Review of August lectures How much to learn

- Slides: 106

Review of August lectures

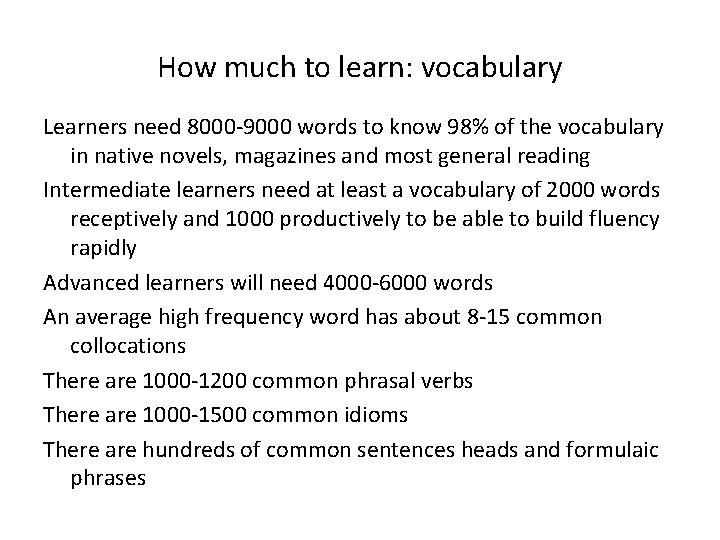

How much to learn: vocabulary Learners need 8000 -9000 words to know 98% of the vocabulary in native novels, magazines and most general reading Intermediate learners need at least a vocabulary of 2000 words receptively and 1000 productively to be able to build fluency rapidly Advanced learners will need 4000 -6000 words An average high frequency word has about 8 -15 common collocations There are 1000 -1200 common phrasal verbs There are 1000 -1500 common idioms There are hundreds of common sentences heads and formulaic phrases

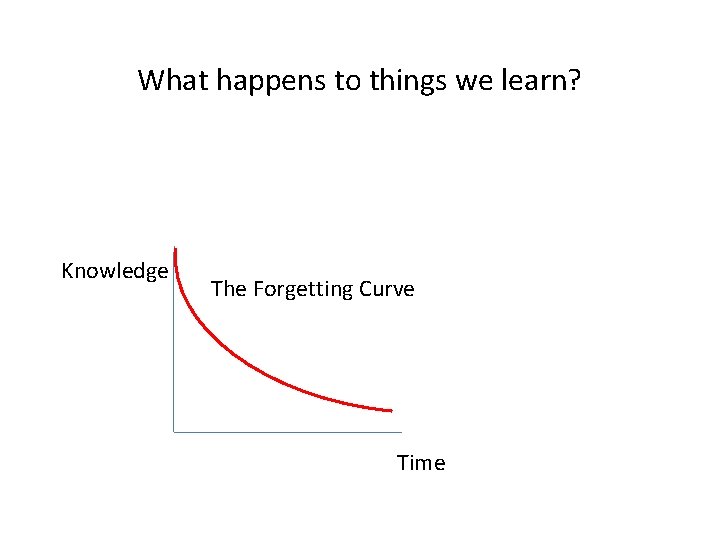

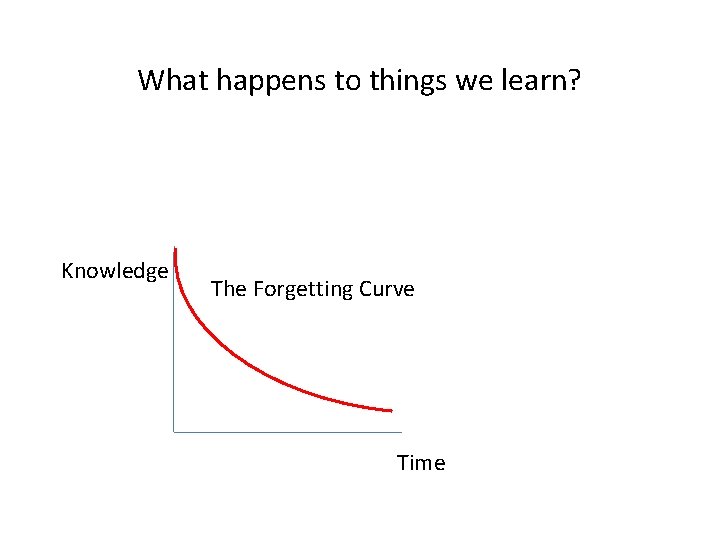

What happens to things we learn? Knowledge The Forgetting Curve Time

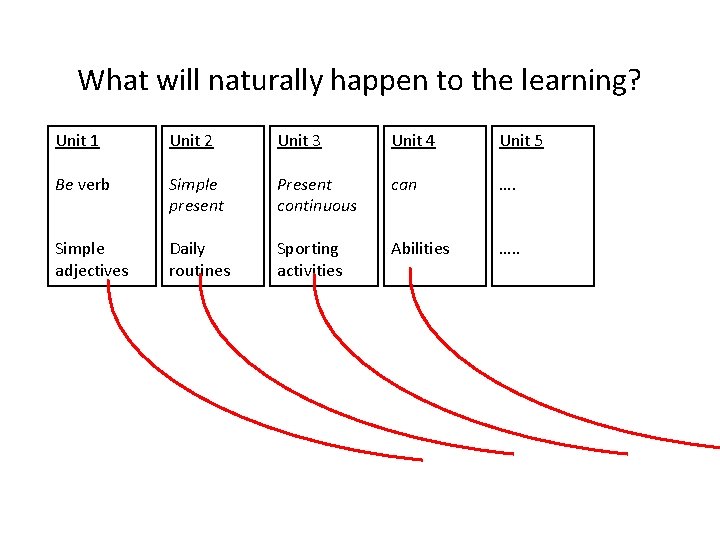

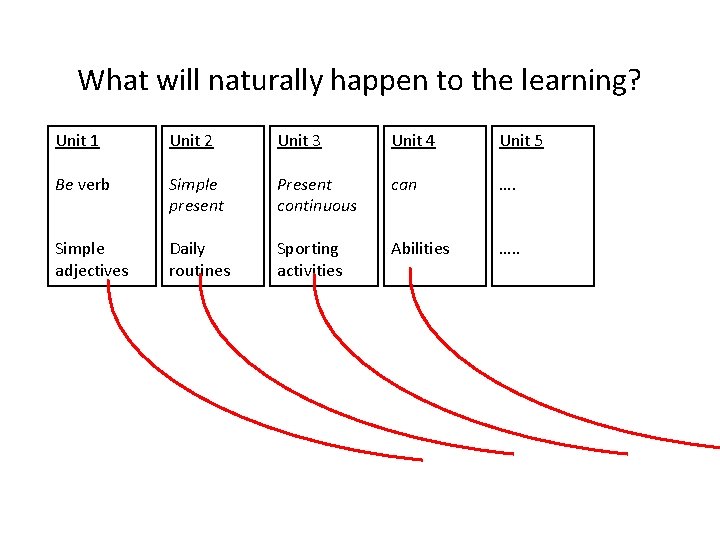

What will naturally happen to the learning? Unit 1 Unit 2 Unit 3 Unit 4 Unit 5 Be verb Simple present Present continuous can …. Simple adjectives Daily routines Sporting activities Abilities …. .

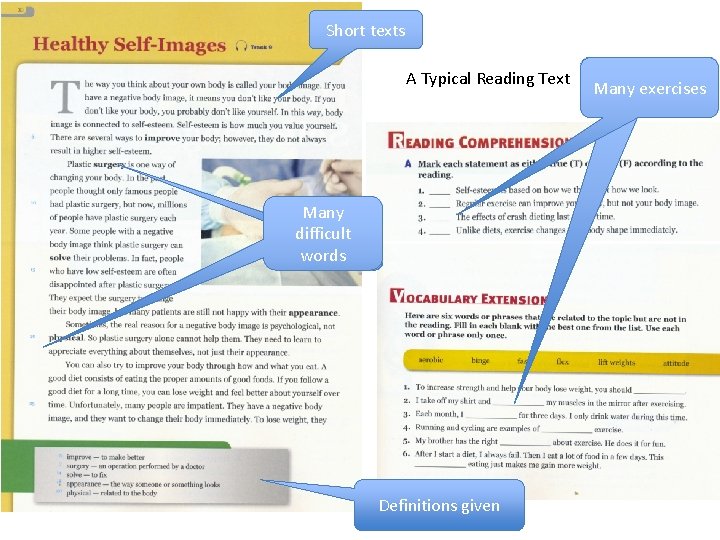

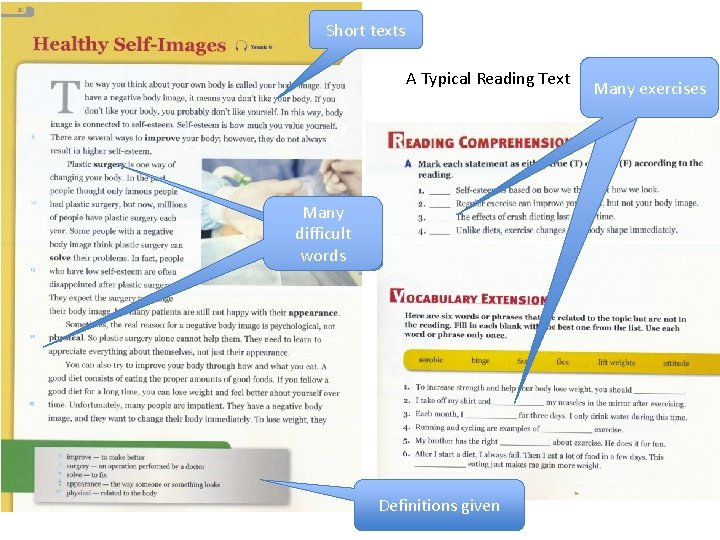

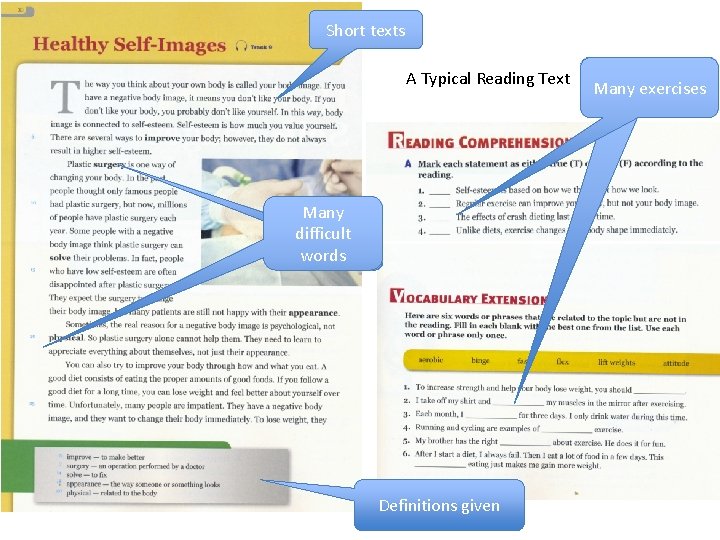

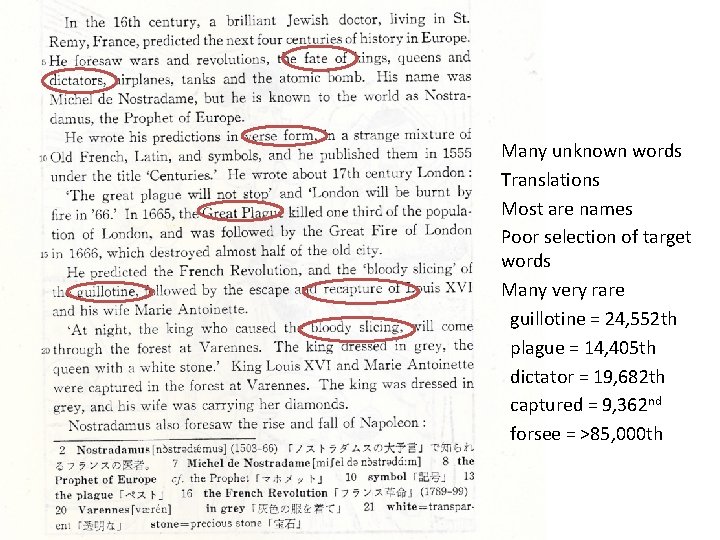

Short texts A Typical Reading Text Many difficult words Definitions given Many exercises

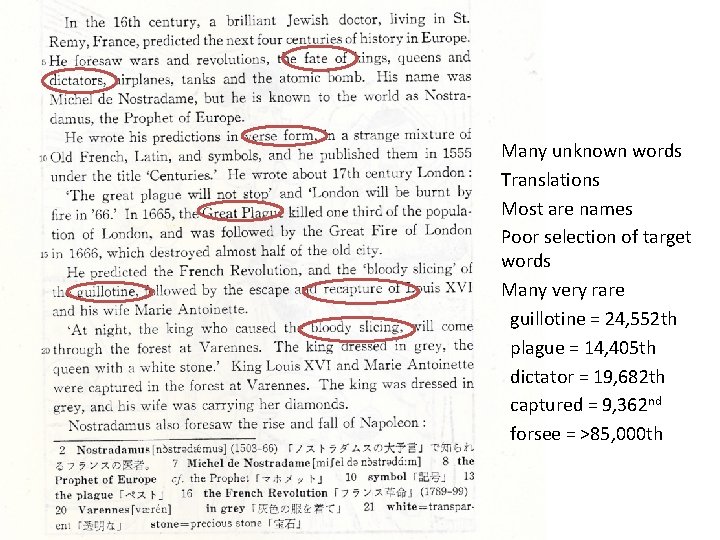

Many unknown words Translations Most are names Poor selection of target words Many very rare guillotine = 24, 552 th plague = 14, 405 th dictator = 19, 682 th captured = 9, 362 nd forsee = >85, 000 th

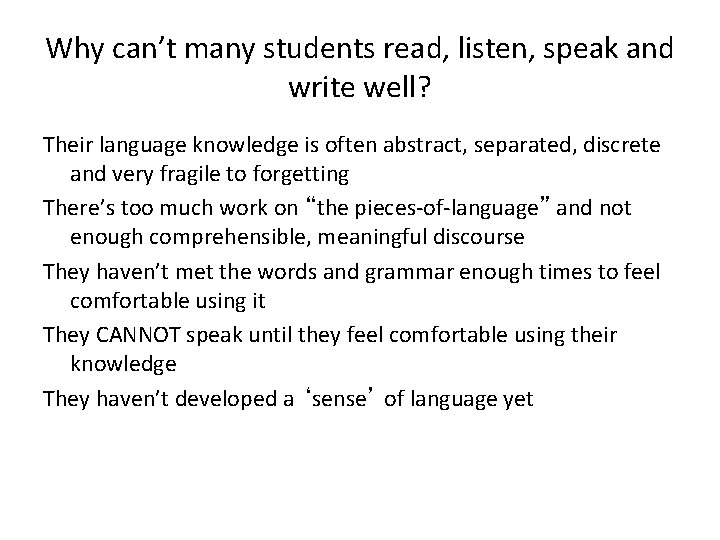

Why can’t many students read, listen, speak and write well? Their language knowledge is often abstract, separated, discrete and very fragile to forgetting There’s too much work on “the pieces-of-language” and not enough comprehensible, meaningful discourse They haven’t met the words and grammar enough times to feel comfortable using it They CANNOT speak until they feel comfortable using their knowledge They haven’t developed a ‘sense’ of language yet

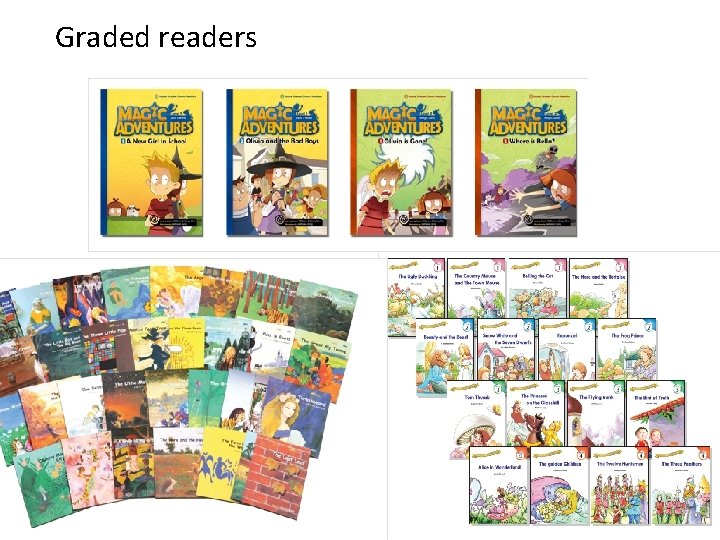

Choice 2: Graded Readers

Graded readers

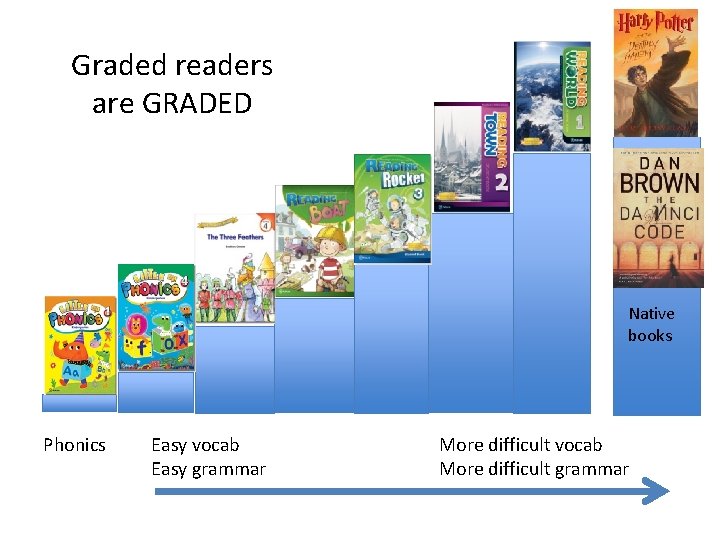

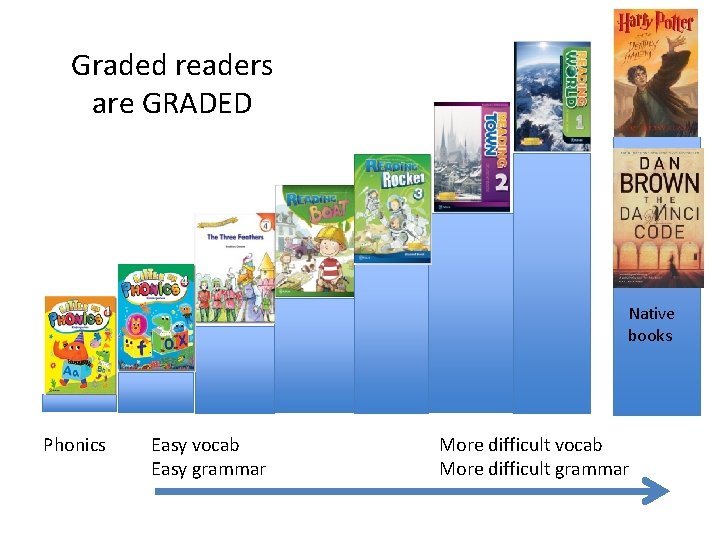

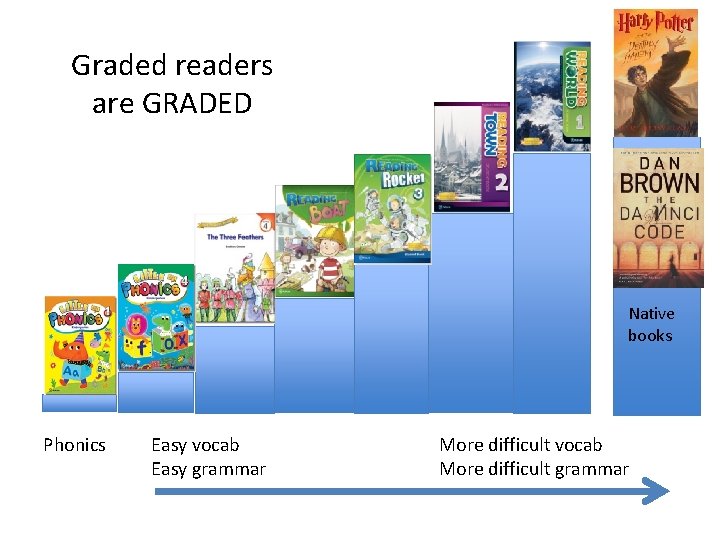

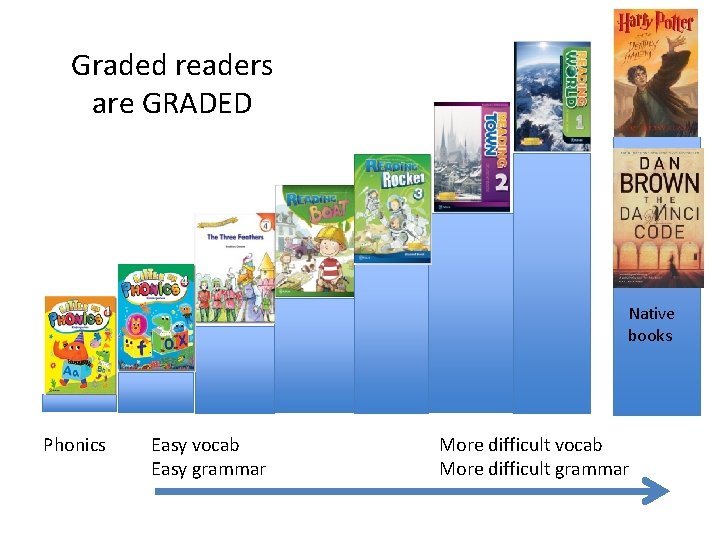

Graded readers are GRADED Native books Phonics Easy vocab Easy grammar More difficult vocab More difficult grammar

Overview of reading and reading research Dr. Rob Waring MSU February 2019

Issues to be discussed • The nature of reading. • How do we read? Models of the reading process. • Text types, reading purpose and reading strategies: How do they interact? • Developing a reading lesson: pre-while-post reading. • Principles for developing reading skills.

Some opening questions • • • What does it mean to ‘read’? What do learners do when they read in the L 1? How is this different in L 2? What is fluency? What do learners have to do to be a fluent reader?

A Definition of Reading (NRP) The term 'reading' means a complex system of deriving meaning from print that requires all of the following: (A) The skills and knowledge to understand how phonemes, or speech sounds, are connected to print. (B) The ability to decode unfamiliar words. (C) The ability to read fluently. (D) Sufficient background information and vocabulary to foster reading comprehension. (E) The development of appropriate active strategies to construct meaning from print. (F) The development and maintenance of a motivation to read.

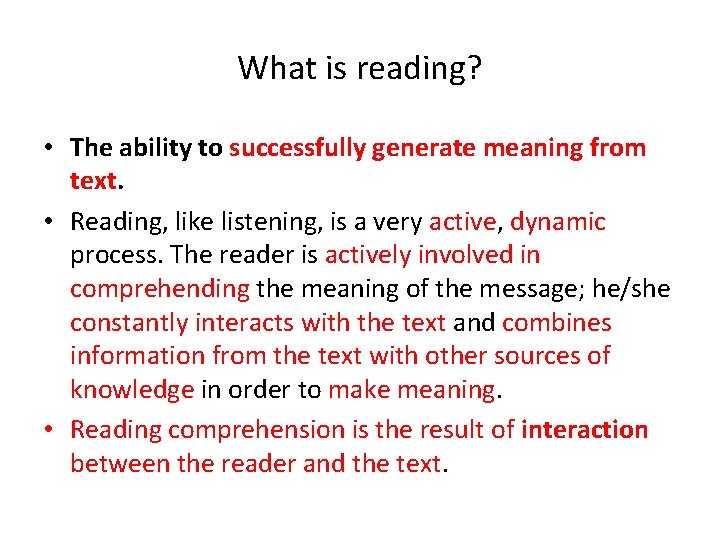

What is reading? • The ability to successfully generate meaning from text. • Reading, like listening, is a very active, dynamic process. The reader is actively involved in comprehending the meaning of the message; he/she constantly interacts with the text and combines information from the text with other sources of knowledge in order to make meaning. • Reading comprehension is the result of interaction between the reader and the text.

What do fluent readers usually do? 1. Read rapidly 2. Recognize words rapidly and automatically 3. Use large vocabulary store 4. Integrate text information with their own knowledge 5. Recognize the purposes

What fluent readers usually do? 6. Comprehend 7. Read strategically 8. Use strategies to monitor 9. Recognize and repair miscomprehension 10. Read critically and evaluate

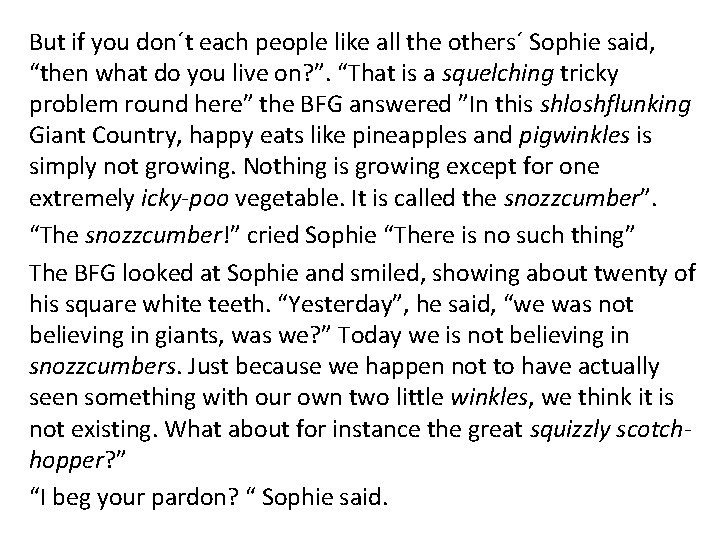

But if you don´t each people like all the others´ Sophie said, “then what do you live on? ”. “That is a squelching tricky problem round here” the BFG answered ”In this shloshflunking Giant Country, happy eats like pineapples and pigwinkles is simply not growing. Nothing is growing except for one extremely icky-poo vegetable. It is called the snozzcumber”. “The snozzcumber!” cried Sophie “There is no such thing” The BFG looked at Sophie and smiled, showing about twenty of his square white teeth. “Yesterday”, he said, “we was not believing in giants, was we? ” Today we is not believing in snozzcumbers. Just because we happen not to have actually seen something with our own two little winkles, we think it is not existing. What about for instance the great squizzly scotchhopper? ” “I beg your pardon? “ Sophie said.

Questions • What sort of book do you think this extract comes from? • Who is BFG and who is Sophie? • Where do you think they are? • What do think the words in italics may mean? • In order to answer questions 1 -4 you made a number of inferences. What kinds of knowledge did you draw upon in order to make your inferences?

Models of reading: 1. Bottom up model Reader builds meaning from the smallest units of meaning (letters, phonemes and words) to achieve comprehension. Example: letters > letter clusters > words > phrases > sentences > longer text > meaning = comprehension. Reading is regarded as a process of “decoding”, which moves from the bottom to the top of the system of language.

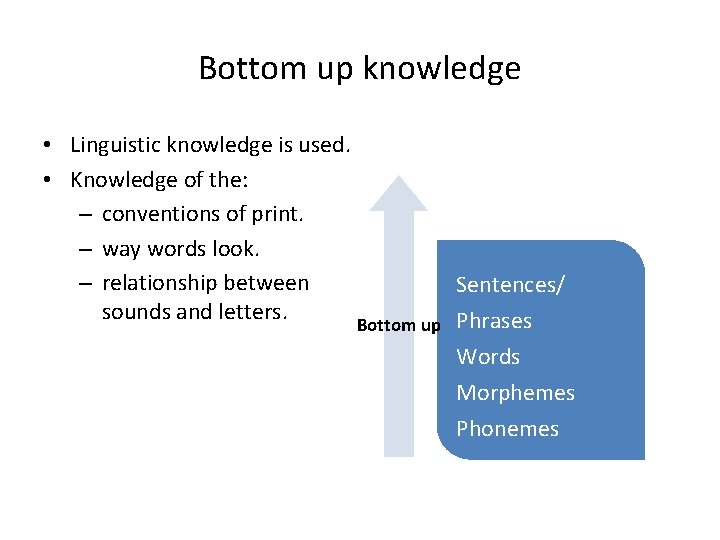

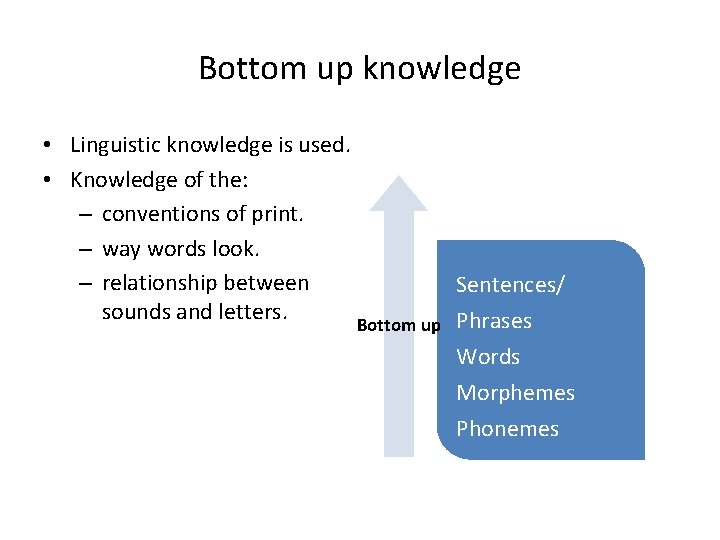

Bottom up knowledge • Linguistic knowledge is used. • Knowledge of the: – conventions of print. – way words look. – relationship between Sentences/ sounds and letters. Bottom up Phrases Words Morphemes Phonemes

Problems with only using the bottom up model • Spelling to sound correspondences are complex and unpredictable. • Processing of every letter in a text in order would slow reading making it difficult for meaning to be retained. • Readers would forget the beginning of a sentence before they have reached the end. • It is often necessary to know the meaning of the word containing the grapheme before you read it.

Models of the reading process: 2. The top-down model • The learner uses pre-existing knowledge (schema) of topic/field, cultural understandings & life experiences to make out what makes sense. • This model emphasises the reconstruction of meaning as the reader interacts with the text. Reader generates meaning by employing background knowledge, expectations, assumptions, and questions. • Using this information the reader forms hypotheses about text elements and then samples the text to determine whether or not his hypotheses are correct. • This model of teaching reading is based on theory in which reading is regarded as a prediction-check process, “a psycholinguistic guessing game” (Goodman, 1970).

The sanction to the Chelsea without signing up to summer of 2020 takes him away from Madrid The plan was more than drawn in the offices of the Santiago Bernabéu. Actually, it was not necessary to pull imagination to configure it, it was simply to trace the Courtois operation step by step. Even the club of origin was the same. Eden Hazard, in his last year of contract, refused to renew with Chelsea and invited Roman Abramovich to sell to Real Madrid. And the Russian tycoon, above all businessman, would end up agreeing to a transfer far below the market value to get enough money to sign with him a substitute guarantees. So was the thing until yesterday at noon everything jumped through the air. FIFA announced a sanction to the Chelsea of two windows without signing - a date of 2019 and January of 2020 - for violations of the regulation of transfer of minors of 18 years. The opinion of the FIFA disciplinary committee specifies that the London club violated the rules in the transfer and registration of 29 players, a case similar to the one that affected Barcelona, Atlético and Madrid. The first two clubs were also sanctioned with two windows without signing, while the white club saw how the CAS reduced its punishment to only one market.

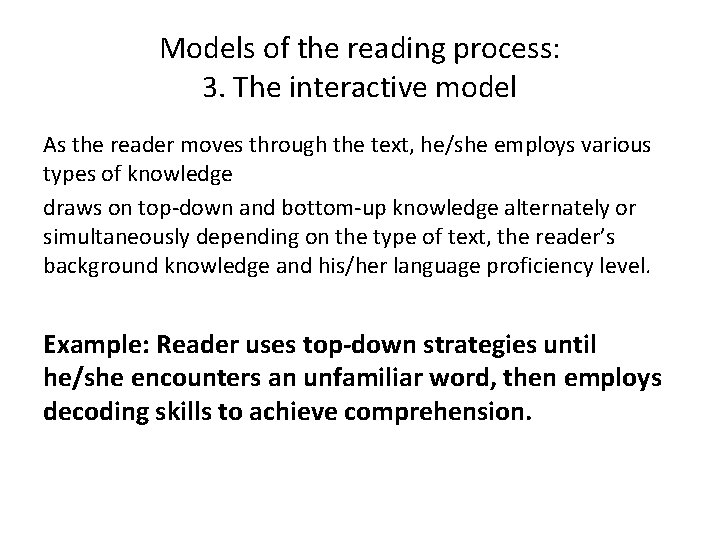

Models of the reading process: 3. The interactive model As the reader moves through the text, he/she employs various types of knowledge draws on top-down and bottom-up knowledge alternately or simultaneously depending on the type of text, the reader’s background knowledge and his/her language proficiency level. Example: Reader uses top-down strategies until he/she encounters an unfamiliar word, then employs decoding skills to achieve comprehension.

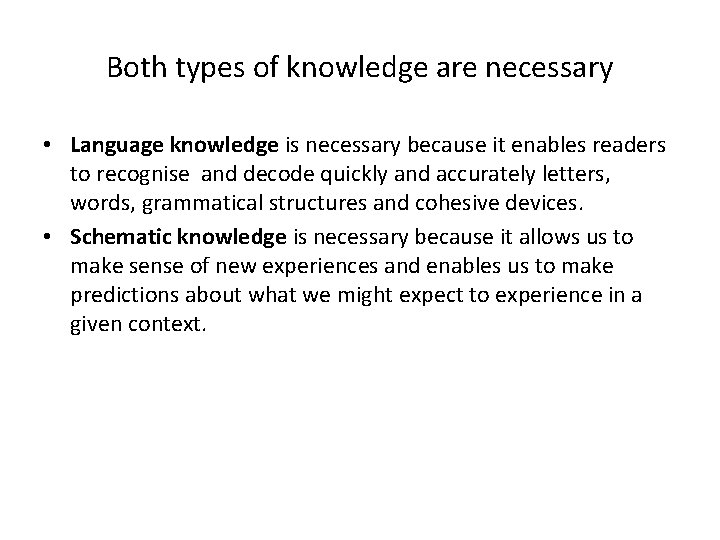

Both types of knowledge are necessary • Language knowledge is necessary because it enables readers to recognise and decode quickly and accurately letters, words, grammatical structures and cohesive devices. • Schematic knowledge is necessary because it allows us to make sense of new experiences and enables us to make predictions about what we might expect to experience in a given context.

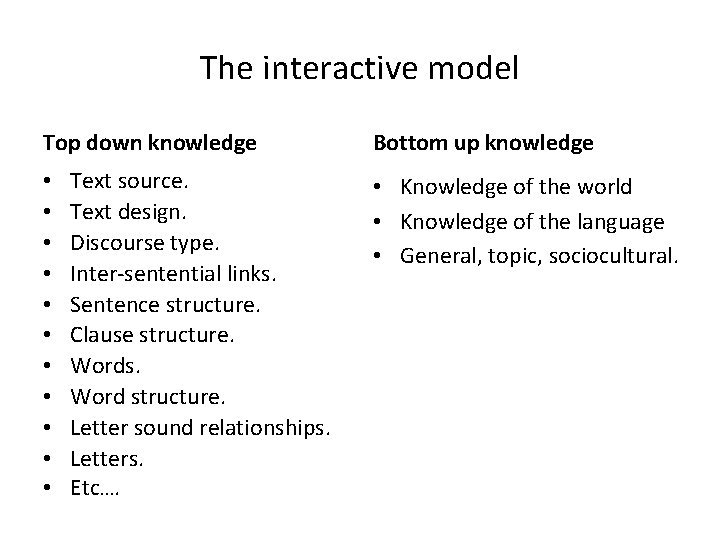

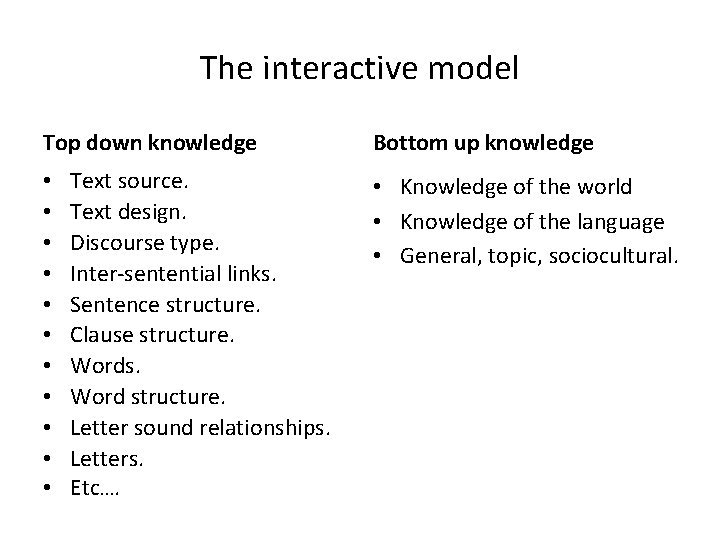

The interactive model Top down knowledge • • • Text source. Text design. Discourse type. Inter-sentential links. Sentence structure. Clause structure. Words. Word structure. Letter sound relationships. Letters. Etc…. Bottom up knowledge • Knowledge of the world • Knowledge of the language • General, topic, sociocultural.

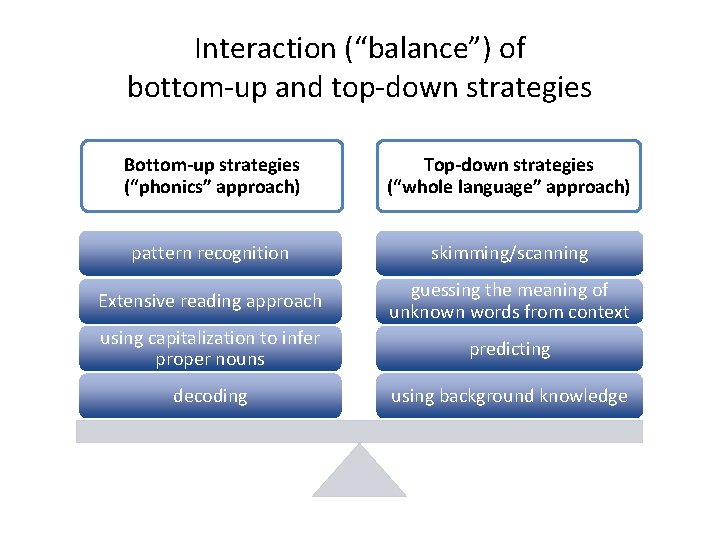

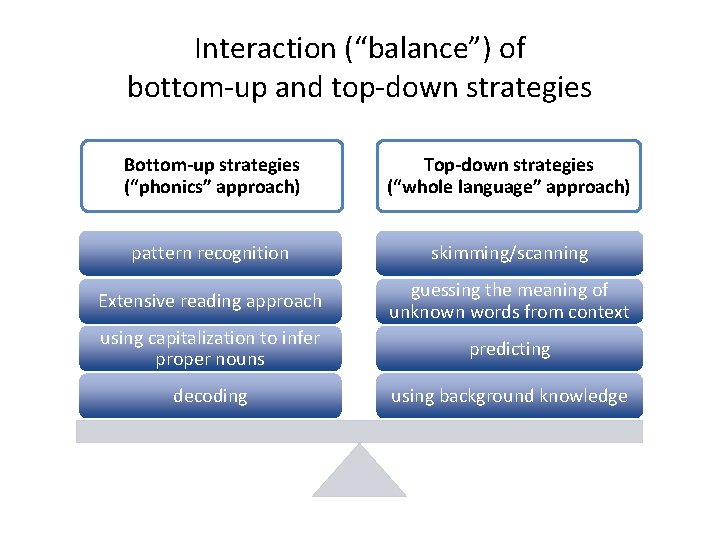

Interaction (“balance”) of bottom-up and top-down strategies Bottom-up strategies (“phonics” approach) Top-down strategies (“whole language” approach) pattern recognition skimming/scanning Extensive reading approach guessing the meaning of unknown words from context using capitalization to infer proper nouns predicting decoding using background knowledge

Summarising our understanding of reading (1/2) In reading, the goal is always comprehension of meaning. Reading is an active process using our: • knowledge of the world (non-visual information), • knowledge of language (visual information), to construct meaning.

Summarising our understanding of reading (2/2) The key to reading is prediction. We use our knowledge of the world and of language to predict what will come next. We test our predictions by reading some of the text and then checking if what we are reading makes sense. If it makes sense we continue reading, if not we go back and revise our predictions. The more knowledge and experience we have on which to base our predictions, the less we need to rely on print.

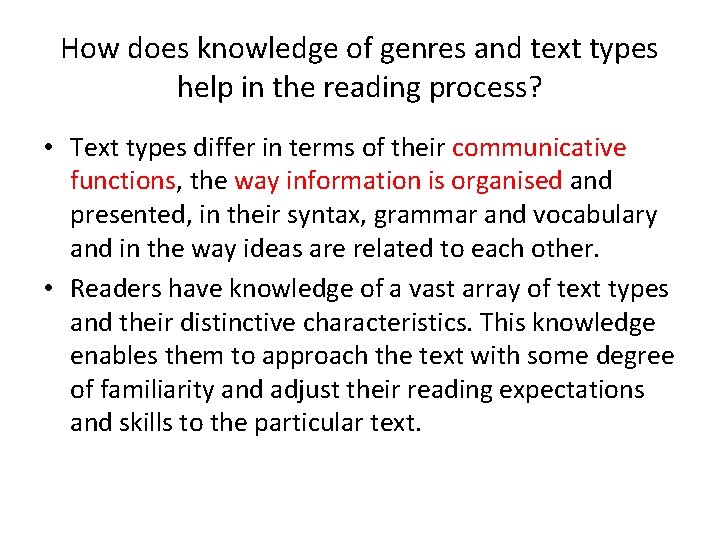

How does knowledge of genres and text types help in the reading process? • Text types differ in terms of their communicative functions, the way information is organised and presented, in their syntax, grammar and vocabulary and in the way ideas are related to each other. • Readers have knowledge of a vast array of text types and their distinctive characteristics. This knowledge enables them to approach the text with some degree of familiarity and adjust their reading expectations and skills to the particular text.

Task 2 • In task 1, the extract was taken from a children’s book (“The BFG”, ) by Roald Dahl (2001). • What are some other text types?

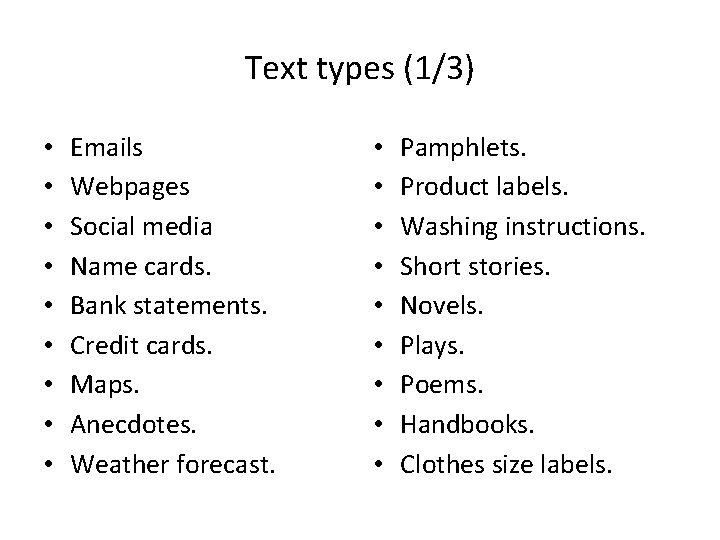

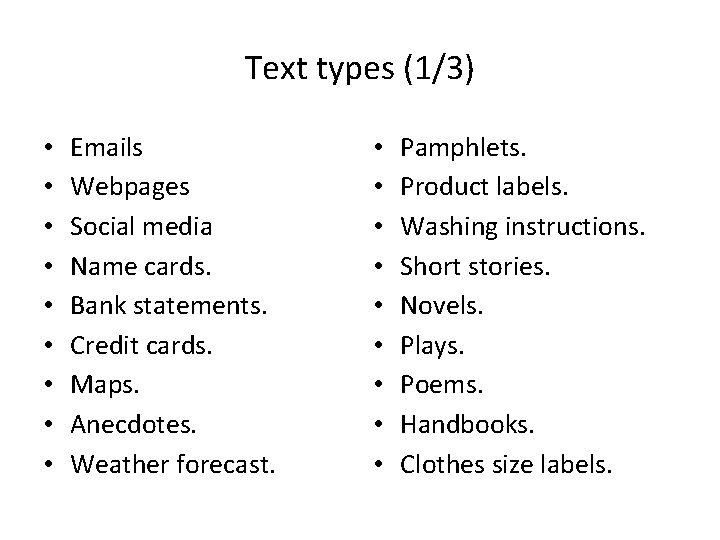

Text types (1/3) • • • Emails Webpages Social media Name cards. Bank statements. Credit cards. Maps. Anecdotes. Weather forecast. • • • Pamphlets. Product labels. Washing instructions. Short stories. Novels. Plays. Poems. Handbooks. Clothes size labels.

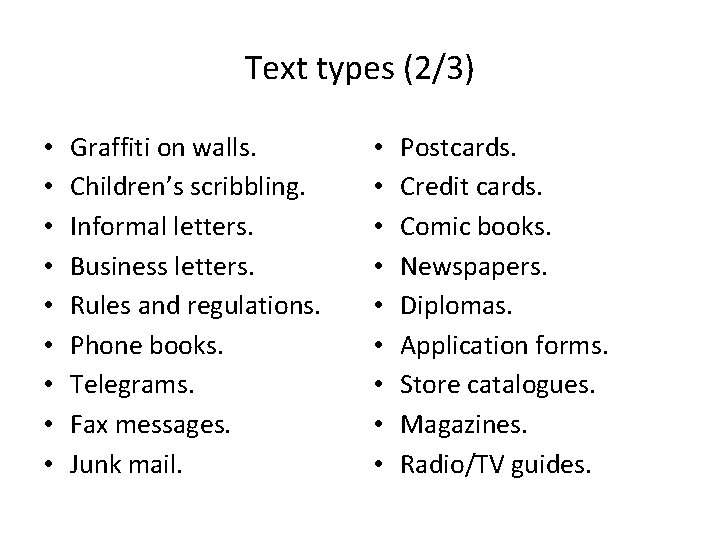

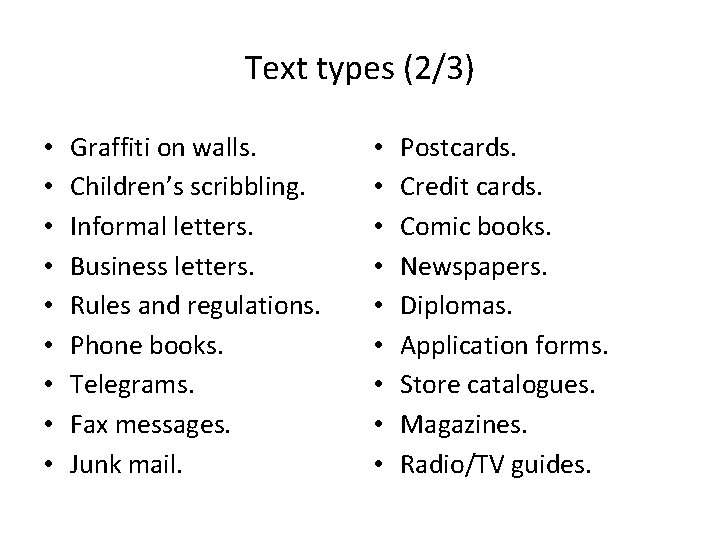

Text types (2/3) • • • Graffiti on walls. Children’s scribbling. Informal letters. Business letters. Rules and regulations. Phone books. Telegrams. Fax messages. Junk mail. • • • Postcards. Credit cards. Comic books. Newspapers. Diplomas. Application forms. Store catalogues. Magazines. Radio/TV guides.

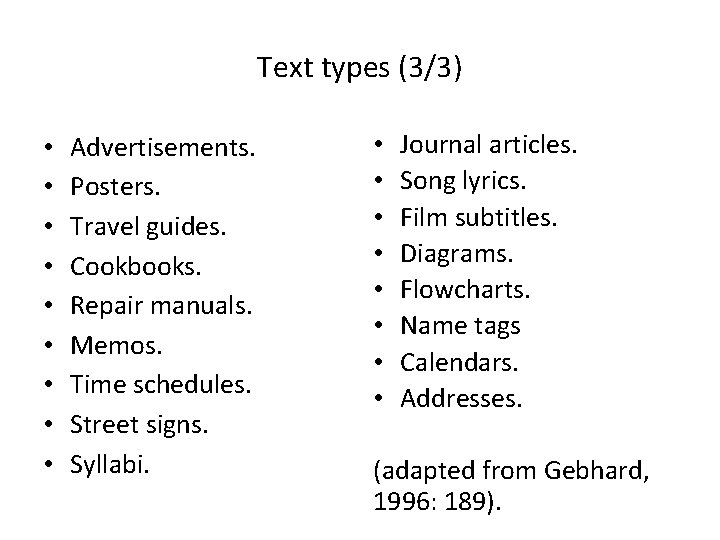

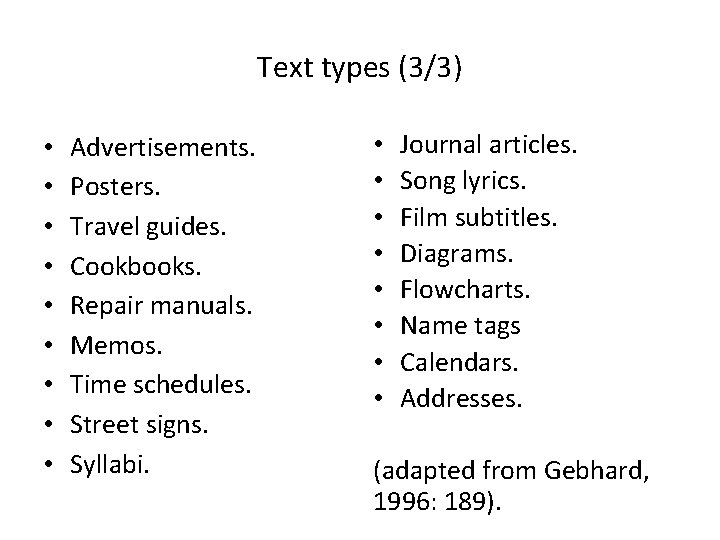

Text types (3/3) • • • Advertisements. Posters. Travel guides. Cookbooks. Repair manuals. Memos. Time schedules. Street signs. Syllabi. • • Journal articles. Song lyrics. Film subtitles. Diagrams. Flowcharts. Name tags Calendars. Addresses. (adapted from Gebhard, 1996: 189).

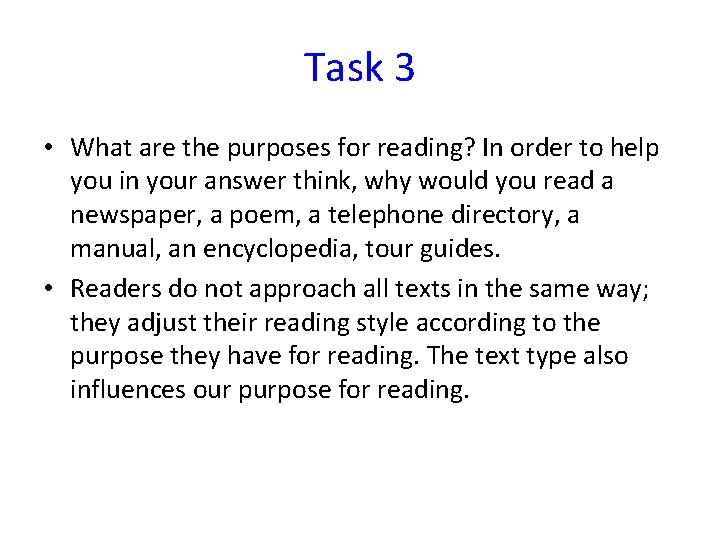

Task 3 • What are the purposes for reading? In order to help you in your answer think, why would you read a newspaper, a poem, a telephone directory, a manual, an encyclopedia, tour guides. • Readers do not approach all texts in the same way; they adjust their reading style according to the purpose they have for reading. The text type also influences our purpose for reading.

Reading purposes To obtain information. To respond to curiosity about a topic. To follow instructions to perform some task. For pleasure, amusement and personal enjoyment. To keep in touch with friends and colleagues. To know what is happening in the world (through newspapers, magazines etc. ). • To find out when and where things are happening. • To extend/enrich our existing knowledge base. (Adapted from Hedge, 2001; Rivers and Temperley, 1978. ) • • •

How do good readers read? • Depending on their reading purpose and the type of text, good readers choose the most appropriate reading strategy(-ies). • We read different things in different ways. • The reading strategies we use depend on what we are reading and our purpose for reading it.

Strategies that effective readers employ (1/3) • Recognise words quickly. • Use text features (i. e. headings, subheadings, pictures) to predict the content of a text. • Deduce the meaning and use of unfamiliar lexical items by using contextual clues. • Read at different speeds for different purposes. • Understand information when not explicitly stated. • Distinguish main ideas from minor ones. • Identify the salient points in a text to summarise.

Strategies that effective readers employ (2/3) • Distinguish between fact and opinion. • Use prior knowledge to work out the meanings within a text. • Understand the relationships between parts of the text from the use of connectives. • Skimming (quickly reading through a text to get the gist). • Scanning (quickly searching a text for a particular piece of information). • Identify the main point in a piece of discourse.

Strategies that effective readers employ (3/3) • Use a dictionary well and understand its limitations. • Use context to build meaning and aid comprehension. • Continue reading even when unsuccessful, at least for a while. • Adjust strategies to the purpose of reading. • Learn to skip over things that are not important • The keep going even if there is a minor comprehension failure (Adapted from Munby, 1978, and Aebersold and Field, 1997. )

Task 4 Which strategies would you use if: • you wanted to find a telephone number in the directory ? • your level is intermediate, and you wanted to find out what a British newspaper opinion towards the Olympic games? • your level is pre-intermediate and you want to decide which places to visit in London through a tour guide?

Approaches to the development of reading skills: 1. Extensive Approach: The assumption behind this approach is that if learners read large quantities of reading materials of their own choosing, their ability to read will constantly improve. They read something they can understand without a dictionary In this approach most of the reading is done outside the classroom without teacher support. The text is always read for comprehension of main ideas not for every detail and word.

What is Extensive Reading?

Graded readers are GRADED Native books Phonics Easy vocab Easy grammar More difficult vocab More difficult grammar

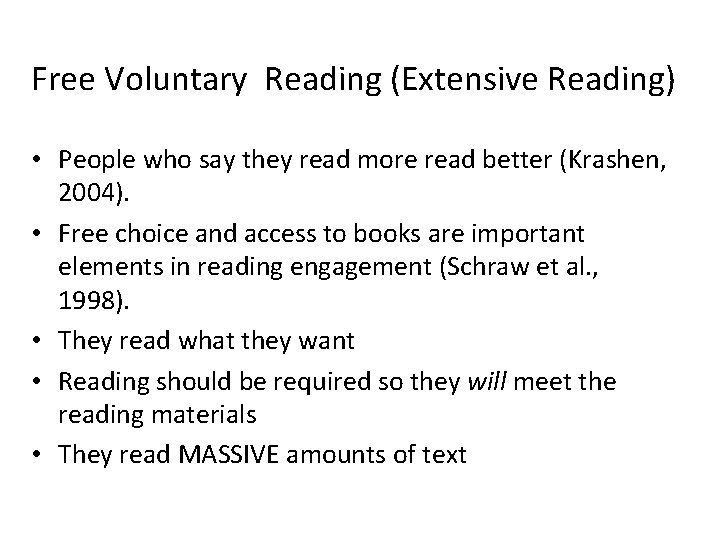

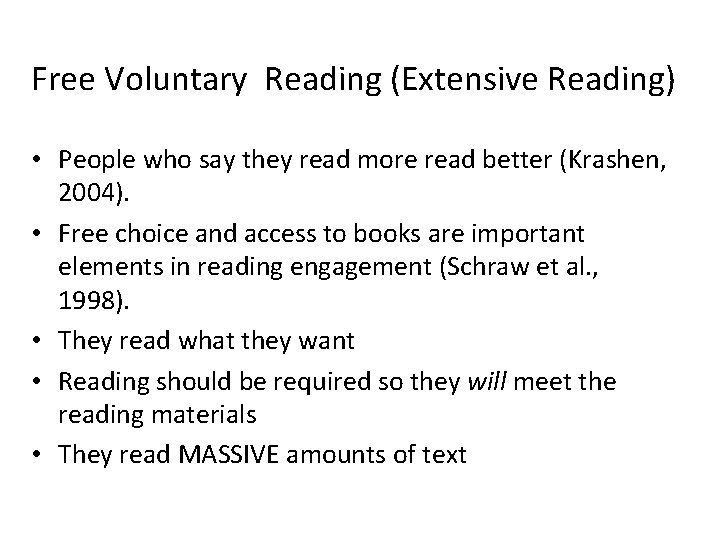

Free Voluntary Reading (Extensive Reading) • People who say they read more read better (Krashen, 2004). • Free choice and access to books are important elements in reading engagement (Schraw et al. , 1998). • They read what they want • Reading should be required so they will meet the reading materials • They read MASSIVE amounts of text

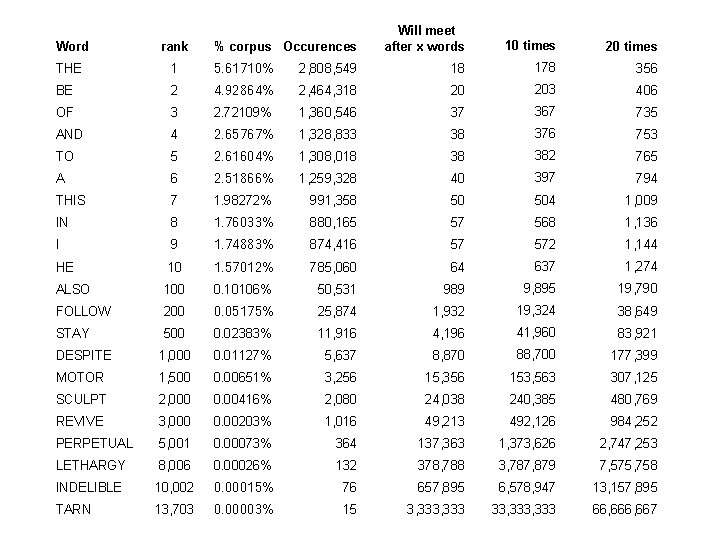

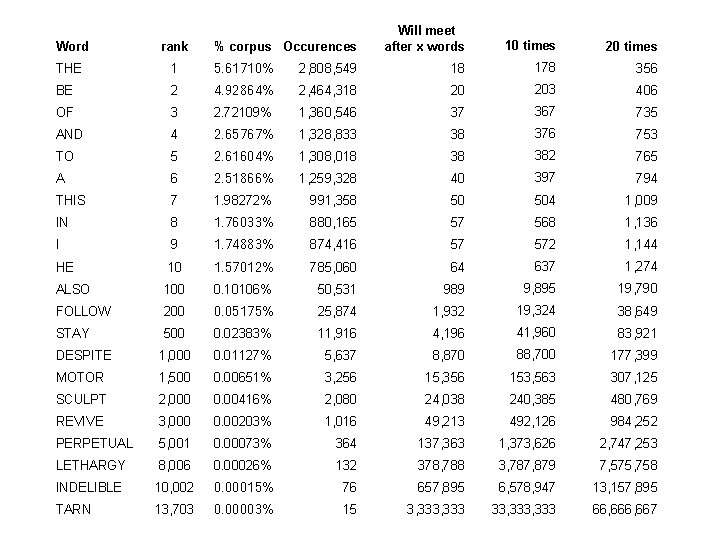

% corpus Occurences Will meet after x words 10 times 20 times Word rank THE 1 5. 61710% 2, 808, 549 18 178 356 BE 2 4. 92864% 2, 464, 318 20 203 406 OF 3 2. 72109% 1, 360, 546 37 367 735 AND 4 2. 65767% 1, 328, 833 38 376 753 TO 5 2. 61604% 1, 308, 018 38 382 765 A 6 2. 51866% 1, 259, 328 40 397 794 THIS 7 1. 98272% 991, 358 50 504 1, 009 IN 8 1. 76033% 880, 165 57 568 1, 136 I 9 1. 74883% 874, 416 57 572 1, 144 HE 10 1. 57012% 785, 060 64 637 1, 274 ALSO 100 0. 10106% 50, 531 989 9, 895 19, 790 FOLLOW 200 0. 05175% 25, 874 1, 932 19, 324 38, 649 STAY 500 0. 02383% 11, 916 4, 196 41, 960 83, 921 DESPITE 1, 000 0. 01127% 5, 637 8, 870 88, 700 177, 399 MOTOR 1, 500 0. 00651% 3, 256 15, 356 153, 563 307, 125 SCULPT 2, 000 0. 00416% 2, 080 24, 038 240, 385 480, 769 REVIVE 3, 000 0. 00203% 1, 016 49, 213 492, 126 984, 252 PERPETUAL 5, 001 0. 00073% 364 137, 363 1, 373, 626 2, 747, 253 LETHARGY 8, 006 0. 00026% 132 378, 788 3, 787, 879 7, 575, 758 INDELIBLE 10, 002 0. 00015% 76 657, 895 6, 578, 947 13, 157, 895 TARN 13, 703 0. 00003% 15 3, 333 33, 333 66, 667

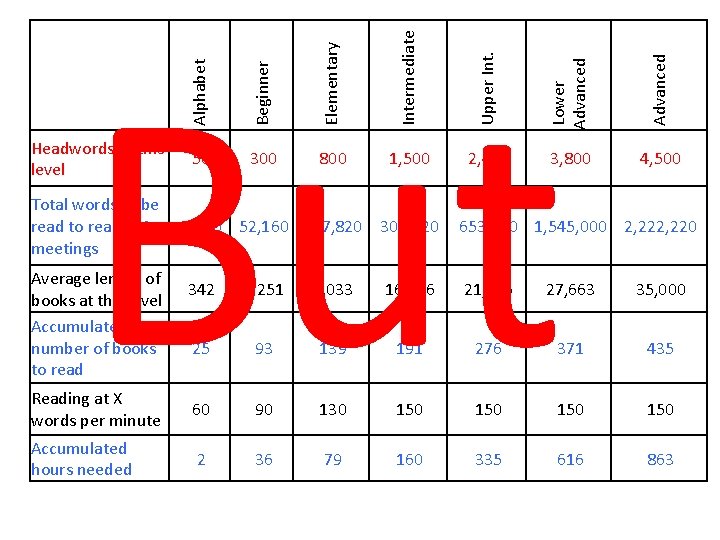

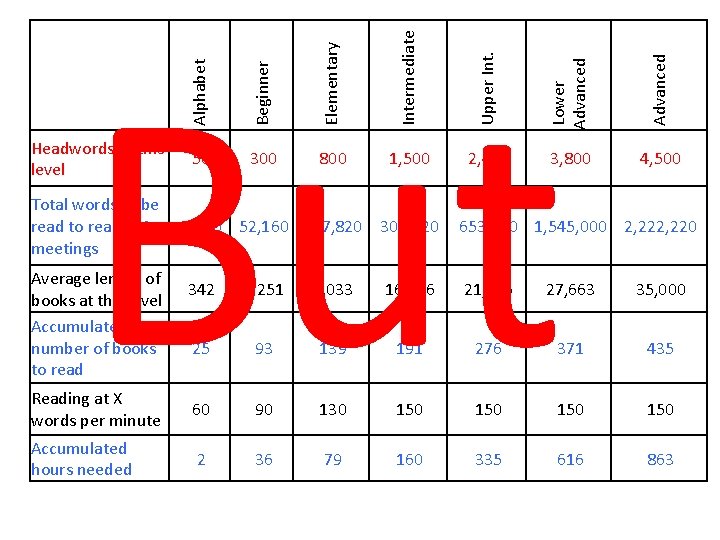

Total words to be read to reach 20 meetings Average length of books at this level Accumulated number of books to read Alphabet Beginner Elementary Intermediate Upper Int. Lower Advanced But Headwords at this level 50 300 800 1, 500 2, 400 3, 800 4, 500 8, 620 52, 160 137, 820 307, 120 653, 600 1, 545, 000 2, 220 342 3, 251 8, 033 16, 776 21, 145 27, 663 35, 000 25 93 139 191 276 371 435 Reading at X words per minute 60 90 130 150 150 Accumulated hours needed 2 36 79 160 335 616 863

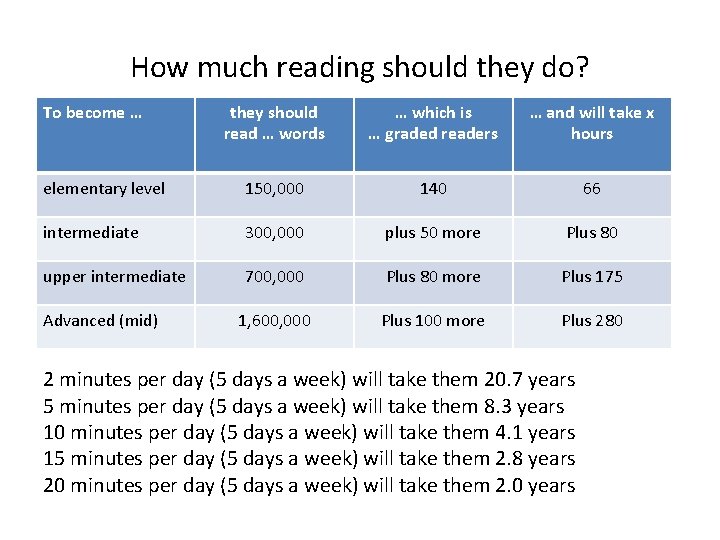

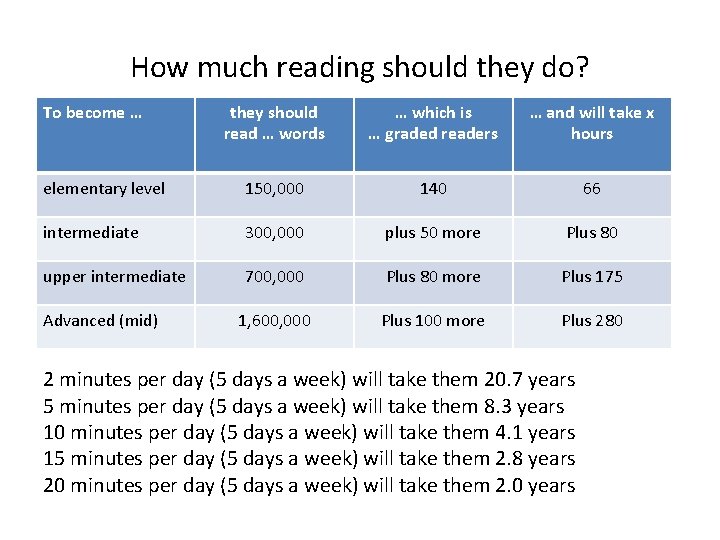

How much reading should they do? To become … they should read … words … which is … graded readers … and will take x hours elementary level 150, 000 140 66 intermediate 300, 000 plus 50 more Plus 80 upper intermediate 700, 000 Plus 80 more Plus 175 1, 600, 000 Plus 100 more Plus 280 Advanced (mid) 2 minutes per day (5 days a week) will take them 20. 7 years 5 minutes per day (5 days a week) will take them 8. 3 years 10 minutes per day (5 days a week) will take them 4. 1 years 15 minutes per day (5 days a week) will take them 2. 8 years 20 minutes per day (5 days a week) will take them 2. 0 years

Free Voluntary Reading: Implications for Practitioners • Maximize access to books through: – – – extended library hours lending “collections” for classrooms; book fairs advocacy for strong material budgets; supplementary sources of funds through grants and other sources. • Advocate for – – – free choice of genre reading levels, varied types of reading for summer reading lists, curriculum-based inquiry units

Free Voluntary Reading: Implications for Practitioners • Integrate the reading into the curriculum • Promote the use of literature circles in classrooms and as part of inquiry learning • Adapt literature circles to information circles for inquiry. • Free Voluntary Reading is pleasant. (Csikszentmihalyi, 1991; Nell, 1988). • Avoid extrinsic rewards for reading!

Approaches to the development of reading skills: Intensive Approach Reading is done in the classroom. Each text is read thoroughly for maximum comprehension using coursebooks. Intensive reading is used to teach and practice a range of reading skills/strategies. Teachers provide direction and learners complete tasks before, during and after reading.

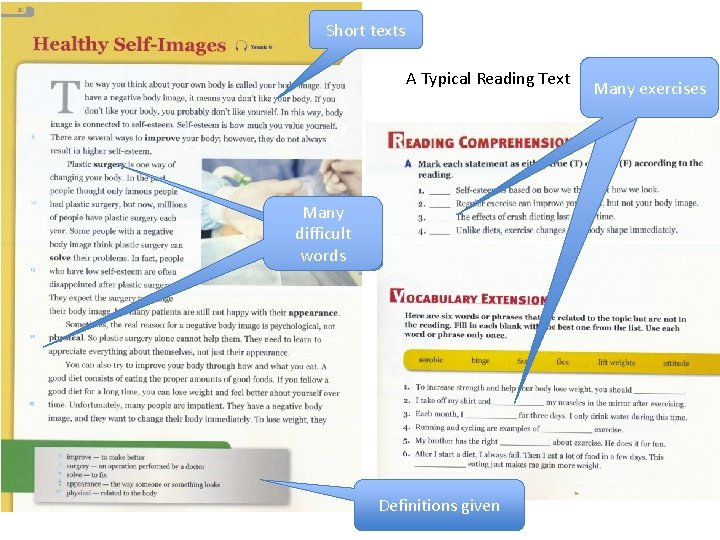

Short texts A Typical Reading Text Many difficult words Definitions given Many exercises

Principles of teaching reading directly • The teaching of reading should focus on developing learners’ reading skills and strategies rather than testing learners’ reading comprehension. • Provide learners opportunities to read a variety of texts. • Provide learners with tasks that have a realistic/authentic purpose. • Design tasks that develop a variety of reading skills. • Work on bottom-up recognition skills and on top-down interpretation skills.

Direct Instruction • Direct Instruction: Research has shown that many learners who read at 3 rd grade level in 3 rd grade will not automatically become proficient comprehenders in later grades (Office of Educational Research and Improvement & Rand Reading Study Group, 1999). • Therefore, teachers must teach comprehension strategies explicitly. • Research shows teachers need expertise to do this, but receive inadequate pre-service training (Ibid. )

Direct Reading Instruction: Implications for Practitioners • Integrate reading for comprehension strategies with inquiry learning and other teaching situations. • Collaborate with classroom teachers to integrate reading strategies with classroom instruction. • Learners need time to practice the strategies and to learn when to apply them.

Direct Reading Instruction: Implications for Practitioners • The primary goal of reading for comprehension is to raise learners awareness of their comprehension breakdown and to supply the tools they need to monitor their comprehension and apply the strategies. • Reading skills are thinking skills. They help learners activate prior knowledge, apply what they know to new situations, analyze, evaluate, and synthesize (create). They are taught in the context of intellectual challenges that require critical thinking.

Task 4 Which approach, intensive (direct instruction) or extensive (free voluntary reading) is better for learners? Why?

Task 6 • What reading comprehension strategies should we teach? • Which not?

Seven Strategies to Teach learners Text Comprehension strategies are conscious plans — sets of steps that good readers use to make sense of text. Comprehension strategy instruction helps learners become purposeful, active readers who are in control of their own reading comprehension. The following seven strategies have research-based evidence for improving text comprehension.

Seven Strategies to Teach learners Text Comprehension 1. Monitoring comprehension 2. Metacognition 3. Graphic and semantic organizers 4. Answering questions 5. Generating questions 6. Recognizing story structure 7. Summarizing

Seven Strategies to Teach learners Text Comprehension Research shows that explicit teaching techniques are particularly effective for comprehension strategy instruction. In explicit instruction, teachers tell readers why and when they should use strategies, what strategies to use, and how to apply them. The steps of explicit instruction typically include direct explanation, teacher modeling ("thinking aloud"), guided practice, and application.

1. Monitoring comprehension learners who are good at monitoring their comprehension know when they understand what they read and when they do not. They have strategies to "fix" problems in their understanding as the problems arise. Research shows that instruction, even in the early grades, can help learners become better at monitoring their comprehension. Comprehension monitoring instruction teaches learners to: Be aware of what they do understand Identify what they do not understand Use appropriate strategies to resolve problems in comprehension

2. Metacognition can be defined as "thinking about thinking. " Good readers use metacognitive strategies to think about and have control over their reading. E. g. Before reading, they might clarify their purpose for reading and preview the text. During reading, they might monitor their understanding, adjusting their reading speed to fit the difficulty of the text and "fixing" any comprehension problems they have. After reading, they check their understanding of what they read.

2. Metacognition learners may use several comprehension monitoring strategies: Identify where the difficulty occurs "I don't understand the second paragraph on page 76. " Identify what the difficulty is "I don't get what the author means when she says, 'Arriving in America was a milestone in my grandmother's life. '” Restate the difficult sentence or passage in their own words "Oh, so the author means that coming to America was a very important event in her grandmother's life. ”

2. Metacognition Look back through the text "The author talked about Mr. Mc. Bride in Chapter 2, but I don't remember much about him. Maybe if I reread that chapter, I can figure out why he's acting this way now. " Look forward in the text for information that might help them to resolve the difficulty "The text says, 'The groundwater may form a stream or pond or create a wetland. People can also bring groundwater to the surface. ' Hmm, I don't understand how people can do that… Oh, the next section is called 'Wells. ' I'll read this section to see if it tells how they do it. "

3. Graphic and semantic organizers Graphic organizers illustrate concepts and relationships between concepts in a text or using diagrams. Graphic organizers are known by different names, such as maps, webs, graphs, charts, frames, or clusters. Regardless of the label, graphic organizers can help readers focus on concepts and how they are related to other concepts. Graphic organizers help learners read and understand textbooks and picture books. Graphic organizers can: Help learners focus on text structure "differences between fiction and nonfiction" as they read Provide learners with tools they can use to examine and show relationships in a text Help learners write well-organized summaries of a text

4. Answering questions Questions can be effective because they: Give learners a purpose for reading Focus learners' attention on what they are to learn Help learners to think actively as they read Encourage learners to monitor their comprehension Help learners to review content and relate what they have learned to what they already know

Levels of reading comprehension 1. Literal Reading what the text actually says what actually happens in a story Assessment is objective and there is a correct answer - who, what, where, when, how - with e. g. multiple choice or fill-in-the-blank tests If learners do not understand at this level, they cannot progress to the next levels Where is she going? Who did she meet? What happened to grandma?

Levels of reading comprehension 2. Inferential or interpretive reading making inferences accessing previous knowledge attaching new learning to old information making educated guess and logical deductions ‘reading between the lines’ Assessment is subjective – why, what if…? Will Red Riding Hood make it to Grandma’s safely? What will happen next? Why didn’t the wolf eat her in the woods?

Levels of reading comprehension 3. Evaluative or applied reading – looking at what happened or what was said and what was meant, by looking at the context and relating the text to other contexts analyzing intentions & motivations synthesizing – seeing connections between texts applying this information to other contexts, the real world fact or opinion, validity personal reaction to the text – desirability of the ideas judgment of the author’s text - style, imagery etc. Assessment is subjective Was it right for the mother to send her daughter to the dangerous woods? How old should a child be before being allowed to go out alone? How would you feel if someone sent you into the dark woods alone? Did the author write at a level the learners could understand?

4. Answering questions The Question-Answer Relationship strategy (QAR) encourages learners to learn how to answer questions better. learners are asked to indicate whether the information they used to answer questions about the text was a) textually explicit information (directly stated in the text), b) textually implicit information (implied in the text), or c) information entirely from the student's own background knowledge. Example: Why was Frog sad? Answer: His friend was leaving.

4. Answering questions There are four different types of QAR questions: 1. "Right There" Questions found right in the text that ask learners to find the one right answer located in one place as a word or a sentence in the passage. Example: Who is Frog's friend? Answer: Toad 2. "Think and Search" Questions based on the recall of facts that can be found directly in the text. Answers are typically found in more than one place, thus requiring learners to "think" and "search" through the passage to find the answer.

4. Answering questions 3. "Author and You" Questions require learners to use what they already know (relate it to their prior knowledge ), with what they have learned from reading the text. Example: How do you think Frog felt when he found Toad? Answer: I think that Frog felt happy because he had not seen Toad in a long time. I feel happy when I get to see my friend who lives far away. 4. "On Your Own" Questions are answered based on a learners prior knowledge and experiences. Reading the text may not be helpful to them when answering this type of question. Example: How would you feel if your best friend moved away? Answer: I would feel very sad if my best friend moved away because I would miss her.

4. Answering questions (QAR) QAR empowers learners to think about the text they are reading and beyond it, too. It inspires them to think creatively and work cooperatively while challenging them to use literal and higherlevel thinking skills. QAR is a simple strategy to teach learners as long as you model, model.

4. Answering questions (QAR) Depending on your learners, you may choose to teach type of question individually or as a group. Explain to learners that there are four types of questions they will encounter. Define each type of question and give an example. Read a short passage aloud to your learners. Have predetermined questions you will ask after you stop reading. When you have finished reading, read the questions aloud to learners and model how you decide which type of question you have been asked to answer. Next, show your learners how find information to answer your question (i. e. , in the text, from your own experiences, etc. ). After you have modeled your thinking process for each type of question, invite learners to read another passage on their own, using a partner to determine the type of question and how to find the answer. After learners have practiced this process for several types of questions and over several lessons, you may invite learners to read passages and try to create different types of questions for the reading. Notes:

5. Generating questions By generating questions, learners • become aware of whether they can answer the questions and if they understand what they are reading. • learn to ask themselves questions that require them to combine information from different segments of text. For example, learners can be taught to ask main idea questions that relate to important information in a text.

6. Recognizing story structure In story structure instruction, learners learn to identify the categories of content (characters, setting, events, problem, resolution) recognize story structure through the use of story maps. improves learners' comprehension. They can also evaluate the story

7. Summarizing requires learners to determine what is important in what they are reading and to put it into their own words. Instruction in summarizing helps learners: Identify or generate main ideas Connect the main or central ideas Eliminate unnecessary information Remember what they read Effective comprehension strategy instruction is explicit

7. Summarizing Direct explanation The teacher explains to learners why the strategy helps comprehension and when to apply the strategy. Modeling The teacher models, or demonstrates, how to apply the strategy, usually by "thinking aloud" while reading the text that the learners are using. Guided practice The teacher guides and assists learners as they learn how and when to apply the strategy. Application The teacher helps learners practice the strategy until they can apply it independently.

Summary of comprehension strategies Cooperative learning instruction has been used successfully to teach comprehension strategies. Learners work together to understand texts, helping each other learn and apply comprehension strategies. Teachers help learners learn to work in groups. Teachers should provide modeling of the comprehension strategies.

Task 7 How much strategy training is enough? • How much time should be spent on developing the reading skills and strategies and how much on actually practicing the reading?

Evidence for ER

Recent ER research Kweon, Kim (2008) found that 12 learners gained in vocabulary after ER and retained most of their gains over time Jeon (2008) -> 17 Airforce subjects who did ER showed an increase in interest in ER, and growth in reading confidence over 22 controls who didn't. Suggested formal evaluation was important. Cha (2009) compared 10 Ss with ER and 10 without. ER group improved significantly in speed and attitude, but not vocab. Reaffirmed reading at the right level and the need for explicit and incidental vocab instruction (NB the reading period was too short)

Recent ER papers Hye (2009) suggests ER be strongly integrated into the curriculum to complement IR and provide the missing massive language input Yang (2010) showed improvements in grammar, vocab, reading speed and attitude for 3 groups doing ER (120 Korean subjects) O (2011) showed ER was helpful for developing reading skills and ER can be implemented in formal Korean settings

Recent ER papers Park (2005) found Korean learners tended to read for survival than reading for pleasure or information Wang and Wang (2009) by reference to Day and Bamford’s (1998) Expectancy-value Model of Motivation for Second Language Reading, showed that a) driving university learners’ motivation to read extensively in English may be better accomplished by raising both the expectancy and value factors with texts that learners are able to read reasonably well, which they also consider very worthwhile reading (i. e. ER) b) ER materials could cover topics that help learners prepare for academic studies abroad and further their career development. The paper concludes that, for university learners, at least, the goals of extensive reading may need focus on ease of reading and entertainment at a level of comfort suitable to the learners.

Recent ER papers Suk (2015) in an extensive study of Korean EFL learners found repeated-measures MANOVA revealed that the experimental classes (ER) significantly outperformed the intensive reading classes on the combination of the three dependent variables (i. e. , reading comprehension, reading rate, and vocabulary acquisition). Fujita (2019) found that fluency increases the more learners read

Recent ER papers in Korea V Park, Isaacs and Woodfield, 2018 • This quasi-experimental study measured partial vocabulary knowledge of specific words encountered through reading • Compared the effects of ER and conventional IR instruction on EFL learners’ vocabulary knowledge development. • Two intact classes of 72 Korean secondary learners (36/class) received either ER or IR instructional treatments over a 12 -week timespan. • ANCOVA results showed that learners benefited significantly more from the ER than from the IR treatment in terms of their knowledge of the meanings and uses of target words. • With regard to proficiency, advanced and intermediate level learners benefited more from ER, while low level learners benefited more from IR. • These findings suggest that EFL practitioners should carefully consider their learners’ proficiency level when selecting a reading approach, in order to optimize learners’ vocabulary development.

Recent ER papers in Korea VI Seog (2016) • Investigated the effects of extracurricular English education, specifically Hagwon education vs. extensive reading on English reading comprehension proficiency • 713 young Korean EFL learners in Korean elementary schools, grades 1 through 6, participated in the study. • Participants were assessed for their English reading comprehension measures during a nationwide reading comprehension assessment event. • Results revealed a significant main effect of grade level and a nonsignificant effect of extracurricular English education on L 2 reading comprehension. However, a closer look revealed interesting insights for the effect of Hagwon education vs. extensive reading on the participants’ L 2 reading comprehension. • There was no significant interaction of grade level and extracurricular English education on L 2 reading comprehension of the young Korean EFL learners.

Recent ER papers in Korea VII Byun (2010) researched 14 teachers reluctant to do ER by requiring them to do ER as learners • A library of 1000 books including graded readers, young adult books, some magazines, best sellers and steady seller books. • The study showed that although the teachers were initially somewhat resistant to the idea of reading English-language books extensively prior to their participation, they became proponents of the approach once they had the experience of pleasure reading. • They also expressed a fondness for graded readers and literature for young adults because of the simplified language and appealing themes that characterize such reading materials, and were willing to introduce them to learners in secondary schools. • Teachers also recognized the linguistic benefits of extensive reading including vocabulary expansion, positive reading attitude, and a sense of accomplishment from reading extensively. • In terms of the applicability issue, however, the participating teachers recommended introducing the approach gradually because of the test-emphasized classroom culture.

Recent ER papers in Korea VIII 박근남 (2017) Korean High School learners’ L 2 Reading Experience in Self-Directed Extensive English Reading • 11 male high school learners read about 10 English books in a self-directed way and wrote 8 narrative writings over 4 months. • Surveys revealed the self-directed extensive English reading, allowed learners to set up their own reading purposes and could choose their own books with satisfaction. • They read books responsibly according to their own plans (place, time, amount of reading and so on) and overcame the dilemmas and were accustomed to reading English books. • learners become much more familiar with English books and confident in English reading while reading and found out the pleasure of reading autonomously.

Furukawa (2008) A concurrent approach from 7 th grade in cram school 80 minutes normal class; 80 minutes ER for 48 weeks 30, 000 books to choose from, 2000 CDs, 100 DVDs By 9 th grade they had read 670, 000 words and outperformed learners 2 years older also attending cram school on the reading and listening aspects of the ACE test after controlling for the same time in classes ER made the difference

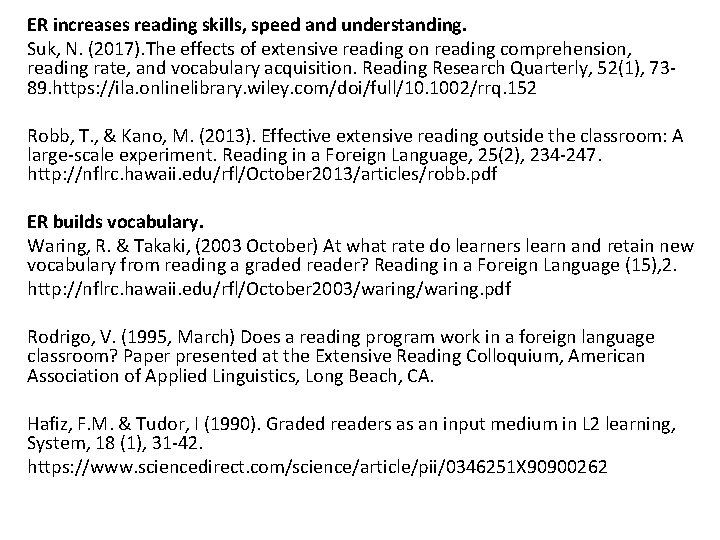

ER increases reading skills, speed and understanding. Suk, N. (2017). The effects of extensive reading on reading comprehension, reading rate, and vocabulary acquisition. Reading Research Quarterly, 52(1), 7389. https: //ila. onlinelibrary. wiley. com/doi/full/10. 1002/rrq. 152 Robb, T. , & Kano, M. (2013). Effective extensive reading outside the classroom: A large-scale experiment. Reading in a Foreign Language, 25(2), 234 -247. http: //nflrc. hawaii. edu/rfl/October 2013/articles/robb. pdf ER builds vocabulary. Waring, R. & Takaki, (2003 October) At what rate do learners learn and retain new vocabulary from reading a graded reader? Reading in a Foreign Language (15), 2. http: //nflrc. hawaii. edu/rfl/October 2003/waring. pdf Rodrigo, V. (1995, March) Does a reading program work in a foreign language classroom? Paper presented at the Extensive Reading Colloquium, American Association of Applied Linguistics, Long Beach, CA. Hafiz, F. M. & Tudor, I (1990). Graded readers as an input medium in L 2 learning, System, 18 (1), 31 -42. https: //www. sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/0346251 X 90900262

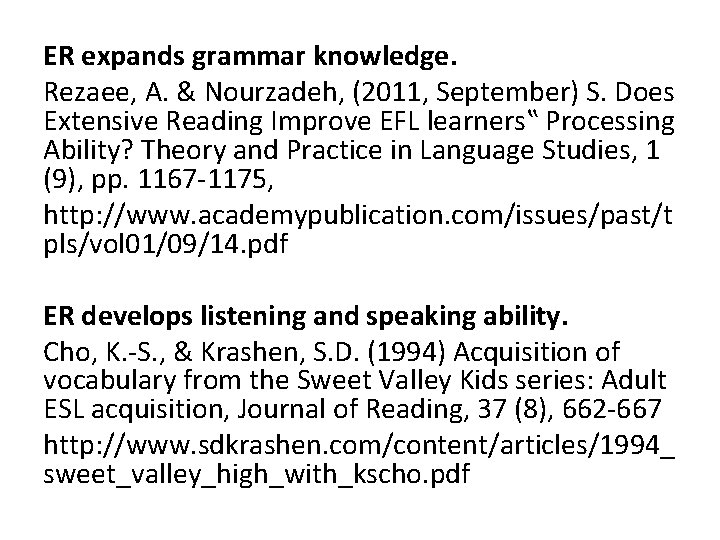

ER expands grammar knowledge. Rezaee, A. & Nourzadeh, (2011, September) S. Does Extensive Reading Improve EFL learners‟ Processing Ability? Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 1 (9), pp. 1167 -1175, http: //www. academypublication. com/issues/past/t pls/vol 01/09/14. pdf ER develops listening and speaking ability. Cho, K. -S. , & Krashen, S. D. (1994) Acquisition of vocabulary from the Sweet Valley Kids series: Adult ESL acquisition, Journal of Reading, 37 (8), 662 -667 http: //www. sdkrashen. com/content/articles/1994_ sweet_valley_high_with_kscho. pdf

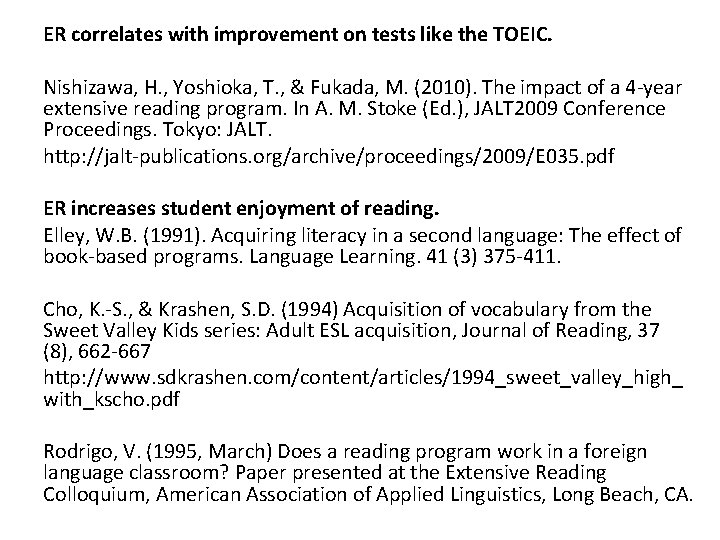

ER correlates with improvement on tests like the TOEIC. Nishizawa, H. , Yoshioka, T. , & Fukada, M. (2010). The impact of a 4 -year extensive reading program. In A. M. Stoke (Ed. ), JALT 2009 Conference Proceedings. Tokyo: JALT. http: //jalt-publications. org/archive/proceedings/2009/E 035. pdf ER increases student enjoyment of reading. Elley, W. B. (1991). Acquiring literacy in a second language: The effect of book-based programs. Language Learning. 41 (3) 375 -411. Cho, K. -S. , & Krashen, S. D. (1994) Acquisition of vocabulary from the Sweet Valley Kids series: Adult ESL acquisition, Journal of Reading, 37 (8), 662 -667 http: //www. sdkrashen. com/content/articles/1994_sweet_valley_high_ with_kscho. pdf Rodrigo, V. (1995, March) Does a reading program work in a foreign language classroom? Paper presented at the Extensive Reading Colloquium, American Association of Applied Linguistics, Long Beach, CA.

ER and Affect - motivation Extensive reading has been discussed and studied in terms of its impact on such variables as attitude toward reading and motivation to read. Al-Hamoud & Schmitt 2009; Al-Nujaidi 2003; Alshamrani 2003; Bamford & Day 1998; Benson 2014; Birketveit, Rimmereide, Bader & Fisher, 2018; Bond 1926; Brantmeier 2005; Burrows 2014; Byun 2010; Caruso 1994; Cheethan, Harper, Elliott & Itoh 2016; Chen 2018; Chew 2003; Cho & Krashen 2001; Chou 2016; Chow 2000; Claridge 2012; Collins 1980; Constantino 1995; Crawford Camiciottoli 2001; Davis, Carbon Gorell, Kline & Hsieh (--) 1992; Day & Bamford 1998; de Burgh-Hirabe & Feryok 2013; de Morgado 2009; Dupuy 1997 a; Dupuy 1997 c; Edy 2015; Eidswick, Rouault & Praver 2011; Elley 1996; Fox 1990; Fredricks & Sobko 2008; Fujigaki 2009; Gee 1999; Gorsuch & Taguchi 2009; Greenberg, Rodrigo, Berry, Brinck & Joseph 2006; Grundy 2004; Hardy 2016; Heal 1998; Hedge 1985; Hickey 1991; Hitosugi & Day 2004; Huang 2015; Jackson 2005; Jacobs & Renandya 2016; Jacobs, Davis & Renandya 1997 (Chapter 17); Judge 2011; Kajinga 2006; Kane 2008; Karlin & Romanko 2010; Kim & Krashen 1997; Kirchhoff 2013; Kitao, Yamamoto, Kitao & Shimatani 1990; Klapper 1992 b; Komiyama 2013; Kong 2010; Krashen 1995; Krashen & Cho 1995; Krulatz & Duggan 2018; Kutiper 1983; Lado 2009; Lake 2014; Lee 2005; Lee, Schallert & Kim 2015; Liem 2005; Lightbown et al 2002; Lipp 1990; Lipp 2017; Liu 2016; Liu & Young 2017; Loucky 2009; Maamouri 2003; Mac. Gillivray, Tse & Mc. Quillan 1995; Martinez 2017; Mason & Krashen 1997 a; Mc. Quillan 1994; Mc. Quillan 1996; Mc. Quillan & Conde 1996; Mikami 2017; Mori 2002; Nakano 2016; Nash & Yuan 1992/93; Nation 1997; Nishino 2007; Petrimoulx 1988; Pilgreen & Krashen 1993; Poulshock 2010; Powell 2002; Powell 2005; Pulido 2009; Rane-Szostak 1997; Raz 2000; Renandya, Rajan & Jacobs 1999; Rivers 1972; Ro 2013; Ro& Chen 2014; Robb 2013; Robb & Susser 1989; Rodrigo 1997; Rodrigo, Greenberg, & Segal 2014; Sachs 2008; Sakurai 2017; Saleem 2010; Schmidt 2007; Schon, Hopkins & Davis 1982; Schon, Hopkins & Vojir 1984; Schon, Hopkins & Vojir 1985; Shemesh 1996; Sheu 2003; Sheu 2004; Sims 1996; Sin 2007; Sin 2000; Suk 2016; Sun 2003; Türkdoğan, G. , & Sivell 2016; Tabata-Sandom 2013; Taboada & Mc. Elvany 2009; Takase 2003; Takase 2007; Takase 2009; Tanaka & Stapleton 2007; Tien 2015; Tse 1996 a; Tse 1996 b; Von Sprecken, Kim & Krashen 2000; Wahjudi 2002; Wardani 2015; Waring 1997; Wong 1993; Yamashita 2004; Yamashita 2007; Yamashita 2013; Yamazaki 1996; Yang 2001; Yau 2007; You & Chen 2009; Yu 1996/1997; Zhang 2004;

ER and its effect on L 2 These are works that contain theories, discussions, and investigations into the role that extensive reading can play in L 2 learning. (See also Comprehensible Input Hypothesis. ) Arnold 2009; Azabdaftari 1992; Bamford & Day 1998; Bearne 1988; Bell 1998; Benson 1991; Bond 1953; Brusch 1991; Byun 2010; Cho & Krashen 1994; Cho & Krashen 1995; Collet al. 1991; Constantino 1995; Constantino 1994; Constantino, Lee, Cho & Krashen 1997; Davis 1995; Dawson 2002; Deckert 2006; Dupuy 1997 a; Dupuy 1997 c; Dupuy, Tse & Cook 1996; Edinburgh Project on Extensive Reading 1992; Elley 1991; Elley & Mangubhai 1983; Ellis & Mc. Rae 1991; Furukawa 2008; Grabe 1986; Grabe 1991; Gradman & Hanania 1991; Green 2005; Grundy 2004; Hafiz & Tudor 1989; Hafiz & Tudor 1990; Hagboldt 1925; Hagboldt 1929; Han 2010; Hedge 1985; Iwahori 2008; Jacobs 1991; Janopoulos 2009; Kawate 2004; Kim & Cho 2005; Kim & Krashen 1998; Klapper 1992 c; Kong 2010; Krashen 1993 a; Krashen 1993 b; Krashen 1997; Krashen 1995; Krashen 1994; Krashen 2007; Krashen & Cho 1995; Krashen, Terrell, Ehrman & Herzog 1984; Lai 1991; Laufer 2003; Lee 2007; Lee 2006; Lee, Krashen & Gribbons 1996; Lehmann 2007; Leung 2002; Li 2007; Lightbown et al 2002; Mangubhai & Elley 1982; Maronpot 1940; Mason 2006; Mason 2009; Mason & Krashen 1997 b; Mason & Krashen, in press ; Mason & Pendergast 1991; Maxim 1999; Maxim 2002; Mc. Quillan 1994; Mc. Quillan 1998; Mc. Quillan & Rodrigo 1995; Mc. Quillan & Tse 1998; Mitchell & Vidal 2001; Mok 1994; Mukundan, Ting & Ali 1998; Murata 2006; Nation 1997; Ng 1994; Ng 1996; Ng & Sullivan 2001; Nunn 2009; O'Sullivan 1987; Piechorowski 1979; Polak & Krashen 1988; Poulshock 2010; Prowse 1999; Renandya 2007; Renandya, Hu & Yu 2015; Renandya, Rajan & Jacobs 1999; Rivers 1964; Rivers 1968; Rodrigo 1997; Rodrigo & Mc. Quillan 1999; Rodrigo, Krashen & Gribbons 2004; Rosszell 2007; Saleem 2010; Schackne 1994; Schmidt 2007; Schmitt 2008; Sheu 2003; Smith 2010; Stephens 2015; Stokes, Krashen & Kartchner 1998; Strong 1996; Taguchi, Takayasu-Maass & Gorsuch 2004; Takase 2003; Takase 2007; Tsang 1997; Tse 1996 b; Tudor & Hafiz 1989; Wang 2008; Waring 2009; Webb 2015; Webb & Macalister 2013; Yamashita 2004; Yamashita 2008; Yang 2001; Yoshida 2006; You & Chen 2009; Yu 1996/1997;

ER’s effects on L 2 reading These works contain theories, discussions, and investigations into the role that extensive reading can play in improving L 2 reading ability. Al-Hamoud & Schmitt 2009; Anderson 1996; Ariyanto 2009; Arnold 2009; Bamford & Day 1997; Bamford & Day 1998; Beglar & Hunt 2014; Beglar, Hunt & Kite 2012; Bell 2001; Bond 1953; Brantmeier 2005; Broughton, Brumfit, Flavel, Hill & Pincas 1978; Bruton 2002; Bryan 2011; Burrows 2014; Byun 2010; Carrell & Carson 1997; Caruso 1994; Chang & Millett 2015; Chew 2003; Chow 2000; Coleman 1930; Constantino 1995; David 2009; Davis 1995; Day & Bamford 1998; de Morgado 2009; Dupuy 1997 a; Dupuy 1997 b; Edinburgh Project on Extensive Reading 1992; Edy 2015; Elley 1984; Elley 1996; Ercetin & Alptekin 2013; Eskey 1973; Eskey 1987; Eskey 2002; Fujigaki 2009; Furukawa 2008; Gorsuch & Taguchi 2009; Grabe 1986; Grabe 2002; Grabe 1991; Grabe 2017; Grabe & Stoller 1997; Grabe & Stoller 2001; Greenberg, Rodrigo, Berry, Brinck & Joseph 2006; Hafiz & Tudor 1989; Han 2010; Hardy 2016; Hassan 2002; Hayashi 1999 a; He 2014; Hedge 1985; Hitosugi & Day 2004; Huffman 2014; Hyland 1990; Ikeda & Mason 1994; Iwahori 2008; Janopoulos 2009; Jeon 2015; Jeon & Day 2016; King 1969; Klapper 1992 a; Klapper 1992 b; Kong 2010; Krashen 1988; Krashen 1993 a; Krashen 1993 b; Krashen 1997; Krashen 1995; Kutiper 1983; Lai 1993 a; Lai 1993 b; Lau 2000; Laufer-Dvorkin 1981; Leow 2009; Liem 2005; Lightbown et al 2002; Lin 2010; Lituanas, Jacobs, & Renandya 1999; Loucky 2009; Martinez 2017; Masuhara, Kimura, Fukada & Takeuchi 1996; Maxim 1999; Mc. Allister 2014; Mclean & Rouault 2017; Mermelstein 2014; Moore 1943; Moore 1942; Morgan 1938; Nakanishi 2014; Nash & Yuan 1992/93; Nation 1997; Nishizawa, Yoshioka & Nagaoka 2018; Nishizawa, Yoshioka & Fukuda 2010; Nunn 2009; Nuttall 1996; Pargment 1943; Pereyra 2015; Petrimoulx 1988; Phillips 2005; Pilgreen & Krashen 1993; Pucci 1998; Pudilo & Hambrick 2008; Pulido 2009; Raemer 1996; Ramaiah 1994; Rees 1992; Renandya 2007; Robb & Susser 1989; Robb & Kano 2013; Rodrigo 1997; Rodriguez-Trujillo 1996; Sakurai 2015; Schackne 1994; Schon, Hopkins & Davis 1982; Schon, Hopkins & Vojir 1984; Schon, Hopkins & Vojir 1985; Sheu 2003; Shih, Chern & Reynolds 2018; Shlayer 1996; Sims 1996; Smith 2006; Smith 2010; Song & Sardegna 2014; Stoller 2015; Susser & Robb 1990; Türkdoğan, G. , & Sivell 2016; Taguchi, Gorsuch & Sasamoto 2006; Taguchi, Takayasu-Maass & Gorsuch 2004; Takase 2003; Takase 2007; Takase 2009; Tanaka & Stapleton 2007; Tien 2015; Tudor & Hafiz 1989; Walker 1997; Waring 2014; Widodo 2009; Wu 2009; Yamanaka 1997; Yamashita 2004; Yamashita 2008; Yamazaki 1996;

ER’s effect on vocabulary learning These are investigations and discussions of how vocabulary may be learned incidentally while reading. Some of these studies investigate ways of making incidental learning more efficient, perhaps by supplementing it with intentional learning. 2003; Al-Hamoud & Schmitt 2009; Alessi & Dwyer 2008; Allan 2009; Alshamrani 2003; Alshwairkh 2004; Anderson 1996; Augustyn 2013; Bagster-Collins 1933; Bamford & Day 1998; Brown, Waring & Donkaewbua 2008; Bruton 2002; Chew 2003; Cho & Krashen 1994; Chow 2000; Chun, Choi & Kim 2012; Coady 1997; Cobb 2008; Cobb 2007; Daskalovska 2018; Davidson 2002; Day, Omura & Hiramatsu 1991; de Morgado 2009; Dupuy 1997 a; Dupuy & Krashen 1997; Elley 1991; Gardner 2004; Gardner 2008; Grabe 1991; Grabe & Stoller 1997; Hayashi 1999 b; Horst 2000; Horst 2005; Horst, Cobb & Meara 1998; Huang 2007; Huckin & Coady 1999; Hunt & Beglar 2007; Karlin & Romanko 2010; Karp 2002; Khonamri & Roostaee 2014; Klapper 1992 c; Krashen 1993 b; Kweon & Kim 2008; Lai 1993 a; Laufer 2003; Lee 2006; Lee 2005; Lehmann 2007; Leung 2002; Lightbown et al 2002; Marianne 2007; Marshall & Gilmour 1993; Martinez 2017; Mason 2006; Mc. Quillan 2016; Mc. Quillan 1996; Mc. Quillan & Krashen 2008; Min 2013; Min 2008; Moore 1942; Moore 1943; Murata 2006; Nation 2002; Nation 2015; Nation & Wang 1999; Nation & Deweerdt 2001; Parry 1991; Petrimoulx 1988; Pigada & Schmitt 2006; Pitts, White & Krashen 1989; Poulshock 2010; Prichard 2008; Pudilo & Hambrick 2008; Raptis 1997; Rodrigo & Mc. Quillan 1999; Rosszell 2007; Rott 1999; Saragi, Nation & Meister 1978; Schmitt 2008; Sheu 2003; Smith 2006; Sonbul & Schmitt 2010; Stewart 2006; Suk 2016; Taylor 2013; Tekmen & Daloglu 2006; Tomlinson 1998; Tran 2006; Vaugn, Martinez, WIlliams & Miciak 2018; Vidal 2011; Wan-a-rom 2008; Waring 2009; Webb 2008; Webb 2015; Webb & Chang 2015; Wesche & Paribakht 1994; Wodinsky & Nation 1988; Yamazaki 1996; Yoshida 2006; Zimmerman 1997;

Kinesthetic imagery

Kinesthetic imagery Empirisk formel

Empirisk formel Decaffeinated hot chocolate

Decaffeinated hot chocolate True or false katniss dismisses haymitch advice

True or false katniss dismisses haymitch advice How much is too much plagiarism

How much is too much plagiarism Rick trebino

Rick trebino Lectures paediatrics

Lectures paediatrics Data mining lectures

Data mining lectures Medicinal chemistry lectures

Medicinal chemistry lectures Uva powerpoint template

Uva powerpoint template Cs614 short lectures

Cs614 short lectures Activity planning software project management

Activity planning software project management Molecular biology lecture

Molecular biology lecture Radio astronomy lectures

Radio astronomy lectures Dr sohail lectures

Dr sohail lectures Utilities and energy lecture

Utilities and energy lecture Introduction to web engineering

Introduction to web engineering Do words have power

Do words have power Frcr physics lectures

Frcr physics lectures Frcr physics lectures

Frcr physics lectures Introduction to recursion

Introduction to recursion Guyton physiology lectures

Guyton physiology lectures Aerodynamics lectures

Aerodynamics lectures Tamara berg husband

Tamara berg husband Power system lectures

Power system lectures Theory and practice of translation lectures

Theory and practice of translation lectures Translation 1

Translation 1 Digital logic design lectures

Digital logic design lectures Computer networks kurose

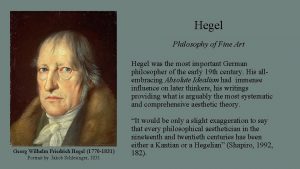

Computer networks kurose Hegel classical art

Hegel classical art Nuclear medicine lectures

Nuclear medicine lectures Cs106b lectures

Cs106b lectures Cdeep lectures

Cdeep lectures Oral communication 3 lectures text

Oral communication 3 lectures text C programming and numerical analysis an introduction

C programming and numerical analysis an introduction Haematology lectures

Haematology lectures Bureau of lectures

Bureau of lectures Slagle lecture

Slagle lecture Theory of translation lectures

Theory of translation lectures Reinforcement learning lectures

Reinforcement learning lectures 13 lectures

13 lectures Reinforcement learning lectures

Reinforcement learning lectures Bba lectures

Bba lectures Medical emergency student lectures

Medical emergency student lectures Medical hematology student lectures

Medical hematology student lectures Rcog eportfolio

Rcog eportfolio Bhadeshia lectures

Bhadeshia lectures Ota resident lectures

Ota resident lectures Comsats virtual campus lectures

Comsats virtual campus lectures Hugh blair lectures on rhetoric

Hugh blair lectures on rhetoric Cern summer student lectures

Cern summer student lectures Pathology lectures for medical students

Pathology lectures for medical students Dr asim lectures

Dr asim lectures Ota resident lectures

Ota resident lectures Anatomy lectures powerpoint

Anatomy lectures powerpoint Cern summer school lectures

Cern summer school lectures Chapter review motion part a vocabulary review answer key

Chapter review motion part a vocabulary review answer key Writ of certiorari ap gov example

Writ of certiorari ap gov example Nader amin-salehi

Nader amin-salehi What is inclusion and exclusion criteria

What is inclusion and exclusion criteria Narrative review vs systematic review

Narrative review vs systematic review Do que miranda amiga de via chamava august

Do que miranda amiga de via chamava august Julie august

Julie august It was late summer 26 august 1910

It was late summer 26 august 1910 Theme of responsibility in fences

Theme of responsibility in fences Agosto 6, 1891

Agosto 6, 1891 Leerexpert august leyweg 4

Leerexpert august leyweg 4 August strindberg giftas

August strindberg giftas Kirjanik 1891 1960

Kirjanik 1891 1960 Famous testimonies

Famous testimonies Three august ones

Three august ones August robert ludwig macke

August robert ludwig macke Full moon august 2011

Full moon august 2011 Diexi slides, sichuan, china, august 1933

Diexi slides, sichuan, china, august 1933 Ano ang pangyayari sa agosto 30 1896

Ano ang pangyayari sa agosto 30 1896 August alsina testimony album download zip file

August alsina testimony album download zip file August shi

August shi Povjestice postolar i vrag

Povjestice postolar i vrag šljivari august šenoa

šljivari august šenoa Moric august benovsky dennik

Moric august benovsky dennik Safety topics for august

Safety topics for august Colestaz

Colestaz Madonna last name

Madonna last name Summary of light in august

Summary of light in august Diane august

Diane august Gottfried august bürger

Gottfried august bürger Themes in fences

Themes in fences Central place theory

Central place theory Chinese names pronunciation

Chinese names pronunciation August kiss

August kiss August šenoa budi svoj analiza

August šenoa budi svoj analiza August de prima porta

August de prima porta Micro computer services began operations on august 1

Micro computer services began operations on august 1 Carl jonas love almqvist kända verk

Carl jonas love almqvist kända verk August strindberg faderen analyse

August strindberg faderen analyse August hlond przepowiednie

August hlond przepowiednie Cnn10 september 7

Cnn10 september 7 15 august 1769

15 august 1769 ångbåtskommissionär

ångbåtskommissionär August 27 2002

August 27 2002 August journal prompts

August journal prompts Fences character analysis

Fences character analysis August 26 2010

August 26 2010 August

August Dr lorraine johnstone

Dr lorraine johnstone August lec 250

August lec 250 11 august microwave

11 august microwave