An Introduction to Experimental Economics How to gain

![Recruiting the subjects Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic] Recruiting the subjects Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/827f64f04b2ea1078e41f23aec405766/image-25.jpg)

![Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic] Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/827f64f04b2ea1078e41f23aec405766/image-26.jpg)

![Experiment session will appear here Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic] Experiment session will appear here Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/827f64f04b2ea1078e41f23aec405766/image-27.jpg)

![Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic] Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/827f64f04b2ea1078e41f23aec405766/image-28.jpg)

![http: //www. iew. uzh. ch/ztree/index. php Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic] http: //www. iew. uzh. ch/ztree/index. php Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/827f64f04b2ea1078e41f23aec405766/image-35.jpg)

- Slides: 65

An Introduction to Experimental Economics: How to gain an insight into human's behaviour and decisions Donhatai Harris dh 293@cam. ac. uk Cambridge Experimental &Behavioural Research Group (CEBEG) Faculty of Economics University of Cambridge, UK

Outline of Today’s Lecture I. Why Experiment? II. What is experimental economics? III. How to conduct an experiment: Key Principles of experimental economics IV. Previous experiment work in Thailand (Harris et al. , 2008) V. Key contributions of Experimental Economics to Economics Discipline and Future Challenges. Donhatai Harris

I. Why experiment? Donhatai Harris

I. Why experiment? § Economics has been regarded as a non-experimental science, where researchers – as in astronomy or meteorology – have had to rely exclusively on field data, that is, direct observations of the real world. § The lack of experimental data meant that when an economic proposition appeared not to be captured by the data or the outcome was not as predicted by theory, the quality of the data was more likely to be questioned than the relevance or quality of theory But theory may not always be correct, particularly in predicting human behaviour! Donhatai Harris

II. What is Experimental Economics? Objectives of Economic Experiments § Testing theories § Establish empirical regularities as a basis for new theories § Testing institutions § Studying preferences and decision-making § Goods (public goods), risk, fairness, time preference § Replication of previous work § Teaching economics Donhatai Harris

II. What is experimental economics? Donhatai Harris

II. What is Experimental Economics? Experimental economics is an empirical tool that enables economists to understand the extent to which an individual’s decision and behaviour are affected by various (testable) factors in a controlled environment. Donhatai Harris

II. What is Experimental Economics? § To establish whether an independent variable influences the dependent variable (outcome) “treatment effect” need to establish counter-factual. § Controlled experiments represent the most convincing method of creating the counterfactual, since they directly construct a control group via randomization. Donhatai Harris

I. Why experiment? An example: Theory: Sub-game perfect equilibrium (Selten, 1965) Experiment: A simple bargaining game with 2 players (Guth, Schmittberger and Schwarze, 1982): § Player 1 makes a proposal for how a sum of money is to be split between players 1 and 2. § Player 2 then either accepts, implementing the proposal, or rejects, in which case the interaction ends with zero payoffs for each. What is SPE? & What do you think happens in the experiment? Donhatai Harris

II. What is Experimental Economics? The result show… § A marked contrast between theory and experiment § But why should we be interested in this result? § Is the experimental environment sufficiently close to the situation of interest to be informative? Rather. . we should ask § How special is the laboratory environment generating the experimental results? § Is it just one result? Can it be replicated? Is it robust? Donhatai Harris

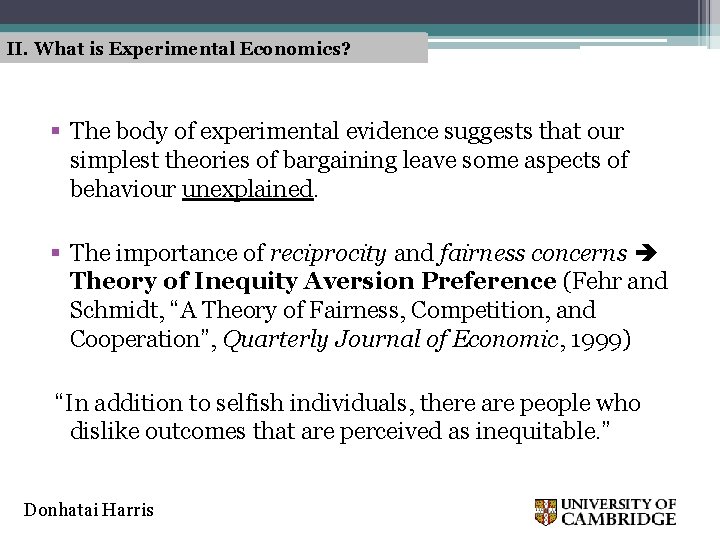

II. What is Experimental Economics? § The body of experimental evidence suggests that our simplest theories of bargaining leave some aspects of behaviour unexplained. § The importance of reciprocity and fairness concerns Theory of Inequity Aversion Preference (Fehr and Schmidt, “A Theory of Fairness, Competition, and Cooperation”, Quarterly Journal of Economic, 1999) “In addition to selfish individuals, there are people who dislike outcomes that are perceived as inequitable. ” Donhatai Harris

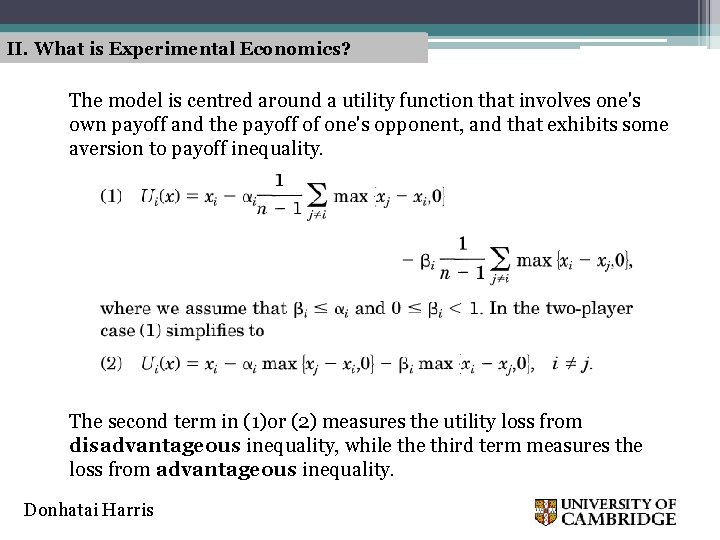

II. What is Experimental Economics? The model is centred around a utility function that involves one's own payoff and the payoff of one's opponent, and that exhibits some aversion to payoff inequality. The second term in (1)or (2) measures the utility loss from disadvantageous inequality, while third term measures the loss from advantageous inequality. Donhatai Harris

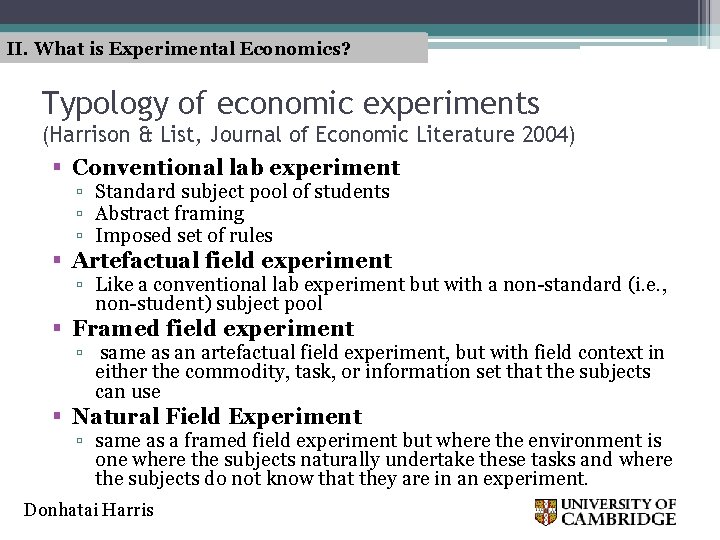

II. What is Experimental Economics? Typology of economic experiments (Harrison & List, Journal of Economic Literature 2004) § Conventional lab experiment ▫ Standard subject pool of students ▫ Abstract framing ▫ Imposed set of rules § Artefactual field experiment ▫ Like a conventional lab experiment but with a non-standard (i. e. , non-student) subject pool § Framed field experiment ▫ same as an artefactual field experiment, but with field context in either the commodity, task, or information set that the subjects can use § Natural Field Experiment ▫ same as a framed field experiment but where the environment is one where the subjects naturally undertake these tasks and where the subjects do not know that they are in an experiment. Donhatai Harris

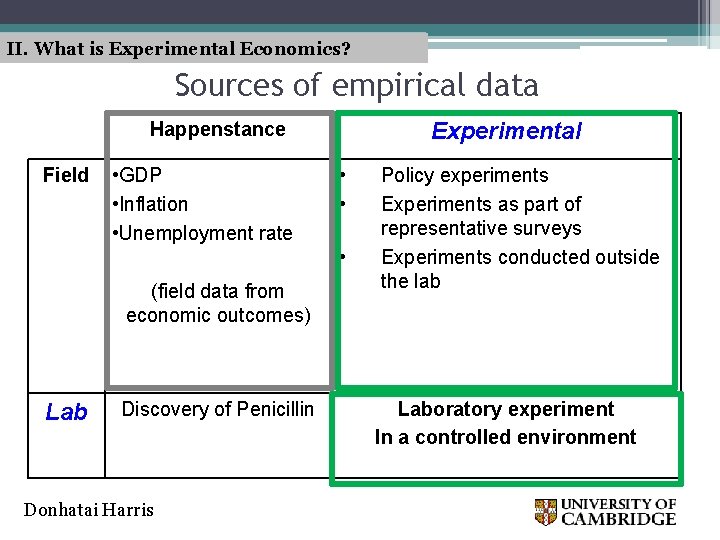

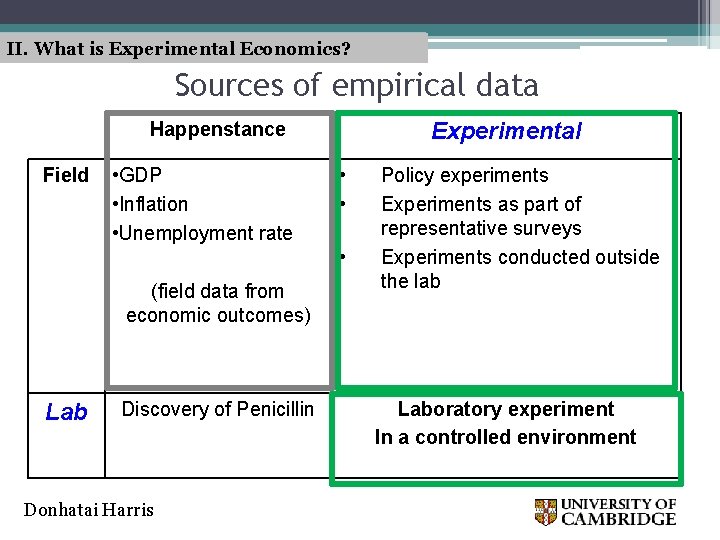

II. What is Experimental Economics? Sources of empirical data Happenstance Field • GDP • Inflation • Unemployment rate Experimental • • • (field data from economic outcomes) Lab Discovery of Penicillin Donhatai Harris Policy experiments Experiments as part of representative surveys Experiments conducted outside the lab Laboratory experiment In a controlled environment

III. How to conduct a laboratory experiment Donhatai Harris

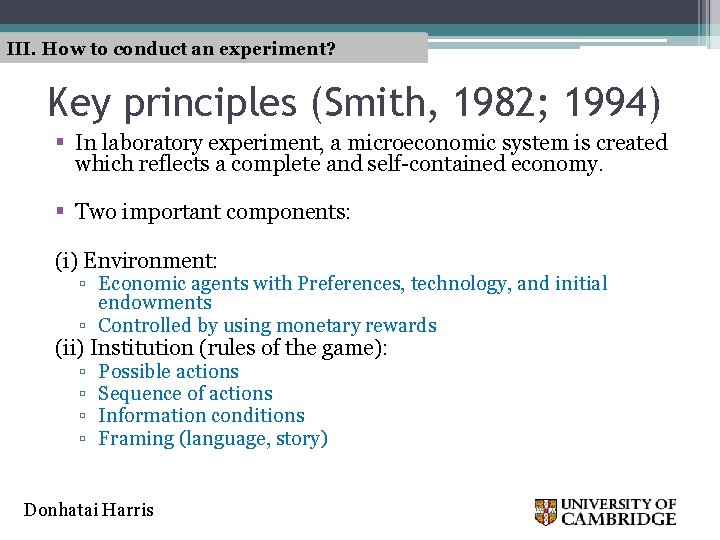

III. How to conduct an experiment? Key principles (Smith, 1982; 1994) § In laboratory experiment, a microeconomic system is created which reflects a complete and self-contained economy. § Two important components: (i) Environment: ▫ Economic agents with Preferences, technology, and initial endowments ▫ Controlled by using monetary rewards (ii) Institution (rules of the game): ▫ ▫ Possible actions Sequence of actions Information conditions Framing (language, story) Donhatai Harris

III. How to conduct an experiment? The Essence of Economic Experiments § Experimenter knows what is exogenous and endogenous. § Experimenter controls information conditions. § Experimenter knows theoretical equilibrium and adjustment can be studied. § Evidence is replicable. Donhatai Harris

III. How to conduct an experiment? Control § To control a variable means fixing and maintaining it at some constant level, or alternatively, set it at different levels across different experiments or at different points of time in the same experiments. § The subjects are likely to have prior characteristics and preferences which are difficult to observe. Therefore, control over preferences is the most significant element of laboratory experiments. § In many experiments the experimenter wants to control subjects’ preferences. How can this be achieved? Donhatai Harris

III. How to conduct an experiment? Theory of Induced Valuation § Subjects’ “homegrown” preferences must be “neutralized” and the experimenter “induces” new preferences. Subjects’ actions should be driven by the induced preferences. § This is done by inducing or controlling valuations by making the objects of trade = valueless tokens, which can be exchanged into real money at the end of the experiment. Donhatai Harris

III. How to conduct an experiment? § Reward Medium: Money m = (m 0 + m) where m 0 represents a subject’s “outside” money, m denotes money earnings in the experiment. § Subject’s unobservable preference: V(m 0 + m, z) where z represents all other motives e. g. boredom § In order to minimise the effects of m 0 and z, whilst maximise the effect of m, laboratory experiments are required to satisfy 5 important conditions which are known as “precepts” Donhatai Harris

III. How to conduct an experiment? Precepts § Precept 1: Nonsatiation and Monotonicity Costless choice between two alternatives, identical (i. e. equivalent) except that the first yields more of a reward medium than the second, the first will always be chosen (i. e. preferred) over the second, by an autonomous individual § Precept 2: Saliency such rewards must be associated indirectly with the message actions (or decisions) of experimental subjects and that they understand this relation Donhatai Harris

III. How to conduct an experiment? § Precept 3: Dominance The reward structure dominates any subjective costs (or values) associated with participation in the activities of an experiment. § Precept 4: Privacy Each subject in an experiment is given information only on his/her own payoff alternatives. § Precept 5: Parallelism The behaviour of individuals and the performance of institutions that have been tested in laboratory microeconomies also apply to non-laboratory microeconomies where similar cateris paribus conditions hold

III. How to conduct an experiment? Experimental Design and Procedure 1) Phases of Economic Experiment § § preliminary phase (experimental design) pilot experiment exploratory experiment (actual experiment) follow-up experiments Donhatai Harris

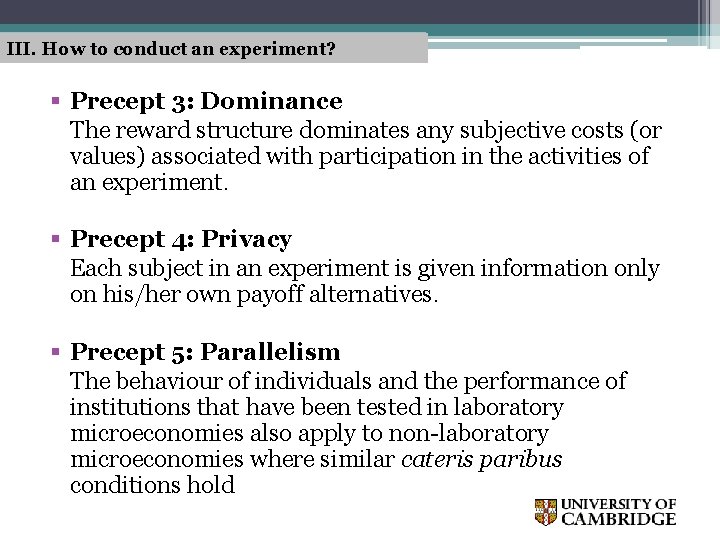

III. How to conduct an experiment? 2) Human Subjects § Student: convenient, low opportunity cost. § Non-student: increases parallelism, but high opportunity cost, risk of unknown confounds. (Minimum of 30 independent observations and Always invite 20% more than you need) Recruiting the subjects is key! § Manual recruitment § computer-assisted recruitment Donhatai Harris

![Recruiting the subjects Centre for Research in Microeconomics CRe Mic Recruiting the subjects Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/827f64f04b2ea1078e41f23aec405766/image-25.jpg)

Recruiting the subjects Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]

![Centre for Research in Microeconomics CRe Mic Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/827f64f04b2ea1078e41f23aec405766/image-26.jpg)

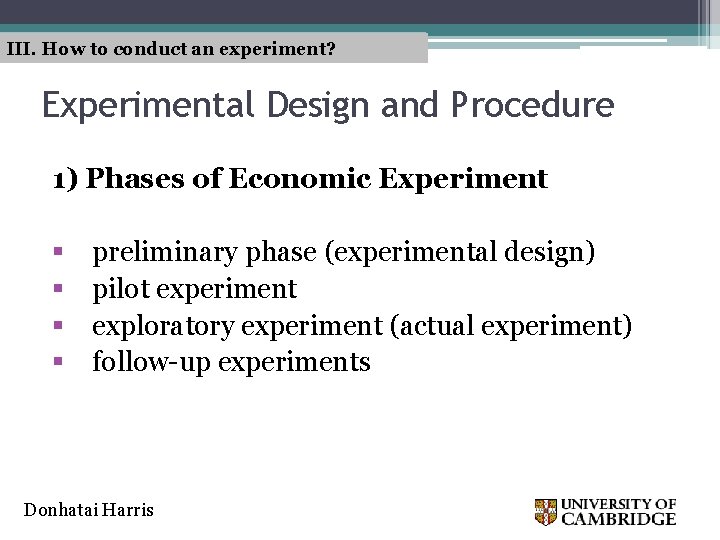

Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]

![Experiment session will appear here Centre for Research in Microeconomics CRe Mic Experiment session will appear here Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/827f64f04b2ea1078e41f23aec405766/image-27.jpg)

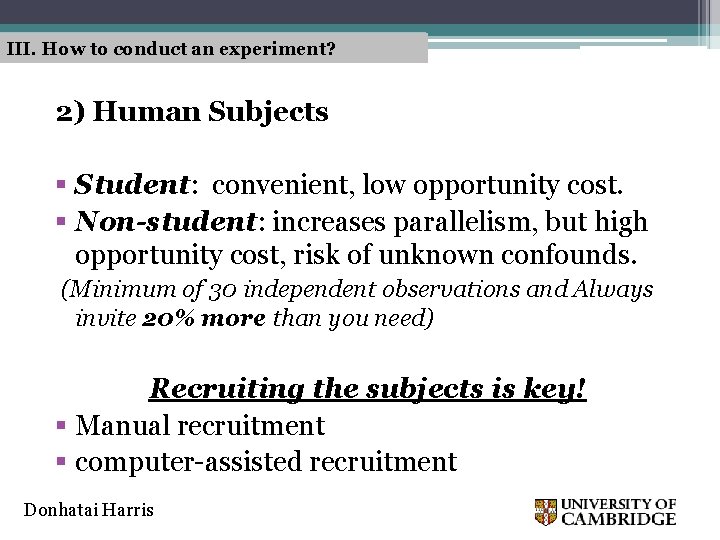

Experiment session will appear here Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]

![Centre for Research in Microeconomics CRe Mic Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/827f64f04b2ea1078e41f23aec405766/image-28.jpg)

Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]

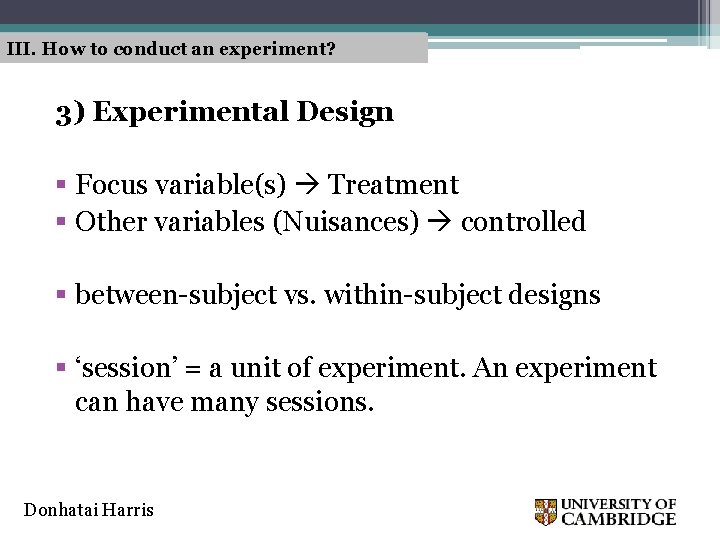

III. How to conduct an experiment? 3) Experimental Design § Focus variable(s) Treatment § Other variables (Nuisances) controlled § between-subject vs. within-subject designs § ‘session’ = a unit of experiment. An experiment can have many sessions. Donhatai Harris

III. How to conduct an experiment? 4) Instructions, Framing, and Anonymity § Instructions tells subjects what they are asked to do in the experiment § Framing: The way in which the instruction is worded can be distinguished into ‘neutral’ or ‘loaded’ frames. § Anonymity Donhatai Harris

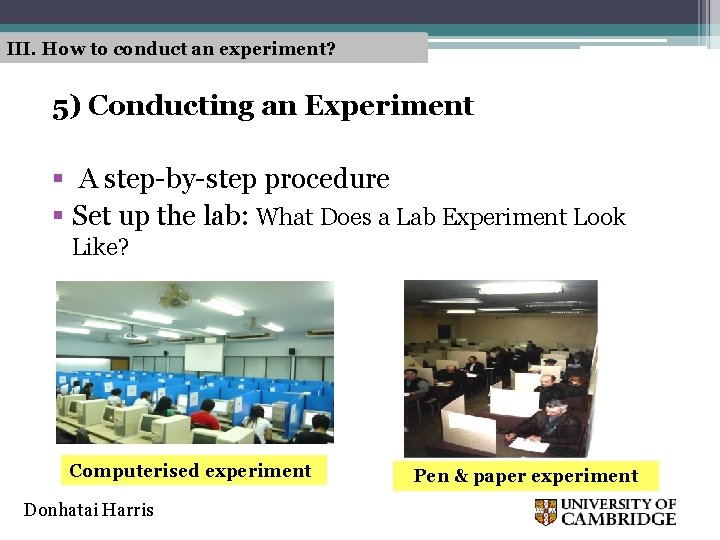

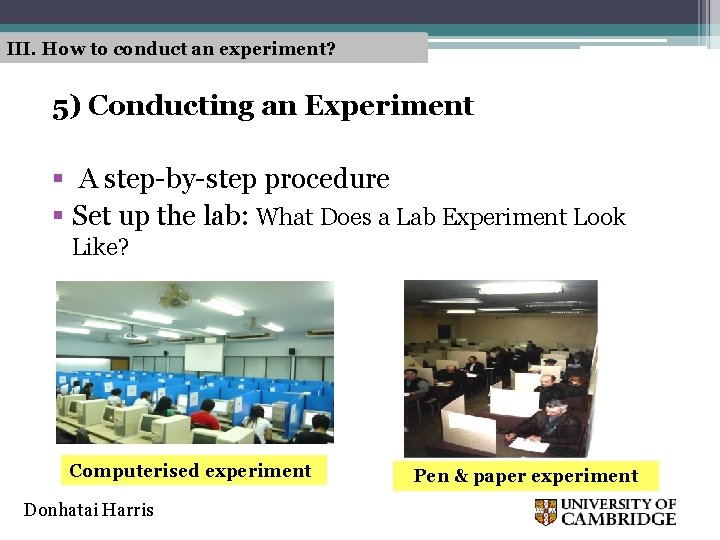

III. How to conduct an experiment? 5) Conducting an Experiment § A step-by-step procedure § Set up the lab: What Does a Lab Experiment Look Like? Computerised experiment Donhatai Harris Pen & paper experiment

III. How to conduct an experiment? Registration • Print a list of subjects for that session for registration

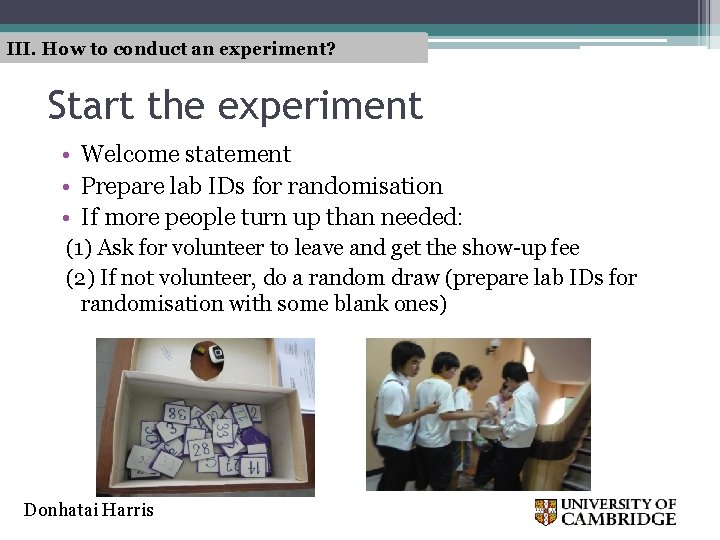

III. How to conduct an experiment? Start the experiment • Welcome statement • Prepare lab IDs for randomisation • If more people turn up than needed: (1) Ask for volunteer to leave and get the show-up fee (2) If not volunteer, do a random draw (prepare lab IDs for randomisation with some blank ones) Donhatai Harris

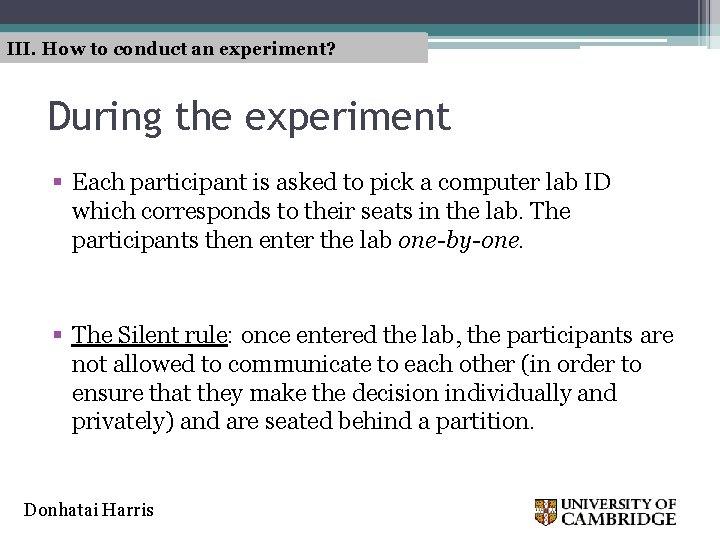

III. How to conduct an experiment? During the experiment § Each participant is asked to pick a computer lab ID which corresponds to their seats in the lab. The participants then enter the lab one-by-one. § The Silent rule: once entered the lab, the participants are not allowed to communicate to each other (in order to ensure that they make the decision individually and privately) and are seated behind a partition. Donhatai Harris

![http www iew uzh chztreeindex php Centre for Research in Microeconomics CRe Mic http: //www. iew. uzh. ch/ztree/index. php Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/827f64f04b2ea1078e41f23aec405766/image-35.jpg)

http: //www. iew. uzh. ch/ztree/index. php Centre for Research in Microeconomics [CRe. Mic]

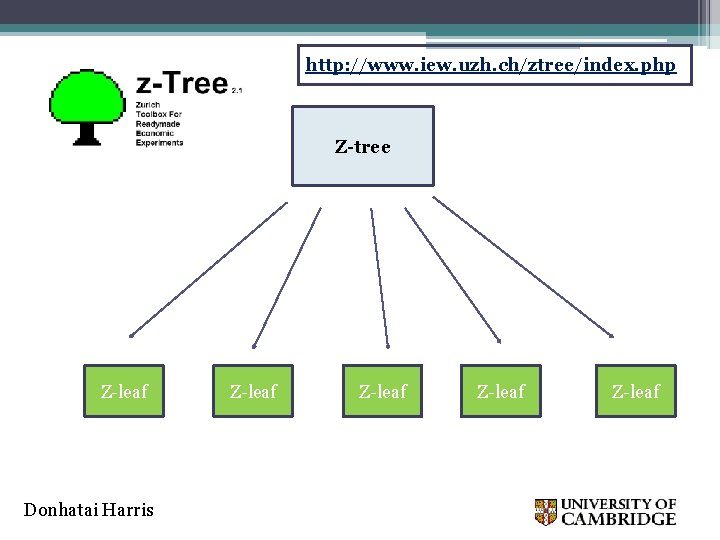

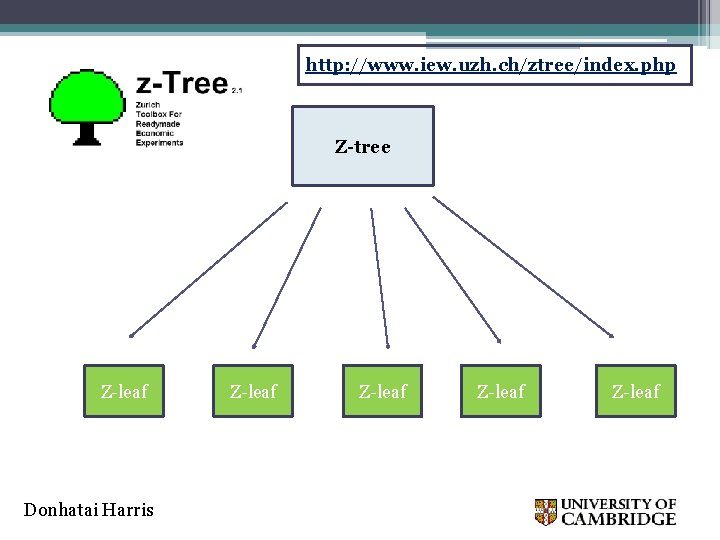

http: //www. iew. uzh. ch/ztree/index. php Z-tree Z-leaf Donhatai Harris Z-leaf

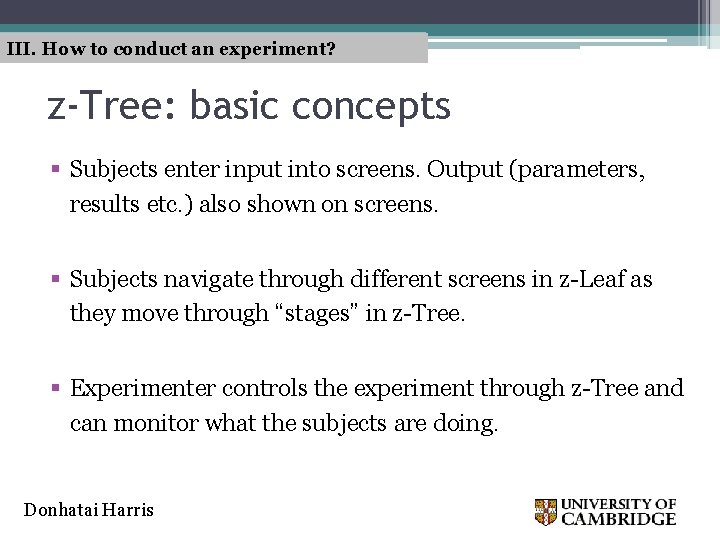

III. How to conduct an experiment? z-Tree: basic concepts § Subjects enter input into screens. Output (parameters, results etc. ) also shown on screens. § Subjects navigate through different screens in z-Leaf as they move through “stages” in z-Tree. § Experimenter controls the experiment through z-Tree and can monitor what the subjects are doing. Donhatai Harris

III. How to conduct an experiment? § Post-experimental questionnaire § Negative Payments or Bankruptcy § Data Recording and Analysis ▫ qualitative or descriptive phase ▫ quantitative analysis of treatment effect i. e. ‘does treatment X affect outcome Y? ’ Donhatai Harris

III. How to conduct an experiment? Internal and external validity § Internal validity: Do the data permit causal inferences? Internal validity is a matter of proper experimental controls, experimental design, and data analysis. § External validity: Can we generalize our inferences from the laboratory to the field? Donhatai Harris

IV. Experimental Study of Favouritism: Thailand vs. UK Donhatai Harris

The Impact of Social Norms on Favouritism Behaviour Donna Harris University of Cambridge dh 293@cam. ac. uk With Benedikt Herrmann (Nottingham) and Andreas Kontoleon (Cambridge)

I. Definition & Research Question § Definition: Favouritism = Preferential treatment giving to one person or group at the expense of another. § Broad research questions: 1) If favouritism creates Pareto inferior outcome, why is it still observed in many countries around the world? 2) Why do we observe varying degrees of favouritism across countries? What is the role of social norms in determining the level of favouritism within a given society?

II. Related Literature § Literature on Favouritism: Previous studies have not explained ‘why’ different levels of favouritism are observed in different countries– most have focused on the ‘effects’ of favouritism. § Social Norms & Enforcement Mechanisms: Most previous studies have only focused on one type of norm, such as the norm of cooperation, or one social group and the enforcement of social norm within that group, except for Bernhard et al. (2006); Goette et al. (2006); Gaechter and Herrmann, 2007; Herrmann et al. (2008).

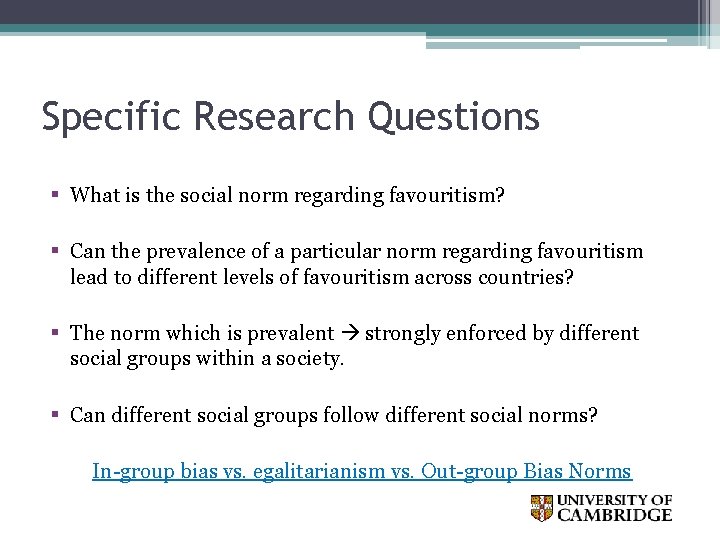

Specific Research Questions § What is the social norm regarding favouritism? § Can the prevalence of a particular norm regarding favouritism lead to different levels of favouritism across countries? § The norm which is prevalent strongly enforced by different social groups within a society. § Can different social groups follow different social norms? In-group bias vs. egalitarianism vs. Out-group Bias Norms

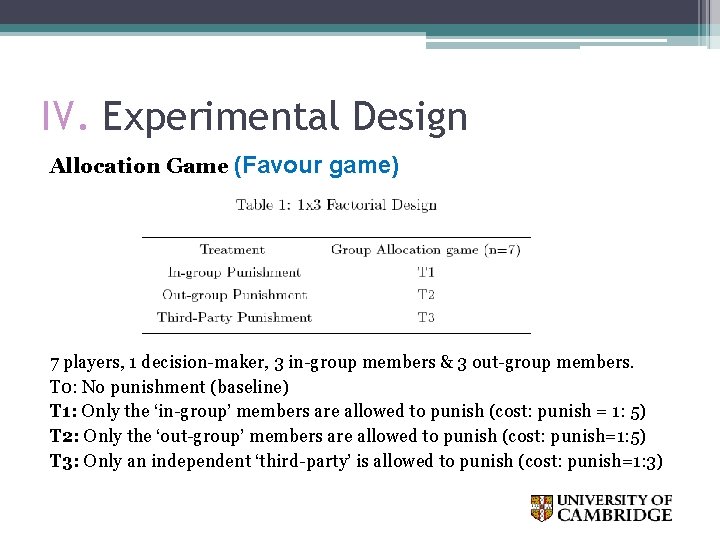

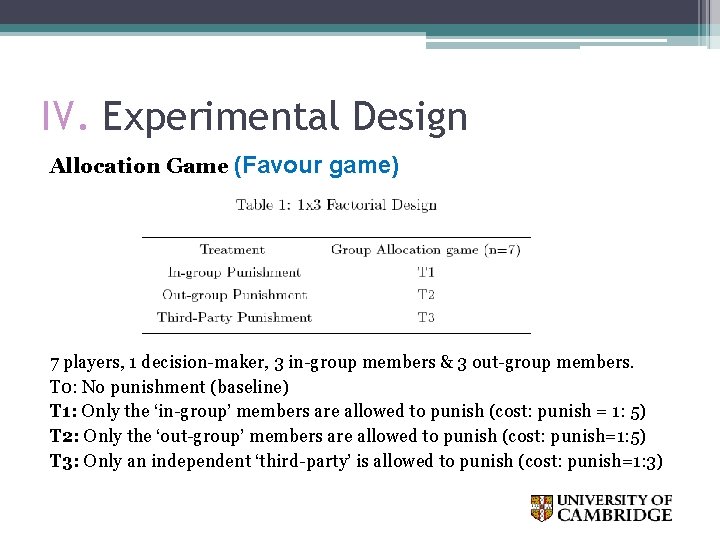

IV. Experimental Design Allocation Game (Favour game) 7 players, 1 decision-maker, 3 in-group members & 3 out-group members. T 0: No punishment (baseline) T 1: Only the ‘in-group’ members are allowed to punish (cost: punish = 1: 5) T 2: Only the ‘out-group’ members are allowed to punish (cost: punish=1: 5) T 3: Only an independent ‘third-party’ is allowed to punish (cost: punish=1: 3)

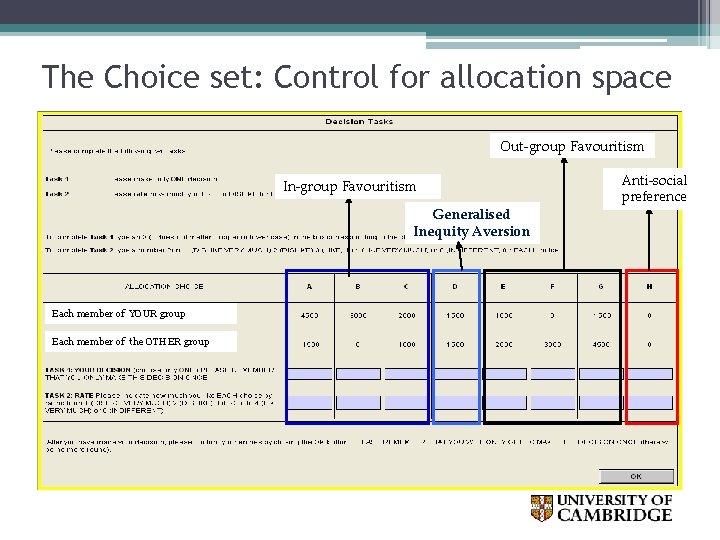

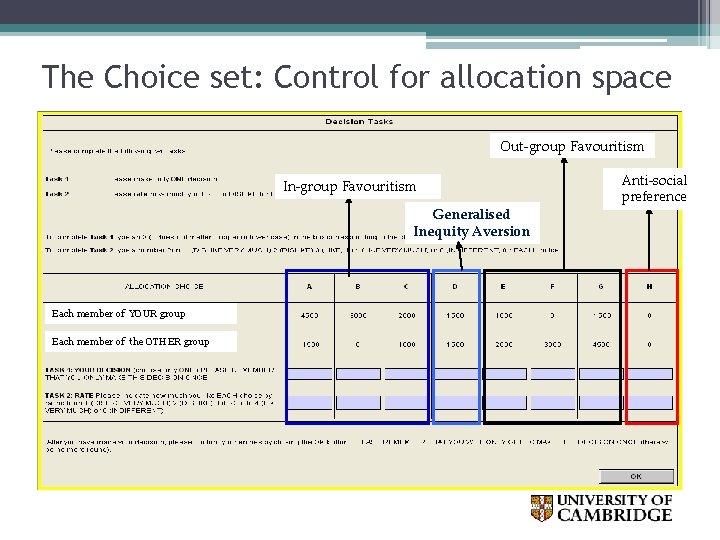

The Choice set: Control for allocation space Out-group Favouritism In-group Favouritism Generalised Inequity Aversion Each member of YOUR group Each member of the OTHER group Anti-social preference

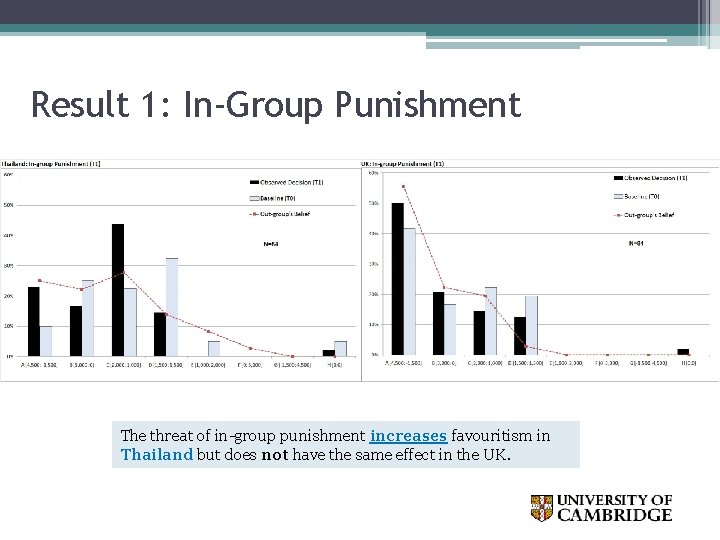

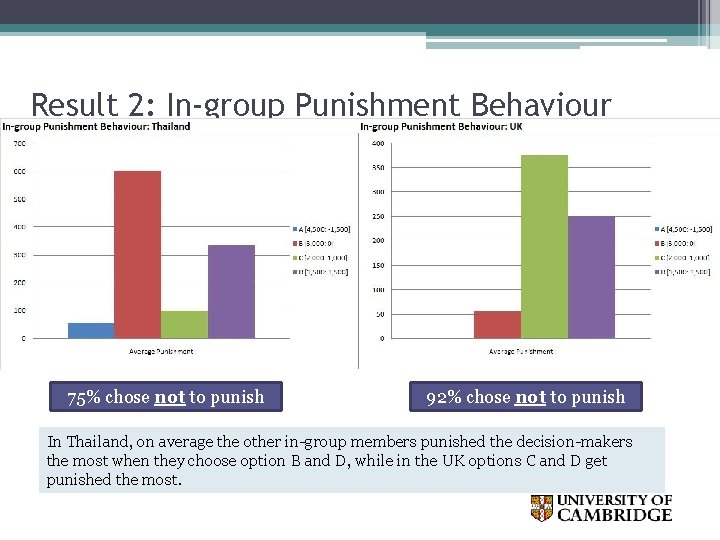

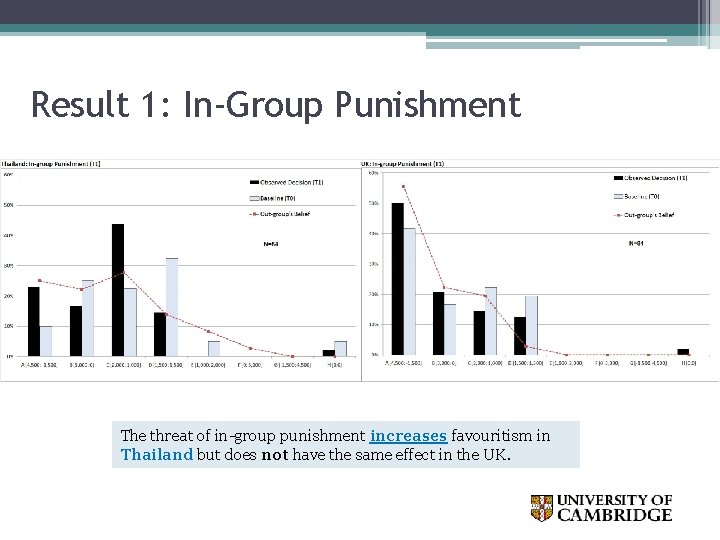

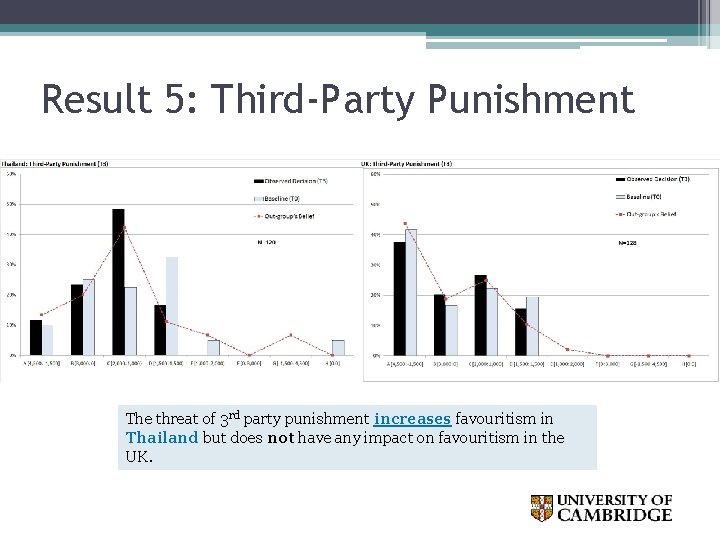

Result 1: In-Group Punishment The threat of in-group punishment increases favouritism in Thailand but does not have the same effect in the UK.

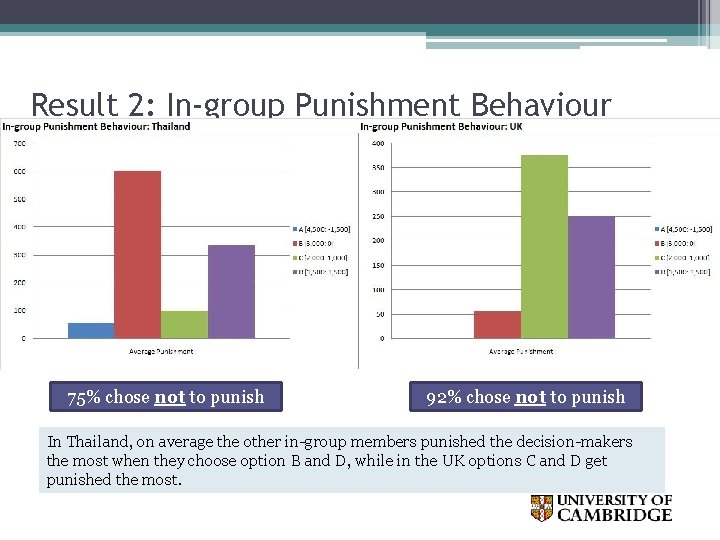

Result 2: In-group Punishment Behaviour 75% chose not to punish 92% chose not to punish In Thailand, on average the other in-group members punished the decision-makers the most when they choose option B and D, while in the UK options C and D get punished the most.

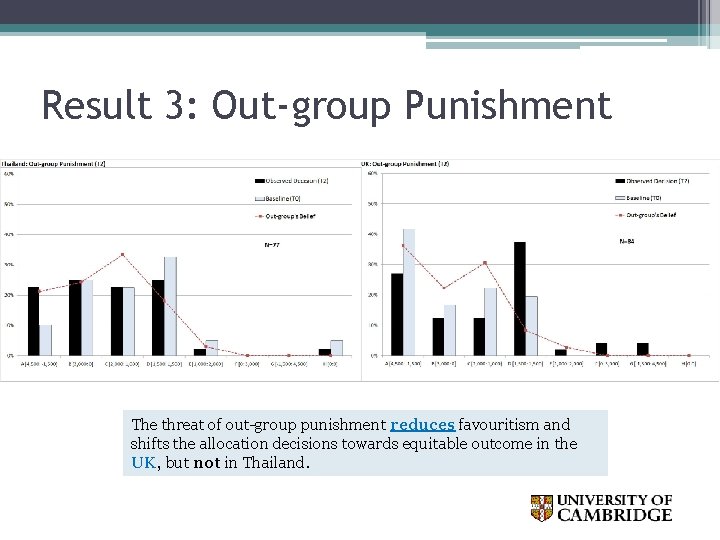

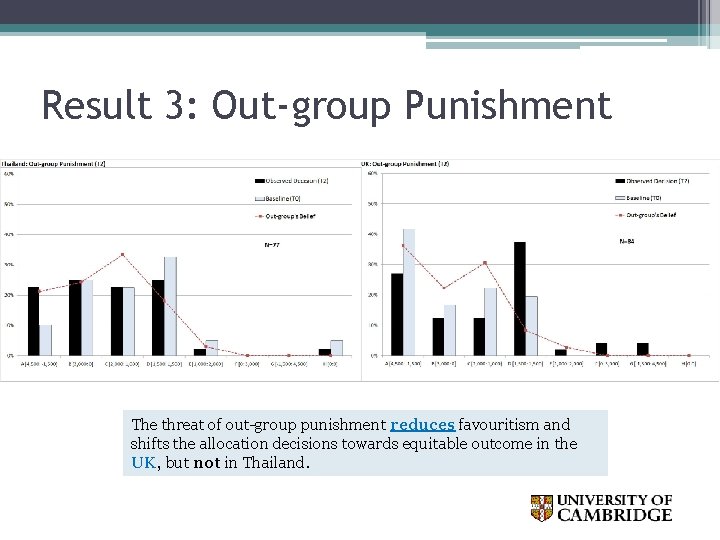

Result 3: Out-group Punishment The threat of out-group punishment reduces favouritism and shifts the allocation decisions towards equitable outcome in the UK, but not in Thailand.

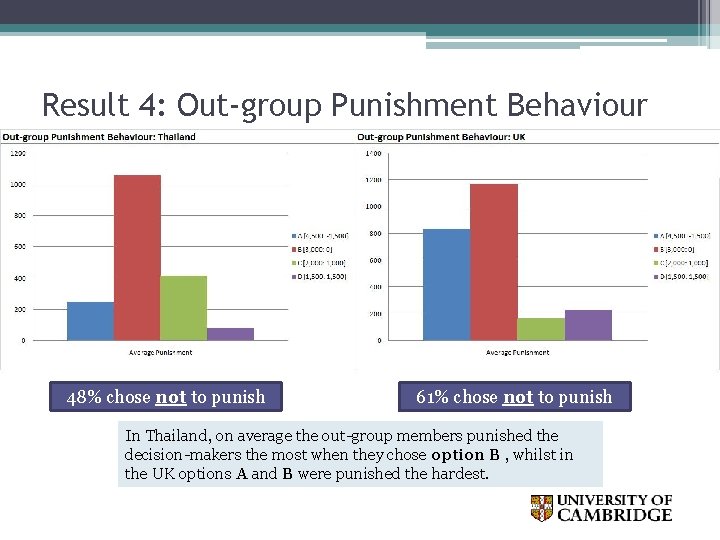

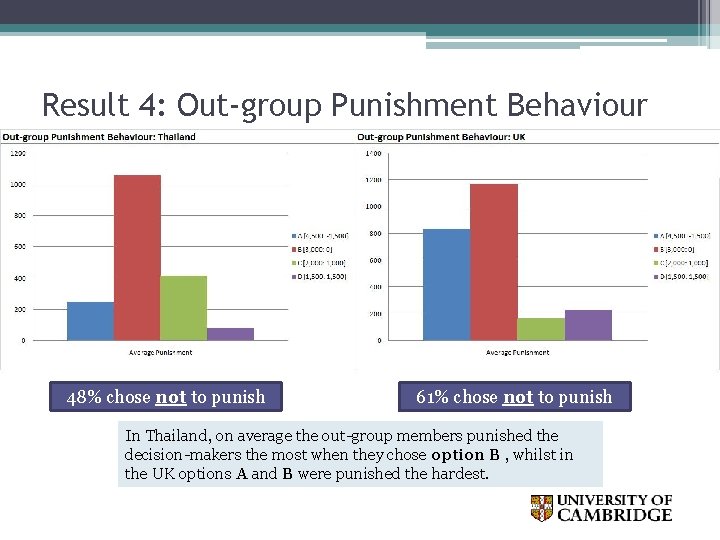

Result 4: Out-group Punishment Behaviour 48% chose not to punish 61% chose not to punish In Thailand, on average the out-group members punished the decision-makers the most when they chose option B , whilst in the UK options A and B were punished the hardest.

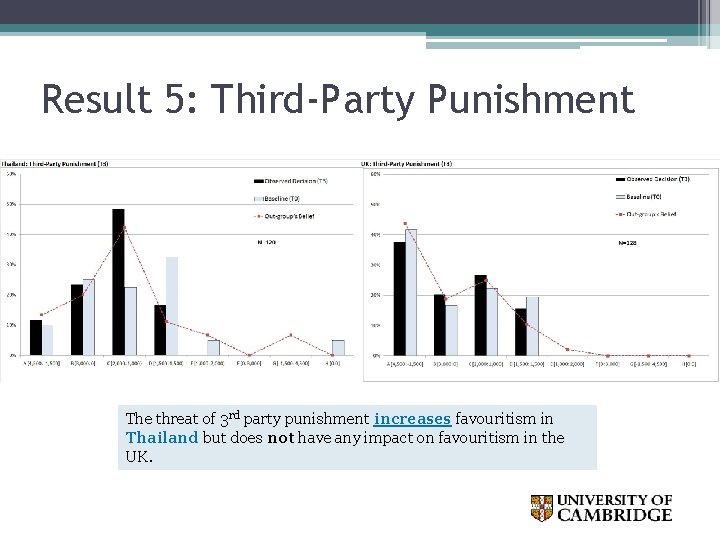

Result 5: Third-Party Punishment The threat of 3 rd party punishment increases favouritism in Thailand but does not have any impact on favouritism in the UK.

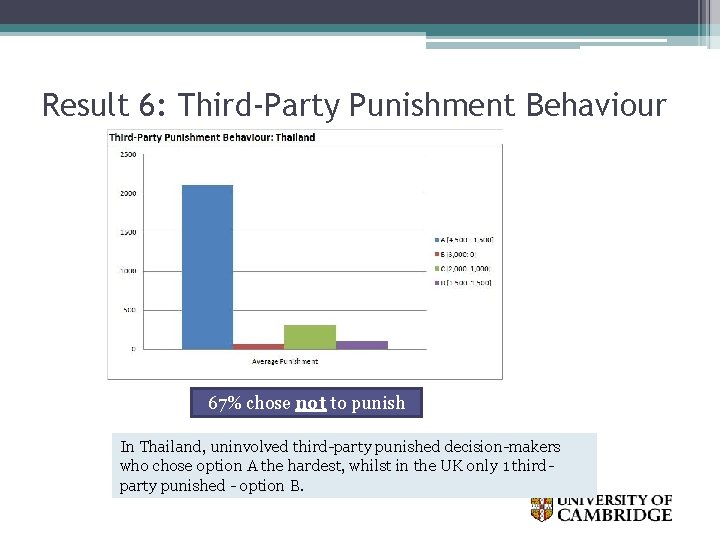

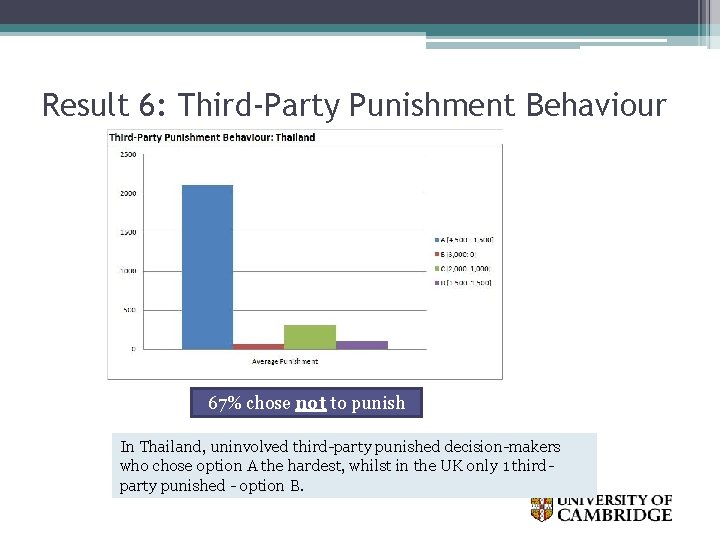

Result 6: Third-Party Punishment Behaviour 67% chose not to punish In Thailand, uninvolved third-party punished decision-makers who chose option A the hardest, whilst in the UK only 1 thirdparty punished - option B.

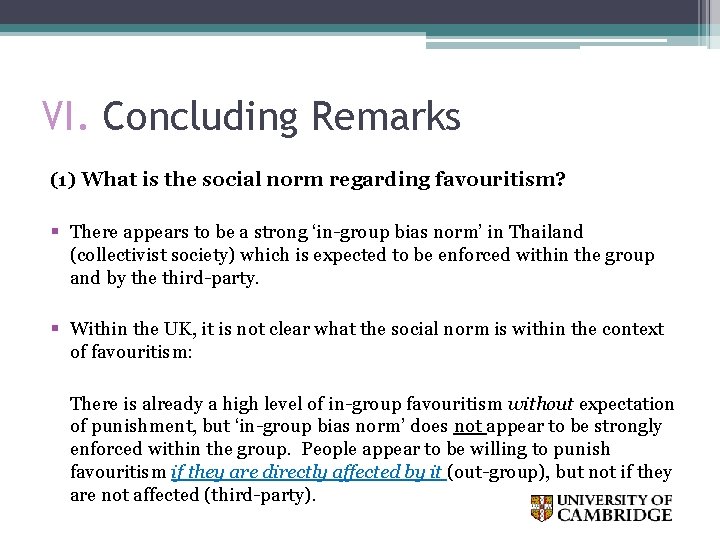

VI. Concluding Remarks (1) What is the social norm regarding favouritism? § There appears to be a strong ‘in-group bias norm’ in Thailand (collectivist society) which is expected to be enforced within the group and by the third-party. § Within the UK, it is not clear what the social norm is within the context of favouritism: There is already a high level of in-group favouritism without expectation of punishment, but ‘in-group bias norm’ does not appear to be strongly enforced within the group. People appear to be willing to punish favouritism if they are directly affected by it (out-group), but not if they are not affected (third-party).

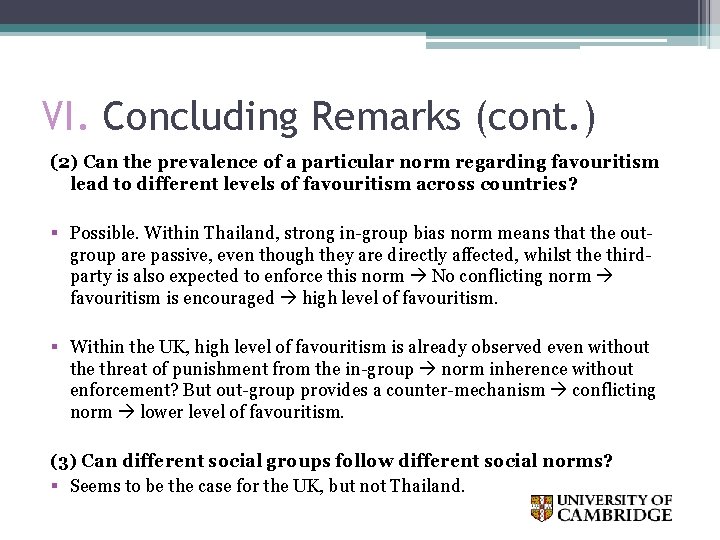

VI. Concluding Remarks (cont. ) (2) Can the prevalence of a particular norm regarding favouritism lead to different levels of favouritism across countries? § Possible. Within Thailand, strong in-group bias norm means that the outgroup are passive, even though they are directly affected, whilst the thirdparty is also expected to enforce this norm No conflicting norm favouritism is encouraged high level of favouritism. § Within the UK, high level of favouritism is already observed even without the threat of punishment from the in-group norm inherence without enforcement? But out-group provides a counter-mechanism conflicting norm lower level of favouritism. (3) Can different social groups follow different social norms? § Seems to be the case for the UK, but not Thailand.

V. Contributions of Experimental Economics and Future Challenges Donhatai Harris

V. What has been done & What’s Next? Summary of Main contributions of experiments to economics § The analysis of markets under perfect or imperfect information e. g. auction, interaction between employer & employee in the labour market. § The understanding of individual decision-making (loss aversion, endowment effect, ambiguity aversion, law of small numbers, preference reversal, …) § The study of social interactions and preferences (altruistic, punishment, trust, fairness, inequality aversion, …) Donhatai Harris

V. What has been done & What’s Next? Some of the important notions in economics have been challenged by experimental research, in particular: § § preferences are not always stable and consistent; the agents do not have perfect knowledge of their preferences; they do not always use all the available information to make decisions. Self-interest is not the only preference that drives the individuals’ decisions. Donhatai Harris

V. What has been done & What’s Next? § Contribution to institutional design/ public policy questions. § Analysis of funding modes of collective goods or political campaigns. § Experiments can help in analyzing the agents’ preferences when markets do not exist. § It also offers academics an innovative teaching tool! (see Charles Holt, 2006, “Markets, Games, and Strategic Behaviour). Donhatai Harris

V. What has been done & What’s Next? Future directions § Interaction with psychology & Development of “behavioural game theory” § Interaction with anthropology & cross-cultural experiment § Interaction with political scientists: voting behaviour & decision-making in committee. Donhatai Harris

V. What has been done & What’s Next? Future direction § Development of “Neuroeconomics” (brain imaging, EEG, PET and f. MRI) and “physionomics” (skin conductance measures, heart rate, measures of hormones, study of pupil dilation). Opening the “black box of brain activity” (Camerer, Loewenstein, and Prelec, 2005) Donhatai Harris

V. What has been done & What’s Next? Future direction § The reinforcement of the realism of economic experiments and the diversification of protocols improving “external validity”. § Field Experiment: Levine and Plott (1978) “A Model of Agenda Influence on Committee Decisions”, AER/ Harrison and List (2004), “Field Experiments”. Journal of Economic Literature. Donhatai Harris

V. What has been done & What’s Next? Major theoretical and methodological challenges § What is the best way to update the standard theories? - Should one incorporate social preferences, and non-monetary sources of motivation in the utility function and where should one put the limit in the manipulation of this function? - When do market forces dominate and when do social preferences dominate? - When do selfish people contaminate the socially-oriented subjects? Donhatai Harris

V. What has been done & What’s Next? Major theoretical and methodological challenges § How to determine what should be the status of agents’ heterogeneity in preferences or abilities ? § A challenge is that a lab experiment must reproduce a theoretical model but it must be at the same time able to mimic the field context reliably. § How can one interpret the differences revealed by the comparison of field and lab experiments? Donhatai Harris

In conclusion… § Experimental economics constitutes a powerful method to develop knowledge in economics. § It helps in identifying empirical regularities and so doing it inspires new research questions. § It contributes to the renewal of economic theory by incorporating emotions, affect and cognition in the analysis of behaviour. § Replication is crucial for certifying the robustness of scientific results from experiments. Donhatai Harris

Thank you for your attention Questions & Comments are welcome Donhatai Harris dh 293@cam. ac. uk Cambridge Behavioural and Experimental Economics Group (CEBG) (www. econ. cam. ac. uk/cebeg)

Experimental vs non experimental

Experimental vs non experimental What is quasi experimental research

What is quasi experimental research Experimental vs non experimental research

Experimental vs non experimental research Non experimental design vs experimental

Non experimental design vs experimental Experimental vs non experimental

Experimental vs non experimental School of business and economics maastricht

School of business and economics maastricht Non mathematical economics

Non mathematical economics Introduction to economics

Introduction to economics Introduction to engineering economics

Introduction to engineering economics Unit 1 introduction to economics

Unit 1 introduction to economics Engineering economy problems

Engineering economy problems Unit 1 introduction to economics

Unit 1 introduction to economics Cleft palate weight gain

Cleft palate weight gain Satuan gain

Satuan gain Ultrasound time gain compensation

Ultrasound time gain compensation Dc gain of transfer function

Dc gain of transfer function Representative or transition elements

Representative or transition elements Spanish

Spanish Minification gain

Minification gain Fluoxitine weight gain

Fluoxitine weight gain Unity gain buffer

Unity gain buffer Applications of amplifiers

Applications of amplifiers Input impedance of op amp

Input impedance of op amp First country to gain independence from britain

First country to gain independence from britain λ/4

λ/4 Marketing information and customer insights are

Marketing information and customer insights are What is proportional gain

What is proportional gain Phase margin and gain margin

Phase margin and gain margin Phase margin gain margin

Phase margin gain margin Transfer function from signal flow graph

Transfer function from signal flow graph Mimr and dash

Mimr and dash Matrice effort gain

Matrice effort gain Information gain feature selection

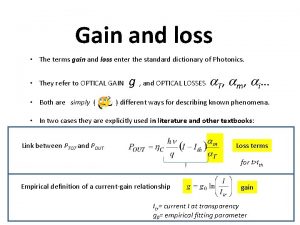

Information gain feature selection Information gain

Information gain Information gain in data mining

Information gain in data mining Lag compensator design example

Lag compensator design example Ackermann method

Ackermann method Examples of contentment

Examples of contentment Gain ratio

Gain ratio Gain ratio

Gain ratio Expected capital gains yield formula

Expected capital gains yield formula Operational amplifier experiment

Operational amplifier experiment Capital gain yield

Capital gain yield A swamping resistor in a common-emitter amplifier

A swamping resistor in a common-emitter amplifier Capital gain yield

Capital gain yield Closed loop gain formula

Closed loop gain formula Voltage gain of amplifier

Voltage gain of amplifier Gain of an op amp

Gain of an op amp A person who scientifically analyzes handwriting

A person who scientifically analyzes handwriting Weight-gaining industry example

Weight-gaining industry example Weight gain in infant

Weight gain in infant Av open

Av open Trazodone mechanism of action

Trazodone mechanism of action Antenna gain formula examples

Antenna gain formula examples Radiation intensity of antenna

Radiation intensity of antenna Zoek dossierbeheerder werkstation

Zoek dossierbeheerder werkstation Capital gain yield

Capital gain yield How to trust your parents

How to trust your parents How many reaping entries will katniss have in her 16th year

How many reaping entries will katniss have in her 16th year Dissociative disorder

Dissociative disorder Radar antenna parameters

Radar antenna parameters Isaac gain more friends

Isaac gain more friends Reading to gain knowledge

Reading to gain knowledge Bipolar junction transistor

Bipolar junction transistor How did william control england

How did william control england Capital gain yield formula

Capital gain yield formula