PREDICATE LOGIC From Propositional Logic to Predicate Logic

- Slides: 86

PREDICATE LOGIC

From Propositional Logic to Predicate Logic Last week, we dealt with propositional (or truth -functional) logic: the logic of truth-functional statements. Today, we are going to deal with predicate (or quantificational) logic. Quantificational logic is an extension of, and thus builds on truth-functional logic.

Recap: Formal Logic Step 1: Use certain symbols to express the abstract form of certain statements Step 2: Use a certain procedure based on these abstract symbolizations to figure out certain logical properties of the original statements.

Recap: Truth Tables Truth-Tables Slow Systematic Reveals consequence as well as non-consequence Only works for truth-functional logic

Recap: Formal Proofs Pretty fast (with practice!) Not systematic Can only reveal consequence Can be made into systematic method (that can then also check for non-consequence) but becomes inefficient Can be used for predicate logic

Recap: Truth Trees Fast Systematic Can reveal consequence as well as non-consequence Can be used for truth-functional as well as predicate logic

QUANTIFIERS

Individual Constants An individual constant is a name for an object. Examples: john, marie, a, b Each name is assumed to refer to a unique individual, i. e. we will not have two objects with the same name. However, each individual object may have more than one name.

Predicates Predicates are used to express properties of objects or relations between objects. Examples: Tall, Cube, Left. Of, = Arity: the number of arguments of a predicate (E. g. Tall: 1, Left. Of: 2)

Interpreted and Uninterpreted Predicates Just as ‘P’ can be used to denote any statement in propositional logic, a predicate like ‘Left. Of’ is left ‘uninterpreted’ in predicate logic. Thus, a statement like Left. Of(a, a) can be true in predicate logic. The predicate ‘=‘ is an exception: it will automatically be interpreted as the identity predicate.

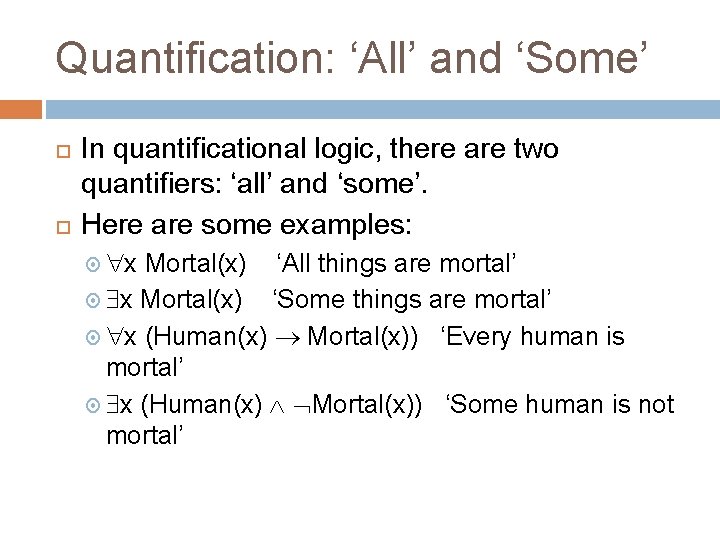

Quantification: ‘All’ and ‘Some’ In quantificational logic, there are two quantifiers: ‘all’ and ‘some’. Here are some examples: x Mortal(x) ‘All things are mortal’ x Mortal(x) ‘Some things are mortal’ x (Human(x) Mortal(x)) ‘Every human is mortal’ x (Human(x) Mortal(x)) ‘Some human is not mortal’

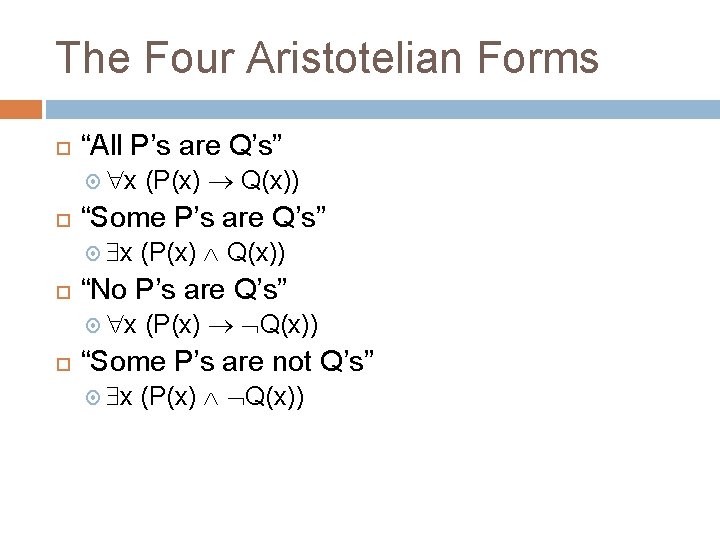

The Four Aristotelian Forms “All P’s are Q’s” x “Some P’s are Q’s” x (P(x) Q(x)) “No P’s are Q’s” x (P(x) Q(x)) “Some P’s are not Q’s” x (P(x) Q(x))

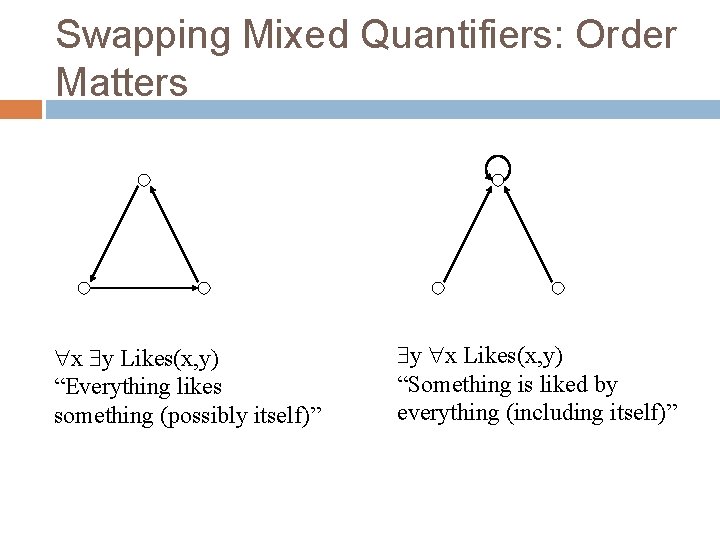

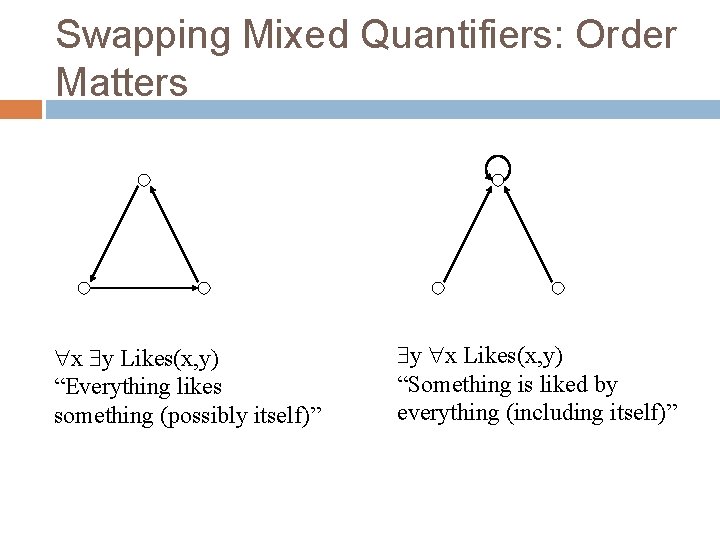

Swapping Mixed Quantifiers: Order Matters x y Likes(x, y) “Everything likes something (possibly itself)” y x Likes(x, y) “Something is liked by everything (including itself)”

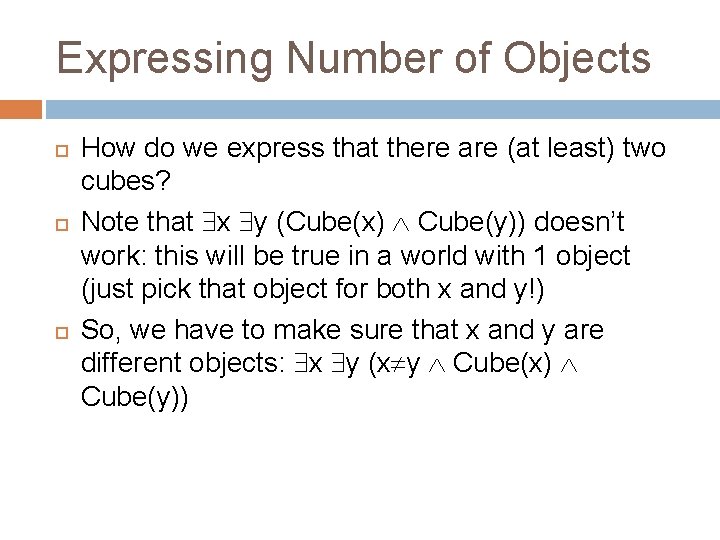

Expressing Number of Objects How do we express that there are (at least) two cubes? Note that x y (Cube(x) Cube(y)) doesn’t work: this will be true in a world with 1 object (just pick that object for both x and y!) So, we have to make sure that x and y are different objects: x y (x y Cube(x) Cube(y))

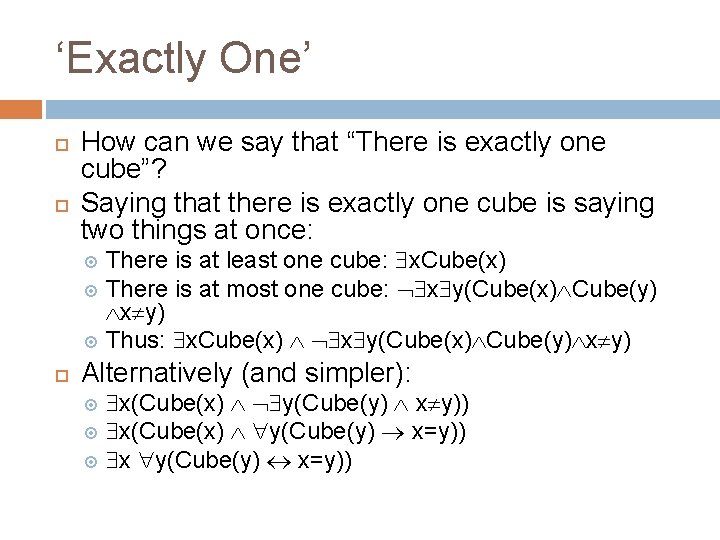

‘Exactly One’ How can we say that “There is exactly one cube”? Saying that there is exactly one cube is saying two things at once: There is at least one cube: x. Cube(x) There is at most one cube: x y(Cube(x) Cube(y) x y) Thus: x. Cube(x) x y(Cube(x) Cube(y) x y) Alternatively (and simpler): x(Cube(x) y(Cube(y) x y)) x(Cube(x) y(Cube(y) x=y)) x y(Cube(y) x=y))

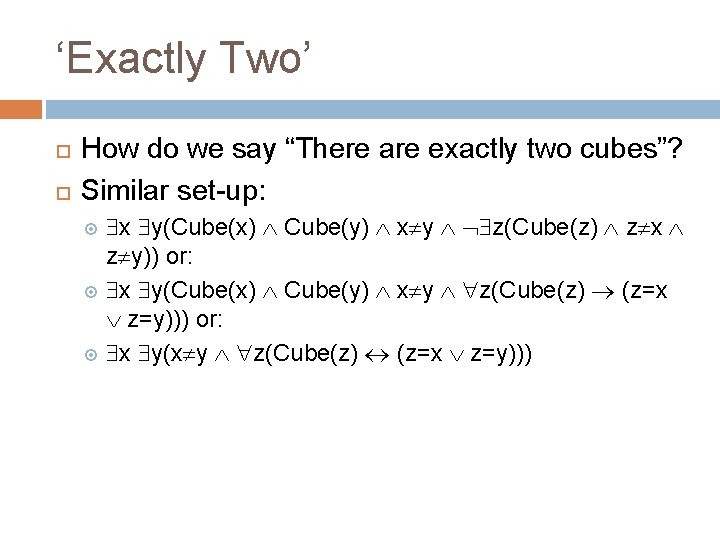

‘Exactly Two’ How do we say “There are exactly two cubes”? Similar set-up: x y(Cube(x) Cube(y) x y z(Cube(z) z x z y)) or: x y(Cube(x) Cube(y) x y z(Cube(z) (z=x z=y))) or: x y(x y z(Cube(z) (z=x z=y)))

THE LOGIC OF QUANTIFIERS

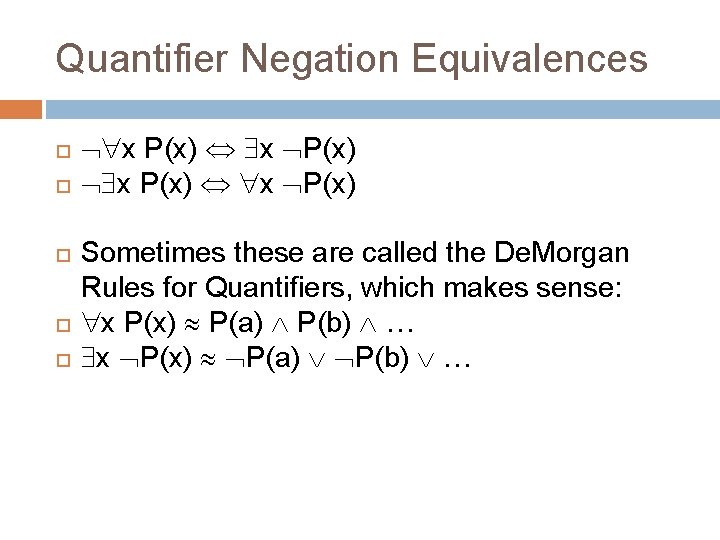

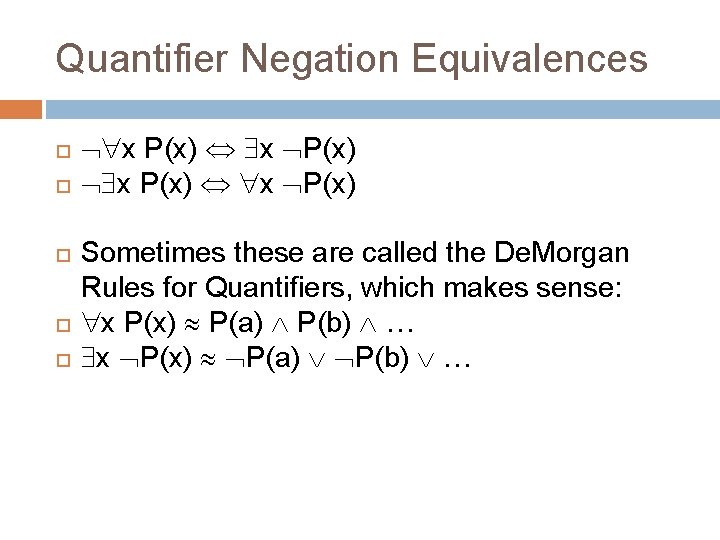

Quantifier Negation Equivalences x P(x) Sometimes these are called the De. Morgan Rules for Quantifiers, which makes sense: x P(x) P(a) P(b) …

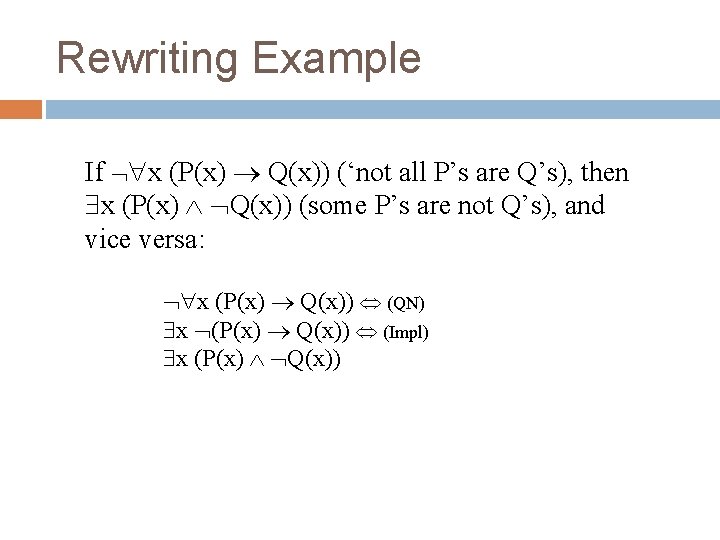

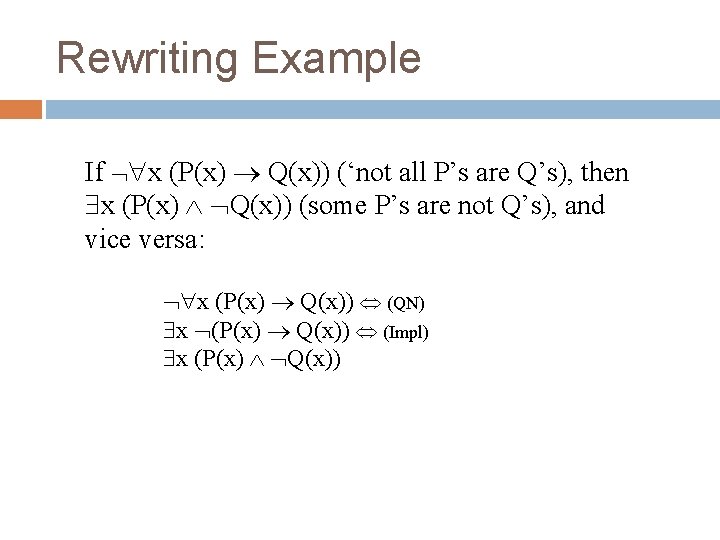

Rewriting Example If x (P(x) Q(x)) (‘not all P’s are Q’s), then x (P(x) Q(x)) (some P’s are not Q’s), and vice versa: x (P(x) Q(x)) (QN) x (P(x) Q(x)) (Impl) x (P(x) Q(x))

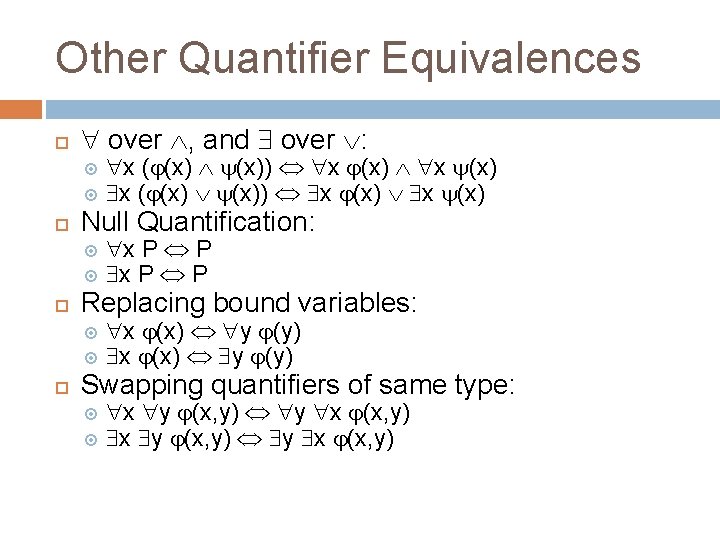

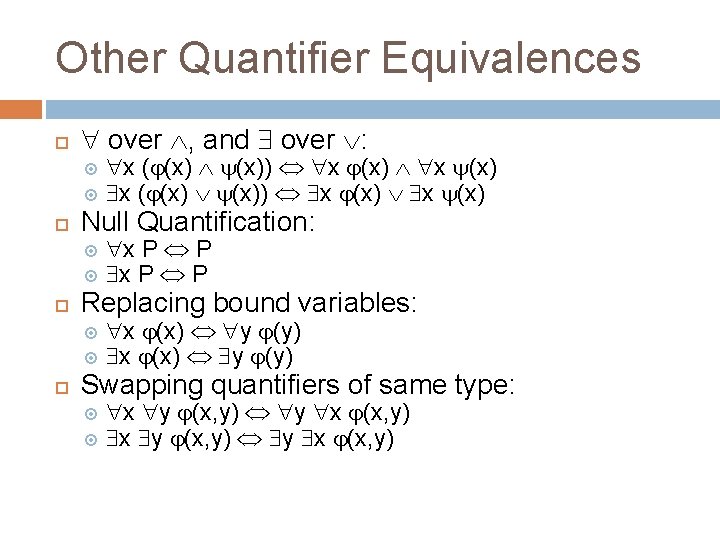

Other Quantifier Equivalences over , and over : Null Quantification: x P P Replacing bound variables: x ( (x)) x (x) x (x) y (y) Swapping quantifiers of same type: x y (x, y) y x (x, y)

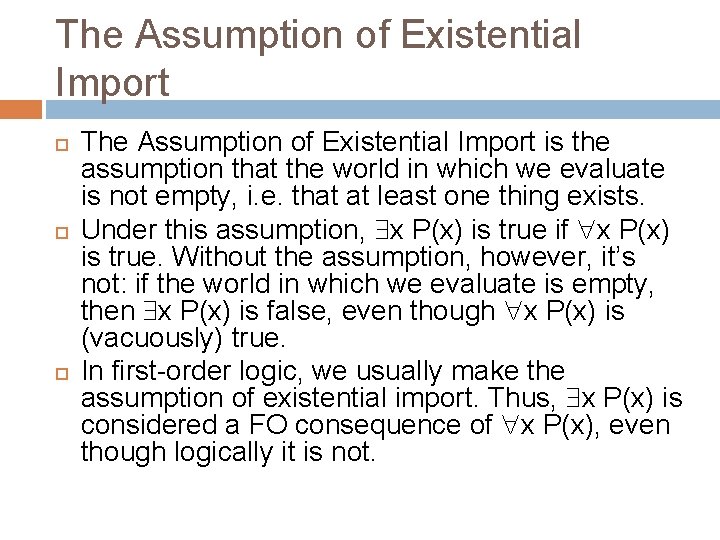

The Assumption of Existential Import The Assumption of Existential Import is the assumption that the world in which we evaluate is not empty, i. e. that at least one thing exists. Under this assumption, x P(x) is true if x P(x) is true. Without the assumption, however, it’s not: if the world in which we evaluate is empty, then x P(x) is false, even though x P(x) is (vacuously) true. In first-order logic, we usually make the assumption of existential import. Thus, x P(x) is considered a FO consequence of x P(x), even though logically it is not.

FORMAL PROOFS FOR QUANTIFIERS

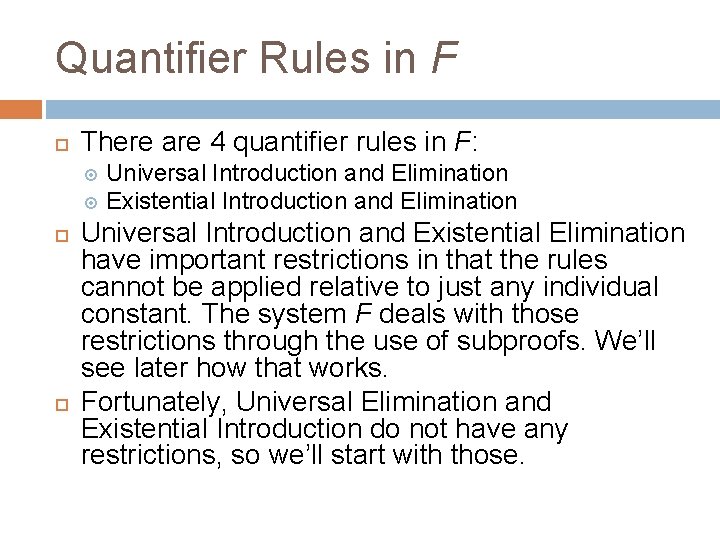

Quantifier Rules in F There are 4 quantifier rules in F: Universal Introduction and Elimination Existential Introduction and Elimination Universal Introduction and Existential Elimination have important restrictions in that the rules cannot be applied relative to just any individual constant. The system F deals with those restrictions through the use of subproofs. We’ll see later how that works. Fortunately, Universal Elimination and Existential Introduction do not have any restrictions, so we’ll start with those.

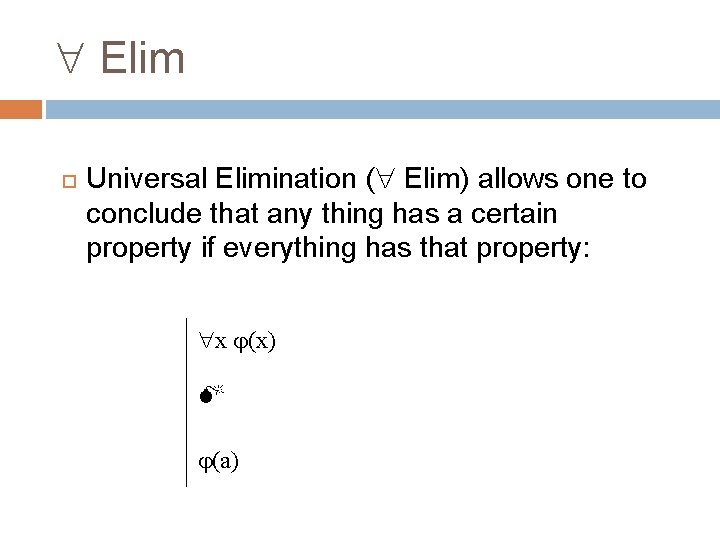

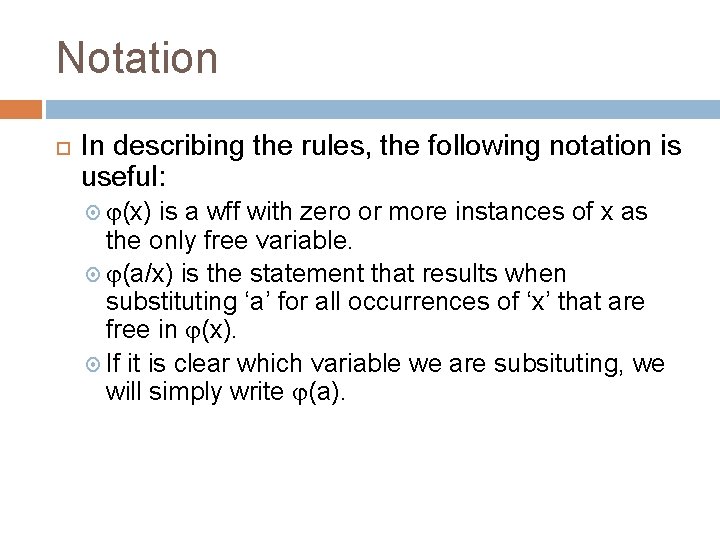

Notation In describing the rules, the following notation is useful: (x) is a wff with zero or more instances of x as the only free variable. (a/x) is the statement that results when substituting ‘a’ for all occurrences of ‘x’ that are free in (x). If it is clear which variable we are subsituting, we will simply write (a).

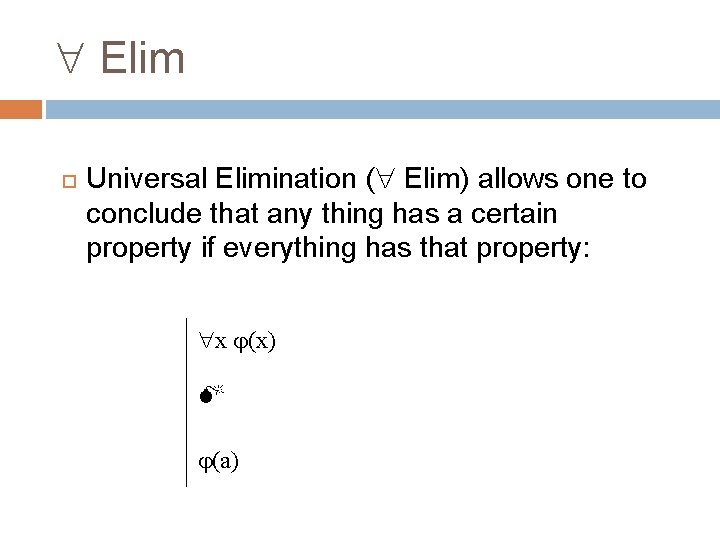

Elim Universal Elimination ( Elim) allows one to conclude that any thing has a certain property if everything has that property: x (x) (a)

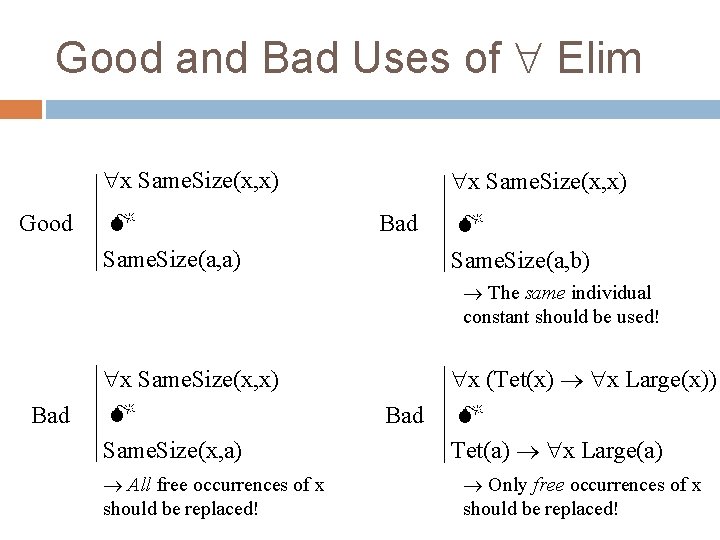

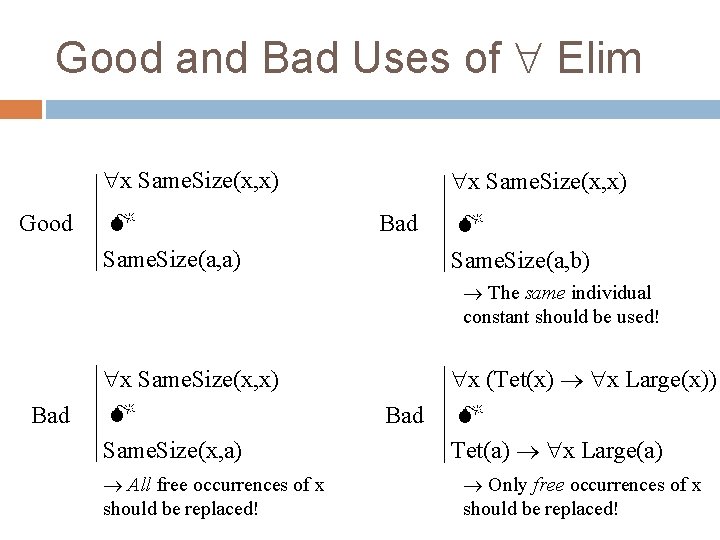

Good and Bad Uses of Elim x Same. Size(x, x) Good Same. Size(a, a) x Same. Size(x, x) Bad Same. Size(a, b) The same individual constant should be used! Bad x Same. Size(x, x) Same. Size(x, a) All free occurrences of x should be replaced! x (Tet(x) x Large(x)) Bad Tet(a) x Large(a) Only free occurrences of x should be replaced!

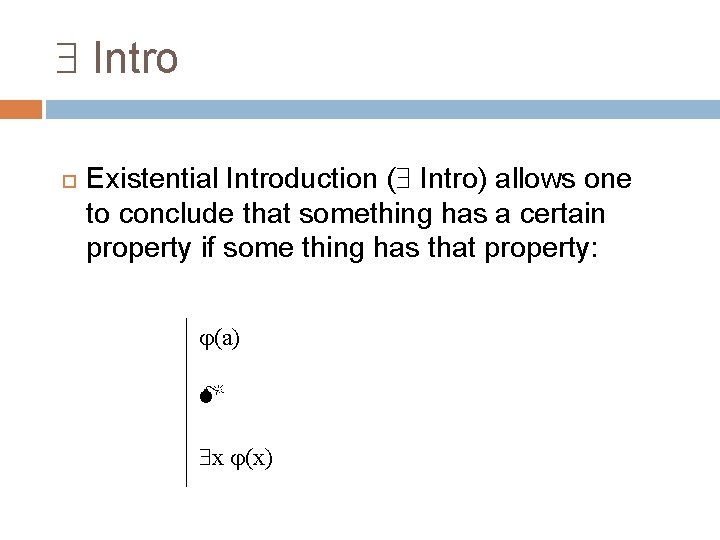

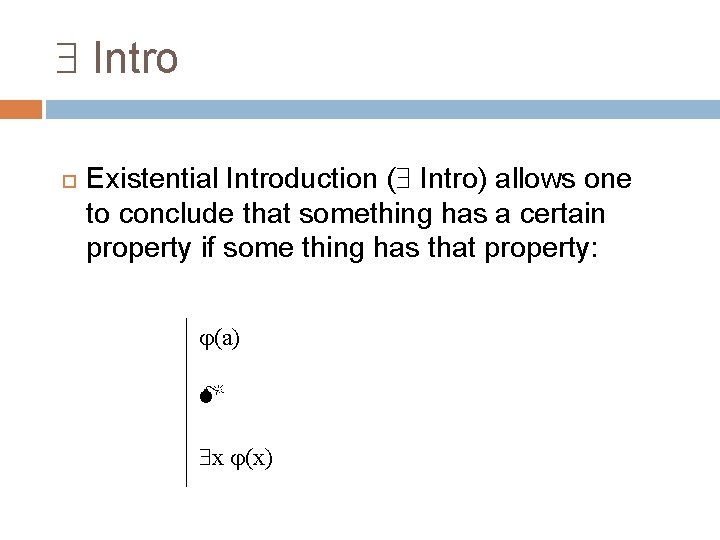

Intro Existential Introduction ( Intro) allows one to conclude that something has a certain property if some thing has that property: (a) x (x)

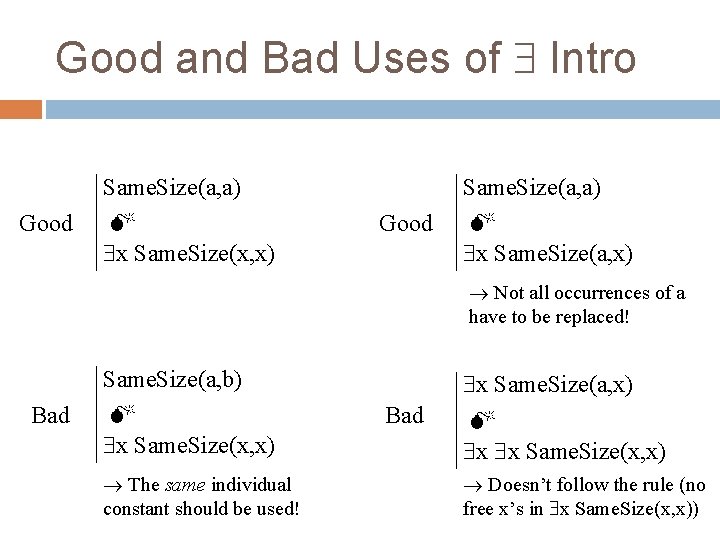

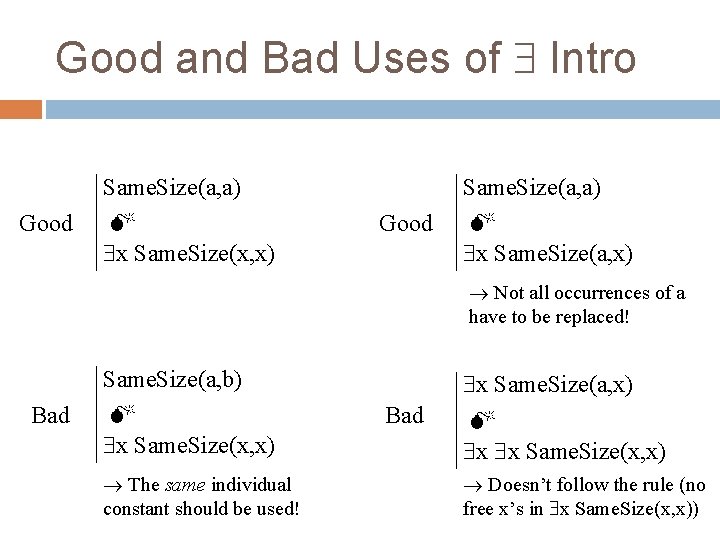

Good and Bad Uses of Intro Same. Size(a, a) Good x Same. Size(x, x) Same. Size(a, a) Good x Same. Size(a, x) Not all occurrences of a have to be replaced! Same. Size(a, b) Bad x Same. Size(x, x) The same individual constant should be used! x Same. Size(a, x) Bad x x Same. Size(x, x) Doesn’t follow the rule (no free x’s in x Same. Size(x, x))

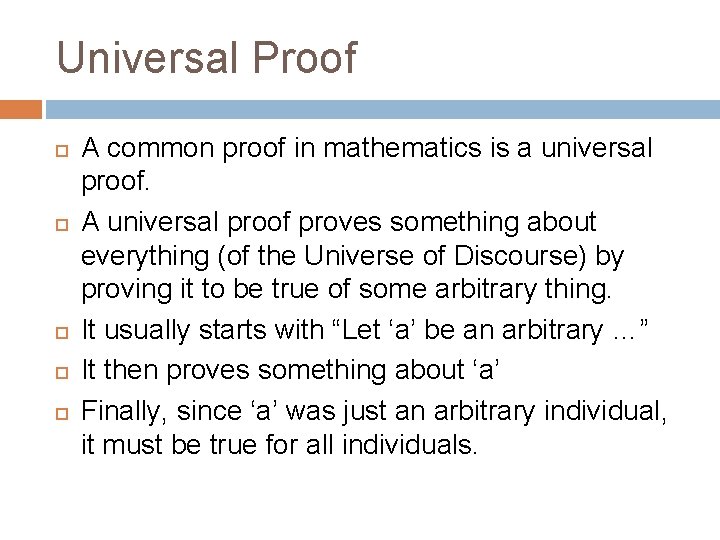

Universal Proof A common proof in mathematics is a universal proof. A universal proof proves something about everything (of the Universe of Discourse) by proving it to be true of some arbitrary thing. It usually starts with “Let ‘a’ be an arbitrary …” It then proves something about ‘a’ Finally, since ‘a’ was just an arbitrary individual, it must be true for all individuals.

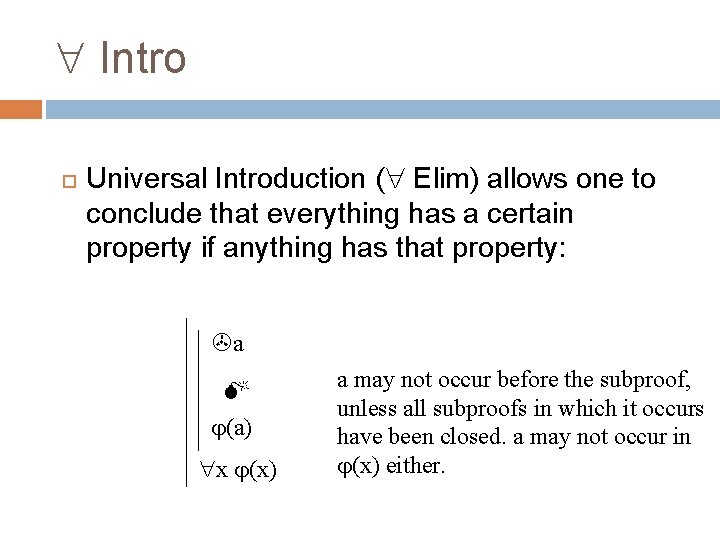

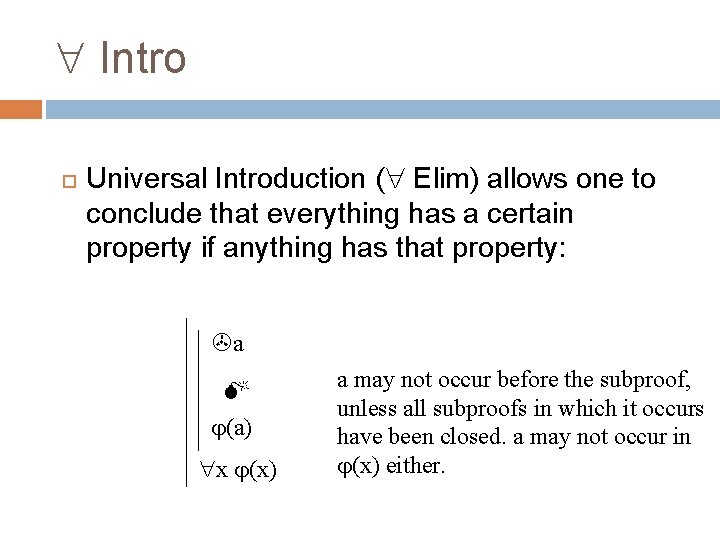

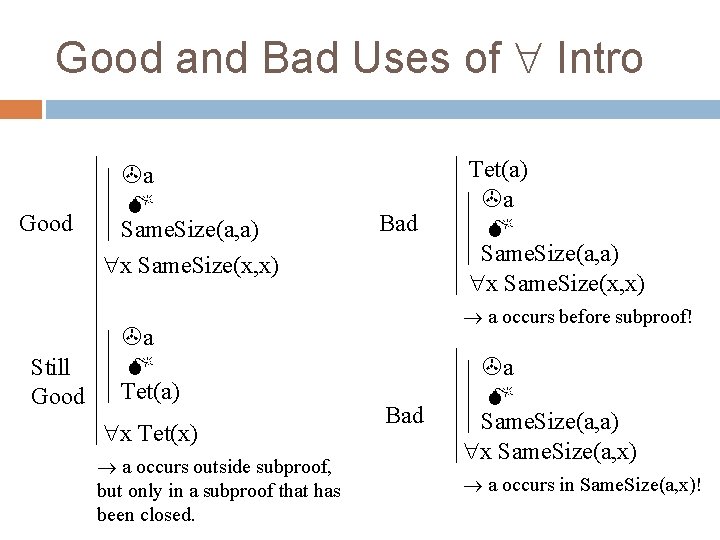

Intro Universal Introduction ( Elim) allows one to conclude that everything has a certain property if anything has that property: a (a) x (x) a may not occur before the subproof, unless all subproofs in which it occurs have been closed. a may not occur in (x) either.

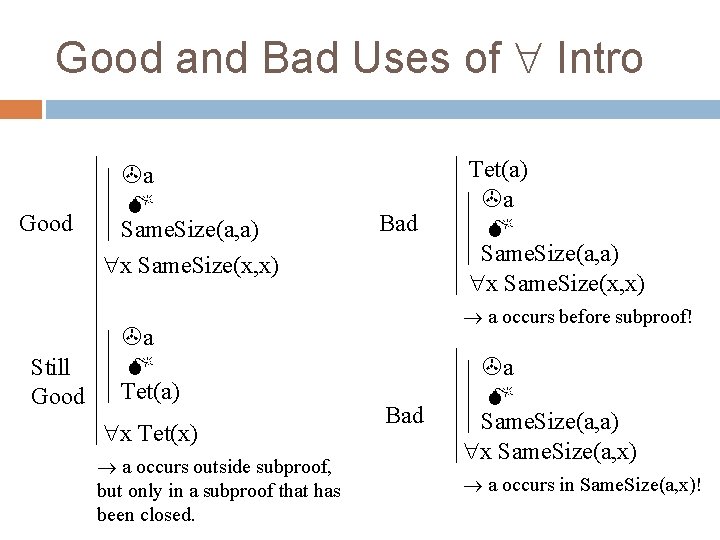

Good and Bad Uses of Intro Good Still Good a Same. Size(a, a) x Same. Size(x, x) a Tet(a) x Tet(x) a occurs outside subproof, but only in a subproof that has been closed. Bad Tet(a) a Same. Size(a, a) x Same. Size(x, x) a occurs before subproof! Bad a Same. Size(a, a) x Same. Size(a, x) a occurs in Same. Size(a, x)!

Existential Proof Sometimes, we know that something has a certain property, but we don’t know who or what this something is. In order to perform some reasoning, we will give this something a name, and whatever we can infer from that point on, we can infer from the original statement. Like the universal proof, the name should be an arbitrary name, but in this case it denotes a specific individual: that individual that had the relevant property.

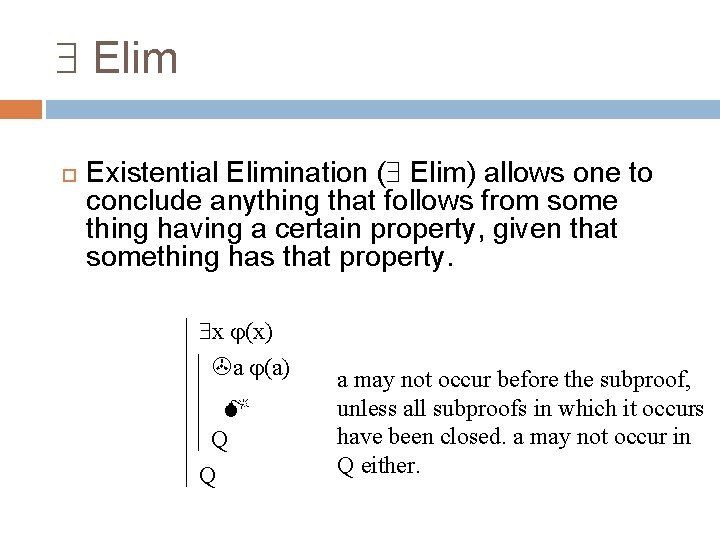

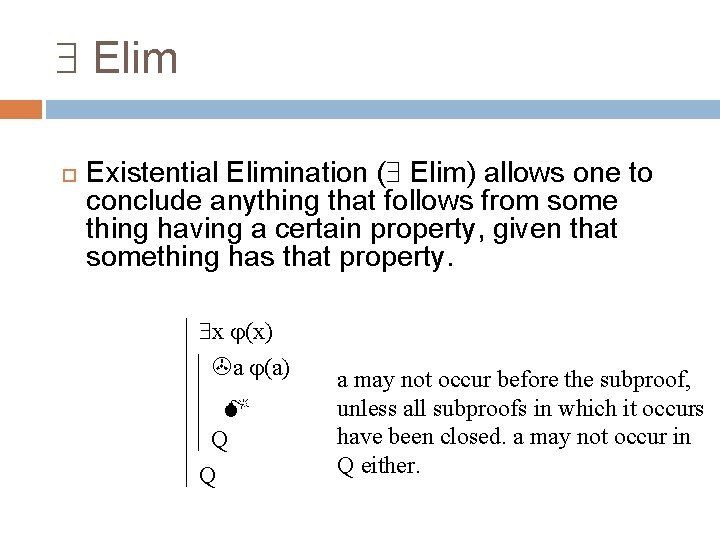

Elim Existential Elimination ( Elim) allows one to conclude anything that follows from some thing having a certain property, given that something has that property. x (x) a (a) Q Q a may not occur before the subproof, unless all subproofs in which it occurs have been closed. a may not occur in Q either.

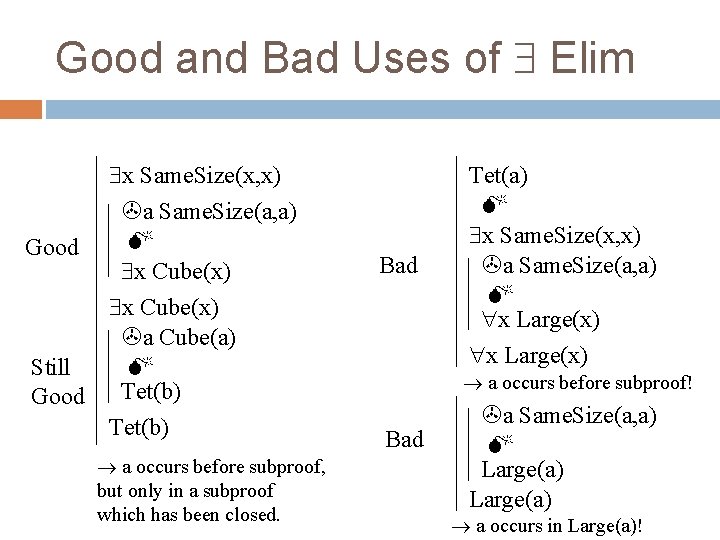

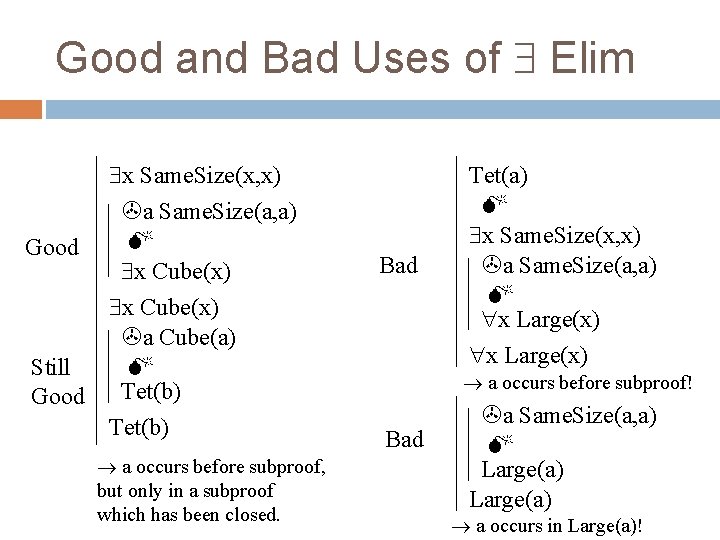

Good and Bad Uses of Elim Good Still Good x Same. Size(x, x) a Same. Size(a, a) x Cube(x) a Cube(a) Tet(b) a occurs before subproof, but only in a subproof which has been closed. Bad Tet(a) x Same. Size(x, x) a Same. Size(a, a) x Large(x) a occurs before subproof! Bad a Same. Size(a, a) Large(a) a occurs in Large(a)!

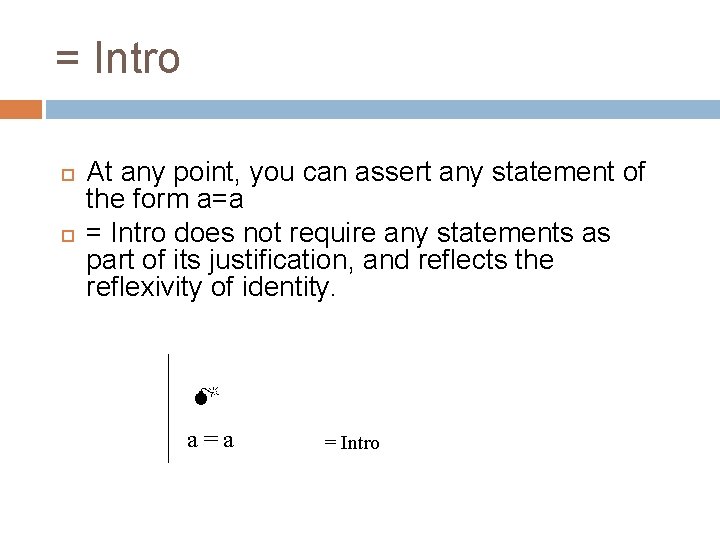

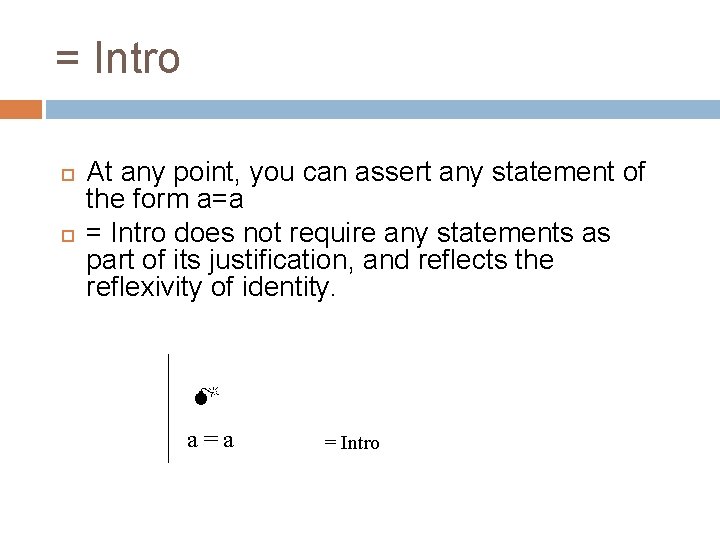

= Intro At any point, you can assert any statement of the form a=a = Intro does not require any statements as part of its justification, and reflects the reflexivity of identity. a=a = Intro

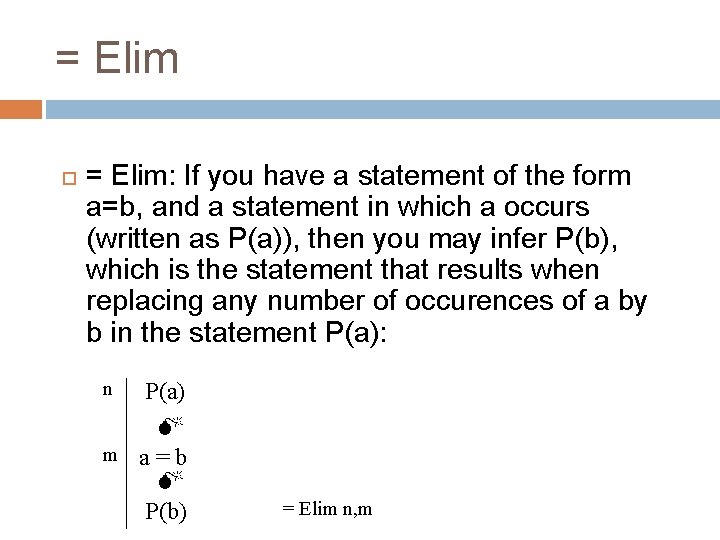

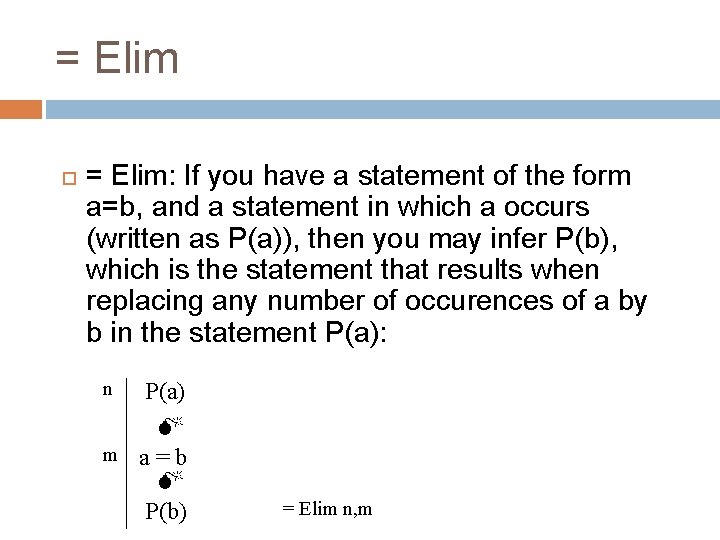

= Elim = Elim: If you have a statement of the form a=b, and a statement in which a occurs (written as P(a)), then you may infer P(b), which is the statement that results when replacing any number of occurences of a by b in the statement P(a): n P(a) m a=b P(b) = Elim n, m

Rules for other Predicates Of course, one could define inference rules for predicates other than ‘=‘. For example, given the reflexivity of the Same. Size relationship, one could make it a rule that Same. Size(a, a) can be inferred at any time. However, ‘=‘ is the only predicate for which F has defined inference rules as it is the only interpreted predicate. We’ll see later how we can deal with logical truths about other predicates.

TRUTH TREES FOR PREDICATE LOGIC

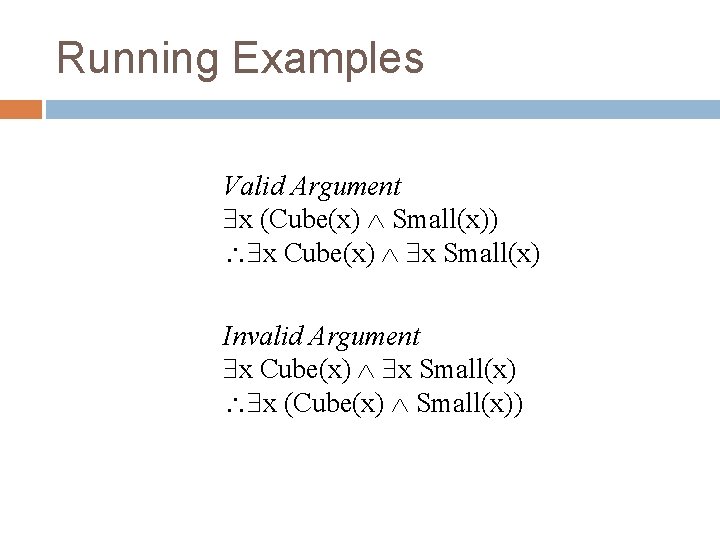

Running Examples Valid Argument x (Cube(x) Small(x)) x Cube(x) x Small(x) Invalid Argument x Cube(x) x Small(x) x (Cube(x) Small(x))

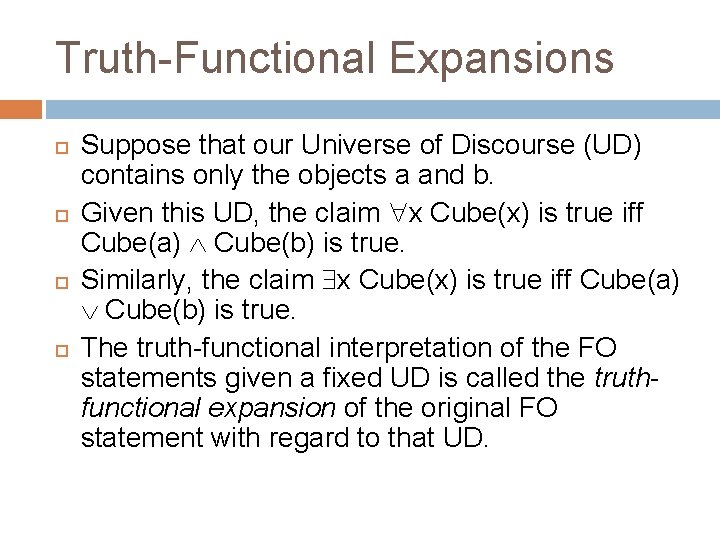

Truth-Functional Expansions Suppose that our Universe of Discourse (UD) contains only the objects a and b. Given this UD, the claim x Cube(x) is true iff Cube(a) Cube(b) is true. Similarly, the claim x Cube(x) is true iff Cube(a) Cube(b) is true. The truth-functional interpretation of the FO statements given a fixed UD is called the truthfunctional expansion of the original FO statement with regard to that UD.

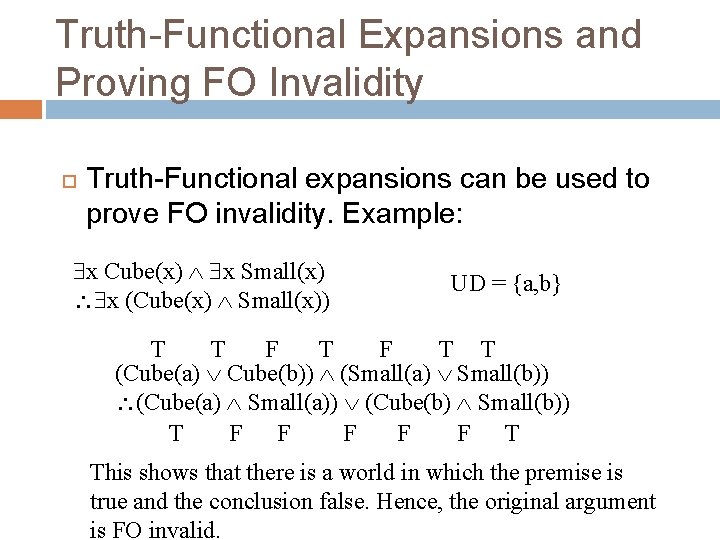

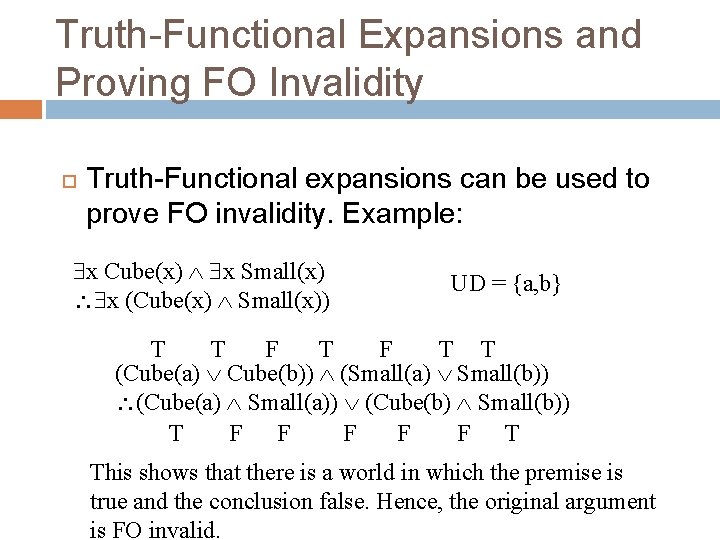

Truth-Functional Expansions and Proving FO Invalidity Truth-Functional expansions can be used to prove FO invalidity. Example: x Cube(x) x Small(x) x (Cube(x) Small(x)) UD = {a, b} T T F T T (Cube(a) Cube(b)) (Small(a) Small(b)) (Cube(a) Small(a)) (Cube(b) Small(b)) T F F F T This shows that there is a world in which the premise is true and the conclusion false. Hence, the original argument is FO invalid.

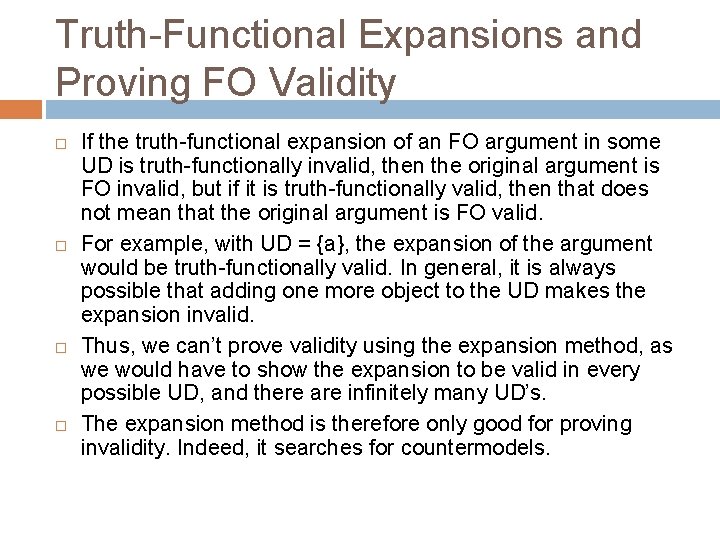

Truth-Functional Expansions and Proving FO Validity If the truth-functional expansion of an FO argument in some UD is truth-functionally invalid, then the original argument is FO invalid, but if it is truth-functionally valid, then that does not mean that the original argument is FO valid. For example, with UD = {a}, the expansion of the argument would be truth-functionally valid. In general, it is always possible that adding one more object to the UD makes the expansion invalid. Thus, we can’t prove validity using the expansion method, as we would have to show the expansion to be valid in every possible UD, and there are infinitely many UD’s. The expansion method is therefore only good for proving invalidity. Indeed, it searches for countermodels.

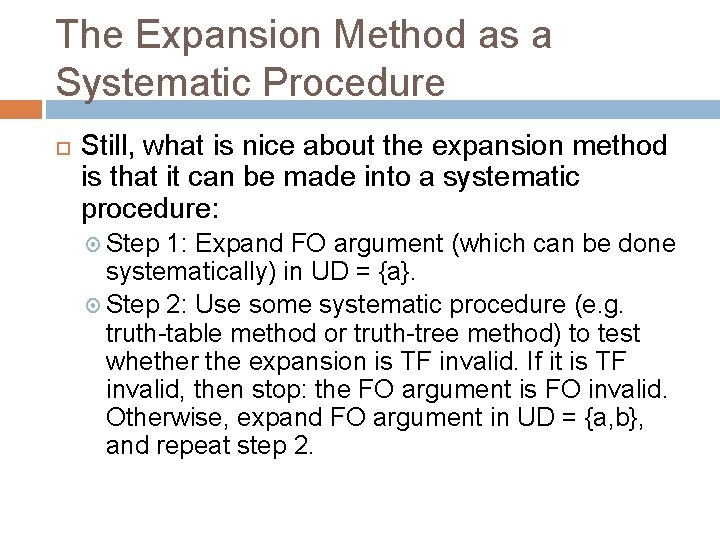

The Expansion Method as a Systematic Procedure Still, what is nice about the expansion method is that it can be made into a systematic procedure: Step 1: Expand FO argument (which can be done systematically) in UD = {a}. Step 2: Use some systematic procedure (e. g. truth-table method or truth-tree method) to test whether the expansion is TF invalid. If it is TF invalid, then stop: the FO argument is FO invalid. Otherwise, expand FO argument in UD = {a, b}, and repeat step 2.

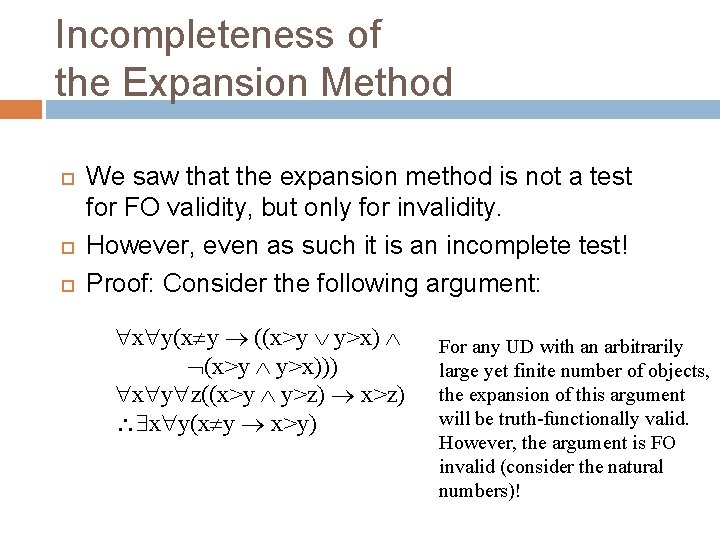

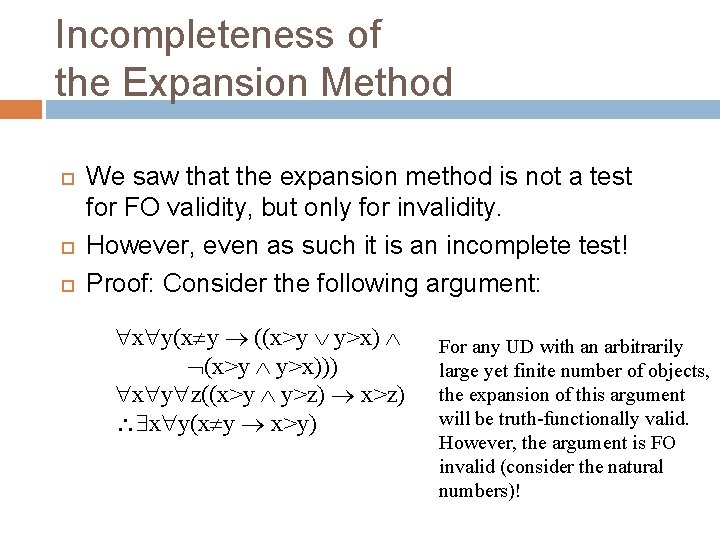

Incompleteness of the Expansion Method We saw that the expansion method is not a test for FO validity, but only for invalidity. However, even as such it is an incomplete test! Proof: Consider the following argument: x y(x y ((x>y y>x) (x>y y>x))) x y z((x>y y>z) x y(x y x>y) For any UD with an arbitrarily large yet finite number of objects, the expansion of this argument will be truth-functionally valid. However, the argument is FO invalid (consider the natural numbers)!

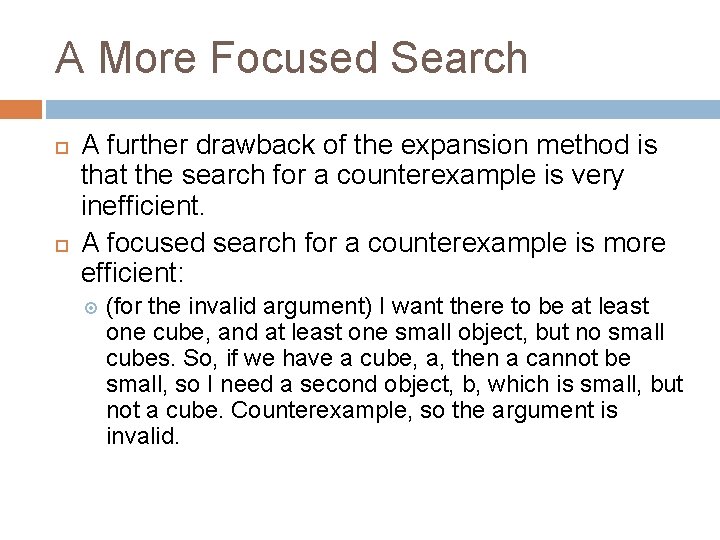

A More Focused Search A further drawback of the expansion method is that the search for a counterexample is very inefficient. A focused search for a counterexample is more efficient: (for the invalid argument) I want there to be at least one cube, and at least one small object, but no small cubes. So, if we have a cube, a, then a cannot be small, so I need a second object, b, which is small, but not a cube. Counterexample, so the argument is invalid.

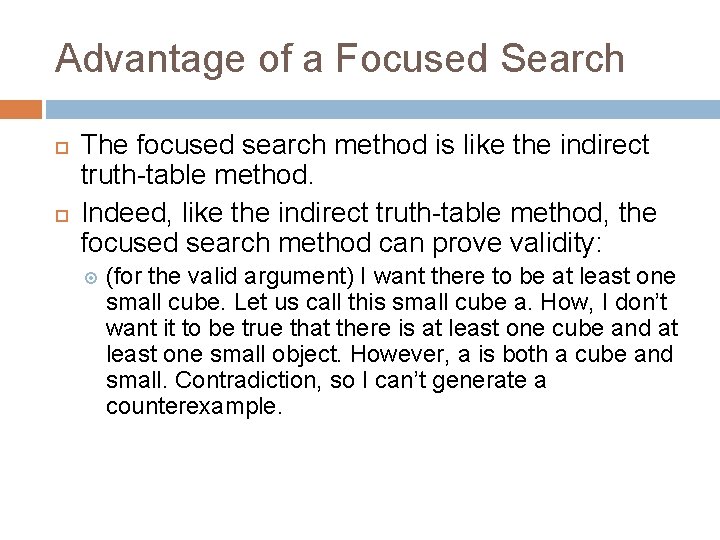

Advantage of a Focused Search The focused search method is like the indirect truth-table method. Indeed, like the indirect truth-table method, the focused search method can prove validity: (for the valid argument) I want there to be at least one small cube. Let us call this small cube a. How, I don’t want it to be true that there is at least one cube and at least one small object. However, a is both a cube and small. Contradiction, so I can’t generate a counterexample.

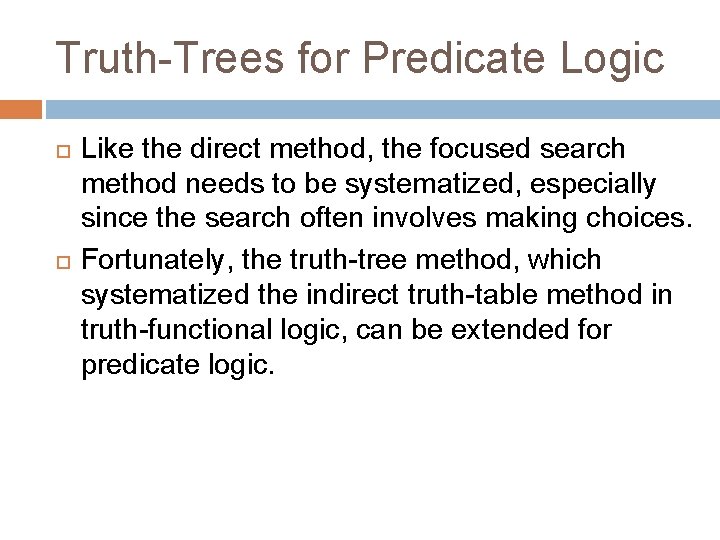

Truth-Trees for Predicate Logic Like the direct method, the focused search method needs to be systematized, especially since the search often involves making choices. Fortunately, the truth-tree method, which systematized the indirect truth-table method in truth-functional logic, can be extended for predicate logic.

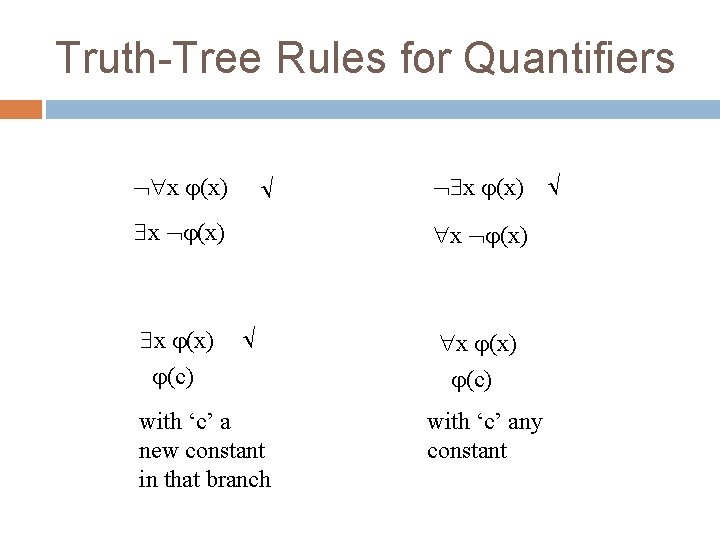

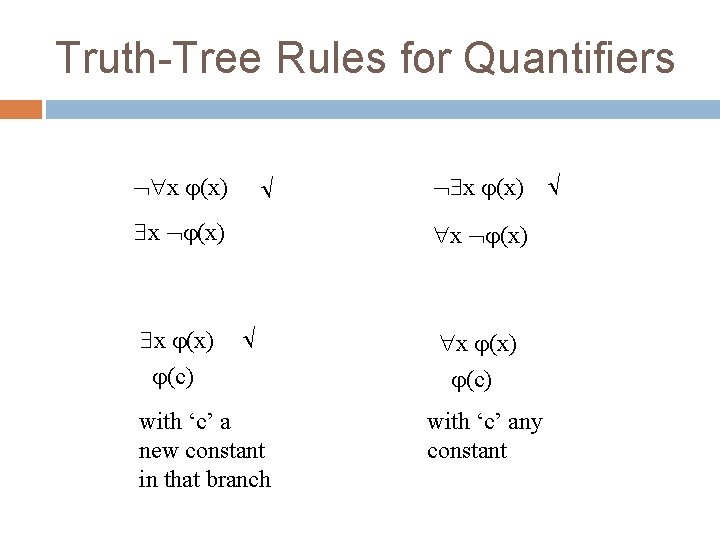

Truth-Tree Rules for Quantifiers x (x) x (x) x (x) (c) x (x) x (x) with ‘c’ a new constant in that branch x (x) (c) with ‘c’ any constant

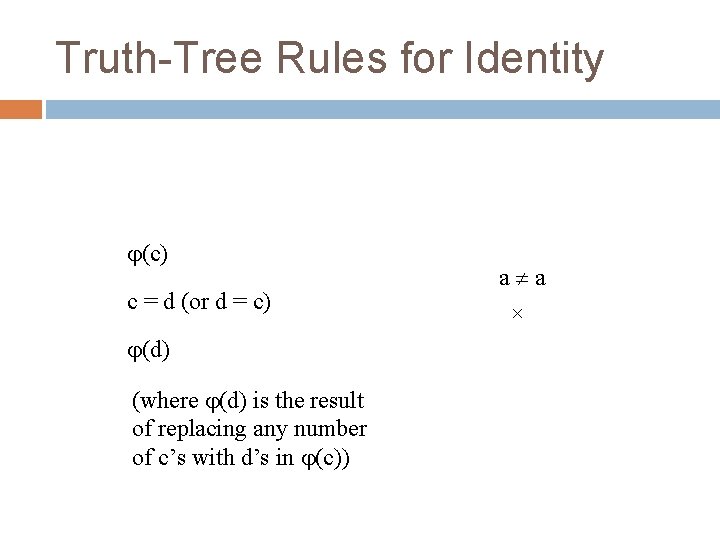

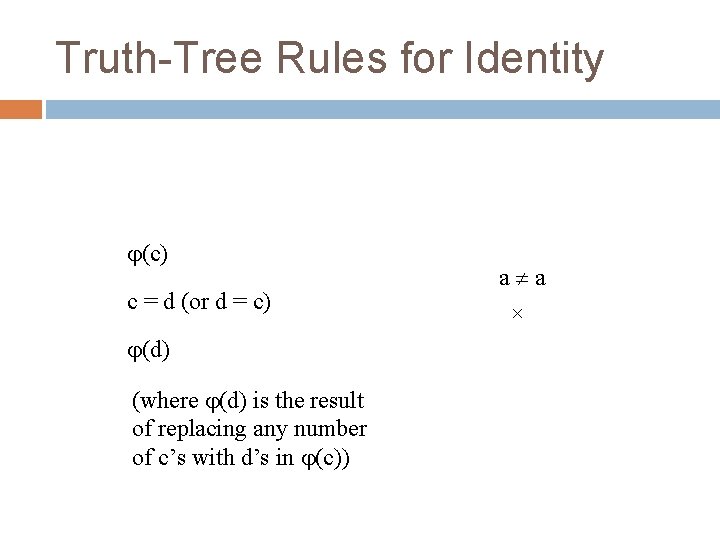

Truth-Tree Rules for Identity (c) c = d (or d = c) (d) (where (d) is the result of replacing any number of c’s with d’s in (c)) a a ×

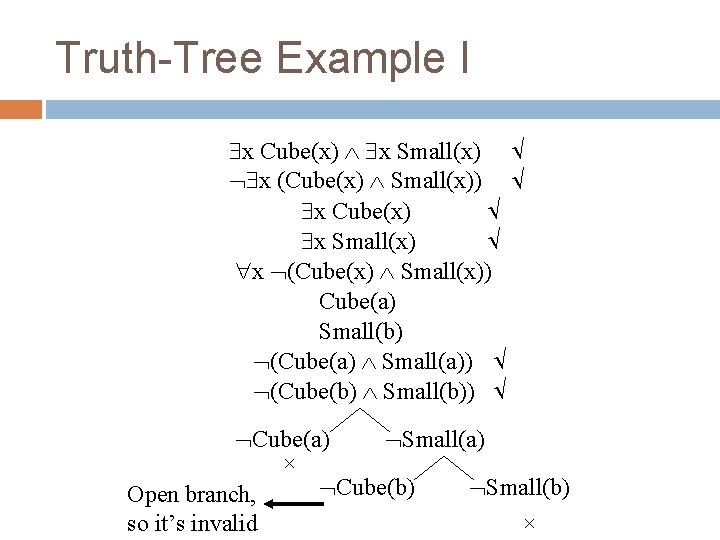

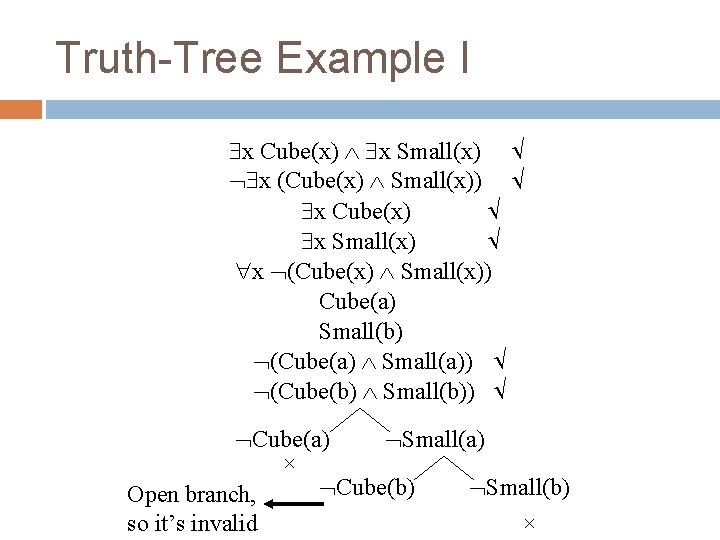

Truth-Tree Example I x Cube(x) x Small(x) x (Cube(x) Small(x)) x Cube(x) x Small(x) x (Cube(x) Small(x)) Cube(a) Small(b) (Cube(a) Small(a)) (Cube(b) Small(b)) Cube(a) Small(a) × Cube(b) Small(b) Open branch, × so it’s invalid

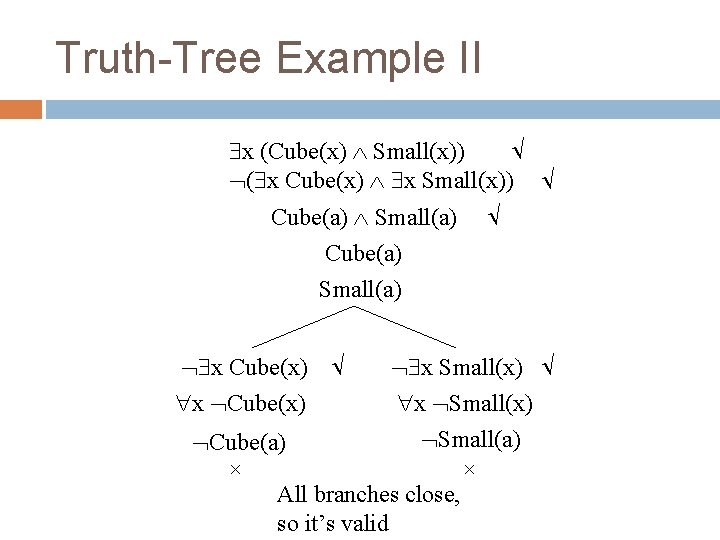

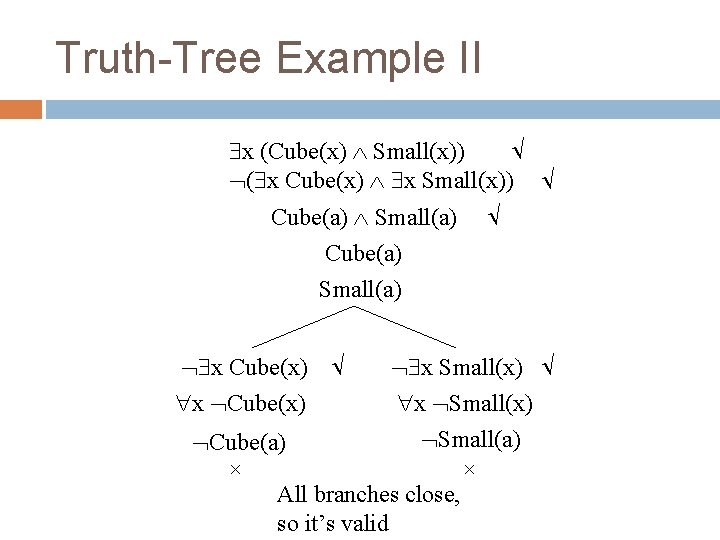

Truth-Tree Example II x (Cube(x) Small(x)) ( x Cube(x) x Small(x)) Cube(a) Small(a) Cube(a) Small(a) x Cube(x) x Small(x) Small(a) Cube(a) × × All branches close, so it’s valid

COMPLETENESS AND INCOMPLETENESS

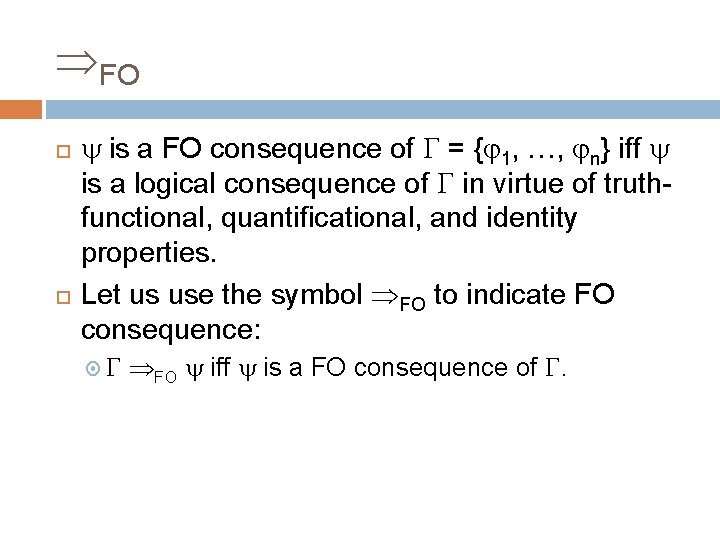

FO is a FO consequence of = { 1, …, n} iff is a logical consequence of in virtue of truthfunctional, quantificational, and identity properties. Let us use the symbol FO to indicate FO consequence: FO iff is a FO consequence of .

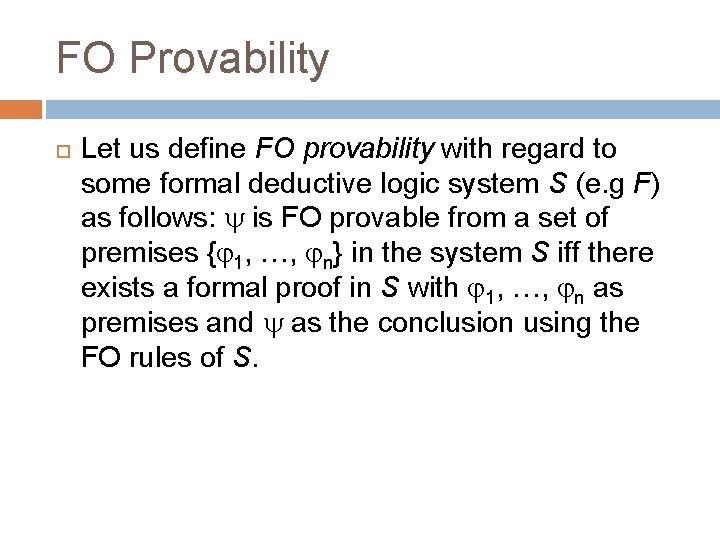

FO Provability Let us define FO provability with regard to some formal deductive logic system S (e. g F) as follows: is FO provable from a set of premises { 1, …, n} in the system S iff there exists a formal proof in S with 1, …, n as premises and as the conclusion using the FO rules of S.

FO(S) Let us use the symbol FO(S) to indicate FO provability in S: FO(S) iff is FO provable from in the system S. The subscript FO(S) indicates that we restrict our proofs to the FO rules of S.

Two Important Properties For every deductive system of formal logic S we can define the following 2 properties: 1. FO Deductive Soundness: A system S is FO deductively sound iff for any and : if FO(S) then FO 2. FO Deductive Completeness: A system S is FO deductively complete iff for any and : if FO then FO(S)

F is FO Sound and Complete F is both FO sound and FO complete! Soundness is pretty tricky to prove. Completeness is very hard to prove. The first proof of completeness was given by Kurt Gödel in 1929. Hence it’s called Gödel’s Completeness Result. If you want to see the proofs, take Computability and Logic

Completeness of the Tree Method The tree method is sound with regard to both FO validity and FO invalidity (i. e. it will never claim something to be FO valid or FO invalid when in fact it is not). Moreover, it can be shown that the tree method is complete with regard to FO validity!

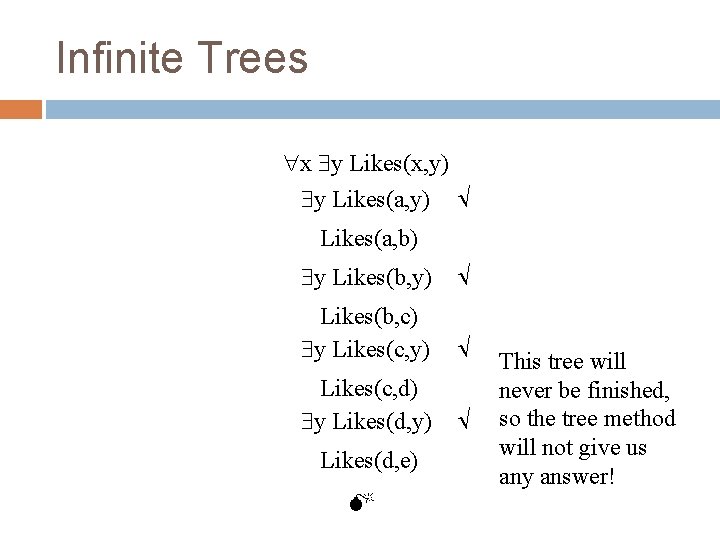

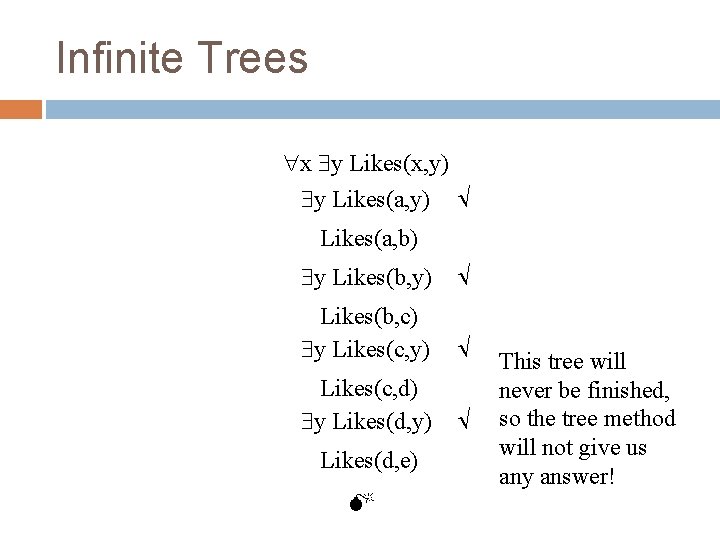

Infinite Trees x y Likes(x, y) y Likes(a, y) Likes(a, b) y Likes(b, y) Likes(b, c) y Likes(c, y) Likes(c, d) y Likes(d, y) Likes(d, e) This tree will never be finished, so the tree method will not give us any answer!

Decision Procedures and Decidability A decision procedure is a systematic procedure that correctly decides whether something is or is not the case for all relevant cases. The truth-table method is a decision procedure for truthfunctional consequence. That is, for any and , the truth-table will systematically and correctly decide whether TF or not. Because a decision procedure for truth-functional consequence exists, we say that truth-functional consequence is decidable. Question: is FO consequence decidable? In other words, could there be a systematic test that correctly decides whether something is a FO consequence of something or not? (maybe FO Con is such a test? )

A Common Response Well, given that we have a sound and complete test for FO validity, we should be able to make this into a test for FO invalidity as follows: Have the procedure test for validity. If it is valid, then eventually the procedure will say it is valid (e. g. it says “Yes, it’s valid”), and hence we will know (because the procedure is sound) that it is not invalid. If it is invalid, then the procedure will not say so (e. g. it outputs “Bananas on Mars”), but we can simply interpret anything other than “Yes, it’s valid” as the claim that it is invalid and, given that the procedure is complete, it should indeed be invalid, for otherwise it would say “Yes, it’s valid”. So, I would have a decision procedure for FO validity!

The Mistake in the Reasoning There are two ways in which a positive test may not say that some thing has some property: The test finishes but does not say that the certain something has that property (“Bananas on Mars”) The test never finishes In the first case we know that the thing does not have the property. But, in the second case, we may not know this, as we may not know whether the test is going to finish or not! The moral: positive tests do not guarantee negative tests and vice versa.

Undecidability of FO validity It can be proven that no such decision procedure can exist. This proof was found by Alonzo Church in 1936. This year is no accident: it’s the year of Turing’s famous paper in which he lays out the Turing-Machine, Turing’s Thesis, The Universal Machine, and the Halting Problem. Indeed, the undecidability of FOL follows from the uncomputability of the Halting Problem. For a full proof, take Computability and Logic.

Extending Our Reasoning Since FO validity is undecidable, we know that for any complete test for validity there exists at least one case of FO invalidity for which the test will never finish. For, if it would always finish, then we in fact could make the positive test into a negative one, and hence FO validity would be decidable after all.

Incompleteness of FO Con Since it is unacceptable for FO Con to never finish, we can’t make FO Con into a positive test. We thus know that FO Con is incomplete with regard to FO validity as well as FO invalidity. Still, FO Con is sound, and will classify most cases of FO validity as FO valid. Moreover, FO Con will also correctly classify many cases of FO invalidity as FO invalid. What I say here about FO Con holds for ATP’s in general of course.

AXIOMATIZATION

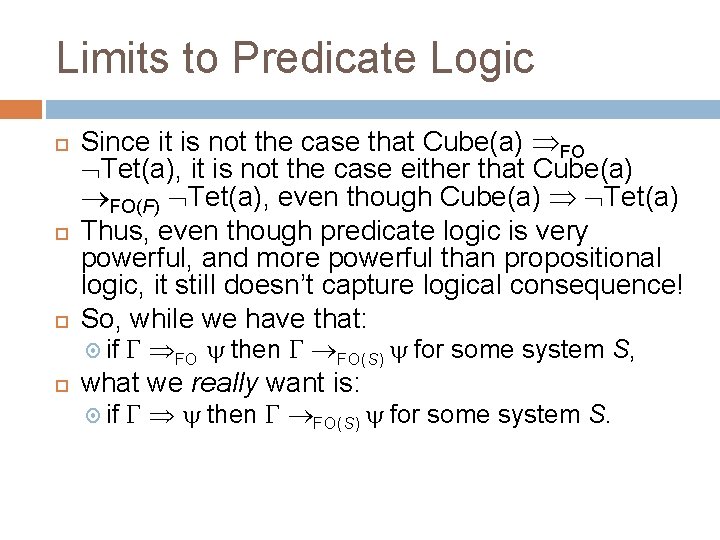

Limits to Predicate Logic Since it is not the case that Cube(a) FO Tet(a), it is not the case either that Cube(a) FO(F) Tet(a), even though Cube(a) Tet(a) Thus, even though predicate logic is very powerful, and more powerful than propositional logic, it still doesn’t capture logical consequence! So, while we have that: if FO then FO(S) for some system S, what we really want is: if then FO(S) for some system S.

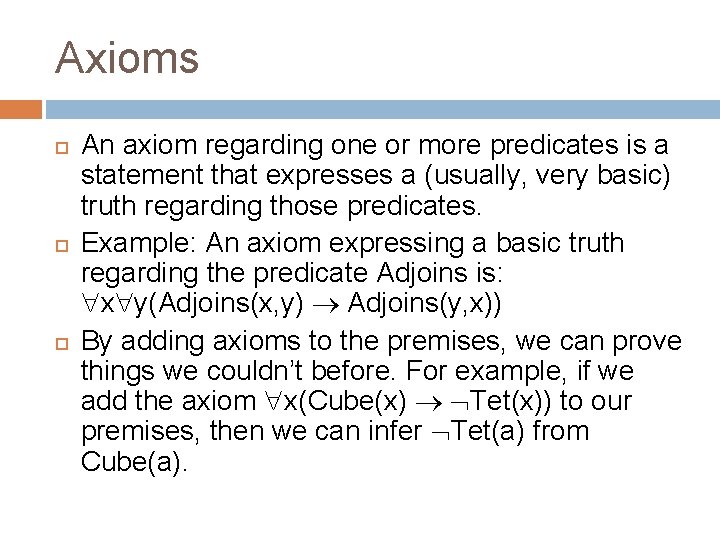

Axioms An axiom regarding one or more predicates is a statement that expresses a (usually, very basic) truth regarding those predicates. Example: An axiom expressing a basic truth regarding the predicate Adjoins is: x y(Adjoins(x, y) Adjoins(y, x)) By adding axioms to the premises, we can prove things we couldn’t before. For example, if we add the axiom x(Cube(x) Tet(x)) to our premises, then we can infer Tet(a) from Cube(a).

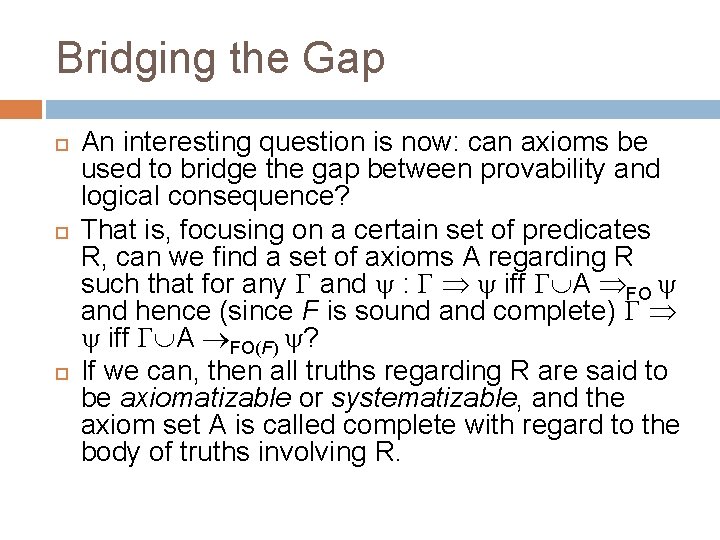

Bridging the Gap An interesting question is now: can axioms be used to bridge the gap between provability and logical consequence? That is, focusing on a certain set of predicates R, can we find a set of axioms A regarding R such that for any and : iff A FO and hence (since F is sound and complete) iff A FO(F) ? If we can, then all truths regarding R are said to be axiomatizable or systematizable, and the axiom set A is called complete with regard to the body of truths involving R.

Axiomatizing Mathematics Around 1900, shortly after the formulation of first-order logic was completed, mathematicians started to wonder if all of mathematics could be axiomatized. That is, is it possible to find a finite set of axioms expressing basic truths regarding mathematics (e. g. x y (x + y = y + x)) such that every mathematical theorem is a logical consequence of these axioms?

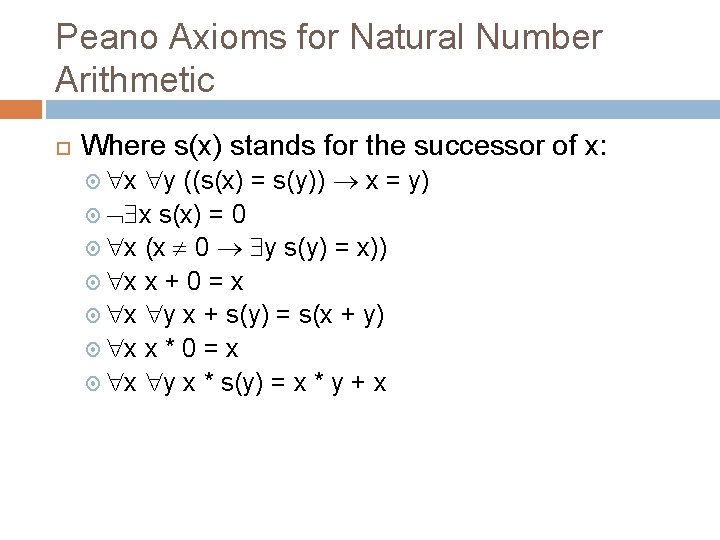

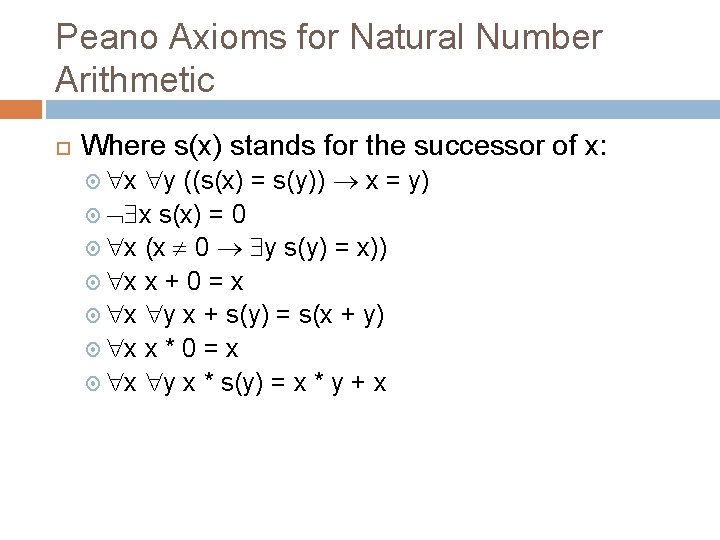

Peano Axioms for Natural Number Arithmetic Where s(x) stands for the successor of x: x y ((s(x) = s(y)) x = y) x s(x) = 0 x (x 0 y s(y) = x)) x x + 0 = x x y x + s(y) = s(x + y) x x * 0 = x x y x * s(y) = x * y + x

Gödel’s Incompleteness Result In 1931, the bomb dropped: Kurt Gödel proved that not all of mathematics is axiomatizable. In fact, hardly anything of mathematics is axiomatizable, as Gödel proved that you can’t even axiomatize all arithmetical truths involving only the addition and multiplication of natural numbers. Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem is regarded as one of the most important theorems of the 20 th century, as it shows fundamental limitations to formal logic and, as such, to symbolic information processing (i. e. computation) in general.

RESOLUTION

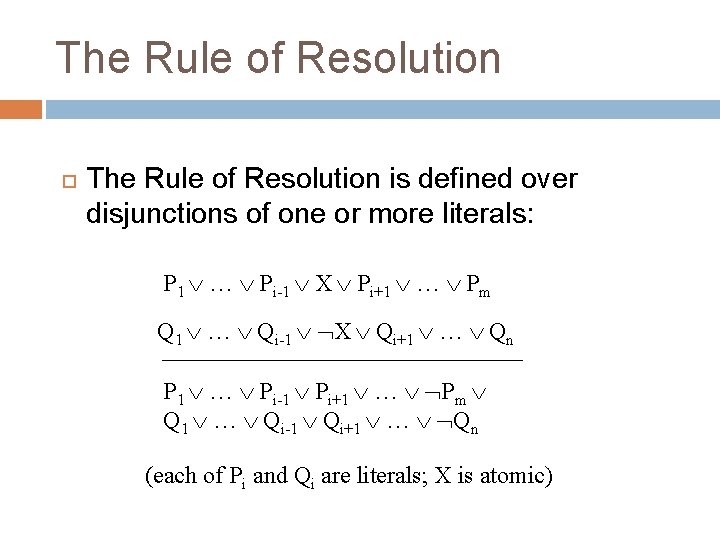

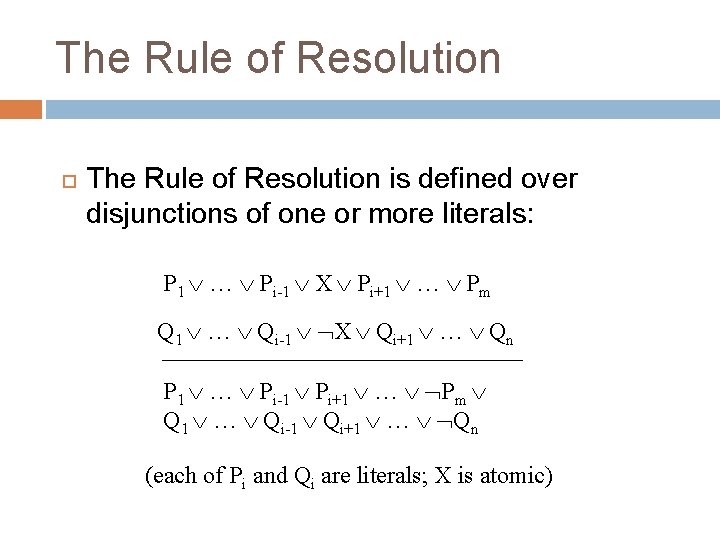

The Rule of Resolution is defined over disjunctions of one or more literals: P 1 … Pi-1 X Pi+1 … Pm Q 1 … Qi-1 X Qi+1 … Qn P 1 … Pi-1 Pi+1 … Pm Q 1 … Qi-1 Qi+1 … Qn (each of Pi and Qi are literals; X is atomic)

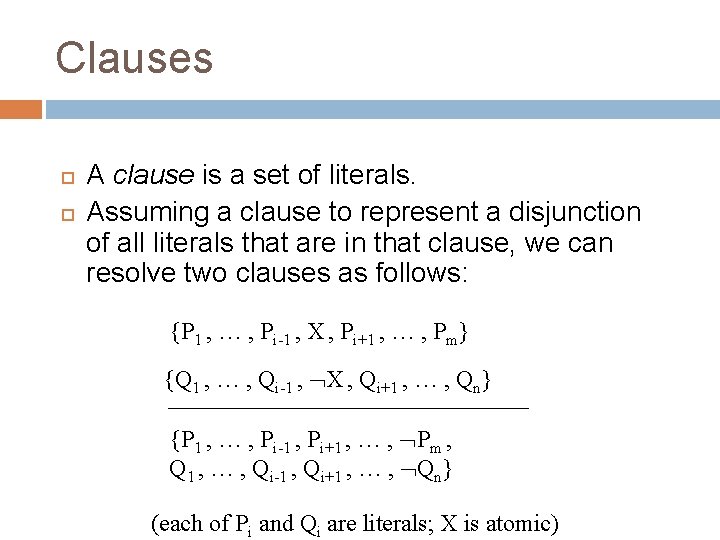

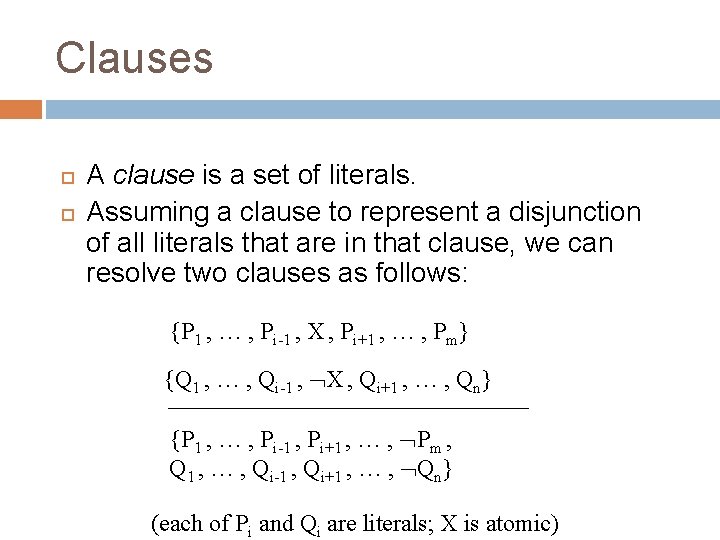

Clauses A clause is a set of literals. Assuming a clause to represent a disjunction of all literals that are in that clause, we can resolve two clauses as follows: {P 1 , … , Pi-1 , X , Pi+1 , … , Pm} {Q 1 , … , Qi-1 , X , Qi+1 , … , Qn} {P 1 , … , Pi-1 , Pi+1 , … , Pm , Q 1 , … , Qi-1 , Qi+1 , … , Qn} (each of Pi and Qi are literals; X is atomic)

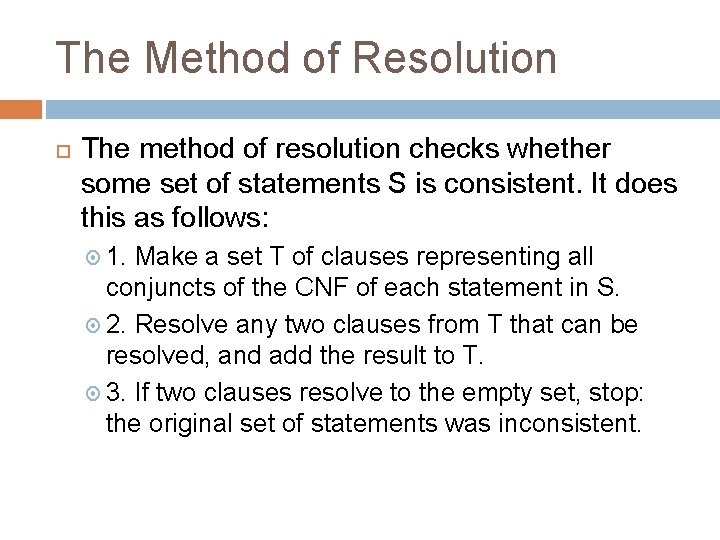

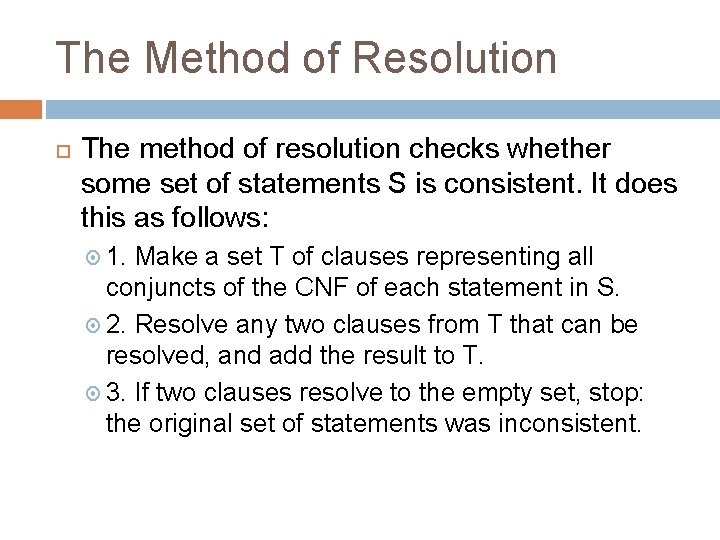

The Method of Resolution The method of resolution checks whether some set of statements S is consistent. It does this as follows: 1. Make a set T of clauses representing all conjuncts of the CNF of each statement in S. 2. Resolve any two clauses from T that can be resolved, and add the result to T. 3. If two clauses resolve to the empty set, stop: the original set of statements was inconsistent.

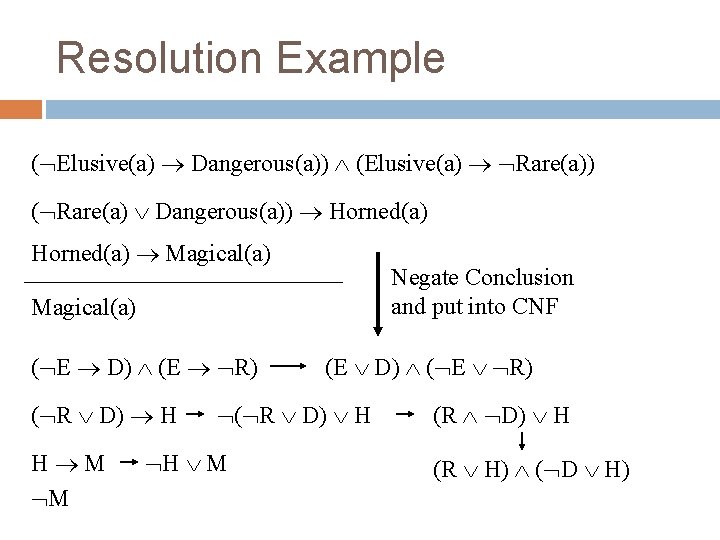

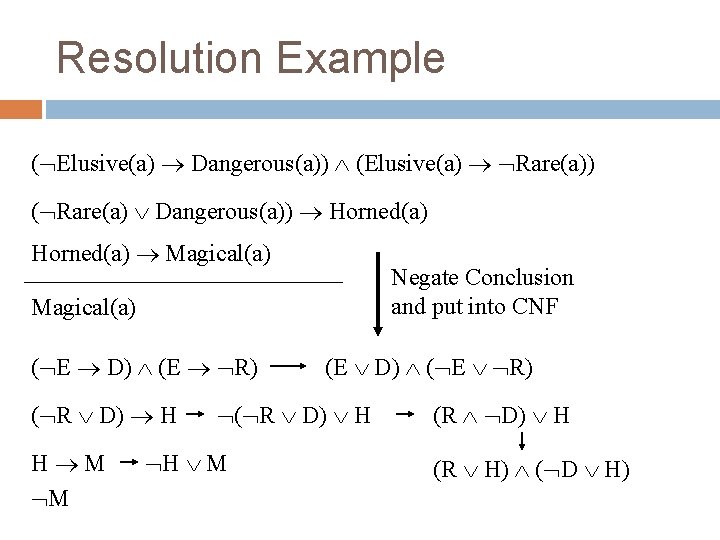

Resolution Example ( Elusive(a) Dangerous(a)) (Elusive(a) Rare(a)) ( Rare(a) Dangerous(a)) Horned(a) Magical(a) Negate Conclusion and put into CNF Magical(a) ( E D) (E R) ( R D) H H M M (E D) ( E R) ( R D) H H M (R D) H (R H) ( D H)

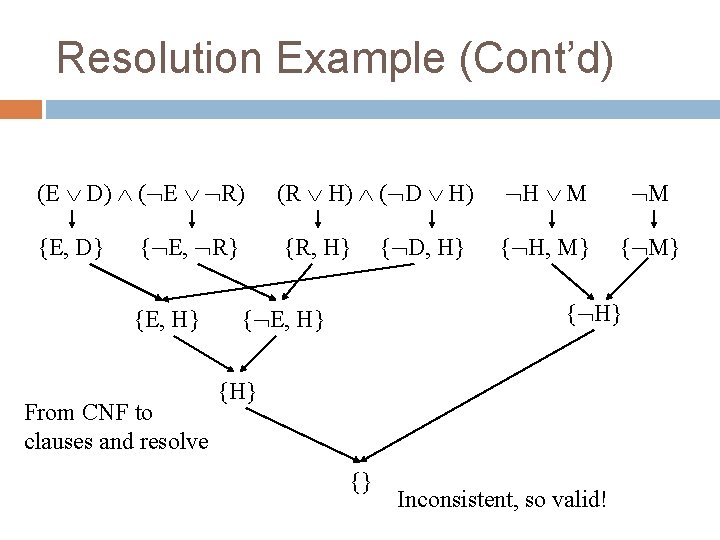

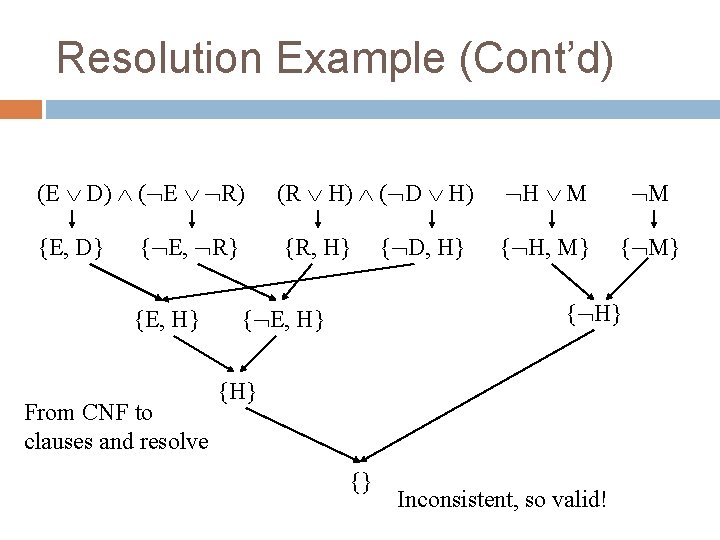

Resolution Example (Cont’d) (E D) ( E R) {E, D} { E, R} {E, H} From CNF to clauses and resolve (R H) ( D H) H M M {R, H} { H, M} { D, H} { E, H} {} Inconsistent, so valid!

Soundness and Completeness of Resolution The method of Resolution is sound and complete with regard to truth-functional consistency in the sense that: If the method finds a set of statements to be inconsistent, then that set of statements is indeed inconsistent (soundness). If a set of statements is inconsistent, then the method can find that set of statements to be inconsistent by deriving the empty clause (completeness).

Algorithms for Resolution and ATP’s Algorithms for resolution will differ in the order in which clauses get resolved. Many ATP’s are based on resolution: Con mechanisms in Fitch Vampire (winner of world-wide ATP competition last few years)

PROLOG

Prolog The programming language Prolog is based on Horn clauses. A Prolog program consists of 2 types of lines: Facts: Statements of the form P. Rules: Statements of the form (P 1 … Pn) Q. A Prolog program is run by asking whether some atomic statement Q follows from the facts and rules. In Prolog: Q? The Prolog program will answer ‘Yes’ or ‘No’.

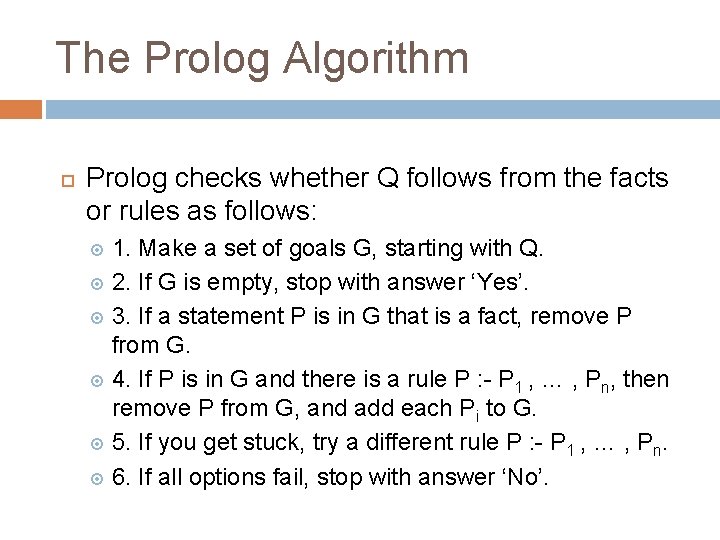

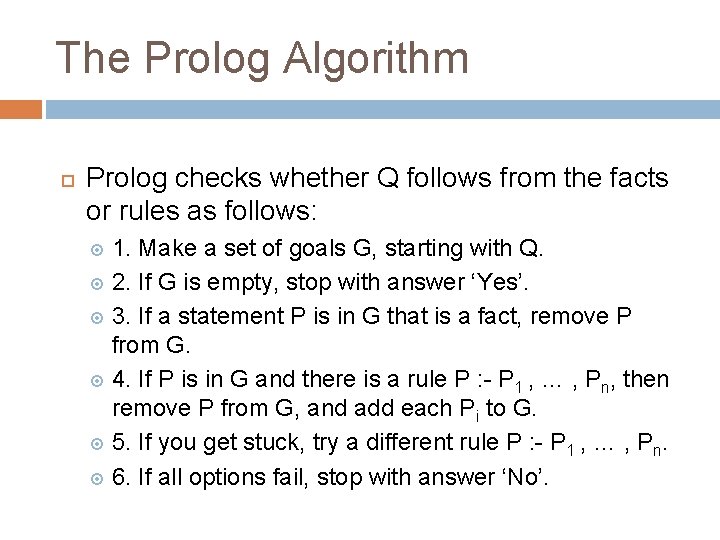

The Prolog Algorithm Prolog checks whether Q follows from the facts or rules as follows: 1. Make a set of goals G, starting with Q. 2. If G is empty, stop with answer ‘Yes’. 3. If a statement P is in G that is a fact, remove P from G. 4. If P is in G and there is a rule P : - P 1 , … , Pn, then remove P from G, and add each Pi to G. 5. If you get stuck, try a different rule P : - P 1 , … , Pn. 6. If all options fail, stop with answer ‘No’.

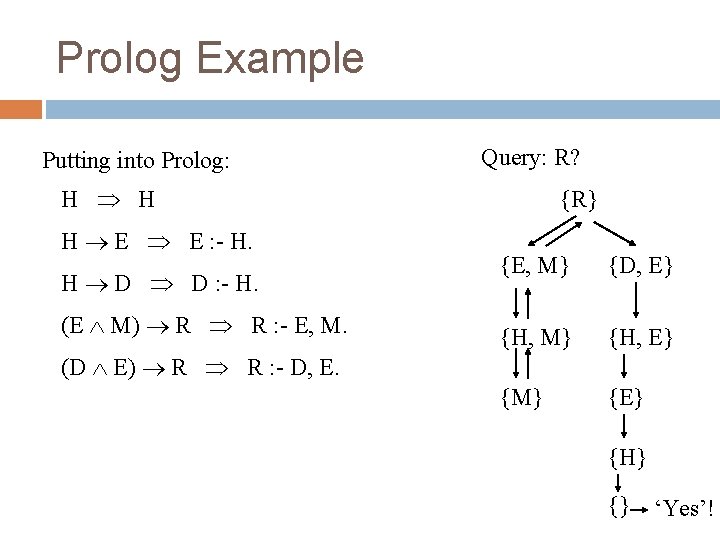

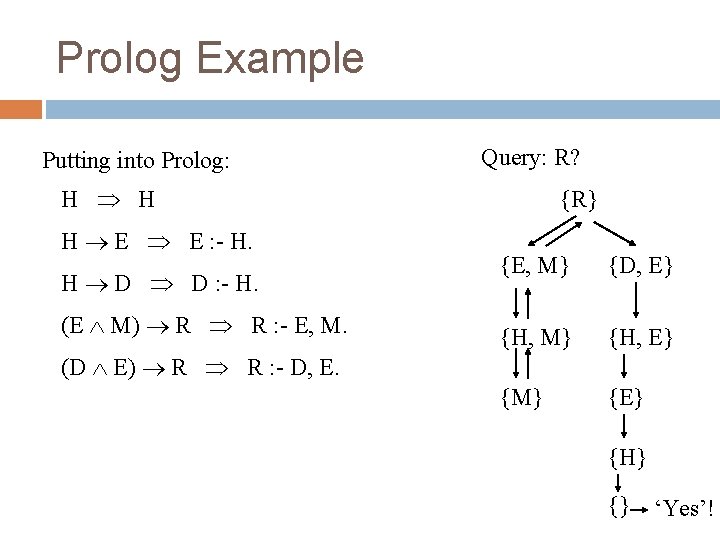

Prolog Example Putting into Prolog: Query: R? H H H E E : - H. H D D : - H. (E M) R R : - E, M. {R} {E, M} {D, E} {H, M} {H, E} {M} {E} (D E) R R : - D, E. {H} {} ‘Yes’!

Power and Limitations of Prolog can only handle arguments whose premises and conclusion are of the type as discussed. So, many logic arguments cannot be verified. However, because of the restriction, Prolog becomes more efficient than general-purpose provers.

Prolog and Production Rules Prolog’s rules are reminiscent of production systems (bunch of if … then … statements). However, one big difference is: production systems are forward chaining systems (start with given facts, apply rules to proceed and get new stuff) Prolog is a backward chaining system (start with the goal, and try and satisfy it, working backwards)