English Language Learners ELLs with LD Presenter Judit

- Slides: 56

English Language Learners (ELLs) with LD Presenter: Judit Gyenes LLED 526

Activity #1 Organize the following aspects of language use into two categories: easier versus more demanding contexts. (Try to infer what makes the context easier or more demanding. ) 1. Writing a report 2. Discussing a topic in a small group 3. Listening to a lecture with gestures, graphic organizers, and pictures 4. Reading about unfamiliar subjects 5. Participating in small talk 6. Listening to a lecture without visual cues 7. Taking a standardized test 8. Participating in a science lesson with physical examples of vocabulary that can be touched 2

Overview I. FOUNDATIONAL THEORIES OF SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION II. A PROMISING ASSESSMENT PROCESS III. ISSUES IN ELL SPECIAL EDUCATION CLASSIFICATION IV. PRE-REFERRAL STRATEGIES IN THE CLASSROOM V. DIAGNOSIS VI. INSTRUCTIONAL PRACTICES VII. ADULT POST-SECONDARY ELL ISSUES 3

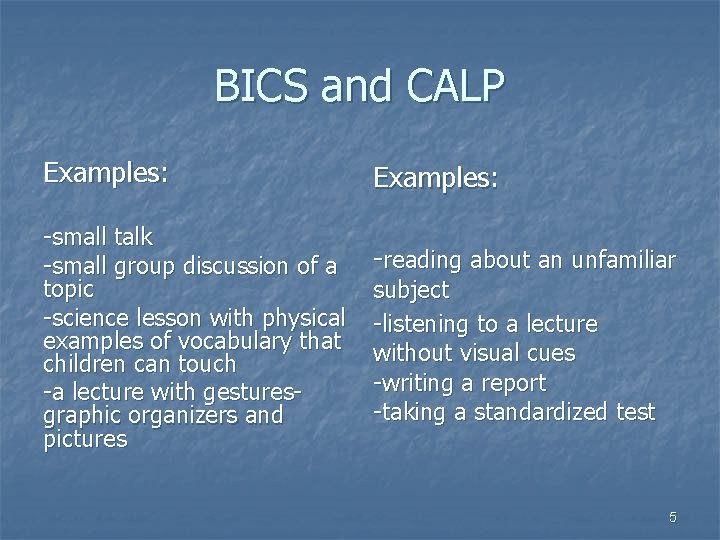

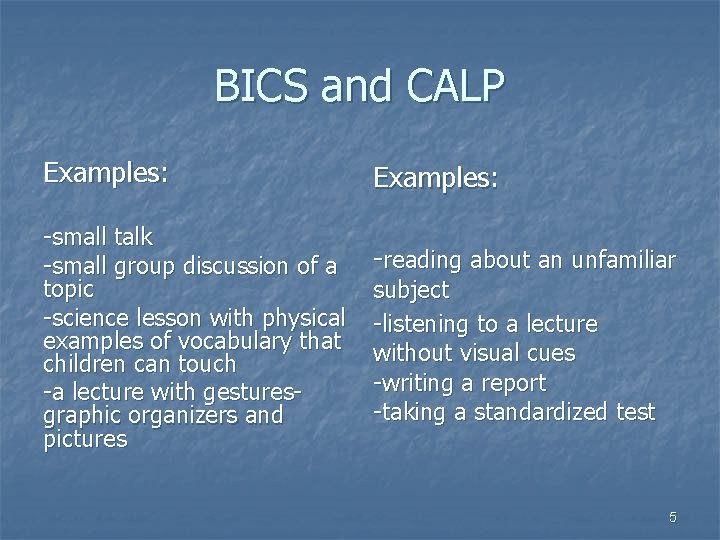

THREE FOUNDATIONAL THEORIES OF SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION 1. Two types of lang. proficiency both in native language (L 1) and additional language (L 2) i. Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS): relies heavily on the context of the conversation (body language, emotions, repetition, physical objects) and takes 1 -2 years to learn in L 2 for normally achieving students ii. Cognitive/Academic Language Proficiency (CALP): needed to understand communication without contextual support and takes 5 -7 years to learn in L 2 for normally achieving students, provided they have strong literate background in L 1 4

BICS and CALP Examples: -small talk -small group discussion of a topic -science lesson with physical examples of vocabulary that children can touch -a lecture with gesturesgraphic organizers and pictures Examples: -reading about an unfamiliar subject -listening to a lecture without visual cues -writing a report -taking a standardized test 5

2. Linguistic interdependence according to Cummins: L 2 proficiency played a less prominent role in L 2 reading than did the level of their strategy usage in their L 1 (Spanish-dominant students in Grade 4). 6

3. Script-dependent hypothesis Skills in one language are primarily influenced by its orthographic structure and the predictability of its grapheme- phoneme correspondence rules. Deficits experienced in learning an L 2 are relative to the orthographic structure of the language (L 2). e. g. : Chinese dyslexics: rapid naming deficit+ orthographic deficit when reading in Chinese but not phonological deficit. (See: OHT) But: When learning in English, Chinese dyslexics have phonological difficulties at the phonemic level. 7

The process of second-language acquisition is influenced by many factors, including: 1. The learner’s socio-cultural environment 2. Language proficiency in L 1 3. Attitudes towards L 1 and L 2 4. Perceptions of others’ attitudes towards L 1 and L 2 5. Inadequate instruction or lack of opportunities to learn. 8

II. PROMISING ASSESSMENT PROCESS FOR ELLS IN CALIFORNIA Stage 1. Teacher initiates referral and Limited–English–Proficient student committee, parents, administrator review case Stage 2. Teacher uses suggested pre-referral strategies and monitors student Stage 3. Pre-referral meeting #2: committee+ school psychologist decide need formal evaluation or need for bilingual assessor to decide if student is ready to be tested only in English (bilingual assessor is not a bilingual psychologist) Stage 4. IEP meeting based on formal assessment results. 9

Weaknesses: bilingual assessor not invited to prereferral meeting#2 and has no contact with team school psychologist perceived as ultimate expert, but often does not have much knowledge about language acquisition often no formal assessment in students’ L 1 as their developed BICS lull teachers and psychologists into belief students are L 2 proficient (See next slide: quote from Bilingual psychologist) 10

“But, actually they are proficient before seven years. If they started here and have been here since kindergarten and they have heard the language every day they should be able to learn it like any other student. So, even though they switch [to using their native tongue] at home, it doesn’t matter. You see, I was born in [a Spanish-speaking country] but I went to an American school all of my life. So, I know what it is like. I’ve been through the experience, so I expect more of them. ” (in Klingner & Harry, 2006) 11

Need for L 1 assessment of language and reading (Siegel et al. , 2003; Lipka et al. , 2005): -more accurate inventory of student’s knowledge and skills (e. g. : helps estimate size of overall conceptual vocabulary knowledge in both languages) -reflects student’s instructional history and opportunity to learn: if good phonological and decoding skills in L 1, but failure to acquire literacy in L 2~problem with amount and quality of L 2 instruction (not LD) if undeveloped L 1 literacy skills, but received instruction in L 1~ probably LD (in alphabetic languages: typically phonological core deficit) 12

Activity #2: Referring ELL student for Psycho-Educational Testing Using the information about referral strategies and L 2 acquisition considerations, discuss if Pablo should be referred to psych-ed. testing. True case: Pablo is a grade two student. He is in an intermediate level English immersion class, where all instruction is received in English. (All classmates are native Spanish speakers. ) The classroom teacher has noted that he has the following difficulties: -a tendency to forget information -problems with attention -more difficulty with decoding than his classmates -problems with retrieving information -lack of English academic vocabulary 13

III. ISSUES IN ELL CLASSIFICATION AND SPECIAL EDUCATION ELIGIBILITY 1. Misclassification 2. Overrepresentation 3. Under representation 14

1. Misclassification Large discrepancies have been reported in the ELL classification practices: due to validity issues (Abedi, 2006) i. Complex Linguistic Structures -Linguistic complexity of test items is source of construct irrelevant variance. -Assessment tools that have complex linguistic structures are found to provide poor achievement outcomes for ELLs. 15

ii. IQ Testing ( Francis et al. , 2005; Gunderson, 2001) IQ tests disadvantage ELLs as students are required to: -understand vocabulary -possess culture specific knowledge -have expressive language similar to English-only speaking peers iii. Content-Based Assessment Studies show a large performance gap in content-based assessment outcomes between ELLs and native English language speakers, raising concerns about validity and authenticity of highstakes assessments and accountability. 16

iv. Poorly Designed L 1 Proficiency Tests Routinely Administered In US, numerous ELLs are identified as “non-nons”(limited abilities in both L 1 and L 2) Language Assessment Scales-Oral Espanola (LAS): 74 % as limited or non-speakers of L 1 Idea Proficiency Test 1 -Oral Spanish (IPT): 90% as limited or nonspeakers of L 1 Low test scores: -tests normed on proficient speakers of standard Spanish -some items require answers complete with Subject and predicate (Spanish does not require overt subjects ) 17

High percentage of “non-nons” contradicts L 1 acquisition research: “by the time children begin school, they have acquired most of the morphological and syntactic rules of their language and possess a grammar essentially indistinguishable from adults” (Macswan & Rolstand, 2006) 18

iv. Problematic Practices (Klinger et al. , 2006) -when interpreters used -only 37% received formal training -school personnel’s impressions of the family -external pressure for identification and placement - exclusion of information on classroom ecology - choice of assessment instruments - arbitrary nature of placement decisions -disregard for established criteria (IDEA’s 2004 exclusionary clause for bilingual students and ELL: identification of LD should be based on students having received an adequate opportunity to learn) 19

2. Overrepresentation (refers to unequal proportions of culturally diverse students in special education programs) Overrepresentation is often assessed by calculating a group’s representation in general education or special education in reference to the representation of a comparison group. In the USA, Artiles et al. (2005) found that the most common groups involved in overrepresentation generally include African American, Chicano/Latino, American Indian and a few subgroups of Asian American students. 20

The typical disability categories included: mild retardation (MMR), emotional-behavioral disorders (EBD), and specific learning disabilities (SLD). ELLs identified by districts as having limited proficiency in both L 1 and L 2: -showed the highest rates of identification in LD both in elementary and secondary levels 21

ELLs with limited L 2: -are slightly overrepresented at secondary levels (G 5 and up) -if SES low, consistently overrepresented in LD programs at all grade levels and at secondary levels in language and speech (LAS) disabilities classes -if high SES, placed in LAS elementary program. WHY the strange pattern based on SES? 22

National Research Council (2002) report: 1. The instances of highest disproportion was found where bilingual programs were small or non-existent. (!) 2. The larger the minority student population is in the school district, the greater the representation of students in spec. ed. 3. The bigger the educational program, the larger the disproportion of minority students. 23

Explanation: Systematic Bias Hypothesis Bias at some level of the system leads to disproportionate identification and placement rates for some groups. Achievement Difference Hypothesis Those students who demonstrate greater need are in fact those who get placed. 24

3. Under representation Oral proficiency in L 2 is poor predictor of correct comprehension of texts. (Oral vocabulary in L 2 is a strong predictor of L 2 word reading. ) Schools may overlook or delay addressing ELLs genuine difficulties with word decoding or language processing typical of RD when teachers perceive educational difficulties of ELL as byproducts of school adjustment or acculturation (D’Angiulli et al. , 2004). Many educators are confused about whether ELLs must have acquired a certain level of proficiency before the referral process can be initiated (Klingner et al. , 2006). 25

IV. PRE-REFERRAL STRATEGIES IN THE CLASSROOM Mc. Cardle et al. (2005) suggest avoiding standardized measures. Instead, alternative assessment (great for instruction, but not valid and reliable evidence base for determining ELL has an LD) : 1. Dynamic assessment (to determine upper limit of school potential) 2. Test-teach-retest (to determine what student can do rather than what student does or does not know) 3. Curriculum-based assessment -Testing-the-limits (to find out from student the thought processes used when performing task) 26

Gottardo in Klingner et al. (2006) found when using curriculum based measures and dynamic assessment: ELLs with LD scored lower on all measures than ELL/bilingual students without LD Barrera (2003) used curriculum based assessment in high school: -handwritten classnotes: ELL with LD tend to write in disjointed fragments and verbatim -oral reading samples taken over several days to determine accuracy and fluency in a grade level reading in student’s text 27

Macswan et al. (2006) suggest alternatives to L 1 standardized language proficiency tests: Natural language measures(=recorded speech samples) should be analyzed Tools and samples available on Child Language Exchange System Project (CHILDES) at http: //childes. psy. cmu. edu 28

V. DIAGNOSIS Ideally, ELLs should be assessed by comparable assessment in both L 1 and L 2. Gottardo (2002) in Klinger et al. (2006) found : -reading and phonological processing are related both within and across languages - L 1 and English phonological processing+ L 1 reading+ English vocabulary= strong predictors of English word reading and text comprehension Warning: since the concepts and language being tested may have no direct translation, the validity of tests translated into a native language is questionable. 29

Possible tests: Test of Phonological Processes in Spanish and Comprehensive + Test of Phonological Processes. (In the latter, “Blending Words and Nonwords” task should not be administered as some vocabulary words might function more as nonwords for ELLs--lowering performance scores) Berninger et al. (2004): Process Assessment of the Learner (PAL) measures decoding (accurate and fluent word reading) and access to lexical representation (only in English) 30

Miramontes and Hardin in Klingner et al. (2006) respectively found that miscue analysis of reading and oral think-alouds reveal more about reading process than traditional tests: -Analysis of oral reading miscues reveal that strategies students used depended on their language dominance. -Think-alouds reflected students’ usage of comprehension strategies: more able readers increased their strategy usage during reading English. L 2 proficiency played a less prominent role in L 2 reading than did the level of their strategy usage in their L 1 (Spanish-dominant students in Grade 4). 31

Lipka et al. (2005) propose that diagnosis of reading disabilities (RD) can be made in similar manner in both ELL and L 1 students : Standardized achievement test of reading, spelling, possibly writing (WRAT-R, Woodcock Reading Mastery Test) Evidence: i. development of reading skills (word recognition, decoding, spelling, comprehension) in normally achieving children is similar in ELLs and children with English as their L 1 ii. ELLs with RD exhibit similar cognitive profiles(phonological processing, syntactic awareness, and working memory) to L 1 students with RD 32

Three research designs to examine whether cognitive processes important to L 1 reading development can discriminate ELLs with RD from normally achieving ELLs: 1. ELLs with RD and without compared on cognitive processes: phonological processing, syntactic awareness, working memory Lesaux& Siegel, 2003: in Kindergarten screening should be based on phonological processing (at risk Ks. weak in all 3 processes; average ELLs weak in syntactic awareness and working memory) Da. Fountoura & Siegel, 1995: Portuguese-Canadian children English syntactic skills in reading differentiated between bilingual RD and normally achieving bilinguals (syntactic skills in L 1 did not differentiate) 33

2. ELLs with RD in English measured on their cognitive processing skills both in English and their L 1: Da Fountoura & Siegel, 1995: Portuguese-Canadian children -if reading problem in English, reading problem in L 1, too -problems in both languages with phonological processing, to a lesser degree with working memory and syntactic awareness -positive transfer of phonological processing for disabled bilinguals (but not for normally achieving bilingual students) 34

-English syntactic skills in reading differentiated between bilingual RD and normally achieving bilinguals Abu-Rabia & Siegel, 2002: Arabic-Canadian children if problem reading in English, similar problem in Arabic (all 3 cognitive processes) 3. ELLs identified as RD compared to Engl. monolinguals with RD: Abu-Rabia & Siegel; Da Fontoura & Siegel; D’Angiulli et al. : -Portuguese–English speakers and Arabic-English speakers with RD had higher scores on English pseudoword reading and spelling tasks than English speakers with RD 35

-possibly due to broader knowledge of phonological processes that come from exposure to more than one phonological system (Arabic has different orthography; but transparent language: predictable grapheme-phoneme conversion rules) -bilingual children with RD had significantly lower scores on oral cloze test (syntactic awareness) than English monolinguals with RD. 36

The Portuguese-Canadian, Arabic-Canadian studies support bilingual education programs: Participation in bilingual programs consistently produced small to moderate differences favoring bilingual education when tests were in English: for reading, language skills, math, and total achievement and when tests were in other languages: for reading, math, writing, social studies, listening comp. , and attitudes toward school and self 37

Future research needs to consider: -specific language groups and their L 1 transfer in acquisition of English as an additional language -age of first exposure to English -level of proficiency in L 1 for ELLs -specific characteristics of L 1 -language program types and their relation to special education labels -quality of English language instruction 38

August et al. (2006): Diagnostic Assessment of Reading Comprehension (DARC) Alternative to traditional standard measures of reading comprehension (Woodcock Johnson Lang. Prof. Battery/Sat-9), which have great decoding, syntax and vocabulary demands that obscure ELL children’s comprehension capacities. ELL students at the lower levels of English proficiency distribution may be misidentified as disabled because their limitations in English may be interpreted as a sign of learning disability 39

When low results: typical intervention focuses on decoding skills and inferencing, but maybe the scores simply reflect difficulty with vocabulary (not LD) DARC designed for K-Grade 3: measures different comprehension processes while minimizing need for decoding and oral proficiency by providing brief narrative texts with vocabulary children likely to know, simple syntactic structures, embedded relational propositions. 40

cognitive processing capacities DARC measures: a. remembering newly read text---text memory statements b. making inferences justified by text--text inferencing statements c. accessing background knowledge from long-term memory -- knowledge access statements d. making inferences that require background knowledge integration with new text --knowledge integration statements 41

Practice Text (G 2 Reading level) including 2 entities: one is a nonsense word Maria likes to eat fruit. Most of all she likes to eat orkers. An orker is like an orange. But an orker is bigger than an orange. Maria likes to eat fruit. Most of all Maria likes to eat orkers. An orange has a peel. You peel an orker to eat it. (Text memory statement) (Knowledge access statement) (Knowledge integration statement) (no text inferencing statement) 42

V. INSTRUCTIONAL PRACTICES Limited English language skills when vocabulary development is slow (fewer words and less knowledge about the meaning of words leads to low comprehension at grade level) i. Insure ELLs know meaning of BICS words: -provide definitional and contextual meaning; -provide multiple exposure; -construct relationship maps among words; -teach word analysis; -predict word meaning from context/ roots or affixes/ using cognates/ or morphological relationships -cloze sentences (August et al. , 2005) 43

ii. research supported literacy instruction and assessment prevents under referrals (D’Anguilli, 2004; Klinger et al. , 2006): -explicit emphasis on sound-symbol relationship -reading comprehension strategy instruction -small group instruction -ESL strategies 44

iii. general instructional strategies (Schwartz& Terrill, 2001): -be highly structured and predictable -teach small amounts of material at one time in sequential steps -include opportunities to use several senses and learning strategies -provide multisensory review -recognize and build on learners’ strengths and prior knowledge -simplify language but not content -reinforce main ideas and concepts through rephrasing rather than through verbatim repetition (Hmmm. ) -organize themes and strands connecting the curriculum across subject areas -provide reassurance -provide a clean, uncluttered, quiet, and well-lit environment 45

iv. educational environment conducive to academic success: -strong administrative leadership -high expectations for student achievement -ongoing and systematic evaluation of student progress -shared decision making among ELL teachers+general education teachers+administrators+parents Ortiz, 2001: “Interventions that focus solely on remediating students’ learning and behavior problems yield limited results when school climate is not supportive and when instruction is not tailored to meet needs of culturally and linguistically diverse students in general education. ” 46

Berninger et al. , 2004: -Process Assessment of the Learner(PAL)--screening measure and -PAL Research-Supported Reading and Writing Lessons Five lesson sets at three tiers 1. early intervention 2. supplementary instructional intervention (24 lessons for reading and writing, respectively) 3. differentiated instruction for treatment for dyslexia and dysgraphia (overall gains tend to be larger for decoding accuracy than for fluency or comprehension according to Foorman, in Wagner et al. , 2005) 47

VII. ADULT POST-SECONDARY ELL ISSUES 1. Lack of expected progress (Schwartz and Terrill, 2001): -Limited academic skills in L 1 due to limited previous education -Lack of effective study habits -The interference of a learner's native language, particularly if the learner is used to a non-Roman alphabet -Stress (related to culture shock) -Trauma that refugees and other immigrants have experienced, causing symptoms such as difficulty in concentration and memory dysfunction 48

-Sociocultural factors such as age, physical health, social identity, and even diet -External problems with work, health, and family -Sporadic attendance -Lack of practice outside the classroom -Undiagnosed vision or hearing problems. These behaviors or problems will most likely affect all learning, whereas a learning disability usually affects only one area of learning Sometimes students have to deal with unexpected problems: -Racial discrimination -Encountering a different education system requiring different 49 study skills (Beard et al. in Peer and Reid, 2000)

2. Assessing adult ELLs: i. interview: educational and language history in both L 1 and L 2, social background, strengths, learner’s perception of the nature of suspected problem ii. learning styles inventory iii. portfolio assessment iv. visual screening and hearing test v. Test of short-term memory, phonological awareness, and sequencing; reading of whole text, single words and non-words; analysis of miscues; spelling error analysis and analysis of free writing (Sunderland in Peer & Reid, 2000) 50

University of Buckingham, England: -Screening: interview+ Dyslexia Adult Screening Test (DAST) -Diagnosis: Weschsler Adult Intelligence Scales (Revised)[ACID] Weschsler Memory Scales (Third edition) Digit Span T. British Ability Scales Test of Immediate Visual Recall Spadafore Diagnostic Reading Test The Wider Range Achievement Spelling Test A free writing task University of Swansea, Wales: -Screening: experimental test: 2 pages of 24 non-words designed on the pattern of CVCVCV (e. g. : gipola) short-term recall and visual processing of words (? ) -structured approach to study skills (due to: slow reading and organizational skills) 51

University of Edinburgh, Scotland: -learning style inventory -Screening interview by Dyslexia Advisor: Quick Scan Screening Test British Spelling Test Series 5 Spadafore Reading Test -Diagnosis: University Psychologist (WAIS) -STAFF DEVELOPMENT SESSIONS THROUHGOUT UNIVERSITY! -staff handbook on dyslexia+multilinguals on: http: //www. bdadyslexia. org. uk/downloads/dsaguidelines. pdf 52

-Study skills tuition -Accommodations: prior sight of lecture notes focused reading lists specific assessment arrangement (extra time, use of word processor, scribe) double-time loan on reserve books weekend borrowing of short-loan books individual study rooms in library 53

English Language Institute of the American University of Washington, DC, USA: -Screening: interview+phonological skills test Specialized curriculum: -teaching self-advocacy skills -English phonology and syllable rules instruction -multisensory instruction -slow paced writing class -limited amount of information required to learn -linguistic “meta-language” simplified -much review and reteaching planned -teaching to mastery 54

References Abedi, J. (2006). Psychometric issues in the ELL assessment and special education eligibility. Teachers College Record , 108, 11, 2282 -2303. August, D. , Carlo, M. , Dressler, C. & Snow, C. ( 2005). The critical role of vocabulary development for English language learners. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice , 20, 1, 50 -57. August, D. , Francis D. J. , Hsu H. A. , & Snow C. E. (2006). Assessing reading comprehension in bilinguals. The Elementary School Journal, 107, 2, 221 -237. Artiles, A. J. , Rueda, R. , Salazar, J. J. & Higareda, I. (2005). Within-group diversity in minority disproportionate representation: English language learners in urban school districts. Council for Exceptional Children, 71, 3, 283 -300. Barrera, M. (2006). Roles of definitional and assessment models in the identification of new or second language learners of English for special education. Journal of Learning Disabilities , 39, 2, 142 -156. Berninger, V. W. Dunn, A. , Lin S. C. & Shimada, S. (2004). Scientist-practitioner educators creating optimal level environments to all students. Journal of Learning Disabilities , 37, 6, 500 -508. D’Angiulli, A. , Siegel, L. S. & Maggi, S. (2004). Literacy instruction, SES, and word-reading achievement in English-language learners and children with English as a first language: A longitudinal study. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice , 19, 4, 202 -213. Da Fontoura H. A. & Siegel, S. L. (1995). Reading, syntactic, and working memory skills of bilingual Portuguese-English Canadian children. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal , 7, 139 -153. Gunderson, L. & Siegel, S. L. (2001). The evils of the use of IQ tests to define learning disabilities in first- and second- language learners. Reading Teacher, 55, 1. Hudson, R. F. & Smith, W. (2001) Effective reading instruction for struggling Spanish-speaking readers: A combination of two literatures. Retrieved March 21, 2007, from http: //www. ldonline. org/article/6363 Klingner, J. , Artiles, J. & Mendez Barlett, L. (2006). English language learners who struggle with reading: Language acquisition or LD? Journal of Learning Disabilities , 39, 2, 108 -128. Klingner, J. & Harry, B. (2006). The special education referral and decision-making process for English language learners: Child study team meetings and placement conferences. Teachers College Record , 108, 11, 2247 -2281. Lesaux, N. (2006). Building consensus: future directions for research on English language learners at risk for learning difficulties. Teachers College Record , 108, 11, 2406 -2438. 55

Limbos, M. & Geva, E. (2001). Accuracy of teacher assessments of second language students at risk for reading disability. Journal of Learning Disabilities , 31, 2, 136 -151. Lipka, O. , Siegel, L. S. & Vukovic, R. (2005). The literacy skills of English language learners in Canada. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 20, 1, 39 -49. Macswan, J. & Rolstad, K. (2006). How language proficiency tests mislead us about ability: Implications for English language learner placement in special education. Teachers College Record , 108, 11, 2304 -2328. Mc. Cardle, P. , Mele-Mc. Carthy, J. & Leos, K. (2005). English language learners and learning disabilities: Research agenda and implications for practice. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice , 20, 1, 68 -78. Ortiz, A. (2001). English language learners with special needs: Effective instructional strategies. Retrieved March 15, 2007, from http: //www. ldonline. org/article/5622 Rueda, R. & Windmueller, M. (2006). English language learners, LD, and overrepresentation: A multiple-level analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities , 39, 2, 99 -107. Schwartz, R. & Terril, L. (2001) ESL instruction and adults with learning disabilities. ERIC Digest. Retrieved March 20, 2007, from http: //www. ericdigests. org/2001 -2/esl. html Smythe, I. & Everatt, J. (2000). Dyslexia diagnosis in different languages. In Peer, L. & Reid, G. (Eds. ), Multilingualism, literacy and dyslexia: A challenge for educators (pp. 12 -22). London: David Fulton Publishers. Wagner, R. , Francis, D. & Morris, R. (2005). Identifying English language learners with Learning disabilities: Key challenges and possible approaches. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice , 20, 1, 6 -15. Wilkinson, C. , Ortiz, A. , Robertson, R. & Kushner, M. (2006). English language learners with reading-related LD: Linking data from multiple sources to make eligibility determinations. Journal of Learning Disabilities , 39, 2, 129 -141. 56