Chapter 9 Empirical Tests of the Factor Endowments

- Slides: 30

Chapter 9 Empirical Tests of the Factor Endowments Approach Mc. Graw-Hill/Irwin Copyright © 2010 by The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

Learning Objectives § Analyze the failure of U. S. trade patterns to conform to H-O predictions. § Examine possible explanations for the U. S. trade paradox. § Describe issues arising from multicountry H-O tests. § Assess the role of trade in generating growing income inequality in developed countries. 9 -2

Leontief’s Test § 1950 s: Leontief conducts the first important test of H-O. § Using U. S. data Leontief calculated • average amount of capital and labor embodied in U. S. exports. • average amount of capital and labor embodied in U. S. imports. 9 -3

Leontief’s Test § Presumably, the U. S. was relatively K-abundant at that time. § Therefore, according to the H-O model, the U. S. should tend to export K-intensive products, and import L-intensive products. § That is, the capital-labor ratio for U. S. exports should be greater than the capital-labor ratio for U. S. imports. 9 -4

The Leontief Paradox § Leontief found something surprising: (K/L)exports = $13, 991 person-year (K/L)imports = $18, 184 person-year § This is the opposite of what the H-O model predicts. § This finding came to be known as the Leontief Paradox. 9 -5

The Leontief Paradox § To see this from another angle, consider the Leontief statistic • [(K/L)imp]/[(K/L)exp] • If H-O-S is correct, this statistic should be less than one for the U. S. § However, Leontief found the statistic to be ($18, 184/$13, 991) or about 1. 3. 9 -6

Explanations for the Leontief Paradox § Much research since Leontief’s time has focused on trying to explain the paradox. § Do any of these explanations “rescue” the H-O model, or is the model just wrong? 9 -7

Explanation #1: Demand Reversals Recall: when the K-abundant country has very strong domestic demand for the K-intensive product, and the Labundant country has very strong domestic demand for L-intensive products, there can be a demand reversal: the K-abundant country will export the L-intensive product because it has the relative cost advantage in it. 9 -8

Explanation #1: Demand Reversals § Therefore, the H-O theorem breaks down. § If demand reversals are commonplace, we might expect the U. S. to export relatively laborintensive products. 9 -9

Explanation #1: Demand Reversals § So: is there any evidence for widespread demand reversals? • No. Demand patterns are actually quite similar, at least among industrialized countries. • Furthermore, demand reversals imply that U. S. wages should be low. This would be a hard argument to support. § We need to look further to explain the paradox. 9 -10

Explanation #2: Factor Intensity Reversals § Recall: a FIR occurs when a good is relatively K-intensive at one set of factor prices, but relatively Lintensive at another. § If FIRs occur often, the H-O theorem cannot be valid for both countries, and so we might expect the Leontief paradox. 9 -11

Explanation #2: Factor Intensity Reversals § Minhas (1962) found evidence that FIRs are fairly commonplace. § Later work by Hufbauer (1966) and Ball (1966) suggests that Minhas overstated the matter; there may be some FIRs in the real world, but not as many as Minhas suggested. § It would seem that if there is an explanation of the Leontief paradox, it lies elsewhere. 9 -12

Explanation #3: The U. S. Tariff Structure § The H-O model assumes free trade, but in fact there are barriers (e. g. , tariffs). § The Stolper-Samuelson theorem leads us to expect that the owners of the scarce factor will be protectionist. § In the U. S. , this will likely mean that it is L-intensive imports that are being kept out. 9 -13

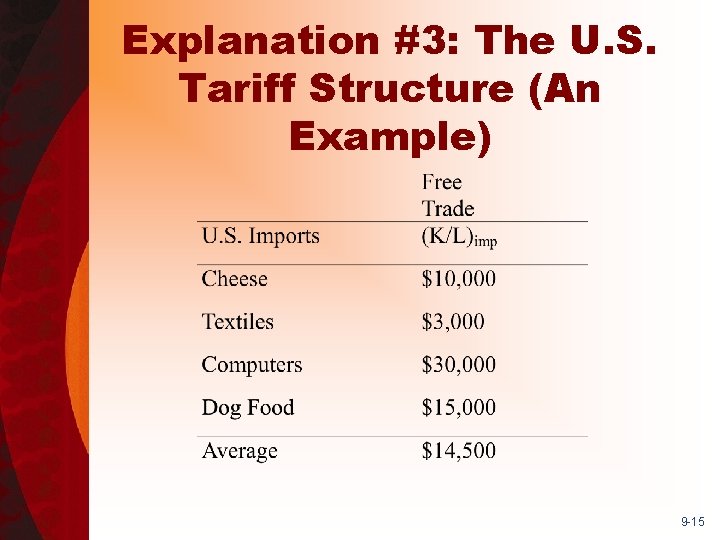

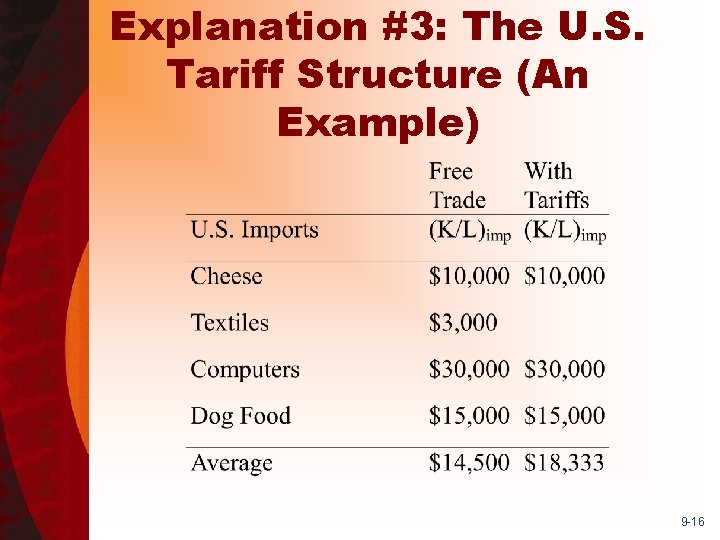

Explanation #3: The U. S. Tariff Structure § The tariff structure could make the Leontief statistic artificially high, and perhaps lead to the paradox. § Consider an example: 9 -14

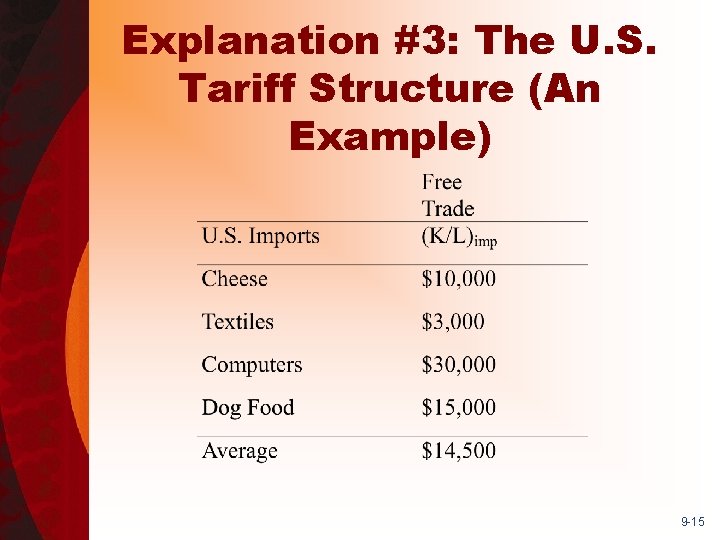

Explanation #3: The U. S. Tariff Structure (An Example) 9 -15

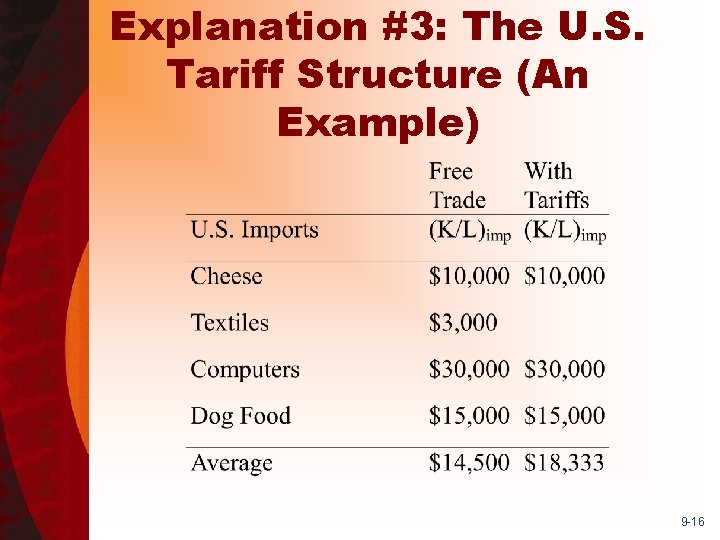

Explanation #3: The U. S. Tariff Structure (An Example) 9 -16

Explanation #3: The U. S. Tariff Structure (An Example) § Suppose that (K/L)exp = $16, 000. § Then the fact that tariffs exist means that the Leontief statistic is $18, 333/$16, 000 = 1. 14; it would have been $14, 500/$16, 000 = 0. 9 under the assumption of free trade. § This means that Leontief’s paradox might be the result of tariffs, and isn’t evidence against the H-O model. 9 -17

Explanation #3: The U. S. Tariff Structure § A study by Baldwin (1971) suggests that (K/L)imp for the U. S. would be about 5% lower if we allow for the tariff structure. § This would lower Leontief’s statistic from 1. 3 to 1. 23. § This lessens the extent of the paradox without explaining it all. 9 -18

Explanation #4: Adding Other Factors of Production § Keesing (1966) suggests subdividing labor into eight skill categories. § He found that the U. S. exports a lot of skilled labor-intensive products; it is the unskilled labor-intensive products that we tend to import. 9 -19

Explanation #4: Adding Other Factors of Production § Since the U. S. is relatively skilled labor-abundant, this suggests that the H-O model does explain trade accurately: the Leontief Paradox disappears. § Later studies have supported this finding. 9 -20

Explanation #4: Adding Other Factors of Production § Leontief (1956) and Hartigan (1981) found that adding natural resources as a factor of production eliminates the paradox. § However, Baldwin (1971) found that adding natural resources does not completely eliminate the paradox. 9 -21

The Leontief Paradox: The Bottom Line § Allowing for demand reversals, FIRs, the tariff structure and natural resources as a factor of production may lessen the extent of the paradox. § Allowing for different levels of skill in the labor force does seem to eliminate the paradox. § The H-O model appears to be serviceable. 9 -22

Tests of the H-O Model for Other Countries § Many studies provide support for H-O • Stolper and Roskamp (1961): East Germany • Tatemoto and Ichimura (1959): Japan • Rosefielde (1974): USSR § Other studies did not support H-O • Wahl (1961): Canada • Bharadwaj (1962): India 9 -23

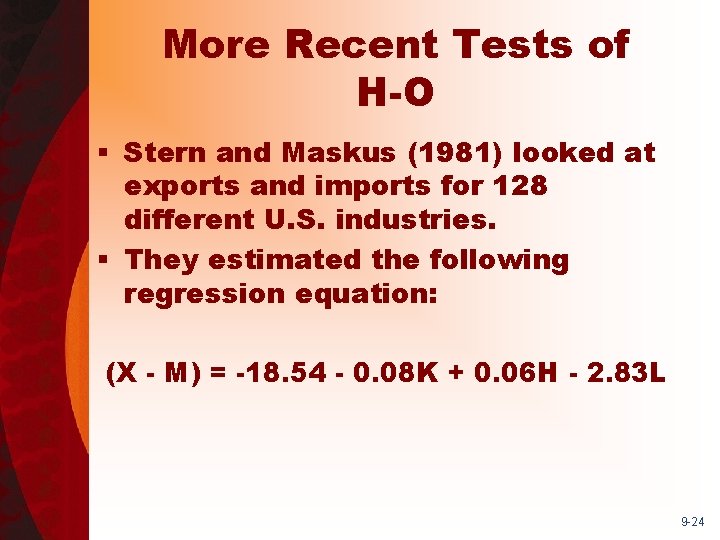

More Recent Tests of H-O § Stern and Maskus (1981) looked at exports and imports for 128 different U. S. industries. § They estimated the following regression equation: (X - M) = -18. 54 - 0. 08 K + 0. 06 H - 2. 83 L 9 -24

More Recent Tests of H-O (X - M) = -18. 54 - 0. 08 K + 0. 06 H - 2. 83 L § Interpretation: • the more K an industry uses the less is exported. • the more labor an industry uses the less is exported. • the more human capital an industry uses the more is exported. § This is basically the same finding as Keesing’s. 9 -25

More Recent Tests of H-O § Harkness and Kyle (1975) • added natural resources to the regression equation. • found similar results: the Leontief paradox can be resolved by considering other factors besides just K and L. 9 -26

More Recent Tests of H-O § Maskus (1985), Bowen et al. (1987), Gourdon (2009), and Muriel and Terra (2009) have also added multiple factors of production. § In general, their results conform with the predictions of the H-O model. 9 -27

More Recent Tests of H-O § However these “H-O – friendly” studies have been called into question. • Differences between calculated and actual factor abundances. • Trefler’s “home bias. ” 9 -28

Testing H-O: The Bottom Line § The H-O model has flaws, especially in its most simplistic forms. § It is still a model that can explain real world trade patterns. 9 -29

The H-O Model and Income Inequality § Over the past several decades, income and wage inequality have been rising in the U. S. and in Europe. § Since this period also involved rising levels of involvement in international trade, some argue that trade has caused the inequality. § While trade may play a role in this, most economists believe it is not a dominant role. 9 -30