Rosen 1 3 Propositional Functions Propositional functions or

- Slides: 30

Rosen 1. 3

Propositional Functions • Propositional functions (or predicates) are propositions that contain variables. • Ex: Let P(x) denote x > 3 • P(x) has no truth value until the variable x is bound by either – assigning it a value or by – quantifying it.

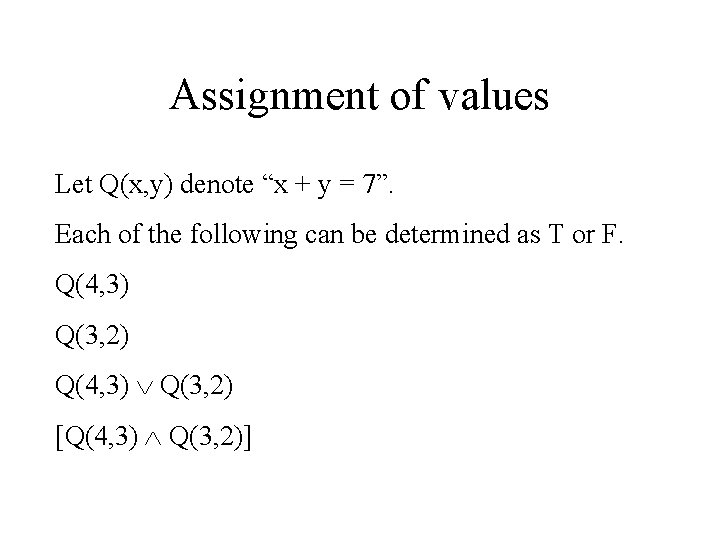

Assignment of values Let Q(x, y) denote “x + y = 7”. Each of the following can be determined as T or F. Q(4, 3) Q(3, 2) Q(4, 3) Q(3, 2) [Q(4, 3) Q(3, 2)]

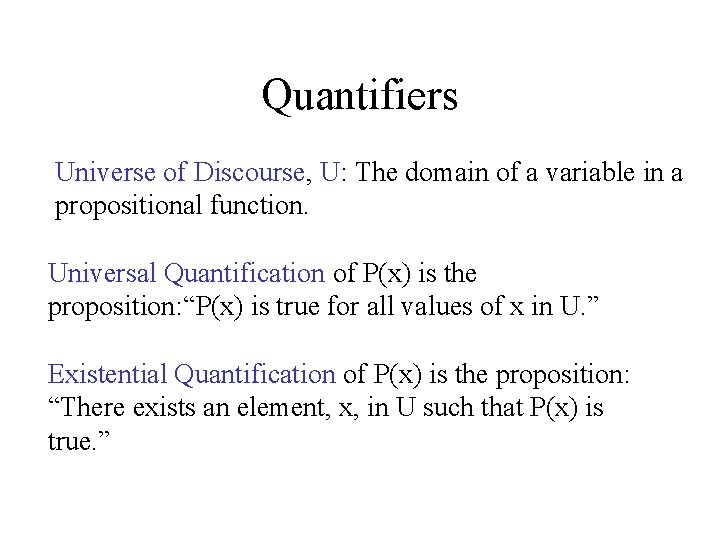

Quantifiers Universe of Discourse, U: The domain of a variable in a propositional function. Universal Quantification of P(x) is the proposition: “P(x) is true for all values of x in U. ” Existential Quantification of P(x) is the proposition: “There exists an element, x, in U such that P(x) is true. ”

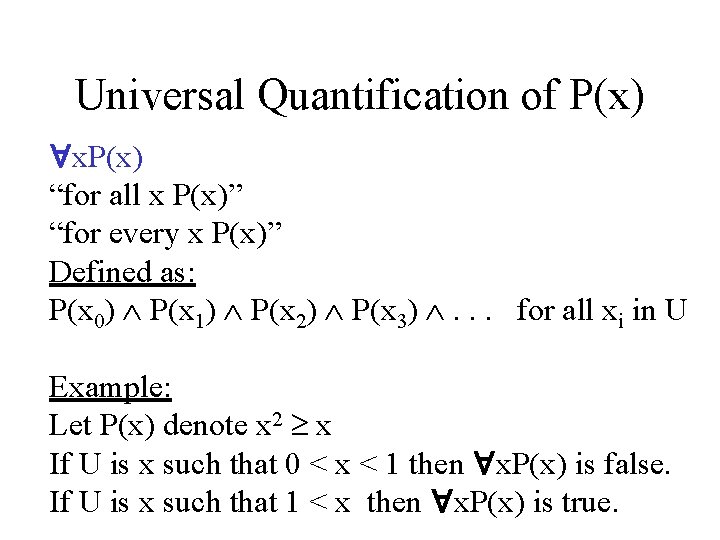

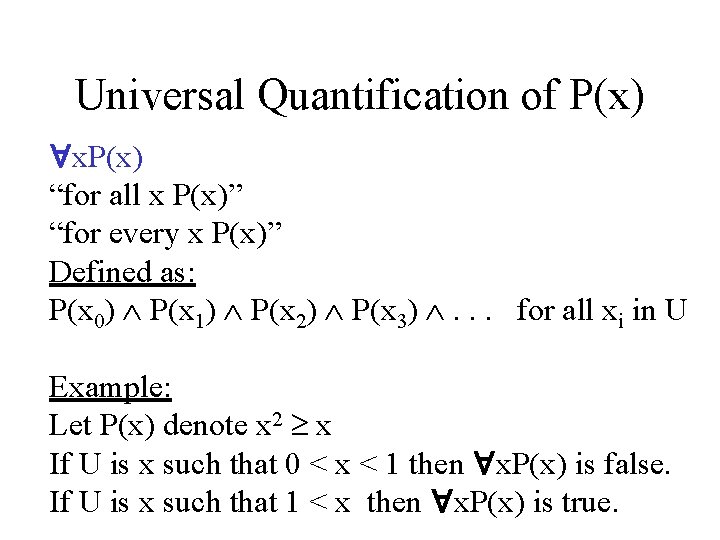

Universal Quantification of P(x) x. P(x) “for all x P(x)” “for every x P(x)” Defined as: P(x 0) P(x 1) P(x 2) P(x 3) . . . for all xi in U Example: Let P(x) denote x 2 x If U is x such that 0 < x < 1 then x. P(x) is false. If U is x such that 1 < x then x. P(x) is true.

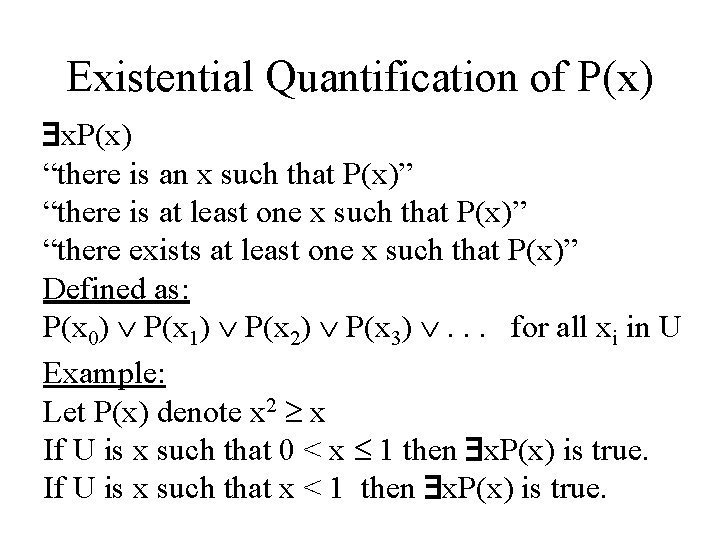

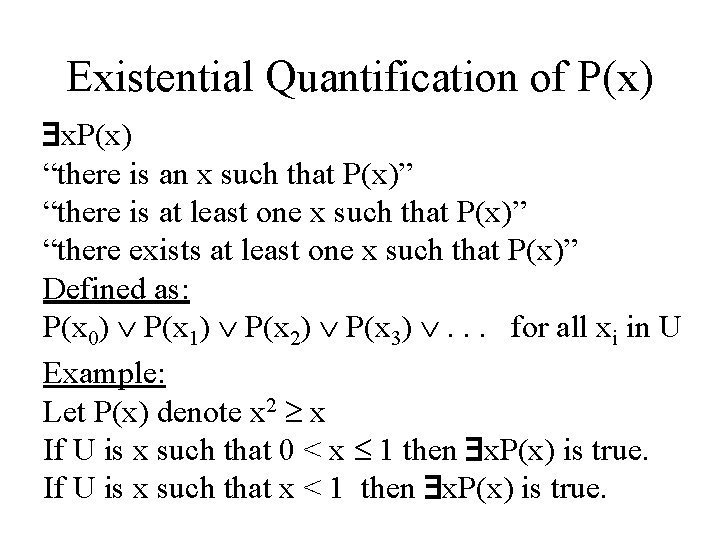

Existential Quantification of P(x) x. P(x) “there is an x such that P(x)” “there is at least one x such that P(x)” “there exists at least one x such that P(x)” Defined as: P(x 0) P(x 1) P(x 2) P(x 3) . . . for all xi in U Example: Let P(x) denote x 2 x If U is x such that 0 < x 1 then x. P(x) is true. If U is x such that x < 1 then x. P(x) is true.

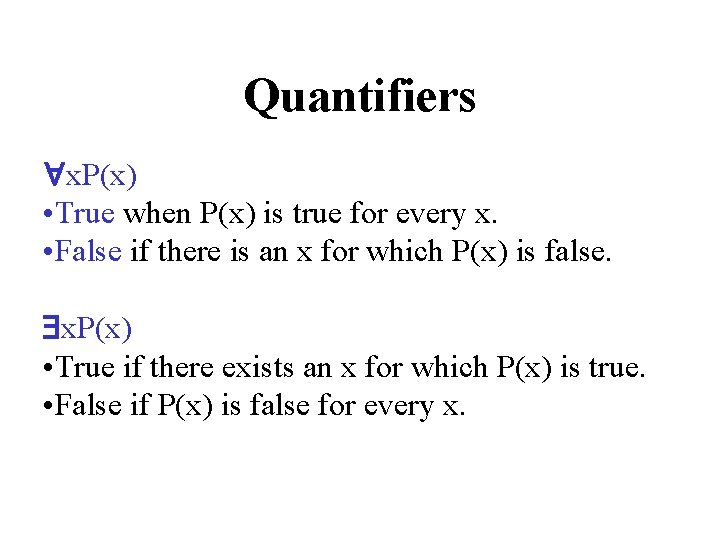

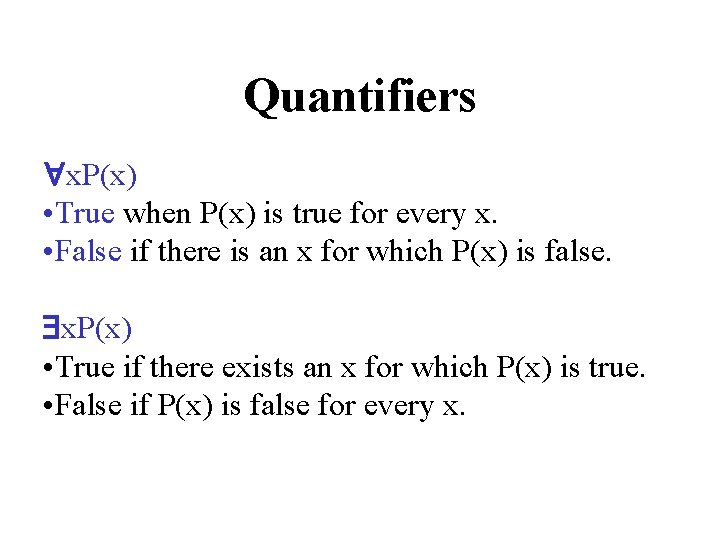

Quantifiers x. P(x) • True when P(x) is true for every x. • False if there is an x for which P(x) is false. x. P(x) • True if there exists an x for which P(x) is true. • False if P(x) is false for every x.

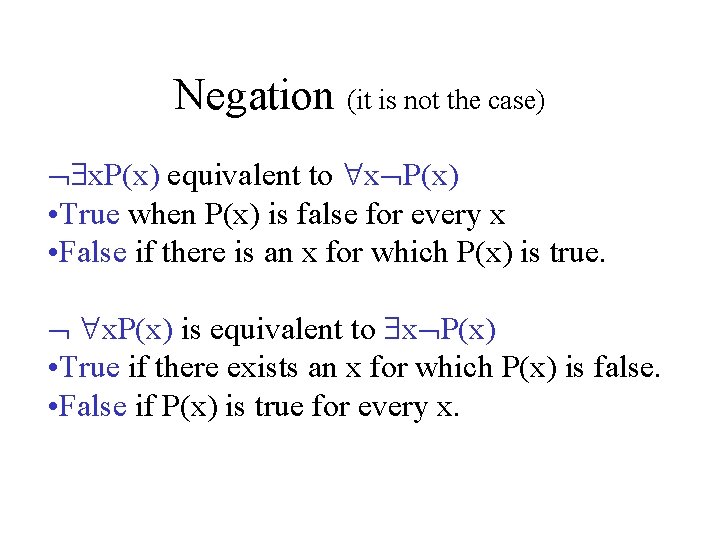

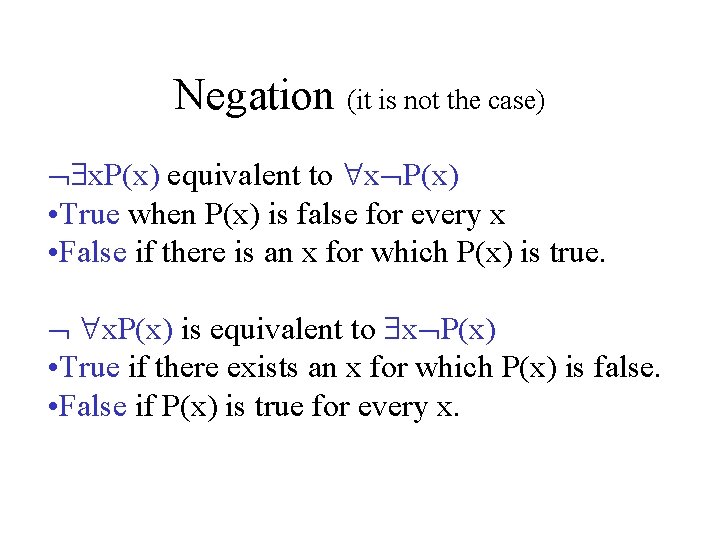

Negation (it is not the case) x. P(x) equivalent to x P(x) • True when P(x) is false for every x • False if there is an x for which P(x) is true. x. P(x) is equivalent to x P(x) • True if there exists an x for which P(x) is false. • False if P(x) is true for every x.

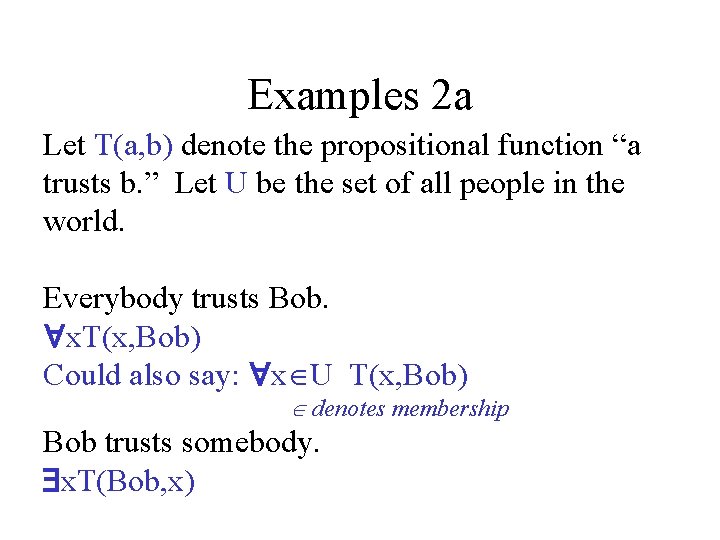

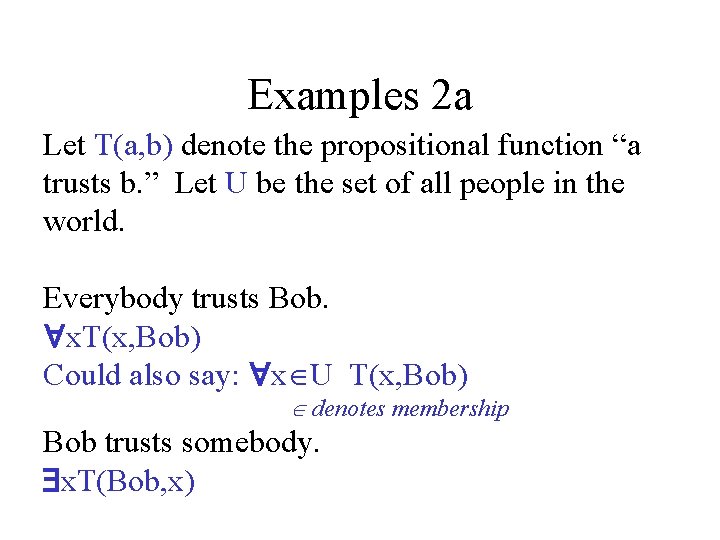

Examples 2 a Let T(a, b) denote the propositional function “a trusts b. ” Let U be the set of all people in the world. Everybody trusts Bob. x. T(x, Bob) Could also say: x U T(x, Bob) denotes membership Bob trusts somebody. x. T(Bob, x)

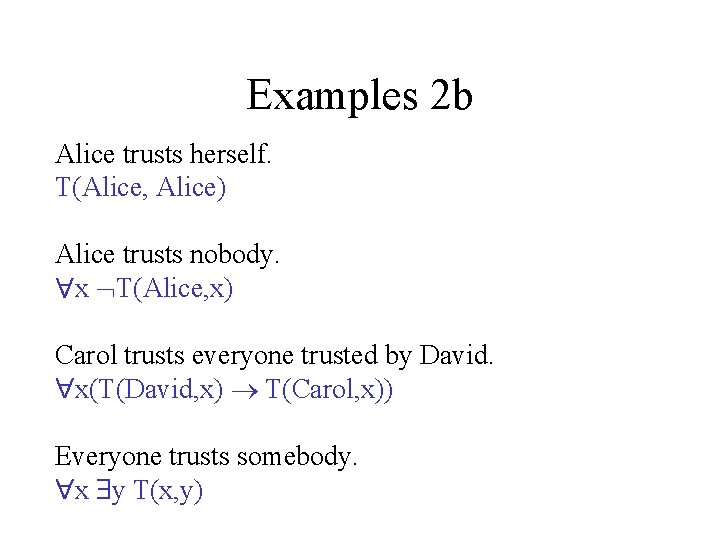

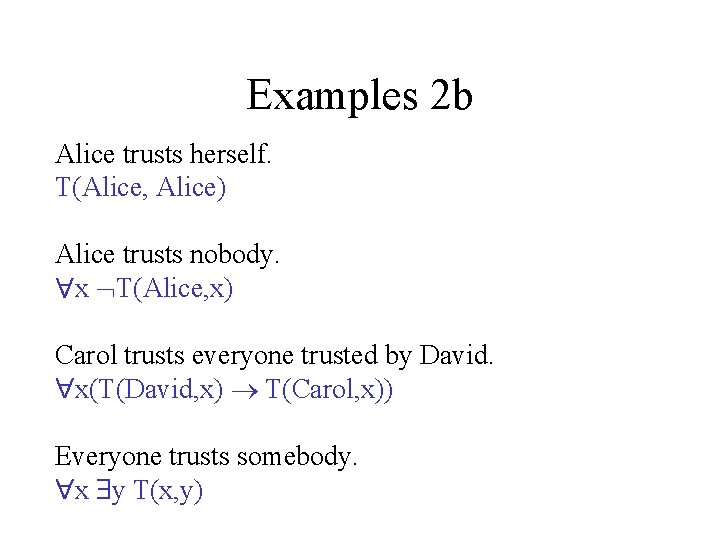

Examples 2 b Alice trusts herself. T(Alice, Alice) Alice trusts nobody. x T(Alice, x) Carol trusts everyone trusted by David. x(T(David, x) T(Carol, x)) Everyone trusts somebody. x y T(x, y)

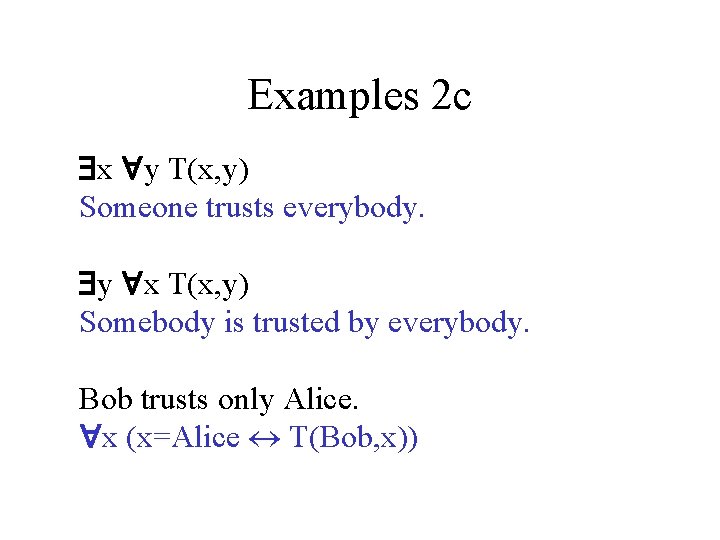

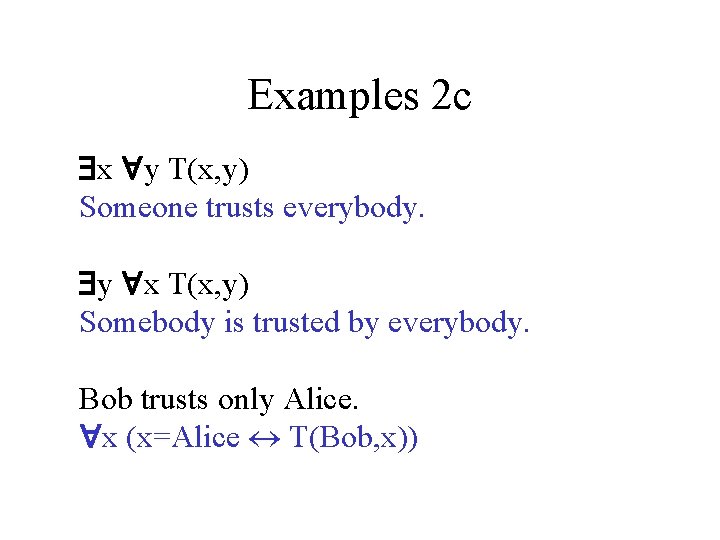

Examples 2 c x y T(x, y) Someone trusts everybody. y x T(x, y) Somebody is trusted by everybody. Bob trusts only Alice. x (x=Alice T(Bob, x))

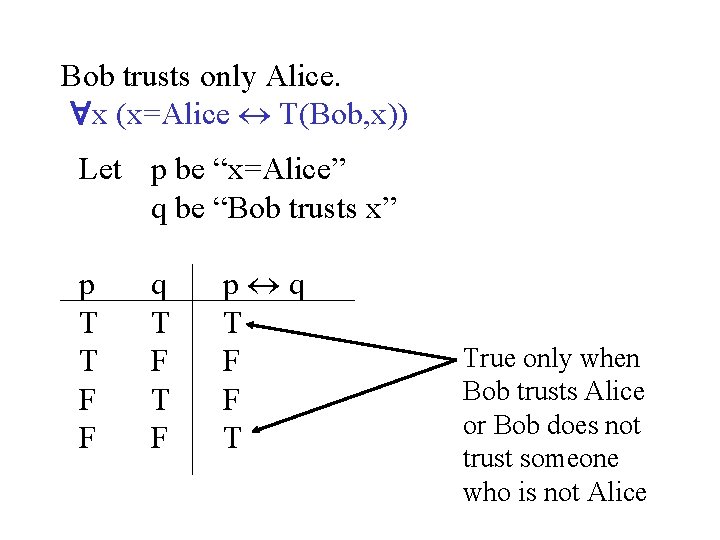

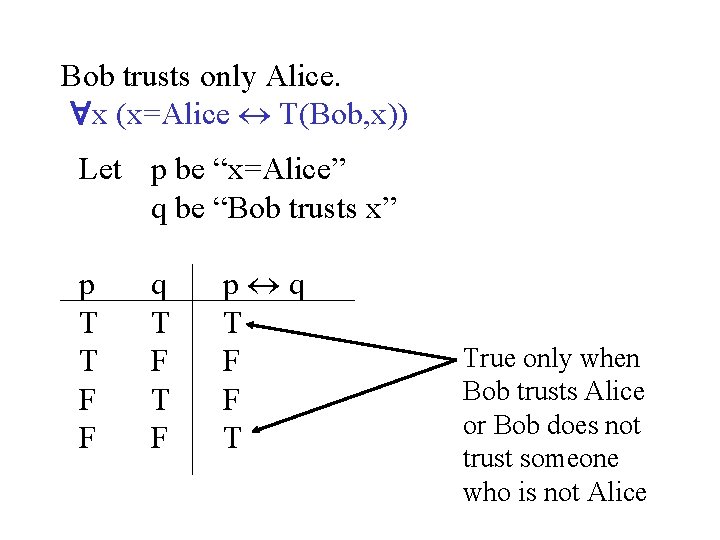

Bob trusts only Alice. x (x=Alice T(Bob, x)) Let p be “x=Alice” q be “Bob trusts x” p T T F F q T F p q T F F T True only when Bob trusts Alice or Bob does not trust someone who is not Alice

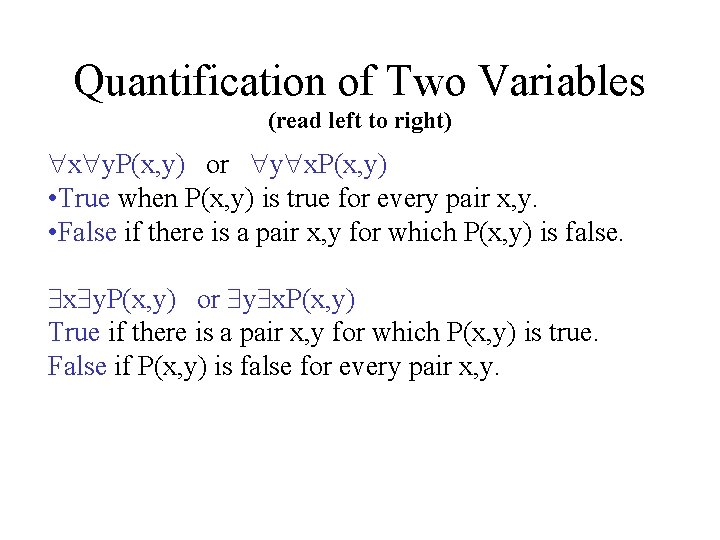

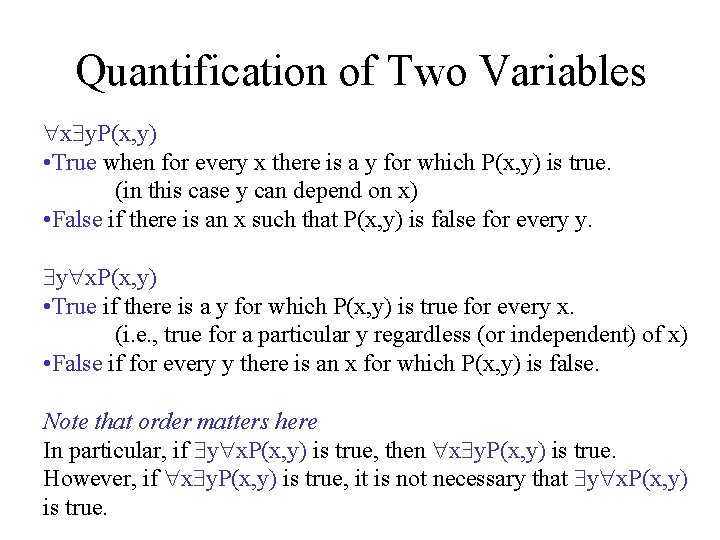

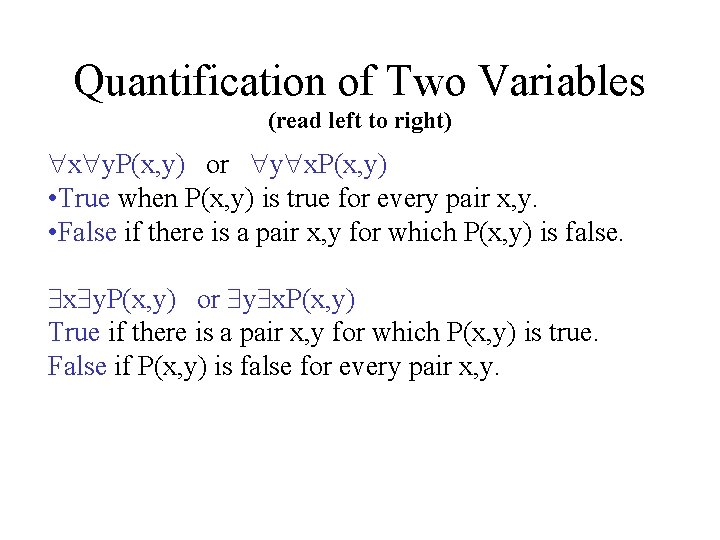

Quantification of Two Variables (read left to right) x y. P(x, y) or y x. P(x, y) • True when P(x, y) is true for every pair x, y. • False if there is a pair x, y for which P(x, y) is false. x y. P(x, y) or y x. P(x, y) True if there is a pair x, y for which P(x, y) is true. False if P(x, y) is false for every pair x, y.

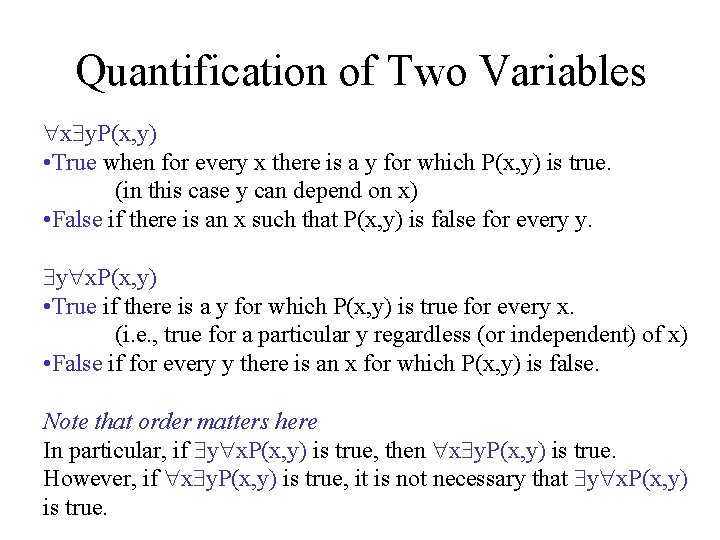

Quantification of Two Variables x y. P(x, y) • True when for every x there is a y for which P(x, y) is true. (in this case y can depend on x) • False if there is an x such that P(x, y) is false for every y. y x. P(x, y) • True if there is a y for which P(x, y) is true for every x. (i. e. , true for a particular y regardless (or independent) of x) • False if for every y there is an x for which P(x, y) is false. Note that order matters here In particular, if y x. P(x, y) is true, then x y. P(x, y) is true. However, if x y. P(x, y) is true, it is not necessary that y x. P(x, y) is true.

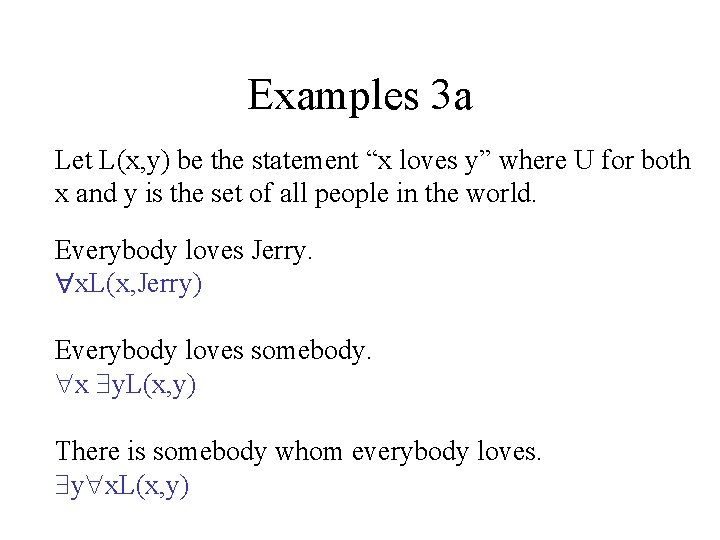

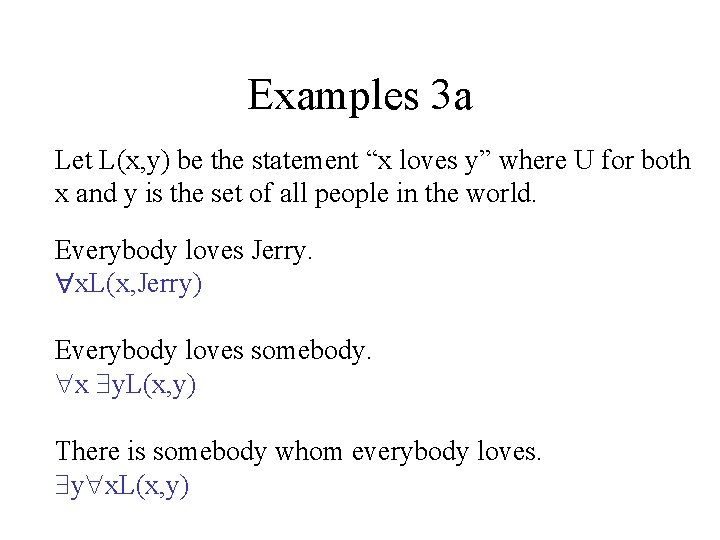

Examples 3 a Let L(x, y) be the statement “x loves y” where U for both x and y is the set of all people in the world. Everybody loves Jerry. x. L(x, Jerry) Everybody loves somebody. x y. L(x, y) There is somebody whom everybody loves. y x. L(x, y)

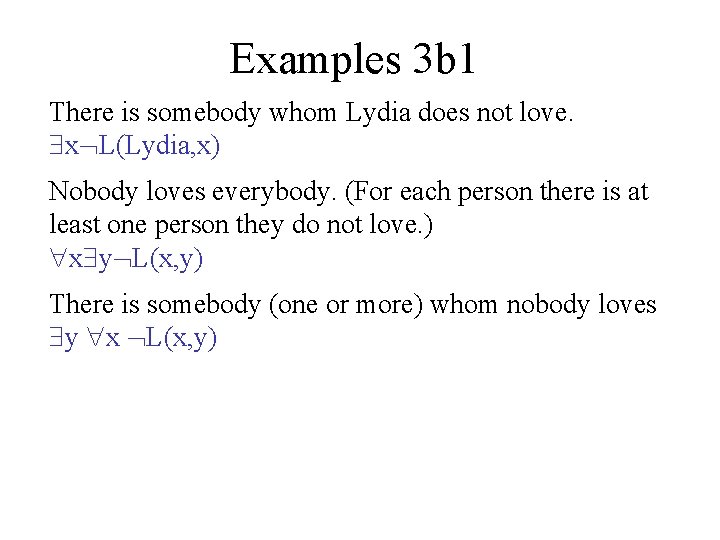

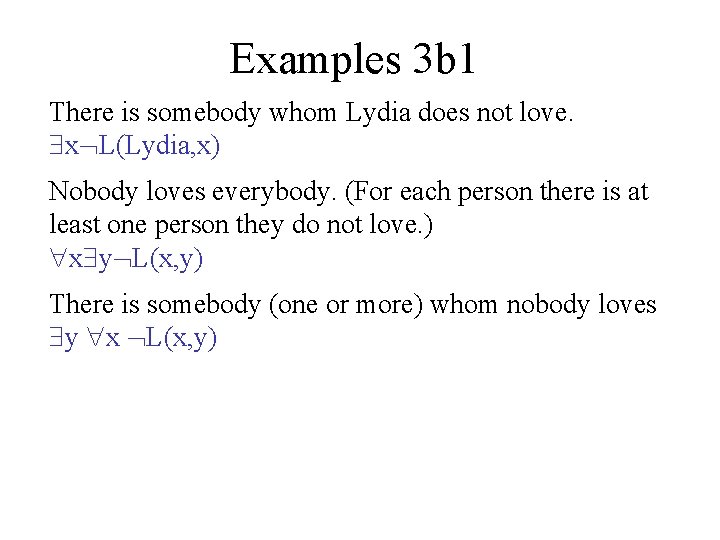

Examples 3 b 1 There is somebody whom Lydia does not love. x L(Lydia, x) Nobody loves everybody. (For each person there is at least one person they do not love. ) x y L(x, y) There is somebody (one or more) whom nobody loves y x L(x, y)

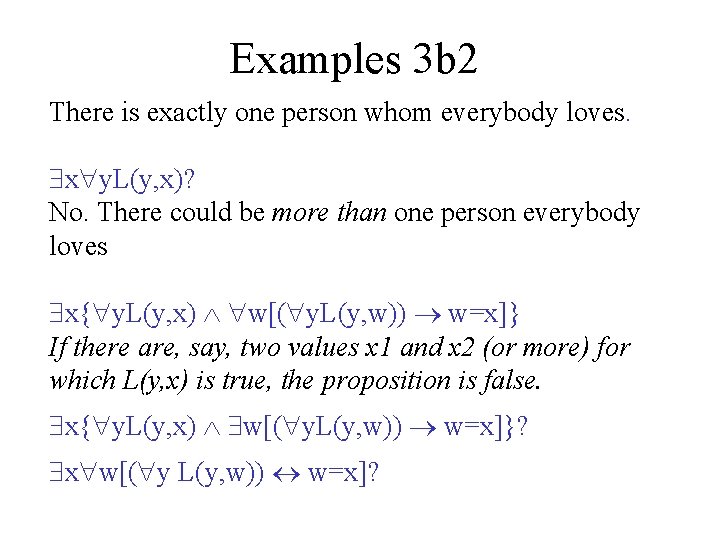

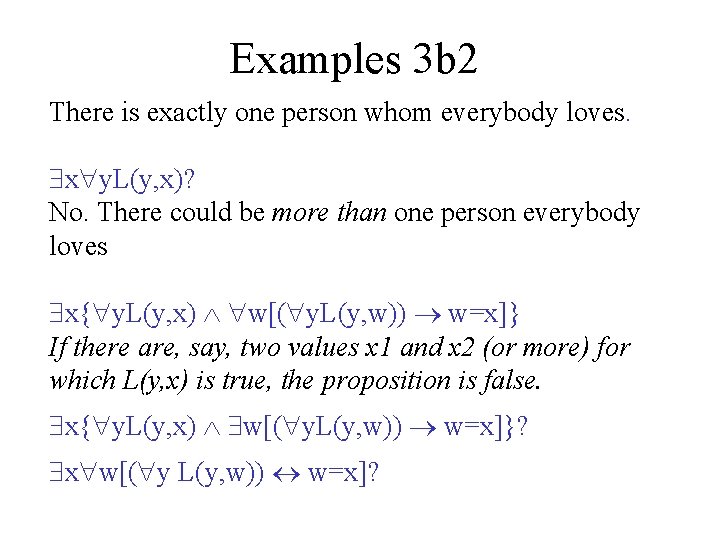

Examples 3 b 2 There is exactly one person whom everybody loves. x y. L(y, x)? No. There could be more than one person everybody loves x{ y. L(y, x) w[( y. L(y, w)) w=x]} If there are, say, two values x 1 and x 2 (or more) for which L(y, x) is true, the proposition is false. x{ y. L(y, x) w[( y. L(y, w)) w=x]}? x w[( y L(y, w)) w=x]?

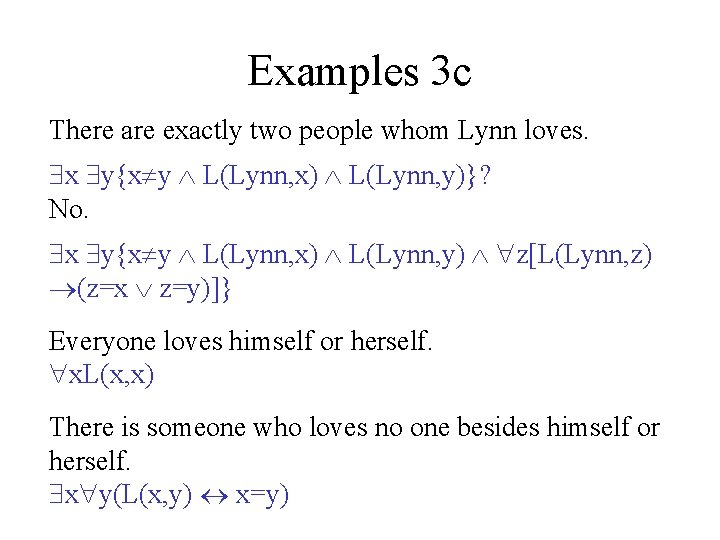

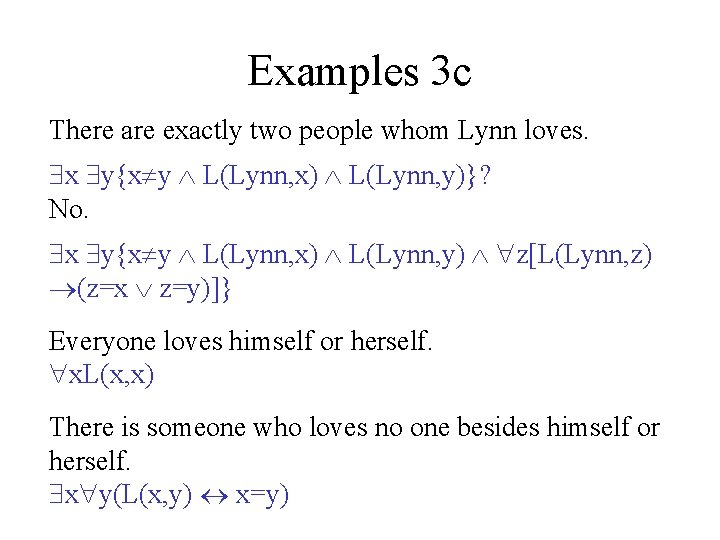

Examples 3 c There are exactly two people whom Lynn loves. x y{x y L(Lynn, x) L(Lynn, y)}? No. x y{x y L(Lynn, x) L(Lynn, y) z[L(Lynn, z) (z=x z=y)]} Everyone loves himself or herself. x. L(x, x) There is someone who loves no one besides himself or herself. x y(L(x, y) x=y)

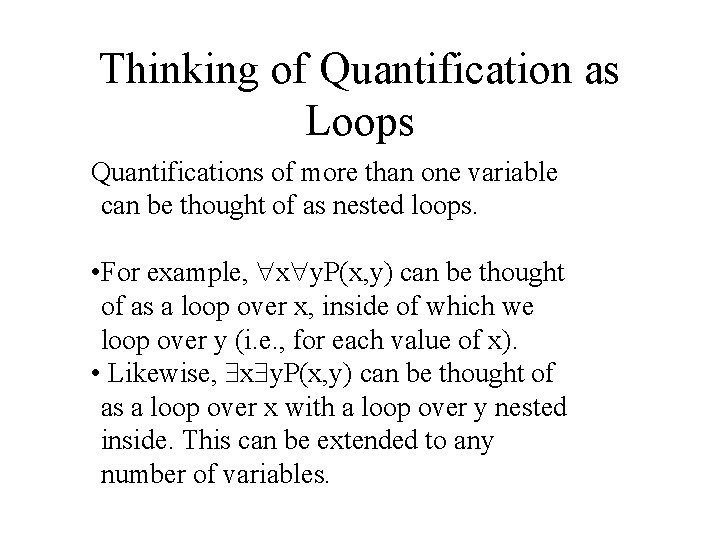

Thinking of Quantification as Loops Quantifications of more than one variable can be thought of as nested loops. • For example, x y. P(x, y) can be thought of as a loop over x, inside of which we loop over y (i. e. , for each value of x). • Likewise, x y. P(x, y) can be thought of as a loop over x with a loop over y nested inside. This can be extended to any number of variables.

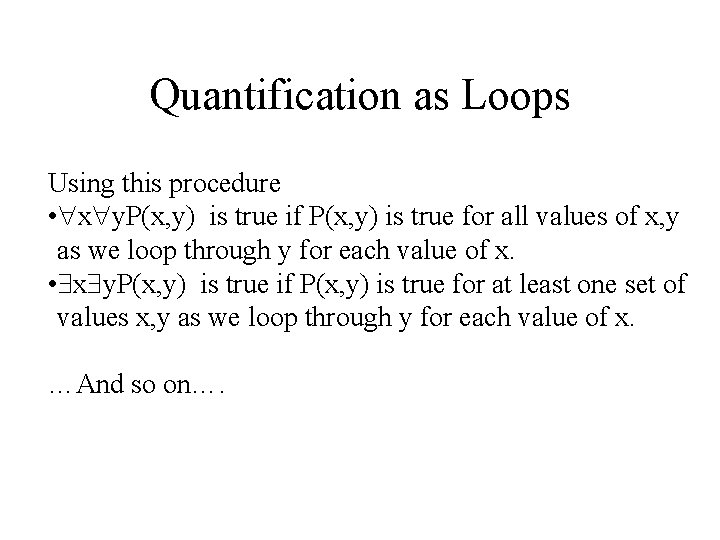

Quantification as Loops Using this procedure • x y. P(x, y) is true if P(x, y) is true for all values of x, y as we loop through y for each value of x. • x y. P(x, y) is true if P(x, y) is true for at least one set of values x, y as we loop through y for each value of x. …And so on….

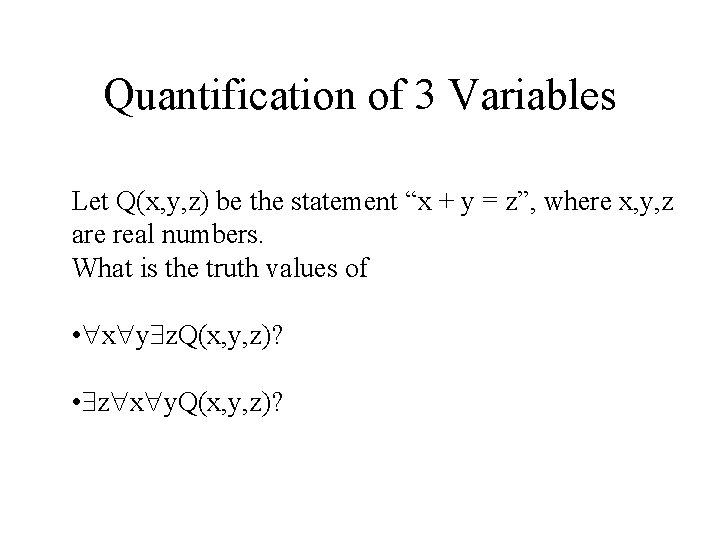

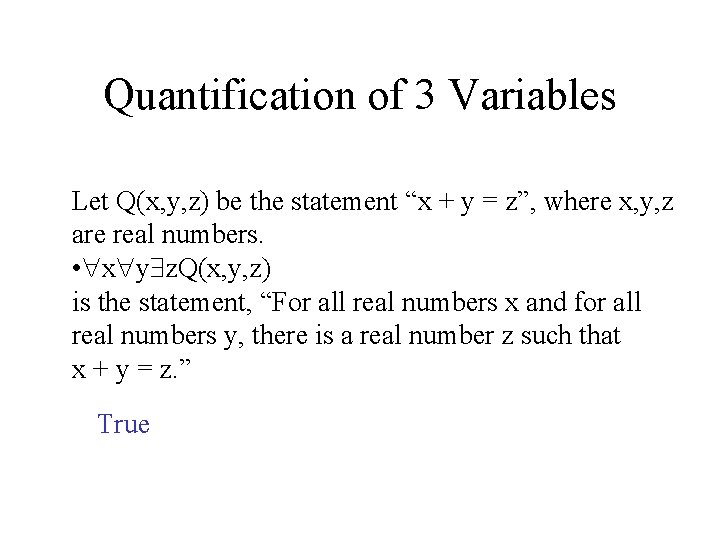

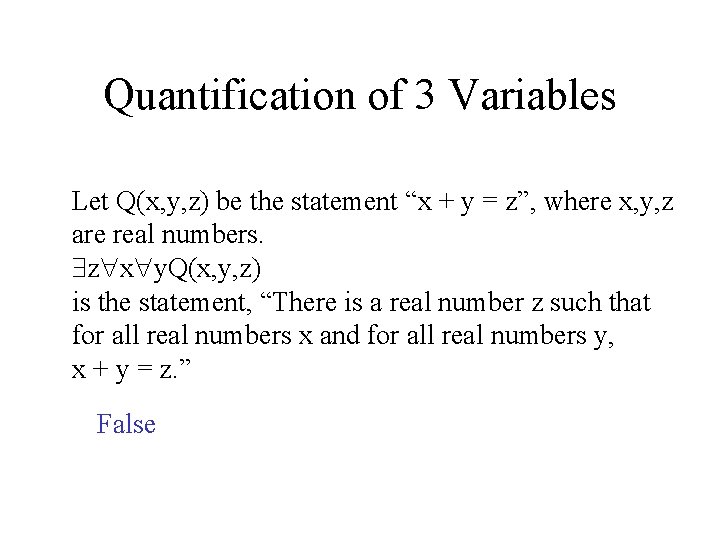

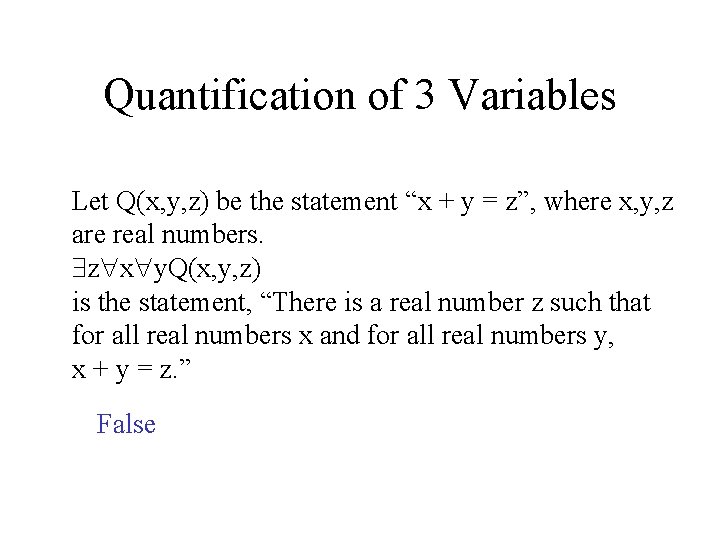

Quantification of 3 Variables Let Q(x, y, z) be the statement “x + y = z”, where x, y, z are real numbers. What is the truth values of • x y z. Q(x, y, z)? • z x y. Q(x, y, z)?

Quantification of 3 Variables Let Q(x, y, z) be the statement “x + y = z”, where x, y, z are real numbers. • x y z. Q(x, y, z) is the statement, “For all real numbers x and for all real numbers y, there is a real number z such that x + y = z. ” True

Quantification of 3 Variables Let Q(x, y, z) be the statement “x + y = z”, where x, y, z are real numbers. z x y. Q(x, y, z) is the statement, “There is a real number z such that for all real numbers x and for all real numbers y, x + y = z. ” False

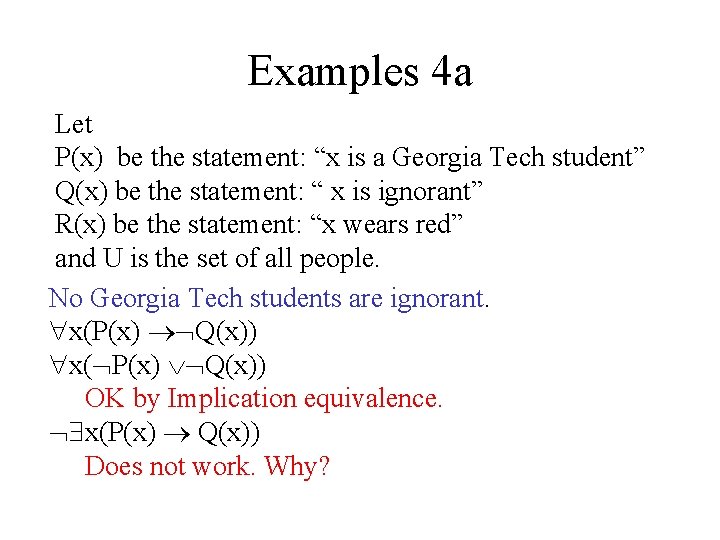

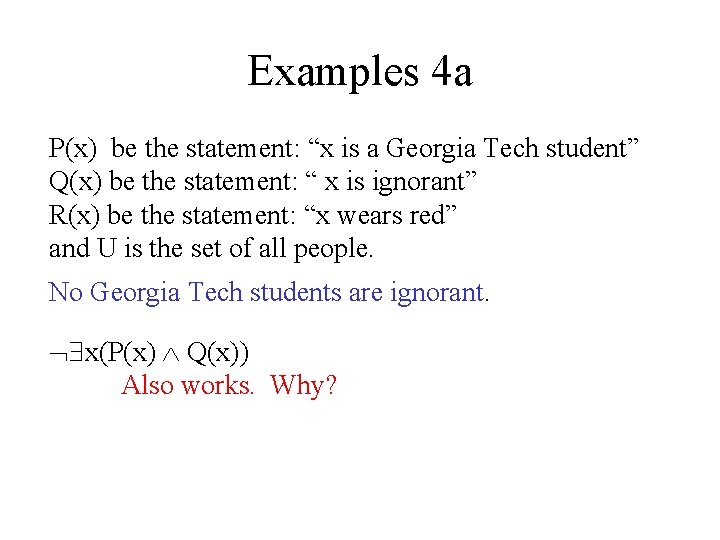

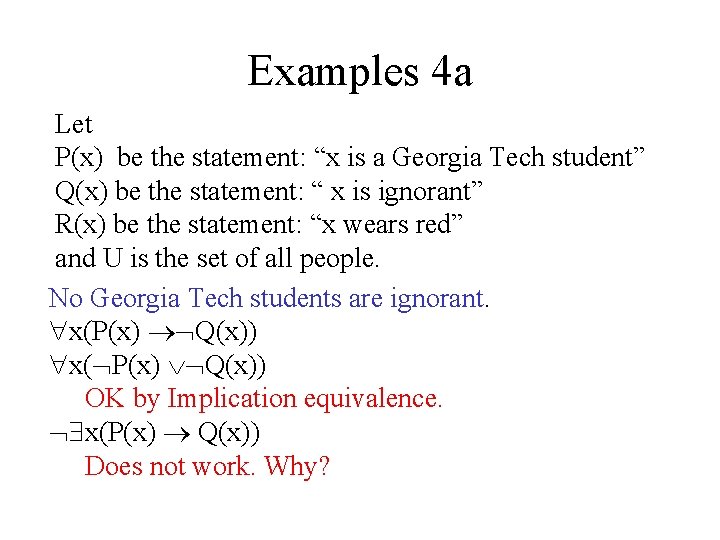

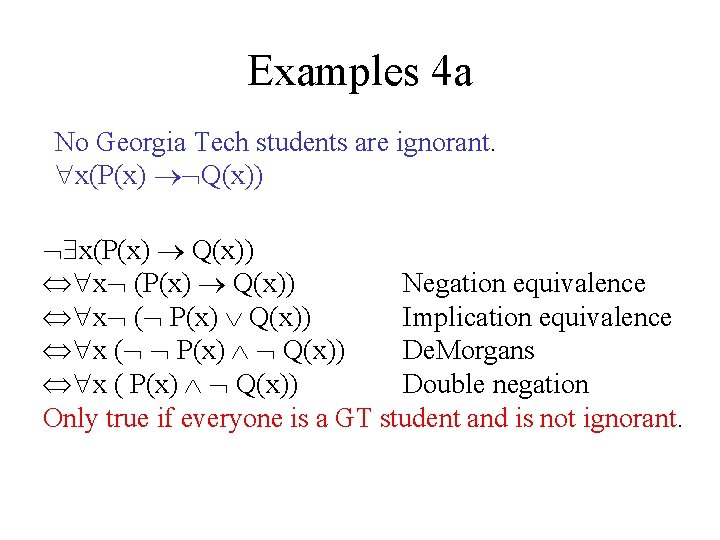

Examples 4 a Let P(x) be the statement: “x is a Georgia Tech student” Q(x) be the statement: “ x is ignorant” R(x) be the statement: “x wears red” and U is the set of all people. No Georgia Tech students are ignorant. x(P(x) Q(x)) x( P(x) Q(x)) OK by Implication equivalence. x(P(x) Q(x)) Does not work. Why?

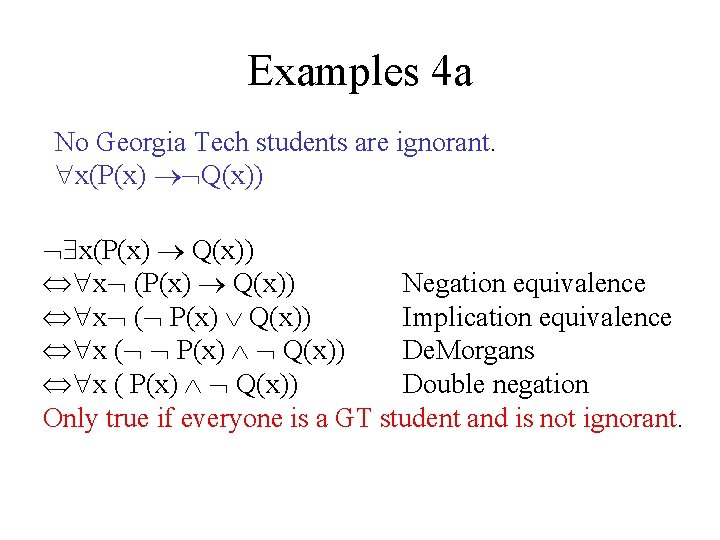

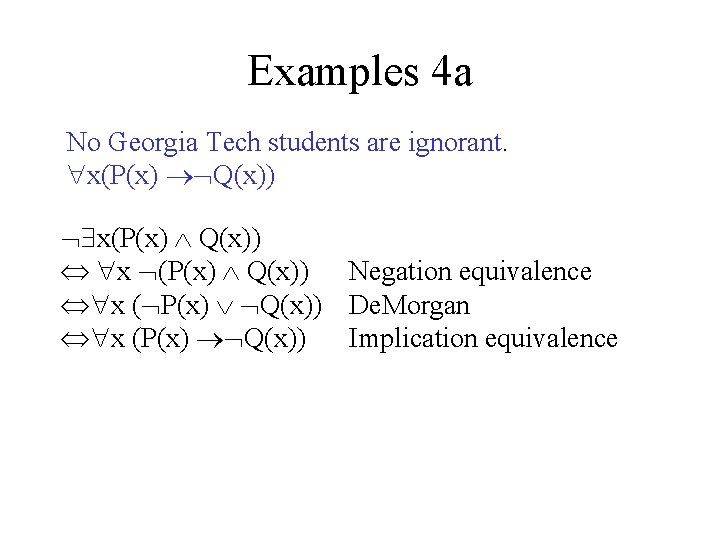

Examples 4 a No Georgia Tech students are ignorant. x(P(x) Q(x)) x (P(x) Q(x)) Negation equivalence x ( P(x) Q(x)) Implication equivalence x ( P(x) Q(x)) De. Morgans x ( P(x) Q(x)) Double negation Only true if everyone is a GT student and is not ignorant.

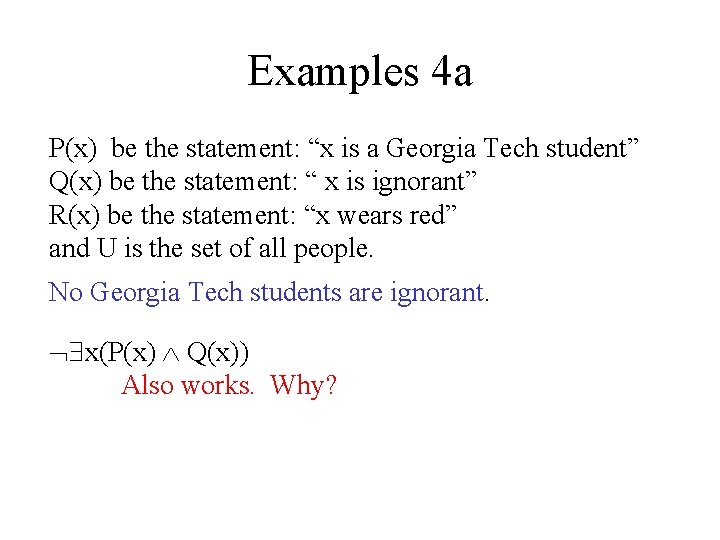

Examples 4 a P(x) be the statement: “x is a Georgia Tech student” Q(x) be the statement: “ x is ignorant” R(x) be the statement: “x wears red” and U is the set of all people. No Georgia Tech students are ignorant. x(P(x) Q(x)) Also works. Why?

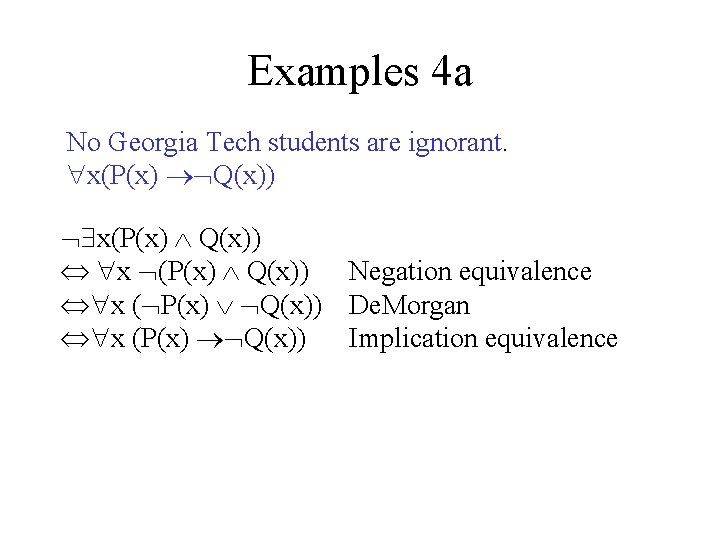

Examples 4 a No Georgia Tech students are ignorant. x(P(x) Q(x)) x (P(x) Q(x)) Negation equivalence x ( P(x) Q(x)) De. Morgan x (P(x) Q(x)) Implication equivalence

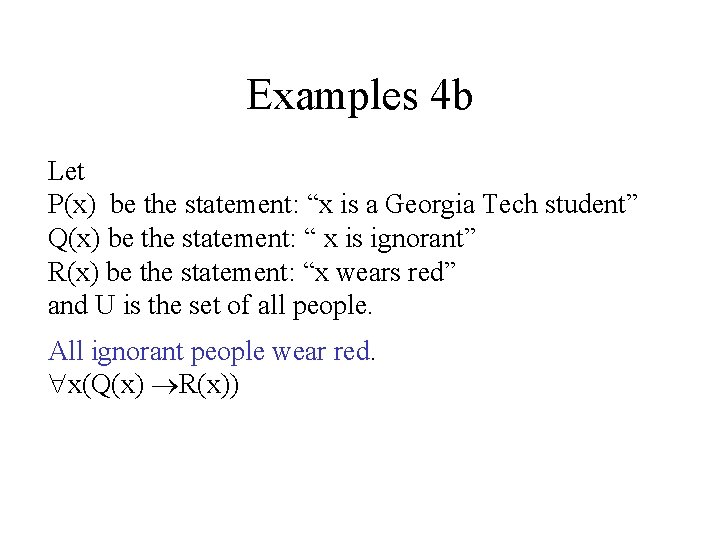

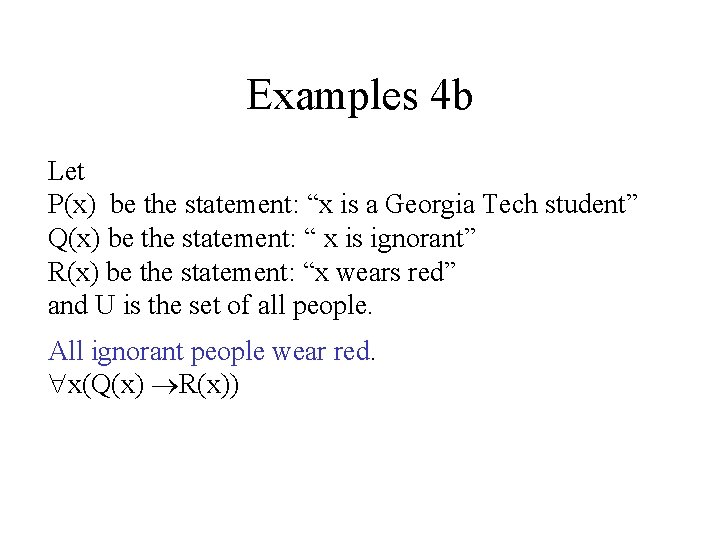

Examples 4 b Let P(x) be the statement: “x is a Georgia Tech student” Q(x) be the statement: “ x is ignorant” R(x) be the statement: “x wears red” and U is the set of all people. All ignorant people wear red. x(Q(x) R(x))

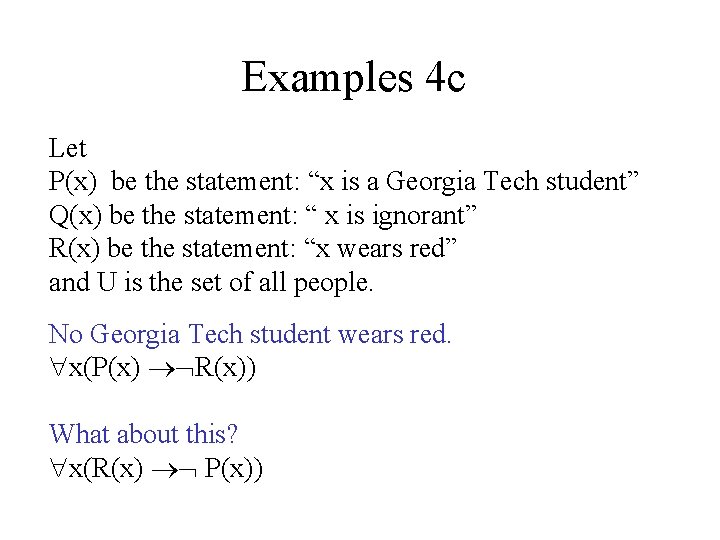

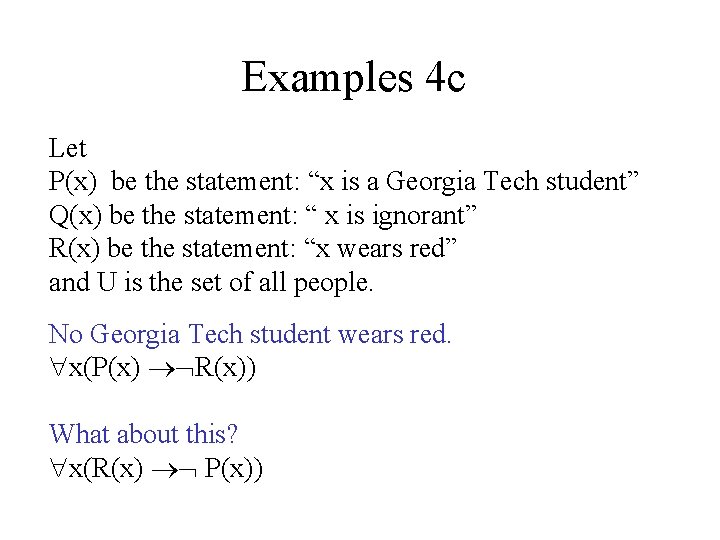

Examples 4 c Let P(x) be the statement: “x is a Georgia Tech student” Q(x) be the statement: “ x is ignorant” R(x) be the statement: “x wears red” and U is the set of all people. No Georgia Tech student wears red. x(P(x) R(x)) What about this? x(R(x) P(x))

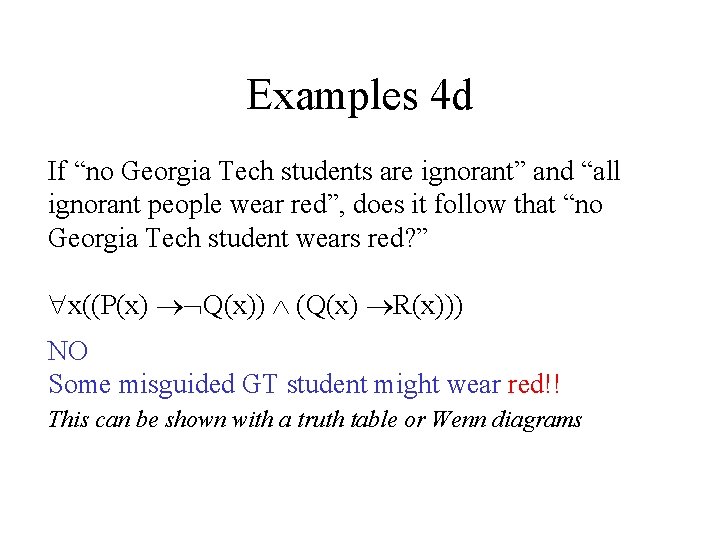

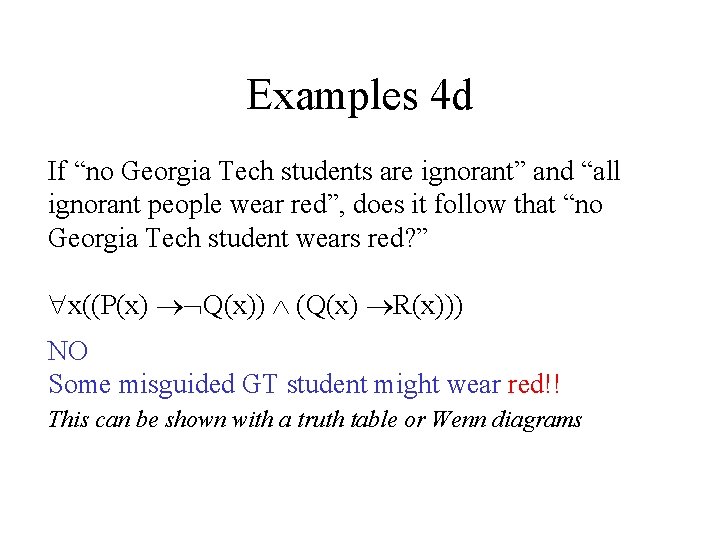

Examples 4 d If “no Georgia Tech students are ignorant” and “all ignorant people wear red”, does it follow that “no Georgia Tech student wears red? ” x((P(x) Q(x)) (Q(x) R(x))) NO Some misguided GT student might wear red!! This can be shown with a truth table or Wenn diagrams