Georgetown University ECON 156 Poverty and Inequality Part

- Slides: 57

Georgetown University, ECON 156: Poverty and Inequality Part 1. 2 History of Economic Thought on Poverty and Inequality Martin Ravallion Georgetown University Lecture notes to accompany Ravallion’s The Economics of Poverty, Oxford University Press (EOP hereafter). 1

Chapter 2: New Thinking on Poverty after 1950 2

The Second Poverty Enlightenment, 1960 -80 3

The second poverty enlightenment • The period since 1800 that has the strongest claim to have been a second “Poverty Enlightenment” is 1960 -80. • Scholarly and popular authors could formulate accessible arguments grounded on a body of theory and data • Data from qualitative observations, sample surveys and much analytic work in measuring living standards and setting poverty lines. • Protests and Civil Rights Movement in US. Left-of-center political/social movements in many countries. Newly independent ex-Colonies looking for rapid escape from poverty. • Political will + analytic expertise => new effort against poverty. 4

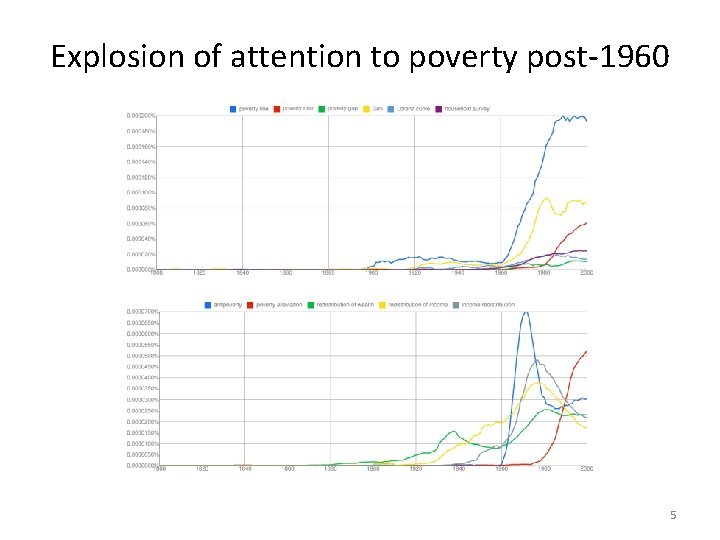

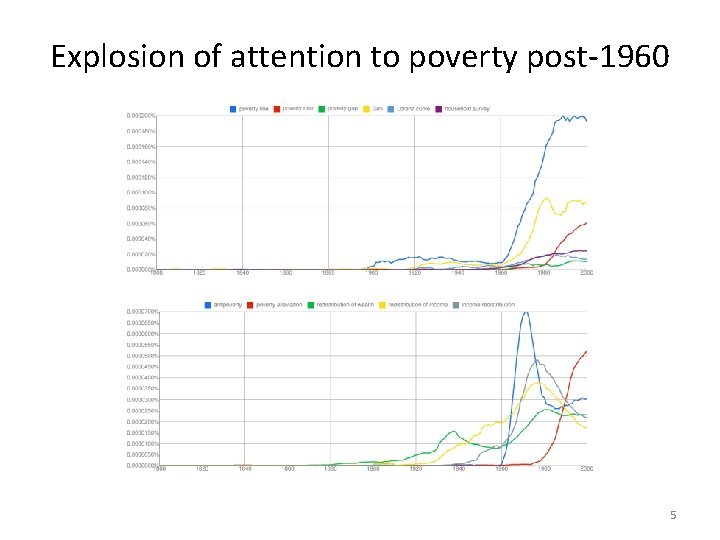

Explosion of attention to poverty post-1960 5

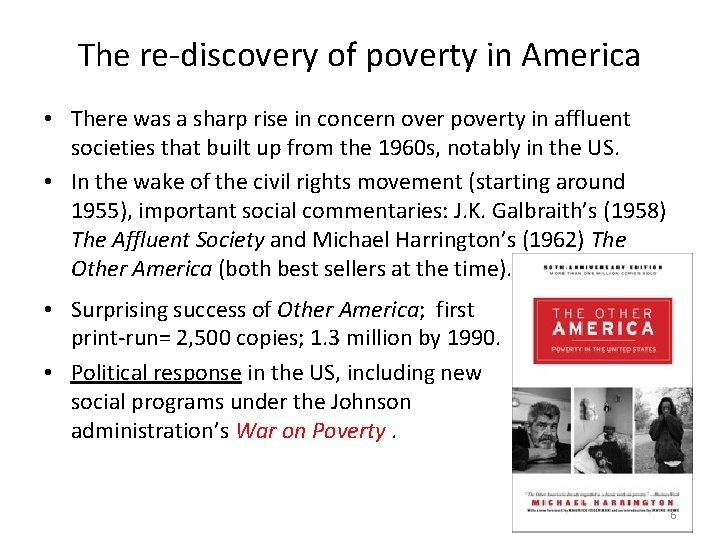

The re-discovery of poverty in America • There was a sharp rise in concern over poverty in affluent societies that built up from the 1960 s, notably in the US. • In the wake of the civil rights movement (starting around 1955), important social commentaries: J. K. Galbraith’s (1958) The Affluent Society and Michael Harrington’s (1962) The Other America (both best sellers at the time). • Surprising success of Other America; first print-run= 2, 500 copies; 1. 3 million by 1990. • Political response in the US, including new social programs under the Johnson administration’s War on Poverty. 6

The rediscovery of poverty came at a time of seemingly ample resources 7

New understanding of poverty as stemming from market failures (Boxes 1. 9 and 2. 2, EOP) • The 1970 s also saw a deeper questioning of the efficiency of competitive market allocations. • The term “market failure” (introduced by Francis Bator, 1958) had become widely used and labor and credit markets imperfections in particular came to be seen as key to understanding poverty. • The idea that labor markets were competitive, such that wage rates adjusted to remove any unemployment, had been in doubt since the Great Depression. 8

The new information economics • George Akerlof (1970) showed how credit (and other) market failures can arise from asymmetric information, such as when lenders are less well-informed about a project than borrowers, thus constraining the flow of credit. • This helped explain the efficiency role of institutions and governments in facilitating better information signals and broader contract choices. 9

Poverty is seen to stem from market failures • In a perfect credit market even poor parents will be able to take out loans for schooling—to be paid back from children’s later earnings. • However, if poor parents are more credit constrained than others then we will see an economic gradient in schooling, whereby the children of poor parents get less schooling. • This is indeed what we see, almost everywhere. There will be too much child labor and too little schooling in poor families. • Poverty will thus persist across generations. • Risk market failures can have similar implications; parents will underinvest in their kid’s schooling when they cannot insure against the risk of a low economic return from that schooling. 10

Understanding poverty in a rich world: imperfect capital markets • Mounting evidence and observations that access to financial capital, and the rates of return to investments in such capital, tend to be lower for the poor. • Financial wealth is very unequally distributed in America; one estimate: wealthiest 1% hold 30% of the wealth. • And the rich tend to receive a higher rate of return on their wealth. • With imperfect credit markets, credit is rationed according to wealth, which determines ability to put up collateral. 11

Understanding poverty in a rich world: dual labor markets • In understanding poverty in rich countries in the 1960 s, the idea of dual labor markets became prominent • One labor market has high wages and good benefits while the second has low wages and little in the way of benefits. • Jeremy Bulow and Larry Summers (1986) showed how this could be an equilibrium given the existence of high costs of monitoring work effort in certain activities, which become the high-wage segment in which profit-maximizing firms pay wages above market-clearing levels. • Other activities with low monitoring costs form the competitive segment, which is where the working poor are found. 12

Rigorous formulations of the incentive constraints on redistribution • The optimal taxation problem: what income tax schedule is best when there is a trade-off between equity and efficiency, given behavioral responses through labor supply and imperfect information? (James Mirrlees, 1971; see box 10. 2*) • Utilitarian objective in Mirrlees. • Alternative (non-welfarist; poverty focused) versions emerged in late 20 th century (Kanbur- Keen-Tuomala). 13

New evidence on incentive effects • With better data on individual labor supply and other behavioral responses we saw new research on incentive effects. • The existence of such effects has often been confirmed. • But it is also clear that many critics of redistributive policy have exaggerated the extent of these effects. Quite modest in practice (with exceptions when marginal tax rates are high). • Also, society can still be willing to accept a leaky bucket (within limits). Here is a summary of one research study of the “leaky bucket. ”) 14

Rawls vs. the utilitarians • John Rawls’s (1971) Theory of Justice was the first serious competitor to utilitarianism as the basis for thinking about the role of the state in social policy. • Unlike utilitarianism this was fundamentally a rights-based approach that put human freedom center stage. • Key issue: the justice of social institutions. Rawls argued that this should be judged by welfare of the least advantaged. – “Veil of ignorance” (including about probabilities) => difference principle – Trade-off rejected; no gain to richest justifies loss to poorest. • Preferences still matter, but only those of the poor. • Viewer: 1975: References to “Rawls” overtook “utilitarianisn” 15

Rawls, Kant and utilitarianism • Recall Immanual Kant’s dictum that people were to be seen as ends, not merely as the means to some end. • Utilitarianism was seen as being in conflict with this idea, since it justified losses to the individual in the name of aggregate happiness. The individual is subordinated to the common good. • But gainers and losers from policy. Who should have veto power? • Rawls argued that poor people have the right to veto any scheme that brings gains to the well-off at their expense. Poverty for some can never be the means to others’ prosperity. • The Rawlsian social contract can thus be said to be “stable” (“the institutions that satisfy it will generate their own support”(Rawls, 1967) unlike a utilitarian one. This set was contentious! 16

Rawls’ re-interpretation of “fraternity” • Recall that fraternity did not get as much attention as liberty or equality at the time of the French Revolution. • Rawls saw the difference principle as defining “fraternity”: “the idea of not wanting to have greater advantages unless this is to the benefit of others who are less well off. ” • If there must be a dictator in social choice then it should be the poorest. • The Rawlsian theory of distributive justice matches closely “liberty, equality and fraternity”: – Liberty: maximum individual freedom consistent with the same freedom for all. – Equality: equality of opportunity – Fraternity: difference principle (“maxi-min”) 17

How egalitarian was Rawls? • Rawlsian “equality” was similar to that in “Liberty, equality, fraternity: ” not understood as equality of outcomes but defined in terms of legal rights of opportunity—that the law must be the same for everyone and so allow all citizens equal opportunity for public positions and jobs, with the assignment determined by ability. • The difference principle in Rawls: subject to the constraint of liberty, social choices should only permit inequality if it is efficient to do so—that a difference is only allowed if both parties are better off as a result. • In short: Rawls took the view that poverty for some can never be the means to others’ prosperity. 18

Rawls and equity cont. , • The difference principle was more radical in its egalitarianism than the French Revolution’s motto. • However, it was not the kind of radical egalitarianism that said that equality always trumped efficiency. • Indeed, society A, with a great deal of inequality, would be preferred by this moral principle to society B with no inequality if the poorest were better off in society A. • Thus the principle amounts to maximizing the advantages of the worst off group and hence became known as “maximin. ” 19

Maximin (Review Box 2. 3, EOP) • The difference principle was not a proposal to maximize the lowest income, as it is sometimes interpreted, but rather to maximize the welfare of the worst off group in society. • The “worst off” people were to be identified by what Rawls called their command over “primary goods. ” • These are all those things needed to assure that one is free to live the life one wants. • This is a broader than what are often called “basic needs” as it includes social inclusion needs and basic liberties—in short, rights as well as resources. • Leximin extension: When it makes no difference to the least advantaged, then look to the next poorest, and so on. 20

Poverty and inequality of what? Amartya Sen • Rawls emphasized “primary goods. ” He clearly had a broad conception of what they meant, including (for example) “selfrespect” (*). • But this was mainly seen as emphasizing command over commodities. • Amartya Sen criticized Rawls for this, and for underplaying the heterogeneity of people in terms of their income needs. (**) • Sen argued instead for viewing human capabilities as the “primary goods. ” 21

The capabilities approach (Review Box 2. 1 EOP) • In the scheme proposed by Amartya Sen, “functionings” are the “beings and doings” of life, such as being safe, able to live to an old age, employed and being able to participate in social and economic activities more generally. • “Capabilities” refers to the set of functionings actually available to a person given his or her circumstances, as determined by the person’s own characteristics and environment. Options in life. • Sen proposed that human welfare should be judged by a person’s capabilities. 22

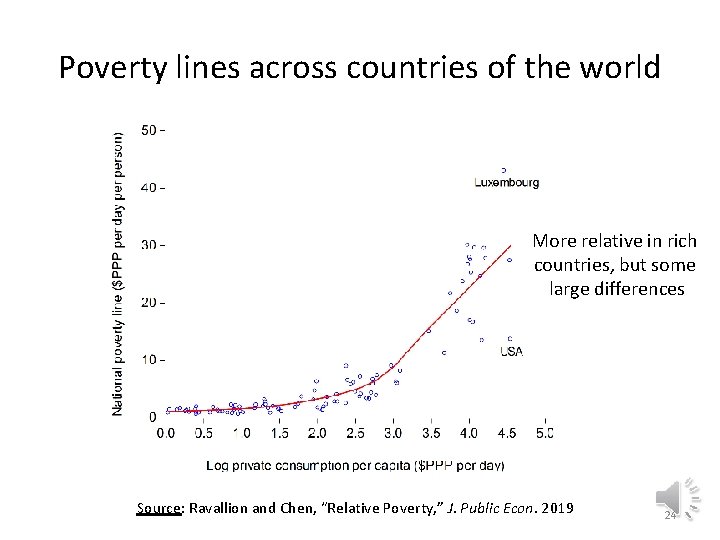

Relative poverty • Prior to the Second Poverty Enlightenment poverty was mainly seen in absolute terms. This changed radically in much of the rich world from around 1960. • New concept of “relative poverty”: the definition of poverty was contingent on the average standard of living in the society one was talking about, and so evolved with the average. • Victor Fuchs (1967) appears to have been the first to propose the sharpest version of this idea; Fuchs proposed that the poverty line should simply be set at 50% of the current median income. • Poverty lines “look relative” across countries => • Part 2 will return to this idea. 23

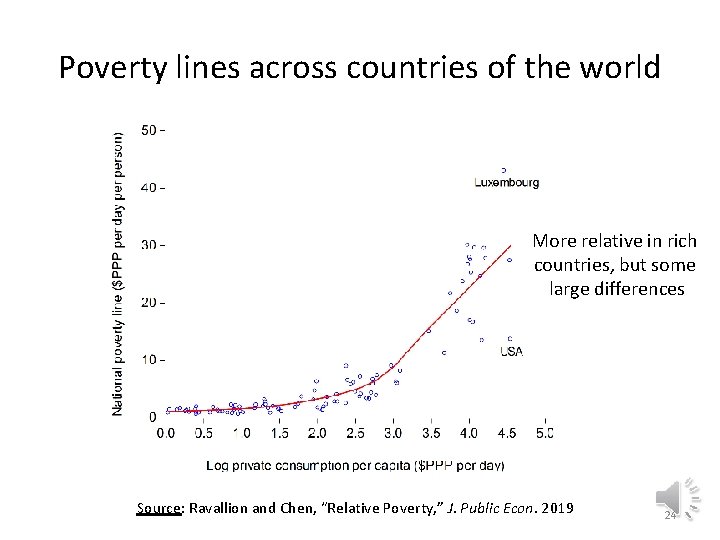

Poverty lines across countries of the world More relative in rich countries, but some large differences Source: Ravallion and Chen, “Relative Poverty, ” J. Public Econ. 2019 24

New knowledge about poor people • Vital registration systems (mid-C 19 th). • Early efforts in India; National Sample Surveys from 1960 s. • The UN National Household Capability Programme helped put household surveys on a sounder and more consistent basis. • World Bank began its efforts to collect high-quality household and community data on a wide range of welfare indicators and their correlates, esp. , the Living Standards Measurement Study. • Just as the poverty studies by Booth and Rowntree were influential in 1890 s England, in 1990 many were shocked to learn that there were about one billion people in the world living on less than $1 per day, at purchasing power parity. • Such data have been the empirical foundation of domestic and international efforts to fight poverty since the 1980 s. 25

New analytic tools • A succession of experiments with the prediction of policy impacts on the poor using Social Accounting Matrices and Computable General Equilibrium models offered promise, particularly in LDCs with relatively advanced basic data. • New partial equilibrium tools esp. , simulations methods, spending incidence studies. • Linking types of data: household surveys and public finance data; macro and micro; geographic data. • Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) enter social policy evaluation from 1960 s (1980 s in development contexts). 26

Backlash: Critics of the new focus on poverty • Robert Nozick put property rights above all else, and argued against Rawls’ idea of distributive justice. But it was unclear why property rights were never to be questioned. • Claims on incentives again: Charles Murray’s (1984) Losing Ground. But weak evidence. Even wrong (Ellwood-Summers) • Welfare reforms in the 1990 s: 30 years after declaring a “War on Poverty, ” America declared a “War on Welfare. ” • Continuing debates today about poverty—its causes and the appropriate policy responses, throughout the world. 27

Thinking about poverty and policy in poor countries post-independence 28

The West’s post-WW 2 discovery of poverty in the “Third World” • Many countries gained independence from Colonial rule in the aftermath of WW 2. • Increasing global awareness of the existence of severe and widespread poverty in the “third world. ” • Debates (popular and scholarly) on how much responsibility people in rich countries have for the global poor. 29

Planning for development as the post. Independence model • The new developing countries were more guided by the state – In marked contrast to the more laissez faire economics of the C 19 th, when today’s rich world was developing more rapidly in the latter half of C 20 th. – This reflected the timing of the “late developers” (C 20 th thinking vs C 18 th and C 19 th) + rejection of the Colonial model of minimal intervention in business. • “Development planning” became the rule. The state was to guide development. 30

Economic planning for poverty reduction • As Nehru (1946) emphasized, India’s National Planning put higher priority on the reduction of poverty and unemployment than on economic growth per se. • The problem was not lack of concern for the poor, but rather the specific policies pursued. • After Independence, India’s First Five‑Year Plan explicitly rejected growth maximization, in favor of anti‑poverty planning. • So did some other plans of the time, notably Sri Lanka's Ten Year Plan. The indigenous traditions documented by Iliffe (1987) demonstrate similar concerns about poverty in Africa. 31

Less emphasis on inequality in the newly independent states • The new countries had a small elite of nationals, now in power. They did not give much attention to vertical redistribution as a strategy. Too few “rich” too many “poor. ” • Emphasis on expanding the fledgling “modern sector” rather than enriching the (poor) traditional sector. • Horizontal redistribution, esp. , by ethnicity/race was another matter. However, this was more often used for political purposes—to secure power for one ruling ethnicity for example. • In some cases, the neglect of inequality in the immediate post -Independence period was to come at a high price, e. g. , Malaysia => 32

The example of Malaysia • At time of Independence in 1957: Large differences in living standards between Malays and Chinese. (Indians between the two. ) • Colonial government had created at least some of this ethnic inequality. • Post-Independence government was a pro-British alliance (literally “Alliance Party”) of elites across ethnic groups. • Little or no attention to inequality for 10+ years. • Ethnic riots broke out in 1969. 600+ dead in a day or two. • Within one year, new policy of radical redistribution favoring the Malays. 33

The emergence of development economics as a field Kuznets Lewis • National accounting methods expand to near global coverage, though with lots of guesswork! • New models of the development process (Lewis, Kuznets). – Emphasis on the economic dualism of developing countries, with a modern urban enclave developing within a poor largely agrarian rural economy. – Models became more realistic over time, such as by allowing for unemployment in the emerging modern sector. • Development Economics and Development Studies emerge as new fields. World Development founded in 1973; Journal of Development Economics founded 1974. 34

Enthusiasm for fighting poverty postindependence, but limited effectiveness • Poverty was not, of course, news to those thinking about policy in post-independence developing countries. • The rhetoric of the post‑independence intellectual climate was sympathetic to the poor. • But effective action was less evident in the early postindependence decades. 35

Frustrated antipoverty plans • Early plans of growth via accelerated capital accumulation were over-hopeful of the capacity of rapid industrialization to raise the demand for labor, and so enrich the poor. • Anti-trade biases: yet the poor tend to earn livings converting non‑tradable inputs, especially labor, into tradables. • Also, the accelerated industrialization was financed by extracting a surplus from agriculture => tax on the poor. • Early ambitious antipoverty plans were soon shelved. 36

East Asian success using promotional antipoverty policies • Taiwan, South Korea and (later) China put greater emphasis on promotion; indeed, arguably protection was under-valued. • They too had directive planning processes, "distorting" prices and foreign trade; extractive from agriculture. • The key difference was that in these countries we saw: – – – Radical redistributive land reforms Public support to human capital formation incl. , poor people Public investment in agriculture (irrigation and crop research) Generally sensible poor-area development plans Support for rural non‑farm enterprises Crucially: capable states. 37

Rebalancing 38

Re-balancing 1: Rural development • Lesson from the history of the rich world: Revolution in agriculture precedes the industrial revolution • Robert Mc. Namara’s (1973) "Nairobi speech: “ – Signaled a shift away from the heavy (and largely urban) infrastructural lending of the 1960 s, – toward rural development designed to benefit the "poorest 40 per cent“ – seen then as mostly "small farmers" rather than as landless laborers. 39

Urban bias • "Urban bias" was increasingly recognized as bad for growth as well as for poverty reduction, though rooted in political structures in much of the developing world. • Hope for smallholder rural development: – “Green revolution" was seen, from the late 1960 s, as potentially able to enrich even very "small" farmers. – Increasing evidence that farm size was inversely related to both employment and annual output per hectare. 40

Re-balancing 2: Informal sector • Early 1970 s+: greater attention on the informal sector in which people are largely beyond the reach of government for the purposes of taxation or regulation: both urban informal activities and traditional agriculture. • High rates of unemployment in urban areas, with many waiting formal-sector jobs. • Challenges for policy: – expand the formal sector; – reduce labor-market rigidities; – focus on the needs of those in the informal sector (credit to informal enterprises or enhancing farm productivity). 41

Re-balancing 3: Gender • Greater attention to gender issues and not just as something relevant to GDP growth. • The gender dimensions of poverty were becoming more prominent in development policy debates from the 1970 s. • UN’s series of World Conferences on Women, starting in Mexico City (1975), Beijing (1995). • Gender equity mainstream debates/writings on development. – – – Schooling and health care disparities Institutions (esp. legal) Intra-household inequalities Vulnerability of specific groups (widows) Abortion debates (global gag rule) 42

Re-balancing 4: Human development • The "basic needs" (BN) approach stressed ". . . human needs in terms of health, food, education, water, shelter, transport" (Streeten et al. 1981). • Amartya Sen criticized Rawls for underplaying heterogeneity of people in terms of their income needs. Argued instead for viewing human capabilities as the “primary goods. ” • Some exaggerated efforts at product differentiation (esp. , international agencies) but a lasting recognition that: – Higher real income need not mean better health, education, drinking water, sanitation, police protection, etc. – Households vary greatly in their capacity to convert commodities into well‑being. 43

Basic needs • The "basic needs" (BN) approach instead stresses ". . . human needs in terms of health, food, education, water, shelter, transport" (Streeten et al. 1981: 7). • Two main arguments were advanced for tracking poverty reduction by observing BN, rather than incomes. – First, increases in real income may be unable to command better health care, education, safe drinking water, sanitation, police protection, etc. These required collective action. – Second, households vary greatly in their capacity to convert commodities into well‑being. For example, there is notable "positive deviance" in the capacity of some poor households to convert income into adequate nutrition. 44

Adjustment with a human face • Structural adjustment programs in the early-mid 1980 s rarely mentioned the impacts on poor people, and were much criticized. • In the early 1980 s, it was almost impossible to persuade donors to design adjustment assistance with a view to improving its impact on the poor. • By the late‑ 1980 s, add‑on programs to "compensate the losers from adjustment" were common, though often focusing on the articulate and somewhat poor, rather than the inarticulate and very poor. • Today it is widely recognized that poverty mitigation has to be designed into economy-wide reform programs initially—not added as a tranquillizer later on. 45

New international commitment • After a lapse for IFIs in 1980 s, in the 1990 s it became widely recognized that poverty mitigation had to be designed into reform programs initially—not added as a tranquillizer later on. “Adjustment with a human face. ” • Early 1990 s: “world free of poverty” became the World Bank’s overarching goal. International line: $1. 25 a day (2005 prices) • The UNDP’s Human Development Reports argued for public action to promote basic health and education. • The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were ratified in 2000 at the UN Millennium Assembly. The first MDG was to halve the 1990 “$1. 25 a day” poverty rate by 2015. Other MDGS of health, schooling, . . • Current debate on next goals: we can lift 1 billion people out of extreme poverty by 2030! 46

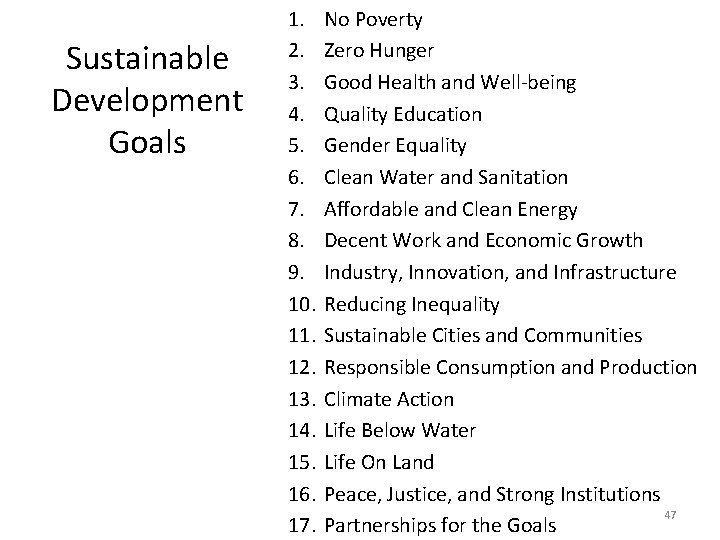

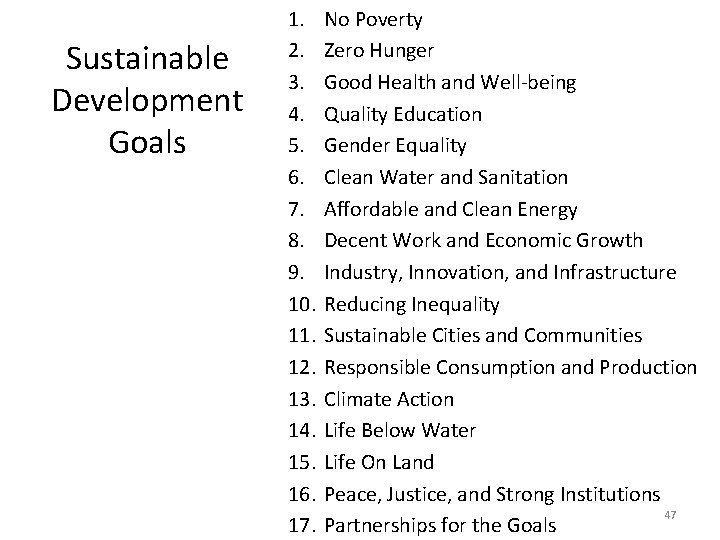

Sustainable Development Goals 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. No Poverty Zero Hunger Good Health and Well-being Quality Education Gender Equality Clean Water and Sanitation Affordable and Clean Energy Decent Work and Economic Growth Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure Reducing Inequality Sustainable Cities and Communities Responsible Consumption and Production Climate Action Life Below Water Life On Land Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions 47 Partnerships for the Goals

The final blow to the idea of the utility of poverty? 48

From the “utility of poverty” to the “inefficiency of poverty” • It has long been understood that the rich have a higher savings rate than the poor. • It was inferred that inequality was good for growth (by generating higher savings) though, by the same token, a higher poverty rate was bad for growth at given mean. • John Maynard Keynes (1936, Ch. 24) questioned the existence of a significant growth-equity tradeoff. (EOP, Box 1. 22) – Lack of consumption prevented full-employment, and so a higher share of national income in the command of poor people (who had a higher propensity to consumer) would promote growth, until full-employment was reached. 49

Costs of inequality even in a fully employed economy • In the latter part of the C 20 th, a new set of ideas emerged that seriously questioned the instrumental case for poverty and inequality. – Borrowing constraints associated with asymmetric information and the inability to write binding enforceable contracts. – Political economy: (i) distortions introduced to address inequality; (ii) inequality/polarization makes it harder to agree on reforms; lobbying by the rich. => High current inequality of wealth reduces an economy’s aggregate efficiency and (hence) growth rate. 50

Poverty comes to be seen as bad for growth, not good for it! • New evidence of an adverse effect on growth of high initial poverty at a given mean (*). – Consistent with models of economic growth incorporating low savings by poor people and/or borrowing constraints. – Also consistent with childhood nutrition => productivity. • Inequality matters, but mainly via poverty. • HD and distortions also matter. • And a high initial incidence of poverty => lower subsequent rate of progress against poverty at given growth rate. • We return to these issues in Chapter 7, Part 3, EOP. 51

Conclusion to Part 1 We have seen that the respect for poor people that emerged in the First Poverty Enlightenment took the form in the Second Poverty Enlightenment of a philosophical and economic case for anti-poverty policy. 52

Continuing debates, but a radical switch in models over 200 years • Model 1: “poor people do not have the potential to be anything else. ” Poverty is blamed on the “bad behaviors” of the poor. Little or no scope seen for policy beyond limited targeted protection from extreme transient poverty. “Poverty is necessary and is to be accepted. “ • Model 2: “poverty is due to market and governmental failures. ” Promotional policies are perfectly consistent with a robust growing economy, and even an important source of growth. • Recognizing the transition in thinking makes one more optimistic that progressive change is possible, and that the idea of eliminating poverty can be more than a dream. 53

Enormous progress against extreme poverty • The first MDG was attained in 2010, a full five years ahead of the goal. • Continuing this success could well lift one billion people out of extreme poverty by 2030, bringing the extreme poverty rate down to 3%. • Tempering this new hope is the specter of rising inequality, which is now seen as a threat to both sustained growth and poverty reduction. Huge challenge for policy making in many countries. • The rest of this course will look more closely at both the economic arguments for this change and the debates about policy responses. 54

Why did we see this change in thinking? The “protection only” equilibrium • When the incidence of poverty is persistently very high, knowledge is poor, and administrative capabilities are weak, the cost to the non-poor of getting people out of a low-level trap may be seen to be prohibitively high. – If pressed, even de Mandeville could well have imagined the possibility of a big push lifting the entire distribution, but this was a fantasy. – Far more modest reforms were all that could be seriously contemplated. – Similarly, very poor countries have low capacity for redistribution, given the extent of poverty and implied tax burdens. • The political-economy may then lead to a situation in which protection is the sole focus. 55

The promotion + protection equilibrium • By contrast, at sufficiently low levels of poverty and with better knowledge, and more capable states, the political economy can switch in favor of a promotion strategy (esp. , human capital investments by poor families). • Thus accelerating toward the eventual elimination of poverty. • More than anytime before, we really can talk seriously about largely eliminating extreme poverty within a generation. 56

But the transition between these two equilibria is not easy • Catch 22: High poverty also impedes overall growth prospects, limiting the available resources for funding social programs. • May also make it harder to implement pro-poor reforms even in a democracy. • Synergistic interaction of improved knowledge + technical progress + political voice + capable states was crucial to the transition in antipoverty policy. • And they will remain crucial to eliminating poverty. Next: How do we measure poverty and inequality? 57

Distinguish between absolute poverty and relative poverty

Distinguish between absolute poverty and relative poverty Inequality and poverty

Inequality and poverty Georgetown university communication culture and technology

Georgetown university communication culture and technology Cct georgetown

Cct georgetown Cct georgetown

Cct georgetown Georgetown university mission statement

Georgetown university mission statement Lesson 1-6 solving compound and absolute value inequalities

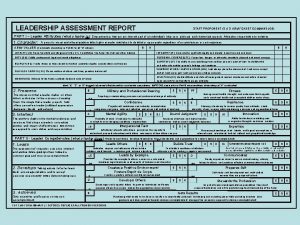

Lesson 1-6 solving compound and absolute value inequalities Cdt cmd form 156-4

Cdt cmd form 156-4 Factors of 156

Factors of 156 Usacc form 156-4

Usacc form 156-4 Artigo 156 cc

Artigo 156 cc 98 156 chia 4 63

98 156 chia 4 63 Scoala 156

Scoala 156 500 hangi yüzlüğe yuvarlanır

500 hangi yüzlüğe yuvarlanır How to find partial pressure

How to find partial pressure 156+232

156+232 Luas alas 196 cm

Luas alas 196 cm Art 156 ctn

Art 156 ctn Ley 24 156

Ley 24 156 Database collection

Database collection 29cfr1910.156

29cfr1910.156 Anne rosenwald georgetown

Anne rosenwald georgetown Addison woods georgetown

Addison woods georgetown Martin ravallion georgetown

Martin ravallion georgetown Nathan edwards georgetown

Nathan edwards georgetown Georgetown school of continuing studies reputation

Georgetown school of continuing studies reputation Georgetown biology department

Georgetown biology department Oded meyer georgetown

Oded meyer georgetown Grace yang georgetown

Grace yang georgetown Artemis kirk

Artemis kirk Georgetown mantra 4 principles

Georgetown mantra 4 principles Relative and absolute poverty

Relative and absolute poverty Poverty and juvenile delinquency

Poverty and juvenile delinquency Esperanza’s house symbolizes poverty and

Esperanza’s house symbolizes poverty and St john chrysostom on wealth and poverty pdf

St john chrysostom on wealth and poverty pdf Poverty and hunger solutions

Poverty and hunger solutions Symbolic interactionism and poverty

Symbolic interactionism and poverty Ministry of housing and urban poverty alleviation

Ministry of housing and urban poverty alleviation Greed and poverty

Greed and poverty Government expenditure multiplier formula

Government expenditure multiplier formula Ib economics fiscal policy

Ib economics fiscal policy Flipit econ

Flipit econ Econ 151

Econ 151 Mid point formula econ

Mid point formula econ Mpc in economics formula

Mpc in economics formula Marginal analysis in economics

Marginal analysis in economics Sports econ austria

Sports econ austria Econ 1410

Econ 1410 Econ 424

Econ 424 Mr darp econ

Mr darp econ What is game theory

What is game theory Positive analysis:

Positive analysis: Econ 134

Econ 134 Econ

Econ Econ chapter 7

Econ chapter 7 Econ muni harmonogram

Econ muni harmonogram Gertler econ

Gertler econ Money growth formula

Money growth formula