Lecture 2 2002 Physiology Psychology Energy Weight Gain

- Slides: 98

Lecture 2 - 2002 • • Physiology Psychology Energy Weight Gain

Physiology of Pregnancy

King J. Physiology of pregnancy and nutrient metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 71 (suppl): 1218 S-25 S

Adjustments in Nutrient Metabolism • Goals – support changes in anatomy and physiology of mother – support fetal growth and development – maintain maternal homeostasis – prepare for lactation • Adjustments are complex and evolve throughout pregnancy

General Concepts • Alterations include: – increased intestinal absorption – reduced excretion by kidney or GI tract • Alterations are driven by: – hormonal changes – fetal demands – maternal nutrient supply

• There may be more than one adjustment for each nutrient. • Maternal behavioral changes augment physiologic adjustments • When adjustment limits are exceeded, fetal growth and development are impaired. • The first half of pregnancy is a time of preparation for the demands of rapid fetal growth in the second half

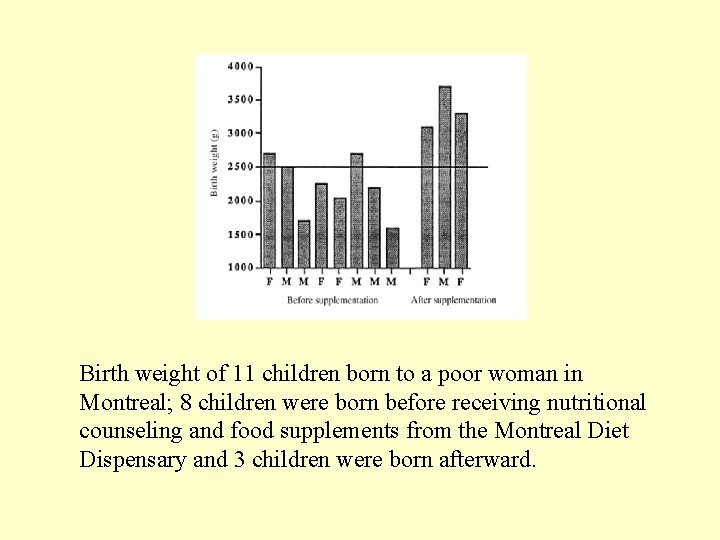

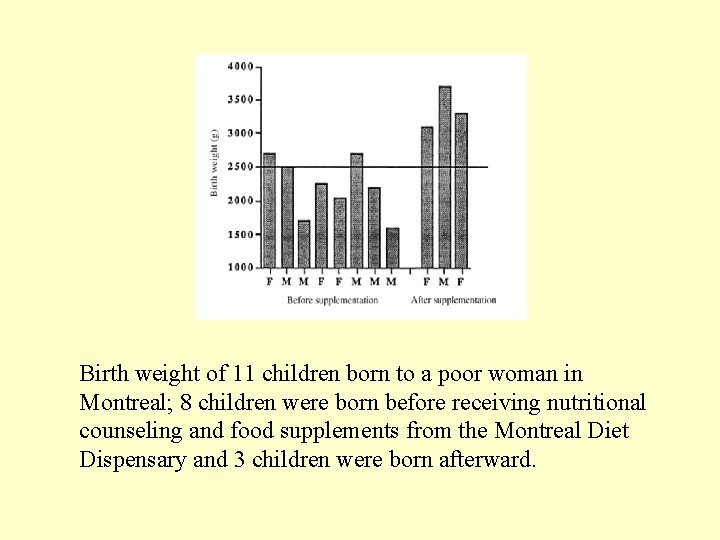

Birth weight of 11 children born to a poor woman in Montreal; 8 children were born before receiving nutritional counseling and food supplements from the Montreal Diet Dispensary and 3 children were born afterward.

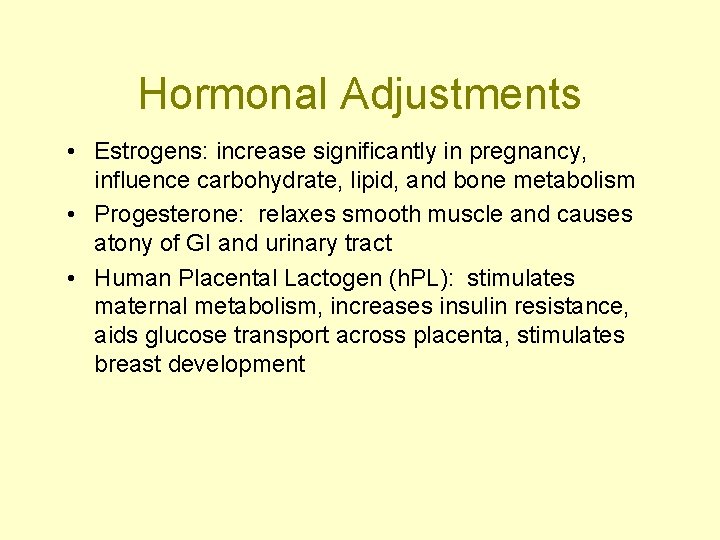

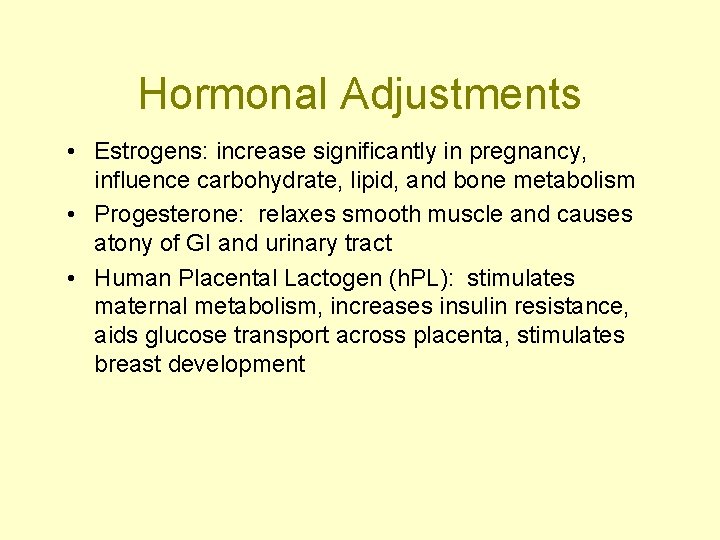

Hormonal Adjustments • Estrogens: increase significantly in pregnancy, influence carbohydrate, lipid, and bone metabolism • Progesterone: relaxes smooth muscle and causes atony of GI and urinary tract • Human Placental Lactogen (h. PL): stimulates maternal metabolism, increases insulin resistance, aids glucose transport across placenta, stimulates breast development

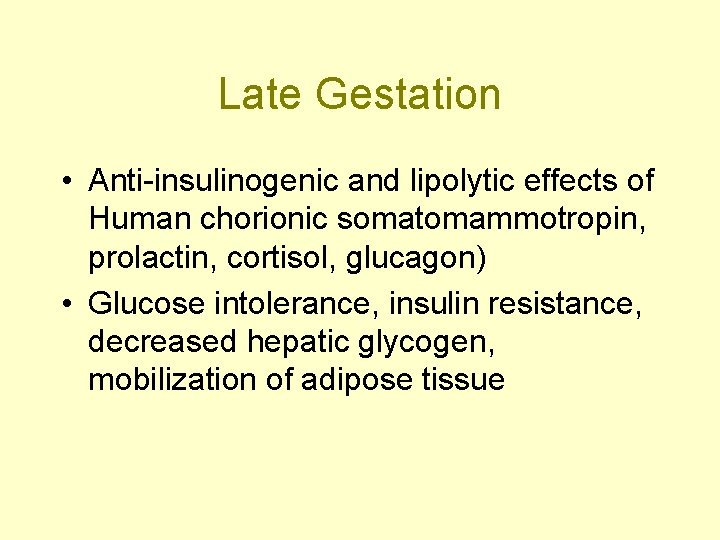

Late Gestation • Anti-insulinogenic and lipolytic effects of Human chorionic somatomammotropin, prolactin, cortisol, glucagon) • Glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, decreased hepatic glycogen, mobilization of adipose tissue

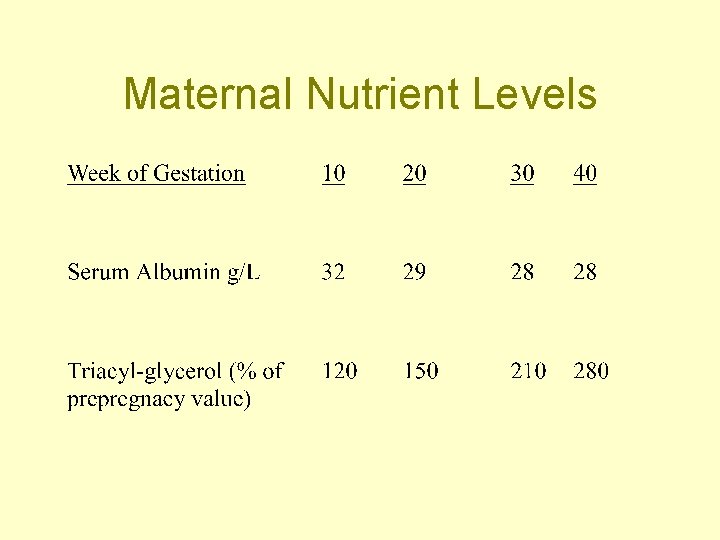

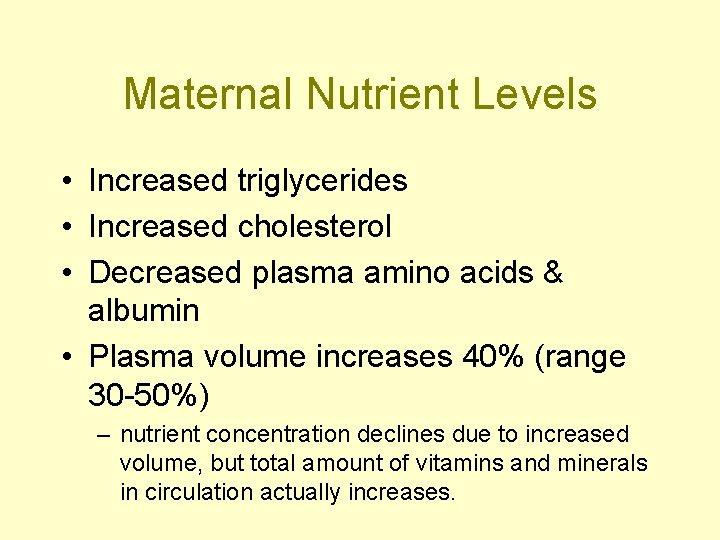

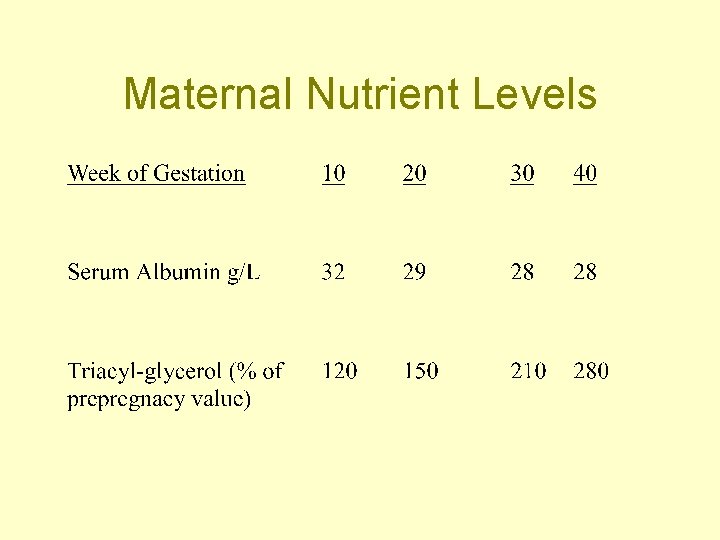

Maternal Nutrient Levels • Increased triglycerides • Increased cholesterol • Decreased plasma amino acids & albumin • Plasma volume increases 40% (range 30 -50%) – nutrient concentration declines due to increased volume, but total amount of vitamins and minerals in circulation actually increases.

Maternal Nutrient Levels

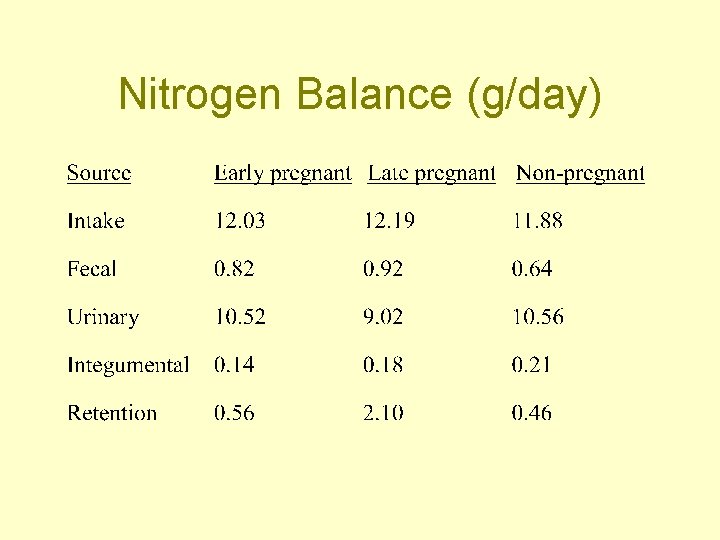

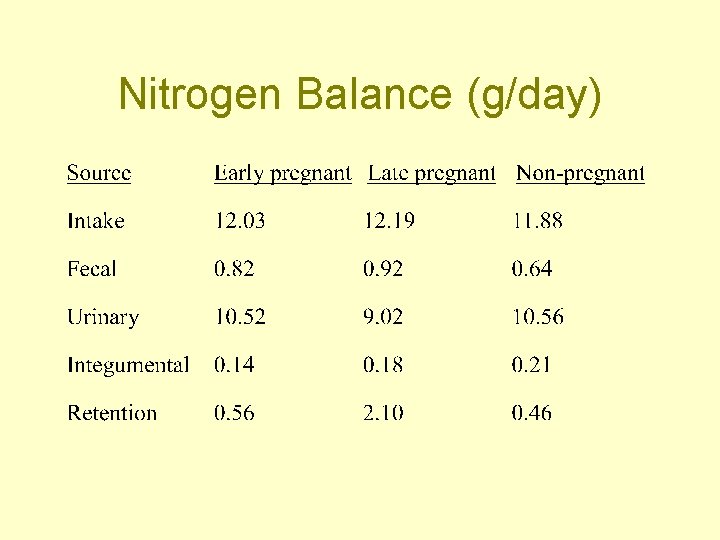

Nitrogen Balance (g/day)

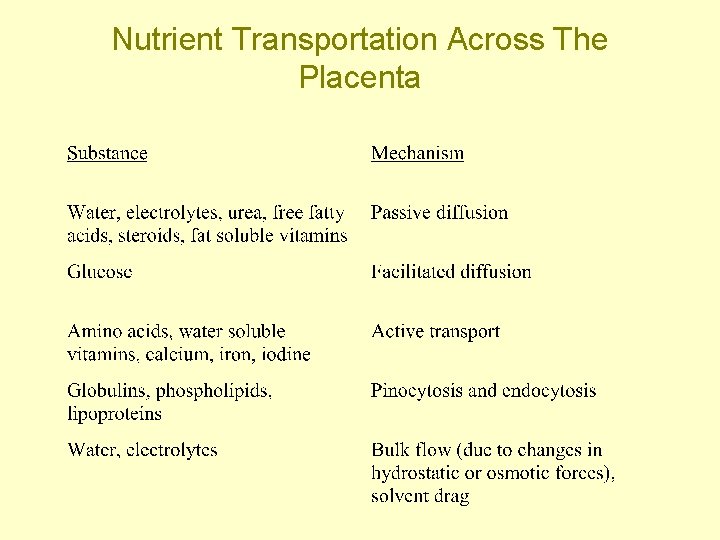

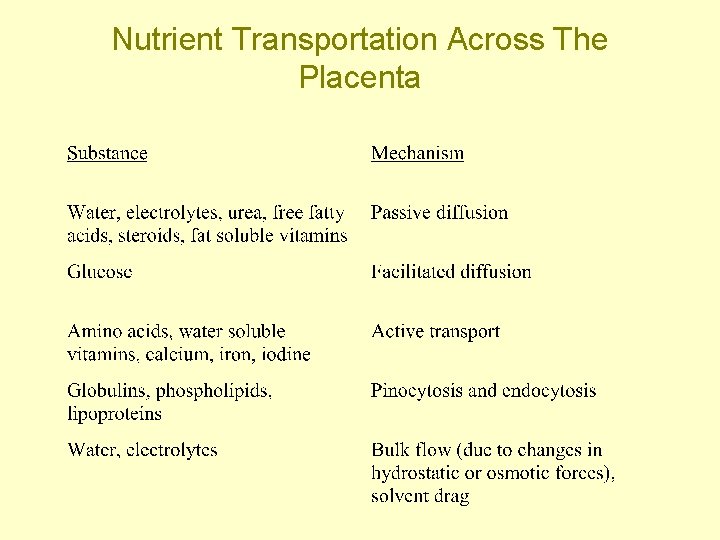

Nutrient Transportation Across The Placenta

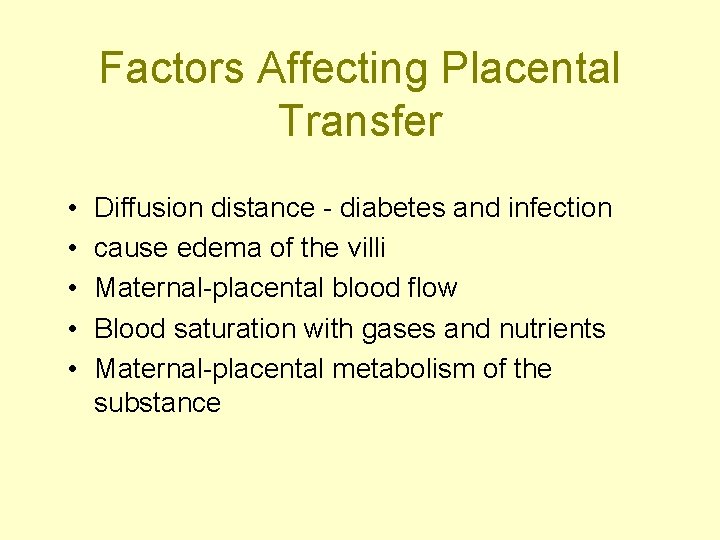

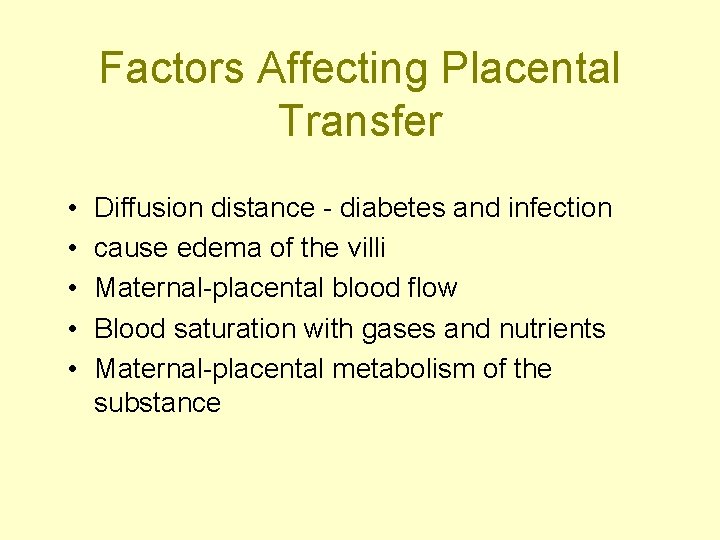

Factors Affecting Placental Transfer • • • Diffusion distance - diabetes and infection cause edema of the villi Maternal-placental blood flow Blood saturation with gases and nutrients Maternal-placental metabolism of the substance

Psychology of Pregnancy • Psychosocial tasks – Rubin – Leaderman’s tasks • Fathers • Cultural awareness

Developmental Tasks of Pregnancy (Rubin, 1984) • Seeking safe passage for herself and her child through pregnancy, labor, and delivery. • Ensuring the acceptance by significant persons in her family of the child she ears. • Binding-in to her unknown baby. • Learning to give of herself.

Lederman, RP. Psychosocial Adaptation in Pregnancy, 2 nd Ed. 1996 • Developmental Tasks of Pregnancy – acceptance of pregnancy – identification with motherhood role – relationship to the mother – relationship to the husband/partner – preparation for labor – processing fear of loss of control & loss of self esteem in labor

Psychosocial adjustment during pregnancy: the experience of mature gravidas (Stark, JOGNN, 1997) • N=64 older gravidas (> 35), 46 younger gravidas (< 32) in third trimester • Lederman prenatal self evaluation questionnaire - examines conflicts for 7 steps • In general conflicts about maternal role were similar in both groups • Older gravidas had less concern about fear of helplessness and loss of control in labor regardless of parity

Developmental Tasks of Fatherhood • • • Accepting the pregnancy Identifying the role of father Reordering relationships Establishing relationship with his child Preparing for the birth experience

Laboring for Relevance: Expectant and New Fatherhood (Jordan, Nursing Research, 1990) • N=56 expectant fathers followed prospectively • “Tasks” – grappling with the reality of the pregnancy and child – struggling for recognition as a parent from mother, coworkers, friends, family baby and society – plugging away at the role-making of involved fatherhood

Jordan, cont. • Identified concerns: – Men not recognized as parents but as helpmates and breadwinners – Men felt excluded from childbearing experience by mates, health care providers, and society – Fathers felt that they had no role models for active and involved parenthood

Energy Requirements in Pregnancy • Energy costs of pregnancy: – increased maternal metabolic rate – fetal tissues – increase in maternal tissues

RDA for Energy in Pregnancy - Old • Energy cost of pregnancy = 80, 000 kcal (Hytten and Leitch, 1971) – maternal gain of 12. 5 kg – infant weight of 3. 3 kg • 80, 000/250 days (days after the first month) • Additional 300 kcal per day recommended in second and third trimester – total of 2, 500 for reference woman

DRI for Energy - New

DRI for Energy in Pregnancy 2002

BEE: Basal Energy Expenditure • Increases due to metabolic contribution of uterus and fetus and increased work of heart and lungs. • Variable for individuals

Growth of Maternal and Fetal Tissues • Still based on work of Hytten • Based on IOM weight gain recommendations

Longitudinal Data from DLW Database • Median TEE (total energy expenditure) change from non-pregnant was 8 kcal/gestational week. • TEE changes little in first trimester.

Variations in Energy Requirements • Body size - especially lbm • Activity: – most women decrease activity in last months of pregnancy if they can – increased energy cost of moving heavier body • BMR – rises in well nourished women (27%) – rises less or not at all in women who are not well nourished • -Diet Induced Thermogenesis?

Evidence of energy sparing in Gambian women during pregnancy: a longitudinal study using whole-body calorimetry (AJCN, 1993) • N=58, initially recruited, ages 18 -40 – 25 became pregnant – 21 participated in study protocols – 9 completed BMR and 24 hour energy expenditure – 12 completed BMR • Adjusted for seasonality, weight loss expected during wet season

Poppitt et al. , cont. • Mean maternal prepregnancy weight was 52 kg • Mean prepregnancy BMI was 21. 2 + 2 • Mean birthweight was 3. 0 + 0. 1 • Mean gestational length was 39. 4 • Mean weight gain was 6. 8 kg • Mean fat gain was 2. 0 kg at 36 weeks

Poppitt et al. , cont. • BMR fell in early pregnancy • Values per kg lbm remained below baseline for duration of pregnancy • Individual variation was high

Poppitt et al. , cont. • Energy sparing mechanisms may act via a suppression of metabolism in women on habitually low intakes. • This maintains positive balance in the mother and protects the fetus from growth retardation

Prentice and Goldberg. Energy Adaptations in human pregnancy: limits and long-term consequences. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000; 71(supple): 1226 S-32 S.

Five Country Study

Longitudinal assessment of energy balance in well-nourished, pregnant women (Koop-Hoolihan et al, AJCN, 1999) • N=16, SF area – 10 became pregnant • BMI range was 19 -26 • Mean weight gain at 36 weeks was 11. 6 +4 • Mean birth weight was 3. 6

Koop-Hoolihan, cont • Protocol: 5 times before pregnancy, 3 times during, once 4 -6 weeks postpartum – RMR (resting metabolic rate/metabolic cart) – DIT (diet induced thermogenesis/metabolic cart) – TEE (total energy expenditure/doubly labeled water) – AEE (activity energy expenditure/difference between TEE and RMR) – EI (energy intake/3 day food records) – Body composition - densitometry, tbw, bmc with absorptiometry

Koop-Hoolihan, cont • Women with the largest cumulative increase in RMR deposited the least fat mass (this was the only prepregnant factor that predicted fat mass gain) • In all indices there was large individual variation • Average total energy cost of pregnancy was similar to work of Hytten and Leitch (1971) • Food intake records indicated 9% increase in kcals with pregnancy, but highly variable

Energy in Pregnancy (Roy Pitkin, AJCN, 1999) • Koop-Hoolihan study design was “Impeccable. ” • Women meet increase energy demands of pregnancy in a variety of ways increased intakes, decreased activity or DIT, limited fat storage. • RDA?

Energy in Pregnancy (Roy Pitkin, AJCN, 1999) • “A prudent course seems to be to permit considerable latitude in energy intake recommendations on the basis of individual preferences and to monitor weight gain carefully, making adjustments in energy intake only in response to the normal pattern of gain. ”

Maternal Obesity • Rates of obesity are increasing worldwide • Obesity before pregnancy is associated with risk of several adverse outcomes

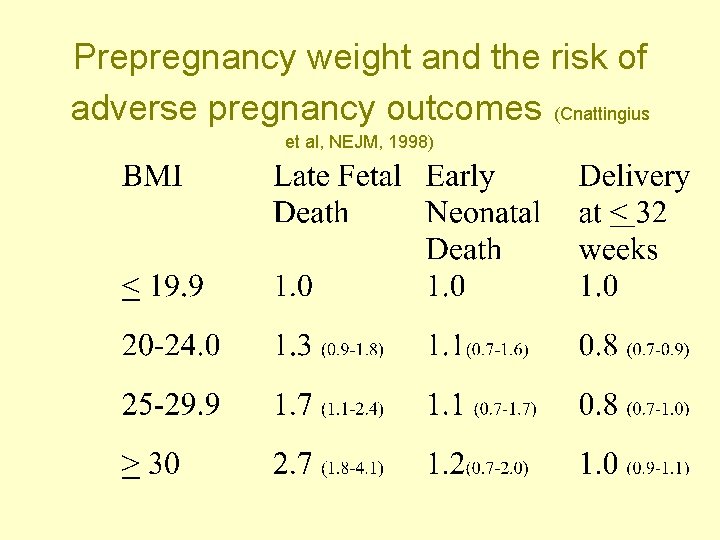

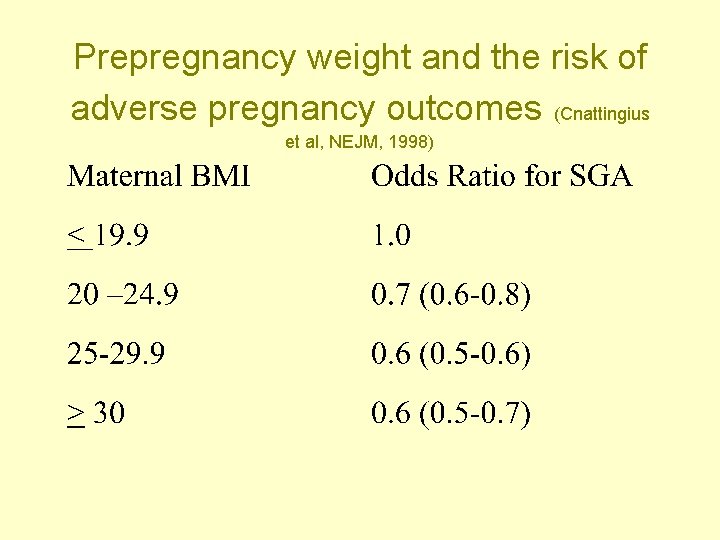

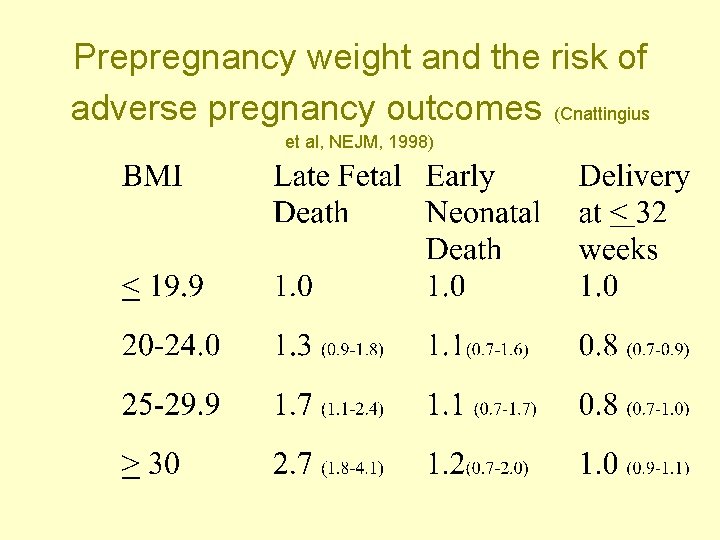

Prepregnancy weight and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes (Cnattingius et al, NEJM, 1998) • N=167, 750 in Sweden, Norway, Finland, or Iceland who gave birth to singleton babies in 1992 and 1993. • Outcome = late fetal death • Adjusted for maternal age, parity, education, smoking, height and living with father

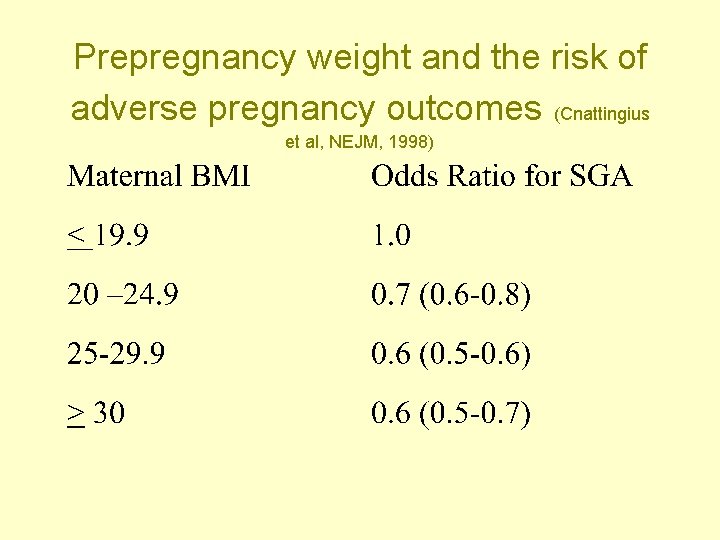

Prepregnancy weight and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes (Cnattingius et al, NEJM, 1998)

Prepregnancy weight and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes (Cnattingius et al, NEJM, 1998)

Cnattingius et al, Discussion • Even lean women were probably well nourished in this cohort. Results in other countries may be different. • Maternal overweight may be major factor in SES differences in perinatal morbidity and mortality • Impetus toward developing strategies to reverse trends toward increasing body weight

Perinatal Outcomes of Obese Women: A Review of the Literature (Morin, JOGNN, 1998) • Extensive Review of Medine and CINAHL • Definitions of obesity vary, but IOM says obesity = BMI > 29

Diagnosis • Menses tend to be irregular and pelvic exams and ultrasound exams may be difficult • AFP values may be lower than norms due to increased plasma volume • Blood pressure monitoring may be difficult

Antepartum Outcomes • Higher rates of NTD even with folic acid supplementation (RR = 3. 0 in one study) • Increased risk for both chronic and pregnancy induced hypertension • Increased risk for severe preeclampsia (BMI < 32. 3, risk was 3. 5 times that of controls) • Increased risk for both GDM, IDD and NIDD. • Increased twining • Increased UTI

Labor and Birth Outcomes • Increased incidence of both primary (31% vs 8. 6%) and secondary cesarean births - often associated with fetal macrosomia and/or failed induction. • Operative times are longer • Increased incidence of blood loss during surgery • ? Differences in responses to anesthesia (greater spread/higher levels)

Postpartum Outcomes • Increased risk for wound and endometrial infection • Increased prevalence of urinary incontinence

Infant Outcomes • Large infants - effect is independent of maternal diabetes • Increased infant mortality - RR for infants born to obese women was 4. 0 compared to women with BMI < 20

Cost • Costs were 3. 2 times higher for women with BMI > 35 • Longer hospitalizations

IOM Recommendations Institute of Medicine. Nutrition during pregnancy, weight gain and nutrient supplements. Report of the Subcommittee on Nutritional Status and Weight Gain during Pregnancy, Subcommittee on Dietary Intake and Nutrient Supplements during Pregnancy, Committee on Nutritional Status during Pregnancy and Lactation, Food and Nutrition Board. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1990

Recommended total weight gain in pregnant women by prepregnancy BMI (in kg/m 2) Weight-for-height category Recommended total gain (kg) Low (BMI <19. 8) 12. 5– 18 Normal (BMI 19. 8– 26. 0) 11. 5– 16 High (BMI >26. 0– 29. 0)2 7– 11. 5 Adolescents and black women should strive for gains at the upper end of the recommended range. Short women (<157 cm) should strive for gains at the lower end of the range. The recommended target weight gain for obese women (BMI >29. 0) is 6. 0.

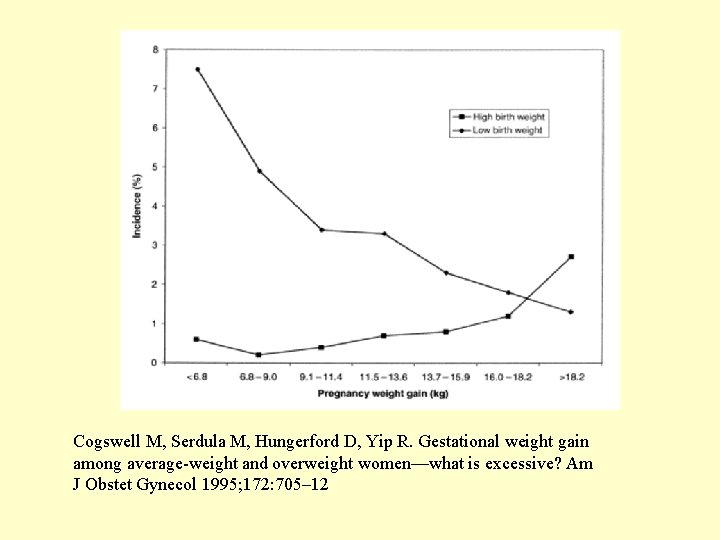

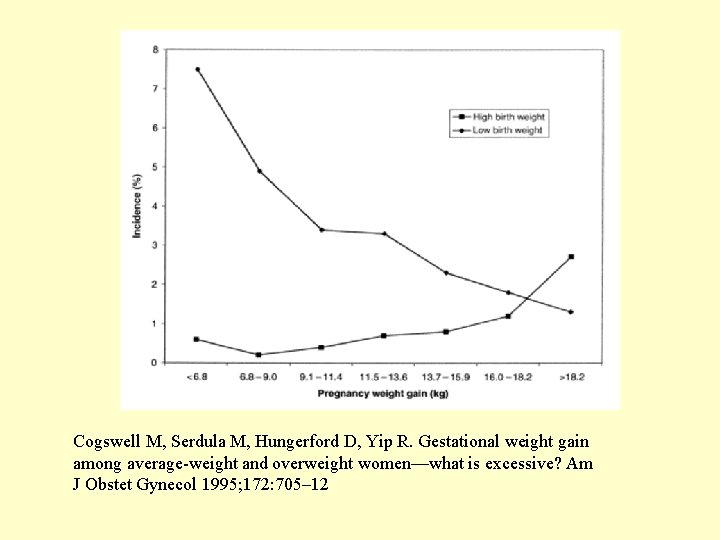

Cogswell M, Serdula M, Hungerford D, Yip R. Gestational weight gain among average-weight and overweight women—what is excessive? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995; 172: 705– 12

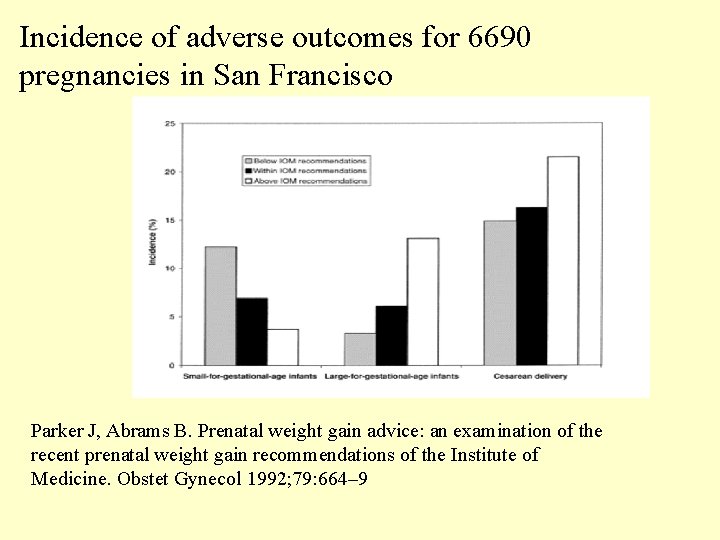

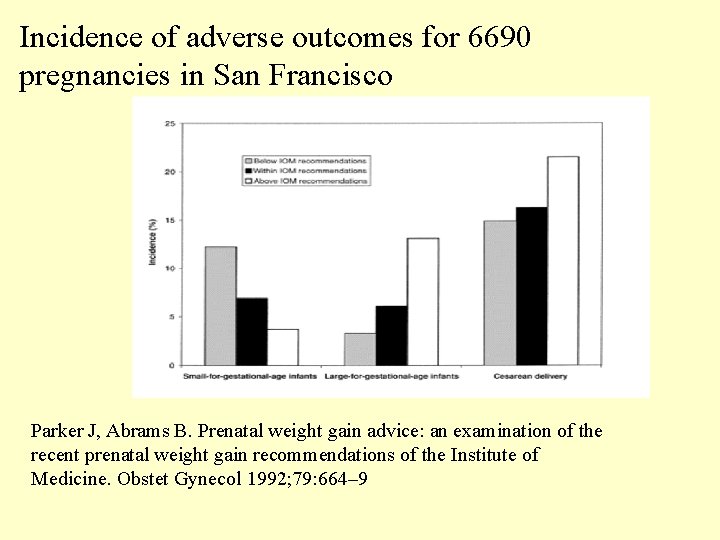

Incidence of adverse outcomes for 6690 pregnancies in San Francisco Parker J, Abrams B. Prenatal weight gain advice: an examination of the recent prenatal weight gain recommendations of the Institute of Medicine. Obstet Gynecol 1992; 79: 664– 9

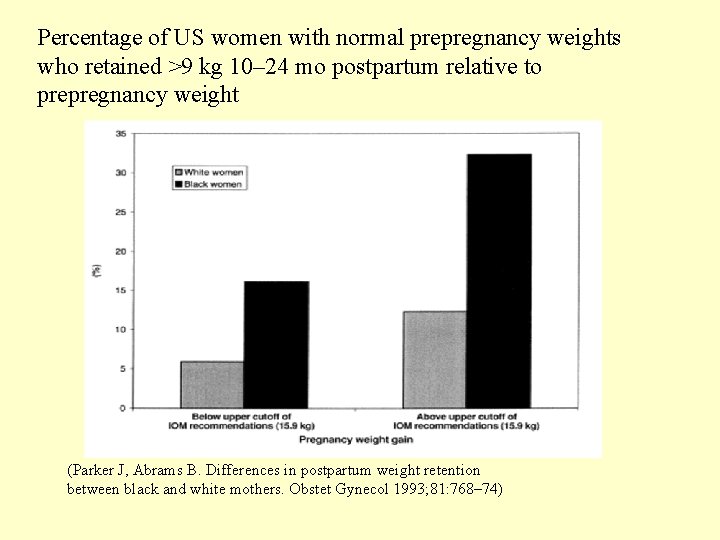

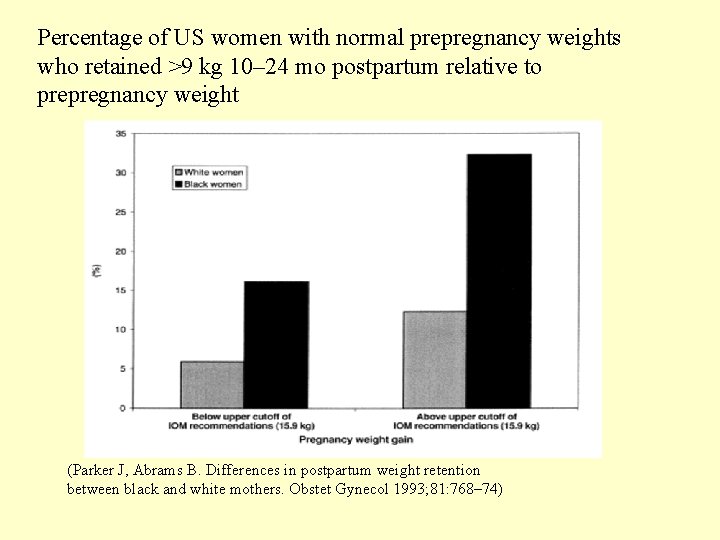

Percentage of US women with normal prepregnancy weights who retained >9 kg 10– 24 mo postpartum relative to prepregnancy weight (Parker J, Abrams B. Differences in postpartum weight retention between black and white mothers. Obstet Gynecol 1993; 81: 768– 74)

Rates of Weight Gain: T 2 and T 3 • Underweight women: 0. 5 kg per week • Normal weight women: 0. 4 kg per week • Overweight women: 0. 3 kg per week

Postpartum Weight • IOM (1990) concluded that childbearing is associated with average weight gain of 1 kg. • There is a large variation in differences between prepregnant weight and weight at 6 to 12 months postpartum (SD of 4. 8 kg) • Analysis is confused by the tendency to gain weight with aging • Years between 25 and 34 are times when American women are most vulnerable to major weight gain

Postpartum Weight • Proportions of black women who have higher postpartum weights is higher in almost all studies. • Smoking is consistently related to less postpartum weight gain.

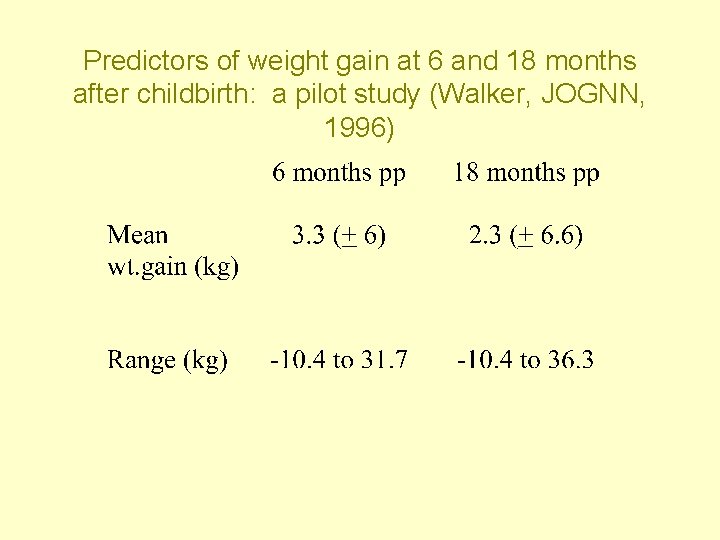

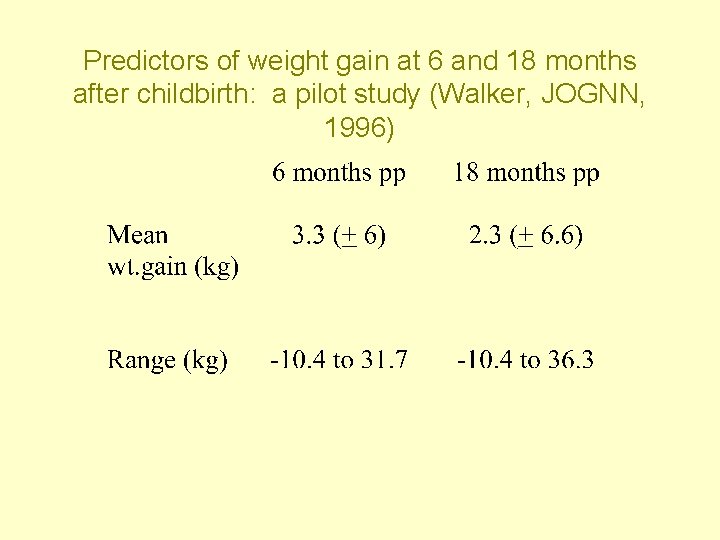

Predictors of weight gain at 6 and 18 months after childbirth: a pilot study (Walker, JOGNN, 1996) • N=88 at 6 months, 75 at 18 months • Out of about 300 who were sent a mailed questionnaire 6 and 18 months postpartum • Predominantly white mothers in the Midwestern US

Predictors of weight gain at 6 and 18 months after childbirth: a pilot study (Walker, JOGNN, 1996) • Battery of tests including: – Health promoting lifestyle profile (48 items on exercise, nutrition, support selfactualization) – Categories of activity level – Weight locus of control scale (internal or external) – Self reported weight and height, method of delivery, method of infant feeding

Predictors of weight gain at 6 and 18 months after childbirth: a pilot study (Walker, JOGNN, 1996)

Walker, Results • At both 6 and 18 months, women who exceeded IOM wt. Gain recommendations had significantly higher pp weight increases.

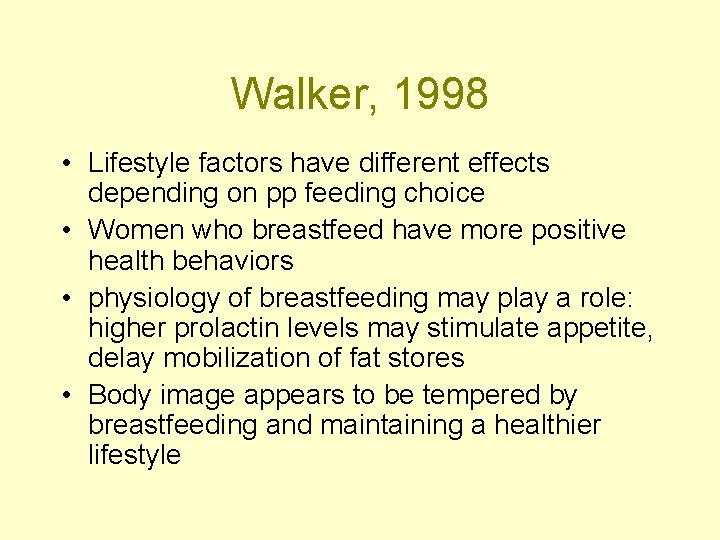

Lifestyle factors related to postpartum weight gain and body image in bottle and breastfeeding women (Walker & Freedlan-Graves, JOGNN, 1998) • • N=207, 73% white, 16% Hispanic, 8% other Mailed 8 page questionnaires after birth Social and demographic variables Body image scale: 30 questions about body parts or functions (appetite, stamina) Exercise questionnaire: current activity level Food Habits Questionnaire: low and high fat intake Personal Lifestyle questionnaire Self control schedule

Walker, 1998 • No differences between breastfeeding and bottle feeding: – postpartum weight gain – body image dissatisfaction – aerobic exercise – self regulation • Trend (p=0. 08 for difference in smoking rates)

Walker, 1998 • Bottle feeding group (n=101) pp weight gain was associated with: – body image dissatisfaction – fat intake habits – smoking – exercise – gestational weight gain – body image dissatisfaction associated with less exercise, less healthy lifestyle and less self-regulatory capabilities

Walker, 1998 • Breastfeeding group (n=106): – Not related to pp weight gain: body image dissatisfaction, lifestyle variables – GWG was related to pp weight – dissatisfaction with body image associated with lower lifestyle and self-regulatory capabilities

Walker, 1998 • Lifestyle factors have different effects depending on pp feeding choice • Women who breastfeed have more positive health behaviors • physiology of breastfeeding may play a role: higher prolactin levels may stimulate appetite, delay mobilization of fat stores • Body image appears to be tempered by breastfeeding and maintaining a healthier lifestyle

Sociocultural and behavioral influences on weight gain during pregnancy Hicky, CA. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000; 71(supple): 1364 S-70 S.

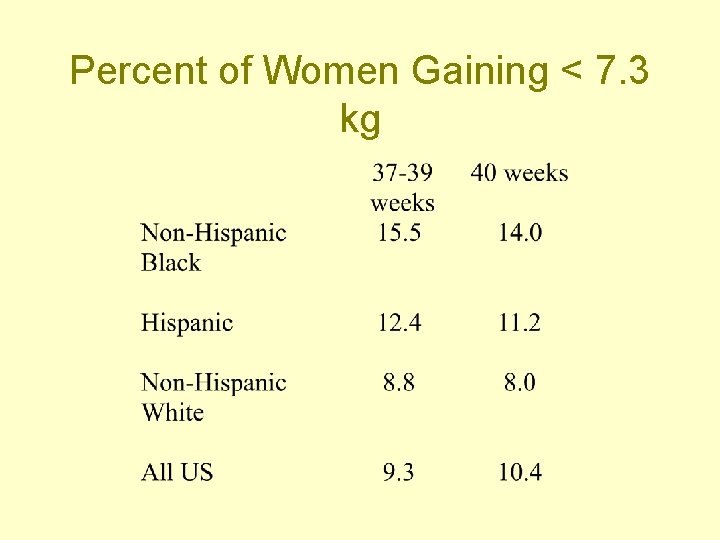

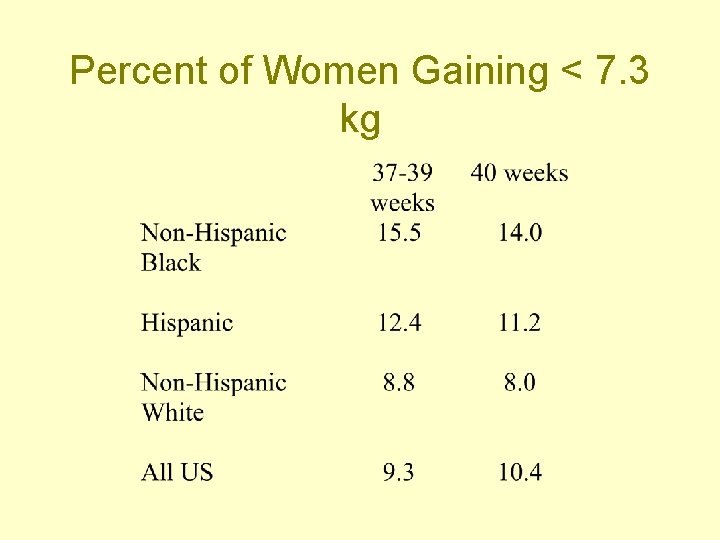

Percent of Women Gaining < 7. 3 kg

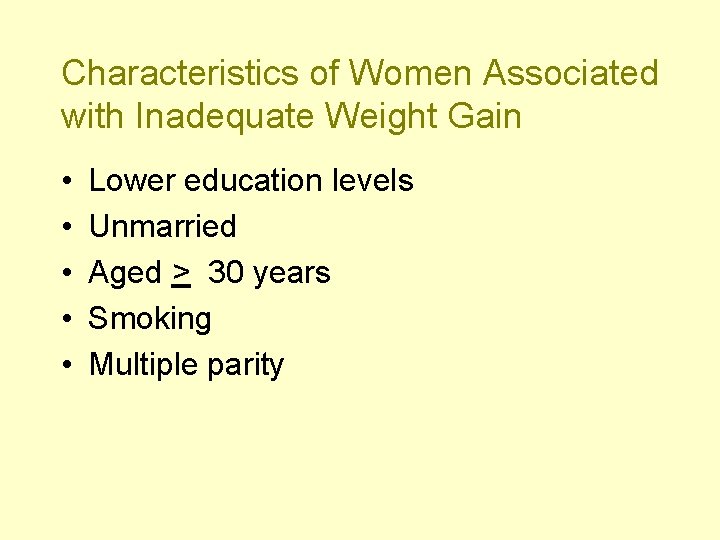

Characteristics of Women Associated with Inadequate Weight Gain • • • Lower education levels Unmarried Aged > 30 years Smoking Multiple parity

• Possibly psycho-social stress and pregnancy intendedness (effects seem to differ by culture) • Low income women had twice the risk in NNS. • Migrant workers have higher risk in WIC populations

1997 Review of Recommendations Maternal Weight Gain: A Report of an Expert Work Group. Suitor, CW. 1997. NCEMCH.

Recent Findings • Maternal water gain, which probably represents lean tissue, is a predictor of birthweight, fat gain is not predictive. • Effect size of energy intake on weight gain is modest. • When maternal weight gain is within IOM range, incidence of SGA & LBW is reduced

Recent Findings, cont. • Increasing prevalence of obesity in population calls for reexamination of effects of pregnancy weight gain & retention • Increased parity is associated with increased weight gain in adulthood. • Post delivery, African American women have greater weight retention than white women with the same pregnancy weight gain.

Recommendations for Practice • Promote use of IOM recommendations for rate of weight gain as well as total weight gain. • Promote strategies for weight gain within recommended ranges. • Promote healthy eating

• Until more is known, two groups of special concern, Adolescents and African American women should be advised to stay within IOM ranges without either restricting weight gain or encouraging weight gain at the upper end of the range.

Multiple Births • Optimal range of birthweight: – Twins: 2500 -2800 g at 36 -37 weeks – Triplets: 1900 -2000 g at 34 -36 weeks • Maternal weight gain of 40 -50 pounds with 1. 5 pounds per week during second half of pregnancy is associated with optimal twin birthweights • Weight gain of < 0. 85 pounds per week before 24 weeks associated with IUGR and morbidity.

Carmichael- what are women actually doing? (AJPH, 1998) • Cohort: 7002 singleton deliveries with good outcomes at UCSF between 19801990 • Good outcomes = vaginal delivery, term (>37 weeks), live, AGA, no maternal diabetes or hypertension

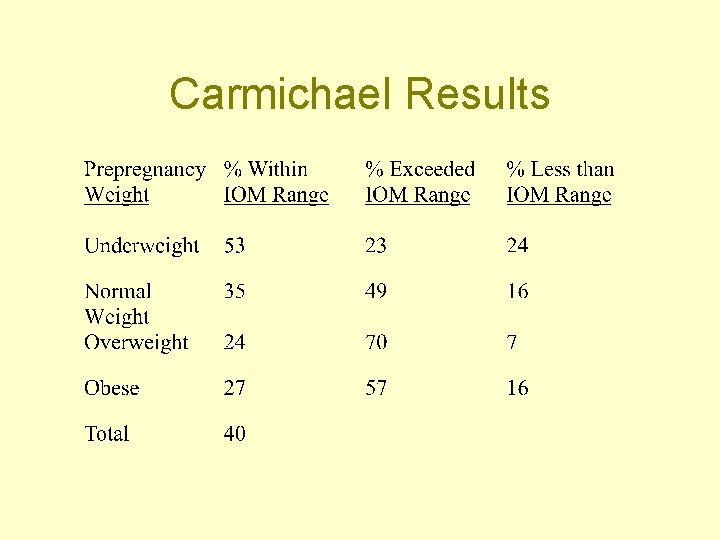

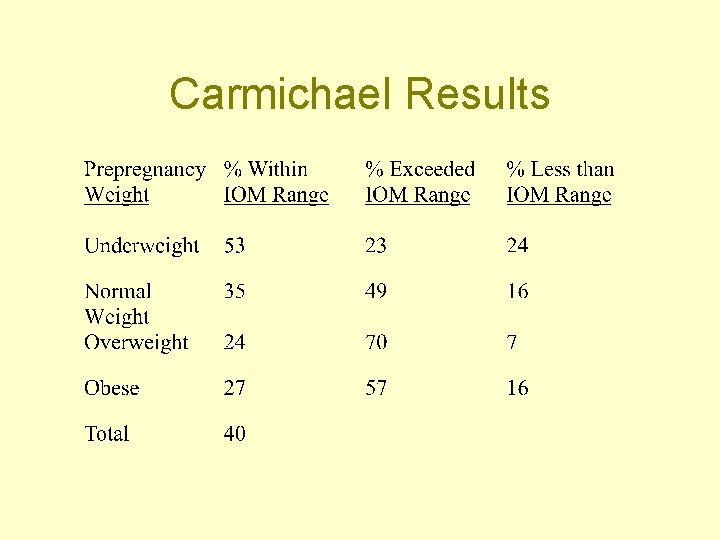

Carmichael Results

Carmichael Discussion • More than half the women fell outside of IOM ranges • Higher gains may be associated with higher postpartum weight retention • Monitoring of weight gain is not highly sensitive when used in isolation • Many questions remain about the utility of monitoring weight gain, standards, and counseling.

Microbial physiology lecture notes

Microbial physiology lecture notes Cleft palate weight gain

Cleft palate weight gain Fluoxitine weight gain

Fluoxitine weight gain Weight gain in infant

Weight gain in infant Trazodone weight gain

Trazodone weight gain Weight gain ggg

Weight gain ggg Lana del ret weight gain

Lana del ret weight gain King lear historical context

King lear historical context Components of weight gain during pregnancy

Components of weight gain during pregnancy Justin moore weight gain

Justin moore weight gain 01:640:244 lecture notes - lecture 15: plat, idah, farad

01:640:244 lecture notes - lecture 15: plat, idah, farad Tolerable weight is a body weight

Tolerable weight is a body weight What is bulk reducing

What is bulk reducing Social psychology lecture

Social psychology lecture Forensic psychology lecture

Forensic psychology lecture Introduction to psychology lecture

Introduction to psychology lecture Definition of health psychology

Definition of health psychology Energy energy transfer and general energy analysis

Energy energy transfer and general energy analysis Energy energy transfer and general energy analysis

Energy energy transfer and general energy analysis Utilities and energy lectures

Utilities and energy lectures Positive psychology ap psychology definition

Positive psychology ap psychology definition Social traps ap psychology definition

Social traps ap psychology definition Fundamental attribution error ap psychology

Fundamental attribution error ap psychology Introspection psychology

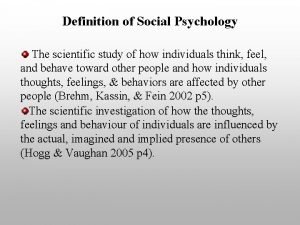

Introspection psychology Social psychology definition psychology

Social psychology definition psychology Health psychology definition ap psychology

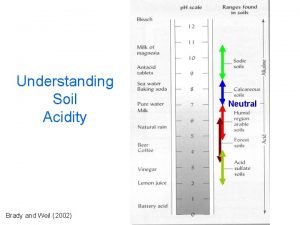

Health psychology definition ap psychology Brady and weil 2002

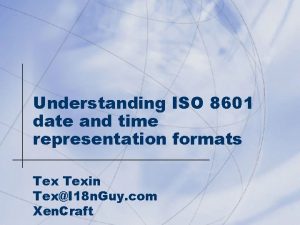

Brady and weil 2002 Time representation format

Time representation format 14/4/2002

14/4/2002 Ccot essay

Ccot essay 08/07/2002

08/07/2002 Rmc 13-82

Rmc 13-82 Access 2002

Access 2002 Marine insurance act uganda

Marine insurance act uganda Loi kouchner du 4 mars 2002 consentement

Loi kouchner du 4 mars 2002 consentement Egumis是什么

Egumis是什么 Samiti sabhya role in odisha

Samiti sabhya role in odisha Flugtag 88

Flugtag 88 Solar eclipse of december 4, 2002

Solar eclipse of december 4, 2002 El decreto 3222 de 2002 en su artículo 1° nos habla de

El decreto 3222 de 2002 en su artículo 1° nos habla de Biologijos egzamino programa

Biologijos egzamino programa Young arthur 2002

Young arthur 2002 Is spiderman a hero

Is spiderman a hero Kota miura

Kota miura Southwest airlines 2002

Southwest airlines 2002 2002

2002 Decreto 1279 de 2002

Decreto 1279 de 2002 Peraturan pembebanan indonesia untuk gedung 1983

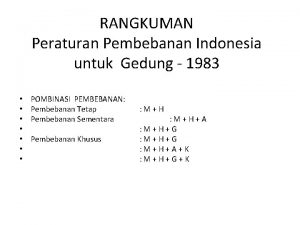

Peraturan pembebanan indonesia untuk gedung 1983 Pocket pc 2002

Pocket pc 2002 Jakob ejersbo 2002

Jakob ejersbo 2002 Joyce weil y calhoun

Joyce weil y calhoun Three days of the condor cda

Three days of the condor cda 2 janvier 2002

2 janvier 2002 Beckham 2002

Beckham 2002 Bonos 2002

Bonos 2002 Carrie 2002

Carrie 2002 Halide with 6 energy levels

Halide with 6 energy levels Cc 2002

Cc 2002 Adaptation. 2002

Adaptation. 2002 Powerpoint 2002

Powerpoint 2002 Copyright 2002

Copyright 2002 Numbers in words and figures

Numbers in words and figures Kouzes and posner transformational leadership model

Kouzes and posner transformational leadership model Ibm soa architecture

Ibm soa architecture San antonio flood 2002

San antonio flood 2002 Espectro vocal

Espectro vocal Duncan 2002

Duncan 2002 Lopegce

Lopegce Outil de la loi 2002

Outil de la loi 2002 Calendrier janvier 2002

Calendrier janvier 2002 Die another day 2002

Die another day 2002 Konzeptmatrix

Konzeptmatrix August 27 2002

August 27 2002 Hubbs-tait et al 2002

Hubbs-tait et al 2002 Kotler 2002

Kotler 2002 Rational rose diagram

Rational rose diagram Index of suspicion definition

Index of suspicion definition 1 mart 2002

1 mart 2002 Spm 2002

Spm 2002 Spm 2002

Spm 2002 Keylozis nedir tıp

Keylozis nedir tıp Visual studio 2002

Visual studio 2002 Dr. kanupriya chaturvedi

Dr. kanupriya chaturvedi Dr. kanupriya chaturvedi

Dr. kanupriya chaturvedi 2002

2002 5 novembre 2002

5 novembre 2002 4122002

4122002 Wolrd cup 2002

Wolrd cup 2002 Nrs 2002 başlangıç taraması

Nrs 2002 başlangıç taraması Feed 2002

Feed 2002 Schofield formülü

Schofield formülü Copyright 2002

Copyright 2002 Calendario escolar 2001-2002 sep

Calendario escolar 2001-2002 sep Billets en francs entre 1800 et 2002

Billets en francs entre 1800 et 2002 Amc 8 2006

Amc 8 2006 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002

1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Undang-undang republik indonesia nomor 23 tahun 2002

Undang-undang republik indonesia nomor 23 tahun 2002 Uu 32 tahun 2002

Uu 32 tahun 2002 T. trimpe 2006 http://sciencespot.net/

T. trimpe 2006 http://sciencespot.net/