Diagnosis Prevention and Management of Statin Adverse Effects

- Slides: 70

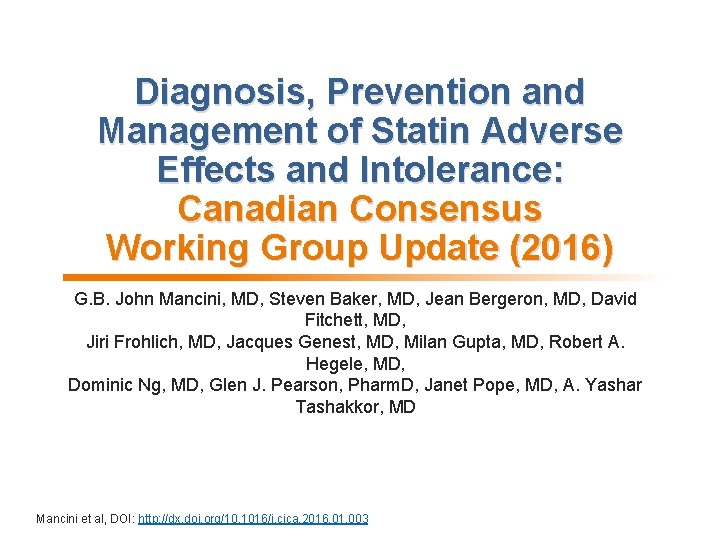

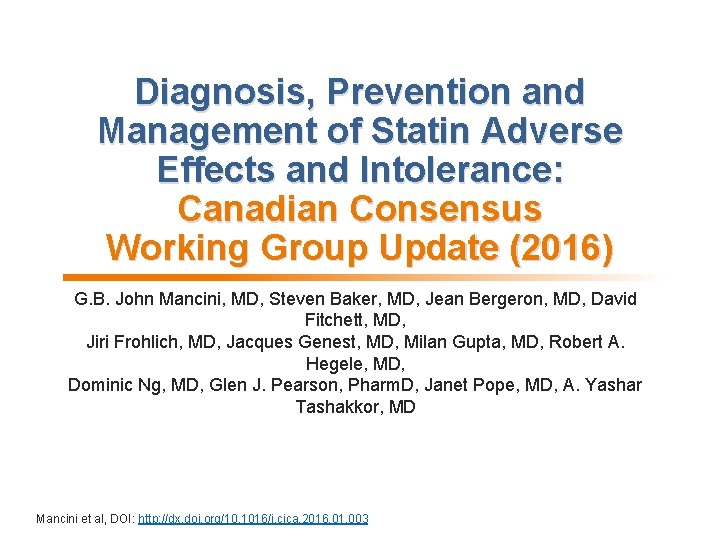

Diagnosis, Prevention and Management of Statin Adverse Effects and Intolerance: Canadian Consensus Working Group Update (2016) G. B. John Mancini, MD, Steven Baker, MD, Jean Bergeron, MD, David Fitchett, MD, Jiri Frohlich, MD, Jacques Genest, MD, Milan Gupta, MD, Robert A. Hegele, MD, Dominic Ng, MD, Glen J. Pearson, Pharm. D, Janet Pope, MD, A. Yashar Tashakkor, MD Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Background • The Canadian Consensus Working Group (CCWG) has published consensus statements in 2011 and 2013 regarding statinassociated adverse effects and intolerance. • The Cardiovascular Imaging Research Core Laboratory (CIRCL), University of British Columbia maintained an updated library of relevant citations from the time of the 2013 publication to December 2015, this 2016 update is based on the latter reference base. • Authors were assigned sections, created summaries and representative slides, presented to each other at a single face-toface meeting and then reviewed, critiqued and finalized a collated document for peer review and publication (CJC 2016). • Logistical support for the meeting was provided by Bridge Medical Communications, Ontario Canada through a contract with AMGEN, Canada. • Content, interpretations and recommendations were created solely andet al, independently by the CCWG. Mancini DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

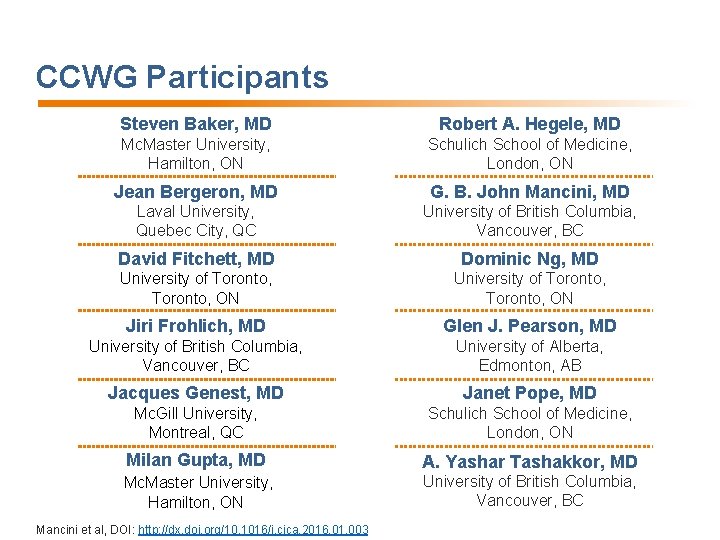

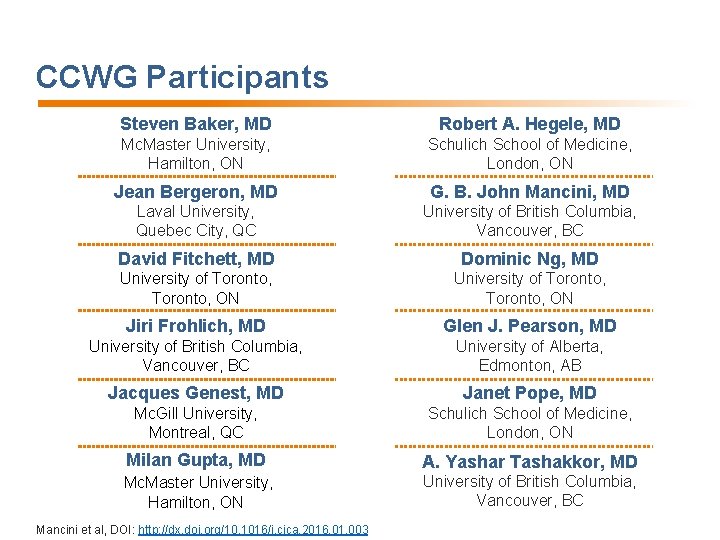

CCWG Participants Steven Baker, MD Robert A. Hegele, MD Mc. Master University, Hamilton, ON Schulich School of Medicine, London, ON Jean Bergeron, MD G. B. John Mancini, MD Laval University, Quebec City, QC University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC David Fitchett, MD Dominic Ng, MD University of Toronto, ON Jiri Frohlich, MD Glen J. Pearson, MD University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB Jacques Genest, MD Janet Pope, MD Mc. Gill University, Montreal, QC Schulich School of Medicine, London, ON Milan Gupta, MD A. Yashar Tashakkor, MD Mc. Master University, Hamilton, ON University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

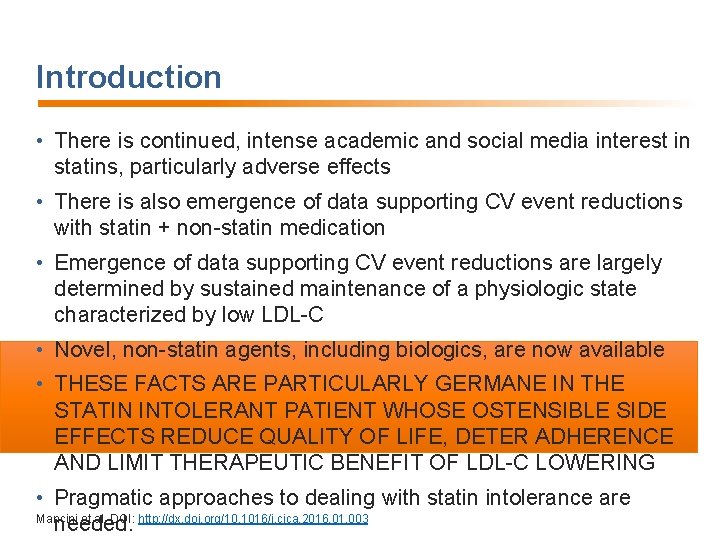

Introduction • There is continued, intense academic and social media interest in statins, particularly adverse effects • There is also emergence of data supporting CV event reductions with statin + non-statin medication • Emergence of data supporting CV event reductions are largely determined by sustained maintenance of a physiologic state characterized by low LDL-C • Novel, non-statin agents, including biologics, are now available • THESE FACTS ARE PARTICULARLY GERMANE IN THE STATIN INTOLERANT PATIENT WHOSE OSTENSIBLE SIDE EFFECTS REDUCE QUALITY OF LIFE, DETER ADHERENCE AND LIMIT THERAPEUTIC BENEFIT OF LDL-C LOWERING • Pragmatic approaches to dealing with statin intolerance are Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 needed.

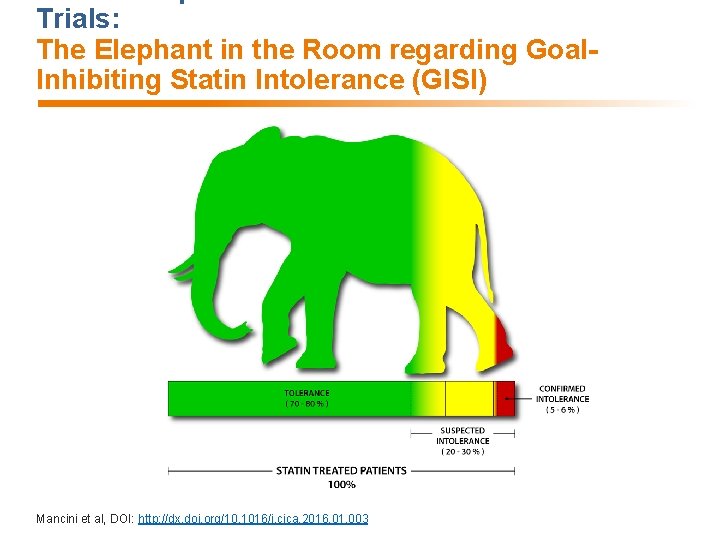

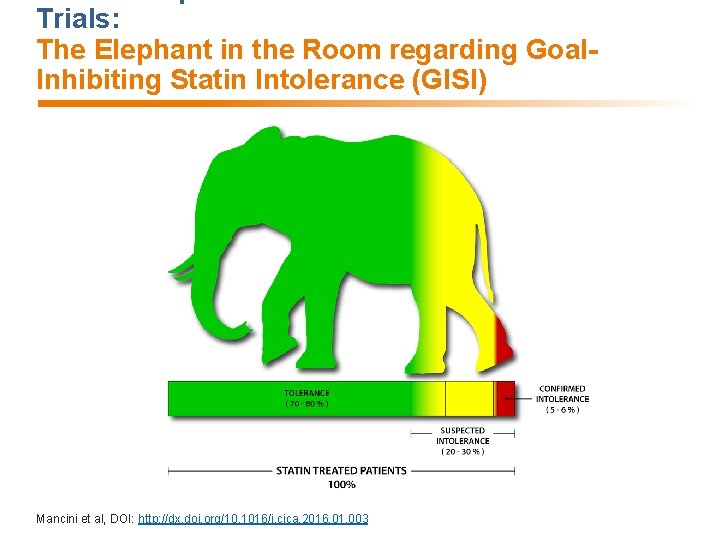

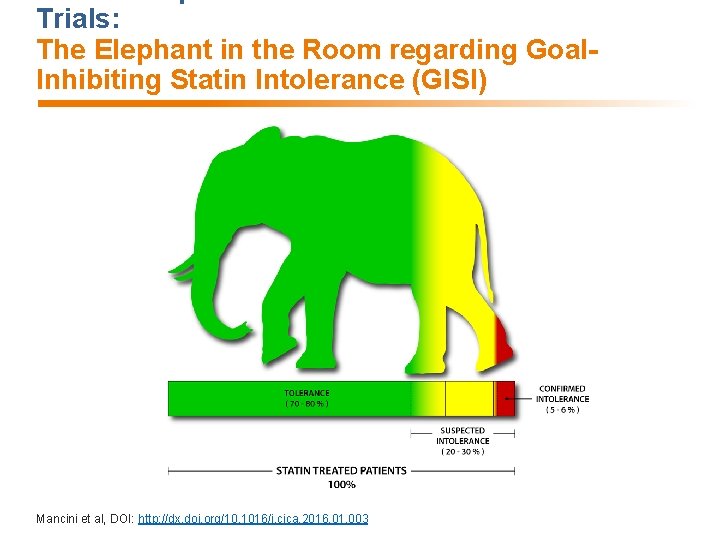

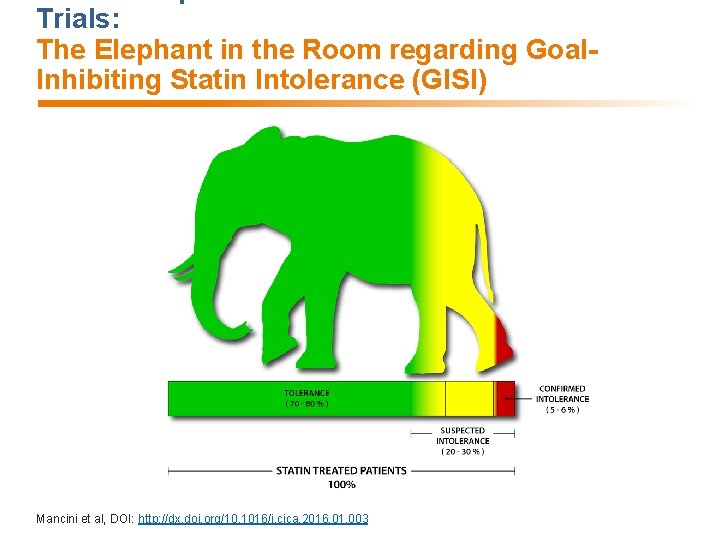

Trials: The Elephant in the Room regarding Goal. Inhibiting Statin Intolerance (GISI) Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

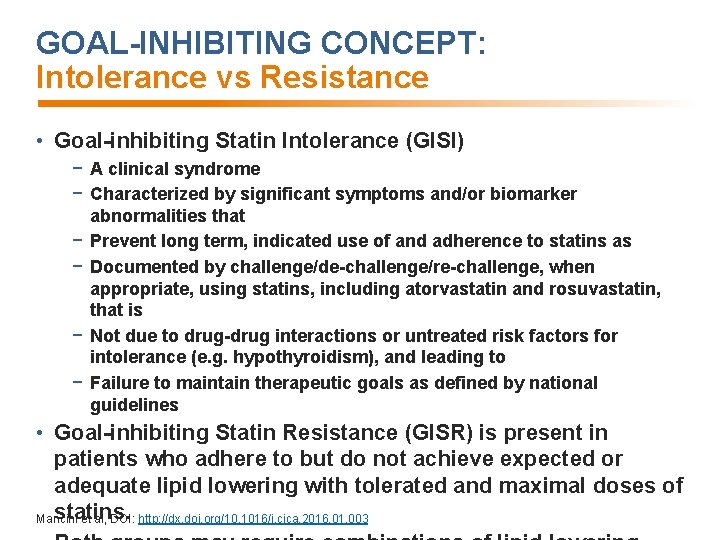

GOAL-INHIBITING CONCEPT: Intolerance vs Resistance • Goal-inhibiting Statin Intolerance (GISI) − A clinical syndrome − Characterized by significant symptoms and/or biomarker abnormalities that − Prevent long term, indicated use of and adherence to statins as − Documented by challenge/de-challenge/re-challenge, when appropriate, using statins, including atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, that is − Not due to drug-drug interactions or untreated risk factors for intolerance (e. g. hypothyroidism), and leading to − Failure to maintain therapeutic goals as defined by national guidelines • Goal-inhibiting Statin Resistance (GISR) is present in patients who adhere to but do not achieve expected or adequate lipid lowering with tolerated and maximal doses of statins. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

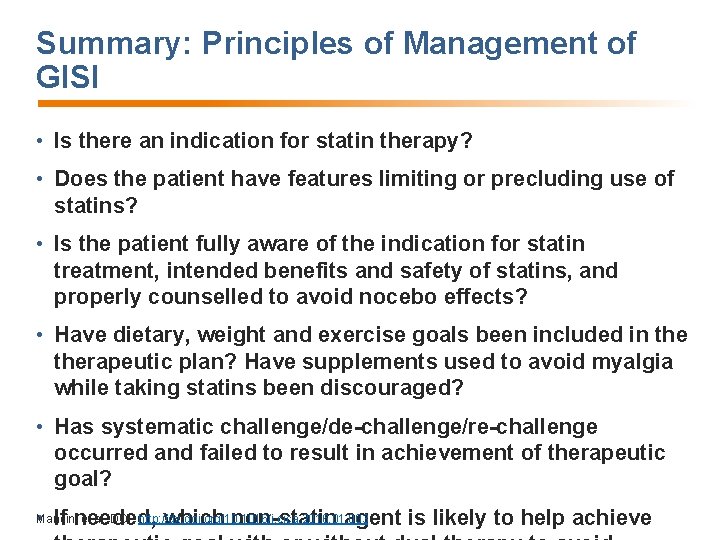

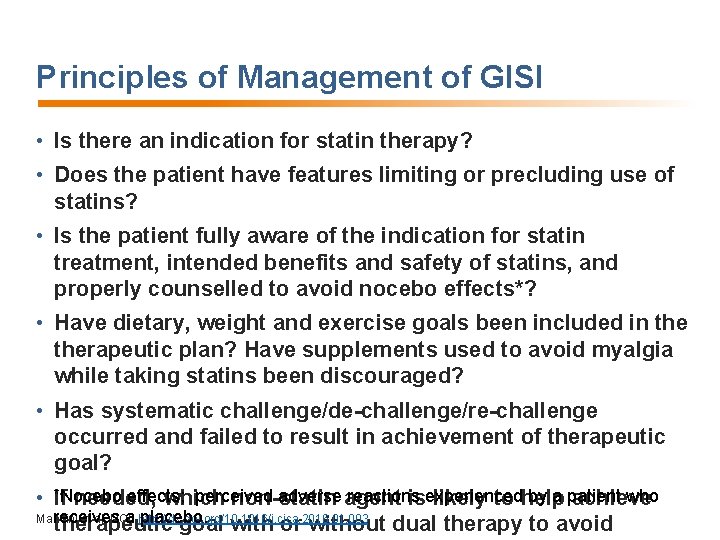

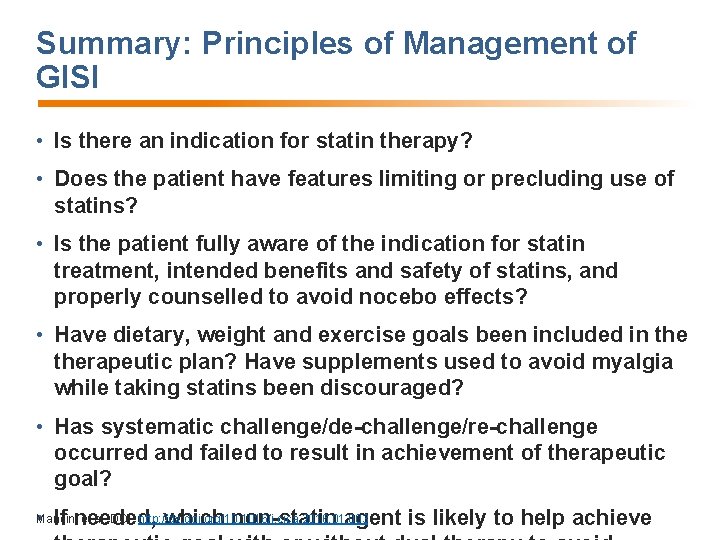

Principles of Management of GISI • Is there an indication for statin therapy? • Does the patient have features limiting or precluding use of statins? • Is the patient fully aware of the indication for statin treatment, intended benefits and safety of statins, and properly counselled to avoid nocebo effects*? • Have dietary, weight and exercise goals been included in therapeutic plan? Have supplements used to avoid myalgia while taking statins been discouraged? • Has systematic challenge/de-challenge/re-challenge occurred and failed to result in achievement of therapeutic goal? effects; perceived adverse agent reactions by a patient who • *Nocebo If needed, which non-statin isexperienced likely to help achieve Mancini et al, DOI: receives a http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 placebo. therapeutic goal with or without dual therapy to avoid

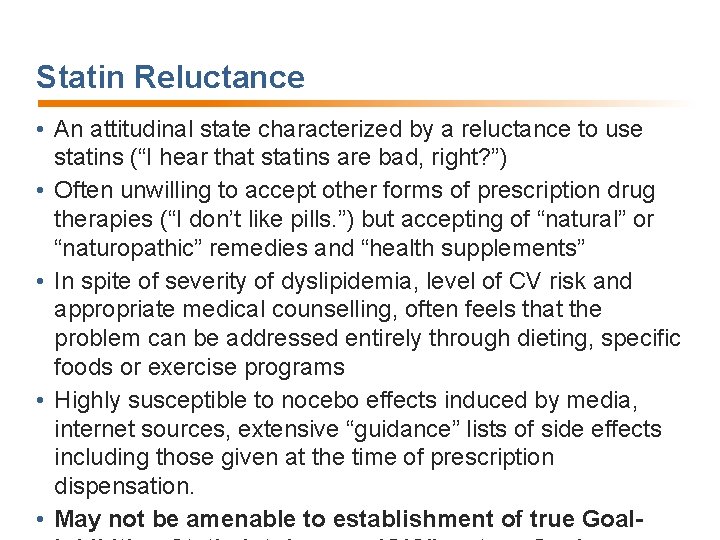

Statin Reluctance • An attitudinal state characterized by a reluctance to use statins (“I hear that statins are bad, right? ”) • Often unwilling to accept other forms of prescription drug therapies (“I don’t like pills. ”) but accepting of “natural” or “naturopathic” remedies and “health supplements” • In spite of severity of dyslipidemia, level of CV risk and appropriate medical counselling, often feels that the problem can be addressed entirely through dieting, specific foods or exercise programs • Highly susceptible to nocebo effects induced by media, internet sources, extensive “guidance” lists of side effects including those given at the time of prescription dispensation. • May not be amenable to establishment of true Goal-

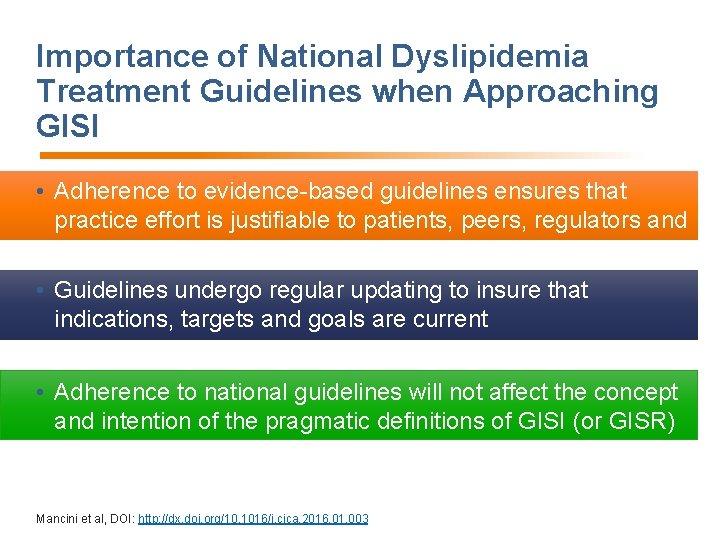

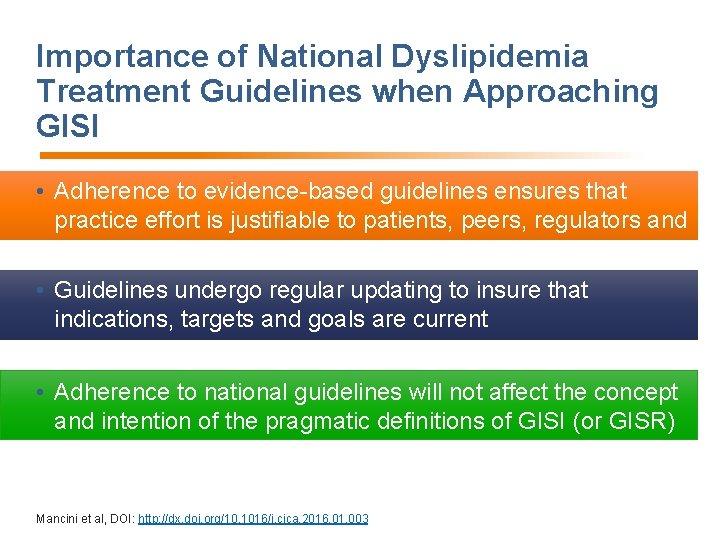

Importance of National Dyslipidemia Treatment Guidelines when Approaching GISI • Adherence to evidence-based guidelines ensures that practice effort is justifiable to patients, peers, regulators and payers • Guidelines undergo regular updating to insure that indications, targets and goals are current • Adherence to national guidelines will not affect the concept and intention of the pragmatic definitions of GISI (or GISR) Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

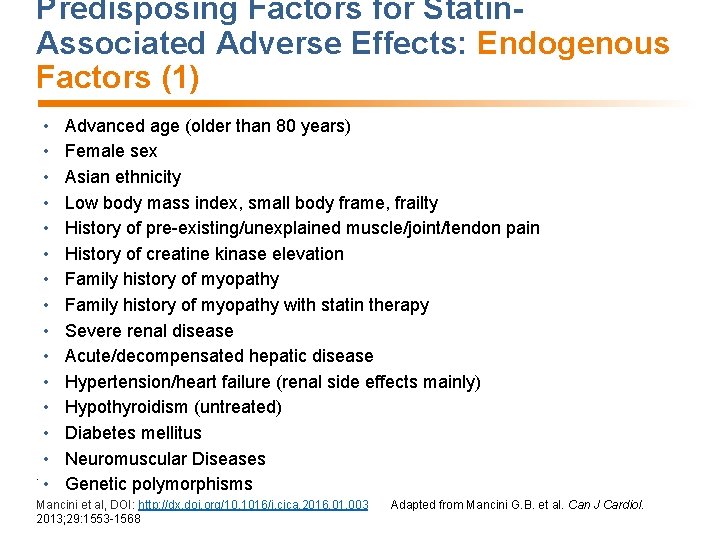

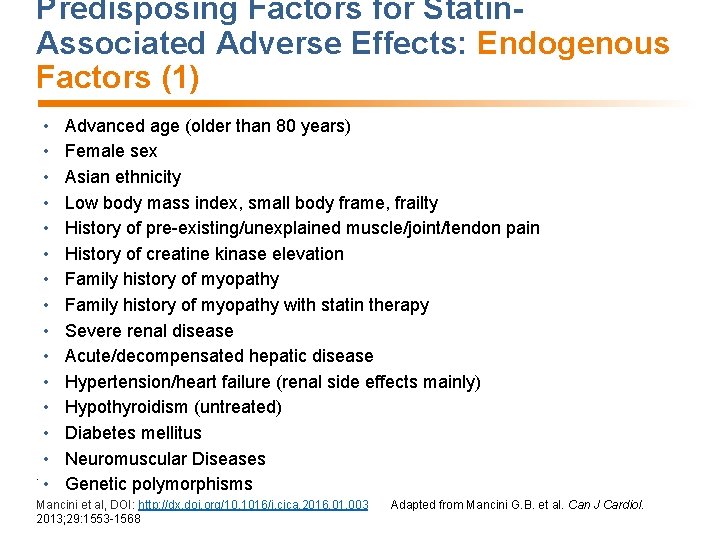

Predisposing Factors for Statin. Associated Adverse Effects: Endogenous Factors (1) • • • • Advanced age (older than 80 years) Female sex Asian ethnicity Low body mass index, small body frame, frailty History of pre-existing/unexplained muscle/joint/tendon pain History of creatine kinase elevation Family history of myopathy with statin therapy Severe renal disease Acute/decompensated hepatic disease Hypertension/heart failure (renal side effects mainly) Hypothyroidism (untreated) Diabetes mellitus Neuromuscular Diseases Genetic polymorphisms Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 2013; 29: 1553 -1568 Adapted from Mancini G. B. et al. Can J Cardiol.

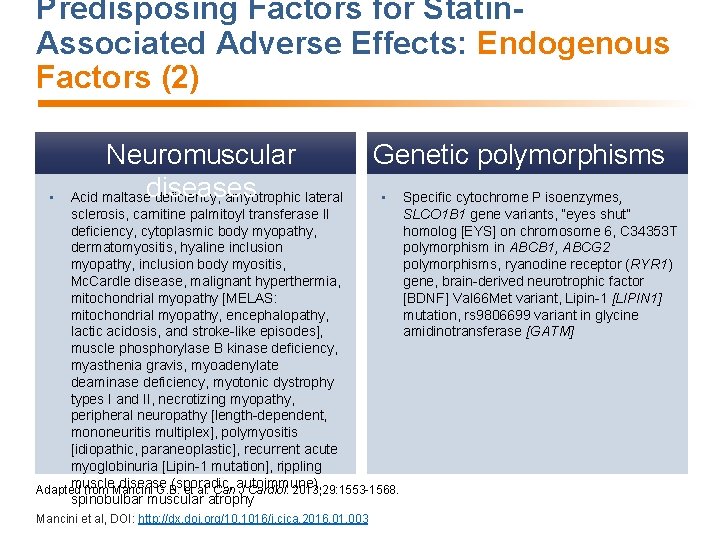

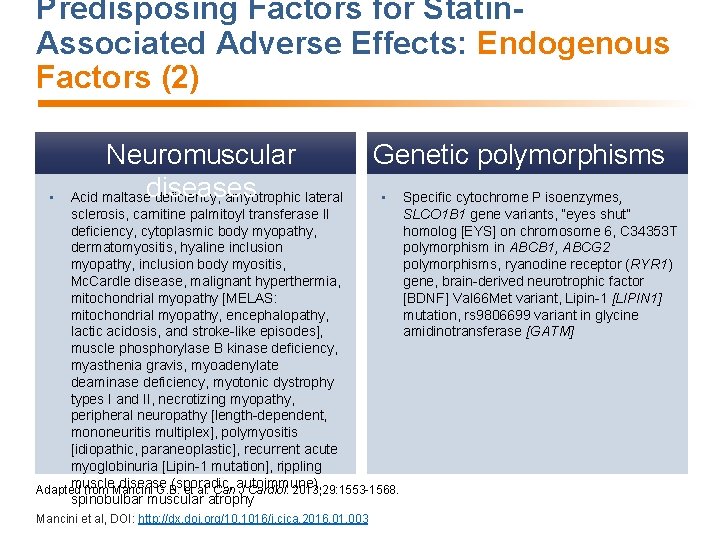

Predisposing Factors for Statin. Associated Adverse Effects: Endogenous Factors (2) • Neuromuscular Acid maltasediseases deficiency, amyotrophic lateral Genetic polymorphisms • sclerosis, carnitine palmitoyl transferase II deficiency, cytoplasmic body myopathy, dermatomyositis, hyaline inclusion myopathy, inclusion body myositis, Mc. Cardle disease, malignant hyperthermia, mitochondrial myopathy [MELAS: mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes], muscle phosphorylase B kinase deficiency, myasthenia gravis, myoadenylate deaminase deficiency, myotonic dystrophy types I and II, necrotizing myopathy, peripheral neuropathy [length-dependent, mononeuritis multiplex], polymyositis [idiopathic, paraneoplastic], recurrent acute myoglobinuria [Lipin-1 mutation], rippling muscle disease (sporadic, autoimmune), Adapted from Mancini G. B. et al. Can J Cardiol. 2013; 29: 1553 -1568. spinobulbar muscular atrophy Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 Specific cytochrome P isoenzymes, SLCO 1 B 1 gene variants, “eyes shut” homolog [EYS] on chromosome 6, C 34353 T polymorphism in ABCB 1, ABCG 2 polymorphisms, ryanodine receptor (RYR 1) gene, brain-derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF] Val 66 Met variant, Lipin-1 [LIPIN 1] mutation, rs 9806699 variant in glycine amidinotransferase [GATM]

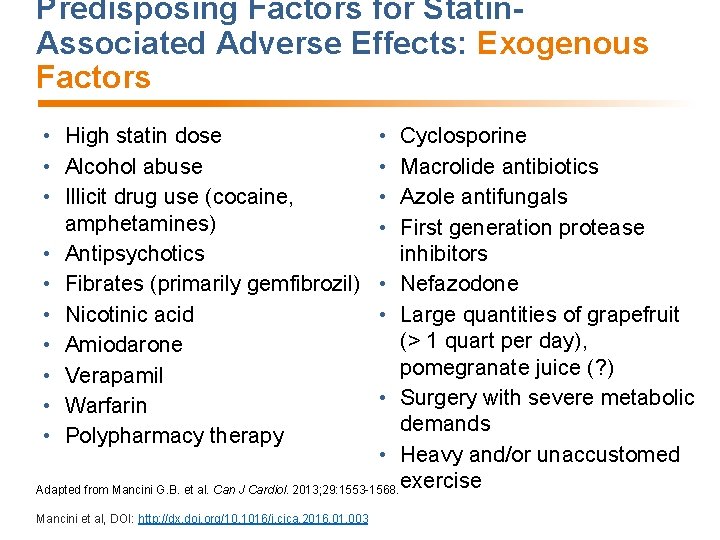

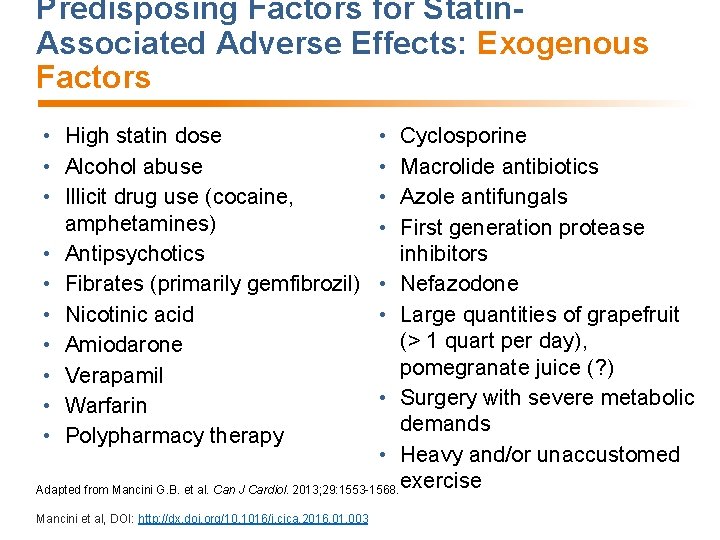

Predisposing Factors for Statin. Associated Adverse Effects: Exogenous Factors • High statin dose • Alcohol abuse • Illicit drug use (cocaine, amphetamines) • Antipsychotics • Fibrates (primarily gemfibrozil) • Nicotinic acid • Amiodarone • Verapamil • Warfarin • Polypharmacy therapy • • Cyclosporine Macrolide antibiotics Azole antifungals First generation protease inhibitors • Nefazodone • Large quantities of grapefruit (> 1 quart per day), pomegranate juice (? ) • Surgery with severe metabolic demands • Heavy and/or unaccustomed Adapted from Mancini G. B. et al. Can J Cardiol. 2013; 29: 1553 -1568. exercise Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Genetic Risk for Goal-inhibiting Statin Intolerance • Both common and rare genetic variants have been studied • Reported genes encode proteins that regulate: − Statin pharmacokinetics (e. g. drug receptors, transporters and metabolizing enzymes) − Statin pharmacodynamics (e. g. muscle metabolizing enzymes) • None consistently replicated or “ready for prime time” clinical use Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Patient Counselling: Avoid Nocebo Effects • Immediate impact of side effects negatively alters perceived longterm CV risk reduction benefit and may often outweigh them • Prepare patients for repository of data on internet, social media, long list of side effects distributed by pharmacies etc • Encourage patient to discuss any concerns with health care provider before jumping to any conclusions or making Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 any treatment changes

Silver Bullets that Don’t Yet Hit the Target! • Some patients attempt to try to “treat” myalgia with supplements while taking statins but patients should be counselled that none have definitely been proven to do so: − Coenzyme Q 10 − Vitamin D − Red yeast rice (N. B unregulated lovastatin-like drug in the rice fungus) − Berberol (plant extract) − Glucosamine IDENTIFY ALL SUPPLEMENTS USED BY THE PATIENT AND READ THEIR LABELS CAREFULLY Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Challenge/De-challenge/Re-challenge: A Cornerstone for Documenting GISI • Everyone has the potential to develop toxicity at a high enough dose of statins but currently available dosage maximums have been shown to be extremely safe • The terms “complete” and “partial” intolerance refer to approved dosages • “Complete intolerance”: inability to tolerate any statin • “Partial intolerance”: ability to tolerate a statin at some dose Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Getting to Goal Pragmatically • Atorvastatin and rosuvastatin are the most potent statins • They are both available in a broad dosage range • They are both more useful than other statins in alternate day or intermittent dosing strategies due to longer half life • They are most likely to achieve goal and so their failure to do so IS A STRONG INDICATION FOR ADDING ANOTHER AGENT to either: − the maximally tolerated dose and dosing frequency of either atorvastatin or rosuvastatin OR − the maximally tolerated dose of less potent statins (e. g. fluvastatin, Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

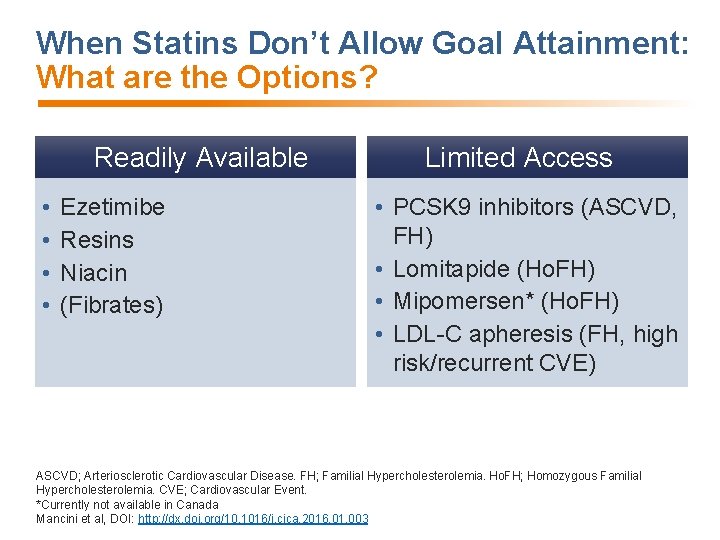

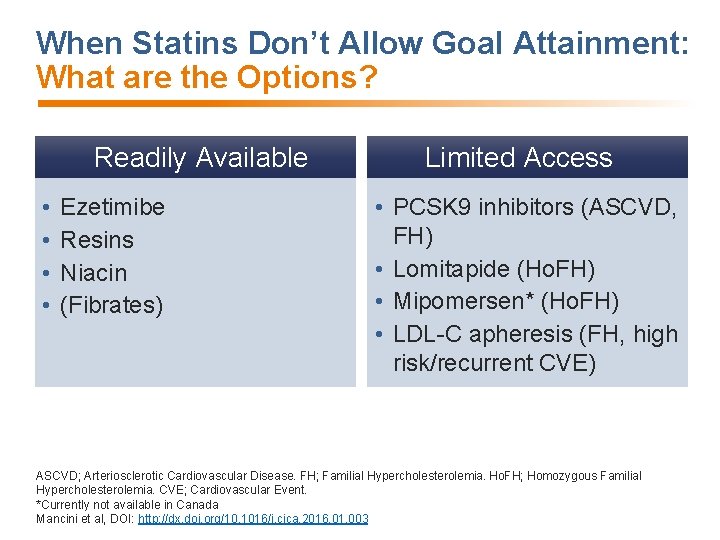

When Statins Don’t Allow Goal Attainment: What are the Options? Readily Available • • Ezetimibe Resins Niacin (Fibrates) Limited Access • PCSK 9 inhibitors (ASCVD, FH) • Lomitapide (Ho. FH) • Mipomersen* (Ho. FH) • LDL-C apheresis (FH, high risk/recurrent CVE) ASCVD; Arteriosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. FH; Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Ho. FH; Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia. CVE; Cardiovascular Event. *Currently not available in Canada Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

GISI in a NUTSHELL START/STOP LOWER ADD Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

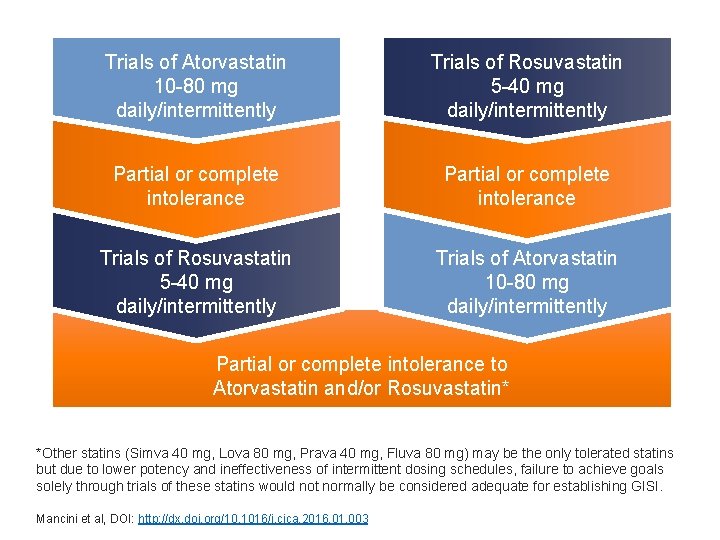

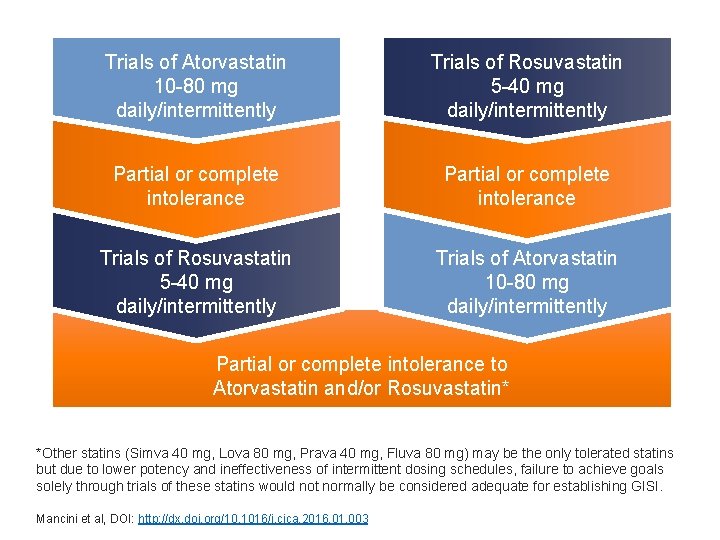

Trials of Atorvastatin 10 -80 mg daily/intermittently Trials of Rosuvastatin 5 -40 mg daily/intermittently Partial or complete intolerance Trials of Rosuvastatin 5 -40 mg daily/intermittently Trials of Atorvastatin 10 -80 mg daily/intermittently Partial or complete intolerance to Atorvastatin and/or Rosuvastatin* *Other statins (Simva 40 mg, Lova 80 mg, Prava 40 mg, Fluva 80 mg) may be the only tolerated statins but due to lower potency and ineffectiveness of intermittent dosing schedules, failure to achieve goals solely through trials of these statins would not normally be considered adequate for establishing GISI. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

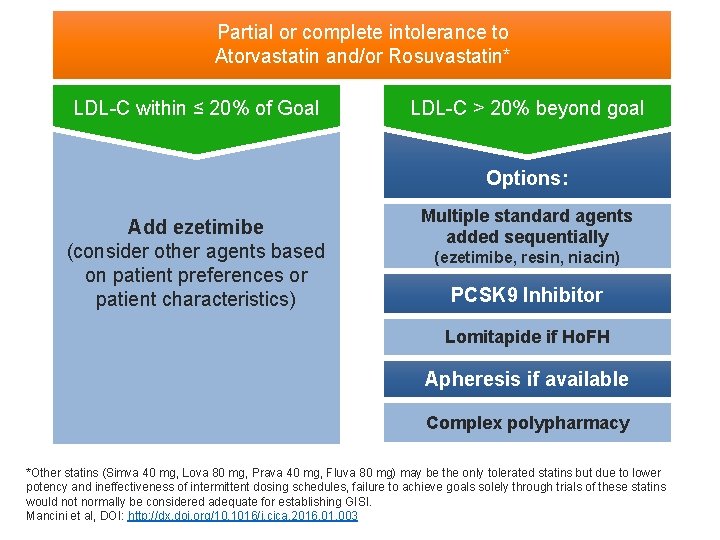

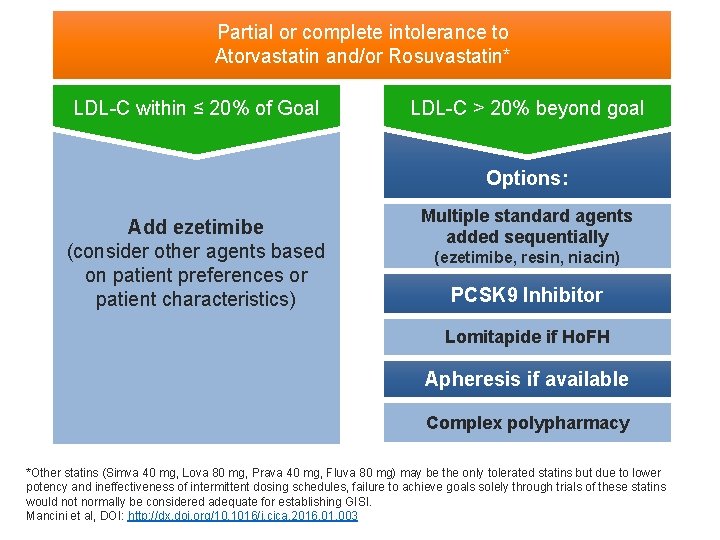

Partial or complete intolerance to Atorvastatin and/or Rosuvastatin* LDL-C within ≤ 20% of Goal LDL-C > 20% beyond goal Options: Add ezetimibe (consider other agents based on patient preferences or patient characteristics) Multiple standard agents added sequentially (ezetimibe, resin, niacin) PCSK 9 Inhibitor Lomitapide if Ho. FH Apheresis if available Complex polypharmacy *Other statins (Simva 40 mg, Lova 80 mg, Prava 40 mg, Fluva 80 mg) may be the only tolerated statins but due to lower potency and ineffectiveness of intermittent dosing schedules, failure to achieve goals solely through trials of these statins would not normally be considered adequate for establishing GISI. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

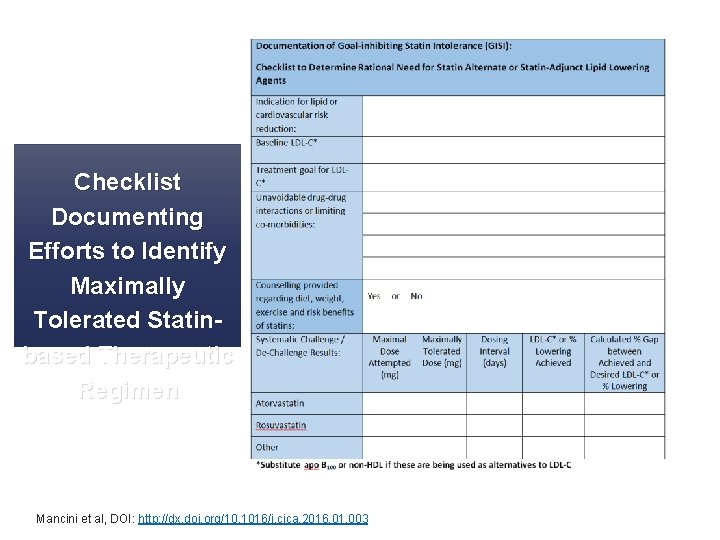

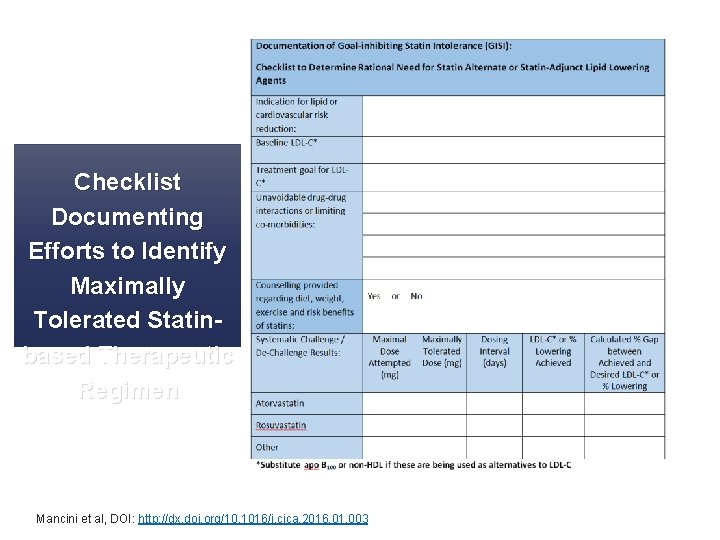

Checklist Documenting Efforts to Identify Maximally Tolerated Statinbased Therapeutic Regimen Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

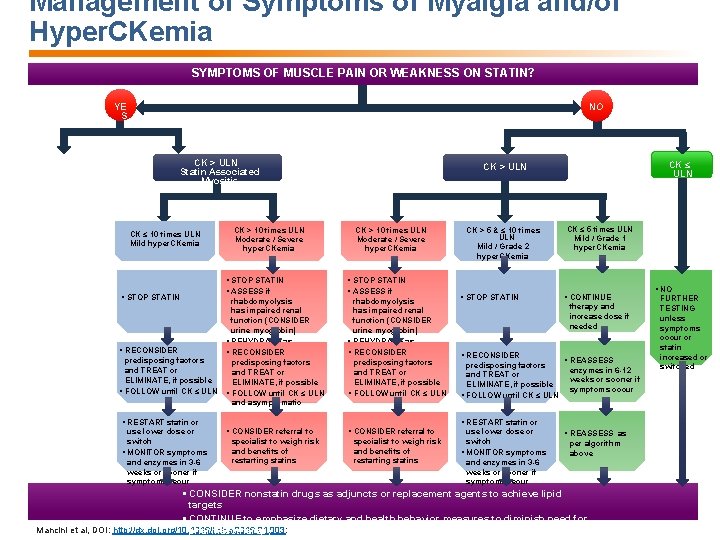

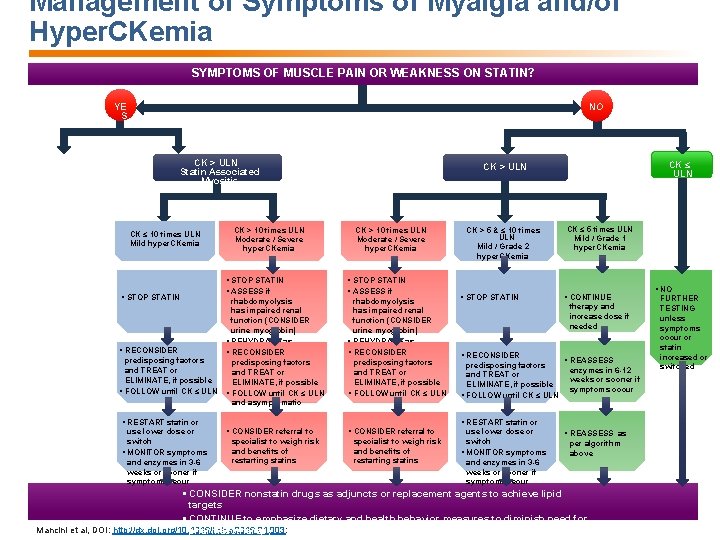

Management of Symptoms of Myalgia and/or Hyper. CKemia SYMPTOMS OF MUSCLE PAIN OR WEAKNESS ON STATIN? YE S NO CK > ULN Statin Associated Myositis CK ≤ 10 times ULN Mild hyper. CKemia § STOP STATIN CK > 10 times ULN Moderate / Severe hyper. CKemia § STOP STATIN § ASSESS if rhabdomyolysis has impaired renal function (CONSIDER urine myoglobin) § REHYDRATE as § RECONSIDER § warranted RECONSIDER predisposing factors and TREAT or ELIMINATE, if possible § FOLLOW until CK ≤ ULN and asymptomatic CK > 10 times ULN Moderate / Severe hyper. CKemia § STOP STATIN § ASSESS if rhabdomyolysis has impaired renal function (CONSIDER urine myoglobin) § REHYDRATE as § warranted RECONSIDER predisposing factors and TREAT or ELIMINATE, if possible § FOLLOW until CK ≤ ULN § RESTART statin or use lower dose or switch § MONITOR symptoms and enzymes in 3 -6 weeks or sooner if symptoms recur CK ≤ ULN CK > 5 & ≤ 10 times ULN Mild / Grade 2 hyper. CKemia § STOP STATIN CK ≤ 5 times ULN Mild / Grade 1 hyper. CKemia § CONTINUE therapy and increase dose if needed § RECONSIDER predisposing factors and TREAT or ELIMINATE, if possible § FOLLOW until CK ≤ ULN § REASSESS enzymes in 6 -12 weeks or sooner if symptoms occur § RESTART statin or § CONSIDER referral to specialist to weigh risk and benefits of restarting statins use lower dose or switch § MONITOR symptoms and enzymes in 3 -6 weeks or sooner if symptoms recur § REASSESS as per algorithm above § CONSIDER nonstatin drugs as adjuncts or replacement agents to achieve lipid targets § CONTINUE to emphasize dietary and health behavior measures to diminish need for Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003: pharmacotherapy § NO FURTHER TESTING unless symptoms occur or statin increased or switched

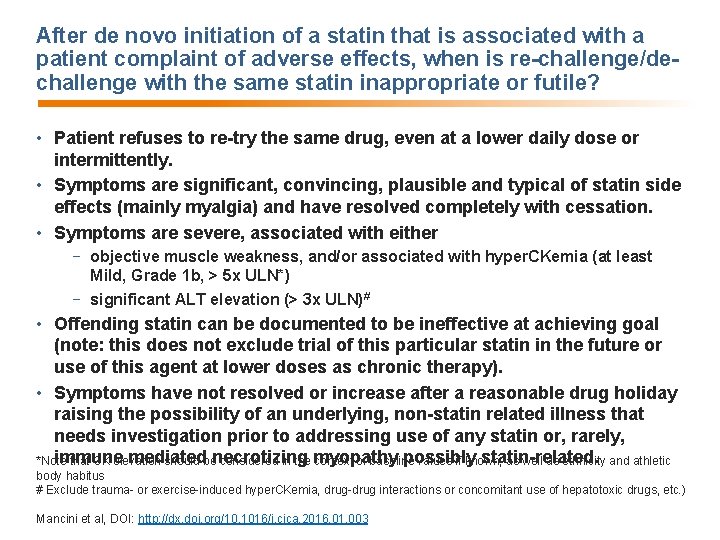

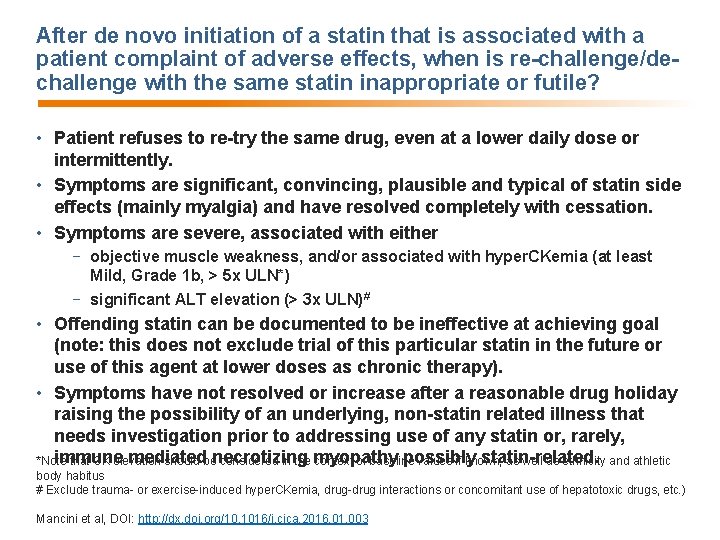

After de novo initiation of a statin that is associated with a patient complaint of adverse effects, when is re-challenge/dechallenge with the same statin inappropriate or futile? • Patient refuses to re-try the same drug, even at a lower daily dose or intermittently. • Symptoms are significant, convincing, plausible and typical of statin side effects (mainly myalgia) and have resolved completely with cessation. • Symptoms are severe, associated with either − objective muscle weakness, and/or associated with hyper. CKemia (at least Mild, Grade 1 b, > 5 x ULN*) − significant ALT elevation (> 3 x ULN)# • Offending statin can be documented to be ineffective at achieving goal (note: this does not exclude trial of this particular statin in the future or use of this agent at lower doses as chronic therapy). • Symptoms have not resolved or increase after a reasonable drug holiday raising the possibility of an underlying, non-statin related illness that needs investigation prior to addressing use of any statin or, rarely, immune mediated possibly statin-related. *Note that CK elevation should benecrotizing considered in the myopathy context of baseline values if known, as well as ethnicity and athletic body habitus # Exclude trauma- or exercise-induced hyper. CKemia, drug-drug interactions or concomitant use of hepatotoxic drugs, etc. ) Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Ezetimibe: Logical Next Choice in GISI within 20% of Goal • Associated with CV risk reduction in combination with statin (SHARP, IMPROVE-IT) • Paucity of side effects • Well documented safety • Muscle-related side effect reports have been rare and not necessarily causal (no known mechanism): − Myopathy (Simard C, Poirier P. Can J Cardiol. 2006; 22: 141 -144; Brahmachari B, Chatterjee S. Indian J Pharmacol. 2015; 47: 563 -564) − Polymyositis (Garcia-Valladares I, Espinoza, L. R. J Rheumatol. 2010; 37: 472) Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

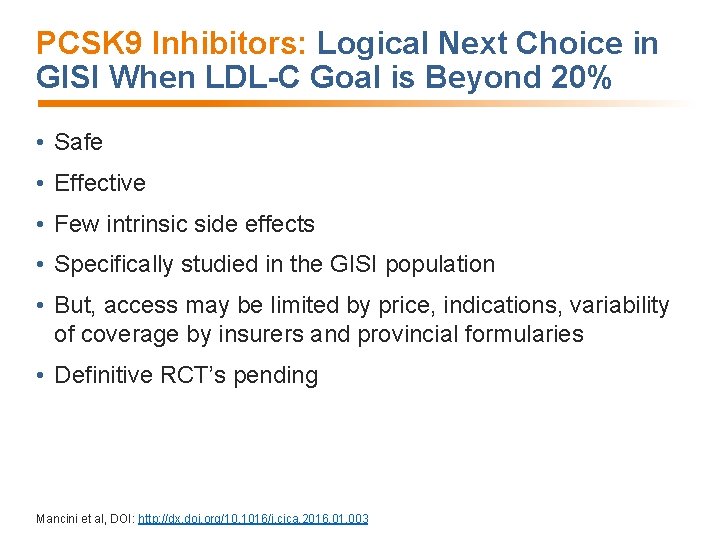

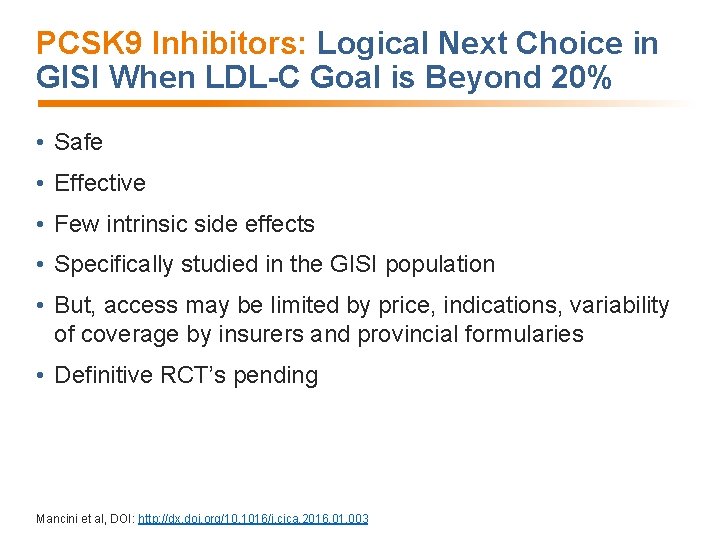

PCSK 9 Inhibitors: Logical Next Choice in GISI When LDL-C Goal is Beyond 20% • Safe • Effective • Few intrinsic side effects • Specifically studied in the GISI population • But, access may be limited by price, indications, variability of coverage by insurers and provincial formularies • Definitive RCT’s pending Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Goal Achievement after Utilizing an Anti-PCSK 9 Antibody in Statin. Intolerant Subjects (GAUSS): Results from a Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo and Ezetimibe Controlled Study David Sullivan, MD, Anders G. Olsson, MD, Rob Scott, MD, Jae B. Kim, MD, Allen Xue, MD, Thomas Liu, MD, Scott M. Wasserman, MD, Evan A. Stein, MD Sullivan D, et al. JAMA. 2012; 308(23): 2497 -2506. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

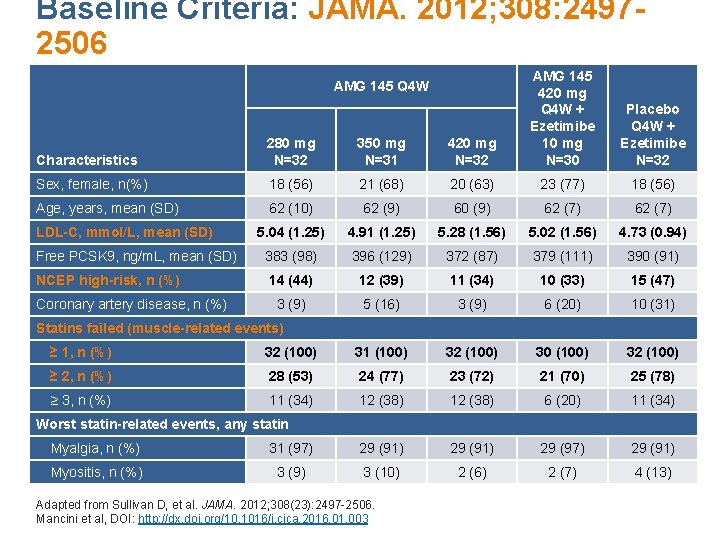

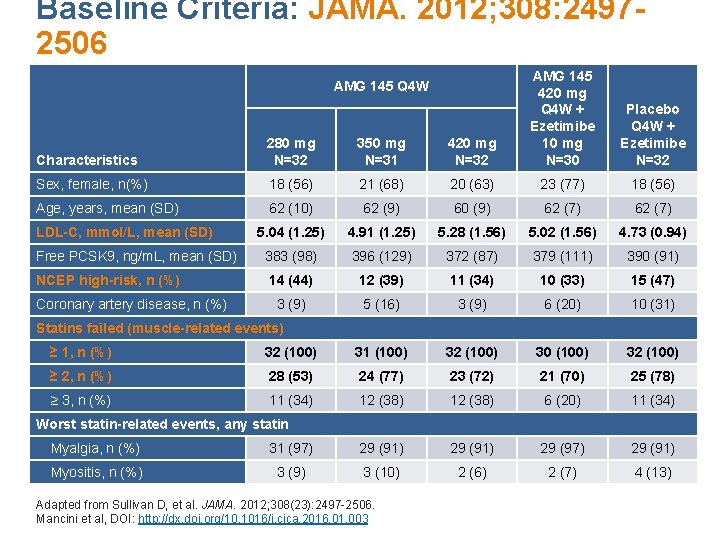

Baseline Criteria: JAMA. 2012; 308: 24972506 Characteristics 280 mg N=32 350 mg N=31 420 mg N=32 AMG 145 420 mg Q 4 W + Ezetimibe 10 mg N=30 Sex, female, n(%) 18 (56) 21 (68) 20 (63) 23 (77) 18 (56) Age, years, mean (SD) 62 (10) 62 (9) 60 (9) 62 (7) 5. 04 (1. 25) 4. 91 (1. 25) 5. 28 (1. 56) 5. 02 (1. 56) 4. 73 (0. 94) Free PCSK 9, ng/m. L, mean (SD) 383 (98) 396 (129) 372 (87) 379 (111) 390 (91) NCEP high-risk, n (%) 14 (44) 12 (39) 11 (34) 10 (33) 15 (47) 3 (9) 5 (16) 3 (9) 6 (20) 10 (31) AMG 145 Q 4 W LDL-C, mmol/L, mean (SD) Coronary artery disease, n (%) Placebo Q 4 W + Ezetimibe N=32 Statins failed (muscle-related events) ≥ 1, n (%) 32 (100) 31 (100) 32 (100) 30 (100) 32 (100) ≥ 2, n (%) 28 (53) 24 (77) 23 (72) 21 (70) 25 (78) ≥ 3, n (%) 11 (34) 12 (38) 6 (20) 11 (34) Worst statin-related events, any statin Myalgia, n (%) 31 (97) 29 (91) 29 (97) 29 (91) Myositis, n (%) 3 (9) 3 (10) 2 (6) 2 (7) 4 (13) Adapted from Sullivan D, et al. JAMA. 2012; 308(23): 2497 -2506. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

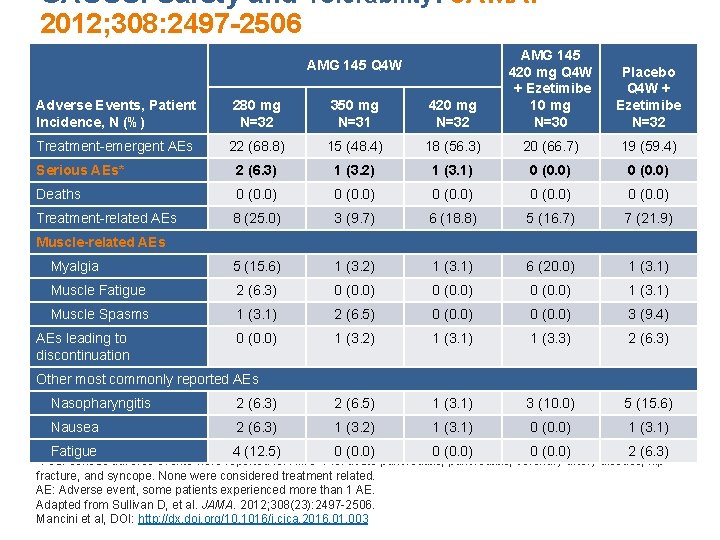

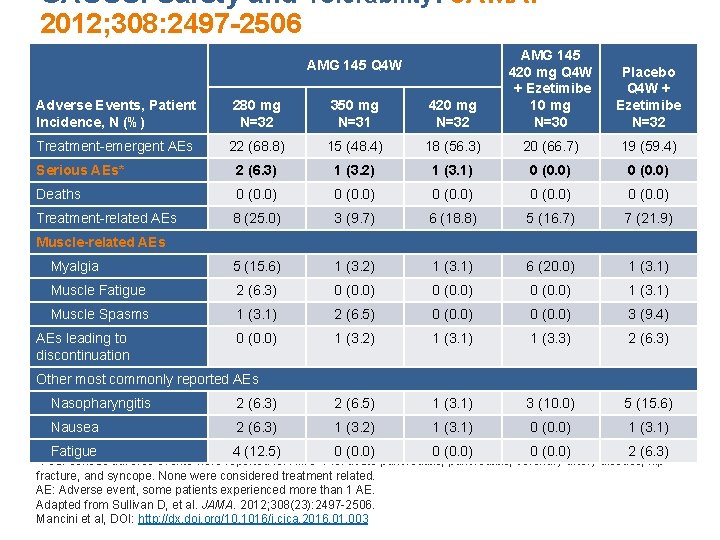

GAUSS: Safety and Tolerability: JAMA. 2012; 308: 2497 -2506 Adverse Events, Patient Incidence, N (%) 280 mg N=32 350 mg N=31 420 mg N=32 AMG 145 420 mg Q 4 W + Ezetimibe 10 mg N=30 Treatment-emergent AEs 22 (68. 8) 15 (48. 4) 18 (56. 3) 20 (66. 7) 19 (59. 4) Serious AEs* 2 (6. 3) 1 (3. 2) 1 (3. 1) 0 (0. 0) Deaths 0 (0. 0) Treatment-related AEs 8 (25. 0) 3 (9. 7) 6 (18. 8) 5 (16. 7) 7 (21. 9) Myalgia 5 (15. 6) 1 (3. 2) 1 (3. 1) 6 (20. 0) 1 (3. 1) Muscle Fatigue 2 (6. 3) 0 (0. 0) 1 (3. 1) Muscle Spasms 1 (3. 1) 2 (6. 5) 0 (0. 0) 3 (9. 4) 0 (0. 0) 1 (3. 2) 1 (3. 1) 1 (3. 3) 2 (6. 3) AMG 145 Q 4 W Placebo Q 4 W + Ezetimibe N=32 Muscle-related AEs leading to discontinuation Other most commonly reported AEs Nasopharyngitis 2 (6. 3) 2 (6. 5) 1 (3. 1) 3 (10. 0) 5 (15. 6) Nausea 2 (6. 3) 1 (3. 2) 1 (3. 1) 0 (0. 0) 1 (3. 1) Fatigue 4 (12. 5) 0 (0. 0) 2 (6. 3) *Four serious adverse events were reported for AMG 145: acute pancreatitis, coronary artery disease, hip fracture, and syncope. None were considered treatment related. AE: Adverse event, some patients experienced more than 1 AE. Adapted from Sullivan D, et al. JAMA. 2012; 308(23): 2497 -2506. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE: Efficacy and safety of alirocumab versus ezetimibe, in patients with statin intolerance defined by placebo run-in and statin rechallenge arm Patrick M Moriarty, MD, Paul D. Thompson, MD, Christopher P. Cannon, MD, John R. Guyton, MD, Jean Bergeron, MD, Franklin J. Zieve, MD, Eric Bruckert, MD Terry A. Jacobson, MD, Marie T. Baccara-Dinet, MD, Jain Zhao, MD, Yunling Du, MD, Ronert Pordy, MD, Daniel Gipe, MD Moriarty P, et al. J Clin Lipidology. 2016; 9(6): 758 -769. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

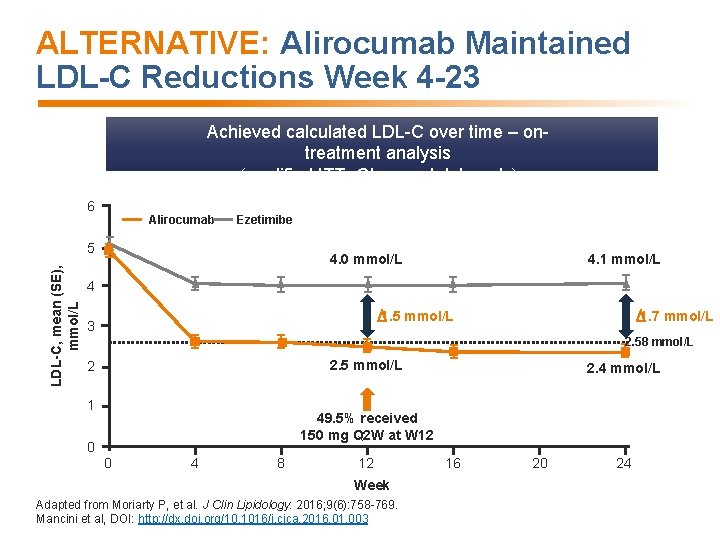

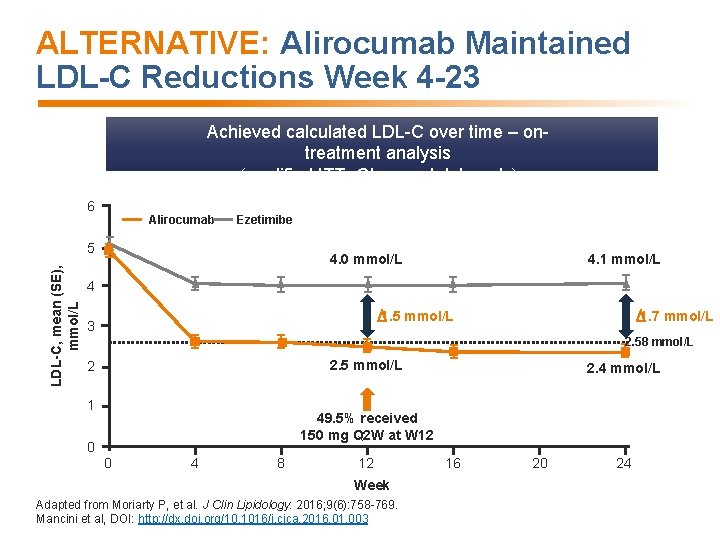

ALTERNATIVE: Alirocumab Maintained LDL-C Reductions Week 4 -23 Achieved calculated LDL-C over time – ontreatment analysis (modified ITT- Observed data only) 6 Alirocumab Ezetimibe LDL-C, mean (SE), mmol/L 5 4. 0 mmol/L 4. 1 mmol/L 4 1. 5 mmol/L 3 1. 7 mmol/L 2. 58 mmol/L 2. 5 mmol/L 2 1 2. 4 mmol/L 49. 5% received 150 mg Q 2 W at W 12 0 0 4 8 12 Week Adapted from Moriarty P, et al. J Clin Lipidology. 2016; 9(6): 758 -769. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 16 20 24

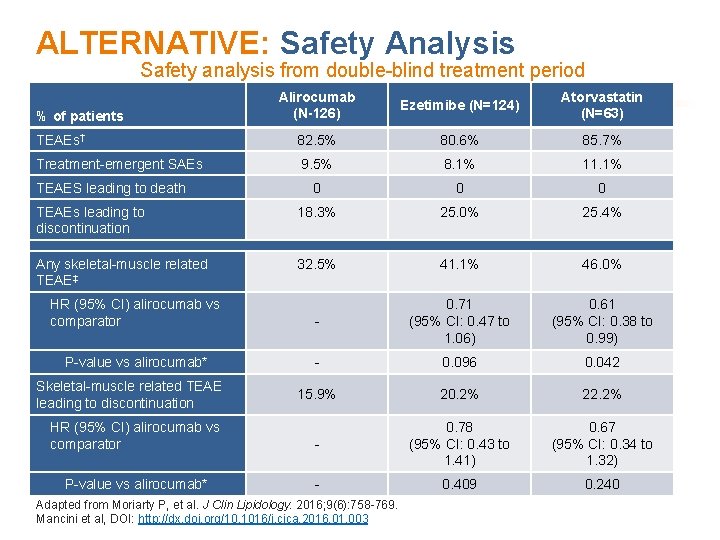

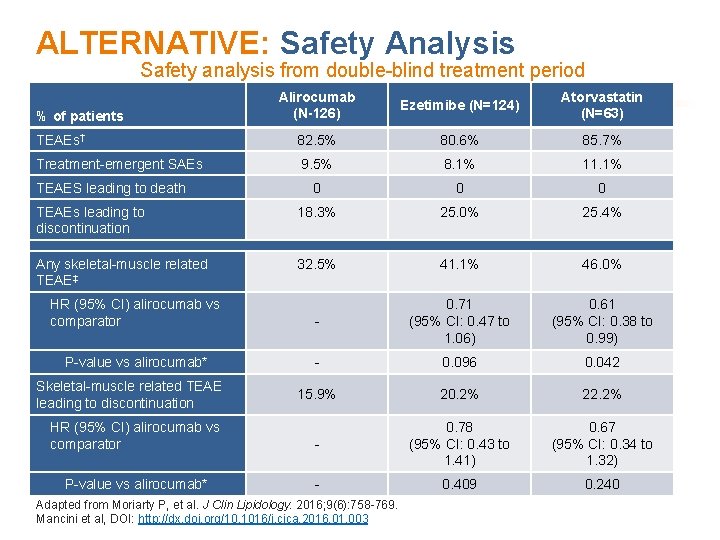

ALTERNATIVE: Safety Analysis Safety analysis from double-blind treatment period Alirocumab (N-126) Ezetimibe (N=124) Atorvastatin (N=63) TEAEs† 82. 5% 80. 6% 85. 7% Treatment-emergent SAEs 9. 5% 8. 1% 11. 1% 0 0 0 TEAEs leading to discontinuation 18. 3% 25. 0% 25. 4% Any skeletal-muscle related TEAE‡ 32. 5% 41. 1% 46. 0% HR (95% CI) alirocumab vs comparator - 0. 71 (95% CI: 0. 47 to 1. 06) 0. 61 (95% CI: 0. 38 to 0. 99) P-value vs alirocumab* - 0. 096 0. 042 15. 9% 20. 2% 22. 2% % of patients TEAES leading to death Skeletal-muscle related TEAE leading to discontinuation HR (95% CI) alirocumab vs 0. 78 0. 67 †TEAE comparator (95% CI: 0. 43 to treatment (95% CI: days. 0. 34 to (treatment emergent adverse event) period = -time from first to last injection of study + 70 SAE = serious adverse event. 1. 41) 1. 32) ‡Pre-defined category including myalgia, muscle spasms, muscular weakness, musculoskeletal stiffness, muscle fatigue. P-value vs alirocumab* 0. 409 *Although not pre-planned analysis, the P-value is shown for descriptive purposes. Adapted from Moriarty P, et al. J Clin Lipidology. 2016; 9(6): 758 -769. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 0. 240

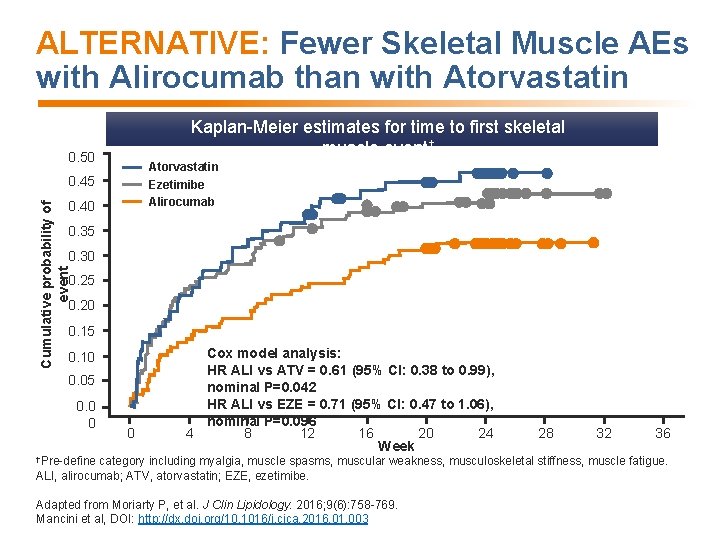

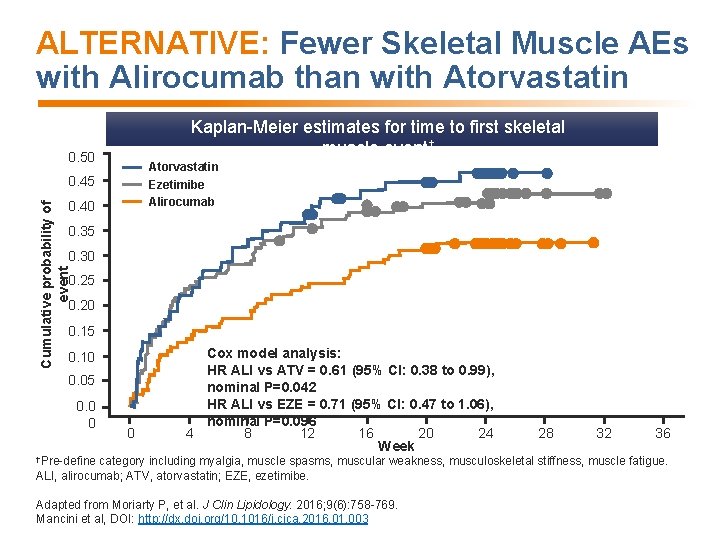

ALTERNATIVE: Fewer Skeletal Muscle AEs with Alirocumab than with Atorvastatin Kaplan-Meier estimates for time to first skeletal muscle event† 0. 50 Atorvastatin 0. 45 Ezetimibe Alirocumab Cumulative probability of event 0. 40 0. 35 0. 30 0. 25 0. 20 0. 15 0. 10 0. 05 0. 0 0 0 Cox model analysis: HR ALI vs ATV = 0. 61 (95% CI: 0. 38 to 0. 99), nominal P=0. 042 HR ALI vs EZE = 0. 71 (95% CI: 0. 47 to 1. 06), nominal P=0. 096 4 8 12 16 20 24 Week †Pre-define 28 32 36 category including myalgia, muscle spasms, muscular weakness, musculoskeletal stiffness, muscle fatigue. ALI, alirocumab; ATV, atorvastatin; EZE, ezetimibe. Adapted from Moriarty P, et al. J Clin Lipidology. 2016; 9(6): 758 -769. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Conclusions and Summary • Adhere to the Principles of Management of Goal-inhibiting Statin Intolerance • Educate patients regarding the “elephant in the room” phenomenon: although many are considered to have GISI, few are verified i. e. the prognosis for symptomatic patients is very good Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Summary: Principles of Management of GISI • Is there an indication for statin therapy? • Does the patient have features limiting or precluding use of statins? • Is the patient fully aware of the indication for statin treatment, intended benefits and safety of statins, and properly counselled to avoid nocebo effects? • Have dietary, weight and exercise goals been included in therapeutic plan? Have supplements used to avoid myalgia while taking statins been discouraged? • Has systematic challenge/de-challenge/re-challenge occurred and failed to result in achievement of therapeutic goal? et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 • Mancini If needed, which non-statin agent is likely to help achieve

Trials: The Elephant in the Room regarding Goal. Inhibiting Statin Intolerance (GISI) Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Supplementary Slides

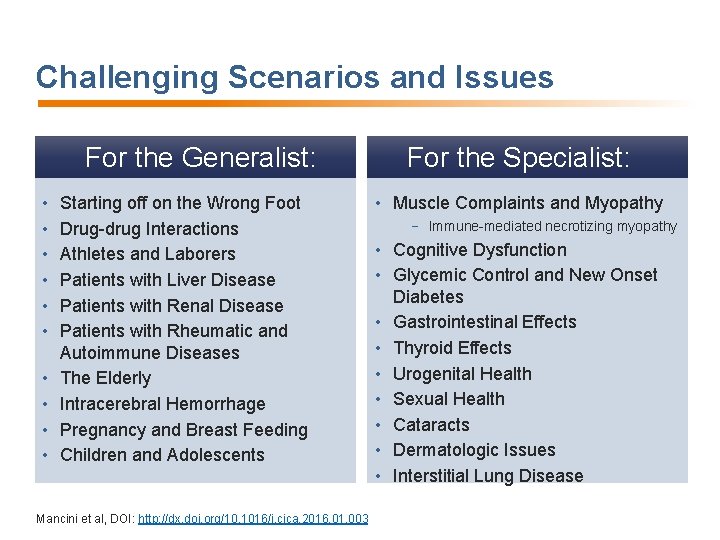

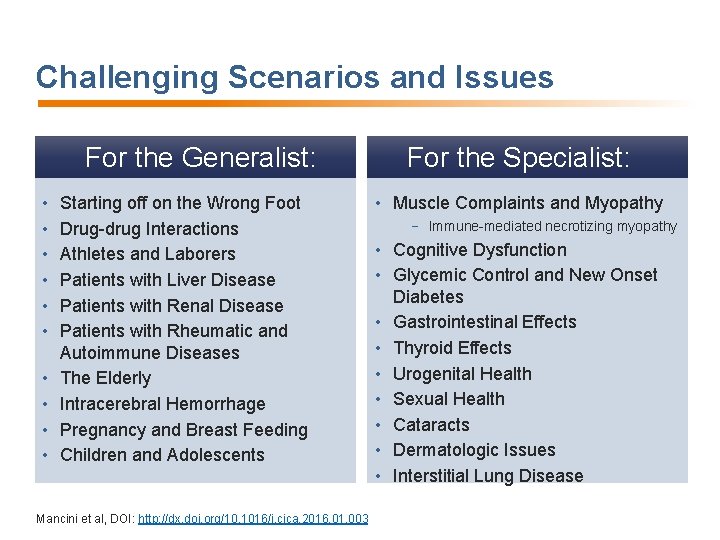

Challenging Scenarios and Issues For the Generalist: • • • Starting off on the Wrong Foot Drug-drug Interactions Athletes and Laborers Patients with Liver Disease Patients with Renal Disease Patients with Rheumatic and Autoimmune Diseases The Elderly Intracerebral Hemorrhage Pregnancy and Breast Feeding Children and Adolescents Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 For the Specialist: • Muscle Complaints and Myopathy − Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy • Cognitive Dysfunction • Glycemic Control and New Onset Diabetes • Gastrointestinal Effects • Thyroid Effects • Urogenital Health • Sexual Health • Cataracts • Dermatologic Issues • Interstitial Lung Disease

Starting Off on the Wrong Foot • Judicious use of baseline and follow-up testing can ensure confidence in patient-physician relationship and avoid nocebo effects • Ensure patient understands rationale for therapy and CV benefits Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

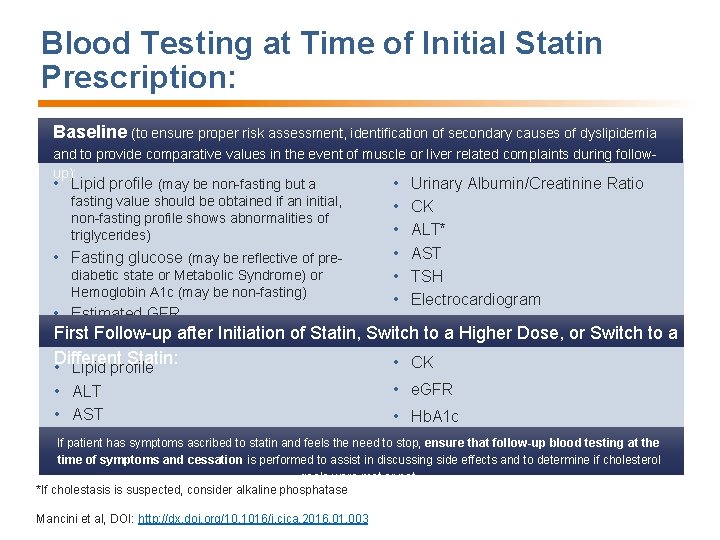

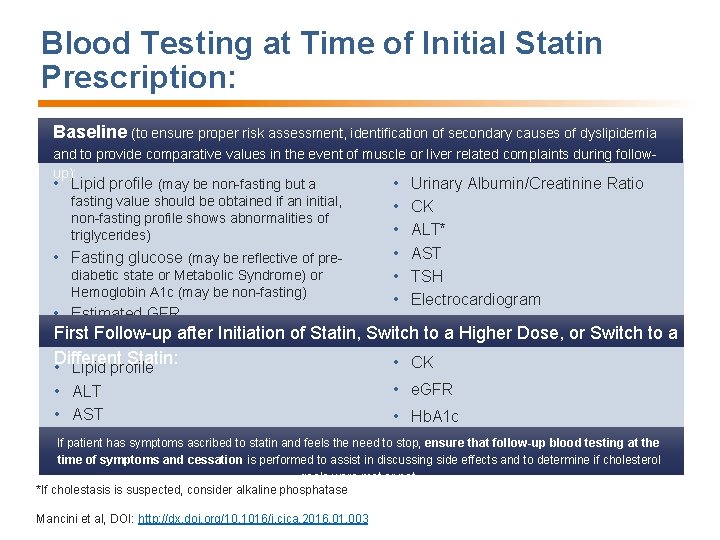

Blood Testing at Time of Initial Statin Prescription: Baseline (to ensure proper risk assessment, identification of secondary causes of dyslipidemia and to provide comparative values in the event of muscle or liver related complaints during followup): • Lipid profile (may be non-fasting but a • Urinary Albumin/Creatinine Ratio fasting value should be obtained if an initial, • CK non-fasting profile shows abnormalities of • ALT* triglycerides) • Fasting glucose (may be reflective of prediabetic state or Metabolic Syndrome) or Hemoglobin A 1 c (may be non-fasting) • Estimated GFR • AST • TSH • Electrocardiogram First Follow-up after Initiation of Statin, Switch to a Higher Dose, or Switch to a Different Statin: • CK • Lipid profile • ALT • AST • e. GFR • Hb. A 1 c If patient has symptoms ascribed to statin and feels the need to stop, ensure that follow-up blood testing at the time of symptoms and cessation is performed to assist in discussing side effects and to determine if cholesterol goals were met or not. *If cholestasis is suspected, consider alkaline phosphatase Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

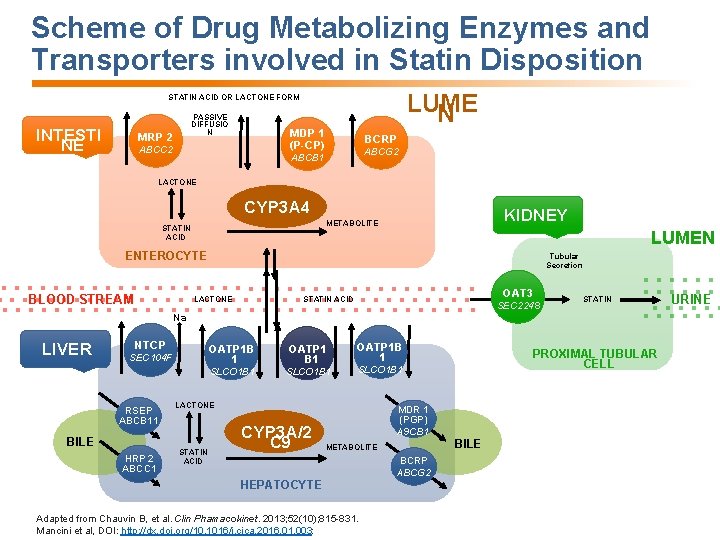

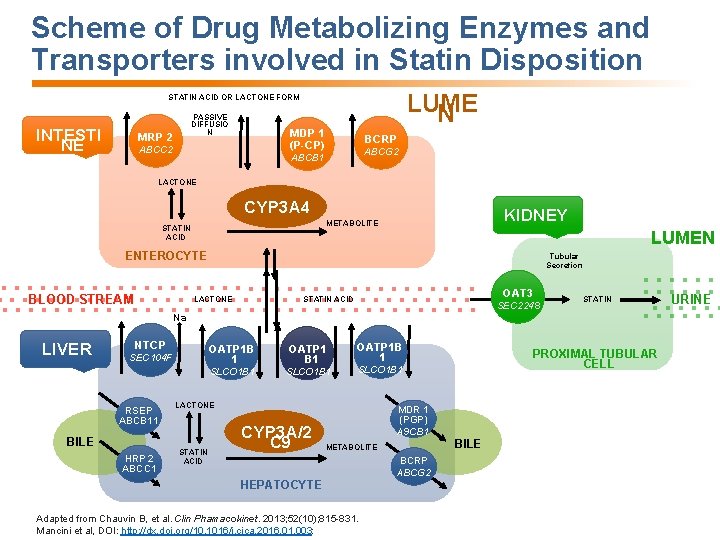

Scheme of Drug Metabolizing Enzymes and Transporters involved in Statin Disposition LUME N STATIN ACID OR LACTONE FORM INTESTI NE PASSIVE DIFFUSIO N MRP 2 MDP 1 (P-CP) ABCC 2 BCRP ABCG 2 ABCB 1 LACTONE CYP 3 A 4 KIDNEY METABOLITE STATIN ACID LUMEN ENTEROCYTE BLOOD STREAM Tubular Secretion OAT 3 STATIN ACID LACTONE SEC 2248 STATIN Na + LIVER NTCP SEC 104 F RSEP ABCB 11 BILE HRP 2 ABCC 1 OATP 1 B 1 OATP 1 B 1 SLCO 1 B 1 OATP 1 B 1 SLCO 1 B 1 LACTONE STATIN ACID CYP 3 A/2 C 9 PROXIMAL TUBULAR CELL MDR 1 (PGP) A 9 CB 1 BILE METABOLITE BCRP ABCG 2 HEPATOCYTE Adapted from Chauvin B, et al. Clin Phamacokinet. 2013; 52(10); 815 -831. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003: URINE

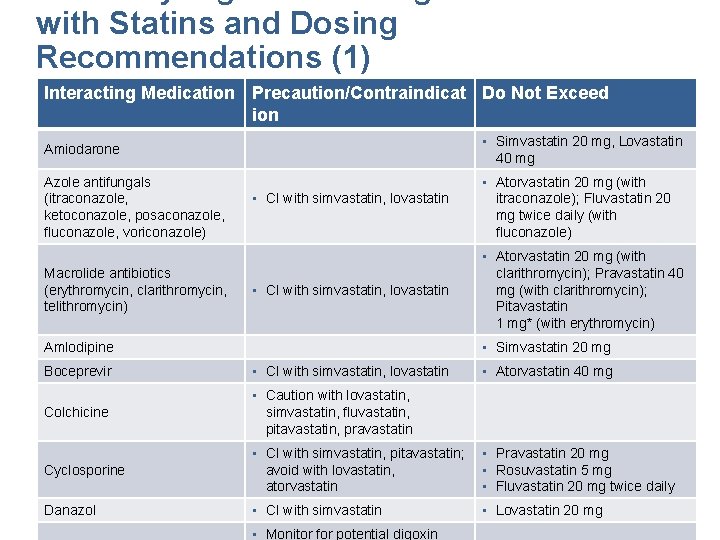

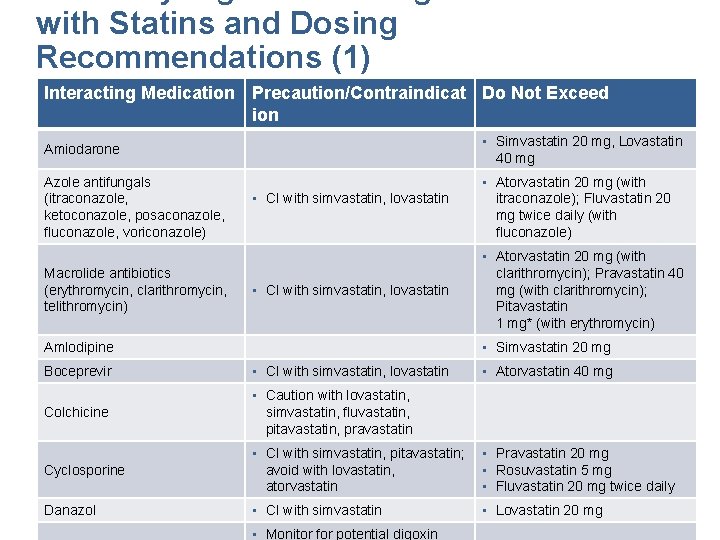

with Statins and Dosing Recommendations (1) Interacting Medication Precaution/Contraindicat Do Not Exceed ion Amiodarone • Simvastatin 20 mg, Lovastatin 40 mg Azole antifungals (itraconazole, ketoconazole, posaconazole, fluconazole, voriconazole) • Atorvastatin 20 mg (with itraconazole); Fluvastatin 20 mg twice daily (with fluconazole) Macrolide antibiotics (erythromycin, clarithromycin, telithromycin) • CI with simvastatin, lovastatin • Simvastatin 20 mg Amlodipine Boceprevir • CI with simvastatin, lovastatin Colchicine • Caution with lovastatin, simvastatin, fluvastatin, pitavastatin, pravastatin Cyclosporine *Not available in Canada • Atorvastatin 20 mg (with clarithromycin); Pravastatin 40 mg (with clarithromycin); Pitavastatin 1 mg* (with erythromycin) • CI with simvastatin, pitavastatin; avoid with lovastatin, atorvastatin • Atorvastatin 40 mg • Pravastatin 20 mg • Rosuvastatin 5 mg • Fluvastatin 20 mg twice daily Finks SW, Campbell JD. Nurse Pract. Vol 39. 2014: 45 -51. Kellick, K. A. , Bottorff, M. , & Toth, P. P. J Clin Lipidol. 2014: 8(3 Danazol • CI with simvastatin • Lovastatin 20 mg Suppl): S 30 -46. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 • Monitor for potential digoxin

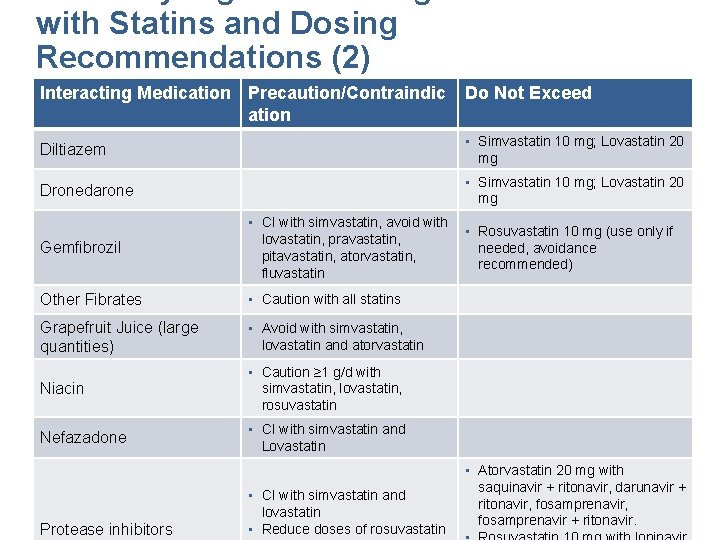

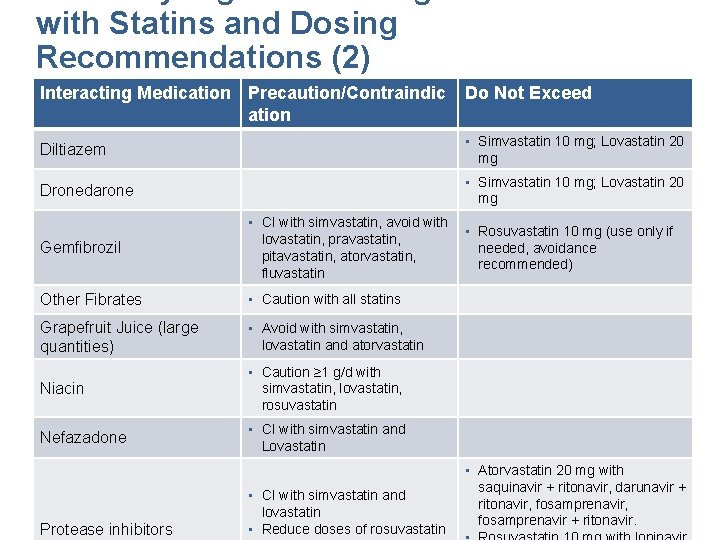

with Statins and Dosing Recommendations (2) Interacting Medication Precaution/Contraindic ation Do Not Exceed Diltiazem • Simvastatin 10 mg; Lovastatin 20 mg Dronedarone • Simvastatin 10 mg; Lovastatin 20 mg Gemfibrozil • CI with simvastatin, avoid with lovastatin, pravastatin, pitavastatin, atorvastatin, fluvastatin Other Fibrates • Caution with all statins Grapefruit Juice (large quantities) • Avoid with simvastatin, lovastatin and atorvastatin Niacin • Caution ≥ 1 g/d with simvastatin, lovastatin, rosuvastatin Nefazadone • CI with simvastatin and Lovastatin • Rosuvastatin 10 mg (use only if needed, avoidance recommended) • Atorvastatin 20 mg with saquinavir + ritonavir, darunavir + • CI with simvastatin and Finks SW, Campbell JD. Nurse Pract. Vol 39. 2014: 45 -51. Kellick, K. A. , Bottorff, M. , ritonavir, & Toth, P. fosamprenavir, P. J Clin Lipidol. 2014: 8(3 lovastatin Suppl): S 30 -46. fosamprenavir + ritonavir. Mancini et al, inhibitors DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 • Reduce doses of rosuvastatin Protease

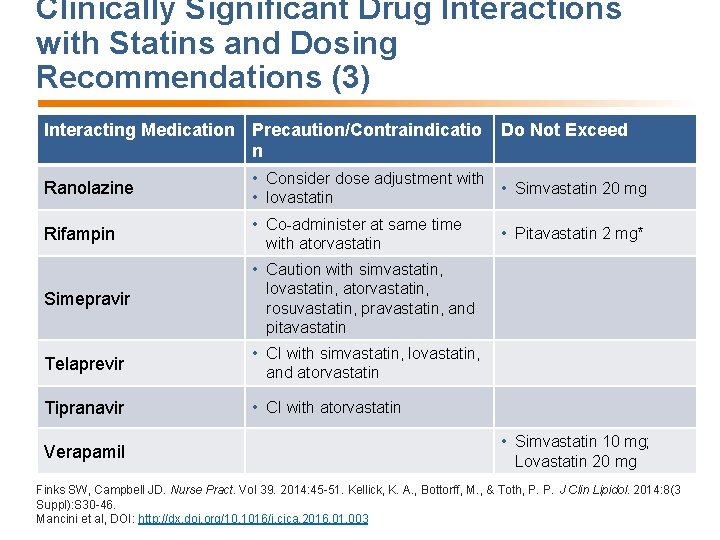

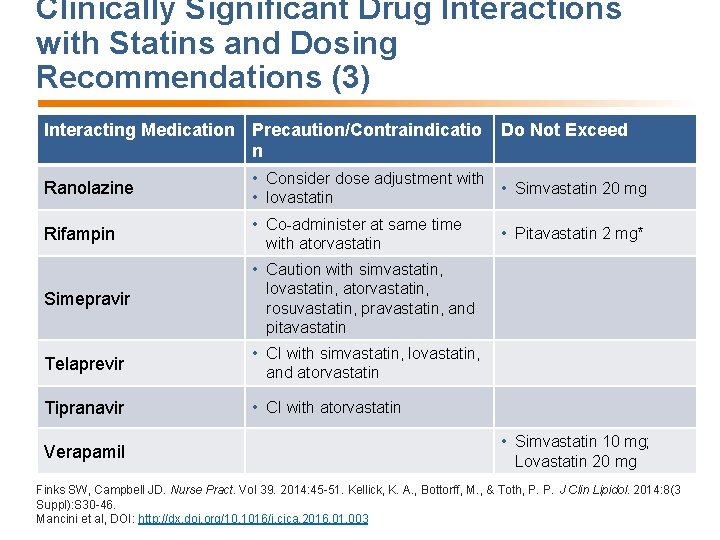

Clinically Significant Drug Interactions with Statins and Dosing Recommendations (3) Interacting Medication Precaution/Contraindicatio n Do Not Exceed Ranolazine • Consider dose adjustment with • Simvastatin 20 mg • lovastatin Rifampin • Co-administer at same time with atorvastatin Simepravir • Caution with simvastatin, lovastatin, atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, pravastatin, and pitavastatin Telaprevir • CI with simvastatin, lovastatin, and atorvastatin Tipranavir • CI with atorvastatin Verapamil *Not available in Canada • Pitavastatin 2 mg* • Simvastatin 10 mg; Lovastatin 20 mg Finks SW, Campbell JD. Nurse Pract. Vol 39. 2014: 45 -51. Kellick, K. A. , Bottorff, M. , & Toth, P. P. J Clin Lipidol. 2014: 8(3 Suppl): S 30 -46. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

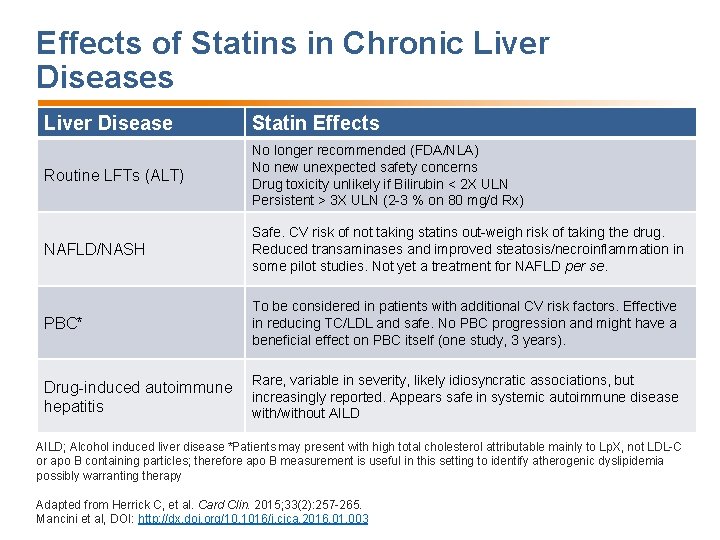

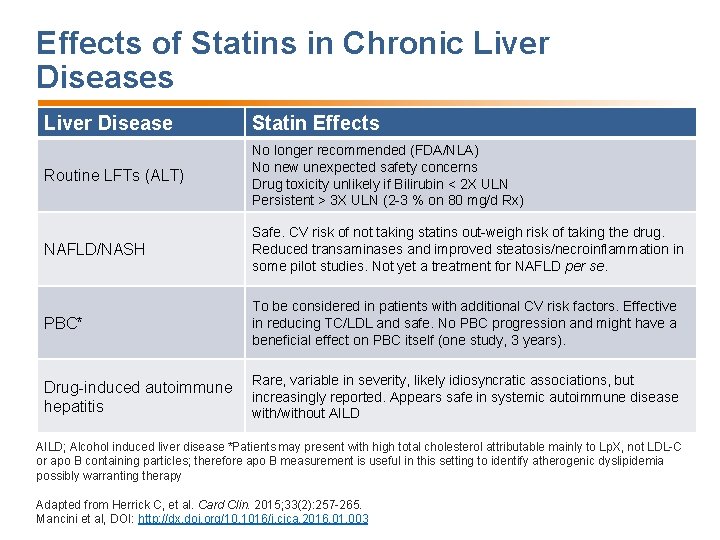

Effects of Statins in Chronic Liver Diseases Liver Disease Statin Effects Routine LFTs (ALT) No longer recommended (FDA/NLA) No new unexpected safety concerns Drug toxicity unlikely if Bilirubin < 2 X ULN Persistent > 3 X ULN (2 -3 % on 80 mg/d Rx) NAFLD/NASH Safe. CV risk of not taking statins out-weigh risk of taking the drug. Reduced transaminases and improved steatosis/necroinflammation in some pilot studies. Not yet a treatment for NAFLD per se. PBC* To be considered in patients with additional CV risk factors. Effective in reducing TC/LDL and safe. No PBC progression and might have a beneficial effect on PBC itself (one study, 3 years). Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis Rare, variable in severity, likely idiosyncratic associations, but increasingly reported. Appears safe in systemic autoimmune disease with/without AILD; Alcohol induced liver disease *Patients may present with high total cholesterol attributable mainly to Lp. X, not LDL-C or apo B containing particles; therefore apo B measurement is useful in this setting to identify atherogenic dyslipidemia possibly warranting therapy Adapted from Herrick C, et al. Card Clin. 2015; 33(2): 257 -265. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

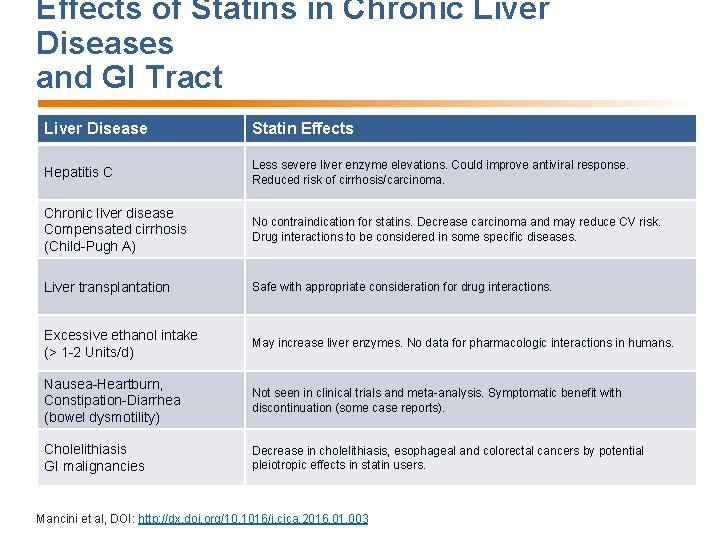

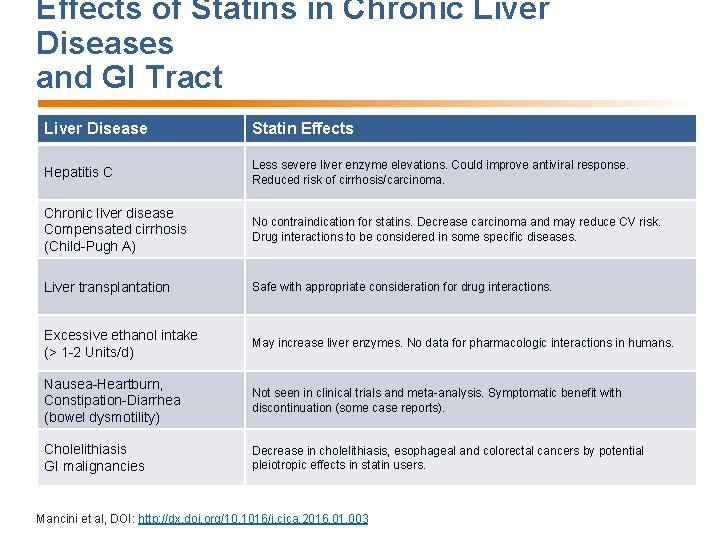

Effects of Statins in Chronic Liver Diseases and GI Tract Liver Disease Statin Effects Hepatitis C Less severe liver enzyme elevations. Could improve antiviral response. Reduced risk of cirrhosis/carcinoma. Chronic liver disease Compensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh A) No contraindication for statins. Decrease carcinoma and may reduce CV risk. Drug interactions to be considered in some specific diseases. Liver transplantation Safe with appropriate consideration for drug interactions. Excessive ethanol intake (> 1 -2 Units/d) May increase liver enzymes. No data for pharmacologic interactions in humans. Nausea-Heartburn, Constipation-Diarrhea (bowel dysmotility) Not seen in clinical trials and meta-analysis. Symptomatic benefit with discontinuation (some case reports). Cholelithiasis GI malignancies Decrease in cholelithiasis, esophageal and colorectal cancers by potential pleiotropic effects in statin users. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

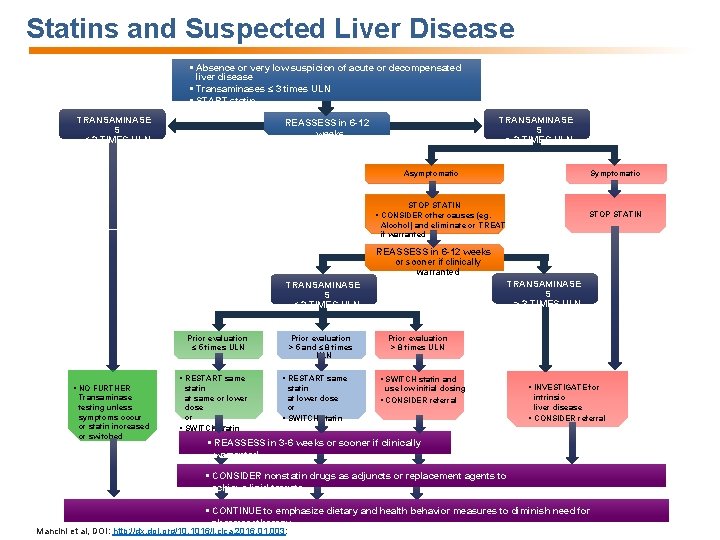

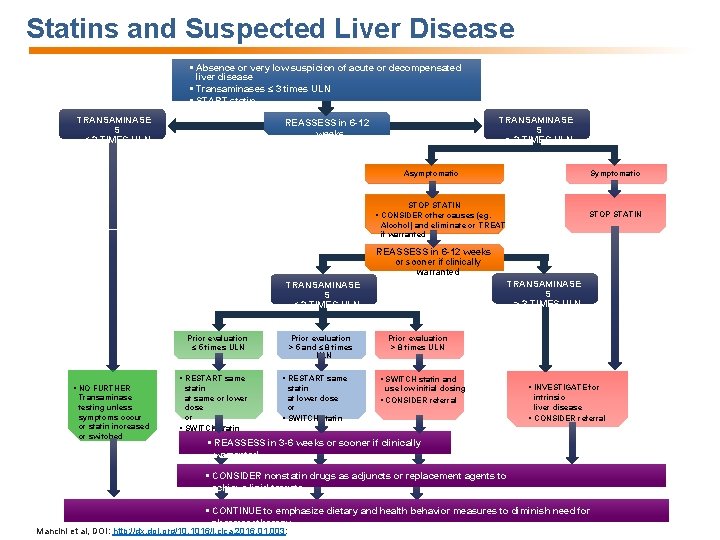

Statins and Suspected Liver Disease § Absence or very low suspicion of acute or decompensated liver disease § Transaminases ≤ 3 times ULN § START statin TRANSAMINASE S ≤ 3 TIMES ULN TRANSAMINASE S > 3 TIMES ULN REASSESS in 6 -12 weeks Symptomatic Asymptomatic STOP STATIN § CONSIDER other causes (eg. Alcohol) and eliminate or TREAT if warranted REASSESS in 6 -12 weeks or sooner if clinically warranted TRANSAMINASE S > 3 TIMES ULN TRANSAMINASE S ≤ 3 TIMES ULN Prior evaluation ≤ 5 times ULN § NO FURTHER Transaminase testing unless symptoms occur or statin increased or switched Prior evaluation > 5 and ≤ 8 times ULN Prior evaluation > 8 times ULN § RESTART same § SWITCH statin and statin at same or lower dose or § SWITCH statin at lower dose or § SWITCH statin § CONSIDER referral use low initial dosing § INVESTIGATE for intrinsic liver disease § CONSIDER referral § REASSESS in 3 -6 weeks or sooner if clinically warranted § CONSIDER nonstatin drugs as adjuncts or replacement agents to achieve lipid targets § CONTINUE to emphasize dietary and health behavior measures to diminish need for pharmacotherapy Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003:

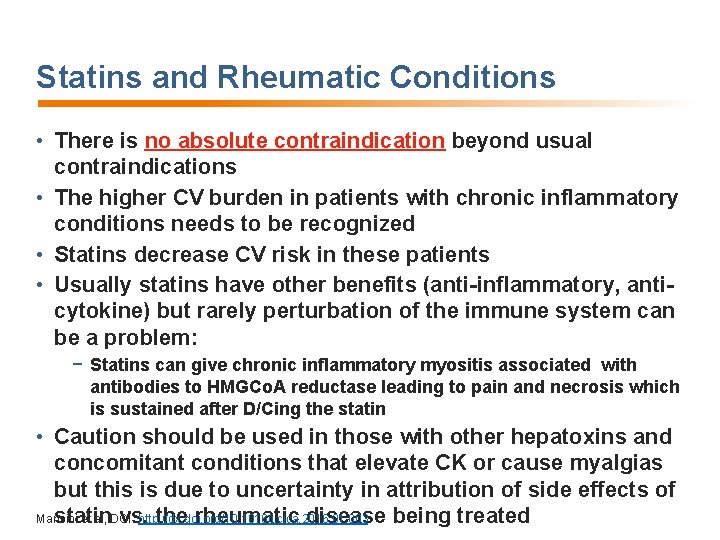

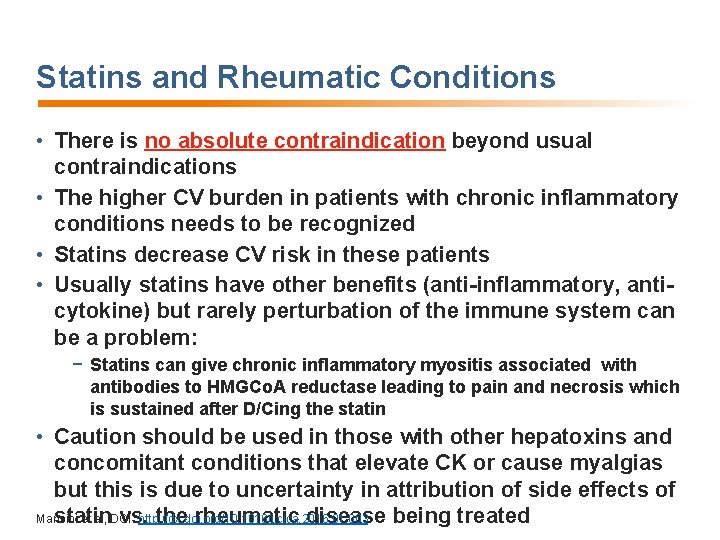

Statins and Rheumatic Conditions • There is no absolute contraindication beyond usual contraindications • The higher CV burden in patients with chronic inflammatory conditions needs to be recognized • Statins decrease CV risk in these patients • Usually statins have other benefits (anti-inflammatory, anticytokine) but rarely perturbation of the immune system can be a problem: − Statins can give chronic inflammatory myositis associated with antibodies to HMGCo. A reductase leading to pain and necrosis which is sustained after D/Cing the statin • Caution should be used in those with other hepatoxins and concomitant conditions that elevate CK or cause myalgias but this is due to uncertainty in attribution of side effects of Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 statin vs. the rheumatic disease being treated

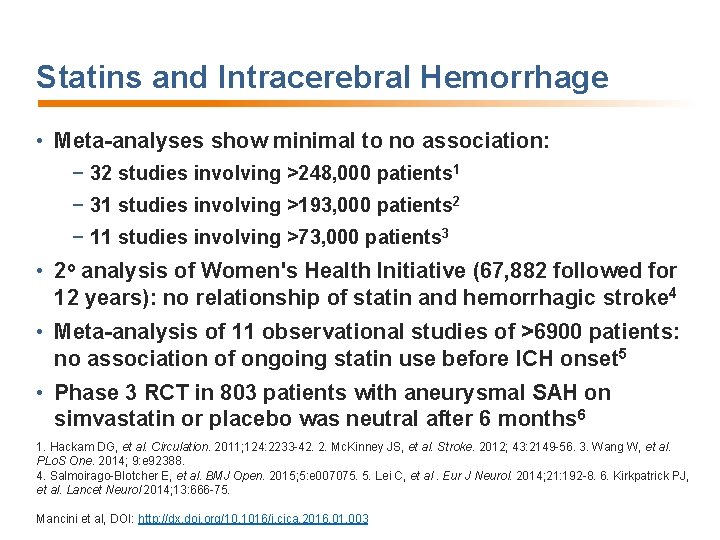

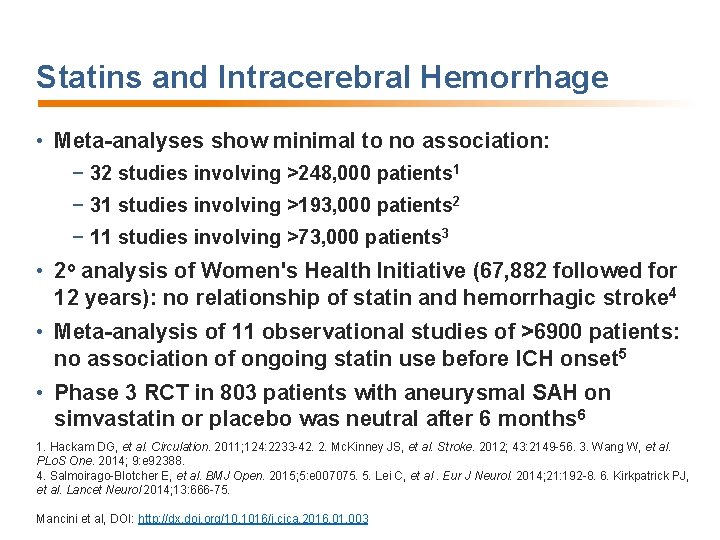

Statins and Intracerebral Hemorrhage • Meta-analyses show minimal to no association: − 32 studies involving >248, 000 patients 1 − 31 studies involving >193, 000 patients 2 − 11 studies involving >73, 000 patients 3 • 2 o analysis of Women's Health Initiative (67, 882 followed for 12 years): no relationship of statin and hemorrhagic stroke 4 • Meta-analysis of 11 observational studies of >6900 patients: no association of ongoing statin use before ICH onset 5 • Phase 3 RCT in 803 patients with aneurysmal SAH on simvastatin or placebo was neutral after 6 months 6 1. Hackam DG, et al. Circulation. 2011; 124: 2233 -42. 2. Mc. Kinney JS, et al. Stroke. 2012; 43: 2149 -56. 3. Wang W, et al. PLo. S One. 2014; 9: e 92388. 4. Salmoirago-Blotcher E, et al. BMJ Open. 2015; 5: e 007075. 5. Lei C, et al. Eur J Neurol. 2014; 21: 192 -8. 6. Kirkpatrick PJ, et al. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13: 666 -75. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Statins and Elderly • Competing morbidity/mortality issues, frailty, patient/family preferences are important factors to weigh for use or nonuse of statins • Statin meta-analyses of RCT’s suggest positive event reductions and good tolerance except in frail elderly • Advanced age is not a contraindication Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

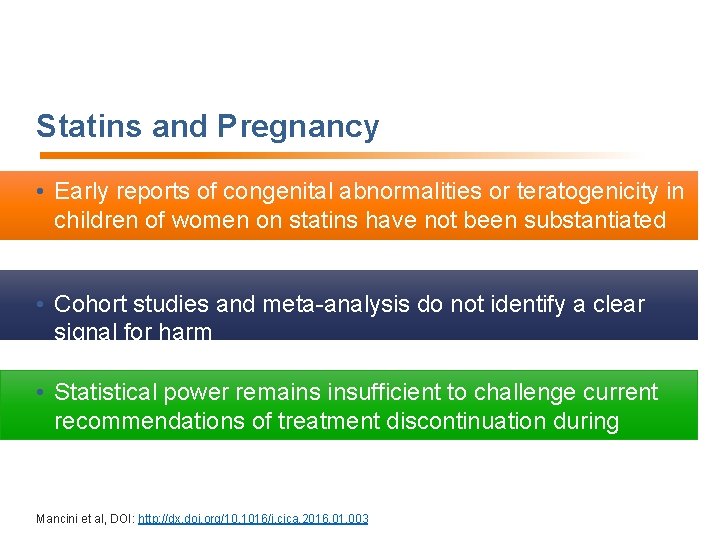

Statins and Pregnancy • Early reports of congenital abnormalities or teratogenicity in children of women on statins have not been substantiated • Cohort studies and meta-analysis do not identify a clear signal for harm • Statistical power remains insufficient to challenge current recommendations of treatment discontinuation during pregnancy Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

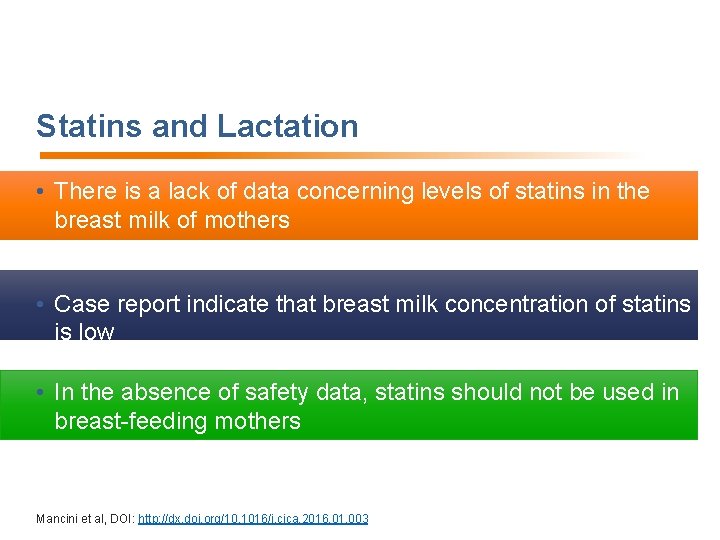

Statins and Lactation • There is a lack of data concerning levels of statins in the breast milk of mothers • Case report indicate that breast milk concentration of statins is low • In the absence of safety data, statins should not be used in breast-feeding mothers Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

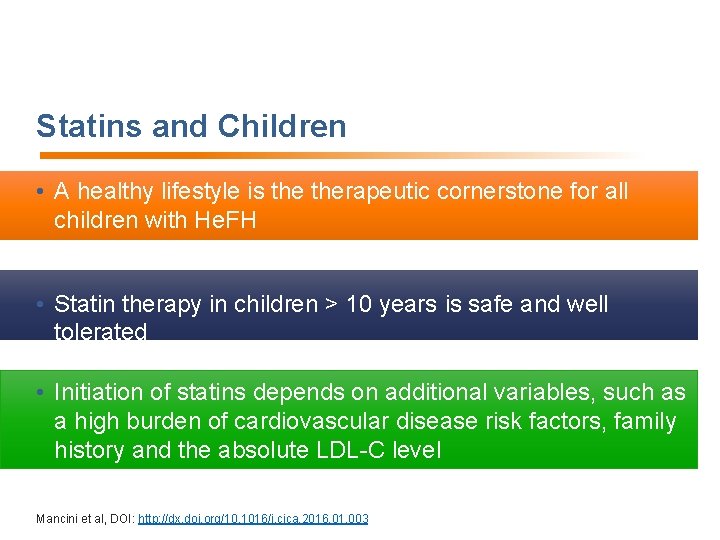

Statins and Children • A healthy lifestyle is therapeutic cornerstone for all children with He. FH • Statin therapy in children > 10 years is safe and well tolerated • Initiation of statins depends on additional variables, such as a high burden of cardiovascular disease risk factors, family history and the absolute LDL-C level Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

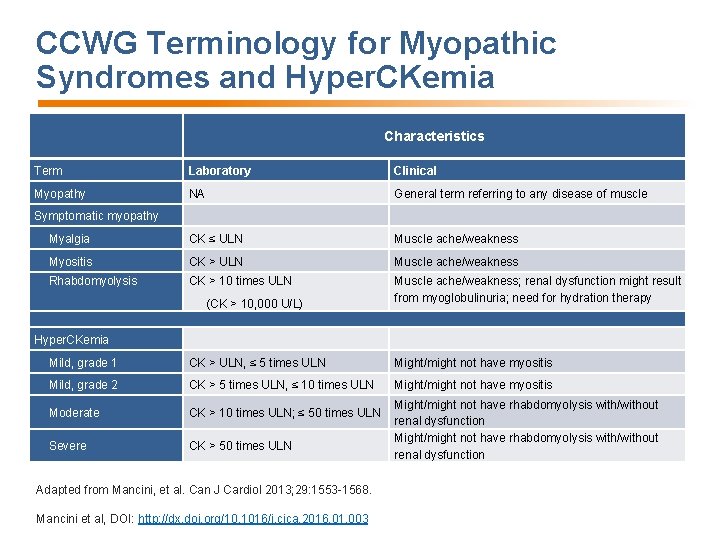

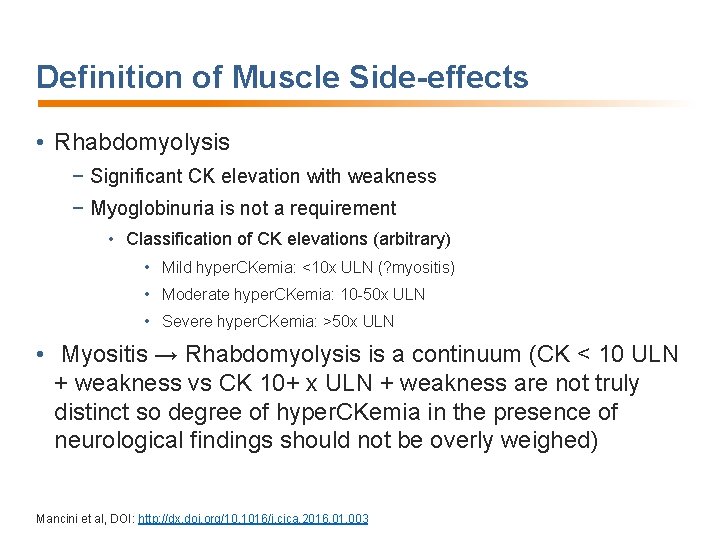

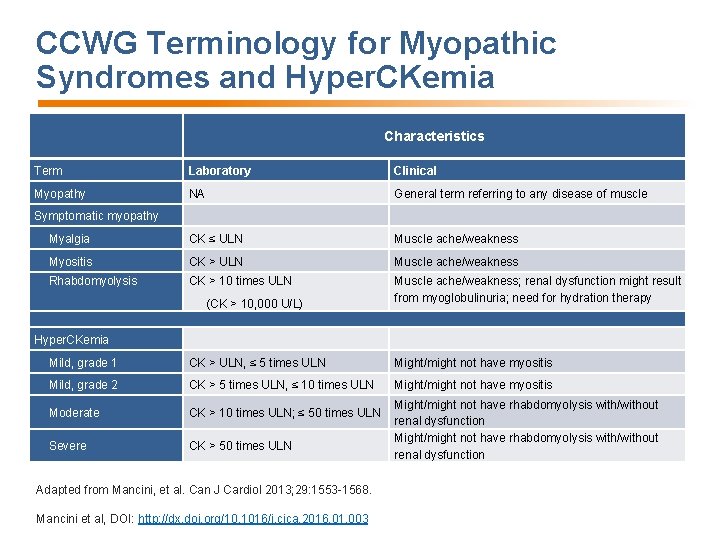

CCWG Terminology for Myopathic Syndromes and Hyper. CKemia Characteristics Term Laboratory Clinical Myopathy NA General term referring to any disease of muscle Myalgia CK ≤ ULN Muscle ache/weakness Myositis CK > ULN Muscle ache/weakness Rhabdomyolysis CK > 10 times ULN Muscle ache/weakness; renal dysfunction might result from myoglobulinuria; need for hydration therapy Symptomatic myopathy (CK > 10, 000 U/L) Hyper. CKemia Mild, grade 1 CK > ULN, ≤ 5 times ULN Might/might not have myositis Mild, grade 2 CK > 5 times ULN, ≤ 10 times ULN Might/might not have myositis Moderate CK > 10 times ULN; ≤ 50 times ULN Severe CK > 50 times ULN Adapted from Mancini, et al. Can J Cardiol 2013; 29: 1553 -1568. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 Might/might not have rhabdomyolysis with/without renal dysfunction

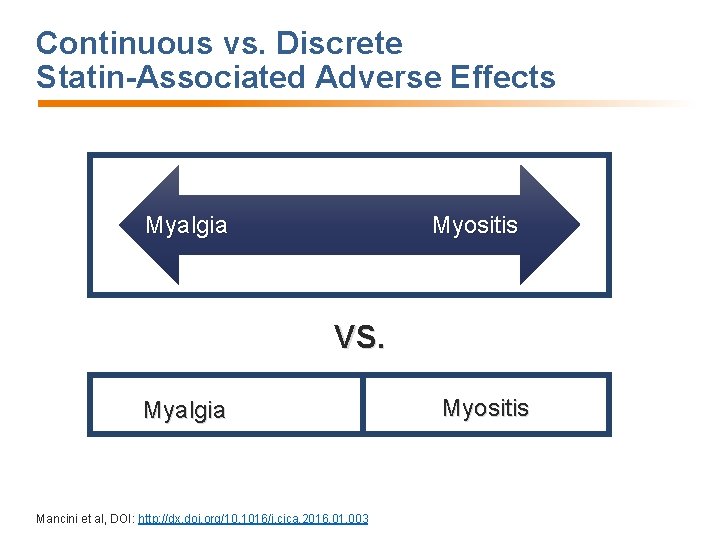

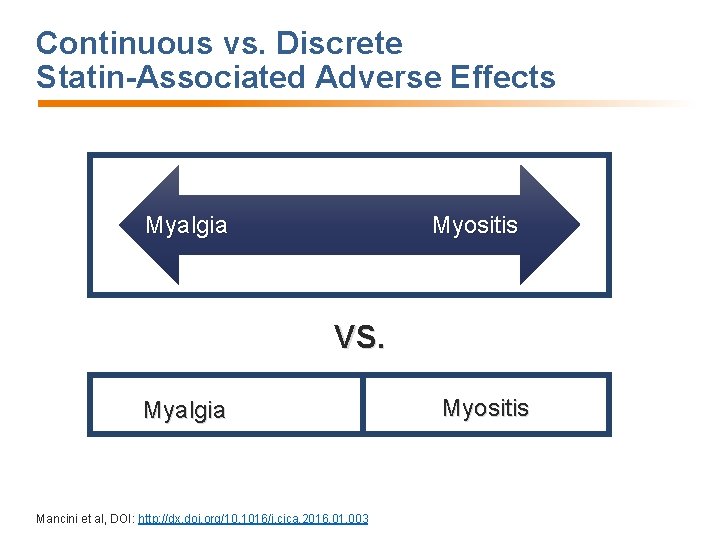

Continuous vs. Discrete Statin-Associated Adverse Effects Myalgia Myositis VS. Myalgia Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 Myositis

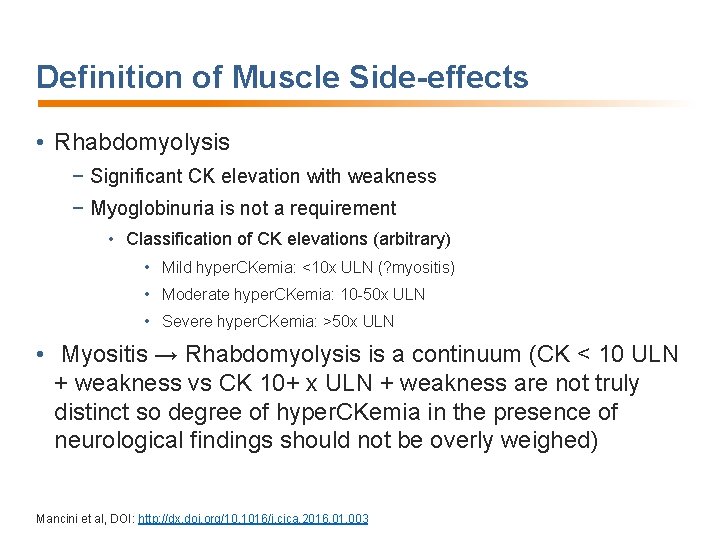

Definition of Muscle Side-effects • Rhabdomyolysis − Significant CK elevation with weakness − Myoglobinuria is not a requirement • Classification of CK elevations (arbitrary) • Mild hyper. CKemia: <10 x ULN (? myositis) • Moderate hyper. CKemia: 10 -50 x ULN • Severe hyper. CKemia: >50 x ULN • Myositis → Rhabdomyolysis is a continuum (CK < 10 ULN + weakness vs CK 10+ x ULN + weakness are not truly distinct so degree of hyper. CKemia in the presence of neurological findings should not be overly weighed) Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

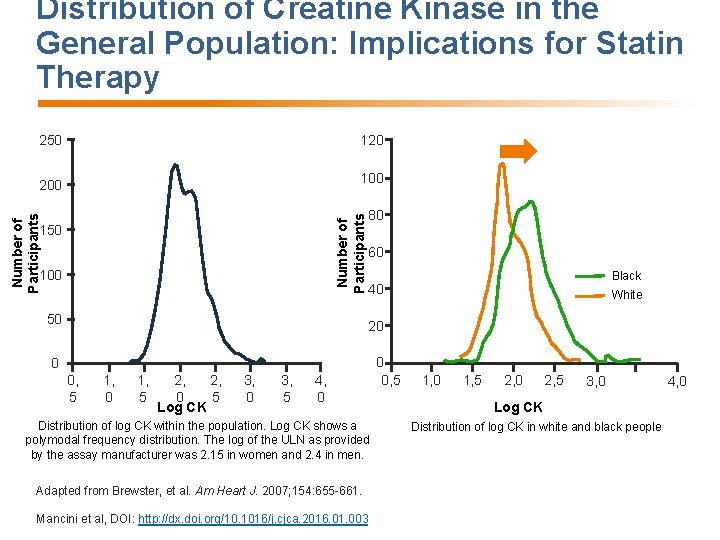

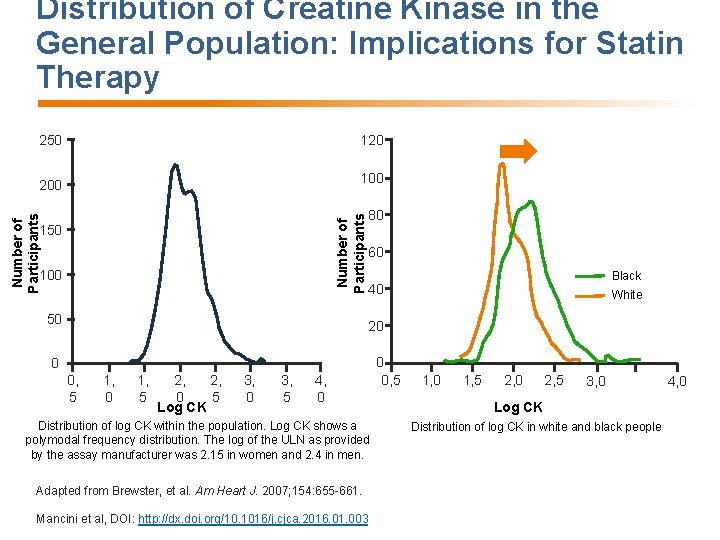

Distribution of Creatine Kinase in the General Population: Implications for Statin Therapy 200 100 Number of Participants 120 Number of Participants 250 100 50 80 60 Black 40 White 20 0 0, 5 1, 0 1, 5 2, 2, 0 5 Log CK 3, 0 3, 5 4, 0 Distribution of log CK within the population. Log CK shows a polymodal frequency distribution. The log of the ULN as provided by the assay manufacturer was 2. 15 in women and 2. 4 in men. Adapted from Brewster, et al. Am Heart J. 2007; 154: 655 -661. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 0 0, 5 1, 0 1, 5 2, 0 2, 5 3, 0 Log CK Distribution of log CK in white and black people 4, 0

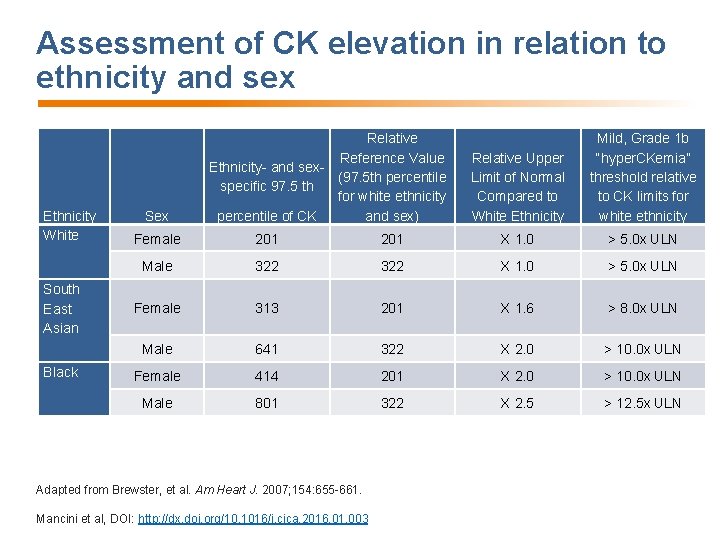

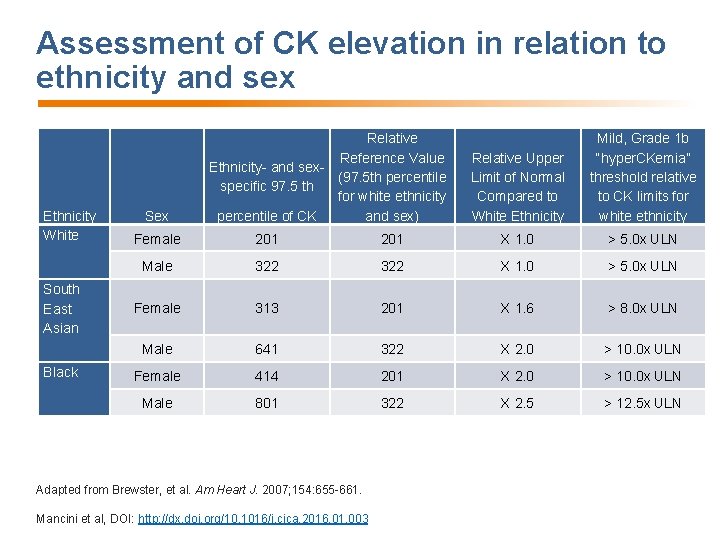

Assessment of CK elevation in relation to ethnicity and sex Ethnicity White South East Asian Black Sex Relative Reference Value Ethnicity- and sex(97. 5 th percentile specific 97. 5 th for white ethnicity percentile of CK and sex) Relative Upper Limit of Normal Compared to White Ethnicity Mild, Grade 1 b “hyper. CKemia” threshold relative to CK limits for white ethnicity Female 201 X 1. 0 > 5. 0 x ULN Male 322 X 1. 0 > 5. 0 x ULN Female 313 201 X 1. 6 > 8. 0 x ULN Male 641 322 X 2. 0 > 10. 0 x ULN Female 414 201 X 2. 0 > 10. 0 x ULN Male 801 322 X 2. 5 > 12. 5 x ULN Adapted from Brewster, et al. Am Heart J. 2007; 154: 655 -661. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

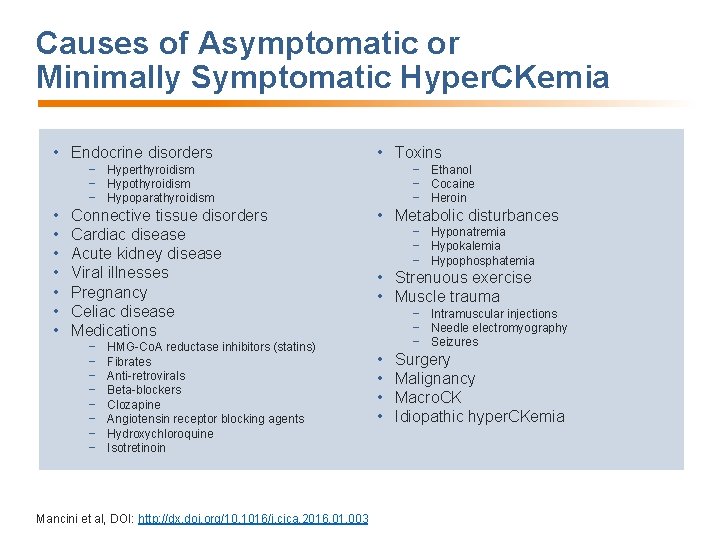

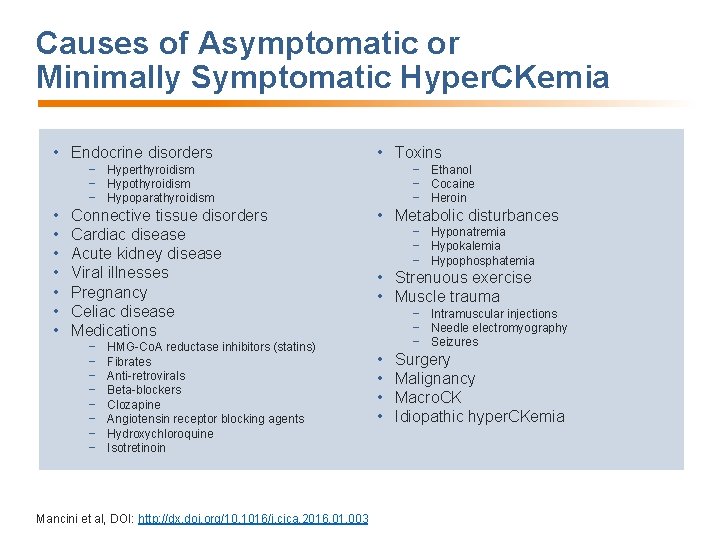

Causes of Asymptomatic or Minimally Symptomatic Hyper. CKemia • Endocrine disorders • Toxins − Hyperthyroidism − Hypoparathyroidism • • Connective tissue disorders Cardiac disease Acute kidney disease Viral illnesses Pregnancy Celiac disease Medications − − − − HMG-Co. A reductase inhibitors (statins) Fibrates Anti-retrovirals Beta-blockers Clozapine Angiotensin receptor blocking agents Hydroxychloroquine Isotretinoin Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 − Ethanol − Cocaine − Heroin • Metabolic disturbances − Hyponatremia − Hypokalemia − Hypophosphatemia • Strenuous exercise • Muscle trauma − Intramuscular injections − Needle electromyography − Seizures • • Surgery Malignancy Macro. CK Idiopathic hyper. CKemia

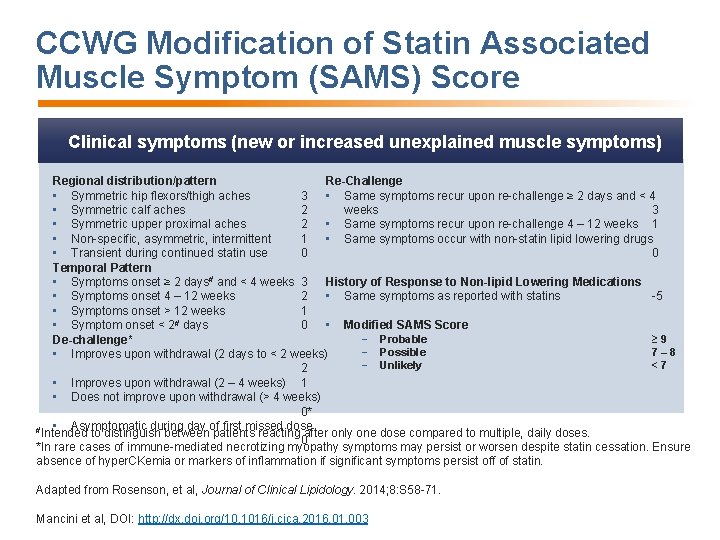

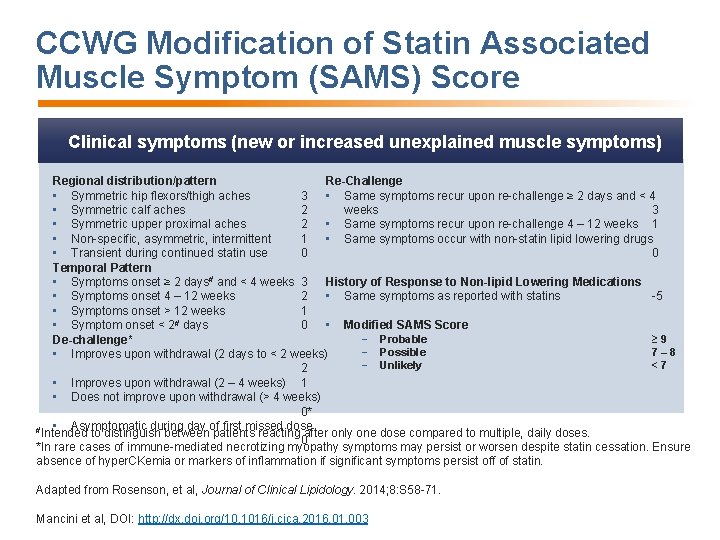

CCWG Modification of Statin Associated Muscle Symptom (SAMS) Score Clinical symptoms (new or increased unexplained muscle symptoms) Regional distribution/pattern Re-Challenge • Symmetric hip flexors/thigh aches 3 • Same symptoms recur upon re-challenge ≥ 2 days and < 4 • Symmetric calf aches 2 weeks 3 • Symmetric upper proximal aches 2 • Same symptoms recur upon re-challenge 4 – 12 weeks 1 • Non-specific, asymmetric, intermittent 1 • Same symptoms occur with non-statin lipid lowering drugs • Transient during continued statin use 0 0 Temporal Pattern • Symptoms onset ≥ 2 days# and < 4 weeks 3 History of Response to Non-lipid Lowering Medications • Symptoms onset 4 – 12 weeks 2 • Same symptoms as reported with statins -5 • Symptoms onset > 12 weeks 1 • Modified SAMS Score • Symptom onset < 2# days 0 − Probable ≥ 9 De-challenge* − Possible 7– 8 • Improves upon withdrawal (2 days to < 2 weeks) − Unlikely <7 2 • Improves upon withdrawal (2 – 4 weeks) 1 • Does not improve upon withdrawal (> 4 weeks) 0* • Asymptomatic during day of first missed dose #Intended to distinguish between patients reacting after only one dose compared to multiple, daily doses. 0 *In rare cases of immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy symptoms may persist or worsen despite statin cessation. Ensure absence of hyper. CKemia or markers of inflammation if significant symptoms persist off of statin. Adapted from Rosenson, et al, Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2014; 8: S 58 -71. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

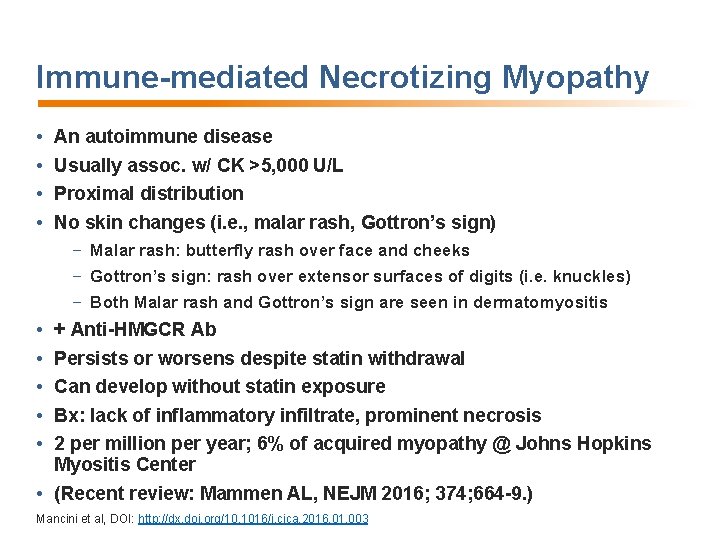

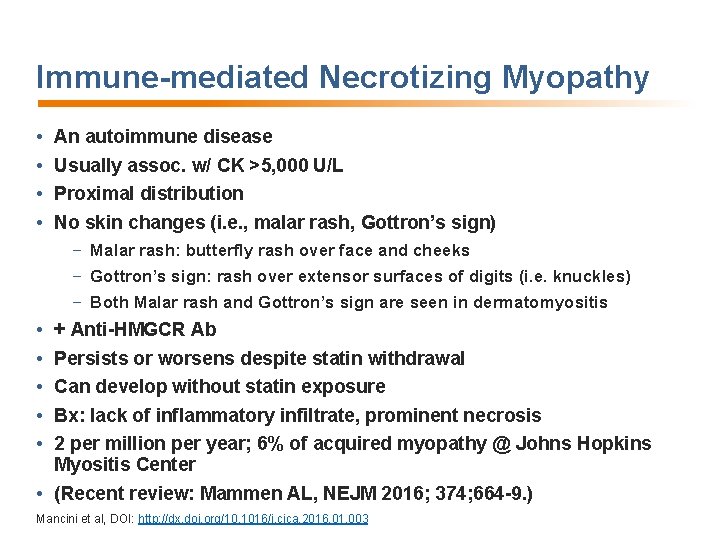

Immune-mediated Necrotizing Myopathy • • An autoimmune disease Usually assoc. w/ CK >5, 000 U/L Proximal distribution No skin changes (i. e. , malar rash, Gottron’s sign) − Malar rash: butterfly rash over face and cheeks − Gottron’s sign: rash over extensor surfaces of digits (i. e. knuckles) − Both Malar rash and Gottron’s sign are seen in dermatomyositis • • • + Anti-HMGCR Ab Persists or worsens despite statin withdrawal Can develop without statin exposure Bx: lack of inflammatory infiltrate, prominent necrosis 2 per million per year; 6% of acquired myopathy @ Johns Hopkins Myositis Center • (Recent review: Mammen AL, NEJM 2016; 374; 664 -9. ) Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

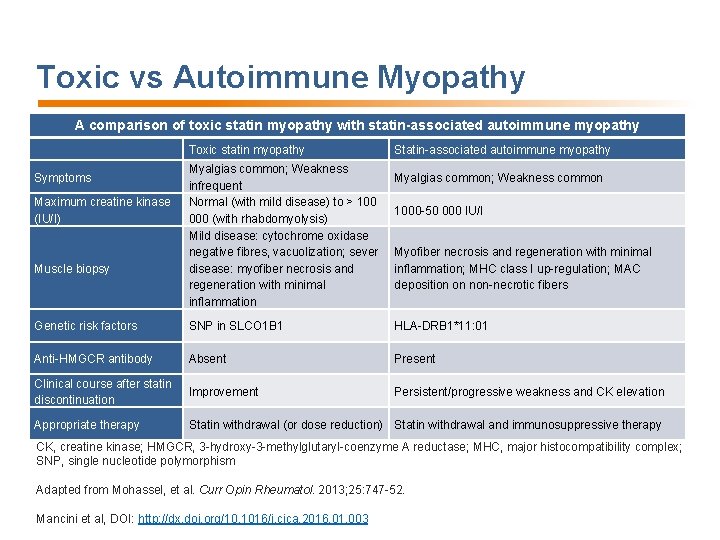

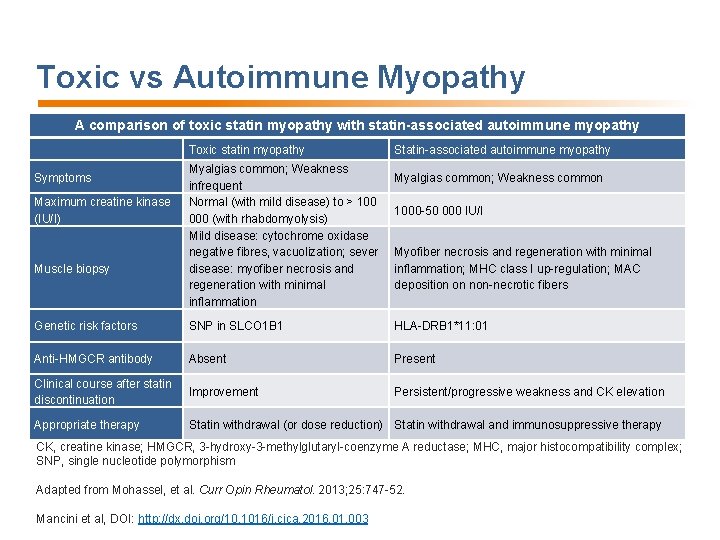

Toxic vs Autoimmune Myopathy A comparison of toxic statin myopathy with statin-associated autoimmune myopathy Toxic statin myopathy Symptoms Maximum creatine kinase (IU/I) Muscle biopsy Myalgias common; Weakness infrequent Normal (with mild disease) to > 100 000 (with rhabdomyolysis) Mild disease: cytochrome oxidase negative fibres, vacuolization; sever disease: myofiber necrosis and regeneration with minimal inflammation Statin-associated autoimmune myopathy Myalgias common; Weakness common 1000 -50 000 IU/I Myofiber necrosis and regeneration with minimal inflammation; MHC class I up-regulation; MAC deposition on non-necrotic fibers Genetic risk factors SNP in SLCO 1 B 1 HLA-DRB 1*11: 01 Anti-HMGCR antibody Absent Present Clinical course after statin discontinuation Improvement Persistent/progressive weakness and CK elevation Appropriate therapy Statin withdrawal (or dose reduction) Statin withdrawal and immunosuppressive therapy CK, creatine kinase; HMGCR, 3 -hydroxy-3 -methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism Adapted from Mohassel, et al. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013; 25: 747 -52. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

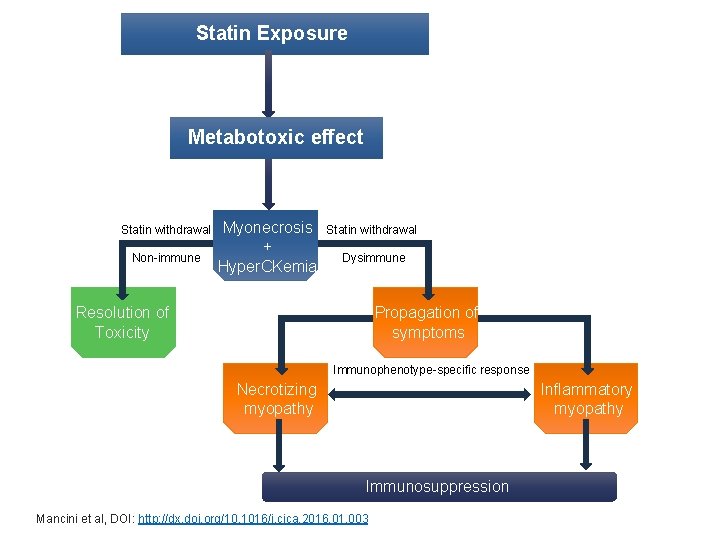

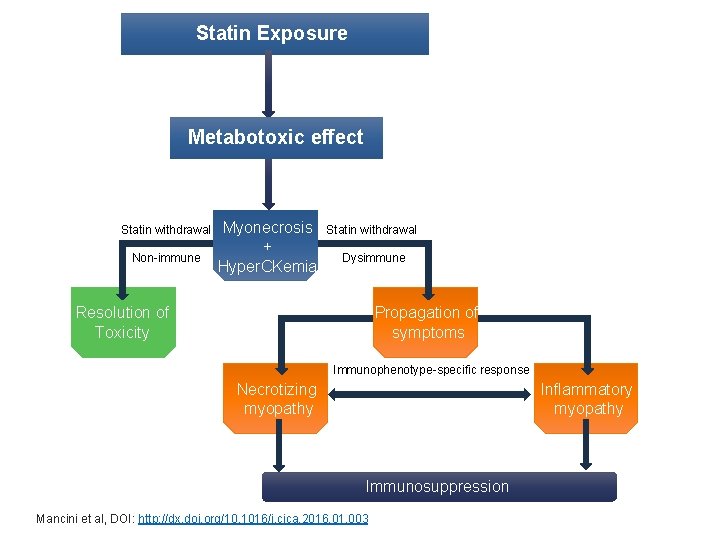

Statin Exposure Metabotoxic effect Statin withdrawal Non-immune Myonecrosis + Hyper. CKemia Statin withdrawal Dysimmune Resolution of Toxicity Propagation of symptoms Immunophenotype-specific response Necrotizing myopathy Inflammatory myopathy Immunosuppression Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

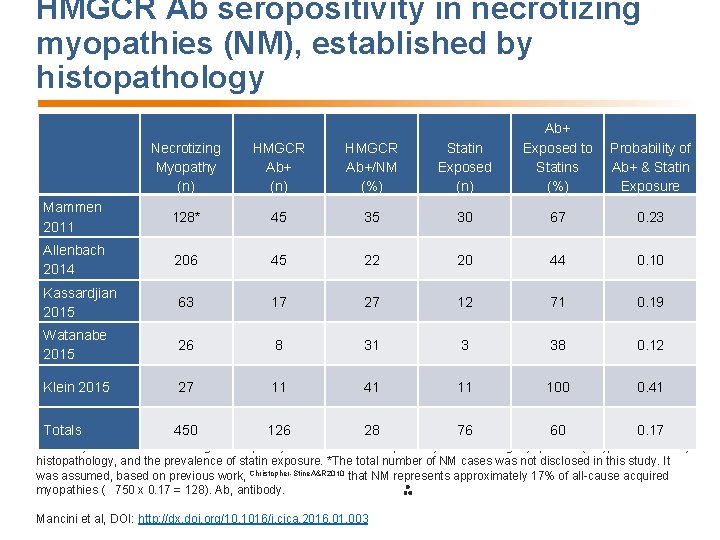

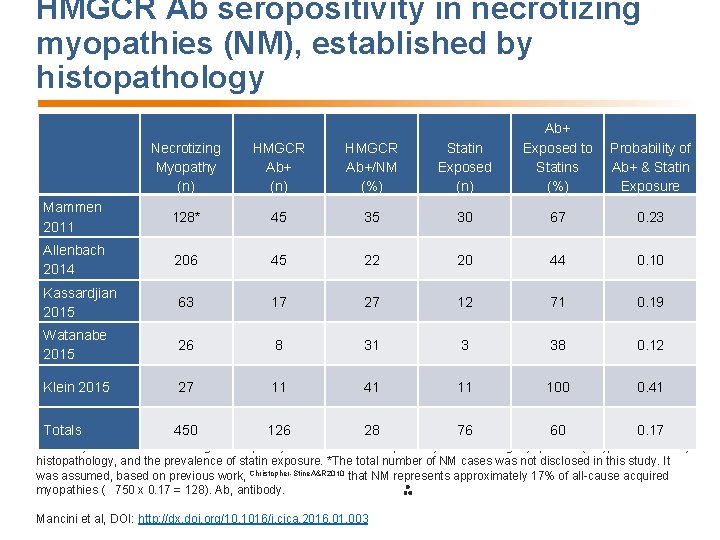

HMGCR Ab seropositivity in necrotizing myopathies (NM), established by histopathology Necrotizing Myopathy (n) HMGCR Ab+/NM (%) Statin Exposed (n) Ab+ Exposed to Statins (%) Mammen 2011 128* 45 35 30 67 0. 23 Allenbach 2014 206 45 22 20 44 0. 10 Kassardjian 2015 63 17 27 12 71 0. 19 Watanabe 2015 26 8 31 3 38 0. 12 Klein 2015 27 11 41 11 100 0. 41 Totals 450 126 28 76 60 0. 17 Probability of Ab+ & Statin Exposure Summary of 5 studies examining the frequency of HMGCR Ab seropositivity in necrotizing myopathies (NM), established by histopathology, and the prevalence of statin exposure. *The total number of NM cases was not disclosed in this study. It was assumed, based on previous work, Christopher-Stine. A&R 2010 that NM represents approximately 17% of all-cause acquired myopathies ( 750 x 0. 17 = 128). Ab, antibody. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

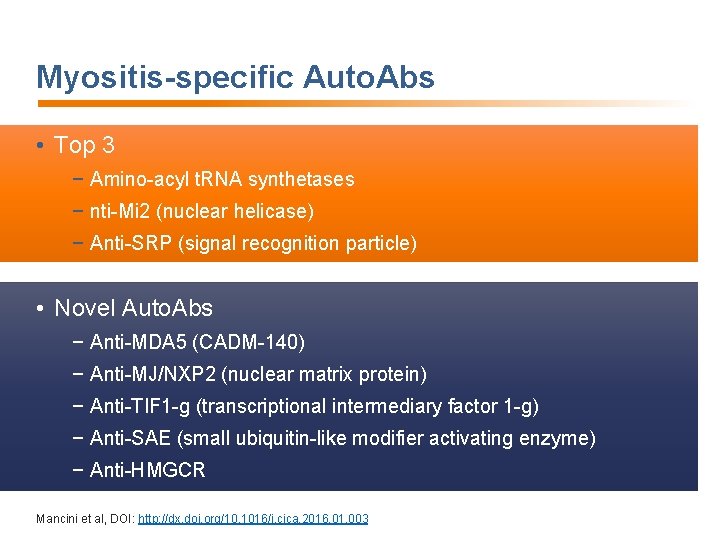

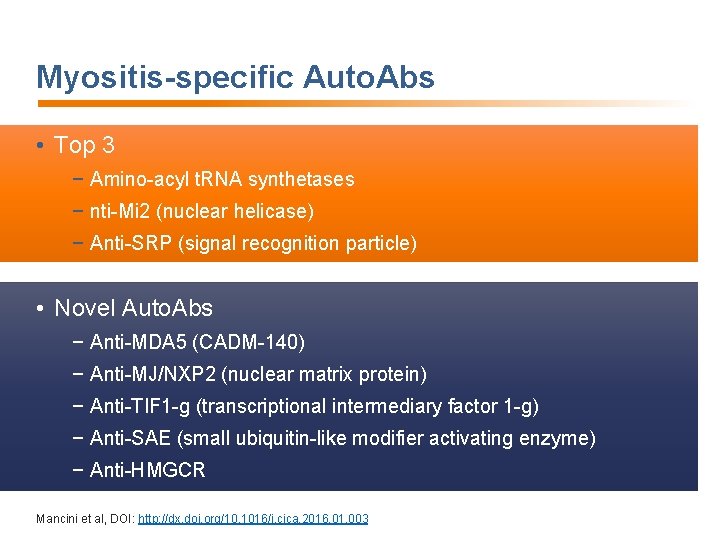

Myositis-specific Auto. Abs • Top 3 − Amino-acyl t. RNA synthetases − nti-Mi 2 (nuclear helicase) − Anti-SRP (signal recognition particle) • Novel Auto. Abs − Anti-MDA 5 (CADM-140) − Anti-MJ/NXP 2 (nuclear matrix protein) − Anti-TIF 1 -g (transcriptional intermediary factor 1 -g) − Anti-SAE (small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme) − Anti-HMGCR Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

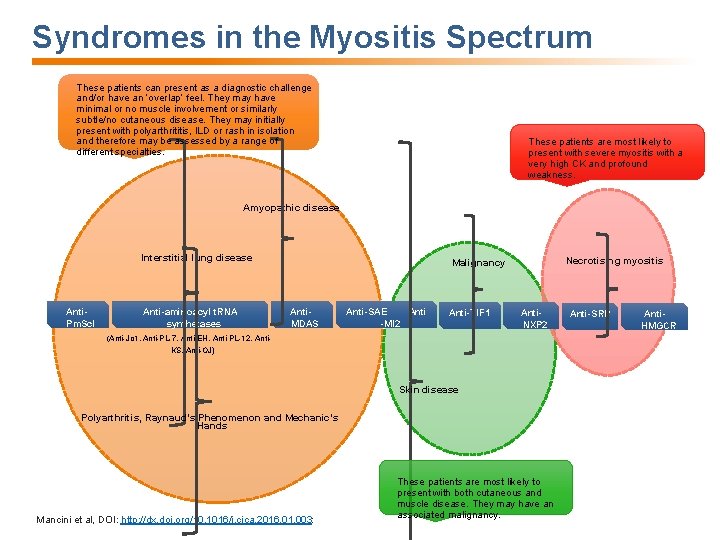

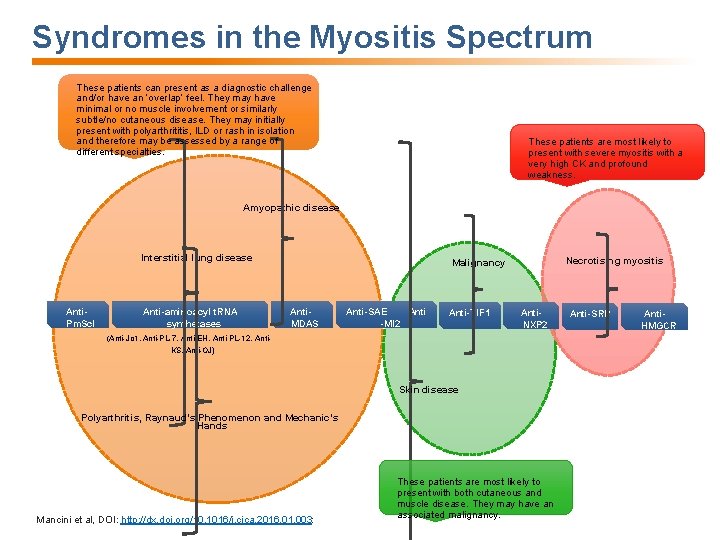

Syndromes in the Myositis Spectrum These patients can present as a diagnostic challenge and/or have an ‘overlap’ feel. They may have minimal or no muscle involvement or similarly subtle/no cutaneous disease. They may initially present with polyarthrititis, ILD or rash in isolation and therefore may be assessed by a range of different specialties. These patients are most likely to present with severe myositis with a very high CK and profound weakness. Amyopathic disease Interstitial lung disease Anti. Pm. Scl Anti-aminoacyl t. RNA synthetases Necrotising myositis Malignancy Anti. MDAS Anti-SAE Anti -MI 2 Anti-TIF 1 Anti. NXP 2 (Anti-Jo 1, Anti-PL-7, Anti-EH, Anti-PL-12, Anti. KS, Anti-OJ) Skin disease Polyarthritis, Raynaud’s Phenomenon and Mechanic’s Hands Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003: These patients are most likely to present with both cutaneous and muscle disease. They may have an associated malignancy. Anti-SRP Anti. HMGCR

Consider a Muscle Biopsy When: 1. Myoglobinuria* 2. Second wind phenomenon* 3. Weakness* 4. Muscle hypertrophy/atrophy* 5. Persistent increase of CK (> 2 -3 above baseline or ULN based on age, sex, ethnicity)* 6. Myopathic EMG (fibrillations and/or +ve sharp waves)* 7. Other considerations: 1. Abnormal neurologic exam 2. CK does not normalize after statin withdrawal 3. Hyper. CKemia with re-exposure to statin 4. + Family History Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003 *European Federation of Neurological Sciences, Kyriakides, et al. Eur J Neurol. 2013; 997 -1005. NB: 2 nd wind (SOB and excessive perceived exertion at onset of exercise that then abates) and hypertrophy are NOT seen with statin myopathy; atrophy is not typical of statin myopathy

Cognitive Adverse Effects • Cognitive considerations should not play a routine role in medical decisions regarding prescription of statins − Decision to prescribe statins should not be altered on this basis for majority of patients • Baseline assessment of cognition prior to initiating statins not warranted − Patient-reported cognitive symptoms should be thoroughly investigated and not readily dismissed • Statins may have a dose and duration related protective effect on certain forms of dementia − Larger/better-designed studies needed to draw unequivocal conclusions about the protective effect of statins on cognition Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Statins and New-Onset Diabetes: Mechanisms • Mechanism remains to be elucidated • Murine studies → upregulation of PTEN, implicated in insulin resistance • Direct effect of HMG Co. A reductase inhibition • Recent FH analysis reveals lower prevalence of DM compared to unaffected relatives, with variability in DM risk by LDL-receptor mutation type; suggesting a link between LDL-receptor mediated cholesterol transport and DM • Statins may therefore cause NOD by upregulating cholesterol transport into hepatocytes and pancreatic beta cells FH; Familial Hypercholesterolemia. NOD; New-onset of diabetes Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Statins and New-Onset Diabetes: Clinical Implications • For every case of NOD caused by statin therapy, several more hard CV events are avoided, both in primary and secondary prevention • General consensus that clinical benefits of statins outweigh risk of NOD • Very long-term risk/benefit ratio remains unclear, though seems favorable from extension studies • Risk of NOD should generally not be a factor in withholding statin therapy from deserving populations Sattar N, et al. Lancet. 2010; 375: 735 -42; Preiss D, et al. JAMA. 2011; 305: 2556 -64; Ridker PM, et al. Lancet. 2012; 380: 565 -71; Waters DD, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61: 148 -52; Kohli P, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015; 65: 402 -4; Fulcher J, et al. Lancet. 2015; 385: 1397 -405; Erqou S, et al. Diabetologia. 2014; 57: 2444 -52; Birnbaum Y, et al. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2014; 28: 447 -57; Besseling J, et al. JAMA. 2015; 313: 1029 -36; Frayling TM. Lancet. 2015; 385: 310 -2. Mancini et al, DOI: http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. cjca. 2016. 01. 003

Primary prevention secondary prevention tertiary prevention

Primary prevention secondary prevention tertiary prevention Statin mechanism of action

Statin mechanism of action Diabetes statin guidelines 2020

Diabetes statin guidelines 2020 Beslenme epidemiyolojisi

Beslenme epidemiyolojisi Mechanism of action of acetaminophen

Mechanism of action of acetaminophen Loop diuretics adverse effects

Loop diuretics adverse effects Analgesic mechanism

Analgesic mechanism Dpp4 inhibitor adverse effects

Dpp4 inhibitor adverse effects Furosemide side effects

Furosemide side effects Loop diuretics adverse effects

Loop diuretics adverse effects Hayanil tablets

Hayanil tablets Drugs that cross placenta mnemonic

Drugs that cross placenta mnemonic Nursing process model

Nursing process model Medical diagnosis and nursing diagnosis difference

Medical diagnosis and nursing diagnosis difference Nursing diagnosis three parts

Nursing diagnosis three parts Nursing process and critical thinking

Nursing process and critical thinking Perbedaan diagnosis gizi dan diagnosis medis

Perbedaan diagnosis gizi dan diagnosis medis Type 1 diabetes in adults diagnosis and management

Type 1 diabetes in adults diagnosis and management Adverse reaction definition

Adverse reaction definition Near miss examples

Near miss examples Adverse selection

Adverse selection Adverse selection

Adverse selection Adverse reaction definition

Adverse reaction definition Adverse reaction definition

Adverse reaction definition Adverse events in hospital

Adverse events in hospital Adverse events in hospital

Adverse events in hospital Adverse events in hospital

Adverse events in hospital Adverse selektion

Adverse selektion Adverse selection

Adverse selection Azalastyna

Azalastyna Adverse treatment

Adverse treatment If you are driving under adverse conditions

If you are driving under adverse conditions Driving in adverse conditions chapter 12

Driving in adverse conditions chapter 12 Adverse selection

Adverse selection Adverse event adalah

Adverse event adalah Beta blocker examples

Beta blocker examples Moa of alpha adrenergic blockers

Moa of alpha adrenergic blockers Alpha blockers classification

Alpha blockers classification Adverse effect of alpha blockers

Adverse effect of alpha blockers Adverse childhood experiences study

Adverse childhood experiences study Adverse yaw

Adverse yaw Adverse childhood experiences study

Adverse childhood experiences study Adverse event

Adverse event Novartis adverse event reporting

Novartis adverse event reporting Adverse childhood experiences study

Adverse childhood experiences study Adverse

Adverse Adverse yaw

Adverse yaw Unanticipated problem vs adverse event

Unanticipated problem vs adverse event Adverse event crf

Adverse event crf Schoolsworkpro

Schoolsworkpro What are adverse childhood experiences

What are adverse childhood experiences Adverse selection

Adverse selection Ae coding

Ae coding What is adverse selection

What is adverse selection Definition of adverse event

Definition of adverse event Driving in adverse conditions

Driving in adverse conditions Overdriving headlights definition

Overdriving headlights definition Tools to help solve adverse selection problems

Tools to help solve adverse selection problems Serious adverse event reconciliation

Serious adverse event reconciliation Adverse food reactions

Adverse food reactions Aefi examples

Aefi examples Irremedial

Irremedial Ahca adverse incident reporting

Ahca adverse incident reporting Spcc template

Spcc template Precca

Precca Colorado jprs

Colorado jprs Injuries first aid

Injuries first aid National and local guidance on falls prevention

National and local guidance on falls prevention Puncture resistant container

Puncture resistant container Chapter 26 infectious disease prevention and control

Chapter 26 infectious disease prevention and control Chapter 19 disease transmission and infection prevention

Chapter 19 disease transmission and infection prevention