ECONOMIES OF AGGLOMERATION ECONOMIES OF AGGLOMERATION Density generates

- Slides: 55

ECONOMIES OF AGGLOMERATION

ECONOMIES OF AGGLOMERATION Ø Density generates costs ü Higher cost of land ü Greater congestion, higher commuting and transport costs Ø Population and economic activity are ever more concentrated in cities Ø There must be offsetting benefits ü Higher productivity for firms ü Higher wages for workers Ø Are these advantages due to agglomeration economies? Ø What are their scale and scope and causes?

v Why is it profitable for firms to concentrate employment? 1. Plant-level economies of scale § Plants produce more efficiently at a larger scale 2. Agglomeration economies § Plants produce more efficiently when close to other plants A. Urbanization economies ü when close to other plants in general B. Localization economies ü when close to other plants in the same industry

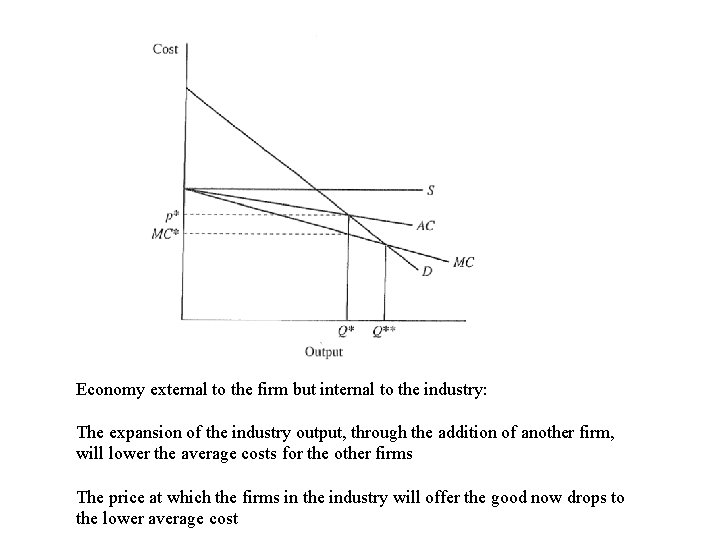

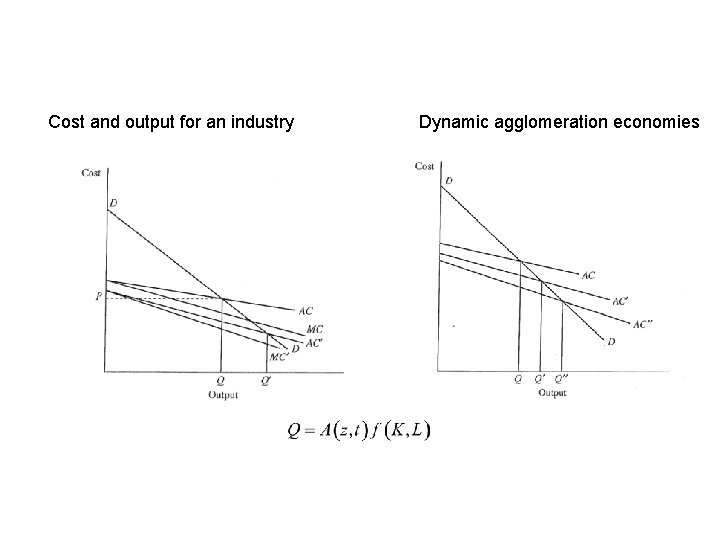

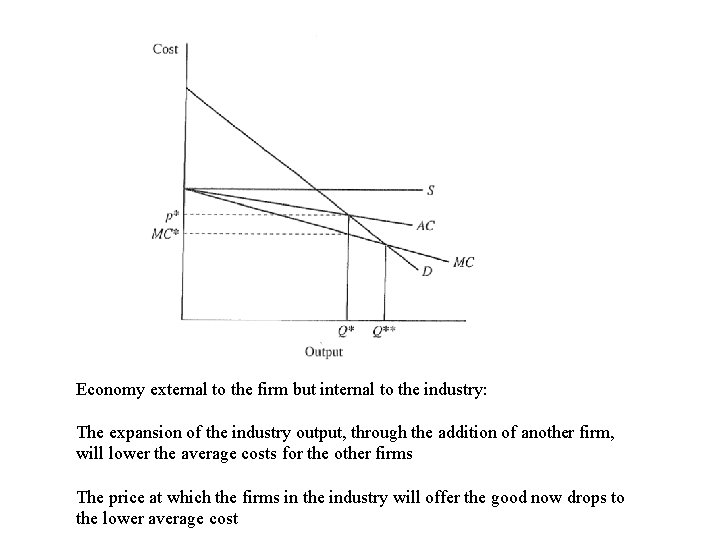

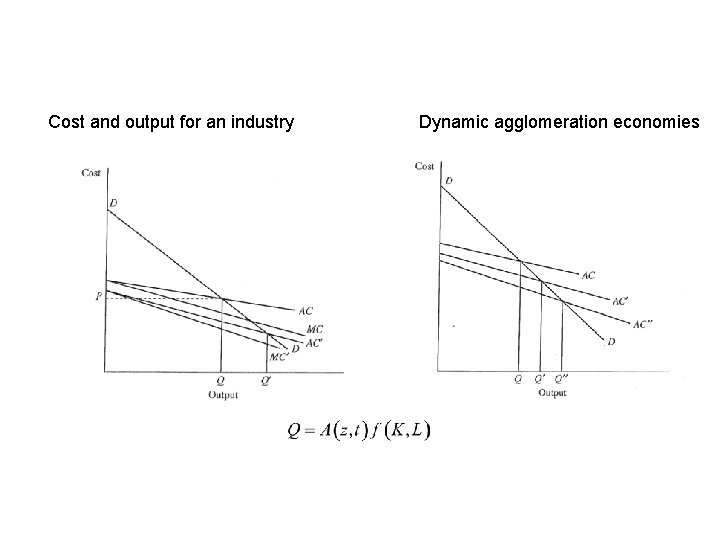

• Economies of agglomeration are externalities • A person who is making an economic decision, such as whether to produce more output, makes the decision on the basis of his own marginal costs and benefits, and ignores costs or benefits that affect others An example • An industry in an urban area: demand, D and supply, S • Made up of a large number of small, competitive firms • Each of these firms has a lon-run average cost curve that has a minimum point at some level of output • In the long run the output of the industry expands by adding more firms • The long-run supply curve of the industry is the horizontal line S • The market price is set equal to long-run average and marginal curve

Economy external to the firm but internal to the industry: The expansion of the industry output, through the addition of another firm, will lower the average costs for the other firms The price at which the firms in the industry will offer the good now drops to the lower average cost

MICRO-FOUNDATIONS OF AGGLOMERATION ECONOMIES • Sharing. • Matching. • Learning.

1. SHARING A. Ø Ø Sharing indivisible facilities Simplest argument to justify the existence of a city Example: ice hockey rink • Expensive facility with substantial fixed costs • Few individuals would hold a rink for themselves • An ice hockey rink is a an indivisible facility that can be shared by many users Ø Factory towns

B. Sharing the gains form the wider variety of input suppliers that can be sustained by a larger final goods industry C. Sharing the gains from the narrower specialisation that can be sustained with larger production

Model of gains from diversity Productive advantages of sharing a wider variety of differentiated intermediate inputs produced by a monopolistically competitive industry ↓ Aggregate returns to scale There are sectors In each sector, perfectly competitive firms produce goods for final consumption under constant returns to scale They use intermediate inputs, which are specific to each sector and enter into plants’ technology with a constant elasticity of substitution The higher the lower the elasticity of substitution

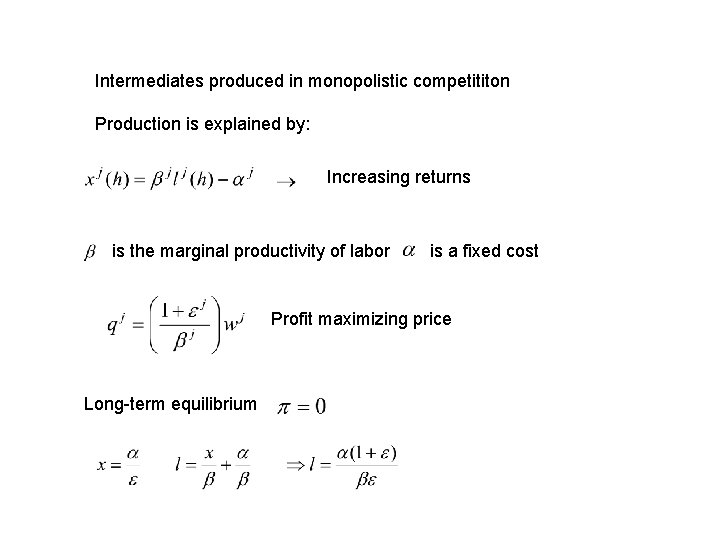

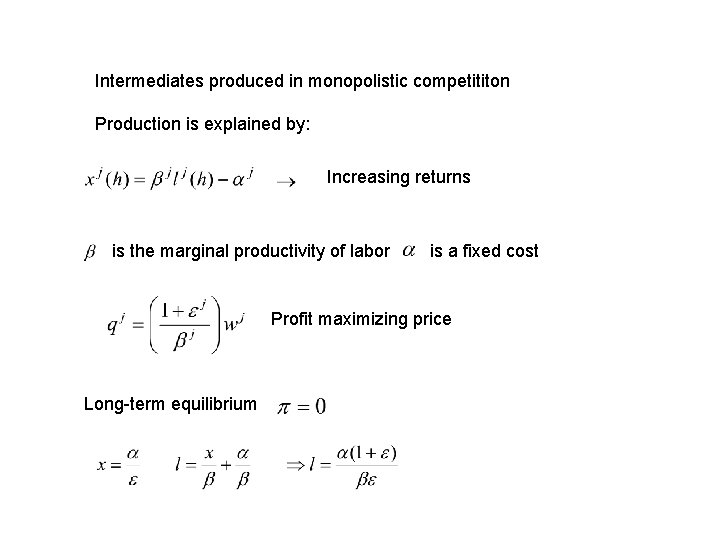

Intermediates produced in monopolistic competititon Production is explained by: Increasing returns is the marginal productivity of labor is a fixed cost Profit maximizing price Long-term equilibrium

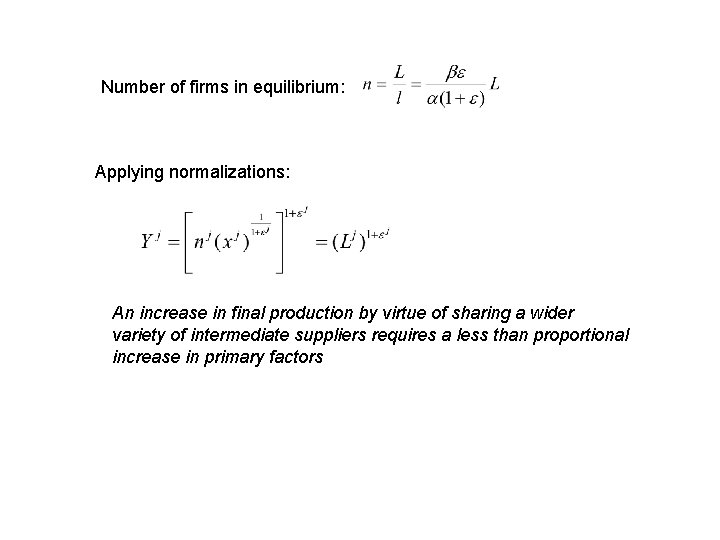

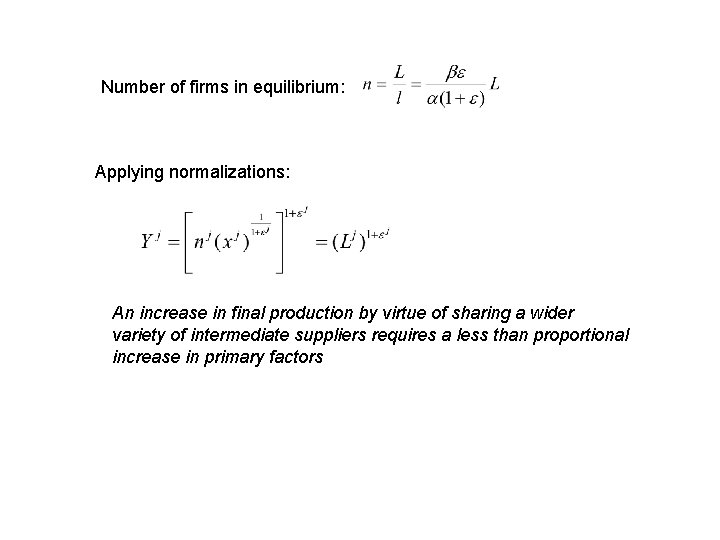

Number of firms in equilibrium: Applying normalizations: An increase in final production by virtue of sharing a wider variety of intermediate suppliers requires a less than proportional increase in primary factors

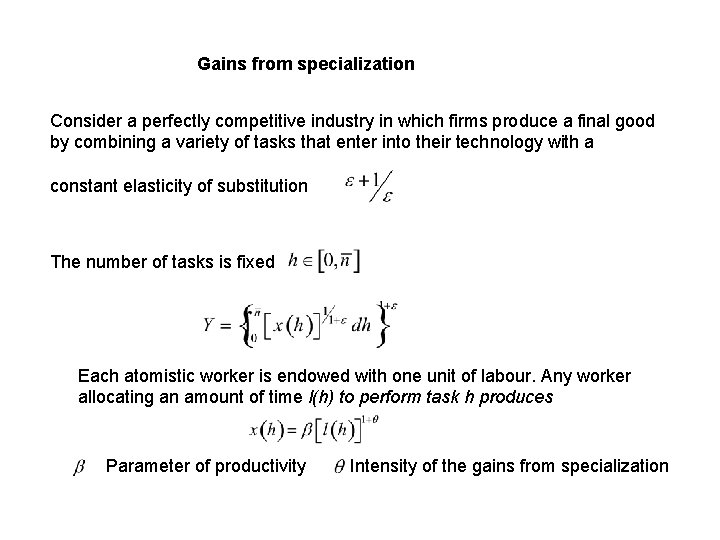

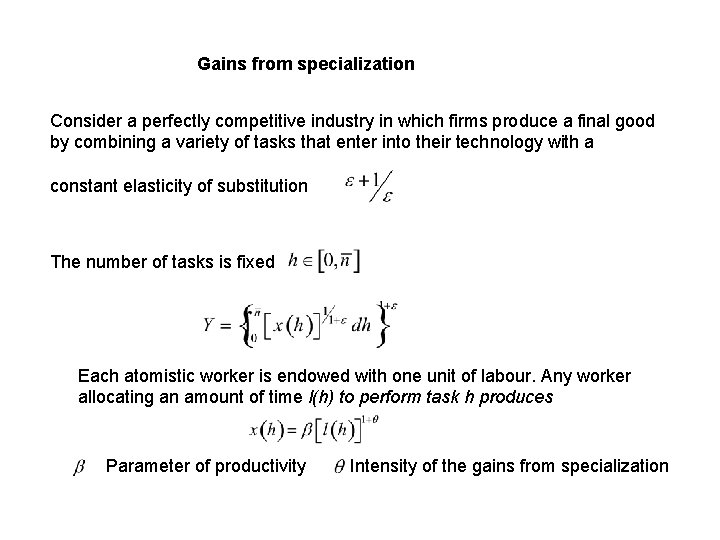

Gains from specialization Consider a perfectly competitive industry in which firms produce a final good by combining a variety of tasks that enter into their technology with a constant elasticity of substitution The number of tasks is fixed Each atomistic worker is endowed with one unit of labour. Any worker allocating an amount of time l(h) to perform task h produces Parameter of productivity Intensity of the gains from specialization

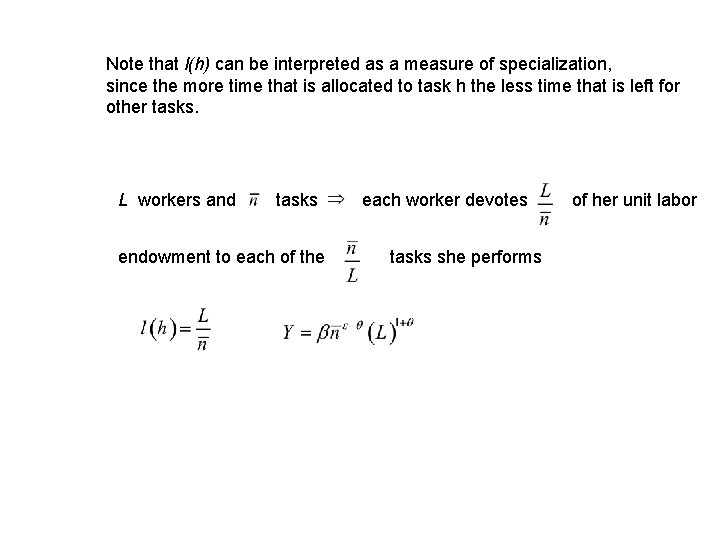

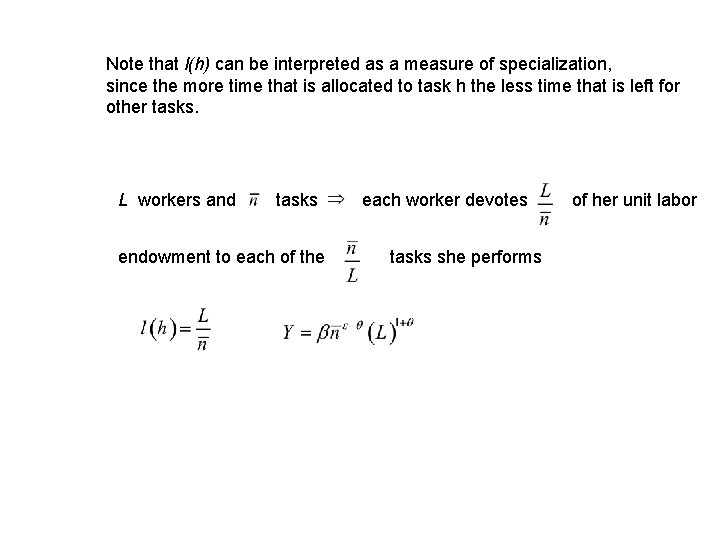

Note that l(h) can be interpreted as a measure of specialization, since the more time that is allocated to task h the less time that is left for other tasks. L workers and tasks endowment to each of the each worker devotes of her unit labor tasks she performs

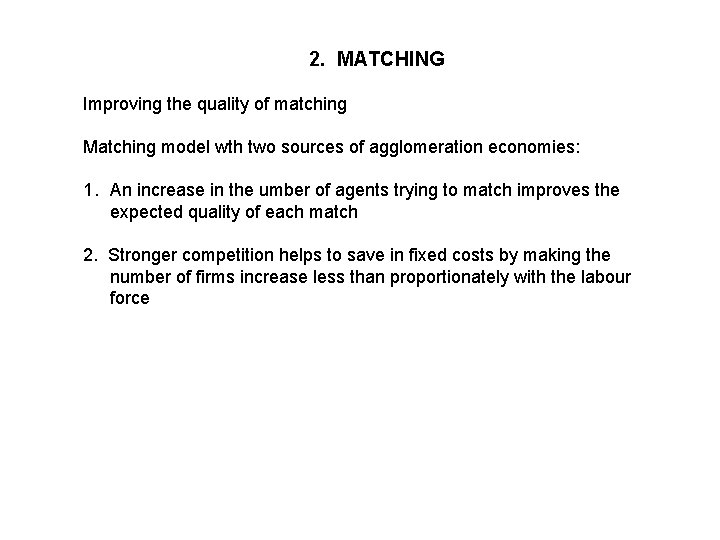

2. MATCHING Improving the quality of matching Matching model wth two sources of agglomeration economies: 1. An increase in the umber of agents trying to match improves the expected quality of each match 2. Stronger competition helps to save in fixed costs by making the number of firms increase less than proportionately with the labour force

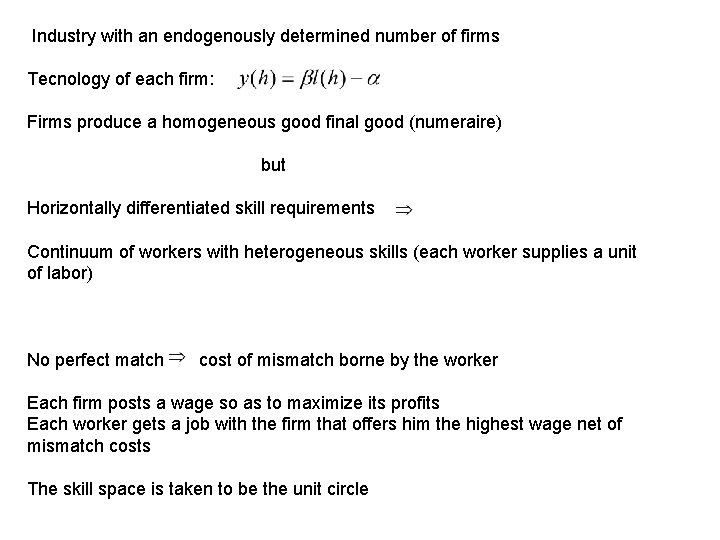

Industry with an endogenously determined number of firms Tecnology of each firm: Firms produce a homogeneous good final good (numeraire) but Horizontally differentiated skill requirements Continuum of workers with heterogeneous skills (each worker supplies a unit of labor) No perfect match cost of mismatch borne by the worker Each firm posts a wage so as to maximize its profits Each worker gets a job with the firm that offers him the highest wage net of mismatch costs The skill space is taken to be the unit circle

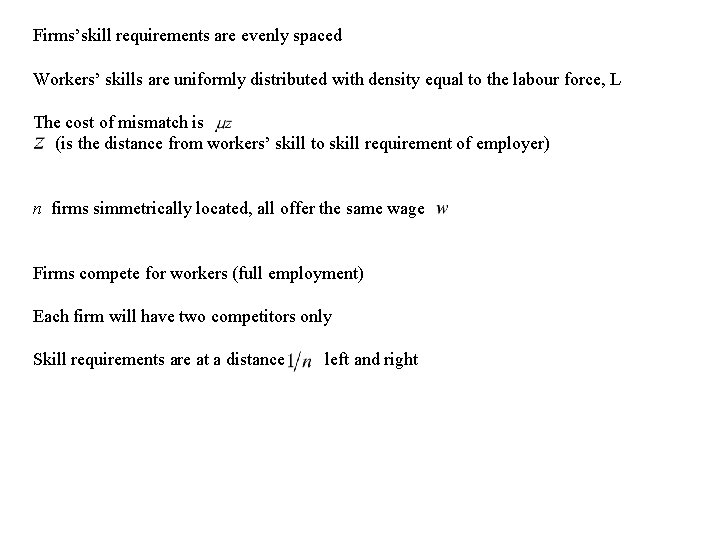

Firms’skill requirements are evenly spaced Workers’ skills are uniformly distributed with density equal to the labour force, L The cost of mismatch is (is the distance from workers’ skill to skill requirement of employer) n firms simmetrically located, all offer the same wage Firms compete for workers (full employment) Each firm will have two competitors only Skill requirements are at a distance left and right

A worker located at z from firm h is indiferent between h and the closest competitor Firm h will hire workers whose skill is within distance z to its skill requirement By offering a higher wage than its competitors a firm can increase its workforce above its proportional labour market share

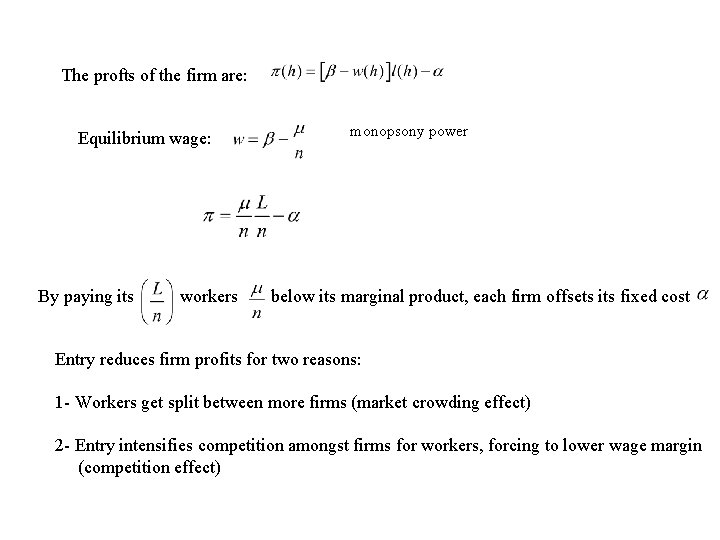

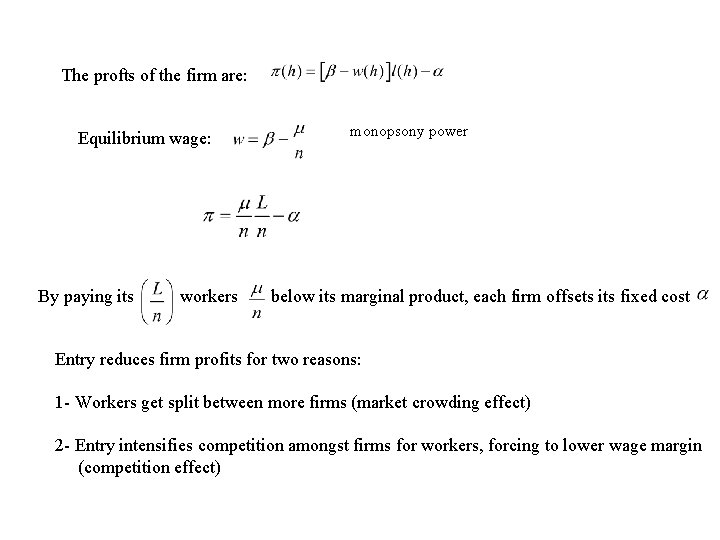

The profts of the firm are: Equilibrium wage: By paying its workers monopsony power below its marginal product, each firm offsets its fixed cost Entry reduces firm profits for two reasons: 1 - Workers get split between more firms (market crowding effect) 2 - Entry intensifies competition amongst firms for workers, forcing to lower wage margin (competition effect)

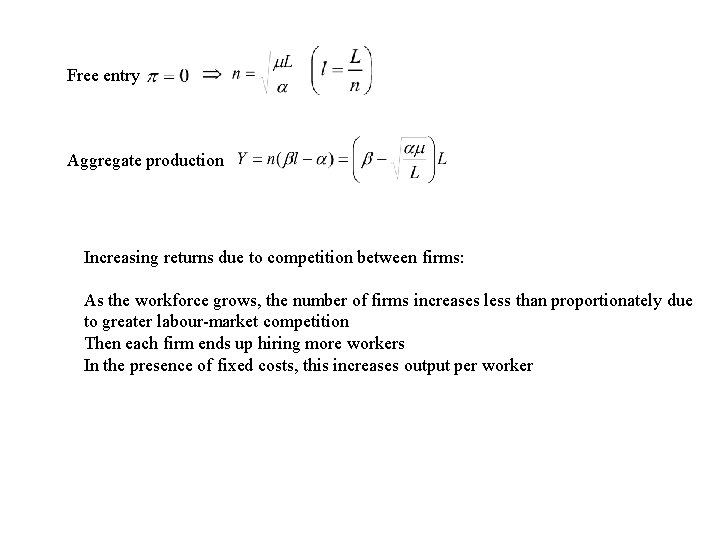

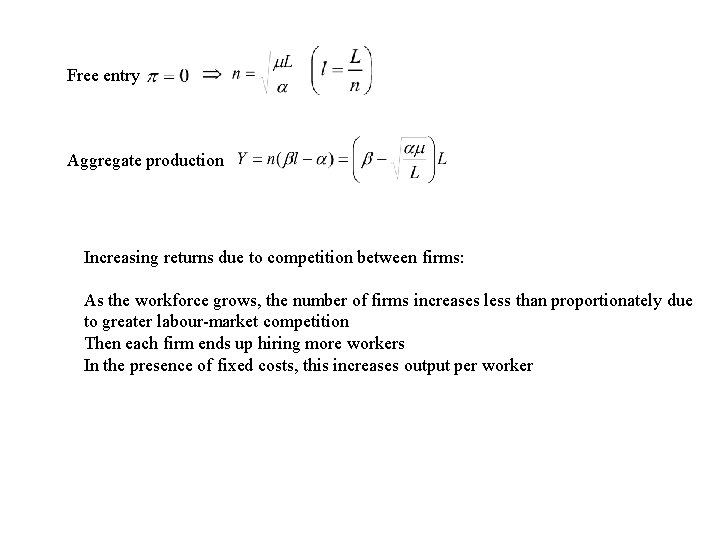

Free entry Aggregate production Increasing returns due to competition between firms: As the workforce grows, the number of firms increases less than proportionately due to greater labour-market competition Then each firm ends up hiring more workers In the presence of fixed costs, this increases output per worker

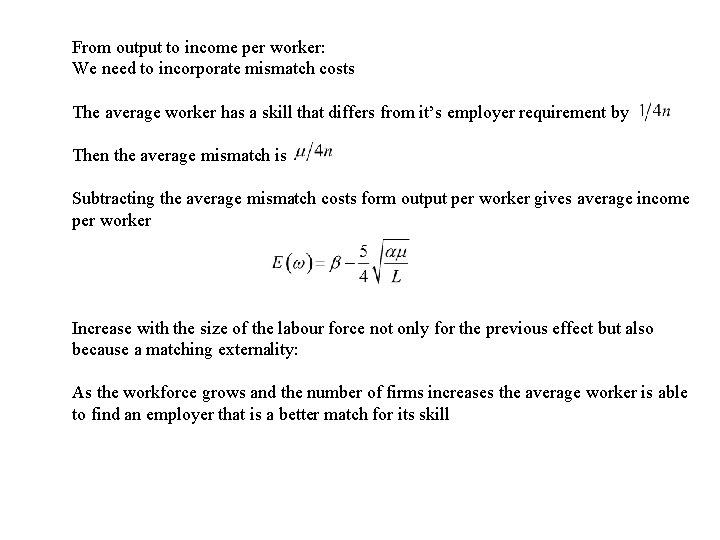

From output to income per worker: We need to incorporate mismatch costs The average worker has a skill that differs from it’s employer requirement by Then the average mismatch is Subtracting the average mismatch costs form output per worker gives average income per worker Increase with the size of the labour force not only for the previous effect but also because a matching externality: As the workforce grows and the number of firms increases the average worker is able to find an employer that is a better match for its skill

3. LEARNING The Obligatory Marshall Quotation When an industry has thus chosen a locality for itself, it is likely to stay there long: so great are the advantages which people following the same skilled trade get from near neighbourhood to one another. The mysteries of the trade become no mysteries; but are as it were in the air, and children learn many of them unconsciously. Good work is rightly appreciated, inventions and improvements in machinery, in processes and the general organization of the business have their merits promptly discussed: if one man starts a new idea, it is taken up by others and combined with suggestions of their own; and thus it becomes the source of further new ideas. Alfred Marshall. 1890. Principles of Economics. London: Macmillan. Book IV, Ch. X, § 3: The advantages of localized industries; hereditary skill.

Cost and output for an industry Dynamic agglomeration economies

Ø Three Types of Externalities (Glaeser et al. 1992) 1. Marshall-Arrow-Romer Local knowledge spillovers between firms in the same industry Specialization and concentration promote growth ü Local monopoly helps growth by internalizing externalities 2. Porter Innovation in competitive industry clusters with many small firms Specialization and fragmentation promote city growth ü Local competition requires firms to innovate or die 3. Jacobs Local knowledge transfers across industries Diversification and fragmentation promote city growth ü “Cross-fertilization” of ideas across different lines of work

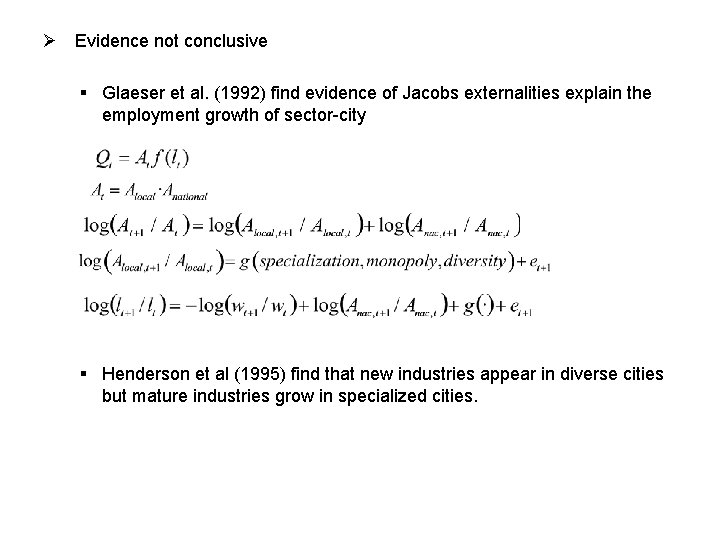

Ø Evidence not conclusive § Glaeser et al. (1992) find evidence of Jacobs externalities explain the employment growth of sector-city § Henderson et al (1995) find that new industries appear in diverse cities but mature industries grow in specialized cities.

Ø Nursery cities (Duranton and Puga, 2001) § Consider a firm that is looking for the ideal production process for a new product § By experimenting with different processes, the firm will find the ideal process § Once found the ideal process, the firm will switch to mass production and start earning a profit § Question is: where should the firm experiment, in a diverse city or a specialized city?

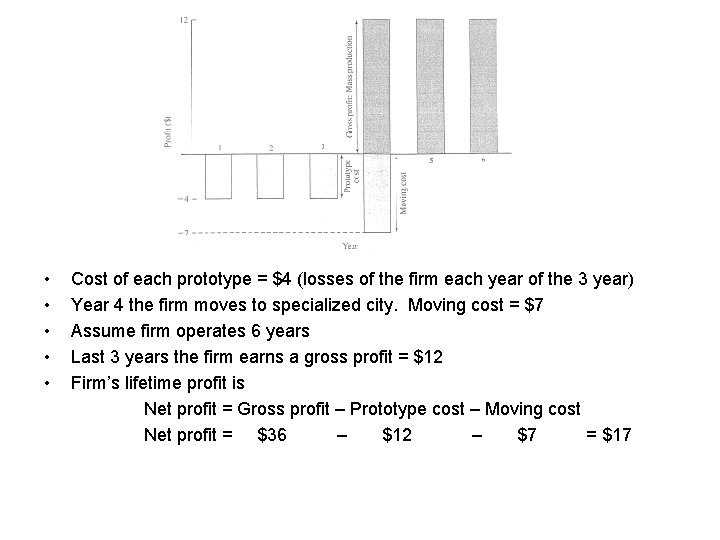

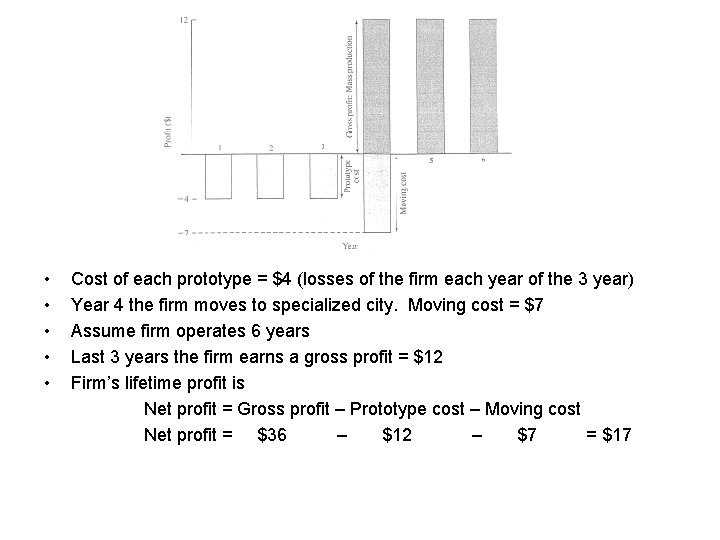

q Cost and Benefits of both options (model) Ø First option → experiment in a diverse city and then move to a specialized city after discovering the ideal process § An experiment entails producing a prototype of the firm’s new product with a particular production process § Suppose there are six processes in the diverse city § Once the prototype from the ideal process is finished, the firm will immediately recognize that it has discovered the ideal process § Assume that it takes on average three years § Once discovered the ideal, the entrepreneur will move to a specialized city and start making profits

• Cost of each prototype = $4 (losses of the firm each year of the 3 year) • Year 4 the firm moves to specialized city. Moving cost = $7 • Assume firm operates 6 years • Last 3 years the firm earns a gross profit = $12 • Firm’s lifetime profit is Net profit = Gross profit – Prototype cost – Moving cost Net profit = $36 – $12 – $7 = $17

Ø Second option → search for the process in the specialized city ü Advantage → lower prototype cost Each specialized city has the specialized inputs for one production process Suppose, prototype cost = $3 · 3 years = $9 ü Disadvantage → Higher moving cost The search for the ideal process would require moves from one specialized city to another An average of three moves, moving costs = $7 · 3 years = $21 Net profit = $36 - $9 - $21 = $6 Ø Profit is lower when experimenting in specialized cities Ø Different roles of diverse and specialized cities

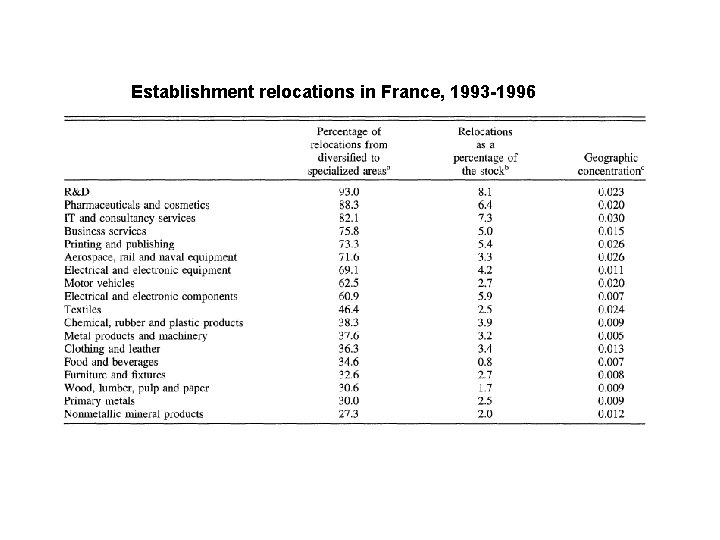

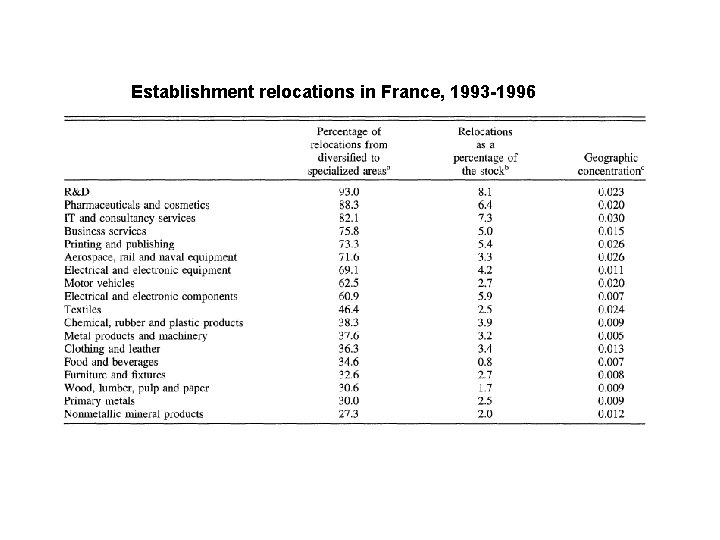

Establishment relocations in France, 1993 -1996

Ø Externalities of human capital Lucas (1988): “Most of what we know we learn form other people. We pay tuition to only a few of these teachers, either directly or indirectly by accepting lower pay so we hang around them, but most of it we get for free, and often in ways that are mutual- without distinction between student and teacher” • The productivity of individual workers is enhanced by an environment of high human capital • ü ü ü Labor and education policy Social returns to skill > private returns to skill Education as a public good Rationale for vast government intervention • Endogenous growth theory ü Lucas (1988) allows a country’s average human capital to increase TFP

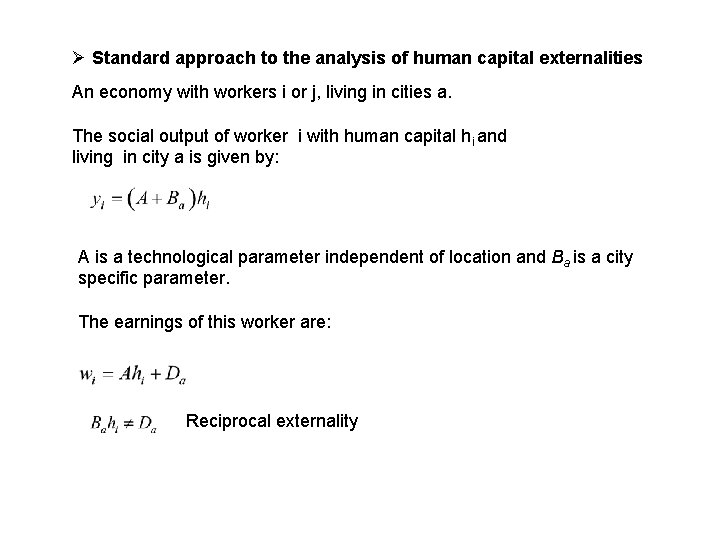

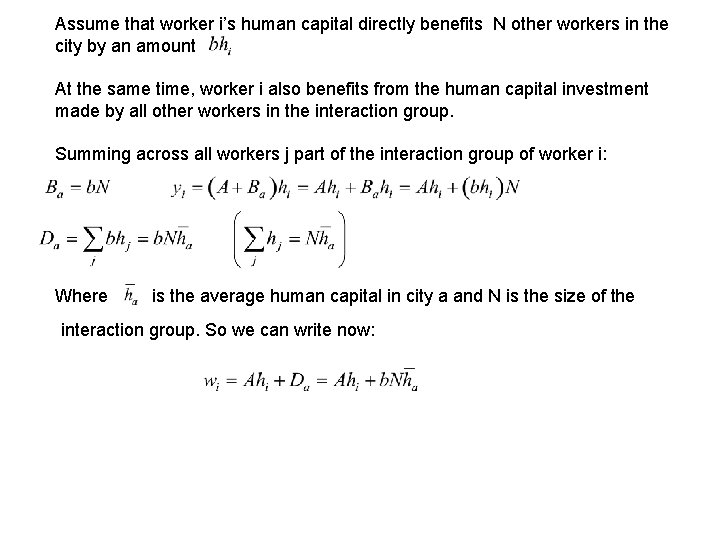

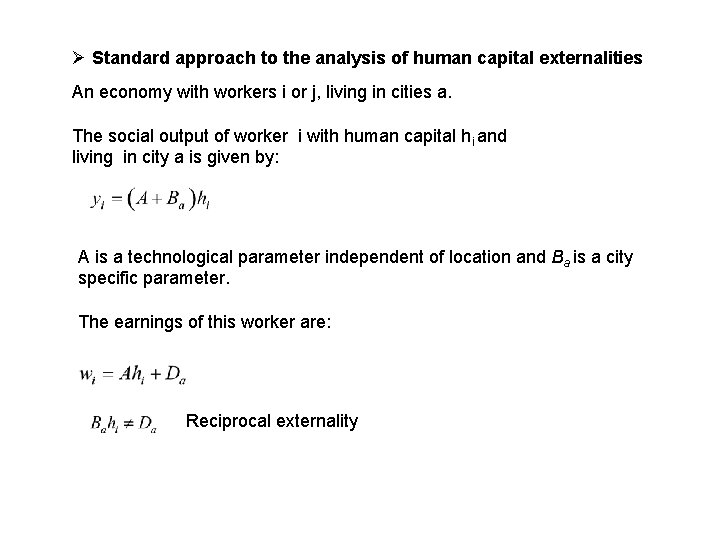

Ø Standard approach to the analysis of human capital externalities An economy with workers i or j, living in cities a. The social output of worker i with human capital hi and living in city a is given by: A is a technological parameter independent of location and Ba is a city specific parameter. The earnings of this worker are: Reciprocal externality

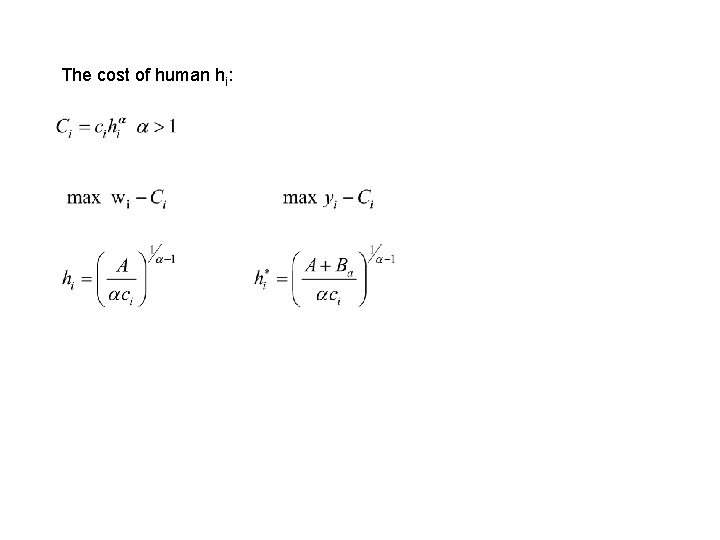

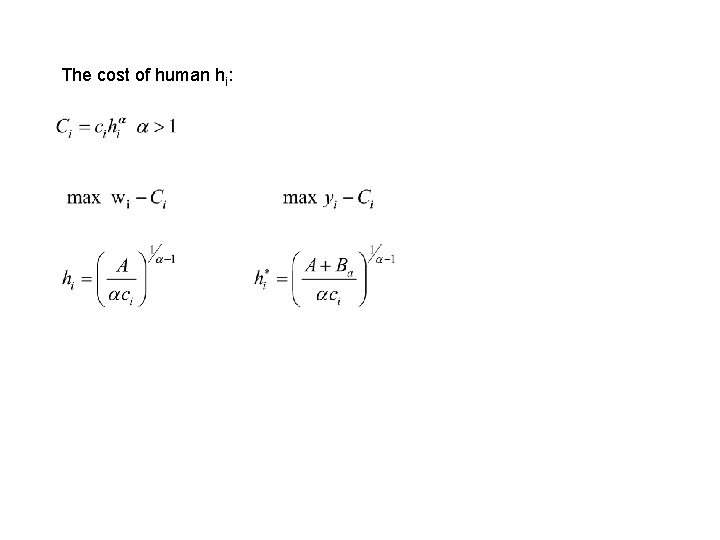

The cost of human hi:

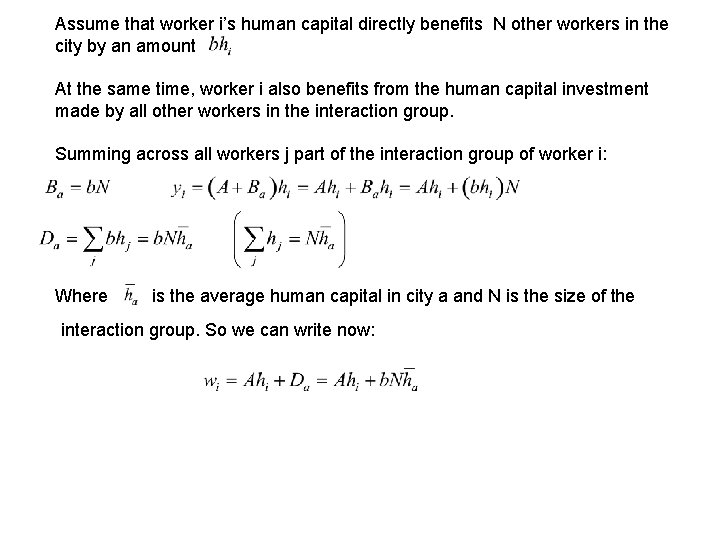

Assume that worker i’s human capital directly benefits N other workers in the city by an amount At the same time, worker i also benefits from the human capital investment made by all other workers in the interaction group. Summing across all workers j part of the interaction group of worker i: Where is the average human capital in city a and N is the size of the interaction group. So we can write now:

HOW TO MEASURE ECONOMIES OF AGGLOMERATION

MEASURING ECONOMIES OF AGGLOMERATION • Agglomeration economies imply that firms located in an agglomeration are able to produce more output with the same inputs The most natural and direct way to quantify agglomeration economies is to estimate the elasticity of some measure of average productivity with respect to some measure of local scale, such as employment density or total population

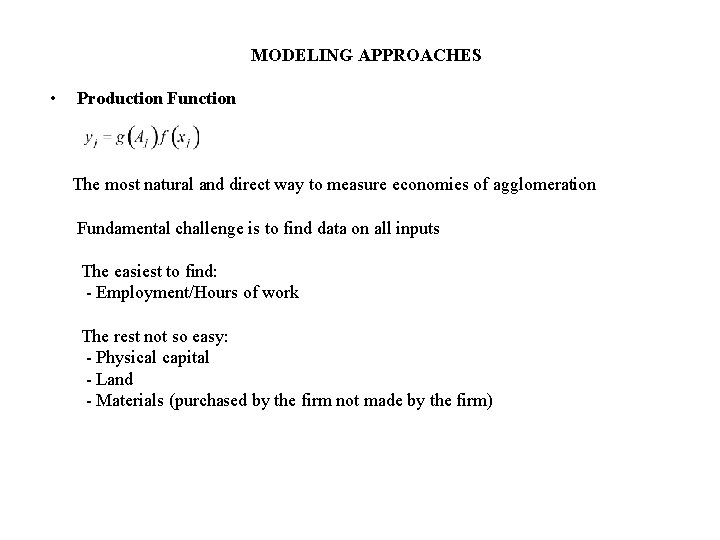

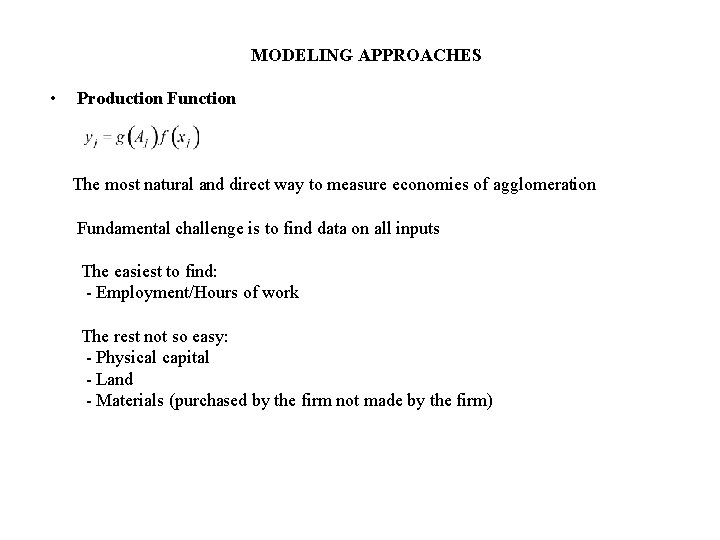

MODELING APPROACHES • Production Function The most natural and direct way to measure economies of agglomeration Fundamental challenge is to find data on all inputs The easiest to find: - Employment/Hours of work The rest not so easy: - Physical capital - Land - Materials (purchased by the firm not made by the firm)

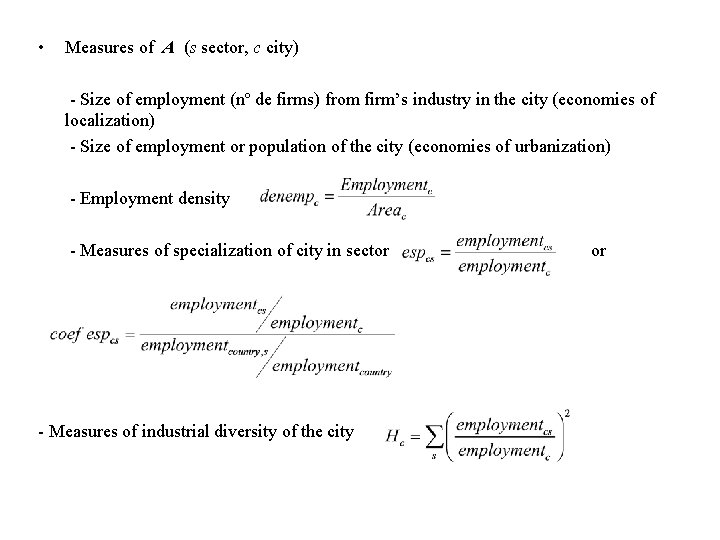

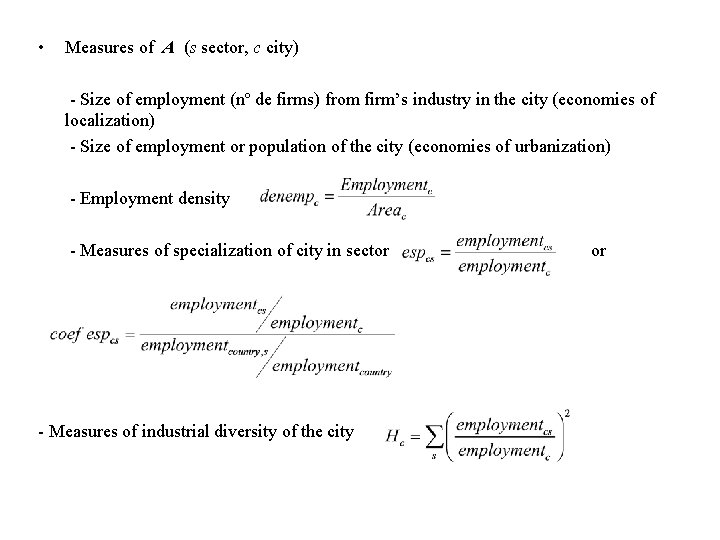

• Measures of A (s sector, c city) - Size of employment (nº de firms) from firm’s industry in the city (economies of localization) - Size of employment or population of the city (economies of urbanization) - Employment density - Measures of specialization of city in sector or - Measures of industrial diversity of the city

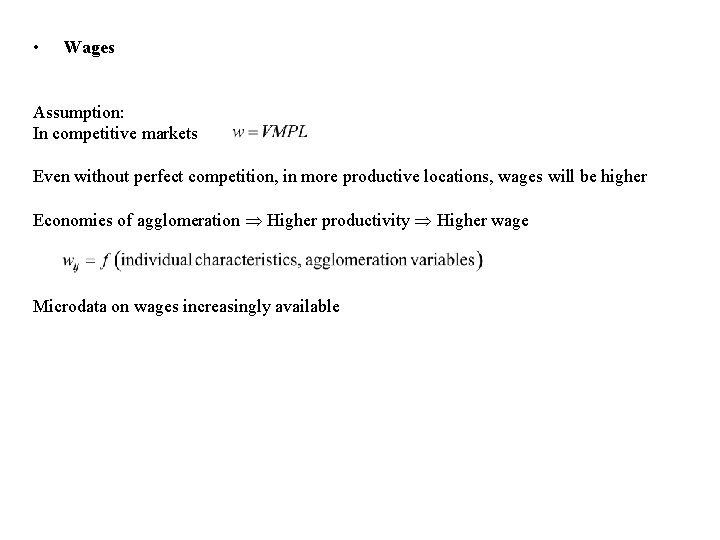

• Wages Assumption: In competitive markets Even without perfect competition, in more productive locations, wages will be higher Economies of agglomeration Higher productivity Higher wage Microdata on wages increasingly available

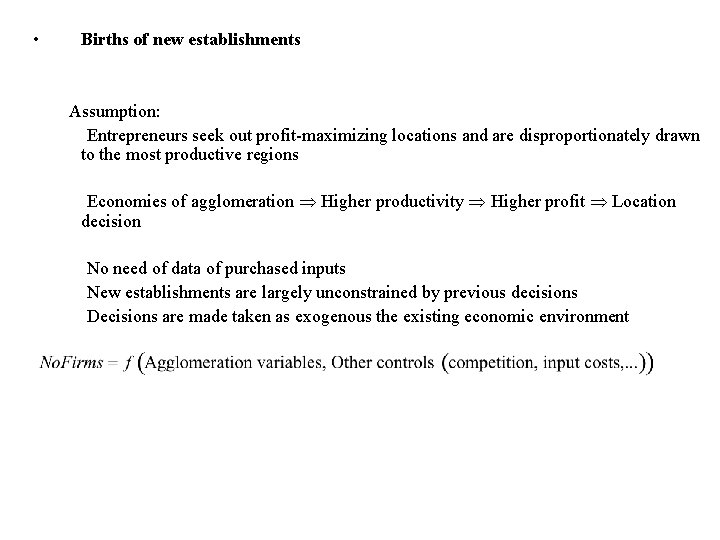

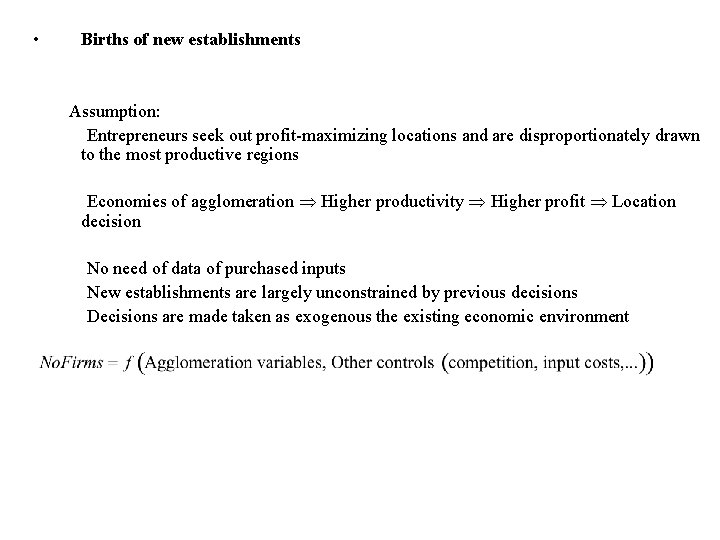

• Births of new establishments Assumption: Entrepreneurs seek out profit-maximizing locations and are disproportionately drawn to the most productive regions Economies of agglomeration Higher productivity Higher profit Location decision No need of data of purchased inputs New establishments are largely unconstrained by previous decisions Decisions are made taken as exogenous the existing economic environment

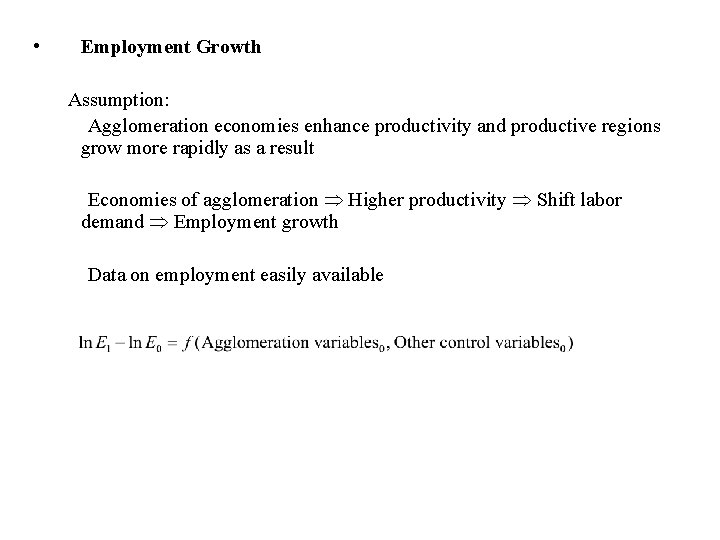

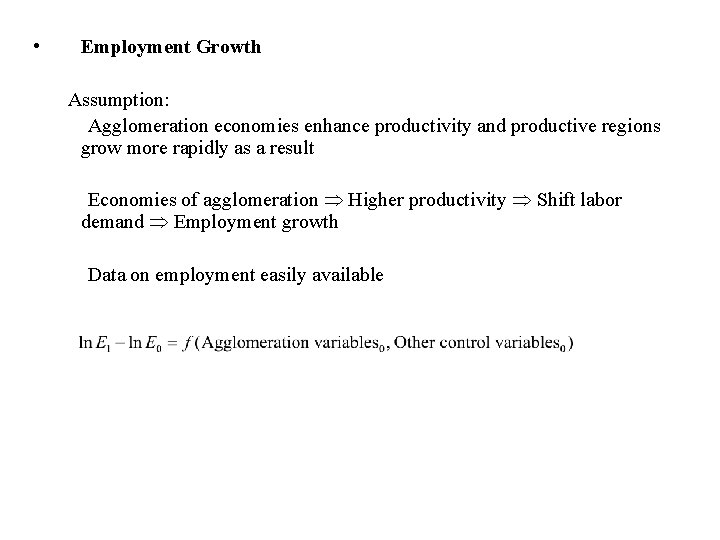

• Employment Growth Assumption: Agglomeration economies enhance productivity and productive regions grow more rapidly as a result Economies of agglomeration Higher productivity Shift labor demand Employment growth Data on employment easily available

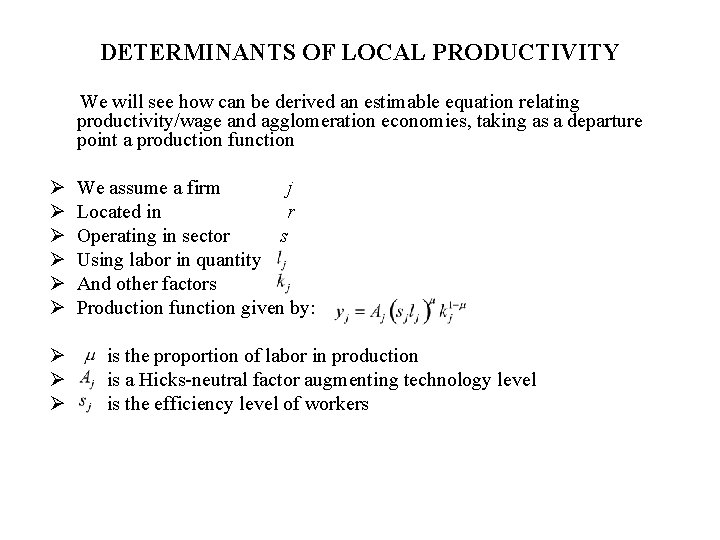

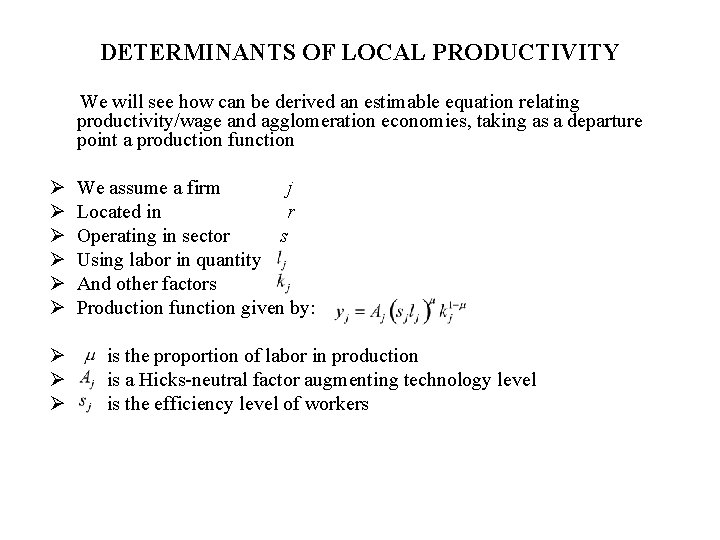

DETERMINANTS OF LOCAL PRODUCTIVITY We will see how can be derived an estimable equation relating productivity/wage and agglomeration economies, taking as a departure point a production function Ø Ø Ø Ø Ø We assume a firm j Located in r Operating in sector s Using labor in quantity And other factors Production function given by: is the proportion of labor in production is a Hicks-neutral factor augmenting technology level is the efficiency level of workers

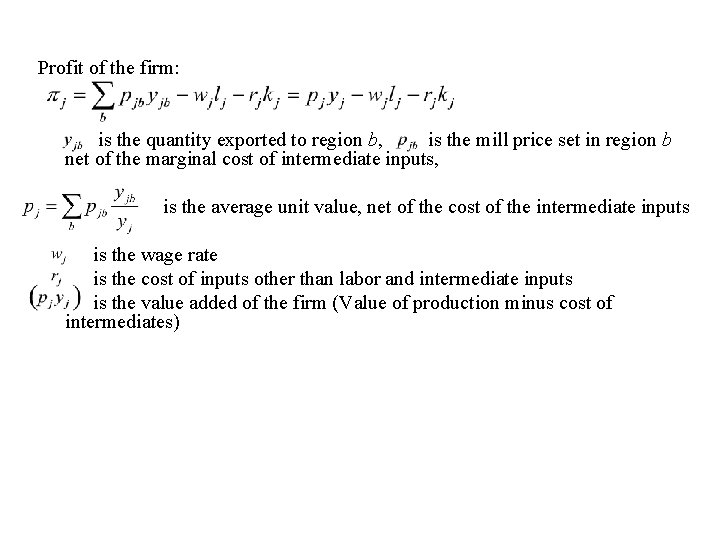

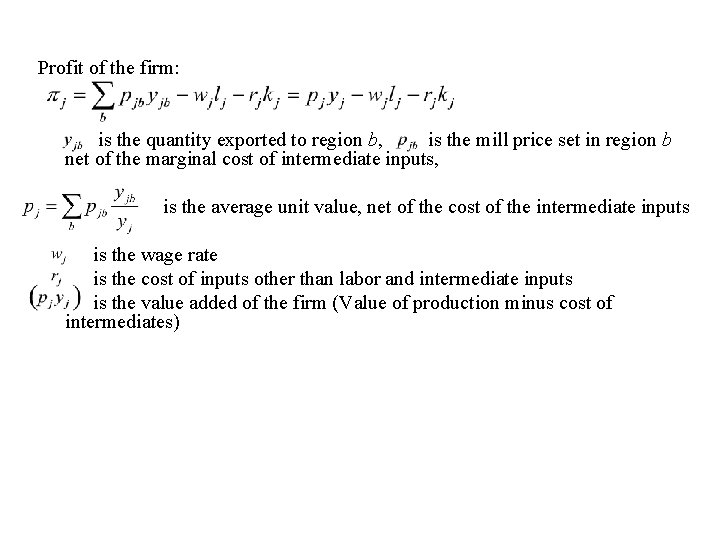

Profit of the firm: is the quantity exported to region b, is the mill price set in region b net of the marginal cost of intermediate inputs, is the average unit value, net of the cost of the intermediate inputs is the wage rate is the cost of inputs other than labor and intermediate inputs is the value added of the firm (Value of production minus cost of intermediates)

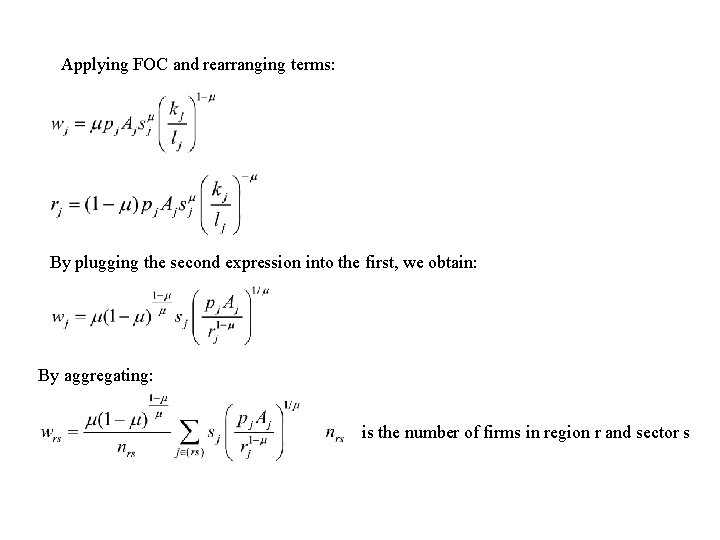

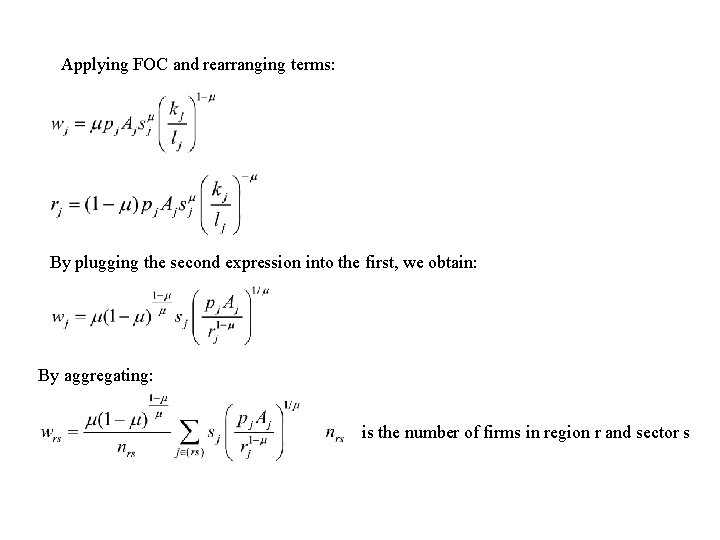

Applying FOC and rearranging terms: By plugging the second expression into the first, we obtain: By aggregating: is the number of firms in region r and sector s

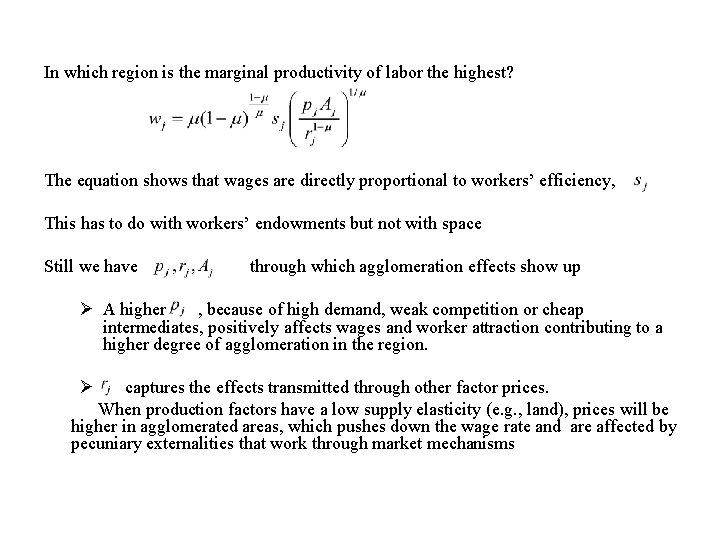

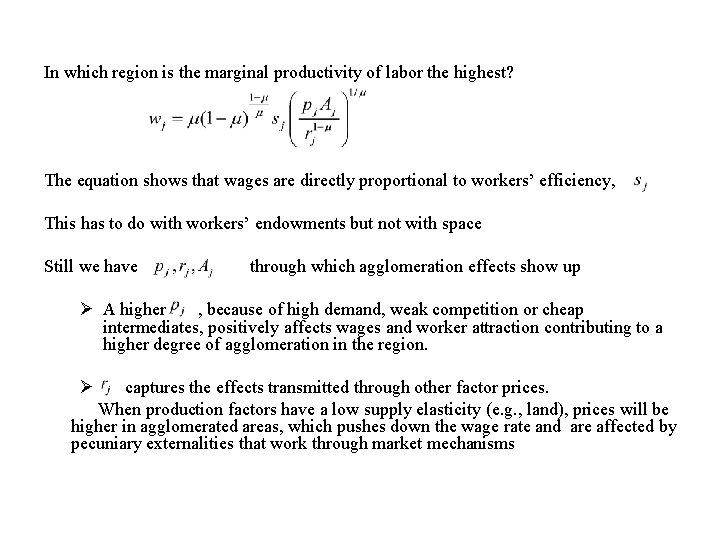

In which region is the marginal productivity of labor the highest? The equation shows that wages are directly proportional to workers’ efficiency, This has to do with workers’ endowments but not with space Still we have through which agglomeration effects show up Ø A higher , because of high demand, weak competition or cheap intermediates, positively affects wages and worker attraction contributing to a higher degree of agglomeration in the region. Ø captures the effects transmitted through other factor prices. When production factors have a low supply elasticity (e. g. , land), prices will be higher in agglomerated areas, which pushes down the wage rate and are affected by pecuniary externalities that work through market mechanisms

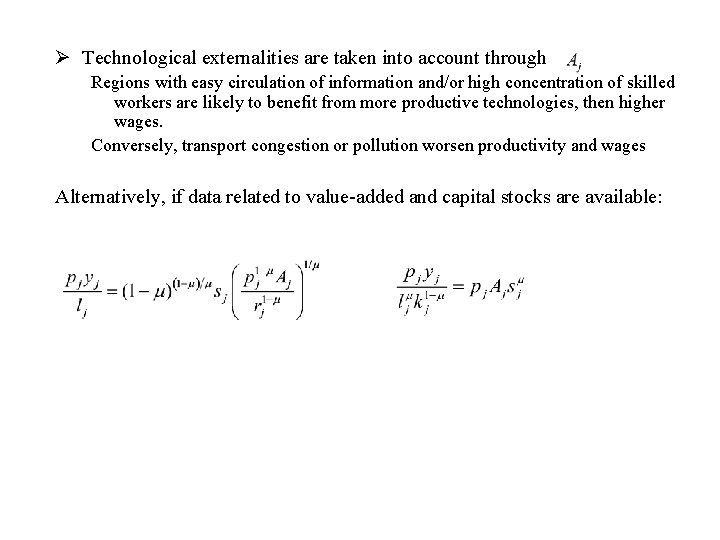

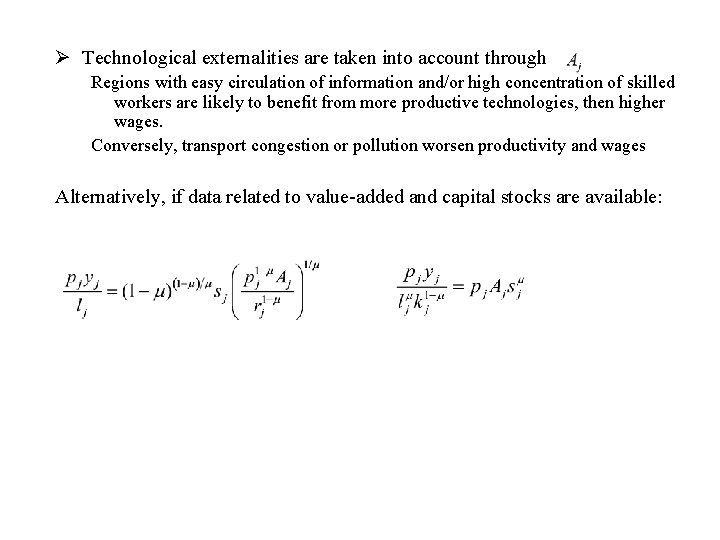

Ø Technological externalities are taken into account through Regions with easy circulation of information and/or high concentration of skilled workers are likely to benefit from more productive technologies, then higher wages. Conversely, transport congestion or pollution worsen productivity and wages Alternatively, if data related to value-added and capital stocks are available:

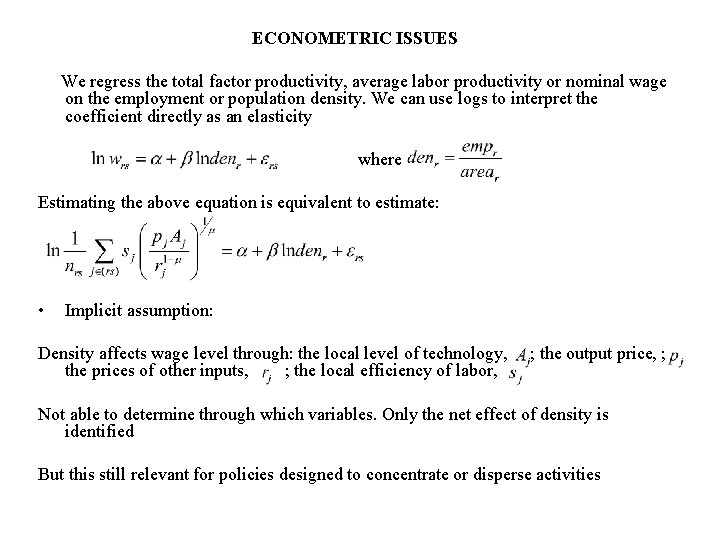

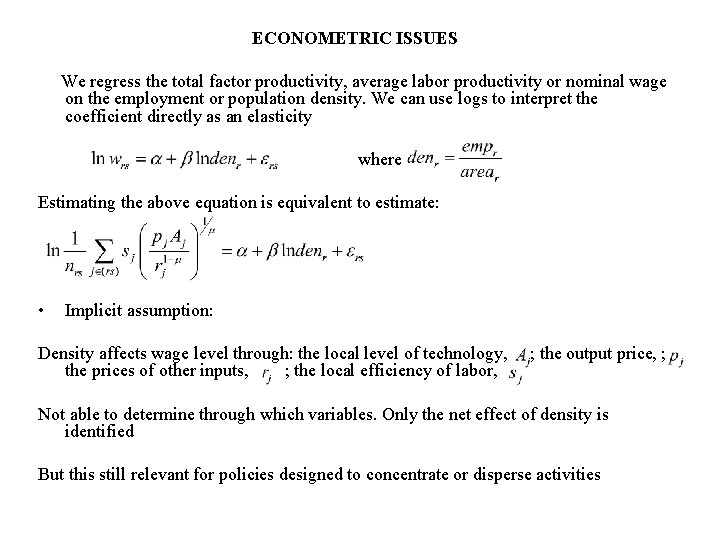

ECONOMETRIC ISSUES We regress the total factor productivity, average labor productivity or nominal wage on the employment or population density. We can use logs to interpret the coefficient directly as an elasticity where Estimating the above equation is equivalent to estimate: • Implicit assumption: Density affects wage level through: the local level of technology, ; the output price, ; the prices of other inputs, ; the local efficiency of labor, Not able to determine through which variables. Only the net effect of density is identified But this still relevant for policies designed to concentrate or disperse activities

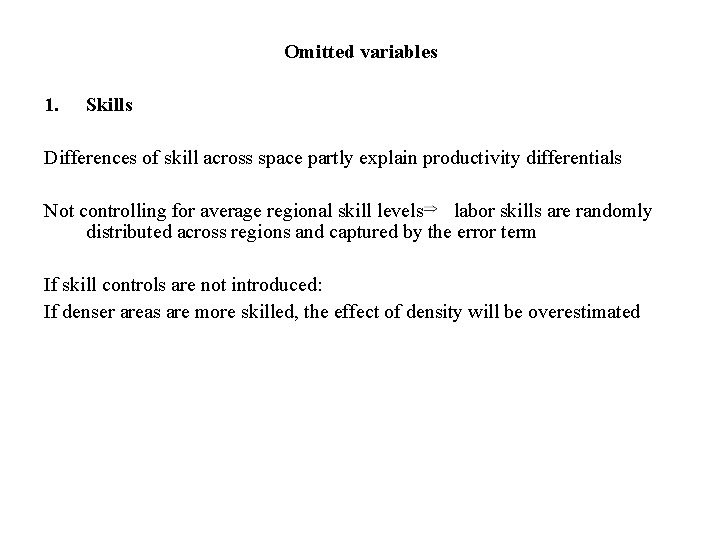

Omitted variables 1. Skills Differences of skill across space partly explain productivity differentials Not controlling for average regional skill levels labor skills are randomly distributed across regions and captured by the error term If skill controls are not introduced: If denser areas are more skilled, the effect of density will be overestimated

2. Intra and Inter-sectorial externalities Wage varies by region and sector but density only varies by region Industrial mix should be controlled Industrial mix is important where: • output is sold to a small number of industries • inputs used are industry specific it affects the level of productivity through price effects specialization index captures intraindustry externalities For interindustry externalities, an “industrial diversity” variables is included (Herfindhal index)

3. Natural amenities and local public goods Amenities: • Naturals: favorable climate, coast-line location, presence of lakes and mountains, natural endowments in raw materials • Man-made: the result of public policy like leisure facilities (theaters, swimming pools, …) or public services (schools, hospitals, …) Local Public Goods → benefits reaped by local consumers LPG can be used by firms: Transport infrastructures, research laboratories, job training centers LPG can affect productivity of production factors If randomly located → captured by Problem: Supply of LPG greater in areas characterized by concentrated activity (public policy decisions) Consequence: overestimation of density effect

But amenities may have additional effects On the supply side: If a region has amenities that attract population → Upward pressure on demand for housing →Pushing up rents On the demand side: Higher land rents → Higher cost for firms → Substitute other production factors, labor, for land → Marginal productivity of labor decreases → Drop in wages If natural amenities are more abundant in heavily populated regions (e. g. , leisure facilities) the effect of density is underestimated

4. Effects of interaction with neighboring regions Some form of density market potential 5. ¿Using fixed effects? If available a panel of industries and regions, it is possible to use fixed effects to control for omitted variables We need to make the assumption that during the panel period, the omitted we want to control for are constant. For example, amenity and public good endowments

Endogeneity bias OLS estimates are biased when some explanatory variables are correlated with the residuals of the regression. These variables are said to be endogenous Assume that a given region experiences a shock observed by economic agents but overlooked by the researcher: Positive shock → some correct decisions made by the regional government that increases productivity Negative shock → an increase of oil price negatively affects regions with intensive use of oil If shocks are localized and affect the location of agents: Positive shocks may attract workers to the affected region where wages are increasing Negative shocks may expel workers from the affected regions

Shocks can have effects on the attraction of regions Impact on activity Impact on employment density Inverse causality: Shocks → → attraction/expulsion of workers → Increase/Decrease of density Low mobility of factors weaker bias However, still endogeneity bias through creation/destruction of jobs

Most common approach to address the problem: Instrumental variables technique finding variables (instruments) correlated with the endogenous variable but not with the residual 1. The first step is regressing the variable we consider endogenous on the chosen instrument. Ciccone & Hall (1996) are the first to take into account the problem of endogeneity in this context. They use as an instrument past density. Instrumental regression: This provides us with a prediction of density: where is the OLS estimator for

2. The density in the initial regression is replaced by its predicted value ( is instrumented) which uncorrelated with the residuals since the instrument is by construction exogenous: The OLS estimate of the equation no longer suffers from endogeneity bias Crucial point: assumption of exogeneity of the instrument Assumption: there is persistence in agglomeration but there is no correlation between past employment density and present productivity shocks Nevertheless a long lag is not a sufficient condition: The source of a shock may be linked to unobserved factors that persist over time

Agglomeration economies

Agglomeration economies Agglomeration economies

Agglomeration economies Webconvergence lyon

Webconvergence lyon Spanishsault

Spanishsault Xerogel

Xerogel Multiple nuclei model

Multiple nuclei model Agglomeration definition ap human geography

Agglomeration definition ap human geography Specific gravity calculation

Specific gravity calculation Nda full dac

Nda full dac Fcc planar density

Fcc planar density Physiological density ap human geography definition

Physiological density ap human geography definition Physiological density vs arithmetic density

Physiological density vs arithmetic density Linear atomic density

Linear atomic density Objective of transaction processing system

Objective of transaction processing system People who own, operate, and take the risk of a business

People who own, operate, and take the risk of a business Generates fresh produce and other farm products

Generates fresh produce and other farm products Leadership generates motivation by

Leadership generates motivation by Generates fresh produce and other farm products

Generates fresh produce and other farm products Which grammar generates regular language?

Which grammar generates regular language? Public provision vs private provision

Public provision vs private provision Discovering computers 2012

Discovering computers 2012 Advantages and disadvantages of diseconomies of scale

Advantages and disadvantages of diseconomies of scale Economies of scale

Economies of scale Characteristics of mixed economies

Characteristics of mixed economies Experience curve benefits

Experience curve benefits Managing economies of scale in a supply chain

Managing economies of scale in a supply chain Sw asian economies comprehension check

Sw asian economies comprehension check Horizontal boundaries of the firm

Horizontal boundaries of the firm Managing economies of scale in a supply chain

Managing economies of scale in a supply chain Define capital formation

Define capital formation Geography

Geography Benefits of economies of scale

Benefits of economies of scale Cube square rule economies of scale

Cube square rule economies of scale Traditional economies meaning

Traditional economies meaning Learning curve economies

Learning curve economies Types of economies of scale

Types of economies of scale Economies of scale ap human geography

Economies of scale ap human geography Economies of scope vs scale

Economies of scope vs scale Faktor penyebab economies of scale

Faktor penyebab economies of scale Economies and diseconomies of work specialization

Economies and diseconomies of work specialization Transition economies

Transition economies Chapter 10 business in a global economy

Chapter 10 business in a global economy Risk bearing economies of scale

Risk bearing economies of scale Bsg footwear industry report

Bsg footwear industry report 3 main questions of economics

3 main questions of economics Section 3 centrally planned economies

Section 3 centrally planned economies Mixed economies in a sentence

Mixed economies in a sentence Se asia's governments comprehension check

Se asia's governments comprehension check Economies of scale graph

Economies of scale graph Five fundamental questions of the market system

Five fundamental questions of the market system Chapter 2 section 4 modern economies worksheet answers

Chapter 2 section 4 modern economies worksheet answers Sw asia economies cloze notes 1

Sw asia economies cloze notes 1 Financial economies of scale

Financial economies of scale A key to reducing lot size without increasing costs is to

A key to reducing lot size without increasing costs is to Chapter 7 section 1 regional economies create differences

Chapter 7 section 1 regional economies create differences Traditional economy

Traditional economy