Janusz Korczak King of the Children United States

- Slides: 31

Janusz Korczak “King of the Children”

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum * Avoid simple answers to complex questions. * Strive for balance in establishing whose perspective informs your study of the Holocaust. * Do not romanticize history. * Translate statistics into people.

Nebraska State Reading/Writing Standards (in reference to this material) 12. 1. 2 By the end of the twelfth grade, students will locate, evaluate and use primary and secondary resources for research. 12. 1. 4 By the end of the twelfth grade, students will analyze literature to identify the stated or implied theme. 12. 1. 6 By the end of the twelfth grade, students will identify and apply knowledge of the text structure and organizational elements to analyze non-fiction or informational text.

Biography Janusz Korczak, was a writer, educator, and physician who lived and worked in Warsaw, Poland from 18781942. He was born Henryk Goldmidt, but took the pen name Janusz Korczak after a famous hero of Polish literature. As the son of an assimilated Jewish family, he only became aware he was Jewish at the age of 6. As an adult, he began to write books, studied medicine, and became the director of the Jewish orphanage in Warsaw, which he directed, with the help of Stefa Wilczynska, from 1912 until the outbreak of World War II.

In 1940, the Nazis ordered him to transfer the orphanage to the area of the Warsaw Ghetto, where he reorganized and renewed his educational activities, and attempted to preserve the “bubble of childhood” in a world ruled by hunger and death.

Although Korczak visited Israel, and fell in love with the country and its pioneers, he felt the longing to return to his children. He felt the evil that the Nazis represented and did not feel as though he could leave his children permanently. He continued to postpone his immigration to Israel from day to day. He considered leaving his children desertion, and perhaps even betrayal of the role assigned to him by fate.

And so, he remained in the Ghetto with his children. In the Ghetto, he was a well-known personality, and even though there was rampant anti-Semitism in Poland, several of his Polish friends, offered him sanctuary and a hiding place outside of the ghetto, but he refused them. He didn’t consider it possible to abandon his two hundred orphans, whose actual physical existence depended on him. Even when he became very ill himself, and worried about how to continually provide for the children, he did not give in. Friends who came into the Ghetto with papers for his removal from the Ghetto returned without him. He refused to leave.

As an educational pioneer, Korczak was one of the first to reach the conclusion that a child had the same rights as an adult – a person in his own right. In the orphanage, the children had almost complete autonomy, able to chose what they wanted to study and for how long of time. In addition, every child had a responsibility to the upkeep of the orphanage, but equal value was placed on every chore, so that all children were equally valued for whatever their contributions were.

Within the orphanage, the children had the same rights as the teachers, including real opportunities for them to take part in decision making. For example, the Children’s Courts in the orphanages were presided over by child judges. Every child with a grievance had the right to summon the offender to face the Court of his peers. Teachers and children were equal before the Court and even Korczak himself had to submit to its judgment.

In August 1942, Korczak received news that he was to report to the Umschlagplatz (central meeting square) with his children and the staff of the orphanage. This was where the deportations were taking place, sending thousands of Jews from the Ghetto to what many thought and hoped was “resettlement” and labor camps further east, Unbeknown to most of these people, their destination was to be the Treblinka extermination camp. Although Korczak had many offers to leave the Ghetto, he refused, and on that fateful day, holding the hands of his children, he boarded the train that led to their deaths.

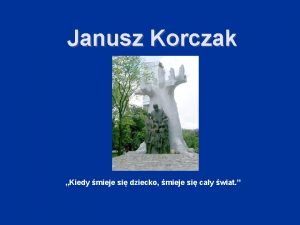

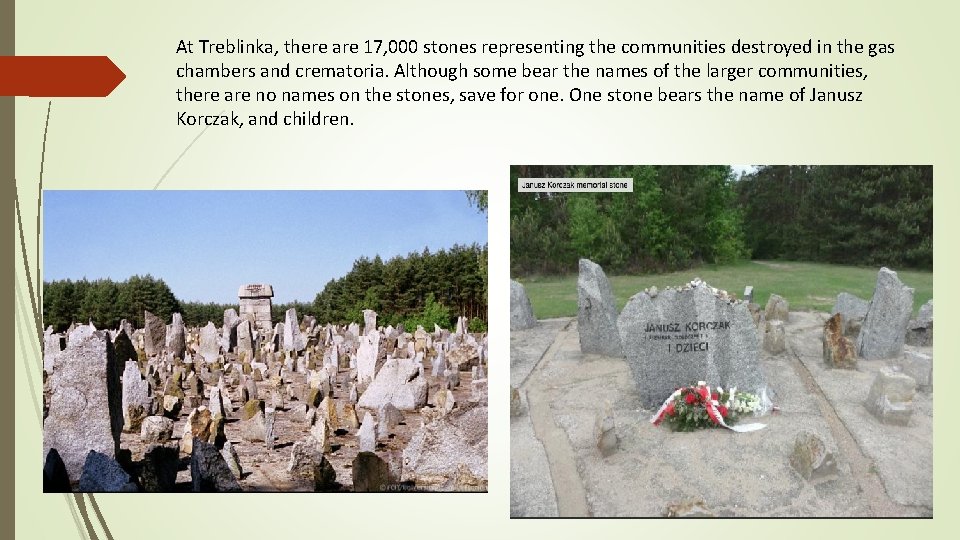

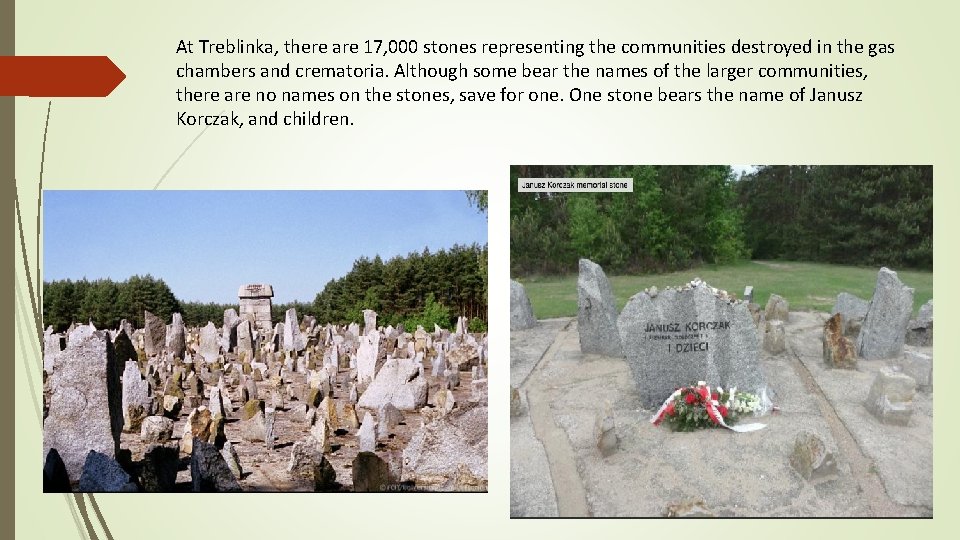

At Treblinka, there are 17, 000 stones representing the communities destroyed in the gas chambers and crematoria. Although some bear the names of the larger communities, there are no names on the stones, save for one. One stone bears the name of Janusz Korczak, and children.

Korczak’s Declaration of Children’s Rights 1. The child has the right to love. 2. The child has the tight to respect. 3. The child has the right to optimal conditions in which to grow and develop. 4. The child has the right to live in the present. 5. The child has the right to be himself or herself. 6. The child has the right to make mistakes. 7. The child has right to fail. 8. The child has the right to be taken seriously. 9. The child has the right to be appreciated for what he is. 10. The child has the right to desire, to claim, to ask.

11. The child has the right to have secrets. 12. The child has the right to “a lie, a deception, a theft”. 13. The child has the right to respect for his possessions and budget. 14. The child has the right to education. 15. The child has the right to resist educational influence that conflicts with his or her own beliefs. 16. The child has the right to protest an injustice. 17. The child has the right to a Children’s Court where he can judge and be judged by his peers. 18. The child has the right to be defended in the juvenilejustice court system. 19. The child has the right to respect for his grief. 20. The child has the right to commune with God. 21. The child has the right to die prematurely

Children’s Court As Korczak believed that children had the same rights as adults, he set up a Children’s Court at the orphanage. It was a difficult challenge at first. He expected the children to be as enthusiastic as he was about their court of peers, but is didn’t turn out that way at first. They couldn’t grasp the concept that suing someone was as effective as hitting someone in the nose, and they didn’t like tattling on each other.

Civil and criminal cases were heard once a week. One student acted as prosecutor and one as the defense lawyer, and there were three children who were the judges. The preamble to the Code reflects Korczak’s belief in forgiveness. It stated, “If anyone has done something bad, it is best to forgive. If it was done because he did not know, he knows now. If he did it intentionally, he will be more careful in the future… But the Court must defend the timid against the bullies, the conscientious against the careless and the idle. ”

The court changed to five judges per week from among the children who had no court cases pending against them, and could cite any of the thousand articles in the Code. Articles 1 -99 covered minor infractions and pardoned the defendant outright. Article 100 was the dividing line between forgiveness and censure. The articles then jumped in units of one hundred, becoming progressively sterner in their moral judgment. Under articles 200 -800, the guilty child’s name was published in the orphanage newspaper or posted on the bulletin board, or he was denied privileges for one week. Article 900 carried the dire warning that the Court had “abandoned hope”: the accused had to find a supporter among the children willing to vouch for him. Article 1, 000, a dreaded verdict, meant expulsion. The guilty party had the right to apply for readmission after three months, but with little hope, for his place would have been taken by another child the day he left.

Korczak was even taken to Court himself five times over a six month period. He felt it was important for the children to know that adults were not above the law simply because they were older. He confessed to “boxing a boy’s ears, throwing a boy out of the dormitory, putting a child in the corner, insulting a judge, and accusing a girl of stealing. He was usually forgiven, however, in one case, where he had put a frightened girl in a tree to make the other children notice her, he was not forgiven by the Court and was given a sentence of 100. Korczak also spent a great deal of his time, freely, with the juvenile justice system, nearly always advocating for the child over the state.

Discipline and Rewards * Korczak had the children vote on the status of new students. Each child had three cards; one plus, one minus, and one zero. They were to place one card into a box which related to their feelings about the child. Once tabulated, the new student would be classified with the top rank of Comrade. Those with a fair number of plusses would be Residents, those with only a few plusses were considered Indifferent Residents, and those with none were Difficult Residents. The higher the rank, the more privileges were available. The newcomer was voted on again after six months.

* His hope was to help the children win the battle with themselves in ways that would not undermine their pride. For example, until they learned to control the rage and frustration that had built up inside them over the years, they had to let off steam, and so fights were allowed. But, with the proviso that one sign up for them in advance, and that the opponents be evenly matched. “If you must hit someone, hit – but not too hard, ” Korczak would tell them, “lose your temper if you must, but only once a day. ”

* “Thanks to theory, I know. Thanks to practice, I feel. Theory enriches intellect, practice deepens feelings, trains the will. ” *. Korczak would place bets with the children in order to change their behavior. If they succeeded that week, they were rewarded with a treat, if they did not succeed, there was no reward, but no punishment. * If perchance he should lose his temper with a child, he would never utter words that could be hurtful. Instead, he would call the child a tomato, a bagpipe, a rook, or any such meaningless term. The student knew he was angry without being hurt by words thrown at him.

* Another strategy was to tell the child he was angry with them, but for a definite time. “I am angry with you until supper. ” The child understood that he was being punished, but also that there was a time limit, after which he could be forgiven and could begin anew. * No matter how difficult the child was, Korczak never resorted to the punishments typical of orphanages of the day, such as beatings or withholding food. If all else failed, a spanking was given out, if it was needed. He felt, “If you must, never without warning, and only in necessary defense – once. And that once, without anger.

* When a child improved his behavior or skills, he was awarded a picture postcard signed by Korczak himself. If he didn’t improve, he might still get a card as an incentive to try harder. The postcard was colorful and inexpensive, and since it was small, it could be stashed away and treasured by the child. The decision as to whom would receive a card was made by the twenty deputies of the Children’s Parliament who were chosen from those who had no court cases for dishonesty against them that year.

Final Stand of Janusz Korczak In August 1942, the deportations in the ghetto were daily occurrences, and finally, on August 5, 1942, the decree came down that Korczak’s orphanage was to report for deportation to the East. The description of the death march of Korczak and his children has become legendary. Weakened by fatigue and severely undernourished, Korczak nonetheless walked with his head held high, leading his 200 children. They walked in calm, orderly ranks through the hushed streets of Warsaw to the train station. They carried the orphanage flag that Korczak had designed – green with white blossoms on one side (King Matt the First’s flag – Korczak’s most famous book) and the blue star of David on the other.

One eyewitness recalled “I will never forget that sight to the end of my life. It was a silent but organized protest against the murderers, a march like which no human eye had ever seen before. It was an unbearably hot day; the children went four by four. Korczak went first carrying one child and leading another by the hand. The second group, of the older children was led by Stefa Wilczynska”.

All around them was chaos, people screaming, running, trying to find family members and begging with the Nazis to be released, or to be allowed to be kept with family. Korczak’s children remained calm and silent, each carrying a favorite toy, blanket or book. When Korczak was recognized, many tried to bargain with the Nazis for his life. One high ranking Nazi official, having worked with Korczak ran to him and said he could get Korczak out and away from the deportation. Korczak then asked about his children and the man replied that he could only spare Korczak’s life, to which he replied, “You do not leave a child in the night, and you do not leave children at a time like this. ” And while he could not offer rescue, he could offer comfort, and so, like a true father, he stayed with them to the very last of their breaths in the gas chambers of Treblinka.

Janusz korczak cytaty

Janusz korczak cytaty Janusz korczak

Janusz korczak Nie takie ważne żeby człowiek dużo wiedział

Nie takie ważne żeby człowiek dużo wiedział Kto to janusz korczak

Kto to janusz korczak Janusz korczak cytaty

Janusz korczak cytaty Plebiscyt życzliwości i niechęci korczaka

Plebiscyt życzliwości i niechęci korczaka Janusz korczak - gesamtschule gütersloh

Janusz korczak - gesamtschule gütersloh Janusz korczak

Janusz korczak Kim był janusz korczak

Kim był janusz korczak Amelia korczak patreon

Amelia korczak patreon Pedagogika janusza korczaka

Pedagogika janusza korczaka Janusz korczak

Janusz korczak Janusz korczak utwory

Janusz korczak utwory Adriana korczak

Adriana korczak Korczak

Korczak Amelia korczak patreon

Amelia korczak patreon Beata korczak

Beata korczak Ibn-tamas v. united states

Ibn-tamas v. united states Afi 36-807

Afi 36-807 Subtropical united states

Subtropical united states United states bicycle route system

United states bicycle route system United states and canada physical map

United states and canada physical map Watts v united states

Watts v united states Expansion of the united states of america 1607 to 1853 map

Expansion of the united states of america 1607 to 1853 map American column & lumber co v united states

American column & lumber co v united states When was awake united states written

When was awake united states written Yosemite sam confederate

Yosemite sam confederate What early industries mechanized the united states?

What early industries mechanized the united states? United states soccer league system

United states soccer league system Growth of the united states to 1853

Growth of the united states to 1853 Model von thunen

Model von thunen United states lactation consultant association

United states lactation consultant association