Course Natural History and Prognosis Major Depressive Disorder

- Slides: 43

Course, Natural History and Prognosis Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

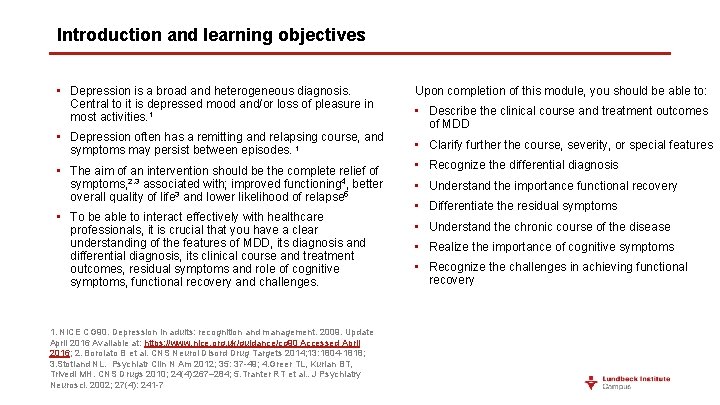

Introduction and learning objectives • Depression is a broad and heterogeneous diagnosis. Central to it is depressed mood and/or loss of pleasure in most activities. 1 • Depression often has a remitting and relapsing course, and symptoms may persist between episodes. 1 • The aim of an intervention should be the complete relief of symptoms, 2, 3 associated with; improved functioning 4, better overall quality of life 3 and lower likelihood of relapse 5 • To be able to interact effectively with healthcare professionals, it is crucial that you have a clear understanding of the features of MDD, its diagnosis and differential diagnosis, its clinical course and treatment outcomes, residual symptoms and role of cognitive symptoms, functional recovery and challenges. 1. NICE CG 90. Depression in adults: recognition and management. 2009. Update April 2016 Available at: https: //www. nice. org. uk/guidance/cg 90 Accessed April 2016; 2. Borolato B et al. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2014; 13: 1804 -1818; 3. Stotland NL. Psychiatr Clin N Am 2012; 35: 37 -49; 4. Greer TL, Kurian BT, Trivedi MH. CNS Drugs 2010; 24(4): 267– 284; 5. Tranter RT et al. . J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2002; 27(4): 241 -7 Upon completion of this module, you should be able to: • Describe the clinical course and treatment outcomes of MDD • Clarify further the course, severity, or special features • Recognize the differential diagnosis • Understand the importance functional recovery • Differentiate the residual symptoms • Understand the chronic course of the disease • Realize the importance of cognitive symptoms • Recognize the challenges in achieving functional recovery

Depression • Depression is a broad and heterogeneous diagnosis. 1, 2, 3, 4 • Commonly used diagnostic manuals include the World Health Organization’s ICD-10 classification system 2 or the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-IV 3 and DSM-5 system 4. • To diagnose depression symptoms should be present for at least 2 weeks and each symptom should be present at sufficient severity for most of every day. 1, 2, 3, 4 • Severity of the disorder is determined by both the number and severity of symptoms, as well as the degree of functional impairment. 1, 2, 3, 4 • Depression often has a remitting and relapsing course, and symptoms may persist between posepisodes. 1, 2, 3, 4 • Where sible, the key goal of an intervention should be complete relief of symptoms (remission), which is associated with better functioning and a lower likelihood of relapse. 1, 2, 3, 4 (1) NICE CG 90. Depression in adults: recognition and management. 2009. Update April 2016 Available at: https: //www. nice. org. uk/guidance/cg 90 Accessed April 2016 (2) WHO. ICD-10 Classification. 1993. Available from: http: //www. who. int/classifications/icd/en/GRNBOOK. pdf. Accessed April 2016. (3). American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. 4 th edition: American Psychiatric Association. 1994: 866; (4) American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5 th edition: American Psychiatric Association. 2013

Depression 1 • Major depressive disorder is characterized by discrete episodes of at least 2 weeks’ duration (although most episodes last considerably longer) involving clear-cut changes in affect, cognition, and neurovegetative functions and inter-episode remissions. 1 • The common feature of all of these disorders is the presence of sad, empty, or irritable mood, accompanied by somatic and cognitive changes that significantly affect the individual’s capacity to function. 1 • A diagnosis based on a single episode is possible, although the disorder is a recurrent one in the majority of cases. 1 • Careful consideration is given to the delineation of normal sadness and grief from a major depressive episode. 1 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5 th edition: American Psychiatric Association. 2013

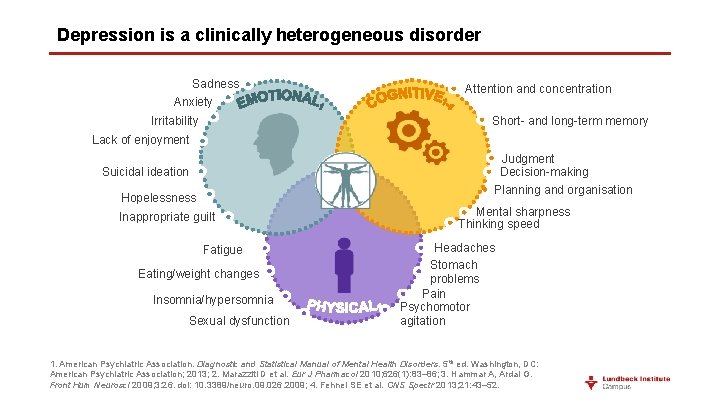

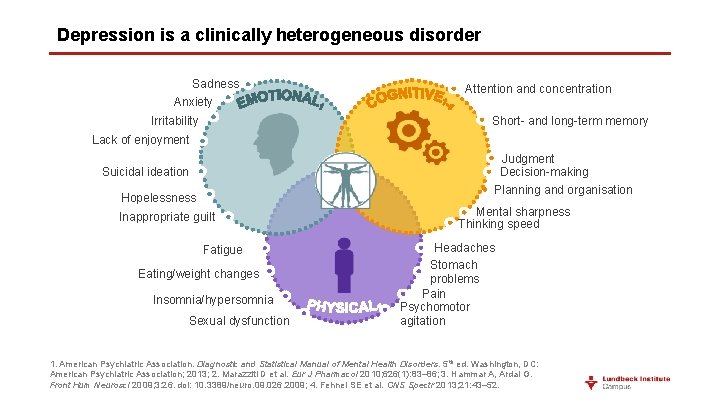

Depression is a clinically heterogeneous disorder Sadness Anxiety Attention and concentration Short- and long-term memory Irritability Lack of enjoyment Judgment Decision-making Suicidal ideation Planning and organisation Hopelessness Inappropriate guilt Fatigue Eating/weight changes Insomnia/hypersomnia Sexual dysfunction Mental sharpness Thinking speed Headaches Stomach problems Pain Psychomotor agitation 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders. 5 th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013; 2. Marazziti D et al. Eur J Pharmacol 2010; 626(1): 83– 86; 3. Hammar A, Ardal G. Front Hum Neurosci 2009; 3: 26. doi: 10. 3389/neuro. 09. 026. 2009; 4. Fehnel SE et al. CNS Spectr 2013; 21: 43– 52.

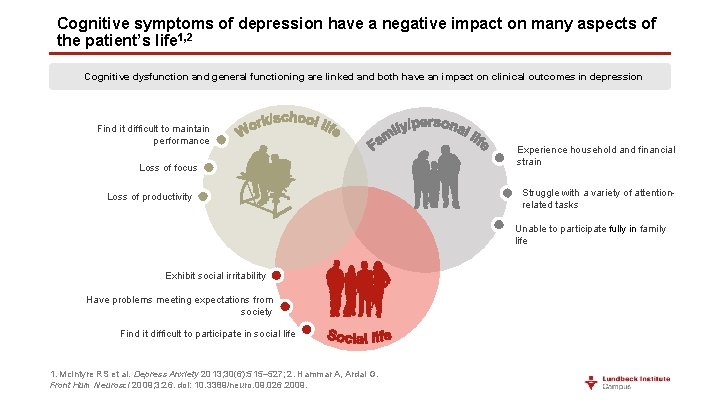

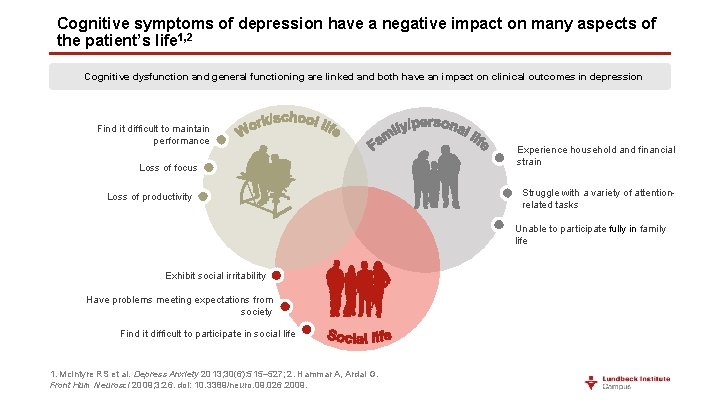

Cognitive symptoms of depression have a negative impact on many aspects of the patient’s life 1, 2 Cognitive dysfunction and general functioning are linked and both have an impact on clinical outcomes in depression Find it difficult to maintain performance Loss of focus Loss of productivity Experience household and financial strain Struggle with a variety of attentionrelated tasks Unable to participate fully in family life Exhibit social irritability Have problems meeting expectations from society Find it difficult to participate in social life 1. Mc. Intyre RS et al. Depress Anxiety 2013; 30(6): 515– 527; 2. Hammar A, Ardal G. Front Hum Neurosci 2009; 3: 26. doi: 10. 3389/neuro. 09. 026. 2009.

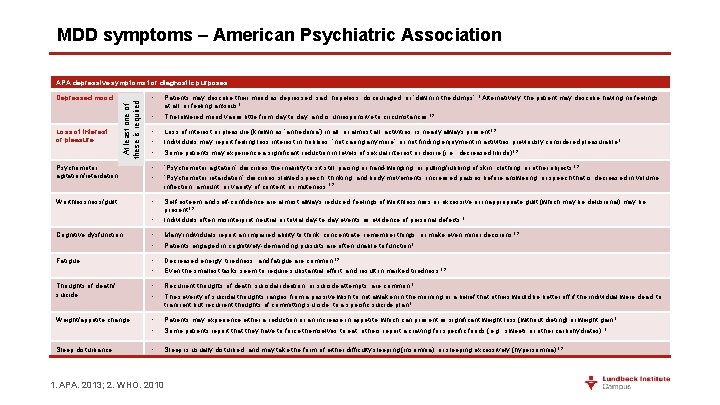

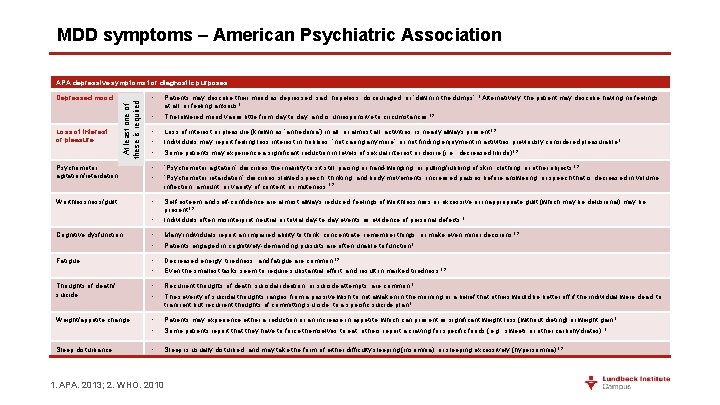

MDD symptoms – American Psychiatric Association APA depressive symptoms for diagnostic purposes • • Patients may describe their mood as depressed, sad, hopeless, discouraged, or ‘down in the dumps’. 1 Alternatively, the patient may describe having no feelings at all, or feeling anxious 1 The lowered mood varies little from day to day, and is unresponsive to circumstances 1, 2 • • • Loss of interest or pleasure (known as ‘anhedonia’) in all, or almost all, activities, is nearly always present 1, 2 Individuals may report feeling less interest in hobbies, ‘not caring anymore’, or not finding enjoyment in activities previously considered pleasurable 1 Some patients may experience a significant reduction in levels of sexual interest or desire (i. e. , decreased libido) 1, 2 Psychomotor agitation/retardation • • ‘Psychomotor agitation’ describes the inability to sit still; pacing or hand-wringing; or pulling/rubbing of skin, clothing, or other objects 1, 2 ‘Psychomotor retardation’ describes slowed speech, thinking, and body movements; increased pauses before answering; or speech that is decreased in volume, inflection, amount, or variety of content, or muteness 1, 2 Worthlessness/guilt • • Self-esteem and self-confidence are almost always reduced; feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional) may be present 1, 2 Individuals often misinterpret neutral or trivial day-to-day events as evidence of personal defects 1 Cognitive dysfunction • • Many individuals report an impaired ability to think, concentrate, remember things, or make even minor decisions 1, 2 Patients engaged in cognitively-demanding pursuits are often unable to function 1 Fatigue • • Decreased energy, tiredness, and fatigue are common 1, 2 Even the smallest tasks seem to require substantial effort, and result in marked tiredness 1, 2 Thoughts of death/ suicide • • Recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, or suicide attempts, are common 1 The severity of suicidal thoughts ranges from a passive wish to not awaken in the morning or a belief that others would be better off if the individual were dead, to transient but recurrent thoughts of committing suicide, to a specific suicide plan 1 Weight/appetite change • • Patients may experience either a reduction or an increase in appetite, which can present as significant weight loss (without dieting) or weight gain 1 Some patients report that they have to force themselves to eat; others report a craving for specific foods (e. g. , sweets or other carbohydrates) 1 Sleep disturbance • Sleep is usually disturbed, and may take the form of either difficulty sleeping (insomnia), or sleeping excessively (hypersomnia) 1, 2 Loss of interest or pleasure At least one of these is required Depressed mood 1. APA. 2013; 2. WHO. 2010

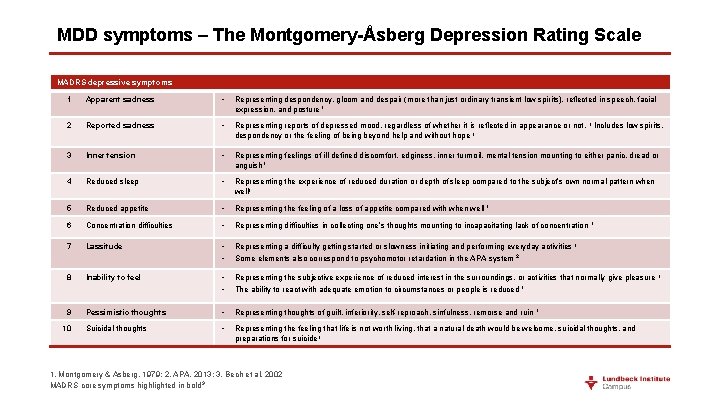

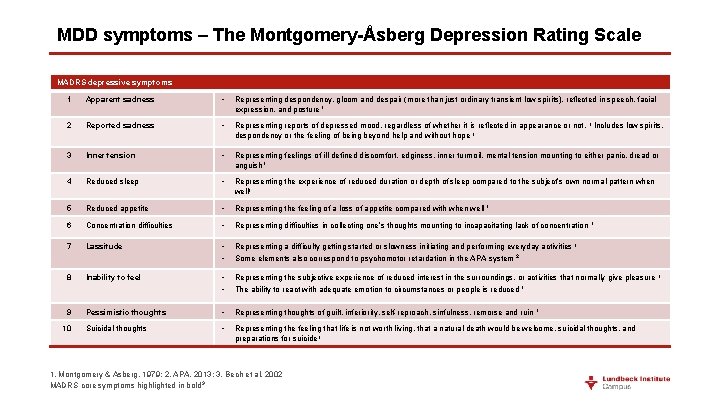

MDD symptoms – The Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale MADRS depressive symptoms 1 Apparent sadness • Representing despondency, gloom and despair (more than just ordinary transient low spirits), reflected in speech, facial expression, and posture 1 2 Reported sadness • Representing reports of depressed mood, regardless of whether it is reflected in appearance or not. 1 Includes low spirits, despondency or the feeling of being beyond help and without hope 1 3 Inner tension • Representing feelings of ill-defined discomfort, edginess, inner turmoil, mental tension mounting to either panic, dread or anguish 1 4 Reduced sleep • Representing the experience of reduced duration or depth of sleep compared to the subject’s own normal pattern when well 1 5 Reduced appetite • Representing the feeling of a loss of appetite compared with when well 1 6 Concentration difficulties • Representing difficulties in collecting one’s thoughts mounting to incapacitating lack of concentration 7 Lassitude • • Representing a difficulty getting started or slowness initiating and performing everyday activities 1 Some elements also correspond to psychomotor retardation in the APA system 2 8 Inability to feel • • Representing the subjective experience of reduced interest in the surroundings, or activities that normally give pleasure The ability to react with adequate emotion to circumstances or people is reduced 1 9 Pessimistic thoughts • Representing thoughts of guilt, inferiority, self-reproach, sinfulness, remorse and ruin 1 Suicidal thoughts • Representing the feeling that life is not worth living, that a natural death would be welcome, suicidal thoughts, and preparations for suicide 1 10 1. Montgomery & Asberg. 1979; 2. APA. 2013; 3. Bech et al. 2002 MADRS core symptoms highlighted in bold 3 1 1

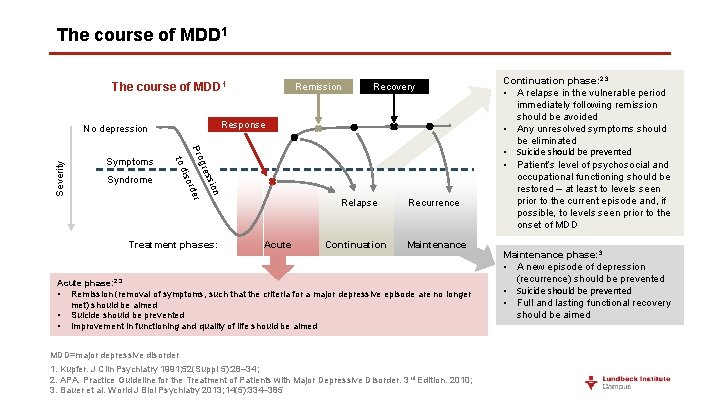

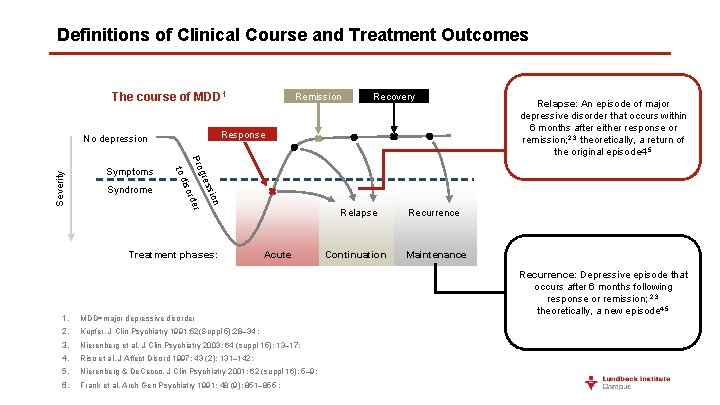

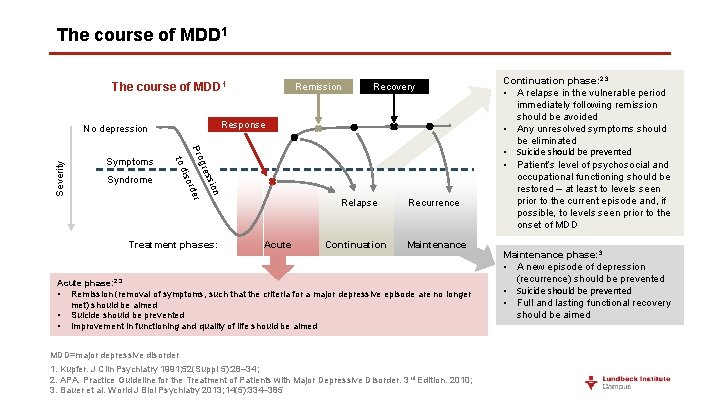

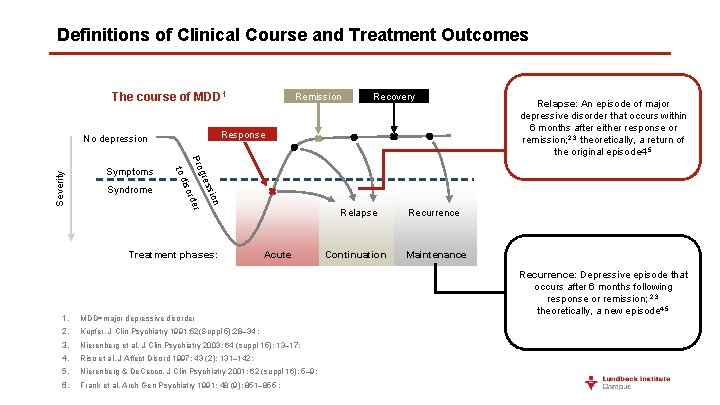

The course of MDD 1 Severity on ssi gre r Pro rde iso to d Syndrome Recovery Response No depression Symptoms Remission Treatment phases: Acute Relapse Recurrence Continuation Maintenance Acute phase: 2, 3 • Remission (removal of symptoms, such that the criteria for a major depressive episode are no longer met) should be aimed • Suicide should be prevented • Improvement in functioning and quality of life should be aimed MDD=major depressive disorder 1. Kupfer. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52(Suppl 5): 28– 34; 2. APA. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. 3 rd Edition. 2010; 3. Bauer et al. World J Biol Psychiatry 2013; 14(5): 334– 385 Continuation phase: 2, 3 • A relapse in the vulnerable period immediately following remission should be avoided • Any unresolved symptoms should be eliminated • Suicide should be prevented • Patient’s level of psychosocial and occupational functioning should be restored – at least to levels seen prior to the current episode and, if possible, to levels seen prior to the onset of MDD Maintenance phase: 3 • A new episode of depression (recurrence) should be prevented • Suicide should be prevented • Full and lasting functional recovery should be aimed

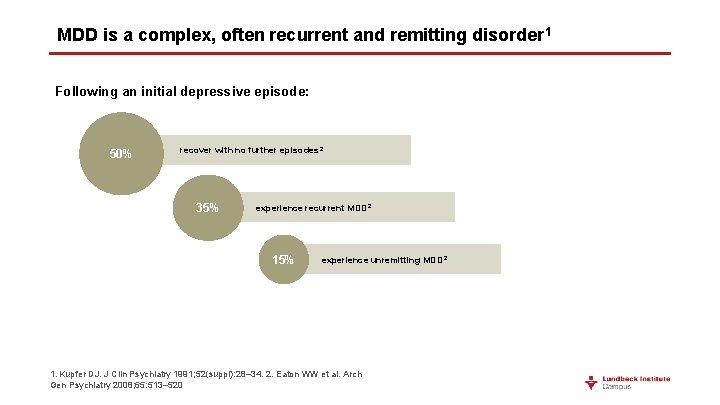

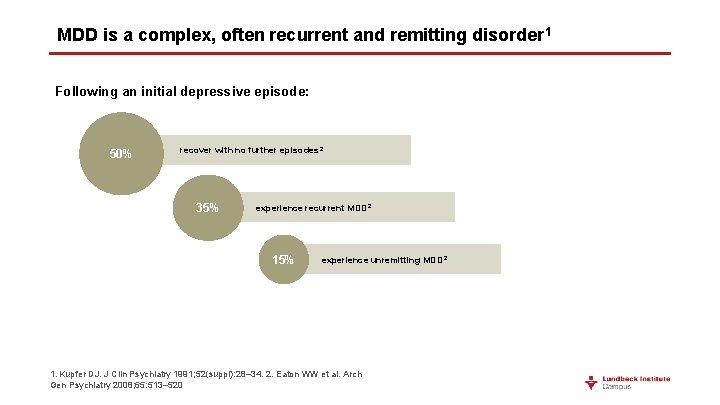

MDD is a complex, often recurrent and remitting disorder 1 Following an initial depressive episode: 50% recover with no further episodes 2 35% experience recurrent MDD 2 15% experience unremitting MDD 2 1. Kupfer DJ. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52(suppl): 28– 34. 2. Eaton WW et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008; 65: 513– 520

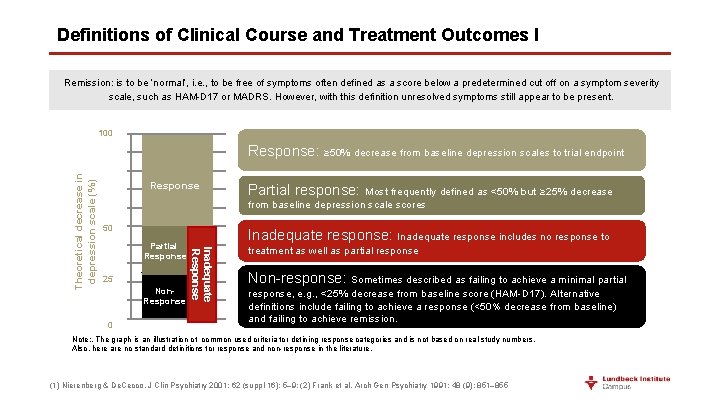

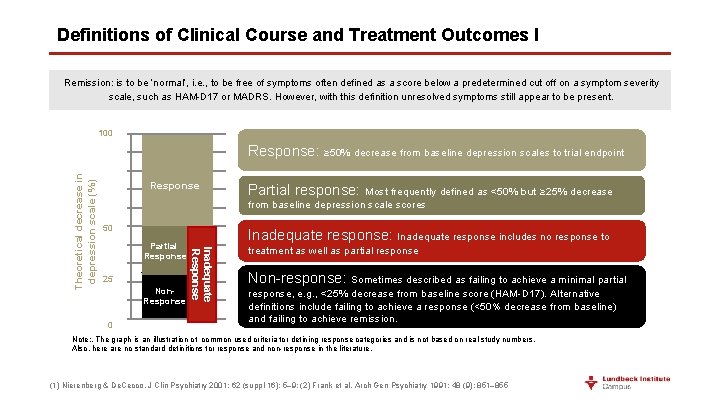

Definitions of Clinical Course and Treatment Outcomes I Remission: is to be ‘normal’, i. e. , to be free of symptoms often defined as a score below a predetermined cut off on a symptom severity scale, such as HAM-D 17 or MADRS. However, with this definition unresolved symptoms still appear to be present. 100% Response: ≥ 50% decrease from baseline depression scales to trial endpoint 80% 70% Response 50% 50 40% 30% 25 20% 10% 0% 0 Partial response: Most frequently defined as <50% but ≥ 25% decrease from baseline depression scale scores 60% Partial Response Non. Response Inadequate response: Inadequate response includes no response to Inadequate Response Theoretical decrease in depression scale (%) 90% treatment as well as partial response Non-response: Sometimes described as failing to achieve a minimal partial response, e. g. , <25% decrease from baseline score (HAM-D 17). Alternative definitions include failing to achieve a response (<50% decrease from baseline) and failing to achieve remission. Note: . The graph is an illustration of common used criteria for defining response categories and is not based on real study numbers. Also, here are no standard definitions for response and non-response in the literature. (1) Nierenberg & De. Cecco. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62 (suppl 16): 5– 9; (2) Frank et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48 (9): 851– 855

Definitions of Clinical Course and Treatment Outcomes The course of MDD 1 Severity on ssi gre r Pro rde iso to d Syndrome Recovery Response No depression Symptoms Remission Treatment phases: Acute 1. MDD=major depressive disorder 2. Kupfer. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52(Suppl 5): 28– 34 ; 3. Nierenberg et al. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64 (suppl 15): 13– 17; 4. Riso et al. J Affect Disord 1997; 43 (2): 131– 142; 5. Nierenberg & De. Cecco. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62 (suppl 16): 5– 9; 6. Frank et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48 (9): 851– 855 ; Relapse Recurrence Continuation Maintenance Relapse: An episode of major depressive disorder that occurs within 6 months after either response or remission; 2, 3 theoretically, a return of the original episode 4, 5 Recurrence: Depressive episode that occurs after 6 months following response or remission; 2, 3 theoretically, a new episode 4, 5

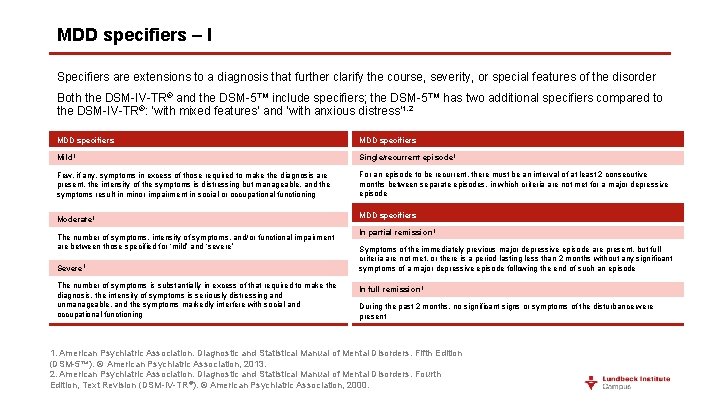

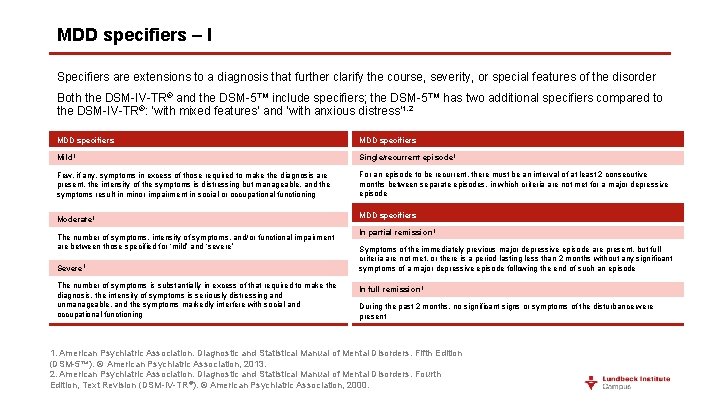

MDD specifiers – I Specifiers are extensions to a diagnosis that further clarify the course, severity, or special features of the disorder Both the DSM-IV-TR® and the DSM-5™ include specifiers; the DSM-5™ has two additional specifiers compared to the DSM-IV-TR®: ‘with mixed features’ and ‘with anxious distress’ 1, 2 MDD specifiers Mild 1 Single/recurrent episode 1 Few, if any, symptoms in excess of those required to make the diagnosis are present, the intensity of the symptoms is distressing but manageable, and the symptoms result in minor impairment in social or occupational functioning For an episode to be recurrent, there must be an interval of at least 2 consecutive months between separate episodes, in which criteria are not met for a major depressive episode Moderate 1 The number of symptoms, intensity of symptoms, and/or functional impairment are between those specified for ‘mild’ and ‘severe’ Severe 1 The number of symptoms is substantially in excess of that required to make the diagnosis, the intensity of symptoms is seriously distressing and unmanageable, and the symptoms markedly interfere with social and occupational functioning MDD specifiers In partial remission 1 Symptoms of the immediately previous major depressive episode are present, but full criteria are not met, or there is a period lasting less than 2 months without any significant symptoms of a major depressive episode following the end of such an episode In full remission 1 During the past 2 months, no significant signs or symptoms of the disturbance were present 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition (DSM-5™). © American Psychiatric Association, 2013. 2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR®). © American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

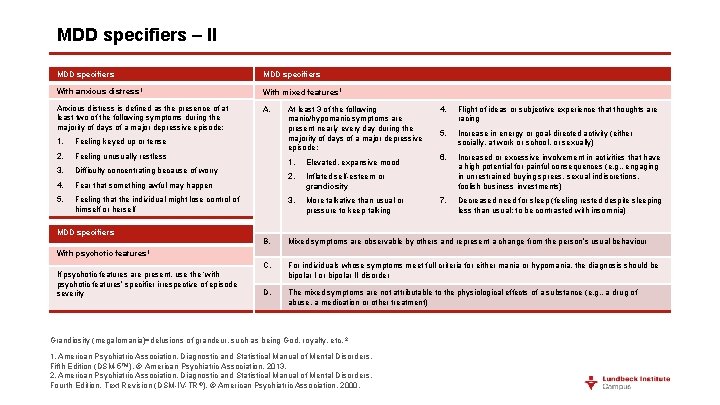

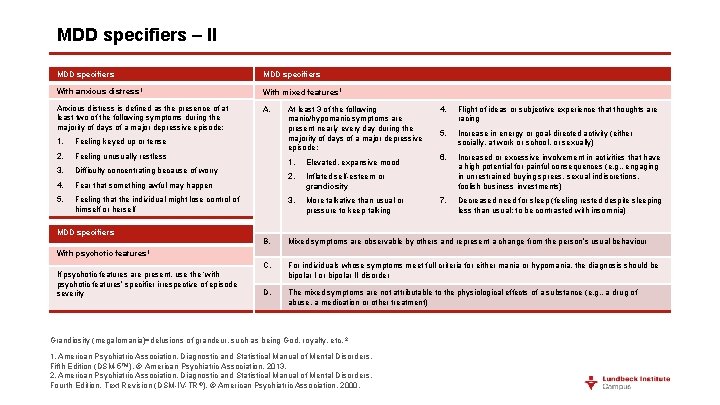

MDD specifiers – II MDD specifiers With anxious distress 1 Anxious distress is defined as the presence of at least two of the following symptoms during the majority of days of a major depressive episode: 1. Feeling keyed up or tense 2. Feeling unusually restless 3. Difficulty concentrating because of worry 4. Fear that something awful may happen 5. Feeling that the individual might lose control of himself or herself MDD specifiers With mixed features 1 A. At least 3 of the following manic/hypomanic symptoms are present nearly every day during the majority of days of a major depressive episode: 1. Elevated, expansive mood 2. Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity 3. More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking 4. Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing 5. Increase in energy or goal-directed activity (either socially, at work or school, or sexually) 6. Increased or excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (e. g. , engaging in unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, foolish business investments) 7. Decreased need for sleep (feeling rested despite sleeping less than usual; to be contrasted with insomnia) MDD specifiers B. Mixed symptoms are observable by others and represent a change from the person’s usual behaviour C. For individuals whose symptoms meet full criteria for either mania or hypomania, the diagnosis should be bipolar I or bipolar II disorder D. The mixed symptoms are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e. g. , a drug of abuse, a medication or other treatment) With psychotic features 1 If psychotic features are present, use the ‘with psychotic features’ specifier irrespective of episode severity Grandiosity (megalomania)=delusions of grandeur, such as being God, royalty, etc. 2 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition (DSM-5™). © American Psychiatric Association, 2013. 2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR ®). © American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

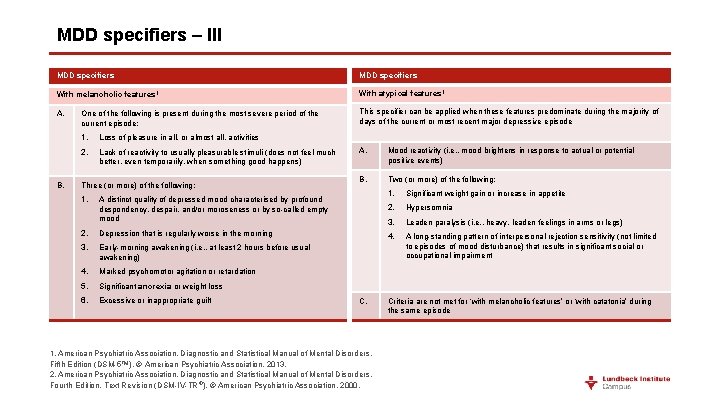

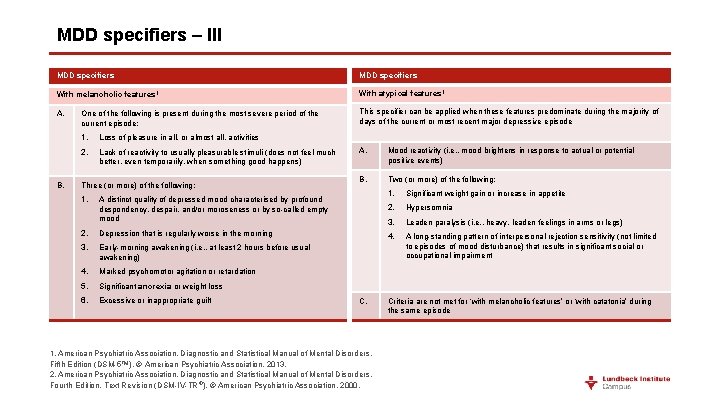

MDD specifiers – III MDD specifiers With melancholic features 1 With atypical features 1 A. This specifier can be applied when these features predominate during the majority of days of the current or most recent major depressive episode B. One of the following is present during the most severe period of the current episode: 1. Loss of pleasure in all, or almost all, activities 2. Lack of reactivity to usually pleasurable stimuli (does not feel much better, even temporarily, when something good happens) Three (or more) of the following: 1. A distinct quality of depressed mood characterised by profound despondency, despair, and/or moroseness or by so-called empty mood 2. Depression that is regularly worse in the morning 3. Early-morning awakening (i. e. , at least 2 hours before usual awakening) 4. Marked psychomotor agitation or retardation 5. Significant anorexia or weight loss 6. Excessive or inappropriate guilt A. Mood reactivity (i. e. , mood brightens in response to actual or potential positive events) B. Two (or more) of the following: C. 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition (DSM-5™). © American Psychiatric Association, 2013. 2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR ®). © American Psychiatric Association, 2000. 1. Significant weight gain or increase in appetite 2. Hypersomnia 3. Leaden paralysis (i. e. , heavy, leaden feelings in arms or legs) 4. A long-standing pattern of interpersonal rejection sensitivity (not limited to episodes of mood disturbance) that results in significant social or occupational impairment Criteria are not met for ‘with melancholic features’ or ‘with catatonia’ during the same episode

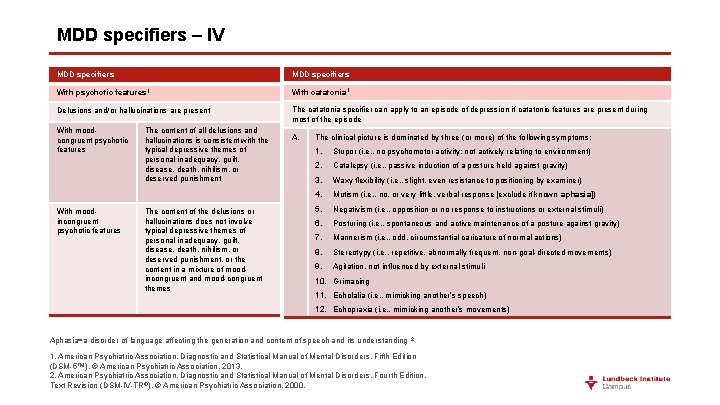

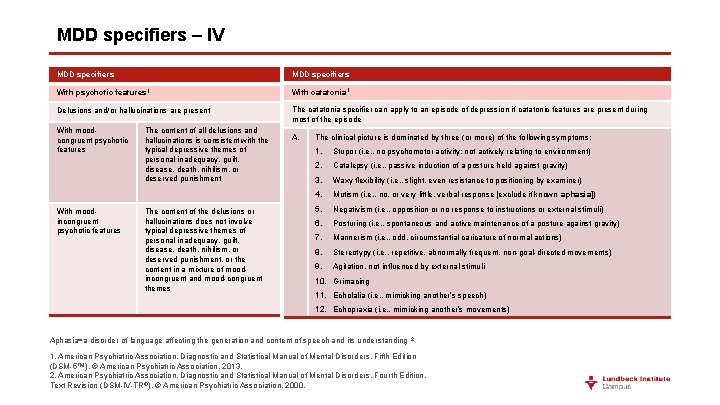

MDD specifiers – IV MDD specifiers With psychotic features 1 With catatonia 1 Delusions and/or hallucinations are present The catatonia specifier can apply to an episode of depression if catatonic features are present during most of the episode With moodcongruent psychotic features A. With moodincongruent psychotic features The content of all delusions and hallucinations is consistent with the typical depressive themes of personal inadequacy, guilt, disease, death, nihilism, or deserved punishment The content of the delusions or hallucinations does not involve typical depressive themes of personal inadequacy, guilt, disease, death, nihilism, or deserved punishment, or the content in a mixture of moodincongruent and mood-congruent themes The clinical picture is dominated by three (or more) of the following symptoms: 1. Stupor (i. e. , no psychomotor activity; not actively relating to environment) 2. Catalepsy (i. e. , passive induction of a posture held against gravity) 3. Waxy flexibility (i. e. , slight, even resistance to positioning by examiner) 4. Mutism (i. e. , no, or very little, verbal response [exclude if known aphasia]) 5. Negativism (i. e. , opposition or no response to instructions or external stimuli) 6. Posturing (i. e. , spontaneous and active maintenance of a posture against gravity) 7. Mannerism (i. e. , odd, circumstantial caricature of normal actions) 8. Stereotypy (i. e. , repetitive, abnormally frequent, non-goal-directed movements) 9. Agitation, not influenced by external stimuli 10. Grimacing 11. Echolalia (i. e. , mimicking another’s speech) 12. Echopraxia (i. e. , mimicking another’s movements) Aphasia=a disorder of language affecting the generation and content of speech and its understanding 2 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition (DSM-5™). © American Psychiatric Association, 2013. 2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR®). © American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

MDD specifiers – V MDD specifiers With peripartum onset 1 With seasonal pattern 1 This specifier can be applied to the current or, if full criteria are not currently met for a major depressive episode, most recent episode of major depression if onset of mood symptoms occurs during pregnancy or in the 4 weeks following delivery This specifier applies to recurrent MDD A. There has been a regular temporal relationship between the onset of major depressive episodes in MDD and a particular time of the year (e. g. , in the fall [autumn] or winter) B. Full remissions (or a change from major depression to mania or hypomania) also occur at a characteristic time of the year (e. g. , depression disappears in the spring) C. In the last 2 years, two major depressive episodes have occurred that demonstrate the temporal seasonal relationships defined above and no non-seasonal major depressive episodes have occurred during that same period D. Seasonal major depressive episodes (as described above) substantially outnumber the non-seasonal major depressive episodes that may have occurred over the individual’s lifetime 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition (DSM-5™). © American Psychiatric Association, 2013. 2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR®). © American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

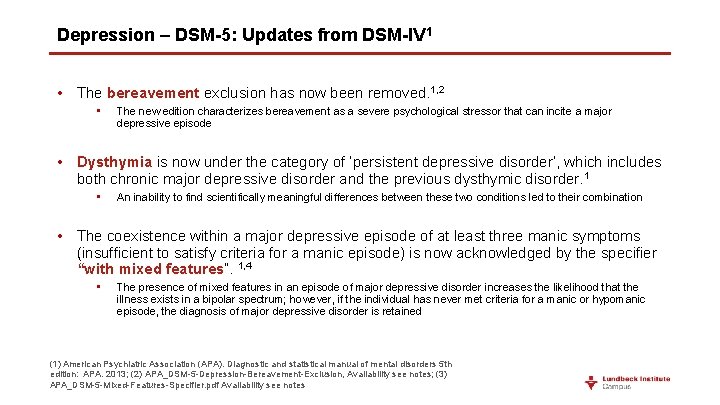

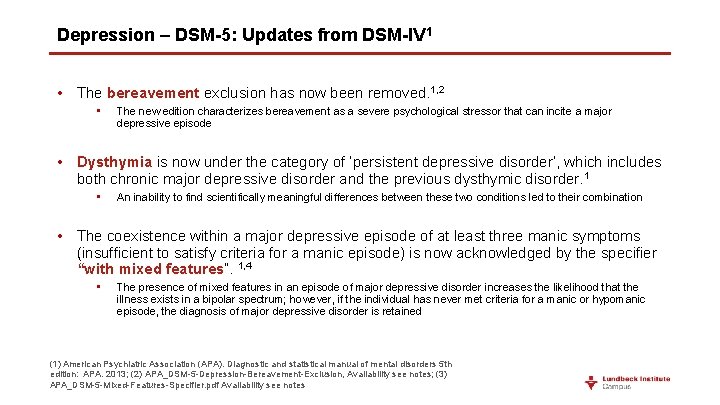

Depression – DSM-5: Updates from DSM-IV 1 • The bereavement exclusion has now been removed. 1, 2 • The new edition characterizes bereavement as a severe psychological stressor that can incite a major depressive episode • Dysthymia is now under the category of ‘persistent depressive disorder’, which includes both chronic major depressive disorder and the previous dysthymic disorder. 1 • An inability to find scientifically meaningful differences between these two conditions led to their combination • The coexistence within a major depressive episode of at least three manic symptoms (insufficient to satisfy criteria for a manic episode) is now acknowledged by the specifier “with mixed features”. 1, 4 • The presence of mixed features in an episode of major depressive disorder increases the likelihood that the illness exists in a bipolar spectrum; however, if the individual has never met criteria for a manic or hypomanic episode, the diagnosis of major depressive disorder is retained (1) American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5 th edition: APA. 2013; (2) APA_DSM-5 -Depression-Bereavement-Exclusion, Availability see notes; (3) APA_DSM-5 -Mixed-Features-Specifier. pdf Availability see notes

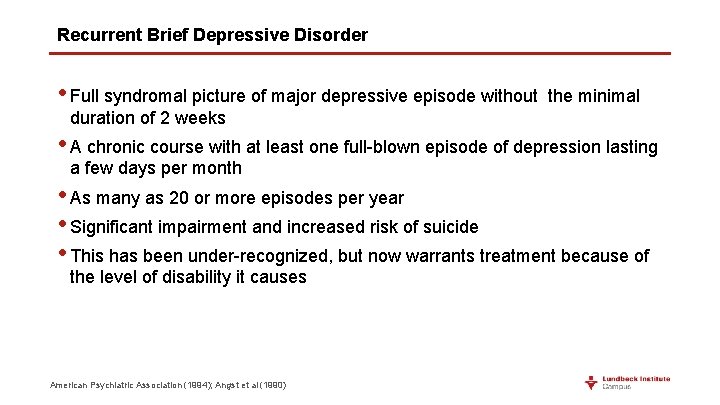

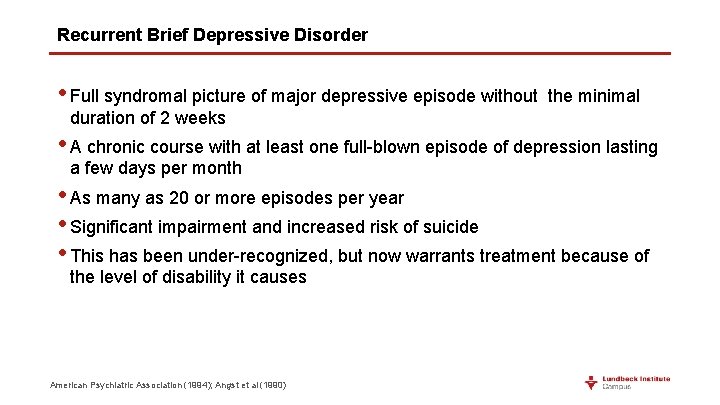

Recurrent Brief Depressive Disorder • Full syndromal picture of major depressive episode without the minimal duration of 2 weeks • A chronic course with at least one full-blown episode of depression lasting a few days per month • As many as 20 or more episodes per year • Significant impairment and increased risk of suicide • This has been under-recognized, but now warrants treatment because of the level of disability it causes American Psychiatric Association (1994); Angst et al (1990)

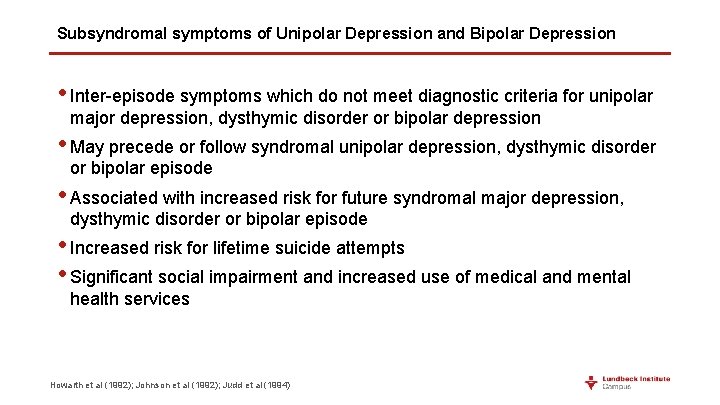

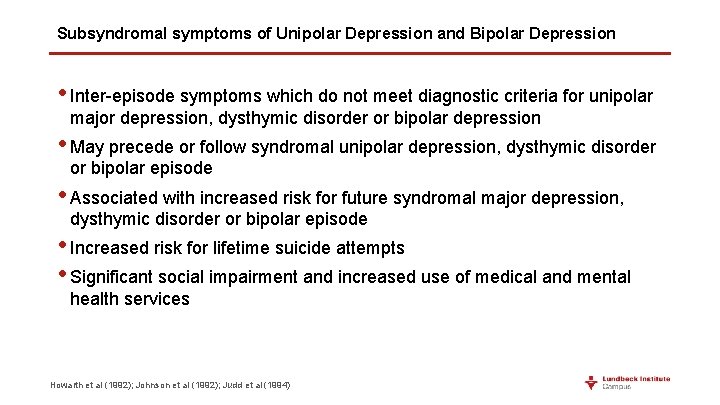

Subsyndromal symptoms of Unipolar Depression and Bipolar Depression • Inter-episode symptoms which do not meet diagnostic criteria for unipolar major depression, dysthymic disorder or bipolar depression • May precede or follow syndromal unipolar depression, dysthymic disorder or bipolar episode • Associated with increased risk for future syndromal major depression, dysthymic disorder or bipolar episode • Increased risk for lifetime suicide attempts • Significant social impairment and increased use of medical and mental health services Howarth et al (1992); Johnson et al (1992); Judd et al (1994)

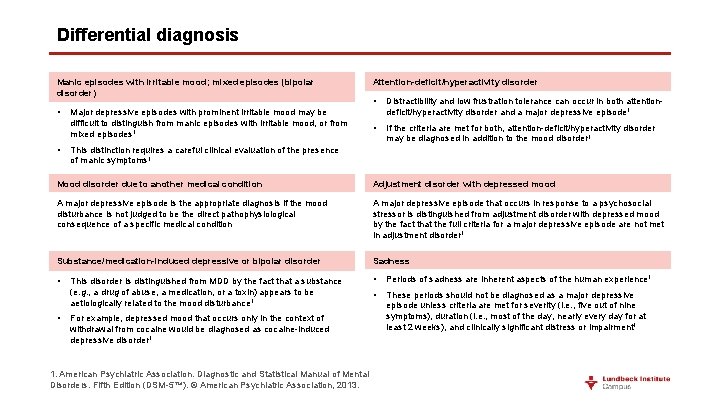

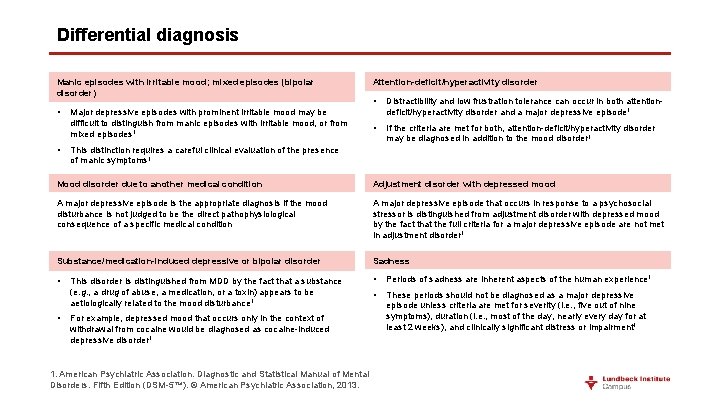

Differential diagnosis Manic episodes with irritable mood; mixed episodes (bipolar disorder) • • Major depressive episodes with prominent irritable mood may be difficult to distinguish from manic episodes with irritable mood, or from mixed episodes 1 Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder • Distractibility and low frustration tolerance can occur in both attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder and a major depressive episode 1 • If the criteria are met for both, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder may be diagnosed in addition to the mood disorder 1 This distinction requires a careful clinical evaluation of the presence of manic symptoms 1 Mood disorder due to another medical condition Adjustment disorder with depressed mood A major depressive episode is the appropriate diagnosis if the mood disturbance is not judged to be the direct pathophysiological consequence of a specific medical condition A major depressive episode that occurs in response to a psychosocial stressor is distinguished from adjustment disorder with depressed mood by the fact that the full criteria for a major depressive episode are not met in adjustment disorder 1 Substance/medication-induced depressive or bipolar disorder Sadness • • Periods of sadness are inherent aspects of the human experience 1 • These periods should not be diagnosed as a major depressive episode unless criteria are met for severity (i. e. , five out of nine symptoms), duration (i. e. , most of the day, nearly every day for at least 2 weeks), and clinically significant distress or impairment 1 • This disorder is distinguished from MDD by the fact that a substance (e. g. , a drug of abuse, a medication, or a toxin) appears to be aetiologically related to the mood disturbance 1 For example, depressed mood that occurs only in the context of withdrawal from cocaine would be diagnosed as cocaine-induced depressive disorder 1 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition (DSM-5™). © American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Functional recovery Social factors, lack of efficacy, tolerability and adherence

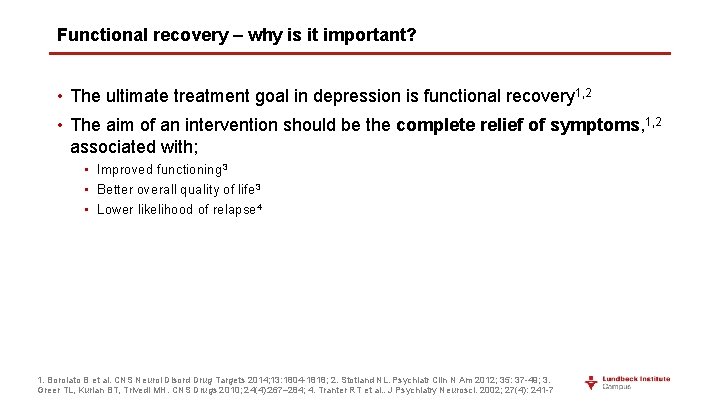

Functional recovery – why is it important? • The ultimate treatment goal in depression is functional recovery 1, 2 • The aim of an intervention should be the complete relief of symptoms, 1, 2 associated with; • Improved functioning 3 • Better overall quality of life 3 • Lower likelihood of relapse 4 1. Borolato B et al. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2014; 13: 1804 -1818; 2. Stotland NL. Psychiatr Clin N Am 2012; 35: 37 -49; 3. Greer TL, Kurian BT, Trivedi MH. CNS Drugs 2010; 24(4): 267– 284; 4. Tranter RT et al. . J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2002; 27(4): 241 -7

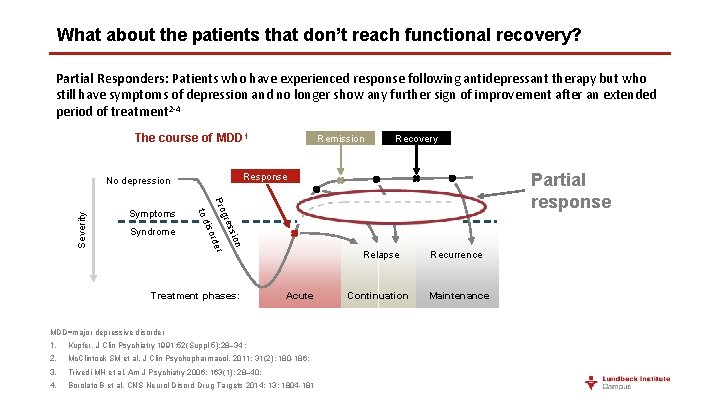

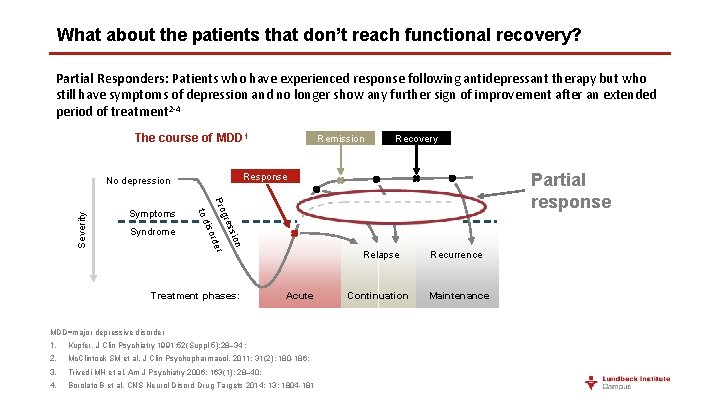

What about the patients that don’t reach functional recovery? Partial Responders: Patients who have experienced response following antidepressant therapy but who still have symptoms of depression and no longer show any further sign of improvement after an extended period of treatment 2 -4 The course of MDD 1 on ssi gre r rde iso Severity Partial response Pro to d Syndrome Recovery Response No depression Symptoms Remission Treatment phases: Acute MDD=major depressive disorder 1. Kupfer. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52(Suppl 5): 28– 34 ; 2. Mc. Clintock SM et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011; 31(2): 180 -186; 3. Trivedi MH et al. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163(1): 28– 40; 4. Borolato B et al. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2014; 13: 1804 -181 Relapse Recurrence Continuation Maintenance

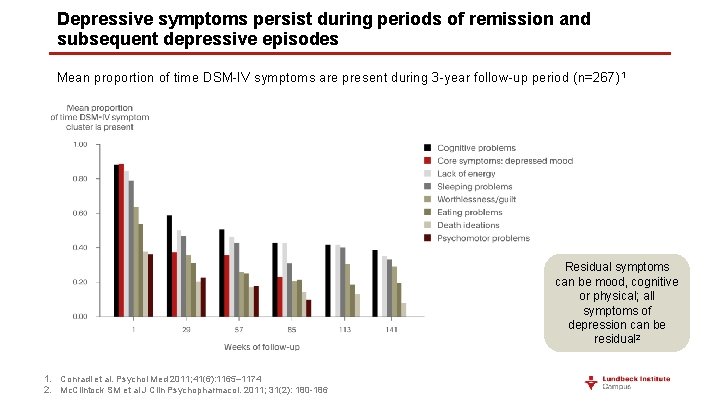

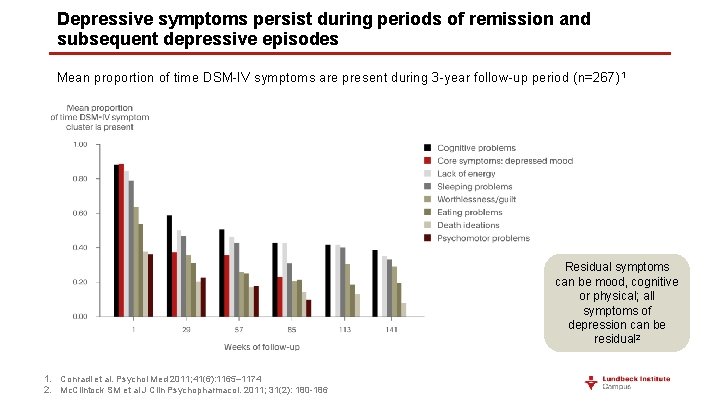

Depressive symptoms persist during periods of remission and subsequent depressive episodes Mean proportion of time DSM-IV symptoms are present during 3 -year follow-up period (n=267)1 Residual symptoms can be mood, cognitive or physical; all symptoms of depression can be residual 2 1. Conradi et al. Psychol Med 2011; 41(6): 1165– 1174 2. Mc. Clintock SM et al J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011; 31(2): 180 -186

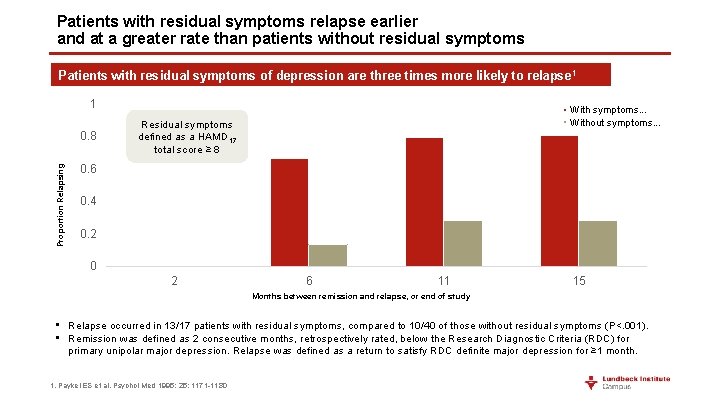

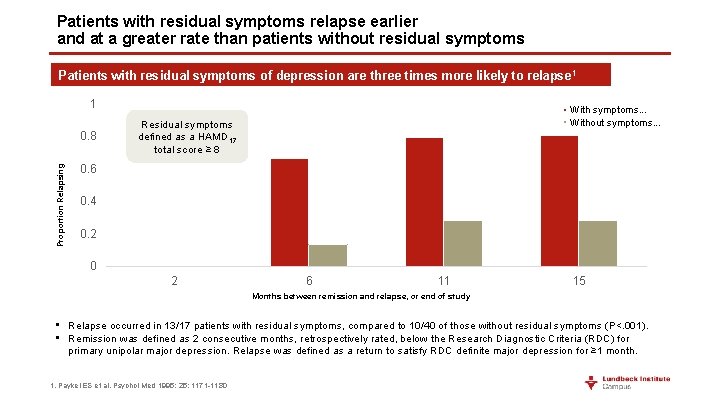

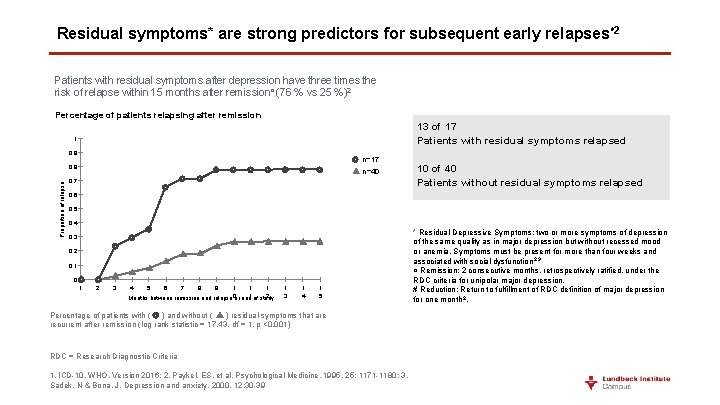

Patients with residual symptoms relapse earlier and at a greater rate than patients without residual symptoms Patients with residual symptoms of depression are three times more likely to relapse 1 1 Proportion Relapsing 0. 8 With symptoms. . . Without symptoms. . . Residual symptoms defined as a HAMD 17 total score ≥ 8 0. 6 0. 4 0. 2 0 2 6 11 15 Months between remission and relapse, or end of study • Relapse occurred in 13/17 patients with residual symptoms, compared to 10/40 of those without residual symptoms (P<. 001). • Remission was defined as 2 consecutive months, retrospectively rated, below the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for primary unipolar major depression. Relapse was defined as a return to satisfy RDC definite major depression for ≥ 1 month. 1. Paykel ES et al. Psychol Med 1995; 25: 1171 -1180

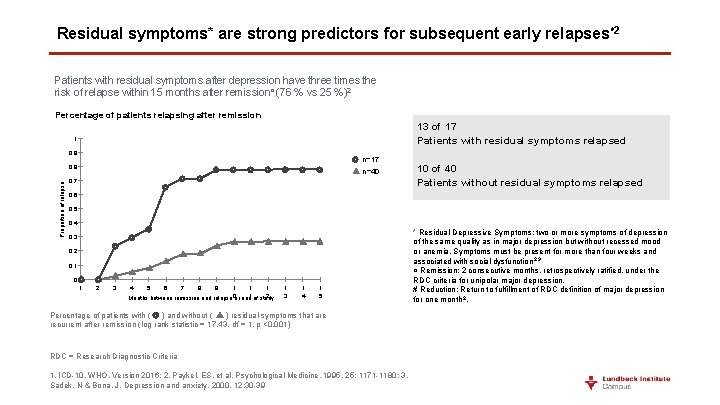

Residual symptoms* are strong predictors for subsequent early relapses 2 # Patients with residual symptoms after depression have three times the risk of relapse within 15 months after remission¤ (76 % vs 25 %)2 Percentage of patients relapsing after remission 13 of 17 Patients with residual symptoms relapsed 1 0, 9 n=17 Proportion of relapse 0, 8 n=40 0, 7 10 of 40 Patients without residual symptoms relapsed 0, 6 0, 5 0, 4 0, 3 0, 2 0, 1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 1 1 2 Months between remission and relapse 0 or end 1 of study 1 3 1 4 1 5 Percentage of patients with ( ) and without ( ) residual symptoms that are recurrent after remission (log rank statistic = 17. 43, df = 1, p <0. 001) RDC = Research Diagnostic Criteria 1. ICD-10, WHO. Version 2016; 2. Paykel, ES. et al. Psychological Medicine, 1995, 25: 1171 -1180; 3. Sadek, N & Bona, J. Depression and anxiety. 2000. 12: 30 -39 * Residual Depressive Symptoms: two or more symptoms of depression of the same quality as in major depression but without recessed mood or anemia. Symptoms must be present for more than four weeks and associated with social dysfunction 2, 3 ¤ Remission: 2 consecutive months, retrospectively ratified, under the RDC criteria for unipolar major depression. # Reduction: Return to fulfillment of RDC definition of major depression for one month 2.

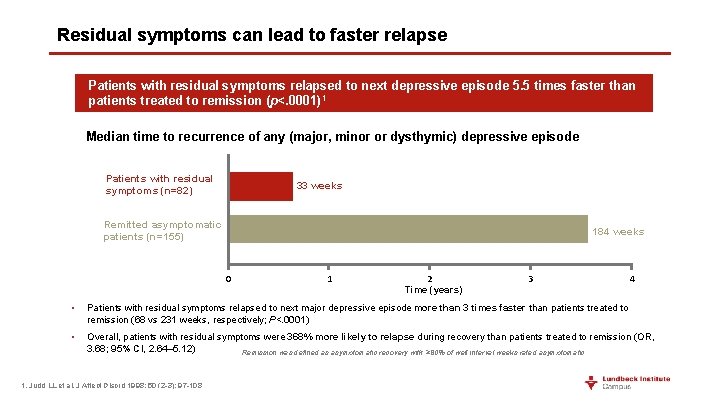

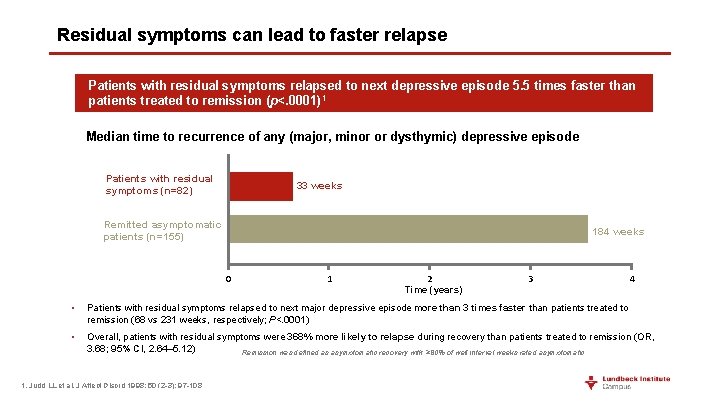

Residual symptoms can lead to faster relapse Patients with residual symptoms relapsed to next depressive episode 5. 5 times faster than patients treated to remission (p<. 0001)1 Median time to recurrence of any (major, minor or dysthymic) depressive episode Patients with residual symptoms (n=82) 33 weeks Remitted asymptomatic patients (n=155) 184 weeks 0 1 2 Time (years) 3 4 • Patients with residual symptoms relapsed to next major depressive episode more than 3 times faster than patients treated to remission (68 vs 231 weeks, respectively; P<. 0001) • Overall, patients with residual symptoms were 368% more likely to relapse during recovery than patients treated to remission (OR, 3. 68; 95% CI, 2. 64– 5. 12) Remission was defined as asymptomatic recovery with ≥ 80% of well interval weeks rated asymptomatic 1. Judd LL et al. J Affect Disord 1998; 50 (2 -3): 97 -108

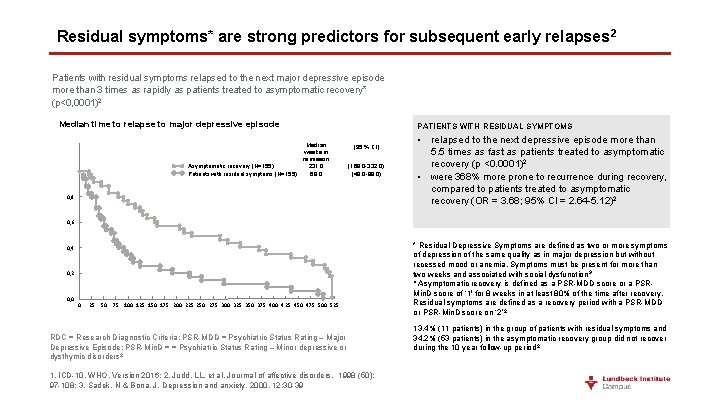

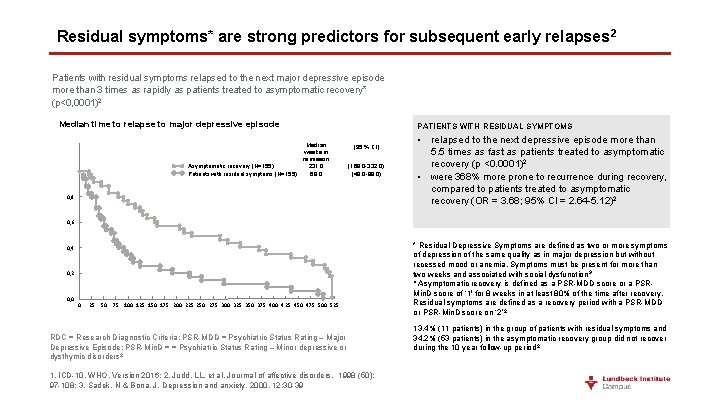

Residual symptoms* are strong predictors for subsequent early relapses 2 Patients with residual symptoms relapsed to the next major depressive episode more than 3 times as rapidly as patients treated to asymptomatic recovery* (p<0, 0001)2 Median time to relapse to major depressive episode Median weeks in remisson Asymptomatic recovery (N=155) 231, 0 Patients with residual symptoms (N=155) 68, 0 PATIENTS WITH RESIDUAL SYMPTOMS (95 % CI) (169, 0 -332, 0) (49, 0 -88, 0) 0, 8 • relapsed to the next depressive episode more than 5. 5 times as fast as patients treated to asymptomatic recovery (p <0. 0001)2 • were 368% more prone to recurrence during recovery, compared to patients treated to asymptomatic recovery (OR = 3. 68; 95% CI = 2. 64 -5. 12)2 0, 6 0, 4 0, 2 0, 0 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 225 250 275 300 325 350 375 400 425 450 475 500 525 RDC = Research Diagnostic Criteria; PSR-MDD = Psychiatric Status Rating – Major Depressive Episode; PSR-Min. D = = Psychiatric Status Rating – Minor depressive or dysthymic disorders 2 1. ICD-10, WHO. Version 2016; 2. Judd, LL. et al. Jourmal of affective disorders. 1998 (50): 97 -108; 3. Sadek, N & Bona, J. Depression and anxiety. 2000. 12: 30 -39 * Residual Depressive Symptoms are defined as two or more symptoms of depression of the same quality as in major depression but without recessed mood or anemia. Symptoms must be present for more than two weeks and associated with social dysfunction 3 ¤ Asymptomatic recovery is defined as a PSR-MDD score or a PSRMin. D score of ‘ 1' for 8 weeks in at least 80% of the time after recovery. Residual symptoms are defined as a recovery period with a PSR-MDD or PSR-Min. D score on ‘ 2’ 2 13. 4% (11 patients) in the group of patients with residual symptoms and 34. 2% (53 patients) in the asymptomatic recovery group did not recover during the 10 year follow-up period 2

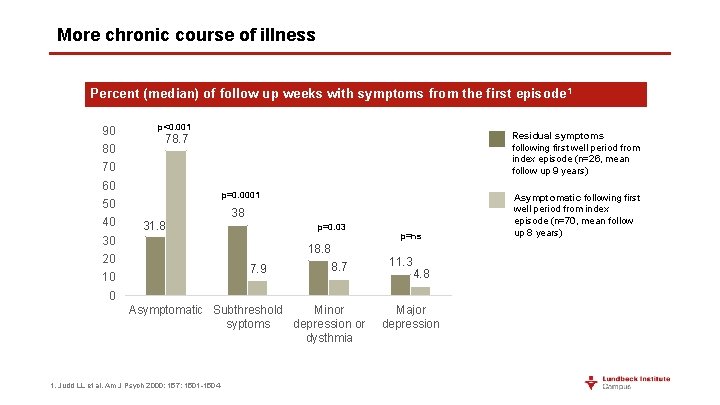

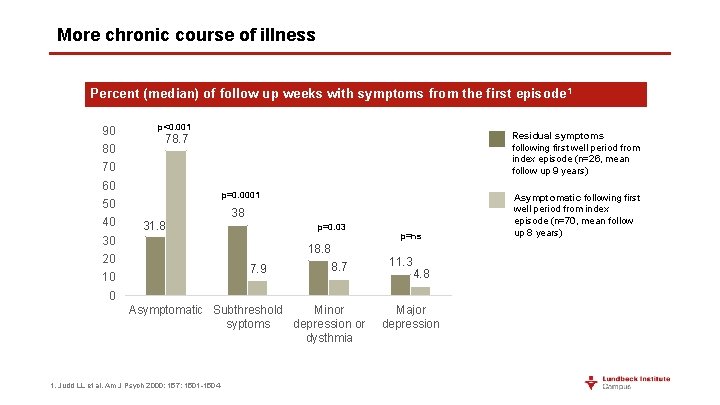

More chronic course of illness Percent (median) of follow up weeks with symptoms from the first episode 1 90 80 p<0. 001 Residual symptoms following first well period from index episode (n=26, mean follow up 9 years) 78. 7 70 60 p=0. 0001 50 40 31. 8 38 p=0. 03 30 p=ns 18. 8 20 7. 9 10 8. 7 11. 3 4. 8 0 Asymptomatic Subthreshold Minor syptoms depression or dysthmia 1. Judd LL et al. Am J Psych 2000; 157: 1501 -1504 Major depression Asymptomatic following first well period from index episode (n=70, mean follow up 8 years)

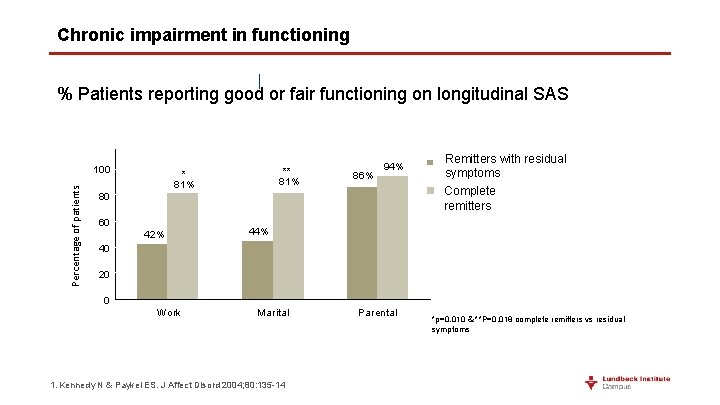

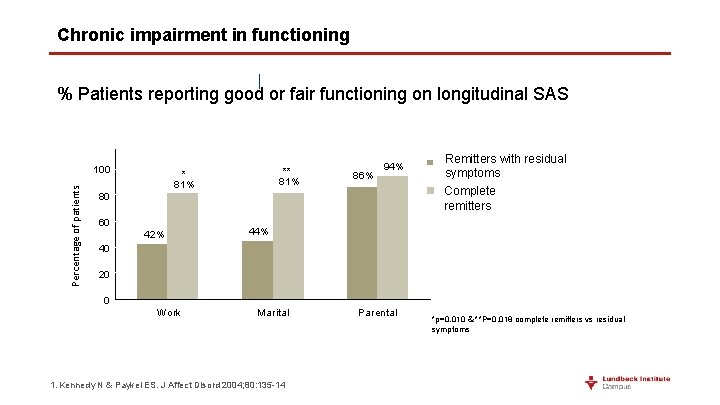

Chronic impairment in functioning % Patients reporting good or fair functioning on longitudinal SAS *P=0. 010 Percentage of patients 100 ** 81% 86% 94% Complete remitters 80 60 Remitters with residual symptoms 44% 42% 40 20 0 Work Marital. - 1. Kennedy N & Paykel ES. J Affect Disord 2004; 80: 135 -14 Parental *p=0. 010 & **P=0. 018 complete remitters vs residual symptoms

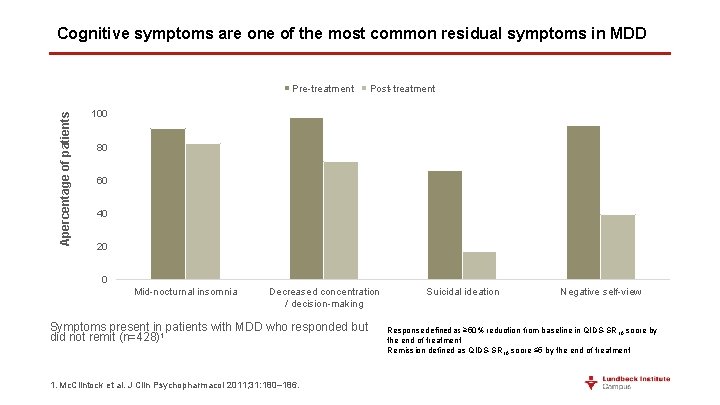

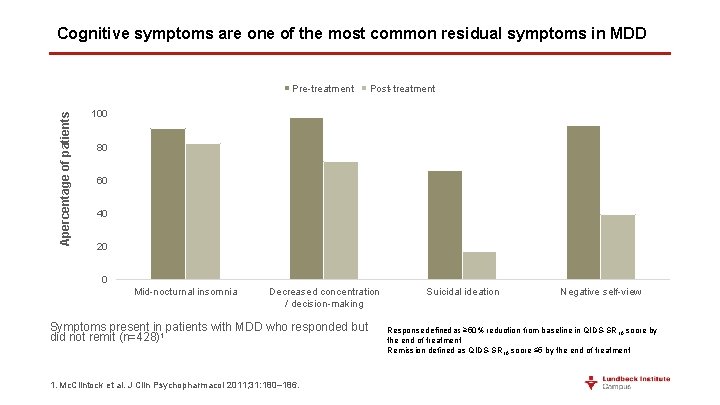

Cognitive symptoms are one of the most common residual symptoms in MDD Apercentage of patients Pre-treatment Post-treatment 100 80 60 40 20 0 Mid-nocturnal insomnia Decreased concentration / decision-making Symptoms present in patients with MDD who responded but did not remit (n=428)1 1. Mc. Clintock et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2011; 31: 180– 186. Suicidal ideation Negative self-view Response defined as ≥ 50% reduction from baseline in QIDS-SR 16 score by the end of treatment Remission defined as QIDS-SR 16 score ≤ 5 by the end of treatment

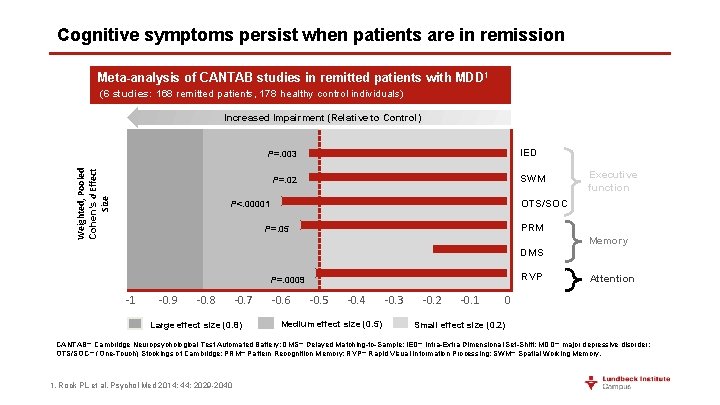

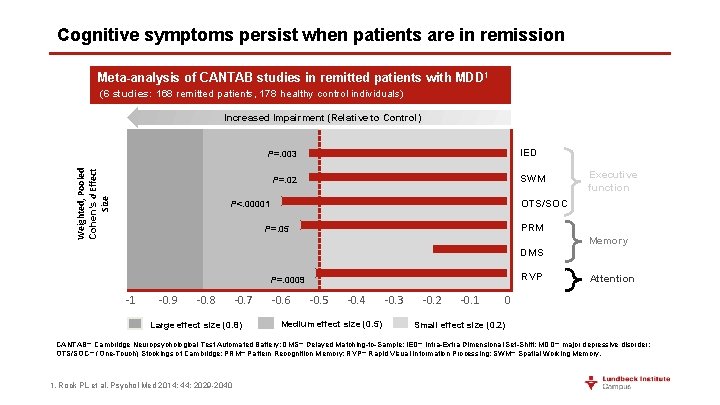

Cognitive symptoms persist when patients are in remission Meta-analysis of CANTAB studies in remitted patients with MDD 1 (6 studies: 168 remitted patients, 178 healthy control individuals) Increased Impairment (Relative to Control) IED Weighted, Pooled Cohen’s d Effect Size P=. 003 SWM P=. 02 Executive function OTS/SOC P<. 00001 PRM P=. 05 Memory DMS RVP P=. 0009 -1 -0. 9 -0. 8 -0. 7 Large effect size (0. 8) -0. 6 -0. 5 -0. 4 Medium effect size (0. 5) -0. 3 -0. 2 -0. 1 Attention 0 Small effect size (0. 2) CANTAB= Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery; DMS= Delayed Matching-to-Sample; IED= Intra-Extra Dimensional Set-Shift; MDD= major depressive disorder; OTS/SOC= (One-Touch) Stockings of Cambridge; PRM= Pattern Recognition Memory; RVP= Rapid Visual Information Processing; SWM= Spatial Working Memory. 1. Rock PL et al. Psychol Med 2014; 44: 2029 -2040

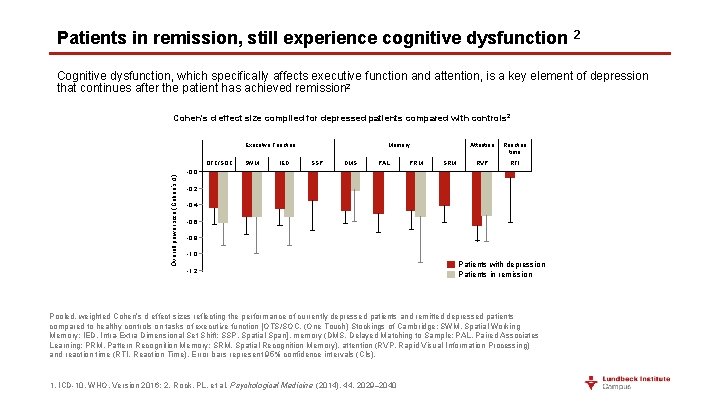

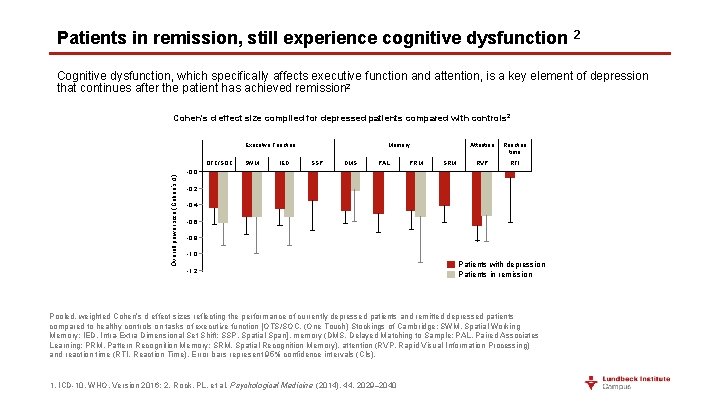

Patients in remission, still experience cognitive dysfunction 2 Cognitive dysfunction, which specifically affects executive function and attention, is a key element of depression that continues after the patient has achieved remission 2 Cohen's d effect size compiled for depressed patients compared with controls 2 Executive Function Overall power size (Cohen’s d) OTC/SOC SWM IED Memory SSP DMS PAL PRM SRM Attention Reaction time RVP RTI -0, 0 -0, 2 . -0, 4 -0, 6 -0, 8 -1, 0 -1, 2 Patients with depression Patients in remission Pooled, weighted Cohen’s d effect sizes reflecting the performance of currently depressed patients and remitted depressed patients compared to healthy controls on tasks of executive function [OTS/SOC, (One Touch) Stockings of Cambridge; SWM, Spatial Working Memory; IED, Intra-Extra Dimensional Set Shift; SSP, Spatial Span], memory (DMS, Delayed Matching to Sample; PAL, Paired Associates Learning; PRM, Pattern Recognition Memory; SRM, Spatial Recognition Memory), attention (RVP, Rapid Visual Information Processing) and reaction time (RTI, Reaction Time). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals (CIs). 1. ICD-10, WHO. Version 2016; 2. Rock, PL. et al. Psychological Medicine (2014), 44, 2029– 2040

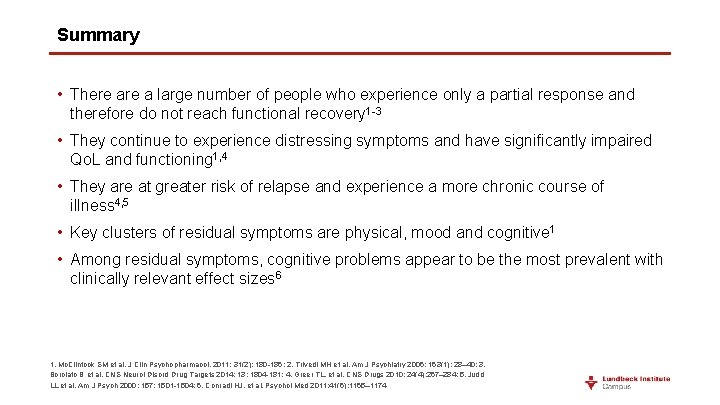

Summary • There a large number of people who experience only a partial response and therefore do not reach functional recovery 1 -3 • They continue to experience distressing symptoms and have significantly impaired Qo. L and functioning 1, 4 • They are at greater risk of relapse and experience a more chronic course of illness 4, 5 • Key clusters of residual symptoms are physical, mood and cognitive 1 • Among residual symptoms, cognitive problems appear to be the most prevalent with clinically relevant effect sizes 6 1. Mc. Clintock SM et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011; 31(2): 180 -186; 2. Trivedi MH et al. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163(1): 28– 40; 3. Borolato B et al. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2014; 13: 1804 -181; 4. Greer TL, et al. CNS Drugs 2010; 24(4): 267– 284; 5. Judd LL et al. Am J Psych 2000; 157: 1501 -1504; 6. Conradi HJ, et al. Psychol Med 2011; 41(6): 1165– 1174

Challenges in achieving functional recovery Social factors, lack of efficacy, tolerability and adherence

Barriers to achieving functional recovery • Chronicity 1 and number of lifetime episodes 1, 2 • Length of current episode 3 • Co-morbidity (e. g. anxiety, 3, 4 personality disorder 5) • Painful symptoms 6 • Childhood maltreatment 7 • Attending a practice with a high Jarman underprivileged area score 8 • Neuroticism 5, 9 • Substance misuse 10 • Stressful life events 2, 11 -12 1. Fournier JC et al. J Consult Clin Psychol 2009; 77: 775 -787; 2. Kendler KS et al. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 1243 -1251; 3. Howland RH et al. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2008; 20: 209 -218; 4. Fava M et al. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165: 342 -351; 5. Mulder RT. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159: 359 -371; 6. De. Veaugh-Geiss AM et al. Pain Medicine 2010; 11: 732 -741; 7. Nanni V et al. Am J Psychiatry 2012; 169(2): 141 -51; 8. Ostler K et al. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178: 12 -17; 9. Lamers F et al. Psychiatry Res 2011; 226 -231; 10. Watkins KE et al. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 125 -132; 11. Kendler KS et al. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159: 1133 -1145; 12. Kendler KS et al. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 115 -124.

Inadequate or partial response to first line SSRI treatment One half unresponsive to first antidepressant in the STAR*D trial 1 Remission rates (using QIDS-SR 16) were: • 37% after first trial • 67% after 3 more trials (cumulative) Few adults experience full symptomatic and functional remission between depressive episodes 2, 3 • Residual symptoms and loss of function are common Recurrence rates range from 40– 85% 2 Inadequate SSRI response increases risk of relapse 1. Rush et al. Am J Psych 2006; 163(11): 1905– 1917 2. Kennedy et al. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2013; 15(2): 3 3. Conradi et al. Psychol Med 2011; 41(6): 1165– 1174

Treatment factors could lead to partial response • If a patient has not adequately responded to their treatment, consider: • Is antidepressant at a therapeutic dose? • Has treatment trial been of sufficient duration? • Is adherence satisfactory? In patients showing no response to treatment after 3– 4 weeks of optimised-dose treatment, consideration should be given to moving to next-step treatments 1 1. NICE (2009) Clinical Guideline 90

Patients frequently discontinue treatment due to adverse events The majority of patients treated with antidepressants experience one or more bothersome side effect 1 ● Side effects often create barriers to achieving remission, and add difficulties in the prevention of relapse and recurrence As many as one quarter of patients discontinue their antidepressants due to difficult-to-tolerate side effects 1 ● Others may continue on antidepressant therapy, but experience diminished quality of life related to troublesome side effects A study by Hu et al (2004) found that 33% of patients discontinued their antidepressant treatment by the end of a 105 -day period 2 ● The most often cited reason for treatment discontinuation was adverse events (36%)1, 2 ● The presence of multiple side effects, or side effects deemed extremely bothersome, significantly increased the odds of discontinuation 1, 2 1. Kelly et al. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2008; 10(4): 409– 418 2. Hu et al. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65(7): 959– 965

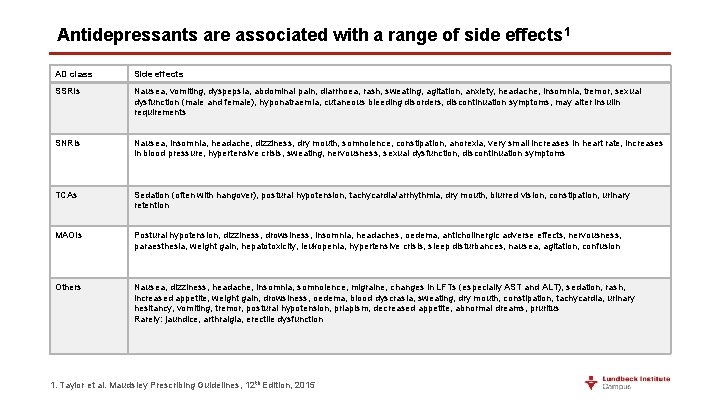

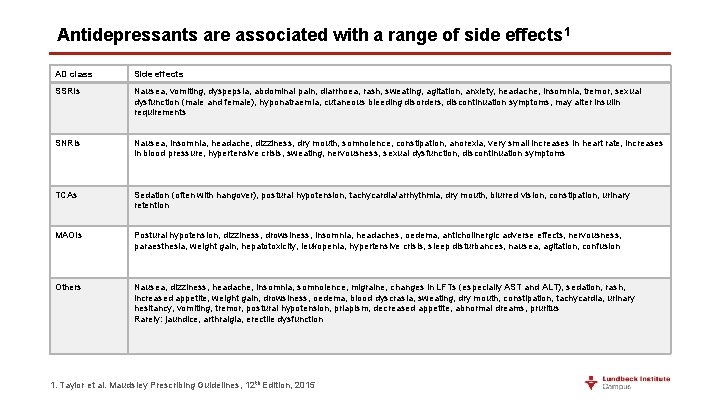

Antidepressants are associated with a range of side effects 1 AD class Side effects SSRIs Nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, rash, sweating, agitation, anxiety, headache, insomnia, tremor, sexual dysfunction (male and female), hyponatraemia, cutaneous bleeding disorders, discontinuation symptoms, may alter insulin requirements SNRIs Nausea, insomnia, headache, dizziness, dry mouth, somnolence, constipation, anorexia, very small increases in heart rate, increases in blood pressure, hypertensive crisis, sweating, nervousness, sexual dysfunction, discontinuation symptoms TCAs Sedation (often with hangover), postural hypotension, tachycardia/arrhythmia, dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, urinary retention MAOIs Postural hypotension, dizziness, drowsiness, insomnia, headaches, oedema, anticholinergic adverse effects, nervousness, paraesthesia, weight gain, hepatotoxicity, leukopenia, hypertensive crisis, sleep disturbances, nausea, agitation, confusion Others Nausea, dizziness, headache, insomnia, somnolence, migraine, changes in LFTs (especially AST and ALT), sedation, rash, increased appetite, weight gain, drowsiness, oedema, blood dyscrasia, sweating, dry mouth, constipation, tachycardia, urinary hesitancy, vomiting, tremor, postural hypotension, priapism, decreased appetite, abnormal dreams, pruritus Rarely: jaundice, arthralgia, erectile dysfunction 1. Taylor et al. Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines, 12 th Edition, 2015

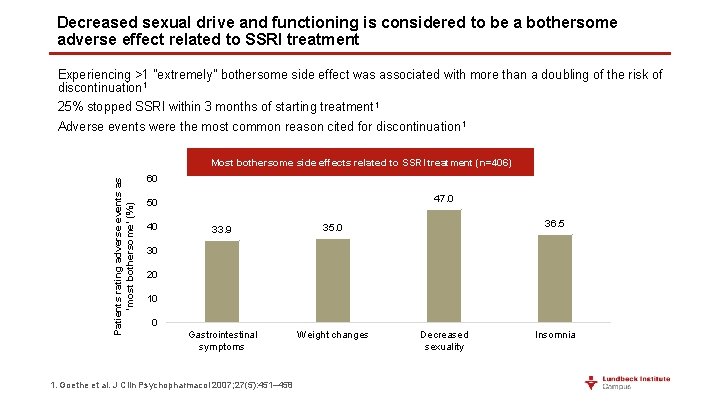

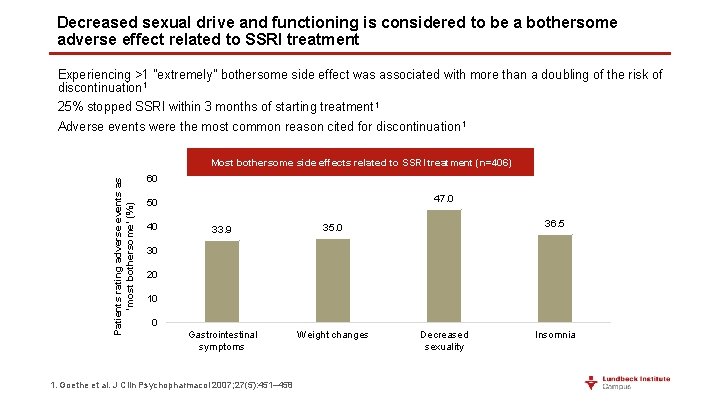

Decreased sexual drive and functioning is considered to be a bothersome adverse effect related to SSRI treatment Experiencing >1 "extremely" bothersome side effect was associated with more than a doubling of the risk of discontinuation 1 25% stopped SSRI within 3 months of starting treatment 1 Adverse events were the most common reason cited for discontinuation 1 Patients rating adverse events as ‘most bothersome’ (%) Most bothersome side effects related to SSRI treatment (n=406) 60 47. 0 50 40 33. 9 35. 0 Gastrointestinal symptoms Weight changes 36. 5 30 20 10 0 1. Goethe et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2007; 27(5): 451– 458 Decreased sexuality Insomnia

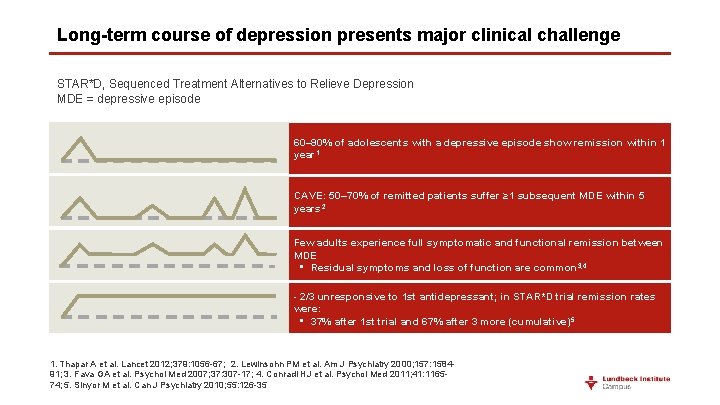

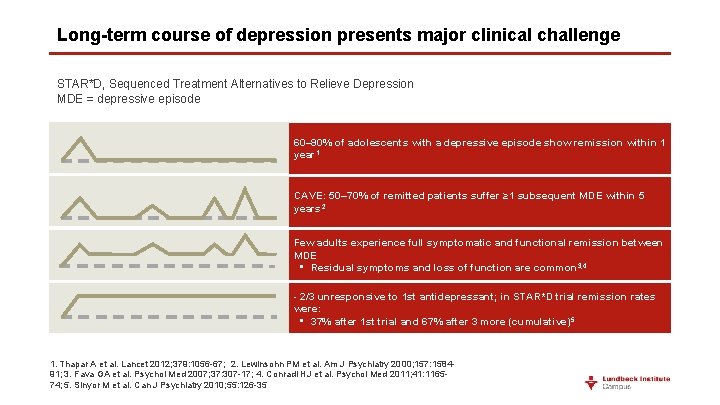

Long-term course of depression presents major clinical challenge STAR*D, Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression MDE = depressive episode 60– 90% of adolescents with a depressive episode show remission within 1 year 1 CAVE: 50– 70% of remitted patients suffer ≥ 1 subsequent MDE within 5 years 2 Few adults experience full symptomatic and functional remission between MDE • Residual symptoms and loss of function are common 3, 4 - 2/3 unresponsive to 1 st antidepressant; in STAR*D trial remission rates were: • 37% after 1 st trial and 67% after 3 more (cumulative) 5 1. Thapar A et al. Lancet 2012; 379: 1056 -67; 2. Lewinsohn PM et al. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 158491; 3. Fava GA et al. Psychol Med 2007; 37: 307 -17; 4. Conradi HJ et al. Psychol Med 2011; 41: 116574; 5. Sinyor M et al. Can J Psychiatry 2010; 55: 126 -35

Major depressive disorder

Major depressive disorder Major depressive disorder

Major depressive disorder What is sadistic personality disorder

What is sadistic personality disorder Chapter 14 depressive disorders

Chapter 14 depressive disorders Grundformen der angst riemann

Grundformen der angst riemann Dsm 5 munchausen by proxy

Dsm 5 munchausen by proxy Orleans hanna algebra prognosis test

Orleans hanna algebra prognosis test Ejemplos de prognosis en trabajo social

Ejemplos de prognosis en trabajo social Ich score prognosis

Ich score prognosis Hellp syndrome meaning

Hellp syndrome meaning Autism prognosis

Autism prognosis Splinter skills

Splinter skills Autism prognosis

Autism prognosis Autism prognosis

Autism prognosis Global developmental delay symptoms

Global developmental delay symptoms Static-99

Static-99 What is prognosis

What is prognosis Prognosis

Prognosis Child-pugh score prognosis

Child-pugh score prognosis Cholangitis prognosis

Cholangitis prognosis Good prognosis

Good prognosis Prognosis of cystic fibrosis

Prognosis of cystic fibrosis Borrmann classification of gastric cancer

Borrmann classification of gastric cancer Good prognosis

Good prognosis Major neurocognitive disorder criteria

Major neurocognitive disorder criteria Mild neurocognitive disorder

Mild neurocognitive disorder Major neurocognitive disorder criteria

Major neurocognitive disorder criteria Course number and title

Course number and title What is half brick wall

What is half brick wall Chaine parallèle muscle

Chaine parallèle muscle Natural capital

Natural capital Apwh course and exam description

Apwh course and exam description Australia major natural resources

Australia major natural resources Japan major natural resources

Japan major natural resources Name the basic parts of the nail unit

Name the basic parts of the nail unit Natural history and spectrum of disease

Natural history and spectrum of disease Natural hazards vs natural disasters

Natural hazards vs natural disasters Higher history course specification

Higher history course specification The plastic pink flamingo: a natural history

The plastic pink flamingo: a natural history Natural history of disease adalah

Natural history of disease adalah Prepathogenesis phase

Prepathogenesis phase Explain the natural history of disease

Explain the natural history of disease Natural history of disease is best studied by

Natural history of disease is best studied by British museum of natural history

British museum of natural history