La rappresentazione dellAltro dalle narrative dellImpero al romanzo

- Slides: 90

La rappresentazione dell’Altro: dalle narrative dell’Impero al romanzo postcoloniale Corso I anno Lettere Moderne (curriculum moderno) A. A. 2015 -2016

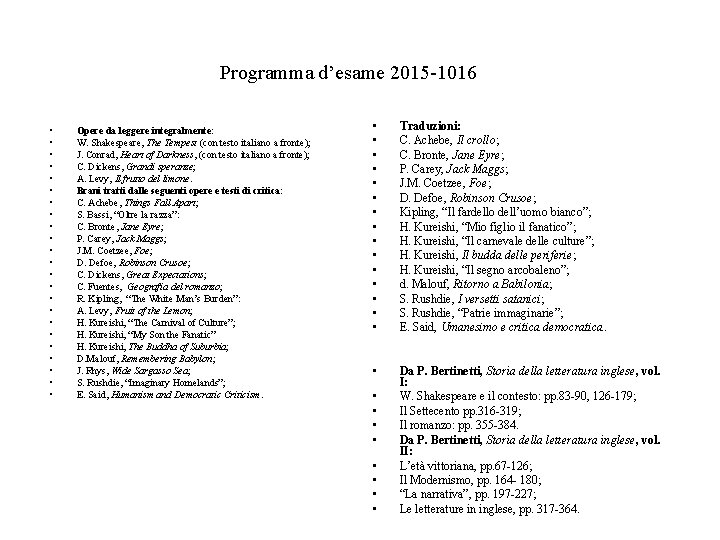

Programma d’esame 2015 -1016 • • • • • • Opere da leggere integralmente: W. Shakespeare, The Tempest (con testo italiano a fronte); J. Conrad, Heart of Darkness, (con testo italiano a fronte); C. Dickens, Grandi speranze; A. Levy, Il frutto del limone. Brani tratti dalle seguenti opere e testi di critica: C. Achebe, Things Fall Apart; S. Bassi, “Oltre la razza”: C. Bronte, Jane Eyre; P. Carey, Jack Maggs; J. M. Coetzee, Foe; D. Defoe, Robinson Crusoe; C. Dickens, Great Expectations; C. Fuentes, Geografia del romanzo; R. Kipling, “The White Man’s Burden”: A. Levy, Fruit of the Lemon; H. Kureishi, “The Carnival of Culture”; H. Kureishi, “My Son the Fanatic” H. Kureishi, The Buddha of Suburbia; D. Malouf, Remembering Babylon; J. Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea; S. Rushdie, “Imaginary Homelands”; E. Said, Humanism and Democratic Criticism. • • • • Traduzioni: C. Achebe, Il crollo; C. Bronte, Jane Eyre; P. Carey, Jack Maggs; J. M. Coetzee, Foe; D. Defoe, Robinson Crusoe; Kipling, “Il fardello dell’uomo bianco”; H. Kureishi, “Mio figlio il fanatico”; H. Kureishi, “Il carnevale delle culture”; H. Kureishi, Il budda delle periferie; H. Kureishi, “Il segno arcobaleno”; d. Malouf, Ritorno a Babilonia; S. Rushdie, I versetti satanici; S. Rushdie, “Patrie immaginarie”; E. Said, Umanesimo e critica democratica. • Da P. Bertinetti, Storia della letteratura inglese, vol. I: W. Shakespeare e il contesto: pp. 83 -90, 126 -179; Il Settecento pp. 316 -319; Il romanzo: pp. 355 -384. Da P. Bertinetti, Storia della letteratura inglese, vol. II: L’età vittoriana, pp. 67 -126; Il Modernismo, pp. 164 - 180; “La narrativa”, pp. 197 -227; Le letterature in inglese, pp. 317 -364. • •

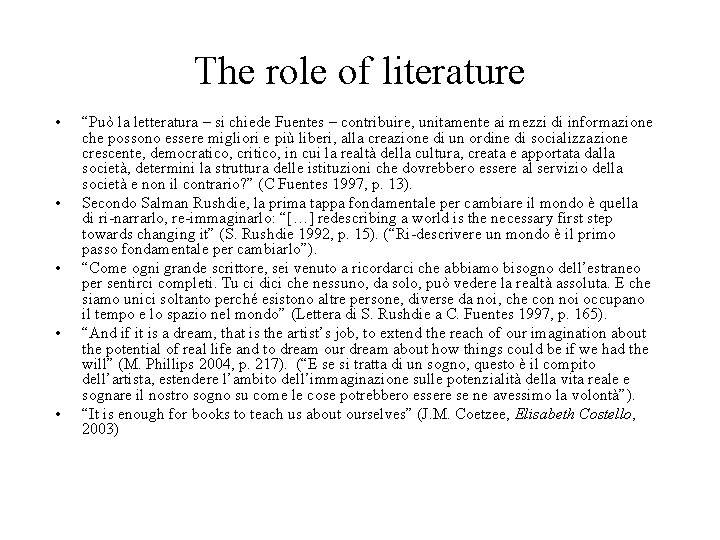

The role of literature • • • “Può la letteratura – si chiede Fuentes – contribuire, unitamente ai mezzi di informazione che possono essere migliori e più liberi, alla creazione di un ordine di socializzazione crescente, democratico, critico, in cui la realtà della cultura, creata e apportata dalla società, determini la struttura delle istituzioni che dovrebbero essere al servizio della società e non il contrario? ” (C Fuentes 1997, p. 13). Secondo Salman Rushdie, la prima tappa fondamentale per cambiare il mondo è quella di ri-narrarlo, re-immaginarlo: “[…] redescribing a world is the necessary first step towards changing it” (S. Rushdie 1992, p. 15). (“Ri-descrivere un mondo è il primo passo fondamentale per cambiarlo”). “Come ogni grande scrittore, sei venuto a ricordarci che abbiamo bisogno dell’estraneo per sentirci completi. Tu ci dici che nessuno, da solo, può vedere la realtà assoluta. E che siamo unici soltanto perché esistono altre persone, diverse da noi, che con noi occupano il tempo e lo spazio nel mondo” (Lettera di S. Rushdie a C. Fuentes 1997, p. 165). “And if it is a dream, that is the artist’s job, to extend the reach of our imagination about the potential of real life and to dream our dream about how things could be if we had the will” (M. Phillips 2004, p. 217). (“E se si tratta di un sogno, questo è il compito dell’artista, estendere l’ambito dell’immaginazione sulle potenzialità della vita reale e sognare il nostro sogno su come le cose potrebbero essere se ne avessimo la volontà”). “It is enough for books to teach us about ourselves” (J. M. Coetzee, Elisabeth Costello, 2003)

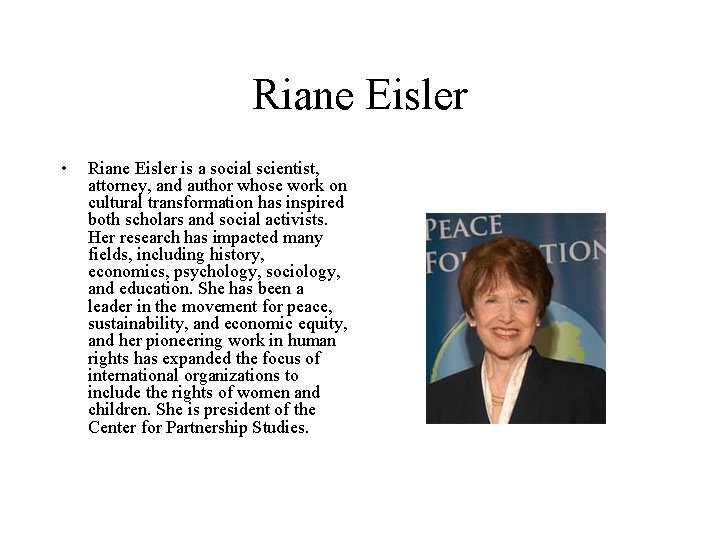

Riane Eisler • Riane Eisler is a social scientist, attorney, and author whose work on cultural transformation has inspired both scholars and social activists. Her research has impacted many fields, including history, economics, psychology, sociology, and education. She has been a leader in the movement for peace, sustainability, and economic equity, and her pioneering work in human rights has expanded the focus of international organizations to include the rights of women and children. She is president of the Center for Partnership Studies.

R. Eisler: Theory of cultural transformation • “Symbols, myths, stories play such a critical role in our lives, they can change our consciousness, therefore literature, education and language are a pivotal force for our cultural and human transformation”. • “Cultural transformation requires structural changes, from the family to politics and economics, and it certainly requires changes in our day-to-day behaviour, in how we treat one-another. A shift from domination to partnership is a shift from relations of top-down rankings, be they man over women, man over man, nation over nation, race over race, religion over religion, and so forth, to relations of mutual benefit, mutual respect, mutual accountability”.

Il compito dell’intellettuale • Said: “to dissolve Blake’s ‘mind-forg’d manacles’ so as to be able to use one’s mind historically and rationally for the purposes of reflective understanding” (Said, “Preface” to Orientalism 2003) (“dissolvere quelle che Blake definiva le ‘manette forgiate dalla mente’ affinché si sia capaci di utilizzare la propria mente storicamente e razionalmente con l’obiettivo di una comprensione riflessiva”). • “Rather than the manifactured clash of civilizations, we need to concentrate on the slow working together of cultures that overlap, borrow from each other, and live together in far more interesting ways than any abridged or inauthentic mode of understanding can allow” (Said 2003, p. 5). ( “Piuttosto che sul costruito scontro di civiltà, è necessario concentrarci sul lento interagire delle culture che si sovrappongono, prendono in prestito l’una dall’altra, e convivono in modi assai più interessanti rispetto a quanto una modalità riduttiva e non autentica di comprensione possa consentire”).

• • • E. Said: biography Edward Said, (born November 1, 1935, Jerusalem—died September 25, 2003, New York, U. S. ), Palestinian American academic, political activist, and literary critic who examined literature in light of social and cultural politics and was an outspoken proponent of the political rights of the Palestinian people and the creation of an independent Palestinian state. Said’s father, Wadie Ibrahim, was a wealthy businessman who had lived some time in the United States and apparently, at some point, took U. S. citizenship. In 1947 Wadie moved the family from Jerusalem to Cairo in order to avoid the conflict that was beginning over the United Nations partition of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab areas (see Arab-Israeli wars). In Cairo, Said was educated in English-language schools before transferring to an exclusive school in Massachusetts in the United States in 1951. He attended Princeton University and Harvard University where he specialized in English literature. He joined the faculty of Columbia University as a lecturer in English in 1963 and in 1967 was promoted to assistant professor of English and comparative literature. Said was promoted to full professor in 1969 and in 1978 published Orientalism, his best-known work and one of the most influential scholarly books of the 20 th century. In it Said examined Western scholarship of the “Orient, ” specifically of the Arab Islamic world (though he was an Arab Christian), and argued that early scholarship by Westerners in that region was biased and projected a false and stereotyped vision of “otherness” on the Islamic world that facilitated and supported Western colonial policy. Although he never taught any courses on the Middle East, Said wrote numerous books and articles in his support of Arab causes and Palestinian rights. He was especially critical of U. S. and Israeli policy in the region, and this led him into numerous, often bitter, polemics with supporters of those two countries. He was elected to the Palestine National Council (the Palestinian legislature in exile) in 1977, and, though he supported a peaceful resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, he became highly critical of the Oslo peace process between the Palestine Liberation Organization and Israel in the early 1990 s. His autobiography, Out of Place (1999), reflects the ambivalence he felt over living in both the Western and Eastern traditions. In addition to his political and academic pursuits, Said was an accomplished musician and pianist.

Edward Said • Orientalism (1978) • The World, The Text and the Critic (1983) • The Question of Palestine (1992) • Culture and Imperialism (1993) • Out of Place (1999) • Humanism and Democratic Criticism (2004)

E. Said: Crossing of borders • “Public intellectual” • Awareness of the relationship between knowledge and power (see Gramsci, Foucault) • Crucial role of the intellectual

Antonio Gramsci (da I Quaderni dal Carcere) • “Gli intellettuali hanno una funzione nell’‘egemonia’ che il gruppo dominante esercita su tutta la società[…]. Gli intellettuali hanno la funzione di organizzare l’egemonia sociale di un gruppo” • “Commessi del gruppo dominante” • Esercizio dell’egemonia attraverso il consenso

Said: l’esercizio della critica • Said lettore attento di Gramsci ma difende il concetto di autonomia dell’attività intellettuale • Intellettuale autonomo e laico è costretto all’‘esilio’ • Attività prima: esercizio della critica Critica: oppositiva, secolare, mondana

“Mondanità” per Said • • • “Abbiamo raggiunto la fase in cui la specializzazione e la professionalizzazione, alleate al dogmatismo della cultura, a un etnocentrismo e a un nazionalismo appena sublimati, e a un quietismo quasi religioso, hanno condotto il critico professionale e accademico […] in tutto un altro mondo. In quel mondo relativamente indisturbato e appartato sembra non esservi alcun contatto con il mondo degli eventi e delle società”. (The World, The Text and the Critic, 1983) “I testi hanno modi di esistenza i quali, anche nella loro forma più rarefatta, sono sempre avviluppati nelle circostanze, nel tempo, nel luogo e nella società – in breve: essi sono nel mondo e di conseguenza sono mondani” (ibid. ) Insofferenza per le teorie astratte, per la testualità autoriflessiva.

Said: la critica secolare • L’intellettuale critico deve concepire se stesso come non subordinato a concetti come la ‘verità’ e ‘la conoscenza’. • Deve sfidare le istituzioni gerarchiche della conoscenza, gli arbitri della ‘verità’.

Said: la funzione oppositiva della critica • La critica si allontana da se stessa se si trasforma in dogma organizzato. • “Nella diffidenza verso le concezioni totalizzanti, nell’insoddisfazione di fronte agli oggetti reificati, nell’insofferenza per le corporazioni, gli interessi particolari, i feudi e gli abiti mentali ortodossi, la critica è in massimo grado se stessa […] La critica si deve concepire come un’istanza vitale, costitutivamente opposta a ogni forma di tirannia, di dominio o di abuso; il suo obiettivo sociale è un sapere non-coercitivo, prodotto nell’interesse della libertà” (The World, the Text and the Critic) • Said non appartiene né organizza una “scuola” critica o teorica. Intellettuale “nomade”

Orientalism (1978) • • Il critico mette a nudo le complicità della cultura occidentale (nella forma di scienza con pretese di obiettività) con il progetto imperiale volto al dominio di altre nazioni Conoscenza e potere (Foucault): ‘Knowledge’ about the ‘Orient’ as it was produced and circulated in Europe was an ideological accompaniment of colonial ‘power’. The book is not about non-Western cultures, but about the Western representation of these cultures (Orientalism as a discipline supported by others such as archeology, philosophy, history, literature etc. ). It investigates how the formal study of the ‘Orient’ contributed to the functioning of colonial power

Orientalism in literature • Said argues that representation of the ‘Orient’ in European literary texts, travelogues and other writings contributes to the creation of a dichotomy between Europe and its ‘others’. • ‘Knowledge’ is seen as a crucial part of maintaining power over the oppressed

“Orientalism” • The study of the Orient was not objective but “a political vision of reality whose structures promoted the difference between the familiar (Europe, the West, ‘us’) and the strange (the Orient, the East, ‘them’)” (Orientalism) • Dicothomy essential in the construction of European self-conception (civilization, progress, rationality, control, masculinity etc. )

Foucault: ‘discourse’ • All ideas are ordered through some “material medium”. This ordering imposes a pattern upon them which F. calls ‘discourse’. • This notion was born from his work on madness (he wanted to recover the voice of insane people) • Madness as a category of human identity is produced and reproduced by various rules, systems which separate it from ‘normalcy’. • Discursive practices make it difficult for individuals to think outside them, hence they are exercises in power and control.

The Question of Palestine (1979) • He explores the complex existential, historical reality lived by the ‘others’ through the eyes of the ‘others’. • History of Palestine and its people as lived and interpreted by them

Culture and Imperialism (1993) • “Overlapping territories, intertwined histories” • Interconnections • It explores literary works (mostly novels) produced by Western writers about other worlds, works characterized by a prejudicial approach to the ‘others’ and by an Orientalist view. • The novel as a literary genre plays a crucial role in creating imperialist attitudes and preconceptions. • Said insists on the importance of narratives in shaping identities, both individual and collective ones. • Homi Bhabha asserts that “Nations are narrations” (Nazioni e narrazioni, 1997). • The literary texts taken into exam are seen as inextricably connected to the imperial system within which they were conceived.

Said, contrapuntual reading (From Culture and Imperialism) • Contrapuntal analysis is used in interpreting colonial texts, considering the perspectives of both the colonizer and the colonized. If one does not read with the right background, one may miss the implications of the presence of Antigua in Mansfield Park, Australia in Great Expectations, or India in Vanity Fair. Interpreting contrapuntally is interpreting different perspectives simultaneously and seeing how the text interacts with other related contexts. It is reading with "awareness both of the metropolitan history that is narrated and of those other histories against which (and together with which) the dominating discourse acts". Contrapuntal reading means reading a text "with an understanding of what is involved when an author shows, for instance, that a colonial sugar plantation is seen as important to the process of maintaining a particular style of life in England".

Said: “pensare in modo contrappuntistico” “Nessuno è oggi esclusivamente “una” cosa sola” (vedi pp. 367 -8 Cultura e imperialismo) “Questo libro è un tentativo di riconciliazione […] questo libro legittima la speranza, non perché l’attuale situazione – fatta di pulizie etniche e di deportazioni – la giustifichi; al contrario, questo è un libro di speranza proprio perché la speranza è ciò di cui si ha più bisogno, e perché la concezione saidiana dell’esperienza condivisa richiama ulteriori narrazioni di storia in comune, le quali sono esse stesse la migliore speranza di superamento delle storie del conflitto, delle separazioni e delle radicali purezza e identità, che rendono il mondo orribile e che sono la sostanza delle morbose e mortuarie culture del radicalismo nazionalistico” (Paul Bové, 1993)

Said: New Humanism (from Humanism and Democratic Criticism, 2004) • • “What concerns me is humanism as a useable praxis for intellectuals and academics who want to know what they are doing, what they are committed to as scholars, and who want also to connect these principles to the world in which they live as citizens”. “Not to see that the essence of humanism is to understand human history as a continuous process of self-understanding and self-realization, not just for us, as white, male, European, and American, but for everyone, is to see nothing at all”. “Humanism is not a way of consolidating and reaffirming what ‘we’ have always known and felt, but rather a means of questioning, upsetting, and reformulating so much of what is presented to us as commodified, packaged, uncontroversial, and uncritically codified certainties, including those contained in the masterpieces herded under the rubric of ‘the classics”. “Humanism is the only – I would go so far as saying the final – resistance we have against the inhuman practices and injustices that disfigure hunan history” (Preface to Orientalism, 2003)

Said: Living in exile (from “The Mind of Winter”, 1987) • “The Exile knows that in a secular and contingent world homes are always provisional. Borders and barriers, which enclose us within the safety of familiar territories, can also become prisons, and are often defended beyond reason or necessity. Exiles cross borders, break barriers of thought and experience”. • “Seeing ‘the entire world as a foreign land’ makes possible originality of vision. Most people are principally aware of one culture, one setting, one home. Exiles are aware of at least two and this plurality of vision gives rise to an awareness of simultaneous dimensions, an awareness that is ‘contrapuntual’”.

La questione del canone • Arbitrarietà nella formulazione del canone e crisi dei paradigmi: “The so called ‘literary canon’, the unquestioned ‘great tradition’ of the ‘national literature’, has to be recognized as a construct, fashioned by particular people for particular reasons at a certain time” (Terry Eagleton, 1983)

Canone e identità nazionale • “As religion progressively ceases to provide the social ‘cement’, affective values and basic mythologies by which a socially turbulent classsociety can be welded together, ‘English’ is constructed as a subject to carry this ideological burden from the Victorian period onwards” (Terry Eagleton 1983)

Apertura del canone • “No single tradition can function as a guarantee of the present, can save us. There are many traditions, constituted by gender, ethnicity, sexuality, race, class, that criss-cross the patterns of our lives. By bringing them into history, into recognition and representation, we appreciate the compexity that challenges the tyranny on the present of a single, official heritage: that of ‘Being British’” (I. Chambers, Narratives of Nationalism”

La funzione del canone letterario nella politica coloniale britannica • • • La politica coloniale di istruzione ha rappresentato un potente apparato ideologico che ha confinato l’Altro a una condizione di inferiorità (giustificazione dell’impresa imperiale) Ngugi wa Thiong’o: Ngugi argues that colonization was not simply a process of physical force. Rather, "the bullet was the means of physical subjugation. Language was the means of the spiritual subjugation. “(Decolonizing the Mind, 1986) Lord Macaulay, ”Minute on Indian Education”, 1835: “We are free, we are civilized to little purpose, if we grudge to any portion of the human race an equal measure of freedom and civilization”. F. Fanon: “Colonialism is not satisfied merely with holding a people in its grip and emptying the native’s brain of all form and content. By a kind of perverted logic, it turns to the past of oppressed people, and distorts, disfigures and destroys it” (Black Skin, White Masks, 1967) “Colonial educational policies were directed towards the suppression of a sense of identity” (Griffiths, 1978)

Letteratura inglese strumento di controllo • Letteratura strumento per formare e “addomesticare” i popoli sottomessi modellati sullo standard della “Englishness” • Imitazione del modello ma replica imperfetta dello stesso: ”mimicry”

The “Other” • “The concept of the Other signifies that which is unfamiliar and extraneous to a dominant subjectivity, the opposite or negative against which an authority is defined. The West thus conceived of its superiority relative to the perceived lack of power, self-consciousness, or ability to think and rule of colonized peoples” (Boehmer, 1995, Colonial and Postcolonial Literatures)

The novel • Il genere del romanzo ha sostenuto l’impresa coloniale. • Nascita del genere è coincisa con il progetto europeo di espansione coloniale. • Il romanzo partecipa al processo di costruzione dell’identità dell’Io e dell’Altro. • “English literature of the XIX century cannot be understood without remembering that imperialism, understood as England’s social mission, was a crucial part of the cultural representation of England to the English” (Spivak, 1985).

The 18 th-century novel • • • Key element of Augustan prose together with Journalism and Satire The word derives from the Latin “novus” and from the Italian “novella” meaning “new” not only because original but because it reported recent events, news. “A fictitious prose narrative of considerable lenght, in which characters and actions representative of real life are portrayed in a plot of more or less complexity” Actions within the range of everyday experience Impressions of real life (attention to details of the environment: goods, forniture, houses, habits, ordinary conversation etc. )

The rise of the novel • • • Realism and attention on the individual who can discover truth through his own senses and affirm himself through his own intelligence and hard work Influence of Methodism (focus on the individual who can save himself through faith and personal effort) Growth of the reading public, also women Diffusion of newspapers Circulating libraries (moderate fees and facilities for borrowing books)

The writer and the reader • • • Growth of the novel reading public Change in the relationship between writer and reader The writer was free from patronage because his profession was profitable He wrote to please a public of largely middle-class readers (shopkeepers, merchants etc. ) The readers wanted to read about things close to their individual experience Writers rejected conventional plots and classical models and looked at reality for inspiration

Realism • Novel became a picture of life, realistic (for both what it presented and how it presented it) • At the centre a new type of protagonist: practical, self-made, self-reliant, with common sense and prudence, the opposite of the heroic, adventurous hero of romances.

Daniel Defoe (1660 -1731) • • Brought up as a Dissenter by the father, a nonconformist merchant, After school he went into business and became a merchant (wine, tobacco) He travelled troughout Europe, then, back in England, he opened a shop and became involved in politics. After he went bunkrupt he ventured into many activities including journalism and literature. After the publication of a satirical pamphet in defence of the Dissenters he was imprisoned for 6 months. He later became a secret agent and government spy. In 1919, at the age of 60, he turned to prose fiction. He considered writing a business activity. He was one of the most prolific authors of his time.

Robinson Crusoe • • - Published in 1719 Based on the experiences of Robert Selkirk, a seaman who was put ashore on a desert island in the Pacific Ocean, later rescued. Defoe took inspiration from travel books fashionable at the times. Travel narrative in 3 parts: R. leaves his family and goes away to sea to make a fortune Shipwrecked on a desert island he tells about his life for 28 years. Detailed record in the journal he keeps. Return to Europe In the second part dairy-like account of how he is able to re-create the world he left behind him, how he saves a young savage and makes him his servant and how he is finally rescued and brought back to England.

To sum up: The Augustan Age, social background • • • The middle class was growing in power and prestige (traders, merchants, bankers etc. ) Favoured by the development of foreign and colonial trade and by the pro-mercantile policy of the Whigs. Mercantilism brought about competition in commerce and an unequal distribution of wealth. Violence, drunkness were very common. Standards of morality very low. Necessity of a moral reform. In 1750 John and Charles Wesley founded Methodism. The movement promoted piety and morality. Living “by the rule and method”, against the apathy and the imperant materialism. Catchwords of the time are: stability, order, discipline, balance. Crucial role of education (circulating libraries, Grand Tour in Europe). Need to improve manners and language. Observation of norms and conventions to be elegant and refined (middle classes lacked a proper cultural background). In literature main tendency was realism (importance of verisimitude and detailed descriptions) Language was ordered, polished and elegant, clear and precise, simple enough to be understood

Robinson Crusoe • “Like Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Robinson Crusoe was part of the process of ‘fixing’ relations between Europe and its ‘others’, of establishing patterns of reading alterity at the same time as it incribed the ‘fixity’ of that alterity, naturalizing ‘difference’ within its own cognitive codes. But the function of such a canonical text at the colonial periphery also becomes an important part of material imperial practice, in that, through educational and critical institutions, it continually displays and repeats for the other the original capture of his/her alterity and the processes of its annihilation, marginalization, or naturalization as if they were axiomatic, culturally ungrounded, ‘universal, natural. ” (Tiffin, 1987)

Robinson Crusoe • • • Ur-text of the English realist novel. It represents the embodiment of the myth of Western imperialism. Enthusiastic narrative of the project of “civilizing”indigenous peoples. “Just a history of facts” (Preface): autobiographical narration. Built around a careful accumulation of circumstantial details. Linear narrative sequence. Illusion of transparent representation of a social world which is infact a construction. New hero of the middle classes: celebration of the ethics of hard work, perseverance, self -reliance, moderation and rational control, cult of profit and myth of success. Reproduction of the old world in the new. The unknown is mapped and thus controlled and tamed (act of taking possession also through naming). Crusoe saves Friday’s life: subjection of the colonized (justification of the colonial enterprise).

The postcolonial rewriting of the classics • • Strategy of cultural decolonization. Means of subverting but also critically appropriating the canon (part of his/her cultural heritage, the culture of the Mother Country cannot be forgotten, ignored or easily removed: cross-cultural fertilizations). Critical, productive dialogue with the canon. Not oppositional attitude but discursive dialectics. Remember the role of the classics in imposing and maintaining the status quo (the teaching of the classics as the masterpieces was one of the many ways in which the Empire asserted its cultural and moral superiority). Rewriting as a means to unveil and resist the assumptions of colonial discourses. The writing back model is adopted with the view of questioning a cultural tyranny while recognizing the precious and inevitable legacy of the Mother country

J. M. Coetzee • Born in Cape Town 1940, now living in Adelaide, Australia • Of Afrikaner origins, he grew up speaking English at home and Afrikaans with his relatives. • He studied English and Maths and then moved to England to work in computers. • Then he taught in Texas and returned to SA in 1972. • Slipperiness of his position: he belongs to the oppressors’ community but he opposes the system which guarantees his privileged status. • Very sophisticated prose, postmodern strategies. He has been accused of irresponsibility because he doesn’t explicitly tackle urgent political and social issues in his works (self-referential, metafictional texts).

Foe (1986) • Story of Susan Barton, female castaway, at her arrival on a desert island. Raised in England, she travelled to Brazil in search of her lost daughter. After a mutiny she is cast adrift which brings the reader to the opening lines of the novel. On the island she meets Cruso and Friday • In the second part, after having being rescued, she looks for the writer Foe to write down the story of her adventure (epistolary part). • In the third part she meets Foe and discusses with him about the relation between truth and fiction and the act of writing itself. • The first part refers explicitly to the source text.

Foe • • Major addition: the female castaway and Foe the writer Cruso (loss of the final ‘e’): not narrator of his story, not interested in making the island his kingdom, not interested in teaching Friday, “indifferent to salvation”. No journal, no progress Friday: ‘negro’, not noble savage of Defoe; lack of tongue, solitary enigmatic mute The island: not lush tropical isle but barren, empty, and silent. Place of exile Susan: recasting of the character of Robinson, energy, spirit of enterprise. Narrating voice. Attention to details, desire to keep a journal and to build all they need to live in a comfortable way. All the novel turns around the issue of silence. Friday is a “hole in the narrative”. His silence is “helpless”. Susan wants to educate him “out of darkness”, to “make his silence speak”. But silence is also Friday’s language of empowerment. Susan claims: “I tell myself I talk to Friday to educate him out of darkness and silence. But is that the truth? There are times when benevolence deserts me and I use words only as the shortest way to subject him to my will”.

Friday: il potere della rappresentazione, parola e silenzio (From Foe) “Friday has no command of words and therefore no defence against being re-shaped day by day in conformity with the desires of others. I say he is a cannibal and he becomes a cannibal. I say he is a laudryman and he becomes a laundryman. What is the truth of Friday? You will respond: he is neither cannibal nor laundryman, these are mere names, they do not touch his essence, he is a substantial body, he is himself, Friday is Friday. But that is not so. No matter what he is to himself (is he anything to himself? How can he tell us? ), what he is to the world is what I make him (pp. 121 -2)

Il romanzo vittoriano • Il romanzo realista ottocentesco narra la realtà da una prospettiva onnisciente che ricalca e radicalizza le opposizioni binarie alle fondamenta della civiltà e della cultura occidentale. • Letteratura “coloniale” prodotta nella fase del “colonialismo informale” (fine ‘ 700 sino agli anni ’ 70 dell’ 800) • Letteratura “colonialista” prodotta nella fase dell’ “Imperialismo classico” (1875 -1914).

La narrativa coloniale: - configura il disegno imperiale come parte dell’ordine naturale delle cose; - rafforza immagine della Gran Bretagna come potenza dominante e costruisce e cementa ilmito della “Englishness”. • A partire dai primi resoconti di viaggio e racconti d’avventura, la letteratura si fa strumento per: dominare l’ignoto; giustificare il dominio su altri popoli. Mappatura dello spazio sconosciuto si traduce in pratica metaforica nel testo letterario che costruisce la realtà dell’Altro (strategia del “naming”) Tutti gli scrittori vittoriani si confrontano con la questione coloniale anche se non sempre ne trattano in termini espliciti. Said: il romanzo realista ottocentesco non può prescindere dal ruolo egemone dell’Impero, si sostanzia del credo che è alle fondamenta dell’ideologia dominante. Ideologia fondata sui concetti di supremazia razziale, morale e culturale. Vedi Robert Knox, The Races of Men (1850) e Darwin, The Origin of Species (1859), possibilità di pianificazione dello sviluppo delle razze (darwinismo sociale) giustifica la pratica di conquista coloniale. Ultimi decenni del secolo studi antropologici a carattere divulgativo che celebrano la connaturata superiorità della razza e civiltà anglosassone.

L’ideologia imperialista nel tardo ‘ 800 • • • Il periodo dell’Imperialismo classico si caratterizza per l’estensione dei possedimenti coloniali, per la formalizzazione dell’ideologia imperialista e per forme aggressive e intolleranti di nazionalismo e sciovinismo. Dagli anni ’ 70 il clima di ottimismo che aveva sostenuto i primi vittoriani, orgogliosi dell’espandersi dell’Impero sotto l’egida della Bibbia, delle armi e del libero commercio, lascia spazio a incertezza e dubbio. Maturano atteggiamenti difensivi e arroganti alle radici dell’imperialismo militante, conservatore e sciovinista del tardo vittorianesimo e dell’epoca edwardiana. Giustificazione ideologica all’impresa di espansione coloniale: missione filantropica e civilizzatrice, redenzione evangelica, diffusione della scienza e del progresso, missione motivata dalla connaturata “inferiorità” delle razze altre. Il romanzo domestico assegna spazio ridotto alle questioni coloniali, ma si sostanzia di quell’ideologia che rafforza e coibenta una società in crisi e sulla quale si costruisce il mito della Englishness (importanza della lettura “contrappuntistica” dei testi per acquisire consapevolezza “both of the metropoitan history that is narrated ad of those other histories against which and together with which the dominanating discourse acts”, 1993).

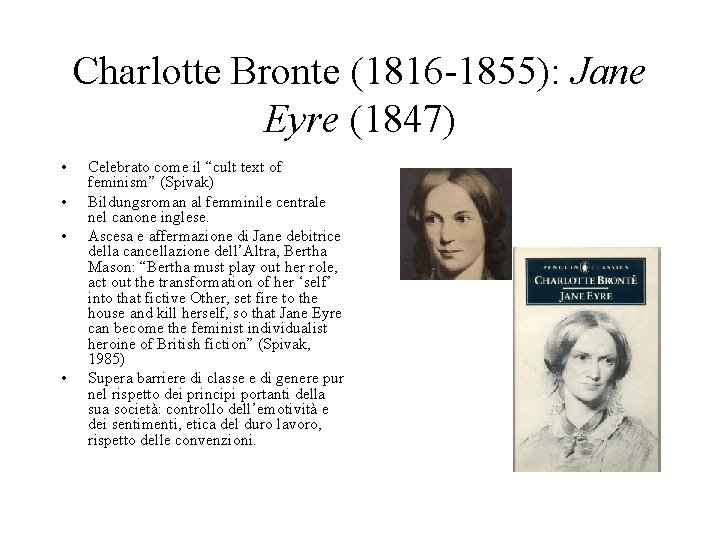

Charlotte Bronte (1816 -1855): Jane Eyre (1847) • • Celebrato come il “cult text of feminism” (Spivak) Bildungsroman al femminile centrale nel canone inglese. Ascesa e affermazione di Jane debitrice della cancellazione dell’Altra, Bertha Mason: “Bertha must play out her role, act out the transformation of her ‘self’ into that fictive Other, set fire to the house and kill herself, so that Jane Eyre can become the feminist individualist heroine of British fiction” (Spivak, 1985) Supera barriere di classe e di genere pur nel rispetto dei principi portanti della sua società: controllo dell’emotività e dei sentimenti, etica del duro lavoro, rispetto delle convenzioni.

Jane Eyre: Jane e Bertha Mason • • • Simbolo della temibile alterità. “mad creole woman” Trasferimento dei tratti di negatività da Jane a Bertha: bestialità, istintualità priva di controllo, pazzia. Figura redentrice di Jane che sottrae Rochester alla condizione di “selvaggio” cui lo ha relegato l’incontro con l’Altra. Dubbio di Jane: Bertha rappresenta il peccato storico commesso dai colonizzatori bianchi. Dubbio fugato dalla fede nella missione civilizzatrice che giustifica violenze e soprusi. Jane redentrice delle donne oppresse. Resta comunque portavoce dei valori dominanti della società borghese vittoriana. Bertha viene introdotta nel romanzo a un terzo dell’azione: risata lugubre, straniante, animalesca che interrompe le profonde riflessioni di Jane sulla marginalità delle donne e sul disagio degli oppressi. Bertha vittima della follia, della sessualità incontrollata, della bestialità. Attraverso lo sguardo di Rochester viene costruita la dicotomia tra le due immagini femminili Bertha estensione del paesaggio infernale dei Caraibi Sacrificio finale della vita di Bertha funzionale all’affermazione di Jane (rivoluzione contro oppressione di genere e classe ma non di razza)

Bertha in Jane Eyre • Described as suhuman, robbed of her human selfhood, no voice rather than the demonic laughter • Her creole savagery leaves the mark when she sets fire to Thornfield Hall • Banished into silence because of her inacceptable madness • Manichean representation by Rochester, opposition between Bertha and Jane.

Jean Rhys Born in the Caribbean in 1890, she moved to England at 16. Various jobs travelling around Europe (theatrical companies), then she permanently settled in England though she hated it. She experienced exile both because of her sex and her colonial background. Welsh father, white creole mother of a family which had owned slaves. Marginality of living in-between as a white creole, double outsider in her comunity, state of permanent exile and uprootedness.

J. Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) • • Parallel between the life of J. Rhys and that of Bertha Mason The writer’s aim is to give the creole woman back a voice and a full human identity She puts her center stage. Antoinette is the white creole daughter of a former slave trader. As a creole she is rejected both by the white community and by the black one. Dissociation of identity, she falls into madness. WSS proceeds through 3 parts. In the first part Antoinette narrates of her childhood in Jamaica soon after the Emancipation Act (1833). Relations between the white and the black communities become very tense. In the second part we find an unnamed male narrator who has married Antoinette and keeps on calling her Bertha (he recalls Rochester). The third part is set in England, A. tells about her life of segregation in a big mansion. She dreams to set the house on fire. When she wakes up she resolves what she has to do. Rochester is represented both as the oppressor and as a victim, the writer does not dehumanise him (tricked into an arranged marriage by his father to secure him a fortune)

C. Dickens, Great Expectations (1961) • Novel at the center of the canon, representative of the myths, values, and triumphant ideology of Victorian society. • It is imbued with and shaped by the spirit of the Empire. • It severely scrutinizes Victorian society: dark novel. • At the end of the 50’s, when D. wrote the novel, he was suffering for his failed marriage and a debilitating illness (strenuous programme of public readings) • After the publication of Darwin’s The Origin of Species (1859) general skepticism, religious codes and morality were weakened, sense of relativism and precariousness.

Great Expectations • • • The novel traces Pip’s development from the good-hearted child, who helps the convict despite his fear, to the snobbish young gentleman who tries to conquer Estella. Bildungsroman: from “gentleman in manners” to “gentleman at true heart” , he comes to recognize the insignificance of material wealth. Magwitch, the transported convict who has devoted all his life to make a gentleman of Pip, secretly returns to England from Australia to meet the young man risking his life. Though Pip describes him as “the turning point of my life”, his character is not satisfactorily explored. Magwithch is depicted according to the stereotypical image of the romantic convict driven to crime by hunger. Though he fulfills the function of catalyst for the development of the protagonist, the narrative devotes him very limited space through the voice of Pip. His character is associated with images of bestiality (see first scenes in the graveyard). Dog metaphor, marshes, Australian desert, cannibalism. He is represented as the Other, contaminated by his experience at the Antipodes. Stigma of his alterity condemns him to remain in Australia, he cannot expect to enter British society. Unwanted although redeemed. Once illegally back to England, he shatters the stability of the centre.

P. Carey, Jack Maggs (1998) Interviews with the writer • • • “Dickens’ Magwitch is foul and dark, frightening, murderous. Dickens encourages us to think of him as the ‘other’. I wanted to reinvent him, to possess him, to act as his advocate. I did not want to diminish his ‘darkness’ or his danger, but I wanted to give him all the love and tender sympathy that Dickens’ first person narrative provides his English hero Pip” (interview with the writer). Dickens’n novel “is (to an Australian) also a way in which the English have colonized our ways of seeing ourselves”. “It seems to me to be such an Aussie story”. Dickens’ point of view is “a point of view of its time and of its period, and I think it’s perfectly fine that it should have that point of view”.

Jack Maggs • • April 1837: the convict Jack Maggs, after a long exile in Australia, returns to London to meet Phipps. His narrative is set centre stage. He retrieves his right to narrate his own story through the letters sent to Phipps. He develops throughout the novel (he is described at the beginning “like an oyster working on a pearl”), he is not a passive, static character entrapped in a prejudicial and sterotyped representation (see Magwith). He is given the complexity of a human being. Tobias Oates, the writer who hypnotizes Maggs, recalls the figure of C. Dickens (several biographical affinities). He is an addition to the source text and plays a crucial part in the novel. He exploits and colonizes Maggs’ mind in order to write his masterpiece to became a writer of great success. He defines himself as the “cartographer of a criminal mind”. Through his writing he manipulates and distorts Magg’s story. Maggs answers back to this official version of his story through his own narrative, disclosing a “hidden history”: “Well, Henry Phipps – he writes in his letters – you will read a different story in the glss, by which I mean – my own”.

David Malouf, Remembering Babylon • The novel was published in 1993. • In 1992 with the famous Mabo sentence the Supreme Court of Australia decided that the application of the terra nullius by the British Crown was to be considered unlawful. It was based on a strongly discriminatory behaviour towards the traditional inhabitants of the land. Consequently, the Aborigines’ right of ownership of their land was officially recognized. • The writer enters the harsh debate of the period with his novel whose aim is to retrieve the past challenging the collective amnesia of the Australian legend. The reappropriation of the past is essential to create a common ground from which to start and build a different future of true reconciliation.

David Malouf, Remembering Babylon (1993) • • • !830 s, Queensland. Fictional story inspired by a true event. Gemmy, a white boy, is stranded along the Australian shores and lives with a group of Aborigines for 16 years. He appears misteriously on the outskirts of the Scottish settlement At first the settlers treat him as a diversion. They try to piece together history from the scraps of his memory. He is taken by the Mc. Ivor family but when two Aboriginals show up in the vicinity the community’s suppressed suspicions surface. He is seen as a threat , an inflitrator, a spy. Harassment of Gemmy. “Mixture of monstrous strangeness and unwelcome likeness”. The settlers’ irrational fears are projected onto the man who seems to be neither black nor white. He is at the margins of two cultures, “inbetween”. Indicated with the pronoun “it”, “a thing”, “not even human”. Intruder who disrupts the balance and the certainties of the white community. He distabilizes rooted dichtomies. Spectre of the unknown. He is at once “brother and other”, a sort of “parody of the white man, an imitation gone wrong”. He “hasd started as white” but had degenerated into a black. How could it be possible? “How could you lose i t? . Not just language but it? ” The white settlers try to rid the unfamiliar land of “every vestige of the native”, to make it “just a bit like home”. They cling to the memories of home, Scotland they try to reproduce the old world in the new. Question of belonging to and relation with the land are foregrounded.

Gemmy, in-between creature • He does not want to abandon his aboriginal tribe, he wants “to be recognized”. He tries to remember his language. He reclaims his double, hybrid identity. • George Abbot and Mr Fraser try “to find words for him”, they do not listen to him, they construct him through their own narrative. • The re-writing of his story disputes any claim of objectivity and neutrality in the writing of history. Gemmy cannot find any place in the official version of history because of his disquieting presence. His story has to be domesticated, shaped by the master narrative. • At the end of the story he turns up at the village school to “claim back his life” which is enclosed in the sheets of paper where they had written his story.

Joseph Conrad • Brn in Polish Ukraine in 1857. His father was a landowner who loved literature and his country was at the time under Russian rule. He participated in the movement for Polish independence and he was exiled with his family. He grew up with the hatred for tiranny and the wish for freedom. • At 17 he went to sea and travelled a lot. • In 1886 he became a British subject. He served for about 20 years in the British Merchant Service. • In the meantime he had learned English and became fascinated by the language (he also knew French). • He left the sea in 1894 because of illness and mental distress and devoted himself to writing. He chose to write his creative works in English. • Died in 1924

Heart of Darkness • The novel is based on Conrad’s personal experience of a voyage as a riverboat pilot in Congo in 1889 -90. It is at the same time a spiritual voyage into knowledge of his inner self. • The narrator is Marlow.

C. Achebe • Born in Eastern Nigeria in 1930, son of one of the early Ibo converts to Christianity. He was a teacher in the Church Missionary School which Achebe attended. • At university, where he studied English literature, the syllabus was that typical of all British universities. He was introduced to the canon of English literature and read Conrad and decided to write about Africa from the inside.

C. Achebe, Things Fall Apart (1958) Interviews with the writer • • • The novel is not a classical re-writing of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, but a peculiar form of “writing back”. Achebe defines Conrad a “thoroughgoing racist” and he claims that the humanity of his people “was totally undermined by the mindlessness of its context and the pretty explicit animal imagery surrounding it” (1980). The Africans are reduced to “limbs and rolling eyes”, deprived of humanity, of the faculty of expressing themselves. Africa is represented as “the other world, the antithesis of Europe and therefore of civilization, a place where man’s vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant bestiality” (1980) Achebe spurs his readers to look at texts such as Conrad’s Heart of Darkness “with a new awareness, and that they may carry that awareness to other things that they see or read, because all we are saying is do not treat any members of the human race as if they were less than human” (1991). “The worst thing that can happen to any people is the loss of their dignity and self-respect”. It is the duty of the writer “to help them regain it by showing them in human terms what happened to them and what they lost” (1973)

Things Fall Apart • • The novel is set in Ibo-land towards the end of the 19 th century, when European where just beginning to penetrate inland in West Africa. It describes the change that comes over an old and firmly established society under the impact of new, different ideas from outside brought about by the culture and social organization of the colonizers. In the first part it shows the community of Umuofia, 9 related villages, just before the arrival of the white man. It offers the readers a detailed picture of the way of life of these peoples. We learn about elaborate social rituals and cerimonies and of how everyday lives are interpenetrated with the otherworld of magic and mystery. Okonkwo, the protagonist, is a man of this old order. Brave, fearless fighter, hard worker, he is highly respected in his clan. In the second part of the novel Okonkwo is in exile and his village has changed dramatically as a consequence of the arrival of the white colonizers. The third part brings the final, tragic phase of Okonkwo’s story. He returns to Umuofia and finds that things have indeed changed. Great crisis and conflicts within the community. In the end, when the Commissioner’s men arrive to arrest him, they find that he has hanged himself, preferring a shameful death to the white man’s justice. The commissioner does not understand the people and its customs but plans t include the “incident” in a paragraph of the book he is writing. Achebe challenges the “white man’s official History” with his novel which gives back Okonkwo his deserved status and which explores his tragic predicament. No just a paragraph, but a whole book will tell his story.

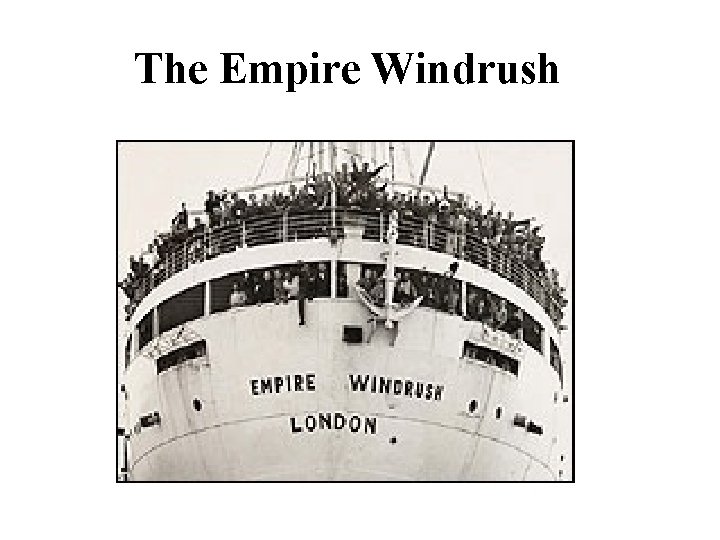

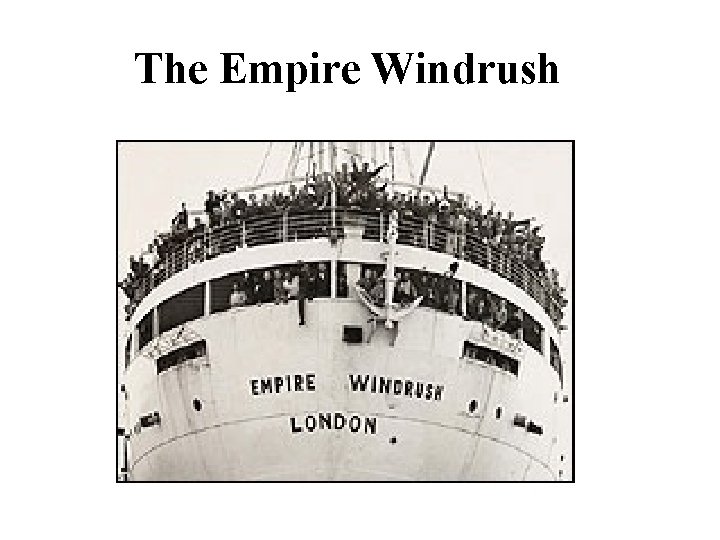

The Empire Windrush

Epilogue (1983) Grace Nichols I have crossed an ocean I have lost my tongue from the root of the old one a new one has sprung

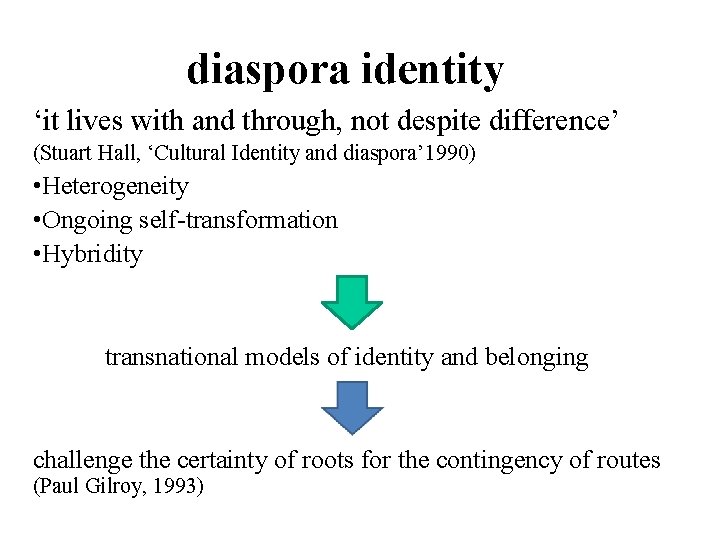

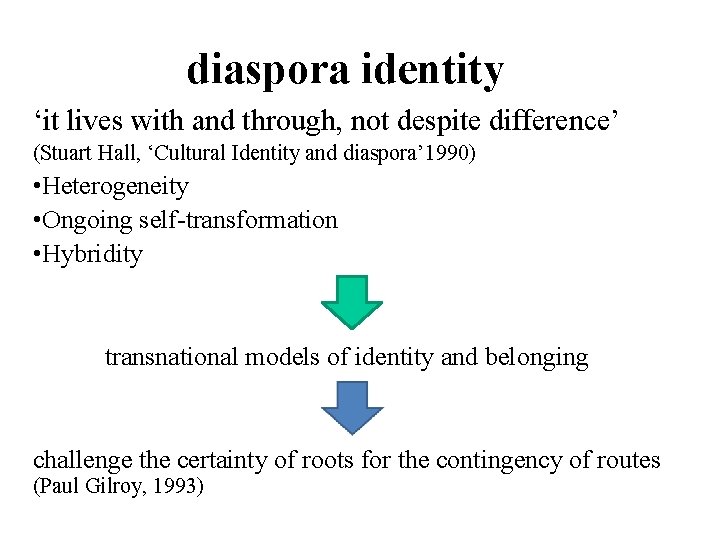

diaspora identity ‘it lives with and through, not despite difference’ (Stuart Hall, ‘Cultural Identity and diaspora’ 1990) • Heterogeneity • Ongoing self-transformation • Hybridity transnational models of identity and belonging challenge the certainty of roots for the contingency of routes (Paul Gilroy, 1993)

Diasporic peoples struggle for different ways to be «British» It means «to be British and something else complexly related to Africa and the America, to shared histories of enslavement, racist subordination, cultural survival, hybridization, resistance and political rebellion» (James Clifford, Routes, 1997)

Role of literature for diasporic peoples • It participates in a healing process. • It partakes of the construction of memory and re-construction of identities

What is Black British literature? Contested definition • literature written in English by Caribbean, Asian, African, and other people who originated from the ex-British Empire • over the years the preoccupation of much of the literature has been with the troubled quest for identity and liberty. • Blackness redefines the concept of Britishness and of British literature

Salman Rushdie

S. Rushdie • Born in Bombay in 1947 into a Muslim family of Kashmiri descent (year of the Partition). • He moved to England as a young boy to attend school and Cambridge university. He eventually settled in London and moved to the United States in 2000.

Rushdie • One of the most popular and controversial writers of the twentieth century, Salman Rushdie is a British Indian essayist and novelist. He has authored several novels and short stories in his life, which has continued to attract the interest of both critics and public. His ability to combine magical realism with historical fiction is an exceptional quality which makes him a truly unique writer. Most of the works written by him feature around the Indian subcontinent and mostly contain themes like migrations to and fro the East and West and the incidences occurring in between them. • It was Rushdie’s fourth novel, ‘The Satanic Verses’, which enraged the Muslim community across the globe to the extent of Ayatollah Khomeini issuing a fatwa (death sentence) against him. However, despite it, Rushdie continued writing and released several books and novels.

Imaginary Homelands (1991) • • Collection of essays published in 1991. In the first one, “Imaginary Homelands”, he reflects upon the process of writing his novel Midnight’s Children (1981) which is set in India and Pakistan. Attempt to restore the world of his childhood home in Bombay. Impossible task to “return home” via the process of writing: he reconstructs an imaginary India, an India of the mind. Sense of dispacement and alienation, the past can be recovered only in fragments. Migrants arrive in new places with baggage (beliefs, values, traditions, customs, behaviours) which often exclude them from being recognized as part of the nation’s people. How can migrant deal with questions of home and belonging? Concept of translation (“we are borne across”) and of the hybridization of identities. Pain of loss, of not being firmly rooted. Deep suffering in being uprooted but also enlargment of critical perspective and privileged point of view. Partial, but at the same time plural view.

Rushdie, a migrant storyteller • • • «Certainly, writing on the East and living in the West engenders friction. But the problem of uprooting is even more important. My family originates in Kashmir, now my family lives in Pakistan and myself in London. The series of uprootings has made me feel split between several worlds» . (Interview, 1984) Rushdie has never been accepted in any of his «homes» . In England he was considered very foreign and exotic; back in India he was ridiculed for his perfect British accent and considered brainwashed and corrupted by the materialiatic West; in Pakistan he is still considered an infidel and a blasphemer. «To migrate is to experience deep changes and wrenches in the soul, but the migrant is not simply transformed by this act, he also transforms the new world» Migration is is a painful but emancipating process: «To be born again, first you have to die» (opening words of The Satanic Verses) All his work is a celebration of hybridity

Rushdie, Midnight’s Children • «The purpose of fiction was in a way paradoxical, that the fiction is telling the truth at a time at which the people who claimed to be telling the truth are making things up. So in a way you have politicians or the media, the people who form opinion, in fact making the fictions. And it becomes the duty of the writer of fiction to start telling the truth» (Rushdie, 1999) • The project of the writer is that of «giving voice» , «to speak up for the great mass who never had the chance to sit down at a table, let alone to win, and this is clearly a literature of the highest importance and value» (Rushdie) • History/stories • History is not univocal , unilateral, impartial.

H. Kureishi • Born in Britain in 1954 with a Pakistani father and English mother. • In his essay “The Rainbow Sign” (1986) he records his experience as a boy growing up in London, a visit to Pakistan as a young man and makes some comparisons between the two locations. • As a child he had no idea of what the subcontinent was like. At school he was mistakenly identified as an Indian by his teacher. Labelled as an outsider by his schoolmates despite the fact that he was British, he wasn’t permitted to belong. • When he goes to Karachi as an adut he finds it difficult to consider this place as “home”. • Identity crisis: “we are Pakistanis, but you, you will always be a Paki”, a relative tells him. • New models of identity, “in-between” positions.

Hanif Kureishi The Buddha of Suburbia (1990)

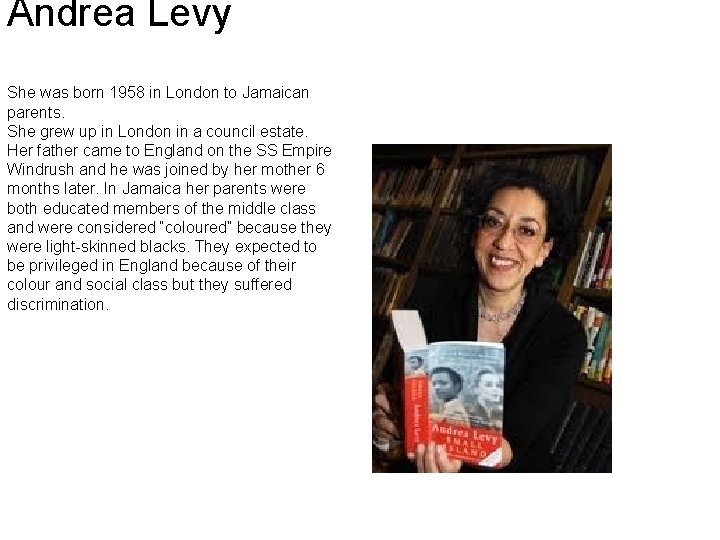

Andrea Levy She was born 1958 in London to Jamaican parents. She grew up in London in a council estate. Her father came to England on the SS Empire Windrush and he was joined by her mother 6 months later. In Jamaica her parents were both educated members of the middle class and were considered “coloured” because they were light-skinned blacks. They expected to be privileged in England because of their colour and social class but they suffered discrimination.

Andrea Levy (from essays and interviews) • • • “I am English born and bred, as the saying gos (as far as I can remember, it is born and bred and not born-and-bred-with-very-long-line-of-white-ancestorsdirectly-descended-from-Anglo-Saxons). England is the only society I tryly know and sometime understand. I don’t look as the English did in the England of the 30’s or before, but being English is my birthright. England is my home. An eccentric place where sometimes I love being English”. “I was educated to be English. Alongside me – learning, watching, eating and playing – were white children. But those white children would never have to grow up to question whether they were English or not”. “So what am I? Where do we fit into Britain, 2000 and beyond? ” “If Englishness doesn’t define me, then I’ll define Englishness” “Englishness must never be allowed to attach itself to ethnicities” “Being Back and British is a dynamic thing. It’s always changing. What we are trying to do is rid ourselves of a racist society. I want equality”

Levy • • Committed writing, literature has a social function. Deconstruction of the official version of Englishness. Her dual cultural heritage positions herself in a hybrid location. Insecurity about her “home” and sense of belonging

Fruit of the Lemon • • • Published in 1999, the novel is partly autobiographical. Bildungsroman set in the 80’s. Faith is a Londoner of Jamaican origins (daughter of Black parents) Her dark skin and background are markers of her alterity. She grows up in London among white English students and friends, knowing nothing about her family (erasures and gaps in her family history), and constantly struggles to achieve a unified identity. She feels out of place. Identity crisis, she is forced to acknowledge her difference. II part of the novel: trip to Jamaica where she rediscovers and retrieves her roots (importance of the stories told by the various narrators, remembering the past as an essential step in the process of re-membering identities). She learns about a complex mixed-race ancestry which calls into question the myth of a pure identity. Faith’s re-birth: sense of pride in being black and awareness of her multiple, hybrid identity as a source of richness and empowerment. She reclaims her postion as the “bastard daughter of the Empire” She goes back to England with a new awareness.

Andrea Levy The Long Song The Fruit of the Lemon (2007) (2010)

W. Shakespeare • Born in 1564 to a successful middle-class glove-maker in Stratford-upon-Avon. • He attended grammar school, no further formal education. He married an older woman and had 3 children. Around 1590 he left his family behind and went to London to work as an actor and playwright. • His career bridged the reigns of Elisabeth I (ruled 15581603) and James I (ruled 1603 -1625) and he was the favorite of both monarchs (James gave the members of his company the title of King’s Men). • Wealthy and renowned, S. retired to Stratford and died in 1616 at the age of 52.

Shakespeare, The Tempest • • The Tempest (1611) is considered by some critics as an allegory of colonialism, written against the background of England’s experiment in colonization. Prospero and Caliban have become synonimous with the figures of coonizer and colonized. S. , like many of his contemporaries, was fascinated by both the commercial and the imaginative possibilities offered by the New World, and this interest informed the writing of his last play. He knew the “Bermuda Pamphlets”, narratives describing the wreck of a ship going to the recently established colony of Virginia in 1609. He was also familiar with other travel narratives about the New World. America excited interest at the beginning of the 17 th century for the commercial and imperial adventure but also because it was considered a tabula rasa, a “natural” environment in which sophisticated European values would be transferred and reassessed. The English colonial project seems to be in S’s mind throughout the Tempest. Almost every character ponders how he would rule the island if he were its king.

The Tempest • Probably written 1610 -1611, first performed at Court by the King’s Men in 1611. The Tempest is most likely the last play written entirely by S.

The Tempest: plot (I Act) • • A storm strikes a ship carrying Alonso, Ferdinand, Antonio, Gonzalo Stephano, Trincolo and Sebastian. They are on their way to Italy from Africa. The royal party is prepared to sink and they all fear for their lives. The second scene begins more quietly. Miranda and Prospero stand on the shore of their island, looking out to sea at the recent shipwreck. Miranda asks her father to do whatever he can to save those poor souls. Prospero reassures her and reveals to her that he orchestrated the shipwreck and tells her the story of their past. Prospero was the duke of Milan until his brother Antonio, conspiring with the King of Naples, Alonso, usurped his position. Kidnapped and left to die at sea, Prospero and his daughter survive. Gonzalo leaves them supplies and Prospero’s books which are the source of his magic and power. They have lived on the island for 12 years. Prospero calls his magical agent, Ariel, who brought the tempest upon the ship and set fire to the mast. He made sure that everyone got safely to the island. Ariel is Prospero’s servant, an airy spirit. Prospero has promised him freedom if he performs tasks such as these without complaining. Prospero reminds him that he rescued him from an horrible fate (he was imprisoned by the witch Sycorax in a tree and then freed by Prospero). Prospero and Miranda go and visit Caliban, prospero’s servant, and the son of the dead Sycorax. Caliban curses Prospero, and they claim that he is ungrateful for what they have given and taught him.

Prospero • • • One of S’s more enigmatic characters. He was wronged by his usurping brother, but he exerts his absolute power over other characters submitting them. The pursuit of knowledge gets him into trouble in the first place. By neglecting everyday matters when he was duke, he gave his brother a chance to rise up against him. His possession of magical knowledge makes him extremely powerful. His punishments of Caliban are petty and vindictive (he calls upon his spirits to pinch C. when he curses). He is very authoritative with Ariel. When Ariel asks him to relieve him of his duties, he bursts into fury and threatens to return him to his former imprisonment and torment. Through his schemes, manipulations, spells, he creates the play itself with its plot. Watching Prospero at work is like watching a dramatist create a play, building a story from material at hand developing the plot to reach the final ending. In his final speech he likens himself to a playwright by asking the audience for applause. The final scene is a celebration of creativity, humanity and art. P. emerges as a more likable and sympathetic figure in the final two acts thanks to his love for Miranda, his forgiveness of his enemies (he also releases his slaves) and the happy ending he orchestrates. He makes his audience share his understanding of the world. It is tempting to think of the Tempest as S’s farwell to the stage because of theme of the great magitian giving up his art.

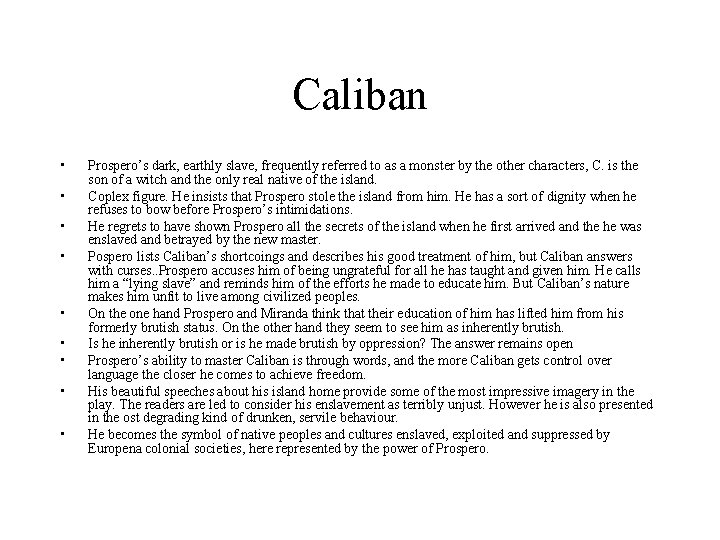

Caliban • • • Prospero’s dark, earthly slave, frequently referred to as a monster by the other characters, C. is the son of a witch and the only real native of the island. Coplex figure. He insists that Prospero stole the island from him. He has a sort of dignity when he refuses to bow before Prospero’s intimidations. He regrets to have shown Prospero all the secrets of the island when he first arrived and the he was enslaved and betrayed by the new master. Pospero lists Caliban’s shortcoings and describes his good treatment of him, but Caliban answers with curses. . Prospero accuses him of being ungrateful for all he has taught and given him. He calls him a “lying slave” and reminds him of the efforts he made to educate him. But Caliban’s nature makes him unfit to live among civilized peoples. On the one hand Prospero and Miranda think that their education of him has lifted him from his formerly brutish status. On the other hand they seem to see him as inherently brutish. Is he inherently brutish or is he made brutish by oppression? The answer remains open Prospero’s ability to master Caliban is through words, and the more Caliban gets control over language the closer he comes to achieve freedom. His beautiful speeches about his island home provide some of the most impressive imagery in the play. The readers are led to consider his enslavement as terribly unjust. However he is also presented in the ost degrading kind of drunken, servile behaviour. He becomes the symbol of native peoples and cultures enslaved, exploited and suppressed by Europena colonial societies, here represented by the power of Prospero.

Legge proust

Legge proust Capitolo 16 le reazioni chimiche soluzioni

Capitolo 16 le reazioni chimiche soluzioni Saluti dalle vacanze

Saluti dalle vacanze Tabella potenziali standard di riduzione zanichelli

Tabella potenziali standard di riduzione zanichelli Dalle alli

Dalle alli Pont dalle nervurée

Pont dalle nervurée La deriva dipende dall'angolo di campanatura delle ruote

La deriva dipende dall'angolo di campanatura delle ruote Guerra del peloponneso schema

Guerra del peloponneso schema Filettatura trapezoidale iso 2901

Filettatura trapezoidale iso 2901 Stereogramma grafico

Stereogramma grafico Che cos'è il mappamondo di babilonia

Che cos'è il mappamondo di babilonia Umberto riva

Umberto riva Quotatura disegno tecnico

Quotatura disegno tecnico Rappresentazione sociale

Rappresentazione sociale Bruner rappresentazione

Bruner rappresentazione Rappresentazione numeri naturali

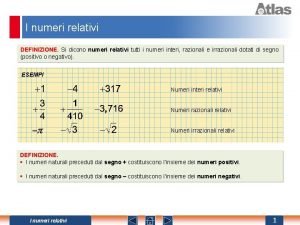

Rappresentazione numeri naturali Rappresentazione simbolica bruner

Rappresentazione simbolica bruner Testo narrativo schema

Testo narrativo schema Tecniche di rappresentazione dello spazio

Tecniche di rappresentazione dello spazio Risoluzione grafica di equazioni e disequazioni

Risoluzione grafica di equazioni e disequazioni Classificazione disequazioni

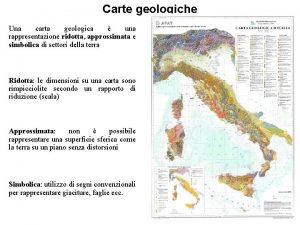

Classificazione disequazioni Carte geologiche pdf

Carte geologiche pdf Potenza numeri relativi

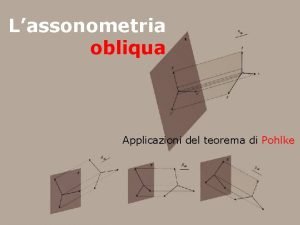

Potenza numeri relativi Teorema de pohlke

Teorema de pohlke Signo dato

Signo dato S p d f chimica

S p d f chimica Rappresentazione intensiva di un insieme

Rappresentazione intensiva di un insieme Algoritmo finito

Algoritmo finito Tecniche di rappresentazione dello spazio

Tecniche di rappresentazione dello spazio Rappresentazione grafica di una porzione di territorio

Rappresentazione grafica di una porzione di territorio Ombre autoportate

Ombre autoportate Rappresentazione numeri reali

Rappresentazione numeri reali Rappresentazione proposizionale

Rappresentazione proposizionale Rappresentazione analogica e discreta

Rappresentazione analogica e discreta Romanzo greco

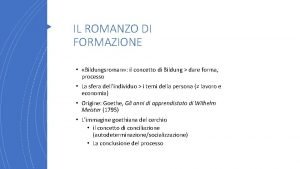

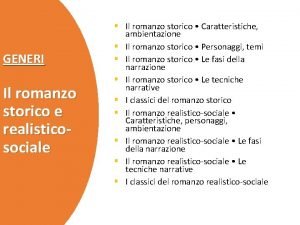

Romanzo greco Il romanzo del 900

Il romanzo del 900 Romanzo psicologico hub scuola

Romanzo psicologico hub scuola Genere narrativo spagnolo del xvi secolo

Genere narrativo spagnolo del xvi secolo Struttura del romanzo

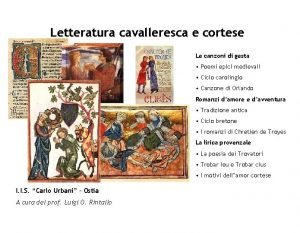

Struttura del romanzo Differenze chanson de geste e romanzo cortese

Differenze chanson de geste e romanzo cortese Romanzo realista schema

Romanzo realista schema Renzo romanzo di formazione

Renzo romanzo di formazione Walter scott romanzi

Walter scott romanzi Bildungsroman significato

Bildungsroman significato La narrativa realista

La narrativa realista Romanzo realista definizione

Romanzo realista definizione Romanzo storico ppt

Romanzo storico ppt Narrativa del 900

Narrativa del 900 Caratteristiche del romanzo

Caratteristiche del romanzo Pinocchio romanzo di formazione

Pinocchio romanzo di formazione I promessi sposi genere letterario

I promessi sposi genere letterario Trifena satyricon

Trifena satyricon Romanzo definizione

Romanzo definizione Esempi di romanzo storico

Esempi di romanzo storico Promessi sposi introduzione

Promessi sposi introduzione Differenza tra canzoni di gesta e romanzo cavalleresco

Differenza tra canzoni di gesta e romanzo cavalleresco Il romanzo vittoriano

Il romanzo vittoriano What is a fictional narrative

What is a fictional narrative Difference between narrative and story

Difference between narrative and story Come e quando matura la conversione di verga il verismo

Come e quando matura la conversione di verga il verismo Elements of narrative texts

Elements of narrative texts Features of narrative paragraph

Features of narrative paragraph Division and classification pattern of development

Division and classification pattern of development Plot line elements

Plot line elements Foil characters

Foil characters Whats a narrative essay

Whats a narrative essay Narrative learning intentions

Narrative learning intentions Third person objective vs omniscient

Third person objective vs omniscient Personal narrative introduction paragraph

Personal narrative introduction paragraph 7 types of characters

7 types of characters Identifying narrative perspective

Identifying narrative perspective Narrative vs narration

Narrative vs narration Dpmap performance elements narrative examples

Dpmap performance elements narrative examples Allusion figurative language

Allusion figurative language Interior monologue examples

Interior monologue examples Narrative format recipe

Narrative format recipe Historical narrative meaning

Historical narrative meaning How long is a paragraph

How long is a paragraph Narrative supervision

Narrative supervision Narrative poem definition

Narrative poem definition Poem with adverbs

Poem with adverbs Narrative conventions

Narrative conventions A narrative must have characters

A narrative must have characters The purpose of narrative is to

The purpose of narrative is to Descriptive method

Descriptive method Map of odysseus journey

Map of odysseus journey Incident response reflection personal narrative

Incident response reflection personal narrative Narrative tenses konu anlatımı

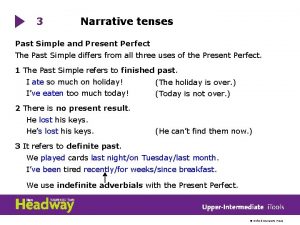

Narrative tenses konu anlatımı Narrative job analysis

Narrative job analysis Types of narrators

Types of narrators Narrative writing strategies

Narrative writing strategies