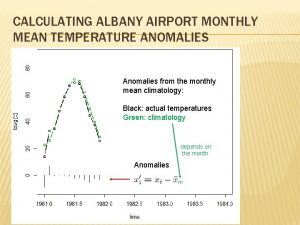

Eccentric and Mean anomalies Keplers equation f g

- Slides: 63

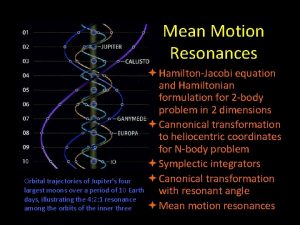

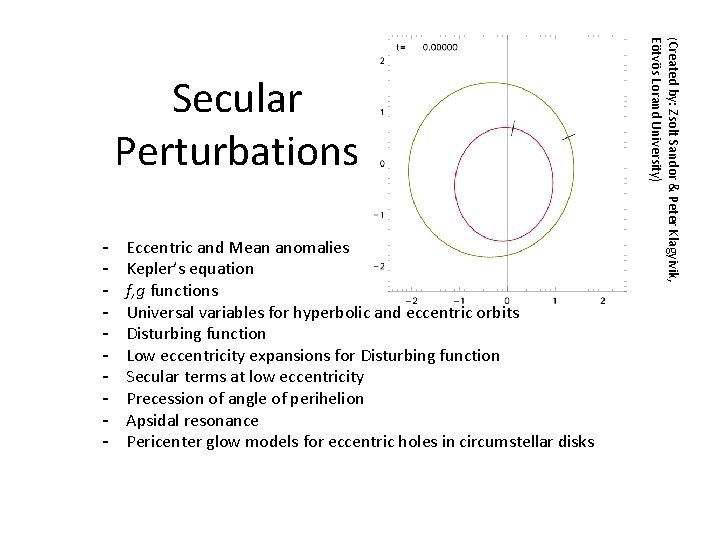

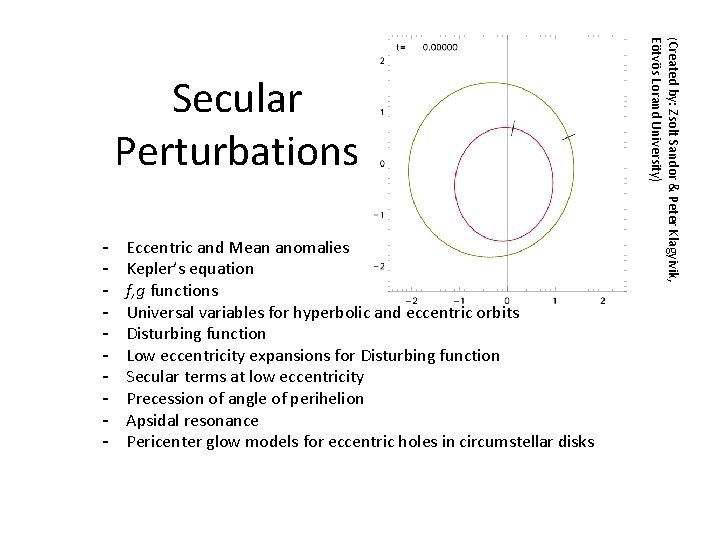

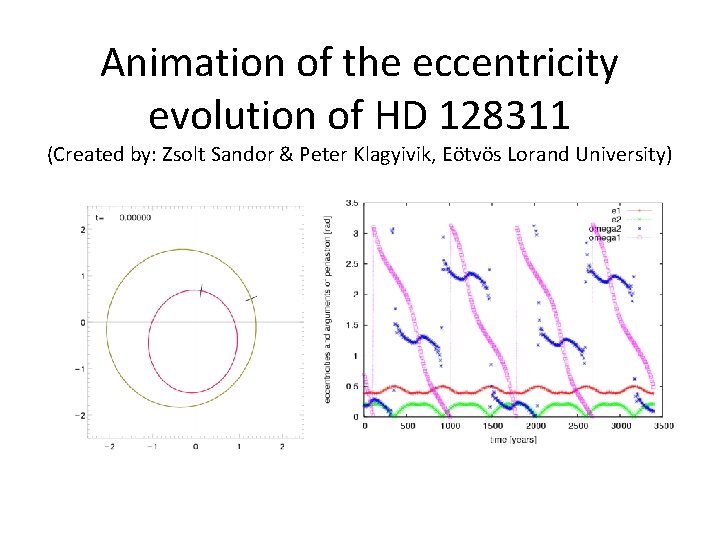

- Eccentric and Mean anomalies Kepler’s equation f, g functions Universal variables for hyperbolic and eccentric orbits Disturbing function Low eccentricity expansions for Disturbing function Secular terms at low eccentricity Precession of angle of perihelion Apsidal resonance Pericenter glow models for eccentric holes in circumstellar disks (Created by: Zsolt Sandor & Peter Klagyivik, Eötvös Lorand University) Secular Perturbations

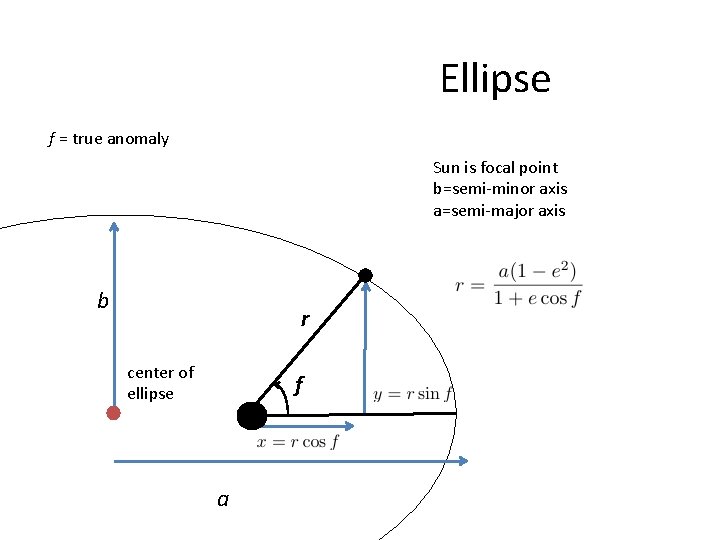

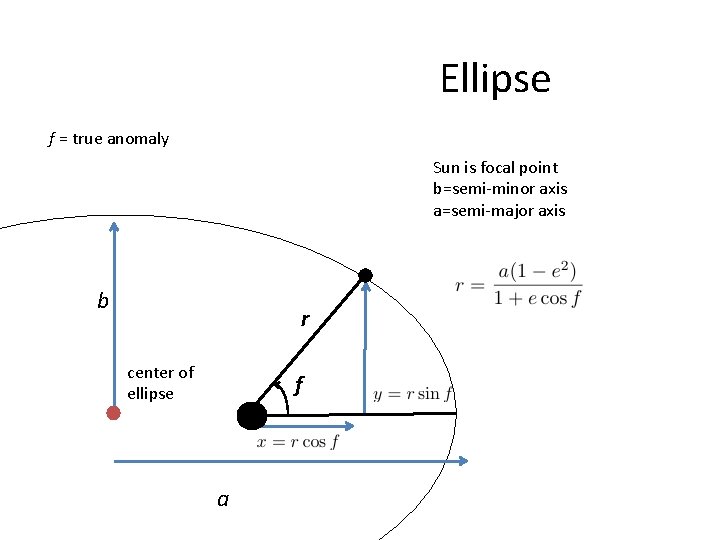

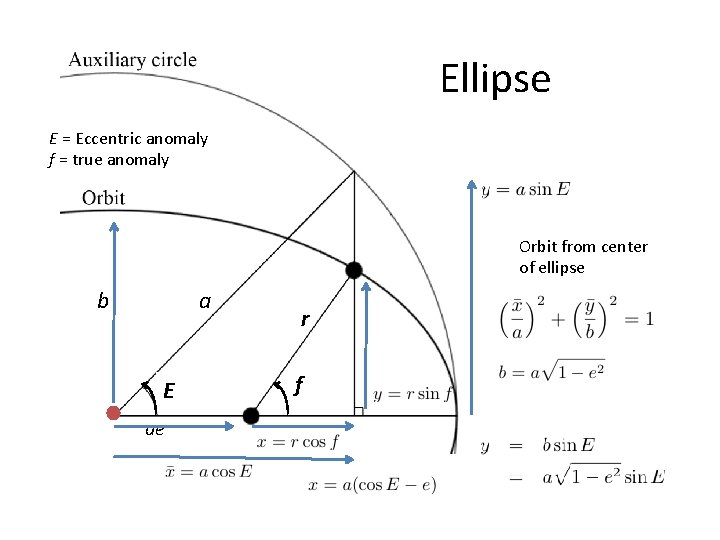

Ellipse f = true anomaly Sun is focal point b=semi-minor axis a=semi-major axis b r center of ellipse f a

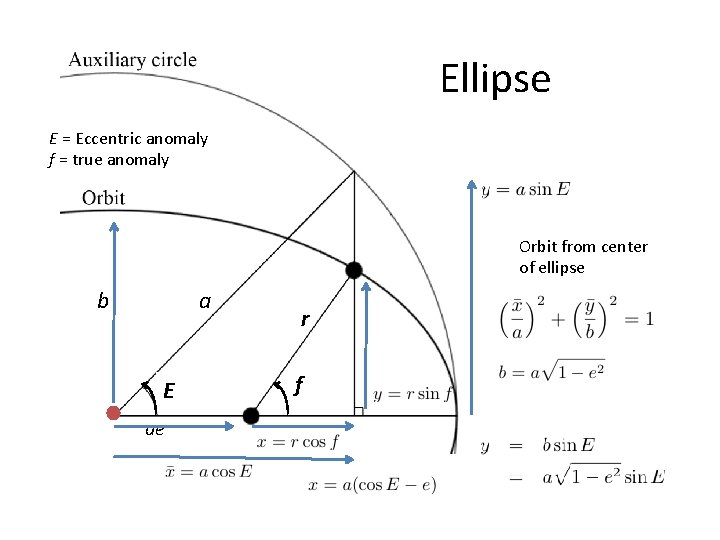

Ellipse E = Eccentric anomaly f = true anomaly Orbit from center of ellipse a b E ae r f

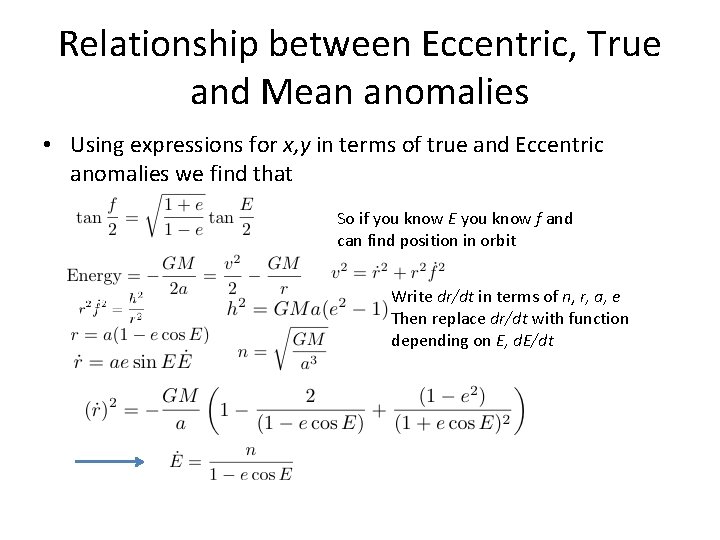

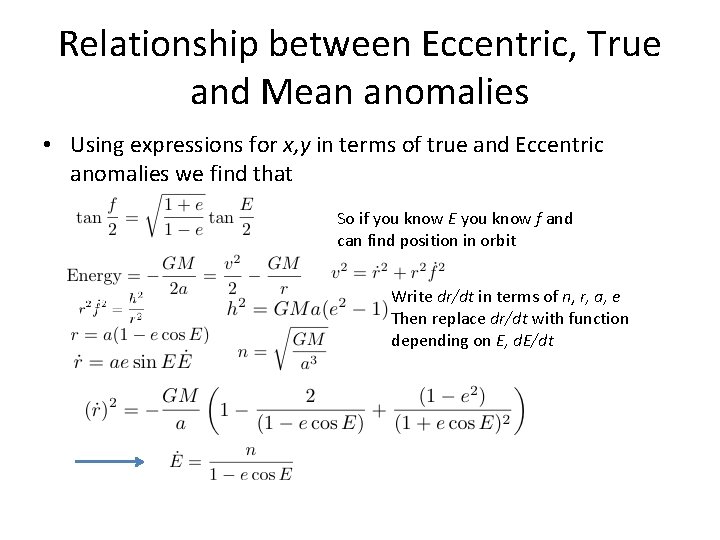

Relationship between Eccentric, True and Mean anomalies • Using expressions for x, y in terms of true and Eccentric anomalies we find that So if you know E you know f and can find position in orbit Write dr/dt in terms of n, r, a, e Then replace dr/dt with function depending on E, d. E/dt

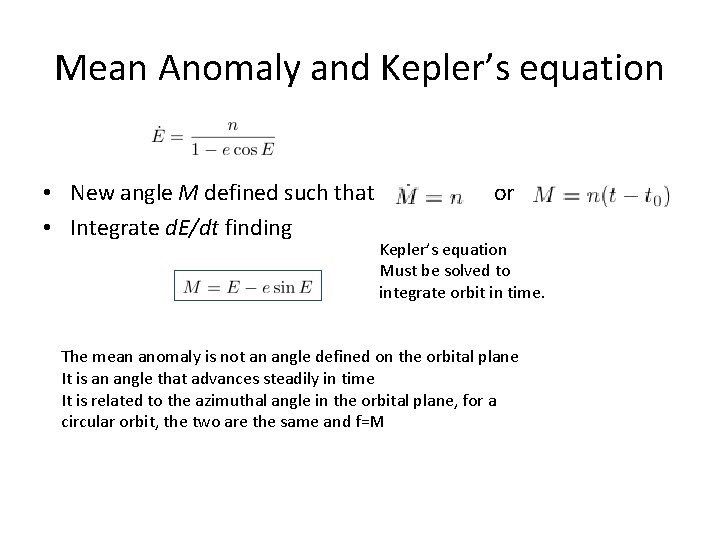

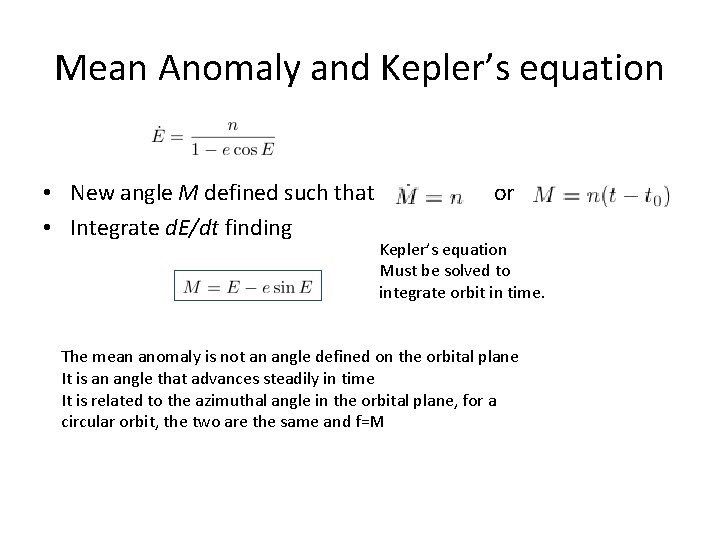

Mean Anomaly and Kepler’s equation • New angle M defined such that • Integrate d. E/dt finding or Kepler’s equation Must be solved to integrate orbit in time. The mean anomaly is not an angle defined on the orbital plane It is an angle that advances steadily in time It is related to the azimuthal angle in the orbital plane, for a circular orbit, the two are the same and f=M

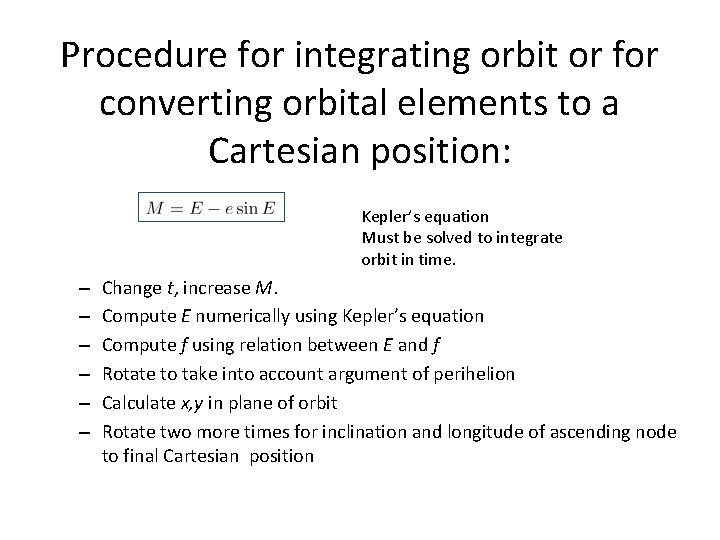

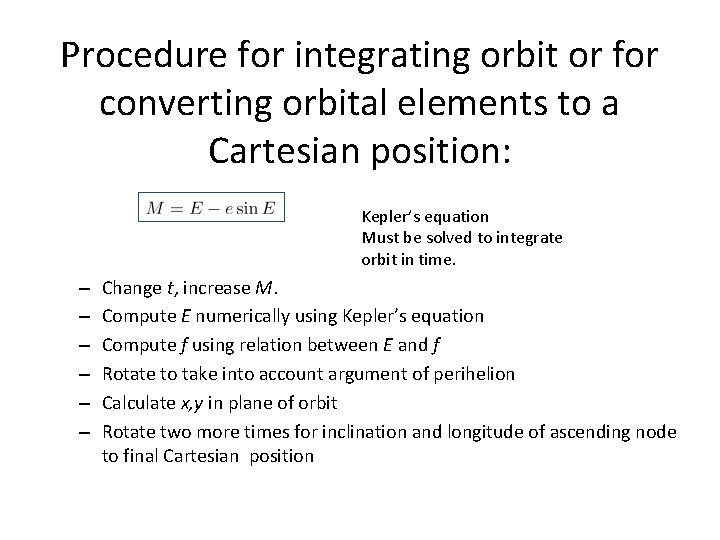

Procedure for integrating orbit or for converting orbital elements to a Cartesian position: Kepler’s equation Must be solved to integrate orbit in time. – – – Change t, increase M. Compute E numerically using Kepler’s equation Compute f using relation between E and f Rotate to take into account argument of perihelion Calculate x, y in plane of orbit Rotate two more times for inclination and longitude of ascending node to final Cartesian position

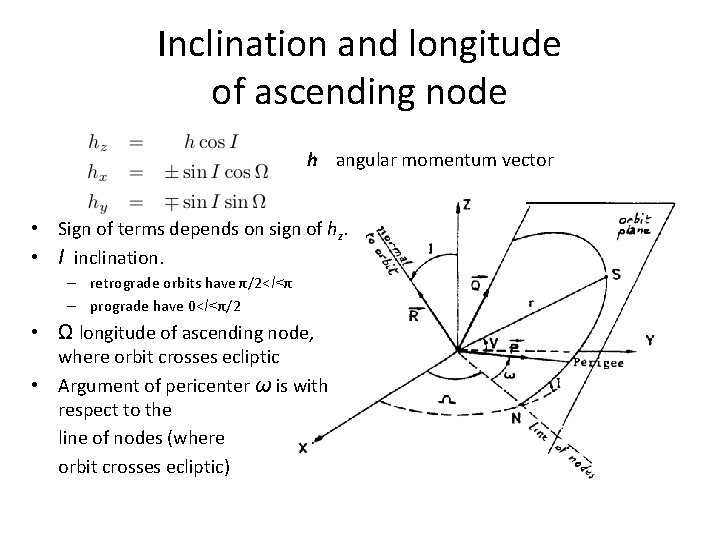

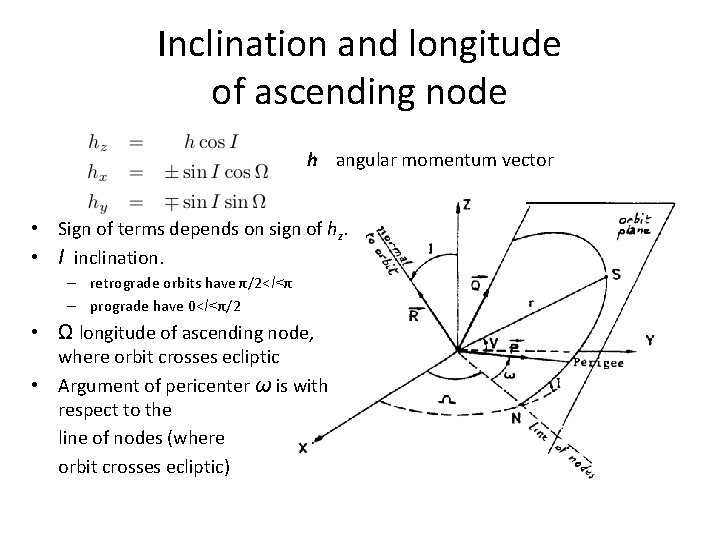

Inclination and longitude of ascending node h angular momentum vector • Sign of terms depends on sign of hz. • I inclination. – retrograde orbits have π/2<I<π – prograde have 0<I<π/2 • Ω longitude of ascending node, where orbit crosses ecliptic • Argument of pericenter ω is with respect to the line of nodes (where orbit crosses ecliptic)

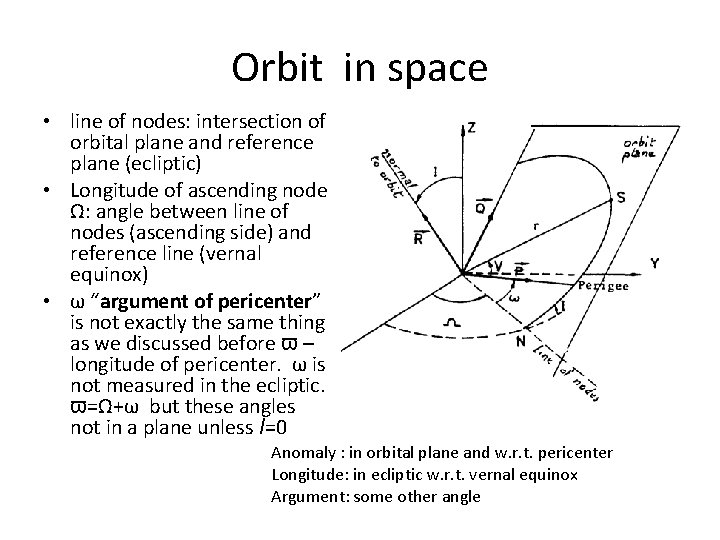

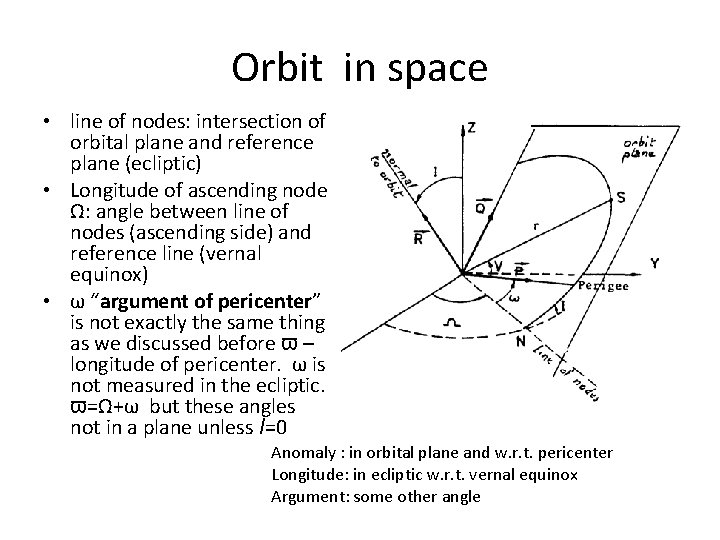

Orbit in space • line of nodes: intersection of orbital plane and reference plane (ecliptic) • Longitude of ascending node Ω: angle between line of nodes (ascending side) and reference line (vernal equinox) • ω “argument of pericenter” is not exactly the same thing as we discussed before ϖ – longitude of pericenter. ω is not measured in the ecliptic. ϖ=Ω+ω but these angles not in a plane unless I=0 Anomaly : in orbital plane and w. r. t. pericenter Longitude: in ecliptic w. r. t. vernal equinox Argument: some other angle

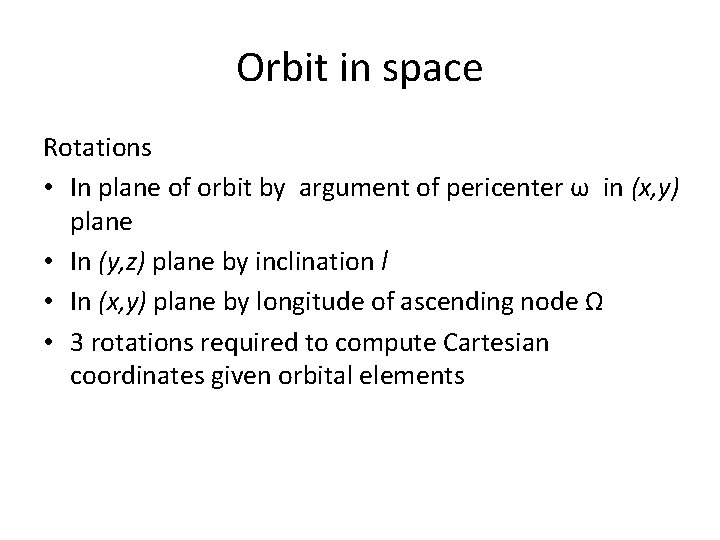

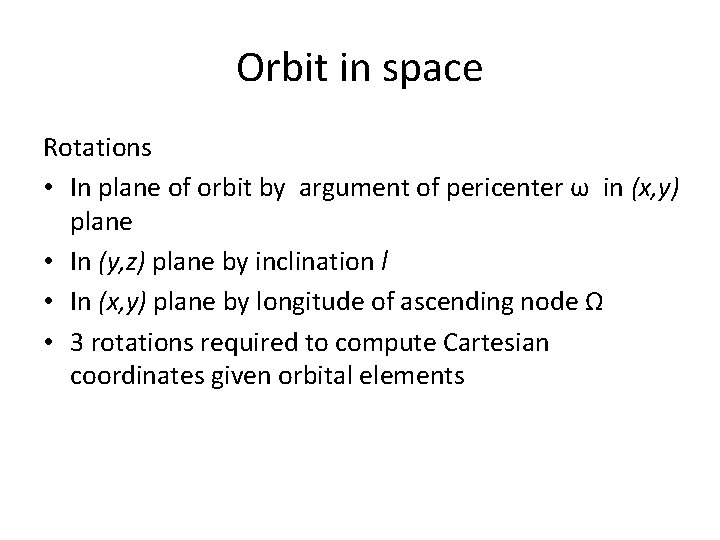

Orbit in space Rotations • In plane of orbit by argument of pericenter ω in (x, y) plane • In (y, z) plane by inclination I • In (x, y) plane by longitude of ascending node Ω • 3 rotations required to compute Cartesian coordinates given orbital elements

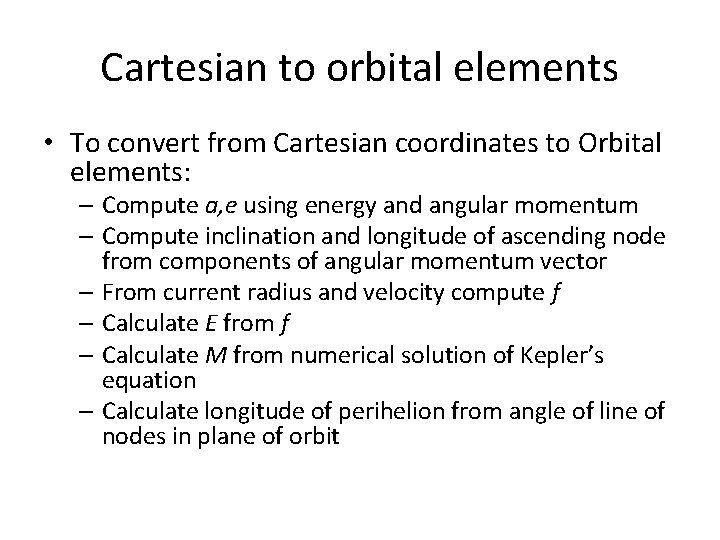

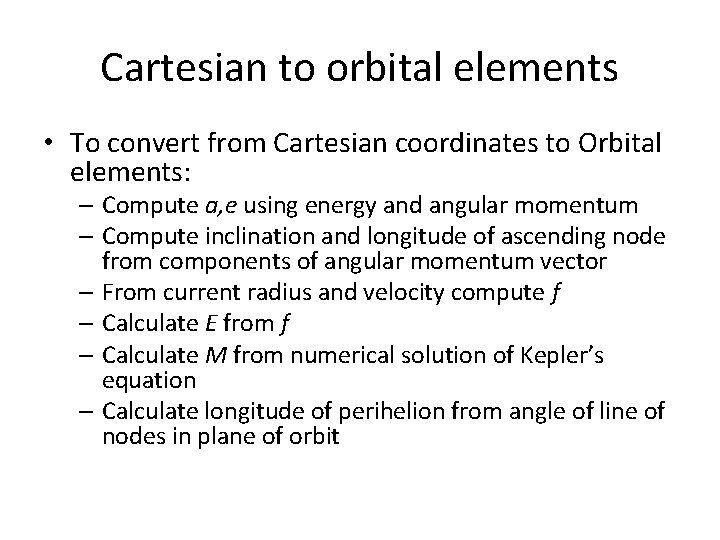

Cartesian to orbital elements • To convert from Cartesian coordinates to Orbital elements: – Compute a, e using energy and angular momentum – Compute inclination and longitude of ascending node from components of angular momentum vector – From current radius and velocity compute f – Calculate E from f – Calculate M from numerical solution of Kepler’s equation – Calculate longitude of perihelion from angle of line of nodes in plane of orbit

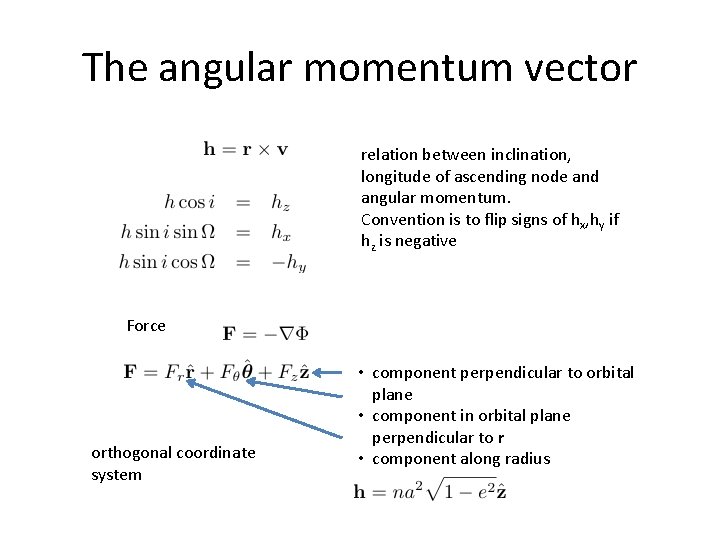

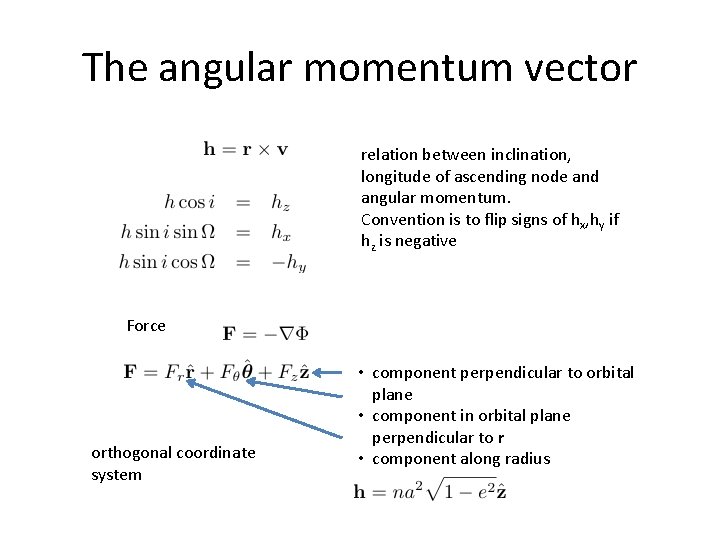

The angular momentum vector relation between inclination, longitude of ascending node and angular momentum. Convention is to flip signs of hx, hy if hz is negative Force orthogonal coordinate system • component perpendicular to orbital plane • component in orbital plane perpendicular to r • component along radius

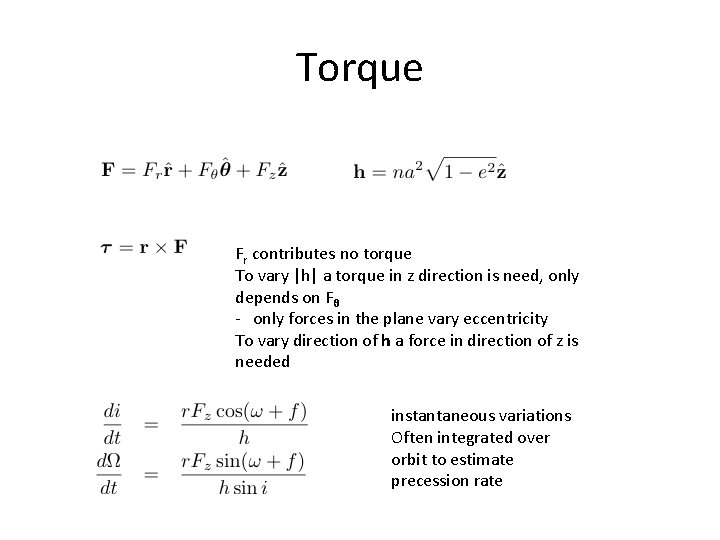

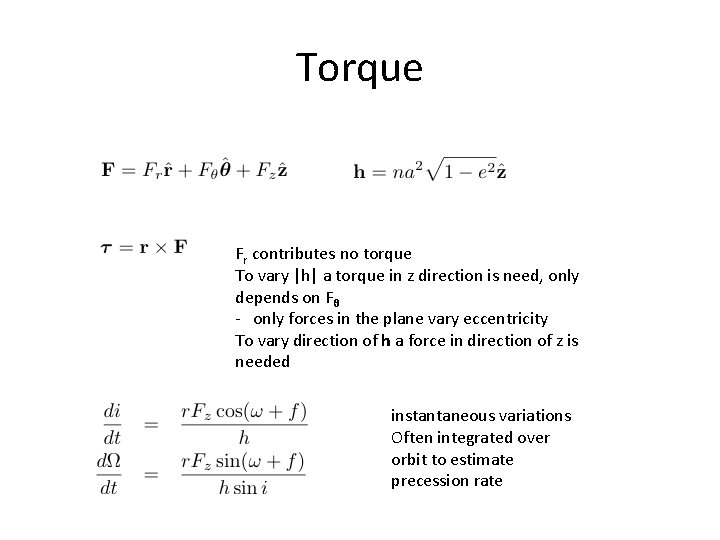

Torque Fr contributes no torque To vary |h| a torque in z direction is need, only depends on Fθ - only forces in the plane vary eccentricity To vary direction of h a force in direction of z is needed instantaneous variations Often integrated over orbit to estimate precession rate

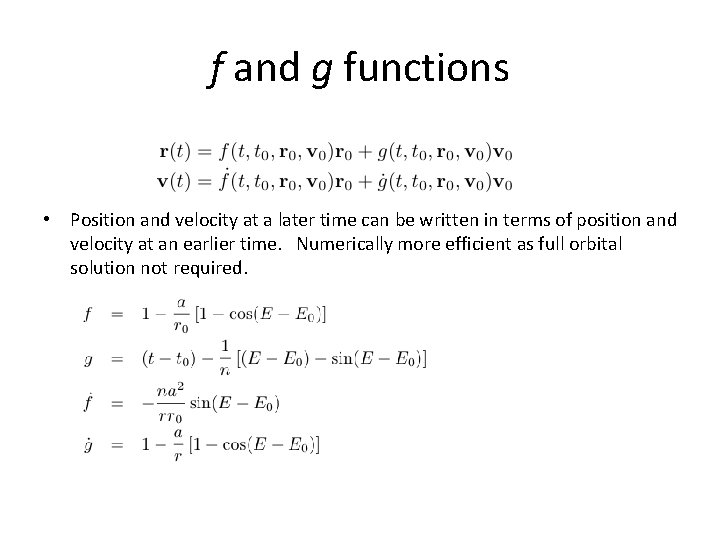

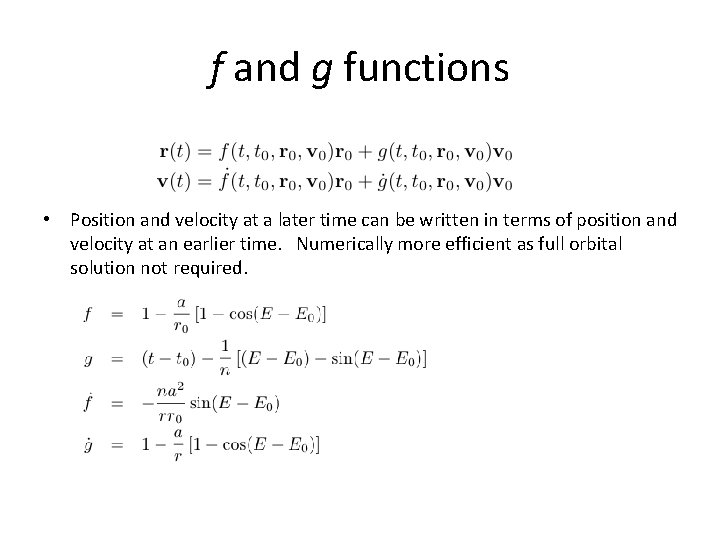

f and g functions • Position and velocity at a later time can be written in terms of position and velocity at an earlier time. Numerically more efficient as full orbital solution not required.

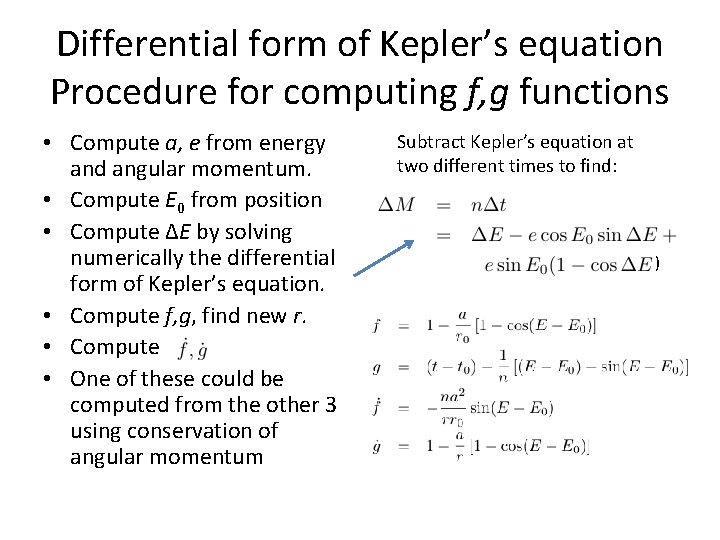

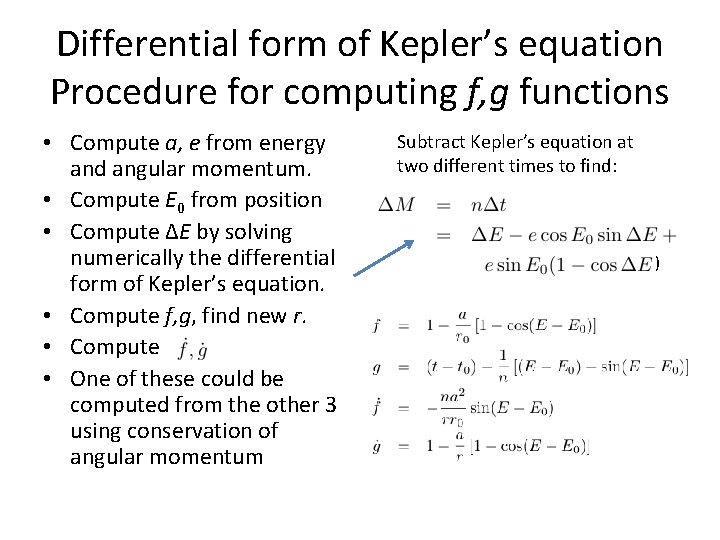

Differential form of Kepler’s equation Procedure for computing f, g functions • Compute a, e from energy and angular momentum. • Compute E 0 from position • Compute ΔE by solving numerically the differential form of Kepler’s equation. • Compute f, g, find new r. • Compute • One of these could be computed from the other 3 using conservation of angular momentum Subtract Kepler’s equation at two different times to find: )

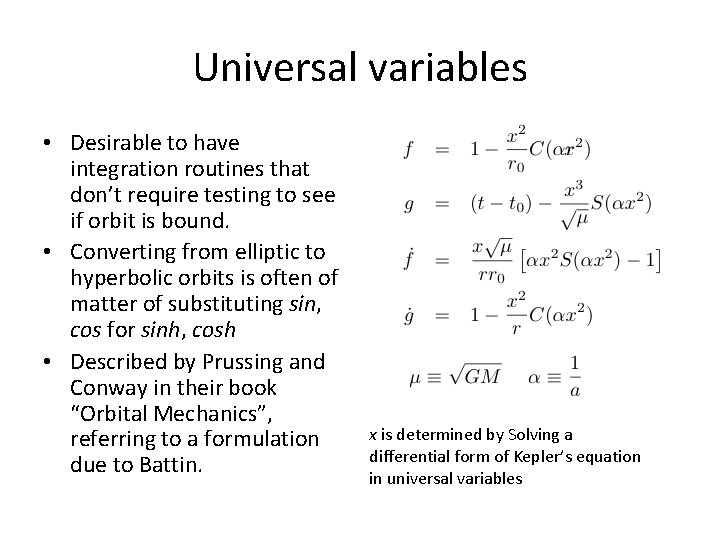

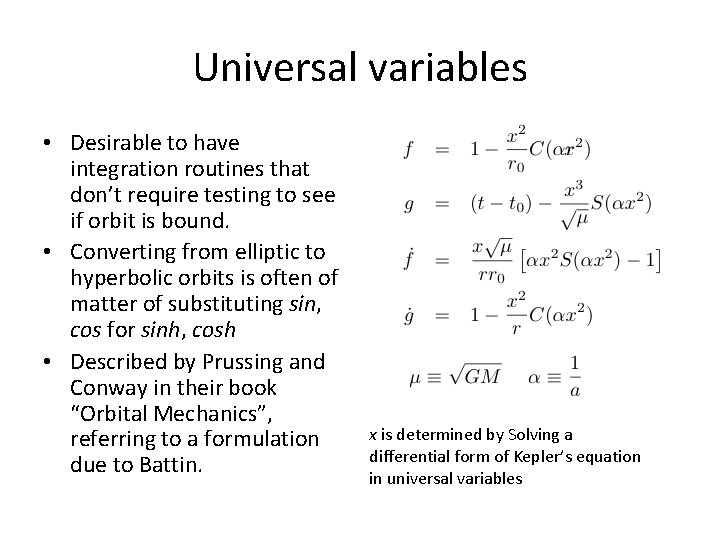

Universal variables • Desirable to have integration routines that don’t require testing to see if orbit is bound. • Converting from elliptic to hyperbolic orbits is often of matter of substituting sin, cos for sinh, cosh • Described by Prussing and Conway in their book “Orbital Mechanics”, referring to a formulation due to Battin. x is determined by Solving a differential form of Kepler’s equation in universal variables

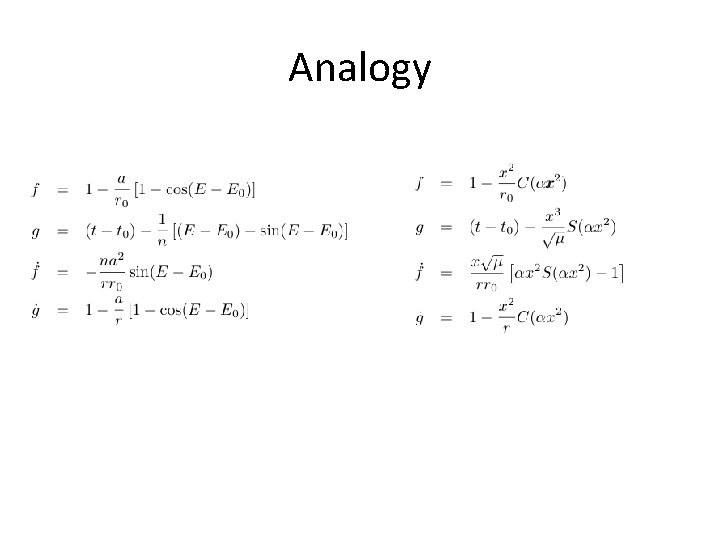

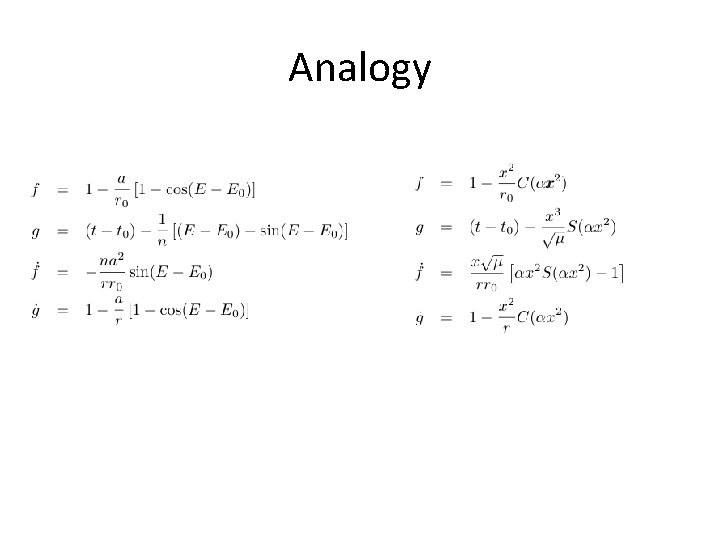

Analogy

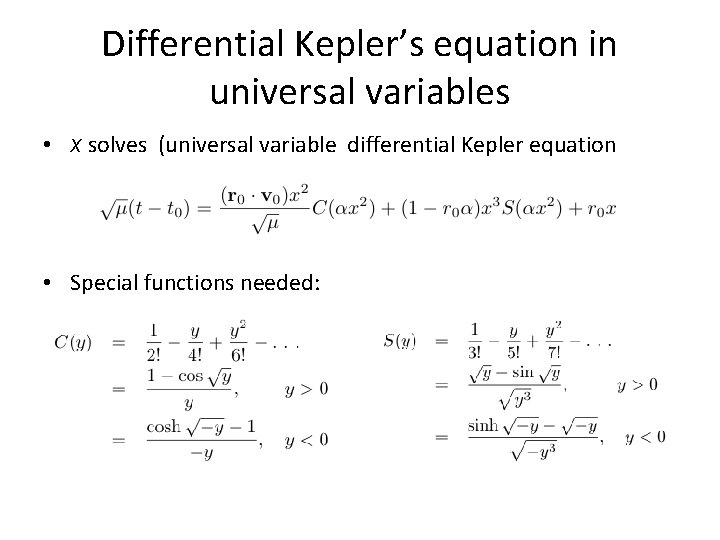

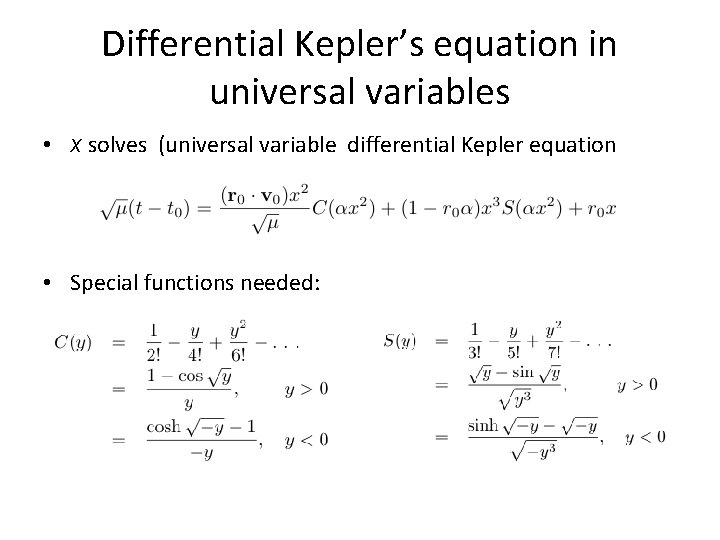

Differential Kepler’s equation in universal variables • x solves (universal variable differential Kepler equation • Special functions needed:

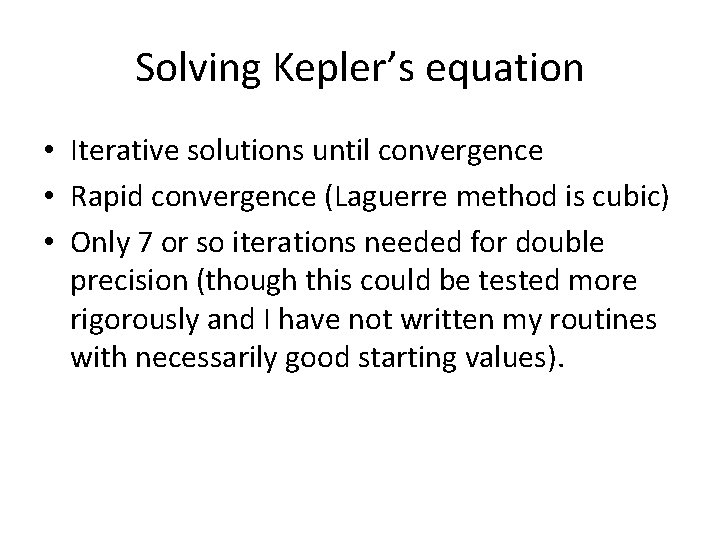

Solving Kepler’s equation • Iterative solutions until convergence • Rapid convergence (Laguerre method is cubic) • Only 7 or so iterations needed for double precision (though this could be tested more rigorously and I have not written my routines with necessarily good starting values).

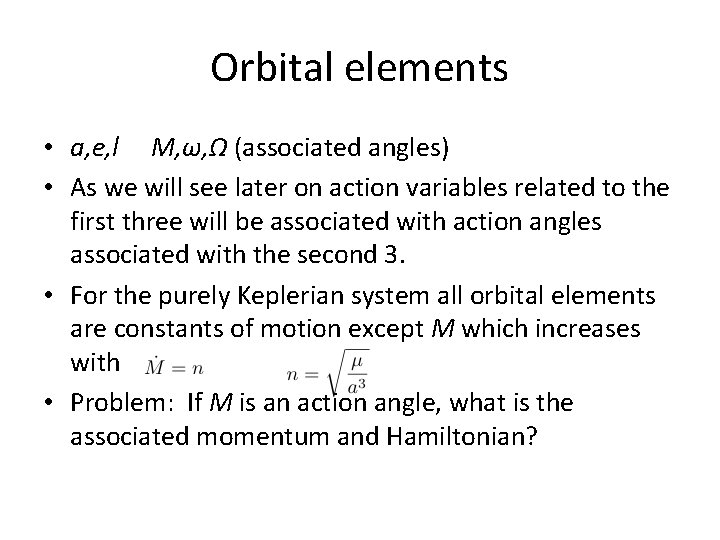

Orbital elements • a, e, I M, ω, Ω (associated angles) • As we will see later on action variables related to the first three will be associated with action angles associated with the second 3. • For the purely Keplerian system all orbital elements are constants of motion except M which increases with • Problem: If M is an action angle, what is the associated momentum and Hamiltonian?

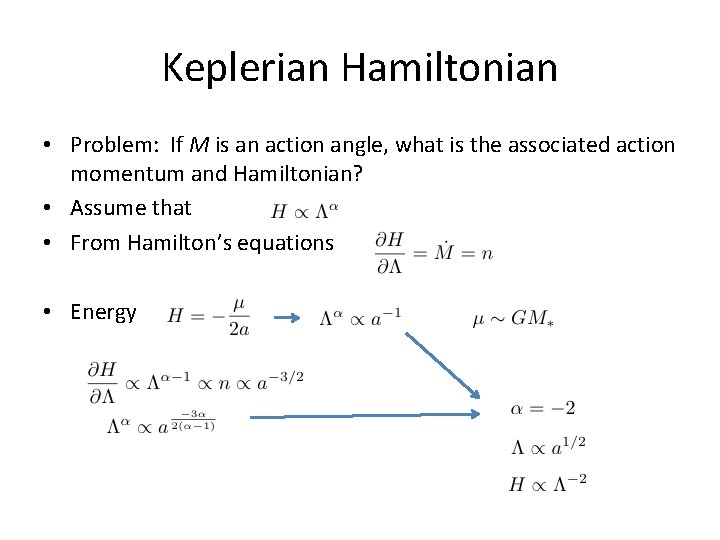

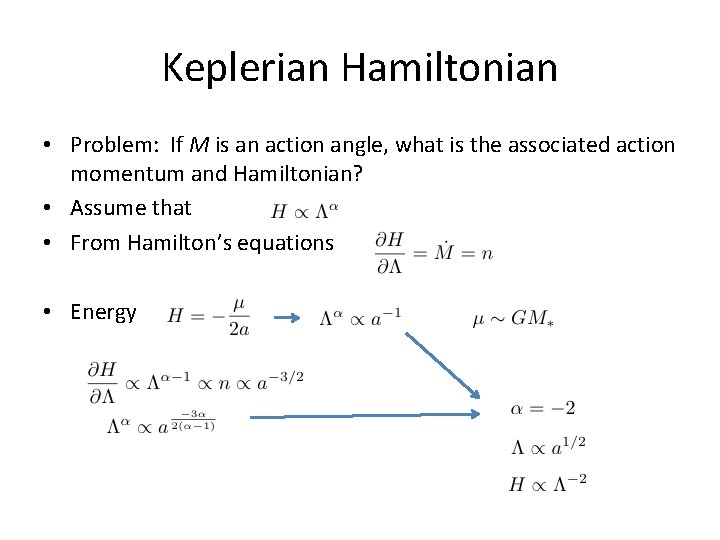

Keplerian Hamiltonian • Problem: If M is an action angle, what is the associated action momentum and Hamiltonian? • Assume that • From Hamilton’s equations • Energy

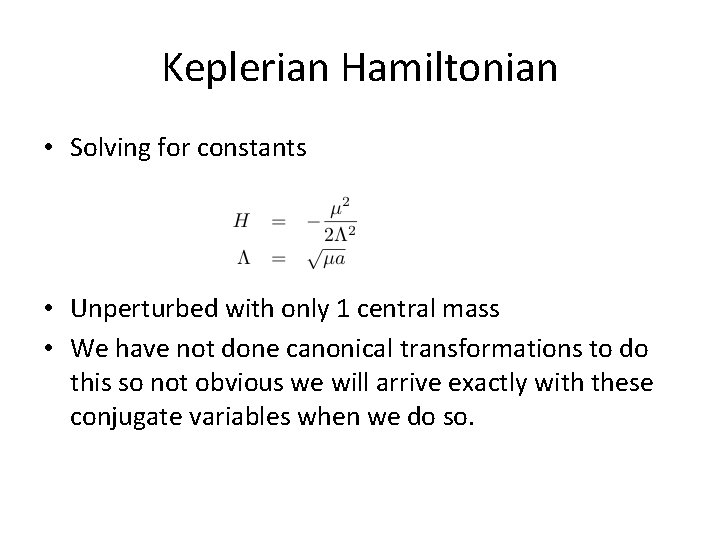

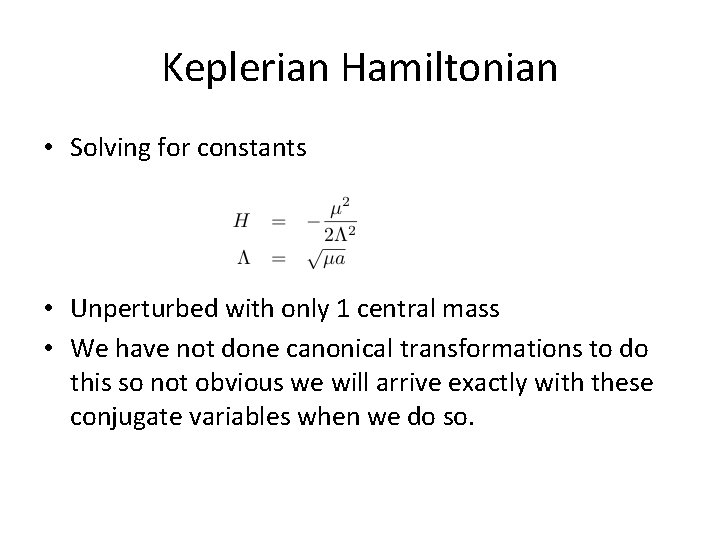

Keplerian Hamiltonian • Solving for constants • Unperturbed with only 1 central mass • We have not done canonical transformations to do this so not obvious we will arrive exactly with these conjugate variables when we do so.

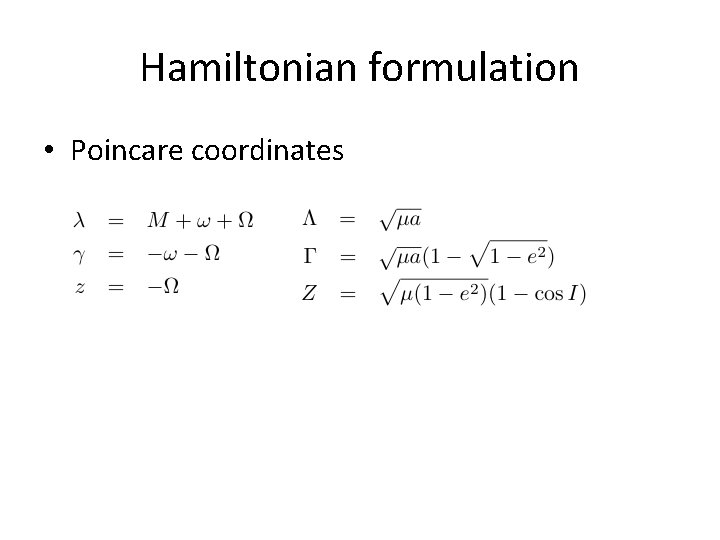

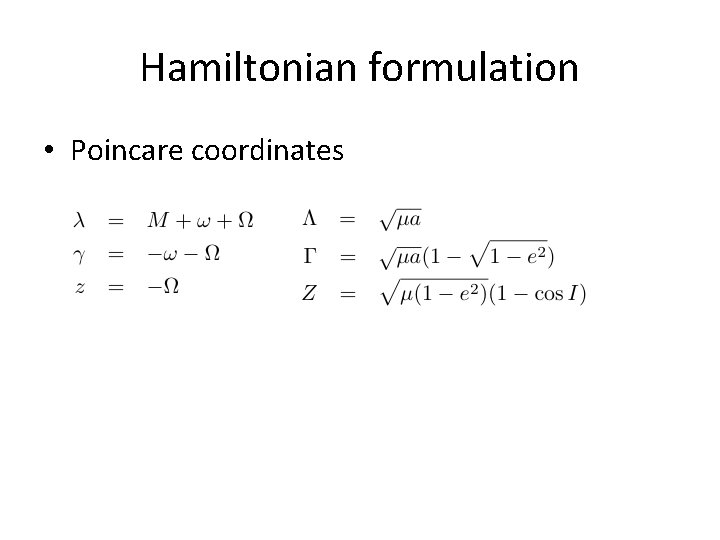

Hamiltonian formulation • Poincare coordinates

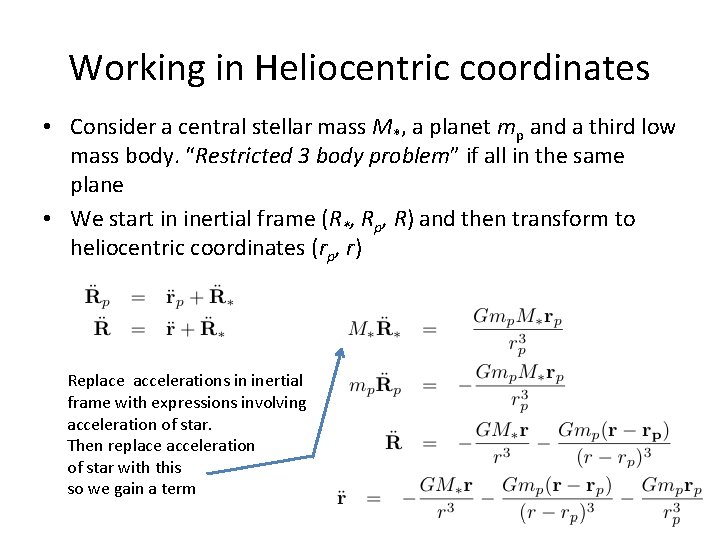

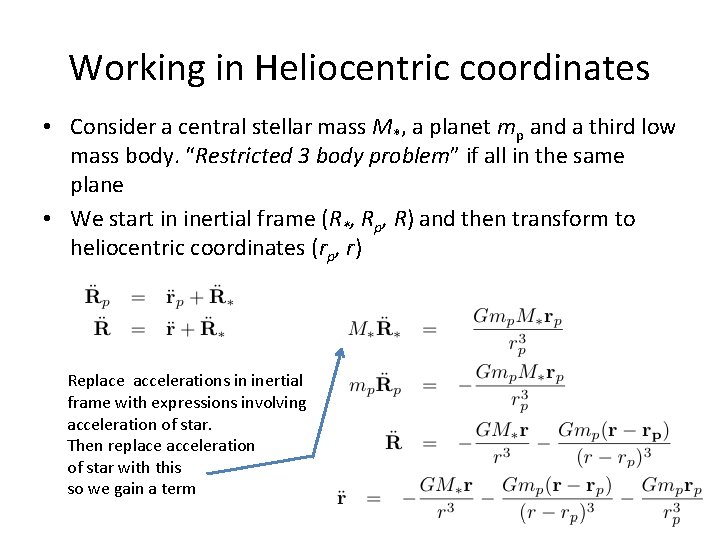

Working in Heliocentric coordinates • Consider a central stellar mass M*, a planet mp and a third low mass body. “Restricted 3 body problem” if all in the same plane • We start in inertial frame (R*, Rp, R) and then transform to heliocentric coordinates (rp, r) Replace accelerations in inertial frame with expressions involving acceleration of star. Then replace acceleration of star with this so we gain a term

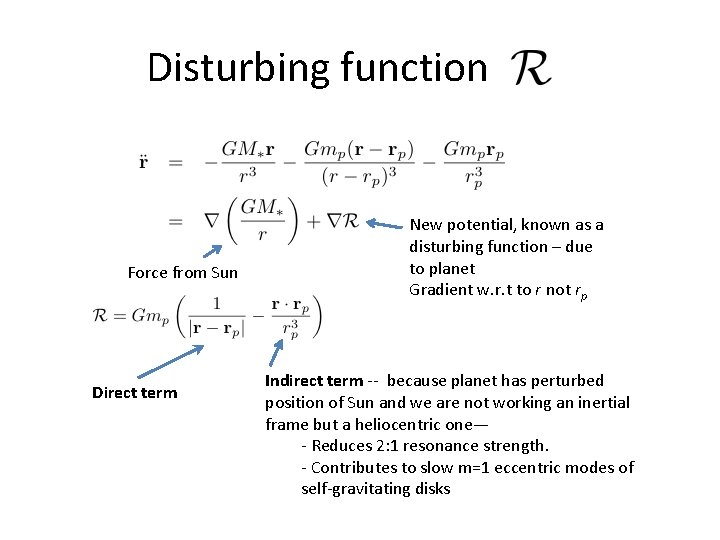

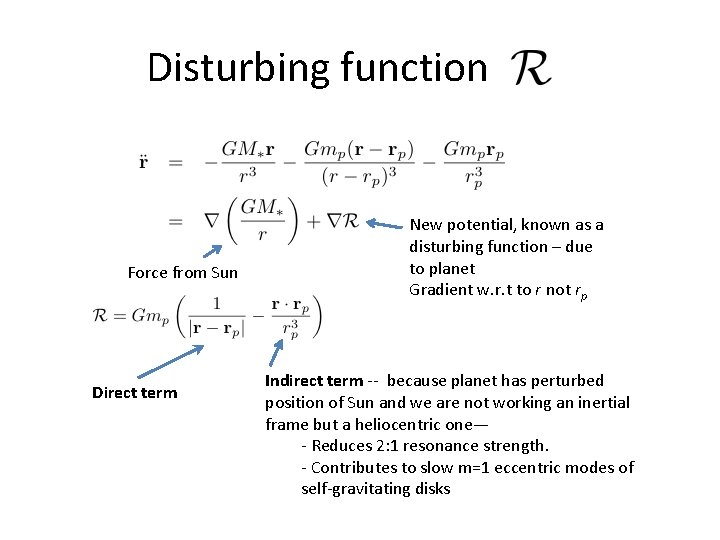

Disturbing function Force from Sun Direct term New potential, known as a disturbing function – due to planet Gradient w. r. t to r not rp Indirect term -- because planet has perturbed position of Sun and we are not working an inertial frame but a heliocentric one— - Reduces 2: 1 resonance strength. - Contributes to slow m=1 eccentric modes of self-gravitating disks

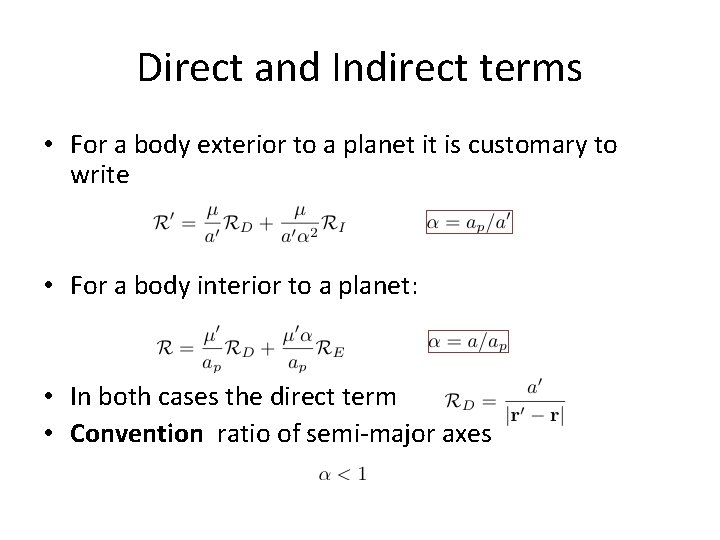

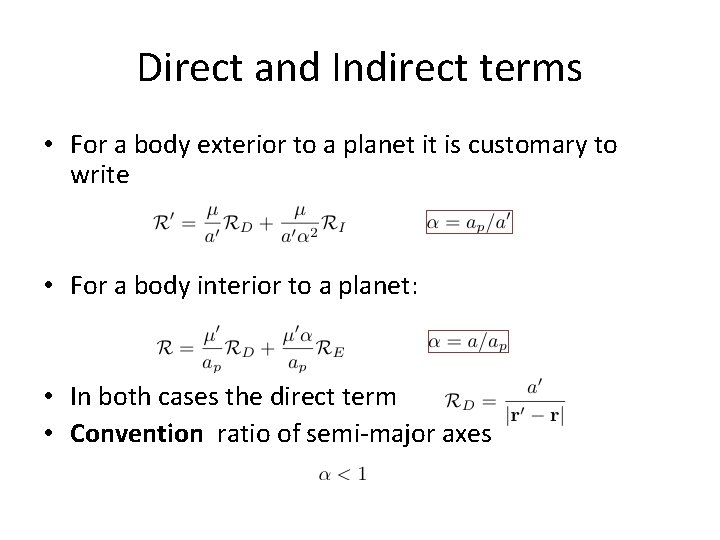

Direct and Indirect terms • For a body exterior to a planet it is customary to write • For a body interior to a planet: • In both cases the direct term • Convention ratio of semi-major axes

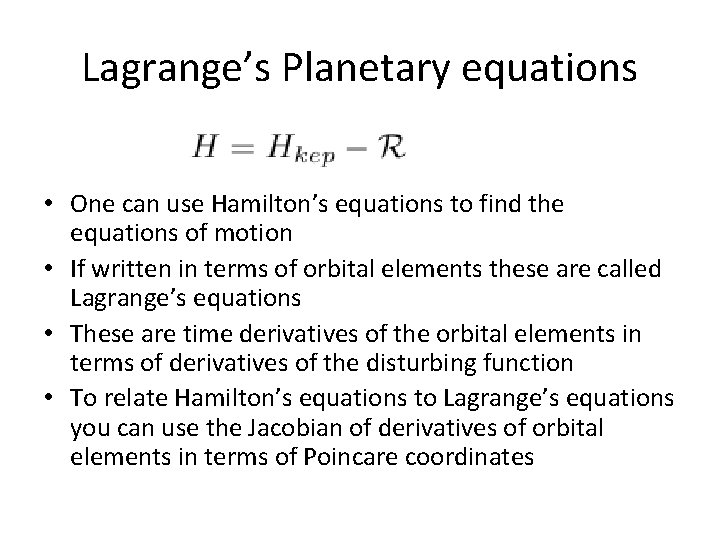

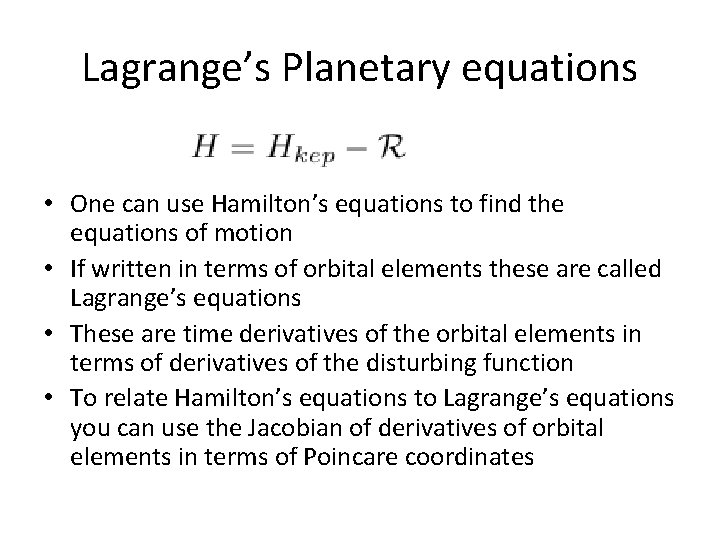

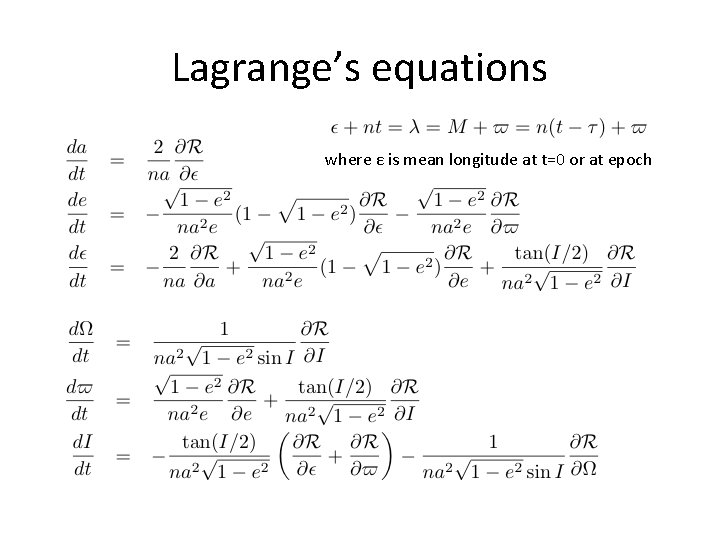

Lagrange’s Planetary equations • One can use Hamilton’s equations to find the equations of motion • If written in terms of orbital elements these are called Lagrange’s equations • These are time derivatives of the orbital elements in terms of derivatives of the disturbing function • To relate Hamilton’s equations to Lagrange’s equations you can use the Jacobian of derivatives of orbital elements in terms of Poincare coordinates

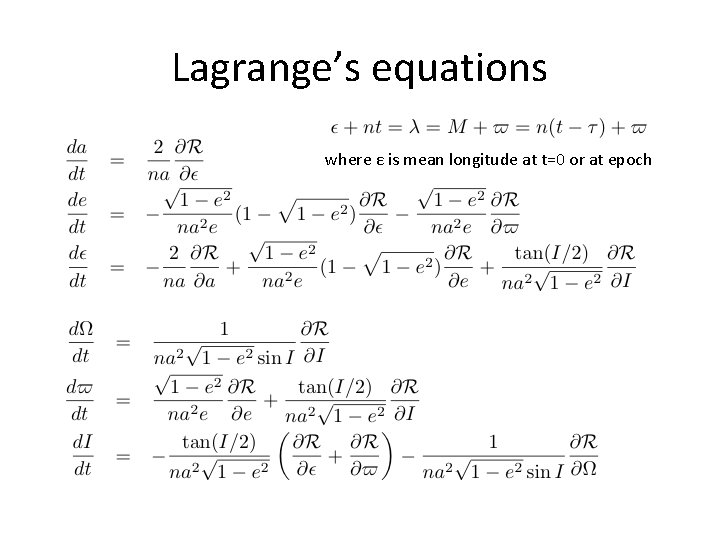

Lagrange’s equations where ε is mean longitude at t=0 or at epoch

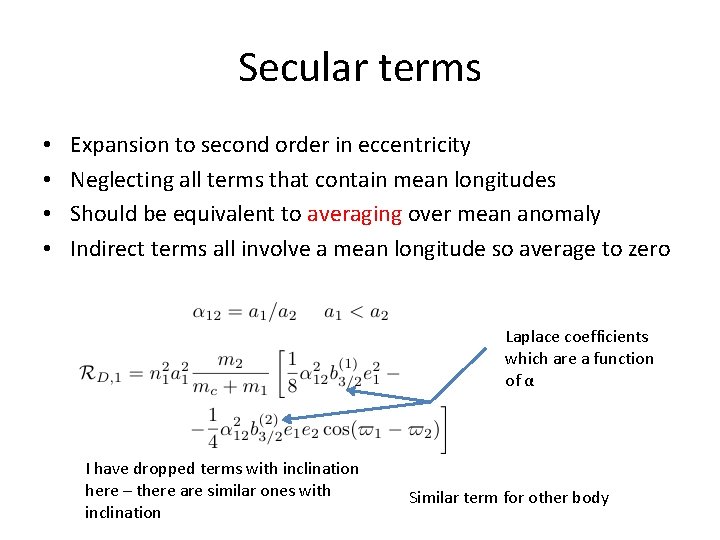

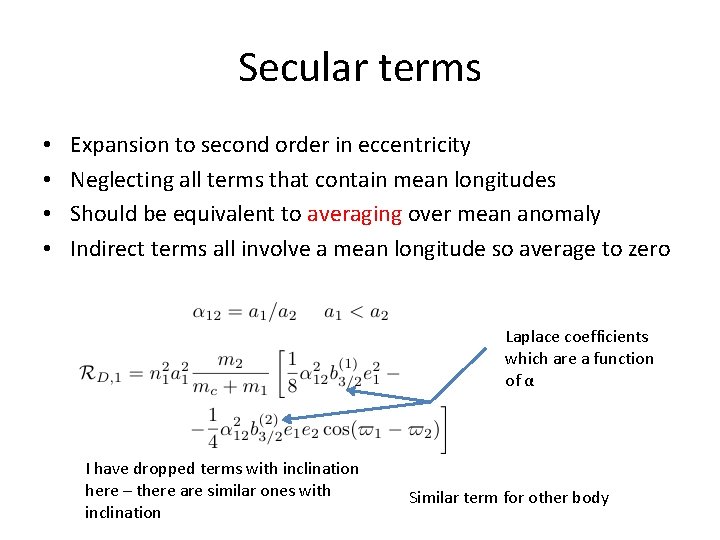

Secular terms • • Expansion to second order in eccentricity Neglecting all terms that contain mean longitudes Should be equivalent to averaging over mean anomaly Indirect terms all involve a mean longitude so average to zero Laplace coefficients which are a function of α I have dropped terms with inclination here – there are similar ones with inclination Similar term for other body

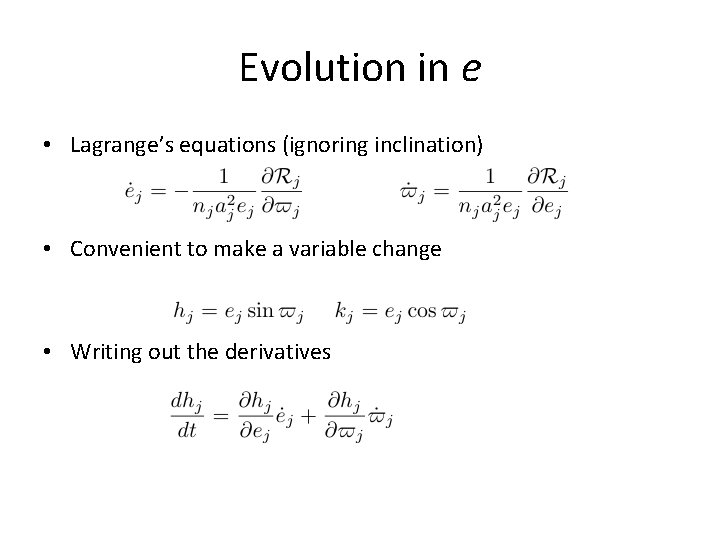

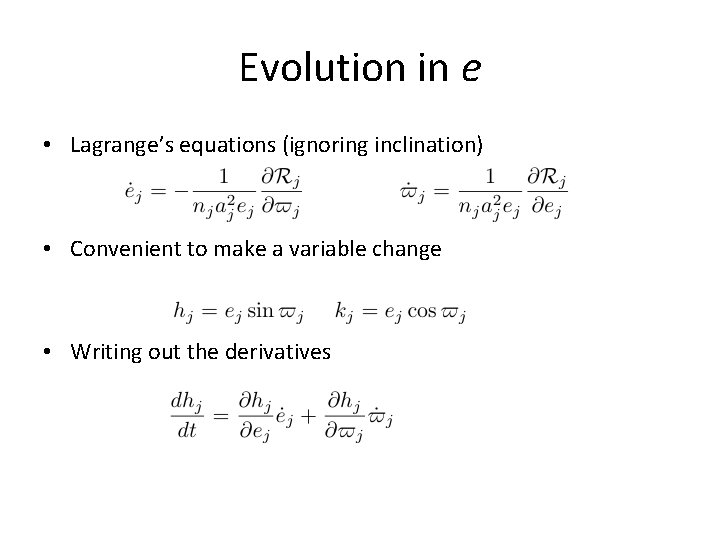

Evolution in e • Lagrange’s equations (ignoring inclination) • Convenient to make a variable change • Writing out the derivatives

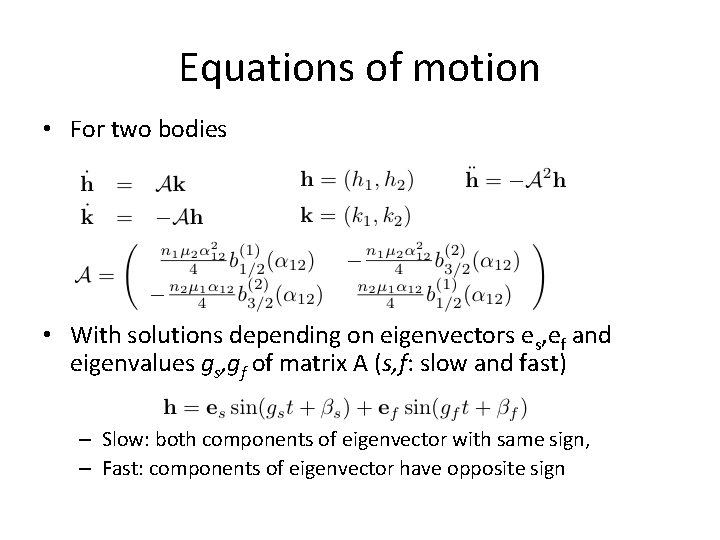

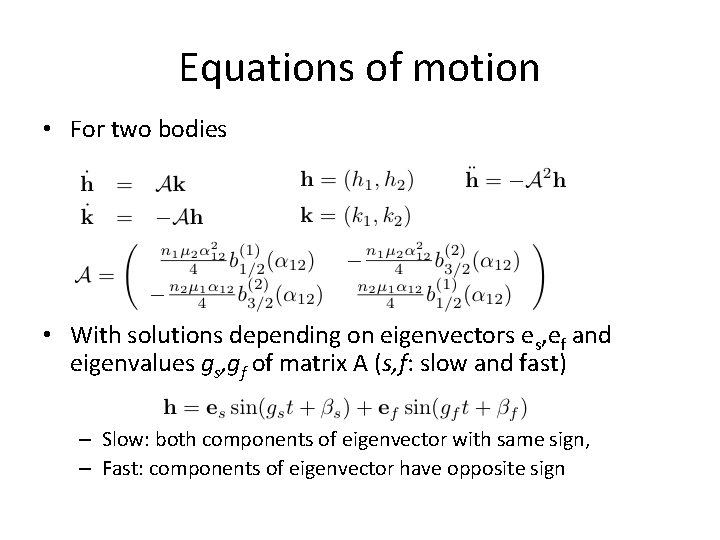

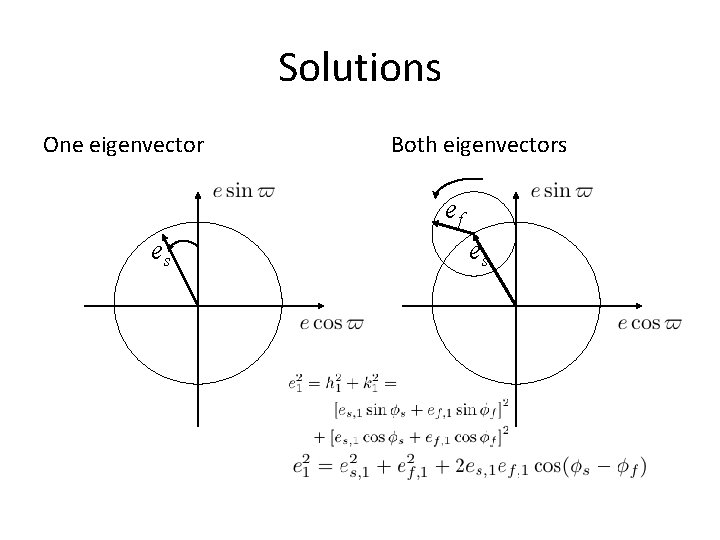

Equations of motion • For two bodies • With solutions depending on eigenvectors es, ef and eigenvalues gs, gf of matrix A (s, f: slow and fast) – Slow: both components of eigenvector with same sign, – Fast: components of eigenvector have opposite sign

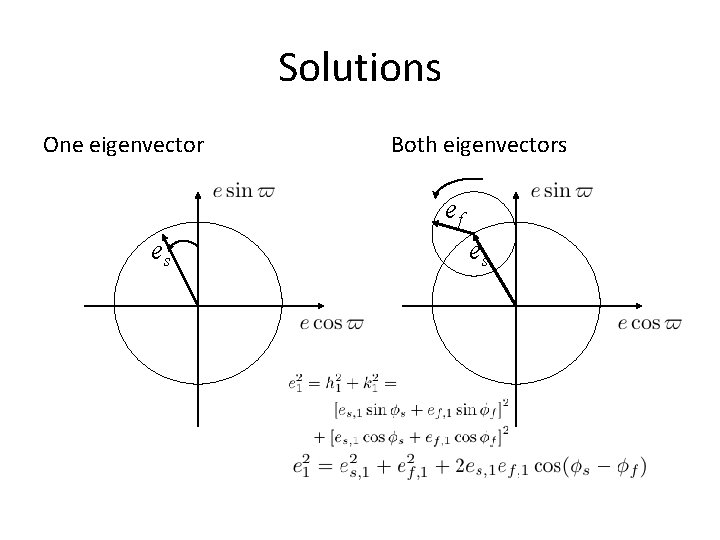

Solutions One eigenvector Both eigenvectors ef es es

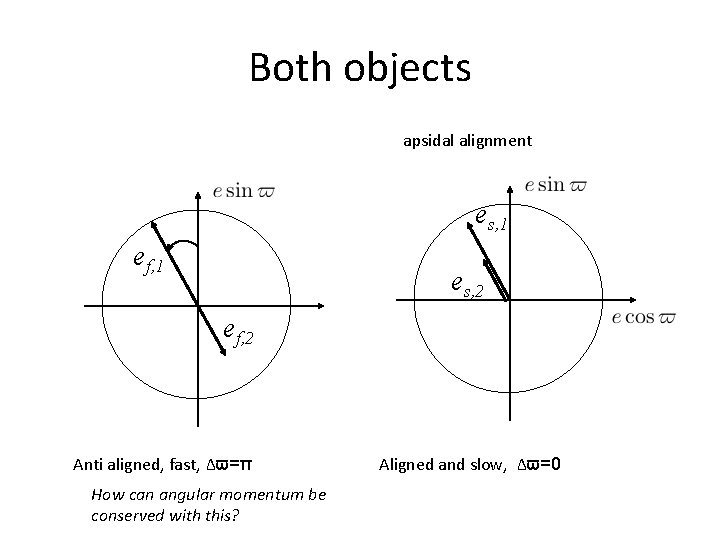

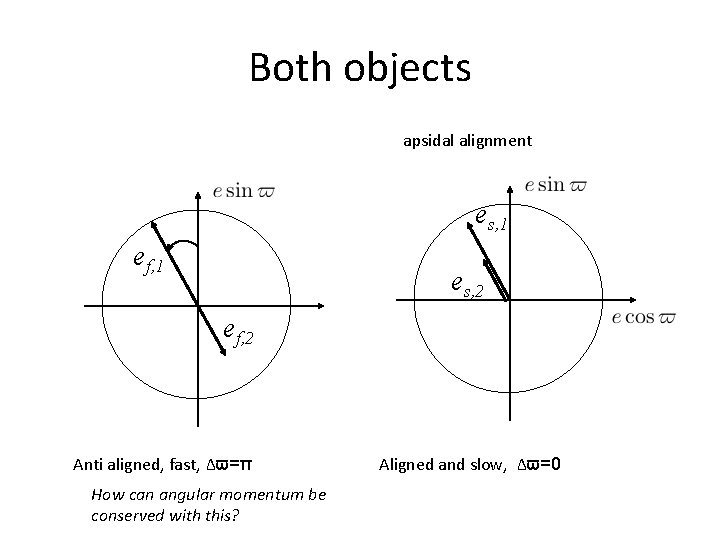

Both objects apsidal alignment es, 1 ef, 1 es, 2 ef, 2 Anti aligned, fast, Δϖ=π How can angular momentum be conserved with this? Aligned and slow, Δϖ=0

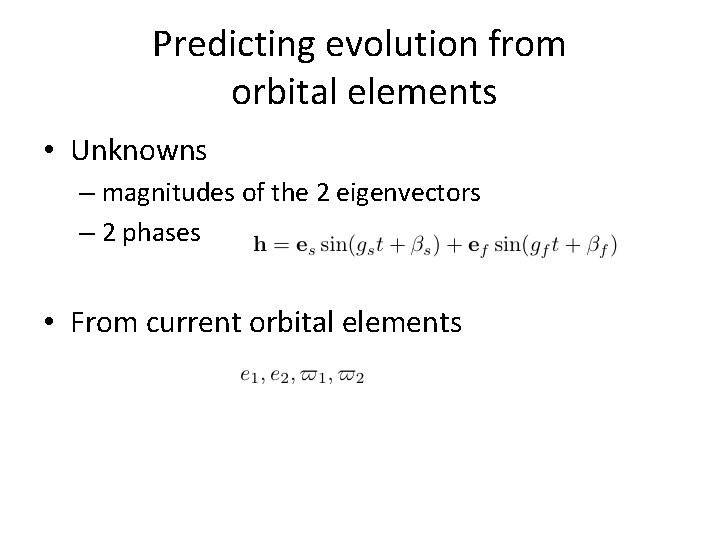

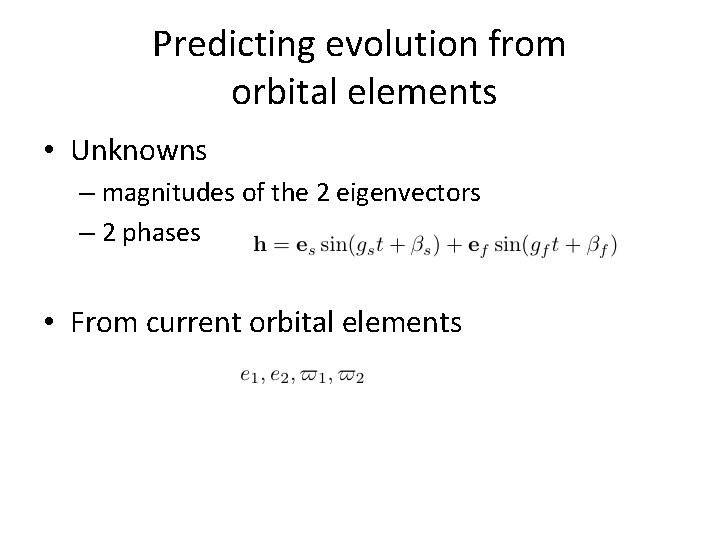

Predicting evolution from orbital elements • Unknowns – magnitudes of the 2 eigenvectors – 2 phases • From current orbital elements

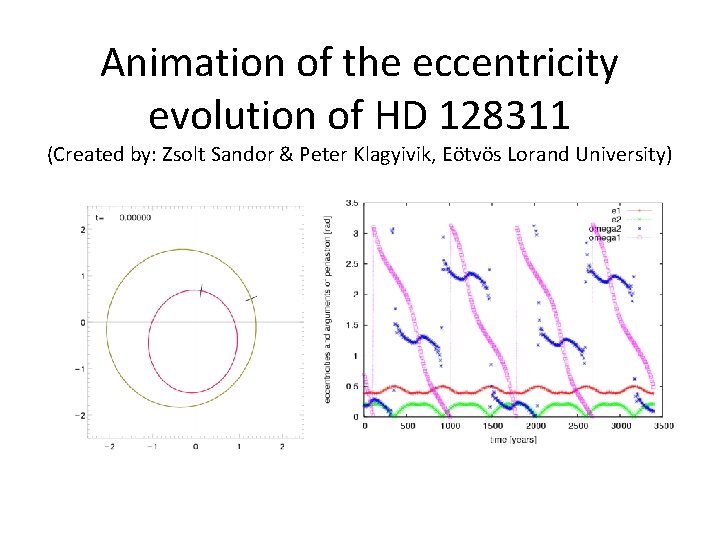

Animation of the eccentricity evolution of HD 128311 (Created by: Zsolt Sandor & Peter Klagyivik, Eötvös Lorand University)

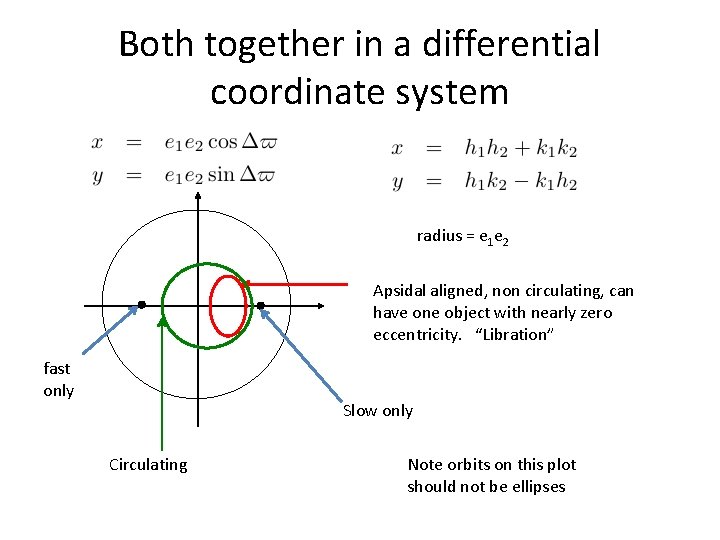

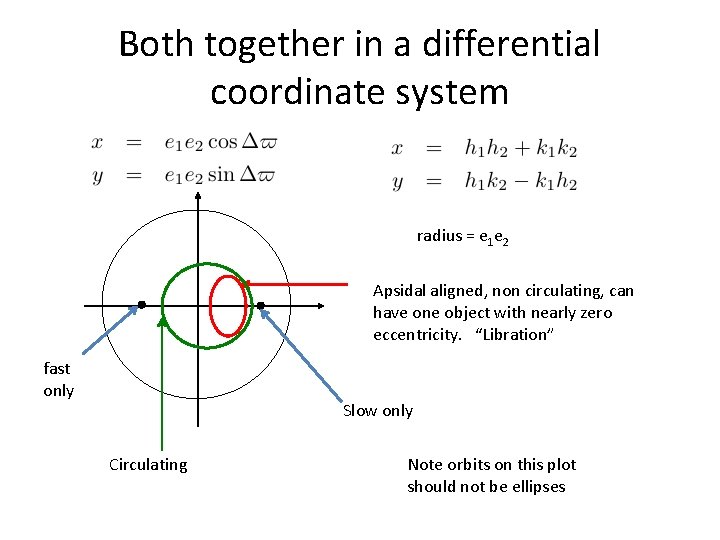

Both together in a differential coordinate system radius = e 1 e 2 Apsidal aligned, non circulating, can have one object with nearly zero eccentricity. “Libration” fast only Slow only Circulating Note orbits on this plot should not be ellipses

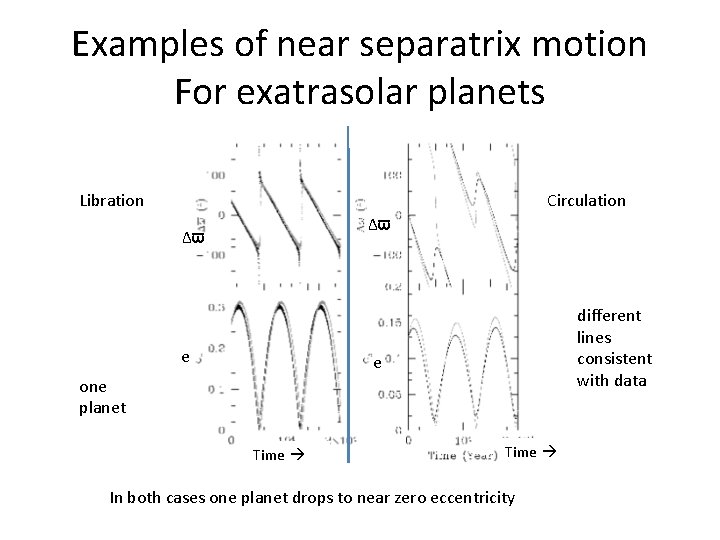

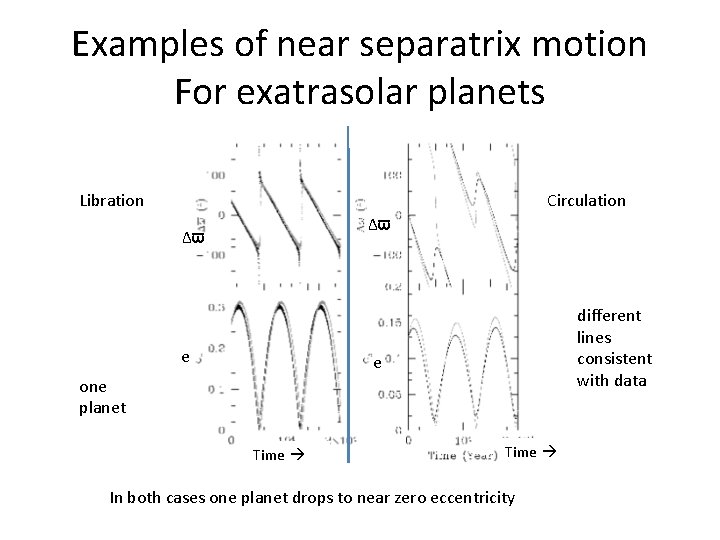

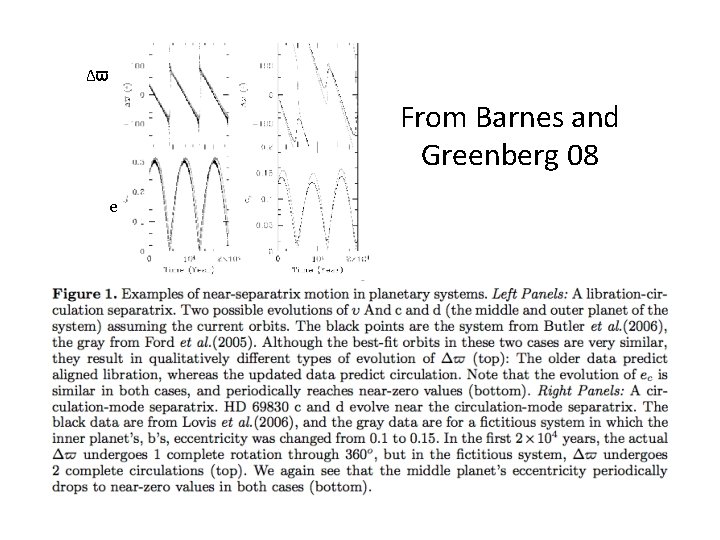

Examples of near separatrix motion For exatrasolar planets Libration Circulation Δϖ Δϖ e different lines consistent with data e one planet Time In both cases one planet drops to near zero eccentricity

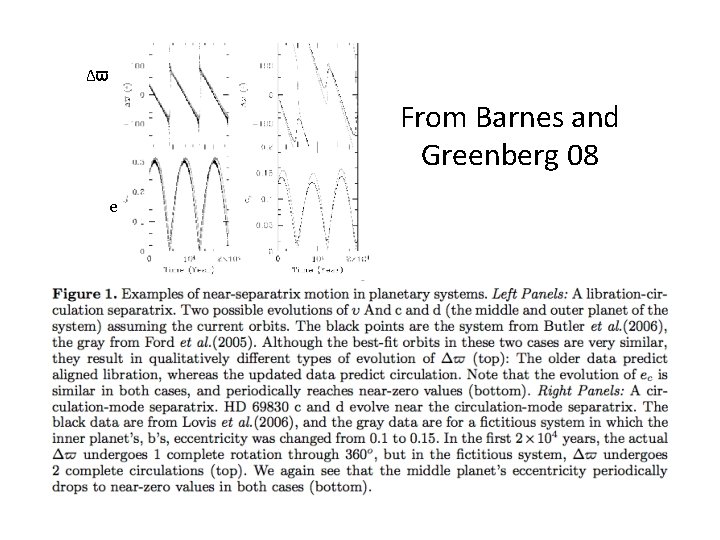

Δϖ From Barnes and Greenberg 08 e

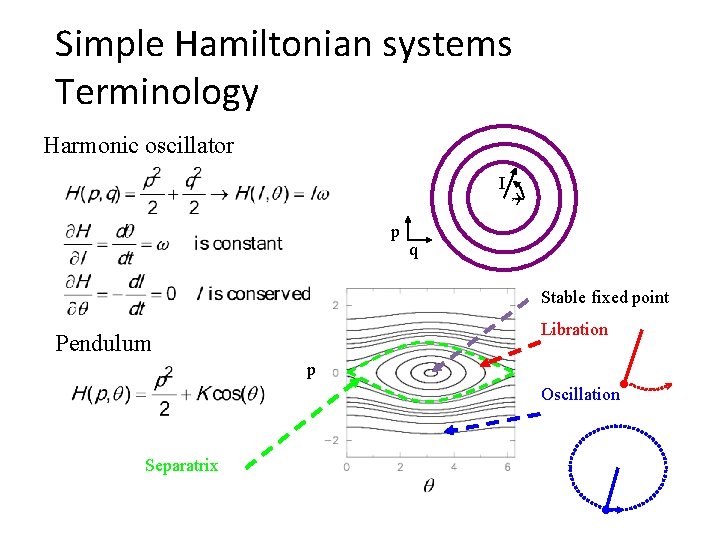

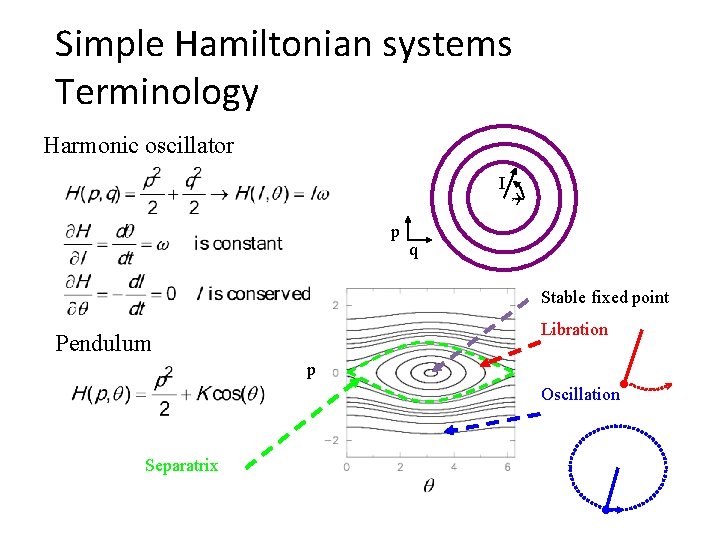

Simple Hamiltonian systems Terminology Harmonic oscillator I p q Stable fixed point Libration Pendulum p Oscillation Separatrix

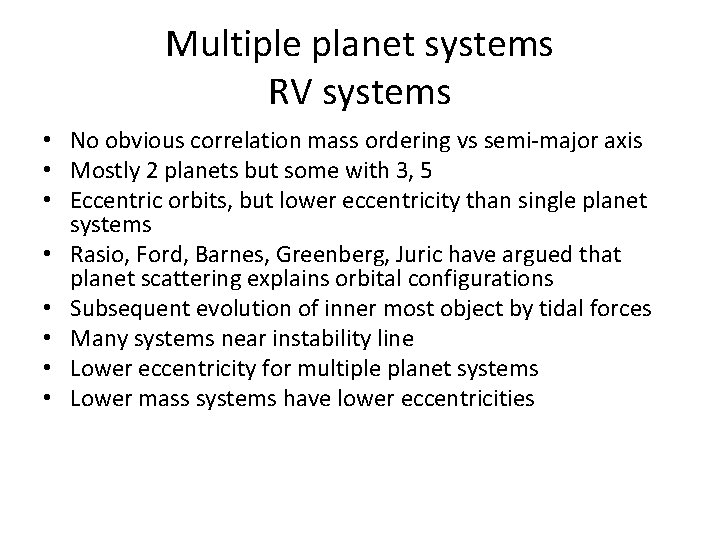

Multiple planet systems RV systems • No obvious correlation mass ordering vs semi-major axis • Mostly 2 planets but some with 3, 5 • Eccentric orbits, but lower eccentricity than single planet systems • Rasio, Ford, Barnes, Greenberg, Juric have argued that planet scattering explains orbital configurations • Subsequent evolution of inner most object by tidal forces • Many systems near instability line • Lower eccentricity for multiple planet systems • Lower mass systems have lower eccentricities

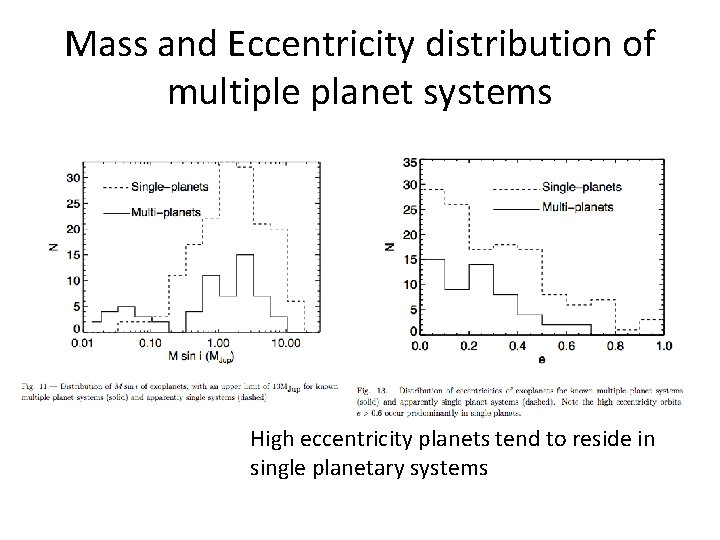

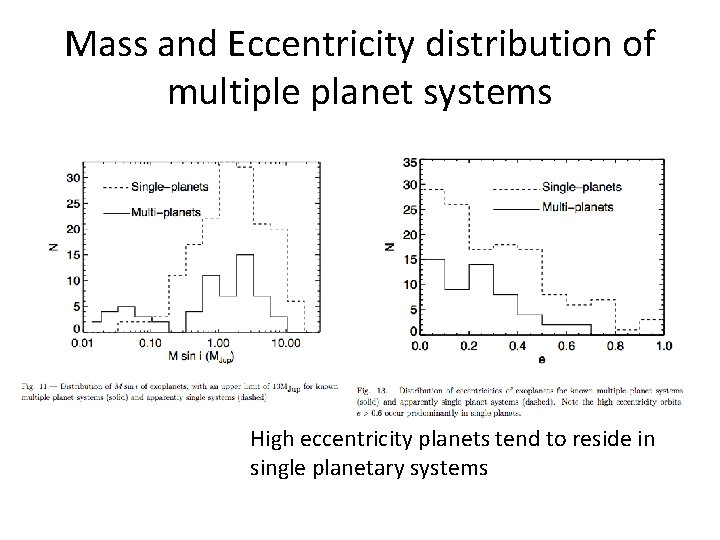

Mass and Eccentricity distribution of multiple planet systems High eccentricity planets tend to reside in single planetary systems

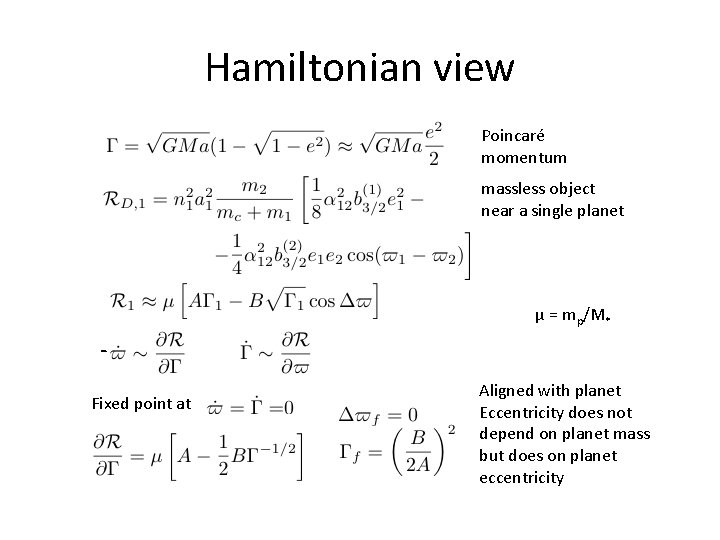

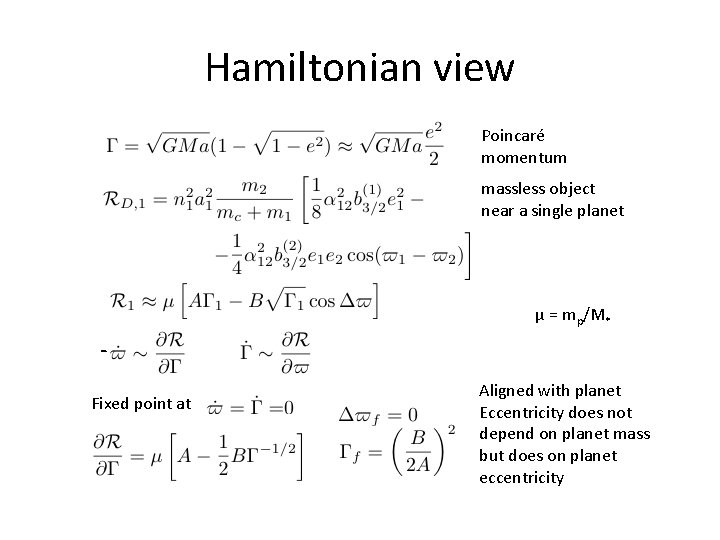

Hamiltonian view Poincaré momentum massless object near a single planet μ = mp/M* Fixed point at Aligned with planet Eccentricity does not depend on planet mass but does on planet eccentricity

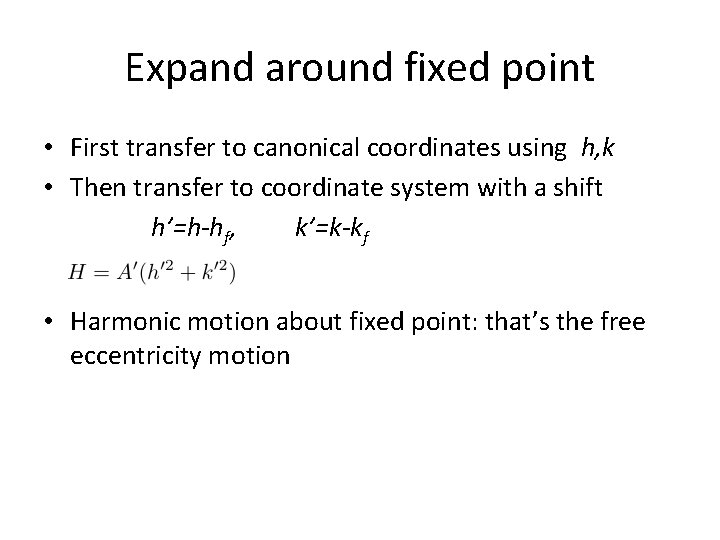

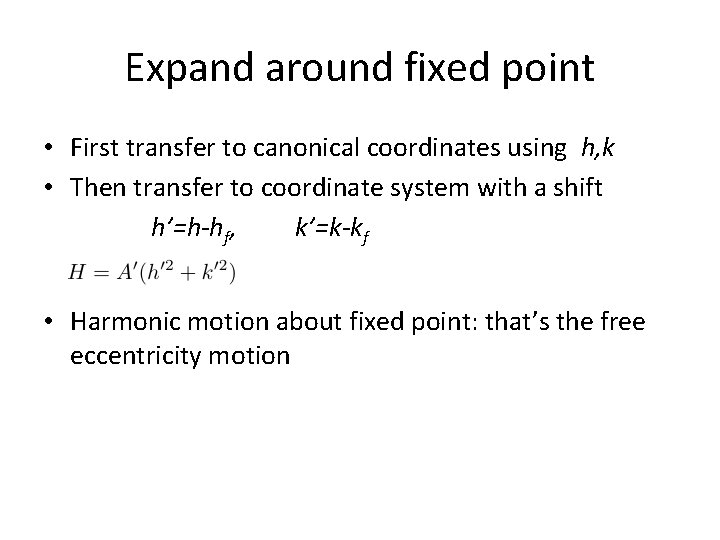

Expand around fixed point • First transfer to canonical coordinates using h, k • Then transfer to coordinate system with a shift h’=h-hf, k’=k-kf • Harmonic motion about fixed point: that’s the free eccentricity motion

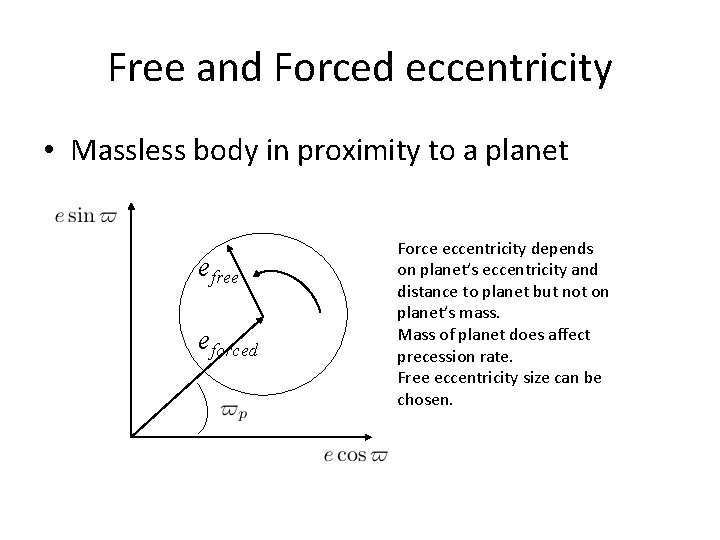

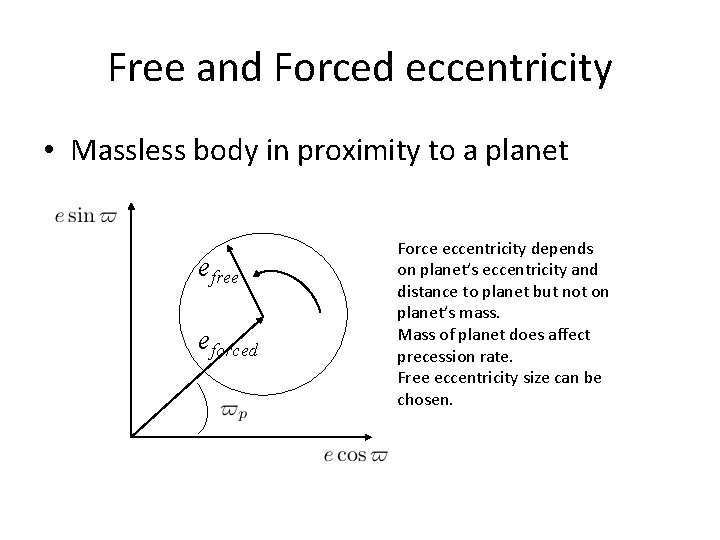

Free and Forced eccentricity • Massless body in proximity to a planet efree eforced Force eccentricity depends on planet’s eccentricity and distance to planet but not on planet’s mass. Mass of planet does affect precession rate. Free eccentricity size can be chosen.

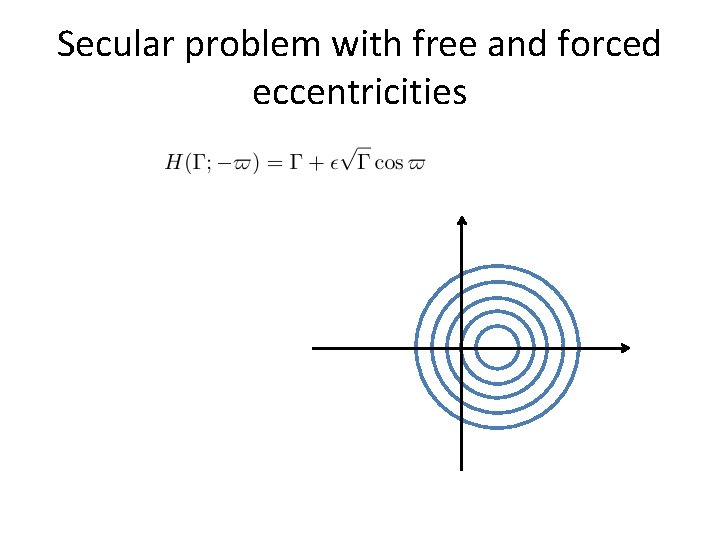

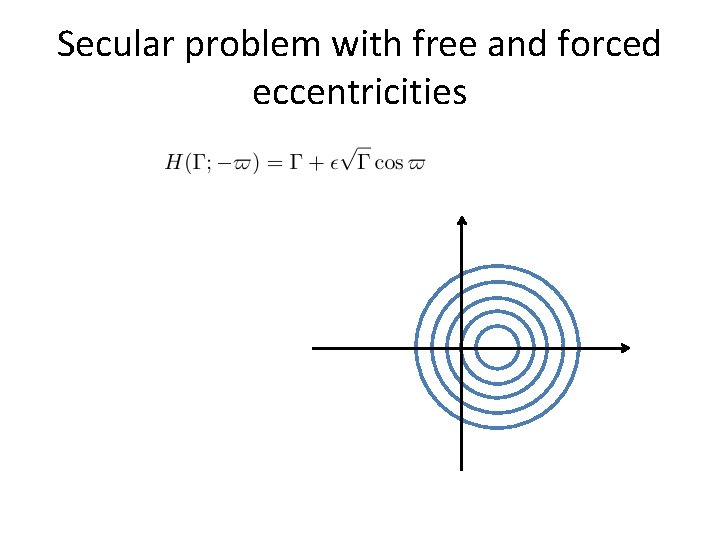

Secular problem with free and forced eccentricities

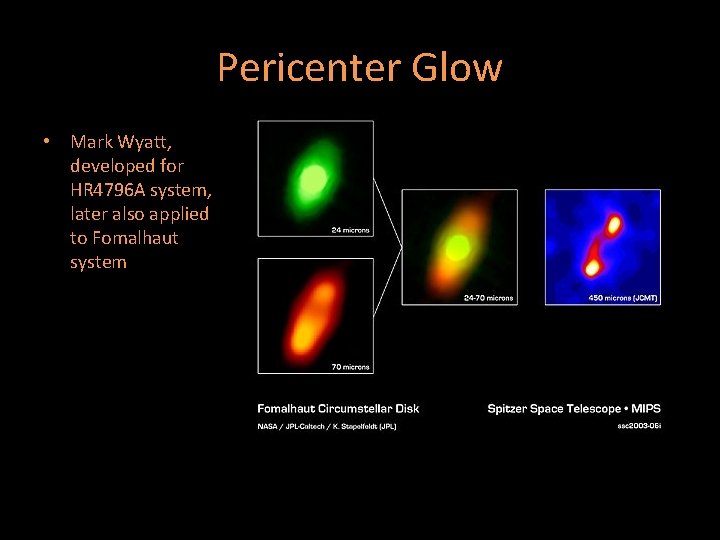

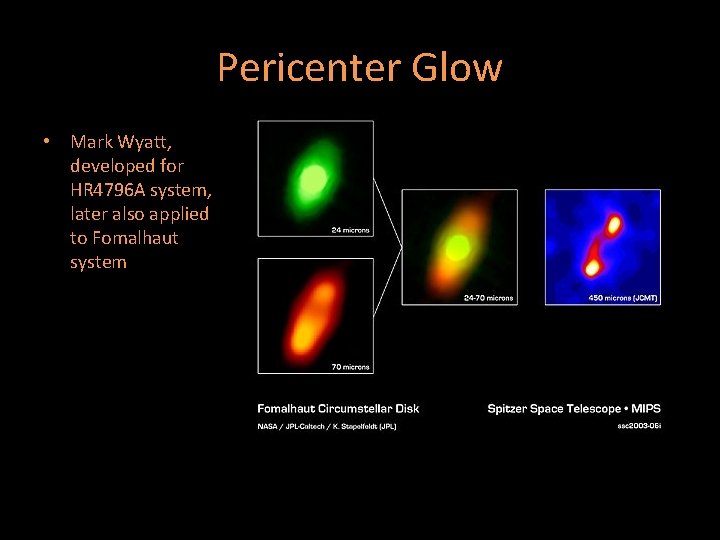

Pericenter Glow • Mark Wyatt, developed for HR 4796 A system, later also applied to Fomalhaut system

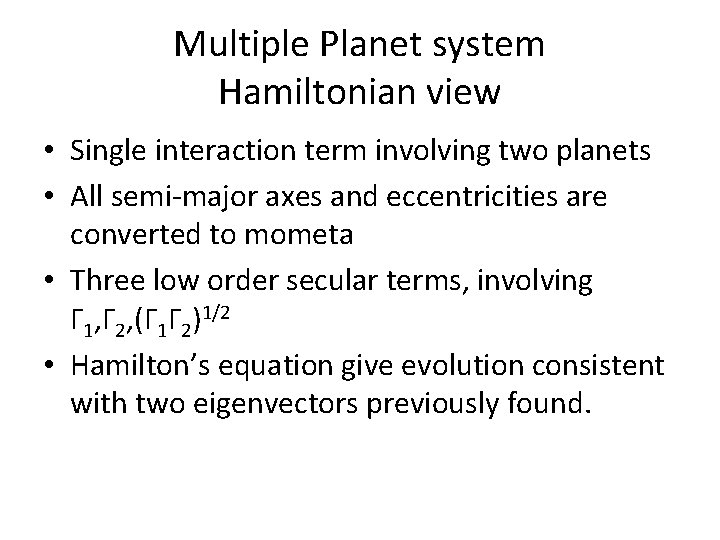

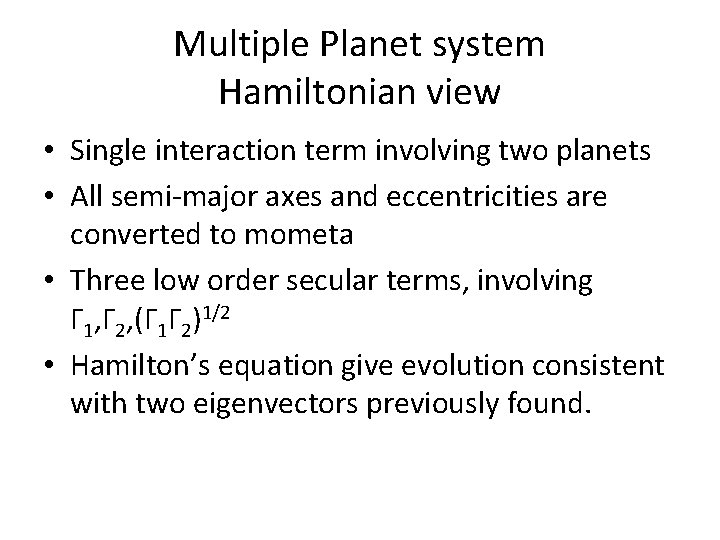

Multiple Planet system Hamiltonian view • Single interaction term involving two planets • All semi-major axes and eccentricities are converted to mometa • Three low order secular terms, involving Γ 1, Γ 2, (Γ 1Γ 2)1/2 • Hamilton’s equation give evolution consistent with two eigenvectors previously found.

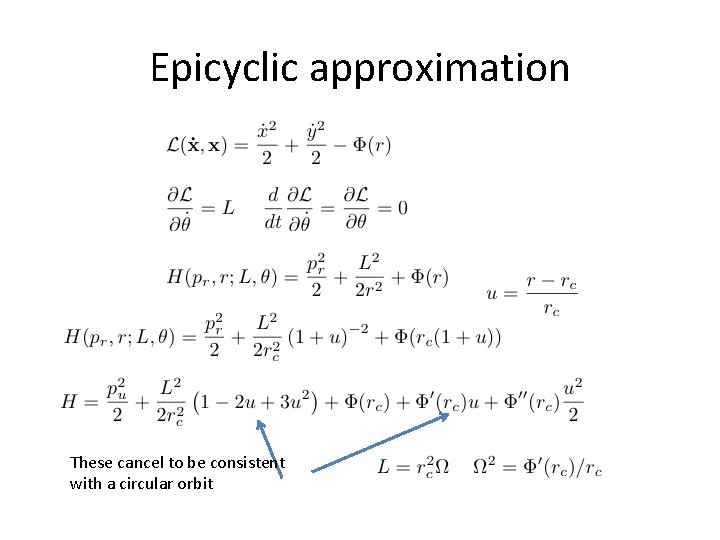

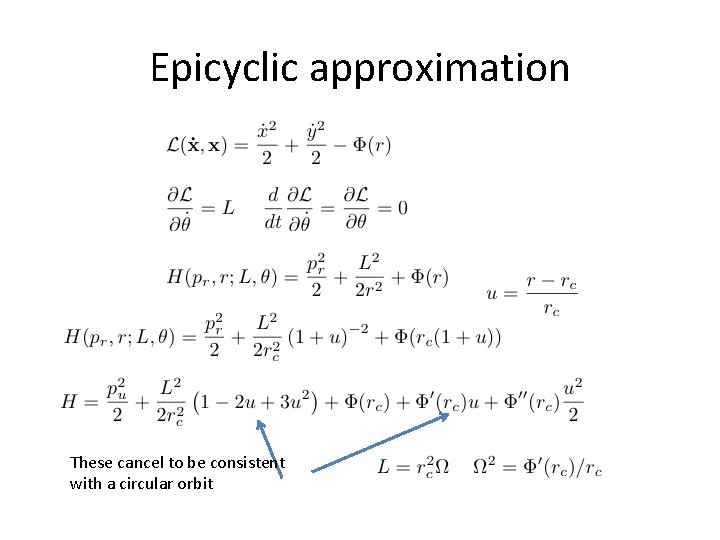

Epicyclic approximation These cancel to be consistent with a circular orbit

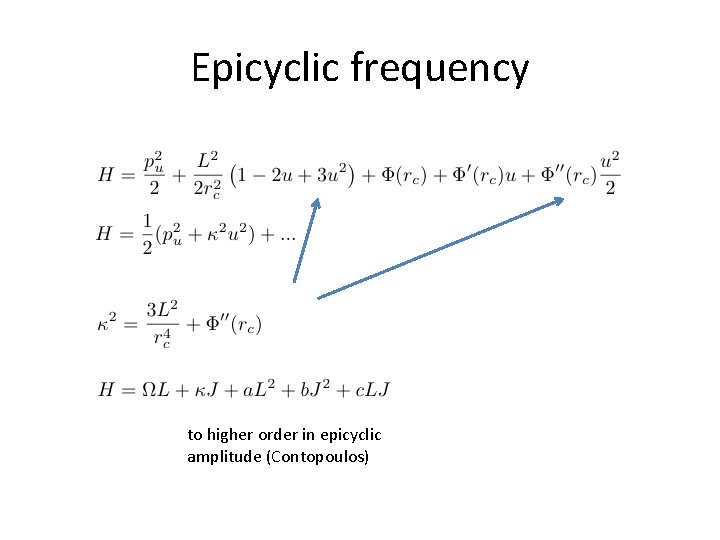

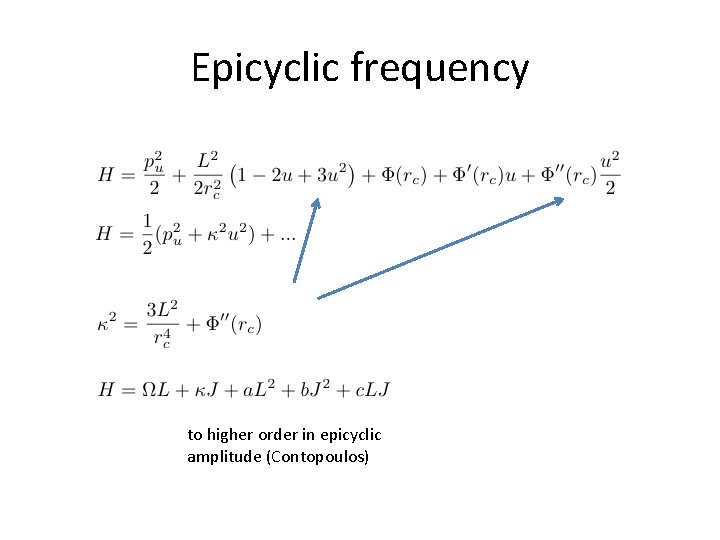

Epicyclic frequency to higher order in epicyclic amplitude (Contopoulos)

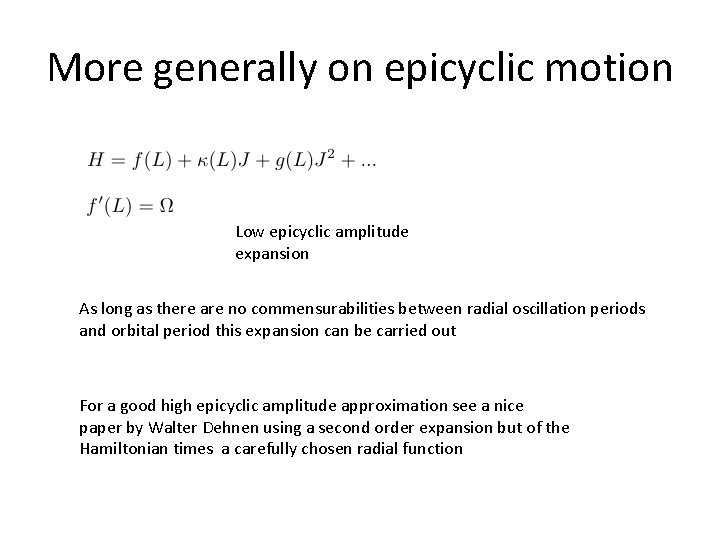

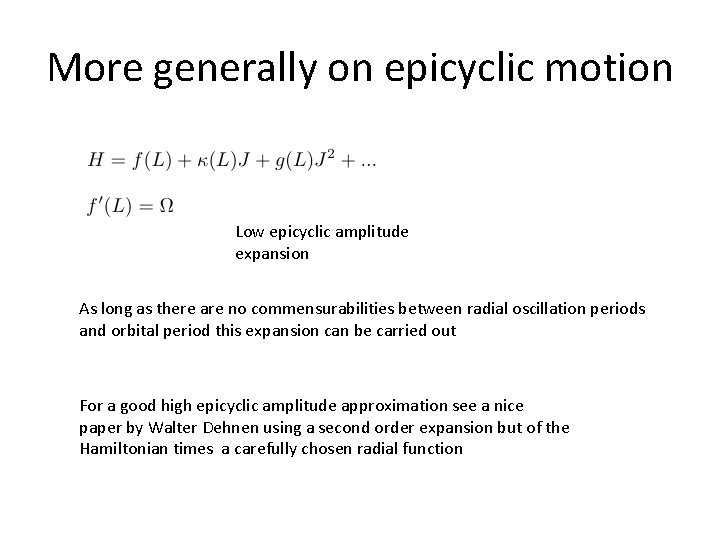

More generally on epicyclic motion Low epicyclic amplitude expansion As long as there are no commensurabilities between radial oscillation periods and orbital period this expansion can be carried out For a good high epicyclic amplitude approximation see a nice paper by Walter Dehnen using a second order expansion but of the Hamiltonian times a carefully chosen radial function

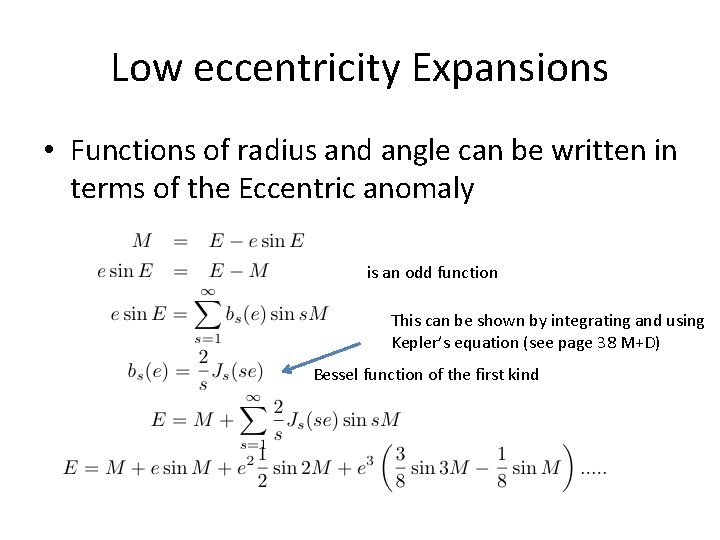

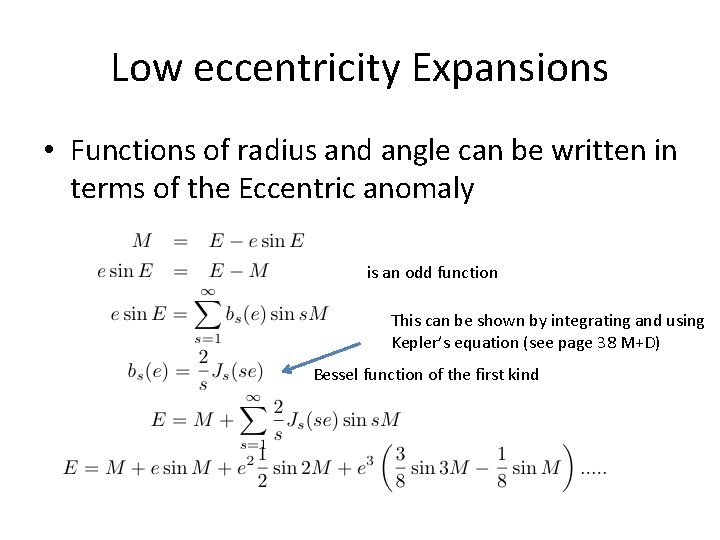

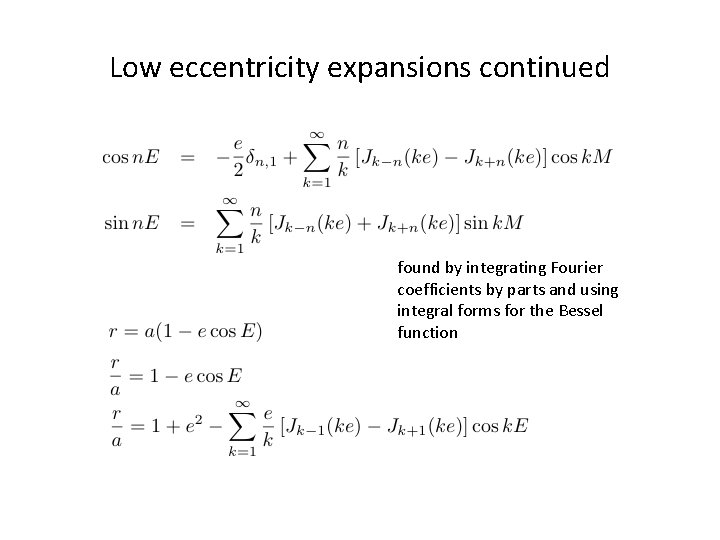

Low eccentricity Expansions • Functions of radius and angle can be written in terms of the Eccentric anomaly is an odd function This can be shown by integrating and using Kepler’s equation (see page 38 M+D) Bessel function of the first kind

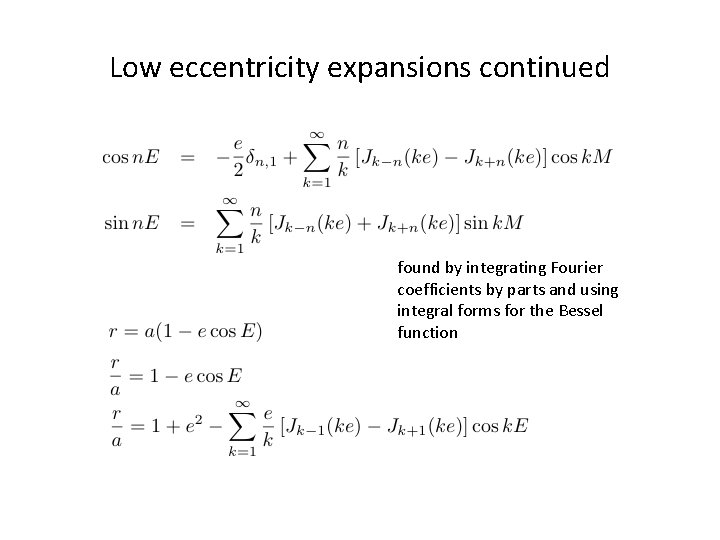

Low eccentricity expansions continued found by integrating Fourier coefficients by parts and using integral forms for the Bessel function

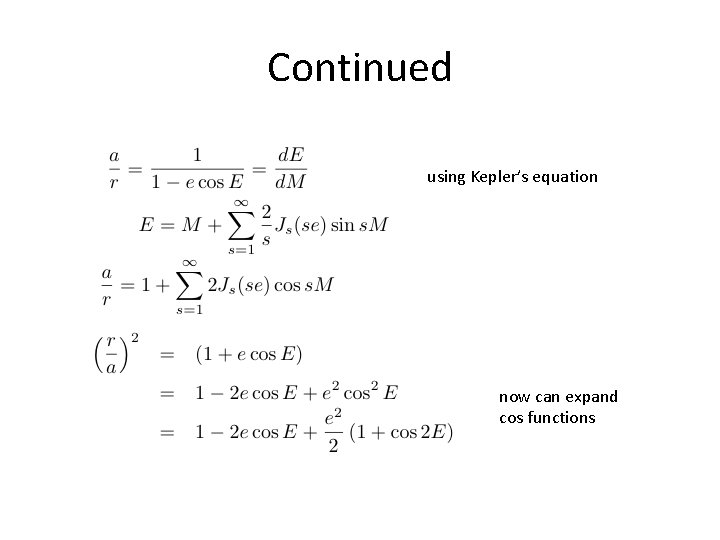

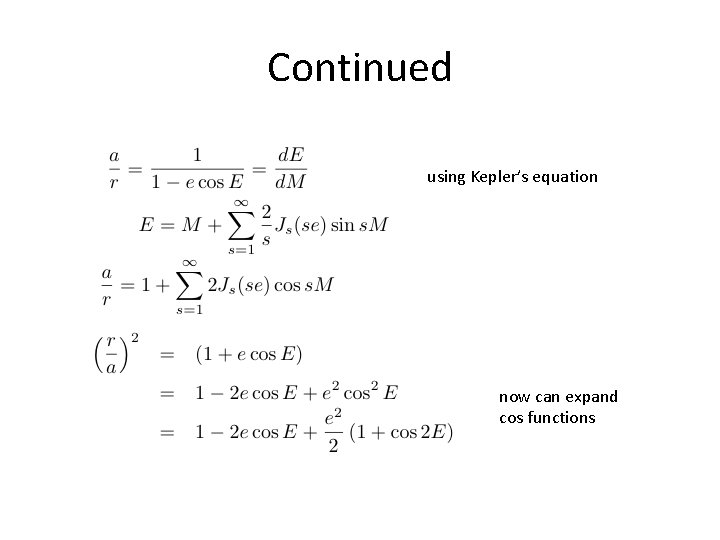

Continued using Kepler’s equation now can expand cos functions

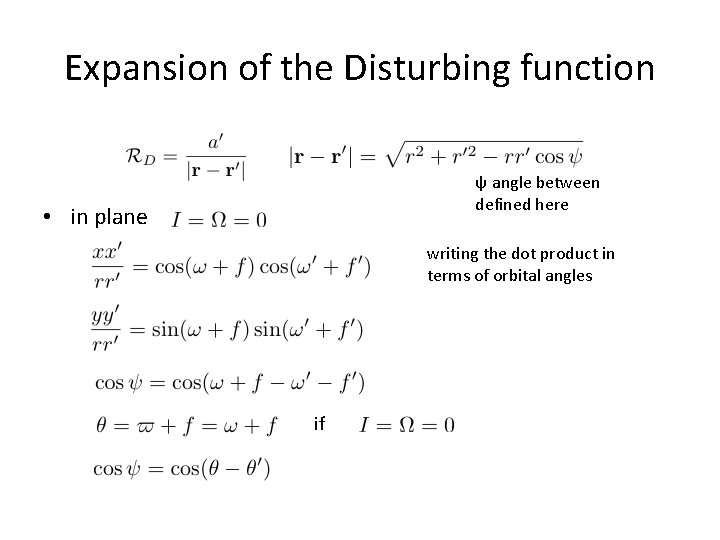

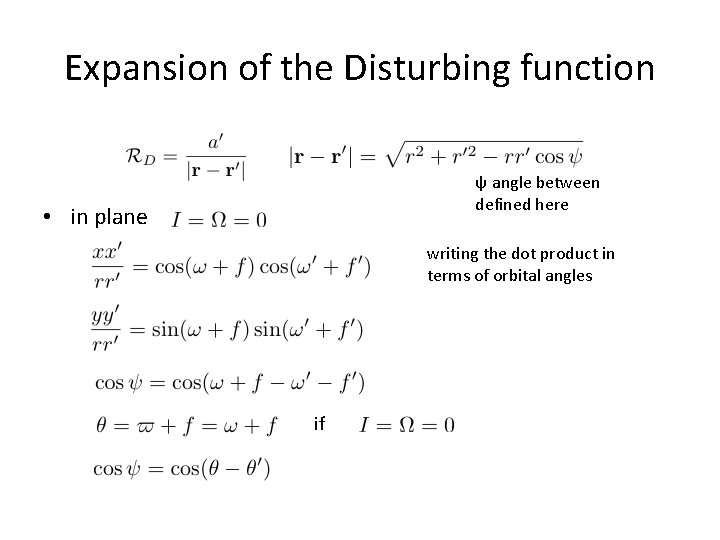

Expansion of the Disturbing function ψ angle between defined here • in plane writing the dot product in terms of orbital angles if

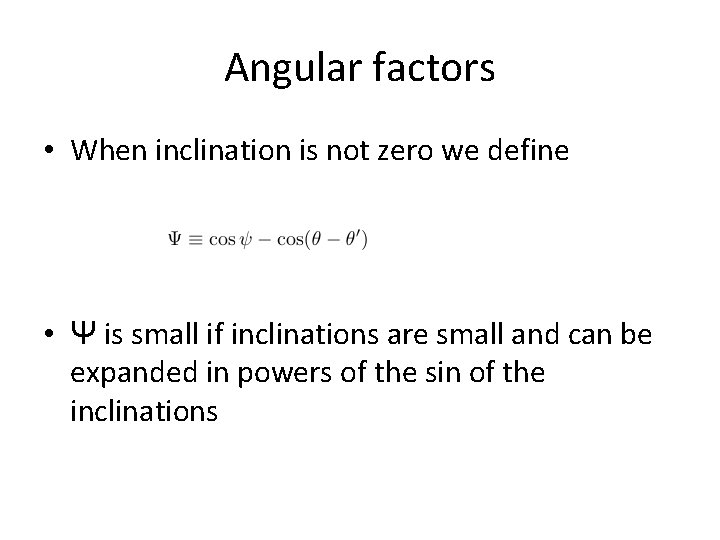

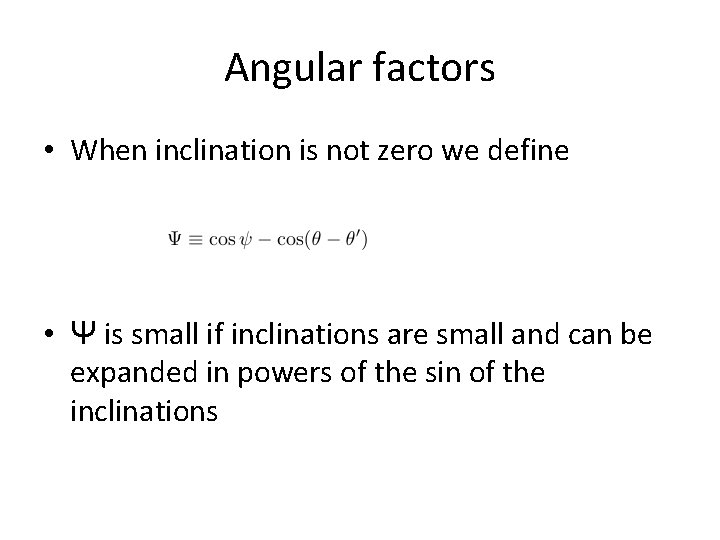

Angular factors • When inclination is not zero we define • Ψ is small if inclinations are small and can be expanded in powers of the sin of the inclinations

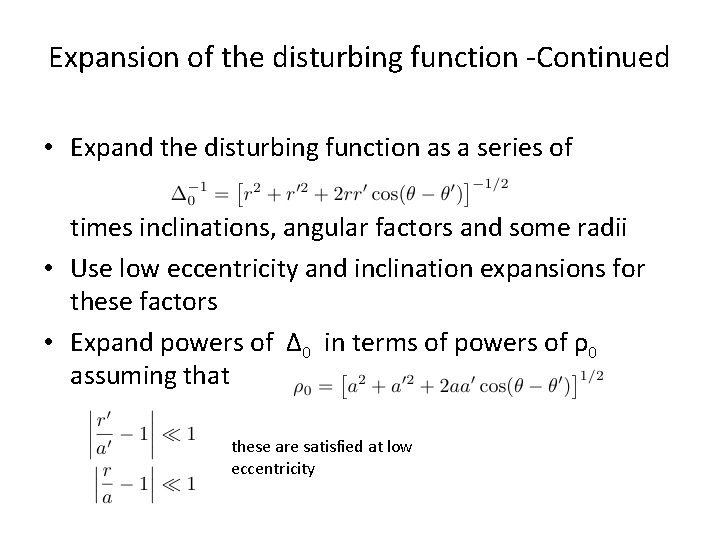

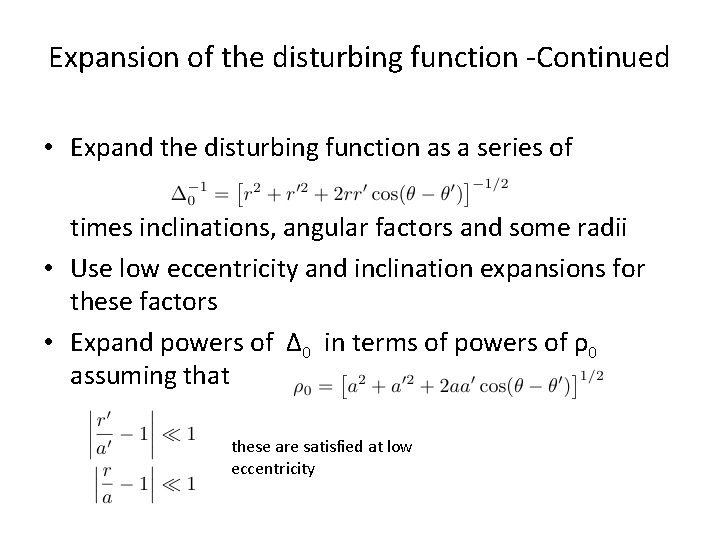

Expansion of the disturbing function -Continued • Expand the disturbing function as a series of times inclinations, angular factors and some radii • Use low eccentricity and inclination expansions for these factors • Expand powers of Δ 0 in terms of powers of ρ0 assuming that these are satisfied at low eccentricity

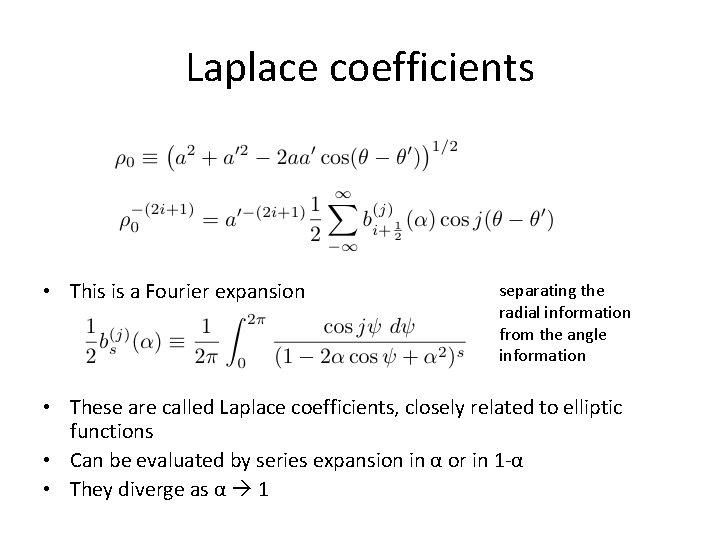

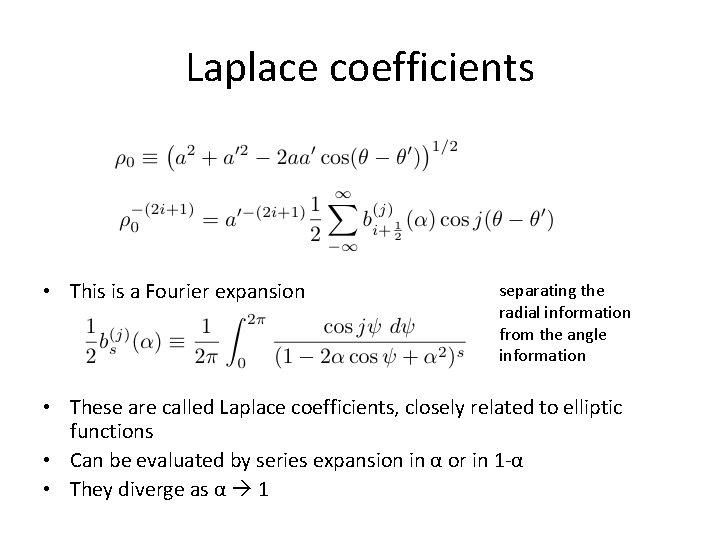

Laplace coefficients • This is a Fourier expansion separating the radial information from the angle information • These are called Laplace coefficients, closely related to elliptic functions • Can be evaluated by series expansion in α or in 1 -α • They diverge as α 1

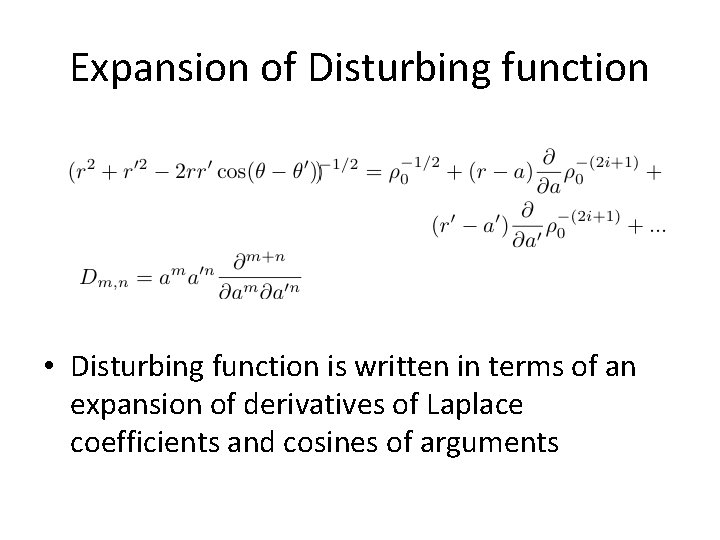

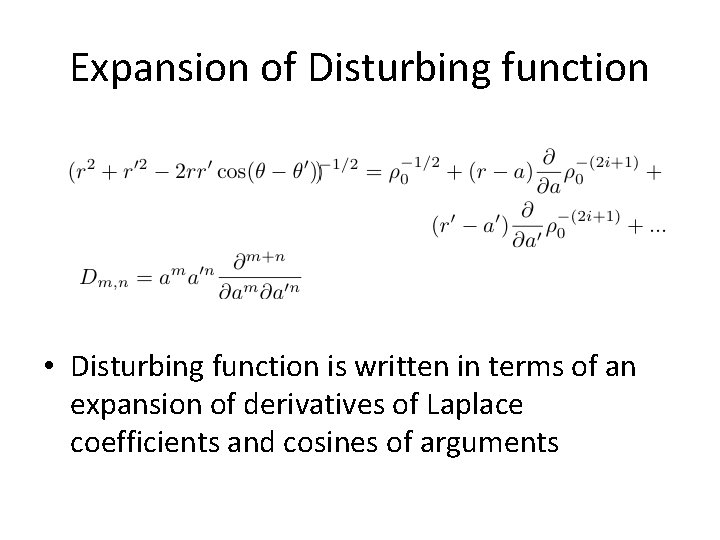

Expansion of Disturbing function • Disturbing function is written in terms of an expansion of derivatives of Laplace coefficients and cosines of arguments

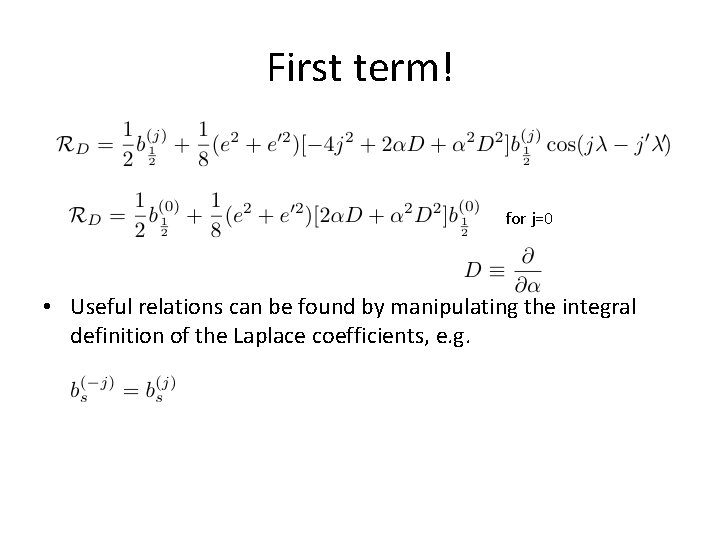

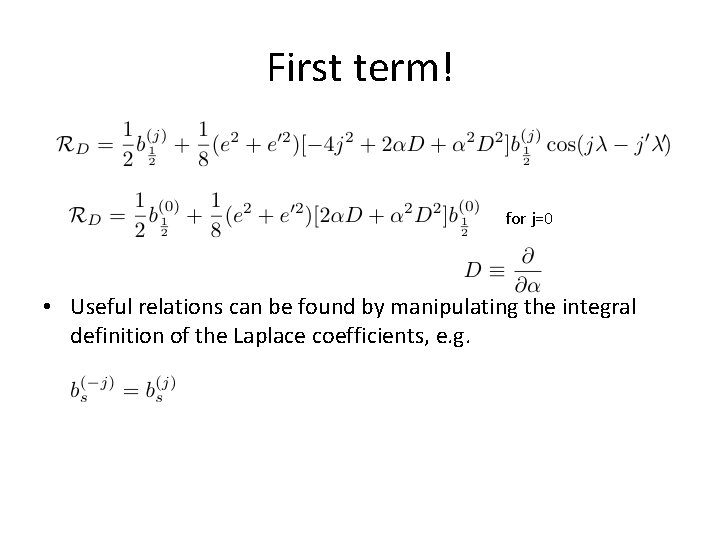

First term! for j=0 • Useful relations can be found by manipulating the integral definition of the Laplace coefficients, e. g.

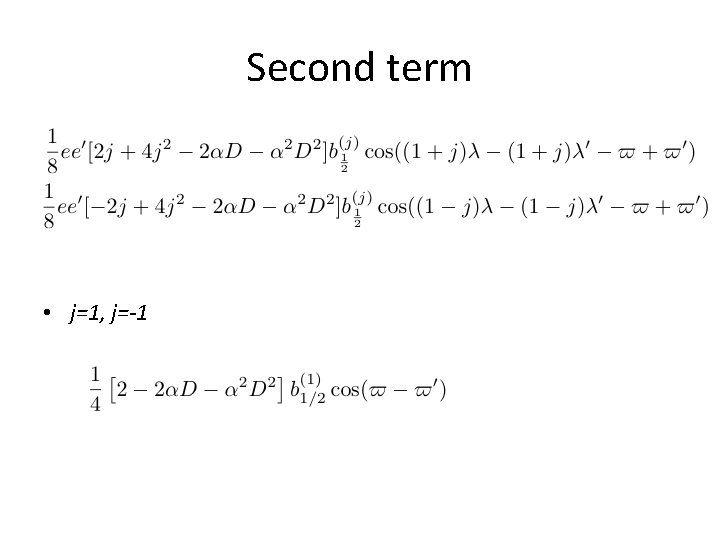

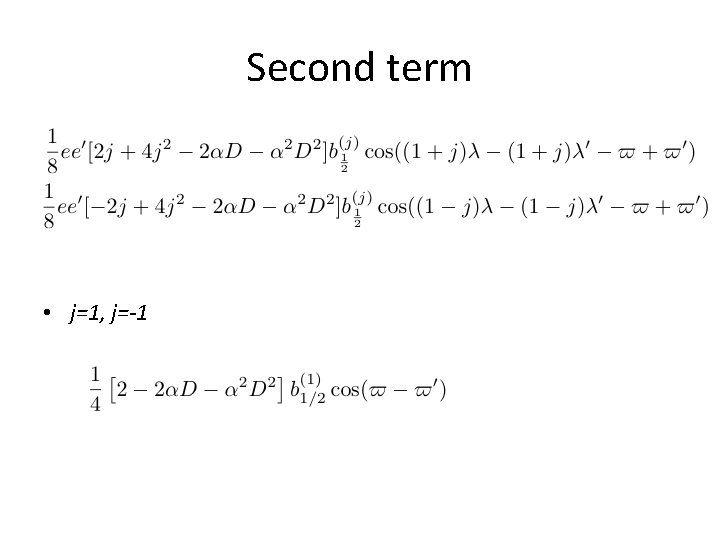

Second term • j=1, j=-1

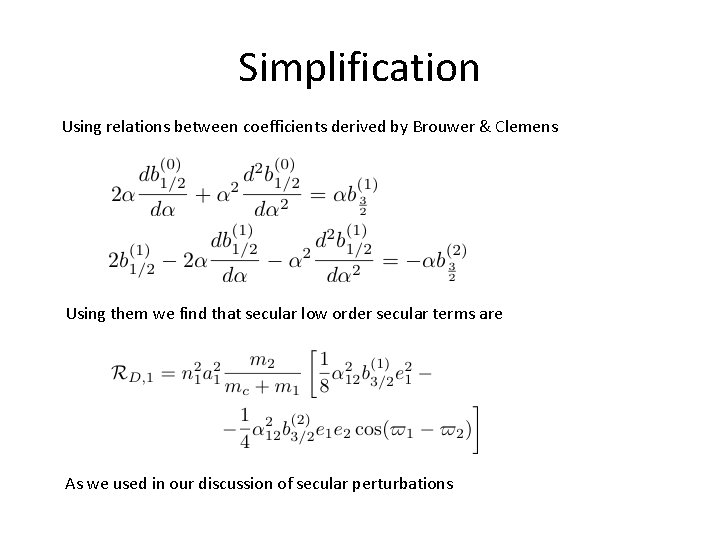

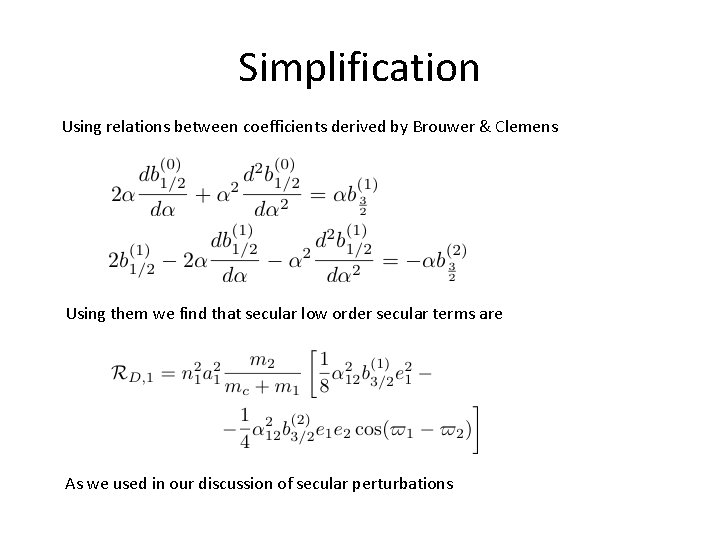

Simplification Using relations between coefficients derived by Brouwer & Clemens Using them we find that secular low order secular terms are As we used in our discussion of secular perturbations

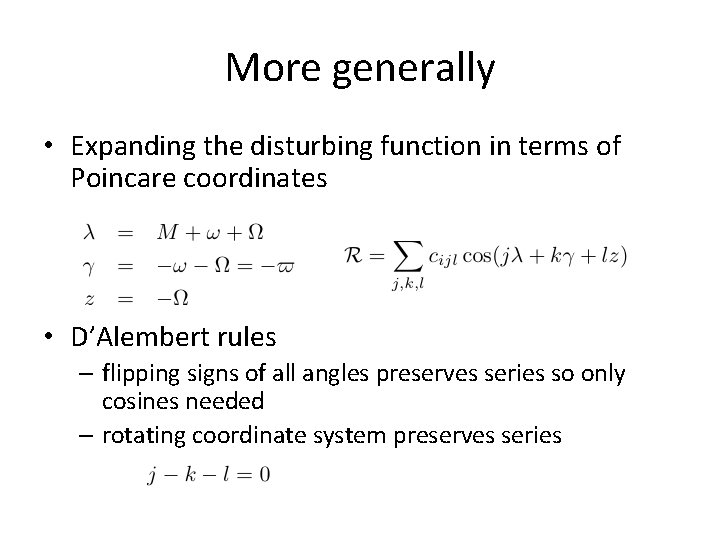

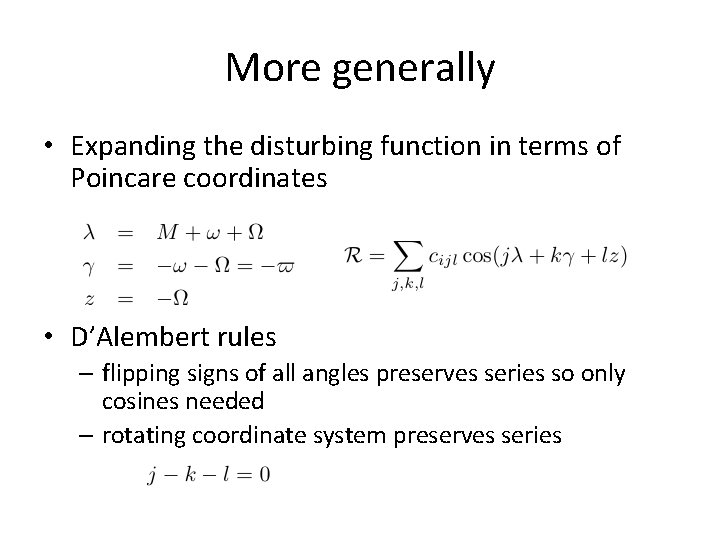

More generally • Expanding the disturbing function in terms of Poincare coordinates • D’Alembert rules – flipping signs of all angles preserves series so only cosines needed – rotating coordinate system preserves series

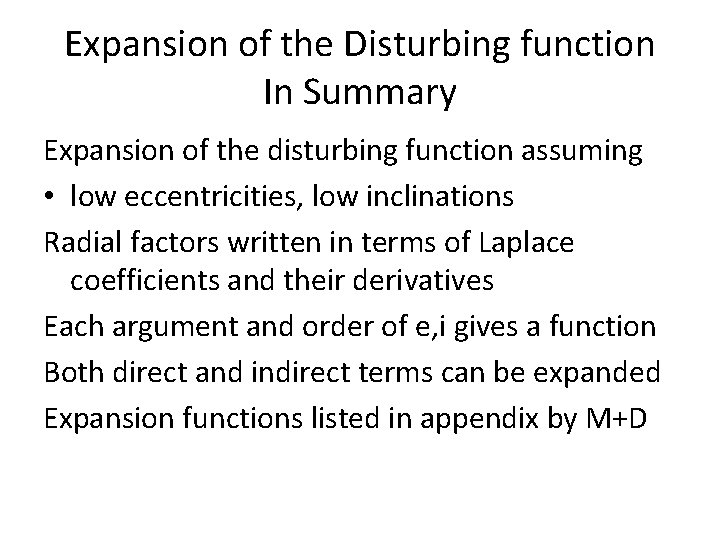

Expansion of the Disturbing function In Summary Expansion of the disturbing function assuming • low eccentricities, low inclinations Radial factors written in terms of Laplace coefficients and their derivatives Each argument and order of e, i gives a function Both direct and indirect terms can be expanded Expansion functions listed in appendix by M+D

Reading: Murray and Dermott Chap 2 Murray and Dermott Chap 6, 7 Prussing and Conway Chap 2 on universal variables Wright et al. 2008, “Ten New and Updated Multiplanet Systems, and a Survey of Exoplanetary Systems” astroph-ar. Xiv: 0812. 1582 v 2 • Malhotra, R. 2002, Ap. J, 575, L 33, A Dynamical Mechanism for Establishing Apsidal Resonance • Barnes and Greenberg, “Extrasolar Planet Interactions”, astro-ph/0801. 3226 • •

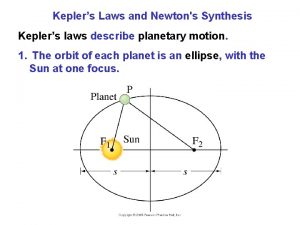

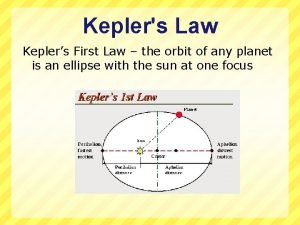

Kepler law

Kepler law Kepler's 3 laws of motion

Kepler's 3 laws of motion Keplers phase funnel

Keplers phase funnel Kepler's law

Kepler's law Concentric eccentric and isometric

Concentric eccentric and isometric Laboratory remount

Laboratory remount Balanced vs unbalanced occlusion

Balanced vs unbalanced occlusion Realeff effect ppt

Realeff effect ppt Spectacle shaped nucleus

Spectacle shaped nucleus Occupational therapy assessments for low vision

Occupational therapy assessments for low vision 321 principle

321 principle Dense regular connective tissue

Dense regular connective tissue Sicipath

Sicipath Smooth muscle gap junctions

Smooth muscle gap junctions The tool used for making internal threads is called as

The tool used for making internal threads is called as Eccentric motivation

Eccentric motivation Data redundancy and update anomalies

Data redundancy and update anomalies Database anomalies

Database anomalies Vitelline fistula

Vitelline fistula Proboscis lateralis

Proboscis lateralis Arytenoid mucosa

Arytenoid mucosa Modification anomalies

Modification anomalies Attention anomalies finance

Attention anomalies finance Anomalie rcf

Anomalie rcf Anomali refraksi

Anomali refraksi Japan population pyramid

Japan population pyramid Anomalies du rcf pendant le travail

Anomalies du rcf pendant le travail Cyptorchism

Cyptorchism Oddball: spotting anomalies in weighted graphs

Oddball: spotting anomalies in weighted graphs Ferri

Ferri Roulure bois

Roulure bois Frazzini

Frazzini Micrognathia definition

Micrognathia definition Spina bifida

Spina bifida Cfsv2 monthly prec anomalies

Cfsv2 monthly prec anomalies Cercumscribe

Cercumscribe Indented nucleus

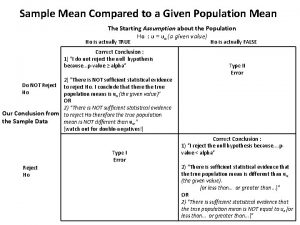

Indented nucleus Population mean and sample mean difference

Population mean and sample mean difference Difference between mean and sample mean

Difference between mean and sample mean Sample mean and population mean

Sample mean and population mean What does mean absolute deviation mean

What does mean absolute deviation mean Mean of the sampling distribution of the sample mean

Mean of the sampling distribution of the sample mean What does mean mean

What does mean mean Define mean deviation

Define mean deviation What does say mean matter mean

What does say mean matter mean Eyring equation and arrhenius equation

Eyring equation and arrhenius equation Linear equation and quadratic equation

Linear equation and quadratic equation Systems of linear and quadratic equations

Systems of linear and quadratic equations Vmax= k2et

Vmax= k2et Eyring equation and arrhenius equation

Eyring equation and arrhenius equation Mean of the sampling distribution

Mean of the sampling distribution Mean motion equation

Mean motion equation Frequency formula

Frequency formula What is mean by linear equation

What is mean by linear equation A + bx → ax + b

A + bx → ax + b Equation of fluid

Equation of fluid Euler cauchy differential equation

Euler cauchy differential equation What is net ionic equation

What is net ionic equation Allusion in macbeth

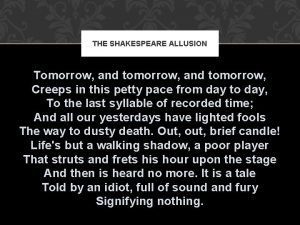

Allusion in macbeth How to find percentile with mean and standard deviation

How to find percentile with mean and standard deviation Find the interquartile range

Find the interquartile range What does it mean to hunger and thirst after righteousness

What does it mean to hunger and thirst after righteousness Interest and hobby

Interest and hobby Road map essay example

Road map essay example