SCOTTISH ENGLISH SCOTTISH ACCENTS What Do We Mean

![DISTINCTIVE FEATURES OF SCOTTISH ENGLISH ACCENTS • glottal stop [ʔ] ( in Scottish English DISTINCTIVE FEATURES OF SCOTTISH ENGLISH ACCENTS • glottal stop [ʔ] ( in Scottish English](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b4aa87d8b33f7a1cd5e738506eec8da8/image-3.jpg)

![Scottish English vowels Pure vowels Help key Scottish English Examples /ɪ/ [ë ~ɪ] bid, Scottish English vowels Pure vowels Help key Scottish English Examples /ɪ/ [ë ~ɪ] bid,](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b4aa87d8b33f7a1cd5e738506eec8da8/image-13.jpg)

- Slides: 19

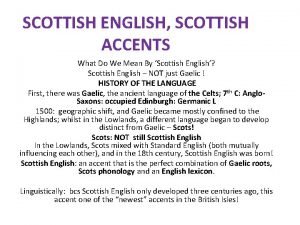

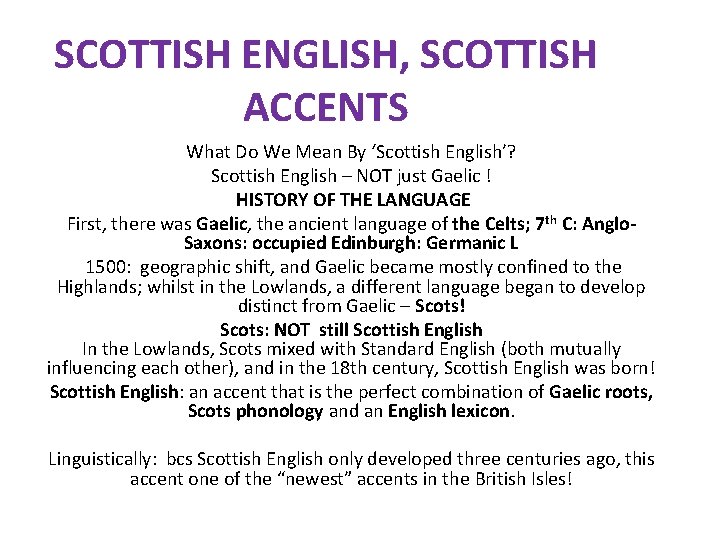

SCOTTISH ENGLISH, SCOTTISH ACCENTS What Do We Mean By ‘Scottish English’? Scottish English – NOT just Gaelic ! HISTORY OF THE LANGUAGE First, there was Gaelic, the ancient language of the Celts; 7 th C: Anglo. Saxons: occupied Edinburgh: Germanic L 1500: geographic shift, and Gaelic became mostly confined to the Highlands; whilst in the Lowlands, a different language began to develop distinct from Gaelic – Scots! Scots: NOT still Scottish English In the Lowlands, Scots mixed with Standard English (both mutually influencing each other), and in the 18 th century, Scottish English was born! Scottish English: an accent that is the perfect combination of Gaelic roots, Scots phonology and an English lexicon. Linguistically: bcs Scottish English only developed three centuries ago, this accent one of the “newest” accents in the British Isles!

History of Scottish Language • What To Look Out For With Scottish English? • Having come from the Celts, Scottish shares similarities with Welsh English; for example, some trilling /r/: apparent in both accents. Phonology: Gaelic/Celtic influence: the /o/ sound in Standard English is often pronounced with an /ae/ sound instead. In Gaelic, this vowel combination /ae/: is very common. e. g. , “cannot” in Standard English. In Scottish English, the /t/ is swallowed [ʔ], and / o/ changes to /ae/, becoming “cannae”.

![DISTINCTIVE FEATURES OF SCOTTISH ENGLISH ACCENTS glottal stop ʔ in Scottish English DISTINCTIVE FEATURES OF SCOTTISH ENGLISH ACCENTS • glottal stop [ʔ] ( in Scottish English](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b4aa87d8b33f7a1cd5e738506eec8da8/image-3.jpg)

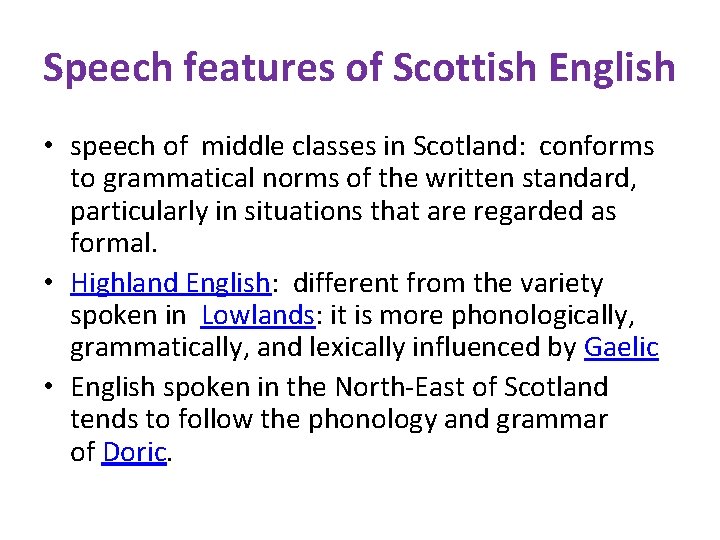

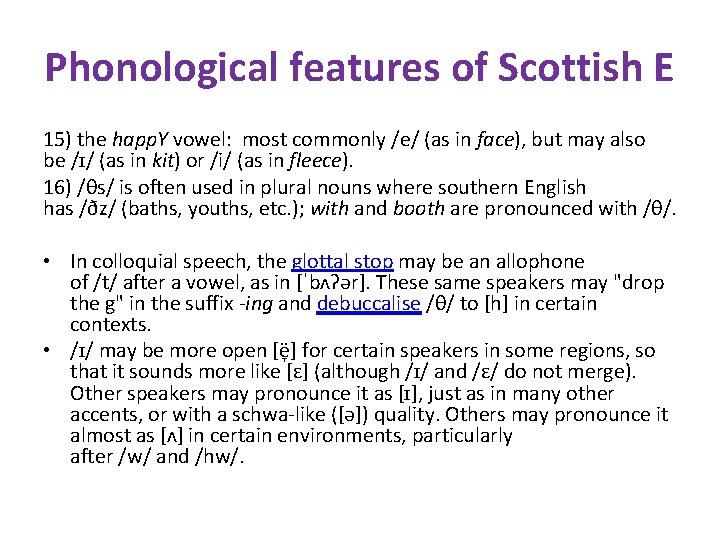

DISTINCTIVE FEATURES OF SCOTTISH ENGLISH ACCENTS • glottal stop [ʔ] ( in Scottish English /t/ seems to be swallowed by the glottal stop) e. g. , “glottal” would become “glo’al” • In spelling: ‘I cannae do it. ’ Not only does the /t/ at the end of “cannot” get swallowed, but “it” also has that distinctive glottal stop after the vowel sound, so you don’t hear /t/ in the sentence at all!

More information about Scottish English • Scottish English includes varieties of English spoken in Scotland. • Main, formal variety : Scottish Standard English or Standard Scottish English (SSE) Scottish Standard English defined as : "the characteristic speech of the professional class [in Scotland] and the accepted norm in schools". • Scottish Standard English is at one end of a bipolar linguistic continuum, with focused broad Scots at the other. Scottish English: influenced to varying degrees by Scots. • Scots speakers separate Scots and Scottish English as different registers depending on social circumstances. Some speakers code switch clearly from one to the other while others style shift in a less predictable and more fluctuating manner. • Generally , shift to Scottish English in formal situations or with individuals of a higher social status

Other characteristic features of Scottish English Language • In addition to distinct pronunciation, grammar and expressions, Scottish English has distinctive vocabulary, particularly pertaining to Scottish institutions such as the Church of Scotland, local government and the education and legal systems

Brief history of Scottish English • Scottish English resulted from language contact between Scots and the Standard English of England after the 17 th century. • shifts to English usage by Scots-speakers resulted in many phonological compromises and lexical transfers, often mistaken for mergers by linguists • also influenced by interdialectal forms, hypercorrections and spelling pronunciations.

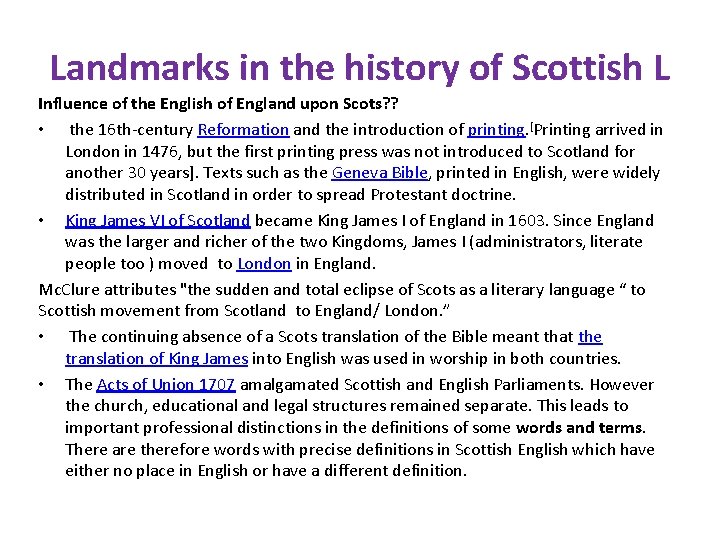

Landmarks in the history of Scottish L Influence of the English of England upon Scots? ? • the 16 th-century Reformation and the introduction of printing. [Printing arrived in London in 1476, but the first printing press was not introduced to Scotland for another 30 years]. Texts such as the Geneva Bible, printed in English, were widely distributed in Scotland in order to spread Protestant doctrine. • King James VI of Scotland became King James I of England in 1603. Since England was the larger and richer of the two Kingdoms, James I (administrators, literate people too ) moved to London in England. Mc. Clure attributes "the sudden and total eclipse of Scots as a literary language “ to Scottish movement from Scotland to England/ London. ” • The continuing absence of a Scots translation of the Bible meant that the translation of King James into English was used in worship in both countries. • The Acts of Union 1707 amalgamated Scottish and English Parliaments. However the church, educational and legal structures remained separate. This leads to important professional distinctions in the definitions of some words and terms. There are therefore words with precise definitions in Scottish English which have either no place in English or have a different definition.

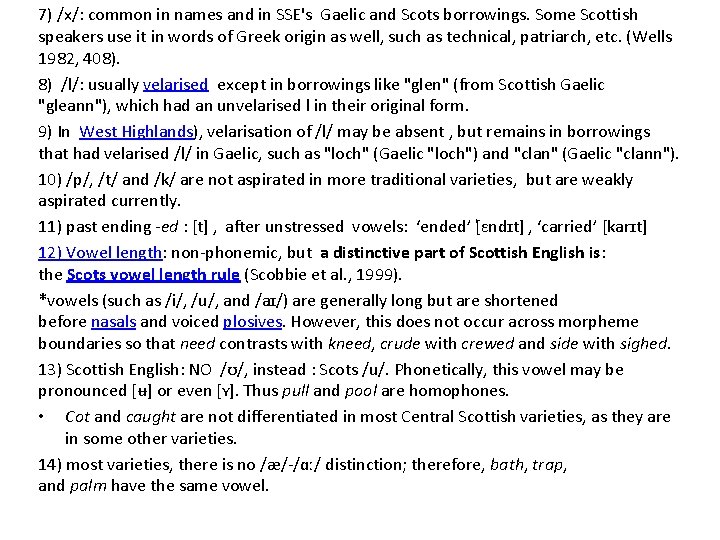

Speech features of Scottish English • speech of middle classes in Scotland: conforms to grammatical norms of the written standard, particularly in situations that are regarded as formal. • Highland English: different from the variety spoken in Lowlands: it is more phonologically, grammatically, and lexically influenced by Gaelic • English spoken in the North-East of Scotland tends to follow the phonology and grammar of Doric.

Phonological features of Scottish E Although pronunciation features vary among speakers (depending on region and social status), there a number of phonological aspects characteristic of Scottish English: 1) Scottish English: rhotic accent, meaning /r/ is typically pronounced in the syllable coda; /r/: postalveolar approximant [ɹ], as in Received Pronunciation or General American, but speakers have also traditionally used for the same phoneme a somewhat more common alveolar tap [ɾ] or, now very rare, the alveolar trill [r] 2) Some dialects have merged non-intervocalic /ɛ/, /ɪ/, /ʌ/ before /r/ (fern–fir–fur merger), BUT Scottish English makes a distinction between the vowels in fern, fir, and fur respectively. 3) Many varieties contrast /o/ and /ɔ/ before /r/ so that hoarse and horse are pronounced differently. 4) /or/ and /ur/: contrasted, so shore and sure are pronounced differently, as are pour and poor. 5) /r/ before /l/ is trill/tap. An epenthetic vowel may occur between /r/ and /l/ so that girl and world are two-syllable words for some speakers. The same may occur between /r/ and /m/, between /r/ and /n/, and between /l/ and /m/. 6) distinction between /w/ and /hw/ in word pairs such as witch and which.

7) /x/: common in names and in SSE's Gaelic and Scots borrowings. Some Scottish speakers use it in words of Greek origin as well, such as technical, patriarch, etc. (Wells 1982, 408). 8) /l/: usually velarised except in borrowings like "glen" (from Scottish Gaelic "gleann"), which had an unvelarised l in their original form. 9) In West Highlands), velarisation of /l/ may be absent , but remains in borrowings that had velarised /l/ in Gaelic, such as "loch" (Gaelic "loch") and "clan" (Gaelic "clann"). 10) /p/, /t/ and /k/ are not aspirated in more traditional varieties, but are weakly aspirated currently. 11) past ending -ed : [t] , after unstressed vowels: ‘ended’ [ ɛndɪt] , ‘carried’ [karɪt] 12) Vowel length: non-phonemic, but a distinctive part of Scottish English is: the Scots vowel length rule (Scobbie et al. , 1999). *vowels (such as /i/, /u/, and /aɪ/) are generally long but are shortened before nasals and voiced plosives. However, this does not occur across morpheme boundaries so that need contrasts with kneed, crude with crewed and side with sighed. 13) Scottish English: NO /ʊ/, instead : Scots /u/. Phonetically, this vowel may be pronounced [ʉ] or even [ʏ]. Thus pull and pool are homophones. • Cot and caught are not differentiated in most Central Scottish varieties, as they are in some other varieties. 14) most varieties, there is no /æ/-/ɑː/ distinction; therefore, bath, trap, and palm have the same vowel.

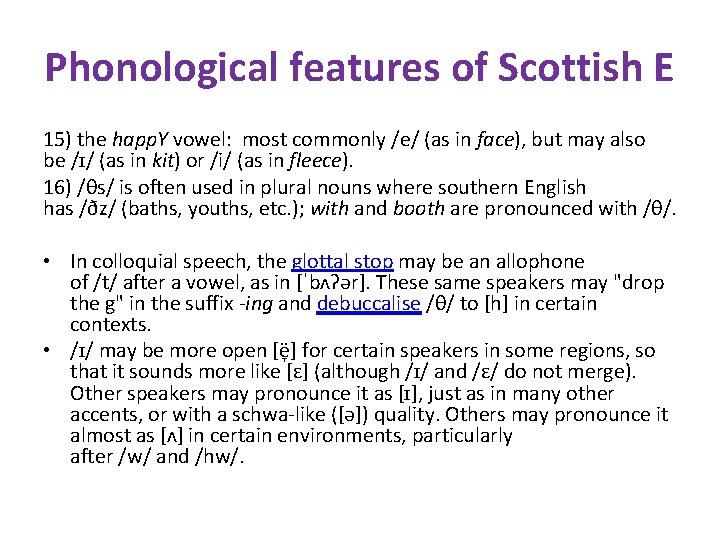

Phonological features of Scottish E 15) the happ. Y vowel: most commonly /e/ (as in face), but may also be /ɪ/ (as in kit) or /i/ (as in fleece). 16) /θs/ is often used in plural nouns where southern English has /ðz/ (baths, youths, etc. ); with and booth are pronounced with /θ/. • In colloquial speech, the glottal stop may be an allophone of /t/ after a vowel, as in [ˈbʌʔər]. These same speakers may "drop the g" in the suffix -ing and debuccalise /θ/ to [h] in certain contexts. • /ɪ/ may be more open [ë ] for certain speakers in some regions, so that it sounds more like [ɛ] (although /ɪ/ and /ɛ/ do not merge). Other speakers may pronounce it as [ɪ], just as in many other accents, or with a schwa-like ([ə]) quality. Others may pronounce it almost as [ʌ] in certain environments, particularly after /w/ and /hw/.

![Scottish English vowels Pure vowels Help key Scottish English Examples ɪ ë ɪ bid Scottish English vowels Pure vowels Help key Scottish English Examples /ɪ/ [ë ~ɪ] bid,](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b4aa87d8b33f7a1cd5e738506eec8da8/image-13.jpg)

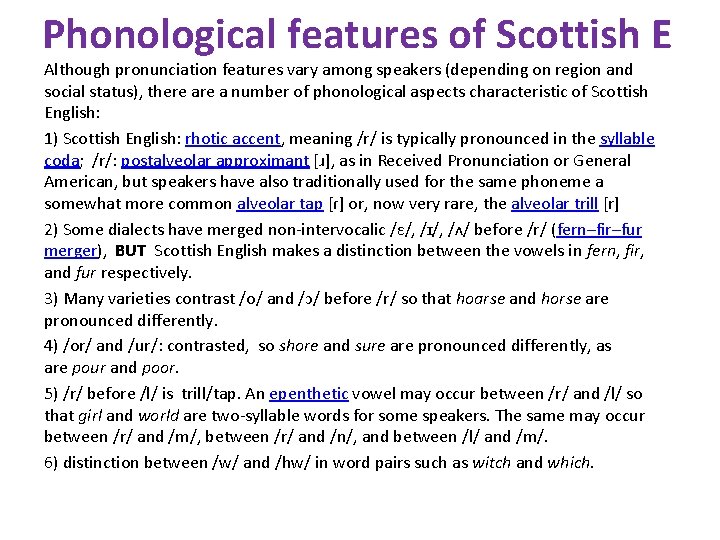

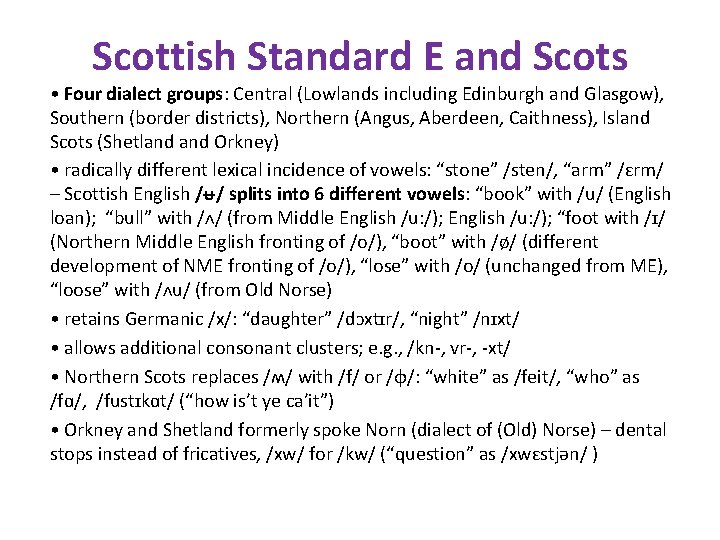

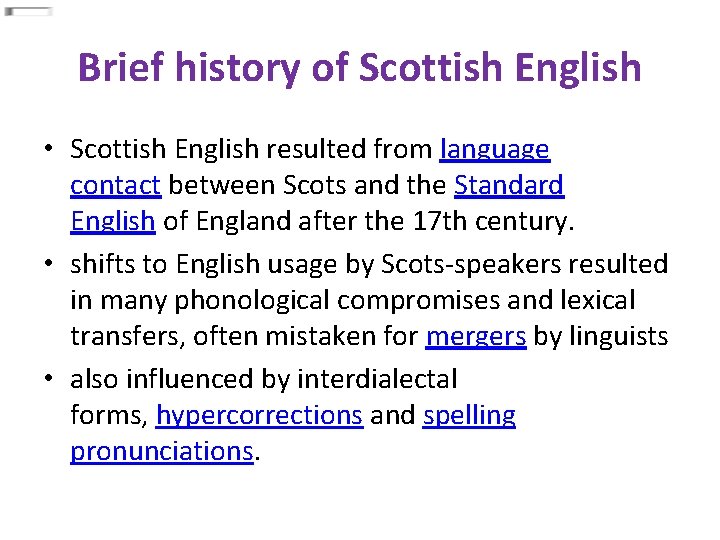

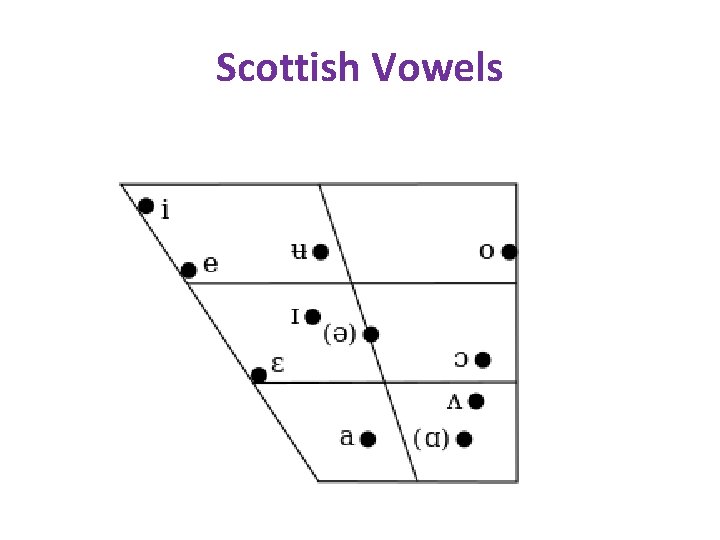

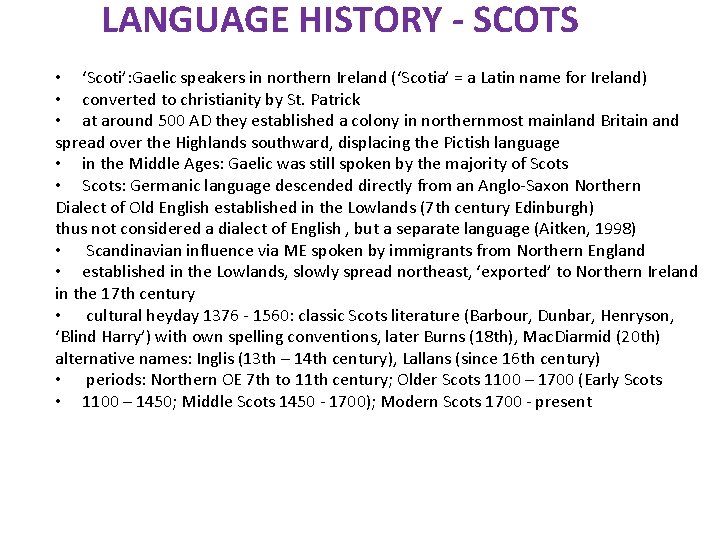

Scottish English vowels Pure vowels Help key Scottish English Examples /ɪ/ [ë ~ɪ] bid, pit /iː/ [i] bead, peat /ɛ/ [ɛ~ɛ ] bed, pet /eɪ/ [e(ː)] bay, hey, fate /æ/ /ɑː/ /ɒ/ /ɔː/ /oʊ/ /uː/ /ʌ/ bad, pat [ä] balm, father, pa bod, pot, cot [ɔ] bawd, paw, caught [o(ː)] road, stone, toe good, foot, put [ʉ] booed, food [ʌ~ɐ] bud, putt Diphthongs /aɪ/ /aʊ/ [ɐi~ɜi~əi] [ɐʉ~ɜʉ~əʉ] buy, ride, write how, pout /ɔɪ/ [oi] boy, hoy /juː/ [jʉ] hue, pew, new R-coloured vowels (these do not exist in Scots) /ɪr/ [ɪɹ] or [ɪɾ] mirror, thirst /ɪər/ [i(ː)ə ɹ] or [iəɾ] beer, mere /ɛr/ [ɛ ɹ] or [ɛ ɾ] berry, merry (also in her) /ɛər/ [e(ː)ə ɹ] or [eəɾ] bear, mare, Mary /ær/ /ɑːr/ /ɒr/ /ɔːr/ [ä(ː)ɹ] or [äɾ] [ɔ(ː)ɹ] or [ɔɾ] barrow, marry bar, card moral, forage born, for [oː(ə )ɹ] or [oɾ] boar, four, more /ʊər/ [ʉɹ] or [ʉɾ] boor, moor /ʌr/ [ʌɹ] or [ʌɾ] hurry, Murray (also in fur) /ɜːr/ 3 -way distinction: [ɪɹ], [ɛ ɹ], [ʌɹ]; or [ɪɾ], [ɛ ɾ], [ʌɾ] bird, herd, furry /ə/ [ə] Rosa's, cuppa /ər/ [əɹ] or [əɾ] runner, mercer Reduced vowels

Scottish Vowels

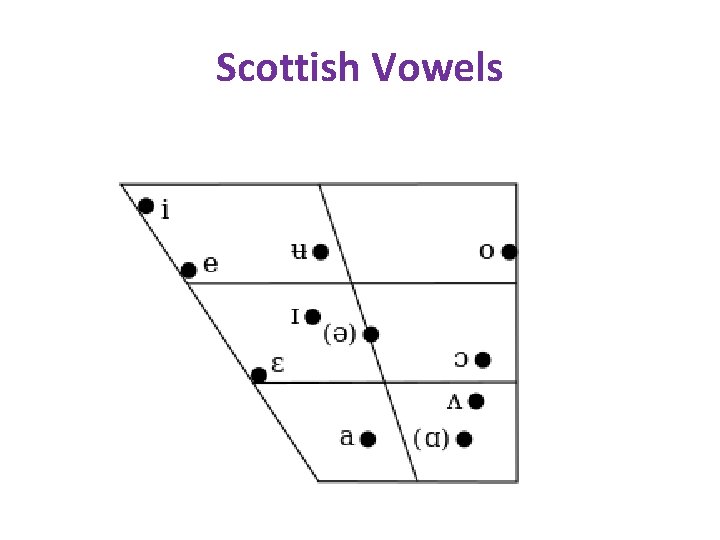

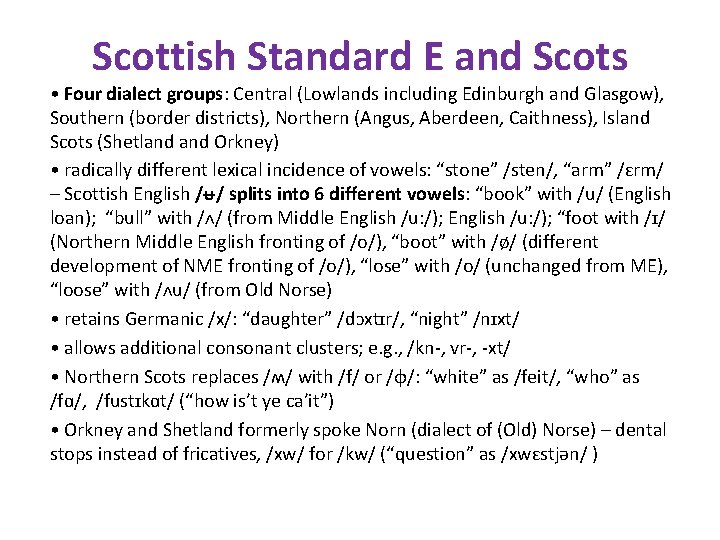

Scottish Standard E and Scots • Four dialect groups: Central (Lowlands including Edinburgh and Glasgow), Southern (border districts), Northern (Angus, Aberdeen, Caithness), Island Scots (Shetland Orkney) • radically different lexical incidence of vowels: “stone” /sten/, “arm” /ɛrm/ – Scottish English /ᵾ/ splits into 6 different vowels: “book” with /u/ (English loan); “bull” with /ᴧ/ (from Middle English /u: /); “foot with /ɪ/ (Northern Middle English fronting of /o/), “boot” with /ø/ (different development of NME fronting of /o/), “lose” with /o/ (unchanged from ME), “loose” with /ᴧu/ (from Old Norse) • retains Germanic /x/: “daughter” /dɔxtɪr/, “night” /nɪxt/ • allows additional consonant clusters; e. g. , /kn-, vr-, -xt/ • Northern Scots replaces /ʍ/ with /f/ or /φ/: “white” as /feit/, “who” as /fɑ/, /fustɪkɑt/ (“how is’t ye ca’it”) • Orkney and Shetland formerly spoke Norn (dialect of (Old) Norse) – dental stops instead of fricatives, /xw/ for /kw/ (“question” as /xwɛstjən/ )

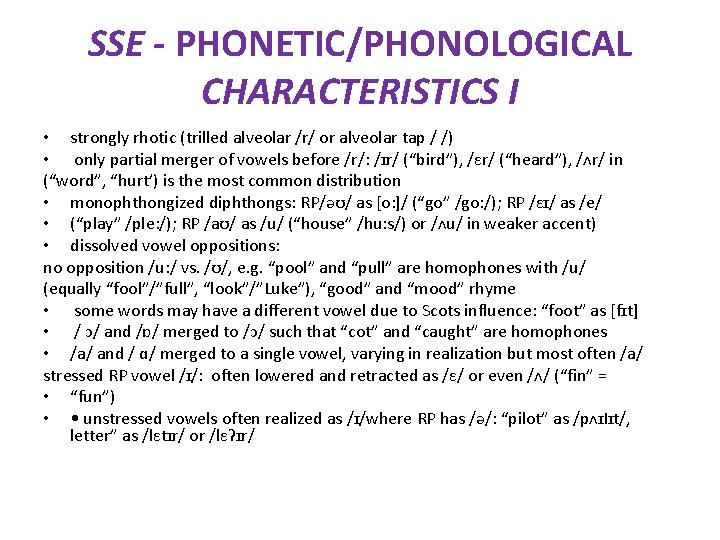

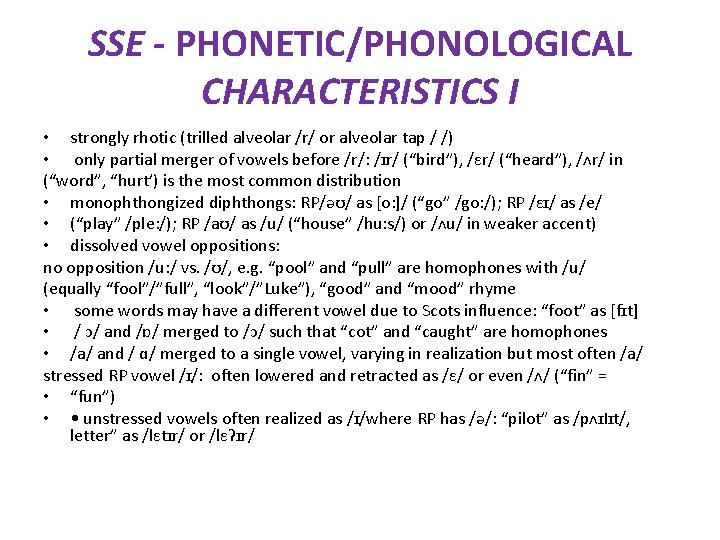

SSE - PHONETIC/PHONOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS I • strongly rhotic (trilled alveolar /r/ or alveolar tap / /) • only partial merger of vowels before /r/: /ɪr/ (“bird”), /ɛr/ (“heard”), /ᴧr/ in (“word”, “hurt’) is the most common distribution • monophthongized diphthongs: RP/əʊ/ as [o: ]/ (“go” /go: /); RP /ɛɪ/ as /e/ • (“play” /ple: /); RP /aʊ/ as /u/ (“house” /hu: s/) or /ᴧu/ in weaker accent) • dissolved vowel oppositions: no opposition /u: / vs. /ʊ/, e. g. “pool” and “pull” are homophones with /u/ (equally “fool”/”full”, “look”/”Luke”), “good” and “mood” rhyme • some words may have a different vowel due to Scots influence: “foot” as [fɪt] • / ɔ/ and /ɒ/ merged to /ɔ/ such that “cot” and “caught” are homophones • /a/ and / ɑ/ merged to a single vowel, varying in realization but most often /a/ stressed RP vowel /ɪ/: often lowered and retracted as /ɛ/ or even /ᴧ/ (“fin” = • “fun”) • • unstressed vowels often realized as /ɪ/where RP has /ə/: “pilot” as /pᴧɪIɪt/, letter” as /lɛtɪr/ or /lɛʔɪr/

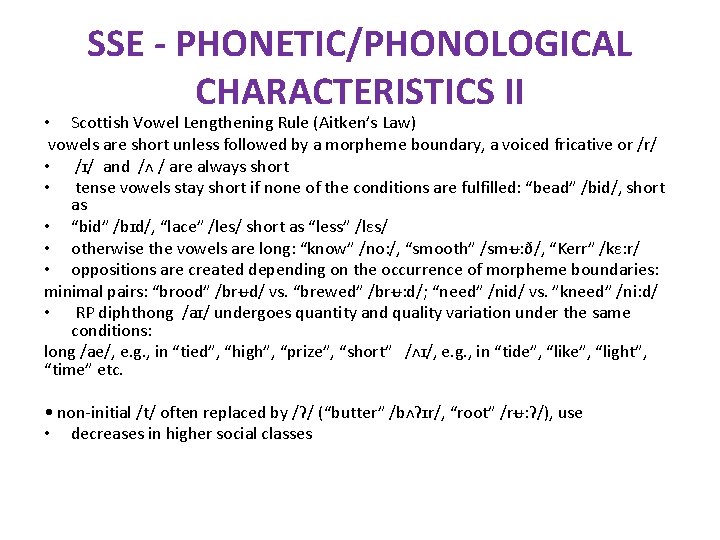

SSE - PHONETIC/PHONOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS II • Scottish Vowel Lengthening Rule (Aitken’s Law) vowels are short unless followed by a morpheme boundary, a voiced fricative or /r/ • /ɪ/ and /ᴧ / are always short • tense vowels stay short if none of the conditions are fulfilled: “bead” /bid/, short as • “bid” /bɪd/, “lace” /les/ short as “less” /lɛs/ • otherwise the vowels are long: “know” /no: /, “smooth” /smᵾ: ð/, “Kerr” /kɛ: r/ • oppositions are created depending on the occurrence of morpheme boundaries: minimal pairs: “brood” /brᵾd/ vs. “brewed” /brᵾ: d/; “need” /nid/ vs. ”kneed” /ni: d/ • RP diphthong /aɪ/ undergoes quantity and quality variation under the same conditions: long /ae/, e. g. , in “tied”, “high”, “prize”, “short” /ᴧɪ/, e. g. , in “tide”, “like”, “light”, “time” etc. • non-initial /t/ often replaced by /ʔ/ (“butter” /bᴧʔɪr/, “root” /rᵾ: ʔ/), use • decreases in higher social classes

LANGUAGE HISTORY - SCOTS • ‘Scoti’: Gaelic speakers in northern Ireland (‘Scotia’ = a Latin name for Ireland) • converted to christianity by St. Patrick • at around 500 AD they established a colony in northernmost mainland Britain and spread over the Highlands southward, displacing the Pictish language • in the Middle Ages: Gaelic was still spoken by the majority of Scots • Scots: Germanic language descended directly from an Anglo-Saxon Northern Dialect of Old English established in the Lowlands (7 th century Edinburgh) thus not considered a dialect of English , but a separate language (Aitken, 1998) • Scandinavian influence via ME spoken by immigrants from Northern England • established in the Lowlands, slowly spread northeast, ‘exported’ to Northern Ireland in the 17 th century • cultural heyday 1376 - 1560: classic Scots literature (Barbour, Dunbar, Henryson, ‘Blind Harry’) with own spelling conventions, later Burns (18 th), Mac. Diarmid (20 th) alternative names: Inglis (13 th – 14 th century), Lallans (since 16 th century) • periods: Northern OE 7 th to 11 th century; Older Scots 1100 – 1700 (Early Scots • 1100 – 1450; Middle Scots 1450 - 1700); Modern Scots 1700 - present

LANGUAGE HISTORY – SCOTTISH ENGLISH • Union of the Crowns (1603): James VI King of Scots becomes King of England at the death of Queen Elizabeth Union of the Parliaments (1707): Scottish Parliament dissolved into an expansion of the English Parliament, creating a British Parliament • steady decline of Scots begins in 16 th century, by the end of the 17 th century English has gained considerable influence in Scotland • no Scots bible translation; English as the language of religion and serious thought • Scots considered provincial and unrefined • after Union English comes to be the official written language of the whole country • continuum of usage from English with weaker or stronger Scottish accents to Scottish Standard English proper to SSE with Scots influence to urban Scots to rural Scots • English learned formally in Highlands and northern and western islands (still Gaelic -speaking), thus no Scots influence

Piano study in mixed accents

Piano study in mixed accents Latin accent rules

Latin accent rules Les accent

Les accent Floral design elements

Floral design elements Irish english accent

Irish english accent Danish pronunciation rules

Danish pronunciation rules French regional accents

French regional accents Scottish accent practice sentences

Scottish accent practice sentences Sample mean and population mean

Sample mean and population mean Absolute deviation

Absolute deviation Sample mean

Sample mean How to get population mean

How to get population mean Mean of the sampling distribution of the sample mean

Mean of the sampling distribution of the sample mean What does mean mean

What does mean mean Mean deviation

Mean deviation Say, mean, matter

Say, mean, matter Ruae techniques

Ruae techniques What does e pluribus unum mean in english

What does e pluribus unum mean in english What does e pluribus unum mean in english

What does e pluribus unum mean in english What is lydende vorm examples

What is lydende vorm examples