Topic 3 Cognitive Errors 1 Prof Dr Chew

- Slides: 36

Topic 3: Cognitive Errors 1 Prof. Dr. Chew Keng Sheng Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak This Open. Course. Ware@UNIMAS and its related course materials are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike 4. 0 International License.

Objectives • By the end of this lecture, the learners will be able to 1. list the classes of cognitive errors 2. describe and give examples of cognitive errors in each of these classes of cognitive errors

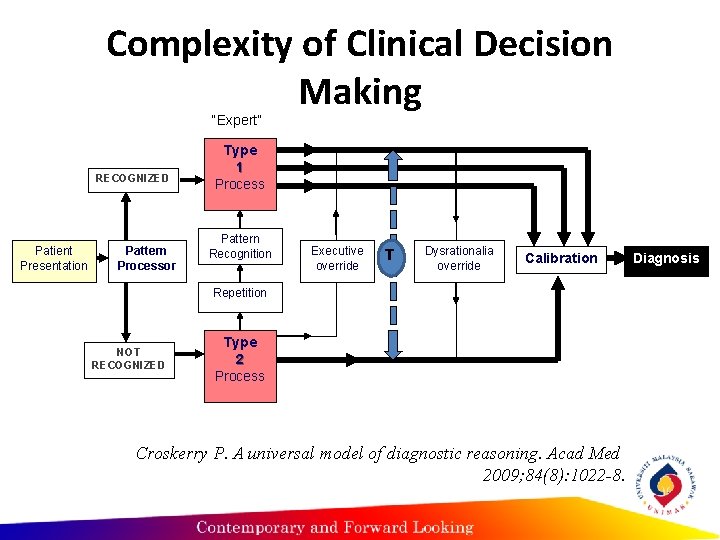

Introduction • Although Type 1 process is often effective in making decisions, it is more affected by cognitive biases or cognitive errors than Type 2 decision making • Cognitive bias or error is defined as our deviations from rationality • May derail a clinician into diagnostic errors if left unchecked

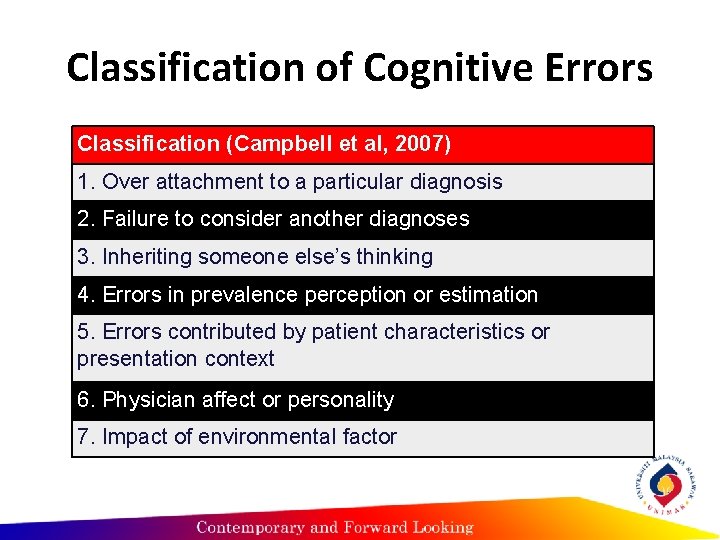

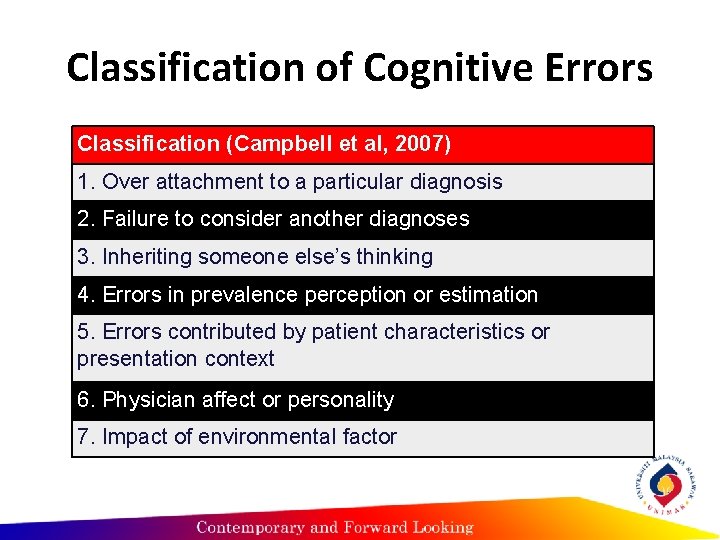

Classification of Cognitive Errors Classification (Campbell et al, 2007) 1. Over attachment to a particular diagnosis 2. Failure to consider another diagnoses 3. Inheriting someone else’s thinking 4. Errors in prevalence perception or estimation 5. Errors contributed by patient characteristics or presentation context 6. Physician affect or personality 7. Impact of environmental factor

Over attachment to a particular diagnosis Anchoring Confirmation Bias Premature closure

Anchoring • This refers to our tendency to fixate our perception on to the salient features in the patient’s initial presentation at an early point of the diagnostic process so much so that we fail to adjust our initial impression even in light of later information.

Confirmation bias • This refers to our tendency to look for confirming evidence to support the diagnosis we are “anchoring” to, while downplaying, or ignoring or not actively seeking evidences that may point to the contrary.

Confirmation bias • This often goes together with anchoring. For example, if a clinician has anchored or fixated the diagnosis of myocardial infarction in his mind, he will have the tendency to look for evidences to support this diagnosis, say, ST segment elevation on electrocardiography even if the amount of elevation does not seem significant.

Confirmation bias • In contrast, even if the patient’s chest X-ray film demonstrates a widened mediastinum with unequal pulses on examination and high blood pressure, the clinician may have ignored such important cues that may point to the life threatening condition of thoracic aortic dissection.

Failure to consider another diagnoses Search satisficing Representativeness restraint

Search satisficing • This refers to our tendency to stop looking or call off a search for a second diagnoses when we have found the first one. • This bias can prove to be detrimental in polytrauma cases

Inheriting someone else’s thinking Triage cueing Diagnostic Momentum

Triage cueing • This is basically a form of anchoring where once a triage tag has been labelled on a patient, the tendency is to look at the patient only from the perspective of the discipline in which the patient is tagged to.

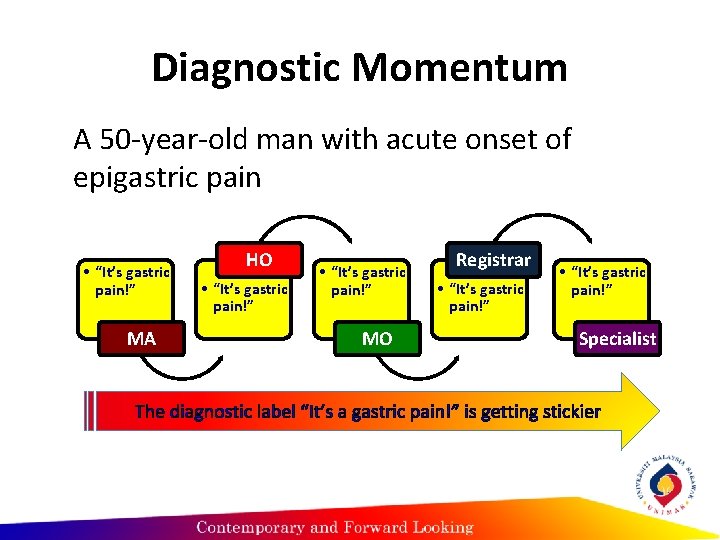

Diagnostic Momentum • Refers to the phenomenon where once diagnostic labels are attached to patients they tend to become stickier and stickier. Through intermediaries, (patients, paramedics, nurses, physicians) what might have started as a possibility gathers increasing momentum until it becomes definite and all other possibilities are excluded.

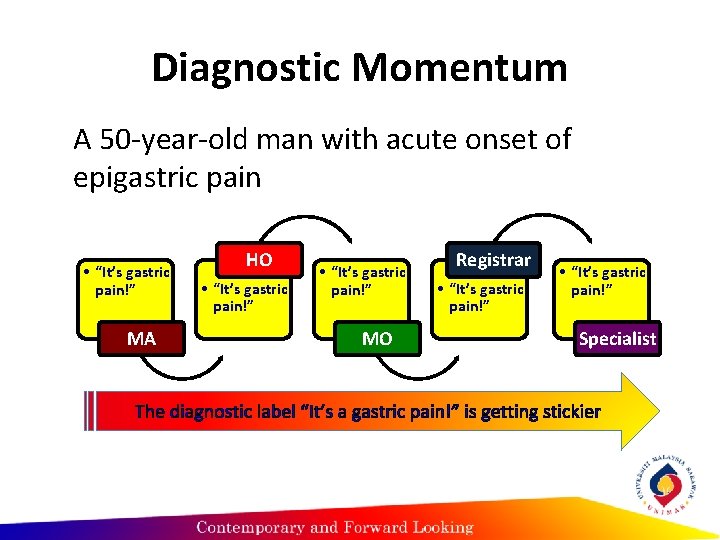

Diagnostic Momentum A 50 -year-old man with acute onset of epigastric pain • “It’s gastric pain!” MA HO • “It’s gastric pain!” MO Registrar • “It’s gastric pain!” Specialist The diagnostic label “It’s a gastric pain!” is getting stickier

Errors in prevalence perception or estimation Availability bias

Availability bias • Availability bias – this refers to our tendency to judge things as being more likely, or frequently occurring, if they readily come to mind. • Therefore, a recent experience with a particular disease, for example, thoracic aortic dissection may inflate likelihood of a clinician to diagnose the patient with this disease every time when the clinician sees a case of chest pain.

Gambler’s fallacy • The concept of this bias is borrowed from the gambling situation where if a coin is tossed ten times, and for every case of the toss, head is shown. • A person with gambler’s fallacy will say that if the coin is tossed for the 11 th time, there must be a greater chance of being tail.

Gambler’s fallacy • The coin actually has no memory and has a 5050 chance of showing tail in each toss, which is independent of the previous outcomes. • Example: a clinician see five cases of shortness of breath (SOB) in the course of a shift; in each case, the patient turns out to be having pneumonia. When the 6 th patient with SOB comes….

Posterior probability error • The opposite of gambler’s fallacy. • In this, if a clinician sees five patients with shortness of breath (SOB) in the course of a working shift, which turn out to be pneumonia in every cases; when the 6 th patient with SOB arrives, the tendency is to believe that this patient must be having pneumonia as well.

Errors contributed by patient characteristics or presentation context Fundamental attribution errors Gender bias Psych out error

Fundamental Attribution Error • Refers to the tendency to attribute the blame for a circumstance or event to the patient’s personal qualities rather than the surrounding situation • Social judgment, hold people responsible for their own behavior • HIV patient with pneumocystis carinii as a result of his lifestyle than the disease process

Physician affect or personality Sunk cost fallacy Ego bias Blind spot bias Over-confidence bias

Sunk-cost fallacy • Refers to the phenomenon where the more a clinician invest in a particular diagnosis, the less likely he/she is to release it and consider alternatives. Common in financial investment. • In clinical setting, the time, mental energy, the ego may prove to be too costly to let go. • Confirmation bias maybe an associated manifestation of such unwillingness to let go of a failing diagnosis.

Ego bias • This refers to our tendency of overestimating the prognosis of one’s own patients compared to that of a population of similar patients under the care of other physicians.

Blind spot bias • This refers to the bias that many people have where they believe that they are less susceptible to errors compared to others. This has some similarities with ego bias.

Overconfidence bias • It refers to our universal tendency to believe that we know more than we do. • Overconfidence reflects a tendency to act upon incomplete information, intuitions, of hunches.

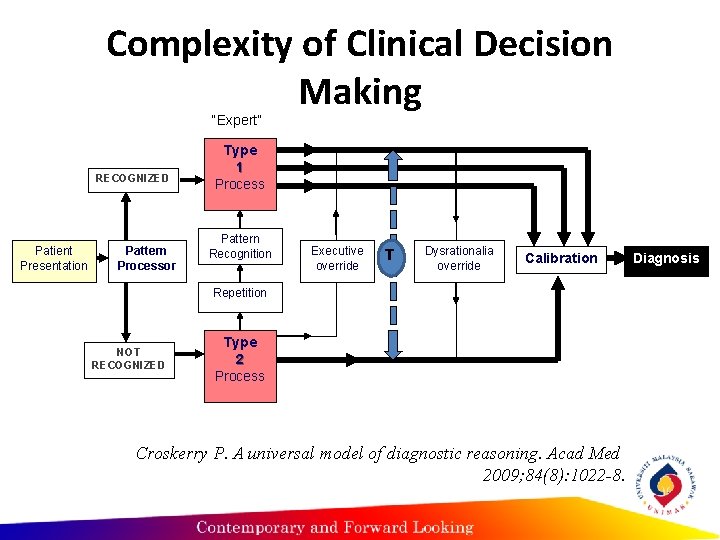

Complexity of Clinical Decision Making “Expert” RECOGNIZED Patient Presentation Pattern Processor Type 1 Process Pattern Recognition Executive override T Dysrationalia override Calibration Repetition NOT RECOGNIZED Type 2 Process Croskerry P. A universal model of diagnostic reasoning. Acad Med 2009; 84(8): 1022 -8. Diagnosis

A combination of both processes • Both experts and novices have been shown to generate diagnostic hypotheses very quickly, presumably based in part on non-analytic references to their past experiences (although the experts are more likely to generate the correct diagnoses) • The strategy employed by both groups indistinguishable (Neufeld et al, 1981) • Both Type 1 and Type 2 processes are not mutually exclusive (Eva, 2004)

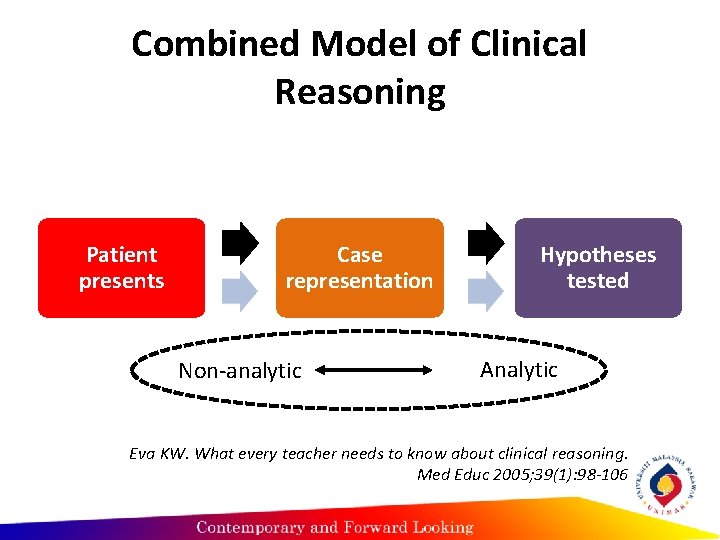

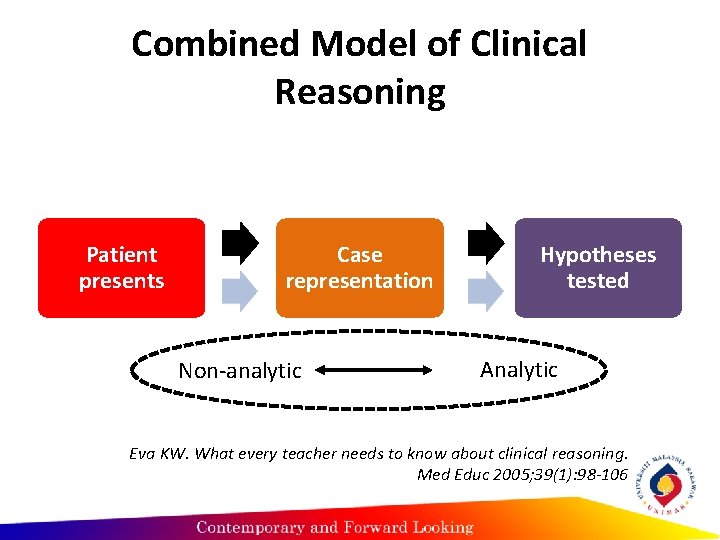

Combined Model of Clinical Reasoning Patient presents Case representation Non-analytic Hypotheses tested Analytic Eva KW. What every teacher needs to know about clinical reasoning. Med Educ 2005; 39(1): 98 -106

Misconceptions on the dual process theory • Misconception #1: DPT implies a dichotomy in our cognitive system • Misconception #2: Type 1 process is responsible for our bad thinking, while Type 2 process is responsible for our good thinking

Type 1 process is responsible for our bad thinking • Hogarth (2001) – for complex problems, Type 1 processing may be more effective • Type 2 analytical processing of complex problems may exceed the capacity of human cognitive load • No correlation between amount of data gathered and diagnostic accuracy, and no relation between amount of data gathered and educational level (Neufeld et al. 1981)

Type 1 process is responsible for our bad thinking • In situations demanding accurate clinical judgment, less is often more (Norman, 2009) • Oskamp (1965) - when clinicians were given additional information about a case, diagnostic accuracy did not improve at all, the clinicians simply became increasingly confident in their diagnosis, whether it was right or wrong.

Type 1 process is responsible for our bad thinking • Instead of defining and cataloging biases, effective teaching must take a very different tack, to enable students to reflect on their own performances and identify places where their reasoning may have failed (Norman, 2009)

References • Campbell SG, Croskerry P, Bond WF. Profiles in patient safety: A "perfect storm" in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2007; 14(8): 743 -9. • Neufeld VR, Norman GR, Feightner JW, Barrows HS. Clinical problem-solving by medical students: a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Med Educ 1981 Sep; 15(5): 315 -22.

References • Eva KW. What every teacher needs to know about clinical reasoning. Med Educ 2005; 39(1): 98 -106. • Norman G. Dual processing and diagnostic errors. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2009; Sep; 14 Suppl 1: 37 -49.