Pregnancy in women with systemic lupus erythematosus Dr

- Slides: 33

Pregnancy in women with systemic lupus erythematosus Dr lalooha

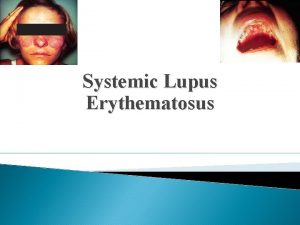

INTRODUCTION �pregnancy in women with SLE carries a higher maternal and fetal risk compared with pregnancy in healthy women. The prognosis for both mother and child is best when SLE has been quiescent for at least six months prior to the pregnancy. Disease flares during SLE pregnancy pose challenges with respect to distinguishing physiologic changes related to pregnancy from disease-related manifestations. Thus, a multidisciplinary approach with close medical, obstetric, and neonatal monitoring is necessary to optimize both maternal and fetal outcomes.

PREGNANCY PLANNING � Ideally, all pregnancies in women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) should be planned during periods of disease quiescence for six months prior to conception. Active SLE at the time of conception is a strong predictor of adverse maternal and obstetrical outcomes. In spite of this risk, the majority of such pregnancies still result in live births.

Preconception evaluation �A preconception assessment is essential in women with SLE to determine whether pregnancy may pose an unacceptably high maternal or fetal risk, to initiate interventions to optimize disease activity, and to adjust medications to those that are least harmful to the fetus. �Women should be advised that discontinuation of medication with conception will increase the risk of lupus flare and pregnancy complications. Ideally, women considering conception should be maintained on medications that are compatible with pregnancy and be advised to continue these medications in pregnancy.

Risk assessment � The preconception evaluation in women with SLE should include an assessment of disease activity and major organ involvement, as well as any history of venous thrombosis, or concurrent medical disorders. � Previous obstetric outcomes should be reviewed, with particular attention paid to history of small for gestational age fetus, preeclampsia, stillbirth, miscarriage, and preterm birth. �Patients with evidence of active SLE, especially lupus nephritis, should be advised to defer pregnancy until the disease is well controlled for at least six months. For those with renal insufficiency, counseling should include an assessment of the risk of temporary or permanent decline in renal function

�Increased severity of maternal disease generally correlates with higher maternal and fetal risk in pregnancy. Thus recent stroke, cardiac involvement, pulmonary hypertension, severe interstitial lung disease, and advanced renal insufficiency can be dangerous to both mother and fetus. Women with these or other worrisome complications should be counseled carefully by a Maternal Fetal Medicine specialist as to their individual risk profile, with clear discussion of the morbidity and mortality risks to both mother and fetus associated with pregnancy. Alternatives such as surrogacy and adoption should be presented. �Maternal antibody status should be assessed. Antiphospholipid antibodies (a. PLs) may increase some obstetric risks, and antibodies to Ro/La predispose to neonatal lupus (NL)

Specific laboratory testing �In addition to routine preconception labs the following should be reviewed during the preconception evaluation. �a. PLs: lupus anticoagulant (LA), immunoglobulin G (Ig. G) and Ig. M anticardiolipin (a. CL) antibodies, and Ig. G and Ig. M antibeta 2 -glycoprotein (GP) I antibodies Ø Anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies Ø Renal function (creatinine, urinalysis with urine sediment, spot urine protein/creatinine ratio) Ø Complete blood count (CBC) Ø Liver function tests Ø Anti-double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (ds. DNA) antibodies Ø Complement (CH 50, or C 3 and C 4) Ø Uric acid

Medications �Medications must be reviewed and adjusted prior to conception with the goal of maintaining disease control with medications with the best safety profile during pregnancy. Although many medications used to treat SLE are potentially harmful or contraindicated during pregnancy, there are some safer options.

Selective use allowed during pregnancy �Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs Ø not strongly associated with congenital anomalies. Ø may impede ovulation or implantation and is best avoided during a conception cycle. Ø during the first trimester increases the risk of spontaneous abortion. Ø in the third trimester may cause premature closure of the ductus arteriosus as well as other complications, and should be avoided during that time. Low-dose aspirin can be safely used in pregnancy and is often indicated to reduce the risk of preeclampsia.

Hydroxychloroquine �Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) should be continued during pregnancy in all patients with SLE, unless otherwise contraindicated. Several studies have demonstrated fewer disease flares and better outcomes in patients continuing HCQ during pregnancy, with no increase in adverse events or congenital malformations. Additionally, some data suggest a decrease in occurrence of congenital heart block in at-risk fetuses of mothers with anti-Ro/SSA and anti-LA/SSB antibodies exposed to HCQ

Glucocorticoids �Glucocorticoids are used for a wide range of maternal diseases in pregnancy. We suggest control of disease with the lowest possible dose of prednisone, ideally less than 10 mg/day. �Glucocorticoid use during the first trimester has been associated with cleft lip, with and without cleft palate.

� Azathioprine – Azathioprine is considered relatively safe during pregnancy, but doses should not exceed 2 mg/kg/day. � Cyclosporine – Limited observations suggest that children exposed in utero to cyclosporine have normal renal function and blood pressure. The manufacturer suggests that use in pregnancy should be limited to when maternal benefit outweighs fetal risk. � ●Tacrolimus – A causal relationship between tacrolimus use and birth defects has not been found, though the number of fetuses exposed in utero has been small. An small case series of nine pregnant lupus patients reported successful disease maintenance or control of lupus nephritis flares with tacrolimus � Antihypertensive medications – Methyldopa, labetalol, nifedipine, and hydralazine are the most commonly used antihypertensives in pregnancy. By comparison, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers are contraindicated during pregnancy. Diuretics should be used with caution. Nitroprusside is the agent of last resort for urgent control of refractory severe hypertension; its use should be limited to a short period of time in an emergency situation.

Selective use with caution in pregnancy �●Biologic medications – Data regarding the use of biologic medications such as the B-cell depleting antibody, rituximab, or the BAFF inhibitor, belimumab, during pregnancy are limited. Case reports suggest that B-cell lymphocytopenia lasting up to six months in rituximab-exposed infants may occur. Thus, we discourage the use of these agents during pregnancy.

Contraindicated in pregnancy � ●Cyclophosphamide – Cyclophosphamide is associated with congenital (or fetal) malformations and should be avoided during the first 10 weeks of gestation, when the fetus is most susceptible to teratogens. However, this medication has been used in late pregnancy in life-threatening clinical situations. � ●Mycophenolate mofetil – Congenital anomalies have been reported in infants exposed to mycophenolate mofetil during pregnancy. This medication should be avoided during pregnancy. � Azathioprine or tacrolimus can be substituted for mycophenolate prior to and during pregnancy, or, alternatively, glucocorticoids may be used at the lowest dose that controls disease activity. � Methotrexate – Methotrexate is teratogenic and should not be used during pregnancy. � ●Leflunomide – Pregnancy should be deferred for two years after discontinuation of leflunomide (or a washout procedure should be employed), since this drug can remain detectable in the serum for up to two years.

�Ideally conception should only be attempted in a state of disease remission or stable disease on medications compatible with pregnancy. However, if pregnancy occurs during a period of disease activity, medications will need to be adjusted for fetal and maternal safety.

SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS DURING PREGNANCY �Exacerbation of SLE — Although it is generally accepted that pregnancy and the postpartum period are associated with a higher rate of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) disease flares, widely variable rates have been reported ranging from 25 to 60 percent. �The following factors are associated with an increased risk of SLE flare during pregnancy: Ø Active disease during the six months prior to conception Ø A history of lupus nephritis Ø Discontinuation of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ)

Impact of lupus on pregnancy �maternal mortality was 20 -fold higher among women with SLE. � two- to fourfold increased rate of obstetric complications including preterm labor, unplanned cesarean delivery, fetal growth restriction, preeclampsia, and eclampsia. �significantly higher risk of thrombosis, infection, thrombocytopenia, and transfusion. �Several predictors of adverse pregnancy outcomes among women with SLE have been identified and include active disease, use of antihypertensives, prior lupus nephritis, the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (a. PLs), and thrombocytopenia

Preeclampsia �Preeclampsia is one of the most frequent complications of pregnancy in SLE, occurring in 16 to 30 percent of women with SLE, compared with 4. 6 percent of pregnancies in the general obstetric population. Risk factors for preeclampsia in women with SLE are the same as those in healthy women. Additional risk factors for preeclampsia that are specific to SLE patients include an active or prior history of lupus nephritis, declining complement levels, and thrombocytopenia. The data on whether a. PLs predispose to preeclampsia is unclear, although some studies suggest an association

Preterm birth � Preterm birth is the most common obstetric complication in women with SLE. Rates of preterm birth from 15 to 50 percent are reported, with increased incidence in women with lupus nephritis or high disease activity. This compares with 12 percent of pregnancies in the general US obstetric population. The presence of lupus nephritis and active disease are the strongest predictors for early delivery. However, the rates of preterm birth are likely better among women without such risk factors

Fetal complications �●Fetal loss – Historically, significantly elevated rates of both early and late pregnancy loss have been seen in women with SLE. Most contemporary studies group all losses from embryonic to stillbirth under the term “fetal loss, ” making it challenging to interpret the risk of early miscarriage versus later fetal death. The effect of SLE on embryonic losses is controversial, with a possible slight increase in risk. Women with SLE are at increased risk of fetal death beyond 10 weeks, particularly in the presence of active SLE, lupus nephritis, and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Overall, fetal loss rates have been declining over the last decades, with increased rates of livebirths. A large observational cohort of patients with inactive lupus or mild to moderate disease activity at conception found that 5 percent of pregnancies ended in fetal or neonatal death.

� Fetal growth restriction – About 10 to 30 percent of pregnancies in women with SLE are complicated by fetal growth restriction and small -for-gestational-age babies compared with about 10 percent of pregnancies in the general obstetric population. . � ●Neonatal lupus – NL is a passively transferred autoimmune disease that occurs in some babies born to mothers with anti-Ro/SSA or anti. LA/SSB antibodies, who may or may not carry the diagnosis of SLE or Sjögren’s. The major manifestations of NL are either cutaneous or cardiac, but other manifestations of NL include hematologic and hepatic abnormalities. The most serious complication in the neonate is congenital complete heart block, which occurs in approximately 2 percent of children born to primigravid women with anti-Ro/SSA antibodies. The risk of complete heart block increases to approximately 16 to 18 percent for subsequent pregnancies, or 10 to 15 percent when a previous infant had cutaneous NL. � SLE does not appear to confer risks for other identifiable congenital abnormalities. Some studies have found that learning disabilities may be more frequent in children, particularly sons, of SLE mothers, but more studies are needed to confirm this

Presence of antiphospholipid antibodies � a. PLs are present in about a quarter to a half of patients with SLE; however, only a few develop thrombotic or obstetric complications related to APS. � Pregnant women with SLE who have an obstetric history suggestive of APS (fetal death after 10 weeks or three or more consecutive miscarriages, or premature birth <34 weeks due to preeclampsia or placental insufficiency) or unexplained venous or arterial thrombotic event, should be tested for the presence of a. PLs (ie, lupus anticoagulant [LA], immunoglobulin G [Ig. G] and Ig. M anticardiolipin [a. CL] antibodies; and Ig. G and Ig. M anti-beta 2 -glycoprotein [GP] I). The clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management of women with a. PL who are contemplating pregnancy or who are pregnant are discussed in more detail separately. � It is unclear whether women with a. PLs without an APS diagnosis are at increased risk of pregnancy loss. Issues associated with the presence of these autoantibodies in pregnant women and the management of such patients is discussed separately.

Presence of anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies �a fetus exposed to anti-Ro/SSA and/or anti-La/SSB antibodies is at an increased risk of developing congenital complete heart block or NL. In most cases, congenital heart block develops between 18 and 24 weeks of gestation. Thus, in some centers, women who have antibodies to Ro/SSA and/or La/SSB undergo increased fetal surveillance for heart block, with differing surveillance protocols at different sites. While there is no therapeutic intervention proven to prevent progression, early detection allows for increased monitoring. HCQ use during pregnancy is associated with reduced rates of congenital heart block.

MANAGEMENT DURING PREGNANCY � Monitoring SLE activity — Women should be assessed by a rheumatologist for disease activity at least once each trimester, and more frequently if they have active SLE. The schedule for monitoring includes: � Initial evaluation — At the first visit after (or at which) pregnancy is confirmed, the following investigations are recommended: Ø Physical examination, including blood pressure Ø Renal function (creatinine, urinalysis, spot urine protein/creatinine ratio) Ø Complete blood count (CBC) Ø Liver function tests Ø Anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies Ø Lupus anticoagulant (LA) and anticardiolipin antibody (a. CL) assays Ø Anti-double stranded DNA (ds. DNA) antibodies Ø Complement (CH 50, or C 3 and C 4) Ø Serum uric acid

�Some physiological changes of pregnancy may overlap with features of active SLE, making differentiation difficult. As an example, laboratory findings that may be observed during a normal pregnancy include mild anemia, mild thrombocytopenia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and proteinuria. Protein excretion increases in the course of normal pregnancy, but should remain below 300 mg/24 hours. A baseline 24 -hour urine collection can be helpful in distinguishing lupus flare from preeclampsia and normal changes later in pregnancy. � Also, during normal pregnancy, complement levels may rise by 10 to 50 percent, and may appear to remain normal despite active SLE. Thus, the trend of complement levels is generally more informative than the actual value. �Thus, laboratory testing must be interpreted in the clinical context and women who show evidence of increased serologic activity but who remain asymptomatic should be monitored more closely. We do not initiate therapy for serologic findings alone.

Laboratory testing � In addition to a physical examination with blood pressure testing, the following laboratory tests are recommended at regular intervals during pregnancy: Ø CBC Ø Creatinine Ø Urinalysis with examination of urinary sediment Ø Spot urine protein/creatinine ratio or 24 -hour urine collection Ø Anti-ds. DNA antibodies Ø Complement (CH 50, or C 3 and C 4) � Ordering additional laboratory tests such as liver function tests and serum uric acid should be guided by the clinical presentation. The frequency of laboratory testing is individualized and varies with disease activity. Patients with stable disease should ideally undergo laboratory testing each trimester, but those with active lupus will require more frequent testing.

Maternal-fetal monitoring � The optimal monitoring schedule to ensure maternal and fetal health during pregnancy is not known. Women with risk factors or poor prognostic indicators may require more frequent monitoring. In addition to routine prenatal care, fetal monitoring for women with SLE includes: Ø First-trimester ultrasound evaluation to establish the estimated date of delivery. A fetal anatomic survey is performed at approximately 18 weeks of gestation. Ø Ultrasound evaluation for fetal growth and placental insufficiency in the third trimester. Frequency of surveillance for fetal growth will depend upon maternal and fetal wellbeing, but typically will be performed approximately every four weeks. More frequent monitoring is indicated if growth restriction or placental insufficiency is suspected, or if maternal disease is active. In these settings, umbilical artery velocimetry is also recommended. Ø Fetal testing with nonstress tests and/or biophysical profile during the final four to six weeks of pregnancy is indicated in most women with lupus, with individual surveillance plans based on fetal and maternal assessment. Ø In patients with positive anti-Ro/SSA and/or anti-La/SSB antibodies, increased surveillance for congenital heart block is recommended.

Preeclampsia �Women with SLE are at higher risk of preeclampsia than the general population. These patients require additional vigilance, as the presentation of hypertension, proteinuria, or end-organ dysfunction after 20 weeks of gestation is concerning for development of preeclampsia. Severe, early -onset growth restriction is similarly concerning for developing preeclampsia. While preeclampsia presenting later in pregnancy can often be managed expectantly, in pre-and peri-viable gestations, delivery is indicated to prevent catastrophic maternal complications. For this reason, early diagnosis is essential. �In women at elevated risk of preeclampsia, aspirin has been shown to reduce the risk of disease by 10 to 20 percent when initiated between 12 to 20 weeks gestation.

Preeclampsia versus lupus nephritis � Differentiating preeclampsia from lupus nephritis or a lupus flare can be challenging. Lupus nephritis flares during pregnancy can mimic preeclampsia, presenting with increasing proteinuria, hypertension, thrombocytopenia, and a deterioration in renal function. Active lupus nephritis and preeclampsia can also occur at the same time. � Laboratory testing may be, but is not always, useful in distinguishing preeclampsia from nephritis or a lupus flare: � Lupus nephritis is often associated with proteinuria and/or an active urine sediment (red and white cells and cellular casts), whereas only proteinuria is seen in preeclampsia. � Flares of SLE are likely to be associated with low or decreasing complement levels and increased titers of anti-ds. DNA antibodies; by comparison, complement levels are usually, but not always, normal or increased in preeclampsia. � Thrombocytopenia, elevated serum levels of liver enzymes and an elevated or rising level of uric acid are more prominent in preeclampsia than lupus nephritis. However, thrombocytopenia may also be seen in association with antiphospholipid antibodies (a. PLs), thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, and immune thrombocytopenia, each of which may complicate pregnancy in women with SLE. � The onset of these overlapping symptoms before 20 weeks of gestation is more consistent with lupus nephritis. Renal biopsy could help differentiate the two conditions, but the higher risk of complications during pregnancy limits the use in pregnancy.

Treating active SLE �The treatment of active SLE during pregnancy is guided by the severity and degree of organ involvement, similar to patients in the non-pregnant state. Treatment should not be withheld due to pregnancy; however, some medications used to treat SLE may cross the placenta and cause fetal harm. Thus, the risks and benefits of treatment during pregnancy must be weighed against the risk of SLE activity having a deleterious effect on the mother and the fetus. �Lupus nephritis in pregnancy requires special consideration because of its potential morbidity and possible confusion with preeclampsia.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS � Ideally, all pregnancies in women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) should be planned during periods of disease quiescence for at least six months prior to conception. Active SLE at the time of conception is a strong predictor of adverse maternal and obstetrical outcomes. In spite of this risk, the majority of such pregnancies still result in live births. � A preconception assessment is essential in women with SLE to determine whether pregnancy may pose an unacceptably high maternal or fetal risk, to initiate interventions to optimize disease activity, and to adjust medications to those that are least harmful to the fetus. � Specific laboratory testing done as part of the preconception evaluation should include antiphospholipid antibodies (a. PLs; lupus anticoagulant [LA], immunoglobulin G [Ig. G] and Ig. M anticardiolipin [a. CL] antibodies, and Ig. G and Ig. M anti-beta 2 -glycoprotein [GP] I antibodies), anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies, anti-double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (ds. DNA) antibodies, TSH, creatinine, urinalysis with urine sediment, spot urine protein/creatinine ratio, complete blood cell count (CBC), liver function tests, and complement levels (CH 50, or C 3 and C 4) and a uric acid. � Medications must be reviewed and adjusted prior to conception with the goal of maintaining disease control with medications with the best safety profile during pregnancy. Although many medications used to treat SLE are potentially harmful or contraindicated during pregnancy, there are some safer options.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS � Other considerations during pregnancy in women with SLE include increased risk of disease flare, particularly among women with a history of lupus nephritis or active nephritis. Pregnancy among lupus patients is also associated with higher rates of complications such as preeclampsia, preterm birth, fetal loss, growth restriction, neonatal lupus (NL) syndromes, and complications of prematurity. � Management of pregnant women with SLE should involve close collaboration between a rheumatologist and an obstetrician experienced in caring for high risk mothers. Women should be assessed by a rheumatologist for disease activity at least once each trimester, and more frequently if they have active SLE. Periodic assessment of disease activity should also be continued through the postpartum period. � Women with risk factors or poor prognostic indicators may require more frequent maternal-fetal monitoring. In patients with positive anti-Ro/SSA and/or anti-La/SSB antibodies, increased surveillance for congenital heart block may be appropriate.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS � Women with SLE and/or a. PLs are at higher risk of preeclampsia than the general population, and treatment with a baby aspirin during pregnancy should be considered. These patients require additional vigilance, as the presentation of hypertension, proteinuria, or endorgan dysfunction after 20 weeks of gestation is concerning for development of preeclampsia. Lupus nephritis flares during pregnancy can mimic preeclampsia, and differentiating one from the other can be challenging. � The treatment of active SLE during pregnancy is guided by the severity and degree of organ involvement, similar to patients in the nonpregnant state. Treatment should not be withheld due to pregnancy; however, some medications used to treat SLE may cross the placenta and cause fetal harm. Thus, the risks and benefits of treatment during pregnancy must be weighed against the risk of SLE activity having a deleterious effect on the mother and the fetus.

Case study 87 systemic lupus erythematosus

Case study 87 systemic lupus erythematosus Type 1 ifn

Type 1 ifn Spotting differential diagnosis

Spotting differential diagnosis Dr michelle petri

Dr michelle petri Lupus fotos

Lupus fotos Lupus definition

Lupus definition Genus and species examples

Genus and species examples Lupus eritematoso sistémico

Lupus eritematoso sistémico Declinazione lupus

Declinazione lupus Ad rivum eundem

Ad rivum eundem Adaptive immunity

Adaptive immunity Homo homini lupus adalah

Homo homini lupus adalah Penyakit

Penyakit Matchstick sign lupus vulgaris

Matchstick sign lupus vulgaris Lupus nefriti sınıflaması

Lupus nefriti sınıflaması Jaccoud's arthropathy lupus

Jaccoud's arthropathy lupus Anti sm antibody

Anti sm antibody Lupus eritematoso sistémico

Lupus eritematoso sistémico Asuhan keperawatan lupus

Asuhan keperawatan lupus Lupus immagini

Lupus immagini Iud and lupus

Iud and lupus Roman hakl

Roman hakl Lupus eritematoso sistémico

Lupus eritematoso sistémico Uveiitis

Uveiitis What is the class of a domestic dog

What is the class of a domestic dog Classification of dog

Classification of dog Lupus tanı kriterleri

Lupus tanı kriterleri Nvle fonds

Nvle fonds Lupus presentation powerpoint

Lupus presentation powerpoint Lupus simptoms

Lupus simptoms Lupus eritematoso sistémico

Lupus eritematoso sistémico Lupus research alliance

Lupus research alliance Ripasso grammatica latina

Ripasso grammatica latina Facies sclerodermica

Facies sclerodermica