snick snack CPSC 121 Models of Computation 2016

- Slides: 62

snick snack CPSC 121: Models of Computation 2016 W 2 Number Representation Steve Wolfman, based on notes by Patrice Belleville and others This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3. 0 Unported License. 1

Outline • Prereqs, Learning Goals, and Quiz Notes • Prelude: “Additive Inverse” • Problems and Discussion – Clock Arithmetic and Two’s Complement – 1/3 Scottish and Fractions in Binary – Programs and Numbers – Programs as Numbers • Next Lecture Notes 2

Learning Goals: Pre-Class By the start of class, you should be able to: – Convert positive numbers from decimal to binary and back. – Convert positive numbers from hexadecimal to binary and back. – Take the two’s complement of a binary number. – Convert signed (either positive or negative) numbers to binary and back. – Add binary numbers. 3

Learning Goals: In-Class By the end of this unit, you should be able to: – Critique the choice of a digital representation scheme—including describing its strengths, weaknesses, and flaws (such as imprecise representation or overflow) —for a given type of data and purpose, such as (1) fixed-width binary numbers using a two’s complement scheme for signed integer arithmetic in computers or (2) hexadecimal for human inspection of raw binary data. 4

Where We Are in The Big Stories Theory Hardware How do we model computational systems? How do we build devices to compute? Now: showing that our logical models can connect smoothly to models of number systems. Now: enabling our hardware to work with data that’s more meaningful to humans. (And once we have numbers, we can represent pictures, words, sounds, and 5 everything else!)

Motivating Problem Understand avoid cases like those at: http: //www. ima. umn. edu/~arnold/455. f 96/disasters. html Photo by Philippe Semanaz (CC by/sa) Death of 28 people caused by failure of an anti-missile system, caused in turn by the misuse of one representation for fractions. Explosion of a $7 billion space vehicle caused by failure of the guidance system, caused in turn by misuse of a 16 -bit signed binary value. (Both representations are discussed in these slides. ) 6

Outline • Prereqs, Learning Goals, and Quiz Notes • Prelude: “Additive Inverse” • Problems and Discussion – Clock Arithmetic and Two’s Complement – 1/3 Scottish and Fractions in Binary – Programs and Numbers – Programs as Numbers • Next Lecture Notes 7

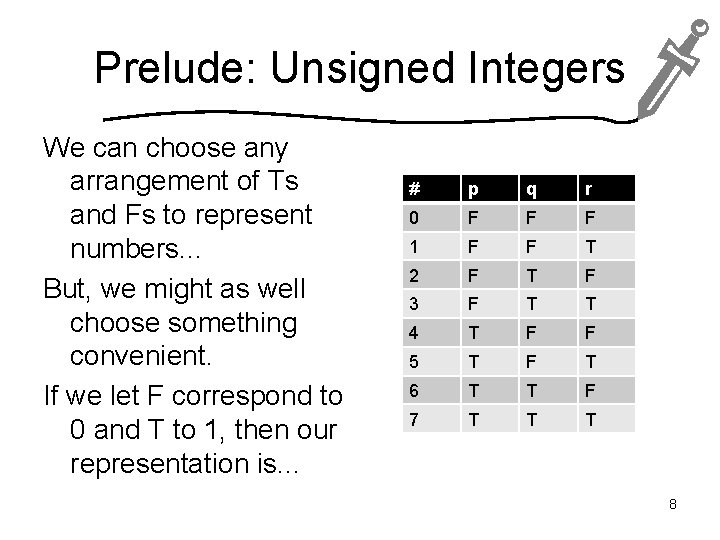

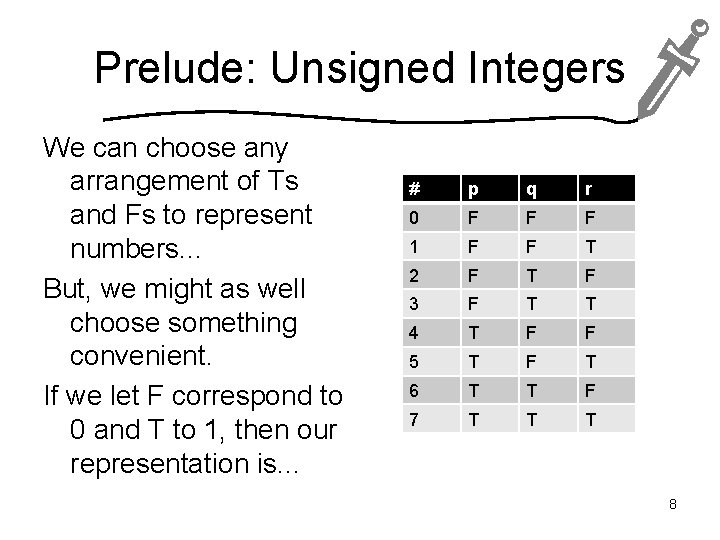

Prelude: Unsigned Integers We can choose any arrangement of Ts and Fs to represent numbers. . . But, we might as well choose something convenient. If we let F correspond to 0 and T to 1, then our representation is. . . # p q r 0 F F F 1 F F T 2 F T F 3 F T T 4 T F F 5 T F T 6 T T F 7 T T T 8

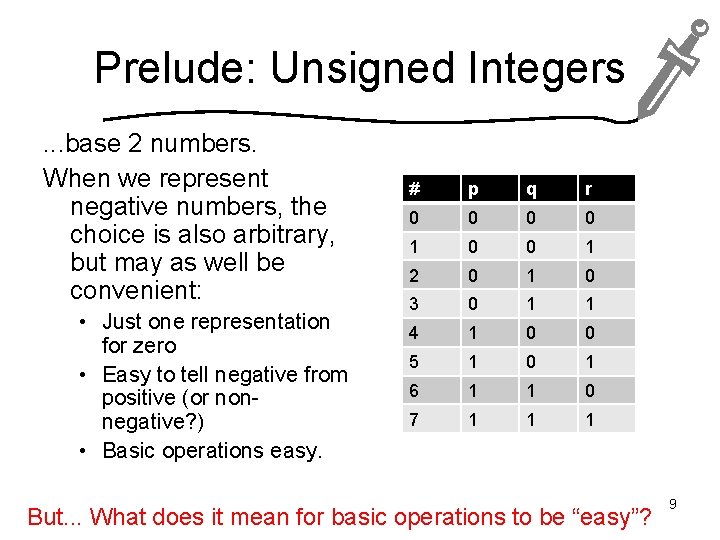

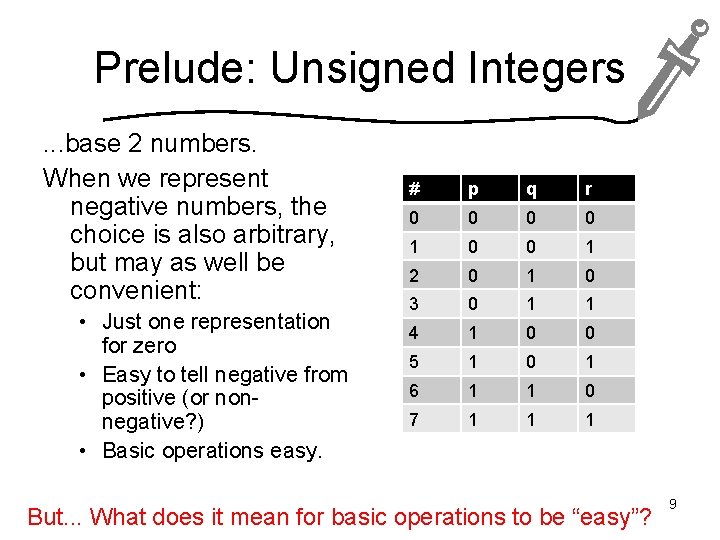

Prelude: Unsigned Integers. . . base 2 numbers. When we represent negative numbers, the choice is also arbitrary, but may as well be convenient: • Just one representation for zero • Easy to tell negative from positive (or nonnegative? ) • Basic operations easy. # p q r 0 0 1 2 0 1 0 3 0 1 1 4 1 0 0 5 1 0 1 6 1 1 0 7 1 1 1 But. . . What does it mean for basic operations to be “easy”? 9

Prelude: Additive Inverse The “additive inverse” of a number x is another number y such that x + y = 0. What is the additive inverse of 3? What is the additive inverse of -7? We want to be able to add signed binary numbers. We need x + -x to be 0. 10 And, we want subtraction to be just addition “plus” negation.

Outline • Prereqs, Learning Goals, and Quiz Notes • Prelude: “Additive Inverse” • Problems and Discussion – Clock Arithmetic and Two’s Complement – 1/3 Scottish and Fractions in Binary – Programs and Numbers – Programs as Numbers • Next Lecture Notes 15

Problem: Clock Arithmetic Problem: It’s 0500 h. How many hours until midnight? Give an algorithm that requires a 24 -hour clock, a level, and no arithmetic. A level is a carpentry tool, essentially a straightedge that indicates when it is either horizontal or vertical. 16

Clock Arithmetic 0500 is five hours from midnight. 1900 is five hours to midnight. 5 and 19 are “additive inverses” in clock arithmetic: 5 + 19 = 0. So are any other numbers that are “across the clock” from each other. That’s even true for 12. Its additive inverse is itself! 17

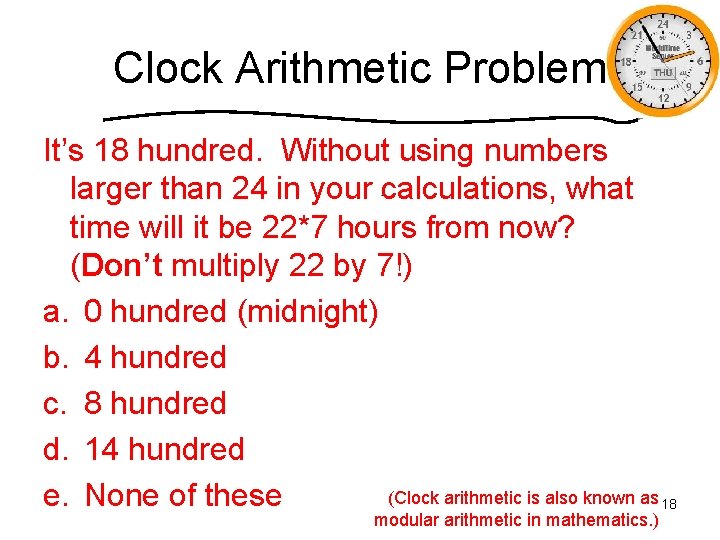

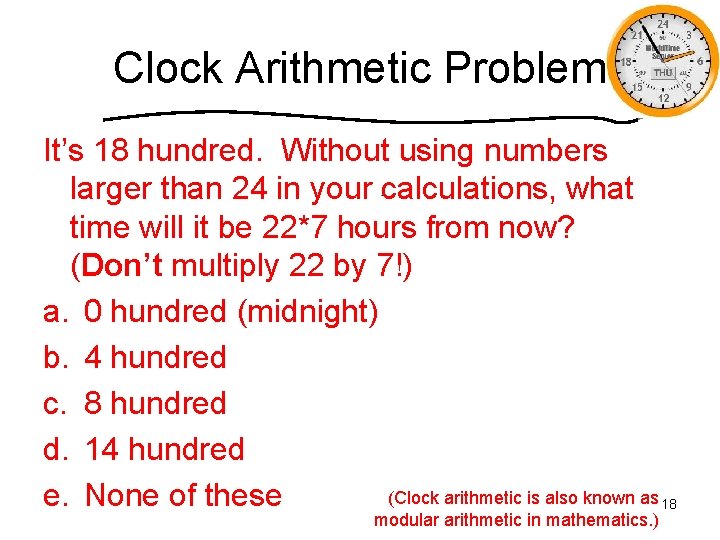

Clock Arithmetic Problem It’s 18 hundred. Without using numbers larger than 24 in your calculations, what time will it be 22*7 hours from now? (Don’t multiply 22 by 7!) a. 0 hundred (midnight) b. 4 hundred c. 8 hundred d. 14 hundred (Clock arithmetic is also known as 18 e. None of these modular arithmetic in mathematics. )

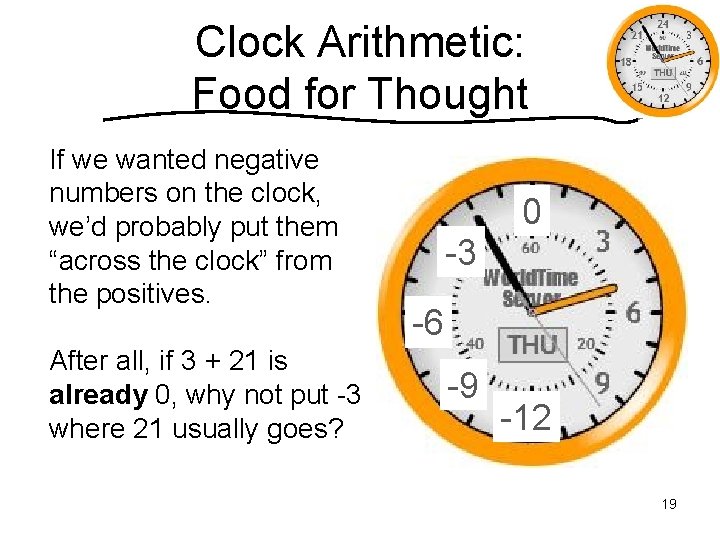

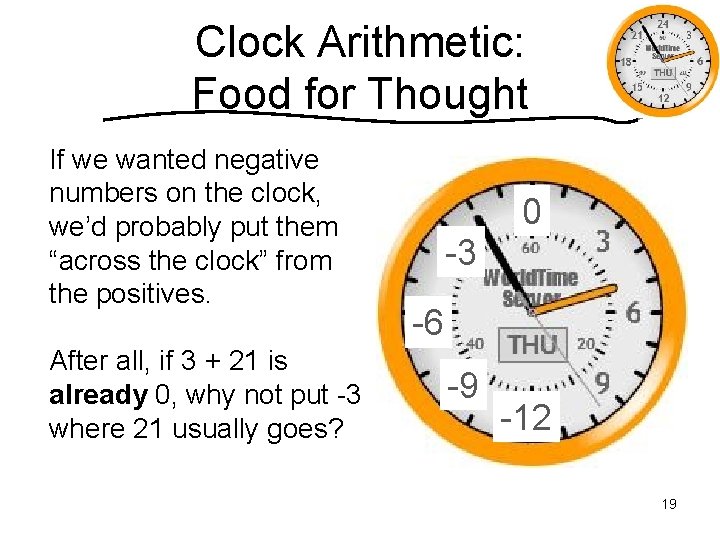

Clock Arithmetic: Food for Thought If we wanted negative numbers on the clock, we’d probably put them “across the clock” from the positives. After all, if 3 + 21 is already 0, why not put -3 where 21 usually goes? 0 -3 -6 -9 -12 19

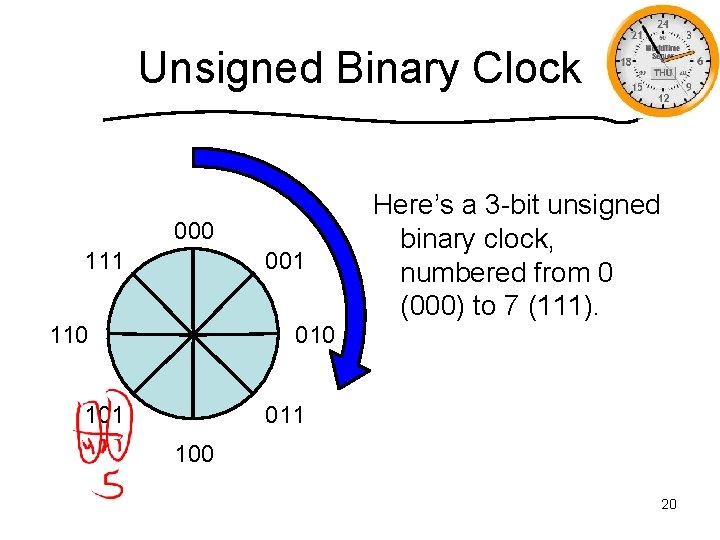

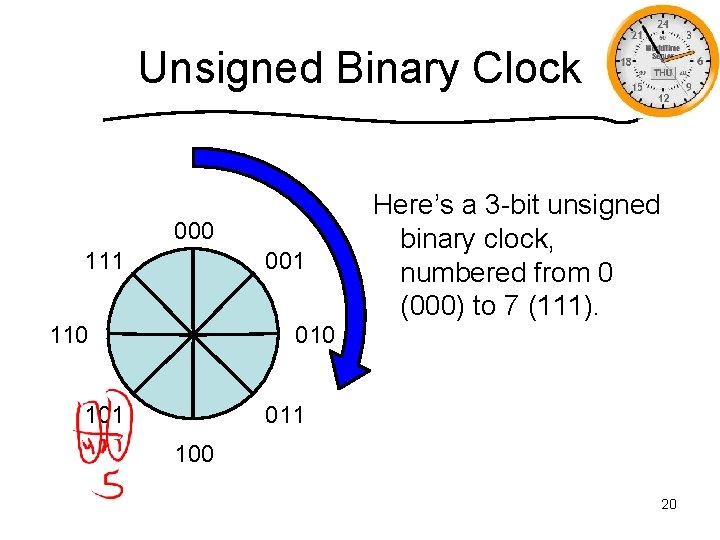

Unsigned Binary Clock 000 111 001 110 Here’s a 3 -bit unsigned binary clock, numbered from 0 (000) to 7 (111). 010 101 011 100 20

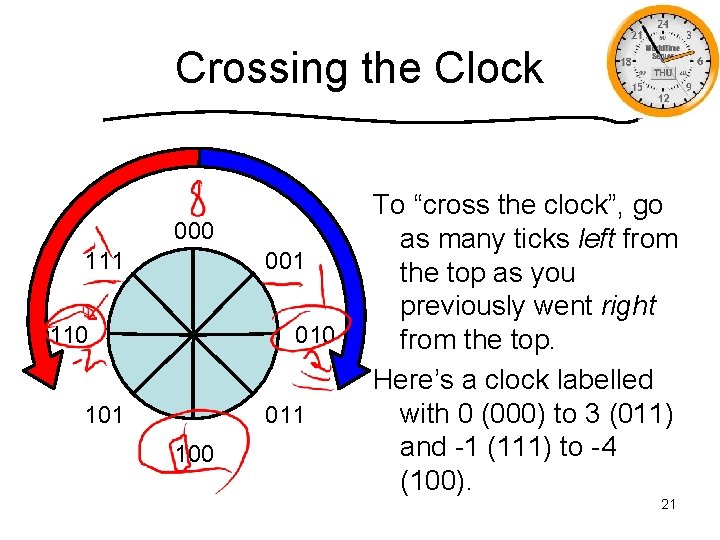

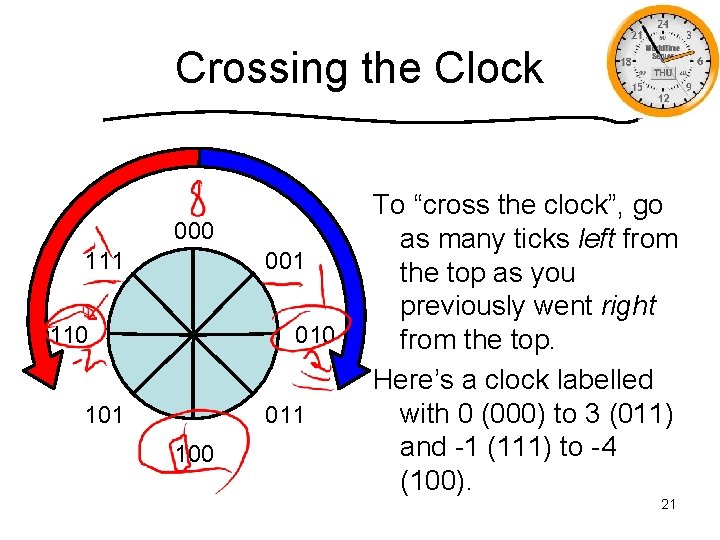

Crossing the Clock 000 111 001 110 010 101 011 100 To “cross the clock”, go as many ticks left from the top as you previously went right from the top. Here’s a clock labelled with 0 (000) to 3 (011) and -1 (111) to -4 (100). 21

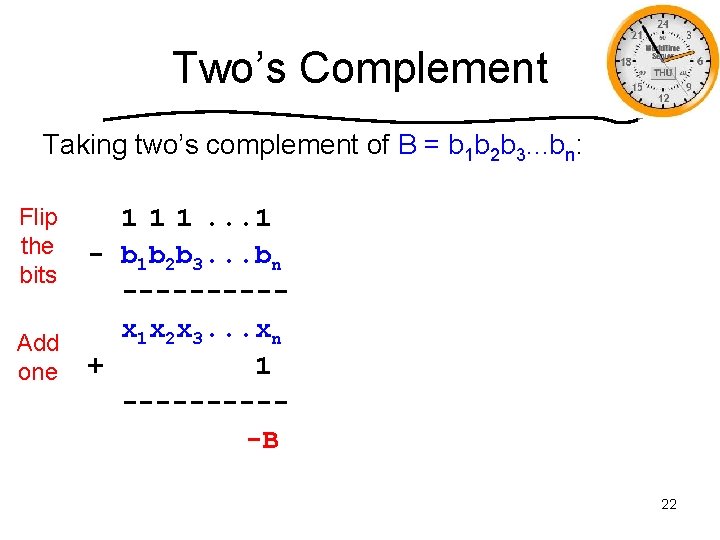

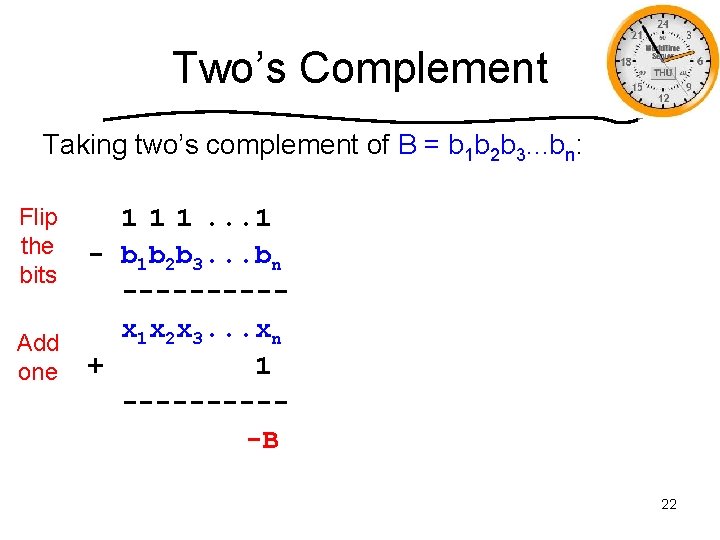

Two’s Complement Taking two’s complement of B = b 1 b 2 b 3. . . bn: Flip 1 1 1. . . 1 the - b b b. . . b 1 2 3 n bits -----x 1 x 2 x 3. . . xn Add 1 one + -----B 22

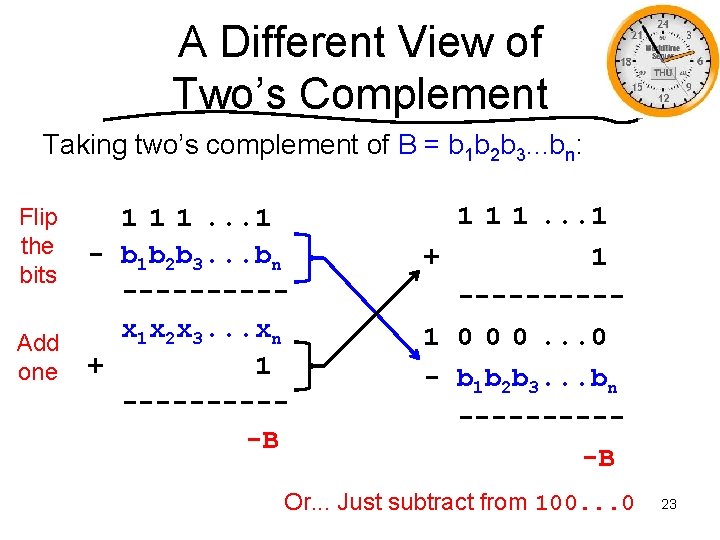

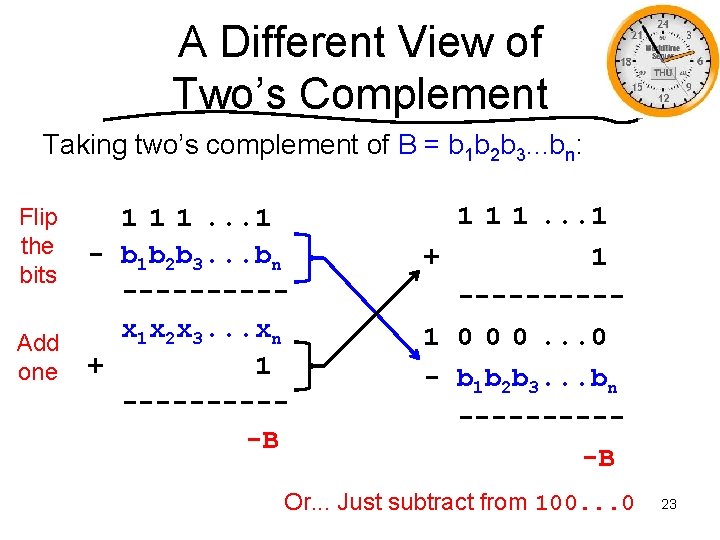

A Different View of Two’s Complement Taking two’s complement of B = b 1 b 2 b 3. . . bn: Flip 1 1 1. . . 1 the - b b b. . . b 1 2 3 n bits -----x 1 x 2 x 3. . . xn Add 1 one + -----B 1 1 1. . . 1 + 1 -----1 0 0 0. . . 0 - b 1 b 2 b 3. . . bn -----B Or. . . Just subtract from 100. . . 0 23

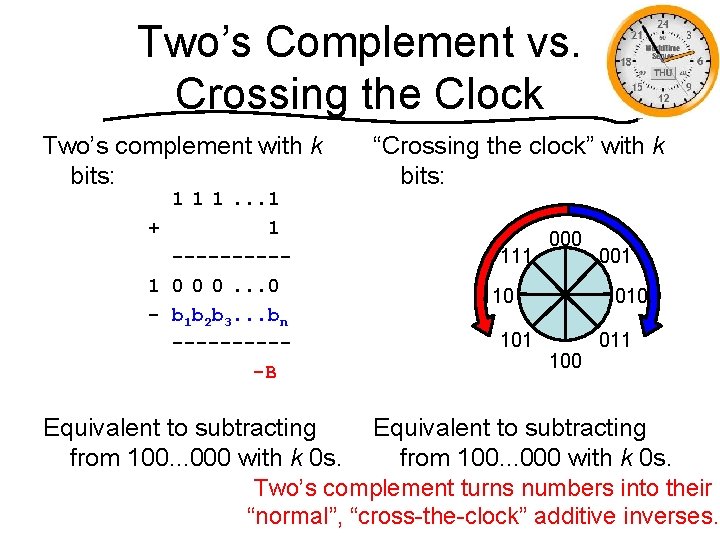

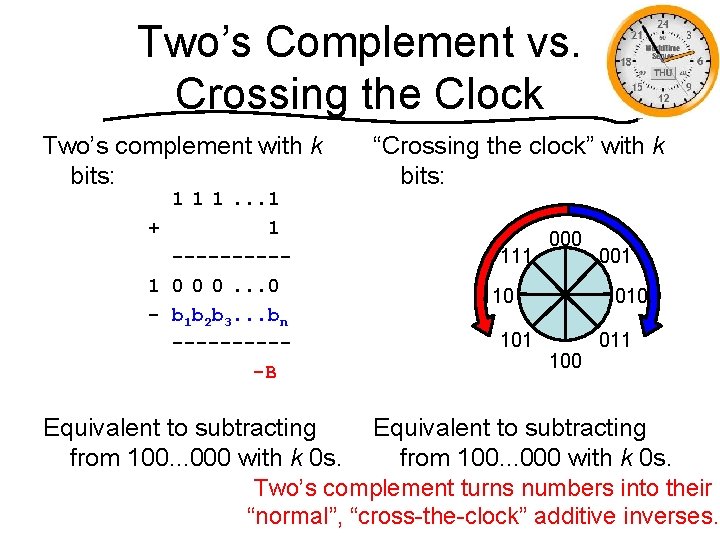

Two’s Complement vs. Crossing the Clock Two’s complement with k bits: 1 1 1. . . 1 + 1 -----1 0 0 0. . . 0 - b 1 b 2 b 3. . . bn -----B “Crossing the clock” with k bits: 111 000 110 101 010 100 011 Equivalent to subtracting from 100. . . 000 with k 0 s. Two’s complement turns numbers into their 24 “normal”, “cross-the-clock” additive inverses.

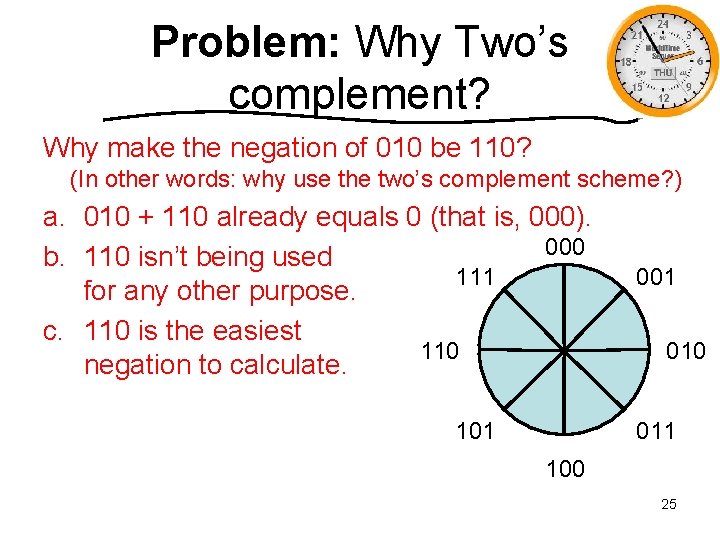

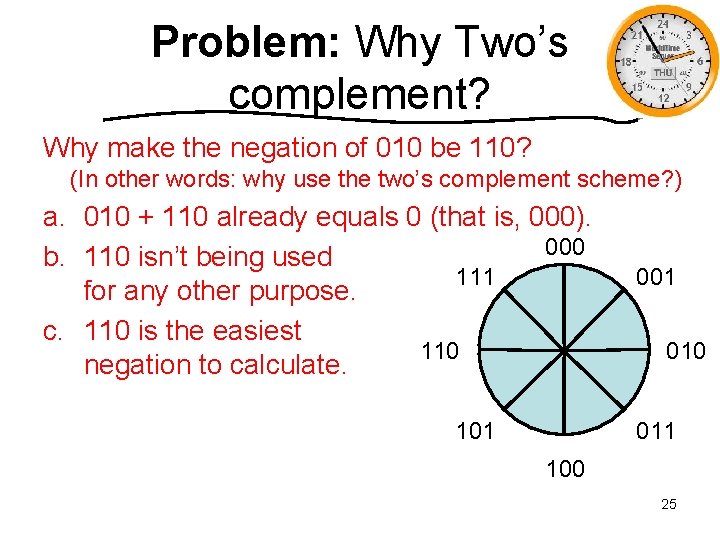

Problem: Why Two’s complement? Why make the negation of 010 be 110? (In other words: why use the two’s complement scheme? ) a. 010 + 110 already equals 0 (that is, 000). 000 b. 110 isn’t being used 111 for any other purpose. c. 110 is the easiest 110 negation to calculate. 101 010 011 100 25

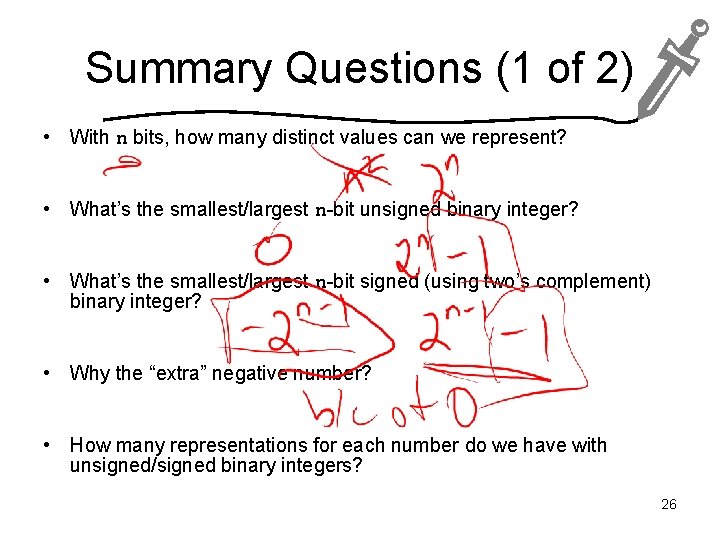

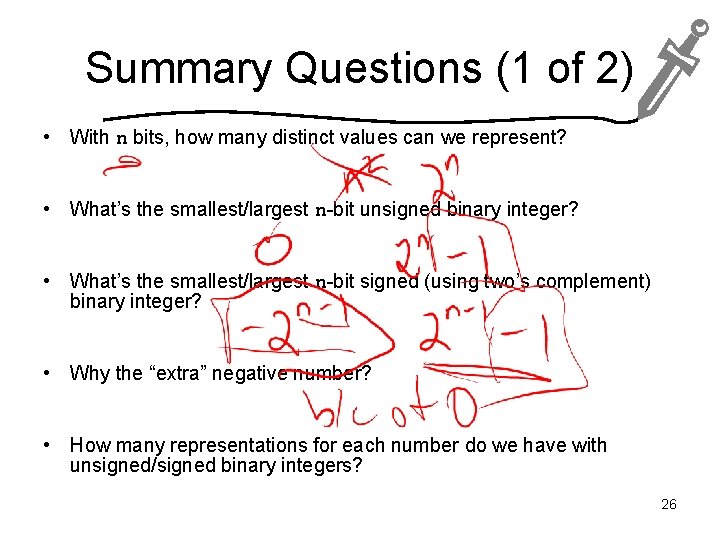

Summary Questions (1 of 2) • With n bits, how many distinct values can we represent? • What’s the smallest/largest n-bit unsigned binary integer? • What’s the smallest/largest n-bit signed (using two’s complement) binary integer? • Why the “extra” negative number? • How many representations for each number do we have with unsigned/signed binary integers? 26

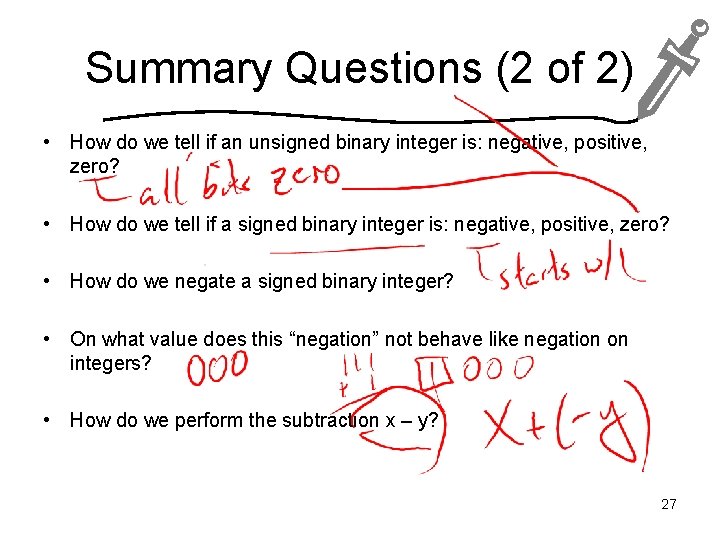

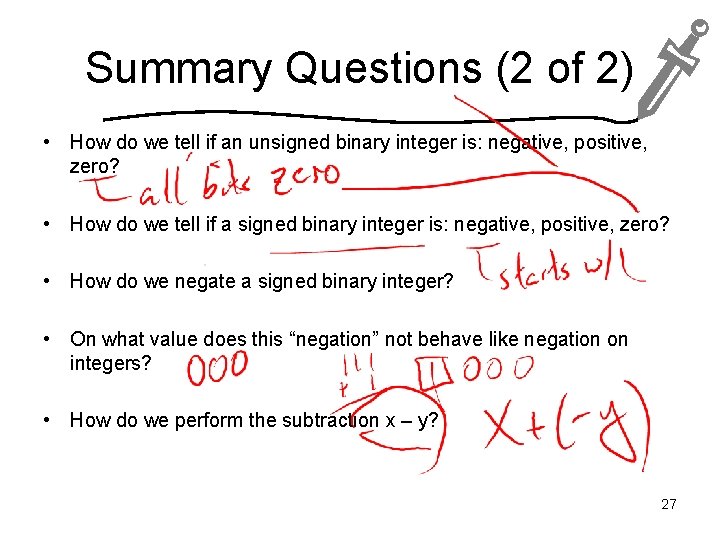

Summary Questions (2 of 2) • How do we tell if an unsigned binary integer is: negative, positive, zero? • How do we tell if a signed binary integer is: negative, positive, zero? • How do we negate a signed binary integer? • On what value does this “negation” not behave like negation on integers? • How do we perform the subtraction x – y? 27

Outline • Prereqs, Learning Goals, and Quiz Notes • Prelude: “Additive Inverse” • Problems and Discussion – Clock Arithmetic and Two’s Complement – 1/3 Scottish and Fractions in Binary – Programs and Numbers – Programs as Numbers • Next Lecture Notes 28

Problem: 1/3 Scottish Problem: Can you be 1/3 Scottish? 29

Problem: 1/3 Scottish Problem: Can you be 1/3 Scottish? To build a model, we must clearly specify the problem. Many problems admit multiple models that lead to fundamentally different results. We’re going to use the model of parentage “endowing” 50% of each parent’s “ishness”. That’s a coarse, even silly model. (By that model, none of us could possibly be at all Canadian, since humans did not originate in Canada. ) Our model is handy for us, but it’s not necessarily what people’s identity is about! 30

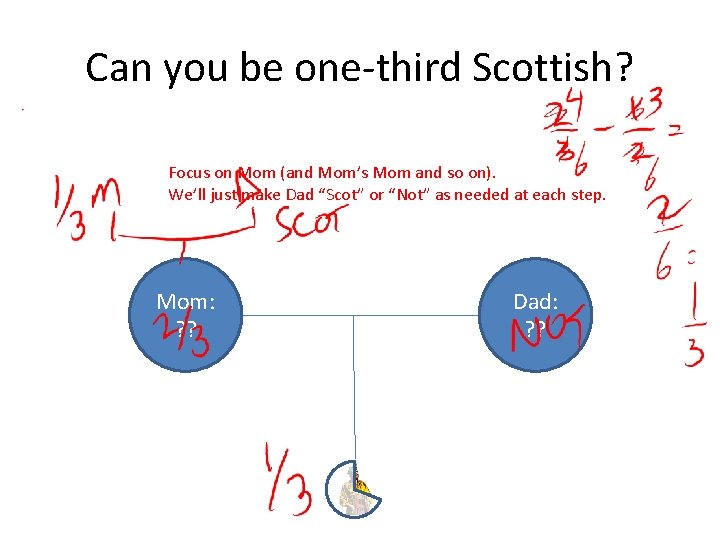

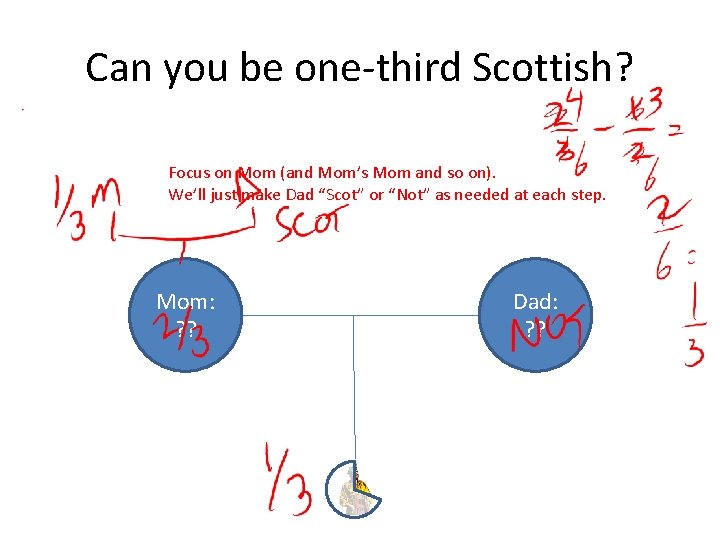

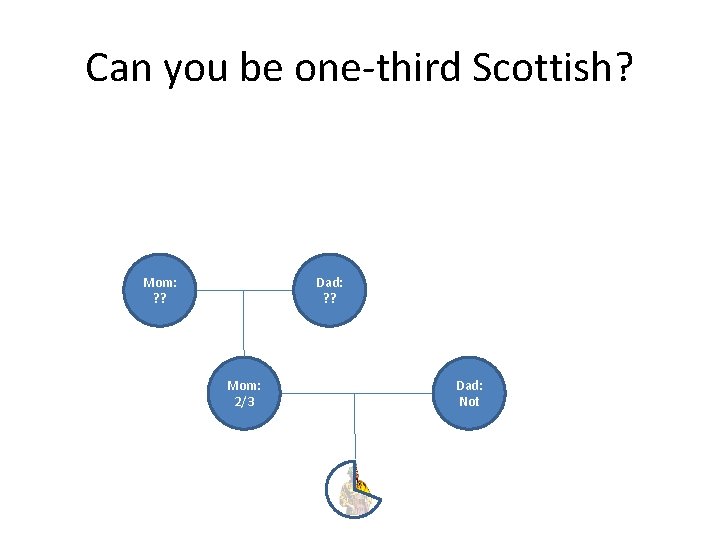

Can you be one-third Scottish? Focus on Mom (and Mom’s Mom and so on). We’ll just make Dad “Scot” or “Not” as needed at each step. Mom: ? ? Dad: ? ?

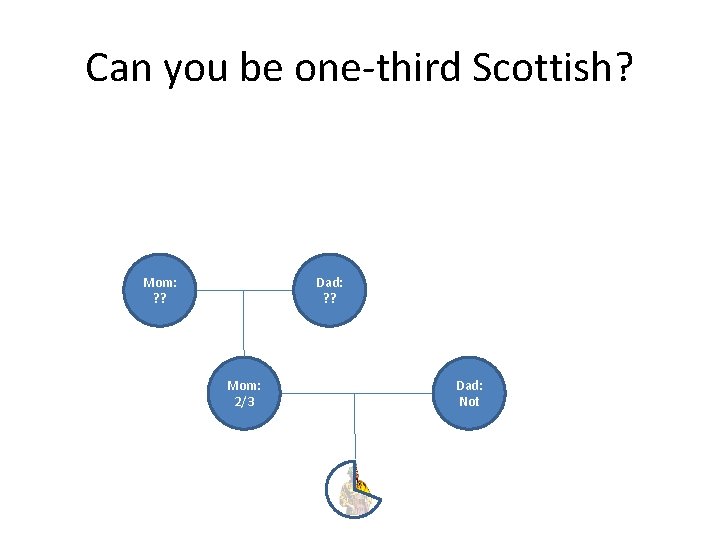

Can you be one-third Scottish? Mom: ? ? Dad: ? ? Mom: 2/3 Dad: Not

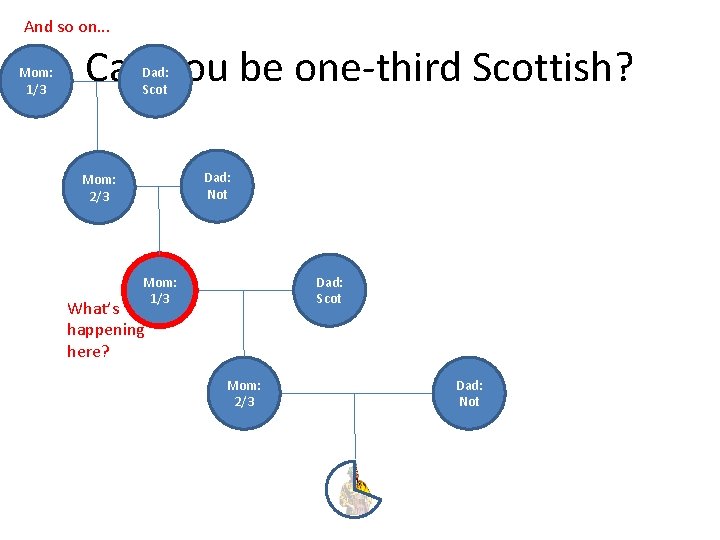

Can you be one-third Scottish? Mom: ? ? Dad: ? ? Mom: 1/3 Dad: Scot Mom: 2/3 Dad: Not

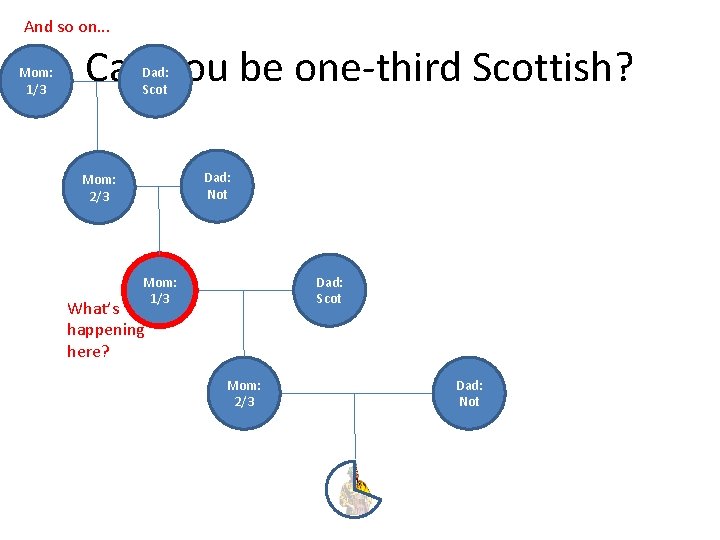

And so on. . . Mom: 1/3 Can you be one-third Scottish? Dad: Scot Dad: Not Mom: 2/3 Mom: 1/3 Dad: Scot What’s happening here? Mom: 2/3 Dad: Not

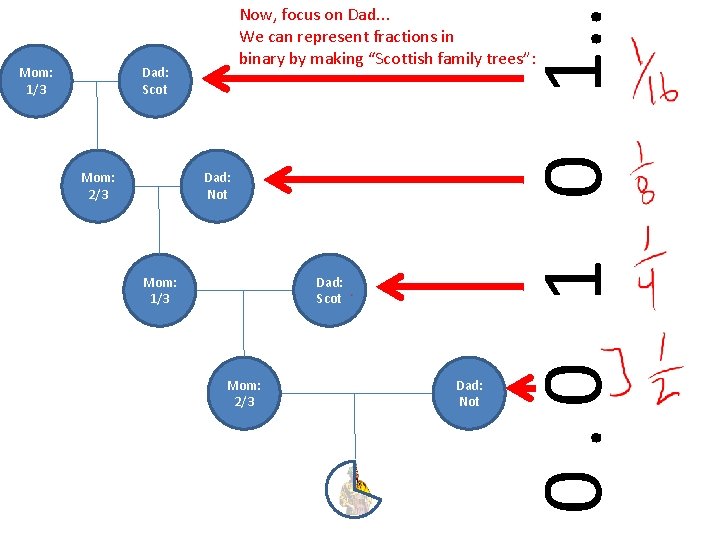

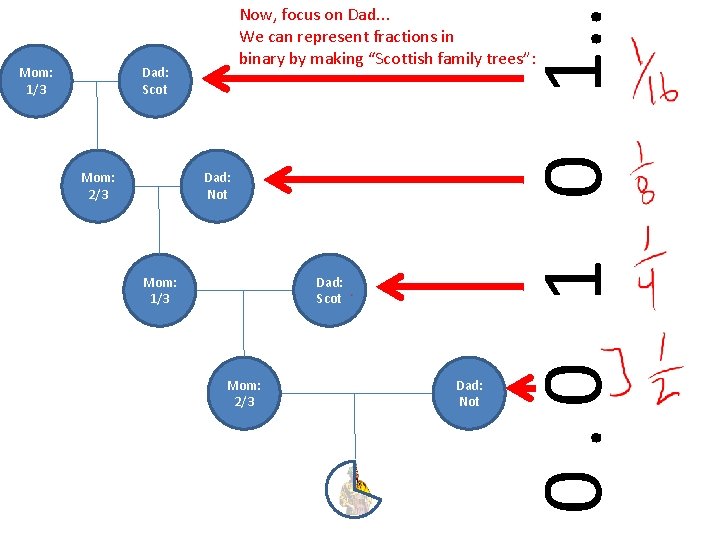

Dad: Scot Mom: 2/3 Dad: Not Mom: 1/3 Dad: Scot Mom: 2/3 Dad: Not 0. 0 1. . Mom: 1/3 Now, focus on Dad. . . We can represent fractions in binary by making “Scottish family trees”:

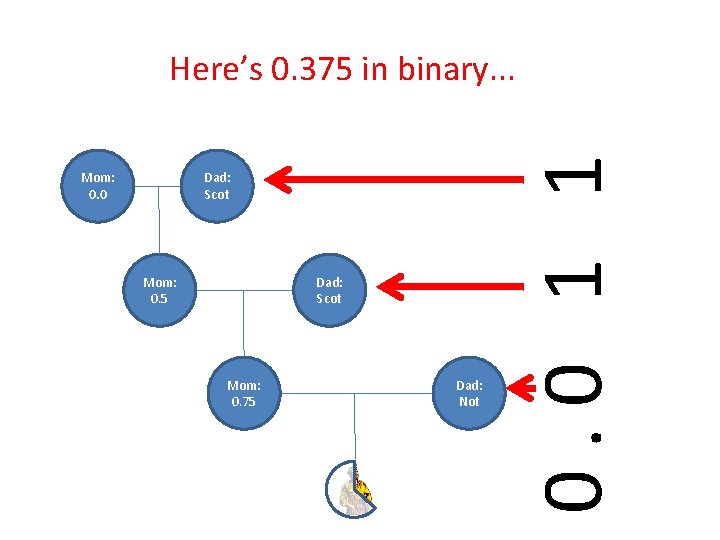

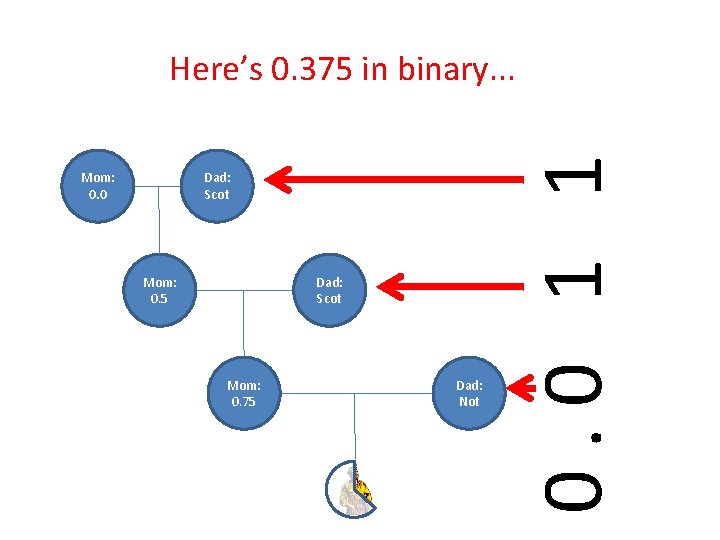

Mom: 0. 0 Dad: Scot Mom: 0. 5 Dad: Scot Mom: 0. 75 Dad: Not 0. 0 1 1 Here’s 0. 375 in binary. . .

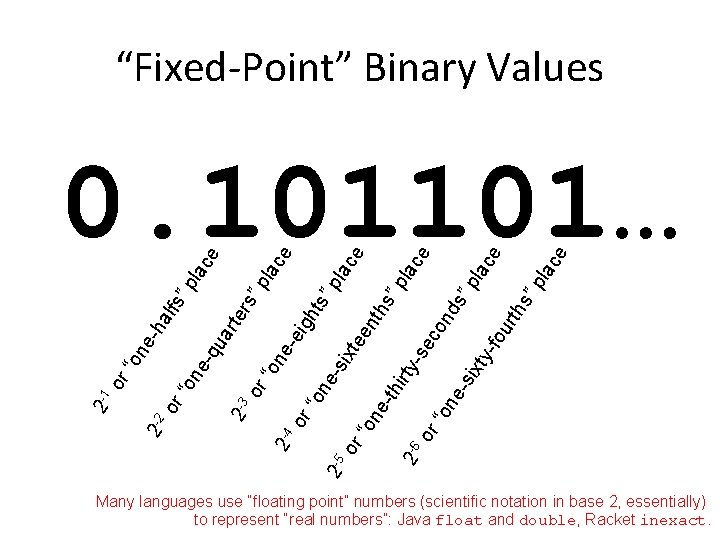

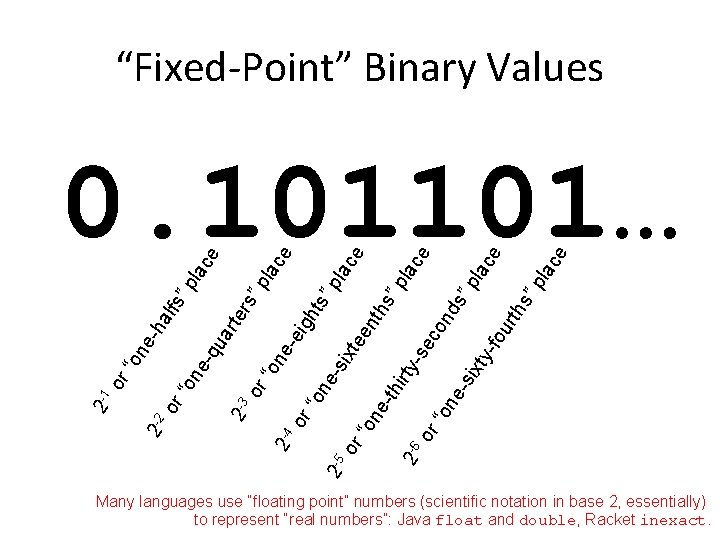

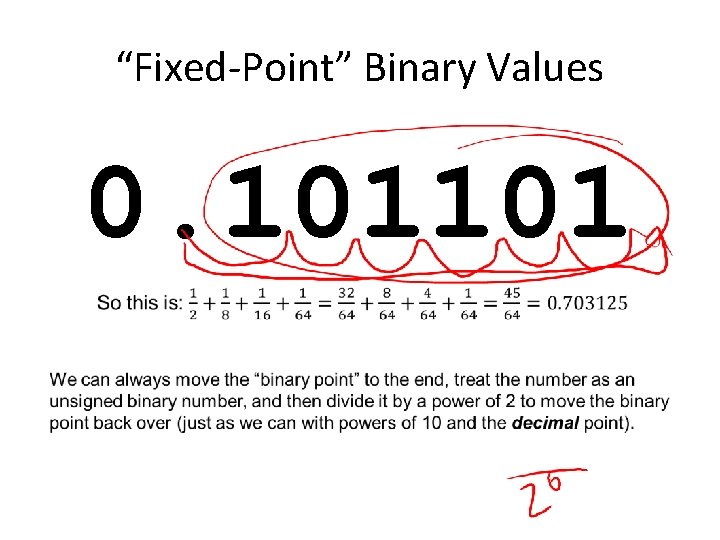

“Fixed-Point” Binary Values pla s” fou rth ty- “o ne -si x irty 2 -6 or ne -th “o 2 -5 or ce ce s” co nd -se tee nth s” pla ce e ac ” p l -si x ne “o 2 -4 or 2 -3 or “o ne -e ig hts ar ter s” -q u ne 2 -2 or “o 2 -1 or “o ne - ha lfs ” p lac e pla ce 0. 101101… Many languages use “floating point” numbers (scientific notation in base 2, essentially) to represent “real numbers”: Java float and double, Racket inexact.

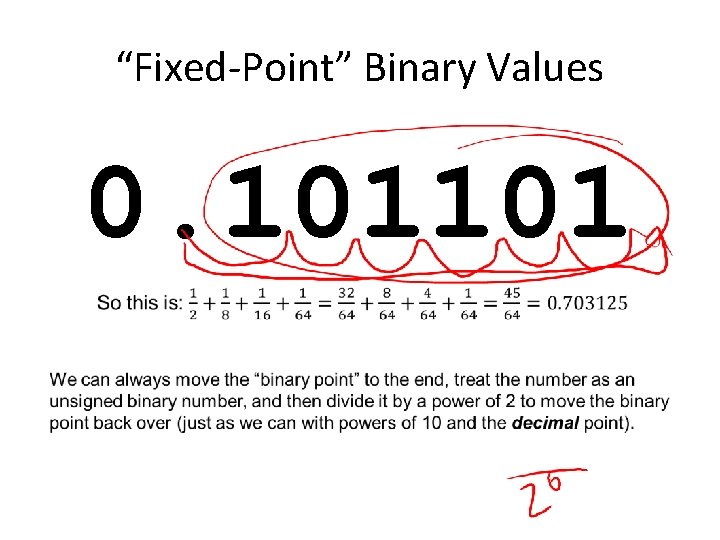

“Fixed-Point” Binary Values 0. 101101

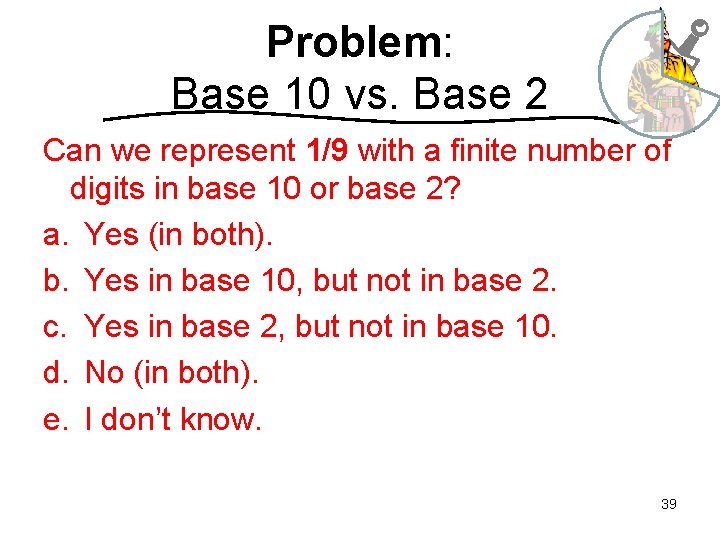

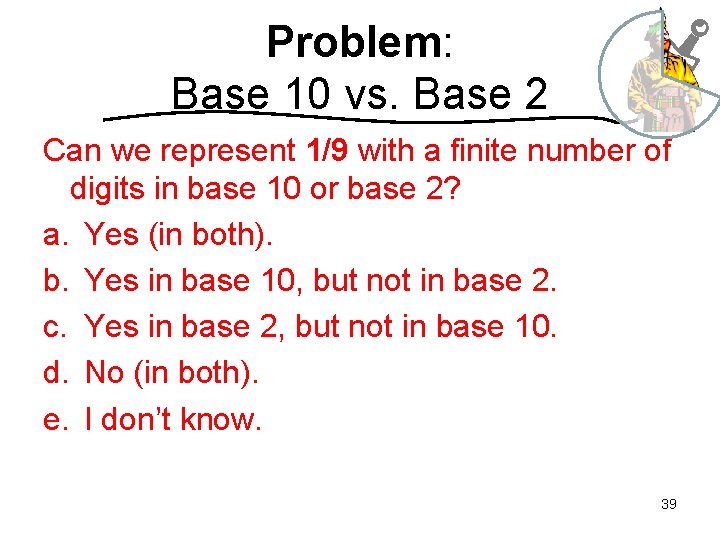

Problem: Base 10 vs. Base 2 Can we represent 1/9 with a finite number of digits in base 10 or base 2? a. Yes (in both). b. Yes in base 10, but not in base 2. c. Yes in base 2, but not in base 10. d. No (in both). e. I don’t know. 39

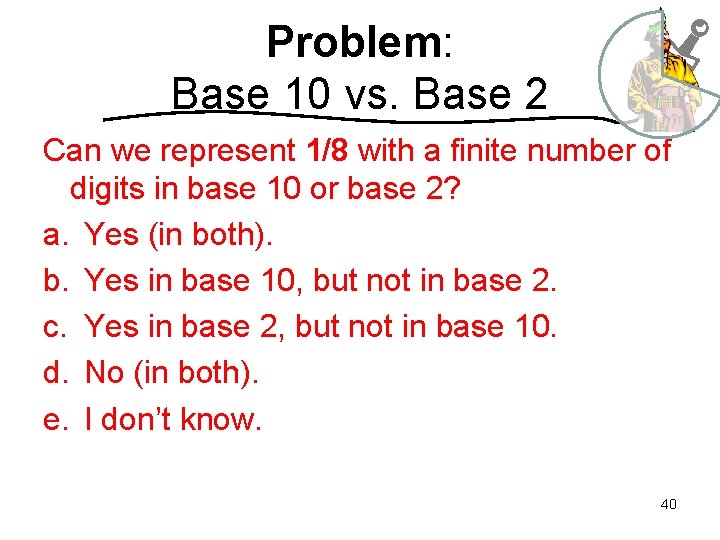

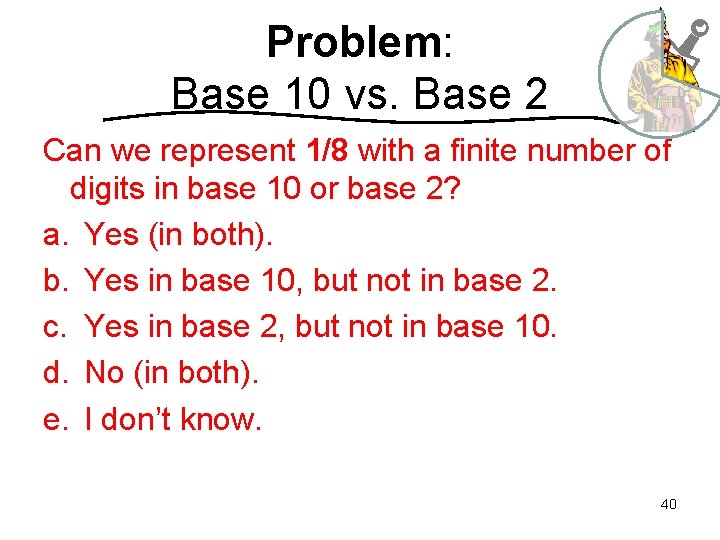

Problem: Base 10 vs. Base 2 Can we represent 1/8 with a finite number of digits in base 10 or base 2? a. Yes (in both). b. Yes in base 10, but not in base 2. c. Yes in base 2, but not in base 10. d. No (in both). e. I don’t know. 40

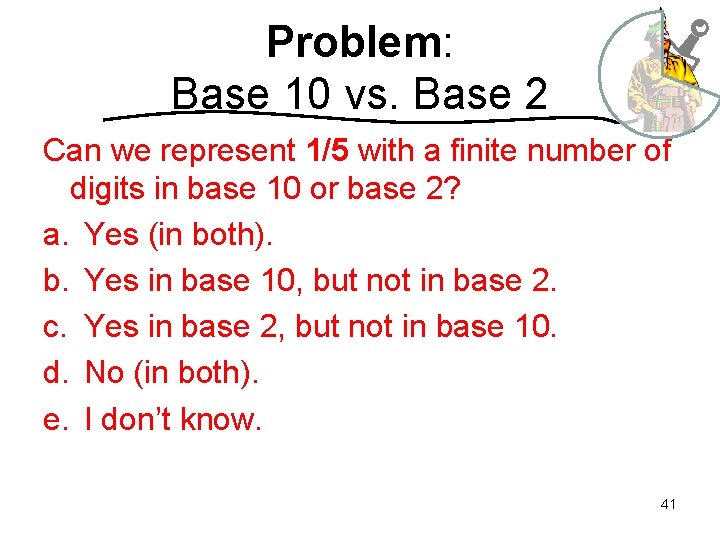

Problem: Base 10 vs. Base 2 Can we represent 1/5 with a finite number of digits in base 10 or base 2? a. Yes (in both). b. Yes in base 10, but not in base 2. c. Yes in base 2, but not in base 10. d. No (in both). e. I don’t know. 41

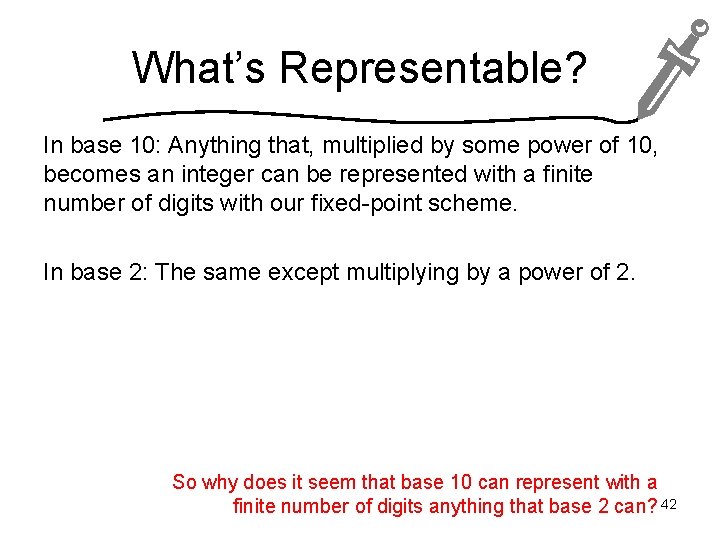

What’s Representable? In base 10: Anything that, multiplied by some power of 10, becomes an integer can be represented with a finite number of digits with our fixed-point scheme. In base 2: The same except multiplying by a power of 2. So why does it seem that base 10 can represent with a finite number of digits anything that base 2 can? 42

So. . . Computers Can’t Represent 1/3? No! Using a different representation scheme (e. g. , a rational number with a separate integer numerator and denominator), computers can perfectly represent 1/3! (You know that from Racket!) The point is: Representations that use a finite number of bits (all of them) have weaknesses. Know those weaknesses and their impact on your computations! 43

Outline • Prereqs, Learning Goals, and Quiz Notes • Prelude: “Additive Inverse” • Problems and Discussion – Clock Arithmetic and Two’s Complement – 1/3 Scottish and Fractions in Binary – Programs and Numbers – Programs as Numbers • Next Lecture Notes 44

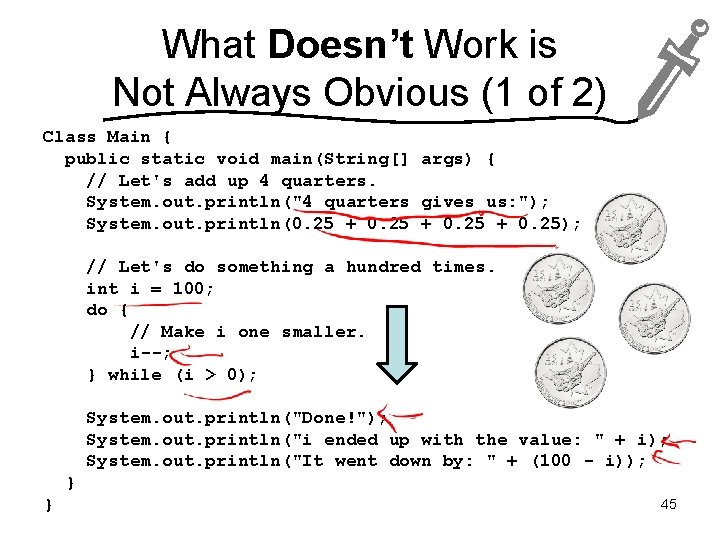

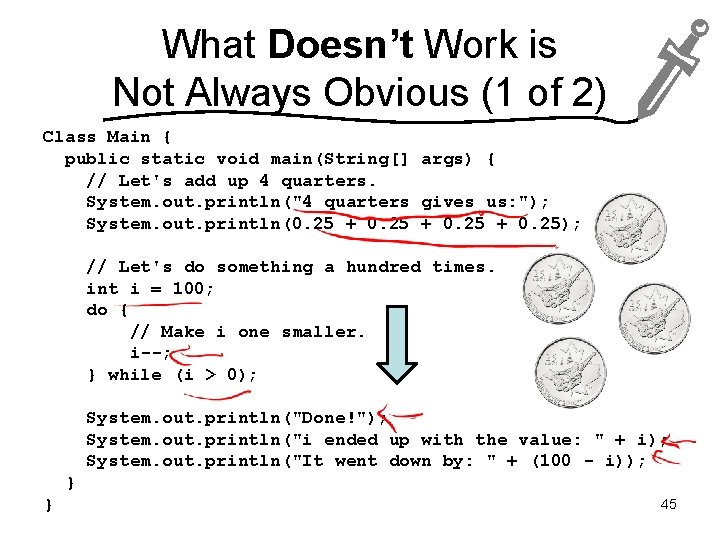

What Doesn’t Work is Not Always Obvious (1 of 2) Class Main { public static void main(String[] args) { // Let's add up 4 quarters. System. out. println("4 quarters gives us: "); System. out. println(0. 25 + 0. 25); // Let's do something a hundred times. int i = 100; do { // Make i one smaller. i--; } while (i > 0); System. out. println("Done!"); System. out. println("i ended up with the value: " + i); System. out. println("It went down by: " + (100 - i)); } } 45

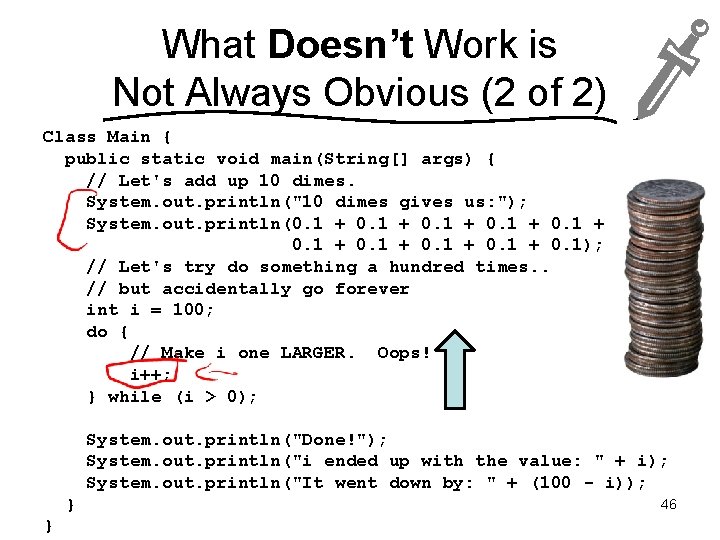

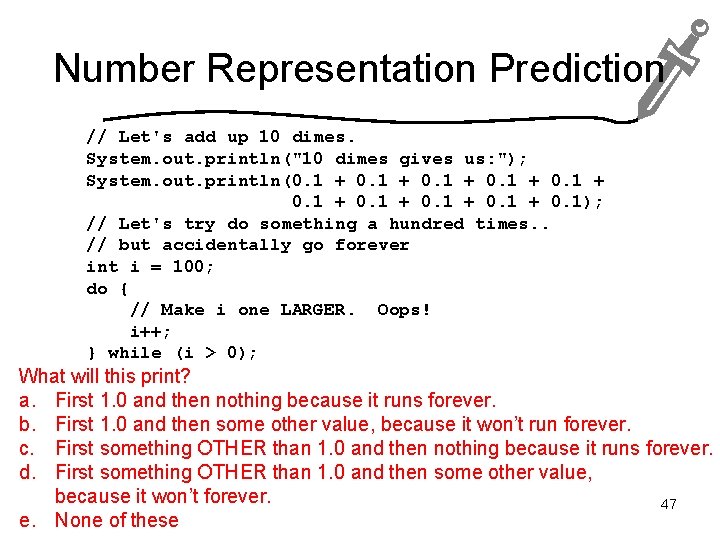

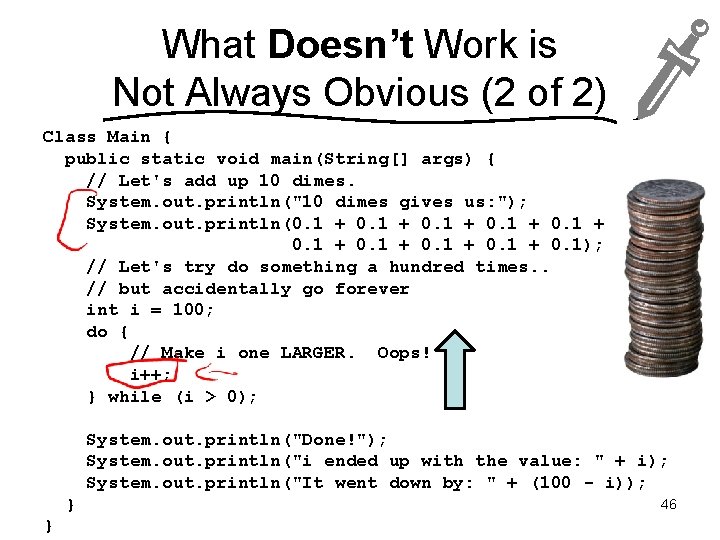

What Doesn’t Work is Not Always Obvious (2 of 2) Class Main { public static void main(String[] args) { // Let's add up 10 dimes. System. out. println("10 dimes gives us: "); System. out. println(0. 1 + 0. 1); // Let's try do something a hundred times. . // but accidentally go forever int i = 100; do { // Make i one LARGER. Oops! i++; } while (i > 0); System. out. println("Done!"); System. out. println("i ended up with the value: " + i); System. out. println("It went down by: " + (100 - i)); } } 46

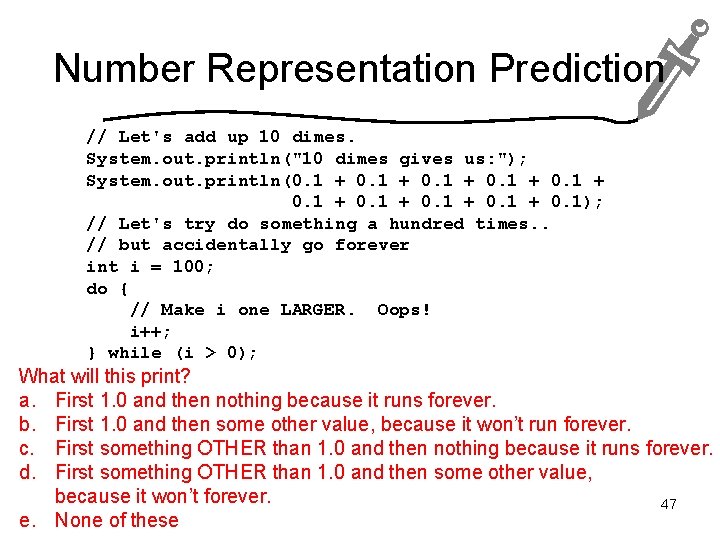

Number Representation Prediction // Let's add up 10 dimes. System. out. println("10 dimes gives us: "); System. out. println(0. 1 + 0. 1); // Let's try do something a hundred times. . // but accidentally go forever int i = 100; do { // Make i one LARGER. Oops! i++; } while (i > 0); What will this print? a. First 1. 0 and then nothing because it runs forever. b. First 1. 0 and then some other value, because it won’t run forever. c. First something OTHER than 1. 0 and then nothing because it runs forever. d. First something OTHER than 1. 0 and then some other value, because it won’t forever. 47 e. None of these

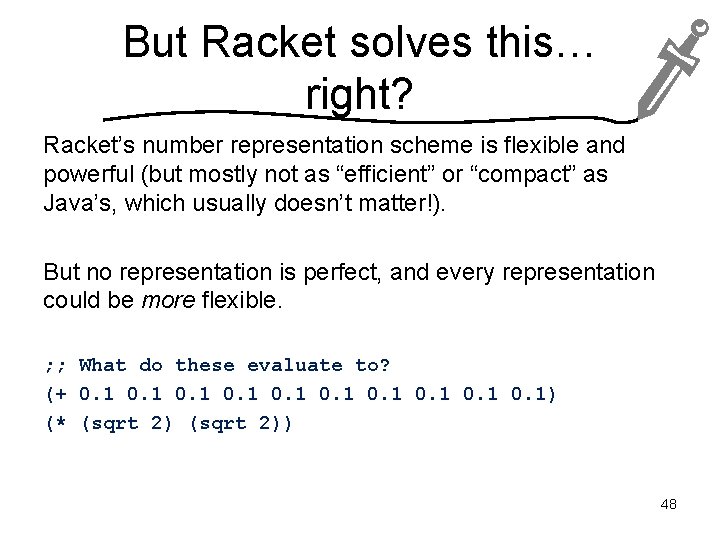

But Racket solves this… right? Racket’s number representation scheme is flexible and powerful (but mostly not as “efficient” or “compact” as Java’s, which usually doesn’t matter!). But no representation is perfect, and every representation could be more flexible. ; ; What do these evaluate to? (+ 0. 1 0. 1) (* (sqrt 2)) 48

Outline • Prereqs, Learning Goals, and Quiz Notes • Prelude: “Additive Inverse” • Problems and Discussion – Clock Arithmetic and Two’s Complement – 1/3 Scottish and Fractions in Binary – Programs and Numbers – Programs as Numbers • Next Lecture Notes 49

Preface: Java Byte Code Programs in the Java programming language are compiled to a language called “byte code” that is then interpreted on a particular computer. Why? Byte code is hard for humans to write, read, and understand. . . but it’s easy to write a program that reads and executes it (compared to writing a program to directly read and execute Java source code). So, if you create a new type of computer tomorrow, and I want to run Java code on it, I don’t have to write a program that works on your computer and knows how to execute Java; I just need to write a program that knows how to execute byte code. Java byte code is also designed to be compact so it’s cheap to transmit across the internet.

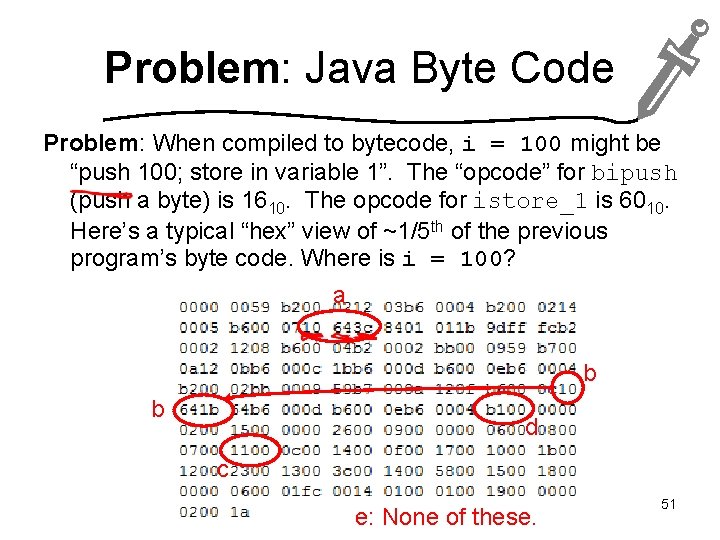

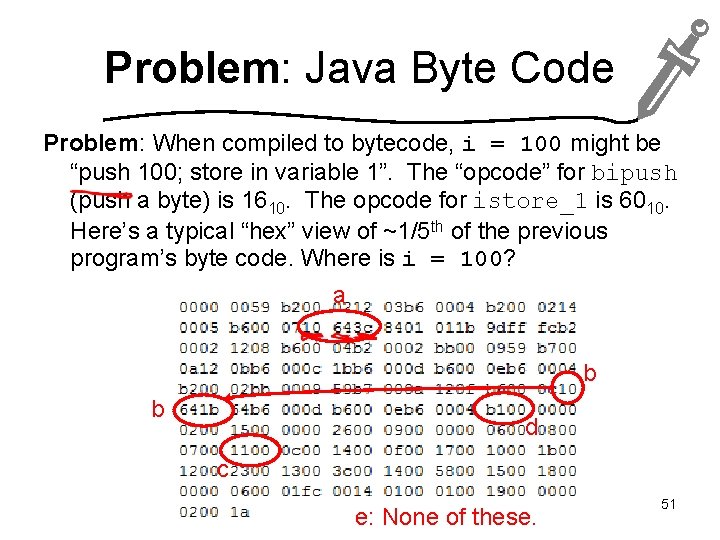

Problem: Java Byte Code Problem: When compiled to bytecode, i = 100 might be “push 100; store in variable 1”. The “opcode” for bipush (push a byte) is 1610. The opcode for istore_1 is 6010. Here’s a typical “hex” view of ~1/5 th of the previous program’s byte code. Where is i = 100? a b b d c e: None of these. 51

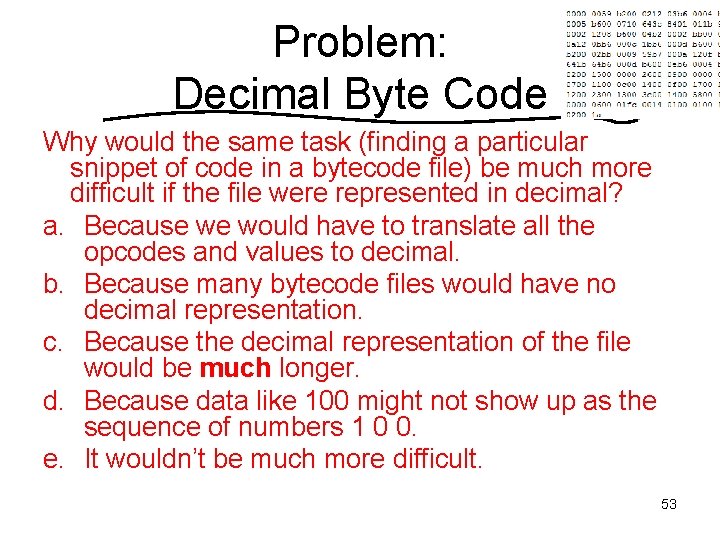

Problem: Binary Byte Code Why would the same task (finding a particular snippet of code in a bytecode file) be much more difficult if the file were represented in binary? a. Because we would have to translate all the opcodes and values to binary. b. Because many bytecode files would have no binary representation. c. Because the binary representation of the file would be much longer. d. Because data like 1100100 (100 in base 2) might not show up as the sequence of numbers 1 1 0 0. e. It wouldn’t be much more difficult. 52

Problem: Decimal Byte Code Why would the same task (finding a particular snippet of code in a bytecode file) be much more difficult if the file were represented in decimal? a. Because we would have to translate all the opcodes and values to decimal. b. Because many bytecode files would have no decimal representation. c. Because the decimal representation of the file would be much longer. d. Because data like 100 might not show up as the sequence of numbers 1 0 0. e. It wouldn’t be much more difficult. 53

Outline • Prereqs, Learning Goals, and Quiz Notes • Prelude: “Additive Inverse” • Problems and Discussion – Clock Arithmetic and Two’s Complement – 1/3 Scottish and Fractions in Binary – Programs and Numbers – Programs as Numbers • Next Lecture Notes 54

Learning Goals: In-Class By the end of this unit, you should be able to: – Critique the choice of a digital representation scheme—including describing its strengths, weaknesses, and flaws (such as imprecise representation or overflow) —for a given type of data and purpose, such as (1) fixed-width binary numbers using a two’s complement scheme for signed integer arithmetic in computers or (2) hexadecimal for human inspection of raw binary data. 55

Next Lecture Learning Goals: Pre-Class By the start of class, you should be able to: – Use truth tables to establish or refute the validity of a rule of inference. – Given a rule of inference and propositional logic statements that correspond to the rule’s premises, apply the rule to infer a new statement implied by the original statements. 56

Next Lecture Prerequisites Read Section 1. 3 (Epp 3 rd ed) or 2. 3 (Epp 4 th ed). Complete the open-book, untimed quiz on Connect that is due before next class. 57

snick snack Some Things to Try. . . (on your own if you have time, not required) 58

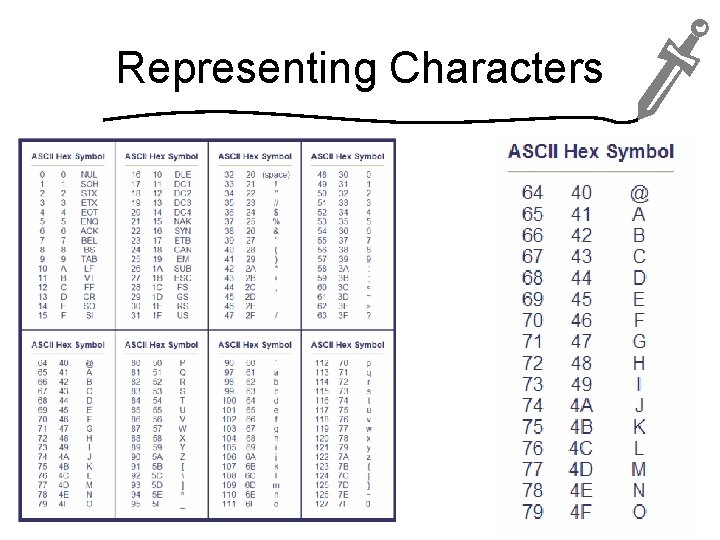

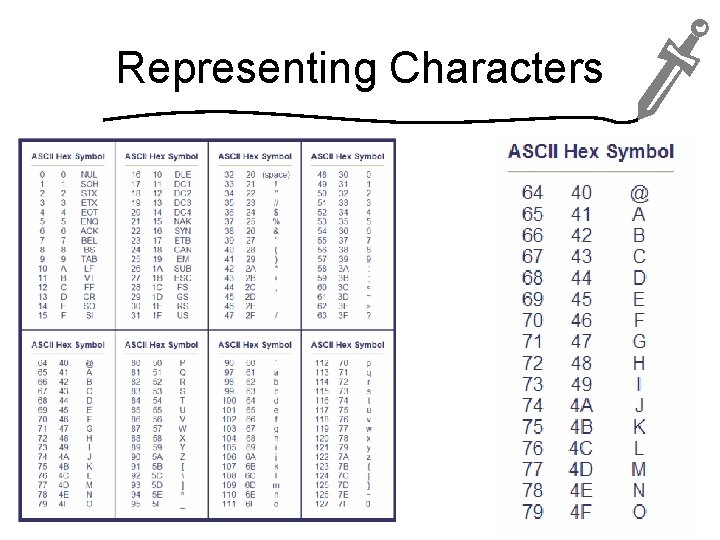

Representing Characters 59

Problem: Weighty Numbers Problem: You have a balance scale and four weights. You may choose the mass of the weights, as long as they’re in whole units of grams. What’s the largest number n such that you can exactly measure every weight 0…n? ? g ? g 60

Problem: Representing Data Problem: Devise two different ways to represent each of the following with bits: • black-and-white images • text • the shape of your face 61

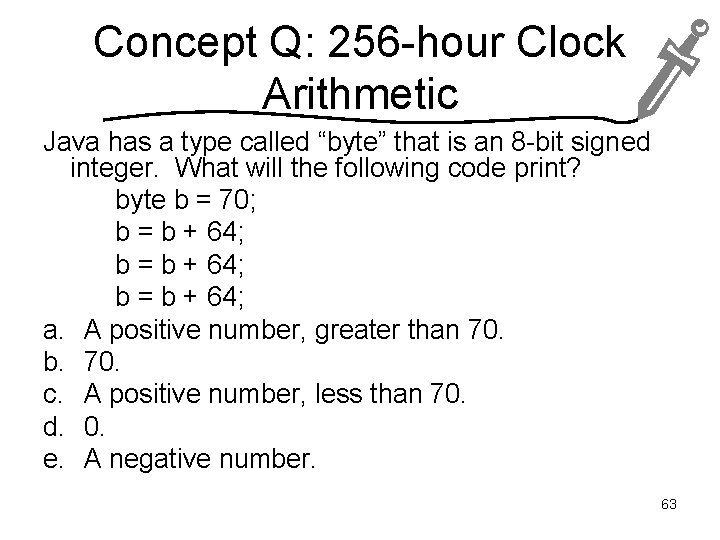

Problem: 256 -hour Clock Arithmetic Problem: Imagine you’ve built a computer that uses 256 -hour clock faces, each with a single dial, as storage units. How would you store, add, subtract, and negate integers? 62

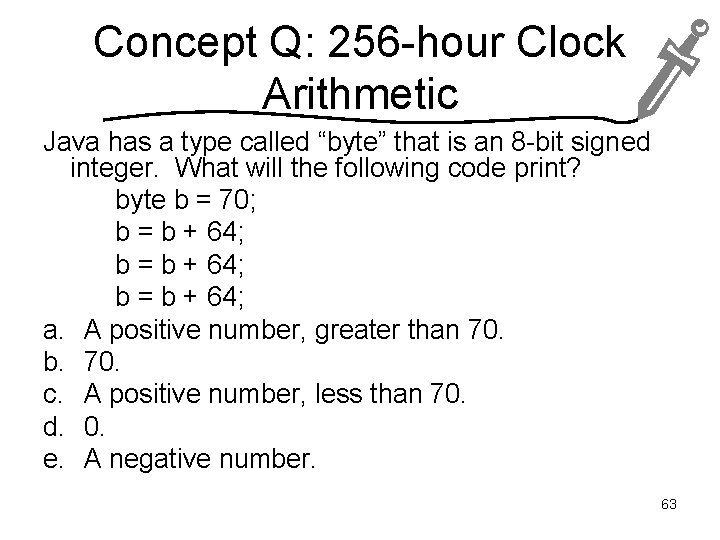

Concept Q: 256 -hour Clock Arithmetic Java has a type called “byte” that is an 8 -bit signed integer. What will the following code print? byte b = 70; b = b + 64; a. A positive number, greater than 70. b. 70. c. A positive number, less than 70. d. 0. e. A negative number. 63

Problem: Number Rep Breakdown Problem: Explain what’s happening in each of these… 64

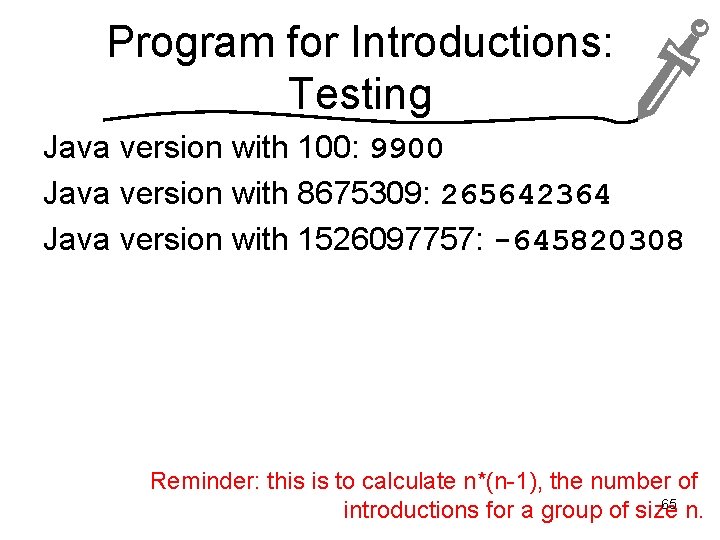

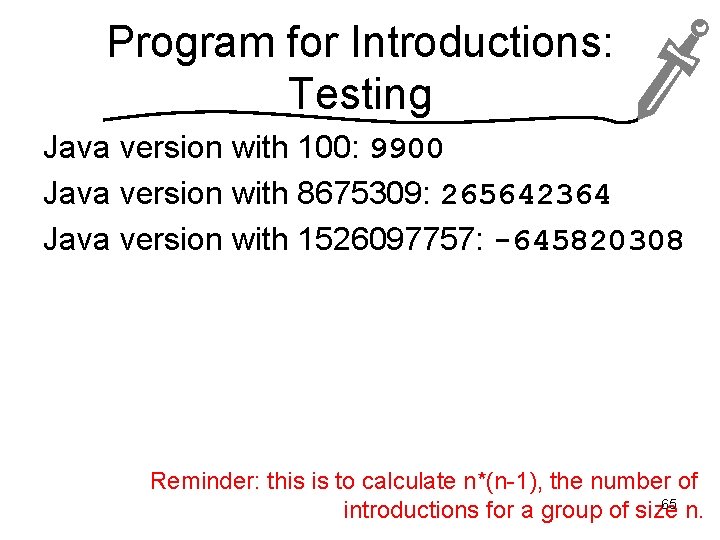

Program for Introductions: Testing Java version with 100: 9900 Java version with 8675309: 265642364 Java version with 1526097757: -645820308 Reminder: this is to calculate n*(n-1), the number of 65 introductions for a group of size n.

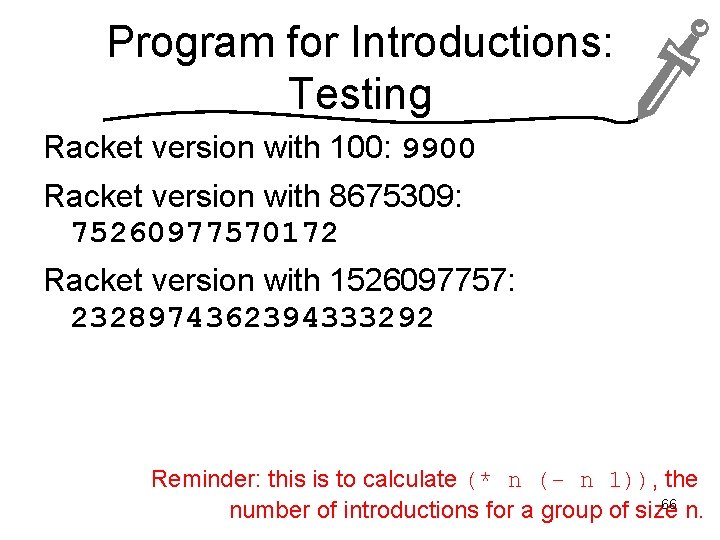

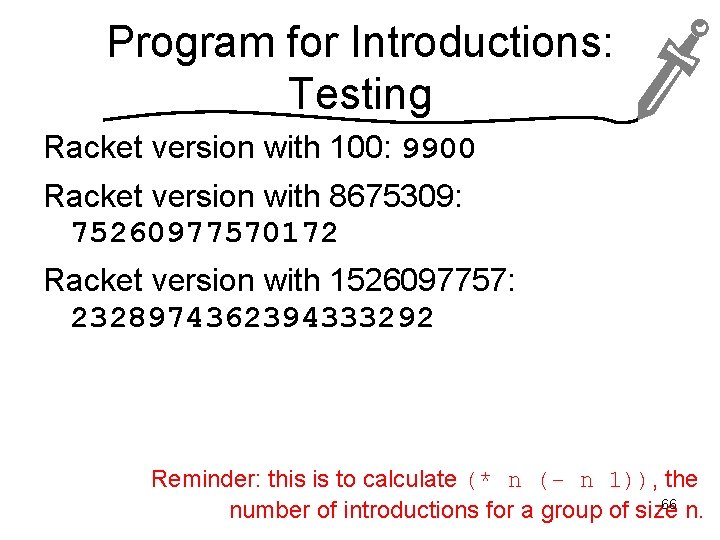

Program for Introductions: Testing Racket version with 100: 9900 Racket version with 8675309: 75260977570172 Racket version with 1526097757: 2328974362394333292 Reminder: this is to calculate (* n (- n 1)), the 66 number of introductions for a group of size n.