NATURAL LANGUAGE UNDERSTANDING 1 Introduction to Language Processing

- Slides: 40

NATURAL LANGUAGE UNDERSTANDING 1. Introduction to Language Processing Language is one of the most distinctive behaviours that sets humans apart from other animals. Other animals communicate with signals, but not with language. Here are some defining characteristics of language (after Edward Sapir ~1920) Arbitrariness: There is no relationship between a sound or sign and its meaning. Cultural transmission: Language is passed from one language user to the next, consciously or unconsciously. Discreteness: Language is composed of discrete units that are used in combination to create meaning. Displacement: Languages can be used to communicate ideas about things that are not in the immediate vicinity either spatially or temporally. Duality: Language works on two levels at once, a surface level and a semantic (meaningful) level. Metalinguistics: Ability to discuss language itself. Productivity: A finite number of units can be used to create an infinite number of utterances.

animal language link #1 animal language link #2

To devise systems which can understand natural language has always been one of the prime objectives of Artificial Intelligence. Language is more than just a communication method. Language can be used in a variety of speech acts: Query Inform Request (directly or indirectly) Direct (or command) Acknowledge Promise Declare (pronounce) The full task of understanding language requires recognizing the nature of the speech act as well as its context, along with the plans that surround the utterance.

When we study language, we usually think in terms of an idealized, grammatically correct form. But everyday use of language is often fragmented, and ungrammatical. Annie Hall link

When we study language, we usually think in terms of an idealized, grammatically correct form. But everyday use of language is often fragmented, and ungrammatical. ANNIE Come on, Alvy, they're only baby ones, for God's sake. ALVY If they're only babies, then you pick 'em up. ANNIE Oh, all right. All right! It's all right. Here. ALVY Don't give it to me. Don't! ANNIE Oooh! Here! ALVY Look! Look, one crawled behind the refrigerator. It'll turn up in our bed at night. Will you get outta here with that thing? Jesus! ANNIE Get him! ALVY Talk to him. You speak shellfish! Hey, look. . . put it in the pot. ANNIE I can't! I can't put him in the pot. I can't put a live thing in hot water. ALVY Gimme! Let me do it! What-what's he think we're gonna do, take him to the movies? ANNIE Oh, God! Here yuh go! Oh, good, now he'll think- Aaaah! Okay.

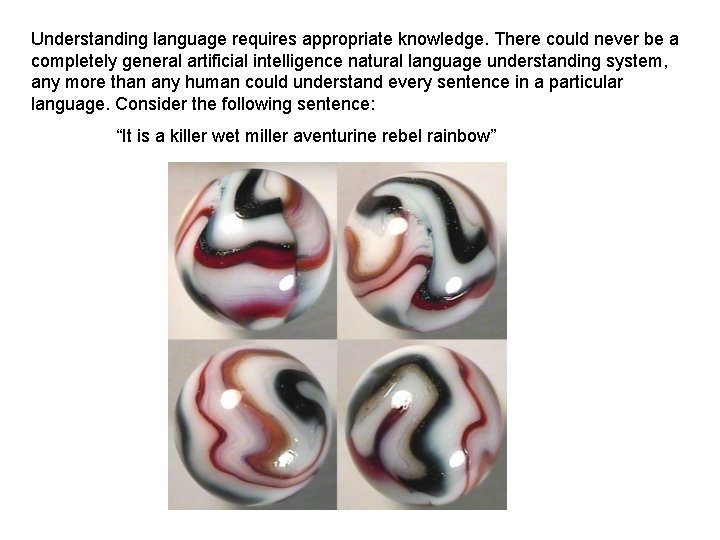

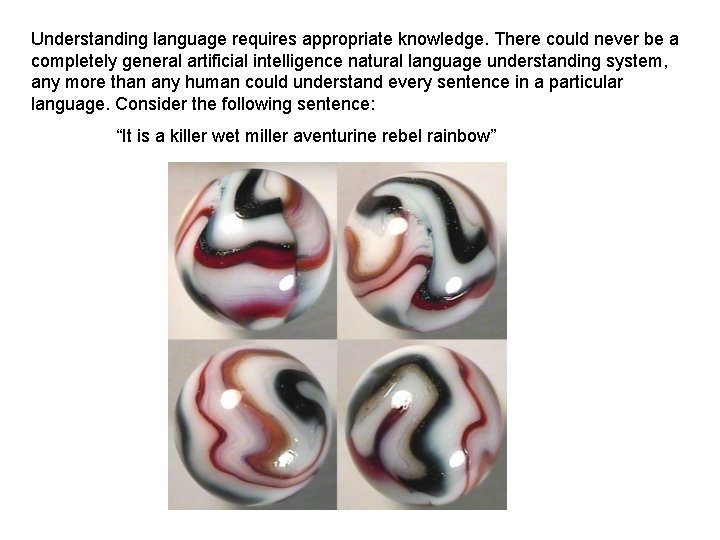

Understanding language requires appropriate knowledge. There could never be a completely general artificial intelligence natural language understanding system, any more than any human could understand every sentence in a particular language. Consider the following sentence: “It is a killer wet miller aventurine rebel rainbow”

Understanding language requires appropriate knowledge. There could never be a completely general artificial intelligence natural language understanding system, any more than any human could understand every sentence in a particular language. Consider the following sentence: “It is a killer wet miller aventurine rebel rainbow”

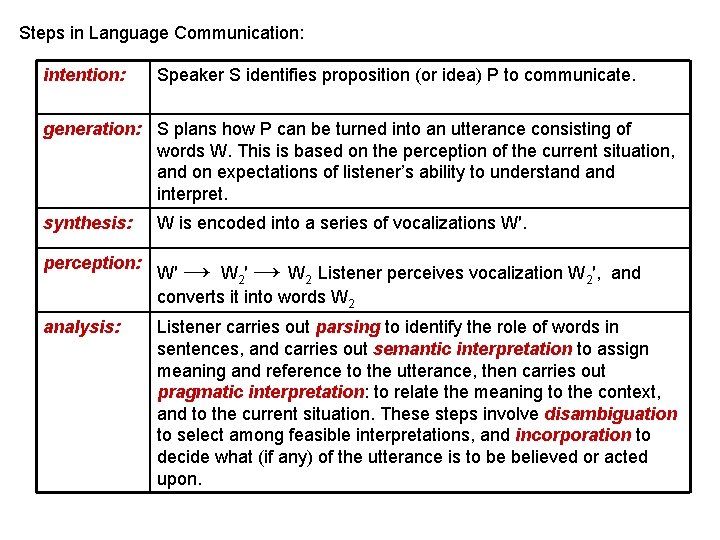

Link to Mc. Guirk effect

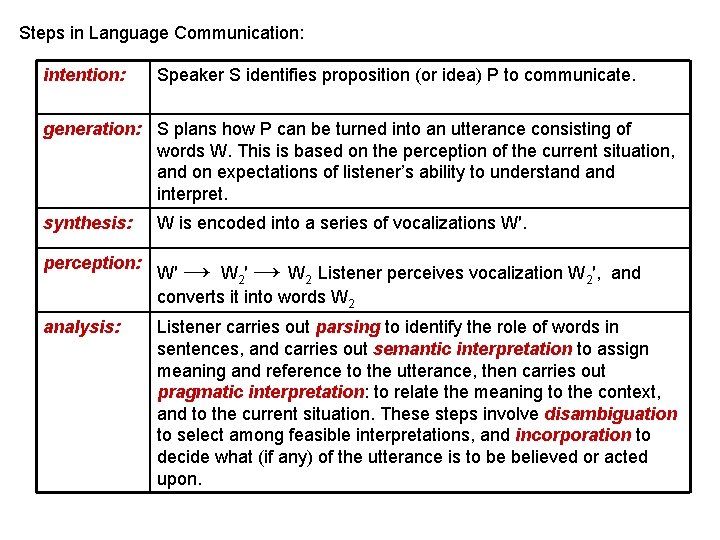

Steps in Language Communication: intention: Speaker S identifies proposition (or idea) P to communicate. generation: S plans how P can be turned into an utterance consisting of words W. This is based on the perception of the current situation, and on expectations of listener’s ability to understand interpret. synthesis: W is encoded into a series of vocalizations W′. perception: W′ → W 2 Listener perceives vocalization W 2′, and converts it into words W 2 analysis: Listener carries out parsing to identify the role of words in sentences, and carries out semantic interpretation to assign meaning and reference to the utterance, then carries out pragmatic interpretation: to relate the meaning to the context, and to the current situation. These steps involve disambiguation to select among feasible interpretations, and incorporation to decide what (if any) of the utterance is to be believed or acted upon.

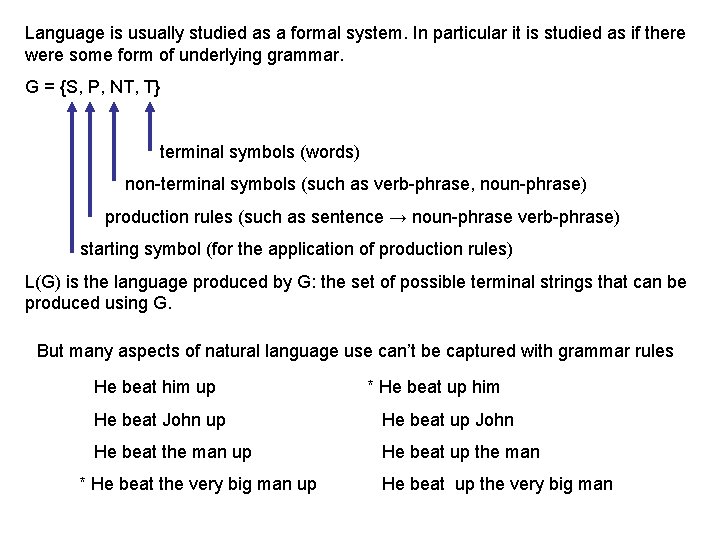

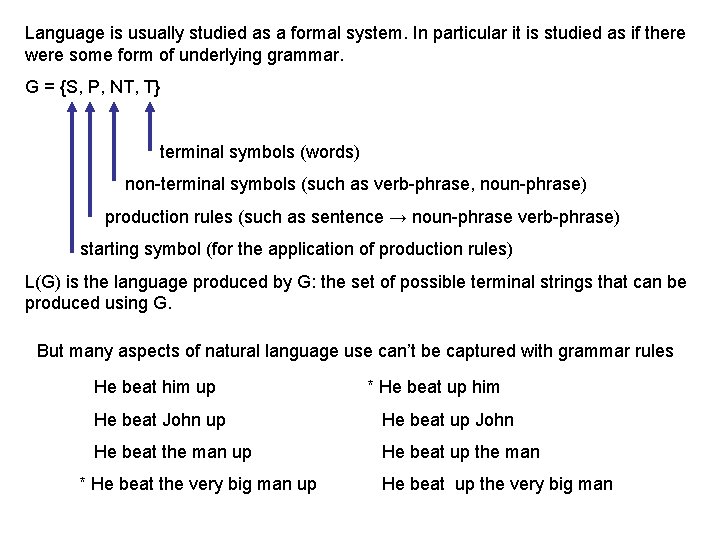

Language is usually studied as a formal system. In particular it is studied as if there were some form of underlying grammar. G = {S, P, NT, T} terminal symbols (words) non-terminal symbols (such as verb-phrase, noun-phrase) production rules (such as sentence → noun-phrase verb-phrase) starting symbol (for the application of production rules) L(G) is the language produced by G: the set of possible terminal strings that can be produced using G. But many aspects of natural language use can’t be captured with grammar rules He beat him up * He beat up him He beat John up He beat up John He beat the man up He beat up the man * He beat the very big man up He beat up the very big man

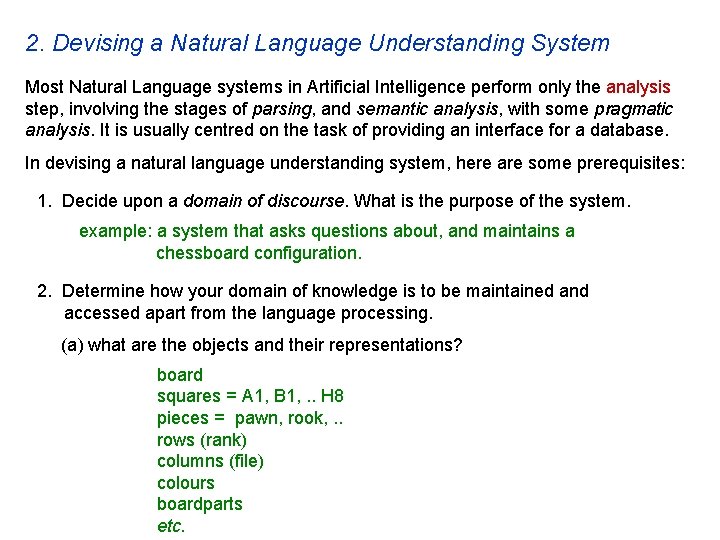

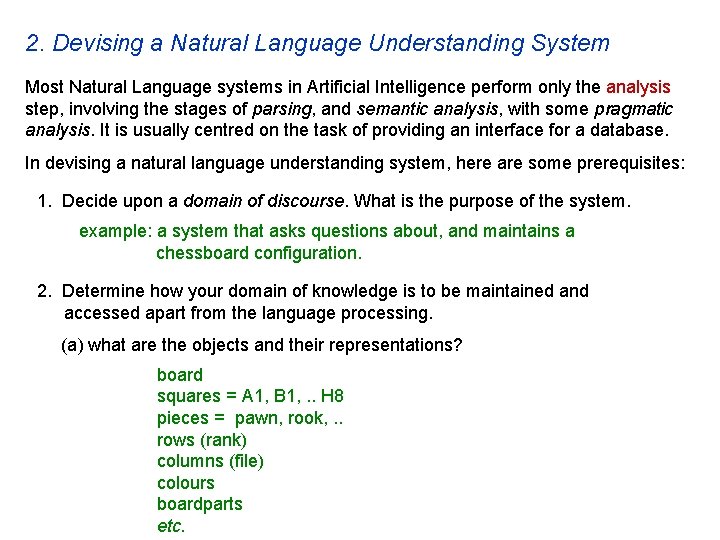

2. Devising a Natural Language Understanding System Most Natural Language systems in Artificial Intelligence perform only the analysis step, involving the stages of parsing, and semantic analysis, with some pragmatic analysis. It is usually centred on the task of providing an interface for a database. In devising a natural language understanding system, here are some prerequisites: 1. Decide upon a domain of discourse. What is the purpose of the system. example: a system that asks questions about, and maintains a chessboard configuration. 2. Determine how your domain of knowledge is to be maintained and accessed apart from the language processing. (a) what are the objects and their representations? board squares = A 1, B 1, . . H 8 pieces = pawn, rook, . . rows (rank) columns (file) colours boardparts etc.

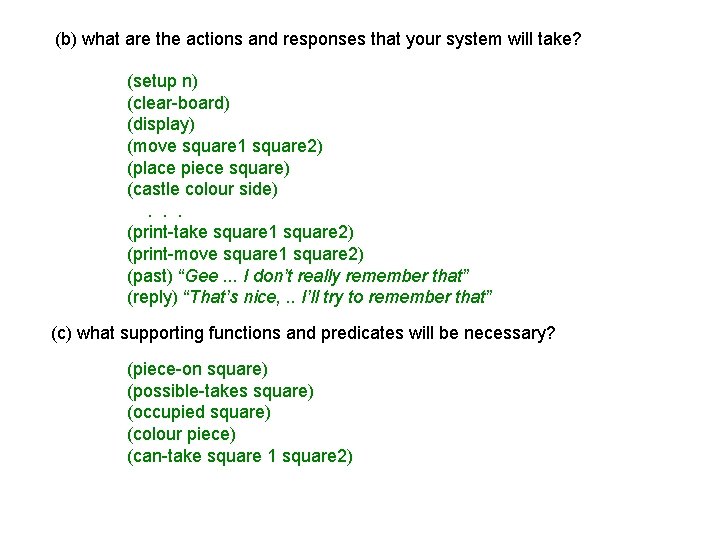

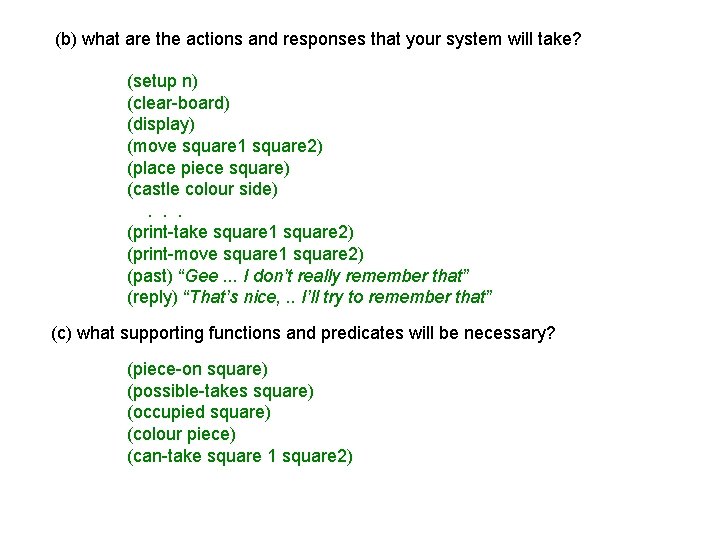

(b) what are the actions and responses that your system will take? (setup n) (clear-board) (display) (move square 1 square 2) (place piece square) (castle colour side). . . (print-take square 1 square 2) (print-move square 1 square 2) (past) “Gee. . . I don’t really remember that” (reply) “That’s nice, . . I’ll try to remember that” (c) what supporting functions and predicates will be necessary? (piece-on square) (possible-takes square) (occupied square) (colour piece) (can-take square 1 square 2)

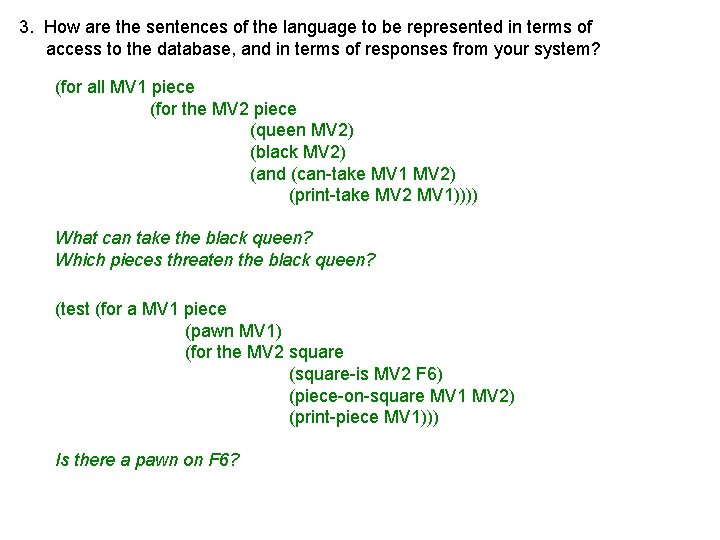

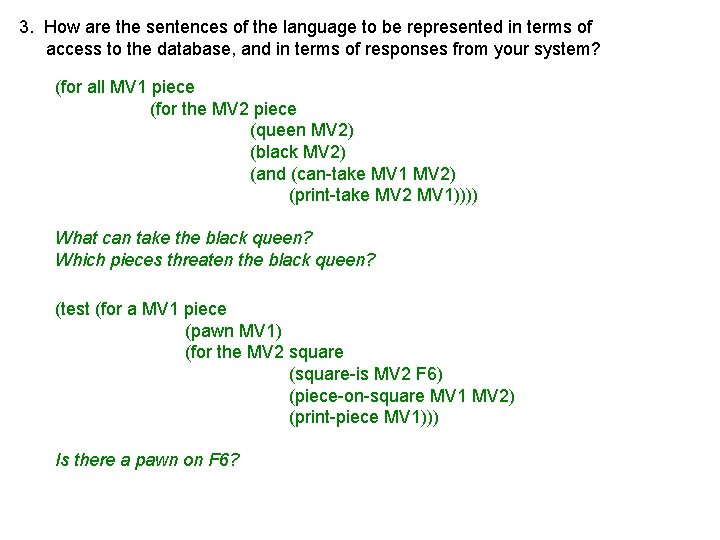

3. How are the sentences of the language to be represented in terms of access to the database, and in terms of responses from your system? (for all MV 1 piece (for the MV 2 piece (queen MV 2) (black MV 2) (and (can-take MV 1 MV 2) (print-take MV 2 MV 1)))) What can take the black queen? Which pieces threaten the black queen? (test (for a MV 1 piece (pawn MV 1) (for the MV 2 square (square-is MV 2 F 6) (piece-on-square MV 1 MV 2) (print-piece MV 1))) Is there a pawn on F 6?

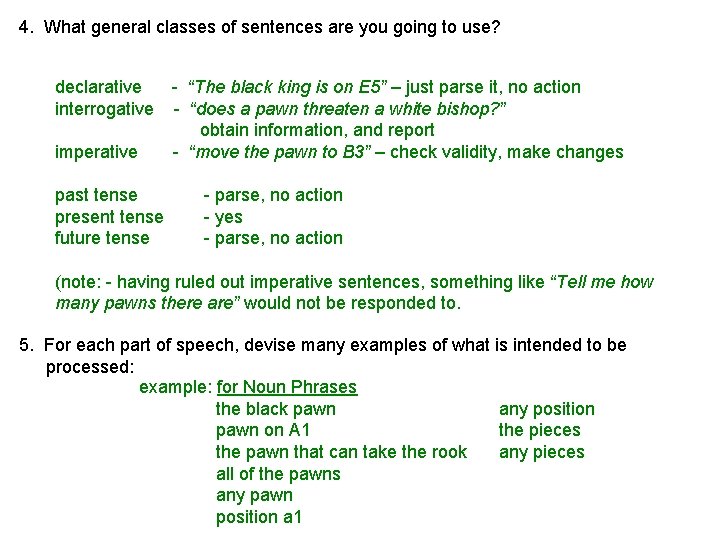

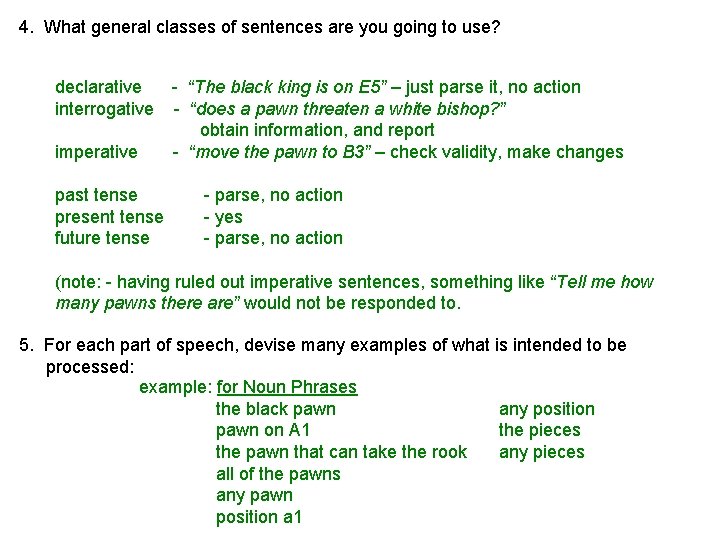

4. What general classes of sentences are you going to use? declarative - “The black king is on E 5” – just parse it, no action interrogative - “does a pawn threaten a white bishop? ” obtain information, and report imperative - “move the pawn to B 3” – check validity, make changes past tense present tense future tense - parse, no action - yes - parse, no action (note: - having ruled out imperative sentences, something like “Tell me how many pawns there are” would not be responded to. 5. For each part of speech, devise many examples of what is intended to be processed: example: for Noun Phrases the black pawn any position pawn on A 1 the pieces the pawn that can take the rook any pieces all of the pawns any pawn position a 1

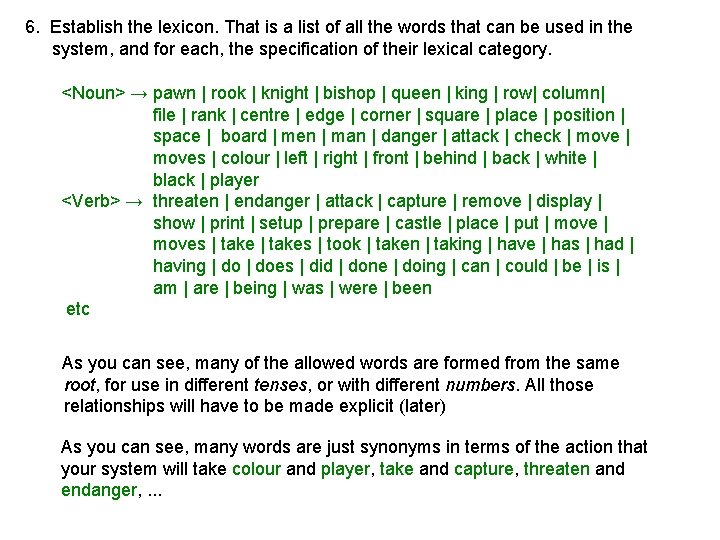

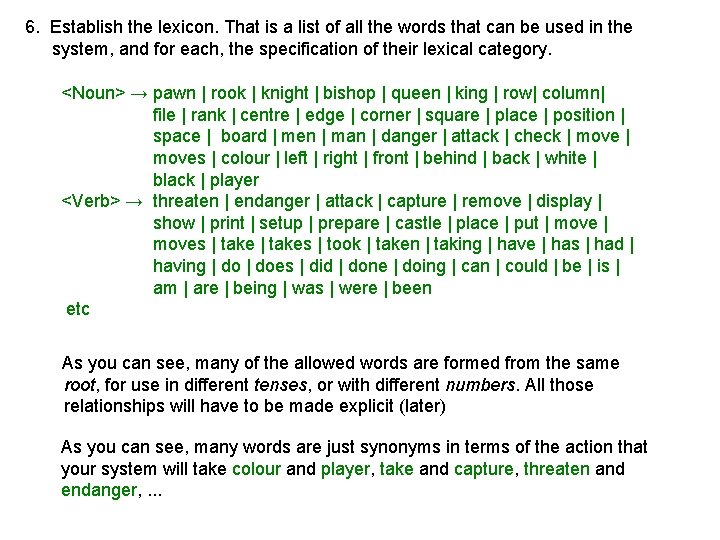

6. Establish the lexicon. That is a list of all the words that can be used in the system, and for each, the specification of their lexical category. <Noun> → pawn | rook | knight | bishop | queen | king | row| column| file | rank | centre | edge | corner | square | place | position | space | board | men | man | danger | attack | check | moves | colour | left | right | front | behind | back | white | black | player <Verb> → threaten | endanger | attack | capture | remove | display | show | print | setup | prepare | castle | place | put | moves | takes | took | taken | taking | have | has | had | having | does | did | done | doing | can | could | be | is | am | are | being | was | were | been etc As you can see, many of the allowed words are formed from the same root, for use in different tenses, or with different numbers. All those relationships will have to be made explicit (later) As you can see, many words are just synonyms in terms of the action that your system will take colour and player, take and capture, threaten and endanger, . . .

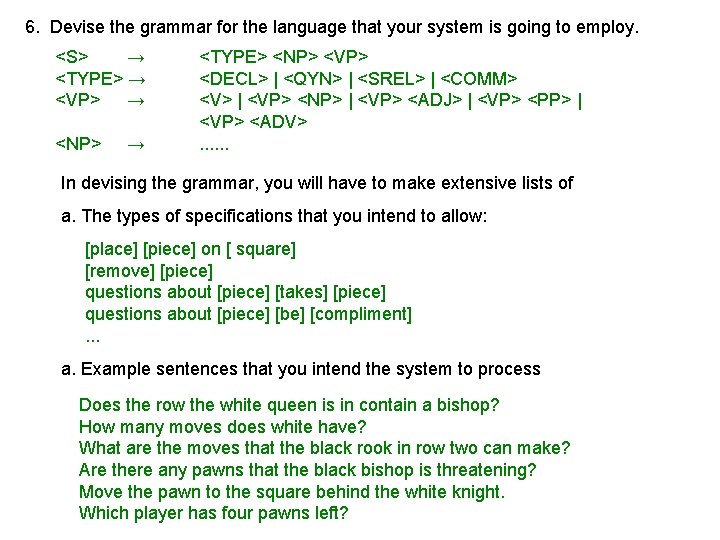

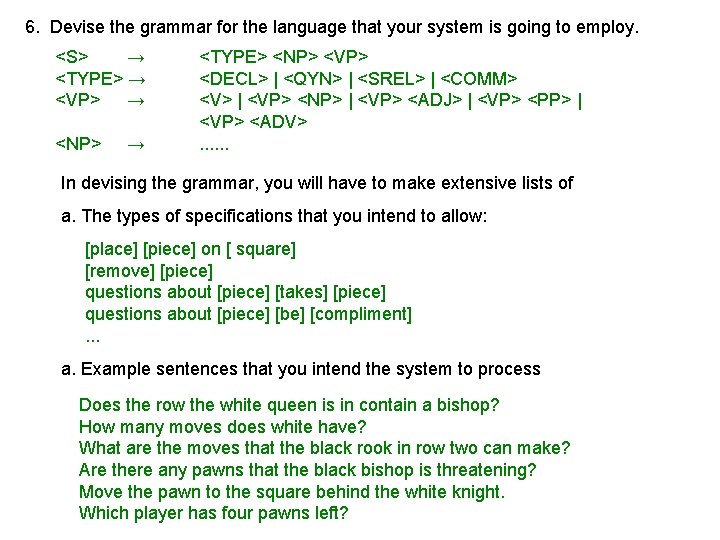

6. Devise the grammar for the language that your system is going to employ. <S> → <TYPE> → <VP> → <NP> → <TYPE> <NP> <VP> <DECL> | <QYN> | <SREL> | <COMM> <V> | <VP> <NP> | <VP> <ADJ> | <VP> <PP> | <VP> <ADV>. . . In devising the grammar, you will have to make extensive lists of a. The types of specifications that you intend to allow: [place] [piece] on [ square] [remove] [piece] questions about [piece] [takes] [piece] questions about [piece] [be] [compliment]. . . a. Example sentences that you intend the system to process Does the row the white queen is in contain a bishop? How many moves does white have? What are the moves that the black rook in row two can make? Are there any pawns that the black bishop is threatening? Move the pawn to the square behind the white knight. Which player has four pawns left?

As one proceeds in constructing a natural language understanding system, there will be discoveries of other words that are applicable, other operations in the database that are desirable, and other desired ways of saying things, and therefore other productions that are required for the grammar. That’s one reason why it is important for NLU systems to be data driven, as much as possible. input sentence PARSER grammar, lexicon parse tree SEMANTIC semantic templates INTERPRETER data-base query DATABASE response database content

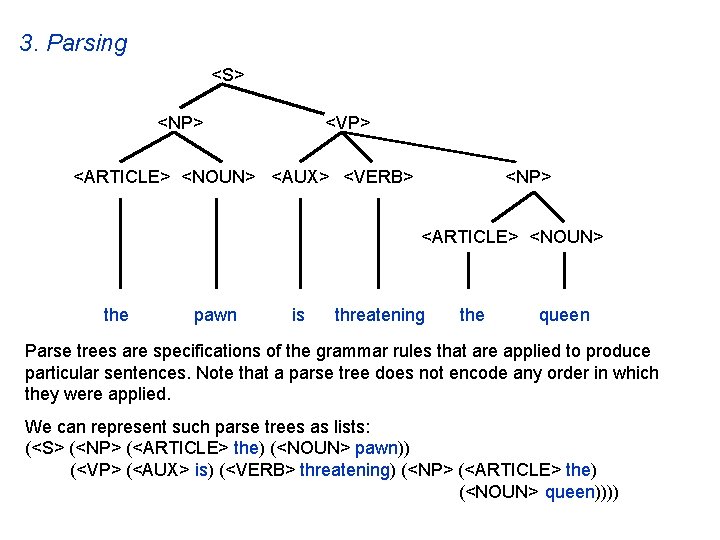

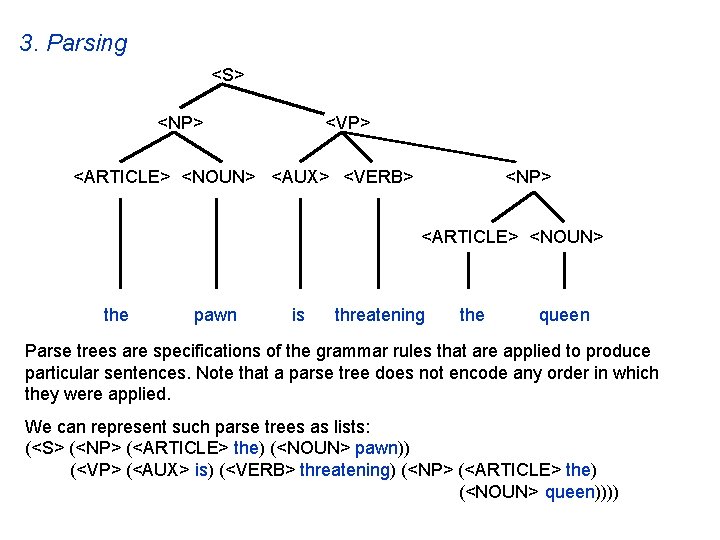

3. Parsing <S> <NP> <VP> <ARTICLE> <NOUN> <AUX> <VERB> <NP> <ARTICLE> <NOUN> the pawn is threatening the queen Parse trees are specifications of the grammar rules that are applied to produce particular sentences. Note that a parse tree does not encode any order in which they were applied. We can represent such parse trees as lists: (<S> (<NP> (<ARTICLE> the) (<NOUN> pawn)) (<VP> (<AUX> is) (<VERB> threatening) (<NP> (<ARTICLE> the) (<NOUN> queen))))

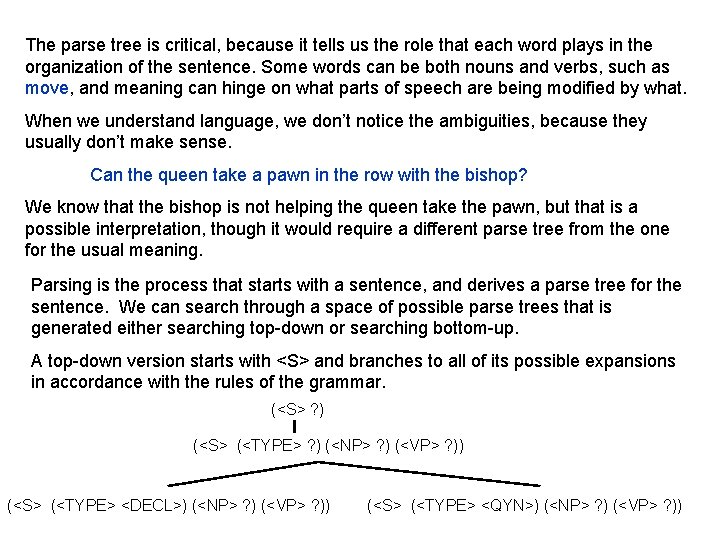

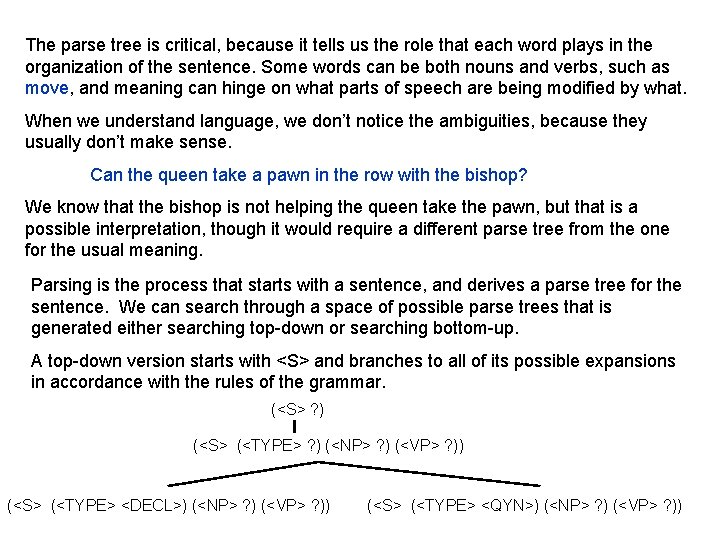

The parse tree is critical, because it tells us the role that each word plays in the organization of the sentence. Some words can be both nouns and verbs, such as move, and meaning can hinge on what parts of speech are being modified by what. When we understand language, we don’t notice the ambiguities, because they usually don’t make sense. Can the queen take a pawn in the row with the bishop? We know that the bishop is not helping the queen take the pawn, but that is a possible interpretation, though it would require a different parse tree from the one for the usual meaning. Parsing is the process that starts with a sentence, and derives a parse tree for the sentence. We can search through a space of possible parse trees that is generated either searching top-down or searching bottom-up. A top-down version starts with <S> and branches to all of its possible expansions in accordance with the rules of the grammar. (<S> ? ) (<S> (<TYPE> ? ) (<NP> ? ) (<VP> ? )) (<S> (<TYPE> <DECL>) (<NP> ? ) (<VP> ? )) (<S> (<TYPE> <QYN>) (<NP> ? ) (<VP> ? ))

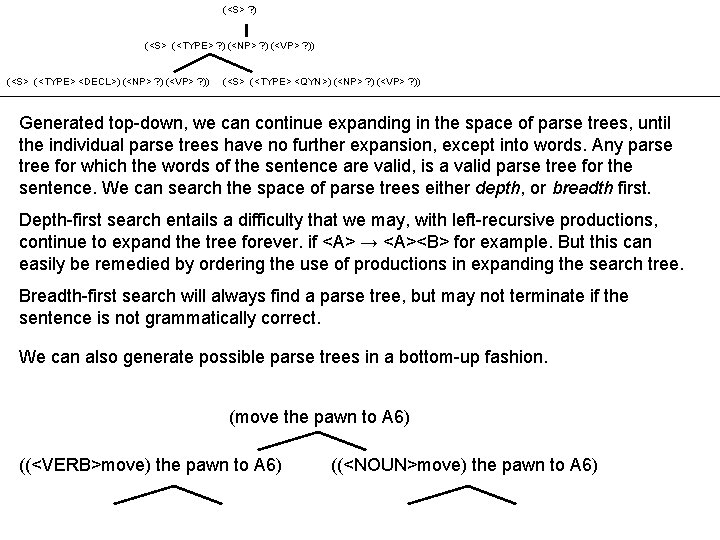

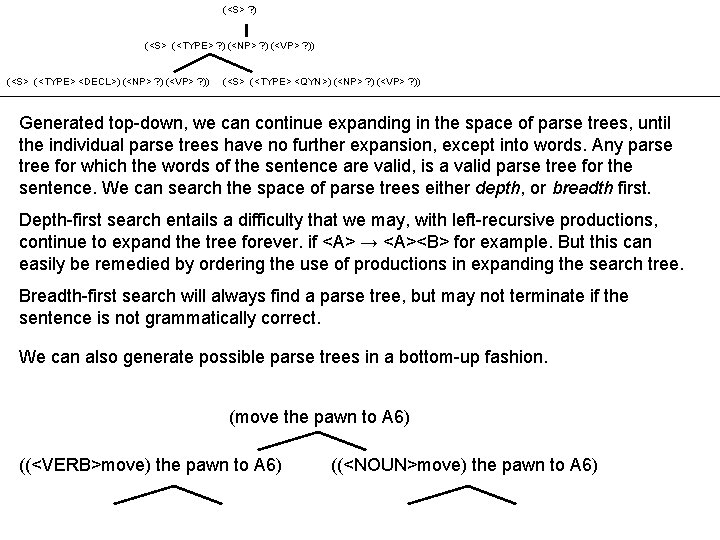

(<S> ? ) (<S> (<TYPE> ? ) (<NP> ? ) (<VP> ? )) (<S> (<TYPE> <DECL>) (<NP> ? ) (<VP> ? )) (<S> (<TYPE> <QYN>) (<NP> ? ) (<VP> ? )) Generated top-down, we can continue expanding in the space of parse trees, until the individual parse trees have no further expansion, except into words. Any parse tree for which the words of the sentence are valid, is a valid parse tree for the sentence. We can search the space of parse trees either depth, or breadth first. Depth-first search entails a difficulty that we may, with left-recursive productions, continue to expand the tree forever. if <A> → <A><B> for example. But this can easily be remedied by ordering the use of productions in expanding the search tree. Breadth-first search will always find a parse tree, but may not terminate if the sentence is not grammatically correct. We can also generate possible parse trees in a bottom-up fashion. (move the pawn to A 6) ((<VERB>move) the pawn to A 6) ((<NOUN>move) the pawn to A 6)

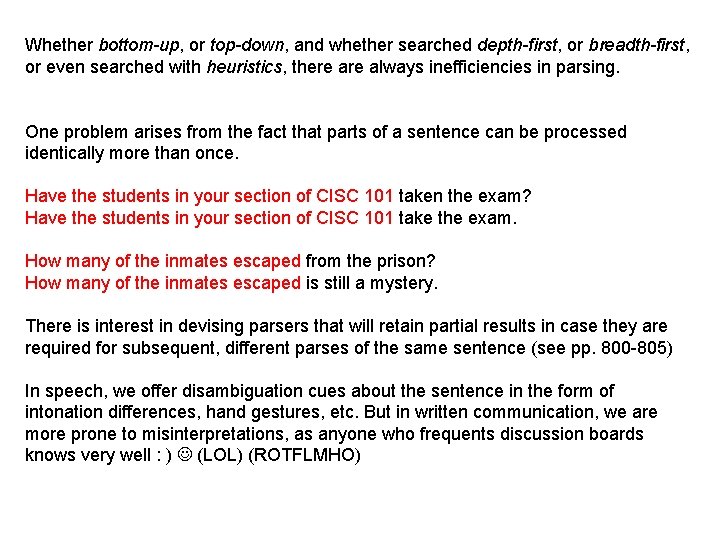

Whether bottom-up, or top-down, and whether searched depth-first, or breadth-first, or even searched with heuristics, there always inefficiencies in parsing. One problem arises from the fact that parts of a sentence can be processed identically more than once. Have the students in your section of CISC 101 taken the exam? Have the students in your section of CISC 101 take the exam. How many of the inmates escaped from the prison? How many of the inmates escaped is still a mystery. There is interest in devising parsers that will retain partial results in case they are required for subsequent, different parses of the same sentence (see pp. 800 -805) In speech, we offer disambiguation cues about the sentence in the form of intonation differences, hand gestures, etc. But in written communication, we are more prone to misinterpretations, as anyone who frequents discussion boards knows very well : ) (LOL) (ROTFLMHO)

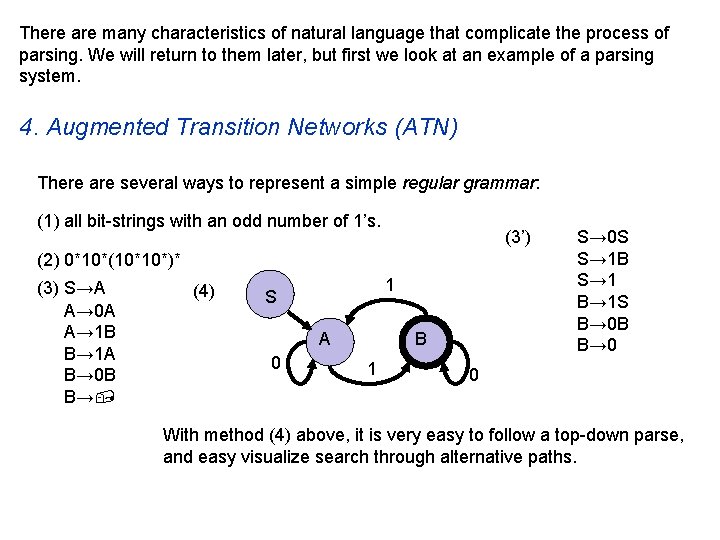

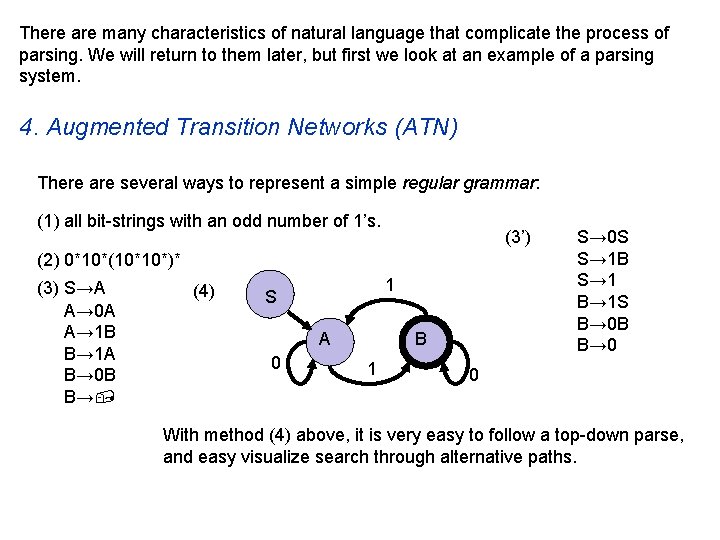

There are many characteristics of natural language that complicate the process of parsing. We will return to them later, but first we look at an example of a parsing system. 4. Augmented Transition Networks (ATN) There are several ways to represent a simple regular grammar: (1) all bit-strings with an odd number of 1’s. (3’) (2) 0*10*(10*10*)* (3) S→A A→ 0 A A→ 1 B B→ 1 A B→ 0 B B→ (4) 1 S A 0 B 1 S→ 0 S S→ 1 B S→ 1 B→ 1 S B→ 0 B B→ 0 0 With method (4) above, it is very easy to follow a top-down parse, and easy visualize search through alternative paths.

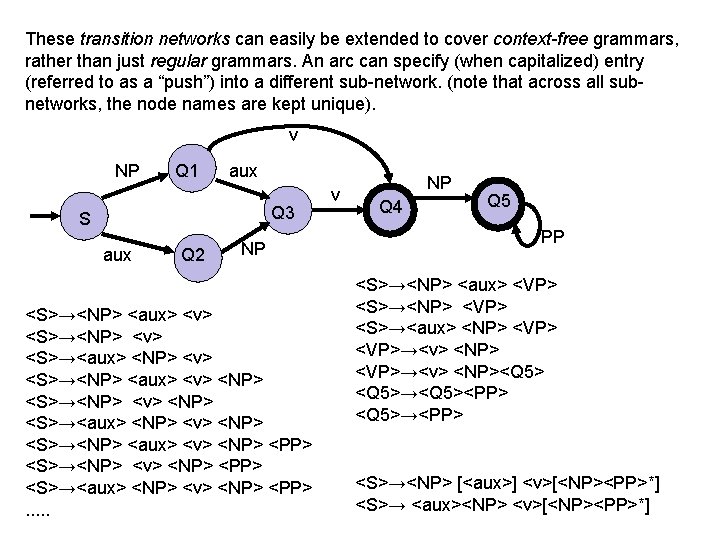

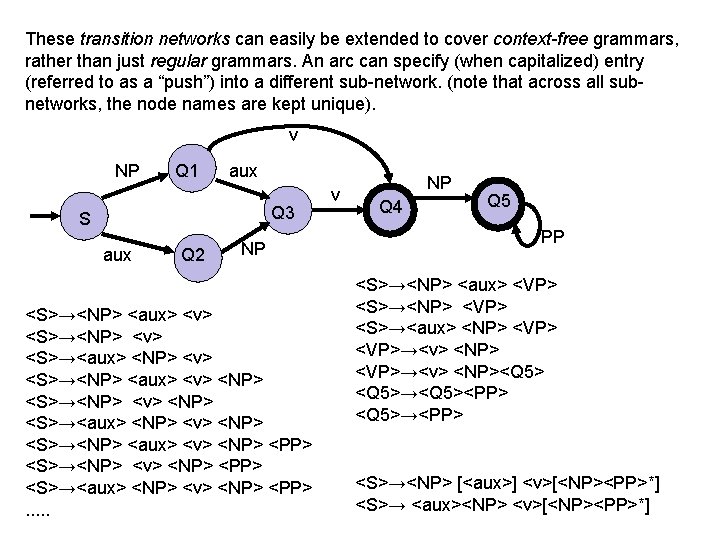

These transition networks can easily be extended to cover context-free grammars, rather than just regular grammars. An arc can specify (when capitalized) entry (referred to as a “push”) into a different sub-network. (note that across all subnetworks, the node names are kept unique). v NP Q 1 aux Q 3 S aux Q 2 NP <S>→<NP> <aux> <v> <S>→<NP> <v> <S>→<aux> <NP> <v> <S>→<NP> <aux> <v> <NP> <S>→<NP> <v> <NP> <S>→<aux> <NP> <v> <NP> <S>→<NP> <aux> <v> <NP> <PP> <S>→<NP> <v> <NP> <PP> <S>→<aux> <NP> <v> <NP> <PP>. . . v NP Q 4 Q 5 PP <S>→<NP> <aux> <VP> <S>→<NP> <VP> <S>→<aux> <NP> <VP>→<v> <NP><Q 5>→<Q 5><PP> <Q 5>→<PP> <S>→<NP> [<aux>] <v>[<NP><PP>*] <S>→ <aux><NP> <v>[<NP><PP>*]

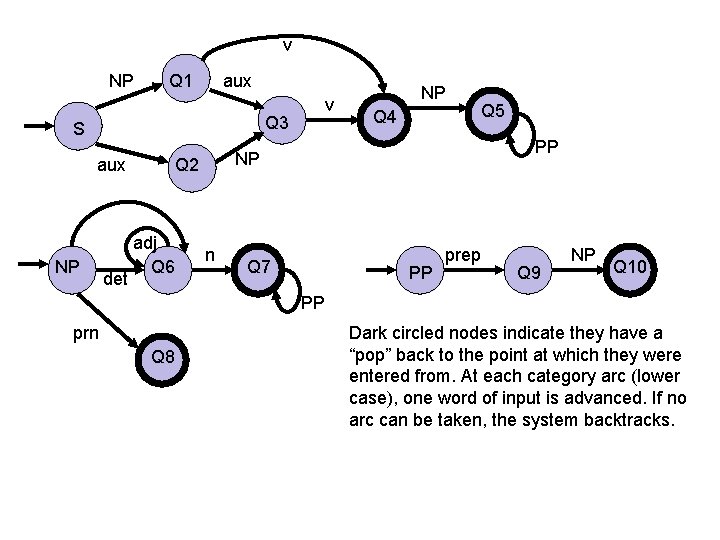

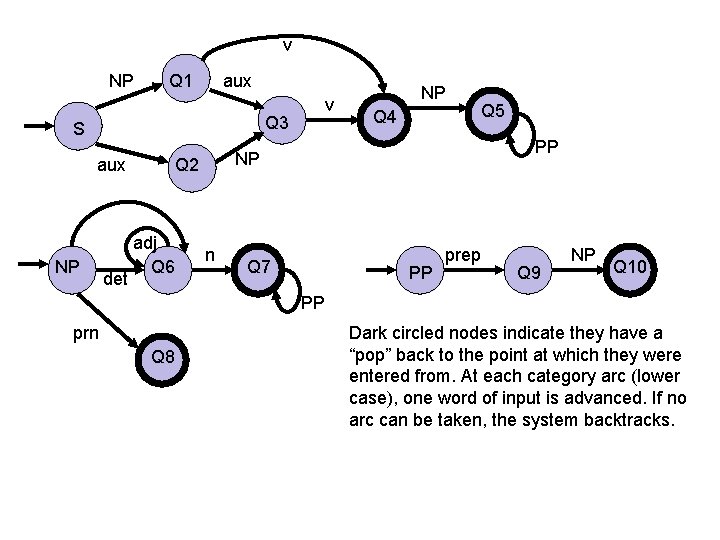

v NP Q 1 aux v Q 3 S aux NP det Q 4 Q 5 PP NP Q 2 adj Q 6 NP n Q 7 PP prep Q 9 NP Q 10 PP prn Q 8 Dark circled nodes indicate they have a “pop” back to the point at which they were entered from. At each category arc (lower case), one word of input is advanced. If no arc can be taken, the system backtracks.

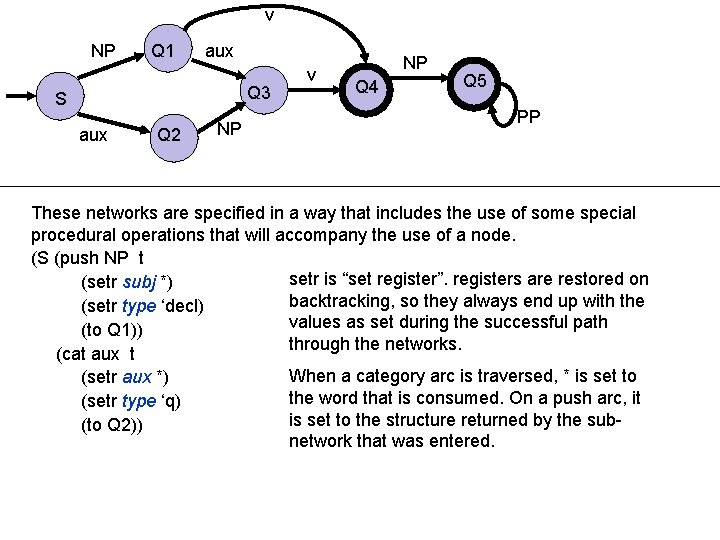

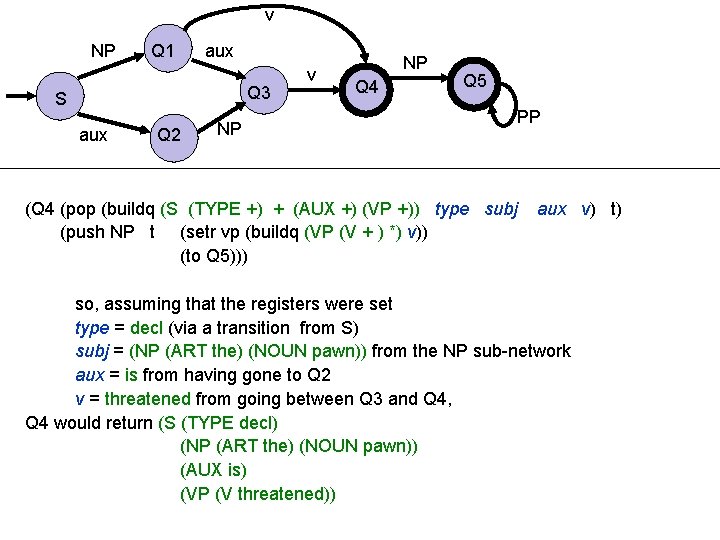

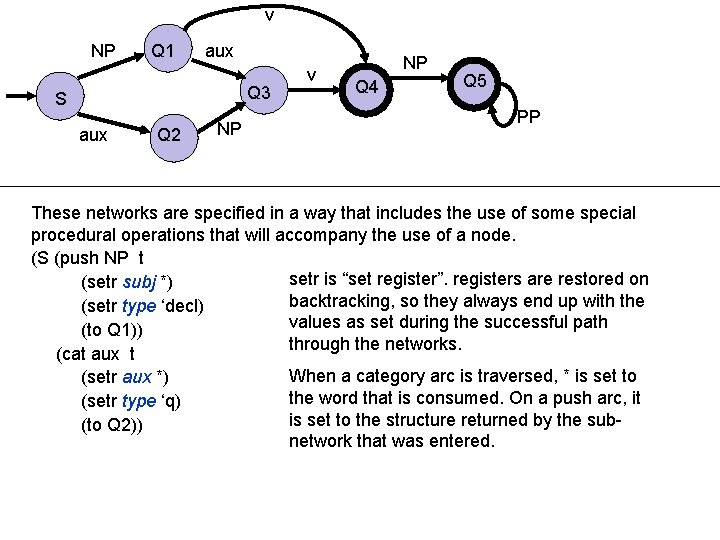

v NP Q 1 aux Q 3 S aux Q 2 NP v NP Q 4 Q 5 PP These networks are specified in a way that includes the use of some special procedural operations that will accompany the use of a node. (S (push NP t setr is “set register”. registers are restored on (setr subj *) backtracking, so they always end up with the (setr type ‘decl) values as set during the successful path (to Q 1)) through the networks. (cat aux t When a category arc is traversed, * is set to (setr aux *) the word that is consumed. On a push arc, it (setr type ‘q) is set to the structure returned by the sub(to Q 2)) network that was entered.

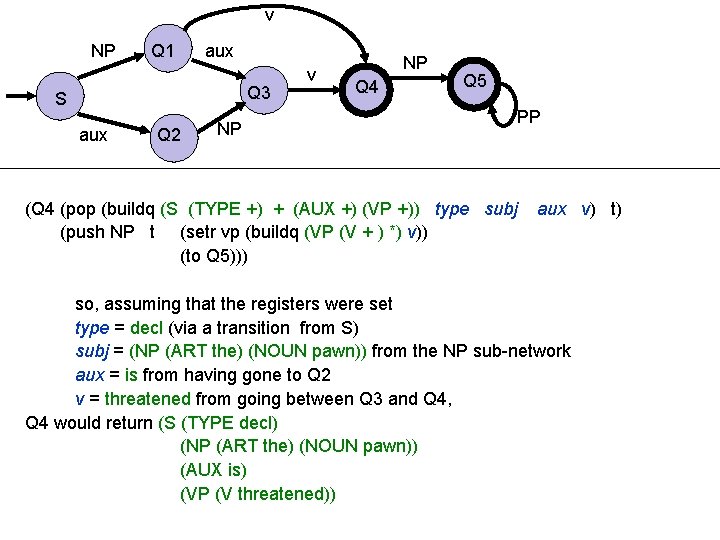

v NP Q 1 aux Q 3 S aux Q 2 NP v NP Q 4 Q 5 PP (Q 4 (pop (buildq (S (TYPE +) + (AUX +) (VP +)) type subj (push NP t (setr vp (buildq (VP (V + ) *) v)) (to Q 5))) aux v) t) so, assuming that the registers were set type = decl (via a transition from S) subj = (NP (ART the) (NOUN pawn)) from the NP sub-network aux = is from having gone to Q 2 v = threatened from going between Q 3 and Q 4, Q 4 would return (S (TYPE decl) (NP (ART the) (NOUN pawn)) (AUX is) (VP (V threatened))

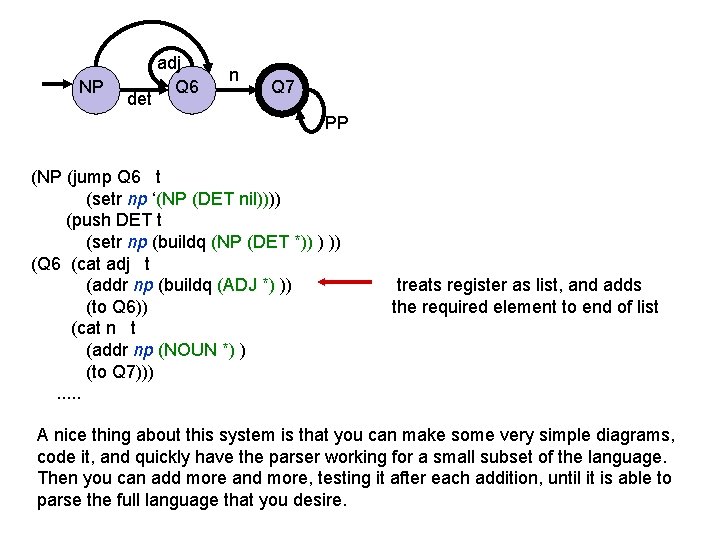

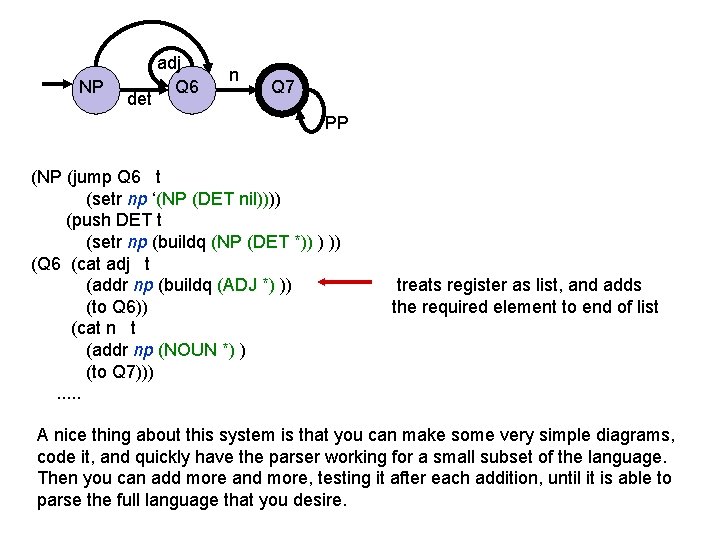

NP det adj Q 6 n Q 7 PP (NP (jump Q 6 t (setr np ‘(NP (DET nil)))) (push DET t (setr np (buildq (NP (DET *)) ) )) (Q 6 (cat adj t (addr np (buildq (ADJ *) )) (to Q 6)) (cat n t (addr np (NOUN *) ) (to Q 7))). . . treats register as list, and adds the required element to end of list A nice thing about this system is that you can make some very simple diagrams, code it, and quickly have the parser working for a small subset of the language. Then you can add more and more, testing it after each addition, until it is able to parse the full language that you desire.

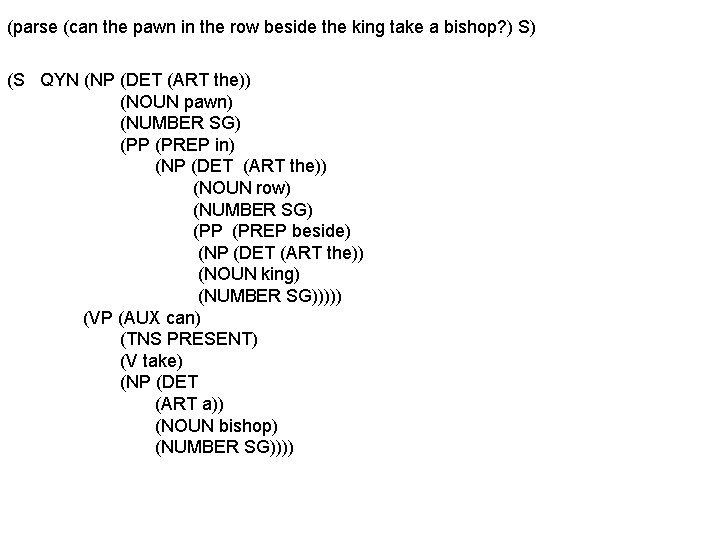

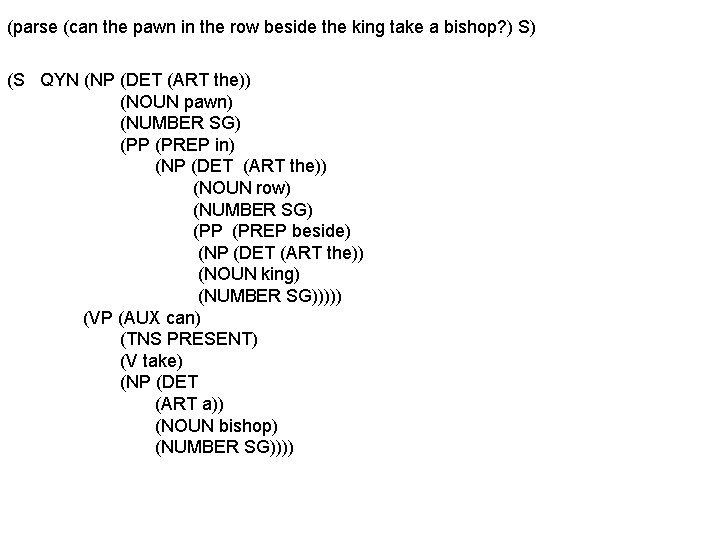

(parse (can the pawn in the row beside the king take a bishop? ) S) (S QYN (NP (DET (ART the)) (NOUN pawn) (NUMBER SG) (PP (PREP in) (NP (DET (ART the)) (NOUN row) (NUMBER SG) (PP (PREP beside) (NP (DET (ART the)) (NOUN king) (NUMBER SG))))) (VP (AUX can) (TNS PRESENT) (V take) (NP (DET (ART a)) (NOUN bishop) (NUMBER SG))))

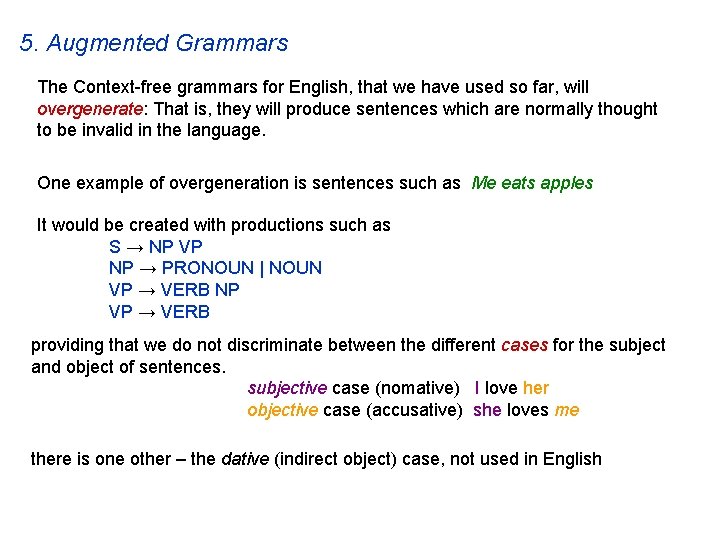

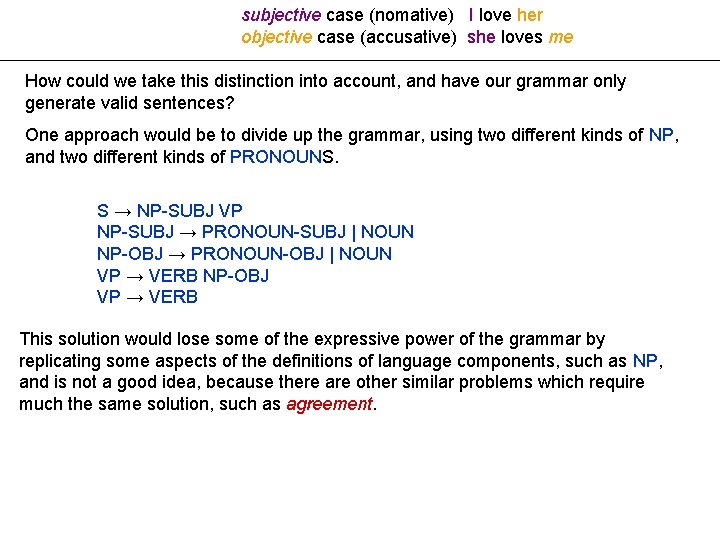

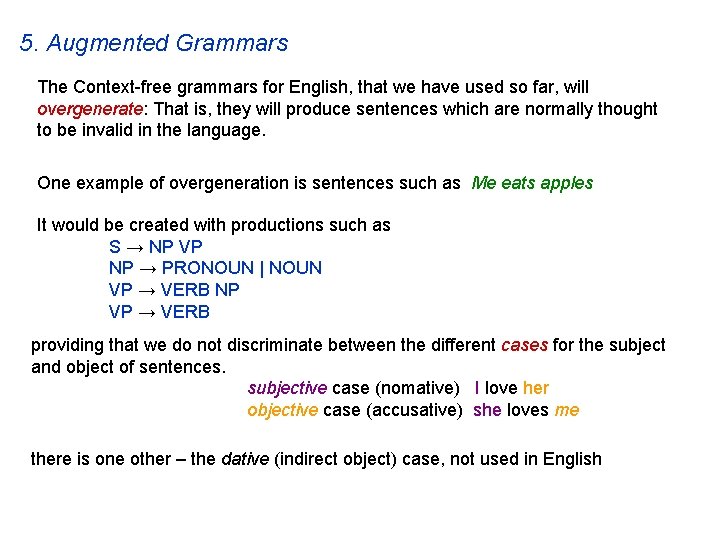

5. Augmented Grammars The Context-free grammars for English, that we have used so far, will overgenerate: That is, they will produce sentences which are normally thought to be invalid in the language. One example of overgeneration is sentences such as Me eats apples It would be created with productions such as S → NP VP NP → PRONOUN | NOUN VP → VERB NP VP → VERB providing that we do not discriminate between the different cases for the subject and object of sentences. subjective case (nomative) I love her objective case (accusative) she loves me there is one other – the dative (indirect object) case, not used in English

subjective case (nomative) I love her objective case (accusative) she loves me How could we take this distinction into account, and have our grammar only generate valid sentences? One approach would be to divide up the grammar, using two different kinds of NP, and two different kinds of PRONOUNS. S → NP-SUBJ VP NP-SUBJ → PRONOUN-SUBJ | NOUN NP-OBJ → PRONOUN-OBJ | NOUN VP → VERB NP-OBJ VP → VERB This solution would lose some of the expressive power of the grammar by replicating some aspects of the definitions of language components, such as NP, and is not a good idea, because there are other similar problems which require much the same solution, such as agreement.

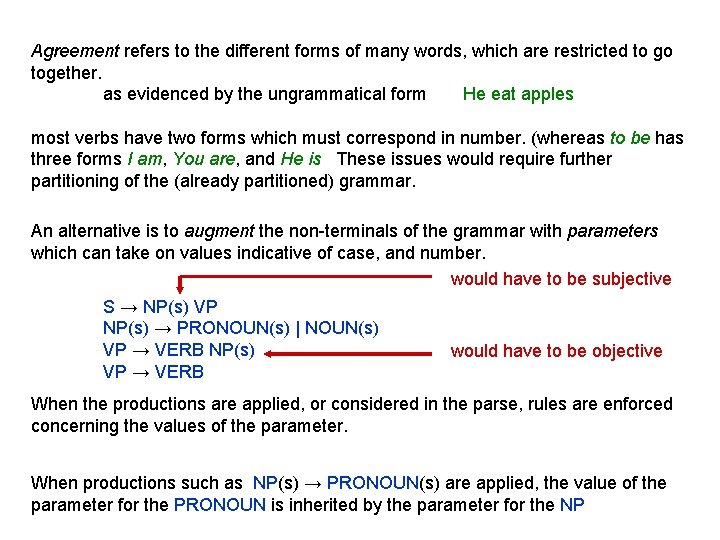

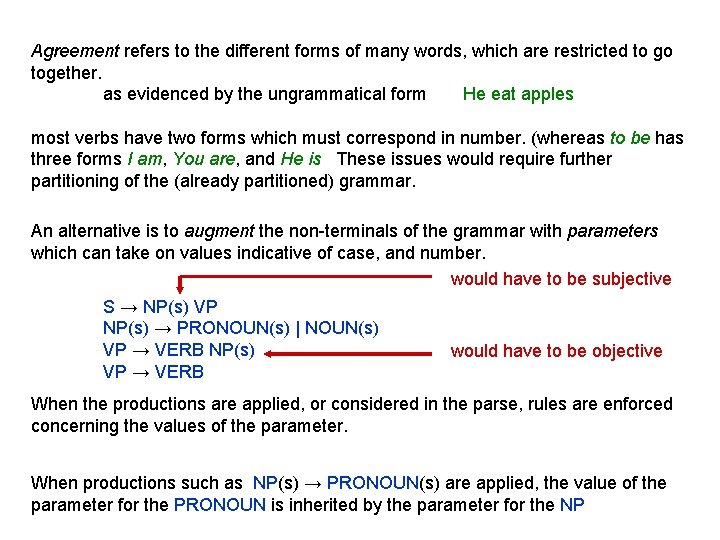

Agreement refers to the different forms of many words, which are restricted to go together. as evidenced by the ungrammatical form He eat apples most verbs have two forms which must correspond in number. (whereas to be has three forms I am, You are, and He is These issues would require further partitioning of the (already partitioned) grammar. An alternative is to augment the non-terminals of the grammar with parameters which can take on values indicative of case, and number. would have to be subjective S → NP(s) VP NP(s) → PRONOUN(s) | NOUN(s) VP → VERB NP(s) VP → VERB would have to be objective When the productions are applied, or considered in the parse, rules are enforced concerning the values of the parameter. When productions such as NP(s) → PRONOUN(s) are applied, the value of the parameter for the PRONOUN is inherited by the parameter for the NP

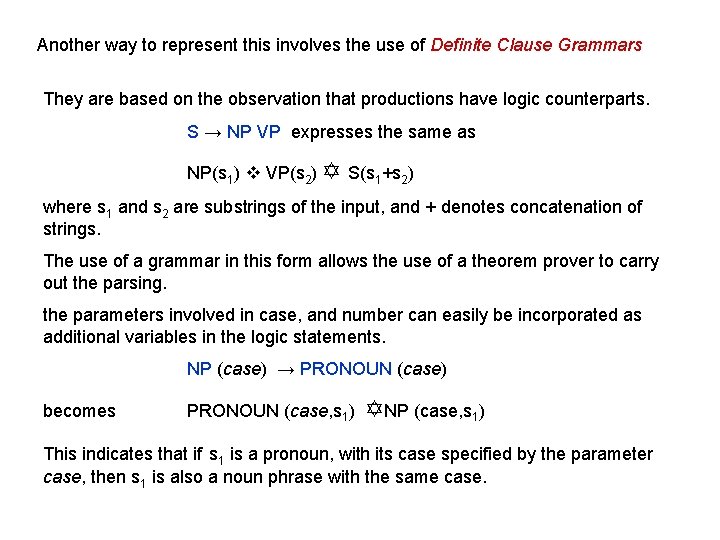

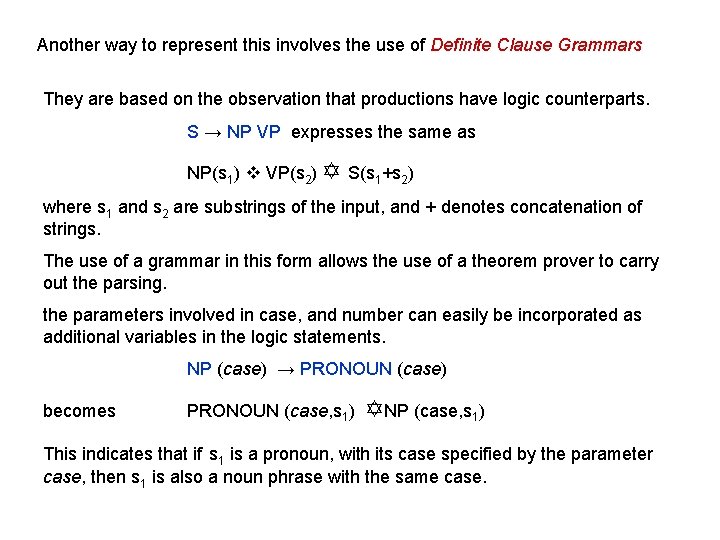

Another way to represent this involves the use of Definite Clause Grammars They are based on the observation that productions have logic counterparts. S → NP VP expresses the same as NP(s 1) VP(s 2) S(s 1+s 2) where s 1 and s 2 are substrings of the input, and + denotes concatenation of strings. The use of a grammar in this form allows the use of a theorem prover to carry out the parsing. the parameters involved in case, and number can easily be incorporated as additional variables in the logic statements. NP (case) → PRONOUN (case) becomes PRONOUN (case, s 1) NP (case, s 1) This indicates that if s 1 is a pronoun, with its case specified by the parameter case, then s 1 is also a noun phrase with the same case.

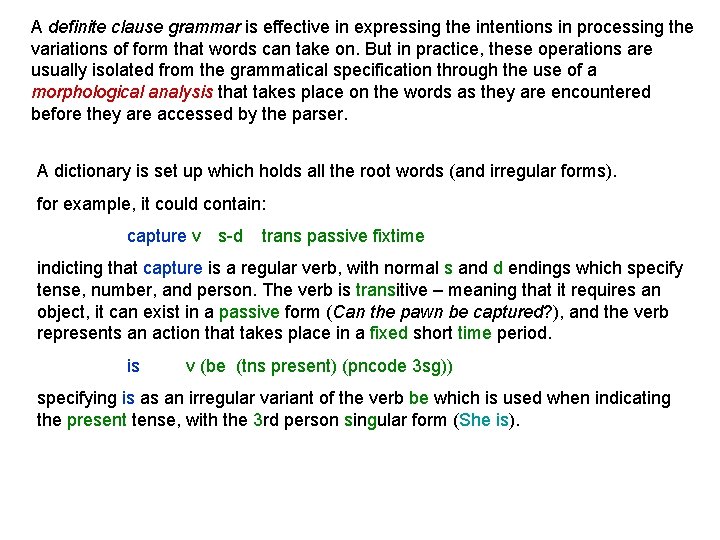

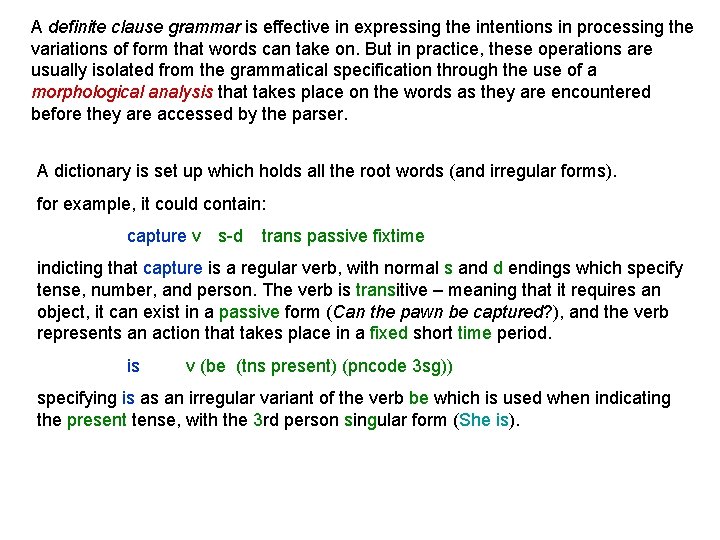

A definite clause grammar is effective in expressing the intentions in processing the variations of form that words can take on. But in practice, these operations are usually isolated from the grammatical specification through the use of a morphological analysis that takes place on the words as they are encountered before they are accessed by the parser. A dictionary is set up which holds all the root words (and irregular forms). for example, it could contain: capture v s-d trans passive fixtime indicting that capture is a regular verb, with normal s and d endings which specify tense, number, and person. The verb is transitive – meaning that it requires an object, it can exist in a passive form (Can the pawn be captured? ), and the verb represents an action that takes place in a fixed short time period. is v (be (tns present) (pncode 3 sg)) specifying is as an irregular variant of the verb be which is used when indicating the present tense, with the 3 rd person singular form (She is).

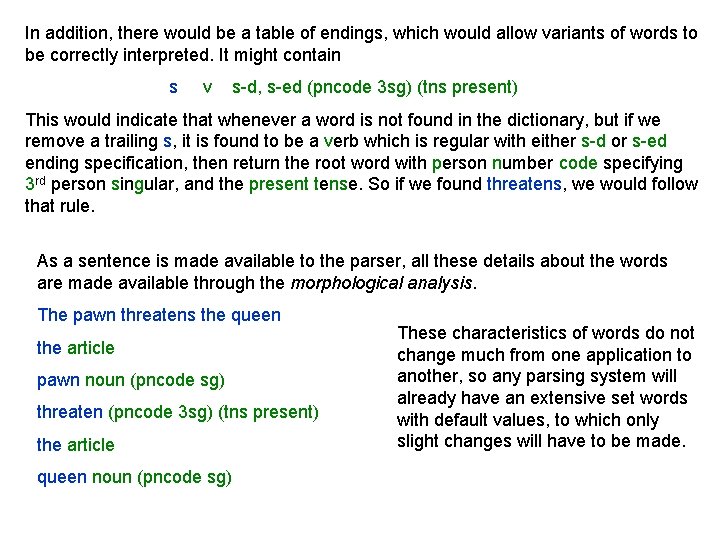

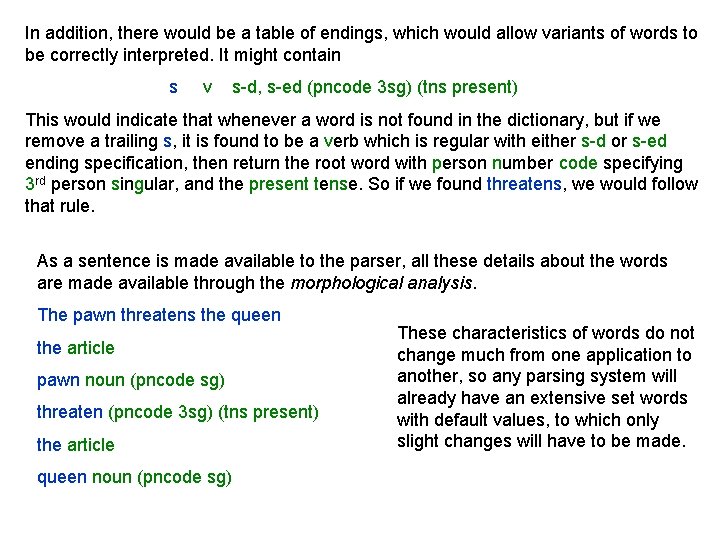

In addition, there would be a table of endings, which would allow variants of words to be correctly interpreted. It might contain s v s-d, s-ed (pncode 3 sg) (tns present) This would indicate that whenever a word is not found in the dictionary, but if we remove a trailing s, it is found to be a verb which is regular with either s-d or s-ed ending specification, then return the root word with person number code specifying 3 rd person singular, and the present tense. So if we found threatens, we would follow that rule. As a sentence is made available to the parser, all these details about the words are made available through the morphological analysis. The pawn threatens the queen the article pawn noun (pncode sg) threaten (pncode 3 sg) (tns present) the article queen noun (pncode sg) These characteristics of words do not change much from one application to another, so any parsing system will already have an extensive set words with default values, to which only slight changes will have to be made.

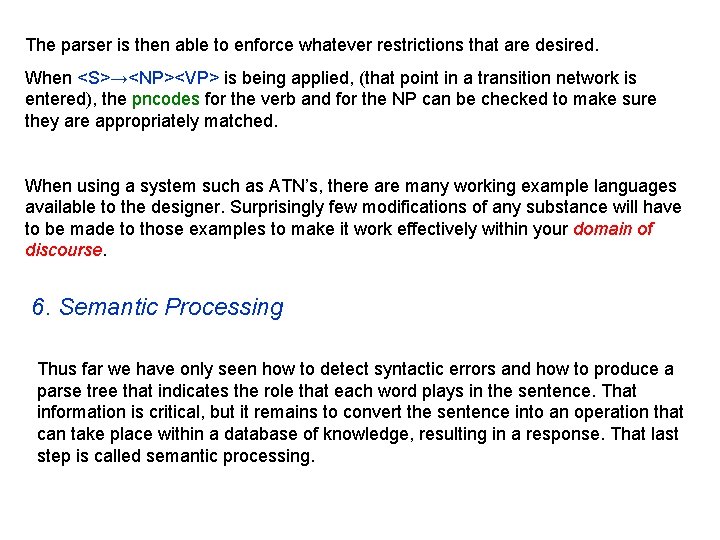

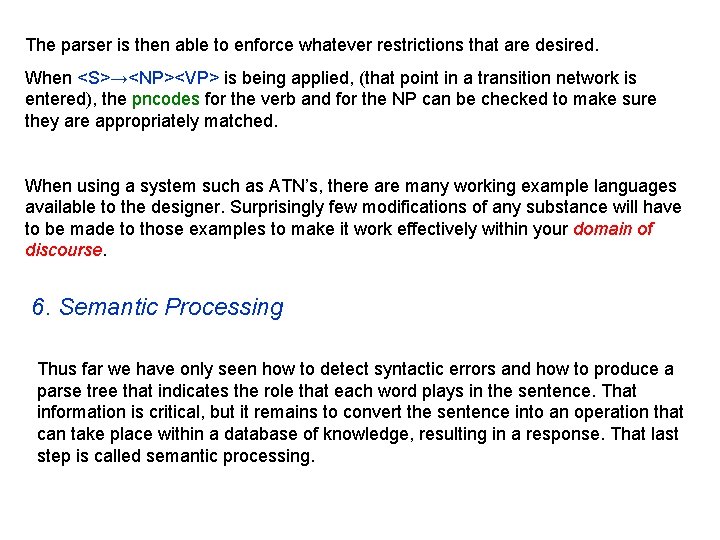

The parser is then able to enforce whatever restrictions that are desired. When <S>→<NP><VP> is being applied, (that point in a transition network is entered), the pncodes for the verb and for the NP can be checked to make sure they are appropriately matched. When using a system such as ATN’s, there are many working example languages available to the designer. Surprisingly few modifications of any substance will have to be made to those examples to make it work effectively within your domain of discourse. 6. Semantic Processing Thus far we have only seen how to detect syntactic errors and how to produce a parse tree that indicates the role that each word plays in the sentence. That information is critical, but it remains to convert the sentence into an operation that can take place within a database of knowledge, resulting in a response. That last step is called semantic processing.

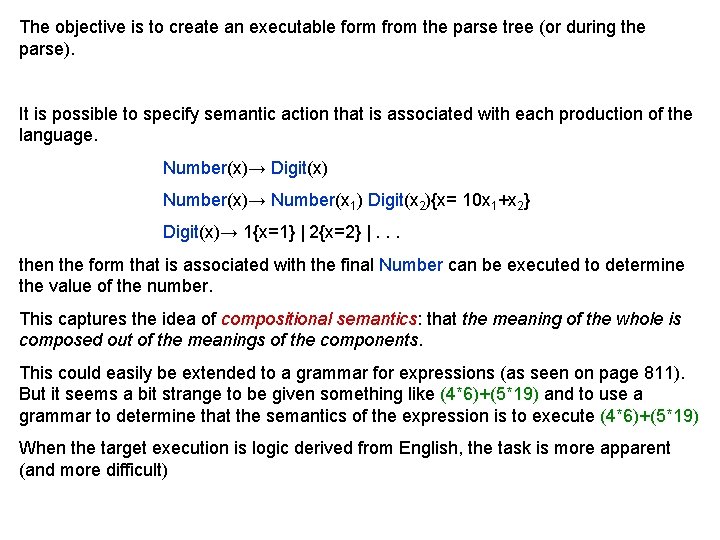

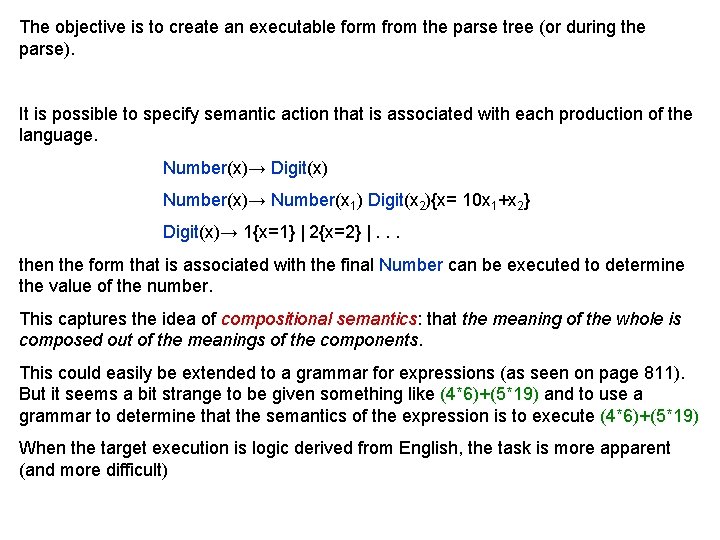

The objective is to create an executable form from the parse tree (or during the parse). It is possible to specify semantic action that is associated with each production of the language. Number(x)→ Digit(x) Number(x)→ Number(x 1) Digit(x 2){x= 10 x 1+x 2} Digit(x)→ 1{x=1} | 2{x=2} |. . . then the form that is associated with the final Number can be executed to determine the value of the number. This captures the idea of compositional semantics: that the meaning of the whole is composed out of the meanings of the components. This could easily be extended to a grammar for expressions (as seen on page 811). But it seems a bit strange to be given something like (4*6)+(5*19) and to use a grammar to determine that the semantics of the expression is to execute (4*6)+(5*19) When the target execution is logic derived from English, the task is more apparent (and more difficult)

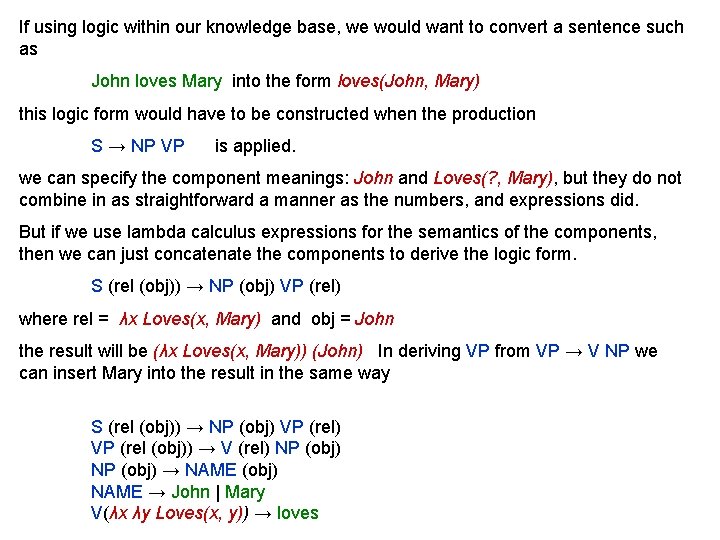

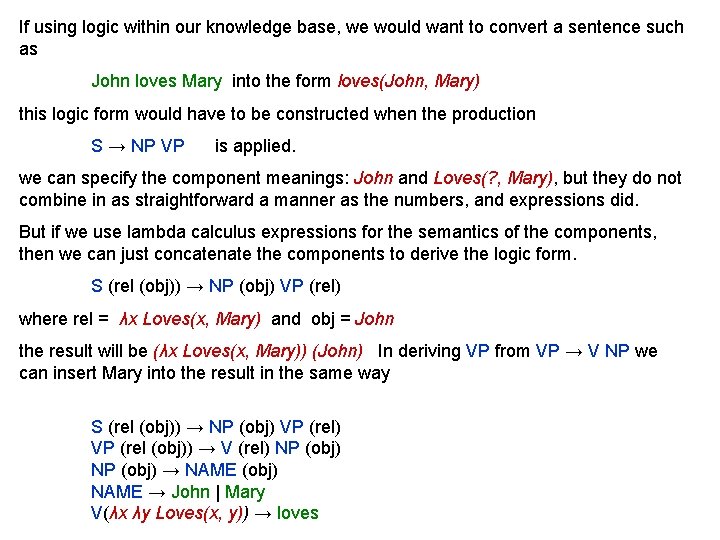

If using logic within our knowledge base, we would want to convert a sentence such as John loves Mary into the form loves(John, Mary) this logic form would have to be constructed when the production S → NP VP is applied. we can specify the component meanings: John and Loves(? , Mary), but they do not combine in as straightforward a manner as the numbers, and expressions did. But if we use lambda calculus expressions for the semantics of the components, then we can just concatenate the components to derive the logic form. S (rel (obj)) → NP (obj) VP (rel) where rel = λx Loves(x, Mary) and obj = John the result will be (λx Loves(x, Mary)) (John) In deriving VP from VP → V NP we can insert Mary into the result in the same way S (rel (obj)) → NP (obj) VP (rel (obj)) → V (rel) NP (obj) → NAME (obj) NAME → John | Mary V(λx λy Loves(x, y)) → loves

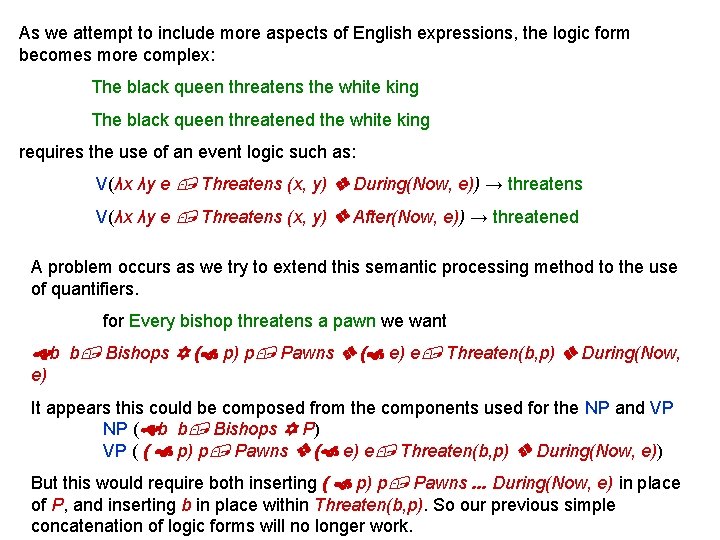

As we attempt to include more aspects of English expressions, the logic form becomes more complex: The black queen threatens the white king The black queen threatened the white king requires the use of an event logic such as: V(λx λy e Threatens (x, y) During(Now, e)) → threatens V(λx λy e Threatens (x, y) After(Now, e)) → threatened A problem occurs as we try to extend this semantic processing method to the use of quantifiers. for Every bishop threatens a pawn we want b b Bishops ( p) p Pawns ( e) e Threaten(b, p) During(Now, e) It appears this could be composed from the components used for the NP and VP NP ( b b Bishops P) VP ( ( p) p Pawns ( e) e Threaten(b, p) During(Now, e)) But this would require both inserting ( p) p Pawns. . . During(Now, e) in place of P, and inserting b in place within Threaten(b, p). So our previous simple concatenation of logic forms will no longer work.

The solution to this problem is to develop special forms which can be built up in a more general way. This could be done through more and more sophisticated logical forms, or by performing matches within the parse tree, looking for subtrees that can be represented as simple database actions, and then building them into more complex actions with higher level matches within the parse trees. In any event, semantics is the most difficult part, and almost always requires implementers to resort to some ad hoc techniques, for which methods that have procedural components have an advantage over methods that are entirely declarative (such as pure logic representations). In any event, there are further difficulties with pragmatics. For example, the sentence: Every bishop threatens a pawn could mean that every bishop threatens the same pawn, which in turn would only make sense if one of the players had already lost both bishops. So the actual situation on the chessboard can contribute to the preferred meaning associated with a sentence.

AIMA references (2 e) communication as action: pages 790 to 795(bottom) formal grammar for English fragment: pages 795(bottom) to 798(top) parsing: pages 798(top) to 800(top) augmented grammars: pages 806 to 810(mid) semantic interpretation: pages 810 to 814(top) AIMA references (3 e) Chapters 22 & 23 include the same material (see especially Ch 23) but with revised emphasis and considerable new material