5212021 2009 American Heart Association All rights reserved

- Slides: 71

5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

AHA/ASA Scientific Statement Guidelines for the Management of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) A Statement for Healthcare Professionals from a Special Writing Group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association Joshua B. Bederson, MD, Chair; E. Sander Connolly, Jr. , MD, FAHA Vice-Chair; H. Hunt Batjer, MD; Ralph G. Dacey, MD, FAHA; Jacques E. Dion, MD, FRCPC; Michael N. Diringer, MD, FAHA, FCCM; John E. Duldner, Jr. , MD, MS; Robert E. Harbaugh, MD, FACS, FAHA; Aman B. Patel, MD; Robert H. Rosenwasser, MD, FACS, FAHA 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Stroke Council Professional Education Committee • This slide presentation was developed by members of the Stroke Council Professional Education committee. – Opeolu Adeoye MD – Dawn Kleindorfer MD 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Citation Information • Key words included in the paper: aneurysm; angiography; cerebrovascular disorders; hemorrhage; stroke; surgery; vasospasm Bederson JB, Connolly ES Jr, Batjer HH, Dacey RG, Dion JE, Diringer MN, Duldner JE Jr, Harbaugh RE, Patel AB, Rosenwasser RH. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke 2009: published online before print January 22, 2009, 10. 1161/STROKEAHA. 108. 191395. 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

This slide set was adapted from the Guidelines for the Management of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage paper This guideline reflects a consensus of expert opinion following thorough literature review that consisted of a look at clinical trials and other evidence related to the management of subarachnoid hemorrhage. 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Applying classification of recommendations and levels of evidence 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Outline • • • Introduction Epidemiology Acute Evaluation and Medical Management Surgical and Endovascular Management of Common In-Hospital SAH Complications Summary and Conclusions 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Introduction • SAH is a common and devastating condition • SAH affects up to 30, 000 persons annually in the United States (US) • Mortality rates are as high as 45% with significant morbidity among survivors • These recommendations summarize the best available evidence for treatment of patients with aneurysmal SAH 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

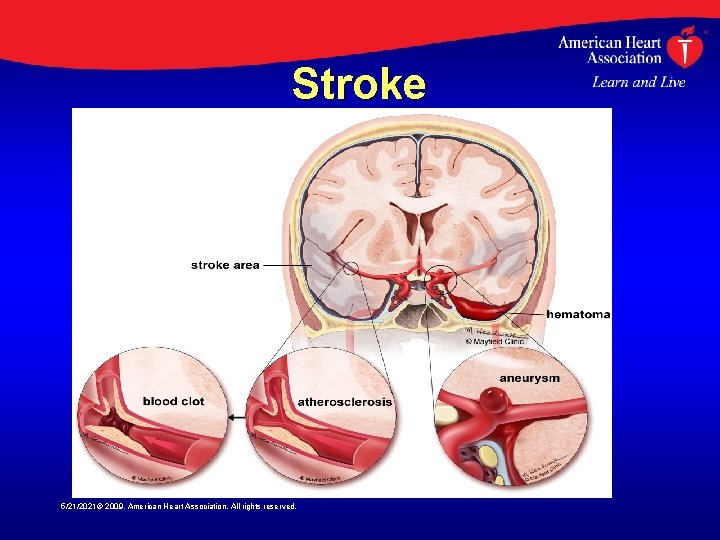

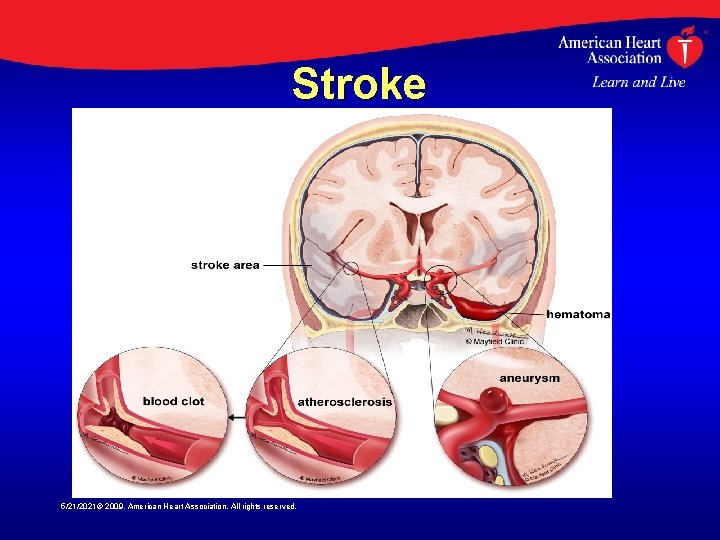

Stroke 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

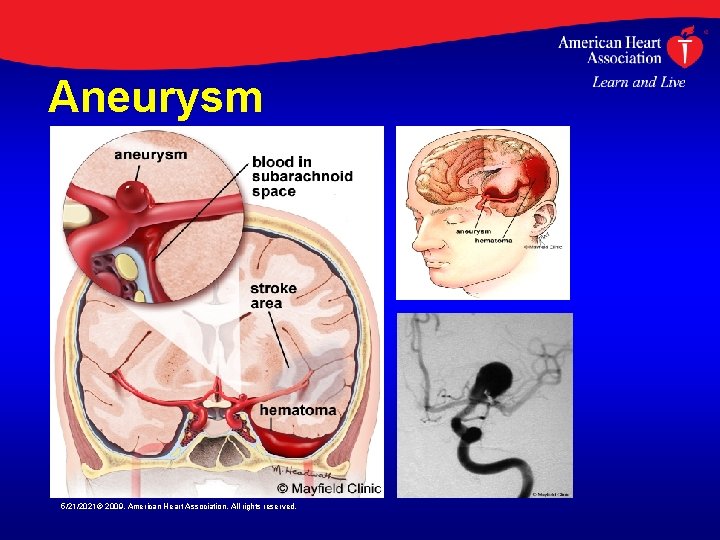

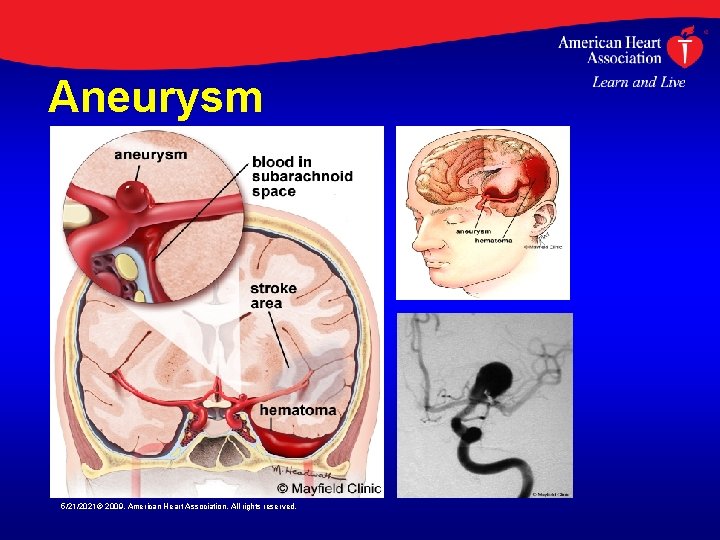

Aneurysm 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Epidemiology • SAH incidence varies greatly between countries, from 2 cases/ 100, 000 in China to 22. 5/100, 000 in Finland • Many cases of SAH are misdiagnosed • Thus, the annual incidence of aneurysmal SAH in the US may exceed 30, 000 • Incidence increases with age, occurring most commonly between 40 and 60 years of age (mean age > 50 years) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Epidemiology • SAH is ~1. 6 times higher in women than men • Risk factors for SAH include hypertension, smoking, female gender and heavy alcohol use • Cocaine-related SAH occurs in younger patients • Familial intracranial aneurysm (FIA) syndrome occurs when two firstthrough third-degree relatives have intracranial aneurysms 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

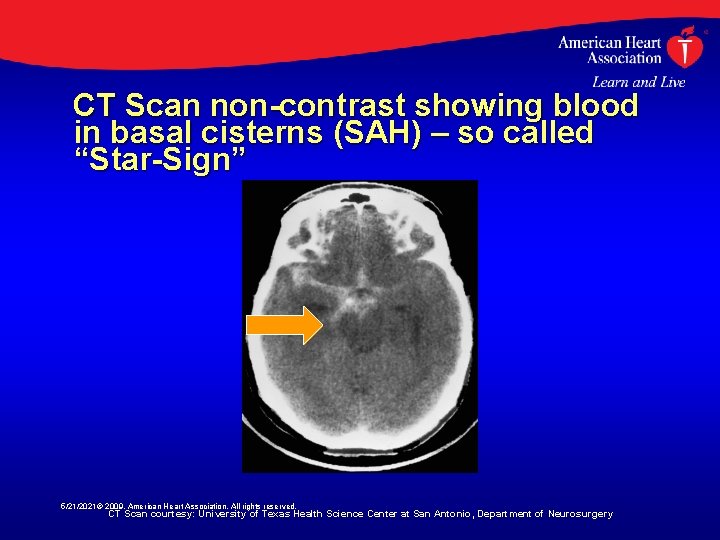

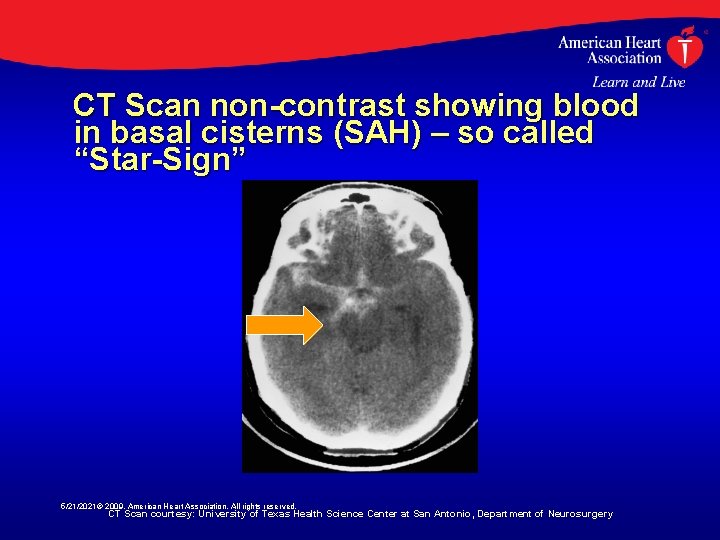

CT Scan non-contrast showing blood in basal cisterns (SAH) – so called “Star-Sign” 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved. CT Scan courtesy: University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Department of Neurosurgery

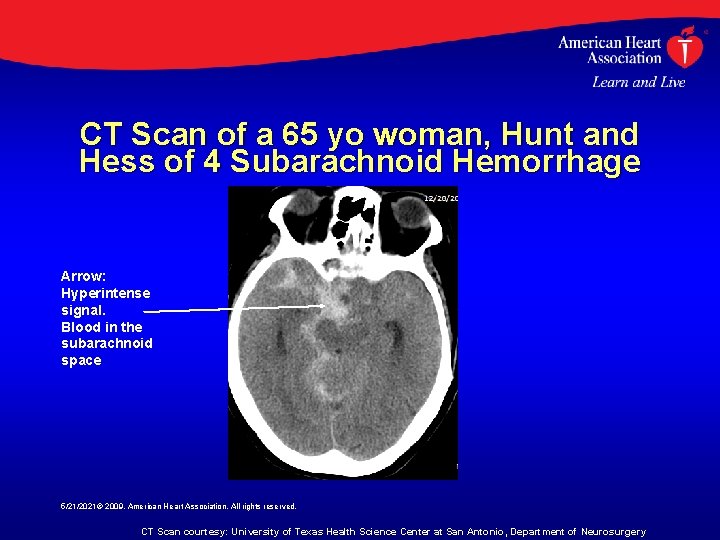

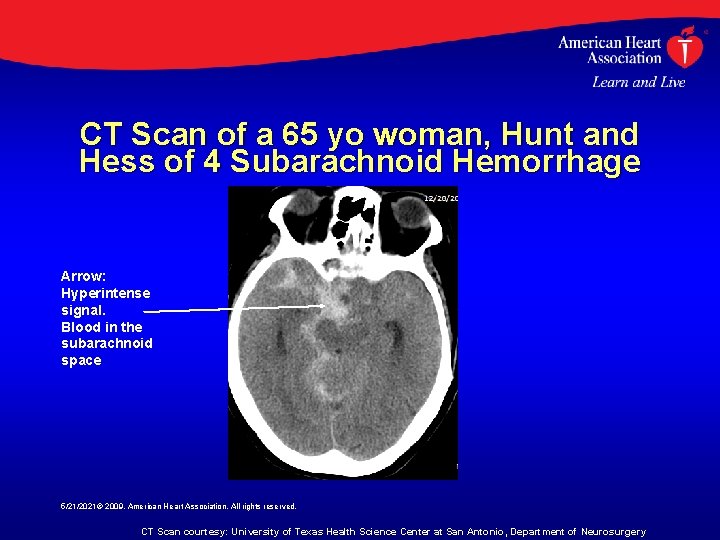

CT Scan of a 65 yo woman, Hunt and Hess of 4 Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Arrow: Hyperintense signal. Blood in the subarachnoid space 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved. CT Scan courtesy: University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Department of Neurosurgery

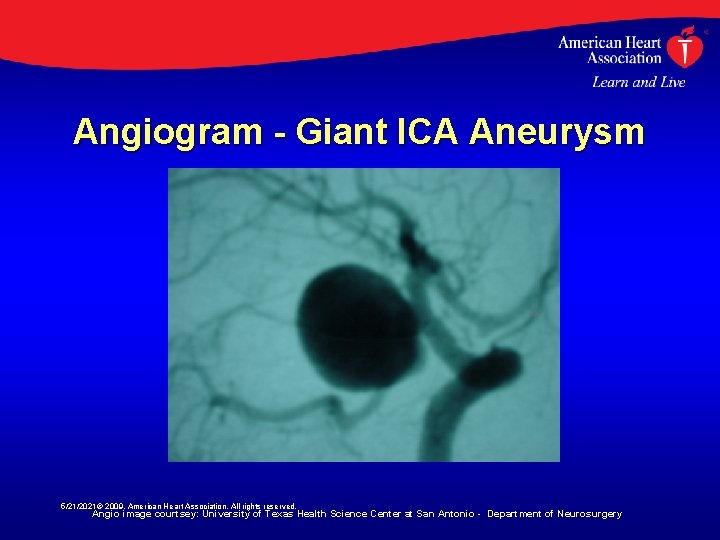

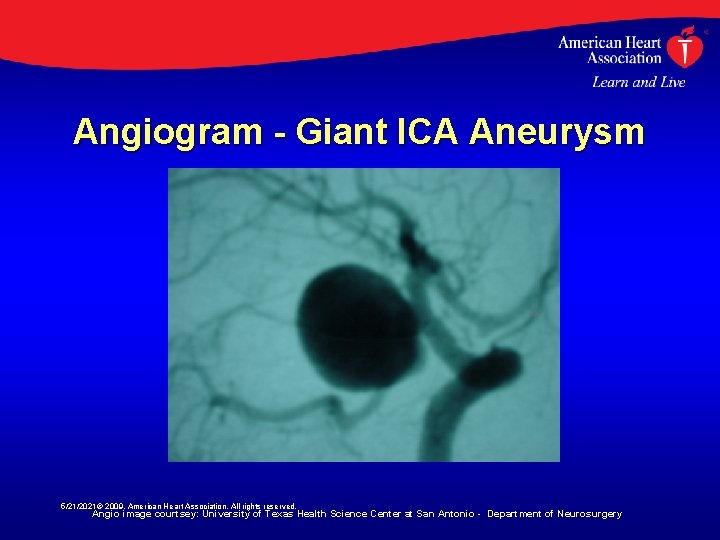

Angiogram - Giant ICA Aneurysm 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved. Angio image courtsey: University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio - Department of Neurosurgery

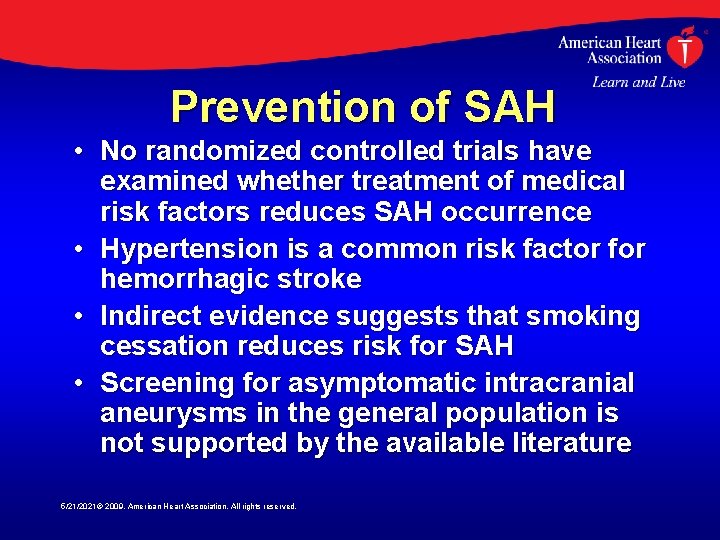

Prevention of SAH • No randomized controlled trials have examined whether treatment of medical risk factors reduces SAH occurrence • Hypertension is a common risk factor for hemorrhagic stroke • Indirect evidence suggests that smoking cessation reduces risk for SAH • Screening for asymptomatic intracranial aneurysms in the general population is not supported by the available literature 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Recommendations for Prevention of SAH • Class I Recommendations – The relationship between hypertension and aneurysmal SAH is uncertain. However, treatment of high blood pressure with antihypertensive medication is recommended to prevent ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage, cardiac, renal, and other end-organ injury (LOE A) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Recommendations for Prevention of SAH • Class II Recommendations – Cessation of smoking is reasonable to reduce the risk of SAH, although evidence for this association is indirect (LOE B). – Screening of certain high-risk populations for unruptured aneurysms is of uncertain value (LOE B); advances in noninvasive imaging may be used for screening, but catheter angiography remains the “gold standard” when it is clinically imperative to know if an aneurysm exists. 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Natural History and Outcome of an Aneurysmal SAH • 30 -day mortality rate after SAH ranges from 3350% • Severity of initial hemorrhage, sex, time to treatment, and medical comorbidities impact SAH outcome • Aneurysm size, location in the posterior circulation, and morphology may also impact outcome • Endovascular services at a given institution, the volume of SAH patients treated, and the facility where the patient is first evaluated may also impact outcome 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Natural History of an Aneurysmal SAH: Recommendations • Class I Recommendations – The severity of the initial bleed should be determined rapidly as it is the most useful indicator of outcome following aneurysmal SAH and grading scales which heavily rely on this factor are helpful in planning future care with family and other physicians (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Natural History of an Aneurysmal SAH: Recommendations • Class I Recommendations – Case review and prospective cohorts have shown that for untreated, ruptured aneurysms, there is at least a 3% to 4% risk of re-bleeding in the first 24 hours and possibly significantly higher, with a high percentage occurring immediately (within 2 to 12 hours) after the initial ictus, a 1% to 2% per day risk in the first month, and a long-term risk of 3% per year after 3 months. Urgent evaluation and treatment of patients with suspected SAH is therefore recommended (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Natural History of an Aneurysmal SAH: Recommendations • Class II Recommendations – In triaging patients for aneurysm repair, factors that can be useful in determining the risk of re-bleeding include severity of the initial bleed, interval to admission, blood pressure, gender, aneurysm characteristics, hydrocephalus, early angiography, and the presence of a ventricular drain (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Acute Evaluation - Diagnosis • “The worst headache of my life” is described by ~80% of patients • “Sentinel” headache is described by ~20% • Nausea/vomiting, stiff neck, loss of consciousness, or focal neurological deficits may occur • Misdiagnosis of SAH occurred in as many as 64% of cases prior to 1985 • Recent data suggest an SAH misdiagnosis rate of approximately 12% 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Acute Evaluation - Diagnosis • Importance of recognition of a warning or sentinel leak cannot be overemphasized • A high index of suspicion is warranted in the ED • The diagnostic sensitivity of CT scanning is not 100%, thus diagnostic lumbar puncture should be performed if the initial CT scan is negative 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Diagnosis of SAH -Recommendations • Class I Recommendations – SAH is a medical emergency that is frequently misdiagnosed. A high level of suspicion for SAH should exist in patients with acute onset of severe headache (LOE B) – CT scanning for suspected SAH is strongly recommended, and lumbar puncture for analysis of cerebrospinal fluid is strongly recommended when the CT scan is negative (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Diagnosis of SAH –Recommendations • Class I Recommendations – Selective cerebral angiography to document the presence and anatomic features of aneurysms is strongly recommended in patients with documented SAH (LOE B) • Class II Recommendations – MRA or CTA can serve as useful alternative diagnostic tools when conventional angiography cannot be performed in a timely fashion (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Acute Evaluation – Emergency Evaluation • Emergency medical services (EMS) is first medical contact in about 2/3 of SAH patients • EMS personnel should receive continuing education regarding signs and symptoms and the importance of rapid neurological assessment in cases of possible SAH • On-scene delays should be avoided • Rapid transport and advanced notification of the ED should occur 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Acute Evaluation – Emergency Evaluation • Airway, breathing, and circulation should be rapidly assessed and managed • Emergency care providers should evaluate SAH patients with an accepted neurologic assessment scale and record it in the ED – Hunt and Hess, Fisher Scale, Glasgow Coma Scale, World Federation of Neurological Surgeons Scale. • Expedient transfer to an appropriate referral center should be considered if necessary 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Emergency Evaluation Recommendations • Class II Recommendations – The degree of neurological impairment using an accepted SAH grading system can be useful for prognosis and triage (LOE B) – A standardized ED management protocol for the evaluation of patients with headaches and other symptoms of potential SAH does not currently exist and needs development (LOE C) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Acute Evaluation – Preventing Re-bleeding • Up to 14% of SAH patients may experience re-bleeding within 2 hours of the initial hemorrhage • Re-bleeding was more common in those with a systolic blood pressure >160 mm Hg • Anti-fibrinolytic therapy may reduce rebleeding but has not been shown to improve outcomes 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Preventing Re-bleeding Recommendations • Class I Recommendations – Blood pressure should be monitored and controlled to balance the risk of strokes, hypertension-related re-bleeding, and maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure (LOE B) • Class II Recommendations – Bed rest alone is not enough to prevent rebleeding after SAH. It may be considered as a component of a broader treatment strategy along with more definitive measures (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Preventing Re-bleeding Recommendations • Class II Recommendations – Recent evidence suggests that early treatment with antifibrinolytic agents, when combined with a program of early aneurysm treatment followed by discontinuation of the antifibrinolytic and prophylaxis against hypovolemia and vasospasm (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Preventing Re-bleeding – Class II Recommendations • Antifibrinolytic therapy to prevent rebleeding may be considered in certain clinical situations, e. g. , patients with a low risk of vasospasm and/or a beneficial effect of delaying surgery (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

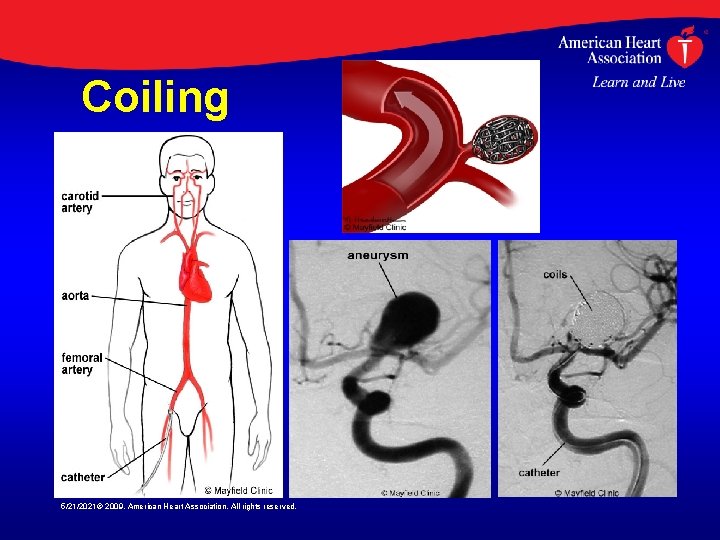

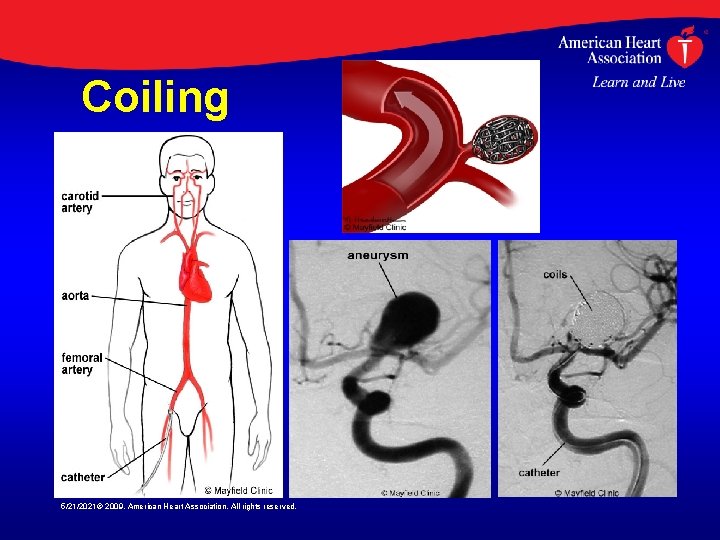

Surgical and Endovascular Management of SAH • Occluding aneurysms using endovascular coils was described in 1991 • Improved outcomes have been linked to hospitals that provide endovascular services • Use of endovascular versus surgical techniques varies greatly across centers • Coil embolization is associated with a 2. 4% risk of aneurysmal perforation and an 8. 5% risk of ischemic complications 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Surgical and Endovascular Management of SAH • A study of 431 patients undergoing coiling of a ruptured aneurysm found an early re-bleeding rate of 1. 4%, with 100% mortality • The ISAT Trial reported a 1 -year rehemorrhage rate of ~2. 9% in aneurysms treated with endovascular therapy • Aneurysm size is an important predictor of hemorrhage risk 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Surgical and Endovascular Management of SAH • The Cooperative Study evaluated 979 patients who underwent intracranial surgery only • Nine of 453 patients (2%) rebled after surgery • Nearly half (n=4) of these hemorrhages occurred in patients with multiple aneurysms 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Surgical and Endovascular Management of SAH • In the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) post-treatment SAH occurred at an annualized rate of 0. 9% with surgical clipping, compared to 2. 9% with endovascular treatment • The rate of incomplete obliteration and recurrence appears significantly lower with surgical clipping than with endovascular treatment 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Surgical and Endovascular Management of SAH • Increased time to treatment is associated with increased rates of preoperative rebleeding – – – 0 to 3 days, 5. 7% 4 to 6 days, 9. 4% 7 to 10 days, 12. 7% 11 to 14 days, 13. 9% 15 to 32 days, 21. 5% • Postoperative re-bleeding did not differ among time intervals (1. 6% overall) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Surgical and Endovascular Management of SAH • Estimating the consequences of complications attributable to an operation may be possible from data regarding surgery for unruptured aneurysms • In-hospital mortality rates vary from 1. 8% to 3. 0% in large multicenter studies • Adverse outcomes in survivors vary from 8. 9% to 22. 4% 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Surgical and Endovascular Management of SAH • The only large prospective, randomized trial to date comparing surgery and endovascular techniques is ISAT • At one year, there was no significant difference in mortality rates (8. 1% vs. 10. 1% endovascular vs. surgical) • Disability rates were greater in surgical versus endovascular patients (21. 6% vs. 15. 6%) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Surgical and Endovascular Management of SAH • Combined morbidity and mortality was significantly greater in surgically treated patients than in those treated with endovascular techniques (30. 9% vs. 23. 5%; absolute risk reduction 7. 4%, P = 0. 0001) • During the short follow-up period in ISAT the re -bleeding rate for coiling was 2. 9% versus 0. 9% for surgery • There have been no randomized comparisons of coiling versus clipping for unruptured aneurysms 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

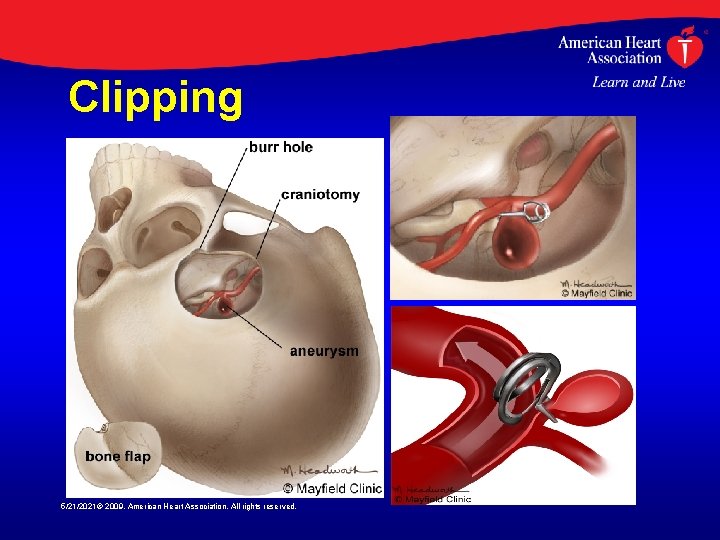

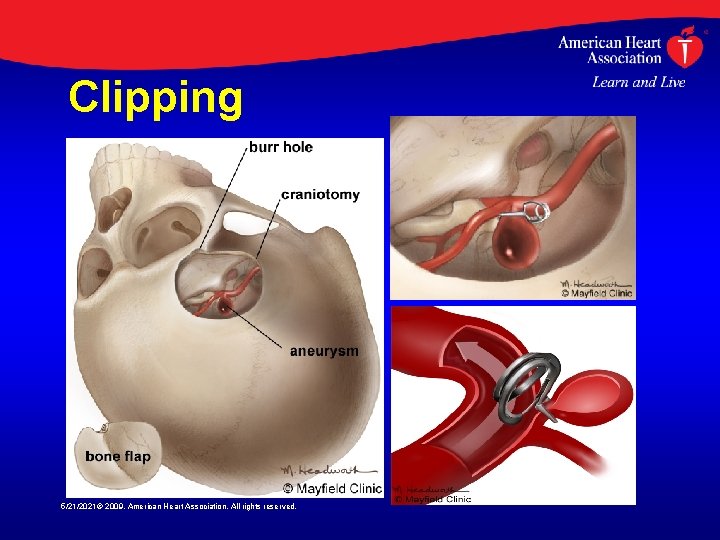

Clipping 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

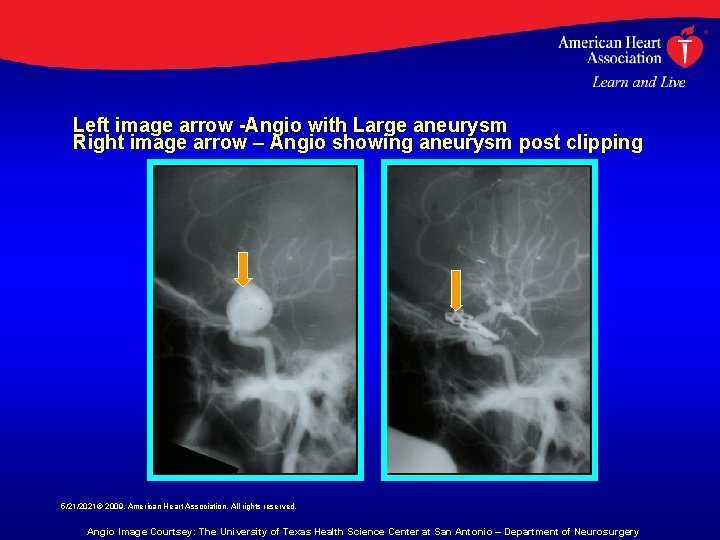

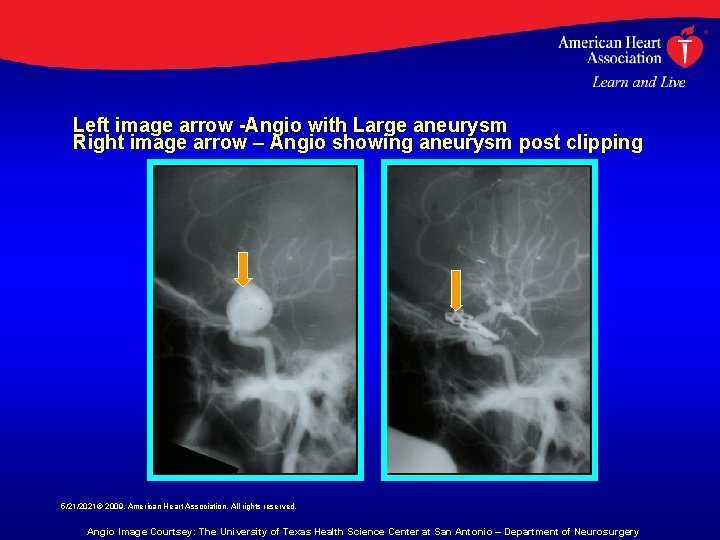

Left image arrow -Angio with Large aneurysm Right image arrow – Angio showing aneurysm post clipping 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved. Angio Image Courtsey: The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio – Department of Neurosurgery

Surgical and Endovascular Management -Recommendations • Class I Recommendations – Surgical clipping or endovascular coiling is strongly recommended to reduce the rate of rebleeding after aneurysmal SAH (LOE B) – Wrapped or coated aneurysms as well as incompletely clipped or coiled aneurysms have an increased risk of re-hemorrhage compared to those completely occluded and therefore require long-term follow-up angiography. Complete obliteration of the aneurysm is recommended whenever possible (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Surgical and Endovascular Management -Recommendations • Class I Recommendations – For patients with ruptured aneurysms judged by an experienced team of cerebrovascular surgeons and endovascular practitioners to be technically amenable to both endovascular coiling and neurosurgical clipping, endovascular coiling can be beneficial (LOE B) • Class II Recommendations – Individual characteristics of the patient and the aneurysm must be considered in deciding the best means of repair, and management of patients in centers offering both techniques is probably recommended (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Coiling 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

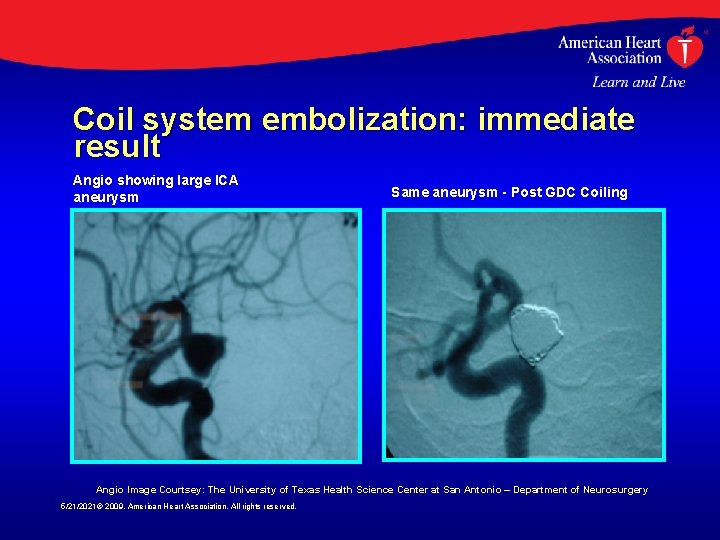

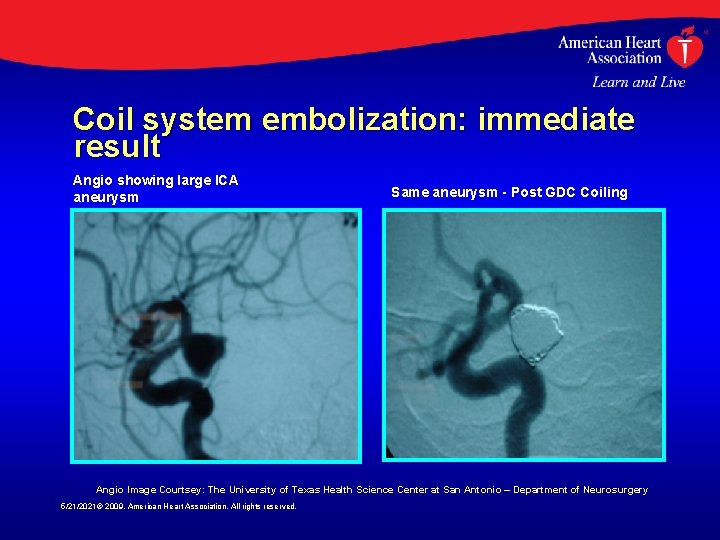

Coil system embolization: immediate result Angio showing large ICA aneurysm Same aneurysm - Post GDC Coiling Angio Image Courtsey: The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio – Department of Neurosurgery 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Surgical and Endovascular Management Recommendations • Class II Recommendations – Although previous studies showed that overall outcome was not different for early versus delayed surgery after SAH, early treatment reduces the risk of rebleeding after SAH, and newer methods may increase the effectiveness of early aneurysm treatment. Early aneurysm treatment is reasonable and is probably indicated in the majority of cases (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Hospital/Systems of Care • Treatment volume is an important determinant of outcome for intracranial aneurysms – higher volume equals lower mortality • This effect may be more important for patients with unruptured aneurysms than for those with ruptured aneurysms • It is uncertain whether the benefits of receiving care at a high-volume center would outweigh the costs and risks of transfer 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Hospital/Systems of Care -Recommendations • Class II Recommendations – Early referral to high-volume centers that have both experienced cerebrovascular surgeons and endovascular specialists is reasonable (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Management of Common In. Hospital SAH Complications • Common issues related to inhospital management of SAH include: – Anesthetic Management – Cerebral Vasospasm – Hydrocephalus – Seizures – Hyponatremia 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Anesthetic Management During Surgical and Endovascular Treatments • Goals of intraoperative anesthetic management during aneurysm treatment include: – limiting the risk of intraprocedural aneurysm rupture – protecting the brain against ischemic injury 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Anesthetic Management -Recommendations • Class II Recommendations – Minimizing the degree and duration of intraoperative hypotension during aneurysm surgery is probably indicated (LOE B) – There are insufficient data on pharmacological strategies and induced hypertension during temporary vessel occlusion to make specific recommendations, but there may be instances where their use can be considered reasonable (LOE C) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Anesthetic Management -Recommendations • Class III Recommendations – Induced hypothermia during aneurysm surgery may be a reasonable option in some cases but is not routinely recommended (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Management of Cerebral Vasospasm after SAH • Following aneurysmal SAH, angiographic vasospasm is seen in 30% to 70% of patients • Typical onset is 3 to 5 days after the hemorrhage, maximal narrowing at 5 to 14 days, and a gradual resolution over 2 to 4 weeks • 15% to 20% of patients with delayed neurologic deficits suffer stroke or die from vasospasm despite maximal therapy • The index of suspicion needs to be higher in poor grade patients even with subtle changes in neurological exam 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Management of Cerebral Vasospasm after SAH • The literature is inconclusive regarding the sensitivity and specificity of TCD monitoring • However, severe spasm can be identified with fairly high reliability using TCD monitoring • Other modalities such as diffusion perfusion, MRI, and xenon-CT cerebral perfusion studies may be complementary in guiding management 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Management of Cerebral Vasospasm after SAH • Hypertensive hypervolemic hemodilution (HHH) therapy has become a mainstay in the management of cerebral vasospasm • Only one randomized study has been performed to assess its efficacy • Two small single-center prospective randomized studies strongly suggest that avoiding hypovolemia is advisable, but there is no evidence for prophylactic hyperdynamic therapy 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Management of Cerebral Vasospasm after SAH • Calcium-channel blockers, particularly nimodipine, have been approved for use for treatment of vasospasm • However, the reduction in morbidity and improvement in functional outcome may have been due more to cerebral protection than actual effect on the cerebral vasculature • Intravenous nicardipine interestingly showed a 30% reduction in spasm but no improvement in outcome 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Management of Cerebral Vasospasm after SAH • Balloon angioplasty has been shown to be effective in reversing cerebral vasospasm in large proximal conducting vessels but has not been shown to improve ultimate outcome • Angioplasty is not effective or safe in distal perforating branches beyond second-order segments • Angioplasty is effective in reducing angiographic spasm, promoting an increase in CBF, and reducing deficits 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Cerebral Vasospasm -Recommendations • Class I Recommendations – Oral nimodipine is strongly recommended to reduce poor outcome related to aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (LOE A) – The value of other calcium antagonists, whether administered orally or intravenously, remains uncertain 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Cerebral Vasospasm -Recommendations • Class II Recommendations – Treatment of cerebral vasospasm begins with early management of the ruptured aneurysm, and in most cases maintaining normal circulating blood volume and avoiding hypovolemia is probably indicated (LOE B) – One reasonable approach to symptomatic cerebral vasospasm is volume expansion, induction of hypertension and hemodilution [Triple-H therapy] (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Cerebral Vasospasm -Recommendations • Class II Recommendations – Alternatively, cerebral angioplasty and/or selective intraarterial vasodilator therapy may also be reasonable, either following, together with, or in the place of, Triple-H therapy depending on the clinical scenario (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Management of Hydrocephalus Associated With SAH • Acute hydrocephalus (ventricular enlargement within 72 hours) occurs in about 20% to 30% of SAH patients • The ventricular enlargement is often, but not always, accompanied by intraventricular blood • Acute hydrocephalus is more frequent in patients with poor clinical grade, and higher Fischer Scale scores • Two single-center series suggested that routine fenestration of the lamina terminalis reduces the incidence of chronic hydrocephalus 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Management of Hydrocephalus -Recommendations • Class I Recommendation – Temporary or permanent CSF diversion is recommended in symptomatic patients with chronic hydrocephalus following SAH (LOE B) • Class II Recommendation – Ventriculostomy can be beneficial in patients with ventriculomegaly and diminished level of consciousness following acute SAH (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Management of Seizures Associated With SAH • A large number of seizure-like episodes are associated with aneurysmal rupture • It is unclear, however, whether all these episodes are truly epileptic • Retrospective reviews report that early seizures occur in 6% to 18% of SAH patients • Non-convulsive seizures may occur in 19% of stuporous or comatose SAH patients • The relationship between seizures and outcome is uncertain 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

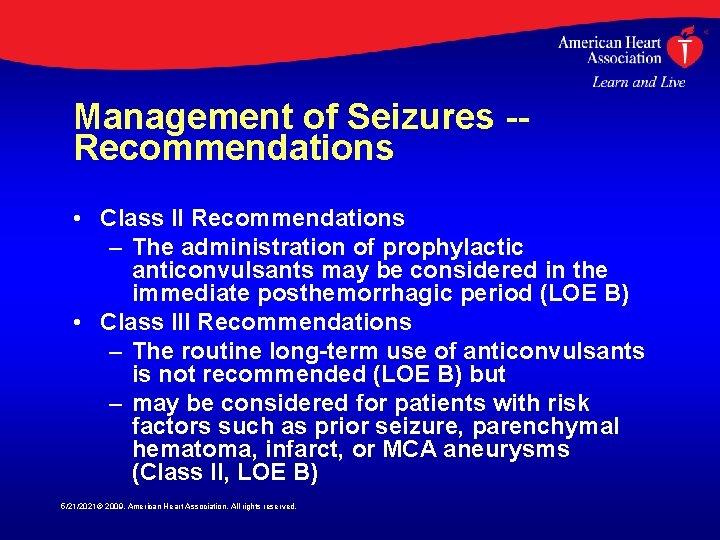

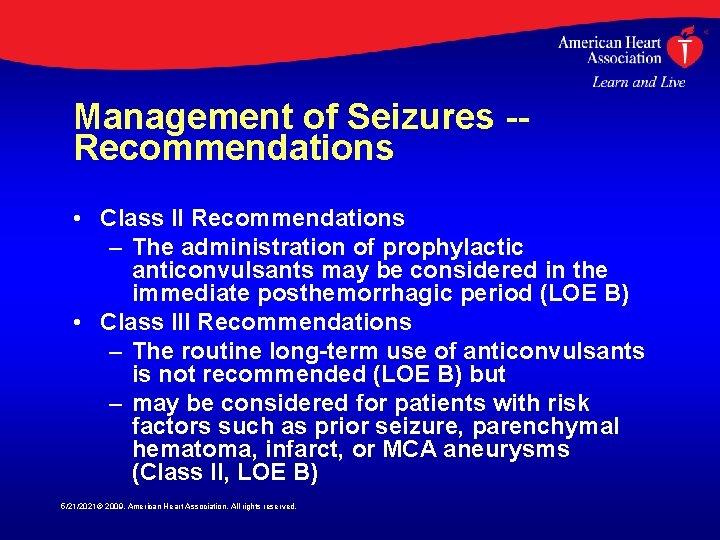

Management of Seizures -Recommendations • Class II Recommendations – The administration of prophylactic anticonvulsants may be considered in the immediate posthemorrhagic period (LOE B) • Class III Recommendations – The routine long-term use of anticonvulsants is not recommended (LOE B) but – may be considered for patients with risk factors such as prior seizure, parenchymal hematoma, infarct, or MCA aneurysms (Class II, LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

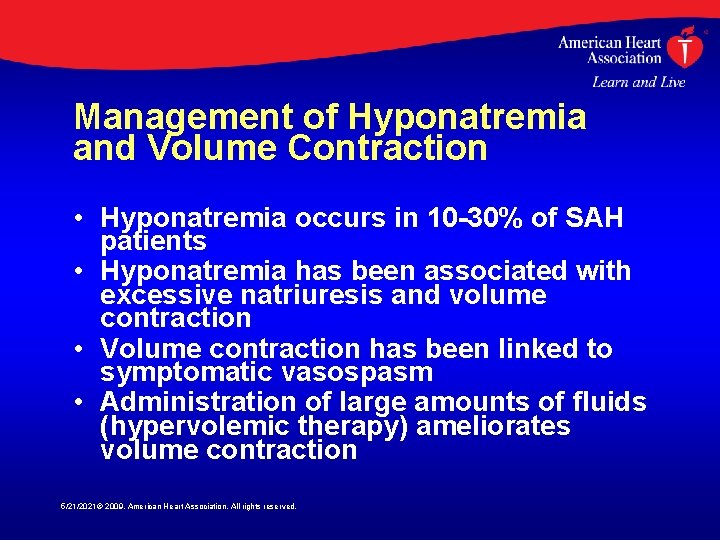

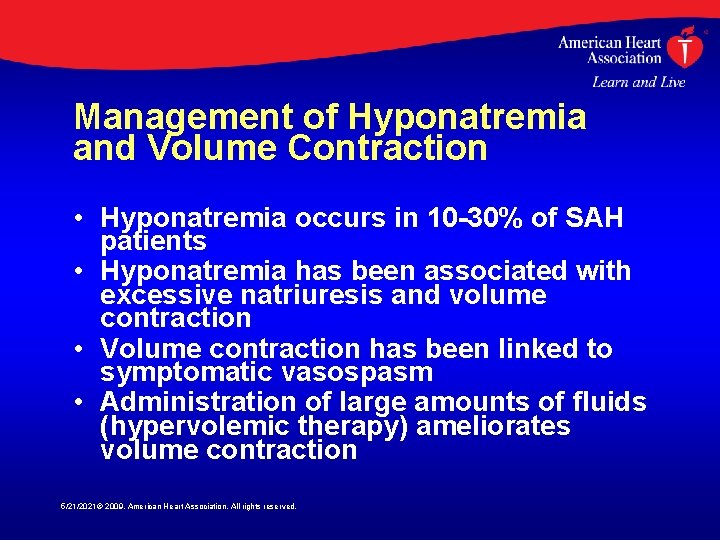

Management of Hyponatremia and Volume Contraction • Hyponatremia occurs in 10 -30% of SAH patients • Hyponatremia has been associated with excessive natriuresis and volume contraction • Volume contraction has been linked to symptomatic vasospasm • Administration of large amounts of fluids (hypervolemic therapy) ameliorates volume contraction 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

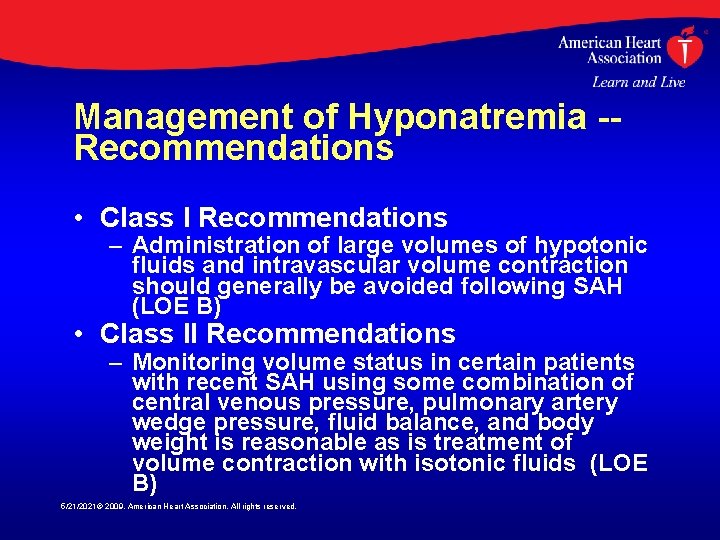

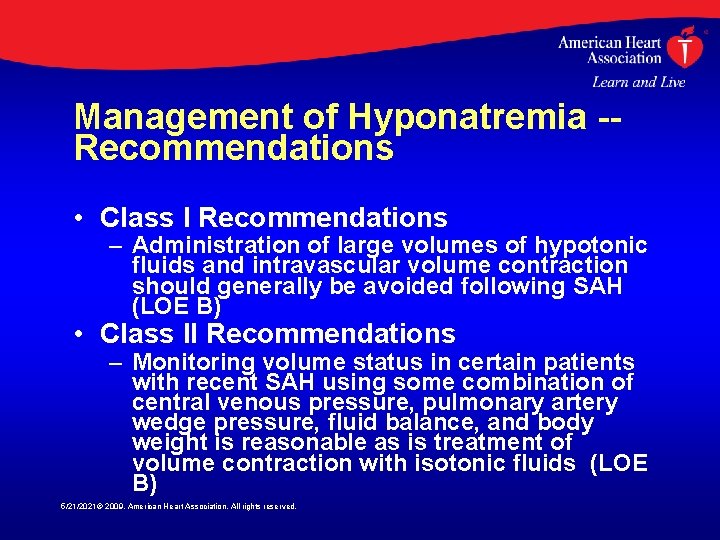

Management of Hyponatremia -Recommendations • Class I Recommendations – Administration of large volumes of hypotonic fluids and intravascular volume contraction should generally be avoided following SAH (LOE B) • Class II Recommendations – Monitoring volume status in certain patients with recent SAH using some combination of central venous pressure, pulmonary artery wedge pressure, fluid balance, and body weight is reasonable as is treatment of volume contraction with isotonic fluids (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

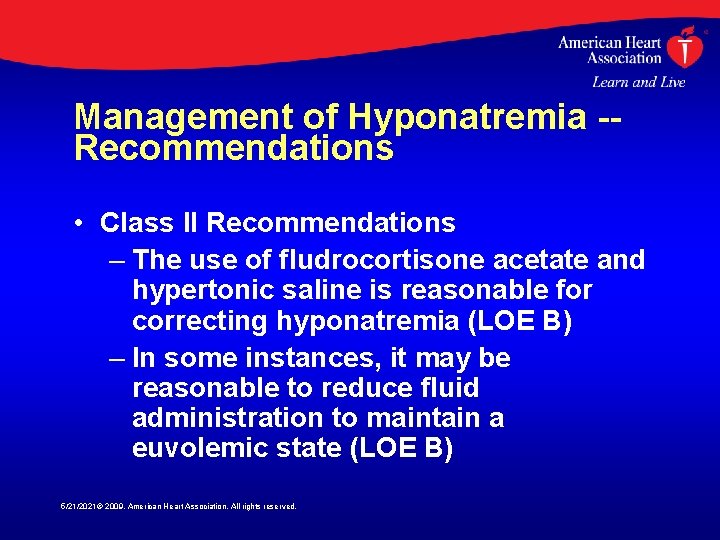

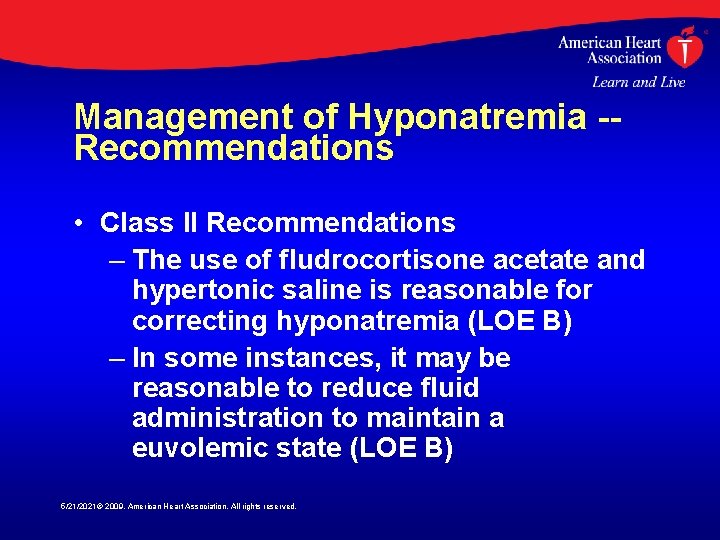

Management of Hyponatremia -Recommendations • Class II Recommendations – The use of fludrocortisone acetate and hypertonic saline is reasonable for correcting hyponatremia (LOE B) – In some instances, it may be reasonable to reduce fluid administration to maintain a euvolemic state (LOE B) 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Summary and Conclusions • The current standard of practice calls for microsurgical clipping or endovascular coiling of the aneurysm neck whenever possible • Treatment morbidity is determined by numerous factors, including patient, aneurysm, and institutional factors 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Summary and Conclusions • Favorable outcomes are more likely in institutions that treat high volumes of patients with SAH, in institutions that offer endovascular services, and in selected patients whose aneurysms are coiled rather than clipped • Optimal treatment requires availability of both experienced cerebrovascular surgeons and endovascular surgeons working in a collaborative effort to evaluate each case of SAH 5/21/2021© 2009, American Heart Association. All rights reserved.

Dell all rights reserved copyright 2009

Dell all rights reserved copyright 2009 All rights reserved example

All rights reserved example Copyright 2015 all rights reserved

Copyright 2015 all rights reserved All rights reserved sentence

All rights reserved sentence Creative commons vs all rights reserved

Creative commons vs all rights reserved Confidential all rights reserved

Confidential all rights reserved Sentinel value

Sentinel value Copyright 2015 all rights reserved

Copyright 2015 all rights reserved Pearson education inc all rights reserved

Pearson education inc all rights reserved Microsoft corporation. all rights reserved.

Microsoft corporation. all rights reserved. Microsoft corporation. all rights reserved

Microsoft corporation. all rights reserved Microsoft corporation. all rights reserved.

Microsoft corporation. all rights reserved. Pearson education inc. all rights reserved

Pearson education inc. all rights reserved Warning all rights reserved

Warning all rights reserved All rights reserved c

All rights reserved c Quadratic equation cengage

Quadratic equation cengage Warning all rights reserved

Warning all rights reserved Confidential all rights reserved

Confidential all rights reserved Microsoft corporation. all rights reserved

Microsoft corporation. all rights reserved 2010 pearson education inc

2010 pearson education inc Copyright © 2018 all rights reserved

Copyright © 2018 all rights reserved Gssllc

Gssllc Pearson education inc all rights reserved

Pearson education inc all rights reserved 2010 pearson education inc

2010 pearson education inc Confidential all rights reserved

Confidential all rights reserved Confidential all rights reserved

Confidential all rights reserved 5212021

5212021 5212021

5212021 R rights reserved

R rights reserved Rights reserved

Rights reserved American heart association recommends child cpr for:

American heart association recommends child cpr for: American heart association cpr in schools

American heart association cpr in schools American heart association 2020

American heart association 2020 Normal blood pressure

Normal blood pressure Hands only cpr american heart association

Hands only cpr american heart association Positive rights vs negative rights

Positive rights vs negative rights Littoral real estate

Littoral real estate Legal rights and moral rights

Legal rights and moral rights Legal rights vs moral rights

Legal rights vs moral rights What are negative rights

What are negative rights Positive vs negative rights

Positive vs negative rights Positive vs negative rights

Positive vs negative rights Negative right

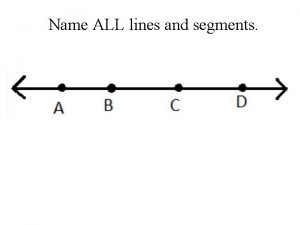

Negative right Draw three noncollinear points j k and l

Draw three noncollinear points j k and l Cardiac dullness

Cardiac dullness Sheep heart labeled

Sheep heart labeled Stars dogs plowhorses and puzzles

Stars dogs plowhorses and puzzles Swedish american heart hospital rockford illinois

Swedish american heart hospital rockford illinois American researcher who involved in getting heart rate

American researcher who involved in getting heart rate Asma math problems

Asma math problems American association for artificial intelligence 17 mar

American association for artificial intelligence 17 mar American galvanizers association

American galvanizers association The added value endowed on products and services is the

The added value endowed on products and services is the American berkshire association

American berkshire association American baking association

American baking association How to in text citation apa format

How to in text citation apa format Style apa adalah

Style apa adalah American psychological association example

American psychological association example American alzheimer's association

American alzheimer's association American library association

American library association Nymhca

Nymhca North american gaming regulators association

North american gaming regulators association North american association for environmental education

North american association for environmental education American library association

American library association American pyrotechnics association

American pyrotechnics association American psychiatric association annual meeting 2020

American psychiatric association annual meeting 2020 American association on health and disability

American association on health and disability American angus gestation calculator

American angus gestation calculator American thyroid association guidelines pregnancy 2017

American thyroid association guidelines pregnancy 2017 American gas association

American gas association Mobile baptist association

Mobile baptist association American academy of private physicians

American academy of private physicians