Climate Change 101 Climate Change Training Module Climate

- Slides: 59

Climate Change 101 Climate Change Training Module Climate Change and Public Health 101 MN Climate & Health Program Minnesota Department of Health Environmental Impacts Analysis Unit October 2012 625 Robert Street North PO Box 64975 St. Paul, MN 55164 -0975

Notice MDH developed this presentation based on scientific research published in peer-reviewed journals. References for information can be found in the relevant slides and/or at the end of the presentation. 2

Outline • Climate Change in Minnesota • Health Impacts of Climate – Extreme Heat Events – Air Quality: Pollutants and Allergens – Flooding and Drought – Other Impacts • The High Cost of Disasters • The Role of Public Health 3

Definitions § Weather – conditions of the atmosphere over a short period of time § Climate – conditions of the atmosphere over long periods of time (30 - year standard averaging period) 4

Definitions § Adaptation – efforts to anticipate and prepare for the effects of climate change, and thereby to reduce the associated health burden § Mitigation – efforts to slow, stabilize, or reverse climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions 5

Outline • Climate Change in Minnesota • Health Impacts of Climate – Extreme Heat Events – Air Quality: Pollutants and Allergens – Flooding and Drought – Other Impacts • The High Cost of Disasters • The Role of Public Health 6

Observed Climate Changes There have been three recent significant observed climate trends in Minnesota: § The average temperature is increasing § The average number of days with a high dew point may be increasing § The character of precipitation is changing 7

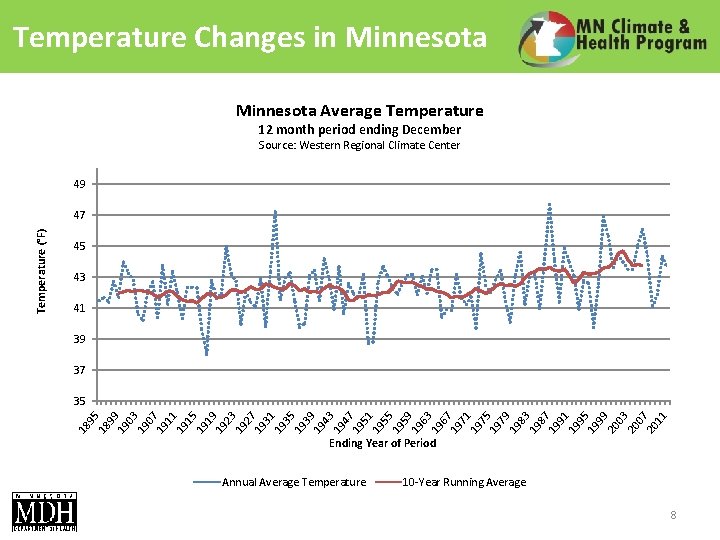

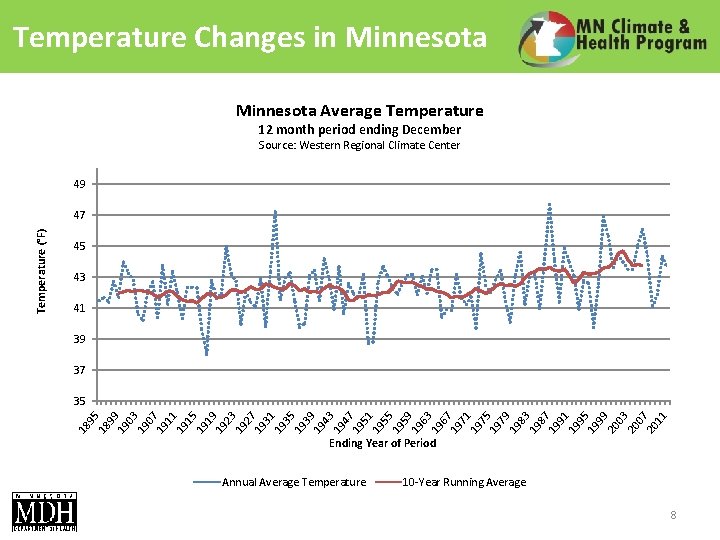

Temperature Changes in Minnesota Average Temperature 12 month period ending December Source: Western Regional Climate Center 49 45 43 41 39 37 35 18 99 19 03 19 07 19 11 19 15 19 19 19 23 19 27 19 31 19 35 19 39 19 43 19 47 19 51 19 55 19 59 19 63 19 67 19 71 19 75 19 79 19 83 19 87 19 91 19 95 19 99 20 03 20 07 20 11 Temperature (°F) 47 Ending Year of Period Annual Average Temperature 10 -Year Running Average 8

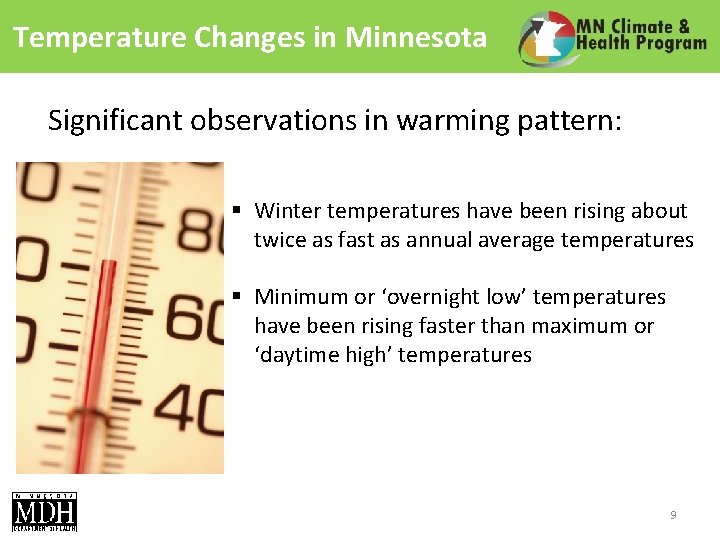

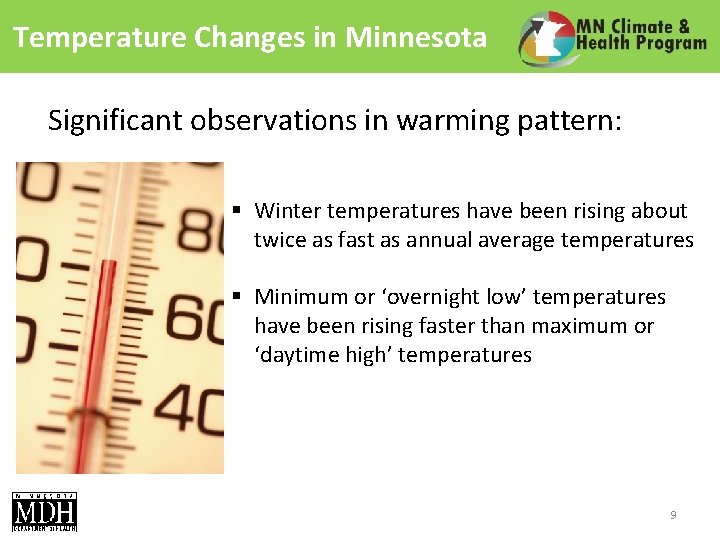

Temperature Changes in Minnesota Significant observations in warming pattern: § Winter temperatures have been rising about twice as fast as annual average temperatures § Minimum or ‘overnight low’ temperatures have been rising faster than maximum or ‘daytime high’ temperatures 9

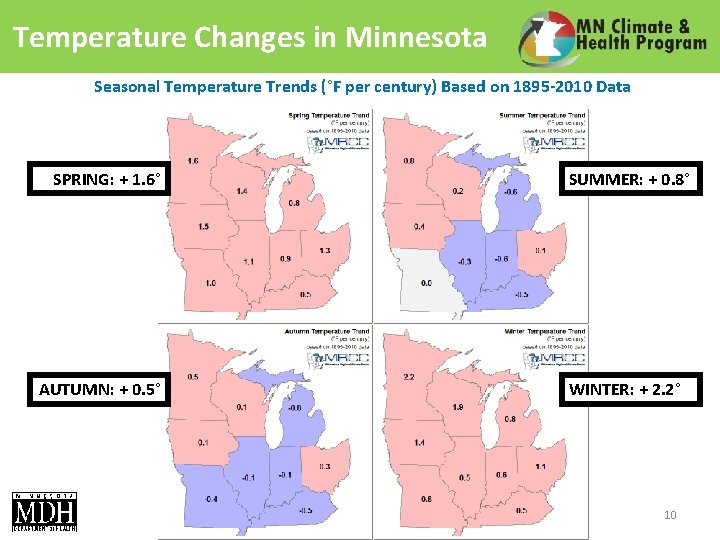

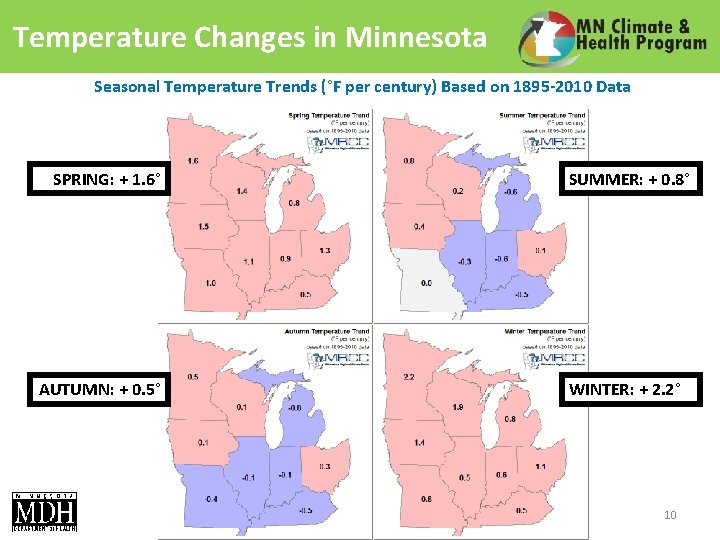

Temperature Changes in Minnesota Seasonal Temperature Trends (°F per century) Based on 1895 -2010 Data SPRING: + 1. 6° AUTUMN: + 0. 5° SUMMER: + 0. 8° WINTER: + 2. 2° 10

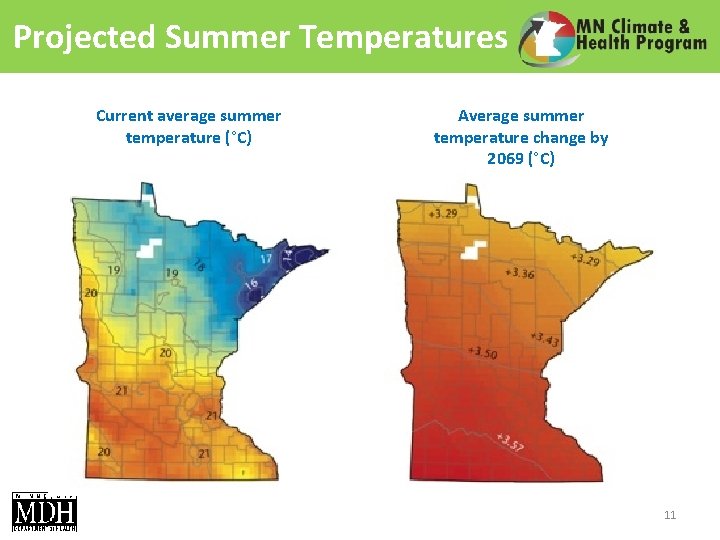

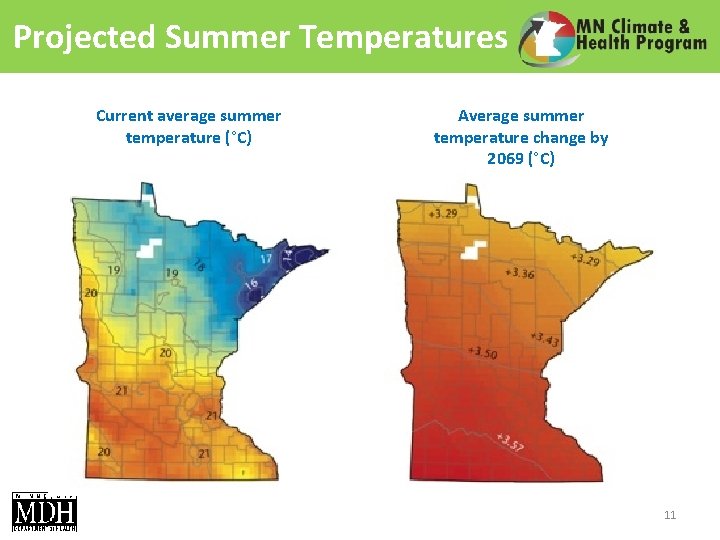

Projected Summer Temperatures Current average summer temperature (°C) Average summer temperature change by 2069 (°C) 11

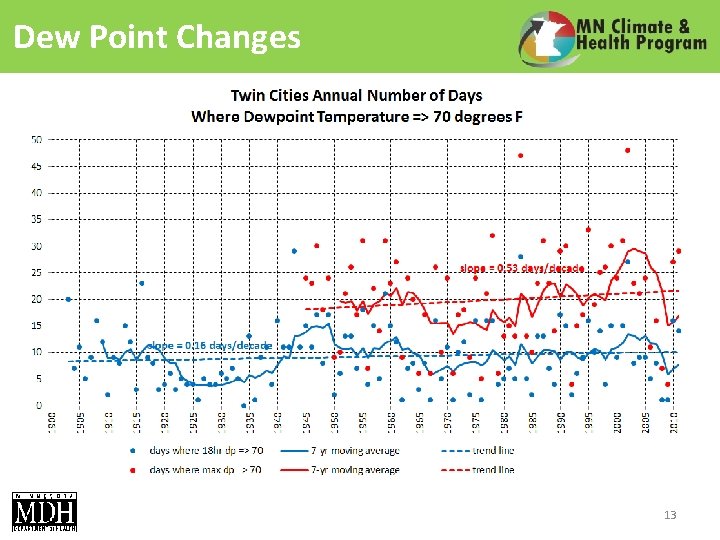

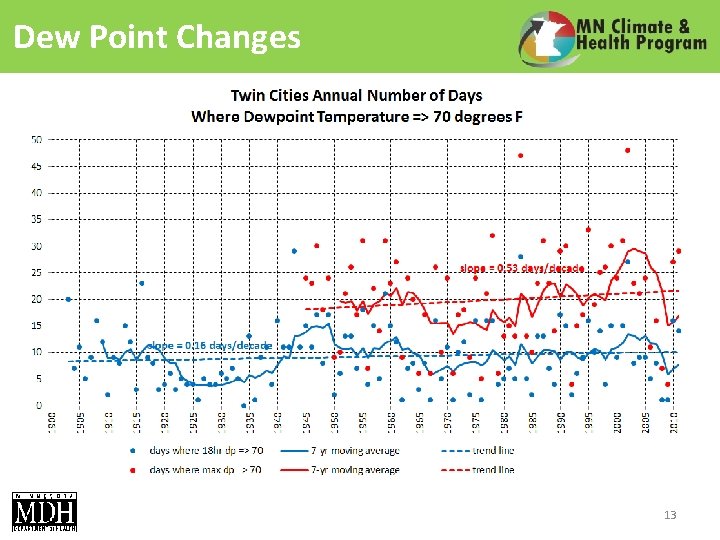

Dew Point Changes § Dew point – a measure of water vapor in the air § A high dew point makes it more difficult for sweat to evaporate off the skin, which is one of the main mechanisms the body uses to cool itself § The number of days with high dew point temperatures (≥ 70°F) may be increasing in Minnesota 12

Dew Point Changes 13

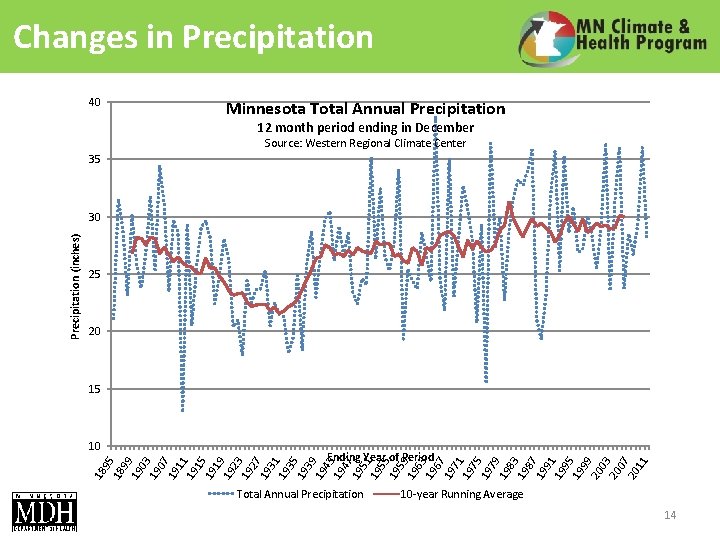

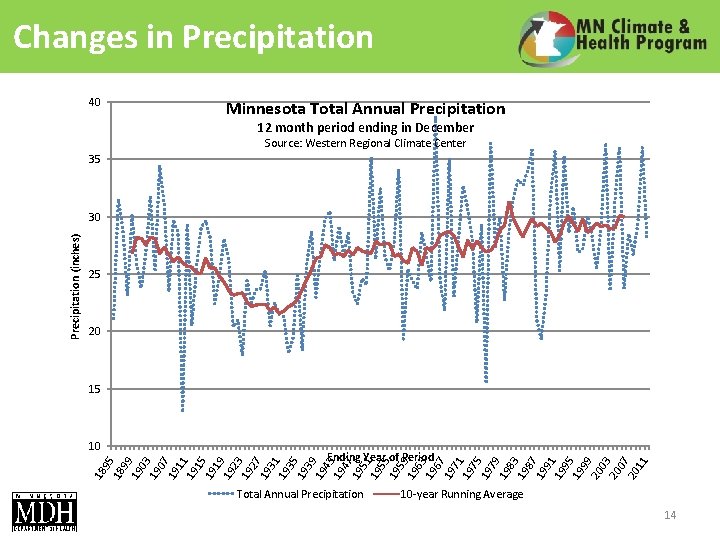

Changes in Precipitation 40 Minnesota Total Annual Precipitation 12 month period ending in December Source: Western Regional Climate Center 35 25 20 15 Ending Year of Period 95 18 99 19 03 19 07 19 11 19 15 19 19 19 23 19 27 19 31 19 35 19 39 19 43 19 47 19 51 19 55 19 59 19 63 19 67 19 71 19 75 19 79 19 83 19 87 19 91 19 95 19 99 20 03 20 07 20 11 10 18 Precipitation (inches) 30 Total Annual Precipitation 10 -year Running Average 14

Changes in Precipitation in Minnesota is changing: § More localized, heavy precipitations events § Potential to cause both increased flooding and drought 15

Outline • Climate Change in Minnesota • Health Impacts of Climate – Extreme Heat Events – Air Quality: Pollutants and Allergens – Flooding and Drought – Other Impacts • The High Cost of Disasters • The Role of Public Health 16

Extreme Heat Events An extreme heat event is characterized by weather that is substantially hotter and/or more humid for a particular location at a particular time 17

Extreme Heat Extreme heat events can cause: § Heat tetany (hyperventilation) § Heat rash § Heat cramps § Heat exhaustion § Heat edema (swelling) § Heat syncope (fainting) § Heat stroke § Death 18

Extreme Heat Risk Factors § § § § § Lack of air conditioning in home Low socioeconomic status Living in urban areas Living in topmost floor of a dwelling Living in nursing homes or being bedridden Living alone or a lack of social or family ties Prolonged sun exposure Drinking alcohol Exercising outside on warm days 19

Extreme Heat Vulnerable Populations § Everyone § Elderly persons 65 years and older § Especially those who live alone § Children § Persons with pre-existing disease conditions § Persons taking certain medications § Athletes § Outdoor workers § Homeless 20

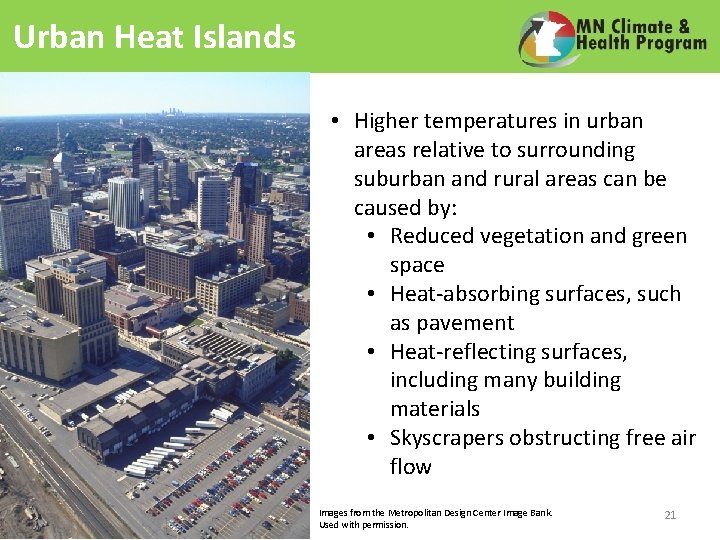

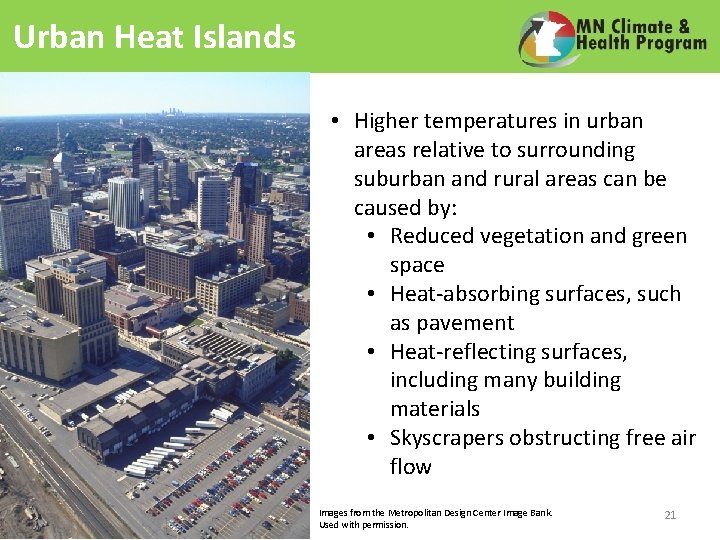

Urban Heat Islands • Higher temperatures in urban areas relative to surrounding suburban and rural areas can be caused by: • Reduced vegetation and green space • Heat-absorbing surfaces, such as pavement • Heat-reflecting surfaces, including many building materials • Skyscrapers obstructing free air flow Images from the Metropolitan Design Center Image Bank. Used with permission. 21

Outline • Climate Change in Minnesota • Health Impacts of Climate – Extreme Heat Events – Air Quality: Pollutants and Allergens – Flooding and Drought – Other Impacts • The High Cost of Disasters • The Role of Public Health 22

Air Pollutants and Allergens Climate change may affect exposures to air pollutants by: § Creating both more windiness and more air stagnation events § Increasing temperatures which. . . § Image from the Metropolitan Design Center Image Bank. Used with permission. § Increase pollution from fossil fuel combustion to meet electricity demand for increased air conditioner use § Increase production of natural sources of air pollutant emissions § Increase formation of ozone Lengthening the allergy season, creating more potent allergens 23

Air Pollutants and Allergens Ground-Level Ozone Health Impacts Populations at Risk Effects of acute exposure: • Acute exposure to elevated ozone can lead to hospitalization or death Due to increased exposure: • Healthy people, especially athletes and outdoor workers in landscape and construction who may be exposed to higher levels of ozone for longer periods of time on high pollution days Effect of long-term exposure: • Decreased lung function and new-onset asthma • Elevated ozone can exacerbate other conditions, such as asthma and allergies Due to sensitivity: • Persons with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases • Older adults and children 24

Air Pollutants and Allergens Particulate Matter Health Impacts Populations at Risk Effects of acute exposure: • Short-term decrease in lung function • Exacerbation of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases • Hospitalization and death Due to increased exposure: • Persons living or working in urban areas, especially near high-traffic corridors and/or stationary sources of PM (such as factories or power plants) Effect of long-term exposure: • Respiratory and cardiovascular diseases • Cardiopulmonary and lung cancer deaths Due to sensitivity: • Persons with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases • Elderly and children • Persons with asthma and/or allergies 25

Air Pollutants and Allergens Climate change impact on allergenic pollen: • Increased pollen production • Longer pollen season • Increased potency of airborne allergens • Proliferation of weedy plant species that are known producers of allergenic pollen • Introduction of new allergenproducing plant species 26

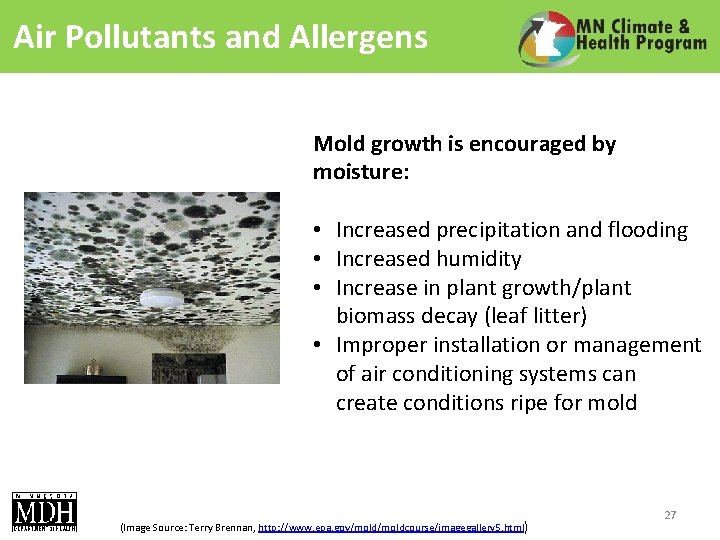

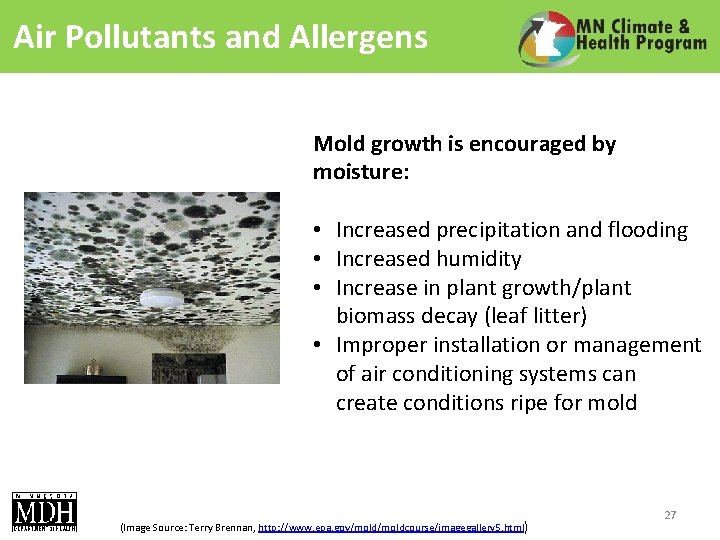

Air Pollutants and Allergens Mold growth is encouraged by moisture: • Increased precipitation and flooding • Increased humidity • Increase in plant growth/plant biomass decay (leaf litter) • Improper installation or management of air conditioning systems can create conditions ripe for mold (Image Source: Terry Brennan, http: //www. epa. gov/moldcourse/imagegallery 5. html) 27

Outline • Climate Change in Minnesota • Health Impacts of Climate – Extreme Heat Events – Air Quality: Pollutants and Allergens – Flooding and Drought – Other Impacts • The High Cost of Disasters • The Role of Public Health 28

Flooding On average, the overall rainfall in Minnesota is increasing. In Minnesota, the frequency of storms with 3 or more inches of rainfall has increased 104% in the last 50 years. Examples of severe floods in Minnesota’s history include: • April 1997: Red River Valley • August 2007: Southeast Minnesota • June 2012: Duluth 29

Flooding Health Impacts §physical injuries (including drowning) §allergies (mold) §food and water-borne illnesses §food security §displacement §mental health issues §interruption of emergency services 30

Drought Changing natural and social factors play a role in how drought affects society, economy, and environment. Factors include: • Timing of drought • Temperature • Population density and growth • Development and implementation of water supply technology • Land use patterns 31

Drought Health Impacts • Reduced lake and wetland levels and stream flows • Potential concentration of pollutants • Decreased water supply for drinking and agriculture • Negative effects on soil moisture and crop progress will impact food security • Increased risk of wildfires 32

Outline • Climate Change in Minnesota • Health Impacts of Climate – Extreme Heat Events – Air Quality: Pollutants and Allergens – Flooding and Drought – Other Impacts • The High Cost of Disasters • The Role of Public Health 33

Other Impacts of Public Health Concern Vectorborne Diseases Climate changes such as warmer temperatures, increased rainfall, longer warm season and less severe winters can impact the range and incidence of vectorborne disease. Risk is also impacted by land use, population density, and human behavior. Black-legged ticks (“deer ticks”), which carry Lyme disease, are most active on warm, humid days. They are also most abundant in wooded or brushy areas with abundant small animals and deer. If those areas are one where many people live, work, or visit for recreation, the incidence of tick-borne disease can be high. For more information on climate and vectorborne disease, visit: http: //www. health. state. mn. us/divs/idepc/dtopics/vectorborne/climate. html 34

Other Impacts of Public Health Concern Power Outages • Demand for electricity increases in warmer climates in order to air condition homes and businesses. • Increased temperatures may reduce the efficiency of power production in facilities that require water for cooling. • Severe storms and flooding can interrupt power service through damaged and destroyed infrastructure • Brownouts: intentionally reduced voltage in a power supply system used for load reduction in an emergency; may prevent black outs but can have other impacts 35

Outline • Climate Change in Minnesota • Health Impacts of Climate – Extreme Heat Events – Air Quality: Pollutants and Allergens – Flooding and Drought – Other Impacts • The High Cost of Disasters • The Role of Public Health 36

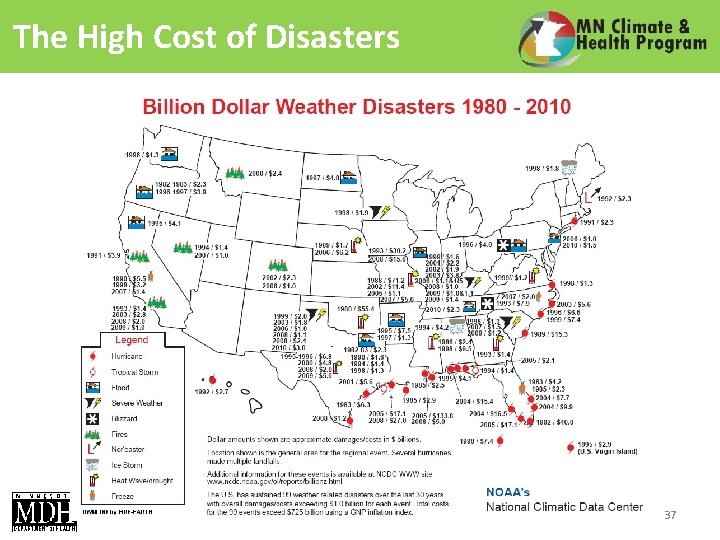

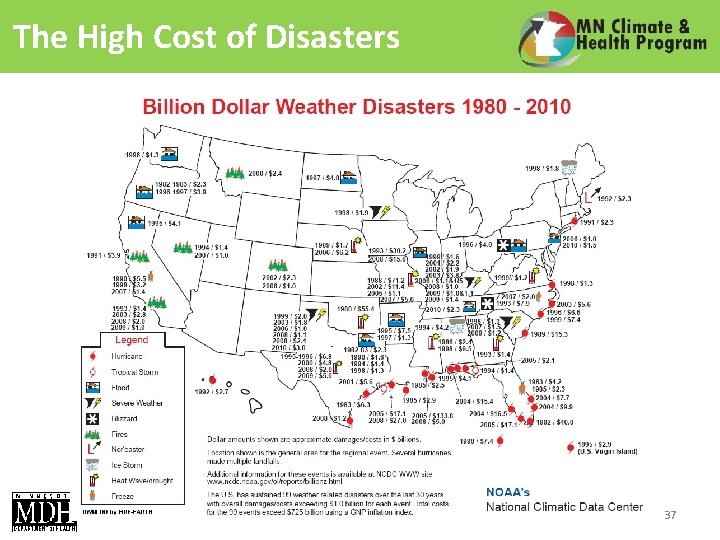

The High Cost of Disasters 37

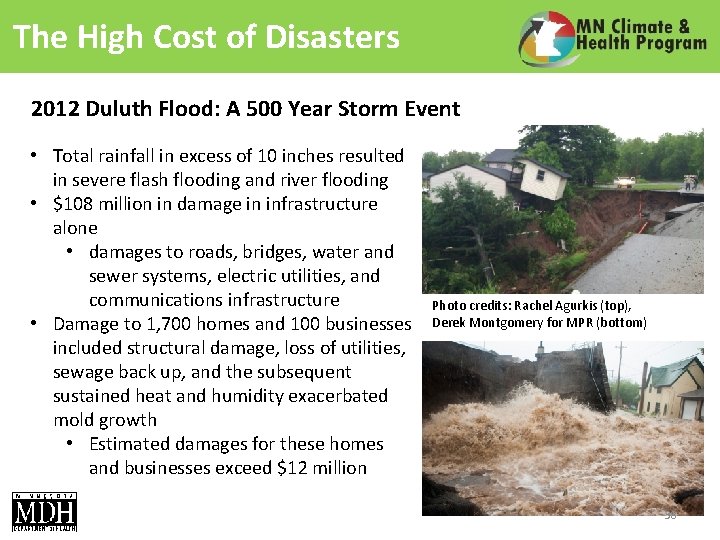

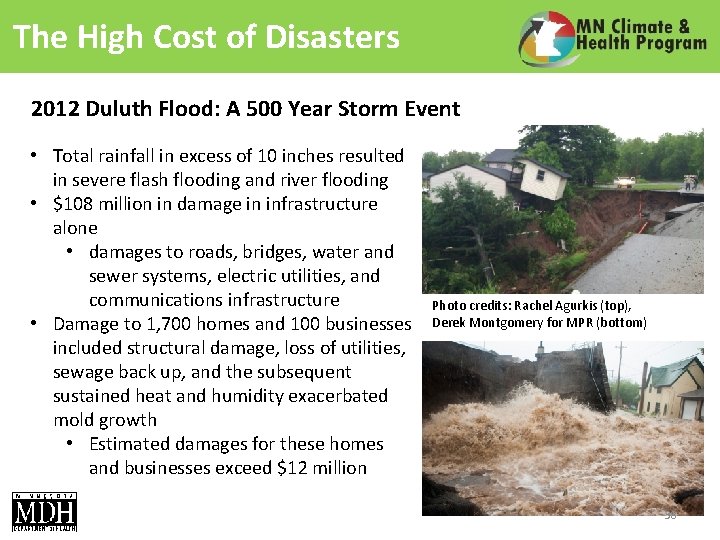

The High Cost of Disasters 2012 Duluth Flood: A 500 Year Storm Event • Total rainfall in excess of 10 inches resulted in severe flash flooding and river flooding • $108 million in damage in infrastructure alone • damages to roads, bridges, water and sewer systems, electric utilities, and communications infrastructure • Damage to 1, 700 homes and 100 businesses included structural damage, loss of utilities, sewage back up, and the subsequent sustained heat and humidity exacerbated mold growth • Estimated damages for these homes and businesses exceed $12 million Photo credits: Rachel Agurkis (top), Derek Montgomery for MPR (bottom) 38

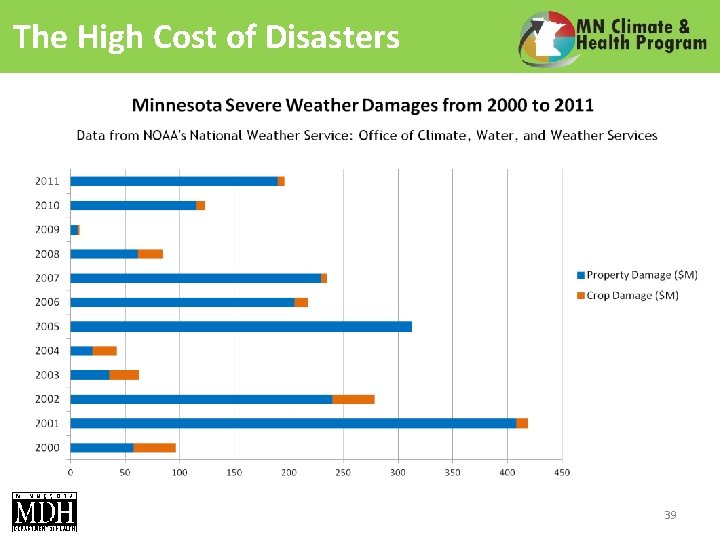

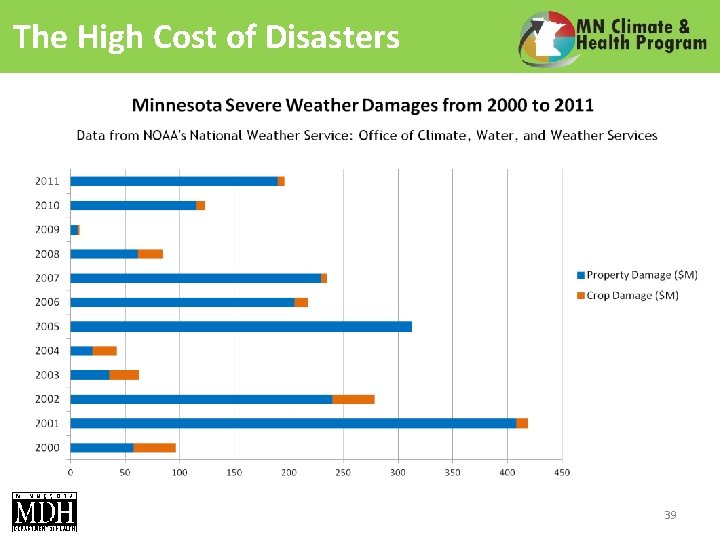

The High Cost of Disasters 39

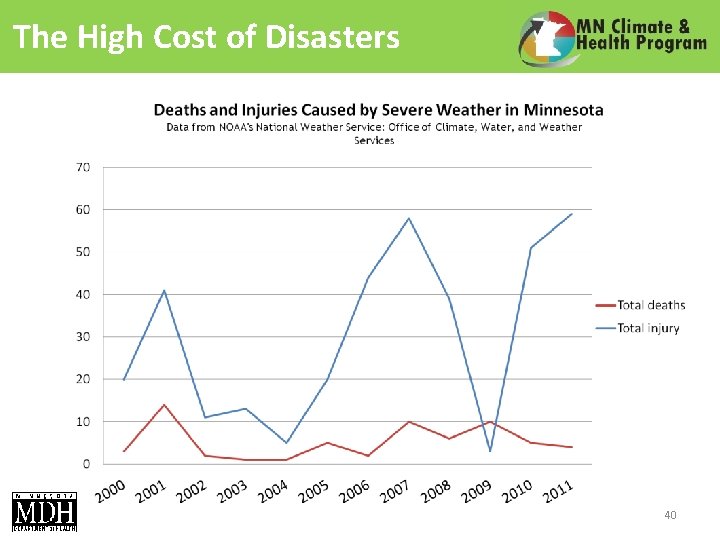

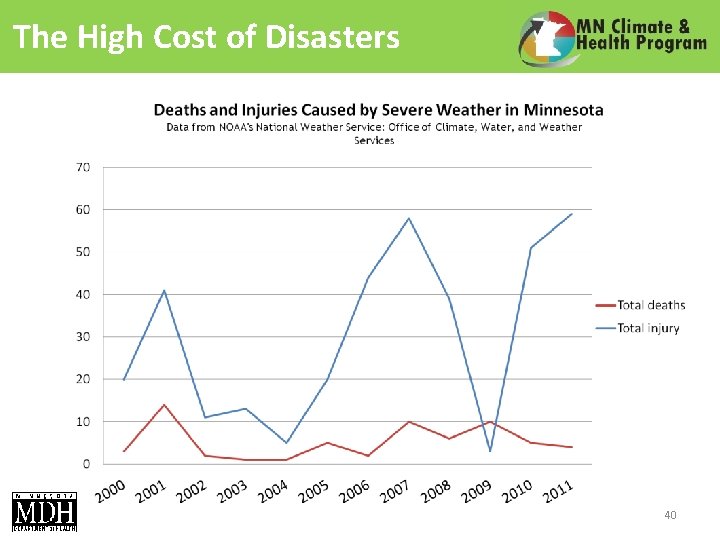

The High Cost of Disasters 40

The High Cost of Disasters • Recent case study analysis of 6 climate-related disasters estimated the associated health care costs: • US Ozone Air Pollution, 2000 -2002 • California Heat Wave, 2006 • Florida Hurricane Season, 2004 • Louisiana West Nile Virus Outbreak, 2002 • North Dakota Red River Flooding, 2009 • Southern California Wildfires, 2003 • The associated health care costs alone topped $14 billion • 1, 689 premature deaths • 8, 992 hospitalizations • 21, 113 emergency visits • 734, 398 outpatient visits 41

Outline • Climate Change in Minnesota • Health Impacts of Climate – Extreme Heat Events – Air Quality: Pollutants and Allergens – Flooding and Drought – Other Impacts • The High Cost of Disasters • The Role of Public Health 42

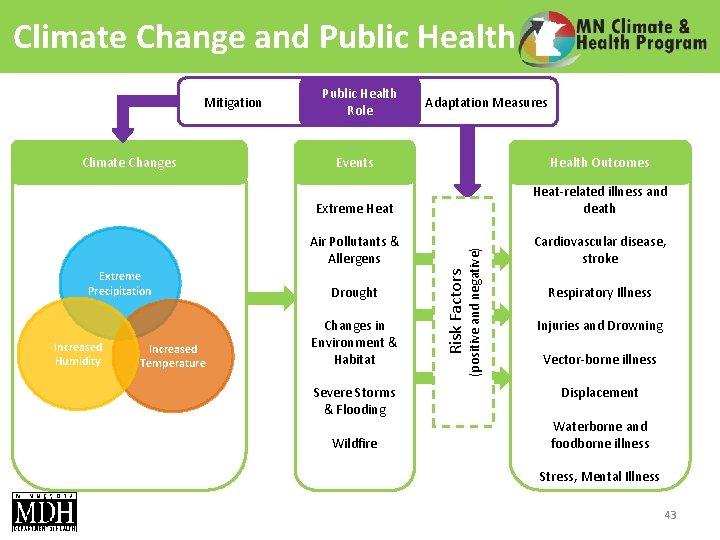

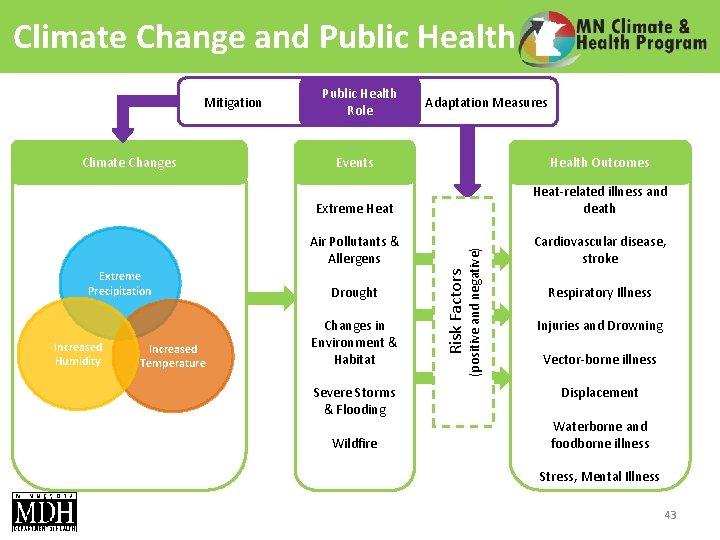

Climate Change and Public Health Extreme Precipitation Increased Humidity Increased Temperature Adaptation Measures Events Health Outcomes Extreme Heat-related illness and death Air Pollutants & Allergens Cardiovascular disease, stroke Drought Changes in Environment & Habitat Severe Storms & Flooding Wildfire (positive and negative) Climate Changes Public Health Role Risk Factors Mitigation Respiratory Illness Injuries and Drowning Vector-borne illness Displacement Waterborne and foodborne illness Stress, Mental Illness 43

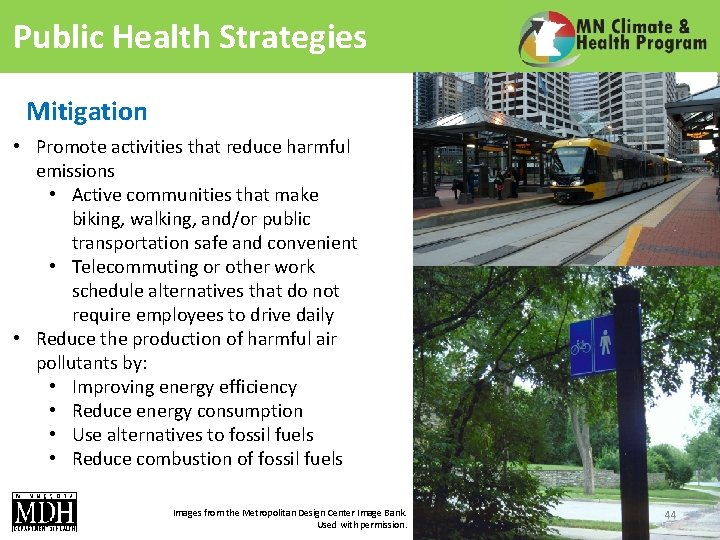

Public Health Strategies Mitigation • Promote activities that reduce harmful emissions • Active communities that make biking, walking, and/or public transportation safe and convenient • Telecommuting or other work schedule alternatives that do not require employees to drive daily • Reduce the production of harmful air pollutants by: • Improving energy efficiency • Reduce energy consumption • Use alternatives to fossil fuels • Reduce combustion of fossil fuels Images from the Metropolitan Design Center Image Bank. Used with permission. 44

Public Health Strategies Adaptation • Monitoring conditions and providing useful information to the public • Extreme heat events • Air Quality Index • Disasters • Community and infrastructure planning • Retention ponds and wetlands increase water storage • Pervious surfaces and rain gardens increase infiltration, reducing runoff • Increasing capacity of stormwater systems • Reduce the urban heat island effect by maintaining green space in urban areas • Emergency Preparedness • Robust all-hazards plans that include annexes for severe storms, extreme heat, power loss • Identification and understanding of high-risk and vulnerable populations 45

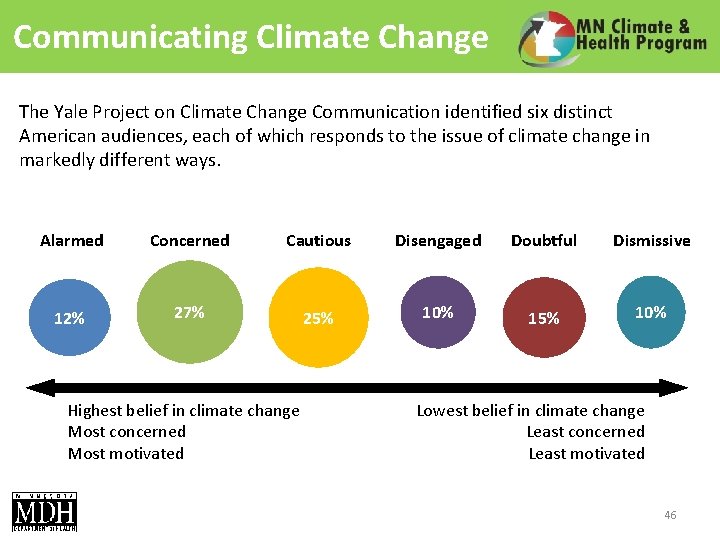

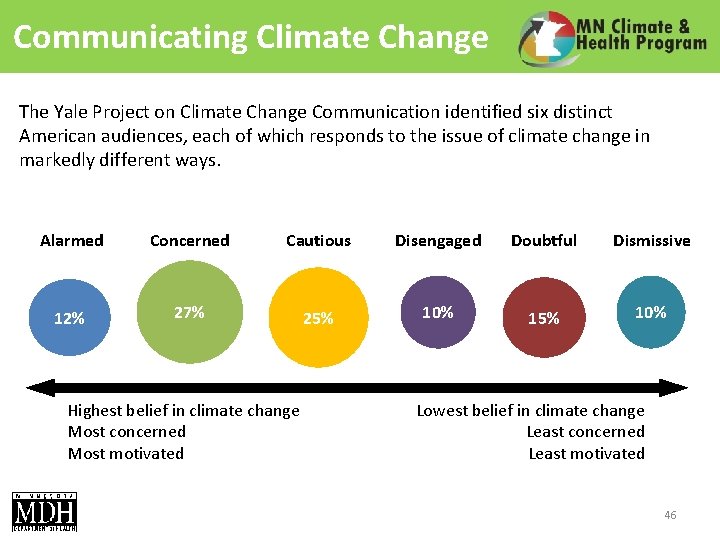

Communicating Climate Change The Yale Project on Climate Change Communication identified six distinct American audiences, each of which responds to the issue of climate change in markedly different ways. Alarmed Concerned Cautious Disengaged Doubtful Dismissive 12% 27% 25% 10% 15% 10% Highest belief in climate change Most concerned Most motivated Lowest belief in climate change Least concerned Least motivated 46

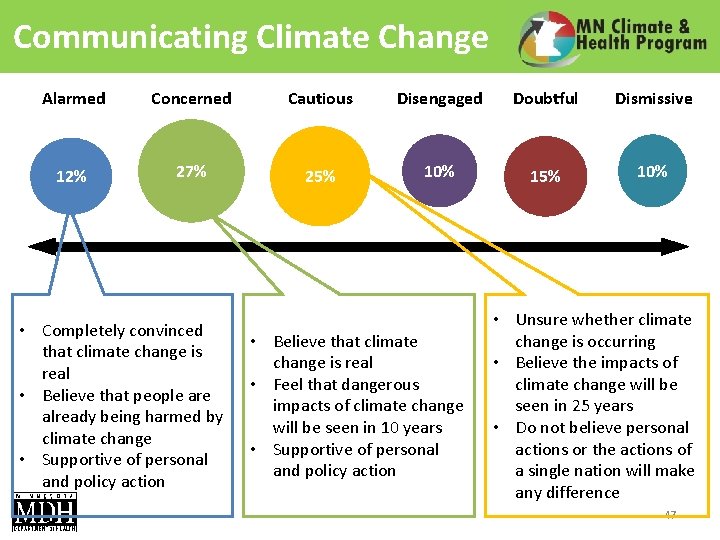

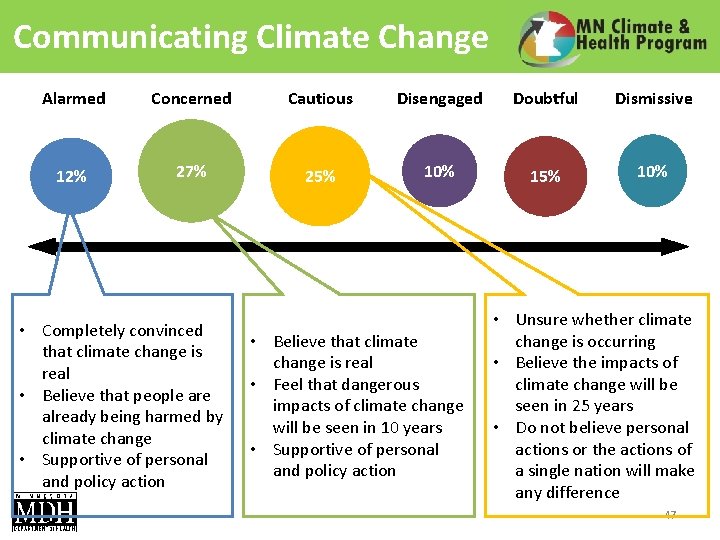

Communicating Climate Change Alarmed Concerned Cautious Disengaged Doubtful Dismissive 12% 27% 25% 10% 15% 10% • Completely convinced that climate change is real • Believe that people are already being harmed by climate change • Supportive of personal and policy action • Believe that climate change is real • Feel that dangerous impacts of climate change will be seen in 10 years • Supportive of personal and policy action • Unsure whether climate change is occurring • Believe the impacts of climate change will be seen in 25 years • Do not believe personal actions or the actions of a single nation will make any difference 47

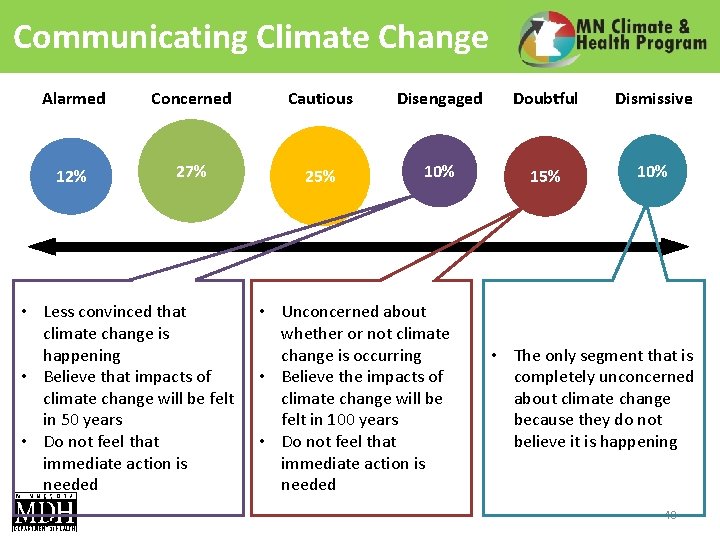

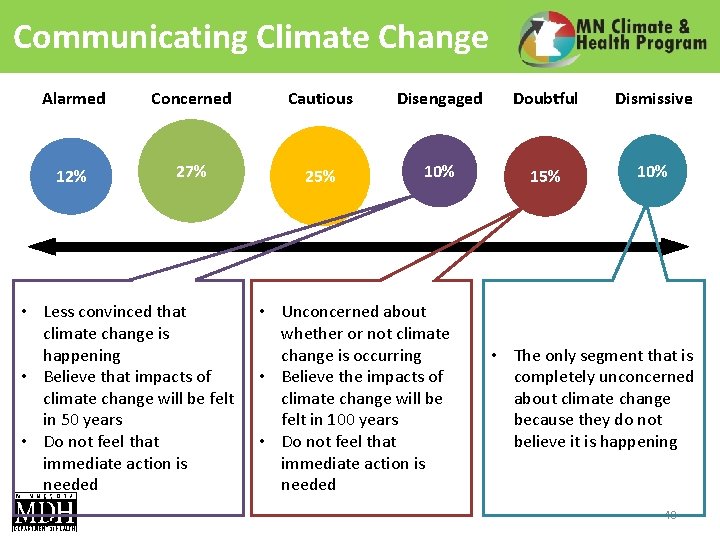

Communicating Climate Change Alarmed Concerned Cautious Disengaged Doubtful Dismissive 12% 27% 25% 10% 15% 10% • Less convinced that climate change is happening • Believe that impacts of climate change will be felt in 50 years • Do not feel that immediate action is needed • Unconcerned about whether or not climate change is occurring • Believe the impacts of climate change will be felt in 100 years • Do not feel that immediate action is needed • The only segment that is completely unconcerned about climate change because they do not believe it is happening 48

Communicating Climate Change • Most Americans think of climate change in geographically and temporally distant terms • Few Americans, without prompting, report that climate change has any connection to human health 49

Communicating Climate Change Communications Strategies • Frame climate change as a human health issue • Localize climate change • Emphasize the health cobenefits associated with climate change action 50

Summary • Minnesota’s climate is changing: – Increases in temperature – Increases in high dew point temperatures – Increases in extreme precipitations events • Climate changes can lead to a variety of events with serious health impacts – Extreme Heat – Air pollution and allergies – Flooding and drought • Public health awareness, education, and mitigation and/or adaptation can reduce the health impacts of climate change 51

Climate Change Training Modules Other modules in this series include: • Extreme Heat Events, Climate Change and Public Health • Air Quality, Climate Change and Public Health • Water Quality and Quantity, Climate Change and Public Health These can all be found on the MN Climate and Health Program’s website: http: //www. health. state. mn. us/divs/climatechange/index. html Upcoming topics include: • Agriculture • Mental Health 52

Acknowledgements This work was supported by cooperative agreement 5 UE 1 EH 000738 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 53

Thank You Questions? Contact Minnesota Climate and Health Program: 651 -201 -4898 651 -201 -5759 TTY health. climatechange@state. mn. us http: //www. health. state. mn. us/divs/climatechange/index. html October 23, 2012 54

References Adcock MP, Bines WH, Smith FW (2000), “Heat-Related Illnesses, Deaths, and Risk Factors – Cincinnati and Dayton, Ohio, 1999, and United States, 19791997, ” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: http: //www. cdc. gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm 4921 a 3. htm. Amann, Swart, Raes, Tuinstra. 2004. A good climate for clean air: linkages between climate change and air pollution. Climatic Change 66: 263– 269. Anderson GB and Bell ML (2011), “Heat waves in the United States: Mortality risk during heat waves and effect modification by heat wave characteristics in 43 US communities, ” Environmental Health Perspectives, 119(2), 210. Bernard SM, Samet JM, Grambsch A, Ebi KL, Romieu I. 2001. The potential impacts of climate variability and change on air pollution-related health effects in the United States. Environmental Health Perspectives Vol 109, Supplement 2, pp 199 -209. California Department of Public Health. 2008. Public Health Climate Change Adaptation Strategy for California. Available online: http: //www. cdph. ca. gov/programs/CCDPHP/Documents/CA_Public_Health_Adaptation_Strategies_final. pdf Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2009), “Extreme Heat: A Prevention Guide to Promote Your Personal Health and Safety, ” Available online: http: //www. bt. cdc. gov/disasters/extremeheat/heat_guide. asp Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2012. Climate and Health, Aero-allergens (website). Accessed May 8, 2012: http: //www. cdc. gov/climatechange/effects/allergens. htm Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Environmental Protection Agency, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency, and America Water Works Association. 2010. "When Every Drop Counts: Protecting Public Health During Drought Conditions-- A Guide for Public Health Professionals. " Atlanta, US Department of Health and Human Services. Clean Air Taskforce. 2010. The Toll from Coal: An Updated Assessment of Death and Disease from America’s Dirtiest Energy Source. Available online: http: //www. catf. us/resources/publications/files/The_Toll_from_Coal. pdf Climate Change Science Program (CCSP). 2008. Analyses of the effects of global change on human health and welfare and human systems. A Report by the U. S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research. [Gamble JL (ed. ), Ebi KL, Sussman FG, Wilbanks TJ, (Authors)]. U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA. Governor Dayton, M. 2012. Individual Assistance request to President Barak Obama. July 19, 2012. Department of Natural Resources (DNR). 2000. Minnesota’s Water Supply: Natural Conditions and Human Impacts. Available online: http: //files. dnr. state. mn. us/publications/waters/mn_water_supply. pdf ______. 2011 a. Drought. Available online: http: //www. dnr. state. mn. us/climate/drought/index. html ______. 2011 b. Lake Level Minnesota. Available online: http: //www. dnr. state. mn. us/climate/waterlevels/lakes/ index. html Ebi KL, Balbus J, Kinney PL, Lipp E, Mills D, O’Neill MS, and Wilson M. 2008. Effects of global change on human health. In: Analyses of the Effects of Global Change on Human Health and Welfare and Human Systems [Gamble JL (ed. ), Ebi KL, Sussman FG, and Wilbanks TJ (authors)]. Synthesis and Assessment Product 4. 6. U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, pp. 39 -87. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). 2012). Floods. Available online: http: //www. ready. gov/floods Frumkin et. al, 2008. Framing Public Health Matters, Climate Change: the Public Health Response, Howard Frumkin, MD, DRPH, Jeremy Hess, MD, MPH, George Luber, Ph. D, Josephine Malilay, Ph. D, MPH, and Michael Mc. Geehin, Ph. D, MSPH, American Journal of Public Health, March 2008, Vol. 98, No. 3, pp 435 -445. Galatowitsch S, Frelich L, and Phillips-Mao L (2009), “Regional Climate Change Adaptation Strategies for Biodiversity Conservation in a Midcontinental Region of North America, ” Biological Conservation 142: 2012– 2022. 55

References Horstmeyer, SL. 2008. Relative humidity. . . Relative to what? The dew point temperature. . . a better approach. Available online: http: //www. shorstmeyer. com/wxfaqs/humidity. html Jacob DJ, Winner DA. 2009. Effect of climate change on air quality. Atmospheric Environment , Vol 34, pp. 51 -63. Kessler R. 2011. Stormwater Strategies: Cities prepare aging infrastructure for climate change. Environmental Health Perspectives. Vol 119, Num 12. Knowlton K, Rotkin-Ellman M, Geballe L, Max W, Solomon GM. 2011. “Six Climate Change-Related Events in The United States Accounted for About $14 Billion in Lost Lives and Health Costs. ” Health Affairs, Vol 30, No. 11, pp. 2167 -76. Kovats RS and Hajat S (2008), “Heat stress and public health: a critical review, ” Annu Rev Public Health; 29: 41 -55. Kundzewicz ZW, Mata LJ, Arnell NW, Döll P, Kabat P, Jiménez B, Miller KA, Oki T, Sen Z and Shiklomanov IA. 2007. Freshwater resources and their management. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, [Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, van der Linden PJ, and Hanson CE(eds. )]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, pp. 617 -652. Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C, Smith N. 2011. “Global Warming’s Six America’s, May 2011. ” Yale University and George Mason University. New Haven, CT: Yale Project on Climate Change Communication. Available online: http: //environment. yale. edu/climate/files/Six. Americas. May 2011. pdf Maibach E, Nisbet M, Weather M. 2011. “Conveying the Human Implications of Climate Change: A Climate Change Communication Primer for Public Health Professionals. ” Fairfax, VA: George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication. Midwestern Regional Climate Center. 2010. Climate Change & Variability in the Midwest. Temperature and Precipitation Trends 1895 – 2010. Available online: http: //mcc. sws. uiuc. edu/climate_midwest/mwclimate_ change. htm Minnesota Department of Health. 2012. Vector-borne Diseases. Available online: http: //www. health. state. mn. us/divs/idepc/dtopics/vectorborne/index. html Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA). 2011. Floods: Minimizing Pollution and Health Risks. Available online: http: //www. pca. state. mn. us/index. php/waste-and-cleanup/cleanup-programs-and-topics/cleanup-programs/emergencyresponse/floods-minimizing-pollution-and-health-risks. html Myers TA, Nisbet MC, Maibach, EW, Leiserowitz AA. 2012. “A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change. ” Climactic Change 113: 1105 -1112. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). 2005. What’s the Difference Between Weather and Climate? Available online: http: //www. nasa. gov/mission_pages/noaa/climate_weather. html National Drought Mitigation Center. 2011. Drought-Ready Communities: A Guide to Community Drought Preparedness. http: //www. drought. unl. edu/portals/0/docs/DRC_Guide. pdf 56

References National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2012 a. National Climactic Data Center, Billion Dollar Weather/Climate Disasters. Available online: http: //www. ncdc. noaa. gov/billions/ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2012 b. Office of Climate, Water, and Weather Services. Available online: http: //www. nws. noaa. gov/os/ National Wildlife Federation. 2010. Extreme Allergies and Global Warming. Available online: www. nwf. org/extremeweather (NWS, 2009 a) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service (June 25, 2009). Retrieved on June 22, 2011 from http: //nws. noaa. gov/glossary/index. php? letter=h (NWS, 2009 b) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service (Modified June 25, 2009). Retrieved on June 22, 2011 from http: //www. epa. gov/heatisld/resources/glossary. htm#u Pope CA, Thun MJ, Namboodiri MM, Dockery DW, Evans JS, Speizer FE, Heath CW. 1995. Particulate air pollution as a predictor of mortality in a prospective study of U. S. adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. vol. 151 no. 3 669 -674 Rogers, CA, PM Wayne, EA Macklin, et al. 2006. Interaction of the onset of spring and elevated atmospheric CO 2 on ragweed pollen production. Environmental Health Perspectives 114: 865 -869. Seeley M. 2012. Climate Trends and Climate Change in Minnesota: A Review. Minnesota State Climatology Office. Available online: http: //climate. umn. edu/seeley/ Shea K et al. 2008. Climate change and allergic disease. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Doi: 10. 1016/j. jaci. 2008. 06. 032 Snyder P (2012), “Islands in the Sun, ” presented January 19, 2012. University of Minnesota Department of Soil, Water, and Climate Spatial Hazard Events and Losses Database for the United States (SHELDUS). Data downloaded April 2012. Available online: http: //webra. cas. sc. edu/hvri/products/sheldus. aspx State Climatology Office. Department of Natural Resources – Division of Ecological and Water Resources and the University of Minnesota – Department of Soil, Water, and Climate. Available online: http: //climate. umn. edu/ Dew Point (http: //climate. umn. edu/doc/twin_cities/mspdewpoint. htm) Dew Point July 19, 2011 Technical Analysis (http: //climate. umn. edu/pdf/july_19_2011_ technical. pdf) Drought Information Resources (http: //www. dnr. state. mn. us/climate/drought/index. html) History Mega-Rain Events in Minnesota (http: //www. climate. umn. edu/doc/journal/mega_rain_events. htm) Union of Concerned Scientists. 2011. Climate Change and Your Health: Rising Temperatures, Worsening Ozone Pollution. Available online: www. ucsusa. org/climateandozonepollution. US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). 2008. A Review of the Impact of Climate Variability and Change on Aeroallergens and Their Associated Effects (Final Report). Available online: http: //www. epa. gov/research/gems/scinews_aeroallergens. htm US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). 2011. Agriculture and Food Supply. Available online: http: //epa. gov/climatechange/effects/agriculture. html US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). 2012. Energy Impacts and Adaptation. Available online: http: //www. epa. gov/climatechange/impactsadaptation/energy. html 57

References US Forest Service Incident Information System. 2011. Pagami Creek Fire. Available online: http: //www. inciweb. org/incident/2534/ US National Hazard Statistics. 2012. Accessed 7/30/2012. Available online: http: //www. nws. noaa. gov/om/hazstats. shtml Western Regional Climate Center. (WRCC) 2011 a. Minnesota Temperature 1890 – 2010: 12 month period ending in December. Generated online November 2011. Available online: http: //www. wrcc. dri. edu/spi/divplot 1 map. html Western Regional Climate Center. (WRCC) 2011 b. Minnesota Precipitation 1890 – 2010: 12 month period ending in December. Generated online November 2011. Available online: http: //www. wrcc. dri. edu/spi/divplot 1 map. html World Health Organization (WHO). 2010. Climate change and health. Fact sheet N° 266. Available online: http: //www. who. int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs 266/en/ Zandlo, Jim 2008. Observing the climate. Minnesota State Climatology Office. Available online: http: //climate. umn. edu/climate. Change. Observed. Nu. htm 58

Image Credits • • • • • • • Slide 4: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 5: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 7: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 9: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 10: Midwest Regional Climate Center Slide 11: Galatowitsch et al. , 2009 Slide 12: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 15: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 17: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 18: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 19: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 20: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 21: Images from Metropolitan Design Center Image Bank. Slide 23: Images from Metropolitan Design Center Image Bank. Slide 26: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 27: Terry Brennan, http: //www. epa. gov/moldcourse/imagegallery 5. html Slide 29: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 30: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 31: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 32: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 35: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 37: NOAA National Climactic Data Center, 2012 Slide 38: Top image from Rachel Agurkis, Bottom image from Derek Montgomery for MPR Slide 41: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 44: Images from Metropolitan Design Center Image Bank. Slide 49: Images from Microsoft Clip Art Slide 50: Images from Microsoft Clip Art 59