OLLI Spring 2017 Dantes Inferno Second class Looking

- Slides: 52

OLLI Spring 2017 Dante’s Inferno Second class

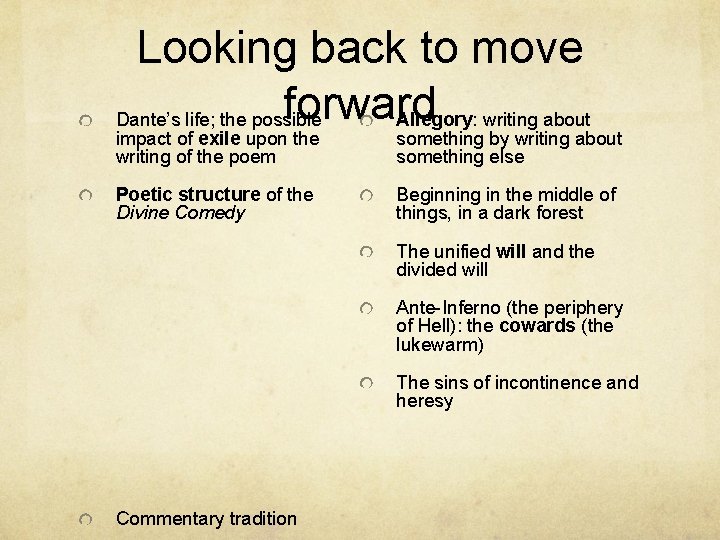

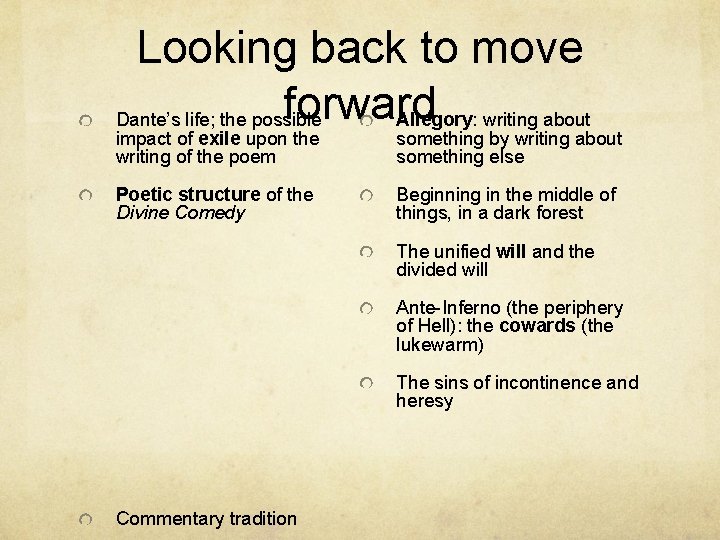

Looking back to move forward Dante’s life; the possible Allegory: writing about impact of exile upon the writing of the poem something by writing about something else Poetic structure of the Divine Comedy Beginning in the middle of things, in a dark forest The unified will and the divided will Ante-Inferno (the periphery of Hell): the cowards (the lukewarm) The sins of incontinence and heresy Commentary tradition

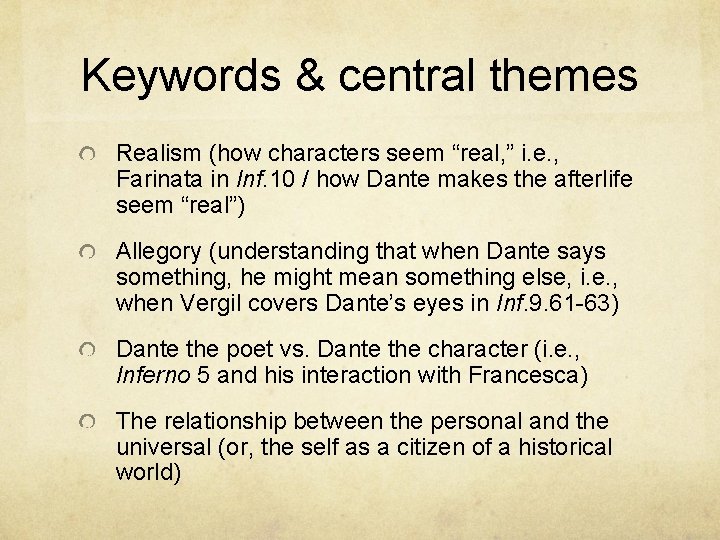

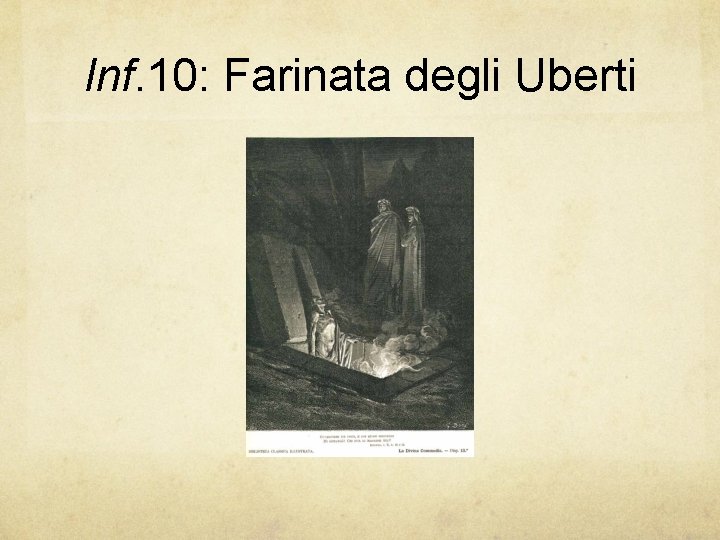

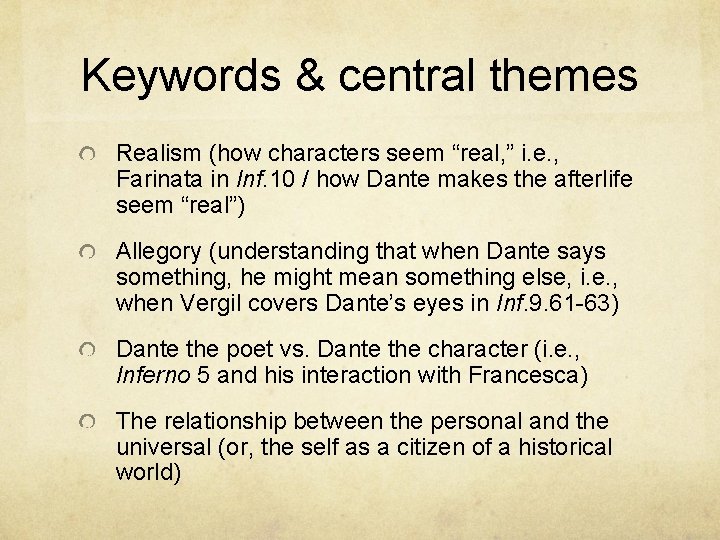

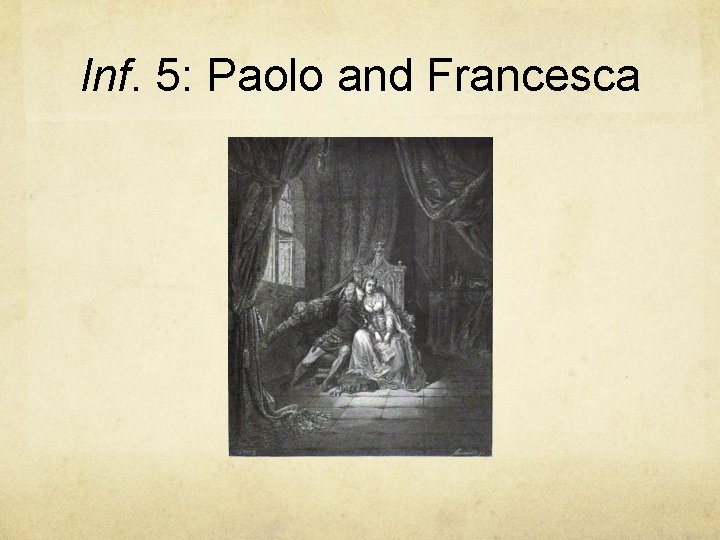

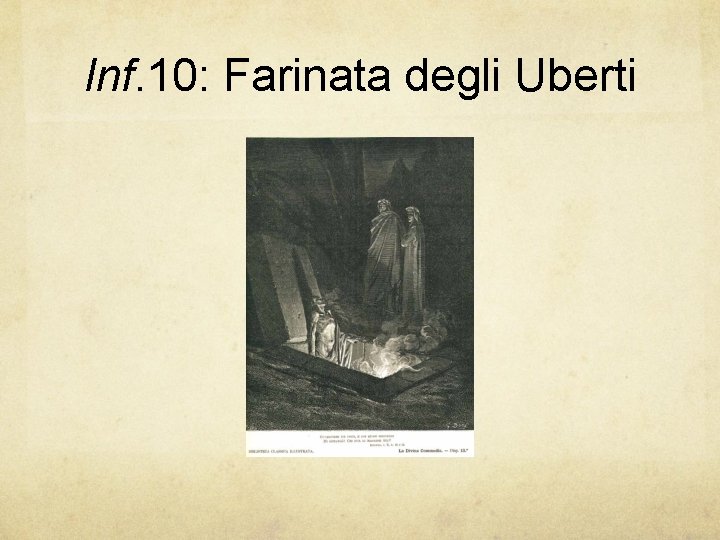

Keywords & central themes Realism (how characters seem “real, ” i. e. , Farinata in Inf. 10 / how Dante makes the afterlife seem “real”) Allegory (understanding that when Dante says something, he might mean something else, i. e. , when Vergil covers Dante’s eyes in Inf. 9. 61 -63) Dante the poet vs. Dante the character (i. e. , Inferno 5 and his interaction with Francesca) The relationship between the personal and the universal (or, the self as a citizen of a historical world)

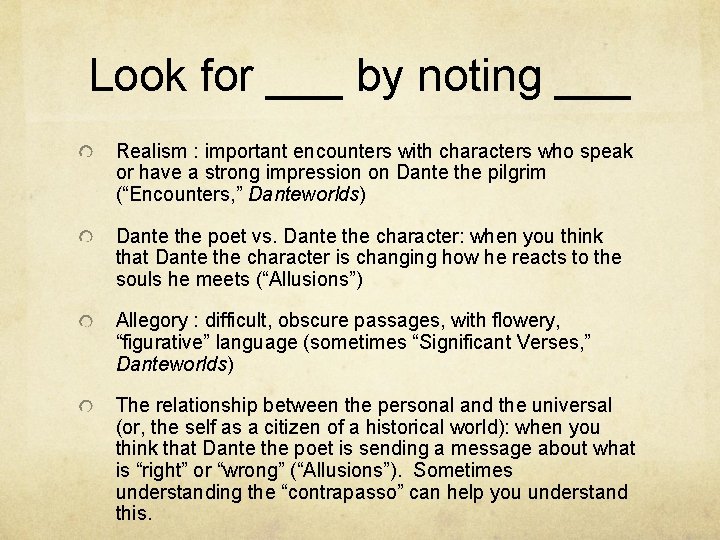

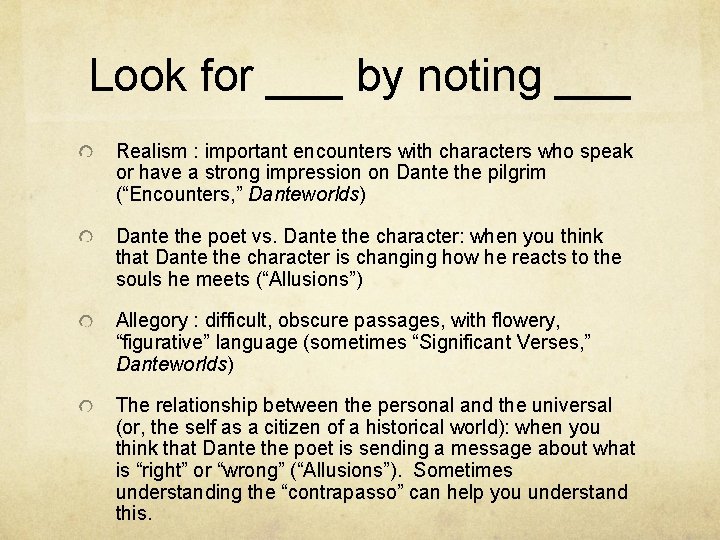

Look for ___ by noting ___ Realism : important encounters with characters who speak or have a strong impression on Dante the pilgrim (“Encounters, ” Danteworlds) Dante the poet vs. Dante the character: when you think that Dante the character is changing how he reacts to the souls he meets (“Allusions”) Allegory : difficult, obscure passages, with flowery, “figurative” language (sometimes “Significant Verses, ” Danteworlds) The relationship between the personal and the universal (or, the self as a citizen of a historical world): when you think that Dante the poet is sending a message about what is “right” or “wrong” (“Allusions”). Sometimes understanding the “contrapasso” can help you understand this.

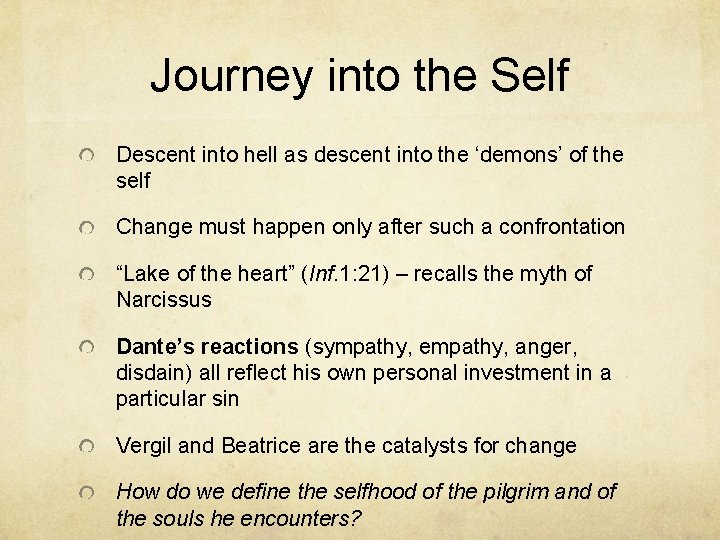

Journey into the Self Descent into hell as descent into the ‘demons’ of the self Change must happen only after such a confrontation “Lake of the heart” (Inf. 1: 21) – recalls the myth of Narcissus Dante’s reactions (sympathy, empathy, anger, disdain) all reflect his own personal investment in a particular sin Vergil and Beatrice are the catalysts for change How do we define the selfhood of the pilgrim and of the souls he encounters?

Dante the Poet vs. Dante the Pilgrim How does Dante develop over the course of the cantos read for today? Does he “progress” or “regress, ” and what does that mean? What are the ways in which Dante “sympathizes” with the souls he encounters? What are the ways in which Dante shows disdain for others?

Inferno 1: Beginning in the middle of things Reading of Inferno 1. 1 -27 “The 'now' is the link of time, as has been said (for it connects past and future time), and it is a limit of time (for it is the beginning of the one and the end of the other). ” (Aristotle’s Physics, 4. 13) “journey of our life” – Inferno 1. 1 Leo Spitzer: “the possessive of human solidarity. ” This is not just Dante’s journey, this is OUR journey. We can identify more with it given the ambiguity of the prologue scene. A journey in peril, in the region of unlikeness (“regio dissimilitudinis”, Augustine)

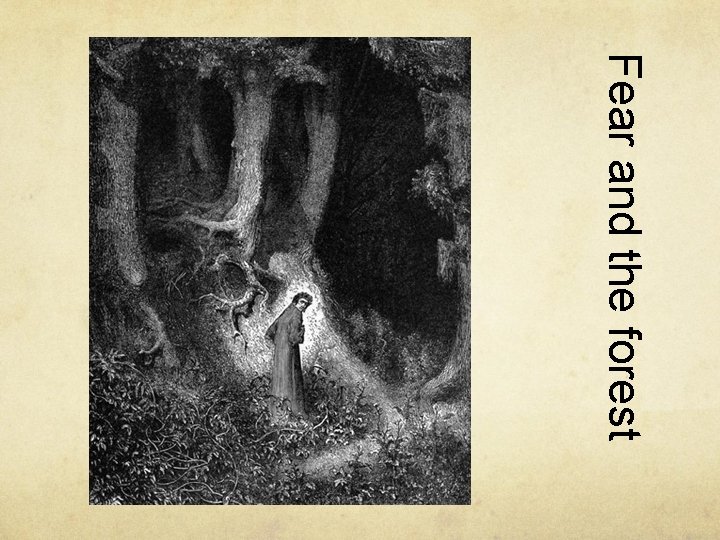

The dark forest Dante, Convivio 4. 25: “Thus the adolescent, who enters into the erroneous forest of this life, would not know how to keep the right way if he were not guided by his elders. ” (selva erronea) Proverbs 2: 13, “Who leave the right way, and walk by dark ways” 2 Peter 2: 15, “Leaving the right way that have gone astray” Augustine’s Confessions 7. 10: in this forest so immense and full of snares and dangers Plato’s Timaeus: the “silva Platonis” Synethesia (mixing of senses): Inferno 1. 60: “where the sun is silent”

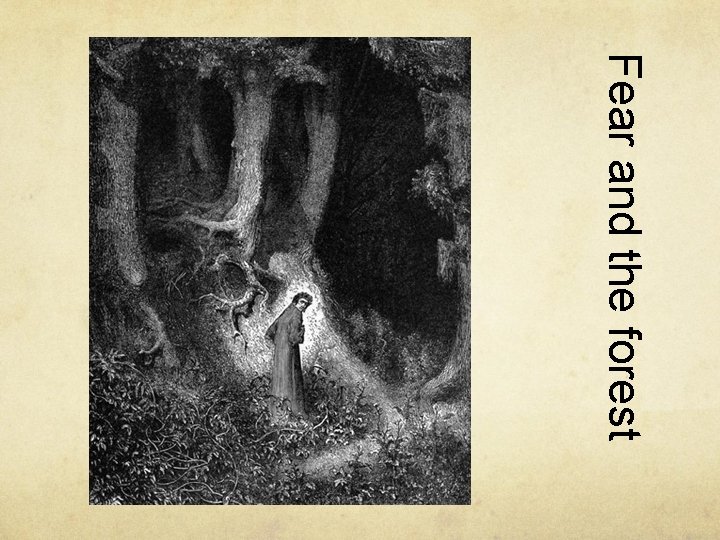

Fear and the forest

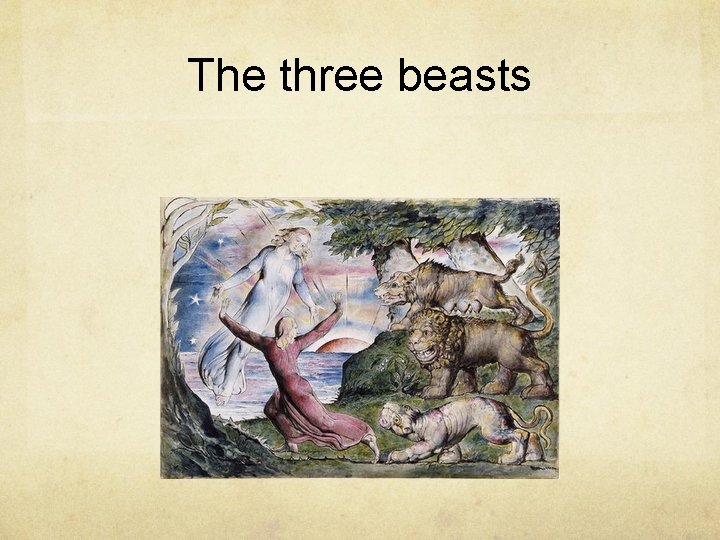

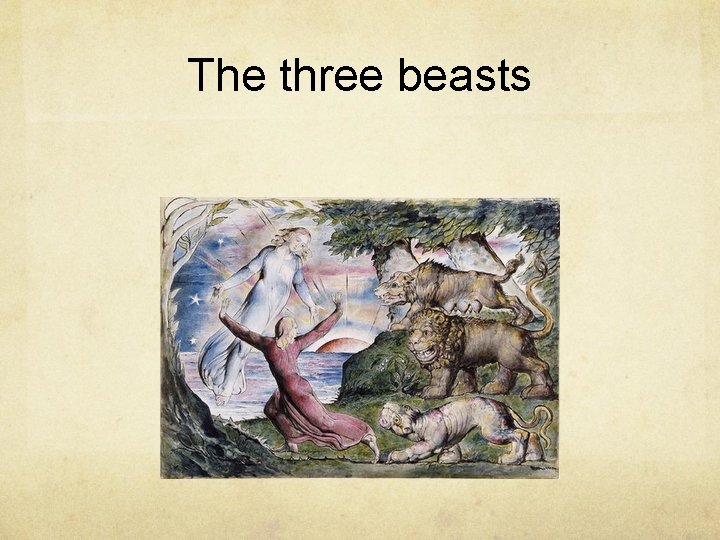

The three beasts

The three beats • John I 2: 16: “the concupiscence of the flesh, the pride of life, and the concupiscence of the eyes, cupidity, greed, and avarice” • Jeremiah 5: 6: “Wherefore a lion out of the wood hath slain them, a wolf in the evening hath spoiled them, a leopard watcheth for their cities: every one that shall go out thence shall be taken, because their transgressions are multiplied, their rebellions are strengthened. ” • Leopard = ? • Lion = ? • She-wolf = ?

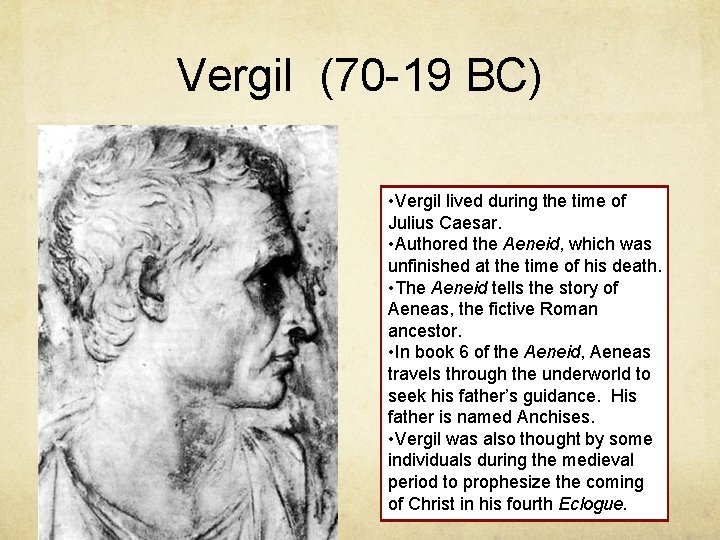

Vergil (70 -19 BC) • Vergil lived during the time of Julius Caesar. • Authored the Aeneid, which was unfinished at the time of his death. • The Aeneid tells the story of Aeneas, the fictive Roman ancestor. • In book 6 of the Aeneid, Aeneas travels through the underworld to seek his father’s guidance. His father is named Anchises. • Vergil was also thought by some individuals during the medieval period to prophesize the coming of Christ in his fourth Eclogue.

The Veltro! (Inferno 1. 100 -111)

The visitatio gratiae: against fear (Inf. 2. 88 -90)

Inferno 2: From a divided to an unified will v. Inferno 2. 32: “I am not Aeneas, I am not Paul” v 2 Corinthians 12: 2 -4: Paul “heard secret words which it is not granted to man to utter” in heaven v. Paul = Christianity, and specifically the Papacy v Aeneas = the Roman Empire v. Augustine says that the will cannot be divided (“not to turn and toss, this way and that, a maimed and half-divided will, struggling, with one part sinking as another rose. ”) v. Dante ends Inferno 2 with a unified will: “a single will fills both of us: / you are my guide, my governor, my master” (vv. 139 -140)

Pilgrim/Sinners/Circles Inf. 2. 45: “your soul has been assailed by cowardice” Inf. 2. 122: “Why does your heart host so much cowardice? ” ***** Inf. 2. 72: “Love prompted me, that Love which makes me speak. ” ******* o Inf. 3. 18: “Those who have lost the good of the intellect. ”

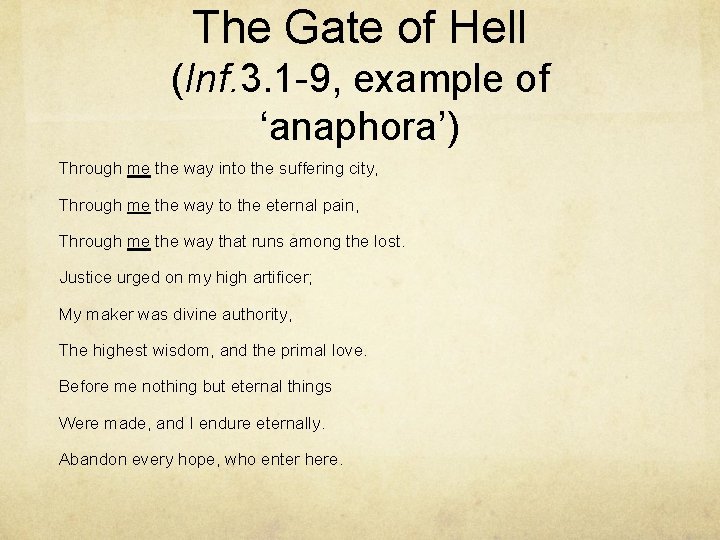

The Gate of Hell (Inf. 3. 1 -9, example of ‘anaphora’) Through me the way into the suffering city, Through me the way to the eternal pain, Through me the way that runs among the lost. Justice urged on my high artificer; My maker was divine authority, The highest wisdom, and the primal love. Before me nothing but eternal things Were made, and I endure eternally. Abandon every hope, who enter here.

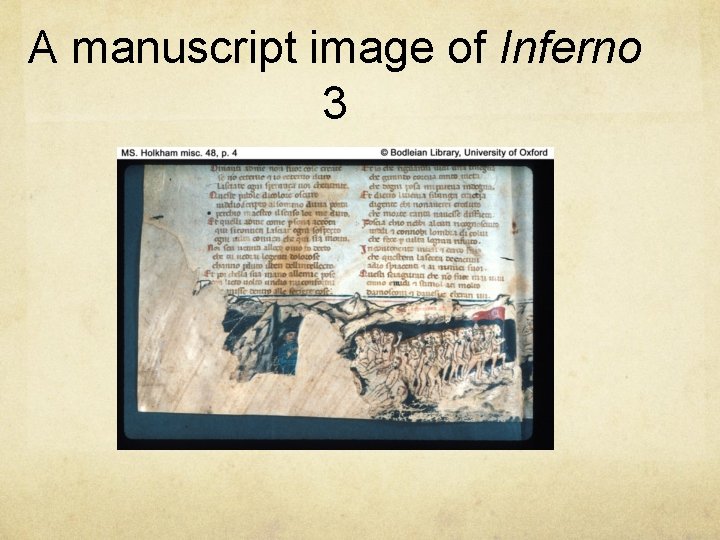

A manuscript image of Inferno 3

Inferno 3:

The cowardly “This miserable way / is taken by the sorry souls of those / who lived without disgrace and without praise. ” (Inf. 3. 35 -36) “let us not talk of them, but look and pass” (Inf. 3. 51)

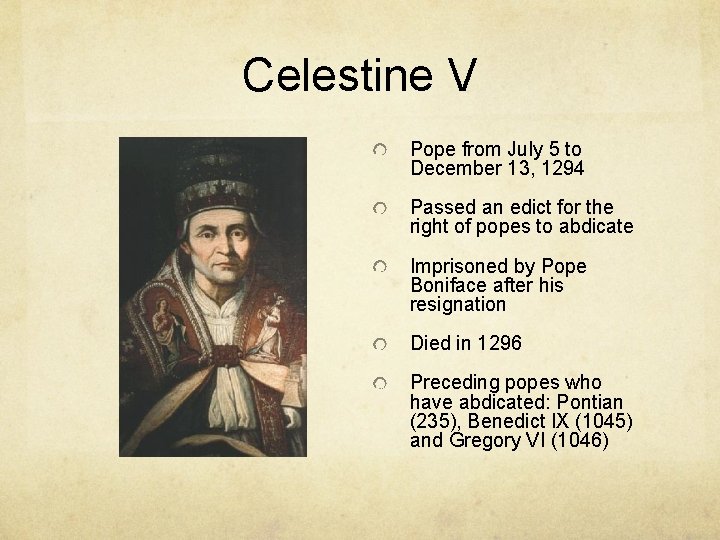

The contrapasso The literary device of the contrapasso is the literalization of a metaphor. How is the contrapasso of the cowardly a fitting punishment? Who made the “great refusal”? (Inf. 3. 60)

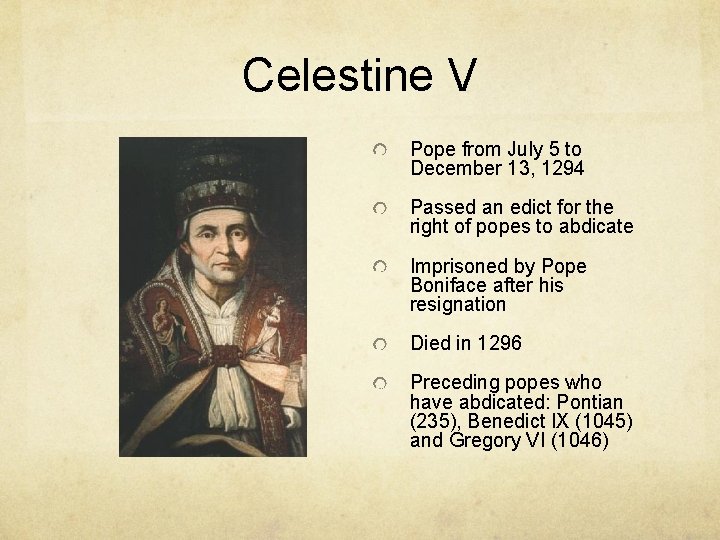

Celestine V Pope from July 5 to December 13, 1294 Passed an edict for the right of popes to abdicate Imprisoned by Pope Boniface after his resignation Died in 1296 Preceding popes who have abdicated: Pontian (235), Benedict IX (1045) and Gregory VI (1046)

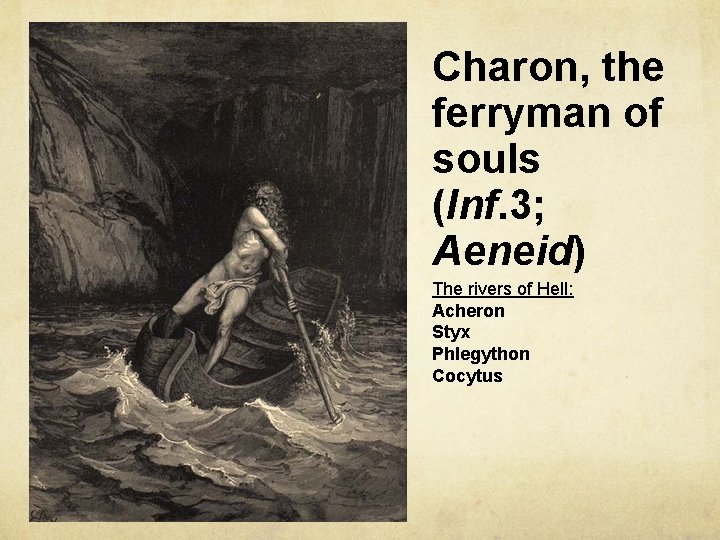

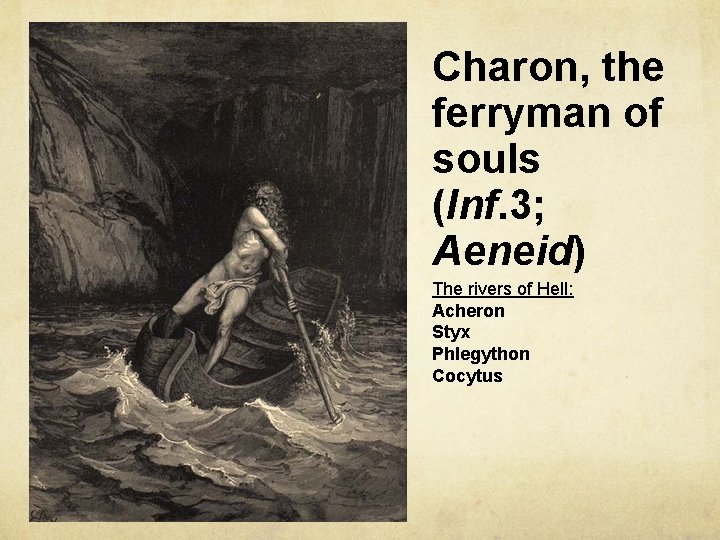

Charon, the ferryman of souls (Inf. 3; Aeneid) The rivers of Hell: Acheron Styx Phlegython Cocytus

Monsters! Charon (Vergil) Minos Cerberus (Vergil) Plutus Phlegyas (Vergil and Statius) Furies and Medusa

How Dante draws on the Aeneid Figure of Charon comes from Aeneid 6. 298 -304, 384 -416) – but in the Aeneid, the Sibyl presents the Golden Bough

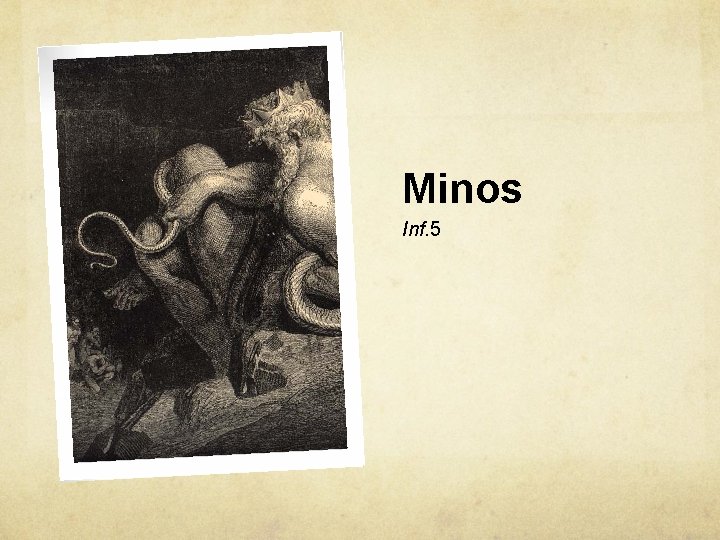

Minos Inf. 5

Non-Trivial Question Which English poet evokes Inf. 3: 57 when he writes “I had not thought death had undone so many”?

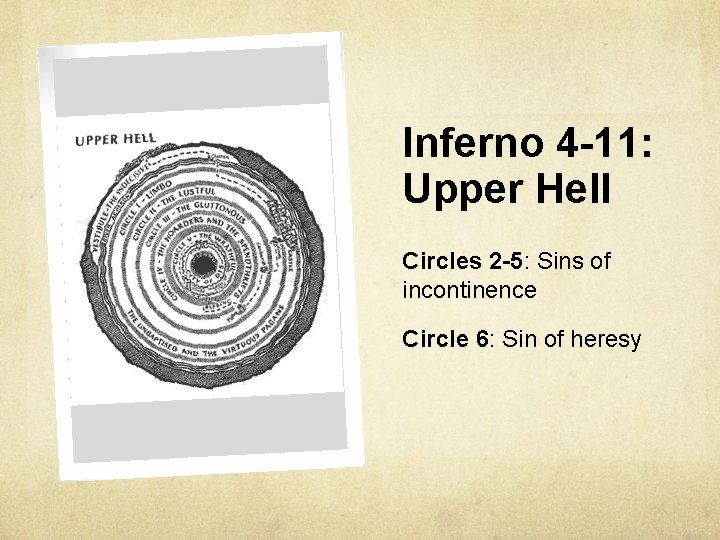

Inferno 4 -11: Upper Hell Circles 2 -5: Sins of incontinence Circle 6: Sin of heresy

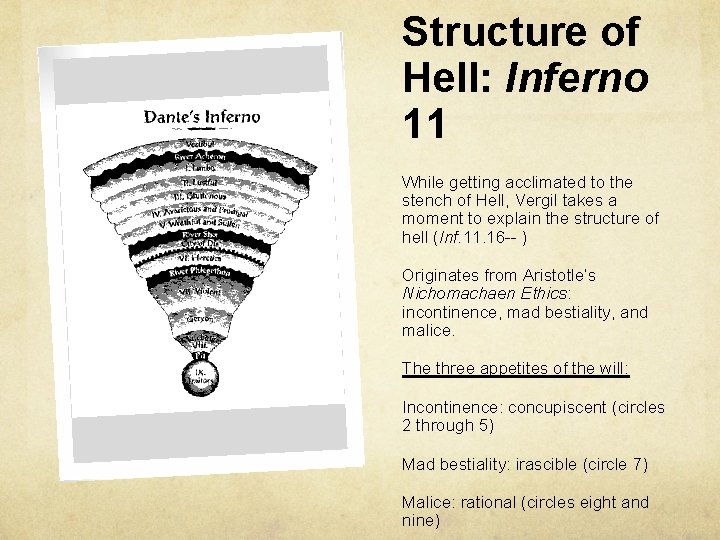

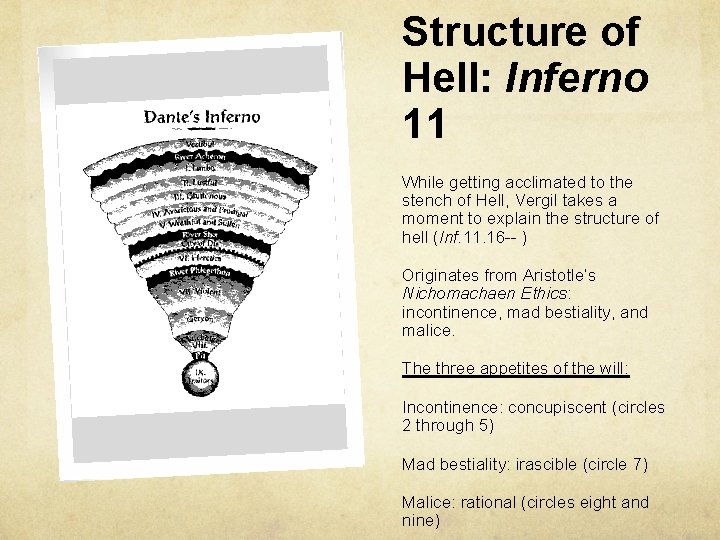

Structure of Hell: Inferno 11 While getting acclimated to the stench of Hell, Vergil takes a moment to explain the structure of hell (Inf. 11. 16 -- ) Originates from Aristotle’s Nichomachaen Ethics: incontinence, mad bestiality, and malice. The three appetites of the will: Incontinence: concupiscent (circles 2 through 5) Mad bestiality: irascible (circle 7) Malice: rational (circles eight and nine)

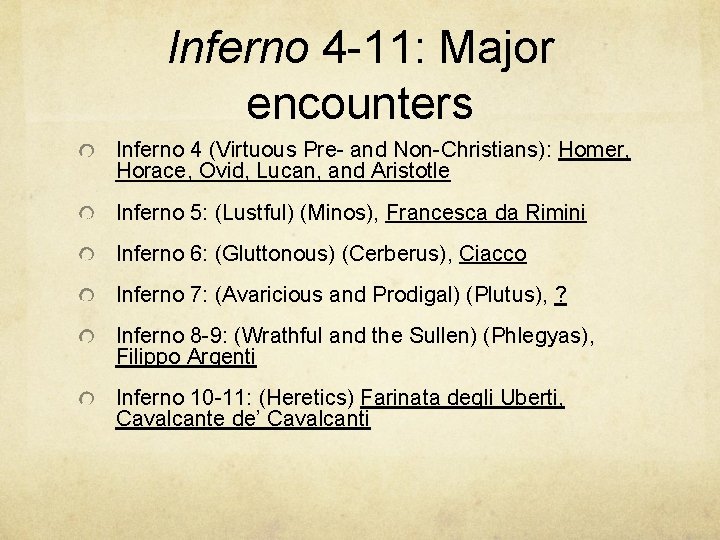

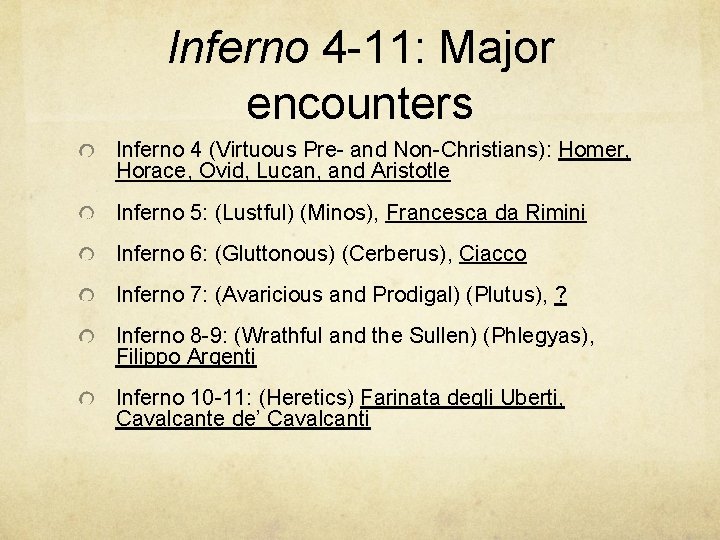

Inferno 4 -11: Major encounters Inferno 4 (Virtuous Pre- and Non-Christians): Homer, Horace, Ovid, Lucan, and Aristotle Inferno 5: (Lustful) (Minos), Francesca da Rimini Inferno 6: (Gluttonous) (Cerberus), Ciacco Inferno 7: (Avaricious and Prodigal) (Plutus), ? Inferno 8 -9: (Wrathful and the Sullen) (Phlegyas), Filippo Argenti Inferno 10 -11: (Heretics) Farinata degli Uberti, Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti

Inf. 4: Limbo, the First Circle (25 -42)

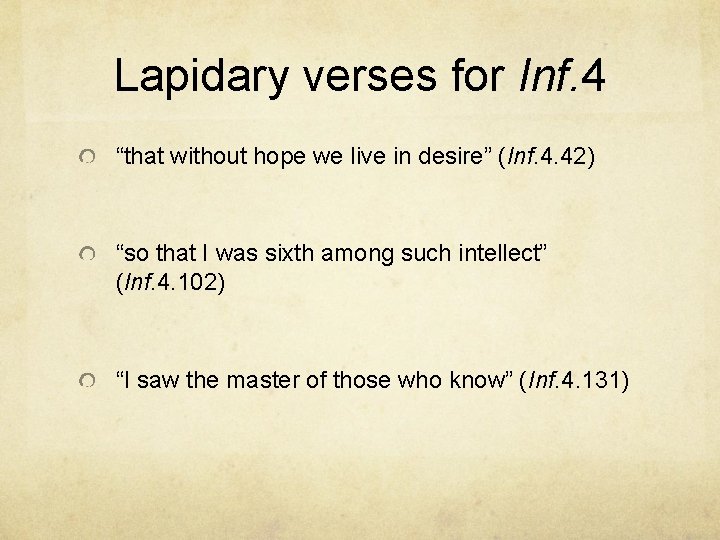

Lapidary verses for Inf. 4 “that without hope we live in desire” (Inf. 4. 42) “so that I was sixth among such intellect” (Inf. 4. 102) “I saw the master of those who know” (Inf. 4. 131)

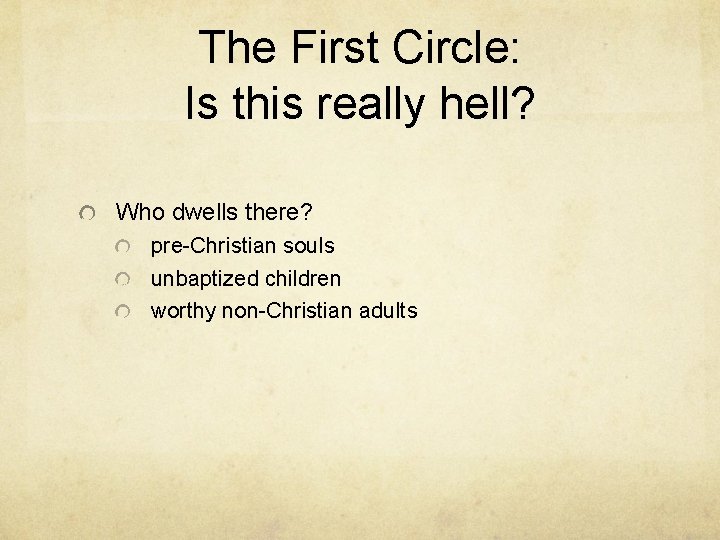

The First Circle: Is this really hell? Who dwells there? pre-Christian souls unbaptized children worthy non-Christian adults

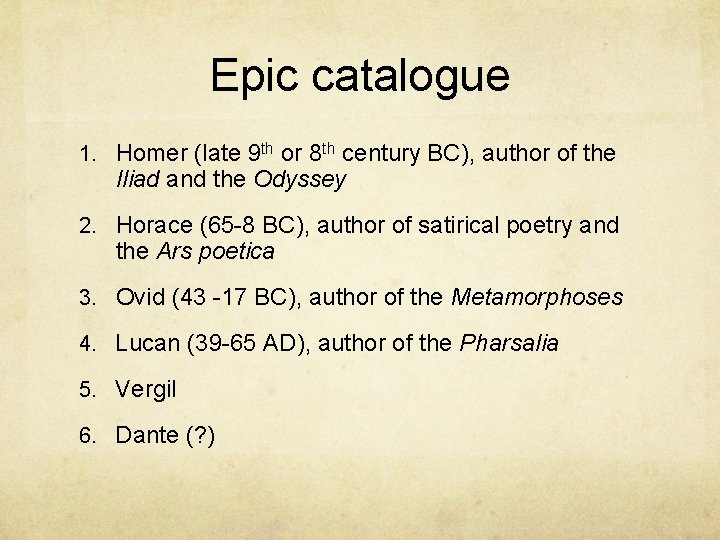

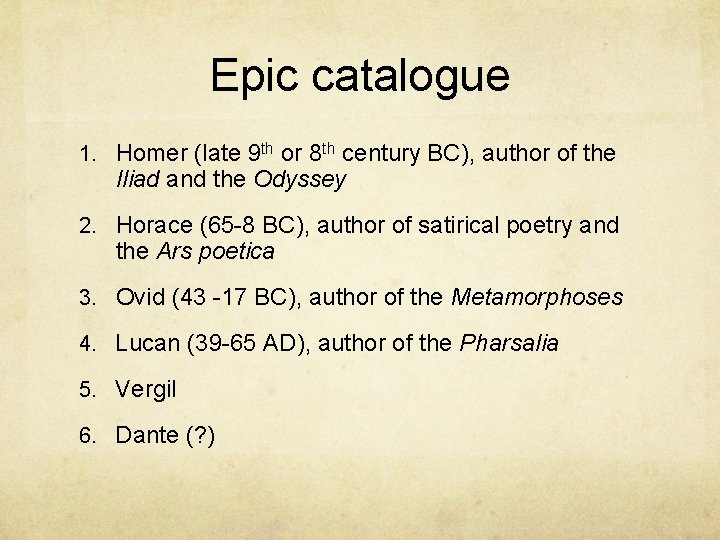

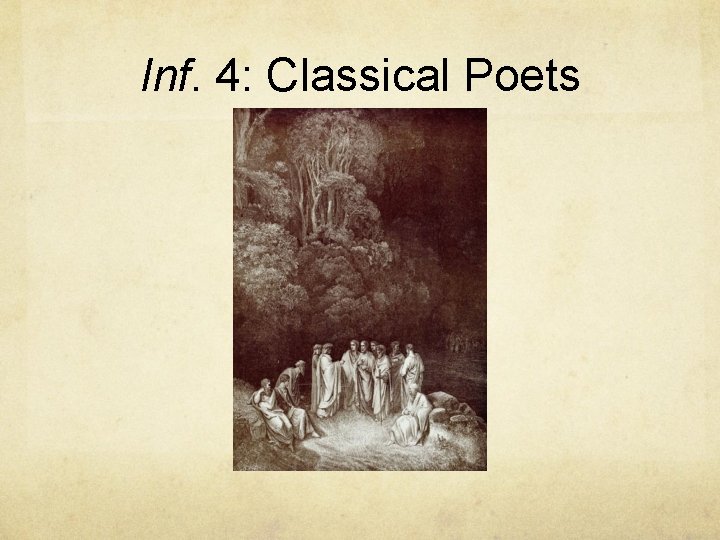

Epic catalogue 1. Homer (late 9 th or 8 th century BC), author of the Iliad and the Odyssey 2. Horace (65 -8 BC), author of satirical poetry and the Ars poetica 3. Ovid (43 -17 BC), author of the Metamorphoses 4. Lucan (39 -65 AD), author of the Pharsalia 5. Vergil 6. Dante (? )

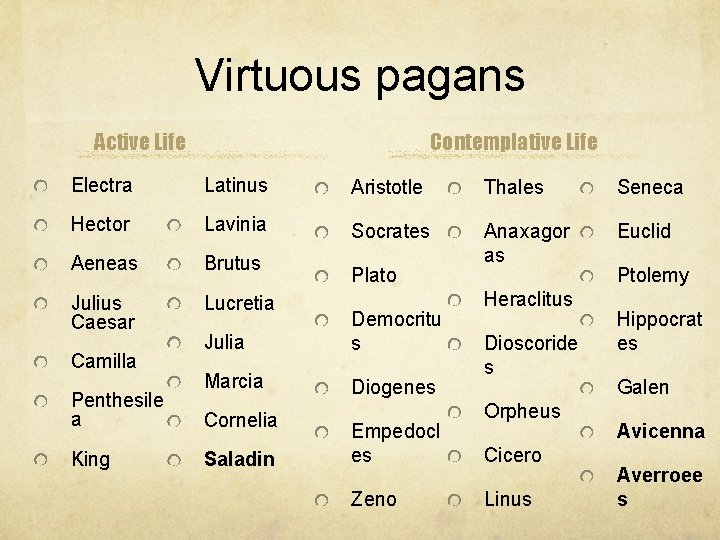

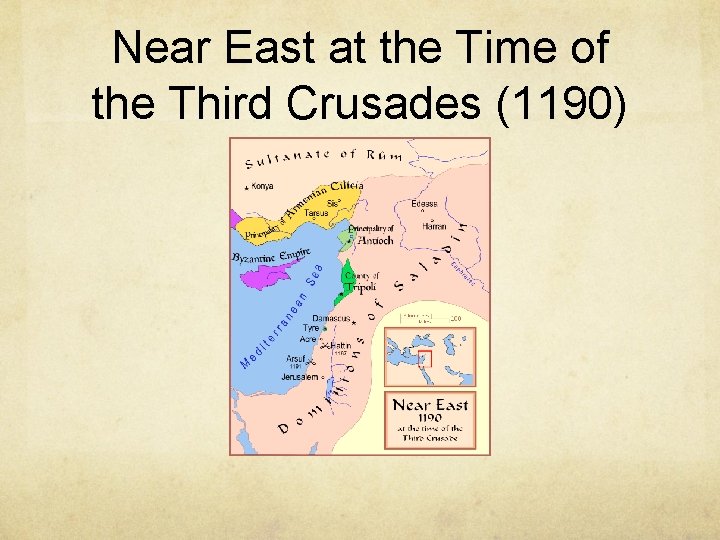

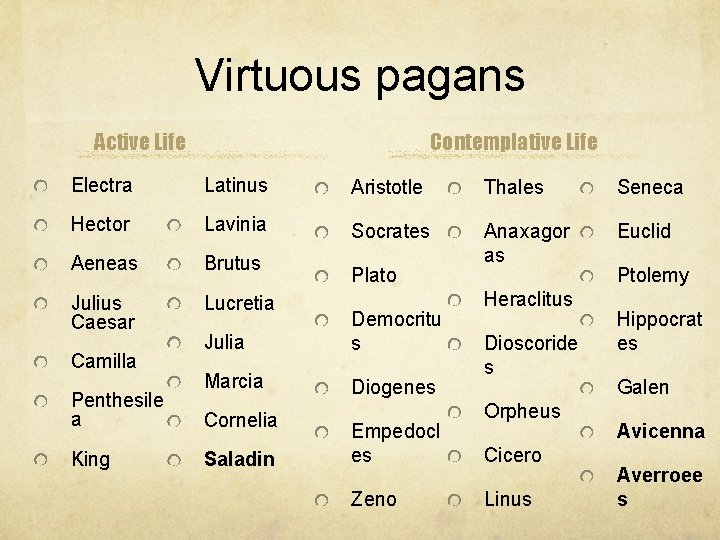

Virtuous pagans Active Life Contemplative Life Electra Latinus Aristotle Thales Seneca Hector Lavinia Socrates Euclid Aeneas Brutus Anaxagor as Julius Caesar Lucretia Camilla Penthesile a King Plato Julia Democritu s Marcia Diogenes Cornelia Saladin Empedocl es Zeno Heraclitus Dioscoride s Orpheus Cicero Linus Ptolemy Hippocrat es Galen Avicenna Averroee s

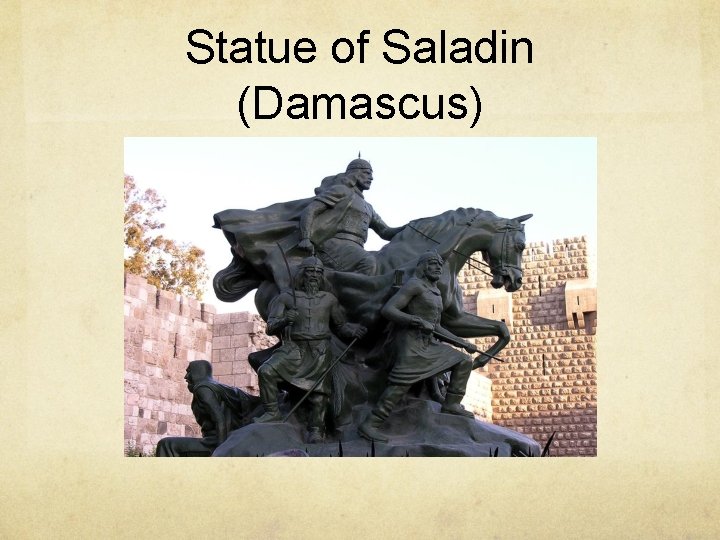

Statue of Saladin (Damascus)

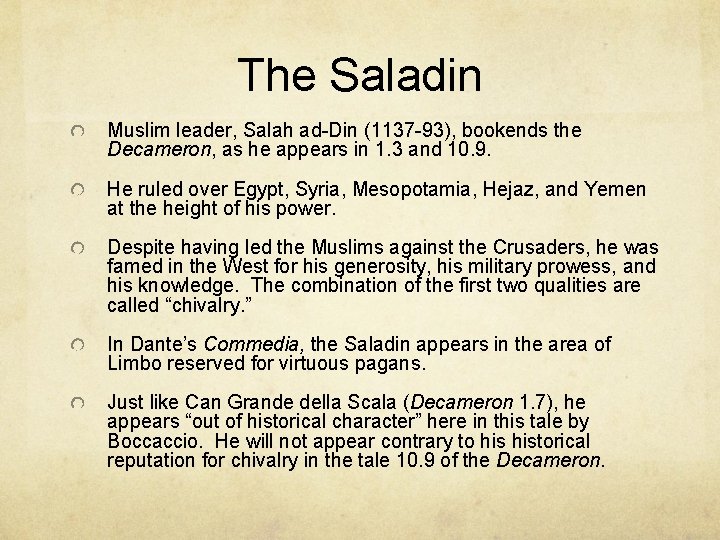

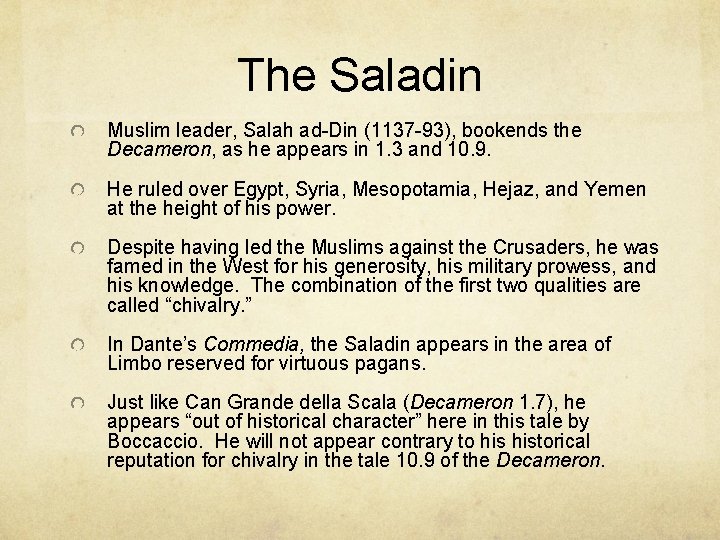

The Saladin Muslim leader, Salah ad-Din (1137 -93), bookends the Decameron, as he appears in 1. 3 and 10. 9. He ruled over Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia, Hejaz, and Yemen at the height of his power. Despite having led the Muslims against the Crusaders, he was famed in the West for his generosity, his military prowess, and his knowledge. The combination of the first two qualities are called “chivalry. ” In Dante’s Commedia, the Saladin appears in the area of Limbo reserved for virtuous pagans. Just like Can Grande della Scala (Decameron 1. 7), he appears “out of historical character” here in this tale by Boccaccio. He will not appear contrary to historical reputation for chivalry in the tale 10. 9 of the Decameron.

Near East at the Time of the Third Crusades (1190)

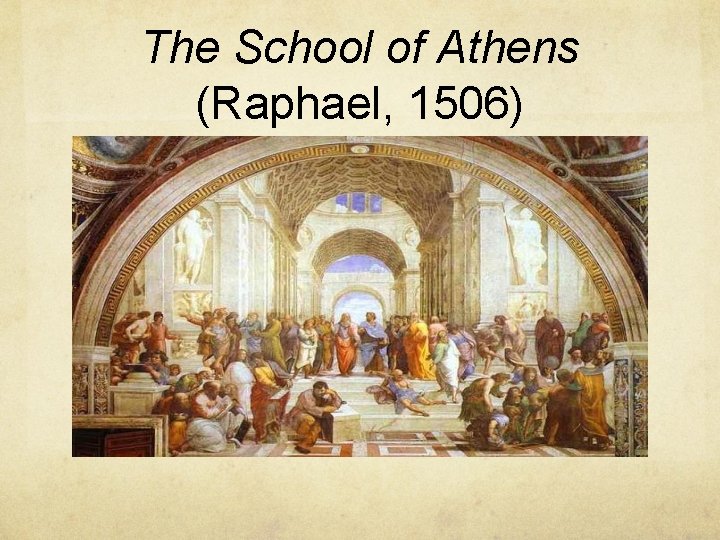

The School of Athens (Raphael, 1506)

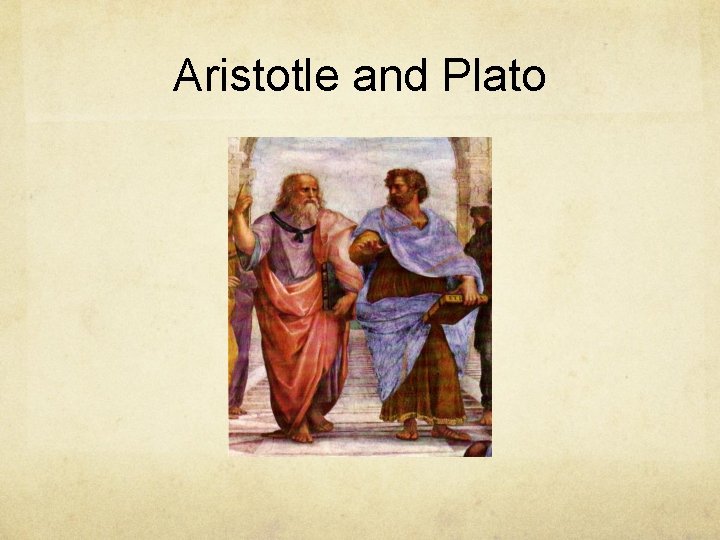

Aristotle and Plato

Inf. 4: Classical Poets

Inf. 5: Paolo and Francesca

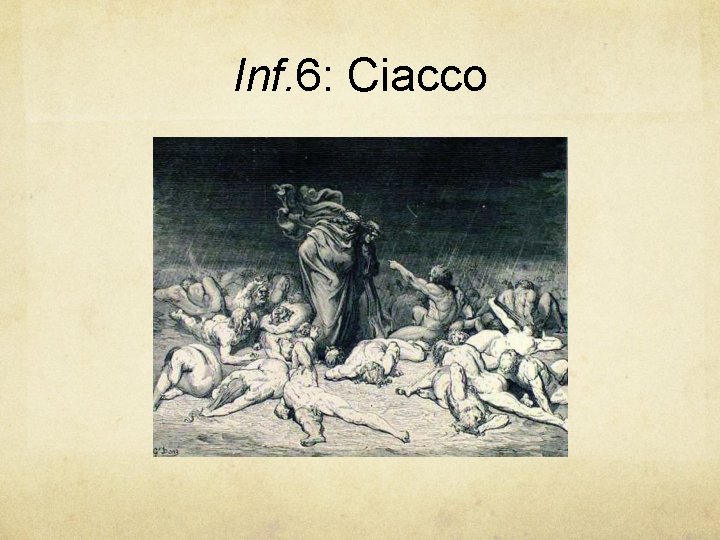

Inf. 6: Ciacco

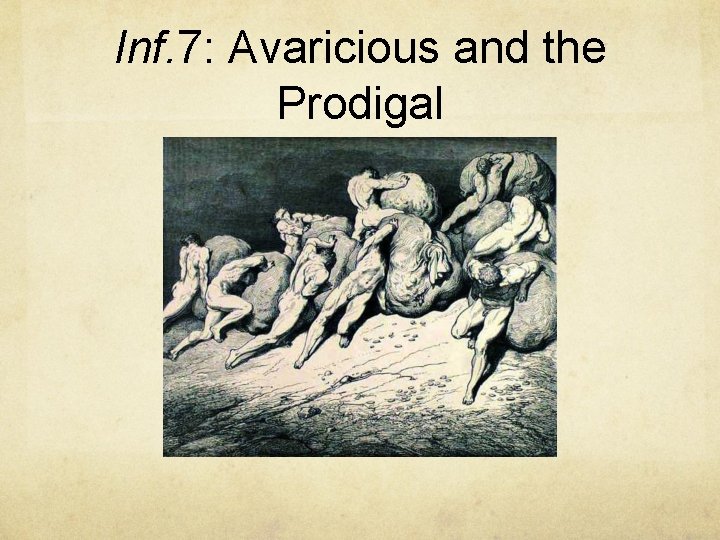

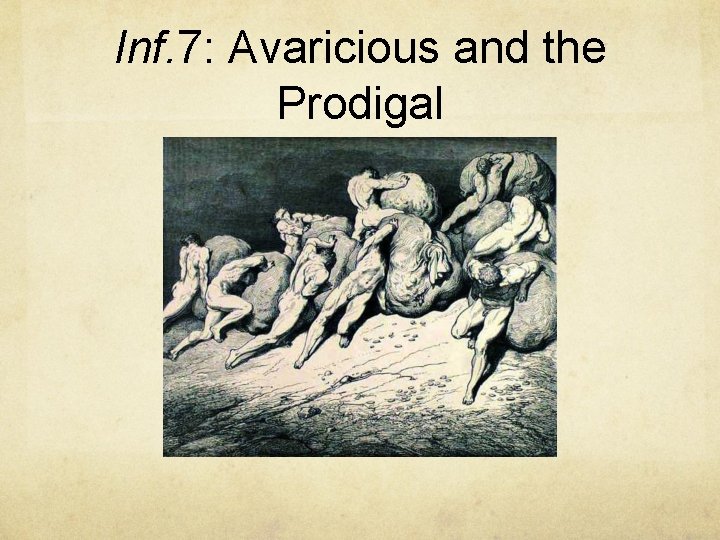

Inf. 7: Avaricious and the Prodigal

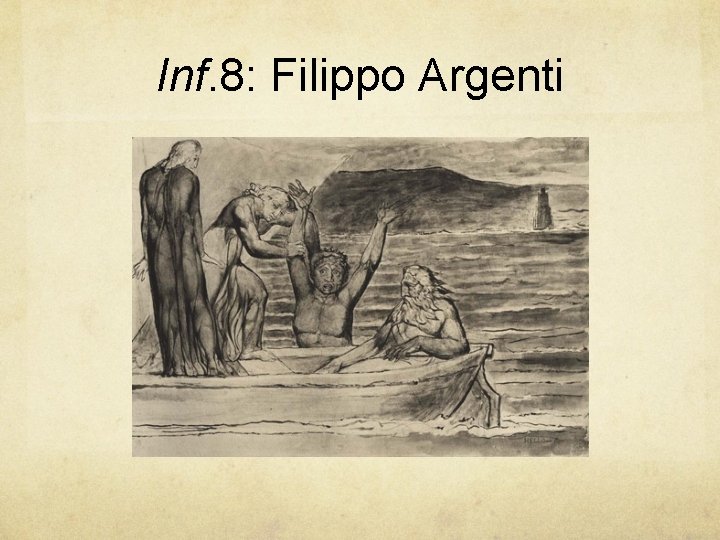

Inf. 8: Filippo Argenti

Inf. 10: Farinata degli Uberti

Reading allegorically At the Gate of Dis, before the Medusa arrives, Vergil insists that he place his hands over Dante’s hands, which are covering the pilgrim’s eyes. Dante writes: O you possessed of sturdy intellects, observe the teaching that is hidden here beneath the veil of verses so obscure (Inf. 9. 61 -63) • Take a few moments to consider the message “in between the lines” of this passage. What does Dante mean by these verses?

What is a commentary? Writers began to “comment” upon, or “gloss, ” the Comedy as early as the century in which he was born. The earliest commentators, we believe, were his sons, Jacopo and Pietro, but they also include Pietro della Lana and Cristoforo Landino, whose commentary was copied into several editions (see upcoming slide). Writing a commentary involves “explaining” (or “explicating”) the poem for readers. It is the act of decoding the text, or making it more comprehensible for its readership. It is the same as paraphrasing. Commenting upon a poem is not a passive or indifferent process. Commentators are powerful insofar as their reading of the poem can possibly “distort” the original meaning of the poem. Over the centuries, many commentators of Dante’s poem have disagreed on how to read many passages.

Allegory, or, why we need commentaries We need commentaries for several reasons -- to understand historical references, for example, but also because the Comedy is a lyric poem that is meant to be ready as an allegory. An allegory can be thought of as an extended metaphor. It literally means to “talk about something else” (allos - Greek for “other” / allogorien - “to talk about something else”). Take, for example, the following: The plane soared into the sky like an eagle. (simile) It soared, an eagle, into the sky. (metaphor, context implies it is a plane) The second sentence uses a symbol to describe the way that the plane soared into the sky. We can infer through context that the author is drawing a comparison to a plane. This can also be thought of as an analogy.

The art of exegesis Reading “allegorically” was the original practice of the Church Fathers (such as St. Augustine) in explicating Scripture. This was especially true for the books of the Old Testament, which were read allegorically to “prefigure” the events of the New Testament. This is known as exegesis. Dante himself provides an example, his letter to Can Grande (thanks, Dante!): Psalm 114 (113 in the Vulgate), begins "In exitu Israel de Aegypto" [When Israel went out of Egypt] (2. 46 -8). “Now if we look at the letter alone, what is signified to us is the departure of the sons of Israel from Egypt during the time of Moses; if at the allegory, what is signified to us is our redemption through Christ; if at the moral sense, what is signified to us is the conversion of the soul from the sorrow and misery of sin to the state of grace; if at the anagogical, what is signified to us is the departure of the sanctified soul from bondage to the corruption of this world into the freedom of eternal glory. And although these mystical senses are called by various names, they may all be called allegorical, since they are all different from the literal or historical. ”

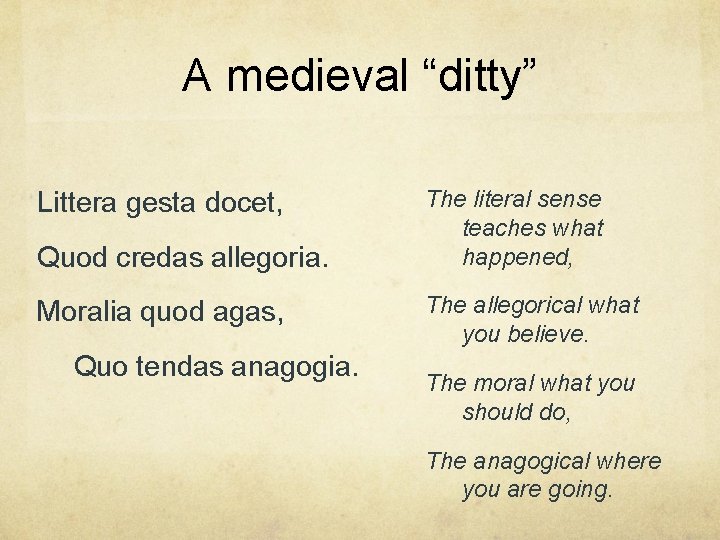

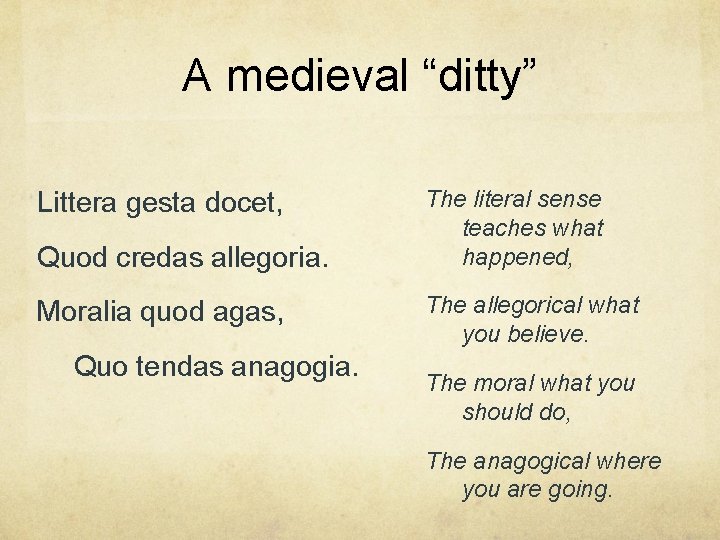

A medieval “ditty” Littera gesta docet, Quod credas allegoria. Moralia quod agas, Quo tendas anagogia. The literal sense teaches what happened, The allegorical what you believe. The moral what you should do, The anagogical where you are going.

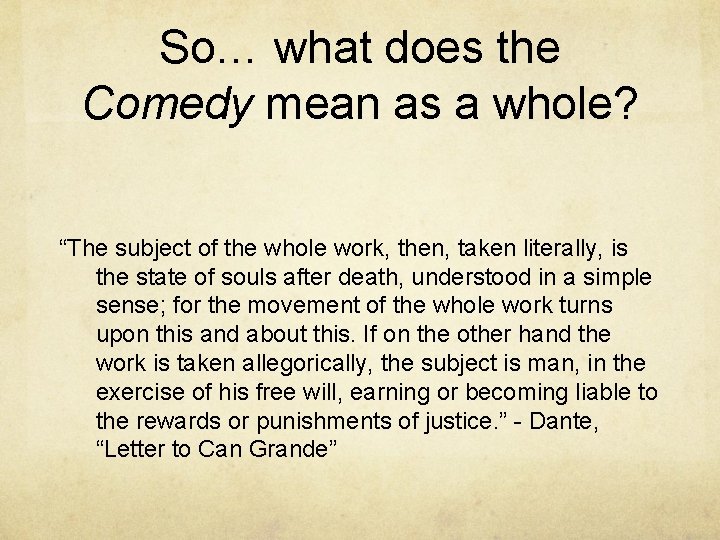

So… what does the Comedy mean as a whole? “The subject of the whole work, then, taken literally, is the state of souls after death, understood in a simple sense; for the movement of the whole work turns upon this and about this. If on the other hand the work is taken allegorically, the subject is man, in the exercise of his free will, earning or becoming liable to the rewards or punishments of justice. ” - Dante, “Letter to Can Grande”