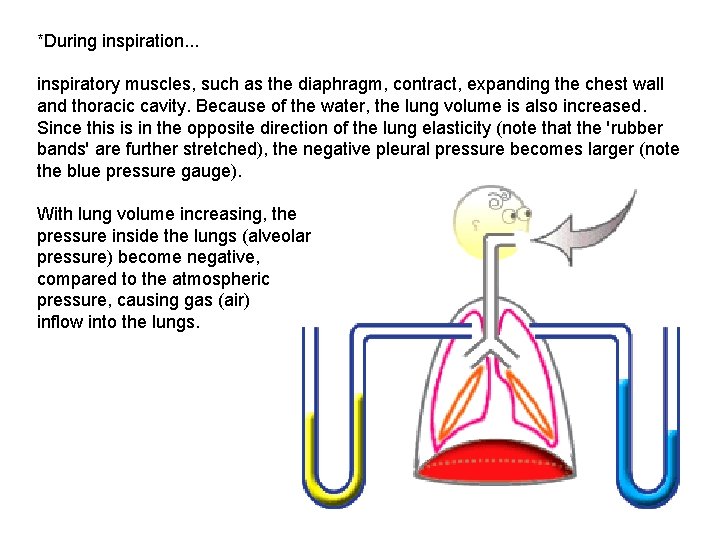

*During inspiration. . . inspiratory muscles, such as the diaphragm, contract, expanding the chest wall and thoracic cavity. Because of the water, the lung volume is also increased. Since this is in the opposite direction of the lung elasticity (note that the 'rubber bands' are further stretched), the negative pleural pressure becomes larger (note the blue pressure gauge). With lung volume increasing, the pressure inside the lungs (alveolar pressure) become negative, compared to the atmospheric pressure, causing gas (air) inflow into the lungs.

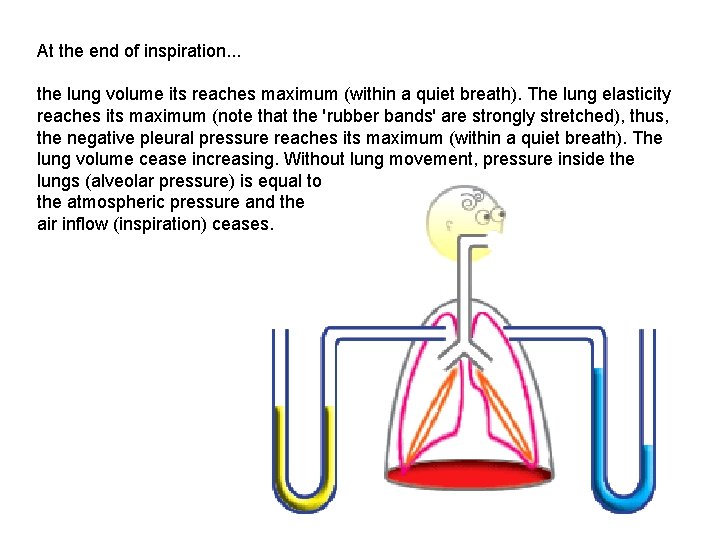

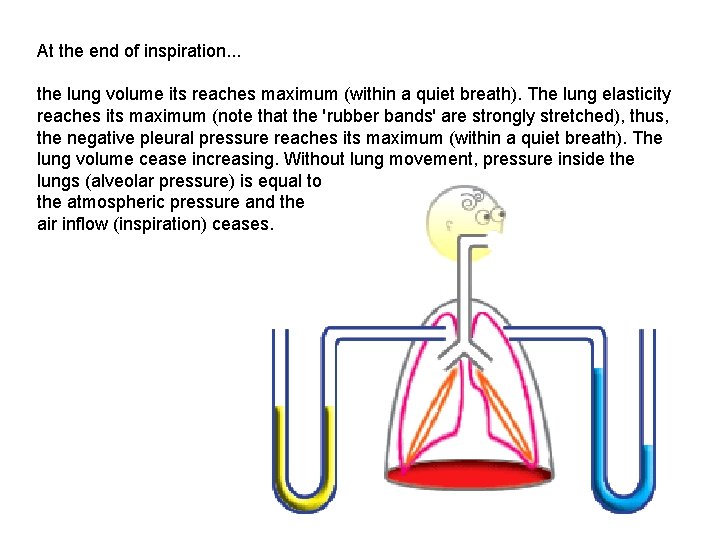

At the end of inspiration. . . the lung volume its reaches maximum (within a quiet breath). The lung elasticity reaches its maximum (note that the 'rubber bands' are strongly stretched), thus, the negative pleural pressure reaches its maximum (within a quiet breath). The lung volume cease increasing. Without lung movement, pressure inside the lungs (alveolar pressure) is equal to the atmospheric pressure and the air inflow (inspiration) ceases.

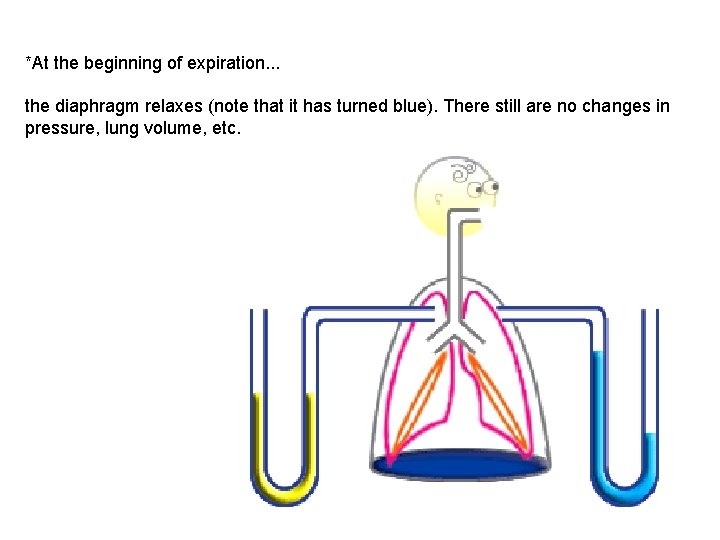

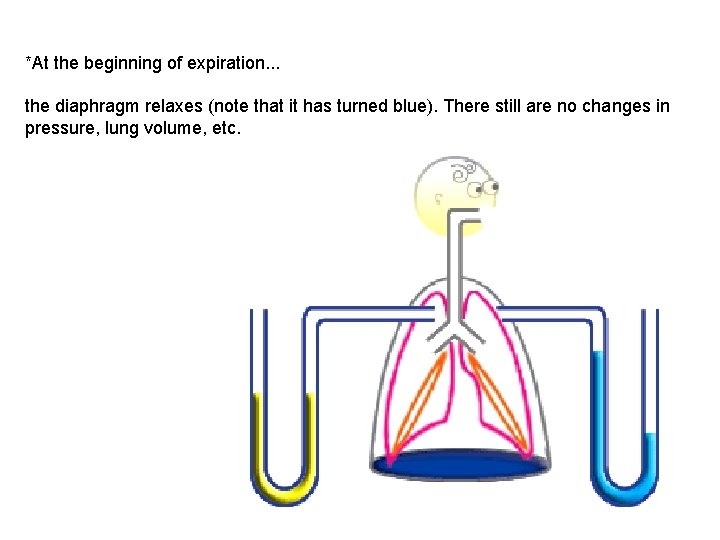

*At the beginning of expiration. . . the diaphragm relaxes (note that it has turned blue). There still are no changes in pressure, lung volume, etc.

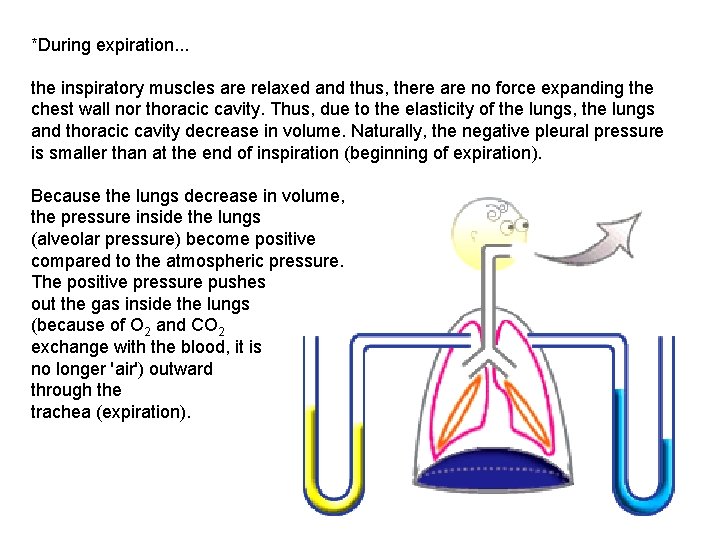

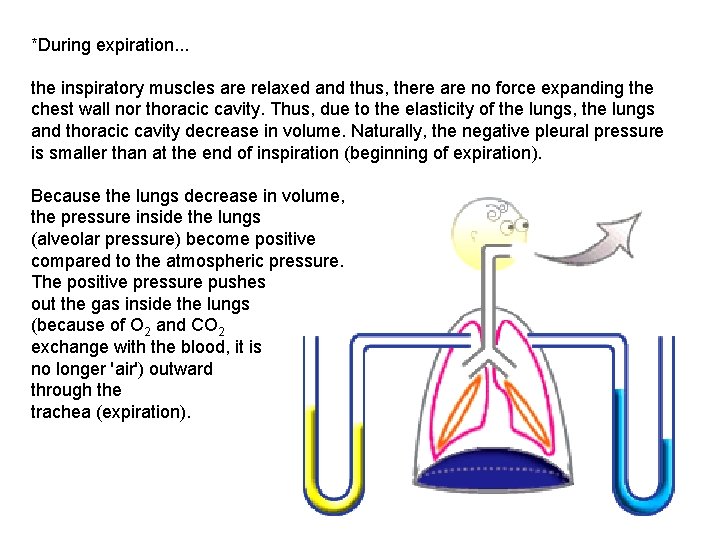

*During expiration. . . the inspiratory muscles are relaxed and thus, there are no force expanding the chest wall nor thoracic cavity. Thus, due to the elasticity of the lungs, the lungs and thoracic cavity decrease in volume. Naturally, the negative pleural pressure is smaller than at the end of inspiration (beginning of expiration). Because the lungs decrease in volume, the pressure inside the lungs (alveolar pressure) become positive compared to the atmospheric pressure. The positive pressure pushes out the gas inside the lungs (because of O 2 and CO 2 exchange with the blood, it is no longer 'air') outward through the trachea (expiration).

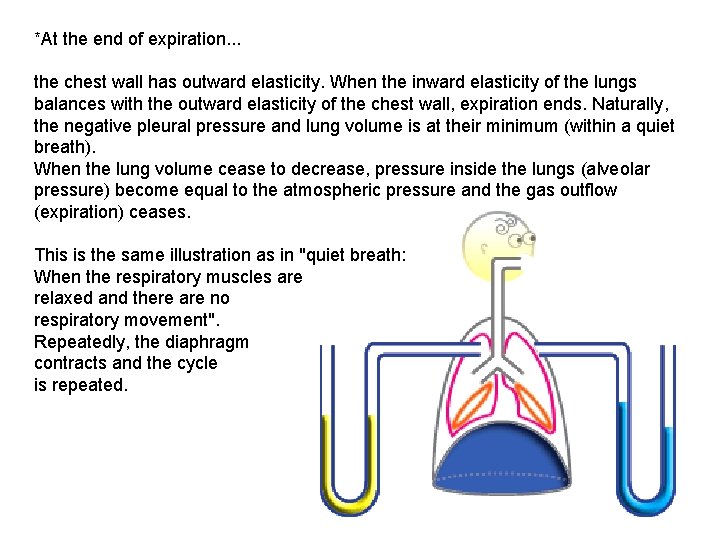

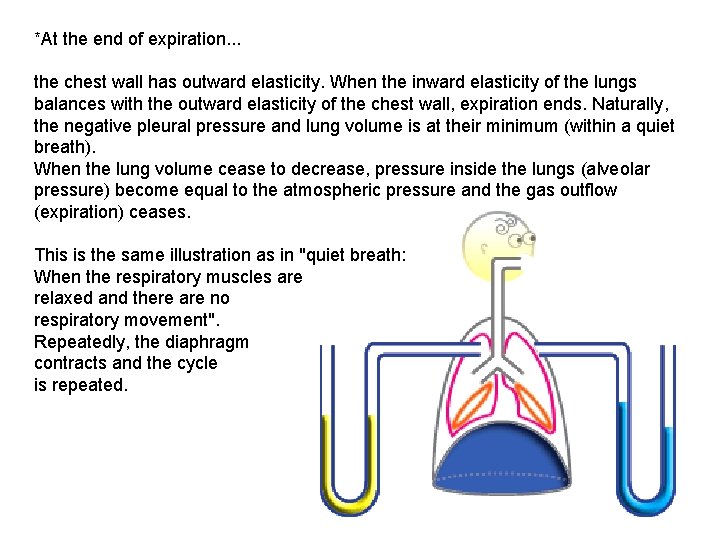

*At the end of expiration. . . the chest wall has outward elasticity. When the inward elasticity of the lungs balances with the outward elasticity of the chest wall, expiration ends. Naturally, the negative pleural pressure and lung volume is at their minimum (within a quiet breath). When the lung volume cease to decrease, pressure inside the lungs (alveolar pressure) become equal to the atmospheric pressure and the gas outflow (expiration) ceases. This is the same illustration as in "quiet breath: When the respiratory muscles are relaxed and there are no respiratory movement". Repeatedly, the diaphragm contracts and the cycle is repeated.

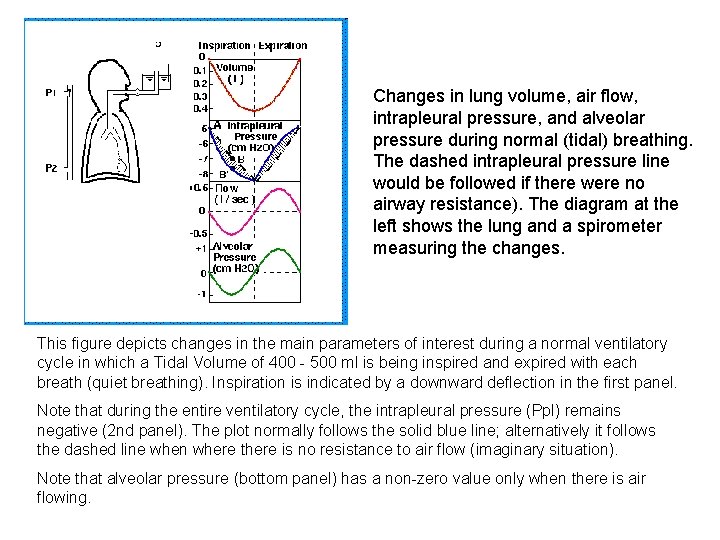

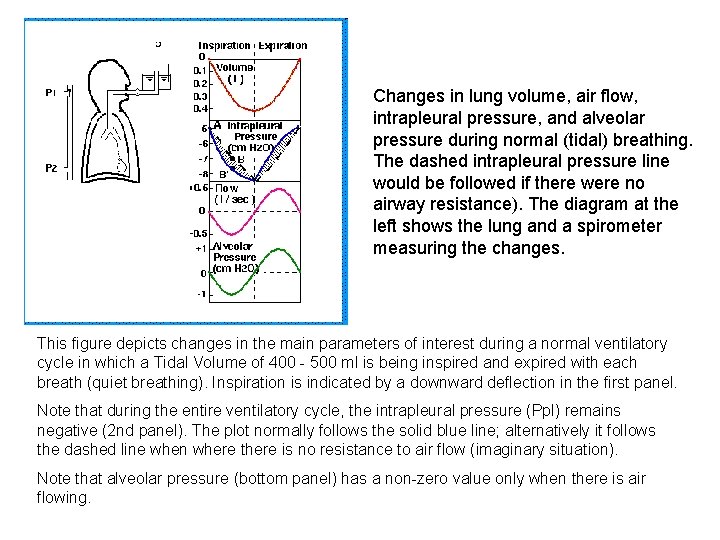

Changes in lung volume, air flow, intrapleural pressure, and alveolar pressure during normal (tidal) breathing. The dashed intrapleural pressure line would be followed if there were no airway resistance). The diagram at the left shows the lung and a spirometer measuring the changes. This figure depicts changes in the main parameters of interest during a normal ventilatory cycle in which a Tidal Volume of 400 - 500 ml is being inspired and expired with each breath (quiet breathing). Inspiration is indicated by a downward deflection in the first panel. Note that during the entire ventilatory cycle, the intrapleural pressure (Ppl) remains negative (2 nd panel). The plot normally follows the solid blue line; alternatively it follows the dashed line when where there is no resistance to air flow (imaginary situation). Note that alveolar pressure (bottom panel) has a non-zero value only when there is air flowing.

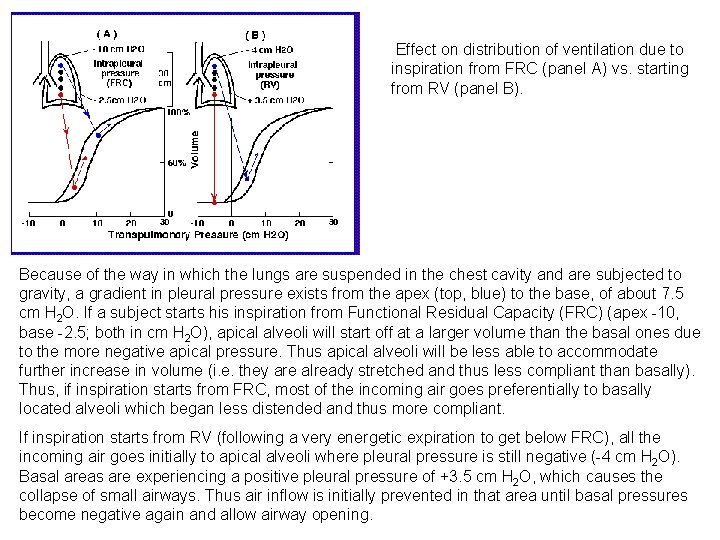

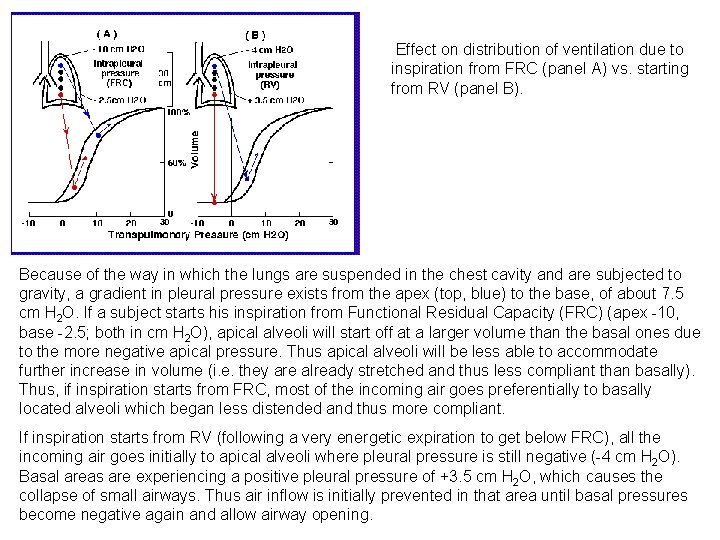

Effect on distribution of ventilation due to inspiration from FRC (panel A) vs. starting from RV (panel B). Because of the way in which the lungs are suspended in the chest cavity and are subjected to gravity, a gradient in pleural pressure exists from the apex (top, blue) to the base, of about 7. 5 cm H 2 O. If a subject starts his inspiration from Functional Residual Capacity (FRC) (apex -10, base -2. 5; both in cm H 2 O), apical alveoli will start off at a larger volume than the basal ones due to the more negative apical pressure. Thus apical alveoli will be less able to accommodate further increase in volume (i. e. they are already stretched and thus less compliant than basally). Thus, if inspiration starts from FRC, most of the incoming air goes preferentially to basally located alveoli which began less distended and thus more compliant. If inspiration starts from RV (following a very energetic expiration to get below FRC), all the incoming air goes initially to apical alveoli where pleural pressure is still negative (-4 cm H 2 O). Basal areas are experiencing a positive pleural pressure of +3. 5 cm H 2 O, which causes the collapse of small airways. Thus air inflow is initially prevented in that area until basal pressures become negative again and allow airway opening.

Presion intrapleural

Presion intrapleural Ejemplos de versos

Ejemplos de versos Coplas de 4 versos y 8 silabas

Coplas de 4 versos y 8 silabas Matronium

Matronium Tuverculosis pulmonar

Tuverculosis pulmonar Ausculta pulmonar

Ausculta pulmonar Circulação

Circulação Miocardio endocardio y pericardio

Miocardio endocardio y pericardio Pulmonar

Pulmonar Complacência pulmonar calculo

Complacência pulmonar calculo Flebografia con contraste

Flebografia con contraste Sdra medicina

Sdra medicina Topografia toracelui

Topografia toracelui Signo de fleischer en tromboembolia pulmonar

Signo de fleischer en tromboembolia pulmonar Cuales son los procesos de ventilacion pulmonar

Cuales son los procesos de ventilacion pulmonar Signos y sintomas de edema pulmonar

Signos y sintomas de edema pulmonar Musculos da respiração

Musculos da respiração Chistul hidatic pulmonar

Chistul hidatic pulmonar Unidades wood resistencia pulmonar

Unidades wood resistencia pulmonar Volumen de reserva inspiratoria

Volumen de reserva inspiratoria Ley de poiseuille medicina

Ley de poiseuille medicina Absceso pulmonar

Absceso pulmonar Opacificacion

Opacificacion Neumopatia

Neumopatia Tuberculosis pulmonar

Tuberculosis pulmonar Corticoide definição

Corticoide definição Ausculta

Ausculta Peribronquitis con insuflación

Peribronquitis con insuflación Pulmonar

Pulmonar Atresia de esofago tipos

Atresia de esofago tipos Respiração

Respiração Masa pulmonar

Masa pulmonar Scifosis

Scifosis Cord pulmonar acut

Cord pulmonar acut Reumatograma

Reumatograma Infarto

Infarto Tuberculosis patogenia

Tuberculosis patogenia Peribronhovascular

Peribronhovascular Grafico espirometria normal

Grafico espirometria normal Enbolia pulmonar

Enbolia pulmonar Pulmones

Pulmones Embolia pulmonar

Embolia pulmonar Score de ginebra tep

Score de ginebra tep Fibrose pulmonar

Fibrose pulmonar Complacência pulmonar calculo

Complacência pulmonar calculo Excrecion pulmonar

Excrecion pulmonar