Chapter Three The Standard Theory of International Trade

- Slides: 25

Chapter Three: The Standard Theory of International Trade

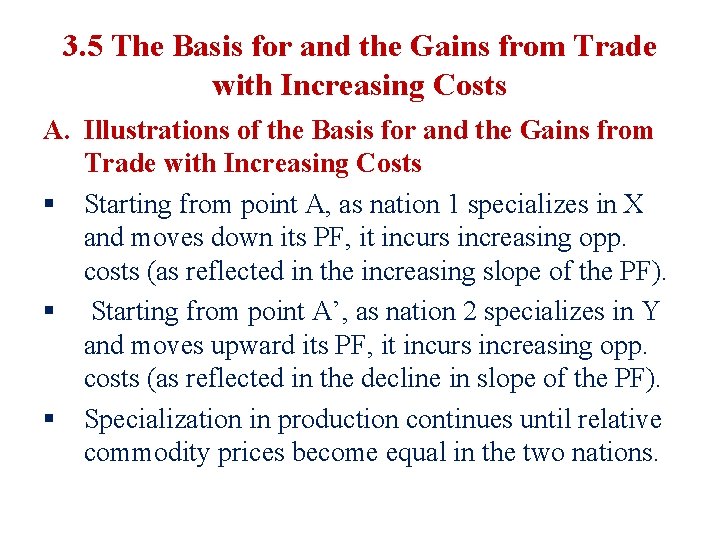

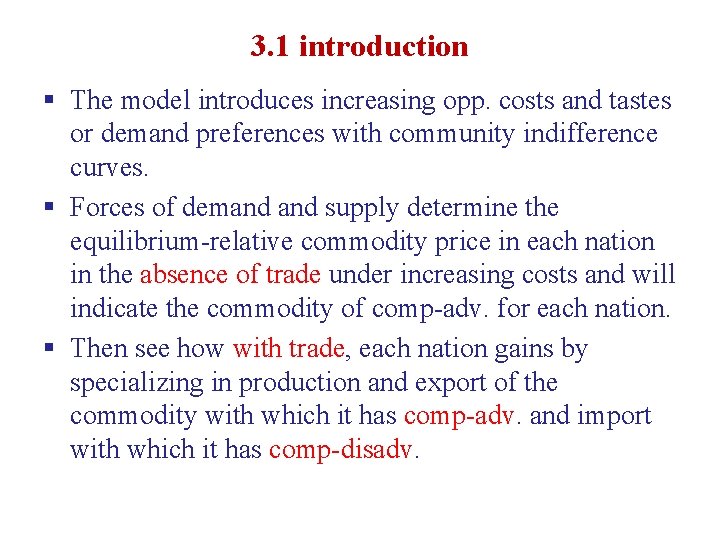

3. 1 introduction § The model introduces increasing opp. costs and tastes or demand preferences with community indifference curves. § Forces of demand supply determine the equilibrium-relative commodity price in each nation in the absence of trade under increasing costs and will indicate the commodity of comp-adv. for each nation. § Then see how with trade, each nation gains by specializing in production and export of the commodity with which it has comp-adv. and import with which it has comp-disadv.

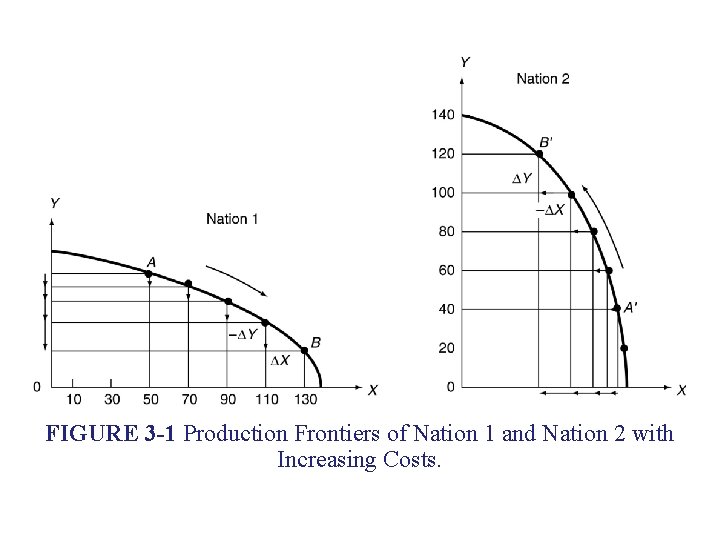

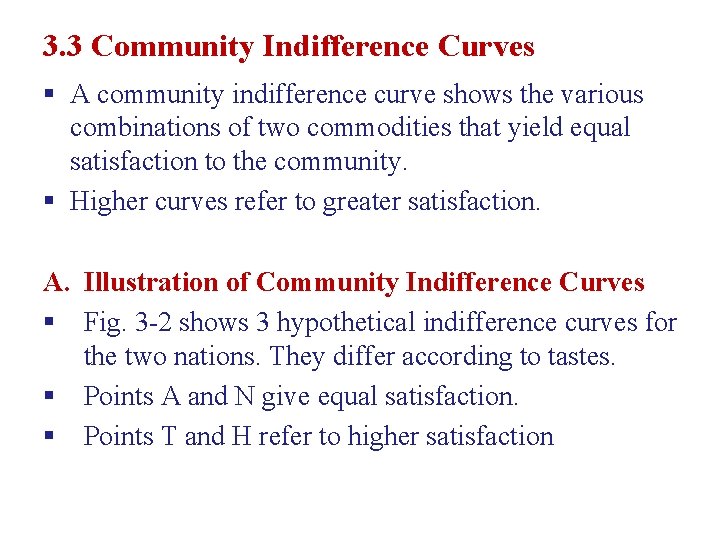

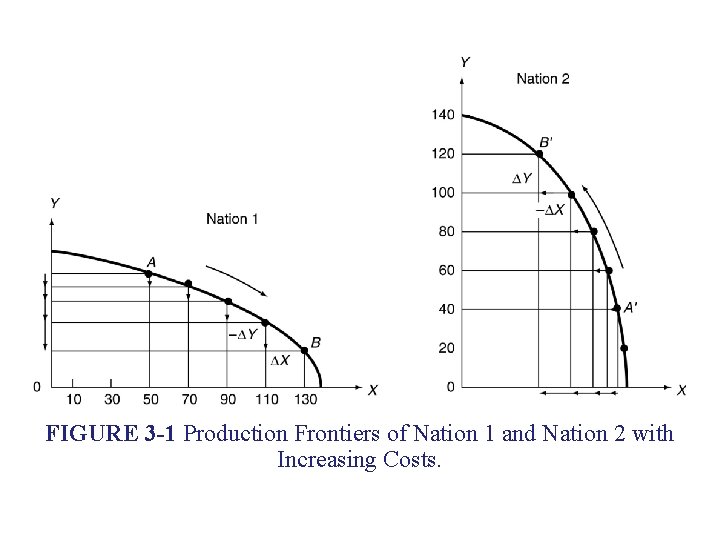

3. 2 Production Frontier with Increasing Costs § Increasing costs mean that the nation must give up more and more of one commodity to release just enough resources to produce each additional unit of another commodity. As a result, the PPF is concave. A. Illustration of Increasing Costs § In Fig. 3 -1, if nation 1 wants to increase output of X (point A), it should reduce output of Y by more and more units. § If nation 2 wants to increase output of Y (point A/), it should reduce output of X by more and more units § Thus, both nations face increasing costs in the production of the two commodities.

FIGURE 3 -1 Production Frontiers of Nation 1 and Nation 2 with Increasing Costs.

B. The Marginal Rate of Transformation (MRT) § The MRT of X for Y refers to the amount of Y that a nation must give up to produce additional unit of X. § It is another name for the opp. cost and is given by the slope of the production frontier at the point of production. § If the MRT of nation 1 at point A is ¼, this means that nation 1 must give up ¼ of a unit of Y to release just enough resources to produce one additional unit of X at this point. § If the MRT at point B is 1, a movement from A to B reflects the increasing opp. costs in producing more X

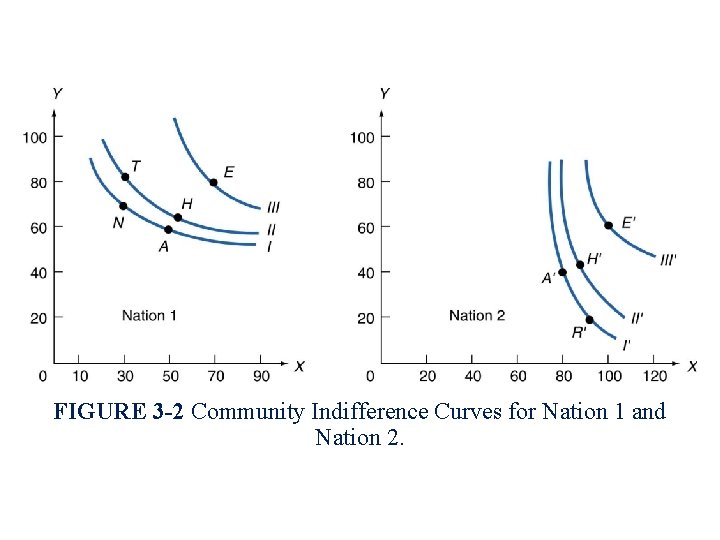

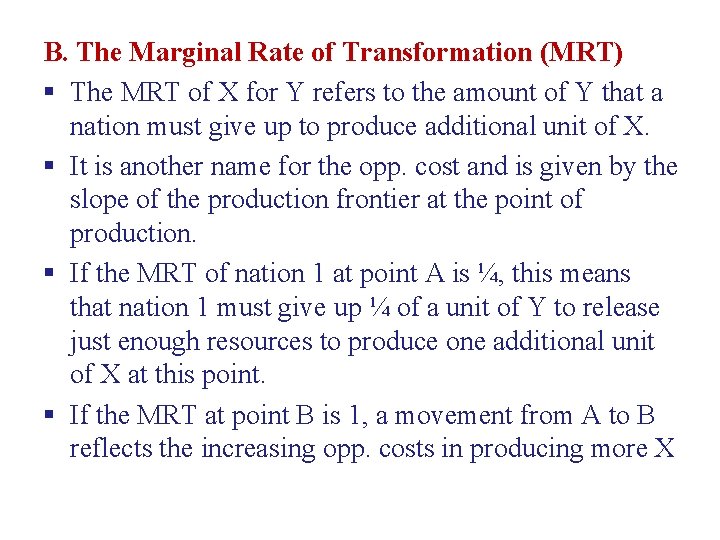

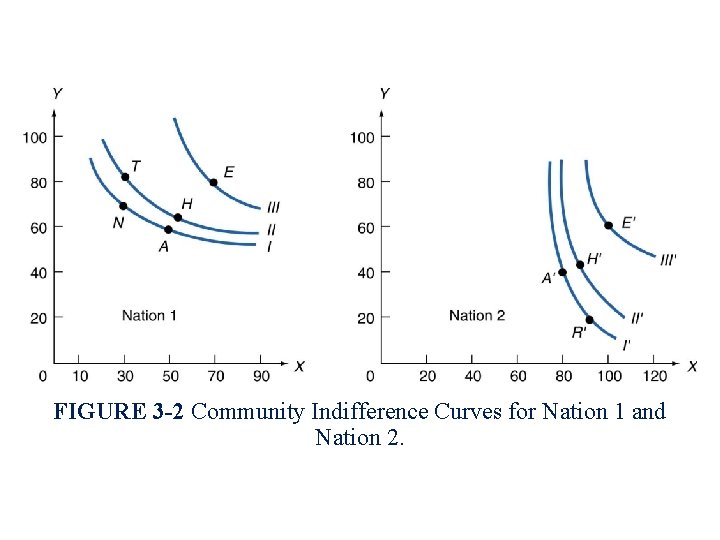

3. 3 Community Indifference Curves § A community indifference curve shows the various combinations of two commodities that yield equal satisfaction to the community. § Higher curves refer to greater satisfaction. A. Illustration of Community Indifference Curves § Fig. 3 -2 shows 3 hypothetical indifference curves for the two nations. They differ according to tastes. § Points A and N give equal satisfaction. § Points T and H refer to higher satisfaction

FIGURE 3 -2 Community Indifference Curves for Nation 1 and Nation 2.

B. The Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS) § The MRS of X for Y in consumption refers to the amount of Y that a nation must give up for one extra unit of X and still remain on the same IC. § This is given by the (absolute) slope of the community IC at the point of consumption and declines as the nation moves down the curve. § The decline in MRS is a reflection of the fact that the more of X and less of Y a nation consumes, the more valuable Y becomes compared to X.

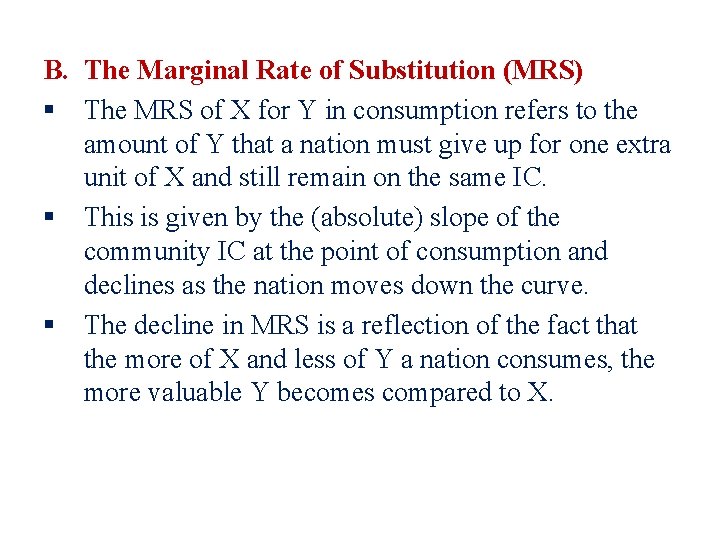

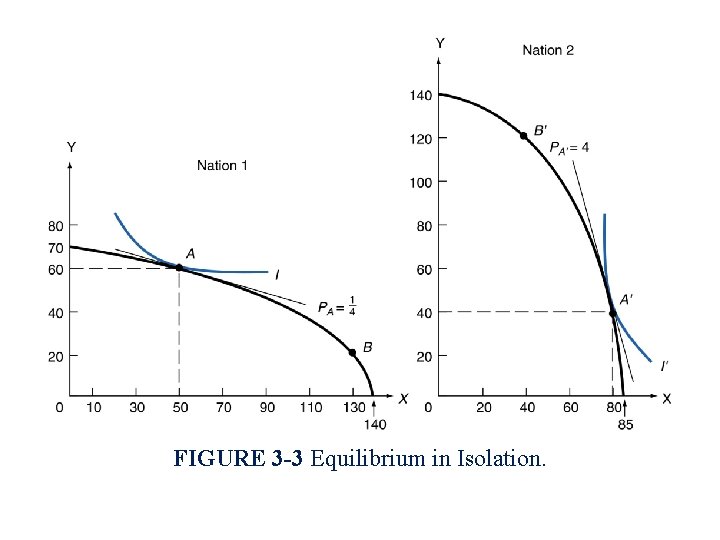

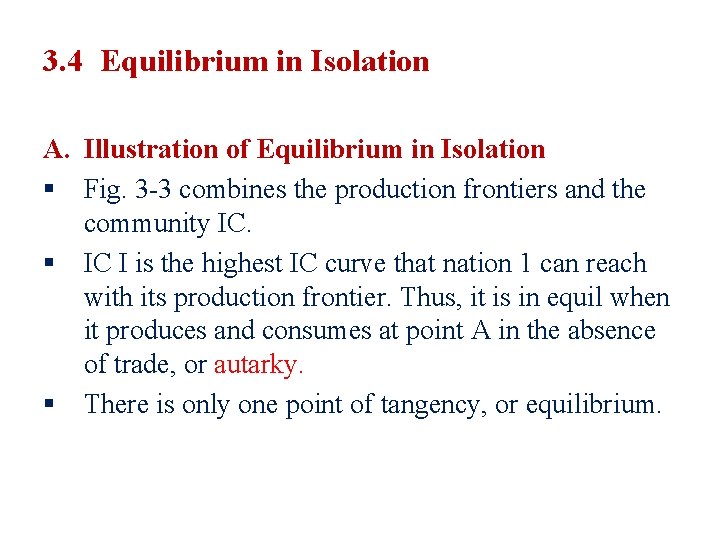

3. 4 Equilibrium in Isolation A. Illustration of Equilibrium in Isolation § Fig. 3 -3 combines the production frontiers and the community IC. § IC I is the highest IC curve that nation 1 can reach with its production frontier. Thus, it is in equil when it produces and consumes at point A in the absence of trade, or autarky. § There is only one point of tangency, or equilibrium.

FIGURE 3 -3 Equilibrium in Isolation.

B. Equilibrium-Relative Commodity Prices and Comparative Advantage § The equil-relative commodity price in isolation is given by the slope of the common tangent to the nation’s production frontier and the IC at the autarky point of production and consumption. § Equil-relative price of X in isolation is PA = PX / PY = ¼ in nation 1 and PA’ = PX / PY =4 in nation 2. § Relative prices are different in the two nations because their production frontiers and ICs differ in shape and location.

§ Since in isolation PA < PA’ nation 1 has a comp- adv in X and nation 2 in Y. Both can gain if nation 1 specializes in X, and nation 2 in Y. § Forces of supply (nation’s PF) and forces of demand (nation’s IC) together determine the equilibriumrelative commodity prices in each nation in autarky.

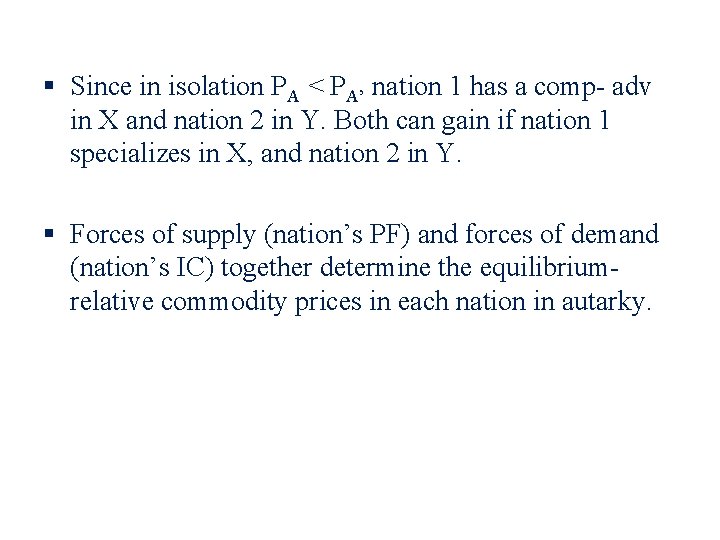

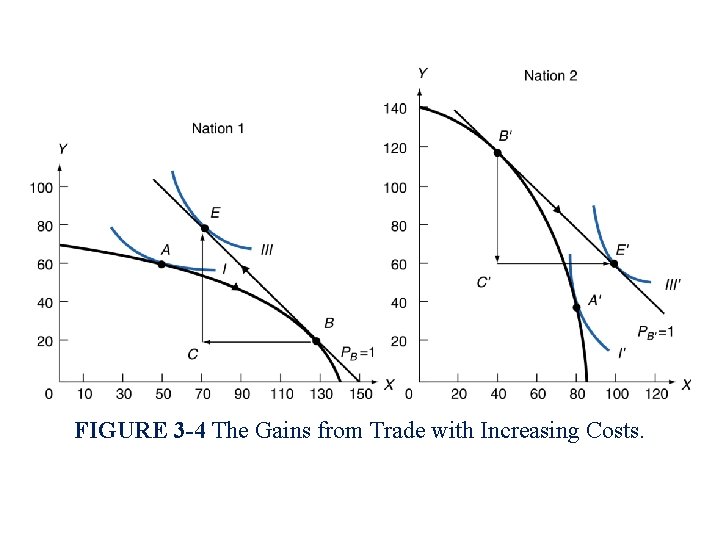

3. 5 The Basis for and the Gains from Trade with Increasing Costs A. Illustrations of the Basis for and the Gains from Trade with Increasing Costs § Starting from point A, as nation 1 specializes in X and moves down its PF, it incurs increasing opp. costs (as reflected in the increasing slope of the PF). § Starting from point A’, as nation 2 specializes in Y and moves upward its PF, it incurs increasing opp. costs (as reflected in the decline in slope of the PF). § Specialization in production continues until relative commodity prices become equal in the two nations.

FIGURE 3 -4 The Gains from Trade with Increasing Costs.

§ The common relative price (slope) with trade will be somewhere between the pretrade relative prices of ¼ and 4, at the level at which trade is balanced. In figure 3 -4, this is PB = PB’ = 1. § With trade, nation 1 moves from A down to B. by exchanging 60 X for 60 Y with nation 2, nation 1 ends up consuming at E (70 X and 80 Y) on its IC III. § This is the highest level of satisfaction that nation 1 can reach with trade at PX/PY = 1. Thus, nation 1 gains 20 X & 20 Y from its no-trade equilibrium point. § Nation 2 moves from A’ to B’, and with trade of 60 Y for 60 X it ends up consuming at E’ (100 X and 60 Y). § Nation 2 gains 20 X & 20 Y from specialization/trade.

B. Equilibrium-Relative Commodity Prices with Trade (ERCPT) § The ERCPT is the common relative price in both nations at which trade is balanced, this is PB= PB’=1. § At this relative, the amount of X that nation 1 wants to export (60 X) equals the amount of X that nation 2 wants to import (60 X). Similarly for nation 2 and Y. § Any other relative price could not persist because trade would be unbalanced. § The greater the desire of nation 1 for Y and the weaker is nation 2’s desire for X, the closer the equil. price with trade will be to 1/4 and the smaller will be nation 1’s share of the gain.

§ Once equil-relative price with trade is determined, gains from trade will be known exactly and the model will be complete. § The equil-relative price of X with trade (PB= PB’=1) results in equal gains (20 X and 20 Y). § If the pretrade - relative price had been the same in both nations, there would be no comp-advantage or disadvantage in either nation, and no specialization in production or mutually beneficial trade would take place.

C. Incomplete Specialization § Under constant costs, both nations specialize completely in production of the commodity of their comparative advantage. § However, under increasing costs there is incomplete specialization in production in both nations. § That is, nation 1 continues producing Y (point B), and nation 2 continues producing X (point B’). § Reason: as nation 1 specializes in X, it incurs increasing opp. costs in production of X. Similarly, as nation 2 produces more Y, it incurs opp. costs in Y (implying decreasing opp. costs of X).

§ With specialization, relative prices move toward each other until they are identical in both nations. § At this point, it does not pay for either nation to continue expanding production of the commodity of its comparative advantage. § This occurs before either nation has completely specialized in production. § In figure 3 -4, before nation 1 or nation 2 has completely specialized in production.

D. Small –Country Case with Increasing Costs § Under constant costs, the small country completely specializes in the production of the commodity of its comparative advantage, but the large country doesn’t § However, under increasing costs, we find incomplete specialization even in the small country case. § Assume nation 1 is the small country. § With no trade, nation 1 at equil. at point A. § Suppose the equil-relative price of X on world market is 1 (PW=1), and not affected by trade with nation 1. § Since the pretrade relative price of X in nation 1 is PA=1/4 is lower than world price, it has comparative advantage in the production of X.

§ With trade, nation 1 specializes in X until it reaches point B where PB=1=PW § Even though nation 1 is a small country, it doesn’t completely specialize in X (as under constant costs). § By exchanging 60 X for 60 Y, nation 1 reaches point E and gains 20 X and 20 Y (compared to autarky; A). § The only difference from the case discussed before is that nation 1 doesn’t affect relative prices in nation 2. § Nation 1 captures all the benefits from trade.

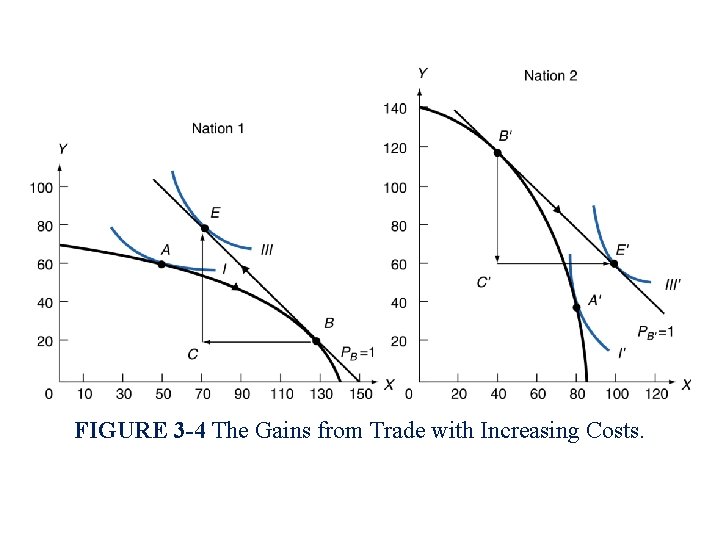

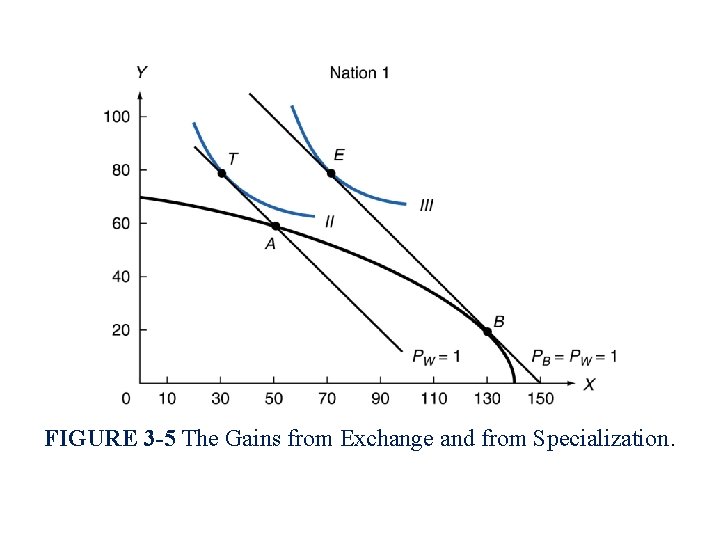

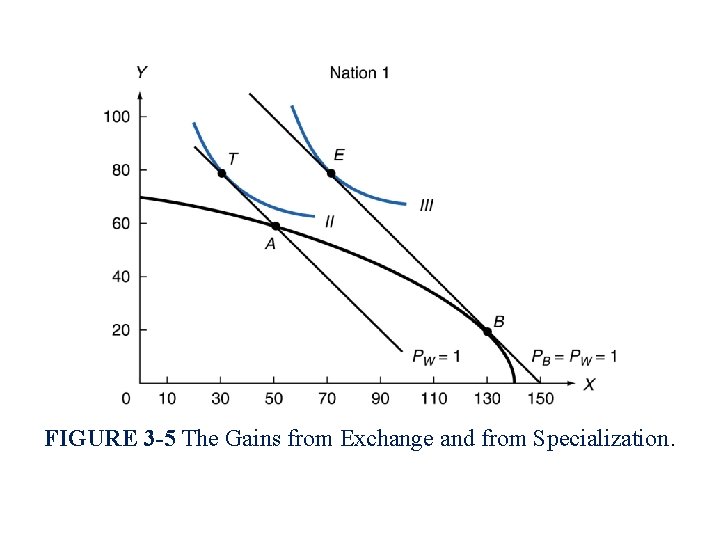

E. The Gains from Exchange and Specialization § A nation’s gains from trade arise from exchange and specialization. § Fig 3 -5 shows this breakdown for the small nation 1 § Suppose nation 1 could not specialize in X with trade and continued produce at A, where MRT=1/4 § Starting from A, nation 1 could export 20 X in exchange for 20 Y at PW =1 and end up at point T. § Although it consumes less of X and more of Y (at T) it is better off than it was in autarky because it is on higher indifference curve. § Movement from A to T in consumption measures the gain from exchange.

FIGURE 3 -5 The Gains from Exchange and from Specialization.

§ If subsequently nation 1 also specialized in X and produced at B, it could then exchange 60 X for 60 Y with the rest of the world and consume at E. § The movement from T to E in consumption measures the gains from specialization in production. § In sum, the movement from A (on IC I) to T (on IC II) made possible by exchange only. § The movement from T (on IC II) to E (on IC III) made possible by specialization in production. § Note that nation 1 is not in equil at point A with trade because MRT < PW. To be in equil in production, it should expand production of X until it reaches point B, where PB = PW =1

Liberal ipe

Liberal ipe Mercantilism and triangular trade

Mercantilism and triangular trade Current theory of international trade adalah

Current theory of international trade adalah International trade theory

International trade theory International trade theory

International trade theory New trade theory

New trade theory Modern theory of trade

Modern theory of trade Eco 303

Eco 303 Product life cycle theory of international trade

Product life cycle theory of international trade Standard theory of trade

Standard theory of trade Standard trade theory

Standard trade theory Chapter 6 theories of international trade and investment

Chapter 6 theories of international trade and investment Chapter 9 application: international trade answers

Chapter 9 application: international trade answers Trade diversion and trade creation

Trade diversion and trade creation Umich

Umich Trade diversion and trade creation

Trade diversion and trade creation The trade in the trade-to-gdp ratio

The trade in the trade-to-gdp ratio Fair trade not free trade

Fair trade not free trade Trade diversion and trade creation

Trade diversion and trade creation Tramp shipping and liner shipping

Tramp shipping and liner shipping Triangular trade definition

Triangular trade definition International specialization and trade

International specialization and trade Difference between balance of trade and balance of payment

Difference between balance of trade and balance of payment Importance of international trade

Importance of international trade The dynamic environment of international trade

The dynamic environment of international trade Certificate in international trade and finance citf

Certificate in international trade and finance citf