Fractures of the Spine in Children Timothy Moore

- Slides: 47

Fractures of the Spine in Children Timothy Moore, MD Original Author: Steven Frick, MD; March 2004 Revised: Steven Frick, MD; August 2006 Timoth Moore, MD; November 2011

Important Pediatric Differences • • Anatomical differences Radiologic differences Increased elasticity Periosteal tube fractures – apparent dislocations • Surgery rarely indicated • Immobilization well tolerated

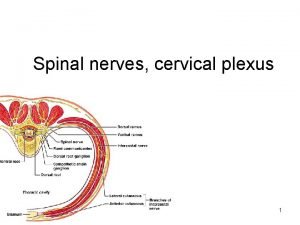

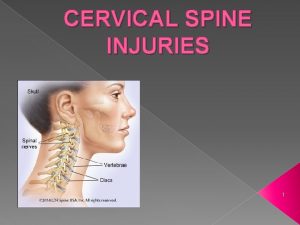

Cervical Spine Injuries • Rare in children - < 1% of children’s fractures • Quoted rates of neurologic injury in children’s C spine injuries vary from “rare” to 44% in large series • Age less than 7 – Majority of C spine injuries are upper cervical, esp. craniocervical junction • Age greater than 7 – Lower C spine injuries predominate Jones. Pediatric cervical spine trauma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011; 19: 600.

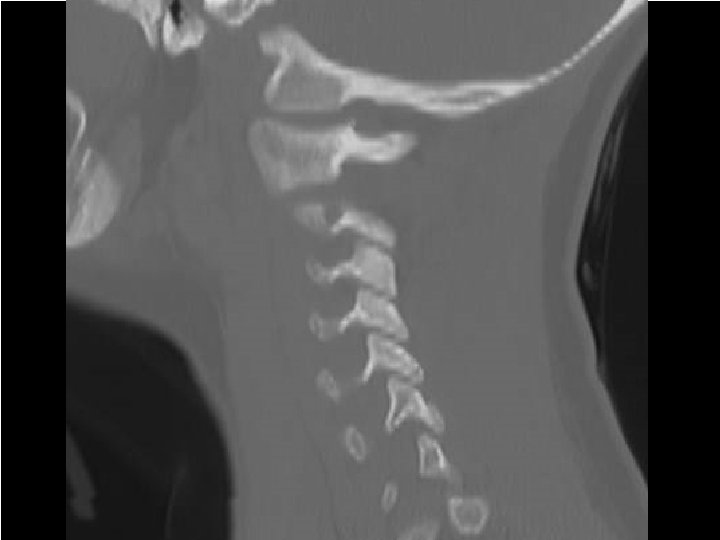

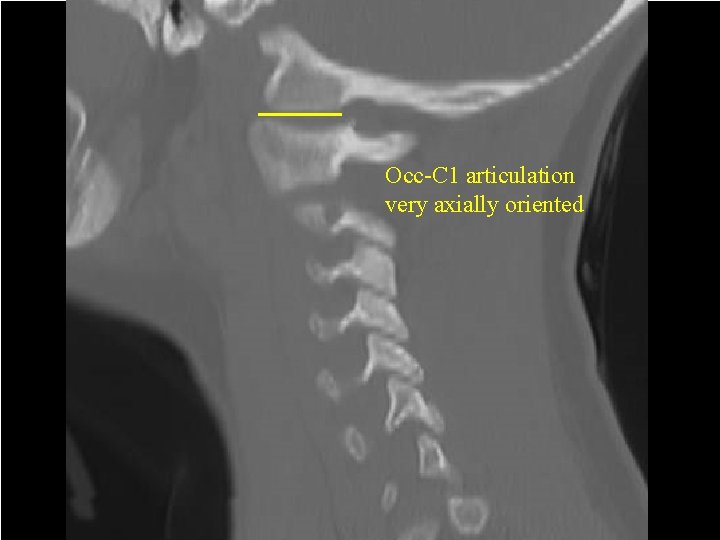

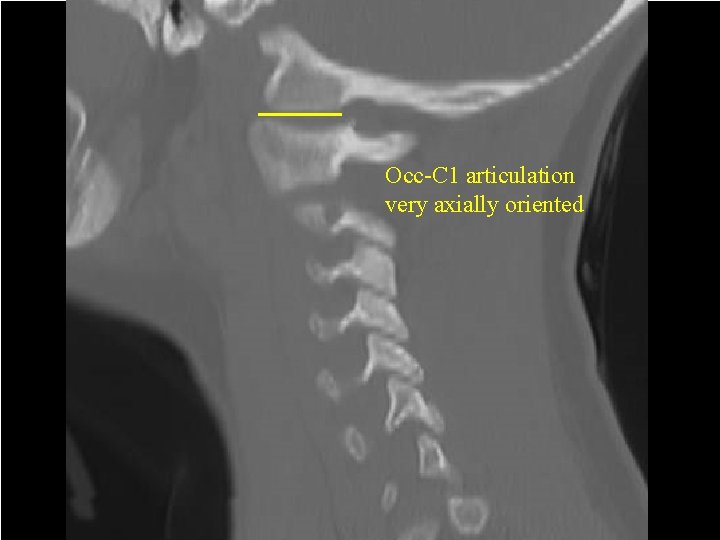

Cervical Spine Injuries • Upper cervical anatomy – Occiput-C 1 articulation – Axially oriented – Prone to occiput-C 1 injury

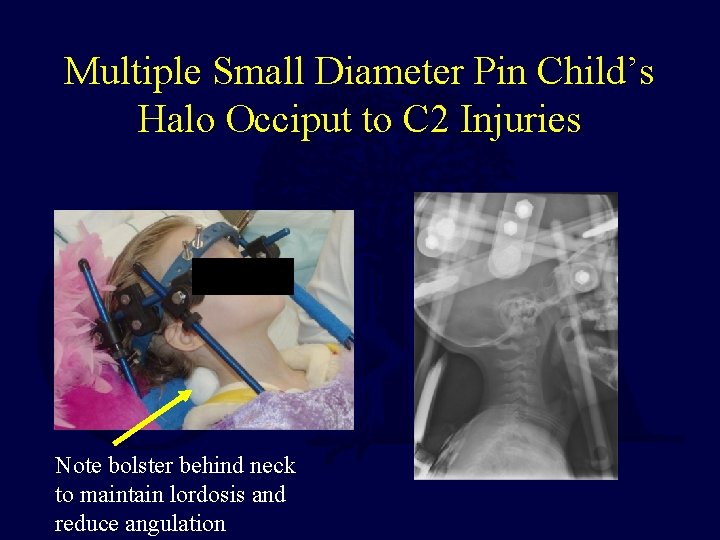

Multiple Small Diameter Pin Child’s Halo for Displaced C 2 Fracture Note bolster behind neck to maintain lordosis and reduce angulation

Multiple Small Diameter Pin Child’s Halo for Displaced C 2 Fracture Occ-C 1 articulation very axially oriented Note bolster behind neck to maintain lordosis and reduce angulation

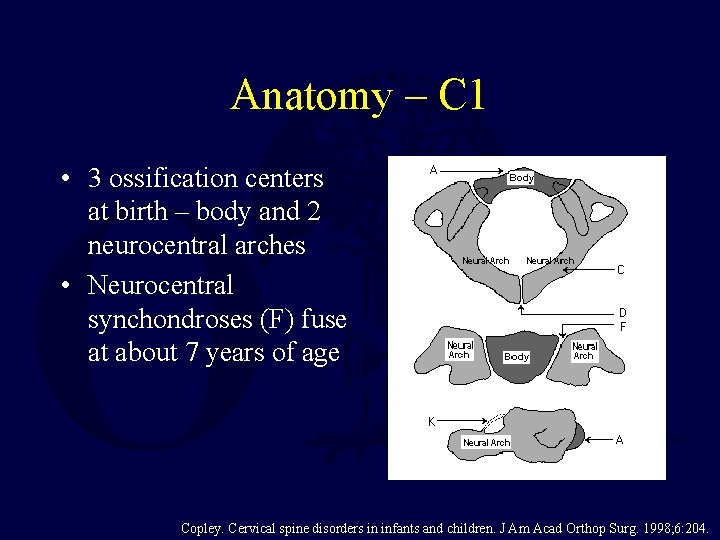

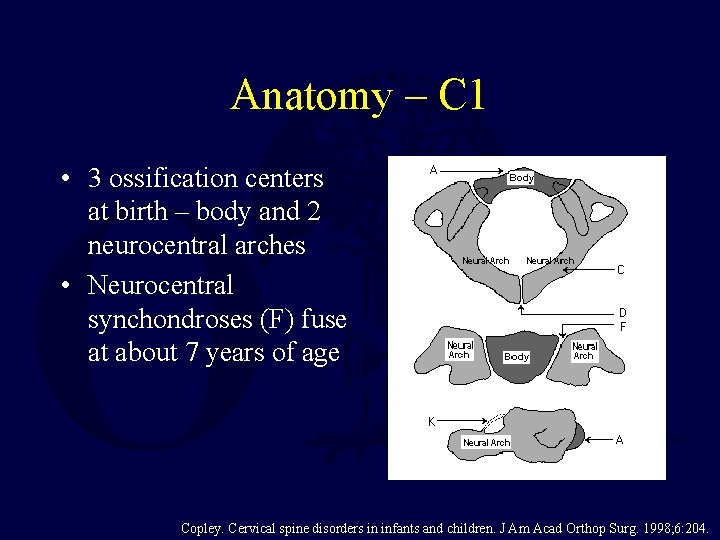

Anatomy – C 1 • 3 ossification centers at birth – body and 2 neurocentral arches • Neurocentral synchondroses (F) fuse at about 7 years of age Copley. Cervical spine disorders in infants and children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998; 6: 204.

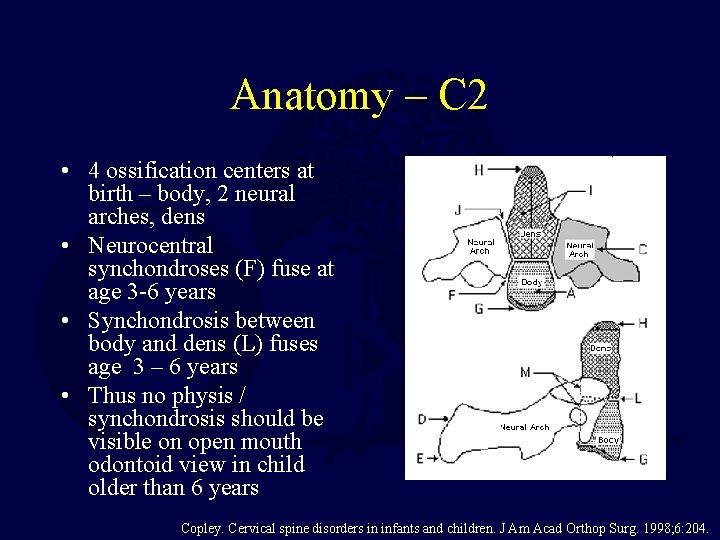

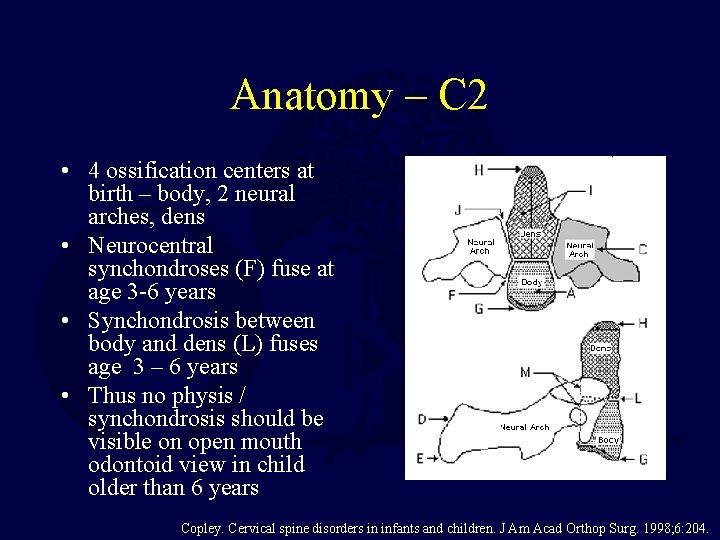

Anatomy – C 2 • 4 ossification centers at birth – body, 2 neural arches, dens • Neurocentral synchondroses (F) fuse at age 3 -6 years • Synchondrosis between body and dens (L) fuses age 3 – 6 years • Thus no physis / synchondrosis should be visible on open mouth odontoid view in child older than 6 years Copley. Cervical spine disorders in infants and children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998; 6: 204.

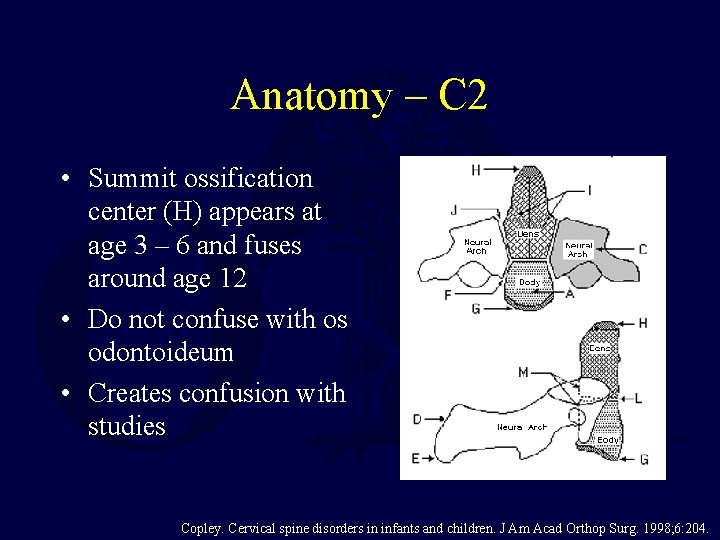

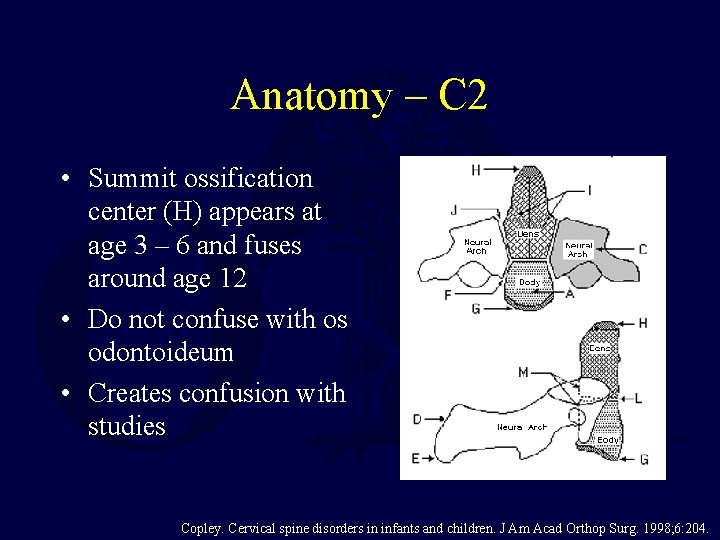

Anatomy – C 2 • Summit ossification center (H) appears at age 3 – 6 and fuses around age 12 • Do not confuse with os odontoideum • Creates confusion with studies Copley. Cervical spine disorders in infants and children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998; 6: 204.

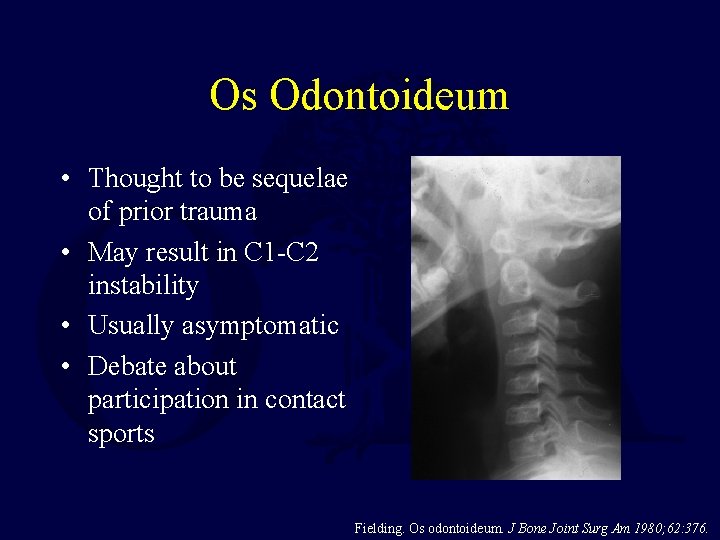

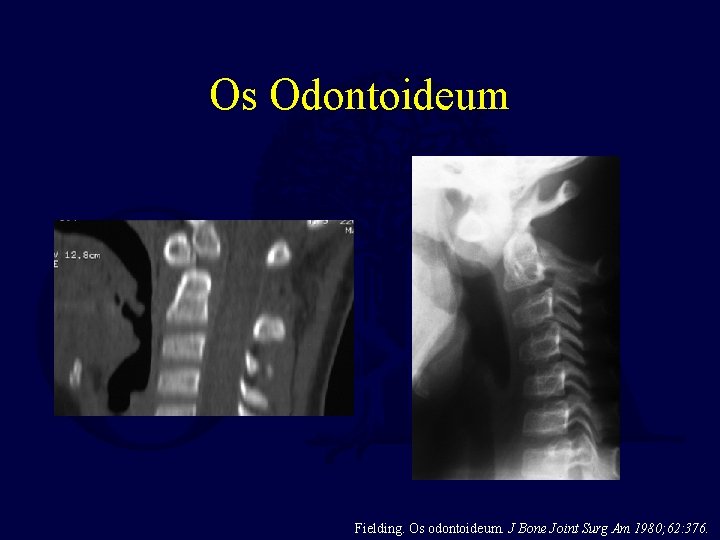

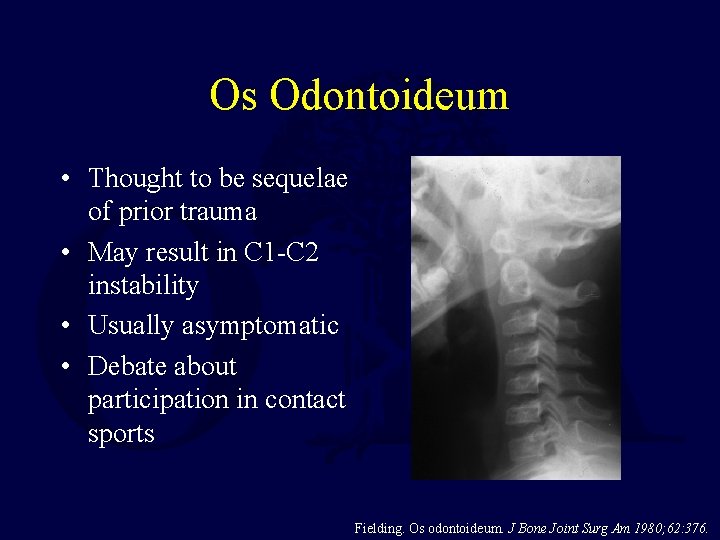

Os Odontoideum • Thought to be sequelae of prior trauma • May result in C 1 -C 2 instability • Usually asymptomatic • Debate about participation in contact sports Fielding. Os odontoideum. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980; 62: 376.

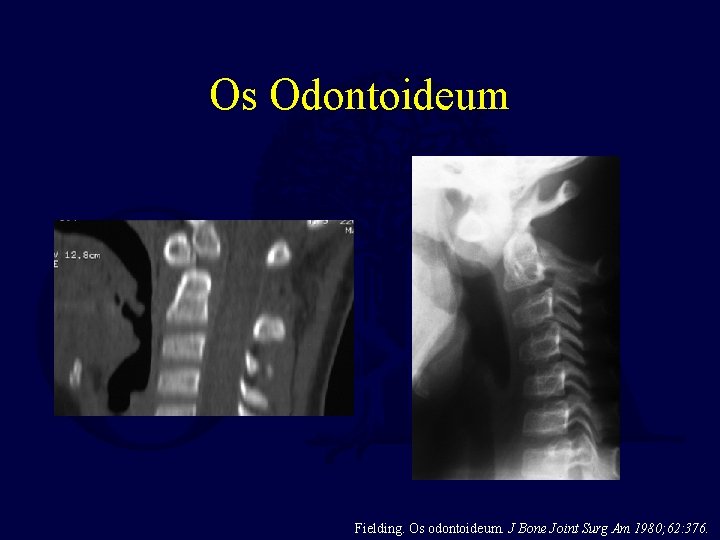

Os Odontoideum Fielding. Os odontoideum. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980; 62: 376.

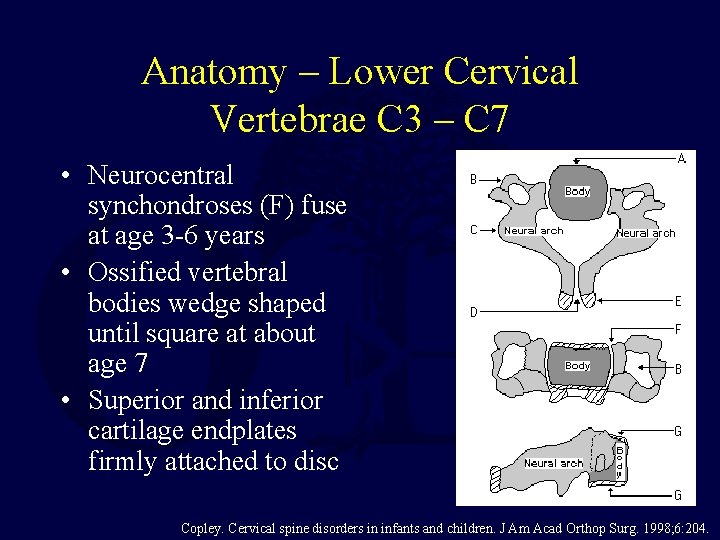

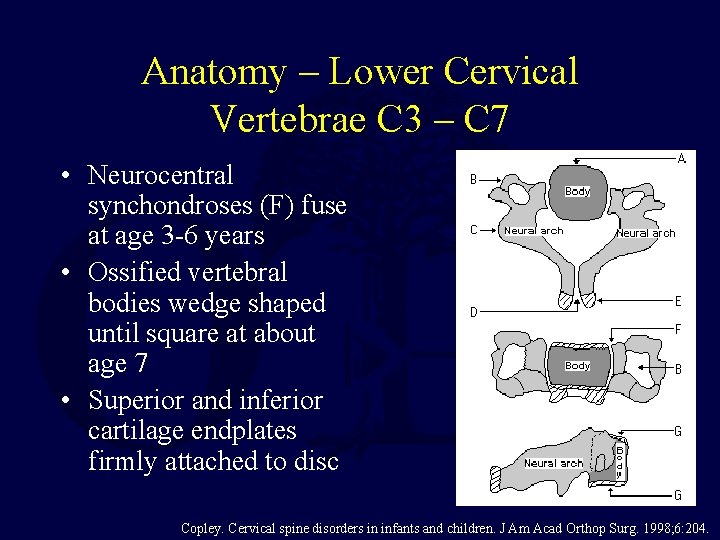

Anatomy – Lower Cervical Vertebrae C 3 – C 7 • Neurocentral synchondroses (F) fuse at age 3 -6 years • Ossified vertebral bodies wedge shaped until square at about age 7 • Superior and inferior cartilage endplates firmly attached to disc Copley. Cervical spine disorders in infants and children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998; 6: 204.

Mechanism of Injury • Child’s neck very mobile – ligamentous laxity and shallow angle of facet joints • Relatively larger head • In younger patients this combination leads to upper cervical injuries • Falls and motor vehicle accidents most common cause in younger children

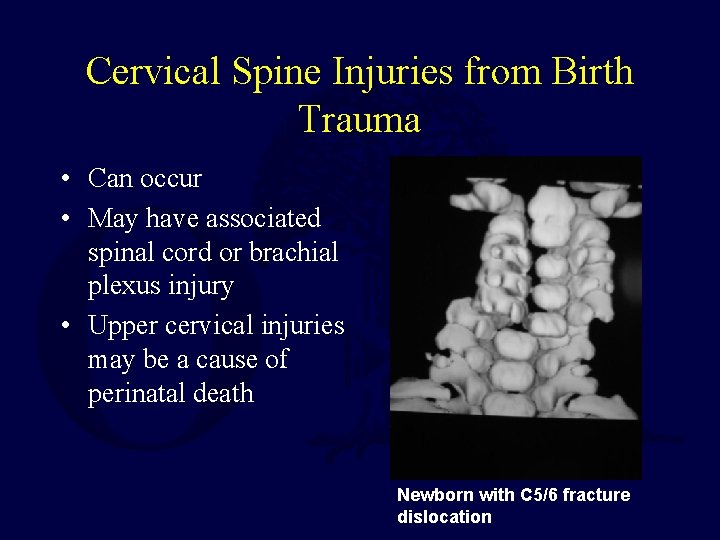

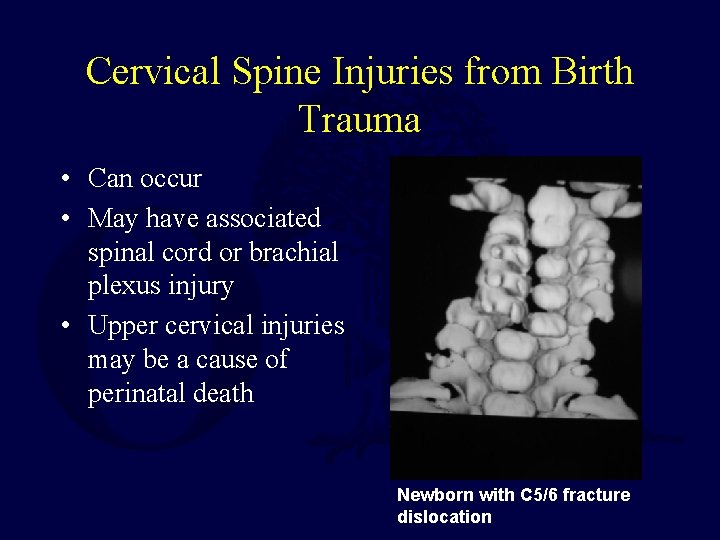

Cervical Spine Injuries from Birth Trauma • Can occur • May have associated spinal cord or brachial plexus injury • Upper cervical injuries may be a cause of perinatal death Newborn with C 5/6 fracture dislocation

Typical Fracture Pattern • Fractures tend to occur within the endplate between the cartilaginous endplate and the vertebral body • Clinically and experimentally fractures occur by splitting the endplate between the columnar growth cartilage and the calcified cartilage • Does not typically occur by fracture through the endplate – disc junction Jones. Pediatric cervical spine trauma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011; 19: 600.

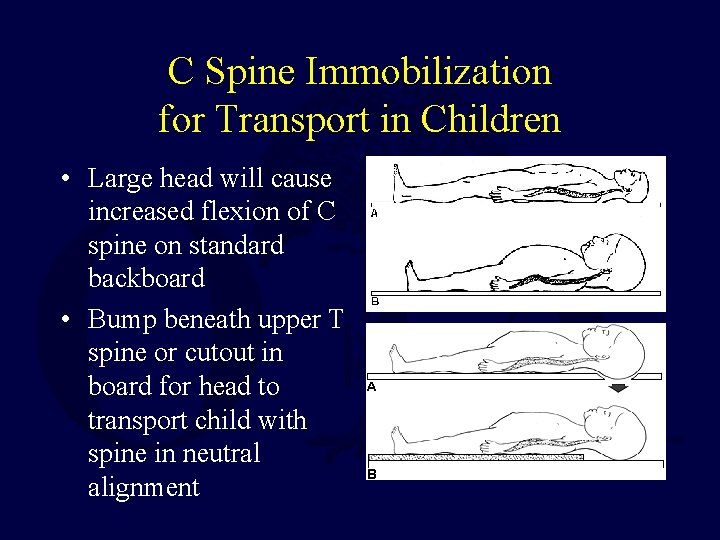

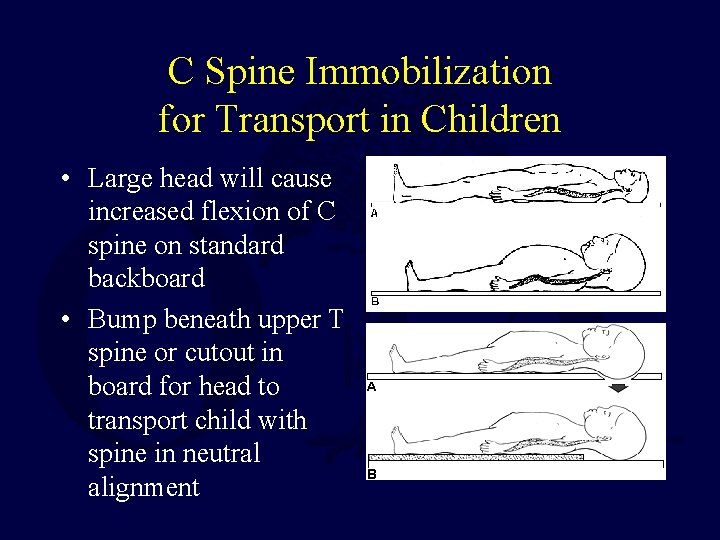

C Spine Immobilization for Transport in Children • Large head will cause increased flexion of C spine on standard backboard • Bump beneath upper T spine or cutout in board for head to transport child with spine in neutral alignment

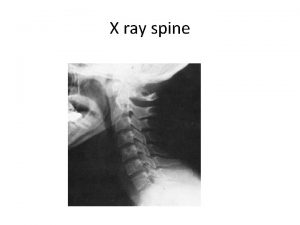

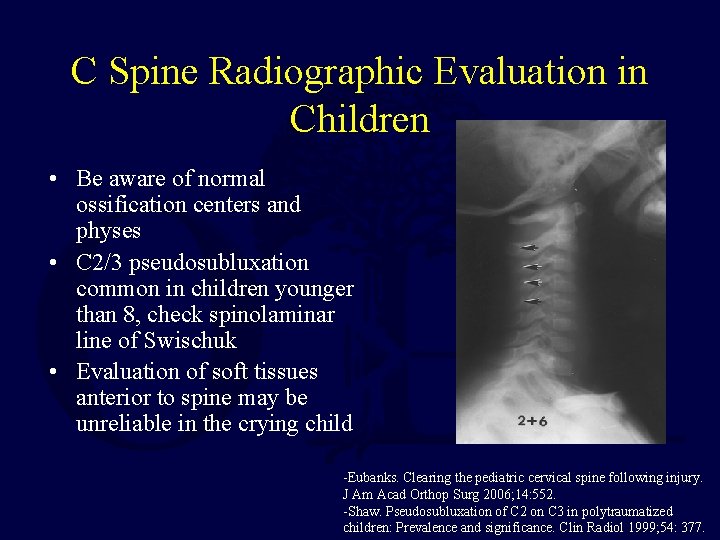

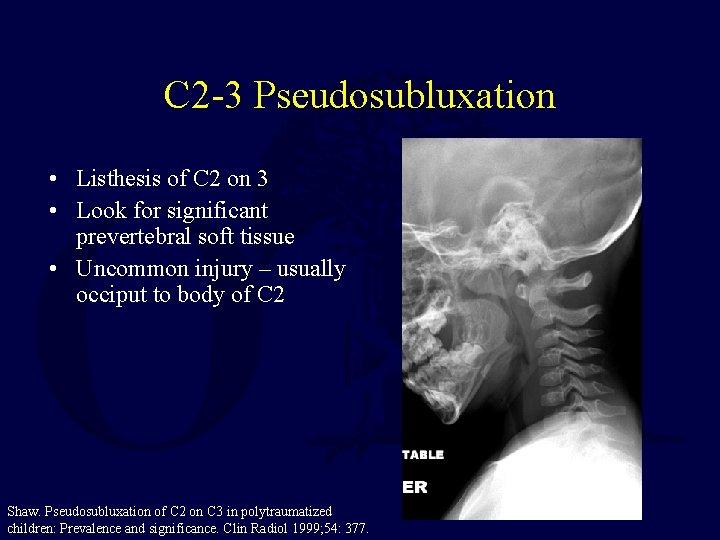

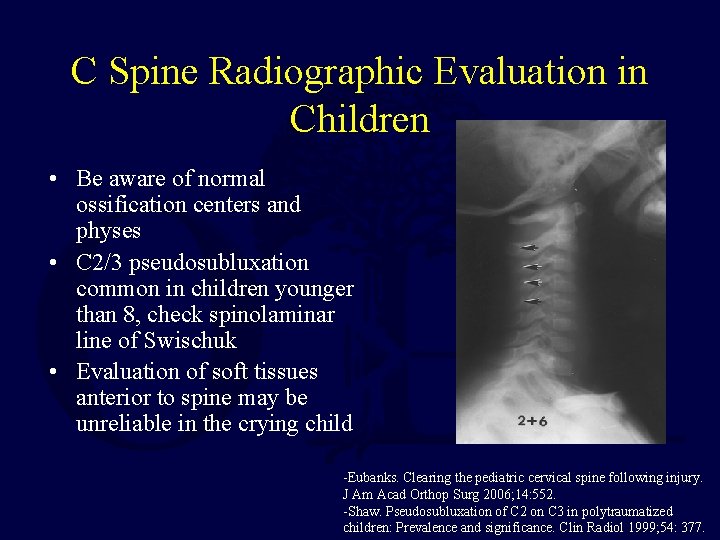

C Spine Radiographic Evaluation in Children • Be aware of normal ossification centers and physes • C 2/3 pseudosubluxation common in children younger than 8, check spinolaminar line of Swischuk • Evaluation of soft tissues anterior to spine may be unreliable in the crying child -Eubanks. Clearing the pediatric cervical spine following injury. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006; 14: 552. -Shaw. Pseudosubluxation of C 2 on C 3 in polytraumatized children: Prevalence and significance. Clin Radiol 1999; 54: 377.

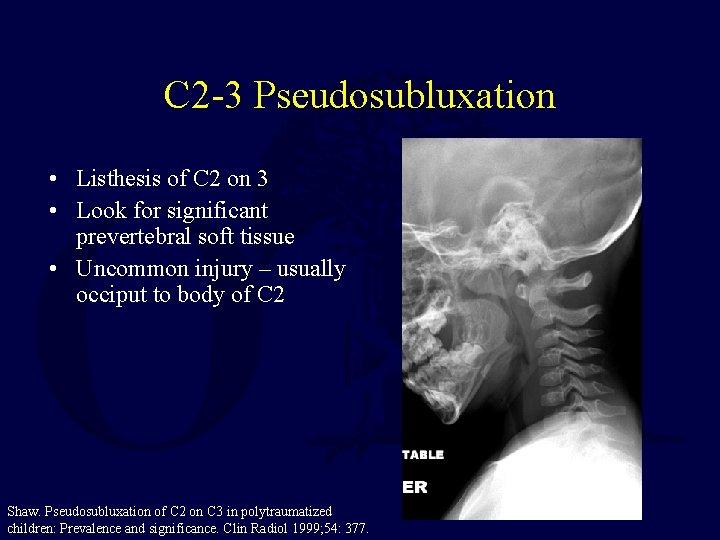

C 2 -3 Pseudosubluxation • Listhesis of C 2 on 3 • Look for significant prevertebral soft tissue • Uncommon injury – usually occiput to body of C 2 Shaw. Pseudosubluxation of C 2 on C 3 in polytraumatized children: Prevalence and significance. Clin Radiol 1999; 54: 377.

C Spine Evaluation in Children • Mechanism of injury is extremely important • Physical exam – tenderness (age, distracting injuries), neurological exam • Xrays not commonly used • CT scan to define bony detail • Low threshold to obtain MRI with stir sequences Anderson. Cervical spine clearance after trauma in children. J Neurosurg. 2006; 105(5 Suppl): 361– 364.

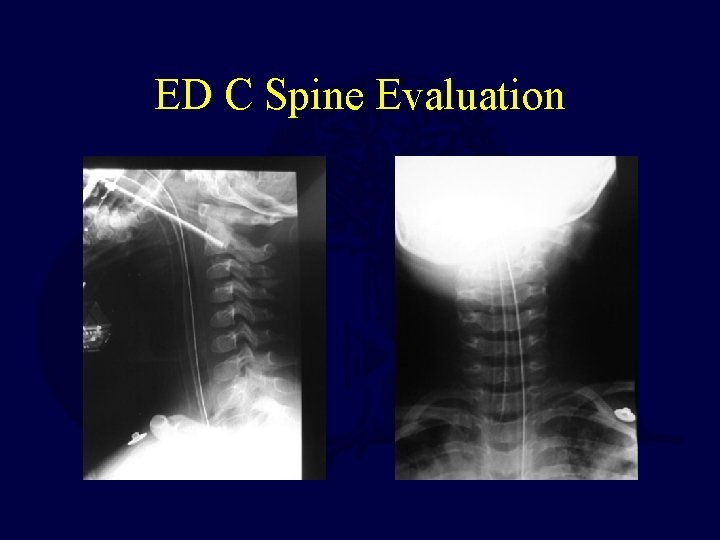

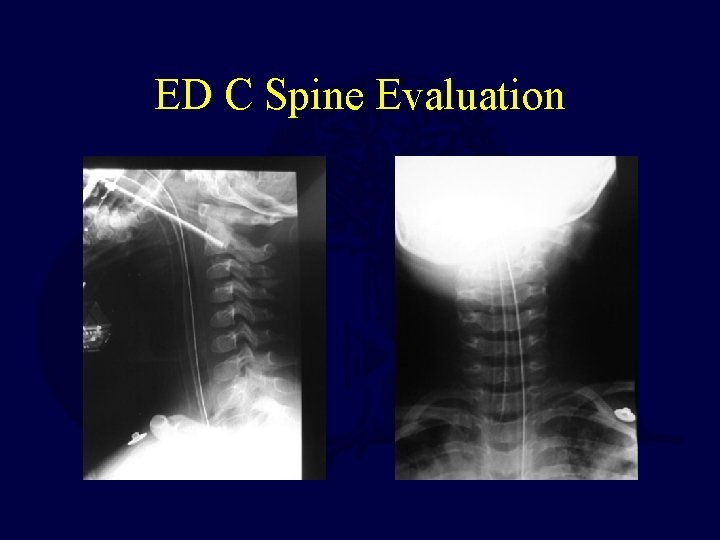

ED C Spine Evaluation

Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury • Rare in children • Better prognosis for recovery than adults • Treat aggressively with immobilization +/decompression • Late sequelae = paralytic scoliosis (almost all quadriplegic children if injured at less than 10 years of age) Parent. Spinal cord injury in the pediatric population: a systematic review of the literature. J. Neurotrauma. 2011; 28: 1515.

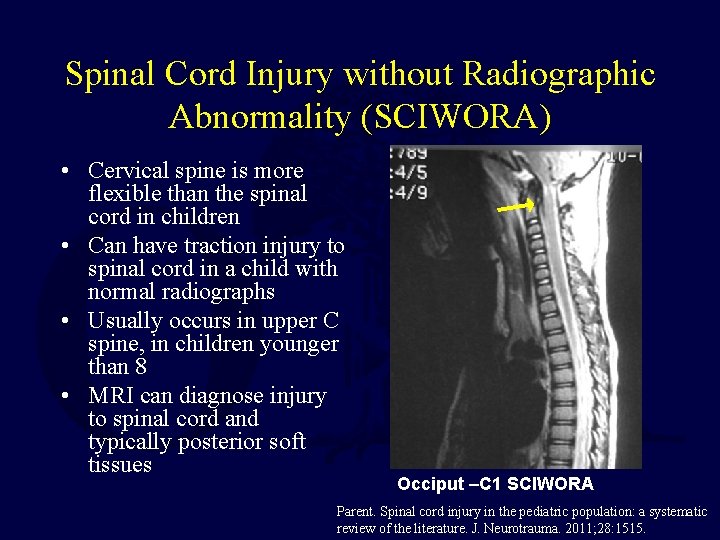

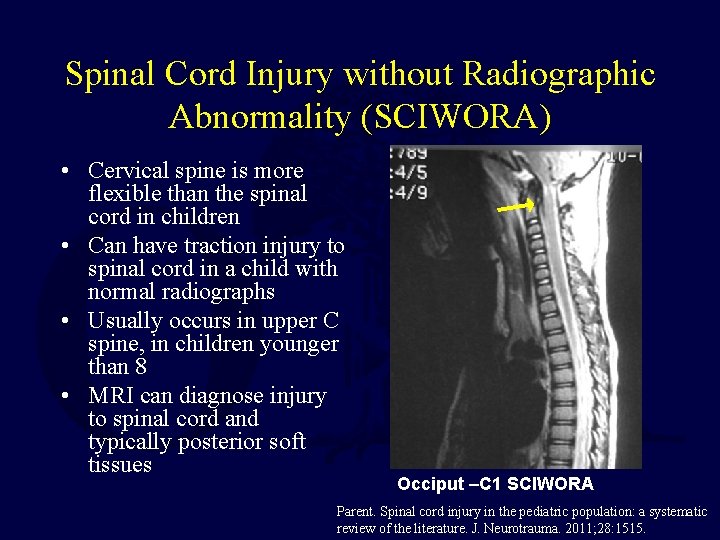

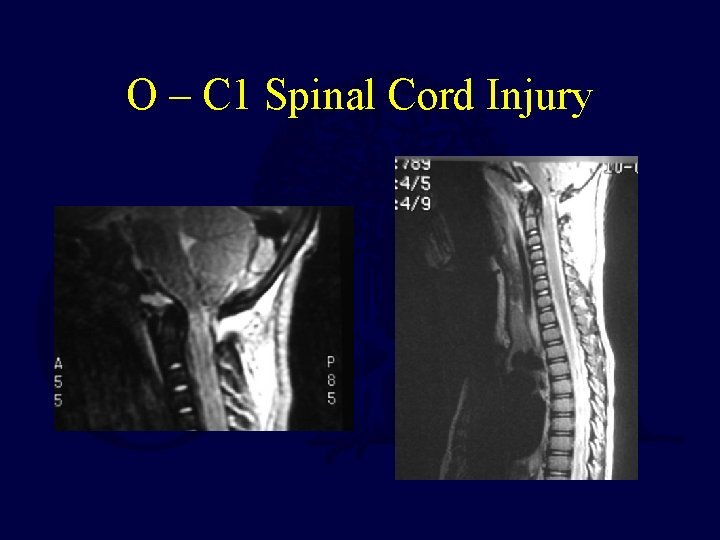

Spinal Cord Injury without Radiographic Abnormality (SCIWORA) • Cervical spine is more flexible than the spinal cord in children • Can have traction injury to spinal cord in a child with normal radiographs • Usually occurs in upper C spine, in children younger than 8 • MRI can diagnose injury to spinal cord and typically posterior soft tissues Occiput –C 1 SCIWORA Parent. Spinal cord injury in the pediatric population: a systematic review of the literature. J. Neurotrauma. 2011; 28: 1515.

SCIWORA • Spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality – Plain x-rays, not MRI • Distraction mechanism of injury • Spinal cord least elastic structure • Young children less than 8 yrs • Be aware in patient with GCS 3 and normal CT head there may be upper cervical spinal cord injury!

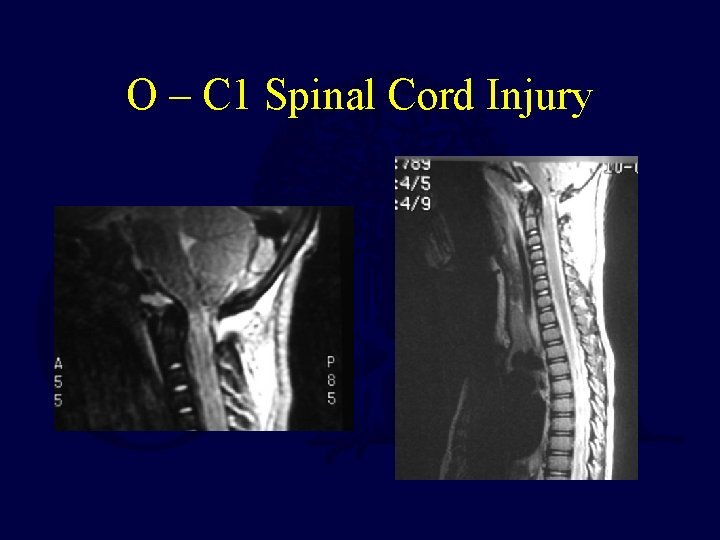

O – C 1 Spinal Cord Injury

Imaging • • 3 view plain film series still used Low threshold for further imaging CT scan upper C-spine (O-C 2) Consider MRI if intubated or obtunded Sharma. Assessment for additional spinal trauma in patients with cervical spine injury. Am Surg. 2007; 73: 70.

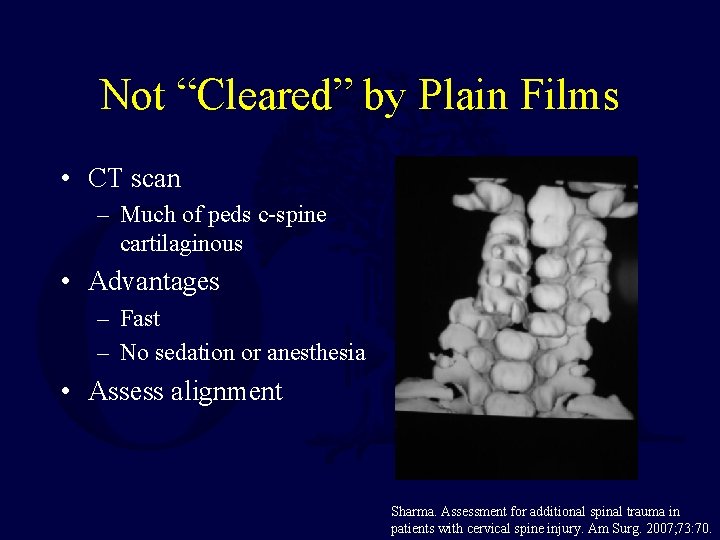

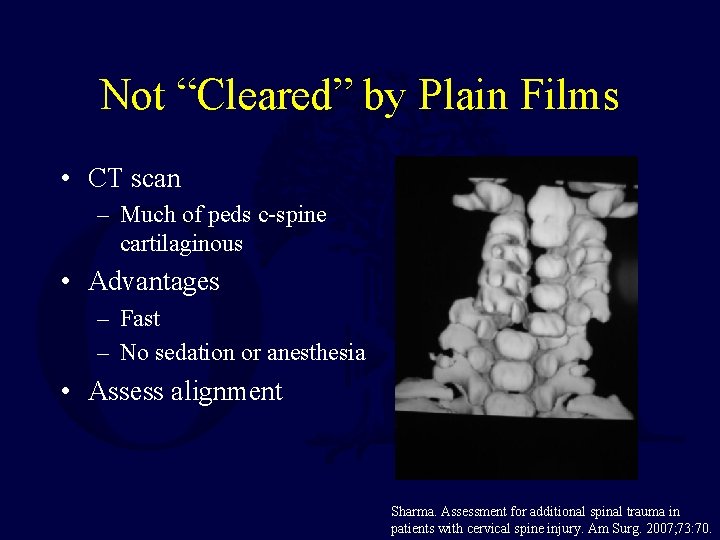

Not “Cleared” by Plain Films • CT scan – Much of peds c-spine cartilaginous • Advantages – Fast – No sedation or anesthesia • Assess alignment Sharma. Assessment for additional spinal trauma in patients with cervical spine injury. Am Surg. 2007; 73: 70.

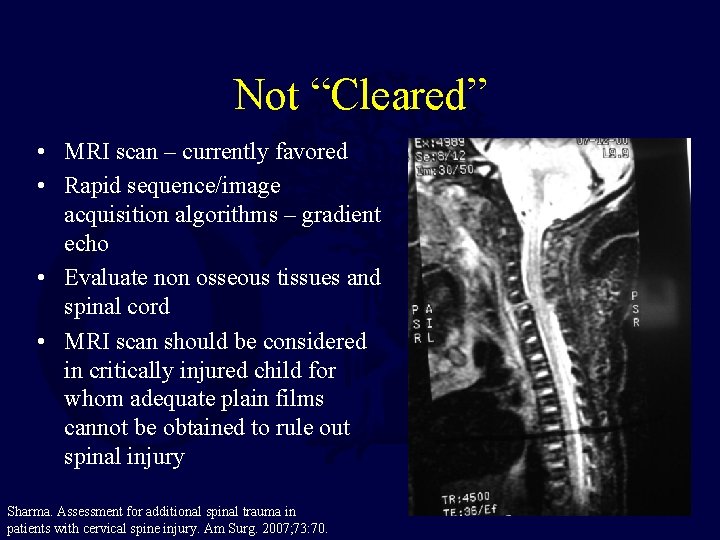

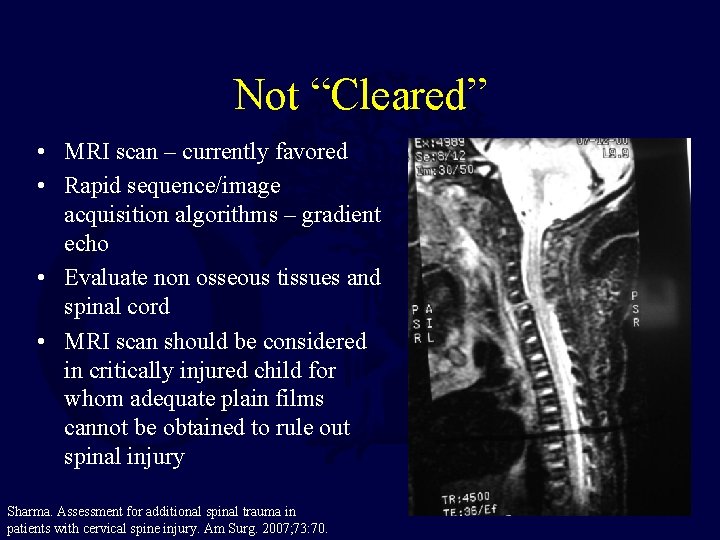

Not “Cleared” • MRI scan – currently favored • Rapid sequence/image acquisition algorithms – gradient echo • Evaluate non osseous tissues and spinal cord • MRI scan should be considered in critically injured child for whom adequate plain films cannot be obtained to rule out spinal injury Sharma. Assessment for additional spinal trauma in patients with cervical spine injury. Am Surg. 2007; 73: 70.

If not “Cleared” within 12 Hours • Switch to pediatric Aspen or Miami J collar • Consider CT or MRI Mc. Call. Cervical spine trauma in children: a review. Neurosurg Focus. 2006; 20(2): E 5.

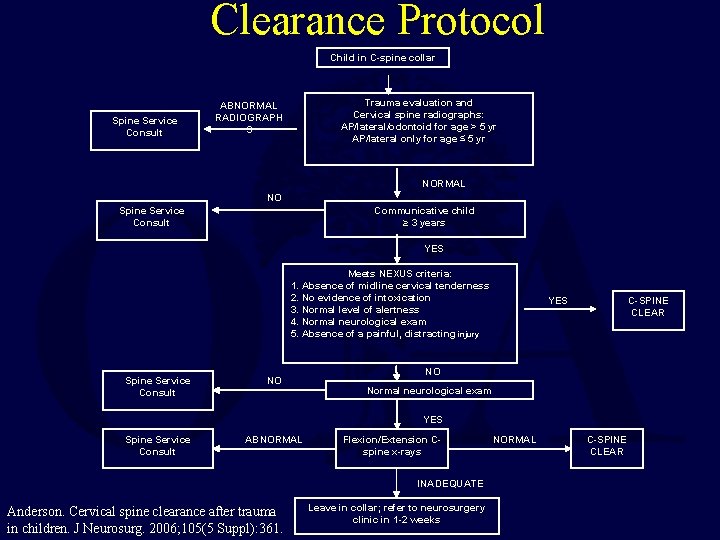

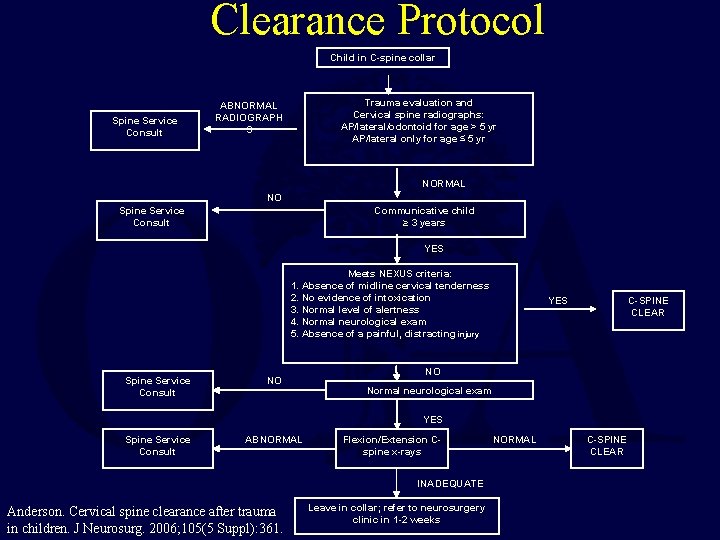

Clearance Protocol Child in C-spine collar Spine Service Consult Trauma evaluation and Cervical spine radiographs: AP/lateral/odontoid for age > 5 yr AP/lateral only for age ≤ 5 yr ABNORMAL RADIOGRAPH S NORMAL NO Spine Service Consult Communicative child ≥ 3 years YES Meets NEXUS criteria: 1. Absence of midline cervical tenderness 2. No evidence of intoxication 3. Normal level of alertness 4. Normal neurological exam 5. Absence of a painful, distracting injury Spine Service Consult NO YES C-SPINE CLEAR NO Normal neurological exam YES Spine Service Consult ABNORMAL Flexion/Extension Cspine x-rays INADEQUATE Anderson. Cervical spine clearance after trauma in children. J Neurosurg. 2006; 105(5 Suppl): 361. Leave in collar; refer to neurosurgery clinic in 1 -2 weeks NORMAL C-SPINE CLEAR

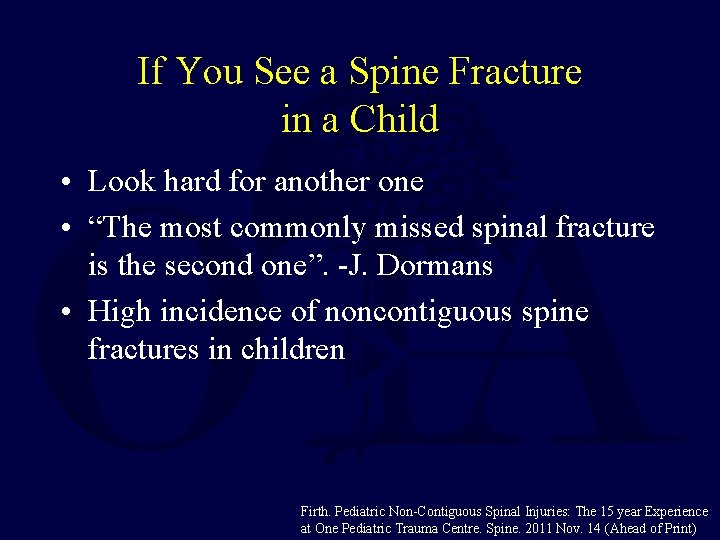

If You See a Spine Fracture in a Child • Look hard for another one • “The most commonly missed spinal fracture is the second one”. -J. Dormans • High incidence of noncontiguous spine fractures in children Firth. Pediatric Non-Contiguous Spinal Injuries: The 15 year Experience at One Pediatric Trauma Centre. Spine. 2011 Nov. 14 (Ahead of Print)

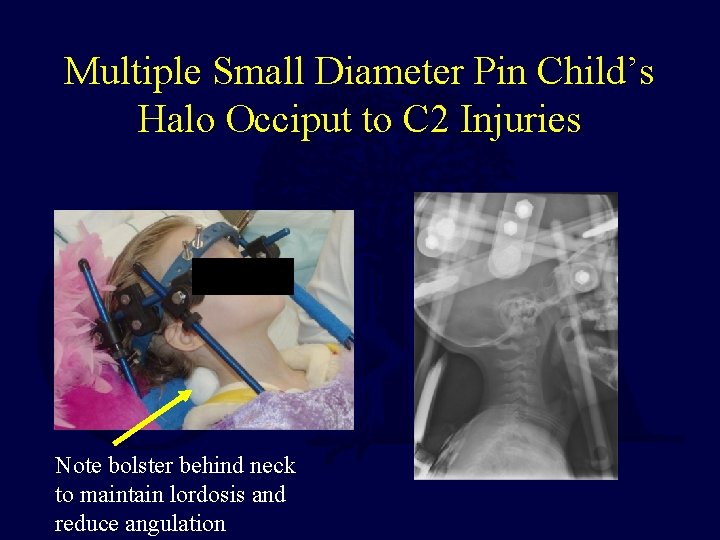

Multiple Small Diameter Pin Child’s Halo Occiput to C 2 Injuries Note bolster behind neck to maintain lordosis and reduce angulation

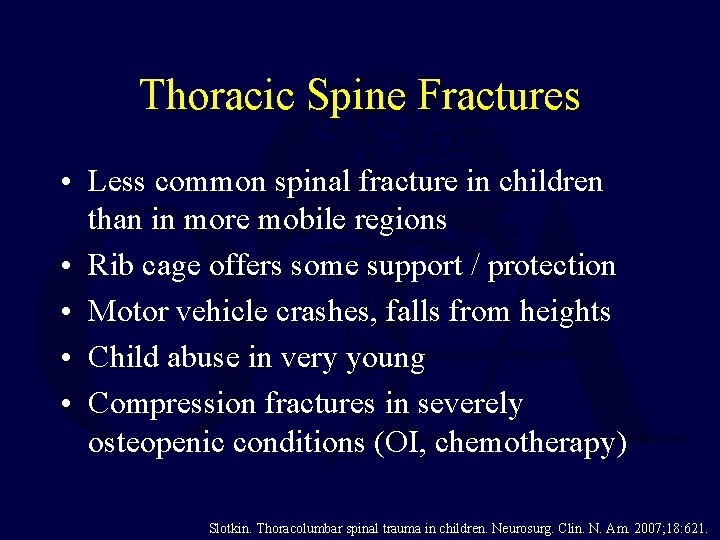

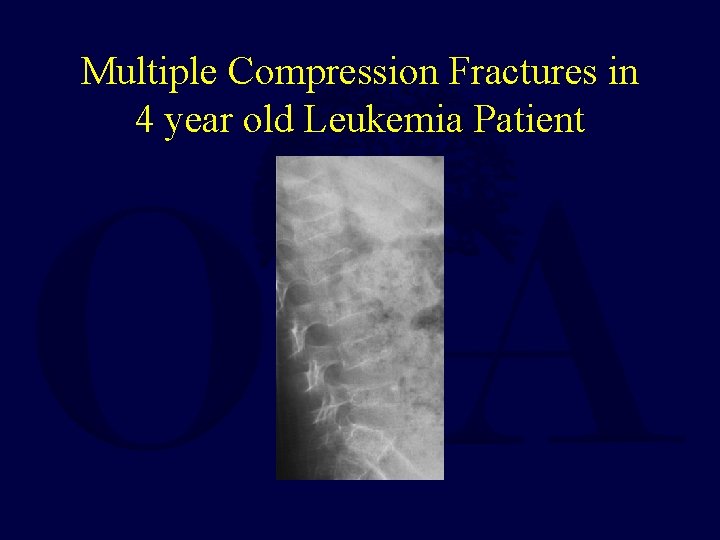

Thoracic Spine Fractures • Less common spinal fracture in children than in more mobile regions • Rib cage offers some support / protection • Motor vehicle crashes, falls from heights • Child abuse in very young • Compression fractures in severely osteopenic conditions (OI, chemotherapy) Slotkin. Thoracolumbar spinal trauma in children. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2007; 18: 621.

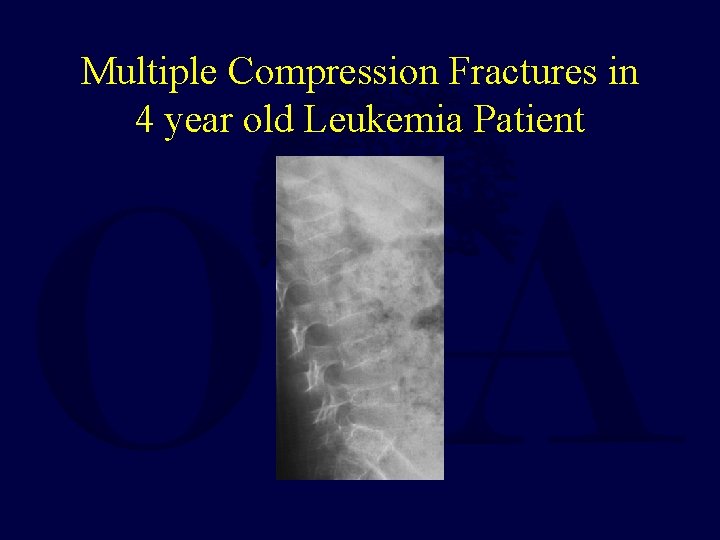

Multiple Compression Fractures in 4 year old Leukemia Patient

Thoracic Spine Fracture Dislocations • High energy mechanisms • Often spinal cord injury, can be transected • Prognosis for recovery most dependent on initial exam – complete deficits unlikely to have recovery • Infarction of cord (artery of Adamkiewicz) may play some role –especially in delayed paraplegia Slotkin. Thoracolumbar spinal trauma in children. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2007; 18: 621.

Thoracolumbar Junction Injuries T 11 -L 2 • Classically lap-belt flexion-distraction injuries • Chance fractures and variants • High association with intraabdominal injury (50 -90%) • Neurologic injury infrequent but can occur Arkader. Pediatric chance fractures: a multicenter perspective. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011; 31: 741.

Chance Fractures and Variants • Flexion over fulcrum • Posterior elements fail in tension, anterior elements in compression – Can occur through bone, soft tissue or combination • Treatment – Pure bony injuries can be treated with immobilization in extension – Partial or whole ligamentous injuries may be best treated with surgical stabilization Arkader. Pediatric chance fractures: a multicenter perspective. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011; 31: 741.

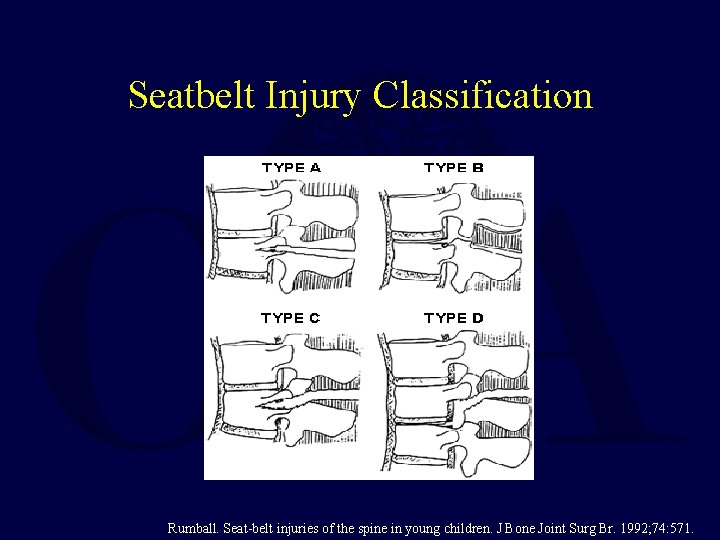

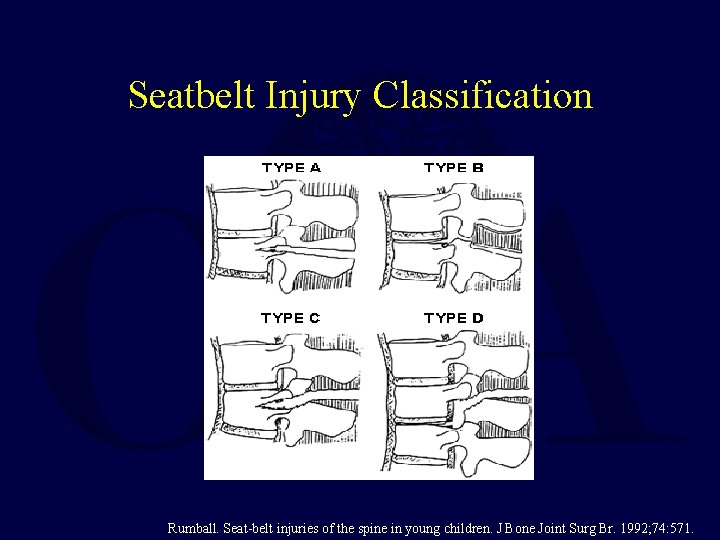

Seatbelt Injury Classification Rumball. Seat-belt injuries of the spine in young children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992; 74: 571.

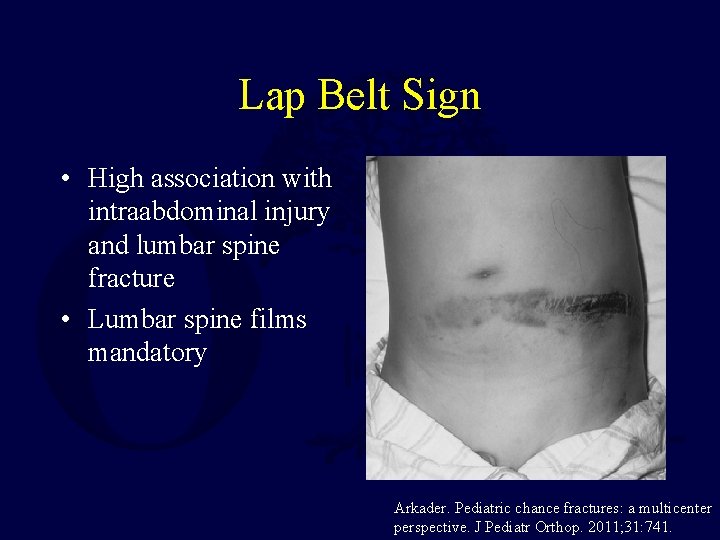

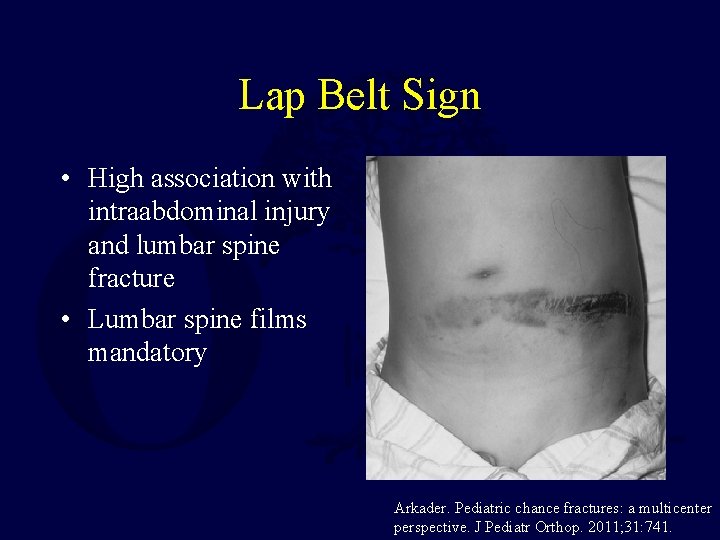

Lap Belt Sign • High association with intraabdominal injury and lumbar spine fracture • Lumbar spine films mandatory Arkader. Pediatric chance fractures: a multicenter perspective. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011; 31: 741.

4 yo Lap Belt Restrained Passenger Intraabdominal Injuries, Paraplegic

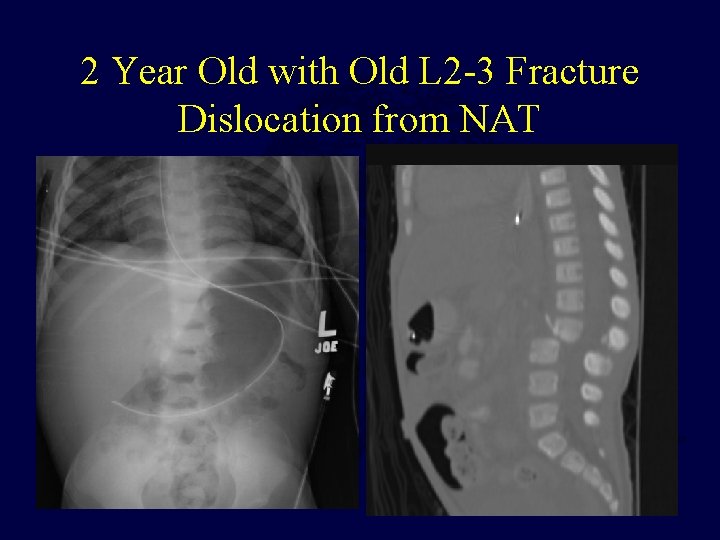

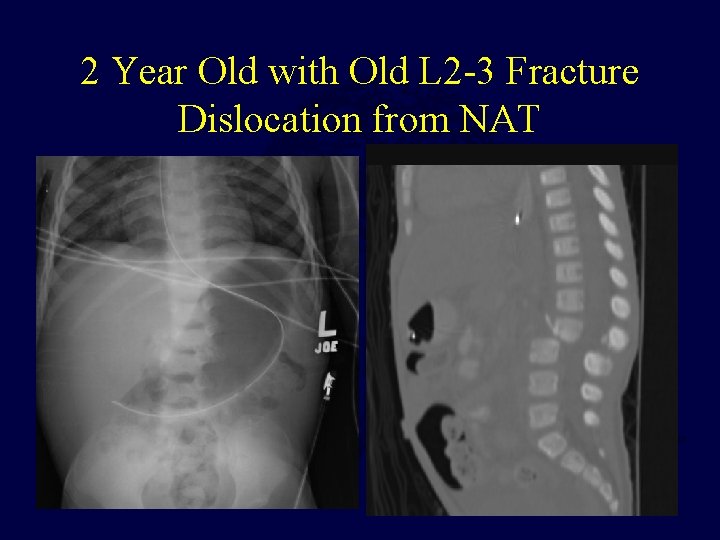

2 Year Old with Old L 2 -3 Fracture Dislocation from NAT

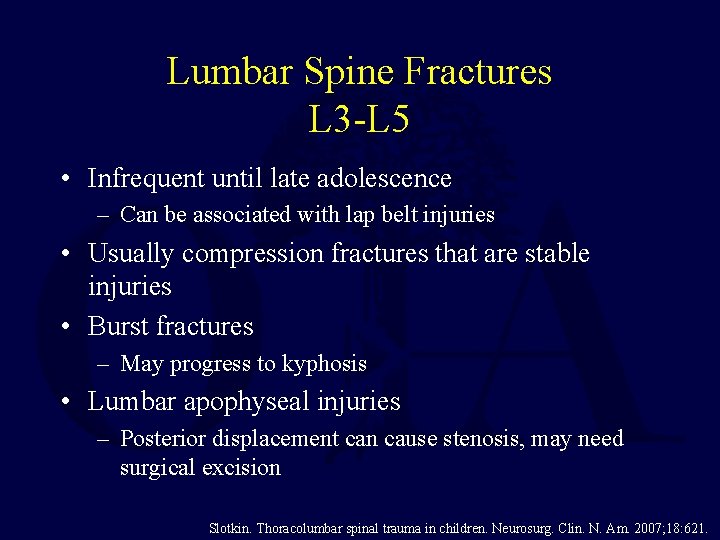

Lumbar Spine Fractures L 3 -L 5 • Infrequent until late adolescence – Can be associated with lap belt injuries • Usually compression fractures that are stable injuries • Burst fractures – May progress to kyphosis • Lumbar apophyseal injuries – Posterior displacement can cause stenosis, may need surgical excision Slotkin. Thoracolumbar spinal trauma in children. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2007; 18: 621.

Flexion-Distraction Injury L 2 -L 3 6 Months after Compression Fixation, Posterolateral Fusion

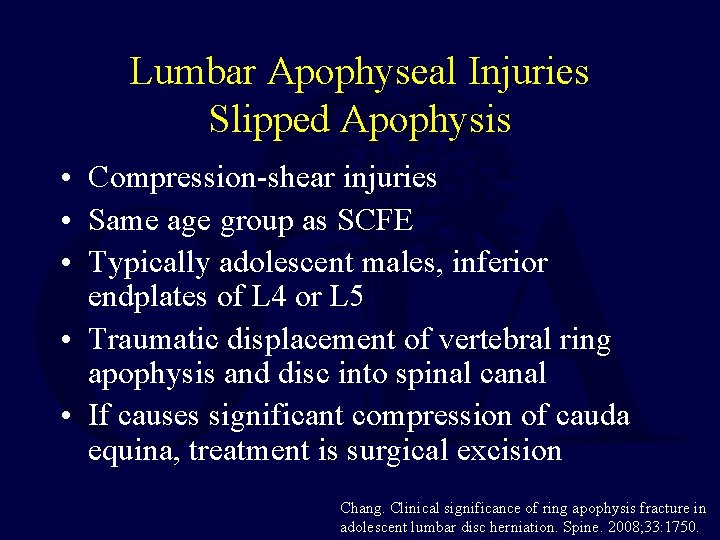

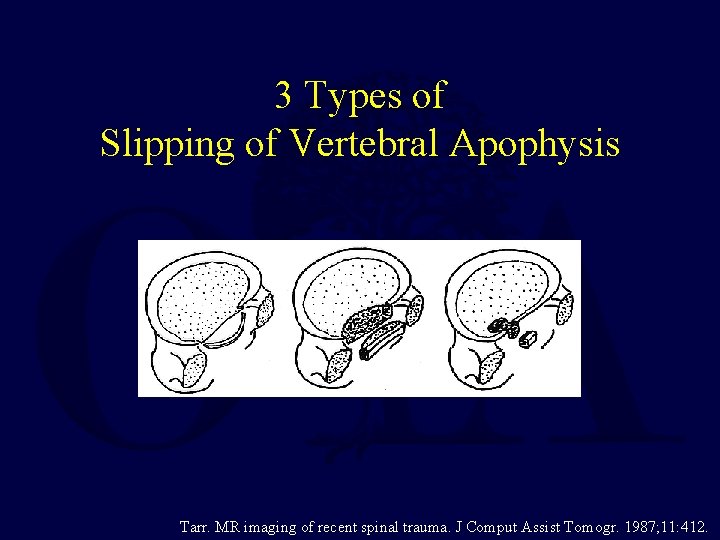

Lumbar Apophyseal Injuries Slipped Apophysis • Compression-shear injuries • Same age group as SCFE • Typically adolescent males, inferior endplates of L 4 or L 5 • Traumatic displacement of vertebral ring apophysis and disc into spinal canal • If causes significant compression of cauda equina, treatment is surgical excision Chang. Clinical significance of ring apophysis fracture in adolescent lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 2008; 33: 1750.

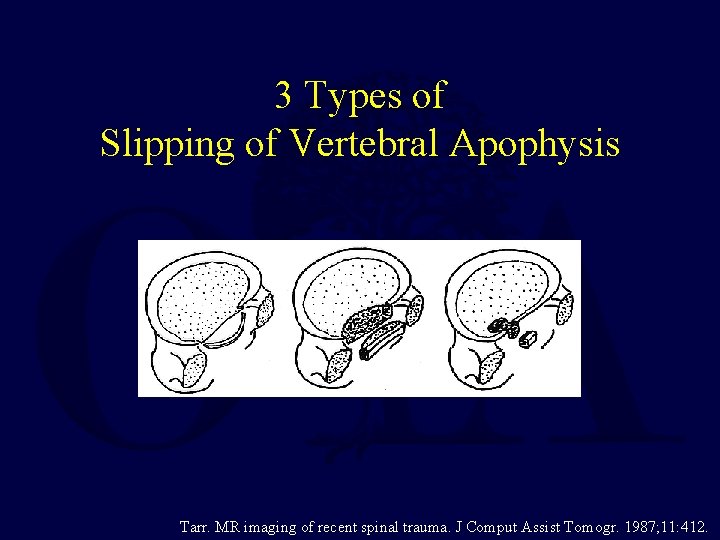

3 Types of Slipping of Vertebral Apophysis Tarr. MR imaging of recent spinal trauma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1987; 11: 412.

Burst Fractures • Usually in older adolescents • Treatment similar to adults • May not need surgery in neurologically intact patient • Injuries at thoracolumbar junction higher risk for progressive kyphosis Slotkin. Thoracolumbar spinal trauma in children. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2007; 18: 621.

Bibliography • • • Anderson RCE, Scaife ER, Fenton SJ, Kan P, Hansen KW, Brockmeyer DL. Cervical spine clearance after trauma in children. J Neurosurg. 2006 Nov. ; 105(5 Suppl): 361– 364. Arkader A, Warner WC, Tolo VT, Sponseller PD, Skaggs DL. Pediatric chance fractures: a multicenter perspective. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011 Sep. ; 31(7): 741– 744. Chang C-H, Lee Z-L, Chen W-J, Tan C-F, Chen L-H. Clinical significance of ring apophysis fracture in adolescent lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 2008 Jul. 15; 33(16): 1750– 1754. Copley LA, Dormans JP. Cervical spine disorders in infants and children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998 Jun. ; 6(4): 204– 214. Eubanks JD, Gilmore A, Bess S, Cooperman DR: Clearing the pediatric cervical spine following injury. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006; 14(9): 552 -564. Fielding JWHensinger RN, Hawkins RJ: Os odontoideum. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980; 62: 376 -383. Firth GB, Kingwell S, Moroz P. Pediatric Non-Contiguous Spinal Injuries: The 15 year Experience at One Pediatric Trauma Centre. Spine. 2011 Nov. 14 (Ahead of Print) Jones TM, Anderson PA, Noonan KJ. Pediatric cervical spine trauma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011 Oct. ; 19(10): 600– 611. Mc. Call T, Fassett D, Brockmeyer D. Cervical spine trauma in children: a review. Neurosurg Focus. 2006; 20(2): E 5. Parent S, Mac-Thiong J-M, Roy-Beaudry M, Sosa JF, Labelle H. Spinal cord injury in the pediatric population: a systematic review of the literature. J. Neurotrauma. 2011 Aug. ; 28(8): 1515– 1524.

Bibliography • • • Rumball K, Jarvis J. Seat-belt injuries of the spine in young children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992 Jul. ; 74(4): 571– 574. Sharma OP, Oswanski MF, Yazdi JS, Jindal S, Taylor M. Assessment for additional spinal trauma in patients with cervical spine injury. Am Surg. 2007 Jan. ; 73(1): 70– 74. Shaw M, Burnett H, Wilson A, Chan O: Pseudosubluxation of C 2 on C 3 in polytraumatized children: Prevalence and significance. Clin Radiol 1999; 54(6): 377 -380. Slotkin JR, Lu Y, Wood KB. Thoracolumbar spinal trauma in children. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2007 Oct. ; 18(4): 621– 630. Tarr RW, Drolshagen LF, Kerner TC, Allen JH, Partain CL, James AE. MR imaging of recent spinal trauma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1987 Apr. ; 11(3): 412– 417. If you would like to volunteer as an author for the Resident Slide Project or recommend updates to any of the following slides, please send an email to ota@ota. org Return to Pediatrics Index

Timothy moore md

Timothy moore md Dr sukhpal singh

Dr sukhpal singh Ao classification of fractures

Ao classification of fractures Ilioposas

Ilioposas Bone cancer fractures

Bone cancer fractures Bobine d andrieu

Bobine d andrieu Irving olecranon fractures

Irving olecranon fractures Open fracture treatment

Open fracture treatment Fracture sus condylienne

Fracture sus condylienne Acetabulum ossification

Acetabulum ossification Panfacial fractures sequencing

Panfacial fractures sequencing Weber classification

Weber classification Concentric fractures

Concentric fractures Lisa cannada md

Lisa cannada md Classification tile bassin

Classification tile bassin Types of glass fractures

Types of glass fractures Daniel tibia

Daniel tibia Glass analysis in forensic science

Glass analysis in forensic science Tubular shaft of a long bone

Tubular shaft of a long bone Canthatomy

Canthatomy Chest tube placement

Chest tube placement Late complications of fractures

Late complications of fractures Pqrst pain scale

Pqrst pain scale Spine vs thorn

Spine vs thorn Schober's test positive

Schober's test positive Peripheral nerves

Peripheral nerves Spine meninges

Spine meninges Frankel a b c d e

Frankel a b c d e Lumbar referral patterns

Lumbar referral patterns Pubic arch

Pubic arch Chapter 20 worksheet the spine

Chapter 20 worksheet the spine Boney spine

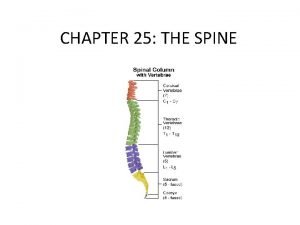

Boney spine 7 12 5 spine

7 12 5 spine Harborside spine and sports

Harborside spine and sports Maxillary sinus

Maxillary sinus Emory spine center

Emory spine center Mental spine of mandible

Mental spine of mandible Interalveolar septa mandible

Interalveolar septa mandible Rattle spine nms

Rattle spine nms Strickler spine and sport

Strickler spine and sport Spine blood spatter definition

Spine blood spatter definition Mental spine

Mental spine Spine palpation landmarks

Spine palpation landmarks Spine store layout

Spine store layout Trunk extensors

Trunk extensors Fabrics on ethernet

Fabrics on ethernet Who made the griffin ford model

Who made the griffin ford model Iliac tubercle

Iliac tubercle