snick snack CPSC 121 Models of Computation 2010

![English-Language Generally Faster Definitions Which one do you want? [Your definitions here. ] a. English-Language Generally Faster Definitions Which one do you want? [Your definitions here. ] a.](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bb051f998153e384fabe04e5fb54c96/image-48.jpg)

![Formal Generally Faster Definitions Which one do you want? [Your definitions here. ] a. Formal Generally Faster Definitions Which one do you want? [Your definitions here. ] a.](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bb051f998153e384fabe04e5fb54c96/image-49.jpg)

- Slides: 74

snick snack CPSC 121: Models of Computation 2010 Winter Term 2 Describing the World with Predicate Logic Steve Wolfman, based on notes by Patrice Belleville and others 1

Outline • Prereqs, Learning Goals, and Quiz Notes • Prelude: Scope and Predicate Definition • Problems and Discussion – Liszt Etudes – Sorted Lists – Comparing Algorithms • Next Lecture Notes 2

Learning Goals: Pre-Class By the start of class, you should be able to: – Evaluate the truth of predicates applied to particular values. – Show predicate logic statements are true by enumerating examples (i. e. , all examples in the domain for a universal or one for an existential). – Show predicate logic statements are false by enumerating counterexamples (i. e. , one counterexample for universals or all in the domain for existentials). – Translate between statements in formal predicate logic notation and equivalent statements in closely matching informal language (i. e. , informal statements with clear and explicitly stated quantifiers). 6

Learning Goals: In-Class By the end of this unit, you should be able to: – Build statements about the relationships between properties of various objects—which may be real-world like “every candidate got votes from at least two people in every province” or computing related like “on the ith repetition of this algorithm, the variable min contains the smallest element in the list between element 0 and element i”)—using predicate logic. 7

Outline • Prereqs, Learning Goals, and Quiz Notes • Prelude: Motivation, Scope & Defining Predicates • Problems and Discussion – Liszt Etudes – Sorted Lists – Comparing Algorithms • Next Lecture Notes 8

Limitations of Propositional Logic as a Model Which of the following can propositional logic model effectively? a. Relationships among factory production lines (e. g. , “wheel assembly” and “frame welding” both feed the undercarriage line). b. Defining what it means for a number to be prime. c. Generalizing from examples to abstract patterns like “everyone takes off their shoes at airport security”. d. Prop logic can model all of these effectively. e. Prop logic cannot model any of these effectively. 9

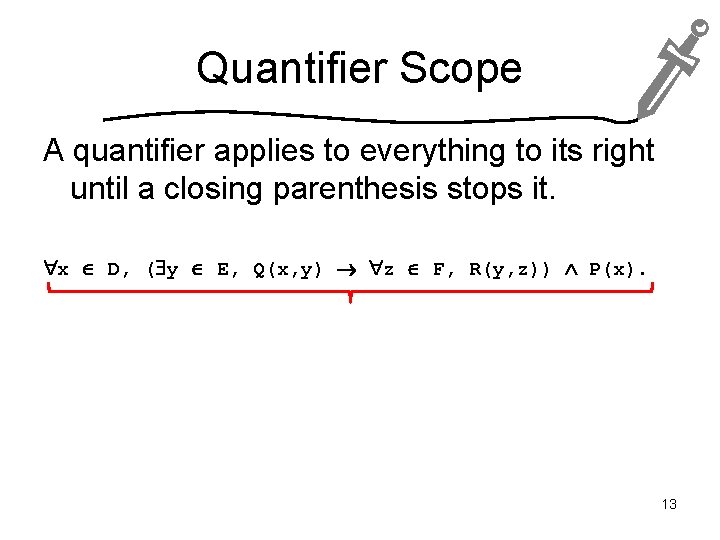

What Does Predicate Logic Model? Propositional logic is a good (but not perfect) model of combinational circuits. What is predicate logic good for modeling? • Relationships among real-world objects • Generalizations about patterns • Infinite domains • Generally, problems where the properties of different concepts, ideas, parts, or entities depend on each other. 10

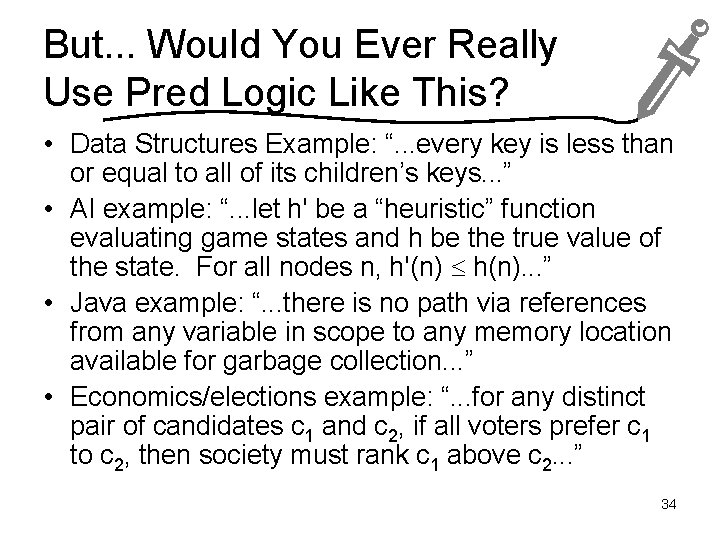

But. . . Would You Ever Really Use Pred Logic Like This? • Data Structures Example: “. . . every key is less than or equal to all of its children’s keys. . . ” • AI example: “. . . let h' be a “heuristic” function evaluating game states and h be the true value of the state. For all nodes n, h'(n) h(n). . . ” • Java example: “. . . there is no path via references from any variable in scope to any memory location available for garbage collection. . . ” • Economics/elections example: “. . . for any distinct pair of candidates c 1 and c 2, if all voters prefer c 1 to c 2, then society must rank c 1 above c 2. . . ” 11

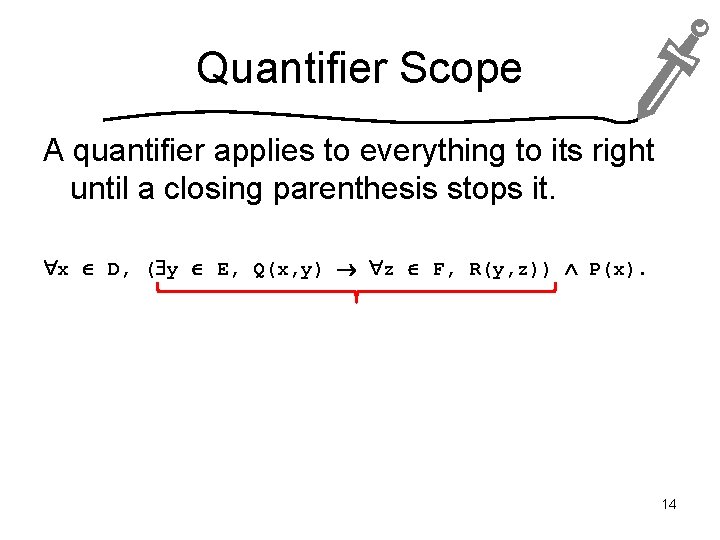

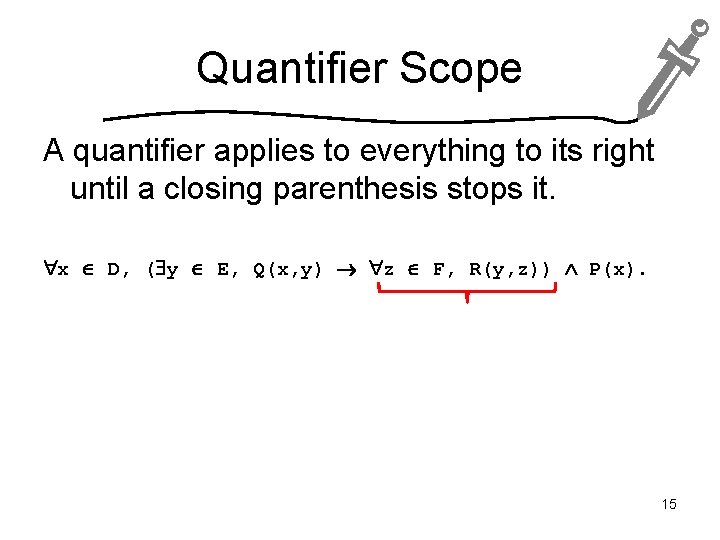

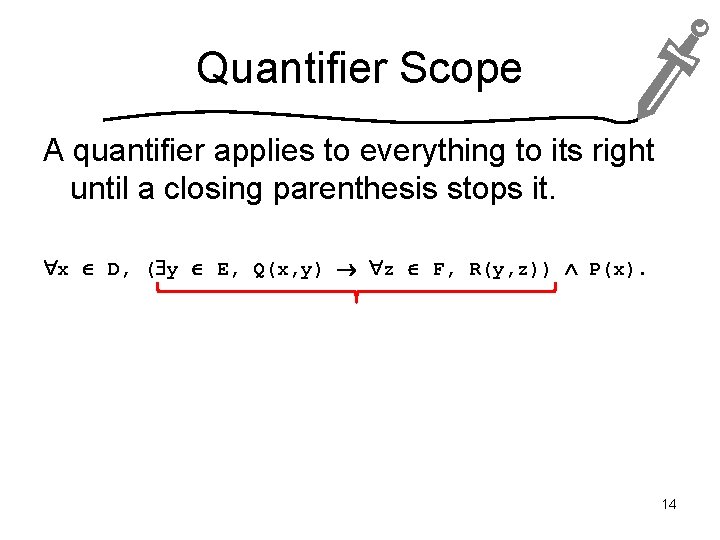

Quantifier Scope A quantifier applies to everything to its right until a closing parenthesis stops it. 12

Quantifier Scope A quantifier applies to everything to its right until a closing parenthesis stops it. x D, ( y E, Q(x, y) z F, R(y, z)) P(x). 13

Quantifier Scope A quantifier applies to everything to its right until a closing parenthesis stops it. x D, ( y E, Q(x, y) z F, R(y, z)) P(x). 14

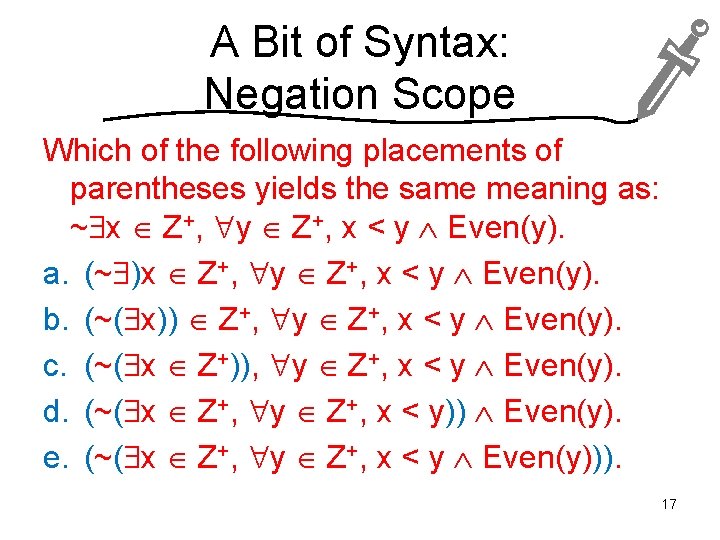

Quantifier Scope A quantifier applies to everything to its right until a closing parenthesis stops it. x D, ( y E, Q(x, y) z F, R(y, z)) P(x). 15

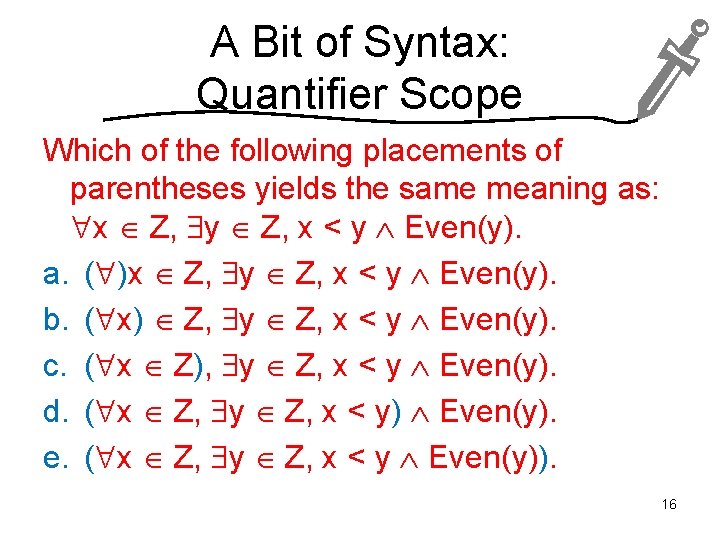

A Bit of Syntax: Quantifier Scope Which of the following placements of parentheses yields the same meaning as: x Z, y Z, x < y Even(y). a. ( )x Z, y Z, x < y Even(y). b. ( x) Z, y Z, x < y Even(y). c. ( x Z), y Z, x < y Even(y). d. ( x Z, y Z, x < y) Even(y). e. ( x Z, y Z, x < y Even(y)). 16

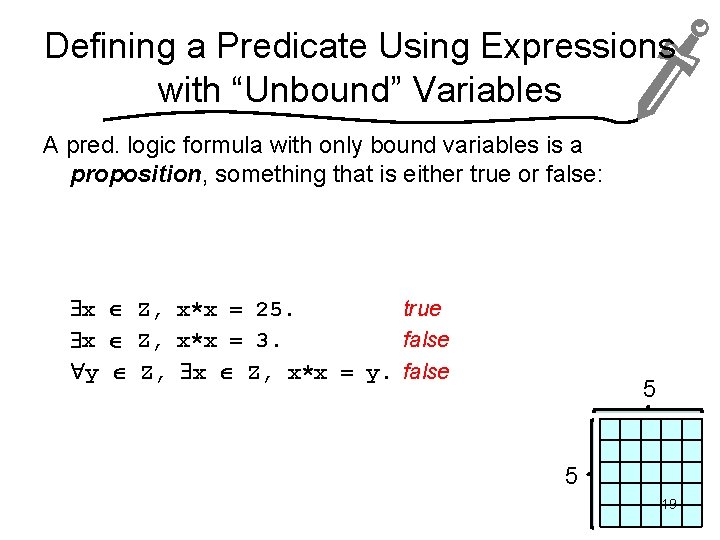

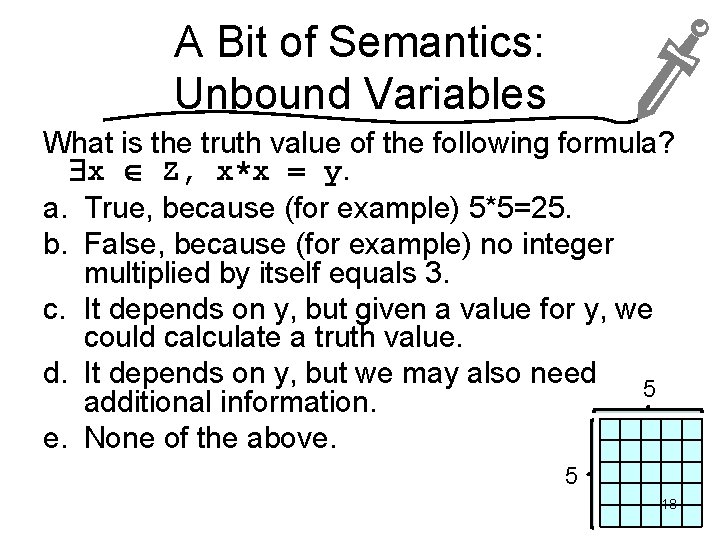

A Bit of Syntax: Negation Scope Which of the following placements of parentheses yields the same meaning as: ~ x Z+, y Z+, x < y Even(y). a. (~ )x Z+, y Z+, x < y Even(y). b. (~( x)) Z+, y Z+, x < y Even(y). c. (~( x Z+)), y Z+, x < y Even(y). d. (~( x Z+, y Z+, x < y)) Even(y). e. (~( x Z+, y Z+, x < y Even(y))). 17

A Bit of Semantics: Unbound Variables What is the truth value of the following formula? x Z, x*x = y. a. True, because (for example) 5*5=25. b. False, because (for example) no integer multiplied by itself equals 3. c. It depends on y, but given a value for y, we could calculate a truth value. d. It depends on y, but we may also need 5 additional information. e. None of the above. 5 18

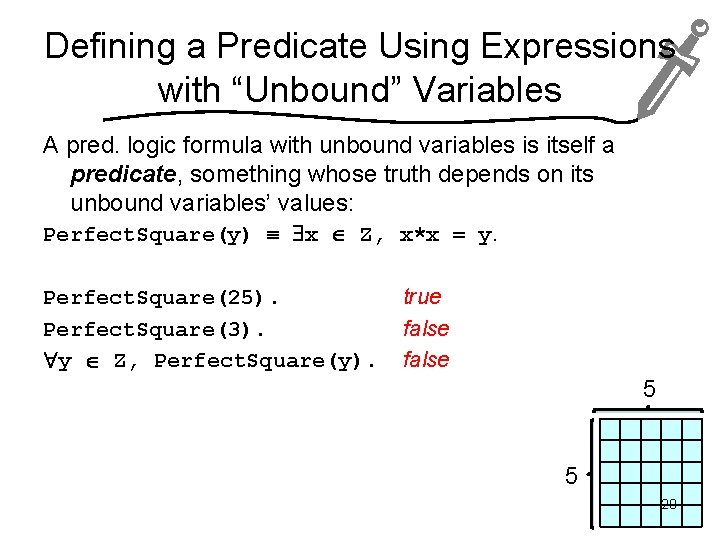

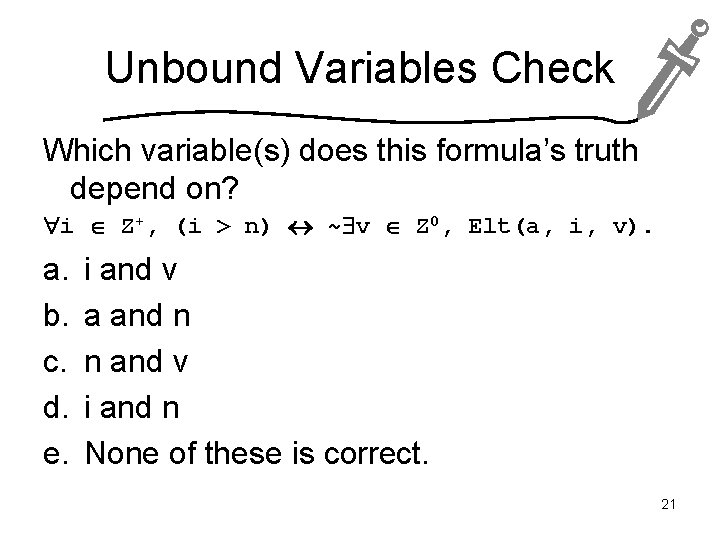

Defining a Predicate Using Expressions with “Unbound” Variables A pred. logic formula with only bound variables is a proposition, something that is either true or false: x Z, x*x = 25. true x Z, x*x = 3. false y Z, x Z, x*x = y. false 5 5 19

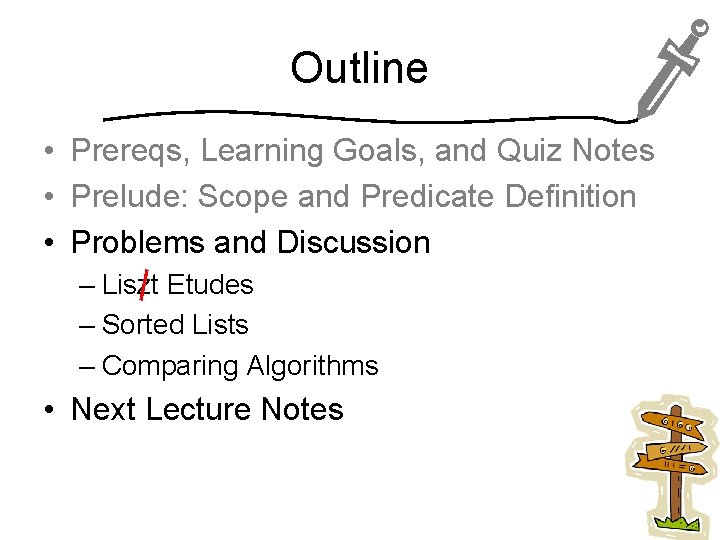

Defining a Predicate Using Expressions with “Unbound” Variables A pred. logic formula with unbound variables is itself a predicate, something whose truth depends on its unbound variables’ values: Perfect. Square(y) x Z, x*x = y. Perfect. Square(25). Perfect. Square(3). y Z, Perfect. Square(y). true false 5 5 20

Unbound Variables Check Which variable(s) does this formula’s truth depend on? i Z+, (i > n) ~ v Z 0, Elt(a, i, v). a. b. c. d. e. i and v a and n n and v i and n None of these is correct. 21

Outline • Prereqs, Learning Goals, and Quiz Notes • Prelude: Scope and Predicate Definition • Problems and Discussion – Liszt Etudes – Sorted Lists – Comparing Algorithms • Next Lecture Notes 22

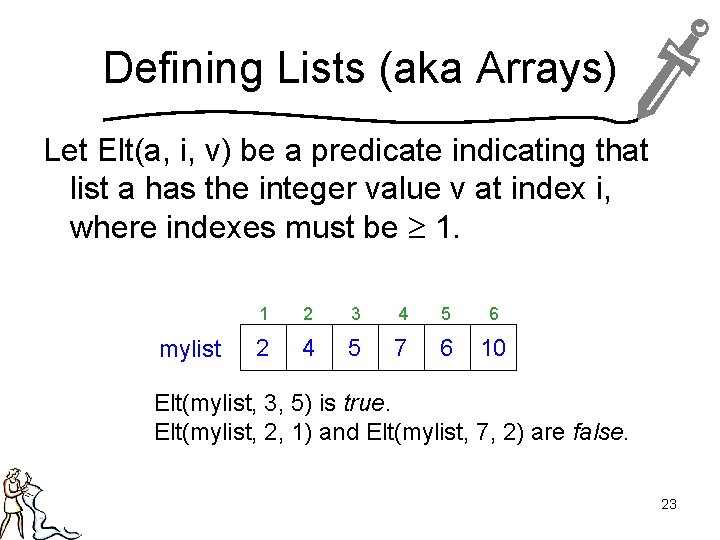

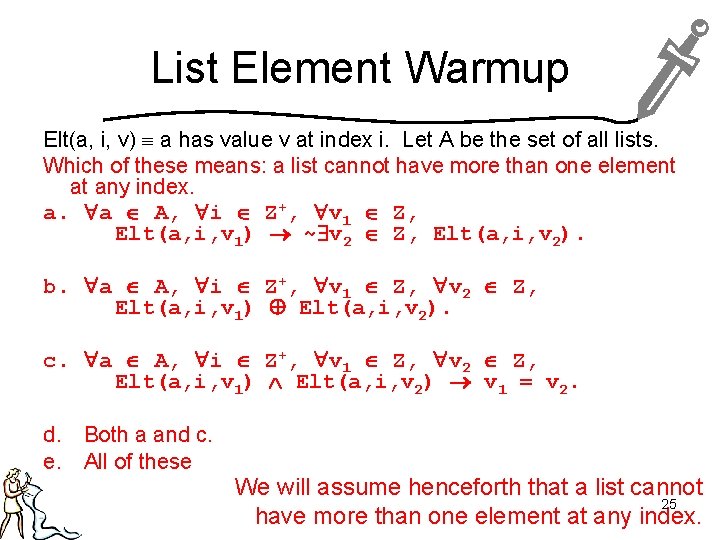

Defining Lists (aka Arrays) Let Elt(a, i, v) be a predicate indicating that list a has the integer value v at index i, where indexes must be 1. mylist 1 2 3 4 5 6 2 4 5 7 6 10 Elt(mylist, 3, 5) is true. Elt(mylist, 2, 1) and Elt(mylist, 7, 2) are false. 23

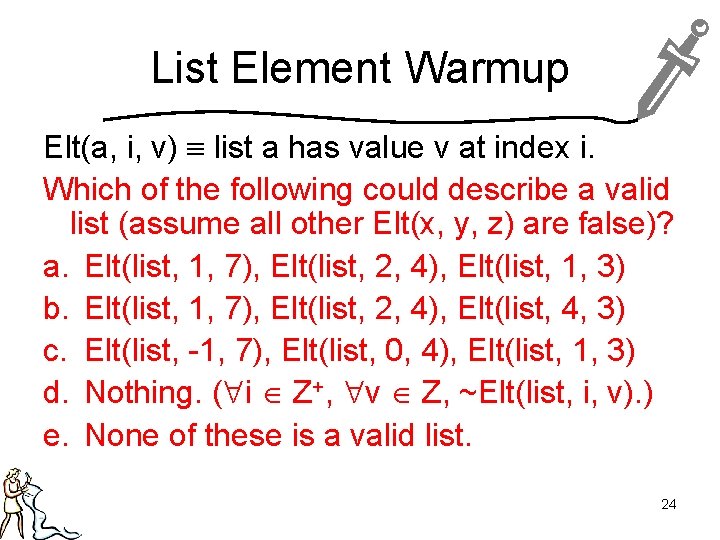

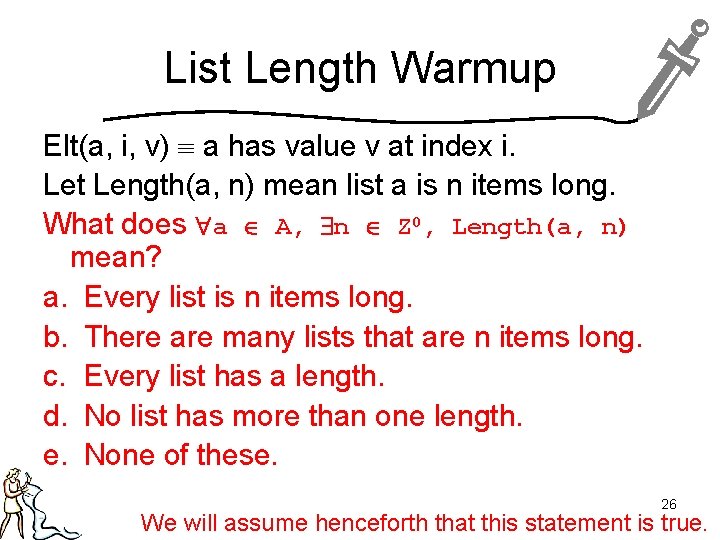

List Element Warmup Elt(a, i, v) list a has value v at index i. Which of the following could describe a valid list (assume all other Elt(x, y, z) are false)? a. Elt(list, 1, 7), Elt(list, 2, 4), Elt(list, 1, 3) b. Elt(list, 1, 7), Elt(list, 2, 4), Elt(list, 4, 3) c. Elt(list, -1, 7), Elt(list, 0, 4), Elt(list, 1, 3) d. Nothing. ( i Z+, v Z, ~Elt(list, i, v). ) e. None of these is a valid list. 24

List Element Warmup Elt(a, i, v) a has value v at index i. Let A be the set of all lists. Which of these means: a list cannot have more than one element at any index. a. a A, i Z+, v 1 Z, Elt(a, i, v 1) ~ v 2 Z, Elt(a, i, v 2). b. a A, i Z+, v 1 Z, v 2 Z, Elt(a, i, v 1) Elt(a, i, v 2). c. a A, i Z+, v 1 Z, v 2 Z, Elt(a, i, v 1) Elt(a, i, v 2) v 1 = v 2. d. Both a and c. e. All of these We will assume henceforth that a list cannot 25 have more than one element at any index.

List Length Warmup Elt(a, i, v) a has value v at index i. Let Length(a, n) mean list a is n items long. What does a A, n Z 0, Length(a, n) mean? a. Every list is n items long. b. There are many lists that are n items long. c. Every list has a length. d. No list has more than one length. e. None of these. 26 We will assume henceforth that this statement is true.

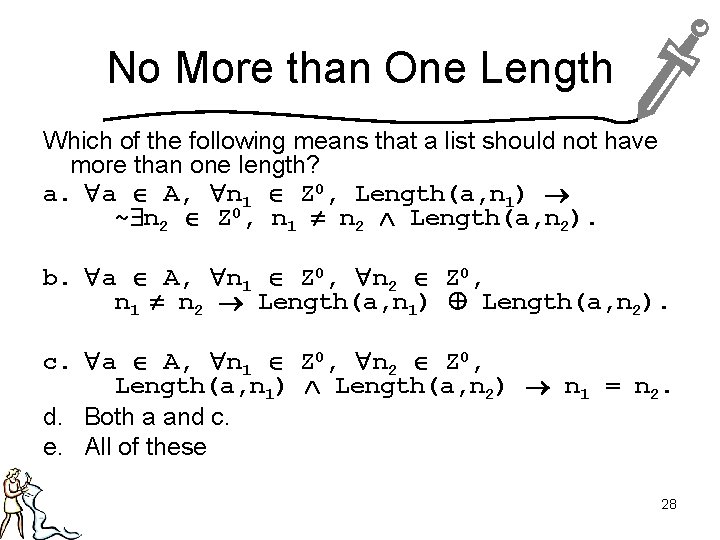

List Length Properties Which of the following should not be true of the length of a list? a. Every list should have a length. b. No list should have more than one length. c. No list should have elements at any index larger than its length. d. A list should have an element at every index up to its length. e. All of these should be true. 27

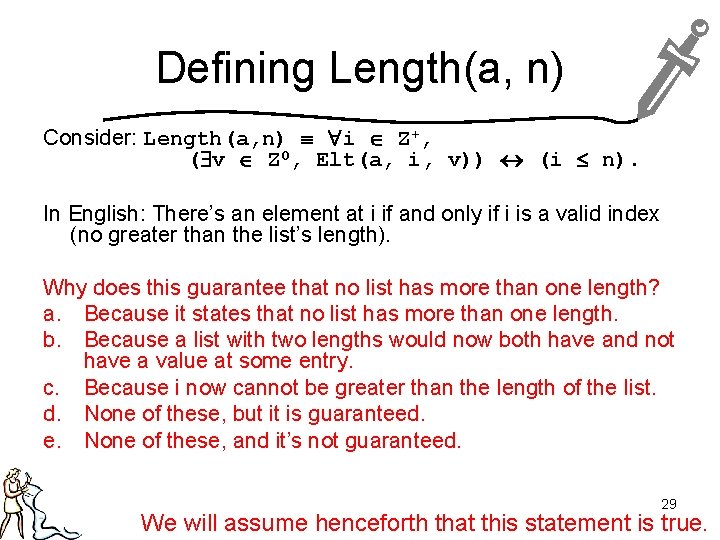

No More than One Length Which of the following means that a list should not have more than one length? a. a A, n 1 Z 0, Length(a, n 1) ~ n 2 Z 0, n 1 n 2 Length(a, n 2). b. a A, n 1 Z 0, n 2 Z 0, n 1 n 2 Length(a, n 1) Length(a, n 2). c. a A, n 1 Z 0, n 2 Z 0, Length(a, n 1) Length(a, n 2) n 1 = n 2. d. Both a and c. e. All of these 28

Defining Length(a, n) Consider: Length(a, n) i Z+, ( v Z 0, Elt(a, i, v)) (i n). In English: There’s an element at i if and only if i is a valid index (no greater than the list’s length). Why does this guarantee that no list has more than one length? a. Because it states that no list has more than one length. b. Because a list with two lengths would now both have and not have a value at some entry. c. Because i now cannot be greater than the length of the list. d. None of these, but it is guaranteed. e. None of these, and it’s not guaranteed. 29 We will assume henceforth that this statement is true.

Outline • Prereqs, Learning Goals, and Quiz Notes • Prelude: Scope and Predicate Definition • Problems and Discussion – Liszt Etudes – Sorted Lists – Comparing Algorithms • Next Lecture Notes 30

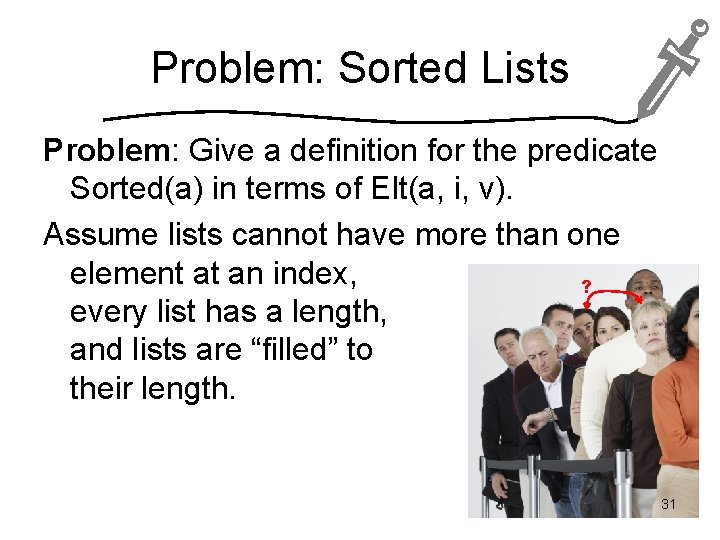

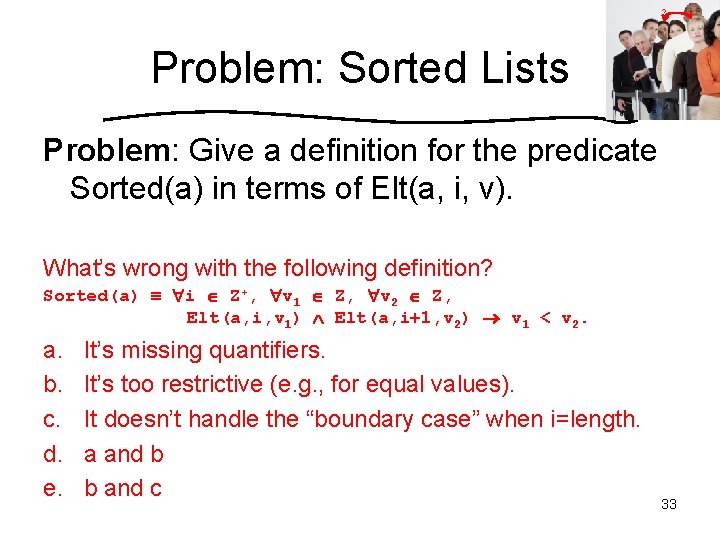

Problem: Sorted Lists Problem: Give a definition for the predicate Sorted(a) in terms of Elt(a, i, v). Assume lists cannot have more than one element at an index, ? every list has a length, and lists are “filled” to their length. 31

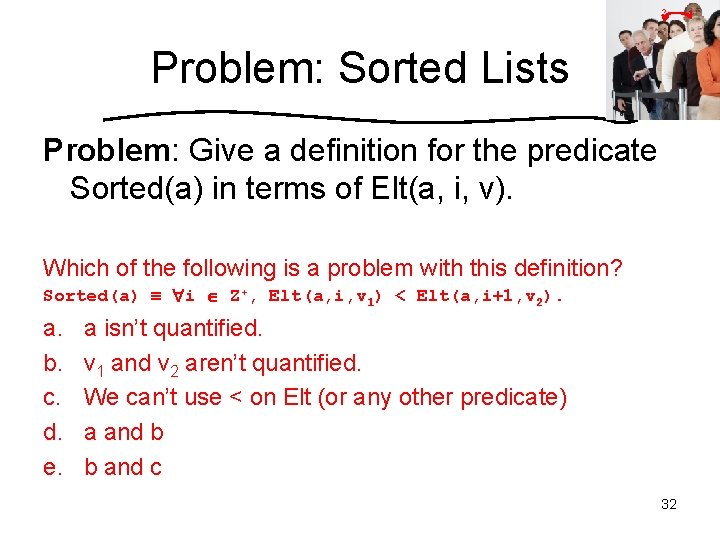

? Problem: Sorted Lists Problem: Give a definition for the predicate Sorted(a) in terms of Elt(a, i, v). Which of the following is a problem with this definition? Sorted(a) i Z+, Elt(a, i, v 1) < Elt(a, i+1, v 2). a. b. c. d. e. a isn’t quantified. v 1 and v 2 aren’t quantified. We can’t use < on Elt (or any other predicate) a and b b and c 32

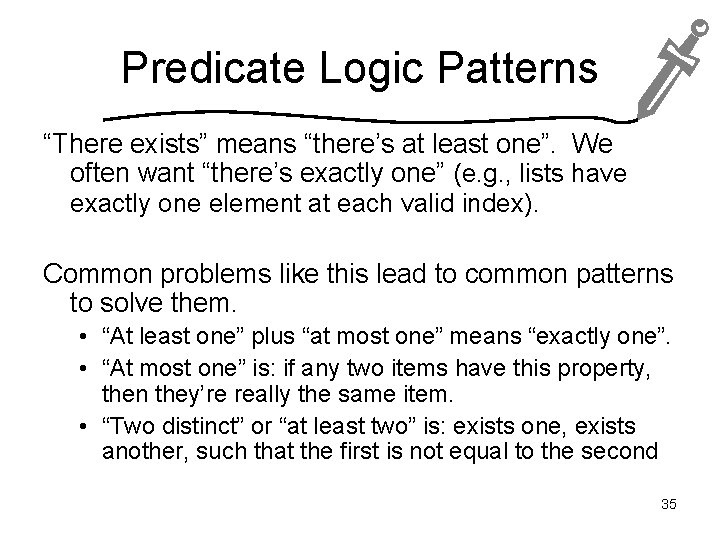

? Problem: Sorted Lists Problem: Give a definition for the predicate Sorted(a) in terms of Elt(a, i, v). What’s wrong with the following definition? Sorted(a) i Z+, v 1 Z, v 2 Z, Elt(a, i, v 1) Elt(a, i+1, v 2) v 1 < v 2. a. b. c. d. e. It’s missing quantifiers. It’s too restrictive (e. g. , for equal values). It doesn’t handle the “boundary case” when i=length. a and b b and c 33

But. . . Would You Ever Really Use Pred Logic Like This? • Data Structures Example: “. . . every key is less than or equal to all of its children’s keys. . . ” • AI example: “. . . let h' be a “heuristic” function evaluating game states and h be the true value of the state. For all nodes n, h'(n) h(n). . . ” • Java example: “. . . there is no path via references from any variable in scope to any memory location available for garbage collection. . . ” • Economics/elections example: “. . . for any distinct pair of candidates c 1 and c 2, if all voters prefer c 1 to c 2, then society must rank c 1 above c 2. . . ” 34

Predicate Logic Patterns “There exists” means “there’s at least one”. We often want “there’s exactly one” (e. g. , lists have exactly one element at each valid index). Common problems like this lead to common patterns to solve them. • “At least one” plus “at most one” means “exactly one”. • “At most one” is: if any two items have this property, then they’re really the same item. • “Two distinct” or “at least two” is: exists one, exists another, such that the first is not equal to the second 35

Intuition ♥ Formality “. . . when we become comfortable with formal manipulations, we can use them to check our intuition, and then we can use our intuition to check our formal manipulations. ” - Epp (3 rd ed), p. 106 -107 We’ll often use predicate logic informally in the future, but the ability to express and reason about ideas formally keeps us honest and helps us discover points we may overlook otherwise. 36

Outline • Prereqs, Learning Goals, and Quiz Notes • Prelude: Scope and Predicate Definition • Problems and Discussion – Liszt Etudes – Sorted Lists – Comparing Algorithms • Next Lecture Notes 37

Efficiency of Algorithms Let’s say each student is in a “MUG” (1 st year orientation group). For each of their MUG-mates, each student has a list of all of their classes. Assume each MUG has 13 students and each student is taking 5 classes. I want to determine how many students in my class have a MUG-mate in my class. 38

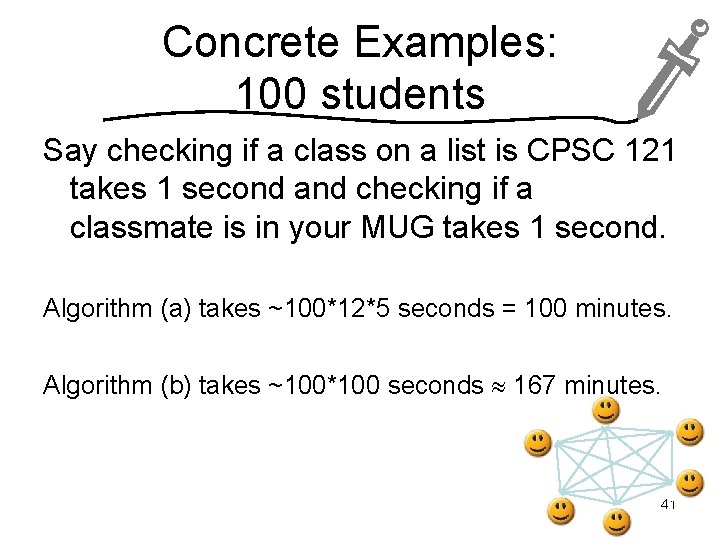

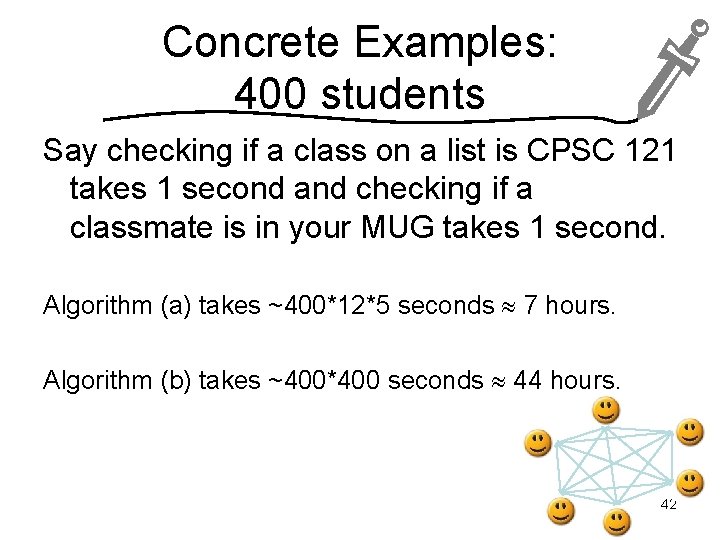

Which algorithm is generally faster? (a) Ask each student for the list of their MUGmates’ classes, and check for each class whether it is CPSC 121. If the answer is ever yes, include the student in my count. (b) For each student s 1 in the class, ask the student for each other student s 2 in the class whether s 2 is a MUG-mate. If the answer is ever yes, include s 1 in my count. (c) Neither. 39

Concrete Examples: 10 students Say checking if a class on a list is CPSC 121 takes 1 second and checking if a classmate is in your MUG takes 1 second. Algorithm (a) takes ~10*12*5 seconds = 10 minutes. Algorithm (b) takes ~10*10 seconds < 2 minutes. 40

Concrete Examples: 100 students Say checking if a class on a list is CPSC 121 takes 1 second and checking if a classmate is in your MUG takes 1 second. Algorithm (a) takes ~100*12*5 seconds = 100 minutes. Algorithm (b) takes ~100*100 seconds 167 minutes. 41

Concrete Examples: 400 students Say checking if a class on a list is CPSC 121 takes 1 second and checking if a classmate is in your MUG takes 1 second. Algorithm (a) takes ~400*12*5 seconds 7 hours. Algorithm (b) takes ~400*400 seconds 44 hours. 42

Which algorithm is generally faster? (a) Ask each student for the list of their MUGmates’ classes, and check for each class whether it is CPSC 121. If the answer is ever yes, include the student in my count. (b) For each student s 1 in the class, ask the student for each other student s 2 in the class whether s 2 is a MUG-mate. If the answer is ever yes, include s 1 in my count. (c) Neither. 43

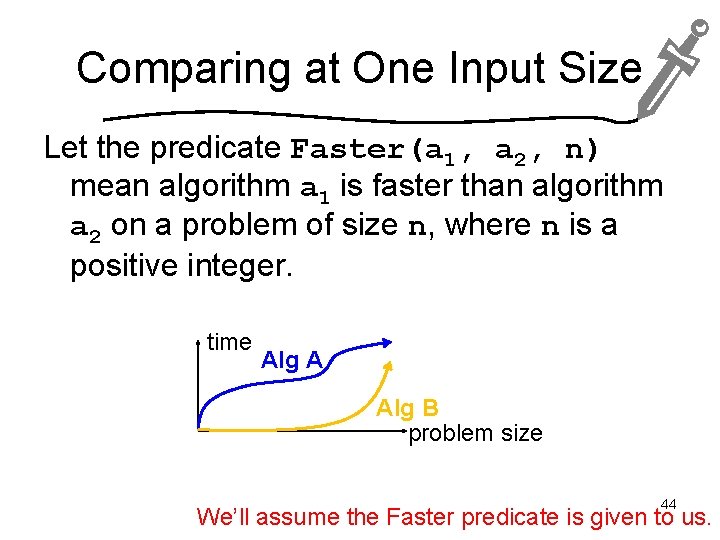

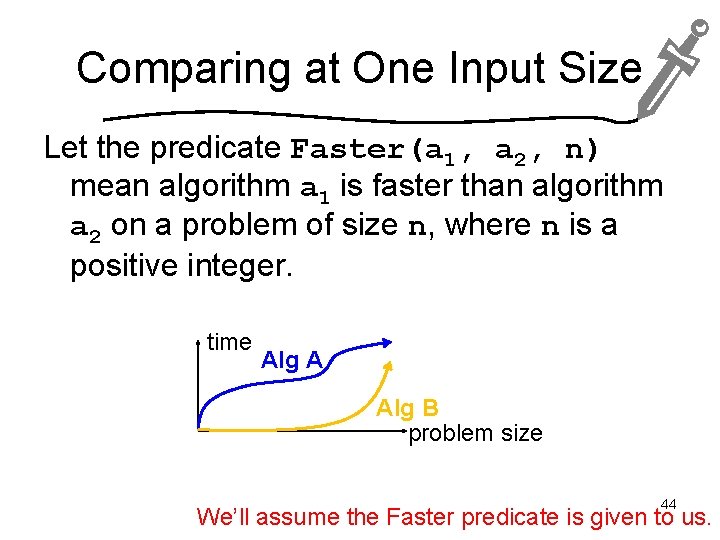

Comparing at One Input Size Let the predicate Faster(a 1, a 2, n) mean algorithm a 1 is faster than algorithm a 2 on a problem of size n, where n is a positive integer. time Alg A Alg B problem size 44 We’ll assume the Faster predicate is given to us.

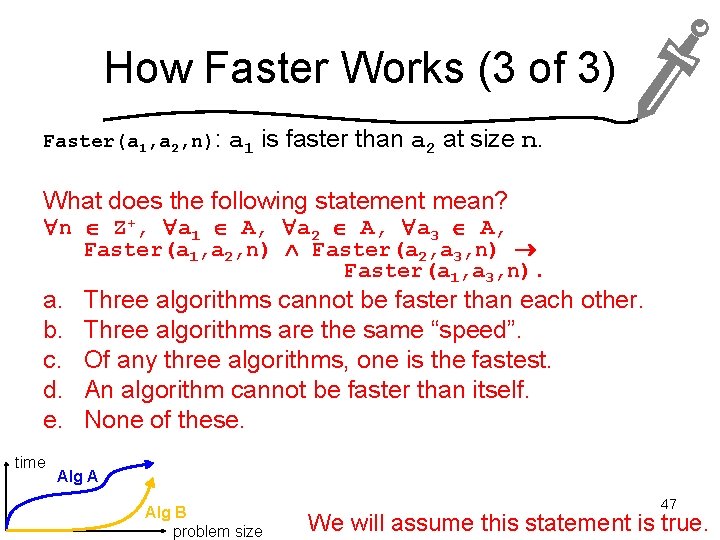

How Faster Works (1 of 3) Faster(a 1, a 2, n): a 1 is faster than a 2 at size n. Which of the following means “no algorithm is ever faster than itself”? a. n Z+, a A, ~Faster(a, a, n). b. n Z+, a 1 A, a 2 A, Faster(a 1, a 2, n) ~Faster(a 2, a 1, n). c. n Z+, a 1 A, a 2 A, a 3 A, Faster(a 1, a 2, n) Faster(a 2, a 3, n) Faster(a 1, a 3, n). d. None of these. time Alg A Alg B problem size 45 We will assume this statement is true.

How Faster Works (2 of 3) Faster(a 1, a 2, n): a 1 is faster than a 2 at size n. Which of the following means “two algorithms cannot be faster than each other”? a. n Z+, a 1 A, Faster(a 1, a 2, n) b. n Z+, a 1 A, Faster(a 1, a 2, n) c. n Z+, a 1 A, Faster(a 1, a 2, n) d. b and c. e. All of these. time a 2 A, ~Faster(a 2, a 1, n). a 2 A, Faster(a 2, a 1, n). Alg A Alg B problem size 46 We will assume this statement is true.

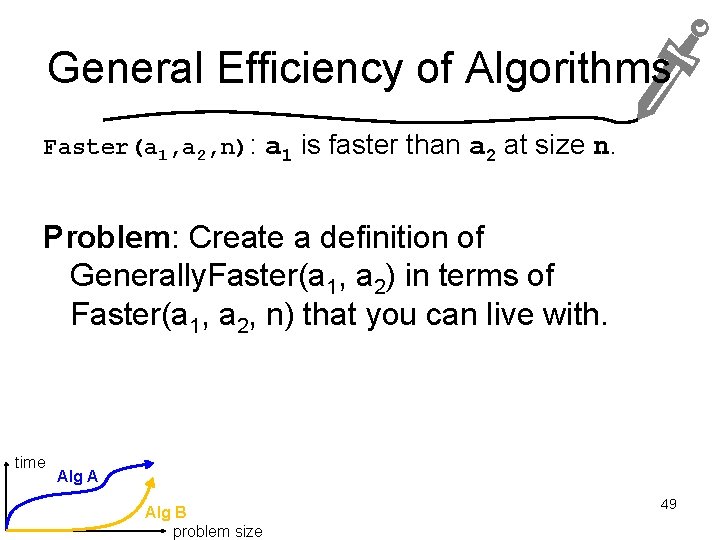

How Faster Works (3 of 3) Faster(a 1, a 2, n): a 1 is faster than a 2 at size n. What does the following statement mean? n Z+, a 1 A, a 2 A, a 3 A, Faster(a 1, a 2, n) Faster(a 2, a 3, n) Faster(a 1, a 3, n). a. b. c. d. e. time Three algorithms cannot be faster than each other. Three algorithms are the same “speed”. Of any three algorithms, one is the fastest. An algorithm cannot be faster than itself. None of these. Alg A Alg B problem size 47 We will assume this statement is true.

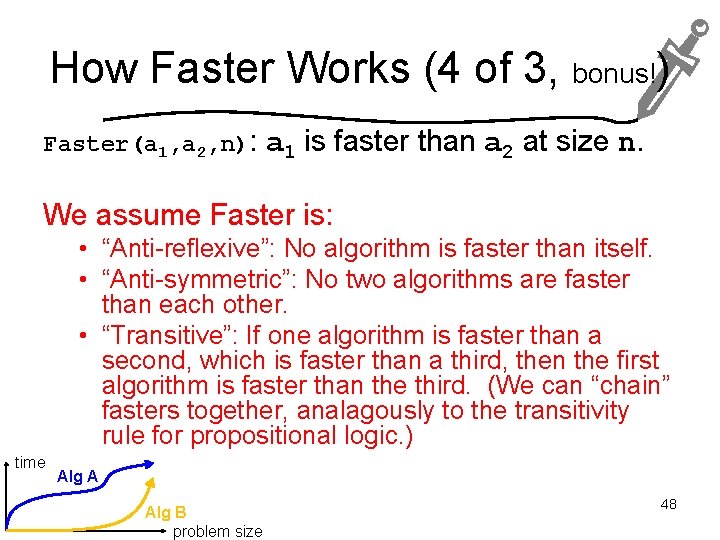

How Faster Works (4 of 3, bonus!) Faster(a 1, a 2, n): a 1 is faster than a 2 at size n. We assume Faster is: • “Anti-reflexive”: No algorithm is faster than itself. • “Anti-symmetric”: No two algorithms are faster than each other. • “Transitive”: If one algorithm is faster than a second, which is faster than a third, then the first algorithm is faster than the third. (We can “chain” fasters together, analagously to the transitivity rule for propositional logic. ) time Alg A Alg B problem size 48

General Efficiency of Algorithms Faster(a 1, a 2, n): a 1 is faster than a 2 at size n. Problem: Create a definition of Generally. Faster(a 1, a 2) in terms of Faster(a 1, a 2, n) that you can live with. time Alg A Alg B problem size 49

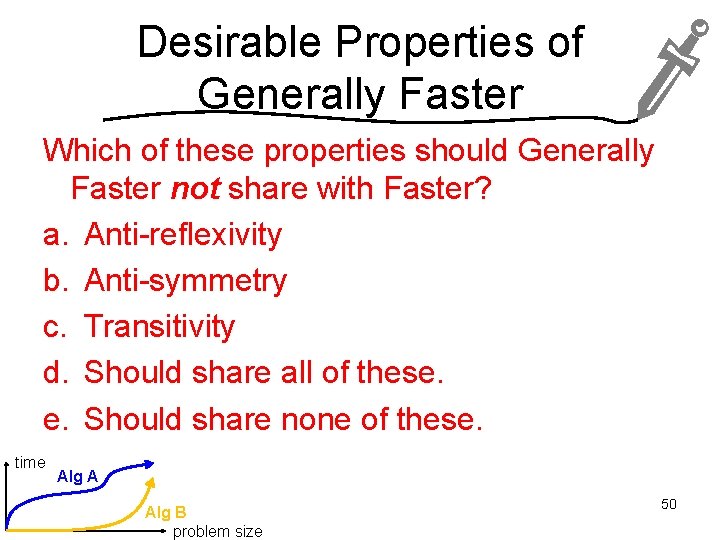

Desirable Properties of Generally Faster Which of these properties should Generally Faster not share with Faster? a. Anti-reflexivity b. Anti-symmetry c. Transitivity d. Should share all of these. e. Should share none of these. time Alg A Alg B problem size 50

![EnglishLanguage Generally Faster Definitions Which one do you want Your definitions here a English-Language Generally Faster Definitions Which one do you want? [Your definitions here. ] a.](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bb051f998153e384fabe04e5fb54c96/image-48.jpg)

English-Language Generally Faster Definitions Which one do you want? [Your definitions here. ] a. b. c. time d. None of these. Alg A Alg B 51

![Formal Generally Faster Definitions Which one do you want Your definitions here a Formal Generally Faster Definitions Which one do you want? [Your definitions here. ] a.](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bb051f998153e384fabe04e5fb54c96/image-49.jpg)

Formal Generally Faster Definitions Which one do you want? [Your definitions here. ] a. b. c. time d. None of these. Alg A Alg B 52

Which algorithm is generally faster? (a) Ask each student for the list of their MUGmates’ classes, and check for each class whether it is CPSC 121. If the answer is ever yes, include the student in my count. (b) For each student s 1 in the class, ask the student for each other student s 2 in the class whether s 2 is a MUG-mate. If the answer is ever yes, include s 1 in my count. (c) Neither. time Alg A Alg B 53

Outline • Prereqs, Learning Goals, and Quiz Notes • Prelude: Scope and Predicate Definition • Problems and Discussion – Liszt Etudes – Sorted Lists – Comparing Algorithms • Next Lecture Notes 54

Learning Goals: In-Class By the start of class, you should be able to: – Build statements about the relationships between properties of various objects—which may be real-world like “every candidate got votes from at least two people in every province” or computing related like “on the ith repetition of this algorithm, the variable min contains the smallest element in the list between element 0 and element i”) using predicate logic. 55

Next Lecture Learning Goals: Pre-Class By the start of class, you should be able to: – Determine the negation of a quantified statement in logical notation as well as English. (But, feel free to entirely or partially translate English to logic in the process!) – Given a quantified statement and an equivalence rule, apply the rule to create an equivalent statement (particularly the De Morgan’s and contrapositive rules). – Prove and disprove quantified statements using the “challenge” method (Epp, 3 rd ed 98 -99, Epp, 4 th ed 118119). – Apply universal instantiation, universal modus ponens, and universal modus tollens to predicate logic statements that correspond to the rules’ premises to infer statements implied by the premises. 56

Next Lecture Prerequisites Reread Sections 3. 1 and 3. 3 (including the negation part that we skipped previously). Read Sections 3. 2 and 3. 4. (See course website for other texts’ sections. ) (You needn’t learn the “diagram” technique, but it may make more sense than other explanations!) Complete the open-book, untimed quiz on Vista that’s due before the next class. 57

snick snack More problems to solve. . . (on your own or if we have time) 58

Problem: Java Collections Problem: Translate the following text from the Java 1. 6. 0 API page for the Collection interface into predicate logic. [T]he specification for the contains(Object o) method says: "returns true if and only if this collection contains at least one element e such that (o==null ? e==null : o. equals(e)). " c ? a : b acts essentially like a multiplexer. 59 If c is true, it evaluates to a; otherwise, it evaluates to b.

Problem: Java Collections Problem: The API goes on to say: This specification should not be construed to imply that invoking Collection. contains with a non-null argument o will cause o. equals(e) to be invoked for any element e. Explain whether and how this is consistent with your definition. 60

More Quantifier Examples Someone is in charge. Everyone except the person in charge reports to someone else. 61

More Quantifier Examples n is a prime number. Note: we use x|y as a predicate meaning x divides y 62 (i. e. , x “goes into” y with no remainder).

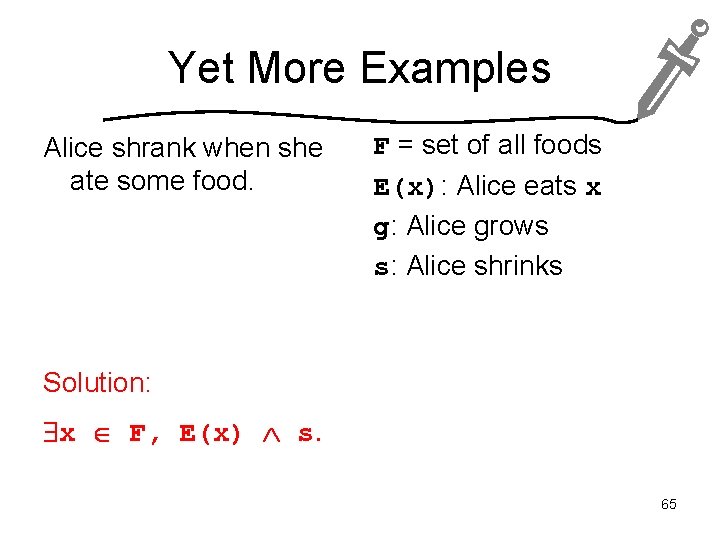

More Quantifier Examples n is a prime number. Let’s define a new predicate P(x) in terms of this “clause”. Then, let’s express… There’s some prime number larger than 10. There’s some prime number larger than every natural number. 63

Yet More Examples Eating food causes Alice to grow or shrink. F = set of all foods E(x): Alice eats x g: Alice grows s: Alice shrinks Solution: x F, E(x) g s. 64

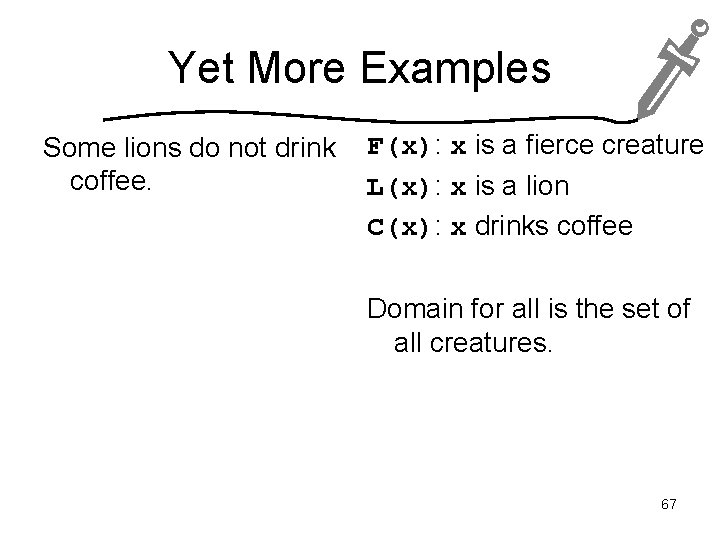

Yet More Examples Alice shrank when she ate some food. F = set of all foods E(x): Alice eats x g: Alice grows s: Alice shrinks Solution: x F, E(x) s. 65

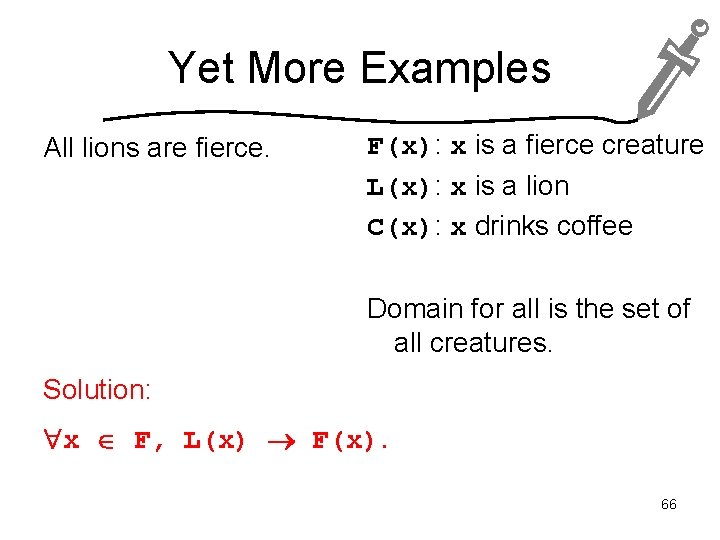

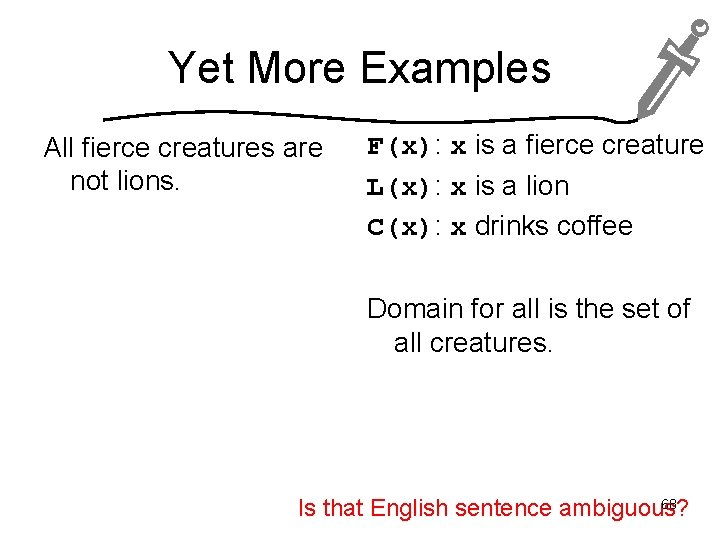

Yet More Examples All lions are fierce. F(x): x is a fierce creature L(x): x is a lion C(x): x drinks coffee Domain for all is the set of all creatures. Solution: x F, L(x) F(x). 66

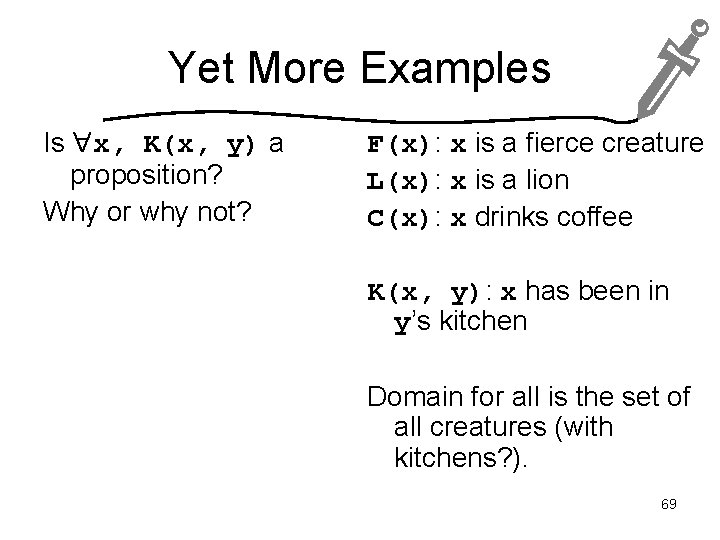

Yet More Examples Some lions do not drink coffee. F(x): x is a fierce creature L(x): x is a lion C(x): x drinks coffee Domain for all is the set of all creatures. 67

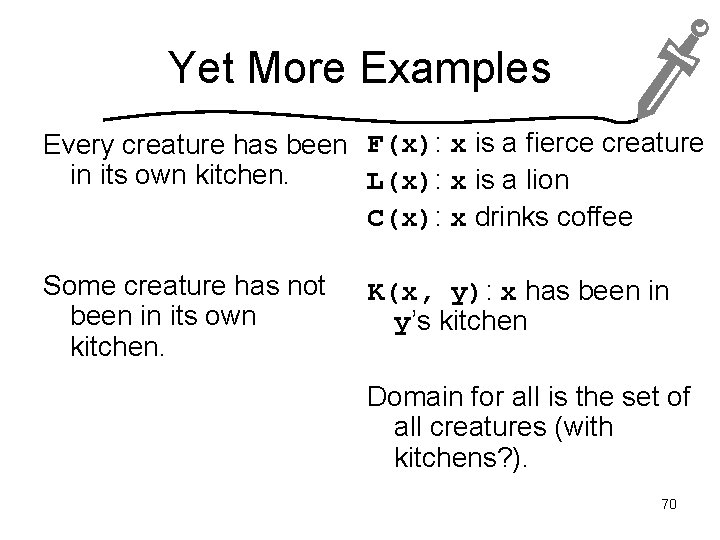

Yet More Examples All fierce creatures are not lions. F(x): x is a fierce creature L(x): x is a lion C(x): x drinks coffee Domain for all is the set of all creatures. 68 Is that English sentence ambiguous?

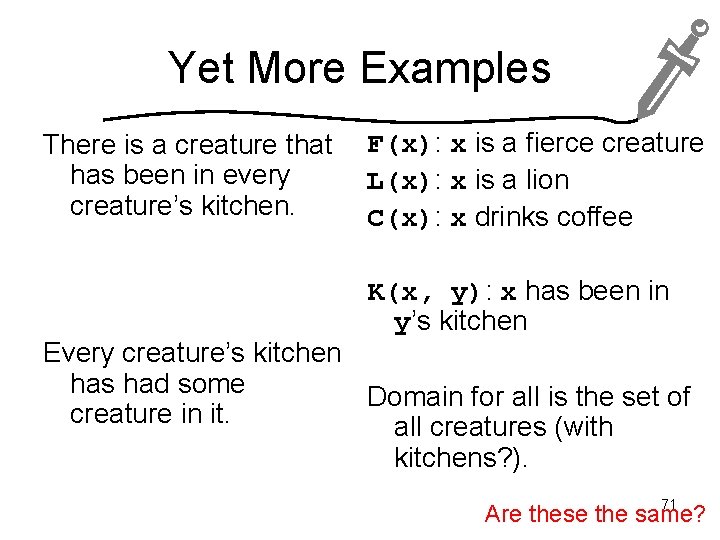

Yet More Examples Is x, K(x, y) a proposition? Why or why not? F(x): x is a fierce creature L(x): x is a lion C(x): x drinks coffee K(x, y): x has been in y’s kitchen Domain for all is the set of all creatures (with kitchens? ). 69

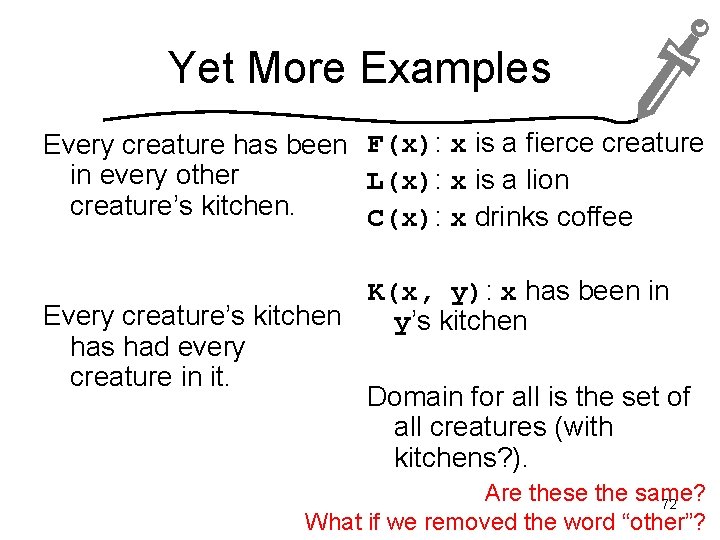

Yet More Examples Every creature has been F(x): x is a fierce creature in its own kitchen. L(x): x is a lion C(x): x drinks coffee Some creature has not been in its own kitchen. K(x, y): x has been in y’s kitchen Domain for all is the set of all creatures (with kitchens? ). 70

Yet More Examples There is a creature that has been in every creature’s kitchen. F(x): x is a fierce creature L(x): x is a lion C(x): x drinks coffee K(x, y): x has been in y’s kitchen Every creature’s kitchen has had some Domain for all is the set of creature in it. all creatures (with kitchens? ). 71 Are these the same?

Yet More Examples Every creature has been F(x): x is a fierce creature in every other L(x): x is a lion creature’s kitchen. C(x): x drinks coffee K(x, y): x has been in Every creature’s kitchen y’s kitchen has had every creature in it. Domain for all is the set of all creatures (with kitchens? ). Are these the same? 72 What if we removed the word “other”?

Problem: Voting Database Consider a database that tracks the votes in an election. In the database, the predicate Tally(d, c, n) means that district d reported that candidate c received n votes, where n is an integer 0. Problem: Define a predicate Got. Vote(c) in terms of Tally whose truth set is the set of all candidates who received at least one vote. 73

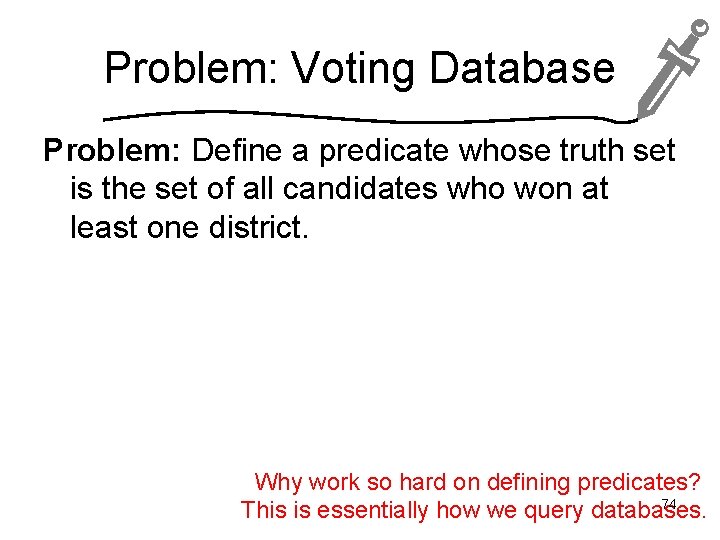

Problem: Voting Database Problem: Define a predicate whose truth set is the set of all candidates who won at least one district. Why work so hard on defining predicates? 74 This is essentially how we query databases.

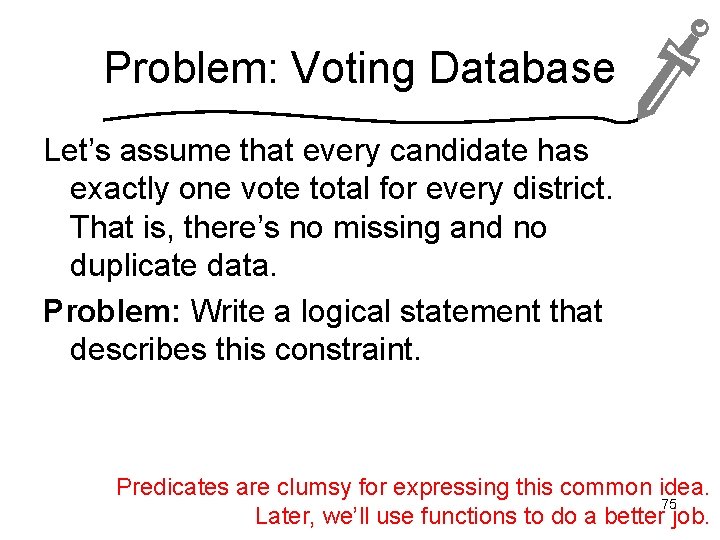

Problem: Voting Database Let’s assume that every candidate has exactly one vote total for every district. That is, there’s no missing and no duplicate data. Problem: Write a logical statement that describes this constraint. Predicates are clumsy for expressing this common idea. 75 Later, we’ll use functions to do a better job.

Problem: Voting Database Let Winner(c) indicate that candidate c is the winner of the election. Problem: Write a logical statement that means that the winner of the election must have received at least one vote. 76

Problem: Voting Database Let D be the set of all districts and C be the set of all candidates. Problem: Determine what the following statement means, whether it is necessarily true (no matter what the actual vote tallies are), and justify your stance: c 1 C, d D, c 2 C, Winner(c 1) c 1 c 2 n 1 Z, n 2 Z, Tally(d, n 1, c 1) Tally(d, n 2, c 2) n 1>n 2 77