The historical sociolinguistics of heritage languages Joseph Salmons

![17 Table 1: Apparent substrate features FEATURE Imposition Final fortition EXAMPLE SOURCES beer[s] stigmatized 17 Table 1: Apparent substrate features FEATURE Imposition Final fortition EXAMPLE SOURCES beer[s] stigmatized](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e3a4c07fc2c27e10e0a4890f00be825e/image-17.jpg)

![24 Southwestern chee[z]e (Richland Center) 24 Southwestern chee[z]e (Richland Center)](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e3a4c07fc2c27e10e0a4890f00be825e/image-24.jpg)

![25 Southeastern cheese /z/ > [s] (Muskego) 25 Southeastern cheese /z/ > [s] (Muskego)](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e3a4c07fc2c27e10e0a4890f00be825e/image-25.jpg)

![47 Parasitic gaps: English vs. German [Which book]1 did you sell t 1 without 47 Parasitic gaps: English vs. German [Which book]1 did you sell t 1 without](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e3a4c07fc2c27e10e0a4890f00be825e/image-47.jpg)

![Wisconsin Heritage German Gap • Sheboygan [is e‘] Stadt die Leit gleichen wennse visit Wisconsin Heritage German Gap • Sheboygan [is e‘] Stadt die Leit gleichen wennse visit](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e3a4c07fc2c27e10e0a4890f00be825e/image-50.jpg)

![65 THANK[s]! Thanks to Luke Annear, Emily Claire, Alicia Groh, Mary Simonsen, Trini Stickle, 65 THANK[s]! Thanks to Luke Annear, Emily Claire, Alicia Groh, Mary Simonsen, Trini Stickle,](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e3a4c07fc2c27e10e0a4890f00be825e/image-65.jpg)

- Slides: 65

The historical sociolinguistics of heritage languages Joseph Salmons with Joshua Bousquette, Christine Evans, Benjamin Frey, Alyson Sewell, Samantha Litty, Mark Livengood, Felecia Lucht, Daniel Nützel, Michael Putnam, Miranda Wilkerson, Brent Allen and many others 7 th Hi. So. N Summer School, Metochi, Greece August 2013

2 Today: Issues and case studies • Questions from last time? • Language shift and substrate influences • Demographics of rapid shift • Structural effects and how they get transferred • Complexity in heritage languages • Syntax • Morphology • Your questions

3 SHIFT AND ITS EFFECTS

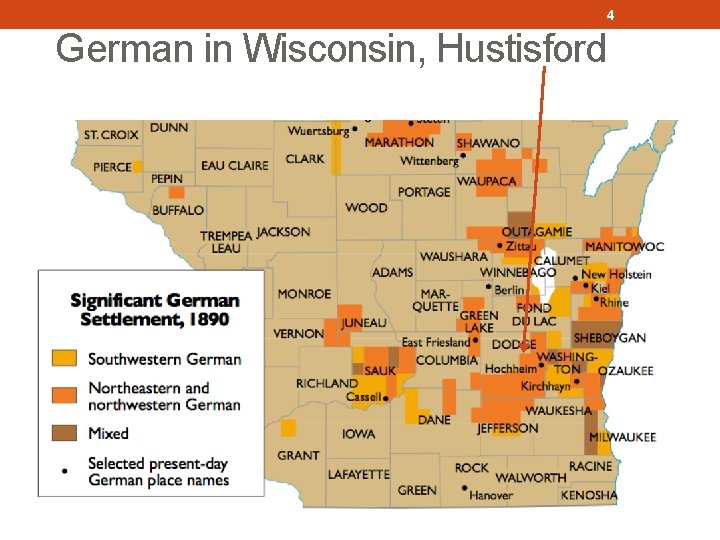

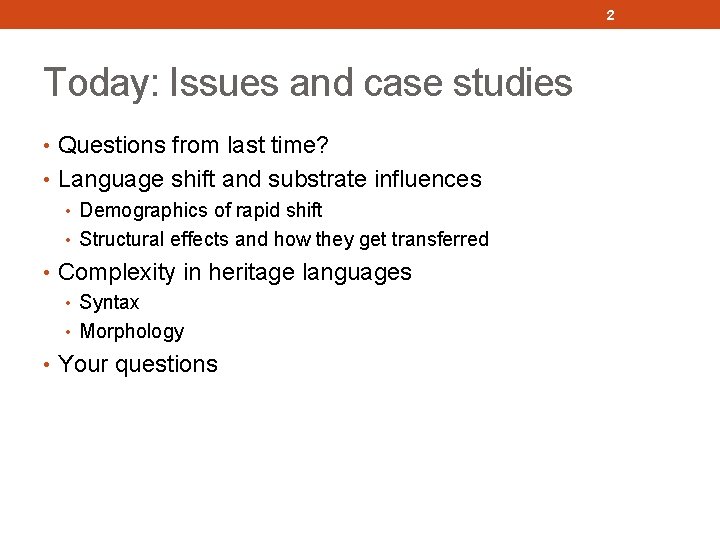

4 German in Wisconsin, Hustisford

Michael Reagan All across the U. S. , hordes of immigrants … are chattering away in their native language and have no intention of learning English – the all-but-official language of the United States …. They are being enabled … to defy the age-old custom of immigrants to our shores who made it one of their first priorities to learn to speak English and to teach their offspring to do likewise. It was a case of sink or swim. If you couldn’t speak English, you couldn’t get by, go to school, get a job, or become a citizen and vote.

Were these true of Wisconsin Germans? Ø Did they always learn English? One of the first priorities? Ø Who were monolinguals? Ø What was their basic demographic profile? Ø Were they economically marginal? Ø Were they Isolated in rural areas or in neighborhoods in town? Ø How did they fit into the social structure? Ø Did they belong to separate churches? Ø Did they attend school? If so, how did they not learn English?

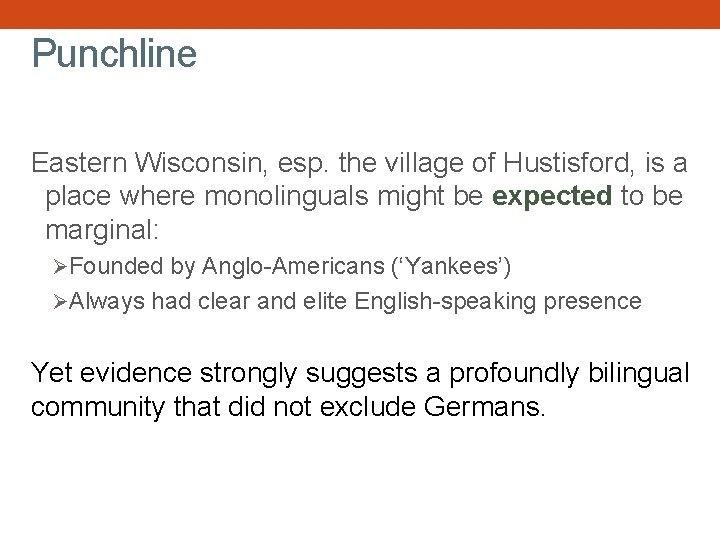

Punchline Eastern Wisconsin, esp. the village of Hustisford, is a place where monolinguals might be expected to be marginal: ØFounded by Anglo-Americans (‘Yankees’) ØAlways had clear and elite English-speaking presence Yet evidence strongly suggests a profoundly bilingual community that did not exclude Germans.

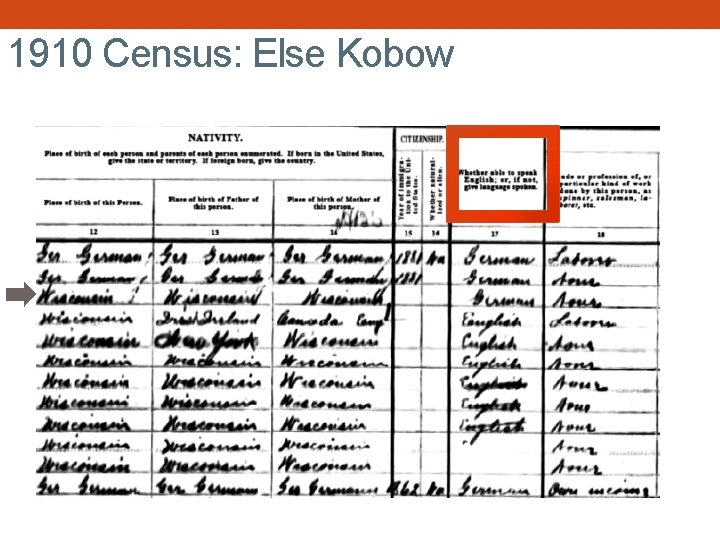

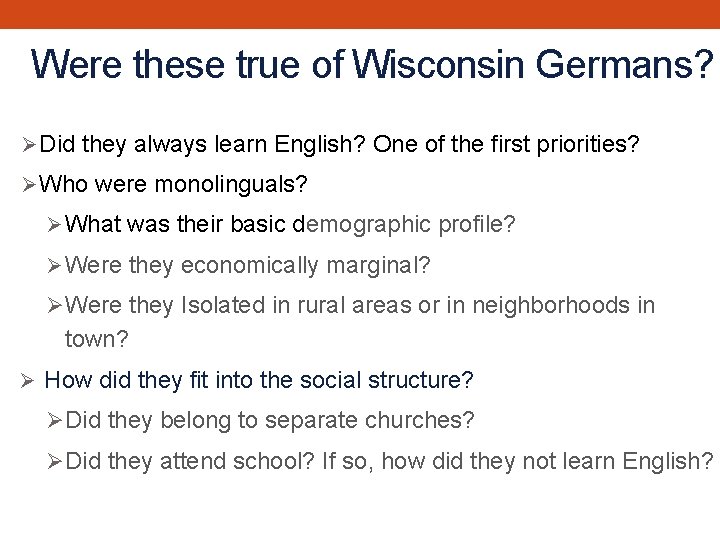

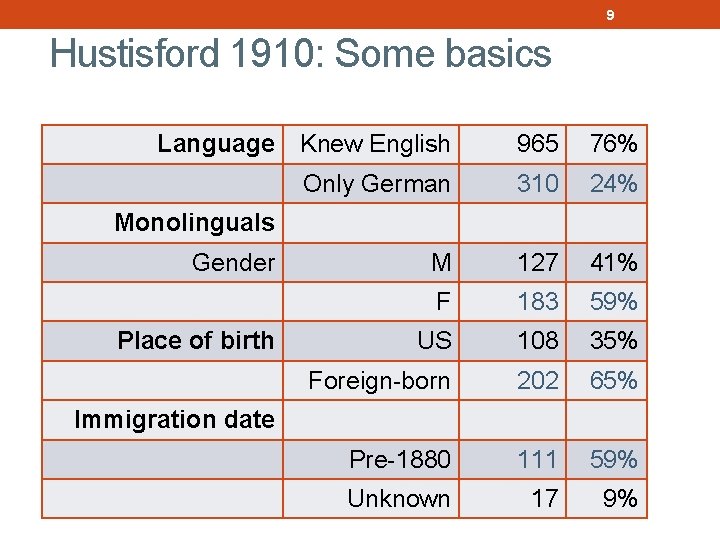

1910 Census: Else Kobow

9 Hustisford 1910: Some basics Language Knew English 965 76% Only German 310 24% M 127 41% F 183 59% US 108 35% Foreign-born 202 65% Pre-1880 111 59% Unknown 17 9% Monolinguals Gender Place of birth Immigration date

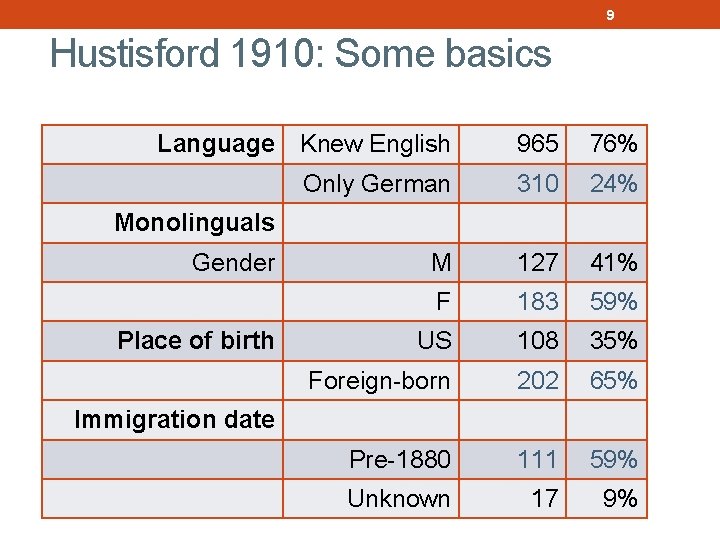

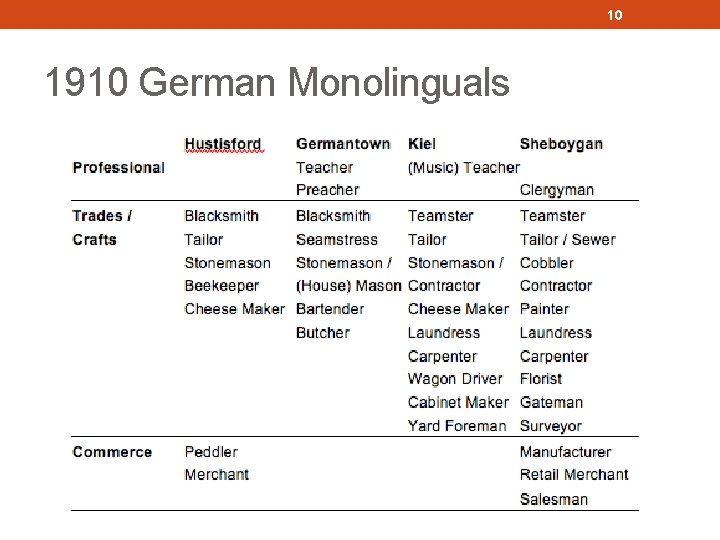

10 1910 German Monolinguals

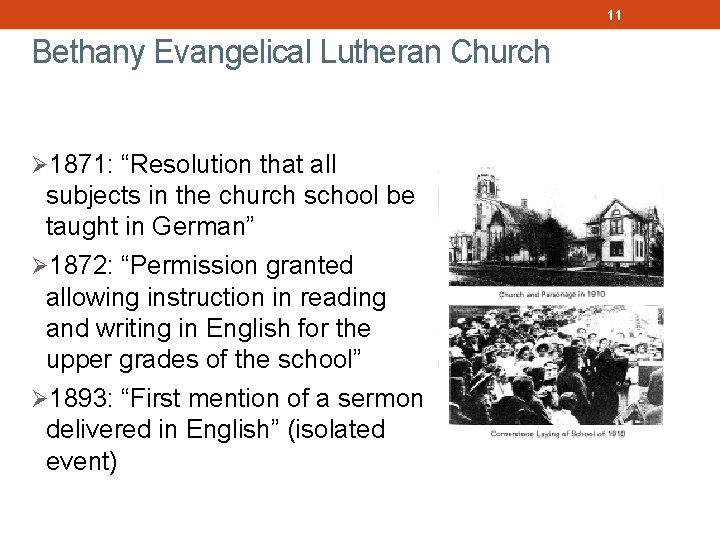

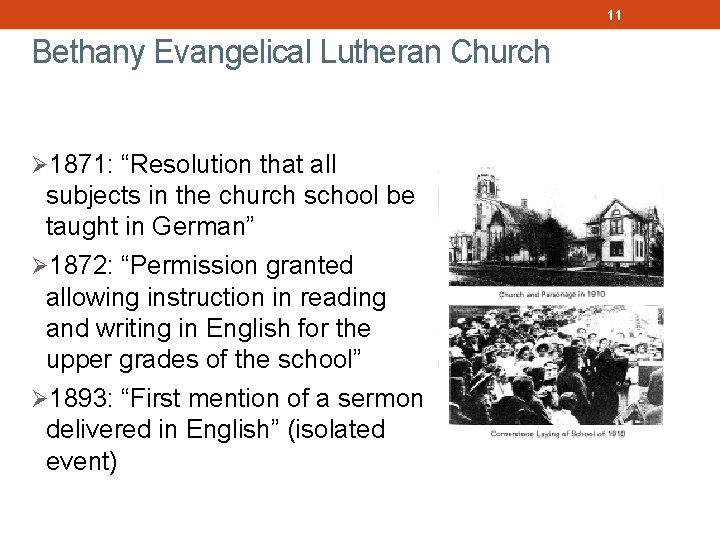

11 Bethany Evangelical Lutheran Church Ø 1871: “Resolution that all subjects in the church school be taught in German” Ø 1872: “Permission granted allowing instruction in reading and writing in English for the upper grades of the school” Ø 1893: “First mention of a sermon delivered in English” (isolated event)

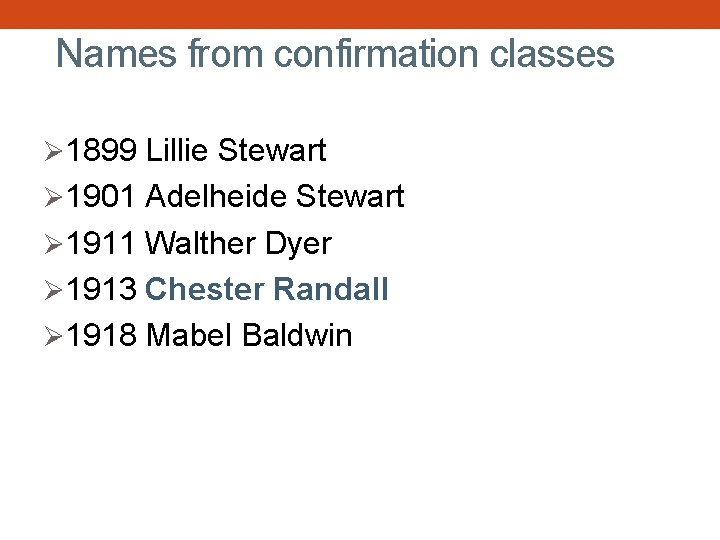

Names from confirmation classes Ø 1899 Lillie Stewart Ø 1901 Adelheide Stewart Ø 1911 Walther Dyer Ø 1913 Chester Randall Ø 1918 Mabel Baldwin

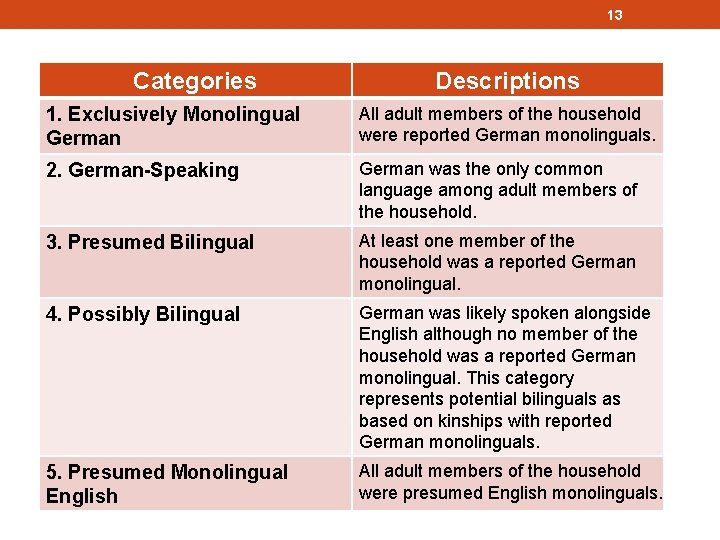

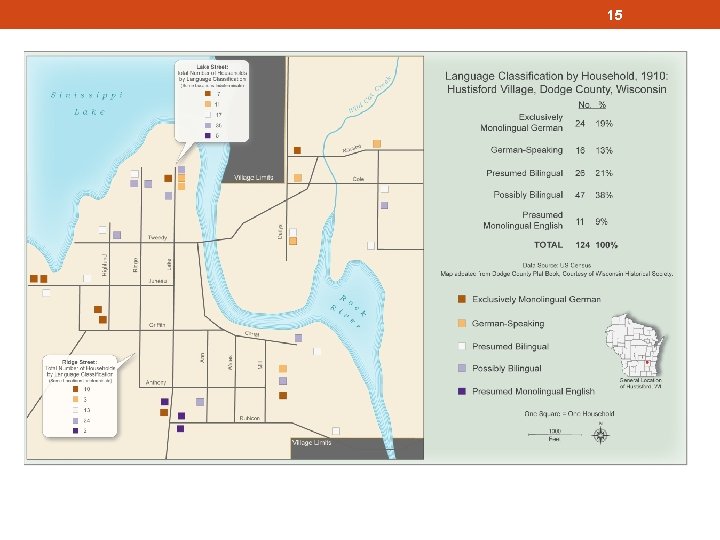

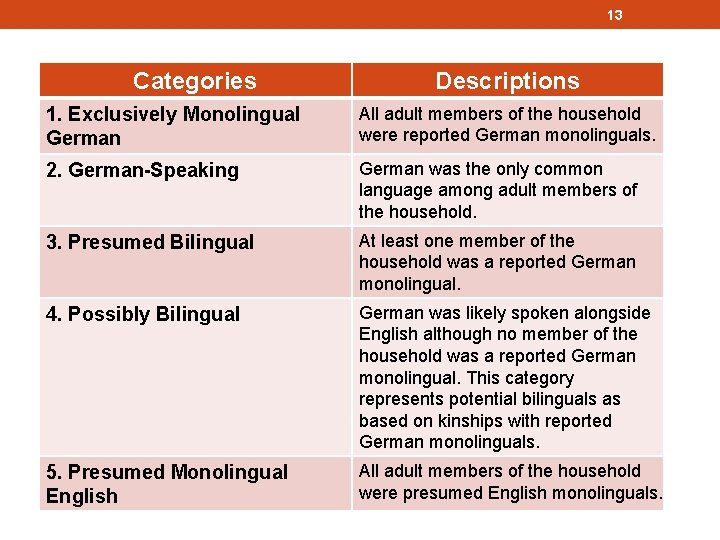

13 Home. Categories Language Descriptions 1. Exclusively Monolingual German All adult members of the household were reported German monolinguals. 2. German-Speaking German was the only common language among adult members of the household. 3. Presumed Bilingual At least one member of the household was a reported German monolingual. 4. Possibly Bilingual German was likely spoken alongside English although no member of the household was a reported German monolingual. This category represents potential bilinguals as based on kinships with reported German monolinguals. 5. Presumed Monolingual English All adult members of the household were presumed English monolinguals.

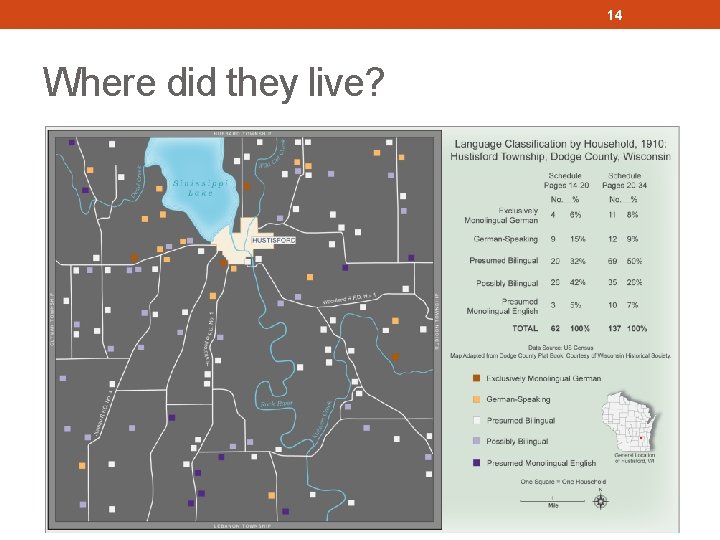

14 Where did they live?

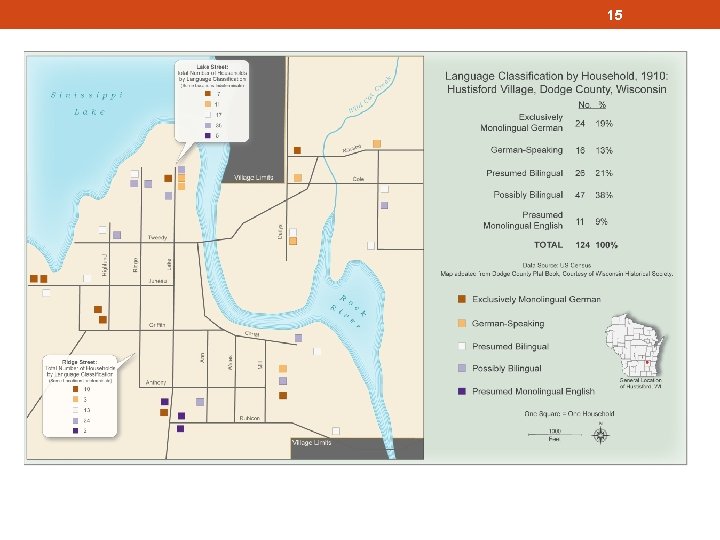

15

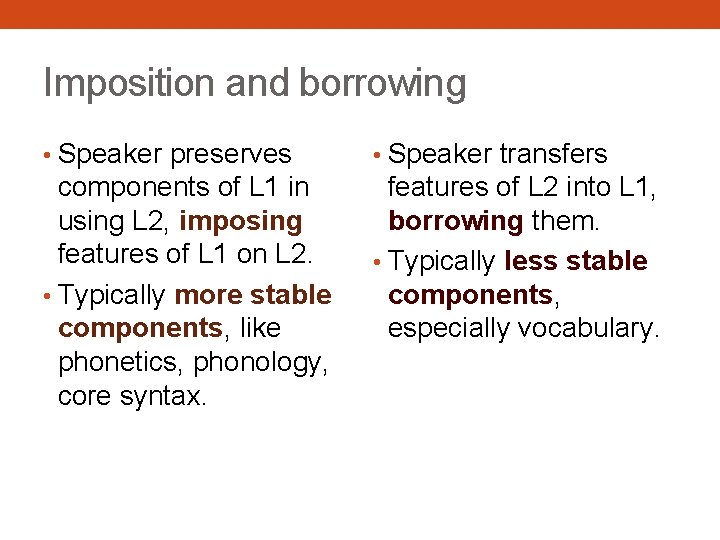

16 Imposition and borrowing • Speaker preserves • Speaker transfers components of L 1 in using L 2, imposing features of L 1 on L 2. • Typically more stable components, like phonetics, phonology, core syntax. features of L 2 into L 1, borrowing them. • Typically less stable components, especially vocabulary.

![17 Table 1 Apparent substrate features FEATURE Imposition Final fortition EXAMPLE SOURCES beers stigmatized 17 Table 1: Apparent substrate features FEATURE Imposition Final fortition EXAMPLE SOURCES beer[s] stigmatized](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e3a4c07fc2c27e10e0a4890f00be825e/image-17.jpg)

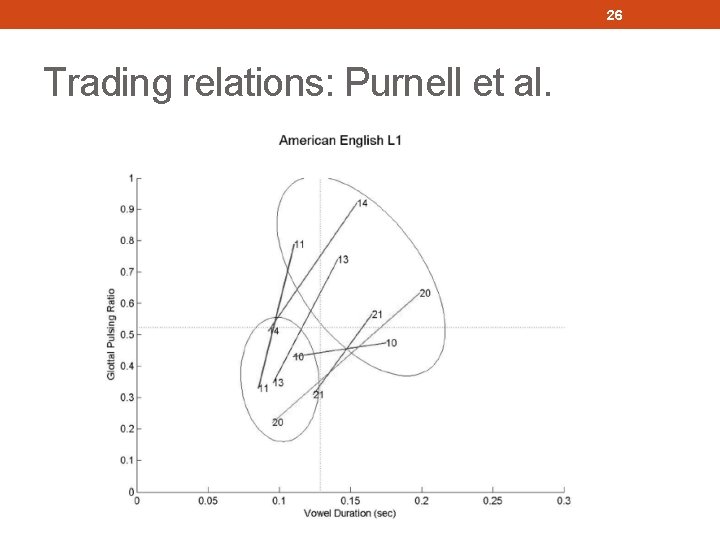

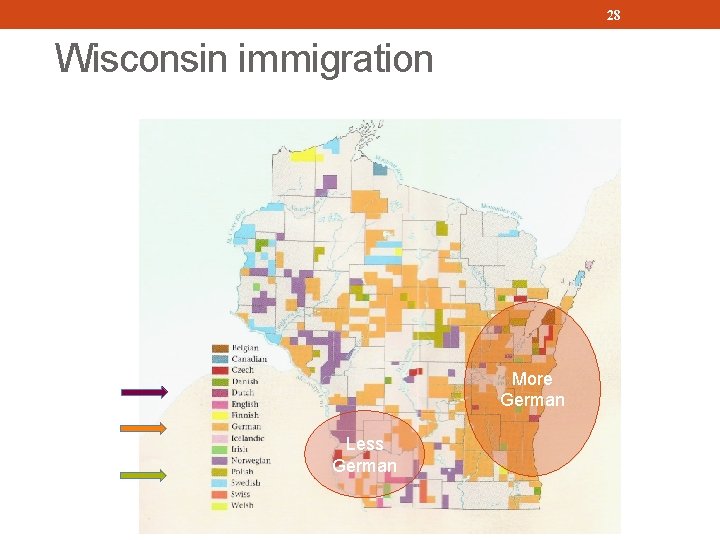

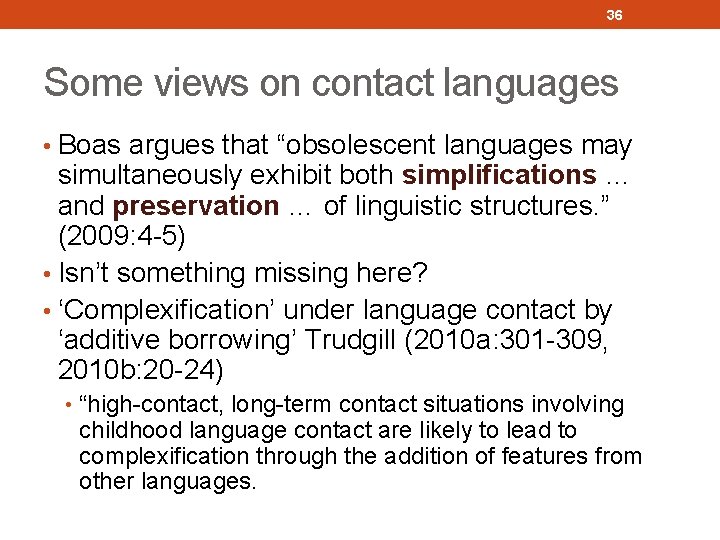

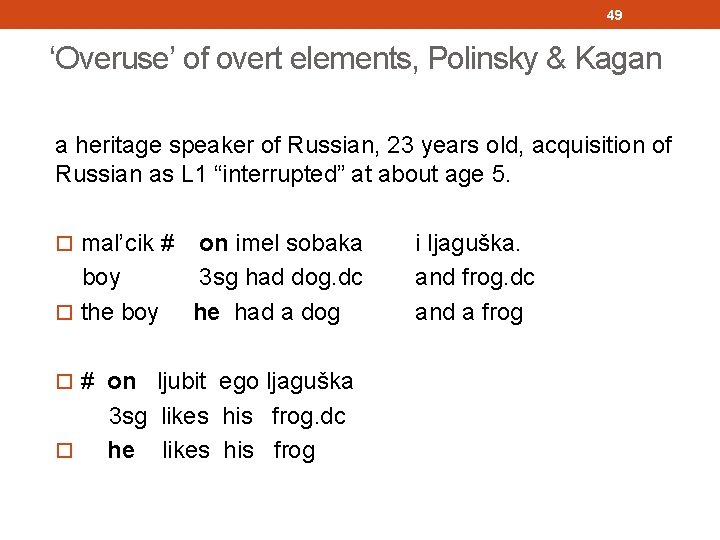

17 Table 1: Apparent substrate features FEATURE Imposition Final fortition EXAMPLE SOURCES beer[s] stigmatized earlier Stopping dem, dere, dose Pluralia tantum Discourse marking Verbparticle Borrowing a scissors German, Dutch, spreading Polish many immigrant recessive languages German, Dutch stable come here once German (Dutch) stable apparently not wanna come with? Pan-Germanic spreading little or none Content lexicon brat, berliner, oma, kaput, dummkopf German recessive, a few yes spreading recessive yes Tag questions ainna? , not? various lgs, these ex German Exclamatio ns etc. ach ya, halt’s maul, sieh mal, macht nichts German TRAJECTORY AWARENESS stigmatized in most groups apparently not

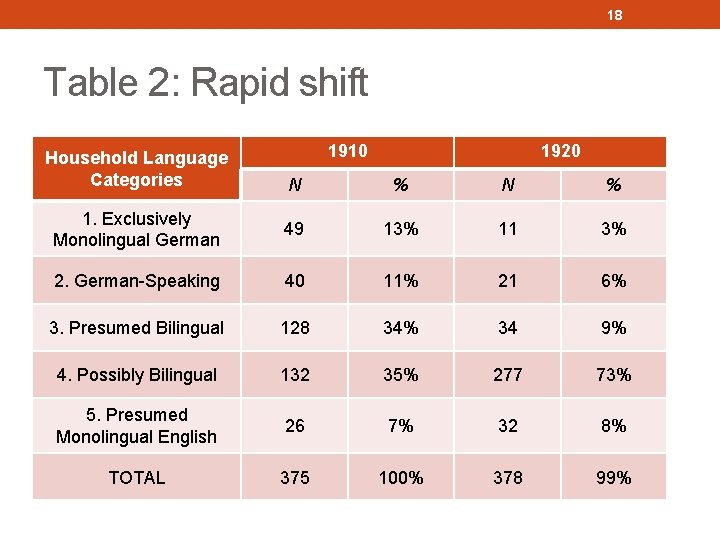

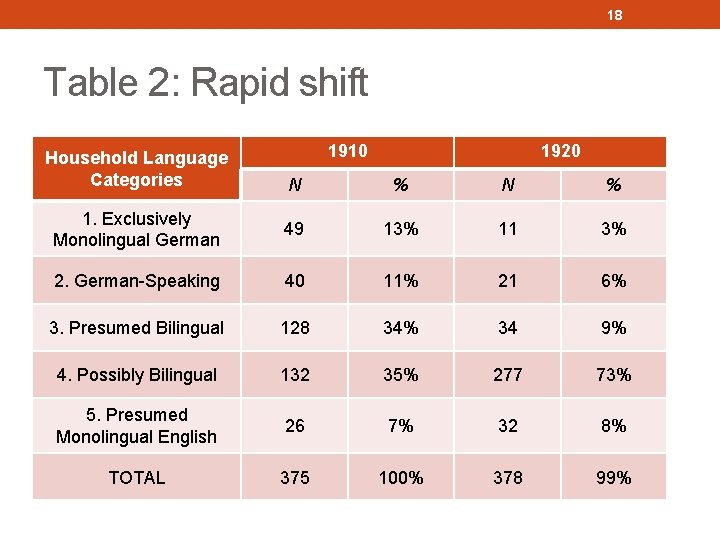

18 Table 2: Rapid shift Household Language Categories 1910 1920 N % 1. Exclusively Monolingual German 49 13% 11 3% 2. German-Speaking 40 11% 21 6% 3. Presumed Bilingual 128 34% 34 9% 4. Possibly Bilingual 132 35% 277 73% 5. Presumed Monolingual English 26 7% 32 8% TOTAL 375 100% 378 99%

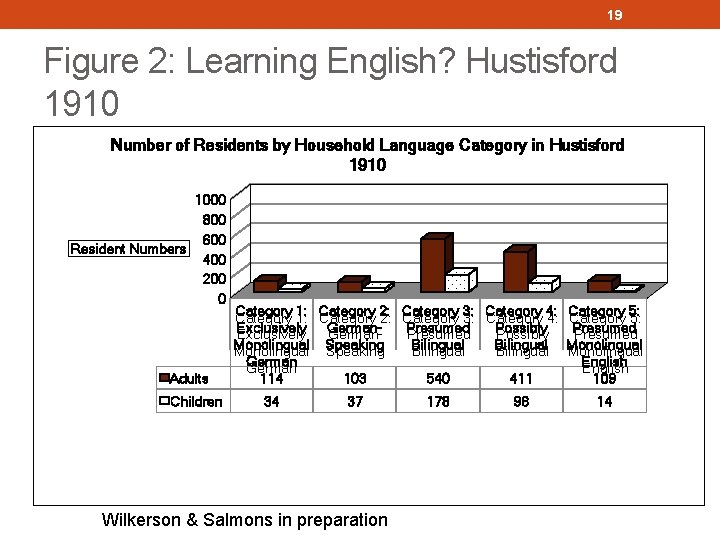

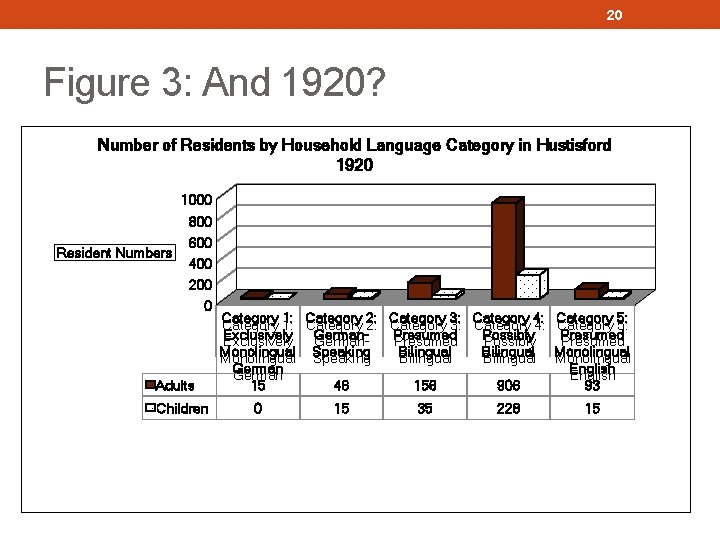

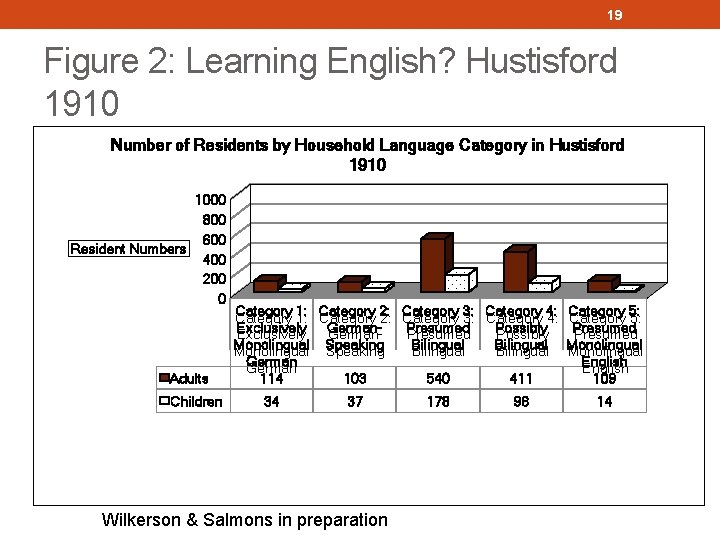

19 Figure 2: Learning English? Hustisford 1910 Number of Residents by Household Language Category in Hustisford 1910 1000 800 600 Resident Numbers 400 200 0 Adults Children Category 1: 1: Category 2: 2: Category 3: 3: Category 4: 4: Category 5: 5: Exclusively German. Presumed Possibly Presumed Monolingual Speaking Bilingual Monolingual German English 114 103 540 411 109 34 37 Wilkerson & Salmons in preparation 178 96 14

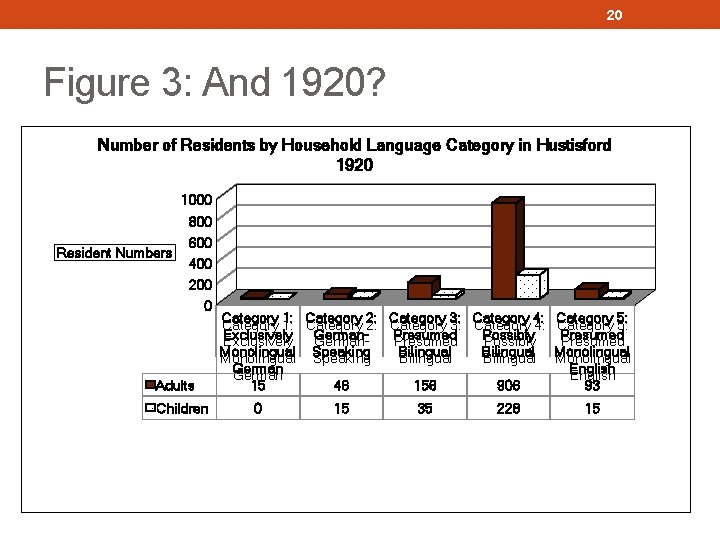

20 Figure 3: And 1920? Number of Residents by Household Language Category in Hustisford 1920 1000 Resident Numbers 800 600 400 200 0 Adults Children Category 1: 1: Category 2: 2: Category 3: 3: Category 4: 4: Category 5: 5: Exclusively German. Presumed Possibly Presumed Monolingual Speaking Bilingual Monolingual German English 15 46 156 906 93 0 15 35 228 15

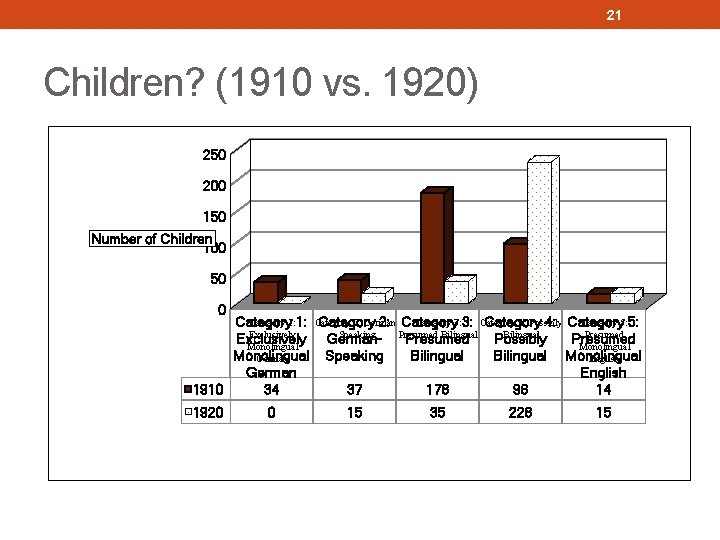

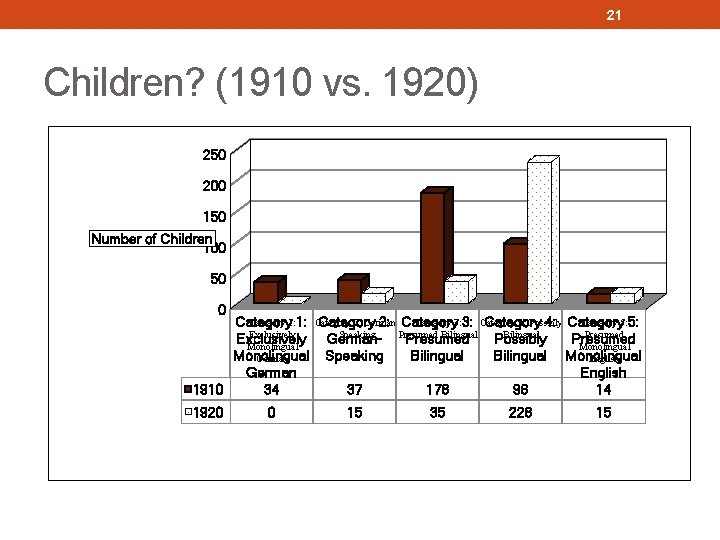

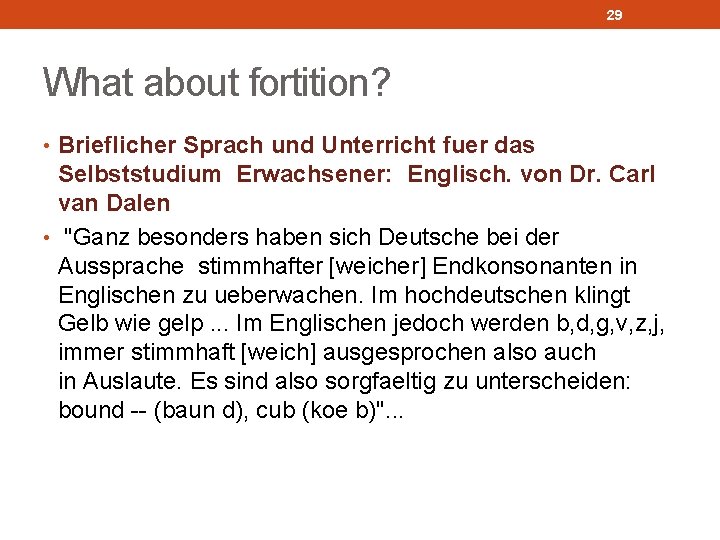

21 Children? (1910 vs. 1920) 250 200 150 Number of Children 100 50 0 Category 1: 1: Category 2: German Category 3: 3: Category 4: Possibly Category 5: 5: Category 2: Category 4: Category Exclusively -Speaking Presumed Bilingual Presumed Exclusively German. Presumed Possibly Presumed Monolingual Speaking Bilingual Monolingual German English 1910 34 37 178 96 14 1920 0 15 35 228 15

22 But it doesn’t stop with shift …

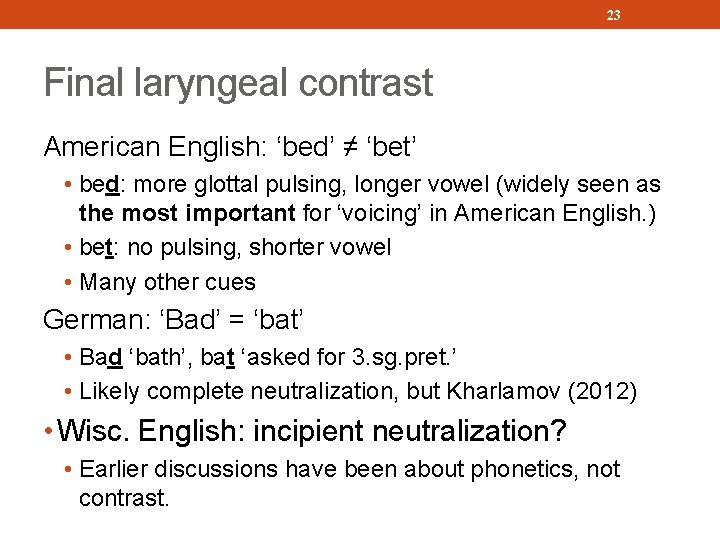

23 Final laryngeal contrast American English: ‘bed’ ≠ ‘bet’ • bed: more glottal pulsing, longer vowel (widely seen as the most important for ‘voicing’ in American English. ) • bet: no pulsing, shorter vowel • Many other cues German: ‘Bad’ = ‘bat’ • Bad ‘bath’, bat ‘asked for 3. sg. pret. ’ • Likely complete neutralization, but Kharlamov (2012) • Wisc. English: incipient neutralization? • Earlier discussions have been about phonetics, not contrast.

![24 Southwestern cheeze Richland Center 24 Southwestern chee[z]e (Richland Center)](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e3a4c07fc2c27e10e0a4890f00be825e/image-24.jpg)

24 Southwestern chee[z]e (Richland Center)

![25 Southeastern cheese z s Muskego 25 Southeastern cheese /z/ > [s] (Muskego)](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e3a4c07fc2c27e10e0a4890f00be825e/image-25.jpg)

25 Southeastern cheese /z/ > [s] (Muskego)

26 Trading relations: Purnell et al.

27 Change in cues, stable contrast in one eastern community

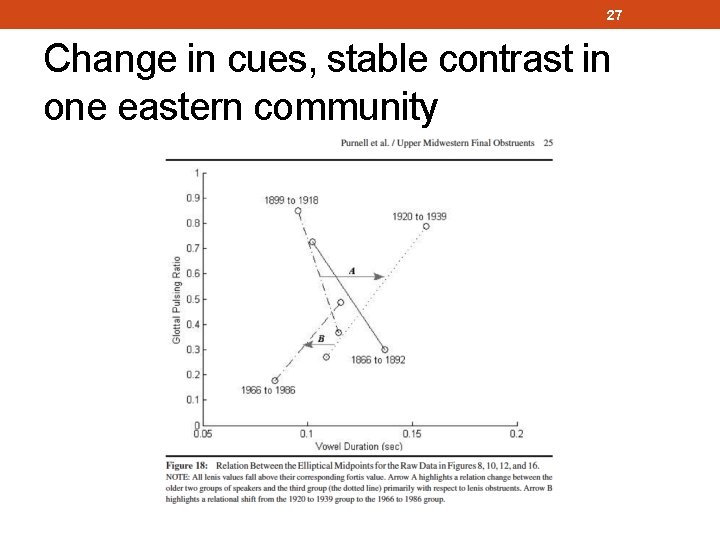

28 Wisconsin immigration More German Less German

29 What about fortition? • Brieflicher Sprach und Unterricht fuer das Selbststudium Erwachsener: Englisch. von Dr. Carl van Dalen • "Ganz besonders haben sich Deutsche bei der Aussprache stimmhafter [weicher] Endkonsonanten in Englischen zu ueberwachen. Im hochdeutschen klingt Gelb wie gelp. . . Im Englischen jedoch werden b, d, g, v, z, j, immer stimmhaft [weich] ausgesprochen also auch in Auslaute. Es sind also sorgfaeltig zu unterscheiden: bound -- (baun d), cub (koe b)". . .

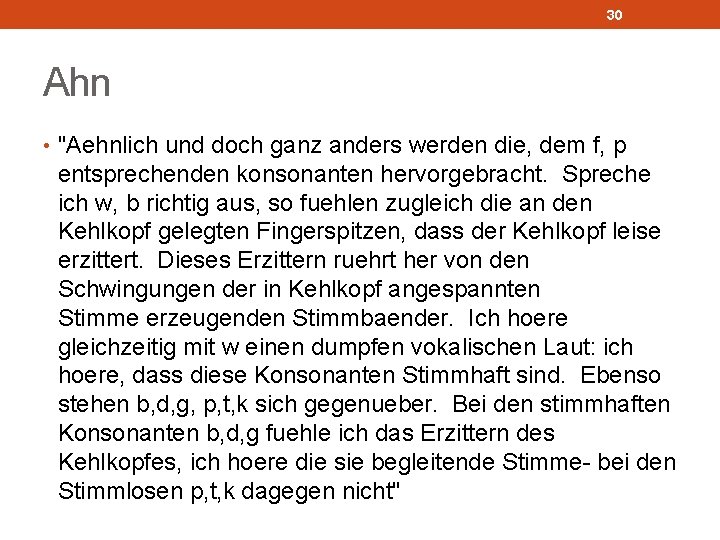

30 Ahn • "Aehnlich und doch ganz anders werden die, dem f, p entsprechenden konsonanten hervorgebracht. Spreche ich w, b richtig aus, so fuehlen zugleich die an den Kehlkopf gelegten Fingerspitzen, dass der Kehlkopf leise erzittert. Dieses Erzittern ruehrt her von den Schwingungen der in Kehlkopf angespannten Stimme erzeugenden Stimmbaender. Ich hoere gleichzeitig mit w einen dumpfen vokalischen Laut: ich hoere, dass diese Konsonanten Stimmhaft sind. Ebenso stehen b, d, g, p, t, k sich gegenueber. Bei den stimmhaften Konsonanten b, d, g fuehle ich das Erzittern des Kehlkopfes, ich hoere die sie begleitende Stimme- bei den Stimmlosen p, t, k dagegen nicht"

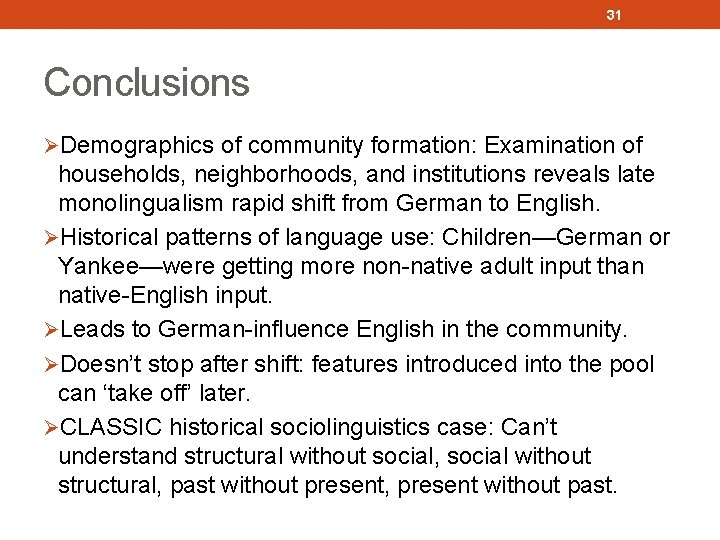

31 Conclusions ØDemographics of community formation: Examination of households, neighborhoods, and institutions reveals late monolingualism rapid shift from German to English. ØHistorical patterns of language use: Children—German or Yankee—were getting more non-native adult input than native-English input. ØLeads to German-influence English in the community. ØDoesn’t stop after shift: features introduced into the pool can ‘take off’ later. ØCLASSIC historical sociolinguistics case: Can’t understand structural without social, social without structural, past without present, present without past.

32 COMPLEXITY

33 The point • Common claim: Languages in contact, obsolescent languages, heritage languages, creoles are all subject to simplification or at most maintain existing complexity. • Our argument: Even an obsolescent heritage language in intense contact in a community where many people haven’t spoken it in decades shows clear increases in complexity. • That holds, it seems, however you define complexity. • Even examples of simplification often have unexpected explanations.

34 A closely related point • The rhetoric about contact languages of virtually any sort — creoles, heritage languages, obsolescent languages — is about deficiency: attrition, incomplete acquisition, loss, not to mention interruption, lack, failure, absence, inability, and on. • But language is about human cognition and we’re dealing with full and complete systems. • De. Graff (2001: 291): Creoles … are reflections of our (species-uniform and species-specific) human biology, … among the “most beautiful and most wonderful [forms that] have been, and are being, evolved” …

35 Complexity • Crystal (2003): Complexity includes “both the formal internal structuring of linguistic units and the psychological difficulty in using or learning them. … However, it has not yet proved feasible to establish independent measures of complexity defined in purely linguistic terms. ” • Nettle (2012): “The complexity of different components of the grammars of human languages can be quantified. For example, languages vary greatly in the size of their phonological inventories, and in the degree to which they make use of inflectional morphology. ” • De. Graff (2001): “Complexity is no simple matter. ” • Roberge (1994): warns us to avoid “simplistic hypotheses” about contact and change.

36 Some views on contact languages • Boas argues that “obsolescent languages may simultaneously exhibit both simplifications … and preservation … of linguistic structures. ” (2009: 4 -5) • Isn’t something missing here? • ‘Complexification’ under language contact by ‘additive borrowing’ Trudgill (2010 a: 301 -309, 2010 b: 20 -24) • “high-contact, long-term contact situations involving childhood language contact are likely to lead to complexification through the addition of features from other languages.

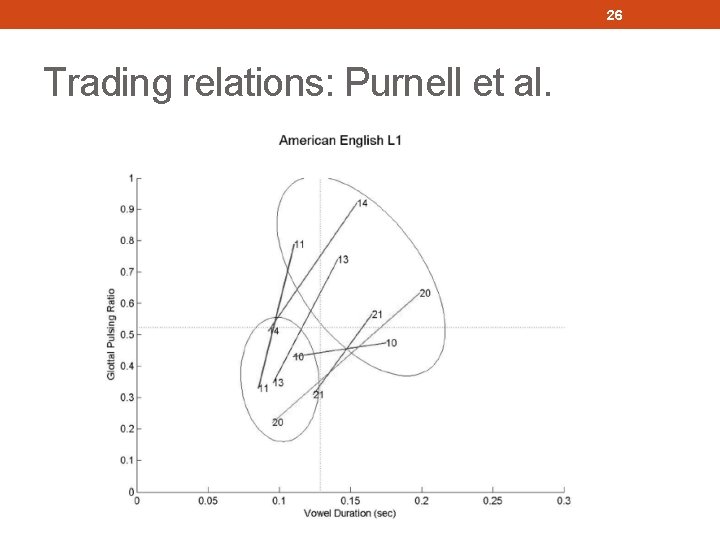

Some testable points in here … • Has Wisconsin Heritage German simplified over time? • Or has it preserved complexity? • Or has it gained complexity? • If the last, is it (only) by addition of features from contact languages or dialects?

38 NEW INFLECTIONAL MORPHOLOGY Complementizer agreement in Wisconsin Heritage German

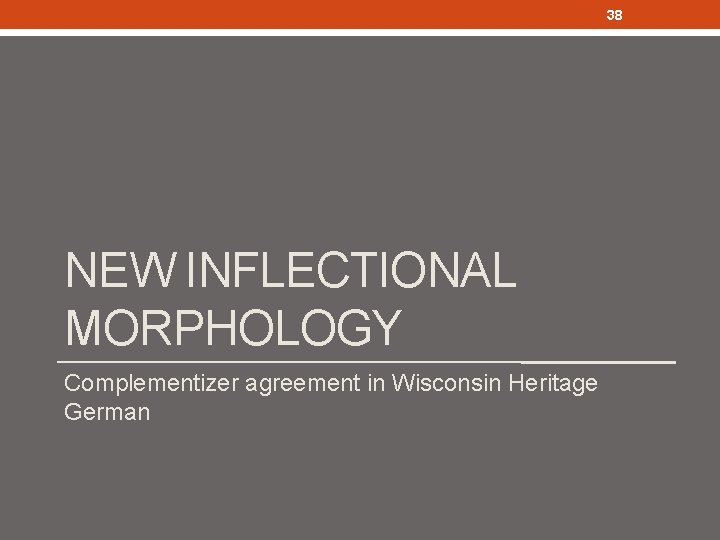

39 Complementizer agreement • Standard German • wenn du willst • if you want to. 2 sg • wenn • if ihr y’all wollt want to. 2 pl • Dialectal German (esp. Southern, also W. Frisian, Dutch) • wennst du willst • if. 2 sg you want to. 2 sg • wennt • if. 2 pl ihr y’all wollt want to. 2 pl

40 Complexification: New inflection • In what sense is C-agr more complex? • Additional inflection • Inflection is the one area where everybody seems to agree that loss comes with contact. • Where did it come from? • Probably present in a few input dialects, but certainly not all; pops up all over West Germanic • Sources • Joshua Bousquette. 2013. Complementizer Agreement in Modern Varieties of West Germanic: A model of reanalysis and renewal. Ph. D. dissertation, UW–Madison. • Joshua Bousquette. Forthcoming. “Complementizer Agreement in Heritage Varieties of Wisconsin German”.

41 The point • C-agr has developed independently • Discontinuous communities and different languages in Europe • Diasporic communities like the Siebenbürger communities in Transylvania and Cimbrian in Italy • C-agr in Wisconsin shares SOME similarities with Continental varieties, but not ALL • different morphological distribution (WI restricted to 2 -sg) • Wisconsin attestations more closely resemble one another; they do not directly match any specific input dialect, which includes the dialects of their first generation ancestors • Speakers acquire C-agr in Wisconsin when their European ancestors’ dialects did not have C-agr • Independent, parallel development? • Result of dialect mixing?

42 Example 1 • Wennsdu rauchen dust… • If-you smoking do … • “If you smoke…” • (Speaker J, Sheboygan, WI)

43 Example 2 • Wennsdu zu mein Haus kommst, dann kannst du Cake haben. • “If you come to my house, then you can have cake. ”

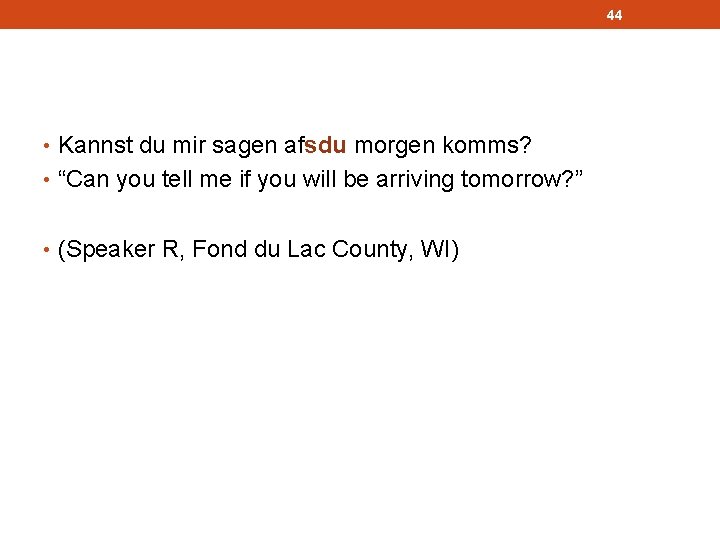

44 • Kannst du mir sagen afsdu morgen komms? • “Can you tell me if you will be arriving tomorrow? ” • (Speaker R, Fond du Lac County, WI)

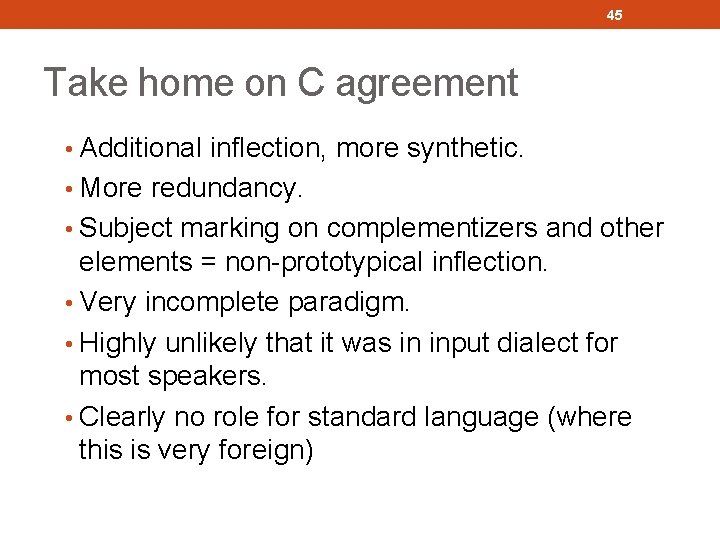

45 Take home on C agreement • Additional inflection, more synthetic. • More redundancy. • Subject marking on complementizers and other elements = non-prototypical inflection. • Very incomplete paradigm. • Highly unlikely that it was in input dialect for most speakers. • Clearly no role for standard language (where this is very foreign)

46 NULL ELEMENTS Multiple gap constructions in Wisconsin Heritage German

![47 Parasitic gaps English vs German Which book1 did you sell t 1 without 47 Parasitic gaps: English vs. German [Which book]1 did you sell t 1 without](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e3a4c07fc2c27e10e0a4890f00be825e/image-47.jpg)

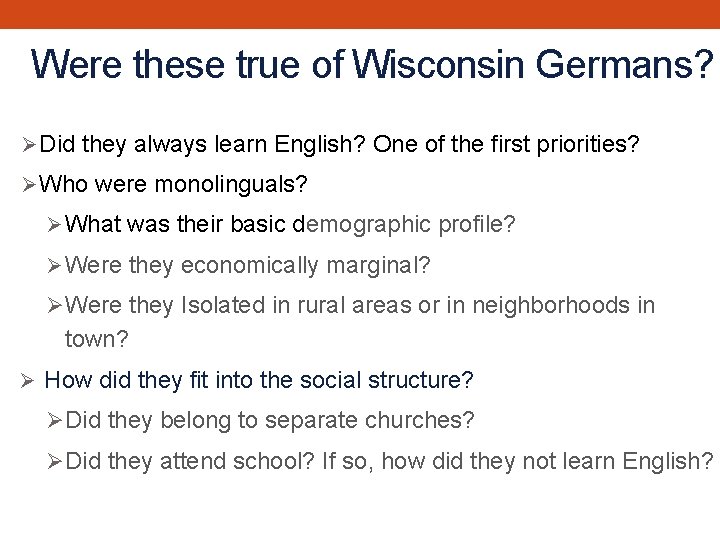

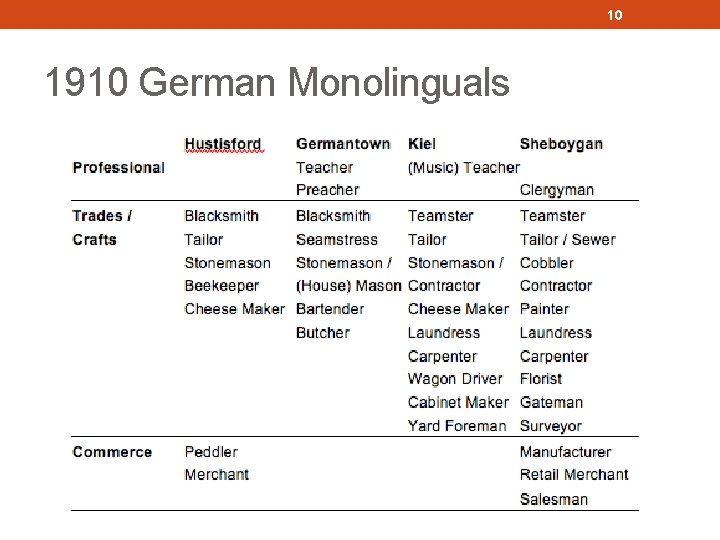

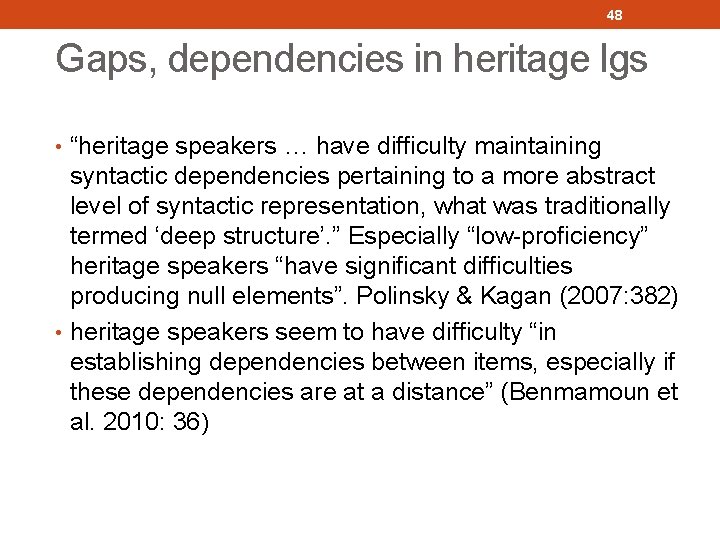

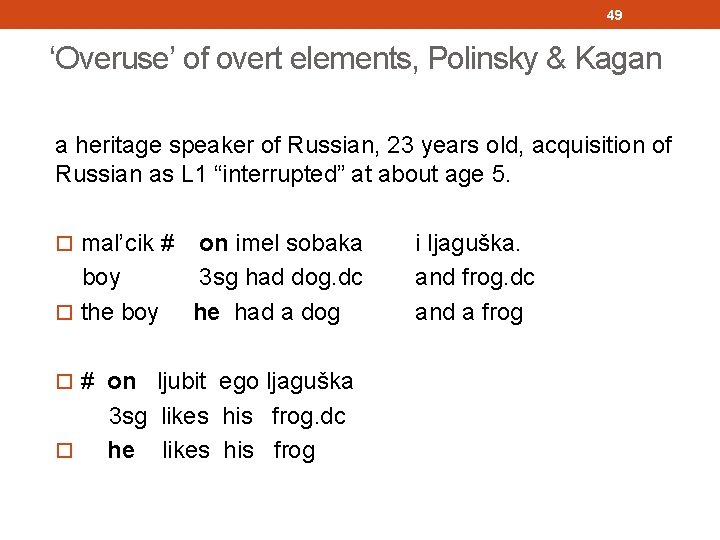

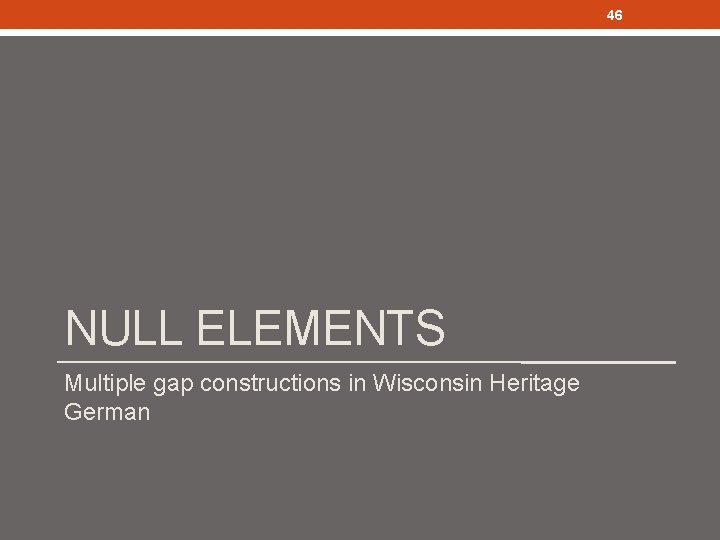

47 Parasitic gaps: English vs. German [Which book]1 did you sell t 1 without reading pg 1? Sheboygan 1 is a city that people like t 1 when they visit pg 1. Welches Buch hast Du verkauft, Which book did you sell t 1, ohne es/*pg zu lesen? without it to read Sheboygan ist eine Stadt, die Leute gern haben, wenn sie/*pg besuchen. Sheboygan 1 is a city that people like t 1 when they it visit.

48 Gaps, dependencies in heritage lgs • “heritage speakers … have difficulty maintaining syntactic dependencies pertaining to a more abstract level of syntactic representation, what was traditionally termed ‘deep structure’. ” Especially “low-proficiency” heritage speakers “have significant difficulties producing null elements”. Polinsky & Kagan (2007: 382) • heritage speakers seem to have difficulty “in establishing dependencies between items, especially if these dependencies are at a distance” (Benmamoun et al. 2010: 36)

49 ‘Overuse’ of overt elements, Polinsky & Kagan a heritage speaker of Russian, 23 years old, acquisition of Russian as L 1 “interrupted” at about age 5. mal’cik # boy the boy on imel sobaka 3 sg had dog. dc he had a dog # on ljubit ego ljaguška 3 sg likes his frog. dc he likes his frog i ljaguška. and frog. dc and a frog

![Wisconsin Heritage German Gap Sheboygan is e Stadt die Leit gleichen wennse visit Wisconsin Heritage German Gap • Sheboygan [is e‘] Stadt die Leit gleichen wennse visit](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e3a4c07fc2c27e10e0a4890f00be825e/image-50.jpg)

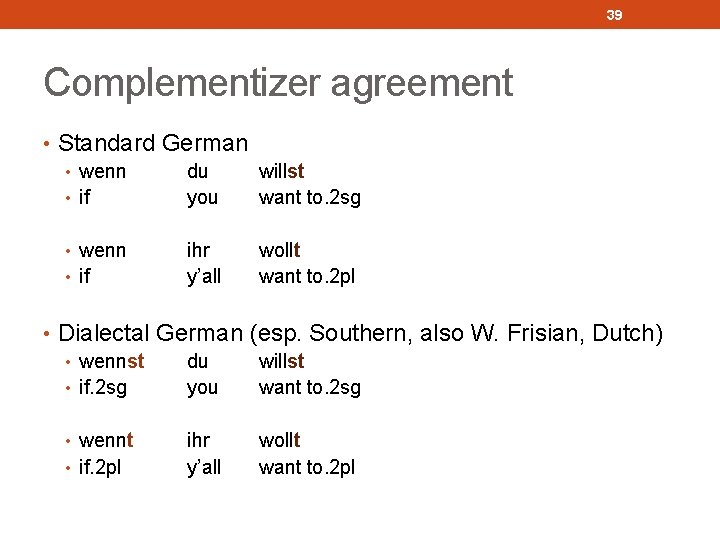

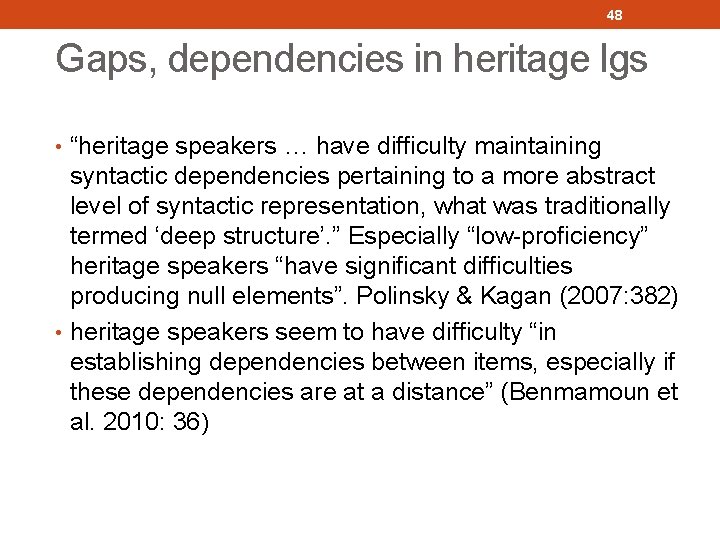

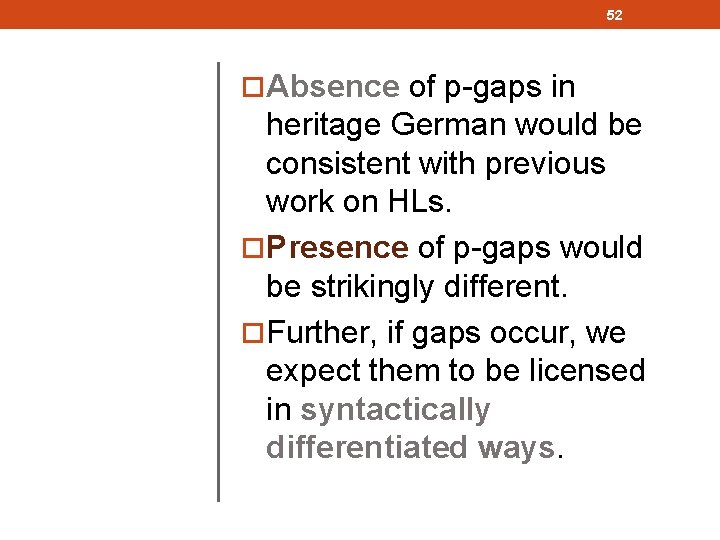

Wisconsin Heritage German Gap • Sheboygan [is e‘] Stadt die Leit gleichen wennse visit No gap • Sheboygan ist eine stadt die de leute die da besuchen sehr gern haben

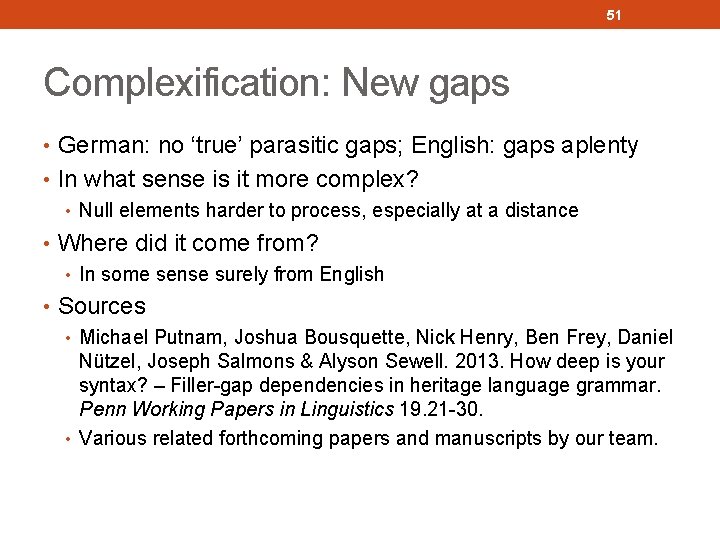

51 Complexification: New gaps • German: no ‘true’ parasitic gaps; English: gaps aplenty • In what sense is it more complex? • Null elements harder to process, especially at a distance • Where did it come from? • In some sense surely from English • Sources • Michael Putnam, Joshua Bousquette, Nick Henry, Ben Frey, Daniel Nützel, Joseph Salmons & Alyson Sewell. 2013. How deep is your syntax? – Filler-gap dependencies in heritage language grammar. Penn Working Papers in Linguistics 19. 21 -30. • Various related forthcoming papers and manuscripts by our team.

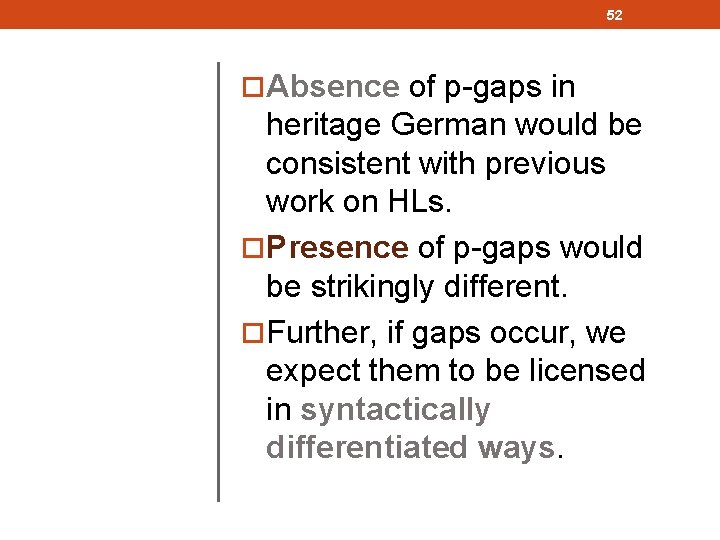

52 Absence of p-gaps in heritage German would be consistent with previous work on HLs. Presence of p-gaps would be strikingly different. Further, if gaps occur, we expect them to be licensed in syntactically differentiated ways.

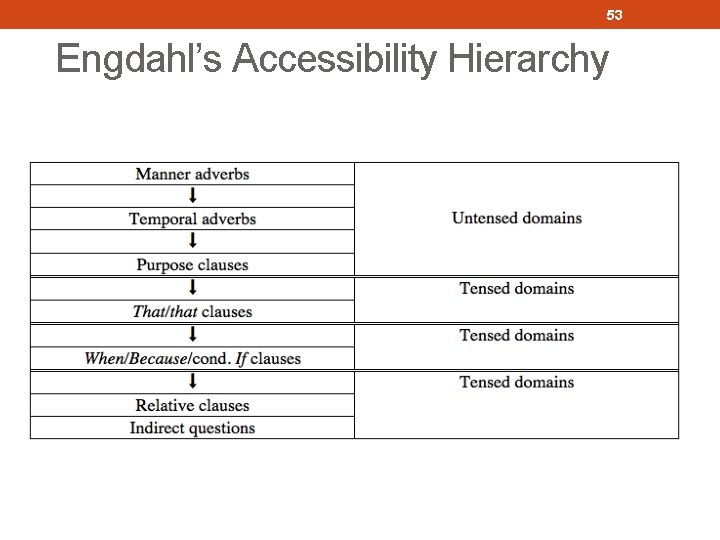

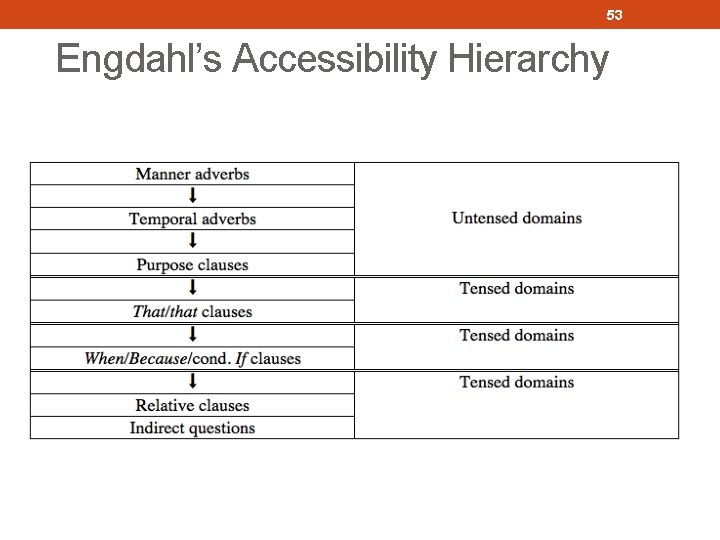

53 Engdahl’s Accessibility Hierarchy

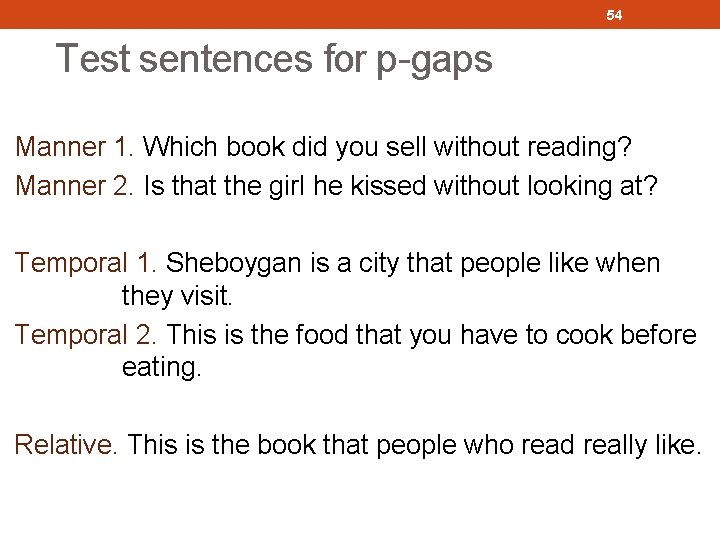

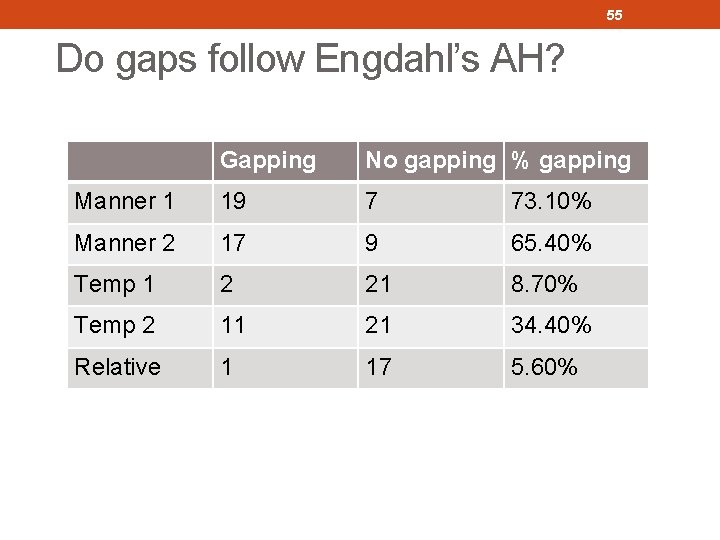

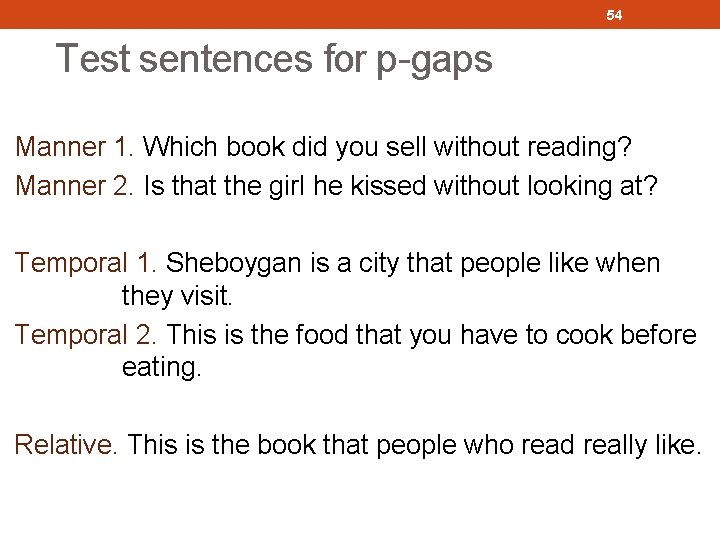

54 Test sentences for p-gaps Manner 1. Which book did you sell without reading? Manner 2. Is that the girl he kissed without looking at? Temporal 1. Sheboygan is a city that people like when they visit. Temporal 2. This is the food that you have to cook before eating. Relative. This is the book that people who read really like.

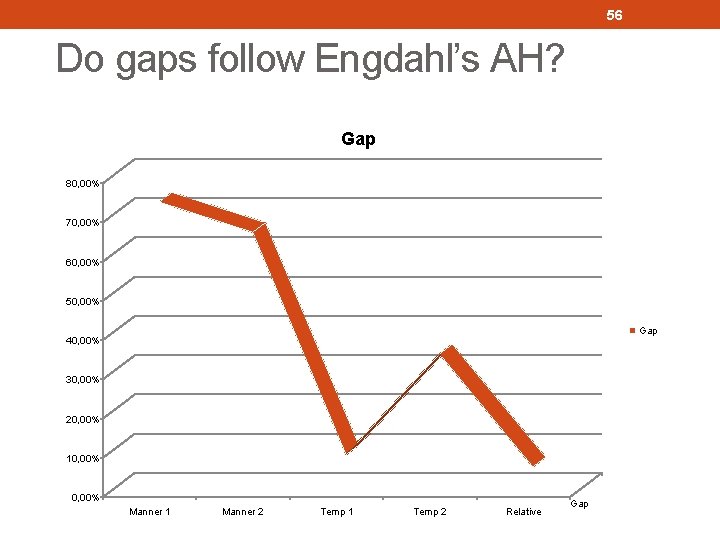

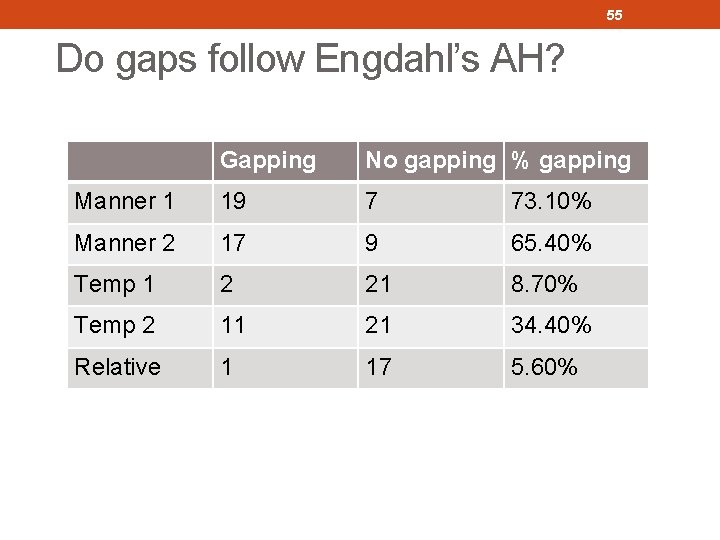

55 Do gaps follow Engdahl’s AH? Gapping No gapping % gapping Manner 1 19 7 73. 10% Manner 2 17 9 65. 40% Temp 1 2 21 8. 70% Temp 2 11 21 34. 40% Relative 1 17 5. 60%

56 Do gaps follow Engdahl’s AH? Gap 80, 00% 70, 00% 60, 00% 50, 00% Gap 40, 00% 30, 00% 20, 00% 10, 00% Manner 1 Manner 2 Temp 1 Temp 2 Relative Gap

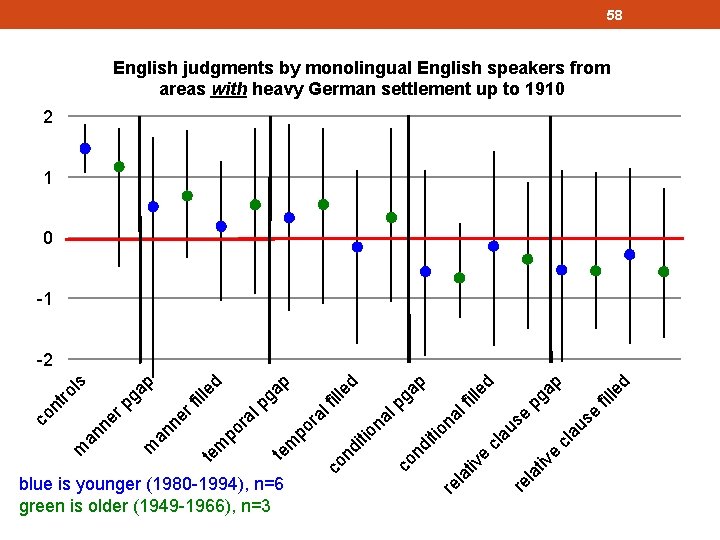

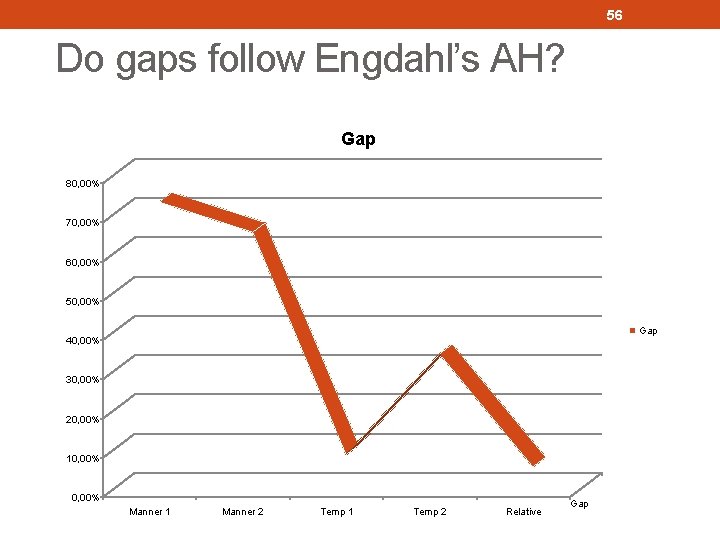

58 English judgments by monolingual English speakers from areas with heavy German settlement up to 1910 2 1 0 -1 e au s re la tiv e cl d fil le cl au se pg ap d ille at iv e nd i co di ti on al tio na lf ille d pg ap re l blue is younger (1980 -1994), n=6 green is older (1949 -1966), n=3 co n te m po ra ra l po m lf pg ap le d fil te m an ne r pg ap an ne r m co nt ro ls -2

59 Take home on gaps Heritage speakers of German produce p-gaps in translation tasks � contrast with European varieties � contrast with claim that heritage speakers have difficultly producing null elements Our speakers produce gaps � far more at the more accessible end of Engdahl’s hierarchy � they tend to restructure more at the less accessible end This looks like an effect of L 2 on L 1, not the inability to produce null elements due to their heritage status BUT tightly structured and indirect.

60 CONCLUSIONS

61 Conclusions • The complexity wars have raged hottest in creole studies, but they lurk everywhere in language contact. • There’s a lot of work on and many more claims about simplicity metrics. We’re looking not for overall measures, but change in particular areas. • Choose your metric for simplicity or simplification, and we’ve got counterexamples from Wisconsin Heritage German. • They aren’t just from English or directly from English. • Even where they are from English or German dialects in some sense, they are quite different from English.

62 Conclusions • We didn’t actually set out to look for issues of complexity or simplicity, but the issues we’ve explored so far show a surprisingly clear directionality. • Not all patterns probably work this way: MLU, passivization, etc. • The contact > simplification game is just dumb; please stop. • These varieties are full products of human cognitive abilities and function as such.

63 Big picture • Hertiage languages can provide incredibly rich data for historical linguistics, sociolinguistics, historical sociolinguistics and structural linguistics. • Requires integrating different sets of data carefullly. • Dative case: story isn’t what it seems • Dialect mixing: more and EARLIER than claimed • Shift: story not what it seems, but facts support path for German influence • Complexification: Plenty of it in a situation where simplification is claimed.

YOUR QUESTIONS?

![65 THANKs Thanks to Luke Annear Emily Claire Alicia Groh Mary Simonsen Trini Stickle 65 THANK[s]! Thanks to Luke Annear, Emily Claire, Alicia Groh, Mary Simonsen, Trini Stickle,](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e3a4c07fc2c27e10e0a4890f00be825e/image-65.jpg)

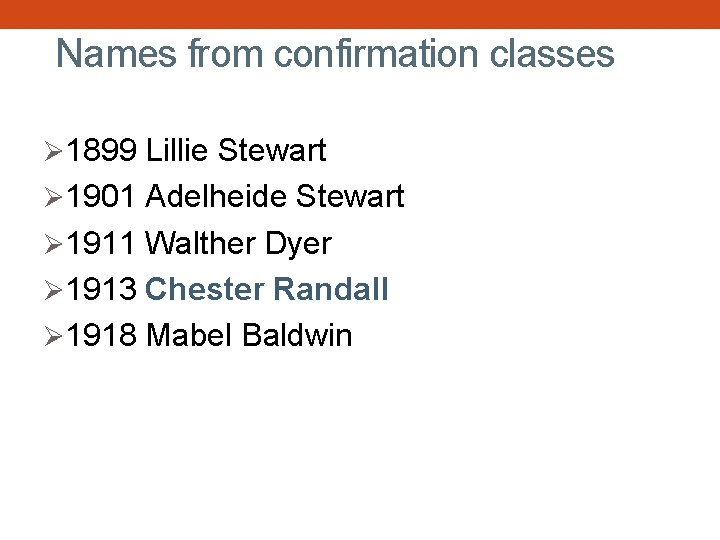

65 THANK[s]! Thanks to Luke Annear, Emily Claire, Alicia Groh, Mary Simonsen, Trini Stickle, Nick Williams.

Classification of property law

Classification of property law World heritage is our heritage slogan

World heritage is our heritage slogan Obstructed heritage and unobstructed heritage

Obstructed heritage and unobstructed heritage Social dialect

Social dialect Register (sociolinguistics)

Register (sociolinguistics) Social markers in sociolinguistics

Social markers in sociolinguistics Sociolinguistic

Sociolinguistic Regional variation in sociolinguistics

Regional variation in sociolinguistics Idiolect definition

Idiolect definition Sociolinguistics symposium 24

Sociolinguistics symposium 24 Solidarity social distance scale

Solidarity social distance scale Sociolinguistics topics for presentation

Sociolinguistics topics for presentation Power dynamics of standard language as school language

Power dynamics of standard language as school language Sociolinguistics slideshare

Sociolinguistics slideshare Sociolinguistics definition

Sociolinguistics definition Idiolect in sociolinguistics

Idiolect in sociolinguistics Warsh accent

Warsh accent Regional variation in sociolinguistics

Regional variation in sociolinguistics Ethnicity in sociolinguistics

Ethnicity in sociolinguistics What is idiolect

What is idiolect What is overt prestige

What is overt prestige Sociolinguistics topics

Sociolinguistics topics Pidgin and creole in sociolinguistics

Pidgin and creole in sociolinguistics Socio dialect

Socio dialect Language dialect and varieties in sociolinguistics

Language dialect and varieties in sociolinguistics Origin of sociolinguistics

Origin of sociolinguistics Code switching in sociolinguistics

Code switching in sociolinguistics Register (sociolinguistics)

Register (sociolinguistics) Language and dialect in sociolinguistics

Language and dialect in sociolinguistics Frozen register

Frozen register Variationist sociolinguistics

Variationist sociolinguistics Sociolinguistics and education

Sociolinguistics and education What is sociolinguistics

What is sociolinguistics Variationist sociolinguistics

Variationist sociolinguistics Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay

Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay Cái miệng nó xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi

Cái miệng nó xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi Mật thư anh em như thể tay chân

Mật thư anh em như thể tay chân Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu

Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Ví dụ về giọng cùng tên

Ví dụ về giọng cùng tên Thẻ vin

Thẻ vin Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào

Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào Thơ thất ngôn tứ tuyệt đường luật

Thơ thất ngôn tứ tuyệt đường luật Hổ đẻ mỗi lứa mấy con

Hổ đẻ mỗi lứa mấy con Diễn thế sinh thái là

Diễn thế sinh thái là Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Lp html

Lp html Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau 101012 bằng

101012 bằng Lời thề hippocrates

Lời thề hippocrates Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể

Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể đại từ thay thế

đại từ thay thế Tư thế worm breton

Tư thế worm breton Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra

Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra Sự nuôi và dạy con của hươu

Sự nuôi và dạy con của hươu Thế nào là mạng điện lắp đặt kiểu nổi

Thế nào là mạng điện lắp đặt kiểu nổi Dot

Dot Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Bổ thể

Bổ thể Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ

Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ Phản ứng thế ankan

Phản ứng thế ankan Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan

Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan Bài hát chúa yêu trần thế alleluia

Bài hát chúa yêu trần thế alleluia Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau điện thế nghỉ

điện thế nghỉ Một số thể thơ truyền thống

Một số thể thơ truyền thống