The Electromagnetic Spectrum In astronomy we cannot perform

- Slides: 51

• The Electromagnetic Spectrum In astronomy, we cannot perform experiments with our objects (stars, galaxies, …). The only way to investigate them, is by analyzing the light (and other radiation) which we observe from them. The study of the universe is so challenging, astronomers cannot ignore any source of information; that is why they use the entire spectrum, from gamma rays to radio waves.

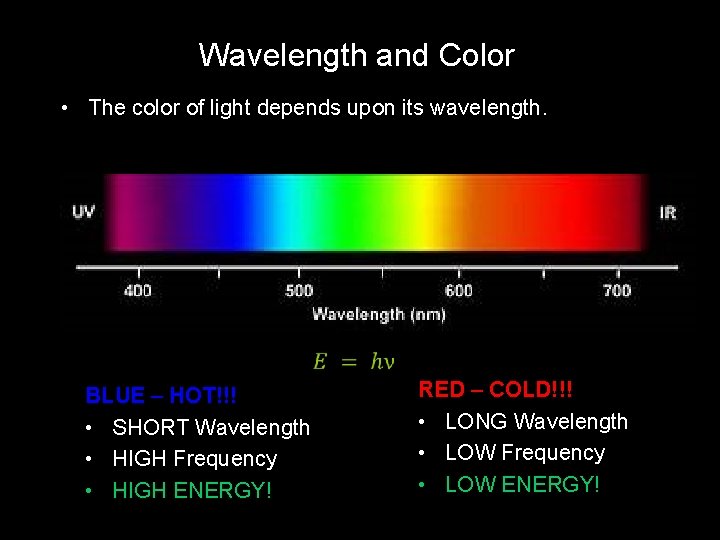

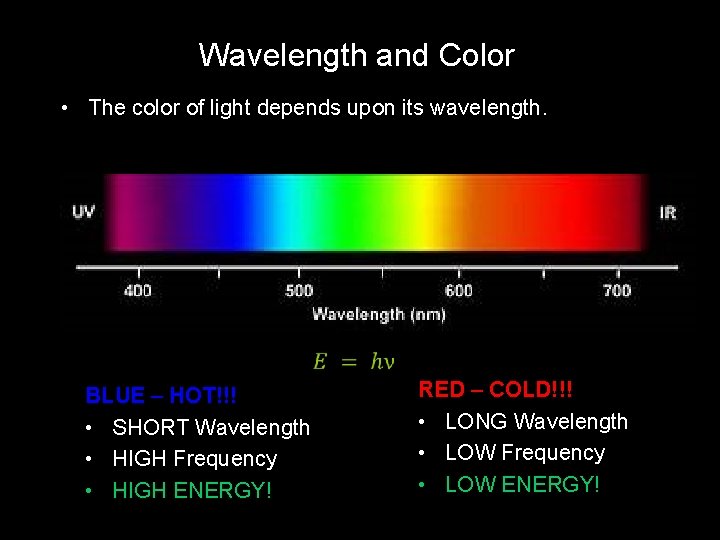

Wavelength and Color • The color of light depends upon its wavelength. BLUE – HOT!!! • SHORT Wavelength • HIGH Frequency • HIGH ENERGY! RED – COLD!!! • LONG Wavelength • LOW Frequency • LOW ENERGY!

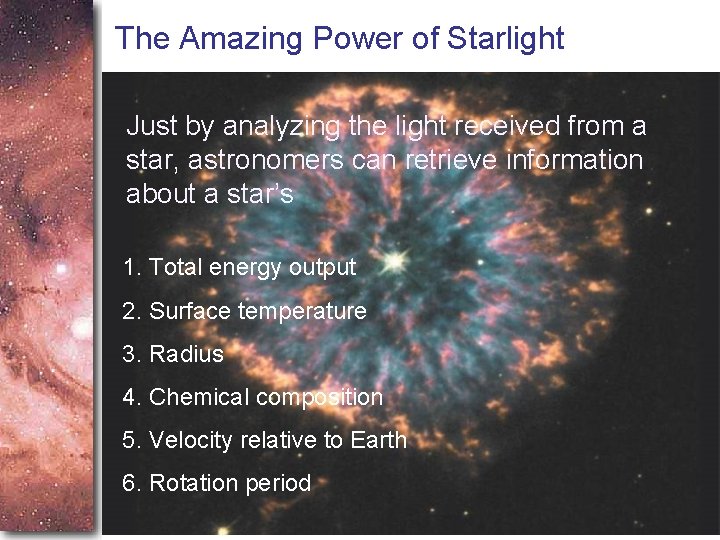

The Amazing Power of Starlight Just by analyzing the light received from a star, astronomers can retrieve information about a star’s 1. Total energy output 2. Surface temperature 3. Radius 4. Chemical composition 5. Velocity relative to Earth 6. Rotation period

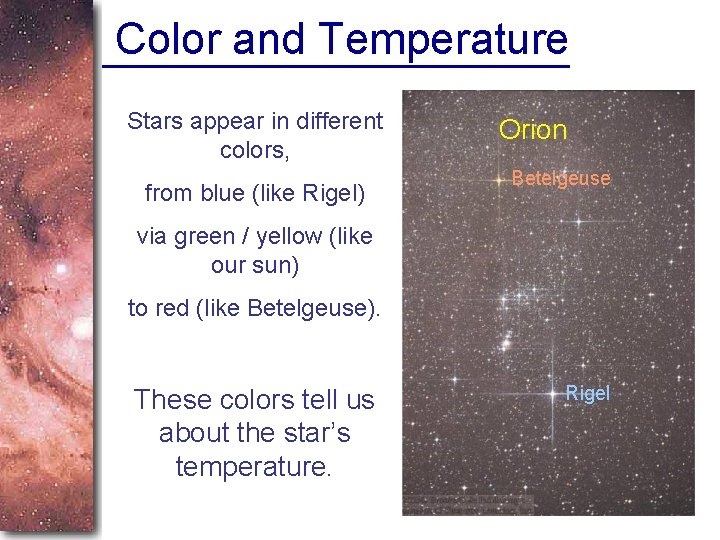

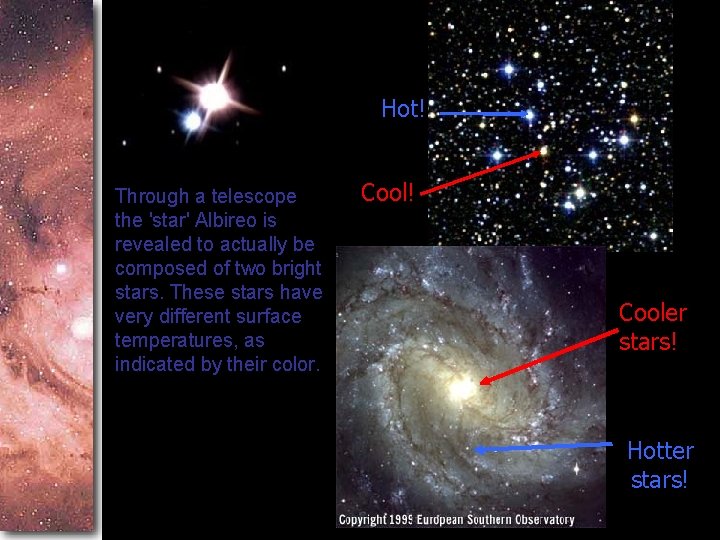

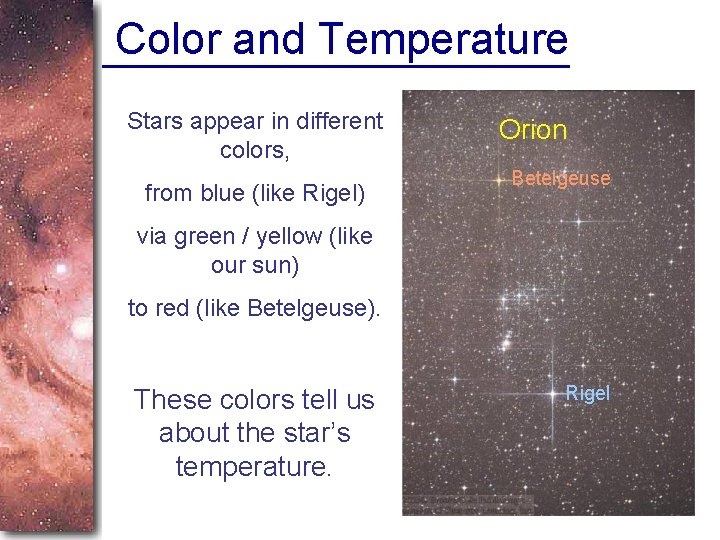

Color and Temperature Stars appear in different colors, from blue (like Rigel) Orion Betelgeuse via green / yellow (like our sun) to red (like Betelgeuse). These colors tell us about the star’s temperature. Rigel

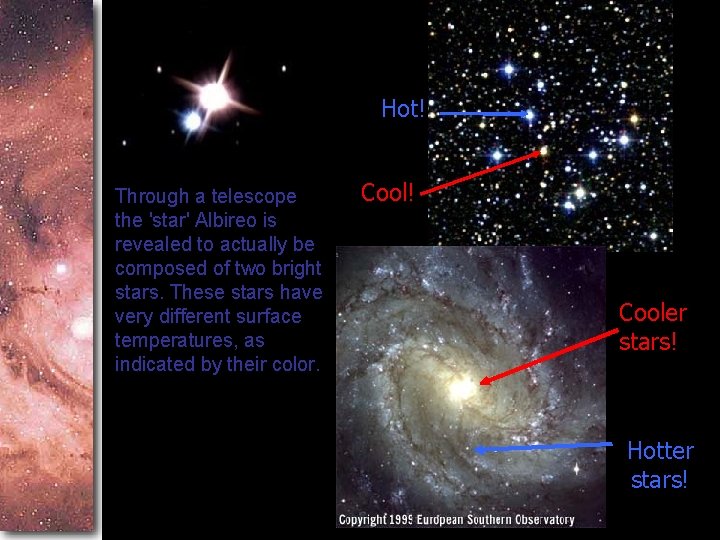

Hot! Through a telescope the 'star' Albireo is revealed to actually be composed of two bright stars. These stars have very different surface temperatures, as indicated by their color. Cool! Cooler stars! Hotter stars!

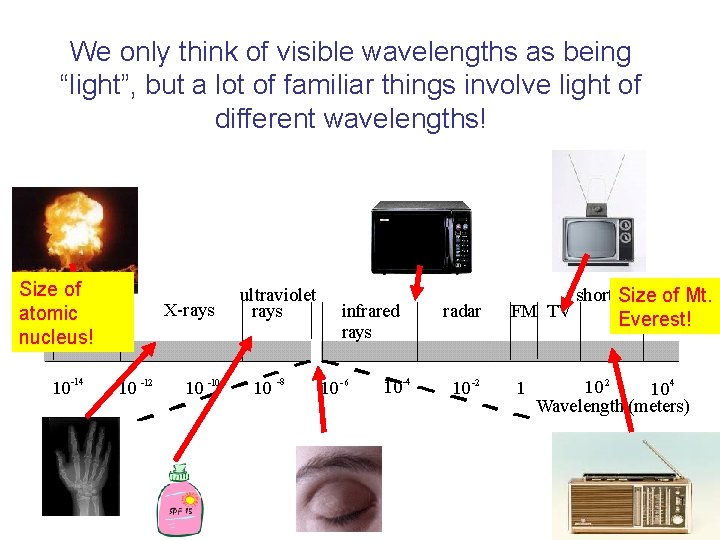

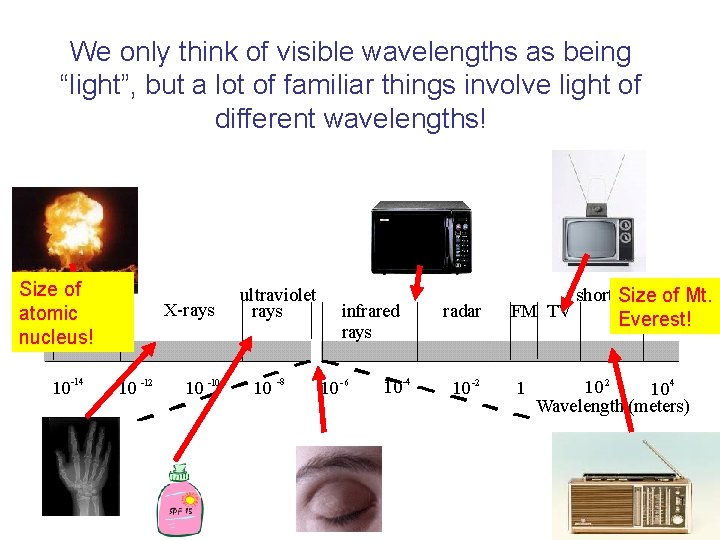

We only think of visible wavelengths as being “light”, but a lot of familiar things involve light of different wavelengths! Size of atomic nucleus! Size of Mt. Everest!

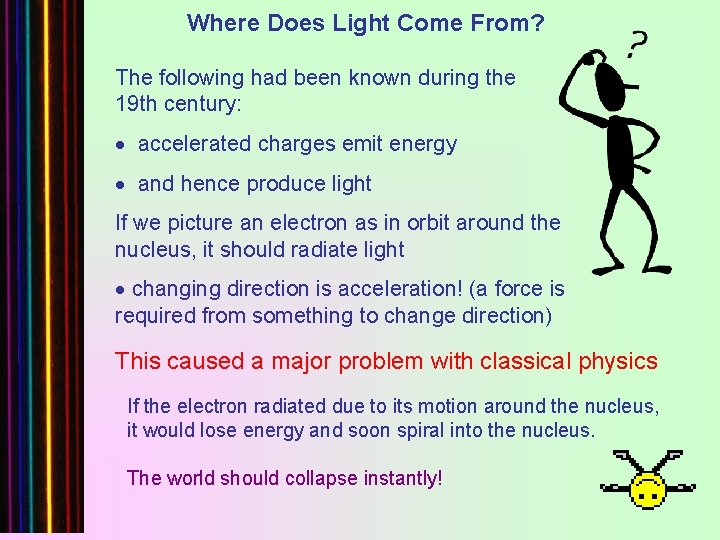

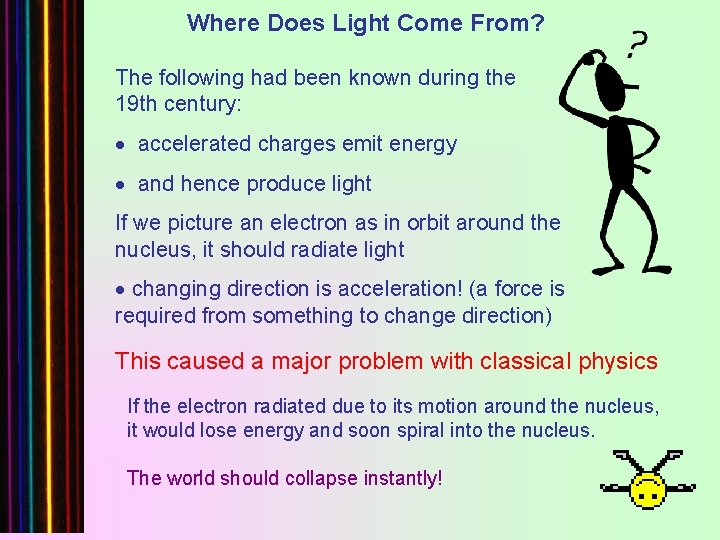

Where Does Light Come From? The following had been known during the 19 th century: accelerated charges emit energy and hence produce light If we picture an electron as in orbit around the nucleus, it should radiate light changing direction is acceleration! (a force is required from something to change direction) This caused a major problem with classical physics If the electron radiated due to its motion around the nucleus, it would lose energy and soon spiral into the nucleus. The world should collapse instantly!

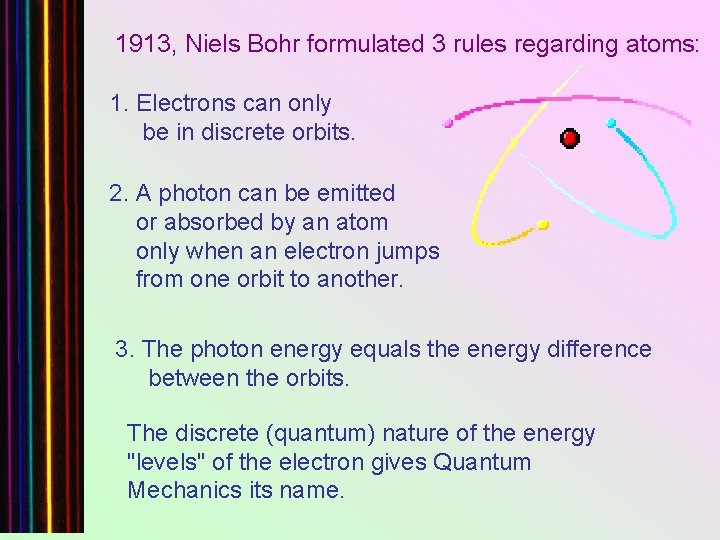

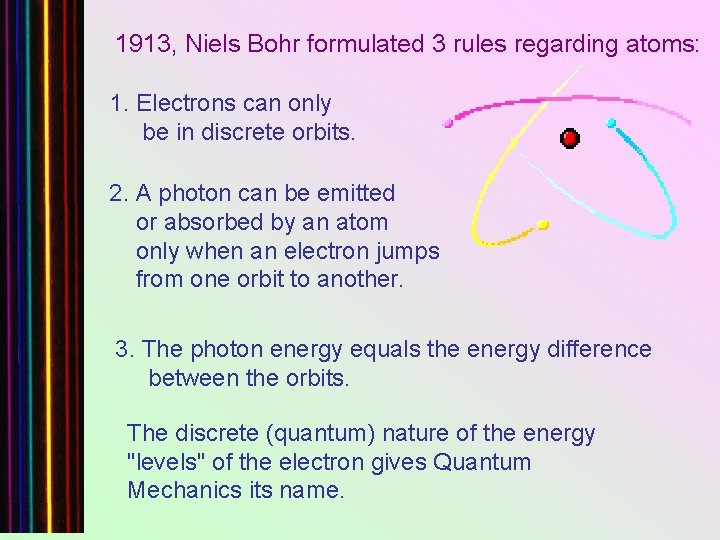

1913, Niels Bohr formulated 3 rules regarding atoms: 1. Electrons can only be in discrete orbits. 2. A photon can be emitted or absorbed by an atom only when an electron jumps from one orbit to another. 3. The photon energy equals the energy difference between the orbits. The discrete (quantum) nature of the energy "levels" of the electron gives Quantum Mechanics its name.

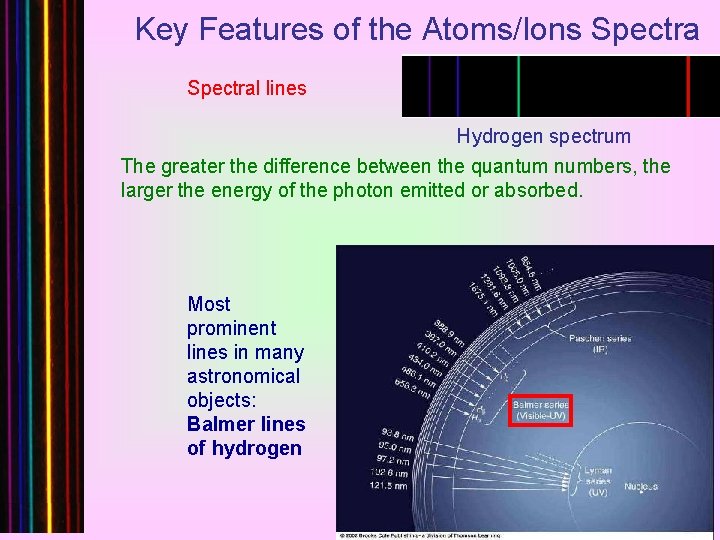

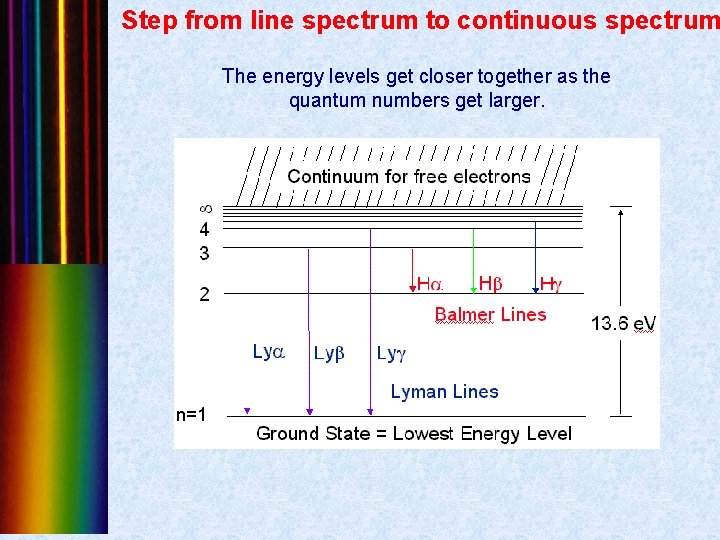

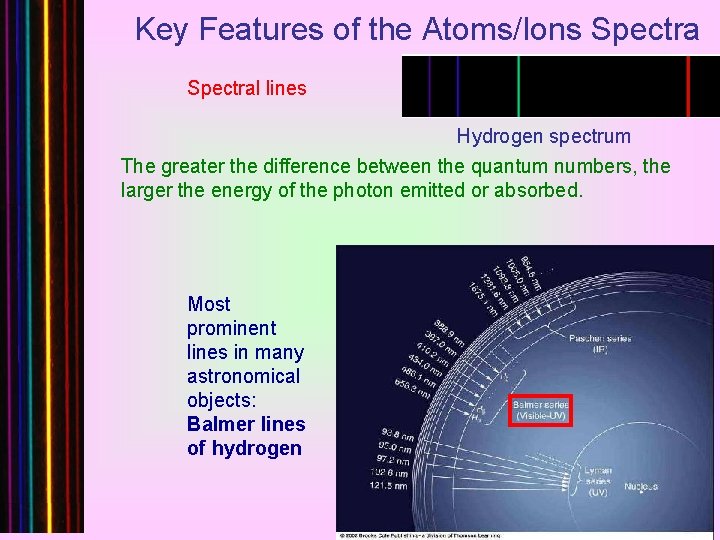

Key Features of the Atoms/Ions Spectral lines Hydrogen spectrum The greater the difference between the quantum numbers, the larger the energy of the photon emitted or absorbed. Most prominent lines in many astronomical objects: Balmer lines of hydrogen

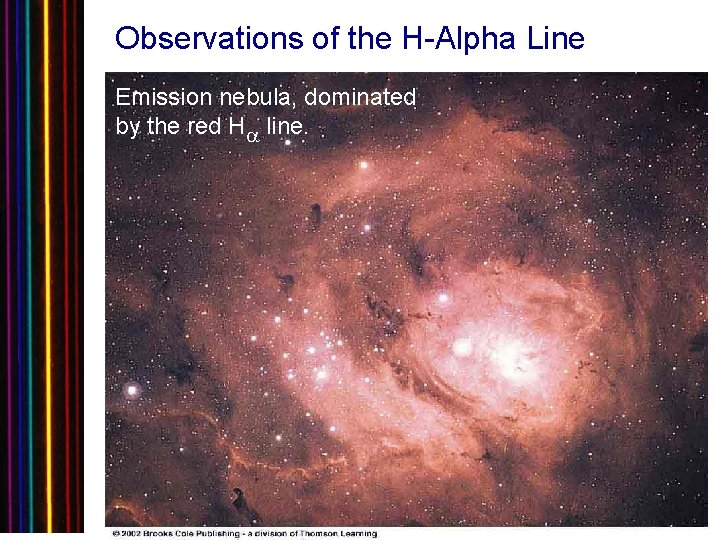

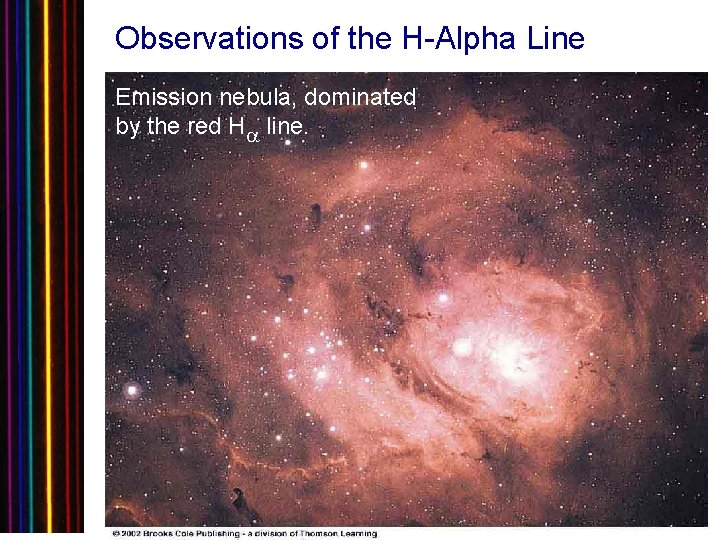

Observations of the H-Alpha Line Emission nebula, dominated by the red Ha line.

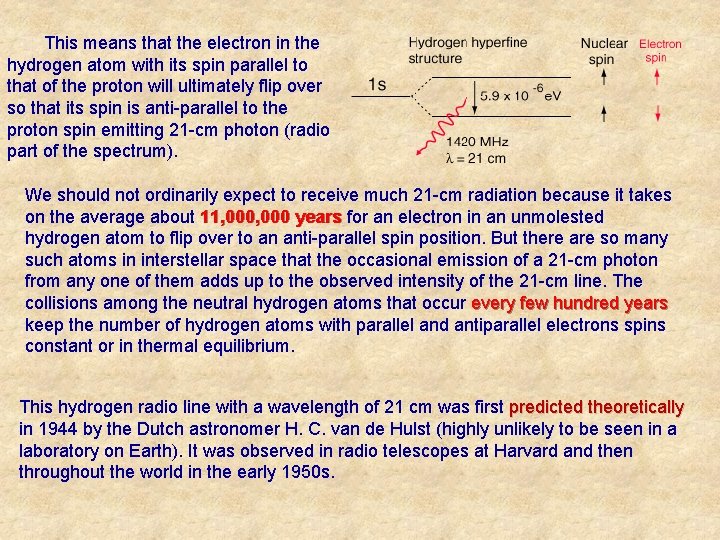

Hydrogen and helium account for nearly all the nuclear matter in today's universe. The abundance of hydrogen by mass, is 73% (Helium is 25%, All other elements 2%). By atomic abundance, hydrogen is 90%, helium 9%, and all other elements 1%. That is, hydrogen is the major constituent of the universe. As we are already talkig about hydrogen let me mention one very interesting fact. I call it: a WOW story of time!!!!!! spin-flip transition even though the atom is in its ground state When a proton captures an electron to form hydrogen atom (after Big Bang) the spins of the two particles either point in the same direction or opposite direction. Due to the spin both electrons and protons behave like little magnets. Hydrogen atom with antiparallel spins is more stable (the electron is more tightly bound to the proton) than the atom with the two spins parallel because unlike poles attract each other and like poles repel. Since a anti-parallel-spin capture is three times as probable as an parallel-spin capture, 75% hydrogen atoms in between the stars is with spins anti-parallel and 25% with parallel-spin.

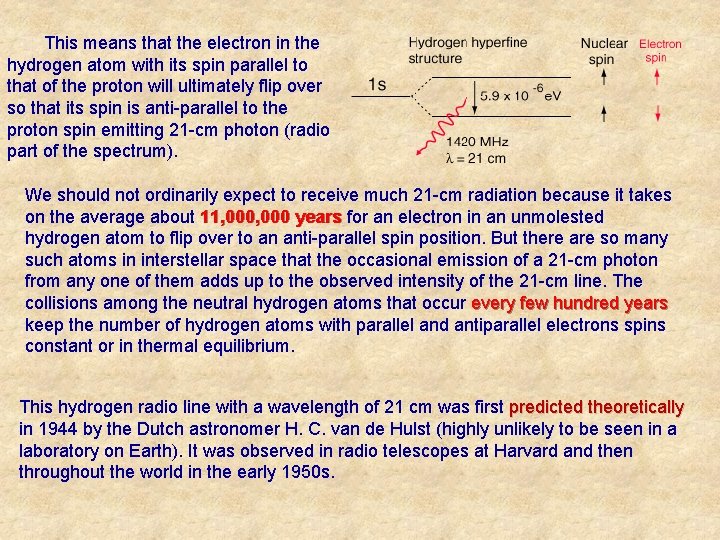

This means that the electron in the hydrogen atom with its spin parallel to that of the proton will ultimately flip over so that its spin is anti-parallel to the proton spin emitting 21 -cm photon (radio part of the spectrum). We should not ordinarily expect to receive much 21 -cm radiation because it takes on the average about 11, 000 years for an electron in an unmolested years hydrogen atom to flip over to an anti-parallel spin position. But there are so many such atoms in interstellar space that the occasional emission of a 21 -cm photon from any one of them adds up to the observed intensity of the 21 -cm line. The collisions among the neutral hydrogen atoms that occur every few hundred years keep the number of hydrogen atoms with parallel and antiparallel electrons spins constant or in thermal equilibrium. This hydrogen radio line with a wavelength of 21 cm was first predicted theoretically in 1944 by the Dutch astronomer H. C. van de Hulst (highly unlikely to be seen in a laboratory on Earth). It was observed in radio telescopes at Harvard and then throughout the world in the early 1950 s.

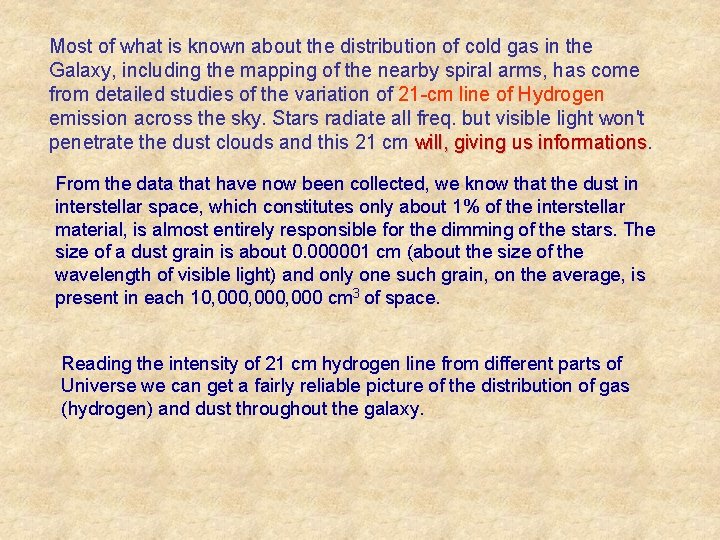

Most of what is known about the distribution of cold gas in the Galaxy, including the mapping of the nearby spiral arms, has come from detailed studies of the variation of 21 -cm line of Hydrogen emission across the sky. Stars radiate all freq. but visible light won't penetrate the dust clouds and this 21 cm will, giving us informations From the data that have now been collected, we know that the dust in interstellar space, which constitutes only about 1% of the interstellar material, is almost entirely responsible for the dimming of the stars. The size of a dust grain is about 0. 000001 cm (about the size of the wavelength of visible light) and only one such grain, on the average, is present in each 10, 000, 000 cm 3 of space. Reading the intensity of 21 cm hydrogen line from different parts of Universe we can get a fairly reliable picture of the distribution of gas (hydrogen) and dust throughout the galaxy.

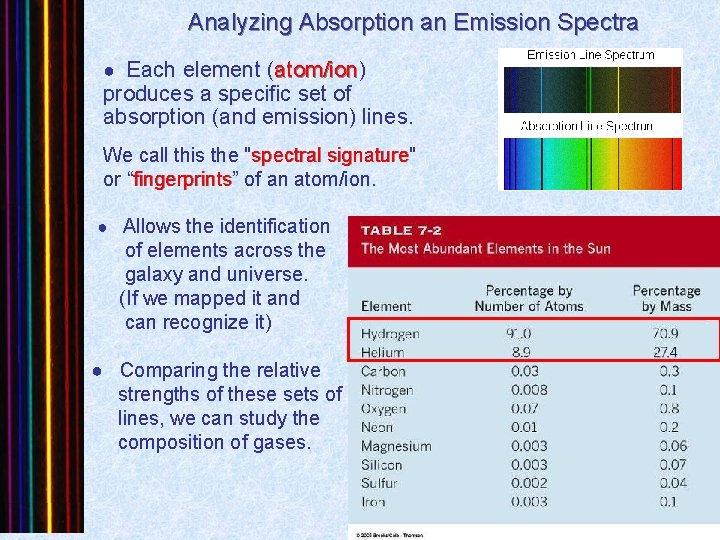

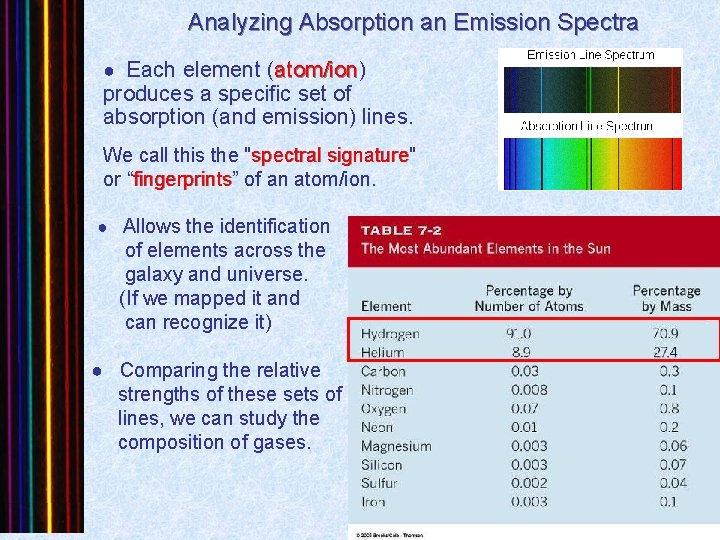

Analyzing Absorption an Emission Spectra ● Each element (atom/ion) atom/ion produces a specific set of absorption (and emission) lines. We call this the "spectral signature" spectral signature or “fingerprints” of an atom/ion. fingerprints ● Allows the identification of elements across the galaxy and universe. (If we mapped it and can recognize it) ● Comparing the relative strengths of these sets of lines, we can study the composition of gases.

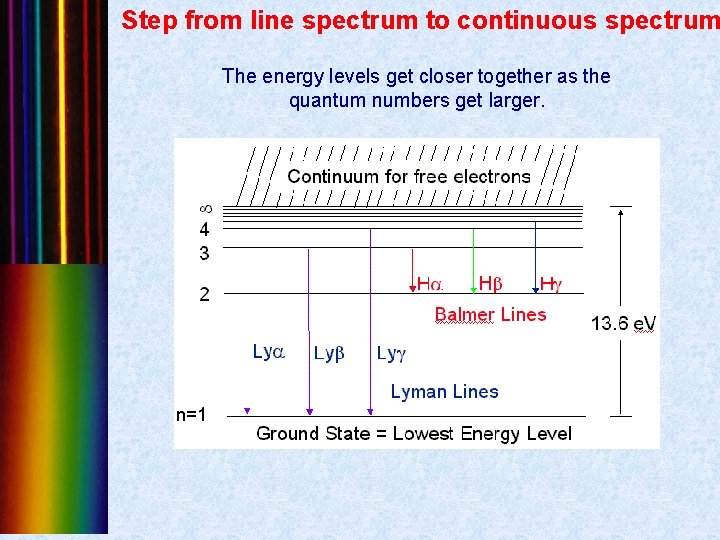

Step from line spectrum to continuous spectrum The energy levels get closer together as the quantum numbers get larger.

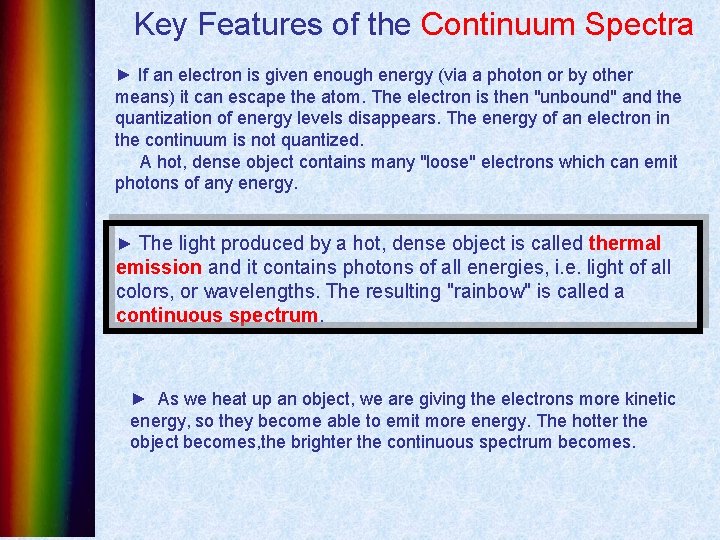

Key Features of the Continuum Spectra ► If an electron is given enough energy (via a photon or by other means) it can escape the atom. The electron is then "unbound" and the quantization of energy levels disappears. The energy of an electron in the continuum is not quantized. A hot, dense object contains many "loose" electrons which can emit photons of any energy. ► The light produced by a hot, dense object is called thermal emission and it contains photons of all energies, i. e. light of all colors, or wavelengths. The resulting "rainbow" is called a continuous spectrum. ► As we heat up an object, we are giving the electrons more kinetic energy, so they become able to emit more energy. The hotter the object becomes, the brighter the continuous spectrum becomes.

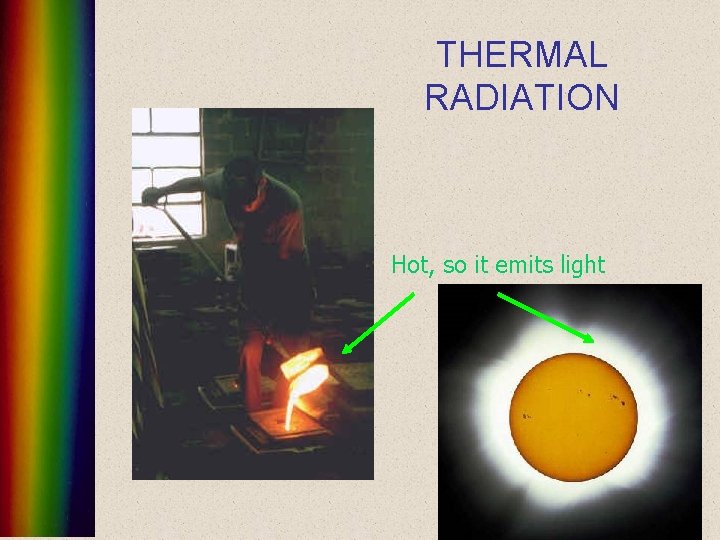

THERMAL RADIATION Hot, so it emits light

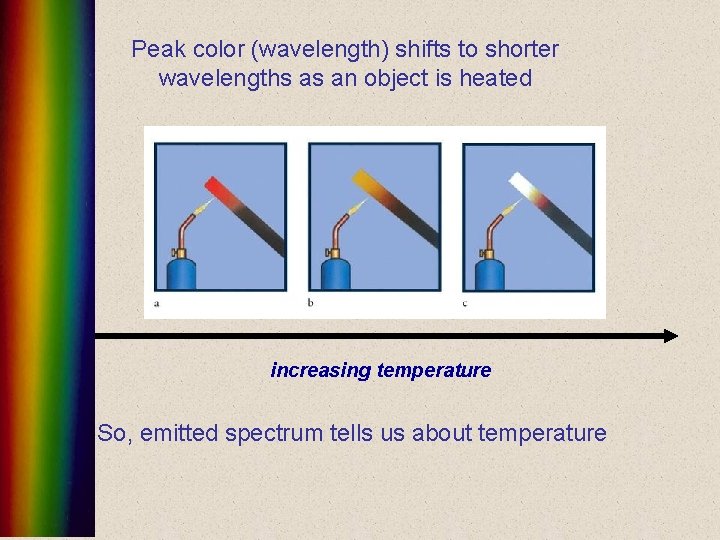

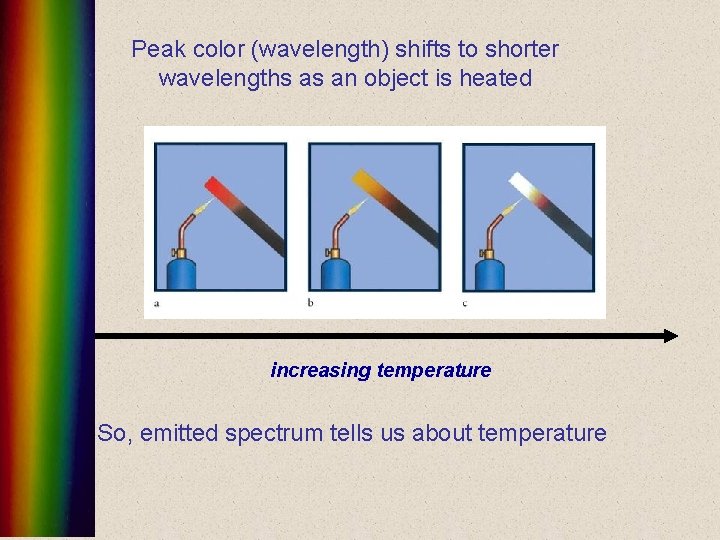

Peak color (wavelength) shifts to shorter wavelengths as an object is heated increasing temperature So, emitted spectrum tells us about temperature

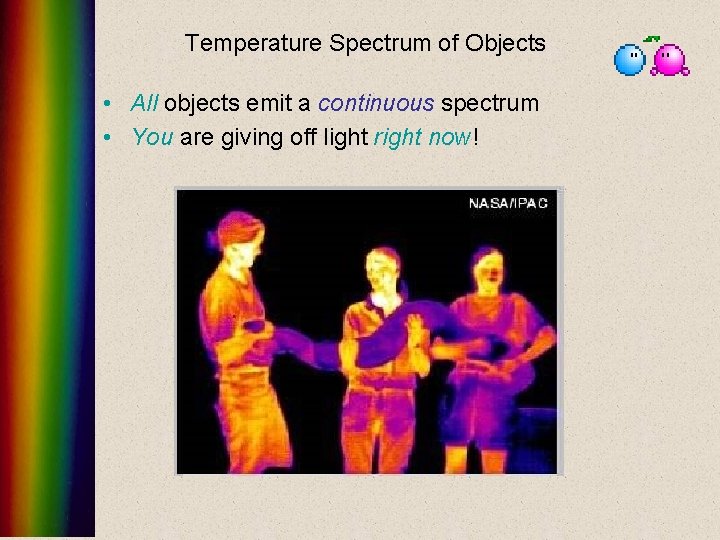

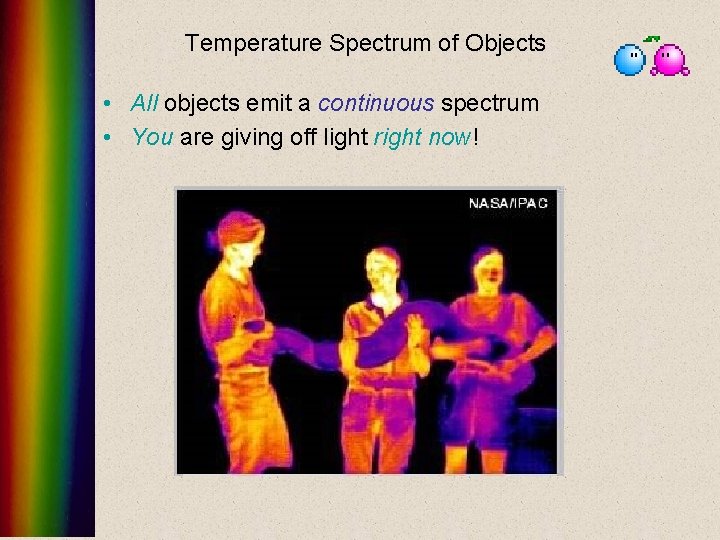

Temperature Spectrum of Objects • All objects emit a continuous spectrum • You are giving off light right now!

If you could fill a teaspoon just with material as dense as the matter in an atomic nucleus, it would weigh ~ 2 billion tons!! just for fun – so cute Kirchoff's Laws of Spectroscopy/Radiation Kirchoff formulated these laws empirically in the mid-19 th century – didn’t explain why – in early 20 th century: QM – nature of atom – beginning of understanding origin of spectra Kirchhoff did not know about the existence of energy levels in atoms. The existence of discrete spectral lines was later explained by the Bohr model of the atom, which helped lead to quantum mechanics.

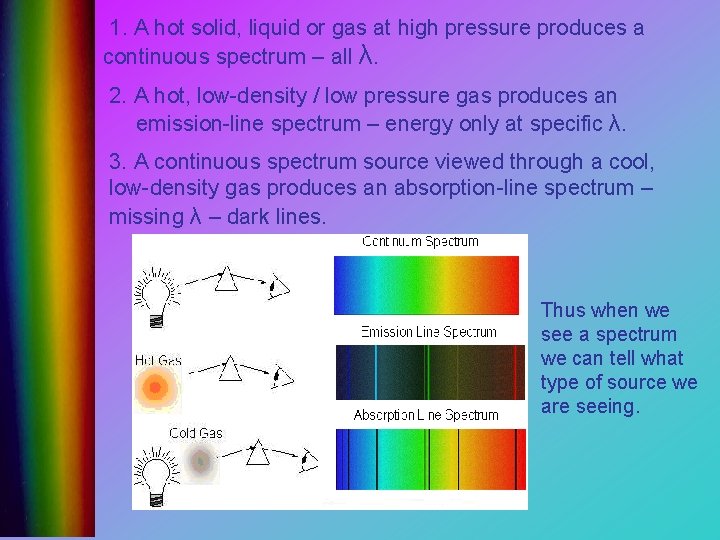

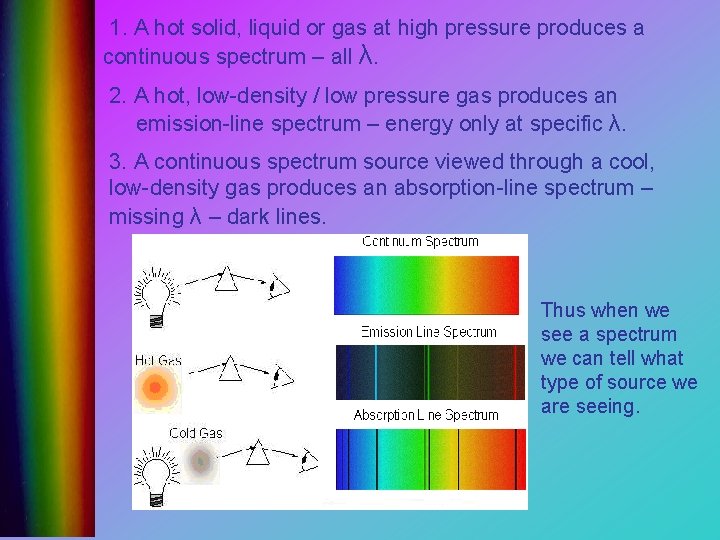

1. A hot solid, liquid or gas at high pressure produces a continuous spectrum – all λ. 2. A hot, low-density / low pressure gas produces an emission-line spectrum – energy only at specific λ. 3. A continuous spectrum source viewed through a cool, low-density gas produces an absorption-line spectrum – missing λ – dark lines. Thus when we see a spectrum we can tell what type of source we are seeing.

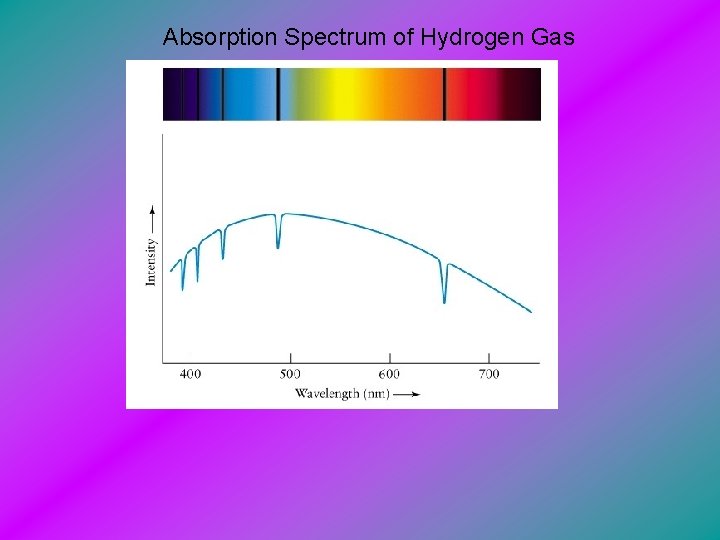

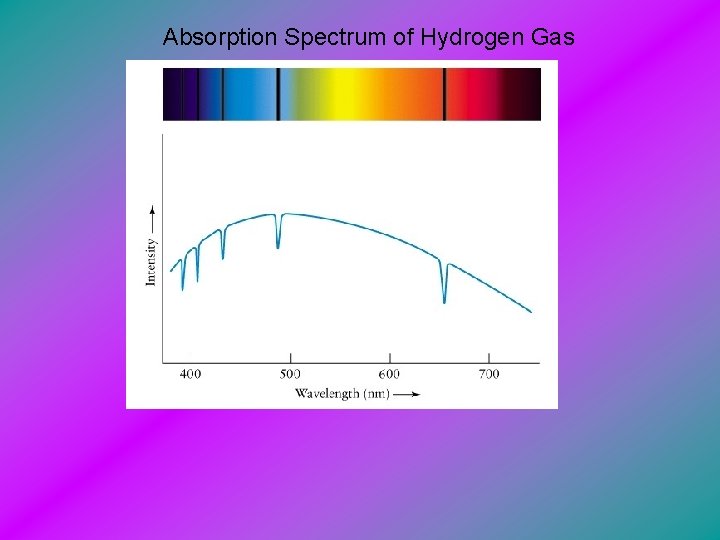

Absorption Spectrum of Hydrogen Gas

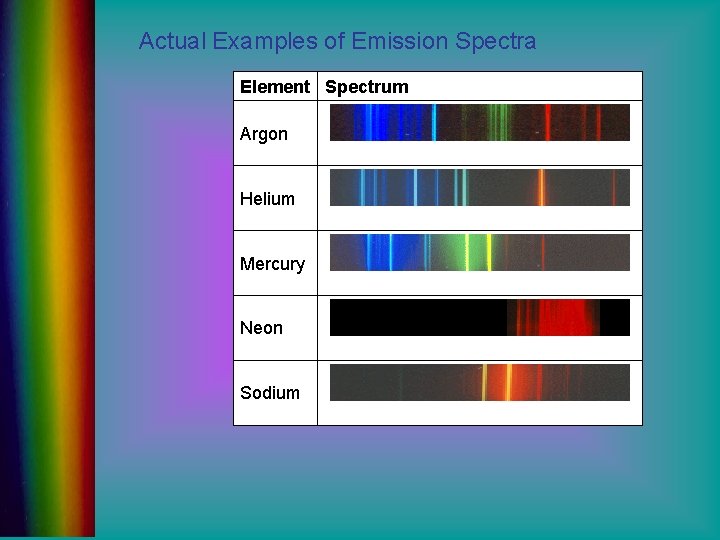

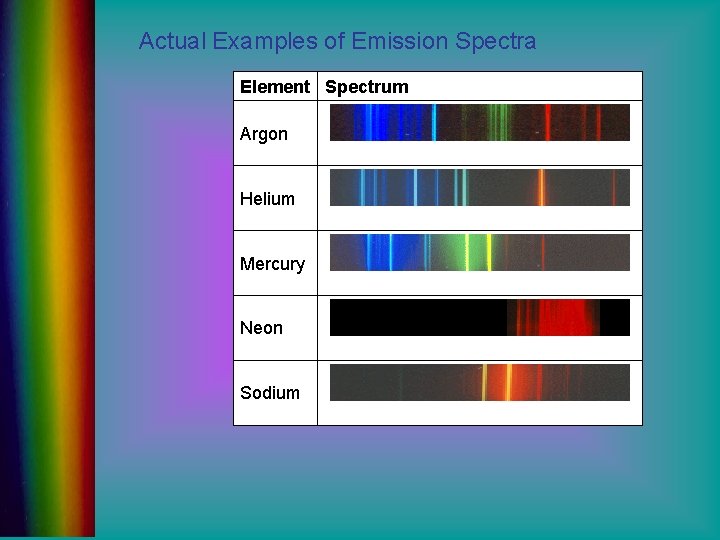

Actual Examples of Emission Spectra Element Spectrum Argon Helium Mercury Neon Sodium

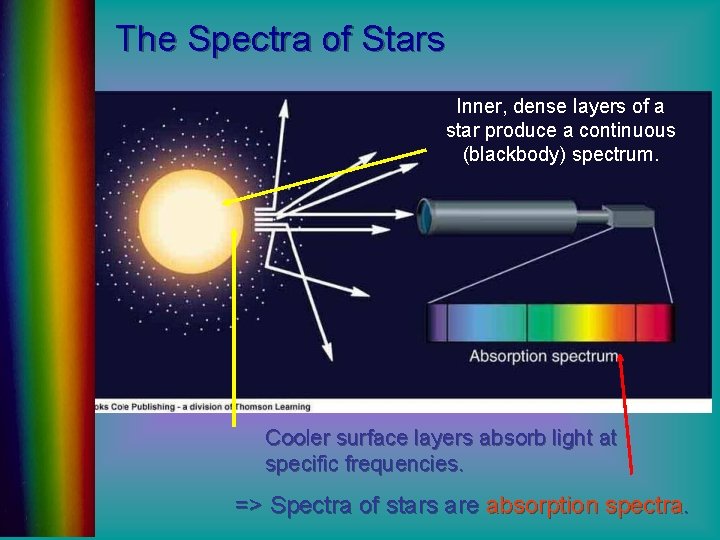

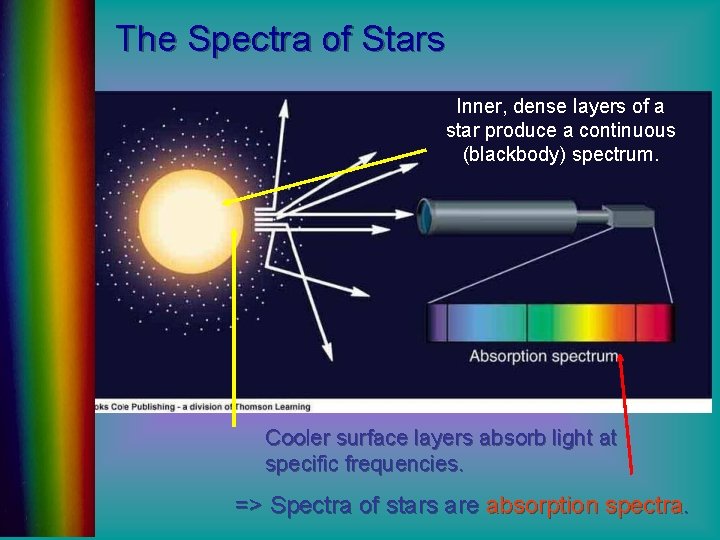

The Spectra of Stars Inner, dense layers of a star produce a continuous (blackbody) spectrum. Cooler surface layers absorb light at specific frequencies. => Spectra of stars are absorption spectra.

To understand the nature, to interpret many beautiful phenomena you have to have a tool. We are introducing something that we know all about and then we’ll compare the nature with that ideal case!!!!!!! Blackbody Radiation A black body is a theoretical object that absorbs 100% of the radiation that hits it. Therefore it reflects no radiation and appears perfectly black. In practice no material has been found to absorb all incoming radiation, but carbon in its graphite form absorbs all but about 3%. It is also a perfect emitter of radiation. At a particular temperature the black body would emit the maximum amount of energy possible for that temperature. This value is known as the black body radiation. It would emit at every wavelength of light as it must be able to absorb every wavelength to be sure of absorbing all incoming radiation.

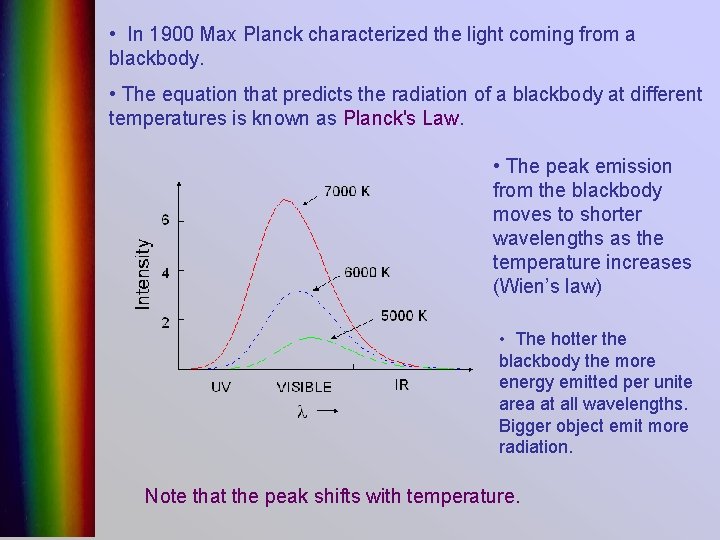

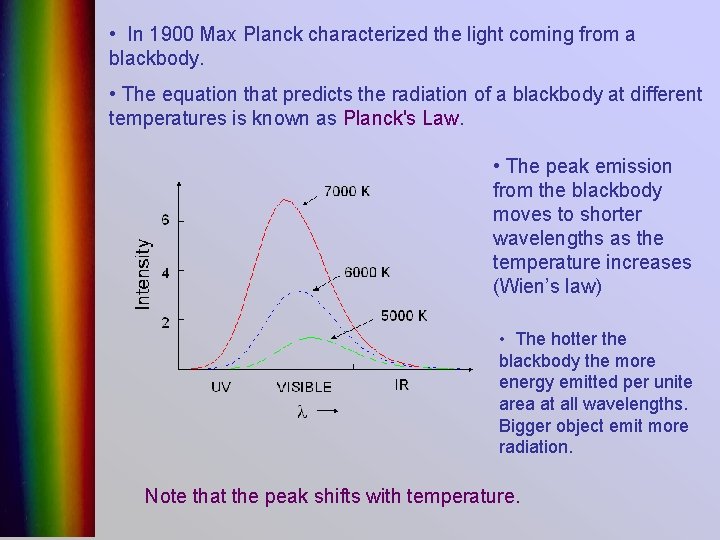

• In 1900 Max Planck characterized the light coming from a blackbody. • The equation that predicts the radiation of a blackbody at different temperatures is known as Planck's Law. • The peak emission from the blackbody moves to shorter wavelengths as the temperature increases (Wien’s law) • The hotter the blackbody the more energy emitted per unite area at all wavelengths. Bigger object emit more radiation. Note that the peak shifts with temperature.

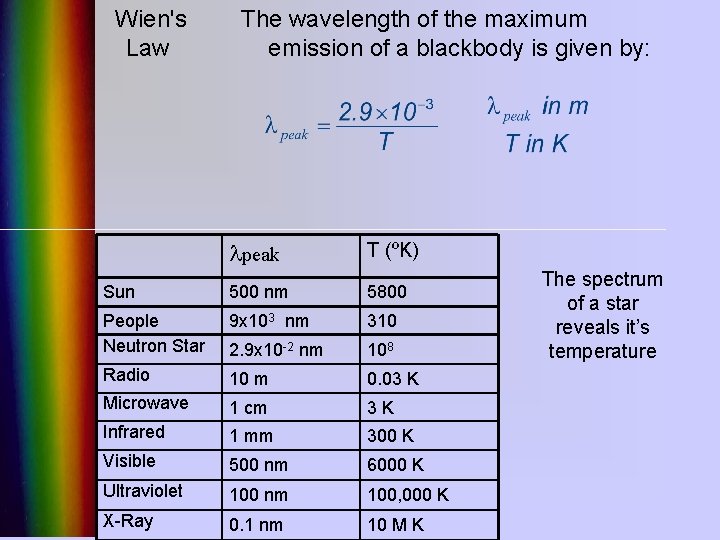

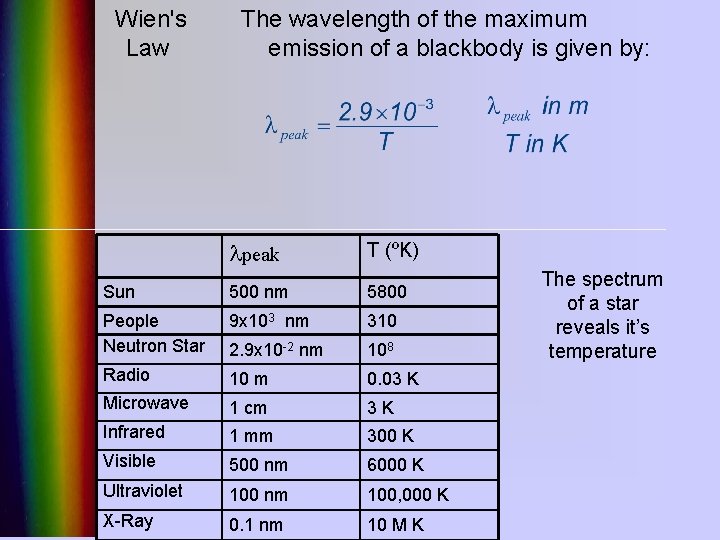

Wien's Law The wavelength of the maximum emission of a blackbody is given by: lpeak T (ºK) Sun 500 nm 5800 People Neutron Star 9 x 103 nm 310 2. 9 x 10 -2 nm 108 Radio 10 m 0. 03 K Microwave 1 cm 3 K Infrared 1 mm 300 K Visible 500 nm 6000 K Ultraviolet 100 nm 100, 000 K X-Ray 0. 1 nm 10 M K The spectrum of a star reveals it’s temperature

Consequences of Wien's Law Hot objects look blue. Cold objects look red. Except for their surfaces, stars behave as blackbodies.

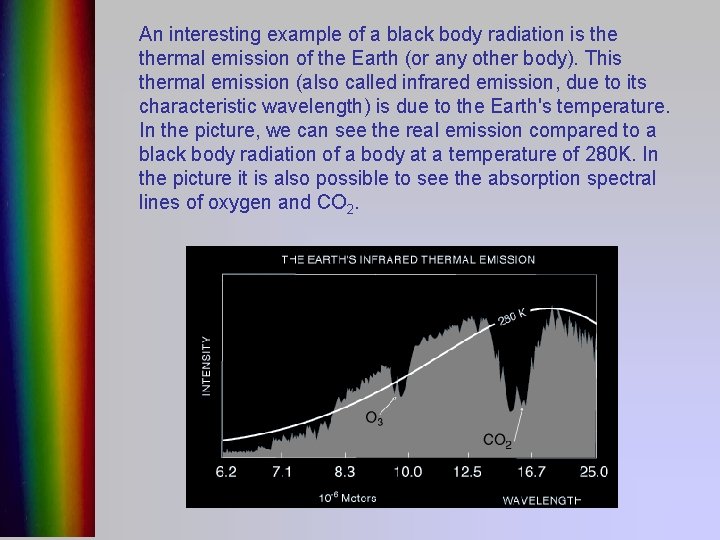

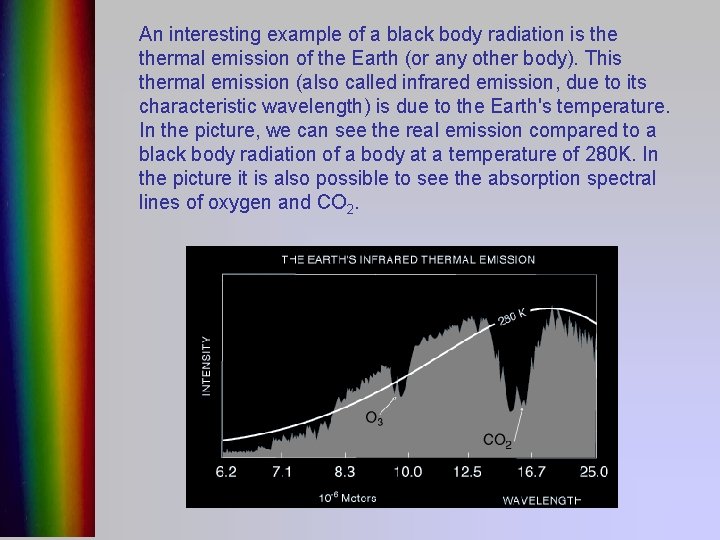

An interesting example of a black body radiation is thermal emission of the Earth (or any other body). This thermal emission (also called infrared emission, due to its characteristic wavelength) is due to the Earth's temperature. In the picture, we can see the real emission compared to a black body radiation of a body at a temperature of 280 K. In the picture it is also possible to see the absorption spectral lines of oxygen and CO 2.

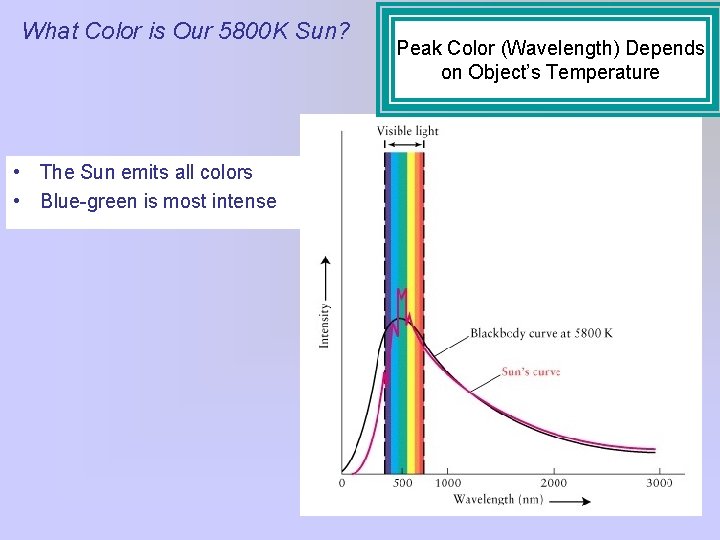

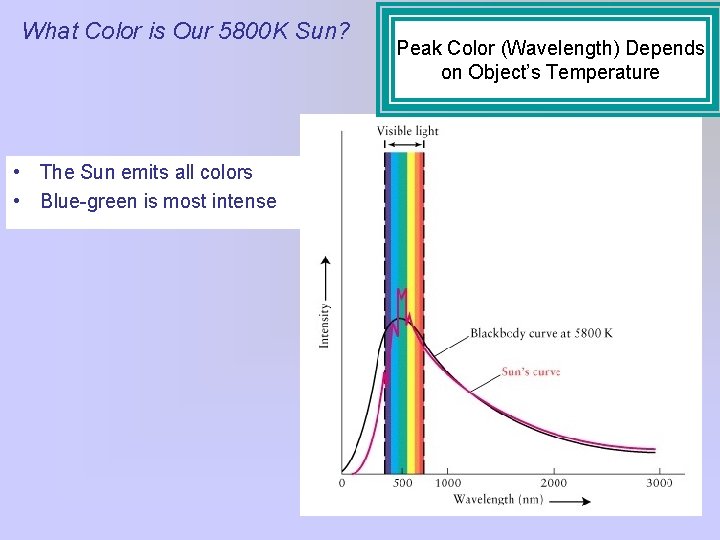

What Color is Our 5800 K Sun? • The Sun emits all colors • Blue-green is most intense Peak Color (Wavelength) Depends on Object’s Temperature

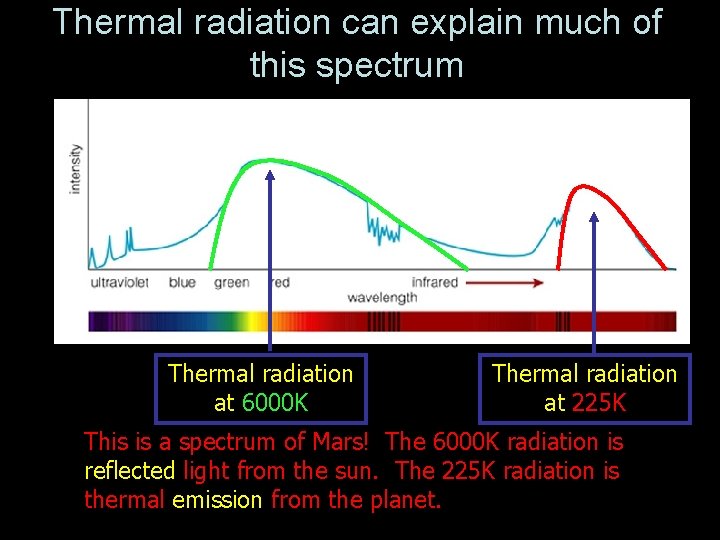

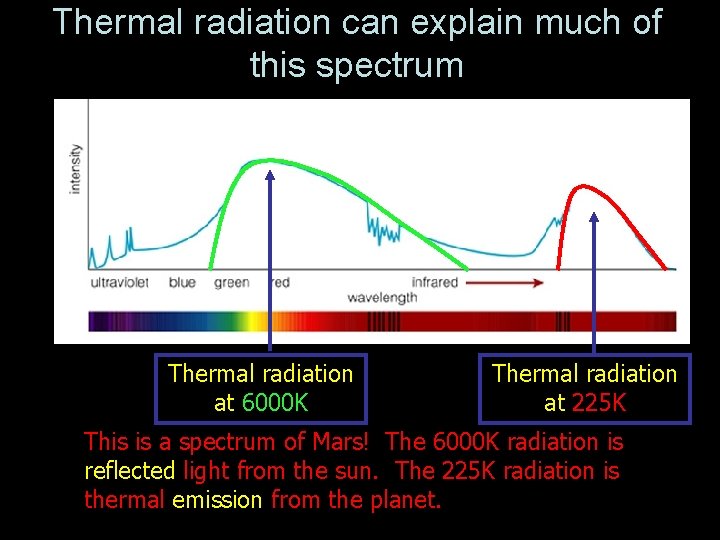

Thermal radiation can explain much of this spectrum Thermal radiation at 6000 K Thermal radiation at 225 K This is a spectrum of Mars! The 6000 K radiation is reflected light from the sun. The 225 K radiation is thermal emission from the planet.

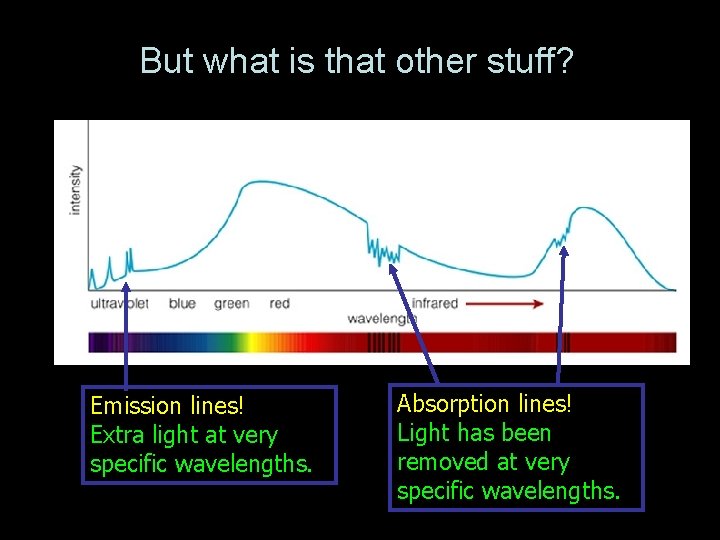

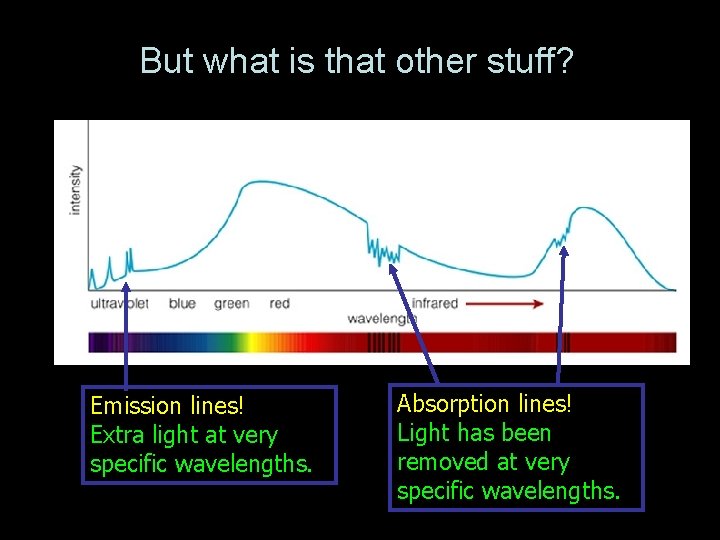

But what is that other stuff? Emission lines! Extra light at very specific wavelengths. Absorption lines! Light has been removed at very specific wavelengths.

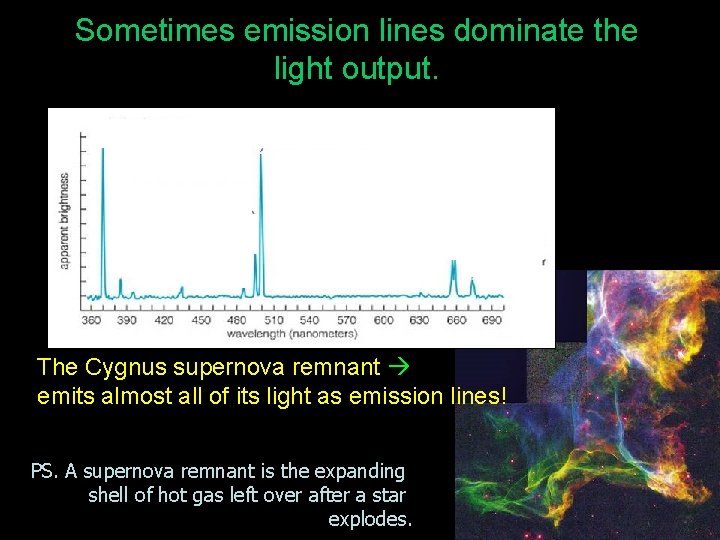

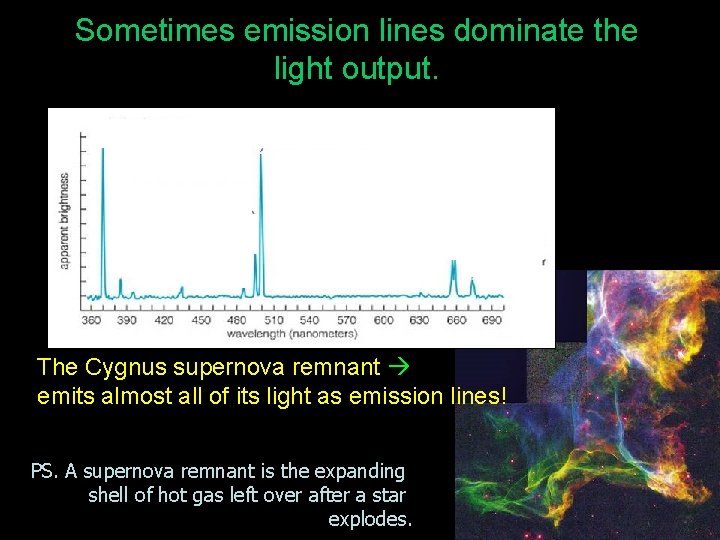

Sometimes emission lines dominate the light output. The Cygnus supernova remnant emits almost all of its light as emission lines! PS. A supernova remnant is the expanding shell of hot gas left over after a star explodes.

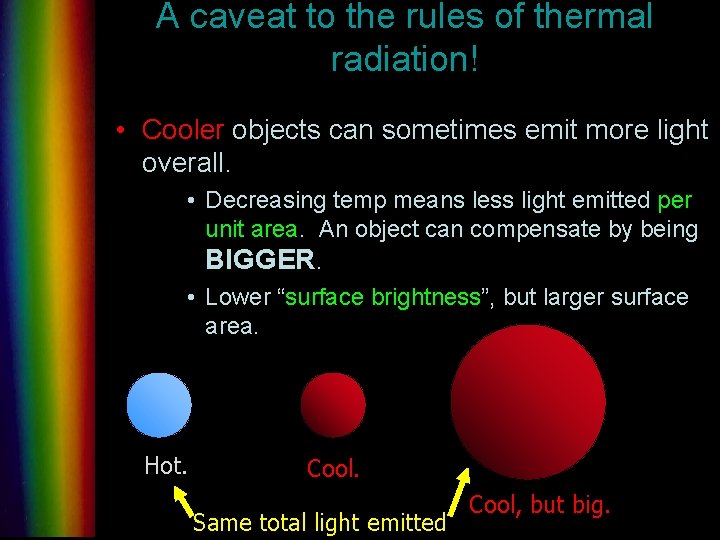

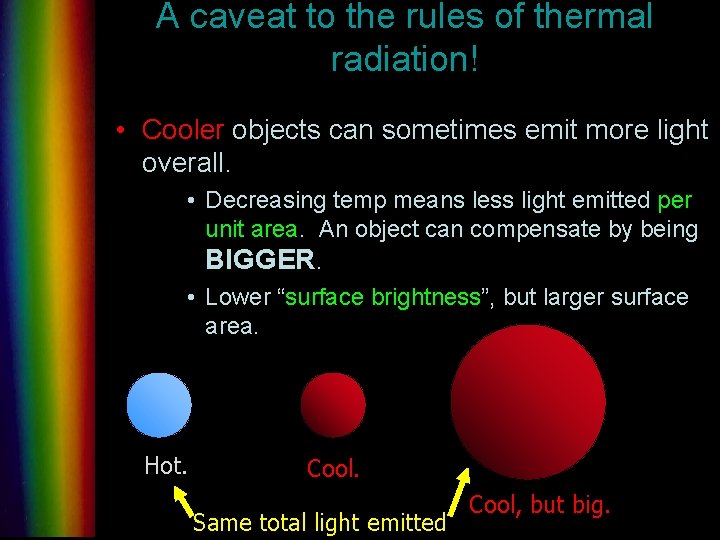

A caveat to the rules of thermal radiation! • Cooler objects can sometimes emit more light overall. • Decreasing temp means less light emitted per unit area. An object can compensate by being BIGGER. • Lower “surface brightness”, but larger surface area. Hot. Cool. Same total light emitted Cool, but big.

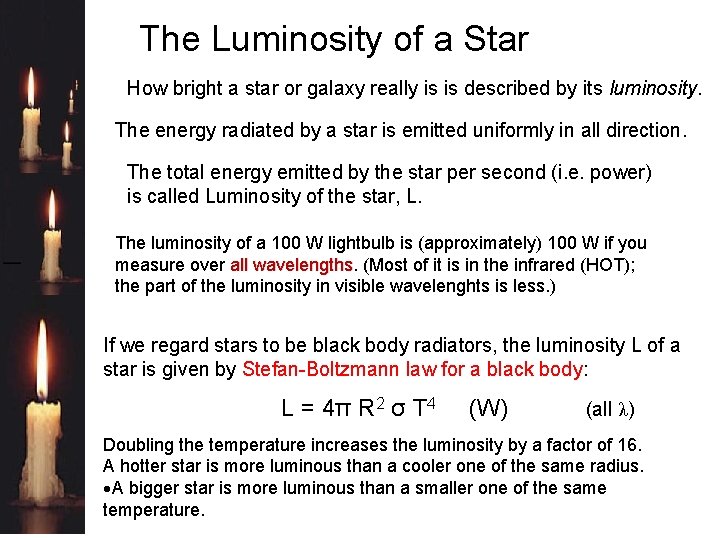

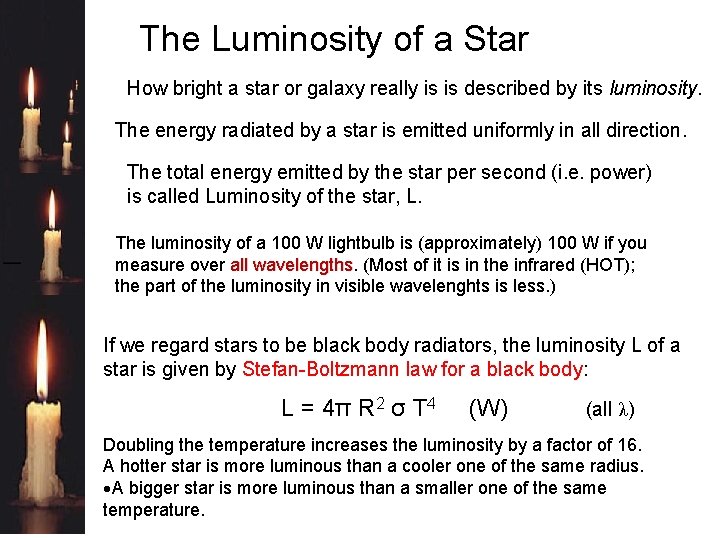

The Luminosity of a Star How bright a star or galaxy really is is described by its luminosity. The energy radiated by a star is emitted uniformly in all direction. The total energy emitted by the star per second (i. e. power) is called Luminosity of the star, L. The luminosity of a 100 W lightbulb is (approximately) 100 W if you measure over all wavelengths. (Most of it is in the infrared (HOT); all wavelengths the part of the luminosity in visible wavelenghts is less. ) If we regard stars to be black body radiators, the luminosity L of a star is given by Stefan-Boltzmann law for a black body: L = 4π R 2 σ T 4 (W) (all λ) Doubling the temperature increases the luminosity by a factor of 16. A hotter star is more luminous than a cooler one of the same radius. A bigger star is more luminous than a smaller one of the same temperature.

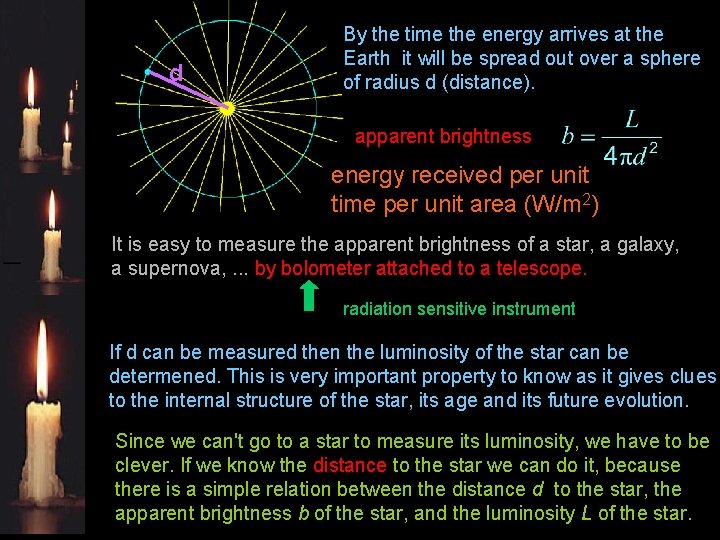

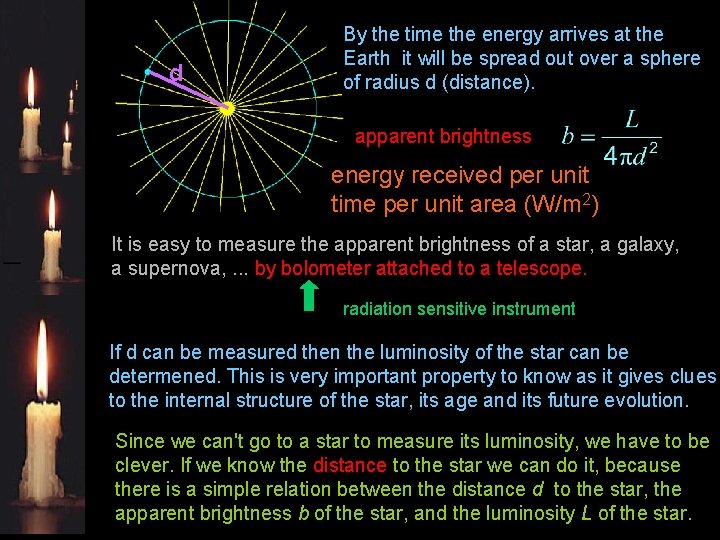

d By the time the energy arrives at the Earth it will be spread out over a sphere of radius d (distance). apparent brightness energy received per unit time per unit area (W/m 2) It is easy to measure the apparent brightness of a star, a galaxy, a supernova, . . . by bolometer attached to a telescope. radiation sensitive instrument If d can be measured then the luminosity of the star can be determened. This is very important property to know as it gives clues to the internal structure of the star, its age and its future evolution. Since we can't go to a star to measure its luminosity, we have to be clever. If we know the distance to the star we can do it, because there is a simple relation between the distance d to the star, the apparent brightness b of the star, and the luminosity L of the star.

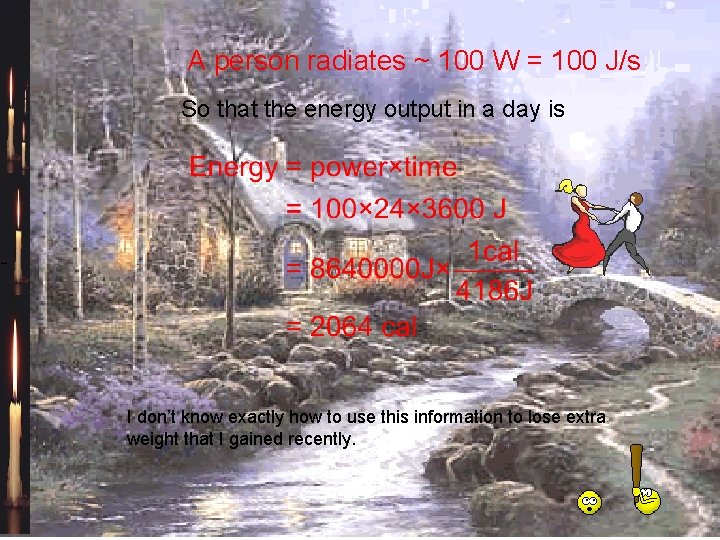

A person radiates ~ 100 W = 100 J/s So that the energy output in a day is I don’t know exactly how to use this information to lose extra weight that I gained recently.

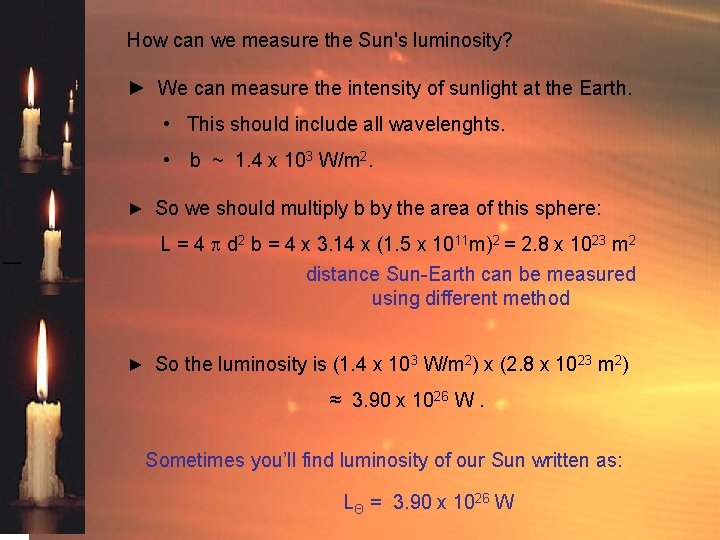

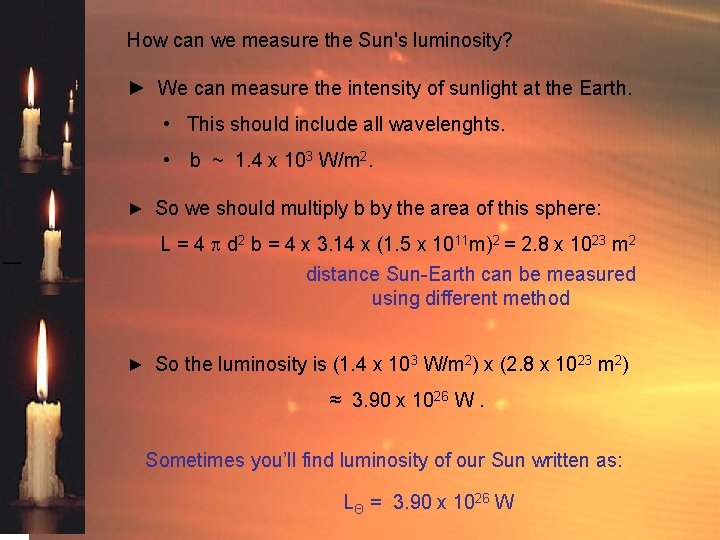

How can we measure the Sun's luminosity? ► We can measure the intensity of sunlight at the Earth. • This should include all wavelenghts. • b ~ 1. 4 x 103 W/m 2. ► So we should multiply b by the area of this sphere: L = 4 p d 2 b = 4 x 3. 14 x (1. 5 x 1011 m)2 = 2. 8 x 1023 m 2 distance Sun-Earth can be measured using different method ► So the luminosity is (1. 4 x 103 W/m 2) x (2. 8 x 1023 m 2) ≈ 3. 90 x 1026 W. Sometimes you’ll find luminosity of our Sun written as: LΘ = 3. 90 x 1026 W

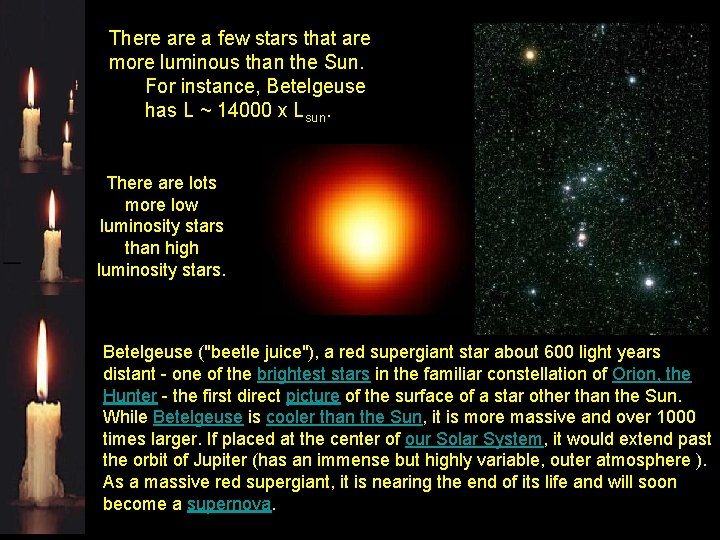

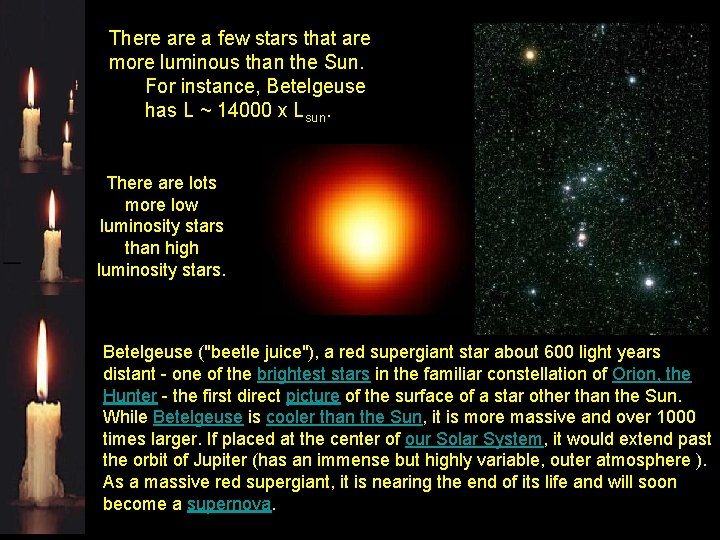

There a few stars that are more luminous than the Sun. For instance, Betelgeuse has L ~ 14000 x Lsun. There are lots more low luminosity stars than high luminosity stars. Betelgeuse ("beetle juice"), a red supergiant star about 600 light years distant - one of the brightest stars in the familiar constellation of Orion, the Hunter - the first direct picture of the surface of a star other than the Sun. While Betelgeuse is cooler than the Sun, it is more massive and over 1000 times larger. If placed at the center of our Solar System, it would extend past the orbit of Jupiter (has an immense but highly variable, outer atmosphere ). As a massive red supergiant, it is nearing the end of its life and will soon become a supernova.

However: knowing how bright a star looks doesn’t really tell us anything about the star itself! We cannot see their size! … if we anly knew the distance

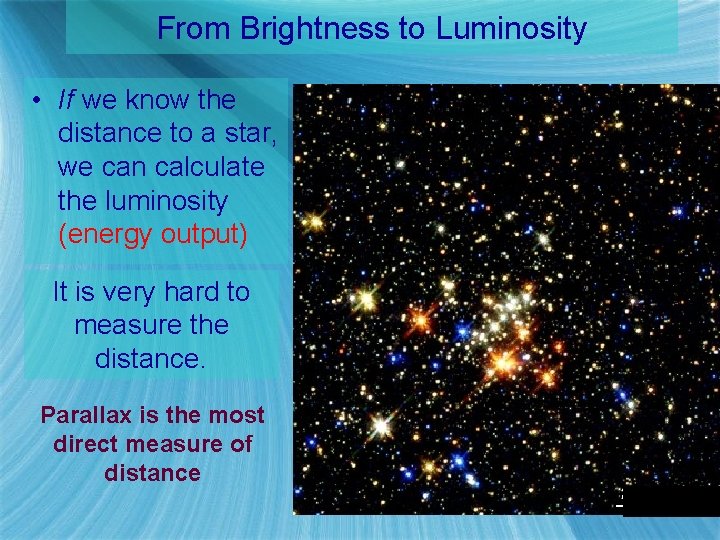

From Brightness to Luminosity • If we know the distance to a star, we can calculate the luminosity (energy output) It is very hard to measure the distance. Parallax is the most direct measure of distance

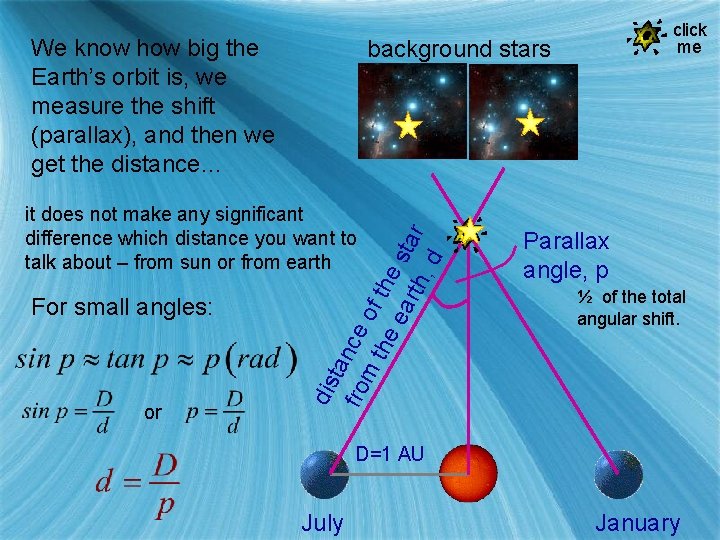

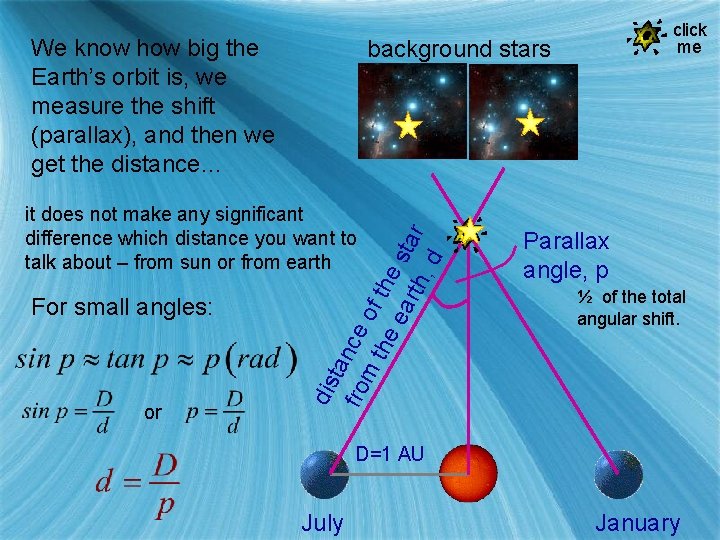

We know how big the Earth’s orbit is, we measure the shift (parallax), and then we get the distance… background stars or dis tan fro ce m of the ea st rth ar , d it does not make any significant difference which distance you want to talk about – from sun or from earth For small angles: click me Parallax angle, p ½ of the total angular shift. D=1 AU July January

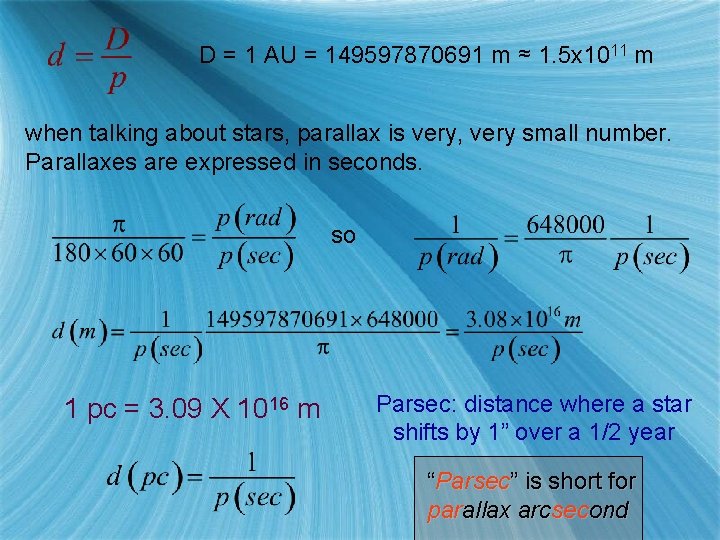

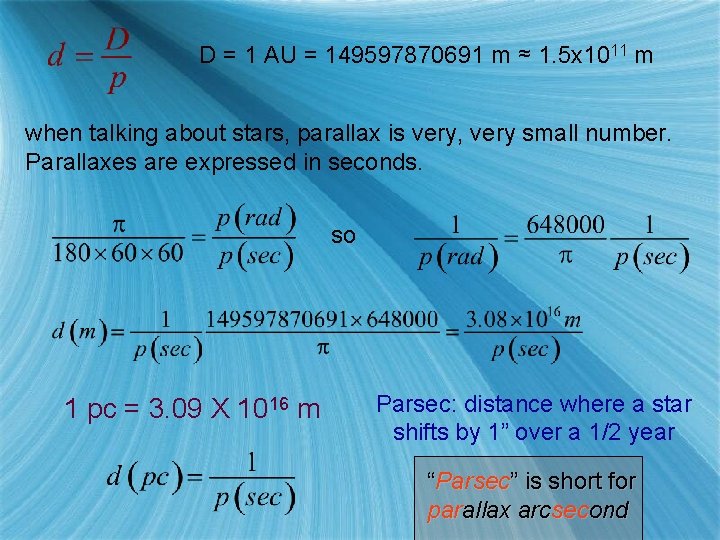

D = 1 AU = 149597870691 m ≈ 1. 5 x 1011 m when talking about stars, parallax is very, very small number. Parallaxes are expressed in seconds. so 1 pc = 3. 09 X 1016 m Parsec: distance where a star shifts by 1” over a 1/2 year “Parsec” is short for parallax arcsecond

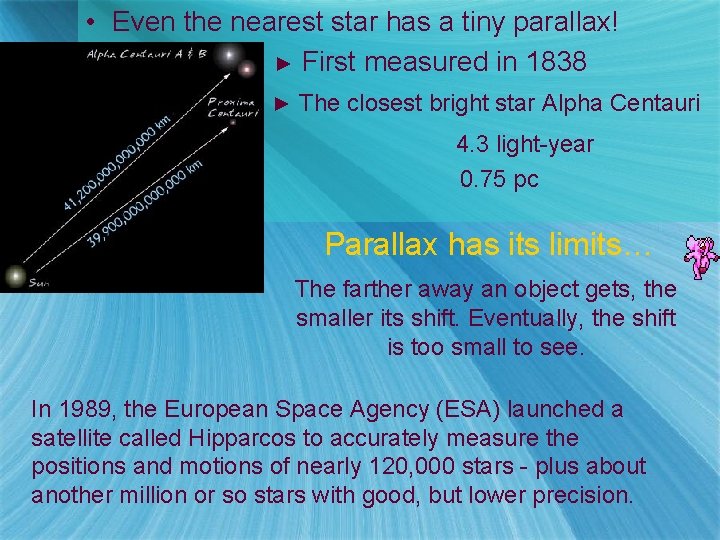

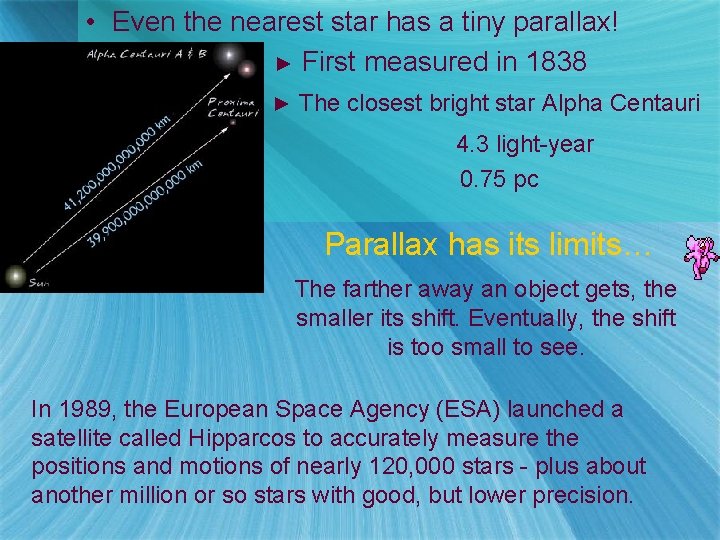

• Even the nearest star has a tiny parallax! ► First measured in 1838 ► The closest bright star Alpha Centauri 4. 3 light-year 0. 75 pc Parallax has its limits… The farther away an object gets, the smaller its shift. Eventually, the shift is too small to see. In 1989, the European Space Agency (ESA) launched a satellite called Hipparcos to accurately measure the positions and motions of nearly 120, 000 stars - plus about another million or so stars with good, but lower precision.

Parallaxes give us distances to stars up to perhaps a few thousand light years. Beyond that distance, parallaxes are so small than they cannot be measured with contemporary instruments. Astronomers use more indirect methods beyond a few thousand light years.

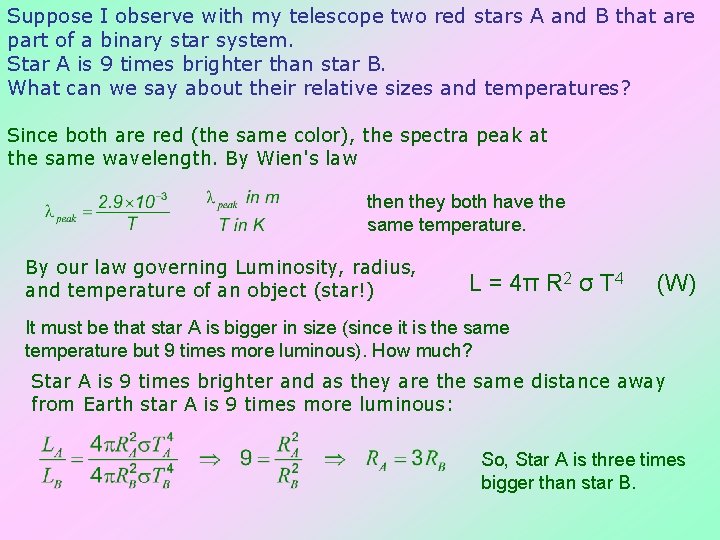

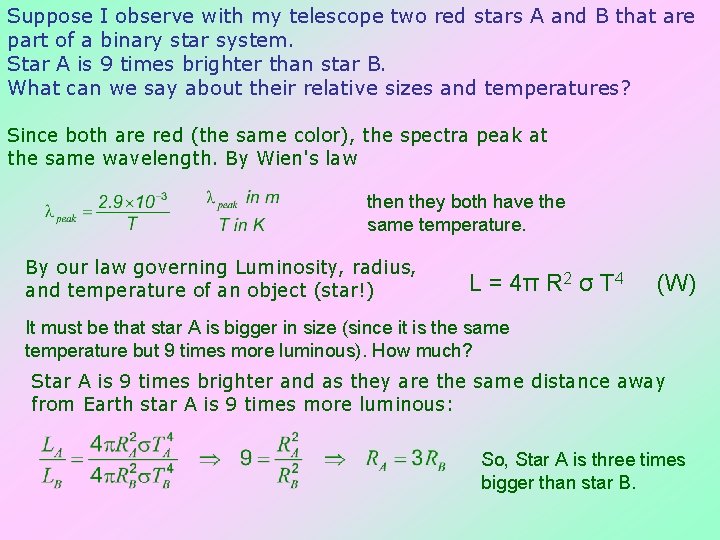

Suppose I observe with my telescope two red stars A and B that are part of a binary star system. Star A is 9 times brighter than star B. What can we say about their relative sizes and temperatures? Since both are red (the same color), the spectra peak at the same wavelength. By Wien's law then they both have the same temperature. By our law governing Luminosity, radius, and temperature of an object (star!) L = 4π R 2 σ T 4 (W) It must be that star A is bigger in size (since it is the same temperature but 9 times more luminous). How much? Star A is 9 times brighter and as they are the same distance away from Earth star A is 9 times more luminous: So, Star A is three times bigger than star B.

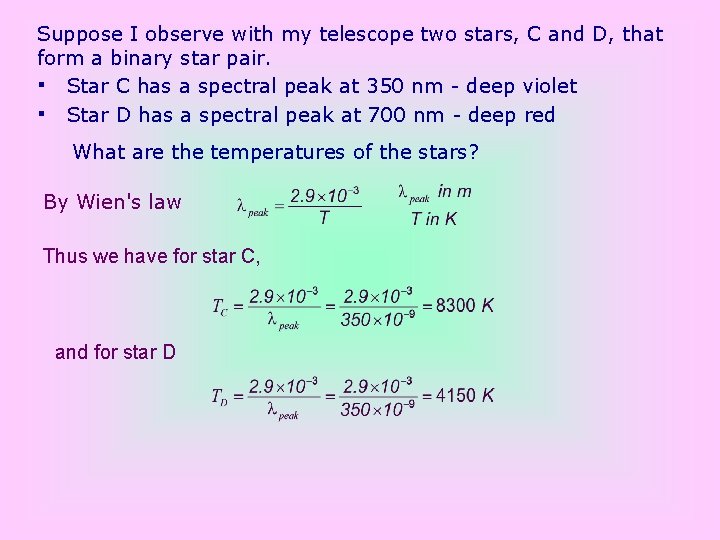

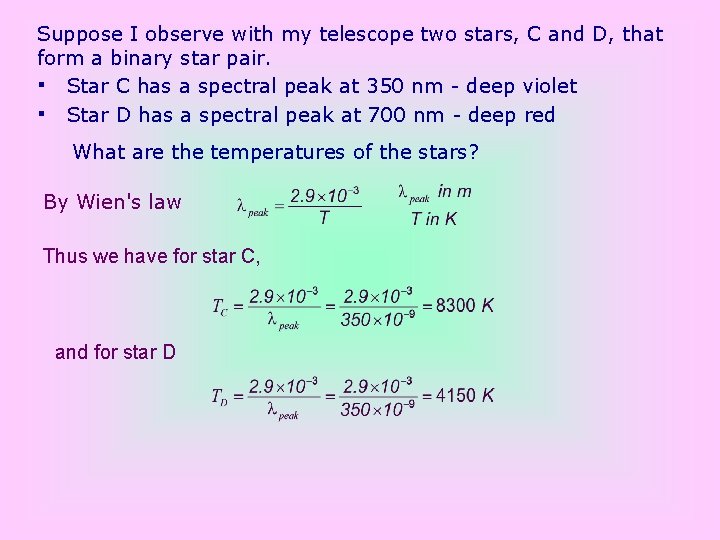

Suppose I observe with my telescope two stars, C and D, that form a binary star pair. ▪ Star C has a spectral peak at 350 nm - deep violet ▪ Star D has a spectral peak at 700 nm - deep red What are the temperatures of the stars? By Wien's law Thus we have for star C, and for star D

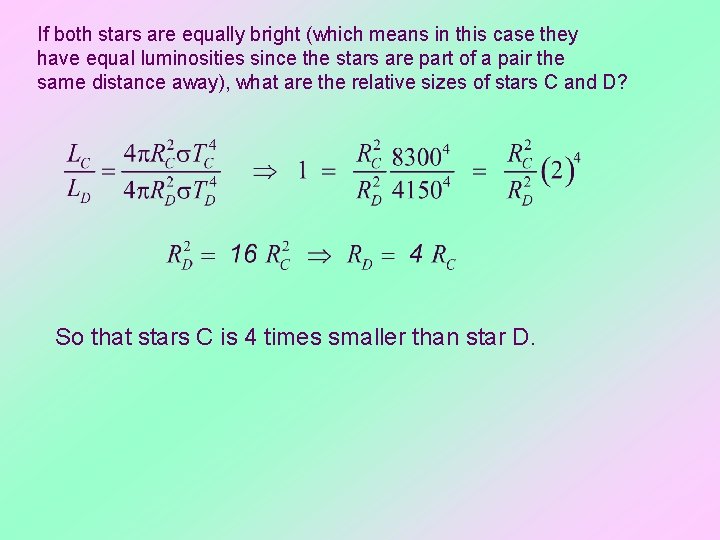

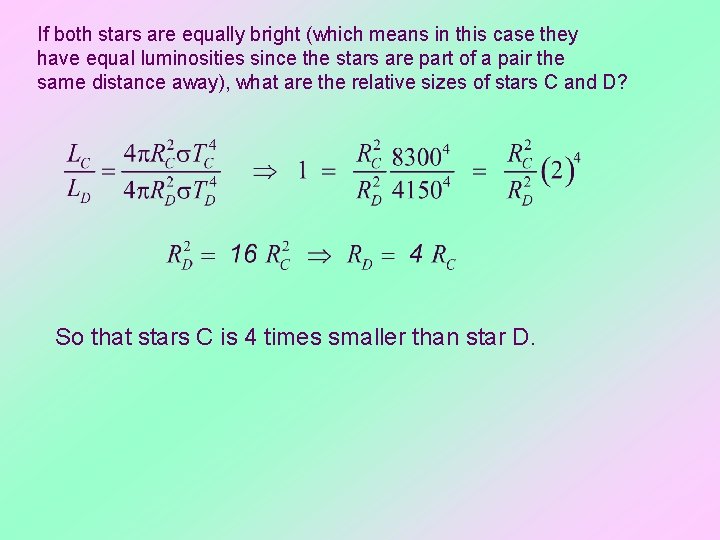

If both stars are equally bright (which means in this case they have equal luminosities since the stars are part of a pair the same distance away), what are the relative sizes of stars C and D? So that stars C is 4 times smaller than star D.

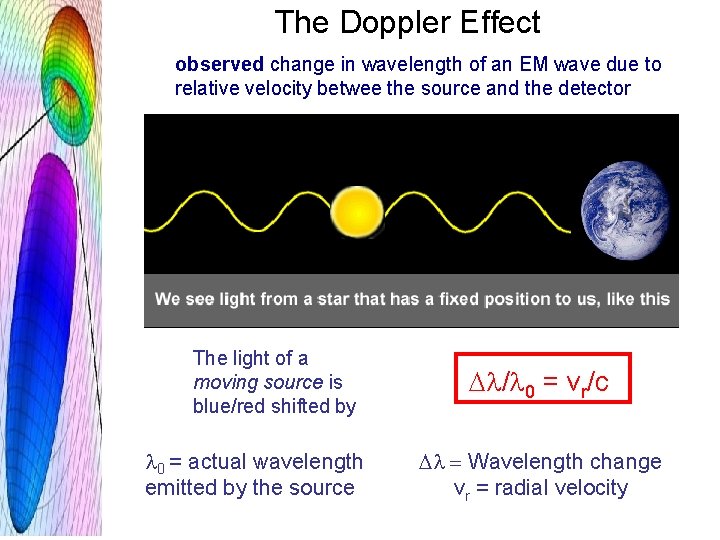

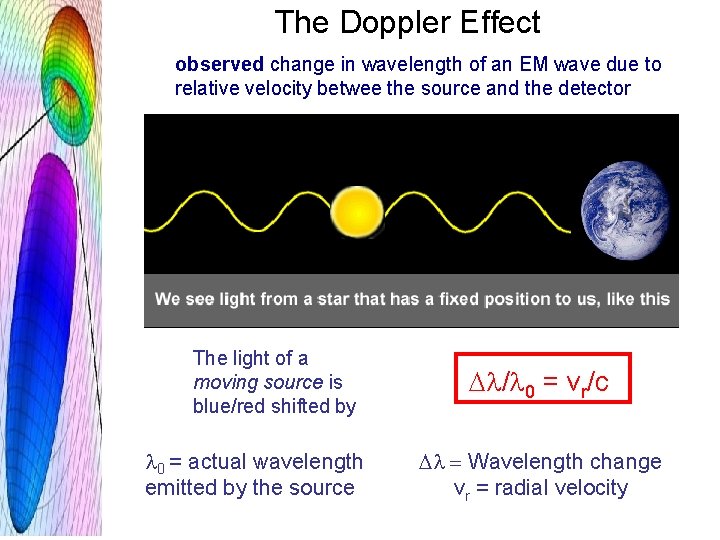

The Doppler Effect observed change in wavelength of an EM wave due to relative velocity betwee the source and the detector The light of a moving source is blue/red shifted by l 0 = actual wavelength emitted by the source Dl/l 0 = vr/c Dl = Wavelength change vr = radial velocity

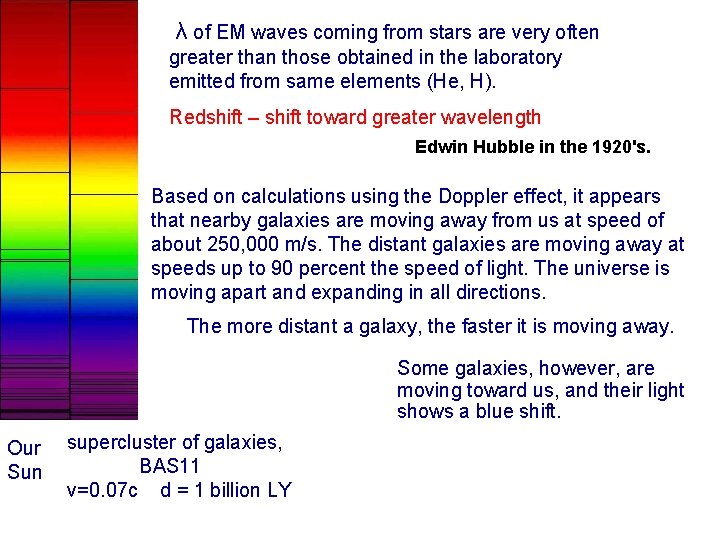

λ of EM waves coming from stars are very often greater than those obtained in the laboratory emitted from same elements (He, H). Redshift – shift toward greater wavelength Edwin Hubble in the 1920's. Based on calculations using the Doppler effect, it appears that nearby galaxies are moving away from us at speed of about 250, 000 m/s. The distant galaxies are moving away at speeds up to 90 percent the speed of light. The universe is moving apart and expanding in all directions. The more distant a galaxy, the faster it is moving away. Some galaxies, however, are moving toward us, and their light shows a blue shift. Our Sun supercluster of galaxies, BAS 11 v=0. 07 c d = 1 billion LY