Foundations of Modern Trade Theory Comparative Advantage Power

- Slides: 75

Foundations of Modern Trade Theory: Comparative Advantage Power. Point slides prepared by: Andreea Chiritescu Eastern Illinois University © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 1

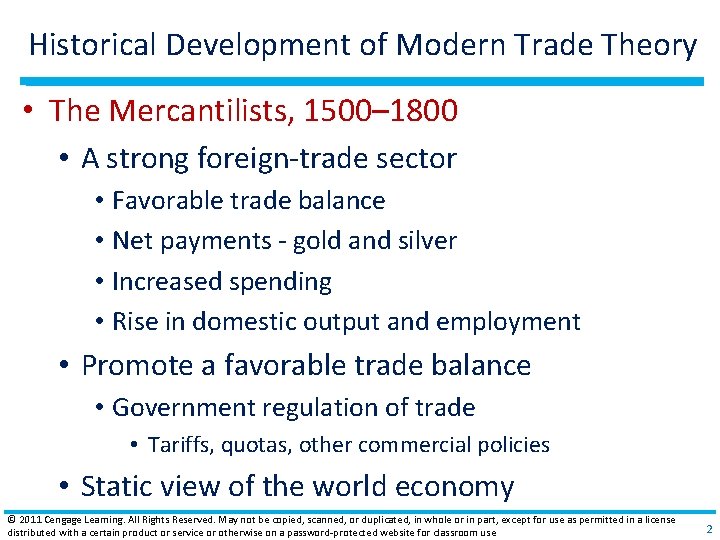

Historical Development of Modern Trade Theory • The Mercantilists, 1500– 1800 • A strong foreign‐trade sector • Favorable trade balance • Net payments ‐ gold and silver • Increased spending • Rise in domestic output and employment • Promote a favorable trade balance • Government regulation of trade • Tariffs, quotas, other commercial policies • Static view of the world economy © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 2

Historical Development of Modern Trade Theory • The Mercantilists under attack • David Hume’s price‐specie‐flow doctrine • A favorable trade balance is possible only in the short run • 1776, Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations • World’s wealth is not a fixed quantity • International trade • Increase the general level of productivity within a country • Increase world output (wealth) © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 3

Historical Development of Modern Trade Theory • Why Nations Trade: Absolute Advantage • Adam Smith – free trade advocate • Production costs differ among nations • Different productivities of factor inputs • Labor – homogenous • Absolute cost advantage • Uses less labor to produce one unit of output © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 4

Historical Development of Modern Trade Theory • Principle of absolute advantage • A two‐nation, two‐product world • International specialization and trade • One nation ‐ absolute cost advantage in one good • The other nation ‐ absolute cost advantage in the other good • Each nation must have a good that it is absolutely more efficient in producing than its trading partner • Import goods – if absolute cost disadvantage • Export goods – if absolute cost advantage © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 5

TABLE 2. 1 Absolute advantage; each nation is more efficient in producing one good © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 6

Historical Development of Modern Trade Theory • Why Nations Trade: Comparative Advantage • 1800, David Ricardo (1772– 1823) • Free trade • Mutually beneficial trade can occur whether or not countries have any absolute advantage • Principle of comparative advantage • Emphasized comparative (relative) cost differences © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 7

Historical Development of Modern Trade Theory • Principle of comparative advantage • Even if a nation has an absolute cost disadvantage in the production of both goods • The less efficient nation • Specialize in and export the good in which it is relatively less inefficient • Where its absolute disadvantage is least • The more efficient nation • Specialize in and export that good in which it is relatively more efficient • Where its absolute advantage is greatest © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 8

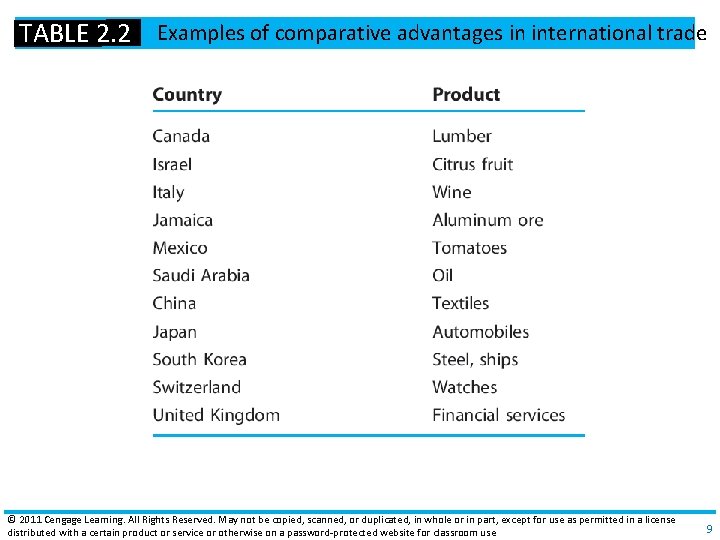

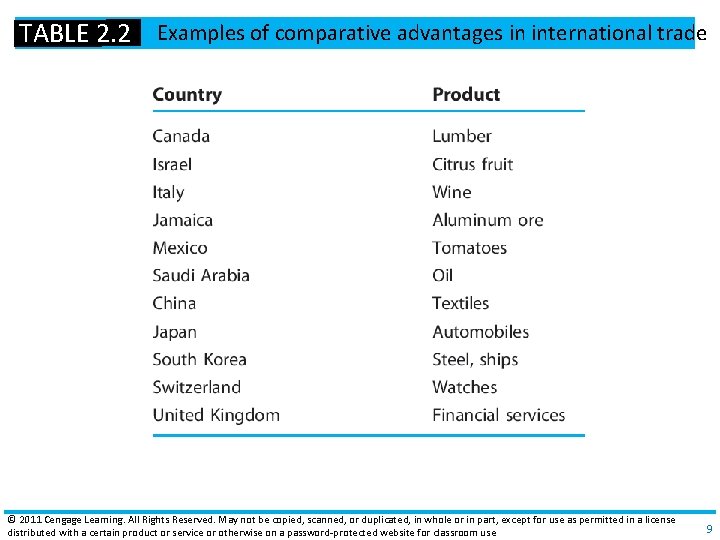

TABLE 2. 2 Examples of comparative advantages in international trade © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 9

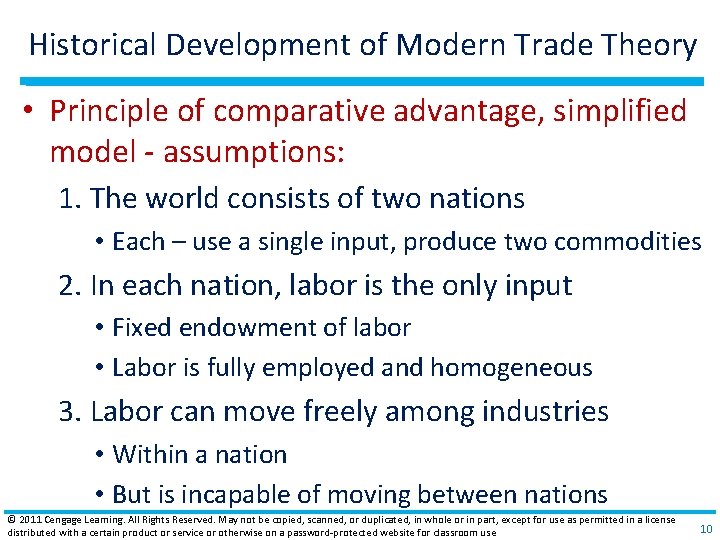

Historical Development of Modern Trade Theory • Principle of comparative advantage, simplified model ‐ assumptions: 1. The world consists of two nations • Each – use a single input, produce two commodities 2. In each nation, labor is the only input • Fixed endowment of labor • Labor is fully employed and homogeneous 3. Labor can move freely among industries • Within a nation • But is incapable of moving between nations © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 10

Historical Development of Modern Trade Theory • Principle of comparative advantage, simplified model ‐ assumptions: 4. Technology ‐ fixed for both nations • Different nations may use different technologies • All firms within each nation ‐ a common production method for each commodity 5. Costs do not vary with the level of production • Proportional to the amount of labor used © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 11

Historical Development of Modern Trade Theory • Principle of comparative advantage, simplified model ‐ assumptions: 6. Perfect competition prevails in all markets • All are price takers • Identical products • Free entry to and exit from an industry • Price of each product = product’s marginal cost of production 7. Free trade occurs between nations • No government barriers to trade © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 12

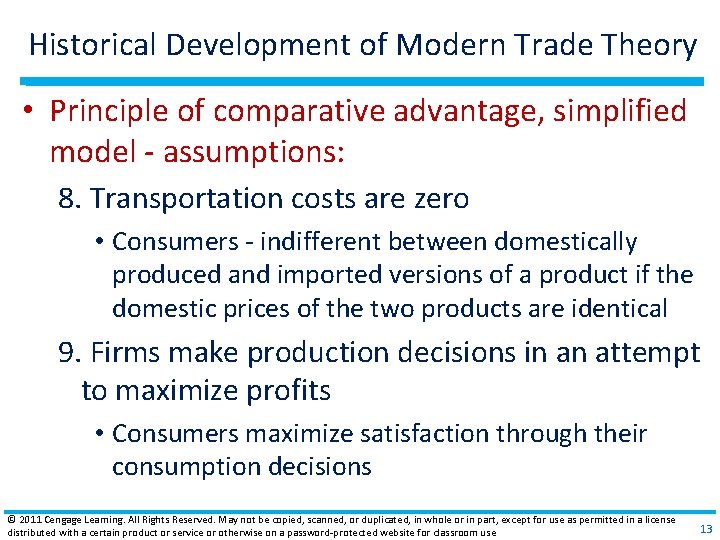

Historical Development of Modern Trade Theory • Principle of comparative advantage, simplified model ‐ assumptions: 8. Transportation costs are zero • Consumers ‐ indifferent between domestically produced and imported versions of a product if the domestic prices of the two products are identical 9. Firms make production decisions in an attempt to maximize profits • Consumers maximize satisfaction through their consumption decisions © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 13

Historical Development of Modern Trade Theory • Principle of comparative advantage, simplified model ‐ assumptions: 10. There is no money illusion • When consumers make their consumption choices and firms make their production decisions, they take into account the behavior of all prices 11. Trade is balanced • Exports must pay for imports • Ruling out flows of money between nations © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 14

TABLE 2. 3 Comparative advantage, U. S. ‐absolute advantage in producing both goods © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 15

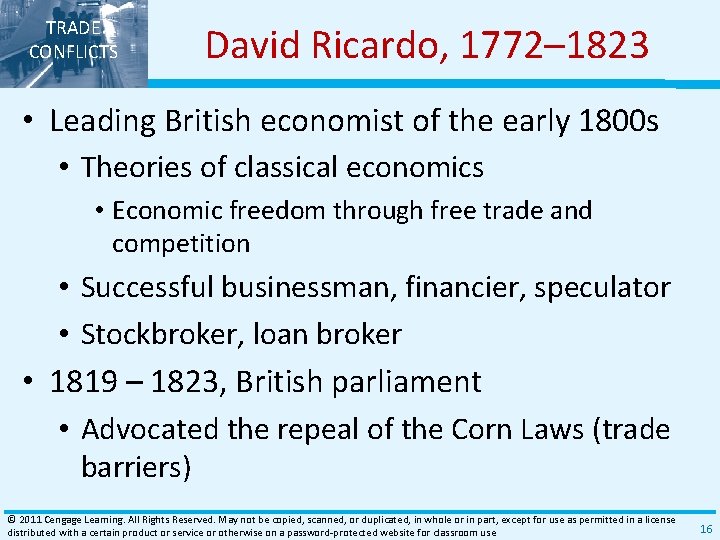

TRADE CONFLICTS David Ricardo, 1772– 1823 • Leading British economist of the early 1800 s • Theories of classical economics • Economic freedom through free trade and competition • Successful businessman, financier, speculator • Stockbroker, loan broker • 1819 – 1823, British parliament • Advocated the repeal of the Corn Laws (trade barriers) © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 16

TRADE CONFLICTS David Ricardo, 1772– 1823 • Interest in economics • Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations • Newspaper articles on economic questions • 1817, The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation • Laid out theory of comparative advantage • Advocate of free trade • Opponent of protectionism © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 17

Production Possibilities Schedules • Modern trade theory • More generalized theory of comparative advantage • Use a production possibilities schedule • Transformation schedule © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 18

Production Possibilities Schedules • Production possibilities schedule • Various alternative combinations of two goods • A nation can produce • When all of its factor inputs • Land, labor, capital, entrepreneurship • Are used in their most efficient manner • Maximum output possibilities of a nation © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 19

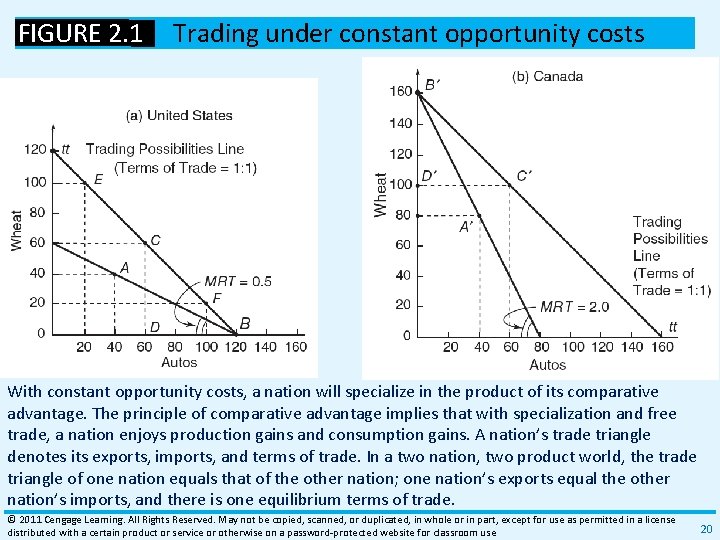

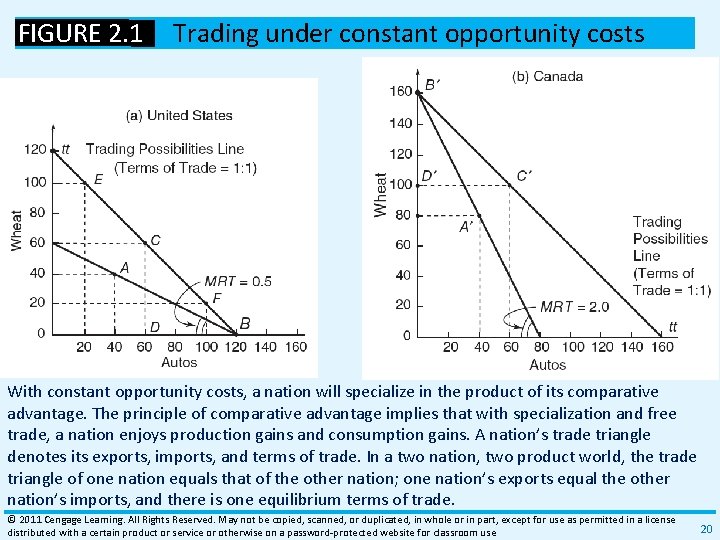

FIGURE 2. 1 Trading under constant opportunity costs With constant opportunity costs, a nation will specialize in the product of its comparative advantage. The principle of comparative advantage implies that with specialization and free trade, a nation enjoys production gains and consumption gains. A nation’s trade triangle denotes its exports, imports, and terms of trade. In a two nation, two product world, the trade triangle of one nation equals that of the other nation; one nation’s exports equal the other nation’s imports, and there is one equilibrium terms of trade. © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 20

Production Possibilities Schedules • Marginal rate of transformation, MRT • The amount of one product a nation must sacrifice to get one additional unit of the other product • Rate of sacrifice = opportunity cost of a product • Absolute value of the slope of production possibilities schedule • For Figure 2. 1 © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 21

Trading Under Constant‐Cost Conditions • Constant opportunity costs • Straight line production possibilities schedules • Factors of production • Perfect substitutes for each other • All units of a given factor are of the same quality • Autarky • Absence of trade © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 22

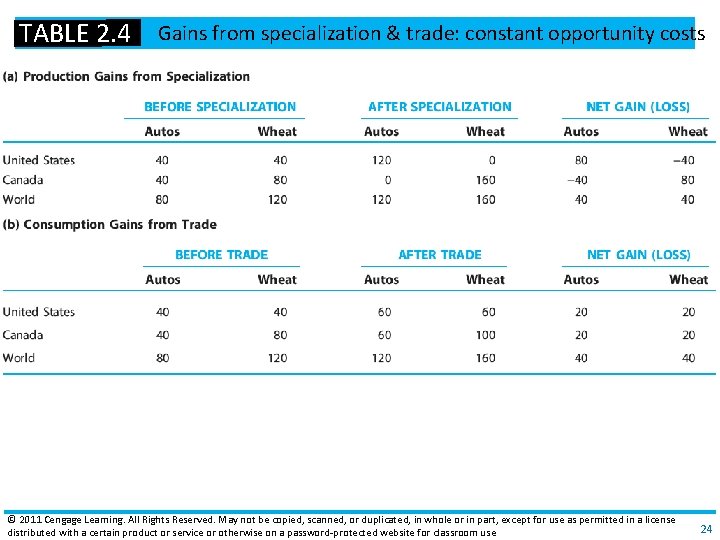

Trading Under Constant‐Cost Conditions • Basis for Trade • Principle of comparative advantage • Direction of Trade • Specialize and export the good with the lowest opportunity cost • Production Gains from Specialization • Production gains for both countries • Arise from the reallocation of existing resources • Static gains from specialization © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 23

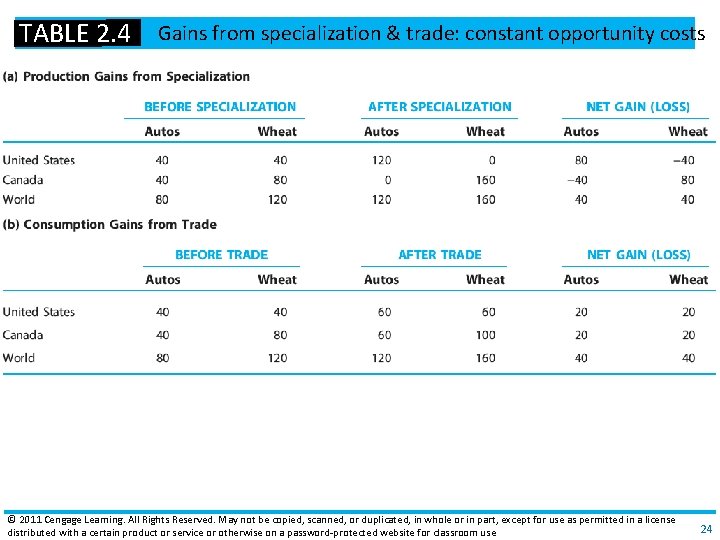

TABLE 2. 4 Gains from specialization & trade: constant opportunity costs © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 24

Trading Under Constant‐Cost Conditions • Consumption Gains from Trade • Trade = consumption gains for both countries • Consumption points • Outside domestic production possibilities schedules • Consume more of both goods • Terms of trade • Rate at which a country’s export product is traded for the other country’s export product • Define the relative prices of the two products © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 25

Trading Under Constant‐Cost Conditions • Domestic rate of transformation • Domestic terms of trade • Slope of the production possibilities schedule • Relative prices that two commodities can be exchanged at home • Terms of trade for exports • More favorable than domestic terms of trade © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 26

Trading Under Constant‐Cost Conditions • Trading possibilities line • International terms of trade for both countries • Trade triangle for a country • Exports – along the horizontal axis • Imports – along the vertical axis • Terms of trade – the slope • Complete specialization • Produce only one product © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 27

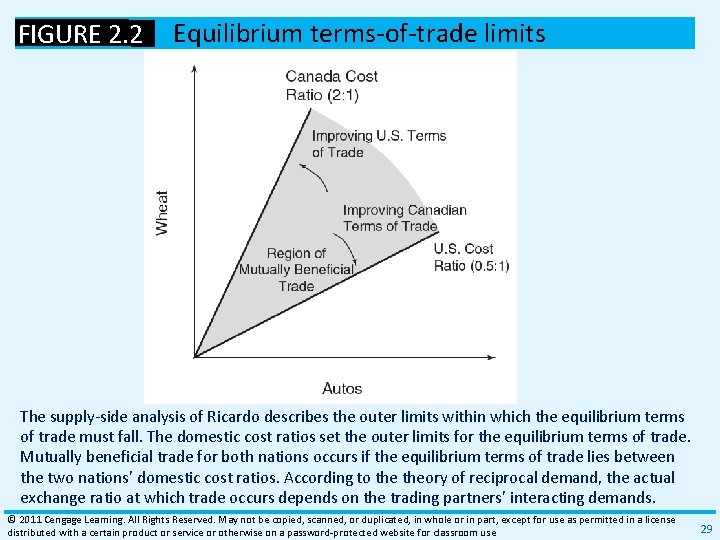

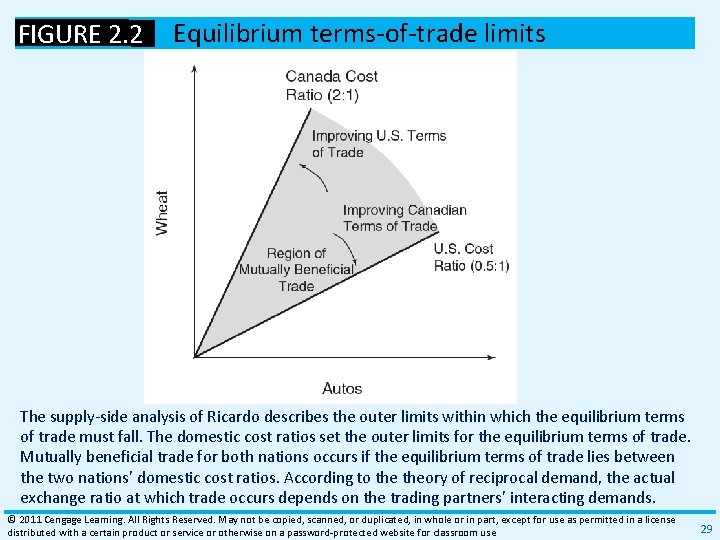

Trading Under Constant‐Cost Conditions • Domestic cost ratio • Negatively sloped production possibilities schedule • Transform into a positively sloped cost‐ratio line • Outer limits for the equilibrium terms of trade • Becomes no‐trade boundary • Region of mutually beneficial trade • Bounded by the cost ratios of the two countries © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 28

FIGURE 2. 2 Equilibrium terms‐of‐trade limits The supply‐side analysis of Ricardo describes the outer limits within which the equilibrium terms of trade must fall. The domestic cost ratios set the outer limits for the equilibrium terms of trade. Mutually beneficial trade for both nations occurs if the equilibrium terms of trade lies between the two nations’ domestic cost ratios. According to theory of reciprocal demand, the actual exchange ratio at which trade occurs depends on the trading partners’ interacting demands. © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 29

Trading Under Constant‐Cost Conditions • Equilibrium Terms of Trade, John Stuart Mill (1806– 1873) • Add the intensity of the trading partners’ demands • Determine the actual terms of trade • The theory of reciprocal demand © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 30

Trading Under Constant‐Cost Conditions • Theory of reciprocal demand • Within the outer limits of the terms of trade • Actual terms of trade are determined by the relative strength of each country’s demand for the other country’s product • Production costs determine the outer limits of the terms of trade • Reciprocal demand determines what the actual terms of trade will be within those limits © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 31

Trading Under Constant‐Cost Conditions • Theory of reciprocal demand • Best applies when both nations are of equal economic size • The demand of each nation ‐ noticeable effect on market price • If two nations are of unequal economic size • The relative demand strength of the smaller nation will be dwarfed by that of the larger nation • Domestic exchange ratio of the larger nation will prevail • The small nation can export as much of the commodity as it desires © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 32

Trading Under Constant‐Cost Conditions • The importance of being unimportant • For two nations engaged in international trade • Same size, similar taste patterns • Gains from trade – shared equally between them • One nation is significantly larger than the other • Larger nation ‐ fewer gains from trade • Smaller nation ‐ most of the gains from trade © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 33

TRADE CONFLICTS Babe Ruth and the principle of comparative advantage • George Herman Ruth (1895– 1948) • 1914 – 1920, Boston Red Sox, 158 games • Left‐handed pitcher • Pitching record: 89 wins and 46 losses • 23 victories in 1916 • 24 victories in 1917 • Babe Ruth • Absolute advantage in pitching • Comparative advantage in hitting © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 34

TRADE CONFLICTS Babe Ruth and the principle of comparative advantage • 1920 – 1934, New York Yankees, Babe Ruth • Ended his pitching career ‐ 2. 28 earned run average • Switched to only hitting • Dominated professional baseball • Teamed with Lou Gehrig • Greatest one‐two hitting punch in baseball • 1927 Yankees ‐ the best in baseball history • Record of 60 home runs © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 35

TRADE CONFLICTS Babe Ruth and the principle of comparative advantage • 1920 – 1934, New York Yankees, Babe Ruth • 1923, Yankee Stadium – nicknamed “The House That Ruth Built” • Baseball Hall of Fame, 1936 • Win four World Series • Most renewed franchise © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 36

Trading Under Constant‐Cost Conditions • Terms‐of‐Trade Estimates • Commodity terms of trade • Barter terms of trade • Measure of the international exchange ratio • Measures the relation between the prices a nation gets for its exports and the prices it pays for its imports © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 37

Trading Under Constant‐Cost Conditions • Improvement in a nation’s terms of trade • Rise in its export prices • Relative to its import prices • A smaller quantity of export goods sold abroad • Required to obtain a given quantity of imports • Deterioration in a nation’s terms of trade • Rise in its import prices • Relative to its export prices • Purchase of a given quantity of imports • Sacrifice of a greater quantity of exports © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 38

TABLE 2. 5 Commodity terms of trade, 2008 (2000 = 100) © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 39

Dynamic Gains From Trade • Dynamic gains from international trade • • More efficient use of an economy’s resources Higher output and income More saving, More investment Higher rate of economic growth Higher productivity Economies of large‐scale production Increased competition © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 40

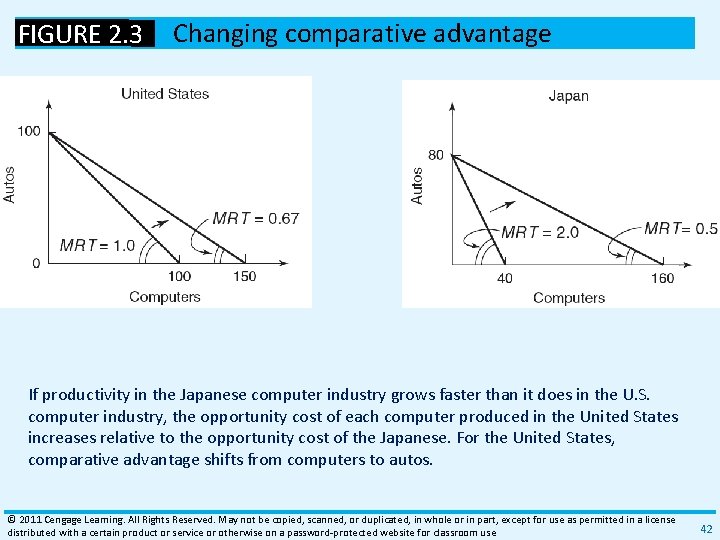

Changing Comparative Advantage • Patterns of comparative advantage change over time • Productivity increases • Production possibilities schedule changes • More output can be produced ‐ with the same amount of resources • Producers ‐ need to hone their skills to compete in more profitable areas © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 41

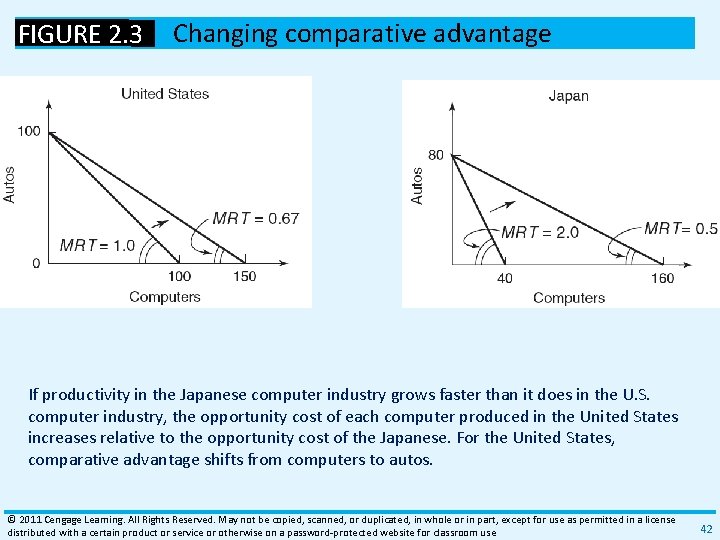

FIGURE 2. 3 Changing comparative advantage If productivity in the Japanese computer industry grows faster than it does in the U. S. computer industry, the opportunity cost of each computer produced in the United States increases relative to the opportunity cost of the Japanese. For the United States, comparative advantage shifts from computers to autos. © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 42

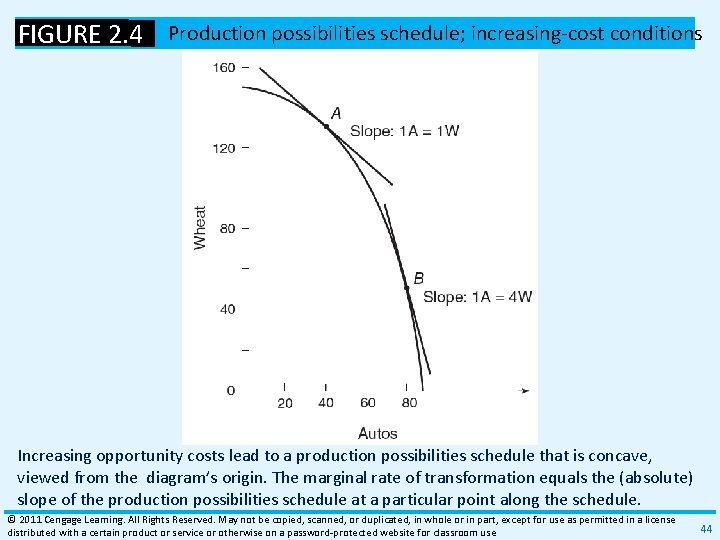

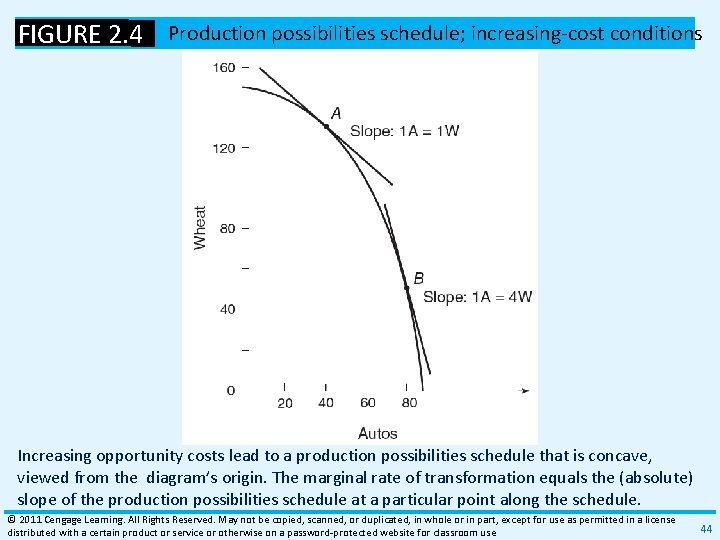

Trading Under Increasing‐Cost Conditions • Increasing opportunity costs • Concave production possibilities schedule • Bowed outward from the diagram’s origin • Inputs are imperfect substitutes for each other • MRT rises • Absolute slope of the production possibilities schedule © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 43

FIGURE 2. 4 Production possibilities schedule; increasing‐cost conditions Increasing opportunity costs lead to a production possibilities schedule that is concave, viewed from the diagram’s origin. The marginal rate of transformation equals the (absolute) slope of the production possibilities schedule at a particular point along the schedule. © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 44

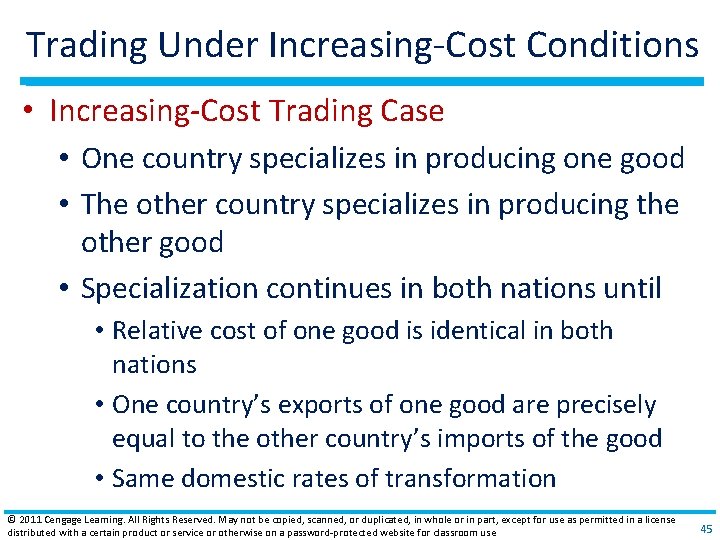

Trading Under Increasing‐Cost Conditions • Increasing‐Cost Trading Case • One country specializes in producing one good • The other country specializes in producing the other good • Specialization continues in both nations until • Relative cost of one good is identical in both nations • One country’s exports of one good are precisely equal to the other country’s imports of the good • Same domestic rates of transformation © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 45

FIGURE 2. 5 Trading under increasing opportunity costs With increasing opportunity costs, comparative product prices in each country are determined by both supply and demand factors. A country tends to partially specialize in the product of its comparative advantage under increasing cost conditions. © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 46

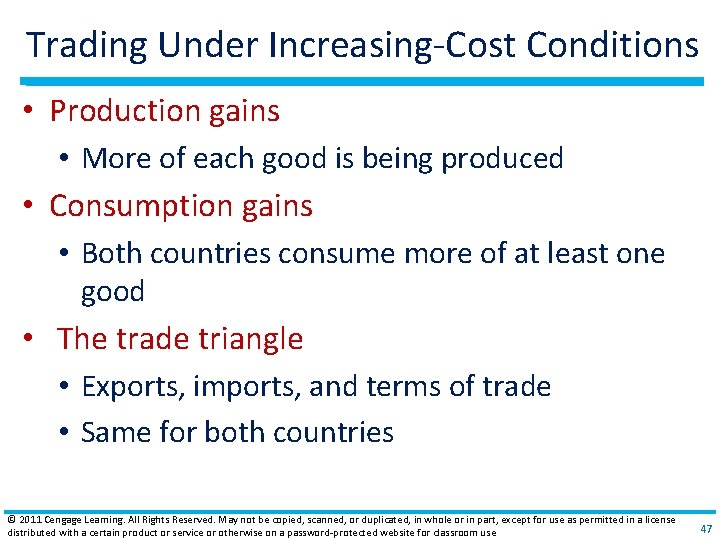

Trading Under Increasing‐Cost Conditions • Production gains • More of each good is being produced • Consumption gains • Both countries consume more of at least one good • The trade triangle • Exports, imports, and terms of trade • Same for both countries © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 47

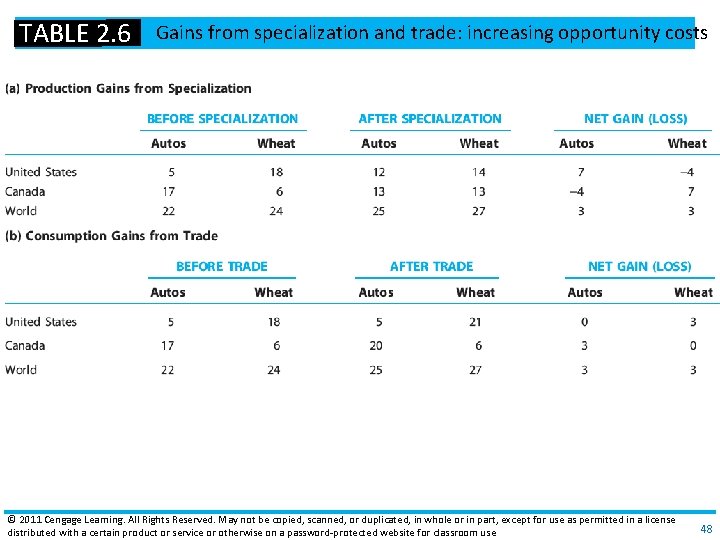

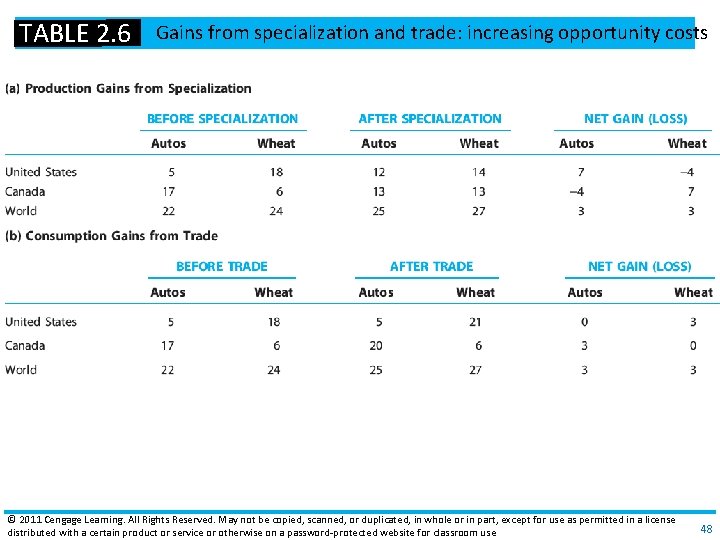

TABLE 2. 6 Gains from specialization and trade: increasing opportunity costs © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 48

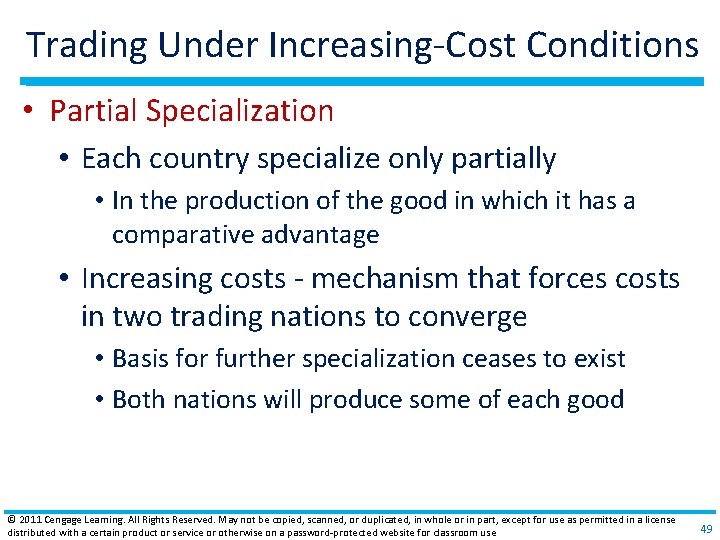

Trading Under Increasing‐Cost Conditions • Partial Specialization • Each country specialize only partially • In the production of the good in which it has a comparative advantage • Increasing costs ‐ mechanism that forces costs in two trading nations to converge • Basis for further specialization ceases to exist • Both nations will produce some of each good © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 49

Trading Under Increasing‐Cost Conditions • Partial Specialization • Not all goods and services are traded internationally • Differing tastes for products • Most products are differentiated © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 50

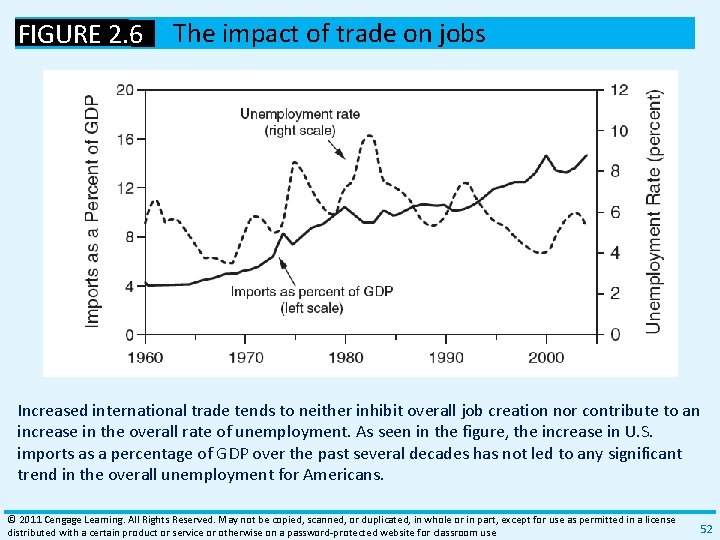

The Impact of Trade on Jobs • Extent to which an economy is open • Influences the mix of jobs within an economy • Can cause dislocation in certain areas or industries • Little effect on the overall level of employment © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 51

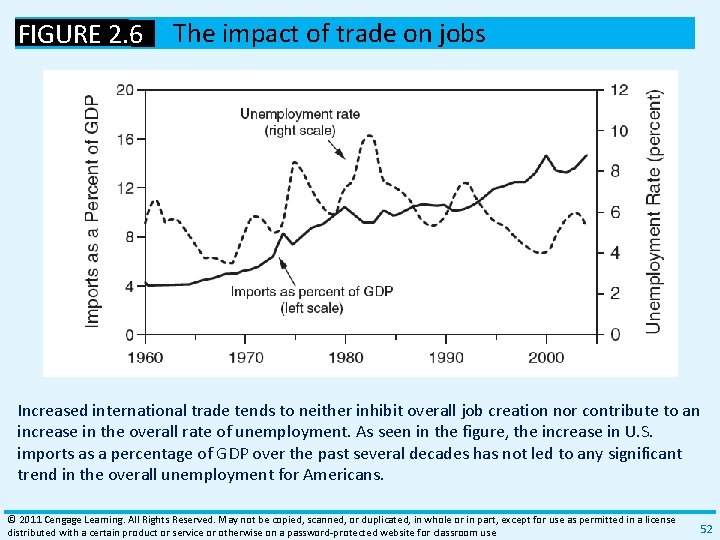

FIGURE 2. 6 The impact of trade on jobs Increased international trade tends to neither inhibit overall job creation nor contribute to an increase in the overall rate of unemployment. As seen in the figure, the increase in U. S. imports as a percentage of GDP over the past several decades has not led to any significant trend in the overall unemployment for Americans. © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 52

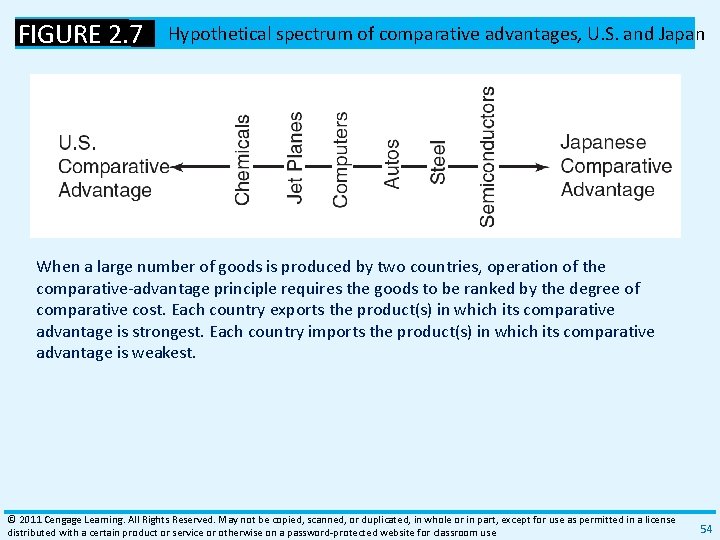

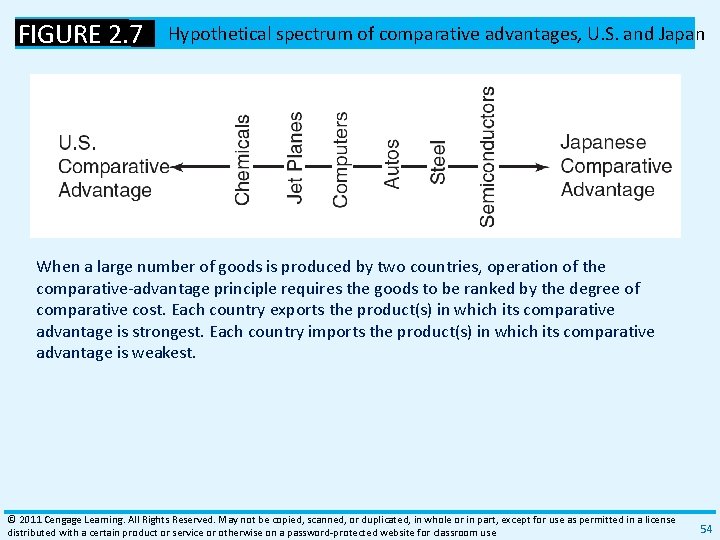

Comparative Advantage Extended to Many Products and Countries • More Than Two Products • Comparative advantage • Rank the goods by the degree of comparative cost • Each country exports the product(s) • Has the greatest comparative advantage • Each country imports the product(s) • Has greatest comparative disadvantage • Cutoff point between exports and imports • Relative strength of international demand © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 53

FIGURE 2. 7 Hypothetical spectrum of comparative advantages, U. S. and Japan When a large number of goods is produced by two countries, operation of the comparative‐advantage principle requires the goods to be ranked by the degree of comparative cost. Each country exports the product(s) in which its comparative advantage is strongest. Each country imports the product(s) in which its comparative advantage is weakest. © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 54

Comparative Advantage Extended to Many Products and Countries • More Than Two Countries • Multilateral trading relations • Bilateral balance should not pertain to any two trading partners • Trade surplus • With trading partners that buy a lot of the things that it supplies at low cost • Trade deficit • With trading partners that are low‐cost suppliers of goods that it imports intensely © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 55

FIGURE 2. 8 Multilateral trade: U. S. , Japan, and OPEC When many countries are involved in international trade, the home country will likely find it advantageous to enter into multilateral trading relations with a number of countries. This figure illustrates the process of multilateral trade for the United States, Japan, and OPEC. © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 56

Exit Barriers • Open trading system • Channeling resources from uses of low productivity to those of high productivity • Competition • High cost plants exit • Low cost plants operate in the long run © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 57

Exit Barriers • Restructuring of inefficient companies • Long time • Cling to capacity • Existence of exit barriers • Various cost conditions ‐make lengthy exit a rational response by companies • Hinder the market adjustments © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 58

Empirical Evidence on Comparative Advantage • The Ricardian model • Nations export goods ‐ their labor productivity is relatively high • Testing the Ricardian model • G. D. A. Mac. Dougall, 1951 • Export patterns of 25 separate industries; United States and United Kingdom, 1937 • 20 industries fit the predicted pattern • Balassa and Stern • Also supported Ricardo’s conclusions © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 59

Empirical Evidence on Comparative Advantage • Testing the Ricardian model • Stephen Golub • Relative unit labor costs and trade for United States • United Kingdom, Japan, Germany, Canada, Australia • Relative unit labor cost helps to explain trade patterns for these nations • Limitations of the Ricardian model • Labor is not the only factor input • Production and distribution costs • Differences in product quality © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 60

FIGURE 2. 9 Relative exports & relative unit labor costs: U. S. /Japan, 1990 The figure displays a scatter plot of U. S. /Japan export data for 33 industries. It shows a clear negative correlation between relative exports and relative unit labor costs. A rightward movement along the figure’s horizontal axis indicates a rise in U. S. unit labor costs relative to Japanese unit labor costs; this correlates with a decline in U. S. exports relative to Japanese exports, a downward movement along the figure’s vertical axis. © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 61

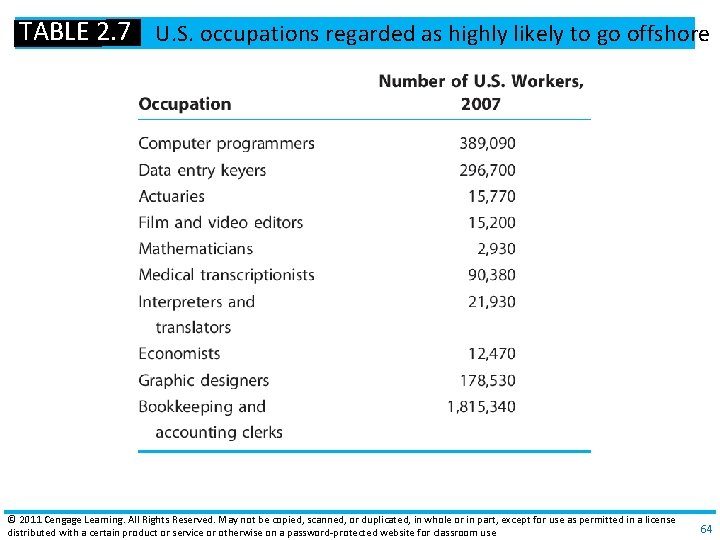

Does Comparative Advantage Apply in the Face of Job Outsourcing? • Comparative advantage • Weakened if resources can move to wherever they are most productive • Relatively few nations with abundant cheap labor • No longer shared gains • Some nations win and others lose © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 62

Does Comparative Advantage Apply in the Face of Job Outsourcing? • Major change in the world economy • Strong educational systems • Millions of skilled workers in developing nations, China and India • As capable as the most highly educated workers in advanced nations • Much lower cost • Inexpensive Internet technology • Many workers to be located anywhere • New political stability • Technology and capital to move more freely around the globe © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 63

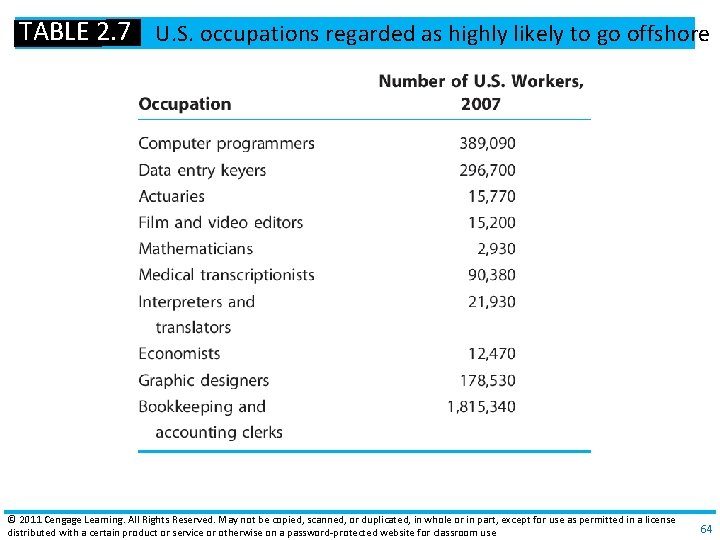

TABLE 2. 7 U. S. occupations regarded as highly likely to go offshore © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 64

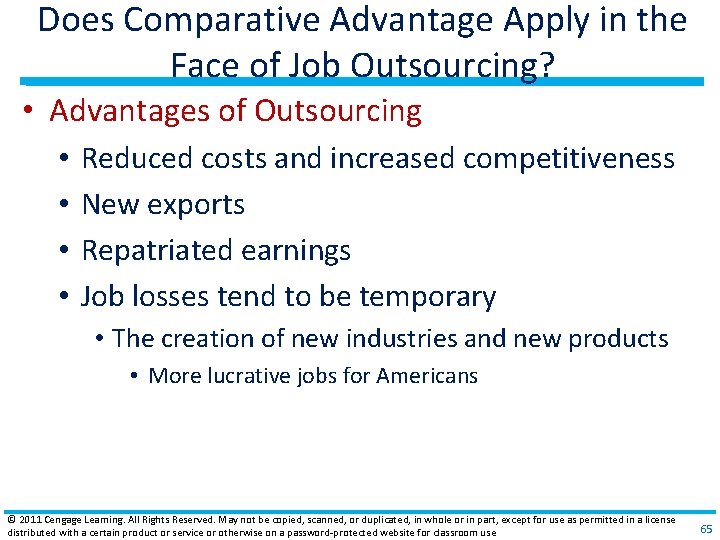

Does Comparative Advantage Apply in the Face of Job Outsourcing? • Advantages of Outsourcing • • Reduced costs and increased competitiveness New exports Repatriated earnings Job losses tend to be temporary • The creation of new industries and new products • More lucrative jobs for Americans © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 65

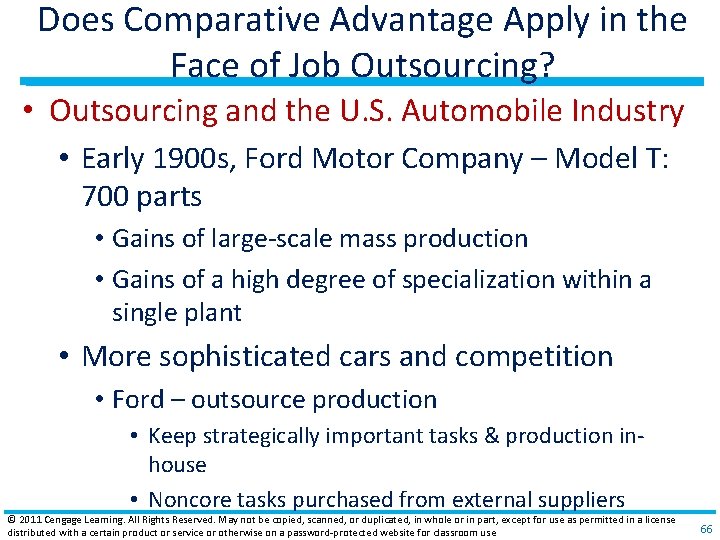

Does Comparative Advantage Apply in the Face of Job Outsourcing? • Outsourcing and the U. S. Automobile Industry • Early 1900 s, Ford Motor Company – Model T: 700 parts • Gains of large‐scale mass production • Gains of a high degree of specialization within a single plant • More sophisticated cars and competition • Ford – outsource production • Keep strategically important tasks & production in‐ house • Noncore tasks purchased from external suppliers © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 66

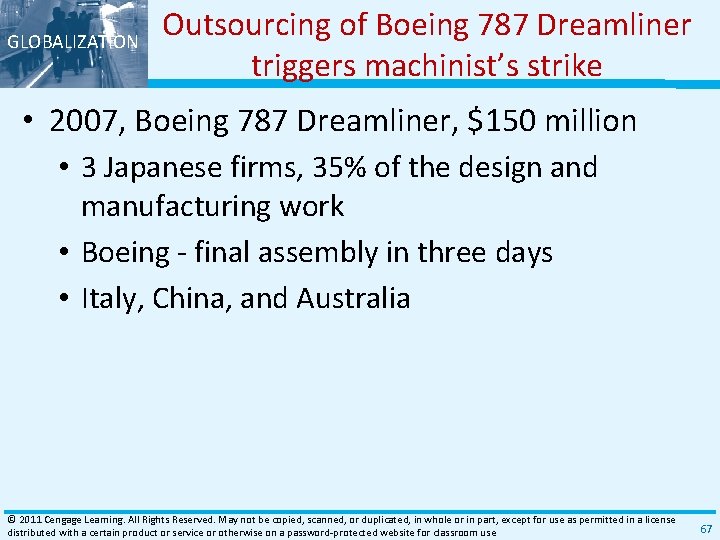

GLOBALIZATION Outsourcing of Boeing 787 Dreamliner triggers machinist’s strike • 2007, Boeing 787 Dreamliner, $150 million • 3 Japanese firms, 35% of the design and manufacturing work • Boeing ‐ final assembly in three days • Italy, China, and Australia © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 67

GLOBALIZATION Outsourcing of Boeing 787 Dreamliner triggers machinist’s strike • Gains from globalization • Decrease the time required to build its jets by more than 50 percent • Decrease costs ‐ Foreign suppliers to absorb some of the costs of developing the plane • Spreading the risk • Engineering talent and technical capacity • Maintain close relationships with its customers © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 68

GLOBALIZATION Outsourcing of Boeing 787 Dreamliner triggers machinist’s strike • Boeing’s suppliers fell behind • Production ‐more than a year behind schedule • Language barriers • Some contractors outsourced chunks of work • Boeing’s union workforce • Anger and anxiety • Fear of losing their jobs to outsourcing • Strike in 2008 • Nearly 27, 000 machinists walked off their jobs © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 69

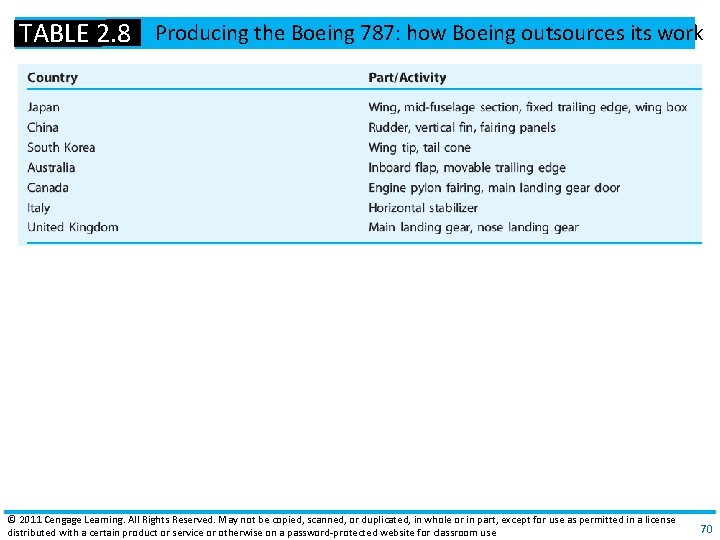

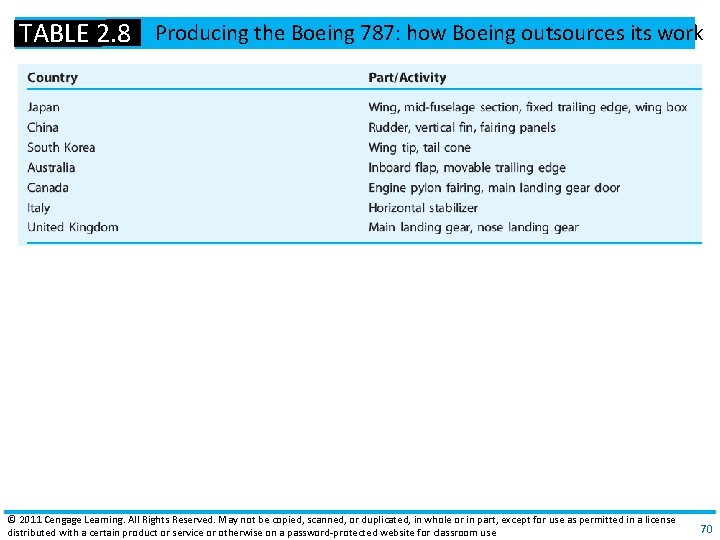

TABLE 2. 8 Producing the Boeing 787: how Boeing outsources its work © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 70

Does Comparative Advantage Apply in the Face of Job Outsourcing? • Outsourcing and the U. S. Automobile Industry • Increasing numbers of parts and services – noncore • Today ‐ about 70% of a typical Ford vehicle • Parts, components, and services purchased from external suppliers © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 71

Does Comparative Advantage Apply in the Face of Job Outsourcing? • Burdens of Outsourcing • Americans who lose their jobs or find lower‐ wage ones • Wages of low‐skilled American workers • High school education or less • Decreased in real terms • Decreased relative to the wages of skilled workers (college education or higher) © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 72

Does Comparative Advantage Apply in the Face of Job Outsourcing? • Technological change and outsourcing • Declining demand for low‐skilled American workers • Outsourcing of high‐skilled jobs • Shift demand to cheaper substitutes in Asia • May yield economic benefits for the nation • Losers – the displaced workers © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 73

Does Comparative Advantage Apply in the Face of Job Outsourcing? • Address the plight of the displaced worker • Generous severance packages, insurance programs • Revamp the U. S. education system • Prepare workers for jobs that cannot easily go overseas • Revise the tax code • Reward firms that produce jobs that stay in the United States © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 74

Does Comparative Advantage Apply in the Face of Job Outsourcing? • Some U. S. Manufacturers Prosper by Keeping Production in the United States • Increase the skill level • Perform tasks more efficiently • Cost‐cutting programs to improve competitiveness • Gained efficiencies • Contracting single suppliers of packing materials and components © 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password‐protected website for classroom use 75

Comparative advantage vs absolute advantage

Comparative advantage vs absolute advantage Modern theory of trade

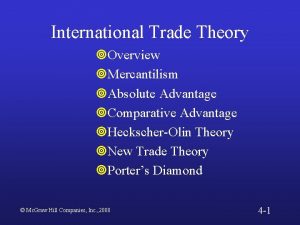

Modern theory of trade International trade theory

International trade theory Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage

Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage Comparative advantage example

Comparative advantage example Power triangle

Power triangle Actual mechanical advantage vs ideal mechanical advantage

Actual mechanical advantage vs ideal mechanical advantage Software architecture foundations theory and practice

Software architecture foundations theory and practice Software architecture foundations theory and practice

Software architecture foundations theory and practice Batch sequential architecture

Batch sequential architecture Domain specific software architecture

Domain specific software architecture Trade diversion and trade creation

Trade diversion and trade creation Umich

Umich Which is the most enduring free trade area in the world?

Which is the most enduring free trade area in the world? The trade in the trade-to-gdp ratio

The trade in the trade-to-gdp ratio Fair trade not free trade

Fair trade not free trade Trade diversion and trade creation

Trade diversion and trade creation Liner trade and tramp trade

Liner trade and tramp trade What is triangle trade

What is triangle trade Recent trends in indian foreign trade

Recent trends in indian foreign trade Is free trade fair? discuss

Is free trade fair? discuss Competitive advantage starbucks

Competitive advantage starbucks Comparative advantage example

Comparative advantage example How to calculate comparative advantage

How to calculate comparative advantage Comparative advantage example

Comparative advantage example Opportunity cost formula

Opportunity cost formula Refutation organizational pattern

Refutation organizational pattern Comparative advantage numerical example

Comparative advantage numerical example Trimalawn

Trimalawn How to calculate comparative advantage

How to calculate comparative advantage Comparative advantage

Comparative advantage Activity 26.5 specialization and trade answers

Activity 26.5 specialization and trade answers Calculating comparative advantage

Calculating comparative advantage Ap macroeconomics frq 2010

Ap macroeconomics frq 2010 Specialization and comparative advantage

Specialization and comparative advantage Protectionism definition economics

Protectionism definition economics Advantedge power island

Advantedge power island Comparative advantage example

Comparative advantage example When discussing comparative and absolute advantage

When discussing comparative and absolute advantage Advantages of using powerpoint

Advantages of using powerpoint Trade union power

Trade union power Modern comparative adjectives

Modern comparative adjectives Mercantilist laws

Mercantilist laws The leontief paradox

The leontief paradox Benefits of protectionism economics

Benefits of protectionism economics Maximum social advantage is achieved when

Maximum social advantage is achieved when What is ipe

What is ipe Mercantilism theory of international trade

Mercantilism theory of international trade Current theory of international trade adalah

Current theory of international trade adalah International trade theory

International trade theory International trade theory

International trade theory New trade theory

New trade theory Country similarity theory

Country similarity theory New trade theory

New trade theory Electrical trade theory n2 conductors and cables

Electrical trade theory n2 conductors and cables Firm based trade theory

Firm based trade theory The capital structure of a company

The capital structure of a company Debt tax shield

Debt tax shield Trade off theory of capital structure

Trade off theory of capital structure Kravis and linder theory of trade

Kravis and linder theory of trade Standard theory of trade

Standard theory of trade Standard trade theory

Standard trade theory New trade theories

New trade theories Global strategic rivalry theory

Global strategic rivalry theory Product life cycle theory of international trade

Product life cycle theory of international trade Comparative education definition

Comparative education definition Write the comparative forms of the adjectives

Write the comparative forms of the adjectives Define casual comparative

Define casual comparative Quasi rent definition

Quasi rent definition Rent principles of economics

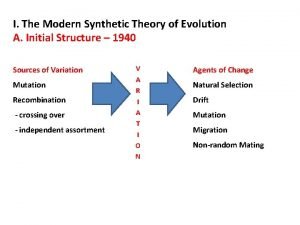

Rent principles of economics Modern synthetic theory of evolution notes

Modern synthetic theory of evolution notes Modern evolution theory

Modern evolution theory Modern cell theory

Modern cell theory Modern portfolio theory

Modern portfolio theory Modern test theory

Modern test theory Modern corporate finance

Modern corporate finance