Multidimensional Poverty Measurement Martin Ravallion Georgetown University 1

- Slides: 16

Multidimensional Poverty Measurement Martin Ravallion Georgetown University 1

Human welfare must be the anchor for poverty measurement • Our concept of “poverty” must be welfare-consistent, meaning that two people judged to be equally well off are treated the same way (both are either “poor” or “not poor”). • “Welfare” depends on consumption of market goods, but also non-market goods (access to public health and education services). And intrahousehold inequalities are hidden from standard data sources. • Africa: The bulk of the undernourished women and children are not found in households identified as “poor” by standard measures.

Standard poverty measures • The theoretical ideal: poverty line is an equivalent income, reflecting non-income dimensions of welfare in the specific context. • In practice, poverty lines have not accommodated important nonincome dimensions of welfare, although this is changing.

Dashboard versus composite indices 1. The dashboard approach: multiple indices covering income poverty + child mortality + schooling rates +…… Example: The MDGs and SDGs are a dashboard. 2. The composite index approach, with weights set by the producer of the index. Example 1: The Human Development Index (HDI) Example 2: The Multidimensional Index of Poverty (MIP) 4

1: Human Development Index (HDI) • Composite index of mean income (GDP per capita), life expectancy and schooling. • The three core dimensions of the HDI are then put on a common (0, 1) scale. • The HDI is then obtained by taking the equally-weighted geometric mean of these re-scaled variables. 5

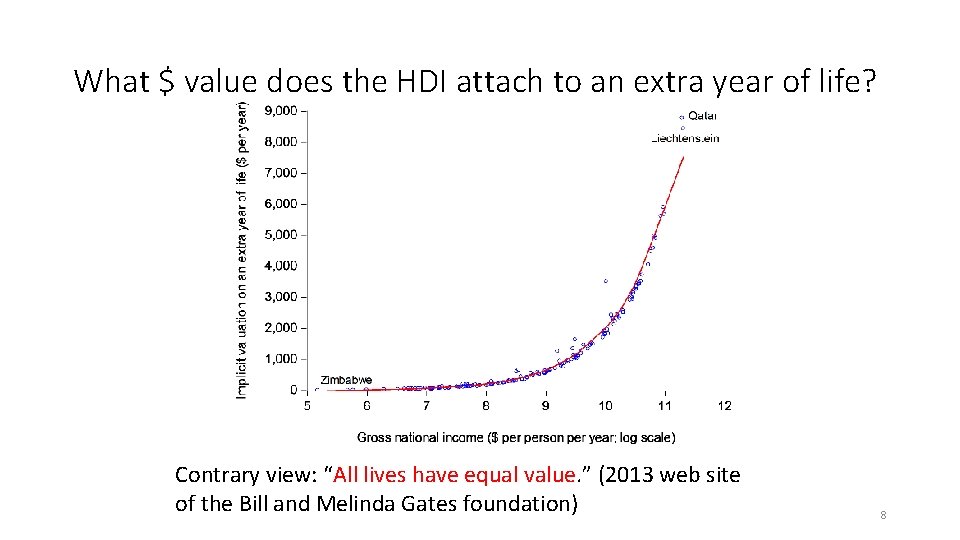

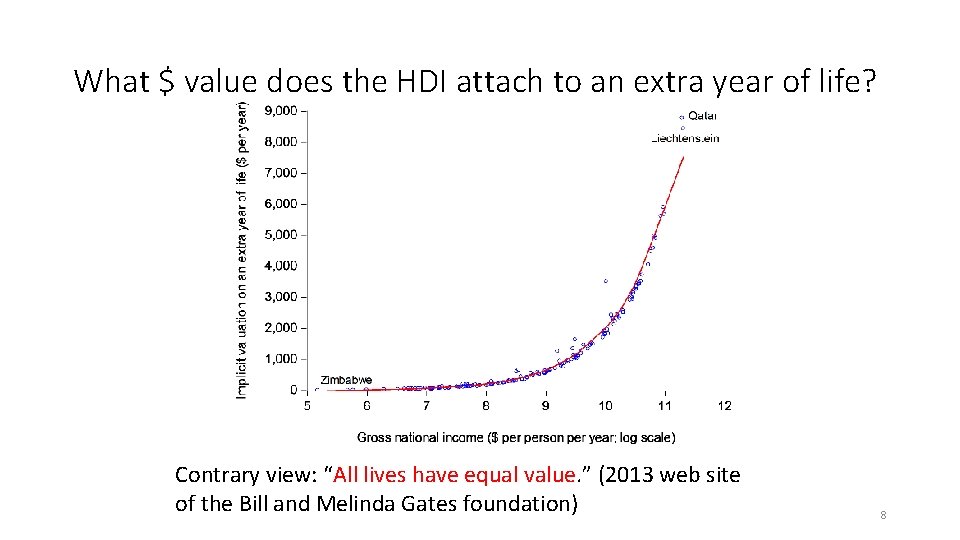

Concerns about the trade-offs implicit in the HDI • When we make a weighted index of “income” with (say) life expectancy we are implicitly giving a monetary value to an extra year of life. • The implied value of extra life varies from very low levels in poor countries— the lowest value of $0. 51 per year is for Zimbabwe to almost $9, 000 per year in the richest countries.

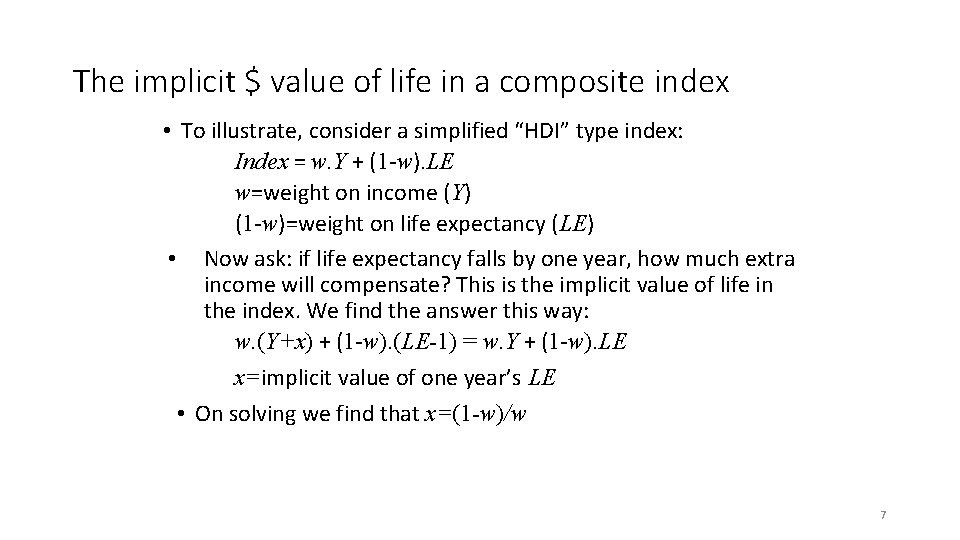

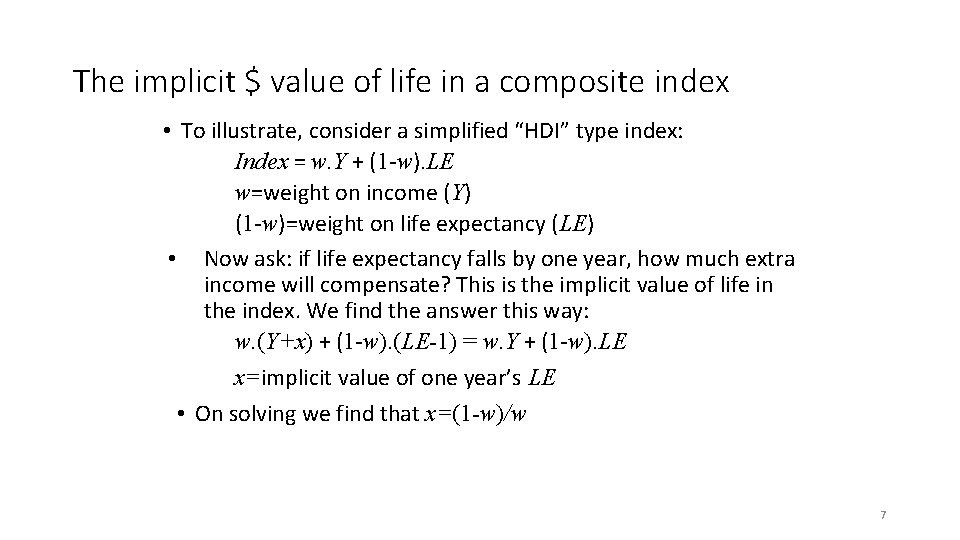

The implicit $ value of life in a composite index • To illustrate, consider a simplified “HDI” type index: Index = w. Y + (1 -w). LE w=weight on income (Y) (1 -w)=weight on life expectancy (LE) • Now ask: if life expectancy falls by one year, how much extra income will compensate? This is the implicit value of life in the index. We find the answer this way: w. (Y+x) + (1 -w). (LE-1) = w. Y + (1 -w). LE x=implicit value of one year’s LE • On solving we find that x=(1 -w)/w 7

What $ value does the HDI attach to an extra year of life? Contrary view: “All lives have equal value. ” (2013 web site of the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation) 8

2: The Multidimensional Index of Poverty (MIP) • Two variables for health (malnutrition, and child mortality), • Two for education (years of schooling and school enrolment), • Six for living standards (namely cooking with wood, charcoal or dung; not having a conventional toilet; lack of easy access to safe drinking water; no electricity; dirt, sand or dung flooring and not owning at least one of a radio, TV, telephone, bike or car). • Poverty is measured separately in each of these 10 dimensions. • The equally-weighted aggregate poverty measures for each of these three main headings are then weighted equally (one-third each) to form the composite index. • A household is identified as being poor if it is deprived across at least 30% of the weighted indicators. 9

The data constraint on the MIP • A MIP requires that we have a survey that covers all the dimensions for each sampled household. • This constrains what dimensions are identified and confines the MIP to a rather narrow set of surveys. • The dashboard approach looks instead for the best survey data source for each dimension, and is not constrained in its choice of dimensions by the need for a single survey.

Aggregation over dimensions: What role for prices? • Using the prices faced by people living at the poverty line guarantees that the poverty bundle accords with choices of people living at the poverty line. • Some advocates of MIPs argue that prices do not exist or are unreliable for valuation. • However, while we can agree that markets and prices are not perfect, prices are still important data for welfare-consistent aggregation. • Aggregation without prices cannot in general yield poverty measures that are consistent with the welfare of someone living at the poverty line. 11

Using subjective welfare data when prices are missing • Economists have long resisted asking people themselves about their welfare. • This is changing: Increasing interest in using subjective welfare data to help calibrate composite indices. • This is a promising direction, but it brings its own (new) problems: • Heterogeneity in the scales used; what it means be “happy” varies systematically. • Personality traits mater.

The danger of multidimensional policy evaluation • While we need to acknowledge that poverty is not just about low income, there is also a risk in setting a large number of goals for poverty and human development policy. • If every policy must attain every goal we may end up judging all policies as failures. • Yet some policies are better for some goals.

Is a single composite index credible for policy making? • For most purposes of poverty measurement we do not want to form a single composite index. • The actionable things are not typically found in the composite index but in its components. • Some of the indices found in practice (such as MIP) can be readily un-packed • But it remains unclear what policy purpose was served by adding them up in the first place.

Conclusions • We will need multiple indices to comprehensively monitor poverty and inform policy making. • Important dimensions of welfare do sometimes get ignored! The dashboard is crucial. • Composite indices guarantee that important stuff is not ignored. But there is also the risk of hiding poor performance in key dimensions and a risk of misguiding policy makers and the public. • If we think something important is missing from standard measures we should flag that fact directly. • We need to focus our efforts on developing the best possible distinct measures of the various dimensions of poverty deemed relevant to a given setting.

Further reading: Martin Ravallion, The Economics of Poverty: History, Measurement and Policy, Oxford University Press, 2016 economicsandpoverty. com Thank you for your attention!

Martin ravallion georgetown

Martin ravallion georgetown Types of poverty

Types of poverty Georgetown university mission statement

Georgetown university mission statement Georgetown university communication culture and technology

Georgetown university communication culture and technology Georgetown university communication culture and technology

Georgetown university communication culture and technology Cct georgetown

Cct georgetown Anne rosenwald

Anne rosenwald Addison woods georgetown

Addison woods georgetown Nathan edwards georgetown

Nathan edwards georgetown Georgetown school of continuing studies reputation

Georgetown school of continuing studies reputation Georgetown biology department

Georgetown biology department Oded meyer georgetown

Oded meyer georgetown Grace yang georgetown

Grace yang georgetown Digital georgetown

Digital georgetown Georgetown mantra 4 principles

Georgetown mantra 4 principles Turing macine

Turing macine Multidimensional expressions

Multidimensional expressions