Power America Powerand and Politics inin America POL

- Slides: 42

Power America Powerand and. Politics inin. America (POL 300, ALHAM 300) (V 53. 0300) Spring 2011: Lecture 4 Fall 2015: Lecture 18 Prof. Patrick Egan Wilf Family Department of Politics

Today • Congress and the President: – The Pivotal Politics model • If time: – Begin the Judiciary

Reminder • Short Exercise is due a week from today at beginning of class.

The Presidency and Congress • So far, we’ve considered Congress and the presidency in isolation. But we know that the enactment of legislation happens as a result of negotiations between both branches of government. • Let’s use our agenda-setting model to capture some of these dynamics.

The Presidency and Congress • To do so, we will incorporate the Hastert Rule: – No bill will come to the floor unless it is supported by a majority of the majority party’s members in Congress What does this mean in practice? – • It must be supported by the median member of the majority party.

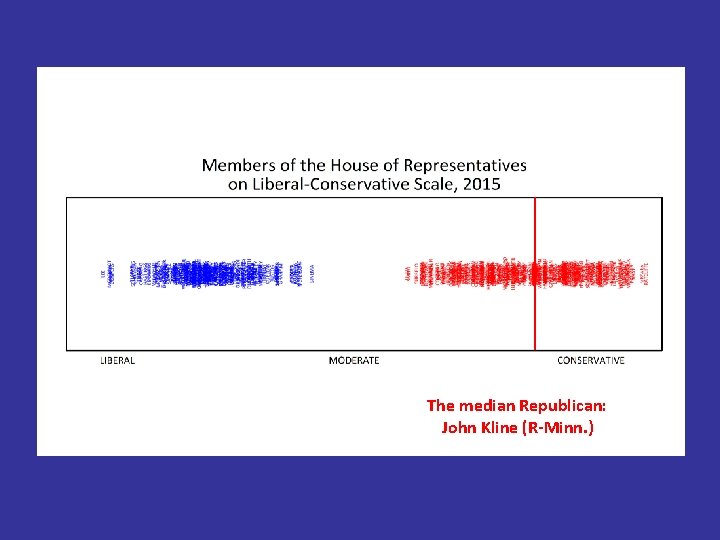

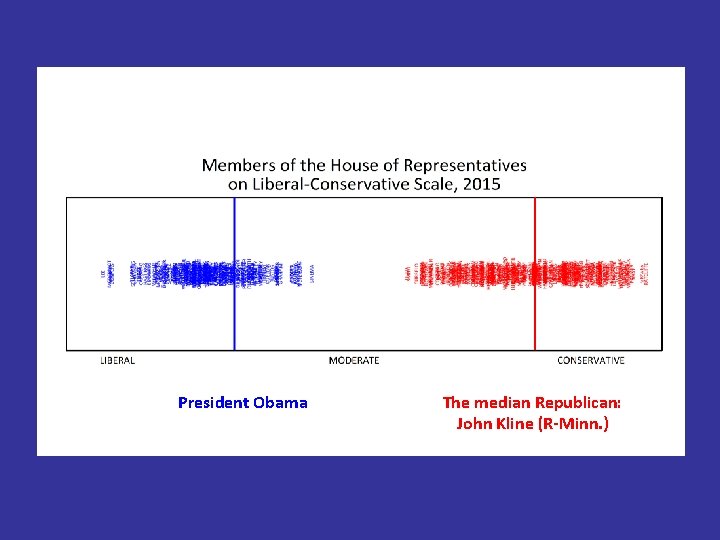

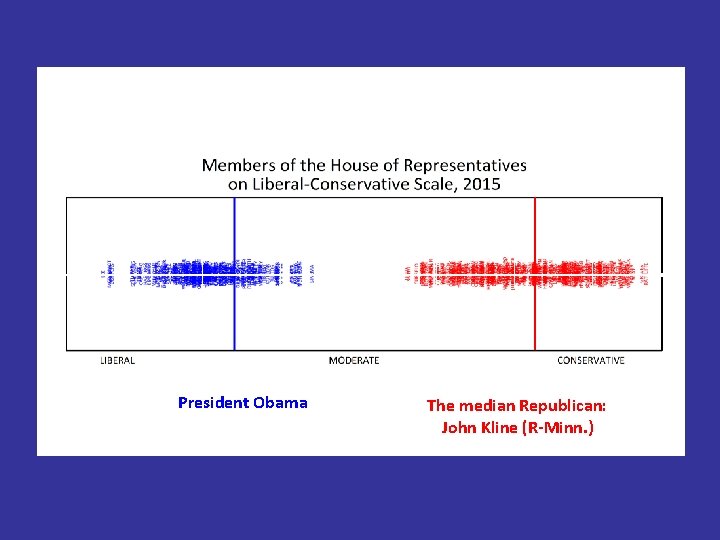

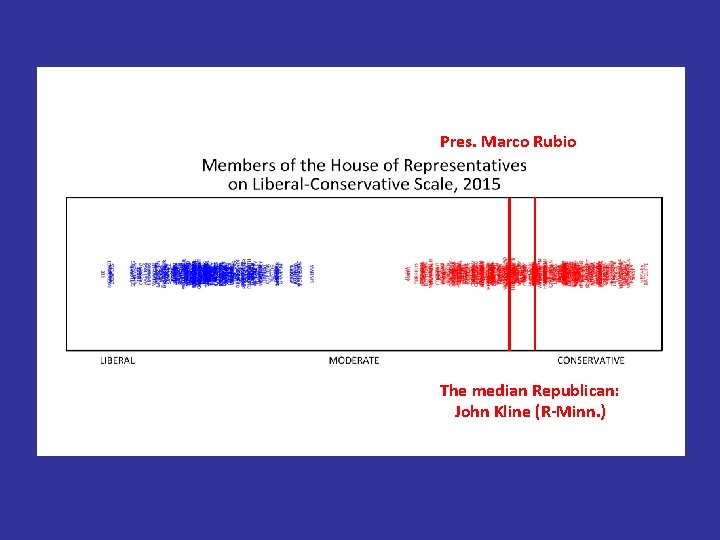

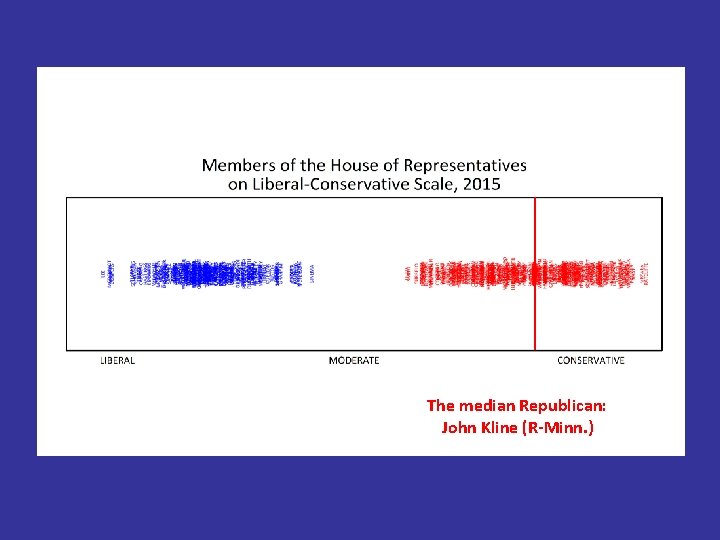

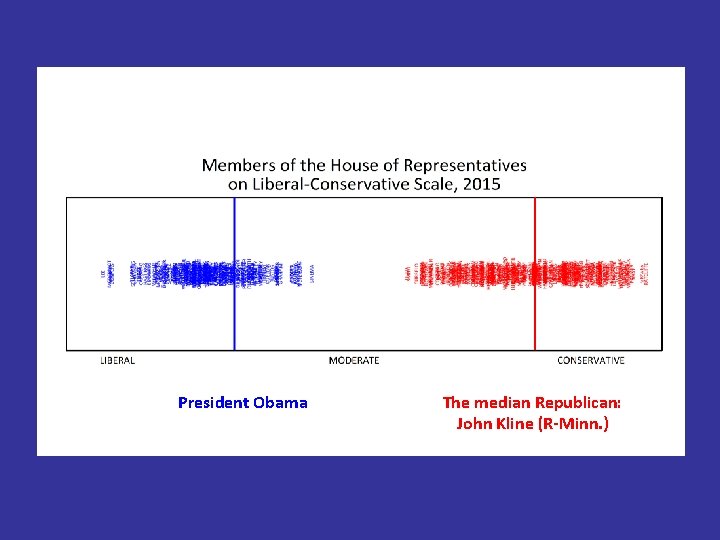

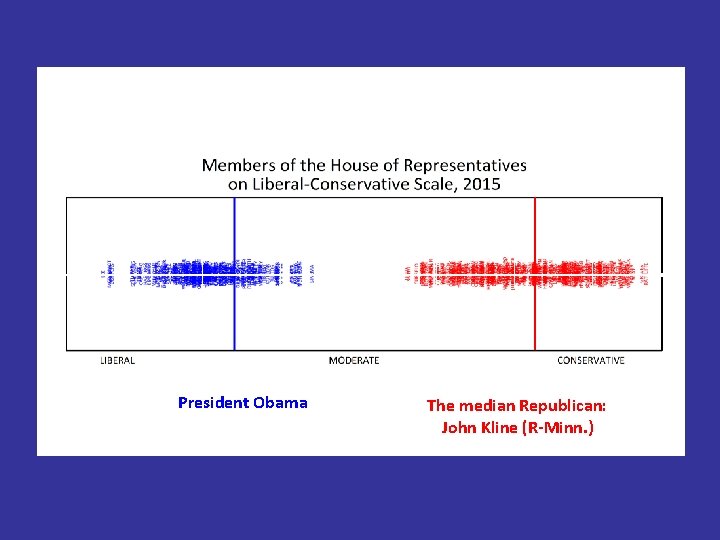

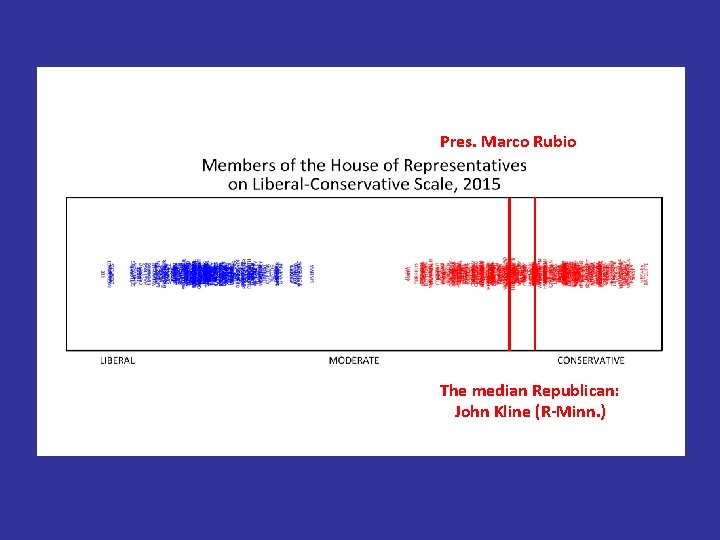

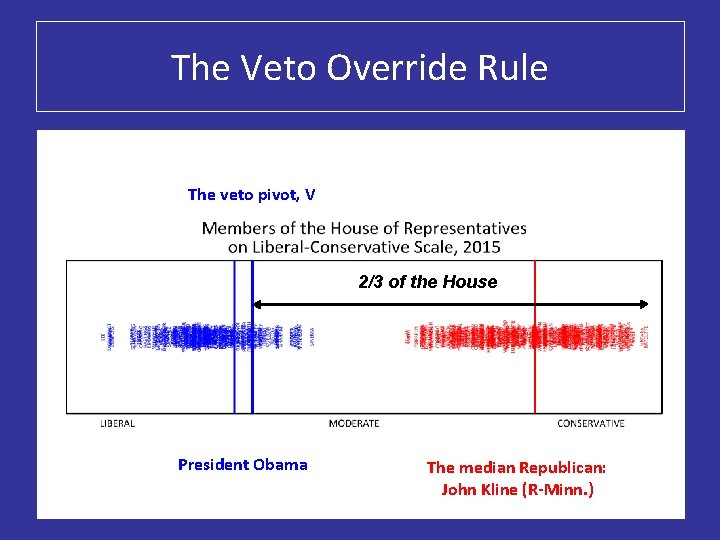

The median Republican: John Kline (R-Minn. )

The Presidency and Congress • As we will see, policy status quos located between the ideal point of the median majority member and the president are very unlikely to change given our system of checks and balances.

President Obama The median Republican: John Kline (R-Minn. )

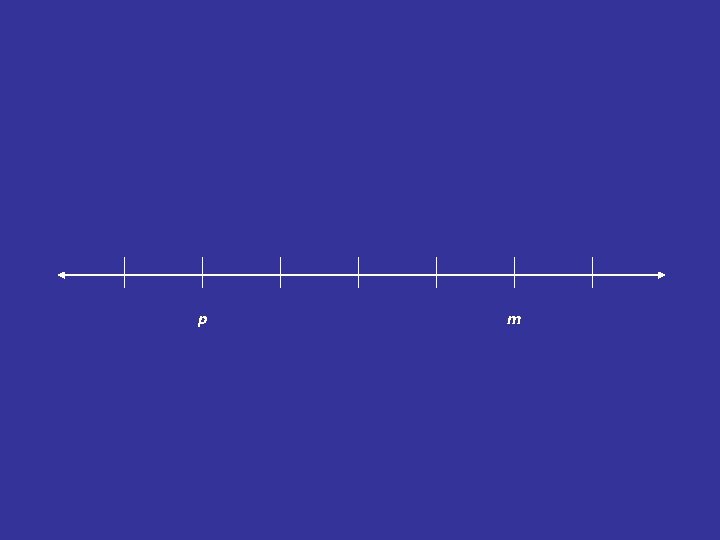

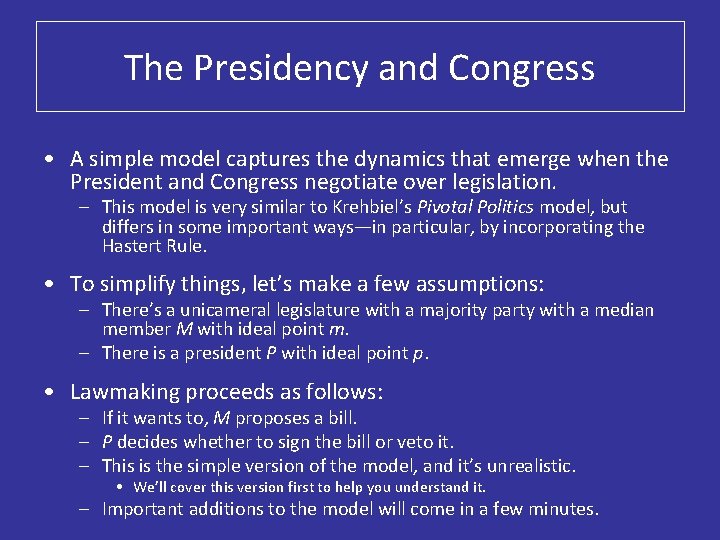

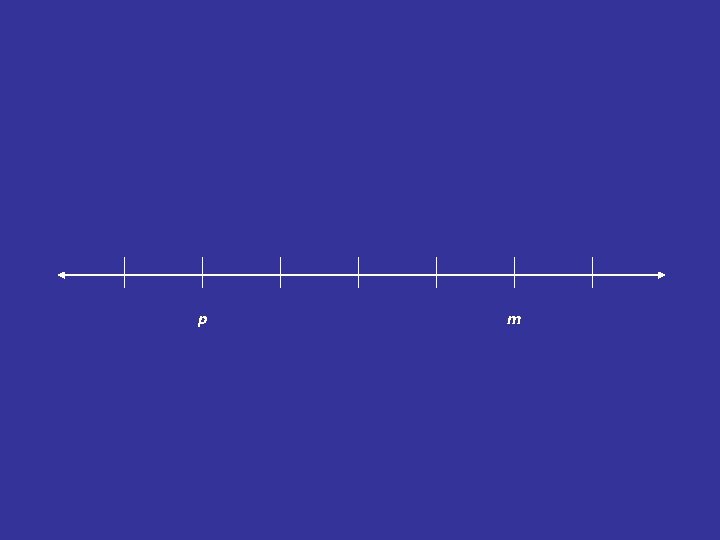

The Presidency and Congress • A simple model captures the dynamics that emerge when the President and Congress negotiate over legislation. – This model is very similar to Krehbiel’s Pivotal Politics model, but differs in some important ways—in particular, by incorporating the Hastert Rule. • To simplify things, let’s make a few assumptions: – There’s a unicameral legislature with a majority party with a median member M with ideal point m. – There is a president P with ideal point p. – Here’s how this looks right now:

President Obama The median Republican: John Kline (R-Minn. )

p m

The Presidency and Congress • A simple model captures the dynamics that emerge when the President and Congress negotiate over legislation. – This model is very similar to Krehbiel’s Pivotal Politics model, but differs in some important ways—in particular, by incorporating the Hastert Rule. • To simplify things, let’s make a few assumptions: – There’s a unicameral legislature with a majority party with a median member M with ideal point m. – There is a president P with ideal point p. • Lawmaking proceeds as follows: – If it wants to, M proposes a bill. – P decides whether to sign the bill or veto it. – This is the simple version of the model, and it’s unrealistic. • We’ll cover this version first to help you understand it. – Important additions to the model will come in a few minutes.

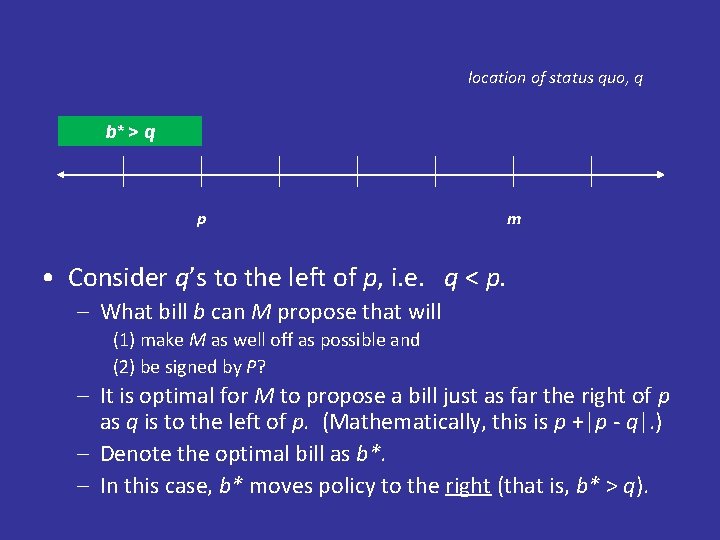

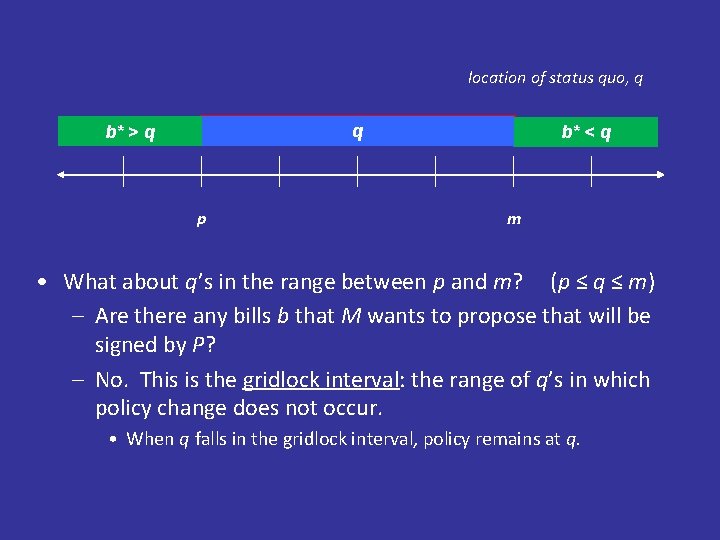

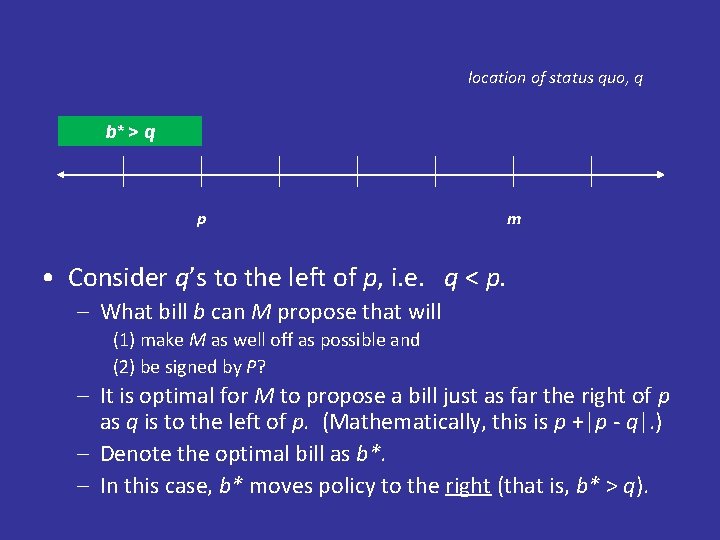

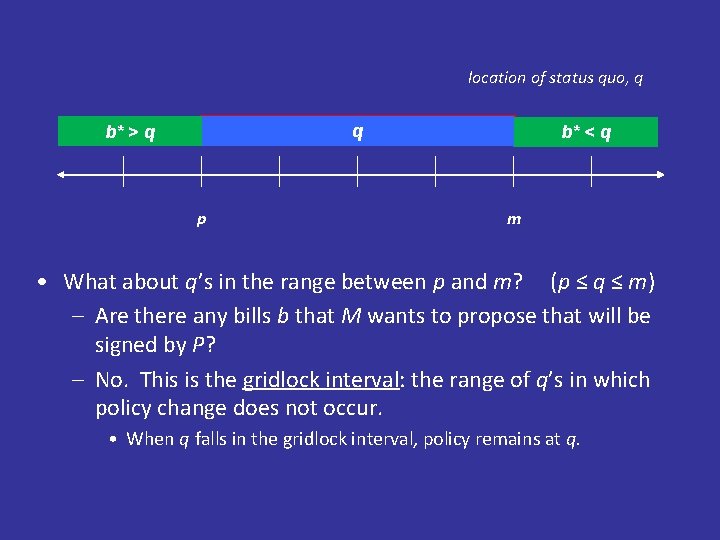

location of status quo, q b* q> q p m • Consider q’s to the left of p, i. e. q < p. – What bill b can M propose that will (1) make M as well off as possible and (2) be signed by P? – It is optimal for M to propose a bill just as far the right of p as q is to the left of p. (Mathematically, this is p +|p - q|. ) – Denote the optimal bill as b*. – In this case, b* moves policy to the right (that is, b* > q).

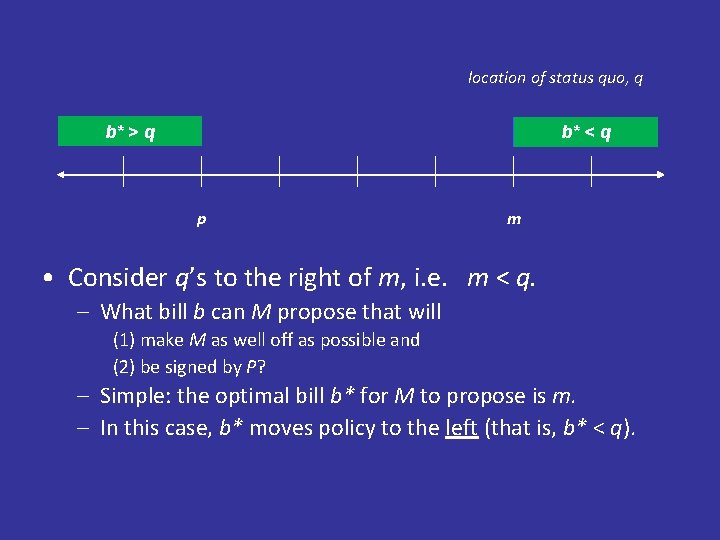

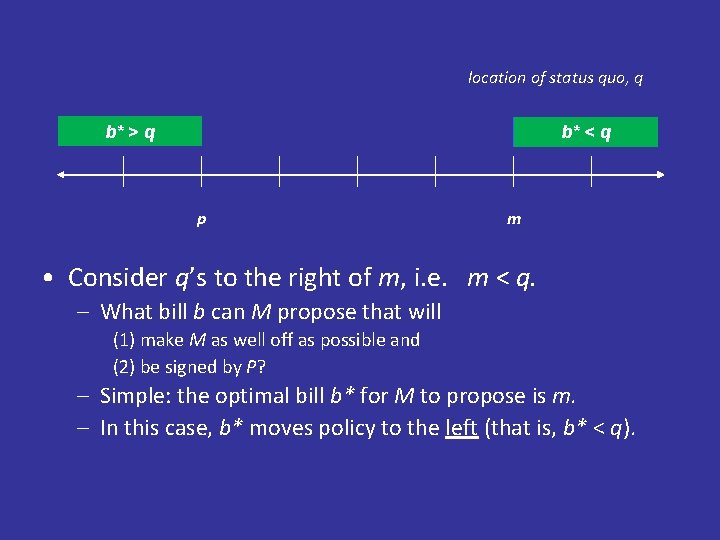

location of status quo, q b* q> q b* q< q p m • Consider q’s to the right of m, i. e. m < q. – What bill b can M propose that will (1) make M as well off as possible and (2) be signed by P? – Simple: the optimal bill b* for M to propose is m. – In this case, b* moves policy to the left (that is, b* < q).

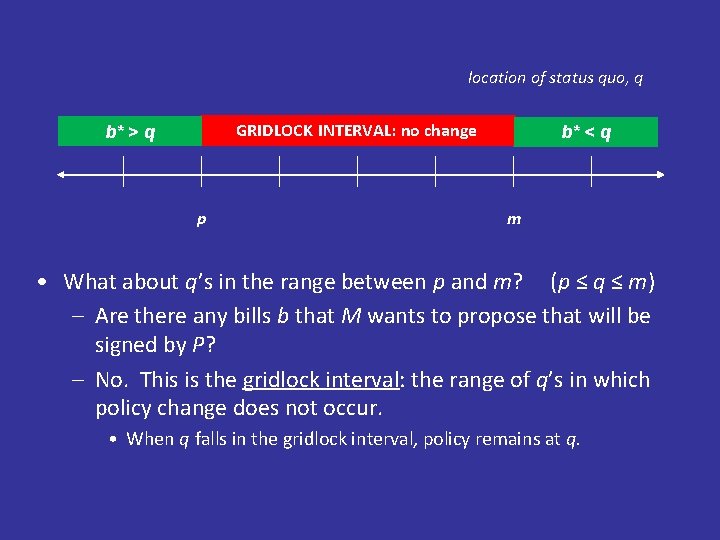

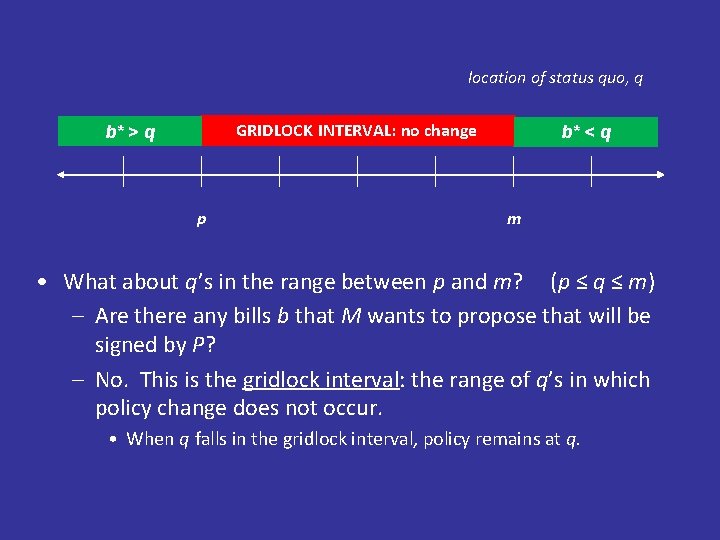

location of status quo, q GRIDLOCK INTERVAL: no change q b* q> q p b* q< q m • What about q’s in the range between p and m? (p ≤ q ≤ m) – Are there any bills b that M wants to propose that will be signed by P? – No. This is the gridlock interval: the range of q’s in which policy change does not occur. • When q falls in the gridlock interval, policy remains at q.

location of status quo, q GRIDLOCK INTERVAL: no change b* q> q p b* q< q m • What about q’s in the range between p and m? (p ≤ q ≤ m) – Are there any bills b that M wants to propose that will be signed by P? – No. This is the gridlock interval: the range of q’s in which policy change does not occur. • When q falls in the gridlock interval, policy remains at q.

From Divided to Unified Government • Our working example has assumed divided government. • How might this change if, say, Marco Rubio gets elected President in 2016 with a Republican Congress?

Pres. Marco Rubio The median Republican: John Kline (R-Minn. )

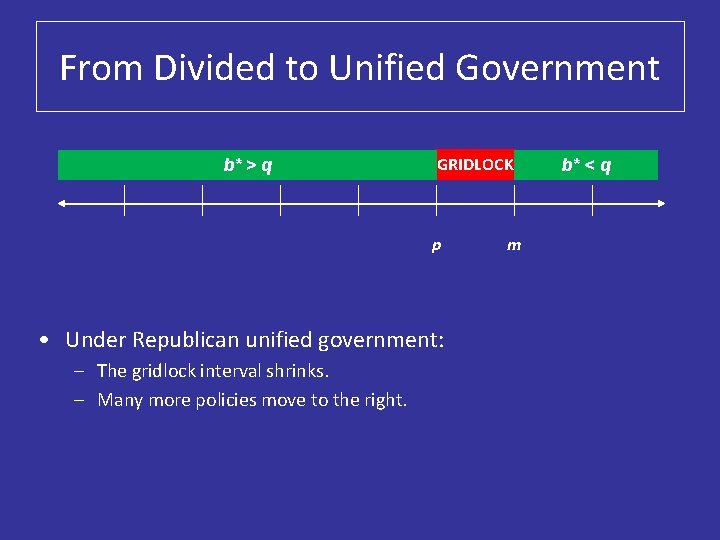

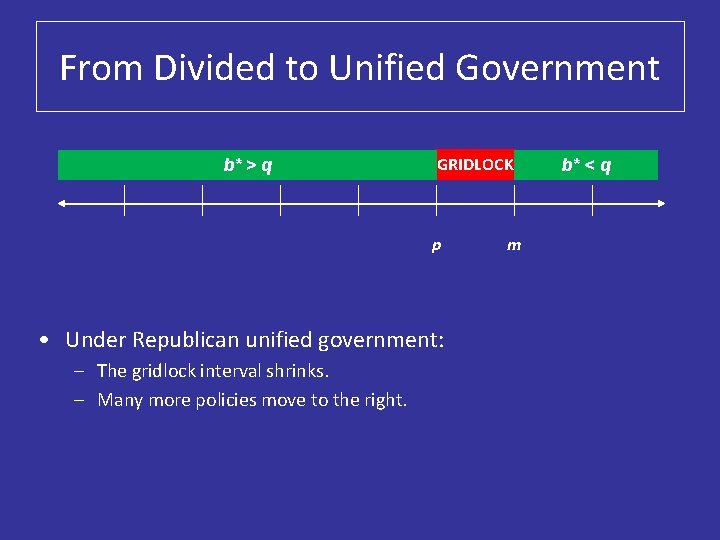

From Divided to Unified Government b* > q GRIDLOCK p • Under Republican unified government: – The gridlock interval shrinks. – Many more policies move to the right. m b* < q

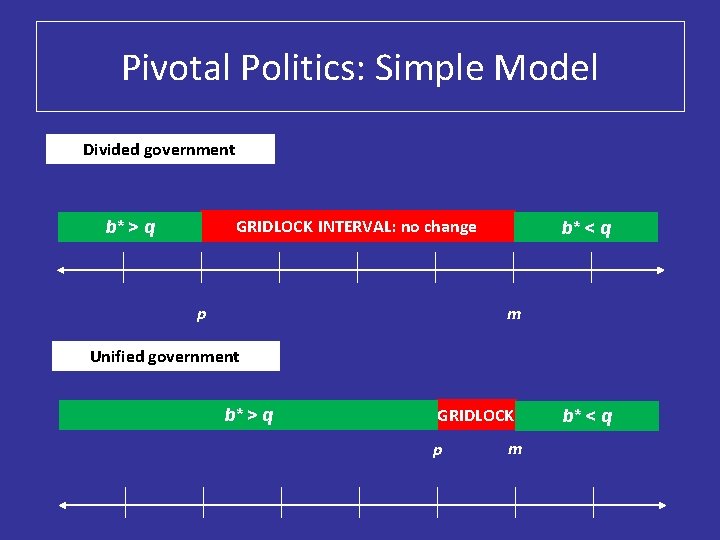

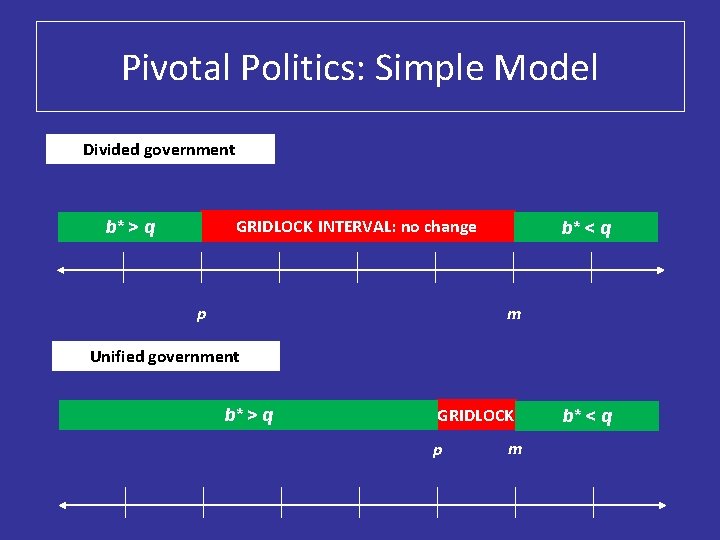

Pivotal Politics: Simple Model Divided government GRIDLOCK INTERVAL: no change b* q> q p b* q< q m Unified government q b* > q GRIDLOCK p m b* q< q

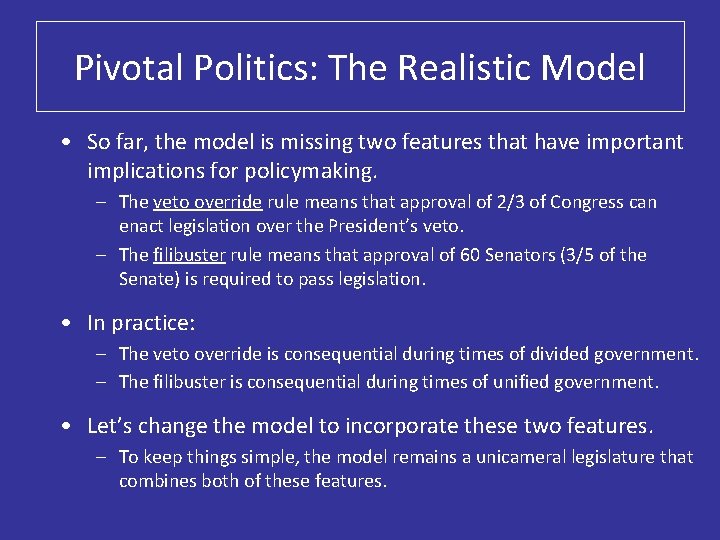

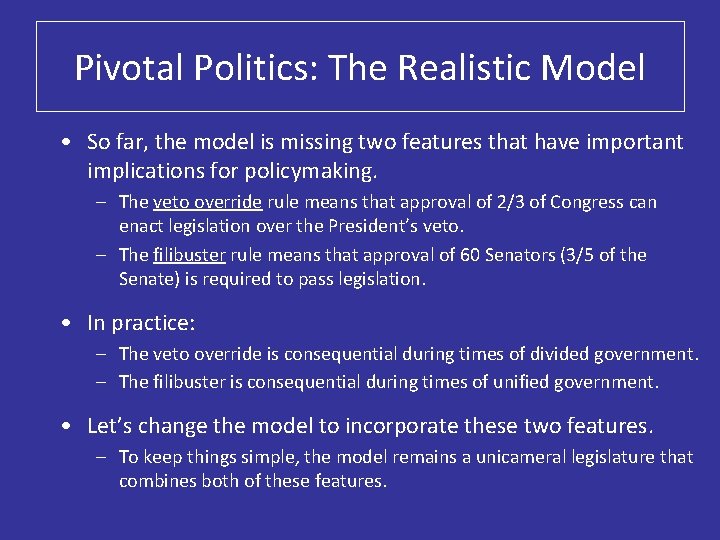

Pivotal Politics: The Realistic Model • So far, the model is missing two features that have important implications for policymaking. – The veto override rule means that approval of 2/3 of Congress can enact legislation over the President’s veto. – The filibuster rule means that approval of 60 Senators (3/5 of the Senate) is required to pass legislation. • In practice: – The veto override is consequential during times of divided government. – The filibuster is consequential during times of unified government. • Let’s change the model to incorporate these two features. – To keep things simple, the model remains a unicameral legislature that combines both of these features.

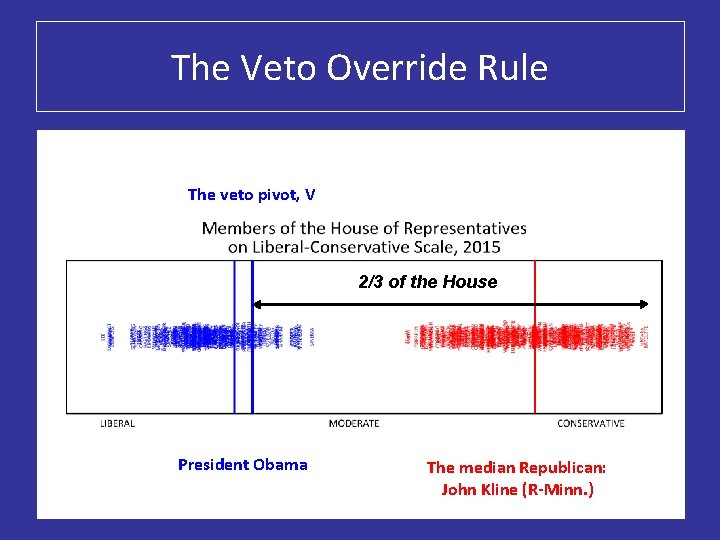

The Veto Override Rule The veto pivot, V 2/3 of the House President Obama The median Republican: John Kline (R-Minn. )

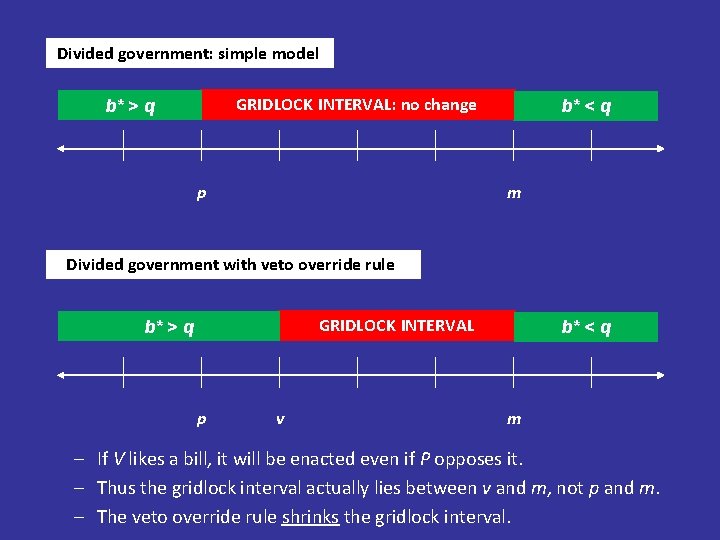

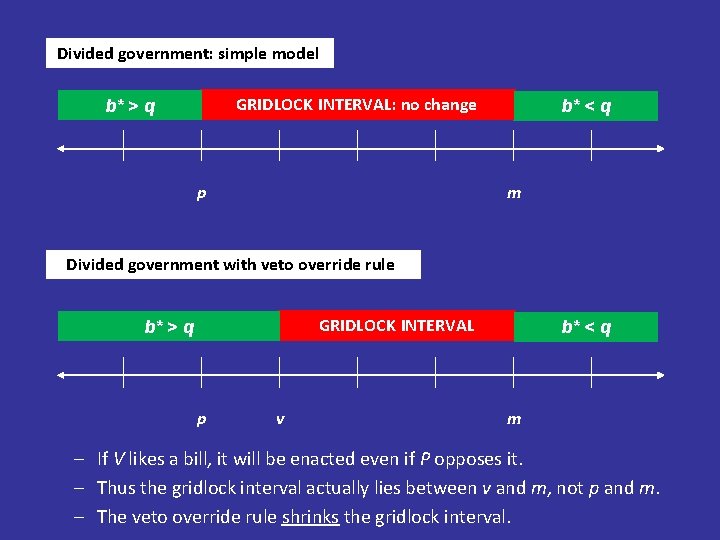

Divided government: simple model GRIDLOCK INTERVAL: no change b* q> q p b* q< q m Divided government with veto override rule GRIDLOCK INTERVAL b* > q p v b* < q m – If V likes a bill, it will be enacted even if P opposes it. – Thus the gridlock interval actually lies between v and m, not p and m. – The veto override rule shrinks the gridlock interval.

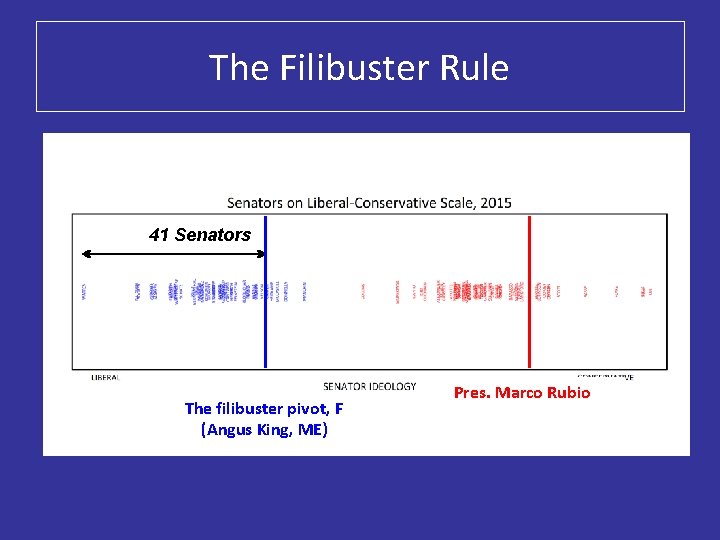

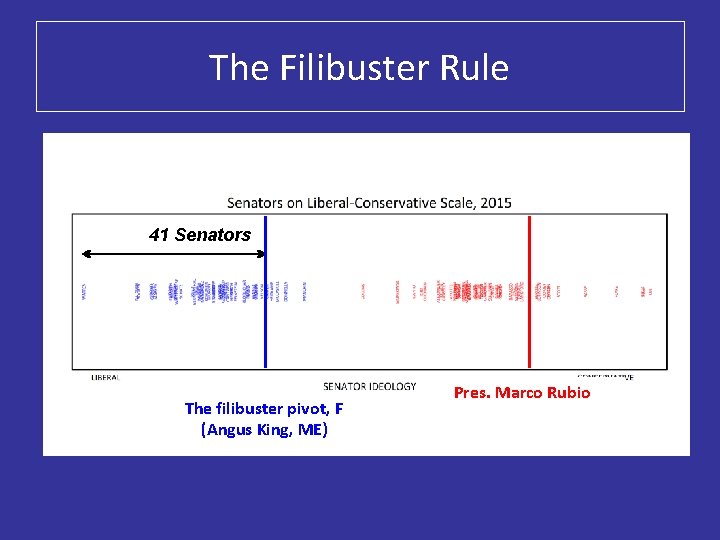

The Filibuster Rule 41 Senators The filibuster pivot, F (Angus King, ME) Pres. Marco Rubio

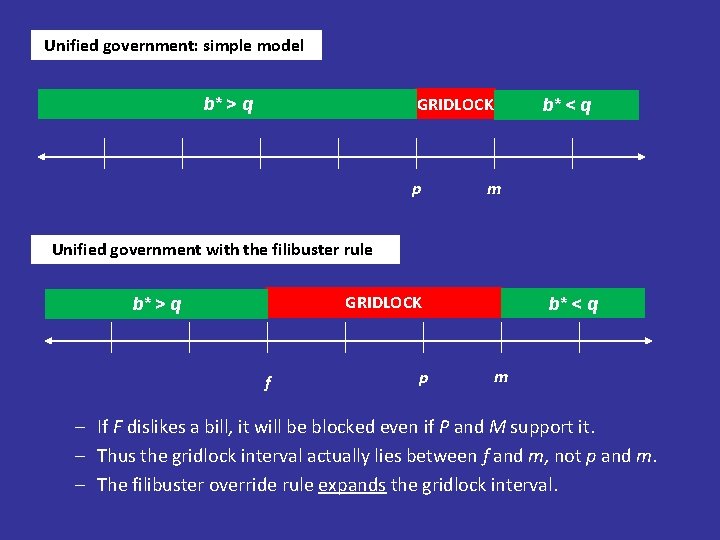

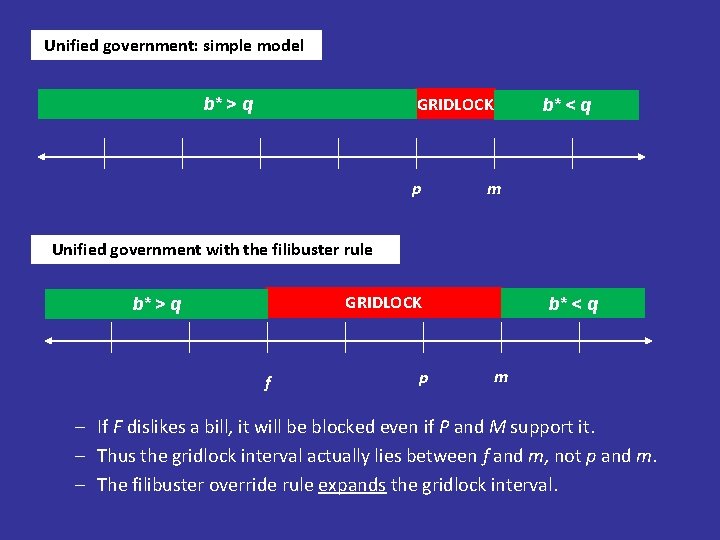

Unified government: simple model q GRIDLOCK b* > q p b* q< q m Unified government with the filibuster rule GRIDLOCK b* > q f p b* < q m – If F dislikes a bill, it will be blocked even if P and M support it. – Thus the gridlock interval actually lies between f and m, not p and m. – The filibuster override rule expands the gridlock interval.

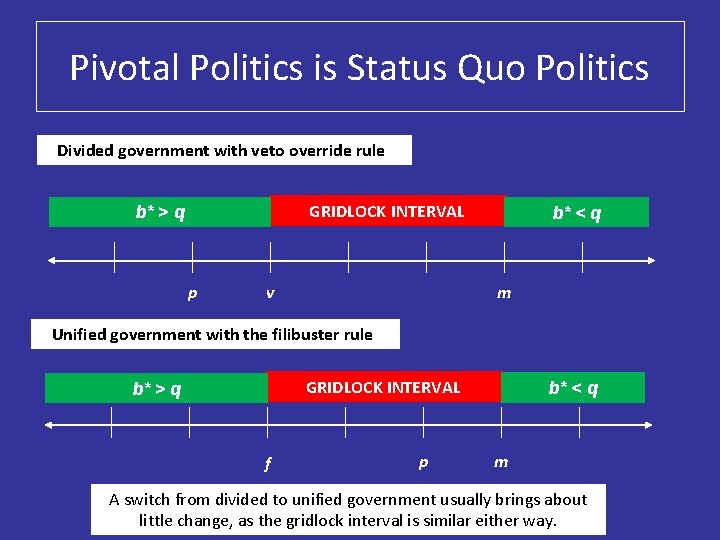

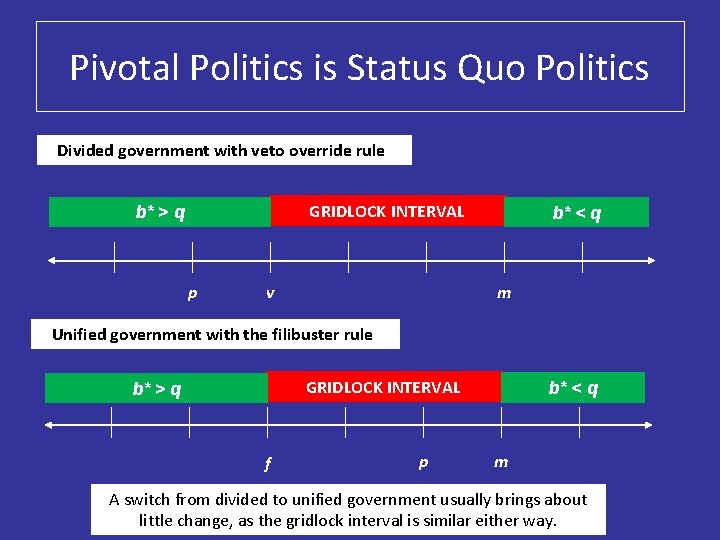

Pivotal Politics is Status Quo Politics Divided government with veto override rule GRIDLOCK INTERVAL b* > q p v b* < q m Unified government with the filibuster rule GRIDLOCK INTERVAL b* > q f p b* < q m A switch from divided to unified government usually brings about little change, as the gridlock interval is similar either way.

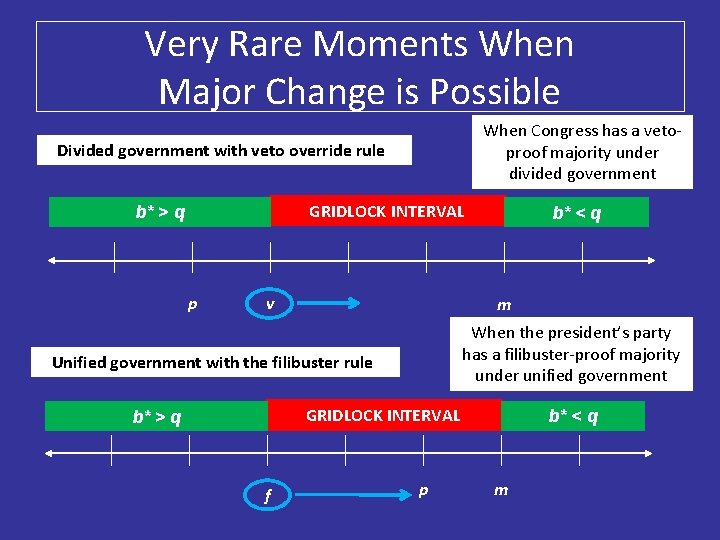

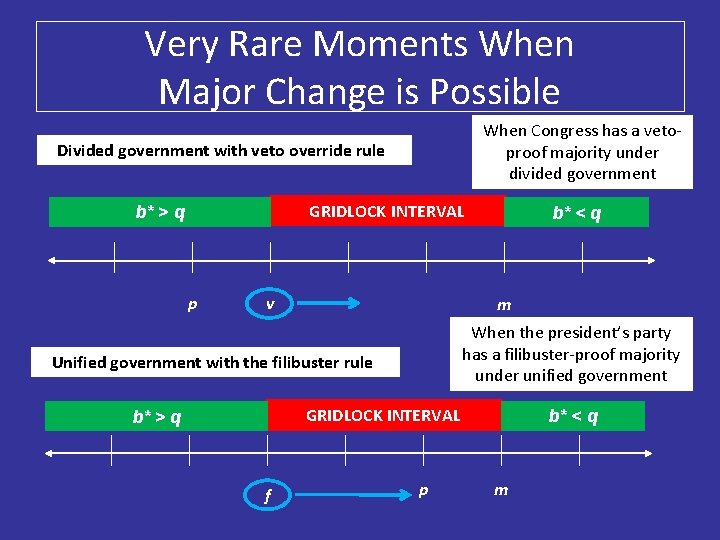

Very Rare Moments When Major Change is Possible When Congress has a vetoproof majority under divided government Divided government with veto override rule GRIDLOCK INTERVAL b* > q p v b* < q m When the president’s party has a filibuster-proof majority under unified government Unified government with the filibuster rule GRIDLOCK INTERVAL b* > q f p b* < q m

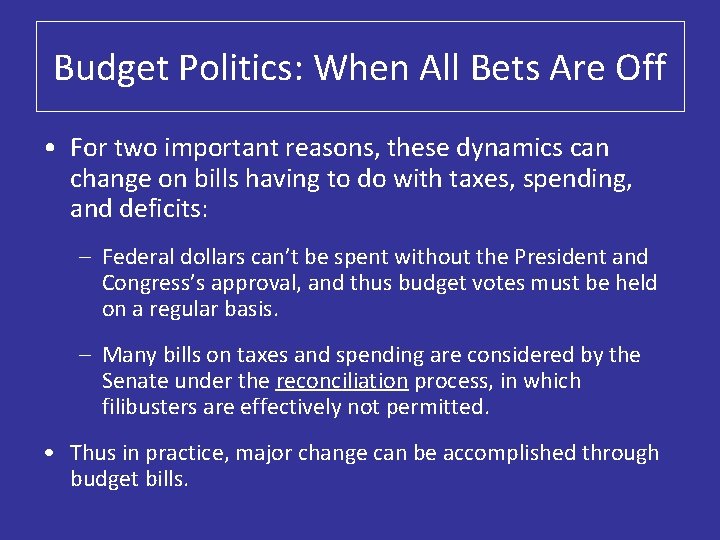

Budget Politics: When All Bets Are Off • For two important reasons, these dynamics can change on bills having to do with taxes, spending, and deficits: – Federal dollars can’t be spent without the President and Congress’s approval, and thus budget votes must be held on a regular basis. – Many bills on taxes and spending are considered by the Senate under the reconciliation process, in which filibusters are effectively not permitted. • Thus in practice, major change can be accomplished through budget bills.

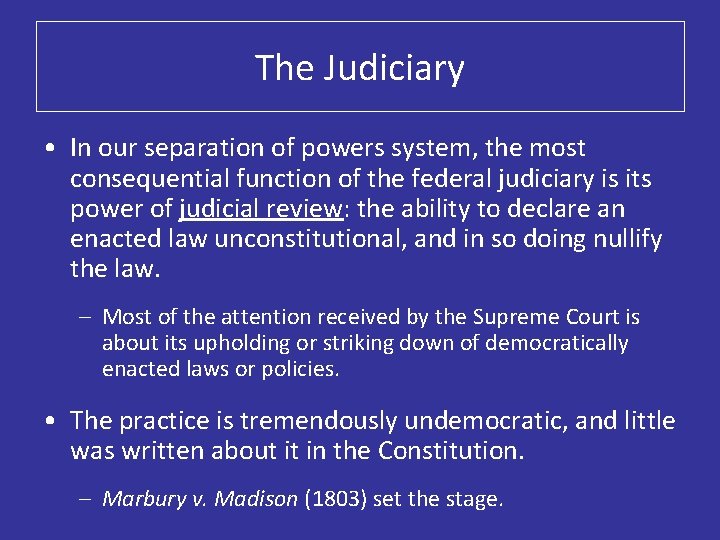

The Judiciary • In our separation of powers system, the most consequential function of the federal judiciary is its power of judicial review: the ability to declare an enacted law unconstitutional, and in so doing nullify the law. – Most of the attention received by the Supreme Court is about its upholding or striking down of democratically enacted laws or policies. • The practice is tremendously undemocratic, and little was written about it in the Constitution. – Marbury v. Madison (1803) set the stage.

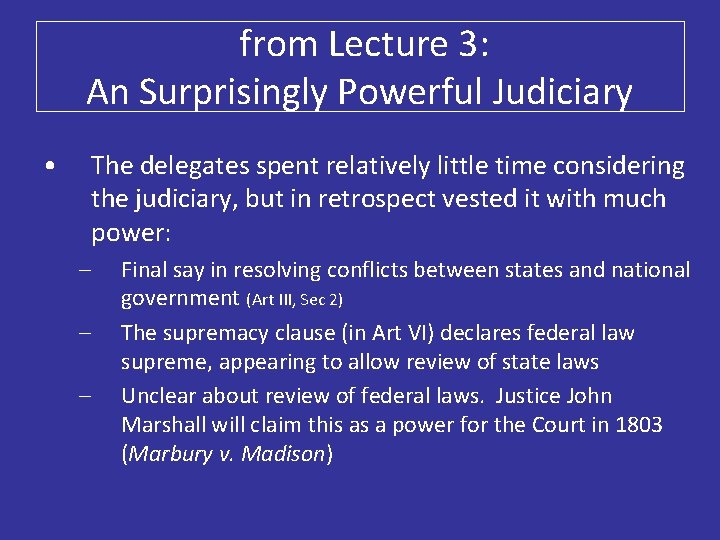

from Lecture 3: An Surprisingly Powerful Judiciary • The delegates spent relatively little time considering the judiciary, but in retrospect vested it with much power: – – – Final say in resolving conflicts between states and national government (Art III, Sec 2) The supremacy clause (in Art VI) declares federal law supreme, appearing to allow review of state laws Unclear about review of federal laws. Justice John Marshall will claim this as a power for the Court in 1803 (Marbury v. Madison)

The twisted tale of Marbury v. Madison • 1800: First inter-party transfer of power: – Control of government passes from the hands of the Federalists to the Democratic-Republicans • Before leaving office, the Federalists pass the Judiciary Act of 1801. – It increased the number of federal courts (and thus judgeships), shrunk the Supreme Court from six to five justices. • Also, outgoing John Adams nominates and Senate confirms secretary of state John Marshall as the new chief justice of the Supreme Court.

The twisted tale of Marbury v. Madison • Marshall stays on as secretary of state to help Adams process the last-minute rush of Federalist judicial appointments – But (really!) Marshall forgets to deliver signed justice-of-the-peace commissions to the president’s desk on the night before Inauguration Day. – Jefferson uses this technicality to order them invalid.

The twisted tale of Marbury v. Madison • Meanwhile, a battle is brewing over the Judiciary Act. – The D-Rs rightly see the judiciary as bulwark against their complete control of the federal government. – They repeal the Judiciary Act on party-line votes in both houses of Congress in 1802. • In March 1803, the Supreme Court agreed that Congress had the authority to do this under Article III (Stuart v. Land). • But six days beforehand, in a case little-noticed at the time, the Court establishes the judiciary branch as having coequal status in Marbury v. Madison.

The twisted tale of Marbury v. Madison • William Marbury was a loyal Federalist set to become a justice of the peace under the flurry of appointments by Adams, but rejected by Jefferson. • He appealed the rejection to the Supreme Court in a suit brought against Jefferson’s secretary of state, James Madison. – His suit asks the Court to issue a writ of mandamus—a judicial instruction to Madison—to deliver the commissions and thus make them valid.

The twisted tale of Marbury v. Madison • The case, in some ways, is a farce. – Marshall is ruling on a screw-up of his own making. • (Should he have recused himself? ) – Madison is likely to ignore any order by the Court, resulting in a major loss of credibility. • Out of this bitter lemon, Marshall makes sweet lemonade.

The twisted tale of Marbury v. Madison • Marshall’s ruling determines that Marbury has a right to the office under the law. • But he rules that the Court does not have jurisdiction to hear the case—despite the fact that Congress explicitly gave the Court the jurisdiction on writs of mandamus. • Marshall’s reasoning: Article III does not give Congress the power to add to the Court’s jurisdiction. • Therefore, the enacted law is in conflict with the Constitution.

The precedent of Marbury v. Madison • Faced with a conflict between enacted law and the Constitution, Marshall rules that: – – – • The Constitution takes precedence Any unconstitutional law is void And the judiciary branch’s responsibility is to determine whether laws are unconstitutional. The political brilliance of the decision is remarkable: – Marshall delivers a face-saving opinion that hurts the Federalists in the short-term, but strengthens the hand of the judiciary in the long-term. • The D-R’s had the incentive to agree to the ruling because, after all, it was in their favor.

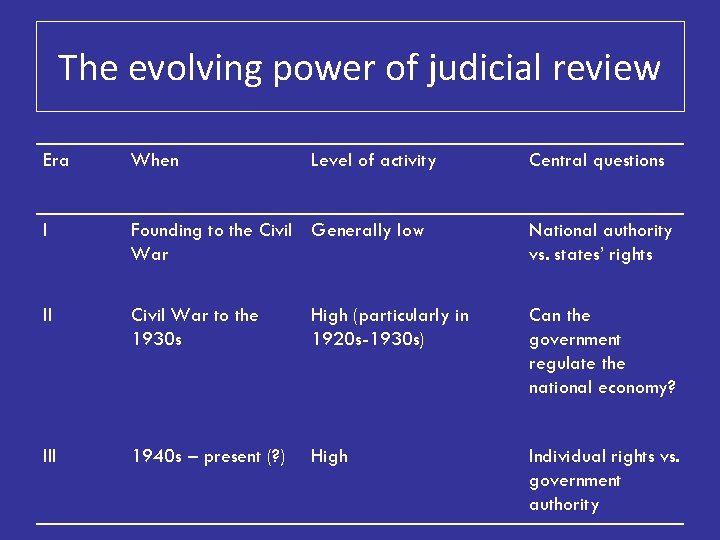

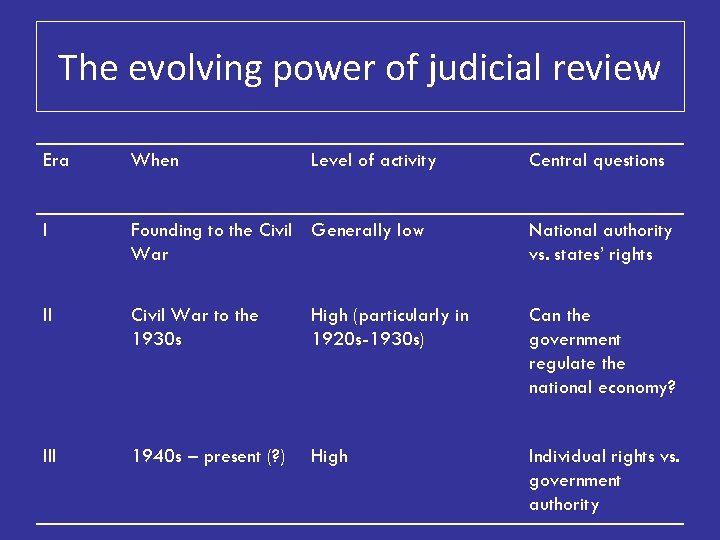

The evolving power of judicial review • The case attracted little attention at the time, and judicial review didn’t become truly consequential until the Civil War era. • Between 1790 and 1860, the Supreme Court struck down only two federal laws as unconstitutional.

The evolving power of judicial review • The case attracted little attention at the time, and judicial review didn’t become truly consequential until the Civil War era. • Between 1790 and 1860, the Supreme Court struck down only two federal laws as unconstitutional. • Scholars generally agree that there have been three eras in which the Court’s judicial review powers have taken on distinct characteristics.

The evolving power of judicial review Era When Level of activity Central questions I Founding to the Civil Generally low War National authority vs. states’ rights II Civil War to the 1930 s High (particularly in 1920 s-1930 s) Can the government regulate the national economy? III 1940 s – present (? ) High Individual rights vs. government authority

Ild nurse

Ild nurse 80 in 50 si kaçtır

80 in 50 si kaçtır Inin.com

Inin.com Inin reactor nuclear

Inin reactor nuclear Power and politics in organizations

Power and politics in organizations Power politics and conflict in organizations

Power politics and conflict in organizations Conflict power and politics

Conflict power and politics Power and politics organizational behavior

Power and politics organizational behavior Power and politics organization theory

Power and politics organization theory Power and politics

Power and politics The nature of power politics and government

The nature of power politics and government Political power

Political power Triangle of power

Triangle of power Pol sezan autoportret

Pol sezan autoportret Dva a pol chlapa zaujimavosti

Dva a pol chlapa zaujimavosti Maskulinost

Maskulinost Kombes pol budi utomo

Kombes pol budi utomo Pol pof

Pol pof Pol parol

Pol parol Vertical heterophoria

Vertical heterophoria Ustal wzor rzeczywisty alkoholu o masie czasteczkowej 62

Ustal wzor rzeczywisty alkoholu o masie czasteczkowej 62 Pol pot

Pol pot Huzjak stjepan

Huzjak stjepan Ja som koza rohata do pol boka odrata

Ja som koza rohata do pol boka odrata Sandra cruz pol

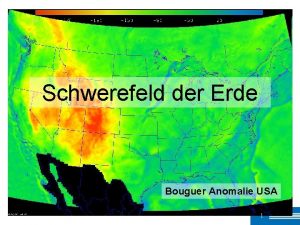

Sandra cruz pol Freiluftanomalie

Freiluftanomalie Martine pol

Martine pol Projectontwikkelaarsresolutie

Projectontwikkelaarsresolutie Myšlenou čárou protínající severní a jižní pól je

Myšlenou čárou protínající severní a jižní pól je Pol camps renom

Pol camps renom Karolina riedel wikipedia

Karolina riedel wikipedia Mag. pol.

Mag. pol. Pol

Pol Pol

Pol Syn boreasza, brat kalaisa

Syn boreasza, brat kalaisa Hakpol zaczarnie

Hakpol zaczarnie Pol wolker

Pol wolker Pol buch

Pol buch Pol puare

Pol puare /pol/

/pol/ Van gogh suncokreti

Van gogh suncokreti Pol1000

Pol1000 Pol success ce

Pol success ce