The Evolving Role of Agriculture in Poverty Reduction

- Slides: 39

The (Evolving) Role of Agriculture in Poverty Reduction Luc Christiaensen (UNU-WIDER), Lionel Demery (Development Consultant), Jesper Kuhl (Development Consultant) Presentation at UN-HQ New York, 2 June, 2010

Four questions 1) 2) 3) Does a focus on agriculture lead to more economic growth than a focus on nonagriculture? Do the poor participate more in growth from agriculture than in growth from nonagriculture? Does potentially greater participation by the poor in ag growth offset potentially slower growth from ag, and under which circumstances?

Findings n Agriculture better at reducing $1 -day poverty; non-agriculture better at reducing $2 -day poverty n High inequality reduces poverty reducing power of agriculture and presence of extractive industries reduces poverty reducing effects of non-agriculture n Results driven by larger participation of poor in growth from agriculture

What follows? 1) A conceptual framework 2) Growth potential across sectors–direct growth effects? 3) Agriculture and the rest of the economy–indirect growth effects? 4) Benefiting from growth – participation effects 5) The (evolving) role of agriculture in poverty reduction - a synthesizing perspective 6) Concluding remarks

Conceptual Framework

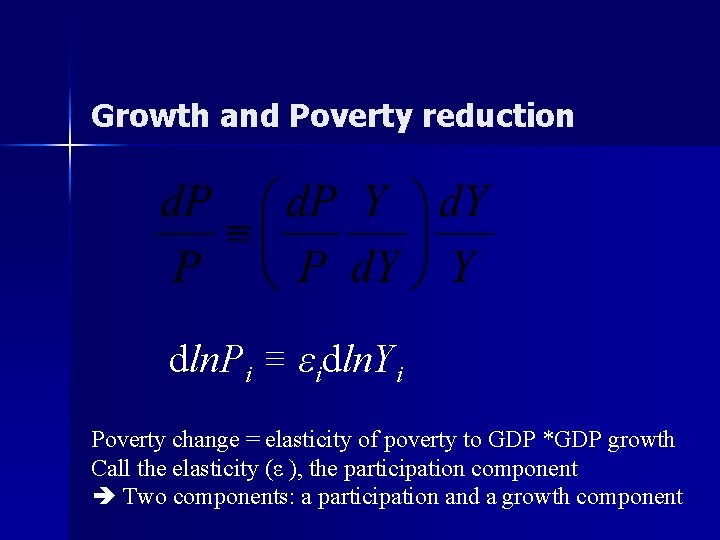

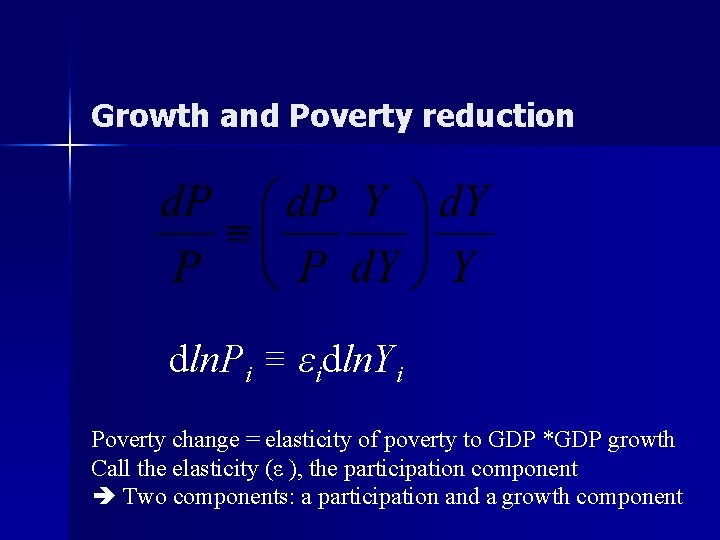

Growth and Poverty reduction dln. Pi ≡ εidln. Yi Poverty change = elasticity of poverty to GDP *GDP growth Call the elasticity (ε ), the participation component Two components: a participation and a growth component

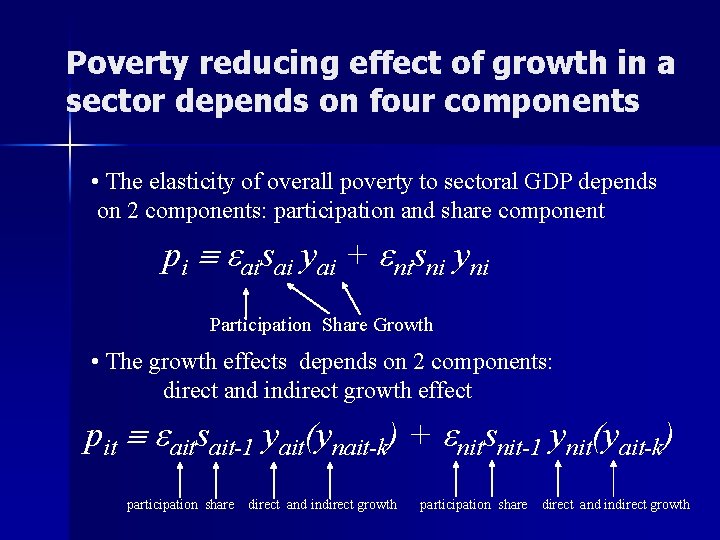

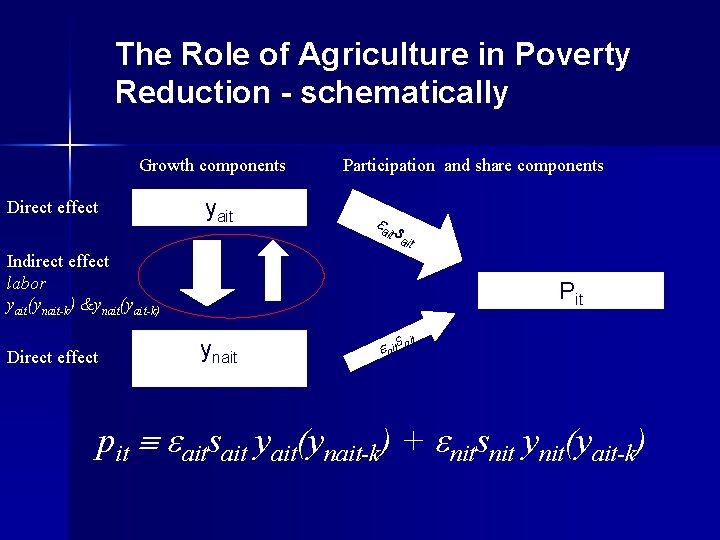

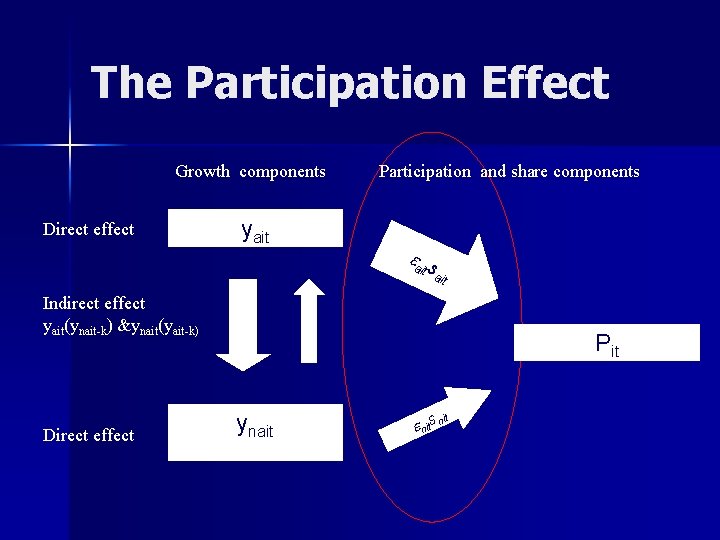

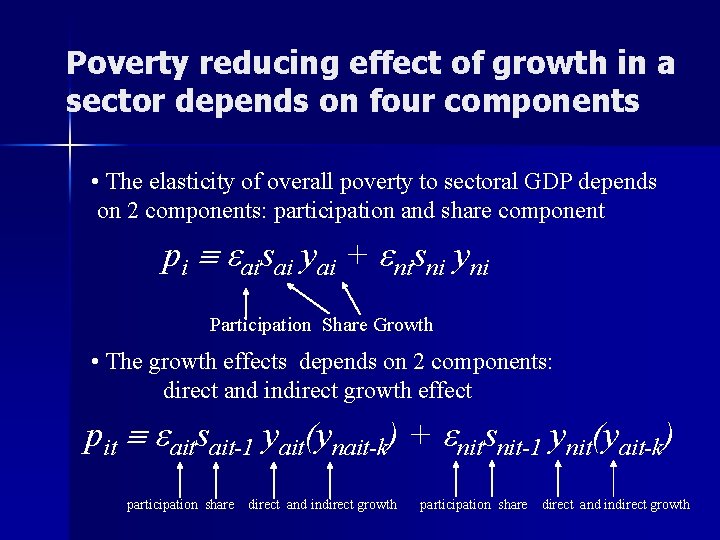

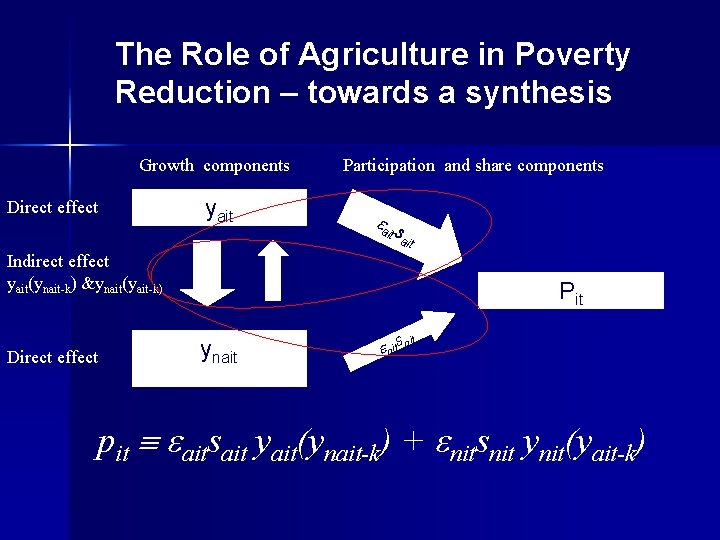

Poverty reducing effect of growth in a sector depends on four components • The elasticity of overall poverty to sectoral GDP depends on 2 components: participation and share component pi aisai yai + nisni yni Participation Share Growth • The growth effects depends on 2 components: direct and indirect growth effect pit aitsait-1 yait(ynait-k) + nitsnit-1 ynit(yait-k) participation share direct and indirect growth

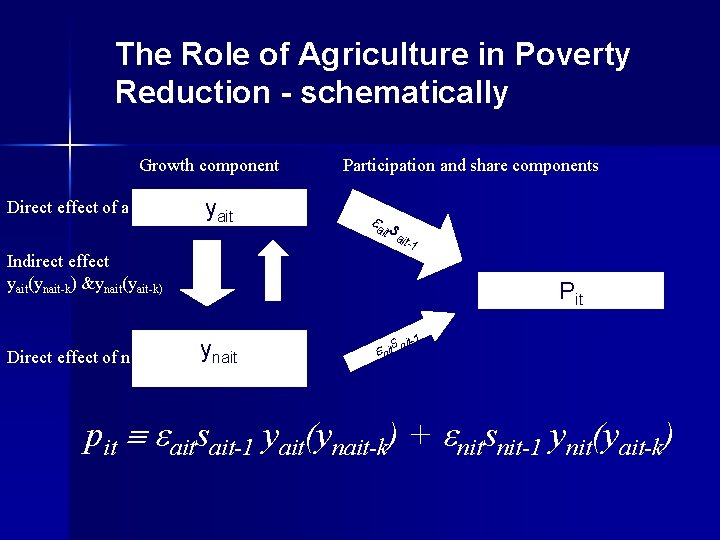

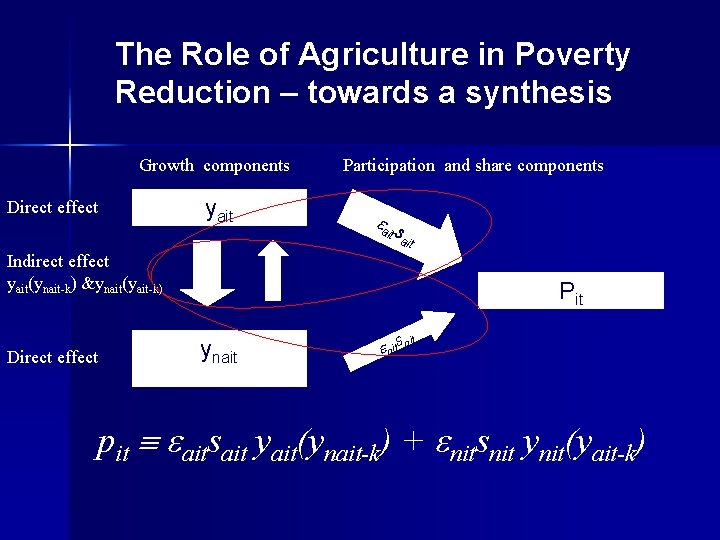

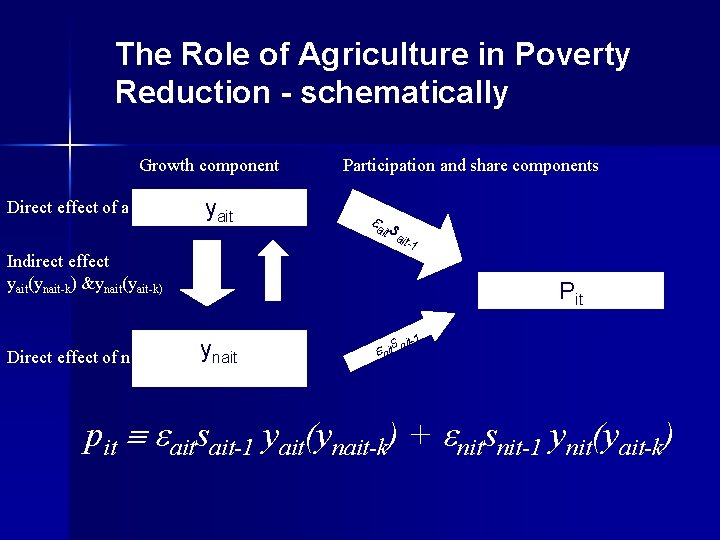

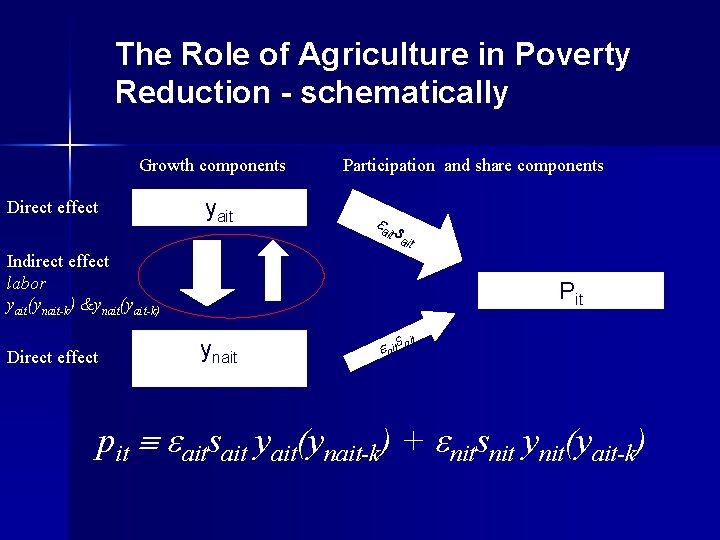

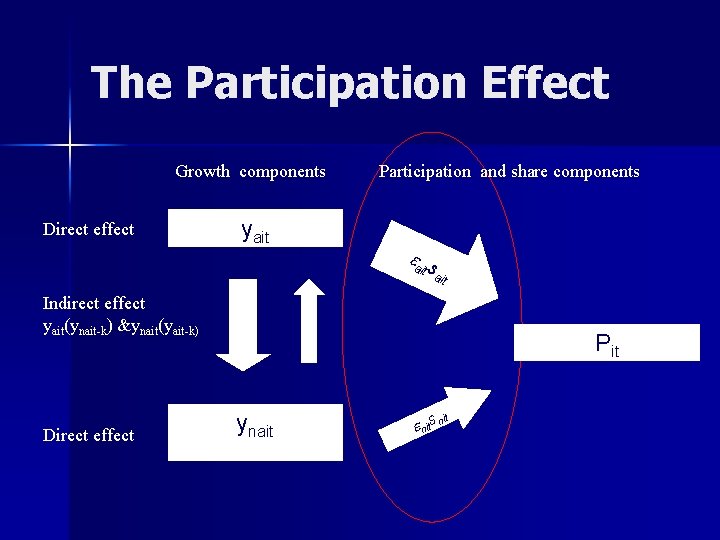

The Role of Agriculture in Poverty Reduction - schematically Growth component Direct effect of a yait Participation and share components a s it a it-1 Indirect effect yait(ynait-k) &ynait(yait-k) Direct effect of n Pit ynait 1 s nit pit aitsait-1 yait(ynait-k) + nitsnit-1 ynit(yait-k)

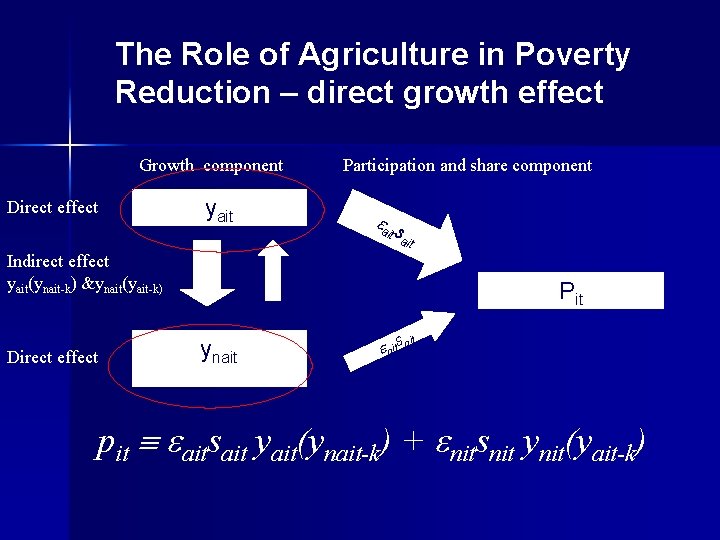

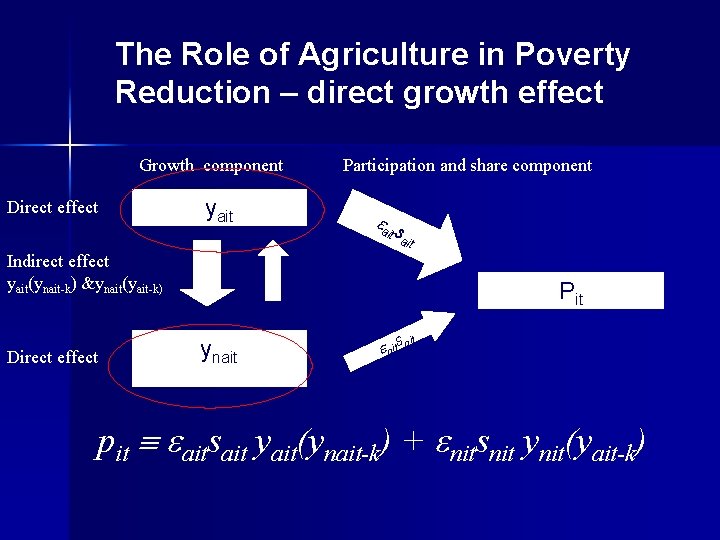

The Role of Agriculture in Poverty Reduction – direct growth effect Growth component Direct effect yait Participation and share component a s it a it Indirect effect yait(ynait-k) &ynait(yait-k) Direct effect Pit ynait nits n it pit aitsait yait(ynait-k) + nitsnit ynit(yait-k)

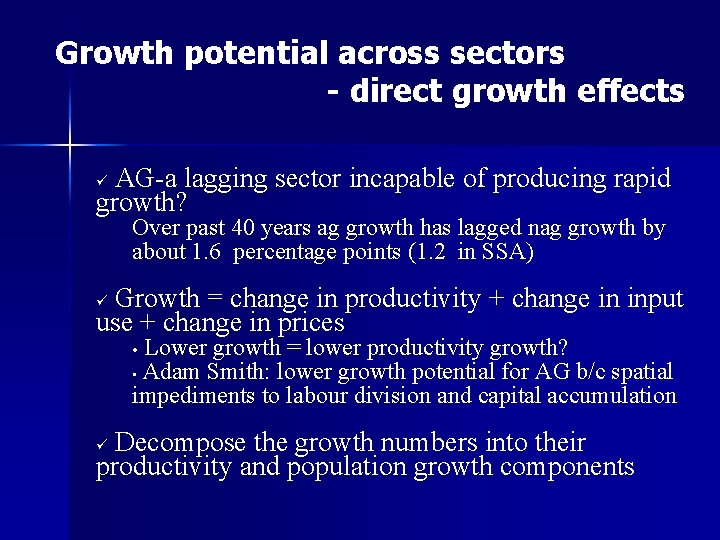

Growth potential across sectors - direct growth effects AG-a lagging sector incapable of producing rapid growth? ü Over past 40 years ag growth has lagged nag growth by about 1. 6 percentage points (1. 2 in SSA) Growth = change in productivity + change in input use + change in prices • Lower growth = lower productivity growth? ü Adam Smith: lower growth potential for AG b/c spatial impediments to labour division and capital accumulation • Decompose the growth numbers into their productivity and population growth components ü

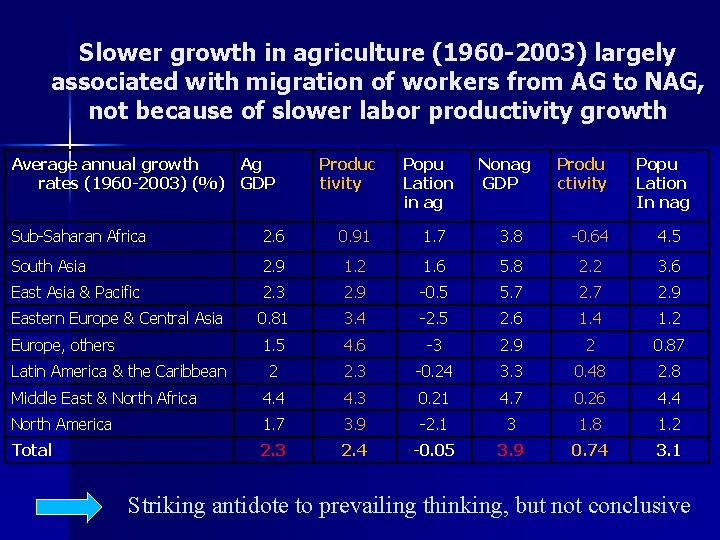

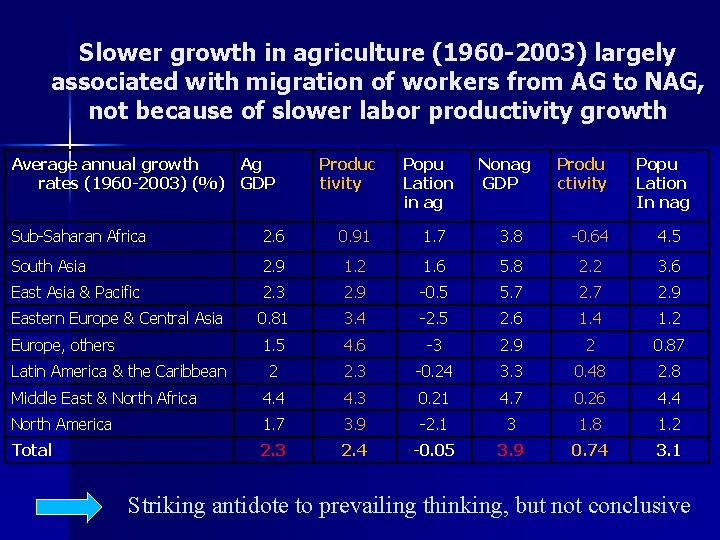

Slower growth in agriculture (1960 -2003) largely associated with migration of workers from AG to NAG, not because of slower labor productivity growth Average annual growth Ag rates (1960 -2003) (%) GDP Produc tivity Popu Lation in ag Nonag GDP Produ ctivity Popu Lation In nag Sub-Saharan Africa 2. 6 0. 91 1. 7 3. 8 -0. 64 4. 5 South Asia 2. 9 1. 2 1. 6 5. 8 2. 2 3. 6 East Asia & Pacific 2. 3 2. 9 -0. 5 5. 7 2. 9 Eastern Europe & Central Asia 0. 81 3. 4 -2. 5 2. 6 1. 4 1. 2 Europe, others 1. 5 4. 6 -3 2. 9 2 0. 87 2 2. 3 -0. 24 3. 3 0. 48 2. 8 Middle East & North Africa 4. 4 4. 3 0. 21 4. 7 0. 26 4. 4 North America 1. 7 3. 9 -2. 1 3 1. 8 1. 2 Total 2. 3 2. 4 -0. 05 3. 9 0. 74 3. 1 Latin America & the Caribbean Striking antidote to prevailing thinking, but not conclusive

Industrial pull or agricultural push? n Industrial pull – wage equilibrating labor movements in response to higher marginal productivity outside AG n Agricultural push – productivity growth in ag leads to deterioration of TOT against ag and thus declining remuneration of factors (labor and capital) in agric, inducing migration n Empirical evidence (manufacturing/industrial and TFP) – Szirmai (2009) ag labor productivity growing faster in 12/16 developing countries (Latin America and Asia) bw 1973 -2005 – from industrial countries suggests TFP growth in ag larger than in nonag sector (Bernard and Jones, 1996) – Recent evidence from developing countries confirms this (Martin and Mitra, 2001)

Emerging insights on agriculture’s growth potential n No superiority in agricultural TFP growth, but debunk the notion that agriculture is a backward sector. n Globally AG will grow slower than NAG due to Engel’s Law, not b/c inferior productivity growth. n Important growth opportunities for some countries given high income elasticity for non-staple food and where international trading opportunities exist (Brazil, Chile) n Recovery in ag TFP in SSA over past decade holds promise and expected higher agricultural commodity prices in medium term provide opportunities , though many challenges remain,

The Role of Agriculture in Poverty Reduction - schematically Growth components Direct effect yait Participation and share components a s it a it Indirect effect labor yait(ynait-k) &ynait(yait-k) Direct effect Pit ynait nits n it pit aitsait yait(ynait-k) + nitsnit ynit(yait-k)

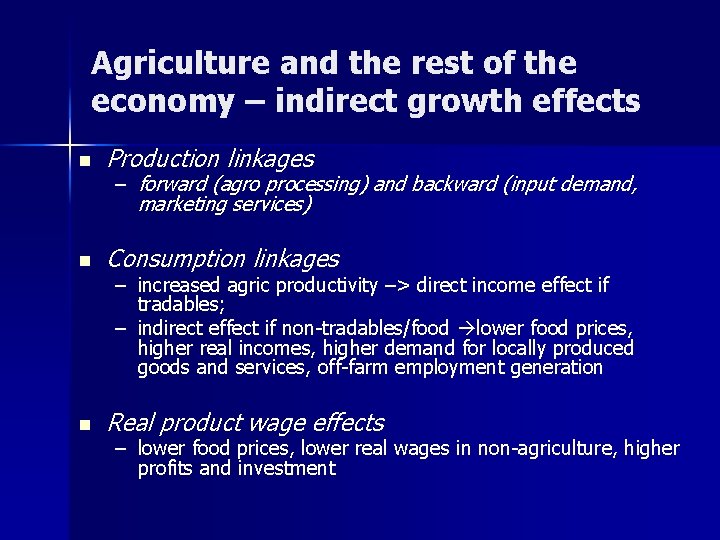

Agriculture and the rest of the economy – indirect growth effects n Production linkages n Consumption linkages – forward (agro processing) and backward (input demand, marketing services) – increased agric productivity –> direct income effect if tradables; – indirect effect if non-tradables/food lower food prices, higher real incomes, higher demand for locally produced goods and services, off-farm employment generation n Real product wage effects – lower food prices, lower real wages in non-agriculture, higher profits and investment

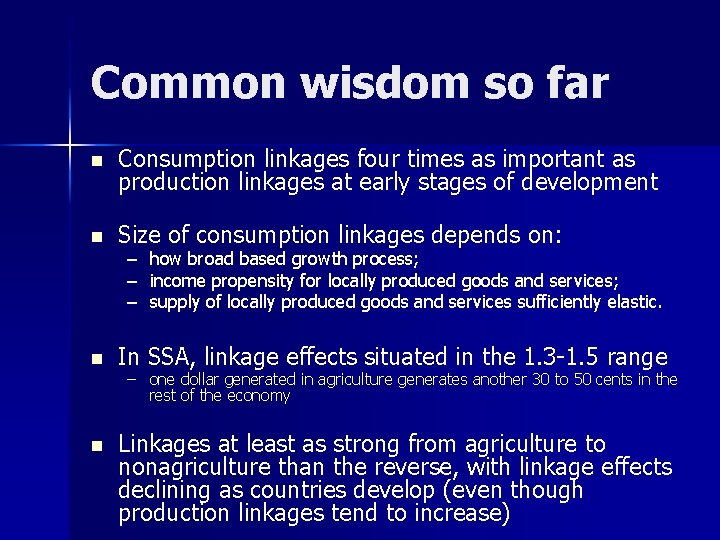

Common wisdom so far n Consumption linkages four times as important as production linkages at early stages of development n Size of consumption linkages depends on: – how broad based growth process; – income propensity for locally produced goods and services; – supply of locally produced goods and services sufficiently elastic. n In SSA, linkage effects situated in the 1. 3 -1. 5 range – one dollar generated in agriculture generates another 30 to 50 cents in the rest of the economy n Linkages at least as strong from agriculture to nonagriculture than the reverse, with linkage effects declining as countries develop (even though production linkages tend to increase)

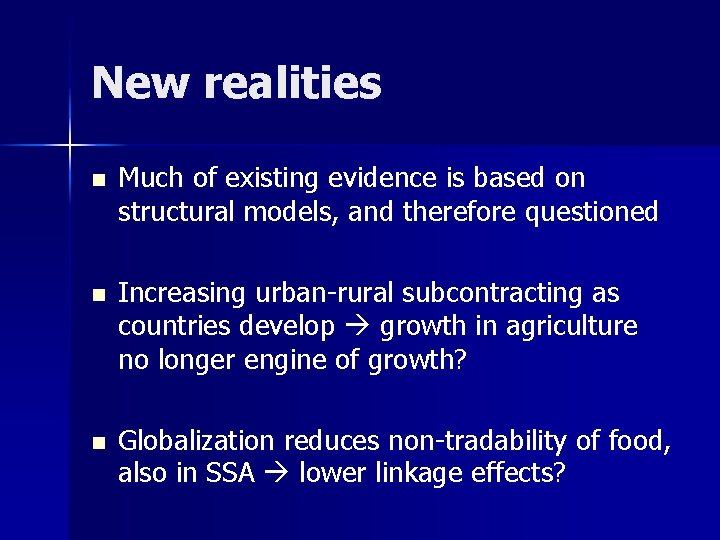

New realities n n n Much of existing evidence is based on structural models, and therefore questioned Increasing urban-rural subcontracting as countries develop growth in agriculture no longer engine of growth? Globalization reduces non-tradability of food, also in SSA lower linkage effects?

The Tradability of Food?

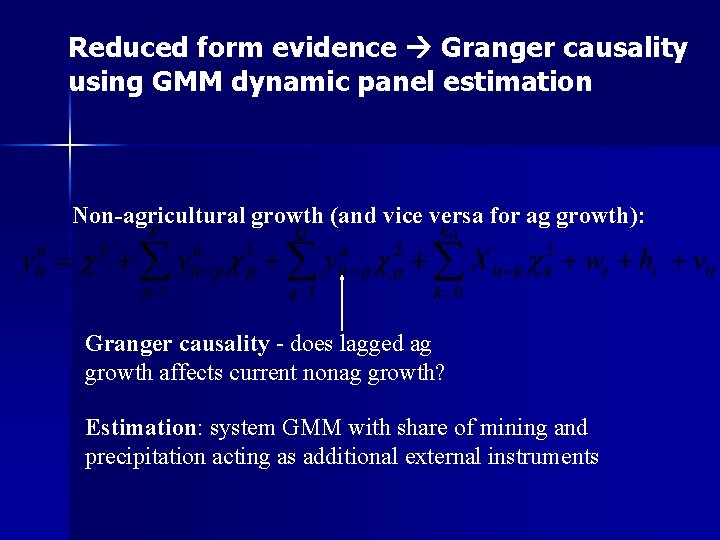

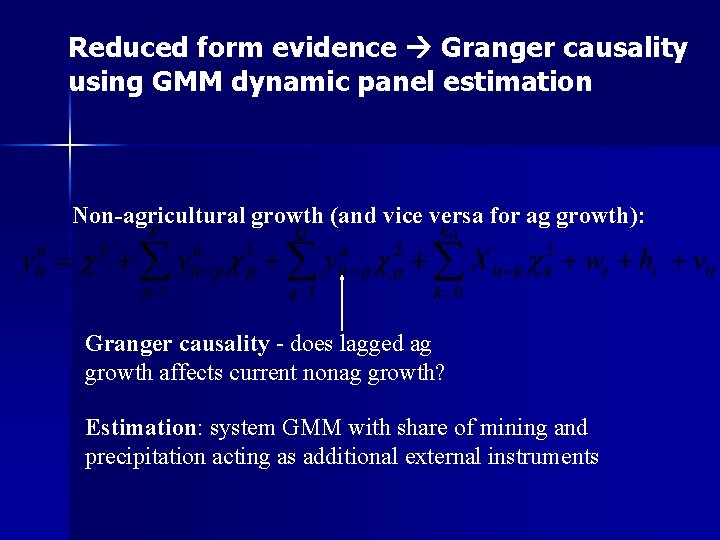

Reduced form evidence Granger causality using GMM dynamic panel estimation Non-agricultural growth (and vice versa for ag growth): Granger causality - does lagged ag growth affects current nonag growth? Estimation: system GMM with share of mining and precipitation acting as additional external instruments

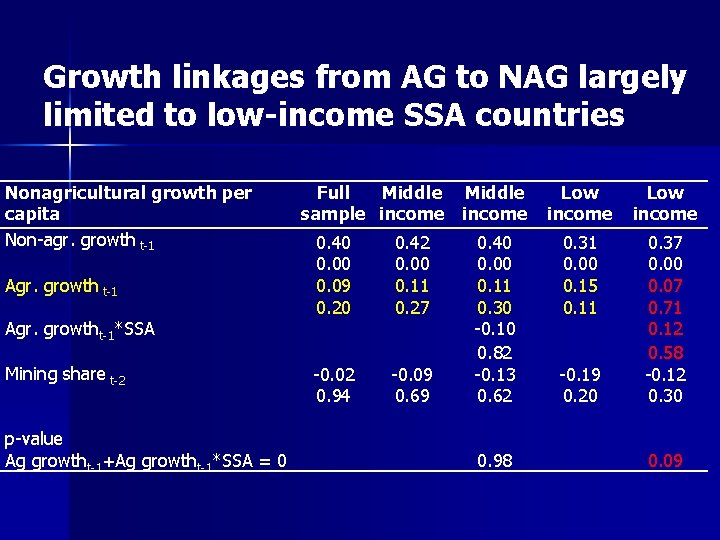

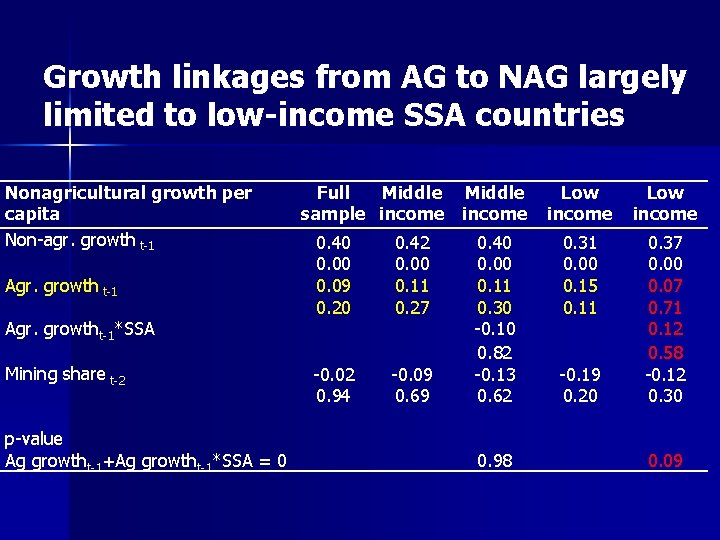

Growth linkages from AG to NAG largely limited to low-income SSA countries Nonagricultural growth per capita Non-agr. growth t-1 Agr. growtht-1*SSA Mining share t-2 p-value Ag growtht-1+Ag growtht-1*SSA = 0 Full Middle sample income 0. 40 0. 09 0. 20 0. 42 0. 00 0. 11 0. 27 -0. 02 0. 94 -0. 09 0. 69 0. 40 0. 00 0. 11 0. 30 -0. 10 0. 82 -0. 13 0. 62 0. 98 Low income 0. 31 0. 00 0. 15 0. 11 0. 37 0. 00 0. 07 0. 71 0. 12 0. 58 -0. 12 0. 30 -0. 19 0. 20 0. 09

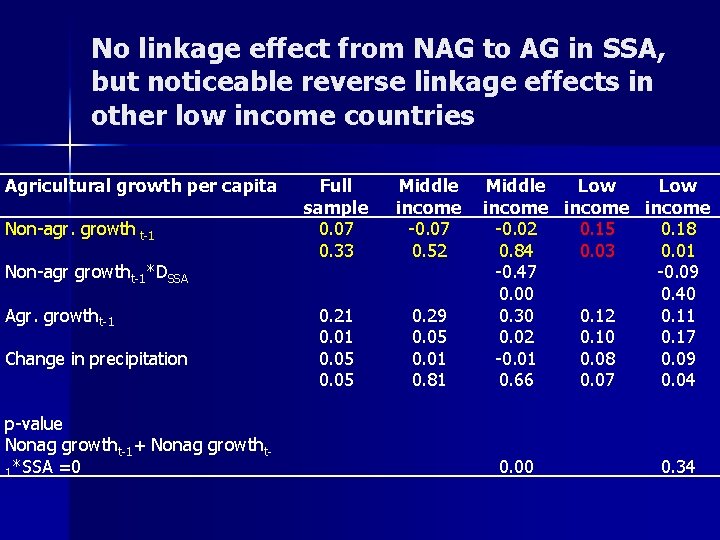

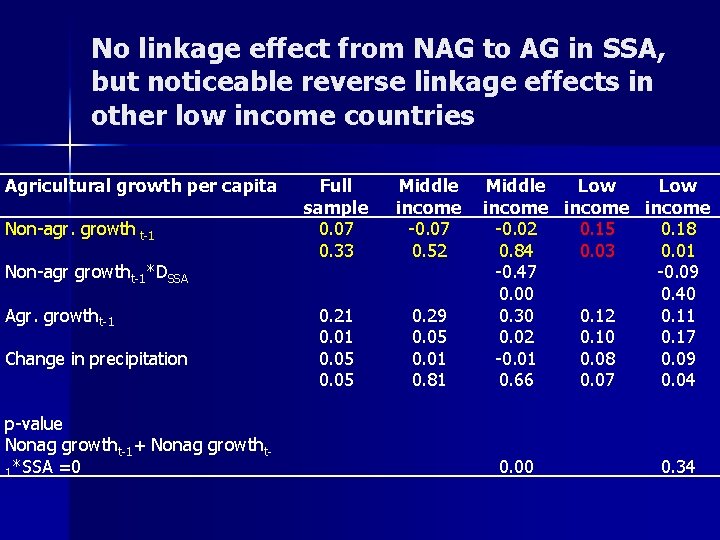

No linkage effect from NAG to AG in SSA, but noticeable reverse linkage effects in other low income countries Agricultural growth per capita Non-agr. growth t-1 Non-agr growtht-1*DSSA Agr. growtht-1 Change in precipitation p-value Nonag growtht-1+ Nonag growtht 1*SSA =0 Full sample 0. 07 0. 33 Middle income -0. 07 0. 52 0. 21 0. 05 0. 29 0. 05 0. 01 0. 81 Middle Low income -0. 02 0. 15 0. 18 0. 84 0. 03 0. 01 -0. 47 -0. 09 0. 00 0. 40 0. 30 0. 12 0. 11 0. 02 0. 10 0. 17 -0. 01 0. 08 0. 09 0. 66 0. 07 0. 04 0. 00 0. 34

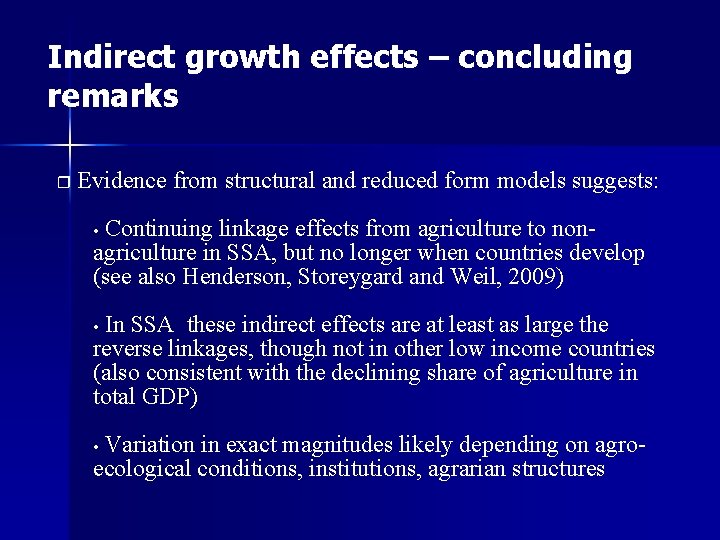

Indirect growth effects – concluding remarks r Evidence from structural and reduced form models suggests: • Continuing linkage effects from agriculture to non- agriculture in SSA, but no longer when countries develop (see also Henderson, Storeygard and Weil, 2009) • In SSA these indirect effects are at least as large the reverse linkages, though not in other low income countries (also consistent with the declining share of agriculture in total GDP) • Variation in exact magnitudes likely depending on agro- ecological conditions, institutions, agrarian structures

The Participation Effect Growth components Direct effect yait Participation and share components a s it a it Indirect effect yait(ynait-k) &ynait(yait-k) Direct effect Pit ynait nits n it

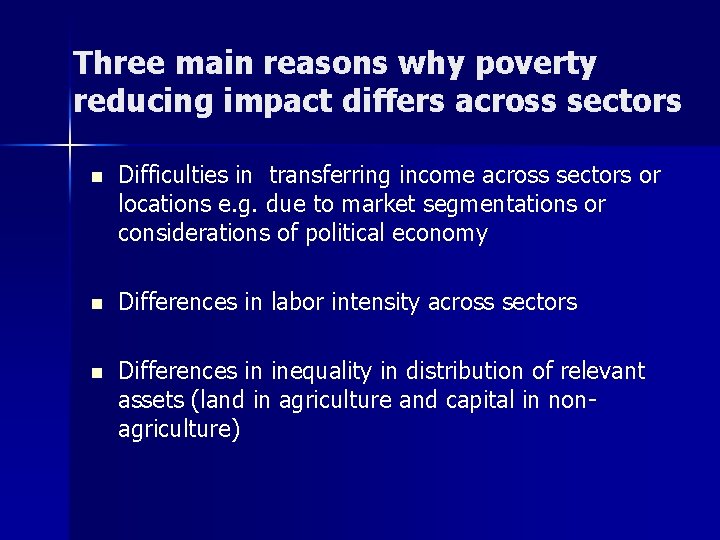

Three main reasons why poverty reducing impact differs across sectors n Difficulties in transferring income across sectors or locations e. g. due to market segmentations or considerations of political economy n Differences in labor intensity across sectors n Differences in inequality in distribution of relevant assets (land in agriculture and capital in nonagriculture)

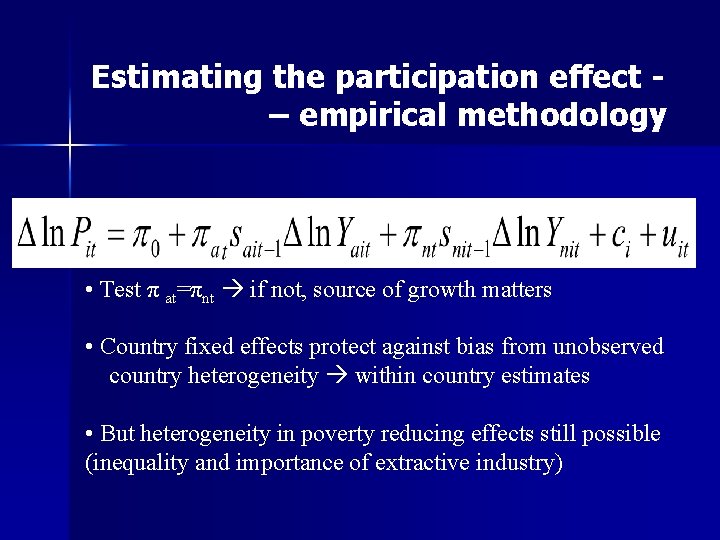

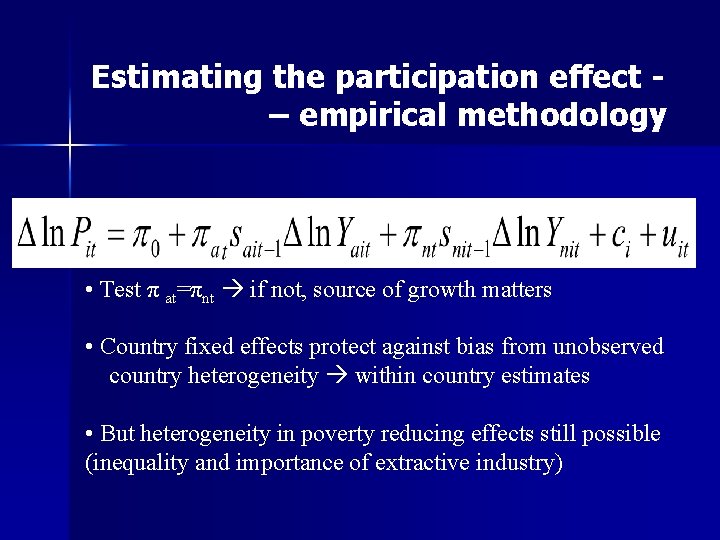

Estimating the participation effect – empirical methodology • Test π at=πnt if not, source of growth matters • Country fixed effects protect against bias from unobserved country heterogeneity within country estimates • But heterogeneity in poverty reducing effects still possible (inequality and importance of extractive industry)

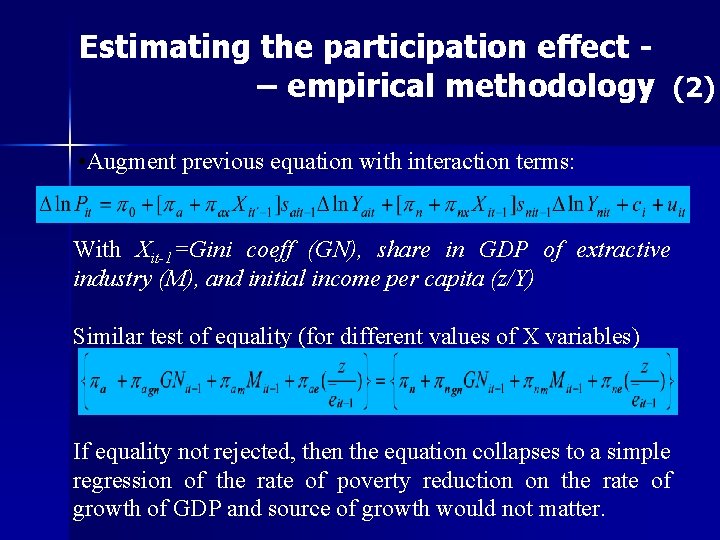

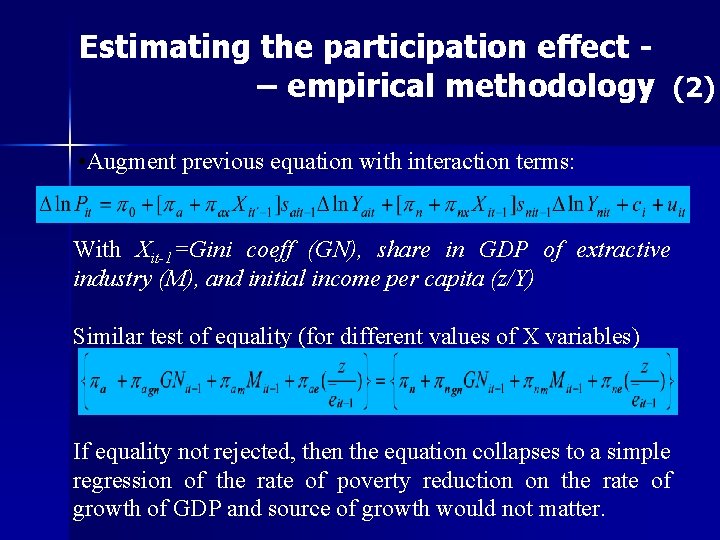

Estimating the participation effect – empirical methodology (2) • Augment previous equation with interaction terms: With Xit-1=Gini coeff (GN), share in GDP of extractive industry (M), and initial income per capita (z/Y) Similar test of equality (for different values of X variables) If equality not rejected, then the equation collapses to a simple regression of the rate of poverty reduction on the rate of growth of GDP and source of growth would not matter.

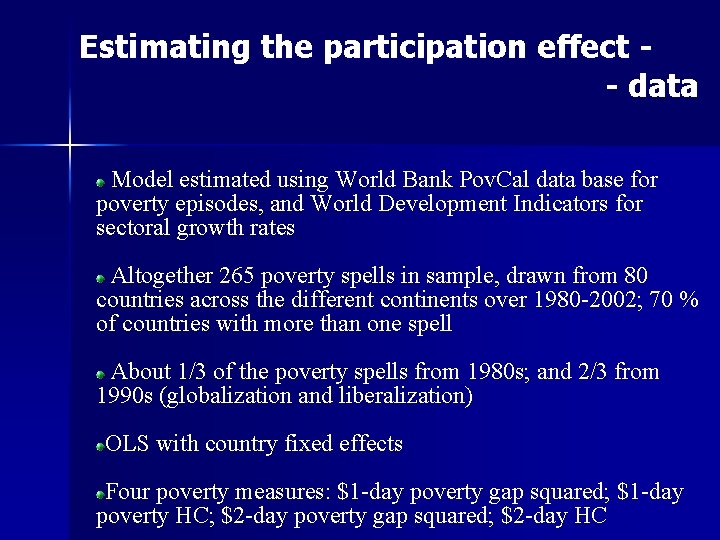

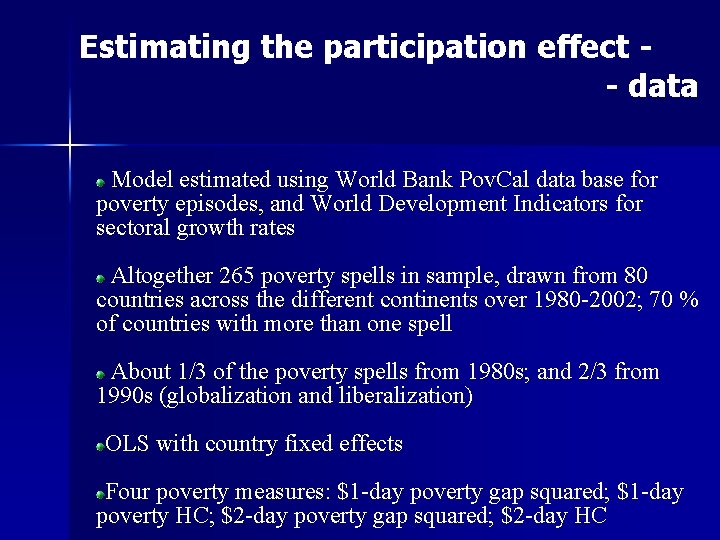

Estimating the participation effect - data Model estimated using World Bank Pov. Cal data base for poverty episodes, and World Development Indicators for sectoral growth rates Altogether 265 poverty spells in sample, drawn from 80 countries across the different continents over 1980 -2002; 70 % of countries with more than one spell About 1/3 of the poverty spells from 1980 s; and 2/3 from 1990 s (globalization and liberalization) OLS with country fixed effects Four poverty measures: $1 -day poverty gap squared; $1 -day poverty HC; $2 -day poverty gap squared; $2 -day HC

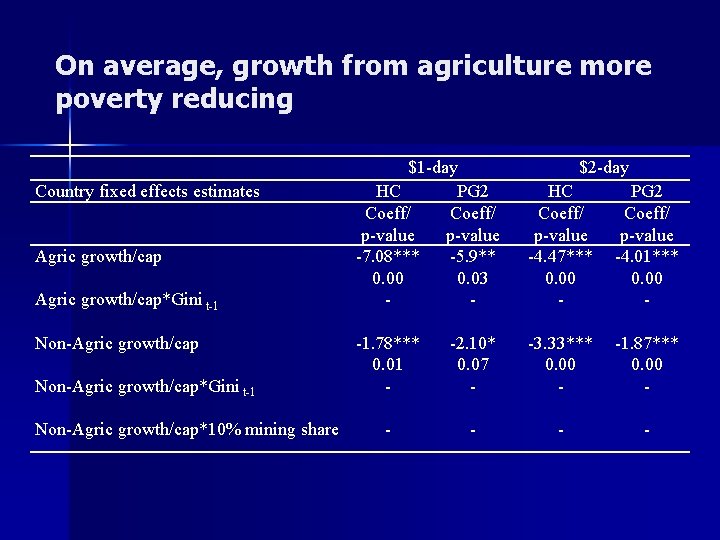

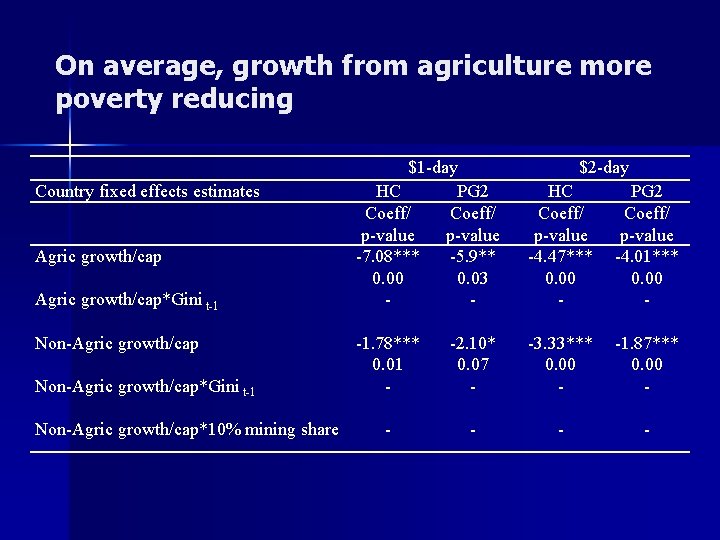

On average, growth from agriculture more poverty reducing Country fixed effects estimates Agric growth/cap*Gini t-1 Non-Agric growth/cap*10% mining share $1 -day HC PG 2 Coeff/ p-value -7. 08*** -5. 9** 0. 00 0. 03 - $2 -day HC Coeff/ p-value -4. 47*** 0. 00 - PG 2 Coeff/ p-value -4. 01*** 0. 00 - -1. 78*** 0. 01 - -2. 10* 0. 07 - -3. 33*** 0. 00 - -1. 87*** 0. 00 - - -

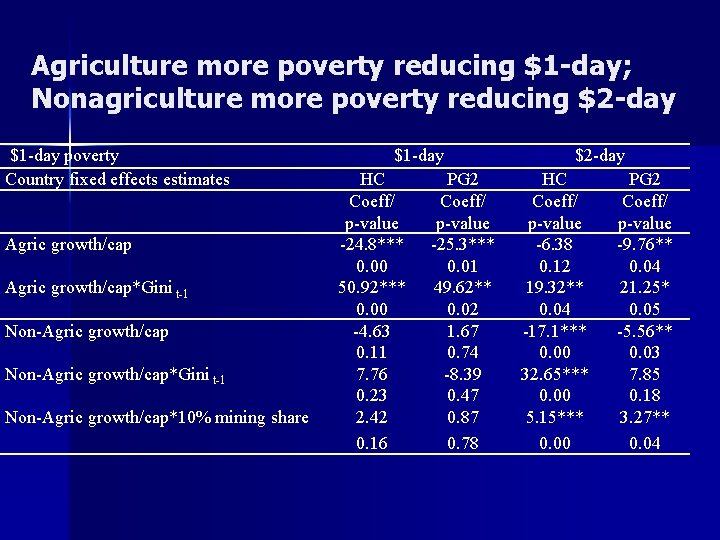

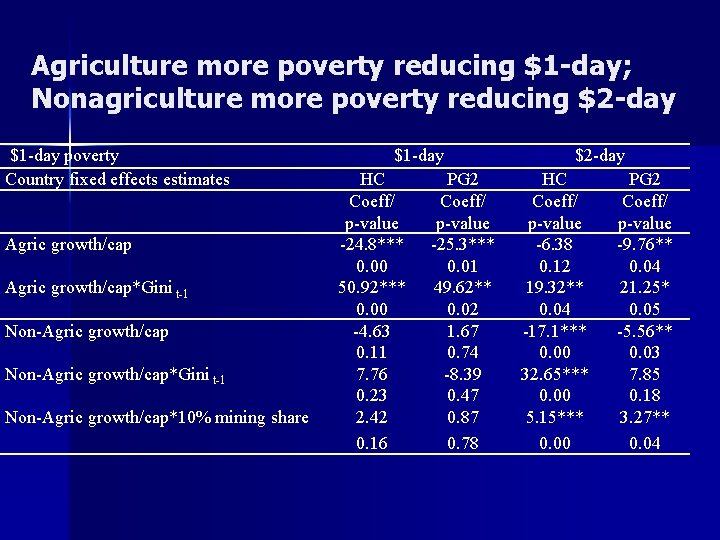

Agriculture more poverty reducing $1 -day; Nonagriculture more poverty reducing $2 -day $1 -day poverty Country fixed effects estimates Agric growth/cap*Gini t-1 Non-Agric growth/cap*10% mining share $1 -day HC Coeff/ p-value -24. 8*** 0. 00 50. 92*** 0. 00 -4. 63 0. 11 7. 76 0. 23 2. 42 0. 16 PG 2 Coeff/ p-value -25. 3*** 0. 01 49. 62** 0. 02 1. 67 0. 74 -8. 39 0. 47 0. 87 0. 78 $2 -day HC Coeff/ p-value -6. 38 0. 12 19. 32** 0. 04 -17. 1*** 0. 00 32. 65*** 0. 00 5. 15*** 0. 00 PG 2 Coeff/ p-value -9. 76** 0. 04 21. 25* 0. 05 -5. 56** 0. 03 7. 85 0. 18 3. 27** 0. 04

Participating in growth – differences across sectors and degrees of poverty n n Agriculture more powerful in reducing $1 day poverty, with its advantage declining as inequality increases Non-agriculture has the edge when it comes to $2 -day poverty, but not if driven by extractive industries and also less effective in poorer countries

The Role of Agriculture in Poverty Reduction – towards a synthesis Growth components Direct effect yait Participation and share components a s it a it Indirect effect yait(ynait-k) &ynait(yait-k) Direct effect Pit ynait nits n it pit aitsait yait(ynait-k) + nitsnit ynit(yait-k)

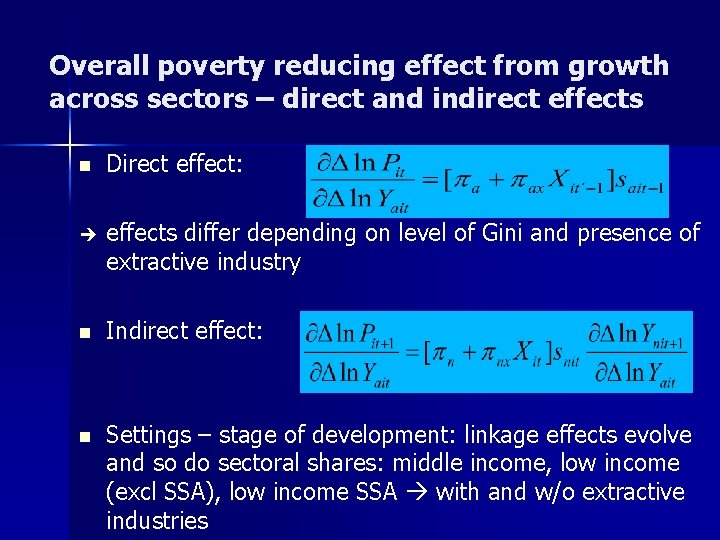

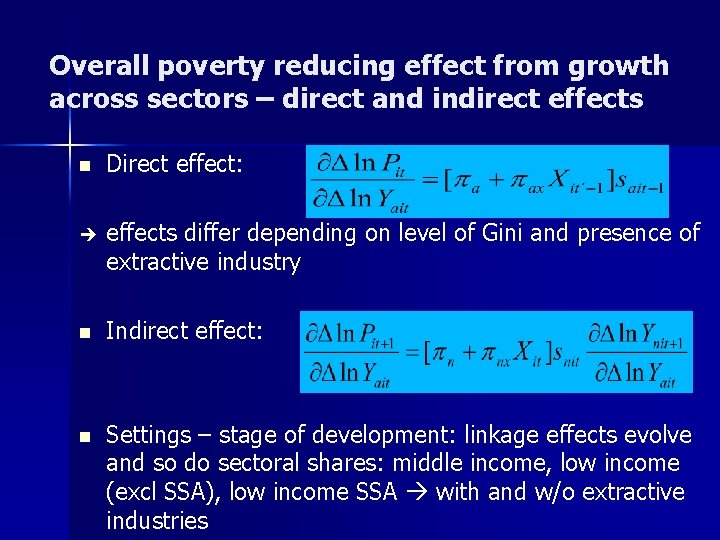

Overall poverty reducing effect from growth across sectors – direct and indirect effects n Direct effect: effects differ depending on level of Gini and presence of extractive industry n Indirect effect: n Settings – stage of development: linkage effects evolve and so do sectoral shares: middle income, low income (excl SSA), low income SSA with and w/o extractive industries

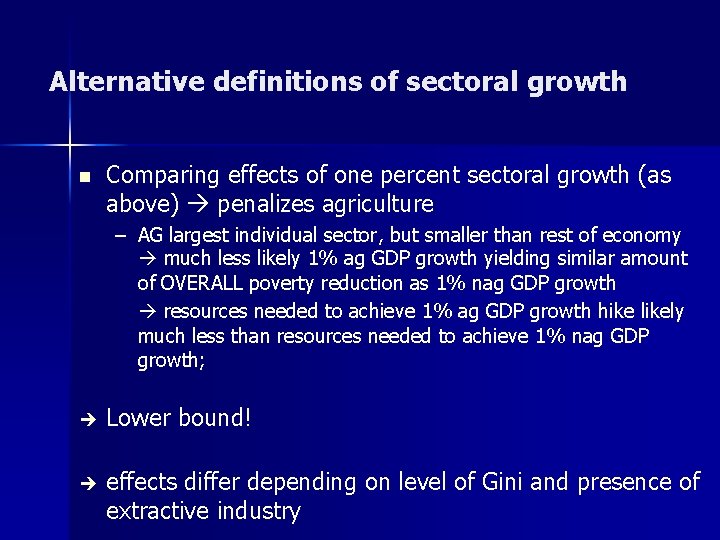

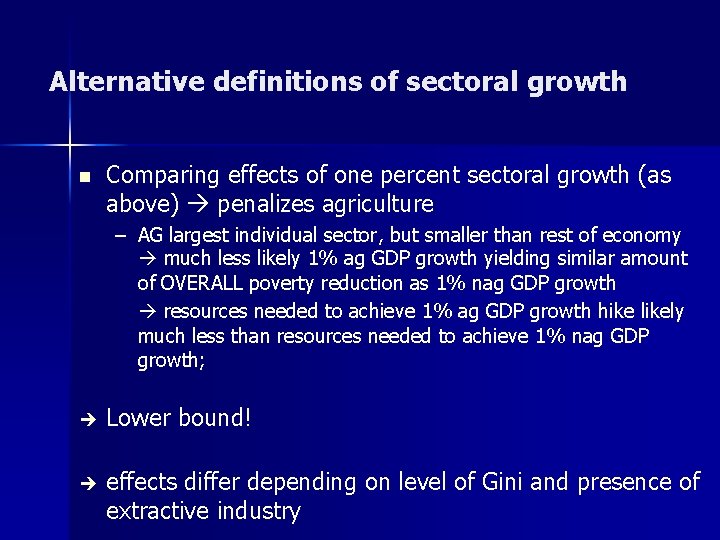

Alternative definitions of sectoral growth n Comparing effects of one percent sectoral growth (as above) penalizes agriculture – AG largest individual sector, but smaller than rest of economy much less likely 1% ag GDP growth yielding similar amount of OVERALL poverty reduction as 1% nag GDP growth resources needed to achieve 1% ag GDP growth hike likely much less than resources needed to achieve 1% nag GDP growth; Lower bound! effects differ depending on level of Gini and presence of extractive industry

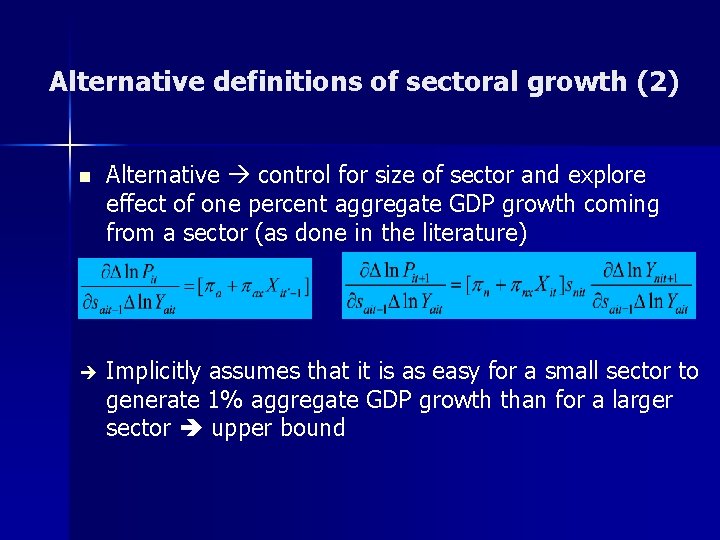

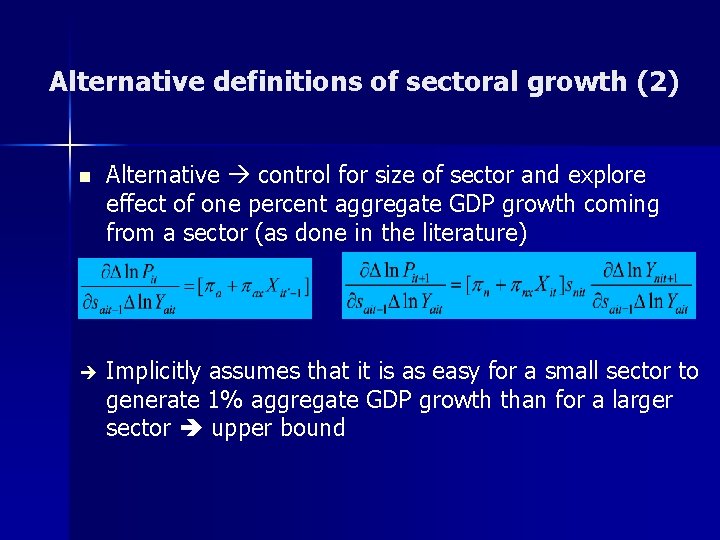

Alternative definitions of sectoral growth (2) n Alternative control for size of sector and explore effect of one percent aggregate GDP growth coming from a sector (as done in the literature) Implicitly assumes that it is as easy for a small sector to generate 1% aggregate GDP growth than for a larger sector upper bound

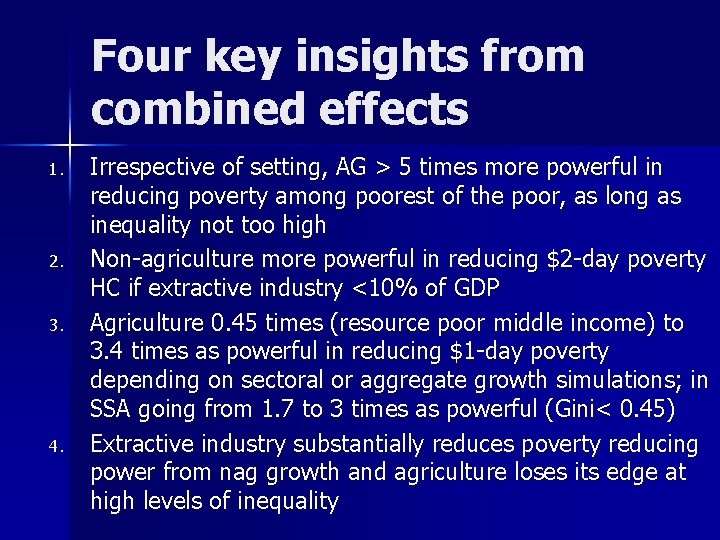

Four key insights from combined effects 1. 2. 3. 4. Irrespective of setting, AG > 5 times more powerful in reducing poverty among poorest of the poor, as long as inequality not too high Non-agriculture more powerful in reducing $2 -day poverty HC if extractive industry <10% of GDP Agriculture 0. 45 times (resource poor middle income) to 3. 4 times as powerful in reducing $1 -day poverty depending on sectoral or aggregate growth simulations; in SSA going from 1. 7 to 3 times as powerful (Gini< 0. 45) Extractive industry substantially reduces poverty reducing power from nag growth and agriculture loses its edge at high levels of inequality

Concluding Remarks (1) 1. 2. Contributions of a sector to poverty reduction : – – direct growth component – growth potential Indirect growth component – interlinkage effects Participation by poor in growth in the sector – inequality/mining Size of the sector in the economy – stage of development Insights by component – Slower agricultural growth follows from Engel’s Law and is not to be equated with inherently lower productivity – Large interlinkage effects from agriculture decline as countries develop, but have not yet disappeared in SSA – Much larger participation by the very poor in growth from agriculture, but not by the $2 -day poor and not in fundamentally unequal societies

Concluding Remarks (2) 3. Simultaneous considerations of indirect growth, participation, and share components shows that growth: – in agriculture at least five times more powerful in reducing poverty among the poorest of the poor ($1 -day poverty gap squared) – In non-agriculture more powerful among better off poor ($2 -day headcount) – In agriculture up to 3. 2 times more effective in low income countries, when accounting for sector size, with the advantage diminishing as countries become richer and inequality becomes high – Poverty reducing effects from nonagricultural growth decline substantially in the presence of extractive industries

Concluding Remarks (3) 4. Implications for agricultural sector strategies in light of global food supply challenge – Most countries increased investment in agriculture as trust in market mediated food security has eroded – Enhancing agricultural productivity indeed a valid entry point also to enhance growth and poverty reduction in most low income countries, especially in SSA and in mineral rich countries – To maximize the poverty reducing effects, smallholder agriculture appears to have an edge Jean Paul Remanoby selected by his village peers in sourthern Madagascar to be the first paricipant in a new programme offering improved farming techniques and modern inputs; IRIN Photo by Tomas de Mul

Thank you! UNU-WIDER WP 36 – The (Evolving) Role of Agriculture in Poverty Reduction – An Empirical Perspective, http: //www. wider. unu. edu/

Relative and absolute poverty difference

Relative and absolute poverty difference Poverty reduction workgroup

Poverty reduction workgroup Evolving

Evolving Evolving design

Evolving design A framework for clustering evolving data streams

A framework for clustering evolving data streams Key evolving signature

Key evolving signature Statuses and their related roles determine the structure

Statuses and their related roles determine the structure Azure web role vs worker role

Azure web role vs worker role Role taking krappmann

Role taking krappmann Sự nuôi và dạy con của hươu

Sự nuôi và dạy con của hươu Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan

Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan điện thế nghỉ

điện thế nghỉ Một số thể thơ truyền thống

Một số thể thơ truyền thống Thế nào là sự mỏi cơ

Thế nào là sự mỏi cơ Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ

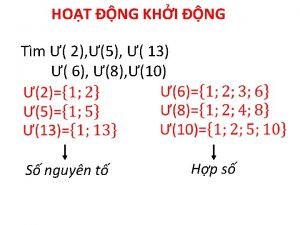

Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ Số nguyên tố là số gì

Số nguyên tố là số gì Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Fecboak

Fecboak Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Hệ hô hấp

Hệ hô hấp Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ

đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ Cái miệng nó xinh thế

Cái miệng nó xinh thế Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể

Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể Mật thư tọa độ 5x5

Mật thư tọa độ 5x5 Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết ưu thế lai là gì

ưu thế lai là gì Gấu đi như thế nào

Gấu đi như thế nào Thẻ vin

Thẻ vin Thể thơ truyền thống

Thể thơ truyền thống Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu

Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu Diễn thế sinh thái là

Diễn thế sinh thái là Lp html

Lp html Giọng cùng tên là

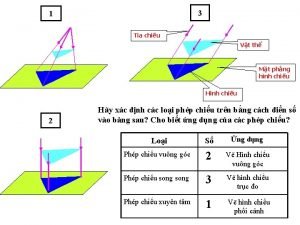

Giọng cùng tên là Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau Phép trừ bù

Phép trừ bù Chúa yêu trần thế

Chúa yêu trần thế Hổ sinh sản vào mùa nào

Hổ sinh sản vào mùa nào