ACHA Philadelphia June 4 2010 Amy R Alson

- Slides: 52

ACHA Philadelphia June 4, 2010 Amy R. Alson, MD University of Virginia Elson Student Health Center Charlottesville, Virginia UNDERSTANDING THE PAINS THAT WON’T GO AWAY HOW TO REDUCE THE BURDEN OF PSYCHOSOMATIC ILLNESS AMONG COLLEGE & UNIVERSITY STUDENTS

Learning Objectives Attendees should be able to: 1. Explain the impact of unidentified psychosomatic Illness on the college and university healthcare system. 2. Identify psychosomatic illness commonly seen among college and university students. 3. Describe strategies to effectively treat students with psychosomatic conditions.

Overview The impact of somatoform disorders Diagnostic terms: now and future Pathophysiology & psychology Treatment recommendations Clinical course & prognosis Cases References

Describing the burden Prevalence of somatoform disorders in general practice reported as high as 30% Unexplained chronic pain affects >25% primary care patients Accrued twice the costs for medical care. Utilized twice the services (out and in-patient) Overuse of specialist consultation Unmeasured impact on patients’ academic & social lives

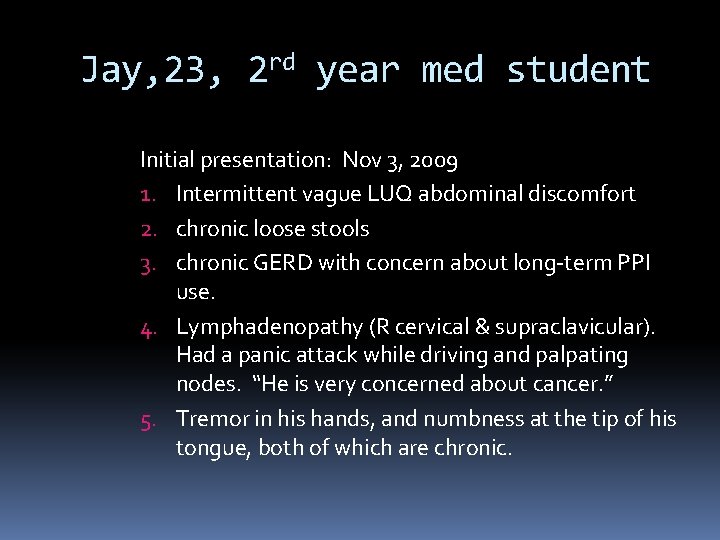

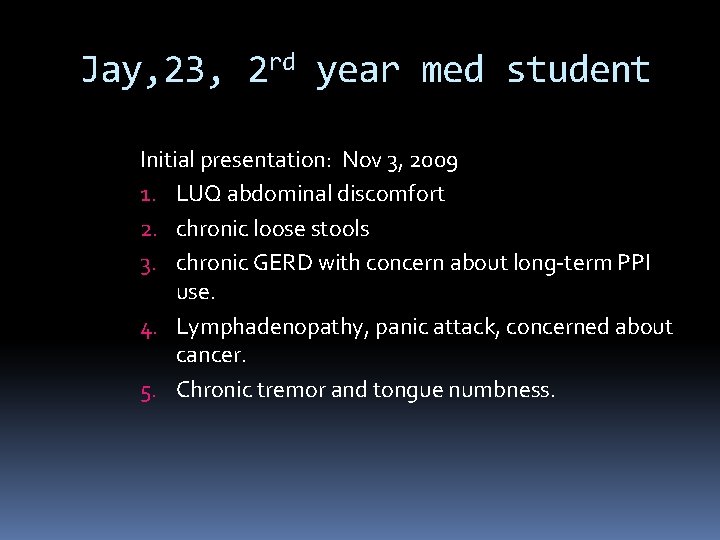

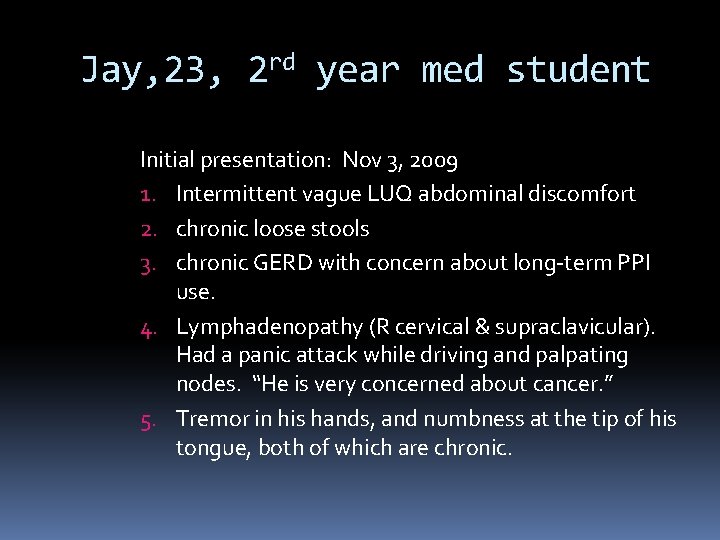

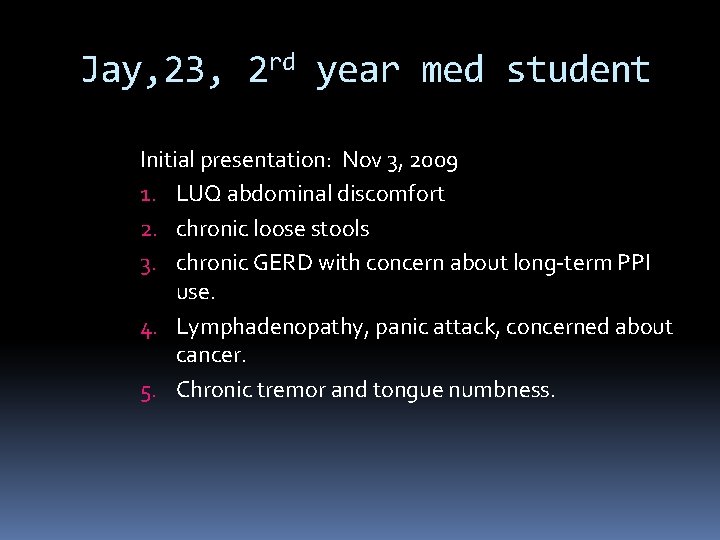

Jay, 23, 2 rd year med student Initial presentation: Nov 3, 2009 1. Intermittent vague LUQ abdominal discomfort 2. chronic loose stools 3. chronic GERD with concern about long-term PPI use. 4. Lymphadenopathy (R cervical & supraclavicular). Had a panic attack while driving and palpating nodes. “He is very concerned about cancer. ” 5. Tremor in his hands, and numbness at the tip of his tongue, both of which are chronic.

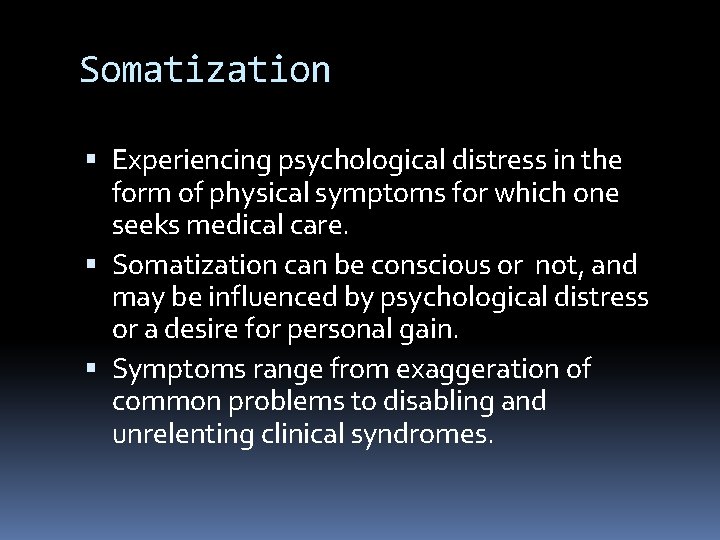

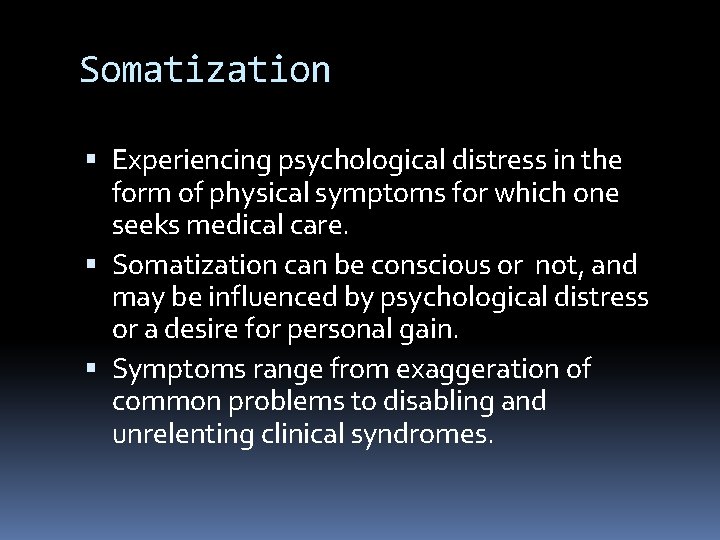

Somatization Experiencing psychological distress in the form of physical symptoms for which one seeks medical care. Somatization can be conscious or not, and may be influenced by psychological distress or a desire for personal gain. Symptoms range from exaggeration of common problems to disabling and unrelenting clinical syndromes.

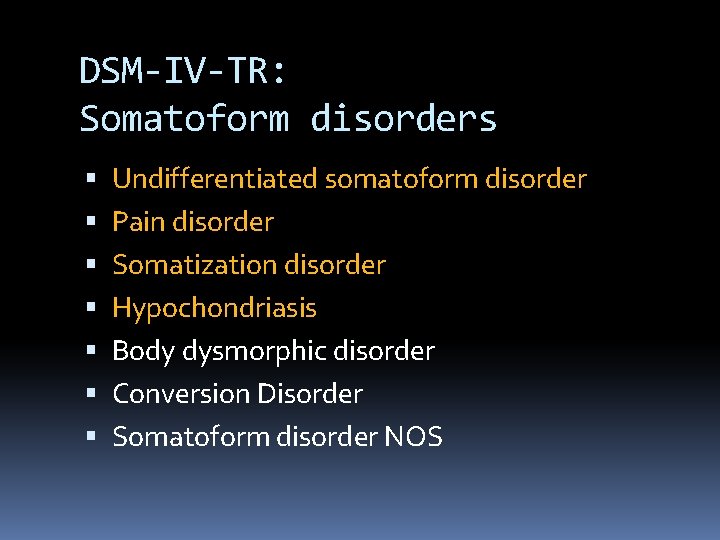

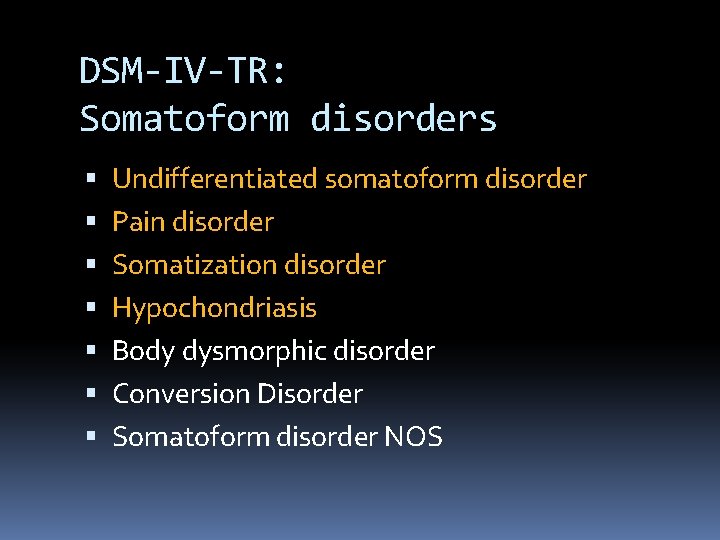

DSM-IV-TR: Somatoform disorders Undifferentiated somatoform disorder Pain disorder Somatization disorder Hypochondriasis Body dysmorphic disorder Conversion Disorder Somatoform disorder NOS

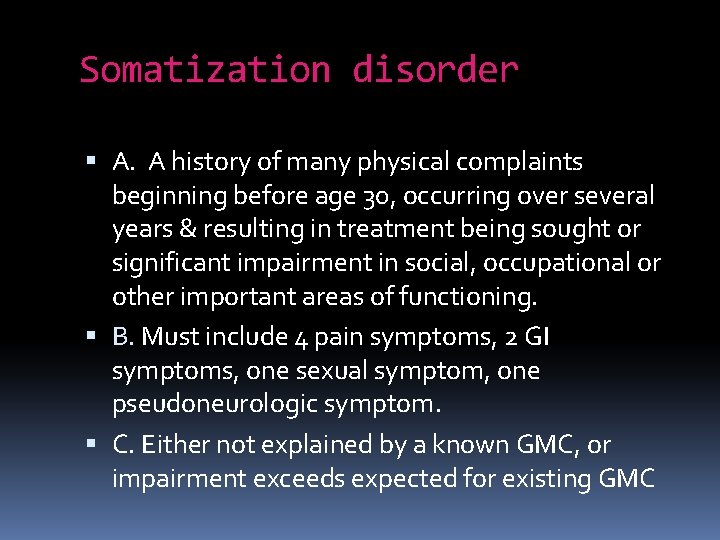

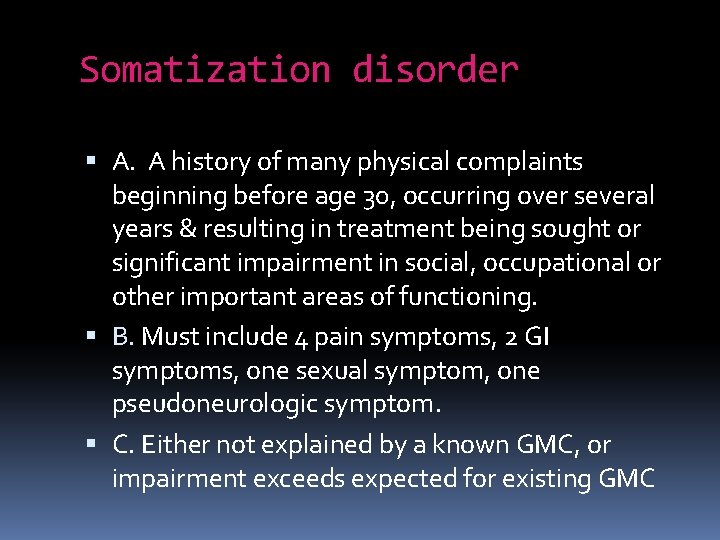

Somatization disorder A. A history of many physical complaints beginning before age 30, occurring over several years & resulting in treatment being sought or significant impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning. B. Must include 4 pain symptoms, 2 GI symptoms, one sexual symptom, one pseudoneurologic symptom. C. Either not explained by a known GMC, or impairment exceeds expected for existing GMC

Somatization disorder Less than 1% of patients with Medically Unexplained Symptoms (MUS) meet criteria for Somatization Disorder. 1 -year prevalence among US adults is 0. 3%.

Hypochondriasis Preoccupation with the fear of having a serious disease based on misinterpretation of bodily symptoms despite appropriate medical evaluation and reassurance. Conviction about illness is not of delusional intensity, and is not restricted to concern about appearance. Preoccupation lasts at least 6 months & causes clinically significant distress or impairment.

Hypochondriasis Male = female prevalence Insight varies among affected patients Commonly co-occurs with anxiety and depressive disorders. Onset is typically later in life than somatization disorder 4 -6% of general medical outpatients

Undifferentiated somatoform disorder: One or more physical symptoms that cause significant distress or impairment in functioning lasting at least 6 months. Pain disorder: Pain in one or more sites, causing significant distress or impairment and associated with psychological factors. May be associated with a psychological factors, or with psychological factors and a GMC. Acute if < 6 months; chronic if 6 months or longer.

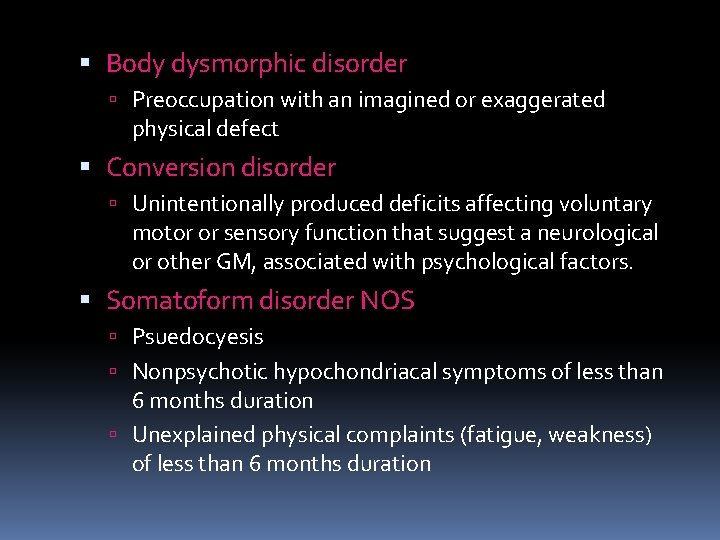

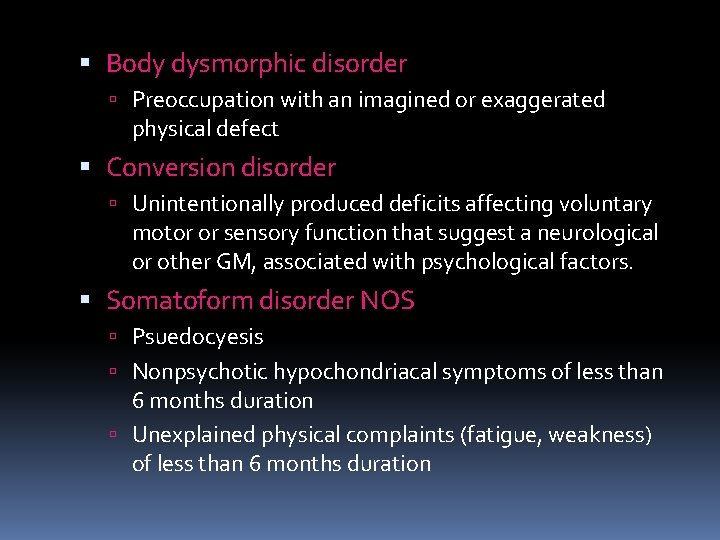

Body dysmorphic disorder Preoccupation with an imagined or exaggerated physical defect Conversion disorder Unintentionally produced deficits affecting voluntary motor or sensory function that suggest a neurological or other GM, associated with psychological factors. Somatoform disorder NOS Psuedocyesis Nonpsychotic hypochondriacal symptoms of less than 6 months duration Unexplained physical complaints (fatigue, weakness) of less than 6 months duration

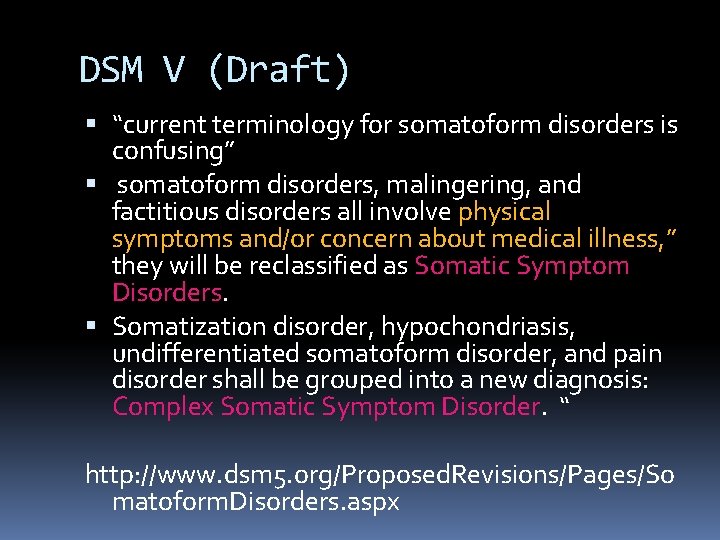

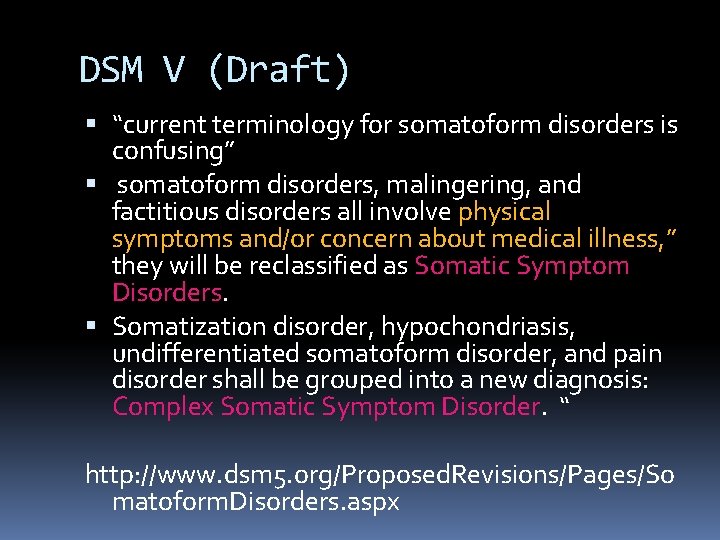

DSM V (Draft) “current terminology for somatoform disorders is confusing” somatoform disorders, malingering, and factitious disorders all involve physical symptoms and/or concern about medical illness, ” they will be reclassified as Somatic Symptom Disorders. Somatization disorder, hypochondriasis, undifferentiated somatoform disorder, and pain disorder shall be grouped into a new diagnosis: Complex Somatic Symptom Disorder. “ http: //www. dsm 5. org/Proposed. Revisions/Pages/So matoform. Disorders. aspx

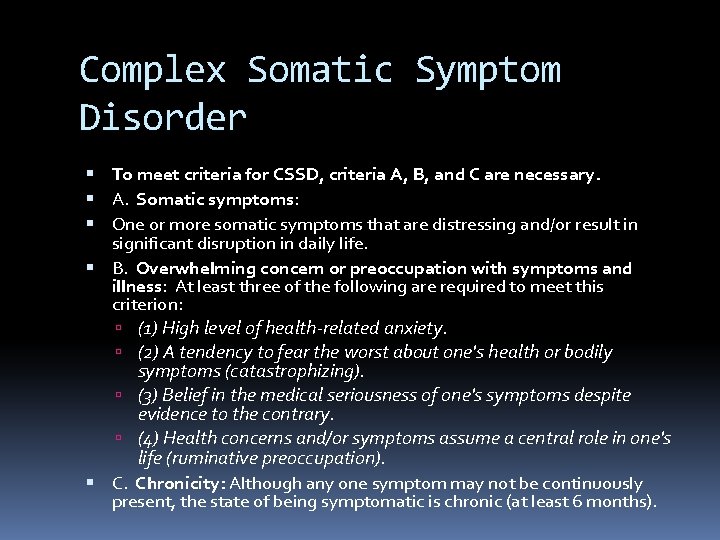

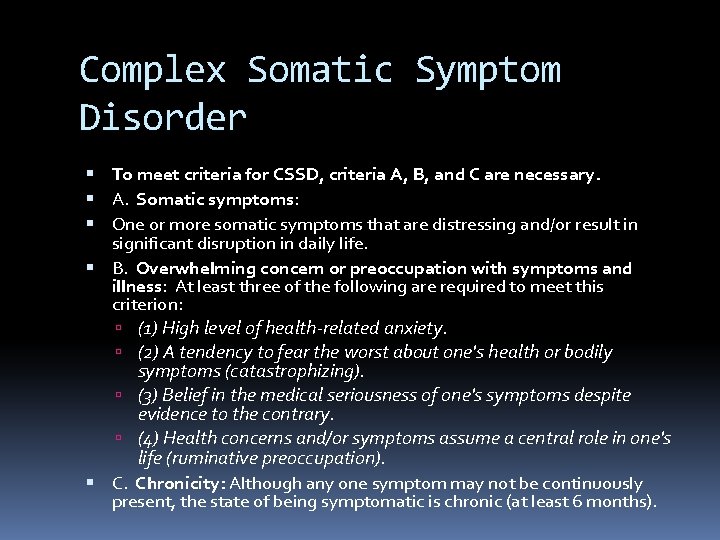

Complex Somatic Symptom Disorder To meet criteria for CSSD, criteria A, B, and C are necessary. A. Somatic symptoms: One or more somatic symptoms that are distressing and/or result in significant disruption in daily life. B. Overwhelming concern or preoccupation with symptoms and illness: At least three of the following are required to meet this criterion: (1) High level of health-related anxiety. (2) A tendency to fear the worst about one's health or bodily symptoms (catastrophizing). (3) Belief in the medical seriousness of one's symptoms despite evidence to the contrary. (4) Health concerns and/or symptoms assume a central role in one's life (ruminative preoccupation). C. Chronicity: Although any one symptom may not be continuously present, the state of being symptomatic is chronic (at least 6 months).

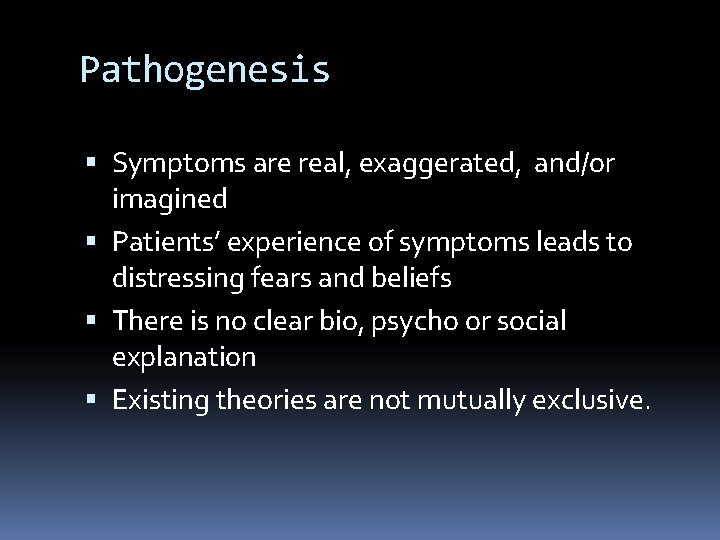

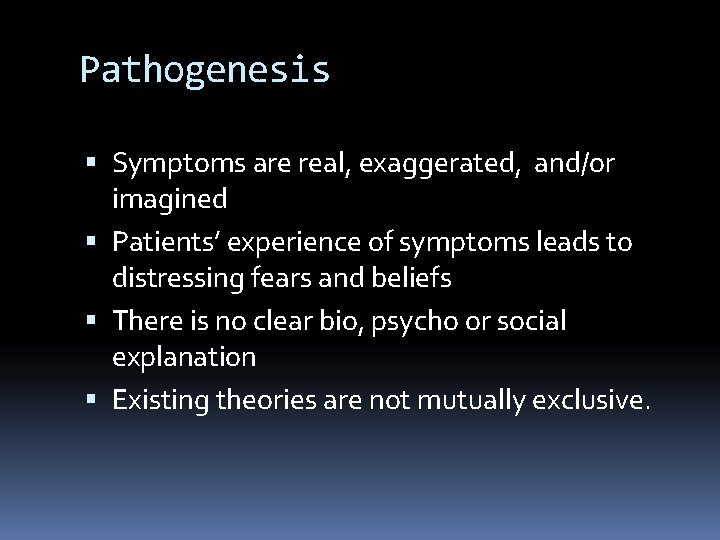

Pathogenesis Symptoms are real, exaggerated, and/or imagined Patients’ experience of symptoms leads to distressing fears and beliefs There is no clear bio, psycho or social explanation Existing theories are not mutually exclusive.

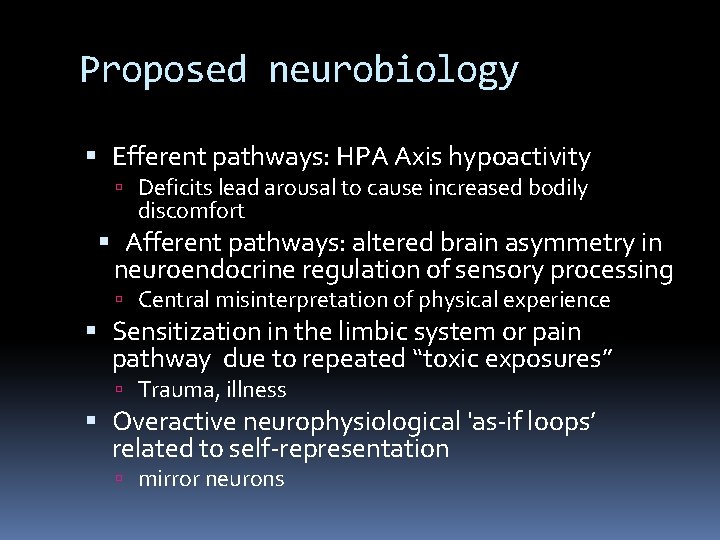

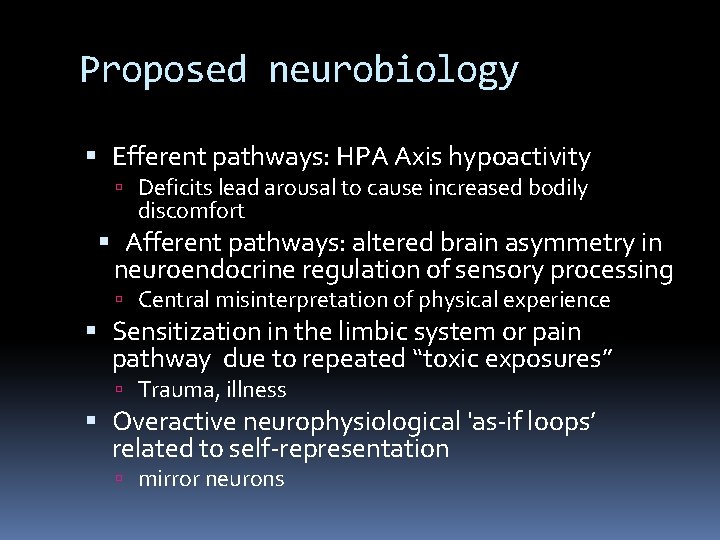

Proposed neurobiology Efferent pathways: HPA Axis hypoactivity Deficits lead arousal to cause increased bodily discomfort Afferent pathways: altered brain asymmetry in neuroendocrine regulation of sensory processing Central misinterpretation of physical experience Sensitization in the limbic system or pain pathway due to repeated “toxic exposures” Trauma, illness Overactive neurophysiological 'as-if loops’ related to self-representation mirror neurons

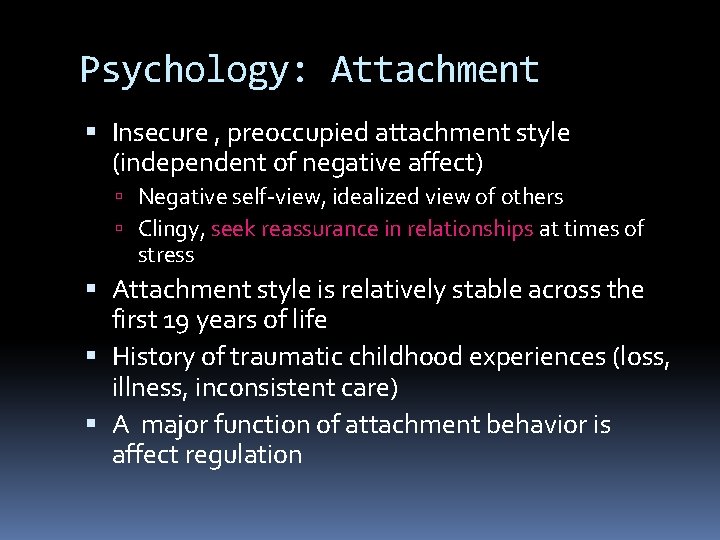

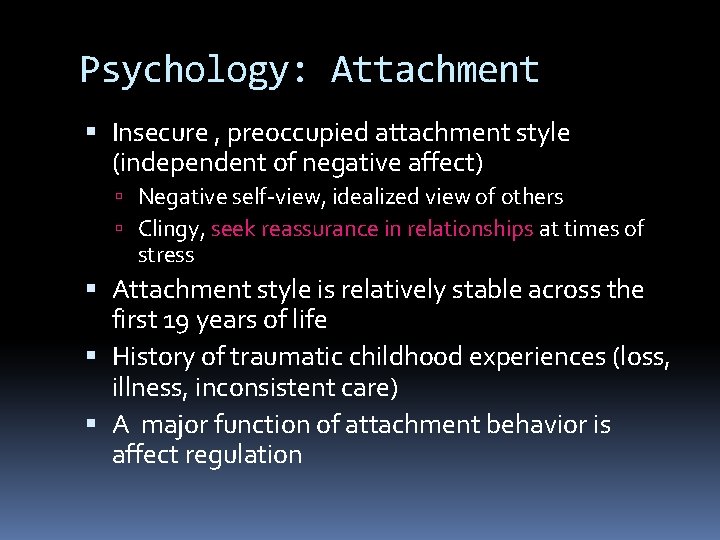

Psychology: Attachment Insecure , preoccupied attachment style (independent of negative affect) Negative self-view, idealized view of others Clingy, seek reassurance in relationships at times of stress Attachment style is relatively stable across the first 19 years of life History of traumatic childhood experiences (loss, illness, inconsistent care) A major function of attachment behavior is affect regulation

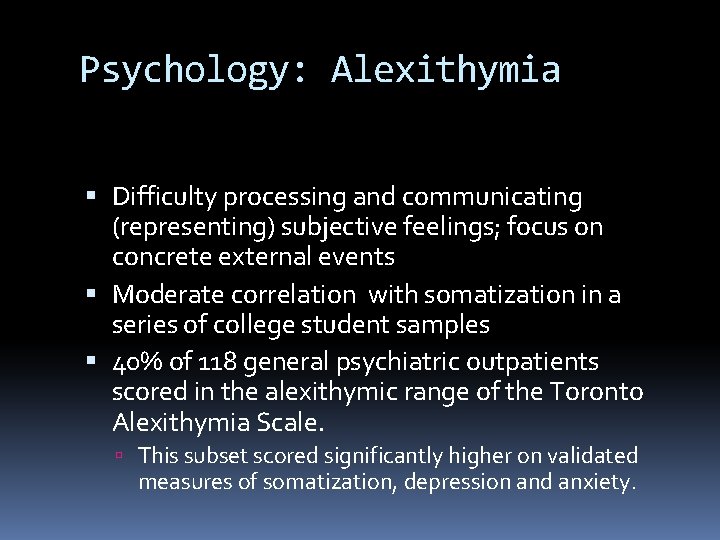

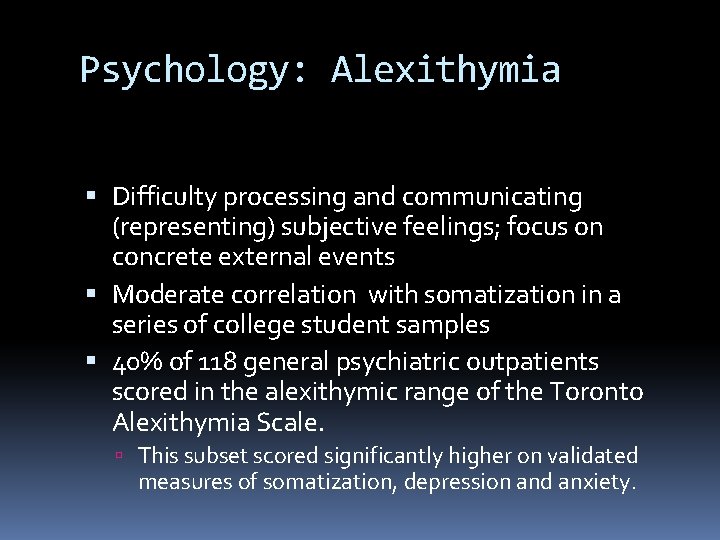

Psychology: Alexithymia Difficulty processing and communicating (representing) subjective feelings; focus on concrete external events Moderate correlation with somatization in a series of college student samples 40% of 118 general psychiatric outpatients scored in the alexithymic range of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale. This subset scored significantly higher on validated measures of somatization, depression and anxiety.

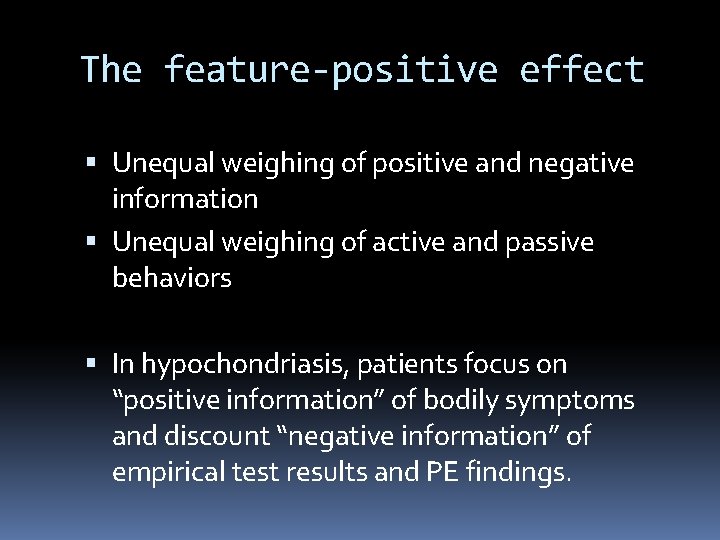

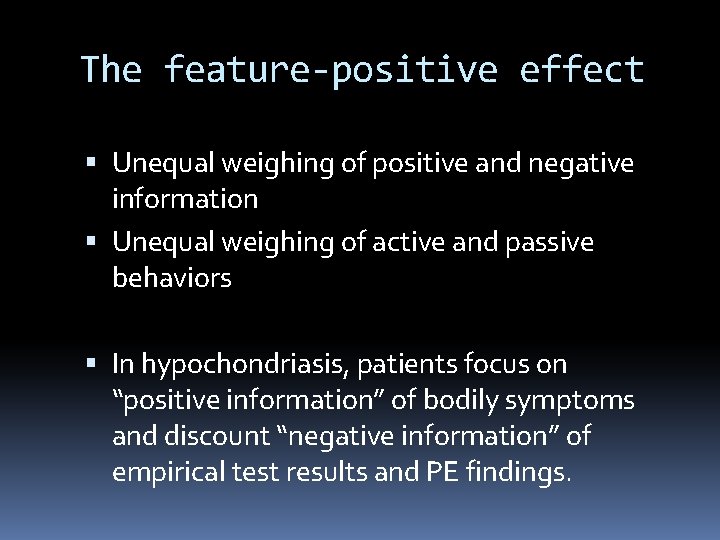

The feature-positive effect Unequal weighing of positive and negative information Unequal weighing of active and passive behaviors In hypochondriasis, patients focus on “positive information” of bodily symptoms and discount “negative information” of empirical test results and PE findings.

Cultural influences “Pain” comes from the Latin ‘poena’, for punishment or penalty Health and illness beliefs are informed by spirituality, superstition, and age Death beliefs affect health anxiety Negative beliefs about death are associated with increased health anxiety Positive beliefs about death are associated with reduced health anxiety

Risk factors? A history of sexual abuse is associated with: functional GI symptoms nonspecific chronic pain psychogenic seizures chronic pelvic pain.

Risk factors? Patients with MUS often had ill parents as children Patients with h/o childhood fatigue are more likely to report noncardiac chest pain. Children with benign murmurs have poor psychosocial outcomes, presumably due to parents’ fear of underlying serious illness

The “worried well” Psychiatric comorbidity: 2/3 of hypochondriacs GAD OCD � 5 -10% of hypochondriacs Social phobia MDD (may present only with somatic features) � 40% of hypochondriacs Panic disorder � 10 -20% of hypochondriacs Substance dependance (opioids)

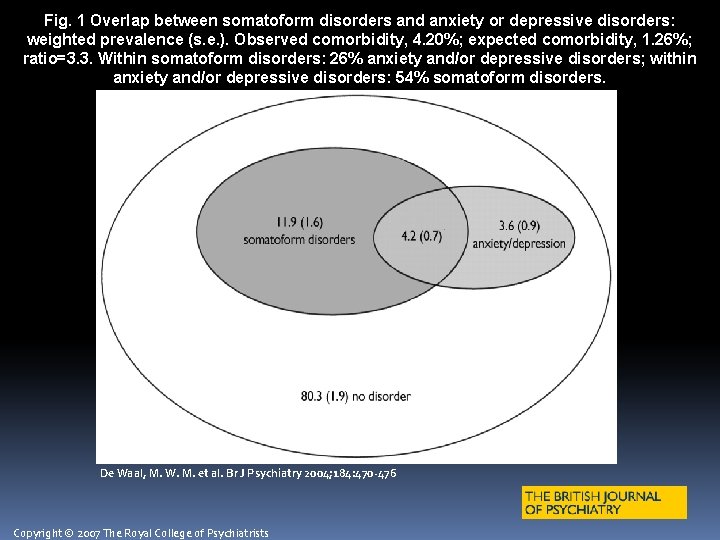

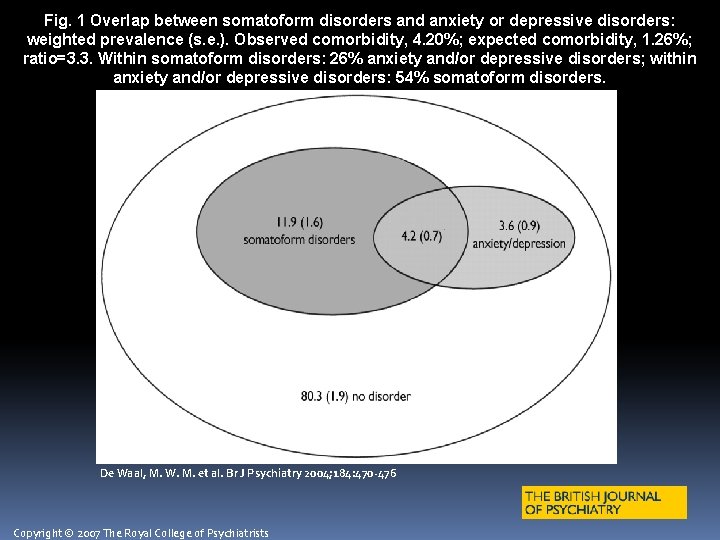

Fig. 1 Overlap between somatoform disorders and anxiety or depressive disorders: weighted prevalence (s. e. ). Observed comorbidity, 4. 20%; expected comorbidity, 1. 26%; ratio=3. 3. Within somatoform disorders: 26% anxiety and/or depressive disorders; within anxiety and/or depressive disorders: 54% somatoform disorders. De Waal, M. W. M. et al. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 184: 470 -476 Copyright © 2007 The Royal College of Psychiatrists

General medical conditions cause these symptoms, too Celiac disease: 1 in 250 Americans IBD: incidence 1 -10 cases per 100, 000; prevalence 200 N. Americans per 100, 000. Ischemic heart disease is rare in young adults

Evaluation History HPI PMH: �include psychiatric history �recent physicians and patient’s experience of them Family history: �especially during patient’s childhood �elicit parental attitudes toward illness Social history: �include history of sexual abuse �childhood illnesses, school avoidance �current academic and social pressures Physical Exam

Medical treatment Structured, scheduled visits with the same clinician minimize crises, reduce urgent contacts Start with weekly or biweekly brief (20 minute) visits progressively lengthen the intervals Centralize care Discuss purpose of and limit referrals, tests, meds

Psychological treatment About 50% of patients refuse psychotherapy referral Most patients with MUS are open to psychosocial treatment provided by PCP, in addition to usual care Clinician must reframe own expectations (“cure” is unlikely)

CBT in Primary care Establish a partnership �minimize shame & fear of abandonment �respond to patient’s emotions and concerns �identify treatment goals �provide education Establish a routine �review interval since last visit �set goals for current visit �assign homework

Psychological treatment CBT by an expert can focus on: misinterpretation of positive symptoms selective attention, safety-seeking, and bodily discomfort due to anxiety revalue negative test results and physical exam findings

Prognosis Medically Unexplained Symptoms 50 -75% improve 10 -30% deteriorate Hypochondriasis 30 -50% recover Number of somatic symptoms and “seriousness of condition” at baseline influences course and prognosis Inconclusive evidence regarding influence of untreated psychiatric comorbidity

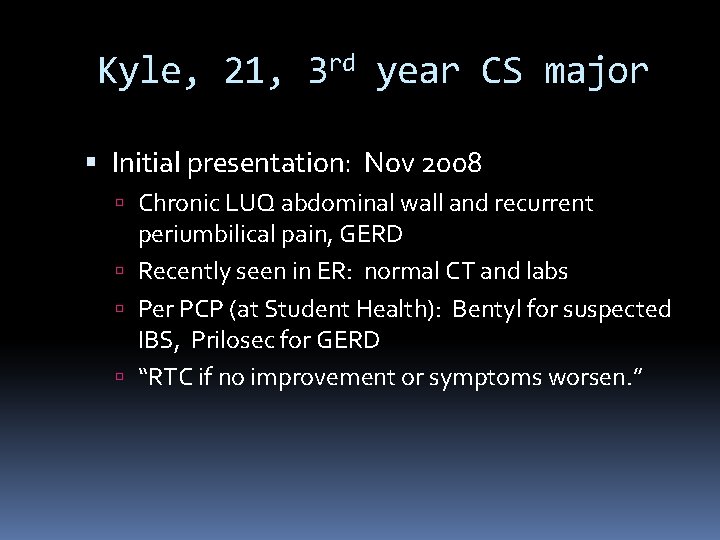

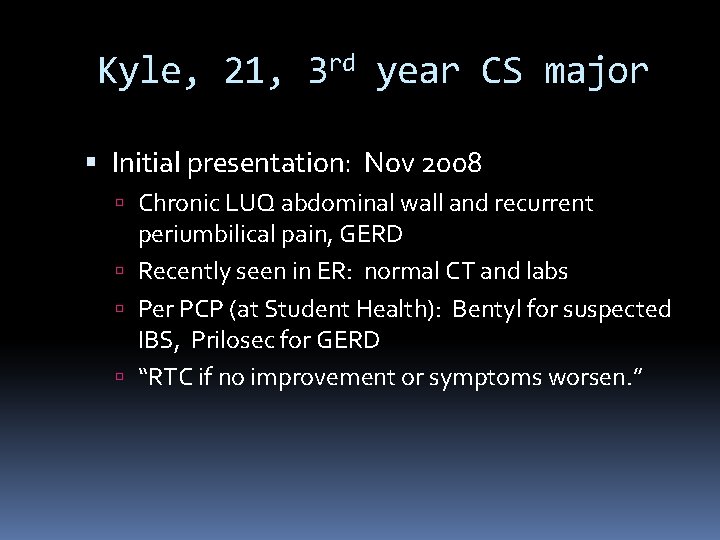

Kyle, 21, 3 rd year CS major Initial presentation: Nov 2008 Chronic LUQ abdominal wall and recurrent periumbilical pain, GERD Recently seen in ER: normal CT and labs Per PCP (at Student Health): Bentyl for suspected IBS, Prilosec for GERD “RTC if no improvement or symptoms worsen. ”

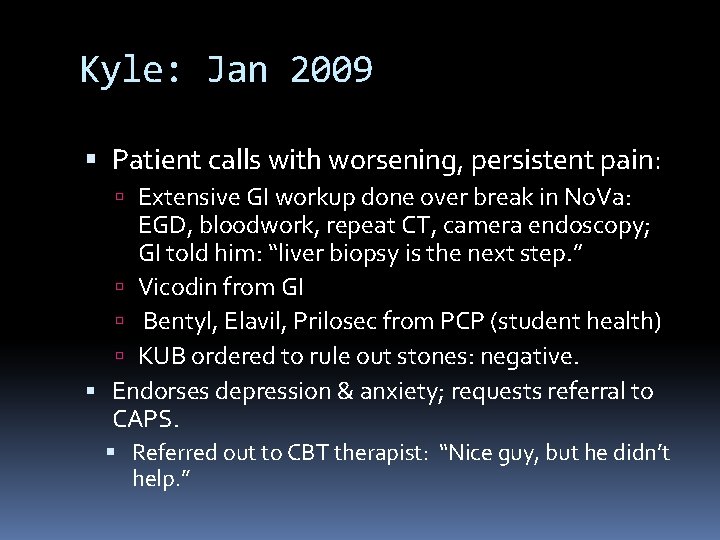

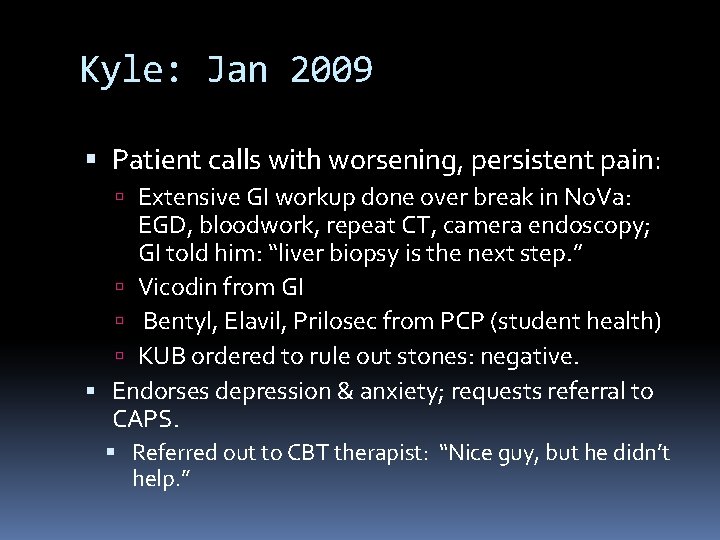

Kyle: Jan 2009 Patient calls with worsening, persistent pain: Extensive GI workup done over break in No. Va: EGD, bloodwork, repeat CT, camera endoscopy; GI told him: “liver biopsy is the next step. ” Vicodin from GI Bentyl, Elavil, Prilosec from PCP (student health) KUB ordered to rule out stones: negative. Endorses depression & anxiety; requests referral to CAPS. Referred out to CBT therapist: “Nice guy, but he didn’t help. ”

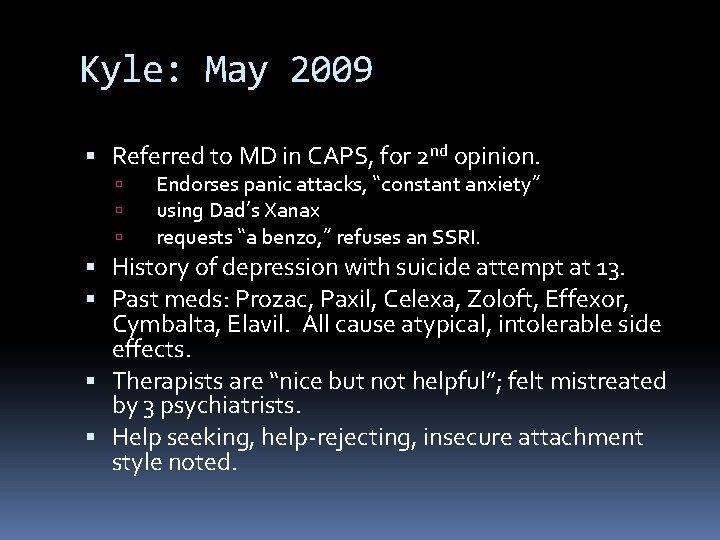

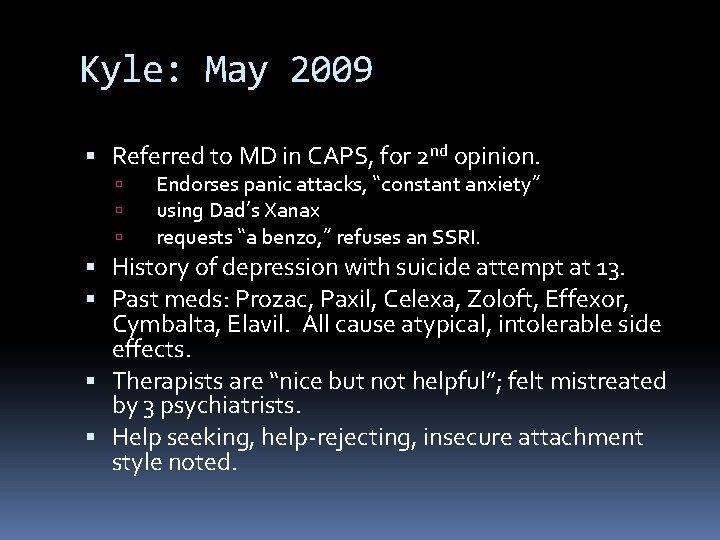

Kyle: May 2009 Referred to MD in CAPS, for 2 nd opinion. Endorses panic attacks, “constant anxiety” using Dad’s Xanax requests “a benzo, ” refuses an SSRI. History of depression with suicide attempt at 13. Past meds: Prozac, Paxil, Celexa, Zoloft, Effexor, Cymbalta, Elavil. All cause atypical, intolerable side effects. Therapists are “nice but not helpful”; felt mistreated by 3 psychiatrists. Help seeking, help-rejecting, insecure attachment style noted.

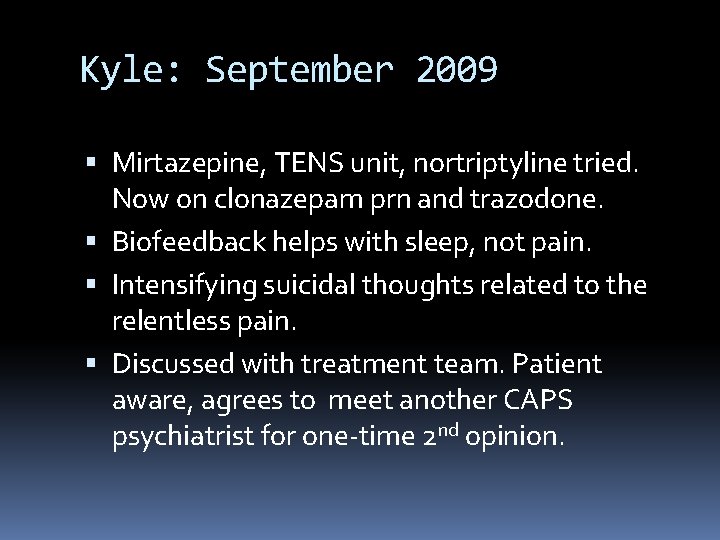

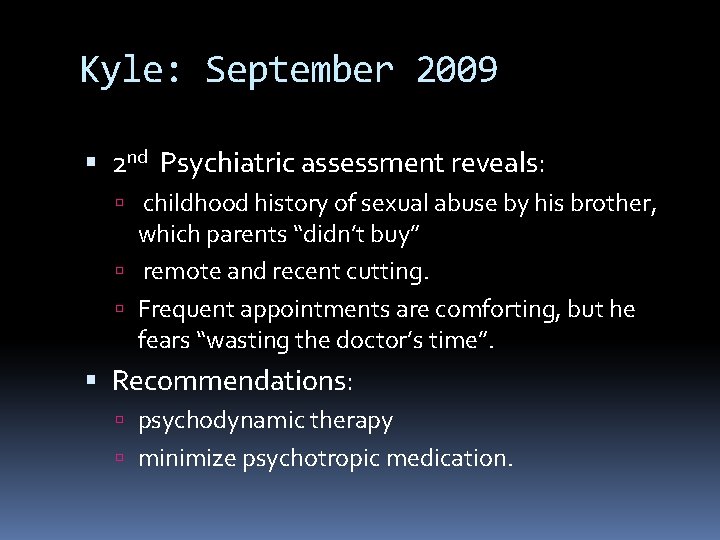

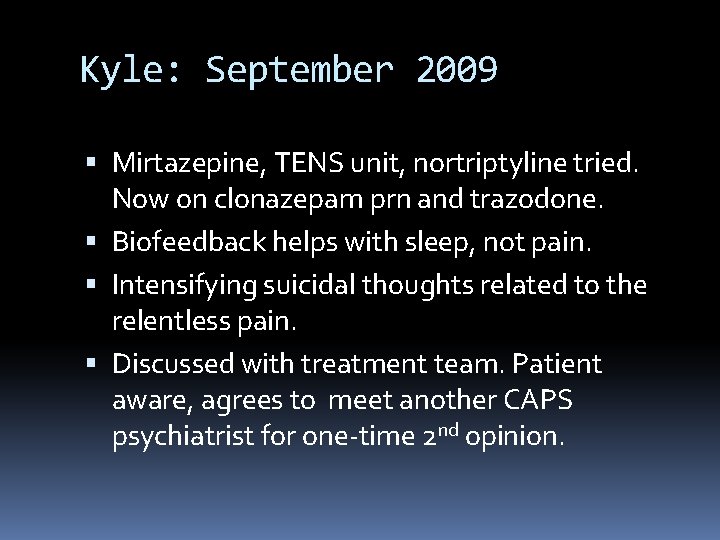

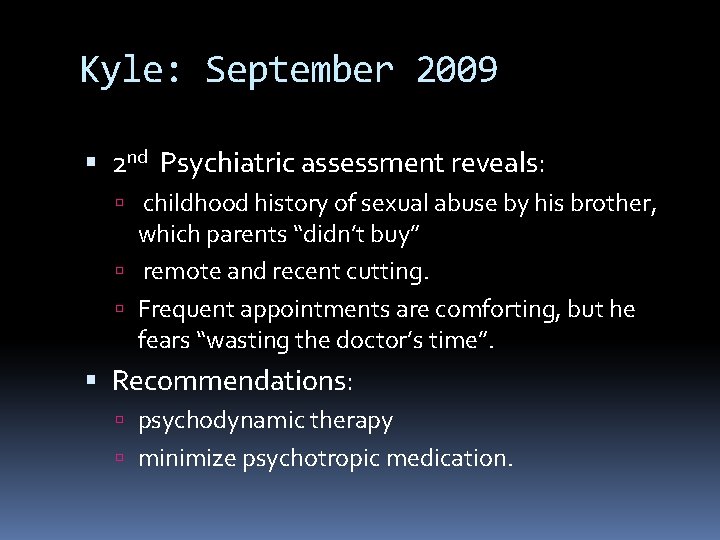

Kyle: September 2009 Mirtazepine, TENS unit, nortriptyline tried. Now on clonazepam prn and trazodone. Biofeedback helps with sleep, not pain. Intensifying suicidal thoughts related to the relentless pain. Discussed with treatment team. Patient aware, agrees to meet another CAPS psychiatrist for one-time 2 nd opinion.

Kyle: September 2009 2 nd Psychiatric assessment reveals: childhood history of sexual abuse by his brother, which parents “didn’t buy” remote and recent cutting. Frequent appointments are comforting, but he fears “wasting the doctor’s time”. Recommendations: psychodynamic therapy minimize psychotropic medication.

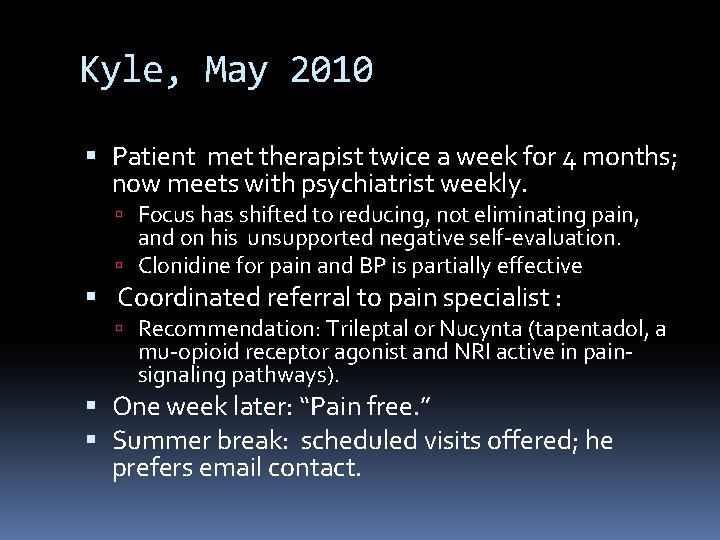

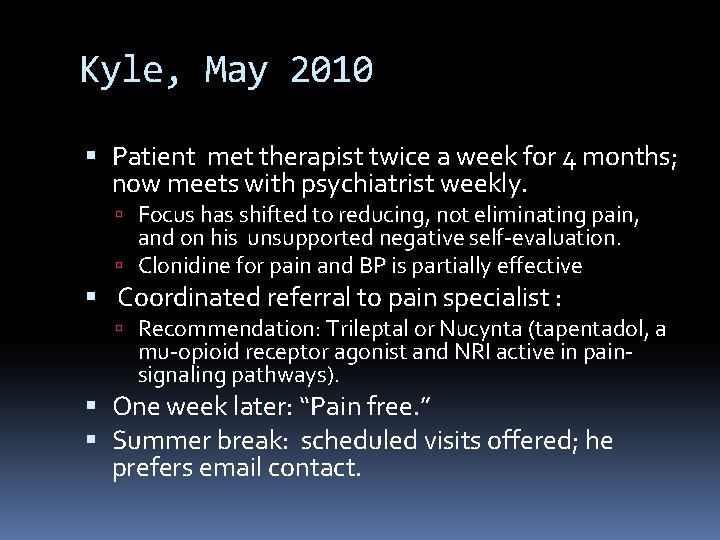

Kyle, May 2010 Patient met therapist twice a week for 4 months; now meets with psychiatrist weekly. Focus has shifted to reducing, not eliminating pain, and on his unsupported negative self-evaluation. Clonidine for pain and BP is partially effective Coordinated referral to pain specialist : Recommendation: Trileptal or Nucynta (tapentadol, a mu-opioid receptor agonist and NRI active in painsignaling pathways). One week later: “Pain free. ” Summer break: scheduled visits offered; he prefers email contact.

Jay, 23, 2 rd year med student Initial presentation: Nov 3, 2009 1. LUQ abdominal discomfort 2. chronic loose stools 3. chronic GERD with concern about long-term PPI use. 4. Lymphadenopathy, panic attack, concerned about cancer. 5. Chronic tremor and tongue numbness.

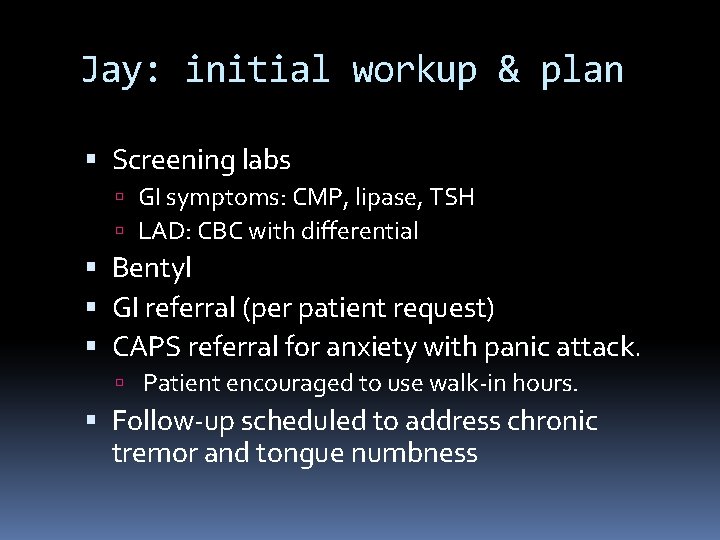

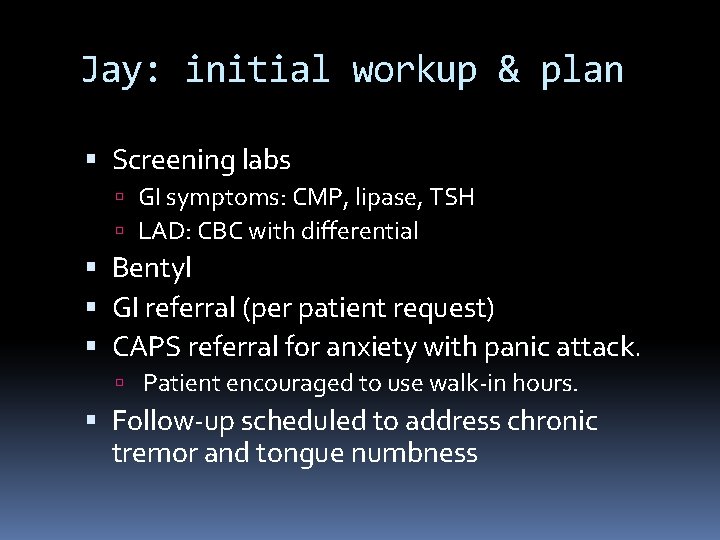

Jay: initial workup & plan Screening labs GI symptoms: CMP, lipase, TSH LAD: CBC with differential Bentyl GI referral (per patient request) CAPS referral for anxiety with panic attack. Patient encouraged to use walk-in hours. Follow-up scheduled to address chronic tremor and tongue numbness

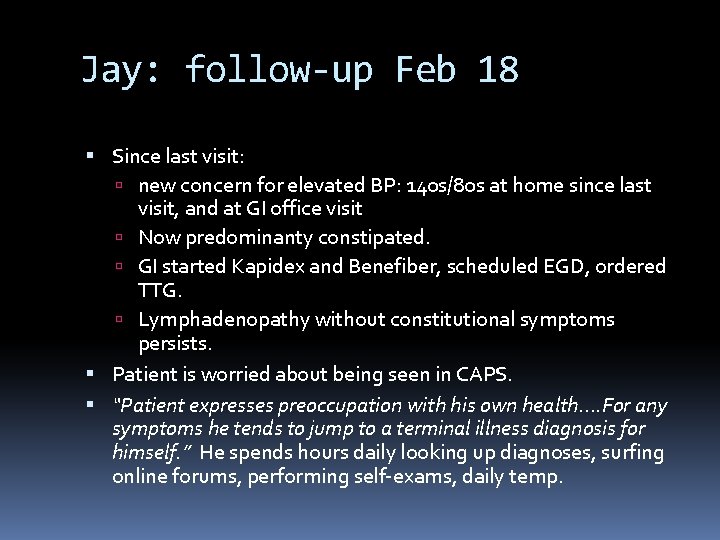

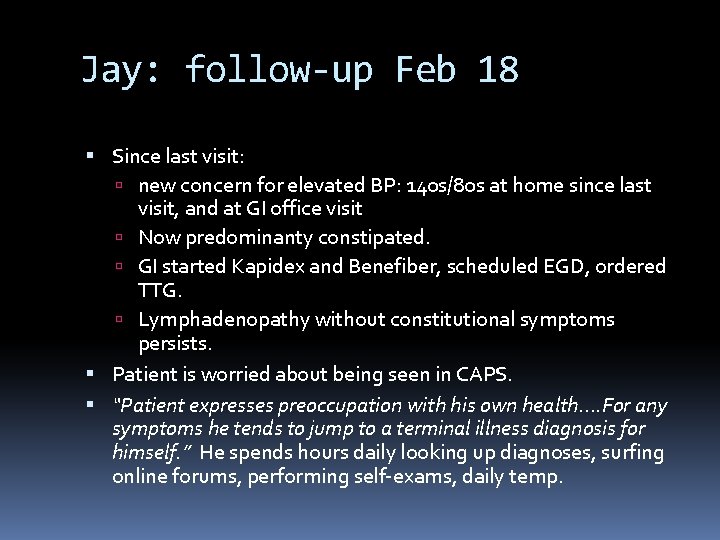

Jay: follow-up Feb 18 Since last visit: new concern for elevated BP: 140 s/80 s at home since last visit, and at GI office visit Now predominanty constipated. GI started Kapidex and Benefiber, scheduled EGD, ordered TTG. Lymphadenopathy without constitutional symptoms persists. Patient is worried about being seen in CAPS. “Patient expresses preoccupation with his own health…. For any symptoms he tends to jump to a terminal illness diagnosis for himself. ” He spends hours daily looking up diagnoses, surfing online forums, performing self-exams, daily temp.

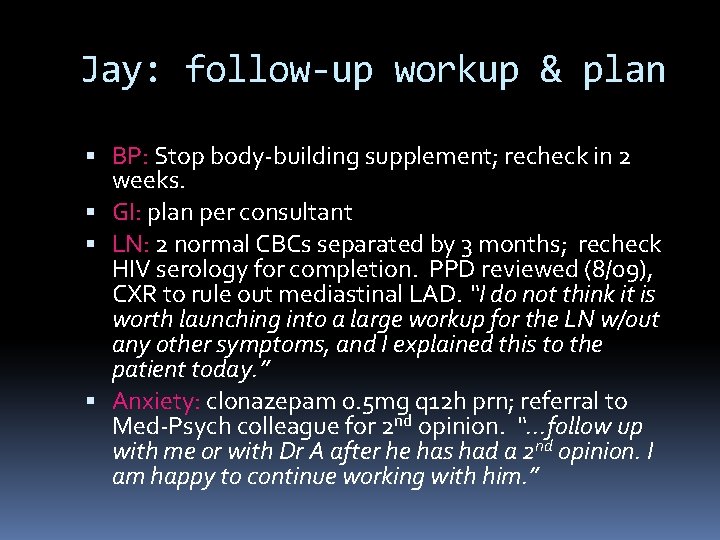

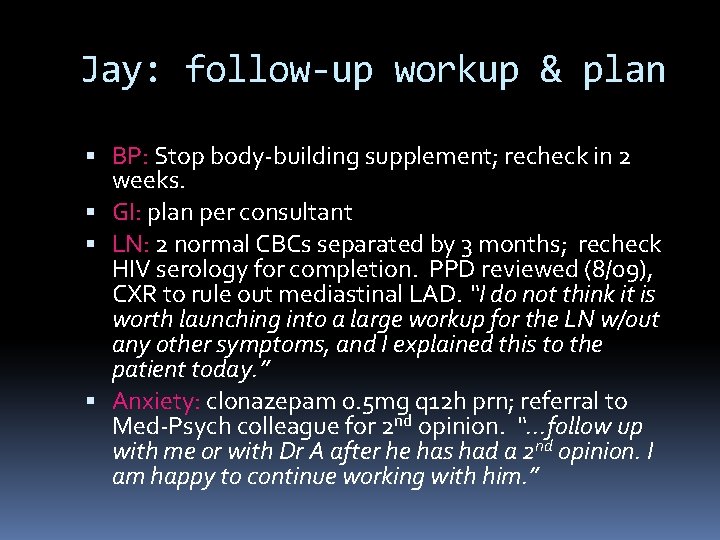

Jay: follow-up workup & plan BP: Stop body-building supplement; recheck in 2 weeks. GI: plan per consultant LN: 2 normal CBCs separated by 3 months; recheck HIV serology for completion. PPD reviewed (8/09), CXR to rule out mediastinal LAD. “I do not think it is worth launching into a large workup for the LN w/out any other symptoms, and I explained this to the patient today. ” Anxiety: clonazepam 0. 5 mg q 12 h prn; referral to Med-Psych colleague for 2 nd opinion. “. . . follow up with me or with Dr A after he has had a 2 nd opinion. I am happy to continue working with him. ”

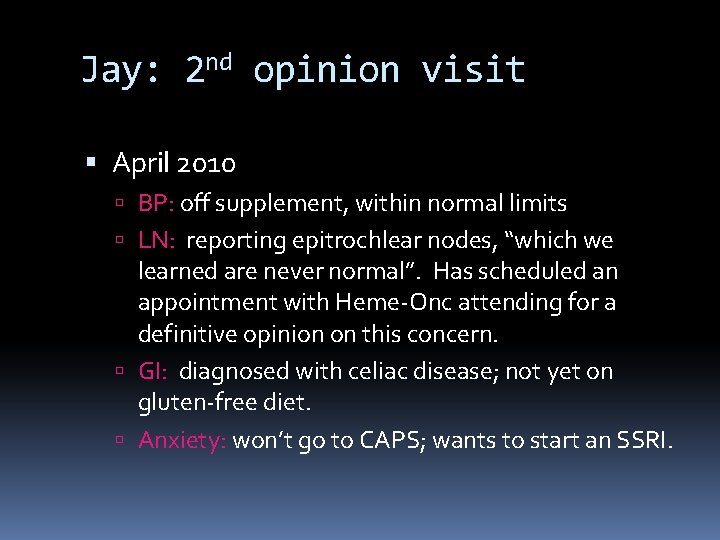

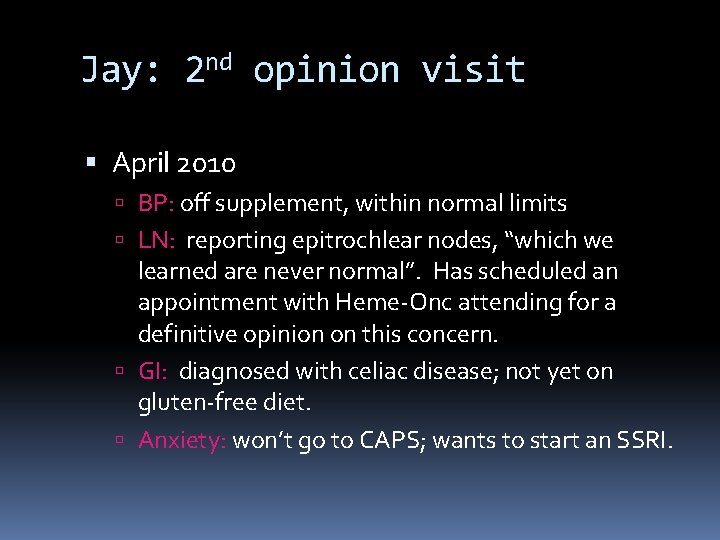

Jay: 2 nd opinion visit April 2010 BP: off supplement, within normal limits LN: reporting epitrochlear nodes, “which we learned are never normal”. Has scheduled an appointment with Heme-Onc attending for a definitive opinion on this concern. GI: diagnosed with celiac disease; not yet on gluten-free diet. Anxiety: won’t go to CAPS; wants to start an SSRI.

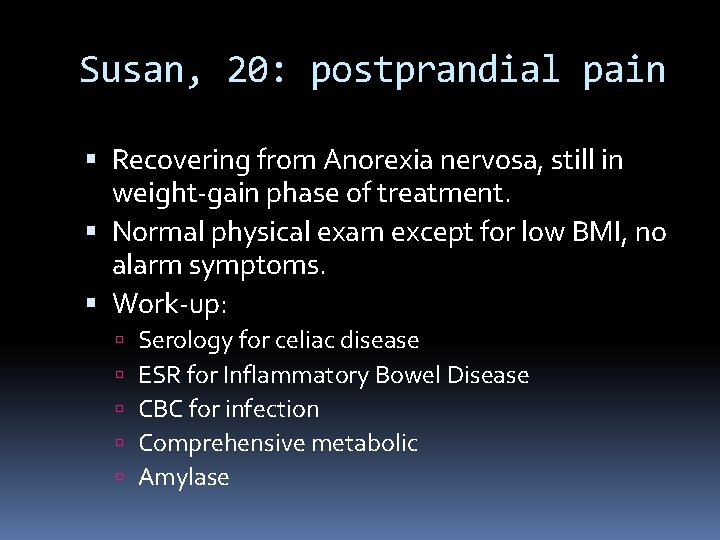

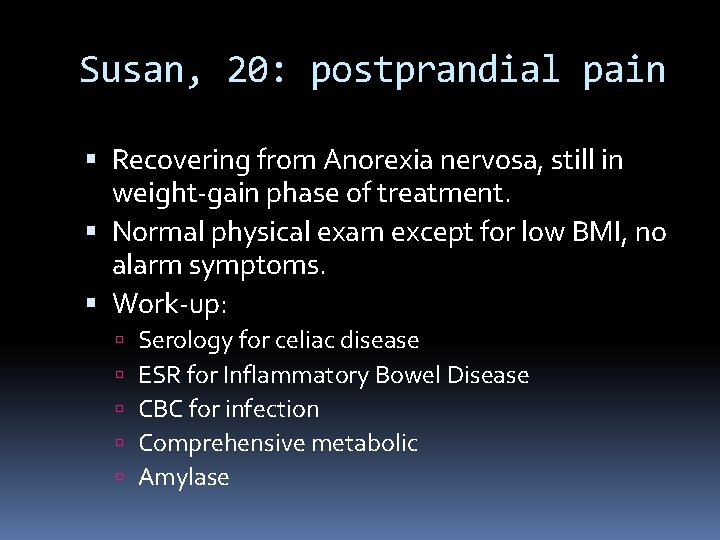

Susan, 20: postprandial pain Recovering from Anorexia nervosa, still in weight-gain phase of treatment. Normal physical exam except for low BMI, no alarm symptoms. Work-up: Serology for celiac disease ESR for Inflammatory Bowel Disease CBC for infection Comprehensive metabolic Amylase

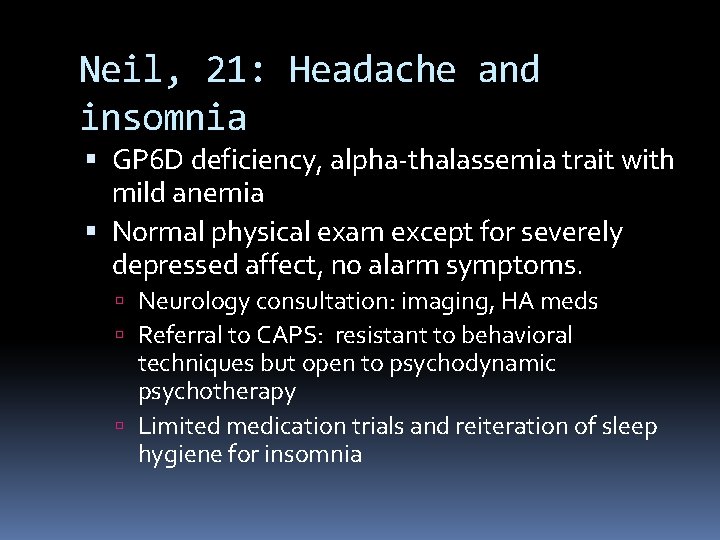

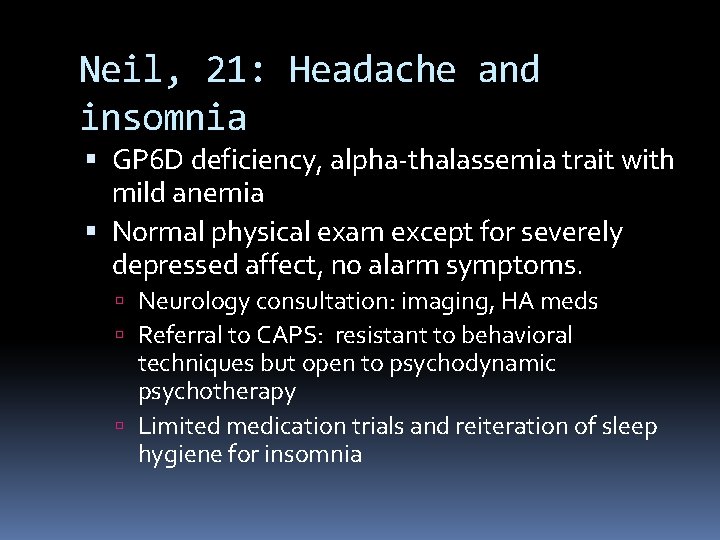

Neil, 21: Headache and insomnia GP 6 D deficiency, alpha-thalassemia trait with mild anemia Normal physical exam except for severely depressed affect, no alarm symptoms. Neurology consultation: imaging, HA meds Referral to CAPS: resistant to behavioral techniques but open to psychodynamic psychotherapy Limited medication trials and reiteration of sleep hygiene for insomnia

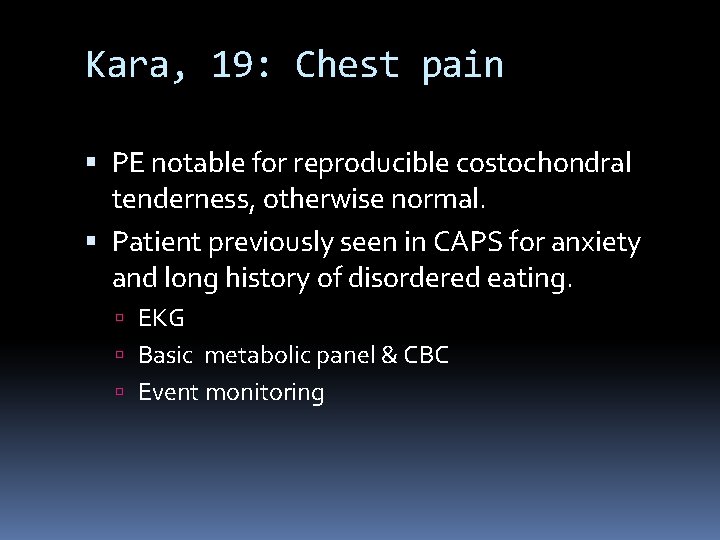

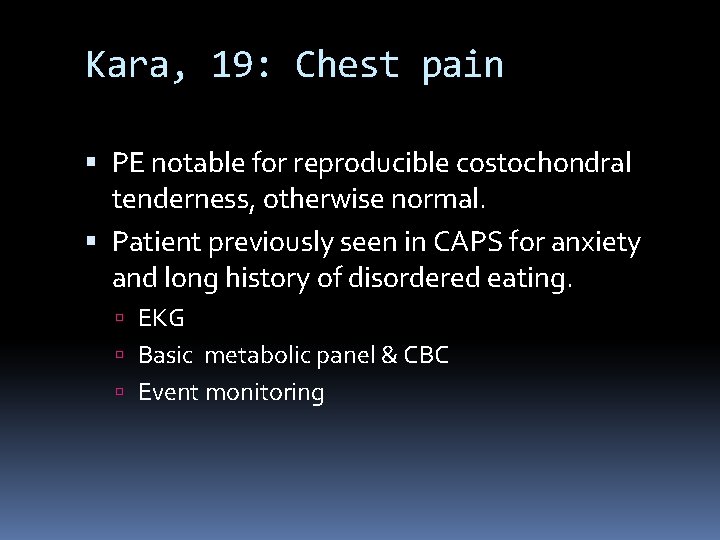

Kara, 19: Chest pain PE notable for reproducible costochondral tenderness, otherwise normal. Patient previously seen in CAPS for anxiety and long history of disordered eating. EKG Basic metabolic panel & CBC Event monitoring

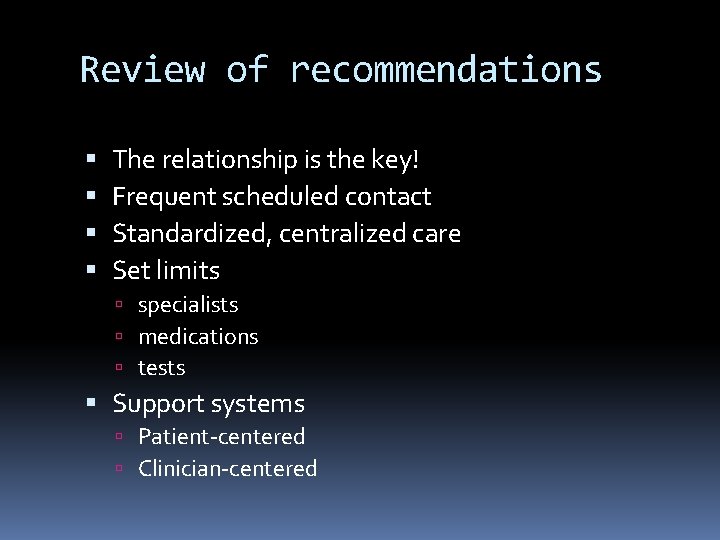

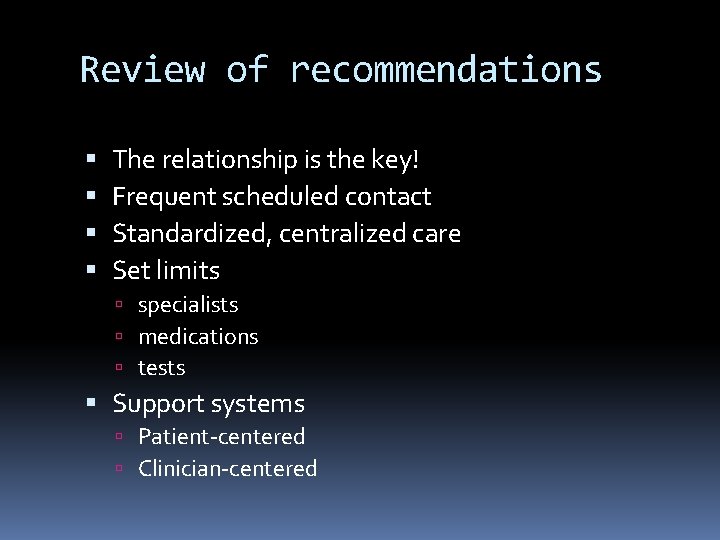

Review of recommendations The relationship is the key! Frequent scheduled contact Standardized, centralized care Set limits specialists medications tests Support systems Patient-centered Clinician-centered

University of Virginia

Acknowledgments My colleagues in General Medicine Meredith Hayden, Amber Pendleton, Neil Silva, Claire Veber My colleagues in CAPS Daniel Ciudin, Emily Lape, Katy Rice, Rafael Triana

References American Psychiatric Assn, DSM-IV-TR, 2000. Barsky, A. N Engl J Med, Vol 345, No 19, (2001) 1395 -1933. Greenberg, DB, “Somatization, ” uptodate. com (version 18. 1 Jan 2010) De Waal, M. W. M. et al. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 184: 470 -476 Gros, D, et al “Frequency and severity of the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome across the anxiety disorders and depression. ” Journal of Anxiety Disorders 23 (2009) 290 -296. Haugaard, J. “Recognizing and Treating Uncommon Behavioral and Emotional Disorders in Children and Adolescents Who have been Severely Maltreated: Somatization and Other Somatoform Disorders. ” Child Maltreatment, Vol 9, No 2 (2004) 169 -176.

Henningsen, P. “The body in the brain: towards a representational neurobiology of somatoform disorders. ” Acta Neuropsychiatrica 2003 15: 157 -160. Hotopf, MB , et al. “Psychosocial and Developmental antecedents of chest pain in young adults, ” Psychosomatic Medicine 61: 861 -867 (1999). James A and Wells A, “Death beliefs, superstitious beliefs and health anxiety. ” British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 41, (2002) 43 -53. Lamberg, L. “New Mind/Body Tactics Target Medically Unexplained Physical Symptoms and Fears. ” JAMA, Vol 294, No 17 (2005) 2152 -2154. olde Harteman, T, et al. “Medically unexplained symptoms, somatisation disorder and hypochondriasis: course and prognosis. A systematic review. ” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 66 (2009) 363377. Rassin, E, et al “The feature-positive effect and hypochondriacal concerns. ” Behaviour Res & Therapy 46 (2008) 263 -269.

Roelofs, K and Spinhoven, P. “Trauma and medically unexplained symptoms: towards an integration of cognitive and neuro-biological accounts. ” Clinical Psychology Review 27 (2007) 798 -820. Smith, R and Dwamena, F. “Primary care management of medically unexplained symptoms, ” uptodate. com (version 18. 1 Jan 2010 ) Taylor, G. et al “Alexithymia and Somatic complaints in Psychiatric out-patients. ” Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Vol 36, No 5, (1992) 417 -424 Tyrer, S. “Psychosomatic Pain. ” British Journal of Psychiatry, 188 (2004) 91 -93. Verhaak, P, et al. “Persistent presentation of medically unexplained symptoms in general practice. ” Family Practice Advance Access, April 2006. Weardon, A et al. “Adult Attachment, Reassurance Seeking and Hypochondriacal Concerns in College Students, ” Journal of Health Psychology, (2006) Vol 11 (6) 877 -886. Wise, T and Birket-Smith, M. “The Somatoform Disorders for DSM-V: The need for changes in process and content. ” Psychosomatics 43: 6, (2002)

Aquele que encontra um amigo encontra um tesouro versiculo

Aquele que encontra um amigo encontra um tesouro versiculo Sara alson

Sara alson June 2007 physics regents answers

June 2007 physics regents answers June 2010 chemistry regents

June 2010 chemistry regents Acha fadila

Acha fadila Hugo acha wikipedia

Hugo acha wikipedia O prego de ferro ab inicialmente não imantado

O prego de ferro ab inicialmente não imantado Acha mum

Acha mum James garrow philadelphia

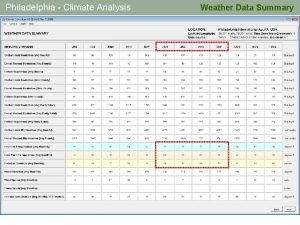

James garrow philadelphia Schuylkill river flooding philadelphia

Schuylkill river flooding philadelphia Philadelphia

Philadelphia 3711 market street philadelphia

3711 market street philadelphia Cromosoma philadelphia

Cromosoma philadelphia Philadelphia confession of faith

Philadelphia confession of faith Physical and man made features

Physical and man made features Seven church ages

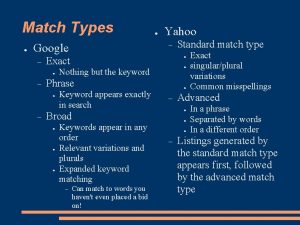

Seven church ages Keyword phrases philadelphia

Keyword phrases philadelphia Niri philadelphia

Niri philadelphia Lennot joensuu philadelphia

Lennot joensuu philadelphia Naval inventory control point philadelphia

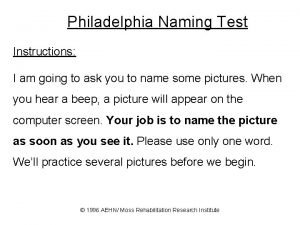

Naval inventory control point philadelphia Philadelphia naming test

Philadelphia naming test Physical and man made features

Physical and man made features Philadelphia recycling mine

Philadelphia recycling mine Alpha kappa alpha national hymn

Alpha kappa alpha national hymn Archbalt.powerschool.com/public

Archbalt.powerschool.com/public Philadelphia

Philadelphia 13 colonies brainpop

13 colonies brainpop 3910 irving street philadelphia pa

3910 irving street philadelphia pa 215-967-4690

215-967-4690 Letter to philadelphia revelation

Letter to philadelphia revelation Us army corps of engineers philadelphia district

Us army corps of engineers philadelphia district Engineering statistics philadelphia university

Engineering statistics philadelphia university Jenkins law library philadelphia

Jenkins law library philadelphia Boston new york map

Boston new york map Inversione pericentrica

Inversione pericentrica Kitchen exhaust cleaning philadelphia

Kitchen exhaust cleaning philadelphia Philadelphia textile

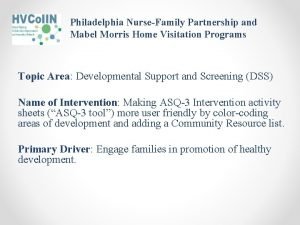

Philadelphia textile Morris home philadelphia

Morris home philadelphia Physical and man made features

Physical and man made features Pontifical mission societies philadelphia

Pontifical mission societies philadelphia Vraj temple philadelphia

Vraj temple philadelphia Philadelphia recovery community center

Philadelphia recovery community center Philadelphia job corps life science institute

Philadelphia job corps life science institute Day proper noun

Day proper noun Dr june james

Dr june james In june

In june June 20 2008

June 20 2008 Cxccxc results 2018

Cxccxc results 2018 June 23

June 23 Lottery in june, corn be heavy soon.

Lottery in june, corn be heavy soon. Workshop expectations

Workshop expectations 2019 june calendar

2019 june calendar Companies in june

Companies in june