WHERE HAVE WE MESHED UP Title courtesy of

- Slides: 154

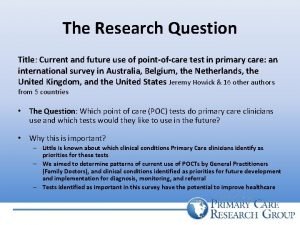

WHERE HAVE WE MESHED UP? (Title courtesy of Carolyn Runowicz)

You deserve to get the most from life. But sometimes the unique health problems facing women can make that challenging. Explore this site to learn about common pelvic health conditions and the latest treatment options. Stop Coping. Start Living. ™ An Odyssey of the Perils and Pitfalls of Improving Surgical Outcomes

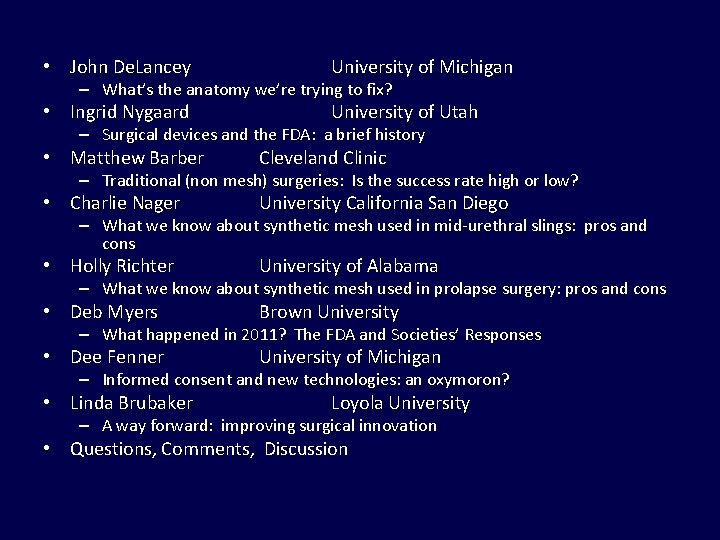

• John De. Lancey University of Michigan • Ingrid Nygaard University of Utah – What’s the anatomy we’re trying to fix? – Surgical devices and the FDA: a brief history • Matthew Barber Cleveland Clinic • Charlie Nager University California San Diego • Holly Richter University of Alabama • Deb Myers Brown University • Dee Fenner University of Michigan – Traditional (non mesh) surgeries: Is the success rate high or low? – What we know about synthetic mesh used in mid-urethral slings: pros and cons – What we know about synthetic mesh used in prolapse surgery: pros and cons – What happened in 2011? The FDA and Societies’ Responses – Informed consent and new technologies: an oxymoron? • Linda Brubaker Loyola University – A way forward: improving surgical innovation • Questions, Comments, Discussion

“What is the anatomy we are trying to fix? ” 2012 AGOS Panel on Surgical Meshes John O. L. De. Lancey, MD Director of Pelvic Floor Research Norman F. Miller Professor of Gynecology Professor of Urology University of Michigan © De. Lancey 2012

University of Michigan Pelvic Floor Research Group “Improving prevention and treatment of women’s pelvic floor disorders” Funded by the NICHD and ORWH SCOR Gynecologists, Engineers, Nurses, Urologists, Physical Therapists, Physiologists, Midwives, Radiologists, Physiatrists, Statisticians, Epidemiologists, Health Services Researchers, Economists, Endocrinologists, Cell Biologists, Veterinarians Translational Research Collaborations: P&G, Kimberly Clark , Johnson and Johnson, AMS

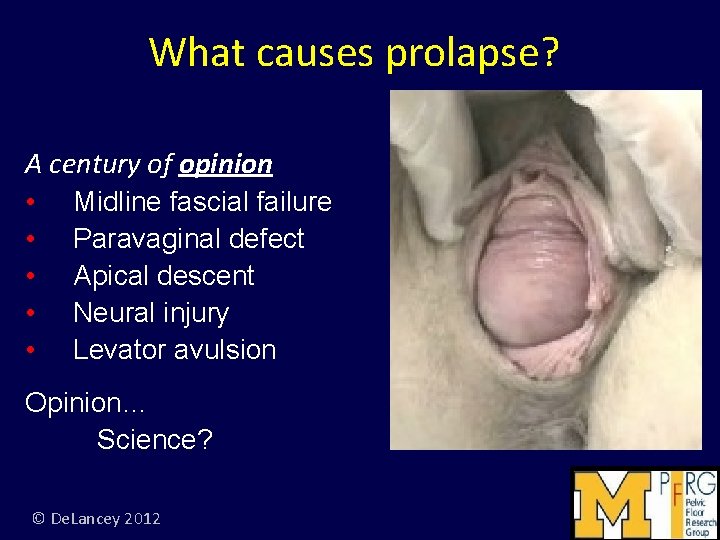

What causes prolapse? A century of opinion • • • Midline fascial failure Paravaginal defect Apical descent Neural injury Levator avulsion Opinion… Science? © De. Lancey 2012

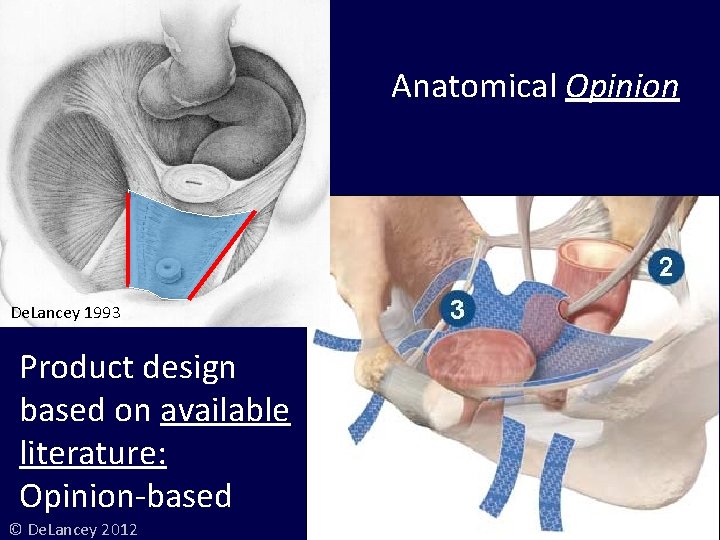

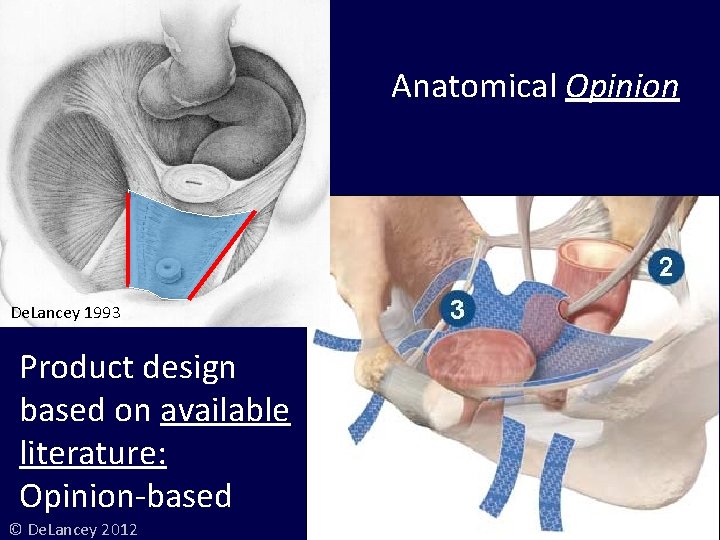

Anatomical Opinion De. Lancey 1993 Product design based on available literature: Opinion-based © De. Lancey 2012

Apical Prolapse after Mesh Repair © De. Lancey 2012

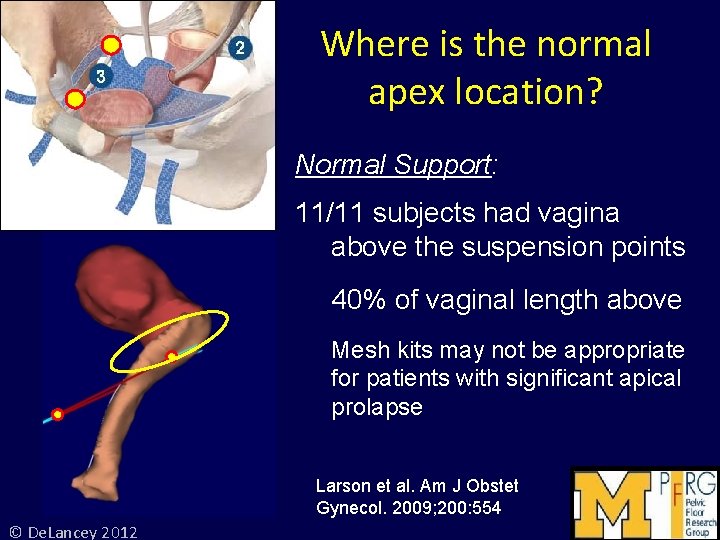

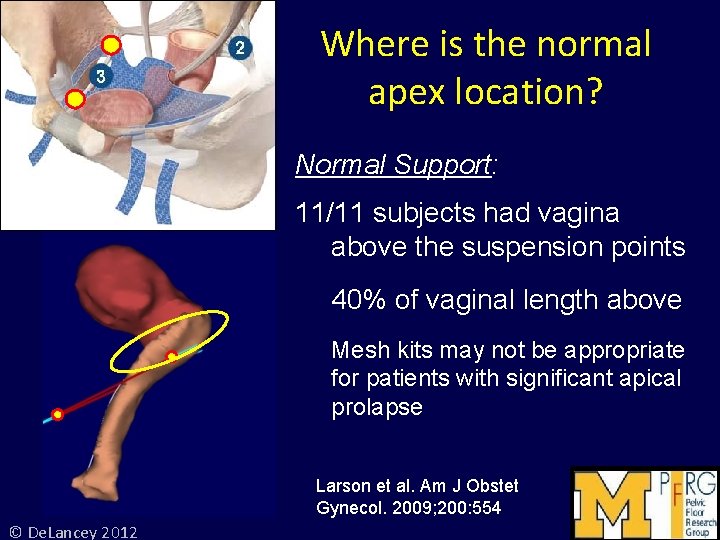

Where is the normal apex location? Normal Support: 11/11 subjects had vagina above the suspension points 40% of vaginal length above Mesh kits may not be appropriate for patients with significant apical prolapse Larson et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 200: 554 © De. Lancey 2012

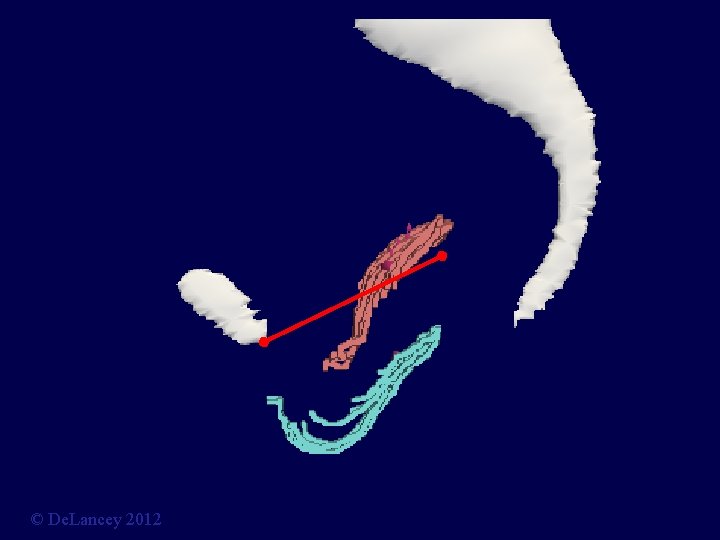

Stress MRI © De. Lancey 2012

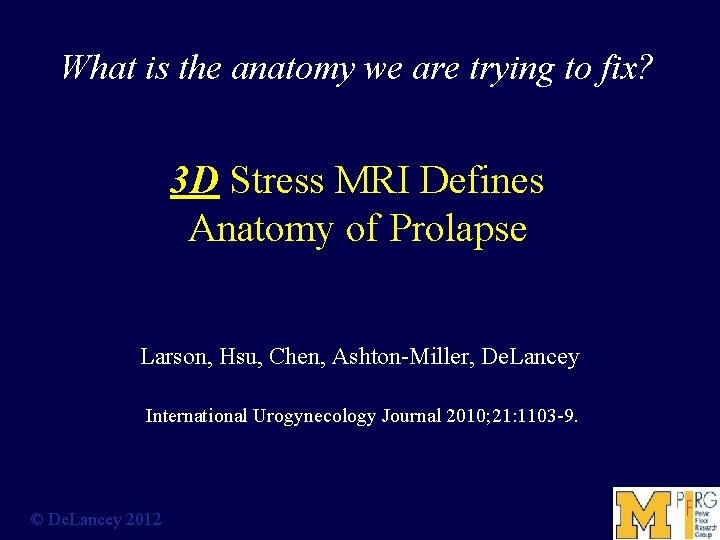

What is the anatomy we are trying to fix? 3 D Stress MRI Defines Anatomy of Prolapse Larson, Hsu, Chen, Ashton-Miller, De. Lancey International Urogynecology Journal 2010; 21: 1103 -9. © De. Lancey 2012

Cystocele at Maximal Valsalva Ut P B V R © De. Lancey 2012

© De. Lancey 2012

© De. Lancey 2012

© De. Lancey 2012

© De. Lancey 2012

Midsagittal = M © De. Lancey 2012

1 Slice to Left = L 1 © De. Lancey 2012

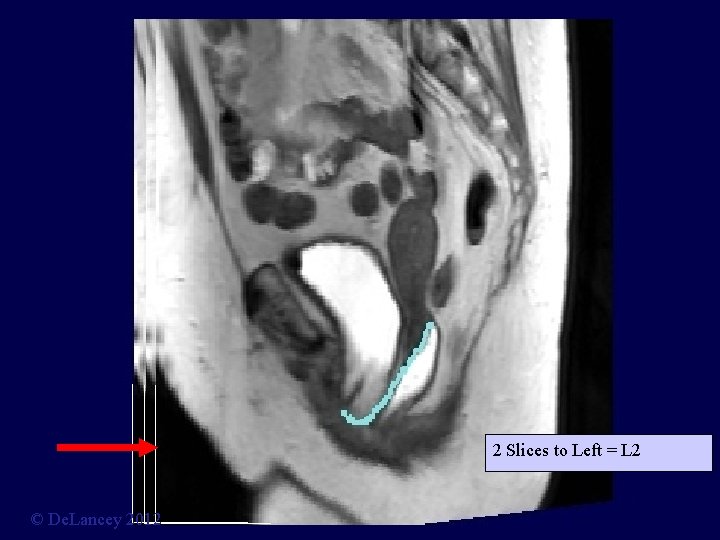

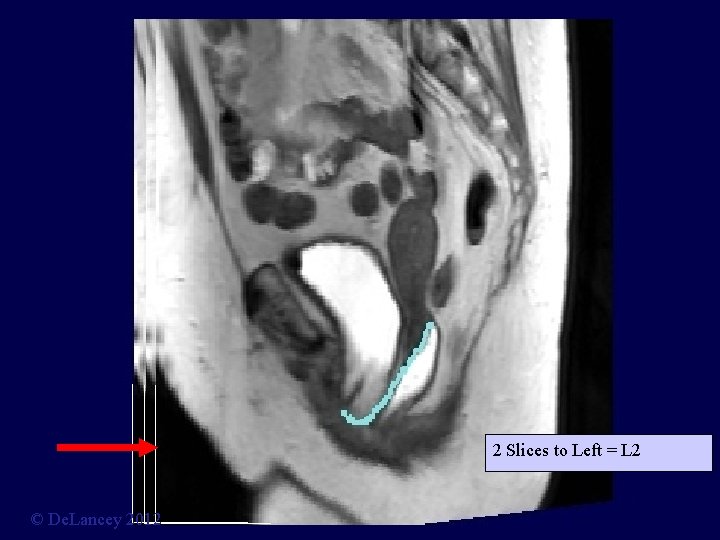

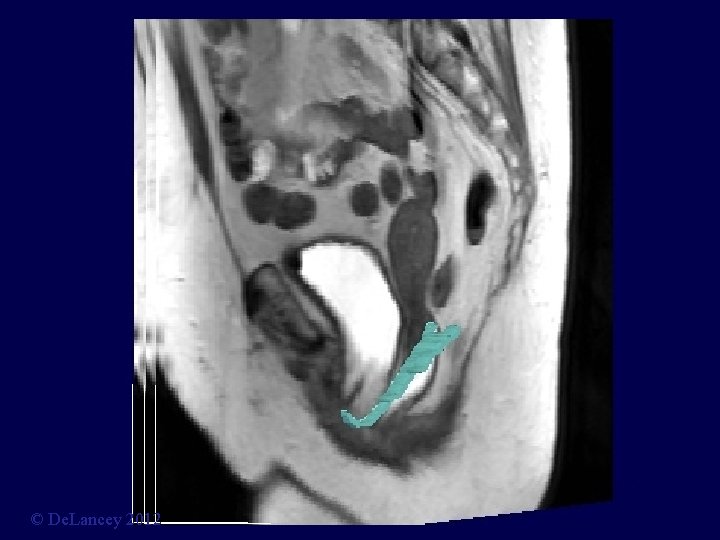

2 Slices to Left = L 2 © De. Lancey 2012

© De. Lancey 2012

© De. Lancey 2012

© De. Lancey 2012

© De. Lancey 2012

© De. Lancey 2012

© De. Lancey 2012

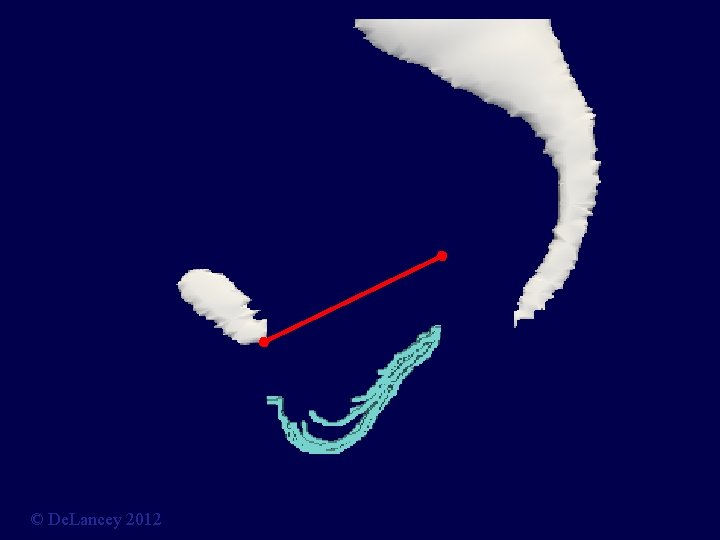

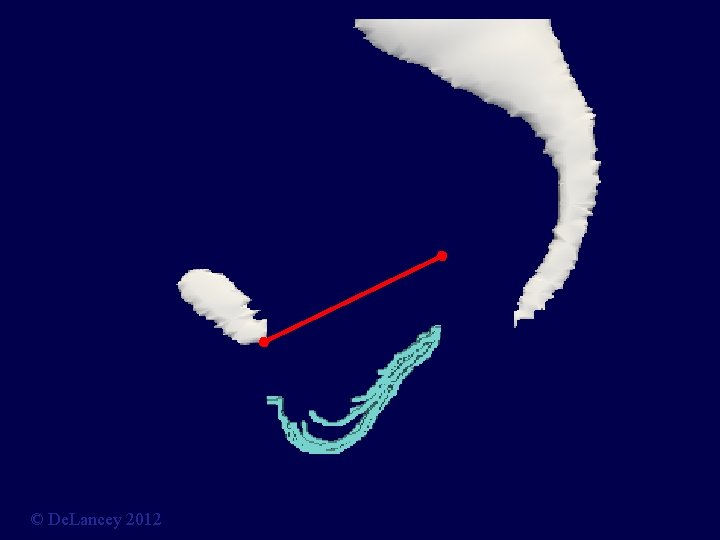

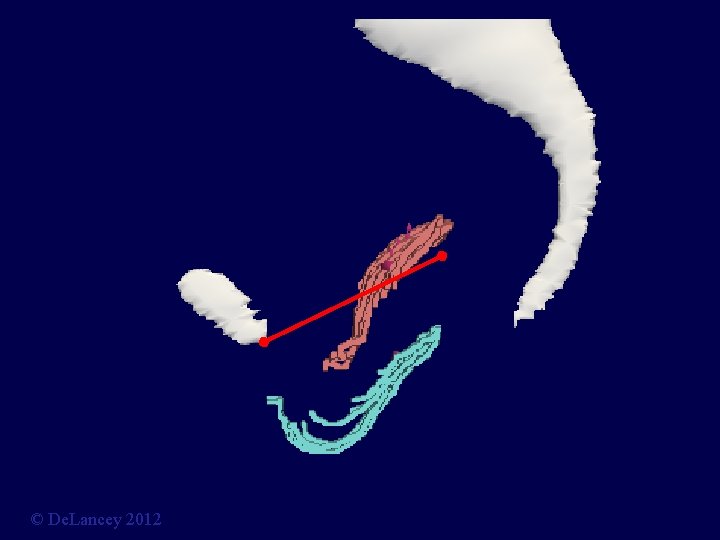

cia s a. F v l Pe. d Ten s u Arc © De. Lancey 2012

© De. Lancey 2012

© De. Lancey 2012

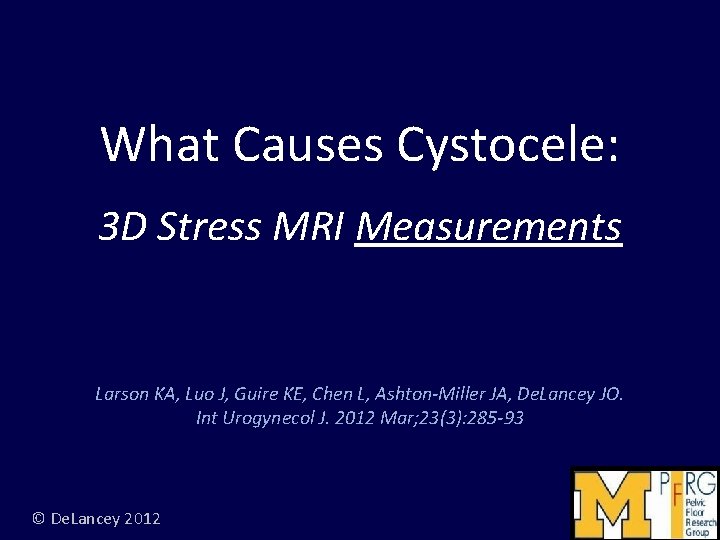

What Causes Cystocele: 3 D Stress MRI Measurements Larson KA, Luo J, Guire KE, Chen L, Ashton-Miller JA, De. Lancey JO. Int Urogynecol J. 2012 Mar; 23(3): 285 -93 © De. Lancey 2012

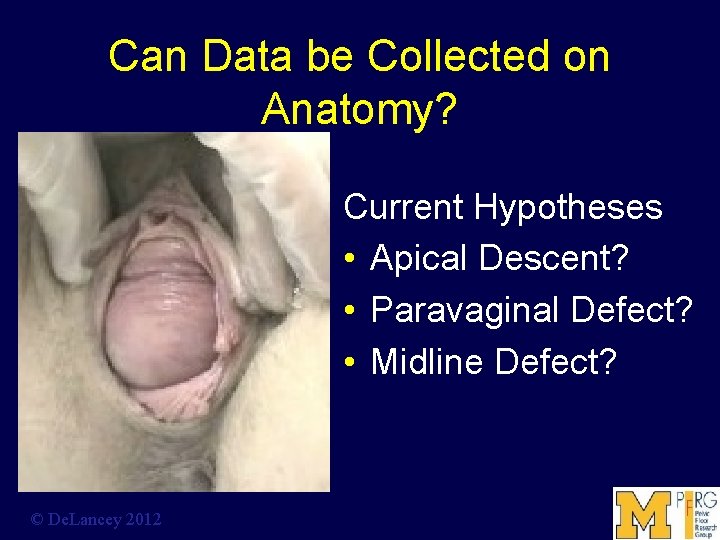

Can Data be Collected on Anatomy? Current Hypotheses • Apical Descent? • Paravaginal Defect? • Midline Defect? © De. Lancey 2012

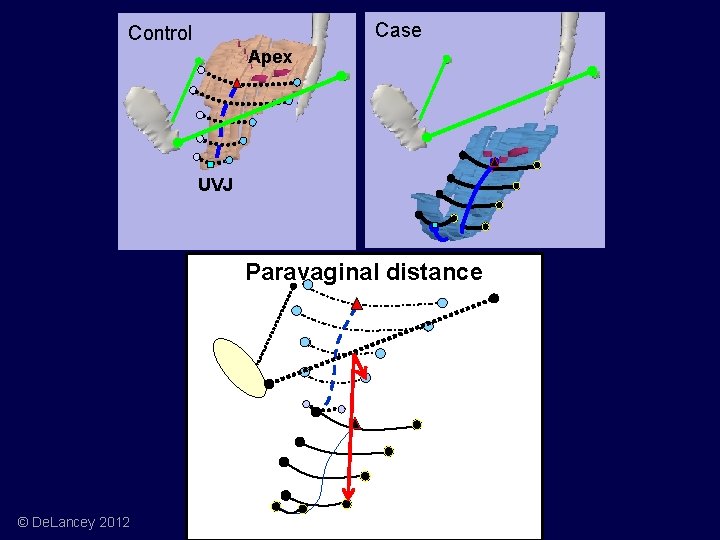

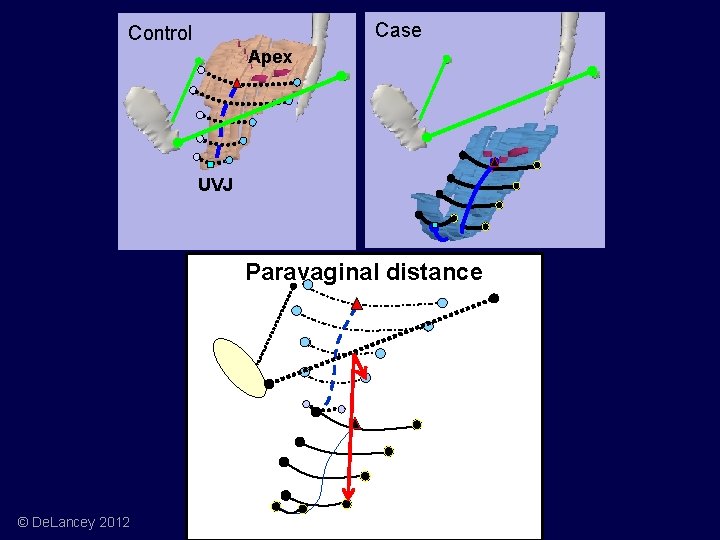

Case Control Apex UVJ Paravaginal distance © De. Lancey 2012

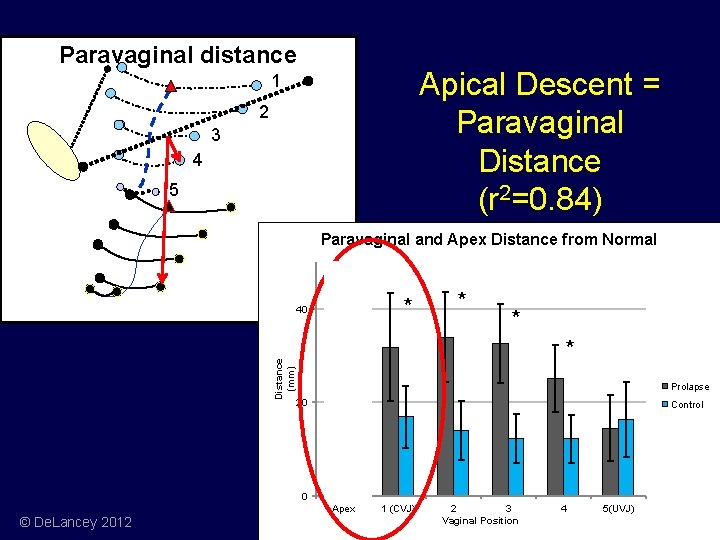

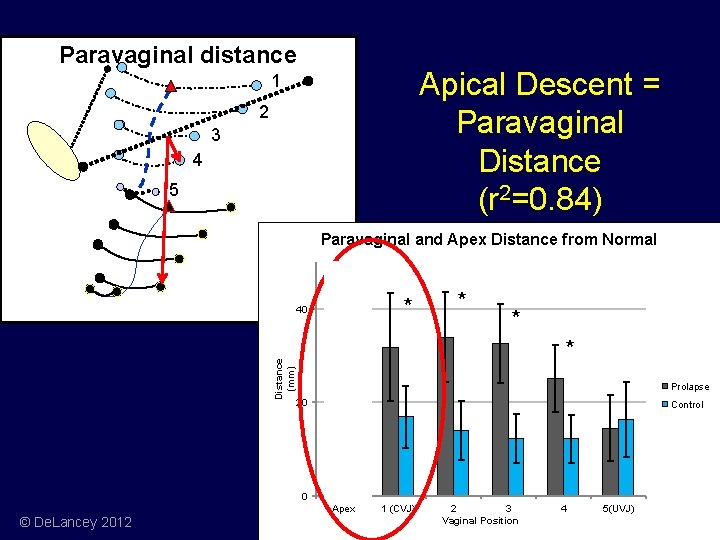

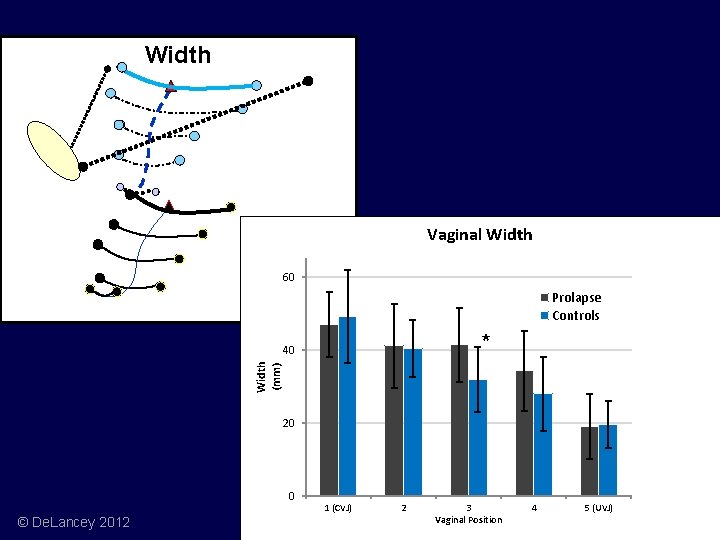

Paravaginal distance Apical Descent = Paravaginal Distance (r 2=0. 84) 1 2 3 4 5 Paravaginal and Apex Distance from Normal * Distance (mm) 40 * * Prolapse 20 Control 0 Apex © De. Lancey 2012 1 (CVJ) 2 3 Vaginal Position 4 5(UVJ)

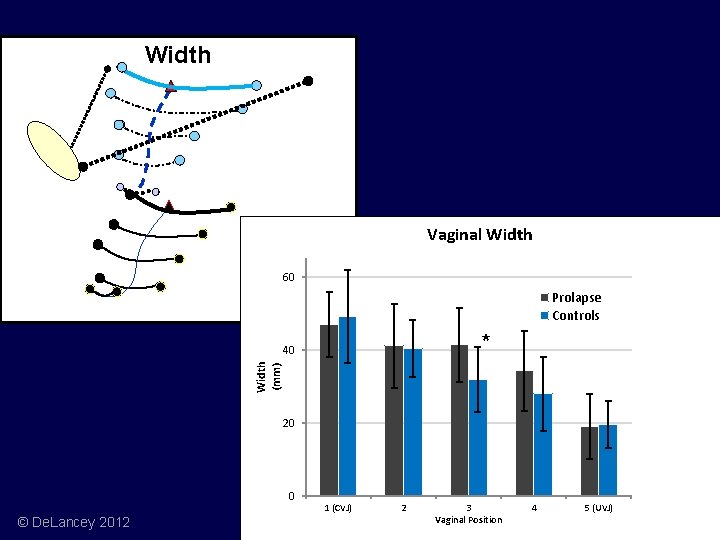

Width Vaginal Width 60 Prolapse Controls * Width (mm) 40 20 0 © De. Lancey 2012 1 (CVJ) 2 3 Vaginal Position 4 5 (UVJ)

What is the anatomy we are trying to fix? How can we avoid experimenting on women? © De. Lancey 2012

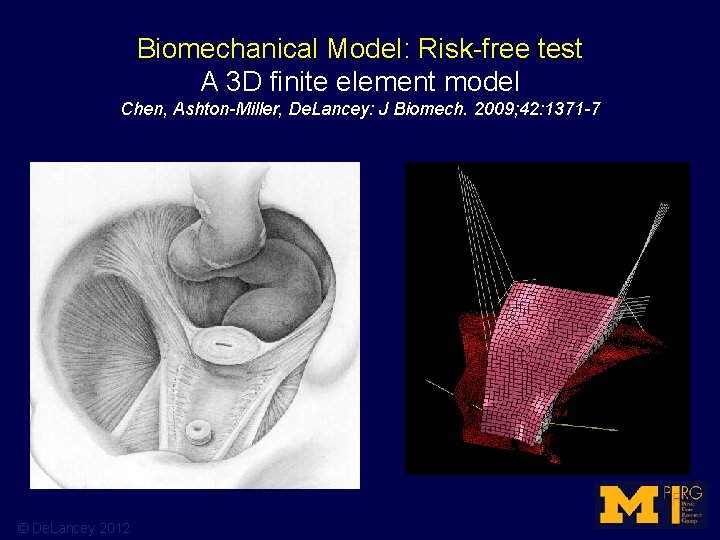

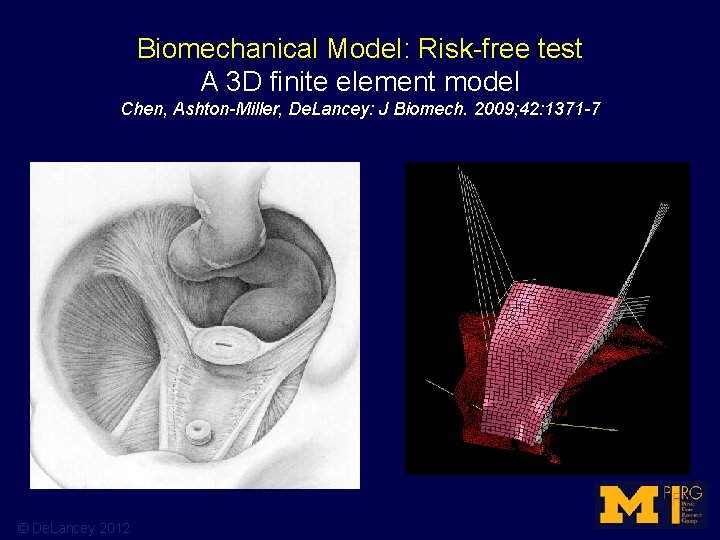

Biomechanical Model: Risk-free test A 3 D finite element model Chen, Ashton-Miller, De. Lancey: J Biomech. 2009; 42: 1371 -7 © De. Lancey 2012

What is the anatomy we are trying to fix? 2012 AGOS Panel on Surgical Meshes John O. L. De. Lancey, MD Director of Pelvic Floor Research Norman F. Miller Professor of Gynecology Professor of Urology University of Michigan © De. Lancey 2012

Surgical devices and the FDA: a brief history Ingrid Nygaard University of Utah

How surgical devices reach the market • 1) Exempt • 2) Premarket Notification (AKA 510(k) process) • 3) Premarket Approval (only these products are actually “FDA approved”).

Device regulation • Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) in the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clears, approves, and regulates medical devices. • Classifies about 1, 700 different types of devices depending on their intended uses and the indications for such use.

Device classification • Class I : usually exempt • Class II : usually marketed through a Premarket Notification • Class III: require actual FDA Premarket Approval.

Class 1 • Manufacturers register their establishment and list the product with the FDA. • Some examples: menstrual pads, hand-held surgical instruments and surgical gloves

Class 2 • Includes most marketed devices in the U. S. , including most of those used to treat POP and UI • Marketed without FDA approval; circumvent the rigorous approval process and gain “clearance” as a Class II device through the Premarket Notification. • Under this process, the manufacturer must states that device is substantially equivalent to a device already on the market (“predicate device”).

Class 3 • About 10% of devices undergo this most rigorous process, Premarket Approval • Needed if product contains new materials or differs in design from products already on the market. • PMA submission is lengthy and includes data from human clinical trials that demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of the device.

UI and POP devices • Class 3: urethral bulking agents • Class 2: marketed mesh kits for SUI and POP – cleared based on similarity to a “predicate device” – not required to undergo clinical testing in women before they were marketed in the U. S.

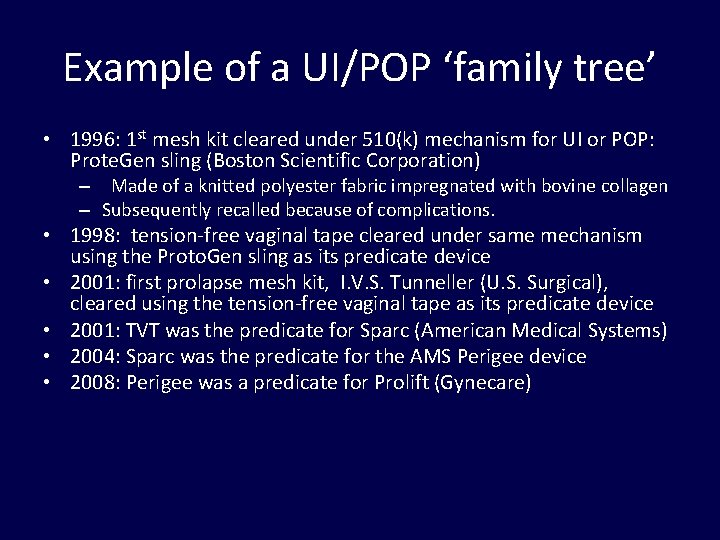

Example of a UI/POP ‘family tree’ • 1996: 1 st mesh kit cleared under 510(k) mechanism for UI or POP: Prote. Gen sling (Boston Scientific Corporation) – Made of a knitted polyester fabric impregnated with bovine collagen – Subsequently recalled because of complications. • 1998: tension-free vaginal tape cleared under same mechanism using the Proto. Gen sling as its predicate device • 2001: first prolapse mesh kit, I. V. S. Tunneller (U. S. Surgical), cleared using the tension-free vaginal tape as its predicate device • 2001: TVT was the predicate for Sparc (American Medical Systems) • 2004: Sparc was the predicate for the AMS Perigee device • 2008: Perigee was a predicate for Prolift (Gynecare)

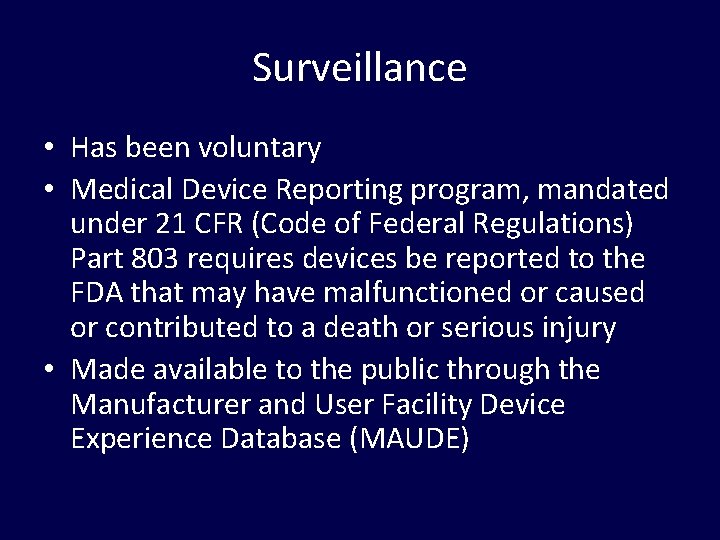

Surveillance • Has been voluntary • Medical Device Reporting program, mandated under 21 CFR (Code of Federal Regulations) Part 803 requires devices be reported to the FDA that may have malfunctioned or caused or contributed to a death or serious injury • Made available to the public through the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience Database (MAUDE)

Traditional (non mesh) surgeries Matthew Barber Cleveland Clinic

Traditional (non-mesh) surgeries: Are the success rates high or low? Yes

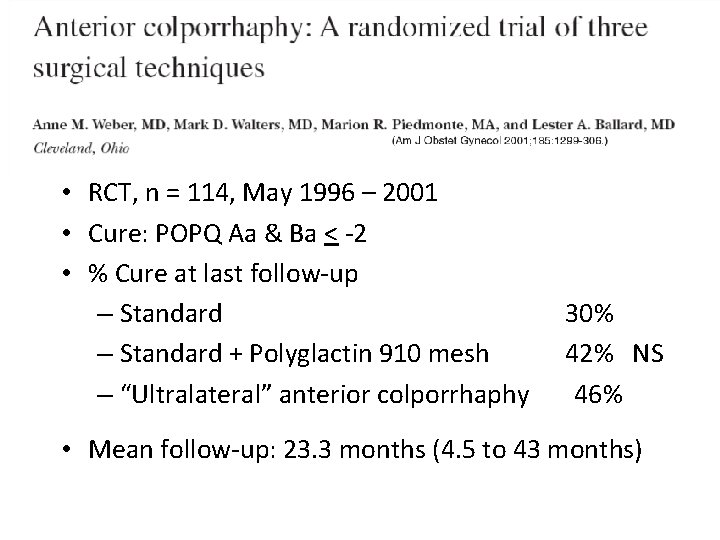

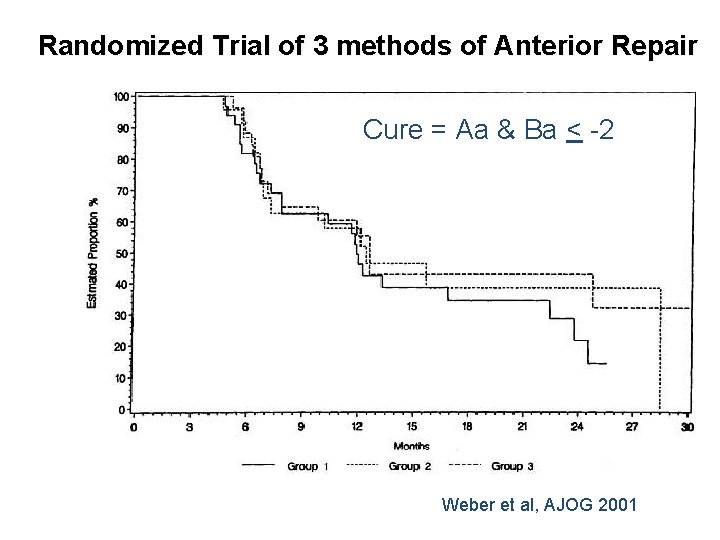

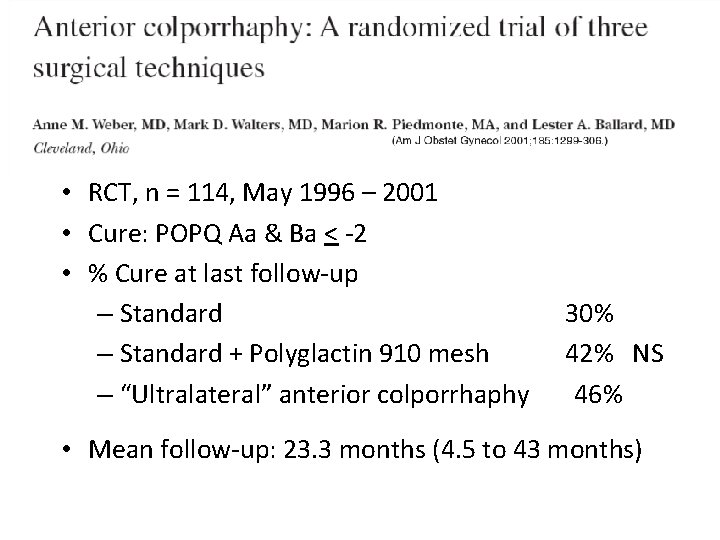

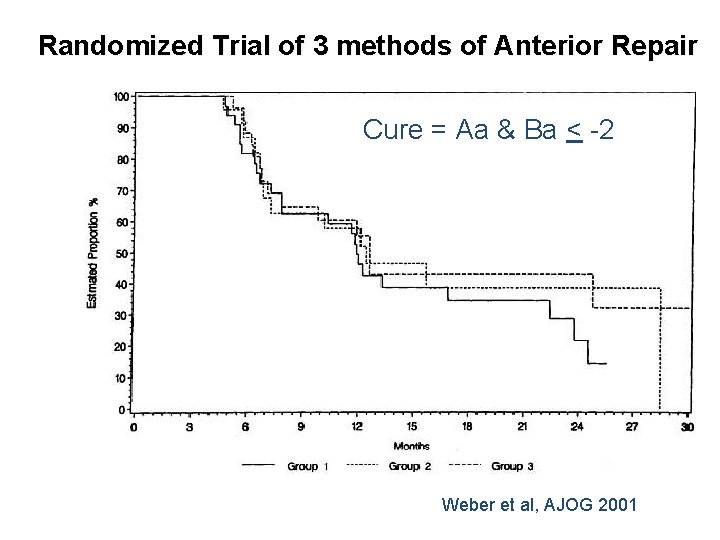

• RCT, n = 114, May 1996 – 2001 • Cure: POPQ Aa & Ba < -2 • % Cure at last follow-up – Standard + Polyglactin 910 mesh – “Ultralateral” anterior colporrhaphy 30% 42% NS 46% • Mean follow-up: 23. 3 months (4. 5 to 43 months)

Randomized Trial of 3 methods of Anterior Repair Cure = Aa & Ba < -2 Weber et al, AJOG 2001

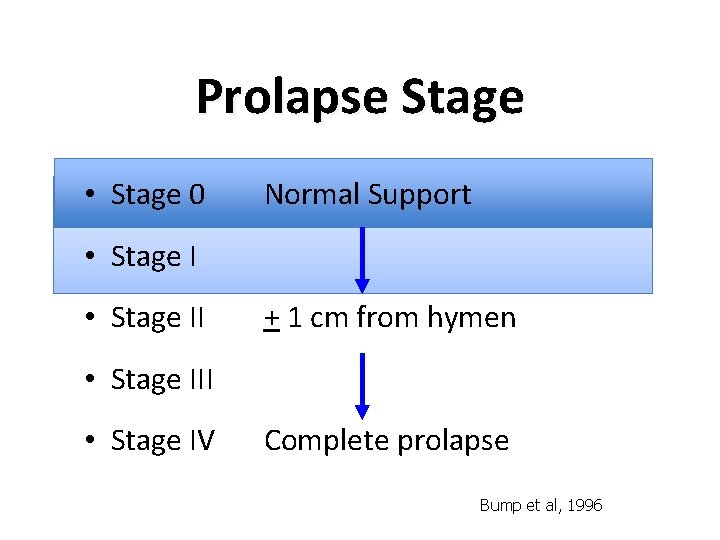

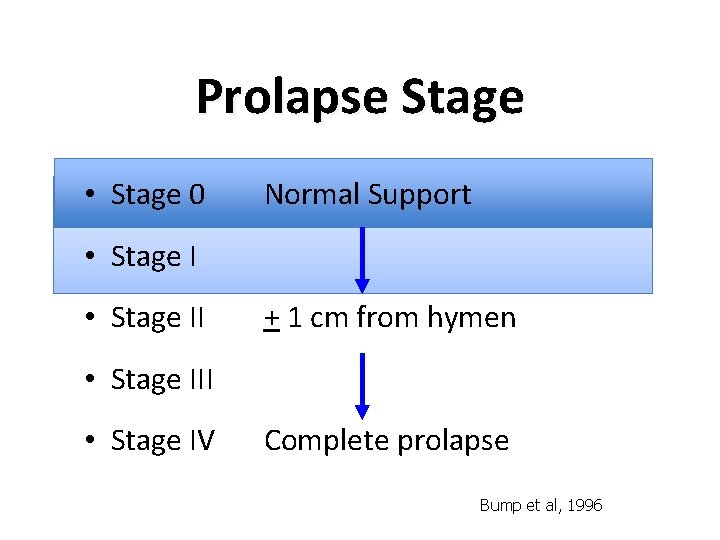

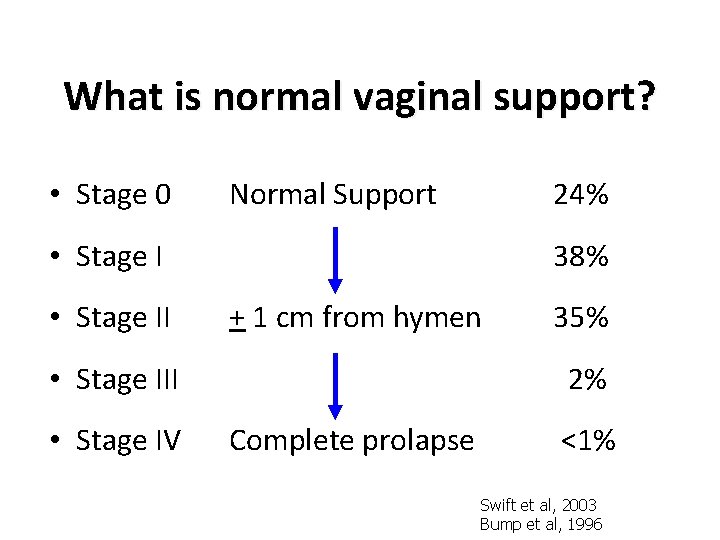

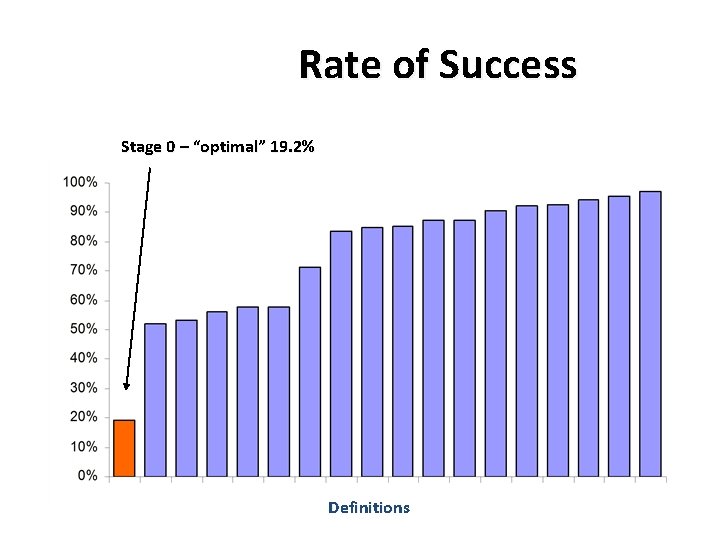

Prolapse Stage • Stage 0 Normal Support • Stage II + 1 cm from hymen • Stage III • Stage IV Complete prolapse Bump et al, 1996

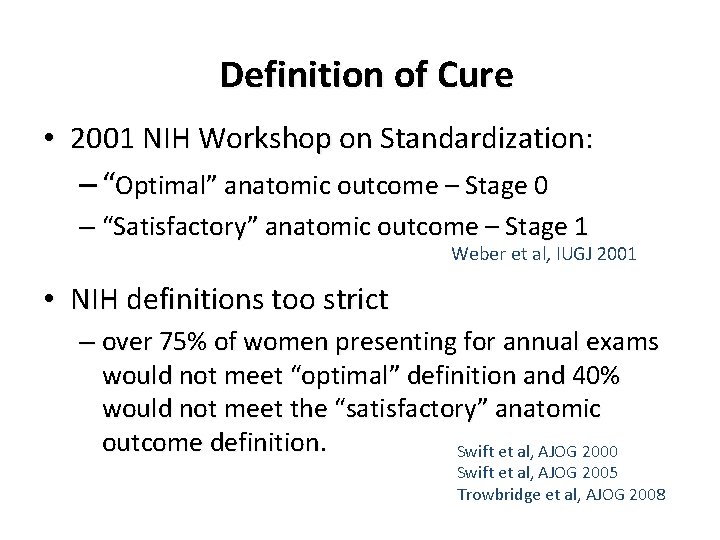

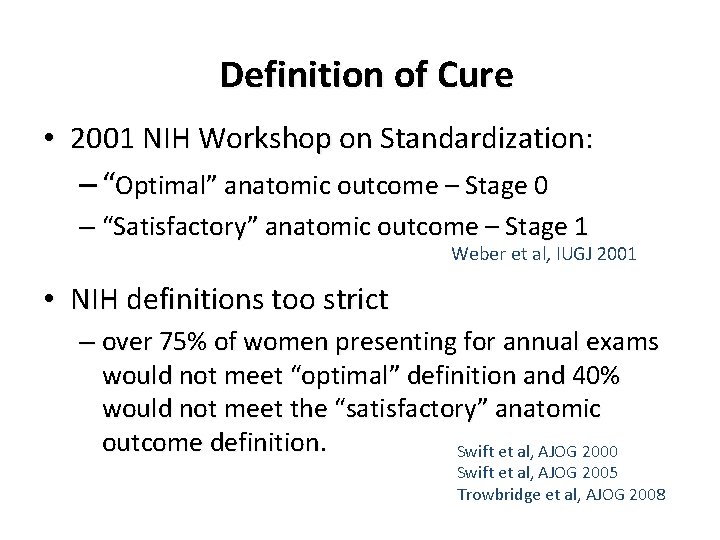

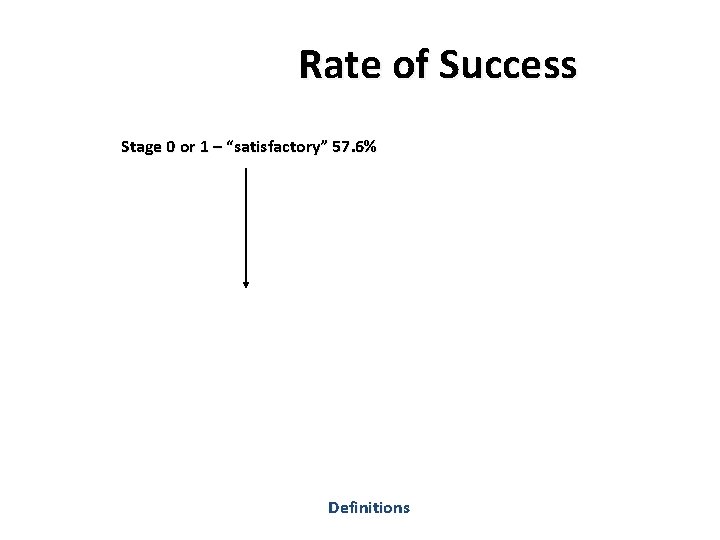

Definition of Cure • 2001 NIH Workshop on Standardization: – “Optimal” anatomic outcome – Stage 0 – “Satisfactory” anatomic outcome – Stage 1 Weber et al, IUGJ 2001 • NIH definitions too strict – over 75% of women presenting for annual exams would not meet “optimal” definition and 40% would not meet the “satisfactory” anatomic outcome definition. Swift et al, AJOG 2000 Swift et al, AJOG 2005 Trowbridge et al, AJOG 2008

NIH Workshop on Standardization Definitions for success after surgery “were made arbitrarily and without the benefit of adequate knowledge of the epidemiology and natural history of pelvic organ prolapse or the relationship between anatomic support and pelvic floor symptoms. ”

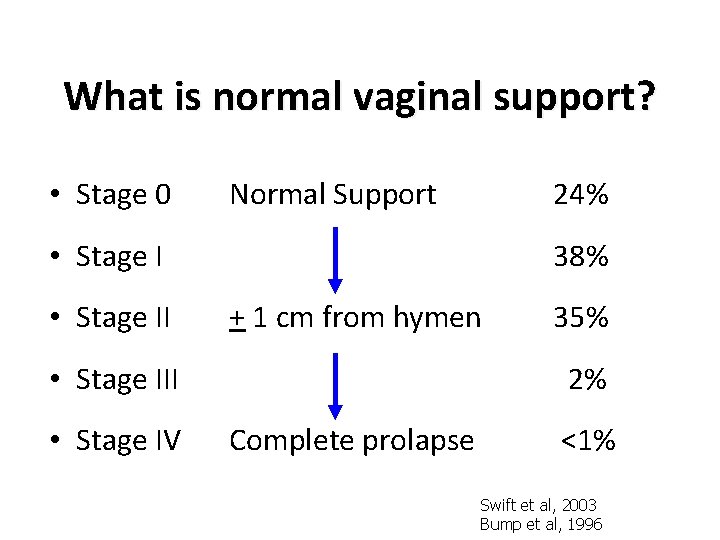

What is normal vaginal support? • Stage 0 Normal Support 24% • Stage II 38% + 1 cm from hymen • Stage III • Stage IV 35% 2% Complete prolapse <1% Swift et al, 2003 Bump et al, 1996

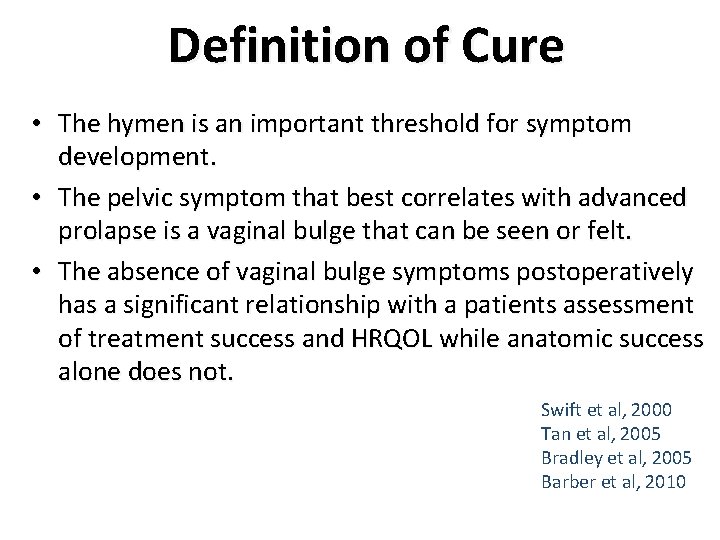

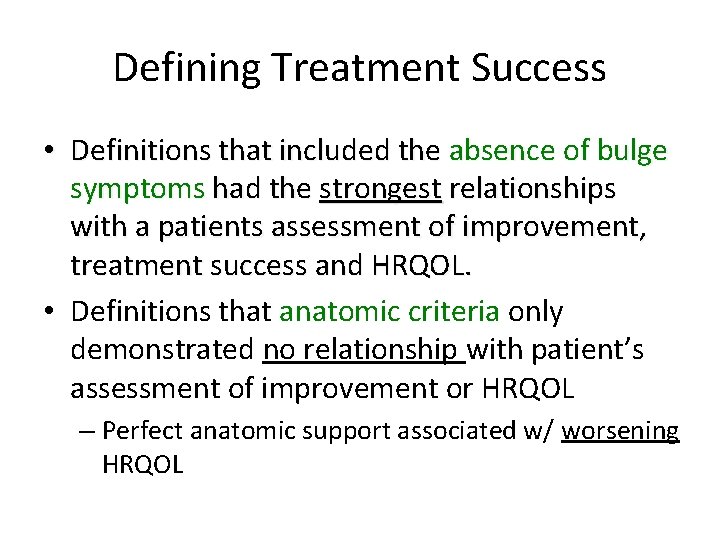

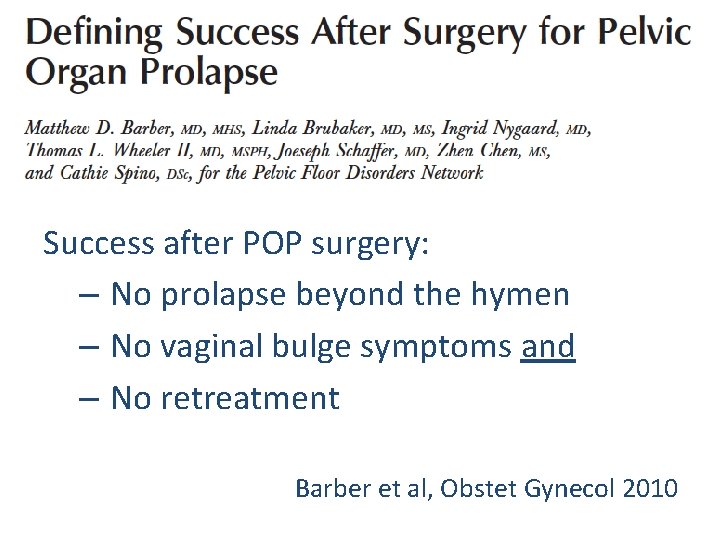

Definition of Cure • The hymen is an important threshold for symptom development. • The pelvic symptom that best correlates with advanced prolapse is a vaginal bulge that can be seen or felt. • The absence of vaginal bulge symptoms postoperatively has a significant relationship with a patients assessment of treatment success and HRQOL while anatomic success alone does not. Swift et al, 2000 Tan et al, 2005 Bradley et al, 2005 Barber et al, 2010

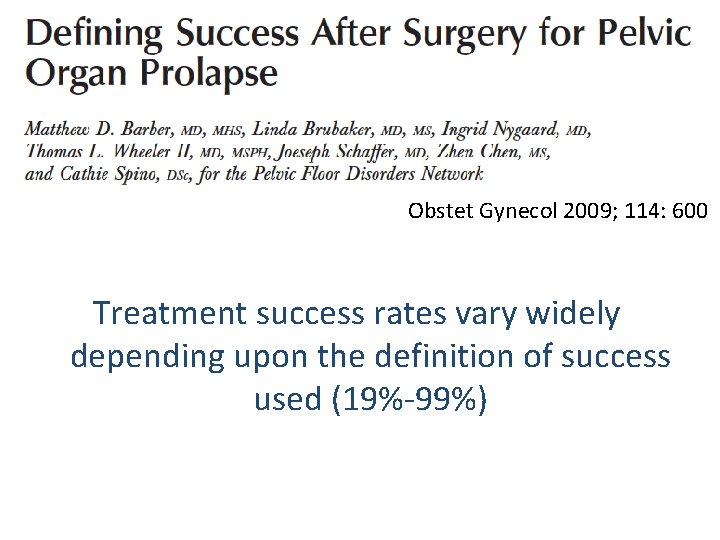

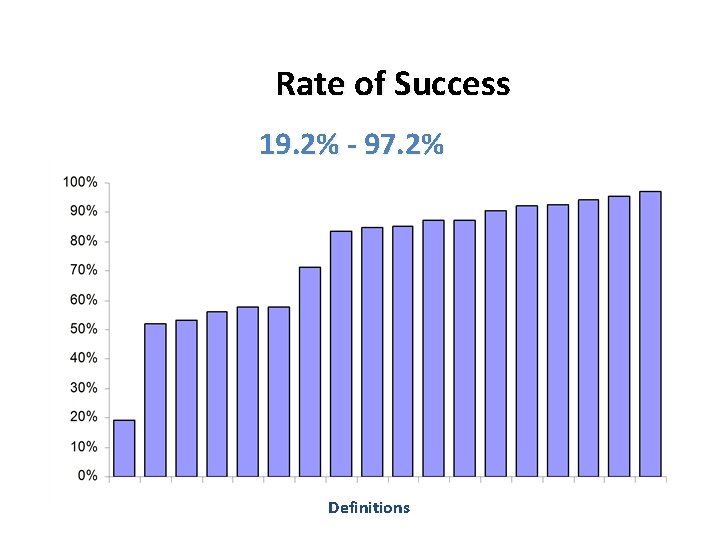

Obstet Gynecol 2009; 114: 600 Treatment success rates vary widely depending upon the definition of success used (19%-99%)

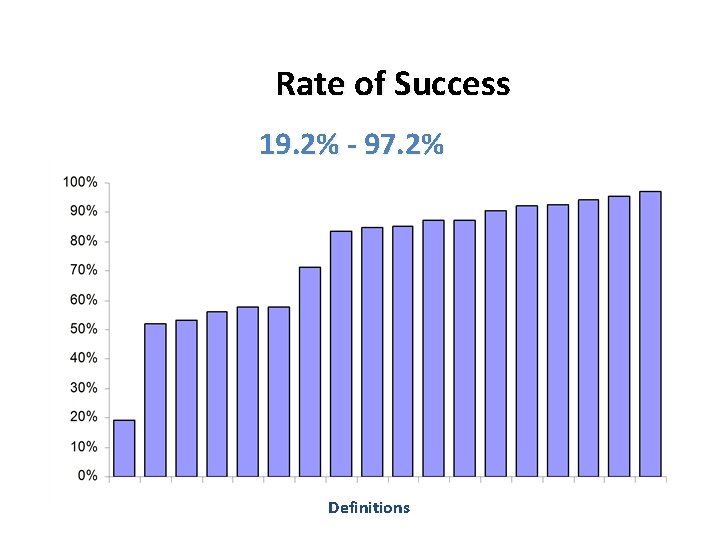

Rate of Success 19. 2% - 97. 2% Definitions

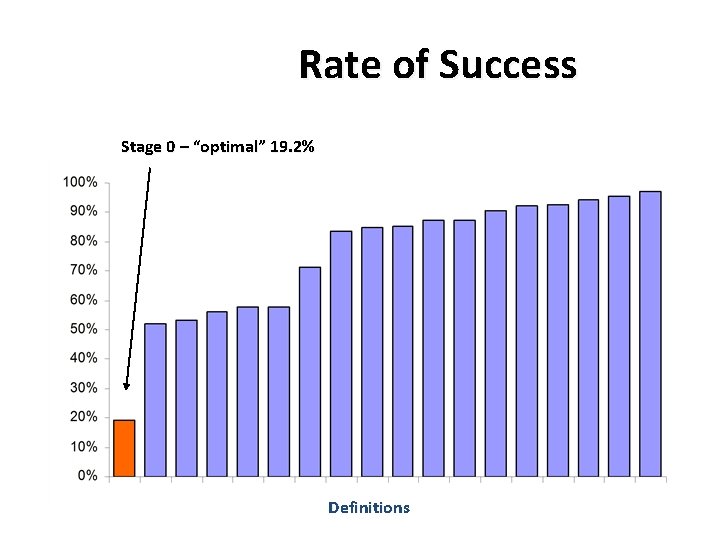

Rate of Success Stage 0 – “optimal” 19. 2% Definitions

Rate of Success Stage 0 or 1 – “satisfactory” 57. 6% Definitions

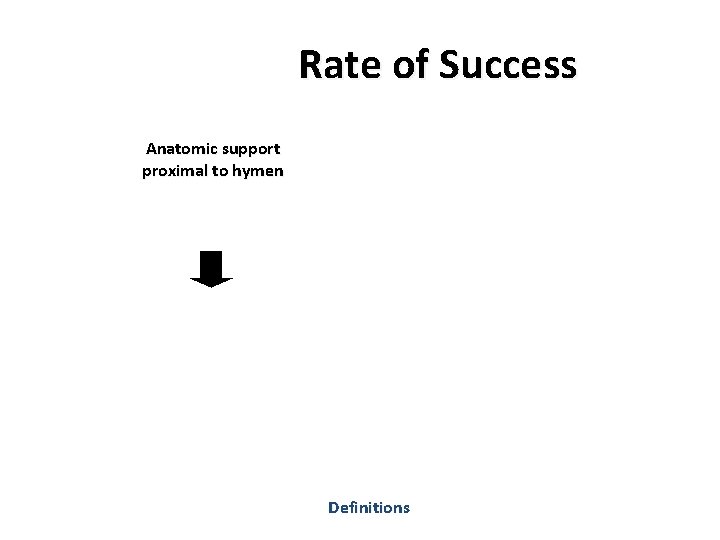

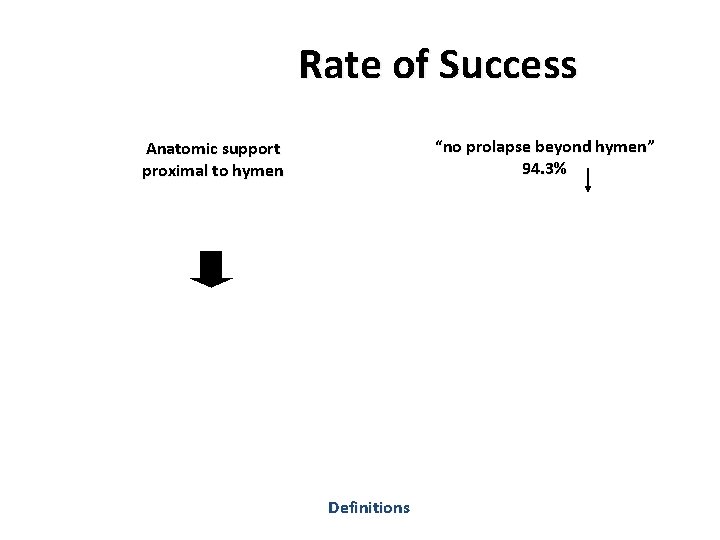

Rate of Success Anatomic support proximal to hymen Definitions

Rate of Success “no prolapse beyond hymen” 94. 3% Anatomic support proximal to hymen Definitions

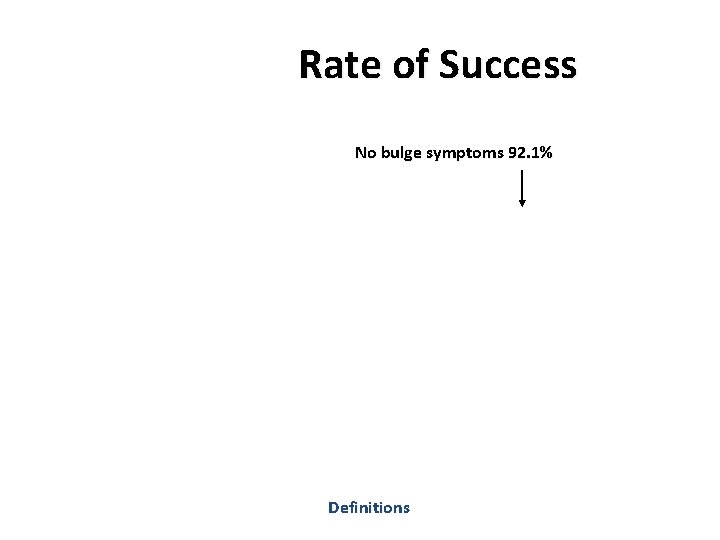

Rate of Success No bulge symptoms 92. 1% Definitions

Rate of Success No Retreatment No bulge symptoms Definitions

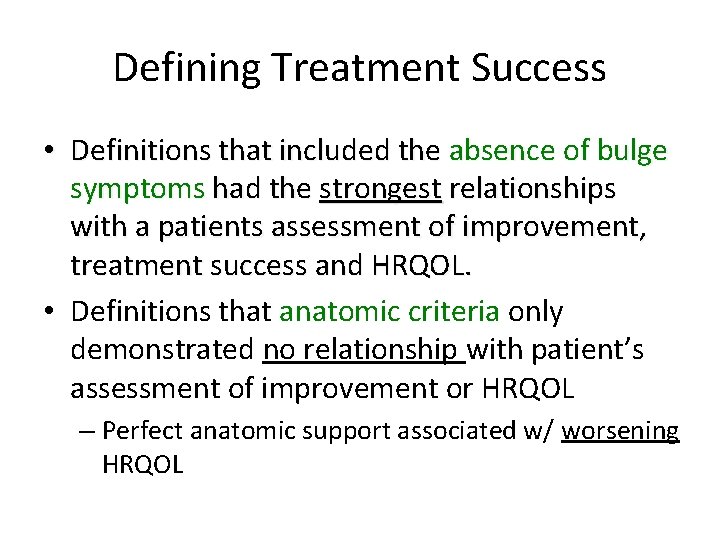

Defining Treatment Success • Definitions that included the absence of bulge symptoms had the strongest relationships with a patients assessment of improvement, treatment success and HRQOL. • Definitions that anatomic criteria only demonstrated no relationship with patient’s assessment of improvement or HRQOL – Perfect anatomic support associated w/ worsening HRQOL

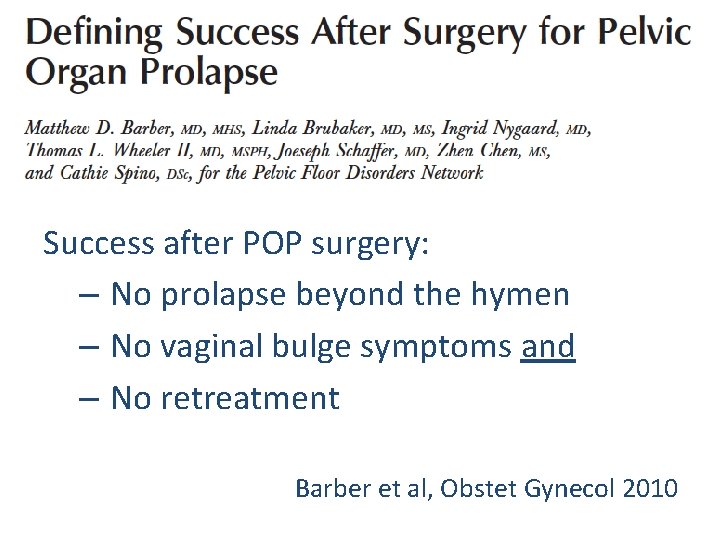

Success after POP surgery: – No prolapse beyond the hymen – No vaginal bulge symptoms and – No retreatment Barber et al, Obstet Gynecol 2010

Reanalysis of Weber et al Chmielewski, AJOG 2011; 105: 69

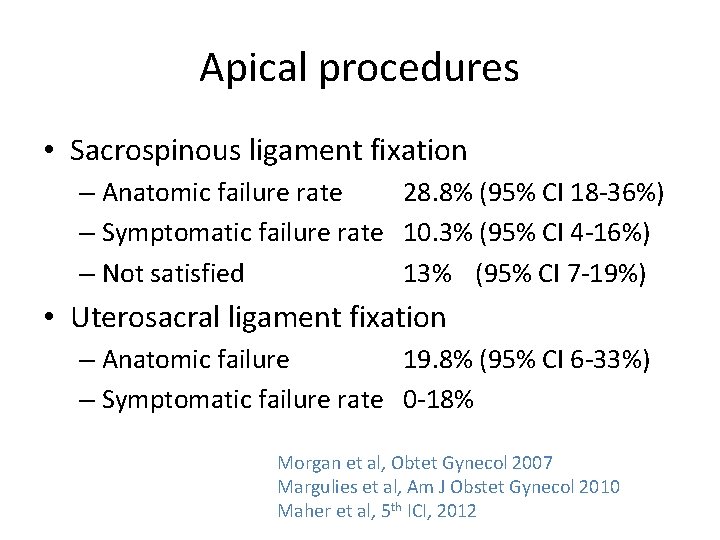

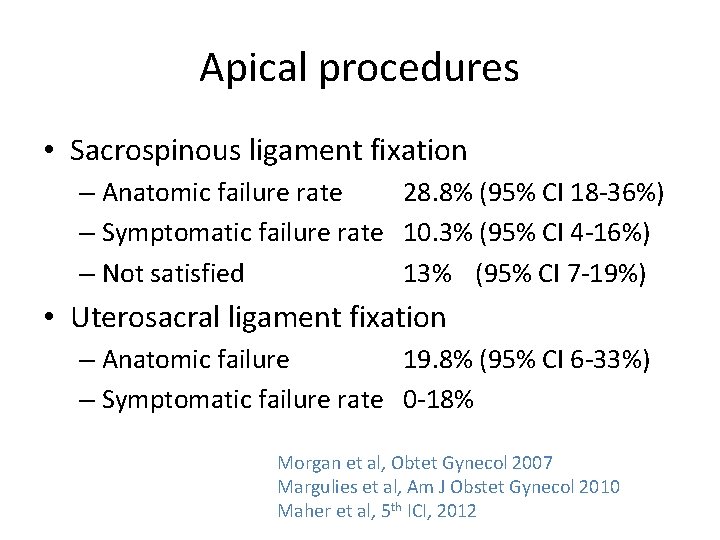

Apical procedures • Sacrospinous ligament fixation – Anatomic failure rate 28. 8% (95% CI 18 -36%) – Symptomatic failure rate 10. 3% (95% CI 4 -16%) – Not satisfied 13% (95% CI 7 -19%) • Uterosacral ligament fixation – Anatomic failure 19. 8% (95% CI 6 -33%) – Symptomatic failure rate 0 -18% Morgan et al, Obtet Gynecol 2007 Margulies et al, Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010 Maher et al, 5 th ICI, 2012

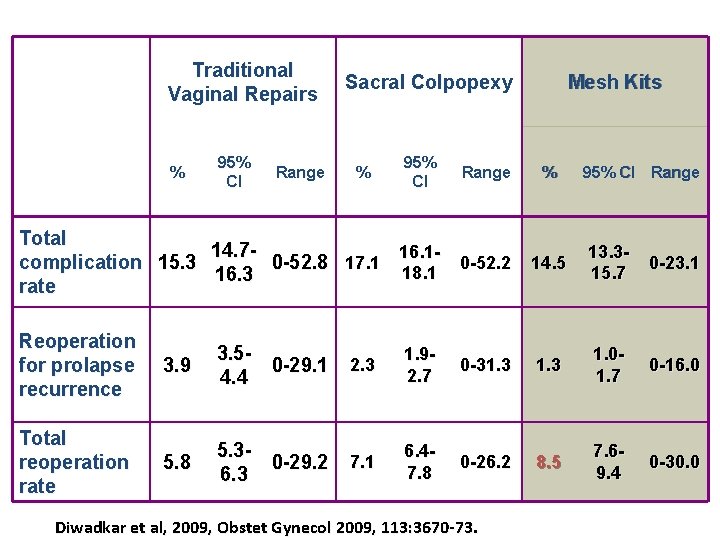

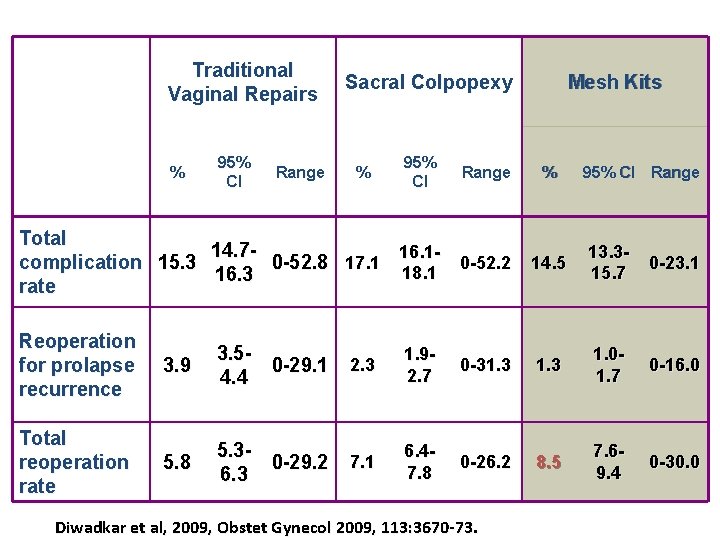

Traditional Vaginal Repairs % 95% CI Range Sacral Colpopexy % 95% CI Range Mesh Kits % 95% CI Range Total 14. 716. 10 -52. 2 14. 5 complication 15. 3 0 -52. 8 17. 1 18. 1 16. 3 rate 13. 315. 7 0 -23. 1 Reoperation for prolapse recurrence 3. 9 3. 50 -29. 1 4. 4 2. 3 1. 92. 7 0 -31. 3 1. 01. 7 0 -16. 0 Total reoperation rate 5. 8 5. 30 -29. 2 6. 3 7. 1 6. 47. 8 0 -26. 2 8. 5 7. 69. 4 0 -30. 0 Diwadkar et al, 2009, Obstet Gynecol 2009, 113: 3670 -73.

Is the Success rate High or Low? • The success rates after POP surgery vary considerably depending upon the definition of treatment success. • Some degree of vaginal relaxation is normal in most parous women. • When strict anatomic criteria are used, the success rate of native tissue repair, particularly anterior repair is low. • However, strict anatomic criteria appear to have little relationship to a patient’s perception of treatment success. • When more clinically relevant criteria are used, treatment success is substantially better.

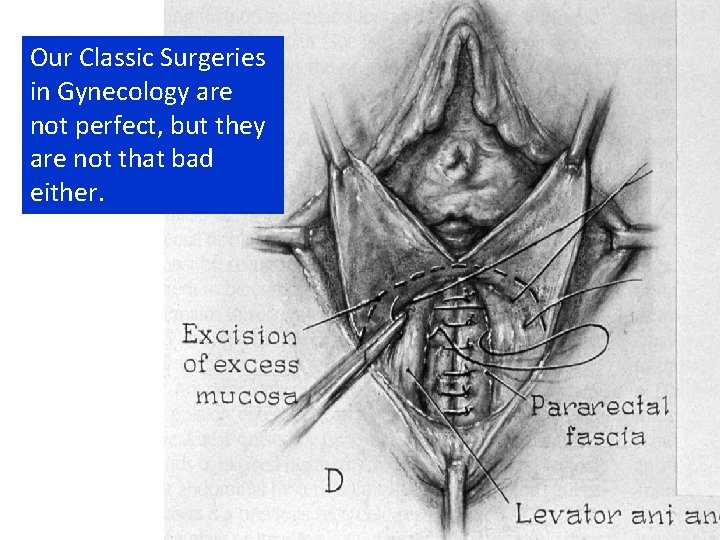

Our Classic Surgeries in Gynecology are not perfect, but they are not that bad either.

What we know about synthetic mesh used in midurethral slings: pros and cons AGOS 2012 Charles W. Nager, M. D. Department of Reproductive Medicine Director, Division of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

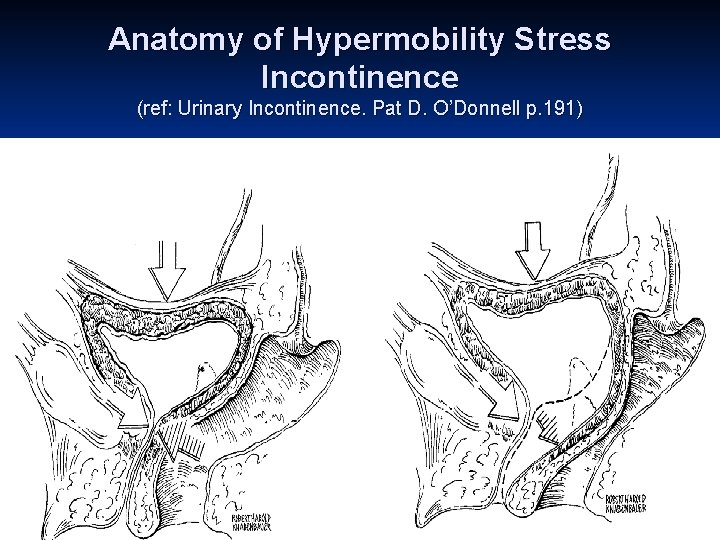

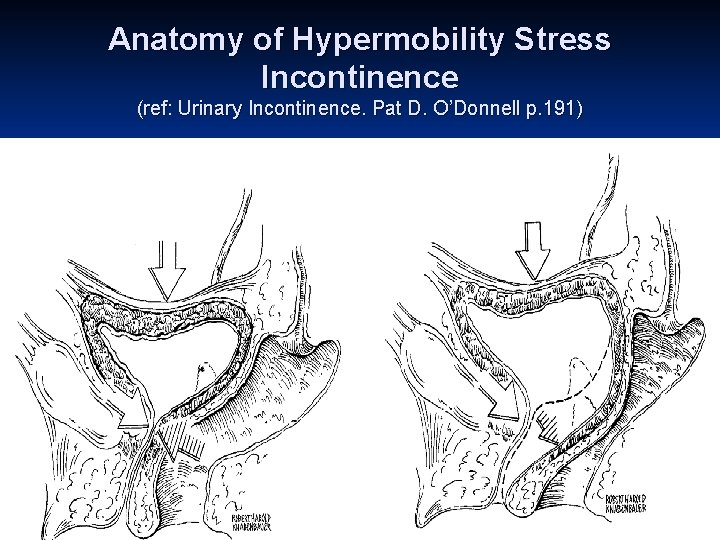

Anatomy of Hypermobility Stress Incontinence (ref: Urinary Incontinence. Pat D. O’Donnell p. 191)

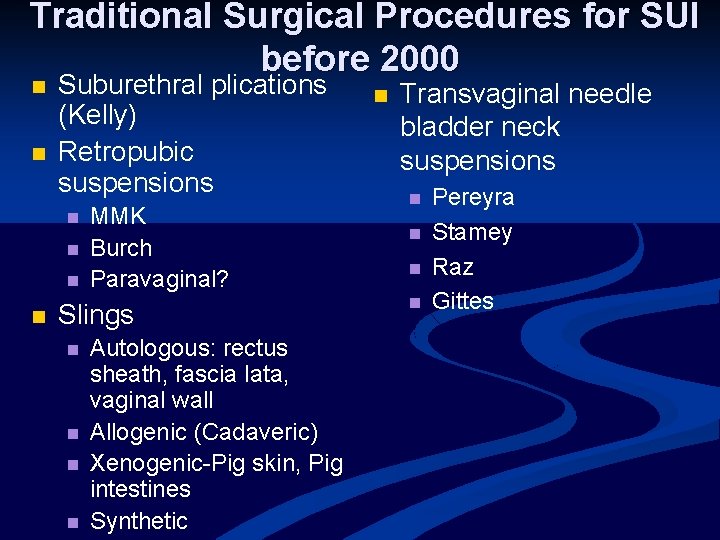

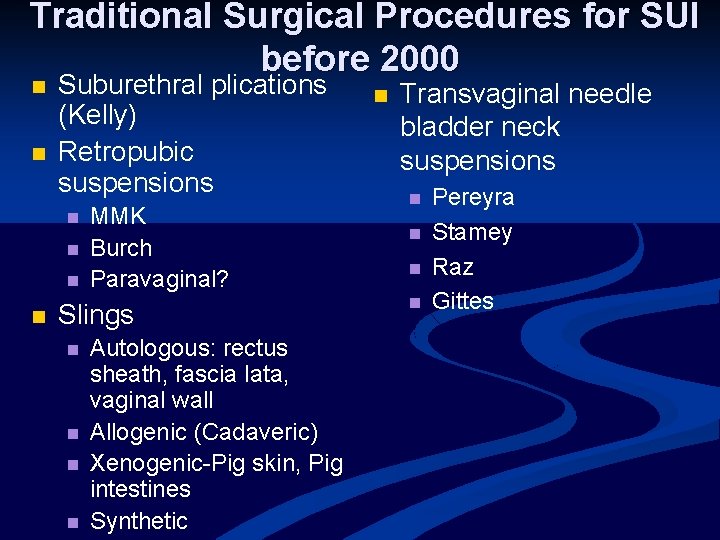

Traditional Surgical Procedures for SUI before 2000 n n Suburethral plications (Kelly) Retropubic suspensions n n MMK Burch Paravaginal? Slings n n Autologous: rectus sheath, fascia lata, vaginal wall Allogenic (Cadaveric) Xenogenic-Pig skin, Pig intestines Synthetic n Transvaginal needle bladder neck suspensions n n Pereyra Stamey Raz Gittes

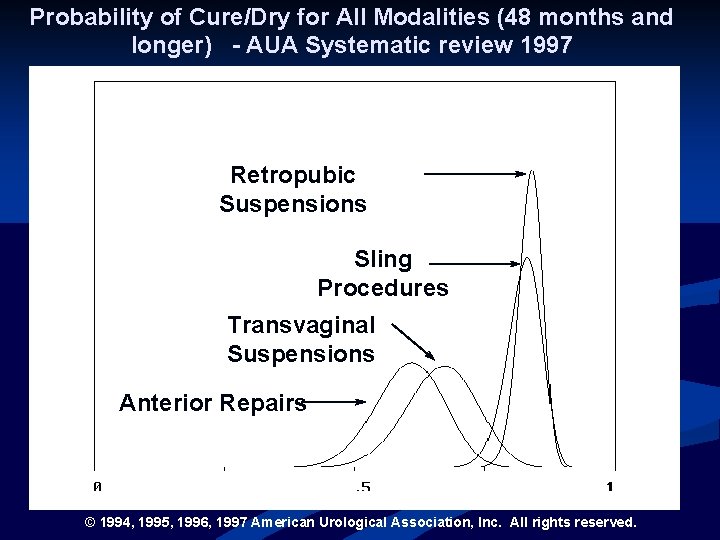

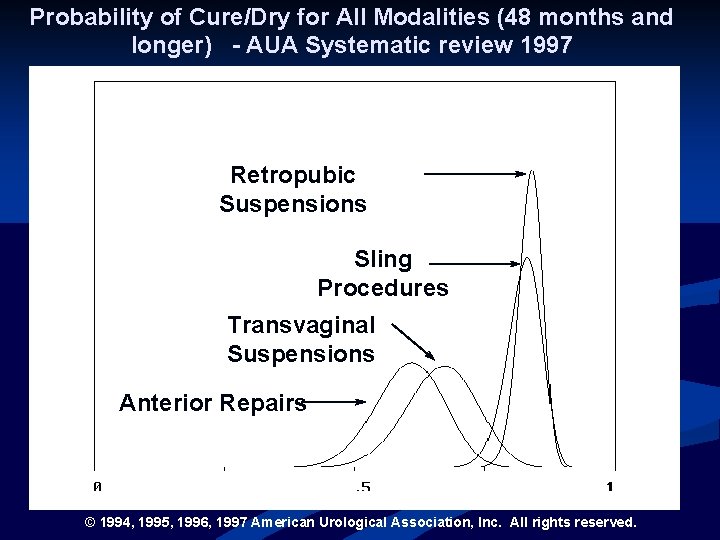

Probability of Cure/Dry for All Modalities (48 months and longer) - AUA Systematic review 1997 Retropubic Suspensions Sling Procedures Transvaginal Suspensions Anterior Repairs © 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997 American Urological Association, Inc. All rights reserved.

Midurethral slings – a trend for minimally invasive procedures Reduce surgical time Reduce length of hospitalization Reduce complication rates/risks Allow quicker return to normal, daily activities Lower costs

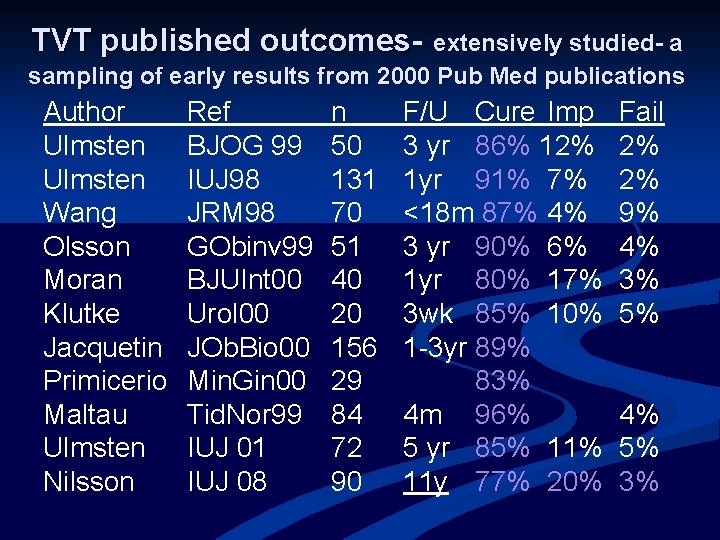

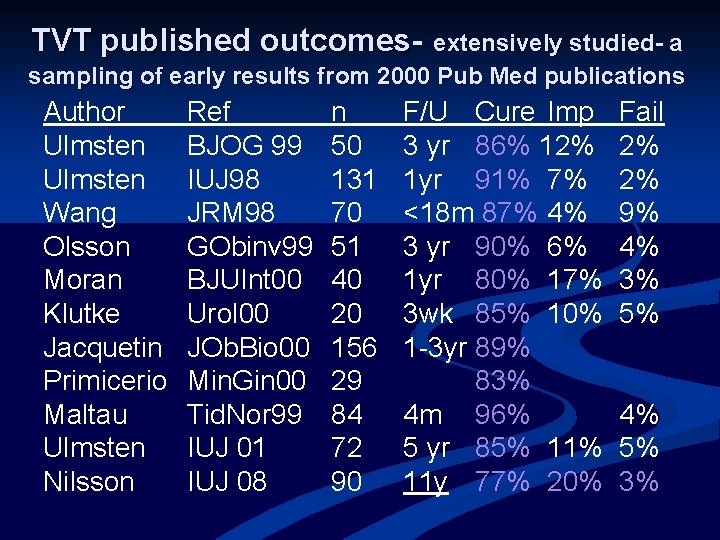

TVT published outcomes- extensively studied- a sampling of early results from 2000 Pub Med publications Author Ulmsten Wang Olsson Moran Klutke Jacquetin Primicerio Maltau Ulmsten Nilsson Ref BJOG 99 IUJ 98 JRM 98 GObinv 99 BJUInt 00 Urol 00 JOb. Bio 00 Min. Gin 00 Tid. Nor 99 IUJ 01 IUJ 08 n 50 131 70 51 40 20 156 29 84 72 90 F/U Cure Imp 3 yr 86% 12% 1 yr 91% 7% <18 m 87% 4% 3 yr 90% 6% 1 yr 80% 17% 3 wk 85% 10% 1 -3 yr 89% 83% 4 m 96% 5 yr 85% 11 y 77% 20% Fail 2% 2% 9% 4% 3% 5% 4% 5% 3%

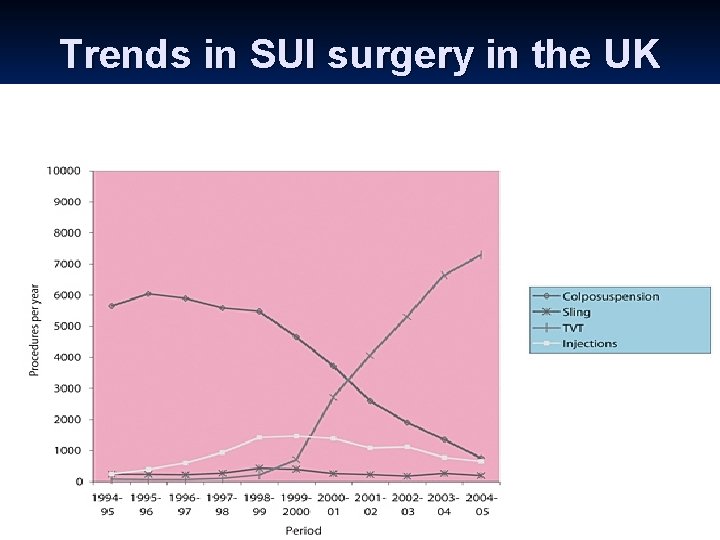

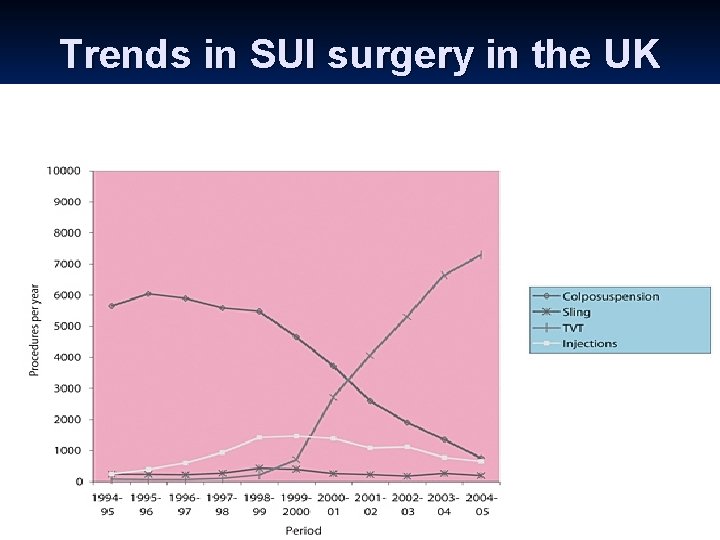

Trends in SUI surgery in the UK

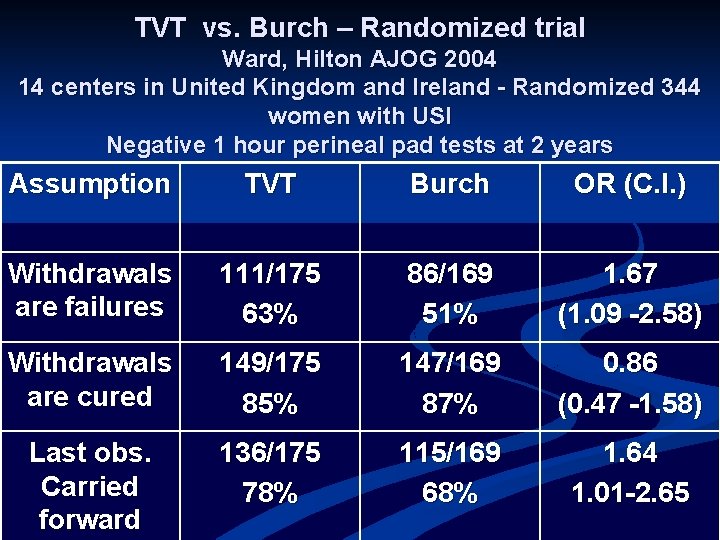

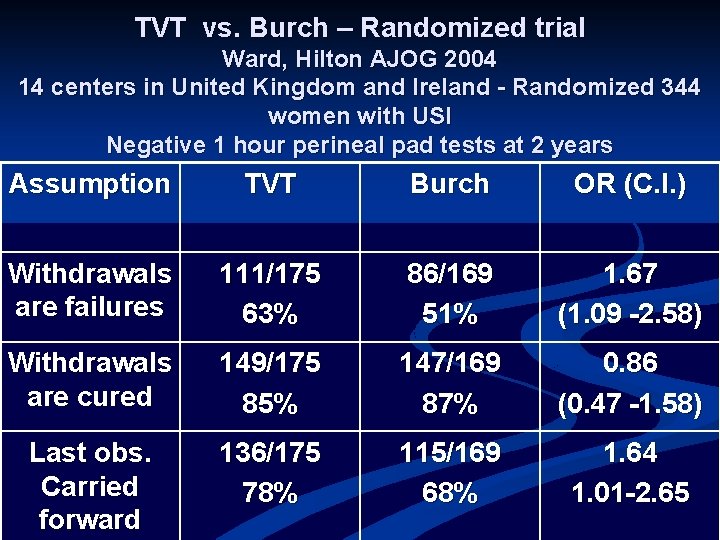

TVT vs. Burch – Randomized trial Ward, Hilton AJOG 2004 14 centers in United Kingdom and Ireland - Randomized 344 women with USI Negative 1 hour perineal pad tests at 2 years Assumption TVT Burch OR (C. I. ) Withdrawals are failures 111/175 63% 86/169 51% 1. 67 (1. 09 -2. 58) Withdrawals are cured 149/175 85% 147/169 87% 0. 86 (0. 47 -1. 58) Last obs. Carried forward 136/175 78% 115/169 68% 1. 64 1. 01 -2. 65

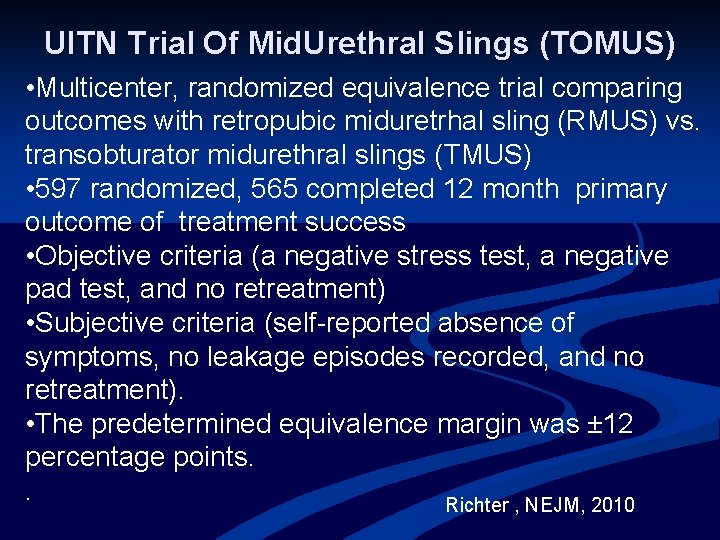

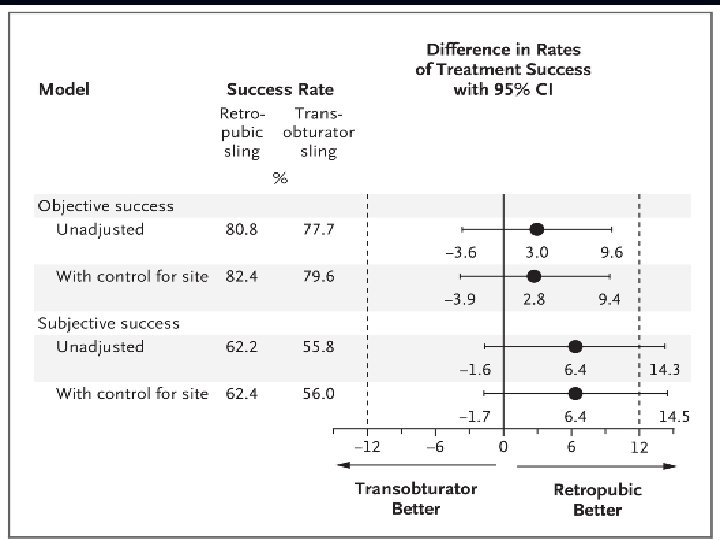

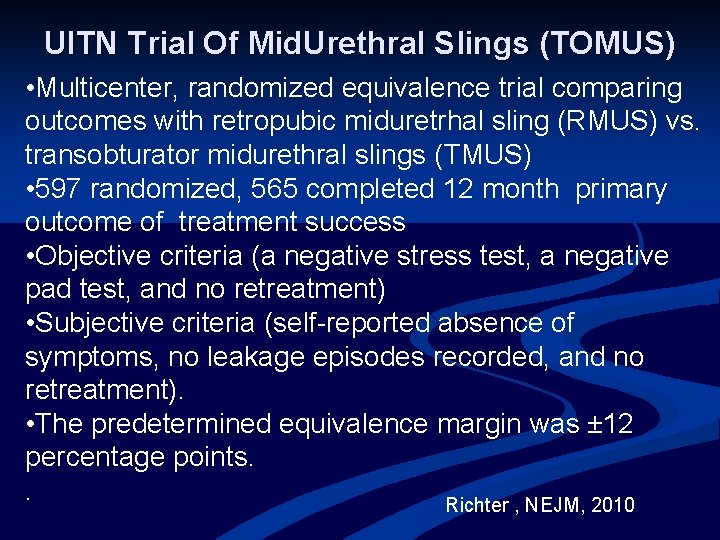

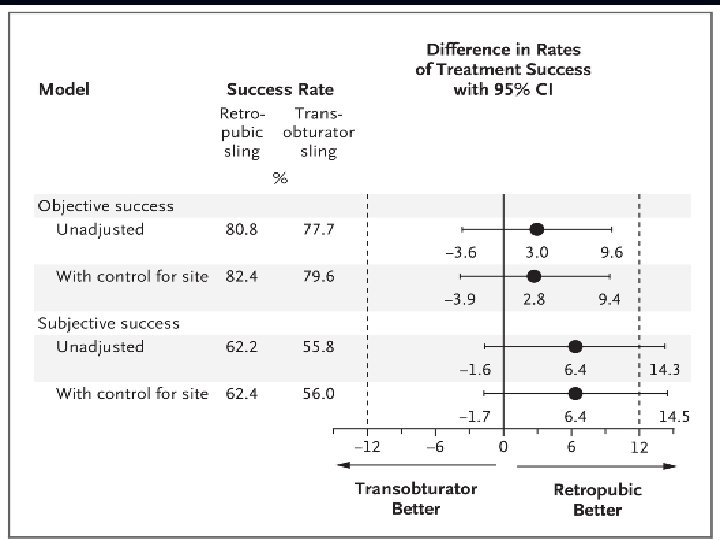

UITN Trial Of Mid. Urethral Slings (TOMUS) • Multicenter, randomized equivalence trial comparing outcomes with retropubic miduretrhal sling (RMUS) vs. transobturator midurethral slings (TMUS) • 597 randomized, 565 completed 12 month primary outcome of treatment success • Objective criteria (a negative stress test, a negative pad test, and no retreatment) • Subjective criteria (self-reported absence of symptoms, no leakage episodes recorded, and no retreatment). • The predetermined equivalence margin was ± 12 percentage points. . Richter , NEJM, 2010

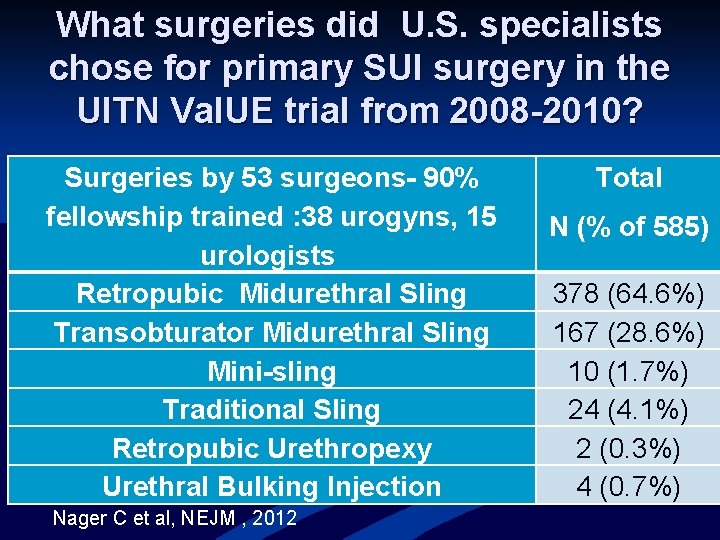

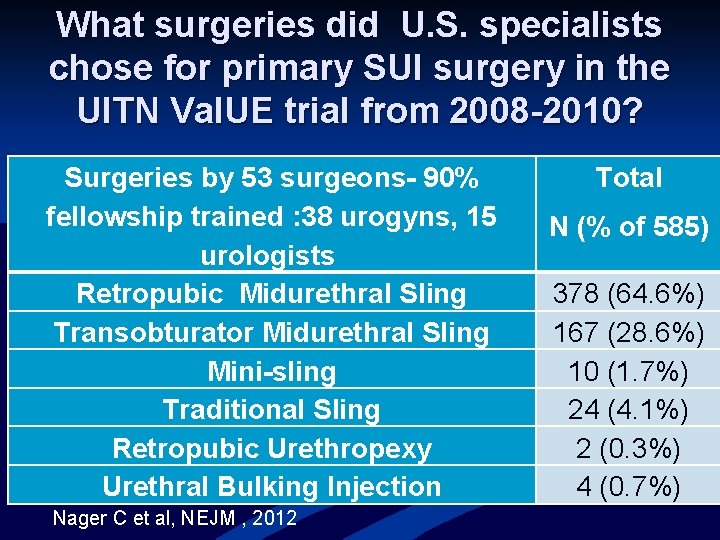

What surgeries did U. S. specialists chose for primary SUI surgery in the UITN Val. UE trial from 2008 -2010? Surgeries by 53 surgeons- 90% fellowship trained : 38 urogyns, 15 urologists Retropubic Midurethral Sling Transobturator Midurethral Sling Mini-sling Traditional Sling Retropubic Urethropexy Urethral Bulking Injection Nager C et al, NEJM , 2012 Total N (% of 585) 378 (64. 6%) 167 (28. 6%) 10 (1. 7%) 24 (4. 1%) 2 (0. 3%) 4 (0. 7%)

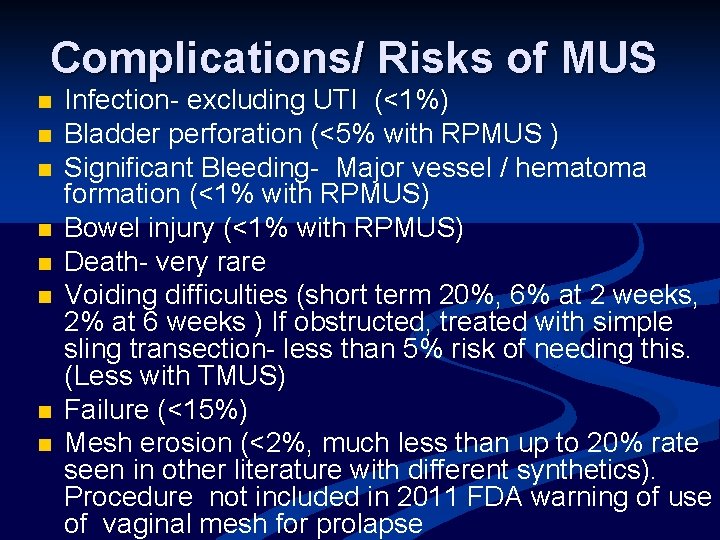

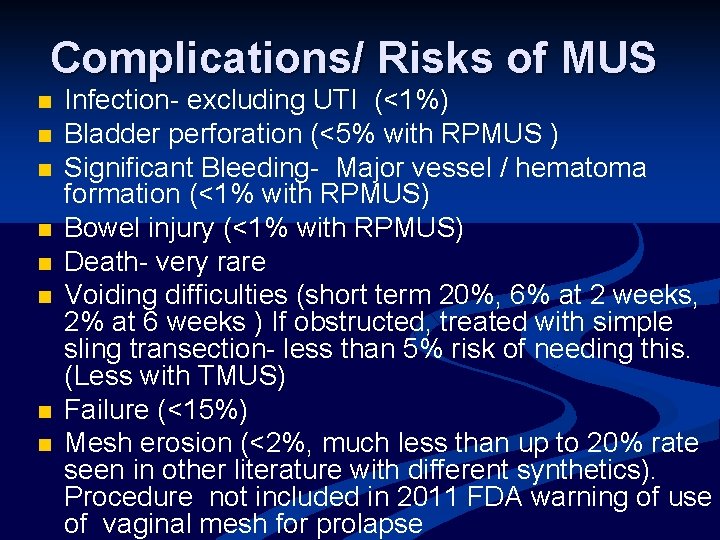

Complications/ Risks of MUS n n n n Infection- excluding UTI (<1%) Bladder perforation (<5% with RPMUS ) Significant Bleeding- Major vessel / hematoma formation (<1% with RPMUS) Bowel injury (<1% with RPMUS) Death- very rare Voiding difficulties (short term 20%, 6% at 2 weeks, 2% at 6 weeks ) If obstructed, treated with simple sling transection- less than 5% risk of needing this. (Less with TMUS) Failure (<15%) Mesh erosion (<2%, much less than up to 20% rate seen in other literature with different synthetics). Procedure not included in 2011 FDA warning of use of vaginal mesh for prolapse

MUS mesh Erosion

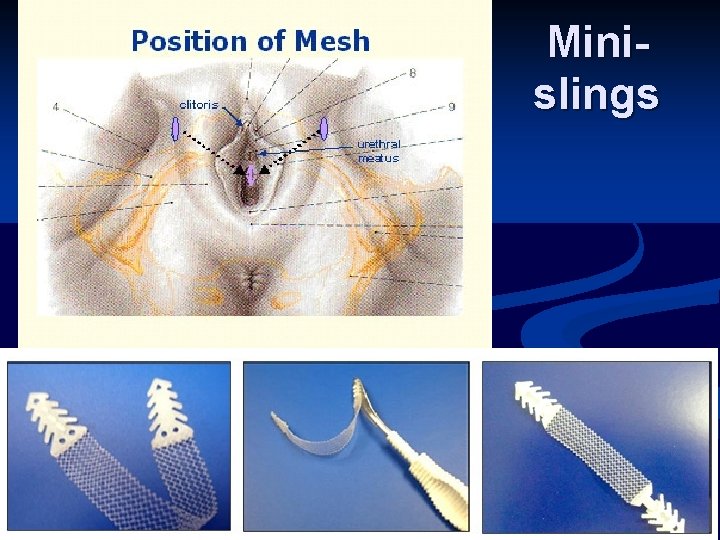

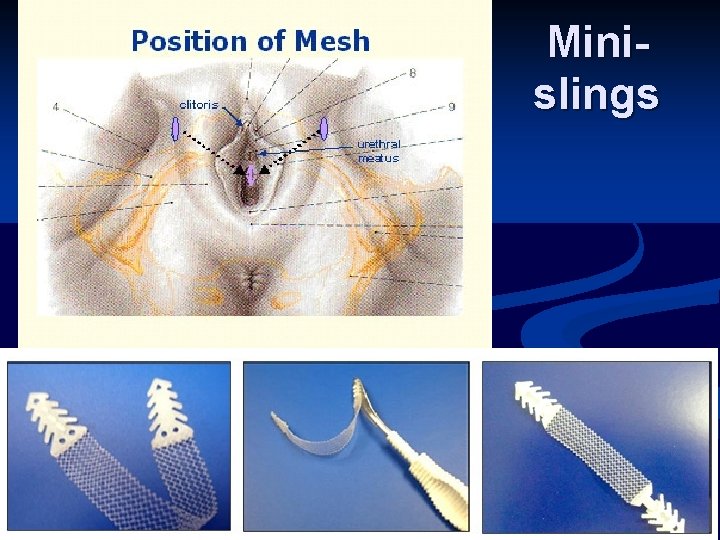

Minislings

522 order for mini-sling manufacturers “…Your device is subject to postmarket surveillance under section 522 When FDA orders postmarket surveillance, the manufacturer must submit a plan to conduct the surveillance. FDA will then determine whether the plan will result in the collection of useful data that can reveal unforeseen adverse events or other information necessary to protect the public health. Here, FDA is concerned with potential safety risks as evidenced by adverse events reported to the FDA. In addition, FDA is concerned with published literature indicating lack of added clinical benefit without reduced rates of repeat surgery compared to multi-incision retropubic or transobturator mesh slings…. ”

Conclusions The risks of mesh erosion, dyspareunia, and pelvic pain are markedly less with synthetic midurethral slings than with transvaginal mesh for prolapse. n Manufacturers of full length midurethral slings did not receive a 522 letter from the FDA, but mini-sling manufacturers did n Synthetic mesh full length midurethral slings remain the dominant surgical procedure for stress urinary incontinence n

Indications, Contraindications, and Complications of Mesh Use in the Surgical Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse Holly E. Richter, Ph. D, MD, FACOG, FACS Professor Obstetrics and Gynecology Director, Division Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery University of Alabama at Birmingham AGOS, September 14, 2012

Disclosures n n Astellas, Investigator Initiated Research Funding Pelvalon, Research Funding NICHD NIDDK

Objectives n n n To provide the rationale for the use of transvaginal synthetic mesh for pelvic organ prolapse repair To understand consensus indications and contraindications for the use of transvaginal synthetic mesh for POP To review the efficacy and safety of transvaginal mesh use for pelvic organ prolapse

Introduction n n National population-based estimate using validated measures reported an overall 2. 9% prevalence of symptomatic prolapse; 1 other estimates as high as 8%2, 3 An estimated 300, 000 surgical procedures performed annually 4 Lifetime risk for intervention, 11 -19% with reoperation rates of 30 -50%5, 6, 7, 8 Efforts to combat high failure rates and improve outcomes has led to the development and introduction of materials including synthetic mesh to augment reconstructive repairs 9

Purpose of Synthetic Graft n To facilitate in-growth of viable tissue to repair a defect n To provide a scaffold, matrix, or bridge through which the host’s tissue may grow, thereby leading to increased strength of that area n To take tension off an area which is undergoing healing

Transvaginal Mesh Kits 1 st FDA 510 -K review 2001 n Relative wide spread use by 2004 n ~100 synthetic mesh devices approved, but 20% of these are actively marketed and sold n Two ultra low density, (one hybrid absorbable/non-absorbable and one thin fiber polypropylene) have been more recently marketed n ACOG/AUGS Committee Opinion, Number 513, December, 2011

~75, 000 Transvaginal Procedures for POP Using Mesh Were Performed in the US in 2010

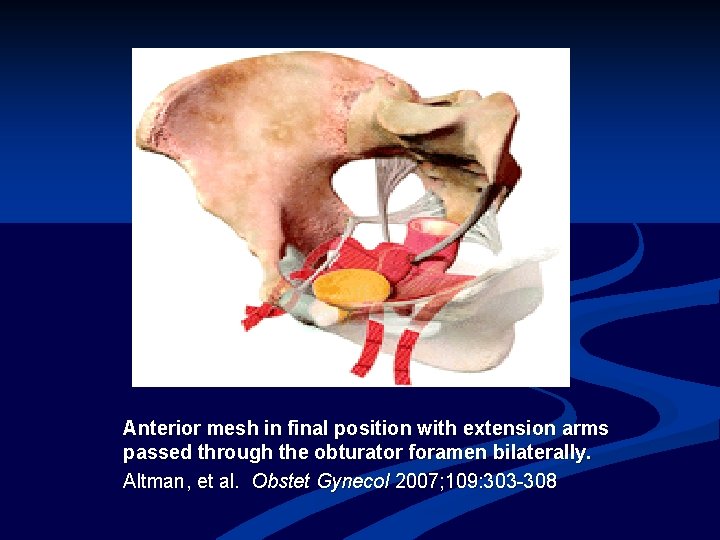

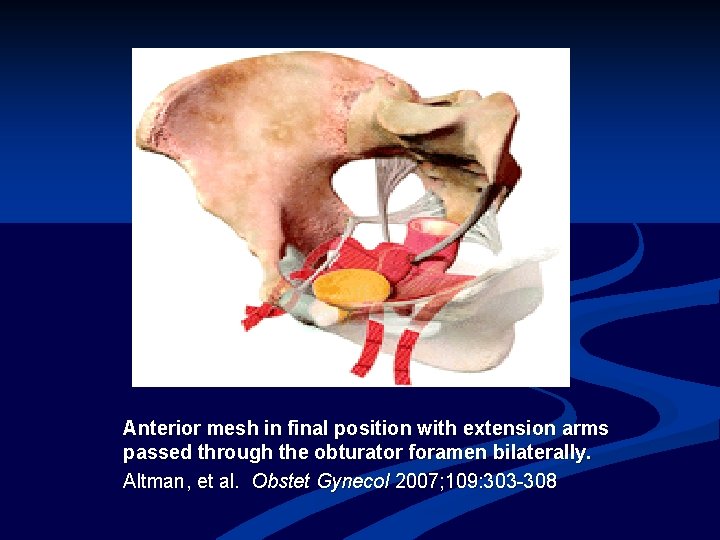

Anterior mesh in final position with extension arms passed through the obturator foramen bilaterally. Altman, et al. Obstet Gynecol 2007; 109: 303 -308

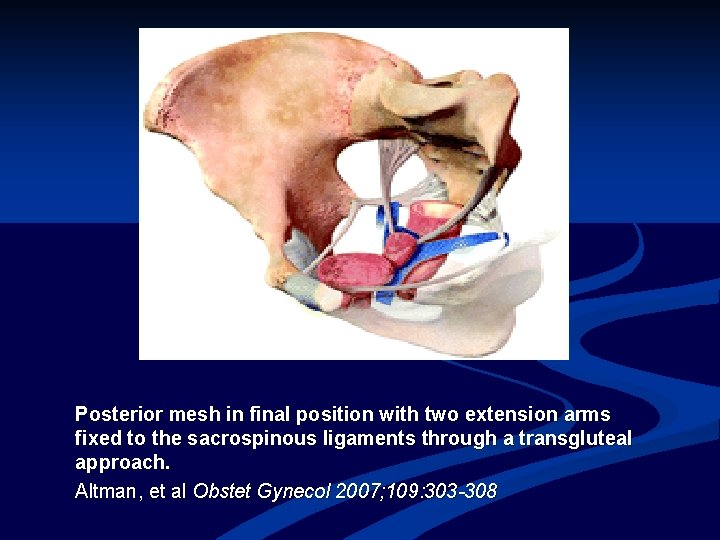

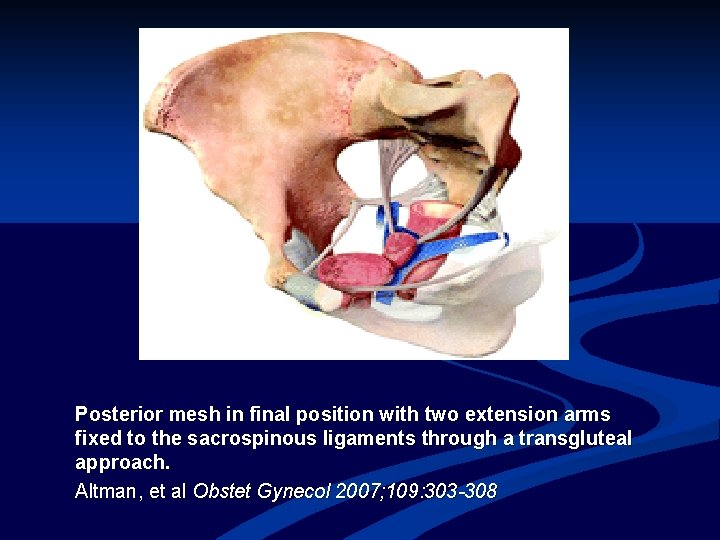

Posterior mesh in final position with two extension arms fixed to the sacrospinous ligaments through a transgluteal approach. Altman, et al Obstet Gynecol 2007; 109: 303 -308

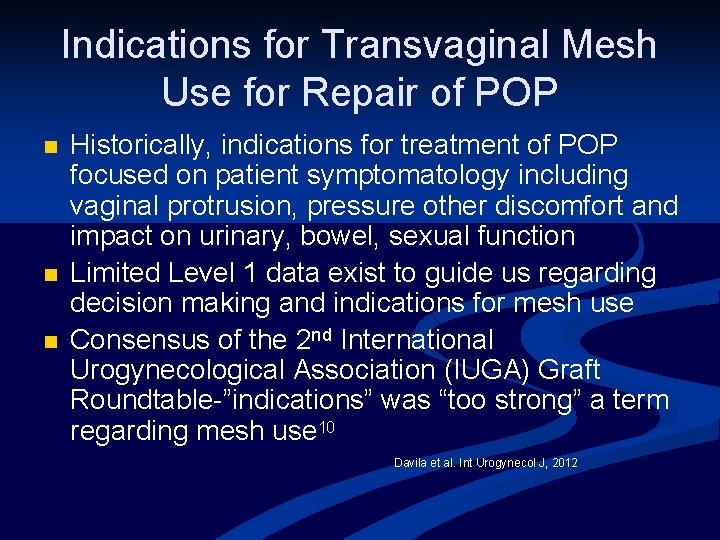

Indications for Transvaginal Mesh Use for Repair of POP n n n Historically, indications for treatment of POP focused on patient symptomatology including vaginal protrusion, pressure other discomfort and impact on urinary, bowel, sexual function Limited Level 1 data exist to guide us regarding decision making and indications for mesh use Consensus of the 2 nd International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) Graft Roundtable-”indications” was “too strong” a term regarding mesh use 10 Davila et al. Int Urogynecol J, 2012

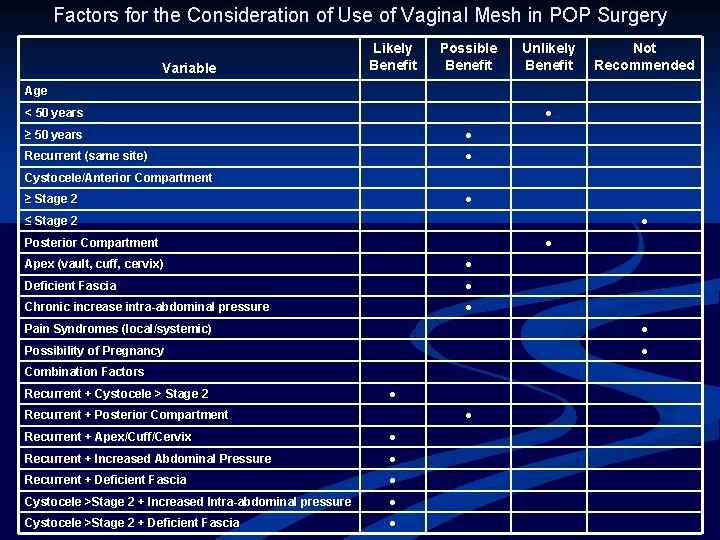

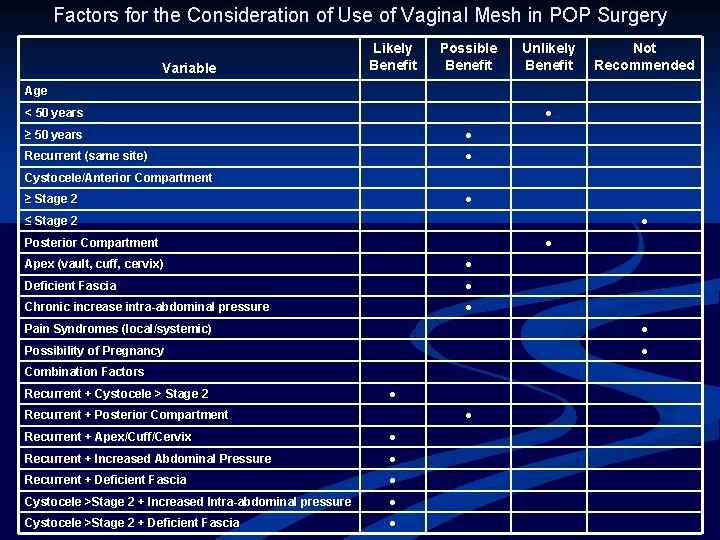

Factors for the Consideration of Use of Vaginal Mesh in POP Surgery Variable Likely Benefit Possible Benefit Unlikely Benefit Not Recommended Age < 50 years ● ≥ 50 years ● Recurrent (same site) ● Cystocele/Anterior Compartment ≥ Stage 2 ● ≤ Stage 2 ● Posterior Compartment ● Apex (vault, cuff, cervix) ● Deficient Fascia ● Chronic increase intra-abdominal pressure ● Pain Syndromes (local/systemic) ● Possibility of Pregnancy ● Combination Factors Recurrent + Cystocele > Stage 2 ● Recurrent + Posterior Compartment ● Recurrent + Apex/Cuff/Cervix ● Recurrent + Increased Abdominal Pressure ● Recurrent + Deficient Fascia ● Cystocele >Stage 2 + Increased Intra-abdominal pressure ● Cystocele >Stage 2 + Deficient Fascia ●

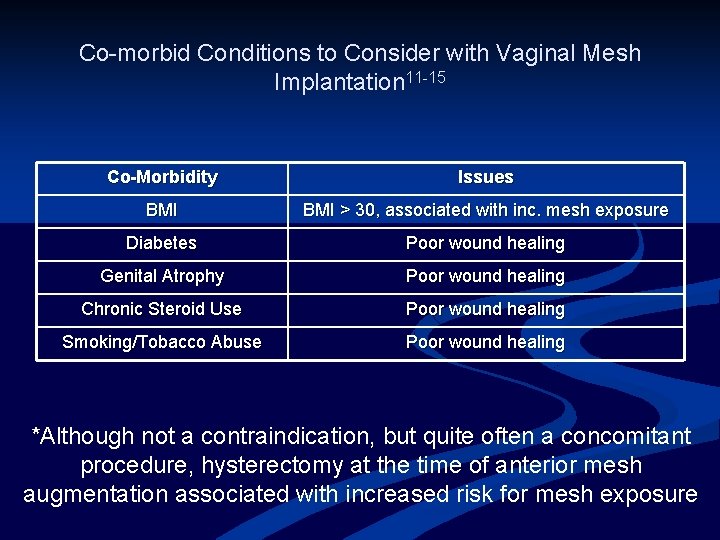

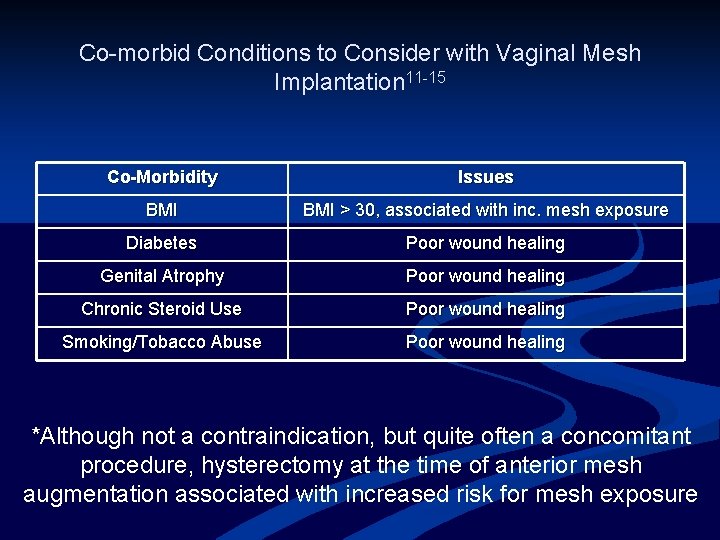

Co-morbid Conditions to Consider with Vaginal Mesh Implantation 11 -15 Co-Morbidity Issues BMI > 30, associated with inc. mesh exposure Diabetes Poor wound healing Genital Atrophy Poor wound healing Chronic Steroid Use Poor wound healing Smoking/Tobacco Abuse Poor wound healing *Although not a contraindication, but quite often a concomitant procedure, hysterectomy at the time of anterior mesh augmentation associated with increased risk for mesh exposure

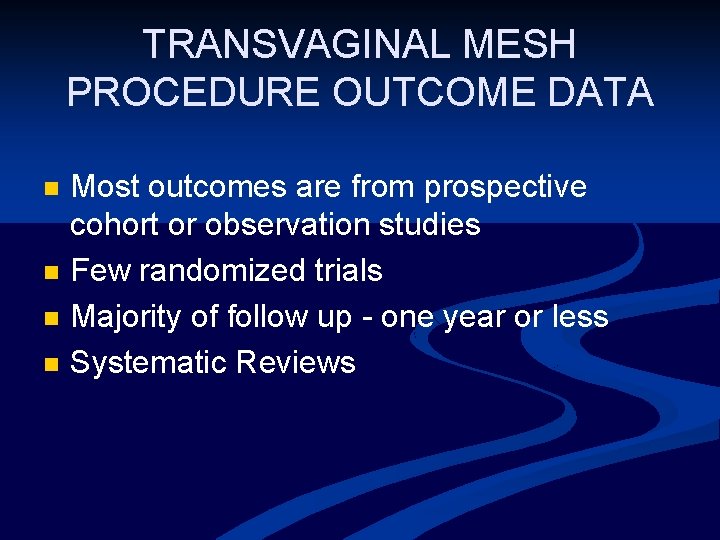

TRANSVAGINAL MESH PROCEDURE OUTCOME DATA n n Most outcomes are from prospective cohort or observation studies Few randomized trials Majority of follow up - one year or less Systematic Reviews

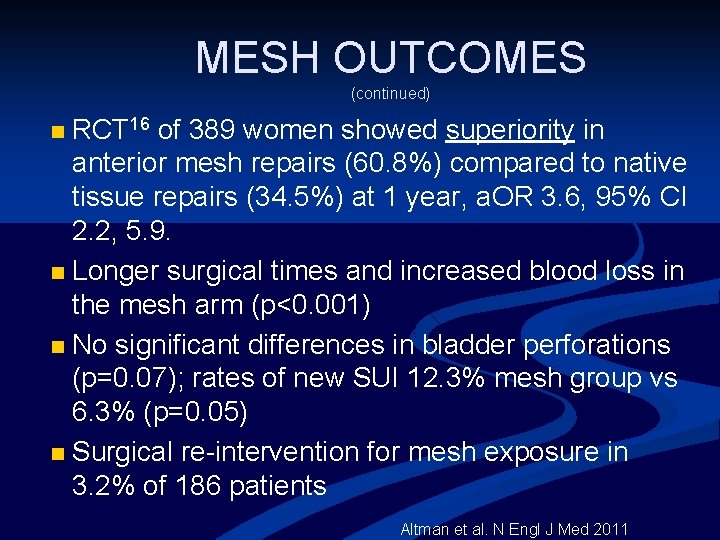

MESH OUTCOMES (continued) RCT 16 of 389 women showed superiority in anterior mesh repairs (60. 8%) compared to native tissue repairs (34. 5%) at 1 year, a. OR 3. 6, 95% CI 2. 2, 5. 9. n Longer surgical times and increased blood loss in the mesh arm (p<0. 001) n No significant differences in bladder perforations (p=0. 07); rates of new SUI 12. 3% mesh group vs 6. 3% (p=0. 05) n Surgical re-intervention for mesh exposure in 3. 2% of 186 patients n Altman et al. N Engl J Med 2011

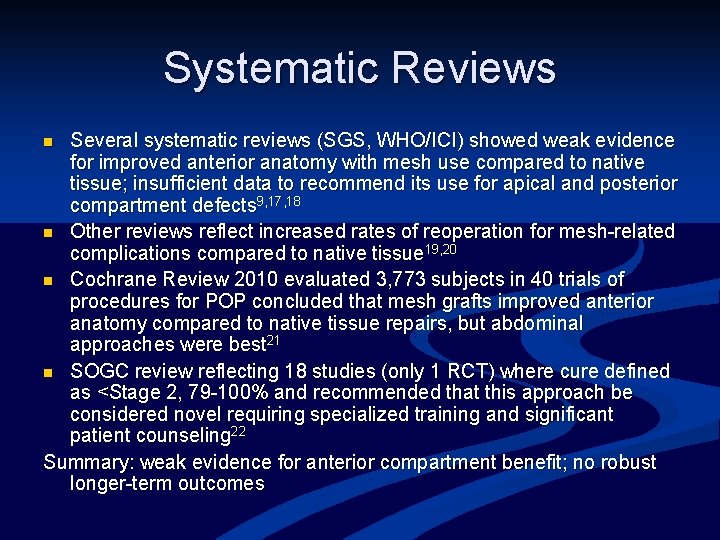

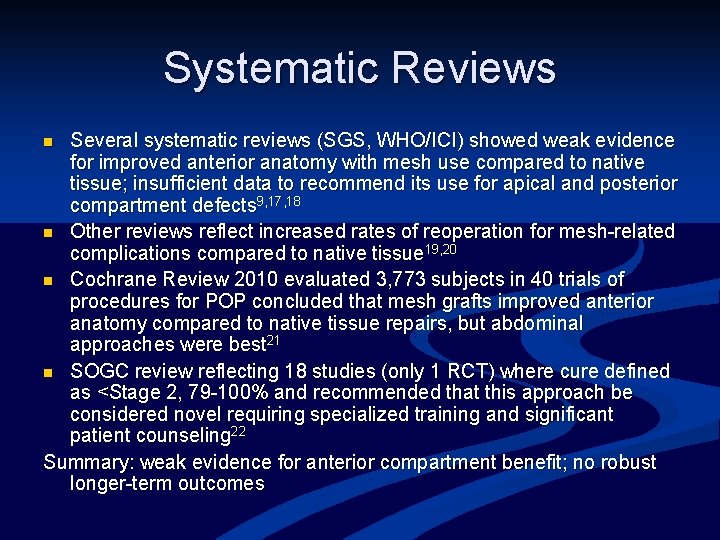

Systematic Reviews Several systematic reviews (SGS, WHO/ICI) showed weak evidence for improved anterior anatomy with mesh use compared to native tissue; insufficient data to recommend its use for apical and posterior compartment defects 9, 17, 18 n Other reviews reflect increased rates of reoperation for mesh-related complications compared to native tissue 19, 20 n Cochrane Review 2010 evaluated 3, 773 subjects in 40 trials of procedures for POP concluded that mesh grafts improved anterior anatomy compared to native tissue repairs, but abdominal approaches were best 21 n SOGC review reflecting 18 studies (only 1 RCT) where cure defined as <Stage 2, 79 -100% and recommended that this approach be considered novel requiring specialized training and significant patient counseling 22 Summary: weak evidence for anterior compartment benefit; no robust longer-term outcomes n

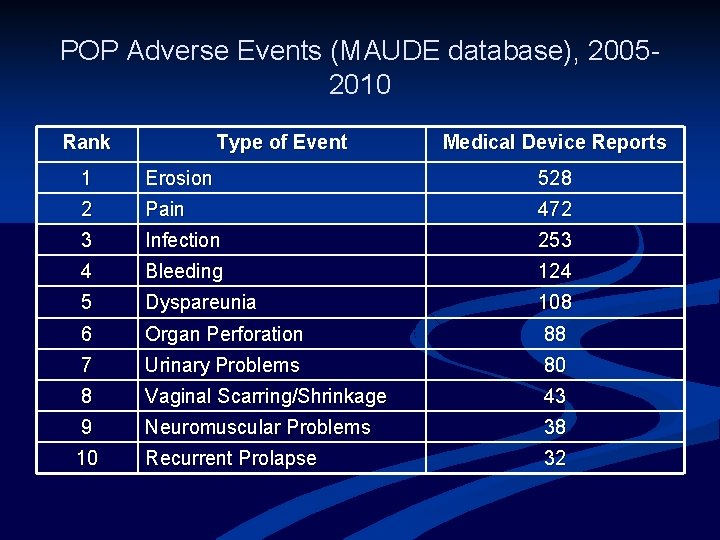

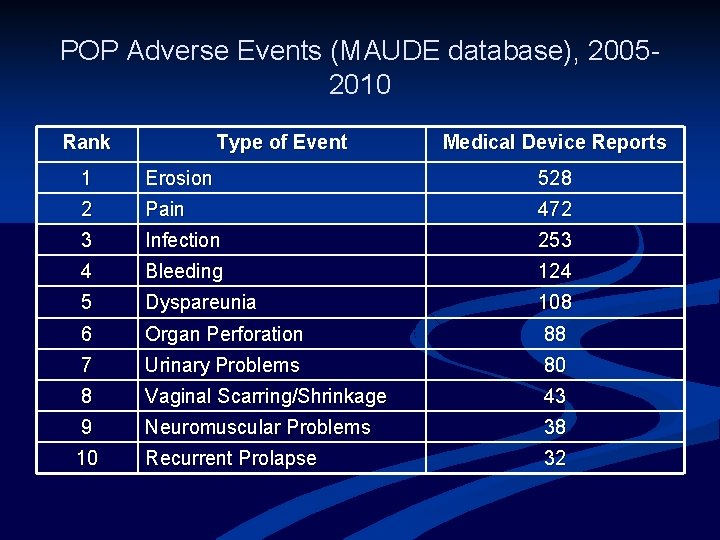

POP Adverse Events (MAUDE database), 20052010 Rank Type of Event Medical Device Reports 1 Erosion 528 2 Pain 472 3 Infection 253 4 Bleeding 124 5 Dyspareunia 108 6 Organ Perforation 88 7 Urinary Problems 80 8 Vaginal Scarring/Shrinkage 43 9 Neuromuscular Problems 38 10 Recurrent Prolapse 32

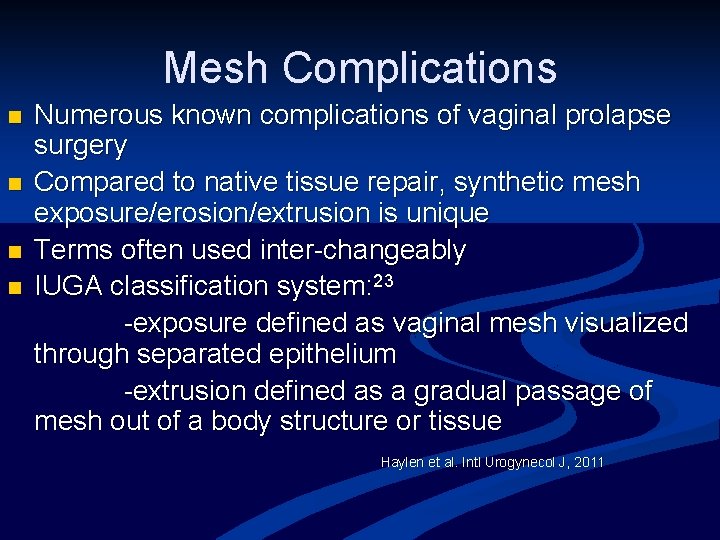

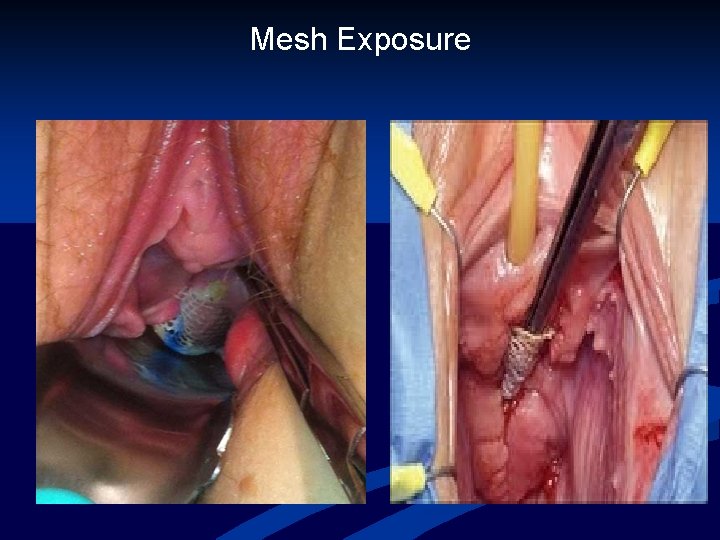

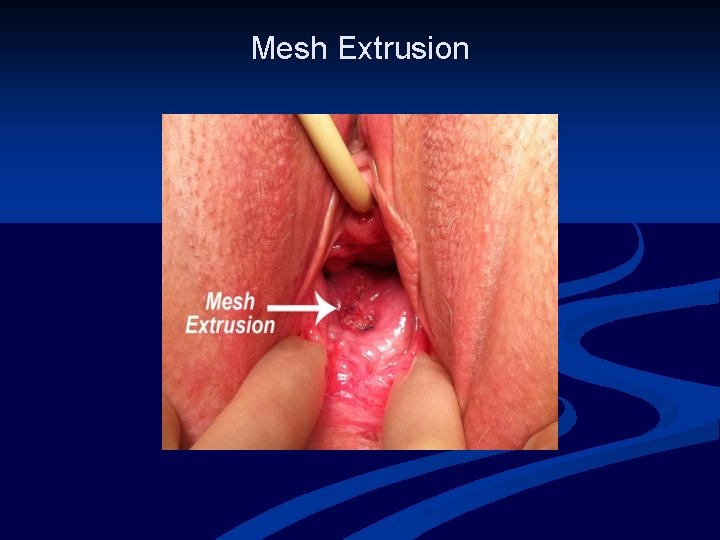

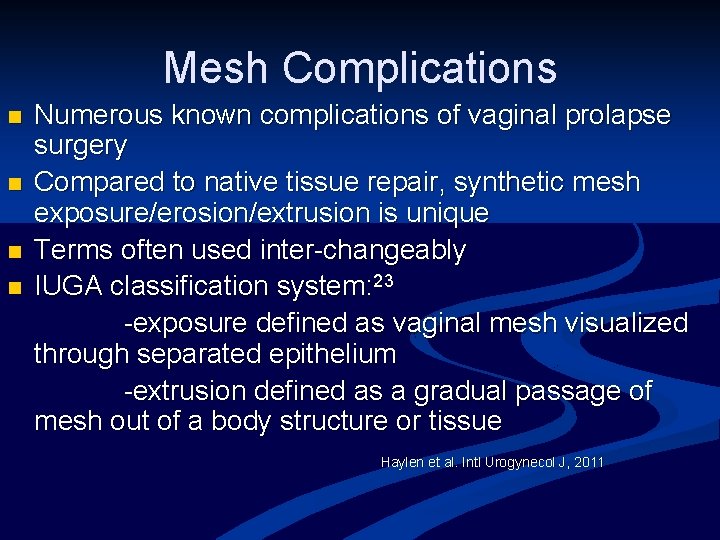

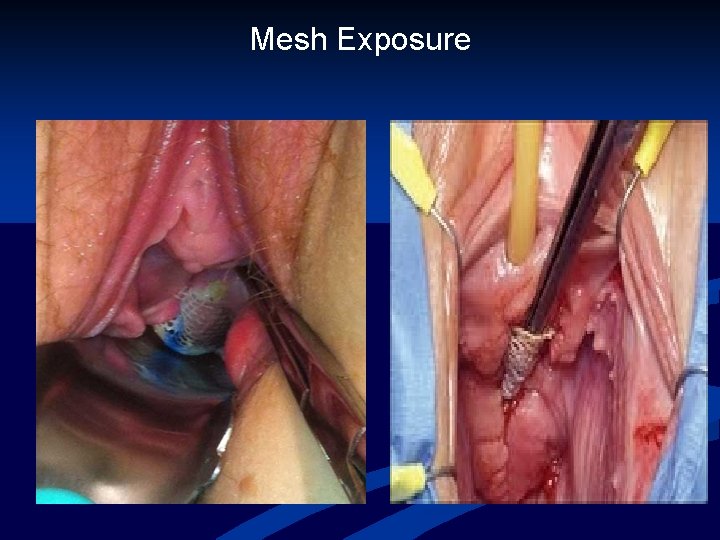

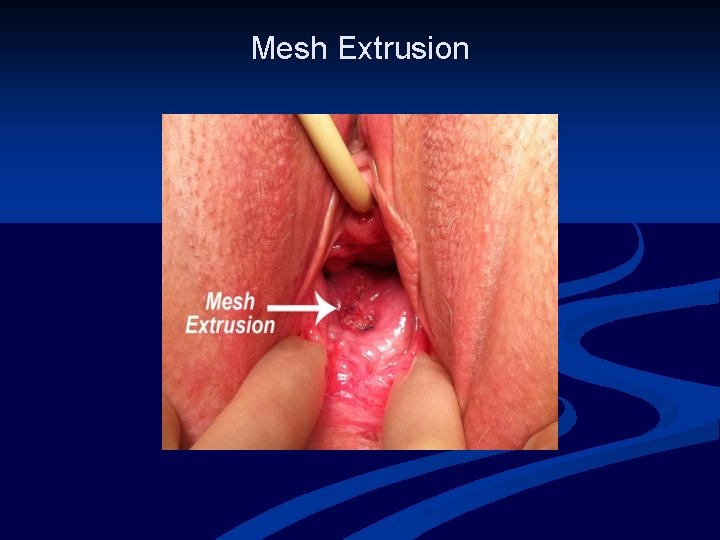

Mesh Complications n n Numerous known complications of vaginal prolapse surgery Compared to native tissue repair, synthetic mesh exposure/erosion/extrusion is unique Terms often used inter-changeably IUGA classification system: 23 -exposure defined as vaginal mesh visualized through separated epithelium -extrusion defined as a gradual passage of mesh out of a body structure or tissue Haylen et al. Intl Urogynecol J, 2011

Mesh Exposure

Mesh Extrusion

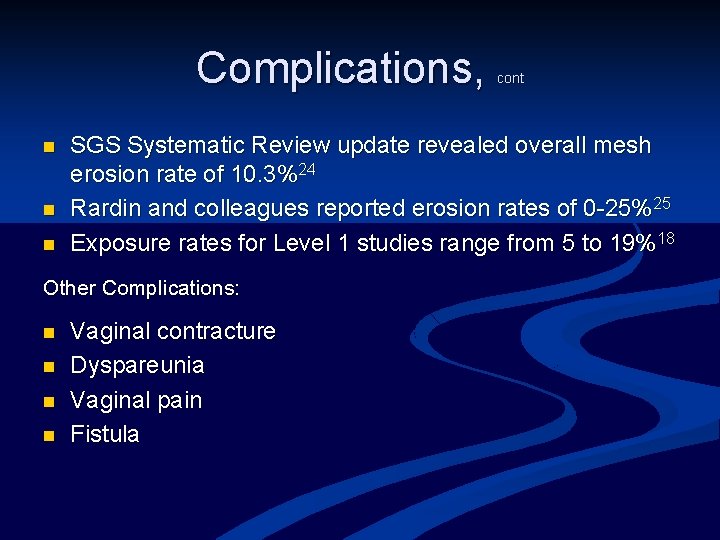

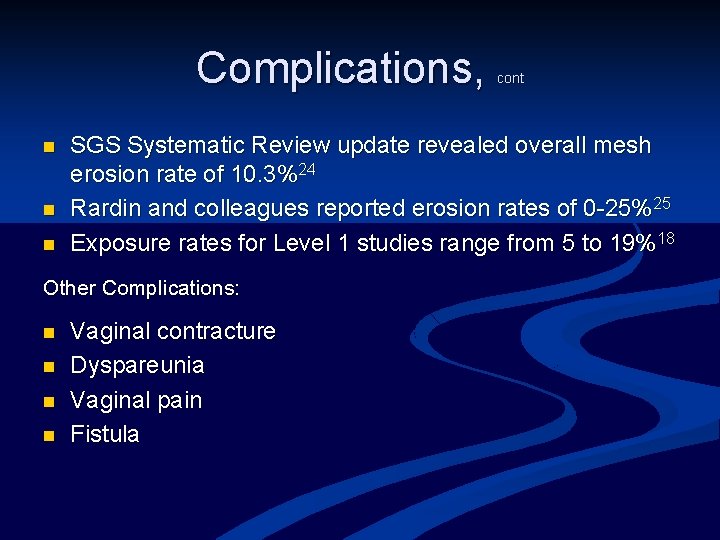

Complications, n n n SGS Systematic Review update revealed overall mesh erosion rate of 10. 3%24 Rardin and colleagues reported erosion rates of 0 -25%25 Exposure rates for Level 1 studies range from 5 to 19%18 Other Complications: n n cont Vaginal contracture Dyspareunia Vaginal pain Fistula

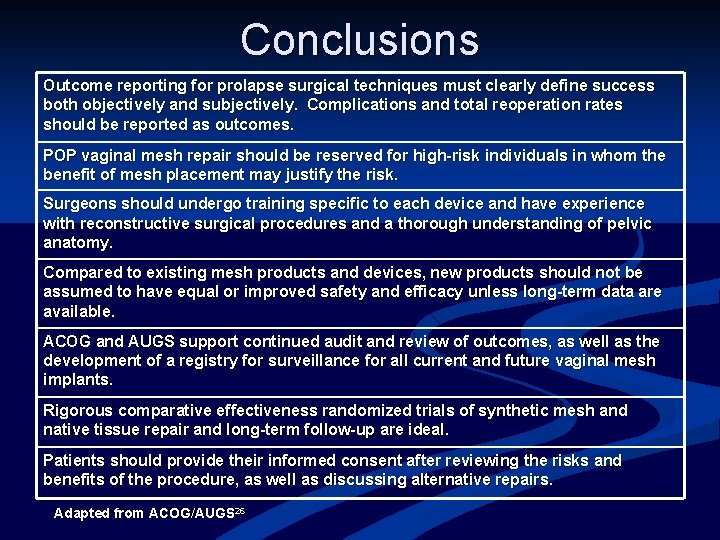

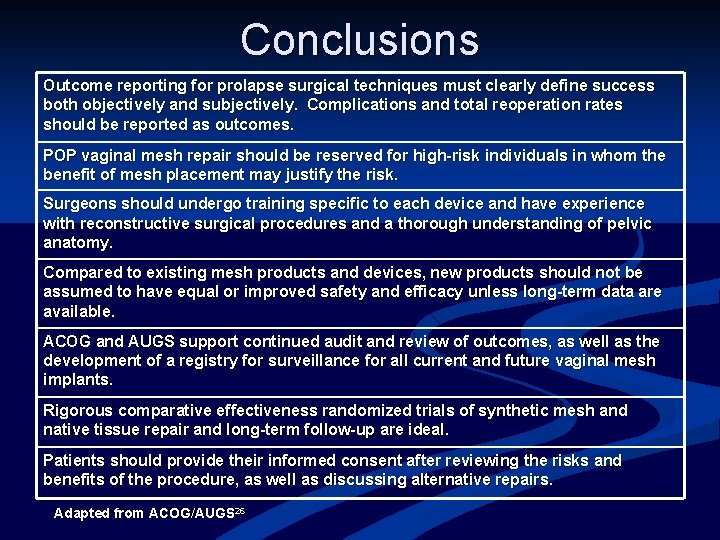

Conclusions Outcome reporting for prolapse surgical techniques must clearly define success both objectively and subjectively. Complications and total reoperation rates should be reported as outcomes. POP vaginal mesh repair should be reserved for high-risk individuals in whom the benefit of mesh placement may justify the risk. Surgeons should undergo training specific to each device and have experience with reconstructive surgical procedures and a thorough understanding of pelvic anatomy. Compared to existing mesh products and devices, new products should not be assumed to have equal or improved safety and efficacy unless long-term data are available. ACOG and AUGS support continued audit and review of outcomes, as well as the development of a registry for surveillance for all current and future vaginal mesh implants. Rigorous comparative effectiveness randomized trials of synthetic mesh and native tissue repair and long-term follow-up are ideal. Patients should provide their informed consent after reviewing the risks and benefits of the procedure, as well as discussing alternative repairs. Adapted from ACOG/AUGS 26

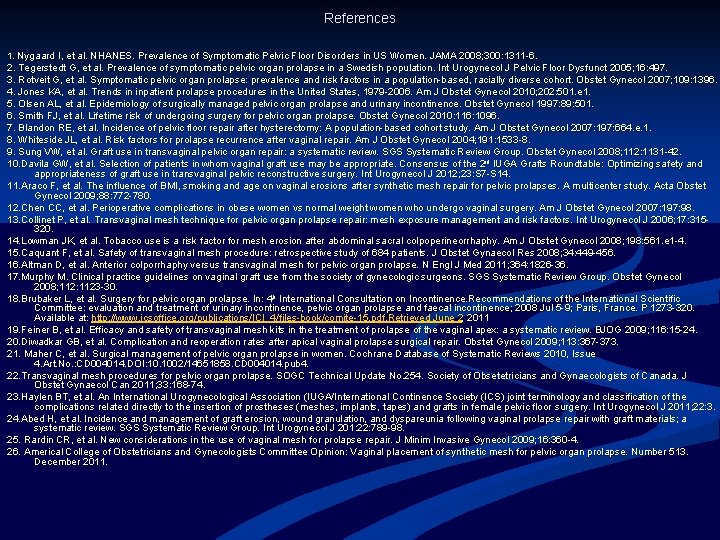

References 1. Nygaard I, et al. NHANES. Prevalence of Symptomatic Pelvic Floor Disorders in US Women. JAMA 2008; 300: 1311 -6. 2. Tegerstedt G, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse in a Swedish population. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2005; 16: 497. 3. Rotveit G, et al. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: prevalence and risk factors in a population-based, racially diverse cohort. Obstet Gynecol 2007; 109: 1396. 4. Jones KA, et al. Trends in inpatient prolapse procedures in the United States, 1979 -2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010; 202: 501. e 1. 5. Olsen AL, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 1997: 89: 501. 6. Smith FJ, et al. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 2010: 116: 1096. 7. Blandon RE, et al. Incidence of pelvic floor repair after hysterectomy: A population-based cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007: 197: 664. e. 1. 8. Whiteside JL, et al. Risk factors for prolapse recurrence after vaginal repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 191: 1533 -8. 9. Sung VW, et al. Graft use in transvaginal pelvic organ repair: a systematic review. SGS Systematic Review Group. Obstet Gynecol 2008; 112: 1131 -42. 10. Davila GW, et al. Selection of patients in whom vaginal graft use may be appropriate. Consensus of the 2 nd IUGA Grafts Roundtable: Optimizing safety and appropriateness of graft use in transvaginal pelvic reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J 2012; 23: S 7 -S 14. 11. Araco F, et al. The influence of BMI, smoking and age on vaginal erosions after synthetic mesh repair for pelvic prolapses. A multicenter study. Acta Obstet Gynecol 2009; 88: 772 -780. 12. Chen CC, et al. Perioperative complications in obese women vs normal weight women who undergo vaginal surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007: 197: 98. 13. Collinet P, et al. Transvaginal mesh technique for pelvic organ prolapse repair: mesh exposure management and risk factors. Int Urogynecol J 2006; 17: 315320. 14. Lowman JK, et al. Tobacco use is a risk factor for mesh erosion after abdominal sacral colpoperineorrhaphy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008; 198: 561. e 1 -4. 15. Caquant F, et al. Safety of transvaginal mesh procedure: retrospective study of 684 patients. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2008; 34: 449 -456. 16. Altman D, et al. Anterior colporrhaphy versus transvaginal mesh for pelvic-organ prolapse. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1826 -36. 17. Murphy M. Clinical practice guidelines on vaginal graft use from the society of gynecologic surgeons. SGS Systematic Review Group. Obstet Gynecol 2008; 112: 1123 -30. 18. Brubaker L, et al. Surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. In: 4 th International Consultation on Incontinence. Recommendations of the International Scientific Committee: evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse and faecal incontinence; 2008 Jul 5 -9; Paris, France. P 1273 -320. Available at: http: //www. icsoffice. org/publications/ICI_4/files-book/comite-15. pdf. Retrieved June 2, 2, 2011 19. Feiner B, et al. Efficacy and safety of transvaginal mesh kits in the treatment of prolapse of the vaginal apex: a systematic review. BJOG 2009; 116: 15 -24. 20. Diwadkar GB, et al. Complication and reoperation rates after apical vaginal prolapse surgical repair. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 113: 367 -373. 21. Maher C, et al. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 4. Art. No. : CD 004014. DOI: 10. 1002/14651858. CD 004014. pub 4. 22. Transvaginal mesh procedures for pelvic organ prolapse. SOGC Technical Update No. 254. Society of Obsetetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2011; 33: 168 -74. 23. Haylen BT, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA/International Continence Society (ICS) joint terminology and classification of the complications related directly to the insertion of prostheses (meshes, implants, tapes) and grafts in female pelvic floor surgery. Int Urogynecol J 2011; 22: 3. 24. Abed H, et al. Incidence and management of graft erosion, wound granulation, and dyspareunia following vaginal prolapse repair with graft materials; a systematic review. SGS Systematic Review Group. Int Urogynecol J 201: 22: 789 -98. 25. Rardin CR, et al. New considerations in the use of vaginal mesh for prolapse repair. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2009; 16: 360 -4. 26. Americal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion: Vaginal placement of synthetic mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Number 513. December 2011.

What happened in 2011? The FDA and Societies’ Responses Deborah L. Myers MD Women & Infants Hospital of RI Warren Alpert School of Medicine at Brown University Providence , RI

FDA Safety Communication July 2011 n FDA Safety Communication released on July 13, 2011 n n addressing increasing concerns from the public, health care providers, and advocates for patient safety about trans-vaginal mesh based upon review of the literature white paper analysis was presented appointed advisory panel meeting

FDA Safety Communication Serious complications associated with trans-vaginal mesh repair of POP are not rare. n Trans-vaginally placed mesh in POP repair does not conclusively improve clinical outcomes over traditional non-mesh repair. n

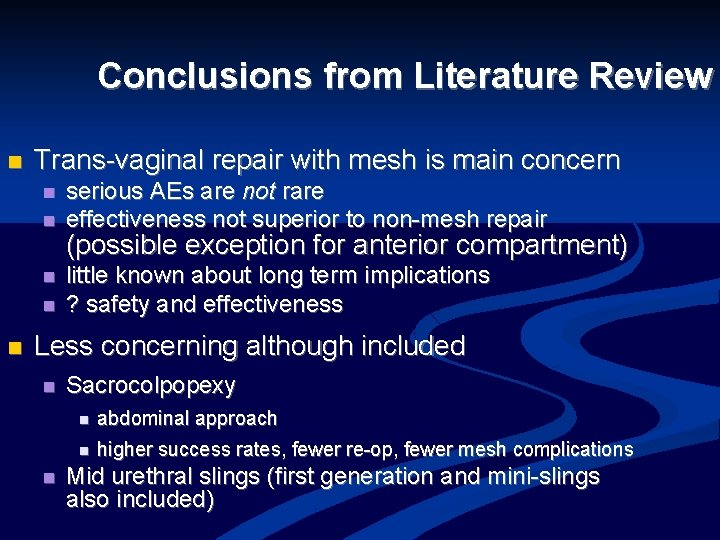

Conclusions from Literature Review n Trans-vaginal repair with mesh is main concern n n serious AEs are not rare effectiveness not superior to non-mesh repair (possible exception for anterior compartment) little known about long term implications ? safety and effectiveness Less concerning although included n n Sacrocolpopexy n abdominal approach n higher success rates, fewer re-op, fewer mesh complications Mid urethral slings (first generation and mini-slings also included)

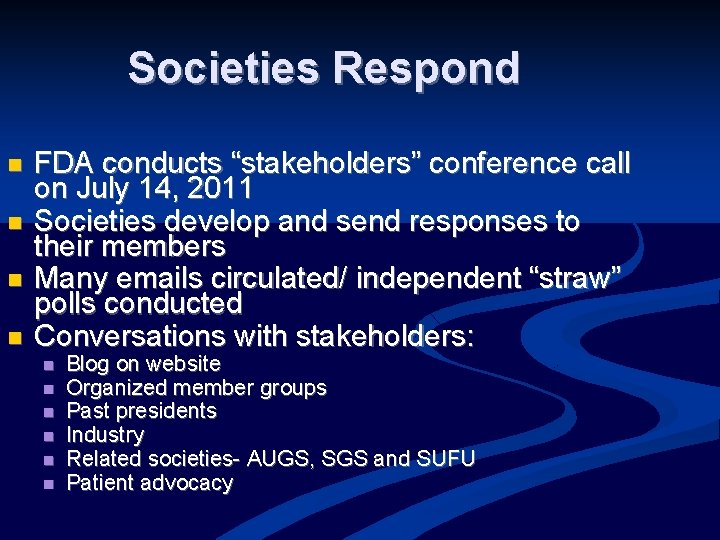

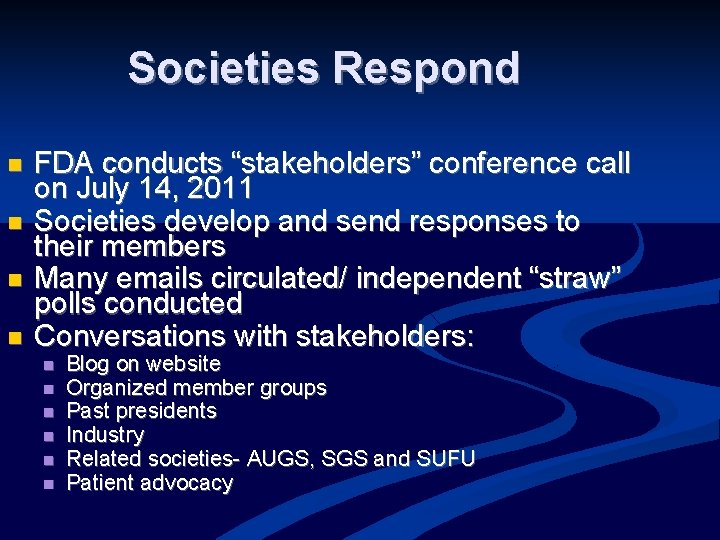

Societies Respond n n FDA conducts “stakeholders” conference call on July 14, 2011 Societies develop and send responses to their members Many emails circulated/ independent “straw” polls conducted Conversations with stakeholders: n n n Blog on website Organized member groups Past presidents Industry Related societies- AUGS, SGS and SUFU Patient advocacy

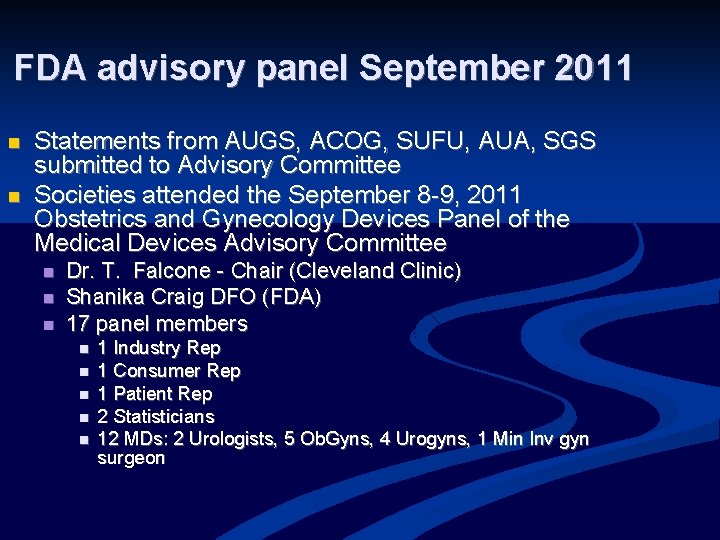

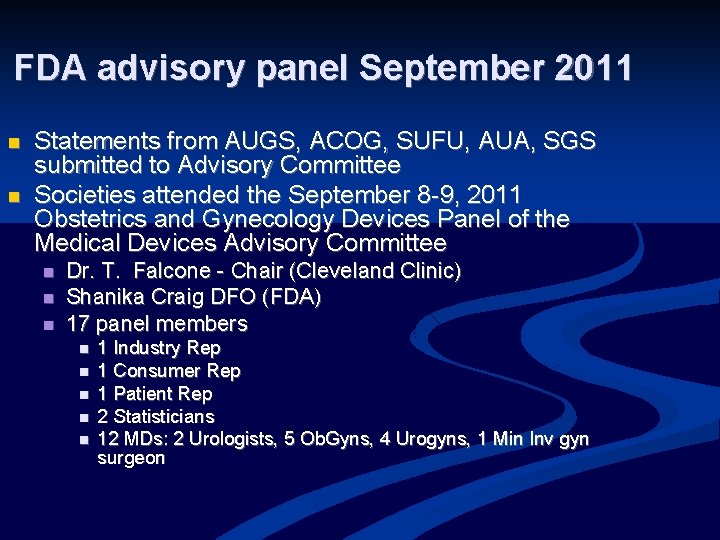

FDA advisory panel September 2011 n n Statements from AUGS, ACOG, SUFU, AUA, SGS submitted to Advisory Committee Societies attended the September 8 -9, 2011 Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee n n n Dr. T. Falcone - Chair (Cleveland Clinic) Shanika Craig DFO (FDA) 17 panel members n n n 1 Industry Rep 1 Consumer Rep 1 Patient Rep 2 Statisticians 12 MDs: 2 Urologists, 5 Ob. Gyns, 4 Urogyns, 1 Min Inv gyn surgeon

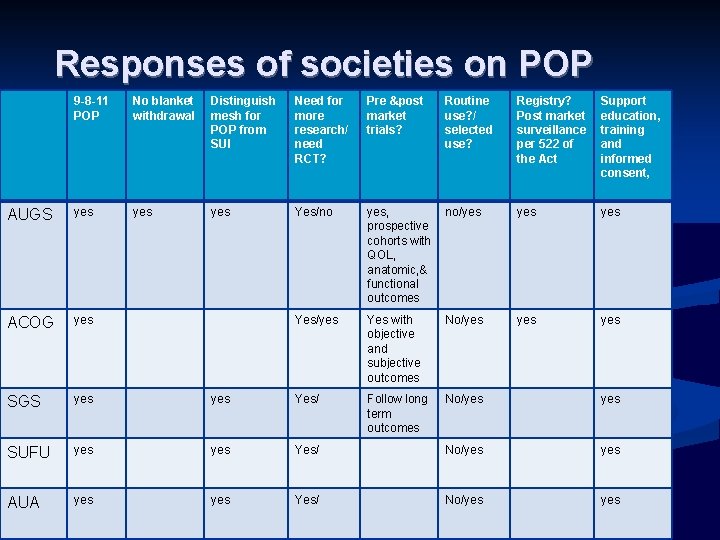

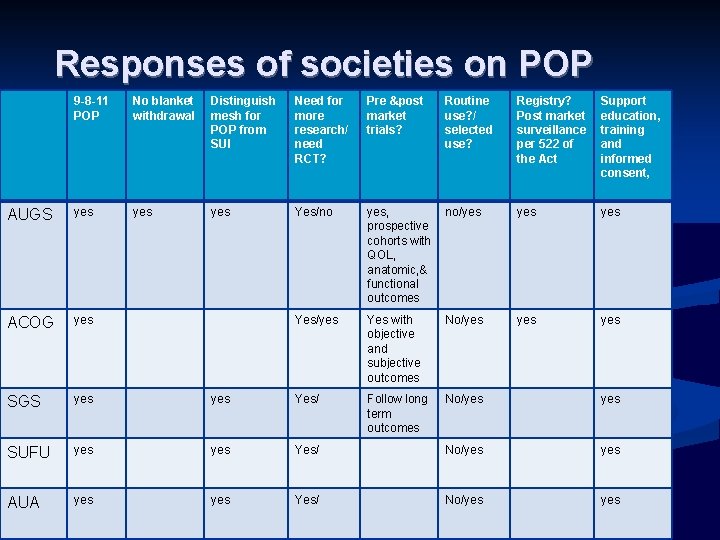

Responses of societies on POP 9 -8 -11 POP No blanket withdrawal Distinguish mesh for POP from SUI Need for more research/ need RCT? Pre &post market trials? Routine use? / selected use? Registry? Post market surveillance per 522 of the Act Support education, training and informed consent, AUGS yes yes Yes/no yes, prospective cohorts with QOL, anatomic, & functional outcomes no/yes yes ACOG yes Yes/yes Yes with objective and subjective outcomes No/yes yes SGS yes Yes/ Follow long term outcomes No/yes SUFU yes Yes/ No/yes AUA yes Yes/ No/yes

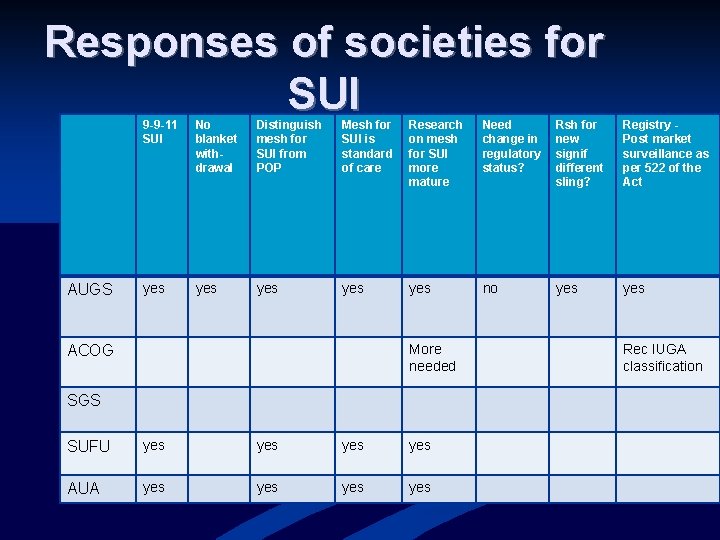

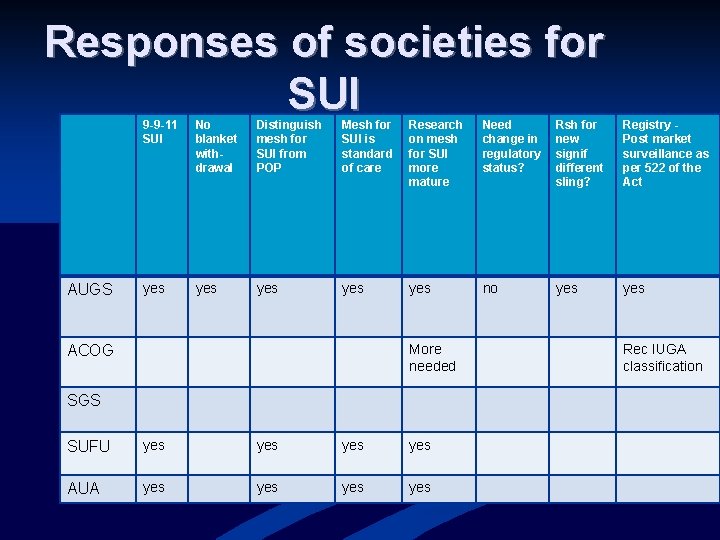

Responses of societies for SUI AUGS 9 -9 -11 SUI No blanket withdrawal Distinguish mesh for SUI from POP Mesh for SUI is standard of care Research on mesh for SUI more mature Need change in regulatory status? Rsh for new signif different sling? Registry Post market surveillance as per 522 of the Act yes yes yes no yes More needed ACOG SGS SUFU yes yes AUA yes yes Rec IUGA classification

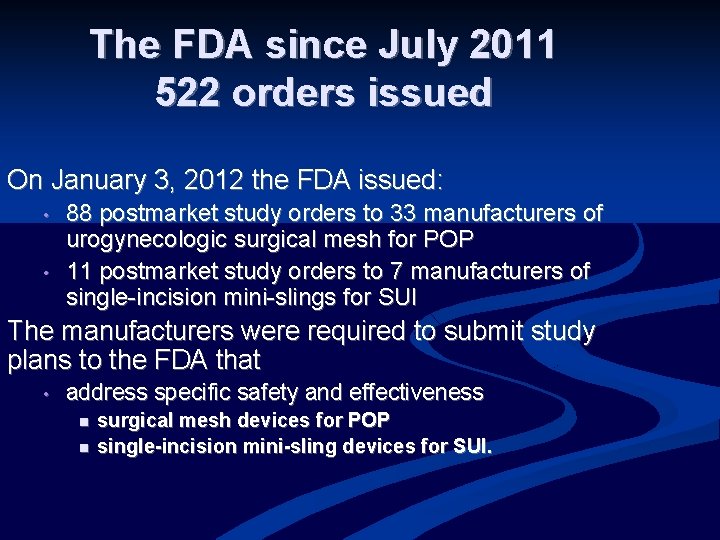

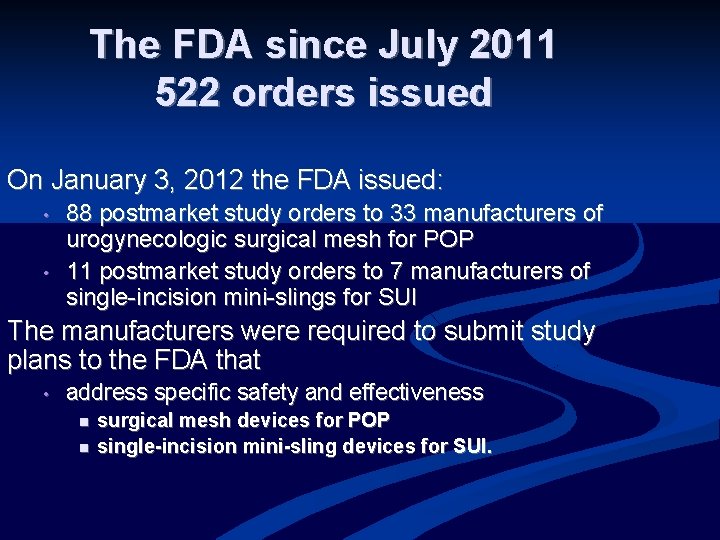

The FDA since July 2011 522 orders issued On January 3, 2012 the FDA issued: • • 88 postmarket study orders to 33 manufacturers of urogynecologic surgical mesh for POP 11 postmarket study orders to 7 manufacturers of single-incision mini-slings for SUI The manufacturers were required to submit study plans to the FDA that • address specific safety and effectiveness n n surgical mesh devices for POP single-incision mini-sling devices for SUI.

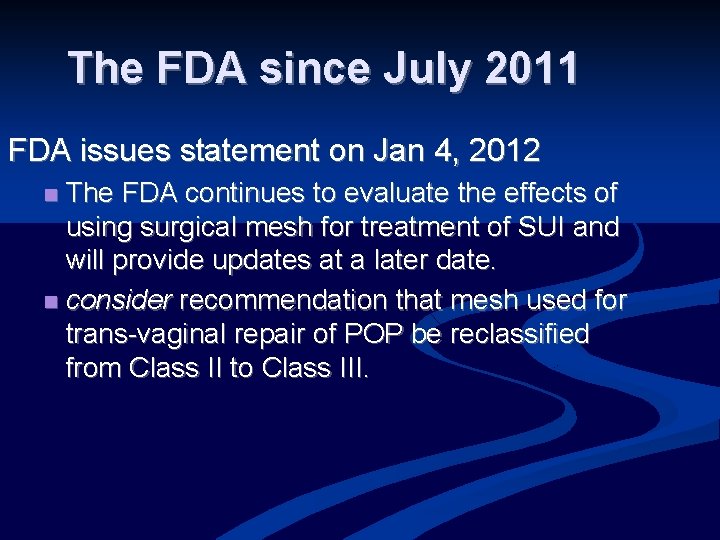

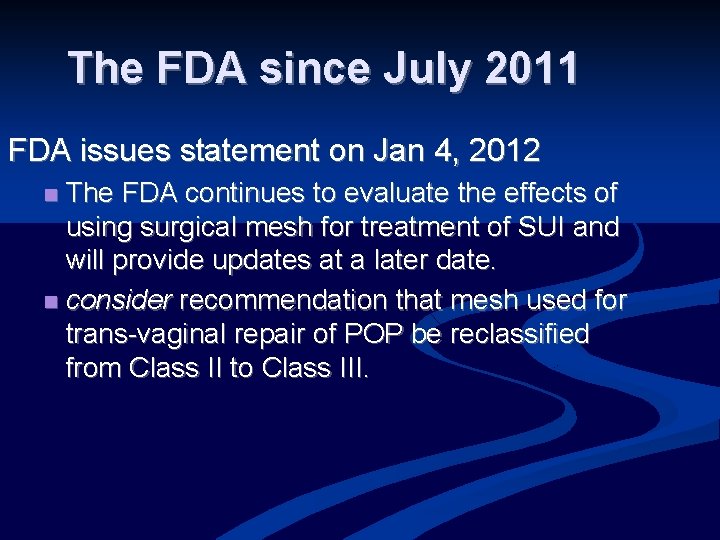

The FDA since July 2011 FDA issues statement on Jan 4, 2012 The FDA continues to evaluate the effects of using surgical mesh for treatment of SUI and will provide updates at a later date. n consider recommendation that mesh used for trans-vaginal repair of POP be reclassified from Class II to Class III. n

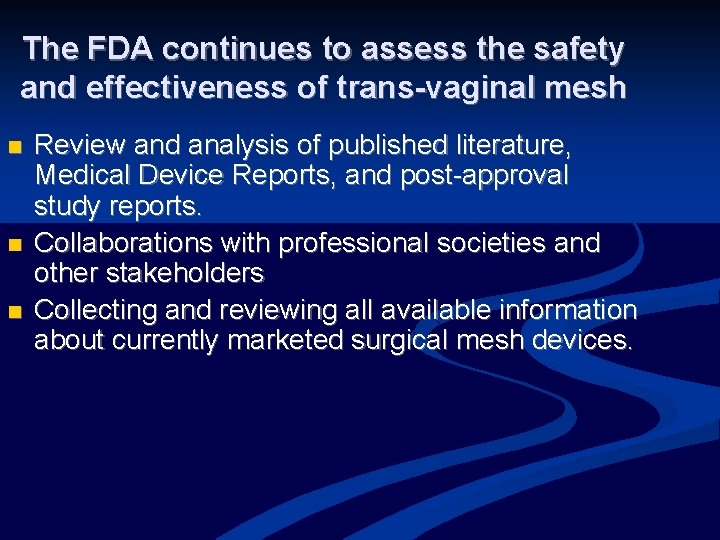

The FDA continues to assess the safety and effectiveness of trans-vaginal mesh n n n Review and analysis of published literature, Medical Device Reports, and post-approval study reports. Collaborations with professional societies and other stakeholders Collecting and reviewing all available information about currently marketed surgical mesh devices.

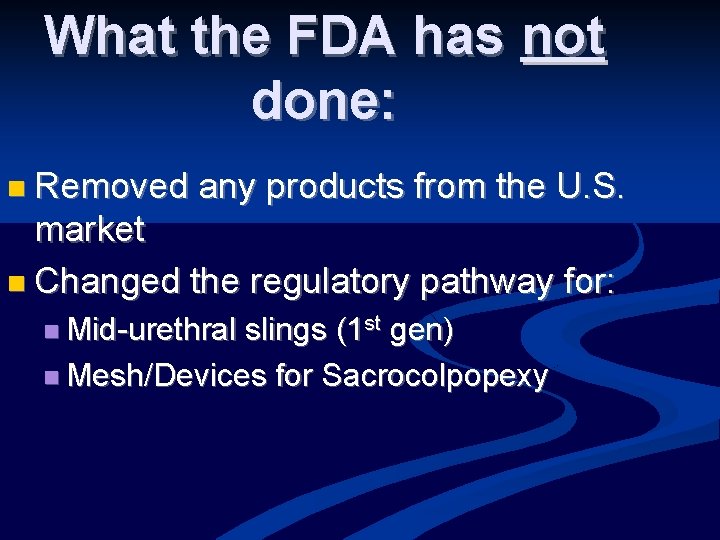

What the FDA has not done: n Removed any products from the U. S. market n Changed the regulatory pathway for: n Mid-urethral slings (1 st gen) n Mesh/Devices for Sacrocolpopexy

Societies since July 2011

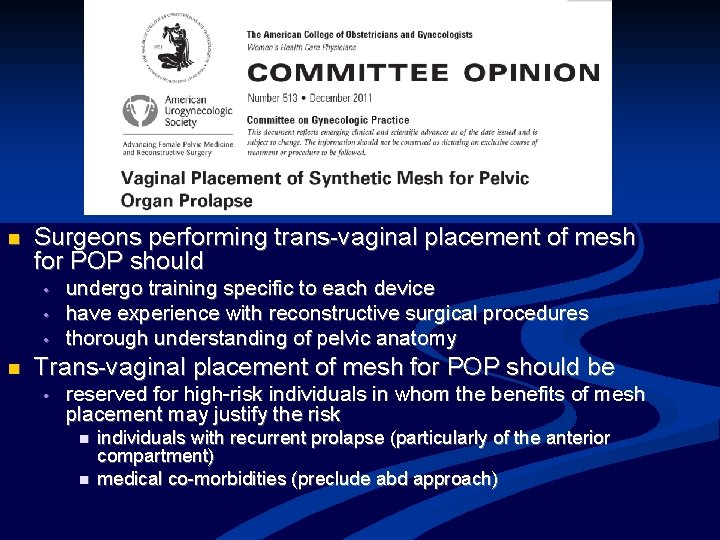

n Surgeons performing trans-vaginal placement of mesh for POP should • • • n undergo training specific to each device have experience with reconstructive surgical procedures thorough understanding of pelvic anatomy Trans-vaginal placement of mesh for POP should be • reserved for high-risk individuals in whom the benefits of mesh placement may justify the risk n n individuals with recurrent prolapse (particularly of the anterior compartment) medical co-morbidities (preclude abd approach)

Societies since July 2011 (con’t) n AUGS informed consent toolkit -providers On-line informed consent “toolbox” n Patient education resources n n Patient information on society websites for patients n n AUA Foundation, AUGS Voices for PFD websites AUGS and other stakeholders working with FDA on registry development

Presentation Title l June 13, 2021 l 130 Female Pelvic Med Reconstru Surg 2012; 18: 194 -7 www. augs. org

Ultimate goals To promote safe and effective care for women with PFD n To encourage innovation while maintaining patient safety n To maintain a broad range of treatment options to meet the varying needs of our patients n

Informed Consent and New Technologies: an oxymoron? Dee E. Fenner, M. D. Furlong Professor of Women’s Health Director of Gynecology University of Michigan

Informed Consent and New Technologies: an oxymoron? What defines “new technology” in surgery? What are the principles of Informed Consent? When is therapy research?

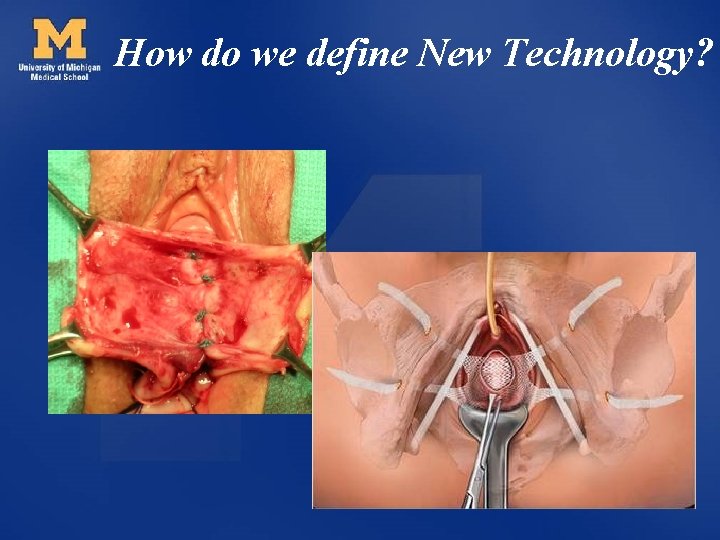

How do we define New Technology?

“Experimental” ASRM “Procedures (including tests, treatments, or other interventions) for the diagnosis or treatment of infertility will be considered experimental or investigational until the published medical evidence regarding their risks, benefits, and overall safety and efficacy is sufficient to regard them as established medical practice. ”

New Technology vs. Accepted Practice has NOT been: • Substantially accepted into general clinical practice. • Critically assessed in peer reviewed medical literature (safety and efficacy). • Presented and discussed at suitable scientific meetings. Sachdeva AK, Russell TR. Safe Introduction of New Procedures and Emerging Technologies in Surgery: Education, Credentialing, and Privileging. Surg Clin N Am 2007; 87: 853 -866.

Informed Consent “ Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what should be done with his own body. ” Justice Cardoza 1914

California Supreme Court 1972 “Describe the proposed therapy, describe the alternatives to it, describe the risks of death or serious bodily injury in the proposed therapy and the alternatives, discuss the problems of recuperation that are anticipated and give any additional information that other health care providers would disclose under similar circumstances. The informational component should be communicated clearly and understood and consent should be given freely, without coercion and absence of fraud. ”

Informed Consent • • • Risks Benefits Complications Alternatives Comparison to a “Gold Standard”

What makes Consent Informed? – Disclosure – Competency • Relative to patient’s therapeutic goals and how treatments work in this context – Choice • Voluntary/not coerced

When is “therapy” research? • Clinical Consent • Balance of expected benefit vs. burdens of implementation. • No equipoise. • Risk is balanced by plausible good. • Less disclosure required. • Research Consent • No balance possible because there is NO known benefit of the experimental therapy over standard care. • Equipoise. • Risk is NOT balanced • More disclosure is required.

Informed Consent and New Technologies: an oxymoron? YES until the principles of Informed Consent can be met.

Linda Brubaker Departments of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Urology Stritch School of Medicine Loyola University, Chicago, Illinois

A Way Forward

Improving knowledge about surgical evidence • There are no perfect surgical trials • Prolapse and UI aren’t “urgent” – There is no “War on Pelvic Floor Disorders”…yet. • Surgeons need to practice self-discipline to curb their urge to “save the patient” with the newest, latest and greatest • Mechanism for aid credentialing groups that allows for flexible, timely updates

Practical Criteria for New vs. Tweak • TWEAKS: should be disseminated into “technical trick” communications and letters to editors or a “technical tweak” forum • NEW: require appropriate oversight (to avoid experimentation without consent), good evaluation and limitation of bias. • NEW: should be disseminated using standard scientific forums (peer-reviewed).

Practical Criteria for New vs. Tweak • Can’t have it both ways • NEW – Blockbuster – amazing innovation…. that was “just a tweak” so it didn’t require consent.

Enhanced Surgical Research Training • Improve core surgical training in OG • Improve research education in OG Residency We Can We SHOULD

Role of Professional Journals • Enhance gynecologic surgeons ability to deal with uncertainty of evidence. • Provide clear and meaningful communication about level of evidence • 2 point-of-view commentaries providing balanced perspective – Time to adopt – Not yet…best to wait • Clear description of what patient consented to ? surgery vs. research

Role of Professional Societies • Professional societies to take larger role in interpreting surgical (and technological evidence) – This will require societies to have separation between evidence-reviewers and marketing arms. • Reduce surgical videos that show unproven, untested techniques • Provide forum for tweaks • Provide forum for NEW, but untested • Elevate discourse in exhibit halls – videos and “hawker-talkers” must be evidence-based

New Materials New Techniques • Preclinical safety and feasibility • Human data – Obtained with proper research oversight • Gynecologic surgical research networks – Modern trial designs, including adaptive trials if appropriate

Improve Research Ability • National reporting of # participants/#patients for relevant conditions to highlight opportunities to enhance research participation. • Remove barriers for research participation – Participant research income = tax-free – Patient-participant friendly consent forms

FPMRS at the Table In Order to Best Serve Our Patients. • National involvement of FPMRS • Given the current scope (& projections) for the number of affected patients, FPMRS providers should be fully involved and “at the table” nationally and within all relevant OG organizations, in parity with the other OG subspecialties.

Lessons Learned • As a profession, we must ALL learn lessons from this experience in FPMRS. • We can find a way forward – That optimizes patient care – Advances knowledge – Maintains the integrity of our profession

It has 6 square faces 8 vertices and 12 edges

It has 6 square faces 8 vertices and 12 edges Greetings farewells and courtesy expressions en español

Greetings farewells and courtesy expressions en español Coe 202

Coe 202 Courtesy traits

Courtesy traits Courtesy

Courtesy Service sequence in serving food and beverage

Service sequence in serving food and beverage How to find empirical formula from percentages

How to find empirical formula from percentages Courtesy award

Courtesy award Vimeforum

Vimeforum Safteng

Safteng Courtesy speeches

Courtesy speeches Courtesy

Courtesy Expression of courtesy

Expression of courtesy Courtesy hor

Courtesy hor Completeness in communication

Completeness in communication Courtesy formulas

Courtesy formulas Courtesy formulas

Courtesy formulas Courtesy reflects a positive attitude

Courtesy reflects a positive attitude Courtesy

Courtesy Umlsec

Umlsec Expressions of courtesy

Expressions of courtesy Dijkstra algorithm

Dijkstra algorithm Concreteness in technical writing

Concreteness in technical writing Courtesy

Courtesy 7 c's effective communication

7 c's effective communication Courtesy notice

Courtesy notice Slide courtesy

Slide courtesy Title title

Title title Prefatory elements in proposal exclude

Prefatory elements in proposal exclude Apa heading format

Apa heading format I have resolved

I have resolved Past tense dari can

Past tense dari can Bill a no mail on saturdays worksheet answers

Bill a no mail on saturdays worksheet answers Ideas have consequences bad ideas have victims

Ideas have consequences bad ideas have victims What is an echinoderm

What is an echinoderm Modal verbs suggestion

Modal verbs suggestion Have been to or have gone to

Have been to or have gone to I have chosen you and not rejected you

I have chosen you and not rejected you I have four legs and a tail i have no teeth

I have four legs and a tail i have no teeth Words have meaning and names have power

Words have meaning and names have power Qualification title

Qualification title Healthy eating title

Healthy eating title The life you save may be your own analysis

The life you save may be your own analysis Current question.title

Current question.title Transition headline

Transition headline Add your title here

Add your title here The great gatsby summary chapter 3

The great gatsby summary chapter 3 Title text goes here

Title text goes here Khalilullah is the title of which prophet

Khalilullah is the title of which prophet Title text here

Title text here Samneric quotes

Samneric quotes Meeting title for discussion

Meeting title for discussion Even the mightiest will fall

Even the mightiest will fall Outlook nbed

Outlook nbed 02.html?page=

02.html?page= Acute variables of training

Acute variables of training Lecture title

Lecture title Bidmae

Bidmae Affiliation title

Affiliation title Collins title productivity

Collins title productivity Failure title

Failure title Shakespeare sonnet 130 rhyme scheme

Shakespeare sonnet 130 rhyme scheme Title iii requirements

Title iii requirements Paraphizing

Paraphizing How to make a creative title

How to make a creative title Dimensioning worksheet

Dimensioning worksheet Orthographic drawing

Orthographic drawing Table html title

Table html title Poster presentation title

Poster presentation title How to put an appendix in a paper mla

How to put an appendix in a paper mla Point proof comment

Point proof comment Title v training

Title v training Character description essay

Character description essay Doctype html html head

Doctype html html head This is your presentation title

This is your presentation title A dolls house motifs

A dolls house motifs Titanic poem

Titanic poem Name of the presenter

Name of the presenter Presenters name

Presenters name Title act interior design

Title act interior design Master title style

Master title style Salvage title

Salvage title Name, title

Name, title Double negative

Double negative Project title page

Project title page Crab game player count

Crab game player count Quotations or italics for article titles

Quotations or italics for article titles By name title date

By name title date Click to add title

Click to add title Conclusion for relationship essay

Conclusion for relationship essay Dc title meta

Dc title meta Emailaddress.com

Emailaddress.com Florence

Florence By name title date

By name title date Feature title

Feature title Acquired traits examples in humans

Acquired traits examples in humans Devops job title

Devops job title 05.html?title=

05.html?title= Title text goes here

Title text goes here Hypothesis title

Hypothesis title 16x9 title safe template

16x9 title safe template Who owns working title films

Who owns working title films Text goes here

Text goes here Nothing gold can stay robert frost

Nothing gold can stay robert frost Main title rebel blockade runner

Main title rebel blockade runner What is the purpose of a title slide

What is the purpose of a title slide Character setting conflict plot and theme

Character setting conflict plot and theme Examples of introduction paragraph

Examples of introduction paragraph 01.html?title=

01.html?title= Book review for grade 3

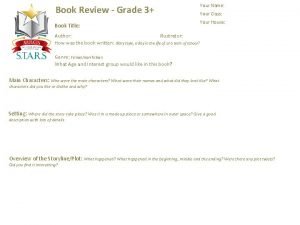

Book review for grade 3 Title lorem ipsum dolor sit amet

Title lorem ipsum dolor sit amet Fun facts title

Fun facts title Titles of single entities

Titles of single entities Poster titles

Poster titles Title of the work

Title of the work Howard spendelow

Howard spendelow What is title in personal information

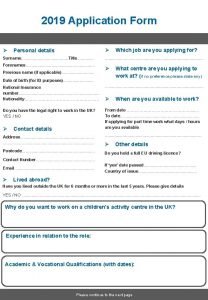

What is title in personal information Project report title

Project report title 02.html?title=

02.html?title= Name title date

Name title date Definition of organizational chart

Definition of organizational chart Surfacing by margaret atwood summary

Surfacing by margaret atwood summary Title text here

Title text here Marriage is a private affair short story characters

Marriage is a private affair short story characters Title vi of the civil rights act of 1964

Title vi of the civil rights act of 1964 By name title

By name title Type your title here

Type your title here Ama format title page

Ama format title page Title thesis statement

Title thesis statement 1.topic/title

1.topic/title This is your presentation title

This is your presentation title In the title

In the title Title text here

Title text here Precis mla format

Precis mla format Nama jabatan

Nama jabatan Title

Title Poster presentation size

Poster presentation size Historians value the writings of ibn battuta because he –

Historians value the writings of ibn battuta because he – Mass effect title

Mass effect title Research title examples

Research title examples Click to edit master title style

Click to edit master title style Presenters name

Presenters name What is the possible title for the poster

What is the possible title for the poster Project title design

Project title design Project title names

Project title names Balance sheet title

Balance sheet title Title of your poster

Title of your poster Lien theory vs title theory

Lien theory vs title theory Title xi of the education amendments of 1972

Title xi of the education amendments of 1972 Add your title here

Add your title here Insert the sub title of your presentation

Insert the sub title of your presentation Title iii symposium

Title iii symposium Comparative study title

Comparative study title The tell tale heart summary

The tell tale heart summary Lamp with ibex design

Lamp with ibex design