FEAR OF GOD TAQWA IN THE QURAN SOME

- Slides: 44

ﺍﻟﺮﺣﻴﻢ ﺍﻟﺮﺣﻤﻦ ﺍﻟﻠﻪ ﺑﺴﻢ FEAR OF GOD (TAQWA∞) IN THE QUR}AN: SOME NOTES ON SEMANTIC SHIFT AND THEMATIC CONTEXT Journal of Semitic Studies Spring 2005 The University of Manchester ERIK S. OHLANDER INDIANA UNIVERSITY - PURDUE UNIVERSITY, FORT WAYNE

• As the late Fazlur Rahman noted in his survey of themes of the Qur’an, the notion of the ‘fear of God’ (taqwa), in addition to being one of the central themes of the Quranic message, is ‘perhaps the most important single term in the Qur’an’. • Fazlur Rahman, Major Themes of the Qur’an, 2 nd edn (Minneapolis 1989), 28.

• The purpose of the present study is to explore, both lexically and semantically, the way in which this term came to be situated within the larger Quranic universe

• empirical survey • its primary analytic framework the Qur’an’s inherent intertextual reflexivity, • in a gesture towards the utility of the conceptual framework informing the exegetical tradition of asbab alnuzul and its echo in modern attempts at periodizationfirst worked • out in the nineteenth century by William Muir, Theodor Noldeke, and Hubert Grimme, and in the twentieth by Richard Bell

Fear (taqwa) as a Quranic Construct • thus al- Jalalayn notes that: • ‘ittaqa means that you guard yourself against Divine punishment by placing between it and yourself the shield of worship ({ibada).

• A word derived from the root W-Q-Y, • which in its most primitive etymology connotes ‘to protect’, ‘to guard’, or ‘to defend’ something against something else • Ibn Man. Aur, Lisan al-{arab

• the guarding of oneself from actions unbecoming of a believer and by extension from the punishment of the Hereafter • Lane, Lexicon

• The occurrence of the word taqwa, which appears only 17 times in the Qur’an, • is, however, statistically much less significant compared to the many other words derived from the root WQ-Y which occur in the text.

• Words derived from this root occur a total of 258 times in the Qur’an, • the most common occurrence being the form VIII verb ittaqa, the verb from which the substantive taqwa derives. • This verb occurs in the perfect active 27 times, the imperfect active (yattaqi) 57 times, the imperative (ittaqi∞) 82 times; the active participle muttaqi being used 49 times.

The remaining occurrences of words derived from this root comprise: • 1) the form I verb waqa which is used in the perfect active 5 times, the imperfect active (yaqi∞) 3 times, the imperative (qi∞) 6 times, the imperfect passive (yuqa∞) 2 times, with the active participle waqi occurring thrice; • 2) the masculine noun taqiy (superlative atqa∞) occurring 5 times; and, 3) the feminine noun tuqat which occurs only twice.

The Semantic Range of Fear • …

Taqwa • this notion itself comprises a number of shades of meaning as well as displaying certain shifts in meaning and usage which appear to be correlated to the text’s chronology.

pre-Islamic parlance • was not commonly used in a religious sense and that with the exception • of poets whom he identifies as being part of a ‘particular circle of hanifs and those who were conspicuously under the influence of Judaism’

• Izutsu proposes that the basic conceptual structure of ittaqa in its pre-Quranic meaning denoted a • state whereby one would: ‘place between himself and something that is threatening him something (like another man) in order to prevent it from reaching him

• Thus in the Muallaqa of An†ara we find the following verse: • ‘when they put me yattaqunani∞] between themselves and the spears of the enemies I did not flinch at all, but I could not in any case advance very much because there was no more place left in front of me’. 16

• In its pre-Islamic context then, the verb is most often used in a physical and material sense, but in a number of cases it is used to articulate a moral point such as in Amr b. al-Ahtam: ‘every man of a noble nature guards [yattaqi∞] against blame with hospitality’.

• As used in the Qur’an, in one sense, the conceptual meaning of taqwa translated the verb’s physical sense into a spiritual one

• The Quranic concept of taqwa originally contained a strong eschatological colouring denoting a particular mood connected directly with the Day of Judgment and its outcomes.

• This eschatological fear, however, is not one of ‘terror’ as connoted by terms such as ru{b and faza{ as these terms are saved for use in threatening and damnatory declarations made by God against the unbelievers. • Neither does it bear a relationship to words derived from the roots R-H-B or SH-F-Q because neither of these occur in eschatological contexts.

• For the early Muslims, as Izutsu points out, fear of the Last Judgment and the Lord of the Day is ‘the most fundamental motive of this new religion and underlies all its aspects and determines its basic mood (because) to believe in God means, briefly, to fear Him.

Taqwa/khawf • Firstly, taqwa is not ordinarily used to describe the state of the infidel whereas khawf is employed throughout the Qur’an in conjunction with both infidels and believers.

• Secondly, while akin to khawf in eschatological contexts, taqwa does not retain the tight net of psychological associations of the former, nor do words derived from khawf function in the broad ethical scope which we see with taqwa.

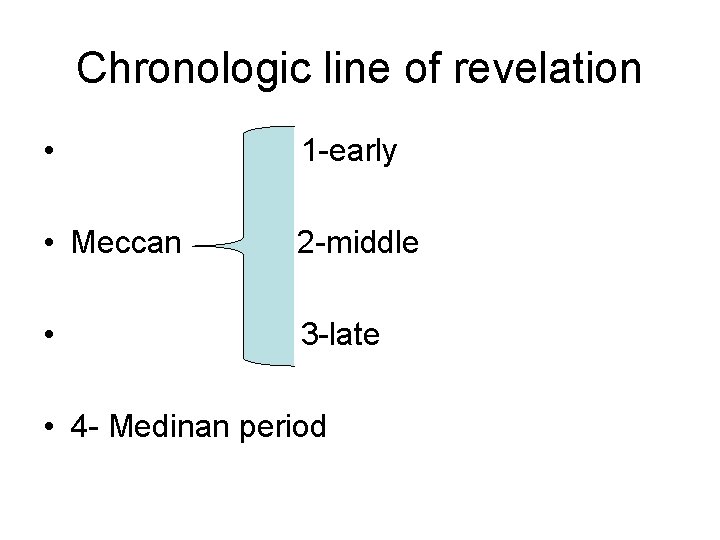

Chronologic line of revelation • 1 -early • Meccan 2 -middle • 3 -late • 4 - Medinan period

1 -early Meccan • In verses dating from the early Meccan period muttaqi is used consistently in wholly eschatological contexts,

2 -middle Meccan • is often connected with issues of prophecy and the danger which befalls those who reject the prophets sent to them. • Here, the ‘fear of God’ begins to take on a particular colouring, namely as a positive moral quality that characterizes the paradigmatic believer (mu’min) and which, conversely, is totally lacking in the unbeliever (kafir).

3 -late Meccan period • this notion begins to be fully connected • with moral and religious praxis,

• Here, taqwa is connected with moral virtues and religious praxis • such as sincerely repenting to God (tawba), • not bearing false witness(al-zur), • not taking a life which ‘God has made sacred except for just cause’ (25: 68), • and working righteous deeds ({amila {amalan ﺯ ali ﺝ an).

This is not to say that … • the motivation behind cultivating such a virtue has changed — eschatological concerns are still quite vivid throughout all of these instances — but rather to say that the semantic field subsumed under the idea of taqwa has been expanded, broadened, and made distinct in both quality and connotation from other types of ‘fear’.

4 -Medinan period • where this semantic expansion is most apparent. It is during this period where the notion of taqwa understood as ‘piety’, in the sense of an active and conscious devotion.

• Here, ‘godfearing’ is invoked in a wide range of settings. • No longer is it always specifically connected with eschatological concerns but is broadened to include legal, moral, cultic, spiritual, and even rather quotidian concerns.

In keeping with the tenor of the Medinan suras in general… • taqwa is fully engaged in both the public and private life of the Muslim;

• it becomes, in essence, an ethical quality by and through which the challenges of daily life can be navigated. • This is where it begins to approach the notion of ‘religious conscience’.

• This virtue is often coupled with other ethical and moral virtues such as patience ( ﺯ abr), belief, and the practice of good works.

a typical Medinan verse ﴾١٨٦﴿ ﺍﻭ ﻭﺍ ﻥ •

• The orthopraxic dimension of taqwa is especially apparent in Medinan verses concerned with cultic matters such as the rites of pilgrimage, prayer and fasting.

Conclusion • taqwa harbours a layered and nuanced set of associations, the semantic boundaries of which overlap with semantically unrelated notions of religious and moral behaviour, social relations, and the psychology of human response to eschatological threat.

• Thank you

Modifier affects your human act

Modifier affects your human act Name some activities the quran prohibits

Name some activities the quran prohibits Flood dream ocean city new jersey 1971

Flood dream ocean city new jersey 1971 Proses terbentuknya iman dan taqwa

Proses terbentuknya iman dan taqwa Implementasi iman dan taqwa

Implementasi iman dan taqwa Mind map iman kepada malaikat

Mind map iman kepada malaikat Taqwa meaning in islam

Taqwa meaning in islam Implementasi iman dan taqwa dalam kehidupan modern

Implementasi iman dan taqwa dalam kehidupan modern Ramadan

Ramadan Peta konsep tentang beriman kepada kitab-kitab allah

Peta konsep tentang beriman kepada kitab-kitab allah Taqwa

Taqwa Putri taqwa prasetyaningrum

Putri taqwa prasetyaningrum Taqwa

Taqwa Does job fear god for nothing

Does job fear god for nothing Ice-cream countable or uncountable

Ice-cream countable or uncountable Some trust in chariots and some in horses song

Some trust in chariots and some in horses song Contact forces

Contact forces Fire and ice diamante poem

Fire and ice diamante poem They say it only takes a little faith to move a mountain

They say it only takes a little faith to move a mountain Sometimes you win some sometimes you lose some

Sometimes you win some sometimes you lose some Some say the world will end in fire some say in ice

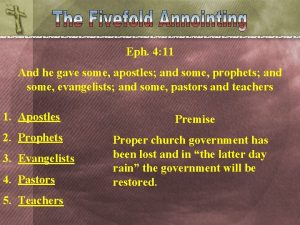

Some say the world will end in fire some say in ice To some he gave apostles

To some he gave apostles Lp html

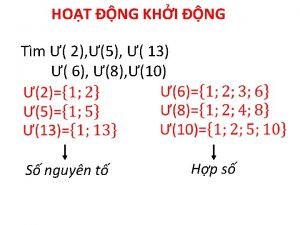

Lp html Các số nguyên tố

Các số nguyên tố Phối cảnh

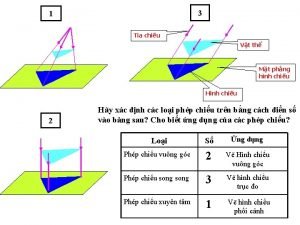

Phối cảnh đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ

đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Chụp phim tư thế worms-breton

Chụp phim tư thế worms-breton Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Sơ đồ cơ thể người

Sơ đồ cơ thể người ưu thế lai là gì

ưu thế lai là gì Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Cái miệng nó xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi

Cái miệng nó xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi Mật thư tọa độ 5x5

Mật thư tọa độ 5x5 Bổ thể

Bổ thể Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Thẻ vin

Thẻ vin Thơ thất ngôn tứ tuyệt đường luật

Thơ thất ngôn tứ tuyệt đường luật Chúa sống lại

Chúa sống lại Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu

Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu Khi nào hổ con có thể sống độc lập

Khi nào hổ con có thể sống độc lập Diễn thế sinh thái là

Diễn thế sinh thái là Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau V cc

V cc