STElevation Myocardial Infarction STEMI Greg Johnsen MD FACC

- Slides: 75

ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) Greg Johnsen, MD, FACC, FSCAI

Epidemiology of Acute Myocardial Infarction Coronary Heart Disease • Leading cause of death in high or middle income countries • Leading cause of death in the USA • Rates of death from CHD have declined in most high income countries • Rates of death from CHD have increased in the developing world • In 2004, CHD became the leading cause of death in India

It is estimated that 1. 25 million Americans have an acute MI each year. ST-Elevation MI accounts for 30 – 40% In the early 1960’s, prior to the era of cardiovascular intensive care units, in-hospital mortality was greater than 30%. Today, in-hospital mortality is 6. 5 – 7. 5%

In the USA All of the Following Risk Factors Are Decreasing Except? 1. Hypertension 2. Smoking 3. Hypercholesterolemia 4. Diabetes

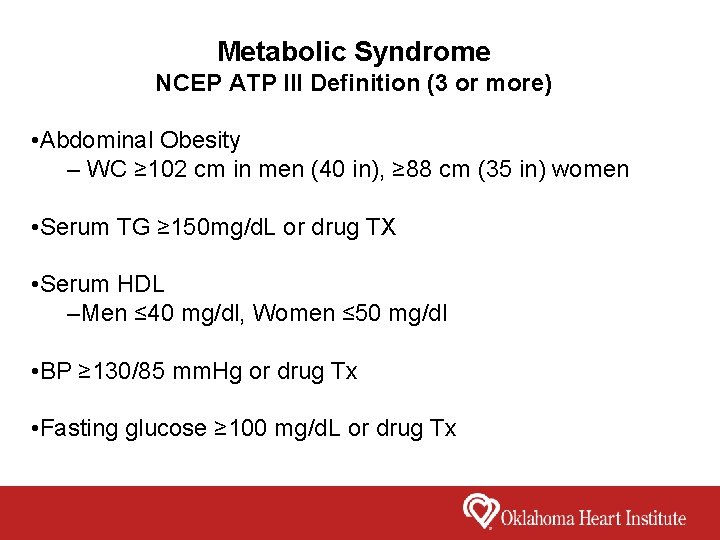

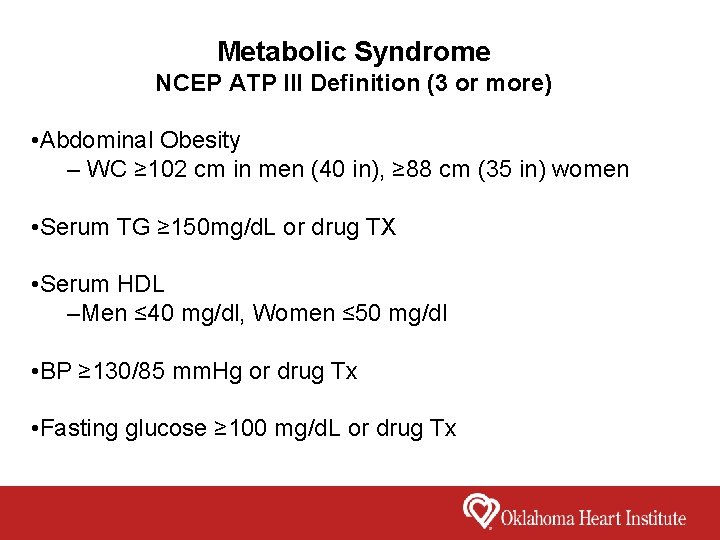

Metabolic Syndrome NCEP ATP III Definition (3 or more) • Abdominal Obesity – WC ≥ 102 cm in men (40 in), ≥ 88 cm (35 in) women • Serum TG ≥ 150 mg/d. L or drug TX • Serum HDL –Men ≤ 40 mg/dl, Women ≤ 50 mg/dl • BP ≥ 130/85 mm. Hg or drug Tx • Fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/d. L or drug Tx

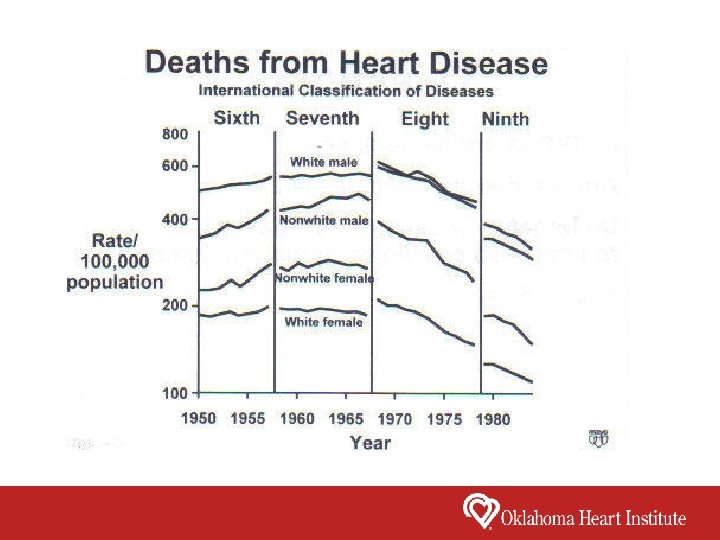

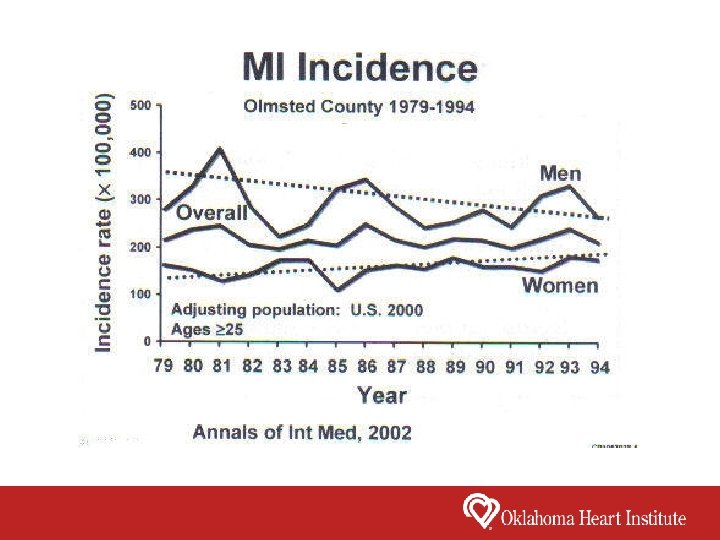

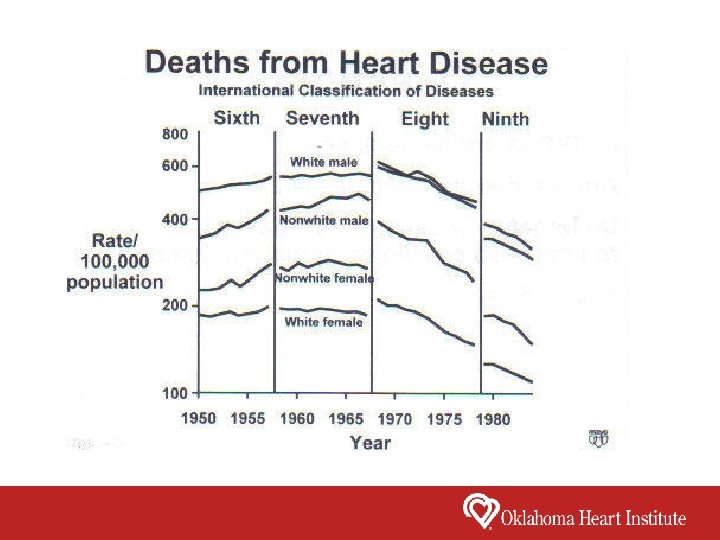

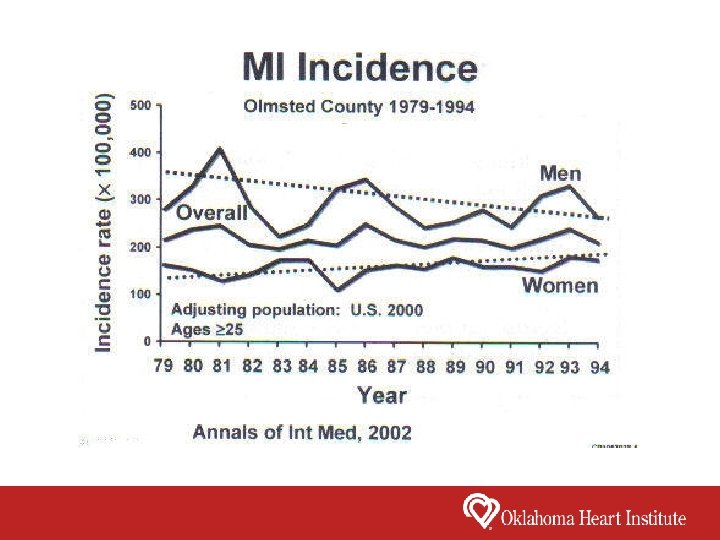

Points to Remember • CV deaths have decline markedly since the 1960 s • It continues to drop in men but not women • CVD is the leading cause of death but shifting from CAD to HF • Prevalence of risk factors decreasing in US except diabetes

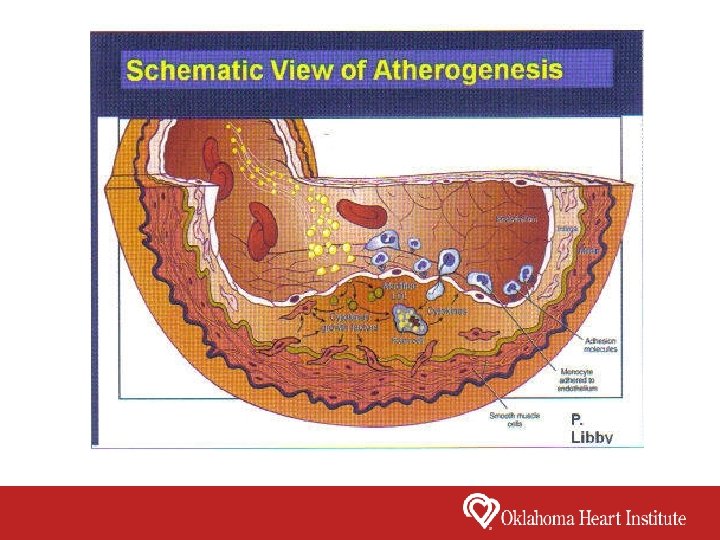

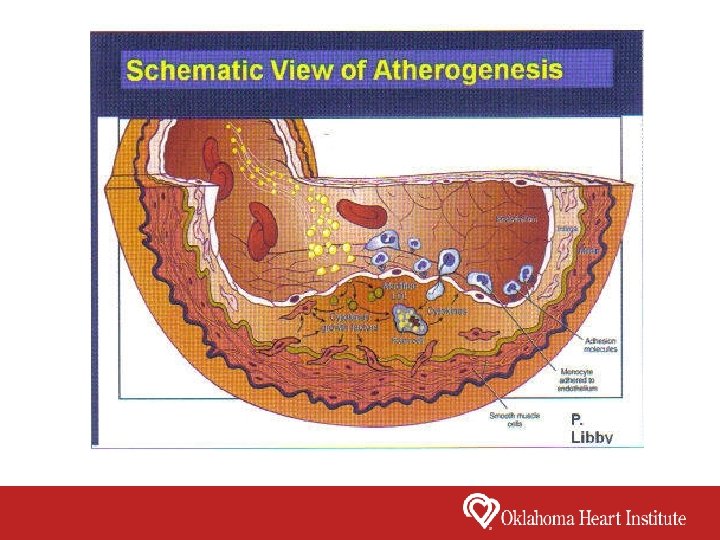

Vascular Injury and Atherosclerosis • Chronic inflammatory process that develops in “response-to-injury” metabolic environmental genetic physical infectious

Summary • Chronic inflammatory process that develops in “response-to-injury” • Lipoprotein accumulation and oxidation • Monocyte and T-lymphocyte recruitment • Leads to plaque progression • Leads to endothelial dysfunction

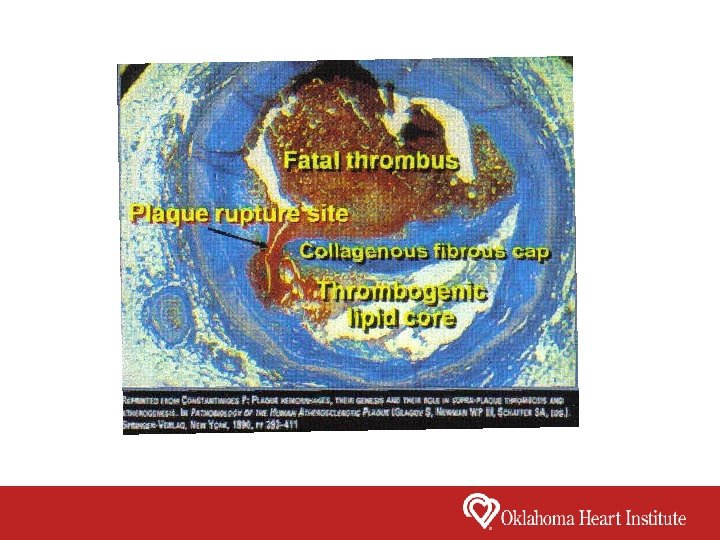

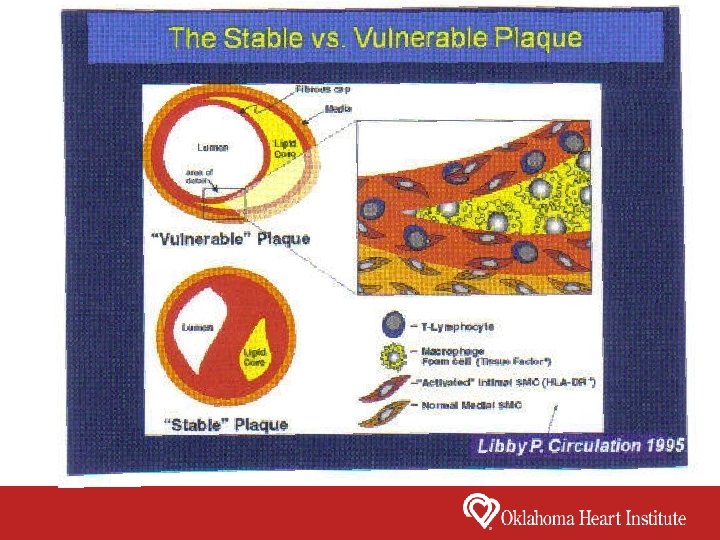

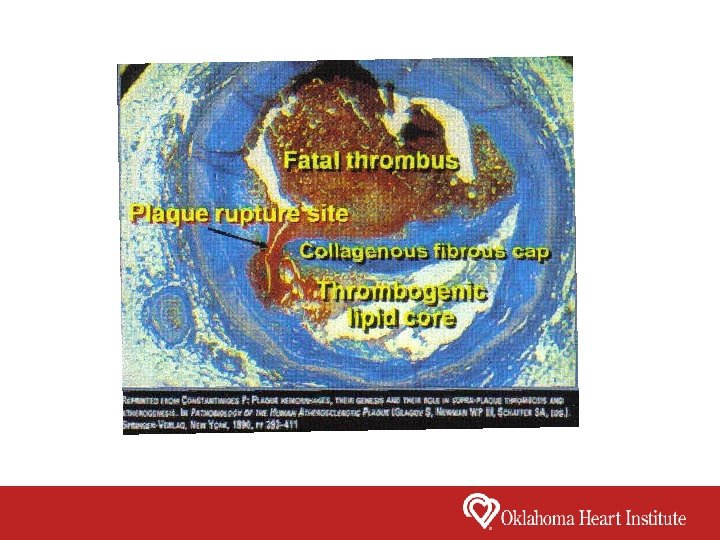

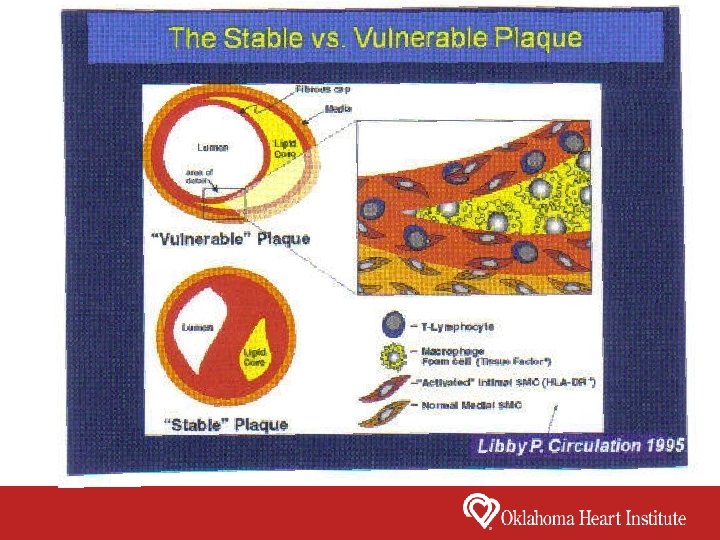

Acute Myocardial Infarction (MI) • Reduction in myocardial perfusion which is sufficient to cause cell necrosis Most Common Mechanism of Myocardial Infarction • Thrombus formation in the coronary artery at the site of a ruptured, eroded, or fissured atherosclerotic plaque • Ruptured plaque exposes the thrombogenic lipids in the plaque to the blood which leads to activation of platelets and clotting factors • Coronary plaques most prone to rupture have a rich lipid core and a thin fibrous plaque

Other Rare Causes of Acute Myocardial Infarction • Coronary artery embolism from a valvular vegetation or intracardiac thrombus • Cocaine use • Coronary artery dissection • Anemia • Hypotension • Coronary Spasm

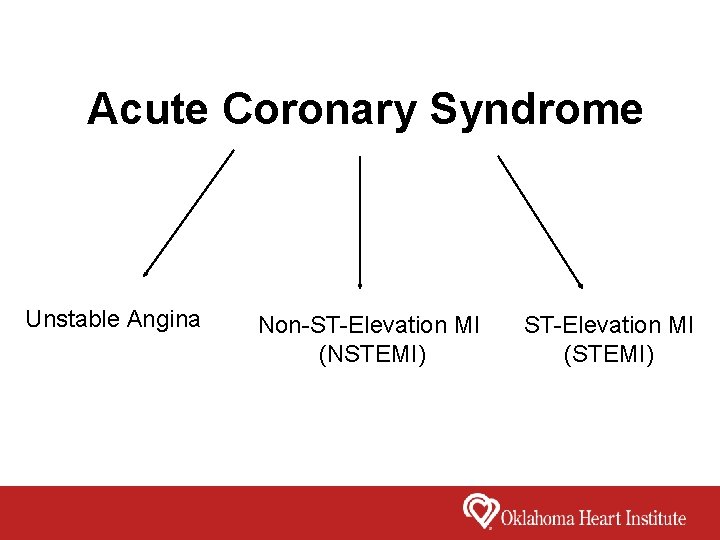

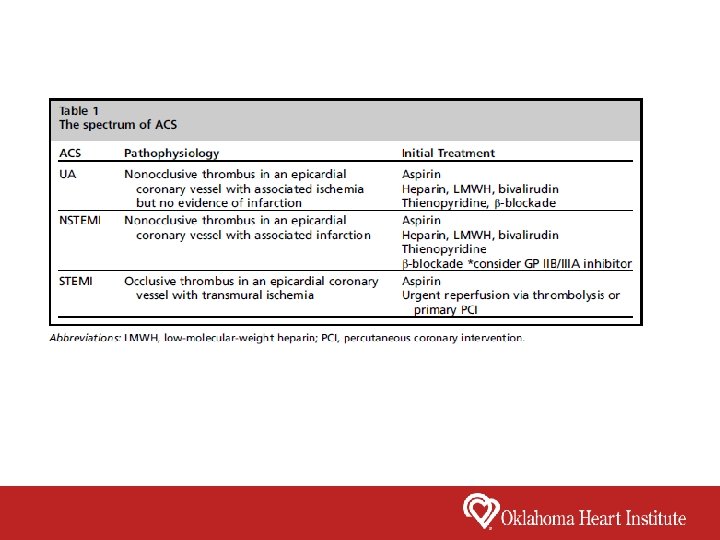

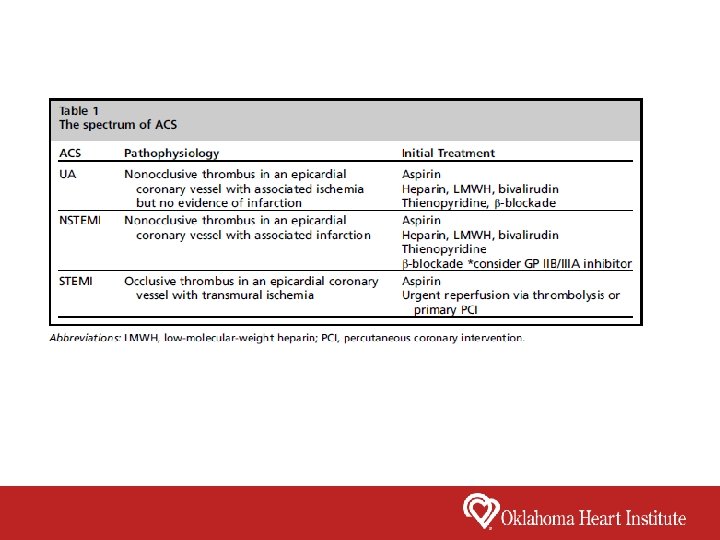

Acute Coronary Syndrome Unstable Angina Non-ST-Elevation MI (NSTEMI) ST-Elevation MI (STEMI)

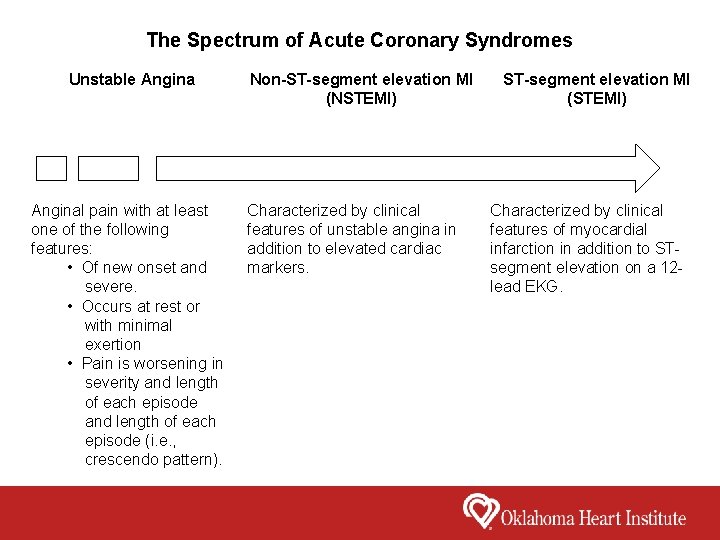

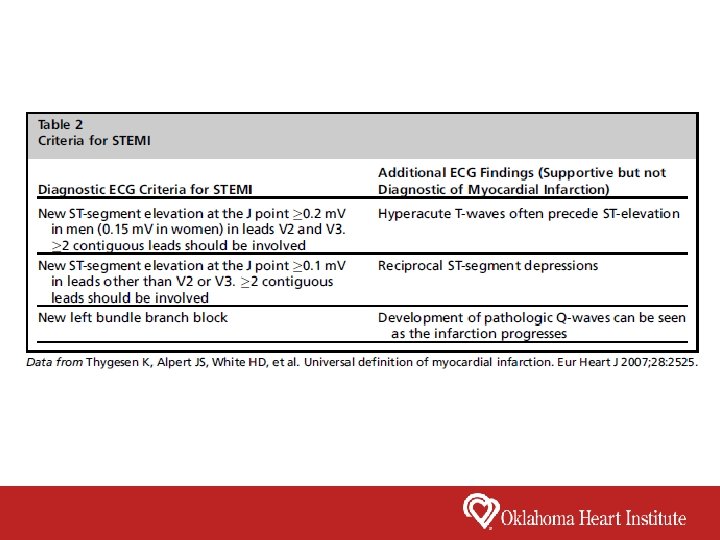

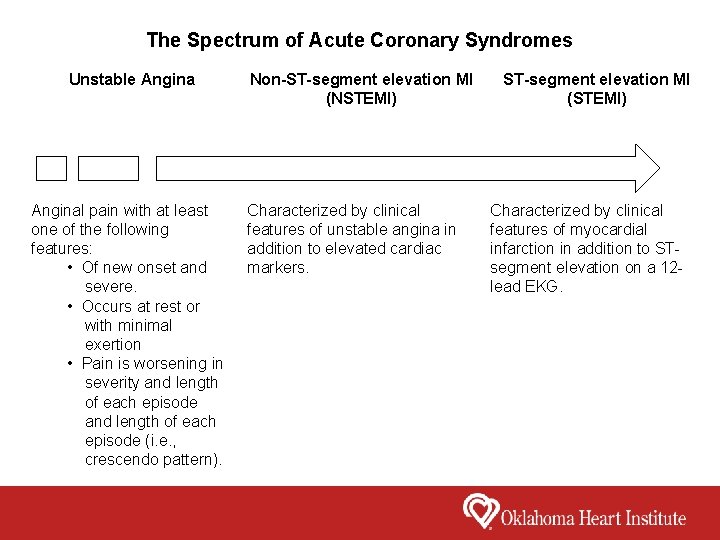

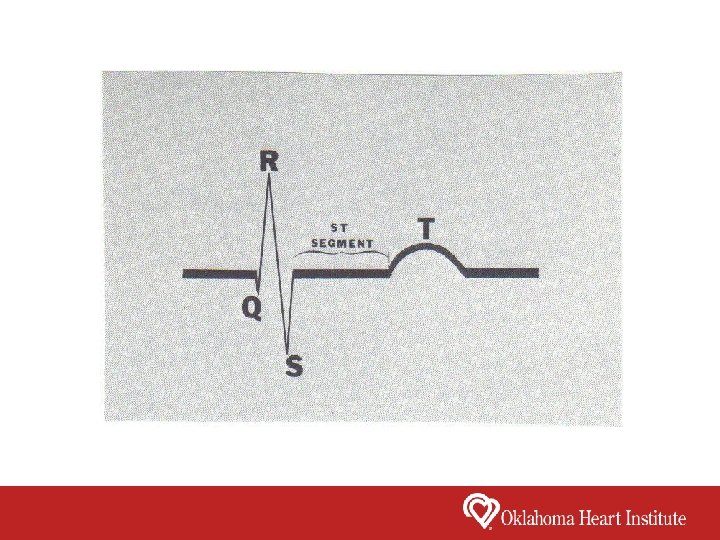

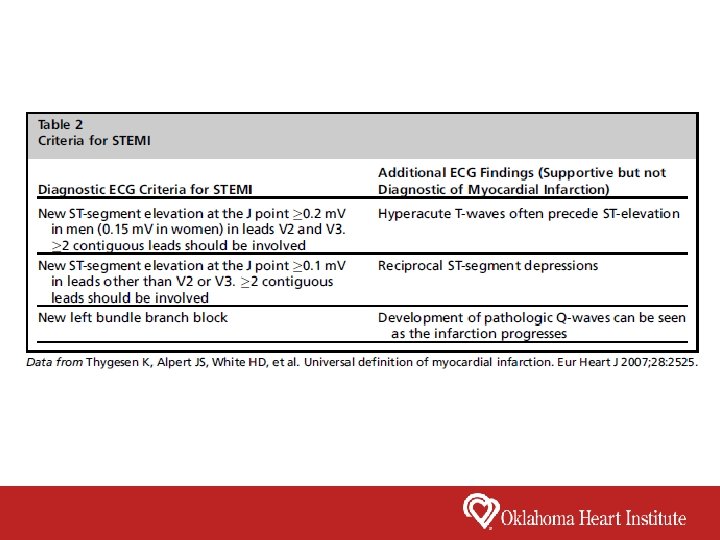

The Spectrum of Acute Coronary Syndromes Unstable Anginal pain with at least one of the following features: • Of new onset and severe. • Occurs at rest or with minimal exertion • Pain is worsening in severity and length of each episode (i. e. , crescendo pattern). Non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI) Characterized by clinical features of unstable angina in addition to elevated cardiac markers. ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) Characterized by clinical features of myocardial infarction in addition to STsegment elevation on a 12 lead EKG.

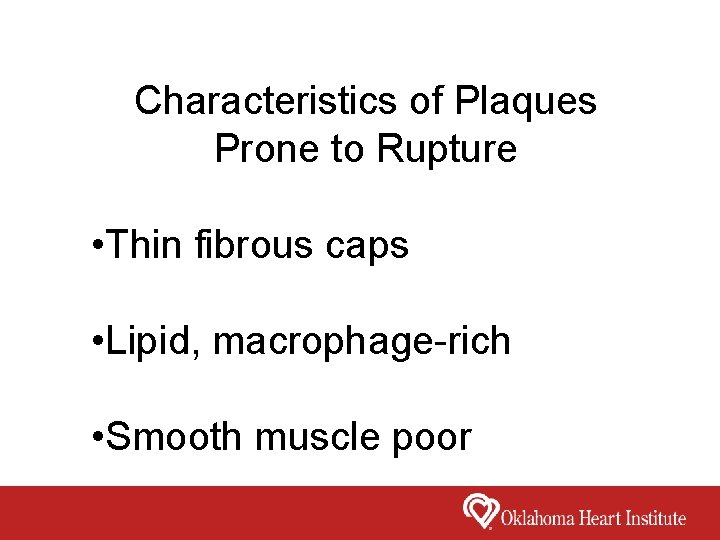

Characteristics of Plaques Prone to Rupture • Thin fibrous caps • Lipid, macrophage-rich • Smooth muscle poor

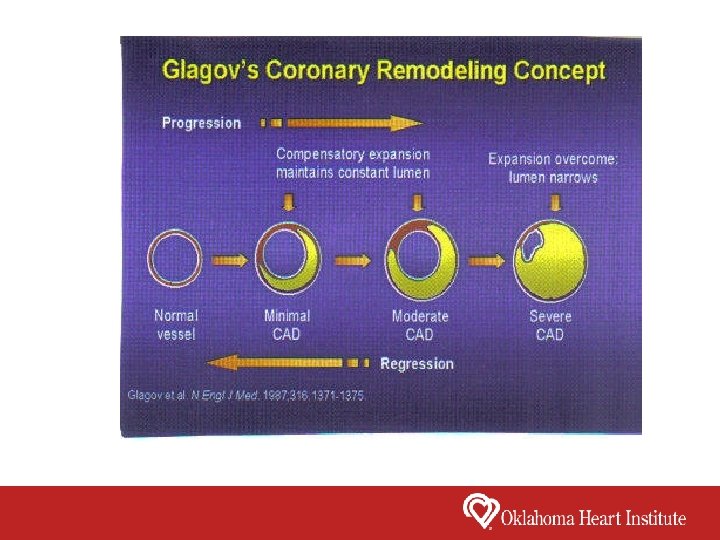

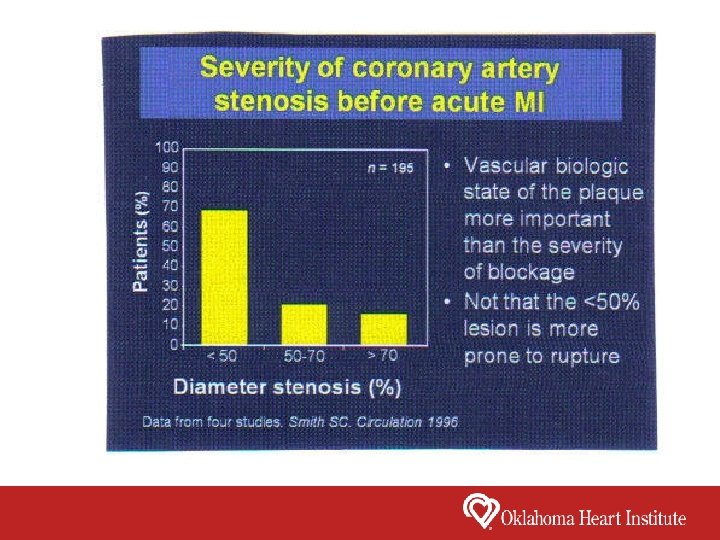

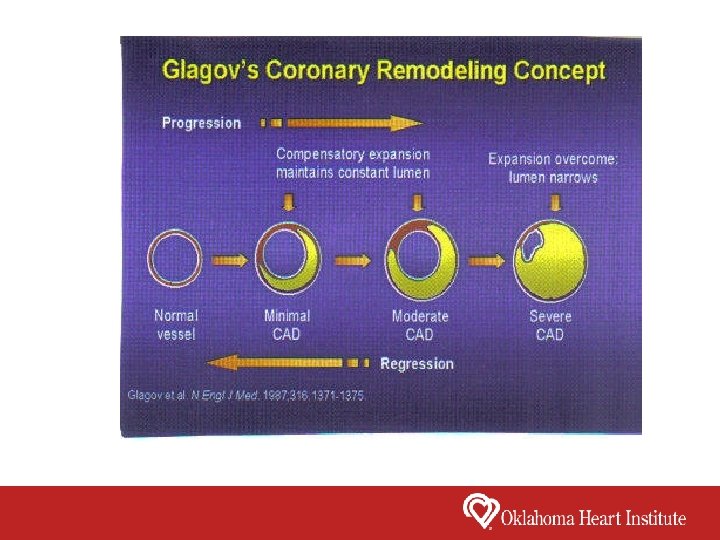

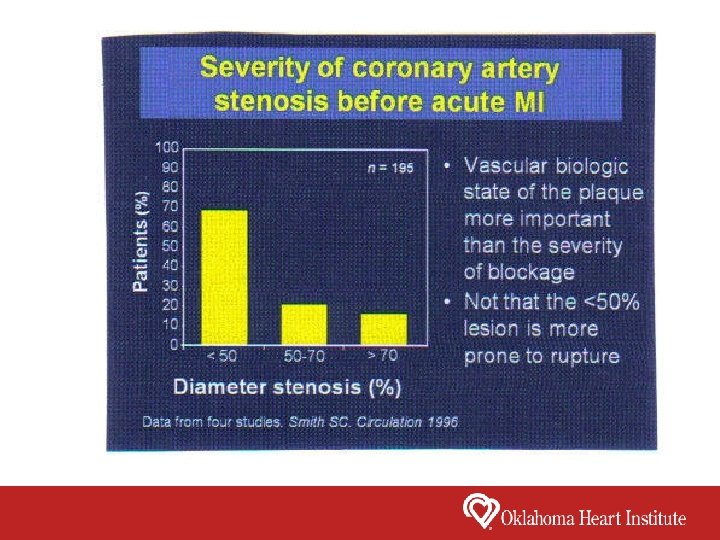

What accounts for the disparity between degree of coronary artery stenosis and producing the acute coronary syndromes? The functional state of the atheroma, not merely its size or the degree of luminal encroachment, determines the propensity for development of acute coronary syndromes

Triggers of Plaque Rupture • Emotional Stress • Physical Activity • Increased Sympathetic Tone

Triggers of Plaque Rupture • Heart Rate & Blood Pressure • Vasoconstriction • High Shear Stress • Physical and Emotional Stress • Infection • Inflammation

In half of patients with STEMI, a precipitating factor or prodromal symptoms can be identified Unusually heavy exercise in habitually inactive patients and emotional stress can precipitate STEMI Accelerating angina and rest angina may culiminate in STEMI Respiratory infections, hypoxemia, cocaine use and noncardiac surgical procedures can predispose to STEMI

Risk Factors for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction & Cardiovascular Disease Non-Modifiable Factors Age Male Gender Family History of Cardiovascular Disease

Risk Factors for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction & Cardiovascular Disease Modifiable Factors Cigarette Smoking Hyperlipidemia Hypertension Diabetes Obesity Physical Inactivity Diet hs. CRP

Controversial Risk Factors for MI • Baldness • Gray Hair • Diagonal Earlobe Crease (Frank’s Sign)

Symptoms of Acute Myocardial Infarction • Substernal chest pressure, usually described as heavy, squeezing, tightness, crushing and sometimes stabbing or burning pain (Levine’s sign). • In STEMI, sudden onset of chest pain often associated with shortness of breath, diaphoresis, weakness, nausea and vomiting. • The pain sometimes radiates to the C 7 – T 4 dermatomes (left arm, shoulders, jaw, neck, back and epigastrium). Radiation to both arms is a strong predictor of acute MI. • In 20% of patients (diabetics, elderly, postoperative or female) chest pain may be absent.

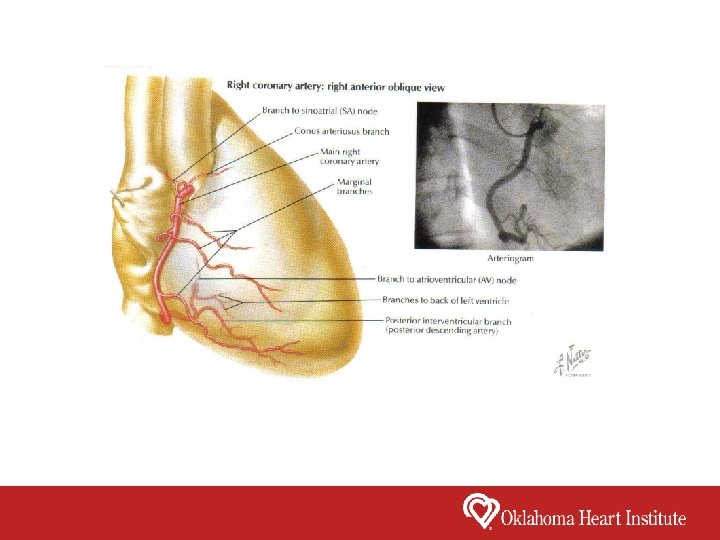

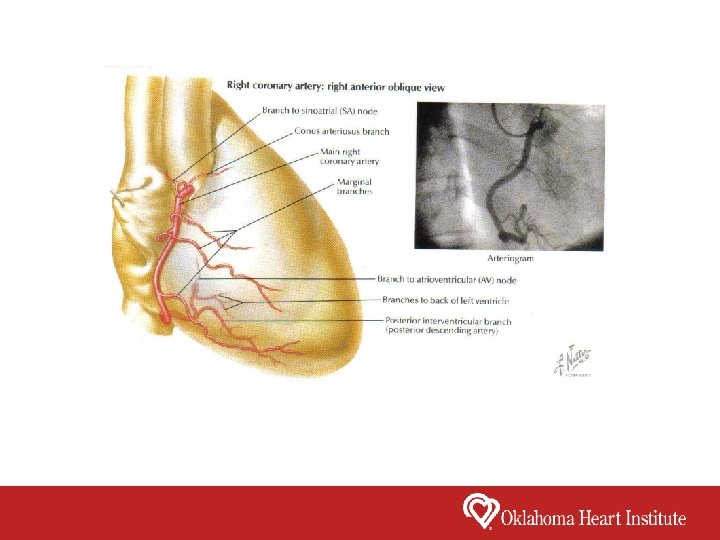

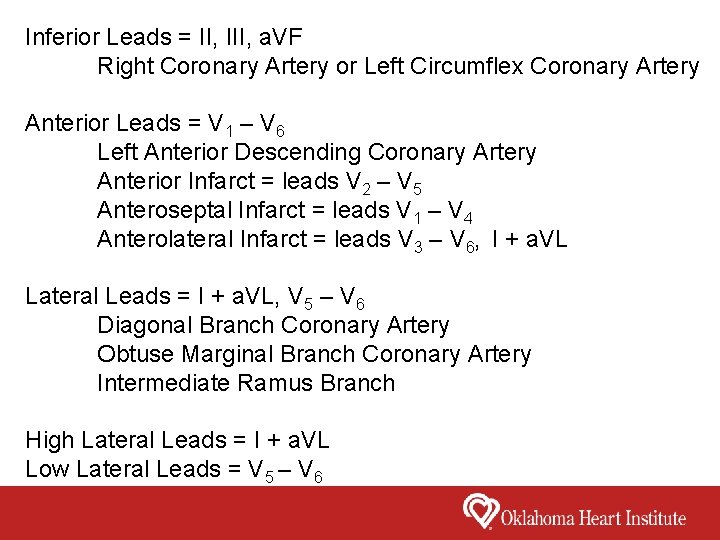

Inferior Leads = II, III, a. VF Right Coronary Artery or Left Circumflex Coronary Artery Anterior Leads = V 1 – V 6 Left Anterior Descending Coronary Artery Anterior Infarct = leads V 2 – V 5 Anteroseptal Infarct = leads V 1 – V 4 Anterolateral Infarct = leads V 3 – V 6, I + a. VL Lateral Leads = I + a. VL, V 5 – V 6 Diagonal Branch Coronary Artery Obtuse Marginal Branch Coronary Artery Intermediate Ramus Branch High Lateral Leads = I + a. VL Low Lateral Leads = V 5 – V 6

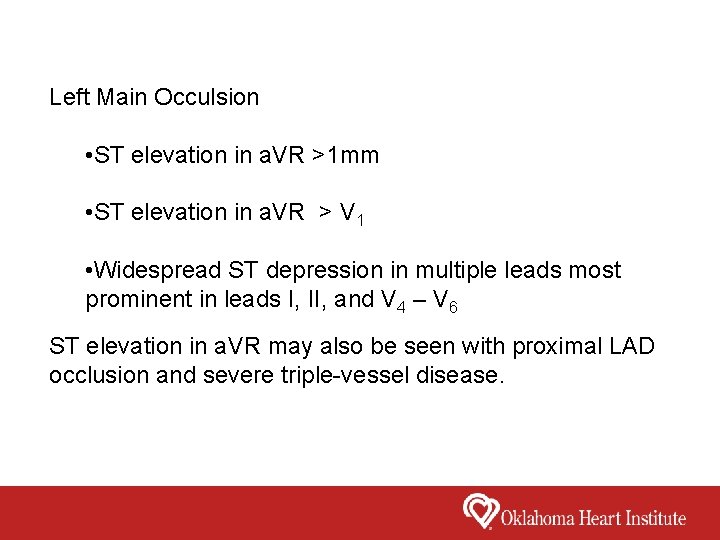

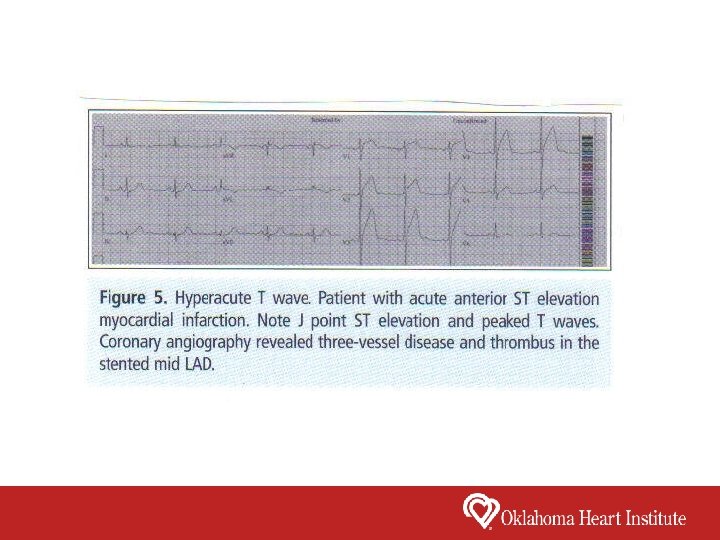

Left Main Occulsion • ST elevation in a. VR >1 mm • ST elevation in a. VR > V 1 • Widespread ST depression in multiple leads most prominent in leads I, II, and V 4 – V 6 ST elevation in a. VR may also be seen with proximal LAD occlusion and severe triple-vessel disease.

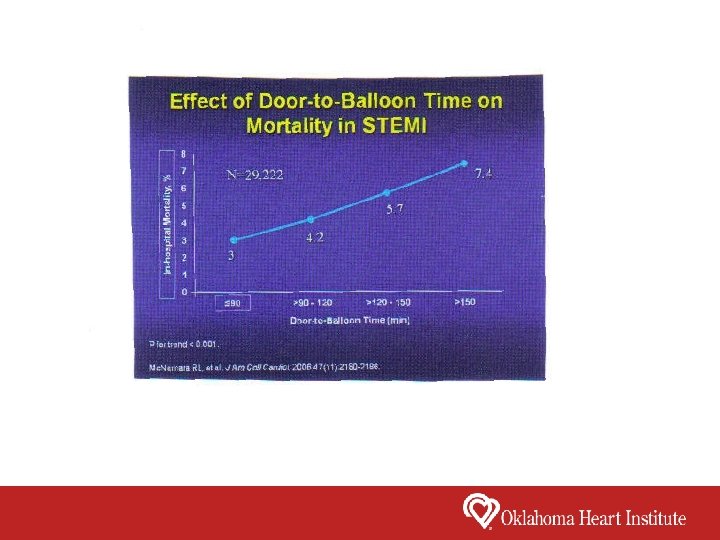

Reperfusion Goals in ST-Elevation MI (PCI = Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) Primary PCI: Door to Balloon Time less than 90 minutes Primary PCI: First medical contact to device time less than 90 minutes Primary PCI: When transferred from a different hospital: First medical contact to device time less than 120 minutes Fibrinolytic therapy: Door to needle time less than 30 minutes

Guidelines for Primary PCI in STEMI Class I • Primary PCI should be performed within 12 hours of onset of STEMI • Primary PCI should be performed within 90 minutes of first medical contact as a systems goal when presenting to a hospital with PCI capability • Primary PCI should be performed within 120 minutes of first medical contact as a systems goal when presenting to a hospital without PCI capability • Primary PCI should be performed in patients with STEMI who develop severe heart failure or cardiogenic shock and are suitable for revascularization as soon as possible

Guidelines for Primary PCI in STEMI Class IIa • Primary PCI is reasonable in STEMI if there is clinical or ECG evidence of ongoing ischemia between 12 and 24 hours after symptom onset • PCI is reasonable in patients with STEMI and clinical evidence for fibrinolytic failure or infarct artery reocclusion

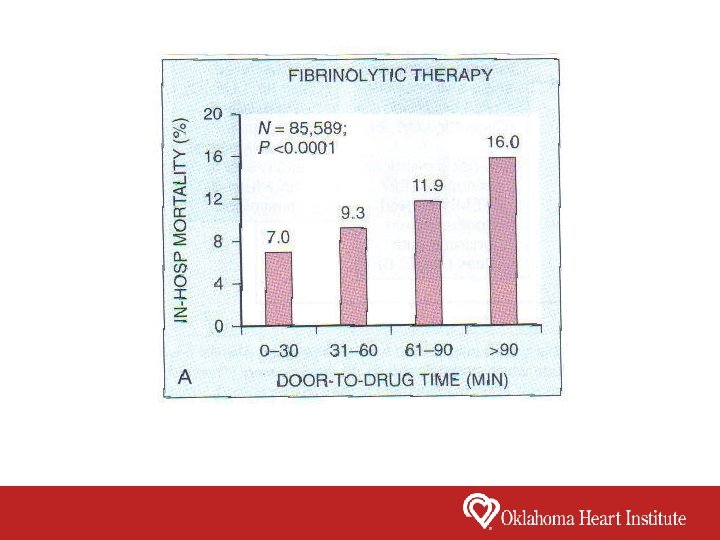

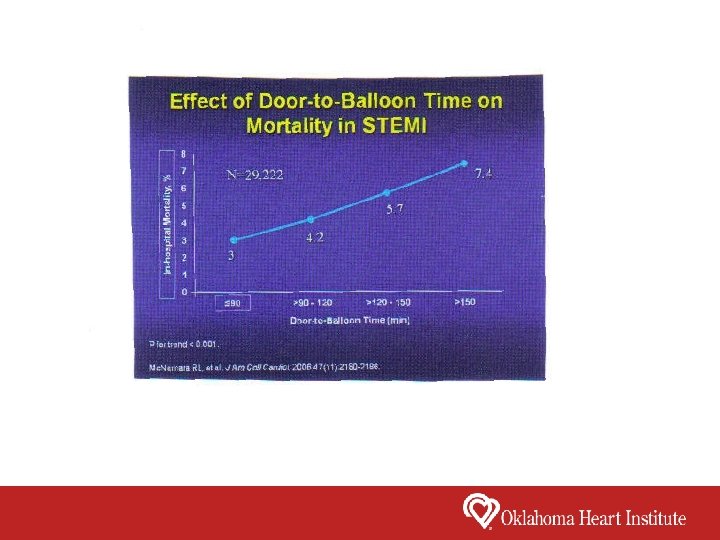

Time Is Muscle

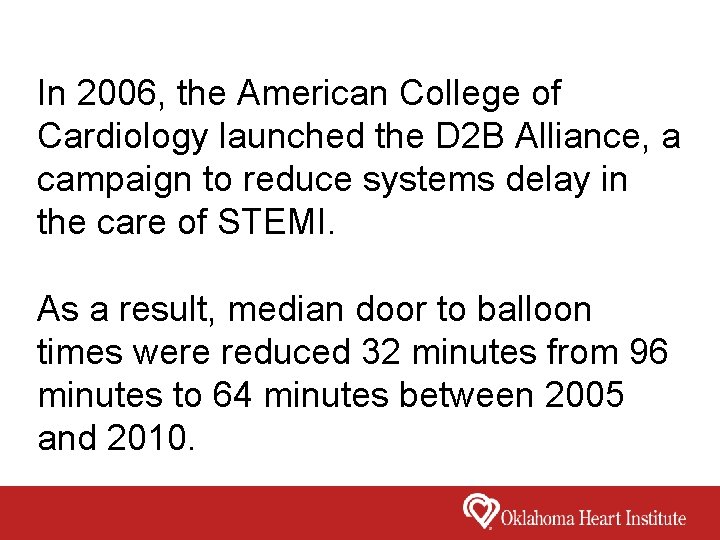

In 2006, the American College of Cardiology launched the D 2 B Alliance, a campaign to reduce systems delay in the care of STEMI. As a result, median door to balloon times were reduced 32 minutes from 96 minutes to 64 minutes between 2005 and 2010.

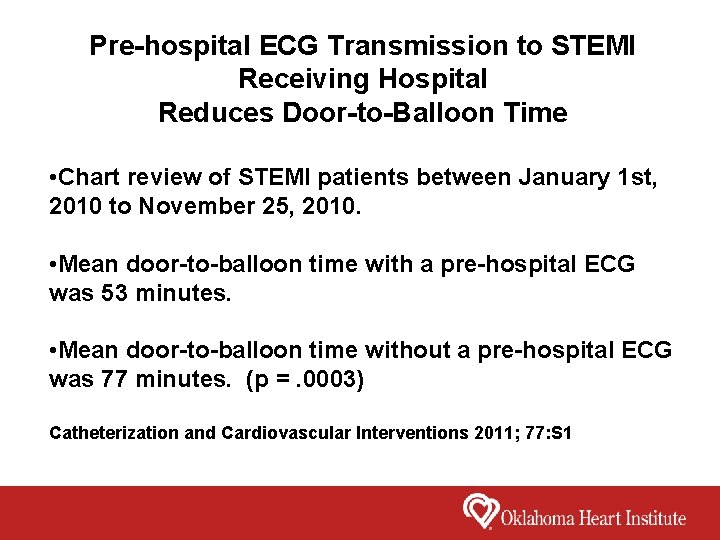

Pre-hospital ECG Transmission to STEMI Receiving Hospital Reduces Door-to-Balloon Time • Chart review of STEMI patients between January 1 st, 2010 to November 25, 2010. • Mean door-to-balloon time with a pre-hospital ECG was 53 minutes. • Mean door-to-balloon time without a pre-hospital ECG was 77 minutes. (p =. 0003) Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 2011; 77: S 1

Acute Treatment of ST-Elevation MI • 4 Aspirin 81 mg chewed • Plavix 600 mg • Heparin 5, 000 units IV • Morphine IV as needed for pain control • Nitrates (NTG – sublingual and IV) – Contraindicated in RV Infarct, Hypotension and severe bradycardia (HR less than 50) • Metoprolol IV – Contraindicated in CHF, Hypotension bradycardia, 1 st degree AV Block, evidence of low-output, asthma, and increased risk of cardiogenic shock

In-Hospital Treatment of ST-Elevation MI • Aspirin • Plavix, Effient, or Ticagrelor (Brilinta) • Beta Blocker (Metoprolol or Carvedilol) • High Dose Statin (Atrovastatin) • ACE Inhibitor (Lisinopril) for LVEF less than 40% and or pulmonary congestion • Aldosterone Antagonist (Aldactone) for CHF

Complications of ST-Elevation MI • • Cardiogenic shock Right Ventricular Infarction Papillary Muscle Rupture Ventricular Septal Rupture Free Wall Rupture Heart Block Ventricular Fibrillation/Ventricular Tachycardia/Atrial Fibrillation

Cardiogenic Shock (7% of Acute MI) • Decreased cardiac output with insufficient tissue perfusion in the presence of adequate intravascular volume • Clinical signs: oliguria, cool, cyanotic extremeties, altered mental status • Hemodynamics; systolic BP less than 90, cardiac index less than 2. 2 and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure greater than 15

Causes of Cardiogenic Shock • Severe LV Dysfunction • Extensive RV Infarction • Mechanical Complications • Acute MR due to papillary muscle rupture or dysfunction • Ventricular Septal Defect • Free wall rupture

Risk Factors for the Development of Cardiogenic Shock • Elderly (Age greater than 70) • Diabetes • Anterior Infarction • Prior MI • 3 Vessel or Left Main Coronary Artery Disease • Early Use of Beta Blockers in Large Infarcts

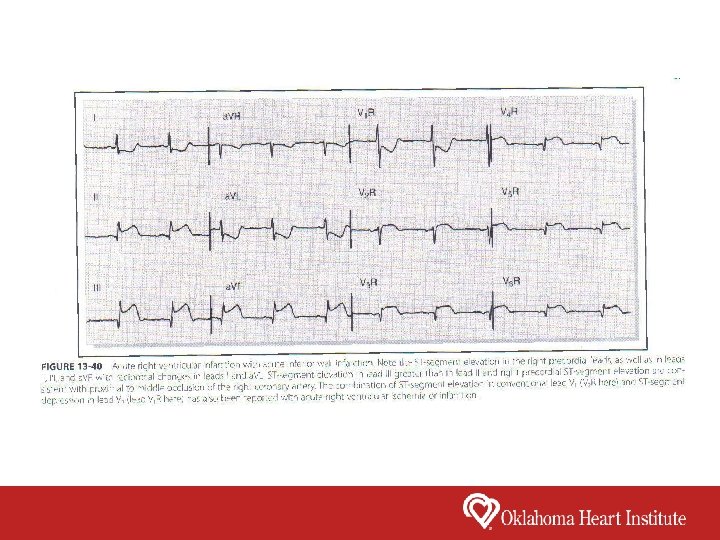

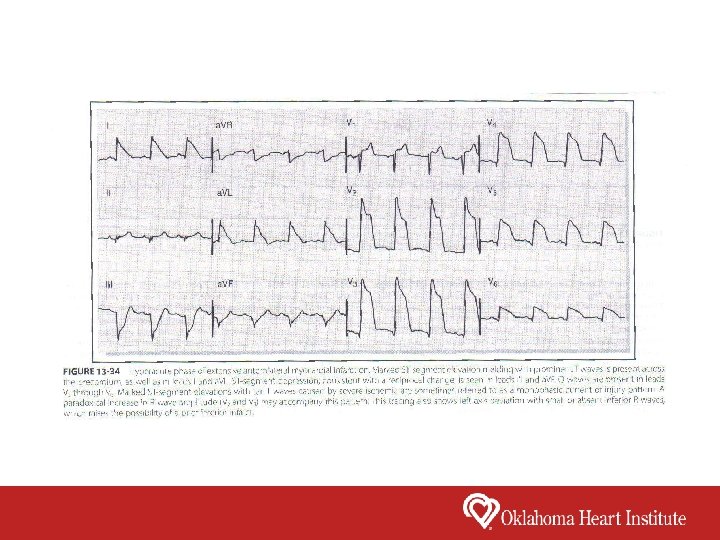

Right Ventricular Infarction • Usually occurs in association with inferior infarction • Clinical findings include shock with clear lungs, elevated jugular venous pressure, Kussmaul sign, and pulsus paradoxus • EKG: ST elevation in right-sided leads V 4 R, V 5 R or V 6 R • Hemodynamics: Elevated Right Atrial Pressure > 12 Normal to low pulmonary pressures Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure < 15 • Management: volume expansion with normal saline IV, prompt reperfusion; nitroglycerin is contraindicated

Acute Mitral Regurgitation Papillary muscle Rupture (90% associated with inferior infarction) • Acute Pulmonary Edema/Cardiogenic Shock • Murmur of MR may be minimal or absent • Diagnosis with Echocardiogram/Transesophageal Echocardiogram • Treatment with Intra-aortic Balloon Pump, Nitroprusside and/or Dobutamine, Mitral Valve Surgery ASAP

Ventricular Septal Defect (55% due to inferior infarction, 45% due to anterior infarction) • Acute onset of biventricular CHF or cardiogenic shock • Holosystolic murmur and a precordial thrill • Diagnosis with Echocardiogram • Treatment with Intra-aortic Balloon Pump, Nitroprusside and/or Dobutamine, eventual surgery • Very high mortality

Free Wall Rupture • LAD, Diagonal or Left Circumflex Coronary Artery Myocardial Infactions. More frequent in elderly patients with a history of hypertension. • Usually presents as a catastrophic event – PEA due to tamponade. Syncope and cardiogenic shock are also common. May have pleuritic chest pain, nausea or restlessness. • Diagnosis with pericardial effusion seen on echocardiogram. • Treatment with emergency surgery, intra-aortic balloon pump.

Peak Time Periods for MI • 6 a. m. – 12 Noon • Monday is the most common day of the week • Top 3 peak days for MI are Christmas day, the day after Christmas, and New Years Day • Spikes in incidence during major sporting events (Superbowl or World Cup) • Spikes in incidence with natural disasters (earthquakes, hurricanes, etc. ) • Recent studies have shown an increased risk of MI after angry outbursts

Higher Risk of MI in the Morning • Surge of stress hormone (cortisol) in the morning • Surge of “fight or flight” (Catecholamines) in the morning • Higher Blood Pressure and Heart Rate • Platelets are more adhesive to the vessel wall in the morning • Natural fibrinolytic system in the body is less active in the morning

Higher Risk of MI in the Winter (Multiple Factors Account for This) • Blood vessels constrict and the blood clots more readily in cold weather • Shoveling snow is a frequent trigger of MI • In Australia, peak MI incidence is in June • Florida, Southern California, and Hawaii also have a peak incidence of MI in the winter months

Higher Risk of MI in the Winter (Multiple Factors Account for This) • Inflammation can trigger a MI by making the coronary plaques less stable • The Flu and respiratory infection cause significant inflammation • The Flu season peaks in the winter months in concert with peak incidence of MI in winter • People eat more, exercise less, smoke more, have more stress, and gain more weight during the holiday season

Higher Risk of MI in the Winter (Multiple Factors Account for This) • Shorter days with less UV radiation which leads to lower Vitamin D levels • Less sunlight and shorter days lead to depression and seasonal affective disorder • People with depression are at an increased risk for developing heart disease • Blood pressure and weight both increase in the winter

The Perfect Storm for a Heart Attack It is Monday morning, the day after Christmas. You are suddenly awakened at 6: 00 a. m. to the shaking and rattling of an Oklahoma earthquake. Because of the surprise of the earthquake, you forget to take your aspirin, plavix, lipitor, metoprolol and metformin. You are angry and depressed because you have just recovered from the flu and you have gained 10 pounds, and you have to go back to work at a high stress job. You have a fight with your father-in-law because he is invading your space and getting on your nerves. For comfort, you eat a large piece of pecan pie and drink a large glass of eggnog for breakfast, and then you smoke a cigarette. At 7: 00 a. m. , you go out into the freezing cold to shovel a foot of snow off of your driveway and it is a full moon. We all know what happens next……. .

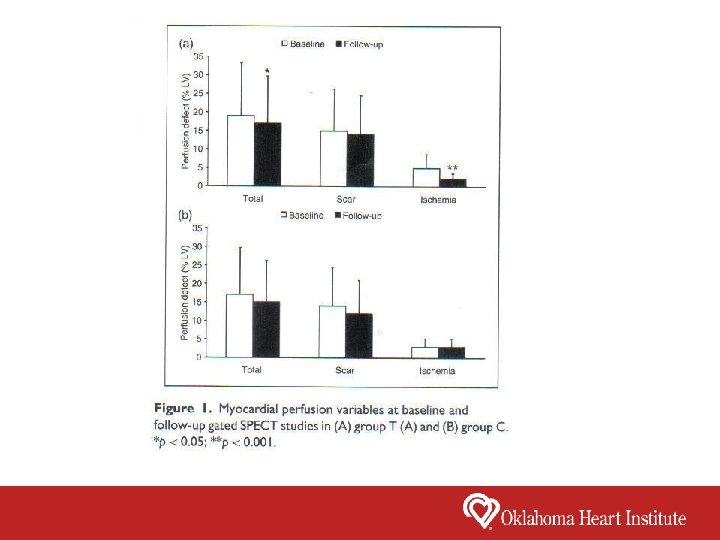

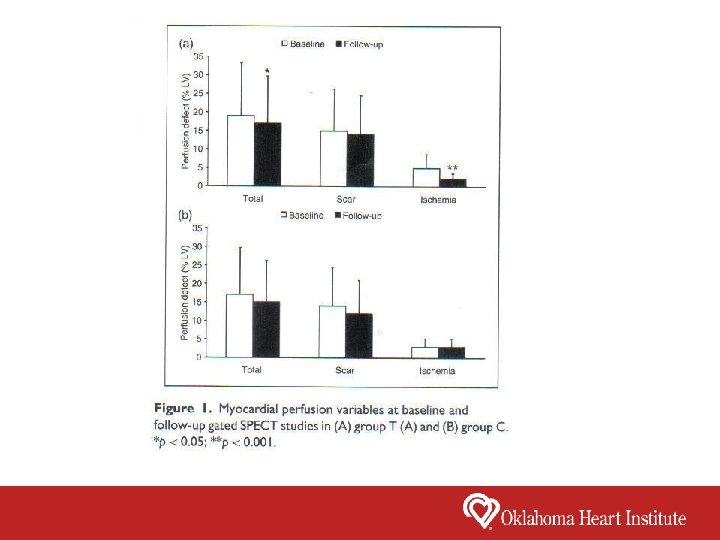

• 50 patients with recent STEMI were randomized into two groups. • 24 enrolled in a 6 month exercise-based cardiac rehab program (Group T) • 26 were discharged with generic instructions for maintaining physical activity and correct lifestyle (Group C) • All patients had an exercise myocardial perfusion study and a cardiopulmonary exercise within 3 weeks after STEMI and at 6 months European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 2012 Dec; 19 (6) 1410 - 1419

At follow up, the cardiac rehab group (Group T) had: • a significant reduction of stress-induced ischemia (p < 0. 001) • improvement in resting and post-stress wall motion (p < 0. 005) • improvement in peak oxygen consumption (p < 0. 001) At follow up, the generic instructions group (Group C) had no change in myocardial perfusion parameters, LV function, and cardiopulmonary indexes.

Secondary Prevention 10 Aspects of Treatment q Smoking q Diabetes q Blood Pressure Control q Antiplatelet agents/anticoagulants q Lipids q RAS Blockers q Physical Activity q Influenza Vaccine q Weight

Benefits of Cardiac Rehabilitation • 20 – 30% reduction in all-cause mortality rates • Decreases mortality at up to 5 years post participation • Reduced symptoms (angina, dyspnea, fatigue) • Reduction in non-fatal recurrent myocardial infarction over a median follow-up 12 months.

Benefits of Cardiac Rehabilitation • Improves adherence with preventive medications • Increased exercise performance • Improved lipids (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and triglycerides) • Improved knowledge about cardiac disease and its management • Enhanced ability to perform activities of daily living

Benefits of Cardiac Rehabilitation • Improved health-related quality of life • Improved psychosocial symptoms and increased selfefficacy • Reduced hospitalization and use of medical resources • Return to work or leisure activities

Summary • In the USA, cardiovascular deaths have declined markedly since the 1960 s. • Rates of death from CHD have declined in most high income countries but are increasing in the developing world. • In the USA, the prevalence of risk factors are all decreasing except for diabetes. • Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory process that develops in “response to injury”. • Most commonly, STEMI occurs secondary to plaque rupture or plaque erosion with total occlusion of the coronary artery with thrombus. • Coronary plaques prone to rupture have a thin fibrous cap with a lipid rich core with a lot of inflammation (T - lymphocytes and macrophages)

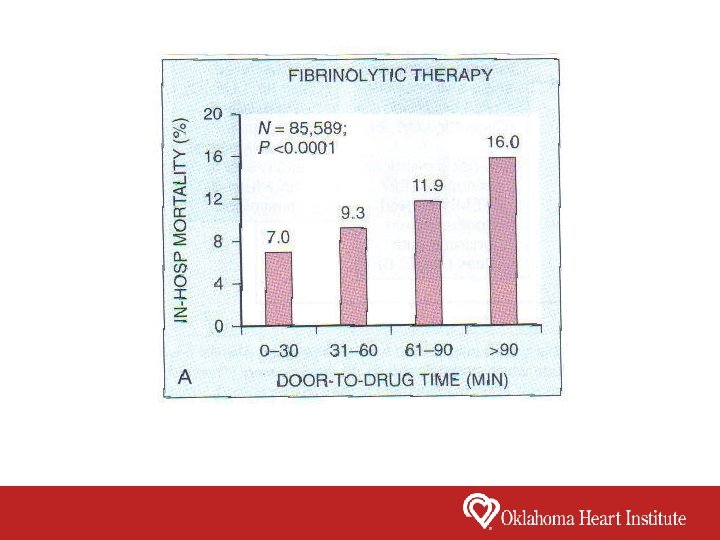

Summary • Triggers of plaque rupture include emotional stress, physical activity and increased sympathetic tone. • Higher risk of mortality and complications in STEMI with a late presentation, inadequate reperfusion or delayed reperfusion. • Higher incidence of MI on Mondays, 6 a. m. to 12 Noon, in the winter, around the holidays, and during flu season. • Higher incidence of MI during natural disasters and with people who have a history of depression and angry outbursts. • Cardiac Rehab has been show to reduce myocardial ischemia. • Cardiac Rehab leads to a 20 – 30% reduction in all cause mortality and a reduction in non-fatal recurrent myocardial infarction.