ACUTE GASTROENTERITIS IN CHILDREN Epidemiology of acute diarrhea

- Slides: 64

ACUTE GASTROENTERITIS IN CHILDREN

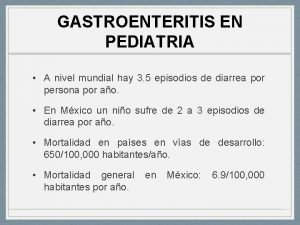

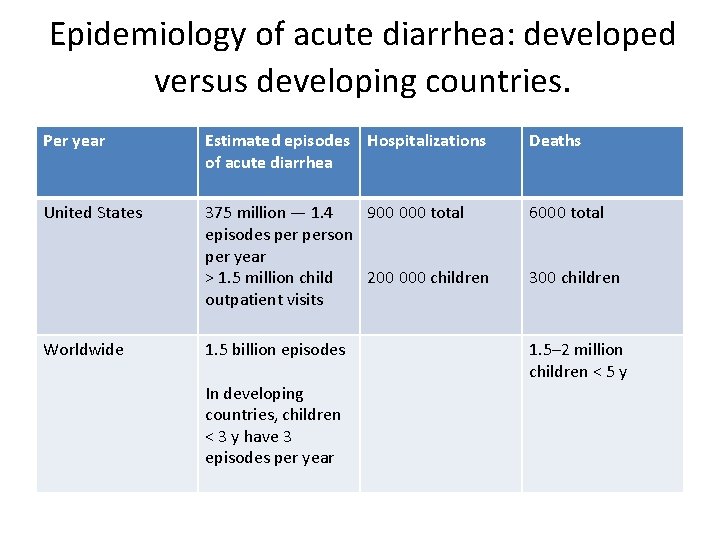

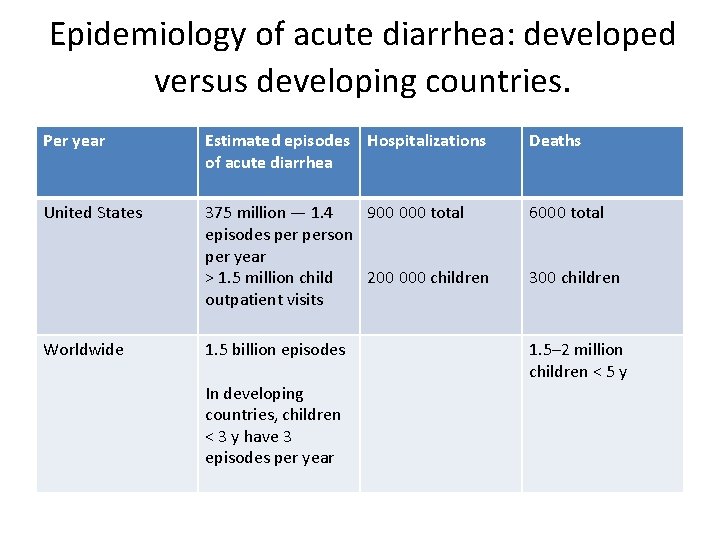

Epidemiology of acute diarrhea: developed versus developing countries. Per year Estimated episodes Hospitalizations of acute diarrhea Deaths United States 375 million — 1. 4 900 000 total episodes person per year > 1. 5 million child 200 000 children outpatient visits 6000 total 1. 5 billion episodes 1. 5– 2 million children < 5 y Worldwide In developing countries, children < 3 y have 3 episodes per year 300 children

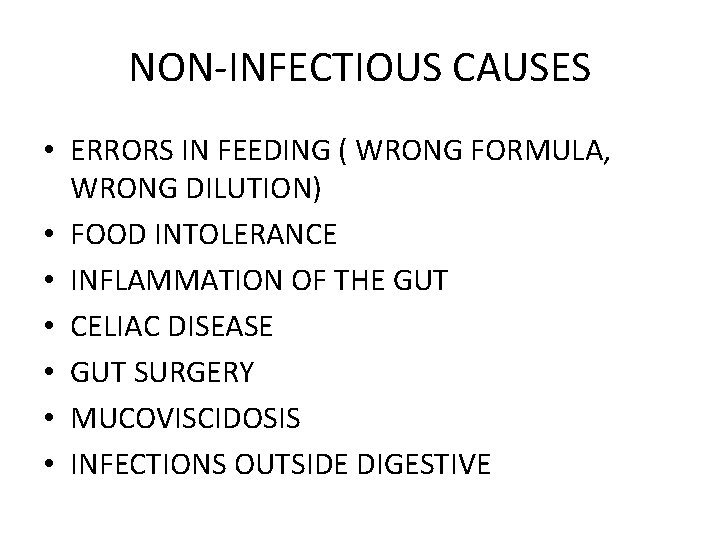

NON-INFECTIOUS CAUSES • ERRORS IN FEEDING ( WRONG FORMULA, WRONG DILUTION) • FOOD INTOLERANCE • INFLAMMATION OF THE GUT • CELIAC DISEASE • GUT SURGERY • MUCOVISCIDOSIS • INFECTIONS OUTSIDE DIGESTIVE

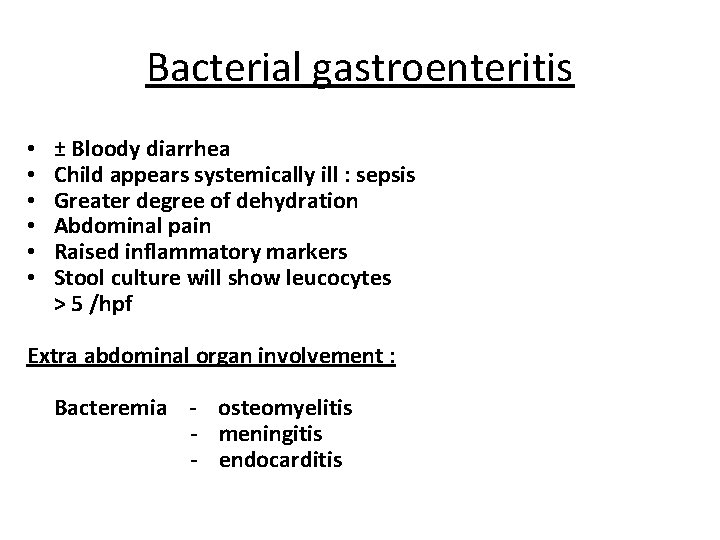

Bacterial gastroenteritis • • • ± Bloody diarrhea Child appears systemically ill : sepsis Greater degree of dehydration Abdominal pain Raised inflammatory markers Stool culture will show leucocytes > 5 /hpf Extra abdominal organ involvement : Bacteremia - osteomyelitis - meningitis - endocarditis

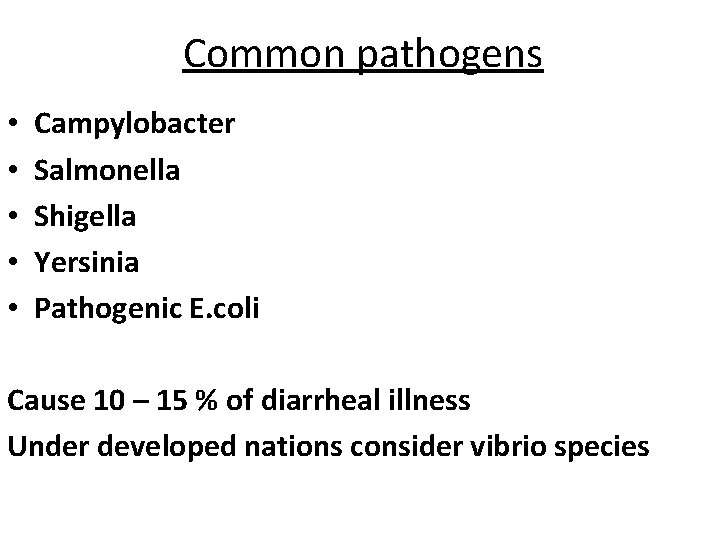

Common pathogens • • • Campylobacter Salmonella Shigella Yersinia Pathogenic E. coli Cause 10 – 15 % of diarrheal illness Under developed nations consider vibrio species

• • • Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. All forms cause disease in children in the developing world, but enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC, including E. coli O 157: H 7) causes disease more commonly in the developed countries. • Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) — traveler’s diarrhea, diarrhea in infants and children in developing countries. • Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) — children < 2 years; chronic diarrhea in children; rarely causes disease in adults. • Enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) — bloody mucoid diarrhea; fever is common. • Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) — bloody diarrhea; severe hemorrhagic colitis and the hemolytic uremic syndrome in 6– 8%; cattle are the predominant reservoir. • Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAgg. EC) — watery diarrhea in young children; persistent diarrhea in children and adults with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

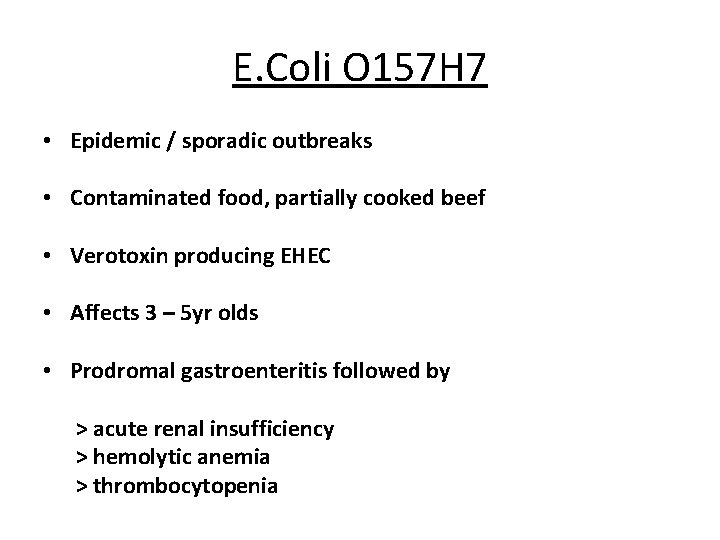

E. Coli O 157 H 7 • Epidemic / sporadic outbreaks • Contaminated food, partially cooked beef • Verotoxin producing EHEC • Affects 3 – 5 yr olds • Prodromal gastroenteritis followed by > acute renal insufficiency > hemolytic anemia > thrombocytopenia

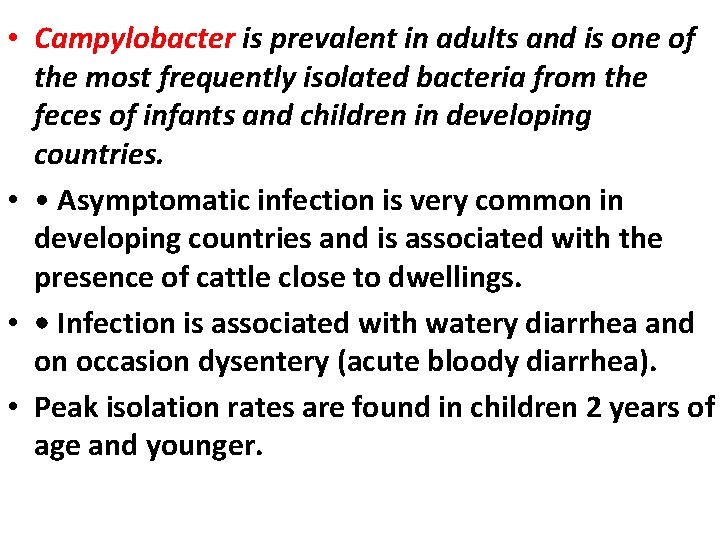

• Campylobacter is prevalent in adults and is one of the most frequently isolated bacteria from the feces of infants and children in developing countries. • • Asymptomatic infection is very common in developing countries and is associated with the presence of cattle close to dwellings. • • Infection is associated with watery diarrhea and on occasion dysentery (acute bloody diarrhea). • Peak isolation rates are found in children 2 years of age and younger.

• • Guillain–Barré syndrome is a rare complication. • • Poultry is an important source of Campylobacter infections in developed countries. • • The presence of an animal in the cooking area is a risk factor in developing countries.

• Shigella species. • • There are 160 million infections annually in developing countries, primarily in children. • • It is more common in toddlers and older children than in infants. • • S. sonnei — mildest illness; seen most commonly in developed countries. • • S. flexneri — dysenteric symptoms and persistent illness; most common in developing countries. • • S. dysenteriae type 1 (Sd 1) — produces Shiga toxin, as does EHEC. It has caused devastating epidemics of bloody diarrhea with case-fatality rates approaching 10% in Asia, Africa, and Central America.

• Vibrio cholerae. • • Many species of Vibrio cause diarrhea in developing countries. • • V. cholerae serogroups O 1 and O 139 cause rapid and severe depletion of volume. • • In the absence of prompt and adequate rehydration, hypovolemic shock and death can occur within 12– 18 h after the onset of the first symptom. • • Stools are watery, colorless, and flecked with mucus.

• • Vomiting is common; fever is rare. • • In children, hypoglycemia can lead to convulsions and death. • • There is a potential for epidemic spread; any infection should be reported promptly to the public health authorities.

• Salmonella. • • All serotypes (> 2000) are pathogenic for humans. • • Infants and the elderly appear to be at the greatest risk. • • Animals are the major reservoir for Salmonellae. • • There is an acute onset of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea that may be watery or dysenteric.

• • Fever develops in 70% of affected children. • • Bacteremia occurs in 1– 5%, mostly in infants. • • Enteric fever — Salmonella typhi or paratyphi A, B, or C (typhoid fever). • • Diarrhea (with or without blood) develops, and fever lasting 3 weeks or more.

• Rotavirus. • • Leading cause of severe, dehydrating gastroenteritis among children. • • One-third of diarrhea hospitalizations and 500 000 deaths worldwide each year. • • Nearly all children in both industrialized and developing countries have been infected with rotavirus by the time they are 3– 5 years of age. Neonatal infections are a common occurrence, but are often asymptomatic. • • The incidence of clinical illness peaks in children between 4 and 23 months of age. • • Rotavirus is associated with gastroenteritis of aboveaverage severity.

Rotavirus • Faeco – oral transmission • 6 – 24 months of age • Sudden onset watery diarrhea and vomiting with little abdominal pain • Self limiting in healthy individuals • 1 – 6 day duration Seasonal - temperate climates: “winter gastro” - tropical climates: summer peak • Treatment : symptomatic

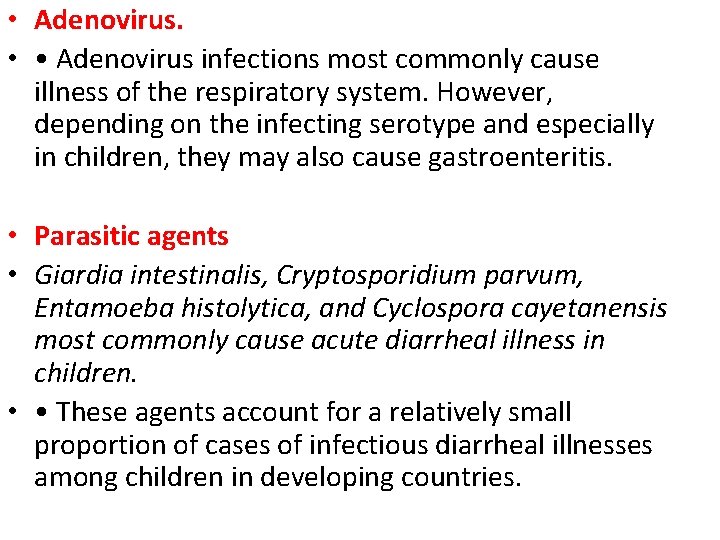

• Adenovirus. • • Adenovirus infections most commonly cause illness of the respiratory system. However, depending on the infecting serotype and especially in children, they may also cause gastroenteritis. • Parasitic agents • Giardia intestinalis, Cryptosporidium parvum, Entamoeba histolytica, and Cyclospora cayetanensis most commonly cause acute diarrheal illness in children. • • These agents account for a relatively small proportion of cases of infectious diarrheal illnesses among children in developing countries.

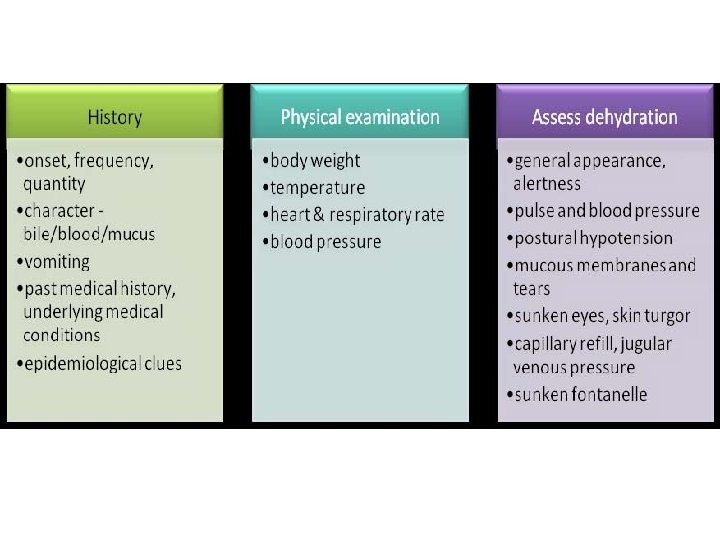

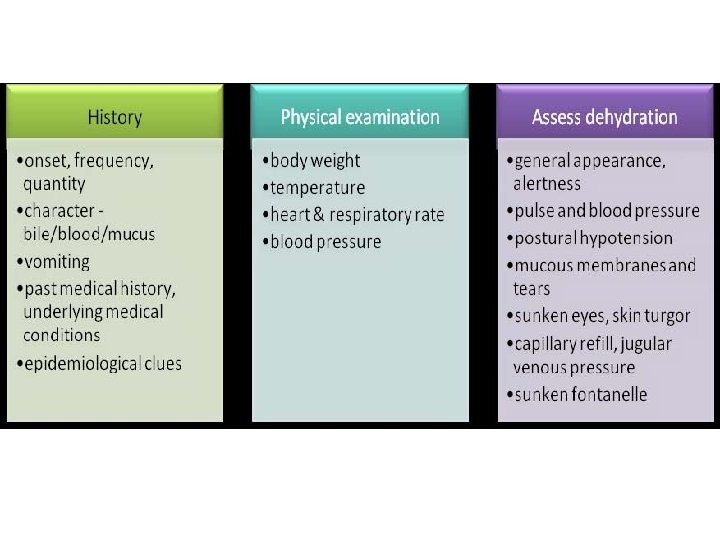

Clinical evaluation • The initial clinical evaluation of the patient should focus on: • • Assessing the severity of the illness and the need for rehydration • • Identifying likely causes on the basis of the history and clinical findings

ONSET

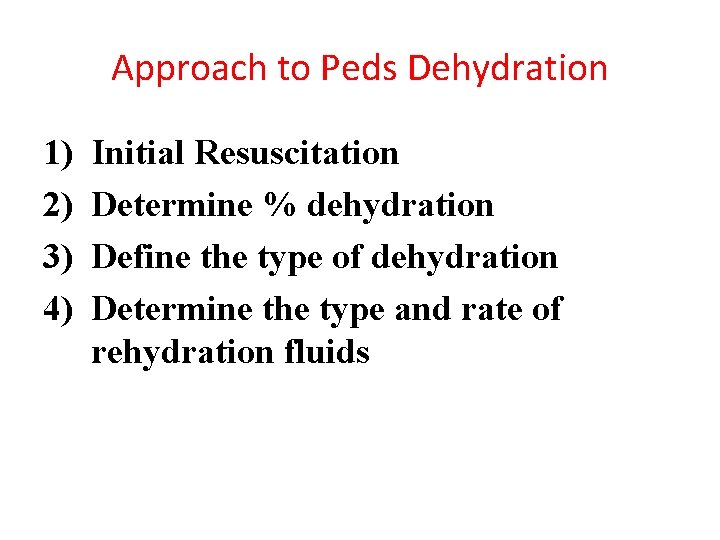

Approach to Peds Dehydration 1) 2) 3) 4) Initial Resuscitation Determine % dehydration Define the type of dehydration Determine the type and rate of rehydration fluids

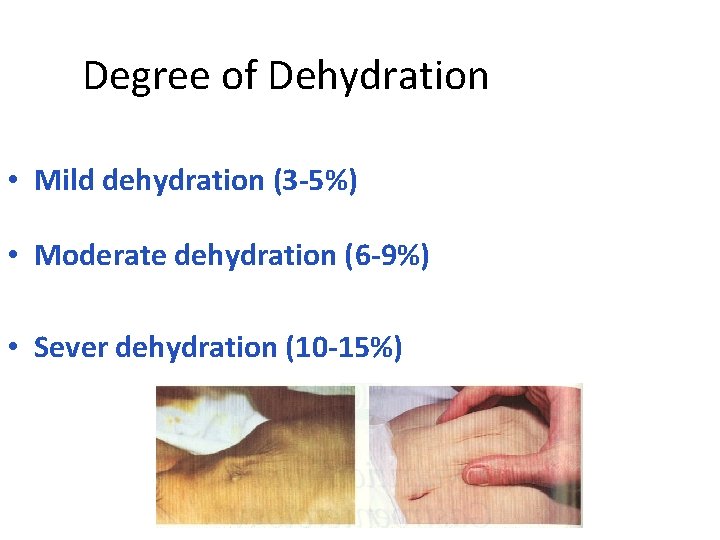

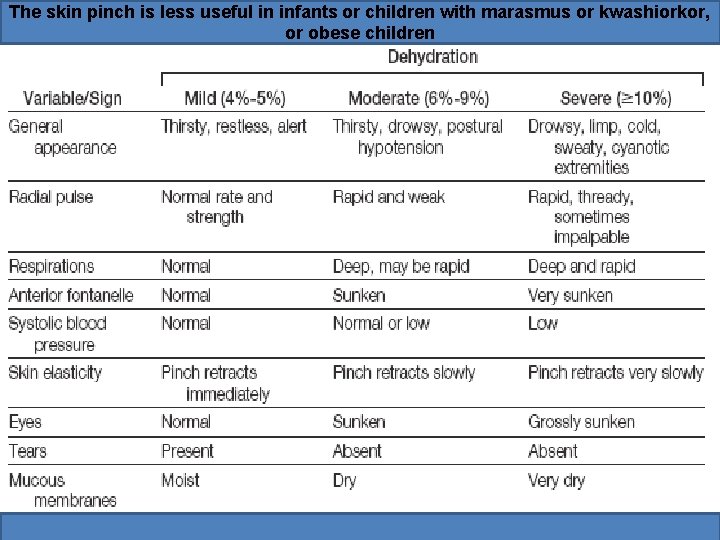

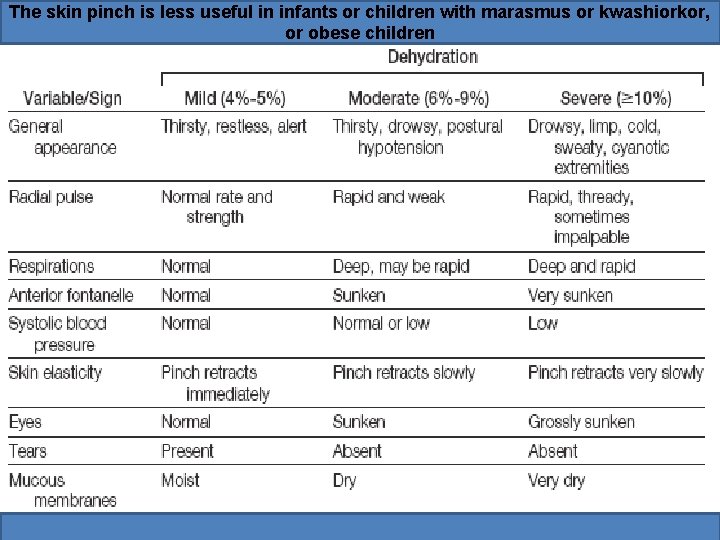

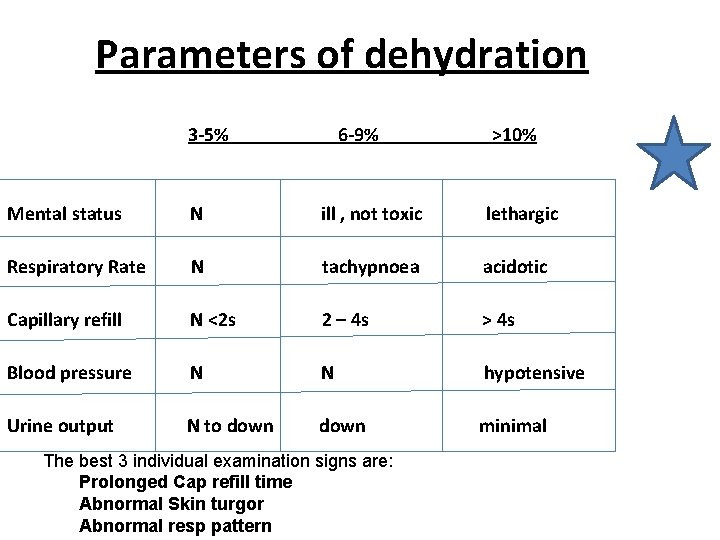

Degree of Dehydration • Mild dehydration (3 -5%) • Moderate dehydration (6 -9%) • Sever dehydration (10 -15%)

The skin pinch is less useful in infants or children with marasmus or kwashiorkor, or obese children

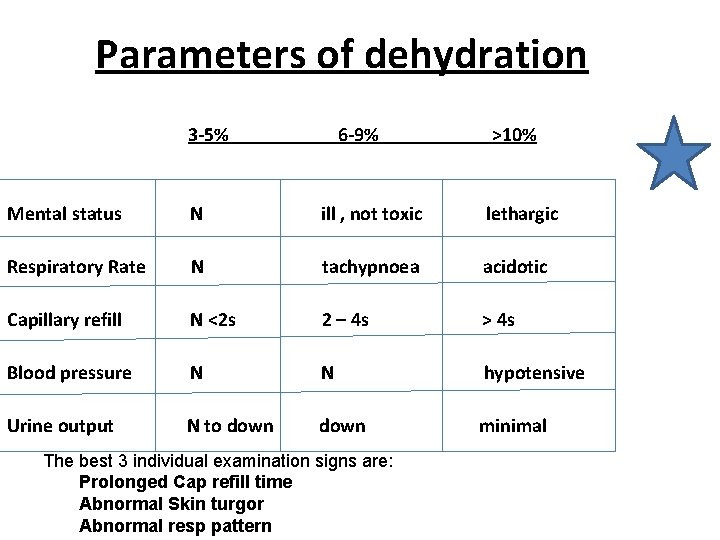

Parameters of dehydration 3 -5% 6 -9% >10% Mental status N ill , not toxic lethargic Respiratory Rate N tachypnoea acidotic Capillary refill N <2 s 2 – 4 s > 4 s Blood pressure N N hypotensive Urine output N to down minimal The best 3 individual examination signs are: Prolonged Cap refill time Abnormal Skin turgor Abnormal resp pattern

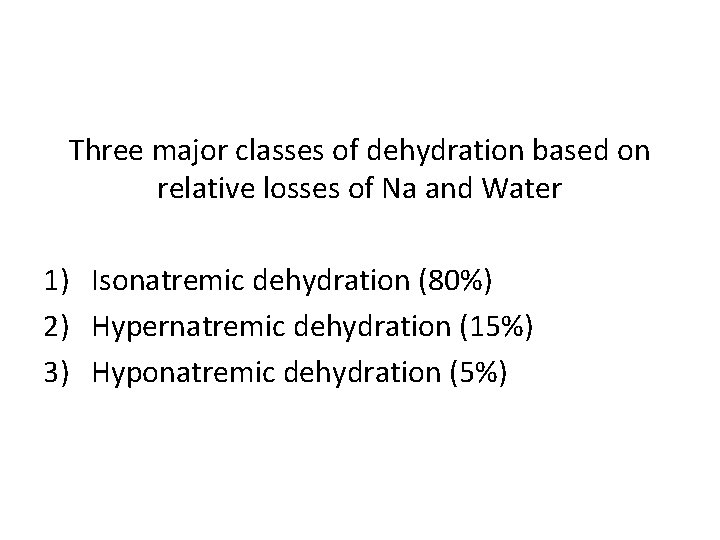

Three major classes of dehydration based on relative losses of Na and Water 1) Isonatremic dehydration (80%) 2) Hypernatremic dehydration (15%) 3) Hyponatremic dehydration (5%)

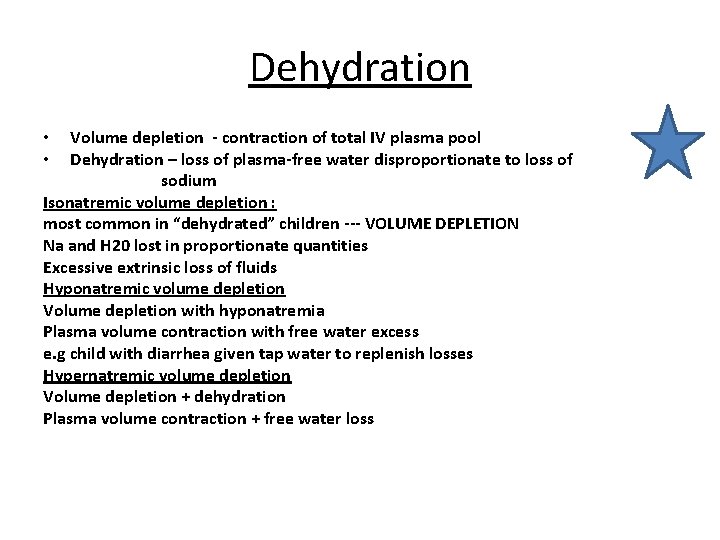

Dehydration Volume depletion - contraction of total IV plasma pool Dehydration – loss of plasma-free water disproportionate to loss of sodium Isonatremic volume depletion : most common in “dehydrated” children --- VOLUME DEPLETION Na and H 20 lost in proportionate quantities Excessive extrinsic loss of fluids Hyponatremic volume depletion Volume depletion with hyponatremia Plasma volume contraction with free water excess e. g child with diarrhea given tap water to replenish losses Hypernatremic volume depletion Volume depletion + dehydration Plasma volume contraction + free water loss • •

Isonatremic dehydration By far the most common Equal losses of Na and Water Na = 130 -150 No significant change between fluid compartments • No need to correct slowly • •

Hypernatremic Dehydration • Water loss > sodium loss • Na >150 mmol/L • Water shifts from ICF ( intracelular fluid) to ECF • Child appears relatively less ill • More intravascular volume • Less physical signs • Alternating between lethargy and hyperirritability

Hypernatremic Dehydration • Physical findings – Dry doughy skin – Increased muscle tone • Correction – Correct Na slowly – If lowered to quickly causes • massive cerebral edema • intractable seizures

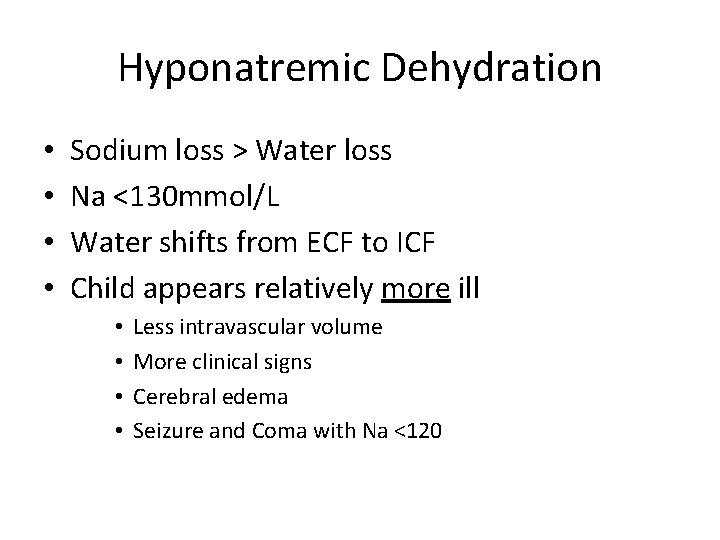

Hyponatremic Dehydration • • Sodium loss > Water loss Na <130 mmol/L Water shifts from ECF to ICF Child appears relatively more ill • • Less intravascular volume More clinical signs Cerebral edema Seizure and Coma with Na <120

Hyponatremic Dehydration • Correction – Must again be performed slowly unless actively seizing – Rapid correction of chronic hyponatremia thought to contribute to…. Central Pontine Myelinolysis • Fluctuating LOC • Pseudobulbar palsy • Quadraparesis

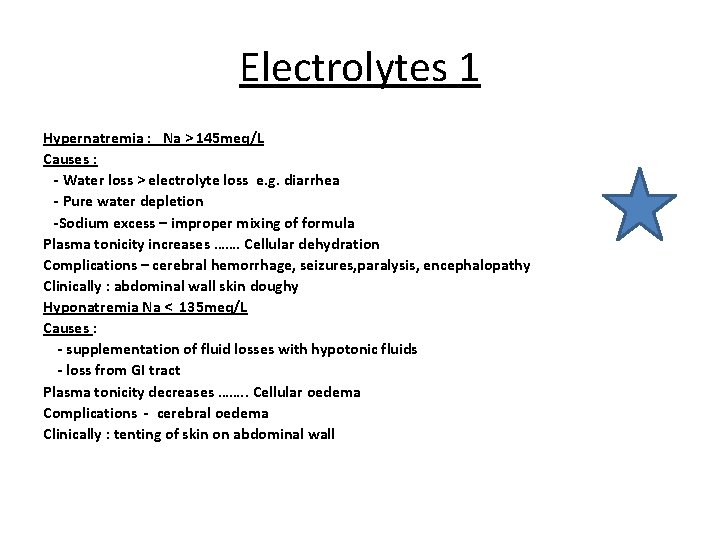

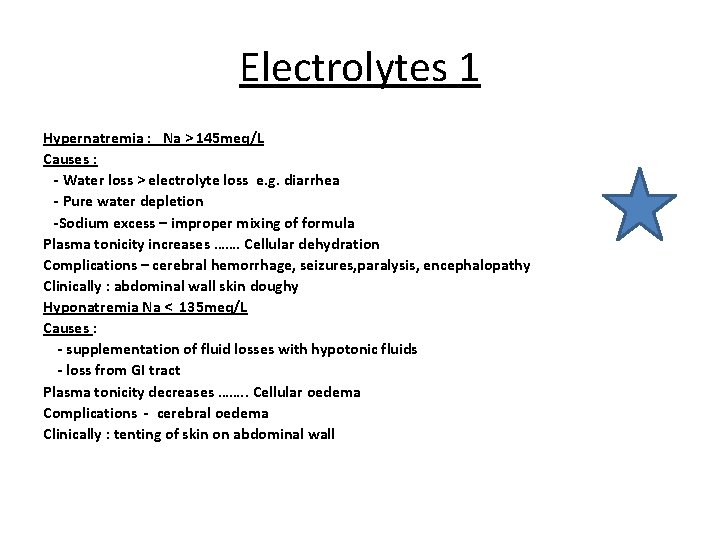

Electrolytes 1 Hypernatremia : Na > 145 meq/L Causes : - Water loss > electrolyte loss e. g. diarrhea - Pure water depletion -Sodium excess – improper mixing of formula Plasma tonicity increases ……. Cellular dehydration Complications – cerebral hemorrhage, seizures, paralysis, encephalopathy Clinically : abdominal wall skin doughy Hyponatremia Na < 135 meq/L Causes : - supplementation of fluid losses with hypotonic fluids - loss from GI tract Plasma tonicity decreases ……. . Cellular oedema Complications - cerebral oedema Clinically : tenting of skin on abdominal wall

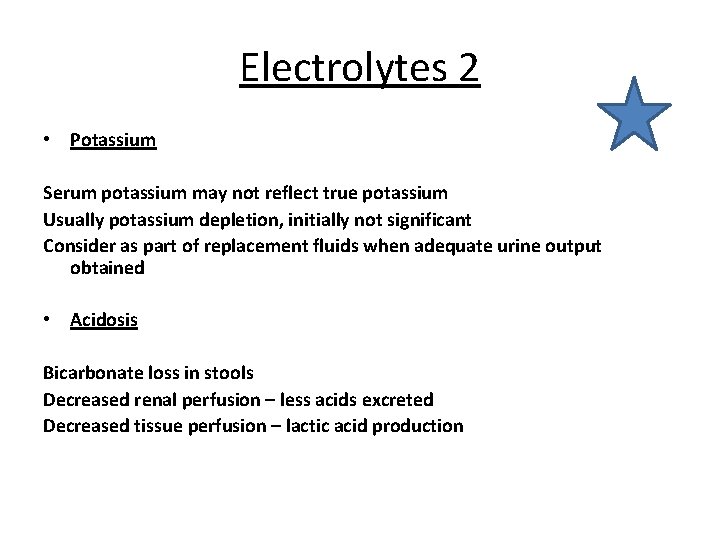

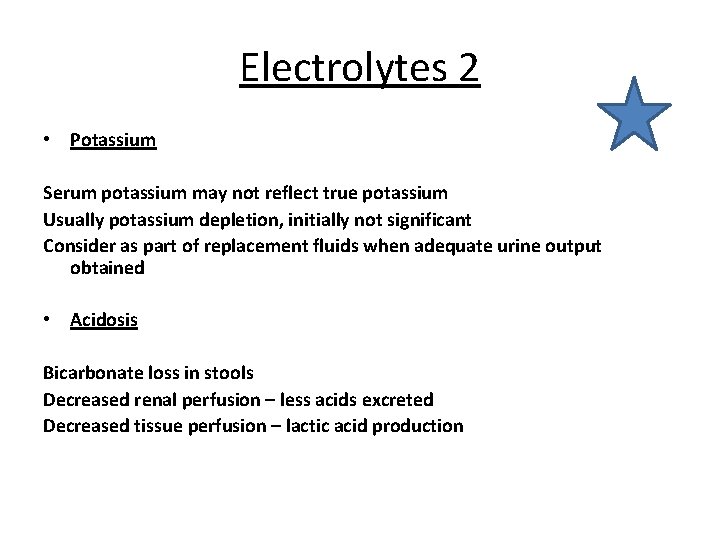

Electrolytes 2 • Potassium Serum potassium may not reflect true potassium Usually potassium depletion, initially not significant Consider as part of replacement fluids when adequate urine output obtained • Acidosis Bicarbonate loss in stools Decreased renal perfusion – less acids excreted Decreased tissue perfusion – lactic acid production

Laboratory • • • CBC Inflamatory tests Stool analysis of leucocytes Stool cultures Measurement of serum electrolytes is only required in children with severe dehydration or with moderate dehydration (hypernatremic dehydration requires specific rehydration methods — irritability and a doughy feel to the skin are typical manifestations and should be sought specifically) • Tests such as BUN and bicarbonate are only helpful when results are markedly abnormal • A normal bicarbonate concentration reduces the likelihood of dehydration • No lab test should be considered definitive for dehydration

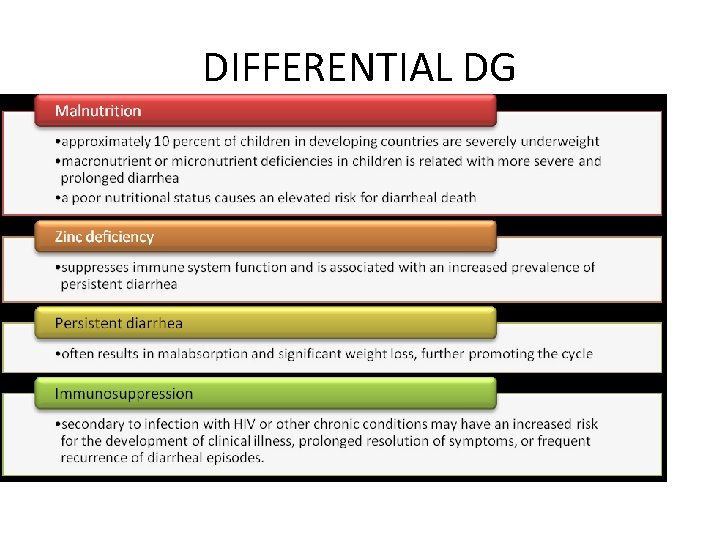

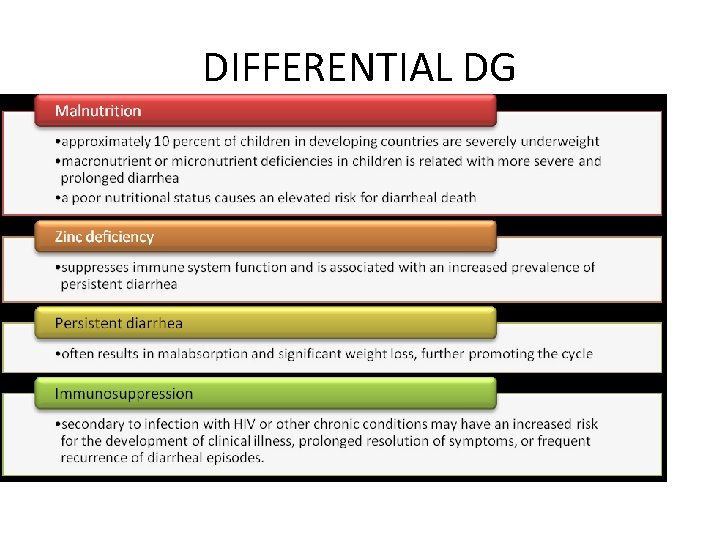

DIFFERENTIAL DG

DIFFERENTIAL DG • • • Meningitis • Bacterial sepsis • Pneumonia • Otitis media • Urinary tract infection

Prevention • • Water, sanitation, and hygiene: • Safe water • Sanitation: houseflies can transfer bacterial pathogens • Hygiene: hand washing • • Safe food: • Cooking eliminates most pathogens from foods • Exclusive breastfeeding for infants • Weaning foods are vehicles of enteric infection • Micronutrient supplementation: the effectiveness of this depends on the child’s overall immunologic and nutritional state; further research is needed.

• Rotavirus: in 1998, a rotavirus vaccine was licensed in the USA for routine immunization of infants. In 1999, production was stopped after the vaccine was causally linked to intussusception in infants. • Currently, two vaccines have been approved: a live oral vaccine (Rota. Teq™) made by Merck for use in children, and GSK’s Rotarix™.

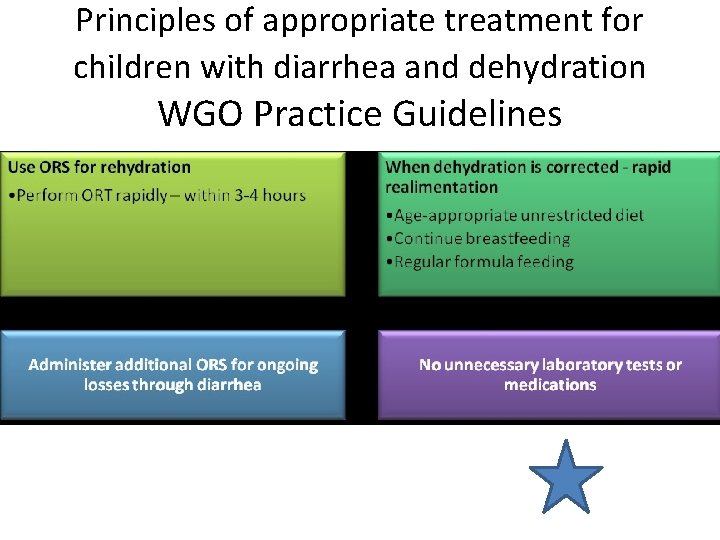

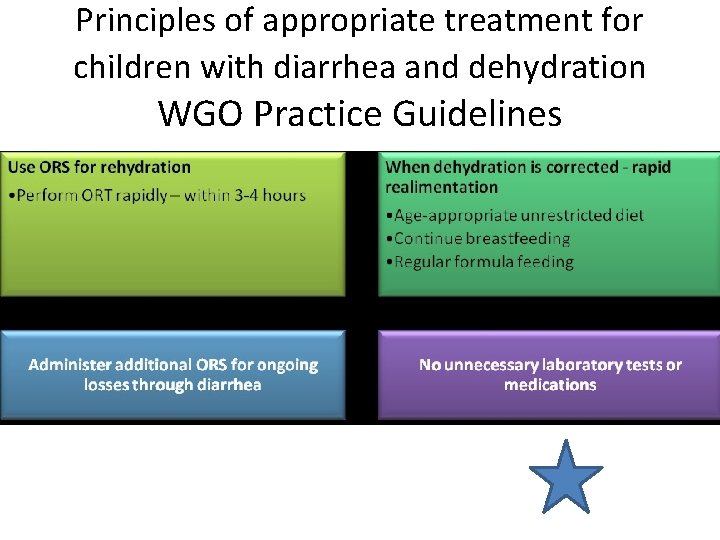

Principles of appropriate treatment for children with diarrhea and dehydration WGO Practice Guidelines

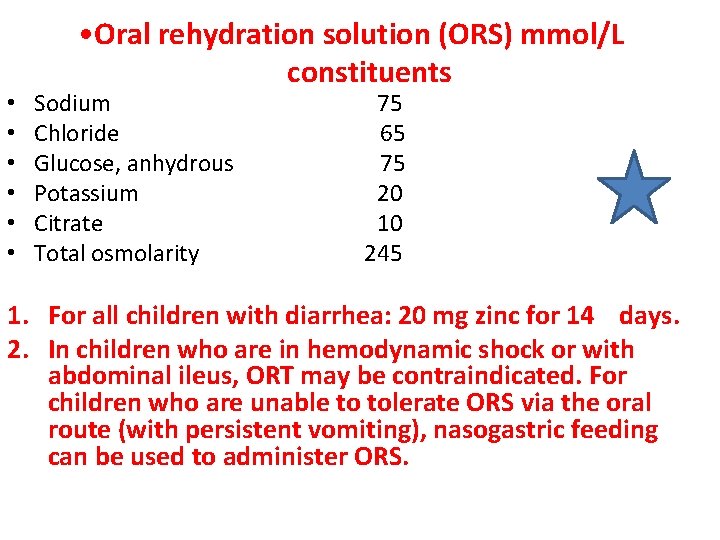

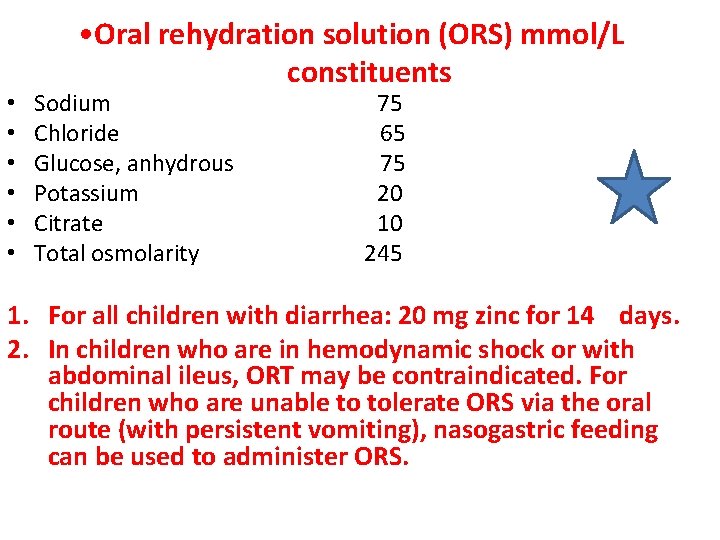

• • Oral rehydration solution (ORS) mmol/L constituents Sodium Chloride Glucose, anhydrous Potassium Citrate Total osmolarity 75 65 75 20 10 245 1. For all children with diarrhea: 20 mg zinc for 14 days. 2. In children who are in hemodynamic shock or with abdominal ileus, ORT may be contraindicated. For children who are unable to tolerate ORS via the oral route (with persistent vomiting), nasogastric feeding can be used to administer ORS.

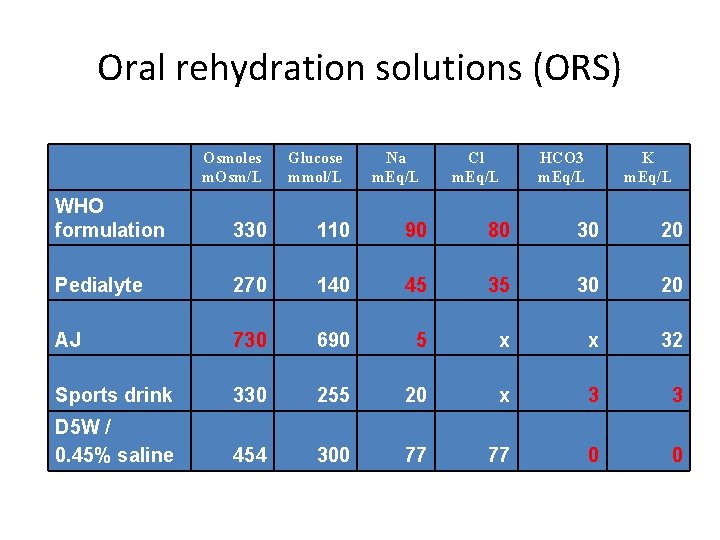

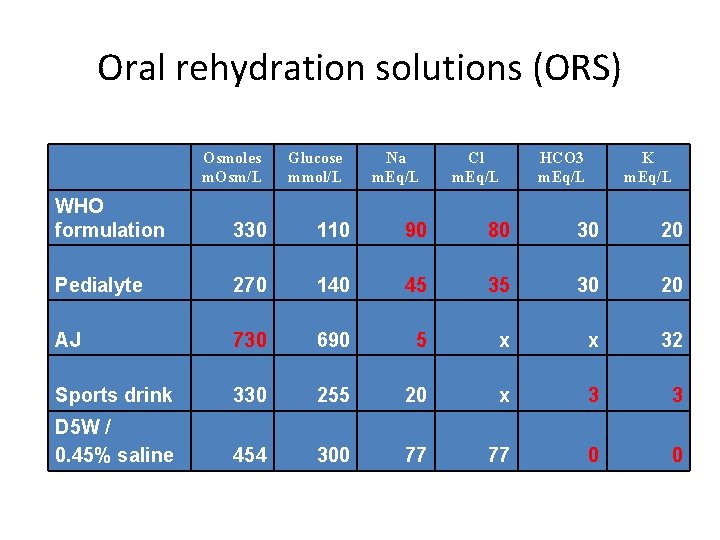

Oral rehydration solutions (ORS) Osmoles m. Osm/L Glucose mmol/L Na m. Eq/L Cl m. Eq/L HCO 3 m. Eq/L K m. Eq/L WHO formulation 330 110 90 80 30 20 Pedialyte 270 140 45 35 30 20 AJ 730 690 5 x x 32 Sports drink 330 255 20 x 3 3 D 5 W / 0. 45% saline 454 300 77 77 0 0

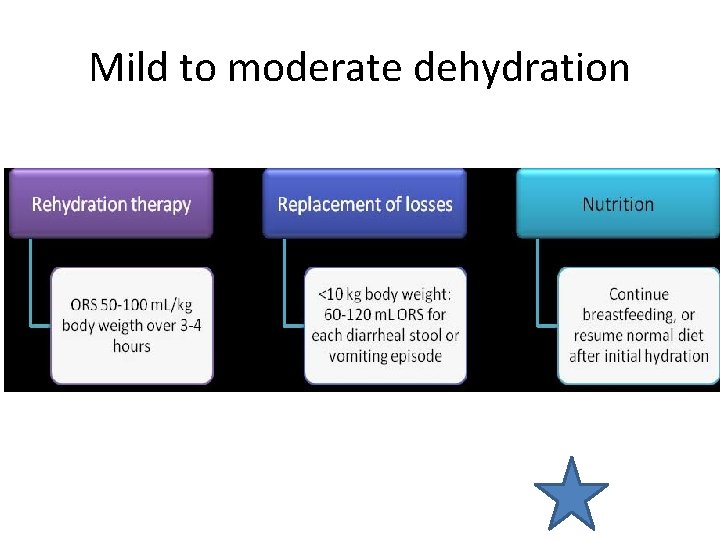

ORT • Oral rehydration therapy • • Appropriate for mild to moderate dehydration Safer Less costly Administered in various clinical settings • Fluid replacement should be over 3 -4 hrs • 50 ml/kg for mild dehydration • 100 ml/kg for moderate dehydration • 10 ml/kg for each episode of vomiting or watery diarrhea

Minimal or no dehydration.

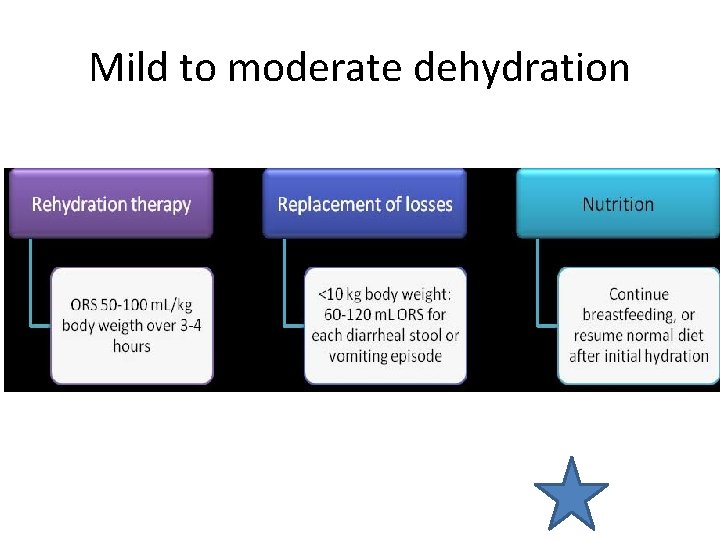

Mild to moderate dehydration

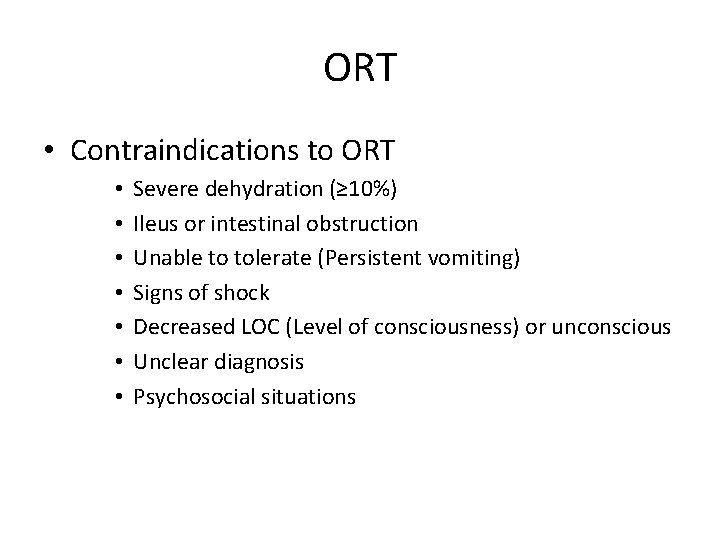

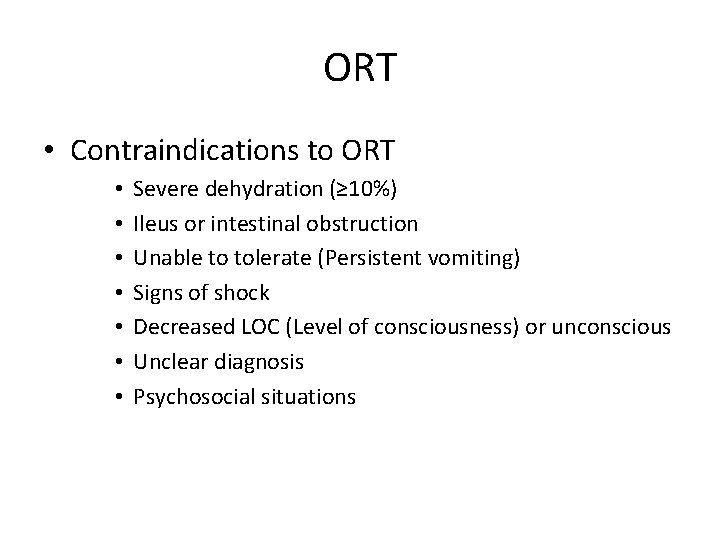

ORT • Contraindications to ORT • • Severe dehydration (≥ 10%) Ileus or intestinal obstruction Unable to tolerate (Persistent vomiting) Signs of shock Decreased LOC (Level of consciousness) or unconscious Unclear diagnosis Psychosocial situations

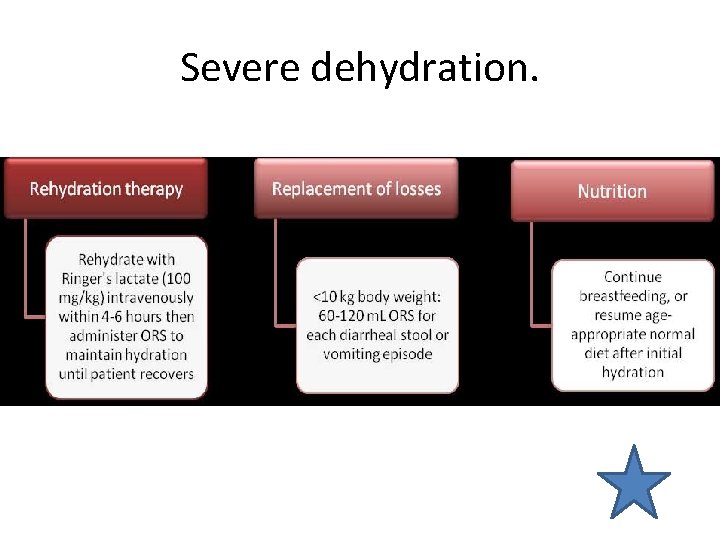

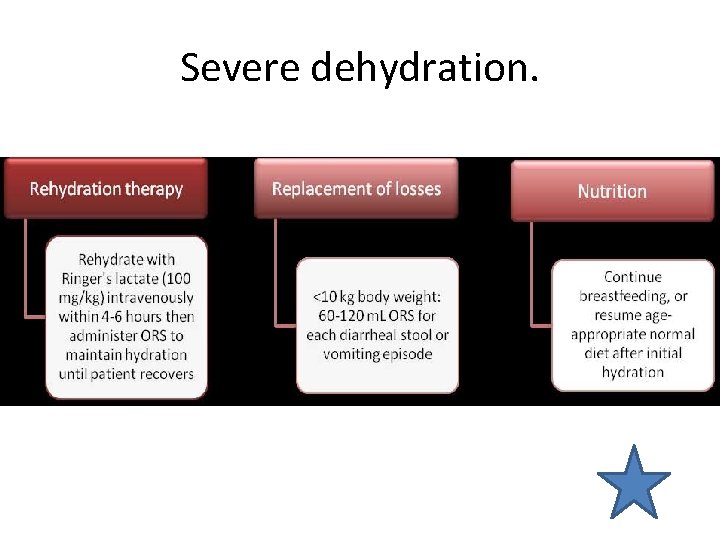

Severe dehydration.

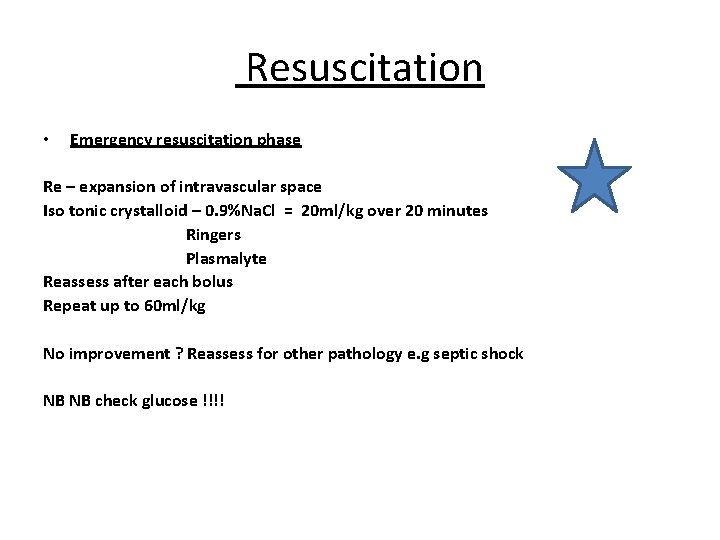

Resuscitation • Emergency resuscitation phase Re – expansion of intravascular space Iso tonic crystalloid – 0. 9%Na. Cl = 20 ml/kg over 20 minutes Ringers Plasmalyte Reassess after each bolus Repeat up to 60 ml/kg No improvement ? Reassess for other pathology e. g septic shock NB NB check glucose !!!!

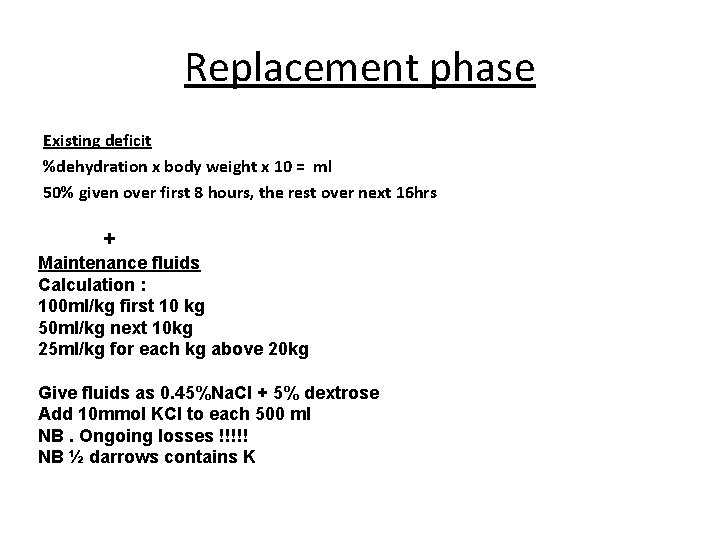

Replacement phase Existing deficit %dehydration x body weight x 10 = ml 50% given over first 8 hours, the rest over next 16 hrs + Maintenance fluids Calculation : 100 ml/kg first 10 kg 50 ml/kg next 10 kg 25 ml/kg for each kg above 20 kg Give fluids as 0. 45%Na. Cl + 5% dextrose Add 10 mmol KCl to each 500 ml NB. Ongoing losses !!!!! NB ½ darrows contains K

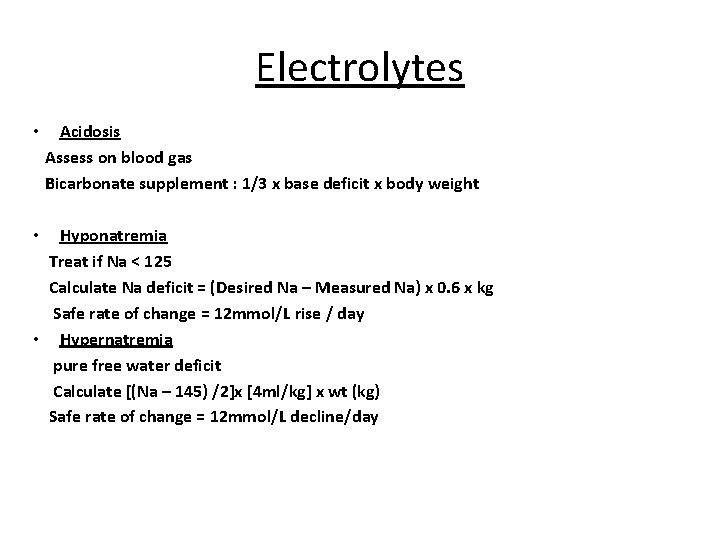

Electrolytes • Acidosis Assess on blood gas Bicarbonate supplement : 1/3 x base deficit x body weight Hyponatremia Treat if Na < 125 Calculate Na deficit = (Desired Na – Measured Na) x 0. 6 x kg Safe rate of change = 12 mmol/L rise / day • Hypernatremia pure free water deficit Calculate [(Na – 145) /2]x [4 ml/kg] x wt (kg) Safe rate of change = 12 mmol/L decline/day •

Severe Dehydration • Management of severe dehydration requires IV fluids • Fluid selection and rate should be dictated by • The type of dehydration • The serum Na • Clinical findings • Aggressive IV NS bolus remains the mainstay of early intervention in all subtypes

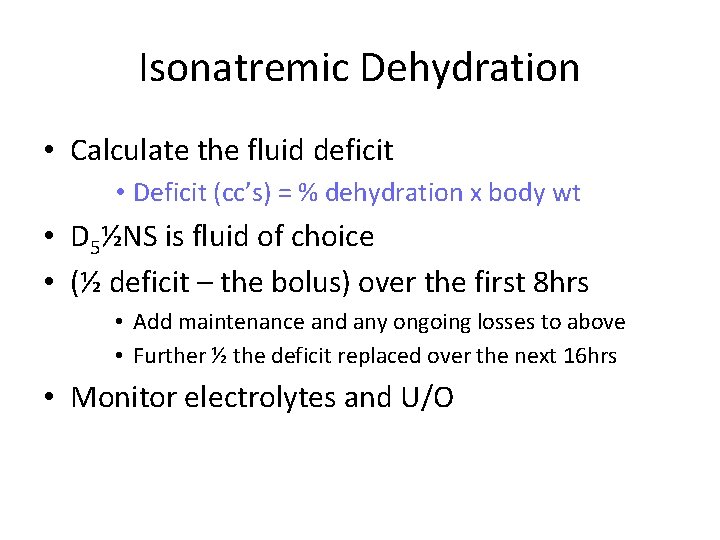

Isonatremic Dehydration • Calculate the fluid deficit • Deficit (cc’s) = % dehydration x body wt • D 5½NS is fluid of choice • (½ deficit – the bolus) over the first 8 hrs • Add maintenance and any ongoing losses to above • Further ½ the deficit replaced over the next 16 hrs • Monitor electrolytes and U/O

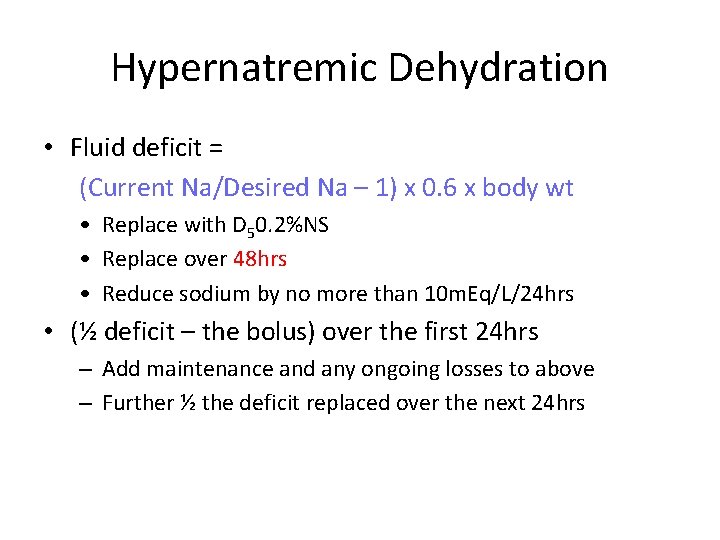

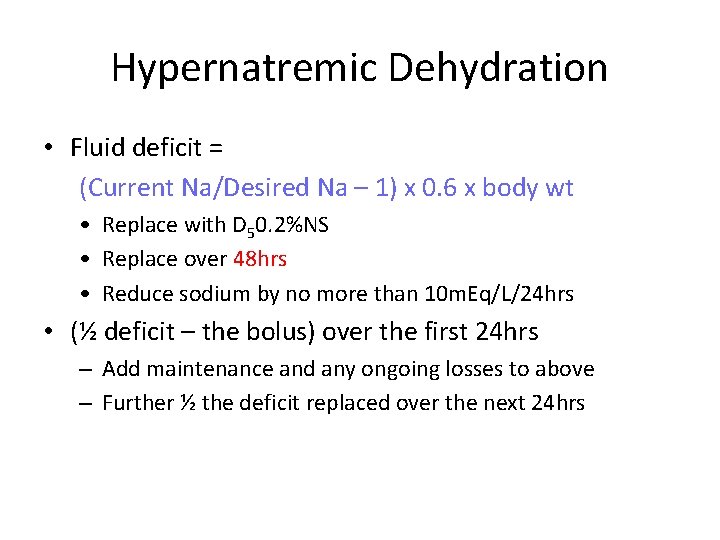

Hypernatremic Dehydration • Fluid deficit = (Current Na/Desired Na – 1) x 0. 6 x body wt • Replace with D 50. 2%NS • Replace over 48 hrs • Reduce sodium by no more than 10 m. Eq/L/24 hrs • (½ deficit – the bolus) over the first 24 hrs – Add maintenance and any ongoing losses to above – Further ½ the deficit replaced over the next 24 hrs

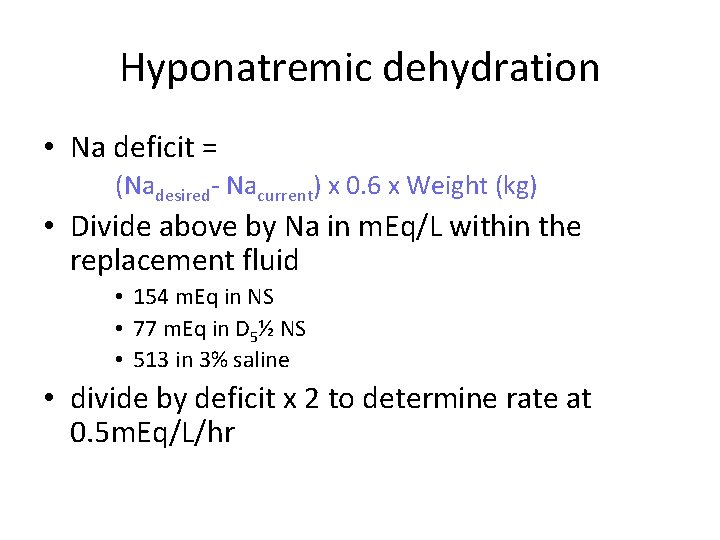

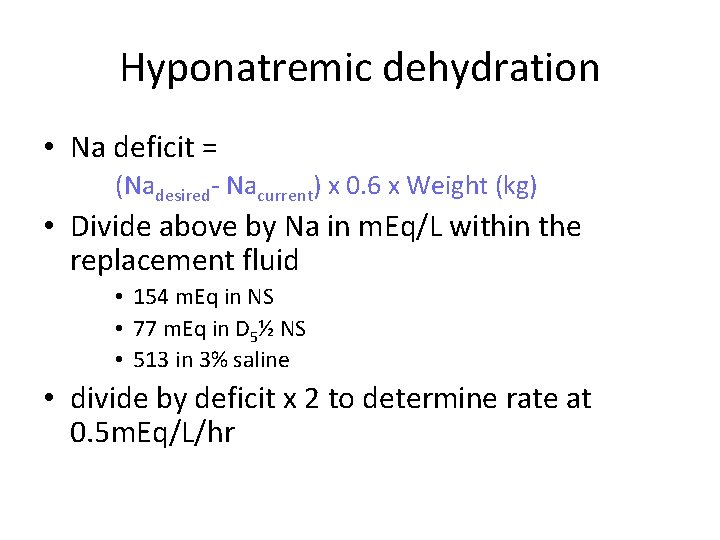

Hyponatremic dehydration • Na deficit = (Nadesired- Nacurrent) x 0. 6 x Weight (kg) • Divide above by Na in m. Eq/L within the replacement fluid • 154 m. Eq in NS • 77 m. Eq in D 5½ NS • 513 in 3% saline • divide by deficit x 2 to determine rate at 0. 5 m. Eq/L/hr

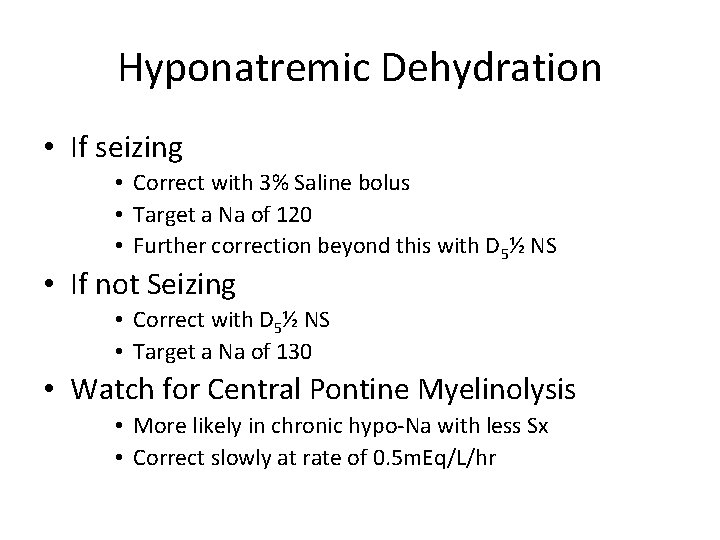

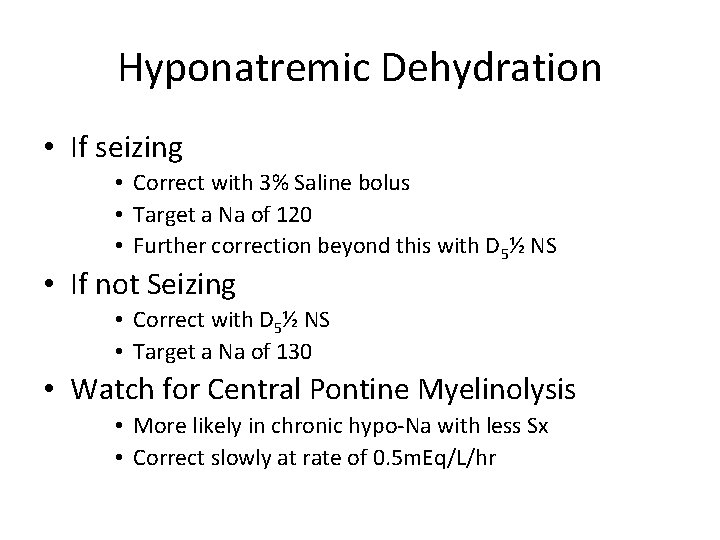

Hyponatremic Dehydration • If seizing • Correct with 3% Saline bolus • Target a Na of 120 • Further correction beyond this with D 5½ NS • If not Seizing • Correct with D 5½ NS • Target a Na of 130 • Watch for Central Pontine Myelinolysis • More likely in chronic hypo-Na with less Sx • Correct slowly at rate of 0. 5 m. Eq/L/hr

• Alternative antimicrobials for treating cholera in children are TMP-SMX (5 mg/kg TMP + 25 mg/kg SMX, b. i. d. for 3 days), furazolidone (1. 25 mg/kg, q. i. d. for 3 days), and norfloxacin.

CAMPYLOBACTER • Erythromycin is hardly used for diarrhea today. Azithromycin is widely available and has the convenience of single dosing. For treating most types of common bacterial infection, the recommended azithromycin dosage is 250 mg or 500 mg once daily for 3– 5 days. Azithromycin dosage for children can range (depending on body weight) from 5 mg to 20 mg per kilogram of body weight per day, once daily for 3– 5 days. • • Quinolone-resistant Campylobacter is present in several areas of South-East Asia (e. g. , in Thailand) and azithromycin is then the appropriate treatment

PROBIOTICS • Several probiotics (Saccharomyces boulardii , Lactobacillus rhamnosus and a mixture of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum) had significant efficacy (at preventing traveler’s diarrhea)” • Probiotics mixture reduced the severity of diarrhea and length of hospital stay in children with acute diarrhea. In addition to restoring beneficial intestinal flora, probiotics may enhance host protective immunity such as down-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and up-regulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines

Antimotility Drugs • loperamide is the agent of choice for adults (4– 6 mg/day; 2– 4 mg /day for children > 8 y). — • for mild to moderate traveler’s diarrhea (without clinical signs of invasive diarrhea). • inhibits intestinal peristalsis and has mild antisecretory properties. • should be avoided in bloody or suspected inflammatory diarrhea (febrile patients). — Significant abdominal pain also suggests inflammatory diarrhea (this is a contraindication for loperamide use). — • loperamide is not recommended for use in children < 2 y.

Antisecretory agents • • Bismuth subsalicylate can alleviate stool output in children or symptoms of diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain in traveler’s diarrhea. • • Racecadotril ( acetetorphan) is an enkephalinase inhibitor (nonopiate) with antisecretory activity, and is now licensed in many countries in the world for use in children. It has been found useful in children with diarrhea, but not in adults with cholera. • Adsorbents: • • Kaolin-pectin, activated charcoal, attapulgite — Inadequate proof of efficacy in acute adult diarrhea

Anti- emetics A single dose of oral Ondansetron (a serotonin antagonist anti-emetic) in children with G/E and dehydration reduces vomiting, facilitate oral rehydration and suitable for the use in emergency department

Suscestible

Suscestible Vpims lucknow

Vpims lucknow A word element attached to the beginning of a word

A word element attached to the beginning of a word Gastroenteritis at a university in texas

Gastroenteritis at a university in texas Gastroenteritis adalah

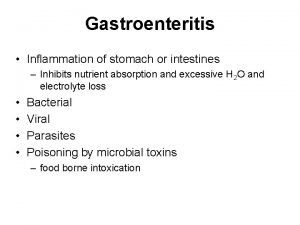

Gastroenteritis adalah Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis Akutni enterokolitis

Akutni enterokolitis Viral gastroenteritis

Viral gastroenteritis Gastroenteritis bacteriana tratamiento

Gastroenteritis bacteriana tratamiento Gastroenteritis prefix and suffix

Gastroenteritis prefix and suffix Akutni gastroenteritis

Akutni gastroenteritis Gastroenteritis bacterial

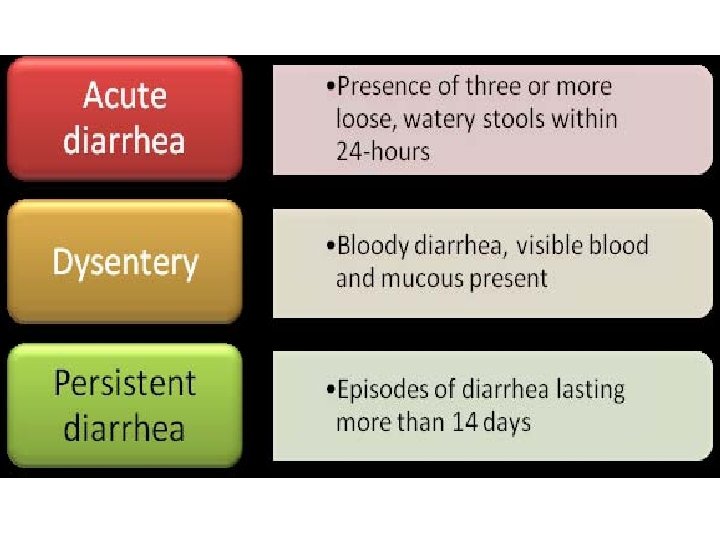

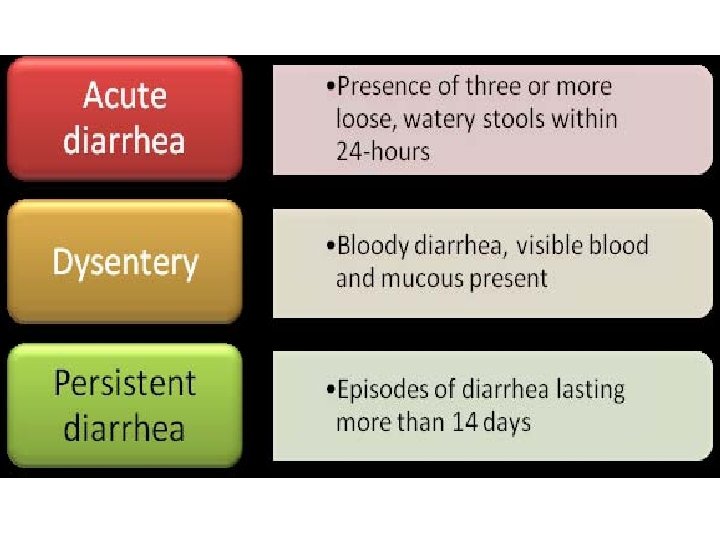

Gastroenteritis bacterial Types of diarrhoea

Types of diarrhoea Best laxative for impacted stool

Best laxative for impacted stool Diarrhea

Diarrhea Diarrhea chief complaint

Diarrhea chief complaint Secretory diarrhea

Secretory diarrhea Secretory diarrhea pathophysiology

Secretory diarrhea pathophysiology Osmolarity versus osmolality

Osmolarity versus osmolality Liemyosarcoma

Liemyosarcoma Plan b of dehydration management

Plan b of dehydration management Diarrhea dan

Diarrhea dan Travelers diarrhea

Travelers diarrhea Chronic diarrhea

Chronic diarrhea Pig diarrhea chart

Pig diarrhea chart Causes of secretory diarrhea

Causes of secretory diarrhea Hip reflexology

Hip reflexology Why does metformin cause gastrointestinal problems

Why does metformin cause gastrointestinal problems Imnci colour code

Imnci colour code Joe harkins

Joe harkins Normal flora of git

Normal flora of git Overflow diarrhea

Overflow diarrhea Bile acid diarrhea pictures

Bile acid diarrhea pictures Factitial diarrhea

Factitial diarrhea What does hiv diarrhea look like

What does hiv diarrhea look like Diarrhea

Diarrhea Types of diarrhea

Types of diarrhea Nicholas seeliger, md flpen panama city beach

Nicholas seeliger, md flpen panama city beach Diarrhea introduction

Diarrhea introduction Diarrhea

Diarrhea Period prevalence formula

Period prevalence formula Descriptive vs analytical epidemiology

Descriptive vs analytical epidemiology Epidemiology triangle

Epidemiology triangle Gate frame epidemiology

Gate frame epidemiology Spurious association

Spurious association Cbic recertification

Cbic recertification Attack rate epidemiology formula

Attack rate epidemiology formula Attack rate epidemiology formula

Attack rate epidemiology formula Logistic regression epidemiology

Logistic regression epidemiology How dr. wafaa elsadr epidemiology professor

How dr. wafaa elsadr epidemiology professor Epi

Epi Distribution in epidemiology

Distribution in epidemiology Defination of epidemiology

Defination of epidemiology Prevalence vs incidence

Prevalence vs incidence Celiac beri beri

Celiac beri beri Epidemiology definition

Epidemiology definition Gordon epidemiology

Gordon epidemiology Ramboman acronym

Ramboman acronym Difference between descriptive and analytical epidemiology

Difference between descriptive and analytical epidemiology Attack rate epidemiology formula

Attack rate epidemiology formula Gametocytes of plasmodium

Gametocytes of plasmodium Epidemiology definition

Epidemiology definition Confounding vs effect modification

Confounding vs effect modification Field epidemiology ppt

Field epidemiology ppt Epidemiology concept

Epidemiology concept