ACCENTS OF ENGLISH 5 th semester INTRODUCTION TO

![Accent vs dialect • E. g. , [ju mᴧst i: t ɪt ᴧp] RP→jə Accent vs dialect • E. g. , [ju mᴧst i: t ɪt ᴧp] RP→jə](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/0e3a9317acbd45e18c5c050ef0b242e2/image-6.jpg)

![Speech Differences within sexual minorities • Some homosexuals lisp (/s/→[ᶿ] or [s dental] • Speech Differences within sexual minorities • Some homosexuals lisp (/s/→[ᶿ] or [s dental] •](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/0e3a9317acbd45e18c5c050ef0b242e2/image-30.jpg)

- Slides: 65

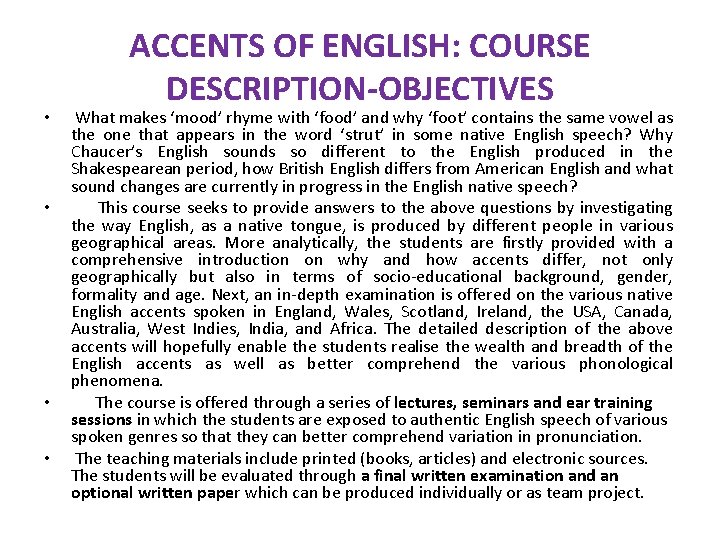

ACCENTS OF ENGLISH 5 th semester Ø INTRODUCTION TO THE COURSE Ø POLICIES Ø GRADE DISTRIBUTION Ø OFFICE HOUR Ø e-class, links

• • ACCENTS OF ENGLISH: COURSE DESCRIPTION-OBJECTIVES What makes ‘mood’ rhyme with ‘food’ and why ‘foot’ contains the same vowel as the one that appears in the word ‘strut’ in some native English speech? Why Chaucer’s English sounds so different to the English produced in the Shakespearean period, how British English differs from American English and what sound changes are currently in progress in the English native speech? This course seeks to provide answers to the above questions by investigating the way English, as a native tongue, is produced by different people in various geographical areas. More analytically, the students are firstly provided with a comprehensive introduction on why and how accents differ, not only geographically but also in terms of socio-educational background, gender, formality and age. Next, an in-depth examination is offered on the various native English accents spoken in England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, the USA, Canada, Australia, West Indies, India, and Africa. The detailed description of the above accents will hopefully enable the students realise the wealth and breadth of the English accents as well as better comprehend the various phonological phenomena. The course is offered through a series of lectures, seminars and ear training sessions in which the students are exposed to authentic English speech of various spoken genres so that they can better comprehend variation in pronunciation. The teaching materials include printed (books, articles) and electronic sources. The students will be evaluated through a final written examination and an optional written paper which can be produced individually or as team project.

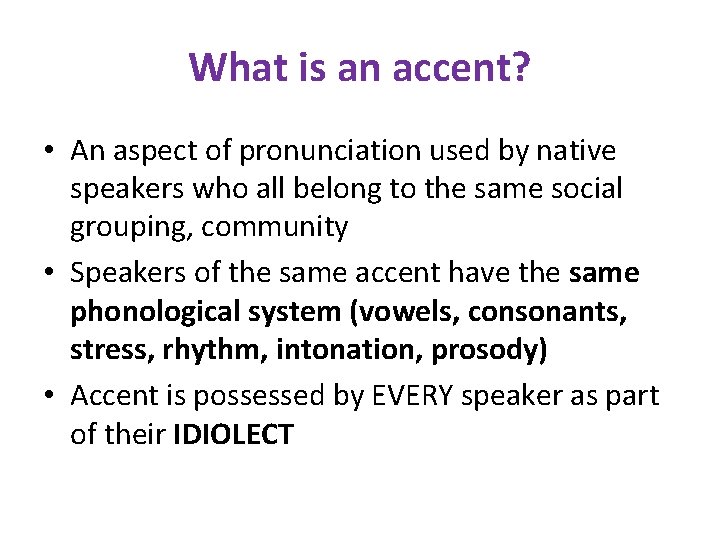

What is an accent? • An aspect of pronunciation used by native speakers who all belong to the same social grouping, community • Speakers of the same accent have the same phonological system (vowels, consonants, stress, rhythm, intonation, prosody) • Accent is possessed by EVERY speaker as part of their IDIOLECT

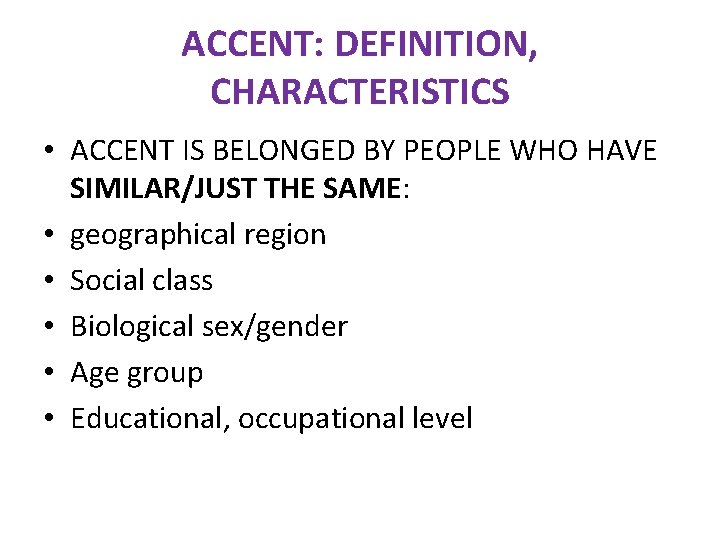

ACCENT: DEFINITION, CHARACTERISTICS • ACCENT IS BELONGED BY PEOPLE WHO HAVE SIMILAR/JUST THE SAME: • geographical region • Social class • Biological sex/gender • Age group • Educational, occupational level

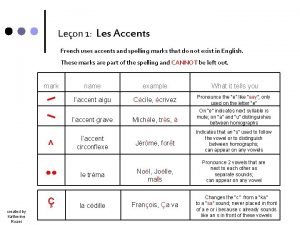

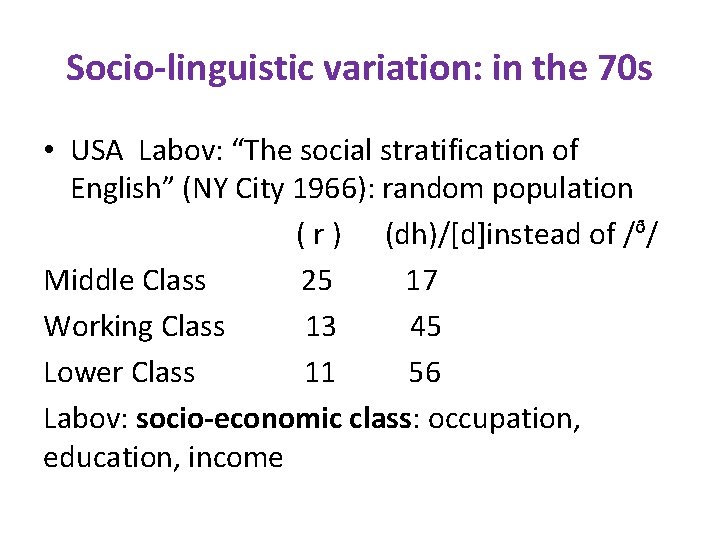

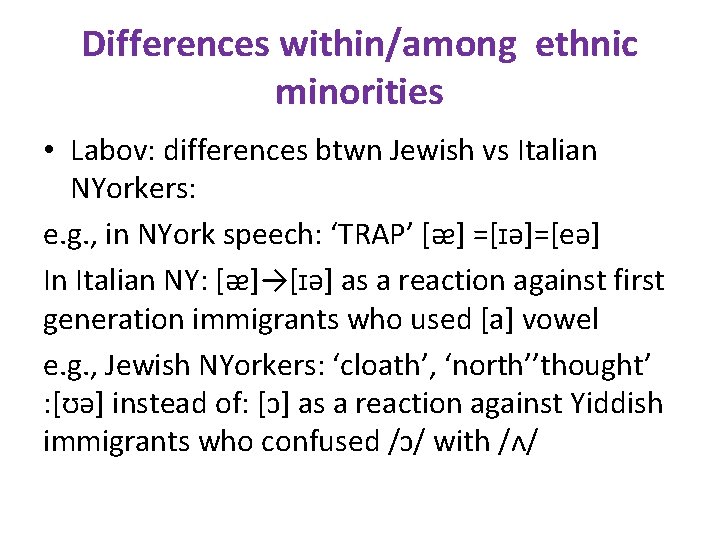

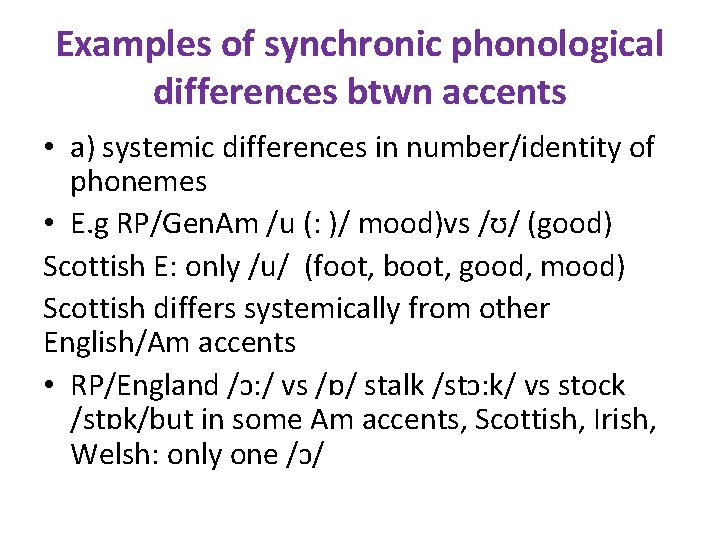

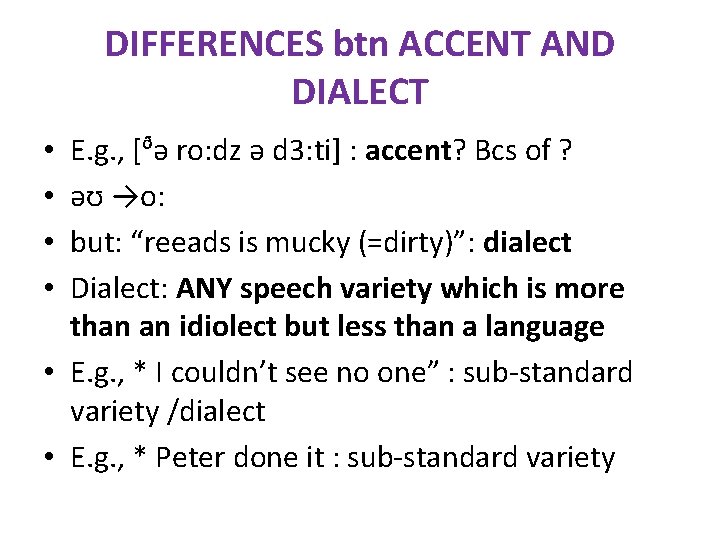

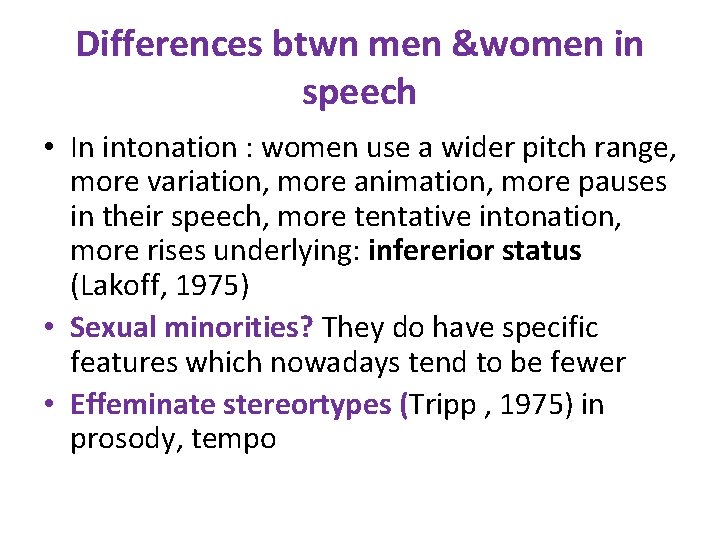

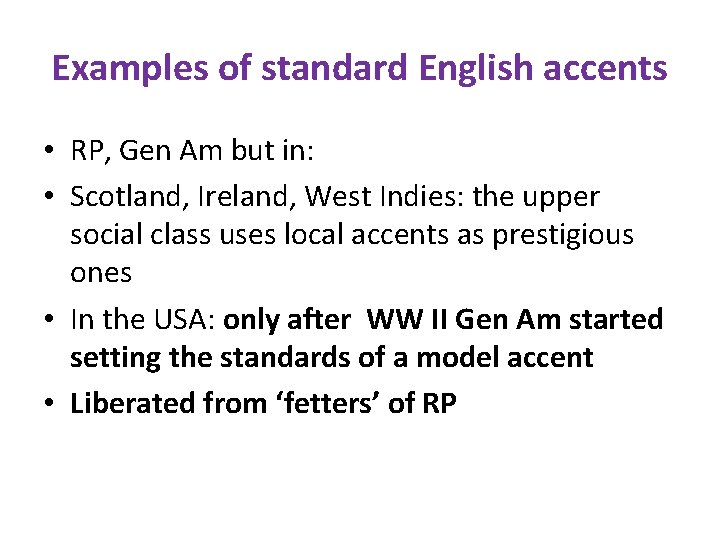

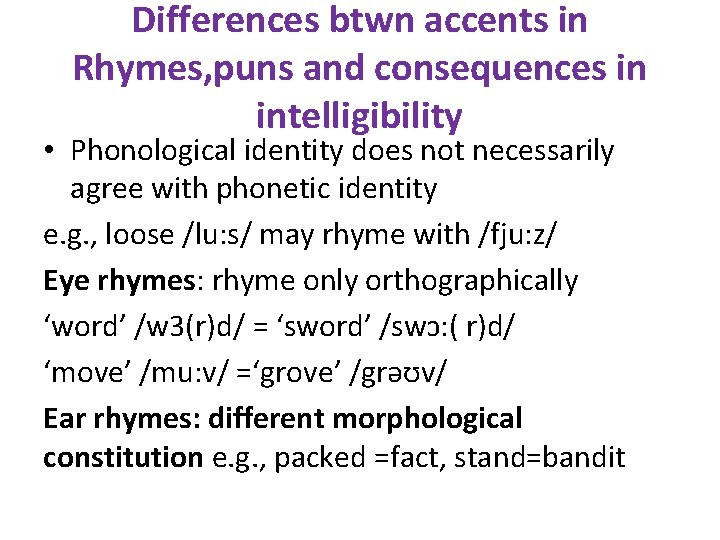

DIFFERENCES btn ACCENT AND DIALECT E. g. , [ᶞə ro: dz ə d 3: ti] : accent? Bcs of ? əʊ →o: but: “reeads is mucky (=dirty)”: dialect Dialect: ANY speech variety which is more than an idiolect but less than a language • E. g. , * I couldn’t see no one” : sub-standard variety /dialect • E. g. , * Peter done it : sub-standard variety • •

![Accent vs dialect E g ju mᴧst i t ɪt ᴧp RPjə Accent vs dialect • E. g. , [ju mᴧst i: t ɪt ᴧp] RP→jə](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/0e3a9317acbd45e18c5c050ef0b242e2/image-6.jpg)

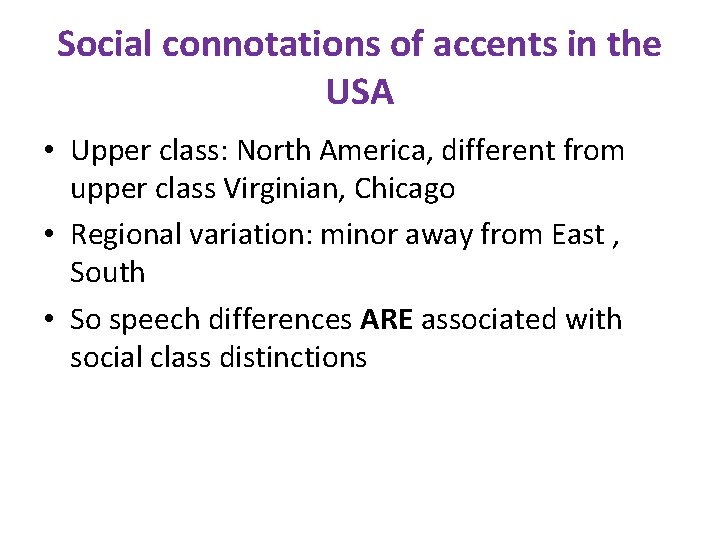

Accent vs dialect • E. g. , [ju mᴧst i: t ɪt ᴧp] RP→jə məst i: t ɪt ʊp Northern E what is a traditional (E)dialect? = local accent : Version restricted to a small geographical area where (E) is spoken as an L 1 E. g. , SCOTS: Eastern, Central, Southern Scotland, North of Ireland E. g. , North, rural West E accents

TRADITIONAL DIALECTS • NOT found outside the British Isles • Are gradually perishing • Spoken by children under 10/or by elderly people • ‘relexification’: replacement of traditional dialect forms by →forms of GE/Standard E

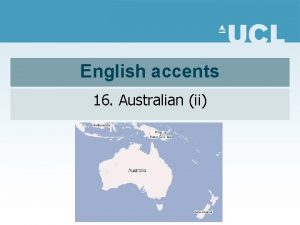

REGIONALITY • Geographical variation=regionality but: • Whether/how much regionality we can recognise from an accent: depends on how familiar we are with the particular accent of the area • More homogeneous territories are: • Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, America Far West

CHARACTERISTICS OF RECEIVED PRONUNCIATION (RP) • In England: some speakers do NOT have a local accent, they have a non-localizable accent: RP: upper, upper-middle class • In the USA: accent reveals little about geographical origin; Gen Am: standard accent That has no Eastern, no Southern coloring

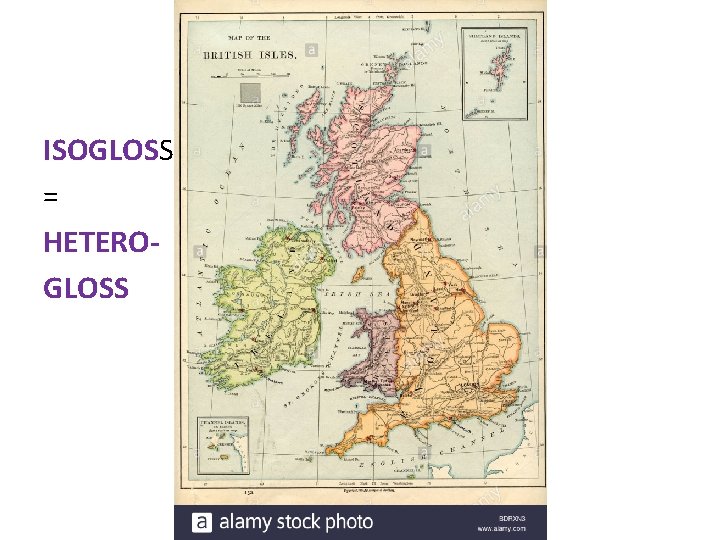

ISOGLOSS: DEFINITION HETEROGLOSS, ISOGLOSS: A SHARP BOUNDARY LINE FROM ONE ACCENT TO THE OTHER IDENTIFYING A SPECIFIC TERRITORY where an accent is spoken BUT: ISOGLOSSES ARE NOT ALWAYS SHARP : There might be a gradual transition from one form→other Isoglosses are difficult to define bcs of : georgaphical mobility, so Peoples’/people’s speech becomes: HETEROGENEOUS

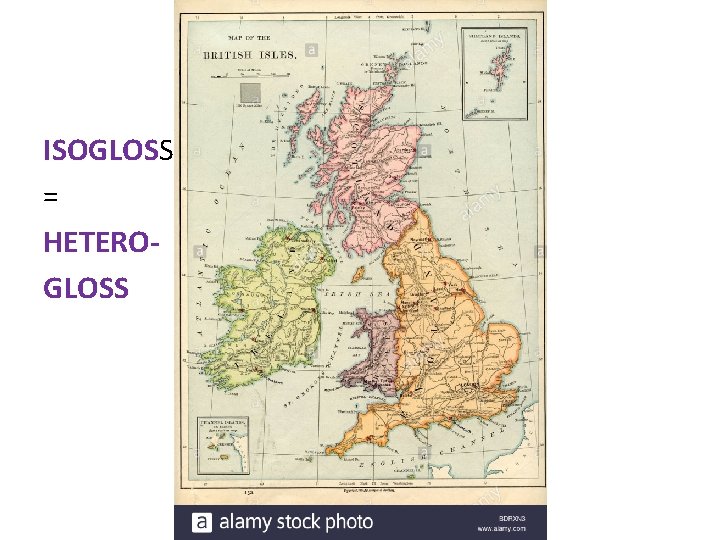

ISOGLOSS = HETEROGLOSS

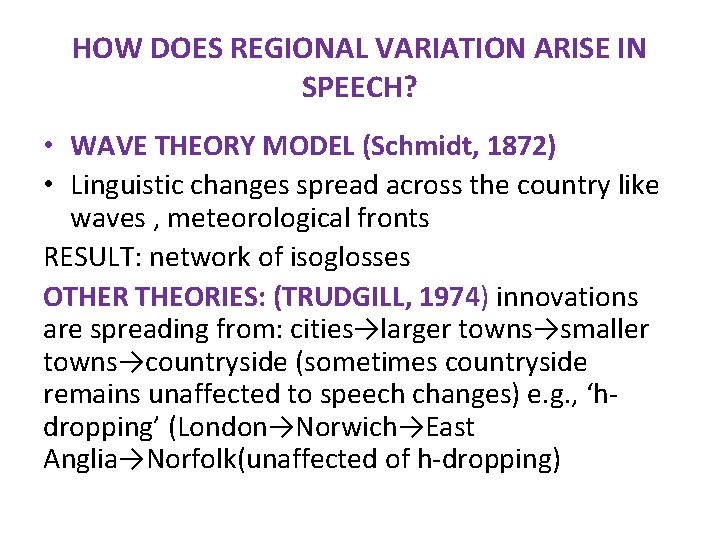

HOW DOES REGIONAL VARIATION ARISE IN SPEECH? • WAVE THEORY MODEL (Schmidt, 1872) • Linguistic changes spread across the country like waves , meteorological fronts RESULT: network of isoglosses OTHER THEORIES: (TRUDGILL, 1974) innovations are spreading from: cities→larger towns→smaller towns→countryside (sometimes countryside remains unaffected to speech changes) e. g. , ‘hdropping’ (London→Norwich→East Anglia→Norfolk(unaffected of h-dropping)

Social class-language/speech • Speech stratification-social stratification (morphology, syntax, vocabulary, accent) In England: pronunciation/accent type: plays a predominant role in distinguishing different social classes ; NOT in North America

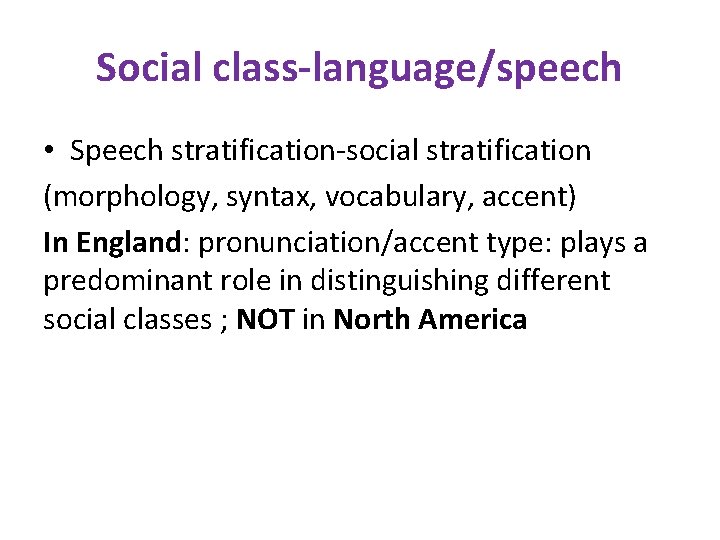

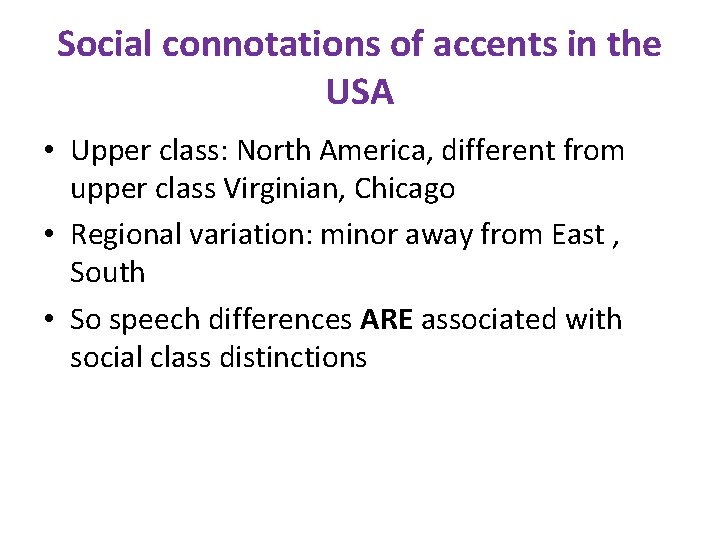

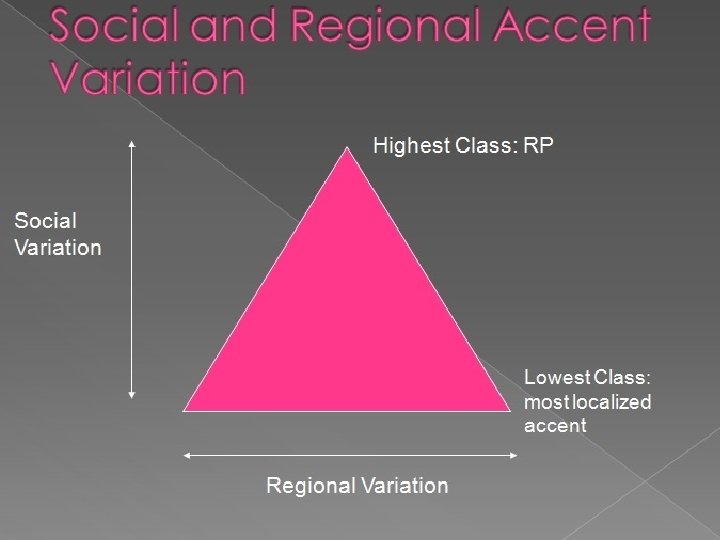

The accents pyramid/triangle

Features of the pyramid/triangle • Any regional accent=NOT an upper class accent • The more localizable (=not an upper class)→the broader an accent is. • AS broad accent: 1) the highest degree of regionality 2) lowest social class • 3) maximal degree of difference from RP/prestigious accent

Social connotations of accents in England • RP: non-localizable accent within England, Wales • ALL accents in England have social connotations but • We cannot extend this model to Scotland, Ireland • In Scotland, Ireland: RP: a foreign E accent

Social connotations of accents in the USA • Upper class: North America, different from upper class Virginian, Chicago • Regional variation: minor away from East , South • So speech differences ARE associated with social class distinctions

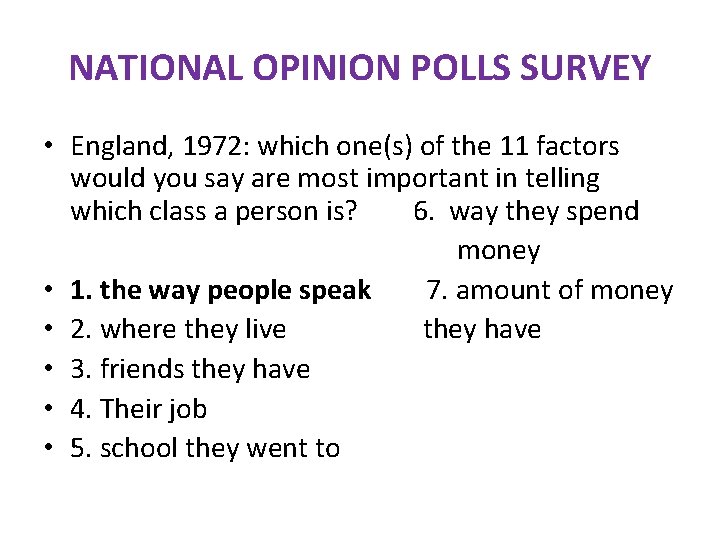

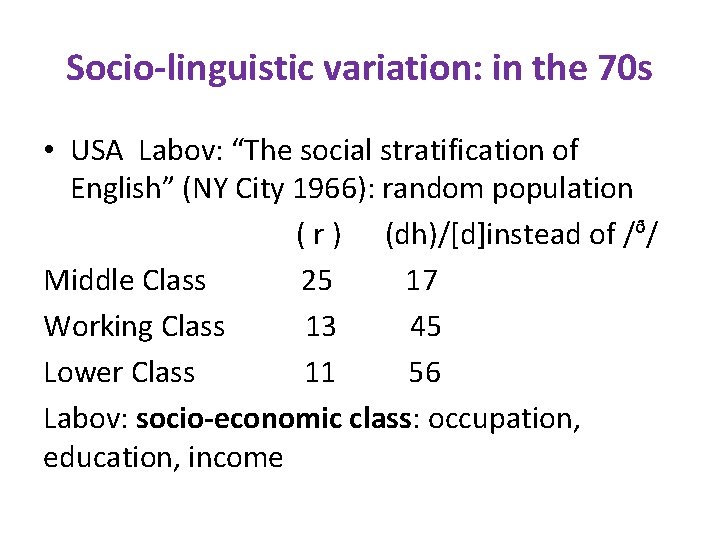

NATIONAL OPINION POLLS SURVEY • England, 1972: which one(s) of the 11 factors would you say are most important in telling which class a person is? 6. way they spend money • 1. the way people speak 7. amount of money • 2. where they live they have • 3. friends they have • 4. Their job • 5. school they went to

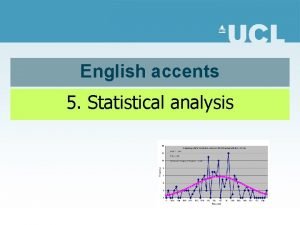

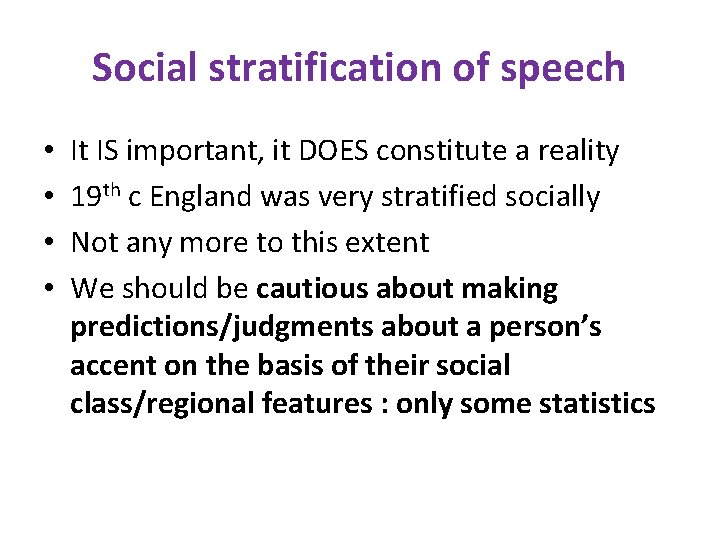

Socio-linguistic variation: in the 70 s • USA Labov: “The social stratification of English” (NY City 1966): random population ( r ) (dh)/[d]instead of /ᶞ/ Middle Class 25 17 Working Class 13 45 Lower Class 11 56 Labov: socio-economic class: occupation, education, income

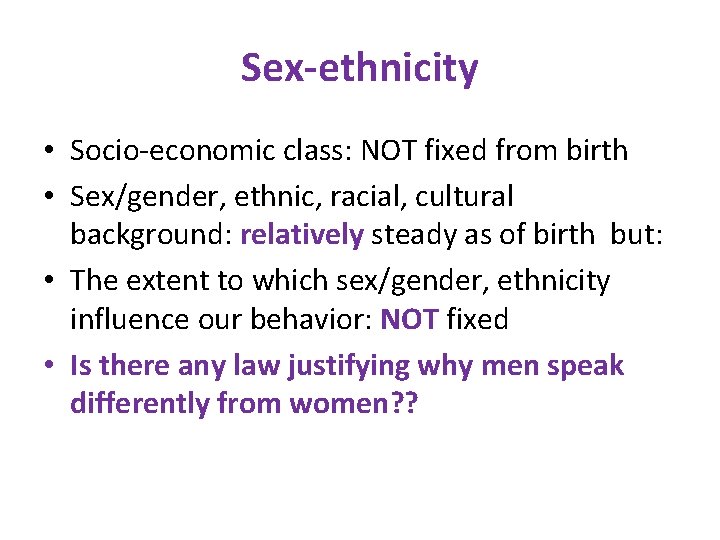

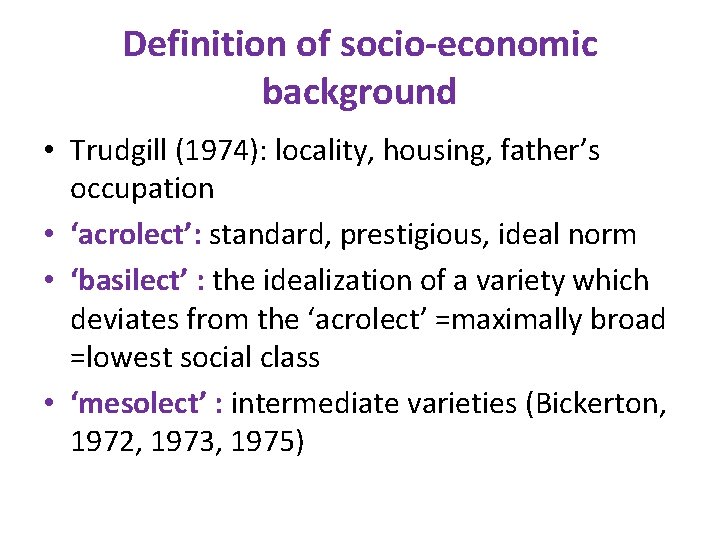

Definition of socio-economic background • Trudgill (1974): locality, housing, father’s occupation • ‘acrolect’: standard, prestigious, ideal norm • ‘basilect’ : the idealization of a variety which deviates from the ‘acrolect’ =maximally broad =lowest social class • ‘mesolect’ : intermediate varieties (Bickerton, 1972, 1973, 1975)

Social stratification of speech • • It IS important, it DOES constitute a reality 19 th c England was very stratified socially Not any more to this extent We should be cautious about making predictions/judgments about a person’s accent on the basis of their social class/regional features : only some statistics

Sex-ethnicity • Socio-economic class: NOT fixed from birth • Sex/gender, ethnic, racial, cultural background: relatively steady as of birth but: • The extent to which sex/gender, ethnicity influence our behavior: NOT fixed • Is there any law justifying why men speak differently from women? ?

Why should men & women speak differently? • Apart from biological/physiological differences in: pitch, voice quality : NO LAW why men should speak differently to women , • Why should different ethnic groups/races speak differently? ?

Why should different races, ethnicities speak differently? • No biological reason for Blacks to talk differently to Whites, Scots from Welshmen, Jewish NYorkers from Italian NYorkers • Yet, there ARE differences in accents bcs of: • Sex • Ethnicity, race, culture In some Ls men +women: different pronunciation, but in most Ls ( E ) : more such differences in morphology, semantics

Why men and women speak differently? • Generally, women achieve high scores, closer to prestigious norms • Fischer (1958): New England: Children: a) Village boys: more [n] for ‘-ing’ than b) Village girls : fewer [n] for ‘-ing’ Trudgill, 1974: Norwich working class adult men: many [n] Why women’s speech tends to be more normative?

Reasons why women’s speech is norm -based/prestigious • Two socially oriented explanations: • a) women: status conscious bcs of their less secure position in society Men define their social status thru: Ø Occupation > property > power but: Women defined their social status through their husband Result: women were (are? ) socially insecure → emphasize their social status thu material, L

Why women project a different speech to men? • b) the toughness, roughness of working class culture have masculinity connotations What do these two factors prove?

Sex differences in accent • Both factors prove sexism in society expressed thru L/accent • What are some other differences in men’s +women’s speech?

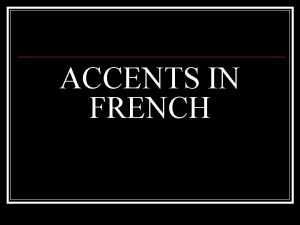

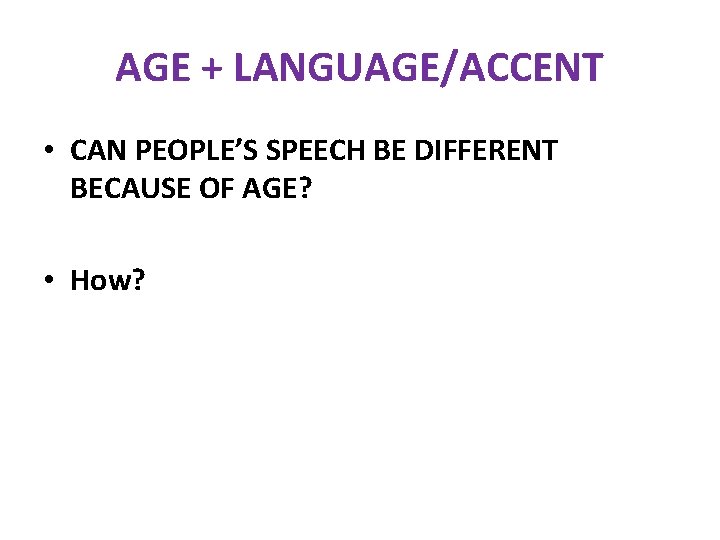

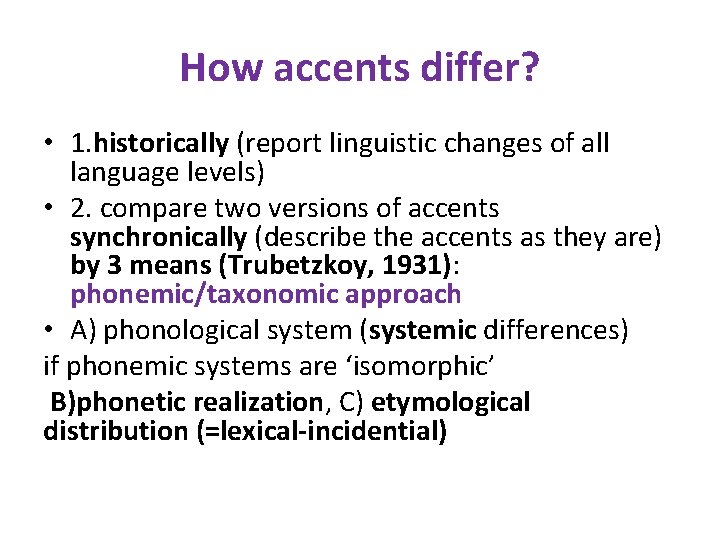

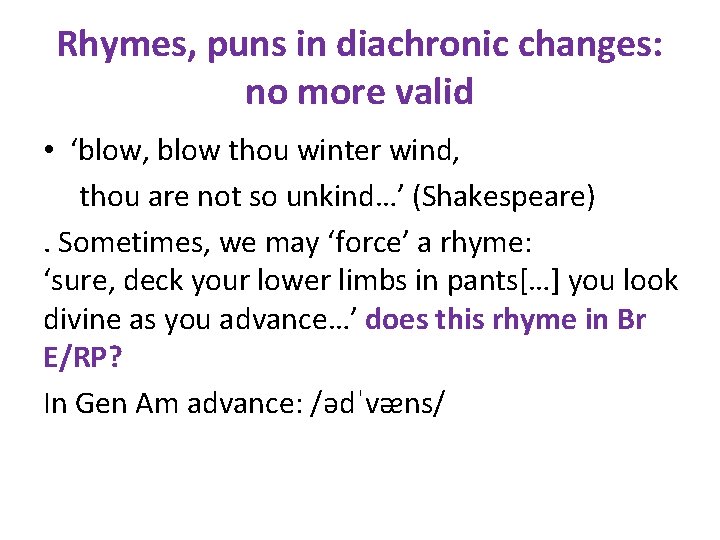

Differences btwn men &women in speech • In intonation : women use a wider pitch range, more variation, more animation, more pauses in their speech, more tentative intonation, more rises underlying: infererior status (Lakoff, 1975) • Sexual minorities? They do have specific features which nowadays tend to be fewer • Effeminate stereortypes (Tripp , 1975) in prosody, tempo

![Speech Differences within sexual minorities Some homosexuals lisp sᶿ or s dental Speech Differences within sexual minorities • Some homosexuals lisp (/s/→[ᶿ] or [s dental] •](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/0e3a9317acbd45e18c5c050ef0b242e2/image-30.jpg)

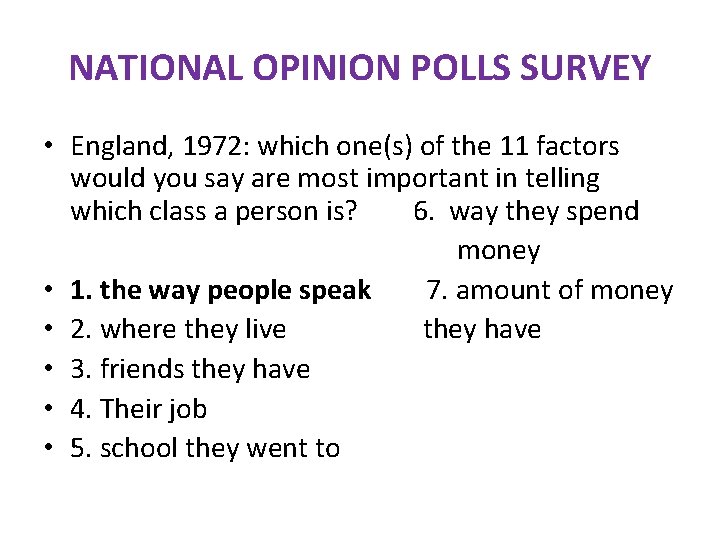

Speech Differences within sexual minorities • Some homosexuals lisp (/s/→[ᶿ] or [s dental] • But effeminacy is relative and may be geographically dependent: • E. g. , in USA: [‘betə] instead of: [‘beɾə]: unmasculine Are dialects/accents ethnically dependent?

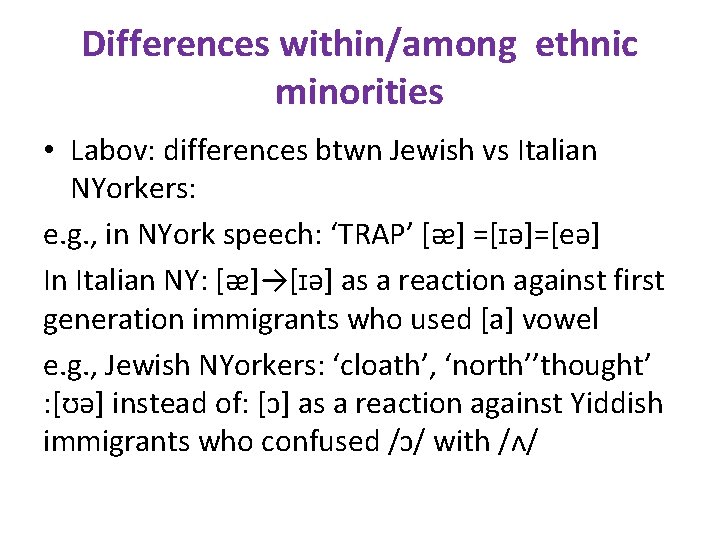

Ethnic origin +accent • Not necessary connection bcs: speakers’ speech is a result of where they were born, raised, exposed to • Many accentual features within an ethnic group may be environmentally dependent • E. g. , parents are speech models for kids in early yrs but peer group’s accent is MORE influential

Differences within/among ethnic minorities • Labov: differences btwn Jewish vs Italian NYorkers: e. g. , in NYork speech: ‘TRAP’ [ᴂ] =[ɪə]=[eə] In Italian NY: [ᴂ]→[ɪə] as a reaction against first generation immigrants who used [a] vowel e. g. , Jewish NYorkers: ‘cloath’, ‘north’’thought’ : [ʊə] instead of: [ɔ] as a reaction against Yiddish immigrants who confused /ɔ/ with /ᴧ/

AGE + LANGUAGE/ACCENT • CAN PEOPLE’S SPEECH BE DIFFERENT BECAUSE OF AGE? • How?

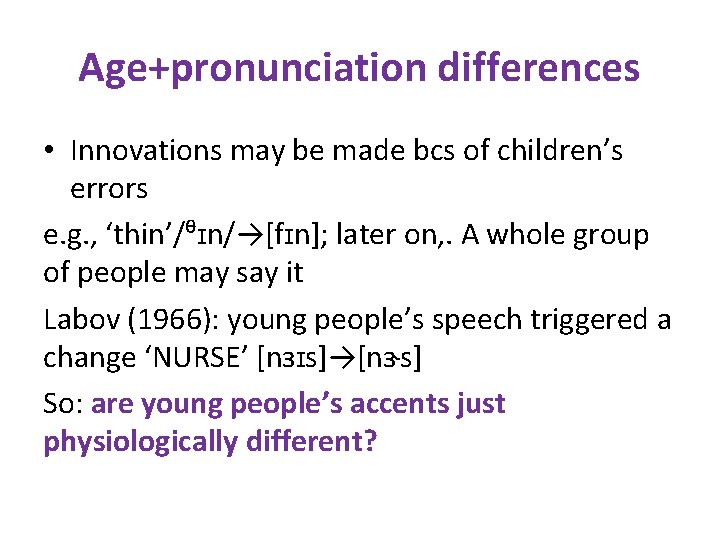

Speech differences and age • Older/younger people’s speech IS physiologically different: changes in vocal tract, vocal folds , in other ways? ? • different generations speak in a different way : old people: more old fashioned • Children’s/adolescents’ accents change • The child forms its own grammar/mental lexicon thru: parents, peers: by hypotheses, predictions NOT through imitation

Age+pronunciation differences • Innovations may be made bcs of children’s errors e. g. , ‘thin’/ᶿɪn/→[fɪn]; later on, . A whole group of people may say it Labov (1966): young people’s speech triggered a change ‘NURSE’ [nɜɪs]→[nɝs] So: are young people’s accents just physiologically different?

Young people and speech innovations • Young people’s speech IS different to older groups’ speech NOT just physiologically But also reflect linguistic innovations which are then adopted by intervening generations

Styles, roles vs accents • In different situations: we use different L/accent: formal vs casual style: reflect differences in social context • Gradation of formality: 1. Reading aloud word lists 2. Reading texts 3. interviews Style differences may reflect socio-economic Class differences in speech; why?

Style differences and accent • The formal style of a low class may resemble the casual style of a high class • Style differences: stereotypes • What is a stereotype? Types of stereotypes?

Social stereotypes • Fixed ideas, prejudices people have about other people/races, sexes, cultures, etc • E. g. , racial, age, profession, gender stereotypes • Social psychologists: RP speakers judged by pronunciation were regarded as: more ambitious, intelligent, self-confident , less talkative, less good natured, less humored (Giles, 1970). What does this stereotype reflect?

What are stereotypes tell us? • Stereotypes may reflect people’s attitudes/beliefs about rural vs urban life • All-but young children-have the ability to ‘raise’ or ‘lower’ the speech features of their social class according to the occasion • Why?

Why change ones’ speech features? • To make one’s speech closer to one’s interlocutors to show: solidarity, sympathy, approval convergence vs divergence Is the self-image speakers have about their speech correct?

How accurate are speakers about the self-image of their speech? • Often: erroneous: they think they pronounce differently/more accurately than they actually do (Labov, 1966) • Examples: women report using more prestigious speech than they actually do • Men report their speech as less prestigious than in reality (Trudgill, 1972) • WHY?

Why men and women report false impressions about their speech? • Covert prestige of non-standard working class, solidarity • Men dare being different • People may often have inaccurate perceptions of accents other than those of their locality • E. g. , to an English person, NY accent is JUST an American accent but a Philadelphian will perceive the difference

Standard accents • At a given time, place: correct model, norm of how: 1. one ought to speak /accurate • 2. encouraged in the classroom • 3. desirable accent as a high status accent Non-standard accent: provincial , low status Are there any legitimate, justified reasons for this classification?

Why classify accents as high prestige vs low prestige? • There is an arbitrary attitude towards them by people • The phonetic characteristics of standard accents hold true/are valid at a certain time, place • The arbitrary attitude is NOT possessed by the public: “inherent value hypothesis” of the public vs ‘imposed norm’ (=prestige of standard accents is a cultural accident) • The ‘imposed norm hypothesis’ prevails as true: (eg. , British undergraduates perceived no ‘aesthetic’ value of the Standard Athenian vs Cretan accent)

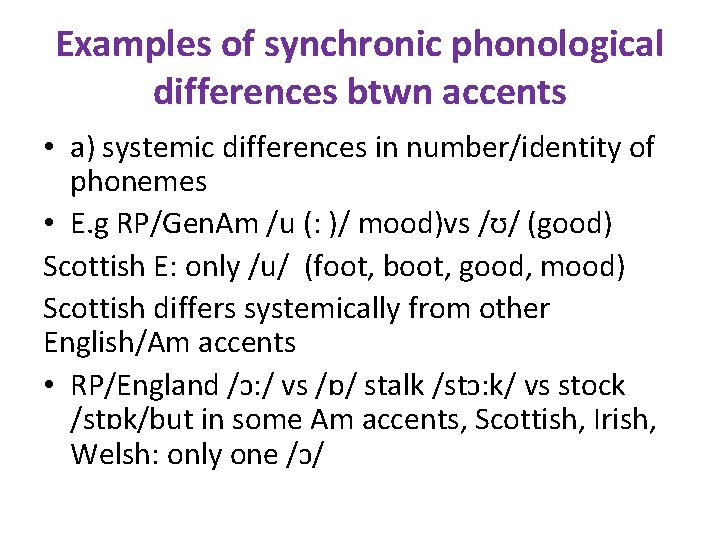

Examples of standard English accents • RP, Gen Am but in: • Scotland, Ireland, West Indies: the upper social class uses local accents as prestigious ones • In the USA: only after WW II Gen Am started setting the standards of a model accent • Liberated from ‘fetters’ of RP

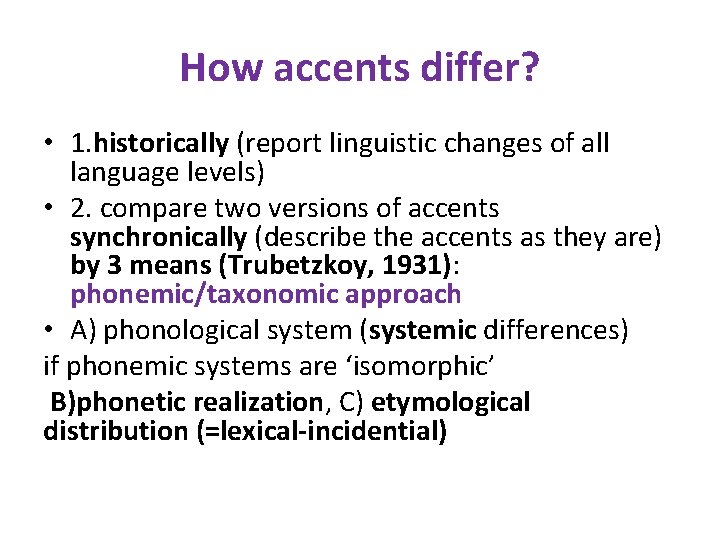

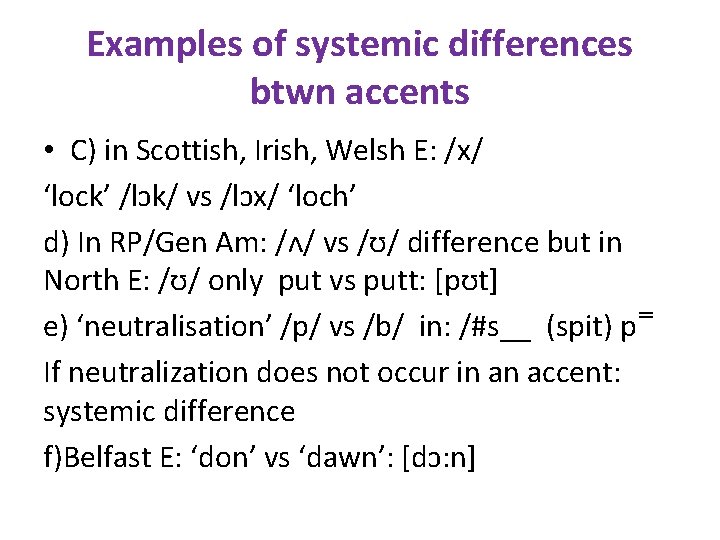

How accents differ? • 1. historically (report linguistic changes of all language levels) • 2. compare two versions of accents synchronically (describe the accents as they are) by 3 means (Trubetzkoy, 1931): phonemic/taxonomic approach • A) phonological system (systemic differences) if phonemic systems are ‘isomorphic’ B)phonetic realization, C) etymological distribution (=lexical-incidential)

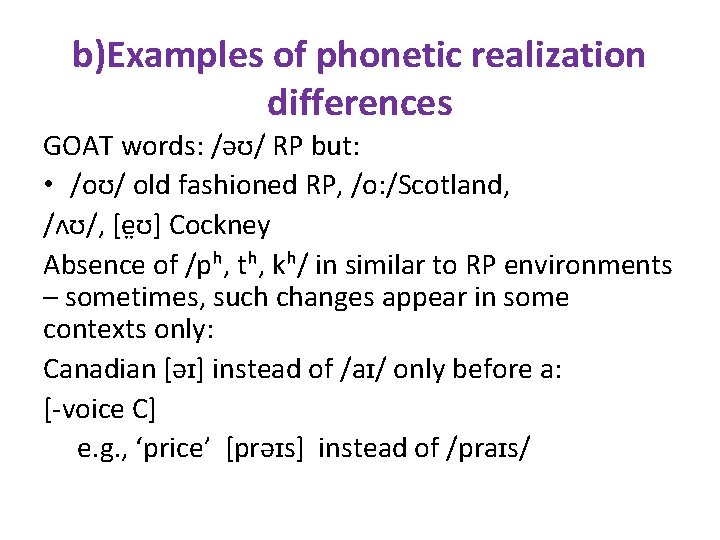

Examples of synchronic phonological differences btwn accents • a) systemic differences in number/identity of phonemes • E. g RP/Gen. Am /u (: )/ mood)vs /ʊ/ (good) Scottish E: only /u/ (foot, boot, good, mood) Scottish differs systemically from other English/Am accents • RP/England /ɔ: / vs /ɒ/ stalk /stɔ: k/ vs stock /stɒk/but in some Am accents, Scottish, Irish, Welsh: only one /ɔ/

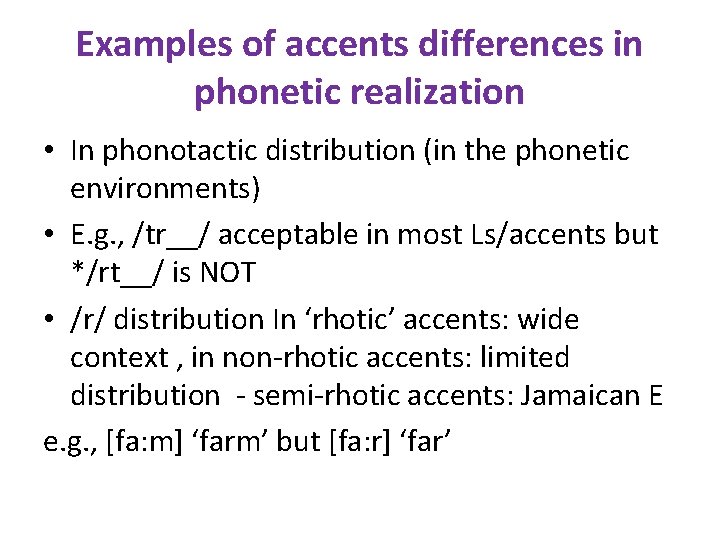

Examples of systemic differences btwn accents • C) in Scottish, Irish, Welsh E: /x/ ‘lock’ /lɔk/ vs /lɔx/ ‘loch’ d) In RP/Gen Am: /ᴧ/ vs /ʊ/ difference but in North E: /ʊ/ only put vs putt: [pʊt] e) ‘neutralisation’ /p/ vs /b/ in: /#s__ (spit) p˭ If neutralization does not occur in an accent: systemic difference f)Belfast E: ‘don’ vs ‘dawn’: [dɔ: n]

b)Examples of phonetic realization differences GOAT words: /əʊ/ RP but: • /oʊ/ old fashioned RP, /o: /Scotland, /ᴧʊ/, [e ʊ] Cockney Absence of /pʰ, tʰ, kʰ/ in similar to RP environments – sometimes, such changes appear in some contexts only: Canadian [əɪ] instead of /aɪ/ only before a: [-voice C] e. g. , ‘price’ [prəɪs] instead of /praɪs/

Examples of accents differences in phonetic realization • In phonotactic distribution (in the phonetic environments) • E. g. , /tr__/ acceptable in most Ls/accents but */rt__/ is NOT • /r/ distribution In ‘rhotic’ accents: wide context , in non-rhotic accents: limited distribution - semi-rhotic accents: Jamaican E e. g. , [fa: m] ‘farm’ but [fa: r] ‘far’

C) Differences btwn accents in lexical distribution • Accents may differ in the phonemes they select for lexical, morpheme representation /different incidence of phonemes in specific wrds: Not productive/predictive, NO ruleseven same speaker may vary in their pronunciation of certain wrds eg. , ‘either’, ‘neither’: [aiᵭə]˜ [i: ᵭə( r )] /ai/ ˜/i (: )/, b) ‘tomato’: [təʽmeɪto]vs [tə ʽma: təʊ] but: /ˈfa: ᵭə/ *[feɪᵭə]

c)Lexical, incidential differences btwn accents • Popular controversies about ‘right’ vs ‘wrong’ pronunciation of specific lexical items reflect speakers’ psychological tendencies and belong to this category: • E. g. , Nazi, accomplish, controversy

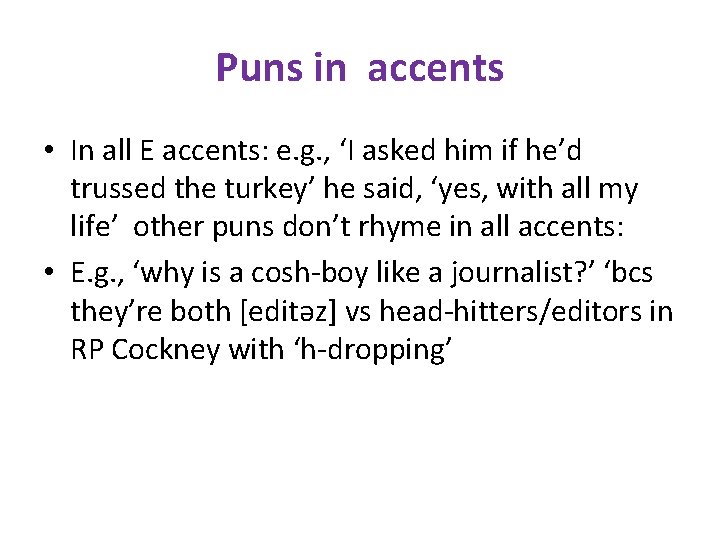

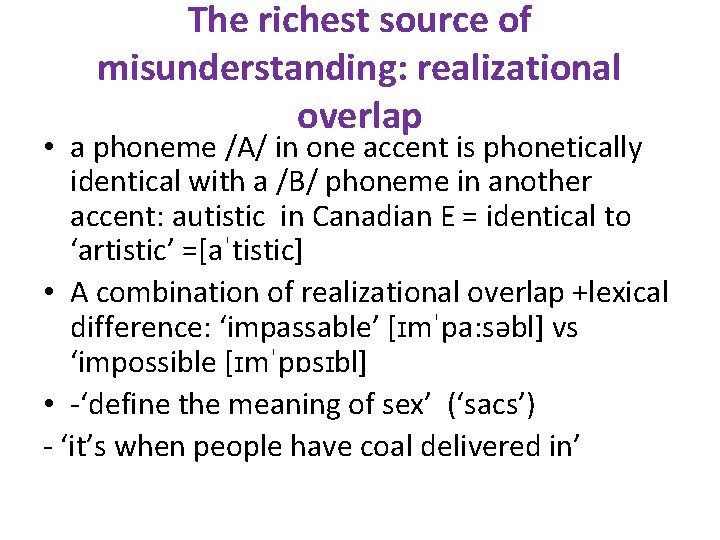

Differences btwn accents in Rhymes, puns and consequences in intelligibility • Phonological identity does not necessarily agree with phonetic identity e. g. , loose /lu: s/ may rhyme with /fju: z/ Eye rhymes: rhyme only orthographically ‘word’ /w 3(r)d/ = ‘sword’ /swɔ: ( r)d/ ‘move’ /mu: v/ =‘grove’ /grəʊv/ Ear rhymes: different morphological constitution e. g. , packed =fact, stand=bandit

Rhymes, puns in diachronic changes: no more valid • ‘blow, blow thou winter wind, thou are not so unkind…’ (Shakespeare). Sometimes, we may ‘force’ a rhyme: ‘sure, deck your lower limbs in pants[…] you look divine as you advance…’ does this rhyme in Br E/RP? In Gen Am advance: /ədˈvᴂns/

Puns in accents • In all E accents: e. g. , ‘I asked him if he’d trussed the turkey’ he said, ‘yes, with all my life’ other puns don’t rhyme in all accents: • E. g. , ‘why is a cosh-boy like a journalist? ’ ‘bcs they’re both [editəz] vs head-hitters/editors in RP Cockney with ‘h-dropping’

The richest source of misunderstanding: realizational overlap • a phoneme /A/ in one accent is phonetically identical with a /B/ phoneme in another accent: autistic in Canadian E = identical to ‘artistic’ =[aˈtistic] • A combination of realizational overlap +lexical difference: ‘impassable’ [ɪmˈpa: səbl] vs ‘impossible [ɪmˈpɒsɪbl] • -‘define the meaning of sex’ (‘sacs’) - ‘it’s when people have coal delivered in’

btwn accents • In Northern E /sᴂks/ = /seks/ • In such cases accusations may appear that particular accents do not speak clearly e. g. , ‘he’s a little [hɔ: s]RP : ambiguous btwn ‘hoarse’ and ‘horse’ in Scottish E Scots, Englishmen: ‘fairies’ vs ‘ferries’ but Americans CANNOT

Rhythmical, pace differences btwn accents • In syllabification: self#ish vs shell#fish in North E not at all distinguished where is the difference in RP/Gen Am? ? • Pace: rate of speech, mean number of syllables per second: urban speech=faster than rural speech BUT: lots of exceptions among specific urban, rural areas, EVERY individual varies their pace according to situation, personal whim

Stress, intonation differences in accents • Even in within the SAME georgraphical area: • ˈexquisite’ or exˈquisite? ˈcontroversy or controˈversy? (UK) • ˈinquiry or inˈquiry • In intonation: the nucleus last accented syllable of the IG in most E accents • A. it was an extremely good PLAN • B. It was an extremely GOOD plan • C. It was an EXTREMELY good plan

Intonational differences btwn accents • In RP: tendency for the nuckeus on the last lexical item/syllable of a content word BUT : in West Indies: nucleus may come early with no deaccentuation: • She thinks I will MARRY her but I don’t WANT to marry her (RP) • She thinks… but I don’t want to MARRY her ()West indies) no deaccentuation

Intonational variation across E accents • Nuclear tones may vary phonologically • Or phonetically (different allotones) • E. g. , fall-rise realised not in the same way or its meaning may be different in different accents • E. g. , a rise-fall in different accents does it mean surprise, emotion? ? • E. g. , in Ulster Irish low rises is associated with? ?

Intonational differences across E accents • In Ulster Irish intonation: low-rises have the meaning of a response-affirmative statement • In RP: low-rise: usually associated with questions • Where do you come from? • Ulster

Voice quality differences btwn accents • Regional, social accents : associated with specific voice quality – setting dependent • Voice quality=quasi-permanent speakers’ features dependent on laryngeal settings • Larynx settings: 1. phonation types (creak) (Norwich, working class: creaky voice) • 2. pitch ranges • 3. loudness voice quality: index to membership (occupational groups: different voices: clergymen, actors, etc )

Accents in music

Accents in music How to split words into syllables

How to split words into syllables What are the 5 french accents?

What are the 5 french accents? Balanced floral arrangement

Balanced floral arrangement Irish accent

Irish accent Danish pronunciation rules

Danish pronunciation rules French regional accents

French regional accents English semester 2 final exam

English semester 2 final exam Situational irony def

Situational irony def English 12 a final exam

English 12 a final exam English 3 fall semester exam review

English 3 fall semester exam review English semester exam

English semester exam Materi sosiologi kelas 12 semester 2

Materi sosiologi kelas 12 semester 2 Materi desain grafis kelas 10 semester 2

Materi desain grafis kelas 10 semester 2 Us history final exam semester 2

Us history final exam semester 2 Tugas tik kelas 9 semester 2

Tugas tik kelas 9 semester 2 Lks tik kelas 8 semester 1

Lks tik kelas 8 semester 1 Chemistry semester 2 review unit 12 thermochemistry

Chemistry semester 2 review unit 12 thermochemistry Kompetensi dasar kelas 3 semester 2

Kompetensi dasar kelas 3 semester 2 Negara yang ditunjukkan oleh anak panah beribukota di

Negara yang ditunjukkan oleh anak panah beribukota di Wharton semester in san francisco

Wharton semester in san francisco Difference between lytic and lysogenic cycle

Difference between lytic and lysogenic cycle Materi segitiga smp kelas 7 semester 2

Materi segitiga smp kelas 7 semester 2 Rangkuman ips kelas 7 semester 2

Rangkuman ips kelas 7 semester 2 Ppt prakarya dan kewirausahaan kelas x semester 2

Ppt prakarya dan kewirausahaan kelas x semester 2 Contoh modus

Contoh modus Materi mice kelas 11 semester 2

Materi mice kelas 11 semester 2 Sayektine apantes tiniru tegese

Sayektine apantes tiniru tegese Materi keuangan kelas 12

Materi keuangan kelas 12 Materi administrasi keuangan kelas 11

Materi administrasi keuangan kelas 11 Materi matematika kelas 11 semester 2

Materi matematika kelas 11 semester 2 Materi pendidikan agama katolik kelas xii semester 2

Materi pendidikan agama katolik kelas xii semester 2 Rangkuman agama kristen kelas 8 semester 1

Rangkuman agama kristen kelas 8 semester 1 Physics semester 1 review

Physics semester 1 review Gunakan 3 cara yang berbeda dalam menamai sudut

Gunakan 3 cara yang berbeda dalam menamai sudut World history semester 2 final review packet

World history semester 2 final review packet World history semester 2 exam review

World history semester 2 exam review Enviromental science final exam

Enviromental science final exam Earth science semester 2 final exam answers

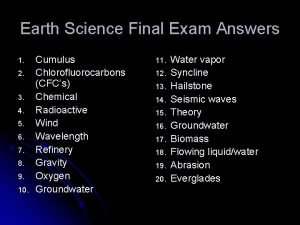

Earth science semester 2 final exam answers Forudsætningskrav sygeplejerske 1 semester

Forudsætningskrav sygeplejerske 1 semester Clock hour to credit hour conversion

Clock hour to credit hour conversion Materi pjok kelas 6 semester 1 atletik

Materi pjok kelas 6 semester 1 atletik Us history semester 2 final exam review

Us history semester 2 final exam review Final exam review algebra 1

Final exam review algebra 1 Unsw academic calendar

Unsw academic calendar Uf law semester in practice

Uf law semester in practice Tugas prakarya kelas xi semester 1

Tugas prakarya kelas xi semester 1 Trigonometri kelas 10 semester 2

Trigonometri kelas 10 semester 2 Kompetensi dasar fisika kelas 11 semester 1

Kompetensi dasar fisika kelas 11 semester 1 Final exam review packet spanish 1 and spanish 2 answer key

Final exam review packet spanish 1 and spanish 2 answer key Materi kuliah sistem informasi manajemen

Materi kuliah sistem informasi manajemen Pengantar teknologi informasi semester 1

Pengantar teknologi informasi semester 1 Humss scheduling of subjects

Humss scheduling of subjects American literature semester 1 final

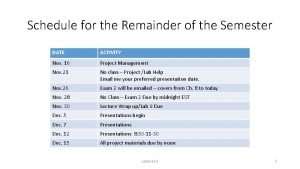

American literature semester 1 final For the remainder of the semester

For the remainder of the semester Mary is trying hard in school this semester her father said

Mary is trying hard in school this semester her father said Edumanage.setiabudi.ac.id

Edumanage.setiabudi.ac.id Physics semester 1 final exam study guide answers

Physics semester 1 final exam study guide answers Peta konsep sosiologi kelas 11

Peta konsep sosiologi kelas 11 Materi pembelajaran pkn smp kelas 8 semester 2

Materi pembelajaran pkn smp kelas 8 semester 2 Materi kelas 12 semester 1

Materi kelas 12 semester 1 Kedudukan garis terhadap garis lainnya

Kedudukan garis terhadap garis lainnya Mata kuliah ilmu alamiah dasar

Mata kuliah ilmu alamiah dasar Soal matematika diskrit

Soal matematika diskrit Hamsahamnida

Hamsahamnida Pasangan sudut yang sehadap

Pasangan sudut yang sehadap