Shetlands Commission on Tackling Inequalities Session 4 Geography

- Slides: 60

Shetland’s Commission on Tackling Inequalities Session 4: Geography and Communities 28 th October, 2015

Introductory Session • Welcome • Background to Commission • Apologies • Note of Last Meeting – Approval – Matters Arising • Report of 3 rd Session

Purpose of Session 4 • To investigate the impact of geography and social isolation on inequalities in Shetland • To explore the ways in which communities are and can overcome any challenges

Shetland’s Communities Research Base

FRAGILE AREAS IN THE SHETLAND ISLANDS Tackling Inequalities Commission Wednesday 28 October 2015

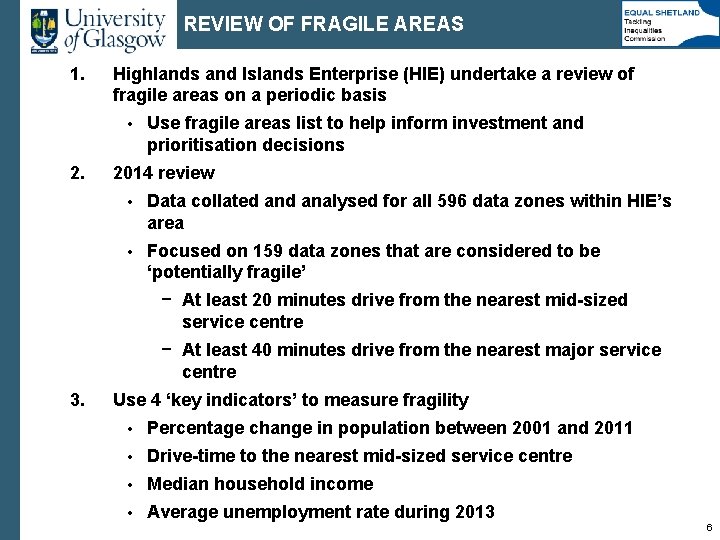

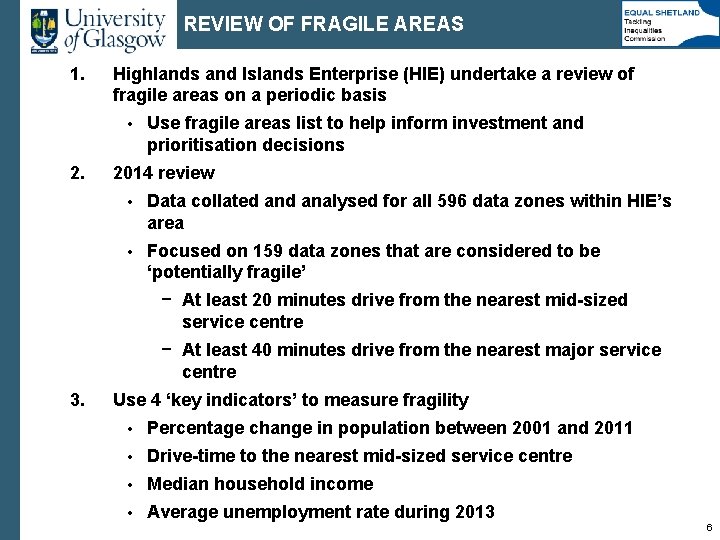

REVIEW OF FRAGILE AREAS 1. Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE) undertake a review of fragile areas on a periodic basis • 2. Use fragile areas list to help inform investment and prioritisation decisions 2014 review • Data collated analysed for all 596 data zones within HIE’s area • Focused on 159 data zones that are considered to be ‘potentially fragile’ − At least 20 minutes drive from the nearest mid-sized service centre − At least 40 minutes drive from the nearest major service centre 3. Use 4 ‘key indicators’ to measure fragility • Percentage change in population between 2001 and 2011 • Drive-time to the nearest mid-sized service centre • Median household income • Average unemployment rate during 2013 6

REVIEW OF FRAGILE AREAS (CONT. ) 4. Choice of indicators reflects HIE’s remits and responsibilities 5. Focus on relative fragility – i. e. which of the data zones are most fragile • 6. As a result, number of data zones defined as fragile should not change significantly over time Also collated range of supplementary indicators 7

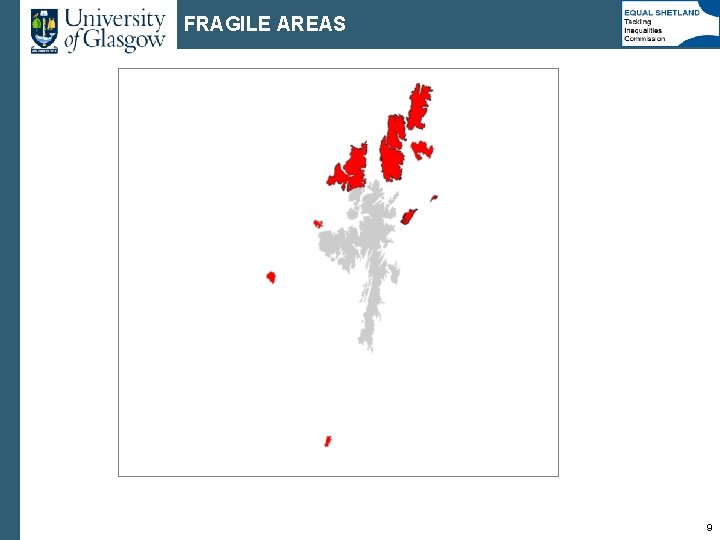

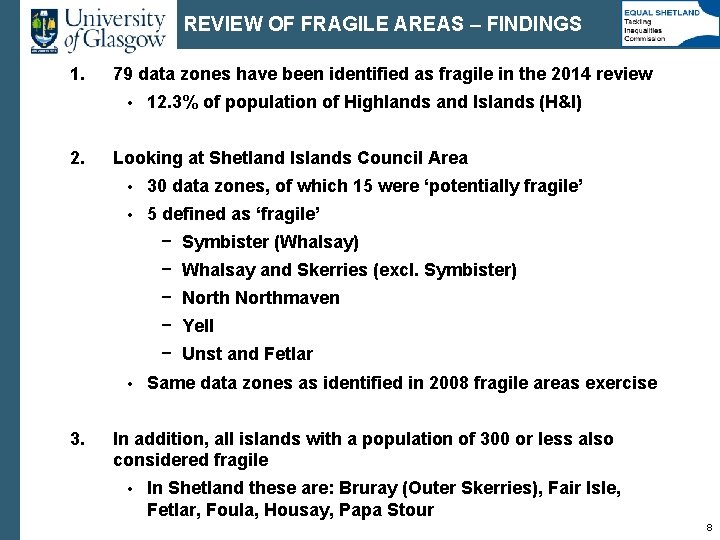

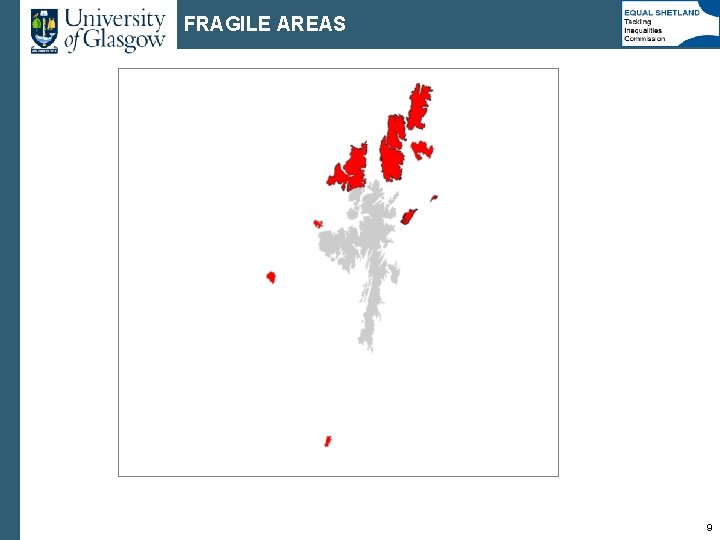

REVIEW OF FRAGILE AREAS – FINDINGS 1. 79 data zones have been identified as fragile in the 2014 review • 2. 12. 3% of population of Highlands and Islands (H&I) Looking at Shetland Islands Council Area • 30 data zones, of which 15 were ‘potentially fragile’ • 5 defined as ‘fragile’ − Symbister (Whalsay) − Whalsay and Skerries (excl. Symbister) − Northmaven − Yell − Unst and Fetlar • 3. Same data zones as identified in 2008 fragile areas exercise In addition, all islands with a population of 300 or less also considered fragile • In Shetland these are: Bruray (Outer Skerries), Fair Isle, Fetlar, Foula, Housay, Papa Stour 8

FRAGILE AREAS 9

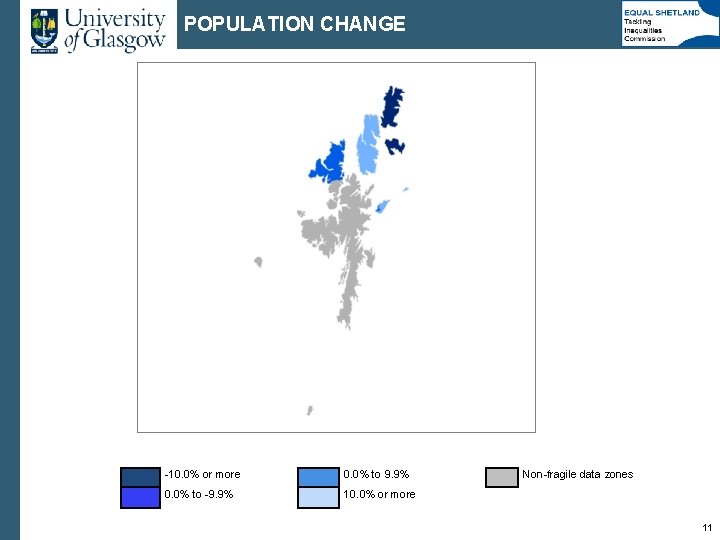

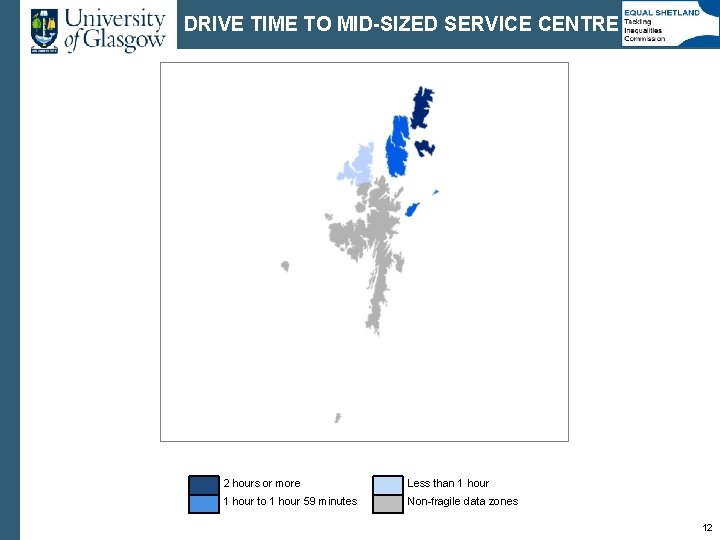

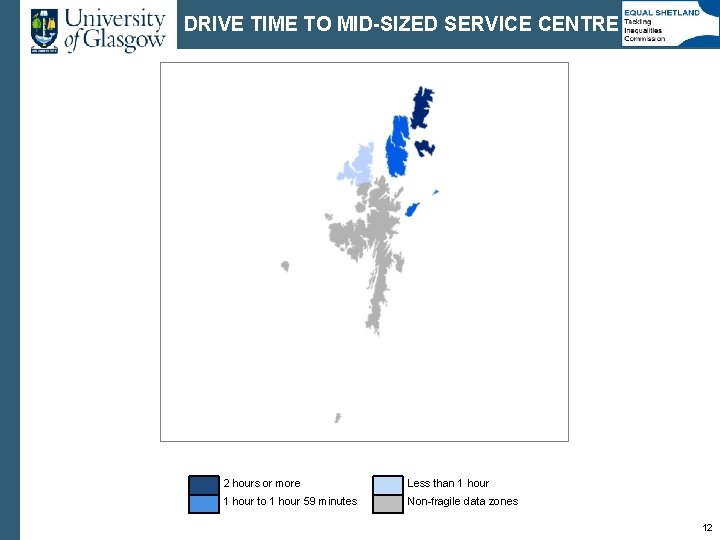

LOOKING AT SHETLAND’S FRAGILE AREA IN MORE DEPTH 1. 3, 440 live within Shetland’s fragile data zones – 14. 8% of Shetland population 2. Overall, population in Shetland’s fragile data zones declined by 3. 2% between 2001 and 2011 − Compared to increase of 5. 4% across Shetland as a whole and 7. 5% across H&I • However, large variations across 5 fragile areas − From decline of 14. 0% in Unst and Fetlar … − … to increase of 7. 5% in Whalsay and Skerries (excluding Symbister) 3. On average 111 minutes to nearest mid-sized service centre (Lerwick) • Compared to 34 minutes for all Shetland data zones 10

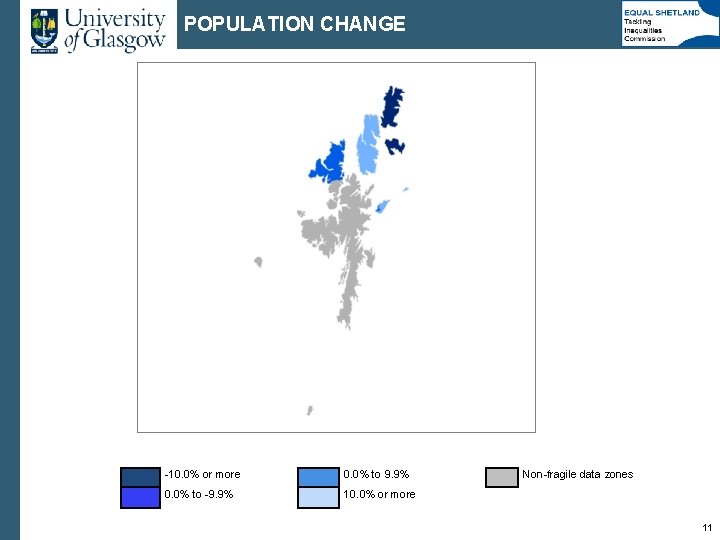

POPULATION CHANGE -10. 0% or more 0. 0% to 9. 9% 0. 0% to -9. 9% 10. 0% or more Non-fragile data zones 11

DRIVE TIME TO MID-SIZED SERVICE CENTRE 2 hours or more Less than 1 hour to 1 hour 59 minutes Non-fragile data zones 12

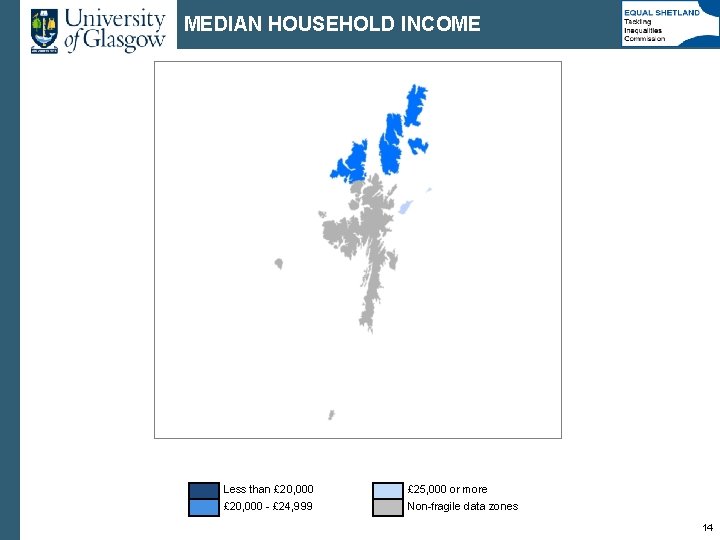

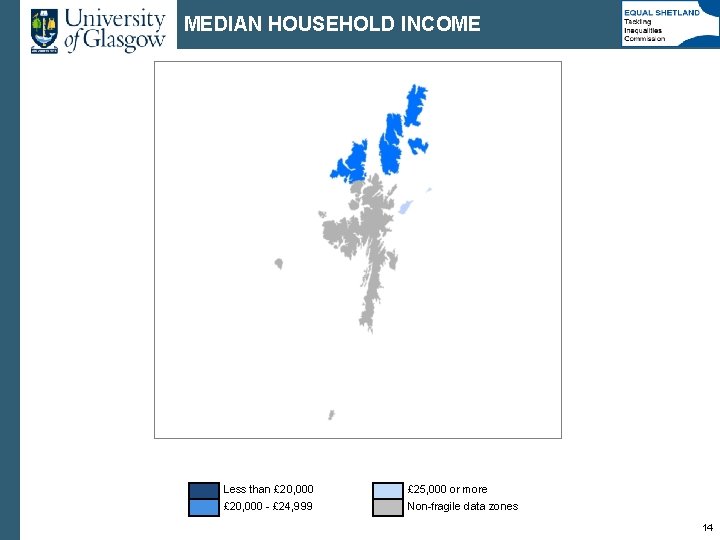

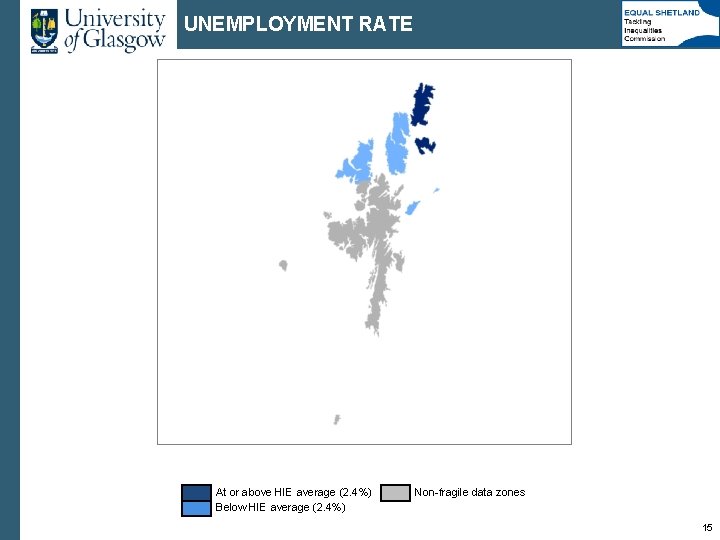

LOOKING AT SHETLAND’S FRAGILE AREA IN MORE DEPTH (CONT. ) 4. Average (median) household income in fragile data zones generally lower than in rest of Shetland • 5. Overall, household incomes in Shetland tend to be amongst highest in Highlands and Islands – but offset by higher cost of living (link to MIS study) Unemployment in fragile data zones very similar to Shetland as a whole (1. 2% vs. 1. 1%) • Considerably below Highlands and Islands rate of 2. 3% 13

MEDIAN HOUSEHOLD INCOME Less than £ 20, 000 £ 25, 000 or more £ 20, 000 - £ 24, 999 Non-fragile data zones 14

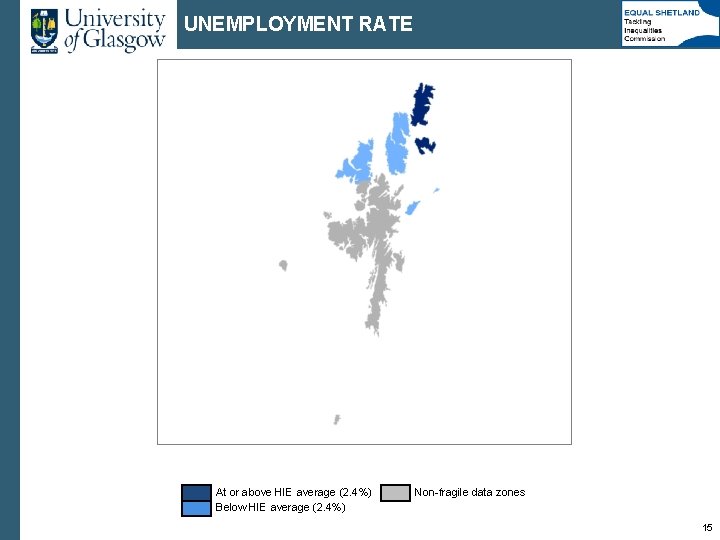

UNEMPLOYMENT RATE At or above HIE average (2. 4%) Below HIE average (2. 4%) Non-fragile data zones 15

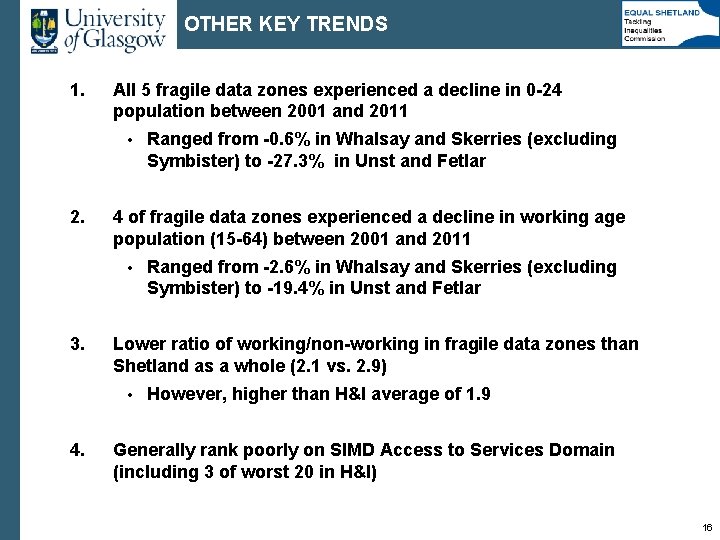

OTHER KEY TRENDS 1. All 5 fragile data zones experienced a decline in 0 -24 population between 2001 and 2011 • 2. 4 of fragile data zones experienced a decline in working age population (15 -64) between 2001 and 2011 • 3. Ranged from -2. 6% in Whalsay and Skerries (excluding Symbister) to -19. 4% in Unst and Fetlar Lower ratio of working/non-working in fragile data zones than Shetland as a whole (2. 1 vs. 2. 9) • 4. Ranged from -0. 6% in Whalsay and Skerries (excluding Symbister) to -27. 3% in Unst and Fetlar However, higher than H&I average of 1. 9 Generally rank poorly on SIMD Access to Services Domain (including 3 of worst 20 in H&I) 16

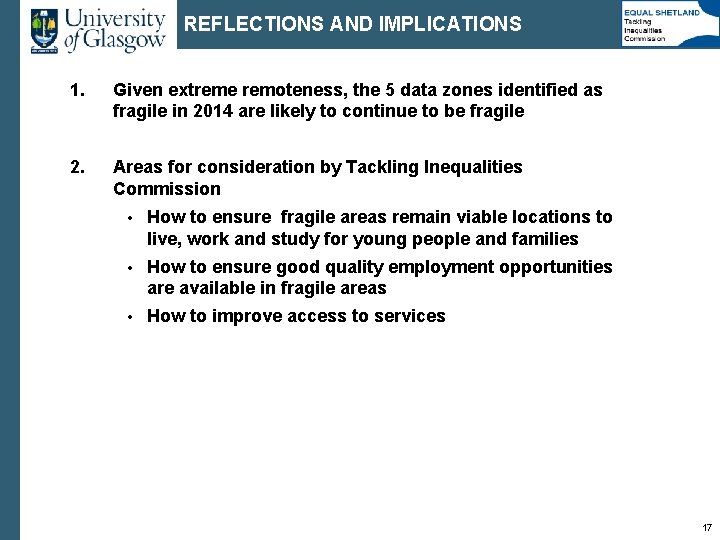

REFLECTIONS AND IMPLICATIONS 1. Given extreme remoteness, the 5 data zones identified as fragile in 2014 are likely to continue to be fragile 2. Areas for consideration by Tackling Inequalities Commission • How to ensure fragile areas remain viable locations to live, work and study for young people and families • How to ensure good quality employment opportunities are available in fragile areas • How to improve access to services 17

Shetland’s Communities Research Additional Information

Additional Data Available • • • Population Change, by Community Council Area (Census) Household Change, by Locality (Census, GRO(S)) Mean Income, by Community Council Area (CACI) Council Tax and / or Housing Benefit, by Locality (Council Tax, SIC) House Sales, by Locality (Scottish Government) House Completions, by Locality (SIC) Property Type, by Locality (SIC) Births and Deaths, by Locality Fuel Poverty Map, by Datazone (Changeworks) Internal Transport Costs, SIC 19

Shetland’s Communities Research Minimum Income Standard

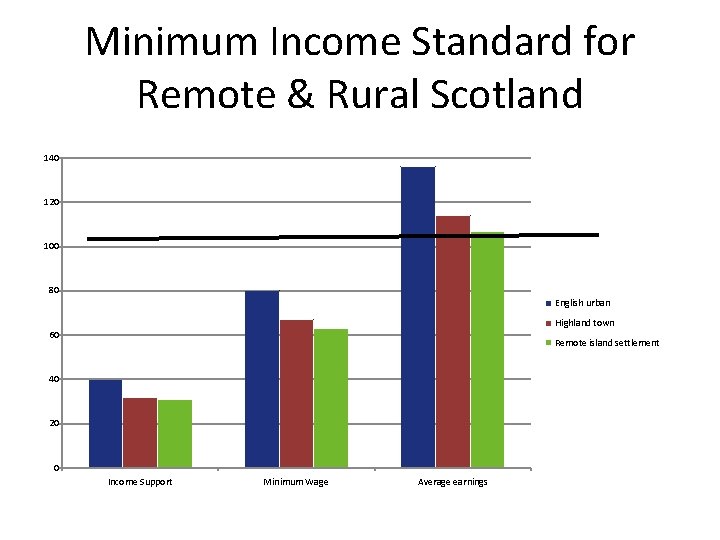

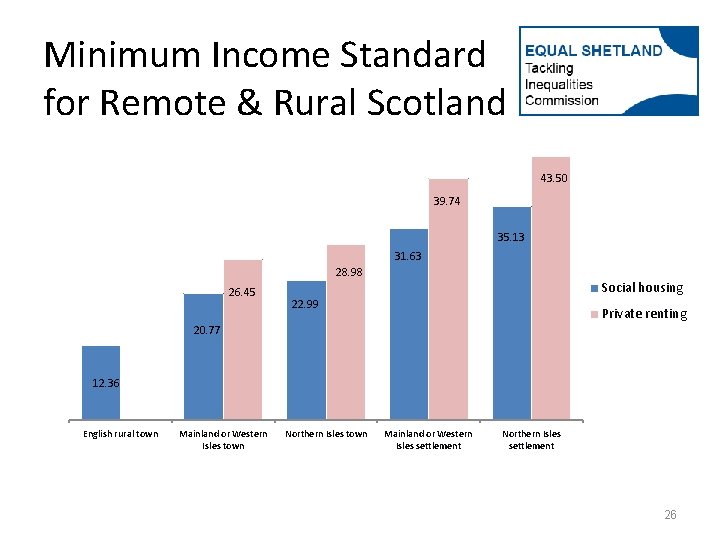

Minimum Income Standard for Remote & Rural Scotland • Research assessed how much it costs for people to live at a minimum acceptable standard in remote rural Scotland • Uses a well-established measure that allows comparisons with the rest of the UK • Considered living costs in remote rural Scotland in the context of the fragility and sustainability of local communities, and the ability of pensioners, working-age adults and families with children, on a range of incomes, to live satisfactory lives there 21

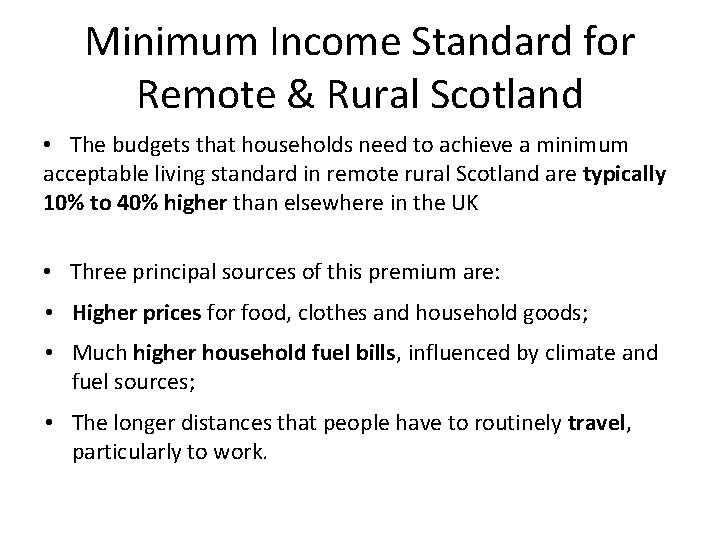

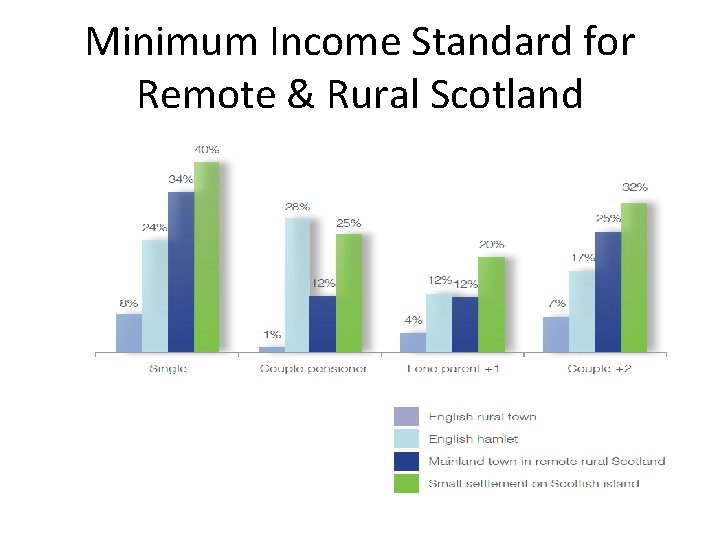

Minimum Income Standard for Remote & Rural Scotland • The budgets that households need to achieve a minimum acceptable living standard in remote rural Scotland are typically 10% to 40% higher than elsewhere in the UK • Three principal sources of this premium are: • Higher prices for food, clothes and household goods; • Much higher household fuel bills, influenced by climate and fuel sources; • The longer distances that people have to routinely travel, particularly to work.

Minimum Income Standard for Remote & Rural Scotland

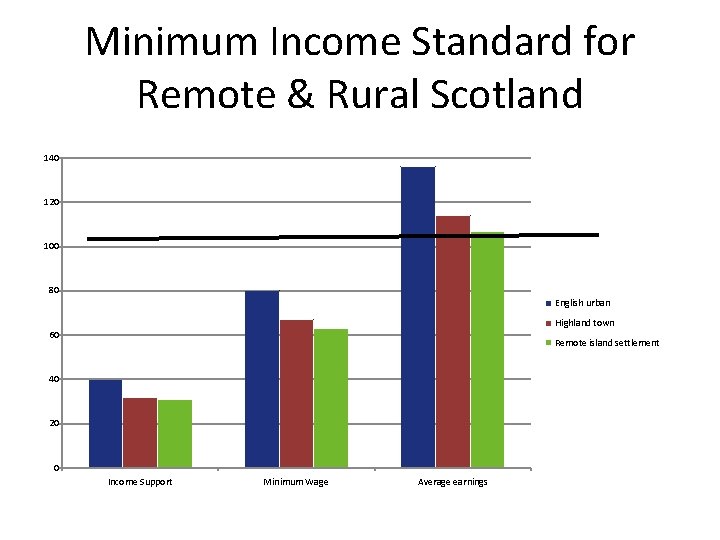

Minimum Income Standard for Remote & Rural Scotland 140 120 100 80 English urban Highland town 60 Remote island settlement 40 20 0 Income Support Minimum Wage Average earnings

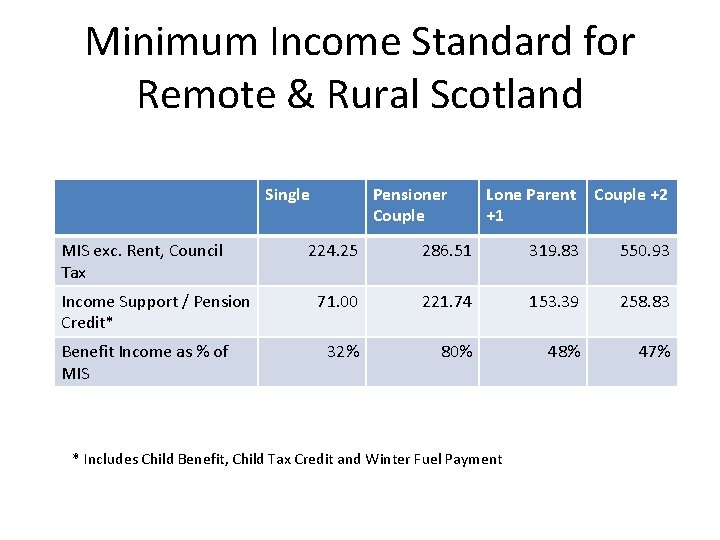

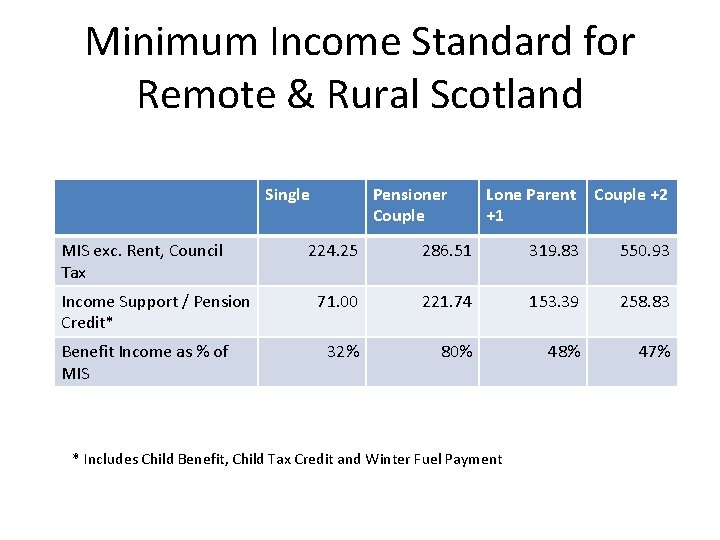

Minimum Income Standard for Remote & Rural Scotland Single MIS exc. Rent, Council Tax Income Support / Pension Credit* Benefit Income as % of MIS Pensioner Couple Lone Parent Couple +2 +1 224. 25 286. 51 319. 83 550. 93 71. 00 221. 74 153. 39 258. 83 32% 80% 48% 47% * Includes Child Benefit, Child Tax Credit and Winter Fuel Payment

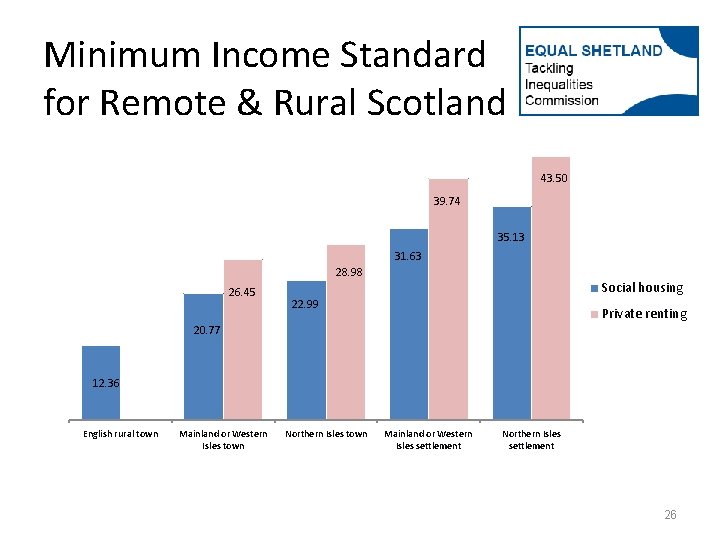

Minimum Income Standard for Remote & Rural Scotland 43. 50 39. 74 35. 13 31. 63 28. 98 26. 45 Social housing 22. 99 Private renting 20. 77 12. 36 English rural town Mainland or Western Isles town Northern Isles town Mainland or Western Isles settlement Northern Isles settlement 26

Minimum Income Standard for Remote & Rural Scotland • Food, particularly inaccessible from town and more so for remote from town; • Fuel, all areas not within Lerwick; • Personal goods and services, particularly remote; • Clothing, all areas, not within Lerwick; • Social and cultural participation, particularly inaccessible and remote; • Alcohol, particularly remote.

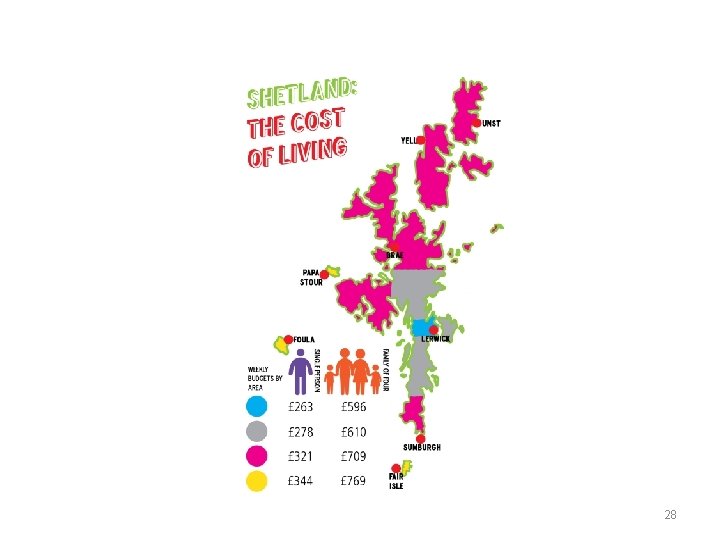

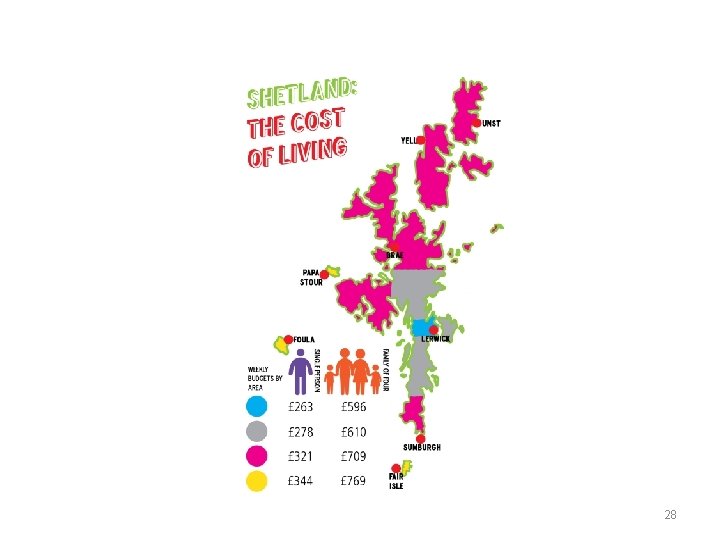

28

MIS, Summary • Areas within 2 hours of Lerwick (monthly supermarket shop, with top up): 15 -20% higher than Lerwick for working age households • More remote areas (entirely local shop): 2530% more 29

Shetland’s Communities Research Social Isolation

Social Isolation: Research into Deprivation and Social Exclusion in Shetland, 2006 • Two thirds felt part of their community – Waved at to being involved in hall / community group – Valued friendliness, trust, caring & sharing • Others felt isolated / left out / unimportant – Within Lerwick – Young People – Those with health issues (substance misuse / mental illness) – Carers – Incomers (working-class) 31

Social Isolation: Research into Deprivation and Social Exclusion in Shetland, 2006 Negative Aspects: • Discrimination: past behaviour / that of family • Lack of privacy, claustrophobic • Cliques, making decisions • Lack of transport / things to do If people felt part of their community, they felt they had a good quality of life. 32

POVERTY IS BAD! LET’S FIX IT! A youth-led participatory investigation into poverty, social exclusion and inequality in Shetland Final Report, 6 th December 2011

Young people’s access to opportunities is unequal Reputation: The nature of Shetland’s small communities means young people can easily develop negative reputations and labels which stick, and impact on their ability to participate in educational, employment and social activities. Reputation is important. Everyone knows you so well, they will never forget what you’ve done. However, some young people claimed that having a ‘bad reputation’ could enhance access to opportunities because you would be ‘noticed’ more, and given support. The Shetland grapevine can be good for finding out about jobs but it can tarnish someone’s reputation easily.

Young people find it hard to be an individual Young people feel considerable pressure to ‘fit in’ and ‘be the same’ as everyone else. Pressure comes mainly from peers and parents and is exacerbated by the fact that communities are small and opportunities to join different social groups is limited. Being different, for example, dressing differently, being lesbian or gay, or simply behaving differently can lead to being labelled and stigmatised which can, in turn, result in isolation from peers and exclusion from social opportunities. It’s just like a circle for teenagers. You can’t be yourself in a group. You have to do what they do. Drinking is a real problem up here. Young people think it’s okay to drink because they have been brought up with it. You can be different but only in the ‘right’ ways. You can’t piss off the teachers in a place where they are your neighbours, even your mum or dad. Shetland is an adult-run place. Young people are not respected. You’ve got to do things the same way as adults. Young people have to follow in the footsteps of their parents. Parents dictate young people’s lives. It’s hard for young people to do what they want to do. It’s the influences that affect your future. If your parents are doing something, like using drugs, you are more likely to do it. When you are growing up in Shetland, you don’t have space to be yourself. You might be brought up to believe something, like you’re brought up to be a Christian. You may not be forced into it but it’s just what you feel you should be doing.

Limited social groups enhances peer pressure on young people Opportunities to join different social groups are limited because communities and class sizes are small. Consequently, young people feel easily pressurised into participating in activities they are not always comfortable with, for example drinking alcohol, smoking and taking drugs. Participating in such activities can lead to further exclusion, for example, from jobs, because they have gained a negative reputation which is hard to shake off. However, young people who had spent time away from Shetland, for example at university, argued that this: - It’s so easy to fall into something like that. You might get pushed out of a popular circle for not doing it. Because everyone knows each other, if there is peer pressure on one group, it just shifts from one to the next. Gave them more confidence to be themselves when they came back to Shetland. Provided opportunities to make new friends when you return to Shetland. I’ve been back properly a month now. I’ve met so There’s not the same sense of pressure if many new people! you’ve been away. You get more confidence when you’re put in a situation where you’re not the only person. You start from scratch. You can just be yourself, where you get nae pressure from the community. By the time I moved to the Anderson, I wanted to get away. There’s only so much of the same people you can take!

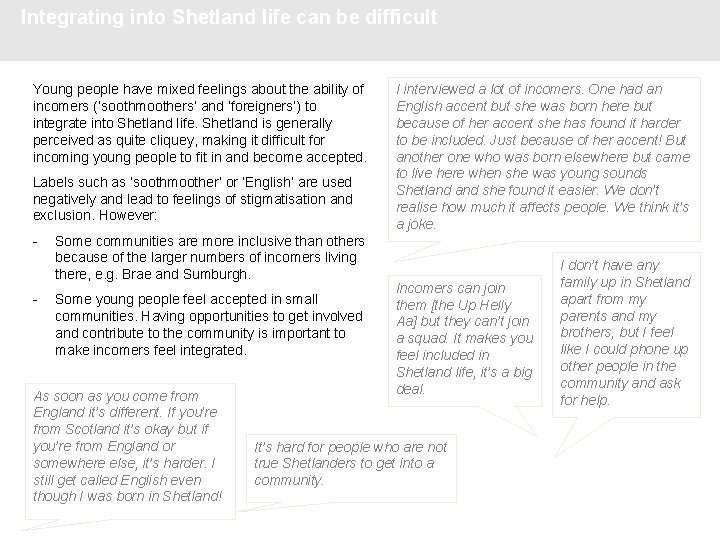

Integrating into Shetland life can be difficult Young people have mixed feelings about the ability of incomers (‘soothmoothers’ and ‘foreigners’) to integrate into Shetland life. Shetland is generally perceived as quite cliquey, making it difficult for incoming young people to fit in and become accepted. Labels such as ‘soothmoother’ or ‘English’ are used negatively and lead to feelings of stigmatisation and exclusion. However: - - Some communities are more inclusive than others because of the larger numbers of incomers living there, e. g. Brae and Sumburgh. Some young people feel accepted in small communities. Having opportunities to get involved and contribute to the community is important to make incomers feel integrated. As soon as you come from England it’s different. If you’re from Scotland it’s okay but if you’re from England or somewhere else, it’s harder. I still get called English even though I was born in Shetland! I interviewed a lot of incomers. One had an English accent but she was born here but because of her accent she has found it harder to be included. Just because of her accent! But another one who was born elsewhere but came to live here when she was young sounds Shetland she found it easier. We don’t realise how much it affects people. We think it’s a joke. Incomers can join them [the Up Helly Aa] but they can’t join a squad. It makes you feel included in Shetland life, it’s a big deal. It’s hard for people who are not true Shetlanders to get into a community. I don’t have any family up in Shetland apart from my parents and my brothers, but I feel like I could phone up other people in the community and ask for help.

Young people in Shetland find it hard to be an individual due to peer pressure and adult judgement. Key message 2

Stigmatisation and labelling due to the ‘Shetland Grapevine’ have very negative impacts on young people. Key message 3

Loneliness • A mismatch of the relationships we have and those we want • An internal trigger telling us to seek company as thirst tells us to drink and hunger tells us to eat • Loneliness describes the pain of being alone as solitude describes the joy of being alone • Isolation is often where there is no choice but to be alone • Some people seek solitude, but few choose to be lonely, primarily because it isn’t good for us

Conviviality “Relationships for conviviality are distinct from other relationship by being relationships of chosen interdependence. ” Lemos G (2000) Homelessness and loneliness, Crisis

Loneliness • Increases risk of depression • 64% increased risk of developing clinical dementia • Increases the risk of high blood pressure • Is an equivalent risk factor for early mortality to smoking 15 cigarettes a day, • A greater impact than other risk factors such as physical inactivity and obesity Lonely people: • Are vulnerable to alcohol problems • Eat less well – they are less likely to eat fruit and vegetables • Are more likely to be smokers and more likely to be overweight • Are less likely to engage in physical activity and exercise

JRF: A neighbourhood approach • Place based approach to loneliness • Asset based approach to community development • Working with people in their neighbourhood to explore what contributes to feelings of overwhelming/problematic loneliness • Exploring factors like location, health and wellbeing, safety, independence, life transitions • Developing and putting into practice local ideas and activities to reduce the effects of loneliness • Making every contact and conversation count

Shetland Approach: Community Connections • Those connections within our communities that some of us take for granted • Tend to be physical / social barriers for some

Lessons • Tends to be a focus on ‘what other services can we offer folk to support them’ • Life impacting outcomes don’t have to cost money • ‘Being good nosey’

Q&A

Shetland’s Communities Challenges and Solutions

Challenges and Solutions Ian Best, Fair Isle

Challenges and Solutions Viviana Di Carlo and Miguel Oliveira, originally from Italy and Portugal

Challenges and Solutions Julie Thomson & Cheryl Jamieson

Q&A

Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act Brendan Hall, Partnership Officer, Community Planning & Development, SIC

Timeline • • Consultation paper Autumn 2014 Draft Bill published Spring 2015 Final Bill published Summer 2015 Royal Assent 24 th July 2015

Aims • Empower community bodies through the ownership of land buildings and strengthening their voices in the decisions that matter to them • Support an increase in the pace and scale of public service reform by cementing the focus on achieving outcomes and improving the process of community planning

Parts • • • National Outcomes Community Planning Participation Requests Community Right to Buy Abandoned, neglected or detrimental land Asset transfer requests Common good property Participation in public decision-making Allotments Forestry and Football Clubs

Inequalities • National Outcomes – “reduction of inequalities of outcome which result from socio-economic disadvantage” • Community Planning – participation (and resources to secure participation); LOIP and Locality Plans • Participation requests – opportunities to tackle inequality; further provisions may be made for additional support to communities experiencing disadvantage • Assets and Land – consideration of how transfer contributes to reducing inequalities

Opportunities • Empowerment – disenfranchised communities? Remote communities? • Participation – influence on decision making; defining priorities; participatory budgeting • Co-production – potential to run services with communities (transport, health and social care) • Assets – can communities make better use of assets to improve outcomes? (transport, community energy, health and social care) • Land/Allotments – access to growing space and benefits of grow-your-own? What other land uses could be considered? • Community Planning – co-ordinated public sector response to inequalities; in Shetland this also includes Trusts, third sector and private sector (SOA 2016 -20)

Questions for Session • What are the inequalities? (including age, gender, opportunities etc. ) • What is the impact on individuals, households and communities of these inequalities? Think about inequality of opportunity, too. • What is the impact on Shetland, thinking about the economy, society (including health, housing and crime), and environment? • What are the big issues, and key challenges in terms of Shetland’s inequalities? • What are the root causes(s)? • What are the solutions / mitigations? • One achievable quick win. . . • What would you like to know more about?

Developing Recommendations • Feedback • Discussion • Proposed Recommendations

Next Steps • Outputs: Note / Report • Media Briefing and Q & A • 23 rd November, 1. 45 pm