Dantes Inferno Biography Dante Alighieri Born May 1265

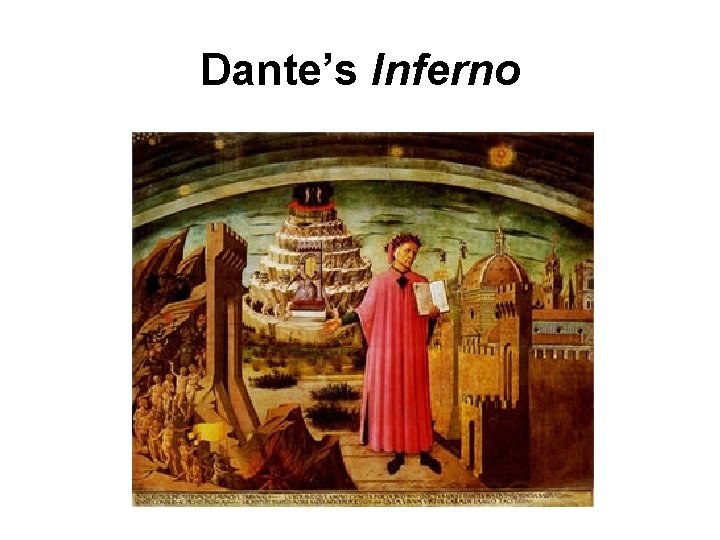

Dante’s Inferno

Biography • Dante Alighieri – Born May, 1265 in Florence, Italy – Family from the merchant class – Received early education in Florence – Attended the University of Bologna – Experiences included a tour in the Florentine Army when he fought in the Battle of Campaldino.

Personal Life – His great love seems to have been Beatrice Portinari. – They met when they were children and spoke only once. – Dante worshipped her. – After her death in 1290, he dedicated a memorial poem “The New Life” (La Vita Nuova) to her. – Though each married, they did not marry each other. – Beatrice was Dante’s inspiration for The Divine Comedy and remains one of history great love stories Idealized Artist’s Image

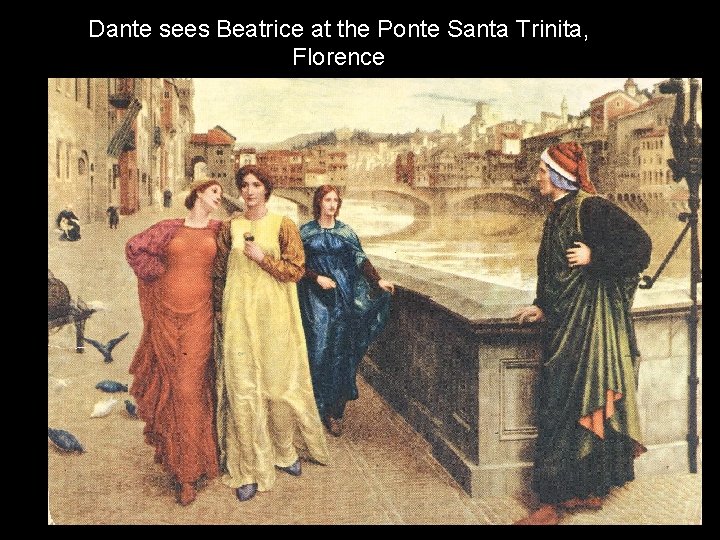

Dante sees Beatrice at the Ponte Santa Trinita, Florence

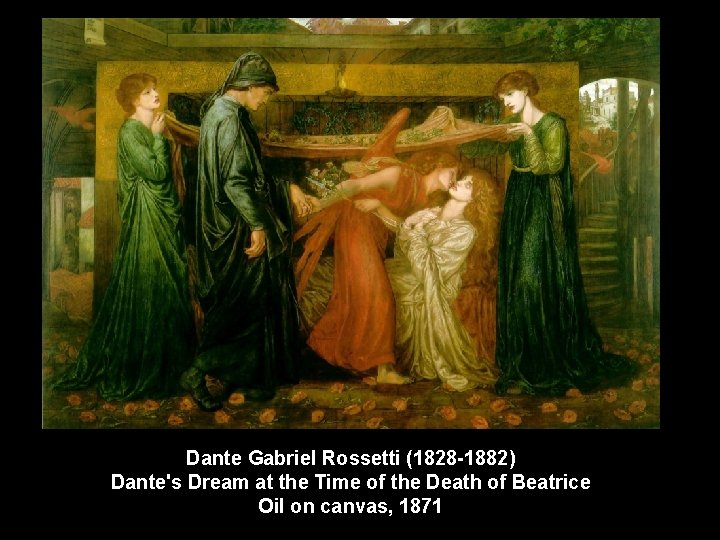

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 -1882) Dante's Dream at the Time of the Death of Beatrice Oil on canvas, 1871

Personal Life • Dante entered an arranged marriage in 1291 with Gemma Donati, a noblewoman. • They had two sons and either one or two daughters. • Records contain little else about their life together.

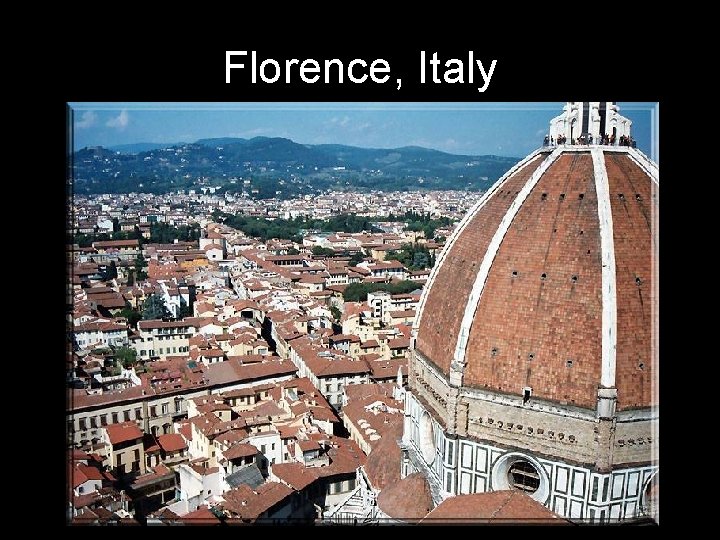

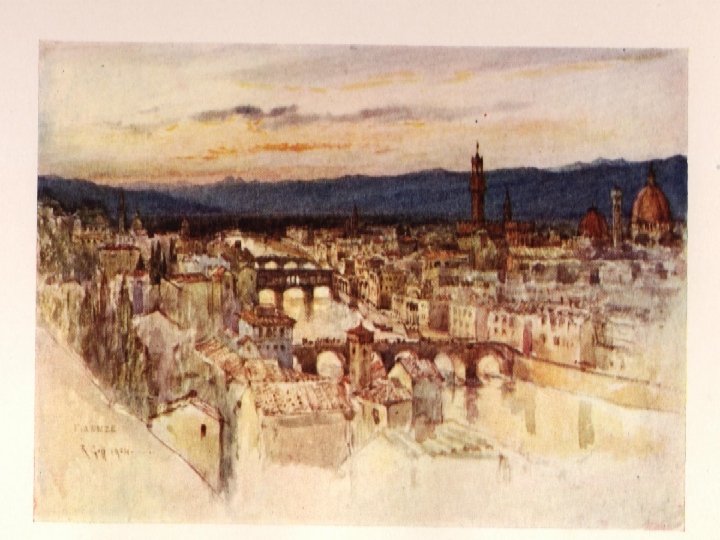

Florence, Italy

Historical Background • The Renaissance (rebirth of learning) began in Italy in the fourteenth century and influenced all of western civilization. • Wealthy families in Italy, such as the Medicis of Florence, were patrons of the arts and sciences. • Trade flourished and prosperity thrived throughout much of the country. • The competition for power, political and economic, created factionalism and violence.

Dante’s Florence • In the 13 th Century, Florence was a walled city of 100, 000 people, very tightly packed together. • The population was socially diverse, with nobility, the middle class and the poor living together in a very public existence where conversations were easily overheard. • Florentine politics were intensely local, and many sources of tension existed.

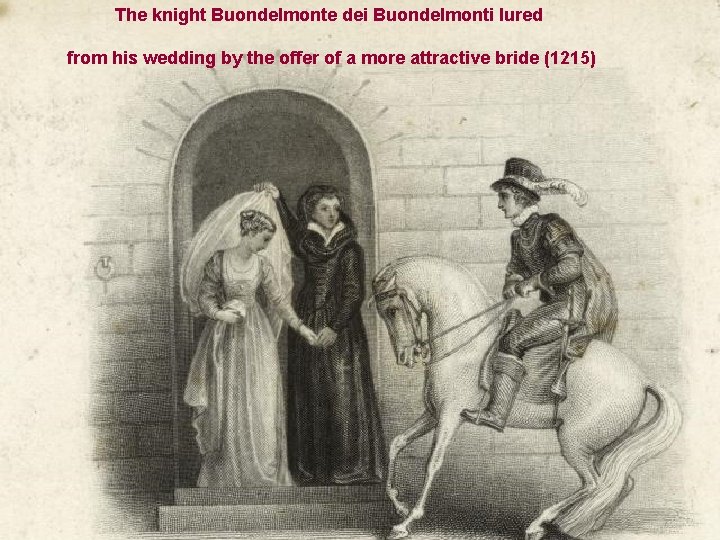

Dante’s Florence • Political strife was caused by disputes among local families. For instance, the breakup of an arrange marriage between two important household in 1215 led to a long-lasting blood feud. • Buondelmonti dei Buondelmonti, a vain and elegant young man, rejected his fiancee, a member of the Amidei family, for a marriage with a member of the wellconnected Donati family. He left his original bride at the alter when he did not show up for the wedding. • Insulted, members of the Uberti family killed him at the foot of the statue of Mars on the Ponte Vecchio as he rode on a while palrey. • Florence was filled with the deadly quarrel of two factions, and the feud was multiplied by the hostility of their partisans. • This was the origin of the Guelf and Ghibelline hatred and fanatical factionalism.

The knight Buondelmonte dei Buondelmonti lured from his wedding by the offer of a more attractive bride (1215)

The Florin

Factionalism in Florence • Political strife was also caused by different factions in the city as they jockeyed for power and quarreled over the best way to govern. • Florence was an independent country with economic power. • Divisions of class and wealth increased with tension between the aristocratic families and the increasingly wealthy merchants. • People wanted power—political and judicial— and competed fiercely for a limited number of offices. • Abuse of official power flourished as those in office tried to perpetuate their own and their family’s power.

The Pinnacle of Florentine Politics • As an adult, Dante was involved in the political life of his native city. • He knew success as a Florentine politician, the climax of which was his service as one of the city priors. • Florence had six priors, officials who served two-month terms as the rulers of Florence. Dante was elected a prior in 1300.

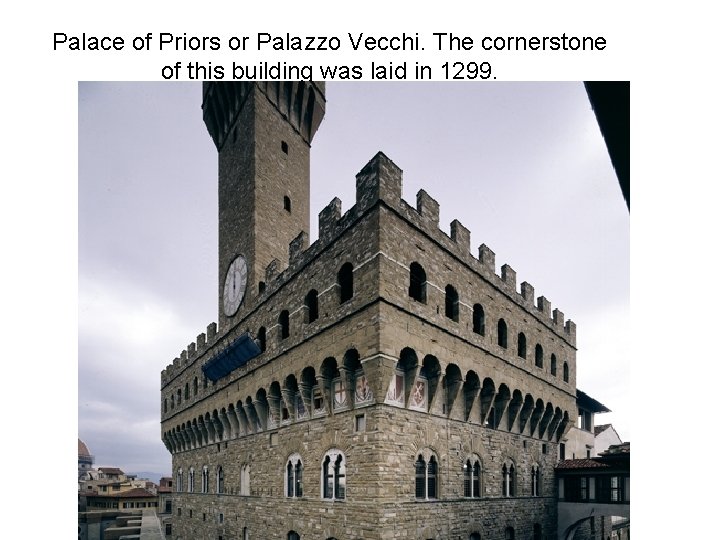

Palace of Priors or Palazzo Vecchi. The cornerstone of this building was laid in 1299.

Guelfs and Ghibellines

Guelfs and Ghibellines • Guelfs – – Anti-imperial Desired constitutional government Represented indigenous peoples Pro-pope (looked to Boniface VIII for support) • Black – Wanted to enhance their papal connections • White – Wanted to minimize all outside interference • Ghibellines – – Pro-imperial (looked to Frederick II for support) Represented aristocracy Opposed papal territorial power Expelled from Florence in 1289

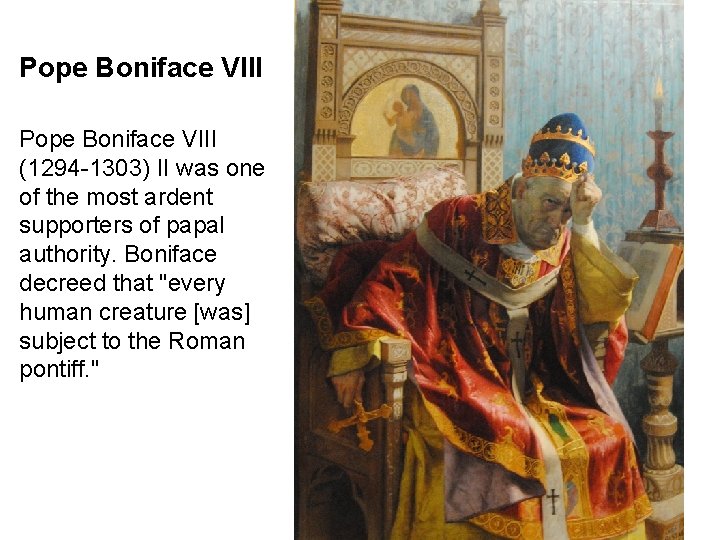

Pope Boniface VIII (1294 -1303) II was one of the most ardent supporters of papal authority. Boniface decreed that "every human creature [was] subject to the Roman pontiff. "

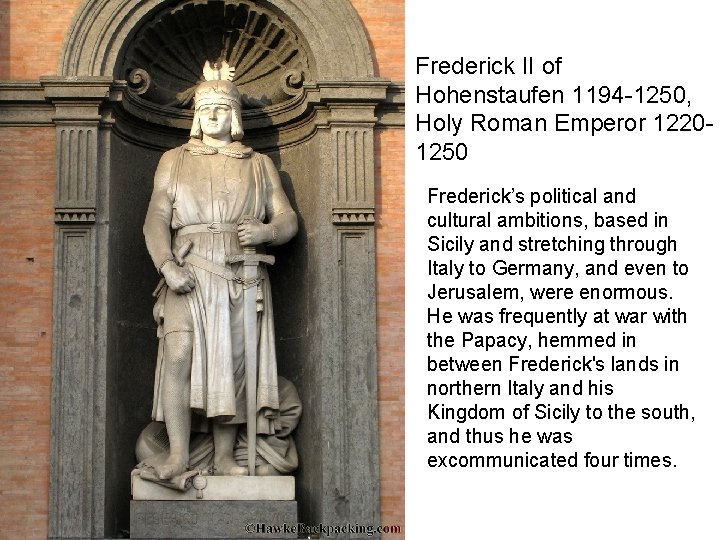

Frederick II of Hohenstaufen 1194 -1250, Holy Roman Emperor 12201250 Frederick’s political and cultural ambitions, based in Sicily and stretching through Italy to Germany, and even to Jerusalem, were enormous. He was frequently at war with the Papacy, hemmed in between Frederick's lands in northern Italy and his Kingdom of Sicily to the south, and thus he was excommunicated four times.

It was all about power: Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor King of Sicily and Jerusalem

Historical Background • Political conflict permeated Italy during the Renaissance. • Rulers of the independent Italian states often fought with each other to increase their power. • Fierce factionalism divided region, cities and citizens. • The Guelf (also Guelph) Political party (which favored local authority) and the Ghibelline Political party (which favored imperial authority) were two such rival factions. – The two had been at war periodically since thirteenth century.

Historical Background • In Italy, the Guelf political party eventually divided into two groups: – The Whites (led by the Cerchi family) – The Blacks (led by the Donati family and later by Pope Boniface VIII). • Dante was a White Guelf – In 1301 Dante served as an ambassador to talk with Pope Boniface VIII in Rome about conditions in Florence and ask for the Pope’s support.

Historical Background While Dante was out of town, the Blacks took over Florence. The Blacks sentenced Dante to banishment from the city. • His punishment for return would be death. • His wanderings gave him time to write and to study the Scriptures. • This banishment also gave Dante his perspective on corruption of the fourteenth century papacy, a view that he would clearly describe in The Inferno.

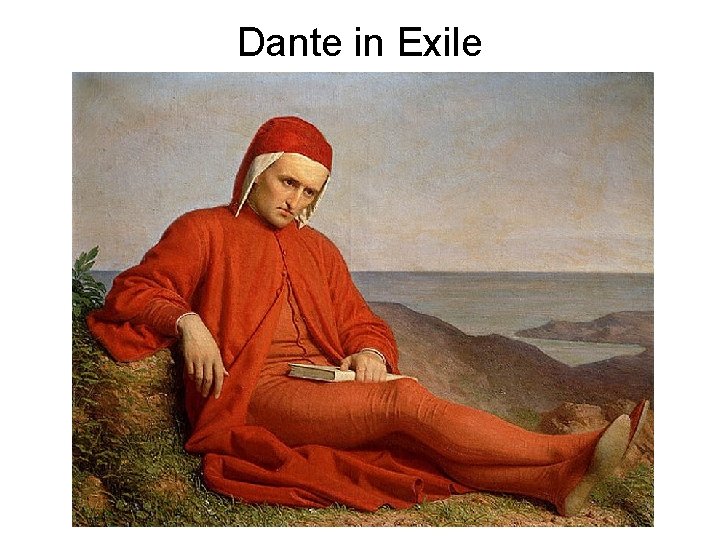

Dante By 1302, Dante was a political exile from Florence. – He started The Divine Comedy while in exile, and he explores theme of exile in Inferno. – Politics, history, mythology, religious leaders, and prominent people of the time, of literature, of the past, and of Dante’s personal life – including Beatrice – appear throughout The Divine Comedy. – He never returned to his native city.

Dante in Exile

Dante and the Commedia • The work was a major departure from the literature of the day since it was written in Italian, not the Latin of most other important writing. • Dante finished The Divine Comedy just before his death on September 14, 1321. – He was still in exile and was living under the protection of Guido da Polenta in Ravenna. – Perhaps still bitter about his expulsion from Florence, Dante wrote on the title page of The Divine Comedy that he was “a Florentine by birth, but not in manner” (Bergin 444).

Dante’s Inferno: Introduction • The Divine Comedy is a narrative poem describing Dante’s imaginary journey. • Midway on his journey through life, Dante realizes he has taken the wrong path. • The Roman poet Virgil searches for the lost Dante at the request of Beatrice. – He finds Dante in the woods on the evening of Good Friday in the year 1300 and serves as a guide as Dante begins his religious pilgrimage to find God. – To reach his goal, Dante passes through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise.

Dante’s Inferno: Introduction • The Divine Comedy was not titled as such by Dante; his title for the work was simply Commedia or Comedy. – Dante’s use of the word “comedy” is medieval by definition. – To Dante and his contemporaries, the term “comedy” meant a tale with a happy ending, not something amusing, as the word has since come to mean.

Dante’s Inferno: Introduction • The Divine Comedy is made up of three parts, corresponding with Dante’s three journeys: Inferno (or Hell); Purgatorio (or Purgatory); and Paridisio (or Paradise). • Each part consists of a prologue and approximately 33 cantos (Inferno has 34. ) • Since the narrative poem is in an exalted form with a hero as its subject, it is an epic poem.

Dante’s Inferno • Dante the Poet’s hero is Dante the Pilgrim, a version of himself when he was deluded by ambition and factionalism. • In Inferno, Dante and Virgil enter the gates of Hell and descend through the nine circles of Hell. • In each circle they see sinners being punished for their sins on Earth; Dante sees the sinner’s torture as Divine justice.

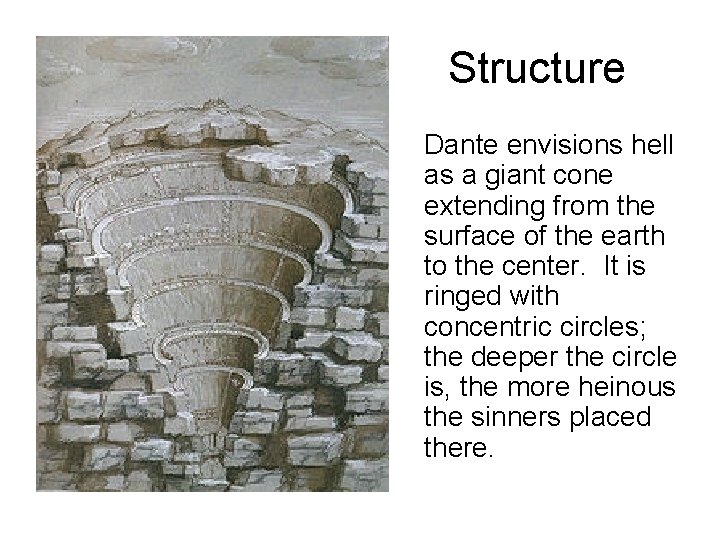

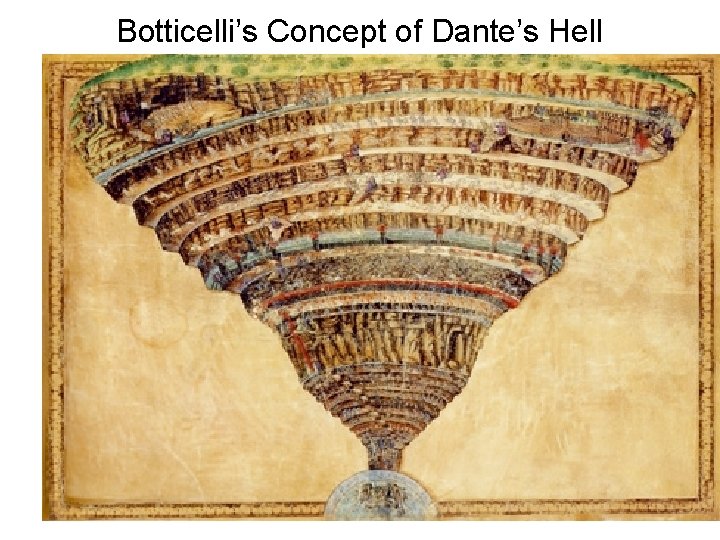

Structure Dante envisions hell as a giant cone extending from the surface of the earth to the center. It is ringed with concentric circles; the deeper the circle is, the more heinous the sinners placed there.

Structure of Inferno The sinners in the circles have committed: Sins of the She-Wolf (incontinence or lack of control) – Circle One – Those in limbo – Circle Two – The lustful – Circle Three – The gluttons – Circle Four – The hoarders – Circle Five – The wrathful --– Circle Six – The heretics --Sins of the Lion (violence) – Circle Seven – • Ring 1: Those who are violent to others • Ring 2: Those who are violent to themselves (suicides) • Ring 3: Those harmful against God, nature, and art

Structure of Inferno • Circle Eight – Sins of the Leopard (Fraud) – – – – – Bolgia (Trench) I: Panderers and Seducers Bolgia II: Flatterers Bolgia III: Simoniacs Bolgia IV: Sorcerers Bolgia V: Grafters Bolgia VI: Hypocrites Bolgia VII: Thieves Bolgia VIII: Counselors Bolgia IX: Sowers of Discord Bolgia X: Falsifiers

Structure of Inferno • Circle Nine – Complex Fraud – Region i: Traitors to their kindred – Region ii: Traitors to their country – Region iii: Traitors to their guests – Region iv: Traitors to their lords

Botticelli’s Concept of Dante’s Hell

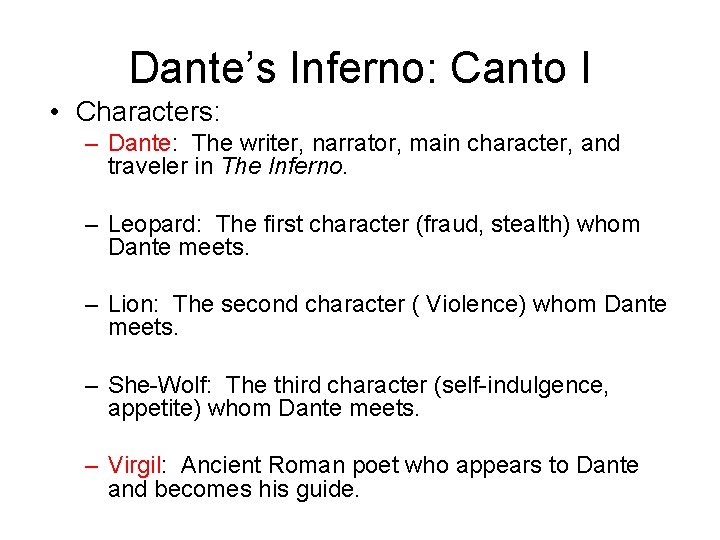

Dante’s Inferno: Canto I • Characters: – Dante: The writer, narrator, main character, and traveler in The Inferno. – Leopard: The first character (fraud, stealth) whom Dante meets. – Lion: The second character ( Violence) whom Dante meets. – She-Wolf: The third character (self-indulgence, appetite) whom Dante meets. – Virgil: Ancient Roman poet who appears to Dante and becomes his guide.

Dante’s Inferno: Canto I • Midway on his journey through life, Dante falls asleep and loses his way. • He wakes during the night of Maundy Thursday (Holy Thursday) to find himself in a dark wood; he does not know he got there. • Dante loses the right way; the narrow road he had wanted to travel has disappeared. • Dante feels some hope when he sees morning rays of sun over the mountain, even though he is still alone in the valley.

Dante in the Dark Wood Dante is disoriented. It is hard to see: there is not enough light. He doesn’t know he go there and he doesn’t know how to get back. He has to be rescue from outside—he can’t rescue himself.

Dante’s Inferno: Canto I • As he scales the mountain, Dante encounters a leopard. – The leopard impedes his progress; it is not frightening, but does not pose an immediate threat.

• The second animal that Dante meets is a fierce, hungry lion, which comes toward him swiftly and savagely.

The third – and worst – animal that Dante encounters is a vicious she-wolf. She terrifies Dante so much that he is unable to continue his travels.

• The shade of the poet Virgil appears to Dante. – Until the greyhound comes to secure the wolf in Hell, Virgil explains, the only way past the wolf is another path. – Virgil offers to show Dante the path to a grim and eternal place where he can see longdeparted souls. – After that, Virgil says, another guide will come and take Dante to a city which Virgil cannot enter. – Dante accepts Virgil’s offer and follows the poet.

Analysis: Canto I • Dante has lost the narrow way to God; he finds himself in the valley of sin and separation from God. – Dante is not sure how he lost the bright, narrow way; the darkness of sin and night (Maundy Thursday before Passover) frightens him. – When Good Friday (the morning of Jesus’ crucifixion) arrives, Dante feels hope as he sees the rays of light (goodness) shine over the mountain – a symbol of the ascent that one must make from error to reach God.

Analysis : Canto I • The three animals – the leopard, lion, and wolf, are images of sin. • The first animal – the leopard – the malicious sins of fraud. • The lion represents the sins of bestial violence. • The wolf represents depicts the sins of self-indulgence or incontinence. • The greyhound is a symbol of the political or religious leader who will come to help rid the world of greed. – It could also symbolize Dante’s friend Can Grande (Italian for “Great Dog”) della Scalla, the Ghibelline leader.

Analysis: Canto I • Virgil represents human reason, which can help – to a point – in bringing Dante out of the wood. • Virgil was the inspiration for Dante. – Virgil’s Aeneid was an inspiration for Dante and a pattern for The Inferno. – It is natural that Virgil should guide Dante when Dante was lost in life just as Virgil guided Dante as Dante wrote. – Virgil’s hoarseness could refer to his not having spoken since he began his journey to Hell, or it could refer to the fact that he had not spoken to the world for some time since he was not a popular writer at the time. – It is significant that Virgil cannot speak until Dante speaks to him. Dante must look for Virgil’s guidance.

Analysis: Canto I • Dante’s journey to the nether regions is vital to The Inferno. • With pilgrimages being common in the 1200 s and 1300 s, and with the influence of Virgil’s writings on Dante, it is not surprising that Dante uses theme of a pilgrimage.

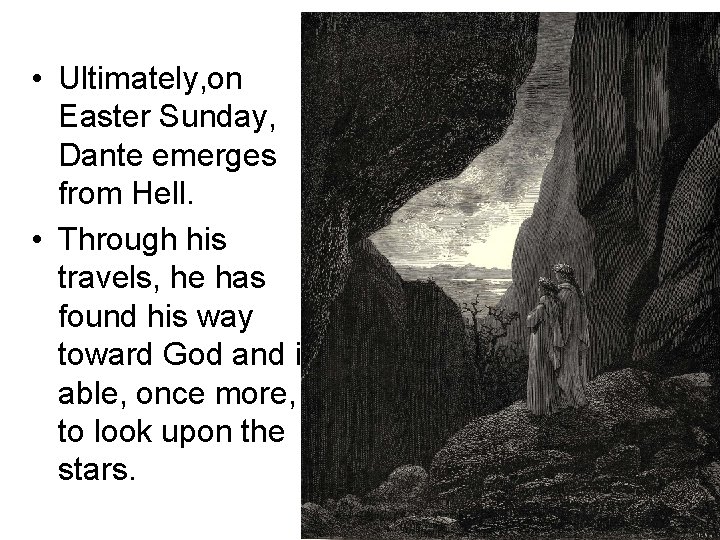

• Ultimately, on Easter Sunday, Dante emerges from Hell. • Through his travels, he has found his way toward God and is able, once more, to look upon the stars.

Analysis: Canto I • A second theme in The Inferno is the survival of the unfittest. – A weak, lost Dante encounters three wild animals and even manages a trip to the depths of Hell and back. • A third main theme is the reversal of fortune. – Dante is lost at the beginning of Canto I, but by the end of The Inferno, he has found his way.

Bibliography Alighieri, Dante. The Inferno. Trans. John Ciardi. New York: Mentor/Penguin, 1982. Chirenza, Marguerite Mills. The Divine Comedy: Tracing God’s Art. Boston: Twayne, 1989. Ciardi, John, ed. and trans. The Inferno. By Dante Alighieri. New York: Mentor/Penguin, 1982. Cook, William R. and Ronad B. Herzman. “Dante’s Divine Comedy Course Guidebook. ” Part 1. Chantilly, Va. : The Teaching Company, 2001. Proctor, George. The History of Italy from the Fall of the Western Empire to the Commencement of the Wars of the French Revolution. London: Wittaker, 1895. Google ebook. Web. 19 Feb. 2012. Toynbee, Paget Jackson. A dictionary of proper names and notable matters in the works of Dante. London: Clarendon/Oxford, 1848. Google ebook. Web. 19 Feb. 2012.

Historical Background • In the year 1310, Henry VII became Holy Roman Emperor. – Dante believed that this German Prince would bring peace. – Henry VII died in 1313 and his Italian campaign collapsed. – Dante became disillusioned and left the political life • He ceased work on other materials he had begun and concentrated on The Divine Comedy.

Historical Background • Dante’s birth in 1265 came at a time when the Guelf party was in control of Florence. • Dante turned away from his Guelf heritage to embrace the imperial philosophy of the Ghibellines. – His change in politics is best summed up in his treatise De Monarchia in which Dante states his belief in the separation of church and state. – The Ghibellines, however, were pushed from power by the Guelfs during Dante’s adulthood and confined to northern Tuscany.

- Slides: 53